Thank you for visiting nature.com. You are using a browser version with limited support for CSS. To obtain the best experience, we recommend you use a more up to date browser (or turn off compatibility mode in Internet Explorer). In the meantime, to ensure continued support, we are displaying the site without styles and JavaScript.

- View all journals

- Explore content

- About the journal

- Publish with us

- Sign up for alerts

- CAREER GUIDE

- 19 December 2018

How to give a great scientific talk

- Nic Fleming 0

Nic Fleming is a freelance science writer based in Bristol, United Kingdom.

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

You have full access to this article via your institution.

Credit: Haykirdi/Getty Images

“It was horrific,” says Eileen Courtney. “I was just a bundle of nerves. I wasn’t able to eat for the whole of the previous day. That’s when I realized I needed to get over my fear of public speaking.”

Courtney is a third year PhD candidate studying interactions between metals and two-dimensional semiconducting materials at the University of Limerick, in the Republic of Ireland. Her moment of revelation came as she contemplated presenting her research at the Microscience Microscopy Congress in Manchester, United Kingdom, in July 2017.

The gut-punch feeling of dread that the prospect of being on stage can trigger will be familiar to many early-career scientists. It could be induced by an invitation to an international conference, an academic group meeting or a public engagement event. Or it might be caused by an all-important presentation as part of an interview process.

Although the audiences and goals of a talk may differ, the skills and techniques required to pull it off are similar. So what differentiates a good presentation from a bad one? How can you up your game in front of the lectern? And is being able to impress an audience really all that important?

The answer to that last question is an emphatic yes, says Susan McConnell, a neurobiologist at Stanford University, in California, who has been giving talks on giving talks for more than a decade. “The whole point of doing science is to be able to communicate it to others,” says McConnell. “Whether it is to our close colleagues, other scientists with a general interest in our area or to non-scientists, clarity of communication is essential.”

Engage like a champ

Great public speaking skills are not sufficient for good presenting, but they help. In August, Ramona J. Smith, a high-school teacher from Houston, Texas, was crowned Toastmasters 2018 World Champion of Public Speaking.

These are her top 10 tips, which she plans to outline in more detail in a forthcoming e-book.

1 Be yourself: people relate to and connect with authenticity.

2 Prepare, practice and perfect: get rid of those crutch words, like ‘um’ and ‘you know’.

3 Describe what you’re telling us: use vivid words to help the audience paint a picture.

4 Vocal variety: change up your tone, volume and pitch to keep the audience engaged.

5 Study the greats: watch what really great speakers do.

6 Get feedback: a practice audience can help you get the bugs out.

7 Appearance: if you look good, you’ll feel good, which will help you give a great speech.

8 Pauses: they give the audience time to think, and help them engage.

9 Body language: use gestures and make use of the space to help deliver your message.

10 Be confident: use your face, body language and stance to own the stage.

Not all researchers recognize the value of taking time out of the lab to tell colleagues about their work. “Some have this idea that if you're spending time giving a talk, you're spending time on marketing which could be better spent doing science,” says Dave Rubenson, co-founder of Los Angeles-based nobadslides.com, a company that provides courses on giving effective slide presentations. “In fact the process of creating a compelling talk and getting your audience to understand it improves both your understanding and theirs, and is central to science itself.” On top of this, Rubenson says, presenting at conferences is a great way to attract the collaborators who can help you break new ground and advance in your career, but only if those listening understand what they’re being shown.

Nature Events Guide 2019

A good place to begin is in your audience’s shoes. They need to know early on why they should care about what you’re saying. What is the ‘story’ at the heart of your presentation? Creating a concise summary of your talk, upon which you can add complexity, is a better starting point than pondering which of your file of 500 slides you can leave out, Rubenson says.

Presenters often fail because they try to deliver too much complex information. Language and content, normally, has to be designed with the non-specialist scientist in mind. “You have to think about the least knowledgeable person in your audience that you care about reaching,” says Rubenson.

Another common mistake is the use of slides as ‘data dumps’. Remember those times you’ve squinted at overly-busy slides packed with eight small graphs and wondered why the presenter mentions only one? Keep that in mind when designing your own slides. Animation software that lets you add information to slides as you talk about it can help.

Above all, it is important to maintain the focus of your audience.

Conquer nerves

Credit: Institute of Physics

Different methods work for different people. Here are Eileen Courtney’s tips for keeping calm at the lectern.

1 Practice in an environment similar to the one in which you will give your talk.

2 Memorize key sentences within an outline, rather than learning it word for word.

3 Ensure you are within the time limit, so the clock is one less thing to worry about.

4 Wear something professional-looking and comfortable, not a new outfit.

5 Avoid overeating and limit coffee intake on the day itself.

You can help to prevent wandering minds by including summary slides at the end of sections. “You can think of a talk as a series of data dives,” says McConnell. “You need to come up for air periodically, and say ‘this is what we just learnt, this is the conclusion and this is how it links to the next part’.”

McConnell describes this and many more ways for researchers to improve their scientific presentation skills in a popular 42-minute online video. Another source of advice is the 2013 book Designing Science Presentations by American neuroscientist Matt Carter. While these offer useful pointers, most people find that when it comes to public speaking and presenting, practice makes, if not perfect, then certainly better.

That notion is central to Toastmasters International, a non-profit organization that helps individuals improve their public speaking skills through its network of more than 16,000 branches in 143 countries. At weekly or fortnightly meetings, members practice speeches and give each other feedback. It was to her local branch that Eileen Courtney turned last summer after realizing her presenting skills needed work. It seems her decision paid off. In May she was runner-up and audience favourite in the 3 Minute Wonder competition, a science communication challenge run by the London-based Institute of Physics in which entrants have one slide and 180 seconds to present their research to non-specialists.

“I’ve recently had to give other presentations and I’ve calmed down a lot, as a result of both going to Toastmasters and through teaching as part of my PhD,” says Courtney. “As you get more experience of speaking in front of a crowd, it becomes a lot less scary.”

Nature 564 , S84-S85 (2018)

doi: https://doi.org/10.1038/d41586-018-07780-5

This article is part of Nature Events Guide 2019 , an editorially independent supplement. Advertisers have no influence over the content.

Related Articles

- Conferences and meetings

- Communication

How I overcame my stage fright in the lab

Career Column 30 MAY 24

China promises more money for science in 2024

News 08 MAR 24

One-third of Indian STEM conferences have no women

News 15 NOV 23

How researchers and their managers can build an actionable career-development plan

Career Column 17 JUN 24

Securing your science: the researcher’s guide to financial management

Career Feature 14 JUN 24

‘Rainbow’, ‘like a cricket’: every bird in South Africa now has an isiZulu name

News 06 JUN 24

Postdoctoral position for EU project ARTiDe: A novel regulatory T celltherapy for type 1 diabetes

Development of TCR-engineered Tregs for T1D. Single-cell analysis, evaluate TCRs. Join INEM's cutting-edge research team.

Paris, Ile-de-France (FR)

French National Institute for Health Research (INSERM)

Postdoc or PhD position: the biology of microglia in neuroinflammatory disease

Join Our Team! Investigate microglia in neuroinflammation using scRNAseq and genetic tools. Help us advance CNS disease research at INEM!

Postdoctoral Researcher Positions in Host-Microbiota/Pathogen Interaction

Open postdoctoral positions in host microbiota/pathogen interaction requiring expertise in either bioinformatics, immunology or cryoEM.

CMU - CIMR Joint Invitation for Global Outstanding Talents

Basic medicine, biology, pharmacy, public health and preventive medicine, nursing, biomedical engineering...

Beijing (CN)

Capital Medical University - Chinese Institutes for Medical Research, Beijing

Spatial & Single-Cell Computational Immunogenomics for Cancer Diagnosis

(Level A) $75,888 to $102,040 per annum plus an employer contribution of 17% superannuation applies. Fixed term, full time position available for ...

Adelaide (Suburb), Metropolitan Adelaide (AU)

University of Adelaide

Sign up for the Nature Briefing newsletter — what matters in science, free to your inbox daily.

Quick links

- Explore articles by subject

- Guide to authors

- Editorial policies

Reference management. Clean and simple.

5 tips for giving a good scientific presentation

What is a scientific presentation?

What is the objective of a scientific presentation, why is giving scientific presentations necessary, how to give a scientific presentation, tip 1: prepare during the days leading up to your talk, tip 2: deal with presentation nerves by practicing simple exercises, tip 3: deliver your talk with intention, tip 4: be adaptable and willing to adjust your presentation, tip 5: conclude your talk and manage questions confidently, concluding thoughts, other sources to help you give a good scientific presentation, frequently asked questions about giving scientific presentations, related articles.

You have made the slides for your scientific presentation. Now, you need to prepare to deliver your talk. But, giving an oral scientific presentation can be nerve-wracking. How do you ensure that you deliver your talk well, and leave a good impression on the audience?

Mastering the skill of giving a good scientific presentation will stand you in good stead for the rest of your career, as it may lead to new collaborations or even new employment opportunities.

In this guide, you’ll find everything you need to know to give a good oral scientific presentation, including

- Why giving scientific presentations is important for your career;

- How to prepare before giving a scientific presentation;

- How to keep the audience engaged and deliver your talk with confidence.

The following tips are a product of our research into the literature on giving scientific presentations as well as our own experiences as scientists in giving and attending talks. We advise on how to make a scientific presentation in another post.

A scientific presentation is a talk or poster where you describe the findings of your research to others. An oral presentation usually involves presenting slides to an audience. You may give an oral scientific presentation at a conference, give an invited seminar at another institution, or give a talk as part of an interview. A PhD thesis defense is one type of scientific presentation.

➡️ Read about how to prepare an excellent thesis defense

The objective of a scientific presentation is to communicate the science such that the audience:

- Learns something new;

- Leaves with a clear understanding of the key message of your research;

- Has confidence in you and your work;

- Remembers you afterward for the right reasons.

As a scientist, one of your responsibilities is disseminating your scientific knowledge by giving presentations. Communicating your research to others is an altruistic act, as it is an opportunity to teach others about your research findings, and the knowledge you have gained while researching your topic.

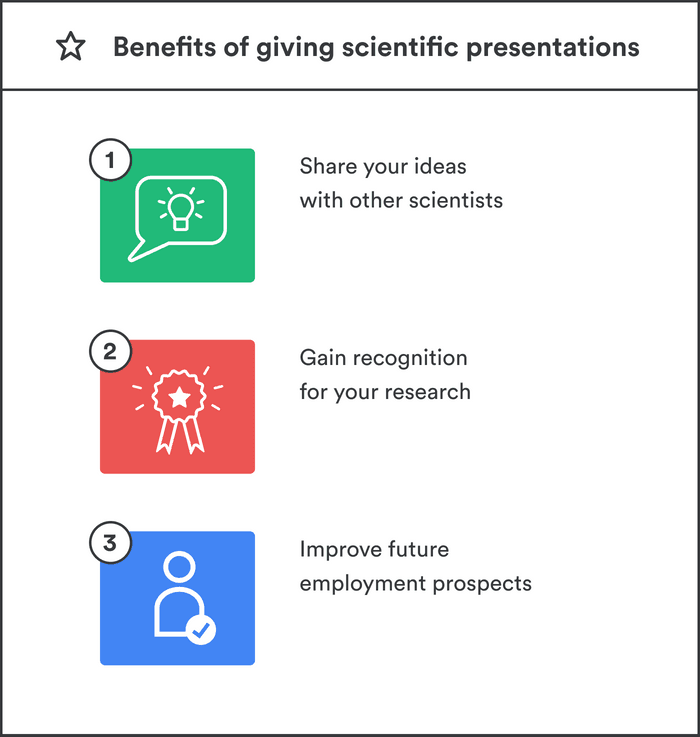

Giving scientific presentations confers many career benefits , such as:

- Having the opportunity to share your ideas and to have insightful conversations with other scientists. For example, a thoughtful question may create a new direction for your research.

- Gaining recognition for your work and generating excitement for your research program can help you to forge new collaborations and to obtain more citations of your papers. It's your chance to impress some of the biggest names in your field, build your reputation as a scientist, and get more people interested in your work.

- Improving your future employment prospects by getting presentation experience in high-stakes settings and by having talks listed on your academic CV.

➡️ Learn how to write an academic CV

You might have just 10 minutes for your talk. But those 10 minutes are your golden ticket. To make them shine, you'll need to put in some homework. You need to think about the story you want to tell , create engaging slides , and practice how you're going to deliver it.

Why all this effort? Because the rewards are potentially huge. Imagine speaking to the top names in your field, boosting your visibility, and getting more eyes on your work. It's more than just a talk; it's your chance to showcase who you are and what you do.

Here we share 5 tips for giving effective scientific presentations.

- Prepare adequately for your talk on the days leading up to it

- Deal with presentation nerves

- Deliver your talk with intention

- Be adaptable

- Conclude your talk with confidence

You should prepare for your talk with the seriousness it deserves and recognize the potential it holds for your career advancement. Here are our suggestions:

- Rehearse your talk multiple times to ensure smooth flow. Know the order of your slides and key transitions without memorizing every word. Practice your speech as though you are discussing with friendly and attentive listeners.

- Record your speech and listen back to yourself giving your talk while doing household chores or while going for a walk. This will help you remember the important points of your talk and feel more comfortable with the flow of it on the day.

- Anticipate potential questions that may arise during your talk, write down your responses to those questions, and practice them aloud.

- Back up your presentation in cloud storage and on a USB key. Bring your laptop with you on the day of your talk, if needed.

- Know the time and location of your talk. Familiarize yourself with the room, if you can. Introduce yourself to the moderator before the session begins.

- Giving a talk is a performance, so preparing yourself physically and mentally is essential. Prioritize good sleep and hydration, and eat healthy, nourishing food on the day of your talk. Plan your attire to be both professional and comfortable.

It’s natural to feel nervous before your talk, but you want to harness that energy to present your work with confidence. Here are some ways to manage your stress levels:

- Remember that your audience want to listen to you and learn from you. Believe that your audience will be kind, friendly, and interested, rather than bored and skeptical.

- Breathing slow and deep before your talk calms the mind and nervous system. Psychologist Amy Cuddy recommends practicing open, confident postures while sitting and standing to help you get into a positive frame of mind.

- Fight off impostor syndrome with positive affirmations. You’ve got this! Remember that you know more about your research than anyone else in the room and you are giving your talk to teach others about it.

Giving your talk with confidence is crucial for your credibility as a scientist. Focusing on your delivery helps ensure that your audience remembers and believes what you say. Here are some techniques to try:

- Before beginning, remember your professional goals and the benefits of giving your presentation. Start with a smile and exhale deeply.

- Memorize a simple opening. After the moderator introduces you, pause and take a breath. Welcome the audience, thank them for coming, and introduce yourself. You don’t need to read the title of your talk. But briefly, say something like, “today I’m going to talk to you about why [topic] is important and [what I hope you will learn from this talk]” in 1-2 sentences. Preparing your opening will settle your nerves and prevent you from starting your talk on a tangential topic, ensuring you stay on time.

- Project confidence outwardly, even if you feel nervous. Stand up tall with your shoulders back and make eye contact with individuals in the audience. Move your focus around the room, so everyone in the audience feels included.

- Maintain open body language and face the audience as much as possible, not your slides.

- Project your voice as much as you can so that people at the back of the room can hear you. Enunciate your words, avoid mumbling, and don’t trail off awkwardly.

- Varying your vocal delivery and intonation will make your talk more interesting and help the audience pay attention, particularly when you want to emphasize key points or transitions.

- Pausing for dramatic effect at crucial moments can help you relax and remember your message, as well as being an effective engagement device.

- A laser pointer can be off-putting for the audience if you are prone to having a shaky hand when nervous. Use a laser pointer only to emphasize information on the slide while providing an explanation. If you design your slides thoughtfully , you won’t need to use a laser pointer.

Not all parts of your talk may go according to plan. Here are some ways to adapt to hitches during your talk:

- Handle talk disruptions gracefully. If you make a mistake, or a technical issue occurs during your talk, remember that it’s okay to skip something and move on without apologizing.

- If you forget to mention something but the audience hasn’t noticed, don’t point it out! They don’t need to know.

- As you give your talk, be time-conscious, and watch the moderator for signals that the time is about to expire. If you realize you won’t have time to discuss all your slides, skip the less important ones. Adjust your presentation on the fly to finish on time, prioritizing content as needed.

- If you run out of time completely, just stop. You don’t have to give a conclusion, but you do need to stop on time! Practicing your talk should prevent this situation.

The ending of your talk is important for emphasizing your key message and ensuring the audience leave with a positive impression of you and your work. Here are some pointers.

- Conclude your talk with a memorized closing statement that summarizes the key take-home message of your research. After making your closing statement, end your talk with a simple “Thank you”. Then pause and wait for the applause. You don’t need to ask if the audience has questions because the moderator will call for questions on your behalf.

- When you receive a question, pause, then repeat the question. This ensures the whole audience understands the question and gives you time to calmly consider your answer.

- In a talk on attaining confidence in your scientific presentations, Michael Alley suggests that if you don’t know the answer to the question, then emphasize what you do know. Say something like, “Although I can’t fully answer your question, I can say [this about the topic].”

- Approach the Q&A with interest rather than anxiety by reframing it as an opportunity to further share your knowledge. Being curious, instead of feeling fearful, can help you shine during what might be the most stressful part of your presentation.

Communicating your research effectively is a key skill for early career scientists to learn. Taking ample time to prepare and practice your presentation is an investment in your scientific development.

But here's the good part: all that effort pays off. Think of your talk as not just a presentation, but as a way to show off what you and your research are all about. Giving a compelling scientific presentation will raise your professional profile as a scientist, lead to more citations of your work, and may even help you obtain a future academic job.

But most importantly of all, giving talks contributes to science, and sharing your knowledge is an act of generosity to the scientific community.

➡️ Questions to ask yourself before you make your talk

➡️ How to give a great scientific talk

1) Have a positive mindset. To help with nerves, breathe deeply and keep in mind that you are an authority on your topic. 2) Be prepared. Have a short list of points for each slide and know the key transition points of your talk. Practice your talk to ensure it flows smoothly. 3) Be well-rested before your talk and eat a light meal on the day of your presentation. A talk is a performance. 4) Project your voice and vary your vocal intonation and pitch to retain the interest of the audience. Take pauses at key moments, for emphasis. 5) Anticipate questions that audience members could ask, and prepare answers for them.

The goal of a scientific presentation is that the audience remembers the key outcomes of your research and that they leave with a good impression of you and your science.

Take a moment to exhale deeply and collect your thoughts after the moderator has introduced you. Don’t read your talk's title. Instead, introduce yourself, thank the audience for attending, and provide a warm welcome. Then say something along the lines of, "Today I'm going to talk to you about why [topic] is important and [what I hope you will learn from this presentation].” A rehearsed opening will ensure that you start your talk on a confident note.

Prepare a memorable closing statement that emphasizes the key message of your talk. Then end with a simple “Thank you”.

Preparation is key. Practice many times to familiarize yourself with the content of your presentation. Before giving your talk, breathe slowly and deeply, and remind yourself that you are the expert on your topic. When giving your talk, stand up tall and use open body language. Remember to project your voice, and make eye contact with members of the audience.

Ten Secrets to Giving a Good Scientific Talk

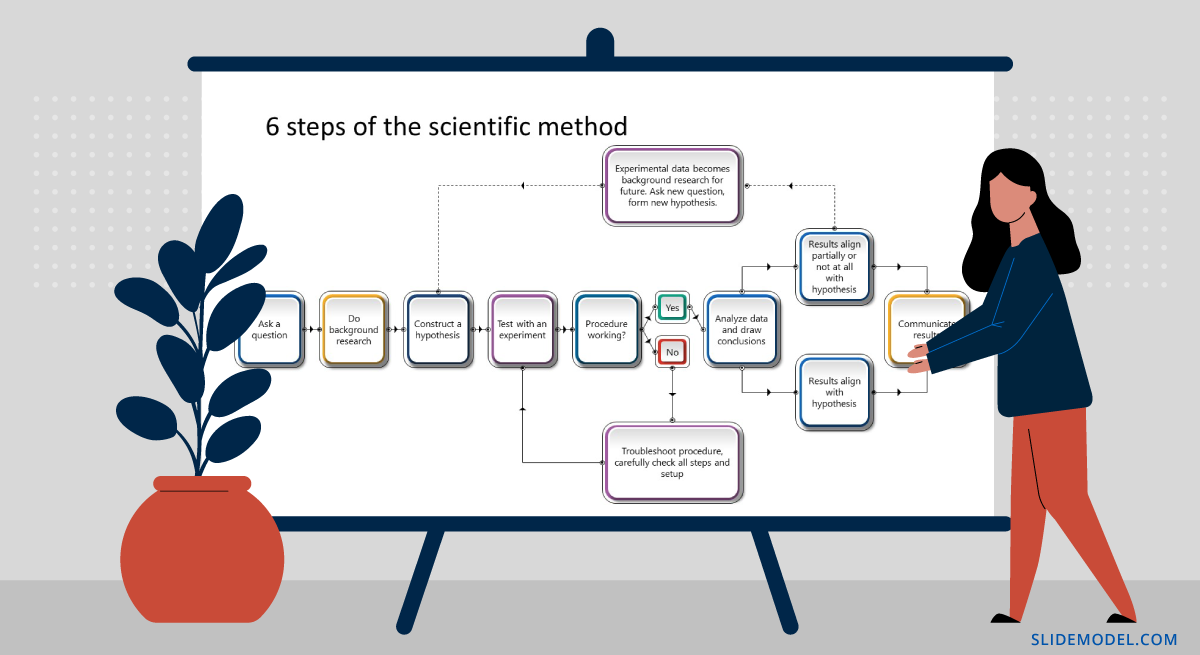

More people will probably listen to your scientific talk than will read the paper you may write. Thus the scientific talk has become one of the most important communication forums for the scientific community. As proof, we need only look at the rising attendance at and the proliferation of meetings. In many ways your research reputation will be enhanced (or diminished) by your scientific talk. The scientific talk, like the scientific paper, is part of the scientific communication process. The modern scientist must be able to deliver a well organized, well delivered scientific talk

I have compiled this personal list of "Secrets" from listening to effective and ineffective speakers. I don't pretend that this list is comprehensive - I am sure there are things I have left out. But, my list probably covers about 90% of what you need to know and do.

Most scientific presentations use visual aids - and almost all scientific presentations are casual and extemporaneous 1 . This "scientific style" places some additional burdens on the speaker because the speaker must both manipulate visual media, project the aura of being at ease with the material, and still have the presence to answer unanticipated questions. No one would argue with the fact that an unprepared, sloppy talk is a waste of both the speaker's and audience's time. I would go further. A poorly prepared talk makes a statement that the speaker does not care about the audience and perhaps does not care much about his subject.

So what are the secrets of a good talk? Here is my list of do's and don'ts.

The Introduction should not just be a statement of the problem - but it should indicate your motivation to solve the problem, and you must also motivate the audience to be interested in your problem. In other words, the speaker must try and convince the audience that the problem is important to them as well as the speaker.

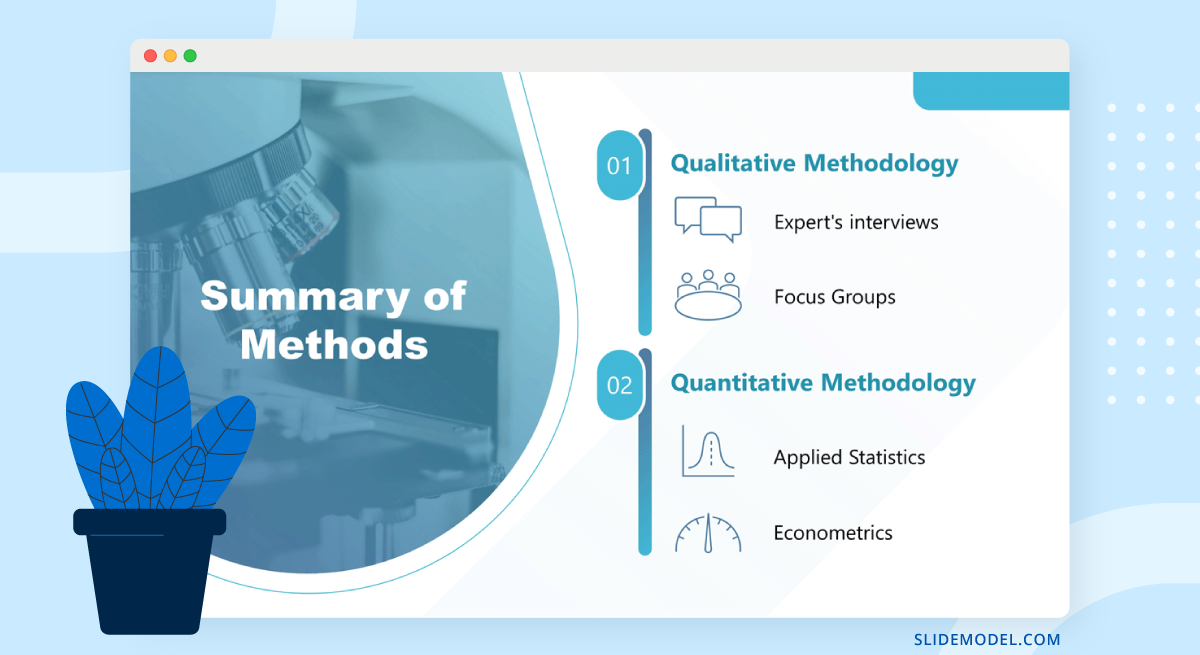

The Method includes your approach and the caveats. To me , the Method becomes more interesting to the listener if this section is "story like" rather than "text book like". In other words "I did this and then I did that, but that didn't work so I did something else." This Rather than, "The final result was obtained using this approach." This adds the human element to your research which is always interesting.

The Results section is a brief summary of your main results. Try and be as clear as possible in explaining your results - include only the most salient details. Less salient details will emerge as people ask questions.

The Conclusion/Summary section should condense your results and implications. This should be brief - a bullet or outline form is especially helpful. Be sure to connect your results with the overview statements in the Introduction . Don't have too many points - three or four is usually the maximum.

These four items are the core of a good talk. Good speakers often broaden the Introduction to set the problem within a very wide context. Good speakers may also add fifth item: Future Research .

- Practice your talk . There is no excuse for this lack of preparation. The best way to familiarize yourself with the material and get the talk's timing right is to practice your talk. Many scientists believe that they are such good speakers, or so super-intelligent that practice is beneath them. This is an arrogant attitude. Practice never hurts and even a quick run through will produce a better talk. Even better, practice in front of a small audience.

- Don't put in too much material . Good speakers will have one or two central points and stick to that material. How many talks have you heard where the speaker squanders their time on unessential details and then runs out of time at the end? The point of a talk is to communicate scientific results, not to show people how smart you are (in case they can't figure it out for themselves). Less is better for a talk . Here is a good rule of thumb - each viewgraph takes about 1.5-2 minutes to show. Thus a 12-minute AGU talk should only have 6-8 viewgraphs. How many "viewgraph movies" have you seen at the AGU? How effective were those presentations? Furthermore, no one has ever complained if a talk finishes early. Finally, assume most of the audience will know very little about the subject, and will need a clear explanation of what you are doing not just details.

- Avoid equations . Show only very simple equations if you show any at all. Ask yourself - is showing the equation important? Is it central to my talk? The problem is that equations are a dense mathematical notation indicating quantitative relationships. People are used to studying equations, not seeing them flashed on the screen for 2 minutes. I have seen talks where giant equations are put up - and for no other purpose than to convince the audience that the speaker must be really smart. The fact is, equations are distracting. People stop listening and start studying the equation. If you have to show an equation - simplify it and talk to it very briefly.

- Have only a few conclusion points . People can't remember more than a couple things from a talk especially if they are hearing many talks at large meetings. If a colleague asks you about someone's talk you heard, how do you typically describe it? You say something like "So and so looked at such and such and they found out this and that." You don't say, "I remember all 6 conclusions points." The fact is, people will only remember one or two things from your talk - you might as well tell them what to remember rather than let them figure it out for themselves.

- Talk to the audience not to the screen . One of the most common problems I see is that the speaker will speak to the viewgraph screen. It is hard to hear the speaker in this case and without eye contact the audience loses interest. Frankly, this is difficult to avoid, but the speaker needs to consciously look at the object on the screen, point to it, and then turn back to the audience to discuss the feature. Here is another suggestion, don't start talking right away when you put up a viewgraph. Let people look at the viewgraph for a few moments - they usually can't concentrate on the material and listen to you at the same time. Speak loudly and slowly. . I like to pick out a few people in the audience and pointedly talk to them as though I were explaining something to them.

- Avoid making distracting sounds . Everyone gets nervous speaking in public. But sometimes the nervousness often comes out as annoying sounds or habits that can be really distracting. Try to avoid "Ummm" or "Ahhh" between sentences. If you put your hands in your pockets, take the keys and change out so you won't jingle them during your talk.

- Use large letters (no fonts smaller than 16 pts!!) To see how your graphics will appear to the audience, place the viewgraph on the floor - can you read it standing up? Special sore points with me are figure axis and captions - usually unreadable.

- Keep the graphic simple . Don't show graphs you won't need. If there are four graphs on the viewgraph and you only talk to one - cut the others out. Don't crowd the viewgraph, don't use different fonts or type styles - it makes your slide look like a ransom note. Make sure the graph is simple and clear. A little professional effort on graphics can really make a talk impressive. If someone in your group has some artistic talent (and you don't) ask for help or opinions.

- Use color . Color makes the graphic stand out, and it is not that expensive anymore. However avoid red in the text - red is difficult to see from a distance. Also, check your color viewgraph using the projector. Some color schemes look fine on paper, but project poorly.

- Use cartoons . I think some of the best talks use little cartoons which explain the science. It is much easier for someone to follow logic if they can see a little diagram of the procedure or thought process that is being described. A Rube-Goldberg sort of cartoon is great for explaining complex ideas.

- Use humor if possible . A joke or two in your presentation spices things up and relaxes the audience. It emphasizes the casual nature of the talk. I am always amazed how even a really lame joke will get a good laugh in a science talk.

- First, repeat the question. This gives you time to think, and the rest of the audience may not have heard the question. Also if you heard the question incorrectly, it presents an opportunity for clarification.

- If you don't know the answer then say "I don't know, I will have to look into that. " Don't try to invent an answer on the fly. Be honest and humble. You are only human and you can't have thought of everything.

- If the questioner disagrees with you and it looks like there will be an argument then defuse the situation. A good moderator will usually intervene for you, but if not then you will have to handle this yourself. e.g. "We clearly don't agree on this point, let's go on to other questions and you and I can talk about this later."

- Never insult the questioner. He/she may have friends, and you never need more enemies.

Miscellaneous Points

Thank you - It is always a good idea to acknowledge people who helped you, and thank the people who invited you to give a talk.

Dress up - People are there to hear your material, but when you dress up you send the message that you care enough about the audience to look nice for them.

Check your viewgraphs before you give the talk . Are they all there? Are they in order? This is especially important with slides. Try to bring them to the meeting in a tray, or at least check them to be sure they are not upside down or backwards when the projectionist gets them. It is especially annoying to watch people fumble to get a viewgraph right side up. Don't do this by looking at the screen. Just look at the viewgraph directly. If it is right side up to you, then it will project correctly on the screen assuming that you are facing the audience. Go over the slides or viewgraphs quickly before the talk. Some people attach little post-it notes to viewgraphs to remind them of points to make. This seems like a good idea to me. However, It is very annoying to watch people peel their viewgraphs from sheets of paper. It suggests that they have never looked at them before. It is faster, more permanent, and you are less likely to have a mixed up shuffle, if you put them into viewgraph holders which clip in to a three ring binder.

If you have an electronic presentation - check out the system well before the talk.

Mark Schoeberl and Brian Toon

1 Amazingly, in the field of literature or history the talks are not given extemporaneously but read from written text. Sometimes this is also done in science talks and it can be an interesting and different experience.

- Program Design

- Peer Mentors

- Excelling in Graduate School

- Oral Communication

- Written communication

- About Climb

A 10-15 Minute Scientific Presentation, Part 1: Creating an Introduction

For many young scientists, the hardest part of a presentation is the introduction. How do you set the stage for your talk so your audience knows exactly where you're going?

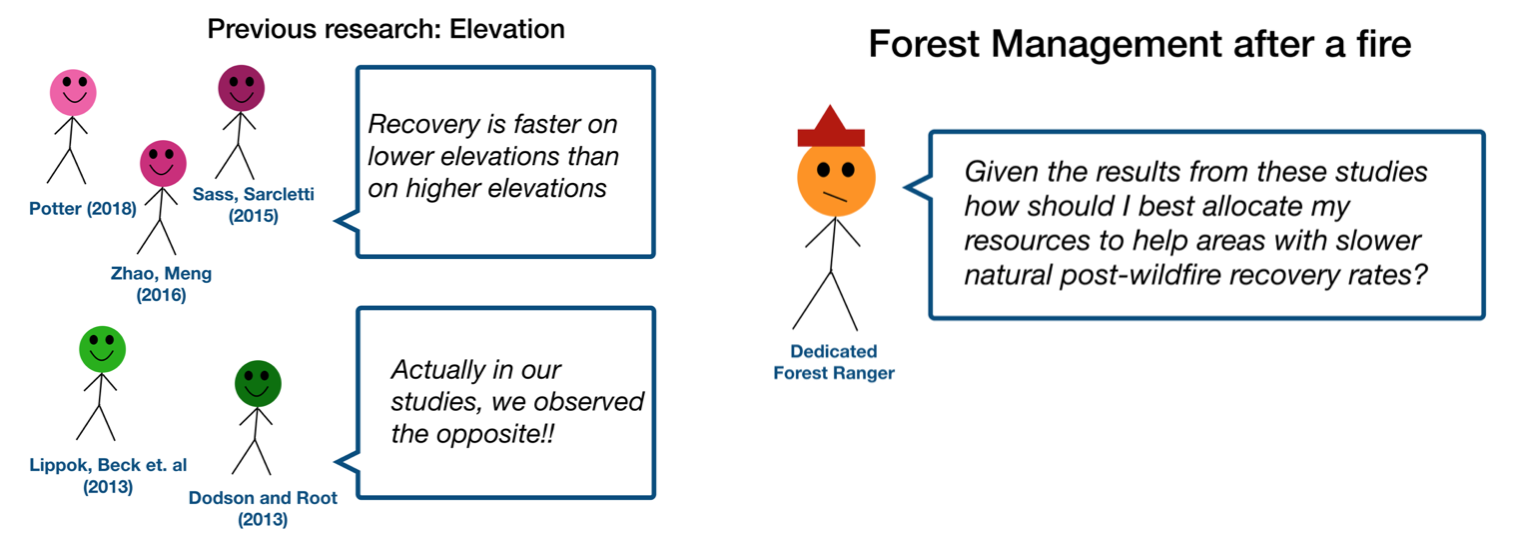

Here's how: follow the the CCQH pattern -- C ontext, C omplication, Q uestion, H ypothesis. Fit your research into this pattern, and you will be able to introduce your work in just a few minutes, using just 1 or 2 slides.

The video below show how to use the CCQH pattern using an example of published scientific research. You will see how powerful -- and how adapatable -- the CCQH pattern is.

Make sure you select 720p HD on the video (bottom right corner) for best resolution and so scientific illustrations and figures are clear.

You can also find this video, and others related to scientific communication, at the CLIMB youtube channel: http://www.youtube.com/climbprogram

Quick Links

Northwestern bioscience programs.

- Biomedical Engineering (BME)

- Chemical and Biological Engineering (ChBE)

- Driskill Graduate Program in the Life Sciences (DGP)

- Interdepartmental Biological Sciences (IBiS)

- Northwestern University Interdepartmental Neuroscience (NUIN)

- Campus Emergency Information

- Contact Northwestern University

- Report an Accessibility Issue

- University Policies

- Northwestern Home

- Northwestern Calendar: PlanIt Purple

- Northwestern Search

Chicago: 420 East Superior Street, Rubloff 6-644, Chicago, IL 60611 312-503-8286

Department of Chemistry

Search form.

- Affiliated Faculty

- Administrators & Staff

- Research Faculty & Staff

- Research Associates

- Graduate Students

- Update/Submit Alumni Information

- Emeritus and Retired Faculty

- In Memoriam

- Research Facilities

- Centers & Programs

- Astrochemistry

- Bioanalytical

- Biophysical Chemistry

- Catalysis and Energy

- Chemical Biology

- Chemical Education Reserach

- Imaging and Sensing

- Inorganic and Organometallic Chemistry

- Nanosciences and Materials

- Organic Chemistry and Synthesis

- Surface Chemistry and Spectroscopy

- Theory and Computation

- Non-Thesis Master's Program (1 Year)

- PhD Program

- Applying to the PhD Program

- Information about Charlottesville

- Chemistry and Multidisciplinary Courses

- Graduate Handbook

- Professional and Career Development Opportunities

- Graduate Chemistry Program Clubs & Organizations

- Fellowships and Awards

- Graduate Program Calendar

- Graduate Student Forms

- 2023-24 Bi-weekly Payroll Calendar

- Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion Initiatives

- Disability Accommodation Information

- Prospective and Transfer Students

- General Chemistry Options

- Undergraduate Advisors

- Process for declaring a major, minor, DMP, or ACS Certification

- B.A. in Chemistry

- B.S. Chemistry

- B.S. Specialization in Biochemistry

- B.S.Specialization in Chemical Education

- B.S. Specialization in Chemical Physics

- B.S. Specialization in Environmental Chemistry

- B.S. Specialization in Materials Science

- B.A./M.S. or B.S./M.S. in Chemistry ("3+1" Degree Option)

- American Chemical Society Poster Session

- Undergraduate Publications

- Undergraduate Research in a pandemic

- How to Prepare and Present a Scientific Poster

How to Prepare and Present a Scientific Talk

- Guidelines for Final Report

- Distinguished Majors

- Study Abroad

- First and Second Years

- Third and Fourth Years

- Graduation Information

- Undergraduate Resources

- Upcoming Seminars

- Seminar Archive

- Request Seminar Date

- Named Lectures

- Spring 2023 Newsletter

Ten Simple Rules for Making Good Oral Presentations

Philip E. Bourne

PLoS Comput Biol 3(4): e77. doi:10.1371/journal.pcbi.0030077

Rule 1: Talk to the Audience

We do not mean face the audience, although gaining eye contact with as many people as possible when you present is important since it adds a level of intimacy and comfort to the presentation. We mean prepare presentations that address the target audience. Be sure you know who your audience is—what are their backgrounds and knowledge level of the material you are presenting and what they are hoping to get out of the presentation? Off-topic presentations are usually boring and will not endear you to the audience. Deliver what the audience wants to hear.

Rule 2: Less is More

A common mistake of inexperienced presenters is to try to say too much. They feel the need to prove themselves by proving to the audience that they know a lot. As a result, the main message is often lost, and valuable question time is usually curtailed. Your knowledge of the subject is best expressed through a clear and concise presentation that is provocative and leads to a dialog during the question-and-answer session when the audience becomes active participants. At that point, your knowledge of the material will likely become clear. If you do not get any questions, then you have not been following the other rules. Most likely, your presentation was either incomprehensible or trite. A side effect of too much material is that you talk too quickly, another ingredient of a lost message.

Rule 3: Only Talk When You Have Something to Say

Do not be overzealous about what you think you will have available to present when the time comes. Research never goes as fast as you would like. Remember the audience’s time is precious and should not be abused by presentation of uninteresting preliminary material.

Rule 4: Make the Take-Home Message Persistent

A good rule of thumb would seem to be that if you ask a member of the audience a week later about your presentation, they should be able to remember three points. If these are the key points you were trying to get across, you have done a good job. If they can remember any three points, but not the key points, then your emphasis was wrong. It is obvious what it means if they cannot recall three points!

Rule 5: Be Logical

Think of the presentation as a story. There is a logical flow—a clear beginning, middle, and an end. You set the stage (beginning), you tell the story (middle), and you have a big finish (the end) where the take-home message is clearly understood.

Rule 6: Treat the Floor as a Stage

Presentations should be entertaining, but do not overdo it and do know your limits. If you are not humorous by nature, do not try and be humorous. If you are not good at telling anecdotes, do not try and tell anecdotes, and so on. A good entertainer will captivate the audience and increase the likelihood of obeying Rule 4.

Rule 7: Practice and Time Your Presentation

This is particularly important for inexperienced presenters. Even more important, when you give the presentation, stick to what you practice. It is common to deviate, and even worse to start presenting material that you know less about than the audience does. The more you practice, the less likely you will be to go off on tangents. Visual cues help here. The more presentations you give, the better you are going to get. In a scientific environment, take every opportunity to do journal club and become a teaching assistant if it allows you to present. An important talk should not be given for the first time to an audience of peers. You should have delivered it to your research collaborators who will be kinder and gentler but still point out obvious discrepancies. Laboratory group meetings are a fine forum for this.

Rule 8: Use Visuals Sparingly but Effectively

Presenters have different styles of presenting. Some can captivate the audience with no visuals (rare); others require visual cues and in addition, depending on the material, may not be able to present a particular topic well without the appropriate visuals such as graphs and charts. Preparing good visual materials will be the subject of a further Ten Simple Rules. Rule 7 will help you to define the right number of visuals for a particular presentation. A useful rule of thumb for us is if you have more than one visual for each minute you are talking, you have too many and you will run over time. Obviously some visuals are quick, others take time to get the message across; again Rule 7 will help. Avoid reading the visual unless you wish to emphasize the point explicitly, the audience can read, too! The visual should support what you are saying either for emphasis or with data to prove the verbal point. Finally, do not overload the visual. Make the points few and clear.

Rule 9: Review Audio and/or Video of Your Presentations

There is nothing more effective than listening to, or listening to and viewing, a presentation you have made. Violations of the other rules will become obvious. Seeing what is wrong is easy, correcting it the next time around is not. You will likely need to break bad habits that lead to the violation of the other rules. Work hard on breaking bad habits; it is important.

Rule 10: Provide Appropriate Acknowledgments

People love to be acknowledged for their contributions. Having many gratuitous acknowledgements degrades the people who actually contributed. If you defy Rule 7, then you will not be able to acknowledge people and organizations appropriately, as you will run out of time. It is often appropriate to acknowledge people at the beginning or at the point of their contribution so that their contributions are very clear.

As a final word of caution, we have found that even in following the Ten Simple Rules (or perhaps thinking we are following them), the outcome of a presentation is not always guaranteed. Audience–presenter dynamics are hard to predict even though the metric of depth and intensity of questions and off-line followup provide excellent indicators. Sometimes you are sure a presentation will go well, and afterward you feel it did not go well. Other times you dread what the audience will think, and you come away pleased as punch. Such is life. As always, we welcome your comments on these Ten Simple Rules by Reader Response.

Acknowledgments

The idea for this particular Ten Simple Rules was inspired by a conversation with Fiona Addison.

Also see the following guides:

Ten Secrets to Giving a Good Scientific Talk in Science and Society V1003 by Mark Schoeberl and Brian Toon

How to Give a Sensational Scientific Talk by Janet B. W. Williams, D.S.W.

How to Give a Talk by James Allan

Giving a Job Talk in the Sciences By Richard M. Reis

Spectacular Scientific Talks by Rachel A. Petkewich

Tips for Giving Clear Talks by IvyPanda

Get in touch

555-555-5555

Limited time offer: 20% off all templates ➞

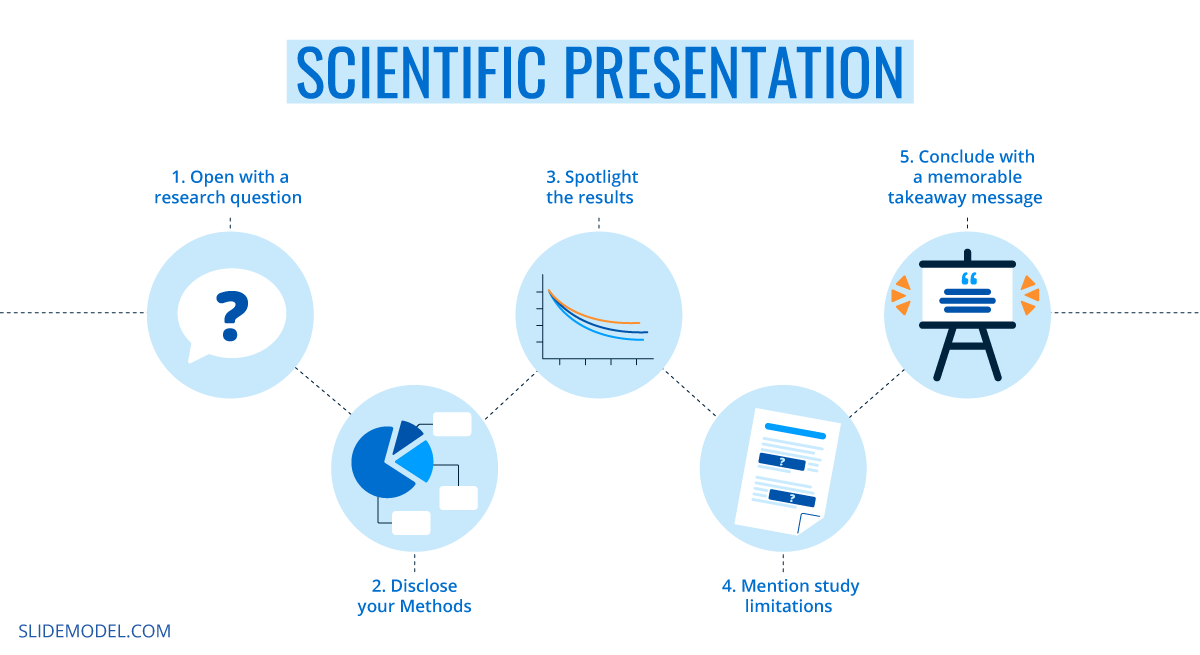

Scientific Presentation Guide: How to Create an Engaging Research Talk

Creating an effective scientific presentation requires developing clear talking points and slide designs that highlight your most important research results..

Scientific presentations are detailed talks that showcase a research project or analysis results. This comprehensive guide reviews everything you need to know to give an engaging presentation for scientific conferences, lab meetings, and PhD thesis talks. From creating your presentation outline to designing effective slides, the tips in this article will give you the tools you need to impress your scientific peers and superiors.

Step 1. Create a Presentation Outline

The first step to giving a good scientific talk is to create a presentation outline that engages the audience at the start of the talk, highlights only 3-5 main points of your research, and then ends with a clear take-home message. Creating an outline ensures that the overall talk storyline is clear and will save you time when you start to design your slides.

Engage Your Audience

The first part of your presentation outline should contain slide ideas that will gain your audience's attention. Below are a few recommendations for slides that engage your audience at the start of the talk:

- Create a slide that makes connects your data or presentation information to a shared purpose, such as relevance to solving a medical problem or fundamental question in your field of research

- Create slides that ask and invite questions

- Use humor or entertainment

Identify Clear Main Points

After writing down your engagement ideas, the next step is to list the main points that will become the outline slide for your presentation. A great way to accomplish this is to set a timer for five minutes and write down all of the main points and results or your research that you want to discuss in the talk. When the time is up, review the points and select no more than three to five main points that create your talk outline. Limiting the amount of information you share goes a long way in maintaining audience engagement and understanding.

Create a Take-Home Message

And finally, you should brainstorm a single take-home message that makes the most important main point stand out. This is the one idea that you want people to remember or to take action on after your talk. This can be your core research discovery or the next steps that will move the project forward.

Step 2. Choose a Professional Slide Theme

After you have a good presentation outline, the next step is to choose your slide colors and create a theme. Good slide themes use between two to four main colors that are accessible to people with color vision deficiencies. Read this article to learn more about choosing the best scientific color palettes .

You can also choose templates that already have an accessible color scheme. However, be aware that many PowerPoint templates that are available online are too cheesy for a scientific audience. Below options to download professional scientific slide templates that are designed specifically for academic conferences, research talks, and graduate thesis defenses.

Step 3. Design Your Slides

Designing good slides is essential to maintaining audience interest during your scientific talk. Follow these four best practices for designing your slides:

- Keep it simple: limit the amount of information you show on each slide

- Use images and illustrations that clearly show the main points with very little text.

- Read this article to see research slide example designs for inspiration

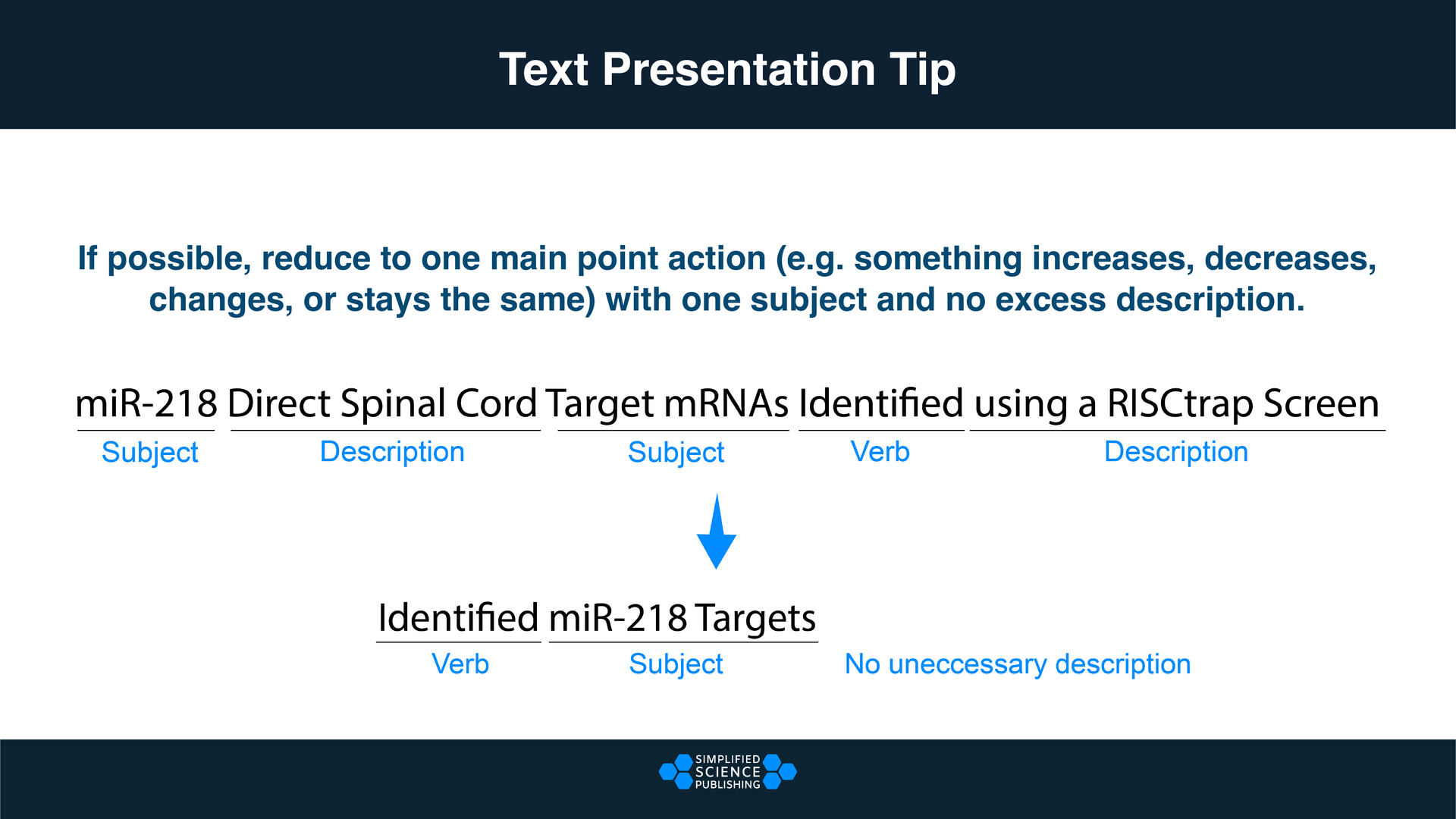

- When you are using text, try to reduce the scientific jargon that is unnecessary. Text on research talk slides needs to be much more simple than the text used in scientific publications (see example below).

- Use appear/disappear animations to break up the details into smaller digestible bites

- Sign up for the free presentation design course to learn PowerPoint animation tricks

Scientific Presentation Design Summary

All of the examples and tips described in this article will help you create impressive scientific presentations. Below is the summary of how to give an engaging talk that will earn respect from your scientific community.

Step 1. Draft Presentation Outline. Create a presentation outline that clearly highlights the main point of your research. Make sure to start your talk outline with ideas to engage your audience and end your talk with a clear take-home message.

Step 2. Choose Slide Theme. Use a slide template or theme that looks professional, best represents your data, and matches your audience's expectations. Do not use slides that are too plain or too cheesy.

Step 3. Design Engaging Slides. Effective presentation slide designs use clear data visualizations and limits the amount of information that is added to each slide.

And a final tip is to practice your presentation so that you can refine your talking points. This way you will also know how long it will take you to cover the most essential information on your slides. Thank you for choosing Simplified Science Publishing as your science communication resource and good luck with your presentations!

Interested in free design templates and training?

Explore scientific illustration templates and courses by creating a Simplified Science Publishing Log In. Whether you are new to data visualization design or have some experience, these resources will improve your ability to use both basic and advanced design tools.

Interested in reading more articles on scientific design? Learn more below:

Data Storytelling Techniques: How to Tell a Great Data Story in 4 Steps

Best Science PowerPoint Templates and Slide Design Examples

Free Research Poster Templates and Tutorials

Content is protected by Copyright license. Website visitors are welcome to share images and articles, however they must include the Simplified Science Publishing URL source link when shared. Thank you!

Online Courses

Stay up-to-date for new simplified science courses, subscribe to our newsletter.

Thank you for signing up!

You have been added to the emailing list and will only recieve updates when there are new courses or templates added to the website.

We use cookies on this site to enhance your user experience and we do not sell data. By using this website, you are giving your consent for us to set cookies: View Privacy Policy

Simplified Science Publishing, LLC

- Enterprise Custom Courses

- Build Your Own Courses

- Help Center

- Clinical Trial Recruitment

- Pharmaceutical Marketing

- Health Department Resources

- Patient Education

- Research Presentation

- Remote Monitoring

- Health Literacy & SciComm

- Student Education & Higher Ed

- Individual Learning

- Member Directory

- Community Chats on Slack

- SciComm Program

- The Story-Driven Method

- The Instructional Method

How to Create an Engaging Science Presentation: A Quick Guide

We’ve all been there – rushing to put slides together for an upcoming talk, filling them with bullet points and text that we want to remember to cover. We aren’t sure exactly what the audience will want to know or how much detail to include, so we default to putting ALL the details in that might be needed. But such efforts often result in presentations that are too long, too confusing, and difficult for both ourselves and our audiences to navigate.

Today I gave a workshop to public health graduate students about how to create more engaging science presentations and talks. I’ve summarized the main takeaways below. I hope this quick guide will be useful to you as you prepare for your next science talk or presentation!

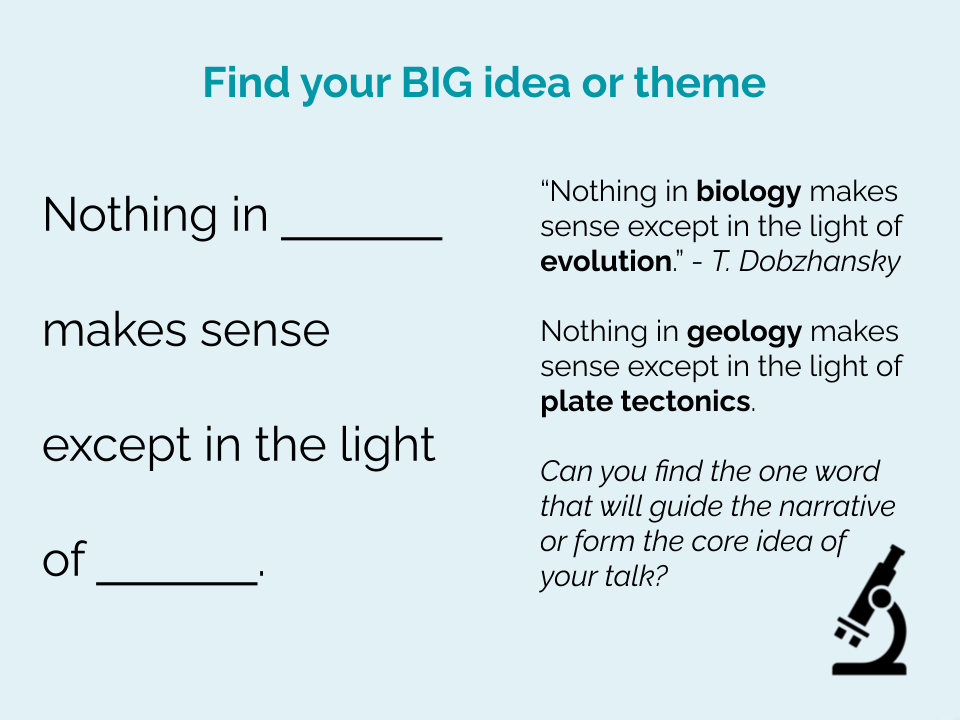

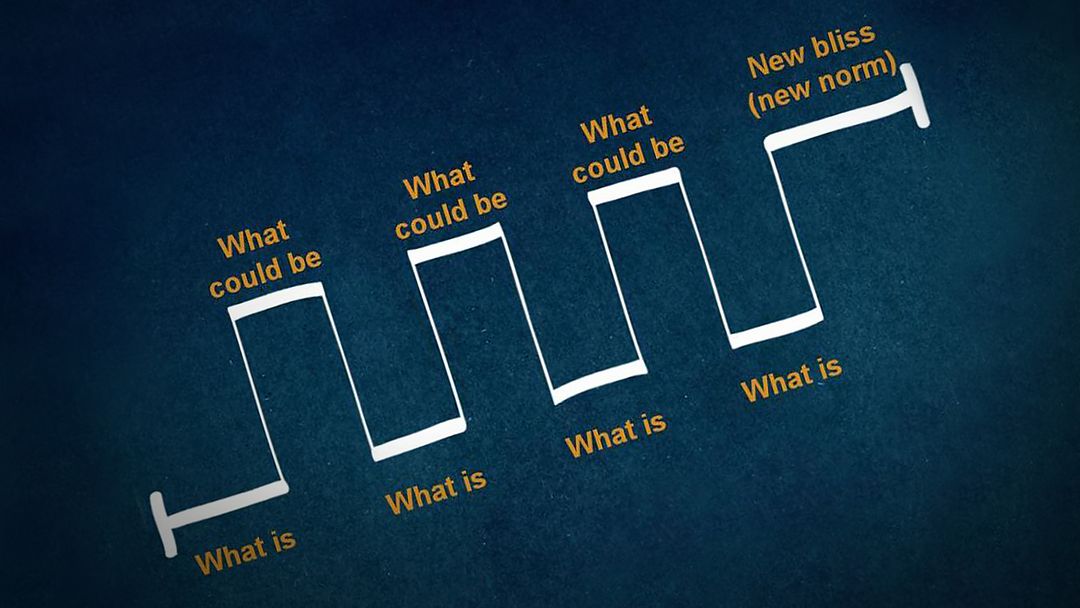

The best science talks start with a process of simplifying – peeling back the layers of information and detail to get at the one core idea that you want to communicate. Over the course of your talk, you may present 2-3 key messages that relate to, demonstrate, provide examples of or underpin this idea. (Three is a nice round number of messages or takeaways that your audience will be able to remember!) But stick to one big idea. Trying to communicate too much in a presentation or talk will overwhelm your audience, and they may walk away without a good memory of any of the ideas you presented.

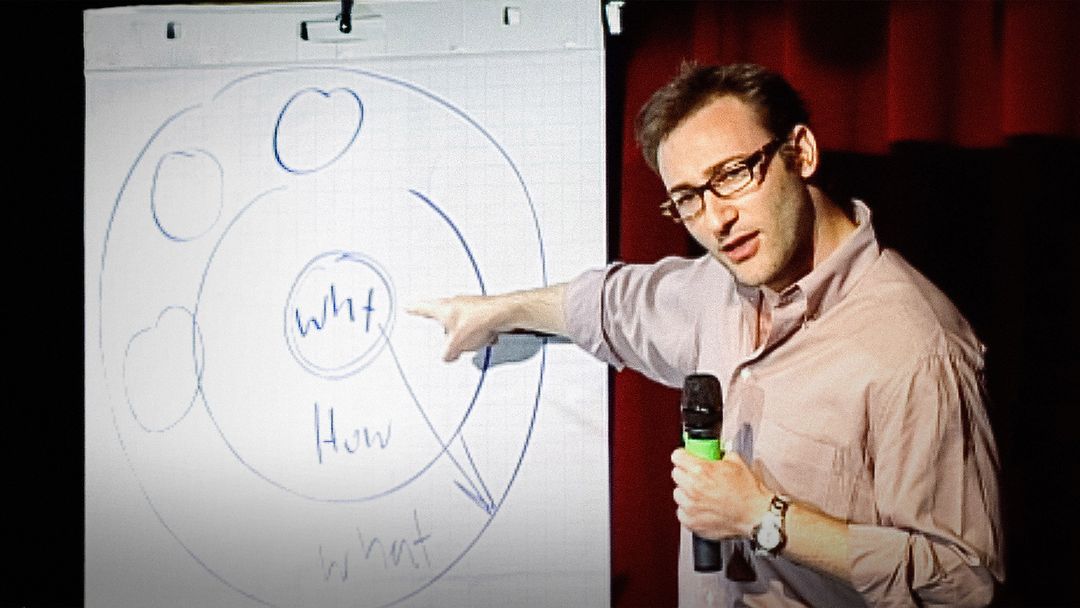

Once you’ve settled on your one big idea, you can develop a theme that will pervade every aspect of your talk. This theme might be a defining element of your big idea and something that can tie all of your data or talking points together. Your theme should inform the examples, anecdotes and analogies that you use to make the science concepts you present more accessible. It should also inform your slides’ very design – the colors, visuals, layout and content flow.

If you have trouble identifying your big idea and your theme, you can try using what scientist and science author Randy Olson calls the “Dobzhansky Template.” Fill in the blanks of this statement: “ Nothing in [your talk topic, research topic or big idea] makes sense, except in the light of [your theme!] .”

Here’s an example for you: “Nothing in the creation of engaging science talks makes sense except in the light of people’s need for personal connection .” With this statement, I’m identifying a key aspect, a unifying theme, for my talk (or blog post) on how to create engaging science talks. We all crave personal connection. Yes, even to the speakers of science talks we listen to! What does this mean in terms of what we want or expect from these speakers? It means we want storytelling . We want to hear their stories, know their background, hear about their struggles and triumphs! We want to be able to step into their shoes and see what they saw. We want to interact with them.

Tell a Story

Narratives engage more than facts. By telling a story , using suspense and characters to pull people through your presentation, you will capture and keep their attention for longer. People also remember information presented in a story format better than they do information presented as disparate facts or bullet points.

“Story is a pull strategy. If your story is good enough, people—of their own free will—come to the conclusion they can trust you and the message you bring.” – Annette Simmons

Storytelling is a powerful science communication tool. In storytelling, both the storyteller and the listener or reader contribute to the story’s meaning through their interpretations, feelings and emotions. Liz Neeley, former executive director of The Story Collider, once said: “Science communicators frequently fail to understand that a feeling is almost never conquered with a fact.”

Stories are exciting. They elicit emotions. They help foster a personal connection between the storyteller and the listener, and a connection between the listener and the topic, characters or ideas presented in the story.

But what IS a story? As humans, we excel at recognizing a story when we hear one, but defining a story’s key characteristics is more difficult than you might think. If you ask anyone to explain what makes for a good story, they likely will have a hard time explaining it.

In her fantastic book Wired for Story , Lisa Cron starts by explaining what a story is NOT.

It is not plot – that is just what happens in the story.

It is not characters , although characters are critical components of storytelling, even if they are not human or even alive. Cells and molecules could be the characters of your next science talk!

It is not suspense or conflict , although these elements get us closer to what defines a good story. But just because your talk builds suspense does not necessarily make it an engaging story. What if we don’t identify with your characters?

The truth is that the key defining element of story is internal change . Think of how every Aesop’s fable communicates a moral or lesson that the main character learned from some journey. As Lisa Cron writes, “A story is how what happens affects someone who is trying to achieve what turns out to be a difficult goal, and how he or she changes as a result.” The key here is the part about “how he or she changes.” A great story calls characters to a great adventure, but the adventure doesn’t leave them just as they were before. The adventure – like a scientific discovery that took years of experimentation (and failure) in the lab – leads to an internal change, in perspective or knowledge or behavior, as a result of conflicts overcome.

This is the secret of storytelling. A story asks characters to change and grow, and so the scientists in our stories must change and grow, discover new things about themselves and overcome challenges that force them to adopt new perspectives. So if you are giving a science talk about your own research, this might look like telling stories about your own struggles, growths and changes in perspective as you made your journey to discovery!

How can you bring a story of internal change to your next science presentation or talk?

What is one of the most common mistakes people make when creating slides to accompany a science talk? They use WAY too much text, and they use visuals as an afterthought. Worse yet, they use visuals that are copyrighted without attribution. They use stock imagery that reinforces stereotypes. They use visuals pasted from a Google search that don’t help the viewer understand or interpret what is said or written on the slides.

Visuals can be a powerful tool to advance audience learning or engagement during your science talks. You can use visuals to provide concrete examples of concepts you are talking about. You can use imagery that sparks thought or emotion. You can use visuals that reinforce your BIG idea or the theme of your talk, in a way that will make your talk more memorable for them. Yes, you might need to use a scientific figure, graph, chart or data visualization here and there if you are giving a more technical scientific talk, and that’s ok as long as you also talk the audience through this visual. Don’t assume they can listen to you talk about something different while also taking the time to interpret the message in this graphic or visualization – they can’t.

The same goes for text. You are demanding way too much brainpower of your audience to expect them to listen to you while also reading your slides. And if you are saying the same things as are written on your slides, they will grow bored. Simple visual aids used the right way, however, can delight your audience and help them better understand what you are saying.

Consider working with a professional artist or designer to create visuals for the slides of your next science talk! They excel at creating visuals that capture people’s attention, curiosity and emotions. And if you do this, your visuals will perfectly match what you are trying to communicate in words, boosting learning and understanding.

Foster Interaction

A good science talk or presentation gives the audience opportunities to interact with you! This could be through questions, activities, discussions or thought experiments. Let the audience explore your data or interpretations with you. They will be more engaged and likely trust you more as a result, because they felt heard .

Personalize!

Most great science speakers make themselves vulnerable in a way – they tell personal stories of struggles, growth and discovery. Personal stories are engaging. They also help the audience care about what the speaker has to say.

It can be scary to talk about yourself, especially for a scientist who has been trained to focus solely on the data. But the humans listening to your talk or presentation crave human connection. They will also grab hold of anything that helps them better relate to you. Give them that in the form of personal stories of obstacles overcome, of personal lessons learned, of work-life balance, of your fears and passions. Better yet, tell personal stories that reinforce your theme and show the power of your big idea!

Do you have other strategies for how you make your science talks and presentations more engaging? Let me know in the comments below!

Share This Story, Choose Your Platform!

About the author: paige jarreau.

Related Posts

Una actividad práctica para ayudarte a comunicar la ciencia de forma culturalmente relevante

The Power of SciComm in Combatting Mental Health Stigma

Make your scicomm more culturally relevant: a practice activity.

Communicating About Postpartum Depression

Science Communication and Genetic Counselling

Creating Analogies: Elevate Your Science with a Lifeology Course

- PRO Courses Guides New Tech Help Pro Expert Videos About wikiHow Pro Upgrade Sign In

- EDIT Edit this Article

- EXPLORE Tech Help Pro About Us Random Article Quizzes Request a New Article Community Dashboard This Or That Game Popular Categories Arts and Entertainment Artwork Books Movies Computers and Electronics Computers Phone Skills Technology Hacks Health Men's Health Mental Health Women's Health Relationships Dating Love Relationship Issues Hobbies and Crafts Crafts Drawing Games Education & Communication Communication Skills Personal Development Studying Personal Care and Style Fashion Hair Care Personal Hygiene Youth Personal Care School Stuff Dating All Categories Arts and Entertainment Finance and Business Home and Garden Relationship Quizzes Cars & Other Vehicles Food and Entertaining Personal Care and Style Sports and Fitness Computers and Electronics Health Pets and Animals Travel Education & Communication Hobbies and Crafts Philosophy and Religion Work World Family Life Holidays and Traditions Relationships Youth

- Browse Articles

- Learn Something New

- Quizzes Hot

- This Or That Game

- Train Your Brain

- Explore More

- Support wikiHow

- About wikiHow

- Log in / Sign up

- Education and Communications

How to Present a Science Project

Last Updated: August 17, 2023 Fact Checked

This article was co-authored by Meredith Juncker, PhD . Meredith Juncker is a PhD candidate in Biochemistry and Molecular Biology at Louisiana State University Health Sciences Center. Her studies are focused on proteins and neurodegenerative diseases. This article has been fact-checked, ensuring the accuracy of any cited facts and confirming the authority of its sources. This article has been viewed 54,022 times.

After creating a science project , you’ll likely have to present your work to your class or at a science fair. Try to give yourself a few weeks to plan and put together your presentation. Outline your main points, make note cards, and practice ahead of time. Make a clear, neat display board or PowerPoint presentation. When it comes time to present, relax, speak clearly and loudly, and avoid reading your presentation word for word.

Putting Together Your Presentation

- Finish up your experiment, research, and other aspects of your project.

- Get the materials you’ll need for your display board.

- Start to imagine how you’ll organize your information.

- An introduction to your topic or the problem you’ve addressed.

- How the problem impacts the real world (such as how a better understanding of the issue can impact humans).

- Your hypothesis, or what you expected to learn about through your experiment.

- The research you did to learn more about your topic.

- The Materials that you used in your project.

- Each step of your experiment’s procedure.

- The results of your experiment.

- Your conclusion, including what you learned and whether your data supports your hypothesis.

- When writing your speech, try to keep it simple, and avoid using phrases that are more complicated than necessary. Try to tailor the presentation to your audience: will you be presenting to your class, judges, a higher grade than yours, or to an honors class?

- Writing out your presentation can also help you manage your time. For example, if you’re supposed to talk for less than five minutes, shoot for less than two pages.

- For example, if you've made a volcano, make sure you know the exact mix of chemicals that will create the eruption.

Creating Your Display Board

- When you purchase your board, you should also acquire other materials, like a glue stick, construction paper, a pencil, markers, and a ruler.

- Consider using the top left corner for your topic introduction, the section under that for your hypothesis, and the bottom left section to discuss your research.

- Use the top right corner to outline your experiment’s procedure. List your results underneath, and finally, put the section with your conclusion under the results.

- Be sure to use a dark font color that’s easy to see from a distance.

- You can also write everything out by hand. Draft your lettering in pencil before using a pen or marker, and use a ruler to make sure everything is straight.

- Before gluing anything, make sure you plan out each section’s position and are sure everything will fit without looking cluttered. Use rulers to make sure everything is positioned evenly.

- Consider including 1 slide for each section, like 1 for the title of your project, 1 for your hypothesis, and 1 that outlines each main point of your research. If a slide becomes too dense, break it down by concept.

- Limit the text to 1 line and include a visual aid, like an image or a graph, that demonstrates the concept or explains the data. [6] X Research source

Giving a Great Presentation

- Take the time to iron your clothes and tuck your shirt in to avoid looking sloppy.

- It’s a good idea to use the restroom before you have to present your project.

- It can be really hard to resist, but try to avoid saying “um” or “uh” during your presentation.

- Speaking when you have a dry mouth can be difficult, so it’s a good idea to keep a water bottle handy.

- Remember it’s better to be honest if you don't know how to answer a question instead of making something up. Ask the person who asked the question to repeat or rephrase it, or say something like, "That's certainly an area I can explore in more detail in the future."

Community Q&A

You Might Also Like

- ↑ https://www.opencolleges.edu.au/informed/teacher-resources/science-fair-projects/#sciencefairpresentation

- ↑ https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=4KVTLT6QeTE

- ↑ https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=NHXidlH-dBw

- ↑ https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=g3hT6Ocf39w

- ↑ https://www.sciencebuddies.org/science-fair-projects/science-fair/judging-tips-to-prepare-science-fair

About This Article

- Send fan mail to authors

Reader Success Stories

Shruti Choudhary

Dec 17, 2017

Did this article help you?

Dec 11, 2017

Dec 5, 2016

Feb 5, 2017

Oct 13, 2017

Featured Articles

Trending Articles

Watch Articles

- Terms of Use

- Privacy Policy

- Do Not Sell or Share My Info

- Not Selling Info

wikiHow Tech Help Pro:

Level up your tech skills and stay ahead of the curve

Unfortunately we don't fully support your browser. If you have the option to, please upgrade to a newer version or use Mozilla Firefox , Microsoft Edge , Google Chrome , or Safari 14 or newer. If you are unable to, and need support, please send us your feedback .

We'd appreciate your feedback. Tell us what you think! opens in new tab/window

How to give a dynamic scientific presentation

August 4, 2015 | 12 min read

By Marilynn Larkin

Convey your ideas and enthusiasm – and avoid the pitfalls that put audiences to sleep

Joann Halpern, PhD, moderates a panel at the German Center for Research and Innovation in New York. (Photo by Nathalie Schueller)

Giving presentations is an important part of sharing your work and achieving recognition in the larger medical and scientific communities. The ability to do so effectively can contribute to career success.

However, instead of engaging audiences and conveying enthusiasm, many presentations fall flat. Pitfalls include overly complicated content, monotone delivery and focusing on what you want to say rather than what the audience is interested in hearing.

Effective presentations appeal to a wide range of audiences — those who work in your area of interest or in related fields, as well as potential funders, the media and others who may find your work interesting or useful.

There are two major facets to a presentation: the content and how you present it. Let’s face it, no matter how great the content, no one will get it if they stop paying attention. Here are some pointers on how to create clear, concise content for scientific presentations – and how to deliver your message in a dynamic way.

Presentation pointers: content

Here are five tips for developing effective content for your presentation:

1. Know your audience.

Gear your presentation to the knowledge level and needs of the audience members. Are they colleagues? Researchers in a related field? Consumers who want to understand the value of your work for the clinic (for example, stem cell research that could open up a new avenue to treat a neurological disease)?

2. Tell audience members up front why they should care and what’s in it for them.

What problem will your work help solve? Is it a diagnostic test strategy that reduces false positives? A new technology that will help them to do their own work faster, better and less expensively? Will it help them get a new job or bring new skills to their present job?

Dr. Marius Stan with Vince Gilligan, creator, producer and head writer for Breaking Bad.

3. Convey your excitement.

Tell a brief anecdote or describe the “aha” moment that convinced you to get involved in your field of expertise. For example, Dr. Marius Stan opens in new tab/window , a physicist and chemist known to the wider world as the carwash owner on Breaking Bad opens in new tab/window , explained that mathematics has always been his passion, and the “explosion” of computer hardware and software early in his career drove his interest to computational science, which involves the use of mathematical models to solve scientific problems. Personalizing makes your work come alive and helps audience members relate to it on an emotional level.

4. Tell your story.

A presentation is your story. It needs a beginning, a middle and an end. For example, you could begin with the problem you set out to solve. What did you discover by serendipity? What gap did you think your work could fill? For the middle, you could describe what you did, succinctly and logically, and ideally building to your most recent results. And the end could focus on where you are today and where you hope to go.

Donald Ingber, MD, PhD, Director of the Wyss Institute for Biologically Inspired Engineering at Harvard University, gives a keynote address at the Society for Laboratory Automation and Screening’s 2015 conference and exhibition in Washington, DC.

Start with context . Cite research — by you and others — that brought you to this point. Where does your work fit within this context? What is unique about it? While presenting on organs-on-chips technology at a recent conference, Dr. Donald Ingber, Director of the Wyss Institute for Biologically Inspired Engineering at Harvard, described the pioneering work of others in the field, touched on its impact, then went on to show his unique contributions to the field. He did not

present his work out of context, as though his group were the only one achieving results.

Frame the problem : “We couldn’t understand why our experiment wasn’t working so we investigated further”; “We saw an opportunity to cut costs and speed things up.”

Prof. Doris Rusch, PhD, talks about creating games to mimic the struggles of anorexia and the anxiety of OCD, at the 12th Annual Games for Change Festival in New York City. (Photo by Gabi Porter)

Provide highlights of what you did, tied to the audience’s expertise and/or reasons for attending your presentation. Present the highlights in a logical order. Avoid going into excruciating detail. If people are interested in steps you don’t cover, they’ll ask and you can expand during the Q&A period. A meeting I covered on educational gaming

gave presenters just 10 minutes each to talk about their work. Most used three to five slides, making sure to include a website address for more information on each slide. Because these speakers were well prepared, they were able to identify and communicate their key points in the short timeframe. They also made sure attendees who wanted more information would be able to find it easily on their websites. So don’t get bogged down in details — the what is often more important than the how .

Conclude by summing up key points and acknowledging collaborators and mentors. Give a peek into your next steps, especially if you’re interested in recruiting partners. Include your contact details and Twitter handle.

5. Keep it simple.

Every field has its jargon and acronyms, and science and medicine are no exceptions. However, you don’t want audience members to get stuck on a particular term and lose the thread of your talk. Even your fellow scientists will appreciate brief definitions and explanations of terminology and processes, especially if you’re working in a field like microfluidics, which includes collaborators in diverse disciplines, such as engineering, biomedical research and computational biology.

I’ve interviewed Nobel laureates who know how to have a conversation about their work that most anyone can understand – even if it involves complex areas such as brain chemistry or genomics. That’s because they’ve distilled their work to its essence, and can then talk about it at the most basic level as well as the most complicated. Regardless of the level of your talk, the goal should be to communicate, not obfuscate.

Presentation pointers: you

Here are 10 tips to help you present your scientific work and leave the audience wanting more.

1. Set the stage.

Get your equipment ready and run through your slides if possible (use the “speaker ready” room if one is available). If you’ve never been in the venue, try getting there early and walk the room. Make sure you have water available.

2. Get ready to perform.

Every presentation is a performance. The most important part is to know your lines and subject. Some people advocate memorizing your presentation, but if you do so, you can end up sounding stilted or getting derailed by an interruption. When you practice, focus on the key points you want to make (note them down if it helps) and improvise different ways of communicating them.

It’s well known that a majority of people fear public speaking — and even those who enjoy it may get stage fright. Fear of public speaking will diminish with experience. I’ve been presenting and performing for many years but still get stage fright. Try these strategies to manage the fear:

Breathe slowly and deeply for a few minutes before your talk.

Visualize yourself giving a relaxed talk to a receptive audience. This works best if you can close your eyes for a few minutes. If you’re sitting in the audience waiting to be introduced and can’t close your eyes, look up at the ceiling and try visualizing that way.

Do affirmations. Tell yourself you are relaxed, confident — whatever works for you. Whether affirmations are effective is a matter of debate, but you won’t know unless you try.

Assume one or more “power poses,” developed by social psychologist and dancer Dr. Amy Cuddy opens in new tab/window of the Harvard Business School, before giving your presentation. She demonstrates them in this TED talk opens in new tab/window . Power poses are part of the emerging field of embodiment research (see a comprehensive collection of articles opens in new tab/window related to this research in the journal Frontiers in Psychology ). Research on power poses has yielded mixed results to date, but they’re worth a try.

3. Stride up to the podium.

Seeing you walk energetically energizes the audience. They expect you to engage them and you have their attention.

4. Stand tall and keep your chest lifted.

It’s more difficult to breathe and speak when your shoulders are rolled forward and your chest caves in. Standing tall is also a way of conveying authority. If you’re presenting from a sitting position, sit up in your seat, keep your arms relaxed and away from your sides (i.e., don’t box yourself in by clasping your arms or clasping your hands in your lap).

Not only will you appear more relaxed if you smile, but research has shown that smiling — even when forced — reduces stress. Plus the audience enjoys watching and listening to someone who’s smiling rather than being stern or overly serious, especially if your topic is complicated.