20 Most Popular Theories of Motivation in Psychology

The many approaches to defining what drives human behavior are best understood when considering the very purpose of creating them, be it increased performance, goal pursuit, resilience, or relapse prevention, to name a few.

There is nothing more practical than a good theory.

There is no single motivation theory that explains all aspects of human motivation, but these theoretical explanations do often serve as the basis for the development of approaches and techniques to increase motivation in distinct areas of human endeavor.

This article briefly summarizes existing theories of motivation and their potential real-world applications.

Before you continue, we thought you might like to download our three Goal Achievement Exercises for free . These detailed, science-based exercises will help you or your clients create actionable goals and master techniques to create lasting behavior change.

This Article Contains:

What is motivation psychology, theories of motivation, content theories of motivation, process theories of motivation, cognitive theories of motivation, motivational theories in business, motivational theories in sports psychology, textbooks on motivation, a take-home message.

Motivation psychologists usually attempt to show how motivation varies within a person at different times or among different people at the same time. The purpose of the psychology of motivation is to explain how and why that happens.

Broad views of how to understand motivation were created by psychologists based on various types of analyses. Cognitive analyses, behavioral anticipation, and affective devices are often used to account for motivation in terms of expecting an end-state or goal.

Motivation psychology is a study of how biological, psychological, and environmental variables contribute to motivation. That is, what do the body and brain contribute to motivation; what mental processes contribute; and finally, how material incentives, goals, and their mental representations motivate individuals.

Psychologists research motivation through the use of two different methods. Experimental research is usually conducted in a laboratory and involves manipulating a motivational variable to determine its effects on behavior.

Correlational research involves measuring an existing motivational variable to determine how the measured values are associated with behavioral indicators of motivation.

Whether you think you can, or think you can’t, you’re right.

Henry Ford, 1863–1947

To be motivated means to be moved into action. We are induced into action or thought by either the push of a motive or the pull of an incentive or goal toward some end-state. Here a motive is understood as an internal disposition that pushes an individual toward a desired end-state where the motive is satisfied, and a goal is defined as the cognitive representation of the desired outcome that an individual attempts to achieve.

While a goal guides a behavior that results in achieving it, an incentive is an anticipated feature of the environment that pulls an individual toward or away from a goal. Incentives usually enhance motivation for goal achievement. Emotions act like motives as well. They motivate an individual in a coordinated fashion along multiple channels of affect, physiology, and behavior to adapt to significant environmental changes.

See our discussion of the motivation cycle and process in the blog post entitled What is Motivation .

In short, content theories explain what motivation is, and process theories describe how motivation occurs.

There are also a large number of cognitive theories that relate to motivation and explain how our way of thinking and perceiving ourselves and the world around us can influence our motives.

From self-concept, dissonance and mindset to values, orientation and perceived control, these theories explain how our preference toward certain mental constructs can increase or impair our ability to take goal-directed action.

Theories of motivation are also grouped by the field of human endeavor they apply to. Several theories relate to motivating employees where incentives and needs take a central stage as well as theories used in sports and performance psychology where affect is considered a more prominent driver of human behavior. Some of these theories are also applied to education and learning.

Read our insightful post on motivation in education .

The self-concordance model of goal setting differentiates between four types of motivation (Sheldon & Elliot, 1999). These are:

External motivation

Goals are heavily guided by external circumstances and would not take place without some kind of reward or to prevent a negative outcome.

For example, an individual who clocks extra hours in their day job purely to receive a bigger paycheck.

Introjected motivation

Goals are characterized by self-image or ego-based motivation, reflecting the need to keep a certain self-image alive.

For example, our worker in the example above staying longer in the office so that they are perceived as a ‘hard worker’ by their manager and co-workers.

Identified motivation

The actions needed to accomplish the goal are perceived as personally important and meaningful, and personal values are the main drivers of goal pursuit.

For example, the worker putting in extra hours because their personal values align with the objective of the project they are working on.

Intrinsic motivation

When a behavior is guided by intrinsic motivation, the individual strives for this goal because of the enjoyment or stimulation that this goal provides. While there may be many good reasons for pursuing the goal, the primary reason is simply the interest in the experience of goal pursuit itself.

For example, the worker spends more time at their job because they enjoy and are energized by using their skills in creativity and problem-solving.

Goals guided by either identified or intrinsic motivation can be considered self-concordant. A self-concordant goal is personally valued, or the process towards the goal is enjoyable and aligns with interests. Self-concordant goals are associated with higher levels of wellbeing, enhanced positive mood, and higher levels of life satisfaction compared to non-self-concordant goals.

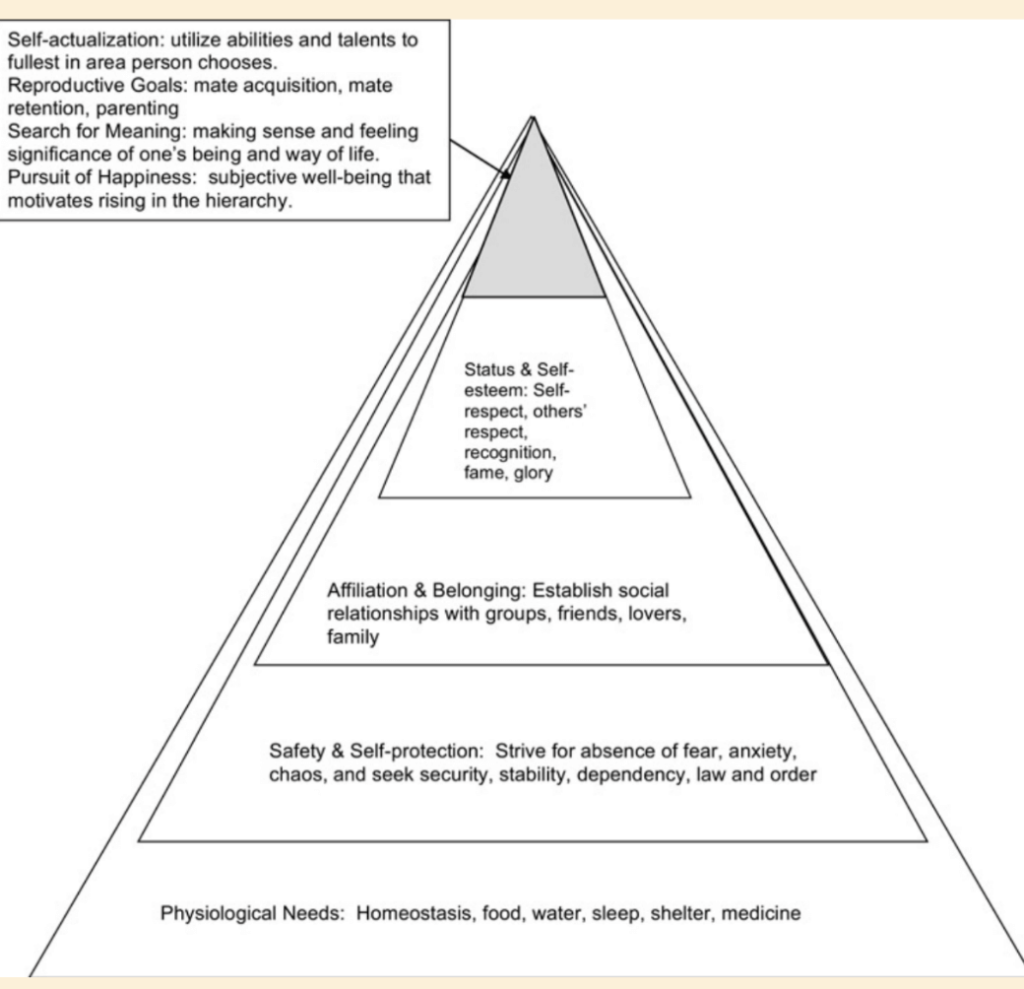

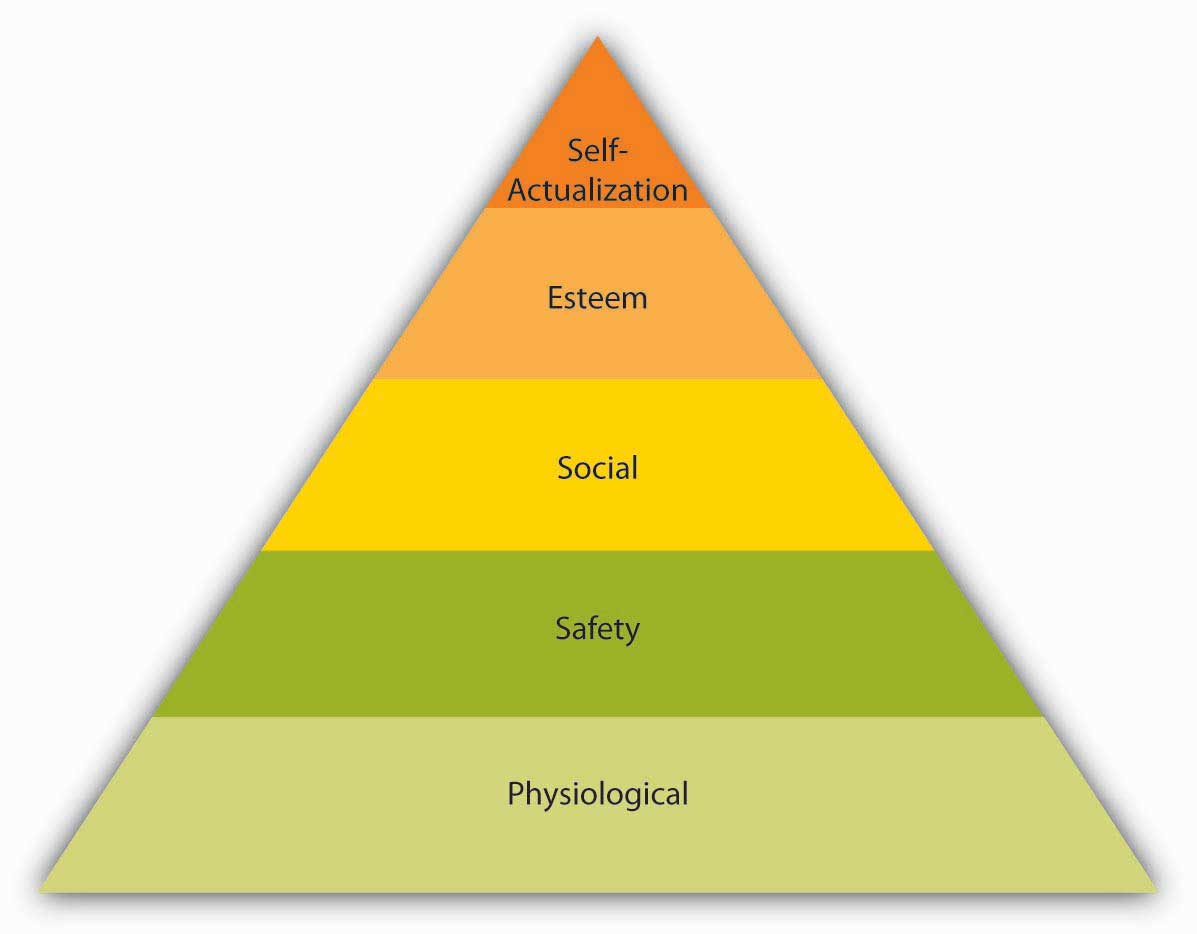

Maslow’s theory of the hierarchy of needs, Alderfer’s ERG theory, McClelland’s achievement motivation theory, and Herzberg’s two-factor theory focused on what motivates people and addressed specific factors like individual needs and goals.

Maslow’s theory of the hierarchy of needs

The most recognized content theory of motivation is that of Abraham Maslow, who explained motivation through the satisfaction of needs arranged in a hierarchical order. As satisfied needs do not motivate, it is the dissatisfaction that moves us in the direction of fulfillment.

Needs are conditions within the individual that are essential and necessary for the maintenance of life and the nurturance of growth and well-being. Hunger and thirst exemplify two biological needs that arise from the body’s requirement for food and water. These are required nutriments for the maintenance of life.

The body of man is a machine which winds its own spring.

J. O. De La Mettrie

Competence and belongingness exemplify two psychological needs that arise from the self’s requirement for environmental mastery and warm interpersonal relationships. These are required nutriments for growth and well-being.

Needs serve the organism, and they do so by:

- generating wants, desires, and strivings that motivate whatever behaviors are necessary for the maintenance of life and the promotion of growth and well-being, and

- generating a deep sense of need satisfaction from doing so.

Maslow’s legacy is the order of needs progressing in the ever-increasing complexity, starting with basic physiological and psychological needs and ending with the need for self-actualization. While basic needs are experienced as a sense of deficiency, the higher needs are experienced more in terms of the need for growth and fulfillment.

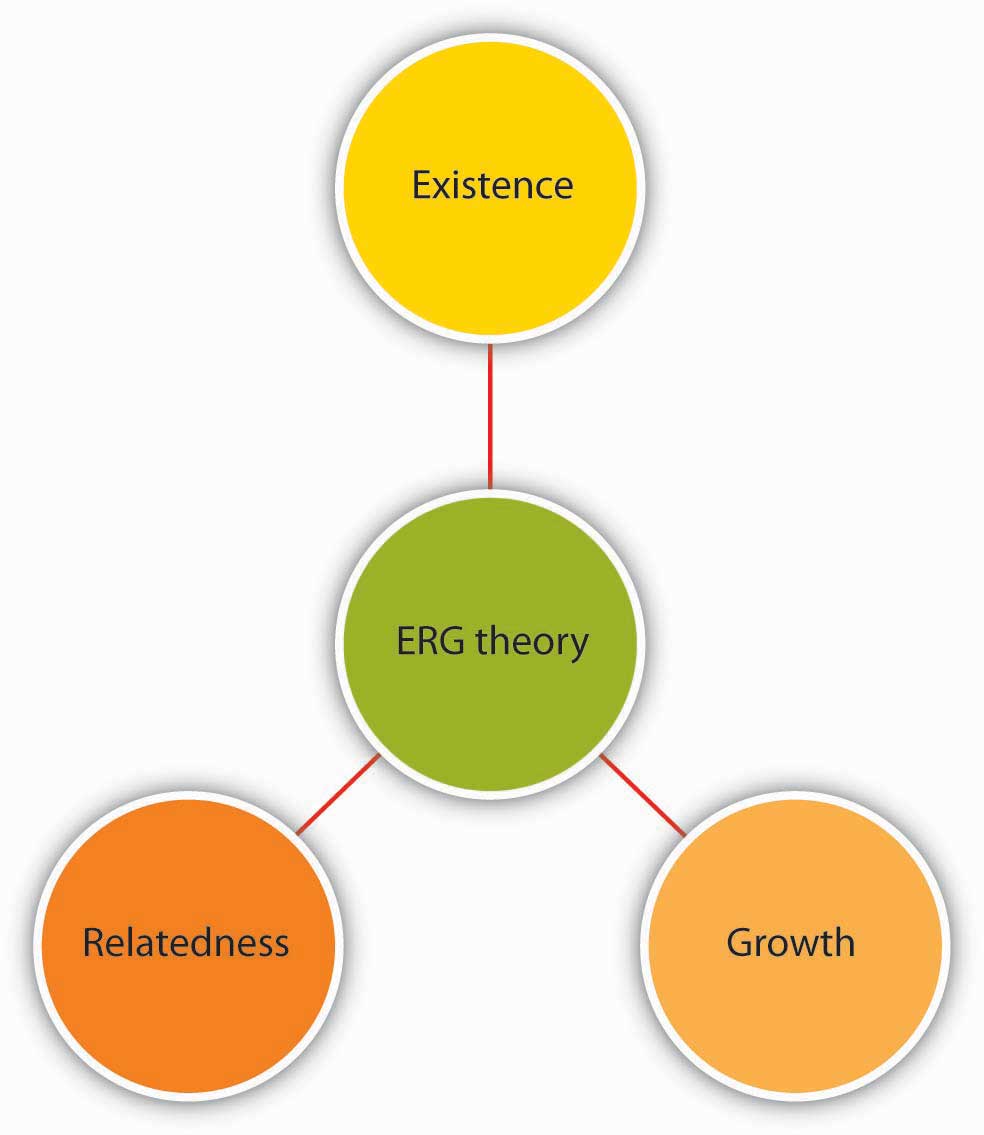

Alderfer’s ERG theory

Alderfer’s theory of motivation expands on the work of Maslow and takes the premise of need categories a bit further. He observes that when lower needs are satisfied, they occupy less of our attention, but the higher needs tend to become more important, the more we pursue them.

He also observed a phenomenon that he called the frustration-regression process where when our higher needs are thwarted, we may regress to lower needs. This is especially important when it comes to motivating employees.

When a sense of autonomy or the need for mastery is compromised, say because of the structure of the work environment, the employee may focus more on the sense of security or relatedness the job provides.

McClelland’s achievement motivation theory

McClelland took a different approach to conceptualize needs and argued that needs are developed and learned, and focused his research away from satisfaction. He was also adamant that only one dominant motive can be present in our behavior at a time. McClelland categorized the needs or motives into achievement, affiliation, and power and saw them as being influenced by either internal drivers or extrinsic factors.

Among all the prospects which man can have, the most comforting is, on the basis of his present moral condition, to look forward to something permanent and to further progress toward a still better prospect.

Immanuel Kant

The drive for achievement arises out of the psychological need for competence and is defined as a striving for excellence against a standard that can originate from three sources of competition: the task itself, the competition with the self, and the competition against others.

High need for achievement can come from one’s social environment and socialization influences, like parents who promote and value pursuit and standards of excellence, but it can also be developed throughout life as a need for personal growth towards complexity (Reeve, 2014).

Herzberg’s motivation-hygiene theory

Herzberg’s two-factor theory, also known as motivation-hygiene theory, was originally intended to address employee motivation and recognized two sources of job satisfaction. He argued that motivating factors influence job satisfaction because they are based on an individual’s need for personal growth: achievement, recognition, work itself, responsibility, and advancement.

On the other hand, hygiene factors, which represented deficiency needs, defined the job context and could make individuals unhappy with their job: company policy and administration, supervision, salary, interpersonal relationships, and working conditions.

Motivation theories explained in 10 minutes – EPM

Process theories like Skinner’s reinforcement theory, Victor Vroom’s expectancy theory, Adams’ equity theory, and Locke’s goal-setting theory set out to explain how motivation occurs and how our motives change over time.

Reinforcement theory

The most well-known process theory of motivation is the reinforcement theory, which focused on the consequences of human behavior as a motivating factor.

Based on Skinner’s operant conditioning theory , it identifies positive reinforcements as promoters that increased the possibility of the desired behavior’s repetition: praise, appreciation, a good grade, trophy, money, promotion, or any other reward (Gordon, 1987).

It distinguished positive reinforcements from negative reinforcement and punishment, where the former gives a person only what they need in exchange for desired behavior, and the latter tries to stop the undesired behavior by inflicting unwanted consequences.

See our articles on Positive Reinforcement in the Workplace and Parenting Children with Positive Reinforcement .

Other process motivation theories combine aspects of reinforcement theory with other theories, sometimes from adjacent fields, to shine a light on what drives human behavior.

Adams’ equity theory of motivation

For example, Adams’ equity theory of motivation (1965), based on Social Exchange theory, states that we are motivated when treated equitably, and we receive what we consider fair for our efforts.

It suggests that we not only compare our contributions to the amount of rewards we receive but also compare them to what others receive for the same amount of input. Although equity is essential to motivation, it does not take into account the differences in individual needs, values, and personalities, which influence our perception of inequity.

Vroom’s expectancy theory

Victor Vroom’s expectancy theory (1964), on the other hand, integrates needs, equity, and reinforcement theories to explain how we choose from alternative forms of voluntary behavior based on the belief that decisions will have desired outcomes. Vroom suggests that we are motivated to pursue an activity by appraising three factors:

- Expectancy that assumes more effort will result in success

- Instrumentality that sees a connection between activity and goal

- Valence which represents the degree to which we value the reward or the results of success.

Locke’s goal-setting theory

Finally, Locke and Latham’s (1990) goal-setting theory, an integrative model of motivation, sees goals as key determinants of behavior. Possibly the most widely applied, the goal-setting theory stresses goal specificity, difficulty, and acceptance and provides guidelines for how to incorporate them into incentive programs and management by objectives (MBO) techniques in many areas.

Lock’s recipe for effective goal setting includes:

- Setting of challenging but attainable goals. Too easy or too difficult or unrealistic goals don’t motivate us.

- Setting goals that are specific and measurable. These can focus us toward what we want and can help us measure the progress toward the goal.

- Goal commitment should be obtained. If we don’t commit to the goals, then we will not put adequate effort toward reaching them, regardless of how specific or challenging they are.

- Strategies to achieve this could include participation in the goal-setting process, the use of extrinsic rewards (bonuses), and encouraging intrinsic motivation through providing feedback about goal attainment. It is important to mention here that pressure to achieve goals is not useful because it can result in dishonesty and superficial performance.

- Support elements should be provided. For example, encouragement, needed materials and resources, and moral support.

- Knowledge of results is essential. Goals need to be quantifiable, and there needs to be feedback.

There are several articles on effective goal setting in our blog series that cover Locke’s theory and it’s many applications.

They address specific cognitive phenomena that can influence motivation, represent a particular factor of motivation, describe a form of expression of motivation, or explain a process through which it can occur or be enhanced.

The list of cognitive phenomena is by no means comprehensive, but it does give us a taste of the complexity of human motivation and includes references for those who want to read further into more nuanced topics:

- Plans (Carver, Scheier, & Weintraub, 1998)

- Goals (Locke & Latham, 2002)

- Implementation intentions (Gollwitzer, 1999)

- Deliberative versus implementation mindsets (Gollwitzer & Kinney, 1989)

- Promotion versus prevention orientations (Higgins, 1997)

- Growth versus fixed mindsets (Dweck, 2006)

- Dissonance (Festinger, 1957; Harmon-Jones & Mills, 1999)

- Self-efficacy (Bandura, 1986)

- Perceived control (Skinner, 1996)

- Reactance theory (Brehm, 1966)

- Learned helplessness theory (Miller & Seligman, 1975)

- Mastery beliefs (Diener & Dweck, 1978)

- Attributions (Wiener, 1986)

- Values (Eccles & Wigfield, 2002)

- Self-concept (Markus, 1977)

- Possible selves (Oyserman, Bybee, & Terry, 2006)

- Identity (Eccles, 2009)

- Self-regulation (Zimmerman, 2000)

- Self-control (Baumeister & Tierney, 2011)

There are also several different approaches to understanding human motivation which we have discussed in greater detail in our article on Benefits and Importance of Motivation which amass a large body of motivational studies and are currently attracting a lot of attention in contemporary research in motivational science, namely intrinsic motivation (Ryan & Deci, 2000) and the flow theory (Csíkszentmihályi, 1975).

In addition to the Two Factor theory and equity theory, some theories focus on autonomy, wellbeing, and feedback as core motivational aspects of employees’ performance; theories X, Y and Z, and the Hawthorne effect, respectively.

Theory X and Theory Y

Douglas McGregor proposed two theories, Theory X and Theory Y, to explain employee motivation and its implications for management. He divided employees into Theory X employees who avoid work and dislike responsibility and Theory Y employees who enjoy work and exert effort when they have control in the workplace.

He postulated that to motivate Theory X employees, the company needs to enforce rules and implement punishments. For Theory Y employees, management must develop opportunities for employees to take on responsibility and show creativity as a way of motivating. Theory X is heavily informed by what we know about intrinsic motivation, and the role satisfaction of basic psychological needs plays in effective employee motivation.

In response to this theory, a third theory, Theory Z, was developed by Dr. William Ouchi. Ouchi’s theory focuses on increasing employee loyalty to the company by providing a job for life and focusing on the employee’s well-being. It encourages group work and social interaction to motivate employees in the workplace.

The Hawthorne Effect

Elton Mayo developed an explanation known as the Hawthorne Effect that suggested that employees are more productive when they know their work is being measured and studied.

Download 3 Free Goals Exercises (PDF)

These detailed, science-based exercises will help you or your clients create actionable goals and master techniques for lasting behavior change.

Download 3 Free Goals Pack (PDF)

By filling out your name and email address below.

- Email Address *

- Your Expertise * Your expertise Therapy Coaching Education Counseling Business Healthcare Other

- Comments This field is for validation purposes and should be left unchanged.

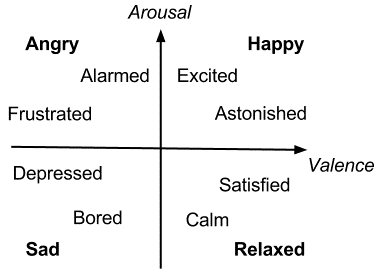

There are also several theories on motivation that are used in sports and performance psychology. The core concept in understanding motivation from the performance perspective is how physiological and psychological arousal accompanies behavior.

Arousal is basically a form of mobilization of energy and activation either before or while engaged in the behavior. Arousal occurs in different modes. Physiological arousal refers to the excitement of the body, while psychological arousal is about how subjectively aroused an individual feels.

When we say that our palms are sweaty or our heart is pounding, it implies physiological arousal. When we feel tense and anxious, it signifies psychological arousal.

Robert Thayer (1989) evolved the theory of psychological arousal into two dimensions: energetic arousal and tense arousal, composed of energetic and tense dimensions. Energetic arousal is associated with positive affect, while tense arousal is associated with anxiety and fearfulness.

Tense arousal can be divided further into two types of anxiety: trait anxiety and state anxiety. One refers to the degree we respond to the environment in general negatively and with worry, while state anxiety refers to feelings of apprehension that occur in response to a particular situation.

Arousal originates from several sources. It can be generated by a stimulus that has an arousing function and a cue function. But background stimuli that do not capture our attention also increase arousal.

Thayer found that arousal varies with time of day, for many of us being highest around noon and lower in the morning and evening. Coffee, for example, can boost arousal, as can an instance of being evaluated during exams, music performance, or sports competitions.

Arousal also depends on more complex variables like novelty, complexity, and incongruity. The interaction of various stimuli explains why sometimes arousal increases behavioral efficiency and in other instances, decreases it.

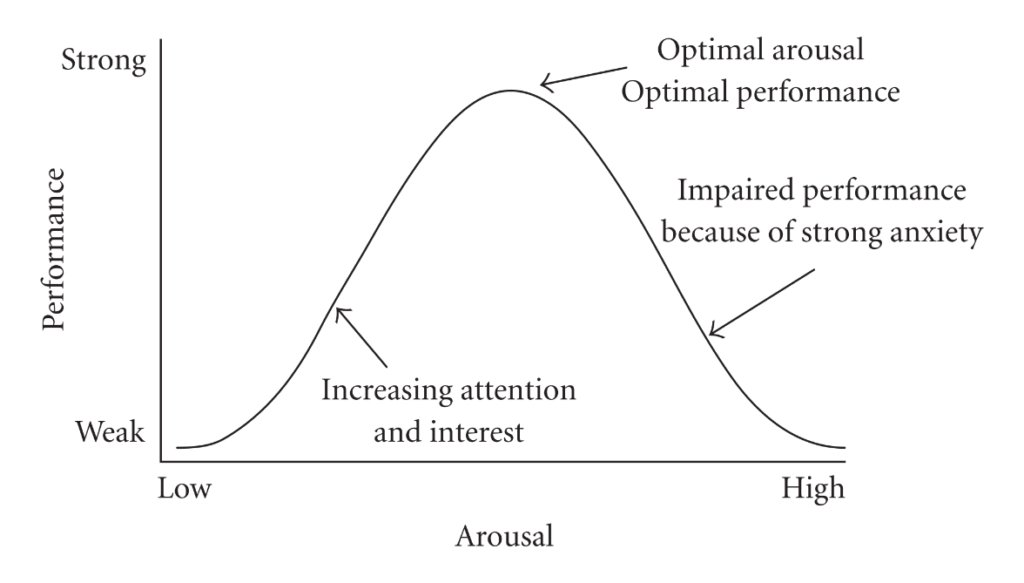

Optimal functioning hypothesis

The zone of optimal functioning hypothesis in sports psychology identifies a zone of optimal arousal where an athlete performs best (Hanin, 1989). As arousal increases, performance on a task increases and then decreases, as can be seen on the inverted-U arousal–performance relationship diagram below.

According to the zone of optimal functioning hypothesis, each individual has her preferred area of arousal based on cognitive or somatic anxiety. The Yerkes–Dodson law explains further that the high point of the inverted-U or arousal–performance relationship depends on the complexity of the task being performed.

Several theories have been proposed to explain the relationship between the inverted-U nature of the arousal–performance relationship.

Hull–Spence drive theory

The classic Hull–Spence drive theory emphasizes how arousal affects performance with little regard for any cognitive awareness by the individual. Also known as drive reduction theory, it postulates that human behavior could be explained by conditioning and reinforcement.

This oversimplification is part of the reason why more nuanced and complex cognitive theories have largely replaced the theory. The cusp catastrophe model in sports psychology, arousal-biased competition theory, processing efficiency theory, and attentional control theory are more concerned with the cognitive aspects of arousal and how this affects behavioral efficiency.

Arousal-biased competition theory

Mather and Sutherland (2011) developed an arousal-biased competition theory to explain the inverted-U arousal–performance relationship. It suggests that arousal exhibits biases toward information that is the focus of our attention.

Arousal effects and therefore increases the priority of processing important information and decrease the priority of processing less critical information. The presence of arousal improves the efficiency of behavior that concerns a crucial stimulus, but it is done at the expense of the background stimuli.

Two memory systems theory

Metcalfe and Jacobs (1998) postulated the existence of two memory systems that influence the level of arousal we experience: a cool memory system and a hot memory system, each in a different area of the brain. The cool system, located in the hippocampus, serves the memory of events occurring in space and time and would allow us to remember where we parked our car this morning.

The hot system in the amygdala serves as the memory of events that occur under high arousal. Metcalfe and Jacobs theorized that the hot system remembers the details of stimuli that predict the onset of highly stressful or arousing events, such as events that predict danger and is responsible for the intrusive memories of individuals who have experienced extremely traumatic events.

Processing efficiency theory

The processing efficiency theory of Eysenck and Calvo theorized on how anxiety, expressed as worry, can influence performance. Preoccupation with being evaluated and being concerned about one’s performance turns to worry, which takes up working memory capacity and causes performance on cognitive tasks to decline (Eysenck & Calvo, 1992).

17 Tools To Increase Motivation and Goal Achievement

These 17 Motivation & Goal Achievement Exercises [PDF] contain all you need to help others set meaningful goals, increase self-drive, and experience greater accomplishment and life satisfaction.

Created by Experts. 100% Science-based.

Here are a suggested book references for tertiary-level study of motivation for those who want to dive deeper into some of these topics:

1. Understanding Motivation and Emotion – Johnmarshall Reeve

IT provides a toolbox of practical interventions and approaches for use in a wide variety of settings.

Available on Amazon .

2. Motivation: Theories and Principles – Robert C. Beck

It covers a broad range of motivational concepts from both human and animal theory and research, with an emphasis on the biological bases of motivation.

3. Motivation – Lambert Deckers

How motivation is the inducement of behavior, feelings, and cognition.

4. Motivation and Emotion Evolutionary Physiological, Developmental, and Social Perspectives – Denys A. deCatanzaro

5. Motivation: A Biosocial and Cognitive Integration of Motivation and Emotion – Eva Dreikurs Ferguson

These include hunger and thirst, circadian and other biological rhythms, fear and anxiety, anger and aggression, achievement, attachment, and love.

6. Human Motivation – Robert E. Franken

7. The Psychology of Action: Linking Cognition and Motivation to Behavior – Peter M. Gollwitzer and John Bargh

These programs are effectively mapping the territory, providing new findings, and suggesting innovative strategies for future research.

8. Motivation and Self-Regulation Across the Life Span – Jutta Heckhausen and Carol S. Dweck

9. Reclaiming Cognition: The Primacy of Action, Intention, and Emotion (Journal of Consciousness Studies) – Rafael Nunez and Walter J. Freeman

This leads to the claim that cognition is representational and best explained using models derived from AI and computational theory. The authors depart radically from this model.

10. Motivation: Theory, Research, and Applications – Herbert L. Petri and John M. Govern

The book clearly presents the advantages and drawbacks to each of these explanations, allowing readers to draw their own conclusions.

11. Intrinsic & Extrinsic Motivation: The Search for Optimal Motivation and Performance – Carol Sansone and Judith M. Harackiewicz

12. The Psychobiology of Human Motivation (Psychology Focus) – Hugh Wagner

It starts from basic physiological needs like hunger and thirst, to more complex aspects of social behavior like altruism.

There is no shortage of explanations for what constitutes human motivation, and the research on the topic is as vast and dense as the field of psychology itself. Perhaps the best course of action is to identify the motivational dilemma we’re trying to solve and then select one approach to motivation if only to try it out.

By annihilating desires you annihilate the mind. Every man without passions has within him no principle of action, nor motive to act.

Claude Adrien Helvetius, 1715–1771

As Dan Kahneman argues, teaching psychology is mostly a waste of time unless we as students can experience what we are trying to learn or teach about human nature and can deduce if it is right for us.

Then and only then, can we choose to act on it, move in the direction of change, or make a choice to remain the same. It’s all about experiential learning and connecting the knowledge we acquire to our own experience.

What motivational theory do you find most useful?

We hope you enjoyed reading this article. Don’t forget to download our three Goal Achievement Exercises for free .

- Image 1 : Maslow pyramid adapted from “Renovating the Pyramid of Needs: Contemporary Extensions Built upon Ancient Foundations” by D. T. Kenrick et al., 2010, Perspectives on Psychological Science, 5, 292–314 (see p. 293), and from “A Theory of Human Needs Should Be Human-Centered, Not Animal-Centered: Commentary on Kenrick et al. (2010)” by S. Kesebir et al., 2010, Perspectives on Psychological Science, 5, 315–319 (see p. 316), and from “Human Motives, Happiness, and the Puzzle of Parenthood: Commentary on Kenrick et al. (2010)” by S. Lyubormirsky & J. K. Boehm, 2010, Perspectives on Psychological Science, 5, 327–334.

- Adams, J. S. (1965). Inequity in social exchange. Advances in experimental social psychology (Vol. 2, pp. 267-299). New York, NY: Academic Press.

- Bandura, A. (1986). Social foundations of thought and action. In D. Marks (Ed.), The health psychology reader (pp. 23-28). Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Sage.

- Baumeister, R. F., & Tierney, J. (2011). Willpower: Rediscovering the greatest human strength. New York, NY: Penguin.

- Brehm, J. (1966). A theory of psychological reactance . New York, NY: Academic Press.

- Carver, C. S., Scheier, M. F., & Weintraub, J. K. (1989). Assessing coping strategies: A theoretically based approach. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 56 (2), 267-283.

- Csíkszentmihályi, M. (1975). Beyond boredom and anxiety: The experience of play in work and games. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

- Diener, C. I., & Dweck, C. S. (1978). An analysis of learned helplessness: Continuous changes in performance, strategy, and achievement cognitions following failure. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 36 (5), 451-462.

- Dweck, C. S. (2006). Mindset: The new psychology of success. New York, NY: Balantine Books.

- Eccles, J. (2009). Who am I and what am I going to do with my life? Personal and collective identities as motivators of action. Educational Psychologist, 44 (2), 78-89.

- Eccles, J. S., & Wigfield, A. (2002). Motivational beliefs, values, and goals. Annual Review of Psychology, 53 (1), 109-132.

- Eysenck, M. W., & Calvo, M. G. (1992). Anxiety and performance: The processing efficiency theory. Cognition & Emotion, 6 (6), 409-434.

- Festinger, L. (1957). A theory of cognitive dissonance . Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press.

- Gollwitzer, P. M. (1999). Implementation intentions: strong effects of simple plans. American Psychologist, 54 (7), 493-503.

- Gollwitzer, P. M., & Kinney, R. F. (1989). Effects of deliberative and implemental mind-sets on illusion of control. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 56 (4), 531-542.

- Gordon, R. M. (1987). The structure of emotions . Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

- Hanin, Y. L. (1989). Interpersonal and intragroup anxiety in sports. In D. Hackfort & C. D. Spielberger (Eds.), Anxiety in sports: An international perspective (pp. 19-28). New York, NY: Hemisphere.

- Harmon-Jones, E., & Mills, J. (Eds.). (1999). Science conference series. Cognitive dissonance: Progress on a pivotal theory in social psychology. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association.

- Higgins, E. T. (1997). Beyond pleasure and pain. American Psychologist, 52 (12), 1280-1300.

- Kenrick, D. T., Griskevicius, V., Neuberg, S. L., & Schaller, M. (2010). Renovating the pyramid of needs: Contemporary extensions built upon ancient foundations. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 5 (3), 292-314.

- Kesebir, S., Graham, J., & Oishi, S. (2010). A theory of human needs should be human-centered, not animal-centered: Commentary on Kenrick et al. (2010). Perspectives on Psychological Science, 5 (3), 315-319.

- Locke, E. A., & Latham, G. P. (1990). A theory of goal setting & task performance . Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall.

- Locke, E. A., & Latham, G. P. (2002). Building a practically useful theory of goal setting and task motivation: A 35-year odyssey. American Psychologist, 57 (9), 705-717.

- Lyubomirsky, S., & Boehm, J. K. (2010). Human motives, happiness, and the puzzle of parenthood: Commentary on Kenrick et al.(2010). Perspectives on Psychological Science, 5 (3), 327-334.

- Markus, H. (1977). Self-schemata and processing information about the self. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 35 (2), 63-78.

- Mather, M., & Sutherland, M. R. (2011). Arousal-biased competition in perception and memory. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 6 (2), 114-133.

- Metcalfe, J., & Jacobs, W. J. (1998). Emotional memory: The effects of stress on “cool” and “hot” memory systems. In D. L. Medin (Ed.), The psychology of learning and motivation: Advances in research and theory (Vol. 38, pp. 187-222). New York, NY: Academic Press.

- Miller, W. R., & Seligman, M. E. (1975). Depression and learned helplessness in man. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 84 (3), 228-238.

- Oyserman, D., Bybee, D., & Terry, K. (2006). Possible selves and academic outcomes: How and when possible selves impel action. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 91 (1), 188-204.

- Reeve, J. (2014). Understanding motivation and emotion (6th ed.). Hoboken, NJ: Wiley.

- Ryan, R. M., & Deci, E. L. (2000). Self-determination theory and the facilitation of intrinsic motivation, social development, and well-being. American Psychologist, 55 (1), 68-78.

- Sheldon, K. M., & Elliot, A. J. (1999). Goal striving, need satisfaction, and longitudinal well-being: The self-concordance model. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 76(3) , 482–497.

- Skinner, E. A. (1996). A guide to constructs of control. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 71 (3), 549-570.

- Thayer, R. L. (1989). The experience of sustainable landscapes. Landscape Journal, 8 (2), 101-110.

- Vroom, V. H. (1964). Work and motivation. New York, NY: Wiley.

- Wiener, B. (1986). Attribution, emotion, and action. In R. M. Sorrentino & E. T. Higgins (Eds.), Handbook of motivation and cognition: Foundations of social behavior (pp. 281–312). New York, NY: Guilford Press.

- Zimmerman, B. J. (2000). Attaining self-regulation: A social cognitive perspective. In M. Boekaerts, P. R. Pintrich, & M. Zeidner (Eds.), Handbook of self-regulation (pp. 13-39). San Diego, CA: Academic Press.

Share this article:

Article feedback

What our readers think.

Thanks for this article, great summary of the content and process theories. I’m studying for my CHRP exam so just trying to condense a lot of info into concise study notes. Have previously taken courses in Organizational Behaviour that explored the theories in much more depth.

Hi Nicole, I love this site! I am a PhD student but in international development, not psychology and my methodology is multi-disciplinary, but that is quite difficult I am finding now I am looking at psychology! I have been sent down a path by an Australian academic about the role of action to motivation to action – do you have any good references to recommend on this? Thx, Sue Cant, Charles Darwin University

It sounds like you’re delving into an exciting interdisciplinary study! The role of action and motivation is indeed a key topic in psychology and relevant to international development too.

First, you might find “ Self-Determination Theory ” by Richard M. Ryan and Edward L. Deci interesting. It delves into the relationship between motivation, action, and human behavior, exploring how our needs for autonomy, competence, and relatedness influence our motivation and actions.

Another reference to consider is “ Mindset: The New Psychology of Success ” by Carol S. Dweck. It explores the concept of “growth mindset” and how our beliefs about our abilities can impact our motivation to act and overcome challenges.

These references should provide a good starting point for understanding the psychological aspects of action and motivation. I hope they prove useful for your research!

Best of luck with your PhD journey!

Kind regards, Julia | Community Manager

I enjoyed the fact that there is plenty information, if I were to write an essay on Motivation.

It’s so informative and inclusive! I just wonder if there are relevant theories on how to motivate communities (e.g. residents, companies, experts) to participate in decision-making (e.g. protection of cultural heritage)? Thank you!

Glad you liked the article! I’m not sure if there are theories that specifically cover this (they may be more in sociology and a bit beyond my expertise). But I’d recommend having a read of my article on positive communities. If you follow some of the references throughout, I suspect you’ll find some great resources and advice, particularly on participative decision-making: https://positivepsychology.com/10-traits-positive-community/

Hope this helps a little!

– Nicole | Community Manager

Deci and Ryans Self Determination Theory needs to be discussed… NOT just given an afterthought. Their argument that human behaviour is driven by the 3 fundamental needs of 1) Affiliation 2) Competence and 3) Self Determination is supported by developmental science (attachment theory, Tomosello’s cross species work, developmental work on competence and learning, and finally the huge body of work on intrinsic motivation and self-regulation.

This overview is well written but appears to have a big hole in it.

Hi Dr. Martin,

Thanks for your comment. We agree SDT is a powerful theory, and it has many different applications. We’ve addressed these in depth in some of our other articles on the topic:

Self-Determination Theory of Motivation: Why Intrinsic Motivation Matters – https://positivepsychology.com/self-determination-theory/ 21 Self-Determination Skills and Activities to Utilize Today: https://positivepsychology.com/self-determination-skills-activities/ Intrinsic Motivation Explained: 10 Factors & Real-Life Examples: https://positivepsychology.com/intrinsic-motivation-examples/

Hey Nicole. This summary is amazing and pin points what I’m looking for. In the case where I have to evaluate this theory for example Maslow’s hierarchy theory in relation to an organization’s needs. How do I go about that or what’s the best way to do so?

Hi Deborah,

So glad you enjoyed the article. Could you please give a little more information about what you’re looking to do? For instance, are you looking for a theory you can apply to assess individual employees’ motivation at work? Note that not all of the theories discussed here are really applicable to an organizational context (e.g., I would personally avoid Maslow’s hierarchy for this), so it would be helpful to have a little more information.

Yes. Precisely that. I am looking for theories that I am adapt to do an intervention , implementation and evaluation of employee motivation in an organization. And how exactly these theories are implemented.

Thank you Nicole. Excellent summary of available theories. Could you tell me please which may be the best theory to explain involvement in extremism and radicalization?

Glad you liked the article. Research on motivations underlying extremism and radicalization tend to point to our beliefs having a central role. This paper by Trip et al. (2019) provides an excellent summary of the thinking in this space. It looks at the factors from an REBT perspective. It addresses a whole range of motivational perspectives including uncertainty-identity theory and integrated threat theory.

I hope this article is helpful for you.

Let us know your thoughts Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published.

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

Related articles

How to Encourage Clients to Embrace Change

Many of us struggle with change, especially when it’s imposed upon us rather than chosen. Yet despite its inevitability, without it, there would be no [...]

Victor Vroom’s Expectancy Theory of Motivation

Motivation is vital to beginning and maintaining healthy behavior in the workplace, education, and beyond, and it drives us toward our desired outcomes (Zajda, 2023). [...]

SMART Goals, HARD Goals, PACT, or OKRs: What Works?

Goal setting is vital in business, education, and performance environments such as sports, yet it is also a key component of many coaching and counseling [...]

Read other articles by their category

- Body & Brain (54)

- Coaching & Application (58)

- Compassion (26)

- Counseling (51)

- Emotional Intelligence (23)

- Gratitude (18)

- Grief & Bereavement (21)

- Happiness & SWB (40)

- Meaning & Values (27)

- Meditation (20)

- Mindfulness (44)

- Motivation & Goals (46)

- Optimism & Mindset (34)

- Positive CBT (30)

- Positive Communication (22)

- Positive Education (48)

- Positive Emotions (32)

- Positive Leadership (19)

- Positive Parenting (16)

- Positive Psychology (34)

- Positive Workplace (37)

- Productivity (18)

- Relationships (45)

- Resilience & Coping (39)

- Self Awareness (21)

- Self Esteem (38)

- Strengths & Virtues (32)

- Stress & Burnout Prevention (34)

- Theory & Books (46)

- Therapy Exercises (37)

- Types of Therapy (64)

3 Goal Achievement Exercises Pack

Advertisement

Theories of Motivation in Education: an Integrative Framework

- Review Article

- Open access

- Published: 30 March 2023

- Volume 35 , article number 45 , ( 2023 )

Cite this article

You have full access to this open access article

- Detlef Urhahne ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-7709-0011 1 &

- Lisette Wijnia ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0001-7395-839X 2

98k Accesses

15 Citations

23 Altmetric

Explore all metrics

Several major theories have been established in research on motivation in education to describe, explain, and predict the direction, initiation, intensity, and persistence of learning behaviors. The most commonly cited theories of academic motivation include expectancy-value theory, social cognitive theory, self-determination theory, interest theory, achievement goal theory, and attribution theory. To gain a deeper understanding of the similarities and differences among these prominent theories, we present an integrative framework based on an action model (Heckhausen & Heckhausen, 2018 ). The basic model is deliberately parsimonious, consisting of six stages of action: the situation, the self, the goal, the action, the outcome, and the consequences. Motivational constructs from each major theory are related to these determinants in the course of action, mainly revealing differences and to a lesser extent commonalities. In the integrative model, learning outcomes represent a typical indicator of goal-directed behavior. Associated recent meta-analyses demonstrate the empirical relationship between the motivational constructs of the six central theories and academic achievement. They provide evidence for the explanatory value of each theory for students’ learning.

Similar content being viewed by others

The use of cronbach’s alpha when developing and reporting research instruments in science education.

Social Learning Theory—Albert Bandura

College Students’ Time Management: a Self-Regulated Learning Perspective

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Motivation is one of the most studied psychological constructs in educational psychology (Koenka, 2020 ). The term is derived from the Latin word “movere,” which means “to move,” as motivation provides the necessary energy to people’s actions (Eccles et al., 1998 ; T. Jansen et al., 2022 ). In the scientific literature, motivation is often defined as “a process in which goal-directed activity is instigated and sustained” (Schunk et al., 2014 , p. 5). Research on academic motivation focuses on explaining why students behave the way they do and how this affects learning and performance (Schunk et al., 2014 ).

Several major theories have been established in research on motivation in education to describe, explain and predict the direction, initiation, intensity, and persistence of learning behaviors (cf. Linnenbrink-Garcia & Patall, 2016 ). Each theory has its own terms and concepts to designate aspects of motivated behavior, contributing to a certain inaccessibility of the field of motivation theories. In addition, motivation researchers create their own terminology, differentiate, and extend existing theoretical conceptions, making it difficult to draw precise boundaries between the models (Murphy & Alexander, 2000 ; Schunk, 2000 ). This leads to the question of whether it would be possible to consider the most important theories of academic motivation against a common background to gain a deeper understanding of the similarities and differences among these prominent theories.

In the past, several researchers have worked to provide an integrative meta-theoretical framework for classifying motivational processes. Hyland’s ( 1988 ) motivational control theory used a system of hierarchically organized control loops to explain the direction and intensity of goal-orientated behavior. Locke ( 1997 ) postulated an integrated model for theories of work motivation, starting from needs, values and personality, and environmental incentives through goal choice and mediating goal and efficacy mechanisms to performance, outcomes, satisfaction, and organizational commitment. Murphy and Alexander ( 2000 ) classified achievement motivation terms into the four domains of goal, interest, intrinsic vs. extrinsic motivation, and self-schema. De Brabander and Martens ( 2014 ) tried to predict a person’s readiness for action primarily from positive and negative, affective and cognitive valences in their unified model of task-specific motivation. Linnenbrink-Garcia and Wormington ( 2019 ) proposed perceived competence, task values, and achievement goals as essential categories to study person-oriented motivation from an integrative perspective. Hattie et al. ( 2020 ) grouped various models of motivation around the essential components of person factors (subdivided into self, social, and cognitive factors), task attributes, goals, perceived costs, and benefits. Finally, Fong ( 2022 ) developed the motivation within changing culturalized contexts model to account for instructional, social, future-oriented, and sociocultural dynamics affecting student motivation in a pandemic context.

In this contribution, we present an integrative framework for theories of motivation in education based on an action model (Heckhausen & Heckhausen, 2018 ). The action model is a further development of an idea by Urhahne ( 2008 ) to classify the most commonly cited theories focusing on academic motivation, including expectancy-value theory, social cognitive theory, self-determination theory, interest theory, achievement goal theory, and attribution theory, into a common frame (Schunk et al., 2014 ). We begin with introducing the basic motivational model and then sort the main concepts and terms of the prominent motivation theories into the action model. Associated recent meta-analyses will illustrate the empirically documented value of each theory in explaining academic achievement.

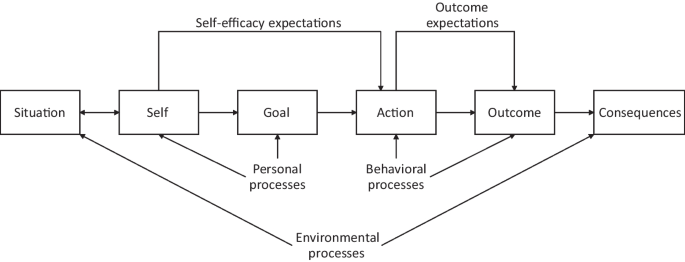

The Basic Motivational Model

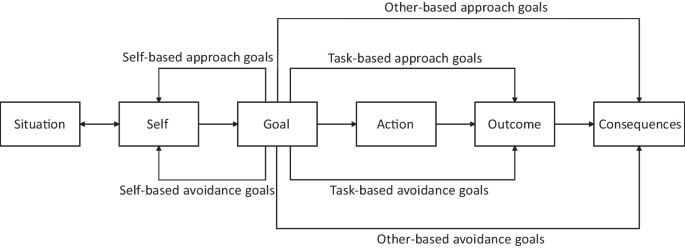

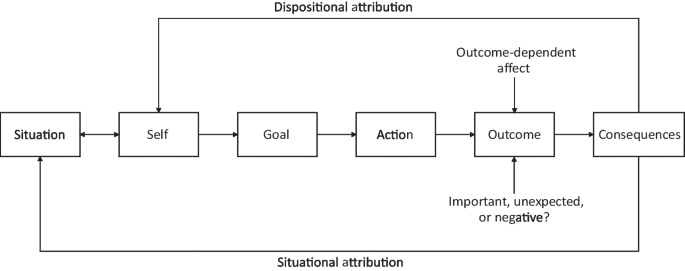

The basic motivational model in Fig. 1 shows the determinants and course of motivated action. The model is grounded on the general model of motivation by Heckhausen and Heckhausen ( 2018 , p. 4) to introduce the universal characteristics of motivated human action. Heckhausen ( 1977 ) had worked early on to organize constructs from different theories into a cognitive model of motivation. The initial model differentiated four types of expectations attached to four different stages in a sequence of events and helped group intrinsic and extrinsic incentive values of an action as well (Heckhausen, 1977 ). Later, Heckhausen and Gollwitzer ( 1987 ) extended the model to the Rubicon model of action phases to define clear boundaries between phases of motivational and volitional mindsets (Achtziger & Gollwitzer, 2018 ; Gollwitzer et al., 1990 ). The four phases of the Rubicon model can be described as follows: In the predecisional phase of motivation, individuals select or set a goal for action on the basis of their wishes and desires. The postdecisional phase of volition is a time of preparation and planning to translate the goal into action. This is followed by the actional phase of volition that involves the actual process of action. Once the action is completed or abandoned, the postactional phase of evaluating the outcome and its consequences has begun (Heckhausen & Heckhausen, 2018 ). Since the Rubicon model depicts the entire action process from an emerging desire to the final evaluation of the action outcome, it provides a broad basis for classifying various current motivational theories.

The basic motivational model

Specifically, our model proposes that motivated behavior arises from the interaction between the person and the environment (Murray, 1938 ). In Fig. 1 , possible incentives such as the prospect of rewards and opportunities of the situation stimulate the motives, needs, wishes, and emotions of a person’s self, which come to life through generating an action goal (Dweck et al., 2003 ; Roeser & Peck, 2009 ). A person’s current goal is translated into an action at a suitable opportunity. The action is carried out, and the action’s outcome indicates whether and to what extent the intended goal has been achieved. The outcome has to be distinguished from the consequences of the action, which may consist of self- and other evaluations, rewards and punishments, achievement emotions, or effects of the outcome on long-term goals (Heckhausen & Heckhausen, 2018 ). The basic model is intentionally parsimonious and somewhat reflects considerations by Hattie et al. ( 2020 ) on integrating theories of motivation that distinguish between self, goals, task (action), and costs and benefits (consequences) as major dimensions of motivation. Similarities also emerge to Locke ( 1997 ), who bases the integrative model of work motivation theories on a comparable action sequence. The specificities of each component of the basic motivational model are now explained in more detail.

The situation represents the social, cultural, and environmental context in which individuals perform motivated actions (Ford, 1992 ). Recently, there has been a trend within motivation research to place greater emphasis on situating motivation (Eccles & Wigfield, 2020 ; Nolen, 2020 ; Nolen et al., 2015 ; Pekrun & Marsh, 2022 ; Wentzel & Skinner, 2022 ). Researchers want to better account for the social and cultural differences between persons (Usher, 2018 ) or take note of the embeddedness of individuals in multiple contexts (Nolen et al., 2015 ). The basic motivational model includes these extensions of current motivation theories and refers to the situatedness of motivation. The situation represents the overarching context for the complete action sequence, even though it is depicted in the basic motivational model by only one box. The situation and the person’s self are intimately interwoven, and motivation can be regarded as a result of their interaction (Roeser & Peck, 2009 ). The situation evokes motivational tendencies in the self, and the self contains experiences about the motivation to avoid or master certain situations (King & McInerney, 2014 ).

The self has not played a major role in motivation research for a long time (Weiner, 1990 ). This was partly due to Freud’s psychoanalytic theories, which recognized the id rather than the ego as the motivational driver of behavior. Moreover, behavioristic approaches that characterized motivation and learning as fully controllable from the outside also neglected mental constructs such as the self (McCombs, 1991 ). It was only with the greater prevalence of cognitive and social-cognitive theories that the self found its way back to motivational research (Weiner, 1990 ). The self is now frequently addressed in hypothetical constructs such as self-efficacy (Bandura, 1977 ), self-determination (Deci & Ryan, 1985 ), self-regulation (Bandura, 1988 ), self-theories (Dweck, 1999 ), ego orientation (Nicholls, 1989 ), self-based goals (Elliot et al., 2011 ), self-serving bias (McAllister, 1996 ; Miller & Ross, 1975 ), and identity (Eccles, 2009 ).

In our model, the self is the starting point of motivated action. It enables people to select goals, initiate behaviors, and sustain them until goals are accomplished (Baumeister, 2010 ; McCombs & Marzano, 1990 ; Osborne & Jones, 2011 ). Thus understood, the self is an active agent that translates a person’s basic psychological needs, motives, feelings, values, and beliefs into volitional actions (McCombs, 1991 ; Roeser & Peck, 2009 ). James ( 1999 ) referred to this part of the self as the “I-self,” the thinking and acting person itself, to distinguish it from the “Me-self,” the reflection of oneself through its physical and mental attributes. The “Me-self” is central to constructs such as self-concept, self-worth, or self-esteem (Harter, 1988 ) and remains important in depicting different motivational constructs in the course of action. However, in the basic motivational model, the “I-self” is recognized as the repository of motivational tendencies and the energizer of motivated action (King & McInerney, 2014 ).

This view of the self corresponds with insights from neuroscientific research. In Northoff’s ( 2016 ) basis model of self-specificity, the self, and in particular self-specificity, is viewed as the most fundamental function of the brain. Self-specificity and self-relatedness refers to “the degree to which internal or external stimuli are related to the self” (Hidi et al., 2019 , p. 15) and references the I-self, the self as subject and agent (Christoff et al., 2011 ). Self-specificity involves spontaneous brain activity—the resting state of the brain and independent of specific tasks or stimuli external to the brain—and is viewed as fundamental in influencing basic and higher-order functions, such as perception, the processing of reward, emotion, memory, and decision-making (Hidi et al., 2019 ; Northoff, 2016 ). Furthermore, Sui and Humphreys ( 2015 ) indicated that self-related information processing functions as an “integrative glue” that influences the integration of different stages of processing, such as linking attention to decision-making. Neuroscientific findings, therefore, seem to support the view of the self as the starting point of motivated behavior.

The goal contains the cognitive representation of an action’s anticipated incentives and consequences. Goals are the basis of all motivated behavior (cf. Elliot & Fryer, 2008 ). This view is consistent with Schunk et al. ( 2014 ), who defined motivation as a process to instigate and sustain goal-directed behavior. Cognitive theories on motivation place special emphasis on the goals that people pursue (Elliot & Hulleman, 2017 ). Goals are intentional rather than impulsive, consciously or unconsciously represented, and guide an individual’s behavior. People are not always aware of the various influences on their goals. Sensations, perceptions, thoughts, beliefs, and emotions that affect goal pursuit are potentially experiential, but typically not consciously perceived (Bargh & Gollwitzer, 2023 ; Dweck et al., 2023 ). Goals are closely related to the person’s self. In line with Dweck et al. ( 2003 , p. 239), we assume that “contents of the self—self-defining beliefs and values—come to life through people’s goals.”

The action is carried out to either approach or avoid an anticipatory goal state (Beckmann & Heckhausen, 2018 ). Thus, motivated behavior can be directed to either approach a positive event or avoid a negative one (Elliot & Covington, 2001 ). An action can be brief or extended over a longer period. If an action goal is considered unattainable, it is devalued, and the action is directed toward other more attractive goals (Heckhausen & Heckhausen, 2018 ). The action may or may not be visible to an observer. Thus, to act is to engage in any form of noticeable or indiscernible behavior, especially cognitive behavior, to reach a desired or avoid an undesired goal state.

The outcome is any physical, affective, or social result of an individual’s behavior. The action outcome is an important indicator of mastering a standard of excellence (Heckhausen, 1991 ). It is often accompanied by intrinsic valences such as feelings of self-worth, self-actualization, or appropriate accomplishment (Mitchell & Albright, 1972 ).

The consequences of an action are far more varied than the mere outcome. Vroom’s ( 1964 ) instrumentality theory considered the outcome of an action as instrumental for reaching subsequent consequences. Vroom ( 1964 ) suggested that the valence of an outcome depends on the valence of the consequences. For example, the value of school grades should depend on how the students themselves, classmates, and parents evaluate the grades achieved, what rewards, punishments, and achievement emotions are associated with the school grades, and whether the grades help achieve long-term goals such as moving up to the next grade level. The consequences of an action are often accompanied by extrinsic valences such as authority, prestige, security, promotion, or recognition (Mitchell & Albright, 1972 ).

In addition, the manifold consequences of an action affect the design of future situations and the goals that can be pursued within these situations. New possibilities to act open up and novel incentives of the situation start to interact with the self. A new action sequence, as shown in Fig. 1 , has begun.

In the following sections, we will use the action model to explain and classify six central motivation theories. Motivated action in the educational context serves to attain academic achievement, and we will make use of meta-analyses to underline what is currently known about the predictive strength of the major theoretical models. Academic achievement is certainly not the only reportable variable related to motivation. However, this visible evidence of learning is an appropriate indicator to convince individuals of the theory’s nature and value (Hattie, 2009 ). The role of affective factors in the action model is explained in more detail in the discussion.

Expectancy-Value Theory

Grounded on the research by Tolman ( 1932 ) and Lewin ( 1951 ), expectancy-value theories depict motivation as the result of the feasibility and desirability of an anticipated action (Achtziger & Gollwitzer, 2018 ; Schnettler et al., 2020 ). The expectancy is usually triggered by the incentives of the situation and expresses the subjective probability of the feasibility of the current action (Atkinson, 1957 ). The value indicates the desirability of an action which is determined by the incentives of the situation and the anticipated consequences of the action. In Atkinson’s ( 1957 ) achievement motivation theory, expectancy and value were assumed to be inversely related. The greater the desirability, the more difficult the feasibility of an action and vice versa. Thus, knowing the subjective probability of success was regarded as sufficient to determine the incentive value of a task. However, it turned out that the assumption of a negative correlation between expectancy and value was not tenable (Wigfield & Eccles, 1992 ). In a more modern view, expectancy and value beliefs are assumed to jointly predict achievement-related choices and performance (Eccles et al., 1983 ; Trautwein et al., 2012 ).

Situated expectancy-value theory (Eccles & Wigfield, 2020 ; Wigfield & Eccles, 2000 ) is a modern theoretical framework for explaining and predicting achievement-related choices and behavior. Expectancy of success and subjective task values are regarded as proximal explanatory factors determined by a person’s goals and self-schemas. These, in turn, are shaped by the individual’s perception and interpretation of their developmental history and sociocultural background. Eccles and Wigfield ( 2020 ) refer to their theory as situated to highlight the importance of the underlying influences on currently held expectancy and value beliefs.

The expectancy component in the situated model (Eccles & Wigfield, 2020 ) is called expectation of success (Atkinson, 1957 ; Tolman, 1932 ). It represents individuals’ belief about how well they will do on an upcoming task, targeting the anticipated outcome of an action. The expectancy component of Eccles’ motivation theory shows some similarity to self-concept of ability and self-efficacy (Bandura, 1977 ; Harter, 2015 ; Schunk & DiBenedetto, 2016 ; Schunk & Pajares, 2009 ). However, the expectation of success does not focus on the present ability (Bong & Skaalvik, 2003 ) but the future (Wigfield & Eccles, 2000 ), and it targets the perceived chances of success rather than the perceived probability of performing an action which may lead to success (Bandura, 1977 ; Muenks et al., 2018 ).

The value component of the situated model is divided into three types of value beliefs and three types of costs that contribute to approaching or avoiding certain tasks (Eccles & Wigfield, 2020 ). The three value beliefs are attainment value, intrinsic value, and utility value. The three types of costs are named opportunity costs, effort costs, and emotional costs (cf. Flake et al., 2015 ; Jiang et al., 2018 ).

Attainment value represents the importance of doing well on a task (Eccles & Wigfield, 2020 ). This belief is strongly associated with the person’s self, as aspects of one’s identity are touched upon during performing an important task (Wigfield et al., 2016 ). Intrinsic value is the enjoyment a person gets from doing a task. Intrinsic value is considered a counterpart to intrinsic motivation in self-determination theory (Ryan & Deci, 2009 ) and interest in person-object theory (Krapp, 1999 ). However, enjoyment and interest should not be viewed as synonyms, making differentiations necessary (Ainley & Hidi, 2014 ; Reeve, 1989 ). Utility value is derived from the meaning of a task in achieving current and future goals (Wigfield et al., 2006 ). Accomplishing the task is only a means to an end; therefore, utility value can be considered a form of extrinsic motivation. Utility value is derived from the meaning of a task in achieving current and future goals (Wigfield et al., 2006 ) in social, educational, professional, or everyday contexts (Gaspard et al., 2015 ).

Opportunity costs arise because the time invested in a task is no longer available for other valued activities. Especially in the case of learning, conflicts with other interests threaten learners’ self-regulation, and opportunity costs can be high (Grund & Fries, 2012 ). Effort costs address the perceived effort in pursuing a task and whether it is worthwhile to finish the task at hand (Eccles, 2005 ). Emotional costs include the perceived affective consequences of participating in an academic activity, such as fear of failure or other negative emotional states (Eccles & Wigfield, 2020 ; Wigfield et al., 2017 ).

Central constructs of the situated expectancy-value framework (Eccles & Wigfield, 2020 ) can be placed within the basic motivational model (see Fig. 2 ). Expectation of success, a person’s subjective estimate of the chances of obtaining a particular outcome, can be represented as a directed link between self and outcome. The expectation of achieving a future outcome with a certain probability is formed in the self and is directed on the desired outcome of the prospective action. This view of expectancy of success is consistent with Skinner’s ( 1996 ) classification of agent-ends relations as individuals’ beliefs about how well they will do on an upcoming task.

Integrating situated expectancy-value theory into the basic motivational model

Figure 2 further shows that the three task values are linked to different processes in the action model. The attainment value of a task is related to the personal significance of the outcome (Eccles & Wigfield, 2020 ). The higher the relative personal importance of the outcome, the higher the attainment value. More recent analyses show that the attainment value can be divided and measured as the importance of achievement and personal importance related to one’s identity (Gaspard et al., 2015 , 2018 , 2020 ). The self, however, is not the valued object but the importance of accomplishing a task to an individual’s identity (Perez et al., 2014 ). In classifying this construct, we chose to focus more on the importance of the outcome and less on the reference to the self. At this point, however, a different mode of presentation is also conceivable. The intrinsic value of the task is linked to the positive aspects of the action. The more pleasurable the action, the higher the intrinsic value. Eccles and Wigfield ( 2020 ) conceptualized the intrinsic value as the anticipated enjoyment of doing a particular task as well as the experienced enjoyment when performing the task. The utility value of a task is linked to the consequences. The more positive the anticipated consequences of an action, the higher the perceived usefulness. As a form of extrinsic motivation, the utility value does not result from performing the task, but from the anticipated consequences of an action to fulfill an individual’s present or future plans (Eccles & Wigfield, 2020 ).

The three types of costs also become relevant at different stages in the action process (see Fig. 2 ). Opportunity costs occur when a decision has been made in favor of a certain action. Alternative courses of action are ruled out as soon as a person is committed to a goal (Locke et al., 1988 ). Opportunity costs are consequently linked to the goal of the action. The person’s time and skills, which from now on are put into the pursuit of intentions, are no longer available for other activities (Eccles & Wigfield, 2020 ). Effort costs are tied to the action itself and are based on the anticipated effort of conducting the task. Effort costs rise with the duration and intensity of an action so that the person needs to anticipate whether the desired action is worth the effort required (Eccles & Wigfield, 2020 ). Finally, emotional costs such as anticipated fear of failure or negative emotional states are connected to the anticipated consequences of an action. These costs arise when the action does not go as desired and are therefore considered as the “perceptions of the negative emotional or psychological consequences in pursuing a task” (Rosenzweig et al., 2019 , p. 622).

Eccles’ expectancy-value framework has often been used to investigate and understand gender differences in motivational beliefs, performance, and career choices, especially in science, technology, engineering, and mathematics (Lesperance et al., 2022 ; Parker et al., 2020 ; Wan et al., 2021 ). In contrast, there has been less meta-analytic research as to whether constructs of the expectancy-value model can predict academic achievement. To not preempt other theoretical conceptions, we only report here findings with a clear relation to the Eccles model.

Generally, expectations of success compared to achievement values are stronger predictors of subsequent performance (cf. Wigfield et al., 2017 ). A meta-analysis by Pinquart and Ebeling ( 2020 ) found a moderate association of expectancies for success with both current ( r = .34) and future academic achievement ( r = .41). Conversely, however, past academic performance could also predict expectancies for success ( r = .35). Credé and Phillips ( 2011 ) reported small relationships for a combination of the three task values with GPA ( r = .12) and grades ( r = .17). The relations in meta-analyses were somewhat higher when individual task values were examined. Camacho-Morles et al. ( 2021 ) found an association of r = .27 between activity-related enjoyment represented in the intrinsic value and academic performance. Barroso et al. ( 2021 ) reported a meta-analytic relationship of r = − .28 between math anxiety, as a form of emotional costs, and mathematics achievement.

Social Cognitive Theory

Within the frame of social cognitive theory, Bandura ( 1977 , 1986 , 1997 ) extended the expectancy concept from achievement motivation theory (Atkinson, 1957 ). Expectancy of success, the subjective probability of attaining a particular outcome, was differentiated by means of two beliefs (Schunk & Zimmerman, 2006 ; Usher, 2016 ). Competence beliefs take effect when learners consider means and processes to accomplish certain tasks (Skinner, 1996 ). Control beliefs signify the perceived extent to which the chosen means and processes lead to the desired outcomes (Schunk & Zimmerman, 2006 ).

For competence beliefs, Bandura ( 1977 ) coined the term self-efficacy to express expectations about one’s capabilities to organize and execute courses of action to produce specific outcomes (Bandura, 1997 ; Schunk & Zimmerman, 2006 ). The belief in self-efficacy is regarded as an essential condition to initiate actions leading to academic success (Klassen & Usher, 2010 ). For control beliefs, Bandura ( 1977 ) used the term outcome expectations to express the perceived relations between possible actions and anticipated outcomes. While expectancy of success sometimes involves competence beliefs, sometimes control beliefs, and sometimes both (Schunk & Zimmerman, 2006 ), Bandura’s construct of self-efficacy has contributed to a necessary differentiation in the course of action and can be viewed as a central variable in research on motivation in education (Schunk & DiBenedetto, 2016 ).

Social cognitive theory is much broader than self-efficacy and outcome expectations and assumes a system of interacting personal, behavioral, and environmental factors (Schunk & diBenedetto, 2021 ). The idea that human agency is neither completely autonomous nor completely mechanical, but is subject to reciprocal determinism, plays a decisive role (Linnenbrink-Garcia & Patall, 2016 ). Thus, personal factors such as perceived self-efficacy enable individuals to initiate and sustain behaviors that translate to effects on the environment. Thoughtful reflection on those actions and their impact feeds back to the person and can, in turn, influence their sense of self-efficacy (Bandura, 1989 ).

Figure 3 shows how the key components of social cognitive theory fit into the action model. The upper part of Fig. 3 is devoted to expectations. Self-efficacy expectations arise when the self has the necessary capabilities to organize and execute courses of action. Outcome expectations, in contrast, refer to the assessment of whether the anticipated action will lead to the desired outcome. The presentation of the two expectations is consistent with Skinner’s ( 1996 ) view in which self-efficacy expectations are referred to as agent-means relations and outcome expectations are referred to as means-ends relations. The lower part of Fig. 3 depicts the model of reciprocal interactions consisting of personal, behavioral, and environmental processes (Schunk & DiBenedetto, 2020 ). Personal processes, as described by Schunk and DiBenedetto ( 2020 ) in a publication on motivation and social cognitive theory, are primarily associated with the self and the goal. The self contains information on self-efficacy, values, expectations, attribution patterns and enables social comparison processes. The goal contains standards for self-evaluations of the action’s progress. Behavioral processes such as activity selection, effort, persistence, regulation, and achievement are closely related to action and outcome of the action model. Environmental processes such as acting of social models, providing instructions, or setting standards for action stem, on the one hand, from the situation, where they set the stage for action. Environmental processes are, on the other hand, located in the consequences, where feedback, opportunities for self-evaluation, and rewards indicate an action’s success or failure (Schunk & DiBenedetto, 2020 ). The listing of the individual components that make up the three interacting processes in reciprocal determinism is not always done in the same way. For example, Schunk and DiBenedetto ( 2021 ) referred to self-efficacy, cognitions, and emotions as personal factors; classroom attendance and task completion as behavioral factors; and classroom, teachers, peers, and classroom climate as environmental factors. However, this does not affect the representation of the three main classes of reciprocal determinism in the basic motivational model and opens up space for the classification of different components.

Integrating social cognitive theory into the basic motivational model

Several meta-analyses have shown that self-efficacy is moderately positively related to academic achievement (Multon et al., 1991 ; Robbins et al., 2004 ). Credé and Phillips ( 2011 ) examined several constructs of social cognitive theory based on the Motivated Strategies for Learning Questionnaire (Pintrich & De Groot, 1990 ). Control beliefs showed small positive correlations with college GPA ( r = .12) and current semester grades ( r = .14). However, of all the constructs measured, self-efficacy showed the strongest associations with GPA ( r =. 18) and grades ( r = .30). Further meta-analyses with university students supported the significant but moderate relationship between academic self-efficacy and academic achievement with correlation coefficients of r = .31 (Richardson et al., 2012 ) and r = .33 (Honicke & Broadbent, 2016 ). Sitzmann and Ely ( 2011 ) reported meta-analytic correlations of r = .18 for pre-training self-efficacy and r = .29 for self-efficacy with learning.

To further clarify the direction of the relationship, Sitzmann and Yeo ( 2013 ) conducted an insightful meta-analysis. They were able to show that self-efficacy expectations are more likely to be a product of past performance ( r = .40) than a driver of future performance ( r = .23). Talsma et al. ( 2018 ) supported these findings with a meta-analytic cross-lagged panel study. They found that prior performance exerted a stronger effect on self-efficacy (β = .21) than existing self-efficacy on subsequent performance (β = .07).

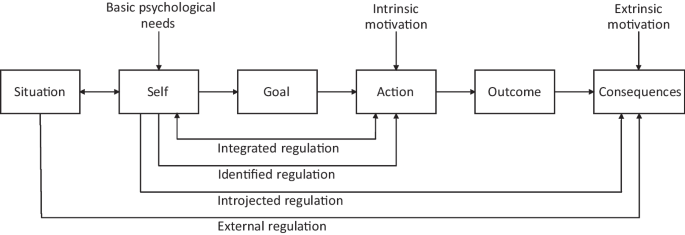

Self-Determination Theory

Self-determination theory by Deci and Ryan ( 1985 , 2000 ) is macro-theory for understanding human motivation, personality, and well-being. The theory has its roots in early explorations of the concept of intrinsic motivation (Deci, 1971 , 1975 ; Ryan & Deci, 2019 ). Self-determination is regarded as the basis for explaining intrinsically motivated behavior where the action is experienced as autonomous and does not rely on controls and reinforcers (Deci & Ryan, 1985 ). Self-determination theory provides a counterweight to expectancy-value theory and social cognitive theory, where the external incentives such as expected or real rewards to motivate behavior are still visible.

The overarching framework of self-determination theory encompasses six mini-theories: basic psychological needs theory, cognitive evaluation theory, organismic integration theory, causality orientations theory, goal contents theory, and relationship motivation theory (Ryan & Deci, 2017 ). Each mini-theory explains specific motivational phenomena that have been tested empirically (Reeve, 2012 ; Ryan & Deci, 2017 ; Vansteenkiste et al., 2010 ; see also Ryan et al., in press ). In the following explanations, we focus on the first three sub-theories with the highest popularity.

Basic psychological needs theory argues that humans are intrinsically motivated and experience well-being when their three innate basic psychological needs for autonomy, competence, and relatedness are satisfied (Conesa et al., 2022 ; Deci & Ryan, 1985 , 2000 ; Ryan & Deci, 2000a , 2000b , 2017 , 2020 ; Vansteenkiste et al., 2020 ). Autonomy refers to a sense of ownership and the need for behavior to emanate from the self. Competence concerns a person’s need to succeed, grow, and feel effective in their goal pursuits (Deci & Ryan, 2000 ; White, 1959 ). Finally, relatedness refers to establishing close emotional connections to others and a sense of belonging to significant others such as parents, teachers, or peers.

Cognitive evaluation theory describes how the social environment affects intrinsic motivation (Deci & Ryan, 1985 , 2000 ; Ryan & Deci, 2000b , 2017 , 2020 ). The mini-theory states that cognitive evaluation of external rewards impacts learners’ perception of their intrinsically motivated behavior. Rewards perceived as controlling weaken intrinsic motivation, whereas rewards providing informational feedback can strengthen acting on one’s own initiative (Deci et al., 1999 ).

Organismic integration theory focuses on the development of extrinsic motivation toward more autonomous or self-determined motivation through the process of internalization (Ryan & Deci, 2017 ). The mini-theory proposes a self-determination continuum that ranges from intrinsic motivation to amotivation, with several types of extrinsic motivation in between (Deci & Ryan, 1985 , 2000 ; Ryan & Deci, 2000a , 2000b , 2017 , 2020 ). The results from the meta-analysis by Howard et al. ( 2017 ) largely supported the continuum-like structure of self-determination theory. Intrinsically motivated individuals engage in activities because they are fun or interesting, whereas extrinsic motivation concerns all other reasons for engaging in activities. Four types of extrinsic motivation are distinguished, and two of these types are assumed to be higher in quality than the other two (Deci & Ryan, 2008 ; Ryan & Deci, 2000b ).

Integrated and identified regulations are considered high-quality autonomous, extrinsic motivation types characterized by volitional engagement in activities. Integrated regulation is the most autonomous form of extrinsic motivation. People with integrated regulation recognize and identify with the activity’s value and find it congruent with their core values and interests (e.g., attending school because it is part of who you are; see Ryan & Deci, 2020 ). In identified regulation, people identify with or personally endorse the value of the activity (e.g., doing schoolwork to learn something from it) and, therefore, experience high degrees of volition.

The other two types of extrinsic motivation are forms of controlled motivation (Deci & Ryan, 2008 ; Ryan & Deci, 2000a , 2000b ). Introjected regulation concerns partially internalized extrinsic motivation; people’s behavior is regulated by an internal pressure to feel pride or self-esteem or to avoid feelings of anxiety, shame, or guilt. Extrinsic regulation refers to behavior regulated by externally imposed rewards and punishments, such as demands from parents or teachers.