STUDENT ESSAY The Disproportional Impact of COVID-19 on African Americans

Volume 22/2, December 2020, pp 299-307

Maritza Vasquez Reyes

Introduction

We all have been affected by the current COVID-19 pandemic. However, the impact of the pandemic and its consequences are felt differently depending on our status as individuals and as members of society. While some try to adapt to working online, homeschooling their children and ordering food via Instacart, others have no choice but to be exposed to the virus while keeping society functioning. Our different social identities and the social groups we belong to determine our inclusion within society and, by extension, our vulnerability to epidemics.

COVID-19 is killing people on a large scale. As of October 10, 2020, more than 7.7 million people across every state in the United States and its four territories had tested positive for COVID-19. According to the New York Times database, at least 213,876 people with the virus have died in the United States. [1] However, these alarming numbers give us only half of the picture; a closer look at data by different social identities (such as class, gender, age, race, and medical history) shows that minorities have been disproportionally affected by the pandemic. These minorities in the United States are not having their right to health fulfilled.

According to the World Health Organization’s report Closing the Gap in a Generation: Health Equity through Action on the Social Determinants of Health , “poor and unequal living conditions are the consequences of deeper structural conditions that together fashion the way societies are organized—poor social policies and programs, unfair economic arrangements, and bad politics.” [2] This toxic combination of factors as they play out during this time of crisis, and as early news on the effect of the COVID-19 pandemic pointed out, is disproportionately affecting African American communities in the United States. I recognize that the pandemic has had and is having devastating effects on other minorities as well, but space does not permit this essay to explore the impact on other minority groups.

Employing a human rights lens in this analysis helps us translate needs and social problems into rights, focusing our attention on the broader sociopolitical structural context as the cause of the social problems. Human rights highlight the inherent dignity and worth of all people, who are the primary rights-holders. [3] Governments (and other social actors, such as corporations) are the duty-bearers, and as such have the obligation to respect, protect, and fulfill human rights. [4] Human rights cannot be separated from the societal contexts in which they are recognized, claimed, enforced, and fulfilled. Specifically, social rights, which include the right to health, can become important tools for advancing people’s citizenship and enhancing their ability to participate as active members of society. [5] Such an understanding of social rights calls our attention to the concept of equality, which requires that we place a greater emphasis on “solidarity” and the “collective.” [6] Furthermore, in order to generate equality, solidarity, and social integration, the fulfillment of social rights is not optional. [7] In order to fulfill social integration, social policies need to reflect a commitment to respect and protect the most vulnerable individuals and to create the conditions for the fulfillment of economic and social rights for all.

Disproportional impact of COVID-19 on African Americans

As noted by Samuel Dickman et al.:

economic inequality in the US has been increasing for decades and is now among the highest in developed countries … As economic inequality in the US has deepened, so too has inequality in health. Both overall and government health spending are higher in the US than in other countries, yet inadequate insurance coverage, high-cost sharing by patients, and geographical barriers restrict access to care for many. [8]

For instance, according to the Kaiser Family Foundation, in 2018, 11.7% of African Americans in the United States had no health insurance, compared to 7.5% of whites. [9]

Prior to the Affordable Care Act—enacted into law in 2010—about 20% of African Americans were uninsured. This act helped lower the uninsured rate among nonelderly African Americans by more than one-third between 2013 and 2016, from 18.9% to 11.7%. However, even after the law’s passage, African Americans have higher uninsured rates than whites (7.5%) and Asian Americans (6.3%). [10] The uninsured are far more likely than the insured to forgo needed medical visits, tests, treatments, and medications because of cost.

As the COVID-19 virus made its way throughout the United States, testing kits were distributed equally among labs across the 50 states, without consideration of population density or actual needs for testing in those states. An opportunity to stop the spread of the virus during its early stages was missed, with serious consequences for many Americans. Although there is a dearth of race-disaggregated data on the number of people tested, the data that are available highlight African Americans’ overall lack of access to testing. For example, in Kansas, as of June 27, according to the COVID Racial Data Tracker, out of 94,780 tests, only 4,854 were from black Americans and 50,070 were from whites. However, blacks make up almost a third of the state’s COVID-19 deaths (59 of 208). And while in Illinois the total numbers of confirmed cases among blacks and whites were almost even, the test numbers show a different picture: 220,968 whites were tested, compared to only 78,650 blacks. [11]

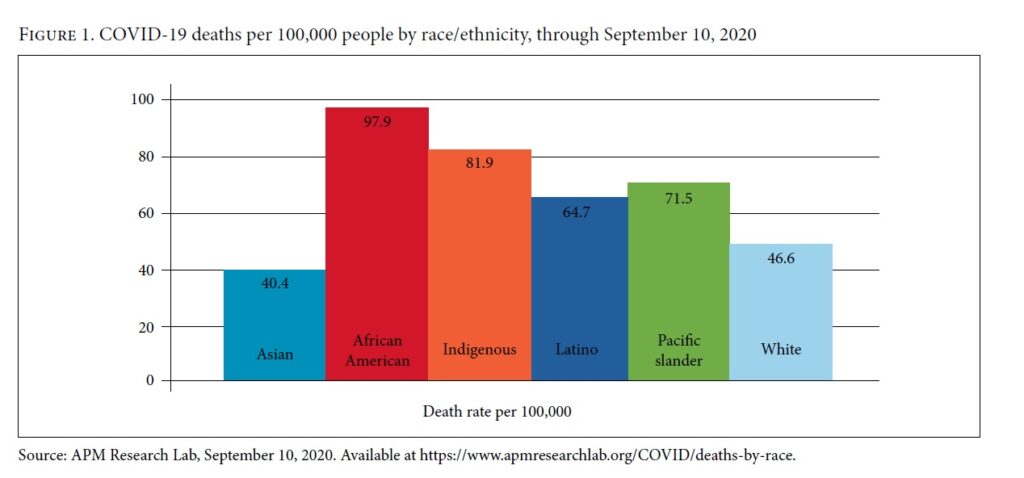

Similarly, American Public Media reported on the COVID-19 mortality rate by race/ethnicity through July 21, 2020, including Washington, DC, and 45 states (see figure 1). These data, while showing an alarming death rate for all races, demonstrate how minorities are hit harder and how, among minority groups, the African American population in many states bears the brunt of the pandemic’s health impact.

Approximately 97.9 out of every 100,000 African Americans have died from COVID-19, a mortality rate that is a third higher than that for Latinos (64.7 per 100,000), and more than double than that for whites (46.6 per 100,000) and Asians (40.4 per 100,000). The overrepresentation of African Americans among confirmed COVID-19 cases and number of deaths underscores the fact that the coronavirus pandemic, far from being an equalizer, is amplifying or even worsening existing social inequalities tied to race, class, and access to the health care system.

Considering how African Americans and other minorities are overrepresented among those getting infected and dying from COVID-19, experts recommend that more testing be done in minority communities and that more medical services be provided. [12] Although the law requires insurers to cover testing for patients who go to their doctor’s office or who visit urgent care or emergency rooms, patients are fearful of ending up with a bill if their visit does not result in a COVID test. Furthermore, minority patients who lack insurance or are underinsured are less likely to be tested for COVID-19, even when experiencing alarming symptoms. These inequitable outcomes suggest the importance of increasing the number of testing centers and contact tracing in communities where African Americans and other minorities reside; providing testing beyond symptomatic individuals; ensuring that high-risk communities receive more health care workers; strengthening social provision programs to address the immediate needs of this population (such as food security, housing, and access to medicines); and providing financial protection for currently uninsured workers.

Social determinants of health and the pandemic’s impact on African Americans’ health outcomes

In international human rights law, the right to health is a claim to a set of social arrangements—norms, institutions, laws, and enabling environment—that can best secure the enjoyment of this right. The International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights sets out the core provision relating to the right to health under international law (article 12). [13] The United Nations Committee on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights is the body responsible for interpreting the covenant. [14] In 2000, the committee adopted a general comment on the right to health recognizing that the right to health is closely related to and dependent on the realization of other human rights. [15] In addition, this general comment interprets the right to health as an inclusive right extending not only to timely and appropriate health care but also to the determinants of health. [16] I will reflect on four determinants of health—racism and discrimination, poverty, residential segregation, and underlying medical conditions—that have a significant impact on the health outcomes of African Americans.

Racism and discrimination

In spite of growing interest in understanding the association between the social determinants of health and health outcomes, for a long time many academics, policy makers, elected officials, and others were reluctant to identify racism as one of the root causes of racial health inequities. [17] To date, many of the studies conducted to investigate the effect of racism on health have focused mainly on interpersonal racial and ethnic discrimination, with comparatively less emphasis on investigating the health outcomes of structural racism. [18] The latter involves interconnected institutions whose linkages are historically rooted and culturally reinforced. [19] In the context of the COVID-19 pandemic, acts of discrimination are taking place in a variety of contexts (for example, social, political, and historical). In some ways, the pandemic has exposed existing racism and discrimination.

Poverty (low-wage jobs, insurance coverage, homelessness, and jails and prisons)

Data drawn from the 2018 Current Population Survey to assess the characteristics of low-income families by race and ethnicity shows that of the 7.5 million low-income families with children in the United States, 20.8% were black or African American (while their percentage of the population in 2018 was only 13.4%). [20] Low-income racial and ethnic minorities tend to live in densely populated areas and multigenerational households. These living conditions make it difficult for low-income families to take necessary precautions for their safety and the safety of their loved ones on a regular basis. [21] This fact becomes even more crucial during a pandemic.

Low-wage jobs: The types of work where people in some racial and ethnic groups are overrepresented can also contribute to their risk of getting sick with COVID-19. Nearly 40% of African American workers, more than seven million, are low-wage workers and have jobs that deny them even a single paid sick day. Workers without paid sick leave might be more likely to continue to work even when they are sick. [22] This can increase workers’ exposure to other workers who may be infected with the COVID-19 virus.

Similarly, the Centers for Disease Control has noted that many African Americans who hold low-wage but essential jobs (such as food service, public transit, and health care) are required to continue to interact with the public, despite outbreaks in their communities, which exposes them to higher risks of COVID-19 infection. According to the Centers for Disease Control, nearly a quarter of employed Hispanic and black or African American workers are employed in service industry jobs, compared to 16% of non-Hispanic whites. Blacks or African Americans make up 12% of all employed workers but account for 30% of licensed practical and licensed vocational nurses, who face significant exposure to the coronavirus. [23]

In 2018, 45% of low-wage workers relied on an employer for health insurance. This situation forces low-wage workers to continue to go to work even when they are not feeling well. Some employers allow their workers to be absent only when they test positive for COVID-19. Given the way the virus spreads, by the time a person knows they are infected, they have likely already infected many others in close contact with them both at home and at work. [24]

Homelessness : Staying home is not an option for the homeless. African Americans, despite making up just 13% of the US population, account for about 40% of the nation’s homeless population, according to the Annual Homeless Assessment Report to Congress. [25] Given that people experiencing homelessness often live in close quarters, have compromised immune systems, and are aging, they are exceptionally vulnerable to communicable diseases—including the coronavirus that causes COVID-19.

Jails and prisons : Nearly 2.2 million people are in US jails and prisons, the highest rate in the world. According to the US Bureau of Justice, in 2018, the imprisonment rate among black men was 5.8 times that of white men, while the imprisonment rate among black women was 1.8 times the rate among white women. [26] This overrepresentation of African Americans in US jails and prisons is another indicator of the social and economic inequality affecting this population.

According to the Committee on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights’ General Comment 14, “states are under the obligation to respect the right to health by, inter alia , refraining from denying or limiting equal access for all persons—including prisoners or detainees, minorities, asylum seekers and illegal immigrants—to preventive, curative, and palliative health services.” [27] Moreover, “states have an obligation to ensure medical care for prisoners at least equivalent to that available to the general population.” [28] However, there has been a very limited response to preventing transmission of the virus within detention facilities, which cannot achieve the physical distancing needed to effectively prevent the spread of COVID-19. [29]

Residential segregation

Segregation affects people’s access to healthy foods and green space. It can also increase excess exposure to pollution and environmental hazards, which in turn increases the risk for diabetes and heart and kidney diseases. [30] African Americans living in impoverished, segregated neighborhoods may live farther away from grocery stores, hospitals, and other medical facilities. [31] These and other social and economic inequalities, more so than any genetic or biological predisposition, have also led to higher rates of African Americans contracting the coronavirus. To this effect, sociologist Robert Sampson states that the coronavirus is exposing class and race-based vulnerabilities. He refers to this factor as “toxic inequality,” especially the clustering of COVID-19 cases by community, and reminds us that African Americans, even if they are at the same level of income or poverty as white Americans or Latino Americans, are much more likely to live in neighborhoods that have concentrated poverty, polluted environments, lead exposure, higher rates of incarceration, and higher rates of violence. [32]

Many of these factors lead to long-term health consequences. The pandemic is concentrating in urban areas with high population density, which are, for the most part, neighborhoods where marginalized and minority individuals live. In times of COVID-19, these concentrations place a high burden on the residents and on already stressed hospitals in these regions. Strategies most recommended to control the spread of COVID-19—social distancing and frequent hand washing—are not always practical for those who are incarcerated or for the millions who live in highly dense communities with precarious or insecure housing, poor sanitation, and limited access to clean water.

Underlying health conditions

African Americans have historically been disproportionately diagnosed with chronic diseases such as asthma, hypertension and diabetes—underlying conditions that may make COVID-19 more lethal. Perhaps there has never been a pandemic that has brought these disparities so vividly into focus.

Doctor Anthony Fauci, an immunologist who has been the director of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases since 1984, has noted that “it is not that [African Americans] are getting infected more often. It’s that when they do get infected, their underlying medical conditions … wind them up in the ICU and ultimately give them a higher death rate.” [33]

One of the highest risk factors for COVID-19-related death among African Americans is hypertension. A recent study by Khansa Ahmad et al. analyzed the correlation between poverty and cardiovascular diseases, an indicator of why so many black lives are lost in the current health crisis. The authors note that the American health care system has not yet been able to address the higher propensity of lower socioeconomic classes to suffer from cardiovascular disease. [34] Besides having higher prevalence of chronic conditions compared to whites, African Americans experience higher death rates. These trends existed prior to COVID-19, but this pandemic has made them more visible and worrisome.

Addressing the impact of COVID-19 on African Americans: A human rights-based approach

The racially disparate death rate and socioeconomic impact of the COVID-19 pandemic and the discriminatory enforcement of pandemic-related restrictions stand in stark contrast to the United States’ commitment to eliminate all forms of racial discrimination. In 1965, the United States signed the International Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Racial Discrimination, which it ratified in 1994. Article 2 of the convention contains fundamental obligations of state parties, which are further elaborated in articles 5, 6, and 7. [35] Article 2 of the convention stipulates that “each State Party shall take effective measures to review governmental, national and local policies, and to amend, rescind or nullify any laws and regulations which have the effect of creating or perpetuating racial discrimination wherever it exists” and that “each State Party shall prohibit and bring to an end, by all appropriate means, including legislation as required by circumstances, racial discrimination by any persons, group or organization.” [36]

Perhaps this crisis will not only greatly affect the health of our most vulnerable community members but also focus public attention on their rights and safety—or lack thereof. Disparate COVID-19 mortality rates among the African American population reflect longstanding inequalities rooted in systemic and pervasive problems in the United States (for example, racism and the inadequacy of the country’s health care system). As noted by Audrey Chapman, “the purpose of a human right is to frame public policies and private behaviors so as to protect and promote the human dignity and welfare of all members and groups within society, particularly those who are vulnerable and poor, and to effectively implement them.” [37] A deeper awareness of inequity and the role of social determinants demonstrates the importance of using right to health paradigms in response to the pandemic.

The Committee on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights has proposed some guidelines regarding states’ obligation to fulfill economic and social rights: availability, accessibility, acceptability, and quality. These four interrelated elements are essential to the right to health. They serve as a framework to evaluate states’ performance in relation to their obligation to fulfill these rights. In the context of this pandemic, it is worthwhile to raise the following questions: What can governments and nonstate actors do to avoid further marginalizing or stigmatizing this and other vulnerable populations? How can health justice and human rights-based approaches ground an effective response to the pandemic now and build a better world afterward? What can be done to ensure that responses to COVID-19 are respectful of the rights of African Americans? These questions demand targeted responses not just in treatment but also in prevention. The following are just some initial reflections:

First, we need to keep in mind that treating people with respect and human dignity is a fundamental obligation, and the first step in a health crisis. This includes the recognition of the inherent dignity of people, the right to self-determination, and equality for all individuals. A commitment to cure and prevent COVID-19 infections must be accompanied by a renewed commitment to restore justice and equity.

Second, we need to strike a balance between mitigation strategies and the protection of civil liberties, without destroying the economy and material supports of society, especially as they relate to minorities and vulnerable populations. As stated in the Siracusa Principles, “[state restrictions] are only justified when they support a legitimate aim and are: provided for by law, strictly necessary, proportionate, of limited duration, and subject to review against abusive applications.” [38] Therefore, decisions about individual and collective isolation and quarantine must follow standards of fair and equal treatment and avoid stigma and discrimination against individuals or groups. Vulnerable populations require direct consideration with regard to the development of policies that can also protect and secure their inalienable rights.

Third, long-term solutions require properly identifying and addressing the underlying obstacles to the fulfillment of the right to health, particularly as they affect the most vulnerable. For example, we need to design policies aimed at providing universal health coverage, paid family leave, and sick leave. We need to reduce food insecurity, provide housing, and ensure that our actions protect the climate. Moreover, we need to strengthen mental health and substance abuse services, since this pandemic is affecting people’s mental health and exacerbating ongoing issues with mental health and chemical dependency. As noted earlier, violations of the human rights principles of equality and nondiscrimination were already present in US society prior to the pandemic. However, the pandemic has caused “an unprecedented combination of adversities which presents a serious threat to the mental health of entire populations, and especially to groups in vulnerable situations.” [39] As Dainius Pūras has noted, “the best way to promote good mental health is to invest in protective environments in all settings.” [40] These actions should take place as we engage in thoughtful conversations that allow us to assess the situation, to plan and implement necessary interventions, and to evaluate their effectiveness.

Finally, it is important that we collect meaningful, systematic, and disaggregated data by race, age, gender, and class. Such data are useful not only for promoting public trust but for understanding the full impact of this pandemic and how different systems of inequality intersect, affecting the lived experiences of minority groups and beyond. It is also important that such data be made widely available, so as to enhance public awareness of the problem and inform interventions and public policies.

In 1966, Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. said, “Of all forms of inequality, injustice in health is the most shocking and inhuman.” [41] More than 54 years later, African Americans still suffer from injustices that are at the basis of income and health disparities. We know from previous experiences that epidemics place increased demands on scarce resources and enormous stress on social and economic systems.

A deeper understanding of the social determinants of health in the context of the current crisis, and of the role that these factors play in mediating the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on African Americans’ health outcomes, increases our awareness of the indivisibility of all human rights and the collective dimension of the right to health. We need a more explicit equity agenda that encompasses both formal and substantive equality. [42] Besides nondiscrimination and equality, participation and accountability are equally crucial.

Unfortunately, as suggested by the limited available data, African American communities and other minorities in the United States are bearing the brunt of the current pandemic. The COVID-19 crisis has served to unmask higher vulnerabilities and exposure among people of color. A thorough reflection on how to close this gap needs to start immediately. Given that the COVID-19 pandemic is more than just a health crisis—it is disrupting and affecting every aspect of life (including family life, education, finances, and agricultural production)—it requires a multisectoral approach. We need to build stronger partnerships among the health care sector and other social and economic sectors. Working collaboratively to address the many interconnected issues that have emerged or become visible during this pandemic—particularly as they affect marginalized and vulnerable populations—offers a more effective strategy.

Moreover, as Delan Devakumar et al. have noted:

the strength of a healthcare system is inseparable from broader social systems that surround it. Health protection relies not only on a well-functioning health system with universal coverage, which the US could highly benefit from, but also on social inclusion, justice, and solidarity. In the absence of these factors, inequalities are magnified and scapegoating persists, with discrimination remaining long after. [43]

This current public health crisis demonstrates that we are all interconnected and that our well-being is contingent on that of others. A renewed and healthy society is possible only if governments and public authorities commit to reducing vulnerability and the impact of ill-health by taking steps to respect, protect, and fulfill the right to health. [44] It requires that government and nongovernment actors establish policies and programs that promote the right to health in practice. [45] It calls for a shared commitment to justice and equality for all.

Maritza Vasquez Reyes, MA, LCSW, CCM, is a PhD student and Research and Teaching Assistant at the UConn School of Social Work, University of Connecticut, Hartford, USA.

Please address correspondence to the author. Email: [email protected].

Competing interests: None declared.

Copyright © 2020 Vasquez Reyes. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Non-Commercial License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/), which permits unrestricted noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

[1] “Coronavirus in the U.S.: Latest map and case count,” New York Times (October 10, 2020). Available at https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2020/us/coronavirus-us-cases.html.

[2] World Health Organization Commission on the Social Determinants of Health, Closing the gap in a generation: Health equity through action on the social determinants of health (Geneva: World Health Organization, 2008), p. 1.

[3] S. Hertel and L. Minkler, Economic rights: Conceptual, measurement, and policy issues (New York: Cambridge University Press, 2007); S. Hertel and K. Libal, Human rights in the United States: Beyond exceptionalism (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2011); D. Forsythe, Human rights in international relations , 2nd edition (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2006).

[4] Danish Institute for Human Rights, National action plans on business and human rights (Copenhagen: Danish Institute for Human Rights, 2014).

[5] J. R. Blau and A. Moncada, Human rights: Beyond the liberal vision (Lanham, MD: Rowman and Littlefield, 2005).

[6] J. R. Blau. “Human rights: What the United States might learn from the rest of the world and, yes, from American sociology,” Sociological Forum 31/4 (2016), pp. 1126–1139; K. G. Young and A. Sen, The future of economic and social rights (New York: Cambridge University Press, 2019).

[7] Young and Sen (see note 6).

[8] S. Dickman, D. Himmelstein, and S. Woolhandler, “Inequality and the health-care system in the USA,” Lancet , 389/10077 (2017), p. 1431.

[9] S. Artega, K. Orgera, and A. Damico, “Changes in health insurance coverage and health status by race and ethnicity, 2010–2018 since the ACA,” KFF (March 5, 2020). Available at https://www.kff.org/disparities-policy/issue-brief/changes-in-health-coverage-by-race-and-ethnicity-since-the-aca-2010-2018/.

[10] H. Sohn, “Racial and ethnic disparities in health insurance coverage: Dynamics of gaining and losing coverage over the life-course,” Population Research and Policy Review 36/2 (2017), pp. 181–201.

[11] Atlantic Monthly Group, COVID tracking project . Available at https://covidtracking.com .

[12] “Why the African American community is being hit hard by COVID-19,” Healthline (April 13, 2020). Available at https://www.healthline.com/health-news/covid-19-affecting-people-of-color#What-can-be-done?.

[13] World Health Organization, 25 questions and answers on health and human rights (Albany: World Health Organization, 2002).

[14] Ibid; Hertel and Libal (see note 3).

[17] Z. Bailey, N. Krieger, M. Agénor et al., “Structural racism and health inequities in the USA: Evidence and interventions,” Lancet 389/10077 (2017), pp. 1453–1463.

[20] US Census. Available at https://www.census.gov/library/publications/2019/demo/p60-266.html.

[21] M. Simms, K. Fortuny, and E. Henderson, Racial and ethnic disparities among low-income families (Washington, D.C.: Urban Institute Publications, 2009).

[23] Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Health Equity Considerations and Racial and Ethnic Minority Groups (2020). Available at https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/community/health-equity/race-ethnicity.html.

[24] Artega et al. (see note 9).

[25] K. Allen, “More than 50% of homeless families are black, government report finds,” ABC News (January 22, 2020). Available at https://abcnews.go.com/US/50-homeless-families-black-government-report-finds/story?id=68433643.

[26] A. Carson, Prisoners in 2018 (US Department of Justice, 2020). Available at https://www.bjs.gov/content/pub/pdf/p18.pdf.

[27] United Nations Committee on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights, General Comment No. 14, The Right to the Highest Attainable Standard of Health, UN Doc. E/C.12/2000/4 (2000).

[28] J. J. Amon, “COVID-19 and detention,” Health and Human Rights 22/1 (2020), pp. 367–370.

[30] L. Pirtle and N. Whitney, “Racial capitalism: A fundamental cause of novel coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic inequities in the United States,” Health Education and Behavior 47/4 (2020), pp. 504–508.

[31] Ibid; R. Sampson, “The neighborhood context of well-being,” Perspectives in Biology and Medicine 46/3 (2003), pp. S53–S64.

[32] C. Walsh, “Covid-19 targets communities of color,” Harvard Gazette (April 14, 2020). Available at https://news.harvard.edu/gazette/story/2020/04/health-care-disparities-in-the-age-of-coronavirus/.

[33] B. Lovelace Jr., “White House officials worry the coronavirus is hitting African Americans worse than others,” CNBC News (April 7, 2020). Available at https://www.cnbc.com/2020/04/07/white-house-officials-worry-the-coronavirus-is-hitting-african-americans-worse-than-others.html.

[34] K. Ahmad, E. W. Chen, U. Nazir, et al., “Regional variation in the association of poverty and heart failure mortality in the 3135 counties of the United States,” Journal of the American Heart Association 8/18 (2019).

[35] D. Desierto, “We can’t breathe: UN OHCHR experts issue joint statement and call for reparations” (EJIL Talk), Blog of the European Journal of International Law (June 5, 2020). Available at https://www.ejiltalk.org/we-cant-breathe-un-ohchr-experts-issue-joint-statement-and-call-for-reparations/.

[36] International Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Racial Discrimination, G. A. Res. 2106 (XX) (1965), art. 2.

[37] A. Chapman, Global health, human rights and the challenge of neoliberal policies (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2016), p. 17.

[38] N. Sun, “Applying Siracusa: A call for a general comment on public health emergencies,” Health and Human Rights Journal (April 23, 2020).

[39] D. Pūras, “COVID-19 and mental health: Challenges ahead demand changes,” Health and Human Rights Journal (May 14, 2020).

[41] M. Luther King Jr, “Presentation at the Second National Convention of the Medical Committee for Human Rights,” Chicago, March 25, 1966.

[42] Chapman (see note 35).

[43] D. Devakumar, G. Shannon, S. Bhopal, and I. Abubakar, “Racism and discrimination in COVID-19 responses,” Lancet 395/10231 (2020), p. 1194.

[44] World Health Organization (see note 12).

Still accepting applications for online and hybrid programs!

- Skip to content

- Skip to search

- Accessibility Policy

- Report an Accessibility Issue

COVID-19 and the Disproportionate Impact on Black Americans

Q&A with Enrique Neblett

Professor of health behavior and health education.

July 1, 2020

Why is the coronavirus pandemic causing Black Americans to be disproportionately affected by COVID-19 and what can we do at the individual and community level to dismantle the systemic racism at the root of these health disparities? We spoke to Enrique Neblett, professor of Health Behavior and Health Education, to learn more.

In what ways has the Black population in the United States been uniquely affected by COVID-19?

There are a few ways in which people have talked about how Black Americans have been affected by the pandemic.

One has to do with higher rates of hospitalization, infections and mortality rates. From very early on in the pandemic, we were appalled by data that showed Black Americans disproportionately represented for these outcomes relative to their percentage of the population.

Milwaukee and Chicago are two examples that come to mind. African Americans in these cities are about a third of the population, but represented over 70% of the deaths. Similarly, in Georgia, African Americans make up a third of the population but represented 80% of hospitalizations. Unfortunately, we see the same things here in Michigan, where African Americans are roughly 14% of the population, yet they represent 33% of the cases, and 41% of deaths.

The second area is the psychological impact of the pandemic. The Black population is among a large group of the essential workers, and many have to make tough decisions with regard to staying home if they get sick or risking lost wages—or even unemployment—in addition to situations such as having to deal with the loss of family members or taking care of family who may be sick. A recent poll found that Black Americans are nearly three times as likely to personally know someone who has died from the virus than white Americans. In some cases, we’re talking about the emotional toll of having to make excruciating decisions about whether to risk getting sick or work while sick and other financial considerations, while also coping with premature and unexpected death and loss.

Why is COVID-19 impacting the Black population disportionately?

There are a complex set of factors that account for why the pandemic is disproportionately affecting Black Americans, but it is important that we name structural and systemic racism as drivers of COVID-19 disparities. There was speculation early on in the pandemic about chronic underlying conditions and how some are more likely to succumb to COVID-19 when they have diabetes or other underlying conditions. Unfortunately, we know that Black Americans are more likely to have high rates of cardiovascular disease and other chronic conditions than whites, in part, due to structural inequities in access to critical resources necessary to maintain health.

Another factor is occupational vulnerability. Black Americans are more likely than white Americans to hold jobs that are essential to the function of critical infrastructure. These are jobs that require continuous interaction with the public and, in some cases, don’t offer benefits such as paid vacation or the option to work from home.

Availability and access to testing is another important factor. In the initial stages of the pandemic, there were many places where testing was limited or unavailable, or there were significant delays in processing the test results. Lack of access to adequate testing and timely results can both be liabilities in getting urgent and needed medical care.

Poverty is another social determinant of health, structured by institutional and systemic racism, that has played a role in COVID-19 disparities. Lack of access to medical care to seek treatment, quality health insurance, healthy food, standard housing, and clean water are all factors that can indirectly contribute to heightened vulnerability to exposure and infection and lead to negative COVID-19 outcomes.

It is critical that we take a close look at how racism and longstanding structural inequities and practices—past and present—shape these factors and contribute to negative COVID-19 outcomes.

If systemic racism is the root cause of COVID-19 related and other health disparities, how do we need to work together to end it?

There are several strategies that can be mobilized in working against systemic racism and, in turn, the impact of COVID-19 on Black Americans. A multi-pronged approach must inform the action steps that we can take as individuals and communities.

Listening to one another, self-educating, reading, and learning about systemic racism and how it operates are a great start. At the individual level, I’ve also seen people using their voices and privilege to raise awareness and propose concrete actions for eradicating racism by writing op-eds, letters, and making phone calls to lawmakers. Community groups and organizations possess valuable knowledge and expertise, represent critical assets, and are also well positioned to write letters and make calls.

Other strategies for mobilizing include investing in capacity building and helping communities to build their infrastructure in order to be able to respond to disasters like COVID-19.

I've been really fortunate in my role as associate director of the Detroit Community-Academic Urban Research Center (Detroit URC) to discuss mobilization efforts with community partners in Detroit. It’s important that we work together to share resources and information with the residents who need them most. Also, it is important to remember that eradicating racism and promoting health equity will require the execution of concrete, specific and measurable actions that will lead to lasting systemic and structural change.

- Listen to Enrique Neblett on the Population Healthy podcast.

- Learn more about Health Behavior and Health Education.

- Health Behavior and Health Education

- Health Disparities

Recent Posts

- Maternal suicide: Study provides insights into complicating factors surrounding perinatal deaths

- Gender disparities in heat wave mortality in India

- Veera Baladandayuthapani named chair of Department of Biostatistics at Michigan Public Health

- SCOTUS to decide if domestic abusers can own guns

What We’re Talking About

- Adolescent Health

- Air Quality

- Alternative Therapies

- Alumni News and Networking

- Biostatistics

- Child Health

- Chronic Disease

- Community Partnership

- Computational Epidemiology and Systems Modeling

- Disaster Relief

- Diversity Equity and Inclusion

- Engaged Learning

- Environmental Health

- Epidemiologic Science

- Epidemiology

- Epigenetics

- First Generation Students

- Food Policy

- Food Safety

- General Epidemiology

- Global Health Epidemiology

- Global Public Health

- Health Care

- Health Care Access

- Health Care Management

- Health Care Policy

- Health Communication

- Health Informatics

- Health for Men

- Health for Women

- Heart Disease

- Hospital Administration

- Hospital and Molecular Epidemiology

- Immigration

- Industrial Hygiene

- Infectious Disease

- Internships

- LGBT Health

- Maternal Health

- Mental Health

- Mobile Health

- Occupational and Environmental Epidemiology

- Pain Management

- Pharmaceuticals

- Precision Health

- Professional Development

- Reproductive Health

- Scholarships

- Sexual Health

- Social Epidemiology

- Social Media

- Student Organizations

- Urban Health

- Urban Planning

- Value-Based Care

- Water Quality

- What Is Public Health?

Information For

- Prospective Students

- Current Students

- Alumni and Donors

- Community Partners and Employers

- About Public Health

- How Do I Apply?

- Departments

- Findings magazine

Student Resources

- Career Development

- Certificates

- The Heights Intranet

- Update Contact Info

- Report Website Feedback

The Disproportional Impact of COVID-19 on African Americans.

Chat with Paper: Save time, read 10X faster with AI

Disparities in COVID-19 Outcomes by Race, Ethnicity, and Socioeconomic Status: A Systematic-Review and Meta-analysis.

L-arginine and covid-19: an update., impact of working from home on activity-travel behavior during the covid-19 pandemic: an aggregate structural analysis, increased risk of herpes zoster in adults ≥50 years old diagnosed with covid-19 in the united states, community-based, cluster-randomized pilot trial of a cardiovascular mhealth intervention: rationale, design, and baseline findings of the faith trial, structural racism and health inequities in the usa: evidence and interventions, the neighborhood context of well-being, racism and discrimination in covid-19 responses., inequality and the health-care system in the usa, racial capitalism: a fundamental cause of novel coronavirus (covid-19) pandemic inequities in the united states., related papers (5), covid-19 and human rights: a new inseparable relationship, the rights of older persons: protection and gaps under human rights law, hre in the era of global aging: the human rights of older persons in contemporary europe, gender, health, and human rights., guest editorial: is health a fundamental right for migrants.

- Publications

- Conferences & Events

- Professional Learning

- Science Standards

- Awards & Competitions

- Instructional Materials

- Free Resources

- American Rescue Plan

- For Preservice Teachers

- NCCSTS Case Collection

- Science and STEM Education Jobs

- Interactive eBooks+

- Digital Catalog

- Regional Product Representatives

- e-Newsletters

- Bestselling Books

- Latest Books

- Popular Book Series

- Prospective Authors

- Web Seminars

- Exhibits & Sponsorship

- Conference Reviewers

- National Conference • Denver 24

- Leaders Institute 2024

- National Conference • New Orleans 24

- Submit a Proposal

- Latest Resources

- Professional Learning Units & Courses

- For Districts

- Online Course Providers

- Schools & Districts

- College Professors & Students

- The Standards

- Teachers and Admin

- eCYBERMISSION

- Toshiba/NSTA ExploraVision

- Junior Science & Humanities Symposium

- Teaching Awards

- Climate Change

- Earth & Space Science

- New Science Teachers

- Early Childhood

- Middle School

- High School

- Postsecondary

- Informal Education

- Journal Articles

- Lesson Plans

- e-newsletters

- Science & Children

- Science Scope

- The Science Teacher

- Journal of College Sci. Teaching

- Connected Science Learning

- NSTA Reports

- Next-Gen Navigator

- Science Update

- Teacher Tip Tuesday

- Trans. Sci. Learning

MyNSTA Community

- My Collections

Middle School High School | Daily Do

What Causes the Disproportionate Impact of COVID-19 on Racial and Ethnic Minority Groups?

By Todd Campbell and Okhee Lee

Share Discuss

Biology Crosscutting Concepts Disciplinary Core Ideas Is Lesson Plan Life Science NGSS Phenomena Science and Engineering Practices Three-Dimensional Learning Middle School High School

Sensemaking Checklist

Teachers and families across the country are facing a new reality of providing opportunities for students to do science through distance and home learning. The Daily Do is one of the ways NSTA is supporting teachers and families with this endeavor. Each weekday, NSTA will share a sensemaking task teachers and families can use to engage their students in authentic, relevant science learning. We encourage families to make time for family science learning (science is a social process!) and are dedicated to helping students and their families find balance between learning science and the day-to-day responsibilities they have to stay healthy and safe.

Interested in learning about other ways NSTA is supporting teachers and families? Visit the NSTA homepage .

Sensemaking is actively trying to figure out how the world works (science) or how to design solutions to problems (engineering). Students do science and engineering through the science and engineering practices . Engaging in these practices necessitates that students be part of a learning community to be able to share ideas, evaluate competing ideas, give and receive critique, and reach consensus. Whether this community of learners is made up of classmates or family members, students and adults build and refine science and engineering knowledge together.

Introduction

In today’s task, students answer the following questions: What are the causes of the disproportionate impact of COVID-19 on racial and ethnic minority groups? Why is the Centers for Disease Control (CDC) and Prevention guidance for how to slow the spread of COVID-19 necessary, but insufficient? What kinds of system-level solutions can our society implement to address the disproportionate impact of COVID-19 on racial and ethnic minority groups?

Students use science and engineering practices alongside disciplinary core ideas and crosscutting concepts to identify and explain the causes of the disproportionate impact of COVID-19 on racial and ethnic minority groups. Then they consider why the CDC guidance for slowing the spread of COVID-19 is necessary, but insufficient to address the causes that have led to the disproportionate impact of COVID-19. Finally, they propose system-level solutions for addressing the disproportionate impact of COVID-19.

Today’s task builds on ideas introduced in the following Daily Dos: How Can We Make Informed Decisions to Keep Ourselves and Our Communities Safe During the COVID-19 Pandemic? by Todd Campbell and Okhee Lee, and Are There Differences in How People Are Affected by the COVID-19 Pandemic in the United States? If So, Why Are There Differences, and What Should We Do About the Disproportionate Impact of COVID-19? by Todd Campbell, Okhee Lee, Eileen Murray, and John Russell.

Daily Do Playlist: Tracking COVID-19 in the United States

What causes the disproportionate impact of COVID-19 on racial and ethnic minority groups? is a stand-alone task. However, it can be taught as part of an instructional sequence in which students are provided authentic opportunities to develop and employ the science and engineering practice Using Mathematics and Computational Thinking to make sense of the spread of COVID-19 through the U.S. population and the disproportionate number of cases and deaths in non-white communities. Students further use data to support them in identifying actions they can take to keep their families and communities safe and in implementing their proposed solutions to ending health disparities.

View Playlist

Part 1. What are the indicators of the disproportionate impact of COVID-19 on racial and ethnic minority groups? [Data Science and Critical Consciousness]

The purpose of Part 1 is to help students see the evidence for the disproportionate impact of COVID-19 on racial and ethnic minority groups. Share the accompanying Student Journal with students before you begin.

What do you notice and wonder? What questions or comments do you have? Figure 1 presents the CDC data on the disproportionate impact of COVID-19 cases, hospitalizations, and deaths by race and ethnicity on certain racial and ethnic populations in the United States.

To begin, in small groups of 2–3 or individually, students share their noticings and wonderings about Figure 1.

Note: From Risk for COVID-19 Infection, Hospitalization, and Death by Race/Ethnicity, by Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2021 ( https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/covid-data/investigations-discovery/hospitalization-death-by-race-ethnicity.html ).

Next, students write the following in their journals:

- Write an argument about which racial and ethnic groups have been most affected by COVID-19.

- Provide evidence for this argument by using the data in Figure 1.

Part 2. What is the CDC guidance for slowing the spread of COVID-19? What are the scientific explanations for the CDC guidance? [Simulations/Computer Science]

The purpose of Part 2 is to help students understand the scientific explanations behind the CDC guidance for slowing the spread of COVID-19. The CDC guidance is presented at the bottom of Figure 1 and explored in more depth through the activities below.

Activity A: Wear a Mask. In this activity, students learn about the role that masks play in slowing the spread of COVID-19.

Students explore this simulation, published by Live Science: To Mask or Not to Mask: This Simulation Shows Why It’s a Good Idea to Wear a Mask . [To play the simulation, scroll down to the last video embedded in the article and click on the white arrow in the middle of the black box.] In their journals, students write a scientific explanation for how masks slow the spread of COVID-19.

Activity B: Stay 6 Feet Apart. In this activity, students learn about the role that staying 6 feet apart plays in slowing the spread of COVID-19.

Students explore this simulation, published in The Washington Post article “ Military-Grade Camera Shows Risks of Airborne Coronavirus Spread .” In their journals, students write a scientific explanation for how staying 6 feet apart slows the spread of COVID-19.

Activity C: Wash Your Hands. In this activity, students learn about the role that handwashing plays in slowing the spread of COVID-19.

Students watch the following video, available at the Health Matters website: How Soap Suds Kill the Coronavirus . In their journals, students write a scientific explanation for how handwashing slows the spread of COVID-19.

Part 3. What are the societal causes of the disproportionate impact of COVID-19 on racial and ethnic minority groups? How are these societal causes connected to the CDC guidance for slowing the spread of COVID-19? [Critical Consciousness]

The purpose of Part 3 is twofold. First, students recognize societal causes of the disproportionate impact of COVID-19 on racial and ethnic minority groups (e.g., individuals from certain racial and ethnic minority groups are overrepresented in the populations of essential workers and those who are incarcerated). Second, students connect these causes to challenges these groups might experience when trying to follow the CDC guidance (e.g., staying 6 feet apart).

Students read four news articles:

- Article 1. " Coronavirus Infection by Race: What’s Behind the Health Disparities? "

- Article 2. " How COVID-19 Is Highlighting Racial Disparities in Americans’ Health "

- Article 3. " In California, the Pandemic Hits Latinos Hard "

- Article 4. “ Exclusive: Indigenous Americans Dying From Covid at Twice the Rate of White Americans ”

After reading each article, students answer these questions in their journals:

- Identify the racial and ethnic minority groups referenced in the article.

- List societal causes identified in the article.

- Connect these societal causes to the CDC guidance that the identified racial and ethnic minority groups might not be able to follow.

Part 4. How does the CDC guidance for slowing COVID-19's spread (wearing a mask, staying 6 feet apart, washing your hands), which is based on science, fail to address how systemic racism is causing inequities related to COVID-19 for racial and ethnic minority groups? [Critical Conciousness]

The purpose of Part 4 is to help students recognize that while following the CDC guidance for slowing the spread of COVID-19 is essential, not all citizens are able to follow this guidance due to the impact of systemic racism in the United States, which has resulted in significant differences among racial and ethnic groups regarding employment opportunities, wages, living arrangements, access to medical care, access to running water, and incarceration rates.

Students combine what they have learned in Part 1 (to what extent racial and ethnic minority groups are disproportionately impacted by COVID-19), Part 2 (scientific explanations in the CDC guidance for slowing the spread of COVID-19), and Part 3 (societal causes that have led to the disproportionate impact of COVID-19 on racial and ethnic minority groups).

In their journals, students write an essay to answer this question:

How does the CDC guidance for slowing the spread of COVID-19 (wearing a mask, staying 6 feet apart, washing your hands), which is based on science, fail to address systemic racism that has created inequities for racial and ethnic minority groups?

Part 5. Beyond individual decision-making related to CDC guidance, what system-level solutions can our society implement to address the disproportionate impact of COVID-19 on racial and ethnic minority groups? [Critical Consciousness, Media Literacy]

The purpose of Part 5 is to help students recognize that beyond following the CDC guidance for slowing the spread of COVID-19, system-level solutions are necessary if the United States is to address the disproportionate impact of COVID-19 on racial and ethnic minority groups. While students should understand the need for individual action to slow the spread of COVID-19 in their communities, they should also understand that without equitable access to resources in society, ethnic and racial minority groups will continue to be disproportionately harmed by COVID-19.

Students watch two videos and explore a website that describe different approaches to addressing systemic racism in the United States.

- Video 1. Inside California Politics: Former Stockton Mayor, Oakland Mayor Talk Guaranteed Income for Residents

- Video 2. Biden Signs Four Executive Actions Focused on Racial Equity

- Website. Racial Equity Tools (Students select one additional system-level solution they believe could help address systemic racism.)

After each activity, students return to their journals to identify (1) what approach is proposed/implemented, (2) how this approach addresses systemic racism, and (3) how this approach could reduce the disproportionate impact of COVID-19 on racial and ethnic minority groups.

Part 6. What system-level solutions can we propose to local, state, or national leaders to address the disproportionate impact of COVID-19 on racial and ethnic minority groups? [Critical Consciousness and Civic Engagement]

Working in groups of 2–3, students propose system-level solutions to the disproportionate impact of COVID-19 on racial and ethnic minority groups and share their ideas with local, state, or national leaders.

Using the Common Cause: Find Your Representatives website, students identify a local, state, or national leader with whom to share their system-level solutions.

( Note: To identify leaders, the site asks for a local address. Students can enter their own address, or the teacher can provide the school's address. After students enter an address, national, state, and local leaders are identified and links to their homepages are provided. Each homepage contains that leader’s contact information [e.g., e-mail and mailing address]. )

Students write a letter proposing one or two approaches for mitigating the disproportionate impact of COVID-19 on racial and ethnic minority groups. Students use this resource for helpful guidance on writing a letter to political leaders: Guidelines: How to Write a Letter to a Politician .

NSTA has created a What causes the disproportionate impact of COVID-19 on racial and ethnic minority groups? collection of resources to support teachers and families using this task. If you're an NSTA member, you can add this collection to your library by clicking on Add to My Library (near top of page).

The NSTA Daily Do is an open educational resource (OER) and can be used by educators and families providing students distance and home science learning. Access the entire collection of NSTA Daily Dos .

You may also like

Reports Article

Web Seminar

Are you a K-12 teacher that works near a Shell asset? If so you could win a science classroom makeover. Join us on Monday, November 4, 2024, from 7:00...

Join us on Monday, September 30, 2024, from 7:00 to 8:00 PM ET, to learn about the Shell Science Teaching Awards....

Join us on Wednesday, August 28, 2024, from 5:00 PM to 6:00 PM ET, to learn about sustainability and renewable energy concepts....

COVID Hurt Student Learning: Key Findings From a Year of Research

- Share article

Dozens of studies have come out over the past months concluding that the pandemic had a negative—and uneven—effect on student learning.

National analyses have shown that students who were already struggling fell further behind than their peers, and that Black and Latino students experienced greater declines in test scores than their peers.

But taken together, what implications do they have for school and district leaders looking for a path forward?

Here are four questions and answers, based on what we’ve learned from the most salient studies, that dig into the evidence.

Did students who stayed in remote learning longer fare worse than those who learned in person?

Generally, yes—but not in every single instance.

School buildings shut down in spring 2020 . By fall 2021, most students were back learning in person. But schools took a variety of different approaches in the middle, during the 2020-21 school year.

Several studies have attempted to examine the effects of the choices that districts made during that time period. And they found that students who were mostly in-person fared better than students who were mostly remote.

An analysis of 2021 spring state test data across 12 states found that districts that offered more access to in-person options saw smaller declines in math and reading scores than districts that offered less access. In reading, the effect was much larger in districts with a higher share of Black and Hispanic students.

Assessment experts, as well as the researchers, have urged caution about these results, noting that it’s hard to draw conclusions from results on spring 2021 state tests, given low rates of participation and other factors that affected how the tests were administered.

But it wasn’t just state test scores that were affected. Interim test scores—the more-frequent assessments that schools give throughout the year—saw declines too.

Another study examined scores on the Measures of Academic Progress assessment, or MAP , an interim test developed by NWEA, a nonprofit assessment provider. Researchers at NWEA, the American Institutes for Research, and Harvard examined data from 2.1 million students during the 2020-21 school year.

Students in districts that were remote during this period had lower achievement growth than students in districts that offered in-person learning. The effects were most substantial for high-poverty schools in remote learning districts.

Still, other research introduces some caveats.

The Education Recovery Scorecard, a collaboration between researchers at Stanford and Harvard, analyzed states’ scores on the 2022 National Assessment of Educational Progress. They compared these scores to the average amount of time that a district in the state spent in remote learning.

For the most part, this analysis confirmed the findings of previous research: In states where districts were remote longer, student achievement was worse. But there were also some outliers, like California. There, students saw smaller declines in math than average, even though the state had the highest closure rates on average. The researchers also noted that even among districts that spent the same amount of time in 2020-21 in remote learning, there were differences in achievement declines.

Are there other factors that could have contributed to these declines?

It’s probable. Remote learning didn’t take place in a vacuum, as educators and experts have repeatedly pointed out. But there’s not a lot of empirical evidence on this question just yet.

Children switched to virtual instruction as the pandemic unfolded around them—parents lost jobs, family members fell sick and died. In many cases, the school districts that chose remote learning served communities that also suffered some of the highest mortality rates from COVID.

The NWEA, AIR, and Harvard researchers—the group that looked at interim test data—note this. “It is possible that the relationships we have observed are not entirely causal, that family stress in the districts that remained remote both caused the decline in achievement and drove school officials to keep school buildings closed,” they wrote.

The Education Recovery Scorecard team plans to investigate the effects of other factors in future research, “such as COVID death rates, broadband connectivity, the predominant industries of employment and occupations for parents in the school district.”

Most of this data is from the 2020-21 school year. What’s happening now? Are students making progress?

They are—but it’s unevenly distributed.

NWEA, the interim assessment provider, recently analyzed test data from spring 2022 . They found that student academic progress during the 2021-22 school did start to rebound.

But even though students at both ends of the distribution are making academic progress, lower-scoring students are making gains at a slower rate than higher-scoring students.

“It’s kind of a double whammy. Lower-achieving students were harder hit in that initial phase of the pandemic, and they’re not achieving as steadily,” Karyn Lewis, the lead author of the brief, said earlier in November .

What should schools do in response? How can they know where to focus their efforts?

That depends on what your own data show—though it’s a good bet that focusing on math, especially for kids who were already struggling, is a good place to start.

Test results across the board, from the NAEP to interim assessment data, show that declines have been larger in math than in reading . And kids who were already struggling fell further behind than their peers, widening gaps with higher-achieving students.

But these sweeping analyses don’t tell individual teachers, or even districts, what their specific students need. That may look different from school to school.

“One of the things we found is that even within a district, there is variability,” Sean Reardon, a professor of poverty and inequality in education at Stanford University and a researcher on the Education Recovery Scorecard, said in a statement.

“School districts are the first line of action to help children catch up. The better they know about the patterns of learning loss, the more they’re going to be able to target their resources effectively to reduce educational inequality of opportunity and help children and communities thrive,” he said.

Experts have emphasized two main suggestions in interviews with Education Week.

- Figure out where students are. Teachers and school leaders can examine interim test data from classrooms or, for a more real-time analysis, samples of student work. These classroom-level data are more useful for targeting instruction than top-line state test results or NAEP scores, experts say.

- Districts should make sure that the students who have been disproportionately affected by pandemic disruptions are prioritized for support.

“The implication for district leaders isn’t just, ‘am I offering the right kinds of opportunities [for academic recovery]?’” Lewis said earlier this month. “But also, ‘am I offering them to the students who have been harmed most?’”

A version of this article appeared in the December 14, 2022 edition of Education Week as COVID Hurt Student Learning: Four Key Findings from A Year of Research

Sign Up for The Savvy Principal

Edweek top school jobs.

Sign Up & Sign In

Writing about COVID-19 in a college admission essay

by: Venkates Swaminathan | Updated: September 14, 2020

Print article

For students applying to college using the CommonApp, there are several different places where students and counselors can address the pandemic’s impact. The different sections have differing goals. You must understand how to use each section for its appropriate use.

The CommonApp COVID-19 question

First, the CommonApp this year has an additional question specifically about COVID-19 :

Community disruptions such as COVID-19 and natural disasters can have deep and long-lasting impacts. If you need it, this space is yours to describe those impacts. Colleges care about the effects on your health and well-being, safety, family circumstances, future plans, and education, including access to reliable technology and quiet study spaces. Please use this space to describe how these events have impacted you.

This question seeks to understand the adversity that students may have had to face due to the pandemic, the move to online education, or the shelter-in-place rules. You don’t have to answer this question if the impact on you wasn’t particularly severe. Some examples of things students should discuss include:

- The student or a family member had COVID-19 or suffered other illnesses due to confinement during the pandemic.

- The candidate had to deal with personal or family issues, such as abusive living situations or other safety concerns

- The student suffered from a lack of internet access and other online learning challenges.

- Students who dealt with problems registering for or taking standardized tests and AP exams.

Jeff Schiffman of the Tulane University admissions office has a blog about this section. He recommends students ask themselves several questions as they go about answering this section:

- Are my experiences different from others’?

- Are there noticeable changes on my transcript?

- Am I aware of my privilege?

- Am I specific? Am I explaining rather than complaining?

- Is this information being included elsewhere on my application?

If you do answer this section, be brief and to-the-point.

Counselor recommendations and school profiles

Second, counselors will, in their counselor forms and school profiles on the CommonApp, address how the school handled the pandemic and how it might have affected students, specifically as it relates to:

- Grading scales and policies

- Graduation requirements

- Instructional methods

- Schedules and course offerings

- Testing requirements

- Your academic calendar

- Other extenuating circumstances

Students don’t have to mention these matters in their application unless something unusual happened.

Writing about COVID-19 in your main essay

Write about your experiences during the pandemic in your main college essay if your experience is personal, relevant, and the most important thing to discuss in your college admission essay. That you had to stay home and study online isn’t sufficient, as millions of other students faced the same situation. But sometimes, it can be appropriate and helpful to write about something related to the pandemic in your essay. For example:

- One student developed a website for a local comic book store. The store might not have survived without the ability for people to order comic books online. The student had a long-standing relationship with the store, and it was an institution that created a community for students who otherwise felt left out.

- One student started a YouTube channel to help other students with academic subjects he was very familiar with and began tutoring others.

- Some students used their extra time that was the result of the stay-at-home orders to take online courses pursuing topics they are genuinely interested in or developing new interests, like a foreign language or music.

Experiences like this can be good topics for the CommonApp essay as long as they reflect something genuinely important about the student. For many students whose lives have been shaped by this pandemic, it can be a critical part of their college application.

Want more? Read 6 ways to improve a college essay , What the &%$! should I write about in my college essay , and Just how important is a college admissions essay? .

Homes Nearby

Homes for rent and sale near schools

How our schools are (and aren't) addressing race

The truth about homework in America

What should I write my college essay about?

What the #%@!& should I write about in my college essay?

Yes! Sign me up for updates relevant to my child's grade.

Please enter a valid email address

Thank you for signing up!

Server Issue: Please try again later. Sorry for the inconvenience

- < Previous

Home > Honors College > Honors Theses > 1912

Honors Theses

An analysis of the effects of covid-19 on students at the university of mississippi: family, careers, mental health.

Hannah Newbold Follow

Date of Award

Spring 5-1-2021

Document Type

Undergraduate Thesis

Integrated Marketing Communication

First Advisor

Second advisor.

Cynthia Joyce

Third Advisor

Marquita Smith

Relational Format

Dissertation/Thesis

This study analyzes the effects of COVID-19 on students at the University of Mississippi. For students, COVID-19 changed the landscape of education, with classes and jobs going online. Students who graduated in May 2020 entered a poor job market and many ended up going to graduate school instead of finding a job. Access to medical and professional help was limited at the very beginning, with offices not taking patients or moving appointments to virtual only. This would require that each student needing help had to have access to quality internet service, which wasn’t always guaranteed, thus producing additional challenges.

These chapters, including a robust literature review of relevant sources, as well as a personal essay, consist further of interviews with students and mental health counselors conducted over the span of several months. These interviews were conducted and recorded over Zoom. The interviews were conducted with individuals who traveled in similar social circles as me. These previously existing relationships allowed the conversation to go deeper than before and allowed new levels of relationship. Emerging from these conversations were six overlapping themes: the importance of family, the need for health over career, the challenge of isolation, struggles with virtual education, assessing mental health, and facing the reality of a bright future not promised. Their revelations of deep academic challenges and fears about the future amid stories of devastating personal loss, produces a striking and complex picture of emerging strength.

Recommended Citation

Newbold, Hannah, "An Analysis Of The Effects Of COVID-19 On Students At The University of Mississippi: Family, Careers, Mental Health" (2021). Honors Theses . 1912. https://egrove.olemiss.edu/hon_thesis/1912

Accessibility Status

Searchable text

Creative Commons License

Since May 10, 2021

Included in

Counseling Commons , Higher Education Commons , Interpersonal and Small Group Communication Commons , Journalism Studies Commons , Psychology Commons

To view the content in your browser, please download Adobe Reader or, alternately, you may Download the file to your hard drive.

NOTE: The latest versions of Adobe Reader do not support viewing PDF files within Firefox on Mac OS and if you are using a modern (Intel) Mac, there is no official plugin for viewing PDF files within the browser window.

- Collections

- Disciplines

Advanced Search

- Notify me via email or RSS

Author Corner

- Submit Thesis

Additional Information

- Request an Accessible Copy

Home | About | FAQ | My Account | Accessibility Statement

Privacy Copyright

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

- My Bibliography

- Collections

- Citation manager

Save citation to file

Email citation, add to collections.

- Create a new collection

- Add to an existing collection

Add to My Bibliography

Your saved search, create a file for external citation management software, your rss feed.

- Search in PubMed

- Search in NLM Catalog

- Add to Search

Disproportionate Impact of COVID-19 Pandemic on Racial and Ethnic Minorities

Affiliations.

- 1 Department of Surgery, Division of Trauma and Surgical Critical Care, 14506Kendall Regional Medical Center, Miami, FL, USA.

- 2 Department of Surgery, University of South Florida, Tampa, FL, USA.

- PMID: 33231496

- PMCID: PMC7691116

- DOI: 10.1177/0003134820973356

Background: Health disparities are prevalent in many areas of medicine. We aimed to investigate the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on racial/ethnic groups in the United States (US) and to assess the effects of social distancing, social vulnerability metrics, and medical disparities.

Methods: A cross-sectional study was conducted utilizing data from the COVID-19 Tracking Project and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Demographic data were obtained from the US Census Bureau, social vulnerability data were obtained from the CDC, social distancing data were obtained from Unacast, and medical disparities data from the Center for Medicare and Medicaid Services. A comparison of proportions by Fisher's exact test was used to evaluate differences between death rates stratified by age. Negative binomial regression analysis was used to predict COVID-19 deaths based on social distancing scores, social vulnerability metrics, and medical disparities.

Results: COVID-19 cumulative infection and death rates were higher among minority racial/ethnic groups than whites across many states. Older age was also associated with increased cumulative death rates across all racial/ethnic groups on a national level, and many minority racial/ethnic groups experienced significantly greater cumulative death rates than whites within age groups ≥ 35 years. All studied racial/ethnic groups experienced higher hospitalization rates than whites. Older persons (≥ 65 years) also experienced more COVID-19 deaths associated with comorbidities than younger individuals. Social distancing factors, several measures of social vulnerability, and select medical disparities were identified as being predictive of county-level COVID-19 deaths.

Conclusion: COVID-19 has disproportionately impacted many racial/ethnic minority communities across the country, warranting further research and intervention.

Keywords: COVID-19; health disparities; racial disparities; social determinants of health.

PubMed Disclaimer

Cumulative crude COVID-19 death rates…

Cumulative crude COVID-19 death rates (per 100 000 population) according to age, race,…

Cumulative crude laboratory-confirmed COVID-19-associated hospitalizations…

Cumulative crude laboratory-confirmed COVID-19-associated hospitalizations rates (data represent the 14 states in the…

Cumulative COVID-19 deaths according to…

Cumulative COVID-19 deaths according to comorbidity and age (data were collected by the…

Similar articles

- A systematic review of racial/ethnic and socioeconomic disparities in COVID-19. Khanijahani A, Iezadi S, Gholipour K, Azami-Aghdash S, Naghibi D. Khanijahani A, et al. Int J Equity Health. 2021 Nov 24;20(1):248. doi: 10.1186/s12939-021-01582-4. Int J Equity Health. 2021. PMID: 34819081 Free PMC article. Review.

- Racial and Ethnic Disparities in Rates of COVID-19-Associated Hospitalization, Intensive Care Unit Admission, and In-Hospital Death in the United States From March 2020 to February 2021. Acosta AM, Garg S, Pham H, Whitaker M, Anglin O, O'Halloran A, Milucky J, Patel K, Taylor C, Wortham J, Chai SJ, Kirley PD, Alden NB, Kawasaki B, Meek J, Yousey-Hindes K, Anderson EJ, Openo KP, Weigel A, Monroe ML, Ryan P, Reeg L, Kohrman A, Lynfield R, Bye E, Torres S, Salazar-Sanchez Y, Muse A, Barney G, Bennett NM, Bushey S, Billing L, Shiltz E, Sutton M, Abdullah N, Talbot HK, Schaffner W, Ortega J, Price A, Fry AM, Hall A, Kim L, Havers FP. Acosta AM, et al. JAMA Netw Open. 2021 Oct 1;4(10):e2130479. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2021.30479. JAMA Netw Open. 2021. PMID: 34673962 Free PMC article.