Advertisement

Students’ online learning challenges during the pandemic and how they cope with them: The case of the Philippines

- Published: 28 May 2021

- Volume 26 , pages 7321–7338, ( 2021 )

Cite this article

- Jessie S. Barrot ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0001-8517-4058 1 ,

- Ian I. Llenares 1 &

- Leo S. del Rosario 1

938k Accesses

247 Citations

4 Altmetric

Explore all metrics

Recently, the education system has faced an unprecedented health crisis that has shaken up its foundation. Given today’s uncertainties, it is vital to gain a nuanced understanding of students’ online learning experience in times of the COVID-19 pandemic. Although many studies have investigated this area, limited information is available regarding the challenges and the specific strategies that students employ to overcome them. Thus, this study attempts to fill in the void. Using a mixed-methods approach, the findings revealed that the online learning challenges of college students varied in terms of type and extent. Their greatest challenge was linked to their learning environment at home, while their least challenge was technological literacy and competency. The findings further revealed that the COVID-19 pandemic had the greatest impact on the quality of the learning experience and students’ mental health. In terms of strategies employed by students, the most frequently used were resource management and utilization, help-seeking, technical aptitude enhancement, time management, and learning environment control. Implications for classroom practice, policy-making, and future research are discussed.

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

Since the 1990s, the world has seen significant changes in the landscape of education as a result of the ever-expanding influence of technology. One such development is the adoption of online learning across different learning contexts, whether formal or informal, academic and non-academic, and residential or remotely. We began to witness schools, teachers, and students increasingly adopt e-learning technologies that allow teachers to deliver instruction interactively, share resources seamlessly, and facilitate student collaboration and interaction (Elaish et al., 2019 ; Garcia et al., 2018 ). Although the efficacy of online learning has long been acknowledged by the education community (Barrot, 2020 , 2021 ; Cavanaugh et al., 2009 ; Kebritchi et al., 2017 ; Tallent-Runnels et al., 2006 ; Wallace, 2003 ), evidence on the challenges in its implementation continues to build up (e.g., Boelens et al., 2017 ; Rasheed et al., 2020 ).

Recently, the education system has faced an unprecedented health crisis (i.e., COVID-19 pandemic) that has shaken up its foundation. Thus, various governments across the globe have launched a crisis response to mitigate the adverse impact of the pandemic on education. This response includes, but is not limited to, curriculum revisions, provision for technological resources and infrastructure, shifts in the academic calendar, and policies on instructional delivery and assessment. Inevitably, these developments compelled educational institutions to migrate to full online learning until face-to-face instruction is allowed. The current circumstance is unique as it could aggravate the challenges experienced during online learning due to restrictions in movement and health protocols (Gonzales et al., 2020 ; Kapasia et al., 2020 ). Given today’s uncertainties, it is vital to gain a nuanced understanding of students’ online learning experience in times of the COVID-19 pandemic. To date, many studies have investigated this area with a focus on students’ mental health (Copeland et al., 2021 ; Fawaz et al., 2021 ), home learning (Suryaman et al., 2020 ), self-regulation (Carter et al., 2020 ), virtual learning environment (Almaiah et al., 2020 ; Hew et al., 2020 ; Tang et al., 2020 ), and students’ overall learning experience (e.g., Adarkwah, 2021 ; Day et al., 2021 ; Khalil et al., 2020 ; Singh et al., 2020 ). There are two key differences that set the current study apart from the previous studies. First, it sheds light on the direct impact of the pandemic on the challenges that students experience in an online learning space. Second, the current study explores students’ coping strategies in this new learning setup. Addressing these areas would shed light on the extent of challenges that students experience in a full online learning space, particularly within the context of the pandemic. Meanwhile, our nuanced understanding of the strategies that students use to overcome their challenges would provide relevant information to school administrators and teachers to better support the online learning needs of students. This information would also be critical in revisiting the typology of strategies in an online learning environment.

2 Literature review

2.1 education and the covid-19 pandemic.

In December 2019, an outbreak of a novel coronavirus, known as COVID-19, occurred in China and has spread rapidly across the globe within a few months. COVID-19 is an infectious disease caused by a new strain of coronavirus that attacks the respiratory system (World Health Organization, 2020 ). As of January 2021, COVID-19 has infected 94 million people and has caused 2 million deaths in 191 countries and territories (John Hopkins University, 2021 ). This pandemic has created a massive disruption of the educational systems, affecting over 1.5 billion students. It has forced the government to cancel national examinations and the schools to temporarily close, cease face-to-face instruction, and strictly observe physical distancing. These events have sparked the digital transformation of higher education and challenged its ability to respond promptly and effectively. Schools adopted relevant technologies, prepared learning and staff resources, set systems and infrastructure, established new teaching protocols, and adjusted their curricula. However, the transition was smooth for some schools but rough for others, particularly those from developing countries with limited infrastructure (Pham & Nguyen, 2020 ; Simbulan, 2020 ).

Inevitably, schools and other learning spaces were forced to migrate to full online learning as the world continues the battle to control the vicious spread of the virus. Online learning refers to a learning environment that uses the Internet and other technological devices and tools for synchronous and asynchronous instructional delivery and management of academic programs (Usher & Barak, 2020 ; Huang, 2019 ). Synchronous online learning involves real-time interactions between the teacher and the students, while asynchronous online learning occurs without a strict schedule for different students (Singh & Thurman, 2019 ). Within the context of the COVID-19 pandemic, online learning has taken the status of interim remote teaching that serves as a response to an exigency. However, the migration to a new learning space has faced several major concerns relating to policy, pedagogy, logistics, socioeconomic factors, technology, and psychosocial factors (Donitsa-Schmidt & Ramot, 2020 ; Khalil et al., 2020 ; Varea & González-Calvo, 2020 ). With reference to policies, government education agencies and schools scrambled to create fool-proof policies on governance structure, teacher management, and student management. Teachers, who were used to conventional teaching delivery, were also obliged to embrace technology despite their lack of technological literacy. To address this problem, online learning webinars and peer support systems were launched. On the part of the students, dropout rates increased due to economic, psychological, and academic reasons. Academically, although it is virtually possible for students to learn anything online, learning may perhaps be less than optimal, especially in courses that require face-to-face contact and direct interactions (Franchi, 2020 ).

2.2 Related studies

Recently, there has been an explosion of studies relating to the new normal in education. While many focused on national policies, professional development, and curriculum, others zeroed in on the specific learning experience of students during the pandemic. Among these are Copeland et al. ( 2021 ) and Fawaz et al. ( 2021 ) who examined the impact of COVID-19 on college students’ mental health and their coping mechanisms. Copeland et al. ( 2021 ) reported that the pandemic adversely affected students’ behavioral and emotional functioning, particularly attention and externalizing problems (i.e., mood and wellness behavior), which were caused by isolation, economic/health effects, and uncertainties. In Fawaz et al.’s ( 2021 ) study, students raised their concerns on learning and evaluation methods, overwhelming task load, technical difficulties, and confinement. To cope with these problems, students actively dealt with the situation by seeking help from their teachers and relatives and engaging in recreational activities. These active-oriented coping mechanisms of students were aligned with Carter et al.’s ( 2020 ), who explored students’ self-regulation strategies.

In another study, Tang et al. ( 2020 ) examined the efficacy of different online teaching modes among engineering students. Using a questionnaire, the results revealed that students were dissatisfied with online learning in general, particularly in the aspect of communication and question-and-answer modes. Nonetheless, the combined model of online teaching with flipped classrooms improved students’ attention, academic performance, and course evaluation. A parallel study was undertaken by Hew et al. ( 2020 ), who transformed conventional flipped classrooms into fully online flipped classes through a cloud-based video conferencing app. Their findings suggested that these two types of learning environments were equally effective. They also offered ways on how to effectively adopt videoconferencing-assisted online flipped classrooms. Unlike the two studies, Suryaman et al. ( 2020 ) looked into how learning occurred at home during the pandemic. Their findings showed that students faced many obstacles in a home learning environment, such as lack of mastery of technology, high Internet cost, and limited interaction/socialization between and among students. In a related study, Kapasia et al. ( 2020 ) investigated how lockdown impacts students’ learning performance. Their findings revealed that the lockdown made significant disruptions in students’ learning experience. The students also reported some challenges that they faced during their online classes. These include anxiety, depression, poor Internet service, and unfavorable home learning environment, which were aggravated when students are marginalized and from remote areas. Contrary to Kapasia et al.’s ( 2020 ) findings, Gonzales et al. ( 2020 ) found that confinement of students during the pandemic had significant positive effects on their performance. They attributed these results to students’ continuous use of learning strategies which, in turn, improved their learning efficiency.

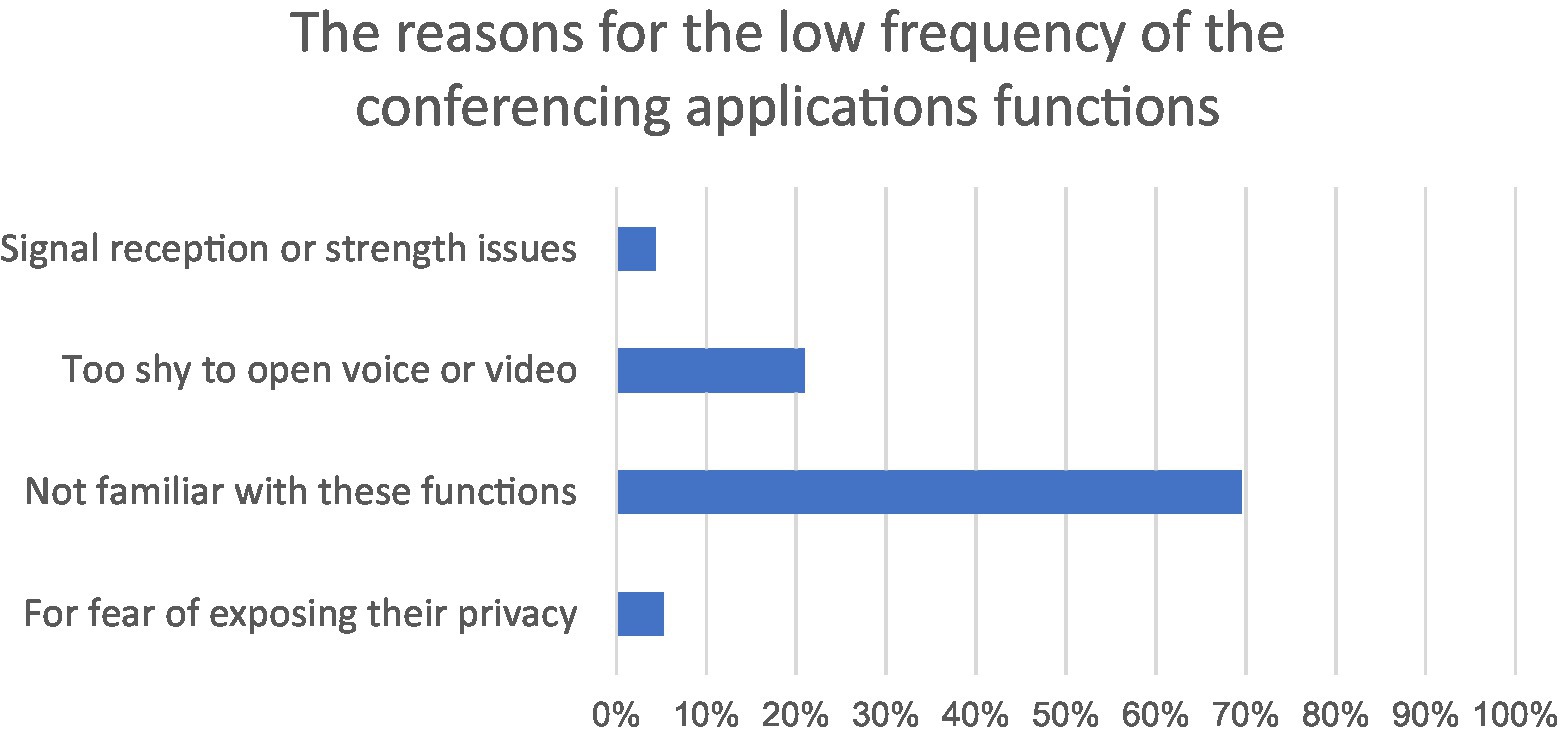

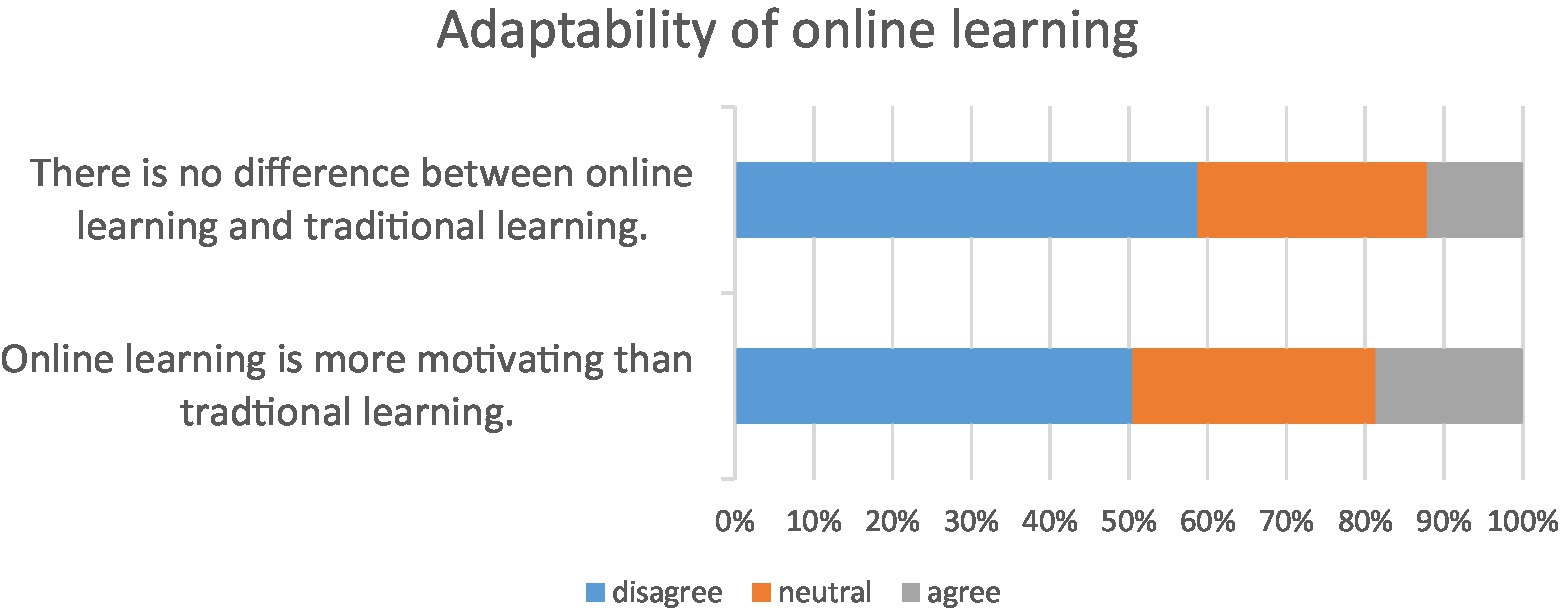

Finally, there are those that focused on students’ overall online learning experience during the COVID-19 pandemic. One such study was that of Singh et al. ( 2020 ), who examined students’ experience during the COVID-19 pandemic using a quantitative descriptive approach. Their findings indicated that students appreciated the use of online learning during the pandemic. However, half of them believed that the traditional classroom setting was more effective than the online learning platform. Methodologically, the researchers acknowledge that the quantitative nature of their study restricts a deeper interpretation of the findings. Unlike the above study, Khalil et al. ( 2020 ) qualitatively explored the efficacy of synchronized online learning in a medical school in Saudi Arabia. The results indicated that students generally perceive synchronous online learning positively, particularly in terms of time management and efficacy. However, they also reported technical (internet connectivity and poor utility of tools), methodological (content delivery), and behavioral (individual personality) challenges. Their findings also highlighted the failure of the online learning environment to address the needs of courses that require hands-on practice despite efforts to adopt virtual laboratories. In a parallel study, Adarkwah ( 2021 ) examined students’ online learning experience during the pandemic using a narrative inquiry approach. The findings indicated that Ghanaian students considered online learning as ineffective due to several challenges that they encountered. Among these were lack of social interaction among students, poor communication, lack of ICT resources, and poor learning outcomes. More recently, Day et al. ( 2021 ) examined the immediate impact of COVID-19 on students’ learning experience. Evidence from six institutions across three countries revealed some positive experiences and pre-existing inequities. Among the reported challenges are lack of appropriate devices, poor learning space at home, stress among students, and lack of fieldwork and access to laboratories.

Although there are few studies that report the online learning challenges that higher education students experience during the pandemic, limited information is available regarding the specific strategies that they use to overcome them. It is in this context that the current study was undertaken. This mixed-methods study investigates students’ online learning experience in higher education. Specifically, the following research questions are addressed: (1) What is the extent of challenges that students experience in an online learning environment? (2) How did the COVID-19 pandemic impact the online learning challenges that students experience? (3) What strategies did students use to overcome the challenges?

2.3 Conceptual framework

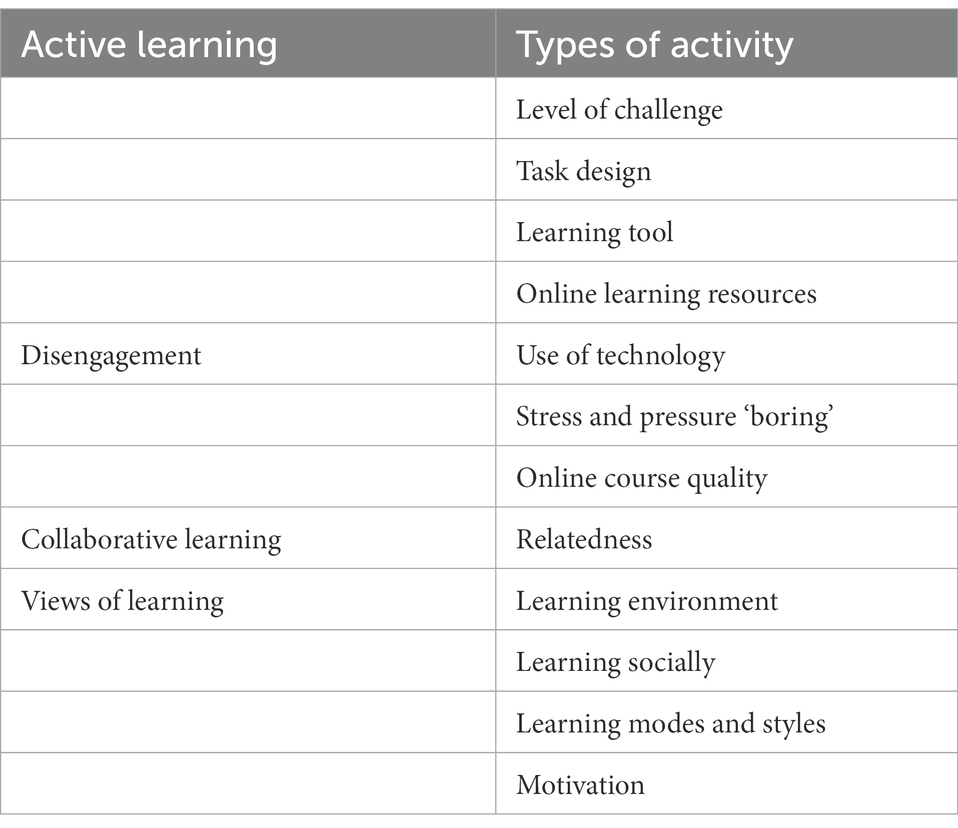

The typology of challenges examined in this study is largely based on Rasheed et al.’s ( 2020 ) review of students’ experience in an online learning environment. These challenges are grouped into five general clusters, namely self-regulation (SRC), technological literacy and competency (TLCC), student isolation (SIC), technological sufficiency (TSC), and technological complexity (TCC) challenges (Rasheed et al., 2020 , p. 5). SRC refers to a set of behavior by which students exercise control over their emotions, actions, and thoughts to achieve learning objectives. TLCC relates to a set of challenges about students’ ability to effectively use technology for learning purposes. SIC relates to the emotional discomfort that students experience as a result of being lonely and secluded from their peers. TSC refers to a set of challenges that students experience when accessing available online technologies for learning. Finally, there is TCC which involves challenges that students experience when exposed to complex and over-sufficient technologies for online learning.

To extend Rasheed et al. ( 2020 ) categories and to cover other potential challenges during online classes, two more clusters were added, namely learning resource challenges (LRC) and learning environment challenges (LEC) (Buehler, 2004 ; Recker et al., 2004 ; Seplaki et al., 2014 ; Xue et al., 2020 ). LRC refers to a set of challenges that students face relating to their use of library resources and instructional materials, whereas LEC is a set of challenges that students experience related to the condition of their learning space that shapes their learning experiences, beliefs, and attitudes. Since learning environment at home and learning resources available to students has been reported to significantly impact the quality of learning and their achievement of learning outcomes (Drane et al., 2020 ; Suryaman et al., 2020 ), the inclusion of LRC and LEC would allow us to capture other important challenges that students experience during the pandemic, particularly those from developing regions. This comprehensive list would provide us a clearer and detailed picture of students’ experiences when engaged in online learning in an emergency. Given the restrictions in mobility at macro and micro levels during the pandemic, it is also expected that such conditions would aggravate these challenges. Therefore, this paper intends to understand these challenges from students’ perspectives since they are the ones that are ultimately impacted when the issue is about the learning experience. We also seek to explore areas that provide inconclusive findings, thereby setting the path for future research.

3 Material and methods

The present study adopted a descriptive, mixed-methods approach to address the research questions. This approach allowed the researchers to collect complex data about students’ experience in an online learning environment and to clearly understand the phenomena from their perspective.

3.1 Participants

This study involved 200 (66 male and 134 female) students from a private higher education institution in the Philippines. These participants were Psychology, Physical Education, and Sports Management majors whose ages ranged from 17 to 25 ( x̅ = 19.81; SD = 1.80). The students have been engaged in online learning for at least two terms in both synchronous and asynchronous modes. The students belonged to low- and middle-income groups but were equipped with the basic online learning equipment (e.g., computer, headset, speakers) and computer skills necessary for their participation in online classes. Table 1 shows the primary and secondary platforms that students used during their online classes. The primary platforms are those that are formally adopted by teachers and students in a structured academic context, whereas the secondary platforms are those that are informally and spontaneously used by students and teachers for informal learning and to supplement instructional delivery. Note that almost all students identified MS Teams as their primary platform because it is the official learning management system of the university.

Informed consent was sought from the participants prior to their involvement. Before students signed the informed consent form, they were oriented about the objectives of the study and the extent of their involvement. They were also briefed about the confidentiality of information, their anonymity, and their right to refuse to participate in the investigation. Finally, the participants were informed that they would incur no additional cost from their participation.

3.2 Instrument and data collection

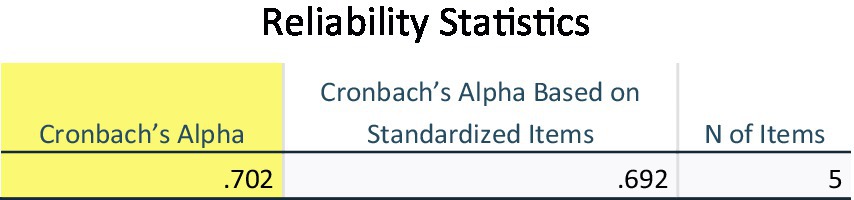

The data were collected using a retrospective self-report questionnaire and a focused group discussion (FGD). A self-report questionnaire was considered appropriate because the indicators relate to affective responses and attitude (Araujo et al., 2017 ; Barrot, 2016 ; Spector, 1994 ). Although the participants may tell more than what they know or do in a self-report survey (Matsumoto, 1994 ), this challenge was addressed by explaining to them in detail each of the indicators and using methodological triangulation through FGD. The questionnaire was divided into four sections: (1) participant’s personal information section, (2) the background information on the online learning environment, (3) the rating scale section for the online learning challenges, (4) the open-ended section. The personal information section asked about the students’ personal information (name, school, course, age, and sex), while the background information section explored the online learning mode and platforms (primary and secondary) used in class, and students’ length of engagement in online classes. The rating scale section contained 37 items that relate to SRC (6 items), TLCC (10 items), SIC (4 items), TSC (6 items), TCC (3 items), LRC (4 items), and LEC (4 items). The Likert scale uses six scores (i.e., 5– to a very great extent , 4– to a great extent , 3– to a moderate extent , 2– to some extent , 1– to a small extent , and 0 –not at all/negligible ) assigned to each of the 37 items. Finally, the open-ended questions asked about other challenges that students experienced, the impact of the pandemic on the intensity or extent of the challenges they experienced, and the strategies that the participants employed to overcome the eight different types of challenges during online learning. Two experienced educators and researchers reviewed the questionnaire for clarity, accuracy, and content and face validity. The piloting of the instrument revealed that the tool had good internal consistency (Cronbach’s α = 0.96).

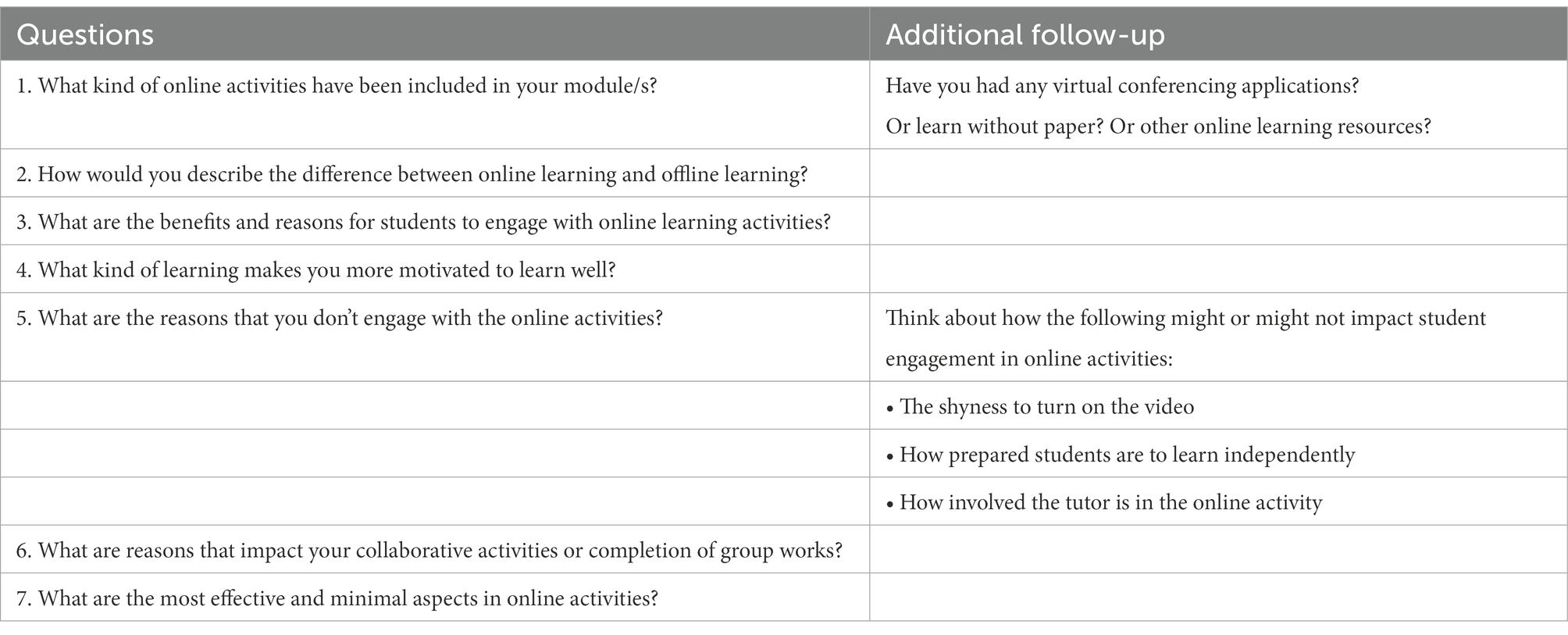

The FGD protocol contains two major sections: the participants’ background information and the main questions. The background information section asked about the students’ names, age, courses being taken, online learning mode used in class. The items in the main questions section covered questions relating to the students’ overall attitude toward online learning during the pandemic, the reasons for the scores they assigned to each of the challenges they experienced, the impact of the pandemic on students’ challenges, and the strategies they employed to address the challenges. The same experts identified above validated the FGD protocol.

Both the questionnaire and the FGD were conducted online via Google survey and MS Teams, respectively. It took approximately 20 min to complete the questionnaire, while the FGD lasted for about 90 min. Students were allowed to ask for clarification and additional explanations relating to the questionnaire content, FGD, and procedure. Online surveys and interview were used because of the ongoing lockdown in the city. For the purpose of triangulation, 20 (10 from Psychology and 10 from Physical Education and Sports Management) randomly selected students were invited to participate in the FGD. Two separate FGDs were scheduled for each group and were facilitated by researcher 2 and researcher 3, respectively. The interviewers ensured that the participants were comfortable and open to talk freely during the FGD to avoid social desirability biases (Bergen & Labonté, 2020 ). These were done by informing the participants that there are no wrong responses and that their identity and responses would be handled with the utmost confidentiality. With the permission of the participants, the FGD was recorded to ensure that all relevant information was accurately captured for transcription and analysis.

3.3 Data analysis

To address the research questions, we used both quantitative and qualitative analyses. For the quantitative analysis, we entered all the data into an excel spreadsheet. Then, we computed the mean scores ( M ) and standard deviations ( SD ) to determine the level of challenges experienced by students during online learning. The mean score for each descriptor was interpreted using the following scheme: 4.18 to 5.00 ( to a very great extent ), 3.34 to 4.17 ( to a great extent ), 2.51 to 3.33 ( to a moderate extent ), 1.68 to 2.50 ( to some extent ), 0.84 to 1.67 ( to a small extent ), and 0 to 0.83 ( not at all/negligible ). The equal interval was adopted because it produces more reliable and valid information than other types of scales (Cicchetti et al., 2006 ).

For the qualitative data, we analyzed the students’ responses in the open-ended questions and the transcribed FGD using the predetermined categories in the conceptual framework. Specifically, we used multilevel coding in classifying the codes from the transcripts (Birks & Mills, 2011 ). To do this, we identified the relevant codes from the responses of the participants and categorized these codes based on the similarities or relatedness of their properties and dimensions. Then, we performed a constant comparative and progressive analysis of cases to allow the initially identified subcategories to emerge and take shape. To ensure the reliability of the analysis, two coders independently analyzed the qualitative data. Both coders familiarize themselves with the purpose, research questions, research method, and codes and coding scheme of the study. They also had a calibration session and discussed ways on how they could consistently analyze the qualitative data. Percent of agreement between the two coders was 86 percent. Any disagreements in the analysis were discussed by the coders until an agreement was achieved.

This study investigated students’ online learning experience in higher education within the context of the pandemic. Specifically, we identified the extent of challenges that students experienced, how the COVID-19 pandemic impacted their online learning experience, and the strategies that they used to confront these challenges.

4.1 The extent of students’ online learning challenges

Table 2 presents the mean scores and SD for the extent of challenges that students’ experienced during online learning. Overall, the students experienced the identified challenges to a moderate extent ( x̅ = 2.62, SD = 1.03) with scores ranging from x̅ = 1.72 ( to some extent ) to x̅ = 3.58 ( to a great extent ). More specifically, the greatest challenge that students experienced was related to the learning environment ( x̅ = 3.49, SD = 1.27), particularly on distractions at home, limitations in completing the requirements for certain subjects, and difficulties in selecting the learning areas and study schedule. It is, however, found that the least challenge was on technological literacy and competency ( x̅ = 2.10, SD = 1.13), particularly on knowledge and training in the use of technology, technological intimidation, and resistance to learning technologies. Other areas that students experienced the least challenge are Internet access under TSC and procrastination under SRC. Nonetheless, nearly half of the students’ responses per indicator rated the challenges they experienced as moderate (14 of the 37 indicators), particularly in TCC ( x̅ = 2.51, SD = 1.31), SIC ( x̅ = 2.77, SD = 1.34), and LRC ( x̅ = 2.93, SD = 1.31).

Out of 200 students, 181 responded to the question about other challenges that they experienced. Most of their responses were already covered by the seven predetermined categories, except for 18 responses related to physical discomfort ( N = 5) and financial challenges ( N = 13). For instance, S108 commented that “when it comes to eyes and head, my eyes and head get ache if the session of class was 3 h straight in front of my gadget.” In the same vein, S194 reported that “the long exposure to gadgets especially laptop, resulting in body pain & headaches.” With reference to physical financial challenges, S66 noted that “not all the time I have money to load”, while S121 claimed that “I don't know until when are we going to afford budgeting our money instead of buying essentials.”

4.2 Impact of the pandemic on students’ online learning challenges

Another objective of this study was to identify how COVID-19 influenced the online learning challenges that students experienced. As shown in Table 3 , most of the students’ responses were related to teaching and learning quality ( N = 86) and anxiety and other mental health issues ( N = 52). Regarding the adverse impact on teaching and learning quality, most of the comments relate to the lack of preparation for the transition to online platforms (e.g., S23, S64), limited infrastructure (e.g., S13, S65, S99, S117), and poor Internet service (e.g., S3, S9, S17, S41, S65, S99). For the anxiety and mental health issues, most students reported that the anxiety, boredom, sadness, and isolation they experienced had adversely impacted the way they learn (e.g., S11, S130), completing their tasks/activities (e.g., S56, S156), and their motivation to continue studying (e.g., S122, S192). The data also reveal that COVID-19 aggravated the financial difficulties experienced by some students ( N = 16), consequently affecting their online learning experience. This financial impact mainly revolved around the lack of funding for their online classes as a result of their parents’ unemployment and the high cost of Internet data (e.g., S18, S113, S167). Meanwhile, few concerns were raised in relation to COVID-19’s impact on mobility ( N = 7) and face-to-face interactions ( N = 7). For instance, some commented that the lack of face-to-face interaction with her classmates had a detrimental effect on her learning (S46) and socialization skills (S36), while others reported that restrictions in mobility limited their learning experience (S78, S110). Very few comments were related to no effect ( N = 4) and positive effect ( N = 2). The above findings suggest the pandemic had additive adverse effects on students’ online learning experience.

4.3 Students’ strategies to overcome challenges in an online learning environment

The third objective of this study is to identify the strategies that students employed to overcome the different online learning challenges they experienced. Table 4 presents that the most commonly used strategies used by students were resource management and utilization ( N = 181), help-seeking ( N = 155), technical aptitude enhancement ( N = 122), time management ( N = 98), and learning environment control ( N = 73). Not surprisingly, the top two strategies were also the most consistently used across different challenges. However, looking closely at each of the seven challenges, the frequency of using a particular strategy varies. For TSC and LRC, the most frequently used strategy was resource management and utilization ( N = 52, N = 89, respectively), whereas technical aptitude enhancement was the students’ most preferred strategy to address TLCC ( N = 77) and TCC ( N = 38). In the case of SRC, SIC, and LEC, the most frequently employed strategies were time management ( N = 71), psychological support ( N = 53), and learning environment control ( N = 60). In terms of consistency, help-seeking appears to be the most consistent across the different challenges in an online learning environment. Table 4 further reveals that strategies used by students within a specific type of challenge vary.

5 Discussion and conclusions

The current study explores the challenges that students experienced in an online learning environment and how the pandemic impacted their online learning experience. The findings revealed that the online learning challenges of students varied in terms of type and extent. Their greatest challenge was linked to their learning environment at home, while their least challenge was technological literacy and competency. Based on the students’ responses, their challenges were also found to be aggravated by the pandemic, especially in terms of quality of learning experience, mental health, finances, interaction, and mobility. With reference to previous studies (i.e., Adarkwah, 2021 ; Copeland et al., 2021 ; Day et al., 2021 ; Fawaz et al., 2021 ; Kapasia et al., 2020 ; Khalil et al., 2020 ; Singh et al., 2020 ), the current study has complemented their findings on the pedagogical, logistical, socioeconomic, technological, and psychosocial online learning challenges that students experience within the context of the COVID-19 pandemic. Further, this study extended previous studies and our understanding of students’ online learning experience by identifying both the presence and extent of online learning challenges and by shedding light on the specific strategies they employed to overcome them.

Overall findings indicate that the extent of challenges and strategies varied from one student to another. Hence, they should be viewed as a consequence of interaction several many factors. Students’ responses suggest that their online learning challenges and strategies were mediated by the resources available to them, their interaction with their teachers and peers, and the school’s existing policies and guidelines for online learning. In the context of the pandemic, the imposed lockdowns and students’ socioeconomic condition aggravated the challenges that students experience.

While most studies revealed that technology use and competency were the most common challenges that students face during the online classes (see Rasheed et al., 2020 ), the case is a bit different in developing countries in times of pandemic. As the findings have shown, the learning environment is the greatest challenge that students needed to hurdle, particularly distractions at home (e.g., noise) and limitations in learning space and facilities. This data suggests that online learning challenges during the pandemic somehow vary from the typical challenges that students experience in a pre-pandemic online learning environment. One possible explanation for this result is that restriction in mobility may have aggravated this challenge since they could not go to the school or other learning spaces beyond the vicinity of their respective houses. As shown in the data, the imposition of lockdown restricted students’ learning experience (e.g., internship and laboratory experiments), limited their interaction with peers and teachers, caused depression, stress, and anxiety among students, and depleted the financial resources of those who belong to lower-income group. All of these adversely impacted students’ learning experience. This finding complemented earlier reports on the adverse impact of lockdown on students’ learning experience and the challenges posed by the home learning environment (e.g., Day et al., 2021 ; Kapasia et al., 2020 ). Nonetheless, further studies are required to validate the impact of restrictions on mobility on students’ online learning experience. The second reason that may explain the findings relates to students’ socioeconomic profile. Consistent with the findings of Adarkwah ( 2021 ) and Day et al. ( 2021 ), the current study reveals that the pandemic somehow exposed the many inequities in the educational systems within and across countries. In the case of a developing country, families from lower socioeconomic strata (as in the case of the students in this study) have limited learning space at home, access to quality Internet service, and online learning resources. This is the reason the learning environment and learning resources recorded the highest level of challenges. The socioeconomic profile of the students (i.e., low and middle-income group) is the same reason financial problems frequently surfaced from their responses. These students frequently linked the lack of financial resources to their access to the Internet, educational materials, and equipment necessary for online learning. Therefore, caution should be made when interpreting and extending the findings of this study to other contexts, particularly those from higher socioeconomic strata.

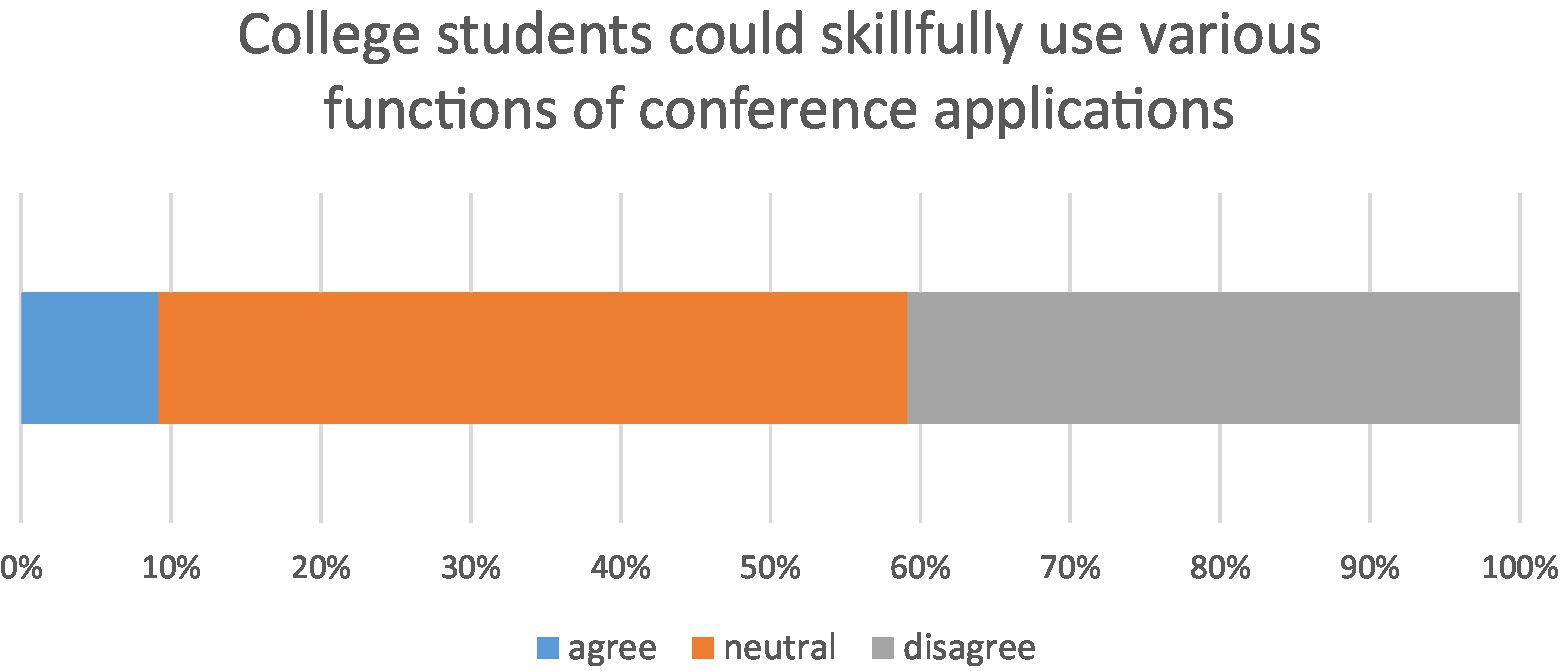

Among all the different online learning challenges, the students experienced the least challenge on technological literacy and competency. This is not surprising considering a plethora of research confirming Gen Z students’ (born since 1996) high technological and digital literacy (Barrot, 2018 ; Ng, 2012 ; Roblek et al., 2019 ). Regarding the impact of COVID-19 on students’ online learning experience, the findings reveal that teaching and learning quality and students’ mental health were the most affected. The anxiety that students experienced does not only come from the threats of COVID-19 itself but also from social and physical restrictions, unfamiliarity with new learning platforms, technical issues, and concerns about financial resources. These findings are consistent with that of Copeland et al. ( 2021 ) and Fawaz et al. ( 2021 ), who reported the adverse effects of the pandemic on students’ mental and emotional well-being. This data highlights the need to provide serious attention to the mediating effects of mental health, restrictions in mobility, and preparedness in delivering online learning.

Nonetheless, students employed a variety of strategies to overcome the challenges they faced during online learning. For instance, to address the home learning environment problems, students talked to their family (e.g., S12, S24), transferred to a quieter place (e.g., S7, S 26), studied at late night where all family members are sleeping already (e.g., S51), and consulted with their classmates and teachers (e.g., S3, S9, S156, S193). To overcome the challenges in learning resources, students used the Internet (e.g., S20, S27, S54, S91), joined Facebook groups that share free resources (e.g., S5), asked help from family members (e.g., S16), used resources available at home (e.g., S32), and consulted with the teachers (e.g., S124). The varying strategies of students confirmed earlier reports on the active orientation that students take when faced with academic- and non-academic-related issues in an online learning space (see Fawaz et al., 2021 ). The specific strategies that each student adopted may have been shaped by different factors surrounding him/her, such as available resources, student personality, family structure, relationship with peers and teacher, and aptitude. To expand this study, researchers may further investigate this area and explore how and why different factors shape their use of certain strategies.

Several implications can be drawn from the findings of this study. First, this study highlighted the importance of emergency response capability and readiness of higher education institutions in case another crisis strikes again. Critical areas that need utmost attention include (but not limited to) national and institutional policies, protocol and guidelines, technological infrastructure and resources, instructional delivery, staff development, potential inequalities, and collaboration among key stakeholders (i.e., parents, students, teachers, school leaders, industry, government education agencies, and community). Second, the findings have expanded our understanding of the different challenges that students might confront when we abruptly shift to full online learning, particularly those from countries with limited resources, poor Internet infrastructure, and poor home learning environment. Schools with a similar learning context could use the findings of this study in developing and enhancing their respective learning continuity plans to mitigate the adverse impact of the pandemic. This study would also provide students relevant information needed to reflect on the possible strategies that they may employ to overcome the challenges. These are critical information necessary for effective policymaking, decision-making, and future implementation of online learning. Third, teachers may find the results useful in providing proper interventions to address the reported challenges, particularly in the most critical areas. Finally, the findings provided us a nuanced understanding of the interdependence of learning tools, learners, and learning outcomes within an online learning environment; thus, giving us a multiperspective of hows and whys of a successful migration to full online learning.

Some limitations in this study need to be acknowledged and addressed in future studies. One limitation of this study is that it exclusively focused on students’ perspectives. Future studies may widen the sample by including all other actors taking part in the teaching–learning process. Researchers may go deeper by investigating teachers’ views and experience to have a complete view of the situation and how different elements interact between them or affect the others. Future studies may also identify some teacher-related factors that could influence students’ online learning experience. In the case of students, their age, sex, and degree programs may be examined in relation to the specific challenges and strategies they experience. Although the study involved a relatively large sample size, the participants were limited to college students from a Philippine university. To increase the robustness of the findings, future studies may expand the learning context to K-12 and several higher education institutions from different geographical regions. As a final note, this pandemic has undoubtedly reshaped and pushed the education system to its limits. However, this unprecedented event is the same thing that will make the education system stronger and survive future threats.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Adarkwah, M. A. (2021). “I’m not against online teaching, but what about us?”: ICT in Ghana post Covid-19. Education and Information Technologies, 26 (2), 1665–1685.

Article Google Scholar

Almaiah, M. A., Al-Khasawneh, A., & Althunibat, A. (2020). Exploring the critical challenges and factors influencing the E-learning system usage during COVID-19 pandemic. Education and Information Technologies, 25 , 5261–5280.

Araujo, T., Wonneberger, A., Neijens, P., & de Vreese, C. (2017). How much time do you spend online? Understanding and improving the accuracy of self-reported measures of Internet use. Communication Methods and Measures, 11 (3), 173–190.

Barrot, J. S. (2016). Using Facebook-based e-portfolio in ESL writing classrooms: Impact and challenges. Language, Culture and Curriculum, 29 (3), 286–301.

Barrot, J. S. (2018). Facebook as a learning environment for language teaching and learning: A critical analysis of the literature from 2010 to 2017. Journal of Computer Assisted Learning, 34 (6), 863–875.

Barrot, J. S. (2020). Scientific mapping of social media in education: A decade of exponential growth. Journal of Educational Computing Research . https://doi.org/10.1177/0735633120972010 .

Barrot, J. S. (2021). Social media as a language learning environment: A systematic review of the literature (2008–2019). Computer Assisted Language Learning . https://doi.org/10.1080/09588221.2021.1883673 .

Bergen, N., & Labonté, R. (2020). “Everything is perfect, and we have no problems”: Detecting and limiting social desirability bias in qualitative research. Qualitative Health Research, 30 (5), 783–792.

Birks, M., & Mills, J. (2011). Grounded theory: A practical guide . Sage.

Boelens, R., De Wever, B., & Voet, M. (2017). Four key challenges to the design of blended learning: A systematic literature review. Educational Research Review, 22 , 1–18.

Buehler, M. A. (2004). Where is the library in course management software? Journal of Library Administration, 41 (1–2), 75–84.

Carter, R. A., Jr., Rice, M., Yang, S., & Jackson, H. A. (2020). Self-regulated learning in online learning environments: Strategies for remote learning. Information and Learning Sciences, 121 (5/6), 321–329.

Cavanaugh, C. S., Barbour, M. K., & Clark, T. (2009). Research and practice in K-12 online learning: A review of open access literature. The International Review of Research in Open and Distributed Learning, 10 (1), 1–22.

Cicchetti, D., Bronen, R., Spencer, S., Haut, S., Berg, A., Oliver, P., & Tyrer, P. (2006). Rating scales, scales of measurement, issues of reliability: Resolving some critical issues for clinicians and researchers. The Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease, 194 (8), 557–564.

Copeland, W. E., McGinnis, E., Bai, Y., Adams, Z., Nardone, H., Devadanam, V., & Hudziak, J. J. (2021). Impact of COVID-19 pandemic on college student mental health and wellness. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 60 (1), 134–141.

Day, T., Chang, I. C. C., Chung, C. K. L., Doolittle, W. E., Housel, J., & McDaniel, P. N. (2021). The immediate impact of COVID-19 on postsecondary teaching and learning. The Professional Geographer, 73 (1), 1–13.

Donitsa-Schmidt, S., & Ramot, R. (2020). Opportunities and challenges: Teacher education in Israel in the Covid-19 pandemic. Journal of Education for Teaching, 46 (4), 586–595.

Drane, C., Vernon, L., & O’Shea, S. (2020). The impact of ‘learning at home’on the educational outcomes of vulnerable children in Australia during the COVID-19 pandemic. Literature Review Prepared by the National Centre for Student Equity in Higher Education. Curtin University, Australia.

Elaish, M., Shuib, L., Ghani, N., & Yadegaridehkordi, E. (2019). Mobile English language learning (MELL): A literature review. Educational Review, 71 (2), 257–276.

Fawaz, M., Al Nakhal, M., & Itani, M. (2021). COVID-19 quarantine stressors and management among Lebanese students: A qualitative study. Current Psychology , 1–8.

Franchi, T. (2020). The impact of the Covid-19 pandemic on current anatomy education and future careers: A student’s perspective. Anatomical Sciences Education, 13 (3), 312–315.

Garcia, R., Falkner, K., & Vivian, R. (2018). Systematic literature review: Self-regulated learning strategies using e-learning tools for computer science. Computers & Education, 123 , 150–163.

Gonzalez, T., De La Rubia, M. A., Hincz, K. P., Comas-Lopez, M., Subirats, L., Fort, S., & Sacha, G. M. (2020). Influence of COVID-19 confinement on students’ performance in higher education. PLoS One, 15 (10), e0239490.

Hew, K. F., Jia, C., Gonda, D. E., & Bai, S. (2020). Transitioning to the “new normal” of learning in unpredictable times: Pedagogical practices and learning performance in fully online flipped classrooms. International Journal of Educational Technology in Higher Education, 17 (1), 1–22.

Huang, Q. (2019). Comparing teacher’s roles of F2F learning and online learning in a blended English course. Computer Assisted Language Learning, 32 (3), 190–209.

John Hopkins University. (2021). Global map . https://coronavirus.jhu.edu/

Kapasia, N., Paul, P., Roy, A., Saha, J., Zaveri, A., Mallick, R., & Chouhan, P. (2020). Impact of lockdown on learning status of undergraduate and postgraduate students during COVID-19 pandemic in West Bengal. India . Children and Youth Services Review, 116 , 105194.

Kebritchi, M., Lipschuetz, A., & Santiague, L. (2017). Issues and challenges for teaching successful online courses in higher education: A literature review. Journal of Educational Technology Systems, 46 (1), 4–29.

Khalil, R., Mansour, A. E., Fadda, W. A., Almisnid, K., Aldamegh, M., Al-Nafeesah, A., & Al-Wutayd, O. (2020). The sudden transition to synchronized online learning during the COVID-19 pandemic in Saudi Arabia: A qualitative study exploring medical students’ perspectives. BMC Medical Education, 20 (1), 1–10.

Matsumoto, K. (1994). Introspection, verbal reports and second language learning strategy research. Canadian Modern Language Review, 50 (2), 363–386.

Ng, W. (2012). Can we teach digital natives digital literacy? Computers & Education, 59 (3), 1065–1078.

Pham, T., & Nguyen, H. (2020). COVID-19: Challenges and opportunities for Vietnamese higher education. Higher Education in Southeast Asia and beyond, 8 , 22–24.

Google Scholar

Rasheed, R. A., Kamsin, A., & Abdullah, N. A. (2020). Challenges in the online component of blended learning: A systematic review. Computers & Education, 144 , 103701.

Recker, M. M., Dorward, J., & Nelson, L. M. (2004). Discovery and use of online learning resources: Case study findings. Educational Technology & Society, 7 (2), 93–104.

Roblek, V., Mesko, M., Dimovski, V., & Peterlin, J. (2019). Smart technologies as social innovation and complex social issues of the Z generation. Kybernetes, 48 (1), 91–107.

Seplaki, C. L., Agree, E. M., Weiss, C. O., Szanton, S. L., Bandeen-Roche, K., & Fried, L. P. (2014). Assistive devices in context: Cross-sectional association between challenges in the home environment and use of assistive devices for mobility. The Gerontologist, 54 (4), 651–660.

Simbulan, N. (2020). COVID-19 and its impact on higher education in the Philippines. Higher Education in Southeast Asia and beyond, 8 , 15–18.

Singh, K., Srivastav, S., Bhardwaj, A., Dixit, A., & Misra, S. (2020). Medical education during the COVID-19 pandemic: a single institution experience. Indian Pediatrics, 57 (7), 678–679.

Singh, V., & Thurman, A. (2019). How many ways can we define online learning? A systematic literature review of definitions of online learning (1988–2018). American Journal of Distance Education, 33 (4), 289–306.

Spector, P. (1994). Using self-report questionnaires in OB research: A comment on the use of a controversial method. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 15 (5), 385–392.

Suryaman, M., Cahyono, Y., Muliansyah, D., Bustani, O., Suryani, P., Fahlevi, M., & Munthe, A. P. (2020). COVID-19 pandemic and home online learning system: Does it affect the quality of pharmacy school learning? Systematic Reviews in Pharmacy, 11 , 524–530.

Tallent-Runnels, M. K., Thomas, J. A., Lan, W. Y., Cooper, S., Ahern, T. C., Shaw, S. M., & Liu, X. (2006). Teaching courses online: A review of the research. Review of Educational Research, 76 (1), 93–135.

Tang, T., Abuhmaid, A. M., Olaimat, M., Oudat, D. M., Aldhaeebi, M., & Bamanger, E. (2020). Efficiency of flipped classroom with online-based teaching under COVID-19. Interactive Learning Environments , 1–12.

Usher, M., & Barak, M. (2020). Team diversity as a predictor of innovation in team projects of face-to-face and online learners. Computers & Education, 144 , 103702.

Varea, V., & González-Calvo, G. (2020). Touchless classes and absent bodies: Teaching physical education in times of Covid-19. Sport, Education and Society , 1–15.

Wallace, R. M. (2003). Online learning in higher education: A review of research on interactions among teachers and students. Education, Communication & Information, 3 (2), 241–280.

World Health Organization (2020). Coronavirus . https://www.who.int/health-topics/coronavirus#tab=tab_1

Xue, E., Li, J., Li, T., & Shang, W. (2020). China’s education response to COVID-19: A perspective of policy analysis. Educational Philosophy and Theory , 1–13.

Download references

No funding was received in the conduct of this study.

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

College of Education, Arts and Sciences, National University, Manila, Philippines

Jessie S. Barrot, Ian I. Llenares & Leo S. del Rosario

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Contributions

Jessie Barrot led the planning, prepared the instrument, wrote the report, and processed and analyzed data. Ian Llenares participated in the planning, fielded the instrument, processed and analyzed data, reviewed the instrument, and contributed to report writing. Leo del Rosario participated in the planning, fielded the instrument, processed and analyzed data, reviewed the instrument, and contributed to report writing.

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Jessie S. Barrot .

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval.

The study has undergone appropriate ethics protocol.

Consent to participate

Informed consent was sought from the participants.

Consent for publication

Authors consented the publication. Participants consented to publication as long as confidentiality is observed.

Additional information

Publisher’s note.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Barrot, J.S., Llenares, I.I. & del Rosario, L.S. Students’ online learning challenges during the pandemic and how they cope with them: The case of the Philippines. Educ Inf Technol 26 , 7321–7338 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10639-021-10589-x

Download citation

Received : 22 January 2021

Accepted : 17 May 2021

Published : 28 May 2021

Issue Date : November 2021

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/s10639-021-10589-x

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Remote learning

- Online learning

- Online learning strategies

- Higher education

- Find a journal

- Publish with us

- Track your research

Click through the PLOS taxonomy to find articles in your field.

For more information about PLOS Subject Areas, click here .

Loading metrics

Open Access

Peer-reviewed

Research Article

COVID-19’s impacts on the scope, effectiveness, and interaction characteristics of online learning: A social network analysis

Roles Data curation, Formal analysis, Methodology, Writing – review & editing

¶ ‡ JZ and YD are contributed equally to this work as first authors.

Affiliation School of Educational Information Technology, South China Normal University, Guangzhou, Guangdong, China

Roles Data curation, Formal analysis, Methodology, Writing – original draft

Affiliations School of Educational Information Technology, South China Normal University, Guangzhou, Guangdong, China, Hangzhou Zhongce Vocational School Qiantang, Hangzhou, Zhejiang, China

Roles Data curation, Writing – original draft

Roles Data curation

Roles Writing – original draft

Affiliation Faculty of Education, Shenzhen University, Shenzhen, Guangdong, China

Roles Conceptualization, Supervision, Writing – review & editing

* E-mail: [email protected] (JH); [email protected] (YZ)

- Junyi Zhang,

- Yigang Ding,

- Xinru Yang,

- Jinping Zhong,

- XinXin Qiu,

- Zhishan Zou,

- Yujie Xu,

- Xiunan Jin,

- Xiaomin Wu,

- Published: August 23, 2022

- https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0273016

- Reader Comments

The COVID-19 outbreak brought online learning to the forefront of education. Scholars have conducted many studies on online learning during the pandemic, but only a few have performed quantitative comparative analyses of students’ online learning behavior before and after the outbreak. We collected review data from China’s massive open online course platform called icourse.163 and performed social network analysis on 15 courses to explore courses’ interaction characteristics before, during, and after the COVID-19 pan-demic. Specifically, we focused on the following aspects: (1) variations in the scale of online learning amid COVID-19; (2a) the characteristics of online learning interaction during the pandemic; (2b) the characteristics of online learning interaction after the pandemic; and (3) differences in the interaction characteristics of social science courses and natural science courses. Results revealed that only a small number of courses witnessed an uptick in online interaction, suggesting that the pandemic’s role in promoting the scale of courses was not significant. During the pandemic, online learning interaction became more frequent among course network members whose interaction scale increased. After the pandemic, although the scale of interaction declined, online learning interaction became more effective. The scale and level of interaction in Electrodynamics (a natural science course) and Economics (a social science course) both rose during the pan-demic. However, long after the pandemic, the Economics course sustained online interaction whereas interaction in the Electrodynamics course steadily declined. This discrepancy could be due to the unique characteristics of natural science courses and social science courses.

Citation: Zhang J, Ding Y, Yang X, Zhong J, Qiu X, Zou Z, et al. (2022) COVID-19’s impacts on the scope, effectiveness, and interaction characteristics of online learning: A social network analysis. PLoS ONE 17(8): e0273016. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0273016

Editor: Heng Luo, Central China Normal University, CHINA

Received: April 20, 2022; Accepted: July 29, 2022; Published: August 23, 2022

Copyright: © 2022 Zhang et al. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Data Availability: The data underlying the results presented in the study were downloaded from https://www.icourse163.org/ and are now shared fully on Github ( https://github.com/zjyzhangjunyi/dataset-from-icourse163-for-SNA ). These data have no private information and can be used for academic research free of charge.

Funding: The author(s) received no specific funding for this work.

Competing interests: The authors have declared that no competing interests exist.

1. Introduction

The development of the mobile internet has spurred rapid advances in online learning, offering novel prospects for teaching and learning and a learning experience completely different from traditional instruction. Online learning harnesses the advantages of network technology and multimedia technology to transcend the boundaries of conventional education [ 1 ]. Online courses have become a popular learning mode owing to their flexibility and openness. During online learning, teachers and students are in different physical locations but interact in multiple ways (e.g., via online forum discussions and asynchronous group discussions). An analysis of online learning therefore calls for attention to students’ participation. Alqurashi [ 2 ] defined interaction in online learning as the process of constructing meaningful information and thought exchanges between more than two people; such interaction typically occurs between teachers and learners, learners and learners, and the course content and learners.

Massive open online courses (MOOCs), a 21st-century teaching mode, have greatly influenced global education. Data released by China’s Ministry of Education in 2020 show that the country ranks first globally in the number and scale of higher education MOOCs. The COVID-19 outbreak has further propelled this learning mode, with universities being urged to leverage MOOCs and other online resource platforms to respond to government’s “School’s Out, But Class’s On” policy [ 3 ]. Besides MOOCs, to reduce in-person gatherings and curb the spread of COVID-19, various online learning methods have since become ubiquitous [ 4 ]. Though Lederman asserted that the COVID-19 outbreak has positioned online learning technologies as the best way for teachers and students to obtain satisfactory learning experiences [ 5 ], it remains unclear whether the COVID-19 pandemic has encouraged interaction in online learning, as interactions between students and others play key roles in academic performance and largely determine the quality of learning experiences [ 6 ]. Similarly, it is also unclear what impact the COVID-19 pandemic has had on the scale of online learning.

Social constructivism paints learning as a social phenomenon. As such, analyzing the social structures or patterns that emerge during the learning process can shed light on learning-based interaction [ 7 ]. Social network analysis helps to explain how a social network, rooted in interactions between learners and their peers, guides individuals’ behavior, emotions, and outcomes. This analytical approach is especially useful for evaluating interactive relationships between network members [ 8 ]. Mohammed cited social network analysis (SNA) as a method that can provide timely information about students, learning communities and interactive networks. SNA has been applied in numerous fields, including education, to identify the number and characteristics of interelement relationships. For example, Lee et al. also used SNA to explore the effects of blogs on peer relationships [ 7 ]. Therefore, adopting SNA to examine interactions in online learning communities during the COVID-19 pandemic can uncover potential issues with this online learning model.

Taking China’s icourse.163 MOOC platform as an example, we chose 15 courses with a large number of participants for SNA, focusing on learners’ interaction characteristics before, during, and after the COVID-19 outbreak. We visually assessed changes in the scale of network interaction before, during, and after the outbreak along with the characteristics of interaction in Gephi. Examining students’ interactions in different courses revealed distinct interactive network characteristics, the pandemic’s impact on online courses, and relevant suggestions. Findings are expected to promote effective interaction and deep learning among students in addition to serving as a reference for the development of other online learning communities.

2. Literature review and research questions

Interaction is deemed as central to the educational experience and is a major focus of research on online learning. Moore began to study the problem of interaction in distance education as early as 1989. He defined three core types of interaction: student–teacher, student–content, and student–student [ 9 ]. Lear et al. [ 10 ] described an interactivity/ community-process model of distance education: they specifically discussed the relationships between interactivity, community awareness, and engaging learners and found interactivity and community awareness to be correlated with learner engagement. Zulfikar et al. [ 11 ] suggested that discussions initiated by the students encourage more students’ engagement than discussions initiated by the instructors. It is most important to afford learners opportunities to interact purposefully with teachers, and improving the quality of learner interaction is crucial to fostering profound learning [ 12 ]. Interaction is an important way for learners to communicate and share information, and a key factor in the quality of online learning [ 13 ].

Timely feedback is the main component of online learning interaction. Woo and Reeves discovered that students often become frustrated when they fail to receive prompt feedback [ 14 ]. Shelley et al. conducted a three-year study of graduate and undergraduate students’ satisfaction with online learning at universities and found that interaction with educators and students is the main factor affecting satisfaction [ 15 ]. Teachers therefore need to provide students with scoring justification, support, and constructive criticism during online learning. Some researchers examined online learning during the COVID-19 pandemic. They found that most students preferred face-to-face learning rather than online learning due to obstacles faced online, such as a lack of motivation, limited teacher-student interaction, and a sense of isolation when learning in different times and spaces [ 16 , 17 ]. However, it can be reduced by enhancing the online interaction between teachers and students [ 18 ].

Research showed that interactions contributed to maintaining students’ motivation to continue learning [ 19 ]. Baber argued that interaction played a key role in students’ academic performance and influenced the quality of the online learning experience [ 20 ]. Hodges et al. maintained that well-designed online instruction can lead to unique teaching experiences [ 21 ]. Banna et al. mentioned that using discussion boards, chat sessions, blogs, wikis, and other tools could promote student interaction and improve participation in online courses [ 22 ]. During the COVID-19 pandemic, Mahmood proposed a series of teaching strategies suitable for distance learning to improve its effectiveness [ 23 ]. Lapitan et al. devised an online strategy to ease the transition from traditional face-to-face instruction to online learning [ 24 ]. The preceding discussion suggests that online learning goes beyond simply providing learning resources; teachers should ideally design real-life activities to give learners more opportunities to participate.

As mentioned, COVID-19 has driven many scholars to explore the online learning environment. However, most have ignored the uniqueness of online learning during this time and have rarely compared pre- and post-pandemic online learning interaction. Taking China’s icourse.163 MOOC platform as an example, we chose 15 courses with a large number of participants for SNA, centering on student interaction before and after the pandemic. Gephi was used to visually analyze changes in the scale and characteristics of network interaction. The following questions were of particular interest:

- (1) Can the COVID-19 pandemic promote the expansion of online learning?

- (2a) What are the characteristics of online learning interaction during the pandemic?

- (2b) What are the characteristics of online learning interaction after the pandemic?

- (3) How do interaction characteristics differ between social science courses and natural science courses?

3. Methodology

3.1 research context.

We selected several courses with a large number of participants and extensive online interaction among hundreds of courses on the icourse.163 MOOC platform. These courses had been offered on the platform for at least three semesters, covering three periods (i.e., before, during, and after the COVID-19 outbreak). To eliminate the effects of shifts in irrelevant variables (e.g., course teaching activities), we chose several courses with similar teaching activities and compared them on multiple dimensions. All course content was taught online. The teachers of each course posted discussion threads related to learning topics; students were expected to reply via comments. Learners could exchange ideas freely in their responses in addition to asking questions and sharing their learning experiences. Teachers could answer students’ questions as well. Conversations in the comment area could partly compensate for a relative absence of online classroom interaction. Teacher–student interaction is conducive to the formation of a social network structure and enabled us to examine teachers’ and students’ learning behavior through SNA. The comment areas in these courses were intended for learners to construct knowledge via reciprocal communication. Meanwhile, by answering students’ questions, teachers could encourage them to reflect on their learning progress. These courses’ successive terms also spanned several phases of COVID-19, allowing us to ascertain the pandemic’s impact on online learning.

3.2 Data collection and preprocessing

To avoid interference from invalid or unclear data, the following criteria were applied to select representative courses: (1) generality (i.e., public courses and professional courses were chosen from different schools across China); (2) time validity (i.e., courses were held before during, and after the pandemic); and (3) notability (i.e., each course had at least 2,000 participants). We ultimately chose 15 courses across the social sciences and natural sciences (see Table 1 ). The coding is used to represent the course name.

- PPT PowerPoint slide

- PNG larger image

- TIFF original image

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0273016.t001

To discern courses’ evolution during the pandemic, we gathered data on three terms before, during, and after the COVID-19 outbreak in addition to obtaining data from two terms completed well before the pandemic and long after. Our final dataset comprised five sets of interactive data. Finally, we collected about 120,000 comments for SNA. Because each course had a different start time—in line with fluctuations in the number of confirmed COVID-19 cases in China and the opening dates of most colleges and universities—we divided our sample into five phases: well before the pandemic (Phase I); before the pandemic (Phase Ⅱ); during the pandemic (Phase Ⅲ); after the pandemic (Phase Ⅳ); and long after the pandemic (Phase Ⅴ). We sought to preserve consistent time spans to balance the amount of data in each period ( Fig 1 ).

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0273016.g001

3.3 Instrumentation

Participants’ comments and “thumbs-up” behavior data were converted into a network structure and compared using social network analysis (SNA). Network analysis, according to M’Chirgui, is an effective tool for clarifying network relationships by employing sophisticated techniques [ 25 ]. Specifically, SNA can help explain the underlying relationships among team members and provide a better understanding of their internal processes. Yang and Tang used SNA to discuss the relationship between team structure and team performance [ 26 ]. Golbeck argued that SNA could improve the understanding of students’ learning processes and reveal learners’ and teachers’ role dynamics [ 27 ].

To analyze Question (1), the number of nodes and diameter in the generated network were deemed as indicators of changes in network size. Social networks are typically represented as graphs with nodes and degrees, and node count indicates the sample size [ 15 ]. Wellman et al. proposed that the larger the network scale, the greater the number of network members providing emotional support, goods, services, and companionship [ 28 ]. Jan’s study measured the network size by counting the nodes which represented students, lecturers, and tutors [ 29 ]. Similarly, network nodes in the present study indicated how many learners and teachers participated in the course, with more nodes indicating more participants. Furthermore, we investigated the network diameter, a structural feature of social networks, which is a common metric for measuring network size in SNA [ 30 ]. The network diameter refers to the longest path between any two nodes in the network. There has been evidence that a larger network diameter leads to greater spread of behavior [ 31 ]. Likewise, Gašević et al. found that larger networks were more likely to spread innovative ideas about educational technology when analyzing MOOC-related research citations [ 32 ]. Therefore, we employed node count and network diameter to measure the network’s spatial size and further explore the expansion characteristic of online courses. Brief introduction of these indicators can be summarized in Table 2 .

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0273016.t002

To address Question (2), a list of interactive analysis metrics in SNA were introduced to scrutinize learners’ interaction characteristics in online learning during and after the pandemic, as shown below:

- (1) The average degree reflects the density of the network by calculating the average number of connections for each node. As Rong and Xu suggested, the average degree of a network indicates how active its participants are [ 33 ]. According to Hu, a higher average degree implies that more students are interacting directly with each other in a learning context [ 34 ]. The present study inherited the concept of the average degree from these previous studies: the higher the average degree, the more frequent the interaction between individuals in the network.

- (2) Essentially, a weighted average degree in a network is calculated by multiplying each degree by its respective weight, and then taking the average. Bydžovská took the strength of the relationship into account when determining the weighted average degree [ 35 ]. By calculating friendship’s weighted value, Maroulis assessed peer achievement within a small-school reform [ 36 ]. Accordingly, we considered the number of interactions as the weight of the degree, with a higher average degree indicating more active interaction among learners.

- (3) Network density is the ratio between actual connections and potential connections in a network. The more connections group members have with each other, the higher the network density. In SNA, network density is similar to group cohesion, i.e., a network of more strong relationships is more cohesive [ 37 ]. Network density also reflects how much all members are connected together [ 38 ]. Therefore, we adopted network density to indicate the closeness among network members. Higher network density indicates more frequent interaction and closer communication among students.

- (4) Clustering coefficient describes local network attributes and indicates that two nodes in the network could be connected through adjacent nodes. The clustering coefficient measures users’ tendency to gather (cluster) with others in the network: the higher the clustering coefficient, the more frequently users communicate with other group members. We regarded this indicator as a reflection of the cohesiveness of the group [ 39 ].

- (5) In a network, the average path length is the average number of steps along the shortest paths between any two nodes. Oliveres has observed that when an average path length is small, the route from one node to another is shorter when graphed [ 40 ]. This is especially true in educational settings where students tend to become closer friends. So we consider that the smaller the average path length, the greater the possibility of interaction between individuals in the network.

- (6) A network with a large number of nodes, but whose average path length is surprisingly small, is known as the small-world effect [ 41 ]. A higher clustering coefficient and shorter average path length are important indicators of a small-world network: a shorter average path length enables the network to spread information faster and more accurately; a higher clustering coefficient can promote frequent knowledge exchange within the group while boosting the timeliness and accuracy of knowledge dissemination [ 42 ]. Brief introduction of these indicators can be summarized in Table 3 .

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0273016.t003

To analyze Question 3, we used the concept of closeness centrality, which determines how close a vertex is to others in the network. As Opsahl et al. explained, closeness centrality reveals how closely actors are coupled with their entire social network [ 43 ]. In order to analyze social network-based engineering education, Putnik et al. examined closeness centrality and found that it was significantly correlated with grades [ 38 ]. We used closeness centrality to measure the position of an individual in the network. Brief introduction of these indicators can be summarized in Table 4 .

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0273016.t004

3.4 Ethics statement

This study was approved by the Academic Committee Office (ACO) of South China Normal University ( http://fzghb.scnu.edu.cn/ ), Guangzhou, China. Research data were collected from the open platform and analyzed anonymously. There are thus no privacy issues involved in this study.

4.1 COVID-19’s role in promoting the scale of online courses was not as important as expected

As shown in Fig 2 , the number of course participants and nodes are closely correlated with the pandemic’s trajectory. Because the number of participants in each course varied widely, we normalized the number of participants and nodes to more conveniently visualize course trends. Fig 2 depicts changes in the chosen courses’ number of participants and nodes before the pandemic (Phase II), during the pandemic (Phase III), and after the pandemic (Phase IV). The number of participants in most courses during the pandemic exceeded those before and after the pandemic. But the number of people who participate in interaction in some courses did not increase.

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0273016.g002

In order to better analyze the trend of interaction scale in online courses before, during, and after the pandemic, the selected courses were categorized according to their scale change. When the number of participants increased (decreased) beyond 20% (statistical experience) and the diameter also increased (decreased), the course scale was determined to have increased (decreased); otherwise, no significant change was identified in the course’s interaction scale. Courses were subsequently divided into three categories: increased interaction scale, decreased interaction scale, and no significant change. Results appear in Table 5 .

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0273016.t005

From before the pandemic until it broke out, the interaction scale of five courses increased, accounting for 33.3% of the full sample; one course’s interaction scale declined, accounting for 6.7%. The interaction scale of nine courses decreased, accounting for 60%. The pandemic’s role in promoting online courses thus was not as important as anticipated, and most courses’ interaction scale did not change significantly throughout.

No courses displayed growing interaction scale after the pandemic: the interaction scale of nine courses fell, accounting for 60%; and the interaction scale of six courses did not shift significantly, accounting for 40%. Courses with an increased scale of interaction during the pandemic did not maintain an upward trend. On the contrary, the improvement in the pandemic caused learners’ enthusiasm for online learning to wane. We next analyzed several interaction metrics to further explore course interaction during different pandemic periods.

4.2 Characteristics of online learning interaction amid COVID-19

4.2.1 during the covid-19 pandemic, online learning interaction in some courses became more active..

Changes in course indicators with the growing interaction scale during the pandemic are presented in Fig 3 , including SS5, SS6, NS1, NS3, and NS8. The horizontal ordinate indicates the number of courses, with red color representing the rise of the indicator value on the vertical ordinate and blue representing the decline.

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0273016.g003

Specifically: (1) The average degree and weighted average degree of the five course networks demonstrated an upward trend. The emergence of the pandemic promoted students’ enthusiasm; learners were more active in the interactive network. (2) Fig 3 shows that 3 courses had increased network density and 2 courses had decreased. The higher the network density, the more communication within the team. Even though the pandemic accelerated the interaction scale and frequency, the tightness between learners in some courses did not improve. (3) The clustering coefficient of social science courses rose whereas the clustering coefficient and small-world property of natural science courses fell. The higher the clustering coefficient and the small-world property, the better the relationship between adjacent nodes and the higher the cohesion [ 39 ]. (4) Most courses’ average path length increased as the interaction scale increased. However, when the average path length grew, adverse effects could manifest: communication between learners might be limited to a small group without multi-directional interaction.