Resetting the relationship between local and national government. Read our Local Government White Paper

Tackling anti-social behaviour: case studies

A series of council case studies on anti-social behaviour.

Foreword by Councillor Nesil Caliskan, Chair of the LGA’s Safer and Stronger Communities Board

Left untackled we know that anti-social behaviour (ASB) can have a devastating impact on communities and individuals. Many ASB offences are serious issues for local residents and businesses, and councils are keen to protect them from offenders who can make the lives of those they target a misery.

When we use the term “anti-social behaviour”, we are referring to behaviour which involves “acting in a manner that causes or is likely to cause harassment, alarm or distress to one or more persons not of the same household”.

We sometimes hear ASB referred to as ‘low-level’ crime, but this dismisses the cumulative impact that anti-social behaviour can have on its victims. As Baroness Newlove, the former Victims Commissioner for England and Wales, highlights in her report “ Anti-Social Behaviour: Living a Nightmare”.

ASB is often downplayed as a petty, ‘low-level’ crime. But put yourself in their shoes – to suffer from ASB is an ordeal that causes misery, disturbs sleep, anxiety, work and relationships – leaving victims feeling unsafe and afraid in their own homes. It can feel like you are living a nightmare.

During the COVID-19 pandemic, the National Police Chiefs’ Council identified an increase in reports of anti-social behaviour, particularly during the lockdown period. In part, they found this could be attributed to noise nuisance and neighbour disputes, as well as wider perceptions of households flouting the social-distancing rules.

Over time, there will need to be a full asessment as to why there has been an increase in ASB referrals during the pandemic and whether this trend continues post-lockdown. What remains clear is that anti-social behaviour continues to be prevalent in our local communities, and all partners need to take action to help prevent and tackle this type of behaviour.

The Anti-social Behaviour, Crime and Policing Act 2014 seeks to place victims at the heart of local responses to anti-social behaviour. Through the introduction of ASB case reviews (known as the ‘Community Trigger’), the Act provides a mechanism to help ASB victims. The Community Trigger also offers an opportunity to review those responses where problems continue, to make sure councils, the police and their partners have done all they can to intervene and take further action where needed.

We have pulled together a series of case studies to highlight some examples of best practice across local government. The case studies highlight how councils have been working in partnership to deliver support for ASB victims and tackle perpetrator’s behaviour.

We also wanted to highlight areas that have taken the ASB Help Pledge , which demonstrates a commitment to improving awareness of the Community Trigger process and using the Community Trigger to put victims first and deter perpetrators. (Further information on the Community Trigger is included within this case studies document, available on this Gov.UK webpage , or included within the Government’s statutory guidance .)

We would like to thank all the councils and their partners who shared their experiences and examples of best practice. We would also like to thank ASB Help, who continue to provide support to councils on taking the ASB Help Pledge.

I hope you find these case studies useful.

North Tyneside Council: working with young people to improve their life chances

Sheffield Council: neighbourhood officers helping to reduce ASB for council housing tenants

Copeland Council: a multi-agency local focus hub to tackle ASB and low-level crime

Lincolnshire Council: sharing information to improve consistency in practice across the county

Portsmouth Council: pandemic response creates opportunities to address homelessness-related ASB

Surrey Council: mediation, coaching and support for victims of anti-social behaviour

Richmondshire Council: preventing anti-social behaviour at Richmond beauty spots

Plymouth Council: community-led action to reduce crime and ASB in North Stonehouse

Derbyshire Council: a consistent approach to the Community Trigger across 10 councils

Sandwell Council: reviewing the Community Trigger process to strengthen support for victims

Community Trigger – explanatory note

The Home Office statutory guidance outlines the following information on the Community Trigger process: Purpose: To give victims and communities the right to request a review of their case where a local threshold is met, and to bring agencies together to take a joined up, problem-solving approach to find a solution for the victim. Relevant bodies and responsible authorities: Councils; Police; Clinical Commissioning Groups in England and Local Health Boards in Wales; and Registered providers of social housing who are co-opted into this group. Threshold: To be defined by the local agencies, but not more than three complaints in the previous six-month period. May also take account of: - the persistence of the anti-social behaviour; - the harm or potential harm caused by the anti-social behaviour; - the adequacy of response to the anti-social behaviour. The relevant bodies (listed above) must publish details of the procedure to ensure that victims are aware that they can apply in appropriate circumstances. Details: When an ASB Case Review is requested, the relevant bodies must decide whether the threshold has been met and communicate this to the victim. If the threshold is met: - a case review will be undertaken by the relevant bodies. They will share information related to the case, review what action has previously been taken and decide whether additional actions are possible. The local ASB Case Review procedure should clearly state the timescales in which the review will be undertaken; - the review will see the relevant bodies adopting a problem-solving approach to ensure that all the drivers and causes of the behaviour are identified and a solution sought, whilst ensuring that the victim receives appropriate support; - the victim is informed of the outcome of the review. Where further actions are necessary an action plan will be discussed with the victim, including timescales. If the threshold is not met: - although the formal procedures will not be invoked, this does provide an opportunity for the relevant bodies to review the case to determine whether there is more that can be done. Agencies have a duty to publish specified data on the Community Trigger at least every twelve months. Who can use the ASB Case Review/Community Trigger procedure: A victim of anti-social behaviour or another person acting on behalf of the victim with his or her consent, such as a carer or family member, Member of Parliament, local councillor or other professional. The victim may be an individual, a business or a community group.

Further information and resources

- Home Office ASB 2014 Act statutory guidance and updated webpage on the community trigger (updated January 2021)

- ACC Andy Prophet’s presentation on ASB statistics (September 2020)

- LGA guidance on the Anti-Social Behaviour, Crime and Policing Act 2014 and Implementing the Community Trigger and LGA guidance on Public Spaces Protection Orders (PSPOs).

- Dame Vera Baird’s presentation to the LGA’s Safer and Stronger Communities Board.

- Local government practitioner, Daryl Edmunds presentation on how councils can make use of ASB tools

If you would like to get in touch about the case studies or discuss this policy issue in further detail, please contact [email protected]

With thanks to Rachel Potter, who the LGA commissioned to write this report.

Responding to anti-social behaviour: Analysis, interventions and the transfer of knowledge

- Original Article

- Published: 21 January 2011

- Volume 13 , pages 1–15, ( 2011 )

Cite this article

- Karen Bullock 1

440 Accesses

3 Citations

Explore all metrics

This article examines contemporary responses to anti-social behaviour (ASB) in England and Wales. Drawing on empirical evidence, it examines how ASB problems are understood and prioritised by practitioners; the nature of the interventions developed and implemented to address problems; and the ways in which outcomes are evaluated. The article points to how systematic analysis of ASB problems is unusual and responses are usually reactive; there has been a focus on enforcement interventions rather than on the development of broader solutions to problems; and evaluation of outcomes is weak. These findings are discussed in relation to the development of the ASB agenda in England and Wales. Implications for solving problems are discussed.

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this article

Price includes VAT (Russian Federation)

Instant access to the full article PDF.

Rent this article via DeepDyve

Institutional subscriptions

Similar content being viewed by others

The Role of Response-Based Practice in Activism

The Complexities, Contradictions and Consequences of Being ‘Anti-social’ in Northern Ireland

African Perspectives on Peaceful Social Protests

The Home Office Anti-Social Behaviour Unit (ASBU) was set up in January 2003 to set develop ASB policy, powers and interventions as well as to support local delivery. In 2004 the ‘Together’ campaign was launched followed by the ‘Respect’ campaign ( Jacobson et al, 2005 ).

Relevant legislation since 1997 includes: Crime and Disorder Act (1998); The Police Reform Act (2002); Anti-Social Behaviour Act (2003); Clean Neighbourhoods and Environment Act (2005); Organised Crime and Police Act (2005); Emergency Workers Obstruction Act (2006); Police and Justice Act (2006); Violent Crime Reduction Act (2006); Housing and Regeneration Act (2008); Criminal Justice and Immigration Act (2008), as well as procedural and rule changes.

Available at http://webarchive.nationalarchives.gov.uk/20100405140447/ , http://asb.homeoffice.gov.uk/members/article.aspx?id=75248482 (24 March 2010).

Occasionally 47 are referred to, as one large project was split into two to aid some analysis.

Available at http://webarchive.nationalarchives.gov.uk/20100405140447/asb.homeoffice.gov.uk/members/case-studies/default.aspx?id=8482 (20 May 2010).

Although this information has been coded, quantified and classified for the purposes of presentation, the findings should be seen as indicative. Coding is not a precise science, the information available was sometimes limited and the categories used are not always mutually exclusive.

Available at http://webarchive.nationalarchives.gov.uk/20100405140447/ , http://asb.homeoffice.gov.uk/members/case-studies/article.aspx?id=8722 (20 May 2010).

Of course the issue of housing tenure was not always relevant to the problem and the response/s. In addition, the housing status of the perpetrator may not have been noted in the case study.

Available at http://webarchive.nationalarchives.gov.uk/20100405140447/ , http://asb.homeoffice.gov.uk/members/case-studies/article.aspx?id=11896 (20 May 2010).

The ‘one’ actually claimed that it was too soon to tell whether it had been successful rather than it had been unsuccessful.

Indeed, the Labour governments made available extensive Web-based guidance for practitioners in tackling ASB (follow the link at note 13). It is revealing that practically nothing has been made available about data, analysis or evaluation.

See http://webarchive.nationalarchives.gov.uk/20100405140447/asb.homeoffice.gov.uk/members/article.aspx?id=7536 (20 May 2010).

www.audit-commission.gov.uk/localgov/audit/nis/pages/default.aspx (10 May 2010).

Following the BCS, this asks respondents to rate the extent to which the following are a problem: noisy neighbours or loud parties, teenagers hanging around the streets, rubbish or litter lying around, vandalism, graffiti and other deliberate damage to property or vehicles, people using or dealing drugs, people being drunk or rowdy in public places, abandoned or burntout cars.

See Hodgkinson and Tilley (2007) and Millie (2009) for some examples of situational approaches to tackling ASB.

See http://webarchive.nationalarchives.gov.uk/20100405140447/asb.homeoffice.gov.uk/members/article.aspx?id=7534 (20 May 2010).

There are many other dimensions to transferring knowledge in the crime reduction field detailed consideration of which are beyond the scope of this article (see Bullock and Ekblom, 2010 ; Ekblom, 2011 ).

www.homeoffice.gov.uk/media-centre/speeches/beyond-the-asbo (3 August 2010).

See http://cfnp.npia.police.uk/8482 (24 March 2010).

Armitage, R. (2002) Tackling Anti-social Behaviour: What Really Works. London: Nacro, http://www.nacro.org.uk/data/files/nacro-2004120296-497.pdf , accessed 25 March 2010.

Google Scholar

Ashworth, A., Gardner, J., Morgan, R., Smith, A.T.H., von Hirsch, A. and Wasik, M. (1998) Neighbouring on the oppressive: The government's ‘anti-social behaviour order' proposals. Criminal Justice 16 (1): 7–14.

Begum, B., Johnson, S. and Ekblom, P. (2009) Anti-Social Behaviour: A Practitioners Guide. London: University College London.

Brown, A. (2004) Anti-social behaviour, crime control and social control. The Howard Journal 43 (2): 203–211.

Article Google Scholar

Burney, E. (2005) Making People Behave: Anti-social Behaviour, Politics and Policy. Cullompton, UK: Willan.

Burney, E. (2009) Respect and the politics of behaviour. In: A. Millie (ed.) Securing Respect: Behavioural Expectations and Anti-Social Behaviour in the UK. Bristol, UK: The Policy Press.

Bullock, K. (2010) Improving accessibility and accountability – Neighbourhood policing and the policing pledge. Safer Communities: International Journal of Community Safety 9 (1): 10–19.

Bullock, K. and Ekblom, P. (2010) Richness retrievability and reliability – Issues in a working knowledge base for good practice in crime prevention. European Journal on Criminal Policy and Research 1 (16): 29–47.

Bullock, K., Erol, R. and Tilley, N. (2006) Problem-Oriented Policing and Partnerships. Cullompton, UK: Willan.

Campbell, C. (2002) A Review of Anti-Social Behaviour Orders. London: Home Office. Home Office Research Study 236, http://www.homeoffice.gov.uk/rds/pdfs2/hors236.pdf , accessed 20 May 2010.

Casey, R. and Flint, J. (2007) Active citizenship in the governance of anti-social behaviour in the UK: Exploring the non-reporting of incidents. People, Place & Policy Online 1 (2): 69–79.

Cooper, C., Brown, G., Powell, H. and Sapsed, E. (2009) Exploration of Local Variations in the Use of Anti-social Behaviour Tools and Powers. London: Home Office. Home Office Research Report 21, http://www.homeoffice.gov.uk/rds/pdfs09/horr21c.pdf , accessed 20 May 2010.

Department for Children Schools Families (DCSF). (2008) Youth Task Force Action Plan. London: Department for Children, Schools and Families, http://www.dcsf.gov.uk/everychildmatters/Youth/youthmatters/youthtaskforce/actionplan/actionplan/ , accessed 2 April 2010.

Ekblom, P. (2011) Crime Prevention, Security and Community Safety using the 5Is Framework. Basingstoke, UK: Palgrave Macmillan, (in press).

Book Google Scholar

Flatley, J., Moley, J. and Hoare, J (2008) Perceptions of Anti-social Behaviour – Findings from the 2007/08 British Crime Survey. London: Home Office. Home Office Statistical Bulletin 15/08, http://www.homeoffice.gov.uk/rds/pdfs08/hosb1508.pdf , accessed 20 May 2010.

Harradine, S., Kodz, J., Lemetti, F. and Jones, B. (2004) Defining and Measuring Antisocial Behaviour. London: Home Office. Home Office Development and Practice Report 26, http://www.homeoffice.gov.uk/rds/pdfs04/dpr26.pdf , accessed 20 May 2010.

Hodgkinson, S. and Tilley, N. (2007) Policing anti-social behaviour: Constraints, dilemmas and opportunities. The Howard Journal 46 (4): 385–400.

Holt, A. (2009) Parent abuse: Some reflections on the adequacy of a youth justice response. Internet Journal of Criminology, http://www.internetjournalofcriminology.com/ , accessed 20 May 2010.

House of Commons. (2007) House of Commons Committee of Public Accounts: Tackling Anti–Social Behaviour Forty-fourth Report of Session 2006–2007. London: The Stationary Office, http://www.parliament.the-stationeryoffice.co.uk/pa/cm200607/cmselect/cmpubacc/246/246.pdf, accessed 20 May 2010.

Jacobson, J., Millie, A. and Hough, M. (2005) Tackling Anti-Social Behaviour: A Critical Review (ICPR Research Paper 2). London: Institute for Criminal Policy Research, King's College London. hdl.handle.net/234/3791, accessed 24 March 2010.

Knutsson, J. (2009) Standard of evaluations in problem-oriented policing projects: Good enough? In: J. Knutsson and N. Tilley (eds.) Evaluating Crime Reduction Initiatives, Crime Prevention Studies, Vol. 24. Monsey, NY: Criminal Justice Press.

Local Government Ombudsman (LGO). (2005) Special Report: Neighbour Nuisance and Anti-social Behaviour. London: LGO, http://www.lgo.org.uk/publications/special-reports/ , accessed 20 May 2010.

Mackenzie, S., Bannister, J., Flint, P., Parr, S., Millie, D. and Fleetwood, J. (2010) The Drivers of Perceptions of Anti-Social Behaviour. London: Home Office. Research Report 34, http://rds.homeoffice.gov.uk/rds/pdfs10/horr34c.pdf .

Millie, A. (2006) Anti-social behaviour: Concerns of minority and marginalised londoners. Internet Journal of Criminology, http://www.internetjournalofcriminology.com , accessed 20 May 2010.

Millie, A. (2009) Anti-social Behaviour. Maidenhead, UK: Open University Press.

Millie, A., Jacobson, J., Hough, M. and Paraskevopoulou, A. (2005) Anti-social Behaviour in London: Setting the Context for the London Anti-Social Behaviour Strategy July 2005. London: Greater London Authority, tps://dspace.lboro.ac.uk/dspace-jspui/handle/2134/95 , accessed 20 May 2010.

Moon, D., Walker, A., Murphy, R., Flatley, J., Parfrement-Hopkins, J. and Hall, P. (2009) Perceptions of crime and anti-social behaviour: Findings from the 2008/09 British crime survey. Supplementary Vol. 1 to Crime in England and Wales 2008/09. Home Office Statistical Bulletin 17/9. London: Home Office, http://rds.homeoffice.gov.uk/rds/pdfs09/hosb1709.pdf , accessed 20 May 2010.

National Audit Office (NAO). (2006) Tackling Anti-social Behaviour. London: The Stationery Office. Report by the Comptroller and Auditor General, HC 99 session 2006–2007, http://www.official-documents.gov.uk/document/hc0607/hc00/0099/0099.pdf , accessed 20 May 2010.

Nixon, J. and Hunter, C. (2009) Disciplining women: Anti-social behaviour and the governance of conduct. In: A. Millie (ed.) Securing Respect: Behavioural Expectations and Anti-social Behaviour in the UK. Bristol, UK: The Policy Press.

Prior, D. (2009) The ‘problem’ of anti-social behaviour and the policy knowledge base: Analysing the power/knowledge relationship. Critical Social Policy 29 (1): 5–23.

Read, T. and Tilley, N. (2000) Not Rocket Science? Problem-solving and Crime Reduction. London: Home Office. Crime Reduction Research Series Paper 6, http://rds.homeoffice.gov.uk/rds/prgpdfs/crrs06.pdf , accessed 1 June 2010.

Respect. (2006) Respect Action Plan. London: Respect, http://webarchive.nationalarchives.gov.uk/20100405140447/http://asb.homeoffice.gov.uk/uploadedFiles/Members_site/Articles/About_Respect/respect_action_plan.pdf , accessed 20 May 2010.

Squires, P. (2006) New labour and the politics of antisocial behaviour. Critical Social Policy 26 (1): 144–168.

Squires, P. and Stephen, D. (2005) Rethinking ASBOs. Critical Social Policy 25 (4): 517–528.

Youth Taskforce. (2008) Youth Taskforce Action Plan. London: Department for Children, Schools and Families, http://www.dcsf.gov.uk/everychildmatters/Youth/youthmatters/youthtaskforce/actionplan/actionplan/ , accessed 20 May 2010.

Download references

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Department of Sociology, University of Surrey, Guildford, GU2 7XH, UK

Karen Bullock

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Bullock, K. Responding to anti-social behaviour: Analysis, interventions and the transfer of knowledge. Crime Prev Community Saf 13 , 1–15 (2011). https://doi.org/10.1057/cpcs.2010.19

Download citation

Published : 21 January 2011

Issue Date : 01 February 2011

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1057/cpcs.2010.19

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- anti-social behaviour

- enforcement

- transfer of knowledge

- Find a journal

- Publish with us

- Track your research

Geopolitics & Security

Rebuilding Communities: Why It’s Time to Put Anti-Social Behaviour Back on the Agenda

Paper 26th April 2022

Harvey Redgrave

Anti-social behaviour is often written off as a “low-level” nuisance and therefore considered less deserving of political attention than other types of criminality.

This is a mistake. The way to think about anti-social behaviour is not as a series of isolated incidents but as a pattern of behaviour that is almost always repetitive and oppressive, often directed at victims who are vulnerable and live in more deprived areas, and is often a prediction of more serious offending later down the line.

That is why I have always believed that a proper policy response to anti-social behaviour is fundamentally a question of social justice: it is about trying to rebalance the system so that it protects those who are least likely to be equipped with the resources to deal with it themselves.

Our approach in government was informed by a profound but simple insight: that our criminal justice system, which has evolved around the principle of protecting the rights of the accused, is woefully ill equipped for dealing with anti-social behaviour.

Of course, many of the behaviours we wanted to stamp out – aggressive drunkenness, drug-dealing and vandalism – were and have long been criminal offences. In theory, each case can be dealt with by the criminal-law process: the police bring a charge, the CPS prosecutes and the court passes a sentence.

But as anyone who works in this area knows, that isn’t what happens in practice. In the real world, so-called low-level crimes are never prosecuted because the sheer weight of process required to secure a conviction means it is just not worth the police hours and resources.

That is why we expended so much capital on dealing with the issue: equipping local agencies with new enforcement powers; ensuring intensive support was available to the most troubled and chaotic families; and, most importantly, guaranteeing that every community would have access to a neighbourhood policing team.

Harvey’s paper details how, during the past decade, much of the architecture that had been established has since been progressively diluted, with powers weakened and visible local policing scaled back. In addition, incidents of anti-social behaviour appear to have been recategorised as public-order offences, further diminishing their significance.

Do not misunderstand me: this is not about going back to the past. What was right for then won’t necessarily be right for today. Problems evolve and so must the policy response.

But what this paper illustrates is a fundamental lack of direction at the top of government. What are the principles that guide this government’s approach to anti-social behaviour? What are the signature policies? It is fine to argue that anti-social behaviour is a local issue but without a push from the centre, there isn’t enough pressure in the system and you end up with drift.

The impact is well documented here: a stark decline in public confidence in the police and the shocking finding that only a quarter of people who experience anti-social behaviour say they have bothered to report it. Our system relies on the consent and cooperation of victims and witnesses. Once they lose faith in it, the entire system risks grinding to a halt.

All of this speaks to what I perceive to be a bigger issue: a decline in law and order, which is seriously damaging our country. Unless people are able to live free of fear, the very possibility of life in a community is undermined. If there is a sense the social norms that bind us together are fraying – that rights have been divorced from obligations – and, worse, that the government is indifferent, this is when despair and bitterness set in.

In time, I hope our paper will provide something of a turning point in the debate about anti-social behaviour and local policing.

Executive Chairman

Having previously been confined to academic debates within criminology, [_] the issue of anti-social behaviour (ASB) was thrust into the political limelight during the 1990s, partly in response to fears that the traditional mechanisms for dealing with such behaviour – family, religion and community – had been weakened.

In the UK, anti-social behaviour was defined in statute in 1998 as behaviour that was “likely to cause harassment, alarm or distress”. To date, no legislation has attempted to break down this broad definition or provide a list of specific behaviours. However, in practice the definition covers a wide range of actions from the dropping of litter on a street to the running of crack-houses.

Strong and secure communities are the essential foundation from which individual potential is realised, quality of life is maximised and other social and economic wellbeing is secured. What makes a strong community isn’t complicated: decent public services, welcoming physical environments and - perhaps most significantly – safety and the ability to live free from fear. Sadly, in too many parts of Britain today, there is a sense that these things have been eroded and undermined.

If this government has a single defining mission, it is to “level up” areas of the country that have previously been left behind. Of course, that is partly about economic reforms necessary for jobs and prosperity but, equally important, are improvements to public services, the public realm and action to tackle ASB and disorder, not least through visible and responsive local policing.

ASB has often been dismissed as “low-level crime”’ and thus less deserving of national policy attention. This is fundamentally mistaken. ASB is often experienced less as a series of isolated incidents and more as a pattern of repetitive behaviour that intensifies over time, causing misery and distress to its victims and the wider community. If left unchecked, it can spiral and turn into more serious crime. In short, a serious policy response to its manifestation would seem critical to any government seriously committed to levelling up areas of the country previously left behind.

Yet, for most of this decade, ASB has been all but ignored by this government, having fallen victim to the fallacy that since it is a “local issue”, it can be entirely delegated to local agencies and that central government has no role to play in tackling it. To make matters worse, neighbourhood policing has been quietly eroded. While many forces continue to deliver some version of neighbourhood policing, its level of resourcing, form and function look very different depending on where you happen to live. This has left the public confused about what they can expect from their local policing service.

We know that one of the issues most central to people’s sense of belonging and pride in the place in which they live is whether or not they feel safe from ASB and crime, and, relatedly, whether they feel able to call upon a strong local-policing presence. This paper sets out a route map for achieving this.

Key Findings

ASB remains an issue of huge public concern. New polling undertaken for this paper has found that a third of people surveyed (32 per cent) think ASB is a big problem where they live.

Despite making “levelling up” its defining mission, this government has been largely silent on ASB.

Its primary contribution was a single white paper entitled “Putting victims first” in 2012, which, if anything, diluted available enforcement powers while establishing a “community trigger” – a tool that few have heard of, let alone used.

At the same time, neighbourhood policing has been allowed to fall into decline, which appears to have dented public confidence. There is a clear correlation between people’s confidence in the police and the decline in visible neighbourhood policing.

Our polling also indicates that the majority of the surveyed public are not confident in how the police and local authorities respond to matters of ASB. Of those who experienced or witnessed ASB in the past year, only 26 per cent said they reported it and only 41 per cent were satisfied with the response they received.

When asked to choose which aspects of local policing matter most to them, the public clearly prioritise responsiveness and accessibility: the top priority is 999 calls being answered, followed by officers that are “approachable and friendly” and a “definite response to all reports of crime and ASB”.

Recommendations

The government should consult on a new local-policing contract, which sets out minimum levels of expectation on visibility, accessibility and responsiveness.

The Home Office should ensure that the police-officer-uplift programme is used to guarantee a minimum level of neighbourhood policing (measured as a proportion of the total workforce), designed around the principles outlined above.

A new white paper setting out a national framework for ASB response is needed. The Home Office should also commission an independent body to undertake a review of the effectiveness of the interventions and powers introduced in 2014, and consult with police officers and local-authority practitioners on the use of existing enforcement powers.

The government should publish guidance making clear that the following circumstances will trigger some kind of parenting or family-based intervention: children excluded from school, persistent truancy, a child found behaving anti-socially or committing crime, and parents themselves involved in drugs or crime.

Anti-social behaviour (ASB) was defined in 1998 as one that “caused or was likely to cause harassment, alarm or distress” although no legislation since has attempted to break down this definition any further. The Crime Survey for England and Wales (CSEW) measures people’s perceptions of levels of anti-social behaviour in their local area according to the following seven strands.

Teenagers hanging around on the streets.

Rubbish or litter lying around.

People using or dealing drugs.

Vandalism, graffiti and other deliberate damage to property.

People being drunk or rowdy in public places.

Noisy neighbours or loud parties.

Abandoned or burnt-out cars.

Local authorities too have adopted their own definitions of ASB, and these were often drawn up by Crime and Disorder Reduction Partnerships (CDRPs) set up after the Crime and Disorder Act 1998. Other examples of ASB include prostitution, hate crime, aggressive begging and illegal street trading.

Where Criminality and Anti-Social Behaviour Meet

ASB occupies the space where criminal and civil law overlap. The legal definition uses concepts from both. Much of what we consider to be anti-social could be covered by criminal law, but there are civil remedies too.

An array of criminal offences can apply to ASB: for example, graffiti can constitute criminal damage under section 1 of the Criminal Damage Act 1971 while being drunk and disorderly is an offence under section 91 of the Criminal Justice Act 1967. This has led some critics to argue that the concept of ASB is too broad and legally unnecessary.

However, criminal law can be a blunt tool. In practice, it has often been difficult to deal with low-level ASB through the courts either because the burden of proof cannot be reached or it is not in the public interest to do so. Therefore, civil and informal remedies are often more practical as a way to deal with the problem.

The Scale of the Problem

Evidence on ASB trends is mixed. The CSEW shows a marked decrease in people’s perceptions of ASB as a “very big” or “fairly big” problem over the past ten years. Overall, 7 per cent of people reported that ASB was a very big problem in 2019/2020 compared with 14 per cent in 2009/2010.

The percentage of people who say that ASB is a very big or fairly big problem has fallen since 2009/2010

Source: CSEW (year ending March 2020)

Similarly, the number of ASB incidents reported to the police has fallen over the past decade from 3.5 million incidents in 2009/2010 to 1.3 million incidents in 2019/2020.

These figures don’t tell the whole story, however. When asked about their direct experience of ASB, 40 per cent said they had experienced or witnessed such behaviour in their local area in 2019/2020. This was up from 27 per cent in 2014/2015.

Direct experiences of ASB have been on the rise in local areas since 2014/2015

Moreover, while reported incidents of ASB have fallen over the past decade, these figures should be treated with caution. Police officers report that many forces have reclassified ASB as public-order offences, with analysis revealing these offences have more than tripled since 2012/2013. As will be shown later in the paper, there is also evidence that a significant majority of the population do not report ASB at all.

Police-recorded public-order offences, which now incorporate some ASB, have more than tripled in England and Wales

Source: CSEW (year ending December 2020)

The Effects of the Pandemic

During the Covid-19 pandemic, reported incidents of ASB have increased significantly within England and Wales. In the year ending March 2021, the police recorded two million incidents, an increase of 48 per cent compared with the previous year. The largest increases correlated with some of the major lockdowns during both spring 2020 (for example, there was a 83 per cent rise in incidents between April and June 2020 compared with the same quarter in 2019) and January to March 2021. The Office for National Statistics (ONS) reported this was likely to “reflect the reporting of breaches to public-health restrictions”. [_]

Similarly, research undertaken by Crest Advisory and the Police Foundation about police demand during the pandemic found there was an increase in ASB incidents in comparison with other offences. During times outside the pandemic, ASB typically comprises between 8 and 9 per cent of all incident demand but it has increased to a peak of 17 per cent during the pandemic. [_] ASB spiked during the first lockdown and did not return to pre-pandemic levels until after March 2021, since when it has dipped. This is likely a reflection of the fact that most of us were restricted to our homes and therefore more likely to experience and witness such incidents.

Why It Matters

In recent years, ASB has received less focus as an issue of national political importance but there are several reasons why tackling it ought to be a priority for the government. First, minor crime and disorder are not only clear drivers of criminality and disorder but are also indicators of more serious, future crime, therefore affording an early opportunity to prevent it. Second, there is evidence that the level of ASB in a local area is one of the primary factors that determines people’s quality of life, wellbeing and sense of community. ASB, particularly when it is repeated during a prolonged period of time, can erode feelings of public safety and undermine community resilience. Third, ASB disproportionately affects the most vulnerable in society and so any effort to level up must take the issue seriously.

The Spreading of Disorder

Minor crime and ASB are drivers of additional crime and disorder. The consequences of this link for public policy are crucial because they show that intervening to reduce ASB is an opportunity to prevent more serious crime before it occurs. As far as back as 1982, social scientists James Q Wilson and George L Kelling theorised in their “Broken Windows” essay that if a window in a building is broken and left unrepaired, this will send “a signal that no one cares, and so breaking more windows costs nothing”. [_] They argued that unchecked minor crimes and signs of disorder would lead to more ASB and more serious crime and thus fixing small problems would avoid bigger problems occurring down the line.

A History of Broken Windows

The broken windows theory gained a number of prominent champions, including former Mayor of New York City Rudy Giuliani and former New York City Police Commissioner William Bratton. The latter’s “zero-tolerance” policing strategy coincided with a fall of 36 per cent in serious-crime rates in New York.

Many social scientists subsequently attacked the theory, [_] arguing that this fall could have been a direct result of other factors including demographic changes, the slowdown in the crack-cocaine epidemic and economic initiatives that coincided with the zero-tolerance policing tactics (combined with consistent attempts to remove signs of disorder) that had also been developed by the theory’s proponents.

However, a 2008 empirical-research study conducted in the Netherlands appeared to add weight to the theory, finding that people became more disobedient in environments plagued by litter and graffiti. They would be more tempted to trespass, drop litter and even steal money if they perceived it was okay to break the rules from within the environment. The authors of the study concluded: “There is a clear message for policymakers and police officers: Early disorder diagnosis and intervention are of vital importance when fighting the spread of disorder.” [_]

More recently, a systematic review in 2015 by Anthony Braga, Brandon Welsh and Cory Schnell found that policing strategies focused on disorder had a statistically significant (if modest) impact on reducing all types of crime. However, the authors stressed this positive effect was driven more by place-based, problem-oriented interventions, such as hotspot policing, than by interventions targeting individual disorderly behaviour. [_]

To this day, the evidence base around broken windows remains contested. However, the weight of evidence would suggest there is a statistically significant effect from policing disorder.

Most criminologists and social scientists agree the onset of criminality is often preceded by ASB, which can manifest in different ways. For example, a drug gang taking over a property to sell drugs generates a great deal of ASB in the immediate term and is also likely to be a predictor of serious violence, as documented in our previous paper .

The link between ASB and crime is also supported by evidence from police-recorded crime statistics, which show that areas with the highest-reported disorder are correlated with areas of highest actual criminal activity.

Comparing the rate of recorded crime (per 1,000 people) with level of public-order offences per police-force area (2021)

Source: ONS

Quality of Life and Community Wellbeing

Not only does minor crime and disorder fuel further crime and disorder, it also sends a signal to the community that the local area is unsafe. While certain minor crimes may be considered less severe in the traditional sense, their accumulated impact on the public’s perceived risk of being a victim of crime may be far more pronounced. This phenomenon, which has become known as the “signal crimes perspective”, [_] describes this type of crime as any criminal incident that brings about a change in the public’s behaviour and/or their beliefs about their own security. A signal disorder is an act that breaches normal conventions of social order and signifies the presence of other risks. A signal disorder may be social, for example noisy youths, or physical, such as vandalism.

There is also evidence that rising ASB is contributing to the decline of connection and belonging within communities. In a 2021 report by Power to Change, it was noted that signs of neighbourhood decline such as empty buildings could contribute towards a “downward spiral of crime, anti-social behaviour and a loss of pride in place”. [_] Similarly, polling conducted for a 2022 report by the think-tank Onward revealed that when people were asked why local pride had declined in their area, the most popular response was a rise of 43 per cent in ASB. [_]

Considering the strong connection between ASB and how people feel about the community in which they live, it is all the more surprising that the government’s white paper on “Levelling Up the United Kingdom” contained such little focus on the issue.

ASB Affects the Most Vulnerable

Dealing with ASB is a question of social justice. The people most likely to be victims tend to live in the most deprived communities. In the figure below, we map reported concern about ASB against household income to show how people in the lowest-income decile groups are almost three times as likely as those in the highest to be concerned.

Percentage of respondents indicating high levels of awareness of ASB versus their household incomes

Anti-social behaviour (ASB) has not been central to this government’s law and order agenda. This has been reflected in the lack of political attention the issue has received, certainly when compared to the previous decade.

In early 2022, the government published its long-awaited white paper, “Levelling Up the United Kingdom”, which attempted to put flesh on the bones of what many have perceived to be the central mission of this administration. However, the white paper was primarily focused on reforms to boost economic productivity and skills rather than to reduce and crime. Aside from the already announced police officer uplift, a £50 million Safer Streets Fund administered to Police and Crime Commissioners appeared to be the sole and tangible policy pledge for dealing with ASB. This funding equates to less than £1,500 for every neighbourhood in England and Wales. [_] The white paper also sets what many will consider to be an unambitious target: to see neighbourhood crime fall by 2030.

The government clearly recognises the impact of ASB can be devastating for victims and the communities in which they live. However, ministers appear to have fallen victim to the fallacy that since ASB is primarily a "local" concern, it is purely a matter for local areas to deal with. In her foreword to the government’s 2012 “Putting victims first” white paper (to date, the only one specifically focused on ASB), former Home Secretary Theresa May made clear how she viewed the issue: “The mistake of the past was to think that the government could tackle antisocial behaviour itself. However, this is a fundamentally local problem that looks and feels different in every area and to every victim.”

This represents muddled thinking. It is true that ASB is a local issue, experienced in different ways by different communities, and that local practitioners are best placed to determine how to tackle it on the ground, rather than civil servants sitting in Whitehall. However, central government still has a responsibility to set the framework in which local areas operate – making clear what outcomes are expected as well as the levers and resources that will be made available to tackle the issue. However, no such framework has ever been set out.

Given the above, it is perhaps unsurprising that much of the architecture established over a decade ago has been subsequently diluted or dismantled. That architecture can broadly be divided into three parts: [_]

The establishment of local partnerships charged with preventing ASB.

Equipping local agencies with new enforcement powers designed to tackle persistent perpetrators.

Measures to turn around the lives of the most problematic families.

This chapter assesses recent developments against each of these three areas.

Local Partnerships

Successive governments have understood that partnerships are crucial in the fight against ASB. Crime and Disorder Reduction Partnerships (CDRPs) were introduced by the Labour government in 1998 to do just this. CDRPs placed local agencies under a statutory duty to cooperate in crime and disorder reduction in their local-authority area. Statutory partners included the police, the local authority, NHS, fire service, probation service and housing associations. Under the previous Labour government, the Home Office made funding available for every CDRP to employ a dedicated ASB coordinator to ensure the issue was properly reflected in the CDRP audit, that each partnership had a ASB strategy and it was delivered, and that a named person acted as a point of contact for central government.

Since 2010, CDRPs – or Community Safety Partnerships (CSPs) as they have been renamed – have ceased to be an effective mechanism for driving action on ASB. First, the focus of many CSPs began to shift away from ASB, edged out by newer competing priorities including the management of harm and vulnerability. [_] (This was also partly a consequence of the Home Office removing the expectation that local plans needed to include a focus on ASB.)

Second, this shift in focus coincided with a significant reduction in the resources allocated to and the relevance of CSPs. Much of their funding was rolled into the Police Main Grant and handed over to Police and Crime Commissioners so that they could deliver their police and crime plans over larger, police-force-level geographies.

The combination of funding insecurity (with cuts of up to 60 per cent to CSPs since 2010), staffing reductions in community-safety teams and the shift in strategic emphasis to the police-force level has left a mixed and fragmented national picture. Many CSPs have been left to wither away, unable to fulfil their statutory obligations. [_]

Enforcement Powers

A central insight by the previous Labour government was that the criminal-justice system was a blunt and largely ineffective instrument in the response to ASB. The nature of ASB – often involving repeated low-level harassment – means it is unlikely to secure a criminal conviction via the courts: a process that typically takes many months and requires a very high evidential standard of proof. Hence the desire to use alternative and swifter means, such as the civil system, to give local agencies new enforcement tools for tackling ASB. To that end, a range of new measures were introduced to punish perpetrators, including Anti-Social Behaviour Orders (ASBOs), parenting and dispersal orders, crack-house closure powers, fixed-penalty notices and other powers.

However, the Conservative-led government introduced new legislation in 2014 that aimed to “radically streamline” ASB-enforcement powers, reducing them from eighteen to six; replace the ASBO and its related orders with measures that more effectively addressed the offending behaviour of individuals; and create new mechanisms for victims to be more involved in the response, such as the “community trigger”.

Consolidating the Powers Available

Concerned that the powers to tackle ASB had become too complex, the government proposed the creation of six new ones to absorb the 18 that existed at the time.

How ASB enforcement powers were consolidated in 2014

Source: House of Commons Library

While the objectives – both to consolidate powers and to provide greater flexibility to agencies on the front-lines – had a clear logic, the lack of a clear national framework for implementing these new powers is likely to have impeded their effectiveness. The government removed any requirement for those implementing enforcement to share any information on their use of the new powers. As a result, there is no longer any centrally published and accredited data, which means we do not have an accurate picture of when and how these powers are being used or who is being affected by them across England and Wales.

Replacing the ASBO

The 2014 Anti-social Behaviour, Crime and Policing Act abolished the ASBO and in its place created a new civil injunction. There are two main differences between the two. First, breaching an ASB civil injunction does not constitute a criminal offence. Second, in addition to prohibiting the behaviours, civil injunctions can require individuals to take part in “positive requirements”, for example an alcohol-awareness course.

There were certainly valid criticisms of ASBOs from the speed of the process involved (sometimes, several months) to the relatively high number (around half) that were breached. Despite this, they were nonetheless clearly understood by the public and had become synonymous with a national desire to tackle the problem. The fact that a breach of an ASBO constituted a criminal offence allowed the system to send a strong signal about unacceptable norms of behaviour and the consequences that would follow.

It is far from clear that the civil injunction achieves similar levels of clarity and there are concerns that the dilution of criminal sanctions may have undermined levels of deterrence. [_] Again though, the lack of robust data on the use and efficacy of the new powers makes an objective assessment impossible.

New Ways for Victims to Influence Action

The government was concerned that in tackling ASB, local agencies did not adequately focus on the needs of victims and, too often, victims reported these problems without a response. To remedy that, the government introduced:

A new out-of-court disposal available to the police called the “community resolution” for which victims are provided an opportunity to influence how their perpetrator is punished.

A new duty on police, local authorities and some other partners to take action to deal with persistent ASB, known as the so-called community trigger.

Community resolutions were designed to give victims a say in how their perpetrator was punished but they have proved controversial. For example, the Magistrates Association has argued that they have resulted in inconsistent outcomes for perpetrators and victims, and these inconsistencies may undermine the legitimacy of the justice system. [_] A recent review of out-of-court disposals suggested there is a lack of data and oversight surrounding the use and effectiveness of community resolutions (despite their making up more than half of out-of-court disposals in England and Wales) while limited enforcement around the conditions set may have led to them being applied inappropriately and in ways that enhance the risk to victims. [_]

The community trigger was intended to provide a mechanism by which victims could require local services to review the handling of their ASB case. In line with ministers’ belief in flexibility locally, the legislation put a duty on local services to agree how to run the trigger and convey it to the local community. Research carried out by the charity ASB Help, however, has found that in practice very few local authorities or police forces have communicated this new power to the public, meaning that awareness of the trigger is low and many victims who would be entitled to activate it are unaware of its existence. Moreover, despite a legal requirement to publish annual data on the use of the trigger, many local authorities have failed to do so and there is confusion around the threshold (the number of complaints) required to activate it. The charity’s report concluded: “The community trigger has proved to be little more than a bureaucratic exercise, creating more paperwork, draining already tight public resources, and yet still not bringing desperately needed respite for victims.” [_]

With no national repository of good practice or learning, there are legitimate concerns about the quality of the entire process.

Troubled Families

One of the central pillars of Labour’s approach to ASB was creating and rolling out interventions targeted at the small number of challenging families responsible for a disproportionate share of that behaviour. Following the publication of the “Respect action plan” in 2006, a national network of Family Intervention Projects (FIPs) was established.

FIPs used an assertive and persistent style of working to challenge and support families to address the root causes of their behaviour whether through anger management, parenting support or addressing educational problems. There were different ways in which the service could be delivered: outreach support to families in their own home; support in temporary (non-secure) accommodation located in the community; and 24-hour support in a residential core unit where the family lived with project staff. Early evaluations showed that FIPs were successful in reduction: while 61 per cent of families were reported to have engaged in four or more types of ASB when they started working with a FIP, this had reduced to 7 per cent when they exited the project. [_]

As it turned out, this was the one part of the previous government’s ASB agenda that the Conservative government decided to build on, rather than dilute. Following the London riots in 2011, David Cameron made a pledge to “turn around the lives of the 100,000 most troubled families”. A new project called the Troubled Families Programme was established under the leadership of Louise Casey and underpinned by £400 million worth of investment, delivering a similar set of interventions. In 2019, when the programme was evaluated, the results were positive and showed statistically significant reductions in the proportion of families involved in ASB, following the intervention. [_] Since 2019, however, the programme has been rebranded and lost much of its original focus.

While the lack of data makes meaningful evaluation difficult, it is hard not to conclude that there been a weakening of policies to tackle ASB over a period of more than ten years. Local partnerships have become less effective, enforcement powers have been diluted (and less transparent) and, after an initial boost, interventions to deal with troubled families have lost focus. This is proven by data showing that the proportion of people who have confidence the authorities will take robust action on ASB has fallen since 2014/2015, after several years of steady rises.

Percentage of people who agreed that the police and the local council have been dealing with the ASB issues that matter in the local area

As ever, this is partly a story of declining resources. But equally, if not more, important has been the lack of focus and priority afforded to the issue of ASB by central government, which has removed an important pressure from the system particularly at a time when local agencies are facing competing demands.

In the next chapter, we assess how the government has fared on the other core plank of an ASB strategy: visible neighbourhood policing.

To a large degree, the government’s stance on neighbourhood policing has followed a similar pattern to its policies on anti-social behaviour (ASB): it is a matter for Police and Crime Commissioners rather than central government. In practice, this has led to a hollowing out of neighbourhood policing as experienced by local communities.

The modern history of neighbourhood policing in England and Wales started with the National Reassurance Policing Programme, which ran in 16 pilot sites between 2003 and 2005. The programme set out to address the “reassurance gap” or the mismatch between falling crime rates and the public’s perception that crime was going up. The approach drew on the “signal crimes” perspective, which held that specific but varying types of crime and disorder – including some incidents not traditionally considered “serious” – could disproportionately convey negative messages to individuals and communities about their security. The implication for the police was that by identifying and targeting the crimes with the strongest local signal values (particularly ASB at the time), they could reduce fear, improve confidence and reassure the public.

The programme was built on three principles:

Providing a visible and accessible policing presence.

Involving communities in identifying priority problems.

Tackling these in collaboration with other agencies and the community through a problem-solving approach.

Evaluation in the pilot sites showed that the approach improved public perceptions of how crime and ASB were dealt with, feelings of safety and confidence in the police. Although it had not been a specified aim, the programme was also found to have had a positive impact on crime, with survey measures showing a decline in victimisation in the community.

Prior to the 2005 general election, the Labour government pledged to ensure that every area in England and Wales would have a dedicated neighbourhood policing team by 2008, supported by more than £50 million of ring-fenced funding and provision of 25,000 Police Community Support Officers (PCSOs). In hindsight, this proved to be the zenith of neighbourhood policing. What followed has been a period in which the concept of a universal neighbourhood-policing offer has been eroded.

In 2016, Her Majesty’s Inspectorate of Constabulary and Fire and Rescue Services (HMICFRS) found that while all forces still allocated at least some resources to the prevention of crime and ASB through neighbourhood teams, there was now considerable variation and inconsistency in how different forces deliver neighbourhood policing. Increasingly, forces had shifted to an integrated or hybrid model, whereby neighbourhood policing was being dissolved into general local policing and/or response policing (with neighbourhood teams used to service reactive demand). [_]

Similarly, in a 2018 report on neighbourhood policing, the Police Foundation documented how several forces had sought to balance competing demands by adopting a more general or hybrid approach in which local police officers performed both response and neighbourhood tasks. [_]

Given the funding pressures that police forces were facing, the shift to a hybrid model made sense from an efficiency perspective although it contained risks from an effectiveness perspective. There is consistent testimony from frontline police officers that a workload containing significant amounts of reactive police work is unsuited to also delivering core neighbourhood-policing activities, such as community engagement and partnership-working, which tend to be more proactive. [_] This is not only a matter of the time that reactive tasks take up but also their high unpredictability, which can in turn undermine efforts to make and keep appointments and commitments.

Realising the drawbacks of hybrid models, a number of forces have subsequently chosen to designate smaller, functionally discrete policing teams to neighbourhood or local preventative duties and to insulate them (partly or wholly) from reactive demand. However, the price of greater functional distinctiveness has been a further shift away from universal neighbourhood policing towards a more narrowly defined, targeted offer, for example one that is limited to high-risk areas.

The shift away from universal neighbourhood policing has been accelerated by a significant reduction in the share of PCSOs within the workforce, with the money diverted to employ more fully warranted officers.

The number of Police Community Support Officers (PCSOs) as a proportion of the total police workforce

Source: Home Office

Inevitably, given the shift in focus described above, there has been an erosion of the traditional outputs associated with neighbourhood policing: community engagement, visibility, community intelligence gathering, local knowledge and proactive prevention.

Variability

Our localised system of policing means that chief constables have a great deal of discretion over how to interpret the priority given to neighbourhood policing as well as the form and function it takes.

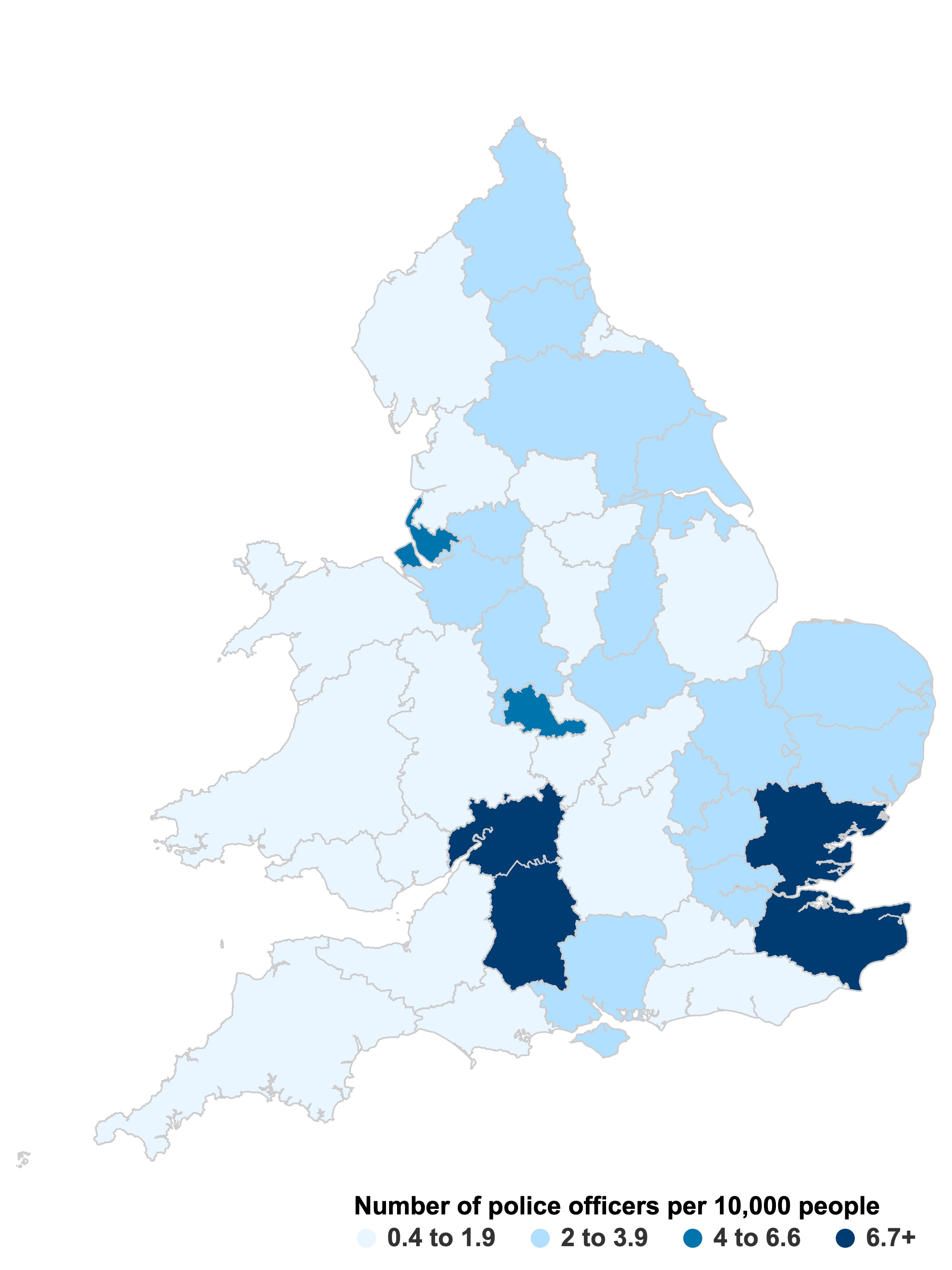

The data show a very mixed picture in terms of the resourcing and prioritisation of neighbourhood policing. This ranges from Avon and Somerset, which dedicates 2.5 per cent of its police officers to neighbourhood policing, to Wiltshire, which allocates 51 per cent. In total, there are now 24 forces that allocate less than 10 per cent of their police officers to neighbourhood policing – more than double the nine forces that did so in 2012. [_]

Number of neighbourhood police officers per 10,000 people (2021)

Source: Home Office, Police Workforce

Over the past decade, neighbourhood policing has encompassed a broader and more varied set of practices than was the case in 2008. In a 2018 report, [_] the Police Foundation documented some of the ways in which that diversity manifested itself:

Workforce mix: Some forces (for example, those in rural areas) delivered neighbourhood policing by relying on PCSOs while others had reduced this proportion and chosen instead to depend on fully warranted officers

Scope of provision: While a small number of forces attempted to retain a universal offering, most forces sought to deliver a narrower, more targeted offer, for example by focusing on areas of the highest risk.

Focus: Some forces continued to approach neighbourhood policing in traditional terms, in other words, largely focused on community engagement, visibility and reassurance, while others sought to define it more broadly, encompassing “harm reduction” and the management of vulnerability.

Partially in response to some of these concerns, the College of Policing published guidance on the delivery of neighbourhood policing in 2019. [_] However, these guidelines “embed a version of neighbourhood policing predominantly oriented towards crime and demand reduction”. [_] This represents a fundamental change in direction from the original premise of neighbourhood policing, which was a distinct (and universal) specialism focused on reassurance, legitimacy and cooperation. As will become apparent in the next chapter, it is far from clear whether this shift is aligned with the public’s priorities.

Impact on Public Confidence

Until the mid-2000s, public confidence in the police service – as measured by the Crime Survey for England and Wales (CSEW) – remained remarkably stable, with approximately half of British adults rating their local policing as, at least, “good”. Between 2006 and 2016, public confidence rose significantly before it started to decline.

Levels of overall public confidence in the police begin declining from 2017

What might explain this recent fall in confidence? One possible explanation is that policing has become less visible, with fewer officers on the streets. As the figure below demonstrates, this appears to be reflected by trends in public perception, which show a similar pattern to the confidence data (perceptions of police visibility rise in the mid-2000s before falling back, albeit before the fall in public confidence).

Percentage of people who said they saw foot patrols on the streets once a week or more (visibility)

In addition to declining visibility, another driver of falling confidence would be the belief that the police are less responsive to local concerns. Again, data suggest this is indeed the case, with a decline in the number of people reporting both that the police understand and deal with local concerns since 2014/2015.

Figure 12 – Percentage of people who believe that the police understand and deal with local concerns (responsiveness)

One can see a similar pattern in the number of officers in neighbourhood roles, with a dramatic fall since 2015/2016. In Michael Barber’s “Strategic Review of Policing in England and Wales”, an explicit connection is made between trends in public confidence, perceptions of police visibility and the rollout of neighbourhood policing. [_] Of course, correlation does not equate to causation but the consistency of the trends is striking. This interpretation would also be consistent with research showing links between public confidence and police visibility, and with the overall number of police officers. [_]

The number of police officers in neighbourhood policing roles in England and Wales has fallen recently from a peak in 2015/2016

Sufficient international evidence confirms that visible and accessible policing can “have positive effects on citizen satisfaction, perceptions of disorder and police legitimacy”. [_] For example, one recent randomised control trial in the United States concluded that a “single instance of positive contact with a uniformed police officer can substantially improve public attitudes toward police, including legitimacy and willingness to cooperate”. [_]

Public Satisfaction Is Down

Analysis of attitudinal data captured by the CSEW reveals that the weakening of policy on ASB combined with the erosion of neighbourhood policing has undermined the public’s confidence. Since 2014/2015, when the Anti-social Behaviour, Crime and Policing Act was introduced and neighbourhood policing numbers began to substantially decline, there have been noticeable falls in the number of people reporting the following:

Confidence that their local police and council were focusing on the ASB and crime issues that matter.

The visibility of the local police patrol.

That the police understand and deal with local concerns.

There are other data to support these trends. For example, the proportion of incidents in which victims were satisfied with the police has fallen over the past decade (from 37 per cent to 32 per cent). [_]

While these figures tell us what the public are unhappy about, they don’t necessarily tell us what the public want to see. That is the subject of the next chapter.

To inform our research, the Tony Blair Institute commissioned a public poll from JL Partners asking people about the scale of the anti-social behaviour (ASB) problem, how well they think local services deal with it and their priorities for local policing. The findings provide stark reading for the government.

Our survey confirms that ASB is of significant concern to the British public. When asked about the scale of the problem in their local area, around a third (32 per cent) of respondents identify it as a “big problem” where they live while more than three-quarters (81 per cent) say it is a problem of “some sort”.

Question to respondents: “Thinking about your experience of where you live, how big of a problem is anti-social behaviour?”

Source: JL Partners

The demographic group that appears most concerned about ASB is young people. Our findings reveal that 45 per cent of people aged between 18 and 24 believe it is a “big problem” in their area (compared with 32 per cent overall). This contrasts sharply with the experience of those aged over 65. Only 18 per cent of this demographic identify ASB as a “big problem”.

Question: “Thinking about your experience of where you live, how big of a problem is anti-social behaviour?” (Responses categorised by age group)

When we consider the regional differences, we see that the greatest concern is reported in London. Almost half the respondents (47 per cent) in the capital believe that ASB is a “big problem” where they live. This is higher than the national average (32 per cent) and contrasts sharply with people in the East of England region (where only 19 per cent recognise it as a big problem). Respondents in the North West (41 per cent) and North East (43 per cent) also identify ASB as a “big problem” in their local areas.

Reporting ASB and the Response of Local Services

More than four in ten respondents (42 per cent) report having had a direct experience of ASB in the past year, a similar level to the 40 per cent measured by the Crime Survey for England and Wales.

Question: “Have you personally experienced or witnessed ASB in the last 12 months?”

In terms of who the public have reported ASB to when they witnessed or experienced it during the past year, the survey shows that more than two-thirds (69 per cent) chose the police while less than half (43 per cent) went to their local authority.

However, when it came to reporting experiences of ASB, the levels were much lower. Only a quarter of people who experienced or witnessed it (26 per cent) reported it to the police or their local authorities. Low levels of reporting are most evident among the young people polled. Only 16 per cent of those aged under 25 who experienced an issue of ASB reported it, compared to 30 per cent of respondents aged between 45 and 54.

Of those who said that they had experienced or witnessed ASB in the last 12 months, the poll asked: “Did you report it?”

Of the people who did report issues of ASB, their experience and satisfaction with the outcome has been highly variable. Only 41 per cent of respondents were satisfied with the response they received while 39 per cent had an unsatisfactory experience. Of greater concern, more than a fifth (22 per cent) admitted they had been very unsatisfied with the response they had received.

Of those who did report ASB, the poll asked: “Were you satisfied with the response that you received after you reported the ASB?”

What the public would like to see from their local police.

In our survey, we asked respondents to prioritise (with a rank out of 10) the elements of local policing that matter most to them, along with an assessment of how well that service is currently being provided (also ranked out of 10).

When it comes to these priorities, “answering 999 calls rapidly” remains the most important aspect of the job (scoring an average of 8.6 out of 10 in terms of importance) according to respondents. This is followed by officers that are “approachable, friendly and professional” (8.1 out of 10) and then ensuring a “definite response to all reports of crime and ASB” and “keeping victims and witnesses informed about their case” (both scored 7.9 out of 10).

Two-part question: “Thinking about how the local police spend their time, 1) score the following in terms of how important it is to you” and 2) "score the following in terms how well you think it is provided by the police"

In terms of people’s perceptions of the level of service they currently receive, the police score best in terms of their response to 999 calls, with an average of 6.4 out of 10 on this task. However, the police score only 5.9 out of 10 on being approachable and friendly. More concerning, a very low proportion of the public feel that the police are doing a good job in providing a definite response on crimes and ASB (4.8 out of 10). The police score lowest with 4.1 out of 10 when it comes to a “visible presence on the streets”, a finding that chimes with the decline in neighbourhood policing we have already discussed.

Polling Backs Our Findings

This polling reinforces our central argument in this paper: in recent years, ASB has not received a great deal of political attention or media coverage but it is viewed by the public as a matter of serious public concern. The fact that such a low proportion of survey respondents (26 per cent) experiencing ASB report it to the authorities suggests a near-complete collapse in confidence in the system to deal with the problems. Our polling also confirms that the public would like to see a local police offering that is responsive, accessible and visible. The force is currently struggling to fulfil any of these objectives.

Polling: Sample Details

Polling conducted by JL Partners for the Tony Blair Institute looked at the importance of the issue of anti-social behaviour to the public, how likely they were to report it, and what they expect from the police. The polling was conducted among a representative sample of 2,024 adults from 4 to 5 April 2022 and weighted to be representative of the population of Great Britain.

Anti-social behaviour (ASB) is often seen as a low-level nuisance – a type of sub-crime – which is somehow less deserving of political attention than more serious offences. This is a mistake. While single incidents can seem trivial in isolation, this overlooks the fact that this behaviour is almost always repetitive and oppressive, often directed at victims who are vulnerable and who live in some of the most deprived parts of the country. The impact is cumulative: when sustained over a period of time, it can have a long and lasting impact on individuals, families and the local communities that have experienced this behaviour. It affects people’s mental health. It makes them want to move home. And collectively, it hastens a sense of local decline, which in turn undermines incentives to invest in the community while hindering regeneration opportunities. That is why it is so important the issue of ASB is tackled quickly and effectively.

For the past decade, ASB has effectively been ignored by the government. Local partnerships have lost focus, enforcement powers have been weakened and action against troubled families has stalled.

At the same time, neighbourhood policing – the bedrock of the British consent-based policing model and a prerequisite for any serious response to ASB – has been eroded. And the visibility of police on the streets has declined across the board. While most police forces have retained some type of neighbourhood-policing offer, the form that it takes and the level of resourcing it receives look very different depending on where you happen to live. This has undermined confidence in the police and left the public confused about the level of service they have a right to expect.

This is not an argument against localism or for the return of top-down control. Locally elected Police and Crime Commissioners and practitioners will continue to be better placed than civil servants to understand what action is required to tackle ASB and other issues of concern within communities. But a local approach should not be confused with an abrogation of responsibility – central government still has a crucial role to play in providing the framework, levers and resources in which localism can flourish.

The polling carried out for this paper illustrates the public’s priorities: when asked to choose from a list of functions, they want a local police team that is responsive, visible and accessible. Below we sketch out what that could look like in practice. We hope it will provide the basis of a new local-policing contract, combining clear minimum standards with the flexibility necessary to allow practitioners the ability to tailor their responses to local needs.

Recommendations: Neighbourhood Policing

Neighbourhood policing is a central pillar of any serious response to ASB and, as this report has illustrated, an important driver of public confidence more broadly.

A New Local-Policing Contract

The lack of clarity and certainty about what to expect from the local police, particularly in terms of the response to ASB, is in danger of creating confusion and undermining confidence.

We recommend that the government consults on the creation of a new local-policing contract in every neighbourhood based on the priorities identified by the public in our polling. At the least, this should include minimum standards on the following three factors:

Responsiveness: How rapidly the police respond to incidents and calls for their service.

Visibility: The extent to which police spend time on patrol.

Accessibility: The extent to which officers are easily contactable and the level of face-to-face interaction whether via police stations, surgeries or online.

To improve transparency and accountability, the government should also publish scorecards, enabling the public to assess the performance of their local-neighbourhood team against a basket of comparable metrics.

Greater Consistency of Approach

There is enormous diversity in how neighbourhood policing is delivered today both in terms of its resourcing, and the form and function it takes. The College of Policing produced guidance in 2019 but it lacked detail on key questions of substance (resourcing) and appeared to encourage a further shift away from neighbourhood policing’s original remit, which was a specialism focused on reassurance, engagement and resilience.

The government should work with the college and the National Police Chiefs’ Council to clarify national expectations around the approach taken to neighbourhood policing, with respect to the chosen remit, form and function. Specifically, this should clarify:

The principal of universal coverage: Every area of the country should be covered by a neighbourhood-policing team.

Functional distinctiveness: Emphasising proactive prevention, confidence and community resilience rather than getting diverted into broader policing aims of harm reduction and vulnerability.

PCSOs: Specifying their role especially in relation to ASB and neighbourhood policing.

Protecting the functions of neighbourhood policing is clearly not cost free, particularly during a time when the police are managing a range of competing demands from serious violence to cyber-related fraud.

The Home Office should ask police forces to guarantee a minimum level of neighbourhood policing (measured as a proportion of the total workforce), designed around the principles outlined above. This will involve deploying a significant proportion of the additional officers recruited since 2019 into neighbourhood policing.

Recommendations: ASB strategy

If the government is serious about “levelling up”, it will need to devote a lot more attention to both understanding the nature and scale of ASB and to setting a clear direction on the action it expects local agencies to take in responding to the problem. A national strategy on ASB will require action at all levels of government, from top to bottom.

Pressure From Above

The government should publish a white paper setting out a national framework for tackling anti-social behaviour, to include the following elements: