Hard evidence: does prison really work?

Senior Lecturer in Social Work, University of Salford

Disclosure statement

Ian Cummins does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

University of Salford provides funding as a founding partner of The Conversation UK.

View all partners

In front of British courts last year were 148,000 people who had 15 or more previous convictions, according to government figures. These reports deserve closer scrutiny.

The justice minister, Chris Grayling, has used these figures to suggest a need to rush through plans to privatise most of the probation service in order to reduce re-offending rates. “The public are fed up with crooks doing their time and going straight back to crime, and so is the government,” Grayling said.

Yet all the signs are that Britain’s probation services are doing their jobs pretty well - and there is a large and long-standing body of evidence that prison itself makes criminals more likely to re-offend.

In 1990, a Conservative white paper concluded: “We know that prison ‘is an expensive way of making bad people worse’.” That report also argued that there should be a range of community-based sentences, which would be cheaper and more effective alternatives to prison.

But just as this report was being published, Douglas Hurd was replaced as home secretary by the more hardline Michael Howard - whose first major move was to throw the white paper away, and to announce to rapturous applause at the Conservative Party conference that “prison works”.

Howard was not an outlier; as crime and punishment has become a key political and social issue over the past 30 years, the old consensus – that prison should be used as a last resort and only for the most serious offences – has disappeared in favour of a harsher approach. Most tellingly, one of the key features of the New Labour political project was a determination never to be outflanked by the Conservatives on law and order.

Blair’s mantra of “tough on crime, tough on the causes of crime” summed up this shift in thinking, and a series of Labour home secretaries ushered in a range of measures such as Anti-Social Behaviour Orders (ASBOs) and changes to sentencing. The result has been a huge increase in the prison population at a time when crime rates have generally been in decline: while ONS figures show that crime rates are at their lowest since 2002-3, statistics from the International Centre for Prison Studies demonstrate the mounting number of inmates:

The UK’s prison population has thus increased by an average rate of 3.6% per year since 1993. As the situation currently stands , England and Wales’s incarceration rate is 148 people per 100,000 - compared to 98 in France, 82 in the Netherlands and 79 in Germany.

Yet while the UK has long pursued a prisons policy that is tough by European standards, questions about the effects of imprisonment have not gone away. Recent comments by Chris Grayling about the rates of re-offending and Vicky Price’s high profile account of her time in prison show how even in the face of serious evidence-based doubts, the idea that more imprisonment is the answer still persists.

While Pryce draws on both personal experience and economic analysis to argue that the prison system creates serious social problems, including re-offending, Grayling (very much a politician in the Howard mould) still cites re-offending rates to instead castigate the Probation Service, which is on the verge of being privatised. But the recidivism rates Grayling has used to argue for privatisation also need to be examined more closely.

The Ministry of Justice statistic bulletin for Probation Trusts for the year to March 2013 shows a re-offending rate of 9.18%, based on a cohort size of 616,252. This is the lowest figure since 2008; the rate of re-offending in 2008-13 has remained fairly constant at around 9.8%.

Even then, the data is not so simple. Recidivism varies sharply with prisoner age and the length of prison terms: while 47% of adults are re-convicted within a year, this applies to 58% of those on shorter sentences, while for those under 18 the figure is an astonishing 73%.

The National Audit Office study Managing Offenders on Short Custodial Sentences calculated in 2010 that the re-offending by ex-offenders in 2007-08 cost the economy between £9.5 and £13 billion – the vast majority due to offenders who have served short sentences. Meanwhile, the Ministry of Justice’s 2013 re-offending statistics show that those on community sentences offended significantly less than those given custodial terms.

While re-offending is obviously a major problem, Grayling is clearly involved in a political move to demonstrate the alleged ineffectiveness of the current probation service – a service that still has some links to the Probation Act of 1907 , which established it was probation officers’ role to “advise, assist and befriend” their clients.

As the Ministry of Justice calculates that the average prison place costs £37,648 per year, around 12 times the price of the average probation or community service order, it is strange to see the apparently effective probation service blamed for problems which many would attribute to prisons themselves.

Perhaps the 1990 white paper, discarded by Michael Howard, should be dusted off again.

Hard Evidence is a series of articles in which academics use research evidence to tackle the trickiest public policy questions.

- Private prisons

- Hard Evidence

PhD Scholarship

Senior Lecturer, HRM or People Analytics

Senior Research Fellow - Neuromuscular Disorders and Gait Analysis

Centre Director, Transformative Media Technologies

Postdoctoral Research Fellowship

Is prison an effective form of punishment?

ULaw Criminology Lecturer Angela Charles completed her BA undergraduate degree in History and Criminology, followed by an MSc in Criminology and Criminal Justice. She is currently completing a PhD which explores the experiences of Black women in UK prisons through an intersectional lens. Her studies focus on the unique impact race and gender has on black female prisoners. Angela has worked within the criminal justice sector in a Secure Training Centre, the National Probation Service, and Youth Justice. Today Angela answers the question – is prison an effective form of punishment?

By Cara Fielder . Published 27 May 2021. Last updated 25 July 2022.

How do we assess the effectiveness of prisons?

Reform is arguably one of the most important reasons why prisons are vital. The gov.uk website talks about providing the right services and opportunities that support rehabilitation to prevent a return to crime. Some of the areas they mention are:

- Improving prisoners’ mental health and tackling substance misuse

- Improving prisoners progress in maths and English

- Increasing the numbers of offenders in employment and accommodation after release.

I would add that offenders should also be supported in learning about money and finance, improving their confidence, developing their understanding of supportive relationships, dealing with issues that may arise or previous traumas. Reform is about equipping someone with the tools to successfully navigate life’s difficulties without resorting to crime.

Life after prison is the final theme on the website and this is the support needed by prisoners once they are released. This includes working with probation services. They highlight the need for services that support prisoners from the transition ‘through the gate’. The main factors being employment and accommodation. When looking at the statistics for prisons achieving their target for accommodation on the first night following release, this is only 17.3%. When we look at employment targets within the first 6 weeks of release, this was at 4%, which is very low. These statistics raise concerns as to whether prison is successful in rehabilitation. Or is it merely a punishment that puts people’s lives on hold?

Real life examples of the prison being effective and ineffective

One woman I interviewed explained that none of the education options in the prison were suitable. She already had a degree, so did not need the English and maths classes that were provided. To her, the prison just wanted to tick a box to show people in prison were engaging in some form of education rather than helping black women progress and gain educational skills that were tailored to an individual’s needs and current level of education .

However, another Black woman said that being in prison had forced her to take level 1 and 2 English and Maths. She had been putting it off when she was in society but being in prison allowed her to take the time to do it. She passed and felt that she would have better prospects leaving the prison than when she came in. Additionally, she had been trained on how to clean up chemical spills and learnt all about the control of substances hazardous to health (COSSH). Again, she learnt new skills that she felt she would be able to use in the outside world.

Relationships

Many women stated that they could speak to their loved ones regularly on the phone, which allowed them stay connected. However, some of the women complained about how costly phone calls were. Also, transport to the prison was an expense that many women’s families could not afford. Therefore, in some cases, relationships with families were put on hold.

One woman talked about her drug recovery and explained how supportive her drug worker had been. They helped her through her recovery and were a source of support and consistency during her prison experience. Even when she moved onto another wing, she mentioned how this staff member still came to check on her. She believes if she had not come to prison, she would still be addicted to drugs. In this case, imprisonment was effective and helped her to rehabilitate.

Another example came from a woman who said that her prison experience allowed her to improve herself, deal with previous traumas, and come up with ways to deal with this. She used the prison experience to identify what things triggered previous traumas and how to deal with this, as well as living in the moment. In this sense, sometimes prison can be used as a period of reflection and self-improvement.

The final example I want to give comes from several women that highlighted the systemic racism they felt was occurring in the prison. The women stated that many of the officers stereotyped them as aggressive, loud troublemakers because of their race. This had a knock-on effect because it affected how long it took for women to get moved from a closed prison to an open prison, be released for day visits, to work and see family. It also meant that they felt like they could not be themselves. For these women, prison was not effective because they were dealing with the disadvantage of being black and female. They had fewer opportunities for employment progression and they had few supportive relationships with staff. When we think about examples like this, we must determine how effective the prison would be for these women. It would be a punishment but would it help rehabilitate them or leave them bitter, angry, frustrated and no better off than before they entered the prison?

Criminological arguments for prisons

One argument for prison is that it is an effective deterrent. Prison can be seen as a tough type of punishment because it takes away your freedom, potential support networks and in many ways, it strips away your identity. The thought of prison is enough for some people to not even contemplate committing a criminal act.

Prison sentences are also a message to the wider public that this is what will happen if you commit a crime. Prison advocates would say this is a message to wider society about what is right and wrong and what will happen if you commit a crime.

Additionally, prison advocates argue that prison is such a difficult time for people that the experience should then deter them from committing any further offences. However, we know that is not the case because many individuals who have committed an offence and go to prison then commit further offences. This makes us question, is prison a) effective and b) enough of a deterrence?

Another argument for prison is that by putting people in prison, we protect the public by ensuring these individuals cannot commit any further offences. Additionally, prison sentences provide a sense of justice to the victims affected by the crime and the public.

Criminological arguments against prisons

The first argument would be that prisons do not work. Those advocating for prison reform highlight reoffending statistics as an example of the ineffectiveness of prisons.

The adult reoffending rate for the October to December 2018 cohort was 27.5%.

Almost 101,000 proven re-offences were committed over the one-year follow-up period by around 25,000 adults. Those that reoffended committed on average 3.97 re-offences. [Source – Home Office – Proven reoffending statistics for England and Wales, published October 2020].

Research shows that long prison sentences have little impact on crime. Time in prison can actually make someone more likely to commit crime — by further exposing them to all sorts of criminal elements. Prisons are also costly, using up funds that could go to other government programs that are more effective at fighting crime.

Additionally, there are arguments that prison does not rehabilitate prisoners. While there are some opportunities in prison, this does not always meet the needs of the prisoners and does not help them on their release due to the views people in society have about imprisonment and criminal records. On release, three-fifths of prisoners have no “identified employment or education or training outcome”. If prison punishes people through the experience itself but then does not offer those individuals the opportunity to improve and change their lives once they are released, can we realistically expect people to be rehabilitated and not return to crime?

Some believe that the whole prison system is an oppressive institution governed by the powerful that cages the marginalised and powerless. They would argue that prison further damages people because it causes further trauma, exposes them to further violence, reinforces disadvantage and creates further crime and social harm. The prison also does very little to tackle the underlying causes of crime in communities. However, some have argued that by reducing the prison population, we are still widening the net and criminalising people, as community sentences and alternatives to custody would be increased rather than looking at some of the structural inequalities that may lead to crime and criminal behaviour.

Others argue that prison mainly holds those that are from lower socio-economic backgrounds and ethnic minorities, punishing poverty and disadvantage while protecting the crimes of the powerful. For example, where are the imprisoned individuals from corporations that cause widespread harm, such as those that need to be held accountable for the Grenfell Tower fire, multi-million corporations and so on?

There are many arguments for abolishing prison, and then there are arguments that recognise prison cannot be abolished completely but needs reforming.

The United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime highlights some of the reasons why prisons need to be reformed. These are:

- Human rights, as prison is a deprivation of the basic right to liberty.

- Imprisonment disproportionately affects individuals and families living in poverty. From the potential loss of income from an individual going to prison, lawyer costs, costs to visit and communicate with that individual, the lack of employment opportunities when released, the marginalisation and so on.

- Public health consequences – It is argued that many prisoners have poor health and existing health problems when entering the prison. These problems are exacerbated due to; overcrowding, poor nutrition, lack of exercise and fresh air. Then there are also the infection rates, self-harm and poor mental health. The argument is that staff will be vulnerable to some of these diseases, and so will the public once these individuals are released.

- Detrimental social impact – Imprisonment disrupts relationships and weakens social cohesion.

- Costs – The cost of each prisoner for their upkeep, but also the social, economic and health costs mentioned previously, which are long-term.

The Howard League for Penal Reform says on their website:

“The prison system is like a river.

The wider it gets, the faster it flows – and the harder it becomes to swim against the tide. Rather than being guided to safer shores, those in the middle are swept into deeper currents of crime, violence and despair. What began as a trickle turns into a torrent, with problems in prisons spilling into the towns and cities around them.”

In conclusion, when we think about the prison, and imprisonment as a punishment and reform option, there is a lot to consider. We need to assess the overall effectiveness of prisons and the need for justice against the harm imprisonment can have on an individual. We must consider the long-term impact the prison has on an individual, not just mentally, but also considering the impact it will have on their life chances and their ability to reintegrate into society.

If you have enjoyed reading this blog post, it is based on one of our Real World Lecture Series aimed at undergraduates. Book your place at our virtual undergraduate events now.

resources Our Recent Blogs

Reddit Roundup: June 2024

How to become a lawyer

Pride at The University of Law: An interview with LGBTQ+ Equalities Officer Francesca Mills

Does Prison Work?

Last Updated on September 21, 2016 by

If your measure of success is rehabilitation and the prevention of re-offending then it appears not: the proven re-offending rate within one year is just under 25%, and about 37% for juveniles.

Possible Reasons why Prison Doesn’t Work

Firstly , most (as in about two thirds) have no qualifications and many prisoners have the reading age of a 10 year old when they go into jail – and lack of educational programmes in jail does little to correct this. Basically most prisoners are unemployable before they go inside, and they are doubly unemployable when they come out with a criminal record.

The result is overcrowding and terrible conditions. It is estimated that 1/5 prisoners spends 22 hours a day in their cells; violence and drugs are rife and suicide rates are at their highest for 25 years.

It costs £36 000 a year to keep someone in jail, maybe this money could be better spent on social schemes to prevent offending?

Share this:

One thought on “does prison work”, leave a reply cancel reply.

This site uses Akismet to reduce spam. Learn how your comment data is processed .

Discover more from ReviseSociology

- Access your dashboard and other settings here.

- My Dashboard

- What's your big question?

- What's New

Does prison work?

If a person commits a crime, they should be punished by going to prison, right? But is this the most suitable outcome for all types of offenders? What about those who have families dependent on them? This needs a little more thought...

Locked up - test your prison knowledge!

In which German prison did Hitler write Mein Kampf?

- Landsberg Prison

- Neustrelitz Prison

- Heidering Prison

In which prison was St Peter said to have been held?

- Casa Reclusione Sant'Angelo dei Lombardi

- Regina Coeli

- Carcere Mamertino

What is John Howard (1726 – 1790) known for?

- Contributing to prison reform.

- Building a circular prison.

- Being the last prisoner in Fleet Prison.

When was hard labour in prisons abolished in England?

How many high-security prisons did Alfred George Hinds (1917 –1991) break out of?

Bastøy Prison is famous for having a low reoffending rate. Which country is it in?

In some old castles, you might find an oubliette. What is an oubliette also known as?

- The forgotten room

- The buried room

- The lost room

Why did the Cebu Provincial Detention and Rehabilitation Center (CPDRC) in the Philippines, make the news?

- Inmates have to pay for their own cells.

- They have dancing inmates.

- Inmates run a restaurant at the prison.

What was unusual about Fremantle Prison?

- It was entirely underwater.

- It was built by prisoners.

- It was on a remote island.

Why do we have prisons?

Is prison the best way to punish criminals, and does putting people in prison reduce crime? Dr Shona Minson (University of Oxford) explains the point of prison and looks at some alternatives…

Prisons exist for several reasons: to punish people; to prevent crime by trying to put people off from either repeating or copying an action; to protect the public, and to get criminals to make up for the bad thing they did.

Dr Shona Minson works in the University of Oxford’s Centre for Criminology and is an expert on prisons. She worked in law before starting her research, which means she knows a lot about different parts of the justice system.

'When I moved into academic research, I was particularly interested in children and families within the criminal justice system and how they’re treated,' she explains, 'and [I] became aware that when children are separated from their parents because their parents are sent to prison, no-one really thinks about what it’s going to be like for them and nobody makes sure that they are being well looked after now that they don’t have their mum or dad taking care of them.'

Effects on families

Dr Minson believes there are some key problems with the prison system which mostly stem from its lack of funding and staffing. As a result, many people who are released from prison often go on to commit further crimes.

'If you think someone is a very dangerous person and you put them in prison, then yes, you’ve got protection for society,' she says.

'But [when it comes to] reform and rehabilitation - i.e. helping people to change their behaviour - prison doesn’t really work for that. At the moment, our prisons are really unsafe. They are hugely overcrowded and understaffed.'

'There has been a reduction of investment in prison staff and the prisons budget itself. At the same time, there has been an increase in more punitive sentencing (stronger punishments). This doesn’t help to achieve anything.'

'People have a view that if somebody has done something bad, send them to prison. You’ve got to ask, "Well, what do we want that person to do because of what they’ve done wrong?" 'If we want them to change, and not do it again, it’s quite unlikely that sending someone to prison is going to do that.'

'Prison itself isn’t a nice place to be - and it’s not a particularly helpful place to be for people who might be suffering from mental health problems. Their situation might improve more with psychiatric treatment and/or support.'

'A lot of the prison population have already suffered huge trauma in their lives,' explains Dr Minson. 'More than 50 per cent of women in prison have said they’ve been abused or subject to domestic violence. Many have not been able to finish their education. A lot have a mental illness. Quite often we’re imprisoning rather than treating people with health problems. I think there’s a lack of understanding of what has caused someone to commit an offence - and therefore how we best move on from that.'

There are also wider issues: if a parent is put in prison that will have an effect on their children and their family.

'When a primary carer goes to prison, it’s devastating for children. It has consequences that quite possibly affect them for the rest of their lives,' says Dr Minson. 'Prison and punishment have been very much treated as something between the state and the offender: somebody breaks the law, therefore the state has a right to punish them for breaking the law. It’s only been quite recently that the law has meant that we consider other people, like victims.'

'But, of course, we live in families, and so when someone is punished that’s going to affect a lot of people, not just themselves.'

Alternatives to prison

So if prison isn’t necessarily the best thing in all situations, what alternatives are there?

Dr Minson thinks there could be better and increased use of sentences in the community. 'For example, things like electronic tagging whereby offenders are on a curfew....their lives would still be very restricted but they’d be able to live in the community, which means if they’re parents or if they’ve got a job or if they care for elderly people they can still do all those roles.'

'Other types of community sentences include unpaid work, to give something back to the community. People can be fined i.e. people can be made to pay back if [their crime is] about stealing money.'

Prison can affect lots of innocent people indirectly, it’s very expensive, and there are other ways in which people can be punished. On the other hand, it's clear that a prison sentence is appropriate in some cases, for serious crimes such as murder, or in situations where the person is a danger to the public and needs to be in prison for safety’s sake.

'Of course, there are things that need to be punished,' says Dr Minson, 'but are we, as a society, cutting off our nose to spite our face by using this huge amount of money to send people to prison?'

In other words, by trying to punish people, is society unintentionally punishing itself because of the financial cost? But maybe this is a price worth paying to show that crime is taken seriously? What do you think?

The Panopticon was designed by philosopher, Jeremy Bentham (1748-1832). It allows all inmates to be observed by a single watchman without them knowing.

In a rotary jail, cells could be moved in a carousel fashion using a crank - allowing only one cell at a time to be accessible from the single opening per level.

Due to its isolation from the mainland by cold, treacherous waters, Alcatraz Island drew upon nature's design to help house prisoners.

This picture shows an overcrowded prison in California: a serious problem worldwide.

There's increasing consideration for how prison architecture affects inmates' mental health. Halden Prison (Norway) was designed to simulate a village so that the prisoners can consider themselves part of society.

Justizzentrum is a court and prison complex in Austria. It operates under the following: " All persons deprived of their liberty shall be treated with humanity and with respect for the inherent dignity of the human person ." Is this fair?

French writer, Victor Hugo (1802-1885) believed in the power of education to give someone the best start in life. He once said: “He who opens a school door, closes a prison”.

French writer, Victor Hugo (1802-1885) believed education could give someone the best start in life. He once said: “He who opens a school door, closes a prison”.

Nature or nurture: what makes someone a criminal?

This short video tackles this age-old debate by exploring why a set of identical twins, Lucky Lyle and Troubled Tim, end up with totally different personalities. Is it environment or genetics? Or perhaps both?

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=k50yMwEOWGU

The cost of UK prisons: what are the alternatives?

The UK prison system is expensive: in 2016-17 the cost per prisoner was £35,571! With an average prison population of 84,750, that comes to a total cost of around £3bn per year! So is the UK prison system worth the public money spent on it? And what are the alternatives?

A paper by the University of Glasgow and the Scottish Centre for Crime & Justice Research gives four key reasons for imprisoning people who have committed a crime: to protect the public, to punish the offender, to serve as a deterrent to the offender and others, and to rehabilitate. Let’s have a look at each of these in turn.

All stats below refer to the UK.

Protecting the public

Generally, imprisoned offenders are effectively kept away from the wider public. In 2015 -16 there were only 8 escapes during escorted journeys - that is journeys to and from courts, hospitals etc. This was down from 13 in 2011-12. Absconds, i.e. a failure to go to prison at a certain time as part of bail conditions, have also been on a downward trend since 2003-04. But is this enough?

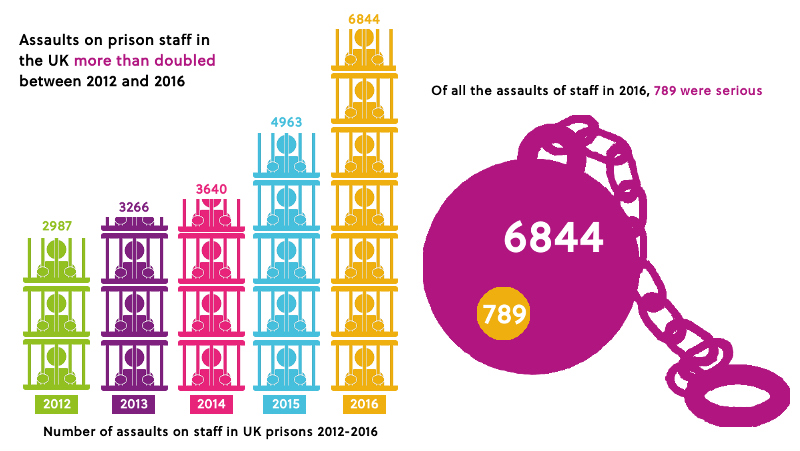

Prisons operating beyond their capacity can lead to violence and unrest. In 2016-17 there were 78,800 certified prison places compared to an average population of 84,750. Between 2012 and 2016, assaults on prison staff in the UK more than doubled. And, of all these incidents in 2016, 789 were serious - so is the justice system doing enough to protect prisoners and those employed to guard them?

Punishing the offender

The most common prison sentence length in England and Wales is 4 years or more for adults and 1-4 years for non-adults. It’s difficult to tell from the stats alone whether these sentences were appropriate in every case for the crimes committed; many moral, practical and legal considerations would have been taken into account by the judge at the time of trial. But given that these sentences are a significant proportion of prisoners’ lives, they certainly seem like a punishment.

Many argue that a lack of prisoner safety, access to purposeful activities, and help when they leave the institution should not be part of the punishment though. A recent Observer investigation found that 80 out 118 adult prisons in England and Wales were providing insufficient or poor standards in at least one of those three areas. 44% were providing poor or insufficient safety and almost half offered insufficient or poor access to meaningful activities. The latter in particular might have serious consequences for offenders’ rehabilitation, as we will discuss later.

So are offenders punished beyond their sentence through poor conditions in jails? And could alternatives such as community service provide better outcomes?

A deterrent to the offender and others

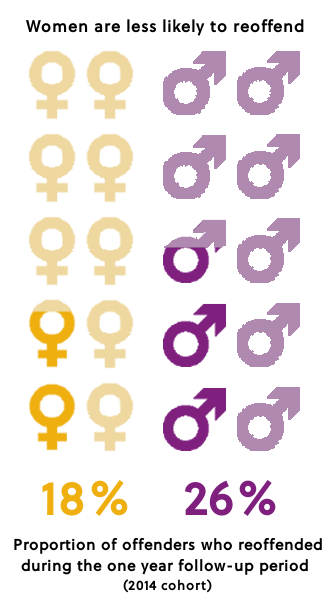

In 2014, 26% of male and 18% of female offenders reoffended during the one year follow-up period. Does it follow that harsher prison sentences lower reoffending rates?

According to a report by the Prison Reform Trust , short prison sentences are less effective than community sentences at reducing reoffending. This is because it was found that people serving prison sentences of less than 12 months had a reoffending rate seven percentage points higher than similar offenders serving a community sentence.

The report also finds that reoffending by all ex-prisoners costs the economy between £9.5bn and £13bn annually, with £7bn-£10bn of that coming from former short-sentenced prisoners.

So how can this figure be reduced? The key seems to lie with rehabilitation programmes, which we'll look at next.

To rehabilitate

Carefully delivered rehabilitation programmes prevent reoffending and could help former offenders get a new start into their lives after prison.

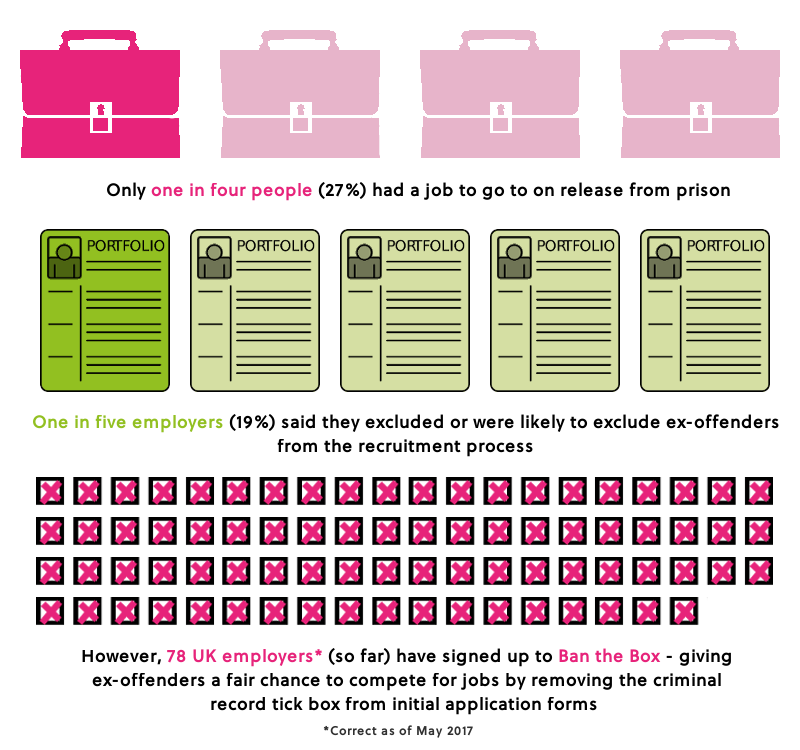

Finding a job after prison is a difficult task though: only one in four people had a job to go to on release from prison, and one in five employers said they excluded or were likely to exclude ex-offenders from the recruitment process.

But there are things that can be done to help prisoners gain a job and make them less likely to reoffend: a US study showed that prisoners who enrol in college/university classes have a 50% lower reoffending rate than prisoners who do not take any classes.

Apart from formal education, other programmes could benefit prisoners too. Recent research from the University of Oxford found that a 10-week yoga course improved prisoners’ mood, reduced their stress levels, and helped them perform better on a task related to behaviour control such as impulsivity and attention.

Another study using Scottish data found that the arts play an important role: learning to play music, for example, and then performing in front of audiences, encourages the improvement of verbal and written literacy skills. In addition, participants learned to work more effectively and developed self-confidence. All this together, the authors of the study argue, motivates prisoners to distance themselves from crime in the future.

So what’s the verdict?

Prisons are expensive but they serve an important role in society. While they protect the wider community as it stands at the moment, it appears that more needs to be done to keep both prisoners and guards safe. One cost-effective option could be rehabilitation programmes: they engage prisoners, help them learn new skills, and make them less likely to re-offend . Setting up these programmes costs money initially, but by decreasing reoffending rates prison populations could be reduced, saving costs in the long-term. Educational programmes could also help former offenders get a job, thereby making them contributors to society and boosting the economy.

So what do you think? Can you think of any alternatives to the current prison system?

The Prisoner’s Dilemma

The Prisoner's Dilemma is a model from the mathematical field of Game Theory. Originally developed by Merrill Flood and Melvin Dresher in 1950, it was later phrased in terms of prison sentence rewards by Albert W. Tucker - hence its name. Let's find out more...

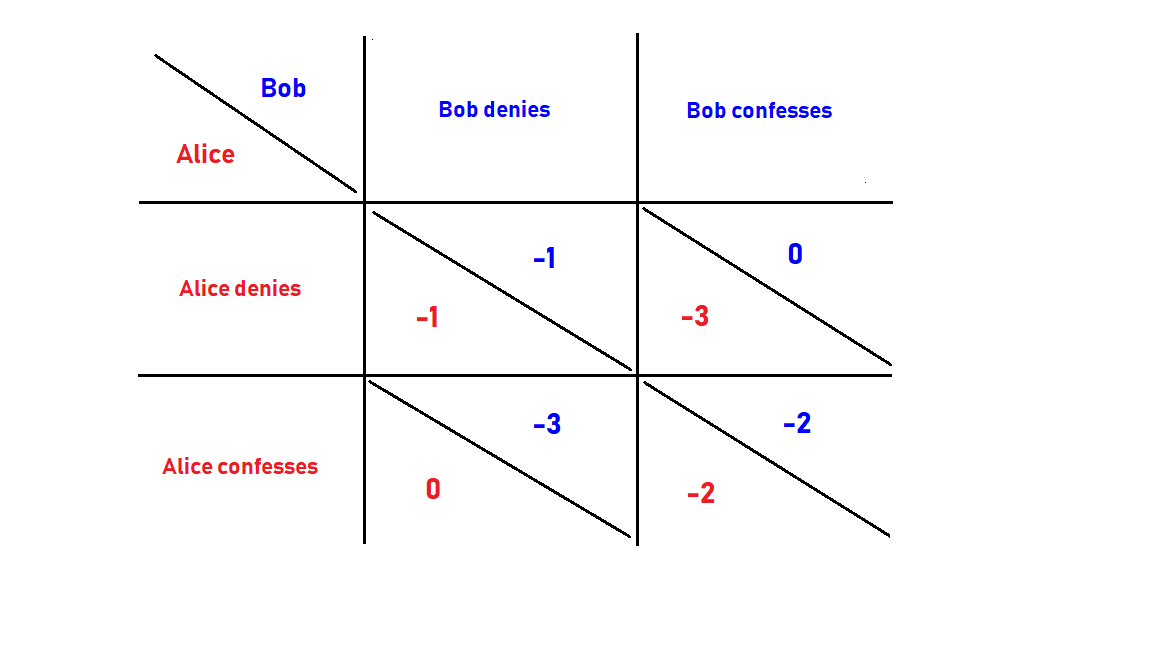

So imagine that there are two suspects - let's call them Alice and Bob - and they have been arrested and imprisoned for a minor offence. Let's say, for trespassing on private property. The police suspect that, in addition to the minor offence, Alice and Bob committed a more serious crime: they stole some goods. However, the police do not have sufficient evidence to convict Alice and Bob of theft. Alice and Bob are held in separate prison cells and are interrogated with no means of communicating with each other. The police offer each of them a deal: If you confess to theft and your partner denies the crime, you will be released and your partner will be sentenced to three years in prison. If both of you confess, then you will each be convicted of theft and be sentenced to two years in prison. If you both deny the theft, you will each be sentenced to one year in prison for trespassing.

Now, we assume that Alice and Bob will each choose to confess or deny solely based on their own self-interest and that they have neither loyalty to each other nor the opportunity to punish or reward the other one for their decision.

In the language of Game Theory, this setup is called a non-cooperative game, and Alice and Bob are called players. The game is non-cooperative because we assume that the players are purely rational and self-interested and do not have to worry about their decision affecting future interactions.

The solution

In Game Theory this table is called a pay-off matrix and it can help to predict the outcome of the game.

Looking at this table we can see that, in order to minimize the total number of years spent in prison, both Alice and Bob should deny the theft. However, if we consider the problem from Alice's and Bob's perspectives individually, we can see why they would choose to confess, betraying each other.

From Alice's perspective, if she thinks that Bob will deny the theft, then she should confess, so that she will be released. If she thinks that Bob will betray her and confess, then she should definitely confess, since two years in prison is better than three. Bob is in the exact same position: He should confess if Alice denies the theft, and he should also confess if she confesses.

Confessing results in a better pay-off for Alice, regardless of Bob's decision and vice versa. Hence, confessing is the dominant strategy for each of them.

The dilemma is that cooperating would have led to a better outcome - not only for the pair as a whole, but also for each of them individually - but each of them could always gain by betraying the other. In game theoretical terms, one says that the globally optimal solution - both Alice and Bob denying the theft - is unstable. The non-cooperative outcome of the game - both Alice and Bob confessing to the theft - is an example of a Nash equilibrium, named after the American mathematician John Forbes Nash Jr.

Real-world applications

Now, for most of us the prison setting is not a scenario that we'll personally encounter. There are however many examples in everyday life that follow the same principle.

One example from economics concerns marketing of a product.

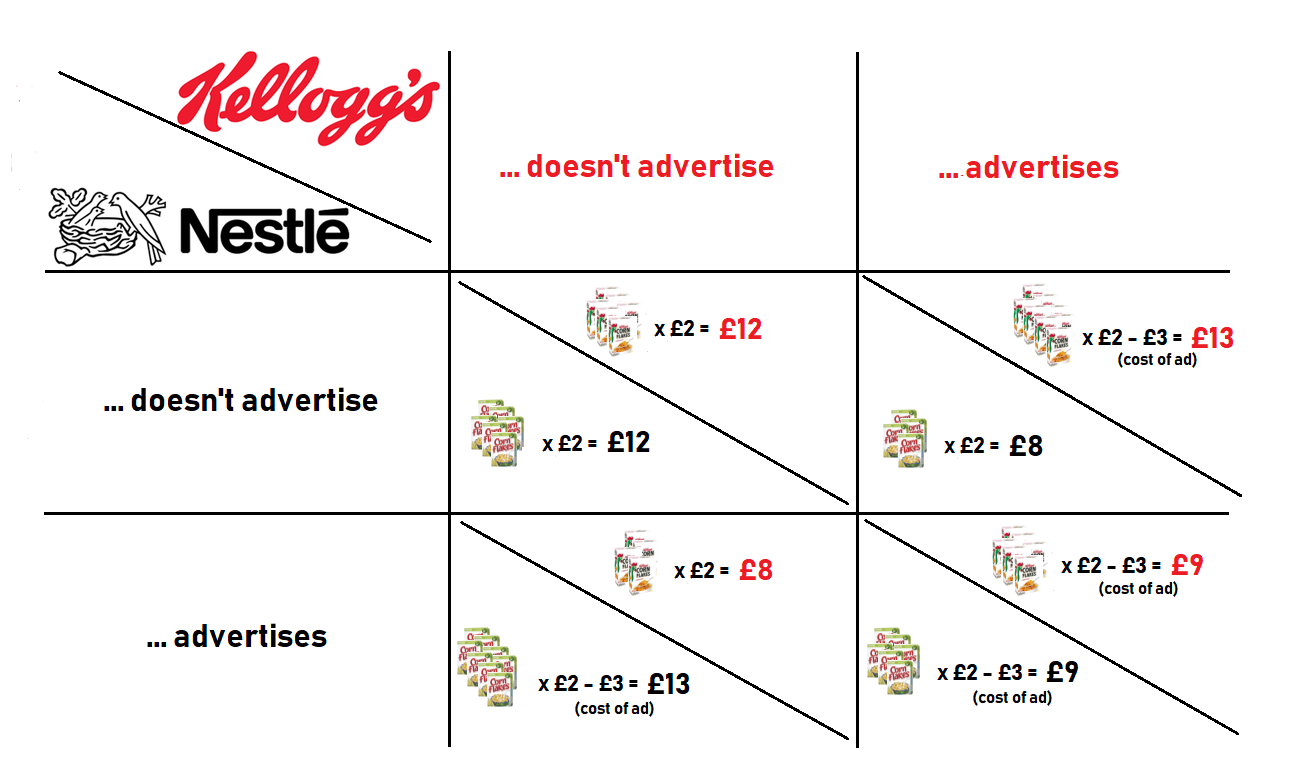

Consider two companies that make identical products. To be concrete, let's take two competing cereal manufacturing companies that produce identical cornflakes: Kellogg's and Nestlé.

Both companies need to decide how much money they spend on advertising. Since the products they make are the same, advertising will have a huge impact on sales.

For simplicity, let's assume that there are no other cornflakes brands on the market and that Kellogg's and Nestlé each have only two options to go about their cornflakes marketing: to advertise or not to advertise.

If neither company advertises, consumers will pick cereal boxes randomly: roughly half of them will buy Kellogg's and the other half will buy Nestlé. Kellogg's and Nestlé will end up sharing the profit margin for cornflakes.

Now if Kellogg's chooses not to advertise, then Nestlé will benefit greatly from advertising. If Nestlé is the only one to advertise, then its profit will increase, outweighing the cost of advertising, while Kellogg's will lose profit.

If both Kellogg's and Nestlé advertise, then the effect of advertising cancels out: consumers will choose cornflakes boxes at random. The two companies share the profit margin roughly equally, but they are left with the cost of advertising, putting them both in a worse position. Although the optimal solution would be for neither company to advertise their cornflakes, individually, each company sees that they can always make more money by advertising. Both Kellogg's and Nestlé advertising is the Nash equilibrium in this scenario and is the likely outcome if we assume non-cooperative behaviour from both companies.

6 unusual things that are banned in UK prisons

There are lots of reasons chewing gum is banned in prison. If you’ve ever looked under a desk at school you know just how messy it can be. It would be pretty gross to have chewing gum all over the floors and walls of the prison, and it could also be used to block the locks on cell doors. And more critically, resourceful prisoners could use it to make impressions of guards' keys if they’re planning a great escape. For many of the same reasons, Blu Tack is banned, and apparently prisoners resort to using toothpaste to stick up posters and family photos – making for quite a minty cell smell!

Prisoners grouping up into gangs can cause serious issues in prison. For this reason, clothes branded with particular sports team logos or national flags aren’t allowed. The idea is to prevent prisoners from identifying people they might gang up with based upon a shared sports team or national identity. There are other rules on clothing too. In the movies, prisoners are quite often shown in black and white striped uniforms – but this couldn’t be further from the truth! In quite a lot of prisons, inmates can wear their own clothing (as an earned privilege), but black and white clothing is banned as it could end up with a prisoner being mistaken for a guard!

The government has recognised that reading can help rehabilitate offenders, but there are still a few restrictions on books in prison. Firstly, in some prisons inmates can’t bring books with them when they arrive because the paper can be used to smuggle in drugs. Also, until 2015, prisoners were only allowed up to 12 books in their cell – even if their friends and family sent them more. This rule was changed, but inmates are still only allowed two boxes worth of stuff in their cell – so they probably don’t have the complete works of Shakespeare! Books ordered by or for prisoners must be from 6 approved retailers, included Waterstones and WHSmiths, and some books are completely banned. This is usually because the prison governor thinks they could have a negative effect on the prisoner’s physical or mental condition, for example if they are extremist or could threaten safety.

As part of the restriction on perks in prison, all 18-rated DVDs have been banned in UK prisons since 2013. Apparently, this ban only applied to DVDs - so if they can find one on Film4 that’s allowed! There are other ways inmates can entertain themselves. Some prisoners with special privileges are allowed game consoles, but any console that connects to the internet is banned – so they have to go retro with consoles like the PS One or Nintendo GameCube. Like with DVDs, 18-rated games aren’t allowed, but that doesn’t stop them having a good game of Mario Kart!

Inmates can’t have rechargeable batteries or anything that uses them (except toothbrushes) because, in theory, they can be adapted to recharge illegal mobile phones. You’d think this wouldn’t be too much of an issue, since mobile phones are banned. But it was reported in 2016 that the number of times banned items were thrown in to prisons had more than doubled in the last two years. People come up with pretty clever ways of disguising these items, like hiding mobile phones in juice cartons and tennis balls and launching them over the prison wall!

Education is becoming more common in prisons, but there are lots of rules on what can be brought into the classroom. Spiral bound notebooks present a major threat. Firstly, they can be cleverly manipulated to pick the locks on prison doors. Secondly, they can be used to construct sharp, potentially deadly weapons. There are plenty of other seemingly safe items that are banned to prevent injury. Most prisoners will want to keep personal jewellery on them, like wedding rings, but if it’s too chunky it’s not allowed. However, whilst banning items usually keeps prisoners safe, the 2017 ban on smoking in long term and maximum security jails could potentially do the opposite. Around 80% of inmates in UK prisons smoke, and a complete ban on smoking is already causing riot and unrest amongst prisoners.

Many prisons lack support for inmates and staff

Although prison might help to protect the public in some ways, it doesn’t quite manage to keep those working and residing in prisons away from risk. Due to lack of funding, under-staffing and overcrowding, many prisons are unsafe for prisoners and guards. What’s more, people who are released from prison often go on to commit further crimes. By keeping prisoners in a violent environment and not being able to offer them enough support in improving their lifestyle when they get out, many argue that prisons fail to bring about real change in offenders’ lives.

It's not just the criminals who are affected

Offenders' families, and in particular children, are affected too. The imprisonment of a parent could mean that a child has to live somewhere else, potentially with strangers; be separated from his or her siblings and change school - all whilst being separated from his or her parent. The parent might also be imprisoned far away making it difficult to organise visits. Overall, this can be distressing for a child, who needs a stable and safe environment. It can potentially have a negative impact on their mental health, future life, and inclusion in society. Many argue that a child should not have to pay for his or her parent's crime in this way. UK law is starting to recognise this and judges have to adapt their sentences, particularly when the criminal is a single parent or the sole guardian of a child. They have to consider the impact on the child of the punishment of the parent, and where possible, imprisonment is suspended or turned into a community order.

They help to do this in at least three ways. First, when a criminal is in prison, they are physically prevented from harming the public. Second, some argue that imprisonment represents an effective punishment, which serves to convince offenders that crime has serious consequences. Third, the possibility of imprisonment prevents many people from committing crimes because they're afraid of going to prison themselves. That said, not all criminals in prison are dangerous e.g. those who have not paid their TV licence. In such cases, could other punishments be more appropriate and less costly? These alternatives could include community services (unpaid work for the good of the community) or sentences in the community, which could include things like electronic tagging whereby there is a curfew. It's about striking a balance but this can be complicated. What do you think?

There's increasing consideration for how prison architecture affects inmates' mental health. Bastøy Prison Prison and Halden Prison (Norway) are good examples of architectural designs that try to create a small community and encourage inmates to better integrate within it. They create a safe and guarded environment in which prisoners can learn or re-learn to be part of a society, care for themselves and have a purpose. Offering meaningful activities to prisoners such as a job or a degree, and helping them find a job when they get out of prison, have been shown to reduce the chance that they commit a crime in the future. What’s more, a lot of prisoners suffer from mental health problems or traumas after violent events. Addressing these issues is also critical. Recent studies show that tending to inmates’ well-being by offering them access to sports or music classes and outdoor activities might also help to improve their self-control and self-confidence.

- Why is it so hard for the wrongfully jailed to get justice?

- Does prison work? Take this further...

- Should you trust unanimous decisions?

- Mass imprisonment in the US

- Mental health and suicide risk in prisons

- Prisons and punishments in the classical world

We use cookies to help give you the best experience on our website. By continuing without changing your cookie settings, we assume you agree to this. Please read our cookie policy to find out more.

Do Prisons Work?

7 Pages Posted: 16 Oct 2023

Shanghai American School

Date Written: September 18, 2023

The question "Does prison work?" has stirred a complex debate and is analyzed through two dominant schools of thought: the humanitarian rationale and the post-modernist perspective. While the humanitarian perspective sees prisons as institutions aimed at rehabilitating offenders for reintegration into society, evidence shows high recidivism rates, insufficient re-education efforts, and criminogenic environments, suggesting failure in this regard. On the other hand, the post-modernist view, particularly influenced by Foucault, suggests that prisons serve as tools for the sovereign power to maintain control and create a class of "delinquents," thereby achieving their intended purpose. The paper argues that the answer to whether prison works is dependent on the perspective from which it is analyzed. From the prisoners' standpoint, the prison fails to achieve its rehabilitative purpose, whereas, from the perspective of sovereign power, it serves its function effectively. Therefore, the query defies a simplistic yes or no answer and requires a nuanced analysis to evaluate its multifaceted purposes and impacts.

Keywords: Prisons, Law, Philosophy, Post-Modernism, Foucault

Suggested Citation: Suggested Citation

Aaron Chen (Contact Author)

Shanghai american school ( email ).

Shanghai China

Do you have a job opening that you would like to promote on SSRN?

Paper statistics, related ejournals, social & political philosophy ejournal.

Subscribe to this free journal for more curated articles on this topic

Philosophy of Law eJournal

Law, international affairs & csr ejournal.

Subscribe to this fee journal for more curated articles on this topic

Continental Philosophy eJournal

Corrections & rehabilitation ejournal, criminology ejournal.

Do prisons work? Lesson 6 of 6

GCSE • Law & The Justice System • Core Curriculum

Share this resource

- Share via email

- Share on Twitter

- Copy page URL

- Share on LinkedIn

This lesson is part 6 of a sequence of six lessons exploring the enquiry: Does our legal system protect citizens’ rights?

This final lesson focuses on the roles of prisons and how well they work to protect the public, limit freedoms, deter crime, and rehabilitate prisoners. Students consolidate their learning and return to the overarching key enquiry question to consider how well the legal system protects the rights of citizens?

Students will work towards answering the following learning questions:

- What is incarceration?

- When are prisons successful and less successful?

- How well do prisons work?

To access this lesson content you need to be a School and College Member . Read more about our KS4 model core curriculum offer and start saving time, effort and money with our complete range of quality-assured resources for every year group, plus unlimited access to online CPD sessions for your entire teaching team.

- Lesson plan and resources

- Lesson slides (PDF)

- Lesson slides editable (pptx)

Related resources

GCSE • Law & The Justice System

Does our legal system protect citizens' rights? (Complete scheme of work)

Key stage 4 Model Curriculum scheme of work on the legal system and rights.

View resource

You need a website profile to access our free or paid resources

Explore our membership packages to suit your needs. We have something for everyone.

- E-membership (free)

- Individual membership (£75 per year)

- School & College membership (£200 per year)

- Organisation membership (£245 per year)

SarahMcCulloch.com | With Strength and Spirit

Writer-thinker-entrepreneur-generally-creative-type-person, why prison doesn’t work: an essay.

Originally written for a competition by the Howard League for Penal Reform for essays on the topic of “Why Prisons Don’t Work”. You can read the winning (and excellent) essays here .

It is often said “prison works”. It is less often said what it means for a prison to “work”. Traditionally prisons have been argued to serve at least one of three functions: to punish the prisoner, to protect the public, and to rehabilitate the offender to prevent them committing another crime. However, on closer inspection, the reasons given seem to have secondary important to the need for society to feel like something is being done, that justice is being served, that law and order is being kept, with near-total disregard for those who find themselves shut out of society with no hope of redemption.

The first function given for prison, punishment, has always seemed to have the least force. Setting aside the dubious civility of a society which seeks revenge upon its citizenry, is spending £30,000 a year on keeping someone in prison when most prisoners really hurting them, or us? (1) Rehabilitation, a far more worthy aim, is chronically underfunded and ultimately useless in a system which is often referred to as a “university of crime”, where young impressionable offenders quickly pick up new skills from veteran prisoners and criminals and escalate their offences when they are released. Which leaves the protection of the public as the remaining reason, and the reason that prisons came about in the first place. Imprisoning those who threaten others seems slightly more justifiable. But this has to be balanced with the human rights of those convicted of crimes themselves – can we justify the imprisonment of such people? Does our society ultimately benefit from keeping people away under lock and key?

In 1993, the psychologist Terrie Moffett published a paper in the Psychological Review that argued that there were two fundamental types of prisoner – the adolescent-limited and the lifelong-persistent. The adolescent-limited are young, primarily men, who commit crime to support themselves, for fun, as part of a gang, or other reasons, who eventually mature, settle down and give up the lifestyle that was contributing to their criminality. The second type, lifelong-persistent, are people who commit crimes casually and often, moving through the criminal justice system in a perpetual cycle of crime-arrest-conviction-incarceration-release-crime and rarely, if ever, breaking out of that cycle. There are a variety of reasons both types end up in prison, including poor education, drug addiction, racism (young black men are twice as likely to go to prison than to university. (2)) and mental health difficulties, which are again rarely, if ever, given the attention they deserve.

Neither type of prisoner are prevented from committing more crime or given the chance to change their lives through serving prison sentences. The adolescent-limited, young and not really thinking about the consequences of their actions, find themselves permanently disadvantaged for the rest of their lives; upon release from prison, they struggle to find housing, meaningful employment and integration into society. It becomes easier to continue to commit more crimes to support themselves. Some will settle down and find councils and employers to give them a chance in life, but their potential, especially the potential of young black men, is severely compromised by serving a prison sentence, a physical block to their life’s progress as well as a permanent addition to their CV. Likewise, the lifelong-persistent are let down by our society. To deal with the reasons for people returning to prison over and over again, we require drug treatment programmes, mental health treatment, adult education, housing programmes, and ways of giving people pride and hope in themselves. But, when regarding that list, how much of it can be achieved effectively in a prison?

However, the rhetoric of the redtops of this country considers such proposals merely “pampering criminals”. Their attitude is largely that prison is for punishing people that society disapproves of. But if by prison “working”, we mean “reduces crime”, the only crime reduced is that which the imprisoned would have committed while doing time – as mentioned earlier, the recidivism rate for people who have been to prison more than twice is nearly 70%, so clearly prison does not “teach people a lesson”. But most advocates of prison do not care about that: they want to “see justice served” as opposed to actually seeing crime reduced and those who commit crime changing their lives. Jon Venables and Robert Thompson were both locked up for ten years – one has now been rehabilitated and is trying to build a new life, one has gone back into prison for breaking his parole. The press wants to see them both imprisoned at great cost to the taxpayer regardless of their current circumstances, and with the broad support of their readers, it seems. With such calls, can we really say society cares about whether prison works or not?

Ultimately, the way we treat prisoners as a society reflect on our humanity. Dostoevsky famously wrote “The degree of civilization in a society can be judged by entering its prisons.” However, it is also the mark of a functional, thriving society that its citizens feel safe and protected from those who would do them harm. People who kill, rape, steal, assault and engage in other anti-social behaviour are causing us as individuals and as a community harm and need to be dealt with. We need evidence-based solutions to tackle the problems that leads people to commit crime. But is prison really effective at this? Can prison deal with poverty, drug addiction, racism, patriarchy, social breakdown, senses of insecurity, resentment, or entitlement? Unlikely. Perhaps prisons “work” to give us a sense of satisfaction that something has been done – but do prisons “work” to create a safer, more secure society that protects its citizens, prevents crime, and rehabilitates those citizens who find themselves on the wrong side of the law? The evidence would suggest that as a society we have got our definition very wrong.

(1) Kanazawa, Satishi (24th August, 2008), “ When crime rates go down, recidivism rates go up ”, Psychology Today. Accessed 19th April, 2010. (2) Smart Justice (2004), “The Racial Justice Gap: Race and the Prison Population Briefing”, pg 2.

Visit the Howard League for Penal Reform .

Subscribe to SarahMcCulloch.com via Email! ( or via RSS! )

8 thoughts on “ Why Prison Doesn’t Work: An Essay ”

Add Comment

“People who kill, rape, steal, assault and engage in other anti-social behaviour are causing us as individuals and as a community harm and need to be dealt with.”

Society itself is guilty of all these crime-actions. You are missing the three most fundamental points :

1. Crime as a concept does not make rational sense. 2. Society has no right to interfere in the criminal acts of any criminal because it created the criminal and commits more crime-acts than any criminal ever possibly could. 3. Society chooses to deliberately sponsor and promote the causes of crime.

Visit MY website Forbidden Truth Media for the Truth on society, crime and humanity.

While you may have a point regarding points 1 and 3, refusing to deal with violent acts at all is quite stupid. Even the most committed anarchists I know, who believe that “crime”is largely a tool of social control, admit that something has to be done about people who are a danger to themselves and others (they usually advocate a form of house arrest, I don’t know what you make of that).

I have looked at your website, and while I am intrigued by your ideas, your argument on crime seems to be that criminals shouldn’t be punished because society commits the same actions all the time. However, your entire website is devoted to condemning the actions of society in this regard. What is the difference between an act of violence perpetrated on the individual by the state, and an act of violence perpetrated on the individual by an individual? There is none.

Sarah has a good point but how can we end crime? We cant, but reduce the amount by treating people who are drug abusers like addict and not someone who rapes steal and kills. But we also forget that rehab would most likely cost more then prison and to do it on a massive level would just be impossible and if the rehab does’t work tons of money would be lost and again on a small scale it work but the real question is Can rehab work on a massive scale?

residential rehab programmes cost about half of what imprisonment costs per week. Don’t forget also that a lot of people would benefit from heroin and cocaine prescription programmes, which cost 15% of the cost of imprisonment.

Somewhere in the region of 80% of all burglaries are committed to support drug habits. Imagine what would happen to crime if we just gave all of the people who commit acquisitive crime the drugs they were after for free. Actually, in Holland, where as soon as you admit you’ve got a problem they put you on a prescription for life, the average age of a heroin user has now risen from 25 to 36. Relatively few people are getting into heroin because there’s no incentive for anyone to start dealing it and lots of help getting off it if you want to.

So rehab can definitely work on a large scale – but in terms of wider crime, there is a significant link between educational attainment and petty crime, as well as the availability of job opportunities. If we sorted those out as a society, most of our prisons would simply be unnecessary.

- Pingback: Rehabilitation Psychologist

You’ll find one of the big advantages of a copper bottom cookware set the moment you start extracting your brand new pans and pots from the box.

It can make terrific and instant meals for breakfast, lunch and dinner, and is perfect for traveling, excursions, and parties. * Practice simple recipes at first to get used to the difference in heat.

what do you mean by is spending £30,000 a year on keeping someone in prison when most prisoners really hurting them, or us?

The average worker in the UK earns £22k a year. Say they lose approximately half that income in taxation. Keeping someone in prison effectively uses up the taxed productivity of three average taxpayers and that’s just hard money, not even considering the social damage done (ie taking parents away from children, being unable to obtain work because of a criminal record etc the damage done to the mental health of prisoners by being in prison) – a significant portion of the taxed earnings of our entire workforce goes towards maintaining this system that is actively harming the social fabric of our country. This is ridiculous.

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

This site uses Akismet to reduce spam. Learn how your comment data is processed .

IMAGES

VIDEO

COMMENTS

Prisons are considered schools of crime. Emotions play crucial role in phase of incarceration. Some researchers have indicated that criminals don't cope well in prisons whereas critics have argued prisons do cope criminals (Frank et al, 2010: 93). According to research conducted by Hurd (2005: 26-27), prisons don't work at all.

Hard evidence: does prison really work? Published: November 6, 2013 1:30am EST. Ian ... The UK's prison population has thus increased by an average rate of 3.6% per year since 1993.

Additionally, prison sentences provide a sense of justice to the victims affected by the crime and the public. Criminological arguments against prisons. The first argument would be that prisons do not work. Those advocating for prison reform highlight reoffending statistics as an example of the ineffectiveness of prisons.

and demonstrating that prison can work. Keywords Incarceration, reform, rehabilitation , punitive, exceptionalism . I. INTRODUCTION There is a clear need for prison systems throughout the world to detain those considered too great of a threat to society. However, with longer sentences, higher rates of conviction per

By focusing on the prison systems in both England and Wales and Finland, this article will argue 1) that prison system in England and Wales has in recent years developed in becoming more focused towards rehabilitation but, still faces numerous challenges including working within predominantly Victorian-era carceral spaces, limited funding, lack ...

Prison Doesn't Work. NB These are the ones we know about, and this is only re-offending within one year, the actual re-offending rates are more than double this figure and the National Audit Office, re offending costs us the equivalent of staging another Olympic Games every year.'. To put these figures in context, if a school had 25-50% of ...

The UK prison system is expensive: in 2016-17 the cost per prisoner was £35,571! With an average prison population of 84,750, that comes to a total cost of around £3bn per year! So is the UK prison system worth the public money spent on it? ... Does prison work? Prisons help protect the public from dangerous criminals .

Contemporary Issues in Prisons and Penology. SID: 1505198 'Prison Works' - Critically discuss. 2000 words. Prisons have been the predominant form of punishment in western societies since the late 1800's, but with the population of prisoners rising, and the lack of rehabilitation evident in society, it poses the question as to whether prisons actually work.

9.4 Work in prison and on release 49 9.5 Drugs and alcohol: breaking the link with reoffending 53 9.6 Diverting mentally ill offenders from the criminal justice system 57 10 What will be the impact of cuts to Ministry of Justice spending? 59 10.1 Efficiency savings in the Prison Service 61 ... Evidence drawn from the UK's trial of two

Does Prison Work? Introduction "A society should be judged not by the way it treats its outstanding citizens, but by the way it ... In this essay, I will address two dominant schools of thought to analyze whether prison works: 1) The humanitarian rationale that prisons are meant to reform prisoners for the greater good of

substantially; in the UK over the last ten years, the average daily population rose from 45,000 in 1991 to 65,000 in 2000, an increase of 44%. Earlier this year the prison population reached 71,000. A s part of it work to rais th level debat about prison and other responses to crime, Rethinking Crime an d Punishment has commissione a numbe

It also showed that mental health professionals who work inside of prisons failed to make referrals when they should have (Prison Reform Trust, n.). Poor mental health before, during and after imprisonment pose a huge threat to society which highlights the need for greater medical assistance in prisons (Moore, 2016).

A Point of View: Prisons don't work. Prison does not work for the majority of inmates either as punishment or rehabilitation, writes Will Self. If you stand on a main road in a British city and ...

According to research conducted by Hurd (2005: 26-27), prisons don't work at all. Increase in imprisonment doesn't reduce crime. He used England and Wales as an example. Number of prisoners increased from 44,000 to 60,000 from 1986 to 1997, but no reduction in crime was recorded.

The prison system is based upon retribution and so the prisoners won't learn how to function in a normal society unless they don't conform to the 'prison society'. The punishment of prisons does not help a person change for the better. References. Justiceinspectorates.gov.uk. (2016). Life in prison: Earning and spending money.

Lesson 6 of 6. This lesson is part 6 of a sequence of six lessons exploring the enquiry: Does our legal system protect citizens' rights? This final lesson focuses on the roles of prisons and how well they work to protect the public, limit freedoms, deter crime, and rehabilitate prisoners. Students consolidate their learning and return to the ...

Originally written for a competition by the Howard League for Penal Reform for essays on the topic of "Why Prisons Don't Work". You can read the winning (and excellent) essays here. It is often said "prison works". It is less often said what it means for a prison to "work". Traditionally prisons have been argued to serve at least ...

average length of prison sentences (the severity of punishment), although interestingly, the study also found a significant effect for unemployment rates too.11 Charles Murray's analysis of the potency of penal policy In 1997, Charles Murray published an essay in the UK entitled Does Prison Work?.12 In it, he showed that crimes

ment services, aimed at smoothing the transition from prison to the community, have been extended (MoJ, 2013b). Promises have been made to deliver full and purposeful prison regimes, to prepare prisoners for release and for prisons and the Probation Service to work together to support the transition through the prison gate (MoJ, 2016: 25).

People in prison are among the most marginalised in societies, often presenting with physical and mental illness.1,2 Their vulnerability is such that international treaties (eg, the UN Standard Minimum Rules for the Treatment of Prisoners known as the Nelson Mandela Rules, 2015) and organisations (eg, the Council of Europe's Committee for the Prevention of Torture [CPT]) are required to ensure ...

Prisons produce 'tedious circles of hypermasculine posturing' (Maruna et al., 2004 in Halsey and Harris, 2011) and the prevailing culture in prison is around hegemonic masculinity, which creates barriers and governs the way that prisoners 'do prison'. For some, violence and crime are at the heart of how they define themselves as men.

Rehabilitation is possible for anyone if they want to change (The in depended News 2007). From the statistic of crime it can be seen the percentage of prisoners who become change their life is increasing for the last few years (NATIONAL STATISTIC). However, there is overcrowding the prisons in England and Wales.

do prisons work essay. Flashcards. Learn. Test. Match. introduction. Click the card to flip 👆. the uk has a high prison population compared to other countries. england and wales lock up 40% more people than in france and twice as many as in germany. however there is no libel between the prison population and rates of crimd.