Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

1-2 The Nature of Evidence: Inductive and Deductive Reasoning

Renate Kahlke; Jonathan Sherbino; and Sandra Monteiro

Different philosophies of science (Chapter 1-1) inform different approaches to research, characterized by different goals, assumptions, and types of data. In this chapter, we discuss how post-positivist, interpretivist, constructivist, and critical philosophies form a foundation for two broad approaches to generating knowledge: quantitative and qualitative research. There are several often-discussed distinctions between these two approaches, stemming from their philosophical roots, specifically, a commitment to objectivity versus subjective interpretation, numbers versus words, generalizability versus transferability, and deductive versus inductive reasoning. While these distinctions often distinguish qualitative and quantitative research, there are always exceptions. These exceptions demonstrate that quantitative and qualitative research approaches have more in common than what superficial descriptions imply.

Key Points of the Chapter

By the end of this chapter the learner should be able to:

- Describe quantitative research methodologies

- Describe qualitative research methodologies

- Compare and contrast these two approaches to interpreting data

Rayna (they/their) stared at the blinking cursor on her screen. They had been recently invited to revise and resubmit their first qualitative research manuscript. Most of the editor and reviewer comments had been relatively easy to handle, but when Rayna reached Reviewer 2’s comments, they were caught off guard. The reviewer acknowledged that they came from a quantitative background, but then went on to write: “I am worried about the generalizability of this study, with a sample of only 25 residents. Wouldn’t it be better to do a survey to get more perspectives?”

Rayna hadn’t seen any other qualitative studies talk about generalizability, so they weren’t entirely sure how to address this comment. Maybe the study won’t be valuable if the results aren’t generalizable! Reviewer 2 might be right that the sample size is too small! They immediately panic-email one of their co-authors:

Hi Rayna, We get these kinds of reviews all the time. Don’t worry, it’s not a flaw in your study. That said, I think we can build our field’s knowledge about qualitative research approaches by explaining some of these concepts. Start with the one by Monteiro et al. and then read the one by Wright and colleagues. These are both good primers and will give you some language to help respond to this reviewer.

With a sigh of relief, Rayna reads through the attached papers (1-8) and continues her mission to craft a response.

Deeper Dive on this Concept

Qualitative and quantitative research are often talked about as two different ways of thinking and generating knowledge. We contrast a reliance on words with a reliance on numbers, a focus on subjectivity with a focus on objectivity. And to some extent these approaches are different, in precisely the ways described. However, many experienced researchers on both sides of the line will tell you that these differences only go so far.

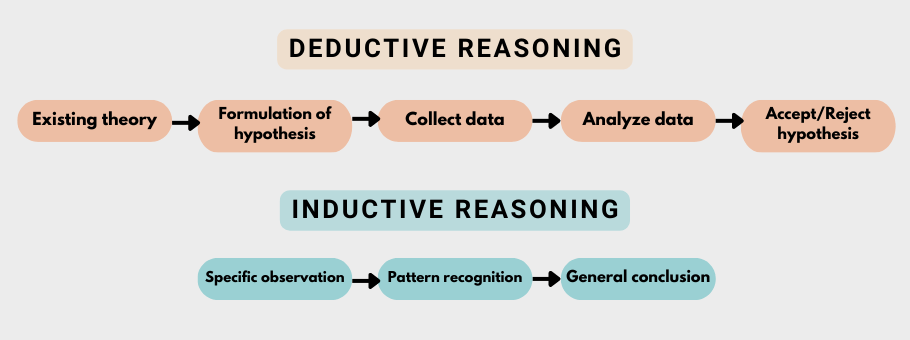

Drawing on Chapter 1-1, there are different philosophies of science that inform researchers and their research products. Generally, quantitative research is associated with post-positivism; researchers seek to be objective and reduce their bias in order to ensure that their results are as close as possible to the truth. Post-positivists, unlike positivists, acknowledge that a singular truth is impossible to define. However, truth can be defined within a spectrum of probability. Quantitative researchers generate and test hypotheses to make conclusions about a theory they have developed. They conduct experiments that generate numerical data that define the extent to which an observation is “true.” The strength of the numerical data suggests whether the observation can be generalized beyond the study population. This process is called deductive reasoning because it starts with a general theory that narrows to a hypothesis that is tested against observations that support (or refute) the theory.

Qualitative researchers, on the other hand, tend to be guided by interpretivism, constructivism, critical theory or other perspectives that value subjectivity. These analytic approaches do not address bias because bias assumes a misrepresentation of “truth” during collection or analysis of data. Subjectivity emphasizes the position and perspective assumed during analysis, articulating that there is no external objective truth, uninformed by context. ( See Chapter 1-1 .) Qualitative methods seek to deeply understand a phenomenon, using the rich meaning provided by words, symbols, traditions, structures, identity constructs and power dynamics (as opposed to simply numbers). Rather than testing a hypothesis, they generate knowledge by inductively generating new insights or theory (i.e. observations are collected and analyzed to build a theory). These insights are contextual, not universal. Qualitative researchers translate their results within a rich description of context so that readers can assess the similarities and differences between contexts and determine the extent to which the study results are transferable to their setting.

While these distinctions can be helpful in distinguishing quantitative and qualitative research broadly, they also create false divisions. The relationships between these two approaches are more complex, and nuances are important to bear in mind, even for novices, lest we exacerbate hierarchies and divisions between different types of knowledge and evidence.

As an example, the interpretation of quantitative results is not always clear and obvious – findings do not always support or refute a hypothesis. Thus, both qualitative and quantitative researchers need to be attentive to their data. While quantitative research is generally thought to be deductive, quantitative researchers often do a bit of inductive reasoning to find meaning in data that hold surprises. Conversely, qualitative data are stereotypically analyzed inductively, making meaning from the data rather than proving a hypothesis. However, many qualitative researchers apply existing theories or theoretical frameworks, testing the relevance of existing theory in a new context or seeking to explain their data using an existing framework. These approaches are often characterized as deductive qualitative work.

As another example, quantitative researchers use numbers, but these numbers aren’t always meaningful without words. In surveys, interpretation of numerical responses may not be possible without analyzing them alongside free-text responses. And while qualitative researchers rarely use numbers, they do need to think through the frequency with which certain themes appear in their dataset. An idea that only appears once in a qualitative study may have great value to the analysis, but it is also important that researchers acknowledge the views that are most prevalent in a given qualitative dataset.

Key Takeaways

- Quantitative research is generally associated with post-positivism. Since researchers seek to get as close to ‘the truth’, as they can, they value objectivity and seek generalizable results. They generate hypotheses and use deductive reasoning and numerical data numbers to prove or disprove their hypotheses. Replicating patterns of data to validate theories and interpretations is one way to evaluate ‘the truth’.

- Qualitative research is generally associated with worldviews that value subjectivity. Since qualitative researchers seek to understand the interaction between person, place, history, power, gender and other elements of context, they value subjectivity (e.g. interpretivism, constructivism, critical theory). Qualitative research does not seek generalizability of findings (i.e. a universal, decontextualized result), rather it produces results that are inextricably linked to the context of the data and analysis. Data tend to take the form of words, rather than numbers, and are analyzed inductively.

- Qualitative and quantitative research are not opposites. Qualitative and quantitative research are often marked by a set of apparently clear distinctions, but there are always nuances and exceptions. Thus, these approaches should be understood as complementary, rather than diametrically opposed.

Vignette Conclusion

Rayna smiled and read over their paper once more. They had included an explanation of qualitative research, and how it’s about depth of information and nuance of experience. The depth of data generated per participant is significant, therefore fewer people are typically recruited in qualitative studies. Rayna also articulated that while the interpretivist approach she used for analysis isn’t focused on generalizing the results beyond a specific context, they were able to make an argument for how the results can transfer to other, similar contexts. Cal provided a bunch of margin comments in her responses to the reviews, highlighting how savvy Rayna had been in addressing the concerns of Reviewer 2 without betraying their epistemic roots. The editor certainly was right – adding more justification and explanation had made the paper stronger, and would likely help others grow to better understand qualitative work. Now the only challenge left was figuring out how to upload the revised documents to the journal submission portal…

- Wright, S., O’Brien, B. C., Nimmon, L., Law, M., & Mylopoulos, M. (2016). Research Design Considerations. Journal of Graduate Medical Education, 8(1), 97–98. doi: 10.4300/JGME-D-15-00566.1

- Monteiro S, Sullivan GM, Chan TM. Generalizability theory made simple (r): an introductory primer to G-studies. Journal of graduate medical education. 2019 Aug;11(4):365-70. doi: 10.4300/JGME-D-19-00464.1

- Goldenberg MJ. On evidence and evidence-based medicine: lessons from the philosophy of science. Social science & medicine. 2006 Jun 1;62(11):2621-32. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2005.11.031

- Varpio L, MacLeod A. Philosophy of science series: Harnessing the multidisciplinary edge effect by exploring paradigms, ontologies, epistemologies, axiologies, and methodologies. Academic Medicine. 2020 May 1;95(5):686-9. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0000000000003142

- Morse JM, Mitcham C. Exploring qualitatively-derived concepts: Inductive—deductive pitfalls. International journal of qualitative methods. 2002 Dec;1(4):28-35. https://doi.org/10.1177/160940690200100404

- Armat MR, Assarroudi A, Rad M, Sharifi H, Heydari A. Inductive and deductive: Ambiguous labels in qualitative content analysis. The Qualitative Report. 2018;23(1):219-21. https://www.proquest.com/docview/2122314268

- Tavakol M, Sandars J. Quantitative and qualitative methods in medical education research: AMEE Guide No 90: Part I. Medical Teacher. 2014 Sep 1;36(9):746-56. doi: 10.3109/0142159X.2014.915298

- Tavakol M, Sandars J. Quantitative and qualitative methods in medical education research: AMEE Guide No 90: Part II. Medical teacher. 2014 Oct 1;36(10):838-48. doi: 10.3109/0142159X.2014.915297

About the authors

name: Renate Kahlke

institution: McMaster University

Renate Kahlke is an Assistant Professor within the Division of Education & Innovation, Department of Medicine. She is a scientist within the McMaster Education Research, Innovation and Theory (MERIT) Program.

name: Jonathan Sherbino

name: Sandra Monteiro

Sandra Monteiro is an Associate Professor within the Department of Medicine, Division of Education and Innovation, Faculty of Health Sciences, McMaster University. She holds a joint appointment within the Department of Health Research Methods, Evidence, and Impact , Faculty of Health Sciences, McMaster University.

1-2 The Nature of Evidence: Inductive and Deductive Reasoning Copyright © 2022 by Renate Kahlke; Jonathan Sherbino; and Sandra Monteiro is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Share This Book

Inductive Approach (Inductive Reasoning)

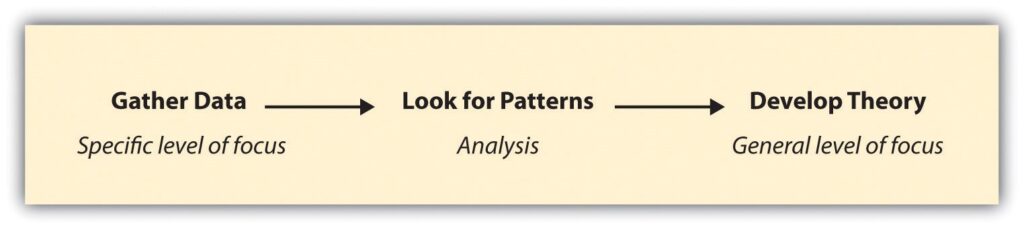

Inductive approach, also known in inductive reasoning, starts with the observations and theories are proposed towards the end of the research process as a result of observations [1] . Inductive research “involves the search for pattern from observation and the development of explanations – theories – for those patterns through series of hypotheses” [2] . No theories or hypotheses would apply in inductive studies at the beginning of the research and the researcher is free in terms of altering the direction for the study after the research process had commenced.

It is important to stress that inductive approach does not imply disregarding theories when formulating research questions and objectives. This approach aims to generate meanings from the data set collected in order to identify patterns and relationships to build a theory; however, inductive approach does not prevent the researcher from using existing theory to formulate the research question to be explored. [3] Inductive reasoning is based on learning from experience. Patterns, resemblances and regularities in experience (premises) are observed in order to reach conclusions (or to generate theory).

Application of Inductive Approach (Inductive Reasoning) in Business Research

Inductive reasoning begins with detailed observations of the world, which moves towards more abstract generalisations and ideas [4] . When following an inductive approach, beginning with a topic, a researcher tends to develop empirical generalisations and identify preliminary relationships as he progresses through his research. No hypotheses can be found at the initial stages of the research and the researcher is not sure about the type and nature of the research findings until the study is completed.

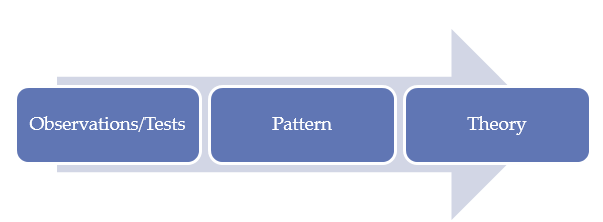

As it is illustrated in figure below, “inductive reasoning is often referred to as a “bottom-up” approach to knowing, in which the researcher uses observations to build an abstraction or to describe a picture of the phenomenon that is being studied” [5]

Here is an example:

My nephew borrowed $100 last June but he did not pay back until September as he had promised (PREMISE). Then he assured me that he will pay back until Christmas but he didn’t (PREMISE). He also failed in to keep his promise to pay back in March (PREMISE). I reckon I have to face the facts. My nephew is never going to pay me back (CONCLUSION).

Generally, the application of inductive approach is associated with qualitative methods of data collection and data analysis, whereas deductive approach is perceived to be related to quantitative methods . The following table illustrates such a classification from a broad perspective:

However, the statement above is not absolute, and in some instances inductive approach can be adopted to conduct a quantitative research as well. The following table illustrates patterns of data analysis according to type of research and research approach .

When writing a dissertation in business studies it is compulsory to specify the approach of are adopting. It is good to include a table comparing inductive and deductive approaches similar to one below [6] and discuss the impacts of your choice of inductive approach on selection of primary data collection methods and research process.

My e-book, The Ultimate Guide to Writing a Dissertation in Business Studies: a step by step assistance contains discussions of theory and application of research approaches. The e-book also explains all stages of the research process starting from the selection of the research area to writing personal reflection. Important elements of dissertations such as research philosophy , research design , methods of data collection , data analysis and sampling are explained in this e-book in simple words.

John Dudovskiy

[1] Goddard, W. & Melville, S. (2004) “Research Methodology: An Introduction” 2nd edition, Blackwell Publishing

[2] Bernard, H.R. (2011) “Research Methods in Anthropology” 5 th edition, AltaMira Press, p.7

[3] Saunders, M., Lewis, P. & Thornhill, A. (2012) “Research Methods for Business Students” 6 th edition, Pearson Education Limited

[4] Neuman, W.L. (2003) “Social Research Methods: Qualitative and Quantitative Approaches” Allyn and Bacon

[5] Lodico, M.G., Spaulding, D.T &Voegtle, K.H. (2010) “Methods in Educational Research: From Theory to Practice” John Wiley & Sons, p.10

[6] Source: Alexandiris, K.T. (2006) “Exploring Complex Dynamics in Multi Agent-Based Intelligent Systems” Pro Quest

Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

4.1 Inductive and deductive reasoning

Learning objectives.

Learners will be able to…

- Describe inductive and deductive reasoning and provide examples of each

- Identify how inductive and deductive reasoning are complementary

Pre-awareness check (Emotion)

When you gain more knowledge, it is normal to experience discomfort as you question what you previously believed to be true. Have you experienced any internal struggles as you have been reading this text? Have any of your preconceived notions regarding your research topic been altered? Do you have any remaining challenges, biases, or blind spots that need to be addressed as you start this chapter?

[NEED AN INTRO TO THIS CHAPTER SECTION]

Inductive and deductive approaches to research are quite different, they can also be complementary. Let’s start by looking at each one and how they differ from one another. Then we’ll move on to thinking about how they complement one another.

Inductive reasoning

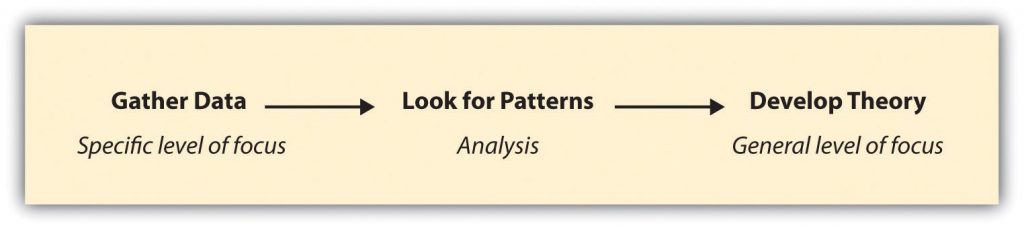

A researcher using inductive reasoning begins by collecting a substantial amount of data that is relevant to their topic of interest. The researcher will then step back from data collection to get a bird’s eye view of their data and look for patterns in the data, working to develop a theory that could explain those patterns. Thus, when researchers take an inductive approach, they start with a particular set of observations and move to a more general set of propositions about those experiences. In other words, they move from data to theory, or from the specific to the general. Figure 4.1 outlines the steps involved with an inductive approach to research.

There are many good examples of inductive research, but we’ll look at just a few here. One fascinating study in which the researchers took an inductive approach is Katherine Allen, Christine Kaestle, and Abbie Goldberg’s (2011) [1] study of how boys and young men learn about menstruation. To understand this process, Allen and her colleagues analyzed the written narratives of 23 young cisgender men in which the men described how they learned about menstruation, what they thought of it when they first learned about it, and what they think of it now. By looking for patterns across all 23 cisgender men’s narratives, the researchers were able to develop a general theory of how boys and young men learn about this aspect of girls’ and women’s biology. They conclude that sisters play an important role in boys’ early understanding of menstruation. Menstruation tends to make boys feel separated from girls, but as they gradually develop into adulthood and form romantic relationships, they simultaneously develop more mature attitudes about menstruation. Note how this study began with the data—men’s narratives of learning about menstruation—and worked to develop a theory.

In another inductive study, Kristin Ferguson and colleagues (Ferguson, Kim, & McCoy, 2011) [2] analyzed empirical data to better understand how to meet the needs of young people who are experiencing homelessness. The authors analyzed focus group data from 20 youth at a shelter. From the data they developed a set of recommendations for those interested in applied interventions that serve youth experiencing homelessness. The researchers also developed hypotheses for others who might wish to conduct further investigation of the topic. Though Ferguson and her colleagues did not test their hypotheses, their study ends where most deductive investigations begin: with a theory and a hypothesis derived from that theory. Section 4.4 discusses the use of mixed methods research as a way for researchers to test hypotheses created in a previous component of the same research project.

As in these examples, inductive reasoning is most commonly found in studies using qualitative methods, such as focus groups and interviews. Because inductive reasoning involves the creation of a new theory, researchers need very nuanced data on how the key concepts in their working research question operate in the real world. Qualitative data are often drawn from lengthy interactions and observations with the individuals and phenomena under examination. For this reason, inductive reasoning is most often associated with qualitative methods, though it is used in both quantitative and qualitative research.

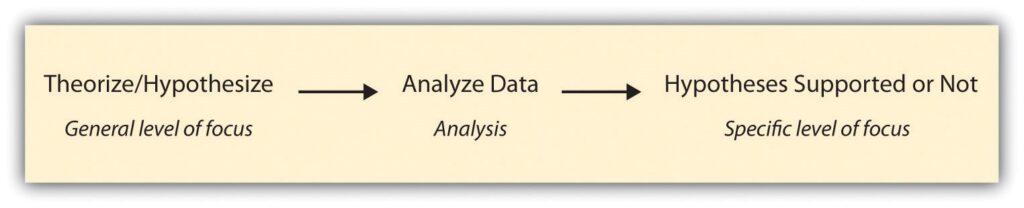

Deductive reasoning

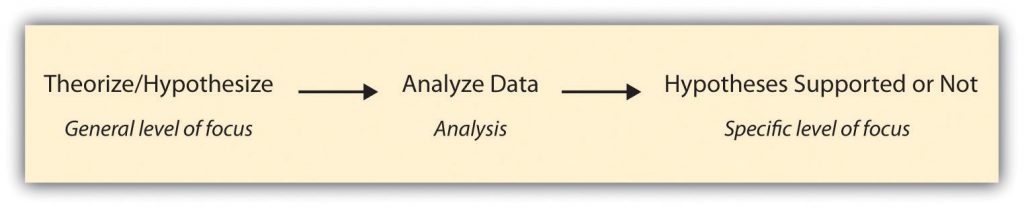

If inductive reasoning is about creating theories from raw data, deductive reasoning is about testing theories using data. Researchers using deductive reasoning take the steps described earlier for inductive research and reverse their order. They start with a compelling social theory, create a hypothesis about how the world should work, collect raw data, and analyze whether their hypothesis was confirmed or not. That is, deductive approaches move from a more general level (theory) to a more specific (data); whereas inductive approaches move from the specific (data) to general (theory).

Deductive approach to research are what many people think of when they think of scientific investigation. Students in English-dominant countries that may be confused by inductive vs. deductive research can rest part of the blame on Sir Arthur Conan Doyle, creator of the Sherlock Holmes character. As Craig Vasey points out in his breezy introduction to logic book chapter , Sherlock Holmes more often used inductive rather than deductive reasoning (despite claiming to use the powers of deduction to solve crimes). By noticing subtle details in how people act, behave, and dress, Holmes finds patterns that others miss. Using those patterns, he creates a theory of how the crime occurred, dramatically revealed to the authorities just in time to arrest the suspect. Indeed, it is these flashes of insight into the patterns of data that make Holmes such a keen inductive reasoner. In social work practice, rather than detective work, inductive reasoning is supported by the intuitions and practice wisdom of social workers, just as Holmes’ reasoning is sharpened by his experience as a detective.

So, if deductive reasoning isn’t Sherlock Holmes’ observation and pattern-finding, how does it work? Figure 4.2 outlines the steps involved with a deductive approach to research.

While not all researchers follow a deductive approach, many do. We’ll now take a look at a couple examples of deductive research.

In a study of U.S. law enforcement responses to hate crimes, Ryan King and colleagues (King, Messner, & Baller, 2009) [3] hypothesized that law enforcement’s response would be less vigorous in areas of the country that had a stronger history of racial violence. The authors developed their hypothesis from prior research and theories on the topic. They tested the hypothesis by analyzing data on states’ lynching histories and hate crime responses. Overall, the authors found support for their hypothesis and illustrated an important application of critical race theory.

In another recent deductive study, Melissa Milkie and Catharine Warner (2011) [4] studied the effects of different classroom environments on first graders’ mental health. Based on prior research and theory, Milkie and Warner hypothesized that negative classroom features, such as a lack of basic supplies and heat, would be associated with emotional and behavioral problems in children. One might associate this research with Maslow’s hierarchy of needs or systems theory. The researchers found support for their hypothesis, demonstrating that policymakers should be paying more attention to the mental health outcomes of children’s school experiences, just as they track academic outcomes (American Sociological Association, 2011). [5]

Complementary approaches

While inductive and deductive approaches to research seem quite different, they can actually be rather complementary. In some cases, researchers will plan for their study to include multiple components, one inductive and the other deductive. In other cases, a researcher might begin a study with the plan to conduct either inductive or deductive research, but then discovers along the way that the other approach is needed to help illuminate findings. Here is an example of each such case.

Dr. Amy Blackstone (2012), author of Principles of sociological inquiry: Qualitative and quantitative methods , relates a story about her mixed methods research on sexual harassment.

We began the study knowing that we would like to take both a deductive and an inductive approach in our work. We therefore administered a quantitative survey, the responses to which we could analyze in order to test hypotheses, and also conducted qualitative interviews with a number of the survey participants. The survey data were well suited to a deductive approach; we could analyze those data to test hypotheses that were generated based on theories of harassment. The interview data were well suited to an inductive approach; we looked for patterns across the interviews and then tried to make sense of those patterns by theorizing about them. For one paper (Uggen & Blackstone, 2004) [6] , we began with a prominent feminist theory of the sexual harassment of adult women and developed a set of hypotheses outlining how we expected the theory to apply in the case of younger women’s and men’s harassment experiences. We then tested our hypotheses by analyzing the survey data. In general, we found support for the theory that posited that the current gender system, in which heteronormative men wield the most power in the workplace, explained workplace sexual harassment—not just of adult women but of younger women and men as well. In a more recent paper (Blackstone, Houle, & Uggen, 2006), [7] we did not hypothesize about what we might find but instead inductively analyzed interview data, looking for patterns that might tell us something about how or whether workers’ perceptions of harassment change as they age and gain workplace experience. From this analysis, we determined that workers’ perceptions of harassment did indeed shift as they gained experience and that their later definitions of harassment were more stringent than those they held during adolescence. Overall, our desire to understand young workers’ harassment experiences fully—in terms of their objective workplace experiences, their perceptions of those experiences, and their stories of their experiences—led us to adopt both deductive and inductive approaches in the work. (Blackstone, n.d., p. 21) [8]

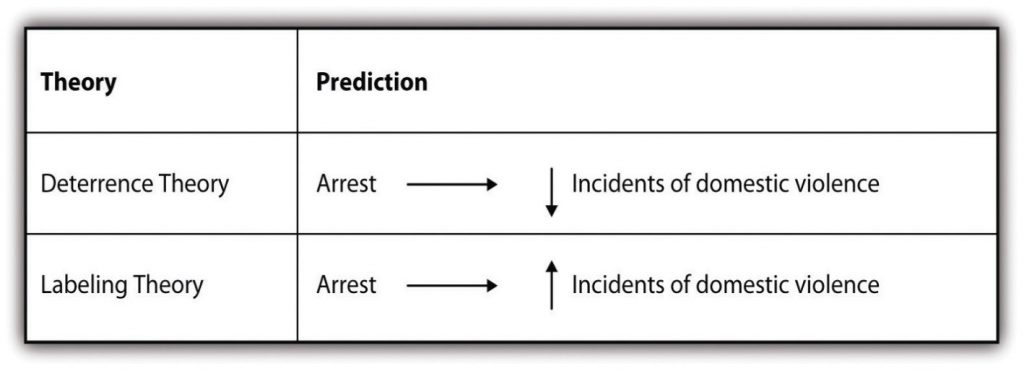

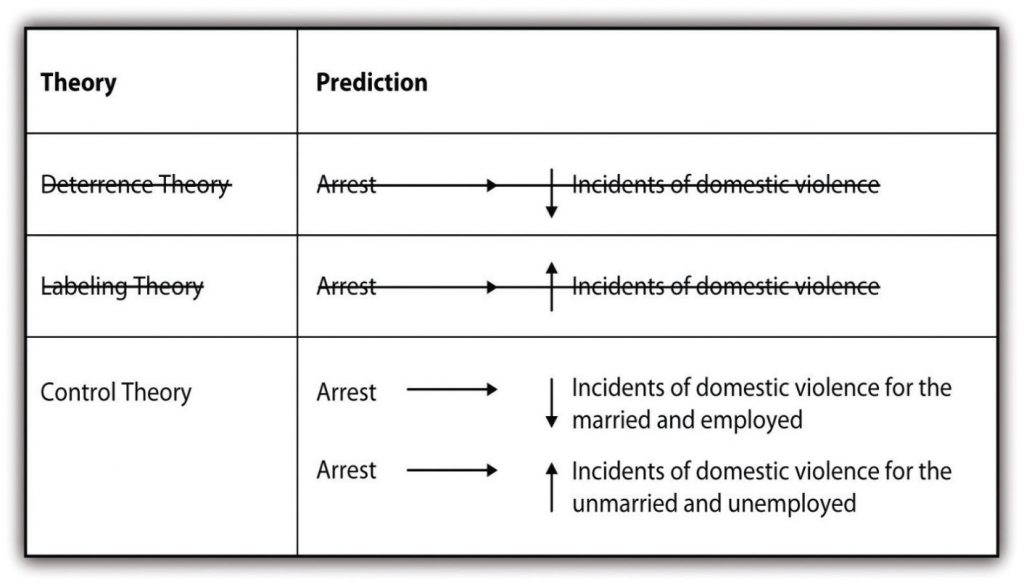

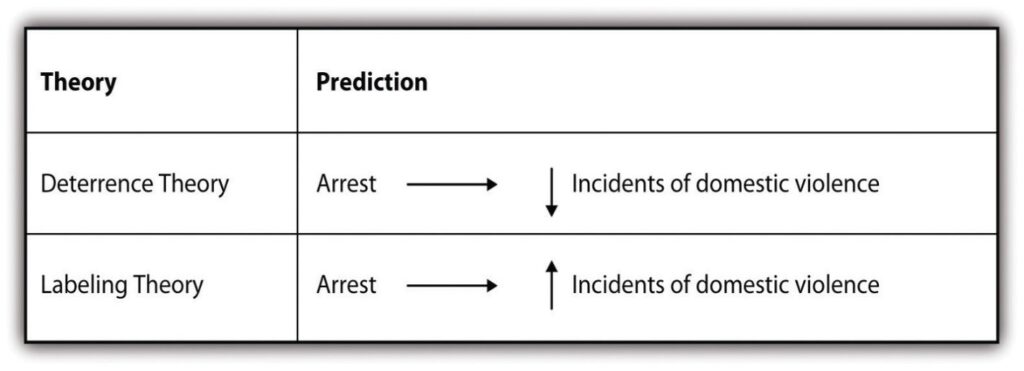

Researchers may not always set out to employ both approaches in their work but sometimes find that their use of one approach leads them to the other. One such example is described eloquently in Russell Schutt’s Investigating the Social World (2006). [9] As Schutt describes, researchers Sherman and Berk (1984) [10] conducted an experiment to test two competing theories of the effects of punishment on deterring deviance (in this case, domestic violence). Specifically, Sherman and Berk hypothesized that deterrence theory (see Williams, 2005 [11] for more information on that theory) would provide a better explanation of the effects of arresting accused perpetrators than labeling theory . Deterrence theory predicts that arresting an accused perpetrators of domestic violence will reduce future incidents of violence. Conversely, labeling theory predicts that arresting alleged perpetrators will increase future incidents (see Policastro & Payne, 2013 [12] for more information on that theory). Figure 4.3 summarizes the two competing theories and the hypotheses Sherman and Berk set out to test.

Sherman and Berk found, after conducting an experiment with the help of local police in one city, that arrest did in fact deter future incidents of violence, thus supporting their hypothesis that deterrence theory would better predict the effect of arrest. After conducting this research, they and other researchers went on to conduct similar experiments in six additional cities (Berk, Campbell, Klap, & Western, 1992; Pate & Hamilton, 1992; Sherman & Smith, 1992). [13]

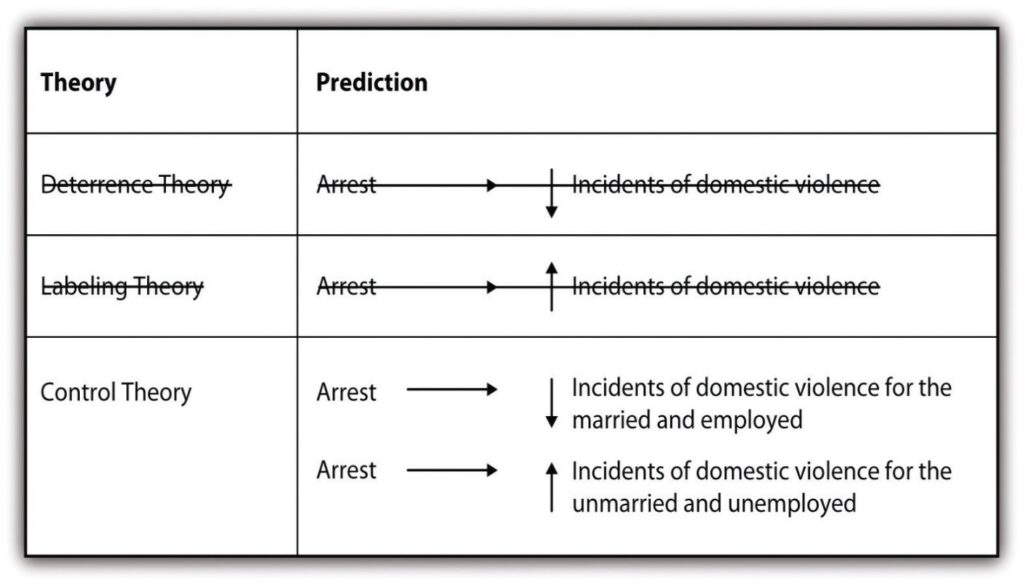

Research from these follow-up studies were mixed. In some cases, arrest deterred future incidents of violence. In other cases, it did not. This left the researchers with new data that they needed to explain. The researchers therefore took an inductive approach in an effort to make sense of their latest empirical observations. The new studies revealed that arrest seemed to have a deterrent effect for those who were married and employed, but that it led to increased offenses for those who were unmarried and unemployed. Researchers thus turned to control theory, which posits that having some stake in conformity through the social ties provided by marriage and employment, as the better explanation (see Davis et al., 2000 [14] for more information on this theory).

What the original Sherman and Berk study, along with the follow-up studies, show us is that we might start with a deductive approach to research, but then, if confronted by new data we must make sense of, we may move to an inductive approach. We will expand on these possibilities in section 4.5 when we discuss mixed methods research.

Ethical and critical considerations

Inductive and deductive reasoning, just like other components of the research process comes with ethical and cultural considerations for researchers. Specifically, deductive research is limited by existing theory. Because scientific inquiry has been shaped by oppressive forces such as sexism, racism, and colonialism, what is considered theory is largely based in Western, white-male-dominant culture. Thus, researchers doing deductive research may artificially limit themselves to ideas that were derived from this context. Non-Western researchers, international social workers, and practitioners working with non-dominant groups may find deductive reasoning of limited help if theories do not adequately describe other cultures.

While these flaws in deductive research may make inductive reasoning seem more appealing, on closer inspection you’ll find similar issues apply. A researcher using inductive reasoning applies their intuition and lived experience when analyzing participant data. They will take note of particular themes, conceptualize their definition, and frame the project using their unique psychology. Since everyone’s internal world is shaped by their cultural and environmental context, inductive reasoning conducted by Western researchers may unintentionally reinforcing lines of inquiry that derive from cultural oppression.

Inductive reasoning is also shaped by those invited to provide the data to be analyzed. For example, I recently worked with a student who wanted to understand the impact of child welfare supervision on children born dependent on opiates and methamphetamine. Due to the potential harm that could come from interviewing families and children who are in foster care or under child welfare supervision, the researcher decided to use inductive reasoning and to only interview child welfare workers.

Talking to practitioners is a good idea for feasibility, as they are less vulnerable than clients. However, any theory that emerges out of these observations will be substantially limited, as it would be devoid of the perspectives of parents, children, and other community members who could provide a more comprehensive picture of the impact of child welfare involvement on children. Notice that each of these groups has less power than child welfare workers in the service relationship. Attending to which groups were used to inform the creation of a theory and the power of those groups is an important critical consideration for social work researchers.

As you can see, when researchers apply theory to research they must wrestle with the history and hierarchy around knowledge creation in that area. In deductive studies, the researcher is positioned as the expert, similar to the positivist paradigm (which will be presented in Chapter 5 ). We’ve discussed a few of the limitations on the knowledge of researchers in this subsection, but the position of the “researcher as expert” is inherently problematic. However, it should also not be taken to an extreme. A researcher who approaches inductive inquiry as a naïve learner is also inherently problematic. Just as competence in social work practice requires a baseline of knowledge prior to entering practice, so does competence in social work research. Because a truly naïve intellectual position is impossible—we all have preexisting ways we view the world and are not fully aware of how they may impact our thoughts—researchers should be well-read in the topic area of their research study but humble enough to know that there is always much more to learn.

Key Takeaways

- Inductive reasoning begins with a set of empirical observations, seeking patterns in those observations, and then theorizing about those patterns.

- Deductive reasoning begins with a theory, developing hypotheses from that theory, and then collecting and analyzing data to test the truth of those hypotheses.

- Inductive and deductive reasoning can be employed together for a more complete understanding of the research topic.

- Though researchers don’t always set out to use both inductive and deductive reasoning in their work, they sometimes find that new questions arise in the course of an investigation that can best be answered by employing both approaches.

TRACK 1 (IF YOU ARE CREATING A RESEARCH PROPOSAL FOR THIS CLASS):

- Identify one theory and how it helps you understand your topic and working research question. Try to find a specific theory from this topic area, rather than relying only on the broad theoretical perspectives like systems theory or the strengths perspective. Those broad theoretical perspectives are okay, but searching for theories about your topic will help you conceptualize and design your research project.

- Using the theory you identified, describe what you expect the answer to be to your working research question.

TRACK 2 (IF YOU AREN’T CREATING A RESEARCH PROPOSAL FOR THIS CLASS):

You are interested in researching teen dating violence and teenagers’ levels of depressive symptoms and self-esteem.

- Develop a working research question for this topic.

- Identify one theory and describe how it helps you understand your topic and working research question. Try to find a specific theory from this topic area, rather than relying only on the broad theoretical perspectives like systems theory or the strengths perspective. Those broad theoretical perspectives are okay, but searching for theories about your topic will help you conceptualize and design your research project.

- Allen, K. R., Kaestle, C. E., & Goldberg, A. E. (2011). More than just a punctuation mark: How boys and young men learn about menstruation. Journal of Family Issues, 32 , 129–156. ↵

- Ferguson, K. M., Kim, M. A., & McCoy, S. (2011). Enhancing empowerment and leadership among homeless youth in agency and community settings: A grounded theory approach. Child and Adolescent Social Work Journal, 28 , 1–22 ↵

- King, R. D., Messner, S. F., & Baller, R. D. (2009). Contemporary hate crimes, law enforcement, and the legacy of racial violence. American Sociological Review, 74 , 291–315. ↵

- Milkie, M. A., & Warner, C. H. (2011). Classroom learning environments and the mental health of first grade children. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 52 , 4–22. ↵

- The American Sociological Association wrote a press release on Milkie and Warner’s findings: American Sociological Association. (2011). Study: Negative classroom environment adversely affects children’s mental health. Retrieved from: https://www.sciencedaily.com/releases/2011/03/110309073717.htm ↵

- Uggen, C., & Blackstone, A. (2004). Sexual harassment as a gendered expression of power. American Sociological Review, 69 , 64–92. ↵

- Blackstone, A., Houle, J., & Uggen, C. “At the time I thought it was great”: Age, experience, and workers’ perceptions of sexual harassment. Presented at the 2006 meetings of the American Sociological Association. ↵

- Blackstone, A. (2012). Inductive or deductive? Two different approaches. Principles of sociological inquiry: Qualitative and quantitative methods. Saylor Foundation. ↵

- Schutt, R. K. (2006). Investigating the social world: The process and practice of research . Thousand Oaks, CA: Pine Forge Press. ↵

- Sherman, L. W., & Berk, R. A. (1984). The specific deterrent effects of arrest for domestic assault. American Sociological Review, 49 , 261–272. ↵

- Williams, K. R. (2005). Arrest and intimate partner violence: Toward a more complete application of deterrence theory. Aggression and Violent Behavior , 10 (6), 660-679. ↵

- Policastro, C., & Payne, B. K. (2013). The blameworthy victim: Domestic violence myths and the criminalization of victimhood. Journal of Aggression, Maltreatment & Trauma , 22 (4), 329-347. ↵

- Berk, R., Campbell, A., Klap, R., & Western, B. (1992). The deterrent effect of arrest in incidents of domestic violence: A Bayesian analysis of four field experiments. American Sociological Review, 57, 698–708; Pate, A., & Hamilton, E. (1992). Formal and informal deterrents to domestic violence: The Dade county spouse assault experiment. American Sociological Review, 57, 691–697; Sherman, L., & Smith, D. (1992). Crime, punishment, and stake in conformity: Legal and informal control of domestic violence. American Sociological Review, 57, 680–690. ↵

- Taylor, B. G., Davis, R. C., & Maxwell, C. D. (2001). The effects of a group batterer treatment program: A randomized experiment in Brooklyn. Justice Quarterly, 18(1), 171-201. ↵

when a researcher starts with a set of observations and then moves from particular experiences to a more general set of propositions about those experiences

starts by reading existing theories, then testing hypotheses and revising or confirming the theory

a statement describing a researcher’s expectation regarding what they anticipate finding

when researchers use both quantitative and qualitative methods in a project

Doctoral Research Methods in Social Work Copyright © by Mavs Open Press. All Rights Reserved.

Share This Book

- school Campus Bookshelves

- menu_book Bookshelves

- perm_media Learning Objects

- login Login

- how_to_reg Request Instructor Account

- hub Instructor Commons

Margin Size

- Download Page (PDF)

- Download Full Book (PDF)

- Periodic Table

- Physics Constants

- Scientific Calculator

- Reference & Cite

- Tools expand_more

- Readability

selected template will load here

This action is not available.

8.1: Inductive and deductive reasoning

- Last updated

- Save as PDF

- Page ID 135125

- Matthew DeCarlo, Cory Cummings, & Kate Agnelli

- Open Social Work Education

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

Learning Objectives

Learners will be able to…

- Describe inductive and deductive reasoning and provide examples of each

- Identify how inductive and deductive reasoning are complementary

Congratulations! You survived the chapter on theories and paradigms. My experience has been that many students have a difficult time thinking about theories and paradigms because they perceive them as “intangible” and thereby hard to connect to social work research. I even had one student who said she got frustrated just reading the word “philosophy.”

Rest assured, you do not need to become a theorist or philosopher to be an effective social worker or researcher. However, you should have a good sense of what theory or theories will be relevant to your project, as well as how this theory, along with your working question, fit within the three broad research paradigms we reviewed. If you don’t have a good idea about those at this point, it may be a good opportunity to pause and read more about the theories related to your topic area.

Theories structure and inform social work research. The converse is also true: research can structure and inform theory. The reciprocal relationship between theory and research often becomes evident to students when they consider the relationships between theory and research in inductive and deductive approaches to research. In both cases, theory is crucial. But the relationship between theory and research differs for each approach.

While inductive and deductive approaches to research are quite different, they can also be complementary. Let’s start by looking at each one and how they differ from one another. Then we’ll move on to thinking about how they complement one another.

Inductive reasoning

A researcher using inductive reasoning begins by collecting data that is relevant to their topic of interest. Once a substantial amount of data have been collected, the researcher will then step back from data collection to get a bird’s eye view of their data. At this stage, the researcher looks for patterns in the data, working to develop a theory that could explain those patterns. Thus, when researchers take an inductive approach, they start with a particular set of observations and move to a more general set of propositions about those experiences. In other words, they move from data to theory, or from the specific to the general. Figure 8.1 outlines the steps involved with an inductive approach to research.

Figure 8.1 Inductive reasoning

There are many good examples of inductive research, but we’ll look at just a few here. One fascinating study in which the researchers took an inductive approach is Katherine Allen, Christine Kaestle, and Abbie Goldberg’s (2011)\(^1\) study of how boys and young men learn about menstruation. To understand this process, Allen and her colleagues analyzed the written narratives of 23 young cisgender men in which the men described how they learned about menstruation, what they thought of it when they first learned about it, and what they think of it now. By looking for patterns across all 23 cisgender men’s narratives, the researchers were able to develop a general theory of how boys and young men learn about this aspect of girls’ and women’s biology. They conclude that sisters play an important role in boys’ early understanding of menstruation, that menstruation makes boys feel somewhat separated from girls, and that as they enter young adulthood and form romantic relationships, young men develop more mature attitudes about menstruation. Note how this study began with the data—men’s narratives of learning about menstruation—and worked to develop a theory.

In another inductive study, Kristin Ferguson and colleagues (Ferguson, Kim, & McCoy, 2011)\(^2\) analyzed empirical data to better understand how to meet the needs of young people who are homeless. The authors analyzed focus group data from 20 youth at a homeless shelter. From these data they developed a set of recommendations for those interested in applied interventions that serve homeless youth. The researchers also developed hypotheses for others who might wish to conduct further investigation of the topic. Though Ferguson and her colleagues did not test their hypotheses, their study ends where most deductive investigations begin: with a theory and a hypothesis derived from that theory. Section 8.4 discusses the use of mixed methods research as a way for researchers to test hypotheses created in a previous component of the same research project.

You will notice from both of these examples that inductive reasoning is most commonly found in studies using qualitative methods, such as focus groups and interviews. Because inductive reasoning involves the creation of a new theory, researchers need very nuanced data on how the key concepts in their working question operate in the real world. Qualitative data is often drawn from lengthy interactions and observations with the individuals and phenomena under examination. For this reason, inductive reasoning is most often associated with qualitative methods, though it is used in both quantitative and qualitative research.

Deductive reasoning

If inductive reasoning is about creating theories from raw data, deductive reasoning is about testing theories using data. Researchers using deductive reasoning take the steps described earlier for inductive research and reverse their order. They start with a compelling social theory, create a hypothesis about how the world should work, collect raw data, and analyze whether their hypothesis was confirmed or not. That is, deductive approaches move from a more general level (theory) to a more specific (data); whereas inductive approaches move from the specific (data) to general (theory).

A deductive approach to research is the one that people typically associate with scientific investigation. Students in English-dominant countries that may be confused by inductive vs. deductive research can rest part of the blame on Sir Arthur Conan Doyle, creator of the Sherlock Holmes character. As Craig Vasey points out in his breezy introduction to logic book chapter , Sherlock Holmes more often used inductive rather than deductive reasoning (despite claiming to use the powers of deduction to solve crimes). By noticing subtle details in how people act, behave, and dress, Holmes finds patterns that others miss. Using those patterns, he creates a theory of how the crime occurred, dramatically revealed to the authorities just in time to arrest the suspect. Indeed, it is these flashes of insight into the patterns of data that make Holmes such a keen inductive reasoner. In social work practice, rather than detective work, inductive reasoning is supported by the intuitions and practice wisdom of social workers, just as Holmes’ reasoning is sharpened by his experience as a detective.

So, if deductive reasoning isn’t Sherlock Holmes’ observation and pattern-finding, how does it work? It starts with what you have already done in Chapters 3 and 4, reading and evaluating what others have done to study your topic. It continued with Chapter 5, discovering what theories already try to explain how the concepts in your working question operate in the real world. Tapping into this foundation of knowledge on their topic, the researcher studies what others have done, reads existing theories of whatever phenomenon they are studying, and then tests hypotheses that emerge from those theories. Figure 8.2 outlines the steps involved with a deductive approach to research.

Figure 8.2 Deductive reasoning

While not all researchers follow a deductive approach, many do. We’ll now take a look at a couple excellentrecent examples of deductive research.

In a study of US law enforcement responses to hate crimes, Ryan King and colleagues (King, Messner, & Baller, 2009)\(^3\) hypothesized that law enforcement’s response would be less vigorous in areas of the country that had a stronger history of racial violence. The authors developed their hypothesis from prior research and theories on the topic. They tested the hypothesis by analyzing data on states’ lynching histories and hate crime responses. Overall, the authors found support for their hypothesis and illustrated an important application of critical race theory.

In another recent deductive study, Melissa Milkie and Catharine Warner (2011)\(^4\) studied the effects of different classroom environments on first graders’ mental health. Based on prior research and theory, Milkie and Warner hypothesized that negative classroom features, such as a lack of basic supplies and heat, would be associated with emotional and behavioral problems in children. One might associate this research with Maslow’s hierarchy of needs or systems theory. The researchers found support for their hypothesis, demonstrating that policymakers should be paying more attention to the mental health outcomes of children’s school experiences, just as they track academic outcomes (American Sociological Association, 2011).\(^5\)

Complementary approaches

While inductive and deductive approaches to research seem quite different, they can actually be rather complementary. In some cases, researchers will plan for their study to include multiple components, one inductive and the other deductive. In other cases, a researcher might begin a study with the plan to conduct either inductive or deductive research, but then discovers along the way that the other approach is needed to help illuminate findings. Here is an example of each such case.

Dr. Amy Blackstone (n.d.), author of Principles of sociological inquiry: Qualitative and quantitative methods , relates a story about her mixed methods research on sexual harassment.

We began the study knowing that we would like to take both a deductive and an inductive approach in our work. We therefore administered a quantitative survey, the responses to which we could analyze in order to test hypotheses, and also conducted qualitative interviews with a number of the survey participants. The survey data were well suited to a deductive approach; we could analyze those data to test hypotheses that were generated based on theories of harassment. The interview data were well suited to an inductive approach; we looked for patterns across the interviews and then tried to make sense of those patterns by theorizing about them.

For one paper (Uggen & Blackstone, 2004)\(^6\), we began with a prominent feminist theory of the sexual harassment of adult women and developed a set of hypotheses outlining how we expected the theory to apply in the case of younger women’s and men’s harassment experiences. We then tested our hypotheses by analyzing the survey data. In general, we found support for the theory that posited that the current gender system, in which heteronormative men wield the most power in the workplace, explained workplace sexual harassment—not just of adult women but of younger women and men as well. In a more recent paper (Blackstone, Houle, & Uggen, 2006),\(^7\) we did not hypothesize about what we might find but instead inductively analyzed interview data, looking for patterns that might tell us something about how or whether workers’ perceptions of harassment change as they age and gain workplace experience. From this analysis, we determined that workers’ perceptions of harassment did indeed shift as they gained experience and that their later definitions of harassment were more stringent than those they held during adolescence. Overall, our desire to understand young workers’ harassment experiences fully—in terms of their objective workplace experiences, their perceptions of those experiences, and their stories of their experiences—led us to adopt both deductive and inductive approaches in the work. (Blackstone, n.d., p. 21)\(^8\)

Researchers may not always set out to employ both approaches in their work but sometimes find that their use of one approach leads them to the other. One such example is described eloquently in Russell Schutt’s Investigating the Social World (2006).\(^9\) As Schutt describes, researchers Sherman and Berk (1984)\(^{10}\) conducted an experiment to test two competing theories of the effects of punishment on deterring deviance (in this case, domestic violence).Specifically, Sherman and Berk hypothesized that deterrence theory (see Williams, 2005 \(^{11}\) for more information on that theory) would provide a better explanation of the effects of arresting accused batterers than labeling theory . Deterrence theory predicts that arresting an accused spouse batterer will reduce future incidents of violence. Conversely, labeling theory predicts that arresting accused spouse batterers will increase future incidents (see Policastro & Payne, 2013\(^{12}\) for more information on that theory). Figure 8.3 summarizes the two competing theories and the hypotheses Sherman and Berk set out to test.

Figure 8.3 Predicting the effects of arrest on future spouse battery: Two different theories

Sherman and Berk found, after conducting an experiment with the help of local police in one city, that arrest did in fact deter future incidents of violence, thus supporting their hypothesis that deterrence theory would better predict the effect of arrest. After conducting this research, they and other researchers went on to conduct similar experiments in six additional cities (Berk, Campbell, Klap, & Western, 1992; Pate & Hamilton, 1992; Sherman & Smith, 1992).\(^{13}\)hat the original Sherman and Berk study, along with the follow-up studies, show us is that we might start with a deductive approach to research, but then, if confronted by new data we must make sense of, we may move to an inductive approach. We will expand on these possibilities in section 8.4 when we discuss mixed methods research.

Research from these follow-up studies were mixed. In some cases, arrest deterred future incidents of violence. In other cases, it did not. This left the researchers with new data that they needed to explain. The researchers therefore took an inductive approach in an effort to make sense of their latest empirical observations. The new studies revealed that arrest seemed to have a deterrent effect for those who were married and employed, but that it led to increased offenses for those who were unmarried and unemployed. Researchers thus turned to control theory, which posits that having some stake in conformity through the social ties provided by marriage and employment, as the better explanation (see Davis et al., 2000 \(^{14}\ ) for more information on this theory).

Figure 8.4 Predicting the effects of arrest on future spouse battery: A third theory

What the original Sherman and Berk study, along with the follow-up studies, show us is that we might start with a deductive approach to research, but then, if confronted by new data we must make sense of, we may move to an inductive approach. We will expand on these possibilities in section 8.4 when we discuss mixed methods research.

Ethical and critical considerations

Deductive and inductive reasoning, just like other components of the research process comes with ethical and cultural considerations for researchers. Specifically, deductive research is limited by existing theory. Because scientific inquiry has been shaped by oppressive forces such as sexism, racism, and colonialism, what is considered theory is largely based in Western, white-male-dominant culture. Thus, researchers doing deductive research may artificially limit themselves to ideas that were derived from this context. Non-Western researchers, international social workers, and practitioners working with non-dominant groups may find deductive reasoning of limited help if theories do not adequately describe other cultures.

While these flaws in deductive research may make inductive reasoning seem more appealing, on closer inspection you’ll find similar issues apply. A researcher using inductive reasoning applies their intuition and lived experience when analyzing participant data. They will take note of particular themes, conceptualize their definition, and frame the project using their unique psychology. Since everyone’s internal world is shaped by their cultural and environmental context, inductive reasoning conducted by Western researchers may unintentionally reinforcing lines of inquiry that derive from cultural oppression.

Inductive reasoning is also shaped by those invited to provide the data to be analyzed. For example, I recently worked with a student who wanted to understand the impact of child welfare supervision on children born dependent on opiates and methamphetamine. Due to the potential harm that could come from interviewing families and children who are in foster care or under child welfare supervision, the researcher decided to use inductive reasoning and to only interview child welfare workers.

Talking to practitioners is a good idea for feasibility, as they are less vulnerable than clients. However, any theory that emerges out of these observations will be substantially limited, as it would be devoid of the perspectives of parents, children, and other community members who could provide a more comprehensive picture of the impact of child welfare involvement on children. Notice that each of these groups has less power than child welfare workers in the service relationship. Attending to which groups were used to inform the creation of a theory and the power of those groups is an important critical consideration for social work researchers.

As you can see, when researchers apply theory to research they must wrestle with the history and hierarchy around knowledge creation in that area. In deductive studies, the researcher is positioned as the expert, similar to the positivist paradigm presented in Chapter 5. We’ve discussed a few of the limitations on the knowledge of researchers in this subsection, but the position of the “researcher as expert” is inherently problematic. However, it should also not be taken to an extreme. A researcher who approaches inductive inquiry as a naïve learner is also inherently problematic. Just as competence in social work practice requires a baseline of knowledge prior to entering practice, so does competence in social work research. Because a truly naïve intellectual position is impossible—we all have preexisting ways we view the world and are not fully aware of how they may impact our thoughts—researchers should be well-read in the topic area of their research study but humble enough to know that there is always much more to learn.

Key Takeaways

- Inductive reasoning begins with a set of empirical observations, seeking patterns in those observations, and then theorizing about those patterns.

- Deductive reasoning begins with a theory, developing hypotheses from that theory, and then collecting and analyzing data to test the truth of those hypotheses.

- Inductive and deductive reasoning can be employed together for a more complete understanding of the research topic.

- Though researchers don’t always set out to use both inductive and deductive reasoning in their work, they sometimes find that new questions arise in the course of an investigation that can best be answered by employing both approaches.

- Identify one theory and how it helps you understand your topic and working question.

I encourage you to find a specific theory from your topic area, rather than relying only on the broad theoretical perspectives like systems theory or the strengths perspective. Those broad theoretical perspectives are okay…but I promise that searching for theories about your topic will help you conceptualize and design your research project.

- Using the theory you identified, describe what you expect the answer to be to your working question.

Inductive and Deductive Reasoning — Strategic approach for conducting research

Karl questioned his research approach before finalizing the hypothesis of his research study. He laid a plan and a procedure that consists of steps of broad assumptions to detailed methods of data collection, analysis, and interpretation, wondering how to reason with your findings!

His supervisor provided him the insights about understanding his role in driving the research question by developing a research approach. The supervisor quoted, “In all the disciplines, research plays an essential role in allowing researchers to expand their theoretical knowledge in the field of their study to verify and justify the existing theories. A well-planned research approach will assist one in understanding and building a relationship between theory and objective of the research study.”

Obediently, Karl jotted down the keywords to research on the internet, understand the reasoning, and define the research approach for his research study.

Table of Contents

What Is a Research Approach?

A research approach is a procedure selected by a researcher to collect, analyze, and interpret data. Based on the methods of data collection and data analysis, research approach methods are of three types: quantitative, qualitative, and mixed methods. However, considering the general plan and procedure for conducting a study, the research approach is divided into three categories:

1. Inductive Approach

The inductive approach begins with a researcher collecting data that is relevant to the research study. Post-data collection, a researcher will analyze this data broadly, looking for patterns in the data to develop a theory that could explain the patterns. Therefore, an inductive approach starts with a set of observations and then moves toward developing a theory.

2. Deductive Approach

The deductive approach is the reverse of the inductive approach. It always starts with a theory, such as one or more general statements or premises, and reaches a logical conclusion. Scientists use this type of reasoning approach to prove their research hypothesis .

3. Abductive Approach

This type of reasoning approach is set to answer the weakness associated with deductive and inductive approaches. While following the abductive reasoning approach, researchers start the process with surprising facts or puzzles while studying some empirical phenomena which cannot be explained with the existing theories. Abductive reasoning will assist researchers in explaining the facts or puzzles. Despite its popularity, the abductive approach is challenging to implement and researchers are advised to use traditional deductive or inductive approaches.

Inductive Vs Deductive Reasoning

What Is Inductive Reasoning?

Inductive reasoning moves away from more specific observations to broader generalizations and theories. Usually, this is against the scientific method, an empirical method of acquiring results based on experimental findings. Inductive reasoning makes generalizations by observing patterns and drawing inferences.

Inductive reasoning is based on strong and weak arguments. When the premise is true then the conclusion of the argument is likely to be true. Such an argument is termed a strong or cogent argument. Meanwhile, weak arguments may be false even if the premises they are based upon are true. An argument is a cogent argument if it is weak or the premise is false.

Types of Inductive Reasoning

1. inductive generalization.

Inductive generalization uses observations about a sample to conclude the population from which the sample was chosen. In simple terms, you use statistical results from samples to make statements about populations. One can evaluate large samples or random sampling using inductive generalizations.

2. Statistical Generalization

Statistical generalization uses specific numbers to create statements about populations. This generalization is a subtype of inductive generalization, and it is also termed statistical syllogism.

3. Causal Reasoning

Causal reasoning links cause and effect between different aspects of the research study. A casual reasoning statement starts with a premise about two events that occur simultaneously, followed by choosing a specific direction of causality or refuting any other direction, and concluding a causal statement about the relationship between two things.

4. Sign Reasoning

Sign reasoning makes correlational connections between different things. Inductive reasoning works on a correlational relationship where nothing causes the other thing to occur. However, sign reasoning proposes that one event may be a ‘sign’ to impact another event’s occurrence.

5. Analogical Reasoning

Analogical reasoning concludes something based on its similarities to another thing. It links two things together and then concludes based on the attributes of one thing which holds for another thing. Analogical reasoning could be literal or figurative. However, literal comparison usually uses a much stronger case while reasoning.

Stages of Inductive Research Approach

- Begin with an observation

- Seek patterns in the observation

- Develop a theory or preliminary conclusion based on the patterns observed

Limitations of an Inductive Approach

A conclusion drawn based on inductive reasoning cannot be proven completely, but it can be invalidated.

What Is Deductive Reasoning?

Deductive reasoning starts with one or more general statements to derive a logical conclusion. Moreover, while conducting deductive research, a researcher starts with a theory. This theory could be derived from inductive reasoning. The approach of deductive reasoning is used to test the stated theory. If the general statement or theory is true, the conclusion derived is valid and vice-versa.

Deductive reasoning produces arguments that may be valid or invalid. If the logic is correct, conclusions flow from the general statement or theory and the arguments are valid. Researchers use deductive reasoning to prove their hypotheses. However, if there is no theory yet, then one cannot conduct deductive research.

Types of Deductive Reasoning

There are three common types of deductive reasoning:

1. Syllogism

Syllogism takes two conditional statements and forms a conclusion by combining the hypothesis of one statement with the conclusion of another. For example —

If brakes fail, the car does not stop.

If the car does not stop, it will cause an accident., therefore, brake failure causes the accident., 2. modus ponens.

Modus ponens is another type of deductive reasoning that follows a pattern that affirms the condition of the reasoning. For example —

If a person is born after 1997, then they are a Gen Z

Ryan was born in 1998., therefore, ryan belongs to gen z..

This type of reasoning affirms the previous statement. Meanwhile, the first premise sets the conditional statement to be affirmed.

3. Modus Tollens

Modus tollens is yet another type of deductive reasoning known as ‘the law of contrapositive’. It is the opposite of modus ponens because it negates the condition of the reasoning. For example —

Bruce is not a Gen Z.

Therefore, bruce was not born after 1997., stages of deductive research approach.

- Begin with an existing theory and create a problem statement

- Formulate a hypothesis based on the existing theory

- Collect and analyze data to test the hypothesis

- Decide if you could reject or accept the hypothesis

Limitations of the Deductive Approach

The conclusions drawn from deductive reasoning can only be true if the theory set in the inductive study is true and the terms are clear.

Combination of Inductive and Deductive Reasoning in Research

When researchers conduct a large research project, they begin with an inductive study. This inductive reasoning assists them in constructing an efficient working theory. Therefore, post inductive reasoning, a deductive reasoning could confirm and conclude the working theory. This helps researchers formulate a structured project and mitigates the risk of research bias in the research study.

After doing thorough research in understanding inductive and deductive reasoning, Karl concluded that:

- Inductive reasoning is known for constructing hypotheses based on existing knowledge and predictions.

- Deductive reasoning could be used to test an inductive research approach.

- People tend to rely on information that is easily accessible and available in the world. While theorizing a research hypothesis , this tendency could introduce biases in the study.

- Inductive reasoning could cause biases which can distort the proper application of inductive argument.

- A good scientific research study must be highly focused and requires both inductive and deductive research approaches.

After a few hours of focused research, Karl understood his supervisor’s approach to creating a well-planned research hypothesis for his research study. Karl dived deeper and understood that he had only touched the tip of an iceberg, and there is much more to induce and deduce before he holds his doctorate!

Have you ever encountered a situation like Karl’s? Trying to understand which research approach to use? Did you find this blog informative? Do write to us or comment below and tell us what you feel!

Rate this article Cancel Reply

Your email address will not be published.

Enago Academy's Most Popular Articles

![does quantitative research use inductive reasoning What is Academic Integrity and How to Uphold it [FREE CHECKLIST]](https://www.enago.com/academy/wp-content/uploads/2024/05/FeatureImages-59-210x136.png)

Ensuring Academic Integrity and Transparency in Academic Research: A comprehensive checklist for researchers

Academic integrity is the foundation upon which the credibility and value of scientific findings are…

- Publishing Research

- Reporting Research

How to Optimize Your Research Process: A step-by-step guide

For researchers across disciplines, the path to uncovering novel findings and insights is often filled…

- Industry News

- Trending Now

Breaking Barriers: Sony and Nature unveil “Women in Technology Award”

Sony Group Corporation and the prestigious scientific journal Nature have collaborated to launch the inaugural…

Achieving Research Excellence: Checklist for good research practices

Academia is built on the foundation of trustworthy and high-quality research, supported by the pillars…

- Promoting Research

Plain Language Summary — Communicating your research to bridge the academic-lay gap

Science can be complex, but does that mean it should not be accessible to the…

Choosing the Right Analytical Approach: Thematic analysis vs. content analysis for…

Comparing Cross Sectional and Longitudinal Studies: 5 steps for choosing the right…

Research Recommendations – Guiding policy-makers for evidence-based decision making

Sign-up to read more

Subscribe for free to get unrestricted access to all our resources on research writing and academic publishing including:

- 2000+ blog articles

- 50+ Webinars

- 10+ Expert podcasts

- 50+ Infographics

- 10+ Checklists

- Research Guides

We hate spam too. We promise to protect your privacy and never spam you.

I am looking for Editing/ Proofreading services for my manuscript Tentative date of next journal submission:

As a researcher, what do you consider most when choosing an image manipulation detector?

The potential of working hypotheses for deductive exploratory research

- Open access

- Published: 08 December 2020

- Volume 55 , pages 1703–1725, ( 2021 )

Cite this article

You have full access to this open access article

- Mattia Casula ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-7081-8153 1 ,

- Nandhini Rangarajan 2 &

- Patricia Shields ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-0960-4869 2

64k Accesses

79 Citations

4 Altmetric

Explore all metrics

While hypotheses frame explanatory studies and provide guidance for measurement and statistical tests, deductive, exploratory research does not have a framing device like the hypothesis. To this purpose, this article examines the landscape of deductive, exploratory research and offers the working hypothesis as a flexible, useful framework that can guide and bring coherence across the steps in the research process. The working hypothesis conceptual framework is introduced, placed in a philosophical context, defined, and applied to public administration and comparative public policy. Doing so, this article explains: the philosophical underpinning of exploratory, deductive research; how the working hypothesis informs the methodologies and evidence collection of deductive, explorative research; the nature of micro-conceptual frameworks for deductive exploratory research; and, how the working hypothesis informs data analysis when exploratory research is deductive.

Similar content being viewed by others

Reflections on Methodological Issues

Research: Meaning and Purpose

Research Design and Methodology

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

Exploratory research is generally considered to be inductive and qualitative (Stebbins 2001 ). Exploratory qualitative studies adopting an inductive approach do not lend themselves to a priori theorizing and building upon prior bodies of knowledge (Reiter 2013 ; Bryman 2004 as cited in Pearse 2019 ). Juxtaposed against quantitative studies that employ deductive confirmatory approaches, exploratory qualitative research is often criticized for lack of methodological rigor and tentativeness in results (Thomas and Magilvy 2011 ). This paper focuses on the neglected topic of deductive, exploratory research and proposes working hypotheses as a useful framework for these studies.

To emphasize that certain types of applied research lend themselves more easily to deductive approaches, to address the downsides of exploratory qualitative research, and to ensure qualitative rigor in exploratory research, a significant body of work on deductive qualitative approaches has emerged (see for example, Gilgun 2005 , 2015 ; Hyde 2000 ; Pearse 2019 ). According to Gilgun ( 2015 , p. 3) the use of conceptual frameworks derived from comprehensive reviews of literature and a priori theorizing were common practices in qualitative research prior to the publication of Glaser and Strauss’s ( 1967 ) The Discovery of Grounded Theory . Gilgun ( 2015 ) coined the terms Deductive Qualitative Analysis (DQA) to arrive at some sort of “middle-ground” such that the benefits of a priori theorizing (structure) and allowing room for new theory to emerge (flexibility) are reaped simultaneously. According to Gilgun ( 2015 , p. 14) “in DQA, the initial conceptual framework and hypotheses are preliminary. The purpose of DQA is to come up with a better theory than researchers had constructed at the outset (Gilgun 2005 , 2009 ). Indeed, the production of new, more useful hypotheses is the goal of DQA”.

DQA provides greater level of structure for both the experienced and novice qualitative researcher (see for example Pearse 2019 ; Gilgun 2005 ). According to Gilgun ( 2015 , p. 4) “conceptual frameworks are the sources of hypotheses and sensitizing concepts”. Sensitizing concepts frame the exploratory research process and guide the researcher’s data collection and reporting efforts. Pearse ( 2019 ) discusses the usefulness for deductive thematic analysis and pattern matching to help guide DQA in business research. Gilgun ( 2005 ) discusses the usefulness of DQA for family research.

Given these rationales for DQA in exploratory research, the overarching purpose of this paper is to contribute to that growing corpus of work on deductive qualitative research. This paper is specifically aimed at guiding novice researchers and student scholars to the working hypothesis as a useful a priori framing tool. The applicability of the working hypothesis as a tool that provides more structure during the design and implementation phases of exploratory research is discussed in detail. Examples of research projects in public administration that use the working hypothesis as a framing tool for deductive exploratory research are provided.

In the next section, we introduce the three types of research purposes. Second, we examine the nature of the exploratory research purpose. Third, we provide a definition of working hypothesis. Fourth, we explore the philosophical roots of methodology to see where exploratory research fits. Fifth, we connect the discussion to the dominant research approaches (quantitative, qualitative and mixed methods) to see where deductive exploratory research fits. Sixth, we examine the nature of theory and the role of the hypothesis in theory. We contrast formal hypotheses and working hypotheses. Seven, we provide examples of student and scholarly work that illustrates how working hypotheses are developed and operationalized. Lastly, this paper synthesizes previous discussion with concluding remarks.

2 Three types of research purposes

The literature identifies three basic types of research purposes—explanation, description and exploration (Babbie 2007 ; Adler and Clark 2008 ; Strydom 2013 ; Shields and Whetsell 2017 ). Research purposes are similar to research questions; however, they focus on project goals or aims instead of questions.