Change Password

Your password must have 6 characters or more:.

- a lower case character,

- an upper case character,

- a special character

Password Changed Successfully

Your password has been changed

Create your account

Forget yout password.

Enter your email address below and we will send you the reset instructions

If the address matches an existing account you will receive an email with instructions to reset your password

Forgot your Username?

Enter your email address below and we will send you your username

If the address matches an existing account you will receive an email with instructions to retrieve your username

- Spring 2024 | VOL. 36, NO. 2 CURRENT ISSUE pp.A4-174

- Winter 2024 | VOL. 36, NO. 1 pp.A5-81

The American Psychiatric Association (APA) has updated its Privacy Policy and Terms of Use , including with new information specifically addressed to individuals in the European Economic Area. As described in the Privacy Policy and Terms of Use, this website utilizes cookies, including for the purpose of offering an optimal online experience and services tailored to your preferences.

Please read the entire Privacy Policy and Terms of Use. By closing this message, browsing this website, continuing the navigation, or otherwise continuing to use the APA's websites, you confirm that you understand and accept the terms of the Privacy Policy and Terms of Use, including the utilization of cookies.

Case Study 1: A 55-Year-Old Woman With Progressive Cognitive, Perceptual, and Motor Impairments

- Scott M. McGinnis , M.D. ,

- Andrew M. Stern , M.D., Ph.D. ,

- Jared K. Woods , M.D., Ph.D. ,

- Matthew Torre , M.D. ,

- Mel B. Feany , M.D., Ph.D. ,

- Michael B. Miller , M.D., Ph.D. ,

- David A. Silbersweig , M.D. ,

- Seth A. Gale , M.D. ,

- Kirk R. Daffner , M.D.

Search for more papers by this author

CASE PRESENTATION

A 55-year-old right-handed woman presented with a 3-year history of cognitive changes. Early symptoms included mild forgetfulness—for example, forgetting where she left her purse or failing to remember to retrieve a take-out order her family placed—and word-finding difficulties. Problems with depth perception affected her ability to back her car out of the driveway. When descending stairs, she had to locate her feet visually in order to place them correctly, such that when she carried her dog and her view was obscured, she had difficulty managing this activity. She struggled to execute relatively simple tasks, such as inserting a plug into an outlet. She lost the ability to type on a keyboard, despite being able to move her fingers quickly. Her symptoms worsened progressively for 3 years, over which time she developed a sad mood and anxiety. She was laid off from work as a nurse administrator. Her family members assumed responsibility for paying her bills, and she ceased driving.

Her past medical history included high blood pressure, Hashimoto’s thyroiditis with thyroid peroxidase antibodies, remote history of migraine, and anxiety. Medications included mirtazapine, levothyroxine, calcium, and vitamin D. She had no history of smoking, drinking alcohol, or recreational drug use. There was no known family history of neurologic diseases.

What Are Diagnostic Considerations Based on the History? How Might a Clinical Examination Help to Narrow the Differential Diagnosis?

Insidious onset and gradual progression of cognitive symptoms over the course of several years raise concern for a neurodegenerative disorder. It is helpful to consider whether or not the presentation fits with a recognized neurodegenerative clinical syndrome, a judgment based principally on familiarity with syndromes and pattern recognition. Onset of symptoms before age 65 should prompt consideration of syndromes in the spectrum of frontotemporal dementia (FTD) and atypical (nonamnesic) presentations of Alzheimer’s disease (AD) ( 1 , 2 ). This patient’s symptoms reflect relatively prominent early dysfunction in visual-spatial processing and body schema, as might be observed in posterior cortical atrophy (PCA), although the history also includes mention of forgetfulness and word-retrieval difficulties. A chief goal of the cognitive examination would be to survey major domains of cognition—attention, executive functioning, memory, language, visual-spatial functioning, and higher somatosensory and motor functioning—to determine whether any domains stand out as more prominently affected. In addition to screening for evidence of focal signs, a neurological examination in this context should assess for evidence of parkinsonism or motor neuron disease, which can coexist with cognitive changes in neurodegenerative presentations.

The patient’s young age and history of Hashimoto’s thyroiditis might also prompt consideration of Hashimoto’s encephalopathy (HE; also known as steroid-responsive encephalopathy), associated with autoimmune thyroiditis. This syndrome is most likely attributable to an autoimmune or inflammatory process affecting the central nervous system. The time course of HE is usually more subacute and rapidly progressive or relapsing-remitting, as opposed to the gradual progression over months to years observed in the present case ( 3 ).

The patient’s mental status examination included the Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA), a brief global screen of cognition ( 4 ), on which she scored 12/30. There was evidence of dysfunction across multiple cognitive domains ( Figure 1 ). She was fully oriented to location, day, month, year, and exact date. When asked to describe a complex scene from a picture in a magazine, she had great difficulty doing so, focusing on different details but having trouble directing her saccades to pertinent visual information. She likewise had problems directing her gaze to specified objects in the room and problems reaching in front of her to touch target objects in either visual field. In terms of other symptoms of higher order motor and somatosensory functioning, she had difficulty demonstrating previously learned actions—for example, positioning her hand correctly to pantomime holding a brush and combing her hair. She was confused about which side of her body was the left and which was the right. She had difficulty with mental calculations, even relatively simple ones such as “18 minus 12.” In addition, she had problems writing a sentence in terms of both grammar and the appropriate spacing of words and letters on the page.

FIGURE 1. Selected elements of a 55-year-old patient’s cognitive examination at presentation a

a BNT-15=Boston Naming Test (15-Item); MoCA=Montreal Cognitive Assessment.

On elementary neurologic examination she had symmetrically brisk reflexes, with spread. She walked steadily with a narrow base, but when asked to pass through a doorway she had difficulty finding her way through it and bumped into the door jamb. Her elemental neurological examination was otherwise normal, including but not limited to brisk, full-amplitude vertical eye movements, normal visual fields, no evidence of peripheral neuropathy, and no parkinsonian signs such as slowness of movement, tremor, or rigidity.

How Does the Examination Contribute to Our Understanding of Diagnostic Considerations? What Additional Tests or Studies Are Indicated?

The most prominent early symptoms and signs localize predominantly to the parietal association cortex: The patient has impairments in visual construction, ability to judge spatial relationships, ability to synthesize component parts of a visual scene into a coherent whole (simultanagnosia or asimultagnosia), impaired visually guided reaching for objects (optic ataxia), and most likely impaired ability to shift her visual attention so as to direct saccades to targets in her field of view (oculomotor apraxia or ocular apraxia). The last three signs constitute Bálint syndrome, which localizes to disruption of dorsal visual networks (i.e., dorsal stream) with key nodes in the posterior parietal and prefrontal cortices bilaterally ( 5 ). She has additional salient symptoms and signs suggesting left inferior parietal dysfunction, including ideomotor limb apraxia and elements of Gerstmann syndrome, which comprises dysgraphia, acalculia, left-right confusion, and finger agnosia ( 6 ). Information was not included about whether she was explicitly examined for finger agnosia, but elements of her presentation suggested a more generalized disruption of body schema (i.e., her representation of the position and configuration of her body in space). Her less prominent impairment in lexical-semantic retrieval evidenced by impaired confrontation naming and category fluency likely localizes to the language network in the left hemisphere. Her impairments in attention and executive functions have less localizing value but would plausibly arise in the context of frontoparietal network dysfunction. At this point, it is unclear whether her impairment in episodic memory mostly reflects encoding and activation versus a rapid rate of forgetting (storage), as occurs in temporolimbic amnesia. Regardless, it does not appear to be the most salient feature of her presentation.

This localization, presenting with insidious onset and gradual progression, is characteristic of a PCA syndrome. If we apply consensus clinical diagnostic criteria proposed by a working group of experts, we find that our patient has many of the representative features of early disturbance of visual functions plus or minus other cognitive functions mediated by the posterior cerebral cortex ( Table 1 ) ( 7 ). Some functions such as limb apraxia also occur in corticobasal syndrome (CBS), a clinical syndrome defined initially in association with corticobasal degeneration (CBD) neuropathology, a 4-repeat tauopathy characterized by achromatic ballooned neurons, neuropil threads, and astrocytic plaques. However, our patient lacks other suggestive features of CBS, including extrapyramidal motor dysfunction (e.g., limb rigidity, bradykinesia, dystonia), myoclonus, and alien limb phenomenon ( Table 1 ) ( 8 ).

| Feature | Posterior cortical atrophy | Corticobasal syndrome |

|---|---|---|

| Cognitive and motor features | Visual-perceptual: space perception deficit, simultanagnosia, object perception deficit, environmental agnosia, alexia, apperceptive prosopagnosia, and homonymous visual field defect | Motor: limb rigidity or akinesia, limb dystonia, and limb myoclonus |

| Visual-motor: constructional dyspraxia, oculomotor apraxia, optic ataxia, and dressing apraxia | ||

| Other: left/right disorientation, acalculia, limb apraxia, agraphia, and finger agnosia | Higher cortical features: limb or orobuccal apraxia, cortical sensory deficit, and alien limb phenomena | |

| Imaging features (MRI, FDG-PET, SPECT) | Predominant occipito-parietal or occipito-temporal atrophy, and hypometabolism or hypoperfusion | Asymmetric perirolandic, posterior frontal, parietal atrophy, and hypometabolism or hypoperfusion |

| Neuropathological associations | AD>CBD, LBD, TDP, JCD | CBD>PSP, AD, TDP |

a Consensus diagnostic criteria for posterior cortical atrophy per Crutch et al. ( 7 ) require at least three cognitive features and relative sparing of anterograde memory, speech-nonvisual language functions, executive functions, behavior, and personality. Diagnostic criteria for probable corticobasal syndrome per Armstrong et al. ( 8 ) require asymmetric presentation of at least two motor features and at least two higher cortical features. AD=Alzheimer’s disease; CBD=corticobasal degeneration; FDG-PET=[ 18 ]F-fluorodexoxyglucose positron emission tomography; JCD=Jakob-Creutzfeldt disease; LBD=Lewy body disease; PSP=progressive supranuclear palsy; SPECT=single-photon emission computed tomography; TDP=TDP–43 proteinopathy.

TABLE 1. Clinical features and neuropathological associations of posterior cortical atrophy and corticobasal syndrome a

In addition to a standard laboratory work-up for cognitive impairment, it is important to determine whether imaging of the brain provides evidence of neurodegeneration in a topographical distribution consistent with the clinical presentation. A first step in most cases would be to obtain an MRI of the brain that includes a high-resolution T 1 -weighted MRI sequence to assess potential atrophy, a T 2 /fluid-attenuated inversion recovery (FLAIR) sequence to assess the burden of vascular disease and rule out less likely etiological considerations (e.g., infection, autoimmune-inflammatory, neoplasm), a diffusion-weighted sequence to rule out subacute infarcts and prion disease (more pertinent to subacute or rapidly progressive cases), and a T 2 *-gradient echo or susceptibility weighted sequence to examine for microhemorrhages and superficial siderosis.

A lumbar puncture would serve two purposes. First, it would allow for the assessment of inflammation that might occur in HE, as approximately 80% of cases have some abnormality of CSF (i.e., elevated protein, lymphocytic pleiocytosis, or oligoclonal bands) ( 9 ). Second, in selected circumstances—particularly in cases with atypical nonamnesic clinical presentations or early-onset dementia in which AD is in the neuropathological differential diagnosis—we frequently pursue AD biomarkers of molecular neuropathology ( 10 , 11 ). This is most frequently accomplished with CSF analysis of amyloid-β-42, total tau, and phosphorylated tau levels. Amyloid positron emission tomography (PET) imaging, and most recently tau PET imaging, represent additional options that are approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration for clinical use. However, insurance often does not cover amyloid PET and currently does not reimburse tau PET imaging. [ 18 ]-F-fluorodeoxyglucose (FDG) PET and perfusion single-photon emission computed tomography imaging may provide indirect evidence for AD neuropathology via a pattern of hypometabolism or hypoperfusion involving the temporoparietal and posterior cingulate regions, though without molecular specificity. Pertinent to this case, a syndromic diagnosis of PCA is most commonly associated with underlying AD neuropathology—that is, plaques containing amyloid-β and neurofibrillary tangles containing tau ( 12 – 15 ).

The patient underwent MRI, demonstrating a minimal burden of T 2 /FLAIR hyperintensities and some degree of bilateral parietal volume loss with a left greater than right predominance ( Figure 2A ). There was relatively minimal medial temporal volume loss. Her basic laboratory work-up, including thyroid function, vitamin B 12 level, and treponemal antibody, was normal. She underwent a lumbar puncture; CSF studies revealed normal cell counts, protein, and glucose levels and low amyloid-β-42 levels at 165.9 pg/ml [>500 pg/ml] and elevated total and phosphorylated tau levels at 1,553 pg/ml [<350 pg/ml] and 200.4 pg/ml [<61 pg/ml], respectively.

FIGURE 2. MRI brain scan of the patient at presentation and 4 years later a

a Arrows denote regions of significant atrophy.

Considering This Additional Data, What Would Be an Appropriate Diagnostic Formulation?

For optimal clarity, we aim to provide a three-tiered approach to diagnosis comprising neurodegenerative clinical syndrome (e.g., primary amnesic, mixed amnesic and dysexecutive, primary progressive aphasia), level of severity (i.e., mild cognitive impairment; mild, moderate or severe dementia), and predicted underlying neuropathology (e.g., AD, Lewy body disease [LBD], frontotemporal lobar degeneration) ( 16 ). This approach avoids problematic conflations that cause confusion, for example when people equate AD with memory loss or dementia, whereas AD most strictly describes the neuropathology of plaques and tangles, regardless of the patient’s clinical symptoms and severity. This framework is important because there is never an exclusive, one-to-one correspondence between syndromic and neuropathological diagnosis. Syndromes arise from neurodegeneration that starts focally and progresses along the anatomical lines of large-scale brain networks that can be defined on the basis of both structural and functional connectivity, a concept detailed in the network degeneration hypothesis ( 17 ). It is important to note that neuropathologies defined on the basis of specific misfolded protein inclusions can target more than one large-scale network, and any given large-scale network can degenerate in association with more than one neuropathology.

The MRI results in this case support a syndromic diagnosis of PCA, with a posteriorly predominant pattern of atrophy. Given the patient’s loss of independent functioning in instrumental activities of daily living (ADLs), including driving and managing her finances, the patient would be characterized as having a dementia (also known as major neurocognitive disorder). The preservation of basic ADLs would suggest that the dementia was of mild severity. The CSF results provide supportive evidence for AD amyloid plaque and tau neurofibrillary tangle (NFT) neuropathology over other pathologies potentially associated with PCA syndrome (i.e., CBD, LBD, TDP-43 proteinopathy, and Jakob-Creutzfeldt disease) ( 13 , 14 ). The patient’s formulation would thus be best summarized as PCA at a level of mild dementia, likely associated with underlying AD neuropathology.

The patient’s symptoms progressed. One year after initial presentation, she had difficulty locating the buttons on her clothing or the food on her plate. Her word-finding difficulties worsened. Others observed stiffness of her right arm, a new symptom that was not present initially. She also had decreased ability using her right hand to hold everyday objects such as a comb, a brush, or a pen. On exam, she was noted to have rigidity of her right arm, impaired dexterity with her right hand for fine motor tasks, and a symmetrical tremor of the arms, apparent when holding objects or reaching. Her right hand would also intermittently assume a flexed, dystonic posture and would sometime move in complex ways without her having a sense of volitional control.

Four to 5 years after initial presentation, her functional status declined to the point where she was unable to feed, bathe, or dress herself. She was unable to follow simple instructions. She developed neuropsychiatric symptoms, including compulsive behaviors, anxiety, and apathy. Her right-sided motor symptoms progressed; she spent much of the time with her right arm flexed in abnormal postures or moving abnormally. She developed myoclonus of both arms. Her speech became slurred and monosyllabic. Her gait became less steady. She underwent a second MRI of the brain, demonstrating progressive bilateral atrophy involving the frontal and occipital lobes in addition to the parietal lobes and with more left > right asymmetry than was previously apparent ( Figure 2B ). Over time, she exhibited increasing weight loss. She was enrolled in hospice and ultimately passed away 8 years from the onset of symptoms.

Does Information About the Longitudinal Course of Her Illness Alter the Formulation About the Most Likely Underlying Neuropathological Process?

This patient developed clinical features characteristic of corticobasal syndrome over the longitudinal course of her disease. With time, it became apparent that she had lost volitional control over her right arm (characteristic of an alien limb phenomenon), and she developed signs more suggestive of basal ganglionic involvement (i.e., limb rigidity and possible dystonia). This presentation highlights the frequent overlap between neurodegenerative clinical syndromes; any given person may have elements of more than one syndrome, especially later in the course of a disease. In many instances, symptomatic features that are less prominent at presentation but evolve and progress can provide clues regarding the underlying neuropathological diagnosis. For example, a patient with primary progressive apraxia of speech or nonfluent-agrammatic primary progressive aphasia could develop the motor features of a progressive supranuclear palsy (PSP) clinical syndrome (e.g., supranuclear gaze impairment, axial rigidity, postural instability), which would suggest underlying PSP neuropathology (4-repeat tauopathy characterized by globose neurofibrillary tangles, tufted astrocytes, and oligodendroglial coiled bodies).

If CSF biomarker data were not suggestive of AD, the secondary elements of CBS would substantially increase the likelihood of underlying CBD neuropathology presenting with a PCA syndrome and evolving to a mixed PCA-CBS. But the CSF amyloid and tau levels are unambiguously suggestive of AD (i.e., very low amyloid-β-42 and very high p-tau levels), the neuropathology of which accounts for not only a vast majority of PCA presentations but also roughly a quarter of cases presenting with CBS ( 18 , 19 ). Thus, underlying AD appears most likely.

NEUROPATHOLOGY

On gross examination, the brain weighed 1,150 g, slightly less than the lower end of normal at 1,200 g. External examination demonstrated mild cortical atrophy with widening of the sulci, relatively symmetrical and uniform throughout the brain ( Figure 3A ). There was no evidence of atrophy of the brainstem or cerebellum. On cut sections, the hippocampus was mildly atrophic. The substantia nigra in the midbrain was intact, showing appropriate dark pigmentation as would be seen in a relatively normal brain. The remainder of the gross examination was unremarkable.

FIGURE 3. Mild cortical atrophy with posterior predominance and neurofibrillary tangles, granulovacuolar degeneration, and a Hirano body a

a Panel A shows the gross view of the brain, demonstrating mild cortical atrophy with posterior predominance (arrow). Panel B shows the hematoxylin and eosin of the hippocampus at high power, demonstrating neurofibrillary tangles, granulovacuolar degeneration, and a Hirano body.

Histological examination confirmed that the neurons in the substantia nigra were appropriately pigmented, with occasional extraneuronal neuromelanin and moderate neuronal loss. In the nucleus basalis of Meynert, NFTs were apparent on hematoxylin and eosin staining as dense fibrillar eosinophilic structures in the neuronal cytoplasm, confirmed by tau immunohistochemistry (IHC; Figure 4 ). Low-power examination of the hippocampus revealed neuronal loss in the subiculum and in Ammon’s horn, most pronounced in the cornu ammonis 1 (CA1) subfield, with a relatively intact neuronal population in the dentate gyrus. Higher power examination with hematoxylin and eosin demonstrated numerous NFTs, neurons exhibiting granulovacuolar degeneration, and Hirano bodies ( Figure 3B ). Tau IHC confirmed numerous NFTs in the CA1 region and the subiculum. Amyloid-β IHC demonstrated occasional amyloid plaques in this region, less abundant than tau pathology. An α-synuclein stain revealed scattered Lewy bodies in the hippocampus and in the amygdala.

FIGURE 4. Tau immunohistochemistry demonstrating neurofibrillary tangles (staining brown) in the nucleus basalis of Meynert, in the hippocampus, and in the cerebral cortex of the frontal, temporal, parietal, and occipital lobes

In the neocortex, tau IHC highlighted the extent of the NFTs, which were very prominent in all of the lobes from which sections were taken: frontal, temporal, parietal and occipital. Numerous plaques on amyloid-β stain were likewise present in all cortical regions examined. The tau pathology was confined to the gray matter, sparing white matter. There were no ballooned neurons and no astrocytic plaques—two findings one would expect to see in CBD ( Table 2 ).

| Feature | Case of PCA/CBS due to AD | Exemplar case of CBD |

|---|---|---|

| Macroscopic findings | Cortical atrophy: symmetric, mild | Cortical atrophy: often asymmetric, predominantly affecting perirolandic cortex |

| Substantia nigra: appropriately pigmented | Substantia nigra: severely depigmented | |

| Microscopic findings | Tau neurofibrillary tangles and beta-amyloid plaques | Primary tauopathy |

| No tau pathology in white matter | Tau pathology involves white matter | |

| Hirano bodies, granulovacuolar degeneration | Ballooned neurons, astrocytic plaques, and oligodendroglial coiled bodies | |

| (Lewy bodies, limbic) |

a AD=Alzheimer’s disease; CBD=corticobasal degeneration; CBS=corticobasal syndrome; PCA=posterior cortical atrophy.

TABLE 2. Neuropathological features of this case compared with a case of corticobasal degeneration a

The case was designated by the neuropathology division as Alzheimer’s-type pathology, Braak stage V–VI (of VI), due to the widespread neocortical tau pathology, with LBD primarily in the limbic areas.

Our patient had AD neuropathology presenting atypically with a young age at onset (52 years old) and a predominantly visual-spatial and corticobasal syndrome as opposed to prominent amnesia. Syndromic diversity is a well-recognized phenomenon in AD. Nonamnesic presentations include not only PCA and CBS but also the logopenic variant of primary progressive aphasia and a behavioral-dysexecutive syndrome ( 20 ). Converging lines of evidence link the topographical distribution of NFTs with syndromic presentations and the pattern of hypometabolism and cortical atrophy. Neuropathological case reports and case series suggest that atypical AD syndromes arise in the setting of higher than normal densities of NFTs in networks subserving the functions compromised, including visual association areas in PCA-AD ( 21 ), the language network in PPA-AD ( 22 ), and frontal regions in behavioral-dysexecutive AD ( 23 ). In a large sample of close to 900 cases of pathologically diagnosed AD employing quantitative assessment of NFT density and distribution in selected neocortical and hippocampal regions, 25% of cases did not conform to a typical distribution of NFTs characterized in the Braak staging scheme ( 24 ). A subset of cases classified as hippocampal sparing with higher density of NFTs in the neocortex and lower density of NFTs in the hippocampus had a younger mean age at onset, higher frequency of atypical (nonamnesic) presentations, and more rapid rate of longitudinal decline than subsets defined as typical or limbic-predominant.

Tau PET, which detects the spatial distribution of fibrillary tau present in NFTs, has corroborated postmortem work in demonstrating distinct patterns of tracer uptake in different subtypes of AD defined by clinical symptoms and topographical distributions of atrophy ( 25 – 28 ). Amyloid PET, which detects the spatial distribution of fibrillar amyloid- β found in amyloid plaques, does not distinguish between typical and atypical AD ( 29 , 30 ). In a longitudinal study of 32 patients at early symptomatic stages of AD, the baseline topography of tau PET signal predicted subsequent atrophy on MRI at the single patient level, independent of baseline cortical thickness ( 31 ). This correlation was strongest in early-onset AD patients, who also tended to have higher tau signal and more rapid progression of atrophy than late-onset AD patients.

Differential vulnerability of selected large-scale brain networks in AD and in neurodegenerative disease more broadly remains poorly understood. There is evidence to support multiple mechanisms that are not mutually exclusive, including metabolic stress to key network nodes, trophic failure, transneuronal spread of pathological proteins (i.e., prion-like mechanisms), and shared vulnerability within network regions based on genetic or developmental factors ( 32 ). In the case of AD, cortical hub regions with high intrinsic functional connectivity to other regions across the brain appear to have high metabolic rates across the lifespan and to be foci of convergence of amyloid-β and tau accumulation ( 33 , 34 ). Tau NFT pathology appears to spread temporally along connected networks within the brain ( 35 ). Patients with primary progressive aphasia are more likely to have a personal or family history of developmental language-based learning disability ( 36 ), and patients with PCA are more likely to have a personal history of mathematical or visuospatial learning disability ( 37 ).

This case highlights the symptomatic heterogeneity in AD and the value of a three-tiered approach to diagnostic formulation in neurodegenerative presentations. It is important to remember that not all AD presents with amnesia and that early-onset AD tends to be more atypical and to progress more rapidly than late-onset AD. Multiple lines of evidence support a relationship between the burden and topographical distribution of tau NFT neuropathology and clinical symptomatology in AD, instantiating network-based neurodegeneration via mechanisms under ongoing investigation.

The authors report no financial relationships with commercial interests.

Supported by NIH grants K08 AG065502 (to Dr. Miller) and T32 HL007627 (to Dr. Miller).

The authors have confirmed that details of the case have been disguised to protect patient privacy.

1 Balasa M, Gelpi E, Antonell A, et al. : Clinical features and APOE genotype of pathologically proven early-onset Alzheimer disease . Neurology 2011 ; 76:1720–1725 Crossref , Medline , Google Scholar

2 Mercy L, Hodges JR, Dawson K, et al. : Incidence of early-onset dementias in Cambridgeshire, United Kingdom . Neurology 2008 ; 71:1496–1499 Crossref , Medline , Google Scholar

3 Kothbauer-Margreiter I, Sturzenegger M, Komor J, et al. : Encephalopathy associated with Hashimoto thyroiditis: diagnosis and treatment . J Neurol 1996 ; 243:585–593 Crossref , Medline , Google Scholar

4 Nasreddine ZS, Phillips NA, Bédirian V, et al. : The Montreal Cognitive Assessment, MoCA: a brief screening tool for mild cognitive impairment . J Am Geriatr Soc 2005 ; 53:695–699 Crossref , Medline , Google Scholar

5 Rizzo M, Vecera SP : Psychoanatomical substrates of Bálint’s syndrome . J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 2002 ; 72:162–178 Crossref , Medline , Google Scholar

6 Rusconi E : Gerstmann syndrome: historic and current perspectives . Handb Clin Neurol 2018 ; 151:395–411 Crossref , Medline , Google Scholar

7 Crutch SJ, Schott JM, Rabinovici GD, et al. : Consensus classification of posterior cortical atrophy . Alzheimers Dement 2017 ; 13:870–884 Crossref , Medline , Google Scholar

8 Armstrong MJ, Litvan I, Lang AE, et al. : Criteria for the diagnosis of corticobasal degeneration . Neurology 2013 ; 80:496–503 Crossref , Medline , Google Scholar

9 Marshall GA, Doyle JJ : Long-term treatment of Hashimoto’s encephalopathy . J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci 2006 ; 18:14–20 Link , Google Scholar

10 Johnson KA, Minoshima S, Bohnen NI, et al. : Appropriate use criteria for amyloid PET: a report of the Amyloid Imaging Task Force, the Society of Nuclear Medicine and Molecular Imaging, and the Alzheimer’s Association . Alzheimers Dement 2013 ; 9:e-1–e-16 Crossref , Medline , Google Scholar

11 Shaw LM, Arias J, Blennow K, et al. : Appropriate use criteria for lumbar puncture and cerebrospinal fluid testing in the diagnosis of Alzheimer’s disease . Alzheimers Dement 2018 ; 14:1505–1521 Crossref , Medline , Google Scholar

12 Alladi S, Xuereb J, Bak T, et al. : Focal cortical presentations of Alzheimer’s disease . Brain 2007 ; 130:2636–2645 Crossref , Medline , Google Scholar

13 Renner JA, Burns JM, Hou CE, et al. : Progressive posterior cortical dysfunction: a clinicopathologic series . Neurology 2004 ; 63:1175–1180 Crossref , Medline , Google Scholar

14 Tang-Wai DF, Graff-Radford NR, Boeve BF, et al. : Clinical, genetic, and neuropathologic characteristics of posterior cortical atrophy . Neurology 2004 ; 63:1168–1174 Crossref , Medline , Google Scholar

15 Victoroff J, Ross GW, Benson DF, et al. : Posterior cortical atrophy: neuropathologic correlations . Arch Neurol 1994 ; 51:269–274 Crossref , Medline , Google Scholar

16 Dickerson BC, McGinnis SM, Xia C, et al. : Approach to atypical Alzheimer’s disease and case studies of the major subtypes . CNS Spectr 2017 ; 22:439–449 Crossref , Medline , Google Scholar

17 Seeley WW, Crawford RK, Zhou J, et al. : Neurodegenerative diseases target large-scale human brain networks . Neuron 2009 ; 62:42–52 Crossref , Medline , Google Scholar

18 Lee SE, Rabinovici GD, Mayo MC, et al. : Clinicopathological correlations in corticobasal degeneration . Ann Neurol 2011 ; 70:327–340 Crossref , Medline , Google Scholar

19 Whitwell JL, Jack CR Jr, Boeve BF, et al. : Imaging correlates of pathology in corticobasal syndrome . Neurology 2010 ; 75:1879–1887 Crossref , Medline , Google Scholar

20 Warren JD, Fletcher PD, Golden HL : The paradox of syndromic diversity in Alzheimer disease . Nat Rev Neurol 2012 ; 8:451–464 Crossref , Medline , Google Scholar

21 Hof PR, Archin N, Osmand AP, et al. : Posterior cortical atrophy in Alzheimer’s disease: analysis of a new case and re-evaluation of a historical report . Acta Neuropathol 1993 ; 86:215–223 Crossref , Medline , Google Scholar

22 Mesulam MM, Weintraub S, Rogalski EJ, et al. : Asymmetry and heterogeneity of Alzheimer’s and frontotemporal pathology in primary progressive aphasia . Brain 2014 ; 137:1176–1192 Crossref , Medline , Google Scholar

23 Blennerhassett R, Lillo P, Halliday GM, et al. : Distribution of pathology in frontal variant Alzheimer’s disease . J Alzheimers Dis 2014 ; 39:63–70 Crossref , Medline , Google Scholar

24 Murray ME, Graff-Radford NR, Ross OA, et al. : Neuropathologically defined subtypes of Alzheimer’s disease with distinct clinical characteristics: a retrospective study . Lancet Neurol 2011 ; 10:785–796 Crossref , Medline , Google Scholar

25 Ossenkoppele R, Lyoo CH, Sudre CH, et al. : Distinct tau PET patterns in atrophy-defined subtypes of Alzheimer’s disease . Alzheimers Dement 2020 ; 16:335–344 Crossref , Medline , Google Scholar

26 Phillips JS, Das SR, McMillan CT, et al. : Tau PET imaging predicts cognition in atypical variants of Alzheimer’s disease . Hum Brain Mapp 2018 ; 39:691–708 Crossref , Medline , Google Scholar

27 Tetzloff KA, Graff-Radford J, Martin PR, et al. : Regional distribution, asymmetry, and clinical correlates of tau uptake on [18F]AV-1451 PET in atypical Alzheimer’s disease . J Alzheimers Dis 2018 ; 62:1713–1724 Crossref , Medline , Google Scholar

28 Xia C, Makaretz SJ, Caso C, et al. : Association of in vivo [18F]AV-1451 tau PET imaging results with cortical atrophy and symptoms in typical and atypical Alzheimer disease . JAMA Neurol 2017 ; 74:427–436 Crossref , Medline , Google Scholar

29 Formaglio M, Costes N, Seguin J, et al. : In vivo demonstration of amyloid burden in posterior cortical atrophy: a case series with PET and CSF findings . J Neurol 2011 ; 258:1841–1851 Crossref , Medline , Google Scholar

30 Lehmann M, Ghosh PM, Madison C, et al. : Diverging patterns of amyloid deposition and hypometabolism in clinical variants of probable Alzheimer’s disease . Brain 2013 ; 136:844–858 Crossref , Medline , Google Scholar

31 La Joie R, Visani AV, Baker SL, et al. : Prospective longitudinal atrophy in Alzheimer’s disease correlates with the intensity and topography of baseline tau-PET . Sci Transl Med 2020 ; 12:12 Crossref , Google Scholar

32 Zhou J, Gennatas ED, Kramer JH, et al. : Predicting regional neurodegeneration from the healthy brain functional connectome . Neuron 2012 ; 73:1216–1227 Crossref , Medline , Google Scholar

33 Buckner RL, Sepulcre J, Talukdar T, et al. : Cortical hubs revealed by intrinsic functional connectivity: mapping, assessment of stability, and relation to Alzheimer’s disease . J Neurosci 2009 ; 29:1860–1873 Crossref , Medline , Google Scholar

34 Hoenig MC, Bischof GN, Seemiller J, et al. : Networks of tau distribution in Alzheimer’s disease . Brain 2018 ; 141:568–581 Crossref , Medline , Google Scholar

35 Liu L, Drouet V, Wu JW, et al. : Trans-synaptic spread of tau pathology in vivo . PLoS One 2012 ; 7:e31302 Crossref , Medline , Google Scholar

36 Rogalski E, Johnson N, Weintraub S, et al. : Increased frequency of learning disability in patients with primary progressive aphasia and their first-degree relatives . Arch Neurol 2008 ; 65:244–248 Crossref , Medline , Google Scholar

37 Miller ZA, Rosenberg L, Santos-Santos MA, et al. : Prevalence of mathematical and visuospatial learning disabilities in patients with posterior cortical atrophy . JAMA Neurol 2018 ; 75:728–737 Crossref , Medline , Google Scholar

- Jeffrey Maneval , M.D. ,

- Kirk R. Daffner , M.D. ,

- Scott M. McGinnis , M.D.

- Seth A. Gale , M.A., M.D. ,

- C. Alan Anderson , M.D. ,

- David B. Arciniegas , M.D.

- Posterior Cortical Atrophy

- Corticobasal Syndrome

- Atypical Alzheimer Disease

- Network Degeneration

- Subscribe to journal Subscribe

- Get new issue alerts Get alerts

Secondary Logo

Journal logo.

Colleague's E-mail is Invalid

Your message has been successfully sent to your colleague.

Save my selection

Case Report of a 63-Year-Old Patient With Alzheimer Disease and a Novel Presenilin 2 Mutation

Wells, Jennie L. BSc, MSc, MD, FACP, FRCPC, CCRP *,† ; Pasternak, Stephen H. MD, PhD, FRCPC †,‡,§

* Department of Medicine, Division of Geriatric Medicine, Schulich School of Medicine and Dentistry, Western University

† St. Joseph’s Health Care London—Parkwood Institute

‡ Molecular Medicine Research Group, Robarts Research Institute

§ Department of Clinical Neurological Sciences, Schulich School of Medicine and Dentistry, University of Western Ontario, London, ON, Canada

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Reprints: Jennie L. Wells, BSc, MSc, MD, FACP, FRCPC, CCRP, Department of Medicine, Division of Geriatric Medicine, St. Joseph’s Health Care London—Parkwood Institute, Room A2-129, P.O. Box 5777 STN B, London, ON, Canada N6A 4V2 (e-mail: [email protected] ).

This is an open access article distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution License 4.0 (CCBY), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited. http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

Early onset Alzheimer disease (EOAD) is a neurodegenerative dementing disorder that is relatively rare (<1% of all Alzheimer cases). Various genetic mutations of the presenilin 1 ( PSEN1 ) and presenilin 2 ( PSEN2 ) as well as the amyloid precursor protein (APP) gene have been implicated. Mutations of PSEN1 and PSEN2 alter γ-secretase enzyme that cleaves APP resulting in increase in the relative amount of the more amyloidogenic Aβ42 that is produced. 1

PSEN2 has been less studied than PSEN1 and fewer mutations are known. Here, we report a case of a 63-year-old woman (at the time of death) with the clinical history consistent with Alzheimer D, an autopsy with brain histopathology supporting Alzheimer disease (AD), congophylic angiopathy, and Lewy Body pathology, and whose medical genetic testing reveals a novel PSEN2 mutation of adenosine replacing cytosine at codon 222, nucleotide position 665 (lysine replacing threonine) that has never been previously reported. This suggests that genetic testing may be useful in older patients with mixed pathology.

CASE REPORT

The patient was referred to our specialty memory clinic at the age of 58 with a 2-year history of repetitiveness, memory loss, and executive function loss. Magnetic resonance imaging scan at age 58 revealed mild generalized cortical atrophy. She is white with 2 years of postsecondary education. Retirement at age 48 from employment as a manager in telecommunications company was because family finances allowed and not because of cognitive challenges with work. Progressive cognitive decline was evident by the report of deficits in instrumental activities of daily living performance over the past 9 months before her initial consultation in the memory clinic. Word finding and literacy skills were noted to have deteriorated in the preceding 6 months according to her spouse. Examples of functional losses were being slower in processing and carrying out instructions, not knowing how to turn off the stove, and becoming unable to assist in boat docking which was the couple’s pastime. She stopped driving a motor vehicle about 6 months before her memory clinic consultation. Her past medical history was relevant for hypercholesterolemia and vitamin D deficiency. She had no surgical history. She had no history of smoking, alcohol, or other drug misuse. Laboratory screening was normal. There was no first-degree family history of presenile dementia. Neurocognitive assessment at the first clinic visit revealed a Mini Mental State Examination (MMSE) score of 14/30; poor verbal fluency (patient was able to produce only 5 animal names and 1 F-word in 1 min) as well as poor visuospatial and executive skills ( Fig. 1 ). She had fluent speech without semantic deficits. Her neurological examination was pertinent for normal muscle tone and power, mild ideomotor apraxia on performing commands for motor tasks with no suggestion of cerebellar dysfunction, normal gait, no frontal release signs. Her speech was fluent with obvious word finding difficulties but with no phonemic or semantic paraphrasic errors. Her general physical examination was unremarkable without evidence of presenile cataracts. She had normal hearing. There was no evidence of depression or psychotic symptoms.

At the time of the initial assessment, her mother was deceased at age 79 after a hip fracture with a history long-term smoking and idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Her family believes that there is possible German and Danish descent on her father’s side. Her father was alive and well at age 80 at the time of her presentation with a history coronary artery disease. He is still alive and well with no functional or cognitive concerns at age 87 at the time of writing this report. Her paternal grandfather died at approximately age 33 of appendicitis with her paternal grandmother living with mild memory loss but without known dementia or motor symptoms until age 76, dying after complications of abdominal surgery. Her paternal uncle was diagnosed with Parkinson disease in his 40s and died at age 58. Her maternal grandmother was reported to be functionally intact, but mildly forgetful at the time of her death at age 89. The maternal grandfather had multiple myocardial infarctions and died of congestive heart failure at age 75. She was the eldest of 4 siblings (ages 44 to 56 at the time of presentation); none had cognitive problems. She had no children.

Because of her young age and clinical presentation with no personality changes, language or motor change, nor fluctuations, EOAD was the most likely clinical diagnosis. As visuospatial challenges were marked at her first visit and poor depth perception developing over time, posterior cortical variant of AD was also on the differential as was atypical presentation of frontotemporal dementias. Without fluctuations, Parkinsonism, falls, hallucinations, or altered attention, Lewy Body dementia was deemed unlikely. After treatment with a cholinesterase inhibitor, her MMSE improved to 18/30, tested 15 months later with stability in function. Verbal fluency improved marginally with 7 animals and 3 F-words. After an additional 18 months, function and cognition declined (MMSE=13/30) so memantine was added. The stabilizing response to the cholinesterase inhibitor added some degree of confidence to the EOAD diagnosis. In the subsequent 4 years, she continued to decline in cognition and function such that admission to a care facility was required with associated total dependence for basic activities of daily living. Noted by family before transfer to the long-term care facility were episodic possible hallucinations. It was challenging to know if what was described was misinterpretation of objects in view or a true hallucination. During this time, she developed muscle rigidity, motor apraxias, worsening perceptual, and language skills and became dependent for all activities of daily livings. At the fourth year of treatment, occasional myoclonus was noted. She was a 1 person assist for walking because of increased risk of falls. After 1 year in the care home, she was admitted to the acute care hospital in respiratory distress. CT brain imaging during that admission revealed marked generalized global cortical atrophy and marked hippocampal atrophy ( Fig. 2 ). She died at age 63 of pneumonia. An autopsy was performed confirming the cause of death and her diagnosis of AD, showing numerous plaques and tangles with congophilic amyloid angiopathy. In addition, there was prominent Lewy Body pathology noted in the amygdala.

Three years before her death informed consent was obtained from the patient and family to perform medical genetic testing for EOAD. The standard panel offered by the laboratory was selected and included PSEN1 , PSEN2 , APP, and apoE analysis. Tests related to genes related to frontotemporal dementia were not requested based on clinical presentation and clinical judgement. This was carried out with blood samples and not cerebrospinal fluid because of patient, family, and health provider preference. The results revealed a novel PSEN2 mutation with an adenosine replacing cytosine at nucleotide position 665, codon 222 [amino acid substation of lysine for threonine at position 221 (L221T)]. This PSEN2 variant was noted to be novel to the laboratory’s database, noting that models predicted that this variant is likely pathogenic. The other notable potentially significant genetic finding is the apoliprotein E genotype was Є 3/4 .

β-amyloid (Aβ) is a 38 to 43 amino acid peptide that aggregates in AD forming toxic soluble oligomers and insoluble amyloid fibrils which form plaques. Aβ is produced by the cleavage of the APP first by an α-secretase, which produces a 99 amino acid C-terminal fragment of APP, and then at a variable “gamma” position by the γ-secretase which releases the Aβ peptide itself. It is this second γ-cleavage which determines the length and therefore the pathogenicity of the Aβ peptides, with 42 amino acid form of Aβ having a high propensity to aggregate and being more toxic.

The γ-secretase is composed of at least 4 proteins, mAph1, PEN2, nicastrin, and presenilin . Of these proteins, presenilin has 2 distinct isoforms ( PSEN1 and PSEN2 ), which contain the catalytic site responsible for the γ-cleavage. PSEN mutants are the most common genetic cause of AD with 247 mutations described in PSEN1 and 48 mutations described in PSEN2 (Alzgene database; www.alzforum.org/mutations ). PSEN2 mutations are reported to be associated with AD of both early onset and variable age onset as well as with other neurodegenerative disorders such as Lewy Body dementia, frontotemporal dementia, Parkinson dementia, and posterior cortical atrophy. 2–4 In addition, PSEN2 has associations with breast cancer and dilated cardiomyopathy. 3

PSEN2 mutants are believed to alter the γ-secretase cleavage of APP increasing the relative amount of the more toxic Aβ42. The mean age of onset in PSEN2 mutations, is 55.3 years but the range of onset is surprisingly wide, spanning 39 to 83 years. Over 52% of cases are over 60 years. All cases have extensive amyloid plaque and neurofibrillary tangles, and many have extensive alpha-synuclein pathology as well. 5

In considering the novelty of this reported PSEN2 mutation, a literature search of Medline, the Alzgene genetic database of PSEN2 and the Alzheimer Disease and Frontotemporal Dementia Mutation Databases (AD&FTMD) were completed ( www.molgen.vib-ua.be/ADMutations ). The mutation presented here (L221T) has never been described before.

Although this mutation has not been described, we believe that it is highly likely to be pathogenic. This mutation is not conservative, as it replaces a lysine residue which is positively charged with threonine which is an uncharged polar, hydrophilic amino acid. The mutation itself occurs in a small cytoplasmic loop between transmembrane domain 4 and 5, which is conserved in the PSEN1 gene, and in PSEN2 is highly conserved across vertebrates, including birds and zebrafish all the way to Caenorhabditis elegans , but differs in Drosophila melanogaster (fruit fly) ( Fig. 3 ). We examined this mutation using several computer algorithms which examine the likelihood that a mutation will not be tolerated. Both SIFT ( http://sift.bii.a-star.edu.sg ) and PolyPhen-2.2.2 (HumVar) ( www.bork.embl-heidelberg.de/PolyPhen ) predicts that this variant is pathogenic. Interestingly, it is noted that PSEN1 mutations after amino acid 200 develop amyloid angiopathy. 5,7

This patient also had an additional risk factor for AD, being a heterozygote for the apoЄ4 allele. Among other mechanisms, its presence reduces clearance of Aβ42 from the brain and increases glial activation. 8 Although the apoЄ4 allele is known to lower the age of onset of dementia in late onset AD, it has not been clearly shown to influence age of onset of EOAD in a limited case series. 9 It should be noted that heterozygote state may have contributed to an acceleration of her course given the known metabolism of apoЄ4 and its association with accelerated cerebral amyloid and known reduction in age of onset. 10

Given that there is no definite family history of autosomal dominant early onset dementia, it is likely that her PSEN2 mutation was a new random event. With the unusually wide age of onset it is conceivable that one of her parents could still harbor this PSEN2 mutation. The patient’s father, however, is currently 87 and living independently at the time of writing this manuscript, making him highly unlikely to be an EOAD carrier. Nonpaternity is an alternate explanation for the lack of known first-degree relative with EOAD; however, this is deemed unlikely by the family member who provided the supplemental history. Her mother died at age 79, so she could conceivably carry our mutation but we do not have access to this genetic material. Without extensive testing of many family members it would be impossible to speculate about autosomal recessive form of gene expression. In addition, the genetic testing requested was limited to presenilins , APP, and apoE mutations. Danish heritage may add Familial Danish dementia as a remote consideration; however, Familial Danish dementia has a much different clinical presentation with long tract signs, cerebellar dysfunction, onset in the fourth decade as well as hearing loss and cataracts at a young age. 11 This disease has high autosomal dominant penetration which also makes it less likely in the patient’s context. This specific gene (chromosome 13) was not tested. The autopsy findings do not support this possibility. There are reports of Familial AD pedigrees in Germany, including a Volga pedigree with PSEN141I mutation in exon 5, but this is clearly separate from our mutation which is in exon 7. Our mutation was also not observed in a recent cohort of 23 German individuals with EOAD which underwent whole genome sequencing, but did find 2 carriers of the Volga pedigree. It is also possible that both the PSEN2 mutation and the ApoE genotype contributed to her disease and early onset presentation. This case illustrates the multiple pathology types which occur in individuals bearing PSEN2 mutations, and highlights the later ages in which patients can present with PSEN2 mutations. 12

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

The authors acknowledge Gwyneth Duhn, RN, BNSc, MSc, for her support of this paper.

- Cited Here |

- View Full Text | PubMed | CrossRef |

- Google Scholar

- PubMed | CrossRef |

Alzheimer disease; presenilin ; mutation

- + Favorites

- View in Gallery

Readers Of this Article Also Read

Frontotemporal dementia knowledge scale: development and preliminary..., epileptic seizures in alzheimer disease: a review.

- Open access

- Published: 10 April 2023

Views of people living with dementia and their carers on their present and future: a qualitative study

- Danielle Nimmons 1 ,

- Jill Manthorpe 2 ,

- Emily West 3 ,

- Greta Rait 1 ,

- Elizabeth L Sampson 3 , 4 ,

- Steve Iliffe 1 &

- Nathan Davies 1 , 3

BMC Palliative Care volume 22 , Article number: 38 ( 2023 ) Cite this article

3223 Accesses

6 Citations

42 Altmetric

Metrics details

Dementia leads to multiple issues including difficulty in communication and increased need for care and support. Discussions about the future often happen late or never, partly due to reluctance or fear. In a sample of people living with dementia and carers, we explored their views and perceptions of living with the condition and their future.

Semi-structured interviews were conducted in 2018-19 with 11 people living with dementia and six family members in England. Interviews were audio-recorded, transcribed and analysed using reflexive thematic analysis.

Findings were explored critically within the theory of social death and three themes were developed: (1) loss of physical and cognitive functions, (2) loss of social identity, and (3) social connectedness. Most participants living with dementia and carers wanted to discuss the present, rather than the future, believing a healthy lifestyle would prevent the condition from worsening. Those with dementia wanted to maintain control of their lives and demonstrated this by illustrating their independence. Care homes were often associated with death and loss of social identity. Participants used a range of metaphors to describe their dementia and the impact on their relationships and social networks.

Focusing on maintaining social identity and connectedness as part of living well with dementia may assist professionals in undertaking advance care planning discussions.

Peer Review reports

Dementia is the most common neurodegenerative condition worldwide and is estimated to affect around 47 million people [ 1 ]. In the early stages people living with dementia often experience early memory loss but as the condition progresses communication becomes more difficult, behaviour can change, walking becomes difficult and there is an increasing need for assistance with activities of daily living [ 1 ]. In the media and general society, the condition is often associated with negative images [ 2 ] and it is not uncommon for people to experience and be affected by stigma [ 3 ]. A UK survey found 62% of adults were worried about dementia in some way, and felt a diagnosis would mean their ‘life was over’ [ 4 ].

Many professionals see it as important that people living with dementia plan for the future through a process of advance care planning (ACP), particularly as the condition is unpredictable, with people experiencing a staggered decline with bouts of good and bad health, sometimes resulting in hospital admission [ 5 ]. In the UK there is a general professional consensus that opportunities for discussions about the future should be offered regularly (including around the time of diagnosis) but must be tailored to the individual, depending on their view of the future and readiness to discuss it [ 6 ]. This respects that people may not want to discuss the future due to fear, worry or denial [ 7 ] or other reasons, even though it means conversations about choices and preferences may not be possible, leaving it to family and/or professionals to make decisions.

Discussions may also not take place due to organisational challenges, such as a lack of access to specialist or primary care [ 8 ], professional inexperience or lack of confidence [ 9 ]. Although there is professional advice that ACP discussions should occur regularly, this does not always happen due to inequity in care provision [ 10 ]. Previous reviews of the literature have recommended that professionals hold several ACP discussions with people living with dementia over a longer period and involve family and significant others as early as possible, including when it is more difficult for the person living with dementia to communicate [ 11 ]. Despite challenges, it is important to discuss the future as ACP in dementia can lead to an increased number of advance directives and greater concordance between the person with dementia’s preferences and relatives’ decisions on their behalf [ 12 , 13 ].

How people living with dementia view their futures is likely to vary. Some studies show negative views, for example, people may experience symptoms that leave them feeling unsure of themselves as the world becomes more unfamiliar [ 14 ]. While other studies have a more positive outlook, where people are not passive in how they experience the condition and use various strategies to cope with its challenges [ 15 ]. A recent Dutch study found those with early-stage dementia were willing to talk about their future, if given the opportunity [ 6 ]. They also felt it was important to live a meaningful life and maintain belongingness until end of life [ 6 ]. In recent years there has been an emphasis on framing the condition more positively and on people ‘living well’ with dementia [ 16 ], despite negatively held assumptions by the public [ 15 ]. Considering the varied views expressed in previous studies, the aim of our study was to explore, with an end-of-life focus, the views and perceptions of dementia and the future of people living with dementia in England.

Qualitative study using semi-structured interviews, analysed using reflexive thematic analysis [ 17 ].

Recruitment procedure

People living with dementia were purposively sampled from a range of sources including NHS memory services, general practice, carer or dementia organisations, and the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Join Dementia Research website. Potential participants from clinical services were identified and invited by a member of the clinical team. Interested and eligible participants either contacted the research team directly or with permission their details were passed to the research team. Recruitment invitations via non-clinical settings were sent by members of the research team or host organisation via email.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

People living with dementia were eligible if they met the following criteria:

Clinical diagnosis of any type of dementia as categorised in ICD-10.

Capacity to provide written informed consent to take part in an interview.

Able to read and speak English.

Clinical teams checked eligibility, which included assessing if they felt potential participants had capacity. Experienced researchers trained in capacity assessment also assessed capacity when taking consent, at the start of the interviews and throughout. Those unable to provide informed written consent were not included. Family members were not recruited separately, only if the person with dementia wanted to be interviewed with them. Family members had to be adults, and able to consent to take part in an interview and to read and speak English.

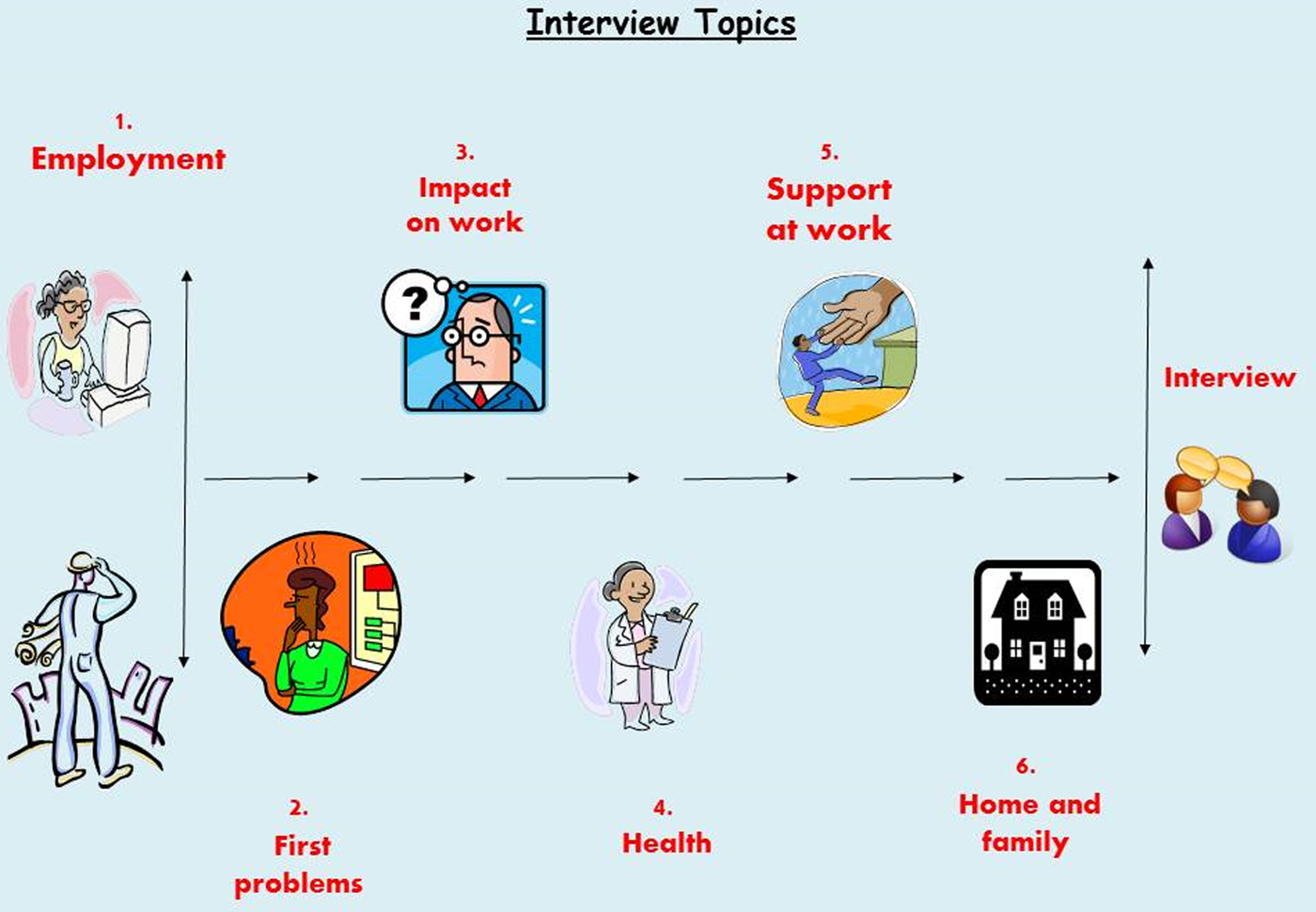

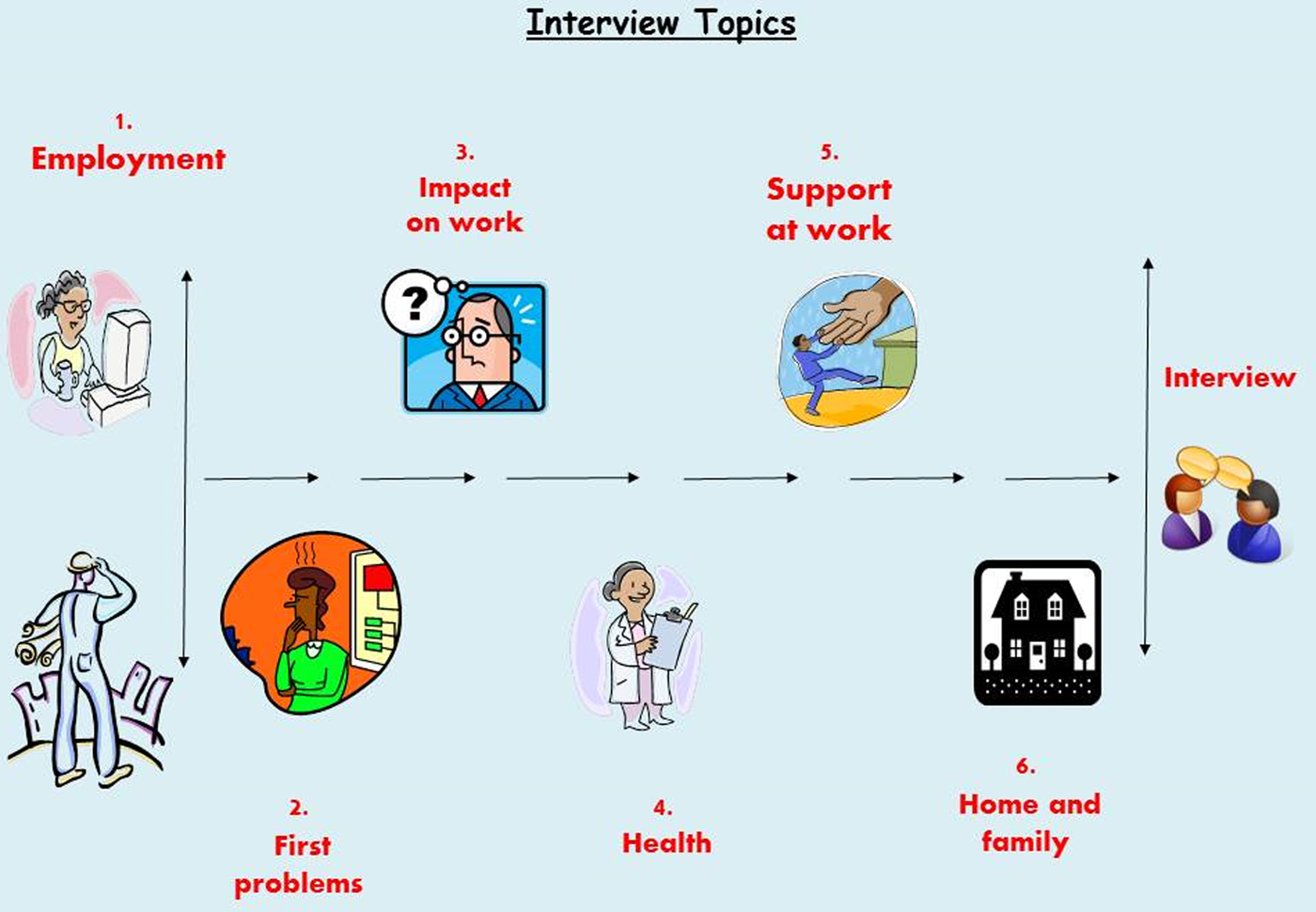

Data collection

Interviews were conducted by either a female research assistant or a male senior researcher, both of whom had training in qualitative research methods. Interviews were guided by an interview schedule which was informed by relevant literature [ 18 , 19 , 20 ], and supplemented with vignettes to prompt discussion [ 21 ]. The interview schedule can be seen in the Supplementary material along with an example vignette. The interview schedule was piloted with the study’s Patient and Public Involvement (PPI) group consisting of former carers, and with the first two participants, and revised. Interviews were conducted with the person with dementia alone, or with a family member if preferred by the participant living with dementia. Where a family member was present and took part in the interview they were consented, and their responses are included in the analysis. During dyadic interviews, participants living with dementia were asked questions first to ensure their views and experiences were heard. Carers were able to contribute when they wanted to but this was not the focus of the interview. All interviews were audio-recorded and transcribed verbatim. A research assistant checked all transcripts against the original audio files for any discrepancies and data were anonymised.

Data analysis

Transcripts were imported into NVivo version 12 to facilitate analysis [ 22 ]. Reflexive thematic analysis was used to analyse data and develop themes [ 17 ]. One member of the research team (DN) coded all transcripts, while two others independently coded a further five. Through a series of discussions initial code lists were refined and initial themes developed by DN. Themes were then refined, while interpretation and meaning of each theme were discussed with the whole team (experienced in gerontology, primary care and palliative care), enabling them to contribute to findings and revise iteratively.

Following coding and the development of initial themes, we identified a similarity to some of the key themes within the concept of social death [ 23 ], a series of losses resulting in a disconnection from social life. Social death was first conceptualised in 1982 by Patterson in relation to slavery to describe how people can be considered unworthy and seen as dead when they are alive [ 24 ]. The theory has also been applied, at times controversially, to patients with chronic diseases, for example people living with dementia or, as it was then perceived, ‘suffering from dementia’ [ 23 ]. A recent concept analysis classified social death into three themes in relation to patients: the loss of social identity, loss of social relations, and deficiencies related to the inefficiency of the body and various diseases [ 25 ]. For example, as some chronic conditions advance, social roles change and people are unable to continue their previous social interactions as they are threatened by the body’s decline [ 23 ]. For some, losing social identity leads to exclusion or withdrawal from the wider community; associated with vulnerability, stigma and loss of physiological functioning [ 23 ]. In light of this, we shaped our findings and organised them within the three concepts underpinning the theory of social death to see if they offered an explanatory model. This enabled us to see if the theory of social death may offer insights into dementia experiences.

Ethics approval

Health Research Authority (HRA) ethical approval was received (London Queen Square Research Ethics Committee (18/LO/0408) on 10.04.2018. Written informed consent was provided by all participants.

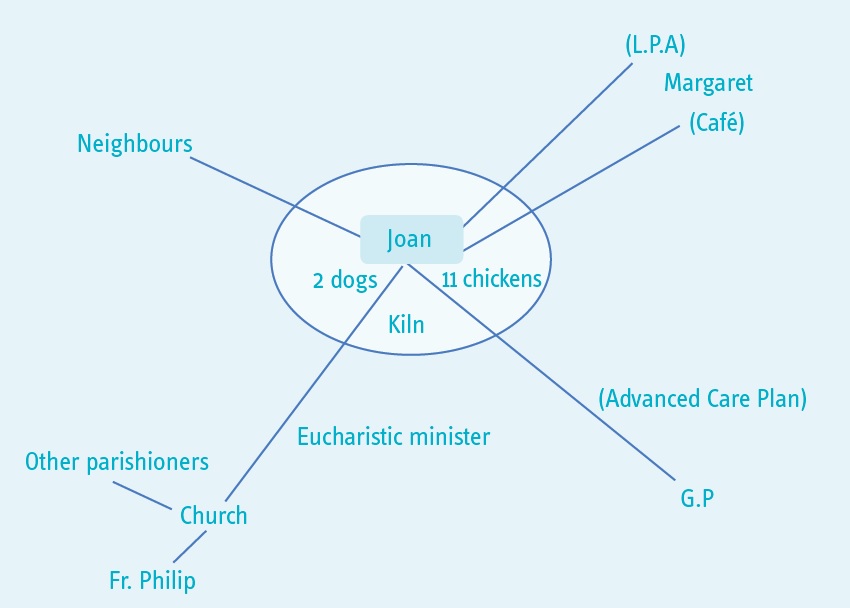

Eleven people living with dementia were recruited, all of whom had capacity. Six were dyadic interviews with a family carer and four were individual interviews. During dyadic interviews, all carers provided answers to all questions. Participant characteristics are presented in Table 1 .

We arranged our themes under the three key concepts of social death theory [ 17 ], however we adapted the names of these concepts to reflect the participants’ words and the context of dementia: (1) loss of physical and cognitive functions, (2) loss of social identity, and (3) social connectedness. Table 2 provides an overview of the adapted concepts of the theory and our themes within them.

Loss of physical and cognitive functions

Across the interviews participants discussed their progressive decline, in particular the decline of their memory and cognitive functions. As discussed in the themes below, the loss of cognitive functions was often the focus of their discussion, rather than a change to physical functioning and abilities, although these often accompany advancing stages of dementia and indeed old age.

Staying present and the importance of maintaining self

Many participants wanted to discuss the present and focus on what they were still able to do, rather than discussing the future and anticipated limitations. This discussion of the present appeared to either be a representation of their role and importance within their family, still demonstrating a sense of purpose or use to others, or more simply as a representation of things they enjoyed doing and as a way of reflecting they still enjoy life:

“But I can still cook, can’t I? I can still wash up.“ Participant 03 “But other than that, I still play golf three times a day – a week” . Participant 02

Maintaining current levels of health and well-being was important to support their mood and some felt this was important to try to minimise the impact or delay the progression of their dementia:

“I mean this morning I’ve done yoga. And we do it – [husband] and I do it every week. And I feel great when I’ve done it. “ Participant 09 “ I still believe that at least I can delay and delay and delay it. ... And I’m still healthy, although I’ve got a heart condition.“ Participant 02

When asked about advanced dementia, many participants focussed on progressive memory loss which would lead to them relying on others such as their family. The narrative of dependence was often dominated by memory and less around physical function. Dementia was therefore seen as a condition of the mind (not the body) which would continue to deteriorate:

“I’m not sure what dementia is, I don’t know what it means. I know it’s a side of the brain and the mind…I have knowledge confirmed of what’s going on in my mind or my brain.” Participant 05

Participants believed that although their mind and memory will inevitably decline, by maintaining physical health they could still ‘get on’ with their lives and not be too restricted by the condition, for example, carrying out activities of daily living and ‘getting by’:

“What is important to me really is to ensure that my health is, continues to be good physically, that I manage and that I can carry on – getting by in terms of memory” . Participant 11

A few participants felt maintaining good physical health could help them ‘mask’ their dementia from other people, enabling them to still partake in enjoyable activities. As one participant said:

“I think I handled it quite well because, as I say, there’s no, there’s no visible sort of way that gives away the fact that you’re suffering with a disease” . Participant 10

This suggests this participant’s perception of dementia being a condition of the mind, instead of the body.

Masking their dementia was important to some participants who were worried about how others would treat or view them if they knew they had dementia. For example, one participant feared that others would point and talk about him if they could see that he had dementia:

“People will think I will get more sensitive if you see me with that [dementia], and particularly for someone, you know, talking to each other, point out, pointing at me…but I’m afraid .“ Participant 02

Discussing the future

Discussing the future is discussed within two subthemes: ‘interviewer as enabler of discussion’ and ‘discussing with others and planning’.

Interview as enabler of advance care planning and discussions around the future

Most participants did not want to discuss the future perhaps because they feared what it entailed, both in terms of losing their cognitive and physical functions, leading to increased need for support and care. They viewed dementia negatively and a condition that would only get worse “[It is] Irreversible. One-way traffic… “. However, for some this was as far as they wanted to initially go in discussing their dementia, with many diverting or closing down the conversation:

“I don’t think about anything really about the future. Okay, so have you… (interviewer) I’m happy as I am.” Participant 08

When asked directly about their future, most said they did not know what would lie ahead. However, as the interview progressed and rapport was built with the interviewer, many also recalled situations of people they knew approaching end of life. This included nursing a friend with terminal cancer, parents who had died in care homes, and friends with more advanced dementia:

So you talked about maybe a need for a conversation now about diagnosis and things. What, as a family, do you understand about maybe the later stages of dementia? (interviewer) ”Not very much ”. Carer of Participant 03

When directly asked, this carer said she did not know what happens in the advanced stages of dementia, however she later discussed a friend whose husband with more advanced dementia was moving to a nursing home:

“I’m getting a bit concerned this week because I have a friend in America with exactly the same problem with her husband. But I had a letter from her this week to say that he’s been taken into a home… through the memory clinic out there. And it’s all very, very distressing for her.“ Carer of Participant 03 (later)

These possible contradictions could suggest a degree of denial and that some carer participants perhaps knew more about later stages of dementia than they wanted to admit or felt uncomfortable talking about in the presence of their relative. Many carers seemed determined to focus on the present and not discuss the future, in part, due to fear and family experiences:

“I think because he [Participant 07] has seen his mum in the home and ... they were lying in the bed all day and nobody came to look. So this is what we have seen in the home and that is in the mind.“ Carer of Participant 07

The interviews appeared at times to enable discussions around the future and advance care planning for participants and their carers, possibly providing them with one of the first opportunities to engage in these conversations either as an individual or with their partner who was being interviewed with them. However, responses to advance care planning questions were always short or vague:

So if you were in that position, when you stopped eating, you’d stopped eating and drinking, and people – your family were trying to say, “No, no, you need to eat, you need to drink,” but you didn’t want to – what would you want them to think about in making that decision whether to stop or whether to think about those other options? (interviewer) ”Hmm, that’s difficult. I don’t know, if I didn’t know, I don’t know. If I didn’t know, I wouldn’t know, I’d have to wait and see what the problem was, you know, how I really, really felt ” Participant 08

This further indicates that participants did not want to talk about the future or were not ready to. This may have been for reasons such as fear, and/or the risk of causing sadness or distress for the person living with dementia. This often resulted in carer participants saying they would talk about these topics at some stage, without committing to a time:

“I mean he gets a bit upset when you start talking about these sorts of things. But I mean I know it has got to be sought after, you know, later on, but I mean, at the moment, he copes very well”. Carer of Participant 11

Planning for the future in discussions with family members

Some participants living with dementia felt it was not worth talking about the future, when they would not be able to understand what was going on around them towards end of life:

“ I mean it has come to my mind, but I just try not to sort of dwell on it really. I just think I’ll take it as it comes. What’s the point of worrying about, you know, all those things that you worry about when you think about what’s going to happen when I die?“ Participant 09

This was despite some family carer participants showing interest in discussing the topic, while the participant living with dementia did not want to. This also illustrates how the interview enabled discussions around planning with family:

“So, even I can picture this to what is lying ahead of us. But, yes, it would be nice to be prepared, or even he would like to – it will be good for him to know as well that what is there to look for” Carer of Participant 07

This could be because several participants living with dementia openly said they would leave end of life decisions to their family carer when the time came, and some carers wanted to be prepared for this:

“ You know, I just think I’m sure my children will sort it out if they have to. I don’t have any great thoughts about it. You know, I try not to because I, you know, I want to enjoy what life that I’ve got without being miserable all the time ”. Participant 09

The default position adopted by participants living with dementia for their carers to make end of life decisions in a future when they no longer have capacity, is another example of how participants living with dementia wanted to stay in the present. This could be viewed as avoidant or a legitimate strategy. It also shows participants relinquishing more active or decision-making roles within their families, onto their children or partners.

By focusing on the present, maintaining current health and well-being, and showing a reluctance to discuss the future, participants living with dementia seemed to be deciding to leave discussions about the future to others while trying in the present to minimise further decline, although they knew their condition would worsen. In some cases, this was felt by interviewers to manifest as anger, as reflected in this participant’s response to his carer who said they had not discussed care homes or later stages of dementia:

“No, this is the first time that it’s – we haven’t spoken about – because I didn’t think that I was about to pop my clogs (die).” Participant 03

Loss of social identity

Throughout the interviews there was an underlying discussion of social identity and how participants perceived and categorised themselves in relation to the progression of their dementia, other people and the world around them. Participants presented a narrative of independence and control to reduce the risk of social exclusion while the anticipated loss of independence was associated with advanced dementia and moving to care homes. We created the following themes within the category of loss of social identity: ‘Power, control and independence’ and ‘Perceptions on support and care homes’.

Power, control and independence

Apart from planning for the future, participants living with dementia wanted to be in control of their lives, mostly in respect of everyday activities. Several participants felt the future was now out of their control, which worried them:

“And people then getting worried about where they are and what they’re doing here and what’s going to happen next. And I’m not, I don’t have any control over it. I think it’s the feeling of lack of control that’s probably most worrying.” Participant 04

However, control was also beginning to be affected by their current limitations. This included no longer being able to drive, cook or go out unaccompanied; activities that many people take for granted:

“Well, you don’t have any choice. Once you’ve been diagnosed, they then say – “Hand in your [driving] licence .” Participant 05 “They told me, didn’t they, that it’s inadvisable to go out unaccompanied, I think, was the expression.” Participant 03

Declining independence seemed to be altering parts of their identity. This was often viewed negatively by those living with dementia, as they felt independence was eroding which prevented them from living their lives as fully as previously. However, participants understood these changes were necessary to ensure their safety:

“Well I can’t drive a car, which is another irritant. But I understand the necessity of stopping people like me driving, because we wouldn’t be safe on the road.” Participant 10

To balance this, carers often focused positively on what their relative could do:

“Well, you’re very independent, yes. You can do your shopping and you can read and you can eat, choose what you want to eat.” Carer of Participant 06

However, many participants living with dementia were now needing assistance in many aspects of their lives, usually from family carers:

“There’s very little I can do without her [wife] input, put it that way.” Participant 05

Several acknowledged they would need more help from family as their dementia advanced. Those who did not have family felt they would have to employ people to help them:

“No, I’ve really got no family that I can turn to. And, you know, they’ve moved on and I really, to some degree, now only got very minimal contact with my brother who lives in another part – he lives in [another part of UK]. So, so, so I would think that in terms of financial affairs, I’d have to employ someone specifically, you know, an accountant or someone to deal with that.” Participant 11

For some participants with substantial resources these were not new arrangements:

“We’ve got staff who look after the place. So you know, we’ve got a gardener, we’ve got a cleaner.” Participant 11

Several participants mentioned role-reversal, where their spouse or children were carrying out the roles/jobs that previously held by the person with dementia. This included roles traditionally seen as signifying independence, such as managing one’s finances:

“But you controlled your own money. I controlled mine and we both controlled ours. But recently I’ve had to do it all for you, haven’t I...” Carer of Participant 08

Again, many participants recognised that they could no longer carry out these duties and some recalled a time when they had held a more active role in the family:

“But, you know, I’ve always been a leader and I don’t mean democratically. I’ve always looked upon the girls and the wives- I bought this house off my mother-in-law…I’ve never found a problem looking after the mother-in-law, both financially, and you know, like elderly ladies have to have baths etc. I never found it a problem,” Participant 03

Not being able to carry out duties of responsibility was also seen as a loss of power by some:

“What she [carer] said that I still want to hold power – in my mind I can correct a little bit what she just mentioned. And I try to hold on – but no, I’m very, very easy-going in my mind, because what can we do if I’m not able to make any decision?” Participant 02

Another participant living with dementia discussed the situation of her mother who was also living with dementia. Evidently, she had arranged a personal alarm for her mother who did not wear it, as she considered it as a loss of independence:

“So she does have an alarm that we pay for, but she refuses to wear it. So there’s many incidences of independence which are almost there in spite of what I’m trying to put in place to help to show how, how much independence you have, which is silly, because you need to wear the alarm.” Participant 06