Anthony Cockerill

| Writing | The written word | Teaching English |

How to write great English literature essays at university

Essential advice on how to craft a great english literature essay at university – and how to avoid rookie mistakes..

If you’ve just begun to study English literature at university, the prospect of writing that first essay can be daunting. Tutors will likely offer little in the way of assistance in the process of planning and writing, as it’s assumed that students know how to do this already. At A-level, teachers are usually very clear with students about the Assessment Objectives for examination components and centre-assessed work, but it can feel like there’s far less clarity around how essays are marked at university. Furthermore, the process of learning how to properly reference an essay can be a steep learning curve.

But essentially, there are five things you’re being asked to do: show your understanding of the text and its key themes, explore the writer’s methods, consider the influence of contextual factors that might influence the writing and reading of the text, read published critical work about the text and incorporate this discourse into your essay, and finally, write a coherent argument in response to the task.

With advice from English teachers, HE tutors and other people who’ve been there and done it, here are the most crucial things to remember when planning and writing an essay.

Read around the subject and let your argument evolve.

‘One of the big step-ups from A-level, where students might only have had to deal with critical material as part of their coursework, is the move toward engaging with the critical debate around a text.’

Reading around the task and making notes is all important. Get familiar with the reading list. Become adept at searching for critical material in books and articles that’s not on the reading list. Talk with the librarian. Make sure you can find your way around the stacks. Get log-ins for the various databases of online criticism, such as the MLA International Bibliography .

‘Tutors are looking for flair… for students to be nuanced and creative with their ideas as opposed to reproducing the same criticism that others already have.’

When reading, keep notes, make summaries and write down useful quotations. Make sure you keep track of what you’ve read as you go. Note the publication details (author, publisher, year and place of publication). If you write down a quotation, note the page number. This will make dealing with citations and writing your bibliography much easier later on, as there’s nothing more annoying than getting to the end of the first draft of your essay and realising you’ve no idea which book or article a quote came from or which page it was on.

‘The more I read, the sharper my own writing style became because I developed an opinion of the writing style I liked and I had a clear sense of the subject matter that I was discussing.’

‘Don’t wing the reading. Or the thinking. Crap writing emerges from style over substance.’

Get to grips with the question and plan a response.

‘Brain dump at the start in the form of a mind map. This will help you focus and relax. You can add to it as go along and can shape it into a brief plan.’

Before writing a single word, brainstorm. Do some free-thinking. Get your ideas down on paper or sticky notes. Cross things out; refine. Allow your planning to be led by ideas that support your argument.

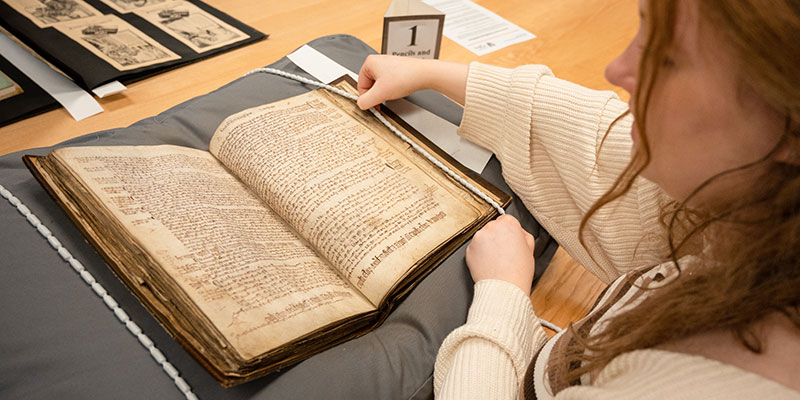

Use different colour-coded sticky notes for your planning. In the example below, the student has used yellow sticky notes for ideas, blue for language, structure and methods, purple for context and green for literary criticism, which makes planning the sequence of the essay much easier.

Structure and sequence your ideas

‘Make your argument clear in your opening paragraph, and then ensure that every subsequent paragraph is clearly addressing your thesis.’

Plan the essay by working out a sequence of your ideas that you believe to be the most compelling. Allow your ideas to serve as structural signposts. Augment these with relevant criticism, context and focus on language and style.

‘Read wide and look at different pieces of criticism of a particular work and weave that in with your own interpretation of said work.’

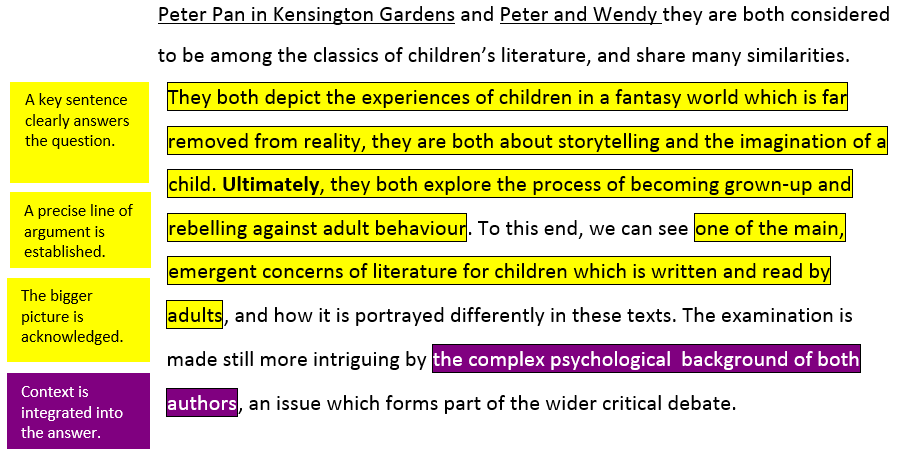

Write a great introduction.

‘By the end of the first paragraph, make sure you have established a very clear thesis statement that outlines the main thrust of the essay.’

Your introduction should make your argument very clear. It’s also a chance to establish working definitions of any problematic terms and to engage with key aspects of the wider critical debate.

Get to grips with academic style and draft the essay

‘[Write with] an ‘exploratory’ tone rather than ‘dogmatic’ one.’

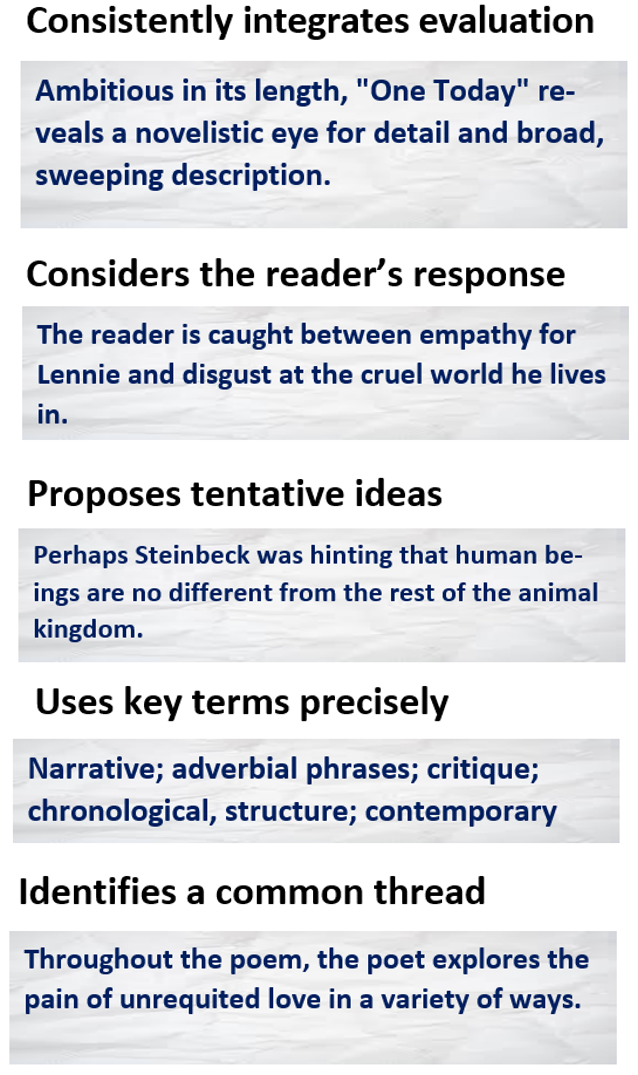

Academic writing is characterised by argument, analysis and evaluation. In an earlier post , I explored how students in high school might improve their analytical writing by adopting three maxims. These maxims are just as helpful for undergraduates. Firstly, aim for precise, cogent expression. Secondly, deliver an individual response supported by your reading – and citing – of published literary criticism. Thirdly, work on your personal voice. In formal analytical writing such as the university essay, your personal voice might be constrained rather more than it would be in a blog or a review, but it must nonetheless be exploratory in tone. Tentativity can be an asset as it suggests appreciation of nuances and alternative ways of thinking.

‘I got to grips with what was being asked of me by reading lots of literary criticism and becoming more familiar with academic writing conventions.’

Avoid unnecessary or clunky sign-post phrases such as ‘in this essay, I am going to…’ or ‘a further thing…’ A transition devices that can work really well is the explicit paragraph link, in which a motif or phrase in the last sentence of a paragraph is repeated in the first sentence of the next paragraph.

Write a killer conclusion

‘There is more emphasis on finding your own voice at university, something which in many ways is inhibited by Assessment Objectives at A-Level. I don’t think ‘good’ academic writing is necessarily taught very well in schools — at least from my experience.’

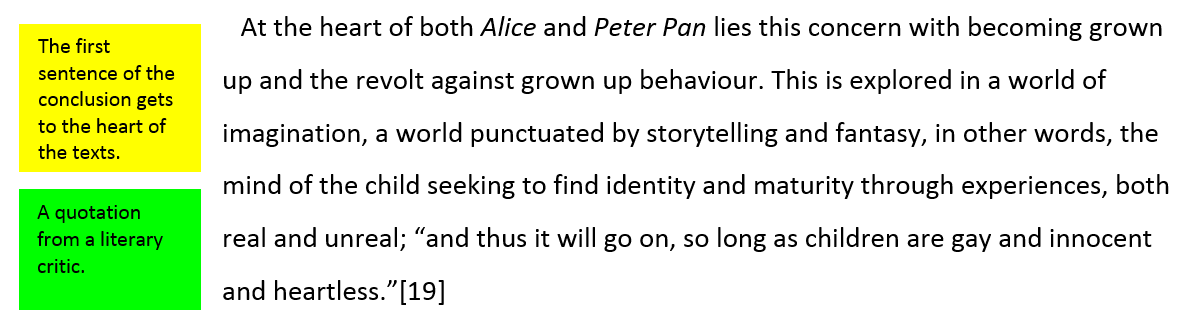

The conclusion is a really important part of your essay. It’s a chance to restate your thesis and to draw conclusions. You might achieve closure or instead, allude to interesting questions or ideas the essay has perhaps raised but not answered. You might synthesise your argument by exploring the key issue. You could zoom-out and explore the issue as part of a bigger picture.

Be meticulous in your referencing.

Having supported your argument with quotations from published critics, it’s important to be meticulous about how you reference these, otherwise you could be accused of plagiarism – passing someone else’s work off as your own. There are three broad ways of referencing: author-date, footnote and endnote. However, within each of these three approaches, there are specific named protocols. Most English literature faculties use either the MLA (Modern Languages Association of America) style or the Harvard style (variants of the author-date approach). It’s important to check what your faculty or department uses, learn how to use it (faculties invariably publish guidance, but ask if you’re unsure) and apply the rules meticulously.

‘Read your work aloud, slowly, sentence by sentence. It’s the best way to spot typos, and it allows you to hear what is awkward and/or ungrammatical. Then read the essay aloud again.’

Write with precision. Use a thesaurus to help you find the right word, but make sure you use it properly and in the right context. Read sentences back and prune unnecessary phrases or redundant words. Similarly, avoid words or phrases which might sound self-important or pompous.

Like those structural signposts that don’t really add anything, some phrases need to be omited, such as ‘many people have argued that…’ or ‘futher to the previous paragraph…’.

Finally, make sure the essay is formatted correctly. University departments are usually clear about their expectations, but font, size, and line spacing are usually stipulated along with any other information you’re expected to include in the essay’s header or footer. And don’t expect the proofing tool to pick up every mistake.

Featured image by Glenn Carstens-Peters on Unsplash

- Click to share on Twitter (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Facebook (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Pinterest (Opens in new window)

- Click to email a link to a friend (Opens in new window)

- analytical writing

- Already have a WordPress.com account? Log in now.

- Subscribe Subscribed

- Copy shortlink

- Report this content

- View post in Reader

- Manage subscriptions

- Collapse this bar

How to Write a Good English Literature Essay

By Dr Oliver Tearle (Loughborough University)

How do you write a good English Literature essay? Although to an extent this depends on the particular subject you’re writing about, and on the nature of the question your essay is attempting to answer, there are a few general guidelines for how to write a convincing essay – just as there are a few guidelines for writing well in any field.

We at Interesting Literature call them ‘guidelines’ because we hesitate to use the word ‘rules’, which seems too programmatic. And as the writing habits of successful authors demonstrate, there is no one way to become a good writer – of essays, novels, poems, or whatever it is you’re setting out to write. The French writer Colette liked to begin her writing day by picking the fleas off her cat.

Edith Sitwell, by all accounts, liked to lie in an open coffin before she began her day’s writing. Friedrich von Schiller kept rotten apples in his desk, claiming he needed the scent of their decay to help him write. (For most student essay-writers, such an aroma is probably allowed to arise in the writing-room more organically, over time.)

We will address our suggestions for successful essay-writing to the average student of English Literature, whether at university or school level. There are many ways to approach the task of essay-writing, and these are just a few pointers for how to write a better English essay – and some of these pointers may also work for other disciplines and subjects, too.

Of course, these guidelines are designed to be of interest to the non-essay-writer too – people who have an interest in the craft of writing in general. If this describes you, we hope you enjoy the list as well. Remember, though, everyone can find writing difficult: as Thomas Mann memorably put it, ‘A writer is someone for whom writing is more difficult than it is for other people.’ Nora Ephron was briefer: ‘I think the hardest thing about writing is writing.’ So, the guidelines for successful essay-writing:

1. Planning is important, but don’t spend too long perfecting a structure that might end up changing.

This may seem like odd advice to kick off with, but the truth is that different approaches work for different students and essayists. You need to find out which method works best for you.

It’s not a bad idea, regardless of whether you’re a big planner or not, to sketch out perhaps a few points on a sheet of paper before you start, but don’t be surprised if you end up moving away from it slightly – or considerably – when you start to write.

Often the most extensively planned essays are the most mechanistic and dull in execution, precisely because the writer has drawn up a plan and refused to deviate from it. What is a more valuable skill is to be able to sense when your argument may be starting to go off-topic, or your point is getting out of hand, as you write . (For help on this, see point 5 below.)

We might even say that when it comes to knowing how to write a good English Literature essay, practising is more important than planning.

2. Make room for close analysis of the text, or texts.

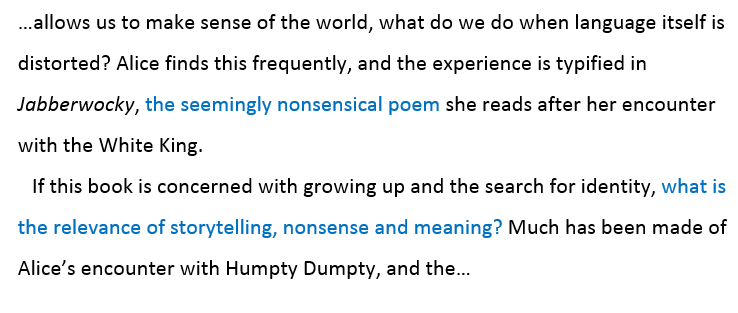

Whilst it’s true that some first-class or A-grade essays will be impressive without containing any close reading as such, most of the highest-scoring and most sophisticated essays tend to zoom in on the text and examine its language and imagery closely in the course of the argument. (Close reading of literary texts arises from theology and the analysis of holy scripture, but really became a ‘thing’ in literary criticism in the early twentieth century, when T. S. Eliot, F. R. Leavis, William Empson, and other influential essayists started to subject the poem or novel to close scrutiny.)

Close reading has two distinct advantages: it increases the specificity of your argument (so you can’t be so easily accused of generalising a point), and it improves your chances of pointing up something about the text which none of the other essays your marker is reading will have said. For instance, take In Memoriam (1850), which is a long Victorian poem by the poet Alfred, Lord Tennyson about his grief following the death of his close friend, Arthur Hallam, in the early 1830s.

When answering a question about the representation of religious faith in Tennyson’s poem In Memoriam (1850), how might you write a particularly brilliant essay about this theme? Anyone can make a general point about the poet’s crisis of faith; but to look closely at the language used gives you the chance to show how the poet portrays this.

For instance, consider this stanza, which conveys the poet’s doubt:

A solid and perfectly competent essay might cite this stanza in support of the claim that Tennyson is finding it increasingly difficult to have faith in God (following the untimely and senseless death of his friend, Arthur Hallam). But there are several ways of then doing something more with it. For instance, you might get close to the poem’s imagery, and show how Tennyson conveys this idea, through the image of the ‘altar-stairs’ associated with religious worship and the idea of the stairs leading ‘thro’ darkness’ towards God.

In other words, Tennyson sees faith as a matter of groping through the darkness, trusting in God without having evidence that he is there. If you like, it’s a matter of ‘blind faith’. That would be a good reading. Now, here’s how to make a good English essay on this subject even better: one might look at how the word ‘falter’ – which encapsulates Tennyson’s stumbling faith – disperses into ‘falling’ and ‘altar’ in the succeeding lines. The word ‘falter’, we might say, itself falters or falls apart.

That is doing more than just interpreting the words: it’s being a highly careful reader of the poetry and showing how attentive to the language of the poetry you can be – all the while answering the question, about how the poem portrays the idea of faith. So, read and then reread the text you’re writing about – and be sensitive to such nuances of language and style.

The best way to become attuned to such nuances is revealed in point 5. We might summarise this point as follows: when it comes to knowing how to write a persuasive English Literature essay, it’s one thing to have a broad and overarching argument, but don’t be afraid to use the microscope as well as the telescope.

3. Provide several pieces of evidence where possible.

Many essays have a point to make and make it, tacking on a single piece of evidence from the text (or from beyond the text, e.g. a critical, historical, or biographical source) in the hope that this will be enough to make the point convincing.

‘State, quote, explain’ is the Holy Trinity of the Paragraph for many. What’s wrong with it? For one thing, this approach is too formulaic and basic for many arguments. Is one quotation enough to support a point? It’s often a matter of degree, and although one piece of evidence is better than none, two or three pieces will be even more persuasive.

After all, in a court of law a single eyewitness account won’t be enough to convict the accused of the crime, and even a confession from the accused would carry more weight if it comes supported by other, objective evidence (e.g. DNA, fingerprints, and so on).

Let’s go back to the example about Tennyson’s faith in his poem In Memoriam mentioned above. Perhaps you don’t find the end of the poem convincing – when the poet claims to have rediscovered his Christian faith and to have overcome his grief at the loss of his friend.

You can find examples from the end of the poem to suggest your reading of the poet’s insincerity may have validity, but looking at sources beyond the poem – e.g. a good edition of the text, which will contain biographical and critical information – may help you to find a clinching piece of evidence to support your reading.

And, sure enough, Tennyson is reported to have said of In Memoriam : ‘It’s too hopeful, this poem, more than I am myself.’ And there we have it: much more convincing than simply positing your reading of the poem with a few ambiguous quotations from the poem itself.

Of course, this rule also works in reverse: if you want to argue, for instance, that T. S. Eliot’s The Waste Land is overwhelmingly inspired by the poet’s unhappy marriage to his first wife, then using a decent biographical source makes sense – but if you didn’t show evidence for this idea from the poem itself (see point 2), all you’ve got is a vague, general link between the poet’s life and his work.

Show how the poet’s marriage is reflected in the work, e.g. through men and women’s relationships throughout the poem being shown as empty, soulless, and unhappy. In other words, when setting out to write a good English essay about any text, don’t be afraid to pile on the evidence – though be sensible, a handful of quotations or examples should be more than enough to make your point convincing.

4. Avoid tentative or speculative phrasing.

Many essays tend to suffer from the above problem of a lack of evidence, so the point fails to convince. This has a knock-on effect: often the student making the point doesn’t sound especially convinced by it either. This leaks out in the telling use of, and reliance on, certain uncertain phrases: ‘Tennyson might have’ or ‘perhaps Harper Lee wrote this to portray’ or ‘it can be argued that’.

An English university professor used to write in the margins of an essay which used this last phrase, ‘What can’t be argued?’

This is a fair criticism: anything can be argued (badly), but it depends on what evidence you can bring to bear on it (point 3) as to whether it will be a persuasive argument. (Arguing that the plays of Shakespeare were written by a Martian who came down to Earth and ingratiated himself with the world of Elizabethan theatre is a theory that can be argued, though few would take it seriously. We wish we could say ‘none’, but that’s a story for another day.)

Many essay-writers, because they’re aware that texts are often open-ended and invite multiple interpretations (as almost all great works of literature invariably do), think that writing ‘it can be argued’ acknowledges the text’s rich layering of meaning and is therefore valid.

Whilst this is certainly a fact – texts are open-ended and can be read in wildly different ways – the phrase ‘it can be argued’ is best used sparingly if at all. It should be taken as true that your interpretation is, at bottom, probably unprovable. What would it mean to ‘prove’ a reading as correct, anyway? Because you found evidence that the author intended the same thing as you’ve argued of their text? Tennyson wrote in a letter, ‘I wrote In Memoriam because…’?

But the author might have lied about it (e.g. in an attempt to dissuade people from looking too much into their private life), or they might have changed their mind (to go back to the example of The Waste Land : T. S. Eliot championed the idea of poetic impersonality in an essay of 1919, but years later he described The Waste Land as ‘only the relief of a personal and wholly insignificant grouse against life’ – hardly impersonal, then).

Texts – and their writers – can often be contradictory, or cagey about their meaning. But we as critics have to act responsibly when writing about literary texts in any good English essay or exam answer. We need to argue honestly, and sincerely – and not use what Wikipedia calls ‘weasel words’ or hedging expressions.

So, if nothing is utterly provable, all that remains is to make the strongest possible case you can with the evidence available. You do this, not only through marshalling the evidence in an effective way, but by writing in a confident voice when making your case. Fundamentally, ‘There is evidence to suggest that’ says more or less the same thing as ‘It can be argued’, but it foregrounds the evidence rather than the argument, so is preferable as a phrase.

This point might be summarised by saying: the best way to write a good English Literature essay is to be honest about the reading you’re putting forward, so you can be confident in your interpretation and use clear, bold language. (‘Bold’ is good, but don’t get too cocky, of course…)

5. Read the work of other critics.

This might be viewed as the Holy Grail of good essay-writing tips, since it is perhaps the single most effective way to improve your own writing. Even if you’re writing an essay as part of school coursework rather than a university degree, and don’t need to research other critics for your essay, it’s worth finding a good writer of literary criticism and reading their work. Why is this worth doing?

Published criticism has at least one thing in its favour, at least if it’s published by an academic press or has appeared in an academic journal, and that is that it’s most probably been peer-reviewed, meaning that other academics have read it, closely studied its argument, checked it for errors or inaccuracies, and helped to ensure that it is expressed in a fluent, clear, and effective way.

If you’re serious about finding out how to write a better English essay, then you need to study how successful writers in the genre do it. And essay-writing is a genre, the same as novel-writing or poetry. But why will reading criticism help you? Because the critics you read can show you how to do all of the above: how to present a close reading of a poem, how to advance an argument that is not speculative or tentative yet not over-confident, how to use evidence from the text to make your argument more persuasive.

And, the more you read of other critics – a page a night, say, over a few months – the better you’ll get. It’s like textual osmosis: a little bit of their style will rub off on you, and every writer learns by the examples of other writers.

As T. S. Eliot himself said, ‘The poem which is absolutely original is absolutely bad.’ Don’t get precious about your own distinctive writing style and become afraid you’ll lose it. You can’t gain a truly original style before you’ve looked at other people’s and worked out what you like and what you can ‘steal’ for your own ends.

We say ‘steal’, but this is not the same as saying that plagiarism is okay, of course. But consider this example. You read an accessible book on Shakespeare’s language and the author makes a point about rhymes in Shakespeare. When you’re working on your essay on the poetry of Christina Rossetti, you notice a similar use of rhyme, and remember the point made by the Shakespeare critic.

This is not plagiarising a point but applying it independently to another writer. It shows independent interpretive skills and an ability to understand and apply what you have read. This is another of the advantages of reading critics, so this would be our final piece of advice for learning how to write a good English essay: find a critic whose style you like, and study their craft.

If you’re looking for suggestions, we can recommend a few favourites: Christopher Ricks, whose The Force of Poetry is a tour de force; Jonathan Bate, whose The Genius of Shakespeare , although written for a general rather than academic audience, is written by a leading Shakespeare scholar and academic; and Helen Gardner, whose The Art of T. S. Eliot , whilst dated (it came out in 1949), is a wonderfully lucid and articulate analysis of Eliot’s poetry.

James Wood’s How Fiction Works is also a fine example of lucid prose and how to close-read literary texts. Doubtless readers of Interesting Literature will have their own favourites to suggest in the comments, so do check those out, as these are just three personal favourites. What’s your favourite work of literary scholarship/criticism? Suggestions please.

Much of all this may strike you as common sense, but even the most commonsensical advice can go out of your mind when you have a piece of coursework to write, or an exam to revise for. We hope these suggestions help to remind you of some of the key tenets of good essay-writing practice – though remember, these aren’t so much commandments as recommendations. No one can ‘tell’ you how to write a good English Literature essay as such.

But it can be learned. And remember, be interesting – find the things in the poems or plays or novels which really ignite your enthusiasm. As John Mortimer said, ‘The only rule I have found to have any validity in writing is not to bore yourself.’

Finally, good luck – and happy writing!

And if you enjoyed these tips for how to write a persuasive English essay, check out our advice for how to remember things for exams and our tips for becoming a better close reader of poetry .

Discover more from Interesting Literature

Subscribe to get the latest posts to your email.

Type your email…

30 thoughts on “How to Write a Good English Literature Essay”

You must have taken AP Literature. I’m always saying these same points to my students.

I also think a crucial part of excellent essay writing that too many students do not realize is that not every point or interpretation needs to be addressed. When offered the chance to write your interpretation of a work of literature, it is important to note that there of course are many but your essay should choose one and focus evidence on this one view rather than attempting to include all views and evidence to back up each view.

Reblogged this on SocioTech'nowledge .

Not a bad effort…not at all! (Did you intend “subject” instead of “object” in numbered paragraph two, line seven?”

Oops! I did indeed – many thanks for spotting. Duly corrected ;)

That’s what comes of writing about philosophy and the subject/object for another post at the same time!

Reblogged this on Scribing English .

- Pingback: Recommended Resource: Interesting Literature.com & how to write an essay | Write Out Loud

Great post on essay writing! I’ve shared a post about this and about the blog site in general which you can look at here: http://writeoutloudblog.com/2015/01/13/recommended-resource-interesting-literature-com-how-to-write-an-essay/

All of these are very good points – especially I like 2 and 5. I’d like to read the essay on the Martian who wrote Shakespeare’s plays).

Reblogged this on Uniqely Mustered and commented: Dedicate this to all upcoming writers and lovers of Writing!

I shall take this as my New Year boost in Writing Essays. Please try to visit often for corrections,advise and criticisms.

Reblogged this on Blue Banana Bread .

Reblogged this on worldsinthenet .

All very good points, but numbers 2 and 4 are especially interesting.

- Pingback: Weekly Digest | Alpha Female, Mainstream Cat

Reblogged this on rainniewu .

Reblogged this on pixcdrinks .

- Pingback: How to Write a Good English Essay? Interesting Literature | EngLL.Com

Great post. Interesting infographic how to write an argumentative essay http://www.essay-profy.com/blog/how-to-write-an-essay-writing-an-argumentative-essay/

Reblogged this on DISTINCT CHARACTER and commented: Good Tips

Reblogged this on quirkywritingcorner and commented: This could be applied to novel or short story writing as well.

Reblogged this on rosetech67 and commented: Useful, albeit maybe a bit late for me :-)

- Pingback: How to Write a Good English Essay | georg28ang

such a nice pieace of content you shared in this write up about “How to Write a Good English Essay” going to share on another useful resource that is

- Pingback: Mark Twain’s Rules for Good Writing | Interesting Literature

- Pingback: How to Remember Things for Exams | Interesting Literature

- Pingback: Michael Moorcock: How to Write a Novel in 3 Days | Interesting Literature

- Pingback: Shakespeare and the Essay | Interesting Literature

A well rounded summary on all steps to keep in mind while starting on writing. There are many new avenues available though. Benefit from the writing options of the 21st century from here, i loved it! http://authenticwritingservices.com

- Pingback: Mark Twain’s Rules for Good Writing | Peacejusticelove's Blog

Comments are closed.

Subscribe now to keep reading and get access to the full archive.

Continue reading

You are using an outdated browser. This site may not look the way it was intended for you. Please upgrade your browser to improve your experience and security.

London School of Journalism

- Tel: +44 (0) 20 7432 8140

- [email protected]

- Student log in

Search courses

English literature essays, an english literature essay archive, written by our students, with subjects ranging from shakespeare to artistotle, and from dickens to hemingway, essay subjects in alphabetical order:.

- Aristotle: Poetics

Margaret Atwood

Margaret atwood 'gertrude talks back'.

- Matthew Arnold

John Bunyan: The Pilgrim's Progress and Geoffrey Chaucer: The Canterbury Tales

- Jonathan Bayliss

- Lewis Carroll, Samuel Beckett

- Saul Bellow and Ken Kesey

- Castiglione: The Courtier

- Joseph Conrad: Heart of Darkness

- Kate Chopin: The Awakening

- T S Eliot, Albert Camus

- Charles Dickens

- John Donne: Love poetry

- John Dryden: Translation of Ovid

- T S Eliot: Four Quartets

- Henry Fielding

- William Faulkner: Sartoris

- Graham Greene: Brighton Rock

- Ibsen, Lawrence, Galsworthy

- Jonathan Swift and John Gay

- Oliver Goldsmith

- Ernest Hemingway

- Nathaniel Hawthorne: The Scarlet Letter

Thomas Hardy: Tess of the d'Urbervilles

- Carl Gustav Jung

James Joyce: A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man

- Jon Jost: American independent film-maker

- Jamaica Kincaid, Merle Hodge, George Lamming

- Rudyard Kipling: Kim

- D. H. Lawrence: Women in Love

Henry Lawson: 'Eureka!'

- Ian McEwan: The Cement Garden

- Jennifer Maiden: The Winter Baby

- Machiavelli: The Prince

- Toni Morrison: Beloved and Jazz

R K Narayan

- R K Narayan: The English Teacher

- R K Narayan: The Guide

- Alexander Pope: The Rape of the Lock

- Brian Patten

- Harold Pinter

- Sylvia Plath and Alice Walker

Jean Rhys: Wide Sargasso Sea. Charlotte Bronte: Jane Eyre

- Edmund Spenser: The Faerie Queene

- Shakespeare: Antony and Cleopatra

- Shakespeare: Coriolanus

- Shakespeare: Hamlet

- Shakespeare: Measure for Measure

Shakespeare: Shakespeare's Women

Shakespeare: the winter's tale and the tempest.

- Shakespeare: Twelfth Night

- Sir Philip Sidney: Astrophil and Stella

- Tom Stoppard

William Styron: Sophie's Choice

- William Wordsworth

Miscellaneous

- Alice, Harry Potter and the computer game

Indian women's writing

- New York! New York!

- Photography and the New Native American Aesthetic

- Renaissance poetry

- Renaissance tragedy and investigator heroes

- Romanticism

- Studying English Literature

- The Age of Reason

- The author, the text, and the reader

- The Spy in the Computer

- What is literary writing?

- Margaret Atwood: Bodily Harm and The Handmaid's Tale

- Margaret Atwood 'Gertrude Talks Back'

- John Bunyan: The Pilgrim's Progress and Geoffrey Chaucer: The Canterbury Tales

- Thomas Hardy: Tess of the d'Urbervilles

- James Joyce: A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man: Will McManus

- James Joyce: A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man: Ian Mackean

- James Joyce: A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man: Ben Foley

- Henry Lawson: 'Eureka!'

- R K Narayan's vision of life

- Jean Rhys: Wide Sargasso Sea. Charlotte Bronte: Jane Eyre: Doubles

- Jean Rhys: Wide Sargasso Sea. Charlotte Bronte: Jane Eyre: Symbolism

- Shakespeare: Shakespeare's Women

- Shakespeare: The Winter's Tale and The Tempest

- William Styron: Sophie's Choice

- William Wordsworth and Lucy

- Indian women's writing

Essay and dissertation writing skills

Planning your essay

Writing your introduction

Structuring your essay

- Writing essays in science subjects

- Brief video guides to support essay planning and writing

- Writing extended essays and dissertations

- Planning your dissertation writing time

Structuring your dissertation

- Top tips for writing longer pieces of work

Advice on planning and writing essays and dissertations

University essays differ from school essays in that they are less concerned with what you know and more concerned with how you construct an argument to answer the question. This means that the starting point for writing a strong essay is to first unpick the question and to then use this to plan your essay before you start putting pen to paper (or finger to keyboard).

A really good starting point for you are these short, downloadable Tips for Successful Essay Writing and Answering the Question resources. Both resources will help you to plan your essay, as well as giving you guidance on how to distinguish between different sorts of essay questions.

You may find it helpful to watch this seven-minute video on six tips for essay writing which outlines how to interpret essay questions, as well as giving advice on planning and structuring your writing:

Different disciplines will have different expectations for essay structure and you should always refer to your Faculty or Department student handbook or course Canvas site for more specific guidance.

However, broadly speaking, all essays share the following features:

Essays need an introduction to establish and focus the parameters of the discussion that will follow. You may find it helpful to divide the introduction into areas to demonstrate your breadth and engagement with the essay question. You might define specific terms in the introduction to show your engagement with the essay question; for example, ‘This is a large topic which has been variously discussed by many scientists and commentators. The principal tension is between the views of X and Y who define the main issues as…’ Breadth might be demonstrated by showing the range of viewpoints from which the essay question could be considered; for example, ‘A variety of factors including economic, social and political, influence A and B. This essay will focus on the social and economic aspects, with particular emphasis on…..’

Watch this two-minute video to learn more about how to plan and structure an introduction:

The main body of the essay should elaborate on the issues raised in the introduction and develop an argument(s) that answers the question. It should consist of a number of self-contained paragraphs each of which makes a specific point and provides some form of evidence to support the argument being made. Remember that a clear argument requires that each paragraph explicitly relates back to the essay question or the developing argument.

- Conclusion: An essay should end with a conclusion that reiterates the argument in light of the evidence you have provided; you shouldn’t use the conclusion to introduce new information.

- References: You need to include references to the materials you’ve used to write your essay. These might be in the form of footnotes, in-text citations, or a bibliography at the end. Different systems exist for citing references and different disciplines will use various approaches to citation. Ask your tutor which method(s) you should be using for your essay and also consult your Department or Faculty webpages for specific guidance in your discipline.

Essay writing in science subjects

If you are writing an essay for a science subject you may need to consider additional areas, such as how to present data or diagrams. This five-minute video gives you some advice on how to approach your reading list, planning which information to include in your answer and how to write for your scientific audience – the video is available here:

A PDF providing further guidance on writing science essays for tutorials is available to download.

Short videos to support your essay writing skills

There are many other resources at Oxford that can help support your essay writing skills and if you are short on time, the Oxford Study Skills Centre has produced a number of short (2-minute) videos covering different aspects of essay writing, including:

- Approaching different types of essay questions

- Structuring your essay

- Writing an introduction

- Making use of evidence in your essay writing

- Writing your conclusion

Extended essays and dissertations

Longer pieces of writing like extended essays and dissertations may seem like quite a challenge from your regular essay writing. The important point is to start with a plan and to focus on what the question is asking. A PDF providing further guidance on planning Humanities and Social Science dissertations is available to download.

Planning your time effectively

Try not to leave the writing until close to your deadline, instead start as soon as you have some ideas to put down onto paper. Your early drafts may never end up in the final work, but the work of committing your ideas to paper helps to formulate not only your ideas, but the method of structuring your writing to read well and conclude firmly.

Although many students and tutors will say that the introduction is often written last, it is a good idea to begin to think about what will go into it early on. For example, the first draft of your introduction should set out your argument, the information you have, and your methods, and it should give a structure to the chapters and sections you will write. Your introduction will probably change as time goes on but it will stand as a guide to your entire extended essay or dissertation and it will help you to keep focused.

The structure of extended essays or dissertations will vary depending on the question and discipline, but may include some or all of the following:

- The background information to - and context for - your research. This often takes the form of a literature review.

- Explanation of the focus of your work.

- Explanation of the value of this work to scholarship on the topic.

- List of the aims and objectives of the work and also the issues which will not be covered because they are outside its scope.

The main body of your extended essay or dissertation will probably include your methodology, the results of research, and your argument(s) based on your findings.

The conclusion is to summarise the value your research has added to the topic, and any further lines of research you would undertake given more time or resources.

Tips on writing longer pieces of work

Approaching each chapter of a dissertation as a shorter essay can make the task of writing a dissertation seem less overwhelming. Each chapter will have an introduction, a main body where the argument is developed and substantiated with evidence, and a conclusion to tie things together. Unlike in a regular essay, chapter conclusions may also introduce the chapter that will follow, indicating how the chapters are connected to one another and how the argument will develop through your dissertation.

For further guidance, watch this two-minute video on writing longer pieces of work .

Systems & Services

Access Student Self Service

- Student Self Service

- Self Service guide

- Registration guide

- Libraries search

- OXCORT - see TMS

- GSS - see Student Self Service

- The Careers Service

- Oxford University Sport

- Online store

- Gardens, Libraries and Museums

- Researchers Skills Toolkit

- LinkedIn Learning (formerly Lynda.com)

- Access Guide

- Lecture Lists

- Exam Papers (OXAM)

- Oxford Talks

Latest student news

CAN'T FIND WHAT YOU'RE LOOKING FOR?

Try our extensive database of FAQs or submit your own question...

Ask a question

How to Write an English Literature Essay?

In A-Level , GCSE by Think Student Editor August 26, 2022 Leave a Comment

Writing an English literature essay can be very stressful, especially if you have never had to write an essay for this subject before. The many steps and parts can be hard to understand, making the whole process feel overwhelming before you even start. As an English literature student, I have written many essays before, and remember how hard it felt at the start. However, I can assure you that this gets far easier with practice, and it even becomes fun! In this article, I will give you tips and tricks to write the best essay you can. As well as a simple step-by-step guide to writing one that will simplify the process.

Writing an English literature essay has 3 main parts: planning, writing and editing. Planning is the most important, as it allows you to clearly structure your essay so that it makes logical sense. After you have planned, write the essay, including an introduction, 3-4 main points/paragraphs, and a conclusion. Then check through the spelling and grammar of your essay to ensure it is readable and has hit all of your assessment objectives.

While this short explanation of the process should have given you an idea of how to write your essay, for key tips and tricks specific to English literature please read on!

Table of Contents

How to plan an English literature essay?

The most important thing in any English essay is the structure. The best way to get a logical and clear structure which flows throughout the essay is to plan before you start . A plan should include your thesis statement, 3-4 main paragraph points, key context and quotes to relate to.

A common way of structuring a plan is in the TIPE method. This involves planning each of your main points and sections on a few lines, in the structure of the main essay, making it easy to write out. Always highlight the key word in the question before you start planning, then also annotate any given extracts for ideas. If you have an extract, the main focus of your essay should be on that.

Planning should take around 10-15 minutes of your exam time for essay questions. This sounds like a lot, but it saves you time later on in writing, making it well worth the effort at the start of an exam.

Start each plan with a mind map of your key moments, quotes, context and ideas about the exam question theme, character, or statement. This helps you get all of your ideas down and figure out which are best. It also creates a bank to come back to later if you have extra time and want to write more.

Once you have created your mind map, find a thesis statement related to the question that you have 3-4 main points to support. It can be tempting to write lots of points, but remember, quality is always better than quantity in English Literature essays.

A useful method to help you plan is by creating a TIPE plan. With the following bullet points, you can now begin your own TIPE plan.

- Introduction

- Points – you should have 3-4 key paragraphs in your essay, including relevant quotes with analysis (and techniques the author is using) and context for each point

- Ending – conclusion

How to write an English literature essay introduction?

Depending on what level of literature essay you are writing, you will need different parts and depths of content . However, one thing that stays fairly consistent is the introduction. Introductions should hook the reader , literally “introducing” them to your essay and writing style, while also keeping them interested in reading on.

Some people find it difficult to write introductions, often because they have not already got into the feeling of the essay. For this, leaving space at the top of the page to write the introduction after you finish the rest of the essay is a great way to ensure your introduction is top quality. Writing essays out of order is ok, as long as you can still make them flow in a logical way.

The first line of any introduction should provide the focus for the whole essay. This is called a thesis statement and defines to the examiner exactly what you will “prove” throughout your essay, using quotes and other evidence. This thesis statement should always include the focus word from the question, linked to the view you will be arguing.

For example, “Throughout Macbeth, Power is presented by Shakespeare as a dangerously addictive quality.” This statement includes the play (or book/poem) title, the theme (or other element, such as the name of a character) stated in the question, and the focus (addiction to power). These qualities clearly show the examiner what to expect, as well as helping you structure your essay.

The rest of the introduction should include a brief note on some context related to the theme or character in question, as well as a very brief summary of your main paragraph points, of which there should be 3-4. This is unique to each essay and text and should be brief points that you elaborate on later.

How to structure an English literature essay?

As already discussed, the plan is the most important part of writing an English literature essay. However, once you start writing, the structure of your essay is key to a succinct and successful argument.

All essays should have an introduction with a thesis statement, 3-4 main points, and a conclusion.

The main part of your essay, and the most important, is the 3-4 main points you use to support your thesis. These should each form one paragraph, with an opening and a conclusion, almost like a mini essay within the main one. These paragraphs can be hard to structure, so many students choose to use the PETAL method.

PETAL paragraphs involve all of the key elements you need to get top marks in any English literature essay: Point, Evidence, Techniques, Analysis and Link.

The point should be the opening of the paragraph, stating what you are looking at within that section, related to your thesis, for example, “Shakespeare uses metaphors to show how the pursuit of power makes Macbeth obsessive and tyrannical”. Then, use a key moment in the play to illustrate the point, with a quote.

Choosing quotes is hard, but remember, quotes that are short and directly related to your thesis are best. Once you have chosen a quote, analyse it in relation to your point, then link to the question. You should also include some context and, at A-Level, different viewpoints or critics.

After these points, you should always include a conclusion. Restate your thesis, introduction and each point, but do not introduce new ideas. Explain and link these points by summarising them, then give your overall idea on the question.

If you have time, including a final sentence about wider social impacts or an overarching moral from the book is a good way to show a deep and relevant understanding of the text, impressing the examiner.

How to write an English literature essay for GCSE?

Marking for GCSE English Literature essays is done based on 4 assessment objectives. These are outlined in the table below. These are the same across all exam boards.

If you follow the structure outlined above, you should easily hit all of these AOs. The first two are the most important, and carry the most points in exams, however the others are what will bring your grade up to the best you can, so remember to include them too.

Context, or AO3, should be used whenever it is relevant to your argument. However, it is always better to include less context points on this than to try and add random bits everywhere, as this will break the flow of your essay, removing AO1 marks. For more information about the assessment objectives for GCSE English Literature, check out this governmental guide .

For more information on GCSEs, and whether you have to take English literature, please read this Think Student guide.

How do you write an English literature essay for A-Level?

Similarly, to GCSE, all A-Level papers are marked on a set of assessment objectives which are also set by Ofqual, so are the same for all exam boards. There are more than at GCSE, as A-Level essays must be in greater depth, and as such have more criteria to mark on. The table below shows the assessment objectives.

AO1 and AO2 are very similar to GCSE, however the writing needed to achieve top marks in them is much harder to reach. It must be very detailed and have a clear, distinct style to reach high marks. These skills are developed through practice, so writing lots of essays over your course will help you to gain the highest marks you can here.

AO3 and AO4 often go together, as literary and historical contexts. AO3 is again similar to GCSE, but in more depth. However, AO4 is new, and involves wider reading around your texts. Links to texts from the same author, time period, or genre make good comparisons, and you only need to make one or two to get the marks in this section.

AO5 is also one of the harder sections, which involves considering interpretations of the text that may not have been your first thought, and that you may not agree with. This can elevate your essay to much higher marks if you can achieve them.

One of the best ways to get AO5 marks is to look at critics of the book you are studying. These are academic views, and to remember quotes from them to put in when they are relevant. For more information about the assessment objectives for A-Level English Literature, check out this guide by AQA.

Which GCSE and A-Level English Literature papers have essay questions?

All GCSE and A-Level English Literature papers will have at least one essay question. Essay questions are usually the longest answers in the paper. However, sometimes other questions may require an essay style format but shorter. The exact structure of the exam paper and where essay questions are will depend on which exam board your GCSE or A-Level qualification is with .

GCSE English Literature paper 1 usually requires 2 essays . Each question in this paper is an essay, and each has an extract to be based around, so focussing your analysis on that extract is the easiest way to get marks.

The marks for these essays vary depending on exam board . However, as they are assessed on the objectives above, you don’t need to think too much about the marks, as it does not work in the same way as other subjects with a mark per point made. Instead, essays are marked cumulatively based on the general level of discussion achieved.

GCSE English Literature paper 2 usually requires 3 essays , one in each section. Sections A and B are an essay each, without an extract, then section C involves a shorter essay on unseen poetry and a short answer question. This type of question is harder, as you have to really know the book you are studying in order to get a good mark and include enough quotes.

A-Level English Literature is based entirely on essay questions. The questions are based on poetry, novels and plays, some seen and some unseen. About half of the essays have an accompanying extract, however you are expected to have very good knowledge of your texts even for extract questions, so do not rely on extracts for quotes and marks.

The information above is mainly based of the AQA exam papers, which you can find the specifications to for GCSE and A-Level by clicking here and here respectively. While this is mainly based of AQA, the exam boards all have rather similar structures and so you will still be able to use this information to get a rough idea.

Top tips for writing the best essay you can in English literature

This section will provide you with some tips to help you with your English literature essay writing. I recommend you also check out this Think Student article on how to revise for English literature. Now without further hesitation, lets jump into them.

Focus on the structure of your English literature essay

A logical and clear structure is key to allowing your essay to stand out to an examiner. They read hundreds of essays, so a good structure will let your creative analysis shine in a way that makes sense and is clear, as well as not confusing them.

The arguments you make in the essay should be coherent, directly linked to the question, and to each other. The easiest way to do this is to ensure you properly plan before you start writing , and to use the acronyms above to make the process as easy as possible in the exam.

Always use examples and quotes in your English literature essay

For every paragraph you need to have at least 1, if not more quotes and references to sections of the text . Ensure that every example you use is directly relevant to your point and to the question. For example, if you have a question about a character in the play, you should use quotes from or about them, rather than quotes about other things.

These quotes should always be analysed in detail, however, so do not use more than you can really look at within the time limit. Always aim for quality over quantity.

Leave time to edit and re-read your English literature essay

After you are finished writing, go back and re-read your essay from start to finish as many times as you can within the exam time limit. Focus first on grammar and spelling mistakes, then on general flow and coherency. If you notice that you have gone off topic, remove the sentence if you can, or edit it to be relevant.

Remember, the most important thing in the exam is that your text makes sense to the reader , so use concise, subject specific terminology, but not unnecessarily. You do not need to memorise big technical words to get good marks, as long as you can say what you mean.

Read other people’s English literature essays

One of the least understood tips for getting good marks at GCSE, A-Level and beyond is to read other people’s essays . Some students feel like reading exemplar essays or essays their classmates have written is cheating, or that it would be stealing their ideas to read their essay. However, this is not the case.

Reading someone else’s essay is a great way to begin to evaluate your own writing. By marking essays or reading others and making mental notes about them, you can begin to apply the same principals to your own essays, as well as improving your writing overall.

Look at how they use quotes, their structure, their main points and their thesis, and compare them to how you write, and to the assessment objectives. Look at their analysis and whether their writing makes sense. This sort of analysis does not involve stealing ideas, but instead learning how best to structure your writing and create an individual style , learning from both good and bad essays.

You should also read widely around your texts in general. Read as much as you can, both texts related and unrelated to the ones you read in class, to gain a wide picture of literature. This will help you in unseen prose, but also widen your vocabulary overall, which in turn will improve your essays.

For more information on why reading is so important for students, please read this Think Student guide.

Trinity College launched the Gould Prize for Essays in English Literature in 2013. This is an annual competition for Year 12 or Lower 6th students. The Prize has been established from a bequest made by Dr Dennis Gould in 2004 for the furtherance of education in English Literature. This Essay Prize has the following aims. First, to encourage talented students with an interest in English Literature to explore their reading interests further in response to questions about the subject. Second, to encourage students with an interest in literature to apply for a University course in English. Finally, to recognise the achievements of high-calibre students from whatever background they may come, as well as the achievements of those who teach them.

Candidates are invited each year to submit an essay of between 1,500 and 2,500 words in answer to a question from our list.

Candidates must write their essays entirely on their own: that is, without help from their school or from artificial intelligence. Your essay should represent your most ambitious, original, and imaginative critical work. We are not looking for submissions in creative writing. We also expect a close engagement with the prompt. Essays can be written on all works of literature composed originally in the English language, from anywhere in the world. Also eligible are all works of literature originally written in the British Isles in any other language (e.g.. Welsh, Scottish Gaelic, Scots, Irish, French, Latin, Greek, etc). Excluded are works from beyond the British Isles that were not originally written in English (e.g. Leo Tolstoy’s Anna Karenina ).

The list of questions for the 2024 competition can be found here .

The deadline is 12 noon UK time on 1 August 2024; late submissions cannot be accepted. Results will be announced around mid-September.

The competition carries a First Prize of £600, to be split equally between the candidate and his or her school or college, and a Second Prize of £400, which again is to be shared equally between the candidate and his or her school or college. The school or college’s portion of each prize will be issued in the form of book tokens with which to buy books of or about English literature (under the broad definition set out above). In addition, further deserving essays of a high quality will receive high commendations or commendations. Authors of prize-winning and highly commended essays will be invited to visit the College.

About your school

Past gould prize-winners.

First Prize: Hazel Morpurgo (Colyton Grammar School) Second Prize: Livia Ursini Parker (North London Collegiate School)

Joint First Prize: Ruby Deakin (High Storrs School, Sheffield) Naomika Saran (The Shri Ram School, India)

First Prize: Mr L Beevers (Heckmondwike Grammar School) Second Prize: Miss E Connor (Kings Norton Girls’ School)

First Prize: Miss M Wu (Wellington College) Second Prize: Miss Crosbie-Chen (Westminster School)

First Prize: Miss E McNeill (Notting Hill & Ealing High School) Second Prize: Miss J Cartwright (St Aidan’s and St John Fisher’s Associated Sixth Form)

First Prize: Mr B Jureidini (Esher College) Second Prize: Miss E Laurence (South Hampstead High School)

First Prize: Miss H Smith (Chelmsford County High School for Girls) Second Prize: Mr C Graff (University College School, London)

First Prize: Miss M Little (Bexhill College) Second Prize: Miss M Abdel-Razek (Wimbledon High School)

Joint First Prize: Miss M Benham (King Edward VI Five Ways School, Birmingham) Mr E Patel (Merchant Taylor’s School, Northwood)

Joint First Prize: Miss A Cattley (Saffron Walden County High School) Miss E Cavell (St Paul’s Girls’ School)

First Prize: Miss E Franklin (King Edward’s Sixth Form College, Stourbridge) Second Prize: Miss J Simms (Greenhead College, Huddersfield)

- Share on Twitter

- Share on Facebook

- Share on LinkedIn

- Share via email

- previous post: Essay Prizes and Competitions

- next post: Linguistics Essay Prize

Access and Outreach Hub

Privacy overview.

Rupert Swallow

"How can we know the dancer from the dance?"

English at University

I loved studying English literature and below you’ll find some of the better English Literature essays I wrote while at Durham University between 2015 and 2018. Enjoy!

First time to the site? Start here

I’ve put these here to help give an idea of what a ‘good’ English essay might look like at university. Hopefully this is useful, particularly for those just starting at University since it’s unfortunately uncommon to see written work by other students and the step up from A levels to University can seem quite daunting.

They are by no means model essays or ‘right’ answers (reading them back I’ve noticed some of the paragraphs are a bit long) but should certainly give you a good idea of what a full-length, First Class piece of undergraduate work looks like. Please take my referencing and bibliographies with a pinch of salt (particularly the earlier ones!) In the unlikely event that you want to quote me in your own work, please reference appropriately.

English Literature essays

- You might also be interested in my 14-part series on writing a dissertation .

Learning and productivity

6 months later: Learning Japanese

6 Months in Japan: a travel guide

AlphaGo and the Future of Games

Make a one-time donation.

Choose an amount

Share this:

- Click to share on Twitter (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on LinkedIn (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on WhatsApp (Opens in new window)

- Click to email a link to a friend (Opens in new window)

- Already have a WordPress.com account? Log in now.

- Subscribe Subscribed

- Copy shortlink

- Report this content

- View post in Reader

- Manage subscriptions

- Collapse this bar

- Study with us

- Your application to university

- Undergraduate degrees

- Integrated foundation years

- Postgraduate degrees

- Higher and degree apprenticeships

- Professional courses

- Short courses

- Student life

- Discover Gloucestershire

- Accommodation

- Your Future Plan

- Students’ Union

- Student Support

- Equity, diversity and inclusion

- Student finance

- Mature students

- Talk to a student

- International

- In your country

- English language courses and testing

- Visas and immigration

- International student support

- Research priority areas

- Research Excellence Framework

- Postgraduate research degrees

- Research repository

- Countryside and Community Research Institute

- How to find us

- Our campuses

- Campus visits

- Offer holder days

- Virtual tours

- Outreach and widening participation

- Business and employers

- Short courses for business

- Venue and facilities hire

- The Growth Hub

- Knowledge transfer partnerships

- Procurement

- Achievements and awards

- Academic schools

- Upcoming events

- Governance and structure

- Our facilities

- Latest news

- Accessibility

English Literature BA (Hons)

Course options.

- Apply for this course

Entry requirements

Course modules.

- Teaching staff

What is English Literature BA (Hons)?

Discover the power to transform yourself and society by studying English Literature at University of Gloucestershire, where the exceptional level of support helps you achieve everything you’re capable of. With no exams, small classes, a personal tutor and a warm and friendly teaching approach, you’ll have every chance to shine academically and have a fantastic experience at the same time.

Our English & Creative Writing courses are ranked in the top 20 in the UK overall by the Guardian University Guide 2023, and our English courses are ranked 11th in the UK for student satisfaction by the Complete University Guide 2024.

The classes are fascinating – you’ll gain deep insight into yourself, your culture and the society you live in, while exploring some of the greatest works ever written in the English language. Your journey will take you into the distant past, exploring some of the myths and legends that lie deep in our consciousness, and then through the eighteenth, nineteenth and twentieth centuries with works that shape the world around us.

In twenty-first century literature, you will discover transgressive texts that rock the foundations of society and allow new ways of thinking and being to emerge. The journey extends beyond these shores as you study travel writing, contemporary American Literature or Irish writing.

To develop your understanding, you will learn powerful techniques for analysing language, from features of historical English to the rhetorical devices that give literature its power to inspire and persuade.

Study style

Modules such as Professional and Critical Writing and Communication and Leadership enable you to develop skills to impress future employers and to lead to your dream career. English Literature at University of Gloucestershire provides a supportive environment to study, a transformative academic journey and a pathway to a meaningful life and career.

The course is primarily taught in small group seminars where students are actively involved in discussions and class activities. Assessment is entirely by coursework and consists of essays, a 9,000 word dissertation, and some creative tasks such as designing posters or making digital stories. You’ll be supported with your own Personal Tutor and one-to-one help with essay writing.

Get English Literature BA (Hons) course updates and hear more about studying with us.

96 – 112 UCAS tariff points, CCC – BBC at A levels, MMM – DMM at BTEC or a Merit in your T-Level.

If you are unsure whether we could make you an offer or you have any questions, just get in touch with our admissions team who will be able to advise you.

English Language or Literature and Maths Grade 4/C in GCSE (or equivalent) are normally required.

This course is available with an additional integrated foundation year. This four year option has lower entry requirements – see below – than the other study type/s available.

Typical offers 48 UCAS tariff points, DD at A levels, PPP at BTEC or a Pass in your T Level.

GCSEs Grade C/4 in English Language/Literature and Mathematics, or equivalent (e.g. Level 2 Functional Skills).

To apply for the integrated foundation year degree, select the ‘With foundation year’ option from the study types listed at the top of this page before clicking ‘Apply’.

See course overview for more information about the interated foundation year option.

We welcome applications from mature students (aged 21 and over) and do not necessarily require the same academic qualifications as school leaving applicants, although some entry requirements may still apply for Professionally Accredited Courses. We accept Access to Higher Education Diplomas and make offers on an individual basis.

Please read the entry requirements for your country – and contact our admissions team if you have questions.

You're viewing course modules for the course option. Choose a different course option to see corresponding course modules.

Here's an example of the types of modules you'll study (the contents and structure of the course are reviewed occasionally, but it is unlikely that there will be significant change).

Module information is not available for this programme.

Fees and costs

You're viewing fees for the course option. Choose a different course option to see corresponding course fees.

Ready to apply?

Uog career promise.

At UoG we create a climate for bravery and growth. We instil confidence in all our students, so you can graduate career-ready and meet your ambitions.

96% of our graduates are in work or further study* , but if you’re not in a job 6 months after graduating we’ll guarantee you 6 months of free support, followed by the offer of a paid internship to kickstart your career – plus we’ll commit to lifetime career coaching. Eligibility conditions apply**

The University has links with the Cheltenham Literature Festival, the Cheltenham Poetry Festival, the Wilson Gallery, the Everyman Theatre, published authors and poets, and many other providers of cultural services.

You’ll have opportunities to undertake internships, creative projects and communication workshops to gain skills and build your CV. With these connections, skills, and experience you’ll graduate career-ready.

Graduates from this course can on to work in management and leadership, cultural industries, corporate and charity communications, lecturing and teaching (after completing teacher training), civil service, publishing, television & journalism and education.

Teaching Staff

Sorry there are no available teaching staff at this time.

Explore the role of literature in shaping the world around us

Gain insight into key issues such as gender, sexuality, class, race and climate change by studying the classic literary works that have shaped our society and transgressive contemporary literature which is trying to reshape it.

Enjoy the culture of Cheltenham

Cheltenham is home to more than thirty festivals including the world-famous Literature Festival and Poetry Festival. Students have the opportunity to take part in festivals in many ways from attending inspirational talks to reading their own creative pieces or actually working for the festivals.

Taught by acclaimed academics

All the staff who will teach you on the English Literature degree have PhDs and have published books, journal articles or book chapters with leading academic publishers. They bring the subject to life with inspiring examples and ideas that have emerged in their journey of research.

School of Creative Arts

Explore and collaborate with creatives from across the spectrum. We offer the perfect environment to practice your craft and prepare you to graduate career-ready.

Ranked in the top 20 in the UK

Our English courses are ranked in the top 20 in the UK by the Guardian University Guide 2023.

Ranked 11th in the UK for student satisfaction

Our English courses are ranked 11th in the UK for student satisfaction by the Complete University Guide 2024.

Ranked in the top 20 in the UK for student and teaching satisfaction

Our English courses are ranked in the top 20 for student satisfaction and teaching satisfaction by the Guardian University Guide 2023.

Ranked in the top 20 in the UK for teaching quality

Our English courses are ranked in the top 20 for teaching quality by The Times Good University Guide 2023.

Related stories

Trips and experiences.

You’ll have chances to experience a great range of theatre and field trips in the UK and abroad. Discover more about the course by visiting our free online taster module .

Keep Me Updated

Other courses you might like, english literature and creative writing ba (hons) , english and creative writing , secondary education english pgce , take a look at our social media.

School of English at St Andrews

Study English literature and Creative Writing in a friendly, supportive and intellectually stimulating environment with a wide range of research topics to choose from. Ranked 1st in the UK in The Guardian University Guide 2024.

I'm Dr Kristen Treen and I'm a lecturer in English here at the University of St Andrews St Andrews is one of the first universities in the world to teach English and today the School of English enjoys an international reputation as a centre for academic research, literary creativity and world class teaching.

Our lecturing staff includes researchers and writers whose work takes in a vast array of topics and interests from older Scots literature Renaissance romance and romantic women writers to Victorian poetry, post-colonial theory and detective fiction.

The School of English is home to award-winning poets, playwrights and novelists - practitioners who teach creative writing across the board.

The English degree at St Andrews is as diverse as it is rigorous.

During their first two years, our undergraduates study a very broad set of authors and time periods our four sub-honours modules are designed to give students an excellent working knowledge of English literature.

Before they go on to specialize at honours level, students can expect to cover texts from the medieval and early modern periods and the long 18th century right the way through to modern and contemporary fiction, poetry and drama.

In the first year we were doing EN1003 so the first broad module that we did. I think that was Culture and Conflicts: 19th and 20th Century Literature that was, I think, initially just aiming to give us the knowledge of close reading and as many different authors and genres as we possibly could in the space of 12 weeks, and it was definitely beneficial to do such a sort of a broad grounding because I think a lot of the text I just never would have gone there myself like Lonely Londoners – I never would have gone there but…

I absolutely loved it - I think that is probably my favourite books.

That's one of my favourite books now, it's amazing! I re-read it!

I first read the list of texts we were going to be studying and there were barely any that I knew.

I was just waiting for Wuthering Heights week, like this week I’m going to know what I’m doing and actually, I wasn't, you know, that wasn't my favourite text to study, so it was, you know, it was really nice to kind of get out your comfort zone because I'm definitely a bit of a creature of habit - it's Austin and Hardy really.

But I felt like that with Jekyll and Hyde - I studied that a few times before I was like I'm so ready for this and then like when we went into the lecture that took it from a completely different perspective from what we've been taught.

It did it from a sexuality perspective that you don't get in secondary school, that it really challenged my views.

It's really good.

So in the second semester we studied Explorers and Revolutionaries from 1680 to 1830 and I found that really interesting because there were quite a few texts that otherwise, again that you were saying, I wouldn’t really have come across or read.

During the first two years of the English degree our students will also experience a whole range of teaching methods and complete several different forms of assessment, while our small group tutorials and close reading exercises give students the opportunity to find their voices and really hone their critical skills, lectures and set essay tasks introduce them to the big picture and encourage them to ask big questions.

Tutorials is a very intimate group of people of about five or six and in these groups you can take what you learn in lectures and discuss it and it almost becomes like a group of friends because you’re all really interested in it and you can all like have a really in-depth discussion and have a chance to share ideas.

Yeah, I know, I definitely thought after the first couple of sessions and get to know everyone it's a really nice environment to kind of just share your ideas.

I was quite self-conscious about what people think of what I have to say and stuff but, yeah, it's really nice having a small group.

We only do two coursework essays so I um and in the EN1004 module we did a close reading and a more kind of analytical anyway but and in terms of essays what they're really looking for is no flowery language, like to use your words efficiently because you don't get too many words so basically to write kind of really pinpoint the argument referred to, like, the novel or the context of what you're studying but really to pinpoint the questions or use your words wisely.

What I actually really like is the way that their coursework essays and the exam actually went hand in hand during that so we had, as you said, a close reading and then one on the whole text and how that was also the structure for the exam, yeah.

Yeah and lectures were really good because the great thing about the English school is it puts novels much more in a historical context yeah and you feel like you're studying history so I, for the first time, became acquainted with the idea like the novel is a historical source rather just a piece of fiction.

So it's like old literature is, kind of, essentially a reaction to society or humanity so you're kind of really getting a specific perspective of society a certain time and that's really fascinating, you know?

Yeah exactly, I think that the thing that I really like about the English department is it has a really nice community and I genuinely really like the atmosphere itself and I've always felt very comfortable in lectures and in tutorials.

Yes, and it feels like the students and the staff are very much on the same page.

Yeah, exactly.

They get along really well.

It makes you write inspired to learn when you just you just like really enjoy not only, like, what you're studying and the course itself, but just the general environment and they're teaching staff.

By the time they meet honours in the third and fourth years our students are ready to specialize.

Whether they choose to take English as a single or joint honours degree, they have a huge variety of modules to choose from and among them they'll find offerings in old and Middle English, Celtic, American and world literature's, creative writing and the Victorian novel.

In terms of, sort of, the format, the big difference I think is once you get honours is you're in much smaller classes and the modules get a little more specific than in first and second year and you get a lot more – you get choice in what you're doing whereas in 1st and 2nd year everyone's doing the same things.

Third and fourth year you get to choose from it's like 40 different modules.

Yeah, you can go from Old English, like the very beginnings of the English language, until the 21st century experimental poetry.