Ruminating…

Random thoughts about conducting scientific research, supervising students and «toys» that make creative activities even funnier….

How many citations are actually a lot of citations?

In a previous blog post , I suggested to my younger colleagues that while they should not care so much about the impact factor of the journals they published in (as long as these journals are well-read in their respective fields of research), they should care quite a lot about these papers being cited, and cited by others not self-cited!

A few months ago, I was listening to the introductory talk of for a prestigious award from our national organization when one statement hit me: a physicist with 2000 or more citations is part of the 1% most cited physicists worldwide. There might have been a bit more to that statement but let’s work with it.

In fact, if you search for highly cited research on Google or any of your favorite search engines, this question (and many related ones) is the subject of intense research in itself. It seems, we human like to be able to put a number and rank on things. We also like to establish a hierarchy among things, even human being. 😉

So according to Wikipedia , from January 2000 to February 2010, the top 1% researchers in physics had about 2073 citations or better, or about slightly fewer than 210 citations per year over a 10-year period. That threshold changes with the field of research, of course, and can be much lower for other fields.

My first impression was that this seems low. However, as one digs deeper, one notices that most published manuscripts are not cited at all…Nature had a nice piece in 2014 about the TOP 100 papers . The infographics below is part of the article and is quite telling.

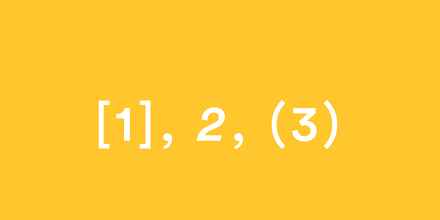

First, almost 44% of all published manuscripts are never cited. If you have even 1 citations for a manuscript you are already (almost!) in the top half (top 55.8%). With 10 or more citations, your work is now in the top 24% of the most cited work worldwide; this increased to the top 1.8% as you reach 100 or more citations. Main take home message: the average citation per manuscript is clearly below 10!

I also found a great blog post by Scott Weingart , which by restricting his analysis to a single journal, Scientometrics, got very similar results, with 50% of all published papers in that journal having fewer than 4 citations, 70% fewer than 7.

Out of curiosity, I decided to look at my own publications. Two tools are available Google Scholar and Thomson Reuters Web of Sciences. These data are presented in the figure below. As expected the number of manuscripts that gather over 100 citations are few. In my case it hovers between 2% to 5% depending on the tool used; both gives over 60% for 10 or more citations: 2 to 5 manuscripts out of a 100 get to be in the top 1.8% most cited manuscripts and 60 out of the same 100 are in the top quarter. Based on the discussion above, I suppose this is a good sign…

Still in Nature, there was yet another piece about the TOP 1% in science . Here is it claimed that fewer than 1% of all researchers have published consistently every year between 1996 and 2011, but those few who have commanded a “market share” of (i.e. are authors on) 41% of all published manuscripts in the same period (original manuscript in PLOS ONE ).

There is, of course, Thomson Reuters that has its own version of the “World’s Most Influential Scientific Mind” for a given year (e.g. 2014 ) and highly cited researchers . Here “hot papers” are defined by being in the top 0.1% (you’ve read correctly) by citations for their field of research and “influential researchers” are those having the largest numbers of these “hot papers” ( generally 15+ ). Before you ask, no I am not listed in the 3500 or so researchers described in there…

Now having said all that, more analysis of all of these “metrics” seems to indicate that there is only a weak correlation between the top 1% of highly cited researchers and Nobel Prize winners. As noted by the first Nature article cited above, many of the very highly cited papers are about tools or methods rather than fundamental scientific discoveries made with these tools or methods…

Here is a quick one that was part of a discussion among friends: two researchers have each a paper with 200+ citations. For the purpose of this blog post let’s say exactly 200 citations. One is for a paper published in what is considered a top journal, let’s say Science or Nature. The other for a manuscript published in a low impact factor journal (5-year IF of 2). Which of these two papers have had:

- The greatest impact on science?

- On their field of research?

Looking forward to reading you!

Share this:

20 thoughts on “ how many citations are actually a lot of citations ”.

Pingback: Can A Paper Garner Numerous Reads Despite Minimal Citations?

Thank you Luc 🙏 . Very interesting.

I have 23 citations on one of my papers. How can I know my percentage. If 10 I will be one of the top 24 what about 23?

Pingback: How to read scientific papers quickly and effectively | Molekule Blog

Pingback: Publications and citations for EB2 NIW green card » EB2 NIW Info

So let say I have 50 citations in Google Scholar as of Feb 23, 2022. What would be the possible rank of mine considering published papers/patent/books? Here is the link https://scholar.google.com/citations?user=pO4oG1kAAAAJ&hl=en Thanks.

These statistics are for a “per paper” using Web of Science (not Google Scholar). The 50 citations your are referring to are for all the documents at your name found by Google Scholar.

Pingback: What Is A Good Number Of Citations - Best College Portal

Pingback: How to read scientific papers quickly and effectively – My Blog

Where did you get the reference to this quote “10 or more citations, your work is now in the top 24% of the most cited work worldwide”?

Hi Carole, you can extract it from the infographic in the post or read the background materials cited.

The Web of Science Highly Cited Researchers are those who have a certain number of papers (not books) that are in the top 1% (not 0.1%) of all cited papers during that year (eg among papers from 2015). And those researchers are in the top 0.1% of all researchers-professors. So its top 1% in terms of citations for the highly cited papers and then 0.1% in terms of all researchers (that latter number may be approximate). This is over a 10 year period. It’s hard to get because you basically need papers that are getting about 50 Google scholar citations per year, which usually means about 20-25 Web of Science citations (Web of Science is stricter), to land the paper in the top 1%. And you need about six of those during a given decade to be in the top 0.1% to get the Highly Cited Researcher award. Top 0.1% means in the top 6000 (out of about 6 million professors and other researchers worldwide).

Pingback: Analysis of publication impact in predatory-journal – Nature – Ruminating…

Interesting post and knowledge. Now I feel proud that couple of my papers went beyond 55 citations.

Very interesting article. I was indeed looking for this information!

Pingback: Another year is over… – Ruminating…

Nice article Luc. A minor observation is that those highly cited papers tend to be slanted towards biological sciences, which also tend to have a fairly high number of publications. Putting individual statistics aside, I wonder if citations is loosely correlated to the number of sub-disciplines.

Defining an ‘expert’ is remarkably different from someone who has a high H-index, # of citations, and other publication metrics, and more to do with things like invited lectures, publications in reports, books, guidance documents, and such which are may not be subjected to indexing.

I whole heartedly agree that, for younger researchers, quantity is important, without forsaking quality. And things like blog-posts, comments, etc all count! Later in ones academic career one can be more picky about where to publish.

My experience is that shooting for number only is not the way to go. I am not saying that number of publication is not important since both for promotion and the purpose of obtaining grants, you do need a certain number of them. However, if your publications are not cited, you can have many hundreds it does not matter: you are having no impact on your field.

In grants committees, my experience is that after a few publications per year, it does not matter so much if you have 18, 22 or 25 in the last 5 years. It will be held against you if you have only 2 or 3 however – unless it is 2-3 Science or Nature (Of course of you have 50+ all in good journals, you are not only a “middle” author on these and you can show that your papers have impact – you will certainly get praised).

I would also say that you have to pick carefully where you published. And here you are right your “forum” depends a lot on the path you are following: top research journals in your field vs more applied (clinical for us) journals vs reports and so on. It also depends I guess if you need to show social impact, academic impact, clinical impact …

There is no simple formula for sure 😉

Very interesting post. It seems like a small number (2000 being the 1%) but I don’t have any papers close to those citation numbers. A couple of years ago I posted a fairly simple analysis of my own citation record. But I thought it would be interesting to see how my papers performed in relation to the impact factor of the journal they were in. Most did pretty well, getting more than expected by the journal. Anyway, I thought that would be an interesting addition to your own self analysis (though it’s complicated by the fact that the impact factor of journals varies over time). Here’s the post if you’re interested: http://jasonya.com/wp/publication-impact-factor-analysis/

Thanks Jason!

Leave a comment Cancel reply

This site uses Akismet to reduce spam. Learn how your comment data is processed .

- Already have a WordPress.com account? Log in now.

- Subscribe Subscribed

- Copy shortlink

- Report this content

- View post in Reader

- Manage subscriptions

- Collapse this bar

University of Illinois Chicago

University library, search uic library collections.

Find items in UIC Library collections, including books, articles, databases and more.

Advanced Search

Search UIC Library Website

Find items on the UIC Library website, including research guides, help articles, events and website pages.

- Search Collections

- Search Website

Measuring Your Impact: Impact Factor, Citation Analysis, and other Metrics: Citation Analysis

- Measuring Your Impact

Citation Analysis

Find your h-index.

- Other Metrics/ Altmetrics

- Journal Impact Factor (IF)

- Selecting Publication Venues

About Citation Analysis

What is Citation Analysis?

The process whereby the impact or "quality" of an article is assessed by counting the number of times other authors mention it in their work.

Citation analysis invovles counting the number of times an article is cited by other works to measure the impact of a publicaton or author. The caviat however, there is no single citation analysis tools that collects all publications and their cited references. For a thorough analysis of the impact of an author or a publication, one needs to look in multiple databases to find all possible cited references. A number of resources are available at UIC that identify cited works including: Web of Science, Scopus, Google Scholar, and other databases with limited citation data.

Citation Analysis - Why use it?

To find out how much impact a particular article or author has had, by showing which other authors cited the work within their own papers. The H-Index is one specific method utilizing citation analysis to determine an individuals impact.

Web of Science

Web of Science provides citation counts for articles indexed within it. It i ndexes over 10,000 journals in the arts, humanities, sciences, and social sciences.

- Enter the name of the author in the top search box (e.g. Smith JT).

- Select Author from the drop-down menu on the right.

- To ensure accuracy for popular names, enter Univ Illinois in the middle search box, then select “Address” from the field drop down menu on the right. (You might have to add the second search box by clicking "add another field" before you enter the address)

- Click on Search

- a list of publications by that author name will appear. To the right of each citation, the number of times the article has been cited will appear. Click the number next to "times cited" to view the articles that have cited your article

Scopus provide citation counts for articles indexed within it (limited to article written in 1996 and after). It indexes o ver 15,000 journals from over 4,000 international publishers across the disciplines.

- Once in Scopus, click on the Author search tab.

- Enter the name of the author in the search box. If you are using initials for the first and/or middle name, be sure to enter periods after the initials (e.g. Smith J.T.).

- To ensure accuracy if it is a popular name, you may enter University of Illinois in the affiliation field.

- If more than one profile appears, click on your profile (or the profile of the person you are examining).

- Once you click on the author's profile, a list of the publications will appear and to the right of each ctation, the number of times the article has been cited will appear.

- Click the number to view the articles that have cited your article

Dimensions (UIC does not subscribe but parts are free to use)

- Indexes over 28000 journals

- Does not display h-index in Dimensions but can calculate or if faculty, look in MyActivities

- Includes Altmetrics score

- Google Scholar

Google Scholar provides citation counts for articles found within Google Scholar. Depending on the discipline and cited article, it may find more cited references than Web of Science or Scopus because overall, Google Scholar is indexing more journals and more publication types than other databases. Google Scholar is not specific about what is included in its tool but information is available on how Google obtains its content . Limiting searches to only publications by a specific author name is complicated in Google Scholar. Using Google Scholar Citations and creating your own profile will make it easy for you to create a list of publications included in Google Scholar. Using your Google Scholar Citations account, you can see the citation counts for your publications and have GS calculate your h-index. (You can also search Google Scholar by author name and the title of an article to retrieve citation information for a specific article.)

- Using your google (gmail) account, create a profile of all your articles captured in Google Scholar. Follow the prompt on the scrren to set up your profile. Once complete, this will show all the times the articles have been cited by other documents in Google Scholar and your h-index will be provided. Its your choice whether you make your profile public or private but if you make it public, you can link to it from your own webpages.

Try Harzing's Publish or Perish Tool in order to more selectively examine published works by a specific author.

Databases containing limited citation counts:

- PubMed Central

- Science Direct

- SciFinder Scholar

About the H-index

The h-index is an index to quantify an individual’s scientific research output ( J.E. Hirsch ) The h-index is an index that attempts to measure both the scientific productivity and the apparent scientific impact of a scientist. The index is based on the set of the researcher's most cited papers and the number of citations that they have received in other people's publications ( Wikipedia ) A scientist has index h if h of [his/her] Np papers have at least h citations each, and the other (Np − h) papers have at most h citations each.

Find your h-index at:

Below are instructions for obtaining your h-index from Web of Science, Scopus, and Google Scholar.

Web of Science provides citation counts for articles indexed within it. It indexes over 12,000 journals in the arts, humanities, sciences, and social sciences. To find an author's h-index in WOS:

- To ensure accuracy for popular names, add an additional search box and enter "Univ Illinois" and then select “Address” from the field drop down menu on the right.

- Click on Citation Report on the right hand corner of the results page. The H-index is on the right of the screen.

- If more than one profile appears, click on your profile (or the profile of the person you are examining). Under the Research section, you will see the h-index listed.

- If you have worked at more than one place, your name may appear twice with 2 separate h-index ratings. Select the check box next to each relevent profile, and click show documents.

Google Scholar

- Using your google (gmail) account, create a profile of all your articles captured in Google Scholar. Follow the prompt on the screen to set up your profile. Once complete, this will show all the times the articles have been cited by other documents in Google Scholar and your h-index will be provided. Its your choice whether you make your profile public or private but if you make it public, you can link to it from your own webpages.

- See Albert Einstein's

- Harzing’s Publish or Perish (POP)

- Publish or Perish Searches Google Scholar. After searching by your name, deselect from the list of articles retrieved those that you did not author. Your h-index will appear at the top of the tool. Note:This tool must be downloaded to use

- << Previous: Measuring Your Impact

- Next: Find Your H-Index >>

- Last Updated: Mar 13, 2024 12:51 PM

- URL: https://researchguides.uic.edu/if

- MJC Library & Learning Center

- Research Guides

Format Your Paper & Cite Your Sources

- APA Style, 7th Edition

- Citing Sources

- Avoid Plagiarism

- MLA Style (8th/9th ed.)

APA Tutorial

Formatting your paper, headings organize your paper (2.27), video tutorials, reference list format (9.43).

- Elements of a Reference

Reference Examples (Chapter 10)

Dois and urls (9.34-9.36), in-text citations.

- In-Text Citations Format

- In-Text Citations for Specific Source Types

NoodleTools

- Chicago Style

- Harvard Style

- Other Styles

- Annotated Bibliographies

- How to Create an Attribution

What is APA Style?

APA style was created by social and behavioral scientists to standardize scientific writing. APA style is most often used in:

- psychology,

- social sciences (sociology, business), and

If you're taking courses in any of these areas, be prepared to use APA style.

For in-depth guidance on using this citation style, refer to Publication Manual of the American Psychological Association , 7th ed. We have several copies available at the MJC Library at the call number BF 76.7 .P83 2020 .

APA Style, 7th ed.

In October 2019, the American Psychological Association made radical changes its style, especially with regard to the format and citation rules for students writing academic papers. Use this guide to learn how to format and cite your papers using APA Style, 7th edition.

You can start by viewing the video tutorial .

For help on all aspects of formatting your paper in APA Style, see The Essentials page on the APA Style website.

- sans serif fonts such as 11-point Calibri, 11-point Arial, or 10-point Lucida Sans Unicode, or

- serif fonts such as 12-point Times New Roman, 11-point Georgia, or normal (10-point) Computer Modern (the default font for LaTeX)

- There are exceptions for the title page , tables , figures , footnotes , and displayed equations .

- Margins : Use 1-in. margins on every side of the page.

- Align the text of an APA Style paper to the left margin . Leave the right margin uneven, or “ragged.”

- Do not use full justification for student papers.

- Do not insert hyphens (manual breaks) in words at the end of line. However, it is acceptable if your word-processing program automatically inserts breaks in long hyperlinks (such as in a DOI or URL in a reference list entry).

- Indent the first line of each paragraph of text 0.5 in . from the left margin. Use the tab key or the automatic paragraph-formatting function of your word-processing program to achieve the indentation (the default setting is likely already 0.5 in.). Do not use the space bar to create indentation.

- There are exceptions for the title page , section labels , abstract , block quotations , headings , tables and figures , reference list , and appendices .

Paper Elements

Student papers generally include, at a minimum:

- Title Page (2.3)

- Text (2.11)

- References (2.12)

Student papers may include additional elements such as tables and figures depending on the assignment. So, please check with your teacher!

Student papers generally DO NOT include the following unless your teacher specifically requests it:

- Running head

- Author note

For complete information on the order of pages , see the APA Style website.

Number your pages consecutively starting with page 1. Each section begins on a new page. Put the pages in the following order:

- Page 1: Title page

- Page 2: Abstract (if your teacher requires an abstract)

- Page 3: Text

- References begin on a new page after the last page of text

- Footnotes begin on a new page after the references (if your teacher requires footnotes)

- Tables begin each on a new page after the footnotes (if your teacher requires tables)

- Figures begin on a new page after the tables (if your teacher requires figures)

- Appendices begin on a new page after the tables and/or figures (if your teacher requires appendices)

Sample Papers With Built-In Instructions

To see what your paper should look like, check out these sample papers with built-in instructions.

APA Style uses five (5) levels of headings to help you organize your paper and allow your audience to identify its key points easily. Levels of headings establish the hierarchy of your sections just like you did in your paper outline.

APA tells us to use "only the number of headings necessary to differentiate distinct section in your paper." Therefore, the number of heading levels you create depends on the length and complexity of your paper.

See the chart below for instructions on formatting your headings:

Use Word to Format Your Paper:

Use Google Docs to Format Your Paper:

Placement: The reference list appears at the end of the paper, on its own page(s). If your research paper ends on page 8, your References begin on page 9.

Heading: Place the section label References in bold at the top of the page, centered.

Arrangement: Alphabetize entries by author's last name. If source has no named author, alphabetize by the title, ignoring A, An, or The. (9.44-9.48)

Spacing: Like the rest of the APA paper, the reference list is double-spaced throughout. Be sure NOT to add extra spaces between citations.

Indentation: To make citations easier to scan, add a hanging indent of 0.5 in. to any citation that runs more than one line. Use the paragraph-formatting function of your word processing program to create your hanging indent.

See Sample References Page (from APA Sample Student Paper):

Elements of Reference List Entries: (Chapter 9)

References generally have four elements, each of which has a corresponding question for you to answer:

- Author: Who is responsible for this work? (9.7-9.12)

- Date: When was this work published? (9.13-9.17)

- Title: What is this work called? (9.18-9.22)

- Source: Where can I retrieve this work? (9.23-9.37)

By using these four elements and answering these four questions, you should be able to create a citation for any type of source.

For complete information on all of these elements, checkout the APA Style website.

This infographic shows the first page of a journal article. The locations of the reference elements are highlighted with different colors and callouts, and the same colors are used in the reference list entry to show how the entry corresponds to the source.

To create your references, you'll simple look for these elements in your source and put them together in your reference list entry.

American Psychological Association. Example of where to find reference information for a journal article [Infographic]. APA Style Center. https://apastyle.apa.org/style-grammar-guidelines/references/basic-principles

Below you'll find two printable handouts showing APA citation examples. The first is an abbreviated list created by MJC Librarians. The second, which is more comprehensive, is from the APA Style website. Feel free to print these for your convenience or use the links to reference examples below:

- APA Citation Examples Created by MJC Librarians for you.

- Common References Examples (APA Handout) Printable handout from the American Psychological Association.

- Journal Article

- Magazine Article

- Newspaper Article

- Edited Book Chapter

- Webpage on a Website

Classroom or Intranet Sources

- Classroom Course Pack Materials

- How to Cite ChatGPT

- Dictionary Entry

- Government Report

- Legal References (Laws & Cases)

- TED Talk References

- Religious Works

- Open Educational Resources (OER)

- Archival Documents and Collections

You can view the entire Reference Examples website below and view a helpful guide to finding useful APA style topics easily:

- APA Style: Reference Examples

- Navigating the not-so-hidden treasures of the APA Style website

- Missing Reference Information

Sometimes you won't be able to find all the elements required for your reference. In that case, see the instructions in Table 9.1 of the APA style manual in section 9.4 or the APA Style website below:

- Direct Quotation of Material Without Page Numbers

The DOI or URL is the final component of a reference list entry. Because so much scholarship is available and/or retrieved online, most reference list entries end with either a DOI or a URL.

- A DOI is a unique alphanumeric string that identifies content and provides a persistent link to its location on the internet. DOIs can be found in database records and the reference lists of published works.

- A URL specifies the location of digital information on the internet and can be found in the address bar of your internet browser. URLs in references should link directly to the cited work when possible.

When to Include DOIs and URLs:

- Include a DOI for all works that have a DOI, regardless of whether you used the online version or the print version.

- If an online work has both a DOI and a URL, include only the DOI.

- For works without DOIs from websites (not including academic research databases), provide a URL in the reference (as long as the URL will work for readers).

- For works without DOIs from most academic research databases, do not include a URL or database information in the reference because these works are widely available. The reference should be the same as the reference for a print version of the work.

- For works from databases that publish original, proprietary material available only in that database (such as the UpToDate database) or for works of limited circulation in databases (such as monographs in the ERIC database), include the name of the database or archive and the URL of the work. If the URL requires a login or is session-specific (meaning it will not resolve for readers), provide the URL of the database or archive home page or login page instead of the URL for the work. (See APA Section 9.30 for more information).

- If the URL is no longer working or no longer provides readers access to the content you intend to cite, try to find an archived version using the Internet Archive , then use the archived URL. If there is no archived URL, do not use that resource.

Format of DOIs and URLs:

Your DOI should look like this:

https://doi.org/10.1037/a0040251

Follow these guidelines from the APA Style website.

APA Style uses the author–date citation system , in which a brief in-text citation points your reader to the full reference list entry at the end of your paper. The in-text citation appears within the body of the paper and briefly identifies the cited work by its author and date of publication. This method enables your reader to locate the corresponding entry in the alphabetical reference list at the end of your paper.

Each work you cite must appear in the reference list, and each work in the reference list must be cited in the text (or in a table, figure, footnote, or appendix) except for the following (See APA, 8.4):

- Personal communications (8.9)

- General mentions of entire websites, whole periodicals (8.22), and common software and apps (10.10) in the text do not require a citation or reference list entry.

- The source of an epigraph does not usually appear in the reference list (8.35)

- Quotations from your research participants do not need citations or reference list entries (8.36)

- References included in a statistical meta-analysis, which are marked with an asterisk in the reference list, may be cited in the text (or not) at the author’s discretion. This exception is relevant only to authors who are conducting a meta-analysis (9.52).

Formatting Your In-Text Citations

Parenthetical and Narrative Citations: ( See APA Section 8.11)

In APA style you use the author-date citation system for citing references within your paper. You incorporate these references using either a parenthetical or a narrative style.

Parenthetical Citations

- In parenthetical citations, the author name and publication date appear in parentheses, separated by a comma. (Jones, 2018)

- A parenthetical citation can appear within or at the end of a sentence.

- When the parenthetical citation is at the end of the sentence, put the period or other end punctuation after the closing parenthesis.

- If there is no author, use the first few words of the reference list entry, usually the "Title" of the source: ("Autism," 2008) See APA 8.14

- When quoting, always provide the author, year, and specific page citation or paragraph number for nonpaginated materials in the text (Santa Barbara, 2010, p. 243). See APA 8.13

- For most citations, the parenthetical reference is placed BEFORE the punctuation: Magnesium can be effective in treating PMS (Haggerty, 2012).

Narrative Citations

In narrative citations, the author name or title of your source appears within your text and the publication date appears in parentheses immediately after the author name.

- Santa Barbara (2010) noted a decline in the approval of disciplinary spanking of 26 percentage points from 1968 to 1994.

In-Text Citation Checklist

- In-Text Citation Checklist Use this useful checklist from the American Psychological Association to ensure that you've created your in-text citations correctly.

In-Text Citations for Specific Types of Sources

Quotations from Research Participants

Personal Communications

Secondary Sources

Use NoodleTools to Cite Your Sources

NoodleTools can help you create your references and your in-text citations.

- NoodleTools Express No sign in required . When you need one or two quick citations in MLA, APA, or Chicago style, simply generate them in NoodleTools Express then copy and paste what you need into your document. Note: Citations are not saved and cannot be exported to a word processor using NoodleTools Express.

- NoodleTools (Login Full Database) This link opens in a new window Create and organize your research notes, share and collaborate on research projects, compose and error check citations, and complete your list of works cited in MLA, APA, or Chicago style using the full version of NoodleTools. You'll need to Create a Personal ID and password the first time you use NoodleTools.

See How to Use NoodleTools Express to Create a Citation in APA Format

Additional NoodleTools Help

- NoodleTools Help Desk Look up questions and answers on the NoodleTools Web site

- << Previous: MLA Style (8th/9th ed.)

- Next: Chicago Style >>

- Last Updated: May 1, 2024 2:04 PM

- URL: https://libguides.mjc.edu/citeyoursources

Except where otherwise noted, this work is licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0 and CC BY-NC 4.0 Licenses .

Citations are a good way to determine the quality of research

- Topical Debate

- Published: 09 November 2020

- Volume 43 , pages 1145–1148, ( 2020 )

Cite this article

- Martin Caon 1 ,

- Jamie Trapp 2 &

- Clive Baldock 3

5644 Accesses

15 Citations

4 Altmetric

Explore all metrics

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction and overview: Clive Baldock, moderator

From the time that Henry Oldenburg created the Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London in the seventeenth century, scientists have endeavoured to share the results of their research efforts to a wider audience by publishing in scientific journals [ 1 ]. Since that time, many new journals have been founded that have given authors many options for publishing. This has been particularly significant in recent years, due to the growth of the internet and the availability of online and open access journals [ 2 , 3 ]. With such growth has come challenges. A significant issue for active research scientists is in keeping up-to-date with published research is due to the large body of research outputs, resulting in only a fraction of the literature being read and subsequently cited [ 4 ]. Due to many published papers going unnoticed or unread, many articles either never get cited or are only self-cited by the authors of the paper. When a paper is published, it has no immediate impact. However, many would contend that the number of times a paper has been subsequently cited is a good indicator of the impact of the paper and therefore the quality of the research [ 5 ].

In this Topical Debate, the previous and current Editors in Chief of this journal engage in a spirited and timely debate regarding citations and whether they are a good way to determine the quality of research. Footnote 1

Arguing for the proposition is Dr. Martin Caon, previous Journal Editor and from Flinders University. Dr Caon was born and grew up in Adelaide. His PhD in Medical Physics was undertaken at the University of South Australia and the Women’s and Children’s Hospital, Adelaide. This came after an undergraduate degree in Physics and Zoology, with honours in Zoology from Adelaide University, a Diploma in Education, and after a Master’s Degree in Science Education from Curtin University. Martin worked as a secondary school teacher in Mount Gambier and Adelaide for ten years before moving to Flinders University in 1988. There, the somewhat unusual undergraduate combination of Physics and Zoology proved useful in the teaching of physical science and anatomy and physiology to health sciences students.

While at Flinders University, his research interests were in the teaching of science to nursing students and in calculating, using Monte Carlo computer methods, the radiation dose to children from CT scanning. This latter work involved constructing anatomically correct mathematical models of child anatomy from medical images, initially using manual and then semi-automatic methods. Commencing in 2003, Martin was Associate Editor of this journal for three years and then Editor in Chief for twelve years. Martin continues as an Associate Editor, but retired from the Editor in Chief position and from Flinders University at the end of 2018. He has spent his retirement playing saxophone, hockey, tennis, bushwalking, running and spending time at his hobby farm and on matters concerning the Friends of the Vulkathunha-Gammon Ranges National Park, of which he is president. He has also completed the recently published 3rd edition of his book: Examination Questions and Answers in Basic Anatomy and Physiology: 2900 multiple choice questions, which has been published by Springer. Additional writing projects have been an article describing the Friends’ work of monitoring Mogurnda clivicola , a land-locked fish found in the Vulkathunha-Gammon Ranges National Park; and researching and writing the 115-year history of the Forestville Hockey Club.

Arguing against the Proposition is Jamie Trapp who is an Associate Professor at Queensland University of Technology (QUT). After completing his PhD at QUT in 2003 he moved to London and worked as a postdoctoral research scientist at the Institute of Cancer Research at the Royal Marsden Hospital. In 2004 he commenced an academic position at Royal Melbourne Institute of Technology, and in 2007 moved back to QUT into a similar position. In 2005 he commenced as an Associate Editor for this journal, in 2016 moved to a Deputy Editor role, and at the end of 2018 became Editor in Chief after Dr Caon’s retirement. He has published over 100 peer reviewed articles in various topics associated with radiation measurement and medical physics.

Opening statement—Martin Caon

How can one determine the quality of a quantum of research? A quantum in this case is an article published in a peer-reviewed scientific journal. One supported by a constituted National or International Society of Scientists sharing a common interest in some field of endeavour, such as this one.

Being published in a journal means that the manuscript has navigated the obstacle course of peer review and been adjudged to be sound, novel and of publishable quality by some members of the academic community. The historical gold standard to assess published articles has been: Be an expert in the field, read a hard copy and assess it in the light of your own expertise. Unfortunately, this method was only available to experts with access to the journal. Fortunately, science advances.

Electronic publication has provided novel, measurable ways to access research. This ability to measure is important. William Thomson said: “When you can measure what you are speaking about, and express it in numbers, you know something about it, when you cannot express it in numbers, your knowledge is of a meagre and unsatisfactory kind” [ 6 ]. Citation metrics mean that the assessment of research quality has left behind the dark ages of meagre and unsatisfactory kinds of knowledge. By expressing quality as a number, we know that we know something about it.

What metrics are available to us? The “number of reads” is a measure of scientific interest. However “Number of Downloads” is a better metric as it implies that the interest is sufficiently deep to require a sustained effort to understand the published work. The NoD is directly proportional to the quality of the article. Contrarily it may be argued that some scientists download rubbish articles to make a point, but people soon tire of reading nonsense, and will return to quality. In fact, the NoD may even underestimate interest as pdf copies electronically sent to colleagues, saves them downloading it anew.

A still better metric is the Number of Citations (NoC) made to published work. Scientists that cite an article are a subset of those that download it. Citing scientists have read the article, found it relevant and useful, and wish to associate their own work with it. Such scientists are themselves researchers who have the expertise to recognise important work. They are part of the community of cognoscenti. Their number can be counted. Now we can say that five scientists have noticed this work, or that 55 scientists approve of the work. We have an improved gold standard. Previously, few people knew how many experts had assessed an article. Its quality was a secret. Now everyone, including the authors, want to know.

The record of quality is permanent. The NoC stays on the record and increases with time making the importance of the work more apparent. Hence the NoC is flexible and responsive to changes in knowledge. It is unlikely that modern day scientists will overlook the work, or the work will be forgotten, as has happened in the past.

The metrification of quality allows for better metrics to be introduced. For example the Relative Citation Ratio measures quality at the article level [ 7 , 8 ]. This metric addresses the widely-acknowledged limitations of metrics such as raw citation count. RCR measures impact while also accounting for field of study and time of publication. This may be done by means of “expected citation rates”, derived from all citations to all contributions of the same type, published in the same year in the same ISI journal.

Just as cobalt machines have been relegated to the basement by modern linacs, x-ray film has been supplanted by digital radiography, CT scanning is now helical, and just as few medical physicists now know what a typewriter is, so the modern assessment of quality has improved and supplanted the historical method. The assessment of quality has been democratised because now Scientists can “vote” on the quality of a manuscript by citing it. Previously quality was assessed subjectively by individual scientists reading the article. Now quality assessment is a transparent collegial exercise in consensus by expert researchers and no longer at the whim of individual scientists.

Opening Statement—Jamie Trapp

The modern concept of citation indexing in research was introduced by Eugene Garfield in 1955, based on the earlier legal citation database Shepard’s Citations which dates back to 1873 [ 9 ]. The purpose of a legal citation database is to ensure that precedents set in legal cases can be found easily and used in later court decisions. Garfield argued that a similar citation database for academic research can be a useful tool to more easily find earlier research in a topic so that it can be built upon by researchers, rather than spending time rediscovering the same, and also that criticisms of earlier research are more easily available to inform future directions. In Garfield’s paper, the term Impact Factor is introduced relating to the number of citations an article or journal receives.

Garfield’s argument that the number of times a particular item/discovery/methodology is subsequently used to build later research [ 9 ] holds true, but simply counting all citations also includes the number of times an item has been criticised. For example, Radicchi showed that papers which have been criticised via Comments are cited more than non-commented papers, and more likely to be among the most cited of a journal [ 10 ]. Although a paper which is commented and criticised is not necessarily of low quality (and the criticism itself is often be debunked by author responses), there are certainly some instances where criticism is valid, yet this very act of criticising a research paper contributes to the ‘impact’ and therefore ‘quality’ via the citation.

It has recently been shown that 74% of citations occur in the Introduction and Discussion sections of papers [ 11 ]. A proper Introduction to a paper puts the present research into context in terms of recent progress in the topic and gaps in the knowledge that need to be filled, and likewise a good Discussion puts the results of the research into context. However, when a paper is cited in an Introduction or Discussion section one has to consider whether it truly informs the present research, or is just listed as a convention where other work is acknowledged, e.g. authors, particularly inexperienced authors, might feel compelled to have a long introduction citing many articles in order to follow the format of other papers they have seen. If these cited papers don’t directly lead to the work being presented, they are essentially just saying ‘these other people worked on something similar to us, but not quite the same’.

Papers which are truly influential, such as introducing a new process, procedure, or discovery are more likely to be cited in the Methodology, as this is where they influence future work. Therefore, one must ask the question of whether citation metrics should be based on all citations, or only the 26% which do not occur in Introductions or Discussions.

The above arguments can be taken further when considering the Matthew effect [ 12 ], which is very eloquently described with an example given by Ioannidis [ 13 ]. In short, the Matthew effect in relation to citations is the concept that a paper with many citations will gather even more citations than, say, a comparable similar paper with fewer or no citations (a self-propagating cycle). Ioannidis describes the situation of over simplified research tools, however the concept can generally be expanded to other situations such as inexperienced authors who might see certain papers being cited in Introductions, which then lead them to think that they should cite the same papers in their own Introductions as some type of unwritten convention in the field (even if not directly relevant), thus the citation cycle is established.

Finally, lack of citations does not mean a piece of work is necessarily of lower quality. The number of citations can be influenced by numerous factors [ 14 ], including age of the article (even Nobel prize winning papers started with 0 citations), discipline norms, access [ 15 ], self-citations (and self-citation schemes) [ 16 ], and even reviewer-coerced citations [ 17 ].

Rebuttal—Martin Caon

Implicit in the statement that “citations are a good way to determine the quality of research” is that the citations are “appropriate” (and appropriately placed within the article). A spurious citation will leave the reader wondering at the quality of the article being read and perhaps to its dismissal as unworthy of study. An article that is cited in the Introduction as reporting a novel result cannot be said to be less worthy of citation than one cited in the Methods section for, say, the kilovoltage selected on the machine. If inappropriate, the snowballing of citations, because “everyone is citing it”, is noticed and dismissed by clever researchers—and that should include all of us.

Peer criticism is an essential part of improving the quality of research and by attracting criticism, the shortcomings of research are uncovered and avoided in future. This improves quality. So while a critical citation may not flag the cited paper as a quality one, it contributes to future quality.

My esteemed colleague contends that lack of citation does not imply lack of quality. I agree, but that is not the proposition we are debating.

Rebuttal—Jamie Trapp

I acknowledge the excellent point of my esteemed colleague that the number of reads and number of downloads of an article is a good measure of its scientific interest. Likewise, the use of normalised citation metrics such as relative citation ratio and others including relative citation impact, relative citation rate, etc. can allow for variations between different research fields.

However, the premise of citation counting is that the total number of citations received is the sole indicator of the quality or impact of a piece of research, regardless of whether the citation is positive, negative, or just there to fill in the introduction and bibliography.

Citation counting is an easy thing to measure, originating from the time when bibliometrics started (when tables of contents and bibliographies were the easiest data to analyse with the tools at the time). To make citation counting appear more meaningful (or perhaps hide the flaws of the system), contemporary research managers and organisations have chosen to use words like ‘research quality’ and ‘impact’ to disguise the fact that it is merely a ‘total citation count’, thereby surreptitiously giving a new, different, definition to these words when the consumer assumes the older, traditional meaning. This is classic case of cognitive bias (imagine, for example, if ‘quality’ suddenly changed to mean ‘word count’, then very long articles would be considered more important than succinct articles, and important works in currently high ranking journals with strict word limits, of say 1500 words, would suffer).

I agree with my esteemed colleague in his point that times change and I would take this a little further. Surely, with the development of data mining techniques a better measure of quality and impact can now be found—there is no longer the need to stick with the ‘easy’ solution.

Note: To support this debate and provide data for the future, a separate article has been produced in this Issue [ 18 ]. The article is intentionally of obvious and deliberate poor quality (in the traditional sense of the word). The purpose of the other article is to act as an experiment within itself, to see if a poor article gains citations how this would be considered for ‘quality’ and ‘impact’ in the contemporary sense used in this debate.

Contributors to Topical Debates are selected for their knowledge and expertise. Their position for or against a proposition may or may not reflect their personal opinions.

Guédon J-C (2001) In oldenburg’s long shadow: librarians, research scientists, publishers and the control of scientific publishing. Association of Research Libraries, Washington, DC

Google Scholar

Lariviére V, Gingras Y, Archambault É (2009) The decline in the concentration of citations, 1900–2007. J Am Soc Inf Sci Tec 60:858–862

Article Google Scholar

Armato S, Baldock C, Orton CG (2015) Hybrid gold is the most appropriate open-access modality for journals like Medical Physics. Med Phys 42(1):1–4

Meho LI (2007) The rise and rise of citation analysis. Phys World 20:32–36

Biagioli M, Lippman A (2020) Metrics and the new ecologies of academic misconduct. In: Biagioli M, Lippman A (eds) Gaming the Metrics: Misconduct and Manipulation in Academic Research. MIT Press, Cambridge MA

Chapter Google Scholar

Lord Kelvin (1883) Lecture to the institution of civil engineers https://todayinsci.com/K/Kelvin_Lord/KelvinLord-MeasureQuote500px.htm . Accessed 11 August 2020

Hutchins BI, Yuan X et al (2016) Relative citation ratio (RCR): a new metric that uses citation rates to measure influence at the article level. PLoS Biol 14(9):e1002541

Purkayastha A, Palmaro E et al (2019) Comparison of two article-level, field-independent citation metrics: Field-Weighted Citation Impact (FWCI) and Relative Citation Ratio (RCR). J Informetrics 13:635–642

Garfield E (1955) Citation indexes for science a new dimention in documentation through association of ideas. Science 122(3159):108–111

Article CAS Google Scholar

Radicchi F (2012) In science “there is no bad publicity”: papers criticized in comments have high scientific impact. Sci Reports 2:815

GerlachM, P-C et al (2019) Large-scale analysis of micro-level citation patterns reveals nuanced selection criteria. Nat Human Behav 3:568–575

Baldock C, Schreiner LJ, Orton, (2017) Famous medical physicists often get more credit for discoveries due to their fame than less prominent scientists who may have contributed as much or earlier to these developments. Med Phys 44(4):1209–1211

Ioannidis JPA (2018) Massive citations to misleading methods and research tools: Matthew effect, quotation error and citation copying. Eur J Epidemiol 33:1021–1023

Tahamtan I, Afshar AS, Ahamdzadeh K (2016) Factors affecting number of citations: a comprehensive review of the literature. Scientometrics 107:1195–1225

De Groote SL (2008) Citation patterns of online and print journals in the digital age. J Med Library Association 96(4):362–369

Ioannidis JPA, Baas J et al (2019) A standardized citation metrics author database annotated for scientific field. PLoS Biol 17(8):e3000384

Wren JD, Valencia A, Kelso J (2019) Reviewer-coerced citation: case report, update on journal policy and suggestions for future prevention. Bioinformatics 35(18):3217–3218

Trapp JV (2020) Citations equals research quality? If you agree then don’t cite this stupid, totally terrible article. Phys Eng Sci Med. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13246-020-00942-8

Article PubMed Google Scholar

Download references

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Clarence Park (retired), Adelaide, Australia

Martin Caon

School of Chemistry, Physics and Mechanical Engineering, Queensland University of Technology, Level 4 O Block, Garden’s Point, Brisbane, QLD, 4001, Australia

Jamie Trapp

Research and Innovation Division, University of Wollongong, Wollongong, NSW, 2522, Australia

Clive Baldock

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Clive Baldock .

Additional information

Publisher's note.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Caon, M., Trapp, J. & Baldock, C. Citations are a good way to determine the quality of research. Phys Eng Sci Med 43 , 1145–1148 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s13246-020-00941-9

Download citation

Published : 09 November 2020

Issue Date : December 2020

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/s13246-020-00941-9

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Find a journal

- Publish with us

- Track your research

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- J Gen Intern Med

- v.37(7); 2022 May

Measures of Impact for Journals, Articles, and Authors

Elizabeth m suelzer.

1 Medical College of Wisconsin, Milwaukee, WI USA

Jeffrey L. Jackson

2 Zablocki VA Medical Center, Milwaukee, WI USA

Journals and authors hope the work they do is important and influential. Over time, a number of measures have been developed to measure author and journal impact. These impact factor instruments are expanding and can be difficult to understand. The varying measures provide different perspectives and have varying strengths and weaknesses. A complete picture of impact for individual researchers and journals requires using multiple measures and does not fully capture all aspects of influence. There are only a few players in the scholarly publishing world that collect data on article citations: Clarivate Analytics, Elsevier, and Google Scholar (Table (Table1). 1 ). Measures of influence for authors and journals based on article citations use one of these sources and may vary slightly because of differing journal coverage.

Citation Databases

Individual Authors

Researchers make contributions to their fields in many ways: through education, advocacy, mentorship, collaboration, reviewing grants and articles, editorial activities, and leadership. For better or worse, their impact is usually based on the number of research articles they publish and how often those articles are cited. Some activities, such as writing editorials for leading journals, book chapters, or other clinical texts; testifying before Congress; or helping to shape government or health system policy, can be highly influential, but not credited in these measures of influence.

A common problem authors have in determining their impact is duplicate names, either from being inconsistent in the name they use (e.g., Jackson JL vs Jackson J) or name changes. There are several ways to establish a persistent and unique digital identifier. Researchers should take advantage of all.

ORCID ( www.orcid.org )

Many funders require an ORCID identifier as part of grant submission. ORCID is free, and all authors can sign up to create a unique identifier. ORCID does not track measures of impact, but cooperates with other sites that do by maintaining a list of publications that authors can review for completeness and accuracy.

ResearcherID ( www.researcherid.com )

This site provides a unique identifier and pulls information from Web of Science (Clarivate) to generate an h -index. It has a dashboard that generates a Web of Science author impact plot, provides authors a year-by-year report on impact, and generates a “citation” map that shows the location of citations. ResearcherID is also used by Publons, another Clarivate product, that tracks peer review and editorial activity. Access requires a subscription.

Scopus and Web of Science

Scopus and Web of Science are independent sites that create unique identifiers for authors based on proprietary software. Identifiers are automatically assigned and may result in the creation of more than one identifier, particularly if authors have had multiple affiliations, have a common name, have changed names, or have been inconsistent in their name. Authors can review the identifiers assigned and merge different listings. Access to these databases requires a subscription.

In addition, authors can create a Google Scholar account, which will also track and assess author impact. Google Scholar is free. Authors should regularly review their account to make sure their article list is accurate.

Measures of Impact for Authors

There are a number of different measures of individual author impact; each has strengths and weaknesses (Table (Table2). 2 ). All are limited in that they do not account for author effort and order. Most can be skewed by self-citation and favor those who have been publishing longer. 2

Author Measures of Influence

H-Index , developed by Jorge E. Hirsch in 2005, is defined as the number of published papers that have been cited at least h times. 3 An h -index of 40 means th.e author has 40 articles cited at least 40 times. This simple metric is widely used for evaluating an authors’ impact. Citation databases like Web of Science, Scopus (Elsevier), and Google Scholar provide h -index information in their author profiles, though the reported h -index may vary due to citation coverage. The h -index favors authors that publish a continuous stream of papers with persistent, above-average impact. It measures the cumulative impact of an author’s work and combines quantity and quality. However, it does not account for the author effort and order, is biased against early-career researchers with fewer publications, and can be skewed by self-citation.

G-Index , created in 2006 by Leo Egghe, is defined as the largest number such that the top “ g ” articles received together at least g 2 citations. 4 This metric favors highly cited articles; a single highly cited article will increase the g -index considerably, while only increasing the h -index by 1.

i-10-Index , calculated by Google Scholar, is a straightforward metric that shows the number of publications with at least 10 citations.

Measures of Impact for Individual Articles

This is an NIH dashboard of bibliometrics for articles. iCite has three modules: Influence, Translation, and Open Citations. Influence is based on a relative citation ratio (RCR), comparing article citations to the median for NIH–funded publications, the value of which is set at 1.0. Among NIH–funded studies, the 90 th percentile for RCR is 3.81. Among all studies, the 90 th percentile is 2.24. Individual paper influence is reported and can be used to select manuscripts that best represent one’s work. Translation provides a measure of translation from bench to bedside by breaking down whether most of the author’s publications are molecular/cellular, animal, or human. Citations provide a count of the total citations and give citation statistics (mean, median, SE, maximum) as well as a list of the citing articles for each paper.

Alternative measures of influence

There are measures of influence of individual articles that are not based on citations. They provide a snapshot of article impact in a number of alternate venues, such as public policy documents, news articles, blogs, and social media.

Altmetric tracks more than 15 different sources, including public policy documents, news articles, blog posts, mentions in syllabi, reference managers, and social networks, such as Twitter and Facebook. The results are weighted; some sources, such as news articles, get greater weight. For example, in 2020, the weights of the various sources were news stories: 8, blogs: 5, Q&A forums: 2.5, Twitter: 1, Google: 1, and Facebook: 0.25. Altmetrics can be displayed as a “badge,” a symbol with a number in the middle of a circle with the strands colored to reflect the elements that went into the score. Researchers can sign up to create an altmetric badge for their articles ( www.altmetric.com ). To create a badge, the article must have a DOI number. Altmetrics for any specific article reflects popular interest in the topic rather than scientific importance. At JGIM, article altmetrics do not correlate with citations. Altmetrics can accumulate quickly; many metrics, such as Twitter and Facebook mentions, tend to occur within days of publication, while citations can take years. Altmetrics can be applied to scholarly products other than research publications, such as curricula and software. However, altmetrics can be gamed; “popular” topics tend to get more play than others. It is still unclear how to use altmetrics; most rank and tenure committees do not include these measures in promotion deliberations.

PlumX Analytics

PlumX gathers metrics into 5 categories: citations, usage, captures, mentions, and social media. Citations include traditional citations as well as ones that may have societal impact, such as policy documents. Usage measures views, downloads, and measures of how often the article is read. Captures indicate that a reader is planning on coming back to the article; it can indicate future citations. Mentions refer to news articles, blog posts, and other public mentions of the paper. PlumX Social Media refers to tweets and Facebook likes and shares, among several sources. It provides a picture of how much public attention articles are getting. PlumX analytics suffer from the same issues as altmetrics and citations. PlumX analytics are embedded in several platforms, including Mendeley, Science Direct, and Scopus and on many open-access journal platforms.

Measures of Impact for Journals

Historically, there were many reasons why certain journals rose to the top: highly respected editors, a long publishing history, and a track record of influential work policy makers and clinicians cared about. In 1975, Thompson Reuters debuted SCI Journal Citation Reports , ranking journals based on article citations. 5 Subsequently, this has been the primary basis for journal prestige.

Journal evaluation metrics that use citation data favor some disciplines over others. Disciplines vary widely in the amount of research output, the number of citations that are normally included in papers, and the tendency of a discipline to cite recent articles. 6 For example, Acta Poetica focuses on literary criticism. Its impact factor would be a poor measure of the journal’s influence. In addition, one needs to consider where the evaluation tool is collecting their data. Databases like Web of Science and Scopus may have stronger coverage of some disciplines, impacting the citation metrics that are generated. 6

Some resources assign journals to subject categories, making it possible to compare journals within their discipline. A good analogy is points scored in sporting events. Seven points in American football is a poor offensive outing, while 7 points in European football is a juggernaut. Comparing journals within the same discipline provides better information about the journal’s relative importance.

Journal Citation Reports

Journal Impact Factor (JIF). This is published annually by Clarivate and uses citation data from Web of Science. It has been the “gold standard” for measuring journal impact since its creation. 7 Journal editors nervously await release of their impact factor every summer. The JIF is calculated by dividing the total number of citations in the previous 2 years by the number of “source” articles published the following year. JGIM had 2810 citations in 2020 for articles published in 2018 and 2019; 548 of these articles were categorized as source material. Dividing 2810/548 yields our 2020 impact factor of 5.128. Not everything journals publish is considered source material. Clarivate does not provide guidance to journals on how they decide what types of material to count. In general, letters and editorials are not included. JGIM falls in the Medicine, General & Internal and the Health Care Sciences & Services categories, ranking 27 th and 11 th , respectively, in each. Seeking high JIF has led some journals to reduce the number of articles they publish, increase the amount of non-source papers, and focus on work they believe will be highly cited. The JIF is also susceptible to journal self-citation.

Journal Citation Indicator (JCI) is a normalized metric that debuted in 2021; a score of 1.0 means that journal articles were cited on average the same as other journals in that category. 8 JGIM has a JCI of 1.48 (Table (Table3), 3 ), meaning we have a 48% more citation impact than other journals in our category. Based on the JCI, JGIM ranks 23 rd in Medicine, General & Internal and 15 th in Health Care Sciences & Services.

Journal Measures of Impact

* Source articles: articles that are counted in the denominator

5-Year Impact Factor is the average number of times articles published in the previous 5 years were cited in the indexed year. It gives information on the sustained influence of journal publications. JGIM’s 2020 score was 6.070, meaning that articles published in 2014–2019 were cited an average of 6 times in 2020.

Immediacy Index is the number of citations that occur in the year of publication. Journals with high immediacy index scores are rapidly cited. JGIM has a score of 1.861. This measure has been criticized for penalizing articles published later in the year.

Eigenfactor Score , a metric created in 2007 by Carl Bergstrom and Jevin West of the University of Washington, is based on the number of times articles from a journal over the past 5 years have been cited in the indexed year and gives citations in highly cited journals more weight than lesser cited ones. Self-citations by the journal are excluded. JGIM’s 2020 eigenfactor score was 0.02895. This measure suffers from being difficult to understand.

The Normalized Eigenfactor Score provides a normalized metric of the Eigenfactor Score, setting a score of 1 as the average for all journals. Like the Eigenfactor Score, citations that come from highly cited journals carry more weight than citations from less cited journals and journal self-citations are excluded. JGIM’s score is 6.07, meaning that JGIM was sixfold more influential than the average journal in the Web of Science database.

Article Influence . This measure is calculated by dividing the Eigenfactor Score by the number of a journal’s articles over the first 5 years after publication. It is calculated by multiplying the Eigenfactor Score by 0.01 and dividing by the number of articles in the journal, then normalized as a fraction of all articles in all publications, such that the mean is 1.0. JGIM’s most recent influence score is 2.579. This indicates that JGIM is more than twice as influential as the average journal.

CiteScore is calculated by dividing the number of citations from documents (articles, reviews, conference papers, book chapters, and data papers) over the previous 4 years by the number of articles indexed in Scopus published by the journal during those years. JGIM’s CiteScore is 4.6. Cite scores are calculated on a monthly basis. Among 122 internal medicine journals, JGIM is ranked 40 th by the CiteScore.

SCImago Journal Rank (SJR) also uses Scopus data and weights citations according to the prestige of the citing journal, taking into account the thematic closeness of the citing and cited journals. 9 It is calculated based on citations in 1 year to articles published in the previous 3 years. JGIM’s SJR is 1.746, which puts us 13 th on the list of “internal medicine” journals.

SCImago H-Index calculates the number of journal articles ( h ) that have been cited at least h times. It is the same calculation used to evaluate authors; SCImago calculates the journal h -index using Scopus citation data. JGIM has an h -index of 180, meaning that 180 of our articles have been cited more than 180 times. The h -index measures the productivity and impact of journal publications.

Source Normalized Impact per Paper (SNIP) compares each journal’s citations per article with the citations expected in its field. It allows a comparison of the journal’s impact across fields, because it adjusts for the likelihood of journal articles in that field being cited. JGIM’s SNIP is 1.471 which ranks us as 23 rd among 112 internal medicine journals.

Google Scholar

H5-index. Google Scholar calculates an H5-index for journals, which is the number of articles in the last 5 years with at least h citations. Google Scholar classifies JGIM as a primary care health journal. JGIM has an H5-index of 65, making it the top-ranked journal in this category. Google Scholar does not make available the citation sources; consequently, it is difficult to tell how complete the data is.

Journal Altmetrics

Like individual articles, altmetrics can be generated for journals. They have the same advantages and disadvantages as individual article altmetrics. In 2020, JGIM had 2.5 million downloads, 61 k linkouts, and 33 k social media mentions. Journal editors may have a poor understanding of altmetrics and struggle to know what to do with the data. Altimetrics reflect popular interest. For example, in 2020, the COVID pandemic captured public interest; articles focused on aspects of the pandemic received considerable public attention. For JGIM, the top altimetric article examined the impact of masking on preventing the spread of COVID and had an altmetric score of 4829.

JGIM is interested in these measures to ensure that we (like our authors) are having an impact. However, we are not obsessed on these measures and will continue to put forward what feels most important and relevant for academic general internists.

Declarations

The authors had no conflicts of interest with this article.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Purdue Online Writing Lab Purdue OWL® College of Liberal Arts

MLA In-Text Citations: The Basics

Welcome to the Purdue OWL

This page is brought to you by the OWL at Purdue University. When printing this page, you must include the entire legal notice.

Copyright ©1995-2018 by The Writing Lab & The OWL at Purdue and Purdue University. All rights reserved. This material may not be published, reproduced, broadcast, rewritten, or redistributed without permission. Use of this site constitutes acceptance of our terms and conditions of fair use.

Guidelines for referring to the works of others in your text using MLA style are covered throughout the MLA Handbook and in chapter 7 of the MLA Style Manual . Both books provide extensive examples, so it's a good idea to consult them if you want to become even more familiar with MLA guidelines or if you have a particular reference question.

Basic in-text citation rules

In MLA Style, referring to the works of others in your text is done using parenthetical citations . This method involves providing relevant source information in parentheses whenever a sentence uses a quotation or paraphrase. Usually, the simplest way to do this is to put all of the source information in parentheses at the end of the sentence (i.e., just before the period). However, as the examples below will illustrate, there are situations where it makes sense to put the parenthetical elsewhere in the sentence, or even to leave information out.

General Guidelines

- The source information required in a parenthetical citation depends (1) upon the source medium (e.g. print, web, DVD) and (2) upon the source’s entry on the Works Cited page.

- Any source information that you provide in-text must correspond to the source information on the Works Cited page. More specifically, whatever signal word or phrase you provide to your readers in the text must be the first thing that appears on the left-hand margin of the corresponding entry on the Works Cited page.

In-text citations: Author-page style

MLA format follows the author-page method of in-text citation. This means that the author's last name and the page number(s) from which the quotation or paraphrase is taken must appear in the text, and a complete reference should appear on your Works Cited page. The author's name may appear either in the sentence itself or in parentheses following the quotation or paraphrase, but the page number(s) should always appear in the parentheses, not in the text of your sentence. For example:

Both citations in the examples above, (263) and (Wordsworth 263), tell readers that the information in the sentence can be located on page 263 of a work by an author named Wordsworth. If readers want more information about this source, they can turn to the Works Cited page, where, under the name of Wordsworth, they would find the following information:

Wordsworth, William. Lyrical Ballads . Oxford UP, 1967.

In-text citations for print sources with known author

For print sources like books, magazines, scholarly journal articles, and newspapers, provide a signal word or phrase (usually the author’s last name) and a page number. If you provide the signal word/phrase in the sentence, you do not need to include it in the parenthetical citation.

These examples must correspond to an entry that begins with Burke, which will be the first thing that appears on the left-hand margin of an entry on the Works Cited page:

Burke, Kenneth. Language as Symbolic Action: Essays on Life, Literature, and Method . University of California Press, 1966.

In-text citations for print sources by a corporate author

When a source has a corporate author, it is acceptable to use the name of the corporation followed by the page number for the in-text citation. You should also use abbreviations (e.g., nat'l for national) where appropriate, so as to avoid interrupting the flow of reading with overly long parenthetical citations.

In-text citations for sources with non-standard labeling systems

If a source uses a labeling or numbering system other than page numbers, such as a script or poetry, precede the citation with said label. When citing a poem, for instance, the parenthetical would begin with the word “line”, and then the line number or range. For example, the examination of William Blake’s poem “The Tyger” would be cited as such:

The speaker makes an ardent call for the exploration of the connection between the violence of nature and the divinity of creation. “In what distant deeps or skies. / Burnt the fire of thine eyes," they ask in reference to the tiger as they attempt to reconcile their intimidation with their relationship to creationism (lines 5-6).

Longer labels, such as chapters (ch.) and scenes (sc.), should be abbreviated.

In-text citations for print sources with no known author

When a source has no known author, use a shortened title of the work instead of an author name, following these guidelines.

Place the title in quotation marks if it's a short work (such as an article) or italicize it if it's a longer work (e.g. plays, books, television shows, entire Web sites) and provide a page number if it is available.

Titles longer than a standard noun phrase should be shortened into a noun phrase by excluding articles. For example, To the Lighthouse would be shortened to Lighthouse .

If the title cannot be easily shortened into a noun phrase, the title should be cut after the first clause, phrase, or punctuation:

In this example, since the reader does not know the author of the article, an abbreviated title appears in the parenthetical citation, and the full title of the article appears first at the left-hand margin of its respective entry on the Works Cited page. Thus, the writer includes the title in quotation marks as the signal phrase in the parenthetical citation in order to lead the reader directly to the source on the Works Cited page. The Works Cited entry appears as follows:

"The Impact of Global Warming in North America." Global Warming: Early Signs . 1999. www.climatehotmap.org/. Accessed 23 Mar. 2009.

If the title of the work begins with a quotation mark, such as a title that refers to another work, that quote or quoted title can be used as the shortened title. The single quotation marks must be included in the parenthetical, rather than the double quotation.

Parenthetical citations and Works Cited pages, used in conjunction, allow readers to know which sources you consulted in writing your essay, so that they can either verify your interpretation of the sources or use them in their own scholarly work.

Author-page citation for classic and literary works with multiple editions