University Library, University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign

Research Posters

- Elements of a poster

CREATING YOUR POSTER

Color scheme choices.

- WHAT TO INCLUDE IN YOUR POSTER

- More helpful tips

- Visualizations & images

- Illinois logo

- Archiving - Grad Students

- More Resources

- Oral Presentations

- 2024 Undergraduate Research Symposium This link opens in a new window

You have two choices when creating a research poster:

- You can create your poster from scratch by using PowerPoint, Adobe InDesign, or a similar design program.

- You can use one of the University of Illinois Research Poster Templates .

Sizing your Poster

- If you are presenting for the Undergraduate Research Symposium , resize your slide to width 48 inches by height 36 inches.

- If you are presenting at a professional conference , your instructions should indicate the size limits of your poster. Standard U.S. conference poster size is 48" by 36".

IMPORTANT: You must change the size of your slide before you start working on your poster. This will ensure that your images and text do not become pixilated when the poster is printed. See below for specific instructions.

How to correctly size your poster in PowerPoint:

- Select the "Design" tab

- Click "Slide Size"

- Select "Page Setup"

- Under the "Slides sized for:" dropdown menu, select "Custom"

- Set the "Width" and "Height" to what is needed for your poster

- Click "OK"

How to correctly size your poster in Adobe InDesign:

When a new document is created in Adobe InDesign, a dialogue box prompts you to enter dimensions:

- Change the dimension metric to inches from the drop down box.

- Margins are intentional space from an object to the edge of the poster, intended not to be trimmed. You can set this to 0 inches on all sides unless you have a specific plan to use margins in your design.

- Bleed shows the printer where to trim white space that occurs when printing color onto white poster paper. If you are printing your poster, include at least a 0.25 inch bleed on each side; remember not to place any content in the bleed as it will be trimmed by the printer.

- Slug is a space for the creator to leave any notes for the printer. You can set this to 0 inches unless you have notes.

If you ever want to change your poster dimensions after starting the poster, you can do so through the Document Setup Menu .

Using multiple font styles can really make your poster stand out and look professional. Consult this graphic to understand different font styles, what fonts work best together, and what fonts to avoid.

Sticking to a color scheme can help your poster look professional. Consistent use of color can help your viewer understand how information is organized on your poster. Not sure where to start with color?

- Pick colors from an image (including a custom one you're planning to use on your poster)

- Use Illinois branding colors

Not sure what to do with the hex code from a brand guide or color palette generator?

- Adobe InDesign

Always check that your text is accessible on background colors using WebAIM's free contrast checker.

If printing your poster, it's a good idea to do a small-scale test print of your poster before getting it printed. Colors often appear brighter and more vibrant on a screen than when printed. There still might be some variation in color depending on the color scale the printer uses, but it will be a closer match on paper than what you see on screen.

- << Previous: Examples

- Next: Visualizations & images >>

- Last Updated: May 13, 2024 2:05 PM

- URL: https://guides.library.illinois.edu/poster

How to Create a Research Poster

- Poster Basics

- Design Tips

- Logos & Images

What is a Research Poster?

Posters are widely used in the academic community, and most conferences include poster presentations in their program. Research posters summarize information or research concisely and attractively to help publicize it and generate discussion.

The poster is usually a mixture of a brief text mixed with tables, graphs, pictures, and other presentation formats. At a conference, the researcher stands by the poster display while other participants can come and view the presentation and interact with the author.

What Makes a Good Poster?

- Important information should be readable from about 10 feet away

- Title is short and draws interest

- Word count of about 300 to 800 words

- Text is clear and to the point

- Use of bullets, numbering, and headlines make it easy to read

- Effective use of graphics, color and fonts

- Consistent and clean layout

- Includes acknowledgments, your name and institutional affiliation

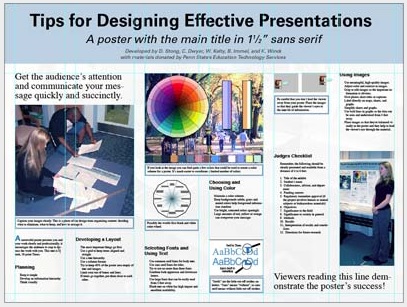

A Sample of a Well Designed Poster

View this poster example in a web browser .

Image credit: Poster Session Tips by [email protected], via Penn State

Where do I begin?

Answer these three questions:.

- What is the most important/interesting/astounding finding from my research project?

- How can I visually share my research with conference attendees? Should I use charts, graphs, photos, images?

- What kind of information can I convey during my talk that will complement my poster?

What software can I use to make a poster?

A popular, easy-to-use option. It is part of Microsoft Office package and is available on the library computers in rooms LC337 and LC336. ( Advice for creating a poster with PowerPoint ).

Adobe Illustrator, Photoshop, and InDesign

Feature-rich professional software that is good for posters including lots of high-resolution images, but they are more complex and expensive. NYU Faculty, Staff, and Students can access and download the Adobe Creative Suite .

Open Source Alternatives

- OpenOffice is the free alternative to MS Office (Impress is its PowerPoint alternative).

- Inkscape and Gimp are alternatives to Adobe products.

- For charts and diagrams try Gliffy or Lovely Charts .

- A complete list of free graphics software .

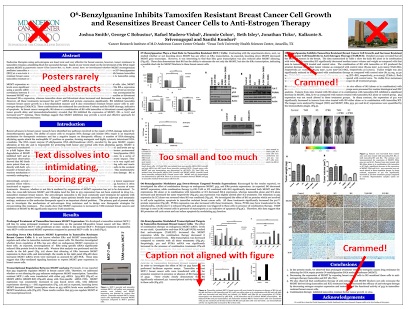

A Sample of a Poorly Designed Poster

View this bad poster example in a browser.

Image Credit: Critique by Better Posters

- Next: Design Tips >>

- Last Updated: Jul 11, 2023 5:09 PM

- URL: https://guides.nyu.edu/posters

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- Health Serv Res

- v.42(1 Pt 1); 2007 Feb

Preparing and Presenting Effective Research Posters

Associated data.

APPENDIX A.2. Comparison of Research Papers, Presentations, and Posters—Contents.

Posters are a common way to present results of a statistical analysis, program evaluation, or other project at professional conferences. Often, researchers fail to recognize the unique nature of the format, which is a hybrid of a published paper and an oral presentation. This methods note demonstrates how to design research posters to convey study objectives, methods, findings, and implications effectively to varied professional audiences.

A review of existing literature on research communication and poster design is used to identify and demonstrate important considerations for poster content and layout. Guidelines on how to write about statistical methods, results, and statistical significance are illustrated with samples of ineffective writing annotated to point out weaknesses, accompanied by concrete examples and explanations of improved presentation. A comparison of the content and format of papers, speeches, and posters is also provided.

Each component of a research poster about a quantitative analysis should be adapted to the audience and format, with complex statistical results translated into simplified charts, tables, and bulleted text to convey findings as part of a clear, focused story line.

Conclusions

Effective research posters should be designed around two or three key findings with accompanying handouts and narrative description to supply additional technical detail and encourage dialog with poster viewers.

An assortment of posters is a common way to present research results to viewers at a professional conference. Too often, however, researchers treat posters as poor cousins to oral presentations or published papers, failing to recognize the opportunity to convey their findings while interacting with individual viewers. By neglecting to adapt detailed paragraphs and statistical tables into text bullets and charts, they make it harder for their audience to quickly grasp the key points of the poster. By simply posting pages from the paper, they risk having people merely skim their work while standing in the conference hall. By failing to devise narrative descriptions of their poster, they overlook the chance to learn from conversations with their audience.

Even researchers who adapt their paper into a well-designed poster often forget to address the range of substantive and statistical training of their viewers. This step is essential for those presenting to nonresearchers but also pertains when addressing interdisciplinary research audiences. Studies of policymakers ( DiFranza and the Staff of the Advocacy Institute 1996 ; Sorian and Baugh 2002 ) have demonstrated the importance of making it readily apparent how research findings apply to real-world issues rather than imposing on readers to translate statistical findings themselves.

This methods note is intended to help researchers avoid such pitfalls as they create posters for professional conferences. The first section describes objectives of research posters. The second shows how to describe statistical results to viewers with varied levels of statistical training, and the third provides guidelines on the contents and organization of the poster. Later sections address how to prepare a narrative and handouts to accompany a research poster. Because researchers often present the same results as published research papers, spoken conference presentations, and posters, Appendix A compares similarities and differences in the content, format, and audience interaction of these three modes of presenting research results. Although the focus of this note is on presentation of quantitative research results, many of the guidelines about how to prepare and present posters apply equally well to qualitative studies.

WHAT IS A RESEARCH POSTER?

Preparing a poster involves not only creating pages to be mounted in a conference hall, but also writing an associated narrative and handouts, and anticipating the questions you are likely to encounter during the session. Each of these elements should be adapted to the audience, which may include people with different levels of familiarity with your topic and methods ( Nelson et al. 2002 ; Beilenson 2004 ). For example, the annual meeting of the American Public Health Association draws academics who conduct complex statistical analyses along with practitioners, program planners, policymakers, and journalists who typically do not.

Posters are a hybrid form—more detailed than a speech but less than a paper, more interactive than either ( Appendix A ). In a speech, you (the presenter) determine the focus of the presentation, but in a poster session, the viewers drive that focus. Different people will ask about different facets of your research. Some might do policy work or research on a similar topic or with related data or methods. Others will have ideas about how to apply or extend your work, raising new questions or suggesting different contrasts, ways of classifying data, or presenting results. Beilenson (2004) describes the experience of giving a poster as a dialogue between you and your viewers.

By the end of an active poster session, you may have learned as much from your viewers as they have from you, especially if the topic, methods, or audience are new to you. For instance, at David Snowdon's first poster presentation on educational attainment and longevity using data from The Nun Study, another researcher returned several times to talk with Snowdon, eventually suggesting that he extend his research to focus on Alzheimer's disease, which led to an important new direction in his research ( Snowdon 2001 ). In addition, presenting a poster provides excellent practice in explaining quickly and clearly why your project is important and what your findings mean—a useful skill to apply when revising a speech or paper on the same topic.

WRITING FOR A VARIED PROFESSIONAL AUDIENCE

Audiences at professional conferences vary considerably in their substantive and methodological backgrounds. Some will be experts on your topic but not your methods, some will be experts on your methods but not your topic, and most will fall somewhere in between. In addition, advances in research methods imply that even researchers who received cutting-edge methodological training 10 or 20 years ago might not be conversant with the latest approaches. As you design your poster, provide enough background on both the topic and the methods to convey the purpose, findings, and implications of your research to the expected range of readers.

Telling a Simple, Clear Story

Write so your audience can understand why your work is of interest to them, providing them with a clear take-home message that they can grasp in the few minutes they will spend at your poster. Experts in communications and poster design recommend planning your poster around two to three key points that you want your audience to walk away with, then designing the title, charts, and text to emphasize those points ( Briscoe 1996 ; Nelson et al. 2002 ; Beilenson 2004 ). Start by introducing the two or three key questions you have decided will be the focus of your poster, and then provide a brief overview of data and methods before presenting the evidence to answer those questions. Close with a summary of your findings and their implications for research and policy.

A 2001 survey of government policymakers showed that they prefer summaries of research to be written so they can immediately see how the findings relate to issues currently facing their constituencies, without wading through a formal research paper ( Sorian and Baugh 2002 ). Complaints that surfaced about many research reports included that they were “too long, dense, or detailed,” or “too theoretical, technical, or jargony.” On average, respondents said they read only about a quarter of the research material they receive for detail, skim about half of it, and never get to the rest.

To ensure that your poster is one viewers will read, understand, and remember, present your analyses to match the issues and questions of concern to them, rather than making readers translate your statistical results to fit their interests ( DiFranza and the Staff of the Advocacy Institute 1996 ; Nelson et al. 2002 ). Often, their questions will affect how you code your data, specify your model, or design your intervention and evaluation, so plan ahead by familiarizing yourself with your audience's interests and likely applications of your study findings. In an academic journal article, you might report parameter estimates and standard errors for each independent variable in your regression model. In the poster version, emphasize findings for specific program design features, demographic, or geographic groups, using straightforward means of presenting effect size and statistical significance; see “Describing Numeric Patterns and Contrasts” and “Presenting Statistical Test Results” below.

The following sections offer guidelines on how to present statistical findings on posters, accompanied by examples of “poor” and “better” descriptions—samples of ineffective writing annotated to point out weaknesses, accompanied by concrete examples and explanations of improved presentation. These ideas are illustrated with results from a multilevel analysis of disenrollment from the State Children's Health Insurance Program (SCHIP; Phillips et al. 2004 ). I chose that paper to show how to prepare a poster about a sophisticated quantitative analysis of a topic of interest to HSR readers, and because I was a collaborator in that study, which was presented in the three formats compared here—as a paper, a speech, and a poster.

Explaining Statistical Methods

Beilenson (2004) and Briscoe (1996) suggest keeping your description of data and methods brief, providing enough information for viewers to follow the story line and evaluate your approach. Avoid cluttering the poster with too much technical detail or obscuring key findings with excessive jargon. For readers interested in additional methodological information, provide a handout and a citation to the pertinent research paper.

As you write about statistical methods or other technical issues, relate them to the specific concepts you study. Provide synonyms for technical and statistical terminology, remembering that many conferences of interest to policy researchers draw people from a range of disciplines. Even with a quantitatively sophisticated audience, don't assume that people will know the equivalent vocabulary used in other fields. A few years ago, the journal Medical Care published an article whose sole purpose was to compare statistical terminology across various disciplines involved in health services research so that people could understand one another ( Maciejewski et al. 2002 ). After you define the term you plan to use, mention the synonyms from the various fields represented in your audience.

Consider whether acronyms are necessary on your poster. Avoid them if they are not familiar to the field or would be used only once or twice on your poster. If you use acronyms, spell them out at first usage, even those that are common in health services research such as “HEDIS®”(Health Plan Employer Data and Information Set) or “HLM”(hierarchical linear model).

Poor: “We use logistic regression and a discrete-time hazards specification to assess relative hazards of SCHIP disenrollment, with plan level as our key independent variable.” Comment: Terms like “discrete-time hazards specification” may be confusing to readers without training in those methods, which are relatively new on the scene. Also the meaning of “SCHIP” or “plan level” may be unfamiliar to some readers unless defined earlier on the poster.

Better: “Chances of disenrollment from the State Children's Health Insurance Program (SCHIP) vary by amount of time enrolled, so we used hazards models (also known as event history analysis or survival analysis) to correct for those differences when estimating disenrollment patterns for SCHIP plans for different income levels.” Comment: This version clarifies the terms and concepts, naming the statistical method and its synonyms, and providing a sense of why this type of analysis is needed.

To explain a statistical method or assumption, paraphrase technical terms and illustrate how the analytic approach applies to your particular research question and data:

Poor : “The data structure can be formulated as a two-level hierarchical linear model, with families (the level-1 unit of analysis) nested within counties (the level-2 unit of analysis).” Comment: Although this description would be fine for readers used to working with this type of statistical model, those who aren't conversant with those methods may be confused by terminology such as “level-1” and “unit of analysis.”

Better: “The data have a hierarchical (or multilevel) structure, with families clustered within counties.” Comment: By replacing “nested” with the more familiar “clustered,” identifying the specific concepts for the two levels of analysis, and mentioning that “hierarchical” and “multilevel” refer to the same type of analytic structure, this description relates the generic class of statistical model to this particular study.

Presenting Results with Charts

Charts are often the preferred way to convey numeric patterns, quickly revealing the relative sizes of groups, comparative levels of some outcome, or directions of trends ( Briscoe 1996 ; Tufte 2001 ; Nelson et al. 2002 ). As Beilenson puts it, “let your figures do the talking,” reducing the need for long text descriptions or complex tables with lots of tiny numbers. For example, create a pie chart to present sample composition, use a simple bar chart to show how the dependent variable varies across subgroups, or use line charts or clustered bar charts to illustrate the net effects of nonlinear specifications or interactions among independent variables ( Miller 2005 ). Charts that include confidence intervals around point estimates are a quick and effective way to present effect size, direction, and statistical significance. For multivariate analyses, consider presenting only the results for the main variables of interest, listing the other variables in the model in a footnote and including complex statistical tables in a handout.

Provide each chart with a title (in large type) that explains the topic of that chart. A rhetorical question or summary of the main finding can be very effective. Accompany each chart with a few annotations that succinctly describe the patterns in that chart. Although each chart page should be self-explanatory, be judicious: Tufte (2001) cautions against encumbering your charts with too much “nondata ink”—excessive labeling or superfluous features such as arrows and labels on individual data points. Strive for a balance between guiding your readers through the findings and maintaining a clean, uncluttered poster. Use chart types that are familiar to your expected audience. Finally, remember that you can flesh out descriptions of charts and tables in your script rather than including all the details on the poster itself; see “Narrative to Accompany a Poster.”

Describing Numeric Patterns and Contrasts

As you describe patterns or numeric contrasts, whether from simple calculations or complex statistical models, explain both the direction and magnitude of the association. Incorporate the concepts under study and the units of measurement rather than simply reporting coefficients (β's) ( Friedman 1990 ; Miller 2005 ).

Poor: “Number of enrolled children in the family is correlated with disenrollment.” Comment: Neither the direction nor the size of the association is apparent.

Poor [version #2]: “The log-hazard of disenrollment for one-child families was 0.316.” Comment: Most readers find it easier to assess the size and direction from hazards ratios (a form of relative risk) instead of log-hazards (log-relative risks, the β's from a hazards model).

Better: “Families with only one child enrolled in the program were about 1.4 times as likely as larger families to disenroll.” Comment: This version explains the association between number of children and disenrollment without requiring viewers to exponentiate the log-hazard in their heads to assess the size and direction of that association. It also explicitly identifies the group against which one-child families are compared in the model.

Presenting Statistical Test Results

On your poster, use an approach to presenting statistical significance that keeps the focus on your results, not on the arithmetic needed to conduct inferential statistical tests. Replace standard errors or test statistics with confidence intervals, p- values, or symbols, or use formatting such as boldface, italics, or a contrasting color to denote statistically significant findings ( Davis 1997 ; Miller 2005 ). Include the detailed statistical results in handouts for later perusal.

To illustrate these recommendations, Figures 1 and and2 2 demonstrate how to divide results from a complex, multilevel model across several poster pages, using charts and bullets in lieu of the detailed statistical table from the scientific paper ( Table 1 ; Phillips et al. 2004 ). Following experts' advice to focus on one or two key points, these charts emphasize the findings from the final model (Model 5) rather than also discussing each of the fixed- and random-effects specifications from the paper.

Presenting Complex Statistical Results Graphically

Text Summary of Additional Statistical Results

Multilevel Discrete-Time Hazards Models of Disenrollment from SCHIP, New Jersey, January 1998–April 2000

Source : Phillips et al. (2004) .

SCHIP, State Children's Health Insurance Program; LRH, log relative-hazard; SE, standard error.

Figure 1 uses a chart (also from the paper) to present the net effects of a complicated set of interactions between two family-level traits (race and SCHIP plan) and a cross-level interaction between race of the family and county physician racial composition. The title is a rhetorical question that identifies the issue addressed in the chart, and the annotations explain the pattern. The chart version substantially reduces the amount of time viewers need to understand the main take-home point, averting the need to mentally sum and exponentiate several coefficients from the table.

Figure 2 uses bulleted text to summarize other key results from the model, translating log-relative hazards into hazards ratios and interpreting them with minimal reliance on jargon. The results for family race, SCHIP plan, and county physician racial composition are not repeated in Figure 2 , averting the common problem of interpreting main effect coefficients and interaction coefficients without reference to one another.

Alternatively, replace the text summary shown in Figure 2 with Table 2 —a simplified version of Table 1 which presents only the results for Model 5, replaces log-relative hazards with hazards ratios, reports associated confidence intervals in lieu of standard errors, and uses boldface to denote statistical significance. (On a color slide, use a contrasting color in lieu of bold.)

Relative Risks of SCHIP Disenrollment for Other * Family and County Characteristics, New Jersey, January 1998–April 2000

Statistically significant associations are shown in bold.

Based on hierarchical linear model controlling for months enrolled, months-squared, race, SCHIP plan, county physician racial composition, and all variables shown here. Scaled deviance =30,895. Random effects estimate for between-county variance =0.005 (standard error =0.006). SCHIP, State Children's Health Insurance Program; 95% CI, 95% confidence interval.

CONTENTS AND ORGANIZATION OF A POSTER

Research posters are organized like scientific papers, with separate pages devoted to the objectives and background, data and methods, results, and conclusions ( Briscoe 1996 ). Readers view the posters at their own pace and at close range; thus you can include more detail than in slides for a speech (see Appendix A for a detailed comparison of content and format of papers, speeches, and posters). Don't simply post pages from the scientific paper, which are far too text-heavy for a poster. Adapt them, replacing long paragraphs and complex tables with bulleted text, charts, and simple tables ( Briscoe 1996 ; Beilenson 2004 ). Fink (1995) provides useful guidelines for writing text bullets to convey research results. Use presentation software such as PowerPoint to create your pages or adapt them from related slides, facilitating good page layout with generous type size, bullets, and page titles. Such software also makes it easy to create matching handouts (see “Handouts”).

The “W's” (who, what, when, where, why) are an effective way to organize the elements of a poster.

- In the introductory section, describe what you are studying, why it is important, and how your analysis will add to the existing literature in the field.

- In the data and methods section of a statistical analysis, list when, where, who, and how the data were collected, how many cases were involved, and how the data were analyzed. For other types of interventions or program evaluations, list who, when, where, and how many, along with how the project was implemented and assessed.

- In the results section, present what you found.

- In the conclusion, return to what you found and how it can be used to inform programs or policies related to the issue.

Number and Layout of Pages

To determine how many pages you have to work with, find out the dimensions of your assigned space. A 4′ × 8′ bulletin board accommodates the equivalent of about twenty 8.5″ × 11″ pages, but be selective—no poster can capture the full detail of a large series of multivariate models. A trifold presentation board (3′ high by 4′ wide) will hold roughly a dozen pages, organized into three panels ( Appendix B ). Breaking the arrangement into vertical sections allows viewers to read each section standing in one place while following the conventions of reading left-to-right and top-to-bottom ( Briscoe 1996 ).

- At the top of the poster, put an informative title in a large, readable type size. On a 4′ × 8′ bulletin board, there should also be room for an institutional logo.

Suggested Layout for a 4′ × 8′ poster.

- In the left-hand panel, set the stage for the research question, conveying why the topic is of policy interest, summarizing major empirical or theoretical work on related topics, and stating your hypotheses or project aims, and explaining how your work fills in gaps in previous analyses.

- In the middle panel, briefly describe your data source, variables, and methods, then present results in tables or charts accompanied by text annotations. Diagrams, maps, and photographs are very effective for conveying issues difficult to capture succinctly in words ( Miller 2005 ), and to help readers envision the context. A schematic diagram of relationships among variables can be useful for illustrating causal order. Likewise, a diagram can be a succinct way to convey timing of different components of a longitudinal study or the nested structure of a multilevel dataset.

- In the right-hand panel, summarize your findings and relate them back to the research question or project aims, discuss strengths and limitations of your approach, identify research, practice, or policy implications, and suggest directions for future research.

Figure 3 (adapted from Beilenson 2004 ) shows a suggested layout for a 4′ × 8′ bulletin board, designed to be created using software such as Pagemaker that generates a single-sheet presentation; Appendix C shows a complete poster version of the Phillips et al. (2004) multilevel analysis of SCHIP disenrollment. If hardware or budget constraints preclude making a single-sheet poster, a similar configuration can be created using standard 8.5″ × 11″ pages in place of the individual tables, charts, or blocks of text shown in Figure 3 .

Find out well in advance how the posters are to be mounted so you can bring the appropriate supplies. If the room is set up for table-top presentations, tri-fold poster boards are essential because you won't have anything to attach a flat poster board or pages to. If you have been assigned a bulletin board, bring push-pins or a staple gun.

Regardless of whether you will be mounting your poster at the conference or ahead of time, plan how the pages are to be arranged. Experiment with different page arrangements on a table marked with the dimensions of your overall poster. Once you have a final layout, number the backs of the pages or draw a rough sketch to work from as you arrange the pages on the board. If you must pin pages to a bulletin board at the conference venue, allow ample time to make them level and evenly spaced.

Other Design Considerations

A few other issues to keep in mind as you design your poster. Write a short, specific title that fits in large type size on the title banner of your poster. The title will be potential readers' first glimpse of your poster, so make it inviting and easy to read from a distance—at least 40-point type, ideally larger. Beilenson (2004) advises embedding your key finding in the title so viewers don't have to dig through the abstract or concluding page to understand the purpose and conclusions of your work. A caution: If you report a numeric finding in your title, keep in mind that readers may latch onto it as a “factoid” to summarize your conclusions, so select and phrase it carefully ( McDonough 2000 ).

Use at least 14-point type for the body of the poster text. As Briscoe (1996) points out, “many in your audience have reached the bifocal age” and all of them will read your poster while standing, hence long paragraphs in small type will not be appreciated! Make judicious use of color. Use a clear, white, or pastel for the background, with black or another dark color for most text, and a bright, contrasting shade to emphasize key points or to identify statistically significant results ( Davis 1997 ).

NARRATIVE TO ACCOMPANY A POSTER

Prepare a brief oral synopsis of the purpose, findings, and implications of your work to say to interested parties as they pause to read your poster. Keep it short—a few sentences that highlight what you are studying, a couple of key findings, and why they are important. Design your overview as a “sound byte” that captures your main points in a succinct and compelling fashion ( Beilenson 2004 ). After hearing your introduction, listeners will either nod and move along or comment on some aspect of your work that intrigues them. You can then tailor additional discussion to individual listeners, adjusting the focus and amount of detail to suit their interests. Gesture at the relevant pages as you make each point, stating the purpose of each chart or table and explaining its layout before describing the numeric findings; see Miller (2005) for guidelines on how to explain tables and charts to a live audience. Briscoe (1996) points out that these mini-scripts are opportunities for you to fill in details of your story line, allowing you to keep the pages themselves simple and uncluttered.

Prepare short answers to likely questions about various aspects of your work, such as why it is important from a policy or research perspective, or descriptions of data, methods, and specific results. Think of these as little modules from an overall speech—concise descriptions of particular elements of your study that you can choose among in response to questions that arise. Beilenson (2004) also recommends developing a few questions to ask your viewers, inquiring about their reactions to your findings, ideas for additional questions, or names of others working on the topic.

Practice your poster presentation in front of a test audience acquainted with the interests and statistical proficiency of your expected viewers. Ideally, your critic should not be too familiar with your work: A fresh set of eyes and ears is more likely to identify potential points of confusion than someone who is jaded from working closely with the material while writing the paper or drafting the poster ( Beilenson 2004 ). Ask your reviewer to identify elements that are unclear, flag jargon to be paraphrased or defined, and recommend changes to improve clarity ( Miller 2005 ). Have them critique your oral presentation as well as the contents and layout of the poster.

Prepare handouts to distribute to interested viewers. These can be produced from slides created in presentation software, printed several to a page along with a cover page containing the abstract and your contact information. Or package an executive summary or abstract with a few key tables or charts. Handouts provide access to the more detailed literature review, data and methods, full set of results, and citations without requiring viewers to read all of that information from the poster ( Beilenson 2004 ; Miller 2005 ). Although you also can bring copies of the complete paper, it is easier on both you and your viewers if you collect business cards or addresses and mail the paper later.

The quality and effectiveness of research posters at professional conferences is often compromised by authors' failure to take into account the unique nature of such presentations. One common error is posting numerous statistical tables and long paragraphs from a research paper—an approach that overwhelms viewers with too much detail for this type of format and presumes familiarity with advanced statistical techniques. Following recommendations from the literature on research communication and poster design, this paper shows how to focus each poster on a few key points, using charts and text bullets to convey results as part of a clear, straightforward story line, and supplementing with handouts and an oral overview.

Another frequent mistake is treating posters as a one-way means of communication. Unlike published papers, poster sessions are live presentations; unlike speeches, they allow for extended conversation with viewers. This note explains how to create an oral synopsis of the project, short modular descriptions of poster elements, and questions to encourage dialog. By following these guidelines, researchers can substantially improve their conference posters as vehicles to disseminate findings to varied research and policy audiences.

CHECKLIST FOR PREPARING AND PRESENTING AN EFFECTIVE RESEARCH POSTERS

- Design poster to focus on two or three key points.

- Adapt materials to suit expected viewers' knowledge of your topic and methods.

- Design questions to meet their interests and expected applications of your work.

- Paraphrase descriptions of complex statistical methods.

- Spell out acronyms if used.

- Replace large detailed tables with charts or small, simplified tables.

- Accompany tables or charts with bulleted annotations of major findings.

- Describe direction and magnitude of associations.

- Use confidence intervals, p -values, symbols, or formatting to denote statistical significance.

Layout and Format

- Organize the poster into background, data and methods, results, and study implications.

- Divide the material into vertical sections on the poster.

- Use at least 14-point type in the body of your poster, at least 40-point for the title.

Narrative Description

- Rehearse a three to four sentence overview of your research objectives and main findings.

- Summary of key studies and gaps in existing literature

- Data and methods

- Each table, chart, or set of bulleted results

- Research, policy, and practice implications

- Solicit their input on your findings

- Develop additional questions for later analysis

- Identify other researchers in the field

- Prepare handouts to distribute to interested viewers.

- Print slides from presentation software, several to a page.

- Or package an executive summary or abstract with a few key tables or charts.

- Include an abstract and contact information.

Acknowledgments

I would like to thank Ellen Idler, Julie Phillips, Deborah Carr, Diane (Deedee) Davis, and two anonymous reviewers for helpful comments on earlier drafts of this work.

Supplementary Material

The following supplementary material for this article is available online:

APPENDIX A.1. Comparison of Research Papers, Presentations, and Posters—Materials and Audience Interaction.

Suggested Layout for a Tri-Fold Presentation Board.

Example Research Poster of Phillips et al. 2004 Study.

- Beilenson J. Developing Effective Poster Presentations. Gerontology News. 2004; 32 (9):6–9. [ Google Scholar ]

- Briscoe MH. Preparing Scientific Illustrations: A Guide to Better Posters, Presentations, and Publications. 2. New York: Springer-Verlag; 1996. [ Google Scholar ]

- Davis M. Scientific Papers and Presentations. New York: Academic Press; 1997. [ Google Scholar ]

- DiFranza JR. A Researcher's Guide to Effective Dissemination of Policy-Related Research. Princeton, NJ: The Robert Wood Johnson Foundation; 1996. the Staff of the Advocacy Institute, with Assistance from the Center for Strategic Communications. [ Google Scholar ]

- Fink A. How to Report on Surveys. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications; 1995. [ Google Scholar ]

- Friedman GD. Be Kind to Your Reader. American Journal of Epidemiology. 1990; 132 (4):591–3. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Maciejewski ML, Diehr P, Smith MA, Hebert P. Common Methodological Terms in Health Services Research and Their Symptoms. Medical Care. 2002; 40 :477–84. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- McDonough J. Experiencing Politics: A Legislator's Stories of Government and Health Care. Berkeley: University of California Press; 2000. [ Google Scholar ]

- Miller JE. The Chicago Guide to Writing about Multivariate Analysis. Chicago Guides to Writing, Editing and Publishing. Chicago: University of Chicago Press; 2005. [ Google Scholar ]

- Nelson DE, Brownson RC, Remington PL, Parvanta C, editors. Communicating Public Health Information Effectively: A Guide for Practitioners. Washington, DC: American Public Health Association; 2002. [ Google Scholar ]

- Phillips JA, Miller JE, Cantor JC, Gaboda D. Context or Composition. What Explains Variation in SCHIP Disenrollment? Health Services Research. 2004; 39 (4, part I):865–8. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Snowdon D. Aging with Grace: What the Nun Study Teaches Us about Leading Longer, Healthier, and More Meaningful Lives. New York: Bantam Books; 2001. [ Google Scholar ]

- Sorian R, Baugh T. Power of Information Closing the Gap between Research and Policy. Health Affairs. 2002; 21 (2):264–73. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Tufte ER. The Visual Display of Quantitative Information. 2. Cheshire, CT: Graphics Press; 2001. [ Google Scholar ]

- - Google Chrome

Intended for healthcare professionals

- Access provided by Google Indexer

- My email alerts

- BMA member login

- Username * Password * Forgot your log in details? Need to activate BMA Member Log In Log in via OpenAthens Log in via your institution

Search form

- Advanced search

- Search responses

- Search blogs

- How to prepare an...

How to prepare an effective research poster

- Related content

- Peer review

- Lucia Hartigan , registrar 1 ,

- Fionnuala Mone , fellow in maternal fetal medicine 1 ,

- Mary Higgins , consultant obstetrician 1 2

- 1 National Maternity Hospital, Dublin

- 2 Obstetrics and Gynaecology, Medicine and Medical Sciences, University College Dublin

- mhiggins{at}nmh.ie

Being asked to give a poster presentation can be exciting, and you need not be daunted by the prospect of working out how to prepare one. As Lucia Hartigan and colleagues explain, many options are available

The long nights are over, the statistics have been run, the abstract has been written, and the email pops into your inbox: “Congratulations! You have been accepted for a poster presentation.”

All that work has been worthwhile. Your consultant congratulates you and your colleagues are envious of your having a legitimate excuse to go away for a couple of days, but now you have to work out how to prepare a poster. Do not despair, for you have many options.

Firstly, take this seriously. A poster is not a consolation prize for not being given an oral presentation. This is your chance to show your work, talk to others in the field, and, if you are lucky, to pick up pointers from experts. Given that just 45% of published abstracts end in a full paper, 1 this may be your only chance to get your work out there, so put some effort into it. If you don’t have access to the services of a graphic designer, then some work will be entailed as it normally takes us a full day to prepare the layout of a poster. If you are lucky enough to have help from a graphic designer, then you will need to check that the data are correct before it is sent to the printer. After all, it will be your name on the poster, not the graphic designer’s.

Secondly, check the details of the requirements. What size poster should you have? If it is too big, it may look arrogant. If it is too small, then it may seem too modest and self effacing. Should it be portrait or landscape? Different meetings have different requirements. Some may stay with traditional paper posters, so you need to factor in printing. Others present them electronically, but may have a deadline by which you need to have uploaded the poster. When planning a meeting the organisers work out how many poster boards there will be and then the numbers, so follow their requirements and read the small print.

Then make a template. It can be tempting to “borrow” a poster template from someone else, and this may buy you some time, but it is important to check what page set-up and size have been selected for the template. If it’s meant for an A2 size and you wish to print your poster on A0 paper, then the stretching may lead to pixillation, which would not look good.

Next, think about your layout. Use text boxes to cover the following areas: title (with authors, institution, and logo), background, methods, results, and conclusions. Check that the text boxes are aligned by using gridlines, and justify your text. Use different colours for titles, and make sure you can read the title from 3 metres away. Some people will put their abstract in a separate box in the top right hand corner underneath the title, and then expand a little in the other areas. That is fine, so long as you follow the golden rule of writing a poster: do not include too much text. One study showed that less than 5% of conference attendees visit posters at meetings and that few ask useful questions. 2 The same research found that, in addition to the scientific content of a poster, the factors that increase visual appeal include pictures, graphs, and a limited use of words. 2 The ideal number of words seems to be between 300 and 400 per square metre.

Now make it look pretty and eye catching, and use lots of graphics. Outline text boxes or fill them with a different colour. If you can present the data using a graph, image, or figures rather than text, then do so, as this will add visual appeal. If you want to put a picture in the background, and it is appropriate to do so, fade the image so that it does not distract from the content.

Fonts are important. Check whether the meeting has set criteria for fonts; if they have, then follow them. You do not want to stand out for the wrong reason. If there are no specified criteria, then the title should be in point size 72-84, depending on the size of the poster. The authors’ names should be either the same size, but in italics, or else a couple of sizes smaller.

If you are including the hospital logo, don’t take a picture that will not size up properly when enlarged. Instead, obtain a proper copy from the hospital administrators.

References can be in small writing. No one is likely to read them, and you are including them only to remind yourself what you learnt in the literature review. One intriguing possibility is the use of a trigger image to link the poster to online content. 3

Finally, there are also things you should not do. Don’t leave your figures unlabelled, include spelling errors, use abbreviations without an explanation, or go outside the boundaries of the poster. Don’t be ashamed that you “only” have a poster. At a good meeting you may find that the comments from passers by are an amazing peer review. We have presented at meetings where world experts have given feedback, and with that feedback we have written the paper on the flight home.

Competing interests: We have read and understood the BMJ Group policy on declaration of interests and have no relevant interests to declare.

- ↵ Scherer RW, Langenberg P, von Elm E. Full publication of results initially presented in abstracts. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2007 ; 2 : MR000005 . OpenUrl PubMed

- ↵ Goodhand JR, Giles CL, Wahed M, Irving PM, Langmead L, Rampton DS. Poster presentations at medical conferences: an effective way of disseminating research? Clin Med 2011 ; 1 : 138 -41. OpenUrl

- ↵ Atherton S, Javed M, Webster S, Hemington-Gorse S. Use of a mobile device app: a potential new tool for poster presentations and surgical education. J Visual Comm Med 2013 ; 36 (1-2): 6 -10. OpenUrl

Gerstein Science Information Centre

Posters and presentations.

- Planning it out

General Poster Design Guides

Video: making an academic research poster using powerpoint, scientific research poster design guides and templates, design inspiration, handout tips.

- Presentation Tips

- Using Images and Data

- Citing Sources

- Printing Posters

- Campus Resources

- U of T poster session opportunities

- Your Comments

Pro tip: Not using a template and starting from scratch?

Remember to resize your canvas to the right size in PowerPoint (often 36x 48 inches or 36x 56 inches , instead of the default 8.5x11 inches).

Photo Credit: widdowquinn via Compfight cc

- Poster Buzz Resource created by design firm SCP; content created in consultation with science faculty from various universities. - Contains Microsoft PowerPoint templates for scientific research - various sizes and content/format types available (e.g. Quantitative, Qualitative, Mixed Methods, etc). - Also contains other resources for academic poster design and printing.

- Faculty of 1000 posters An open access repository of biology and medicine posters from 180+ international conferences

- Couldn't fit everything into your poster? Include extra key information , in an concise 1-page handout.

- Include your Works Cited list and any supplementary readings your audience might find of interest.

- Don't have time to make a handout from scratch? Print out colour mini copies of your poster to distribute, so that attendees won't have to rely on their grainy photos of your poster.

- << Previous: Planning it out

- Next: Presentation Tips >>

- Last Updated: May 1, 2024 12:49 AM

- URL: https://guides.library.utoronto.ca/posters_presentations

Library links

- Gerstein Home

- U of T Libraries Home

- Renew items and pay fines

- Library hours

- Contact Gerstein

- University of Toronto Libraries

- UT Mississauga Library

- UT Scarborough Library

- Information Commons

- All libraries

© University of Toronto . All rights reserved.

Connect with us

Learn more about how the Cal Poly Humboldt Library can help support your research and learning needs.

Stay updated at Campus Ready .

- Cal Poly Humboldt Library

- Research Guides

Creating a Research Poster

- Creating your poster step by step

- Getting Started

- Citing Images

- Creative Commons Images

- Printing options

- More Resources

Preparing your poster

There are three components to your poster session:

- Your poster

All three components should complement one another, not repeat each other.

Poster: Your poster should be an outline of your research with interesting commentary about what you learned along the way.

You: You should prepare a 10-30 second elevator pitch and a 1-2 minute lightning talk about your research. This should be a unique experience or insight you had about your research that adds depth of understanding to what the attendee can read on your poster.

Handout: Best practices for handouts - Your handout should be double-sided. The first side of the paper should include a picture of your poster (this can be in black and white or color). The second side of the handout should include your literature review, cited references, further information about your topic and your contact information.

Creating your poster by answering 3 questions:

- What is the most important and/or interesting finding from my research project?

- How can I visually share my research with conference attendees? Should I use charts, graphs, images, or a wordcloud?

- What kind of information do I need to share during my lightning talk that will complement my poster?

- *Title (at least 72 pt font).

- Research question or hypothesis (all text should be at least 24 pt font).

- Methodology. What is the research process that you used? Explain how you did your research.

- Your interview questions.

- Observations. What did you see? Why is this important?

- *Findings. What did you learn? Summarize your conclusions.

- Pull out themes in the literature and list in bullet points.

- Consider a brief narrative of what you learned - what was the most interesting/surprising part of your project?

- Interesting quotes from your research.

- Turn your data into charts or tables.

- Use images (visit the "Images" tab in the guide for more information). Take your own or legally use others.

- Recommendations and/or next steps for future research.

- You can include your list of citations on your poster or in your handout.

- *Make sure your name, and Cal Poly Humboldt University is on your poster.

*Required. Everything else is optional - you decide what is important to put on your poster. These are just suggestions. Use the tabs in this guide for more tips on how to create your poster.

Poster Sizes

You can create your poster from scratch by using PowerPoint or a similar design program.

Resize the slide to fit your needs before you begin adding any content. Standard poster sizes range from 40" by 30" and 48" by 36" but you should check with the conference organizers. If you don't resize your design at the beginning, when it is printed the image quality will be poor and pixelated if it is sized up to poster dimensions.

The standard poster sizes for ideaFest are 36" x 48" and 24" by 36".

To resize in PowerPoint, go to "File" then "Page Setup..." and enter your dimensions in the boxes for "width" and "height". Make sure to select "OK" to save your changes.

To resize in Google Slides, go to "File" then "Page setup" and select the "Custom" option in the drop down menu. Enter the dimensions for your poster size and then select "Apply" to save your changes.

Step Four: Final checklist

Final checklist for submitting your poster for printing:.

- Proofread your poster for spelling and grammar mistakes. Ask a peer to read your poster, they will catch the mistakes that you miss. Print your poster on an 8 1/2" by 11" sheet of paper - it is easier to read for mistakes and to judge your design.

- Make sure you followed Step 3 and resized your PPT slide correctly.

- Does your poster have flow? Did you "chunk" information into easily read pieces of information?

- Do your visualizations (e.g. charts, graphs, tag clouds, etc.) tell a story? Are they properly labeled and readable?

- Make sure that your images we not resized in PPT. You should use the original size of the image or try an image editor (e.g. Photoshop). Did you cite your image?

- Is your name, department, and affiliation on your poster?

- Did you want to include acknowlegments on your poster? This may be appropriate if your advisor and a graduate student provided leadership during the research process.

- Most importantly- Save your PPT slide to PDF before you send to the printer in order to avoid any printing mishaps. You should also double-check the properties to make sure it is still sized correctly in PDF.

- << Previous: Getting Started

- Next: Images >>

Undergraduate Research: Posters

- Topics & Search Tools

- Search Strategies

- Literature Reviews

- Annotated Bibliographies

- Office of Undergraduate Research

- Tips for Designing Better Research Posters

Online Tutorials

- UT at Austin: Guide to Creating Research Posters This sources contains samples and examples of posters alongside tips for messaging, reviewing, printing, and presenting your poster.

- UNC: Poster and Presentation Resources The academic poster design portion of this guide contains useful links to support creating a research poster. Other portions of this site will help with presenting your research and poster.

- NCSU: Creating Effective Poster Presentations Designed and organized like a research poster, this source contains an introduction to research posters along with other tools to support poster creation.

Blogs and Sites

- Better Posters: A Resource for Improving Poster Presentations Blog

- Colin Purrington: Designing Conference Posters This page gives a summary of what research posters are and how to get started. The subpages detail what you should put in different sections, provide free templates, and give tips on avoiding common mistakes.

Free Fonts and Palettes

- Fontsquirrel

- 1001 Free Fonts

- Coolors Palette Generator

- COLOURlovers

Undergraduate Research Services Librarian

Print on Campus

- Biological Sciences Department

- Newman Library Posting printing information is available under the dropdown "Plotter Printer."

- << Previous: Annotated Bibliographies

- Next: Citation >>

- Last Updated: Jul 11, 2020 3:06 PM

- URL: https://guides.lib.vt.edu/ur

How to create a research poster

- Getting Started

- Planning your Poster

- Designing a Poster

- Poster Templates & Examples

- Printing your Poster

- Additional Guides

What is a research poster?

A research poster is a visual way to summarize and communicate the results of a research project to a general audience. A good poster should include the goal of the research, its methodology, results, and discussion/conclusion, in clear and concise language.

Research posters will often include photos, maps, graphs and other images to present information in an attractive way.

Why a poster?

Research posters are a common form of research presentation in conferences, seminars, and symposiums. Some of the main advantages of presenting a poster rather than a conference paper are:

- Knowledge sharing with a wider audience: with poster presentations, researchers usually stand beside their posters and can interact directly with the public.

- Opportunity to explore different ways to present information: posters are ideal for highly visual topics.

- Networking: presenting posters can help researchers identify potential collaborators, spark further discussion, make contacts, etc.

- Opportunity to improve verbal presentation skills: researchers can talk about their research without having to observe the stricter guidelines of other types of conference presentations.

- Opportunity to showcase research to potential employers.

Branding requirements

Yukon University's branding guidelines may be applicable when presenting research results. This can vary depending on course/assignment requirements, whether the research is directly sponsored/funded by the institution, and how and where the poster will be presented.

For YukonU students: check with your instructor if branding is required for your situation.

YukonU faculty/staff: YukonU's branding guidelines can be found on https://yukoncollege.sharepoint.com/sites/yc/offices/relations (Sharepoint login required).

- Next: Planning your Poster >>

- Last Updated: Apr 12, 2023 2:45 PM

- URL: https://yukonu.libguides.com/research_poster

- Skip to main content

- Skip to primary sidebar

- Skip to footer

Additional menu

FreshSpectrum - Data Visualization Made Easy

Learn how you can use simple methods and tools, like Canva, Flourish, and Datawrapper, to improve your data communication skills.

How to design a research poster using Canva

Today’s post is about designing research poster presentations using Canva. Even if you’ve never created a research poster in your life, I think this post can really help you get a solid jump on your next design.

Because ready or not, it’s happening. After a long COVID-19 break, a bunch of evaluation conferences are going to be live again. And with live conferences you also get actual live presentations. And you also get those big poster presentation nights.

In this post:

- I’ll show you how to create a research poster, including a new approach I really appreciate.

- Grid based design and why planning your poster in content blocks is a good idea.

- A bunch of alternative poster styles that use the same underlying grid.

- Free research poster Canva templates, and some tools to help you design your next poster.

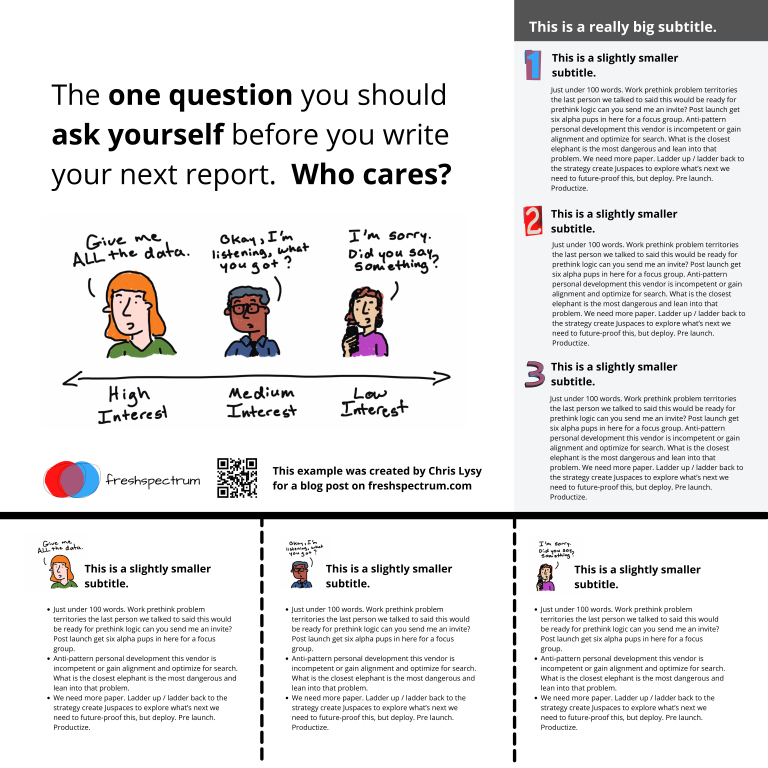

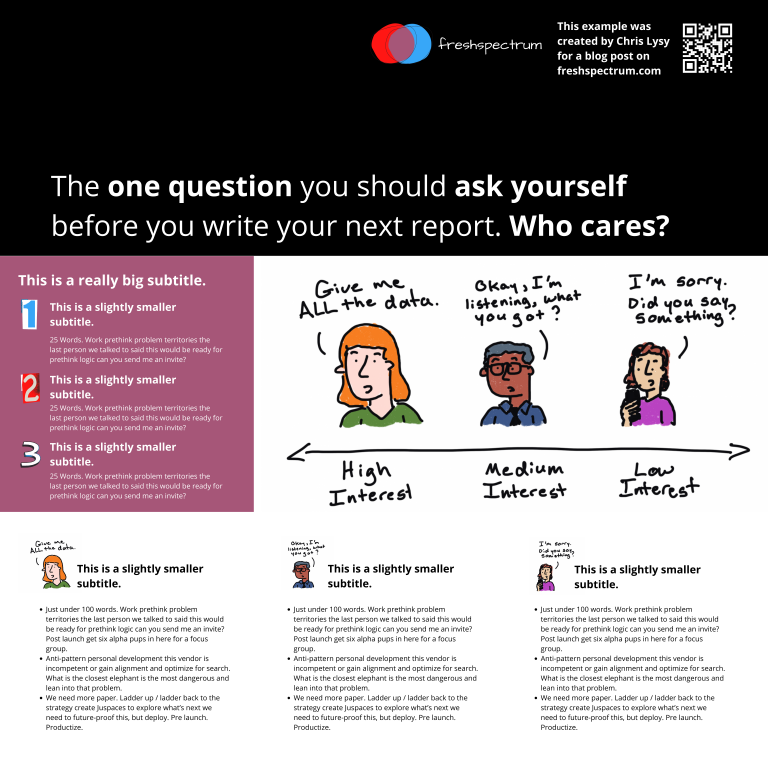

The research poster presentation mindset.

So imagine yourself in a room standing in front of a research poster surrounded by people just like you. The attendees at the session might be holding drinks and are continuously running into old friends. Some glance at your work and keep right on walking. Others might ask you a question or two as they peruse your poster.

And there you are, standing in front of your poster that you’ve agonized over. The one you had to carry in a big tube through a crowded airport and then inside a crowded airport shuttle.

A research poster isn’t some stand alone document or social media infographic. It’s your wingman. Your partner in crime. It stays by your side, supporting the communication of your work. A better poster design won’t just help you communicate, it can also make your time in that room feel a little less awkward.

The usual approach to research poster design.

Most research posters tend to just be adaptations of a research paper. As such, a lot of academics will simply take their paper title and put it at the top of the research poster. They will then create sections on the poster that mirror the sections in their paper.

Ultimately they end up with a research poster outline that looks just like a research paper outline. This is definitely not my preferred approach to research poster design. But if this is the way that you decide to create your poster, at least take some basic steps to ensure it’s readable.

Years ago, Stephanie Evergreen and Chris Metzner created a quick little guide on how to design a research poster for the American Evaluation Association’s Potent Presentations Initiative. Definitely check it out . Especially if you just want to polish a poster you’ve already created.

How to create a better research poster in less time.

I really like the poster approach outlined by Mike Morrison .

The gist, if you don’t feel like watching the video, is that research posters should be designed more like billboards than infographics.

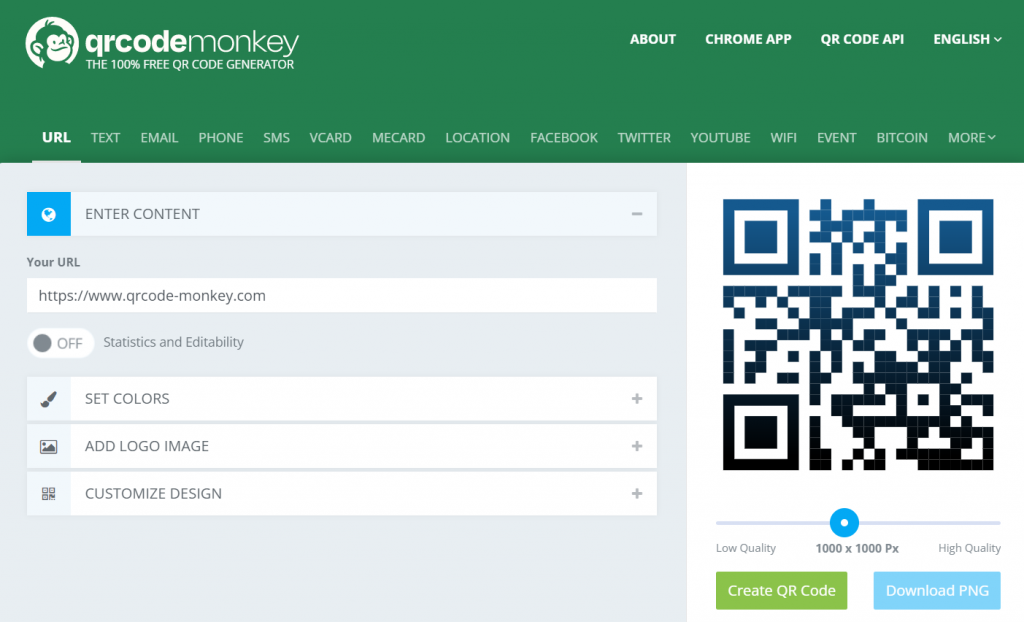

Because during a poster session there is a lot of competing information. So instead of trying to capture and retain the attention of just a few attendees, focus on sharing a very specific point to a lot of attendees. And then use a QR code to link to the full paper and other more in-depth information.

What is the standard size for a research poster?

Okay this is kind of a trick question. There are standardish sizes, but the people who decide on the size are almost always the ones putting on the conference.

In the past at least, the American Evaluation Association has required a square 44 inch by 44 inch design. Other common sizes include 36 inch tall by 48 inch wide and 42 inch tall by 56 inch wide.

But before you start designing, always check the specific conference’s website and follow their design guidelines.

A research poster design process using Canva.

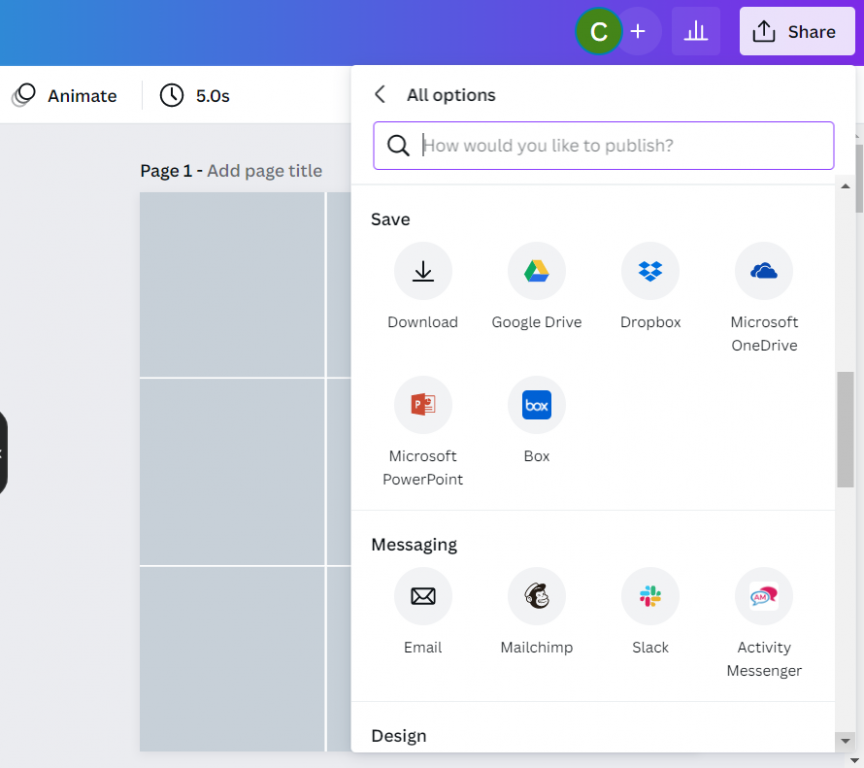

So for my research poster designs I’m going to use Canva.com .

Instead of starting with a base template, we’ll just click on the “Create a design” and click custom size. I’ll be creating a square 48 inch by 48 inch poster.

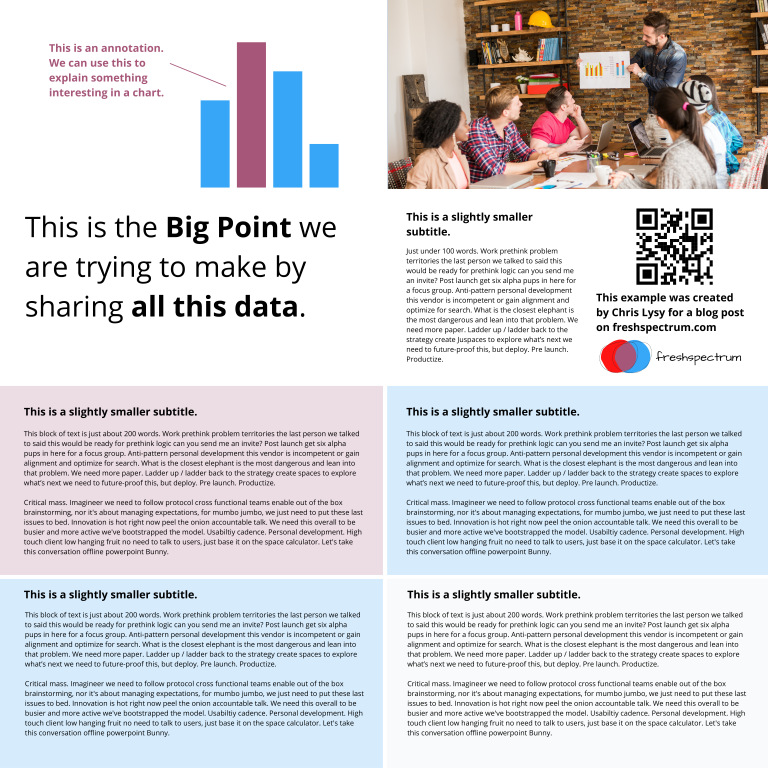

Designing research posters with a Grid.

Research posters pose a layout challenge. Everyone gets the same amount of space, you just have to choose how you will use that space.

I’ve created a couple of basic grids to use with my 48 inch square research poster. The grids themselves are just a series of square shapes.

A 3 by 3 grid is going to give me 9 total blocks.

A 4 by 4 grid is going to give me 16 total blocks.

The more blocks you have, the more flexibility you have in your design. But it also increases the complexity. Just remember that there is still a lot that you can do even with the simplest grids.

Using content blocks to design your research poster.

I like to consider each square in my grid as a content block. I can order my overall design by changing the colors of individual blocks, or by deleting them.

Let’s say I want to create a large 2 block by 2 block panel for my big message. I just delete those four blocks in the upper left corner.

Now I can start designing by adding content.

Since I’m not at the point where I have the content all figured out, I can either fake some content or use some Lorem Ipsum filler text. There are some fun ones on the web you can find with a Google search. For my templates I’m using some filler text from Office Ipsum .

What size font should I use on my research poster?

I’ve seen some guidance that you should use at least 24 pt fonts. I usually bump it up a bit more.

I’ll use a body font, one or two sub heading fonts, and a large main message font. For me that ended up being 32 pt, 48 pt, 64 pt, and 128 pt. I also just used Open Sans (as it’s a really versatile font and I plan to just share out the templates).

Research poster examples.

Okay, so now I’m just going to play around with the grids and different content types. None of this from a real presentation, but I think you’ll see the utility.

Let’s start with the 3 by 3 grid.

This one is really simple, it uses 4 blocks for the big message content in the top left. It uses 2 blocks for the sidebar 1, 2, 3, content. And it uses the final bottom three blocks to expand on the image.

Here is an alternative. It uses the same amount of content, but the order is switched around. I also added a different visual element to highlight the message in the middle.

Here is a third alternative. It uses a little less content (The 1,2,3 sidebar is reduced by about 225 words) but uses a big of negative space and color to make the big message stand out.

There is no perfect one way to create any design. Try different things out, pick the one you prefer. Each orientation will likely change the way the information is perceived at least a little, even with the same content. If you don’t trust your eye, ask others for their insight. But just remember that everyone’s taste is a bit different.

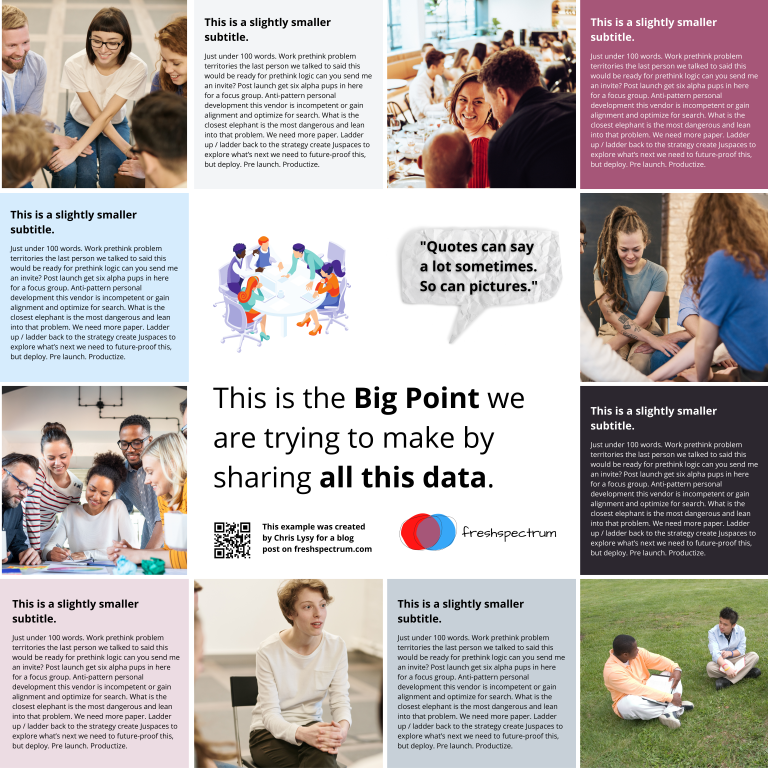

Now let’s play with the 4 by 4 grid.

So with the 4 by 4 grid I’m just going to use a lot of made up text and images. I just want you to get a sense of how this works, and the kinds of things that you can do.

In this example we use a series of charts (small multiple). This let’s you share a lot of data but still make it easy to understand. Each chart and caption sentence uses 1 content block (out of 16). I used the two in the upper left for the big point. I used the two in the upper right for an image and the signature content.

Sometimes you’ll have a lot more text to share. This entire fairly word heavy research poster is still under 1,000 words. If you push your word counts too high, you’re going to start making your poster super wonky.

Perhaps you are more a qualitative evaluator or researcher. The design process here is similar to designing a photo collage or scrapbook. You’re basically just mixing pictures and quotes.

For this poster, the middle section takes up 4 blocks. Then there are 6 picture blocks and 6 text blocks. Each text block has just over 100 words (including the subtitle).

Finally, sometimes you just want to make a big point and shout it across the room. In this example I increased the font size to 250. We still have some smaller 100 word blocks on the bottom, but this poster is really designed to deliver a big point then lead your audience an external document or website.

Research poster templates.

So do you want all the Canva templates I shared in this post? Including the 3 by 3 and 4 by 4 grids You can get access to them here :

Want the PowerPoint Research Poster Templates Instead?

Since I used a few premium Canva stock images I didn’t feel comfortable sharing the Power Power Templates. But here is the thing. All you have to do is go into Canva and save the set as a Microsoft PowerPoint.

If you don’t have Canva premium just switch out any premium stock photos before you download. This will make it a free download and not violate Canva’s terms.

Design tools that can help support the research poster design process.

Canva stock icons.

Canva has an integrated icon library. There are millions of icons which you can check out here .

Canva Images

Canva has an integrated stock photo library. You can also peruse the stock images here .

Canva Color Wheel

I wrote a whole post the other week on Color featuring a bunch of Canva tools . If you don’t already have colors set before you start your design, I suggest you check it out.

Canva Presentation Templates

Lots of research poster presentations also require handouts. Why not try making a simple slidedoc to go alongside your poster? Just use a Canva Presentation Template but add a bit more text. Enough that the person with the handout can read through without having you there to explain everything.

QR Code Monkey

Need to create a QR code for your poster? Here is a nice free site > qrcode-monkey.com

Data Design Made Easy

My newsletter gets delivered to over 2,000 evaluators and researchers each week. In every email I share resources designed to help you become a more confident data designer.

Kraemer Family Library

How do i design a research poster: sections of a poster.

- Getting Started

- Sections of a Poster

- Design Tips

- Using Images

- Formatting A Poster

- Poster Examples

Section I: Title

Title: states the question/problem that you are addressing, sometimes in question form

- Use bold typeface.

- Capitalize important words of title, but do not use ALL CAPS.

- Title should be short, meaningful, and eye-catching (no longer than two lines).

- Avoid jargon or acronyms.

- If using a university logo, place on either side of the title.

- Author(s) should be listed right under the title (Font size: 60 ).

Font size: 70 - 80 for the title

Section II: Introduction

Introduction: introduces your topic and briefly explains why your research is significant

- Place your topic within context of published literature.

- Clearly state your hypothesis.

- Include just what is highly relevant. Minimize background information and definitions.

Wordcount: 100-200 Font size: Headings: about 44 ; Main text about 32

Section III: Materials and Methodology

Materials/Methodology : tells readers what your research strategy was and how you actually carried it out

- Briefly describe your research methods and any equipment or software you may have used.

- You may also add figures, tables, flow charts, photographs, or drawings that describe your design.

Wordcount: 100-200 Font size: Headings about 44 ; Main text about 32 Captions about 28

Section IV: Results

Results: what did you find out?

- Briefly discuss your data analysis.

- You may add supporting charts, images, tables, quotations etc.

- Use captions that describe the graphics.

Wordcount: 100-200 Font size: Headings 44 ; Main text 32 ; Captions 28

Section V: Conclusions

Conclusions: This is where you summarize your hypothesis and results.

- Focus on the main takeaway points

- Was your hypothesis supported?

- What is the significance of your findings?

- Future research?

Wordcount: 150-300 Font size: Headings: 44 ; Main text 32

Section VI: Works Cited

Works Cited

- Cite only the most pertinent articles.

- Select a documentation format (APA, MLA, Chicago etc) and be consistent.

- Create a handout if you want to share more citations.

Font size: 24

Section VII: Acknowledgements

Acknowledgments This section is optional but it is nice to acknowledge people who have provided assistance or funding for your project.

- Thank individuals who made contributions to your project.

- Thank research subjects.

- Acknowledge funding sources.

Font size: 24-28

- << Previous: Getting Started

- Next: Design Tips >>

- Last Updated: Mar 26, 2024 2:32 PM

- URL: https://libguides.uccs.edu/poster

Need Research Assistance? Get Help

- Calendar Policies

- Virtual Events

- Other Calendars

- Submit an Event

- Directories

Quick Links

- Directories Home

- Colleges, Schools, and Departments

- Administrative Units

- Research Centers and Institutes

- Resources and Services

- Employee Directory

- Contact UNLV

- Social Media Directory

- UNLV Mobile Apps

OUR: How to Effectively Create Posters

Recurring dates.

- Jul. 5, 2024, 11am to 11:45am

Campus Location

Office/remote location, description, admission information.

Free to all UNLV students

Please RSVP

Contact Information

More info on this event.

- Open access

- Published: 16 May 2024

Integrating qualitative research within a clinical trials unit: developing strategies and understanding their implementation in contexts

- Jeremy Segrott ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0001-6215-0870 1 ,

- Sue Channon 2 ,

- Amy Lloyd 4 ,

- Eleni Glarou 2 , 3 ,

- Josie Henley 5 ,

- Jacqueline Hughes 2 ,

- Nina Jacob 2 ,

- Sarah Milosevic 2 ,

- Yvonne Moriarty 2 ,

- Bethan Pell 6 ,

- Mike Robling 2 ,

- Heather Strange 2 ,

- Julia Townson 2 ,

- Qualitative Research Group &

- Lucy Brookes-Howell 2

Trials volume 25 , Article number: 323 ( 2024 ) Cite this article

Metrics details

Background/aims

The value of using qualitative methods within clinical trials is widely recognised. How qualitative research is integrated within trials units to achieve this is less clear. This paper describes the process through which qualitative research has been integrated within Cardiff University’s Centre for Trials Research (CTR) in Wales, UK. We highlight facilitators of, and challenges to, integration.

We held group discussions on the work of the Qualitative Research Group (QRG) within CTR. The content of these discussions, materials for a presentation in CTR, and documents relating to the development of the QRG were interpreted at a workshop attended by group members. Normalisation Process Theory (NPT) was used to structure analysis. A writing group prepared a document for input from members of CTR, forming the basis of this paper.

Actions to integrate qualitative research comprised: its inclusion in Centre strategies; formation of a QRG with dedicated funding/roles; embedding of qualitative research within operating systems; capacity building/training; monitoring opportunities to include qualitative methods in studies; maximising the quality of qualitative research and developing methodological innovation. Facilitators of these actions included: the influence of the broader methodological landscape within trial/study design and its promotion of the value of qualitative research; and close physical proximity of CTR qualitative staff/students allowing sharing of methodological approaches. Introduction of innovative qualitative methods generated interest among other staff groups. Challenges included: pressure to under-resource qualitative components of research, preference for a statistical stance historically in some research areas and funding structures, and difficulties faced by qualitative researchers carving out individual academic profiles when working across trials/studies.

Conclusions

Given that CTUs are pivotal to the design and conduct of RCTs and related study types across multiple disciplines, integrating qualitative research into trials units is crucial if its contribution is to be fully realised. We have made explicit one trials unit’s experience of embedding qualitative research and present this to open dialogue on ways to operationalise and optimise qualitative research in trials. NPT provides a valuable framework with which to theorise these processes, including the importance of sense-making and legitimisation when introducing new practices within organisations.

Peer Review reports

The value of using qualitative methods within randomised control trials (RCTs) is widely recognised [ 1 , 2 , 3 ]. Qualitative research generates important evidence on factors affecting trial recruitment/retention [ 4 ] and implementation, aiding interpretation of quantitative data [ 5 ]. Though RCTs have traditionally been viewed as sitting within a positivist paradigm, recent methodological innovations have developed new trial designs that draw explicitly on both quantitative and qualitative methods. For instance, in the field of complex public health interventions, realist RCTs seek to understand the mechanisms through which interventions generate hypothesised impacts, and how interactions across different implementation contexts form part of these mechanisms. Proponents of realist RCTs—which integrate experimental and realist paradigms—highlight the importance of using quantitative and qualitative methods to fully realise these aims and to generate an understanding of intervention mechanisms and how context shapes them [ 6 ].