Advertisement

Supported by

Eternal Life

- Share full article

By Lisa Margonelli

- Feb. 5, 2010

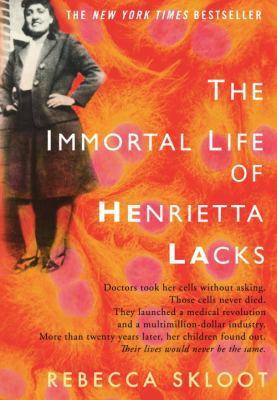

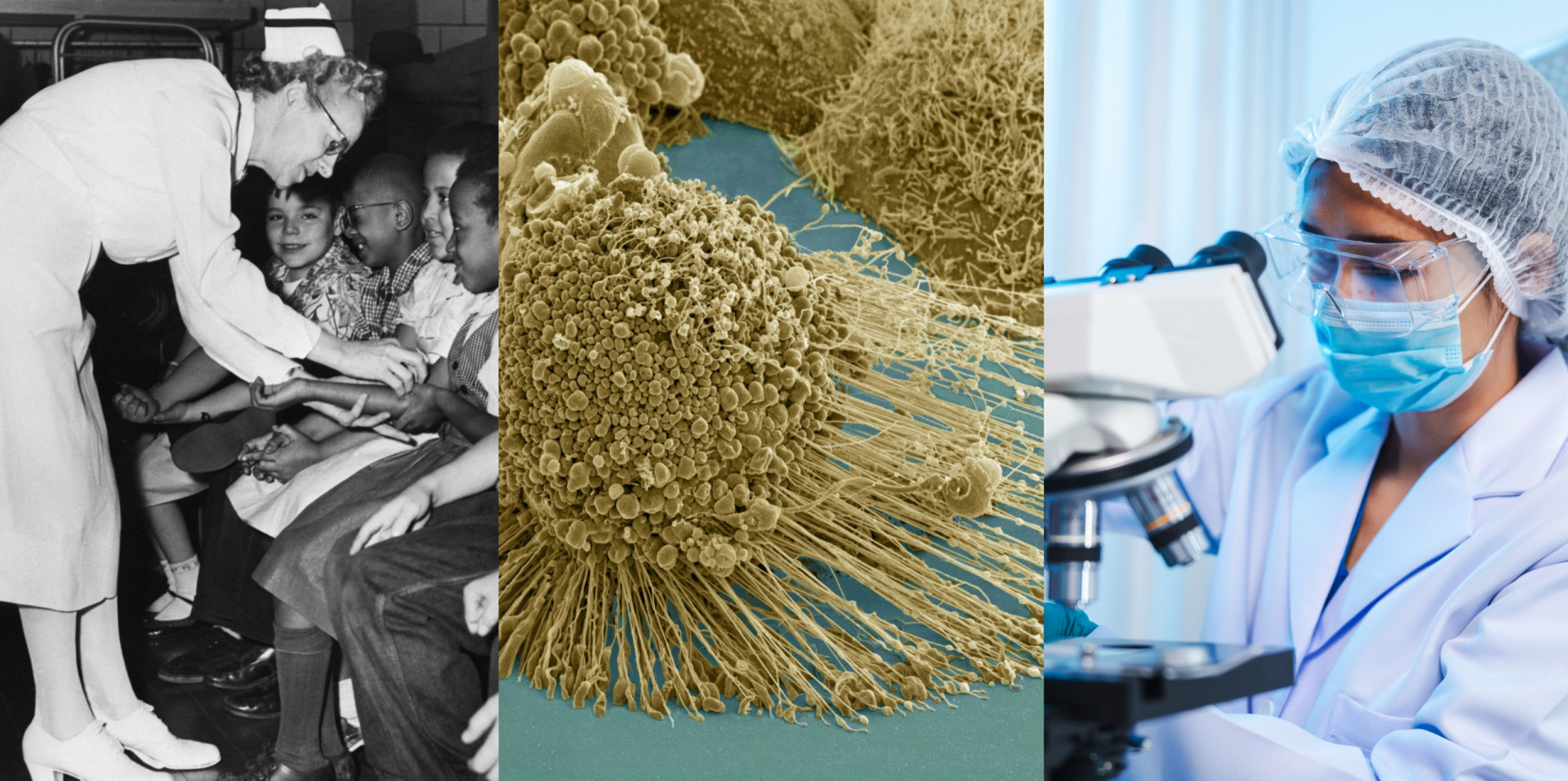

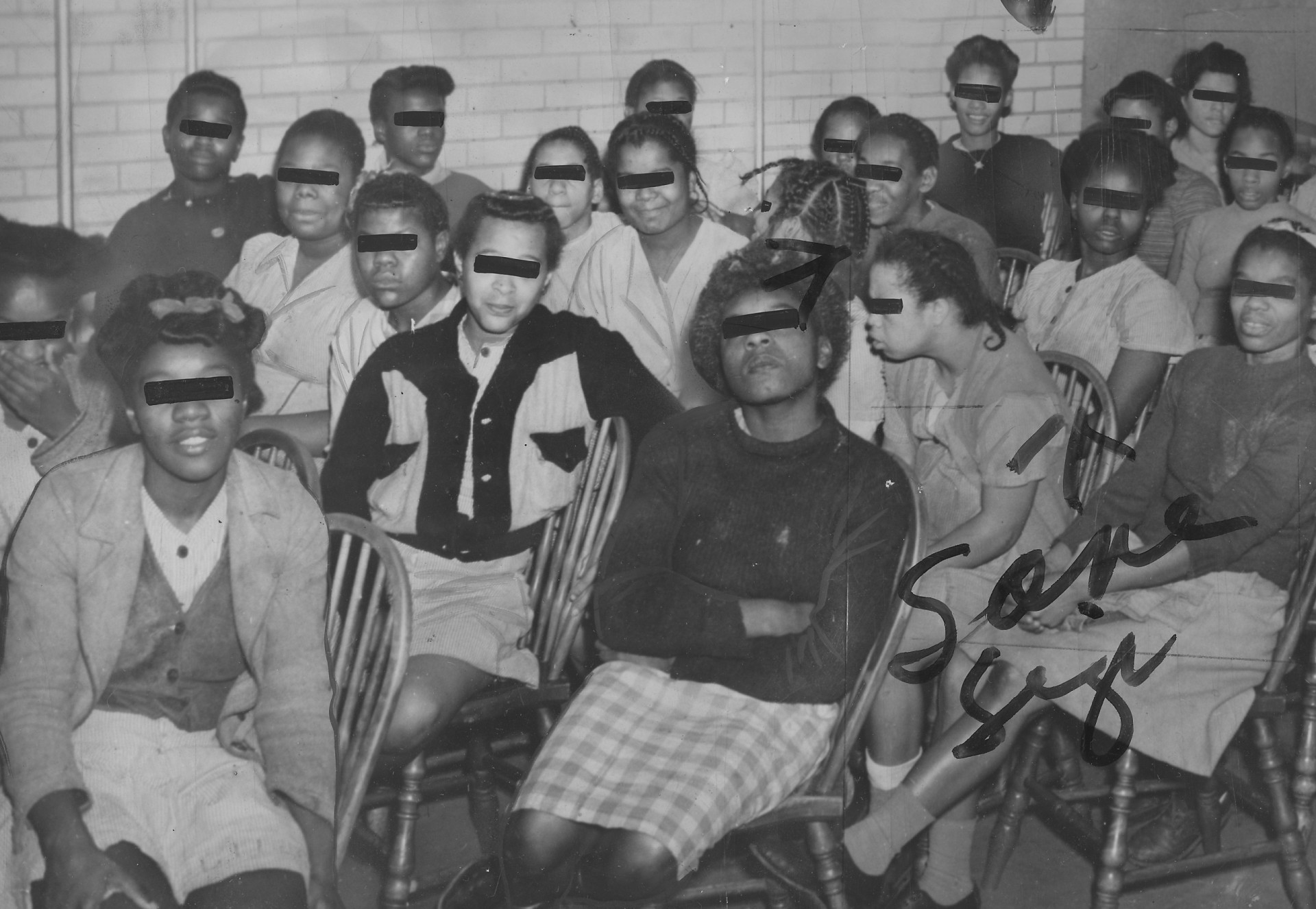

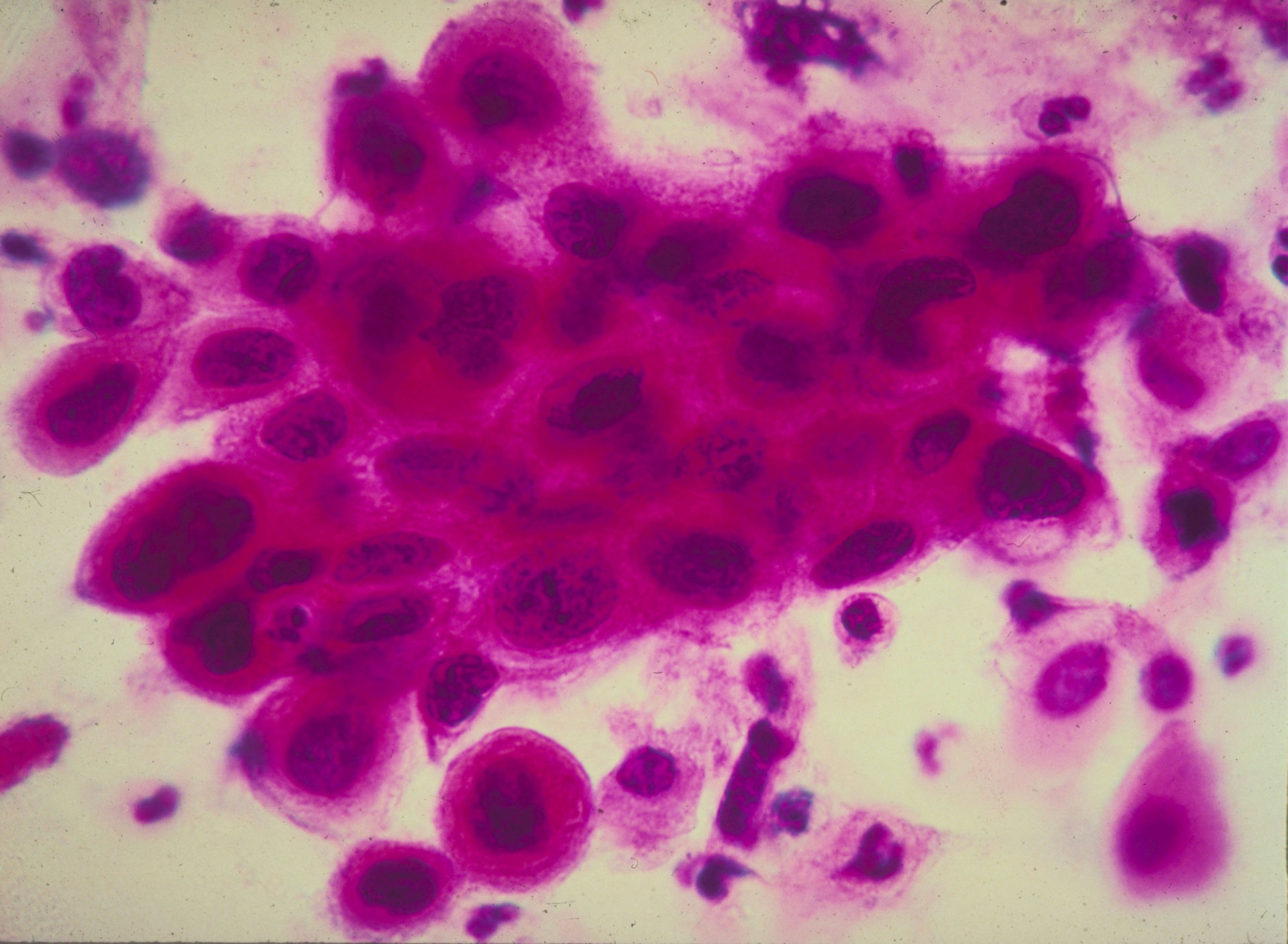

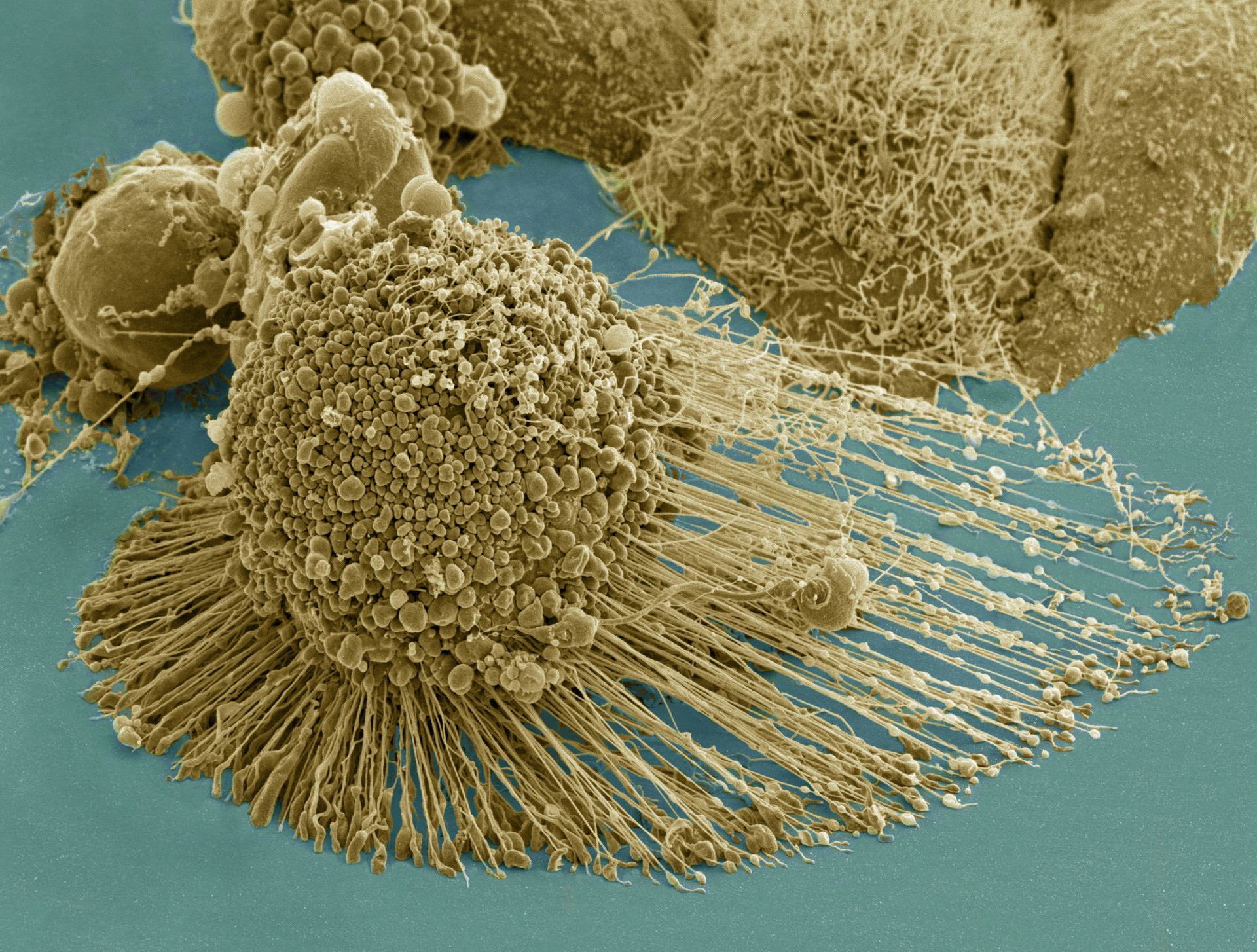

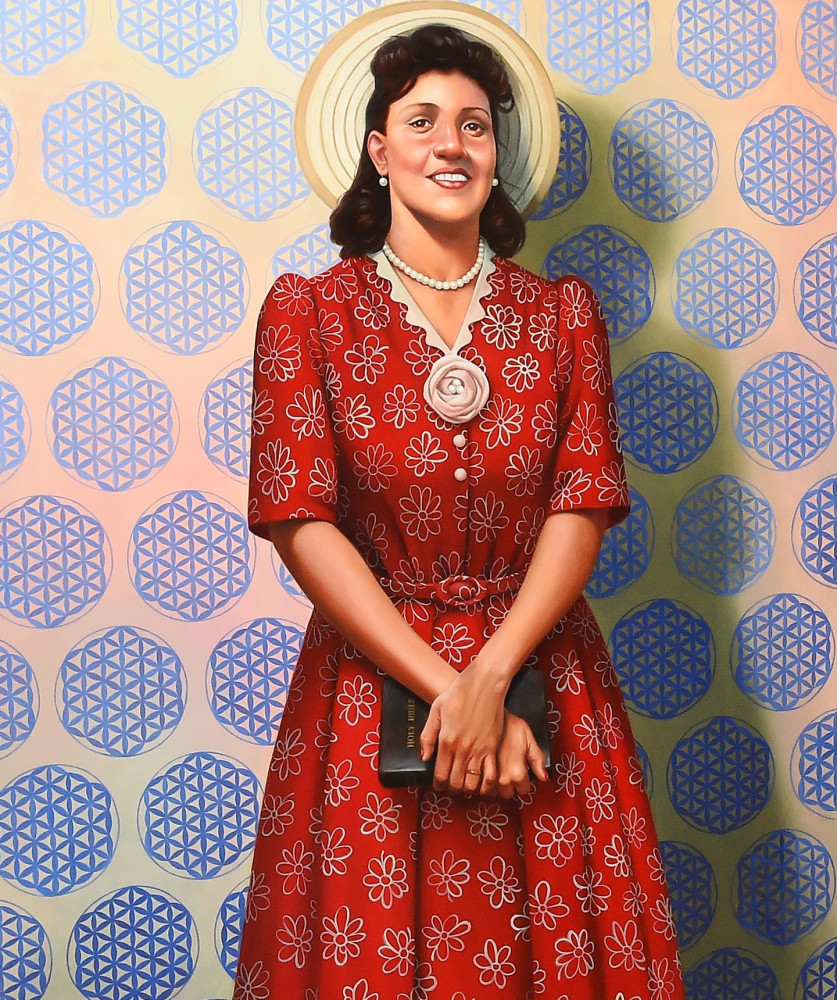

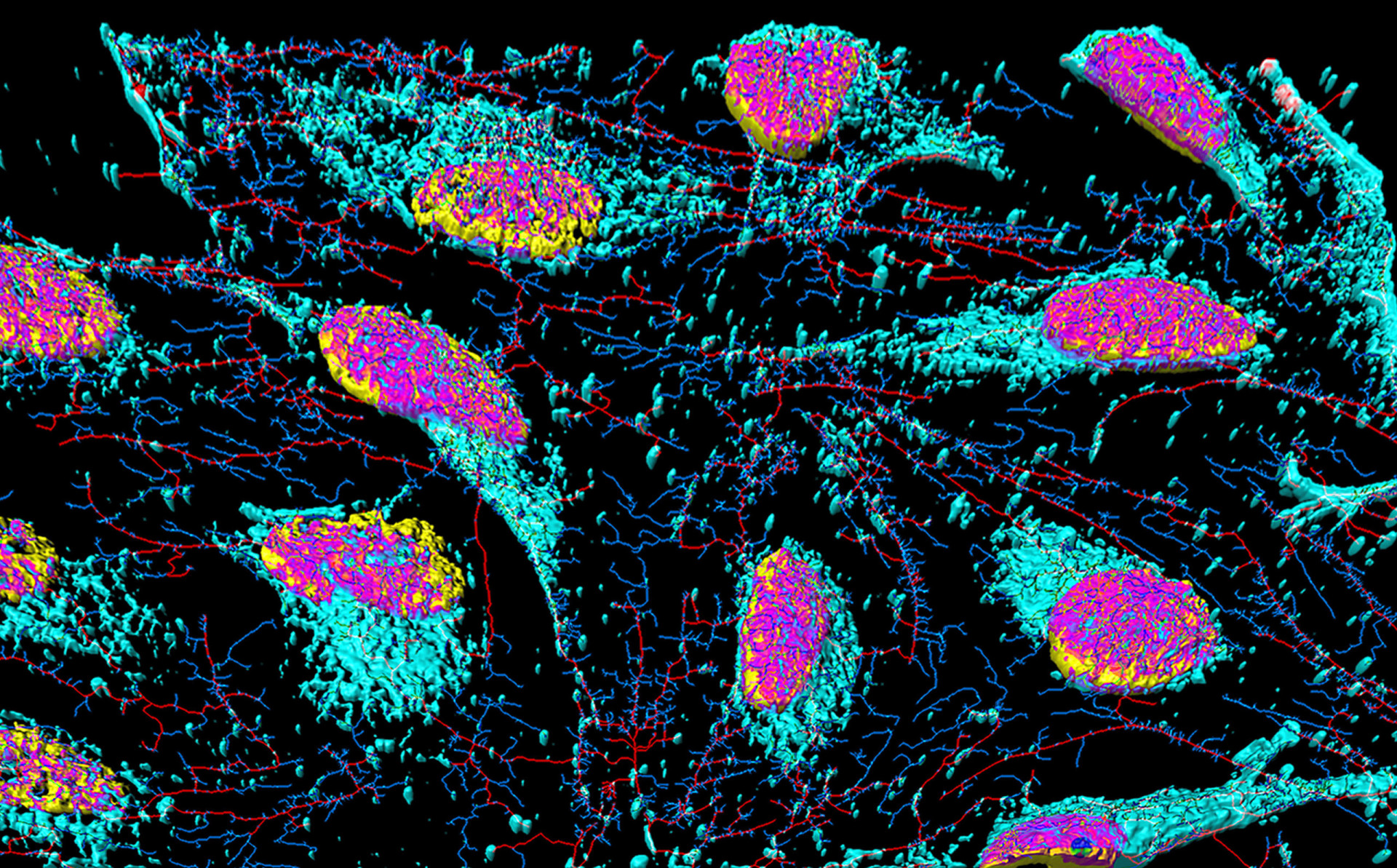

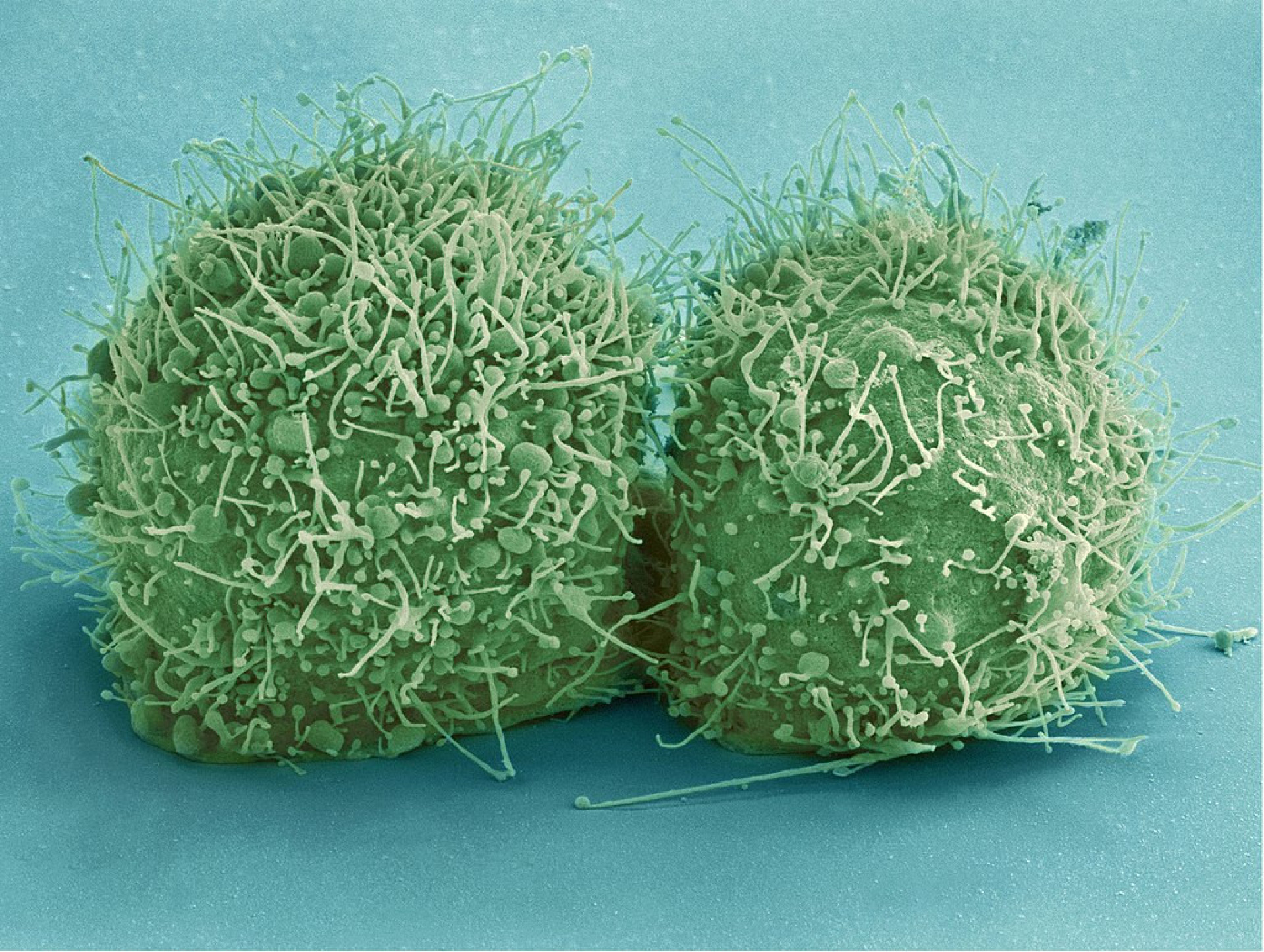

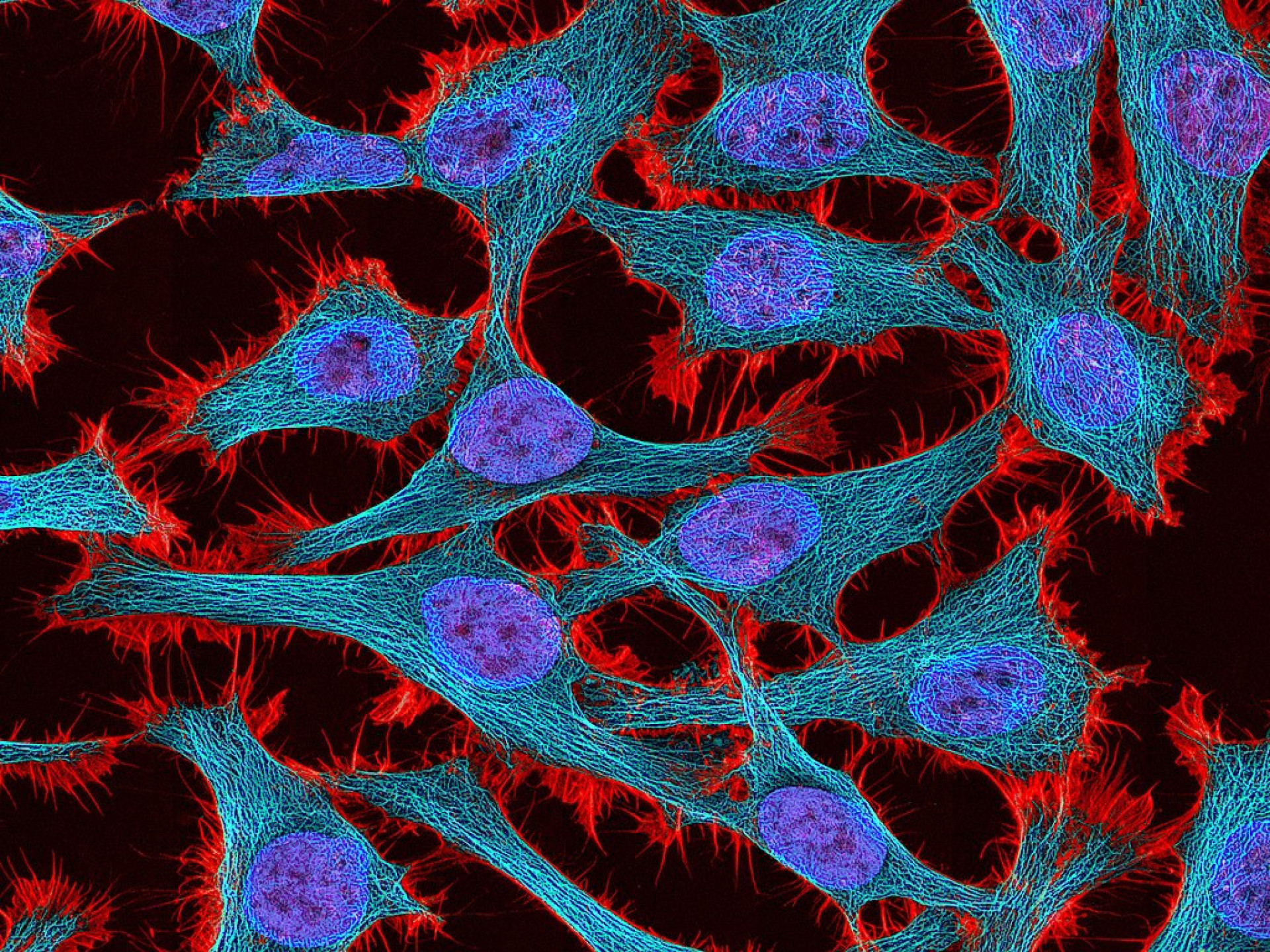

From the very beginning there was something uncanny about the cancer cells on Henrietta Lacks ’s cervix. Even before killing Lacks herself in 1951, they took on a life of their own. Removed during a biopsy and cultured without her permission, the HeLa cells (named from the first two letters of her first and last names) reproduced boisterously in a lab at Johns Hopkins — the first human cells ever to do so. HeLa became an instant biological celebrity, traveling to research labs all over the world. Meanwhile Lacks, a vivacious 31-year-old African-American who had once been a tobacco farmer, tended her five children and endured scarring radiation treatments in the hospital’s “colored” ward.

After Henrietta Lacks’s death, HeLa went viral, so to speak, becoming the godmother of virology and then biotech, benefiting practically anyone who’s ever taken a pill stronger than aspirin. Scientists have grown some 50 million metric tons of her cells, and you can get some for yourself simply by calling an 800 number. HeLa has helped build thousands of careers, not to mention more than 60,000 scientific studies, with nearly 10 more being published every day, revealing the secrets of everything from aging and cancer to mosquito mating and the cellular effects of working in sewers.

HeLa is so outrageously robust that if one cell lands in a petri dish, it proceeds to take over. And so, like any good celebrity, HeLa had a scandal: In 1966 it became clear that HeLa had contaminated hundreds of cell lines, destroying research as far away as Russia. By 1973, when Lacks’s children were shocked to learn that their mother’s cells were still alive, HeLa had already been to outer space.

During the eight months that Lacks herself was dying of cancer, the HeLa cells so thoroughly eclipsed her that a lab assistant at her autopsy glanced at her painted red toes and thought: “Oh jeez, she’s a real person. . . . I started imagining her sitting in her bathroom painting those toenails, and it hit me for the first time that those cells we’d been working with all this time and sending all over the world, they came from a live woman. I’d never thought of it that way.”

In “The Immortal Life of Henrietta Lacks,” Rebecca Skloot introduces us to the “real live woman,” the children who survived her, and the interplay of race, poverty, science and one of the most important medical discoveries of the last 100 years. Skloot narrates the science lucidly, tracks the racial politics of medicine thoughtfully and tells the Lacks family’s often painful history with grace. She also confronts the spookiness of the cells themselves, intrepidly crossing into the spiritual plane on which the family has come to understand their mother’s continued presence in the world. Science writing is often just about “the facts.” Skloot’s book, her first, is far deeper, braver and more wonderful.

Skloot didn’t know what she was getting into when she began researching the book as a graduate student in 1999. The first time she called Lacks’s widower, then living in Baltimore, the person who answered the phone simply heard her voice and yelled, “Get Pop, lady’s on the phone about his wife cells.” Over the years it took Skloot to gain the family’s trust, she came to understand that the only time white people ever called the house was when they wanted something to do with the HeLa cells. Some of the family feel they’ve been ripped off, cheated by either Johns Hopkins (though the hospital never sold the cells) or the entire medical establishment, which has made enormous profits from the cells.

Skloot traces the family’s emotional ordeal, the changing ethics and law around tissue collections, and the inadvertently careless journalists and researchers who violated the family’s privacy by publishing everything from Henrietta’s medical records to the family’s genetic information. She tacks between the perspective of the scientists and the family evenly and fairly, arriving at a paradox described by Henrietta’s daughter Deborah. “Truth be told, I can’t get mad at science, because it help people live, and I’d be a mess without it. I’m a walking drugstore! . . . But I won’t lie, I would like some health insurance so I don’t got to pay all that money every month for drugs my mother cells probably helped make.”

Deborah, a generous spirit, becomes the book’s driving force, as Skloot joins her in her “lifelong struggle to make peace with the existence of those cells, and the science that made them possible.” To find the mother she never got to know, she read hundreds of articles about HeLa research, which led her to believe that her mother was “eternally suffering” from all the experiments performed on her cells. In unsentimental prose, Skloot describes traveling with her to Clover, Va., where Henrietta grew up in her grandfather’s cabin, former slave quarters in a town where the black Lackses and the white Lackses don’t mix. Suffering from hives and extreme anxiety, Deborah seeks out a relative who channels the voice of God. He tells Deborah to let Skloot carry the “burden” of the cells from now on, explaining that the cells have become heavenly bodies, immortal angels.

But “The Immortal Life of Henrietta Lacks” is much more than a portrait of the Lacks family. It is also a critique of science that insists on ignoring the messy human provenance of its materials. “Scientists don’t like to think of HeLa cells as being little bits of Henrietta because it’s much easier to do science when you dissociate your materials from the people they come from,” a researcher named Robert Stevenson tells Skloot in one of the many ethical discussions seeded throughout the book.

The ethical issues implicated in the HeLa story are many and tangled. Since 1951, science has progressed much faster than our ability to figure out what is right and wrong about tissue culture. In the 1980s a doctor who had removed the cancer-ridden spleen of a man named John Moore patented some of the cells to create a cell line then valued at more than $3 billion, without Moore’s knowledge. Moore sued, and on appeal the court ruled that patients had the right to control their tissues, but soon that was struck down by the California Supreme Court, which said that tissue removed from the body had been abandoned as medical waste. The cell line created by the doctor had been “transformed” via his “inventive effort,” and to say otherwise would “destroy the economic incentive to conduct important medical research.” The court said that doctors should disclose their financial interests and called on legislators to increase patient protections and regulation, but this has hardly hindered the growth of the field. In 1999 the RAND Corporation estimated that American labs alone held more than 307 million tissue samples from some 178 million people. Not only is the question of payment for profitable tissues unresolved, Skloot notes, but it’s still not necessary to obtain consent to store cells and tissue taken in diagnostic procedures and then use the samples for research.

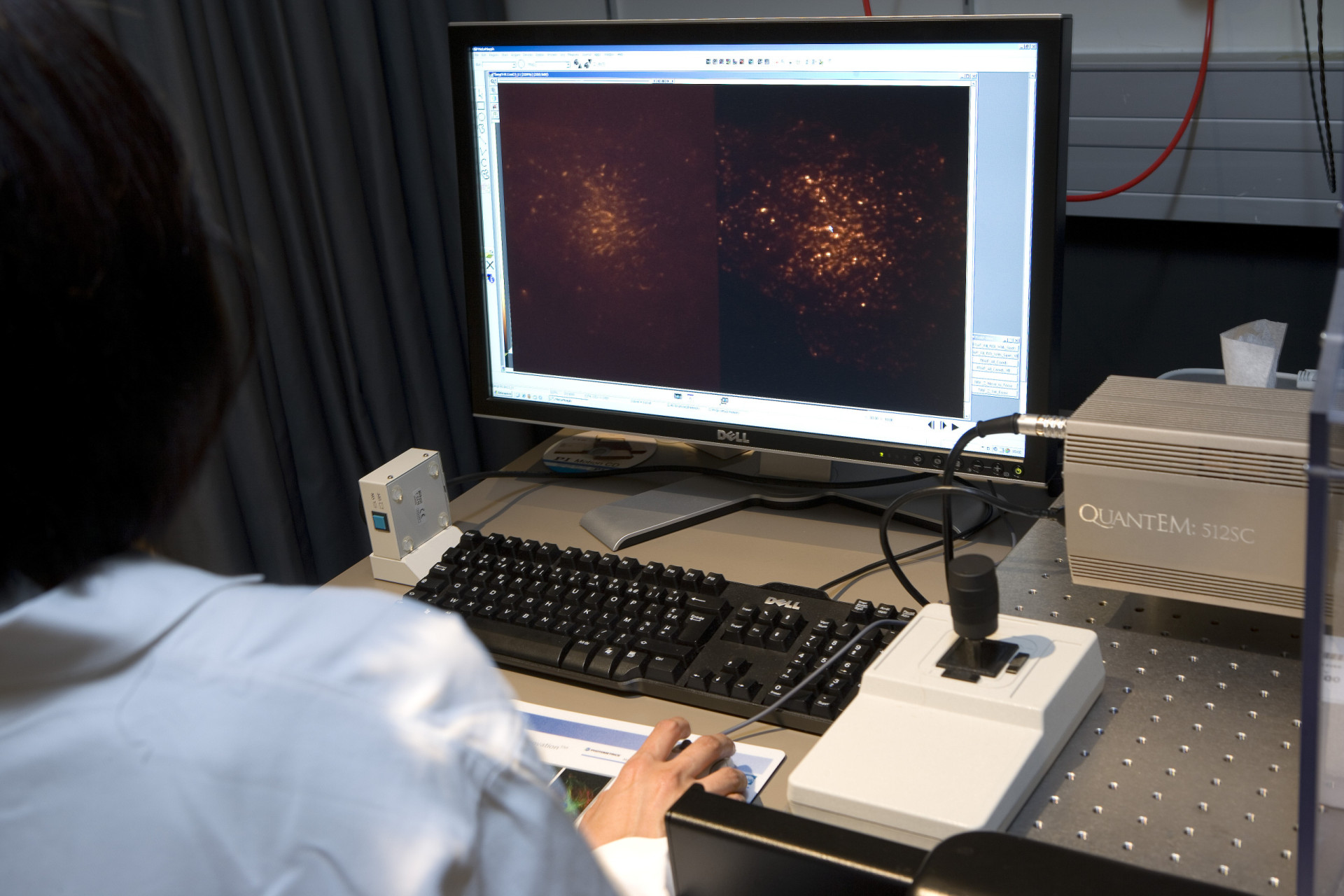

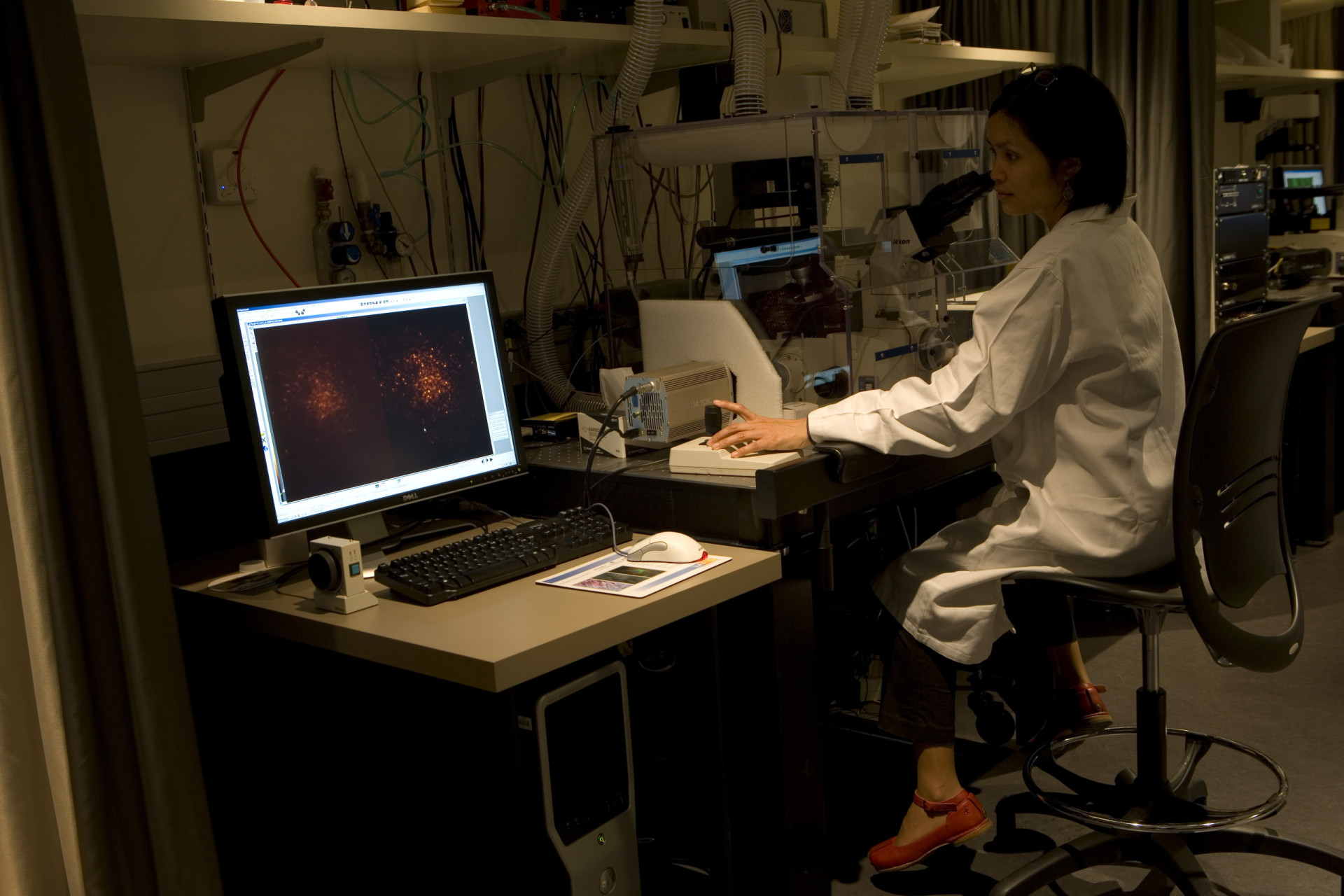

The scene in this book that made my hair stand on end occurred when the Lackses followed Skloot into the world of science, just as she had followed them into the world of faith. In 2001, an Austrian researcher at Johns Hopkins named Christoph Lengauer invited the family to his lab. When Deborah and her brother visited, he led them to the basement, where they “saw” their mother for the first time, warming frozen test tubes of HeLa in their hands and watching as a cell divided into two under a microscope while Lengauer explained his work. Deborah pressed a cold vial to her lips. “You’re famous,” she whispered. “Just nobody knows it.”

THE IMMORTAL LIFE OF HENRIETTA LACKS

By Rebecca Skloot

Illustrated. 369 pp. Crown Publishers. $26

Lisa Margonelli is a senior research fellow at the New America Foundation and the author of “Oil on the Brain: Petroleum’s Long, Strange Trip to Your Tank.”

Explore More in Books

Want to know about the best books to read and the latest news start here..

As book bans have surged in Florida, the novelist Lauren Groff has opened a bookstore called The Lynx, a hub for author readings, book club gatherings and workshops , where banned titles are prominently displayed.

Eighteen books were recognized as winners or finalists for the Pulitzer Prize, in the categories of history, memoir, poetry, general nonfiction, fiction and biography, which had two winners. Here’s a full list of the winners .

Montreal is a city as appealing for its beauty as for its shadows. Here, t he novelist Mona Awad recommends books that are “both dreamy and uncompromising.”

The complicated, generous life of Paul Auster, who died on April 30 , yielded a body of work of staggering scope and variety .

Each week, top authors and critics join the Book Review’s podcast to talk about the latest news in the literary world. Listen here .

Book Review: The Immortal Life of Henrietta Lacks

Contingency has been on my mind quite often these days. What would life look like today if the ancestors of the first land-dwelling vertebrates had two legs instead of four? How would non-avian dinosaurs continue to have evolved if they had not been wiped out 65 million years ago? What if, like many other prehistoric apes, our own ancestors fell into extinction during the Pliocene? Any one of these events would have changed the history of life on earth, and even though there are not answers to these questions they still remind me of how historical quirks can have major effects.

Though it has nothing at all to do with fossils or evolution, Rebecca Skloot’s The Immortal Life of Henrietta Lacks is also a tale of contingency. In February of 1951 doctors at Johns Hopkins Hospital removed cancerous cells from the cervix of a 30 year old African American woman who had come in complaining of a painful “knot” inside of her. She had no idea that the sample of her cells had been taken, but this small event of one woman’s life would end up changing the world in ways that no one expected.

This woman was Henrietta Lacks , and even though she died from the cancer in October of 1951 the descendants of the cells taken from her over a half century ago are still thriving in laboratories around the world. Because of a biological quirk scientists were able to turn her cells into the first “immortal” cell line, called HeLa, the study of which has greatly increased our knowledge of ourselves and led to the effective treatment of numerous diseases. Her cells have affected the lives of people all over the world, and this makes it all the more shameful that, until now, almost no one knew anything about her.

The true strength of Skloot’s book is that it is not a simple celebration of science. Innumerable articles and several books have been written about the HeLa cell line before, but they largely ignored Henrietta and her family. The story of the poor black woman who had her cells taken from her without her knowledge or consent just did not register with most writers (especially since it was decades before anyone knew her real name), and the attitudes of journalists and scientists made Henrietta’s family increasingly bitter about the entire affair. While medical companies made millions off of Henrietta’s cells they remained poor and could barely afford health insurance even in the best of times. And as famous as Henrietta’s cells were her family knew almost nothing about what happened to her or what was taken from her. While Skloot ably covers the science of HeLa, the real story is the personal drama of Henrietta and her family, in which Skloot comes to play a substantial part.

As I read through this story of science, race relations, medicine, and poverty I could not help but wonder how things would have been if small events had turned out differently. What if doctors and scientists had informed the Lacks family about HeLa earlier, and what would have happened if the scientists that finally did were not so inept at communicating what had happened to Henrietta? What if Skloot had never followed her deep desire to know who Henrietta was, or what if the Lacks family, frustrated that another journalist was coming around asking questions, decided to ignore Skloot’s persistent phone calls? Would Henrietta’s life have remained a mystery even to her own family?

The Immortal Life of Henrietta Lacks is a triumph of science writing (it is truly one of the best nonfiction books I have ever read), and I was deeply affected by it on a personal level. The story reaffirmed that small events can have major repercussions, and as sad and angry as the tale of the Lacks family made me by the end of the book I was glad that Skloot had worked so hard to reach them. Through something as simple as wanting to learn more about Henrietta’s life Skloot and the Lacks family were able to create a fitting tribute to Henrietta and her legacy. For the first time, the most important woman in modern medicine is having her story told, and I truly hope that it gets the attention it deserves.

You can contribute to the Henrietta Lacks Foundation here .

[Be sure to check out the reviews of The Immortal Life of Henrietta Lacks at the New York Times and Not Exactly Rocket Science , as well.]

For Hungry Minds

Related topics.

- SCIENCE AND TECHNOLOGY

- HISTORY AND CIVILIZATION

- Environment

- Perpetual Planet

History & Culture

- History & Culture

- History Magazine

- Mind, Body, Wonder

- Terms of Use

- Privacy Policy

- Your US State Privacy Rights

- Children's Online Privacy Policy

- Interest-Based Ads

- About Nielsen Measurement

- Do Not Sell or Share My Personal Information

- Nat Geo Home

- Attend a Live Event

- Book a Trip

- Inspire Your Kids

- Shop Nat Geo

- Visit the D.C. Museum

- Learn About Our Impact

- Support Our Mission

- Advertise With Us

- Customer Service

- Renew Subscription

- Manage Your Subscription

- Work at Nat Geo

- Sign Up for Our Newsletters

- Contribute to Protect the Planet

Copyright © 1996-2015 National Geographic Society Copyright © 2015-2024 National Geographic Partners, LLC. All rights reserved

- International edition

- Australia edition

- Europe edition

The Immortal Life of Henrietta Lacks by Rebecca Skloot

I n old-fashioned museums you can see the unconscious benefactors of mankind, trapped in glass cases: the freaks and monsters of their day, the anomalies, sometimes skeletonised and entire, sometimes cut into parts and labelled. When we look at them, fascination and repulsion uneasily mixed, we bow our heads to their contribution to knowledge, but it is hard to locate their humanity. The thread of empathy has frayed and snapped. They have become objects, more stone than flesh: petrified, post-human.

Henrietta Lacks is a medical specimen of quite another kind. No dead woman has done more for the living, and yet we can imagine her easily from her photograph, a vivacious woman who was only 31 years when she died in 1951 in a "coloured ward" in Johns Hopkins Hospital in Baltimore. Beloved by her family, a lively, open-hearted woman, Henrietta died in intractable pain, and at the autopsy her body's interior was pearled by tumours. Towards the end she had been given only palliative treatment, but no one had explained this to her family, who still hoped she might be cured. She left behind a husband and five children, the youngest only a baby. But she also left behind a slice of tissue, a piece excised from the cervical cancer that was her primary tumour. From this sample her cells were cultured.

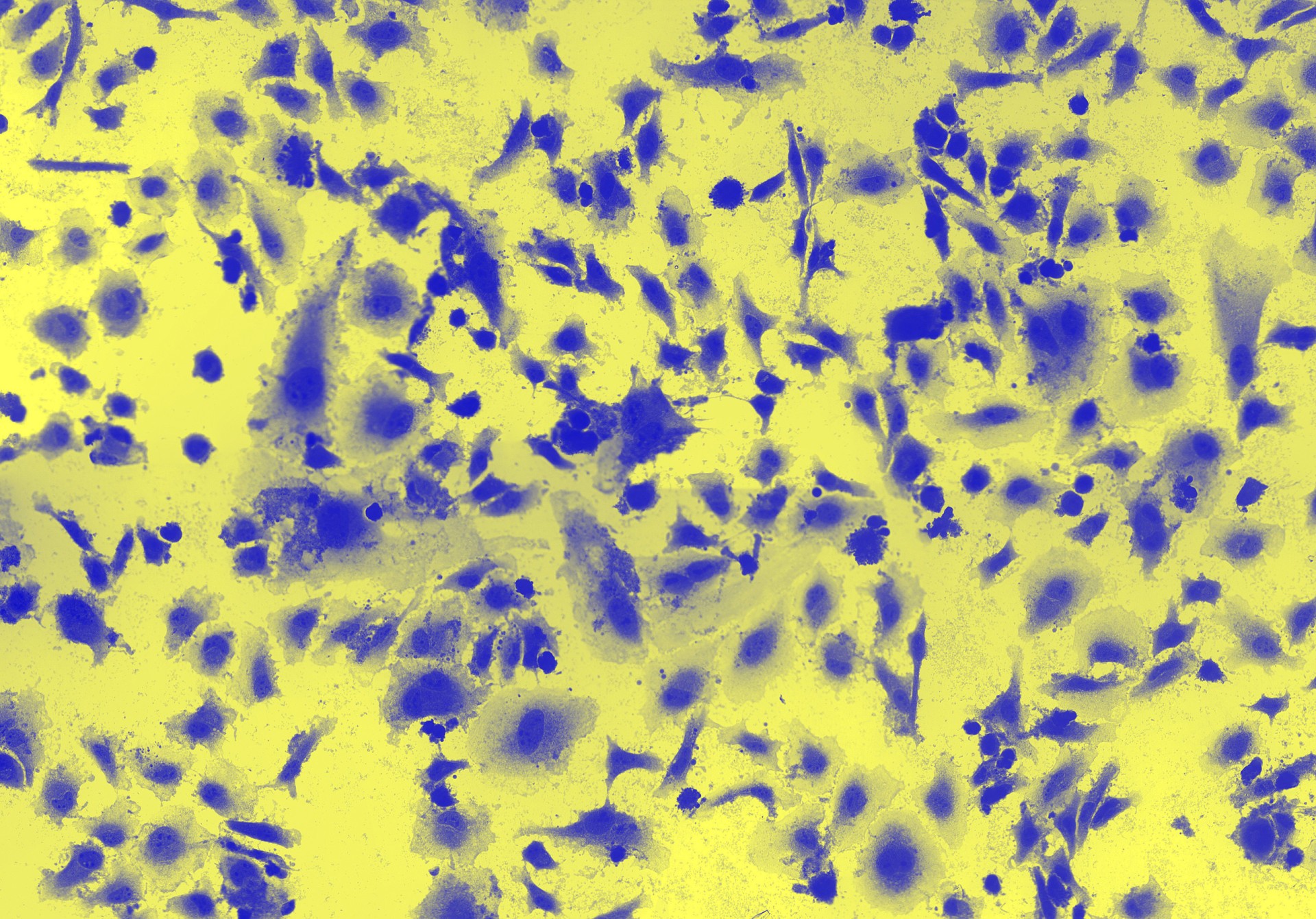

Previously, researchers had found it frustratingly difficult to keep alive fragile human cell lines, but these cells were robust and multiplied at an astonishing rate. In the years following Henrietta's death, the cell line, by laboratory convention known as HeLa, became an unparalleled research tool. Cells were sent to laboratories through the world, bought and sold by research teams. They could be frozen, and their development paused and restarted. Because of them, thousands of experiments on live animals were not needed. Trillions of them are still alive, more than ever grew in Henrietta's living body. They have been employed in research into the polio vaccine, and into the effects of atomic warfare; they were shot into space, used in AIDS research. But the woman who generated them, frequently misnamed, remained largely unknown, and her family benefited not at all from the unwitting donation of her money-spinning tissues.

Who was Henrietta Lacks? She was born in Virginia in 1920. Her mother died in giving birth to the last of ten children, and the family were split up, Henrietta going to her grandfather. The family lived in a log cabin, former slave quarters, and tended the tobacco fields as their slave ancestors had done. Henrietta married her cousin and had her first child at 14. She and her husband moved to Baltimore in the hope of greater prosperity, but although she seems to have been a woman of pride and spirit, life dealt her a bad hand. She already had syphilis when her cancer was diagnosed. Her deaf daughter, Elsie, was institutionalised, and the recovery of the circumstances of the child's short life form a grim part of this narrative. Henrietta's other children were brought up in cold, abusive circumstances, knowing little of their mother as a person, and nothing of her part in medical history. When they were told, more than 20 years after her death, that her cells were still alive, they developed not just a sense that they were owed money but also a series of torturing misapprehensions. A cousin explained to the author: "Nobody round here ever understood how she dead and that thing still living. That's where the mystery's at." Joe, Henrietta's youngest son, was born when she was already ill; he served a long prison sentence for homicide and his lifelong delinquencies were attributed by the family to the poisoned environment of his mother's womb. Deborah, Henrietta's daughter, believed that her mother had been cloned, and that she was suffering the pains of all the diseases that her cells had helped to cure.

It is not surprising they harboured such fears. Black oral history for years featured "night doctors" who abducted children for gruesome experiments, and the folk-beliefs were not entirely irrational. In public hospitals, experiments on black patients – experiments sometimes dangerous and unethical – were considered quid pro quo for free treatment. In the shameful Tuskegee project, carried out over forty years, black men were allowed to die from syphilis so that the progress of the disease could be studied. The dark, inhuman face of unpoliced science shows itself throughout this story, side by side with the bright face of discovery and humanitarian advance. The ironies are no less bitter because they are plain: today, Henrietta's descendents cannot afford health insurance. Henrietta was buried in an unmarked grave, in a cemetery with her black ancestors, and with white ancestors who, when the author inquired, would not acknowledge her.

Rebecca Skloot revivifies Henrietta, studying her not only as the originator of her cell line but as a woman embedded in history. Her absorbing book is not just about medicine and science but about colour, race, class, superstition and enlightenment, about the painful, transfixing romance of being American. Her tenacious detective work into family history, her crisp and lively summation of the science, are virtues that compensate – just about – for a folksy, intrusive, condescending tone. Skloot is a teacher of "creative non-fiction", and here the "creative" part consists in zigzagging the chronology and appending picturesque details to humanise the hard data. But is the effort needed? If, when Henrietta's cells were first brought into the lab, the technician was eating a tuna salad sandwich, do we really need our brains burdened by that information? It would have been better to trust the story and tell it in as straightforward a way as possible. Skloot's final discussion of the ethics of the use of human tissue is followed by nine pages of acknowledgments that are more than usually fatuous and self-regarding, and the author's determination to write herself into the story distracts the reader from the dense factual background. But The Immortal Life of Henrietta Lacks succeeds despite itself: it is a fascinating, harrowing and necessary book, marred only slightly by the fact that the author wishes to be considered a heroine for writing it.

- Science and nature books

- Biography books

Comments (…)

Most viewed.

Subscribe or renew today

Every print subscription comes with full digital access

Science News

Book review: the immortal life of henrietta lacks by rebecca skloot.

A new book tells the story of the unknown woman behind the famous cells

Share this:

By Laura Sanders

March 12, 2010 at 12:22 pm

Combining careful reporting with vivid narration, science writer Rebecca Skloot describes how cancerous cells growing in the cervix of a poor black tobacco farmer named Henrietta Lacks changed the face of modern medical science. In the book, Skloot expertly explains the science behind the cells and their significance, but more importantly, she makes it clear that the story is not just about the cells’ utility to scientists. It’s the story of the unknown woman behind the famous cells. A dime-sized sample of Lacks’ cells, sliced away in 1951 without permission, quickly became an invaluable research tool. Unlike normal cells that stop dividing soon after they leave the body, these cancer cells have a special genetic structure that allows them to live on forever. Even now, almost 60 years after Lacks’ death, tubes, flasks and beakers of her cells flourish in laboratories around the world. They are grown under the name HeLa cells, short for Henrietta Lacks, though many students still learn the cells came from Helen Lane — a name doctors originally made up to hide Lacks’ identity. Studies using HeLa cells have led to new cancer drugs, flu treatments, the first polio vaccine and countless other medical advances. Lacks’ family was left in the dark about the research, confused and angry about what they perceived as scientists making big money from stolen cells while the family couldn’t afford health care. Whether they should have shared in the profits, Skloot refrains from judging. Instead, she paints a nuanced portrait of a complicated, emotion-laden sequence of events, raising many more questions than she answers.

More Stories from Science News on Science & Society

A hidden danger lurks beneath Yellowstone

Online spaces may intensify teens’ uncertainty in social interactions

Want to see butterflies in your backyard? Try doing less yardwork

Ximena Velez-Liendo is saving Andean bears with honey

‘Flavorama’ guides readers through the complex landscape of flavor

Rain Bosworth studies how deaf children experience the world

Separating science fact from fiction in Netflix’s ‘3 Body Problem’

Language models may miss signs of depression in Black people’s Facebook posts

Subscribers, enter your e-mail address for full access to the Science News archives and digital editions.

Not a subscriber? Become one now .

- ADMIN AREA MY BOOKSHELF MY DASHBOARD MY PROFILE SIGN OUT SIGN IN

THE IMMORTAL LIFE OF HENRIETTA LACKS

by Rebecca Skloot ‧ RELEASE DATE: Feb. 9, 2010

Skloot's meticulous, riveting account strikes a humanistic balance between sociological history, venerable portraiture and...

A dense, absorbing investigation into the medical community's exploitation of a dying woman and her family's struggle to salvage truth and dignity decades later.

In a well-paced, vibrant narrative, Popular Science contributor and Culture Dish blogger Skloot (Creative Writing/Univ. of Memphis) demonstrates that for every human cell put under a microscope, a complex life story is inexorably attached, to which doctors, researchers and laboratories have often been woefully insensitive and unaccountable. In 1951, Henrietta Lacks, an African-American mother of five, was diagnosed with what proved to be a fatal form of cervical cancer. At Johns Hopkins, the doctors harvested cells from her cervix without her permission and distributed them to labs around the globe, where they were multiplied and used for a diverse array of treatments. Known as HeLa cells, they became one of the world's most ubiquitous sources for medical research of everything from hormones, steroids and vitamins to gene mapping, in vitro fertilization, even the polio vaccine—all without the knowledge, must less consent, of the Lacks family. Skloot spent a decade interviewing every relative of Lacks she could find, excavating difficult memories and long-simmering outrage that had lay dormant since their loved one's sorrowful demise. Equal parts intimate biography and brutal clinical reportage, Skloot's graceful narrative adeptly navigates the wrenching Lack family recollections and the sobering, overarching realities of poverty and pre–civil-rights racism. The author's style is matched by a methodical scientific rigor and manifest expertise in the field.

Pub Date: Feb. 9, 2010

ISBN: 978-1-4000-5217-2

Page Count: 320

Publisher: Crown

Review Posted Online: Dec. 22, 2010

Kirkus Reviews Issue: Jan. 1, 2010

BIOGRAPHY & MEMOIR | HEALTH & FITNESS | GENERAL BIOGRAPHY & MEMOIR

Share your opinion of this book

More by Rebecca Skloot

BOOK REVIEW

edited by Rebecca Skloot and Floyd Skloot

by Elie Wiesel & translated by Marion Wiesel ‧ RELEASE DATE: Jan. 16, 2006

The author's youthfulness helps to assure the inevitable comparison with the Anne Frank diary although over and above the...

Elie Wiesel spent his early years in a small Transylvanian town as one of four children.

He was the only one of the family to survive what Francois Maurois, in his introduction, calls the "human holocaust" of the persecution of the Jews, which began with the restrictions, the singularization of the yellow star, the enclosure within the ghetto, and went on to the mass deportations to the ovens of Auschwitz and Buchenwald. There are unforgettable and horrifying scenes here in this spare and sombre memoir of this experience of the hanging of a child, of his first farewell with his father who leaves him an inheritance of a knife and a spoon, and of his last goodbye at Buchenwald his father's corpse is already cold let alone the long months of survival under unconscionable conditions.

Pub Date: Jan. 16, 2006

ISBN: 0374500010

Page Count: 120

Publisher: Hill & Wang

Review Posted Online: Oct. 7, 2011

Kirkus Reviews Issue: Jan. 15, 2006

BIOGRAPHY & MEMOIR | HOLOCAUST | HISTORY | GENERAL BIOGRAPHY & MEMOIR | GENERAL HISTORY

More by Elie Wiesel

by Elie Wiesel ; edited by Alan Rosen

by Elie Wiesel ; illustrated by Mark Podwal

by Elie Wiesel ; translated by Marion Wiesel

Awards & Accolades

Our Verdict

Google Rating

Kirkus Reviews' Best Books Of 2016

New York Times Bestseller

Pulitzer Prize Finalist

WHEN BREATH BECOMES AIR

by Paul Kalanithi ‧ RELEASE DATE: Jan. 19, 2016

A moving meditation on mortality by a gifted writer whose dual perspectives of physician and patient provide a singular...

A neurosurgeon with a passion for literature tragically finds his perfect subject after his diagnosis of terminal lung cancer.

Writing isn’t brain surgery, but it’s rare when someone adept at the latter is also so accomplished at the former. Searching for meaning and purpose in his life, Kalanithi pursued a doctorate in literature and had felt certain that he wouldn’t enter the field of medicine, in which his father and other members of his family excelled. “But I couldn’t let go of the question,” he writes, after realizing that his goals “didn’t quite fit in an English department.” “Where did biology, morality, literature and philosophy intersect?” So he decided to set aside his doctoral dissertation and belatedly prepare for medical school, which “would allow me a chance to find answers that are not in books, to find a different sort of sublime, to forge relationships with the suffering, and to keep following the question of what makes human life meaningful, even in the face of death and decay.” The author’s empathy undoubtedly made him an exceptional doctor, and the precision of his prose—as well as the moral purpose underscoring it—suggests that he could have written a good book on any subject he chose. Part of what makes this book so essential is the fact that it was written under a death sentence following the diagnosis that upended his life, just as he was preparing to end his residency and attract offers at the top of his profession. Kalanithi learned he might have 10 years to live or perhaps five. Should he return to neurosurgery (he could and did), or should he write (he also did)? Should he and his wife have a baby? They did, eight months before he died, which was less than two years after the original diagnosis. “The fact of death is unsettling,” he understates. “Yet there is no other way to live.”

Pub Date: Jan. 19, 2016

ISBN: 978-0-8129-8840-6

Page Count: 248

Publisher: Random House

Review Posted Online: Sept. 29, 2015

Kirkus Reviews Issue: Oct. 15, 2015

GENERAL BIOGRAPHY & MEMOIR | GENERAL CURRENT EVENTS & SOCIAL ISSUES | BIOGRAPHY & MEMOIR | CURRENT EVENTS & SOCIAL ISSUES

- Discover Books Fiction Thriller & Suspense Mystery & Detective Romance Science Fiction & Fantasy Nonfiction Biography & Memoir Teens & Young Adult Children's

- News & Features Bestsellers Book Lists Profiles Perspectives Awards Seen & Heard Book to Screen Kirkus TV videos In the News

- Kirkus Prize Winners & Finalists About the Kirkus Prize Kirkus Prize Judges

- Magazine Current Issue All Issues Manage My Subscription Subscribe

- Writers’ Center Hire a Professional Book Editor Get Your Book Reviewed Advertise Your Book Launch a Pro Connect Author Page Learn About The Book Industry

- More Kirkus Diversity Collections Kirkus Pro Connect My Account/Login

- About Kirkus History Our Team Contest FAQ Press Center Info For Publishers

- Privacy Policy

- Terms & Conditions

- Reprints, Permission & Excerpting Policy

© Copyright 2024 Kirkus Media LLC. All Rights Reserved.

Popular in this Genre

Hey there, book lover.

We’re glad you found a book that interests you!

Please select an existing bookshelf

Create a new bookshelf.

We can’t wait for you to join Kirkus!

Please sign up to continue.

It’s free and takes less than 10 seconds!

Already have an account? Log in.

Trouble signing in? Retrieve credentials.

Almost there!

- Industry Professional

Welcome Back!

Sign in using your Kirkus account

Contact us: 1-800-316-9361 or email [email protected].

Don’t fret. We’ll find you.

Magazine Subscribers ( How to Find Your Reader Number )

If You’ve Purchased Author Services

Don’t have an account yet? Sign Up.

To revisit this article, visit My Profile, then View saved stories .

- Backchannel

- Newsletters

- WIRED Insider

- WIRED Consulting

Brian Switek

Book Review: The Immortal Life of Henrietta Lacks

Contingency has been on my mind quite often these days. What would life look like today if the ancestors of the first land-dwelling vertebrates had two legs instead of four? How would non-avian dinosaurs continue to have evolved if they had not been wiped out 65 million years ago? What if, like many other prehistoric apes, our own ancestors fell into extinction during the Pliocene? Any one of these events would have changed the history of life on earth, and even though there are not answers to these questions they still remind me of how historical quirks can have major effects.

Though it has nothing at all to do with fossils or evolution, Rebecca Skloot's The Immortal Life of Henrietta Lacks is also a tale of contingency. In February of 1951 doctors at Johns Hopkins Hospital removed cancerous cells from the cervix of a 30 year old African American woman who had come in complaining of a painful "knot" inside of her. She had no idea that the sample of her cells had been taken, but this small event of one woman's life would end up changing the world in ways that no one expected.

This woman was Henrietta Lacks , and even though she died from the cancer in October of 1951 the descendants of the cells taken from her over a half century ago are still thriving in laboratories around the world. Because of a biological quirk scientists were able to turn her cells into the first "immortal" cell line, called HeLa, the study of which has greatly increased our knowledge of ourselves and led to the effective treatment of numerous diseases. Her cells have affected the lives of people all over the world, and this makes it all the more shameful that, until now, almost no one knew anything about her.

The true strength of Skloot's book is that it is not a simple celebration of science. Innumerable articles and several books have been written about the HeLa cell line before, but they largely ignored Henrietta and her family. The story of the poor black woman who had her cells taken from her without her knowledge or consent just did not register with most writers (especially since it was decades before anyone knew her real name), and the attitudes of journalists and scientists made Henrietta's family increasingly bitter about the entire affair. While medical companies made millions off of Henrietta's cells they remained poor and could barely afford health insurance even in the best of times. And as famous as Henrietta's cells were her family knew almost nothing about what happened to her or what was taken from her. While Skloot ably covers the science of HeLa, the real story is the personal drama of Henrietta and her family, in which Skloot comes to play a substantial part.

As I read through this story of science, race relations, medicine, and poverty I could not help but wonder how things would have been if small events had turned out differently. What if doctors and scientists had informed the Lacks family about HeLa earlier, and what would have happened if the scientists that finally did were not so inept at communicating what had happened to Henrietta? What if Skloot had never followed her deep desire to know who Henrietta was, or what if the Lacks family, frustrated that another journalist was coming around asking questions, decided to ignore Skloot's persistent phone calls? Would Henrietta's life have remained a mystery even to her own family?

The Immortal Life of Henrietta Lacks is a triumph of science writing (it is truly one of the best nonfiction books I have ever read), and I was deeply affected by it on a personal level. The story reaffirmed that small events can have major repercussions, and as sad and angry as the tale of the Lacks family made me by the end of the book I was glad that Skloot had worked so hard to reach them. Through something as simple as wanting to learn more about Henrietta's life Skloot and the Lacks family were able to create a fitting tribute to Henrietta and her legacy. For the first time, the most important woman in modern medicine is having her story told, and I truly hope that it gets the attention it deserves.

You can contribute to the Henrietta Lacks Foundation here .

[Be sure to check out the reviews of The Immortal Life of Henrietta Lacks at the New York Times and Not Exactly Rocket Science , as well.]

Jared Keller

Reece Rogers

Brian Barrett

Lauren Goode

Jessica Rawnsley

Leila Sloman

John Timmer, Ars Technica

Emily Mullin

Matt Reynolds

Maanvi Singh

Physiology News Magazine

- Summer 2013 - Issue Number 91

Book review: The Immortal Life of Henrietta Lacks By Rebecca Skloot

Sarah Hall Cardiff University, UK

Keith Siew University of Cambridge, UK

https://doi.org/10.36866/pn.91.51

Even if they’ve never used a HeLa cell in their own research, most physiologists probably know a colleague who has, or have read a paper reporting data from these cells. Over the decades, HeLa cells have led to important advances in gene mapping and in vitro fertilisation, as well as the life-saving development of vaccines for polio and cancer. Yet, despite this, some could not tell you that the acronym HeLa refers to Henrietta Lacks, an African-American woman who died of cervical cancer aged 31 and who, arguably, has contributed more to biomedical science than any other person to date. Henrietta’s story and the development of the HeLa cell line are at the heart of Rebecca Skloot’s first book, The Immortal Life of Henrietta Lacks .

Skloot’s account of Henrietta’s life is told with sensitivity and genuine warmth; the explanation of attempts to culture cells and the subsequent commercialisation of the cell line have sufficient scientific integrity, despite the author’s lack of scientific training. Part historical account, part detective story and part ethical debate, The Immortal Life of Henrietta Lacks combines these narrative threads into an absorbing and challenging book that should be on every physiologist’s reading list.

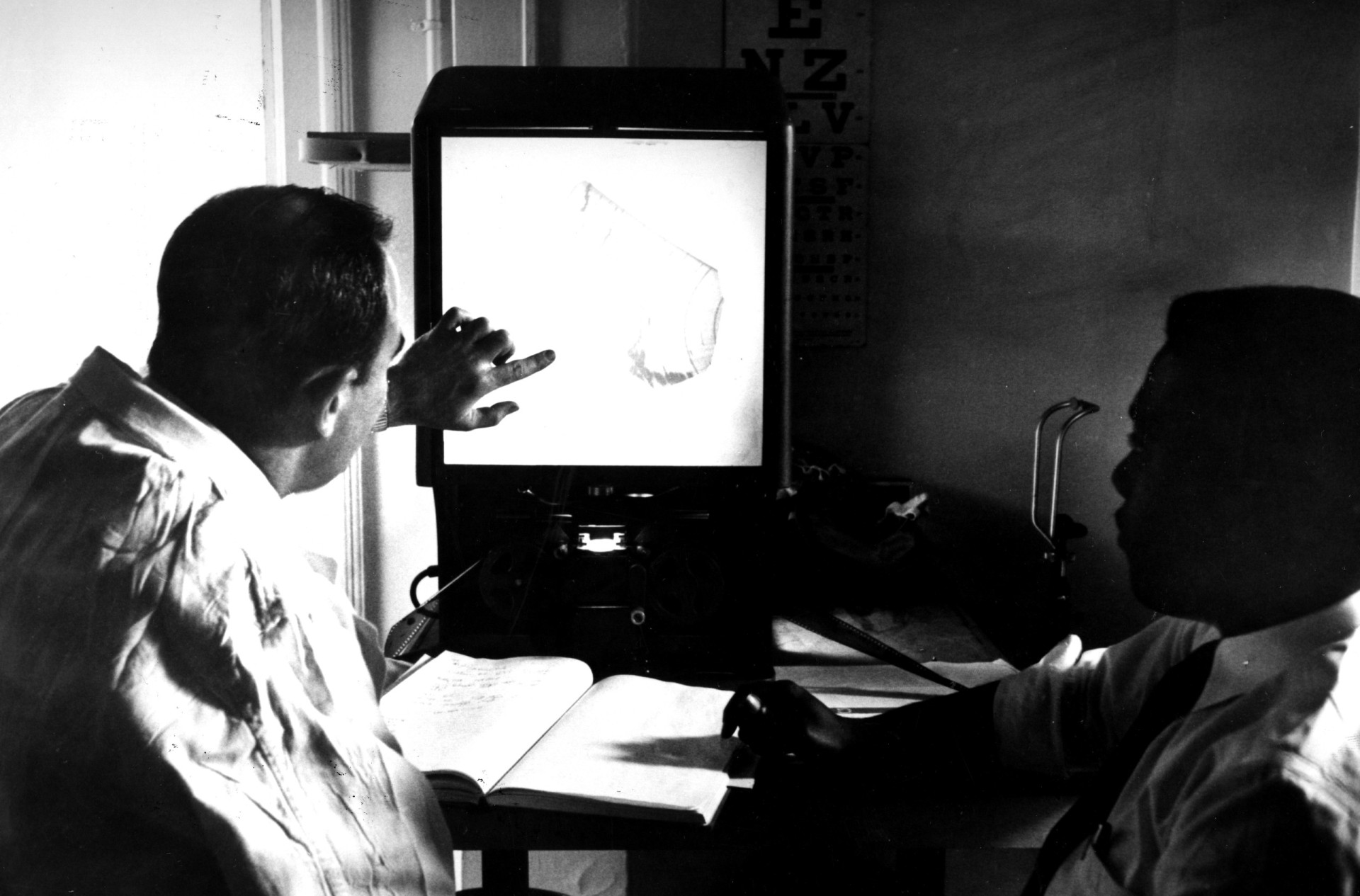

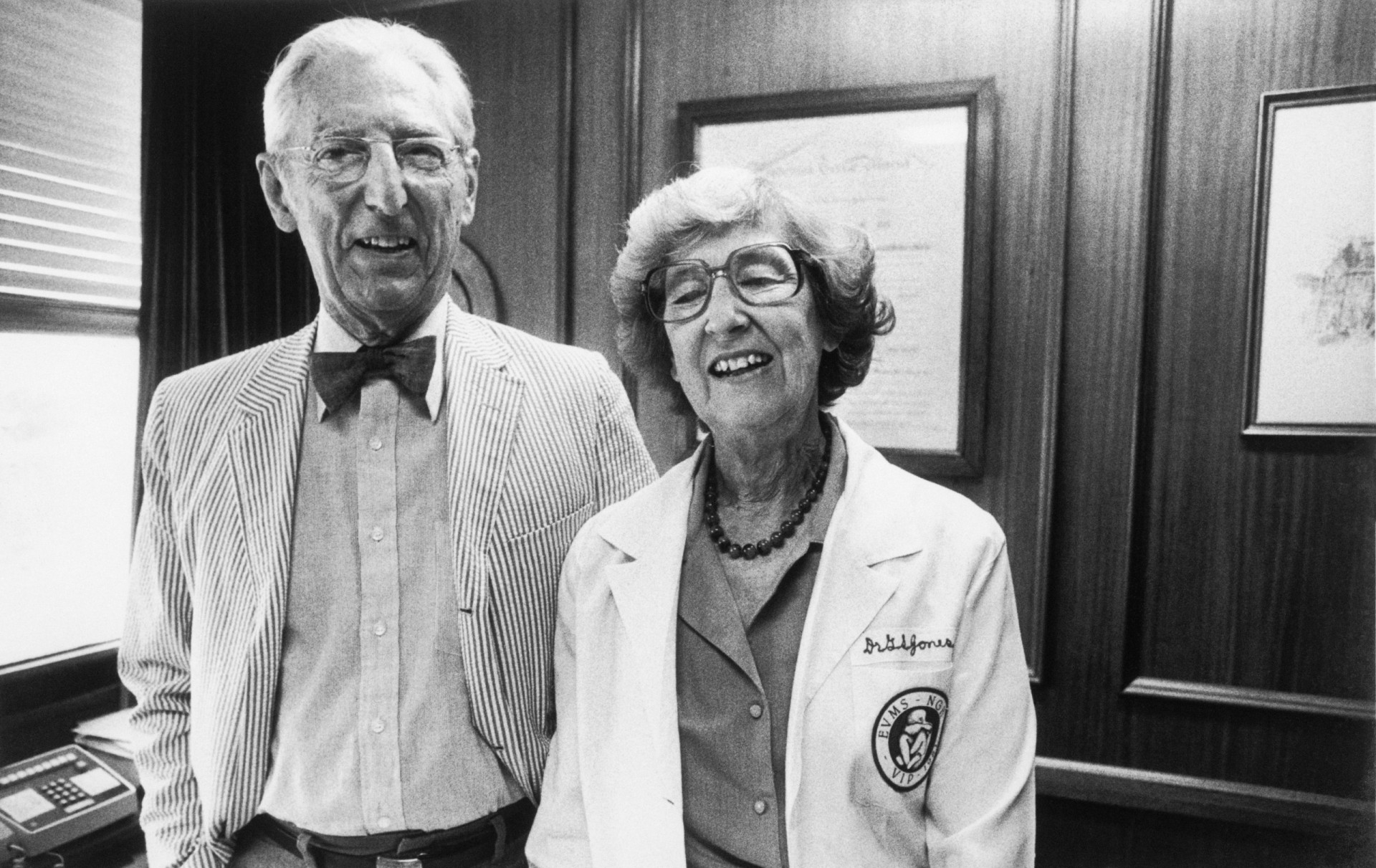

Henrietta was born in 1920 to a family of tobacco farmers in Virginia. After her marriage to David ‘Day’ Lacks, she settled in Baltimore to work and raise her family of five children. When she became ill, she went to Johns Hopkins University which, at the time, was the only place offering medical treatment without charge to the black community. In that same hospital, Dr George Gey and his team were working to develop the first human cell culture, but were finding little success. They were excited when a sample of Henrietta’s cancer cells, unlike any of the other tissue samples they had tried, grew quickly and easily in the culture lab.

Unbeknown to Henrietta’s family, news of this breakthrough spread throughout the scientific community as Dr Gey began distributing his ‘HeLa’ cells to other researchers. They were first sent to local labs, where they continued to replicate, then across the country and eventually all over the world. Widespread scientific interest in these cells rapidly birthed a multi-billion dollar industry that revolutionised medical research, and the book relays how reputations and fortunes were made, while Henrietta remained anonymous and her family unaware. It was not until some 20 years after her death that the Lacks family would learn the life-changing news of their mother’s “immortal” cells and their subsequent exploitation for profit. The author’s role in this aspect of the story detracts somewhat from the main focus of the book, but the family’s reactions to the news reveal a heart-breaking chasm between cutting-edge science and the lives of these ordinary Americans.

Skloot has managed to capture the emotional story of Henrietta Lacks and her family, while diligently chronicling the development of a new scientific arena and documenting what could be considered the first case study of medical research ethics. A quick search of the current literature reveals almost 2000 papers using HeLa cells were published last year alone. Even if you don’t read any of these papers, it is worth making time to read The Immortal Life of Henrietta Lacks as a complex and thought-provoking reminder of the broader context of this scientific endeavour.

Site search

Content type.

- Latest News

- Upcoming Events

- Team Members

- Honorary Fellows

Book Review: The Immortal Life of Henrietta Lacks

The Immortal Life of Henrietta Lacks, written by Rebecca Skloot, is a book detailing the life of Henrietta Lacks. Henrietta Lacks unknowingly donated her cells to one of the most important fields of research, cancer cures. Her tumor cells, also known as “HeLa”, are extraordinary in that they replicate fast enough to create a whole new human in under 48 hours. This book is fascinating in more than one way: it explores the history of her and her cells, and it explores some gray areas in rights to cells and parts of dead entities. Instead of focusing just on one topic and one family, it expands to include many that have had to deal with bio material rights. I personally found this an interesting but slightly disturbing read. I recommend reading this one to learn about the history of cell rights and their gray areas.

- Bookreporter

- ReadingGroupGuides

- AuthorsOnTheWeb

The Book Report Network

Sign up for our newsletters!

Regular Features

Author spotlights, "bookreporter talks to" videos & podcasts, "bookaccino live: a lively talk about books", favorite monthly lists & picks, seasonal features, book festivals, sports features, bookshelves.

- Coming Soon

Newsletters

- Weekly Update

- On Sale This Week

- Summer Reading

- Spring Preview

- Winter Reading

- Holiday Cheer

- Fall Preview

Word of Mouth

Submitting a book for review, write the editor, you are here:, the immortal life of henrietta lacks.

Science journalist Rebecca Skloot unravels the story behind the first immortal human cells, known by the code name HeLa. Skloot’s fascination with these cells began as a teen in a biology class when her professor mentioned that what scientists know about cancer cells came from studying the cells of a woman named Henrietta Lacks. He went on to state that Henrietta died from an aggressive form of cervical cancer in 1951. Without Henrietta’s knowledge or consent, samples of her tumor were cultured. Although scientists had been trying to keep human cells alive in order to study them, they had had no luck --- but Henrietta’s cancer cells not only lived, they reproduced rapidly. HeLa cells continued to reproduce, dividing constantly and indefinitely; hence, they are “immortal.”

"As Skloot skillfully weaves together the stories of Henrietta, the evolution of her immortal cells and the reactions of her family members, readers will find themselves entranced."

Henrietta’s cells are still reproducing. They are bought and sold to labs all over the world by the billions. It is said that if one were to weigh all of Henrietta’s cells that have been grown since she died, the total would be a staggering 50 million metric tons. These immortal cells have been one of the most important innovations for modern science and medicine because scientists can study the effects of experiments they cannot perform on living people. HeLa cells were onboard during the first space mission so scientists could study what happens to human cells in space. Because of HeLa cells, scientists know the effects an atom bomb has on human tissue. Henrietta’s cells were also instrumental in developing the vaccine for polio. They have been the cells used in studies for in vitro fertilization, chemotherapy, cloning, gene mapping, and much, much more.

Skloot’s teacher off-handedly mentioned that Henrietta was African-American. But Skloot’s questioning about her personal life met a dead end, and the consequent researching revealed nothing about her. She became obsessed with Henrietta, and her fascination turned into a passion that she pursued for 10 years in order to write this book.

One of Skloot’s driving questions was about Henrietta’s family: Did she have children? Did they know about their mother’s cells and their contribution to science? She not only learns the answers to these questions, she also forms a relationship with Henrietta’s daughter, Deborah. Along the way, we learn about Henrietta’s life. As part of a poor tobacco farm family, young Henrietta lived with her grandfather after her parents died. She and the rest of the family worked the same tobacco fields that their ancestors worked as slaves. After marrying her cousin, David, Henrietta’s life continued to be difficult. She had her first child when she was barely 14. The second child she bore had developmental challenges and was reluctantly institutionalized. Despite her hard life, the people who knew Henrietta remembered her as beautiful, outgoing and hospitable.

As Skloot skillfully weaves together the stories of Henrietta, the evolution of her immortal cells and the reactions of her family members, readers will find themselves entranced. Exploring the topic of scientific exploitation --- in which her cells have been used and sold without family knowledge or consent --- leads to a description of the historical use of African-American research subjects and to a discussion of the policies and ethics governing the use of patients’ tissues. During the course of the book, we travel with the writer to Henrietta’s unmarked grave, to scientific laboratories, and to a church service. We are present during a touching scene in which two of Henrietta’s children examine HeLa cells.

Interspersing these human elements with scientific explanations, Skloot has fashioned a compelling multi-layered tale that will keep readers unable to resist turning pages until they reach the end.

Reviewed by Terry Miller Shannon on January 22, 2011

The Immortal Life of Henrietta Lacks by Rebecca Skloot

- Publication Date: April 4, 2017

- Genres: Biography , Nonfiction , Science

- Paperback: 400 pages

- Publisher: Broadway Books

- ISBN-10: 0804190100

- ISBN-13: 9780804190107

- Politics & Social Sciences

- Social Sciences

Enjoy fast, free delivery, exclusive deals, and award-winning movies & TV shows with Prime Try Prime and start saving today with fast, free delivery

Amazon Prime includes:

Fast, FREE Delivery is available to Prime members. To join, select "Try Amazon Prime and start saving today with Fast, FREE Delivery" below the Add to Cart button.

- Cardmembers earn 5% Back at Amazon.com with a Prime Credit Card.

- Unlimited Free Two-Day Delivery

- Streaming of thousands of movies and TV shows with limited ads on Prime Video.

- A Kindle book to borrow for free each month - with no due dates

- Listen to over 2 million songs and hundreds of playlists

- Unlimited photo storage with anywhere access

Important: Your credit card will NOT be charged when you start your free trial or if you cancel during the trial period. If you're happy with Amazon Prime, do nothing. At the end of the free trial, your membership will automatically upgrade to a monthly membership.

Buy new: .savingPriceOverride { color:#CC0C39!important; font-weight: 300!important; } .reinventMobileHeaderPrice { font-weight: 400; } #apex_offerDisplay_mobile_feature_div .reinventPriceSavingsPercentageMargin, #apex_offerDisplay_mobile_feature_div .reinventPricePriceToPayMargin { margin-right: 4px; } -56% $8.44 $ 8 . 44 FREE delivery Tuesday, May 21 on orders shipped by Amazon over $35 Ships from: Amazon.com Sold by: Amazon.com

Return this item for free.

Free returns are available for the shipping address you chose. You can return the item for any reason in new and unused condition: no shipping charges

- Go to your orders and start the return

- Select the return method

Save with Used - Very Good .savingPriceOverride { color:#CC0C39!important; font-weight: 300!important; } .reinventMobileHeaderPrice { font-weight: 400; } #apex_offerDisplay_mobile_feature_div .reinventPriceSavingsPercentageMargin, #apex_offerDisplay_mobile_feature_div .reinventPricePriceToPayMargin { margin-right: 4px; } $7.60 $ 7 . 60 FREE delivery May 28 - June 3 on orders shipped by Amazon over $35 Ships from: Amazon Sold by: Jenson Books Inc

Download the free Kindle app and start reading Kindle books instantly on your smartphone, tablet, or computer - no Kindle device required .

Read instantly on your browser with Kindle for Web.

Using your mobile phone camera - scan the code below and download the Kindle app.

Follow the author

Image Unavailable

- To view this video download Flash Player

The Immortal Life of Henrietta Lacks Paperback – Abridged, March 8, 2011

Purchase options and add-ons.

- Print length 381 pages

- Language English

- Publisher Crown

- Publication date March 8, 2011

- Dimensions 5.22 x 1.08 x 8 inches

- ISBN-10 1400052181

- Lexile measure 1140L

- See all details

Frequently bought together

Similar items that may deliver to you quickly

From the Publisher

Editorial Reviews

About the author.

REBECCA SKLOOT is an award-winning science writer whose work has appeared in The New York Times Magazine; O, The Oprah Magazine; Discover; and many others. She is coeditor of The Best American Science Writing 2011 and has worked as a correspondent for NPR’s Radiolab and PBS’s Nova ScienceNOW . She was named one of five surprising leaders of 2010 by the Washington Post . Skloot's debut book, The Immortal Life of Henrietta Lacks, took more than a decade to research and write, and instantly became a New York Times bestseller. It was chosen as a best book of 2010 by more than sixty media outlets, including Entertainment Weekly , People , and the New York Times . It is being translated into more than twenty-five languages, adapted into a young reader edition, and being made into an HBO film produced by Oprah Winfrey and Alan Ball. Skloot is the founder and president of The Henrietta Lacks Foundation. She has a B.S. in biological sciences and an MFA in creative nonfiction. She has taught creative writing and science journalism at the University of Memphis, the University of Pittsburgh, and New York University. She lives in Chicago. For more information, visit her website at RebeccaSkloot.com, where you’ll find links to follow her on Twitter and Facebook.

Excerpt. © Reprinted by permission. All rights reserved.

Product details.

- Publisher : Crown; Reprint edition (March 8, 2011)

- Language : English

- Paperback : 381 pages

- ISBN-10 : 1400052181

- Lexile measure : 1140L

- Item Weight : 2.31 pounds

- Dimensions : 5.22 x 1.08 x 8 inches

- #1 in History of Medicine (Books)

- #2 in History & Philosophy of Science (Books)

- #6 in Medical Professional Biographies

Videos for this product

Click to play video

Must Watch Before You Buy

Watch an Author Video

Merchant Video

Very disappointed

The Immortal Life of Henrietta Lacks

Omnivoracious Podcast: Rebecca Skloot on The Immortal Life of Henrietta Lacks, Part 2: The Family

About the author, rebecca skloot.

Rebecca Skloot is an award-winning science writer whose articles have appeared in The New York Times Magazine; O, The Oprah Magazine; Discover; and others. She has worked as a correspondent for NPR’s Radiolab and PBS’s NOVA scienceNOW, and is a contributing editor at Popular Science magazine and guest editor of The Best American Science Writing 2011. She is a former Vice President of the National Book Critics Circle and has taught creative nonfiction and science journalism at the University of Memphis, the University of Pittsburgh, and New York University. Her debut book, The Immortal Life of Henrietta Lacks, took more than ten years to research and write, and became an instant New York Times bestseller. She has been featured on numerous television shows, including CBS Sunday Morning and The Colbert Report. Her book has received widespread critical acclaim, with reviews appearing in The New Yorker, Washington Post, Science, Entertainment Weekly, People, and many others. It won the Chicago Tribune Heartland Prize and the Wellcome Trust Book Prize, and was named The Best Book of 2010 by Amazon.com, and a Best Book of the Year by Entertainment Weekly; O, The Oprah Magazine; The New York Times; Washington Post; US News & World Report; and numerous others.

The Immortal Life of Henrietta Lacks is being translated into more than twenty languages, and adapted into a young adult book, and an HBO film produced by Oprah Winfrey and Alan Ball. Skloot lives in Chicago but regularly abandons city life to write in the hills of West Virginia, where she tends to find stray animals and bring them home. She travels extensively to speak about her book. For more information, visit RebeccaSkloot.com, where you will find book special features, including photos and videos, as well as her book tour schedule, and links to follow her and The Immortal Life on Twitter and Facebook.

Customer reviews

Customer Reviews, including Product Star Ratings help customers to learn more about the product and decide whether it is the right product for them.

To calculate the overall star rating and percentage breakdown by star, we don’t use a simple average. Instead, our system considers things like how recent a review is and if the reviewer bought the item on Amazon. It also analyzed reviews to verify trustworthiness.

Reviews with images

- Sort reviews by Top reviews Most recent Top reviews

Top reviews from the United States

There was a problem filtering reviews right now. please try again later..

Top reviews from other countries

- Amazon Newsletter

- About Amazon

- Accessibility

- Sustainability

- Press Center

- Investor Relations

- Amazon Devices

- Amazon Science

- Sell on Amazon

- Sell apps on Amazon

- Supply to Amazon

- Protect & Build Your Brand

- Become an Affiliate

- Become a Delivery Driver

- Start a Package Delivery Business

- Advertise Your Products

- Self-Publish with Us

- Become an Amazon Hub Partner

- › See More Ways to Make Money

- Amazon Visa

- Amazon Store Card

- Amazon Secured Card

- Amazon Business Card

- Shop with Points

- Credit Card Marketplace

- Reload Your Balance

- Amazon Currency Converter

- Your Account

- Your Orders

- Shipping Rates & Policies

- Amazon Prime

- Returns & Replacements

- Manage Your Content and Devices

- Recalls and Product Safety Alerts

- Conditions of Use

- Privacy Notice

- Consumer Health Data Privacy Disclosure

- Your Ads Privacy Choices

- Getting Started

- Start a Book Club

- Book Club Ideas/Help▼

- Our Featured Clubs ▼

- Popular Books

- Book Reviews

- Reading Guides

- Blog Home ▼

- Find a Recipe

- About LitCourse

- Course Catalog

Immortal Life of Henrietta Lacks (Skloot)

The Immortal Life of Henrietta Lacks Rebecca Skloot, 2010 Crown Publishing 381 pp. ISBN-13: 9781400052189 Summary Her name was Henrietta Lacks, but scientists know her as HeLa. She was a poor Southern tobacco farmer who worked the same land as her slave ancestors, yet her cells—taken without her knowledge—became one of the most important tools in medicine.

The first "immortal" human cells grown in culture, they are still alive today, though she has been dead for more than sixty years. If you could pile all HeLa cells ever grown onto a scale, they'd weigh more than 50 million metric tons—as much as a hundred Empire State Buildings. HeLa cells were vital for developing the polio vaccine; uncovered secrets of cancer, viruses, and the atom bomb's effects; helped lead to important advances like in vitro fertilization, cloning, and gene mapping; and have been bought and sold by the billions.

Yet Henrietta Lacks remains virtually unknown, buried in an unmarked grave.

Now Rebecca Skloot takes us on an extraordinary journey, from the "colored" ward of Johns Hopkins Hospital in the 1950s to stark white laboratories with freezers full of HeLa cells; from Henrietta's small, dying hometown of Clover, Virginia—a land of wooden slave quarters, faith healings, and voodoo—to East Baltimore today, where her children and grandchildren live and struggle with the legacy of her cells.

Henrietta's family did not learn of her "immortality" until more than twenty years after her death, when scientists investigating HeLa began using her husband and children in research without informed consent. And though the cells had launched a multimillion-dollar industry that sells human biological materials, her family never saw any of the profits. As Rebecca Skloot so brilliantly shows, the story of the Lacks family—past and present—is inextricably connected to the dark history of experimentation on African Americans, the birth of bioethics, and the legal battles over whether we control the stuff we are made of.

Over the decade it took to uncover this story, Rebecca became enmeshed in the lives of the Lacks family—especially Henrietta's daughter Deborah, who was devastated to learn about her mother's cells. She was consumed with questions: Had scientists cloned her mother? Did it hurt her when researchers infected her cells with viruses and shot them into space? What happened to her sister, Elsie, who died in a mental institution at the age of fifteen? And if her mother was so important to medicine, why couldn't her children afford health insurance?

Intimate in feeling, astonishing in scope, and impossible to put down, The Immortal Life of Henrietta Lacks captures the beauty and drama of scientific discovery, as well as its human consequences. ( From the publisher .)

Author Bio Rebecca Skloot is a science writer whose articles have appeared in the New York Times Magazine, O-The Oprah Magazine, Discover, Prevention, Glamour , and others.

She has worked as a correspondent for NPR’s Radio Lab and PBS’s NOVA ScienceNow , and is a contributing editor at Popular Science magazine. Her work has been anthologized in several collections, including The Best Food Writing and The Best Creative Nonfiction .

She is a former vice president of the National Book Critics Circle, and has taught nonfiction in the creative writing programs at the University of Memphis and the University of Pittsburgh, and science journalism at New York University’s Science, Health, and Environmental Reporting Program. She blogs about science, life, and writing at Culture Dish, hosted by Seed magazine. This is her first book. ( From the publisher .)

Book Reviews One of the most graceful and moving nonfiction books I've read in a very long time. A thorny and provocative book about cancer, racism, scientific ethics and crippling poverty, The Immortal Life of Henrietta Lacks also floods over you like a narrative dam break, as if someone had managed to distill and purify the more addictive qualities of "Erin Brockovich," Midnight in the Garden of Good and Evil and The Andromeda Strain. More than 10 years in the making, it feels like the book Ms. Skloot was born to write. It signals the arrival of a raw but quite real talent.... [ The Immortal Life of Henrietta Lacks ] has brains and pacing and nerve and heart, and it is uncommonly endearing. Dwight Garner - New York Times Rebecca Skloot introduces us to the "real live woman," the children who survived her, and the interplay of race, poverty, science and one of the most important medical discoveries of the last 100 years. Skloot narrates the science lucidly, tracks the racial politics of medicine thoughtfully and tells the Lacks family's often painful history with grace. She also confronts the spookiness of the cells themselves, intrepidly crossing into the spiritual plane on which the family has come to understand their mother's continued presence in the world. Science writing is often just about "the facts." Skloot's book, her first, is far deeper, braver and more wonderful. Lisa Margonelli - New York Times Book Review Skloot's vivid account...reads like a novel. The prose is unadorned, crisp and transparent.... This book, labeled "science--cultural studies," should be treated as a work of American history. It's a deftly crafted investigation of a social wrong committed by the medical establishment, as well as the scientific and medical miracles to which it led. Skloot's compassionate account can be the first step toward recognition, justice and healing. Eric Roston - Washington Post Science journalist Skloot makes a remarkable debut with this multilayered story about “faith, science, journalism, and grace.” It is also a tale of medical wonders and medical arrogance, racism, poverty and the bond that grows, sometimes painfully, between two very different women—Skloot and Deborah Lacks—sharing an obsession to learn about Deborah’s mother, Henrietta, and her magical, immortal cells. Henrietta Lacks was a 31-year-old black mother of five in Baltimore when she died of cervical cancer in 1951. Without her knowledge, doctors treating her at Johns Hopkins took tissue samples from her cervix for research. They spawned the first viable, indeed miraculously productive, cell line—known as HeLa. These cells have aided in medical discoveries from the polio vaccine to AIDS treatments. What Skloot so poignantly portrays is the devastating impact Henrietta’s death and the eventual importance of her cells had on her husband and children. Skloot’s portraits of Deborah, her father and brothers are so vibrant and immediate they recall Adrian Nicole LeBlanc’s Random Family . Writing in plain, clear prose, Skloot avoids melodrama and makes no judgments. Letting people and events speak for themselves, Skloot tells a rich, resonant tale of modern science, the wonders it can perform and how easily it can exploit society’s most vulnerable people. Publishers Weekly This distinctive work skillfully puts a human face on the bioethical questions surrounding the HeLa cell line. Henrietta Lacks, an African American mother of five, was undergoing treatment for cancer at Johns Hopkins University in 1951 when tissue samples were removed without her knowledge or permission and used to create HeLa, the first "immortal" cell line. HeLa has been sold around the world and used in countless medical research applications, including the development of the polio vaccine. Science writer Skloot, who worked on this book for ten years, entwines Lacks's biography, the development of the HeLa cell line, and her own story of building a relationship with Lacks's children. Full of dialog and vivid detail, this reads like a novel, but the science behind the story is also deftly handled. Verdict: While there are other titles on this controversy (e.g., Michael Gold's A Conspiracy of Cells: One Woman's Immortal Legacy—and the Medical Scandal It Caused ), this is the most compelling account for general readers, especially those interested in questions of medical research ethics. Highly recommended. — Carla Lee, Univ. of Virginia Lib., Charlottesville Library Journal ( Starred review .) Writing with a novelist's artistry, a biologist's expertise, and the zeal of an investigative reporter, Skloot tells a truly astonishing story of racism and poverty, science and conscience, spirituality and family driven by a galvanizing inquiry into the sanctity of the body and the very nature of the life force. Booklist A dense, absorbing investigation into the medical community's exploitation of a dying woman and her family's struggle to salvage truth and dignity decades later. In a well-paced, vibrant narrative, Popular Science contributor and Culture Dish blogger Skloot (Creative Writing/Univ. of Memphis) demonstrates that for every human cell put under a microscope, a complex life story is inexorably attached, to which doctors, researchers and laboratories have often been woefully insensitive and unaccountable. In 1951, Henrietta Lacks, an African-American mother of five, was diagnosed with what proved to be a fatal form of cervical cancer. At Johns Hopkins, the doctors harvested cells from her cervix without her permission and distributed them to labs around the globe, where they were multiplied and used for a diverse array of treatments. Known as HeLa cells, they became one of the world's most ubiquitous sources for medical research of everything from hormones, steroids and vitamins to gene mapping, in vitro fertilization, even the polio vaccine—all without the knowledge, must less consent, of the Lacks family. Skloot spent a decade interviewing every relative of Lacks she could find, excavating difficult memories and long-simmering outrage that had lay dormant since their loved one's sorrowful demise. Equal parts intimate biography and brutal clinical reportage, Skloot's graceful narrative adeptly navigates the wrenching Lack family recollections and the sobering, overarching realities of poverty and pre-civil-rights racism. The author's style is matched by a methodical scientific rigor and manifest expertise in the field. Skloot's meticulous, riveting account strikes a humanistic balance between sociological history, venerable portraiture, and Petri dish politics. Kirkus Reviews

Discussion Questions Use our LitLovers Book Club Resources; they can help with discussions for any book:

• How to Discuss a Book (helpful discussion tips) • Generic Discussion Questions—Fiction and Nonfiction • Read-Think-Talk (a guided reading chart)

Also consider these LitLovers talking points to help get a discussion started for The Immortal Life of Henrietta Lacks :

1. Start by unraveling the complicated history of Henrietta Lacks's tissue cells. Who did what with the cells, when, where and for what purpose? Who benefited, scientifically, medically, and monetarily?

2. What are the specific issues raised in the book—legally and ethically? Talk about the 1980s John Moore case: the appeal court decision and its reversal by the California Supreme Court.

3. Follow-up to Question #2: Should patient consent be required to store and distribute their tissue for research? Should doctors disclose their financial interests? Would this make any difference in achieving fairness? Or is this not a matter of fairness or an ethical issue to begin with?

4. What are the legal ramifications regarding payment for tissue samples? Consider the the RAND corporation estimation that 304 million tissue samples, from 178 million are people, are held by labs.

5. What are the spiritual and religious issues surrounding the living tissue of people who have died? How do Henrietta's descendants deal with her continued "presence" in the world...and even the cosmos (in space)?

6. Were you bothered when researcher Robert Stevenson tells author Skloot that "scientists don’t like to think of HeLa cells as being little bits of Henrietta because it’s much easier to do science when you dissociate your materials from the people they come from"? Is that an ugly outfall of scientific resarch...or is it normal, perhaps necessary, for a scientist to distance him/herself? If "yes" to the last part of that question, what about research on animals...especially for research on cosmetics?

7. What do you think of the incident in which Henrietta's children "see" their mother in the Johns Hopkins lab? How would you have felt? Would you have sensed a spiritual connection to the life that once created those cells...or is the idea of cells simply too remote to relate to?

8. Is race an issue in this story? Would things have been different had Henrietta been a middle class white woman rather than a poor African American woman? Consider both the taking of the cell sample without her knowledge, let alone consent... and the questions it is raising 60 years later when society is more open about racial injustice?

9. Author Rebecca Skloot is a veteran science writer. Did you find it enjoyable to follow her through the ins-and-outs of the laboratory and scientific research? Or was this a little too "petri-dishish" for you?

10. What did you learn from reading The Immortal Life ? What surprised you the most? What disturbed you the most?

( Questions by LitLovers. Please feel free to use them, online or off, with attribution. Thanks .) top of page (summary)

LitLovers © 2024

- Biggest New Books

- Non-Fiction

- All Categories

- First Readers Club Daily Giveaway

- How It Works

The Immortal Life of Henrietta Lacks

Embed our reviews widget for this book

Get the Book Marks Bulletin

Email address:

- Categories Fiction Fantasy Graphic Novels Historical Horror Literary Literature in Translation Mystery, Crime, & Thriller Poetry Romance Speculative Story Collections Non-Fiction Art Biography Criticism Culture Essays Film & TV Graphic Nonfiction Health History Investigative Journalism Memoir Music Nature Politics Religion Science Social Sciences Sports Technology Travel True Crime

Book Review: The Immortal Life of Henrietta Lacks by Rebecca Skloot

August 2, 2019 by Bloom Ob/Gyn

There are moments in scientific discovery that are undeniably important in modern medicine and research. Take Andrew Fleming, for example, who mistakenly discovered Penicillin in 1928. Dr. Fleming returned from a two week vacation to find mold contaminating one of his bacterial culture plates. But he also noticed that this mold prevented the growth of his bacteria – and thus was the advent of Penicillin. Unlike Fleming’s fairly innocuous discovery, The Immortal Life of Henrietta Lacks by Rebecca Skloot captures the story of another major scientific discovery – this one with grave human consequences.

Published in 2010, this novel tells the story of a mother and poor Southern tobacco farmer named Henrietta Lacks. She passed away at a young age and, from the beginning, her doctors knew that there was something unusual about the cancer cells on her cervix. Henrietta’s cells – Hela cells – were taken without her knowledge and have become one of the most important tools in medicine. In fact, if you Google “HeLa cells,” your search will yield 30,000,000+ hits. Why is it then that few have heard of their namesake?

HeLa cells are still alive today even though she died nearly seventy years ago. These cells grow unusually fast, doubling their count in only 24 hours. They are also immortal – meaning they will divide again and again and again without dying off. This makes them ideal for large scale testing. HeLa cells were vital for developing the polio vaccine; uncovering secrets of cancer and viruses; helped lead to important advances like in vitro fertilization and gene mapping; and have been bought and sold by the billions. Their chromosomes and proteins have been studied with such precision that scientists know their every detail. Like mice, Henrietta’s cells have become the standard laboratory workhorse.

Yet Henrietta Lacks remains virtually unknown, buried in an unmarked grave.

In The Immortal Life of Henrietta Lacks, Rebecca Skloot takes us from the cancer ward at Johns Hopkins Hospital in the 1950s to stark laboratories with freezers full of HeLa cells. From Henrietta’s small hometown in Virginia to East Baltimore in the early 2000s where her children and grandchildren live and struggle with the legacy of her short life and immortal cells.

Henrietta’s family did not learn of her “immortality” until nearly twenty years after her death, when scientists investigating HeLa began using her husband and children in research without informed consent. Even though these cells launched a multimillion-dollar industry, her family never saw a portion of the profits. The story of the Lacks family is connected to the history of experimentation on African Americans, the birth of ethics in medicine and research, and the legal battles over whether we control the stuff we are made of.

Over the course of a decade, Rebecca Skloot carefully researched and uncovered the story of Henrietta Lacks’ immortal cells. In that process, she becomes entangled in the lives of Henrietta’s family – especially her daughter Deborah who was devastated to learn about her mother’s cells. She was consumed with questions:

Had scientists cloned her mother? Did it hurt her when researchers infected her cells with viruses? And if her mother was so important to medicine, why couldn’t she afford health insurance?

In her words, Rebecca writes:

“The Lackses challenged everything I thought I knew about faith, science, journalism, and race. Ultimately, this book is the result. It’s not only the story of HeLa cells and Henrietta Lacks, but of Henrietta’s family—particularly Deborah—and their lifelong struggle to make peace with the existence of those cells, and the science that made them possible.”

The Immortal Life of Henrietta Lacks is intimate, astonishingly broad in scope, and nearly impossible to put down.

4001 Brandywine St. NW Suite 300 Washington, DC 20016

Phone: (202) 449-9570

Medical Records Fax: (844) 768-4889

Fax: (202) 449-9513

Office Hours

- Monday: 8:30am - 4:45pm

- Tuesday: 8:30am - 4:45pm

- Wednesday: 8:30am - 4:45pm

- Thursday: 8:30am - 4:45pm

- Friday: 8:30am - 4:45pm

- Saturday & Sunday: Closed

Subscribe to Email Updates

Stay up-to-date with all of Bloom OB/GYN news, events, and headline articles delivered straight to your mailbox.

Email Address

StarsInsider

HeLa cells: The most influential and controversial discovery in medicine

Posted: May 14, 2024 | Last updated: May 14, 2024

Discoveries that change the face of medicine overnight come along only once in a generation. The medical professionals behind these life-changing and lifesaving developments are almost always given their due praise and fanfare as saviors of humanity, true and just egalitarians dedicated to the greater good. But while that is often true, it is also true that their discoveries were often built on the backs of other members of society who may have been exploited, abused, or subjected to unethical medical practices, and have never received their own recognition or compensation. The most infamous story of this occurrence is the story of Henrietta Lacks, whose cells were taken without her knowledge and consent.

Click on to learn more about the fascinating story of medicine's greatest unsung hero.

You may also like: 20 years after 'Sex and The City', see where the actors are now!

A young girl in Roanoke

The woman who should be known the world over as Henrietta Lacks was born Loretta Pleasant on August 1, 1920, in rural Roanoke, Virginia.

Loretta was one of 10 children born to Johnny and Eliza Pleasant. When Loretta was only four, her mother died while giving birth to her 10th child, forcing her impoverished father to distribute his children amongst family members around Virginia. Loretta was placed in the care of her maternal grandfather, Thomas Lacks. It was around this time that, for reasons we may never know, Loretta's name was changed to Henrietta.

You may also like: Anti-acne diet: foods you should eat and avoid to reduce skin problems

A Virginia wedding

When Henrietta was 20 years old, she married her cousin, whom she had grown up with working on a tobacco farm with their grandfather. The two were married on April 10, 1941. By the time of their marriage, the couple had already welcomed two children.

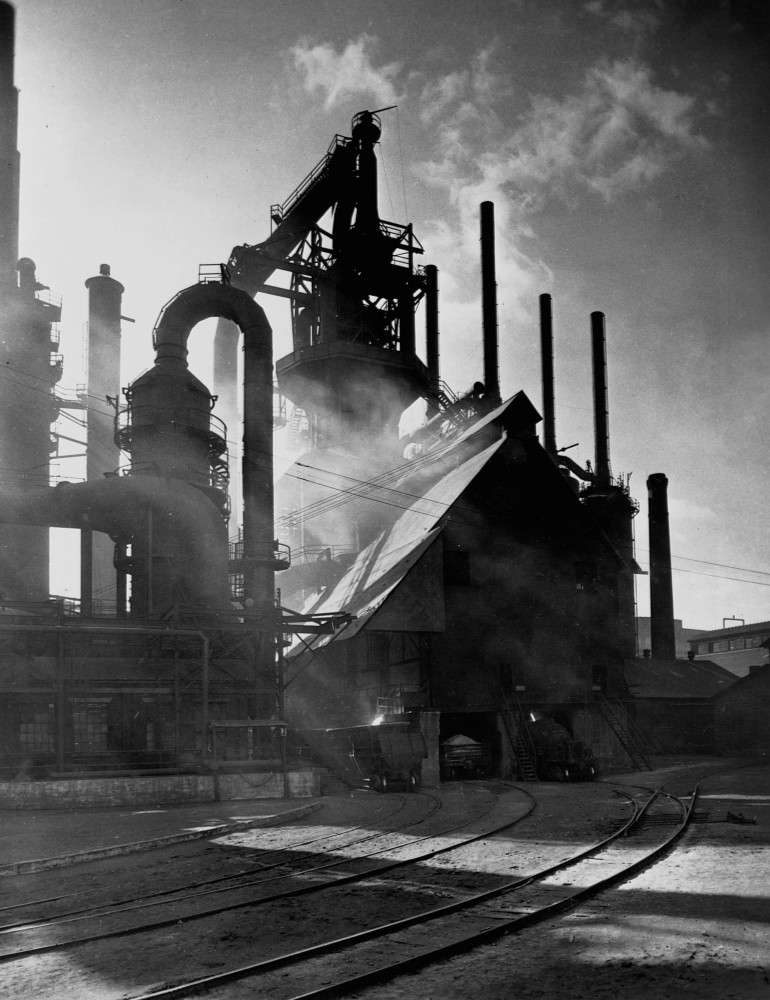

The move to Maryland

Shortly after their wedding, the new Lacks family moved north to Maryland at the behest of a friend who ensured Henrietta's husband, David, could find work in the far more industrialized region of Baltimore.

You may also like: Australian celebrities that are actually Kiwis

Turner Station, Maryland

The two settled in Turner Station, and David began working at a nearby Bethlehem Steel factory. In Maryland, Henrietta gave birth to three more healthy children.

The Lacks family

The family was large and not without its worries. While there was no lack of love, the family's health became an unforgiving source of pain and sorrow.

You may also like: Celebrities who have sued their own parents

Elsie Lacks

Henrietta's second-eldest child, Elsie, had been born with severe epilepsy and cerebral palsy. Neither the family nor the society they found themselves in had the means to provide the treatment young Elsie needed.

Elsie's tragedy

Shortly before her mother's death, Elsie was transferred to Crownsville Hospital, a segregated insane asylum that, even in the mid-20th century, had a horrifying reputation of abuse, including, but not limited to, unethical and nonconsensual medical experiments.

You may also like: The Last Supper: famous final feasts

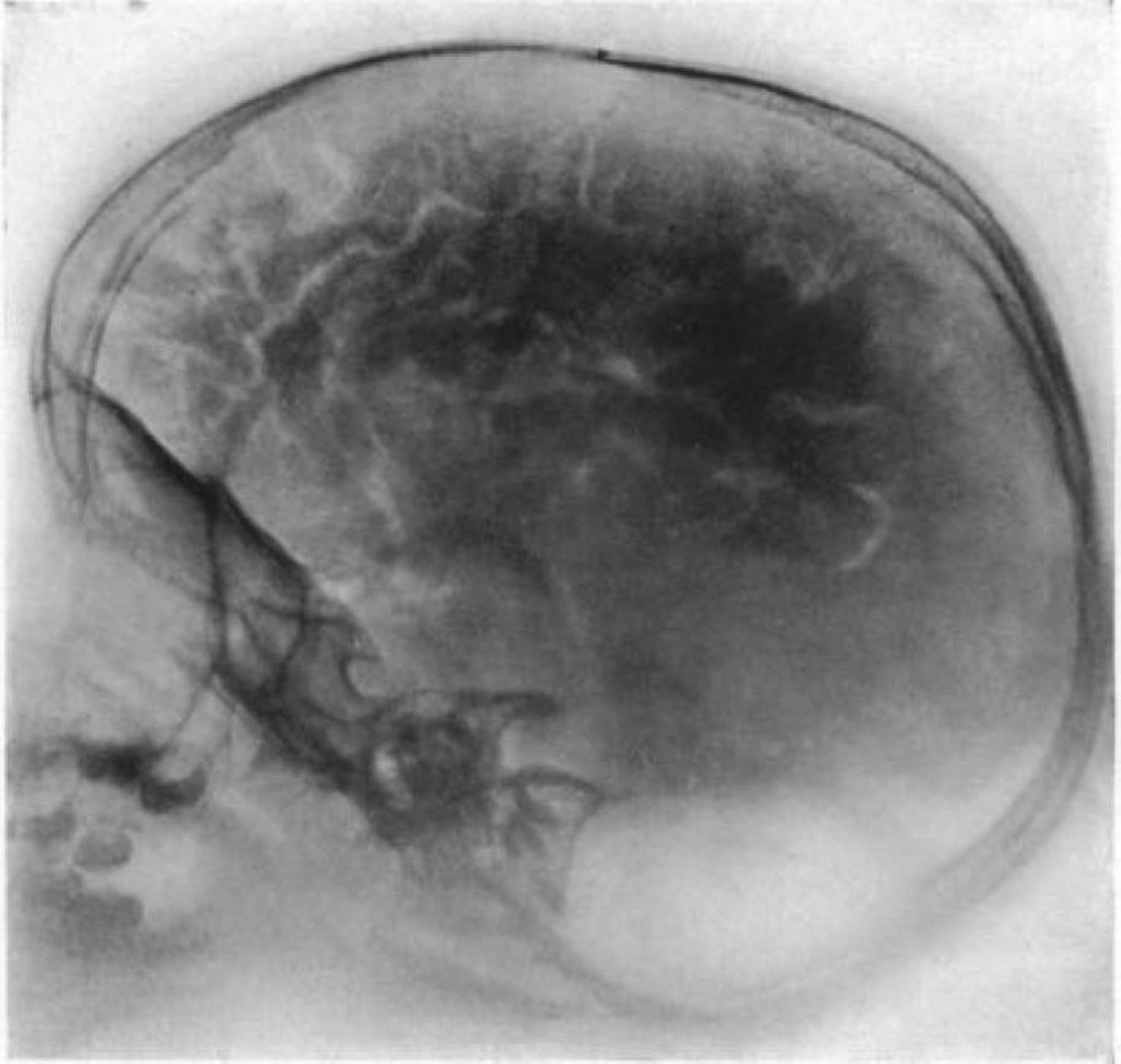

Pneumoencephalography

Elsie died at the age of 15 at Crownsville Hospital. Although the official cause of death provided by the asylum cited respiratory failure, further investigations have pointed towards pneumoencephalography, a procedure now considered barbaric that involves draining the skull of the fluid around the brain so as to take clearer X-ray images. The procedure, if repeated more than once, was extremely dangerous. Given the asylum's, and the wider nation's, reputation for using incarcerated minorities for medical experimentations, it is highly likely that this procedure was performed on Elsie numerous times, leading to her death.

A knot in the womb

Just before Elsie was sent to her doom, Henrietta Lacks had gone to doctors at Johns Hopkins Hospital. Lacks complained of severe abdominal and cervical pain, which she described as a "knot in the womb." She was told, partially correctly, that there was nothing wrong; Lacks was simply pregnant with her fifth child.

You may also like: The most bizarre TripAdvisor reviews

The first miracle of Joseph Lacks

Sure enough, Henrietta gave birth to Joseph Lacks in November of 1950. This was only a few short months before Henrietta was diagnosed with advanced cervical cancer. This revelation has led family members, including Joseph himself, to deem his birth a "miracle," saying he was "fighting off the cancer cells growing all around him."

The diagnosis

Henrietta's diagnosis came in January 1951, after she had returned to Johns Hopkins complaining of a post-natal hemorrhage and informing the doctors that the "knot" in her womb had still not gone away. After a biopsy was performed, Lacks was diagnosed with advanced cervical cancer.

You may also like: The unusual names of Aussie celebrity children

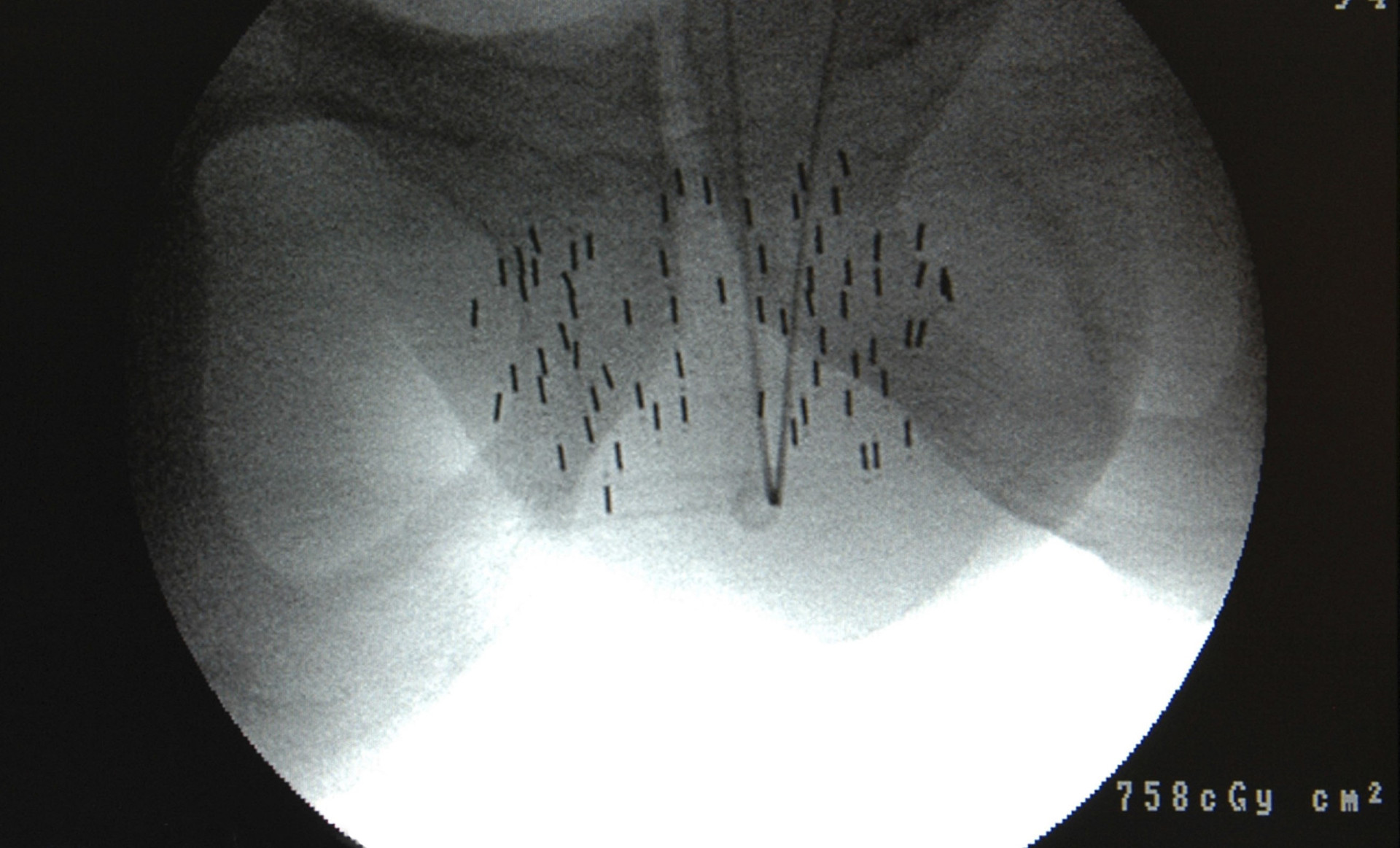

The treatment

Lacks was summarily hospitalized and received a round of brachytherapy, a radiation treatment that involves physically inserting radium tubes into the cancerous area. After this, Lacks was sent home and told to come back for occasional X-rays.

John Hopkins Hospital