How to Write a Self-Portrait Essay

How to Create a Life Map

A self-portrait essay is a paper that describes you -- and what's important to you -- to your reader. Choosing what aspects of yourself you want to describe before you begin your essay will help you choose the most evocative images and events to include in your essay. Using specific images from your life will give your reader a physical image of who you are.

Reflect on Your Experiences

Before you begin writing your self-portrait essay, reflect on yourself. Think about the sort of personality you have, what types of people you get along with and your goals and aspirations. Once you've taken time to look at yourself, think about what aspects of yourself you want to focus on. To make your essay engaging, pick an area that challenges you. For instance, you might write about how you try to form new friendships despite your anxieties, or how you commit to your convictions even if it brings you into conflict with others. You can also explore what ideas -- religion, philosophy, ethics -- are important to you. Deciding on two or three aspects you wish to focus on will help you narrow down what you include in your writing.

Introduce Yourself

Begin writing your essay by introducing your reader to yourself. Describe where you live and your family, and provide a physical description of yourself. To make your introduction catchy and interesting, avoid listing these details as if you're just answering a series of questions. Working them into physical descriptions of your life can make this information more interesting. For instance, if you're 17, you might introduce your age by saying: "We moved into this squat brick house 15 years ago -- two years after I was born."

You can also use a picture of yourself -- a literal self-portrait -- as an image to begin your essay. Find a picture of yourself from your past, and describe what that picture shows about you. For instance, if your picture shows you when you were upset, you might say that you can remember being sad when you were a child, but you can't quite remember why. This can be an excellent way of bringing in your reader and beginning to discuss how you have or haven't changed over time.

Tell Your Stories

The body of your essay should explore the aspects of yourself you decided to write about. For each aspect, pick two or three events from your life and write a paragraph for each. If you want to show your determination, for instance, you might describe a time that you ran all the way to school when your bus didn't come. If you hold steadfast to your opinions, you could describe a long political argument you had with your family, and the mixture of pride and anger you felt afterward. These events will show your personality and give you the opportunity to describe physical locations and actions, which will make your self-portrait feel more real to your reader.

In addition to using events from your life to illustrate your personality, describe yourself using objects from your life. If you're an avid reader, spend part of your essay describing the large bookshelves in your room. If you're meticulous about your hobbies, use an image of a plant that you keep on your windowsill.

The conclusion paragraph of your essay should tie your paper together. It should draw on the aspects of your personality and the events in your life that you've described and ask where you're going in the future, or what you feel about yourself now that those events are in the past. Don't summarize or restate the items you've already described. Instead, tie them together or build on them. For instance, if you described making art in the past, talk about how you hope to rediscover your creativity. If you know you'll have to deal with ideas you don't agree with in the future, write how you think you'll handle them.

Alternatively, conclude your essay by restating the details from your introduction in a different light. By tying the beginning and end of your essay together, you will give a sense of completion to your reader. For instance, if you describe your house as "gloomy" in your introduction, but spend your paper talking about the fun you've had with your siblings, you might conclude your essay by saying: "Yes, it's a gloomy house, but we know how to make it shine."

Related Articles

How to Write a Narrative Essay

How to Write an Autobiography for a College Assignment

What Should a Narrative Essay Format Look Like?

How to Write a Short Essay Describing Your Background

How to Start a Personal Essay for High School English

How to Build an Outline for a Personal Narrative

How to Write a Descriptive Essay on an Influential Person in Your Life

How to write an essay with a thesis statement.

- Napa Valley College: Self Portrait (Description) Essay

- Teen Ink: Self Portrait

Jon Zamboni began writing professionally in 2010. He has previously written for The Spiritual Herald, an urban health care and religious issues newspaper based in New York City, and online music magazine eBurban. Zamboni has a Bachelor of Arts in religious studies from Wesleyan University.

- Essay Topic Generator

- Summary Generator

- Thesis Maker Academic

- Sentence Rephraser

- Read My Paper

- Hypothesis Generator

- Cover Page Generator

- Text Compactor

- Essay Scrambler

- Essay Plagiarism Checker

- Hook Generator

- AI Writing Checker

- Notes Maker

- Overnight Essay Writing

- Topic Ideas

- Writing Tips

- Essay Writing (by Genre)

- Essay Writing (by Topic)

Self-Portrait Essay: Examples and How to Write a Portrait

A portrait essay presents a personality to the readers. It usually focuses on the aspects of life that are the most exciting or unique.

It comprises two types of papers: a self-portrait essay and a portrait of another person. This article explains how to write these assignments with utmost efficiency. You will find the best tips, ideas, and samples to describe yourself or someone else as precisely as possible.

👧 Self-Portrait Essay

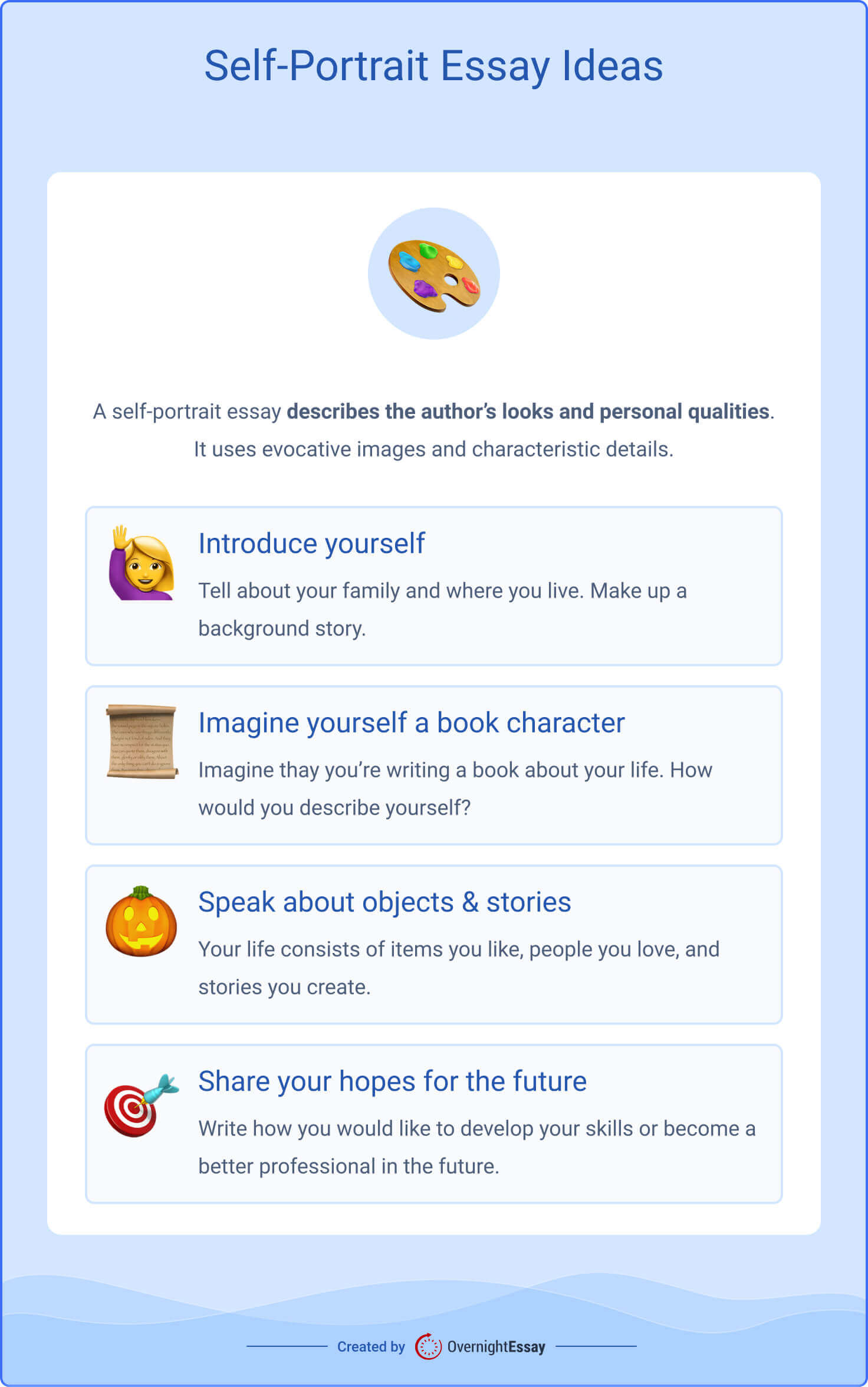

A self-portrait essay is a piece of writing that describes the author’s looks and personal qualities . It uses evocative images and characteristic details to show why this person stands out from the crowd. As a rule, it is a descriptive or reflective essay. Still, it can be argumentative if you want to contradict someone else’s opinion about you.

How to Write a Self-Portrait

Below you’ll find several ideas for a self-portrait essay. These are just general guidelines. If you need a creative and well-formulated topic, you are welcome to use our topic-generating tool .

- Start the introduction with an introduction. We are not talking about “Hi, my name is Cathy,” although this variant is also possible in some contexts. Tell about your family and where you live. Do not just list facts as if you are answering a questionnaire. Make up a background story.

- Imagine yourself a book character. How would you describe yourself if you wrote a book about your life ? This approach can make your self-portrait essay more poetic and literary. Replace the epithets that can describe many people (straight nose, thin lips, high forehead) with metaphors (a nose as straight as an arrow, paper-thin lips, expansive forehead). It will make your essay more memorable.

- Speak about objects & stories. Appearance is only a tiny part of your personality. Your life consists of items you like, people you love, and stories you create. That’s what you readers will enjoy reading!

- Conclude with your hopes for the future. Do not reiterate what you said before, even if you cannot imagine anything new. Write how you would like to develop your skills or become a better professional in the future. Make your essay open-ended, as any human life is.

Self-Portrait Essay Example

Who am I? What kind of person am I? What do I like? What do I want to become? In this essay, I will describe my appearance and how it reflects my inner world. Looking in the mirror, I see a slender but slightly skinny girl. I have an oval face, a small straight nose, and sparkling eyes. It is the eyes that make my friends and acquaintances look at my face. They are profound, although they add playfulness to my face. In cloudy weather, they acquire a dark steel shade. When it is sunny, they brighten up. In general, I have kind gray eyes. As my friends say, it seems that they “laugh.” That’s what I am all about. I am kind, cheerful, moderately strict, and responsive. I have a high forehead, hidden behind curtain bangs, and beautiful thick eyebrows of the correct shape hidden under the bangs. But this is not a gift from nature. I had to work on the form of the eyebrows on my own. My lips are not thin, but not full either. Behind them, there are snow-white teeth. The hair is straight, although I always wanted to have curls. It is wheat-colored and reaches the shoulders. I am a purposeful person, so I always set tasks that I immediately try to accomplish. But I never stop in my development. I raise the bar even higher and confidently put the next goal. It is essential for me to be the best in everything, so I have to work harder. Most likely, this is my drawback, but this quality fuels me to keep on growing. I would like to become firm, successful, and self-confident.

👨🎨️ Descriptive Portrait Essay

A descriptive essay about a person is a genre that analyzes the individual features and human qualities of a given person. People have so many different sides that there is a broad array of possibilities in this genre. Write of someone you know well enough (to have sufficient material).

Essay About a Person: Ideas

Below you’ll find six great ideas for an essay about a person.

- Describe appearance . First impressions are the most lasting . Your readers will get your message better if you give them a “picture.” It will play the role of a whiteboard where you’ll attack all the other traits.

- Link appearance to personality traits . But looks are not everything. They are the top of the iceberg. Show your reader why you paid attention to those characteristics and which conclusions you made.

- Mention their manners . It is optional but quite exciting to track. We are not stable, and our manners reflect those emotional shifts. Describe how the person behaves in stressful situations .

- Spot the emotions they raise in you . This part will make a perfect conclusion. Share your feelings with the readers to build empathy.

- Balance between being concise and informative . Avoid overwhelming your reader with irrelevant details. If the described person is someone you know well, it may be challenging to point out what is worth mentioning and what is not.

- Learn how to describe from professionals . If you wish to learn how to write, you should read a lot. In particular, you should read works of the same genre. Write down the metaphors and epithets your favorite author uses in their character descriptions.

How to Write a Portrait

We have prepared for you a mini guide on how to write a portrait of a person. Just follow these 8 simple steps:

- Collect information about a person . It is crucial to write about a person you know well, like a close friend, a classmate, or a family member. Consider conducting an interview with this person or talking with other people who know this individual to gain more insights and observations.

- Create a thesis and an outline . Choose interesting details, anecdotes, unique features, or qualities of your chosen person that are worth describing in your essay. Organize all the information logically in an outline to make writing easier. Also, create a thesis statement, which must include the person you write about and your purpose for describing them.

- Start with a physical description . At this stage, you need to be as specific as possible. Try to describe not only the appearance of the person but add details about their smell, voice, etc.

- Describe the behavior . Focus on what makes this person unique — their laugh, a manner of talking, a way of moving, etc.

- Demonstrate your character’s reputation . To do so, show how your described person makes others feel, treats others, and contributes to the world.

- Show your character’s environment and belongings . A person’s environment and belongings can reveal much about their personality, interests, and values. So, include details about what things are important to your described individual and whether their environment looks tidy, cluttered, dirty, etc.

- Write about their manner of speech . Describe the person’s choice of words and intonation to reflect their education level, confidence or fear, and unique worldview.

- Conclude by summarizing unique qualities . In your last paragraph, summarize what makes your described person unique. Add a concluding sentence conveying the final impression they have made on you.

Descriptive Portrait Essay Example

My best friend is a person who deserves a separate book. She had a complicated but interesting life. She is the third child in a large family and wants to become a nurse. I will dedicate this essay to her features and personal qualities to show that you can be a good person despite anything. Mary’s appearance is unremarkable and even plain. She is tall and plump, and her gestures are indecisive. The girl seems to be shy, but she becomes very confident when her family or values are harmed. One could see a strict line between her eyebrows. It marks her inner strength and decisiveness. The look of her grey eyes is attentive and benevolent. It helps her win the interlocutor in an argument. By the way, communication skills are the strongest part of her character. She is open and cheerful but sometimes too impulsive. The way she speaks and behaves comforts me, like a cold winter evening in front of a fireplace. She is kind and caring, and always does her best to make any interaction pleasurable. Still, when someone acts with hypocrisy, she prefers to break up with such a person. It is hard for Mary to give people a second chance. This feature has its drawbacks, but it also makes her friends’ circle tight and reliable. Mary wants to become a nursery teacher because she loves children. At the moment, she is studying for that, and I am sure she will succeed. This girl has taught me that people can combine mutually exclusive features in themselves and remain to be nice friends and intelligent specialists.

We hope we’ve inspired you to write your portrait essay. If you have already written your text and want it to be read aloud, you are welcome to use our text-to-speech tool .

❓ Portrait Essay FAQ

How to write a portrait essay.

1. Make a list of the most remarkable facial features and character traits of the person in question. 2. Relate the above to their character. 3. Group your findings into categories. 4. Dedicate one main body paragraph to each category.

How to Start a Portrait Essay?

Any essay should start with background information. In the case of a portrait essay, you could mention how you got to know the person or what your first impression was. Or, you can give general information about their family and work. Finish your introduction with a thesis statement, informing the reader of the purpose of your writing.

How to Write a Self-portrait Essay?

1. Sit in front of the mirror and think about which of your features differ you from other people. 2. Write the main body, dedicating each paragraph to a different aspect of your appearance. 3. Write the introduction about what kind of person you are and how you came to the place where you are now. 4. Write the conclusion about your future intentions.

How Do You Write a Character Portrait Essay?

1. Carefully read all the author’s descriptions of the character. 2. Link them to the plot as most characters reveal themselves gradually. 3. Think what impressed you the most about the character. 4. Write your opinion using the image the author created and your own imagination.

🔗 References

- Descriptive Essays | Purdue Online Writing Lab

- Descriptive Essay Examples – YourDictionary

- How to Give a Description of a Character – wikiHow

- How to Write About Yourself | Indeed.com

- 7 Helpful Tips on How to Write a Memorable Personal Essay

- Personal Essay Topics and Prompts – ThoughtCo

Home » Writers-House Blog » Self-Portrait Essays: Writing Tips

Self-Portrait Essays: Writing Tips

Self-portrait essays are aimed to describe the author. When writing a self-portrait essay, you should think of your audience and find the best approaches to describe yourself to its members. Use evocative images and specific details to make your description more vivid and engaging. Writing consultants from Writers-house.com service wrote this quick guide to help you write an outstanding self-portrait essay.

Think of Your Experiences

First, take your time and reflect on yourself. Think about your personality, your aspirations, and goals. What people you like to see around yourself? What you’d like to achieve in the future? We recommend that you choose a relatively challenging area to make your essay more engaging. For example, if you suffer from anxiety, you can describe how you overcome it to build relationships with other people. You may write about how you keep standing your ground despite the pressure from others. You may also write about your ethical, philosophical, or religious views. The main thing is to clearly define the focus of your essay.

Describe Yourself

You should begin your essay with an introduction. You need to introduce yourself and to provide a general description that will allow your readers to quickly learn the most important things about you. However, avoid simply listing the details about yourself because you don’t want the introduction to be boring. For example, if you want to say that you’re 16 years old, you can tell your readers how you and your parents moved to a new place 13 years ago, when you were three years old.

A good approach is to take a picture of yourself or take a look at your old pictures and describe what this picture can tell about you. For example, if you look happy on this picture, tell your readers about that day and why you were happy. A picture from the past is also a great opportunity to discuss how you’ve changed over time.

Tell Your Story

The main part of your essay must provide your readers with insights into the chosen area of yourself. When writing about some aspects of your life, make sure to illustrate them with specific events. Devote one body paragraph to one aspect, and provide some opinions. For example, you may mention a political argument with your family or explain what do you think about the overall quality of life in the town where you were born. You should show your personality and illustrate it with such details as events, locations, etc.

We recommend that you don’t use an opportunity to make your self-description more vivid by describing objects that surround your everyday life. For example, describe your room or tell your readers something about your hobbies and passions.

The Conclusion

The last paragraph of your essay should wrap it up and tie together all the pieces of information about yourself, creating a complete image. The conclusion is a great place to tell your readers what you think about your life now, and what you’re going to do in the future. We recommend that you don’t restate any information that you’ve already mentioned in the body of your essay. Don’t write a summary. Instead, provide a new perspective. Writing about your goals and plans is a great solution.

We also recommend that you conclude the essay by considering things you’ve been addressing in the introduction in a different light. If your introduction and conclusion are connected to each other, your essay will create a sense of completion. Make sure that different sections of your essay are logically connected to each other and your story is consistent.

Leave a Reply

Be the First to Comment!

Place your order

- Essay Writer

- Essay Writing Service

- Term Paper Writing

- Research Paper Writing

- Assignment Writing Service

- Cover Letter Writing

- CV Writing Service

- Resume Writing Service

- 5-Paragraph Essays

- Paper By Subjects

- Affordable Papers

- Prime quality of each and every paper

- Everything written per your instructions

- Native-speaking expert writers

- 100% authenticity guaranteed

- Timely delivery

- Attentive 24/7 customer care team

- Benefits for return customers

- Affordable pricing

- Entertainment

- Environment

- Information Science and Technology

- Social Issues

Home Essay Samples Art Selfie

Selfie as the Modernised Version of Self-Portrait

Introduction.

*minimum deadline

Cite this Essay

To export a reference to this article please select a referencing style below

- Metropolitan Museum of Art

- Japanese Art

- Michelangelo

- Art Movement

Related Essays

Need writing help?

You can always rely on us no matter what type of paper you need

*No hidden charges

100% Unique Essays

Absolutely Confidential

Money Back Guarantee

By clicking “Send Essay”, you agree to our Terms of service and Privacy statement. We will occasionally send you account related emails

You can also get a UNIQUE essay on this or any other topic

Thank you! We’ll contact you as soon as possible.

- Craft Essays

- Teaching Resources

Here’s Looking at Me: Lessons in Memoir from Self-Portraiture

Conveying ourselves as characters on the page is tricky business, like expecting a butterfly to pin its own wings. As James Hall explains in The Self-Portrait: A Cultural History , when Montaigne put pen to paper, he referenced those who had put brush to canvas, citing King René of Anjou: “I saw…King Francis II being presented with a self-portrait by King René as a souvenir of him. Why is it not equally permissible to portray yourself with your pen as he did with his brush?”

But a slimly pen-stroked “I” isn’t a portrait: We need to convey detail, texture, shadow. And in this, visual artists have much to teach us.

Look Me in the Eye When American street photographer Vivian Maier’s work was discovered after her death, her self-portraits proved especially compelling. “…[A] self-portrait is a unique confession by an artist. It tells us both how they view themselves, as well as how they perceive the world around them,” wrote John Maloof in the foreword to Vivian Maier Self-Portraits . Maier’s portraits ranged from the head-on mirror shot to the outlined shadow to a combination of the two . In some shots, her shadow seemed almost a mistake or coincidence , as did her reflection , though the sly smile in one hints that perhaps the reflections and shadows are precisely the point of these images.

What does Maier show us? The details of her face, her haircut, her clothing and her photographic gear all come into focus in her most direct shots. But to me, more intriguing are those that “show” her more obliquely: the contents of the handbag next to her shadow , the blurred larger image with the distant in-focus one reflected near her heart , the angles from which she chooses to observe others and those she allows into the frame with her . How she looks is interesting; what she looks at is compelling.

Head-on: Photograph yourself in a mirror. Write a description of yourself as if you were describing someone unknown to you.

What catches your eye? Throughout a day or a weekend, snap images of where your gaze settles: the irritating scuff on the white-painted stair riser heading up to your bedroom; the dog’s wagging tale as its dream delights it; the way the water pools on the barbecue lid in the rain. Print out the images. What insights might a stranger discovering your collection draw from these photos?

I Didn’t Mean to Show You That—Did I?

Eggs in an Egg Crate was the first work Canadian painter Mary Pratt completed after miscarrying twins. Pratt later wrote that the image was inspired as she made a birthday cake, placing the spent shells back in the carton as she used them. But it wasn’t until the painting was finished and she shared it with a friend that she fully realized what she’d captured: “[S]he pointed out to me that the eggs were empty.”

Sometimes an artist is more direct in revealing her subconscious. Frida Kahlo’s painting What I Saw in the Water (also sometimes referred to as What the Water Gave Me ) is, for Kahlo, uncharacteristically surreal: an image of memories from her life floating in the water, her feet poking above them at the tub’s top end.

What draws you? What do you collect? Treasure? Find difficult to let go of? Whether it’s your collection of Pez dispensers or the penny you keep in your pocket for good luck, choose an object that you are drawn to, and describe it deeply, closely. As you observe it, what do you see, feel, smell, taste, hear? Put the writing aside for a week. When you return to the description, what does what you’ve captured on the page reveal about you?

What haunts you? What memories repeat themselves for you? What dreams—or nightmares—return again and again? What song lyrics linger? What smells transport you? Find a place in your daily environment that allows you to stare into the distance or some not-quite-reflective surface—a deck chair overlooking the water, the subway window, or, like Kahlo, the bathtub. Describe the setting first. Then, call up your ghosts and describe them as they inhabit the air around you or the surface before you.

Is That You, Leonardo?

It’s said to be a Renaissance maxim: “Every painter paints himself.” There are those who would have us believe Mona Lisa’s smile hides Leonardo’s self-portrait , and many artists have inserted themselves into a painted scene, as J ulia Fiore writes on Artsy : from Raphael peeking from behind an arch in his Vatican fresco, to Caravaggio as the decapitated Goliath, to Dutch artist Clara Peters cleverly hidden in the reflection of a goblet’s pewter lid. Caravaggio was a repeat offender: In The Taking of Christ , he appears at the frame’s edge, holding up a lantern, in what The Self-Portrait author James Hall categorizes as a “bystander self-portrait”—distinct from the “group self-portrait” where the artist appears as themself with “family, associates or even the Virgin Mary.”

Who’s in your group? If you were to paint a group self-portrait of you at 17, who else would be in the frame? Describe them—both the real people and the influential figures who loomed large (your Virgin Marys). Now step back and describe yourself as each of them sees you. Try it at 27. 57. 77.

Wish I’d been there: What moment in history would you most like to have witnessed? Research the scene—and then place yourself in it, but at its fringes. Are you Caravaggio holding the lantern? The short-order cook at the Greensboro Sit-In? The kid behind the kid who caught a World Series home run baseball? Be as true to you as you can be: What do you see of yourself in this imagined scene that you might miss revealing in a more factual moment?

One Final Art Lesson

In Likeness: Fathers, Sons, A Portrait , author David Macfarlane spends months contemplating a portrait of himself painted by John Hartman. “I’m not sure how much the painting looks like me,” writes Macfarlane. “I can tell you that it feels like one of those candid shots that surprise you, not always pleasantly. It’s not at all how you picture yourself. But you sense somehow that a certain truth has been captured. …It looks like it has the same memories I do.”

I’ve used the exercises here to reveal my self to myself, then gone back to an essay I’m working on to weave in an insight here or a glimpse of my character there—and in doing so, tried to ensure there isn’t a blank spot on the canvas where I should be.

And that, perhaps, is what as memoirists, as essayists, we might strive for: not a perfect portrait of a flawless subject, but an image that captures a moment of truth, of who we were and what we’ve lived through. ___

Kim Pittaway is the executive director of the MFA in Creative Nonfiction program at the University of King’s College in Halifax, Nova Scotia, Canada. She is the co-author, with Toufah Jallow, of Toufah: The Woman Who Inspired an African #MeToo Movement , due out from Steerforth Press in October 2021. She is at work on a memoir with the working title Grudge: My Ten-Year Fight with Forgiveness . Her e-newsletter on writing craft, I Have Thoughts , is available at kim.substack.com .

| says: Sep 15, 2021 | ) |

| says: Sep 15, 2021 |

| says: Sep 16, 2021 |

| says: Sep 17, 2021 |

| says: Sep 19, 2021 |

| says: Sep 20, 2021 |

| Name required | Email required | Website |

XHTML: You can use these tags: <a href="" title=""> <abbr title=""> <acronym title=""> <b> <blockquote cite=""> <cite> <code> <del datetime=""> <em> <i> <q cite=""> <s> <strike> <strong>

Click here to cancel reply.

© 2024 Brevity: A Journal of Concise Literary Nonfiction. All Rights Reserved!

Designed by WPSHOWER

The Art of Self-Portrait: Rembrandt by Rembrandt Research Paper

- To find inspiration for your paper and overcome writer’s block

- As a source of information (ensure proper referencing)

- As a template for you assignment

Introduction

The art of portrait in baroque, rembrandt’s vast heritage in self-portraits, the evolution of style and meaning in rembrandt’s self-portraits, works cited.

Since times immemorial, art has been a way of reflecting and interpreting the reality surrounding people in their daily life. In order to comprehend the reality in all its variety, artists have striven to depict as many objects and phenomena as they could only find.

One of the most intriguing subjects for reflecting upon via art is human being, and this fact is confirmed by the vast amount of works of art depicting people. In painting, portrait as a way of contemplation on the human nature has enjoyed enormous popularity for centuries on end.

Artists of various époques, styles, and nationalities have depicted people of all possible ages, social backgrounds, and occupations. Among portraits, the genre of self-portrait appears most attractive due to the specific quality of the artist’s self-reflection present in the paintings.

The present paper focuses on the works of one of the most famous portraitists in Baroque period, Rembrandt van Rijn (1606–1669), whose oeuvre cannot be imagined without a multitude of his self-portraits.

Against the background of the general popularity of portraits in the seventeenth century, the gallery of Rembrandt’s self-portraits stands out as an exciting encyclopedia of the evolution in the artist’s personality. This artistic transformation can be observed through tracing the changes in the elements of the techniques, the style, and the tone in Rembrandt’s paintings.

After the rejection of any individualism and the resulting oblivion of the portrait genre in the art of the Dark Ages, the era between the late Middle Ages and the seventeenth century celebrated the renascence of portraiture. The commonly known anthropocentrism that dominated the Renaissance art resulted in a dramatic increase in the artists’ interest to human personality, which in its turn found reflection in the genre of portrait.

Creatively responding to the growing popularity of portrait, artists elaborated on the genre; as a result, a whole range of sub-genres emerged, featuring “full-length portrait”, “three-quarter-length portrait”, and various kinds of “head-and-shoulder portrait”. [1] Within those sub-genres, different poses and positions of the sitters were practised, with the most widespread being the “profile view”, the “three-quarters view”, the “half-length” and the frontal, or “full-face view” (Schneider 6).

In addition to developing variations within the genre of portrait, by the seventeenth century artists had sufficiently expanded the range of their subjects, depicting not only the aristocracy and the clergy, but also members of many other social groups. “Merchants, craftsmen, bankers, humanist scholars and artists” themselves sat for portraits and thus appeared in the public eye (Schneider 6).

The latter addition to the subject range appears especially revealing for our discussion, since it means that artists started to openly depict themselves and thus emphasize their own social significance.

The tendency to individualism and personal identification in painting reflects the general interest to personality in the art that continued the anthropocentric ideas of the Renaissance and developed throughout the Baroque époque. In the literature of the period, one can observe a definite interest to various kinds of autobiographic narrative, and more and more self-portraits appear among the paintings as a kind of autobiographic sketches made by the artists (Schneider 113).

It is noteworthy, however, that the notion of self-portrait as such did not exist at the time, and what we now call a ‘self-portrait’ would then be described as the artist’s “own picture & done by himself” (van de Vall 98).

Although the genre of self-portrait was popular and widely practised by most artists in the Baroque period, Rembrandt remains unsurpassed in terms of the quantity of autobiographic images: apart from multiple etches, over forty paintings of himself have survived up to the present time (van de Vall 98).

A popular cartoon depicts Rembrandt as “a rather plump, jowly artist, palette and brush in hand, turning from his easel and calling [to his girlfriend]: “Hendrickje, I feel another self-portrait coming on. Bring in the funny hats” (qtd. in Wheelock 13). However, there is probably much more behind the multitude of Rembrandt’s self-portraits than a mere wish to try on another fancy headwear.

The reasons for emergence of this many Rembrandt’s self-portraits can be searched for in two directions. On the one hand, the artist could have used his own body as a material for exploring the complexity of human nature on the whole. On the other hand, Rembrandt’s self-portraits can be viewed as an opportunity for self-investigation and revelation of the artistic inner self. In addition, there might emerge still another interpretation: since Rembrandt’s self-portraits were meant for the market and sold, they could serve as a way “to gain honour and immortality and thus fame, and to appeal to a public of buyers and connoisseurs” (de Winkel 135).

Such commercial intent can also be interpreted more deeply, since through looking at the artist’s self-portrait the connoisseurs of his work could admire both the artist’s personality and his excellent technique (van de Vall 99). In each separate case, the intent behind Rembrandt’s self-portraits can be deduced individually, since in various periods of his life the artist produced astonishingly different samples of autobiographic paintings.

Conventionally, Rembrandt’s self-portraits can be grouped according to the three chronological periods: the early years in 1620s, the middle years spanning the next two decades, and the late years starting from the late 1640s. Each of those periods can be characterized by a certain purpose that inspired Rembrandt to paint his self-portraits, as well as features stylistic peculiarities indicative of deep internal motives underlying each painting.

The early years

The époque of Baroque brought about an obvious progress in exploration of the emotional side of personality. While the masters of the Renaissance observed the ways to render the inner emotion through pose and gesture, the art of Baroque expanded the artistic techniques by adding facial expression to the wealth of expressive means. Thus the interpretation of feelings in painting could be dramatically intensified and varied.

In his early self-portraits, Rembrandt definitely explores the multiple effects of facial expressions. Face becomes the focal point of his compositions, performing the key function of feeling representation. “Alarm, worry, torment, fear” — those are but a few of emotions depicted in etchings and paintings of the 1920s (Schneider 113).

Experimenting with his own face in front of the mirror, Rembrandt worked out a whole list of facial features, the interplay of which could render a widest possible range of emotions: “a forehead, two eyes, above them two eyebrows, and two cheeks beneath; further, between nose and chin, a mouth with two lips and all that is contained within it” (qtd. in Bruyn, van Rijn, & van de Wetering 165).

A brilliant expert in facial anatomy, Rembrandt apparently taught his pupils to closely observe one’s own face: “thus must one transform oneself entirely into an actor (…) in front of the mirror, being both performer and beholder” (qtd. in Bruyn, van Rijn, & van de Wetering 165).

One of the most significant facial features possessing an extreme expressive power was viewed by the seventeenth-century artists — and Rembrandt himself — in the mouth and the musculature surrounding it (Bruyn, van Rijn, & van de Wetering 165). This being a difficult facial element to depict, Rembrandt spent years perfecting his skill in constructing various facial expressions with the help of different mouth positions.

Experimenting with the shades of colors and the play of light and shadow, Rembrandt seeks for the most successful rendition of most varied emotions. Self-portraits with open mouth let him place in the teeth as an additional expressive touch. A mouth open in a cry of astonishment, surprise, despair, joy, or without any obvious reason — all this diversity can be seen in Rembrandt’s early autobiographic sketches.

As a result of his multiple experiences with facial expressions, by 1630s Rembrandt had worked out an encyclopedia of human emotions that he could apply in his later works. Such, for example, is the famous laughing face which occurs not only in the early self-portraits, but also in those of the late years (Bruyn, van Rijn, & van de Wetering 165).

A remarkable feature of Rembrandt’s early self-portraits is that — however renown the artist is for his ingenious depiction of clothes — there is hardly any attire in his early sketches. The reason for this can be found in the fact that during the initial period of his artistic work, Rembrandt appears to work in the tradition of a so-called tronie.

By this word is meant a picture that focuses on a certain detail of face, without emphasizing the unique personality of the sitter (de Winkel 137). Therefore, familiar and recognizable stereotypes were depicted, such as a wrinkled old man, a soldier, or a pretty young girl.

Since the image stopped at the level of the sitter’s shoulders, not much of clothing could be fitted in the picture. Rembrandt’s depicting himself as a tronie can be seen as a way of de-individualizing the image in terms of clothes. However, this lack of outward information was compensated by a splendid rendition of facial expression.

The middle years

As Rembrandt gradually gained social recognition and enjoyed considerable success as a commercial artist, his self-portraits demonstrate a tendency to a multitude of experiments.

It appears quite laborious to investigate all the range of techniques he employed in his paintings of 1630s, since it is extremely wide. The reasons for this can be found in the fact that Rembrandt ran a series of workshops at the time, and due to time pressure he often had to resort to assistants’ help in finishing the paintings.

Such can be the case with some of the self-portraits as well: while Rembrandt outlined the composition in general, especially talented apprentices were allowed to work on details of body and clothes in order to speed up the process (Wheelock 19). While the result of such collective work demonstrates excellent painting technique, it is difficult to assert whether some of Rembrandt’s self-portraits are his own works or workshop productions.

Against the background of social success, Rembrandt gained the opportunity to experiment with a large number of altering roles and social positions in his self-portraits.

Making use of the general understanding of clothes as a way of creating the desired image of self, Rembrandt juggled an endless number of costumes and attributes creating a new character in every painting. The question of which image reflects ‘the real’ Rembrandt of the time still remains unsolved: was it a prosperous burgher, a learned gentleman, or an insightful artist that he really was?

In terms of costume in Rembrandt’s self-portraits, one can single out three main tendencies: self-portraits in contemporary clothing, in antiquated costume, and in working dress.

It is quite rare that Rembrandt depicts himself in a formal pose and a fashionable dress. The reason for such preferences in attire can be viewed in the fact that Rembrandt wanted to show his difference from the average customers that ordered their portraits from him. Unlike other artists who depicted themselves in the same sumptuous robes as their customers, Rembrandt positions himself independently from the general crowd.

Taking into consideration that the artist was wealthy enough at the time to allow rich garments, such reluctance to mix with the general style can be viewed from the perspective of social inappropriateness of exuberant clothing for lower estate. Despite the exception provided to talented painters for breaking social stratification, Rembrandt apparently prefers to preserve the distinction of his class (de Winkel 147).

Perhaps one of the details that immediately springs to one’s mind when thinking about Rembrandt’s self-portraits is the beret. Indeed, in the self-portraits of the middle period, the painter used this kind of headwear most frequently. The more surprising is the fact that in the seventeenth century beret was an outdated type of clothing, either worn by servants or used as a part of official scholar costumes (de Winkel 164).

It can be therefore suggested that by widely using the outdated beret in his self-portraits, Rembrandt demonstrated a connection with the famous engravers of the previous century, Lucas and Dürer, highly appraised by him (de Winkel 188). Thus Rembrandt’s historicism and reverence for the art of the past can be deciphered through one small detail of costume.

Depicting himself in a working dress, Rembrandt demonstrates yet another peculiar way of distinguishing himself from the generally accepted standards.

As of the seventeenth century, there existed no specific occupational dress for the artists of the time, and yet Rembrandt appears in a working dress now and again in his self-portraits (de Winkel 151). Not only can working clothing be noticed on the paintings of the middle years, but it is also the dominant attire in Rembrandt’s late self-portraits.

Taking into account the peculiarities of Rembrandt’s late style (to be discussed below), this deviation from the rules and appearance in everyday clothes can be interpreted as the artist’s statement of individual freedom and non-conformance to the generally accepted standards.

The late years

As compared to the flamboyant images of the middle years, Rembrandt’s self-portraits of the late period demonstrate a dramatic change in tone and style. An “increased sense of gravity and serenity” dominate the portraits of the impoverished artist who enters “a brutally honest phase in his life” (Stein & Rosen 116).

Critics remark on the especial “fuzziness” and “lack of sharpness” in the images (van de Vall 93). Although this quality can be ascribed to the artist’s worsening eye-sight, there can be yet another explanation. By alternating the areas of sharpness and blurredness in his self-portraits, Rembrandt creates a lifelike effect of really looking at a person.

This effect corresponds to what happens in normal communication, when people tend to alternate direct look and side glances at the interlocutor. Therefore, the “moments of blindness or unfocused seeing are just as essential as moments of sharp sight” for perceiving the image (van de Vall 105).

Another peculiar quality that strikes the viewer in the late Rembrandt’s self-portraits is the authenticity with which the painter renders the eyes in his face. Having gathered the experience of his whole life, Rembrandt reveals himself as “a virtuoso of vision, both with regard to what he saw and also with regard to the way in which he represented seeing” (Durham 14).

“Believable eyes, living eyes, seeing eyes, even eyes looking at something we cannot see” are impeccably rendered by Rembrandt with a highest professionalism ever reached in the history of painting (Durham 14).

His look pierces the viewer of his late self-portraits, as if extending the frame of the picture and letting the image step out of it. Through this mastery of the eyes, Rembrandt renders the message of an extremely deepened spirituality he achieved in the last period of his paintings.

During the Baroque period, the genre of self-portrait enjoyed its golden age in the studio of Rembrandt van Rijn. Through his many autobiographic works, one can trace Rembrandt’s astonishing evolution from an artist experimenting with the expressive potential of mimics, through an artist playing with his social positions, to an artist deeply submerged in the spirituality of painting. Thus, self-portrait for Rembrandt becomes a way to reflect not only the outward changes but also the crucial inner transformations in the artist’s world.

- Schneider, Norbert. The Art of the Portrait: Masterpieces of European Portrait-Painting, 1420-1670 . Trans. Iain Galbraith. Köln: Taschen, 2002. Print.

- Bruyn, J., van Rijn, Rembrandt Harmenszoon, & van de Wetering, Ernst. A Corpus of Rembrandt Paintings: The Self-Portraits . Dordrecht: Springer, 2005. Print.

- Durham, John I. The Biblical Rembrandt: Human Painter in a Landscape of Faith . Macon, GA: Mercer University Press, 2004. Print.

- Stein, Murray, & Rosen, David H. Transformation: Emergence of the Self . Texas A&M University Press, 2005. Print.

- van de Vall, Renée. “Touching the Face: The Ethics of Visuality between Levinas and a Rembrandt Self-Portrait.” Compelling Visuality: The Work of Art in and out of History . Eds. Claire J. Farago and Robert Zwijnenberg. Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota Press, 2003. 93–111. Print.

- Wheelock, Arthur K., Jr. “Rembrandt Self-Portraits: The Creation of a Myth.” Rembrandt, Rubens, and the Art of Their Time: Recent Perspectives . Eds. Roland E. Fleischer and Susan C. Scott. University Park, Center County, PA: The Pennsylvania State University, 1997. 12–35. Print.

- de Winkel, Marieke. Fashion and Fancy: Dress and Meaning in Rembrandt’s Paintings . Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press, 2006. Print.

- Paintings by Rembrandt and Holbein the Younger Compared

- Portrait of "Herman Doomer" by Rembrandt and "Young Sailor II" by Matisse

- Yue Minjun’s Self-Portraits As Modern Art

- Leon Golub: Historical witness

- The Development of Twentieth-Century Music: Schoenberg vs. Stravinsky

- Chicago: Crossroads of America

- ART VITALIS The New Jersey New Music Forum - CONCERT REPORT

- Stylistic Analysis of Film Script

- Chicago (A-D)

- Chicago (N-B)

IvyPanda. (2018, May 14). The Art of Self-Portrait: Rembrandt by Rembrandt. https://ivypanda.com/essays/the-art-of-self-portrait-rembrandt-by-rembrandt/

"The Art of Self-Portrait: Rembrandt by Rembrandt." IvyPanda , 14 May 2018, ivypanda.com/essays/the-art-of-self-portrait-rembrandt-by-rembrandt/.

IvyPanda . (2018) 'The Art of Self-Portrait: Rembrandt by Rembrandt'. 14 May.

IvyPanda . 2018. "The Art of Self-Portrait: Rembrandt by Rembrandt." May 14, 2018. https://ivypanda.com/essays/the-art-of-self-portrait-rembrandt-by-rembrandt/.

1. IvyPanda . "The Art of Self-Portrait: Rembrandt by Rembrandt." May 14, 2018. https://ivypanda.com/essays/the-art-of-self-portrait-rembrandt-by-rembrandt/.

Bibliography

IvyPanda . "The Art of Self-Portrait: Rembrandt by Rembrandt." May 14, 2018. https://ivypanda.com/essays/the-art-of-self-portrait-rembrandt-by-rembrandt/.

Toll-Free US & Canada 24/7:

1-770-659-7014

As a precautionary health measure for our support specialists in light of COVID-19, our phone support option will be temporarily unavailable. However, orders are processed online as usual and communication via live chat, messenger, and email is conducted 24/7. There are no delays with processing new and current orders.

Portrait Essay Example

Look through this Portrait Essay Example created by BookWormLab!

Compare ready samples with your papers and improve them

Want us to make a unique Creative Writing Examples for you?

How can I go about writing a portrait essay? In order to write a portrait essay, we must understand the meaning of a portrait. A portrait is a painting, a photograph, sculpture or any other artistic rendition of a person, in which the face and its expression is the main area of interest. A portrait custom essay could be easily written about how to paint or photograph a portrait. Also a portrait essay could be written about how to make a sculpture of a person.

Self Portrait Essay Writing

Since everyone may know the basic meaning of a portrait, a general portrait essay can be written very easily. But if we have to go deeper into what a portrait means to the artist, and what the artist is trying to bring out, then a portrait essay can be written on every portrait! For example, an entire essay could be written just about the Mona Lisa painting. Likewise, if you take sculptures by Michelangelo, you can write a portrait essay about each of his sculptures. Each portrait makes for an excellent portrait essay if carefully considered. Every portrait that exists, no matter how good or bad it may be to behold, it till carries a lot of meaning with it.

Portrait Character Essay Papers

Sometimes, an artist creates a self-image of himself. These images are called self portraits. When an artist creates a self portrait, usually there is a lot of meaning attached to it. A portrait essay explaining the nature of the portrait and the circumstances in which he created the portrait, would make an excellent portrait essay.

One could even write about the origin of self portraits, and what they meant to each civilisation in the portrait essays. In some cases, some people write articles like a portrait of the artist as a young man essays, which may talk about the life of the artist, with the main topic being his self portrait. Some good titles of essays of the modern era worth mentioning, include “portrait of the essay as a warm body” and “portrait of a teacher essay”. Portrait Essay Sample:

If you still think that writing a portrait essay is difficult, then you could always seek help. There are people like Professional Content Writers, who are specialised in writing custom essays including custom portrait essay. You could either buy portrait essay that is already written or ask them to write a portrait essay for you.

Even if you need a portrait essay for your websites or blogs, you can be assured that a portrait essay written by one of our writers, will get you a lot of internet traffic, as these essays will be keyword rich and at the same time, will be rich in content!

Plagiarism-free

- Art Appreciation Paper

- Pornography Essay

Related Essay Samples

Saturn Essay Student although have a very good knowledge of the entire planetary system at their school level. However, when it comes to write an essay on particular planets for example a Saturn and its rings essay, students find it very difficult...

Help with Writing Your Essay on Morality Papers Morality Issues differ from one person to the other; and Morality Essay can be written on these morality issues by a sociologist, a psychologist, an author, a student, or a teacher from any part...

Narration involves recreating an experience from your point of view or a collective standpoint. With good writing skills, one can come close to replicating the same experience to the reader. This realism is what separates an excellent narrative essay from a bland...

Academia.edu no longer supports Internet Explorer.

To browse Academia.edu and the wider internet faster and more securely, please take a few seconds to upgrade your browser .

Enter the email address you signed up with and we'll email you a reset link.

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

Britain and Self-Portraiture: essay for Art UK

Art Fund Magazine

Related Papers

Jeremy Wood

Eighteenth-Century Life

Bradford K Mudge

A number of years ago, Mark Hallett published an important and influential essay on Joshua Reynolds, Royal Academy exhibitions, and eighteenthcentury British spectatorship that should have become an inflection point for scholars of the portrait.1 The essay focused on a single painting from 1784, Reynolds's equestrian portrait of the Prince of Wales. The essay's larger purpose was to suggest a different way of thinking about how eighteenth-century paintings functioned as a result of their appearance at Somerset House. Using Edward Burney's detailed renderings of the Great Room, Hallett argued that viewers at the time were fluent in the language of display, so much so that they could "read the walls" and understand the picture in question as participating in-and in fact, being defined by-a variety of different visual "narratives," some artistic, some social, some political, all of which derived from the logic of the hang. Moreover, he argued, dominant narratives from previous years could also come back into play, the speech acts from any one exhibition thus tied to those before and after. Eloquent about the forces at work "beyond the boundaries of individual canvases," Hallett nevertheless ignored the radical implications of his own essay and opted instead for a polite request that we remember that "works of art were often defined by the company they kept" (581, 604).

Ilaria Miarelli Mariani

Bulletin of the John Rylands Library

Edward Wouk

Rylands English MS 60, compiled for the Spencer family in the eighteenth century, contains 130 printed portraits of early modern artists gathered from diverse sources and mounted in two albums: 76 portraits in the rst volume, which is devoted to northern European artists, and 54 in the second volume, containing Italian and French painters. Both albums of this 'Collection of Engravings of Portraits of Painters' were initially planned to include a written biography of each artist copied from the few sources available in English at the time, but that part of the project was abandoned. This article relates English MS 60 to shiiing practices of picturing art history. It examines the rise of printed artists' portraits, tracing the divergent histories of the genre south and north of the Alps, and explores how biographical approaches to the history of art were being replaced, in the eighteenth century, by the development of illustrated texts about art.

Journal for Eighteenth-Century Studies

Shearer West

Alex Warrender

Around the age of thirty-three, Anthony van Dyck embarked on a project that would expand not only his public recognition but also his artistic creative praxis: A series of portrait prints know as the Iconography. While this project has justly benefitted from significant study, its ideological, chronological and methodological scope remains out of focus.It is the very liminality of its origins, in both technical method and publication, that support the notion that in the case of Van Dyck’s Iconography, it is the process of becoming that is of most interest, rather than the finished project or plate. In bridging the gap between the loose, immediate capturing of a likeness through a drawing and the eventual result of a tonal, painterly engraving, Van Dyck worked between a variety of different mediums and techniques. What were his reasons for using such a wide variety of media to work out the compositions for his etched and engraved works? What does his handling of the medium reveal about his relationship to the printed plate? Why did he allow the intermediary steps between primi pensieri and seemingly completed engraving to be publicly circulated? Why did Van Dyck choose to dedicate himself to a reproducible visual collection of dignified individuals related to the humanities? This text seeks to approach these questions from an intermedial perspective, exploring the ways in which Van Dyck’s fluid use of media – as an intermedial praxis – throws into relief his humanist philosophy and reveals a conscious use of intermedial experimentation that goes beyond technical practicality. Selectively following the theoretical developments and artistic traditions evolving throughout the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, Van Dyck expanded his portraiture in the Iconography across a spectrum of media not only to reach the perfect engraved print, but to publish his procedural creative workings, solidifying his position as a master of the arts.

George P Landow

Literature Compass

Douglas Fordham

This essay examines new developments in the history of eighteenth-century British art since the publication of David Solkin's Painting for Money: The Visual Arts and the Public Sphere in Eighteenth-Century England in 1993. While Solkin's account of an urban professional class recasting a civic humanist ideology in its own polite and commercial image continues to hold tremendous sway in the field, this state of the field article identifies three major trends that have tempered and challenged that account. Recent scholarship dealing with gender, space, and empire has subtly reoriented the field towards a more inclusive notion of artistic agency and reception, a more synchronic and spatial approach, and an increasingly global perspective.

Francis Bacon: Painting, Philosophy, Psychoanalysis (Thames & Hudson)

Loading Preview

Sorry, preview is currently unavailable. You can download the paper by clicking the button above.

RELATED PAPERS

Mihaela Irimia

Joanna Woodall

Kate Grandjouan

Julie Codell

Deborah Mazza

Catherine Roach

C. Brook and V. Curzi (eds), Hogarth, Reynolds, Turner: British Painting and the Rise of Modernity

Adriano Aymonino

Melissa Lee Hyde

Kate Anderson

The Art Book

Richard Taws

Oxford Art Journal

A. Cassandra Albinson

Cynthia Rodríguez Juárez

Theatralia, 24.1, pp. 313–356.

M. A. Katritzky

The Historical Journal

Catriona Murray

M. De Mey, M. P. J. Martens, C. Stroo (ed.), Vision and Material: Interaction between Art and Science in Jan van Eyck's time.

Till-Holger Borchert

Visual Culture in Britain

Amelia Yeates

English Literary Renaissance

Clark Hulse

Times Literary Supplement

Daniel Vuillermin

Material Matters, Winterthur Program in American Material Culture

Alba Campo Rosillo

Roemisches Jahrbuch der Bibliotheca Hertziana

Patrizia Cavazzini

Marjorie Munsterberg

RELATED TOPICS

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

- Find new research papers in:

- Health Sciences

- Earth Sciences

- Cognitive Science

- Mathematics

- Computer Science

- Academia ©2024

Home / Essay Samples / Art / Two Fridas / Self Portraits And The Evolution Of Selfies

Self Portraits And The Evolution Of Selfies

- Category: Art

- Topic: Selfie , Two Fridas

Pages: 1 (467 words)

- Downloads: -->

--> ⚠️ Remember: This essay was written and uploaded by an--> click here.

Found a great essay sample but want a unique one?

are ready to help you with your essay

You won’t be charged yet!

Graffiti Essays

Selfie Essays

Frida Kahlo Essays

Pablo Picasso Essays

Modernism Essays

Related Essays

We are glad that you like it, but you cannot copy from our website. Just insert your email and this sample will be sent to you.

By clicking “Send”, you agree to our Terms of service and Privacy statement . We will occasionally send you account related emails.

Your essay sample has been sent.

In fact, there is a way to get an original essay! Turn to our writers and order a plagiarism-free paper.

samplius.com uses cookies to offer you the best service possible.By continuing we’ll assume you board with our cookie policy .--> -->