10 therapy tasks practiced most frequently by survivors of stroke

Stroke can impact all aspects of life—movement, communication, thinking, and autonomic functions such as swallowing and breathing. Research shows that early and specialized stroke rehabilitation can help to optimize an individual’s physical and cognitive recovery and enhance quality of life. Here, we identify the Constant Therapy tasks used most often by those recovering from stroke.

The goal of stroke therapy: help people regain lost skills

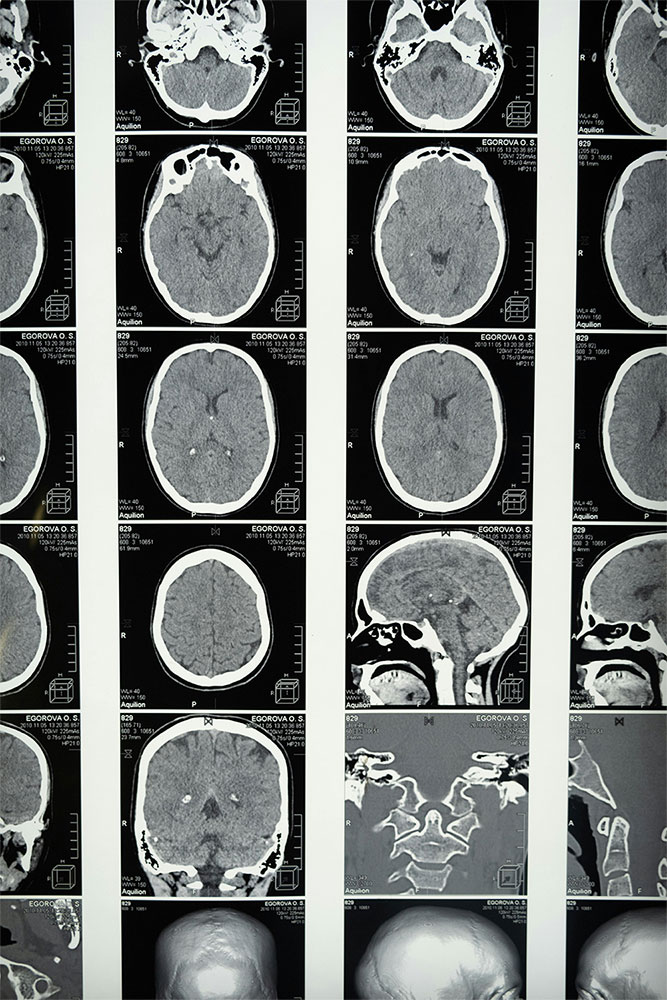

According to the Centers for Disease Control , about 87 percent of all strokes are ischemic strokes, in which blood flow to the brain is blocked. According to the American Speech-Language-Hearing Association, individuals with aphasia or other cognitive-communication issues represent up to 20 percent of the adult caseload for speech-language pathologists in the United States.

Typical goals of stroke therapy include:

- Restoring physical function and enhance the skills needed to perform daily activities

- Building strength, improving balance and regaining mobility

- Improving areas such as speech, language, cognition, or swallowing

- Developing new behavioral or compensatory strategies

Analysis: how is Constant Therapy being used with this population?

Constant Therapy uses artificial intelligence and data analytics to provide each user with a personalized brain exercise program targeting areas such as memory, attention, problem-solving, math, language, reading, writing, and many other skills. Research published in the Journal Frontiers in Human Neuroscience showed a significant improvement in standardized tests for survivors of stroke using the iPad-based rehabilitation technology of Constant Therapy.

An analysis of Constant Therapy users identified what tasks are assigned most frequently by clinicians working with survivors of stroke.

- We looked at data on 18,230 users who identified a diagnosis of stroke on the app.

- These 18,230 users completed an average of 572 tasks each

- Total tasks completed numbered 837,700.

The Constant Therapy tasks listed below are the 10 most frequently assigned by clinicians for their clients recovering from stroke.

The top 10 Constant Therapy exercises assigned by clinicians to patients recovering from stroke

1. Follow instructions you hear : Works on auditory memory and auditory comprehension through following directions . Individuals Assigned: 10,207 Percent of Users Identified As Recovering from Stroke 56%

2. Find the same symbols : Cognitive skills such as attention can be affected after a stroke. Find the same symbols targets a variety of skills which includes attention, visuospatial processing, and executive functioning . Individuals Assigned: 9,216 Percent of Users Identified As Recovering from Stroke: 51%

3. Put steps in order : For people recovering from a stroke, executive functioning skills may be affected. In this planning & organizing task , you are presented with steps of daily activities, and must drag these steps into the correct order. This is a great task for people working on sentence level reading comprehension too! Individuals Assigned: 8,814 Percent of Users Identified As Recovering from Stroke: 48%

4. Match pictures : For people with cognitive, speech, or language disorders, this task helps visual memory by matching pictures displayed on a grid. For people recovering from a stroke who are working on word retrieval, they can also practice naming the pairs of pictures that they match . Individuals Assigned: 7,629 Percent of Users Identified As Recovering from Stroke: 42%

5. Remember pictures in order (N-Back) : This memory task specifically targets an aspect of working memory called updating . There are 3 levels of difficulty. In Level 1, you must remember the order of the pictures from 1 picture ago. In level 3 you must recall 3 pictures ago. Want more N-Back Tasks? Do Remember spoken word order (N-Back) and Remember written words in order (N-back) , too! Individuals Assigned: 7,213 Percent of Users Identified As Recovering from Stroke: 40%

6. Do clock math : Stroke can affect number skills, math skills, and word finding. This task helps improve time-based calculation skills by answering math questions associated with clocks . Individuals Assigned: 6,701 Percent of Users Identified As Recovering from Stroke: 37%

7. Name Pictures : Helps improve word retrieval skills by speaking the name of presented images. There are 3 levels to this task, with each level increasing in word difficulty. Different cues include semantic, phonemic, graphemic, and whole word cues . Individuals Assigned: 6,635 Percent of Users Identified As Recovering from Stroke: 36%

8. Repeat a pattern : This task works on attention, visual working memory, and visuospatial skills . Individuals Assigned: 6,433 Percent of Users Identified As Recovering from Stroke: 35%

9. Understand voicemail : This functional task works on comprehension and memory of everyday language by answering questions about voicemails. Looking for a bigger challenge? Check out Infer from voicemail as well . Individuals Assigned: 6,085| Percent of Users Identified As Recovering from Stroke: 33%

10. Remember the right card : This task works on attention, disinhibition, and processing speed. The patient is asked to remember a playing card and tap on that card whenever it is presented in a series of cards . Individuals Assigned: 5,690 Percent of Users Identified As Recovering from Stroke: 31%

- Des Roches, C., Kiran, S. and Balachandran, I. (2015). Frontiers in Human Neuroscience, Effectiveness of an impairment-based individualized rehabilitation program using an iPad-based software platform , 2015 Jan 5. doi: 10.3389/fnhum.2014.01015.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (2018). Stroke Facts .

- ASHA (2017). SLP Healthcare Survey: Caseload Characterisics .

Tackle your speech therapy goals, get top-notch support

Related articles, 11 comments.

Do you get this from the App Store? What is the cost?

Hi Lisa. Yes, check out the app store. Our monthly plan is $25 and an annual plan is $250 with a free tablet. If you want to set up a trial and need support, give us a call or email. 1-888-233-1399 or [email protected]

When I purchased a whole year package in 2023 I never received a free tablet. Is this something new?

Hi Todd, thank you so much for subscribing to Constant Therapy! Apologies for the confusion, this is an older comment and we discontinued this program back in 2019. If you have any questions or concerns about the device you use for Constant Therapy feel free to reach out to our Support Team at [email protected] .

What is the app name please?

- Constant Therapy

Thanks have learnt something. Am struggling with after stroke effects especially speech

Is there a way to have the math word problem questions read to you? My brother is working on math as well as re learning reading. He cannot read the questions yet to do the math problem…

Great question! This is a feature that we are working to add in the near future – keep an eye out for announcements in our weekly emails once we have that feature ready to use!

What exercises are recommended for people with primary progressive apraxia?

Hello Alberta, thank you for your question! We spoke with a Speech Language Pathologist and they said that difficulty levels will depend on the condition’s progression. You may be interested at looking into these exercises: Imitate Words, Imitate Sentences, Form and Say Active Sentences, and Form and Say Passive Sentences . These tasks will allow you practice with articulating speech at various levels of complexity. Hope this is helpful!

Submit a Comment Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Constant Therapy Health

- Partner with us

- Try for free

- Request a Demo

- Conditions we support

- For clinicians

- For patients

- For veterans

Support + Resources

- Printable Resources

- Testimonials

Join the Conversation

Last updated on June 21, 2024

While games can be enjoyable for individuals of every age, games for stroke patients can actually promote recovery. During rehabilitation, it is critical to stay active, both physically and mentally. While many individuals focus heavily on physical recovery, cognitive recovery can be equally as important.

Because such a wide variety of games have been developed, survivors can often find at least one game that targets the specific cognitive skills they are hoping to improve. Stimulating the brain through games can activate neuroplasticity , the brain’s natural repair mechanism. Therefore, repetitively practicing cognitive skills through games can allow survivors to regain and maintain functions that were impaired or lost after stroke.

This article provides an overview of many fun and challenging games that are ideal for improving cognitive function among stroke patients. These are organized by the types of cognitive skills addressed, with three difficulty levels provided in each category. Use the links below to jump directly to any section.

- Memory and attention games

- Games to improve processing speed

- Developing language skills through games

- Games for improving visual skills

- Further considerations

Memory and Attention Games

The cognitive skills of memory and attention are essential for playing almost any game. Long-term memories may be drawn upon when replaying a game that an individual had played in the past, while working memory is vital to learn and remember how new games are played. The skills of sustained and selective attention are also necessary to focus on game play and tune out any unrelated distractions.

Games that specifically address memory and attention include:

- Beginner: Old Maid or Go Fish . These simple card games can be a great starting point for individuals whose memory and attention skills have been severely affected. Since these games are relatively quick, they require a limited amount of sustained attention. Short-term and working memory can also be challenged when trying to remember which players have which cards.

- Intermediate: Concentration or Guess Who? During the game of Concentration, survivors can challenge their working memory and sustained attention skills by try to pick two matching cards from a set of cards laid out on the table. Guess Who? can also address these skills, while also allowing individuals to work on mental organization and classification skills when grouping characters together by their similarities and differences.

- Advanced: Clue or Azul . These more complex games can be used to fine-tune memory and attention skills, while also exercising reasoning and problem-solving abilities.

Improving Processing Speed through Games

Certain games for stroke patients can also help to increase processing speed. While individuals may require extra time to play these games initially, with practice, their processing speed may improve. Games that can help improve processing speed include:

- Beginner: Dutch Blitz or Spoons . These fast-paced card games require skills such as pattern recognition and sequencing, as well as adequate fine motor skills to quickly grasp and manipulate the cards. Practicing these games independently before playing with more players can be an excellent way to gradually improve processing speed as well.

- Intermediate: Perfection . This game, which involves placing uniquely shaped pieces into their matching holes before a timer goes off, can challenge both fine motor skills and processing speed. To begin with, individuals may choose to practice this game without the timer or use a stopwatch to see how fast they can place all of the pieces into their respective positions.

- Advanced: Pictionary or Charades . Playing games during which individuals draw, act out, or describe a specific item can be a fun yet challenging way to work on improving processing speed. Since the individual depicting the targeted word is constantly adapting their presentation, survivors have to use rapid processing skills in order to provide accurate guesses.

Games that Promote Language Skills

The ability to express and comprehend language is frequently impaired after stroke. The following games may help survivors who experience communication challenges due to aphasia, apraxia of speech, or dysarthria .

- Beginner: Boggle . Played by connecting adjacent letters to create words, Boggle is a great game for individuals targeting word-finding skills. Language expression skills can also be practiced by writing or verbally stating the words found in the game. Some survivors may also benefit from initially playing independently without any time constraints to create a low-pressure and enjoyable atmosphere.

- Intermediate: Catch Phrase or Taboo . These fast-paced word games can challenge both receptive and expressive language skills as players race to guess which word the speaker is describing. Although against the official rules, players may choose to allow gestures to boost communication and even the playing field.

- Advanced: Bananagrams or Scrabble . Both involving small letter tiles to create words, playing Bananagrams or Scrabble can be a great way to promote language skills and word-finding abilities. If trying to use the letters already in play to create words is too challenging, players can simply take 25 tiles and attempt to make as many words as possible.

Games Focused on Visual Skills

A stroke may affect vision , causing challenges such as visual field deficits or problems with visual attention. For example, individuals with hemianopia or hemineglect may be unable to see or perceive anything on one side of their body.

While most games involve at least some visual components, the games below can be particularly helpful for addressing visual skills.

- Beginner: Connect 4 or Sequence . These games, which involve connecting multiple game chips in a row, column or on diagonal, can promote visual scanning skills and cognitive flexibility. Since Sequence is a little more complicated, it may be best to try Connect 4 before playing Sequence. Furthermore, some survivors may benefit from trying the “giant” versions of Connect 4 or Sequence to enhance visual awareness of a larger area and improve gross motor skills.

- Intermediate: Spot It! or Blink . Card games, such as Spot It! or Blink, can exercise skills such as visual memory, visual discrimination, and visual scanning. While these games are designed to be fast-paced, slowing them down can make game play more enjoyable for survivors while they are improving.

- Advanced: Battleship . This game can challenge visuospatial skills while also exercising reasoning and problem-solving abilities. Fine motor precision skills may also be challenged.

Considerations Regarding Games for Stroke Patients

While the list above provides a starting point for stroke survivors hoping to enhance their cognitive skills through games, it is by no means exhaustive. A speech or occupational therapist may be able to provide more personalized recommendations.

Finding a game that is appropriately challenging, yet still enjoyable, can sometimes be difficult. Many games have a junior or kid’s version, which may help survivors who need just a little more practice before trying the standard game. Alternatively, adding more players, time constraints, or external distractions can make games a little more challenging.

Survivors who are looking to fine-tune their cognitive skills may benefit from playing more advanced strategy games. These games often require intense concentration, long periods of sustained attention, and high-level problem-solving skills.

Example strategy games for stroke patients include:

- Carcassonne : a puzzle-based game that can challenge visuospatial skills and problem-solving

- Chess : a traditional game requiring planning, judgement and reasoning

- Catan : a building and trading game requiring constant cognitive flexibility and social skills

Finally, some survivors prefer to use gamified rehabilitation technology, such as the CT Speech and Cognitive Therapy App , FitMi , or the MusicGlove . These devices and programs can address cognitive and/or physical functions while adapting to the survivor’s skill level to provide a just-right challenge. By combining the motivational qualities of gaming with the therapeutic benefits of rehabilitation, survivors can get the best of both worlds.

Finding the Best Games for Stroke Patients

Games can be an engaging option for improving cognitive skills after stroke and can help promote a faster and fuller recovery from stroke. Different games will engage different parts of the brain to target specific cognitive skills.

Therefore, it is important to choose games that will address the survivor’s targeted skills. Games can also be modified to offer an appropriate challenge without becoming overwhelming.

The best games for stroke patients will vary depending on the individual’s needs and skill level. However, games can be an excellent tool to use to boost motivation and brighten a survivor’s recovery journey.

Keep It Going: Download Our Stroke Recovery Ebook for Free

Get our free stroke recovery ebook by signing up below! It contains 15 tips every stroke survivor and caregiver must know. You’ll also receive our weekly Monday newsletter that contains 5 articles on stroke recovery. We will never sell your email address, and we never spam. That we promise.

Related Articles

Top 7 Vitamins for Stroke Recovery Based on the Latest Clinical Evidence

Understanding Chronic Stroke: What It Means & How to Recover

Why "One More Time" Matters in Stroke Rehab

Discover award-winning neurorehab tools.

Do you have these 25 pages of rehab exercises?

Get a free copy of our ebook Full Body Exercises for Stroke Patients. Click here to get instant access.

You're on a Roll: Read More Popular Recovery Articles

“Use It or Lose It:” What This Popular Neurorehab Phrase Means

Shoulder Exercises for Stroke Patients to Improve Stability, Mobility and Strength

10 Swallowing Exercises for Stroke Patients to Recover from Dysphagia

You’re Really on a Roll! See how Jerry is regaining movement with FitMi home therapy

My husband is getting better and better!

“My name is Monica Davis but the person who is using the FitMi is my husband, Jerry. I first came across FitMi on Facebook. I pondered it for nearly a year. In that time, he had PT, OT and Speech therapy, as well as vision therapy.

I got a little more serious about ordering the FitMi when that all ended 7 months after his stroke. I wish I hadn’t waited to order it. He enjoys it and it is quite a workout!

He loves it when he levels up and gets WOO HOOs! It is a wonderful product! His stroke has affected his left side. Quick medical attention, therapy and FitMi have helped him tremendously!”

– Monica & Jerry’s FitMi review

What are these “WOO HOOs” about?

FitMi is like your own personal therapist encouraging you to accomplish the high repetition of exercise needed to improve.

When you beat your high score or unlock a new exercise, FitMi provides a little “woo hoo!” as auditory feedback. It’s oddly satisfying and helps motivate you to keep up the great work.

In Jerry’s photo below, you can see him with the FitMi pucks below his feet for one of the leg exercises:

FitMi is beloved by survivors and used in America’s top rehab clinics

Many therapists recommend using FitMi at home between outpatient therapy visits and they are amazed by how much faster patients improve when using it.

It’s no surprise why over 14,000 OTs voted for FitMi as “Best of Show” at the annual AOTA conference; and why the #1 rehabilitation hospital in America, Shirley Ryan Ability Lab, uses FitMi with their patients.

This award-winning home therapy device is the perfect way to continue recovery from home. Read more stories and reviews by clicking the button below:

Support @ flintrehab.com

1-800-593-5468

Mon-Fri 9am-5pm PST

Get Started

Our Products

Grab a free rehab exercise ebook!

Sign up to receive a free PDF ebook with recovery exercises for stroke, traumatic brain injury, or spinal cord injury below:

Government Contract Vehicles | Terms of Service | Return Policy | Privacy Policy | My Account

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- Ann Behav Med

Psychological Stress Management and Stress Reduction Strategies for Stroke Survivors: A Scoping Review

Madeleine hinwood.

School of Medicine and Public Health, The University of Newcastle, Callaghan, NSW, Australia

Hunter Medical Research Institute, New Lambton Heights, NSW, Australia

Marina Ilicic

School of Biomedical Sciences and Pharmacy, The University of Newcastle, Callaghan, NSW, Australia

Priority Research Centre for Stroke and Brain Injury, The University of Newcastle, Callaghan, NSW, Australia

Prajwal Gyawali

School of Health and Wellbeing, Faculty of Health, Engineering and Sciences, University of Southern Queensland, Darling Heights, QLD, Australia

Kirsten Coupland

Murielle g kluge.

Centre for Advanced Training Systems, The University of Newcastle, Callaghan, NSW, Australia

Angela Smith

HNE Health Libraries, Hunter New England Local Health District, New Lambton, NSW, Australia

Consumer Investigator, Moon River Turkey, Bathurst, NSW, Australia

Michael Nilsson

Centre for Rehab Innovations, The University of Newcastle, Callaghan, NSW, Australia

LKC School of Medicine, Nanyang Technological University, Singapore

Frederick Rohan Walker

Associated data.

Stroke can be a life-changing event, with survivors frequently experiencing some level of disability, reduced independence, and an abrupt lifestyle change. Not surprisingly, many stroke survivors report elevated levels of stress during the recovery process, which has been associated with worse outcomes.

Given the multiple roles of stress in the etiology of stroke recovery outcomes, we aimed to scope the existing literature on stress management interventions that have been trialed in stroke survivors.

We performed a database search for intervention studies conducted in stroke survivors which reported the effects on stress, resilience, or coping outcome. Medline (OVID), Embase (OVID), CINAHL (EBSCO), Cochrane Library, and PsycInfo (OVID) were searched from database inception until March 11, 2019, and updated on September 1, 2020.

Twenty-four studies met the inclusion criteria. There was significant variation in the range of trialed interventions, as well as the outcome measures used to assess stress. Overall, just over half (13/24) of the included studies reported a benefit in terms of stress reduction. Acceptability and feasibility were considered in 71% (17/24) and costs were considered in 17% (4/24) of studies. The management of stress was rarely linked to the prevention of symptoms of stress-related disorders. The overall evidence base of included studies is weak. However, an increase in the number of studies over time suggests a growing interest in this subject.

Conclusions

Further research is required to identify optimum stress management interventions in stroke survivors, including whether the management of stress can ameliorate the negative impacts of stress on health.

In this review, we found that interventions to reduce stress in stroke survivors were highly variable, and although more than half reported a positive effect in reducing stress, the feasibility of deploying these interventions in practice was rarely considered.

Introduction

Advances in the treatment of stroke, particularly the introduction of clot-busting drugs and clot retrieval technologies, have significantly reduced stroke mortality [ 1 ]. Improvements in diagnosis and rehabilitation have also improved stroke outcomes; however, many stroke survivors continue to experience poor health outcomes for their remaining lifespan. Stroke is one of the five leading global causes of disability-adjusted life years, and the number of years lost as a result of poor health or disability from cardiovascular disease (CVD), including stroke, is greater than the number of years lost to cardiovascular death globally [ 2 ]. This suggests an urgent need to identify new targets and interventions to improve quality of life (QoL) following stroke.

Psychosocial wellbeing after stroke has been relatively neglected compared with motor and other physical symptoms, which are often the primary focus of rehabilitation efforts. One emerging prognostic factor determining the quality of psychological and emotional recovery from stroke is stress [ 3 , 4 ]. Stroke survivors report experiencing persistently high levels of stress, with greater levels of perceived stress poststroke associated with poorer long-term outcomes [ 5–10 ]. Several observational studies have consistently reported significant correlations between stress and worse stroke outcomes, including functional independence, psychological outcomes such as depression, and cognitive function. Likewise, greater resilience, which is defined as the capacity to withstand adversity and “bounce back” after a stressful event, is associated with better QoL poststroke [ 7 , 11 ]. Further, stress is among the strongest proximal risk factors for depression and anxiety disorders, and the risk of these stress-related mental health disorders is significantly greater in stroke survivors compared with the general population [ 12 ]. In the 2 years immediately following stroke, the risk of depression for stroke survivors was around 25%, compared with 8% in a control group of people the same age [ 12 ]. Stroke survivors are also at increased risk of other stress-related disorders, including post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and anxiety disorders [ 13 , 14 ]. These psychological problems are independently associated with increased morbidity, mortality, and disability [ 15 , 16 ]. In addition to a heightened risk of stress-related disorders, the recovery domains influenced by stress broadly contribute to worse QoL, reduced motivation and lower levels of self-reported wellbeing, which in turn may negatively impact participation in rehabilitation. This is likely to potentiate a positive feedback loop between heightened stress perception and poor participation in rehabilitation.

There is clear evidence that rehabilitation interventions can influence patient outcomes after stroke [ 15 , 17 ]. Therefore, identifying and modifying alternative prognostic factors for recovery outcomes are of vital importance to improve trajectories for stroke survivors. Studies highlighting the association between stress and significant downstream effects such as emotional and cognitive problems and poor functional recovery suggest that managing stress may be beneficial to stroke survivors [ 8–10 ]. There is some evidence that stress management interventions in populations with other chronic illnesses, particularly cancer and CVD, can decrease symptoms of depression, and promote resilience [ 18 , 19 ]. However, it is unclear which interventions to mitigate stress have been trialed for stroke survivors.

Psychological stress is a complex phenomenon, and numerous theoretical models of stress have been proposed. There are also various terminologies in the literature to describe the evaluation of state stress. Variations in terminology connected to stress as a short- or long-term outcome may include stress, distress, depression, anxiety, coping, and QoL. The converse can also be identified; although stress exposure can have lasting negative impacts on psychological health and wellbeing, not all individuals will go on to develop these outcomes, and resilience scores are therefore also frequently examined [ 19 ]. In this study, we conceptualized psychological stress according to the stress, appraisal, and coping framework proposed by Lazarus and Folkman [ 20 ], adapted for the stroke setting in Fig. 1 , where stress is a consequence of an individual’s appraisal of their environment, and their perceived ability to cope with a situation or incident. Therefore, depending on how it is appraised, a stressor may have differential short- and long-term effects upon an individual. Interventions to manage stress may be deployed at any point along a spectrum, with primary interventions primarily concerned with stressor reduction, secondary with stress management, and tertiary with remedial support or treatment of stress-related conditions. Here, we expected to find most interventions at the secondary (stress management) level, with outcomes primarily based on the effectiveness of the intervention in the short term (e.g., reduction in perceived stress or other stress marker; improvement in coping skills; or improvement in resilience), and on the ability of the intervention to prevent other downstream effects of stress, such as symptoms of anxiety and depression. Our framework guided the design of the research questions, literature search, identification of studies, and the collation of results.

Conceptual framework of stress processes after stroke, and spectrum of interventions to manage or reduce stress (adapted from Folkman and Lazarus [ 20 ]).

Given that research into stress management strategies for stroke survivors is an emerging area of research, we collated the results of existing studies under several broad topic areas. In addition to mapping and assessing the reported effectiveness of interventions, we also aimed to collate information on the stress outcome measures used, whether long-term effects of stress were considered, and implementation outcomes (specifically acceptability, feasibility, and economic analyses).

Given the breadth of information to be accumulated, we decided to perform a scoping rather than a systematic review. Scoping reviews are designed to assess the coverage of a body of literature, and to identify gaps and map available evidence. Systematic reviews in health care tend to be more focused on confirming or refuting whether current practice is based on evidence, and to establish the quality of that evidence [ 21 ]. Our overall aim was to broadly map the body of literature concerning stress management interventions in stroke survivors. Further, we aimed to synthesize existing results and approaches around stress interventions in stroke survivors to guide the development and implementation of stress management in future studies, identify knowledge gaps, and clarify key concepts around the measurement of stress in stroke survivors. Therefore, as we were mapping a heterogeneous body of literature rather than synthesizing the best available research to answer a specific question, a scoping review methodology was considered most appropriate.

This scoping review was conducted in accordance with the PRISMA extension for scoping reviews [ 22 ].

A protocol was published prior to conducting this review [ 23 ] based upon the framework proposed by Arksey and O’Malley [ 24 ] and updated by Levac et al. [ 25 ], and the methods outlined in the Joanna Briggs Institute Reviewers’ Manual [ 26 ]. The scoping review process is an iterative one, and the inclusion and exclusion criteria were refined during full-text review for clarity and specificity to the review’s objectives following discussion among the research team. The PRISMA Extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR) checklist was referenced to ensure systematic reporting of this scoping review [ 22 ].

Identification of the Research Question

Overall, we were interested in mapping the existing intervention literature for stress reduction or stress management in stroke survivors. As an emerging and inconsistently defined field, we anticipated enormous heterogeneity in the way stress is defined, operationalized, and measured across studies, and in the way that stress and stress prevention studies are designed. Based on the conceptual framework presented in Fig. 1 , we included any intervention studies which measured stress or a related concept as an outcome; therefore, the included studies encompassed both interventions specifically designed for stress reduction, and interventions that did not explicitly aim to reduce stress, but which reported a reduction in a stress-related outcome, such as self-reported stress. The following broad aims, which attempt to capture this heterogeneity of studies under the Lazarus and Folkman framework [ 20 ], guided this scoping review:

- To map the range of interventions trialed addressing stress management in stroke survivors and to identify which interventions are potentially efficacious for reducing stress, or increasing resilience and coping skills.

- To identify the average duration of study length and follow-up. Stroke is a chronic condition with recovery occurring for months and years after the initial event. Further, it would be of interest to assess the potential impact of interventions on longer-term outcomes that may be affected by acute improvements in stress management. Ideally, stress intervention models would match the natural history of stroke and stress-related problems, and this would be reflected in follow-up times of adequate duration.

- To map the multidimensional range of outcome measures that have been used for stress, resilience, and coping in stroke survivors. We anticipated heterogeneous literature, with no broadly accepted outcome measure for psychological stress. Acute and chronic stress can be quantified using various approaches including self-reported, psychometric assessments, as well as physiological biomarkers.

- To identify whether early intervention for stress translates into a reduction in longer-term stress-related clinical outcomes as shown in Fig. 1 , including depression, anxiety, and PTSD. Although we do not expect psychological stress to be the sole cause of mental disorders poststroke, most cases of depression and anxiety can, to some extent, be traced back to the influence of exogenous or endogenous stressors [ 27 ]. Therefore, although an improvement in stress management or coping, or a reduction in perceived stress will not explain all the variation in poststroke depression or anxiety, we would expect a positive effect on mood disorders due to a preventive effect. However, since stress management does not specifically treat mood symptoms, significant changes in mood, and diagnosis with stress-related disorders, may not be observed.

- The success of any intervention is in part dependent on the successful implementation within its environment and context. Therefore, we collected information on whether studies considered implementation outcomes, including potential barriers and limitations, feasibility and acceptability, and economic considerations. This is particularly relevant for stress management approaches, as they may be time consuming, expensive, and difficult to scale up to larger populations.

Search and Screening Methods

The search strategy was designed around the aims of the review and included two key concepts, stroke and stress. The search was designed to align with the stress, appraisal, and coping framework used to conceptualize stress in this review. Broadly, interventions for stress reduction were operationalized in the following way: any intervention (pharmacological or nonpharmacological) delivered in individual, family, or group settings, incorporating strategies to prevent or delay the development of excessive stress, promote coping strategies or resilience, to improve optimism and wellbeing, or to improve or relieve stress-related outcomes, including symptoms of mood disturbance. We included all types of intervention studies (randomized controlled trials [RCTs] and quasi-experimental designs). The research question and corresponding search strategy are defined using the Population, Intervention, Comparator, Outcome, Study design (PICOS) framework (see Supplementary File 1 ). A complete description of the strategies for database searching, filtering methods, abstract identification, and screening was provided in a previously published protocol [ 23 ]. The search for this scoping review was iterative in nature. It began with a gold standard set of articles that informed the selection of medical subject headings (MeSH), keywords, and keyword phrases. The strategy was further refined through reference checking and forward and backward citation checking. Search strategies from reviews in relevant areas were also searched. The search strategy drew on the work of the Cochrane Stroke Group to operationalize search terms for stroke. The search strategy was developed in Medline before being optimized for Embase, resulting in the need to include some additional Emtree terms to capture additional relevant citations. The strategy was then translated to PsycInfo, CINAHL, and the Cochrane Library. All databases were searched from inception until March 11, 2019, and updated on December 12, 2019. The search was updated again prior to submission on September 1, 2020 ( Supplementary File 2 ). Database searches were restricted to subjects and English language citations only. Primary evidence (empirical research) only was included.

An assessment of study quality is optional in scoping reviews; however, may be conducted to gain an appreciation of the quality of evidence in a field. We did not exclude articles based on quality or design; however, we did conduct an assessment of study quality using the Cochrane Risk of Bias tool or the Mixed Methods Appraisal Tool (MMAT), where appropriate, in order to evaluate the existing quality of evidence in the area.

Identifying Relevant Studies

The search yield was imported into Covidence software and duplicates were removed. Title and abstract, and full-text screening were completed separately by members of the research team (M.H., M.I., P.G., M.K., and KC), with each article independently screened by two team members. Discrepancies during screening and reviewing were resolved by a consensus among all reviewers. Inconsistencies were discussed and resolved, and inclusion criteria were refined to improve the application of inclusion/exclusion criteria.

To be included, studies had to meet the following criteria: (a) include an intervention; (b) involve human adult stroke survivors (age ≥18 years); (c) be written in English; and (d) include at least one outcome measure related to stress or resilience. Outcome measures were consistent with the Lazarus and Folkman [ 20 ] stress–coping–appraisal framework, and incorporated changes in direct measures including perceived stress, resiliency, coping skills, and problem-solving, as well as measures of changes in state stress and aligned constructs, including emotional distress, coping, resilience, QoL, and symptoms of anxiety or depression. Although some of the latter measures do not measure stress directly, they were included as outcomes in several publications consistent with the Lazarus and Folkman framework [ 20 ] which aimed to improve coping or problem-solving skills, were hypothesized to thereby improve QoL, and reduce emotional distress in stroke survivors [ 28–31 ], and were therefore included in this review. This reflects the substantial impact that stress can have on physical and mental health. Exclusion criteria included: (a) nonexperimental (e.g., observational, case–control, cross-sectional, longitudinal) studies (i.e., without implementation of an intervention); and (b) relevant reviews (systematic and meta-analysis), but reference lists were hand-searched to identify additional eligible articles. Studies could be randomized or nonrandomized (quasi-experimental).

Charting the Data

Data extraction was independently completed by five reviewers (M.H., M.I., P.G., M.K., and K.C.). The data extraction spreadsheet was designed to capture all relevant details required to answer the research questions and included: author, year published, country, sample size, and population characteristics were recorded (e.g., age, stroke type, and time since stroke, severity measures, comorbidities), outcome measures associated with stress, length of follow-up, type of intervention, duration of intervention, control group, any measures of acceptability and feasibility, any measures of barriers, study limitations, and any measures of cost or cost-effectiveness. The spreadsheet was refined via an iterative process in collaboration with all reviewers.

Collating, Summarizing, and Reporting the Results

We tabulated key information from included studies descriptively. We categorized interventions by intervention type, study duration, and follow-up (in line with aims 1 and 2), explored how stress and stress-related disorders were measured in these studies (in line with aims 3 and 4), and assessed effectiveness (in line with aim 1) and other measures that may affect implementation, including barriers, acceptability, and cost-effectiveness (in line with aim 5). Records in the PsycInfo database receive a classification code, which is used to categorize the document according to the primary subject matter. We used these classification codes to map interventions to higher-order keywords to categorize them. Findings were presented in a narrative synthesis.

Deviations From the Protocol

We originally stated that we would identify potential findings which may help to inform practice and/or guidelines. Some recent guidelines for CVD identify stress as an important risk factor [ 32 ]; however, there are no best-practice recommendations for the management or reduction of stress in stroke survivors. The included studies were overwhelmingly early phase and/or feasibility trials, and as such no recommendation for an approach to stress management could be determined based on the evidence synthesis included in this review.

Assessment of Study Quality

Quality appraisal was used to broadly assess the quality of the literature, to determine where the field currently lies in terms of evidence development. It was not intended to stratify papers into a hierarchy of evidence, and publications were not excluded from the review based on quality. To assess the quality of the quantitative studies, the Cochrane Risk of Bias 2 (RoB2) quality appraisal tool was used [ 33 ]. For any included qualitative or mixed-method studies, the MMAT was used [ 34 ]. The MMAT does not have an overall rating category, and therefore we used the following guide to assess the overall risk of bias associated with each publication: (a) strong (80% or more of the quality indicators were met), (b) moderate (between 40% and 80% of the quality indicators were met), and (c) weak (less than 40% of the quality indicators were met).

Included and Excluded Articles

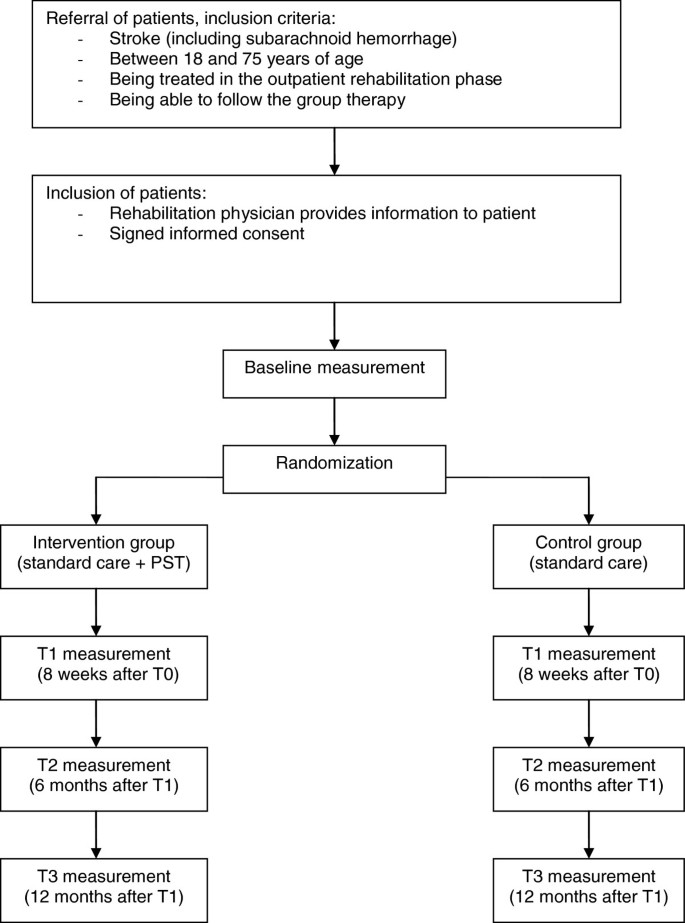

The study selection process is summarized in the PRISMA flow diagram ( Fig. 2 ) [ 35 ]. The initial search, which was conducted on March 11, 2019, identified 2,653 references after deduplication. The search was updated on December 12, 2019, and again prior to submission on September 1, 2020, after which there was a total of 3,140 studies imported to Covidence, with 3,048 available for screening following deduplication. Of these, 116 articles were considered potentially relevant after initial exclusions of titles and abstracts. A further 92 were excluded after a two-person review of the full text. A total of 24 articles were included in this review [ 28–31 , 36–55 ].

PRISMA flow diagram [ 35 ].

Study Characteristics

Study characteristics, including country, study design, participants, intervention, comparator, and length of follow-up, are summarized in Supplementary File 3 . Included studies were published between 1992 and 2020, with most ( n = 17; 70%) published in the last 5 years [ 28 , 31 , 36 , 38–42 , 45–48 , 51–55 ].

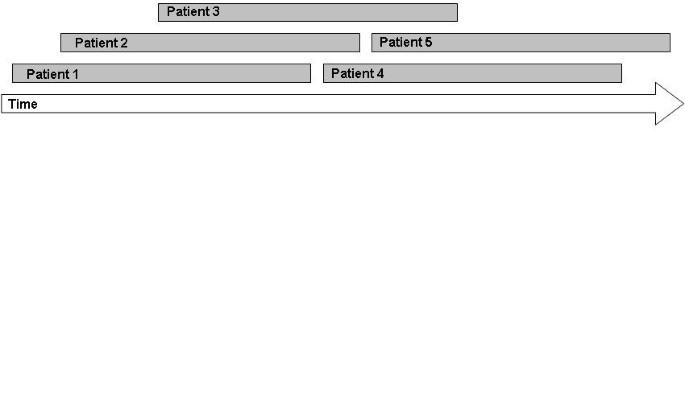

There was significant variability in study design, including RCTs and non-RCTs, and uncontrolled before and after studies. The type, duration, and frequency of intervention used also varied across studies, with interventions running from five sessions over 1 week (aromatherapy foot bath and massage) [ 46 ], to 6 months (antidepressant treatment with sertraline [ 49 ]; home-based psychoeducational program [ 50 ]). Most interventions ran weekly sessions over approximately 8–12 weeks ( n = 15) [ 29–31 , 40–42 , 44 , 45 , 48–52 , 54 , 55 ]. The duration of follow-up also varied significantly between studies, ranging from 0 (immediate follow-up) to 12 months. Finally, as we placed no restrictions on study type beyond intervention studies, three studies used qualitative thematic analyses (via survey or interview) [ 37 , 40 , 48 ], in which stress emerged as a theme.

Whilst the reported sample sizes varied from 8 to 166 participants, most of the included studies had relatively small sample sizes, with 16 out of 24 studies recruiting fewer than 50 participants [ 28 , 29 , 36 , 37 , 39–42 , 44–48 , 51–54 ].

The populations in the included studies varied in terms of time poststroke, and whether a broad or selected population was recruited. Most studies reported time postonset of stroke; only Nour et al. [ 29 ] and Chouliara and Lincoln [ 40 ] did not explicitly define time poststroke; Nour et al. [ 29 ] stated that participants had finished active rehabilitation. We categorized the populations according to the critical time points of stroke recovery proposed in Bernhardt et al. [ 56 ], including hyperacute (0–24 hr), acute (1–7 days), subacute (7 days to 6 months), and chronic (>6 months) phases. The majority of studies ( n = 15) [ 28 , 30 , 31 , 41 , 43–48 , 50–54 ] involved participants recruited in the chronic phase of recovery. Five studies involved participants recruited during the subacute phase of stroke [ 37 , 38 , 42 , 49 , 55 ]. Two studies recruited participants during the acute period, whilst patients were hospitalized [ 36 , 39 ]. We based our assessments on the mean or median times poststroke reported in the studies; therefore, a small number of studies may have included participants across multiple phases of recovery, primarily subacute to chronic. Studies rarely specified whether included participants were first or recurrent stroke survivors or details of stroke type.

Three of the included studies used a selected population (i.e., those reporting high distress, or those with an existing diagnosis of depression, anxiety, or fatigue [ 41 , 49 , 52 ]), in order to assess the effect of an intervention on these outcomes. Many studies excluded people with a progressive neurological disorder or cognitive dysfunction, reduced life expectancy, subdural hematomas, moderate or severe aphasia, or who partook in excessive drinking or drug abuse [ 31 , 38 , 39 ]. Studies typically justified this approach by stating that collecting and reliably interpreting data from these patients can present significant challenges.

Study Interventions

The types of interventions trialed for stress management across the included studies are summarized in Table 1 .

Characteristics of interventions used to address stress levels in stroke survivors

| Type | Subtype | Theory/hypothesis | Studies |

|---|---|---|---|

| Psychosocial | |||

| Social support networks | Social support | Social support intervention would improve the support experienced by stroke survivors, as such leading to better psychosocial outcome. | Friedland and McColl (1992) [ ] |

| Cognitive processes | MBSR | MBSR will reduce mental fatigue after stroke and TBI. | Johansson et al. (2012) [ ] |

| Problem-solving therapy | Problem-solving therapy will improve coping strategy, QoL, and reduce emotional distress in stroke survivors. | Visser et al. (2016) [ ] Chalmers et al. (2019) [ ] | |

| Meditation | Meditation will cultivate mindfulness to train ttention and awareness, to achieve a mentally clear and emotionally calm and stable state. | Love et al. (2020) [ ] | |

| Rehabilitation/ neuropsychological rehabilitation | Memory rehabilitation | Memory rehabilitation will develop patients’ ability to cope with or compensate for residual memory deficits, as well as promoting participation. | Chouliara and Lincoln (2016) [ ] |

| Leisure rehabilitation | Leisure education will improve QoL and depression in stroke survivors. | Nour et al. (2002) [ ] | |

| Behavioral | Proactive coping intervention | Stroke survivors with better proactive coping skills will experience improved self-efficacy and QoL. | Tielemans et al. (2015) [ ] |

| Motor processes | Physical activity program/exercise | Improving and maintaining physical activity levels will improve the overall health, including psychological functioning, cognitive functioning, and sleep, of adults with acquired brain injury. | Jones et al. (2016) [ ] Colledge et al. (2017) [ ] |

| Aquatic therapy | Aquatic therapy will minimize anxiety, fatigue, and depression, which tend to be barriers to stroke rehabilitation. | Perez-de la Cruz (2020) [ ] | |

| Psychotherapy | Positive psychotherapy | Positive psychotherapy will alleviate psychological distress after acquired brain injury. | Cullen et al. (2018) [ ] Terrill et al. (2018) [ ] |

| SFBT | SFBT will reduce depression and anxiety symptoms, generate a constructive attitude, and increase self-efficacy in patients poststroke. | Wichowicz et al. (2017) [ ] | |

| Creative arts therapy | Person-centered arts program | Participation in an arts program will improve the emotional and mental wellbeing of stroke survivors. | Baumann et al. (2013) [ ] |

| Treatment | cCBT | cCBT will alleviate emotional distress and mental health problems such as anxiety and depression after experiencing a stroke. | Simblett et al. (2017) [ ] |

| PosMT | Training in positivity using the PosMT audio tool could be added to rehabilitation for prevention or management of poststroke psychological problems. | Mavaddat et al. (2017) [ ] | |

| Multicomponent | Psychoeducation (mailed and home visit) | Home-based psychoeducation will improve the perceived health of stroke survivors by decreasing depression, fatigue, and the negative impact of stroke. | Ostwald et al. (2014) [ ] Stubberud et al. (2019) [ ] |

| Promoting psychosocial wellbeing following stroke | Applying a dialog-based intervention drawing on narrative theory, supported conversation for people with aphasia, and guided self-determination will promote a sense of coherence in life and reduce threats to wellbeing after stroke, such as feelings of chaos and lack of control. | Bragstad et al. (2020) [ ] | |

| Training | Skills-based intervention informed by CBT, DBT, and trauma-informed care | Training in areas including cognitive restructuring/reappraisals, adaptive thinking, mindfulness, distress tolerance, impact of the illness/injury, understanding triggers, and role and identity changes will prevent chronic emotional distress in stroke survivors and their caregivers. | Bannon et al. (2020) [ ] |

| Biofeedback training | HRV biofeedback will improve autonomic dysfunction, cognitive impairment, and psychological distress. | Chang et al. (2020) [ ] | |

| Alternative medicine | |||

| Alternative medicine | Aromatherapy (foot bath and massage) | Back massage and foot bath using essential oils will improve stress, body temperature, mood state, and fatigue levels of stroke patients. | Lee et al. (2017) [ ] |

| Pharmacological | |||

| Antidepressant drugs | Sertraline (50–100 mg daily) | Sertraline, a SSRI, will have positive effects on both depressive symptoms and other relevant poststroke domains including emotional distress and QoL. | Murray et al. (2005) [ ] |

cCBT computerized cognitive behavior therapy; DBT dialectical behavior therapy; HRV heart rate variability; MBSR mindfulness-based stress reduction; PosMT positive mental training; QoL quality of life; SFBT solution-focused brief therapy; SSRI selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor; TBI traumatic brain injury.

We used the PsycInfo database to map each intervention to its broader subject heading category and identified the theory or hypothesis associated with each that would lead to an improvement in stress-related outcomes. Although there was wide variability in the types of intervention trialed, most (22; 92%) utilized psychosocial interventions targeted at the individual level. These include social support [ 43 ], cognitive processes including mindfulness-based stress reduction, meditation and problem-solving therapy [ 28 , 31 , 44 , 47 ], rehabilitation or neuropsychological rehabilitation targeted at memory or leisure [ 29 , 40 ], a behavioral proactive coping intervention [ 30 ], physical activity programs [ 41 , 45 , 51 ], psychotherapy including both positive psychotherapy [ 42 , 54 ] and solution-focused brief therapy [ 55 ], creative arts therapy [ 37 ], cognitive behavioral therapy or positive mental training [ 48 , 52 ], multicomponent interventions consisting of home-based visits and mailed information, based on principles of psychoeducation [ 38 , 50 , 53 ] and training modules based on developing skills in either cognitive behavior therapy/cognitive reappraisal or heart rate variability biofeedback [ 36 , 39 ]. The remaining two studies assessed alternative medicine (aromatherapy massage and foot bath [ 46 ]), and pharmacological treatment (the selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor antidepressant sertraline [ 49 ]). There were no organizational-level interventions in the included studies.

Stress Outcome Metrics

Table 2 summarizes how stress or stress-relevant outcomes were measured in the included studies. Not all studies were designed to examine stress or resilience as a primary outcome, and as such the included outcomes were not necessarily primary outcomes. Studies were included into this scoping review only if the stress was specifically discussed in the results section of the study. This may include data from qualitative interviews or surveys, or within a subscale of another measure (e.g., QoL).

Characteristics of outcome measures used to assess interventions for stress measurement

| Outcome type | Outcome measurement scale | Studies |

|---|---|---|

| Stress | 10-item Perceived Stress Scale (PSS-10) | Colledge et al. (2017) [ ] Ostwald et al. (2014) [ ] |

| Depression Anxiety Stress Scales (DASS-21) | Cullen et al. (2018) [ ] | |

| General Health Questionnaire (GHQ) | Friedland and McColl (1992) [ ] | |

| Kessler Psychological Distress Scale (K10) | Jones et al. (2016) [ ] | |

| Mental Fatigue Scale (MFS) | Johansson et al. (2012) [ ] | |

| Social Readjustment Rating Scale (SRRS) | Lee et al. (2017) [ ] | |

| Emotional Distress Scale (EDS) | Murray et al. (2005) [ ] | |

| Coping | Utrecht Proactive Coping Competence scale (UPCC) | Tielemans et al. (2015) [ ] |

| Coping Inventory for Stressful Situations | Visser et al. (2016) [ ] | |

| Problem-solving | Social Problem-Solving Inventory-Revised (SPSIR) | Chalmers et al. (2019) [ ] Visser et al. (2016) [ ] |

| Resilience | 10-item Connor Davidson Resilience Scale (CD-RISC) | Terrill et al. (2018) [ ] Perez-de la Cruz (2020) [ ] |

| Brief Resilience Scale (BRS) | Love et al. (2020) [ ] | |

| Depression/anxiety/mood | Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale (CES-D) | Chalmers et al. (2019) [ ] Visser et al. (2016) [ ] Love et al. (2020) [ ] |

| Beck Depression Inventory (BDI) | Colledge et al. (2017) [ ] Nour et al. (2002) [ ] Simblett et al. (2017) [ ] | |

| Beck Anxiety Inventory(BAI) | Simblett et al. (2017) [ ] | |

| Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS) | Chalmers et al. (2019) [ ] Stubberud et al. (2019) [ ] Tielemans et al. (2015) [ ] Wichowicz et al. (2017) [ ] | |

| Comprehensive Psychopathological Rating Scale (CPRS) | Johansson et al. (2012) [ ] | |

| Multiple Affective Adjective Checklist (MAACL) | Lee et al. (2017) [ ] | |

| Montgomery–Åsberg Depression Rating Scale (MADRS) | Murray et al. (2005) [ ] | |

| Presence of emotionalism (increased tearfulness and pathologic crying was recorded as a dichotomous variable) | Murray et al. (2005) [ ] | |

| Geriatric Depression Scale (GDS) | Ostwald et al. (2014) [ ] | |

| PROMIS-Depression Short Form 8b | Terrill et al. (2018) [ ] | |

| State-Trait Anxiety Inventory (STAI-Y) | Love et al. (2020) [ ] | |

| Quality of life | Stroke Specific Quality of Life Scale (SS-QOL) | Chalmers et al. (2019) [ ] Tielemans et al. (2015) [ ] Visser et al. (2016) [ ] |

| Global subjective rating of change in quality of life (QoL) was measured according to a validated visual analog scale | Murray et al. (2005) [ ] | |

| Sickness Impact Profile | Nour et al. (2002) [ ] Friedland and McColl (1992) [ ] | |

| Older People’s Quality of Life Questionnaire (OPQOL) | Terrill et al. (2018) [ ] | |

| Short From 36 Health Survey (SF-36) | Perez-de la Cruz (2020) [ ] | |

| EuroQol EQ-5D-5L | Visser et al. (2016) [ ] | |

| Life satisfaction | Satisfaction with Life Scale (SWLS) | Colledge et al. (2017) [ ] |

| Authentic Happiness Inventory (AHI) | Cullen et al. (2018) [ ] | |

| Leisure Satisfaction Scale | Nour et al. (2002) [ ] | |

| Likert scales: current life satisfaction, and the difference from prestroke life satisfaction | Cullen et al. (2018) [ ] | |

| Qualitative analysis | Open-ended descriptive survey | Chalmers et al. (2019) [ ] |

| Semi-structured interviews | Chouliara and Lincoln (2016) [ ] Mavaddat et al. (2017) [ ] Baumann et al. (2013) [ ] |

Several different psychometric scales were used to assess stress or related constructs; however, we found no studies assessing stress biomarkers. In our search strategy, we included terms for coping and resilience, resulting in the inclusion of studies that measured stress, and resilience, coping, problem-solving, stress-related disorders (including anxiety, depression, and PTSD), life satisfaction, and QoL measures, where stress was reported as a subcomponent of the measure. Of the 14 studies which included a psychometric measurement of stress, coping, or resilience, 8 reported using a stress-specific outcome measure [ 41–46 , 49 , 50 ], with others recording stress-related constructs via a coping scale [ 30 , 31 ], problem-solving scale [ 28 , 31 ], or resilience scale [ 47 , 51 , 54 ].

Most studies measured stress-related disorders via a scale for symptoms of depression, anxiety, or mood ( n = 16) [ 28–31 , 36 , 39 , 41 , 44 , 46 , 47 , 49 , 50 , 52–55 ]. The Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale (CES-D) [ 28 , 31 , 47 ], Beck Depression Inventory (BDI) [ 29 , 41 , 52 ], and the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS) [ 28 , 30 , 36 , 39 , 53 , 55 ] were the most commonly used measures.

Ten studies assessed QoL and/or life satisfaction [ 28–31 , 41–43 , 49 , 51 , 54 ]; some studies reported a stress measure as a subscale of this. For example, Friedland and McColl [ 43 ] used the General Health Questionnaire (GHQ) and the Sickness Impact Profile (SIP) to measure “psychosocial adjustment”. As mentioned above three qualitative thematic analysis studies [ 37 , 40 , 48 ] were included which did not measure stress outcomes but which highlighted stress as an emerging theme. For example, Baumann et al. [ 37 ], a descriptive study of an art therapy program aiming to reduce distress during rehabilitation, did not explicitly measure stress but described individual participants’ experiences of distress associated with stroke.

Effectiveness and Implementation Outcomes

For each intervention, we assessed the effectiveness in terms of both reduction in stress or related construct, and reduction in stress-related mental health disorders (anxiety, depression, or PTSD); implementation measures including barriers and limitations, feasibility and acceptability, and any cost analysis or cost-effectiveness, were reported. Collectively, these features are likely to inform the further development of an intervention for eventual use in practice ( Table 3 ).

Measures of effectiveness, acceptability, feasibility, and cost-effectiveness

| Study | Stress reduction | Reduction in anxiety or mood disorder | Barriers and limitations | Feasibility and acceptability | Cost-effectiveness |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bannon et al. (2020) [ ] | Increased scores on resiliency variables, including self-efficacy, mindfulness, and perceived coping in Recovering Together training dyads, but not control dyads from baseline to post-test. | Participation in Recovering Together was associated with baseline to post-test decrease in symptoms of depression, anxiety, and PTS in stroke survivors and caregivers. | Small feasibility trial Patients discharged before they could be approached Low internal consistency on measures with reversed scored items for patients at baseline | Clinical staff not invested in project Low recruitment Treatment satisfaction was high Adherence and acceptability of procedures was high | NR |

| Baumann et al. (2013) [ ] | Weekly art sessions during rehabilitation. Participants reported that the sessions offered a source of relaxation, tranquility or calmness(qualitative analysis). | NR | No long-term follow-up (1 week after final session) Small sample size ( = 18) | All but one patient indicated a wish to continue arts activities in the future | NR |

| Bragstad et al. (2020) [ ] | No between-group differences in psychosocial wellbeing at 12 months poststroke. | No statistically significant between-group difference in depression, sense of coherence, or health-related QoL at 12 months. | The intervention was designed both to be delivered uniformly and to be individualized. The competing aims may have compromised session delivery Sample may not be representative; informed consent was difficult to obtain in the stroke unit | Composite adherence score showed that 117 (80.1%) of the intervention trajectories satisfied the criteria for high-fidelity intervention adherence Participants reported finding the intervention helpful | NR |

| Chalmers et al. (2019) [ ] | Problem-solving therapy did not produce a significant change in overall problem-solving (SPISR; proxy measure for emotional distress). | Slight reduction after therapy on the CES-D and no reduction on the HADS-A. | No randomization Use of waitlist control group No controlling for confounding Problems with recruitment Small sample size ( = 28) | Participants generally reported that each therapy session was helpful and enjoyable | NR |

| Chang et al. (2020) [ ] | Average HR decreased compared with baseline in the HRVBF, but no significant difference between groups. | HADS score significantly decreased in the HRVBF group at 1 and 3 months but not in the control group. | Small sample size Short follow-up time Did not log self-practice during follow-up | 5/40 patients dropped out after randomization Study reported that the intervention was feasible, but it was not clear on what basis this was reported | NR |

| Chouliara and Lincoln (2016) [ ] | Memory rehabilitation led to perceived benefits in participants’ ability to effectively manage stress (qualitative analysis). | NR | Small sample size ( = 20) Qualitative analysis did not directly assess some aspects Separate results not reported for stroke survivors only | NR | NR |

| Colledge et al. (2017) [ ] | No effect of exercise training on perceived stress. | Descriptive reduction in depressive symptoms at follow-up. | Small sample size ( = 32) Exploratory trial (descriptive analysis only) Selection bias No nonintervention control group | NR | NR |

| Cullen et al. (2018) [ ] | Mean difference of −5.8 points on the DASS-21 Stress scale (intervention vs. controls) at week 20 after positive psychology intervention. | Mean difference of −9.6 points on the DASS-21 Anxiety scale (intervention vs. controls) at week 20 after positive psychology intervention. | Small sample size ( = 37) Exploratory trial Not designed or powered for efficacy | 63% retention (15 completers) Authors considered intervention feasible to deliver and acceptable to participants | NR |

| Friedland and McColl (1992) [ ] | No differences between social support intervention and control groups on psychosocial variables including the GHQ. | NR | Relatively high attrition rate Timing of intervention | NR | NR |

| Johansson et al. (2012) [ ] | Statistically significant reduction in reported mental fatigue, including reduction in sensitivity to stress item, following MBSR compared with baseline and controls. | Significantly decreased scores for depression and anxiety on the CPRS after 8 weeks of MBSR. | Small sample size ( = 29) Some participants who discontinued found the program time consuming, or difficult to travel to attend appointments | NR | NR |

| Jones et al. (2016) [ ] | A statistically significant reduction in psychological distress (K10 scale) of 2.76 points immediately after the myMoves program ( = .001). | NR | Small sample size ( = 24) Contact with study participants occurred outside of the intervention program Mixed population (stroke and TBI) | Participants completed an average of 5.6/6 sessions Participants reported a high level of overall satisfaction with the program (95.7%) The program required little clinician contact time, with an average of 32.8 min per participant over 8 weeks | NR |

| Lee et al. (2017) [ ] | Statistically significant reduction in the social readjustment rating scale (means not reported). | NR | Small sample size ( = 14) Poor reporting of study methodology and results | NR | NR |

| Love et al. (2020) [ ] | Small, but nonsignificant, postmeditation increase in resilience observed. | NR | Small sample size ( = 35) No control group Selection bias Sampling in single stroke clinic Exclusion of participants lost to follow-up | NR | NR |

| Mavaddat et al. (2017) [ ] | In qualitative interviews, stroke survivors reported benefits of the positive mental training program in handling stress, improved mood, and coping ability. | Four stroke survivors had improved scores on PANAS; two stroke survivors had improved scores, and one stroke survivor had a worse score on the HADS. | Small sample size ( = 10) Self-selected sample Not all participants completed the full 12-week program | 7/10 stroke survivors reported positive benefits from listening and would recommend to others Participants with moderate aphasia found it difficult to concentrate and did not persist with the study | £38 for access to the full audio program (in 2013 GBP). |

| Murray et al. (2005) [ ] | No statistically significant effect of sertraline treatment on EDS score, however there was a reduction from baseline in both groups regardless of treatment. Some improvement in QoL and emotionalism. | The MADRS score decreased substantially in both treatment groups, with no significant differences between them at 6 and 26 weeks. | High discontinuation rate (39% in the treatment and 49% in the placebo group) Selection of patients with minor depression only | NR | NR |

| Nour et al. (2002) [ ] | At post-test, the experimental group (leisure rehabilitation) obtained statistically significantly better scores for total, psychological, and physical QoL, although effect sizes were small. | No statistically significant difference between groups for depression (BDI). | Small sample size Extra time (on average 20 min per session) provided to intervention group Some participants did not complete the program | Participants reported satisfaction with leisure activities following the intervention | NR |

| Ostwald et al. (2014) [ ] | No effect of mailed or home-based psychoeducational intervention on stress as measured by the PSS-10. | No effect of mailed or home-based psychoeducational intervention on depression scores (GDS). | Sample size not large enough for subgroup analyses The sample is not representative—included only those over 50 years of age who were being discharged home with a spouse Analysis of multiple outcomes in this study possibly increased the type I error rate. | 84% of the dyads completed the study 12-month follow-up. Dyads that did not complete the study were older, had higher caregiver support scores and spent more days in inpatient rehabilitation than those who finished the study | Number, length, and content of each contact was tracked, allowing for analysis of costs. An average of two home visits a month during the initial 6 months at home postdischarge from inpatient rehabilitation could be delivered at a mean cost of $2,500 per dyad. |

| Perez-de la Cruz (2020) [ ] | In the experimental group, significant differences from baseline were found in the resilience variables ( < .001) and these improvements were maintained 1 month after completing the treatment program. | NR | Small sample size ( = 41) Short follow-up (1 month) | All the participants completed all the sessions and complied with the proposed program | NR |

| Simblett et al. (2017) [ ] | All groups demonstrated a decrease in symptoms of distress, measured via the BDI and BAI, and the NEADL across time associated with computerized CBT and computerized cognitive remediation therapy. | Trend toward reduced depression scores on the BDI for computerized CBT and computerized cognitive remediation therapy. Smaller trend for anxiety symptoms. | Small sample size ( = 28) Feasibility and acceptability were the primary outcomes for this study, not efficacy No blinding to intervention of outcome assessors | Feasibility and acceptability were the primary outcomes for this study. Recruitment rate for the intervention ran below the expected rate Broadly feasible, although some aspects required more flexibility Majority suggested intervention was useful, relevant and easy to use | Not explicitly measured. However, the idea of small groups was primarily introduced as a means of improving the feasibility of delivery by reducing costs associated with providing psychological therapy. |

| Stubberud et al. (2019) [ ] | No change in self-efficacy after training in metacognitive strategies for improving attention, problem-solving, fatigue management, adaptive coping responses, and the use of CBT techniques as measured using the GSE scale. | Decrease in overall score on the HADS, driven by a change in the anxiety subscale. No change in the depression subscale. | Small sample size ( = 8, of which 5 are stroke survivors) Results not presented separately for stroke and TBI survivors Self-reported outcomes only No control group | All subjects completed the interventions | NR |

| Terrill et al. (2018) [ ] | Study not designed to measure effect of intervention—the data collected in this study were used to identify feasibility of a positive psychology app. 8/10 dyads still used positive psychology in their everyday lives at follow-up. Measured CD-RISC, but results not reported. | Measured PROMIS-Depression Short Form 8b, but results not reported. | Small sample size; 11 stroke survivor/carer dyads. One dyad discontinued, final 10 dyads | Participants reported satisfaction with the intervention Stroke survivors were fatigued by training session One of the dyads dropped out of the study Remaining dyads engaged in a mean of 4.08 individual and 3.62 couple activities per week | Not explicitly reported; referenced a Cochrane review stating that use of apps to administer self-management programs was cost-effective. |

| Tielemans et al. (2015) [ ] | No effect of self-management intervention compared with an education intervention in coping skills on the UPCC scale. | Trend favoring the self-management intervention on the HADS. | Study did not include more severely affected stroke survivors Self-assessment used to assess outcomes Outcome measures too generic to detect changes Study too small to detect outcome differences in partners ( = 57 partners) Sample selected by hospital staff Usual care was not controlled | Of 58 patients assigned to the self-management intervention, 56 started the intervention and 46 attended at least three quarters of the intervention sessions | NR |

| Visser et al. (2016) [ ] | Improvement in coping strategy as measured by the Coping Inventory for Stressful Situations between groups (problem-solving therapy vs. control). | Depression score did not differ significantly between the groups over time (CES-D). | No active control groups Intervention was investigated within outpatient rehabilitation and may not be generalizable to other settings Sample reported a relatively high utility score compared with other stroke populations | The low dropout rate and positive feedback suggest that an open group design is feasible and effective in outpatient stroke rehabilitation | NR |

| Wichowicz et al. (2017) [ ] | Increased self-efficacy and constructive attitudes in the SFBT group compared with controls (Mini-Mental Adjustment to Cancer and Self-efficacy Scale). | Reduced anxiety and depression scores in the SFBT group compared with controls (HADS). | 62 completers (100 randomized) Participants relatively fit and may not be representative 35 withdrawals from study Lengthy procedure Lack of complete randomization | Potential SFBT participants who refused to participate may have found the procedure of psychotherapy too lengthy | NR |

BAI Beck Anxiety Inventory; BDI Beck Depression Inventory; CD-RISC 10-item Connor Davidson Resilience Scale; CES-D Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale; CPRS Comprehensive Psychopathological Rating scale; DASS-21 Depression Anxiety Stress Scales; EDS Emotional Distress Scale; GBP British pounds; GDS Geriatric Depression Scale; GHQ General Health Questionnaire; GSE General Self-Efficacy; HADS Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale; HR heart rate; HRVBF heart rate variability biofeedback; MADRS Montgomery–Åsberg Depression Rating Scale; MBSR mindfulness-based stress reduction; NEADL Nottingham Extended Activities of Daily Living; NR not reported; PANAS Positive and Negative Affect Schedule; PROMIS Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System; PSS-10 Perceived Stress Scale; PTS post-traumatic stress; QoL quality of life; SFBT solution-focused brief therapy; SPISR Social Problem-Solving Inventory-revised; TBI traumatic brain injury; UPCC Utrecht Proactive Coping Competence.

In order to address our research question “to identify which interventions are potentially efficacious for reducing stress or increasing resilience and coping” we compiled a descriptive overview of the reported effectiveness of the intervention in each study. Positive effects on stress, resilience, coping, or psychological QoL/life satisfaction were reported in 13 of the 24 included studies [ 29 , 31 , 36 , 37 , 40 , 42 , 44–46 , 48 , 51 , 52 , 55 ]. Baumann et al. [ 37 ] and Chouliara and Lincoln [ 40 ] reported qualitative reductions in stress associated with an inpatient art program and memory rehabilitation, respectively. The other studies reported a quantitative improvement in stress-related outcomes associated with a number of intervention types: skills-based training based on principles of cognitive behavior therapy [ 36 ], positive psychology [ 42 , 48 ], mindfulness-based stress reduction [ 44 ], physical activity program [ 45 ], aromatherapy massage, and footbath [ 46 ], leisure rehabilitation [ 29 ], aquatic therapy [ 51 ], computerized cognitive behavior therapy or cognitive remediation [ 52 ], problem-solving therapy [ 31 ], and solution-focused brief therapy [ 55 ]. Whilst this represents many included studies (54%), most of these had relatively small sample sizes, ranging from 14 to 166, with 10/13 studies recruiting fewer than 30 stroke survivors. Most of these were reported as exploratory, quasi-experimental, or feasibility studies, and reported other methodological concerns including lack of active control group and significant dropout rates. Some of these results were also not numerically reported or reported as a qualitative perceived reduction only.

The impact of the interventions on longer-term stress-related problems, primarily symptoms of depression or anxiety, were considered in 75% (18/24) included studies. Of these, seven reported a quantitative decrease in these symptoms [ 36 , 39 , 42 , 44 , 47 , 53 , 55 ].

In addition to effectiveness results, we also collated implementation outcomes reported across studies, primarily acceptability and feasibility, in order to assess whether the potential long-term sustainability of intervention had been considered in the included studies. Where studies included an explicit measure of feasibility or acceptability from participants, feedback was generally positive [ 28 , 29 , 31 , 36–39 , 42 , 45 , 46 , 48 , 50–52 , 54 ]. Several studies reported low dropout rates and high adherence to the intervention strategy ( n = 8) [ 31 , 36 , 38 , 45 , 50 , 51 , 53 , 54 ]. Broadly, this suggests a willingness to participate in these intervention studies. However, several studies did report problems with recruitment or other barriers to participation, including potential refusal to participate based on the time commitments or participation burden required for some interventions ( n = 8) [ 30 , 36 , 42–44 , 50 , 54 , 55 ]. Further, some interventions reported differential dropout rates for different groups of participants, particularly those with aphasia ( n = 2) [ 30 , 48 ].

We also investigated whether studies reported some measure of cost or cost-effectiveness analysis. This is also an important consideration for upscaling and eventually implementing a novel intervention in practice. Only four of the included studies referred to or measured the costs of the intervention. Mavaddat et al. [ 48 ] and Ostwald et al. [ 50 ] both reported the costs of providing the intervention per participant. In Terrill et al. [ 54 ] and Simblett et al. [ 52 ], although costs were not explicitly measured, both reported that the intervention was expected to be cost-effective based on its features. The cost-effectiveness of any intervention was not reported.