Have a language expert improve your writing

Run a free plagiarism check in 10 minutes, automatically generate references for free.

- Knowledge Base

- Dissertation

How to Write a Dissertation Proposal | A Step-by-Step Guide

Published on 14 February 2020 by Jack Caulfield . Revised on 11 November 2022.

A dissertation proposal describes the research you want to do: what it’s about, how you’ll conduct it, and why it’s worthwhile. You will probably have to write a proposal before starting your dissertation as an undergraduate or postgraduate student.

A dissertation proposal should generally include:

- An introduction to your topic and aims

- A literature review of the current state of knowledge

- An outline of your proposed methodology

- A discussion of the possible implications of the research

- A bibliography of relevant sources

Dissertation proposals vary a lot in terms of length and structure, so make sure to follow any guidelines given to you by your institution, and check with your supervisor when you’re unsure.

Instantly correct all language mistakes in your text

Be assured that you'll submit flawless writing. Upload your document to correct all your mistakes.

Table of contents

Step 1: coming up with an idea, step 2: presenting your idea in the introduction, step 3: exploring related research in the literature review, step 4: describing your methodology, step 5: outlining the potential implications of your research, step 6: creating a reference list or bibliography.

Before writing your proposal, it’s important to come up with a strong idea for your dissertation.

Find an area of your field that interests you and do some preliminary reading in that area. What are the key concerns of other researchers? What do they suggest as areas for further research, and what strikes you personally as an interesting gap in the field?

Once you have an idea, consider how to narrow it down and the best way to frame it. Don’t be too ambitious or too vague – a dissertation topic needs to be specific enough to be feasible. Move from a broad field of interest to a specific niche:

- Russian literature 19th century Russian literature The novels of Tolstoy and Dostoevsky

- Social media Mental health effects of social media Influence of social media on young adults suffering from anxiety

The only proofreading tool specialized in correcting academic writing

The academic proofreading tool has been trained on 1000s of academic texts and by native English editors. Making it the most accurate and reliable proofreading tool for students.

Correct my document today

Like most academic texts, a dissertation proposal begins with an introduction . This is where you introduce the topic of your research, provide some background, and most importantly, present your aim , objectives and research question(s) .

Try to dive straight into your chosen topic: What’s at stake in your research? Why is it interesting? Don’t spend too long on generalisations or grand statements:

- Social media is the most important technological trend of the 21st century. It has changed the world and influences our lives every day.

- Psychologists generally agree that the ubiquity of social media in the lives of young adults today has a profound impact on their mental health. However, the exact nature of this impact needs further investigation.

Once your area of research is clear, you can present more background and context. What does the reader need to know to understand your proposed questions? What’s the current state of research on this topic, and what will your dissertation contribute to the field?

If you’re including a literature review, you don’t need to go into too much detail at this point, but give the reader a general sense of the debates that you’re intervening in.

This leads you into the most important part of the introduction: your aim, objectives and research question(s) . These should be clearly identifiable and stand out from the text – for example, you could present them using bullet points or bold font.

Make sure that your research questions are specific and workable – something you can reasonably answer within the scope of your dissertation. Avoid being too broad or having too many different questions. Remember that your goal in a dissertation proposal is to convince the reader that your research is valuable and feasible:

- Does social media harm mental health?

- What is the impact of daily social media use on 18– to 25–year–olds suffering from general anxiety disorder?

Now that your topic is clear, it’s time to explore existing research covering similar ideas. This is important because it shows you what is missing from other research in the field and ensures that you’re not asking a question someone else has already answered.

You’ve probably already done some preliminary reading, but now that your topic is more clearly defined, you need to thoroughly analyse and evaluate the most relevant sources in your literature review .

Here you should summarise the findings of other researchers and comment on gaps and problems in their studies. There may be a lot of research to cover, so make effective use of paraphrasing to write concisely:

- Smith and Prakash state that ‘our results indicate a 25% decrease in the incidence of mechanical failure after the new formula was applied’.

- Smith and Prakash’s formula reduced mechanical failures by 25%.

The point is to identify findings and theories that will influence your own research, but also to highlight gaps and limitations in previous research which your dissertation can address:

- Subsequent research has failed to replicate this result, however, suggesting a flaw in Smith and Prakash’s methods. It is likely that the failure resulted from…

Next, you’ll describe your proposed methodology : the specific things you hope to do, the structure of your research and the methods that you will use to gather and analyse data.

You should get quite specific in this section – you need to convince your supervisor that you’ve thought through your approach to the research and can realistically carry it out. This section will look quite different, and vary in length, depending on your field of study.

You may be engaged in more empirical research, focusing on data collection and discovering new information, or more theoretical research, attempting to develop a new conceptual model or add nuance to an existing one.

Dissertation research often involves both, but the content of your methodology section will vary according to how important each approach is to your dissertation.

Empirical research

Empirical research involves collecting new data and analysing it in order to answer your research questions. It can be quantitative (focused on numbers), qualitative (focused on words and meanings), or a combination of both.

With empirical research, it’s important to describe in detail how you plan to collect your data:

- Will you use surveys ? A lab experiment ? Interviews?

- What variables will you measure?

- How will you select a representative sample ?

- If other people will participate in your research, what measures will you take to ensure they are treated ethically?

- What tools (conceptual and physical) will you use, and why?

It’s appropriate to cite other research here. When you need to justify your choice of a particular research method or tool, for example, you can cite a text describing the advantages and appropriate usage of that method.

Don’t overdo this, though; you don’t need to reiterate the whole theoretical literature, just what’s relevant to the choices you have made.

Moreover, your research will necessarily involve analysing the data after you have collected it. Though you don’t know yet what the data will look like, it’s important to know what you’re looking for and indicate what methods (e.g. statistical tests , thematic analysis ) you will use.

Theoretical research

You can also do theoretical research that doesn’t involve original data collection. In this case, your methodology section will focus more on the theory you plan to work with in your dissertation: relevant conceptual models and the approach you intend to take.

For example, a literary analysis dissertation rarely involves collecting new data, but it’s still necessary to explain the theoretical approach that will be taken to the text(s) under discussion, as well as which parts of the text(s) you will focus on:

- This dissertation will utilise Foucault’s theory of panopticism to explore the theme of surveillance in Orwell’s 1984 and Kafka’s The Trial…

Here, you may refer to the same theorists you have already discussed in the literature review. In this case, the emphasis is placed on how you plan to use their contributions in your own research.

You’ll usually conclude your dissertation proposal with a section discussing what you expect your research to achieve.

You obviously can’t be too sure: you don’t know yet what your results and conclusions will be. Instead, you should describe the projected implications and contribution to knowledge of your dissertation.

First, consider the potential implications of your research. Will you:

- Develop or test a theory?

- Provide new information to governments or businesses?

- Challenge a commonly held belief?

- Suggest an improvement to a specific process?

Describe the intended result of your research and the theoretical or practical impact it will have:

Finally, it’s sensible to conclude by briefly restating the contribution to knowledge you hope to make: the specific question(s) you hope to answer and the gap the answer(s) will fill in existing knowledge:

Like any academic text, it’s important that your dissertation proposal effectively references all the sources you have used. You need to include a properly formatted reference list or bibliography at the end of your proposal.

Different institutions recommend different styles of referencing – commonly used styles include Harvard , Vancouver , APA , or MHRA . If your department does not have specific requirements, choose a style and apply it consistently.

A reference list includes only the sources that you cited in your proposal. A bibliography is slightly different: it can include every source you consulted in preparing the proposal, even if you didn’t mention it in the text. In the case of a dissertation proposal, a bibliography may also list relevant sources that you haven’t yet read, but that you intend to use during the research itself.

Check with your supervisor what type of bibliography or reference list you should include.

Cite this Scribbr article

If you want to cite this source, you can copy and paste the citation or click the ‘Cite this Scribbr article’ button to automatically add the citation to our free Reference Generator.

Caulfield, J. (2022, November 11). How to Write a Dissertation Proposal | A Step-by-Step Guide. Scribbr. Retrieved 24 June 2024, from https://www.scribbr.co.uk/thesis-dissertation/proposal/

Is this article helpful?

Jack Caulfield

Other students also liked, what is a dissertation | 5 essential questions to get started, what is a literature review | guide, template, & examples, what is a research methodology | steps & tips.

Developing the Research Question for a Thesis, Dissertation, or Doctoral Project Study

MethodSpace will explore phases of the research process throughout 2021. In the first quarter will explore design steps, starting with a January focus on research questions. Find the unfolding series here .

Dr. Gary Burkholder is a co-author of Research Design and Methods: An Applied Guide for the Scholar-Practitioner . Dr. Burkholder was a Mentor in Residence on SAGE MethodSpace in December 2019, and is a regular contributor. See his practical advice for research faculty and students here .

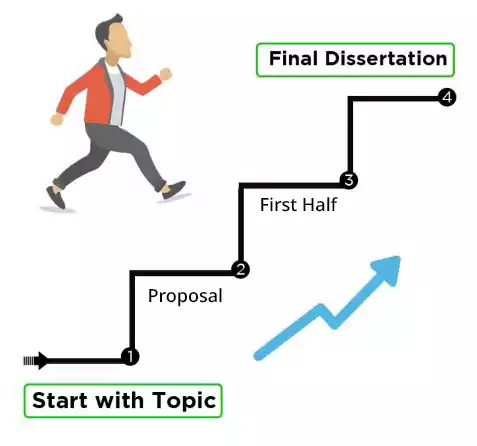

Contrary to what you may think or have heard, creating a suitable research question to guide a thesis, dissertation, or doctoral project study does not necessarily follow a linear process. However, this does not mean that getting to the research question is not rigorous! There are clear steps to get to the research question (see Crawford, Burkholder, & Cox, 2020).

Generate the initial idea.

Complete a thorough investigation of the literature in the relevant domains.

For those pursuing the research doctorate, identify gaps in theory and empirical knowledge that result in a research problem and purpose statement.

For those pursuing the applied doctorate, draw upon expertise to identify gaps in practice that allow the development of the practice-based problem and purpose statement.

Identify the principal research questions from the problem and purpose statements.

Generating the Initial Idea . This is arguably the most creative part of the process and generates the initial enthusiasm in engaging in formal research. Most of the time, whether theoretical or practical, students get an idea because of something that sparks their interest. Someone having a personal experience with obesity and subsequent weight loss and have an interest in learning more about why particular weight loss programs seem to work. In professional settings, the practitioner may notice that a process or activity isn’t working correctly. For example, children in school may not be adapting to online learning as quickly as they should. In a company setting, a middle manager may be surprised that employees are not adapting to working remotely as quickly as they had thought. In a healthcare setting, a nurse notices that patients are taking too much time completing forms in the clinical practice office and that there may be other more efficient ways to complete this activity that would result in less waiting time. Whatever the source, consider these observations as initial “hunches” that might lead to an interesting research study that can allow you to contribute to theory or practice in a way that suits your own expertise.

Reviewing the Literature . The purpose of original research is to address a lack of knowledge in theory or practice. Therefore, once you have your initial idea, the next step is to take a look at the literature that addresses the topic of your idea. There is a vast selection of journals in all disciplines, both theoretical and practice-oriented, that provide excellent resources for your investigation. The goal for now is to read enough literature to establish that this is an important topic for further exploration and to see if anyone has written about it. Has research already been completed that provides ways to address your initial idea? If yes, then the study probably won’t be worthy of doctoral level research (although you may actually find the answers to issues in the workplace that you are looking for!). Whether you are trying to solve a problem in practice or theory, reviewing the existing literature is important to see what others have already done. Remember, the goal of doctoral level scholarship is to add to the existing body of knowledge regarding theory or practice. At this stage, if you find sufficient literature to help you address your initial question, then it is time to put that idea aside and pursue others that may yield a more innovative contribution.

Developing the Problem in Research or Practice . The problem statement is probably the most important part of the doctoral capstone. In your problem statement, you succinctly identify what is currently know about the area of interest and what is not known. It is what is NOT known that identifies your unique contribution to scholarship in theory or practice. If you cannot identify what is not known, or what is commonly referred to as the gap in theory or the gap in practice, then you probably don’t have a study worthy of doctoral level scholarship. Once you identify the gap in theory or practice, you can then develop the statement of purpose that defines for the reader exactly what your study will add to the existing body of scholarship and/or practice.

The Research Question . Once you have identified the practice or theory-based problem, you are then ready to propose the formal research question that guides your study. This is a succinct question that provides focus, describes the scope of the study, and provides insight into the direction of inquiry. There are important ideas to remember when crafting the research question.

All studies are guided by one or more research questions, regardless of whether they are quantitative, qualitative, or mixed methods.

Fewer research questions are better than many. In most cases, studies are addressing one primary research question (and likely never more than 2 or 3). The research question provides focus of the study. The more research questions, the more unfocused the study may become.

For those doing qualitative studies or studies with qualitative components, do not confuse the research question with interview questions. There will likely be several interview questions, but interview questions are in service to addressing the key research question guiding the overall study.

In general, questions should not be framed as “yes or no”. For example, “What is the extent of understanding teachers have regarding training first graders to use tablets in acquiring knowledge?” is better than “Do teachers know how to train first graders to use tablets in acquiring knowledge?” The former is worded in a way that supports depth and breadth of observation and analysis.

Research questions must be aligned with other aspects of the thesis, dissertation, or project study proposal, such as the problem statement, research design, and analysis strategy.

To summarize: Idea >Reviewing literature > Identifying the gap in theory or practice >Problem and Purpose Statements >Research question

Thus, there is a clear process for getting to the research question. However, there is fluidity in terms of how that process unfolds. Ideas, when explored further, may turn out to be just that and have to be scrapped for a different idea that can be pursued. Ideas can come from intuitive hunches or from extensive exploration and knowledge of a particular theory or practice. They may emerge from conversations with mentors or other experts in the field. This dance of ideas creates the initial sparks of excitement in social science research that leads to a rigorous and scientific process of generating the research question ultimately guiding the study.

Research Design and Methods

Crawford, L. M., Burkholder, G. J., & Cox, K. (2020). Writing the research proposal. In G. J. Burkholder, K. A. Cox, L. M. Crawford, & J. H. Hitchcock (Eds.), Research Design and Methods: An Applied Guide for the Scholar-Practitioner (pp. 309-334). SAGE Publications.

Hypotheses: Introduction & selection of articles

Practical <> conceptual questions.

The Ultimate Guide to Writing Your Dissertation Proposal

Introduction to the Dissertation Proposal

Generating Initial Ideas

Reviewing Timelines and Deadlines

Initial Research and Reading

Choosing Your Dissertation Topic

Seeking Feedback

Final Submission

Conclusion

Additional Resources

Writing a dissertation proposal is one of the most critical steps in your academic journey. It sets the stage for your entire research project and can significantly influence the success of your dissertation.

This guide will take you through the early stages of writing a dissertation proposal, from the moment it's introduced in your class to the final submission. We'll cover idea generation, timelines and deadlines, initial research, and reading, all aimed at helping you craft a compelling and feasible proposal.

Introduction to the Dissertation Proposal

Understanding the importance.

A dissertation proposal is a document that outlines what you intend to research , why it is worth studying, and how you plan to investigate it. It's not just a formality but a crucial part of your research process. A well-crafted proposal can:

Define the scope and objectives of your study: Clearly delineating what you will and will not cover helps to focus your research.

Demonstrate the relevance and originality of your research: Show how your research fills gaps in existing knowledge or offers a new perspective.

Provide a clear plan for data collection and analysis: Lay out your methodological approach to ensure a structured and systematic investigation.

Secure approval from your academic supervisors and ethics committees: A solid proposal is often required for funding applications and ethical review processes.

Initial Briefing

Typically, the journey begins with your course leader introducing the dissertation proposal in a class session. This briefing will cover essential details like the purpose of the proposal, the expected structure, and key milestones. Pay close attention during this session as it provides the foundation for your entire project. Take detailed notes and ask questions to clarify any uncertainties.

Generating Initial Ideas

Identifying your interests.

Start by reflecting on your academic interests. What topics have you found most engaging in your coursework? What areas sparked your curiosity during lectures or assignments? Your dissertation is a lengthy commitment, so it's crucial to choose a topic that genuinely interests you. Consider the following:

Past coursework: Review your previous essays, projects, and exams to identify recurring themes or topics you enjoyed.

Personal experiences: Think about any personal experiences or observations that have piqued your interest in certain areas.

Current events: Stay informed about recent developments in your field and consider how they might influence your research interests.

Brainstorming

Once you have a broad idea of your interests, begin brainstorming specific topics. Write down all potential ideas, no matter how vague they seem. Discuss these ideas with classmates, professors, and mentors to refine them. This collaborative process can help you identify gaps in existing research and narrow down your focus.

Mind mapping: Use mind maps to visually organize your thoughts and explore connections between different ideas.

Free writing: Spend 10-15 minutes writing continuously about your topic ideas without worrying about structure or grammar. This can help you generate new ideas and clarify your thinking.

Group discussions: Organize brainstorming sessions with peers to exchange ideas and receive feedback.

Feasibility Check

Assess the feasibility of your potential topics. Consider the following questions:

Do you have access to the necessary resources and data? Ensure that you can obtain the data you need, whether it's through surveys, experiments, archival research, or other means.

Is the topic manageable within the given timeline and scope? Be realistic about what you can achieve in the time available.

Are you equipped with the required skills and knowledge to undertake this research? Consider whether you need to acquire any new skills or knowledge before starting your research.

Reviewing Timelines and Deadlines

Course leader’s timeline.

Your course leader will provide a detailed timeline outlining key milestones and deadlines . These typically include:

Initial Proposal Submission: This is your first formal submission where you present your research idea, objectives, and methodology.

Ethics Approval: If your research involves human subjects, you must get approval from the ethics committee . This ensures your research complies with ethical standards.

Intermediate Drafts and Reviews: There will be deadlines for submitting drafts and receiving feedback from your supervisors.

Final Proposal Submission: This is the polished version of your proposal, incorporating all feedback and revisions.

Final Dissertation Submission: The ultimate deadline for submitting your completed dissertation.

Creating a Personal Timeline

Based on the provided timeline, create a personal schedule. Break down each stage into manageable tasks and set internal deadlines. This proactive approach will help you stay on track and avoid last-minute rushes.

Backward planning: Start with your final deadline and work backward to set intermediate deadlines.

Milestone chart: Create a chart that outlines key milestones and deadlines. Use it to track your progress and stay motivated.

Time blocking: Allocate specific blocks of time each week for dissertation work. Consistency is key to making steady progress.

Initial Research and Reading

Conducting preliminary research.

Before finalizing your dissertation topic, conduct preliminary research. This involves:

Literature Review: Read existing research papers, articles, and books related to your topic. Identify key theories, methodologies, and findings. This will help you understand the current state of research and find gaps your study can fill.

Key questions: What are the main arguments and findings in the literature? What gaps or limitations exist? How can your research contribute to this body of knowledge?

Identifying Key Sources: Make a list of essential resources and databases. These will be your go-to sources throughout your research.

Databases: Use academic databases like JSTOR, PubMed, Google Scholar, and your university's library resources.

Taking Notes: As you read, take detailed notes. Highlight important points, jot down questions, and note any ideas for your research.

Notetaking systems: Use a systematic approach to organize your notes , such as digital note-taking apps (e.g., Evernote, OneNote) or traditional methods (e.g., index cards, notebooks).

Annotated Bibliography

Create an annotated bibliography of the key sources you’ve identified. This should include a brief summary of each source and its relevance to your research. An annotated bibliography will be useful when writing your literature review and justifying your research proposal.

Structure: For each source, include the citation, a brief summary, and a reflection on its relevance to your research.

Usefulness: Annotated bibliographies help you critically engage with your sources and provide a valuable reference tool as you write your proposal and dissertation.

Choosing Your Dissertation Topic

Refining your topic.

Based on your preliminary research, refine your topic. Narrow down your focus to a specific research question or hypothesis. Ensure it is clear, concise, and researchable within your timeline and resource constraints.

Specificity: Your topic should be specific enough to allow for in-depth analysis but broad enough to find sufficient resources.

Relevance: Ensure your topic is relevant to current debates and issues in your field.

Originality: Aim for a topic that offers a new perspective or addresses an underexplored area.

Structuring Your Proposal

A typical dissertation proposal includes the following sections:

Introduction: Introduce your research topic and explain its significance. Provide some background information and state your research question or hypothesis.

Literature Review: Summarize existing research on your topic . Highlight key findings, gaps, and debates. Explain how your research will contribute to the field.

Research Objectives: Clearly state the aims and objectives of your study . What do you hope to achieve?

Methodology: Describe the methods you will use to collect and analyze data . Justify your choice of methods and explain how they are appropriate for your research question.

Ethical Considerations: Discuss any ethical issues related to your research and how you plan to address them. This is crucial if your study involves human subjects.

Timeline: Provide a detailed timeline of your research activities . Include key milestones and deadlines.

References: List all the sources you have cited in your proposal. Follow the required citation style.

Writing Tips

Be Clear and Concise: Avoid jargon and complex language. Your proposal should be easy to understand.

Be Specific: Clearly define your research question, objectives, and methods. Avoid vague statements.

Be Persuasive: Convince your readers that your research is significant and feasible. Provide evidence and justification for your choices.

Seeking Feedback

Before submitting your proposal, seek feedback from your supervisor and peers. They can provide valuable insights and identify any weaknesses or gaps. Revise your proposal based on their feedback.

Supervisor meetings: Schedule regular meetings with your supervisor to discuss your progress and receive guidance.

Peer review: Share your proposal with classmates or colleagues for constructive feedback.

Revision: Be prepared to revise your proposal multiple times based on feedback. Each revision will strengthen your final submission.

Final Submission

Once you have incorporated all feedback and made necessary revisions, prepare your final proposal for submission. Ensure it meets all formatting and submission guidelines provided by your course leader.

Proofreading: Carefully proofread your proposal for any errors or inconsistencies.

Formatting: Follow the required formatting guidelines, including citation style, font, and spacing.

Submission: Submit your proposal by the deadline and keep a copy for your records.

Writing a dissertation proposal is a significant milestone in your academic journey. This comprehensive guide has walked you through the early stages of proposal writing, from initial idea generation to the final submission. By understanding the importance of a well-crafted proposal, you can set a strong foundation for your research project.

Start by identifying your interests and brainstorming potential topics, ensuring they are feasible and within your skillset. Review the timeline and deadlines set by your course leader and create a personal schedule to stay on track. Conduct preliminary research and reading to inform your topic choice and develop an annotated bibliography to support your literature review.

When structuring your proposal, clearly articulate your research question, objectives, and methodology. Address ethical considerations and provide a detailed timeline of your research activities. Seek feedback from your supervisor and peers to refine your proposal and ensure it is compelling and feasible.

By staying organized, managing your time effectively, and incorporating feedback, you can craft a dissertation proposal that not only meets academic standards but also sets the stage for a successful research project. With dedication and careful planning, your proposal will pave the way for a meaningful and impactful dissertation.

Additional Resources

Embarking on the journey of writing a dissertation proposal can be challenging, but there are numerous resources available to support you through the process. Here are some additional resources, including highly recommended books available on Amazon, to help you develop a compelling and feasible dissertation proposal.

"How to Write a Thesis" by Umberto Eco

Description: This classic guide by Umberto Eco provides practical advice on the entire thesis-writing process, from choosing a topic to writing and revising your final draft. Eco's engaging style makes complex concepts accessible and offers invaluable insights for students at all levels.

"Writing Your Dissertation in Fifteen Minutes a Day" by Joan Bolker

Description: This book offers a practical approach to dissertation writing, emphasizing consistent, manageable work habits and breaking the process into achievable steps. It also includes strategies for overcoming writer’s block and maintaining motivation.

" A Manual for Writers of Research Papers, Theses, and Dissertations" by Kate L. Turabian

Description: Often referred to as "Turabian," this guide is an authoritative resource for writing and formatting academic papers. It covers everything from formulating research questions to structuring your argument and citing sources properly.

Lined and Blank Notebooks: Available for purchase from Amazon, we offer a selection of lined and blank notebooks designed for students to capture all dissertation-related thoughts and research in one centralized place, ensuring that you can easily access and review your work as the project evolves.

The lined notebooks provide a structured format for detailed notetaking and organizing research questions systematically

The blank notebooks offer a free-form space ideal for sketching out ideas, diagrams, and unstructured notes.

These resources are designed to support you through the various stages of your research journey, from initial topic selection to the final presentation of your findings. Leveraging them can enhance the quality and impact of your work, helping you to produce a well-researched and compelling thesis.

As an Amazon Associate, I may earn from qualifying purchases.

Dissertation Methodology Unpacked: Explaining Your Approach

Crafting your thesis statement: formulating a strong research question.

- Home »

find your perfect postgrad program Search our Database of 30,000 Courses

Writing a dissertation proposal.

What is a dissertation proposal?

Dissertation proposals are like the table of contents for your research project , and will help you explain what it is you intend to examine, and roughly, how you intend to go about collecting and analysing your data. You won’t be required to have everything planned out exactly, as your topic may change slightly in the course of your research, but for the most part, writing your proposal should help you better identify the direction for your dissertation.

When you’ve chosen a topic for your dissertation , you’ll need to make sure that it is both appropriate to your field of study and narrow enough to be completed by the end of your course. Your dissertation proposal will help you define and determine both of these things and will also allow your department and instructors to make sure that you are being advised by the best person to help you complete your research.

A dissertation proposal should include:

- An introduction to your dissertation topic

- Aims and objectives of your dissertation

- A literature review of the current research undertaken in your field

- Proposed methodology to be used

- Implications of your research

- Limitations of your research

- Bibliography

Although this content all needs to be included in your dissertation proposal, the content isn’t set in stone so it can be changed later if necessary, depending on your topic of study, university or degree. Think of your dissertation proposal as more of a guide to writing your dissertation rather than something to be strictly adhered to – this will be discussed later.

Why is a dissertation proposal important?

A dissertation proposal is very important because it helps shape the actual dissertation, which is arguably the most important piece of writing a postgraduate student will undertake. By having a well-structured dissertation proposal, you will have a strong foundation for your dissertation and a good template to follow. The dissertation itself is key to postgraduate success as it will contribute to your overall grade . Writing your dissertation will also help you to develop research and communication skills, which could become invaluable in your employment success and future career. By making sure you’re fully briefed on the current research available in your chosen dissertation topic, as well as keeping details of your bibliography up to date, you will be in a great position to write an excellent dissertation.

Next, we’ll be outlining things you can do to help you produce the best postgraduate dissertation proposal possible.

How to begin your dissertation proposal

1. Narrow the topic down

It’s important that when you sit down to draft your proposal, you’ve carefully thought out your topic and are able to narrow it down enough to present a clear and succinct understanding of what you aim to do and hope to accomplish in your dissertation.

How do I decide on a dissertation topic?

A simple way to begin choosing a topic for your dissertation is to go back through your assignments and lectures. Was there a topic that stood out to you? Was there an idea that wasn’t fully explored? If the answer to either of these questions is yes, then you have a great starting point! If not, then consider one of your more personal interests. Use Google Scholar to explore studies and journals on your topic to find any areas that could go into more detail or explore a more niche topic within your personal interest.

Keep track of all publications

It’s important to keep track of all the publications that you use while you research. You can use this in your literature review.

You need to keep track of:

- The title of the study/research paper/book/journal

- Who wrote/took part in the study/research paper

- Chapter title

- Page number(s)

The more research you do, the more you should be able to narrow down your topic and find an interesting area to focus on. You’ll also be able to write about everything you find in your literature review which will make your proposal stronger.

While doing your research, consider the following:

- When was your source published? Is the information outdated? Has new information come to light since?

- Can you determine if any of the methodologies could have been carried out more efficiently? Are there any errors or gaps?

- Are there any ethical concerns that should be considered in future studies on the same topic?

- Could anything external (for example new events happening) have influenced the research?

Read more about picking a topic for your dissertation .

How long should the dissertation proposal be?

There is usually no set length for a dissertation proposal, but you should aim for 1,000 words or more. Your dissertation proposal will give an outline of the topic of your dissertation, some of the questions you hope to answer with your research, what sort of studies and type of data you aim to employ in your research, and the sort of analysis you will carry out.

Different courses may have different requirements for things like length and the specific information to include, as well as what structure is preferred, so be sure to check what special requirements your course has.

2. What should I include in a dissertation proposal?

Your dissertation proposal should have several key aspects regardless of the structure. The introduction, the methodology, aims and objectives, the literature review, and the constraints of your research all need to be included to ensure that you provide your supervisor with a comprehensive proposal. But what are they? Here's a checklist to get you started.

- Introduction

The introduction will state your central research question and give background on the subject, as well as relating it contextually to any broader issues surrounding it.

The dissertation proposal introduction should outline exactly what you intend to investigate in your final research project.

Make sure you outline the structure of the dissertation proposal in your introduction, i.e. part one covers methodology, part two covers a literature review, part three covers research limitations, and so forth.

Your introduction should also include the working title for your dissertation – although don't worry if you want to change this at a later stage as your supervisors will not expect this to be set in stone.

Dissertation methodology

The dissertation methodology will break down what sources you aim to use for your research and what sort of data you will collect from it, either quantitative or qualitative. You may also want to include how you will analyse the data you gather and what, if any, bias there may be in your chosen methods.

Depending on the level of detail that your specific course requires, you may also want to explain why your chosen approaches to gathering data are more appropriate to your research than others.

Consider and explain how you will conduct empirical research. For example, will you use interviews? Surveys? Observation? Lab experiments?

In your dissertation methodology, outline the variables that you will measure in your research and how you will select your data or participant sample to ensure valid results.

Finally, are there any specific tools that you will use for your methodology? If so, make sure you provide this information in the methodology section of your dissertation proposal.

- Aims and objectives

Your aim should not be too broad but should equally not be too specific.

An example of a dissertation aim could be: ‘To examine the key content features and social contexts that construct successful viral marketing content distribution on X’.

In comparison, an example of a dissertation aim that is perhaps too broad would be: ‘To investigate how things go viral on X’.

The aim of your dissertation proposal should relate directly to your research question.

- Literature review

The literature review will list the books and materials that you will be using to do your research. This is where you can list materials that gave you more background on your topic, or contain research carried out previously that you referred to in your own studies.

The literature review is also a good place to demonstrate how your research connects to previous academic studies and how your methods may differ from or build upon those used by other researchers. While it’s important to give enough information about the materials to show that you have read and understood them, don’t forget to include your analysis of their value to your work.

Where there are shortfalls in other pieces of academic work, identify these and address how you will overcome these shortcomings in your own research.

Constraints and limitations of your research

Lastly, you will also need to include the constraints of your research. Many topics will have broad links to numerous larger and more complex issues, so by clearly stating the constraints of your research, you are displaying your understanding and acknowledgment of these larger issues, and the role they play by focusing your research on just one section or part of the subject.

In this section it is important to Include examples of possible limitations, for example, issues with sample size, participant drop out, lack of existing research on the topic, time constraints, and other factors that may affect your study.

- Ethical considerations

Confidentiality and ethical concerns are an important part of any research.

Ethics are key, as your dissertation will need to undergo ethical approval if you are working with participants. This means that it’s important to allow for and explain ethical considerations in your dissertation proposal.

Keep confidentiality in mind and keep your participants informed, so they are aware of how the data provided is being used and are assured that all personal information is being kept confidential.

Consider how involved your patients will be with your research, this will help you think about what ethical considerations to take and discuss them fully in your dissertation proposal. For example, face-to-face participant interview methods could require more ethical measures and confidentiality considerations than methods that do not require participants, such as corpus data (a collection of existing written texts) analysis.

3. Dissertation proposal example

Once you know what sections you need or do not need to include, it may help focus your writing to break the proposal up into separate headings, and tackle each piece individually. You may also want to consider including a title. Writing a title for your proposal will help you make sure that your topic is narrow enough, as well as help keep your writing focused and on topic.

One example of a dissertation proposal structure is using the following headings, either broken up into sections or chapters depending on the required word count:

- Methodology

- Research constraints

In any dissertation proposal example, you’ll want to make it clear why you’re doing the research and what positives could come from your contribution.

Dissertation proposal example table

This table outlines the various stages of your dissertation proposal.

|

|

|

| Working title | This is not set in stone and is open to being changed further down the line. |

| Introduction | Background information to your dissertation, including details of the basic facts, reasons for your interest in this area, and the importance of your research to the relevant industry. |

| Methodology | Details of the sources you are planning to use – eg surveys, modelling, case studies. Are you collecting quantitative or qualitative data? Explain how you will analyse this data. |

| Objectives | List out the goals that you are hoping to achieve through your research project. |

| Literature review | Titles and URLs of proposed texts and websites that you are planning to use in your research project. |

| Constraints & limitations | Clearly state the potential limitations of your research project, eg sample size, time constraints, etc. |

| Ethical considerations | If your dissertation involves using participants, it will need to undergo ethical approval – explain any ethical considerations in the dissertation proposal. |

| References | All factual information that is not your original work needs to be accompanied by a reference to its source. |

Apply for one of our x5 bursaries worth £2,000

We've launched our new Postgrad Solutions Study Bursaries for 2024. Full-time, part-time, online and blended-learning students eligible. 2024 & 2025 January start dates students welcome. Study postgraduate courses in any subject taught anywhere worldwide.

Related articles

What Is The Difference Between A Dissertation & A Thesis

Dissertation Methodology

Top Tips When Writing Your Dissertation

How To Survive Your Masters Dissertation

Everything You Need To Know About Your Research Project

Postgrad Solutions Study Bursaries

Exclusive bursaries Open day alerts Funding advice Application tips Latest PG news

Sign up now!

Take 2 minutes to sign up to PGS student services and reap the benefits…

- The chance to apply for one of our 5 PGS Bursaries worth £2,000 each

- Fantastic scholarship updates

- Latest PG news sent directly to you.

- Affiliate Program

- UNITED STATES

- 台灣 (TAIWAN)

- TÜRKIYE (TURKEY)

- Academic Editing Services

- - Research Paper

- - Journal Manuscript

- - Dissertation

- - College & University Assignments

- Admissions Editing Services

- - Application Essay

- - Personal Statement

- - Recommendation Letter

- - Cover Letter

- - CV/Resume

- Business Editing Services

- - Business Documents

- - Report & Brochure

- - Website & Blog

- Writer Editing Services

- - Script & Screenplay

- Our Editors

- Client Reviews

- Editing & Proofreading Prices

- Wordvice Points

- Partner Discount

- Plagiarism Checker

- APA Citation Generator

- MLA Citation Generator

- Chicago Citation Generator

- Vancouver Citation Generator

- - APA Style

- - MLA Style

- - Chicago Style

- - Vancouver Style

- Writing & Editing Guide

- Academic Resources

- Admissions Resources

How to Write a Good Research Question (w/ Examples)

What is a Research Question?

A research question is the main question that your study sought or is seeking to answer. A clear research question guides your research paper or thesis and states exactly what you want to find out, giving your work a focus and objective. Learning how to write a hypothesis or research question is the start to composing any thesis, dissertation, or research paper. It is also one of the most important sections of a research proposal .

A good research question not only clarifies the writing in your study; it provides your readers with a clear focus and facilitates their understanding of your research topic, as well as outlining your study’s objectives. Before drafting the paper and receiving research paper editing (and usually before performing your study), you should write a concise statement of what this study intends to accomplish or reveal.

Research Question Writing Tips

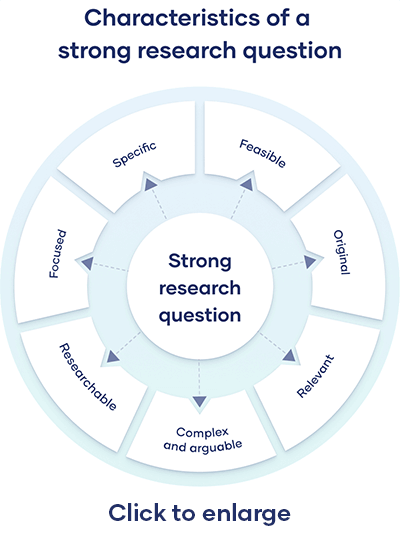

Listed below are the important characteristics of a good research question:

A good research question should:

- Be clear and provide specific information so readers can easily understand the purpose.

- Be focused in its scope and narrow enough to be addressed in the space allowed by your paper

- Be relevant and concise and express your main ideas in as few words as possible, like a hypothesis.

- Be precise and complex enough that it does not simply answer a closed “yes or no” question, but requires an analysis of arguments and literature prior to its being considered acceptable.

- Be arguable or testable so that answers to the research question are open to scrutiny and specific questions and counterarguments.

Some of these characteristics might be difficult to understand in the form of a list. Let’s go into more detail about what a research question must do and look at some examples of research questions.

The research question should be specific and focused

Research questions that are too broad are not suitable to be addressed in a single study. One reason for this can be if there are many factors or variables to consider. In addition, a sample data set that is too large or an experimental timeline that is too long may suggest that the research question is not focused enough.

A specific research question means that the collective data and observations come together to either confirm or deny the chosen hypothesis in a clear manner. If a research question is too vague, then the data might end up creating an alternate research problem or hypothesis that you haven’t addressed in your Introduction section .

| What is the importance of genetic research in the medical field? | |

| How might the discovery of a genetic basis for alcoholism impact triage processes in medical facilities? |

The research question should be based on the literature

An effective research question should be answerable and verifiable based on prior research because an effective scientific study must be placed in the context of a wider academic consensus. This means that conspiracy or fringe theories are not good research paper topics.

Instead, a good research question must extend, examine, and verify the context of your research field. It should fit naturally within the literature and be searchable by other research authors.

References to the literature can be in different citation styles and must be properly formatted according to the guidelines set forth by the publishing journal, university, or academic institution. This includes in-text citations as well as the Reference section .

The research question should be realistic in time, scope, and budget

There are two main constraints to the research process: timeframe and budget.

A proper research question will include study or experimental procedures that can be executed within a feasible time frame, typically by a graduate doctoral or master’s student or lab technician. Research that requires future technology, expensive resources, or follow-up procedures is problematic.

A researcher’s budget is also a major constraint to performing timely research. Research at many large universities or institutions is publicly funded and is thus accountable to funding restrictions.

The research question should be in-depth

Research papers, dissertations and theses , and academic journal articles are usually dozens if not hundreds of pages in length.

A good research question or thesis statement must be sufficiently complex to warrant such a length, as it must stand up to the scrutiny of peer review and be reproducible by other scientists and researchers.

Research Question Types

Qualitative and quantitative research are the two major types of research, and it is essential to develop research questions for each type of study.

Quantitative Research Questions

Quantitative research questions are specific. A typical research question involves the population to be studied, dependent and independent variables, and the research design.

In addition, quantitative research questions connect the research question and the research design. In addition, it is not possible to answer these questions definitively with a “yes” or “no” response. For example, scientific fields such as biology, physics, and chemistry often deal with “states,” in which different quantities, amounts, or velocities drastically alter the relevance of the research.

As a consequence, quantitative research questions do not contain qualitative, categorical, or ordinal qualifiers such as “is,” “are,” “does,” or “does not.”

Categories of quantitative research questions

| Attempt to describe the behavior of a population in regard to one or more variables or describe characteristics of those variables that will be measured. These are usually “What?” questions. | Seek to discover differences between groups within the context of an outcome variable. These questions can be causal as well. Researchers may compare groups in which certain variables are present with groups in which they are not. | Designed to elucidate and describe trends and interactions among variables. These questions include the dependent and independent variables and use words such as “association” or “trends.” |

Qualitative Research Questions

In quantitative research, research questions have the potential to relate to broad research areas as well as more specific areas of study. Qualitative research questions are less directional, more flexible, and adaptable compared with their quantitative counterparts. Thus, studies based on these questions tend to focus on “discovering,” “explaining,” “elucidating,” and “exploring.”

Categories of qualitative research questions

| Attempt to identify and describe existing conditions. | Attempt to describe a phenomenon. | Assess the effectiveness of existing methods, protocols, theories, or procedures. |

| Examine a phenomenon or analyze the reasons or relationships between subjects or phenomena. | Focus on the unknown aspects of a particular topic. |

Quantitative and Qualitative Research Question Examples

| Descriptive research question | |

| Comparative research question | |

| Correlational research question | |

| Exploratory research question | |

| Explanatory research question | |

| Evaluation research question |

Good and Bad Research Question Examples

Below are some good (and not-so-good) examples of research questions that researchers can use to guide them in crafting their own research questions.

Research Question Example 1

The first research question is too vague in both its independent and dependent variables. There is no specific information on what “exposure” means. Does this refer to comments, likes, engagement, or just how much time is spent on the social media platform?

Second, there is no useful information on what exactly “affected” means. Does the subject’s behavior change in some measurable way? Or does this term refer to another factor such as the user’s emotions?

Research Question Example 2

In this research question, the first example is too simple and not sufficiently complex, making it difficult to assess whether the study answered the question. The author could really only answer this question with a simple “yes” or “no.” Further, the presence of data would not help answer this question more deeply, which is a sure sign of a poorly constructed research topic.

The second research question is specific, complex, and empirically verifiable. One can measure program effectiveness based on metrics such as attendance or grades. Further, “bullying” is made into an empirical, quantitative measurement in the form of recorded disciplinary actions.

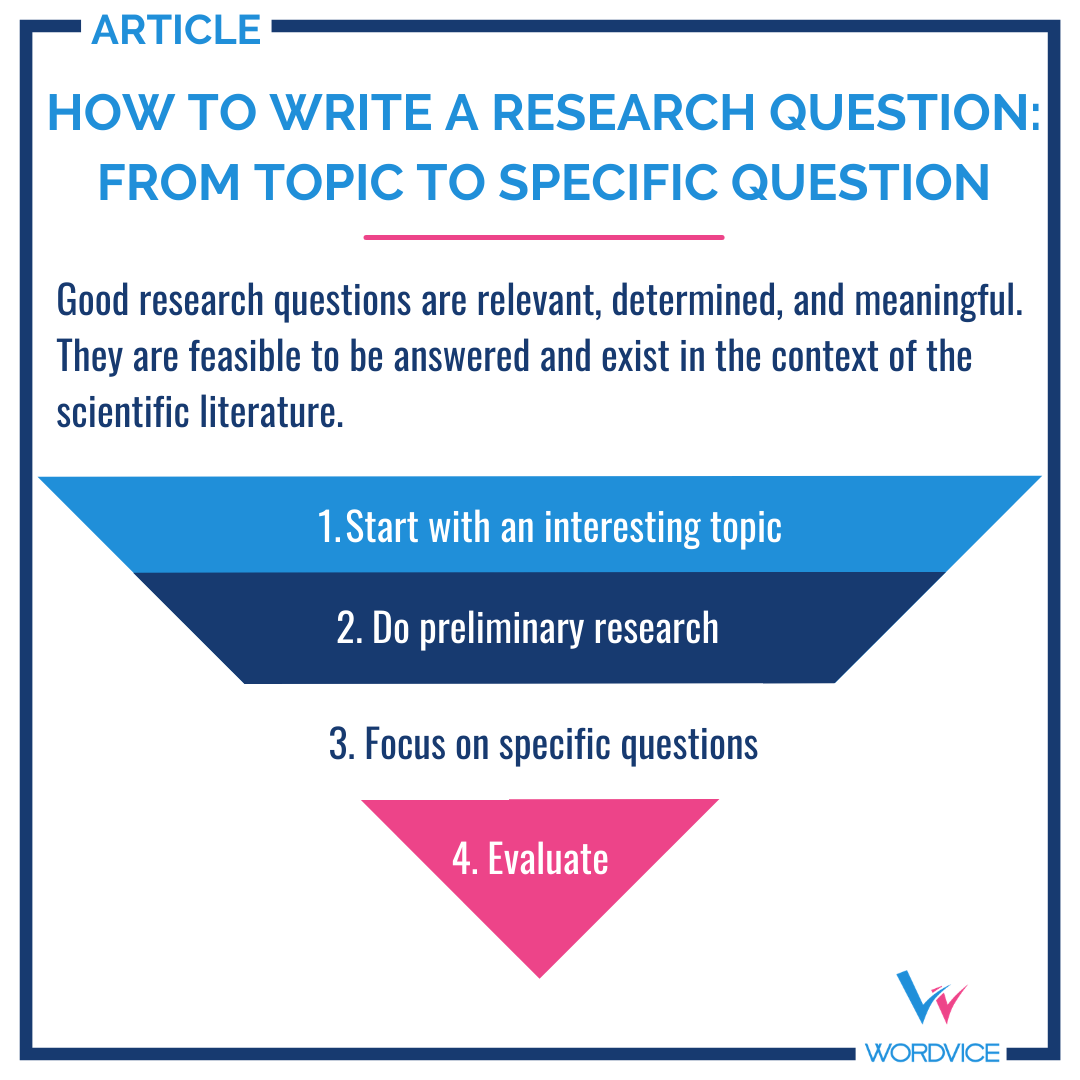

Steps for Writing a Research Question

Good research questions are relevant, focused, and meaningful. It can be difficult to come up with a good research question, but there are a few steps you can follow to make it a bit easier.

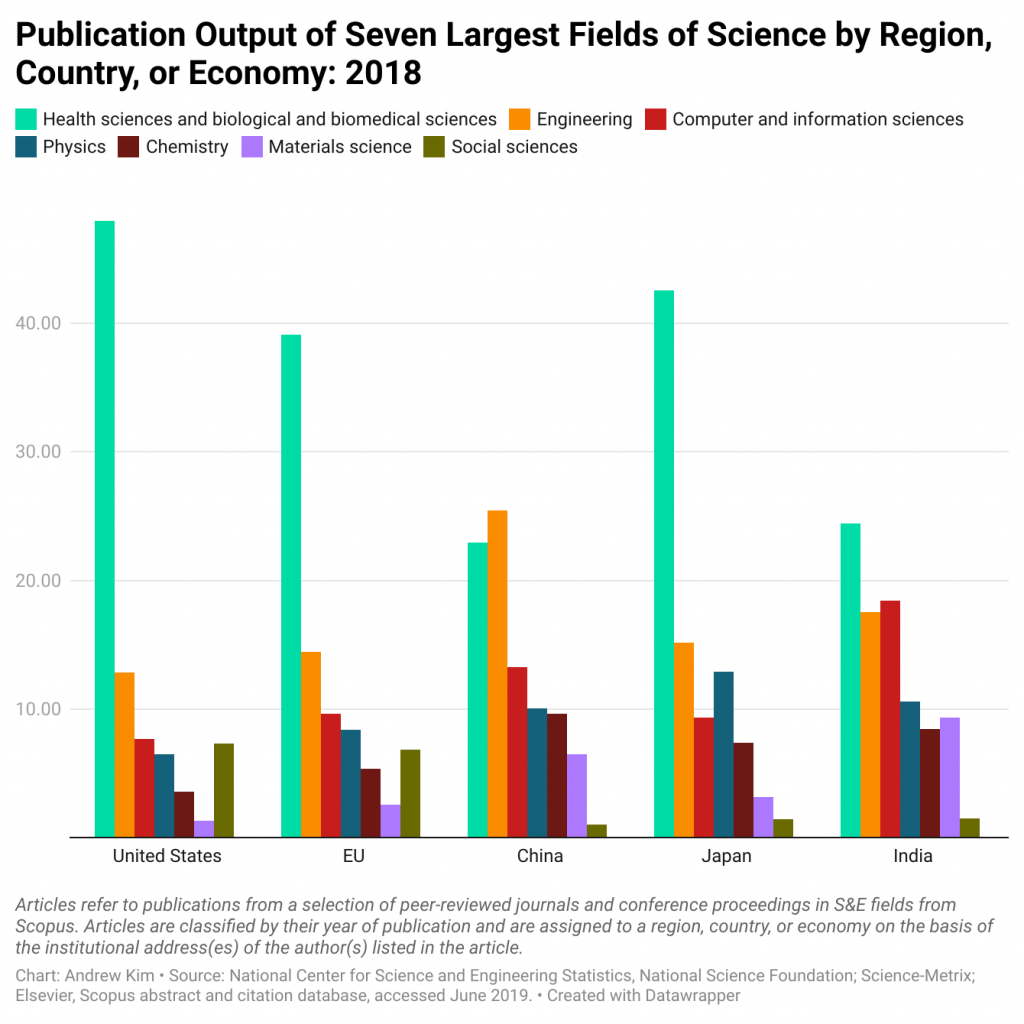

1. Start with an interesting and relevant topic

Choose a research topic that is interesting but also relevant and aligned with your own country’s culture or your university’s capabilities. Popular academic topics include healthcare and medical-related research. However, if you are attending an engineering school or humanities program, you should obviously choose a research question that pertains to your specific study and major.

Below is an embedded graph of the most popular research fields of study based on publication output according to region. As you can see, healthcare and the basic sciences receive the most funding and earn the highest number of publications.

2. Do preliminary research

You can begin doing preliminary research once you have chosen a research topic. Two objectives should be accomplished during this first phase of research. First, you should undertake a preliminary review of related literature to discover issues that scholars and peers are currently discussing. With this method, you show that you are informed about the latest developments in the field.

Secondly, identify knowledge gaps or limitations in your topic by conducting a preliminary literature review . It is possible to later use these gaps to focus your research question after a certain amount of fine-tuning.

3. Narrow your research to determine specific research questions

You can focus on a more specific area of study once you have a good handle on the topic you want to explore. Focusing on recent literature or knowledge gaps is one good option.

By identifying study limitations in the literature and overlooked areas of study, an author can carve out a good research question. The same is true for choosing research questions that extend or complement existing literature.

4. Evaluate your research question

Make sure you evaluate the research question by asking the following questions:

Is my research question clear?

The resulting data and observations that your study produces should be clear. For quantitative studies, data must be empirical and measurable. For qualitative, the observations should be clearly delineable across categories.

Is my research question focused and specific?

A strong research question should be specific enough that your methodology or testing procedure produces an objective result, not one left to subjective interpretation. Open-ended research questions or those relating to general topics can create ambiguous connections between the results and the aims of the study.

Is my research question sufficiently complex?

The result of your research should be consequential and substantial (and fall sufficiently within the context of your field) to warrant an academic study. Simply reinforcing or supporting a scientific consensus is superfluous and will likely not be well received by most journal editors.

Editing Your Research Question

Your research question should be fully formulated well before you begin drafting your research paper. However, you can receive English paper editing and proofreading services at any point in the drafting process. Language editors with expertise in your academic field can assist you with the content and language in your Introduction section or other manuscript sections. And if you need further assistance or information regarding paper compositions, in the meantime, check out our academic resources , which provide dozens of articles and videos on a variety of academic writing and publication topics.

- How it works

Research Question Examples – Guide & Tips

Published by Owen Ingram at August 13th, 2021 , Revised On April 4, 2024

All research questions should be focused, researchable, feasible to answer, specific to find results, complex, and relevant to your field of study. The research question’s factors will be; the research problem , research type , project length, and time frame.

Research questions provide boundaries to your research project and provide a clear approach to collect and compile data. Understanding your research question better is necessary to find unique facts and figures to publish your research.

Search and study some research question examples or research questions relevant to your field of study before writing your own research question.

Research Questions for Dissertation Examples

Below are 10 examples of research questions that will enable you to develop research questions for your research.

These examples will help you to check whether your chosen research questions can be addressed or whether they are too broad to find a conclusive answer.

| Research Question | Explanation |

|---|---|

| 1. How gifted children aren’t having their needs met in schools. | This research question already reflects the results and makes the assumption. The researcher can reshape the question objectively: ‘A review of the claim that genius children require more attention at prepubertal age in school. |

| 2. Preschool children on gallery visits: which workshop pedagogies best help them engage with artworks at Tate Britain? | It is a better question, has a clear perspective, and has a single focus. It has a precise location to relate to other scenarios. |

| 3. A review of support for children with dyslexia in schools in the UK. | This question is uncertain and ambitious to be put into practice. How many schools are in the United Kingdom? Is there any age filter? How can this be complied with and measured? It indicates that the question was not specific enough to answer and involves some constraints. |

| 4. A review of the Son-Rise and Lovaas methods for helping children with autism: which is most effective for encouraging verbal communication with a small group of seven-year-olds? | It is a clear and focused question that cites specific instances to be reviewed. It doesn’t require any intervention. |

| 5. Learning in museums: how well is it done? | It is an indefinite and uncertain question because it initiates several questions. What type of learning? Who will learn? Which museum(s)? Who will be the sample population? |

| 6. How well do school children manage their dyslexia in maintained primary schools? A case study of a Key Stage 2 boy. | This study has a precise explanation, but it doesn’t have a narrow approach. It will be obvious, feasible, and clear if the students provide a researchable rationale. If the conclusion supports the case, then it will be a good contribution to the current practice. |

| 7. An investigation into the problems of children whose mothers work full-time. | This research question also makes an assumption. A better question will be – ‘A survey of full-time employed parents, and their children. If you still find it unsatisfactory, you can add a specific location to improve the first version. |

Does your Research Methodology Have the Following?

Orders completed by our expert writers are

- Great Research/Sources

- Perfect Language

- Accurate Sources

If not, we can help. Our panel of experts makes sure to keep the 3 pillars of Research Methodology strong.

A dissertation is an important milestone no matter what academic level or subject it is. You will be asked to write a dissertation on a topic of your choice and make a substantial contribution to academic and scientific communities.

The project will start with the planning and designing of a project before the actual write-up phase. There are many stages in the dissertation process , but the most important is developing a research question that guides your research.

If you are starting your dissertation, you will have to conduct preliminary research to find a problem and research gap as the first step of the process. The second step is to write research questions that specify your topic and the relevant problem you want to address.

How can we Help you with Research Questions?

If you are still unsure about writing dissertation research questions and perhaps want to see more examples , you might be interested in getting help from our dissertation writers.

At ResearchProspect, we have UK-qualified writers holding Masters and PhD degrees in all academic subjects. Whether you need help with only developing research questions or any other aspect of your dissertation paper , we are here to help you achieve your desired grades for an affordable price.

Frequently Asked Questions

What are some examples of a research question.

Examples of research questions:

- How does social media influence self-esteem in adolescents?

- What are the economic impacts of climate change on agriculture?

- What factors contribute to employee job satisfaction in the tech industry?

- How does exercise frequency affect cardiovascular health?

- What is the relationship between sleep duration and academic performance in college students?

What are some examples of research questions in the classroom?

- How do interactive whiteboards impact student engagement?

- Does peer tutoring improve maths proficiency?

- How does classroom seating arrangement influence student participation?

- What’s the effect of gamified learning on student motivation?

- Does integrating technology in lessons enhance critical thinking skills?

- How does feedback frequency affect student performance?

What are some examples of research questions in Geography?

- How does urbanisation impact local microclimates?

- What factors influence water scarcity in Region X?

- How do migration patterns correlate with economic disparities?

- What’s the relationship between deforestation and soil erosion in Area Y?

- How have coastlines changed over the past decade?

- Why are certain regions’ biodiversity hotspots?

What are some examples of research questions in Psychology?

- How does social media usage affect adolescent self-esteem?

- What factors contribute to resilience in trauma survivors?

- How does sleep deprivation impact decision-making abilities?

- Are certain teaching methods more effective for children with ADHD?

- What are the psychological effects of long-term social isolation?

- How do early attachments influence adult relationships?

What are the three basic research questions?

The three basic types of research questions are:

- Descriptive: Seeks to depict a phenomenon or issue. E.g., “What are the symptoms of depression?”

- Relational: Investigates relationships between variables. E.g., “Is there a correlation between stress and heart disease?”

- Causal: Determines cause and effect. E.g., “Does smoking cause lung cancer?”

You May Also Like

Find how to write research questions with the mentioned steps required for a perfect research question. Choose an interesting topic and begin your research.

Struggling to find relevant and up-to-date topics for your dissertation? Here is all you need to know if unsure about how to choose dissertation topic.

How to write a hypothesis for dissertation,? A hypothesis is a statement that can be tested with the help of experimental or theoretical research.

USEFUL LINKS

LEARNING RESOURCES

COMPANY DETAILS

- How It Works

Dissertation Proposal | Examples, Steps & Structure

Introduction

What is the dissertation proposal process, what is the difference between a dissertation and a dissertation proposal, what are the elements of a dissertation proposal, what does a good dissertation proposal look like, how do you present a dissertation proposal.

With the dissertation as the culminating work that leads to successful completion of a doctoral degree, the dissertation proposal or thesis proposal serves as the backbone of the research that will ultimately inform your research agenda in the dissertation stage and beyond. A well-crafted proposed study details the research problem , your research question , and your methodology for studying the dissertation topic.

In this article, we will provide a brief introduction of the components of a good dissertation proposal, why they are important, and what needs to be incorporated into a proposal to allow your committee to conduct further study on your topic.

A typical doctoral program requires a dissertation or thesis through which a doctoral student demonstrates their knowledge and expertise in the prevailing theories and methodologies in their chosen research area. By the time a student is ready for the dissertation proposal stage, they will have taken the necessary coursework on theory and research methods or have demonstrated their expertise in lab work or written publications.

Most doctoral programs also require students to complete comprehensive examinations (these may go by other names such as qualifying exams or preliminary exams). These assess the ability to understand and synthesize scientific knowledge in a given research field. What separates the dissertation proposal from these examinations is that the dissertation proposal asks students to create an entirely new study that builds on that existing knowledge, separating fully-fledged researchers and scientists from merely scholars familiar with expert knowledge.

Needless to say, the dissertation proposal is the precursor to the eventual dissertation. Think of the proposal as a request for permission to conduct the study that you need to conduct to write and defend your dissertation.

Because a rigorous research process is also extensive and drawn out, the proposal is also a reflection of the expertise you have about the dissertation topic. Committee members want to know if you have the necessary knowledge about the existing research to be able to generate empirical knowledge through a full dissertation study.

Once you have conducted your research, the dissertation itself will often take components from your written proposal in providing a comprehensive report on the scholarly knowledge you have generated and how you generated it. That said, the overall scholarly work will likely evolve between the proposal stage and the final dissertation, making the proposal a useful foundation on which your entire research agenda is built.

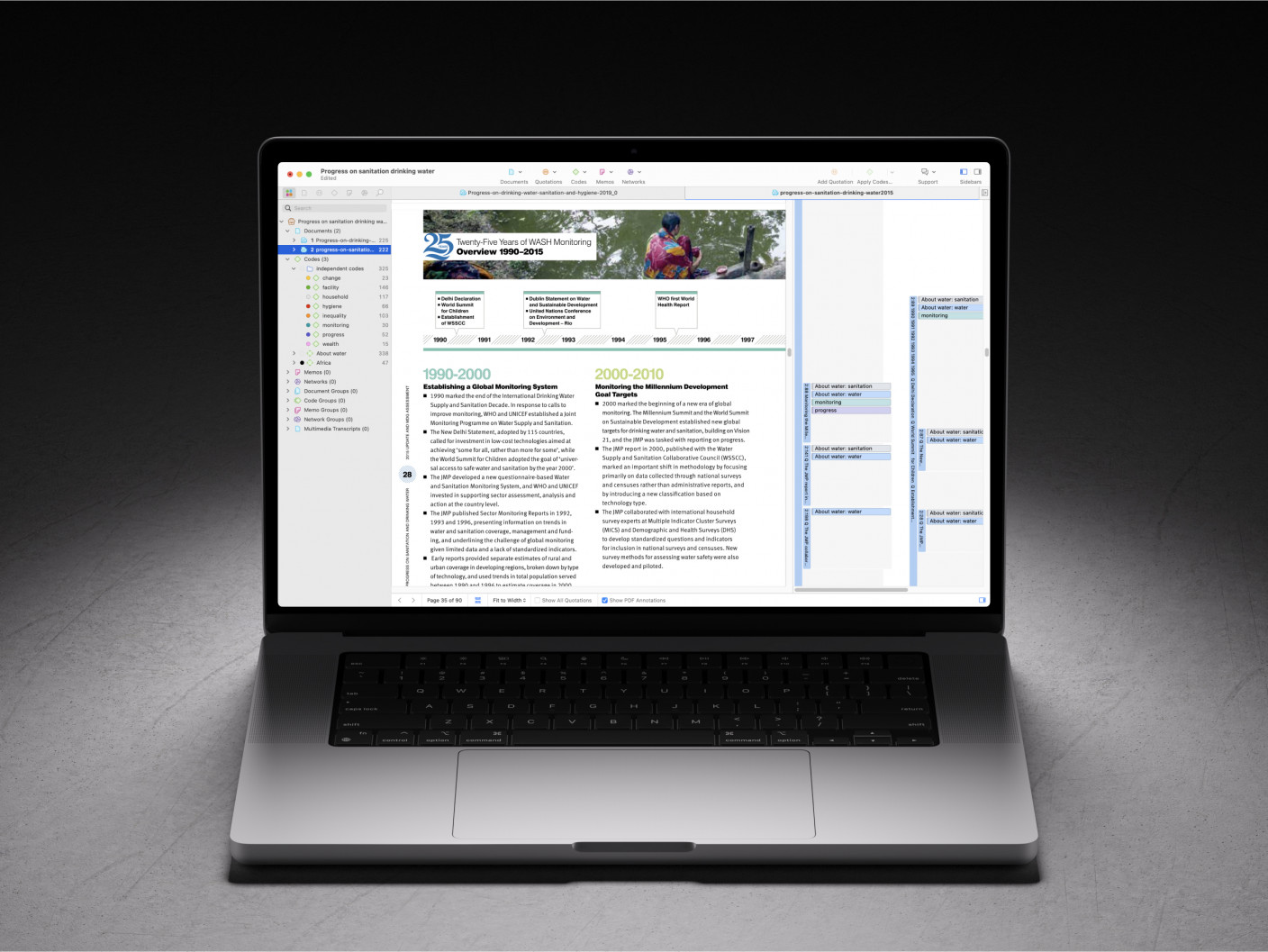

Turn data into insights with ATLAS.ti

Powerful data analysis built into an intuitive interface. Try ATLAS.ti with a free trial today.

By this point in a doctoral program, a student is already familiar with components in a research paper such as a thesis statement, a research question , methodology , and findings and discussion sections. These aspects are commonly found in journal articles and conference presentations. However, a dissertation proposal is most likely a lengthy document as your dissertation committee will expect certain things that may not always belong in a journal article with the level of detail found in a proposal.

Problem statement

A clear dissertation proposal outlines the problem that the proposed research aims to address. An effective problem statement can identify the potential value of the research if it is approved and conducted. It also elevates the research from an inquiry generated from pure intellectual curiosity to a directed study that the greater academic community will find relevant and compelling.

Identifying a problem that research can solve is less about a personal interest and more about justifying why the research deserves to go forward. A good dissertation proposal should make the case that the research can expand theoretical knowledge or identify applications to address practical concerns.

Research questions are the product of a good problem statement. Whereas a useful problem statement will establish the relevance of the study, a research question will focus on aspects of the problem that, when addressed through research, will yield useful theoretical developments or practical insights.

Research background

Once the proposed project is justified in terms of its potential value, the next question is whether existing research has something to say about the problem. A thorough literature review is necessary to be able to identify the necessary gaps in the theory or methodology.

A thorough survey of the research background can also provide a useful theoretical framework that researchers can use to conduct data collection and analysis . Basing your analytical approach on published research will establish useful connections between your research and existing scientific knowledge, a quality that your committee will look for in determining the importance of your proposed study.

Proposed methodology

With a useful theoretical background in mind, the methodology section lays out what the study will look like if it is approved. In a nutshell, a comprehensive treatment of the methodology should include descriptions of the research context (e.g., the participants and the broader environment they occupy), data collection procedures, data analysis strategies, and any expected outcomes.

A thorough explanation of the methodological approach you will apply to your study is critical to a successful proposal. Compared to an explanation of methods in a peer-reviewed journal article, the methodology is expected to take up an entire chapter in your dissertation, so the methods section in your proposal should be just as long. Be prepared to explain not only what strategies for data collection and analysis you choose but why they are appropriate for your research topic and research questions.

The expected outcomes represent the student's best guess as to what might happen and what insights might be collected during the course of the study. This is similar to a research hypothesis in that an expected outcome provides a sort of baseline that the researcher should use to determine the extent of the novelty in the findings.

At this point, dissertation committee members are looking at the extent to which a doctoral student can design a transparent and rigorous study that can contribute new knowledge to the existing body of relevant literature on a given research topic. Especially in the social sciences, the approach a researcher takes in generating new knowledge is often more important than the new knowledge itself, making the methods section arguably the most critical component in your proposal.

Successful dissertation proposals serve both as compelling arguments justifying future research as well as written knowledge that can be incorporated into the eventual dissertation. Oftentimes, students are advised that the dissertation proposal has a similar structure to that of the first few chapters of a dissertation, as they describe the research problem , background, and methodology .

In that sense, a good proposal will help the student save time in writing what will be an even lengthier dissertation. To your advisor and your committee, a successful proposal is less an examination than it is a tool or formal process to help you through the doctoral journey.

Throughout the process of writing your proposal, it's important to communicate with the members of your dissertation committee so they can clarify their expectations regarding what belongs in the proposal. Ultimately, beyond the accepted norms regarding what goes into a typical dissertation proposal, it is up to your committee to determine if you have the expertise and appropriate methodological approach to conduct novel research.

The proposal will most likely be the longest report you will write in your doctoral program, with the exception of the dissertation itself. That's because you will need to describe your research design in the kind of painstaking detail that often isn't included in a typical peer-reviewed research article or academic presentation.

In general terms, the more detail that you can provide in your proposal, the clearer your research agenda as you collect and analyze data , and the easier your dissertation will be to write. However, a dissertation proposal is more than simply a word or page count. It is a document that is intended to "sell" the value of your research to your committee.

Your committee will be made up of your advisor and other faculty members in your university (with some exceptions depending on your doctoral program). These members need to be convinced that your research can contribute to the larger body of scholarly knowledge within the university and in the greater academic community as a whole. As a result, a good proposal is not an encyclopedic presentation of knowledge, but an informed synthesis of theory and methodology that points out where research in a particular topic should be conducted next.

In addition to the substance of your proposal, also pay attention to the packaging of your proposal. Little details such as the title page and reference list also provide indicators that you have carefully thought about the research you want to conduct, and show your level of commitment as a future career scholar. As with submitting a research paper for publication in a peer-reviewed journal, developing the dissertation proposal should also be done with the necessary care that demonstrates a professional attitude toward literacy practices and best practices in academic research.