Essay on Relationship Between Human And Nature

Students are often asked to write an essay on Relationship Between Human And Nature in their schools and colleges. And if you’re also looking for the same, we have created 100-word, 250-word, and 500-word essays on the topic.

Let’s take a look…

100 Words Essay on Relationship Between Human And Nature

The bond with nature.

People and nature are interconnected. We rely on the environment for survival, using its resources for food, shelter, and air. Nature, in return, benefits from our care and protection.

Respecting Nature

Respecting nature is essential. By protecting the environment, we ensure our own survival. We must recycle, reduce waste, and conserve energy to maintain this balance.

The Consequences of Neglect

Ignoring nature’s needs leads to problems like climate change and species extinction. These issues affect us directly, threatening our health and lifestyle.

Our relationship with nature is a delicate balance. By respecting and caring for the environment, we ensure a healthier, brighter future for all.

250 Words Essay on Relationship Between Human And Nature

The intrinsic connection, dependence and impact.

Nature provides essential resources such as air, water, food, and raw materials. These resources are not only crucial for our survival, but they also form the basis of our economic systems. However, our reliance on nature has led to significant environmental impacts. Deforestation, pollution, and climate change are direct consequences of human activities, threatening biodiversity and the stability of ecosystems.

The Reciprocal Relationship

The human-nature relationship is reciprocal. While we shape nature through our actions, nature, in turn, influences human behavior, culture, and mental health. Exposure to natural environments has been linked to reduced stress levels, improved mood, and enhanced cognitive function.

A Need for Rebalance

The current environmental crisis calls for a rebalance in the human-nature relationship. It necessitates a shift from exploitation to sustainable coexistence, where we respect and preserve nature’s intrinsic value. This shift requires a deeper understanding of our interconnectedness with nature and a collective effort to reduce our environmental impact.

In conclusion, the human-nature relationship is a complex and dynamic interaction that has significant implications for both parties. As we move forward, it is essential to foster a relationship of mutual respect and sustainability with nature to ensure the survival and wellbeing of all life on Earth.

500 Words Essay on Relationship Between Human And Nature

The intricate dance: human and nature.

The relationship between humans and nature is a complex interplay of dependence, respect, exploitation, and evolution. This relationship is not just crucial for our survival, but it also shapes our culture, beliefs, and our very identity.

Dependence: The Lifeline

Respect: the forgotten virtue.

Historically, humans have revered nature. Many ancient cultures worshipped nature deities and respected the land, the sea, and the sky. This respect was born out of an understanding of our dependence on nature, and the need to maintain a harmonious relationship with it. However, with the advent of industrialization and modernization, this respect has often been forgotten. We have begun to see nature as a resource to be exploited, rather than a partner to be respected.

Exploitation: The Double-Edged Sword

Our exploitation of nature has led to unprecedented advancements in technology, medicine, and living standards. However, it has also led to environmental degradation, loss of biodiversity, climate change, and a host of other problems. Our exploitation of nature has become a double-edged sword, providing us with short-term gains but threatening our long-term survival.

Evolution: The Path Forward

Conclusion: redefining the relationship.

The relationship between humans and nature is at a crossroads. We can continue down the path of exploitation and face the consequences, or we can choose a new path of respect, sustainability, and coexistence. The choice is ours to make. As we stand at this juncture, let us remember that our relationship with nature is not just about survival, but also about who we are as a species. It is about our values, our beliefs, and our legacy. It is about our future.

That’s it! I hope the essay helped you.

Happy studying!

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

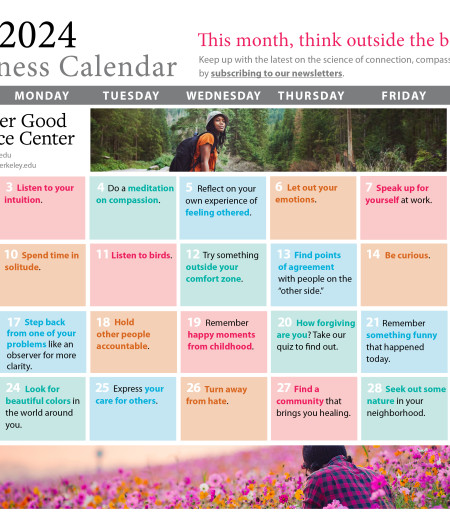

Greater Good Science Center • Magazine • In Action • In Education

What Happens When We Reconnect With Nature

Humans have long intuited that being in nature is good for the mind and body. From indigenous adolescents completing rites of passage in the wild, to modern East Asian cultures taking “forest baths,” many have looked to nature as a place for healing and personal growth.

Why nature? No one knows for sure; but one hypothesis derived from evolutionary biologist E. O. Wilson’s “ biophilia ” theory suggests that there are evolutionary reasons people seek out nature experiences. We may have preferences to be in beautiful, natural spaces because they are resource-rich environments—ones that provide optimal food, shelter, and comfort. These evolutionary needs may explain why children are drawn to natural environments and why we prefer nature to be part of our architecture.

Now, a large body of research is documenting the positive impacts of nature on human flourishing—our social, psychological, and emotional life. Over 100 studies have shown that being in nature, living near nature, or even viewing nature in paintings and videos can have positive impacts on our brains, bodies, feelings, thought processes, and social interactions. In particular, viewing nature seems to be inherently rewarding, producing a cascade of position emotions and calming our nervous systems. These in turn help us to cultivate greater openness, creativity, connection, generosity, and resilience.

In other words, science suggests we may seek out nature not only for our physical survival, but because it’s good for our social and personal well-being.

How nature helps us feel good and do good

The naturalist John Muir once wrote about the Sierra Nevada Mountains of California: “We are now in the mountains and they are in us, kindling enthusiasm, making every nerve quiver, filling every pore and cell of us.” Clearly, he found nature’s awe-inspiring imagery a positive, emotive experience.

But what does the science say? Several studies have looked at how viewing awe-inspiring nature imagery in photos and videos impacts emotions and behavior. For example, in one study participants either viewed a few minutes of the inspiring documentary Planet Earth , a neutral video from a news program, or funny footage from Walk on the Wild Side . Watching a few minutes of Planet Earth led people to feel 46 percent more awe and 31 percent more gratitude than those in the other groups. This study and others like it tell us that even brief nature videos are a powerful way to feel awe , wonder, gratitude , and reverence—all positive emotions known to lead to increased well-being and physical health.

Positive emotions have beneficial effects upon social processes, too—like increasing trust, cooperation, and closeness with others. Since viewing nature appears to trigger positive emotions, it follows that nature likely has favorable effects on our social well-being.

This has been robustly confirmed in research on the benefits of living near green spaces. Most notably, the work of Frances Kuo and her colleagues finds that in poorer neighborhoods of Chicago people who live near green spaces—lawns, parks, trees—show reductions in ADHD symptoms and greater calm, as well as a stronger sense of connection to neighbors, more civility, and less violence in their neighborhoods. A later analysis confirmed that green spaces tend to have less crime.

Viewing nature in images and videos seems to shift our sense of self, diminishing the boundaries between self and others, which has implications for social interactions. In one study , participants who spent a minute looking up into a beautiful stand of eucalyptus trees reported feeling less entitled and self-important. Even simply viewing Planet Earth for five minutes led participants to report a greater sense that their concerns were insignificant and that they themselves were part of something larger compared with groups who had watched neutral or funny clips.

Need a dose of nature?

A version of this essay was produced in conjunction with the BBC's newly released Planet Earth II : an awe-inspiring tour of the world from the viewpoint of animals.

Several studies have also found that viewing nature in images or videos leads to greater “prosocial” tendencies—generosity, cooperation, and kindness. One illustrative study found that people who simply viewed 10 slides of really beautiful nature (as opposed to less beautiful nature) gave more money to a stranger in an economic game widely used to measure trust.

All of these findings raise the intriguing possibility that, by increasing positive emotions, experiencing nature even in brief doses leads to more kind and altruistic behavior.

How nature helps our health

Besides boosting happiness, positive emotion, and kindness, exposure to nature may also have physical and mental health benefits.

The benefits of nature on health and well-being have been well-documented in different European and Asian cultures. While Kuo’s evidence suggests a particular benefit for those from nature-deprived communities in the United States, the health and wellness benefits of immersion in nature seem to generalize across all different class and ethnic backgrounds.

Why is nature so healing? One possibility is that having access to nature—either by living near it or viewing it—reduces stress. In a study by Catharine Ward Thompson and her colleagues, the people who lived near larger areas of green space reported less stress and showed greater declines in cortisol levels over the course of the day.

In another study , participants who viewed a one-minute video of awesome nature rather than a video that made them feel happy reported feeling as though they had enough time “to get things done” and did not feel that “their lives were slipping away.” And studies have found that people who report feeling a good deal of awe and wonder and an awareness of the natural beauty around them actually show lower levels of a biomarker (IL-6) that could lead to a decreased likelihood of cardiovascular disease, depression, and autoimmune disease.

Though the research is less well-documented in this area than in some others, the results to date are promising. One early study by Roger Ulrich found that patients recovered faster from cardiovascular surgery when they had a view of nature out of a window, for example.

A more recent review of studies looking at different kinds of nature immersion—natural landscapes during a walk, views from a window, pictures and videos, and flora and fauna around residential or work environments—showed that nature experiences led to reduced stress, easier recovery from illness, better physical well-being in elderly people, and behavioral changes that improve mood and general well-being.

Why we need nature

All of these findings converge on one conclusion: Being close to nature or viewing nature improves our well-being. The question still remains…how?

There is no question that being in nature—or even viewing nature pictures—reduces the physiological symptoms of stress in our bodies. What this means is that we are less likely to be anxious and fearful in nature, and thereby we can be more open to other people and to creative patterns of thought.

Also, nature often induces awe, wonder, and reverence, all emotions known to have a variety of benefits, promoting everything from well-being and altruism to humility to health.

There is also some evidence that exposure to nature impacts the brain. Viewing natural beauty (in the form of landscape paintings and video, at least) activates specific reward circuits in the brain associated with dopamine release that give us a sense of purpose, joy, and energy to pursue our goals.

But, regrettably, people seem to be spending less time outdoors and less time immersed in nature than before. It is also clear that, in the past 30 years, people’s levels of stress and sense of “busyness” have risen dramatically. These converging forces have led environmental writer Richard Louv to coin the term “ nature deficit disorder ”—a form of suffering that comes from a sense of disconnection from nature and its powers.

Perhaps we should take note and try a course corrective. The 19th century philosopher Ralph Waldo Emerson once wrote about nature, “There I feel that nothing can befall me in life—no disgrace, no calamity (leaving me my eyes), which nature cannot repair.” The science speaks to Emerson’s intuition. It’s time to realize nature is more than just a material resource. It’s also a pathway to human health and happiness.

About the Authors

Kristophe Green

Uc berkeley.

Kristophe Green is a senior Psychology major at UC Berkeley. He is fascinated with the study of positive emotions and how they inform pro-social behavior such as empathy, altruism and compassion.

Dacher Keltner

Dacher Keltner, Ph.D. , is the founding director of the Greater Good Science Center and a professor of psychology at the University of California, Berkeley. He is the author of The Power Paradox: How We Gain and Lose Influence and Born to Be Good , and a co-editor of The Compassionate Instinct .

You May Also Enjoy

A Walk in the Park

How nature can make you kinder, happier, and more creative.

How to Raise an Environmentalist

Why Your Office Needs More Nature

Do your kids have “nature deficit disorder”.

Green Cities, Happy Cities

Nature Essay for Students and Children

500+ words nature essay.

Nature is an important and integral part of mankind. It is one of the greatest blessings for human life; however, nowadays humans fail to recognize it as one. Nature has been an inspiration for numerous poets, writers, artists and more of yesteryears. This remarkable creation inspired them to write poems and stories in the glory of it. They truly valued nature which reflects in their works even today. Essentially, nature is everything we are surrounded by like the water we drink, the air we breathe, the sun we soak in, the birds we hear chirping, the moon we gaze at and more. Above all, it is rich and vibrant and consists of both living and non-living things. Therefore, people of the modern age should also learn something from people of yesteryear and start valuing nature before it gets too late.

Significance of Nature

Nature has been in existence long before humans and ever since it has taken care of mankind and nourished it forever. In other words, it offers us a protective layer which guards us against all kinds of damages and harms. Survival of mankind without nature is impossible and humans need to understand that.

If nature has the ability to protect us, it is also powerful enough to destroy the entire mankind. Every form of nature, for instance, the plants , animals , rivers, mountains, moon, and more holds equal significance for us. Absence of one element is enough to cause a catastrophe in the functioning of human life.

We fulfill our healthy lifestyle by eating and drinking healthy, which nature gives us. Similarly, it provides us with water and food that enables us to do so. Rainfall and sunshine, the two most important elements to survive are derived from nature itself.

Further, the air we breathe and the wood we use for various purposes are a gift of nature only. But, with technological advancements, people are not paying attention to nature. The need to conserve and balance the natural assets is rising day by day which requires immediate attention.

Get the huge list of more than 500 Essay Topics and Ideas

Conservation of Nature

In order to conserve nature, we must take drastic steps right away to prevent any further damage. The most important step is to prevent deforestation at all levels. Cutting down of trees has serious consequences in different spheres. It can cause soil erosion easily and also bring a decline in rainfall on a major level.

Polluting ocean water must be strictly prohibited by all industries straightaway as it causes a lot of water shortage. The excessive use of automobiles, AC’s and ovens emit a lot of Chlorofluorocarbons’ which depletes the ozone layer. This, in turn, causes global warming which causes thermal expansion and melting of glaciers.

Therefore, we should avoid personal use of the vehicle when we can, switch to public transport and carpooling. We must invest in solar energy giving a chance for the natural resources to replenish.

In conclusion, nature has a powerful transformative power which is responsible for the functioning of life on earth. It is essential for mankind to flourish so it is our duty to conserve it for our future generations. We must stop the selfish activities and try our best to preserve the natural resources so life can forever be nourished on earth.

{ “@context”: “https://schema.org”, “@type”: “FAQPage”, “mainEntity”: [ { “@type”: “Question”, “name”: “Why is nature important?”, “acceptedAnswer”: { “@type”: “Answer”, “text”: “Nature is an essential part of our lives. It is important as it helps in the functioning of human life and gives us natural resources to lead a healthy life.” } }, { “@type”: “Question”, “name”: “How can we conserve nature?”, “acceptedAnswer”: { “@type”: “Answer”, “text”: “We can take different steps to conserve nature like stopping the cutting down of trees. We must not use automobiles excessively and take public transport instead. Further, we must not pollute our ocean and river water.” } } ] }

Customize your course in 30 seconds

Which class are you in.

- Travelling Essay

- Picnic Essay

- Our Country Essay

- My Parents Essay

- Essay on Favourite Personality

- Essay on Memorable Day of My Life

- Essay on Knowledge is Power

- Essay on Gurpurab

- Essay on My Favourite Season

- Essay on Types of Sports

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Download the App

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- Front Public Health

The Human–Nature Relationship and Its Impact on Health: A Critical Review

Valentine seymour.

1 Department of Civil, Environmental and Geomatic Engineering, University College London, London, UK

Within the past four decades, research has been increasingly drawn toward understanding whether there is a link between the changing human–nature relationship and its impact on people’s health. However, to examine whether there is a link requires research of its breadth and underlying mechanisms from an interdisciplinary approach. This article begins by reviewing the debates concerning the human–nature relationship, which are then critiqued and redefined from an interdisciplinary perspective. The concept and chronological history of “health” is then explored, based on the World Health Organization’s definition. Combining these concepts, the human–nature relationship and its impact on human’s health are then explored through a developing conceptual model. It is argued that using an interdisciplinary perspective can facilitate a deeper understanding of the complexities involved for attaining optimal health at the human–environmental interface.

Introduction

During the last century, research has been increasingly drawn toward understanding the human–nature relationship ( 1 , 2 ) and has revealed the many ways humans are linked with the natural environment ( 3 ). Some examples of these include humans’ preference for scenes dominated by natural elements ( 4 ), the sustainability of natural resources ( 5 , 6 ), and the health benefits associated with engaging with nature ( 7 – 9 ).

Of these examples, the impacts of the human–nature relationship on people’s health have grown with interest as evidence for a connection accumulates in research literature ( 10 ). Such connection has underpinned a host of theoretical and empirical research in fields, which until now have largely remained as separate entities.

Since the late nineteenth century a number of descriptive models have attempted to encapsulate the dimensions of human and ecosystem health as well as their interrelationships. These include the Environment of Health ( 11 ), the Mandala of Health ( 12 ), the Wheel of Fundamental Human Needs ( 13 ), the Healthy Communities ( 14 ), the One Health ( 15 ), and the bioecological systems theory ( 16 ). Each, however, have not fully incorporated all relevant dimensions, balancing between the biological, social, and spatial perspectives ( 17 , 18 ). In part this is due to the challenges of the already complex research base in relation to its concept, evidence base, measurement, and strategic framework. Further attention to the complexities of these aspects, interlinkages, processes, and relations is required for a deeper sense of understanding and causal directions to be identified ( 19 ).

This article reviews the interconnectivities between the human–nature relationship and human health. It begins by reviewing the each of their concepts and methodological approaches. These concepts will be converged to identify areas of overlap as well as existing research on the potential health impacts in relation to humanity’s degree of relationship to nature and lifestyle choices. From this, a developing conceptual model is proposed, to be inclusive of the human-centered perspective of health, viewing animals and the wider environment within the context of their relationship to humans. The model combines theoretical concepts and methodological approaches from those research fields examined in this review, to facilitate a deeper understanding of the intricacies involved for improving human health.

Defining the Human–Nature Relationship

It is beyond the scope of this paper to review the various connections at the intersect of humanity and the natural environment. Instead, I summarize key concepts and approaches from those four research fields ( Evolutionary Biology , Social Economics , Evolutionary Psychology , and Environmentalism ) outlined below, which have paid most attention to studying this research area. I then summarize areas of convergence between these connections in an attempt to describe the human–nature relationship, which will serve as background to this review.

It is anticipated that through drawing on these different fields of knowledge, a deeper level of understanding can be brought to the growing issue of humanity’s relationship with nature and its impact on health. This is because examining the human–nature relationship from a single disciplinary perspective could lead to partial findings that neglect other important sources as well as the complexities that exist between interlinkages, causal directions, processes, and relations.

Evolutionary Biology

Evolutionary biology is a branch of research that shortly followed Darwin’s ( 20 ) Theory of Evolution. It concerns the adaptive nature of variation in all animal and plant life, shaped by genetic architecture and developmental processes over time and space ( 21 ). Since its emergence over a century ago, the field has made some significant advances in scientific knowledge, but with intense debate still remaining among its central questions, including the rate of evolutionary change, the nature of its transitional processes (e.g., natural selection) ( 22 ). This in part owes to the research field’s interdisciplinary structure, formulated on the foundations of genetics, molecular biology, phylogeny, systematics, physiology, ecology, and population dynamics, integrating a diverging range of disciplines thus producing a host of challenging endeavors ( 23 , 24 ). Spanning each of these, human evolution centers on humanity’s life history since the lineage split from our ancestral primates and our adaptive synergy with nature.

In the last four decades, evolutionary biology has focused much attention on the cultural–genetic interaction and how these two inherent systems interrelate in relation to lifestyle and dietary choices [ Culturgen Evolution ( 25 ); Semi-Independent ( 26 ); Dual-Inheritance model ( 27 )]. Some of the well-known examples include humans’ physiological adaptation to agricultural sustenance ( 28 ), the gradual increase in lactose tolerance ( 29 ) as well as the susceptibility of allergic diseases (e.g., asthma and hay fever) in relation to decreasing microbial exposure ( 30 ).

This coevolutionary perspective between human adaptation and nature has been further conceptualized by Gual and Norgaard ( 31 ) as embedding three integrated systems (biophysical, biotic, and cultural). In this, culture is both constrained and promoted by the human genetics via a dynamic two-way interaction. However, bridging the gap between these research fields continues to generate much controversy, particularly as the nature of these evolutionary development processes differs widely (e.g., internal and external factors). This ongoing discussion is fueled by various scholars from multiple disciplines. Some have argued that one cannot assume all evolutionary mechanisms can be carried over into other areas ( 32 , 33 ), where genomes cannot evolve as quickly to meet modern lifestyle and dietary requirements ( 34 ). Conversely, others believe that humans have not entirely escaped the mechanisms of biological evolution in response to our cultural and technological progressions ( 35 ).

Evolutionary Psychology

Evolutionary psychology is a recently developed field of study, which has grown exponentially with interest since the 1980s. It centers on the adaptation of psychological characteristics said to have evolved over time in response to social and ecological circumstances within humanity’s ancestral environments ( 36 – 38 ). This reverse engineering approach to understanding the design of the human mind was first kindled by evolutionary theorist Charles Darwin ( 20 ) in the last few pages of Origin of Species ;

In the distant future … Psychology will be based on a new foundation, that of the necessary acquirement of each mental power and capacity by gradation [p. 447].

As such, evolutionary psychology is viewed by some to offer a metatheory that dissolves the traditional boundaries held in psychology (e.g., cognitive, social, personality, and development). Within this metatheory, all psychological theories implicitly believed by some to unify under this umbrella ( 37 ). However, the application of evolution to the study of psychology has not been without controversial debate in areas relating to cognitive adaptation, testability of hypotheses, and the uniformity of human nature ( 39 ).

During the past few decades, the field has presented numerous concepts and measures to describe human connectedness to nature. These include Deep Ecology ( 40 ), Extinction of Experience ( 41 ), Inclusion of Nature in Self ( 42 ), and Connectedness to Nature ( 43 ). However, the Biophilia hypothesis ( 44 ) remains the most substantially contributed to theory and argues for the instinctive esthetic preference for natural environments and subconscious affiliation for other living organisms. Supportive findings include humans’ preference for scenes dominated by natural elements ( 4 ), improved cognitive functioning through connectivity with nature ( 45 ) as well as instinctive responses to specific natural stimuli or cues (e.g., a common phobia of snakes) ( 46 ). More recently, evidence is emerging to suggest that connectivity to nature can generate positive impacts on one’s health, increasing with intensity and duration ( 47 ).

The underpinning of the Biophilia hypothesis centers on humanity’s source of attachment to nature beyond those on the surface particulars. Instead, it reflects thousands of years of evolutionary experience closely bonding with other living organisms ( 44 ). Such process is mediated by the rules of prepared and counter-prepared learning that shape our cognitive and emotional apparatus; evolving by natural selection via a cultural context ( 48 ). This innate value for nature is suggested to be reflected in the choices we make, experiences expressed as well as our longstanding actions to maintain our connection to nature ( 49 ). Nevertheless, many have gone on to recognize the research field’s need for revision and further evidentiary support through empirical analysis ( 50 ). Similarly, as other researchers have argued, these innate values should be viewed in complementary to other drivers and affinities from different sources that can also be acquired (e.g., technology and urban landscapes). This is because at the commonest level, as Orr ( 51 ) explains, humanity can learn to love what becomes familiar, a notion also reflected in the Topophilia (“love of place”) hypothesis ( 52 ).

Social Economics

Social economics is a metadiscipline in which economics is embedded in social, political, and cultural behaviors. It examines institutions, choice behavior, rationality as well as values in relation to markets ( 53 ). Owing to its diverse structure, the human–nature relationship has been explored in various contexts. These include the reflections of society’s values and identities in natural landscapes ( 54 ), condition of placelessness ( 55 ), and humanity’s growing ecosynchronous tendencies ( 56 ) as well as how the relationship has evolved with historical context ( 57 – 59 ). While the dynamics of human and nature coupled systems has become a growing interdisciplinary field of research, past work within social economics has remained more theoretical than empirically based ( 59 ).

The connection between the start of industrialized societies and the dynamically evolving human–nature relationship has been discussed by many ( 60 ), revealing a host of economic–nature conflicts. One example includes those metaphorically outlined in the frequently cited article “ The Tragedy of the Commons .” In this, it argues that the four laws of ecology are counter intuitive with the four laws of capitalism ( 5 , 6 ). Based on this perspective, the human–nature relationship is simplified to one of exchange value, where adverse costs to the environment are rarely factored into the equation ( 6 ). However, this is not to say that humanity’s increasing specialization and complexity in most contemporary societies are distinct from nature but still depend on nature to exert ( 61 ).

Central to the tenets outlined in Tragedy of the Commons is the idea of “gradually diminishing freedom” where a population can increasingly exceed the limits of its resources if avoidance measures are not implemented (e.g., privatization or publicly owned property with rights of entry) ( 5 , 62 ). Yet, such avoidance measures can be seen to reflect emerging arguments in the field of environmental justice, which researches the inequalities at the intersection between environmental quality, accessibility, and social hierarchies ( 63 ). These arguments derive from the growing evidence that suggests the human–nature relationship is seemingly disproportionate to those vulnerable groups in society (e.g., lack of green spaces and poor air quality), something public health researchers believe to be a contributing factor to health inequities ( 64 ). As such, conflicts between both private and collective interests remain a challenge for future social economic development ( 65 ). This was explored more fully in Ostrom’s ( 66 ) research on managing a common pool of resources.

Environmentalism

Environmentalism can be broadly defined as an ideology or social movement. It focuses on fundamental environmental concerns as well as associated underlying social, political, and economic issues stemming from humanity’s interactions affecting the natural environment ( 67 , 68 ). In this context, the human–nature relationship has been explored through various human-related activities, from natural resource extraction and environmental hazards to habitat management and restoration. Within each of these reflects a common aspect of “power” visible in much of the literature that centers on environmental history ( 69 ). Some examples included agricultural engineering ( 70 ), the extinction of animals through over hunting ( 71 ) as well as the ecological collapse on Easter Island from human overexploitation of natural resources, since disproven ( 72 – 74 ). Yet, in the last decade, the field’s presupposed dichotomy between humans and nature in relation to power has been critically challenged by Radkau ( 75 ) who regards this perspective as misleading without careful examination. Instead, they propose the relationship to be more closely in synchrony.

Power can be characterized as “ A person, institution, physical event or idea … because it has an impact on society: It affects what people do, think and how they live ” ( 76 ). Though frequently debated in other disciplines, in the context of the human–nature relationship, the concept of “power” can be exerted by both nature and humanity. In regards to nature’s power against humanity, it has the ability to sustain society as well as emphasize its conditional awareness, environmental constraints, and fragilities ( 77 ). In contrast, humanity’s power against nature can take the form of institutions, artifacts, practices, procedures, and techniques ( 70 ). In the context of this review, it focuses on nature’s powers against humanity.

It has been argued that human power over nature has altered and weakened in dominance ( 75 ) since the emergence of Rachel Carson’s book Silent Spring in 1962, and later concepts of Gaia ( 78 ), Deep Ecology ( 40 ), and Sustainable Development ( 79 ). Instead, humanity’s power toward nature has become one of a moral sense of protectionism or the safeguarding of the environment ( 80 ). This conservative behavior (e.g., natural defenses, habitat management, and ecological restoration) can be termed “Urgent Biophilia” ( 81 ) and is the conscious urge to express affinity for nature pending an environmental disaster. As Radkau ( 69 ) suggests, with warnings of climatic change, biodiversity loss, and depletions in natural resources, this poses a threat to humanity. As such, this will eventually generate a turning point where human power is overwhelmed by the power of nature, bringing nature and power into a sustainable balance. Nonetheless, as many also highlight, humanity’s responses to environmental disasters can directly impinge on an array of multi-causalities of intervening variables (e.g., resource depletion and social economics) and the complexity of outcomes ( 82 ).

An Interdisciplinary Perspective of the Human–Nature Relationship

Through exploring the key concepts found in evolutionary biology, social economics, evolutionary psychology, and environmentalism, this has enabled a broader understanding of the various ways humans are connected to the natural environment. Each should not be viewed as separate entities, but rather that they share commonalities in terms of mutual or conjoint information and active research areas where similarities can occur (see Table Table1 1 below). For example, there is a clear connection between social economics, evolutionary psychology, and biology in areas of health, lifestyle, and biophilic nature ( 40 , 53 , 81 ) as well as between social economics and the environment in regards to balancing relationships of power ( 5 , 75 ). Similarly, economic–nature conflicts can occur between disciplines evolutionary psychology and social economics in relation to people’s affiliation for nature and industrial growth.

A summarized overview of human–nature relationship connections between those research fields explored .

| Research field | Type of connection | Description | Examples |

|---|---|---|---|

| Evolutionary biology | Cultural–genetic interaction (coevolution) | The interrelationship between two or more inherent systems (e.g., biophysical, biotic, and cultural). Examples used in this review related to lifestyle and dietary choices Overlaps identified between the following research disciplines and fields: human health (see ), genetics, evolutionary studies, culture, and social economic behaviors | Lumsden and Wilson ( ); Boyd and Richerson ( ); Cohen and Armelagos ( ); Laland et al. ( ); Bloomfield et al. ( ); Gual and Norgaard ( ); Simon ( ); Nelson ( ); Carrera-Bastos et al. ( ); and Powell ( ) |

| Evolutionary psychology | Affiliation to nature | The instinctive esthetic preference and value for nature. Examples used in this review related to people’s feelings of connectedness to nature Overlaps identified between the following research disciplines and fields: evolution, mental health and well-being (see ), social and behavioral ecology, psychology, culture, and human development | Wilson ( ); Naess ( ); Pyle ( ); Schultz ( ); Mayer and Frantz ( ); Howell et al. ( ); Ulrich ( ); Gullone ( ); Depledge et al. ( ); Joye and van den Berg ( ); Orr ( ); and Tuan ( ) |

| Social economics | Economic–nature conflicts | The values of nature are counter intuitive with those values and actions of capitalism. Examples used in this review related to natural resource management Overlaps identified between the following research disciplines and fields: social economics, ecosystem accounting (see ), power relationships, conservation and resource management, affiliation to nature, and biophysical systems | Relph ( ); Hay ( ); Glacken ( ); Buckeridge ( ); Small and Jollands ( ); Hardin ( ); Van Vugt ( ); and Ostrom ( ) |

| Environmentalism | Power relationships | Those power relationships exerted by both nature and humanity. Examples used in this review related to conservation behaviors and management of the natural environment Overlaps identified between the following research disciplines and fields: economic–nature conflicts, conservation management, social and cultural behaviors, social health (see ), affiliation to nature, and biophysical systems | Radkau ( ); Richards ( ); Whited ( ); Hodder and Bullock ( ); Tidball ( ); and Adger et al. ( ) |

Our understanding of the human–nature relationship and its underlying mechanisms could be further understood from an interdisciplinary perspective. In essence, the human–nature relationship can be understood through the Biophilia concept of humanity’s affiliation with nature as well as related concepts and measures to describe human connectedness to nature ( 49 – 53 ). Equally, Orr’s ( 51 ) perspective that at the commonest level humans can acquire other affinities to or learn to love different elements than those of the natural world (e.g., technology and urban environments) adds to this understanding. Further, while humanity, and indeed nature also, has not entirely escaped change, it cannot be assumed that all have been shaped by evolutionary mechanisms ( 42 , 44 ). Some have been shaped by what Radkau ( 75 ) terms as the power shift between humans and nature, which is evolving, as it has and will keep on doing. As such, the human–nature relationship goes beyond the extent to which an individual believes or feels they are part of nature. It can also be understood as, and inclusive of, our adaptive synergy with nature as well as our longstanding actions and experiences that connect us to nature. Over time, as research and scientific knowledge progresses, it is anticipated that this definition of the human–nature relationship will adapt, featuring the addition of other emerging research fields and avenues.

Defining Health

Conceptualizing “health” has often generated complex debates across different disciplines owing to its multidimensional and dynamic nature ( 83 ). It is, however, beyond the scope of this paper to review the many ways these concepts have been previously explored ( 84 – 86 ). Instead, “health” is reviewed and viewed more generally through the lens of the World Health Organization 1948 definition.

The World Health Organization defined “health” simply as the physical, social, and mental well-being of humanity, in which “health” was widened beyond those biomedical aspects (e.g., disease and illness) to encompass the socioeconomic and psychological domains ( 85 ). This classical definition advocated health’s shift toward a holistic perspective, with emphasis on more positive attributes ( 84 , 87 ) and was not simply “ the mere absence of disease and infirmity ” [( 83 ), p. 1]. It also reflected people’s ambitious outlook after the Second World War, when health and peace were seen as inseparable ( 83 , 84 ). Since then, this shift has seen a major growth in the last 30 years, primarily in areas of positive health and psychology ( 88 – 92 ).

Despite its broad perspective of human health, the definition has also encountered criticism in relation to its description and its overall reflectance of modern society. For instance, the use of the term “completeness” when describing optimal health has been regarded by many as impractical. Instead, Huber et al ( 83 ) propose health to be the “ability to adapt and to self-manage” and invite the continuation of further discussions and proposals of this definition to be characterized as well as measured through its three interrelated dimensions; physical, mental, and social health. Similarly, others have highlighted the need to distinguish health from happiness ( 84 ) or its inability to fully reflect modern transformations in knowledge and development (e.g., technology, medicine, genomics as well as physical and social environments) ( 86 ). As such, there have been calls to reconceptualize this definition, to ensure further clarity and relevance for our adaptive societies ( 83 ).

Broadly, health has been measured through two theoretical approaches; subjective and objective ( 85 ). The subjective approach is based on individual’s perceived physical, emotional, and cognitive experiences or functioning. By contrast, the objective approach measures those variables, which are existing and measurable external to an individual’s internal experience such as living conditions or human needs that enable people to lead a good life (e.g., health markers, education, environment, occupational attainment, and civic involvement) ( 85 ). Together, these approaches provide a more comprehensive picture of a person’s health status, which are applicable across its three health components (physical, mental, and social), as described below.

First, physical health is defined as a healthy organism capable of maintaining physiological fitness through protective or adaptive responses during changing circumstances ( 83 ). While it centers on health-related behaviors and fitness (including lifestyle and dietary choices), physiological fitness is considered one of the most important health markers thought to be an integral measure of most bodily functions involved in the performance of daily physical exercise ( 93 ). These can be measured through various means, with examples including questionnaires, behavioral observations, motion sensors, and physiological markers (e.g., heart rate) ( 94 ).

Second, mental health is often regarded as a broad concept to define, encapsulating both mental illness and well-being. It can be characterized as the positive state of well-being and the capacity of a person to cope with life stresses as well as contribute to community engagement activities ( 83 , 95 ). It has the ability to both determine as well as be determined by a host of multifaceted health and social factors being inextricably linked to overall health, inclusive of diet, exercise, and environmental conditions. As a result, there are no single definitive indicators used to capture its overall measurement. This owes in part to the breadth of methods and tends to represent hedonic (e.g., life satisfaction and happiness) and eudaimonic (e.g., virtuous activity) aspects of well-being, each known to be useful predictors of physical health components ( 96 ).

Third, social health can be generalized as the ability to lead life with some degree of independence and participate in social activities ( 83 ). Indicators of the concept revolve around social relationships, social cohesion, and participation in community activities. Further, such mechanisms are closely linked to improving physical and mental well-being as well as forming constructs, which underline social capital. Owing to its complexity, its measurement focuses on strengths of primary networks or relationships (e.g., family, friends, neighborliness, and volunteering in the community) at local, neighborhood, and national levels ( 97 ).

Current Knowledge on the Human–Nature Relationship and Health

This section summarizes existing theoretical and literature research at the intersection of the human–nature relationship and health, as defined in this review. This has been explored through three Subsections “ Physical Health ,” “ Mental Health ,” and “ Social Health .” It aims to identify areas of convergence as well as gaps and limitations.

Physical Health

Though it is widely established that healthy eating and regular exercise have major impacts on physical health ( 98 ), within the past 30 years research has also identified that exposure to nature (e.g., visual, multisensory, or by active engagement) is equally effective for regulating our diurnal body rhythms to ensure physical vitality ( 99 ). Such notion stems from Wilson’s ( 44 ) proposed “Three Pillars of Biophilia” experience categories (Nature of Space, Natural Analogs, and Nature in Space), which relate to natural materials and patterns experienced in nature, inducing a positive impact on health ( 9 ). Empirical research in this domain was first carried out by Ulrich ( 46 ) who found that those hospital patients exposed to natural scenery from a window view experienced decreased levels of pain and shorter recovery time after surgery. Following this, research in this academic field has grown exponentially and encompasses a large literature base on nature’s health benefits. These include improvements in neurological and circadian rhythms relating to exposures to natural sunlight ( 100 , 101 ), undergoing “Earthing” or physical contact with the Earth’s surface regulates diurnal body rhythms ( 102 ) as well as walking activities in forest environments reducing blood pressure levels ( 8 ).

In spite of its increasing findings, some have suggested the need for further objective research at the intersect of nature-based parameters and human health ( 9 ). One reason for this is that most studies have yet to be scrutinized to empirical scientific analysis ( 55 , 103 ) owing to the research area’s reliance on self-reported measures with the need for inclusion of more quantitative forms of data (e.g., physiological and biochemical indicators). This presents inherent difficulty in comparing assessment measures or different data types relative to the size and scale of the variables being evaluated ( 9 ). Further, there still remain evidence gaps in data on what activities might increase levels of physical health as well as limited amount of longitudinal datasets from which the frequency, duration, and causal directions could be inferred ( 104 ).

Mental Health

Mental health studies in the context of connecting with nature have also generated a growing research base since the emergence of the Biophilia concept in the mid-1980s ( 45 ). Much of its research within the Evolutionary Psychology discipline examines the recuperative effects of nature on well-being and its beneficial properties following researcher’s arguments of humanity’s affiliation for nature ( 105 ). Supporting research has been well documented in literature during the last few decades. These include “Heraclitean motion” or natural movement ( 14 ), natural sounds ( 106 ), children’s engagement activities within green settings ( 7 , 107 ) as well as esthetic preferences for nature and natural forms ( 4 , 49 ).

Criticisms of this research area center on the inability to decipher causal effects and direction of such benefits and in part relates to its predominant focus on “recuperative measure” than that of detecting its “source” ( 105 ). In light of this, reviewers repeatedly remark on researchers’ tendencies to focus on outcomes of well-being, neglecting the intervening mechanisms that sustain or inhibit well-being ( 108 ). Similarly, further mixed-method approaches and larger sample sizes are needed in this research field. This would enhance existing evidence gaps to enhance existing knowledge of variable interlinkages with other important sources (e.g., physical and social health aspects) as well as the diversity that exists between individuals ( 104 ).

Social Health

In the last two decades, the relationship between people and place in the context of green spaces has received much attention in academic literature in regards to its importance for the vitality of communities and their surrounding environments ( 109 ). As studies have shown, the presence of green space can promote social cohesion and group-based activities, aspects that are crucial for maintaining social ties, developing communities, and increasing individual’s well-being (e.g., horticulture and ecological restoration) ( 110 ). Examples of findings include usage of outdoor space exponentially increases with number and locality of trees ( 111 ), children’s activities in green spaces improves social development ( 7 ) as well as accessibility to green spaces enhances social bonds in communities ( 112 ).

One of the main limitations within this field relates to the generally perceived idea that public green spaces are freely open to everyone in all capacities ( 113 ). This limitation has been, as already, highlighted from the emerging arguments in the field of environmental justice and economic–nature conflicts ( 63 ). As such, many researchers highlight the need to maintain awareness of other barriers that might hinder cohesion and community participation (e.g., semi-public space and social exclusion). Further, there still remains a gap between academic research and local knowledge, which would otherwise lead to more effective interventions. However, without implementing participatory engagement, many studies risk misrepresenting the true social, economic, and political diversity that would increase both our understanding of “real life” problems of concern as well as bringing depth to data collected ( 114 ). Nonetheless, for such approach to be implemented requires sufficient time, cost, and an adequate scale of resources to ensure for aspects of coordination, communication, and data validation ( 115 ).

Impacts of the Human–Nature Relationship on Health

During the past four decades, researchers, health practitioners, and environmentalists alike have begun to explore the potential link between the human–nature relationship and its impact people’s health ( 10 ). This in part owes to the increasing evidence accumulating in research literature centering on the relationships between the following areas: chronic diseases and urbanization, nature connectedness and happiness, health implications of contemporary society’s lifestyle choices as well as the adverse impacts of environmental quality on the health of humans and non-humans alike ( 116 , 117 ).

Such health-related effects that have been alluded to include chronic diseases, social isolation, emotional well-being as well as other psychiatric disorders (e.g., attention deficit disorders and anxiety) and associated physical symptoms ( 7 , 118 ). Reasons for these proposed links have been suggested to stem from various behavioral patterns (e.g., unhealthy diets and indoor lifestyles) associated with consumerism, urbanization, and anthropogenic polluting activities ( 117 , 119 ). Further, these suggested links have been inferred, by some, to be visible in other species (e.g., insects, mice, and amphibians) as a consequence to living in unnatural habitats or enclosures ( 120 – 122 ). Nonetheless, research within this field remains speculative with few counter examples (e.g., some species of wildlife adapting to urban environments), requiring further empirical analysis ( 108 ).

With a growing trend in the number of chronic diseases and psychiatric disorders, costs to the U. K.’s National Health Service (NHS) could rise as the use of prescriptive drugs and medical interventions increases ( 123 ). However, this anticipated trend is considered to be both undesirable and expensive to the already overwhelmed health-care system ( 124 ). In concurrence are the associated impacts on health equity ( 125 , 126 ), equating to further productivity and tax losses every year in addition to a growing gap in health inequalities ( 127 ).

Furthermore, population growth in urbanized areas is expected to impact future accessibility to and overall loss of natural spaces. Not only would this have a direct detrimental effect on the health of both humans and non-humans but equally the functioning and integrity of ecosystem services that sustain our economic productivity ( 128 ). Thereby, costs of sustaining our human-engineered components of social–ecological systems could rise, having an indirect impact on our economic growth and associated pathways connecting to health ( 129 , 130 ). As such, researchers have highlighted the importance of implementing all characteristics when accounting ecosystem services, particularly the inclusion of natural and health-related capital, as well as their intervening mechanisms. This is an area, which at present remains difficult to synthesize owing to fragmented studies from a host of disciplines that are more conceptually rather than empirically based ( 131 ).

Toward an Interdisciplinary Perspective of Human and Ecosystem Health

Since the late nineteenth century, a number of descriptive models have been developed to encapsulate the dimensions of human health and the natural environment as well as their interrelationships ( 17 ). These include the Environment of Health ( 11 ), the Mandala of Health ( 12 ), the Wheel of Fundamental Human Needs ( 13 ), and the Healthy Communities ( 14 ). As VanLeeuwen et al ( 17 ) highlight in their review, each have not fully incorporated all relevant characteristics of ecosystems (e.g., multiple species, trade-offs, and feedback loops, as well as the complex interrelationships between socioeconomic and biophysical environments). Further, the Bioecological systems theory model encapsulates the biopsychological characteristics of an evolving theoretical system for scientific study of human development over time ( 16 , 132 ). However, the model has been suggested by some ( 133 , 134 ) to be static and compartmentalized in nature, emphasizing instead the importance of evolving synergies between biology, culture, and technology.

More recently, the concept “One Health” has gradually evolved and increased with momentum across various disciplines ( 15 ). It is broadly defined as the attainment of optimal health across the human–animal–environmental interfaces at local, national, and global levels. It calls for a holistic and universal approach to researching health, an ideology said to be traceable to pathologist Rudolf Virchow in 1858 ( 18 ). Yet, the concept has received criticisms regarding its prominence toward the more biological phenomena (e.g., infectious diseases) than those of a social science and spatial perspective ( 18 , 135 ). Some have therefore suggested its need to adopt an interdisciplinary approach to facilitate a deeper understanding of the complexities involved ( 13 ).

To address these limitations identified in the above models, a suggested conceptual model has been outlined below (Figure (Figure1). 1 ). It is both inclusive of all relevant characteristics of ecosystems, their continuously evolving synergies with human health as well as a balance between the biological, social, and spatial perspectives. This is achieved through combining the perspective of the human–nature relationship, as summarized in Section “ Defining the Human–Nature Relationship ” of this review, with those human-centered components of health (physical, mental, and social), as defined by the World Health Organization in 1948 in Section “ Defining Health .” It aims to facilitate a deeper understanding of the complexities involved for attaining optimal human health ( 19 ). I will now describe the conceptual model.

Interdisciplinary perspective of human and ecosystem health [image on the inside circle is by Baird ( 136 ) with the background image, added text, and embedded illustrations being the author’s own work] .

First, the outer circle is representative of “nature” that both encompasses and interconnects with the three human-centered components of health (physical, mental, and social). Through this it emphasizes humanity’s interrelationship with the environment. As identified in Section “ Defining the Human–Nature Relationship ” of this review, the human–nature relationship can be experienced through various biological, ecological, and behavioral connections. For instance, social, political, and economic issues stemming from humanity’s interactions affecting the natural environment (e.g., natural resources, environmental hazards, habitat management, and restoration), as explored in Subsections “ Social Economics ” and “ Environmentalism .”

Second, in the inner circle, the three components of human health (physical, mental, and social) are interconnected through a cohesive triangle to reflect their interdisciplinary and dynamic natures, as outlined in Section “ Defining Health .” Further, this cohesive triangle acts on two levels. First, as a single construct of health based on these components combined. Second, the underlying intervening mechanisms that sustain or inhibit health, which can derive from each of these separately ( 105 ). Thereby, it not only focuses on the outcomes or “recuperative measure” of health but also the source of such outcomes and their directions, as highlighted in Section “ Mental Health ” ( 104 ).

The middle circle represents the interconnected relationship between humanity and the natural environment with relevance to human health (see Current Knowledge on the Human–Nature Relationship and Health ). This has been indicated by the two-way arrows and incorporates Gual and Norgaard’s ( 31 ) coevolutionary perspective between human adaptation and the natural environment. In this way, the relationship is continually interconnected via two-way physical and perceptual interactions. These are embedded within three integrated systems (biophysical, biotic, and cultural), with all humanity knows of the world comes through such mediums ( 31 ). As such, the human–nature relationship goes beyond the extent to which an individual believes or feels they are affiliated with nature (e.g., Biophilia concept). It can also be understood as, and inclusive of, our adaptive synergy with nature as well as our longstanding actions and experiences that connect us to nature.

Utilizing this developing conceptual model, methodological approaches can be employed from those research fields explored in this review, enabling a more interdisciplinary framework. The characteristics, descriptions, implications, and practicalities of this are detailed in Table Table2 2 below. The advantage of this is that a multitude of knowledge from both rigorous scientific analysis as well as collaborative participatory research can be combined bringing a greater depth to data collected ( 114 ). This could be achieved through using more mixed-method approaches and adopting a pragmatic outlook in research. In this way, the true social, economic, and political diversity of “real life” as well as the optimal human health at the human–environmental interface can be identified. As such, a more multidimensional perspective of human health would be gained, knowledge that could be implemented to address those issues identified in Section “ Impacts of the Human–Nature Relationship on Health ” (e.g., improving nature and health ecosystem service accounting). Nonetheless, adopting a pragmatic outlook brings its own challenges, as explored by Onwuegbuzie and Leech ( 137 ), with several researchers proposing frameworks that could be implemented to address these concerns ( 138 , 139 ).

A summarized overview of human and ecosystem health from an interdisciplinary perspective .

| Characteristics | Description | Implications and practicalities | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Human health (inner circle) | Physical, mental, and social health | The three components of human health (see ): physical, mental, and social | This acts on 2 levels: collectively and intervening mechanisms |

| To identify and evaluate the sources, directions as well as outcomes of health. To measure these through both objective and subjective indicators, using a mixed-method approach. Examples include questionnaires, governmental and public datasets, behavioral observations, and physiological markers | |||

| To enhance understanding and accounting of health capital as well as intervening mechanisms. To use such knowledge to foster and support healthy lifestyles and communities | |||

| Human–nature relationship (middle circle) | Biophysical, biotic, and cultural interaction | Describes humans’ connections with the natural environment (see ) and the interrelationship between two or more inherent systems (e.g., biophysical, biotic, and cultural) | This refers to a two-way relationship between human health and nature |

| These connections were explored and summarized from those four research fields, which have paid most attention to studying the interface of humanity and the natural environment: evolutionary biology, evolutionary psychology, social economics, and environmentalism | To identify and evaluate the sources, directions as well as outcomes of these 4 human–nature connections, using an interdisciplinary perspective. To measure these through both objective and subjective indicators, using a mixed-method approach. Examples include participatory research methods, governmental and public datasets, as well as systematic and thematic reviews | ||

| To enhance ecosystem services accounting, to be inclusive of natural and health-related capital. To integrate nature-based activities into health-care systems. To design human environments, social economic systems, and “power” relationships to be more in balance with nature | |||

| Nature (outer circle) | Nature in space, nature of space, and natural analogs | Describes humanity’s exposure to nature and experience categories, which relate to natural materials and patterns experienced in nature, both visually and non-visually (see and ) | Exposure refers to those visual, multisensory, or by active engagement |

| To identify and evaluate the sources, directions as well as outcomes of exposure to nature. To measure these through both objective and subjective indicators, using a mixed-method approach. Examples include interviews, governmental and public datasets, and questionnaires | |||

| To enhance understanding and accounting of natural capital as well as intervening mechanisms. To include such knowledge in human practices (e.g., public policies) and design | |||

Summary and Conclusion

One of the imperatives for this article is to review existing theoretical and research literature on the many ways that humans are linked with the natural environment within various disciplines. Although widely discussed across the main four research fields – evolutionary psychology, environmentalism, evolutionary biology, and social economics – there has been comparatively little discussion of convergence between them on defining the human–nature relationship. This paper therefore attempts to redefine the human–nature relationship to bring further understanding of humanity’s relationship with the natural environment from an interdisciplinary perspective. The paper also highlights important complex debates both within and across these disciplines.

The central discussion was to explore the interrelationships between the human–nature relationship and its impact on human health. In questioning the causal relationship, this paper addresses existing research on potential adverse and beneficial impacts in relation to humanity’s degree of relationship to nature and lifestyle choices. The paper also acknowledged current gaps and limitations of this link relative to the different types of health (physical, mental, and social), as characterized by the World Health Organization in 1948. Most of these relate to research at the intersect of nature-based parameters and human health being in its relative infancy. It has also been highlighted that the reorientation of health toward a well-being perspective brings its own challenges to the already complex research base in relation to its concept, measurement, and strategic framework. For a deeper sense of understanding and causal directions to be identified requires further attention to the complexities of these aspects’ interlinkages, processes, and relations.

Finally, a developing conceptual model of human and ecosystem health that is inclusive of the human-centered perspective is proposed. It is based on an interdisciplinary outlook at the intersection of the human–nature relationship and human health, addressing the limitations identified in existing models. To achieve this, it combines theoretical concepts and methodological approaches from those research fields examined in this review, bringing a greater depth to data collected. In attempting this, a balance between both rigorous scientific analysis as well as collaborative participatory research will be required, adopting a pragmatic outlook. In this way, an interdisciplinary approach can facilitate a deeper understanding of the complexities involved for attaining optimal health at the human–environmental interface.

Author Contributions

The author confirms being the sole contributor of this work and approved it for publication.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The author declares that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

The author would like to thank the following people for their advice and feedback during the writing of this manuscript: Muki Haklay, Pippa Bark-Williams, Mike Wood, Peter J. Burt, Catherine Holloway, Jenny Mindell, Claire Ellul, Elizabeth H. Boakes, Gianfranco Gliozzo, Chris Spears, Louisa Hooper, and Roberta Antonica. University College London and The Conservation Volunteers sponsored this research.

Click through the PLOS taxonomy to find articles in your field.

For more information about PLOS Subject Areas, click here .

Loading metrics

Open Access

Peer-reviewed

Research Article

Human-nature relationships in context. Experiential, psychological, and contextual dimensions that shape children’s desire to protect nature

Roles Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Validation, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing

* E-mail: [email protected]

Affiliation Department of Building Engineering, Energy Systems and Sustainability Science, University of Gävle, Gävle, Sweden

- Matteo Giusti

- Published: December 5, 2019

- https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0225951

- Reader Comments

What relationship with nature shapes children’s desire to protect the environment? This study crosses conventional disciplinary boundaries to explore this question. I use qualitative and quantitative methods to analyse experiential, psychological, and contextual dimensions of Human-Nature Connection (HNC) before and after children participate in a project of nature conservation. The results from the interviews (N = 25) suggest that experiential aspects of saving animals enhance children’s appreciation and understanding for animals, nature, and nature conservation. However, the analysis of children’s psychological HNC (N = 158) shows no statistical difference before and after children participate in the project. Analysing the third dimension–children’s contextual HNC–provides further insights. Including children’s contextual relations with home, nature, and city, not only improves the prediction of their desire to work for nature, but also exposes a form of Human-Nature Disconnection (HND) shaped by children’s closeness to cities that negatively influence it. Overall, combining experiential, psychological, and contextual dimensions of HNC provides rich insights to advance the conceptualisation and assessment of human-nature relationships. People’s relationship with nature is better conceived and analysed as systems of relations between mind, body, culture, and environment, which progress through complex dynamics. Future assessments of HNC and HND would benefit from short-term qualitative and long-term quantitative evaluations that explicitly acknowledge their spatial and cultural contexts. This approach would offer novel and valuable insights to promote the psychological and social determinants of resilient sustainable society.

Citation: Giusti M (2019) Human-nature relationships in context. Experiential, psychological, and contextual dimensions that shape children’s desire to protect nature. PLoS ONE 14(12): e0225951. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0225951

Editor: Stefano Federici, Università degli Studi di Perugia, ITALY

Received: April 11, 2019; Accepted: November 15, 2019; Published: December 5, 2019

Copyright: © 2019 Matteo Giusti. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Data Availability: All relevant data are within the manuscript and its Supporting Information files.

Funding: I thank the Formas supported project ZEUS (ref no.: 2016- 01193) granted to S.B. for supporting this work. formas.se.

Competing interests: The authors have declared that no competing interests exist.

Introduction

Living within sustainable boundaries is a challenge that concerns this and the future generations of humans [ 1 ]. How future generations will develop the desire to protect the environment and live sustainably is a research subject that is receiving exponential attention [ 2 ]. Across environmental and conservation psychology [ 3 , 4 ], landscape management [ 5 , 6 ], biological conservation [ 7 , 8 ] and social-ecological sustainability research [ 9 – 12 ], a personal connection with nature is considered a core determinant for environmental protection and sustainable living. However, many in academia recognise that the ability to appreciate, and eventually protect, the biosphere is threatened by children’s lack of direct nature experiences [ 13 – 16 ] and by the increasing virtualisation of children’s lives [ 17 – 19 ]. These pressures—and the urgent need to create sustainable living standards—are driving a new multidisciplinary arena that investigates how psychological and social determinants of sustainable societies develop in people [ 4 , 20 – 22 ]. Hence, human-nature relationships are studied across many disciplines, but oftentimes disciplinary boundaries limit the valuable integration of the complementary insights produced [ 2 ]. This study addresses this interdisciplinary research gap.

This study aims to advance the conceptualisation and assessment of human-nature relationships to better understand what promotes children’s desire to protect nature. To achieve this aim, this study investigates how participating in a project of nature conservation affects children’s human-nature relationship. In the sections below, I introduce the different dimensions of human-nature relationships that exist within disciplines, I described how the study is designed and the conservation project under examination, and then list the methods used. Afterwards, I describe the results of the study, summarise them in the context of the nature conservation project, and then discuss how they contribute to improving the conceptualisation and assessment of human-nature relationships to better predict children’s desire to work for nature in the future.

Psychological, experiential, and contextual human-nature connection

Human-Nature Connection (HNC) is a concept that emerges from a multidisciplinary review of the body of knowledge on human-nature relationships [ 2 ]. This concept joins three complementary dimensions of human-nature relationships that are often studied in isolation from each other. The first dimension ( psychological HNC ) emerges from research that considers human-nature relationships as an attribute of the mind. This body of literature studies the psychological connection to an abstract form of nature. Changes in people’s connection with nature are measured using quantitative methods often to describe psychological dynamics or to predict specific pro-environmental behaviours (for examples see [ 23 , 24 ]). The second dimension ( experiential HNC ) is representative of qualitative research that describes human-nature relationships as experiences of being in nature. Here, researchers observe and describe people’s interaction with local nature (for example see [ 25 ]). The last dimension ( contextual HNC ) emerges from research on ‘sense of place’ and it investigates human-nature relationships as the sense of belonging that people develop through time with geographical areas. Typically, these studies use questionnaires to study people’s attachment to specific natural landscapes (for review see [ 6 ]).

Despite these psychological, experiential, and contextual dimensions of human-nature relationships being investigated and reported on, single studies usually focus only on one dimension. In doing so, the valuable cross-fertilization across these bodies of knowledge is largely missing [ 2 ]. Beyond the missed opportunity for valuable interdisciplinary insights, disciplinary boundaries have shown to limit the analysis of human-nature relationships. For instance, the predictive power of psychological HNC alone for pro-environmental behaviours is limited when contextual factors are introduced [ 26 – 28 ]. Duffy and Verges [ 26 ] show that seasonal and meteorological factors meaningfully influence people’s association with nature. Contextual influences to psychological HNC are also evident when the RSPB [ 29 ] reports that, somehow counterintuitively, British children are psychologically closer to nature in urban rather than in rural areas. Geographical access to nature experiences is shown to promote children’s psychological HNC [ 30 ], but it stands to question to what kind of nature children develop their appreciation for. Not all nature experiences are equal [ 31 – 33 ] and there is initial indication that different kinds of nature experiences contribute to different aspects of children’s relationship with nature [ 34 ]. This study operationalises, analyses, and discusses the three dimensions of HNC jointly and offers interdisciplinary insights to address some of these limitations.

Study design

Empirically, this study focuses on children. This is because nature experiences during childhood can promote the psychological foundation for a multitude of environmentally conscious behaviours [ 35 – 37 ] and for an adult life devoted to environmental protection [ 38 – 41 ]. In this study, the experiential dimension of HNC is assessed qualitatively after children participate in a project of nature conservation (see section below for details). The impact of this nature experience on children’s psychological and contextual dimensions of HNC is then quantitatively evaluated. This numerical data is analysed to understand what best predicts children’s desire to protect the environment in the future or work for environmental organisations.

The design of this study responds to the need to analyse all dimensions of HNC simultaneously, by using a multi-method approach on a large dataset of participants in combination with some control over socio-demographic factors [ 42 ]. This design addresses two critiques common to retrospective research on nature experiences: first, participants have a nearly identical socio-cultural background (e.g. age, level of education, and culture) and, second, they are assessed when memories are still vivid [ 43 ]. This multi-dimensional and interdisciplinary investigation provides a set of results useful to discuss the constituents of human-nature relationships and to debate what shapes children’s desire to protect nature.

The salamander project