Should Gay Marriage Be Legal?

ARCHIVED WEBSITE

This site was archived on Dec. 15, 2021. A reconsideration of the topic on this site is possible in the future.

On June 26, 2015, the US Supreme Court ruled that gay marriage is a right protected by the US Constitution in all 50 states. Prior to their decision, same-sex marriage was already legal in 37 states and Washington DC, but was banned in the remaining 13. US public opinion had shifted significantly over the years, from 27% approval of gay marriage in 1996 to 55% in 2015, the year it became legal throughout the United States, to 61% in 2019.

Proponents of legal gay marriage contend that gay marriage bans are discriminatory and unconstitutional, and that same-sex couples should have access to all the benefits enjoyed by different-sex couples.

Opponents contend that marriage has traditionally been defined as being between one man and one woman, and that marriage is primarily for procreation. Read more background…

Pro & Con Arguments

Pro 1 To deny some people the option to marry would be discriminatory and would create a second class of citizens. Same-sex couples should have access to the same benefits enjoyed by heterosexual married couples. On July 25, 2014 Miami-Dade County Circuit Court Judge Sarah Zabel ruled Florida’s gay marriage ban unconstitutional and stated that the ban “serves only to hurt, to discriminate, to deprive same-sex couples and their families of equal dignity, to label and treat them as second-class citizens, and to deem them unworthy of participation in one of the fundamental institutions of our society.” [ 105 ] As well as discrimination based on sexual orientation, gay marriage bans discriminated based on one’s sex. As David S. Cohen, JD, Associate Professor at the Drexel University School of Law, explained, “Imagine three people—Nancy, Bill, and Tom… Nancy, a woman, can marry Tom, but Bill, a man, cannot… Nancy can do something (marry Tom) that Bill cannot, simply because Nancy is a woman and Bill is a man.” [ 122 ] Over 1,000 benefits, rights and protections are available to married couples in federal law alone, including hospital visitation, filing a joint tax return to reduce a tax burden, access to family health coverage, US residency and family unification for partners from another country, and bereavement leave and inheritance rights if a partner dies. [ 6 ] [ 86 ] [ 95 ] Married couples also have access to protections if the relationship ends, such as child custody, spousal or child support, and an equitable division of property. [ 93 ] Married couples in the US armed forces are offered health insurance and other benefits unavailable to domestic partners. [ 125 ] The IRS and the US Department of Labor also recognize married couples, for the purpose of granting tax, retirement and health insurance benefits. [ 126 ] An Oct. 2, 2009 analysis by the New York Times estimated that same-sex couples denied marriage benefits incurred an additional $41,196 to $467,562 in expenses over their lifetimes compared with married heterosexual couples. [ 7 ] Additionally, legal same-sex marriage comes with mental and physical health benefits. The American Psychological Association, American Psychiatric Association, and others concluded that legal gay marriage gives couples “access to the social support that already facilitates and strengthens heterosexual marriages, with all of the psychological and physical health benefits associated with that support.” [ 47 ] A study found that same-sex married couples were “significantly less distressed than lesbian, gay, and bisexual persons not in a legally recognized relationship.” [ 113 ] A 2010 analysis found that after their states had banned gay marriage, gay, lesbian and bisexual people suffered a 37% increase in mood disorders, a 42% increase in alcohol-use disorders, and a 248% increase in generalized anxiety disorders. [ 69 ] Read More

Pro 2 Gay marriages bring financial gain to federal, state, and local governments, and boost the economy. The Congressional Budget Office estimated in 2004 that federally-recognized gay marriage would cut the budget deficit by around $450 million a year. [ 89 ] In July 2012 New York City Mayor Michael Bloomberg announced that gay marriage had contributed $259 million to the city’s economy in just a year since the practice became legal there in July 2011. [ 43 ] Government revenue from marriage comes from marriage licenses, higher income taxes in some circumstances (the so-called “marriage penalty”), and decreases in costs for state benefit programs. [ 4 ] In 2012, the Williams Institute at the University of California at Los Angeles (UCLA) found that in the first five years after Massachusetts legalized gay marriage in 2004, same-sex wedding expenditures (such as venue rental, wedding cakes, etc.) added $111 million to the state’s economy. [ 114 ] Read More

Pro 3 Legal marriage is a secular institution that should not be limited by religious objections to same-sex marriage. Religious institutions can decline to marry gay and lesbian couples if they wish, but they should not dictate marriage laws for society at large. As explained by People for the American Way, “As a legal matter, marriage is a civil institution… Marriage is also a religious institution, defined differently by different faiths and congregations. In America, the distinction can get blurry because states permit clergy to carry out both religious and civil marriage in a single ceremony. Religious Right leaders have exploited that confusion by claiming that granting same-sex couples equal access to civil marriage would somehow also redefine the religious institution of marriage… this is grounded in falsehood and deception.” [ 132 ] Nancy Cott, PhD, testified in Perry v. Schwarzenegger that “[c]ivil law has always been supreme in defining and regulating marriage.” [ 41 ] Read More

Pro 4 The concept of “traditional marriage” has changed over time, and the idea that the definition of marriage has always been between one man and one woman is historically inaccurate. Harvard University historian Nancy F. Cott stated that until two centuries ago, “monogamous households were a tiny, tiny portion” of the world’s population, and were found only in “Western Europe and little settlements in North America.” [ 106 ] Official unions between same-sex couples, indistinguishable from marriages except for gender, are believed by some scholars to have been common until the 13th Century in many countries, with the ceremonies performed in churches and the union sealed with a kiss between the two parties. [ 106 ] Polygamy has been widespread throughout history, according to Brown University political scientist Rose McDermott, PhD. [ 106 ] [ 110 ] Read More

Pro 5 Gay marriage is a civil right protected by the US Constitution’s commitments to liberty and equality, and is an internationally recognized human right for all people. The NAACP (National Association for the Advancement of Colored People), on May 21, 2012, named same-sex marriage as “one of the key civil rights struggles of our time.” [ 61 ] In 1967 the US Supreme Court unanimously confirmed in Loving v. Virginia that marriage is “one of the basic civil rights of man.” [60] In 2014, the White House website listed same-sex marriage amongst a selection of civil rights, along with freedom from employment discrimination, equal pay for women, and fair sentencing for minority criminals. [ 118 ] The US Supreme Court ruled 7-2 in the 1974 case Cleveland Board of Education v. LaFleur that the “freedom of personal choice in matters of marriage and family life is one of the liberties protected by the Due Process Clause” of the US Constitution. US District Judge Vaughn Walker wrote on Aug. 4, 2010 that Prop. 8 in California banning gay marriage was “unconstitutional under both the Due Process and Equal Protection Clauses.” [ 41 ] The Due Process Clause in both the Fifth and 14th Amendments of the US Constitution states that no person shall be “deprived of life, liberty, or property, without due process of law.” [ 111 ] The Equal Protection Clause in the 14th Amendment states that no state shall “deny to any person within its jurisdiction the equal protection of the laws.” [ 112 ] Since 1888 the US Supreme Court has declared at least 14 times that marriage is a fundamental right for all. [ 3 ] Article 16 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights guarantees “men and women of full age, without any limitation due to race, nationality or religion… the right to marry and to found a family. They are entitled to equal rights as to marriage, during marriage and at its dissolution.” [ 103 ] Amnesty International states that “this non-discrimination principle has been interpreted by UN treaty bodies and numerous inter-governmental human rights bodies as prohibiting discrimination based on gender or sexual orientation. Non-discrimination on grounds of sexual orientation has therefore become an internationally recognized principle.” [ 104 ] Read More

Pro 6 Marriage is not only for procreation, otherwise infertile couples or couples not wishing to have children would be prevented from marrying. Ability or desire to create offspring has never been a qualification for marriage. From 1970 through 2012 roughly 30% of all US households were married couples without children, and in 2012, married couples without children outnumbered married couples with children by 9%. [ 96 ] 6% of married women aged 15-44 are infertile, according to the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. [ 97 ] In a 2010 Pew Research Center survey, both married and unmarried people rated love, commitment, and companionship higher than having children as “very important” reasons to get married, and only 44% of unmarried people and 59% of married people rated having children as a very important reason. [ 42 ] As US Supreme Court Justice Elena Kagan noted, a marriage license would be granted to a couple in which the man and woman are both over the age of 55, even though “there are not a lot of children coming out of that marriage.” [ 88 ] Read More

Con 1 The institution of marriage has traditionally been defined as being between a man and a woman. Civil unions and domestic partnerships could provide the protections and benefits gay couples need without changing the definition of marriage. John F. Harvey, late Catholic priest, wrote in July 2009 that “Throughout the history of the human race the institution of marriage has been understood as the complete spiritual and bodily communion of one man and one woman.” [ 18 ] [ 109 ] In upholding gay marriage bans in Kentucky, Michigan, Ohio and Tennessee on Nov. 6, 2014, 6th US District Court of Appeals Judge Jeffrey S. Sutton wrote that “marriage has long been a social institution defined by relationships between men and women. So long defined, the tradition is measured in millennia, not centuries or decades. So widely shared, the tradition until recently had been adopted by all governments and major religions of the world.” [ 117 ] In the Oct. 15, 1971 decision Baker v. Nelson, the Supreme Court of Minnesota found that “the institution of marriage as a union of man and woman, uniquely involving the procreation and rearing of children within a family, is as old as the book of Genesis.” [ 49 ] Privileges available to couples in civil unions and domestic partnerships can include health insurance benefits, inheritance without a will, the ability to file state taxes jointly, and hospital visitation rights. [ 155 ] [ 156 ] New laws could enshrine other benefits for civil unions and domestic partnerships that would benefit same-sex couple as well as heterosexual couples who do not want to get married. 2016 presidential candidate and former Hewlett-Packard CEO Carly Fiorina stated that civil unions are adequate as an equivalent to marriage: “Benefits are being bestowed to gay couples [in civil unions]… I believe we need to respect those who believe that the word marriage has a spiritual foundation… Why can’t we respect and tolerate that while at the same time saying government cannot bestow benefits unequally.” [ 157 ] 43rd US President George W. Bush expressed his support for same-sex civil unions while in office: “I don’t think we should deny people rights to a civil union, a legal arrangement, if that’s what a state chooses to do so… I strongly believe that marriage ought to be defined as between a union between a man and a woman. Now, having said that, states ought to be able to have the right to pass laws that enable people to be able to have rights like others.” [158] Read More

Con 2 Marriage is for procreation. Same sex couples should be prohibited from marriage because they cannot produce children together. The purpose of marriage should not shift away from producing and raising children to adult gratification. [ 19 ] A California Supreme Court ruling from 1859 stated that “the first purpose of matrimony, by the laws of nature and society, is procreation.” [ 90 ] Nobel Prize-winning philosopher Bertrand Russell stated that “it is through children alone that sexual relations become important to society, and worthy to be taken cognizance of by a legal institution.” [ 91 ] Court papers filed in July 2014 by attorneys defending Arizona’s gay marriage ban stated that “the State regulates marriage for the primary purpose of channeling potentially procreative sexual relationships into enduring unions for the sake of joining children to both their mother and their father… Same-sex couples can never provide a child with both her biological mother and her biological father.” [ 98 ] Contrary to the pro gay marriage argument that some different-sex couples cannot have children or don’t want them, even in those cases there is still the potential to produce children. Seemingly infertile heterosexual couples sometimes produce children, and medical advances may allow others to procreate in the future. Heterosexual couples who do not wish to have children are still biologically capable of having them, and may change their minds. [ 98 ] Read More

Con 3 Gay marriage has accelerated the assimilation of gays into mainstream heterosexual culture to the detriment of the homosexual community. The gay community has created its own vibrant culture. By reducing the differences in opportunities and experiences between gay and heterosexual people, this unique culture may cease to exist. Lesbian activist M.V. Lee Badgett, PhD, Director of the Center for Public Policy and Administration at the University of Massachusetts at Amherst, stated that for many gay activists “marriage means adopting heterosexual forms of family and giving up distinctively gay family forms and perhaps even gay and lesbian culture.” [14] Paula Ettelbrick, JD, Professor of Law and Women’s Studies, wrote in 1989, “Marriage runs contrary to two of the primary goals of the lesbian and gay movement: the affirmation of gay identity and culture and the validation of many forms of relationships.” [15] Read More

Con 4 Marriage is an outmoded, oppressive institution that should have been weakened, not expanded. LGBT activist collective Against Equality stated, “Gay marriage apes hetero privilege… [and] increases economic inequality by perpetuating a system which deems married beings more worthy of the basics like health care and economic rights.” [ 84 ] The leaders of the Gay Liberation Front in New York said in July 1969, “We expose the institution of marriage as one of the most insidious and basic sustainers of the system. The family is the microcosm of oppression.” [ 16 ] Queer activist Anders Zanichkowsky stated in June 2013 that the then campaign for gay marriage “intentionally and maliciously erases and excludes so many queer people and cultures, particularly trans and gender non-conforming people, poor queer people, and queer people in non-traditional families… marriage thinks non-married people are deviant and not truly deserving of civil rights.” [ 127 ] Read More

Con 5 Gay marriage is contrary to the word of God and is incompatible with the beliefs, sacred texts, and traditions of many religious groups. The Bible, in Leviticus 18:22, states: “Thou shalt not lie with mankind, as with womankind: it is abomination,” thus condemning homosexual relationships. [ 120 ] The Catholic Church, United Methodist Church, Southern Baptist Convention, Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, National Association of Evangelicals, and American Baptist Churches USA all oppose same-sex marriage. [ 119 ] According to a July 31, 2003 statement from the Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith and approved by Pope John Paul II, marriage “was established by the Creator with its own nature, essential properties and purpose. No ideology can erase from the human spirit the certainty that marriage exists solely between a man and a woman.” [ 54 ] Pope Benedict stated in Jan. 2012 that gay marriage threatened “the future of humanity itself.” [ 145 ] Two orthodox Jewish groups, the Orthodox Agudath Israel of America and the Orthodox Union, also oppose gay marriage, as does mainstream Islam. [ 13 ] [ 119 ] In Islamic tradition, several hadiths (passages attributed to the Prophet Muhammad) condemn gay and lesbian relationships, including the sayings “When a man mounts another man, the throne of God shakes,” and “Sihaq [lesbian sex] of women is zina [illegitimate sexual intercourse].” [ 121 ] Read More

Con 6 Homosexuality is immoral and unnatural, and, therefore, same sex marriage is immoral and unnatural. J. Matt Barber, Associate Dean for Online Programs at Liberty University School of Law, stated, “Every individual engaged in the homosexual lifestyle, who has adopted a homosexual identity, they know, intuitively, that what they’re doing is immoral, unnatural, and self-destructive, yet they thirst for that affirmation.” [ 149 ] A 2003 set of guidelines signed by Pope John Paul II stated: “There are absolutely no grounds for considering homosexual unions to be in any way similar or even remotely analogous to God’s plan for marriage and family… Marriage is holy, while homosexual acts go against the natural moral law.” [ 147 ] Former Arkansas governor and Republican presidential candidate Mike Huckabee stated that gay marriage is “inconsistent with nature and nature’s law.” [ 148 ] J. Matt Barber, Associate Dean for Online Programs at Liberty University School of Law, stated, “Every individual engaged in the homosexual lifestyle, who has adopted a homosexual identity, they know, intuitively, that what they’re doing is immoral, unnatural, and self-destructive, yet they thirst for that affirmation.” [ 149 ] A 2003 set of guidelines signed by Pope John Paul II stated: “There are absolutely no grounds for considering homosexual unions to be in any way similar or even remotely analogous to God’s plan for marriage and family… Marriage is holy, while homosexual acts go against the natural moral law.” [ 147 ] Read More

| Did You Know? |

|---|

| 1. The world's first legal gay marriage ceremony took place in the Netherlands on Apr. 1, 2001, just after midnight. The four couples, one female and three male, were married in a televised ceremony officiated by the mayor of Amsterdam. [ ] |

| 2. On May 17, 2004, the first legal gay marriage in the United States was performed in Cambridge, MA between Tanya McCloskey, a massage therapist, and Marcia Kadish, an employment manager at an engineering firm. [ ] |

| 3. The June 26, 2015 Obergefell v. Hodges US Supreme Court ruling made gay marriage legal in all 50 US states. [ ] |

| 4. An estimated 293,000 American same-sex couples have married since June 26, 2015, bringing the total number of married same-sex couples to about 513,000 in the US. [ ] |

| 5. On May 26, 2020, Costa Rica became the first Central American country to legalize same-sex marriage. [ ] |

| People who view this page may also like: |

|---|

| 1. |

| 2. |

| 3. |

Our Latest Updates (archived after 30 days)

ProCon/Encyclopaedia Britannica, Inc. 325 N. LaSalle Street, Suite 200 Chicago, Illinois 60654 USA

Natalie Leppard Managing Editor [email protected]

© 2023 Encyclopaedia Britannica, Inc. All rights reserved

- Gay Marriage – Pros & Cons

- Pro & Con Quotes

- History of Gay Marriage

- Did You Know?

- Gay Marriage around the World

- Gay Marriage Timeline

- State-by-State History of Banning and Legalizing Gay Marriage

- Gay Marriage in the US Supreme Court: Obergefell v. Hodges

Cite This Page

- Artificial Intelligence

- Private Prisons

- Space Colonization

- Social Media

- Death Penalty

- School Uniforms

- Video Games

- Animal Testing

- Gun Control

- Banned Books

- Teachers’ Corner

ProCon.org is the institutional or organization author for all ProCon.org pages. Proper citation depends on your preferred or required style manual. Below are the proper citations for this page according to four style manuals (in alphabetical order): the Modern Language Association Style Manual (MLA), the Chicago Manual of Style (Chicago), the Publication Manual of the American Psychological Association (APA), and Kate Turabian's A Manual for Writers of Term Papers, Theses, and Dissertations (Turabian). Here are the proper bibliographic citations for this page according to four style manuals (in alphabetical order):

[Editor's Note: The APA citation style requires double spacing within entries.]

[Editor’s Note: The MLA citation style requires double spacing within entries.]

Evidence is clear on the benefits of legalising same-sex marriage

PhD Candidate, School of Arts and Social Sciences, James Cook University

Disclosure statement

Ryan Anderson does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

James Cook University provides funding as a member of The Conversation AU.

View all partners

Emotive arguments and questionable rhetoric often characterise debates over same-sex marriage. But few attempts have been made to dispassionately dissect the issue from an academic, science-based perspective.

Regardless of which side of the fence you fall on, the more robust, rigorous and reliable information that is publicly available, the better.

There are considerable mental health and wellbeing benefits conferred on those in the fortunate position of being able to marry legally. And there are associated deleterious impacts of being denied this opportunity.

Although it would be irresponsible to suggest the research is unanimous, the majority is either noncommittal (unclear conclusions) or demonstrates the benefits of same-sex marriage.

Further reading: Conservatives prevail to hold back the tide on same-sex marriage

What does the research say?

Widescale research suggests that members of the LGBTQ community generally experience worse mental health outcomes than their heterosexual counterparts. This is possibly due to the stigmatisation they receive.

The mental health benefits of marriage generally are well-documented . In 2009, the American Medical Association officially recognised that excluding sexual minorities from marriage was significantly contributing to the overall poor health among same-sex households compared to heterosexual households.

Converging lines of evidence also suggest that sexual orientation stigma and discrimination are at least associated with increased psychological distress and a generally decreased quality of life among lesbians and gay men.

A US study that surveyed more than 36,000 people aged 18-70 found lesbian, gay and bisexual individuals were far less psychologically distressed if they were in a legally recognised same-sex marriage than if they were not. Married heterosexuals were less distressed than either of these groups.

So, it would seem that being in a legally recognised same-sex marriage can at least partly overcome the substantial health disparity between heterosexual and lesbian, gay, and bisexual persons.

The authors concluded by urging other researchers to consider same-sex marriage as a public health issue.

A review of the research examining the impact of marriage denial on the health and wellbeing of gay men and lesbians conceded that marriage equality is a profoundly complex and nuanced issue. But, it argued that depriving lesbians and gay men the tangible (and intangible) benefits of marriage is not only an act of discrimination – it also:

disadvantages them by restricting their citizenship;

hinders their mental health, wellbeing, and social mobility; and

generally disenfranchises them from various cultural, legal, economic and political aspects of their lives.

Of further concern is research finding that in comparison to lesbian, gay and bisexual respondents living in areas where gay marriage was allowed, living in areas where it was banned was associated with significantly higher rates of:

mood disorders (36% higher);

psychiatric comorbidity – that is, multiple mental health conditions (36% higher); and

anxiety disorders (248% higher).

But what about the kids?

Opponents of same-sex marriage often argue that children raised in same-sex households perform worse on a variety of life outcome measures when compared to those raised in a heterosexual household. There is some merit to this argument.

In terms of education and general measures of success, the literature isn’t entirely unanimous. However, most studies have found that on these metrics there is no difference between children raised by same-sex or opposite-sex parents.

In 2005, the American Psychological Association released a brief reviewing research on same-sex parenting. It unambiguously summed up its stance on the issue of whether or not same-sex parenting negatively impacts children:

Not a single study has found children of lesbian or gay parents to be disadvantaged in any significant respect relative to children of heterosexual parents.

Further reading: Same-sex couples and their children: what does the evidence tell us?

Drawing conclusions

Same-sex marriage has already been legalised in 23 countries around the world , inhabited by more than 760 million people.

Despite the above studies positively linking marriage with wellbeing, it may be premature to definitively assert causality .

But overall, the evidence is fairly clear. Same-sex marriage leads to a host of social and even public health benefits, including a range of advantages for mental health and wellbeing. The benefits accrue to society as a whole, whether you are in a same-sex relationship or not.

As the body of research in support of same-sex marriage continues to grow, the case in favour of it becomes stronger.

- Human rights

- Same-sex marriage

- Same-sex marriage plebiscite

PhD Scholarship

Senior Lecturer, HRM or People Analytics

Senior Research Fellow - Neuromuscular Disorders and Gait Analysis

Centre Director, Transformative Media Technologies

Postdoctoral Research Fellowship

The strongest argument against same-sex marriage: traditional marriage is in the public interest

by German Lopez

Opponents of same-sex marriage argued that individual states are acting in the public interest by encouraging heterosexual relationships through marriage policies, so voters and legislators in each state should be able to set their own laws.

Some groups, such as the United States Conference of Catholic Bishops, cited the secular benefits of heterosexual marriages, particularly the ability of heterosexual couples to reproduce, as Daniel Silliman reported at the Washington Post .

”It is a mistake to characterize laws defining marriage as the union of one man and one woman as somehow embodying a purely religious viewpoint over against a purely secular one,” the bishops said in their amicus brief . “Rather, it is a common sense reflection of the fact that [homosexual] relationships do not result in the birth of children, or establish households where a child will be raised by its birth mother and father.”

Other groups, like the conservative Family Research Council, warned that allowing same-sex couples to marry would lead to the breakdown of traditional families. But keeping marriage to heterosexual couples, FRC argued in an amicus brief , allows states to “channel the potential procreative sexual activity of opposite-sex couples into stable relationships in which the children so procreated may be raised by their biological mothers and fathers.”

To defend same-sex marriage bans, opponents had to convince courts that there’s a compelling state interest in encouraging heterosexual relationships that isn’t really about discriminating against same-sex couples.

But a majority of Supreme Court justices and most of the lower courts widely rejected this argument, arguing that same-sex marriage bans are discriminatory and unconstitutional.

Most Popular

The supreme court just lit a match and tossed it into dozens of federal agencies, the silver lining to biden’s debate disaster, the supreme court just made a massive power grab it will come to regret, can democrats replace biden as their nominee, democrats can and should replace joe biden, today, explained.

Understand the world with a daily explainer plus the most compelling stories of the day.

More in archives

The Supreme Court will decide if the government can ban transgender health care

On the Money

Total solar eclipse passes over US

The 2024 Iowa caucuses

The Big Squeeze

Abortion medication in America: News and updates

How Democrats got here

Why the Supreme Court just ruled in favor of over 300 January 6 insurrectionists

What about Kamala?

The Democrats who could replace Biden if he steps aside

Hawk Tuah Girl, explained by straight dudes

Gay Marriage Is Good for America

Subscribe to governance weekly, jonathan rauch jonathan rauch senior fellow - governance studies @jon_rauch.

June 21, 2008

By order of its state Supreme Court, California began legally marrying same-sex couples this week. The first to be wed in San Francisco were Del Martin and Phyllis Lyon, pioneering gay-rights activists who have been a couple for more than 50 years.

More ceremonies will follow, at least until November, when gay marriage will go before California’s voters. They should choose to keep it. To understand why, imagine your life without marriage. Meaning, not merely your life if you didn’t happen to get married. What I am asking you to imagine is life without even the possibility of marriage.

Re-enter your childhood, but imagine your first crush, first kiss, first date and first sexual encounter, all bereft of any hope of marriage as a destination for your feelings. Re-enter your first serious relationship, but think about it knowing that marrying the person is out of the question.

Imagine that in the law’s eyes you and your soul mate will never be more than acquaintances. And now add even more strangeness. Imagine coming of age into a whole community, a whole culture, without marriage and the bonds of mutuality and kinship that go with it.

What is this weird world like? It has more sex and less commitment than a world with marriage. It is a world of fragile families living on the shadowy outskirts of the law; a world marked by heightened fear of loneliness or abandonment in crisis or old age; a world in some respects not even civilized, because marriage is the foundation of civilization.

This was the world I grew up in. The AIDS quilt is its monument.

Few heterosexuals can imagine living in such an upside-down world, where love separates you from marriage instead of connecting you with it. Many don’t bother to try. Instead, they say same-sex couples can get the equivalent of a marriage by going to a lawyer and drawing up paperwork – as if heterosexual couples would settle for anything of the sort.

Even a moment’s reflection shows the fatuousness of “Let them eat contracts.” No private transaction excuses you from testifying in court against your partner, or entitles you to Social Security survivor benefits, or authorizes joint tax filing, or secures U.S. residency for your partner if he or she is a foreigner. I could go on and on.

Marriage, remember, is not just a contract between two people. It is a contract that two people make, as a couple, with their community – which is why there is always a witness. Two people can’t go into a room by themselves and come out legally married. The partners agree to take care of each other so the community doesn’t have to. In exchange, the community deems them a family, binding them to each other and to society with a host of legal and social ties.

This is a fantastically fruitful bargain. Marriage makes you, on average, healthier, happier and wealthier. If you are a couple raising kids, marrying is likely to make them healthier, happier and wealthier, too. Marriage is our first and best line of defense against financial, medical and emotional meltdown. It provides domesticity and a safe harbor for sex. It stabilizes communities by formalizing responsibilities and creating kin networks. And its absence can be calamitous, whether in inner cities or gay ghettos.

In 2008, denying gay Americans the opportunity to marry is not only inhumane, it is unsustainable. History has turned a corner: Gay couples – including gay parents – live openly and for the most part comfortably in mainstream life. This will not change, ever.

Because parents want happy children, communities want responsible neighbors, employers want productive workers, and governments want smaller welfare caseloads, society has a powerful interest in recognizing and supporting same-sex couples. It will either fold them into marriage or create alternatives to marriage, such as publicly recognized and subsidized cohabitation. Conservatives often say same-sex marriage should be prohibited because it does not exemplify the ideal form of family. They should consider how much less ideal an example gay couples will set by building families and raising children out of wedlock.

Nowadays, even opponents of same-sex marriage generally concede it would be good for gay people. What they worry about are the possible secondary effects it could have as it ramifies through law and society. What if gay marriage becomes a vehicle for polygamists who want to marry multiple partners, egalitarians who want to radically rewrite family law, or secularists who want to suppress religious objections to homosexuality?

Space doesn’t permit me to treat those and other objections in detail, beyond noting that same-sex marriage no more leads logically to polygamy than giving women one vote leads to giving men two; that gay marriage requires only few and modest changes to existing family law; and that the Constitution provides robust protections for religious freedom.

I’ll also note, in passing, that these arguments conscript homosexuals into marriagelessness in order to stop heterosexuals from making bad decisions, a deal to which we gay folks say, “Thanks, but no thanks.” We wonder how many heterosexuals would give up their own marriage, or for that matter their own divorce, to discourage other people from making poor policy choices. Any volunteers?

Honest advocacy requires acknowledging that same-sex marriage is a significant social change and, as such, is not risk-free. I believe the risks are modest, manageable, and likely to be outweighed by the benefits. Still, it’s wise to guard against unintended consequences by trying gay marriage in one or two states and seeing what happens, which is exactly what the country is doing.

By the same token, however, honest opposition requires acknowledging that there are risks and unforeseen consequences on both sides of the equation. Some of the unforeseen consequences of allowing same-sex marriage will be good, not bad. And barring gay marriage is risky in its own right.

America needs more marriages, not fewer, and the best way to encourage marriage is to encourage marriage, which is what society does by bringing gay couples inside the tent. A good way to discourage marriage, on the other hand, is to tarnish it as discriminatory in the minds of millions of young Americans. Conservatives who object to redefining marriage risk redefining it themselves, as a civil-rights violation.

There are two ways to see the legal marriage of Del Martin and Phyllis Lyon. One is as the start of something radical: an experiment that jeopardizes millennia of accumulated social patrimony. The other is as the end of something radical: an experiment in which gay people were told that they could have all the sex and love they could find, but they could not even think about marriage. If I take the second view, it is on conservative – in fact, traditional – grounds that gay souls and straight society are healthiest when sex, love and marriage all walk in step.

Children & Families

Governance Studies

Michael R. Glass, Taylor B. Seybolt, Phil Williams Enrique Desmond Arias, Roberto Briceño-Leon, Jon Coaffee, Savannah Cox, Daniel E. Esser, Vanda Felbab-Brown, Michael R. Glass, Kim Gounder, Brij Maharaj, Eduardo Moncada, Daniel Núñez, Taylor B. Seybolt, Phil Williams

January 21, 2022

John Hudak, William G. Gale, Darrell M. West, Vanda Felbab-Brown, Rashawn Ray, Molly E. Reynolds, Elaine Kamarck, William A. Galston, Gabriel R. Sanchez

January 5, 2022

Caitlin Talmadge

June 2, 2020

Read the essay that helped start the gay marriage movement in America

It started in 1989.

Andrew Sullivan wrote a cover story for The New Republic arguing for gay marriage . It was at the time a radical proposition — although Sullivan's argument came from a philosophically conservative place.

This was a key paragraph:

Legalizing gay marriage would offer homosexuals the same deal society now offers heterosexuals: general social approval and specific legal advantages in exchange for a deeper and harder-to-extract-yourself from commitment to another human being. Like straight marriage, it would foster social cohesion, emotional security, and economic prudence. Since there’s no reason gays should not be allowed to adopt or be foster parents, it could also help nurture children. And its introduction would not be some sort of radical break with social custom. As it has become more acceptable for gay people to acknowledge their loves publicly, more and more have committed themselves to one another for life in full view of their families and their friends, A law institutionalizing gay marriage would merely reinforce a healthy social trend. It would also, in the wake of AIDS, qualify as a genuine public health measure. Those conservatives who deplore promiscuity among some homosexuals should be among the first to support it. Burke could have written a powerful case for it.

Related stories

There is plenty of history of the gay marriage movement before Sullivan's essay, but his advocacy helped bring it in to the mainstream.

In a post on his blog, The Daily Dish , Sullivan recalls a moment debating gay marriage on TV shortly after his essay came out. "It was Crossfire, as I recall, and Gary Bauer’s response to my rather earnest argument after my TNR cover-story on the matter was laughter. 'This is the loopiest idea ever to come down the pike,' he joked. 'Why are we even discussing it?'"

No one is laughing anymore.

A lot of the themes from Sullivan's original essay — inclusion, social cohesion, responsibility, and family support — are echoed in today's decision, written by Justice Anthony Kennedy . This is the powerful last paragraph:

No union is more profound than marriage, for it embodies the highest ideals of love, fidelity, devotion, sacrifice, and family. In forming a marital union, two people become something greater than once they were. As some of the petitioners in these cases demonstrate, marriage embodies a love that may endure even past death. It would misunderstand these men and women to say they disrespect the idea of marriage. Their plea is that they do respect it, respect it so deeply that they seek to find its fulfillment for themselves. Their hope is not to be condemned to live in loneliness, excluded from one of civilization’s oldest institutions. They ask for equal dignity in the eyes of the law. The Constitution grants them that right.

Sullivan is now officially a retired blogger. But he returned today to write about the decision. This is his response :

I never believed this would happen in my lifetime when I wrote my first several TNR essays and then my book, Virtually Normal, and then the anthology and the hundreds and hundreds of talks and lectures and talk-shows and call-ins and blog-posts and articles in the 1990s and 2000s. I thought the book, at least, would be something I would have to leave behind me – secure in the knowledge that its arguments were, in fact, logically irrefutable, and would endure past my own death, at least somewhere. I never for a millisecond thought I would live to be married myself. Or that it would be possible for everyone, everyone in America.

Twenty-six years later, Sullivan's seemingly radical idea is the law of the land.

Watch: Here are all the best moments from Donald Trump's presidential announcement

- Main content

Last updated 27/06/24: Online ordering is currently unavailable due to technical issues. We apologise for any delays responding to customers while we resolve this. For further updates please visit our website: https://www.cambridge.org/news-and-insights/technical-incident

We use cookies to distinguish you from other users and to provide you with a better experience on our websites. Close this message to accept cookies or find out how to manage your cookie settings .

Login Alert

- > Journals

- > Volume 15 Issue 43

- > WHY SAME-SEX MARRIAGE IS UNJUST

Article contents

Why same-sex marriage is unjust.

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 29 March 2016

Proponents of same-sex marriage often defend their view by appealing to the concept of justice. But a significant argument from justice against same-sex marriage can be made also, as follows. Heterosexual union has special social value because it is the indispensable means by which humans come into existence. What has special social value deserves special recognition and sanction. Civil ordinances that recognize same-sex marriage as comparable to heterosexual marriage constitute a rejection of the special social value of heterosexual unions, and to deny such special social value is unjust.

Access options

1 I take this to be obvious, and I would not bother to mention it except for the fact that my argument pivots on this point. Shakespeare's Hamlet entertained the question whether it is better to live or not to live. Although some would answer negatively regarding his or similarly agonizing cases, as applied to the existence of humanity in toto the correct answer to Hamlet's question is clearly affirmative.

2 Furthermore, as some have observed, homosexuals do enjoy the privilege to marry, so long as they do so with someone of the opposite sex. This might seem to be an empty or even mocking point because it ignores the distinct sexual desires of homosexuals. But there are many other civil privileges the criteria for which are similarly unyielding to the unique desires of particular citizens, such as the disqualification of the severely visually impaired when it comes to obtaining a driver's license or joining the armed forces.

3 By most counts, there are over 1,100 benefits provided to married couples by the U.S. federal government and many more benefits provided at the state level, including automatic inheritance, divorce protections, burial determination privileges, automatic housing lease transfer, domestic violence protection, joint bankruptcy privileges, and wrongful death benefits.

This article has been cited by the following publications. This list is generated based on data provided by Crossref .

- Google Scholar

View all Google Scholar citations for this article.

Save article to Kindle

To save this article to your Kindle, first ensure [email protected] is added to your Approved Personal Document E-mail List under your Personal Document Settings on the Manage Your Content and Devices page of your Amazon account. Then enter the ‘name’ part of your Kindle email address below. Find out more about saving to your Kindle .

Note you can select to save to either the @free.kindle.com or @kindle.com variations. ‘@free.kindle.com’ emails are free but can only be saved to your device when it is connected to wi-fi. ‘@kindle.com’ emails can be delivered even when you are not connected to wi-fi, but note that service fees apply.

Find out more about the Kindle Personal Document Service.

- Volume 15, Issue 43

- James S. Spiegel

- DOI: https://doi.org/10.1017/S1477175616000075

Save article to Dropbox

To save this article to your Dropbox account, please select one or more formats and confirm that you agree to abide by our usage policies. If this is the first time you used this feature, you will be asked to authorise Cambridge Core to connect with your Dropbox account. Find out more about saving content to Dropbox .

Save article to Google Drive

To save this article to your Google Drive account, please select one or more formats and confirm that you agree to abide by our usage policies. If this is the first time you used this feature, you will be asked to authorise Cambridge Core to connect with your Google Drive account. Find out more about saving content to Google Drive .

Reply to: Submit a response

- No HTML tags allowed - Web page URLs will display as text only - Lines and paragraphs break automatically - Attachments, images or tables are not permitted

Your details

Your email address will be used in order to notify you when your comment has been reviewed by the moderator and in case the author(s) of the article or the moderator need to contact you directly.

You have entered the maximum number of contributors

Conflicting interests.

Please list any fees and grants from, employment by, consultancy for, shared ownership in or any close relationship with, at any time over the preceding 36 months, any organisation whose interests may be affected by the publication of the response. Please also list any non-financial associations or interests (personal, professional, political, institutional, religious or other) that a reasonable reader would want to know about in relation to the submitted work. This pertains to all the authors of the piece, their spouses or partners.

We use cookies to enhance our website for you. Proceed if you agree to this policy or learn more about it.

- Essay Database >

- Essay Examples >

- Essays Topics >

- Essay on Love

Gay Marriage Argument Essays: Should It Be Legalized

Type of paper: Argumentative Essay

Topic: Love , Same Sex Marriage , LGBT , Relationships , Marriage , Gay , Homosexuality , Family

Words: 2750

Published: 03/31/2020

ORDER PAPER LIKE THIS

Introduction

The legalization of Gay marriage has stirred a lot of controversies in America, and the world in general. Traditionally, marriage has been rooted in many cultures, practices and even traditions, as the union of a man and a woman. Same sex marriages or relationships have been prohibited all along, and people that went against these practices were often termed as outcasts. But in the recent years, the rate of gay marriages and relationships has been on the rise. This has stirred a lot of debate on whether they should be legalized or not. Movements and societies have been formed to protects the gay rights and ensure that their traits are accepted by the society. The church and some individuals in the society, including politicians and Anti- gay movements, have been beating their heads on the wall trying to come up with reasons why it should not be legalized, and at the same time, trying to convince the states that have accepted same sex marriages to overturn the courts decisions. As the society evolves, the traits and changes that come with it should be embraced. The society has come from far concerning so many issues, from racism to accepting divorce in the marriage institution. All these factors do not matter in this day age and age in America. Same way as these was accepted in our society, so should homosexuality be accepted. Gay marriages should be legalized, amidst all the controversies that come with it, since intimate matters should be of private concern and the society is evolving.

The circus of Gay marriages

Gay marriages have been in the community for a long time, but the controversies of these relationships rose up in 1990’s, when a court in Hawaii ruled in favor of a gay couple that had been denied the right to marry each other, in 1996. This decision stirred a lot of debate where many people were against it and termed it as an abomination. The constitution was later changed to prohibit same sex marriages in the state. This debate became more than a state matter since it blew the interests of people to a national level. These debates have been ongoing up to date with parties from both the opposing and the supporting side exchanging words, each in favor of their side. Canada allowed same sex marriages1n 2004, saying that prohibiting gay couples from their rights will be a matter of discrimination. America has followed suit in legalizing gay marriages where states like Massachusetts passed a law to allow same sex couples to marry. It goes without saying that a great deal of politics has also been associated with homosexuality, where some of the politicians are against it, and others are in favor of it. The marriage institution is under both the law of any land, and under the laws of the church, or any religion for that matter. Some people therefore argue that each state should have laws governing the marriage institutions in their own states, others argue that as much as the church and the government have laws concerning the marriage institution, it should not be any of their concern especially when it comes to who marries who in the society (Burns 45). In America, sixteen states already allow marriages of the same sex couples. In 1996, the U. S congress passed the DOMA law (Defense of Marriage Act), in an attempt to define and limit marriage to only a man and a woman, and not people of the same sex. A group of activists took the matter to the high court in 2005, but the case was overturned by the U. S Eight Circuit Court of appeals the next year, 2006. Later in the year, the same court held that DOMA was unconstitutional and was depriving homosexuals the equality rights that they should be enjoying. The Supreme Court ruled it unconstitutional for the federal government to deny same sex married couples their rights, saying that it was unconstitutional. They made this ruling on 26th June 2013, but it is only limited to the states that have legalized same sex marriages(Family Guy).

Anti- gay movements

Anti- gay movements have been widely recognized for not supporting same sex marriages. Their campaigns to stop legalization of gay marriages have worked in some states, where and have opposed any form of legal protections on gays. These restrictions include denying gays rights to protect their families and rights to bond with their children (Rimmerman and Wilcox 179). However, these movements have been associated with the spread of mere propaganda concerning gays in the community. Their claims on the ‘evils’ that these unions bring are baseless. Some of anti- gay people claimed that the gay people were mostly involved in crimes, and that they actually perpetrated most of the crimes in the country. They were accused of dealing in drugs, and being the, main of the widespread of sexually transmitted diseases. All the claims were baseless and they had no prove of them, because, for example, the spread of sexually transmitted diseases, is also experienced among many straight marriages, especially due to infidelity.

Gay marriages and literary works

Many productions have been coming up recently, especially in the motion pictures word, all in support of gay marriages. They all depict families with gay people, from parents to the children and how they cope with each other, the love and harmony that they have in their families, despite their sexual orientations, for example, Family guy, the Simpsons and the likes. Comic books too have had their own share of the story with Astonishing X-Men comic series, depicting the marriage of the super hero, Jean-Paul Beaubier to his partner Kyle Jinadu. All these works at aiming at promoting the same sex marriage institution, and letting people know that the sexual orientations of individuals do not affect their productivity or their way of associating with other members of the society (Astonishing X-Men).

Why it should not be legalized

The marriage institution has been known over time to contain a relationship between a man and a woman; a relationship that is made through understanding, love and more importantly, the sexual relationship which is the proper pro- creation process. Gay couples cannot bear children of their own, even with the advanced technologies in the present day and age, which will force them to adopt children. One of the most important things of bringing up children in a family made up of a woman and a man is that, they will get to experience the worlds of having both a father and a mother. This will be hard for children brought up in gay marriages, because they will get to experience the worlds of having either two mothers or two fathers. This will be violence against the children’s development process as their world will not be in the best or the agreeable environment for human development (Burns 27). Its legalization will also be undermining the natural sex laws that people know, and have been practiced for ages now. Children will be brought up in confused society that does not know how to support and fight for the morality of its people.

Homosexuality and religion (why it should not be legalized)

Religious leaders have been on the front line to bar same sex marriages and relationships. The bible has been used as the main guide to morality in the society over the past centuries. Many verses can be quoted from the bible, where the institutions of same marriages have been termed as evil and unreligious. The punishment of these practices has also been detailed, with eternal life in hell being the main highlight (King James Bible, Rev. 21). Christian leaders argue that same sex marriage is not only prohibited in Christianity, but across all other religions. Their stand against this debate is one that has been held for a long time, and they are still going strong, with some even suggesting jailing and even killing of people found marrying from the same sex. Some of the religious institutions may be adamant on providing services like accommodation, employment, adoption and others to same sex partners. It still doesn’t matter whether these religious leaders support it or not, bottom line is, if homosexuality is legalized, this will be against the laws and commandments of God. From the beginning of the world and creation, in the Garden of Eden, God mad man (Adam), in His own image, and later on, made a woman for him from his rib, Eve, and told them to go fill the world (King James Bible, Gen. 1). Pro- creation and marriage institution was set to be between a man and a woman, right from the beginning of the world, not between a man and a man, or a woman and a woman. Legalization of these unions will therefore be against the laws of the church and the laws of creation in general.

Gay marriage and other laws (why it should not be legalized)

The legalization of same sex marriages has been argued to bring about a spin in the legalization of other unacceptable traits and behaviors. Many have argued that if it is legalized, laws on incest, polygamy and even bestiality. Many religious leaders and activists have associated homosexuality with bestiality, polygamy and pedophilia among others, and they argue that, if homosexuality is legalized, we will observe a wave of moral values erosion in the society. Children will be brought up in a society with no moral values and will be led to believe that homosexuality is an ideal lifestyle and an acceptable trait. The rates of children molestation will be on the rise in the society (Rimmerman and Wilcox 179). It is believed that the legalization will make homosexuality more acceptable in the society, lead to the fracture of the family system, and it also can be a major setback on the scale of the Supreme Court when it legalized abortion. Activists believe that the fight will be long with the court, so as to overturn the court’s decision.

Advantages of legalization

It is believed that legalization of gay marriages will lead to an improvement in the lives of heterosexuals. Due to the stigma that come a long with coming out of the closet; many gay people do not come into the light. The need to be accepted by the society, whether in family and social gatherings, the wish to be accepted by people around just like any heterosexual person and the fear of being denied employment and other societal values, have led gay people to unwanted marriages. Most of the gay people have been married to people they really do not love just to hide their identity from the society. These fraudulent marriages are not good, for both parties, and even the children. If the same sex marriage institution is legalized, the high rate of divorces that is being experienced at the moment will go down; since gays will stop marrying people of the opposite side to just enable them hide their sex orientation. A reduction in the divorce rates will promote more stable families in the society and due to this; many children will be brought up in stable families. Another advantage of these marriages is that many orphaned children will get stable families, and be brought up in much better conditions when they are adopted. This will lead to the improvement of struggling communities: for example, the number of children who will be homeless and in the foster system will go down (Alvear 1). Another importance of legalizing gay marriages and relationships is that the rate of suicides associated with gay teenagers will reduce. Teenagers and young man and ladies have been committing suicide for the reasons quiet obvious; negativities associated with homosexuality. They feel different from their age mates and they alienate themselves from their peers for fear of being bullied. This alienation and lack of somebody to talk to makes them feel lonely and they are usually in their own world mostly. This leads to suicide since they that feel no one understands. Others have turned to substance abuse to just relieve them from the guilt of being different from the rest of the world. All these factors, especially substance abuse, lead to high rates of crime in the country, especially among the youths and teenagers. Legalization of same sex marriages will help them feel acceptable to the society, and due to this, they will no longer have the urge to turn to drugs for refuge, or suicide for that matter(Moats 45). This discrimination against gay people hurts everyone in the society, whether they are gay or not. When the gay in the community are not accepted, they end up marrying people they do not love, and being in the closet about their sexual orientation, their partners may be really in love with them. The gay person in the marriage will be hurt, since they will feel unappreciated and not satisfied. A marriage should have the happiness and satisfaction of both parties, failure to which, it seizes to be a stable relationship, and it faces many challenges. The other party in the relationship will also not be satisfied because their partner will not be comfortable sharing the many aspects of intimacy with them. This is what leads to divorces, hurting both parties, especially those who had no idea that there partner was gay. If that family had children, their dreams and hopes of growing up in a complete and happy family are shattered. They become the laughing stock among their peers, who do not appreciate gay relationships, due to what they hear from the society about them. These factors can all be avoided if same sex marriages are legalized in the country, and in all the states(Gay Marriage opponents). Though Christians tend to hate on the gay people and condemn them, it leaves the question of what happened to the biblical commandment of loving one another. This legalization will be able to open up their minds and even their hearts to their gay brothers and sisters. In turn, this will promote the spirit of togetherness in America, where people can interact without hating each on other based on their sexual orientation. A more co-ordinate community, that is united by love and peace progresses both economically and socially, and this, will be at the advantage of everybody in the country.

Same sex marriage should be legalized in all states since it has many advantages, and with the changing society, people should learn to embrace these changes. When it is legalized, the perception of people will change over time and all will be the same within no time.

Works Cited

Alvear, Michael. “Q: Would thhttp://minfin.com.ua/currency/nbu/e Legalization of Gay Marriage Result in a Net Benefit to Heterosexuals? Yes: Divorce Rates Triggered by Fraudulent Marriages Will Go Down and More Children Will Grow Up in stable Homes.’’ Insight on the News 22 Dec. 2003: 1. Print Astonishing X-Men.Dir. Joss Whedon.Perf. John Cassady . Shout Factoey, 2012. DVD. Burns, Kate. Gay marriage. Detroit: Greenhaven Press, 2005. Print. Family Guy.Dir. Seth MacFarlane.Perf Seth Mac Farlene. 20th Century Fox Home Entertainment, 2012.DVD. Gay Marriage opponents see Massachusetts legalization as major setback. Knight Ridder Tribune.Business News.McClatchy- Tribune Information Services. 2004. Highbeam Research. 14 Mar. 2014 <http/www.highbeam.com>. Moats, David. Civil wars: a battle for gay marriages. Orlando: Harcourt, 2004. Print. King James Bible.Ed. Gordon Campbell.Oxford University Press, 2010. Print. Rimmerman, Craig A., and Clyde Wilcox.The Politics of same- sex marriage. Chicago:

Cite this page

Share with friends using:

Removal Request

Finished papers: 523

This paper is created by writer with

ID 267095354

If you want your paper to be:

Well-researched, fact-checked, and accurate

Original, fresh, based on current data

Eloquently written and immaculately formatted

275 words = 1 page double-spaced

Get your papers done by pros!

Other Pages

Road case studies, fishing case studies, gene case studies, hypertension case studies, privacy case studies, developing reports, intern research papers, inducing research papers, internal medicine research papers, calculation essays, overheard essays, soliloquy essays, skyscraper essays, stereo essays, drain essays, reservoir essays, jacket essays, creationist essays, adagio essays, grande essays, inman essays, molloy essays, walters essays, terhune essays, helles essays, idea analysis paper essay example, research statement question what are the ethical issues in the tuskegee experiments essay example, business plan on psychological factors, example of research paper on history of western dress, example of essay on technology, free research paper on management purchases related to project, pare details report example, report on presenting business plans, example of course work on inline css styles, example of trusted computing base course work, example of essay on forget what you know about good study habits, social network and privacy research proposal example, finance course work, stressed essay example, the volumetric analysis of the amount of vitamin c in a tablet essay example, term paper on social interactions language development hypothesis, research paper on people of the middle east, example of research paper on research in psychology.

Password recovery email has been sent to [email protected]

Use your new password to log in

You are not register!

By clicking Register, you agree to our Terms of Service and that you have read our Privacy Policy .

Now you can download documents directly to your device!

Check your email! An email with your password has already been sent to you! Now you can download documents directly to your device.

or Use the QR code to Save this Paper to Your Phone

The sample is NOT original!

Short on a deadline?

Don't waste time. Get help with 11% off using code - GETWOWED

No, thanks! I'm fine with missing my deadline

Essay Service Examples Social Issues Same-sex Marriage

Why Same Sex Marriage Should Be Legal Essay

Introduction

- Proper editing and formatting

- Free revision, title page, and bibliography

- Flexible prices and money-back guarantee

Our writers will provide you with an essay sample written from scratch: any topic, any deadline, any instructions.

Cite this paper

Related essay topics.

Get your paper done in as fast as 3 hours, 24/7.

Related articles

Most popular essays

- Religious Beliefs

- Same-sex Marriage

Religion has always been an integral part of every nation, every nation or every culture....

In this chapter we shall be having an overview of same-sex marriage. The main purpose of this, is...

Same sex marriage has become so prevalent in our society and is still becoming more rampant as the...

- Gay Marriage

This essay is titled “Same-Sex Marriage Weakens the Institution of Marriage. It is written by an...

- Discrimination

Today, there are many developed countries in the world that still do not accept gay marriages and...

The contemporary LGBT movement started in 1969, however the struggle for their rights have been...

- Sex, Gender and Sexuality

One of the many unfortunate realities of our society is that race has played a major role in how...

Modernization and the altered views of Millennials compared to Generation X and Baby Boomers have...

Since the 2016 election, social-political issues including race, abortion, and equality between...

Join our 150k of happy users

- Get original paper written according to your instructions

- Save time for what matters most

Fair Use Policy

EduBirdie considers academic integrity to be the essential part of the learning process and does not support any violation of the academic standards. Should you have any questions regarding our Fair Use Policy or become aware of any violations, please do not hesitate to contact us via [email protected].

We are here 24/7 to write your paper in as fast as 3 hours.

Provide your email, and we'll send you this sample!

By providing your email, you agree to our Terms & Conditions and Privacy Policy .

Say goodbye to copy-pasting!

Get custom-crafted papers for you.

Enter your email, and we'll promptly send you the full essay. No need to copy piece by piece. It's in your inbox!

Numbers, Facts and Trends Shaping Your World

Read our research on:

Full Topic List

Regions & Countries

- Publications

- Our Methods

- Short Reads

- Tools & Resources

Read Our Research On:

- In Gay Marriage Debate, Both Supporters and Opponents See Legal Recognition as ’Inevitable’

Table of Contents

- Section 1: Same-Sex Marriage, Civil Unions and Inevitability

- Section 2: Views of Gay Men and Lesbians, Roots of Homosexuality, Personal Contact with Gays

- Section 3: Religious Belief and Views of Homosexuality

- About the Survey

As support for gay marriage continues to increase, nearly three-quarters of Americans – 72% – say that legal recognition of same-sex marriage is “inevitable.” This includes 85% of gay marriage supporters, as well as 59% of its opponents.

The national survey by the Pew Research Center, conducted May 1-5 among 1,504 adults, finds that support for same-sex marriage continues to grow: For the first time in Pew Research Center polling, just over half (51%) of Americans favor allowing gays and lesbians to marry legally. Yet the issue remains divisive, with 42% saying they oppose legalizing gay marriage. Opposition to gay marriage – and to societal acceptance of homosexuality more generally – is rooted in religious attitudes, such as the belief that engaging in homosexual behavior is a sin.

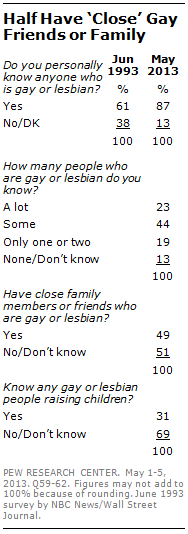

At the same time, more people today have gay or lesbian acquaintances, which is associated with acceptance of homosexuality and support for gay marriage. Nearly nine-in-ten Americans (87%) personally know someone who is gay or lesbian (up from 61% in 1993). About half (49%) say a close family member or one of their closest friends is gay or lesbian. About a quarter (23%) say they know a lot of people who are gay or lesbian, and 31% know a gay or lesbian person who is raising children. The link between these experiences and attitudes about homosexuality is strong. For example, roughly two-thirds (68%) of those who know a lot of people who are gay or lesbian favor gay marriage, compared with just 32% of those who don’t know anyone.

Part of this is a matter of who is more likely to have many gay acquaintances: the young, city dwellers, women, and the less religious, for example. But even taking these factors into account, the relationship between personal experiences and acceptance of homosexuality is a strong one.

Yet opposition to gay marriage remains substantial, and religious beliefs are a major factor in opposition. Just under half of Americans (45%) say they think engaging in homosexual behavior is a sin, while an equal number says it is not. Those who believe homosexual behavior is a sin overwhelmingly oppose gay marriage. Similarly, those who say they personally feel there is a lot of conflict between their religious beliefs and homosexuality (35% of the public) are staunchly opposed to same-sex marriage.

The survey finds that as support for same-sex marriage has risen, other attitudes about homosexuality have changed as well. In a 2004 Los Angeles Times poll, most Americans (60%) said they would be upset if they had a child who told them that they were gay or lesbian; 33% said they would be very upset over this. Today, 40% say they would be upset if they learned they had a gay or lesbian child, and just 19% would be very upset.

Favorable opinions of both gay men and lesbians have risen since 2003. Moreover, by nearly two-to-one (60% to 31%), more Americans say that homosexuality should be accepted rather than discouraged by society. A decade ago, opinions about societal acceptance of homosexuality were evenly divided (47% accepted, 45% discouraged).

The religious basis for opposition to homosexuality is seen clearly in the reasons people give for saying it should be discouraged by society. By far the most frequently cited factors –mentioned by roughly half (52%) of those who say homosexuality should be discouraged – are moral objections to homosexuality, that it conflicts with religious beliefs, or that it goes against the Bible. No more than about one-in-ten cite any other reasons as to why homosexuality should be discouraged by society.

Widespread Belief that Legal Recognition Is ‘Inevitable’

Despite the increasing support for legal same-sex marriage in recent years, opinions about the issue remain deeply divided by age, partisanship and religious affiliation.

By contrast, large majorities across most demographic groups think that legal recognition of same-sex marriage is inevitable.

Republicans (73%) are as likely as Democrats (72%) or independents (74%) to view legal recognition for gay marriage as inevitable. Just 31% of Republicans favor allowing gays and lesbians to marry legally, compared with majorities of Democrats (59%) and independents (58%).

Similarly, people 65 and older are 30 points more likely to view legal recognition of same-sex marriage as inevitable than to favor it (69% vs. 39%). Among those younger than 30, about as many see legal same-sex marriage as inevitable as support gay marriage (69%, 65%).

Just 22% of white evangelical Protestants favor same-sex marriage, but about three times that percentage (70%) thinks legal recognition for gay marriage is inevitable. Among other religious groups, there are smaller differences in underlying opinions about gay marriage and views of whether it is inevitable.

Sign up for our weekly newsletter

Fresh data delivery Saturday mornings

Sign up for The Briefing

Weekly updates on the world of news & information

- Beliefs & Practices

- National Conditions

- Political Issues

- Same-Sex Marriage

6 facts about religion and spirituality in East Asian societies

Religion and spirituality in east asian societies, how common is religious fasting in the united states, 8 facts about atheists, spirituality among americans, most popular, report materials.

- Voices : Views of Same-Sex Marriage, Homosexuality

- Graphic : Changing Attitudes on Same Sex Marriage, Gay Friends and Family

- May 2013 Political Survey

1615 L St. NW, Suite 800 Washington, DC 20036 USA (+1) 202-419-4300 | Main (+1) 202-857-8562 | Fax (+1) 202-419-4372 | Media Inquiries

Research Topics

- Email Newsletters

ABOUT PEW RESEARCH CENTER Pew Research Center is a nonpartisan fact tank that informs the public about the issues, attitudes and trends shaping the world. It conducts public opinion polling, demographic research, media content analysis and other empirical social science research. Pew Research Center does not take policy positions. It is a subsidiary of The Pew Charitable Trusts .

© 2024 Pew Research Center

Human rights abuses are happening right now – start a monthly gift today.

- Videos & Photos

- Take Action

Philippines Should Adopt Same-Sex Marriage

Duterte Turnaround Signals Lack of Commitment to LGBT Rights

@carloshconde

Share this via Facebook Share this via X Share this via WhatsApp Share this via Email Other ways to share Share this via LinkedIn Share this via Reddit Share this via Telegram Share this via Printer

Philippine President Rodrigo Duterte on Monday reversed a campaign promise to push for legalization of same-sex marriage. “That [same-sex marriage] won’t work for us. We’re Catholics,” he said in a speech before the Filipino community in Burma. “And there’s the Civil Code , which says that [a man] can only marry a woman.”

Your tax deductible gift can help stop human rights violations and save lives around the world.

More reading, misuse of texas troopers has broader implications for the us.

Myanmar: Junta Evading International Sanctions

Out of Step

U.S. Policy on Voting Rights in Global Perspective

Education under Occupation

Forced Russification of the School System in Occupied Ukrainian Territories

Most Viewed

"how come you allow little girls to get married".

Leave No Girl Behind in Africa

“I Sleep in My Own Deathbed”

Kenya: Witnesses Describe Police Killing Protesters

Victory for Same-Sex Marriage in Thailand

Protecting Rights, Saving Lives

Human Rights Watch defends the rights of people in close to 100 countries worldwide, spotlighting abuses and bringing perpetrators to justice

Get updates on human rights issues from around the globe. Join our movement today.

Every weekday, get the world’s top human rights news, explored and explained by Andrew Stroehlein.

By providing an email address. I agree to the Terms of Use and acknowledge that I have read the Privacy Policy .

The best argument against same-sex marriage

FILIPINOS, SPORTING #LoveWins hashtags and slapping rainbows onto their Facebook profile pictures, have been swept up in the euphoria over the US Supreme Court decision declaring same-sex marriage a fundamental human right. Law professors are heartened to see Justice Anthony Kennedy’s poetic Obergefell decision shared in social media. However, we must also read the powerful dissents and ask why we might prefer that our unelected justices decide this sensitive issue instead of our elected legislators.

Inquirer 2bu quoted teenagers opining that anyone with the capacity to love deserves to have his/her chosen relationship validated. Obergefell’s logic is equally simple. Forget “substantive due process,” “decisional privacy” and “equal protection.” It takes the simple premise that human liberty necessarily goes beyond physical liberty, and includes an unwritten right to make fundamental life choices. Choosing a life partner is one such fundamental choice and the decision of two people to formalize their relationship must be accorded utmost dignity.

The typical arguments against this simple idea are so intellectually discredited that Obergefell no longer discussed them. (My Philippine Law Journal article “Marriage through another lens,” 81 PHIL. L.J. 789 [2006], tried applying them to bisexual and transgender Filipinos.)

One cannot solely invoke religious doctrine, even if thinly veiled as secular “morality.” Religious groups may confront this issue but not impose their choices on others. Their often vindictive tone contrasts sharply with Kennedy’s, and increasingly alienates millennials who revel in individuality. Those criticized as religious zealots should at least strive to be up-to-date, more sophisticated religious zealots.

The most common argument, procreation, is also the easiest to refute. Philippine Family Code author Judge Alicia Sempio-Diy wrote: “The [Code] Committee believes that marriage … may also be only for companionship, as when parties past the age of procreation still get married.”

Another argument reduces marriage to a series of economic benefits and suggests a “domestic partnership” system to govern same-sex couples’ property and other rights. This parallels having separate schools for white and black children and claiming they are equal because both have schools. It implies that some relationships so lack dignity that they must be called something else.