- Bipolar Disorder

- Therapy Center

- When To See a Therapist

- Types of Therapy

- Best Online Therapy

- Best Couples Therapy

- Best Family Therapy

- Managing Stress

- Sleep and Dreaming

- Understanding Emotions

- Self-Improvement

- Healthy Relationships

- Student Resources

- Personality Types

- Guided Meditations

- Verywell Mind Insights

- 2024 Verywell Mind 25

- Mental Health in the Classroom

- Editorial Process

- Meet Our Review Board

- Crisis Support

The Difference Between Morals and Ethics

Brittany is a health and lifestyle writer and former staffer at TODAY on NBC and CBS News. She's also contributed to dozens of magazines.

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/VerywellProfile-3df8c258c46d4cc796273b15ad22ba4b.jpg)

Steven Gans, MD is board-certified in psychiatry and is an active supervisor, teacher, and mentor at Massachusetts General Hospital.

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/steven-gans-1000-51582b7f23b6462f8713961deb74959f.jpg)

Stockarm / Getty Images

What Is Morality?

What are ethics, ethics, morals, and mental health, are ethics and morals relative, discovering your own ethics and morals, frequently asked questions.

Are ethics vs. morals really just the same thing? It's not uncommon to hear morality and ethics referenced in the same sentence. That said, they are two different things. While they definitely have a lot of commonalities (not to mention very similar definitions!), there are some distinct differences.

Below, we'll outline the difference between morals and ethics, why it matters, and how these two words play into daily life.

Morality is a person or society's idea of what is right or wrong, especially in regard to a person's behavior.

Maintaining this type of behavior allows people to live successfully in groups and society. That said, they require a personal adherence to the commitment of the greater good.

Morals have changed over time and based on location. For example, different countries can have different standards of morality. That said, researchers have determined that seven morals seem to transcend across the globe and across time:

- Bravery: Bravery has historically helped people determine hierarchies. People who demonstrate the ability to be brave in tough situations have historically been seen as leaders.

- Fairness: Think of terms like "meet in the middle" and the concept of taking turns.

- Defer to authority: Deferring to authority is important because it signifies that people will adhere to rules that attend to the greater good. This is necessary for a functioning society.

- Helping the group: Traditions exist to help us feel closer to our group. This way, you feel more supported, and a general sense of altruism is promoted.

- Loving your family: This is a more focused version of helping your group. It's the idea that loving and supporting your family allows you to raise people who will continue to uphold moral norms.

- Returning favors : This goes for society as a whole and specifies that people may avoid behaviors that aren't generally altruistic .

- Respecting others’ property: This goes back to settling disputes based on prior possession, which also ties in the idea of fairness.

Many of these seven morals require deferring short-term interests for the sake of the larger group. People who act purely out of self-interest can often be regarded as immoral or selfish.

Many scholars and researchers don't differentiate between morals and ethics, and that's because they're very similar. Many definitions even explain ethics as a set of moral principles.

The big difference when it comes to ethics is that it refers to community values more than personal values. Dictionary.com defines the term as a system of values that are "moral" as determined by a community.

In general, morals are considered guidelines that affect individuals, and ethics are considered guideposts for entire larger groups or communities. Ethics are also more culturally based than morals.

For example, the seven morals listed earlier transcend cultures, but there are certain rules, especially those in predominantly religious nations, that are determined by cultures that are not recognized around the world.

It's also common to hear the word ethics in medical communities or as the guidepost for other professions that impact larger groups.

For example, the Hippocratic Oath in medicine is an example of a largely accepted ethical practice. The American Medical Association even outlines nine distinct principles that are specified in medical settings. These include putting the patient's care above all else and promoting good health within communities.

Since morality and ethics can impact individuals and differ from community to community, research has aimed to integrate ethical principles into the practice of psychiatry.

That said, many people grow up adhering to a certain moral or ethical code within their families or communities. When your morals change over time, you might feel a sense of guilt and shame.

For example, many older people still believe that living with a significant other before marriage is immoral. This belief is dated and mostly unrecognized by younger generations, who often see living together as an important and even necessary step in a relationship that helps them make decisions about the future. Additionally, in many cities, living costs are too high for some people to live alone.

However, even if younger person understands that it's not wrong to live with their partner before marriage they might still feel guilty for doing so, especially if they were taught that doing so was immoral.

When dealing with guilt or shame, it's important to assess these feelings with a therapist or someone else that you trust.

Morality is certainly relative since it is determined individually from person to person. In addition, morals can be heavily influenced by families and even religious beliefs, as well as past experiences.

Ethics are relative to different communities and cultures. For example, the ethical guidelines for the medical community don't really have an impact on the people outside of that community. That said, these ethics are still important as they promote caring for the community as a whole.

This is important for young adults trying to figure out what values they want to carry into their own lives and future families. This can also determine how well young people create and stick to boundaries in their personal relationships .

Part of determining your individual moral code will involve overcoming feelings of guilt because it may differ from your upbringing. This doesn't mean that you're disrespecting your family, but rather that you're evolving.

Working with a therapist can help you better understand the moral code you want to adhere to and how it ties in aspects of your past and present understanding of the world.

A Word From Verywell

Understanding the difference between ethics vs. morals isn't always cut and dry. And it's OK if your moral and ethical codes don't directly align with the things you learned as a child. Part of growing up and finding autonomy in life involves learning to think for yourself. You determine what you will and will not allow in your life, and what boundaries are acceptable for you in your relationships.

That said, don't feel bad if your ideas of right and wrong change over time. This is a good thing that shows that you are willing to learn and understand those with differing ideas and opinions.

Working with a therapist could prove to be beneficial as you sort out what you do and find to be acceptable parts of your own personal moral code.

Morals refer to a sense of right or wrong. Ethics, on the other hand, refer more to principles of "good" versus "evil" that are generally agreed upon by a community.

Examples of morals can include things such as not lying, being generous, being patient, and being loyal. Examples of ethics can include the ideals of honesty, integrity, respect, and loyalty.

Because morals involve a personal code of conduct, it is possible for people to be moral but not ethical. A person can follow their personal moral code without adhering to a more community-based sense of ethical standards. In some cases, a persons individual morals may be at odds with society's ethics.

Dictionary.com. Morality .

Curry OS, Mullins DA, Whitehouse H. Is it good to cooperate? Testing the theory of morality-as-cooperation in 60 societies . Current Anthropology. 2019;60(1):47-69. doi:10.1086/701478

Dictionary.com. Ethics .

Crowden A. Ethically Sensitive Mental Health Care: Is there a Need for a Unique Ethics for Psychiatry? Australian & New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry . 2003;37(2):143-149.

By Brittany Loggins Brittany is a health and lifestyle writer and former staffer at TODAY on NBC and CBS News. She's also contributed to dozens of magazines.

- school Campus Bookshelves

- menu_book Bookshelves

- perm_media Learning Objects

- login Login

- how_to_reg Request Instructor Account

- hub Instructor Commons

Margin Size

- Download Page (PDF)

- Download Full Book (PDF)

- Periodic Table

- Physics Constants

- Scientific Calculator

- Reference & Cite

- Tools expand_more

- Readability

selected template will load here

This action is not available.

5.1: Moral Philosophy – Concepts and Distinctions

- Last updated

- Save as PDF

- Page ID 86935

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

Before examining some standard theories of morality, it is important to understand basic terms and concepts that belong to the specialized language of ethical studies. The concepts and distinctions presented in this section will be useful for characterizing the major theories of right and wrong we will study in subsequent sections of this unit. The general area of concepts and foundations of ethics explained here is referred to as meta-ethics .

5.1.1 The Language of Ethics

Ethics is about values, what is right and wrong, or better or worse. Ethics makes claims, or judgments, that establish values. Evaluative claims are referred to as normative, or prescriptive, claims . Normative claims tell us, or affirm, what ought to be the case. Prescriptive claims need to be seen in contrast with descriptive claims , which simply tell us, or affirm, what is the case, or at least what is believed to be the case.

For example, this claim is descriptive:, it describes what is the case:

“Low sugar consumption reduces risk of diabetes and heart failure.”

On the other hand, this claim is normative:

“Everyone ought to reduce consumption of sugar.”

This distinction between descriptive and normative (prescriptive) claims applies in everyday discourse in which we all engage. In ethics, however, normative claims have essential significance. A normative claim may, depending upon other considerations, be taken to be a “moral fact.”

Note: Many philosophers agree that the truth of an “is” statement in itself does not infer an “ought” claim. The fact the low sugar consumption leads to better health does not imply, on its own, that everyone should reduce their sugar intake. A good logical argument would require further reasons (premises) to reach the “ought” conclusion/claim. An “ought” claim inferred directly from an “is” statement is referred to as the naturalistic fallacy .

A supplemental resource is available (bottom of page) on the distinction between descriptive and normative claims.

5.1.2 How Are Moral Facts Real?

When we talk about “moral facts” typically we are referring to claims about values, duties, standards for behavior, and other evaluative prescriptions. The following concepts describe the sense in which moral facts are real in terms of:

- the degree of universality, or lack thereof, with which the moral claims are held, and

- the extent to which moral facts stand independently of other considerations.

Moral Objectivism

The view that moral facts exist, in the sense that they hold for everyone, is called moral (or ethical) objectivism. From the viewpoint of objectivism, moral facts do not merely represent the beliefs of the person making the claim, they are facts of the world. Furthermore, such moral facts/claims have no dependencies on other claims nor do they have any other contingencies.

Moral Subjectivism

Moral (or ethical) subjectivism holds that moral facts are not universal, they exist only in the sense that those who hold them believe them to exist. Such moral facts sometimes serve as useful devices to support practical purposes. According to the viewpoint of subjectivism, moral facts (values, duties, and so forth) are entirely dependent on the beliefs of those who hold them.

Moral Absolutism

Moral absolutism is an objectivist view that there is only one true moral system with specific moral rules (or facts) that always apply, can never be disregarded. At least some rules apply universally, transcending time, culture. and personal belief. Actions of a specific sort are always right (or wrong) independently of any further considerations, including their consequences.

Moral Relativism

Moral relativism is the view that there are no universal standards of moral value, that moral facts, values, and beliefs are relative to individuals or societies that hold them. The rightness of an action depends on the attitude taken toward it by the society or culture of the person doing the action.

- Moral relativism as it relates to an individual is a form of ethical subjectivism.

- As it relates to a society or culture, moral relativism is referred to as “cultural relativism” and is also subjectivist in that moral facts depend entirely on the beliefs of those who hold them, they are not universal.

Note that some accounts of meta-ethical concepts do not use both “objectivism” and “absolutism” or use them interchangeably. The important relationship to keep in mind is that both objectivism and absolutism stand in contrast to relativism and subjectivism.

Here are several arguments in support of moral relativism. The “objection” following each one is an argument against moral relativism and in favor of moral objectivism.

- Objection: “Is” does not imply “ought.” Further, the fact that there are diverse cultural values does not necessarily imply that there are no objective values.

- Objection: That we cannot yet justify objective values does not mean that such a foundation could not be developed.

- Objection: This entails that we tolerate oppressive systems that are intolerant themselves. Further, this argument seems to confer objective value on “tolerance” and further still, “tolerance” is not the same as “respect.”

Here are some additional arguments against moral relativism:

- If values for right and wrong are relative to a specific moral standpoint or culture, anything can be justified, even practices that seem objectively unconscionable.

- Ethical relativism would diminish our possibility for making moral judgments of others and other societies. However, we do make moral judgments of others and believe we are justified in making these moral judgments.

- Ethical relativism says that moral values are determined by ‘the group’, but it is difficult to determine who ‘the group’ is. Anyone in the “group” who disagrees is immoral.

- If people were ethical relativists in practice (that is, if everyone was a ethical subjectivist), there would be moral chaos.

A supplemental resource is available (bottom of page) on moral relativism.

Do you think that there are objective moral values? Or do you believe that all moral values are relative to either cultures or individuals? Include your reasons.

Note: Submit your response to the appropriate Assignments folder.

5.1.3 How Do We Know What is Right?

The question at hand is about moral epistemology. How do we know what is right or wrong? What prompts our moral sentiments, our values, our actions? Are our moral assessments made on a purely rational basis, or do they stem from our emotional nature? There are contemporary philosophers who support each position, but we will return to some “old” friends we met in our unit on epistemology, Immanuel Kant and David Hume. They were hardly on the “same page” when it came to how and if we can know anything at all, and it’s hardly surprising that we find them at odds on what motivates moral choices, how we know what is right.

When we met Immanuel Kant (1724-1804) in our study of epistemology, we read passages from his Prolegomena to any Future Metaphysic (1783). In that work, he applied a slightly less intricate and perplexing presentation of topics from his masterwork on metaphysics and epistemology, the Critique of Pure Reason (1781). His next project involved application of his same rigorous reasoning method to moral philosophy. In 1785, Kant published Fundamental Principles of the Metaphysic of Morals; it introduced concepts that he expanded subsequently in the Critique of Practical Reason (1788). The short excerpts that follow are from Fundamental Principles of the Metaphysic of Morals.

Recall that Kant’s epistemology required both reason and empirical experience, each in its proper role. Kant believed that human action could be evaluated only by the logical distinctions based in synthetic a priori judgments.

In the following excerpt, Kant explains that a clear understanding of the moral law is not to be found in the empirical world but is a matter of pure reason.

Everyone must admit that if a law is to have moral force, i.e., to be the basis of an obligation, it must carry with it absolute necessity; that, for example, the precept, “Thou shalt not lie,” is not valid for men alone, as if other rational beings had no need to observe it; and so with all the other moral laws properly so called; that, therefore, the basis of obligation must not be sought in the nature of man, or in the circumstances in the world in which he is placed, but a priori simply in the conception of pure reason; and although any other precept which is founded on principles of mere experience may be in certain respects universal, yet in as far as it rests even in the least degree on an empirical basis, perhaps only as to a motive, such a precept, while it may be a practical rule, can never be called a moral law. Thus not only are moral laws with their principles essentially distinguished from every other kind of practical knowledge in which there is anything empirical, but all moral philosophy rests wholly on its pure part.

However, there is some correspondence between the study of natural world and of ethics. Both have an empirical dimension as well as a rational one. When Kant speaks of “anthropology” he refers to the empirical study of human nature.

…there arises the idea of a twofold metaphysic- a metaphysic of nature and a metaphysic of morals. Physics will thus have an empirical and also a rational part. It is the same with Ethics; but here the empirical part might have the special name of practical anthropology, the name morality being appropriated to the rational part.

So, while the nature of moral duty must be sought a priori “in the conception of pure reason,” empirical knowledge of human nature has a supporting role in distinguishing how to apply moral laws and in dealing with “so many inclinations” – the confusing array of emotions, impulses, desires that bombard us and contradict the command of reason. Our emotions (inclinations) are hardly the source of moral knowledge; they interfere with the human capability for practical pure reason.

Thus not only are moral laws with their principles essentially distinguished from every other kind of practical knowledge in which there is anything empirical, but all moral philosophy rests wholly on its pure part.When applied to man, it does not borrow the least thing from the knowledge of man himself (anthropology), but gives laws a priori to him as a rational being. No doubt these laws require a judgment sharpened by experience, in order on the one hand to distinguish in what cases they are applicable, and on the other to procure for them access to the will of the man and effectual influence on conduct; since man is acted on by so many inclinations that, though capable of the idea of a practical pure reason, he is not so easily able to make it effective in concreto in his life.

Kant sees his project on moral law, or “practical reason,” to be a less complicated project than Critique of Pure Reason, his “critical examination of the pure speculative reason, already published.” According to Kant, “moral reasoning can easily be brought to a high degree of correctness and completeness”, whereas speculative reason is “dialectical” – laden with opposing forces. Furthermore, a complete “critique” of practical reason entails “a common principle” that can cover any situation – “for it can ultimately be only one and the same reason which has to be distinguished merely in its application.”

Intending to publish hereafter a metaphysic of morals, I issue in the first instance these fundamental principles. Indeed there is properly no other foundation for it than the critical examination of a pure practical reason; just as that of metaphysics is the critical examination of the pure speculative reason, already published. But in the first place the former is not so absolutely necessary as the latter, because in moral concerns human reason can easily be brought to a high degree of correctness and completeness, even in the commonest understanding, while on the contrary in its theoretic but pure use it is wholly dialectical; and in the second place if the critique of a pure practical Reason is to be complete, it must be possible at the same time to show its identity with the speculative reason in a common principle, for it can ultimately be only one and the same reason which has to be distinguished merely in its application.

In the next section of this unit, we will see where Kant goes with this project and its “common principle” the applies universally. For now, keep in mind that Kant sees moral judgment as a reason-based activity, and that emotions/inclinations diminish our moral judgments. Many philosophers agree that making moral judgments and taking moral actions are rationally contemplated undertakings.

David Hume (1711-1776) , as we learned in our epistemology unit, doubted that the principles of cause and effect and that induction could lead to truth about the natural world. Recall his picture of reason, his version of the distinction between a prior and a posteriori knowledge:

- Relations of ideas are beliefs grounded wholly on associations formed within the mind; they are capable of demonstration because they have no external referent.

- Matters of fact are beliefs that claim to report the nature of existing things; they are always contingent.

In both his Treatise of Human Nature (1739) and An Enquiry concerning the Principles of Morals (1751) relations-of-ideas and matters-of-fact figure in his position that human agency and moral obligation are best considered as functions of human passions rather than as the dictates of reason. The excerpts that follow are from the Treatise (Book III, Part I, Sections I and II).

If reason were the source of moral sensibility, then either relations of ideas or matters-of-fact would need to be involved:

As the operations of human understanding divide themselves into two kinds, the comparing of ideas, and the inferring of matter of fact; were virtue discovered by the understanding; it must be an object of one of these operations, nor is there any third operation of the understanding. which can discover it.

Relations of ideas involve precision and certainty (as with geometry or algebra) that arise out of pure conceptual thought and logical operations. A relationship between “vice and virtue” cannot be demonstrated in this way.

There has been an opinion very industriously propagated by certain philosophers, that morality is susceptible of demonstration; and though no one has ever been able to advance a single step in those demonstrations; yet it is taken for granted, that this science may be brought to an equal certainty with geometry or algebra. Upon this supposition vice and virtue must consist in some relations; since it is allowed on all hands, that no matter of fact is capable of being demonstrated….. For as you make the very essence of morality to lie in the relations, and as there is no one of these relations but what is applicable… RESEMBLANCE, CONTRARIETY, DEGREES IN QUALITY, and PROPORTIONS IN QUANTITY AND NUMBER; all these relations belong as properly to matter, as to our actions, passions, and volitions. It is unquestionable, therefore, that morality lies not in any of these relations, nor the sense of it in their discovery.

Hume goes on to explain how moral distinctions do not arise from of matters of fact:

Take any action allowed to be vicious: Willful murder, for instance. Examine it in all lights, and see if you can find that matter of fact, or real existence, which you call vice. In which-ever way you take it, you find only certain passions, motives, volitions and thoughts. There is no other matter of fact in the case. The vice entirely escapes you, as long as you consider the object. You never can find it, till you turn your reflection into your own breast, and find a sentiment of disapprobation, which arises in you, towards this action. Here is a matter of fact; but it is the object of feeling, not of reason. It lies in yourself, not in the object.

And so, Hume concludes that moral distinctions are not derived from reason, rather they come from our feelings, or sentiments.

Thus the course of the argument leads us to conclude, that since vice and virtue are not discoverable merely by reason, or the comparison of ideas, it must be by means of some impression or sentiment they occasion, that we are able to mark the difference betwixt them……Morality, therefore, is more properly felt than judged of”

Hume’s view that our moral judgments and actions arise not from our rational capacities but from our emotional nature and sentiments, is contrary to several of the major normative theories we will explore. However, it is interesting to note that some present-day philosophers regard the domain of emotion as a primary source of moral action, and also that work in neuroscience suggests that Hume may have been on the right track.

Economist Jeremy Rifkin provides an absorbing and fast-moving chalk-talk on human empathy, as demonstrated by neuroscience. (10+ minutes) Note: Cartoon depictions of humans are unclothed RSA Animate . [CC-BY-NC-ND]

Optional Video

Trust, morality – and oxytocin? . [CC-BY-NC-ND] Neuro-economist Paul Zak believe he has identified the “moral molecule” in the brain. (16+ minutes)

An additional supplemental video (bottom of page) explores moral judgments and neuroscience even further.

What do you think about the connection between morality and the neurobiology of our brains? Do you think these findings affect arguments for or against ethical relativism?

Note: Post your response in the appropriate Discussion topic.

5.1.4 Psychological Influences

Various psychological characterizations of human nature have had significant influence on views about morality. We will see in this Ethics unit and the next on Social and Political Philosophy that particular conceptions of human nature may be at the center of theories about moral actions of individuals and about ethical interaction among individuals in social communities.

Egoism is the view that by nature we are selfish, that our actions, even our ostensibly generous ones, are motivated by selfish desire. Ethical egoism is the belief that pursuing ones own happiness is the highest moral value, that moral decisions should be guided by self-interest.

Another view of human nature holds that the primary motivation for all of our actions is pleasure. Hedonism is the view that pleasure is the highest or only good worth seeking, that we should, in fact, seek pleasure.

A different take on human nature is that we have innate capacity for benevolence (empathy) toward other people. (Recall the the mirror neurons in the Jeremy Rifkin video.) Altruism is the view that moral decisions should be guided by consideration for the interests and well-being of other people rather than by self-interest.

5.1.5 The Meaning of “Good”

In Ethics, we refer to what is “good” as a general term of approval, for what is of value, for example, a particular action, a quality, a practice, a way of life. Among the aspects of “good” that philosophers discuss is whether a particular thing is valued because it is good in and of itself, or because it leads to some other “good.”

- An intrinsic good is something that is good in and of itself, not because of something else that may result from it. In ethics, a “value” possesses intrinsic worth. For example, with hedonism, pleasure is the only intrinsic good, or value. In some normative theories, a particular type of action may possess intrinsic worth, or good.

- An instrumental good , on the other hand, is useful for attaining something else that is good. It is instrumental in that it that leads to another good, but it is not good is and of itself. For example, for an egoist, an action such as generosity to others can be seen as an instrumental good if it leads to to self-fulfillment, which is an intrinsic good valued in and of itself by an egoist.

As we look more closely at some major normative theories, the distinction between intrinsic and instrumental good will be among the considerations of interest. Understanding normative theories, also involves these questions:

- How do we determine what the right action is?

- What are the standards that we use to judge if a particular action is good or bad?

The following normative theories will be addressed:

- Deontology (from the Greek for “obligation, or duty”) is concerned rules and motives for actions.

- Utilitarianism, a consequentialist theory, is interested in the good outcomes of actions.

- Virtue Ethics values actions in terms of what a person of good character would do.

Supplemental Resources

Descriptive and Normative Claims

Fundamentals: Normative and Descriptive Claims . This 4-minute video is a quick review with examples, on the differences between descriptive and normative claims.

Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy (IEP). Moral Relativism . Read section “3. Arguments for Moral Relativism” and section “4. Objections to Moral Relativism.”

Moral Judgment and Neuroscience

The Neuroscience behind Moral Judgments . Alan Alda talks with an MIT neuroscientist about neurological connections with moral judgments. (5+ minutes)

- 5.1 Moral Philosophy - Concepts and Distinctions. Authored by : Kathy Eldred. Provided by : Pima Community College. License : CC BY: Attribution

Ethics and Morality

Morality, Ethics, Evil, Greed

Reviewed by Psychology Today Staff

To put it simply, ethics represents the moral code that guides a person’s choices and behaviors throughout their life. The idea of a moral code extends beyond the individual to include what is determined to be right, and wrong, for a community or society at large.

Ethics is concerned with rights, responsibilities, use of language, what it means to live an ethical life, and how people make moral decisions. We may think of moralizing as an intellectual exercise, but more frequently it's an attempt to make sense of our gut instincts and reactions. It's a subjective concept, and many people have strong and stubborn beliefs about what's right and wrong that can place them in direct contrast to the moral beliefs of others. Yet even though morals may vary from person to person, religion to religion, and culture to culture, many have been found to be universal, stemming from basic human emotions.

- The Science of Being Virtuous

- Understanding Amorality

- The Stages of Moral Development

Those who are considered morally good are said to be virtuous, holding themselves to high ethical standards, while those viewed as morally bad are thought of as wicked, sinful, or even criminal. Morality was a key concern of Aristotle, who first studied questions such as “What is moral responsibility?” and “What does it take for a human being to be virtuous?”

We used to think that people are born with a blank slate, but research has shown that people have an innate sense of morality . Of course, parents and the greater society can certainly nurture and develop morality and ethics in children.

Humans are ethical and moral regardless of religion and God. People are not fundamentally good nor are they fundamentally evil. However, a Pew study found that atheists are much less likely than theists to believe that there are "absolute standards of right and wrong." In effect, atheism does not undermine morality, but the atheist’s conception of morality may depart from that of the traditional theist.

Animals are like humans—and humans are animals, after all. Many studies have been conducted across animal species, and more than 90 percent of their behavior is what can be identified as “prosocial” or positive. Plus, you won’t find mass warfare in animals as you do in humans. Hence, in a way, you can say that animals are more moral than humans.

The examination of moral psychology involves the study of moral philosophy but the field is more concerned with how a person comes to make a right or wrong decision, rather than what sort of decisions he or she should have made. Character, reasoning, responsibility, and altruism , among other areas, also come into play, as does the development of morality.

The seven deadly sins were first enumerated in the sixth century by Pope Gregory I, and represent the sweep of immoral behavior. Also known as the cardinal sins or seven deadly vices, they are vanity, jealousy , anger , laziness, greed, gluttony, and lust. People who demonstrate these immoral behaviors are often said to be flawed in character. Some modern thinkers suggest that virtue often disguises a hidden vice; it just depends on where we tip the scale .

An amoral person has no sense of, or care for, what is right or wrong. There is no regard for either morality or immorality. Conversely, an immoral person knows the difference, yet he does the wrong thing, regardless. The amoral politician, for example, has no conscience and makes choices based on his own personal needs; he is oblivious to whether his actions are right or wrong.

One could argue that the actions of Wells Fargo, for example, were amoral if the bank had no sense of right or wrong. In the 2016 fraud scandal, the bank created fraudulent savings and checking accounts for millions of clients, unbeknownst to them. Of course, if the bank knew what it was doing all along, then the scandal would be labeled immoral.

Everyone tells white lies to a degree, and often the lie is done for the greater good. But the idea that a small percentage of people tell the lion’s share of lies is the Pareto principle, the law of the vital few. It is 20 percent of the population that accounts for 80 percent of a behavior.

We do know what is right from wrong . If you harm and injure another person, that is wrong. However, what is right for one person, may well be wrong for another. A good example of this dichotomy is the religious conservative who thinks that a woman’s right to her body is morally wrong. In this case, one’s ethics are based on one’s values; and the moral divide between values can be vast.

Psychologist Lawrence Kohlberg established his stages of moral development in 1958. This framework has led to current research into moral psychology. Kohlberg's work addresses the process of how we think of right and wrong and is based on Jean Piaget's theory of moral judgment for children. His stages include pre-conventional, conventional, post-conventional, and what we learn in one stage is integrated into the subsequent stages.

The pre-conventional stage is driven by obedience and punishment . This is a child's view of what is right or wrong. Examples of this thinking: “I hit my brother and I received a time-out.” “How can I avoid punishment?” “What's in it for me?”

The conventional stage is when we accept societal views on rights and wrongs. In this stage people follow rules with a good boy and nice girl orientation. An example of this thinking: “Do it for me.” This stage also includes law-and-order morality: “Do your duty.”

The post-conventional stage is more abstract: “Your right and wrong is not my right and wrong.” This stage goes beyond social norms and an individual develops his own moral compass, sticking to personal principles of what is ethical or not.

New data suggest LLMs can provide moral advice rated more thoughtful, trustworthy, and correct than that of laypeople and experts.

Personal Perspective: Humanism has its roots in Darwin's ideas, which put the entirety of life on the same playing field. We need a humanist approach now more than ever.

Conformity to morality is often mistaken as a panacea for societal issues. Cognitions of reality represent the confounding variable responsible for moral attribution.

Eating disorder treatment is rife with sensitive and ethical treatment considerations. Adding telehealth therapy to the mix creates new opportunities and potential risks.

A holistic, compassionate view of who and what we wear raises wide-ranging ethical questions about social justice, freedom, human and nonhuman well-being, and sustainability.

Personal Perspective: Corporations' legal protections tend to overwhelm the struggle for social justice. It takes a brave person, a hero, to go against the odds.

On current vaccine controversies and the challenges confronting low-to-middle-income countries.

The question of whether a therapist can or should provide conjoint individual and couples therapy is a hotly debated issue with no clear guidelines or answers.

Why Michael Cohen is apologizing and atoning for his mistakes in the New York Supreme Court case against Donald J. Trump.

A Personal Perspective: When we choose which ideas should be given the right of freedom of expression and which shouldn't, democracy suffers for all of us.

- Find a Therapist

- Find a Treatment Center

- Find a Psychiatrist

- Find a Support Group

- Find Online Therapy

- United States

- Brooklyn, NY

- Chicago, IL

- Houston, TX

- Los Angeles, CA

- New York, NY

- Portland, OR

- San Diego, CA

- San Francisco, CA

- Seattle, WA

- Washington, DC

- Asperger's

- Bipolar Disorder

- Chronic Pain

- Eating Disorders

- Passive Aggression

- Personality

- Goal Setting

- Positive Psychology

- Stopping Smoking

- Low Sexual Desire

- Relationships

- Child Development

- Self Tests NEW

- Therapy Center

- Diagnosis Dictionary

- Types of Therapy

At any moment, someone’s aggravating behavior or our own bad luck can set us off on an emotional spiral that threatens to derail our entire day. Here’s how we can face our triggers with less reactivity so that we can get on with our lives.

- Emotional Intelligence

- Gaslighting

- Affective Forecasting

- Neuroscience

McCombs School of Business

- Español ( Spanish )

Videos Concepts Unwrapped View All 36 short illustrated videos explain behavioral ethics concepts and basic ethics principles. Concepts Unwrapped: Sports Edition View All 10 short videos introduce athletes to behavioral ethics concepts. Ethics Defined (Glossary) View All 58 animated videos - 1 to 2 minutes each - define key ethics terms and concepts. Ethics in Focus View All One-of-a-kind videos highlight the ethical aspects of current and historical subjects. Giving Voice To Values View All Eight short videos present the 7 principles of values-driven leadership from Gentile's Giving Voice to Values. In It To Win View All A documentary and six short videos reveal the behavioral ethics biases in super-lobbyist Jack Abramoff's story. Scandals Illustrated View All 30 videos - one minute each - introduce newsworthy scandals with ethical insights and case studies. Video Series

Ethics Defined UT Star Icon

Morals are society’s accepted principles of right conduct that enable people to live cooperatively.

Morals are the prevailing standards of behavior that enable people to live cooperatively in groups. Moral refers to what societies sanction as right and acceptable.

Most people tend to act morally and follow societal guidelines. Morality often requires that people sacrifice their own short-term interests for the benefit of society. People or entities that are indifferent to right and wrong are considered amoral, while those who do evil acts are considered immoral.

While some moral principles seem to transcend time and culture, such as fairness, generally speaking, morality is not fixed. Morality describes the particular values of a specific group at a specific point in time. Historically, morality has been closely connected to religious traditions, but today its significance is equally important to the secular world. For example, businesses and government agencies have codes of ethics that employees are expected to follow.

Some philosophers make a distinction between morals and ethics. But many people use the terms morals and ethics interchangeably when talking about personal beliefs, actions, or principles. For example, it’s common to say, “My morals prevent me from cheating.” It’s also common to use ethics in this sentence instead.

So, morals are the principles that guide individual conduct within society. And, while morals may change over time, they remain the standards of behavior that we use to judge right and wrong.

Related Terms

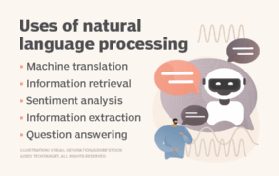

Ethics refers to both moral principles and to the study of people’s moral obligations in society.

Prosocial Behavior

Prosocial Behavior occurs when people voluntarily help others.

Values are society’s shared beliefs about what is good or bad and how people should act.

Stay Informed

Support our work.

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- Sage Choice

The Psychology of Morality: A Review and Analysis of Empirical Studies Published From 1940 Through 2017

Naomi ellemers.

1 Utrecht University, The Netherlands

Jojanneke van der Toorn

2 Leiden University, The Netherlands

Yavor Paunov

3 Mannheim University, Germany

Thed van Leeuwen

Associated data.

Supplemental material, APPENDIX_1._Exclusion_of_papers_in_review for The Psychology of Morality: A Review and Analysis of Empirical Studies Published From 1940 Through 2017 by Naomi Ellemers, Jojanneke van der Toorn, Yavor Paunov and Thed van Leeuwen in Personality and Social Psychology Review

Supplemental material, APPENDIX_2._Reference_list_of_all_studies_included_in_review_(1940-2017) for The Psychology of Morality: A Review and Analysis of Empirical Studies Published From 1940 Through 2017 by Naomi Ellemers, Jojanneke van der Toorn, Yavor Paunov and Thed van Leeuwen in Personality and Social Psychology Review

Supplemental material, APPENDIX_3._Bibliometric_indicators_used for The Psychology of Morality: A Review and Analysis of Empirical Studies Published From 1940 Through 2017 by Naomi Ellemers, Jojanneke van der Toorn, Yavor Paunov and Thed van Leeuwen in Personality and Social Psychology Review

Supplemental material, Supplementary_Figures for The Psychology of Morality: A Review and Analysis of Empirical Studies Published From 1940 Through 2017 by Naomi Ellemers, Jojanneke van der Toorn, Yavor Paunov and Thed van Leeuwen in Personality and Social Psychology Review

Supplemental material, Supplementary_Tables for The Psychology of Morality: A Review and Analysis of Empirical Studies Published From 1940 Through 2017 by Naomi Ellemers, Jojanneke van der Toorn, Yavor Paunov and Thed van Leeuwen in Personality and Social Psychology Review

We review empirical research on (social) psychology of morality to identify which issues and relations are well documented by existing data and which areas of inquiry are in need of further empirical evidence. An electronic literature search yielded a total of 1,278 relevant research articles published from 1940 through 2017. These were subjected to expert content analysis and standardized bibliometric analysis to classify research questions and relate these to (trends in) empirical approaches that characterize research on morality. We categorize the research questions addressed in this literature into five different themes and consider how empirical approaches within each of these themes have addressed psychological antecedents and implications of moral behavior. We conclude that some key features of theoretical questions relating to human morality are not systematically captured in empirical research and are in need of further investigation.

This review aims to examine the “psychology of morality” by considering the research questions and empirical approaches of 1,278 empirical studies published from 1940 through 2017. We subjected these studies to expert content analysis and standardized bibliometric analysis to characterize relevant trends in this body of research. We first identify key features that characterize theoretical approaches to human morality, extract five distinct classes of research questions from the studies conducted, and visualize how these aim to address the psychological antecedents and implications of moral behavior. We then compare this theoretical analysis with the empirical approaches and research paradigms that are typically used to address questions within each of these themes. We identify emerging trends and seminal publications, specify conclusions that can be drawn from studies conducted within each research theme, and outline areas in need of further investigation.

Morality indicates what is the “right” and “wrong” way to behave, for instance, that one should be fair and not unfair to others ( Haidt & Kesebir, 2010 ). This is considered of interest to explain the social behavior of individuals living together in groups ( Gert, 1988 ). Results from animal studies (e.g., de Waal, 1996 ) or insights into universal justice principles (e.g., Greenberg & Cropanzano, 2001 ) do not necessarily help us to address moral behavior in modern societies. This also requires the reconciliation of people who endorse different political orientations ( Haidt & Graham, 2007 ) or adhere to different religions ( Harvey & Callan, 2014 ). The observation that “good people can do bad things” further suggests that we should look beyond the causes of individual deviance or delinquency to understand moral behavior. In our analysis, we consider key explanatory principles emerging from prominent theoretical approaches to capture important features characterizing human morality ( Tomasello & Vaish, 2013 ). These relate to (a) the social anchoring of right and wrong, (b) conceptions of the moral self, and (c) the interplay between thoughts and experiences. We argue that these three key principles explain the interest of so many researchers in the topic of morality and examine whether and how these are addressed in empirical research available to date.

Through an electronic literature search (using Web of Science [WoS]) and manual selection of relevant entries, we collected empirical publications that contained an empirical measure and/or manipulation that was characterized by the authors as relevant to “morality.” With this procedure, we found 1,278 papers published from 1940 through 2017 that report research addressing morality. Notwithstanding the enormous research interest visible in empirical publications on morality, a comprehensive overview of this literature is lacking. In fact, the review paper on morality that was most frequently cited in our set was published more than 35 years ago ( Blasi, 1980 ). As it stands, separate strands of research seem to be driven by different questions and empirical approaches that do not connect to a common approach or research agenda. This makes it difficult to draw summary conclusions, to integrate different sets of findings, or to chart important avenues for future research.

To organize and understand how results from empirical studies relate to each other, we identify the relations that are implicitly seen to connect different research questions. The rationales provided to study specific issues commonly refer to the psychological antecedents and implications of moral behavior and thus are seen to capture “the psychology of morality.” By content-analyzing the study reports provided, we classify the studies included in this review into five groups of thematic research questions and characterize the empirical approaches typically used in studies addressing each of these themes. With the help of bibliometric techniques, we then quantify emerging trends and consider how different clusters of study approaches relate to questions in each of the research themes examined. This allows us to clarify the theoretical conclusions that can be drawn from empirical work so far and to identify less examined issues in need of further study.

Morality and Social Order

Moral principles indicate what is a “good,” “virtuous,” “just,” “right,” or “ethical” way for humans to behave ( Haidt, 2012 ; Haidt & Kesebir, 2010 ; Turiel, 2006 ). Moral guidelines (“do no harm”) can induce individuals to display behavior that has no obvious instrumental use or no direct value for them, for instance, when they show empathy, fairness, or altruism toward others. Moral rules—and sanctions for those who transgress them—are used by individuals living together in social communities, for instance, to make them refrain from selfish behavior and to prevent them from lying, cheating, or stealing from others ( Ellemers, 2017 ; Ellemers & Van den Bos, 2012 ; Ellemers & Van der Toorn, 2015 ).

The role of morality in the maintenance of social order is recognized by scholars from different disciplines. Biologists and evolutionary scientists have documented examples of selfless and empathic behaviors observed in communities of animals living together, considering these as relevant origins of human morality (e.g., de Waal, 1996 ). The main focus of this work is on displays of fairness, empathy, or altruism in face-to-face groups, where individuals all know and depend on each other. In the analysis provided by Tomasello and Vaish (2013) , this would be considered the “first tier” of morality, where individuals can observe and reciprocate the treatment they receive from others to elicit and reward cooperative and empathic behaviors that help to protect individual and group survival.

Philosophers, legal scholars, and political scientists have addressed more abstract moral principles that can be used to regulate and govern the interactions of individuals in larger and more complex societies (e.g., Haidt, 2012 ; Mill 1861/1962 ). Here, the nature of cooperative or empathic behavior is much more symbolic as it depends less on direct exchanges between specific individuals, but taps into more abstract and ambiguous concepts such as “the greater good.” Scholarly efforts in this area have considered how specific behaviors might (not) be in line with different moral principles and which guidelines and procedures might institutionalize social order according to such principles (e.g., Churchland, 2011 ; Morris, 1997 ). These approaches tap into what Tomasello and Vaish (2013) consider the “second tier” of morality, which emphasizes the social signaling functions of moral behavior and distinguishes human from animal morality (see also Ellemers, 2018 ). At this level, behavioral guidelines that have lost their immediate survival value in modern societies (such as specific dress codes or dietary restrictions) may nevertheless come to be seen as prescribing essential behavior that is morally “right.” Specific behaviors can acquire this symbolic moral value to the extent that they define how individuals typically mark their religious identity, communicate respect for authority, or secure group belonging for those adhering to them ( Tomasello & Vaish, 2013 ). Moral judgments that function to maintain social order in this way rely on complex explanations and require verbal exchanges to communicate the moral overtones of behavioral guidelines. Language-driven interpretations and attributions are needed to capture symbolic meanings and inferred intentions that are not self-evident in behavioral displays or outwardly visible indicators of emotions ( Ellemers, 2018 ; Kagan, 2018 ).

The interest of psychologists in moral behavior as a factor in maintaining social order has long been driven by developmental questions (how do children acquire the ability to do this, for example, Kohlberg, 1969 ) and clinical implications (what are origins of social deviance and delinquency, for example, Rest, 1986 ). Jonathan Haidt’s (2001) publication, on the role of quick intuition versus deliberate reflection in distinguishing between right and wrong, marked a turning point in the interest of psychologists in these issues. The consideration of specific psychological mechanisms involved in moral reasoning prompted many psychological researchers to engage with this area of inquiry. This development also facilitated the connection of psychological theory to neurobiological mechanisms and inspired attempts to empirically examine underlying processes at this level—for instance, by using functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) measures to monitor the brain activity of individuals confronted with moral dilemmas ( Greene, 2013 ; Greene, Sommerville, Nystrom, Darley, & Cohen, 2001 ).

Below, we will consider influential approaches that have advanced the understanding of human morality in social psychology, organizing them according to their main explanatory focus. These characterize the “second tier” ( Tomasello & Vaish, 2013 ) implications of morality that go beyond more basic displays of empathy and altruism observed in animal studies that form the root of biological and evolutionary explanations. From the theoretical perspectives currently available, we extract three key principles that capture the essence of human morality.

Social Anchoring of Right and Wrong

The first principle refers to the social implications of judgments about right and wrong. This has been emphasized as a defining characteristic of morality in different theoretical perspectives. For instance, Skitka (2010) and colleagues have convincingly argued that beliefs about what is morally right or wrong are unlike other attitudes or convictions ( Mullen & Skitka, 2006 ; Skitka, Bauman, & Sargis, 2005 ; Skitka & Mullen, 2002 ). Instead, moral convictions are seen as compelling mandates, indicating what everyone “ought” to or “should” do. This has important social implications, as people also expect others to follow these behavioral guidelines. They are emotionally affected and distressed when this turns out not to be the case, find it difficult to tolerate or resolve such differences, and may even resort to violence against those who challenge their views ( Skitka & Mullen, 2002 ).

This socially defined nature of moral guidelines is explicitly acknowledged in several theoretical perspectives on moral behavior. The Theory of Planned Behavior (e.g., Ajzen, 1991 ) offers a framework that clearly specifies how behavioral intentions are determined in an interplay of individual dispositions and social norms held by self-relevant others ( Ajzen & Fishbein, 1974 ; Fishbein & Ajzen, 1974 ). For instance, research based on this perspective has been used to demonstrate that the adoption of moral behaviors, such as expressing care for the environment, can be enhanced when relevant others think this is important ( Kaiser & Scheuthle, 2003 ).

In a similar vein, Haidt (2001) argued that judgments of what are morally good versus bad behaviors or character traits are specified in relation to culturally defined virtues. This allows shared ideas about right and wrong to vary, depending on the cultural, religious, or political context in which this is defined ( Giner-Sorolla, 2012 ; Haidt & Graham, 2007 ; Haidt & Kesebir, 2010 ; Rai & Fiske, 2011 ). Haidt (2001) accordingly specifies that moral intuitions are developed through implicit learning of peer group norms and cultural socialization. This position is supported by empirical evidence showing how moral behavior plays out in groups ( Graham, 2013 ; Graham & Haidt, 2010 ; Janoff-Bulman & Carnes, 2013 ). This work documents the different principles that (groups of) people use in their moral reasoning ( Haidt, 2012 ). By connecting judgments about right and wrong to people’s group affiliations and social identities, this perspective clarifies why different religious, political, or social groups sometimes disagree on what is moral and find it difficult to understand the other position ( Greene, 2013 ; Haidt & Graham, 2007 ).

We argue that all these notions point to the socially defined and identity-affirming properties of moral guidelines and moral behaviors. Conceptions of right and wrong reflect the values that people share with important others and are anchored in the social groups to which they (hope to) belong ( Ellemers, 2017 ; Ellemers & Van den Bos, 2012 ; Ellemers & Van der Toorn, 2015 ; Leach, Bilali, & Pagliaro, 2015 ). This also implies that there is no inherent moral value in specific actions or overt displays, for instance, of empathy or helping. Instead, the same behaviors can acquire different moral meanings, depending on the social context in which they are displayed and the relations between actors and targets involved in this context ( Blasi, 1980 ; Gray, Young, & Waytz, 2012 ; Kagan, 2018 ; Reeder & Spores, 1983 ).

Thus, a first question to be answered when reviewing the empirical literature, therefore, is whether and how the socially shared and identity relevant nature of moral guidelines—central to key theoretical approaches—is adressed in the studies conducted to examine human morality.

Conceptions of the Moral Self

A second principle that is needed to understand human morality—and expands evolutionary and biological approaches—is rooted in the explicit self-awareness and autobiographical narratives that characterize human self-consciousness, and moral self-views in particular ( Hofmann, Wisneski, Brandt, & Skitka, 2014 ).

Because of the far-reaching implications of moral failures, people are highly motivated to protect their self-views of being a moral person ( Pagliaro, Ellemers, Barreto, & Di Cesare, 2016 ; Van Nunspeet, Derks, Ellemers, & Nieuwenhuis, 2015 ). They try to escape self-condemnation, even when they fail to live up to their own moral standards. Different strategies have been identified that allow individuals to disengage their self-views from morally questionable actions ( Bandura, 1999 ; Bandura, Barbaranelli, Caprara, & Pastorelli, 1996 ; Mazar, Amir, & Ariely, 2008 ). The impact of moral lapses or moral transgressions on one’s self-image can be averted by redefining one’s behavior, averting responsibility for what happened, disregarding the impact on others, or excluding others from the right to moral treatment, to name just a few possibilities.

A key point to note here is that such attempts to protect moral self-views are not only driven by the external image people wish to portray toward others. Importantly, the conviction that one qualifies as a moral person also matters for internalized conceptions of the moral self ( Aquino & Reed, 2002 ; Reed & Aquino, 2003 ). This can prompt people, for instance, to forget moral rules they did not adhere to ( Shu & Gino, 2012 ), to fail to recall their moral transgressions ( Mulder & Aquino, 2013 ; Tenbrunsel, Diekmann, Wade-Benzoni, & Bazerman, 2010 ), or to disregard others whose behavior seems morally superior ( Jordan & Monin, 2008 ).

As a result, the strong desire to think of oneself as a moral person not only enhances people’s efforts to display moral behavior ( Ellemers, 2018 ; Van Nunspeet, Ellemers, & Derks, 2015 ). Instead, sadly, it can also prompt individuals to engage in symbolic acts to distance themselves from moral transgressions ( Zhong & Liljenquist, 2006 ) or even makes them relax their behavioral standards once they have demonstrated their moral intentions ( Monin & Miller, 2001 ). Thus, tendencies for self-reflection, self-consistency, and self-justification are both affected by and guide moral behavior, prompting people to adjust their moral reasoning as well as their judgments of others and to endorse moral arguments and explanations that help justify their own past behavior and affirm their worldviews ( Haidt, 2001 ).

A second important question to consider when reviewing the empirical literature on morality, thus, is whether and how studies take into account these self-reflective mechanisms in the development of people’s moral self-views. From a theoretical perspective, it is therefore relevant to examine antecedents and correlates of tendencies to engage in self-defensive and self-justifying responses. From an empirical perspective, it also implies that it is important to consider the possibility that people’s self-reported dispositions and stated intentions may not accurately indicate or predict the moral behavior they display.

The Interplay Between Thoughts and Experiences

A third principle that connects different theoretical perspectives on human morality is the realization that this involves deliberate thoughts and ideals about right and wrong, as well as behavioral realities and emotional experiences people have, for instance, when they consider that important moral guidelines are transgressed by themselves or by others. Traditionally, theoretical approaches in moral psychology were based on the philosophical reasoning that is also reflected in legal and political scholarship on morality. Here, the focus is on general moral principles, abstract ideals, and deliberate decisions that are derived from the consideration of formal rules and their implications ( Kohlberg, 1971 ; Turiel, 2006 ). Over the years, this perspective has begun to shift, starting with the observation made by Blasi (1980 , p. 1) that

Few would disagree that morality ultimately lies in action and that the study of moral development should use action as the final criterion. But also few would limit the moral phenomenon to objectively observable behavior. Moral action is seen, implicitly or explicitly, as complex, imbedded in a variety of feelings, questions, doubts, judgments, and decisions . . . . From this perspective, the study of the relations between moral cognition and moral action is of primary importance.

This perspective became more influential as a result of Haidt’s (2001) introduction of “moral intuition” as a relevant construct. Questions about what comes first, reasoning or intuition, have yielded evidence showing that both are possible (e.g., Feinberg, Willer, Antonenko, & John, 2012 ; Pizarro, Uhlmann, & Bloom, 2003 ; Saltzstein & Kasachkoff, 2004 ). That is, reasoning can inform and shape moral intuition (the classic philosophical notion), but intuitive behaviors can also be justified with post hoc reasoning (Haidt’s position). The important conclusion from this debate thus seems to be that it is the interplay between deliberate thinking and intuitive knowing that shapes moral guidelines ( Haidt, 2001 , 2003 , 2004 ). This points to the importance of behavioral realities and emotional experiences to understand how people reflect on general principles and moral ideals.

A first way in which this has been addressed resonates with the evolutionary survival value of moral guidelines to help avoid illness and contamination as sources of physical harm. In this context, it has been argued and shown that nonverbal displays of disgust and physical distancing can emerge as unthinking embodied experiences to morally aversive situations that may subsequently invite individuals to reason why similar situations should be avoided in the future ( Schnall, Haidt, Clore, & Jordan, 2008 ; Tapp & Occhipinti, 2016 ). The social origins of moral guidelines are acknowledged in approaches explaining the role of distress and empathy as implicit cues that can prompt individuals to decide which others are worthy of prosocial behavior ( Eisenberg, 2000 ). In a similar vein, the experience of moral anger and outrage at others who violate important guidelines is seen as indicating which guidelines are morally “sacred” ( Tetlock, 2003 ). Experiences of disgust, empathy, and outrage all indicate relatively basic affective states that are marked with nonverbal displays and have direct implications for subsequent actions ( Ekman, 1989 ; Ekman, 1992 ).

In addition, theoretical developments in moral psychology have identified the experience of guilt and shame as characteristic “moral” emotions. Compared with “primary” affective responses, these “secondary” emotions are used to indicate more complex, self-conscious states that are not immediately visible in nonverbal displays ( Tangney & Dearing, 2002 ; Tangney, Stuewig, & Mashek, 2007 ). These moral emotions are seen to distinguish humans from most animals. Indeed, affording to others the perceived ability to experience such emotions communicates the degree to which we consider them to be human and worthy of moral treatment ( Haslam & Loughnan, 2014 ). The nature of guilt and shame as “self-condemning” moral emotions indicates their function to inform self-views and guide behavioral adaptations rather than communicating one’s state to others.

At the same time, it has been noted that feelings of guilt and shame can be so overwhelming that they raise self-defensive responses that stand in the way of behavioral improvement ( Giner-Sorolla, 2012 ). This can occur at the individual level as well as the group level, where the experience of “collective guilt” has been found to prevent intergroup reconciliation attempts ( Branscombe & Doosje, 2004 ). Accordingly, it has been noted that the relations between the experience of guilt and shame as moral emotions and their behavioral implications depend very much on further appraisals relating to the likelihood of social rejection and self-improvement that guide self-forgiveness ( Leach, 2017 ).

Regardless of which emotions they focus on, these theoretical perspectives all emphasize that moral concerns and moral decisions arise from situational realities, characterized by people’s experiences and the (moral) emotions these evoke. A third question emerging from theoretical accounts aiming to understand human morality, therefore, is whether and how the interplay between the thoughts people have about moral ideals (captured in principles, judgments, reasoning), on one hand, and the realities they experience (embodied behaviors, emotions), on the other, is explicitly addressed in empirical studies.

Empirical Approaches

Now that we have identified that socially shared, self-reflective, and experiential mechanisms represent three key principles that are seen as essential for the understanding of human morality in theory , it is possible to explore how these are reflected in the empirical work available. An initial answer to this question can be found by considering which types of research paradigms and classes of measures are frequently used in studies on morality. Do study designs typically take into account the way different social norms can shape individual moral behavior? Do instruments that are developed to assess people’s morality incorporate the notion that explicit self-reports do not necessarily capture their actual moral responses? And do responses that are assessed allow researchers to connect moral thoughts people have with their actual experiences?

We examined this by reviewing the empirical literature. Through an electronic literature search, we collected empirical studies reporting on manipulations and/or empirical measures that authors of these studies identified as being relevant to “morality.” In a first wave of data collection (see the “Method” section for further details), we extracted 419 empirical studies on morality that were published from 2000 through 2013. These were manually processed and content-coded to determine for each publication the research question that was asked, the research design that was employed to examine this, and the measures that were used (for details of how this was done, see Ellemers, Van der Toorn, & Paunov, 2017 ). We distinguished between correlational and experimental designs and assessed which manipulations were used to compare different responses (see Supplementary Table A ). We also listed and classified “named” scales and measures that were employed in these studies (see Table 1 ) and additionally indicated which types of responses were captured, in moral judgments provided, emotional and behavioral indicators, or with standardized scales (see Supplementary Table B ).

Four Types of Scales Used to Examine Morality in 91 Publications, With N Indicating the Number of Publications Using a Scale Type, Indicated in Order of Most Frequently Used (First Scale Mentioned) to Least Frequently Used (Last Scale Mentioned).

| Hypothetical moral dilemmas ( = 27) | Self-reported traits/behaviors of self/other ( = 32) | Endorsement of abstract moral rules ( = 31) | Position on specific moral issues ( = 20) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Defining Issues Test (DIT) ( ) Prosocial Moral Reasoning Measure (PROM) ( ) Accounting Specific Defining Issues Test (ADIT) ( ) Revised Moral Authority Scale (MAS-R) ( ) Moral/Conventional Distinction Task ( ; ) Moral Emotions Task ( ) Moral Judgment Test (MJT) ( ) | Moral Identity Scale ( ) HEXACO-PI ( ) Implicit Association Task (IAT) ( ) Cognitive Reflection Test (CRT) ( ) Index of Moral Behaviors ( ) Josephson Institute Report Card on the Ethics of American Youth ( ) Moral Entrepreneurial Personality (MEP) ( ) Moral Functioning Model ( ) Tennessee Self-Concept Scale ( ) Washington Sentence Completion Test of Ego Development ( ) Moral Exemplarity ( ) | Moral Foundations Questionnaire (MFQ) ( ) Schwartz Value Survey (SVS) ( ) Ethics Position Questionnaire (EPQ) ( ) Integrity Scale ( ) Moral Motives Scale (MMS) ( ) Identification with all Humanities Scale ( ) Moral Character ( ) Value Survey Module ( ) Community Autonomy Divinity Scale (CADS) ( ) Moral Foundations Dictionary ( ) | Moral Disengagement Scale ( ) Sensitivity to Injustice ( ) Sociomoral Reflection Measure–Short Form (SRM-SF) ( ) Beliefs About Morality (BAM) ( ) Dubious Behaviors ( ) Morally Debatable Behaviors Scale (MDBS) ( ) Moral Disengagement Tool ( ) Self-reported Inappropriate Negotiation Strategies Scale (SINS scale) ( ) TRIM-18R ( ) |

Note. A single publication can contain multiple scales.

Are Social Influences Taken Into Account?

An overview of the research designs that were coded in this way (see Supplementary Table A , final column) first reveals that a substantial proportion of these studies (185 of 419 studies examined; 44%) used correlational designs to examine, for instance, which traits people associate with particular targets or how self-reported beliefs, convictions, principles, or norms relate to self-stated intentions. Of the studies using an experimental design, a substantial number (91 studies; about 22%) examined the impact of some situational prime intended to activate specific goals, rules, or experiences. Furthermore, a substantial number of studies examined the impact of manipulating specific target characteristics (51 studies; 12%) or moral concerns (51 studies; 12%). However, experimental studies examining the impact of specific social norms (31 studies; 7%) or a group-based participant identity were relatively rare (four studies; less than 1%). This suggests that the socially shared nature of moral guidelines is not systematically addressed in this body of research.

Do Standard Instruments Rely on Self-Reports?

The types of responses typically examined in these studies can be captured by looking in more detail at the nature of the scales, tests, tasks, and questionnaires that were used. Our manual content analysis yielded 38 different scales, tests, tasks, and questionnaires that were used in 91 of the 419 studies examined (see Table 1 ). We clustered these according to their nature and intent, which yielded four distinct categories. We found seven different measures (used in 27 studies; 30%) that rely on hypothetical moral dilemmas , where people have to weigh different moral principles against each other (e.g., stealing from one person to help another person), and indicate what should be done in these situations. We found 11 additional measures (used in 12 studies; 13%) consisting of lists of traits or behaviors (e.g., honesty, helpfulness) that can be used to indicate the general character/personality type of the self or a known other (friend, family member). Here, we included measures such as the HEXACO Personality Inventory (HEXACO-PI; Lee & Ashton, 2004 ) and the moral identity scale ( Aquino & Reed, 2002 ). Third, we found 11 different measures (used in 31 studies; 34%) that assess the endorsement of abstract moral rules (e.g., “do no harm”). A representative example is the Moral Foundations Questionnaire ( Graham et al., 2011 ), which distinguishes between statements indicating concern for “individualizing” principles (harm/care, fairness) and “binding” principles (loyalty, authority, purity). Fourth, we found nine different measures (used in 20 studies; 22%) aiming to capture people’s position on specific moral issues (e.g., “it is important to tell the truth”; “it is ok for employees to take home a few office supplies”). We also included in this category different lists of behaviors (for instance, the Morally Debatable Behaviors Scale [MDBS]; Katz, Santman, & Lonero, 1994 ) that focus on the endorsement of behaviors considered relevant to morality (e.g., corruption, violence, discrimination, or misrepresentation).

Importantly, all four clusters of measures we found to rely on self-reported preferences and stated character traits or intentions, describing overall tendencies and general behavioral guidelines. However, it is less evident that such measures can be used to understand how people will actually behave in real-life situations, where they may have to choose which of different competing guidelines to apply or where it is unclear how the general principles they endorse translate to a specific act or decision in that context.

Are “Thoughts” Connected to “Experiences?”

Our manual coding of the different dependent measures that were used (see Supplementary Table B , final column) reveals that the majority of measures aimed to capture either general moral principles that people endorse (72 of 445 measures coded; 16%) or their moral evaluations of specific individuals, groups, or companies (72 measures; 16%). In addition, a substantial proportion of studies examined people’s positions on specific issues, such as abortion, gossiping, or specific political convictions (61 measures; 14%). Substantial numbers of measures assessed the perceived implications of one’s moral principles (48 measures; 11%) or the willingness to be cooperative or truthful in hypothetical situations (44 measures; 10%). Notably, a relatively small proportion of measures actually tried to capture cooperative or cheating behavior in experimental or real-life situations (51 measures; 12%). Similarly, empathy with others and moral emotions such as guilt, shame, and disgust were assessed in 15% (67) of the measures that were coded. Thus, the majority of measures used focuses on “thoughts” relating to morality, as these capture abstract principles, overall judgments, or hypothetical intentions, while much less attention has been devoted to examining behavioral displays or emotions characterizing the actual “experiences” people have in relation to these “thoughts.”