- Subject List

- Take a Tour

- For Authors

- Subscriber Services

- Publications

- African American Studies

- African Studies

- American Literature

- Anthropology

- Architecture Planning and Preservation

- Art History

- Atlantic History

- Biblical Studies

- British and Irish Literature

- Childhood Studies

- Chinese Studies

- Cinema and Media Studies

- Communication

- Criminology

- Environmental Science

- Evolutionary Biology

- International Law

- International Relations

- Islamic Studies

- Jewish Studies

- Latin American Studies

- Latino Studies

- Linguistics

- Literary and Critical Theory

- Medieval Studies

- Military History

- Political Science

- Public Health

- Renaissance and Reformation

- Social Work

- Urban Studies

- Victorian Literature

- Browse All Subjects

How to Subscribe

- Free Trials

In This Article Expand or collapse the "in this article" section Conformity, Compliance, and Obedience

Introduction, general overviews and textbooks.

- Compliments

- Disrupt-Then-Reframe

- Door-in-the-Face

- Fear-Then-Relief

- Foot-in-the-Door

- That’s Not All

- Physical Attractiveness

- Social Proof

- Affective Influence

- Cultural Perspectives

- Gender Differences

- Nonthoughtfulness

- Social Impact Theory

Related Articles Expand or collapse the "related articles" section about

About related articles close popup.

Lorem Ipsum Sit Dolor Amet

Vestibulum ante ipsum primis in faucibus orci luctus et ultrices posuere cubilia Curae; Aliquam ligula odio, euismod ut aliquam et, vestibulum nec risus. Nulla viverra, arcu et iaculis consequat, justo diam ornare tellus, semper ultrices tellus nunc eu tellus.

- Authoritarian Personality

- Behavioral Economics

- Social Cognition

- Stanford Prison Experiment (SPE): Icon and Controversy

Other Subject Areas

Forthcoming articles expand or collapse the "forthcoming articles" section.

- Data Visualization

- Executive Functions in Childhood

- Remote Work

- Find more forthcoming articles...

- Export Citations

- Share This Facebook LinkedIn Twitter

Conformity, Compliance, and Obedience by Leandre R. Fabrigar , Meghan E. Norris , Devin Fowlie LAST REVIEWED: 26 August 2020 LAST MODIFIED: 26 August 2020 DOI: 10.1093/obo/9780199828340-0075

Social influence refers to the ways people influence the beliefs, feelings, and behaviors of others. Each day we are bombarded by countless attempts by others to influence us, and as such, the study of social influence has long been a central topic of inquiry for social psychologists and researchers in many other social sciences (e.g., marketing, organizational behavior, political science). Theorists have typically distinguished between four types of social influence. Compliance is when an individual changes his or her behavior in response to an explicit or implicit request made by another person. Compliance is often referred to as an active form of social influence in that it is usually intentionally initiated by a person. It is also conceptualized as an external form of social influence in that its focus is a change in overt behavior. Although compliance may sometimes occur as a result of changes in people’s internal beliefs and/or feelings, such internal changes are not the primary goal of compliance, nor are they necessarily required for the request to be successful. In contrast, conformity refers to when people adjust their behaviors, attitudes, feelings, and/or beliefs to fit to a group norm. Conformity is generally regarded as a passive form of influence in that members of the group do not necessarily actively attempt to influence others. People merely observe the actions of group members and adjust their behaviors and/or views accordingly. The focus of conformity can be either external (overt behaviors) or internal (beliefs and feelings) in nature. Obedience is a change in behavior as a result of a direct command from an authority figure. Obedience is an active form of influence in that it is usually directly initiated by an authority figure and is typically external in that overt behaviors are generally the focus of commands. The final form of social influence is persuasion, which refers to an active attempt to change another person’s attitudes, beliefs, or feelings, usually via some form of communication. Persuasion is an active form of influence and is internal in its focus in that changes in people’s beliefs and/or feelings are the goal of such influence. Typically, persuasion is treated as a distinct literature from that of the other three forms of social influence and is usually included as a major area of inquiry within the broader attitudes literature. As such, this article will focus primarily on literature related to compliance, conformity, and obedience.

There are a number of sources, appropriate for different audiences, that provide overviews of the literature. These resources provide broad-level insights into social influence processes that would be informative for both academics and nonacademics. Both Milgram 1992 and Harkins, et al. 2017 provide useful, general overviews that are suitable for a range of audiences. Similarly, Cialdini 2001 would be useful for not only students but also those with nonacademic backgrounds who have an interest in social influence. In contrast, Cialdini and Griskevicius 2010 and Cialdini and Trost 1998 are geared more toward graduate students and researchers. Hogg 2010 provides a scholarly overview of social influence literature.

Cialdini, R. B. 2001. Influence: Science and practice . 4th ed. Boston: Allyn and Bacon.

This book is among the most popular in any area of social psychology. It remains a popular text for classes on social influence but is sufficiently engaging with its effective use of real-world examples that is appealing to readers outside the academic context. This resource covers content including the six principles of influence: reciprocation, commitment and consistency, social proof, liking, authority, and scarcity.

Cialdini, R. B., and V. Griskevicius. 2010. Social influence. In Advanced social psychology: The state of the science . Edited by R. Baumeister and E. Finkel, 385–418. New York: Oxford Univ. Press.

An academic review of social influence research. In contrast to Cialdini 2001 , this book is best suited for a scholarly audience and would be a useful resource for senior undergraduate and graduate students.

Cialdini, R. B., and M. R. Trost. 1998. Social influence: Social norms, conformity, and compliance. In The handbook of social psychology . 4th ed. Vol. 2. Edited by D. T. Gilbert, S. T. Fiske, and G. Lindzey, 151–192. New York: McGraw-Hill.

This chapter is a comprehensive, scholarly review of psychological research on social influence. It provides a detailed summary of research on norms, conformity, and compliance.

Harkins, S. G., K. D. Williams, and J. M. Burger, eds. 2017. The Oxford handbook of social influence . New York: Oxford Univ. Press.

This handbook provides a generally accessible overview of topics and current research in social influence, including intra- and interpersonal processes, intragroup processes, and applied social influence. This is broadly applicable, but is also suitable for nonacademics or students.

Hogg, M. A. 2010. “Influence and leadership.” In The handbook of social psychology . 5th ed. Vol. 2. Edited by S. T. Fiske, D. T. Gilbert, and G. Lindzey, 1166–1206. Hoboken, NJ: Wiley.

This chapter provides a scholarly overview of social influence literature, with a somewhat different emphasis in coverage than that of Cialdini and colleagues. This chapter is best suited for graduate students, scholars, and researchers. It provides distinctions between compliance, conformity, and obedience literature.

Milgram, S. 1992. The individual in a social world: Essays and experiments . 2d ed. Edited by J. Sabini and M. Silver. McGraw-Hill Series in Social Psychology. New York: McGraw-Hill.

This series of writings by Stanley Milgram covers a variety of aspects of social influence, among other topics. This writing is suitable for students or professionals, but may be of interest more generally.

back to top

Users without a subscription are not able to see the full content on this page. Please subscribe or login .

Oxford Bibliographies Online is available by subscription and perpetual access to institutions. For more information or to contact an Oxford Sales Representative click here .

- About Psychology »

- Meet the Editorial Board »

- Abnormal Psychology

- Academic Assessment

- Acculturation and Health

- Action Regulation Theory

- Action Research

- Addictive Behavior

- Adolescence

- Adoption, Social, Psychological, and Evolutionary Perspect...

- Advanced Theory of Mind

- Affective Forecasting

- Affirmative Action

- Ageism at Work

- Allport, Gordon

- Alzheimer’s Disease

- Ambulatory Assessment in Behavioral Science

- Analysis of Covariance (ANCOVA)

- Animal Behavior

- Animal Learning

- Anxiety Disorders

- Art and Aesthetics, Psychology of

- Artificial Intelligence, Machine Learning, and Psychology

- Assessment and Clinical Applications of Individual Differe...

- Attachment in Social and Emotional Development across the ...

- Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD) in Adults

- Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD) in Childre...

- Attitudinal Ambivalence

- Attraction in Close Relationships

- Attribution Theory

- Bayesian Statistical Methods in Psychology

- Behavior Therapy, Rational Emotive

- Behavioral Genetics

- Belief Perseverance

- Bereavement and Grief

- Biological Psychology

- Birth Order

- Body Image in Men and Women

- Bystander Effect

- Categorical Data Analysis in Psychology

- Childhood and Adolescence, Peer Victimization and Bullying...

- Clark, Mamie Phipps

- Clinical Neuropsychology

- Clinical Psychology

- Cognitive Consistency Theories

- Cognitive Dissonance Theory

- Cognitive Neuroscience

- Communication, Nonverbal Cues and

- Comparative Psychology

- Competence to Stand Trial: Restoration Services

- Competency to Stand Trial

- Computational Psychology

- Conflict Management in the Workplace

- Conformity, Compliance, and Obedience

- Consciousness

- Coping Processes

- Correspondence Analysis in Psychology

- Counseling Psychology

- Creativity at Work

- Critical Thinking

- Cross-Cultural Psychology

- Cultural Psychology

- Daily Life, Research Methods for Studying

- Data Science Methods for Psychology

- Data Sharing in Psychology

- Death and Dying

- Deceiving and Detecting Deceit

- Defensive Processes

- Depressive Disorders

- Development, Prenatal

- Developmental Psychology (Cognitive)

- Developmental Psychology (Social)

- Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM...

- Discrimination

- Dissociative Disorders

- Drugs and Behavior

- Eating Disorders

- Ecological Psychology

- Educational Settings, Assessment of Thinking in

- Effect Size

- Embodiment and Embodied Cognition

- Emerging Adulthood

- Emotional Intelligence

- Empathy and Altruism

- Employee Stress and Well-Being

- Environmental Neuroscience and Environmental Psychology

- Ethics in Psychological Practice

- Event Perception

- Evolutionary Psychology

- Expansive Posture

- Experimental Existential Psychology

- Exploratory Data Analysis

- Eyewitness Testimony

- Eysenck, Hans

- Factor Analysis

- Festinger, Leon

- Five-Factor Model of Personality

- Flynn Effect, The

- Forensic Psychology

- Forgiveness

- Friendships, Children's

- Fundamental Attribution Error/Correspondence Bias

- Gambler's Fallacy

- Game Theory and Psychology

- Geropsychology, Clinical

- Global Mental Health

- Habit Formation and Behavior Change

- Health Psychology

- Health Psychology Research and Practice, Measurement in

- Heider, Fritz

- Heuristics and Biases

- History of Psychology

- Human Factors

- Humanistic Psychology

- Implicit Association Test (IAT)

- Industrial and Organizational Psychology

- Inferential Statistics in Psychology

- Insanity Defense, The

- Intelligence

- Intelligence, Crystallized and Fluid

- Intercultural Psychology

- Intergroup Conflict

- International Classification of Diseases and Related Healt...

- International Psychology

- Interviewing in Forensic Settings

- Intimate Partner Violence, Psychological Perspectives on

- Introversion–Extraversion

- Item Response Theory

- Law, Psychology and

- Lazarus, Richard

- Learned Helplessness

- Learning Theory

- Learning versus Performance

- LGBTQ+ Romantic Relationships

- Lie Detection in a Forensic Context

- Life-Span Development

- Locus of Control

- Loneliness and Health

- Mathematical Psychology

- Meaning in Life

- Mechanisms and Processes of Peer Contagion

- Media Violence, Psychological Perspectives on

- Mediation Analysis

- Memories, Autobiographical

- Memories, Flashbulb

- Memories, Repressed and Recovered

- Memory, False

- Memory, Human

- Memory, Implicit versus Explicit

- Memory in Educational Settings

- Memory, Semantic

- Meta-Analysis

- Metacognition

- Metaphor, Psychological Perspectives on

- Microaggressions

- Military Psychology

- Mindfulness

- Mindfulness and Education

- Minnesota Multiphasic Personality Inventory (MMPI)

- Money, Psychology of

- Moral Conviction

- Moral Development

- Moral Psychology

- Moral Reasoning

- Nature versus Nurture Debate in Psychology

- Neuroscience of Associative Learning

- Nonergodicity in Psychology and Neuroscience

- Nonparametric Statistical Analysis in Psychology

- Observational (Non-Randomized) Studies

- Obsessive-Complusive Disorder (OCD)

- Occupational Health Psychology

- Olfaction, Human

- Operant Conditioning

- Optimism and Pessimism

- Organizational Justice

- Parenting Stress

- Parenting Styles

- Parents' Beliefs about Children

- Path Models

- Peace Psychology

- Perception, Person

- Performance Appraisal

- Personality and Health

- Personality Disorders

- Personality Psychology

- Person-Centered and Experiential Psychotherapies: From Car...

- Phenomenological Psychology

- Placebo Effects in Psychology

- Play Behavior

- Positive Psychological Capital (PsyCap)

- Positive Psychology

- Posttraumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD)

- Prejudice and Stereotyping

- Pretrial Publicity

- Prisoner's Dilemma

- Problem Solving and Decision Making

- Procrastination

- Prosocial Behavior

- Prosocial Spending and Well-Being

- Protocol Analysis

- Psycholinguistics

- Psychological Literacy

- Psychological Perspectives on Food and Eating

- Psychology, Political

- Psychoneuroimmunology

- Psychophysics, Visual

- Psychotherapy

- Psychotic Disorders

- Publication Bias in Psychology

- Reasoning, Counterfactual

- Rehabilitation Psychology

- Relationships

- Reliability–Contemporary Psychometric Conceptions

- Religion, Psychology and

- Replication Initiatives in Psychology

- Research Methods

- Risk Taking

- Role of the Expert Witness in Forensic Psychology, The

- Sample Size Planning for Statistical Power and Accurate Es...

- Schizophrenic Disorders

- School Psychology

- School Psychology, Counseling Services in

- Self, Gender and

- Self, Psychology of the

- Self-Construal

- Self-Control

- Self-Deception

- Self-Determination Theory

- Self-Efficacy

- Self-Esteem

- Self-Monitoring

- Self-Regulation in Educational Settings

- Self-Report Tests, Measures, and Inventories in Clinical P...

- Sensation Seeking

- Sex and Gender

- Sexual Minority Parenting

- Sexual Orientation

- Signal Detection Theory and its Applications

- Simpson's Paradox in Psychology

- Single People

- Single-Case Experimental Designs

- Skinner, B.F.

- Sleep and Dreaming

- Small Groups

- Social Class and Social Status

- Social Neuroscience

- Social Support

- Social Touch and Massage Therapy Research

- Somatoform Disorders

- Spatial Attention

- Sports Psychology

- Stereotype Threat

- Stereotypes

- Stress and Coping, Psychology of

- Student Success in College

- Subjective Wellbeing Homeostasis

- Taste, Psychological Perspectives on

- Teaching of Psychology

- Terror Management Theory

- Testing and Assessment

- The Concept of Validity in Psychological Assessment

- The Neuroscience of Emotion Regulation

- The Reasoned Action Approach and the Theories of Reasoned ...

- The Weapon Focus Effect in Eyewitness Memory

- Theory of Mind

- Therapy, Cognitive-Behavioral

- Thinking Skills in Educational Settings

- Time Perception

- Trait Perspective

- Trauma Psychology

- Twin Studies

- Type A Behavior Pattern (Coronary Prone Personality)

- Unconscious Processes

- Video Games and Violent Content

- Virtues and Character Strengths

- Women and Science, Technology, Engineering, and Math (STEM...

- Women, Psychology of

- Work Well-Being

- Workforce Training Evaluation

- Wundt, Wilhelm

- Privacy Policy

- Cookie Policy

- Legal Notice

- Accessibility

Powered by:

- [66.249.64.20|81.177.182.174]

- 81.177.182.174

PSYCH101: Introduction to Psychology

Conformity, compliance, and obedience.

Read this text, which describes two famous experiments.

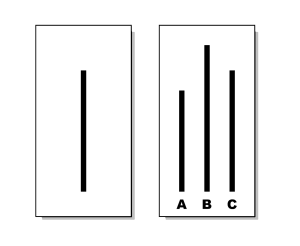

Solomon Asch (1907–1996), a Polish-American pioneer in social psychology, focused on group behavior – specifically persuading members of a group to change their attitudes even if it is wrong. In his classic experiment, he found a conformity effect ("Asch effect") that occurs when a group convinces a member of an untrue fact. The person changes their attitude to conform to the consensus of the group.

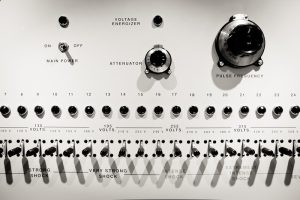

Stanley Milgram (1933–1984), an American social psychologist, researched obedience to authority in his famous study at Yale University. He used confederates to pressure study participants to administer (fake) electric shocks to other people. The participants did not know the shocks were never administered, so many left his experiment assuming they had caused great bodily harm to another person.

Pay attention to the definitions for groupthink, group polarization, and social loafing.

In this section, we discuss additional ways in which people influence others. The topics of conformity, social influence, obedience, and group processes demonstrate the power of the social situation to change our thoughts, feelings, and behaviors. We begin this section with a discussion of a famous social psychology experiment that demonstrated how susceptible humans are to outside social pressures.

- The size of the majority: The greater the number of people in the majority, the more likely an individual will conform. There is, however, an upper limit: a point where adding more members does not increase conformity. In Asch's study, conformity increased with the number of people in the majority – up to seven individuals. At numbers beyond seven, conformity leveled off and decreased slightly.

- The presence of another dissenter: If there is at least one dissenter, conformity rates drop to near zero.

- The public or private nature of the responses: When responses are made publicly (in front of others), conformity is more likely; however, when responses are made privately (e.g., writing down the response), conformity is less likely.

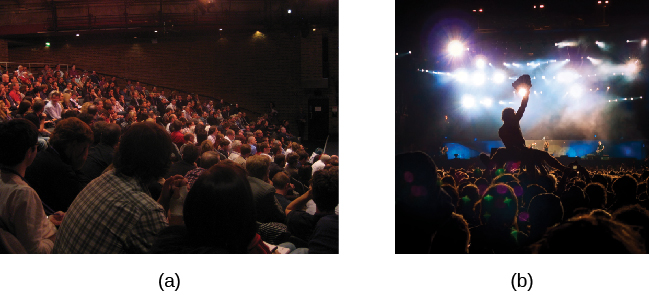

An example of informational social influence may be what to do in an emergency situation. Imagine that you are in a movie theater watching a film and what seems to be smoke comes in the theater from under the emergency exit door. You are not certain that it is smoke - it might be a special effect for the movie, such as a fog machine. When you are uncertain you will tend to look at the behavior of others in the theater. If other people show concern and get up to leave, you are likely to do the same. However, if others seem unconcerned, you are likely to stay put and continue watching the movie (Figure 12.19).

Figure 12.19 People in crowds tend to take cues from others and act accordingly. (a) An audience is listening to a lecture and people are relatively quiet, still, and attentive to the speaker on the stage. (b) An audience is at a rock concert where people are dancing, singing, and possibly engaging in activities like crowd surfing.

How would you have behaved if you were a participant in Asch's study? Many students say they would not conform, that the study is outdated, and that people nowadays are more independent. To some extent this may be true. Research suggests that overall rates of conformity may have reduced since the time of Asch's research. Furthermore, efforts to replicate Asch's study have made it clear that many factors determine how likely it is that someone will demonstrate conformity to the group. These factors include the participant's age, gender, and socio-cultural background.

Stanley Milgram's Experiment

Conformity is one effect of the influence of others on our thoughts, feelings, and behaviors. Another form of social influence is obedience to authority. Obedience is the change of an individual's behavior to comply with a demand by an authority figure. People often comply with the request because they are concerned about a consequence if they do not comply. To demonstrate this phenomenon, we review another classic social psychology experiment.

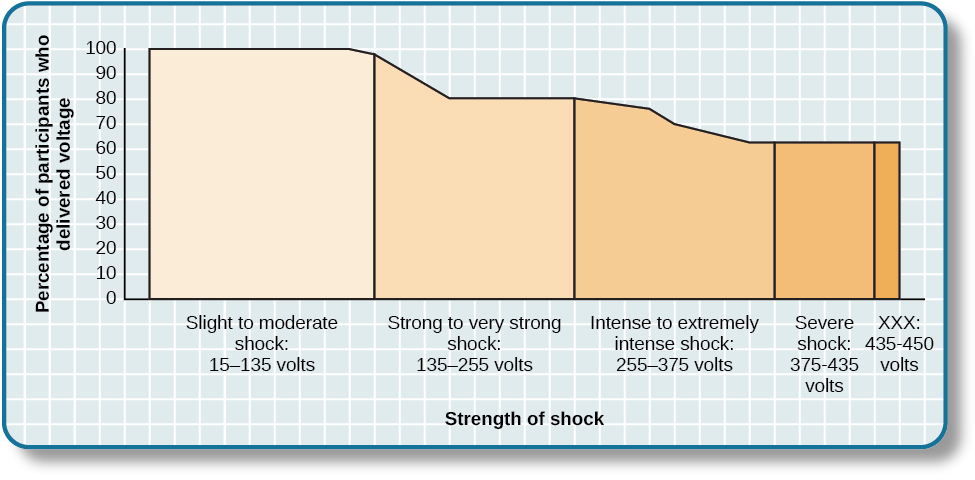

In response to a string of incorrect answers from the learners, the participants obediently and repeatedly shocked them. The confederate learners cried out for help, begged the participant teachers to stop, and even complained of heart trouble. Yet, when the researcher told the participant-teachers to continue the shock, 65% of the participants continued the shock to the maximum voltage and to the point that the learner became unresponsive (Figure 12.20). What makes someone obey authority to the point of potentially causing serious harm to another person?

This case is still very applicable today. What does a person do if an authority figure orders something done? What if the person believes it is incorrect, or worse, unethical? In a study by Martin and Bull (2008), midwives privately filled out a questionnaire regarding best practices and expectations in delivering a baby. Then, a more senior midwife and supervisor asked the junior midwives to do something they had previously stated they were opposed to. Most of the junior midwives were obedient to authority, going against their own beliefs. Burger (2009) partially replicated this study. He found among a multicultural sample of women and men that their levels of obedience matched Milgram's research. Doliński et al. (2017) performed a replication of Burger's work in Poland and controlled for the gender of both participants and learners, and once again, results that were consistent with Milgram's original work were observed.

When in group settings, we are often influenced by the thoughts, feelings, and behaviors of people around us. Whether it is due to normative or informational social influence, groups have power to influence individuals. Another phenomenon of group conformity is groupthink. Groupthink is the modification of the opinions of members of a group to align with what they believe is the group consensus (Janis, 1972). In group situations, the group often takes action that individuals would not perform outside the group setting because groups make more extreme decisions than individuals do. Moreover, groupthink can hinder opposing trains of thought. This elimination of diverse opinions contributes to faulty decision by the group.

Dig Deeper: Groupthink in the U.S. Government

There have been several instances of groupthink in the U.S. government. One example occurred when the United States led a small coalition of nations to invade Iraq in March 2003. This invasion occurred because a small group of advisors and former President George W. Bush were convinced that Iraq represented a significant terrorism threat with a large stockpile of weapons of mass destruction at its disposal.

Although some of these individuals may have had some doubts about the credibility of the information available to them at the time, in the end, the group arrived at a consensus that Iraq had weapons of mass destruction and represented a significant threat to national security. It later came to light that Iraq did not have weapons of mass destruction, but not until the invasion was well underway. As a result, 6000 American soldiers were killed and many more civilians died. How did the Bush administration arrive at their conclusions?

Why does groupthink occur? There are several causes of groupthink, which makes it preventable. When the group is highly cohesive, or has a strong sense of connection, maintaining group harmony may become more important to the group than making sound decisions. If the group leader is directive and makes his opinions known, this may discourage group members from disagreeing with the leader. If the group is isolated from hearing alternative or new viewpoints, groupthink may be more likely. How do you know when groupthink is occurring?

There are several symptoms of groupthink including the following:

- perceiving the group as invulnerable or invincible - believing it can do no wrong

- believing the group is morally correct

- self-censorship by group members, such as withholding information to avoid disrupting the group consensus

- the quashing of dissenting group members' opinions

- the shielding of the group leader from dissenting views

- perceiving an illusion of unanimity among group members

- holding stereotypes or negative attitudes toward the out-group or others' with differing viewpoints

Given the causes and symptoms of groupthink, how can it be avoided? There are several strategies that can improve group decision making including seeking outside opinions, voting in private, having the leader withhold position statements until all group members have voiced their views, conducting research on all viewpoints, weighing the costs and benefits of all options, and developing a contingency plan.

Group Polarization

Social traps refer to situations that arise when individuals or groups of individuals behave in ways that are not in their best interest and that may have negative, long-term consequences. However, once established, a social trap is very difficult to escape. For example, following World War II, the United States and the former Soviet Union engaged in a nuclear arms race. While the presence of nuclear weapons is not in either party's best interest, once the arms race began, each country felt the need to continue producing nuclear weapons to protect itself from the other.

Social Loafing

Interestingly, the opposite of social loafing occurs when the task is complex and difficult. In a group setting, such as the student work group, if your individual performance cannot be evaluated, there is less pressure for you to do well, and thus less anxiety or physiological arousal. This puts you in a relaxed state in which you can perform your best, if you choose. If the task is a difficult one, many people feel motivated and believe that their group needs their input to do well on a challenging project.

Deindividuation

Table 12.2 summarizes the types of social influence you have learned about in this chapter.

Types of Social Influence

12.4 Conformity, Compliance, and Obedience

Learning objectives.

By the end of this section, you will be able to:

- Explain the Asch effect

- Define conformity and types of social influence

- Describe Stanley Milgram’s experiment and its implications

- Define groupthink, social facilitation, and social loafing

In this section, we discuss additional ways in which people influence others. The topics of conformity, social influence, obedience, and group processes demonstrate the power of the social situation to change our thoughts, feelings, and behaviors. We begin this section with a discussion of a famous social psychology experiment that demonstrated how susceptible humans are to outside social pressures.

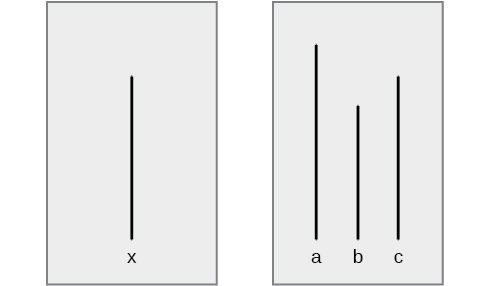

Solomon Asch conducted several experiments in the 1950s to determine how people are affected by the thoughts and behaviors of other people. In one study, a group of participants was shown a series of printed line segments of different lengths: a, b, and c ( Figure 12.17 ). Participants were then shown a fourth line segment: x. They were asked to identify which line segment from the first group (a, b, or c) most closely resembled the fourth line segment in length.

Each group of participants had only one true, naïve subject. The remaining members of the group were confederates of the researcher. A confederate is a person who is aware of the experiment and works for the researcher. Confederates are used to manipulate social situations as part of the research design, and the true, naïve participants believe that confederates are, like them, uninformed participants in the experiment. In Asch’s study, the confederates identified a line segment that was obviously shorter than the target line—a wrong answer. The naïve participant then had to identify aloud the line segment that best matched the target line segment.

How often do you think the true participant aligned with the confederates’ response? That is, how often do you think the group influenced the participant, and the participant gave the wrong answer? Asch (1955) found that 76% of participants conformed to group pressure at least once by indicating the incorrect line. Conformity is the change in a person’s behavior to go along with the group, even if he does not agree with the group. Why would people give the wrong answer? What factors would increase or decrease someone giving in or conforming to group pressure?

The Asch effect is the influence of the group majority on an individual’s judgment.

What factors make a person more likely to yield to group pressure? Research shows that the size of the majority, the presence of another dissenter, and the public or relatively private nature of responses are key influences on conformity.

- The size of the majority: The greater the number of people in the majority, the more likely an individual will conform. There is, however, an upper limit: a point where adding more members does not increase conformity. In Asch’s study, conformity increased with the number of people in the majority—up to seven individuals. At numbers beyond seven, conformity leveled off and decreased slightly (Asch, 1955).

- The presence of another dissenter: If there is at least one dissenter, conformity rates drop to near zero (Asch, 1955).

- The public or private nature of the responses: When responses are made publicly (in front of others), conformity is more likely; however, when responses are made privately (e.g., writing down the response), conformity is less likely (Deutsch & Gerard, 1955).

The finding that conformity is more likely to occur when responses are public than when they are private is the reason government elections require voting in secret, so we are not coerced by others ( Figure 12.18 ). The Asch effect can be easily seen in children when they have to publicly vote for something. For example, if the teacher asks whether the children would rather have extra recess, no homework, or candy, once a few children vote, the rest will comply and go with the majority. In a different classroom, the majority might vote differently, and most of the children would comply with that majority. When someone’s vote changes if it is made in public versus private, this is known as compliance. Compliance can be a form of conformity. Compliance is going along with a request or demand, even if you do not agree with the request. In Asch’s studies, the participants complied by giving the wrong answers, but privately did not accept that the obvious wrong answers were correct.

Now that you have learned about the Asch line experiments, why do you think the participants conformed? The correct answer to the line segment question was obvious, and it was an easy task. Researchers have categorized the motivation to conform into two types: normative social influence and informational social influence (Deutsch & Gerard, 1955).

In normative social influence , people conform to the group norm to fit in, to feel good, and to be accepted by the group. However, with informational social influence , people conform because they believe the group is competent and has the correct information, particularly when the task or situation is ambiguous. What type of social influence was operating in the Asch conformity studies? Since the line judgment task was unambiguous, participants did not need to rely on the group for information. Instead, participants complied to fit in and avoid ridicule, an instance of normative social influence.

An example of informational social influence may be what to do in an emergency situation. Imagine that you are in a movie theater watching a film and what seems to be smoke comes in the theater from under the emergency exit door. You are not certain that it is smoke—it might be a special effect for the movie, such as a fog machine. When you are uncertain you will tend to look at the behavior of others in the theater. If other people show concern and get up to leave, you are likely to do the same. However, if others seem unconcerned, you are likely to stay put and continue watching the movie ( Figure 12.19 ).

How would you have behaved if you were a participant in Asch’s study? Many students say they would not conform, that the study is outdated, and that people nowadays are more independent. To some extent this may be true. Research suggests that overall rates of conformity may have reduced since the time of Asch’s research. Furthermore, efforts to replicate Asch’s study have made it clear that many factors determine how likely it is that someone will demonstrate conformity to the group. These factors include the participant’s age, gender, and socio-cultural background (Bond & Smith, 1996; Larsen, 1990; Walker & Andrade, 1996).

Link to Learning

Watch this video of a replication of the Asch experiment to learn more.

Stanley Milgram’s Experiment

Conformity is one effect of the influence of others on our thoughts, feelings, and behaviors. Another form of social influence is obedience to authority. Obedience is the change of an individual’s behavior to comply with a demand by an authority figure. People often comply with the request because they are concerned about a consequence if they do not comply. To demonstrate this phenomenon, we review another classic social psychology experiment.

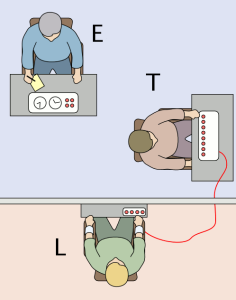

Stanley Milgram was a social psychology professor at Yale who was influenced by the trial of Adolf Eichmann, a Nazi war criminal. Eichmann’s defense for the atrocities he committed was that he was “just following orders.” Milgram (1963) wanted to test the validity of this defense, so he designed an experiment and initially recruited 40 men for his experiment. The volunteer participants were led to believe that they were participating in a study to improve learning and memory. The participants were told that they were to teach other students (learners) correct answers to a series of test items. The participants were shown how to use a device that they were told delivered electric shocks of different intensities to the learners. The participants were told to shock the learners if they gave a wrong answer to a test item—that the shock would help them to learn. The participants believed they gave the learners shocks, which increased in 15-volt increments, all the way up to 450 volts. The participants did not know that the learners were confederates and that the confederates did not actually receive shocks.

In response to a string of incorrect answers from the learners, the participants obediently and repeatedly shocked them. The confederate learners cried out for help, begged the participant teachers to stop, and even complained of heart trouble. Yet, when the researcher told the participant-teachers to continue the shock, 65% of the participants continued the shock to the maximum voltage and to the point that the learner became unresponsive ( Figure 12.20 ). What makes someone obey authority to the point of potentially causing serious harm to another person?

Several variations of the original Milgram experiment were conducted to test the boundaries of obedience. When certain features of the situation were changed, participants were less likely to continue to deliver shocks (Milgram, 1965). For example, when the setting of the experiment was moved to an off-campus office building, the percentage of participants who delivered the highest shock dropped to 48%. When the learner was in the same room as the teacher, the highest shock rate dropped to 40%. When the teachers’ and learners’ hands were touching, the highest shock rate dropped to 30%. When the researcher gave the orders by phone, the rate dropped to 23%. These variations show that when the humanity of the person being shocked was increased, obedience decreased. Similarly, when the authority of the experimenter decreased, so did obedience.

This case is still very applicable today. What does a person do if an authority figure orders something done? What if the person believes it is incorrect, or worse, unethical? In a study by Martin and Bull (2008), midwives privately filled out a questionnaire regarding best practices and expectations in delivering a baby. Then, a more senior midwife and supervisor asked the junior midwives to do something they had previously stated they were opposed to. Most of the junior midwives were obedient to authority, going against their own beliefs. Burger (2009) partially replicated this study. He found among a multicultural sample of women and men that their levels of obedience matched Milgram's research. Doliński et al. (2017) performed a replication of Burger's work in Poland and controlled for the gender of both participants and learners, and once again, results that were consistent with Milgram's original work were observed.

When in group settings, we are often influenced by the thoughts, feelings, and behaviors of people around us. Whether it is due to normative or informational social influence, groups have power to influence individuals. Another phenomenon of group conformity is groupthink. Groupthink is the modification of the opinions of members of a group to align with what they believe is the group consensus (Janis, 1972). In group situations, the group often takes action that individuals would not perform outside the group setting because groups make more extreme decisions than individuals do. Moreover, groupthink can hinder opposing trains of thought. This elimination of diverse opinions contributes to faulty decision by the group.

Groupthink in the U.S. Government

There have been several instances of groupthink in the U.S. government. One example occurred when the United States led a small coalition of nations to invade Iraq in March 2003. This invasion occurred because a small group of advisors and former President George W. Bush were convinced that Iraq represented a significant terrorism threat with a large stockpile of weapons of mass destruction at its disposal. Although some of these individuals may have had some doubts about the credibility of the information available to them at the time, in the end, the group arrived at a consensus that Iraq had weapons of mass destruction and represented a significant threat to national security. It later came to light that Iraq did not have weapons of mass destruction, but not until the invasion was well underway. As a result, 6000 American soldiers were killed and many more civilians died. How did the Bush administration arrive at their conclusions? View this video of Colin Powell, 10 years after his famous United Nations speech, discussing the information he had at the time that his decisions were based on. ("CNN Official Interview: Colin Powell now regrets UN speech about WMDs," 2010).

Do you see evidence of groupthink?

Why does groupthink occur? There are several causes of groupthink, which makes it preventable. When the group is highly cohesive, or has a strong sense of connection, maintaining group harmony may become more important to the group than making sound decisions. If the group leader is directive and makes his opinions known, this may discourage group members from disagreeing with the leader. If the group is isolated from hearing alternative or new viewpoints, groupthink may be more likely. How do you know when groupthink is occurring?

There are several symptoms of groupthink including the following:

- perceiving the group as invulnerable or invincible—believing it can do no wrong

- believing the group is morally correct

- self-censorship by group members, such as withholding information to avoid disrupting the group consensus

- the quashing of dissenting group members’ opinions

- the shielding of the group leader from dissenting views

- perceiving an illusion of unanimity among group members

- holding stereotypes or negative attitudes toward the out-group or others’ with differing viewpoints (Janis, 1972)

Given the causes and symptoms of groupthink, how can it be avoided? There are several strategies that can improve group decision making including seeking outside opinions, voting in private, having the leader withhold position statements until all group members have voiced their views, conducting research on all viewpoints, weighing the costs and benefits of all options, and developing a contingency plan (Janis, 1972; Mitchell & Eckstein, 2009).

Group Polarization

Another phenomenon that occurs within group settings is group polarization. Group polarization (Teger & Pruitt, 1967) is the strengthening of an original group attitude after the discussion of views within a group. That is, if a group initially favors a viewpoint, after discussion the group consensus is likely a stronger endorsement of the viewpoint. Conversely, if the group was initially opposed to a viewpoint, group discussion would likely lead to stronger opposition. Group polarization explains many actions taken by groups that would not be undertaken by individuals. Group polarization can be observed at political conventions, when platforms of the party are supported by individuals who, when not in a group, would decline to support them. Recently, some theorists have argued that group polarization may be partly responsible for the extreme political partisanship that seems ubiquitous in modern society. Given that people can self-select media outlets that are most consistent with their own political views, they are less likely to encounter opposing viewpoints. Over time, this leads to a strengthening of their own perspective and of hostile attitudes and behaviors towards those with different political ideals. Remarkably, political polarization leads to open levels of discrimination that are on par with, or perhaps exceed, racial discrimination (Iyengar & Westwood, 2015). A more everyday example is a group’s discussion of how attractive someone is. Does your opinion change if you find someone attractive, but your friends do not agree? If your friends vociferously agree, might you then find this person even more attractive?

Social traps refer to situations that arise when individuals or groups of individuals behave in ways that are not in their best interest and that may have negative, long-term consequences. However, once established, a social trap is very difficult to escape. For example, following World War II, the United States and the former Soviet Union engaged in a nuclear arms race. While the presence of nuclear weapons is not in either party's best interest, once the arms race began, each country felt the need to continue producing nuclear weapons to protect itself from the other.

Social Loafing

Imagine you were just assigned a group project with other students whom you barely know. Everyone in your group will get the same grade. Are you the type who will do most of the work, even though the final grade will be shared? Or are you more likely to do less work because you know others will pick up the slack? Social loafing involves a reduction in individual output on tasks where contributions are pooled. Because each individual's efforts are not evaluated, individuals can become less motivated to perform well. Karau and Williams (1993) and Simms and Nichols (2014) reviewed the research on social loafing and discerned when it was least likely to happen. The researchers noted that social loafing could be alleviated if, among other situations, individuals knew their work would be assessed by a manager (in a workplace setting) or instructor (in a classroom setting), or if a manager or instructor required group members to complete self-evaluations.

The likelihood of social loafing in student work groups increases as the size of the group increases (Shepperd & Taylor, 1999). According to Karau and Williams (1993), college students were the population most likely to engage in social loafing. Their study also found that women and participants from collectivistic cultures were less likely to engage in social loafing, explaining that their group orientation may account for this.

College students could work around social loafing or “free-riding” by suggesting to their professors use of a flocking method to form groups. Harding (2018) compared groups of students who had self-selected into groups for class to those who had been formed by flocking, which involves assigning students to groups who have similar schedules and motivations. Not only did she find that students reported less “free riding,” but that they also did better in the group assignments compared to those whose groups were self-selected.

Interestingly, the opposite of social loafing occurs when the task is complex and difficult (Bond & Titus, 1983; Geen, 1989). In a group setting, such as the student work group, if your individual performance cannot be evaluated, there is less pressure for you to do well, and thus less anxiety or physiological arousal (Latané, Williams, & Harkens, 1979). This puts you in a relaxed state in which you can perform your best, if you choose (Zajonc, 1965). If the task is a difficult one, many people feel motivated and believe that their group needs their input to do well on a challenging project (Jackson & Williams, 1985).

Deindividuation

Another way that being part of a group can affect behavior is exhibited in instances in which deindividuation occurs. Deindividuation refers to situations in which a person may feel a sense of anonymity and therefore a reduction in accountability and sense of self when among others. Deindividuation is often pointed to in cases in which mob or riot-like behaviors occur (Zimbardo, 1969), but research on the subject and the role that deindividuation plays in such behaviors has resulted in inconsistent results (as discussed in Granström, Guvå, Hylander, & Rosander, 2009).

Table 12.2 summarizes the types of social influence you have learned about in this chapter.

As an Amazon Associate we earn from qualifying purchases.

This book may not be used in the training of large language models or otherwise be ingested into large language models or generative AI offerings without OpenStax's permission.

Want to cite, share, or modify this book? This book uses the Creative Commons Attribution License and you must attribute OpenStax.

Access for free at https://openstax.org/books/psychology-2e/pages/1-introduction

- Authors: Rose M. Spielman, William J. Jenkins, Marilyn D. Lovett

- Publisher/website: OpenStax

- Book title: Psychology 2e

- Publication date: Apr 22, 2020

- Location: Houston, Texas

- Book URL: https://openstax.org/books/psychology-2e/pages/1-introduction

- Section URL: https://openstax.org/books/psychology-2e/pages/12-4-conformity-compliance-and-obedience

© Jan 6, 2024 OpenStax. Textbook content produced by OpenStax is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution License . The OpenStax name, OpenStax logo, OpenStax book covers, OpenStax CNX name, and OpenStax CNX logo are not subject to the Creative Commons license and may not be reproduced without the prior and express written consent of Rice University.

Social Psychology

Conformity and Obedience

Learning objectives.

- Describe the results of research on conformity, and distinguish between normative and informational social influence.

- Describe Stanley Milgram’s experiment and its implications

Solomon Asch conducted several experiments in the 1950s to determine how people are affected by the thoughts and behaviors of other people. In one study, a group of participants was shown a series of printed line segments of different lengths: a, b, and c (Figure 1). Participants were then shown a fourth line segment: x. They were asked to identify which line segment from the first group (a, b, or c) most closely resembled the fourth line segment in length.

Each group of participants had only one true, naïve subject. The remaining members of the group were confederates of the researcher. A confederate is a person who is aware of the experiment and works for the researcher. Confederates are used to manipulate social situations as part of the research design, and the true, naïve participants believe that confederates are, like them, uninformed participants in the experiment. In Asch’s study, the confederates identified a line segment that was obviously shorter than the target line—a wrong answer. The naïve participant then had to identify aloud the line segment that best matched the target line segment.

How often do you think the true participant aligned with the confederates’ response? That is, how often do you think the group influenced the participant, and the participant gave the wrong answer? Asch (1955) found that 76% of participants conformed to group pressure at least once by indicating the incorrect line. Conformity is the change in a person’s behavior to go along with the group, even if he does not agree with the group. Why would people give the wrong answer? What factors would increase or decrease someone giving in or conforming to group pressure?

The Asch effect is the influence of the group majority on an individual’s judgment.

What factors make a person more likely to yield to group pressure? Research shows that the size of the majority, the presence of another dissenter, and the public or relatively private nature of responses are key influences on conformity.

- The size of the majority: The greater the number of people in the majority, the more likely an individual will conform. There is, however, an upper limit: a point where adding more members does not increase conformity. In Asch’s study, conformity increased with the number of people in the majority—up to seven individuals. At numbers beyond seven, conformity leveled off and decreased slightly (Asch, 1955).

- The presence of another dissenter: If there is at least one dissenter, conformity rates drop to near zero (Asch, 1955).

- The public or private nature of the responses: When responses are made publicly (in front of others), conformity is more likely; however, when responses are made privately (e.g., writing down the response), conformity is less likely (Deutsch & Gerard, 1955).

The finding that conformity is more likely to occur when responses are public than when they are private is the reason government elections require voting in secret, so we are not coerced by others (Figure 2). The Asch effect can be easily seen in children when they have to publicly vote for something. For example, if the teacher asks whether the children would rather have extra recess, no homework, or candy, once a few children vote, the rest will comply and go with the majority. In a different classroom, the majority might vote differently, and most of the children would comply with that majority. When someone’s vote changes if it is made in public versus private, this is known as compliance. Compliance can be a form of conformity. Compliance is going along with a request or demand, even if you do not agree with the request. In Asch’s studies, the participants complied by giving the wrong answers, but privately did not accept that the obvious wrong answers were correct.

Now that you have learned about the Asch line experiments, why do you think the participants conformed? The correct answer to the line segment question was obvious, and it was an easy task. Researchers have categorized the motivation to conform into two types: normative social influence and informational social influence (Deutsch & Gerard, 1955).

In normative social influence , people conform to the group norm to fit in, to feel good, and to be accepted by the group. However, with informational social influence , people conform because they believe the group is competent and has the correct information, particularly when the task or situation is ambiguous. What type of social influence was operating in the Asch conformity studies? Since the line judgment task was unambiguous, participants did not need to rely on the group for information. Instead, participants complied to fit in and avoid ridicule, an instance of normative social influence.

An example of informational social influence may be what to do in an emergency situation. Imagine that you are in a movie theater watching a film and what seems to be smoke comes in the theater from under the emergency exit door. You are not certain that it is smoke—it might be a special effect for the movie, such as a fog machine. When you are uncertain you will tend to look at the behavior of others in the theater. If other people show concern and get up to leave, you are likely to do the same. However, if others seem unconcerned, you are likely to stay put and continue watching the movie (Figure 3).

How would you have behaved if you were a participant in Asch’s study? Many students say they would not conform, that the study is outdated, and that people nowadays are more independent. To some extent this may be true. Research suggests that overall rates of conformity may have reduced since the time of Asch’s research. Furthermore, efforts to replicate Asch’s study have made it clear that many factors determine how likely it is that someone will demonstrate conformity to the group. These factors include the participant’s age, gender, and socio-cultural background (Bond & Smith, 1996; Larsen, 1990; Walker & Andrade, 1996).

You can view the transcript for “The Asch Experiment” here (opens in new window) .

Stanley Milgram’s Experiment

Conformity is one effect of the influence of others on our thoughts, feelings, and behaviors. Another form of social influence is obedience to authority. Obedience is the change of an individual’s behavior to comply with a demand by an authority figure. People often comply with the request because they are concerned about a consequence if they do not comply. To demonstrate this phenomenon, we review another classic social psychology experiment.

Stanley Milgram was a social psychology professor at Yale who was influenced by the trial of Adolf Eichmann, a Nazi war criminal. Eichmann’s defense for the atrocities he committed was that he was “just following orders.” Milgram (1963) wanted to test the validity of this defense, so he designed an experiment and initially recruited 40 men for his experiment. The volunteer participants were led to believe that they were participating in a study to improve learning and memory. The participants were told that they were to teach other students (learners) correct answers to a series of test items. The participants were shown how to use a device that they were told delivered electric shocks of different intensities to the learners. The participants were told to shock the learners if they gave a wrong answer to a test item—that the shock would help them to learn. The participants gave (or believed they gave) the learners shocks, which increased in 15-volt increments, all the way up to 450 volts. The participants did not know that the learners were confederates and that the confederates did not actually receive shocks.

In response to a string of incorrect answers from the learners, the participants obediently and repeatedly shocked them. The confederate learners cried out for help, begged the participant teachers to stop, and even complained of heart trouble. Yet, when the researcher told the participant-teachers to continue the shock, 65% of the participants continued the shock to the maximum voltage and to the point that the learner became unresponsive (Figure 4). What makes someone obey authority to the point of potentially causing serious harm to another person?

Several variations of the original Milgram experiment were conducted to test the boundaries of obedience. When certain features of the situation were changed, participants were less likely to continue to deliver shocks (Milgram, 1965). For example, when the setting of the experiment was moved to an office building, the percentage of participants who delivered the highest shock dropped to 48%. When the learner was in the same room as the teacher, the highest shock rate dropped to 40%. When the teachers’ and learners’ hands were touching, the highest shock rate dropped to 30%. When the researcher gave the orders by phone, the rate dropped to 23%. These variations show that when the humanity of the person being shocked was increased, obedience decreased. Similarly, when the authority of the experimenter decreased, so did obedience.

This case is still very applicable today. What does a person do if an authority figure orders something done? What if the person believes it is incorrect, or worse, unethical? In a study by Martin and Bull (2008), midwives privately filled out a questionnaire regarding best practices and expectations in delivering a baby. Then, a more senior midwife and supervisor asked the junior midwives to do something they had previously stated they were opposed to. Most of the junior midwives were obedient to authority, going against their own beliefs.

Link to learning

Watch a modern example of the Milgram experiment here .

- Conduct a conformity study the next time you are in an elevator. After you enter the elevator, stand with your back toward the door. See if others conform to your behavior. Did your results turn out as expected?

- Most students adamantly state that they would never have turned up the voltage in the Milgram experiment. Do you think you would have refused to shock the learner? Looking at your own past behavior, what evidence suggests that you would go along with the order to increase the voltage?

CC licensed content, Shared previously

- Conformity, Compliance, and Obedience. Authored by : OpenStax College. Located at : https://openstax.org/books/psychology-2e/pages/12-4-conformity-compliance-and-obedience . License : CC BY: Attribution . License Terms : Download for free at https://openstax.org/books/psychology-2e/pages/1-introduction

All rights reserved content

- The Asch Experiment. Authored by : Question Everything. Located at : https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=qA-gbpt7Ts8 . License : Other . License Terms : Standard YouTube License

- abc news Primetime Milgram. Authored by : EightYellowFlowers. Located at : https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=HwqNP9HRy7Y&list=PLsjOSJm46miabqNKVfh8VrzHtKZym3lQs&index=4 . License : Other . License Terms : Standard YouTube License

person who works for a researcher and is aware of the experiment, but who acts as a participant; used to manipulate social situations as part of the research design

when individuals change their behavior to go along with the group even if they do not agree with the group

group majority influences an individual’s judgment, even when that judgment is inaccurate

change of behavior to please an authority figure or to avoid aversive consequences

General Psychology Copyright © by OpenStax and Lumen Learning is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Share This Book

Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

14 Conformity and Obedience

We often change our attitudes and behaviors to match the attitudes and behaviors of the people around us. One reason for this conformity is a concern about what other people think of us. This process was demonstrated in a classic study in which college students deliberately gave wrong answers to a simple visual judgment task rather than go against the group. Another reason we conform to the norm is because other people often have information we do not, and relying on norms can be a reasonable strategy when we are uncertain about how we are supposed to act. Unfortunately, we frequently misperceive how the typical person acts, which can contribute to problems such as the excessive binge drinking often seen in college students. Obeying orders from an authority figure can sometimes lead to disturbing behavior. This danger was illustrated in a famous study in which participants were instructed to administer painful electric shocks to another person in what they believed to be a learning experiment. Despite vehement protests from the person receiving the shocks, most participants continued the procedure when instructed to do so by the experimenter. The findings raise questions about the power of blind obedience in deplorable situations such as atrocities and genocide. They also raise concerns about the ethical treatment of participants in psychology experiments.

Learning Objectives

- Become aware of how widespread conformity is in our lives and some of the ways each of us changes our attitudes and behavior to match the norm.

- Understand the two primary reasons why people often conform to perceived norms.

- Appreciate how obedience to authority has been examined in laboratory studies and some of the implications of the findings from these investigations.

- Consider some of the remaining issues and sources of controversy surrounding Milgram’s obedience studies.

Introduction

When he was a teenager, my son often enjoyed looking at photographs of me and my wife taken when we were in high school. He laughed at the hairstyles, the clothing, and the kind of glasses people wore “back then.” And when he was through with his ridiculing, we would point out that no one is immune to fashions and fads and that someday his children will probably be equally amused by his high school photographs and the trends he found so normal at the time.

Everyday observation confirms that we often adopt the actions and attitudes of the people around us. Trends in clothing, music, foods, and entertainment are obvious. But our views on political issues, religious questions, and lifestyles also reflect to some degree the attitudes of the people we interact with. Similarly, decisions about behaviors such as smoking and drinking are influenced by whether the people we spend time with engage in these activities. Psychologists refer to this widespread tendency to act and think like the people around us as conformity .

What causes all this conformity? To start, humans may possess an inherent tendency to imitate the actions of others. Although we usually are not aware of it, we often mimic the gestures, body posture, language, talking speed, and many other behaviors of the people we interact with. Researchers find that this mimicking increases the connection between people and allows our interactions to flow more smoothly ( Chartrand & Bargh, 1999 ).

Beyond this automatic tendency to imitate others, psychologists have identified two primary reasons for conformity. The first of these is normative influence . When normative influence is operating, people go along with the crowd because they are concerned about what others think of them. We don’t want to look out of step or become the target of criticism just because we like different kinds of music or dress differently than everyone else. Fitting in also brings rewards such as camaraderie and compliments.

How powerful is normative influence? Consider a classic study conducted many years ago by Solomon Asch ( 1956 ). The participants were male college students who were asked to engage in a seemingly simple task. An experimenter standing several feet away held up a card that depicted one line on the left side and three lines on the right side. The participant’s job was to say aloud which of the three lines on the right was the same length as the line on the left. Sixteen cards were presented one at a time, and the correct answer on each was so obvious as to make the task a little boring. Except for one thing. The participant was not alone. In fact, there were six other people in the room who also gave their answers to the line-judgment task aloud. Moreover, although they pretended to be fellow participants, these other individuals were, in fact, confederates working with the experimenter. The real participant was seated so that he always gave his answer after hearing what five other “participants” said. Everything went smoothly until the third trial, when inexplicably the first “participant” gave an obviously incorrect answer. The mistake might have been amusing, except the second participant gave the same answer. As did the third, the fourth, and the fifth participant. Suddenly the real participant was in a difficult situation. His eyes told him one thing, but five out of five people apparently saw something else.

It’s one thing to wear your hair a certain way or like certain foods because everyone around you does. But, would participants intentionally give a wrong answer just to conform with the other participants? The confederates uniformly gave incorrect answers on 12 of the 16 trials, and 76 percent of the participants went along with the norm at least once and also gave the wrong answer. In total, they conformed with the group on one-third of the 12 test trials. Although we might be impressed that the majority of the time participants answered honestly, most psychologists find it remarkable that so many college students caved in to the pressure of the group rather than do the job they had volunteered to do. In almost all cases, the participants knew they were giving an incorrect answer, but their concern for what these other people might be thinking about them overpowered their desire to do the right thing.

Variations of Asch’s procedures have been conducted numerous times ( Bond, 2005 ; Bond & Smith, 1996 ). We now know that the findings are easily replicated, that there is an increase in conformity with more confederates (up to about five), that teenagers are more prone to conforming than are adults, and that people conform significantly less often when they believe the confederates will not hear their responses ( Berndt, 1979 ; Bond, 2005 ; Crutchfield, 1955 ; Deutsch & Gerard, 1955 ). This last finding is consistent with the notion that participants change their answers because they are concerned about what others think of them. Finally, although we see the effect in virtually every culture that has been studied, more conformity is found in collectivist countries such as Japan and China than in individualistic countries such as the United States ( Bond & Smith, 1996 ). Compared with individualistic cultures, people who live in collectivist cultures place a higher value on the goals of the group than on individual preferences. They also are more motivated to maintain harmony in their interpersonal relations.

The other reason we sometimes go along with the crowd is that people are often a source of information. Psychologists refer to this process as informational influence . Most of us, most of the time, are motivated to do the right thing. If society deems that we put litter in a proper container, speak softly in libraries, and tip our waiter, then that’s what most of us will do. But sometimes it’s not clear what society expects of us. In these situations, we often rely on descriptive norms ( Cialdini, Reno, & Kallgren, 1990 ). That is, we act the way most people—or most people like us—act. This is not an unreasonable strategy. Other people often have information that we do not, especially when we find ourselves in new situations. If you have ever been part of a conversation that went something like this,

“Do you think we should?” “Sure. Everyone else is doing it.”,

you have experienced the power of informational influence.

However, it’s not always easy to obtain good descriptive norm information, which means we sometimes rely on a flawed notion of the norm when deciding how we should behave. A good example of how misperceived norms can lead to problems is found in research on binge drinking among college students. Excessive drinking is a serious problem on many campuses ( Mita, 2009 ). There are many reasons why students binge drink, but one of the most important is their perception of the descriptive norm. How much students drink is highly correlated with how much they believe the average student drinks ( Neighbors, Lee, Lewis, Fossos, & Larimer, 2007 ). Unfortunately, students aren’t very good at making this assessment. They notice the boisterous heavy drinker at the party but fail to consider all the students not attending the party. As a result, students typically overestimate the descriptive norm for college student drinking ( Borsari & Carey, 2003 ; Perkins, Haines, & Rice, 2005 ). Most students believe they consume significantly less alcohol than the norm, a miscalculation that creates a dangerous push toward more and more excessive alcohol consumption. On the positive side, providing students with accurate information about drinking norms has been found to reduce overindulgent drinking ( Burger, LaSalvia, Hendricks, Mehdipour, & Neudeck, 2011 ; Neighbors, Lee, Lewis, Fossos, & Walter, 2009 ).

Researchers have demonstrated the power of descriptive norms in a number of areas. Homeowners reduced the amount of energy they used when they learned that they were consuming more energy than their neighbors ( Schultz, Nolan, Cialdini, Goldstein, & Griskevicius, 2007 ). Undergraduates selected the healthy food option when led to believe that other students had made this choice ( Burger et al., 2010 ). Hotel guests were more likely to reuse their towels when a hanger in the bathroom told them that this is what most guests did ( Goldstein, Cialdini, & Griskevicius, 2008 ). And more people began using the stairs instead of the elevator when informed that the vast majority of people took the stairs to go up one or two floors ( Burger & Shelton, 2011 ).

Although we may be influenced by the people around us more than we recognize, whether we conform to the norm is up to us. But sometimes decisions about how to act are not so easy. Sometimes we are directed by a more powerful person to do things we may not want to do. Researchers who study obedience are interested in how people react when given an order or command from someone in a position of authority. In many situations, obedience is a good thing. We are taught at an early age to obey parents, teachers, and police officers. It’s also important to follow instructions from judges, firefighters, and lifeguards. And a military would fail to function if soldiers stopped obeying orders from superiors. But, there is also a dark side to obedience. In the name of “following orders” or “just doing my job,” people can violate ethical principles and break laws. More disturbingly, obedience often is at the heart of some of the worst of human behavior—massacres, atrocities, and even genocide.

It was this unsettling side of obedience that led to some of the most famous and most controversial research in the history of psychology. Milgram ( 1963 , 1965 , 1974 ) wanted to know why so many otherwise decent German citizens went along with the brutality of the Nazi leaders during the Holocaust. “These inhumane policies may have originated in the mind of a single person,” Milgram ( 1963 , p. 371) wrote, “but they could only be carried out on a massive scale if a very large number of persons obeyed orders.”

To understand this obedience, Milgram conducted a series of laboratory investigations. In all but one variation of the basic procedure, participants were men recruited from the community surrounding Yale University, where the research was carried out. These citizens signed up for what they believed to be an experiment on learning and memory. In particular, they were told the research concerned the effects of punishment on learning. Three people were involved in each session. One was the participant. Another was the experimenter. The third was a confederate who pretended to be another participant.

The experimenter explained that the study consisted of a memory test and that one of the men would be the teacher and the other the learner. Through a rigged drawing, the real participant was always assigned the teacher’s role and the confederate was always the learner. The teacher watched as the learner was strapped into a chair and had electrodes attached to his wrist. The teacher then moved to the room next door where he was seated in front of a large metal box the experimenter identified as a “shock generator.” The front of the box displayed gauges and lights and, most noteworthy, a series of 30 levers across the bottom. Each lever was labeled with a voltage figure, starting with 15 volts and moving up in 15-volt increments to 450 volts. Labels also indicated the strength of the shocks, starting with “Slight Shock” and moving up to “Danger: Severe Shock” toward the end. The last two levers were simply labeled “XXX” in red.

Through a microphone, the teacher administered a memory test to the learner in the next room. The learner responded to the multiple-choice items by pressing one of four buttons that were barely within reach of his strapped-down hand. If the teacher saw the correct answer light up on his side of the wall, he simply moved on to the next item. But if the learner got the item wrong, the teacher pressed one of the shock levers and, thereby, delivered the learner’s punishment. The teacher was instructed to start with the 15-volt lever and move up to the next highest shock for each successive wrong answer.

In reality, the learner received no shocks. But he did make a lot of mistakes on the test, which forced the teacher to administer what he believed to be increasingly strong shocks. The purpose of the study was to see how far the teacher would go before refusing to continue. The teacher’s first hint that something was amiss came after pressing the 75-volt lever and hearing through the wall the learner say “Ugh!” The learner’s reactions became stronger and louder with each lever press. At 150 volts, the learner yelled out, “Experimenter! That’s all. Get me out of here. I told you I had heart trouble. My heart’s starting to bother me now. Get me out of here, please. My heart’s starting to bother me. I refuse to go on. Let me out.”

The experimenter’s role was to encourage the participant to continue. If at any time the teacher asked to end the session, the experimenter responded with phrases such as, “The experiment requires that you continue,” and “You have no other choice, you must go on.” The experimenter ended the session only after the teacher stated four successive times that he did not want to continue. All the while, the learner’s protests became more intense with each shock. After 300 volts, the learner refused to answer any more questions, which led the experimenter to say that no answer should be considered a wrong answer. After 330 volts, despite vehement protests from the learner following previous shocks, the teacher heard only silence, suggesting that the learner was now physically unable to respond. If the teacher reached 450 volts—the end of the generator—the experimenter told him to continue pressing the 450 volt lever for each wrong answer. It was only after the teacher pressed the 450-volt lever three times that the experimenter announced that the study was over.

If you had been a participant in this research, what would you have done? Virtually everyone says he or she would have stopped early in the process. And most people predict that very few if any participants would keep pressing all the way to 450 volts. Yet in the basic procedure described here, 65 percent of the participants continued to administer shocks to the very end of the session. These were not brutal, sadistic men. They were ordinary citizens who nonetheless followed the experimenter’s instructions to administer what they believed to be excruciating if not dangerous electric shocks to an innocent person. The disturbing implication from the findings is that, under the right circumstances, each of us may be capable of acting in some very uncharacteristic and perhaps some very unsettling ways.