Skip to Main Content - Keyboard Accessible

Freedom of speech: historical background.

- U.S. Constitution Annotated

First Amendment :

Congress shall make no law respecting an establishment of religion, or prohibiting the free exercise thereof; or abridging the freedom of speech, or of the press; or the right of the people peaceably to assemble, and to petition the Government for a redress of grievances.

Madison’s version of the speech and press clauses, introduced in the House of Representatives on June 8, 1789, provided: “The people shall not be deprived or abridged of their right to speak, to write, or to publish their sentiments; and the freedom of the press, as one of the great bulwarks of liberty, shall be inviolable.” 1 Footnote 1 Annals of Cong. 434 (1789) . Madison had also proposed language limiting the power of the states in a number of respects, including a guarantee of freedom of the press. Id. at 435 . Although passed by the House, the amendment was defeated by the Senate. See “Amendments to the Constitution, Bill of Rights and the States,” supra . The special committee rewrote the language to some extent, adding other provisions from Madison’s draft, to make it read: “The freedom of speech and of the press, and the right of the people peaceably to assemble and consult for their common good, and to apply to the government for redress of grievances, shall not be infringed.” 2 Footnote Id. at 731 (August 15, 1789). In this form it went to the Senate, which rewrote it to read: “That Congress shall make no law abridging the freedom of speech, or of the press, or the right of the people peaceably to assemble and consult for their common good, and to petition the government for a redress of grievances.” 3 Footnote The Bill of Rights: A Documentary History 1148–49 (B. Schwartz ed. 1971) . Subsequently, the religion clauses and these clauses were combined by the Senate. 4 Footnote Id. at 1153 . The final language was agreed upon in conference.

Debate in the House is unenlightening with regard to the meaning the Members ascribed to the speech and press clause, and there is no record of debate in the Senate. 5 Footnote The House debate insofar as it touched upon this amendment was concerned almost exclusively with a motion to strike the right to assemble and an amendment to add a right of the people to instruct their Representatives. 1 Annals of Cong. 731–49 (Aug. 15, 1789) . There are no records of debates in the states on ratification. In the course of debate, Madison warned against the dangers that would arise “from discussing and proposing abstract propositions, of which the judgment may not be convinced. I venture to say, that if we confine ourselves to an enumeration of simple, acknowledged principles, the ratification will meet with but little difficulty.” 6 Footnote Id. at 738 . That the “simple, acknowledged principles” embodied in the First Amendment have occasioned controversy without end both in the courts and out should alert one to the difficulties latent in such spare language.

Insofar as there is likely to have been a consensus, it was no doubt the common law view as expressed by Blackstone. “The liberty of the press is indeed essential to the nature of a free state; but this consists in laying no previous restraints upon publications, and not in freedom from censure for criminal matter when published. Every freeman has an undoubted right to lay what sentiments he pleases before the public; to forbid this, is to destroy the freedom of the press: but if he publishes what is improper, mischievous, or illegal, he must take the consequences of his own temerity. To subject the press to the restrictive power of a licenser, as was formerly done, both before and since the Revolution, is to subject all freedom of sentiment to the prejudices of one man, and make him the arbitrary and infallible judge of all controverted points in learning, religion and government. But to punish as the law does at present any dangerous or offensive writings, which, when published, shall on a fair and impartial trial be adjudged of a pernicious tendency, is necessary for the preservation of peace and good order, of government and religion, the only solid foundations of civil liberty. Thus, the will of individuals is still left free: the abuse only of that free will is the object of legal punishment. Neither is any restraint hereby laid upon freedom of thought or inquiry; liberty of private sentiment is still left; the disseminating, or making public, of bad sentiments, destructive to the ends of society, is the crime which society corrects.” 7 Footnote 4 W. Blackstone’s Commentaries on the Laws of England 151–52 (T. Cooley, 2d rev. ed. 1872) . See 3 J. Story , Commentaries on the Constitution of the United States 1874–86 (1833) . The most comprehensive effort to assess theory and practice in the period prior to and immediately following adoption of the Amendment is L. Levy , Legacy of Suppression: Freedom of Speech and Press in Early American History (1960) , which generally concluded that the Blackstonian view was the prevailing one at the time and probably the understanding of those who drafted, voted for, and ratified the Amendment.

Whatever the general unanimity on this proposition at the time of the proposal of and ratification of the First Amendment , 8 Footnote It would appear that Madison advanced libertarian views earlier than his Jeffersonian compatriots, as witness his leadership of a move to refuse officially to concur in Washington’s condemnation of “[c]ertain self-created societies,” by which the President meant political clubs supporting the French Revolution, and his success in deflecting the Federalist intention to censure such societies. I. Brant , James Madison: Father of the Constitution 1787–1800 at 416–20 (1950) . “If we advert to the nature of republican government,” Madison told the House, “we shall find that the censorial power is in the people over the government, and not in the government over the people.” 4 Annals of Cong. 934 (1794) . On the other hand, the early Madison, while a member of his county’s committee on public safety, had enthusiastically promoted prosecution of Loyalist speakers and the burning of their pamphlets during the Revolutionary period. 1 Papers of James Madison 147, 161–62, 190–92 (W. Hutchinson & W. Rachal, eds., 1962) . There seems little doubt that Jefferson held to the Blackstonian view. Writing to Madison in 1788, he said: “A declaration that the Federal Government will never restrain the presses from printing anything they please, will not take away the liability of the printers for false facts printed.” 13 Papers of Thomas Jefferson 442 (J. Boyd ed., 1955) . Commenting a year later to Madison on his proposed amendment, Jefferson suggested that the free speech-free press clause might read something like: “The people shall not be deprived or abridged of their right to speak, to write or otherwise to publish anything but false facts affecting injuriously the life, liberty, property, or reputation of others or affecting the peace of the confederacy with foreign nations.” 15 Papers , supra , at 367. it appears that there emerged in the course of the Jeffersonian counterattack on the Sedition Act 9 Footnote The Act, 1 Stat. 596 (1798), punished anyone who would “write, print, utter or publish . . . any false, scandalous and malicious writing or writings against the government of the United States, or either house of the Congress of the United States, or the President of the United States, with intent to defame the said government, or either house of the said Congress, or the said President, or to bring them, or either of them, into contempt or disrepute.” See J. Smith , Freedom’s Fetters: The Alien and Sedition Laws and American Civil Liberties (1956) . and the use by the Adams Administration of the Act to prosecute its political opponents, 10 Footnote Id. at 159 et seq. something of a libertarian theory of freedom of speech and press, 11 Footnote L. Levy , Legacy of Suppression: Freedom of Speech and Press in Early American History ch. 6 (1960) ; New York Times Co. v. Sullivan, 376 U.S. 254, 273–76 (1964) . But compare L. Levy , Emergence of a Free Press (1985) , a revised and enlarged edition of Legacy of Expression , in which Professor Levy modifies his earlier views, arguing that while the intention of the Framers to outlaw the crime of seditious libel, in pursuit of a free speech principle, cannot be established and may not have been the goal, there was a tradition of robust and rowdy expression during the period of the framing that contradicts his prior view that a modern theory of free expression did not begin to emerge until the debate over the Alien and Sedition Acts. which, however much the Jeffersonians may have departed from it upon assuming power, 12 Footnote L. Levy , Jefferson and Civil Liberties: The Darker Side (1963) . Thus President Jefferson wrote to Governor McKean of Pennsylvania in 1803: “The federalists having failed in destroying freedom of the press by their gag-law, seem to have attacked it in an opposite direction; that is, by pushing its licentiousness and its lying to such a degree of prostitution as to deprive it of all credit. . . . This is a dangerous state of things, and the press ought to be restored to its credibility if possible. The restraints provided by the laws of the States are sufficient for this if applied. And I have, therefore, long thought that a few prosecutions of the most prominent offenders would have a wholesome effect in restoring the integrity of the presses. Not a general prosecution, for that would look like persecution; but a selected one.” 9 Works of Thomas Jefferson 449 (P. Ford ed., 1905) . was to blossom into the theory undergirding Supreme Court First Amendment jurisprudence in modern times. Full acceptance of the theory that the Amendment operates not only to bar most prior restraints of expression but subsequent punishment of all but a narrow range of expression, in political discourse and indeed in all fields of expression, dates from a quite recent period, although the Court’s movement toward that position began in its consideration of limitations on speech and press in the period following World War I. 13 Footnote New York Times Co. v. Sullivan, 376 U.S. 254 (1964) , provides the principal doctrinal justification for the development, although the results had long since been fully applied by the Court. In Sullivan , Justice Brennan discerned in the controversies over the Sedition Act a crystallization of “a national awareness of the central meaning of the First Amendment ,” id. at 273 , which is that the “right of free public discussion of the stewardship of public officials . . . [is] a fundamental principle of the American form of government.” Id. at 275 . This “central meaning” proscribes either civil or criminal punishment for any but the most maliciously, knowingly false criticism of government. “Although the Sedition Act was never tested in this Court, the attack upon its validity has carried the day in the court of history. . . . [The historical record] reflect[s] a broad consensus that the Act, because of the restraint it imposed upon criticism of government and public officials, was inconsistent with the First Amendment .” Id. at 276 . Madison’s Virginia Resolutions of 1798 and his Report in support of them brought together and expressed the theories being developed by the Jeffersonians and represent a solid doctrinal foundation for the point of view that the First Amendment superseded the common law on speech and press, that a free, popular government cannot be libeled, and that the First Amendment absolutely protects speech and press. 6 Writings of James Madison , 341–406 (G. Hunt ed., 1908) . Thus, in 1907, Justice Holmes could observe that, even if the Fourteenth Amendment embodied prohibitions similar to the First Amendment , “still we should be far from the conclusion that the plaintiff in error would have us reach. In the first place, the main purpose of such constitutional provisions is 'to prevent all such previous restraints upon publications as had been practiced by other governments,' and they do not prevent the subsequent punishment of such as may be deemed contrary to the public welfare. The preliminary freedom extends as well to the false as to the true; the subsequent punishment may extend as well to the true as to the false. This was the law of criminal libel apart from statute in most cases, if not in all.” 14 Footnote Patterson v. Colorado, 205 U.S. 454, 462 (1907) (emphasis in original, citation omitted). Justice Frankfurter had similar views in 1951: “The historic antecedents of the First Amendment preclude the notion that its purpose was to give unqualified immunity to every expression that touched on matters within the range of political interest. . . . ‘The law is perfectly well settled,’ this Court said over fifty years ago, ‘that the first ten amendments to the Constitution, commonly known as the Bill of Rights, were not intended to lay down any novel principles of government, but simply to embody certain guaranties and immunities which we had inherited from our English ancestors, and which had from time immemorial been subject to certain well-recognized exceptions arising from the necessities of the case. In incorporating these principles into the fundamental law there was no intention of disregarding the exceptions, which continued to be recognized as if they had been formally expressed.’ Robertson v. Baldwin, 165 U.S. 275, 281 (1897) . That this represents the authentic view of the Bill of Rights and the spirit in which it must be construed has been recognized again and again in cases that have come here within the last fifty years.” Dennis v. United States, 341 U.S. 494, 521–522, 524 (1951) (concurring opinion). But as Justice Holmes also observed, “[t]here is no constitutional right to have all general propositions of law once adopted remain unchanged.” 15 Footnote Patterson v. Colorado, 205 U.S. 454, 461 (1907) .

But, in Schenck v. United States , 16 Footnote 249 U.S. 47, 51–52 (1919) (citations omitted). the first of the post-World War I cases to reach the Court, Justice Holmes, in his opinion for the Court upholding convictions for violating the Espionage Act by attempting to cause insubordination in the military service by circulation of leaflets, suggested First Amendment restraints on subsequent punishment as well as on prior restraint. “It well may be that the prohibition of laws abridging the freedom of speech is not confined to previous restraints, although to prevent them may have been the main purpose . . . . We admit that in many places and in ordinary times the defendants in saying all that was said in the circular would have been within their constitutional rights. But the character of every act depends upon the circumstances in which it is done. . . . The most stringent protection of free speech would not protect a man in falsely shouting fire in a theatre and causing a panic. . . . The question in every case is whether the words used are used in such a nature as to create a clear and present danger that they will bring about the substantive evils that Congress has a right to prevent.”

Justice Holmes, along with Justice Brandeis, soon went into dissent in their views that the majority of the Court was misapplying the legal standards thus expressed to uphold suppression of speech that offered no threat to organized institutions. 17 Footnote Debs v. United States, 249 U.S. 211 (1919) ; Abrams v. United States, 250 U.S. 616 (1919) ; Schaefer v. United States, 251 U.S. 466 (1920) ; Pierce v. United States, 252 U.S. 239 (1920) ; United States ex rel. Milwaukee Social Democratic Pub. Co. v. Burleson, 255 U.S. 407 (1921) . A state statute similar to the federal one was upheld in Gilbert v. Minnesota, 254 U.S. 325 (1920) . But it was with the Court’s assumption that the Fourteenth Amendment restrained the power of the states to suppress speech and press that the doctrines developed. 18 Footnote Gitlow v. New York, 268 U.S. 652 (1925) ; Whitney v. California, 274 U.S. 357 (1927) . The Brandeis and Holmes dissents in both cases were important formulations of speech and press principles. At first, Holmes and Brandeis remained in dissent, but, in Fiske v. Kansas , 19 Footnote 274 U.S. 380 (1927) . the Court sustained a First Amendment type of claim in a state case, and in Stromberg v. California , 20 Footnote 283 U.S. 359 (1931) . By contrast, it was not until 1965 that a federal statute was held unconstitutional under the First Amendment . Lamont v. Postmaster General, 381 U.S. 301 (1965) . See also United States v. Robel, 389 U.S. 258 (1967) . voided a state statute on grounds of its interference with free speech. 21 Footnote See also Near v. Minnesota ex rel. Olson, 283 U.S. 697 (1931) ; Herndon v. Lowry, 301 U.S. 242 (1937) ; DeJonge v. Oregon, 299 U.S. 353 (1937) ; Lovell v. City of Griffin, 303 U.S. 444 (1938) . State common law was also voided, with the Court in an opinion by Justice Black asserting that the First Amendment enlarged protections for speech, press, and religion beyond those enjoyed under English common law. 22 Footnote Bridges v. California, 314 U.S. 252, 263–68 (1941) (overturning contempt convictions of newspaper editor and others for publishing commentary on pending cases).

Development over the years since has been uneven, but by 1964 the Court could say with unanimity: “we consider this case against the background of a profound national commitment to the principle that debate on public issues should be uninhibited, robust, and wide-open, and that it may well include vehement, caustic, and sometimes unpleasantly sharp attacks on government and public officials.” 23 Footnote New York Times Co. v. Sullivan, 376 U.S. 254, 270 (1964) . And, in 1969, the Court said that the cases “have fashioned the principle that the constitutional guarantees of free speech and free press do not permit a State to forbid or proscribe advocacy of the use of force or of law violation except where such advocacy is directed to inciting or producing imminent lawless action and is likely to incite or produce such action.” 24 Footnote Brandenburg v. Ohio, 395 U.S. 444, 447 (1969) . This development and its myriad applications are elaborated in the following sections.

The following state regulations pages link to this page.

First Amendment – Freedom of the Press

The First Amendment protects the free press, including television, radio and the Internet. The media are free to distribute a wide range of news, facts, opinions and pictures.

1735 Truth Is A Defense Against Libel Charge

New York printer John Peter Zenger is tried on charges of seditious libel for publishing criticism of the royal governor. English law – asserting that the greater the truth, the greater the libel – prohibits any published criticism of the government that would incite public dissatisfaction with it. Zenger’s lawyer, Andrew Hamilton, convinces the jury that Zenger should be acquitted because the articles were, in fact, true, and that New York libel law should not be the same as English law. The Zenger case is a landmark in the development of protection of freedom of speech and the press.

1787 Federalist Papers’ Publication Starts

The first of 85 essays written under the pen name Publius by Alexander Hamilton, James Madison and John Jay begin to appear in the New York Independent Journal. The essays, called the Federalist Papers, support ratification of the Constitution approved by the Constitutional Convention on Sept. 17, 1787. In Federalist Paper No. 84, Hamilton discusses “liberty of the press.”

1791 First Amendment Is Ratified

The First Amendment is ratified when Virginia becomes the 11th state to approve the first 10 amendments to the Constitution, known as the Bill of Rights. The amendment, drafted primarily by James Madison, guarantees basic freedoms for citizens: freedom of speech, press, religion, assembly and petition.

1798 Alien And Sedition Acts Signed Into Law

While the nation’s leaders believe an outspoken press was justified during the war for independence, they take a different view when they are in power. The Federalist-controlled Congress passes the Alien and Sedition Acts. Aimed at quashing criticism of Federalists, the Sedition Act makes it illegal for anyone to express “any false, scandalous and malicious writing” against Congress or the president.

The United States is in an undeclared war with France, and Federalists say the law is necessary to protect the nation from attacks and to protect the government from false and malicious words. Republicans argue for a free flow of information and the right to publicly examine officials’ conduct.

1864 Lincoln Orders Two Newspapers Shut

President Abraham Lincoln orders Union Gen. John Dix to stop publication of the New York Journal of Commerce and the New York World after they publish a forged presidential proclamation calling for another military draft. The editors also are arrested. After the authors of the forgery are arrested, the newspapers are allowed to resume publication.

1907 Court Refuses To Review Publisher’s Conviction

In Patterson v. Colorado , the U.S. Supreme Court says it does not have jurisdiction to review the criminal contempt conviction of U.S. Sen. Thomas Patterson, who published articles and a cartoon critical of the state Supreme Court. The Court says that the rights of free speech and free press protect only against prior restraint and do not prevent “subsequent punishment.”

1918 Sedition Act Of 1918 Punishes Critics Of WWI

An amendment to the Espionage Act of 1917, the Sedition Act is passed by Congress. It goes much further than its predecessor, imposing severe criminal penalties on all forms of expression that are critical of the government, its symbols, or its mobilization of resources for World War I. Ultimately, about 900 people will be convicted under the law. Hundreds of noncitizens will be deported without a trial; 249 of them, including anarchist Emma Goldman, will be sent to the Soviet Union.

1925 Court: First Amendment Applies To States’ Laws

In Gitlow v. New York , the U.S. Supreme Court concludes that the free speech clause of the First Amendment applies not just to laws passed by Congress, but also to those passed by the states.

1931 Prior Restraint Ruled Unconstitutional

Near v. Minnesota is the first U.S. Supreme Court decision to invoke the First Amendment’s press clause. A Minnesota law prohibited the publication of “malicious, scandalous, and defamatory” newspapers. It was aimed at the Saturday Press, which had run a series of articles about corrupt practices by local politicians and business leaders. The justices rule that prior restraints against publication violate the First Amendment, meaning that once the press possesses information that it deems newsworthy, the government can seldom prevent its publication. The Court also says the protection is not absolute, suggesting that information during wartime or obscenity or incitement to acts of violence may be restricted.

1936 Court: Newspaper Circulation Tax Unconstitutional

In Grosjean v. American Press Co. , the U.S. Supreme Court decides that governments may not impose taxes on a newspaper’s circulation. The Court says such a tax is unconstitutional because “it is seen to be a deliberate and calculated device … to limit the circulation of information to which the public is entitled.”

1952 Justices Uphold Group Libel Law

In Beauharnais v. Illinois , the U.S. Supreme Court upholds the conviction of a white supremacist for passing out leaflets that characterized African Americans as dangerous criminals. The “group libel” law under which Joseph Beauharnais was prosecuted makes it a crime to make false statements about people of a particular “race, color, creed or religion” for no other reason than to harm that group. The Court rules that libel against groups, like libel against individuals, has no place in the marketplace of ideas.

1964 Court Establishes ‘Actual Malice’ Standard

In New York Times Co. v. Sullivan , the U.S. Supreme Court establishes the “actual malice” standard when it reverses a civil libel judgment against the New York Times. The newspaper was sued for libel by Montgomery, Ala.’s police commissioner after it published a full-page ad that criticized anti-civil rights activities in Montgomery. The court rules that debate about public issues and officials is central to the First Amendment. Consequently, public officials cannot sue for libel unless they prove that a statement was made with “actual malice,” meaning it was made “with knowledge that it was false or with reckless disregard of whether it was false or not.”

1969 Justices Uphold FCC’s Fairness Doctrine

Because of the limits of the broadcast spectrum, the U.S. Supreme Court holds that the government may require radio and TV broadcasters to present balanced discussions of public issues on the airwaves. In Red Lion Broadcasting v. FCC , the Court upholds the Federal Communications Commission’s fairness doctrine and “personal attack” rule – the right of a person criticized on a broadcast station to respond to the criticism over the same airwaves – saying they do not violate the right to free speech.

1971 Newspapers Win Pentagon Papers Case

The New York Times and the Washington Post obtain secret Defense Department documents that detail U.S. involvement in Vietnam in the years leading up to the Vietnam War. Citing national security, the U.S. government gets temporary restraining orders to halt publication of the documents, known as the Pentagon Papers. But, acting with unusual haste, the U.S. Supreme Court finds in New York Times v. United States that prior restraint on the documents’ publication violates the First Amendment. National security concerns are too speculative to overcome the “heavy presumption” in favor of the First Amendment’s guarantee of freedom of the press, the Court says.

1972 Court: No Reporter’s Privilege Before Grand Juries

Branzburg v. Hayes is a landmark decision in which the U.S. Supreme Court rejects First Amendment protection for reporters called before a grand jury to reveal confidential information or sources. Reporters argued that if they were forced to identify their sources, their informants would be reluctant to provide information in the future. The Court decides reporters are obliged to cooperate with grand juries just as average citizens are. The justices do allow a small exception for grand jury investigations that are not conducted or initiated in good faith.

1974 Equal Space Law For Candidates Struck Down

In Miami Herald v. Tornillo , the U.S. Supreme Court strikes down a Florida law requiring newspapers to give equal space to candidates running for office. The justices say a candidate is not entitled to equal space to reply to a newspaper’s attack. Compulsory publication, the court says, intrudes on the right of newspaper editors to decide what they want to publish.

1975 Court Allows Publication Of Sex-Crime Victim’s Name

In Cox Broadcasting Corp. v. Cohn , the U.S. Supreme Court rules that a state cannot prevent a newspaper from publishing the name of a rape victim in a criminal case when the name already was included in a court document available to the public.

1976 Justices Say Gag Orders On Press Are Prior Restraint

Nebraska Press Association v. Stuart pits the right of a free press against the right to a fair trial. In a multiple-murder case in Nebraska, a local judge imposed a gag order to prevent news coverage that might make it difficult to seat an impartial jury. However, the U.S. Supreme Court rules that judges cannot impose gag orders on reporters covering a criminal trial because they are a form of prior restraint. However, the justices also note that there may be cases in which a gag order might be justified to protect the defendant’s rights.

1977 Court Allows Publication Of Juvenile’s Identity

In Oklahoma Publishing Company v. District Court , the U.S. Supreme Court finds that when a newspaper obtains the name and photograph of a juvenile involved in a juvenile court proceeding, it is unconstitutional to prevent publication of the information, even though the juvenile has a right to confidentiality in such proceedings. A similar ruling will be made by the court two years later, in Smith v. Daily Mail Publishing Company , when the Court finds that a newspaper’s First Amendment right takes precedence over a juvenile’s right to anonymity.

1977 Publication Of Juvenile’s Name, Photograph Is Upheld

In the case Oklahoma Publishing Company v. District Court , the U.S. Supreme Court finds that when a newspaper obtains a name and photograph of a juvenile involved in a juvenile court proceeding, it is an unconstitutional restriction on the press to prevent publication of that information, even though the juvenile has a right to confidentiality in such proceedings. A similar ruling is made two years later, in Smith v. Daily Mail Publishing Company , when the Court finds that a newspaper’s First Amendment right must take precedence over a juvenile’s right to anonymity.

1978 Justices Allow Search Warrants For Newsrooms

In Zurcher v. Stanford Daily , the U.S. Supreme Court finds that the First Amendment does not protect the press and its newsrooms from search warrants. Police in Palo Alto, Calif., had obtained a warrant to search the newsroom of the student newspaper at Stanford University. Police believed the newspaper had photos of a violent clash between protesters and police and were trying to identify the assailants.

1979 Court: No Shield On Editorial Process Inquiries

In Herbert v. Lando , the U.S. Supreme Court decides that the press clause in the First Amendment does not include a privilege that would empower a journalist to decline to testify about editorial decision-making in civil discovery. The Court says that protecting the editorial process from inquiry would add to the already substantial burden of proving actual malice.

1979 Court Allows Publication Of Juvenile Offender’s Name

In Smith v. Daily Publishing Co. , the U.S. Supreme Court decides that a newspaper cannot be liable for publishing the name of a juvenile offender in violation of a West Virginia law declaring such information to be private. The Court writes: “If a newspaper lawfully obtains truthful information about a matter of public significance then state officials may not constitutionally punish publication of the information, absent a need to further a state interest of the highest order.”

1979 Right To Public Trial Is To Protect Defendant

In Gannett Co. v. DePasquale , the U.S. Supreme Court denies a claim by members of the press and public who were barred from a pretrial hearing in a criminal case. The Court rules that extensive pretrial publicity threatened the defendant’s ability to get a fair trial. The Court holds that the Sixth Amendment right to a public trial is first and foremost for the benefit of the defendant and does not give the press or public an absolute right to attend criminal trials.

1980 Justices Uphold Right To Attend Criminal Trials

In Richmond Newspapers v. Virginia , the U.S. Supreme Court asserts that the public and the press have a First Amendment right to observe criminal trials. The justices say this right is not absolute, but can be restricted only if the judge decides there are no other means to protect the defendant’s right to a fair trial. The other means include a change of venue, jury sequestration, extensive questioning of potential jurors, trial postponement, emphatic jury instructions, and gag orders on trial participants. The Court says open trials help maintain public confidence in the justice system. In 1984, the Court extends its ruling to jury selection. In Press-Enterprise Co. v. Superior Court of California , the justices rule that the right to attend criminal trials includes the right to attend jury selection.

1982 Court: Press Has Right To Cover All Trials

Globe Newspaper Co. v. Superior Court establishes broad rights of the press to cover trials of all types. In 1979, three teenage girls accused a man of rape. Massachusetts law required that sex-crime trials involving victims 18 and younger be closed. The Globe Newspaper Co. challenged the law, and after a long legal battle, the case reached the U.S. Supreme Court. By that time, the trial was over, but the justices review the case since the issue will likely arise again. The court strikes down the law as too broad and says the circumstances when a courtroom can be closed are limited.

1983 Media Access Limited In Grenada, Panama Invasions

Media access is banned for the first two days when the United States invades Grenada, its first military action since the Vietnam War. Journalists are kept 170 miles away on the island of Barbados. In response to complaints afterward, the Department of Defense National Media Pool is created. The Pentagon agrees to take in this group with the first wave of troops in future military actions. But in the 1989 invasion of Panama, the pool of reporters again is not allowed to cover early fighting.

1988 Court Allows Censorship Of School Publications

In Hazelwood School District v. Kuhlmeier , the U.S. Supreme Court rules that public school administrators can censor speech by students in publications (or activities) that are funded by the school – such as a yearbook, newspaper, play, or art exhibit – if they have a valid educational reason for doing so.

1988 Parody Of Public Figures Ruled Constitutional

In Hustler Magazine v. Falwell , the U.S. Supreme Court applies the “actual malice” standard, saying the First Amendment protects the right to parody public figures, even if the parodies are “outrageous” or inflict severe emotional distress. The case arose from a parody of Campari liqueur ads in which celebrities spoke about their “first time” drinking the liqueur. Jerry Falwell – a well-known conservative minister and political commentator – was the subject of such a parody in Hustler, a sexually explicit magazine. The Court rules that public figures may not be awarded damages for the intentional infliction of emotional distress without showing that false factual statements were made with “actual malice.”

1990 Court Decides Opinion Not Always Protected

In Milkovich v. Lorain Journal Co. , the U.S. Supreme Court decides that the First Amendment does not absolutely protect expressions of opinion from being found libelous. The Court makes a distinction between pure opinion and opinion that implies “an assertion of objective fact” that a plaintiff can prove is false. Chief Justice William H. Rehnquist writes that “loose, figurative or hyperbolic language” is protected because it would “negate the impression” that the writer is making serious accusations based on fact.

1991 Court: Newspapers Can Be Sued For Revealing Source

Cohen v. Cowles Media Co. establishes that newspapers are subject to liability for breach of contract claims when the identity of a confidential source is revealed. During a Minnesota election, political activist Dan Cohen gave reporters court documents about a candidate after they promised him anonymity. In subsequent articles, Cohen was identified as the source of the documents and fired. He sued the two newspapers, alleging fraudulent misrepresentation and breach of contract. The Court rejects the newspapers’ claim to the right to publish Cohen’s name, saying that in this context, the First Amendment offers no special protection.

1991 Media Coverage Limited In Gulf War

The Pentagon imposes rules for media coverage of the war in the Persian Gulf, citing the possibility that some news – including information on downed aircrafts, specific troop numbers, and names of operations – may endanger lives or jeopardize U.S. military strategy. Nine news organizations file a lawsuit questioning the constitutionality of limiting media access to the battleground. But a court rules the question moot when the war ends before the case is decided.

2001 Disclosure Of Illegally Intercepted Communications Protected

In the joined cases of United States v. Vopper and Bartnicki v. Vopper , the U.S. Supreme Court rules that the media cannot be held liable for publishing or broadcasting the illegally intercepted contents of telephone calls or other electronic communications as long as the information is of “public concern” and the media did not participate in the illegal interception.

Related Resources

- Video: Freedom of the Press: New York Times v. United States

- Book: Chapter 7: The Right to Freedom of the Press

- Book: Chapter 15: Freedom of the Press in a Free Society

- ENCYCLOPEDIA

- IN THE CLASSROOM

Home » Articles » Topic » Groups and Organizations » Federalists

Federalists

Written by Mitzi Ramos, published on July 31, 2023 , last updated on February 11, 2024

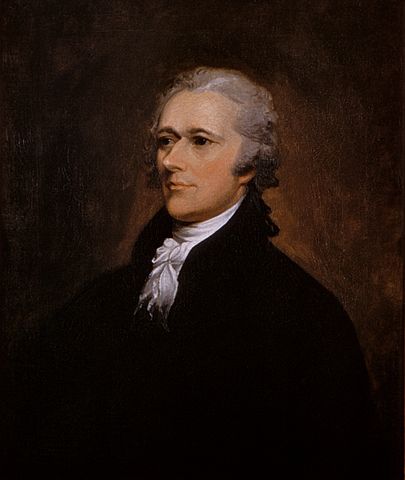

The name Federalists was adopted both by the supporters of ratification of the U.S. Constitution and by members of one of the nation’s first two political parties. Alexander Hamilton was an influential Federalist who wrote many of the essays in The Federalist, published in 1788. These articles advocated the ratification of the Constitution. Later, those who supported Hamilton’s aggressive fiscal policies formed the Federalist Party, which grew to support a strong national government, an expansive interpretation of congressional powers under the Constitution through the elastic clause, and a more mercantile economy. (Image via Wikimedia Commons, painted by John Trumbull circa 1805, public domain)

The name Federalists was adopted both by the supporters of ratification of the U.S. Constitution and by members of one of the nation’s first two political parties.

Federalists battled for adoption of the Constitution

In the clash in 1788 over ratification of the Constitution by nine or more state conventions, Federalist supporters battled for a strong union and the adoption of the Constitution, and Anti-Federalists fought against the creation of a stronger national government and sought less drastic changes to the Articles of Confederation, the predecessor of the Constitution.

The Federalists included big property owners in the North, conservative small farmers and businessmen, wealthy merchants, clergymen, judges, lawyers, and professionals. They favored weaker state governments, a strong centralized government, the indirect election of government officials, longer term limits for officeholders, and representative, rather than direct, democracy.

Federalists published papers in New York City newspapers

Faced with forceful Anti-Federalist opposition to a strong national government, the Federalists published a series of 85 articles in New York City newspapers in which they advocated ratification of the Constitution. A compilation of these articles written by James Madison , Alexander Hamilton , and John Jay (under the pseudonym Publius), were published as The Federalist in 1788.

Through these papers and other writings, the Federalists successfully articulated their position in favor of adoption of the Constitution. Anti-Federalists wrote many essays of their own, but the Federalists were better organized; were (as their name suggested) advocating positive changes by proposing an alternative to the Articles of Confederation, which were generally considered to be inadequate; had strong support in the press of the day; and ultimately prevailed in state ratification debates. These papers remain a vital source for understanding key provisions within the Constitution and their underlying principles. The Federalist/Anti-Federalist debates further illustrate the vigor of the rights to freedom of speech and press in the United States, even before the Constitution and the Bill of Rights was adopted.

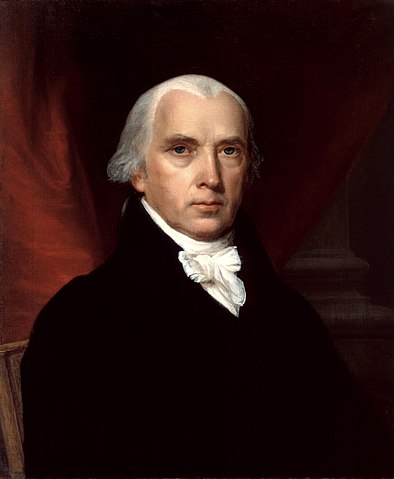

James Madison was another author of the Federalist Papers. To ensure adoption of the Constitution, the Federalists, such as James Madison, promised to add amendments specifically protecting individual liberties. These amendments, including the First Amendment, became the Bill of Rights. James Madison later became a Democratic-Republican and opposed many Federalist policies. (Image via the White House Historical Association, painted by John Vanderlyn in 1816, public domain)

Federalists argued separation of powers protected rights

In light of charges that the Constitution created a strong national government, they were able to argue that the separation of powers among the three branches of government protected the rights of the people. Because the three branches were equal, none could assume control over the other.

When challenged over the lack of individual liberties, the Federalists argued both that the Constitution already contained some such protections in Article I, Sections 9 and 10, that respectively limited Congress and the states; that the entire Constitution, with its institutional restraints and checks and balances was, in effect, a Bill of Rights; and that the Constitution did not include a bill of rights because the new Constitution did not vest the new government with the authority to suppress individual liberties.

The Federalists further argued that because it would be impossible to list all the rights afforded to Americans, it would be best to list none.

Prominent Anti-federalists like Patrick Henry , George Mason , and James Monroe and supporters of the new constitution like Thomas Jefferson , continued to argue that the people were entitled to more explicit declarations of their rights under the new government.

Federalists agree to add Bill of Rights

In the end, however, to ensure adoption of the Constitution, the Federalists promised to add amendments specifically protecting individual liberties. That is, Federalists such as James Madison ultimately agreed to support a bill of rights largely to head off the possibility of a second convention that might undo the work of the first.

Thus upon ratification of the Constitution and his election to the U.S. House of Representatives, Madison introduced proposals that were incorporated in 12 amendments by Congress in 1789. States ratified 10 of these amendments, now designated as the Bill of Rights , in 1791.

The first of these amendments contains guarantees of freedom of religion , speech , press , peaceable assembly , and petition and has also been interpreted to protect the right of association . Initially adopted to limit only the national government, these provisions have now been recognized as also limiting the states through the due process clause of the 14th Amendment, which was adopted after the Civil War in 1868.

In 1798, during the administration of John Adams, the Federalists attempted to squelch dissent by adopting the Sedition Act, which restricted freedom of speech and the press. Although the Federalist Party was strong in New England and the Northeast, it was left without a strong leader after the death of Alexander Hamilton and retirement of Adams. Its increasingly aristocratic tendencies and its opposition to the War of 1812 helped to fuel its demise in 1816. (Image via the U.S. Navy, painted by Asher Brown Durand between 1735 and 1826, public domain)

Federalist Party supported Alexander Hamilton’s policies

Although the Bill of Rights enabled Federalists and Anti-Federalists to reach a compromise that led to the adoption of the Constitution, this harmony did not extend into the presidency of George Washington ; political divisions within the cabinet of the newly created government emerged in 1792 over national fiscal policy, splitting those who previously supported the Constitution into rival groups, some of whom allied with former Anti-Federalists.

Those who supported Treasury Secretary Alexander Hamilton’s aggressive fiscal policies formed the Federalist Party, which supported a strong national government, an expansive interpretation of congressional powers under the Constitution through the elastic clause, and a more mercantile economy.

Their Democratic-Republican opponents, led by Secretary of State Thomas Jefferson and James Madison, tended to emphasize states’ rights and agrarianism.

In 1798, during the administration of John Adams , the Federalists attempted to squelch dissent by adopting the Sedition Act , which restricted freedom of speech and the press when directed against the government and its officials, but opposition to this law helped Democratic-Republicans gain victory in the elections of 1800. As the new president, Jefferson pardoned those who had been convicted under the Sedition Act.

Federalist Party ended in 1816

Although the Federalist Party was strong in New England and the Northeast, it was left without a strong leader after the death of Alexander Hamilton and retirement of John Adams. Its increasingly aristocratic tendencies and its opposition to the War of 1812 helped to fuel its demise in 1816.

This party was later succeeded by the Whig Party, which in turn was succeeded by the Republican Party. The Democratic-Republican Party was reformed by Andrew Jackson and became the modern Democrat Party.

This article was originally published in 2009 and was updated in February 2024 by John R. Vile, dean of the Honors College at Middle Tennessee State University. Mitzi Ramos is an Instructor of Political Science at Northeastern Illinois University.

Send Feedback on this article

How To Contribute

The Free Speech Center operates with your generosity! Please donate now!

- History Classics

- Your Profile

- Find History on Facebook (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on Twitter (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on YouTube (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on Instagram (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on TikTok (Opens in a new window)

- This Day In History

- History Podcasts

- History Vault

Federalist Papers

By: History.com Editors

Updated: June 22, 2023 | Original: November 9, 2009

The Federalist Papers are a collection of essays written in the 1780s in support of the proposed U.S. Constitution and the strong federal government it advocated. In October 1787, the first in a series of 85 essays arguing for ratification of the Constitution appeared in the Independent Journal , under the pseudonym “Publius.” Addressed to “The People of the State of New York,” the essays were actually written by the statesmen Alexander Hamilton , James Madison and John Jay . They would be published serially from 1787-88 in several New York newspapers. The first 77 essays, including Madison’s famous Federalist 10 and Federalist 51 , appeared in book form in 1788. Titled The Federalist , it has been hailed as one of the most important political documents in U.S. history.

Articles of Confederation

As the first written constitution of the newly independent United States, the Articles of Confederation nominally granted Congress the power to conduct foreign policy, maintain armed forces and coin money.

But in practice, this centralized government body had little authority over the individual states, including no power to levy taxes or regulate commerce, which hampered the new nation’s ability to pay its outstanding debts from the Revolutionary War .

In May 1787, 55 delegates gathered in Philadelphia to address the deficiencies of the Articles of Confederation and the problems that had arisen from this weakened central government.

A New Constitution

The document that emerged from the Constitutional Convention went far beyond amending the Articles, however. Instead, it established an entirely new system, including a robust central government divided into legislative , executive and judicial branches.

As soon as 39 delegates signed the proposed Constitution in September 1787, the document went to the states for ratification, igniting a furious debate between “Federalists,” who favored ratification of the Constitution as written, and “Antifederalists,” who opposed the Constitution and resisted giving stronger powers to the national government.

The Rise of Publius

In New York, opposition to the Constitution was particularly strong, and ratification was seen as particularly important. Immediately after the document was adopted, Antifederalists began publishing articles in the press criticizing it.

They argued that the document gave Congress excessive powers and that it could lead to the American people losing the hard-won liberties they had fought for and won in the Revolution.

In response to such critiques, the New York lawyer and statesman Alexander Hamilton, who had served as a delegate to the Constitutional Convention, decided to write a comprehensive series of essays defending the Constitution, and promoting its ratification.

Who Wrote the Federalist Papers?

As a collaborator, Hamilton recruited his fellow New Yorker John Jay, who had helped negotiate the treaty ending the war with Britain and served as secretary of foreign affairs under the Articles of Confederation. The two later enlisted the help of James Madison, another delegate to the Constitutional Convention who was in New York at the time serving in the Confederation Congress.

To avoid opening himself and Madison to charges of betraying the Convention’s confidentiality, Hamilton chose the pen name “Publius,” after a general who had helped found the Roman Republic. He wrote the first essay, which appeared in the Independent Journal, on October 27, 1787.

In it, Hamilton argued that the debate facing the nation was not only over ratification of the proposed Constitution, but over the question of “whether societies of men are really capable or not of establishing good government from reflection and choice, or whether they are forever destined to depend for their political constitutions on accident and force.”

After writing the next four essays on the failures of the Articles of Confederation in the realm of foreign affairs, Jay had to drop out of the project due to an attack of rheumatism; he would write only one more essay in the series. Madison wrote a total of 29 essays, while Hamilton wrote a staggering 51.

Federalist Papers Summary

In the Federalist Papers, Hamilton, Jay and Madison argued that the decentralization of power that existed under the Articles of Confederation prevented the new nation from becoming strong enough to compete on the world stage or to quell internal insurrections such as Shays’s Rebellion .

In addition to laying out the many ways in which they believed the Articles of Confederation didn’t work, Hamilton, Jay and Madison used the Federalist essays to explain key provisions of the proposed Constitution, as well as the nature of the republican form of government.

'Federalist 10'

In Federalist 10 , which became the most influential of all the essays, Madison argued against the French political philosopher Montesquieu ’s assertion that true democracy—including Montesquieu’s concept of the separation of powers—was feasible only for small states.

A larger republic, Madison suggested, could more easily balance the competing interests of the different factions or groups (or political parties ) within it. “Extend the sphere, and you take in a greater variety of parties and interests,” he wrote. “[Y]ou make it less probable that a majority of the whole will have a common motive to invade the rights of other citizens[.]”

After emphasizing the central government’s weakness in law enforcement under the Articles of Confederation in Federalist 21-22 , Hamilton dove into a comprehensive defense of the proposed Constitution in the next 14 essays, devoting seven of them to the importance of the government’s power of taxation.

Madison followed with 20 essays devoted to the structure of the new government, including the need for checks and balances between the different powers.

'Federalist 51'

“If men were angels, no government would be necessary,” Madison wrote memorably in Federalist 51 . “If angels were to govern men, neither external nor internal controls on government would be necessary.”

After Jay contributed one more essay on the powers of the Senate , Hamilton concluded the Federalist essays with 21 installments exploring the powers held by the three branches of government—legislative, executive and judiciary.

Impact of the Federalist Papers

Despite their outsized influence in the years to come, and their importance today as touchstones for understanding the Constitution and the founding principles of the U.S. government, the essays published as The Federalist in 1788 saw limited circulation outside of New York at the time they were written. They also fell short of convincing many New York voters, who sent far more Antifederalists than Federalists to the state ratification convention.

Still, in July 1788, a slim majority of New York delegates voted in favor of the Constitution, on the condition that amendments would be added securing certain additional rights. Though Hamilton had opposed this (writing in Federalist 84 that such a bill was unnecessary and could even be harmful) Madison himself would draft the Bill of Rights in 1789, while serving as a representative in the nation’s first Congress.

HISTORY Vault: The American Revolution

Stream American Revolution documentaries and your favorite HISTORY series, commercial-free.

Ron Chernow, Hamilton (Penguin, 2004). Pauline Maier, Ratification: The People Debate the Constitution, 1787-1788 (Simon & Schuster, 2010). “If Men Were Angels: Teaching the Constitution with the Federalist Papers.” Constitutional Rights Foundation . Dan T. Coenen, “Fifteen Curious Facts About the Federalist Papers.” University of Georgia School of Law , April 1, 2007.

Sign up for Inside History

Get HISTORY’s most fascinating stories delivered to your inbox three times a week.

By submitting your information, you agree to receive emails from HISTORY and A+E Networks. You can opt out at any time. You must be 16 years or older and a resident of the United States.

More details : Privacy Notice | Terms of Use | Contact Us

Founders Online --> [ Back to normal view ]

The federalist number 10, [22 november] 1787, the federalist number 10.

[22 November 1787]

Among the numerous advantages promised by a well constructed union, none deserves to be more accurately developed than its tendency to break and control the violence of faction. 1 The friend of popular governments, never finds himself so much alarmed for their character and fate, as when he contemplates their propensity to this dangerous vice. He will not fail therefore to set a due value on any plan which, without violating the principles to which he is attached, provides a proper cure for it. The instability, injustice and confusion introduced into the public councils, have in truth been the mortal diseases under which popular governments have every where perished; as they continue to be the favorite and fruitful topics from which the adversaries to liberty derive their most specious declamations. The valuable improvements made by the American constitutions on the popular models, both antient and modern, cannot certainly be too much admired; but it would be an unwarrantable partiality, to contend that they have as effectually obviated the danger on this side as was wished and expected. Complaints are every where heard from our most considerate and virtuous citizens, equally the friends of public and private faith, and of public and personal liberty; that our governments are too unstable; that the public good is disregarded in the conflicts of rival parties; and that measures are too often decided, not according to the rules of justice, and the rights of the minor party; but by the superior force of an interested and over-bearing majority. However anxiously we may wish that these complaints had no foundation, the evidence of known facts will not permit us to deny that they are in some degree true. It will be found indeed, on a candid review of our situation, that some of the distresses under which we labour, have been erroneously charged on the operation of our governments; but it will be found at the same time, that other causes will not alone account for many of our heaviest misfortunes; and particularly, for that prevailing and increasing distrust of public engagements, and alarm for private rights, which are echoed from one end of the continent to the other. These must be chiefly, if not wholly, effects of the unsteadiness and injustice, with which a factious spirit has tainted our public administration.

By a faction I understand a number of citizens, whether amounting to a majority or minority of the whole, who are united and actuated by some common impulse of passion, or of interest, adverse to the rights of other citizens, or to the permanent and aggregate interests of the community.

There are two methods of curing the mischiefs of faction: The one, by removing its causes; the other, by controlling its effects.

There are again two methods of removing the causes of faction: The one by destroying the liberty which is essential to its existence; the other, by giving to every citizen the same opinions, the same passions, and the same interests.

It could never be more truly said than of the first remedy, that it is worse than the disease. Liberty is to faction, what air is to fire, an aliment without which it instantly expires. But it could not be a less folly to abolish liberty, which is essential to political life, because it nourishes faction, than it would be to wish the annihilation of air, which is essential to animal life because it imparts to fire its destructive agency.

The second expedient is as impracticable, as the first would be unwise. As long as the reason of man continues fallible, and he is at liberty to exercise it, different opinions will be formed. As long as the connection subsists between his reason and his self-love, his opinions and his passions will have a reciprocal influence on each other; and the former will be objects to which the latter will attach themselves. The diversity in the faculties of men from which the rights of property originate, is not less an insuperable obstacle to an uniformity of interests. The protection of these faculties is the first object of government. From the protection of different and unequal faculties of acquiring property, the possession of different degrees and kinds of property immediately results: And from the influence of these on the sentiments and views of the respective proprietors, ensues a division of the society into different interests and parties.

The latent causes of faction are thus sown in the nature of man; and we see them every where brought into different degrees of activity, according to the different circumstances of civil society. A zeal for different opinions concerning religion, concerning government, and many other points, as well of speculation as of practice; an attachment to different leaders ambitiously contending for pre-eminence and power; or to persons of other descriptions whose fortunes have been interesting to the human passions, have in turn divided mankind into parties, inflamed them with mutual animosity, and rendered them much more disposed to vex and oppress each other, than to co-operate for their common good. So strong is this propensity of mankind to fall into mutual animosities, that where no substantial occasion presents itself, the most frivolous and fanciful distinctions have been sufficient to kindle their unfriendly passions, and excite their most violent conflicts. But the most common and durable source of factions, has been the various and unequal distribution of property. Those who hold, and those who are without property, have ever formed distinct interests in society. Those who are creditors, and those who are debtors, fall under a like discrimination. A landed interest, a manufacturing interest, a mercantile interest, a monied interest, with many lesser interests, grow up of necessity in civilized nations, and divide them into different classes, actuated by different sentiments and views. The regulation of these various and interfering interests forms the principal task of modern legislation, and involves the spirit of party and faction in the necessary and ordinary operations of government.

No man is allowed to be a judge in his own cause; because his interest would certainly bias his judgment, and, not improbably, corrupt his integrity. With equal, nay with greater reason, a body of men, are unfit to be both judges and parties, at the same time; yet, what are many of the most important acts of legislation, but so many judicial determinations, not indeed concerning the rights of single persons, but concerning the rights of large bodies of citizens; and what are the different classes of legislators, but advocates and parties to the causes which they determine? Is a law proposed concerning private debts? It is a question to which the creditors are parties on one side, and the debtors on the other. Justice ought to hold the balance between them. Yet the parties are and must be themselves the judges; and the most numerous party, or, in other words, the most powerful faction must be expected to prevail. Shall domestic manufactures be encouraged, and in what degree, by restrictions on foreign manufactures? are questions which would be differently decided by the landed and the manufacturing classes; and probably by neither, with a sole regard to justice and the public good. The apportionment of taxes on the various descriptions of property, is an act which seems to require the most exact impartiality, yet there is perhaps no legislative act in which greater opportunity and temptation are given to a predominant party, to trample on the rules of justice. Every shilling with which they over-burden the inferior number, is a shilling saved to their own pockets.

It is in vain to say, that enlightened statesmen will be able to adjust these clashing interests, and render them all subservient to the public good. Enlightened statesmen will not always be at the helm: Nor, in many cases, can such an adjustment be made at all, without taking into view indirect and remote considerations, which will rarely prevail over the immediate interest which one party may find in disregarding the rights of another, or the good of the whole.

The inference to which we are brought, is, that the causes of faction cannot be removed; and that relief is only to be sought in the means of controlling its effects .

If a faction consists of less than a majority, relief is supplied by the republican principle, which enables the majority to defeat its sinister views by regular vote: It may clog the administration, it may convulse the society; but it will be unable to execute and mask its violence under the forms of the constitution. When a majority is included in a faction, the form of popular government on the other hand enables it to sacrifice to its ruling passion or interest, both the public good and the rights of other citizens. To secure the public good, and private rights against the danger of such a faction, and at the same time to preserve the spirit and the form of popular government, is then the great object to which our enquiries are directed. Let me add that it is the great desideratum, by which alone this form of government can be rescued from the opprobrium under which it has so long labored, and be recommended to the esteem and adoption of mankind.

By what means is this object attainable? Evidently by one of two only. Either the existence of the same passion or interest in a majority at the same time, must be prevented; or the majority, having such co-existent passion or interest, must be rendered, by their number and local situation, unable to concert and carry into effect schemes of oppression. If the impulse and the opportunity be suffered to coincide, we well know that neither moral nor religious motives can be relied on as an adequate control. They are not found to be such on the injustice and violence of individuals, and lose their efficacy in proportion to the number combined together; that is, in proportion as their efficacy becomes needful. 2

From this view of the subject, it may be concluded that a pure democracy, by which I mean a society, consisting of a small number of citizens, who assemble and administer the government in person, can admit of no cure for the mischiefs of faction. A common passion or interest will, in almost every case, be felt by a majority of the whole; a communication and concert results from the form of government itself; and there is nothing to check the inducements to sacrifice the weaker party, or an obnoxious individual. Hence it is, that such democracies have ever been spectacles of turbulence and contention; have ever been found incompatible with personal security, or the rights of property; and have in general been as short in their lives, as they have been violent in their deaths. Theoretic politicians, who have patronized this species of government, have erroneously supposed, that by reducing mankind to a perfect equality in their political rights, they would, at the same time, be perfectly equalized, and assimilated in their possessions, their opinions, and their passions.

A republic, by which I mean a government in which the scheme of representation takes place, opens a different prospect, and promises the cure for which we are seeking. Let us examine the points in which it varies from pure democracy, and we shall comprehend both the nature of the cure, and the efficacy which it must derive from the union.

The two great points of difference between a democracy and a republic, are first, the delegation of the government, in the latter, to a small number of citizens elected by the rest; secondly, the greater number of citizens, and greater sphere of country, over which the latter may be extended.

The effect of the first difference is, on the one hand, to refine and enlarge the public views, by passing them through the medium of a chosen body of citizens, whose wisdom may best discern the true interest of their country, and whose patriotism and love of justice, will be least likely to sacrifice it to temporary or partial considerations. Under such a regulation, it may well happen that the public voice pronounced by the representatives of the people, will be more consonant to the public good, than if pronounced by the people themselves convened for the purpose. On the other hand, the effect may be inverted. Men of factious tempers, of local prejudices, or of sinister designs, may by intrigue, by corruption, or by other means, first obtain the suffrages, and then betray the interests of the people. The question resulting is, whether small or extensive republics are most favourable to the election of proper guardians of the public weal; and it is clearly decided in favour of the latter by two obvious considerations.

In the first place it is to be remarked, that however small the republic may be, the representatives must be raised to a certain number, in order to guard against the cabals of a few; and that however large it may be, they must be limited to a certain number, in order to guard against the confusion of a multitude. Hence the number of representatives in the two cases not being in proportion to that of the constituents, and being proportionally greatest in the small republic, it follows, that if the proportion of fit characters be not less in the large than in the small republic, the former will present a greater option, and consequently a greater probability of a fit choice.

In the next place, as each representative will be chosen by a greater number of citizens in the large than in the small republic, it will be more difficult for unworthy candidates to practise with success the vicious arts, by which elections are too often carried; and the suffrages of the people being more free, will be more likely to centre on men who possess the most attractive merit, and the most diffusive and established characters.

It must be confessed, that in this, as in most other cases, there is a mean, on both sides of which inconveniencies will be found to lie. By enlarging too much the number of electors, you render the representative too little acquainted with all their local circumstances and lesser interests; as by reducing it too much, you render him unduly attached to these, and too little fit to comprehend and pursue great and national objects. The federal constitution forms a happy combination in this respect; the great and aggregate interests being referred to the national, the local and particular to the state legislatures.

The other point of difference is, the greater number of citizens and extent of territory which may be brought within the compass of republican, than of democratic government; and it is this circumstance principally which renders factious combinations less to be dreaded in the former, than in the latter. The smaller the society, the fewer probably will be the distinct parties and interests composing it; the fewer the distinct parties and interests, the more frequently will a majority be found of the same party; and the smaller the number of individuals composing a majority, and the smaller the compass within which they are placed, the more easily will they concert and execute their plans of oppression. Extend the sphere, and you take in a greater variety of parties and interests; you make it less probable that a majority of the whole will have a common motive to invade the rights of other citizens; or if such a common motive exists, it will be more difficult for all who feel it to discover their own strength, and to act in unison with each other. Besides other impediments, it may be remarked, that where there is a consciousness of unjust or dishonourable purposes, communication is always checked by distrust, in proportion to the number whose concurrence is necessary.

Hence it clearly appears, that the same advantage, which a republic has over a democracy, in controlling the effects of faction, is enjoyed by a large over a small republic—is enjoyed by the union over the states composing it. Does this advantage consist in the substitution of representatives, whose enlightened views and virtuous sentiments render them superior to local prejudices, and to schemes of injustice? It will not be denied, that the representation of the union will be most likely to possess these requisite endowments. Does it consist in the greater security afforded by a greater variety of parties, against the event of any one party being able to outnumber and oppress the rest? In an equal degree does the encreased variety of parties, comprised within the union, encrease this security. Does it, in fine, consist in the greater obstacles opposed to the concert and accomplishment of the secret wishes of an unjust and interested majority? Here, again, the extent of the union gives it the most palpable advantage.

The influence of factious leaders may kindle a flame within their particular states, but will be unable to spread a general conflagration through the other states: A religious sect, may degenerate into a political faction in a part of the confederacy; but the variety of sects dispersed over the entire face of it, must secure the national councils against any danger from that source: A rage for paper money, for an abolition of debts, for an equal division of property, or for any other improper or wicked project, will be less apt to pervade the whole body of the union, than a particular member of it; in the same proportion as such a malady is more likely to taint a particular county or district, than an entire state. 3

In the extent and proper structure of the union, therefore, we behold a republican remedy for the diseases most incident to republican government. And according to the degree of pleasure and pride, we feel in being republicans, ought to be our zeal in cherishing the spirit, and supporting the character of federalists.

McLean description begins The Federalist, A Collection of Essays, written in favour of the New Constitution, By a Citizen of New-York. Printed by J. and A. McLean (New York, 1788). description ends , I, 52–61.

1 . Douglass Adair showed chat in preparing this essay, especially that part containing the analysis of factions and the theory of the extended republic, JM creatively adapted the ideas of David Hume (“‘That Politics May Be Reduced to a Science’: David Hume, James Madison, and the Tenth Federalist,” Huntington Library Quarterly , XX [1956–57], 343–60). The forerunner of The Federalist No. 10 may be found in JM’s Vices of the Political System ( PJM description begins William T. Hutchinson et al., eds., The Papers of James Madison (10 vols. to date; Chicago, 1962——). description ends , IX, 348–57 ). See also JM’s first speech of 6 June and his first speech of 26 June 1787 at the Federal Convention, and his letter to Jefferson of 24 Oct. 1787 .

2 . In Vices of the Political System JM listed three motives, each of which he believed was insufficient to prevent individuals or factions from oppressing each other: (1) “a prudent regard to their own good as involved in the general and permanent good of the Community”; (2) “respect for character”; and (3) religion. As to “respect for character,” JM remarked that “in a multitude its efficacy is diminished in proportion to the number which is to share the praise or the blame” ( PJM description begins William T. Hutchinson et al., eds., The Papers of James Madison (10 vols. to date; Chicago, 1962——). description ends , IX, 355–56 ). For this observation JM again drew upon David Hume. Adair suggests that JM deliberately omitted his list of motives from The Federalist . “There was a certain disadvantage in making derogatory remarks to a majority that must be persuaded to adopt your arguments” (“‘That Politics May Be Reduced to a Science,’” Huntington Library Quarterly , XX [1956–57], 354). JM repeated these motives in his first speech of 6 June 1787, in his letter to Jefferson of 24 Oct. 1787 , and alluded to them in The Federalist No. 51 .

3 . The negative on state laws, which JM had unsuccessfully advocated at the Federal Convention, was designed to prevent the enactment of “improper or wicked” measures by the states. The Constitution did include specific prohibitions on the state legislatures, but JM dismissed these as “short of the mark.” He also doubted that the judicial system would effectively “keep the States within their proper limits” ( JM to Jefferson, 24 Oct. 1787 ).

Index Entries

You are looking at.

Explore the Constitution

- The Constitution

- Read the Full Text

Dive Deeper

Constitution 101 course.

- The Drafting Table

- Supreme Court Cases Library

- Founders' Library

- Constitutional Rights: Origins & Travels

Start your constitutional learning journey

- News & Debate Overview

- Constitution Daily Blog

- America's Town Hall Programs

- Special Projects

Media Library

America’s Town Hall

Watch videos of recent programs.

- Education Overview

Constitution 101 Curriculum

- Classroom Resources by Topic

- Classroom Resources Library

- Live Online Events

- Professional Learning Opportunities

- Constitution Day Resources

Explore our new 15-unit high school curriculum.

- Explore the Museum

- Plan Your Visit

- Exhibits & Programs

- Field Trips & Group Visits

- Host Your Event

- Buy Tickets

New exhibit

The first amendment, we the people, james madison, ratification, and the federalist papers.

September 16, 2021

September 17 is Constitution Day—the anniversary of the framers signing the Constitution in 1787. This week’s episode dives into what happened after the Constitution was signed—when it had to be approved by “we the people,” a process known as ratification—and the arguments made on behalf of the Constitution. A major collection of those arguments came in the form of a series of essays, today often referred to as The Federalist Papers, which were written by Alexander Hamilton, James Madison, and John Jay using the pen name Publius and published initially in newspapers in New York. Guests Judge Gregory Maggs, author of the article “A Concise Guide to The Federalist Papers as a Source of the Original Meaning of the United States Constitution,” and Colleen Sheehan, professor and co-editor of The Cambridge Companion to The Federalist, shed light on the questions: What do The Federalist Papers say? What did their writers set out to achieve by writing them? How do they explain the ideas behind the Constitution’s structure and design—and where did those ideas come from? And why is it important to read The Federalist Papers today?

FULL PODCAST

This episode was produced by Jackie McDermott and engineered by Kevin Kilbourne. Research was provided by Sam Desai, John Guerra, and Lana Ulrich.

PARTICIPANTS

Colleen Sheehan is the Director of Graduate Studies at the Arizona State School of Civic and Economic Thought and Leadership. She is author of numerous books, including several on James Madison, and she co-edited The Cambridge Companion to The Federalist .

Judge Gregory E. Maggs is a judge on the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Armed Forces. He was a member of the full-time faculty at GW Law School from 1993 to 2018. He is the author of numerous works including the article “A Concise Guide to The Federalist Papers as a Source of the Original Meaning of the United States Constitution.”

Jeffrey Rosen is the president and CEO of the National Constitution Center, a nonpartisan nonprofit organization devoted to educating the public about the U.S. Constitution. Rosen is also professor of law at The George Washington University Law School and a contributing editor of The Atlantic .

Stay Connected and Learn More

Questions or comments about the show? Email us at [email protected] .

Continue today’s conversation on Facebook and Twitter using @ConstitutionCtr .

Sign up to receive Constitution Weekly, our email roundup of constitutional news and debate, at bit.ly/constitutionweekly .

Please subscribe to We the People and L ive at the National Constitution Center on Apple Podcasts , Stitcher , or your favorite podcast app.

This transcript may not be in its final form, accuracy may vary, and it may be updated or revised in the future.