An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- Glob J Health Sci

- v.8(6); 2016 Jun

Communication Barriers Perceived by Nurses and Patients

Roohangiz norouzinia.

1 School of Paramedical, Alborz University of Medical Sciences, Karaj, Iran

Maryam Aghabarari

2 Nursing and Midwifery Care Research Center, School of Nursing and Midwifery, Tehran University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran

3 School of Nursing and Midwifery, Alborz University of Medical Sciences, Karaj, Iran

Maryam Shiri

Mehrdad karimi.

4 School of Public Health, Department of Epidemiology and Biostatistics, Tehran University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran

Elham Samami

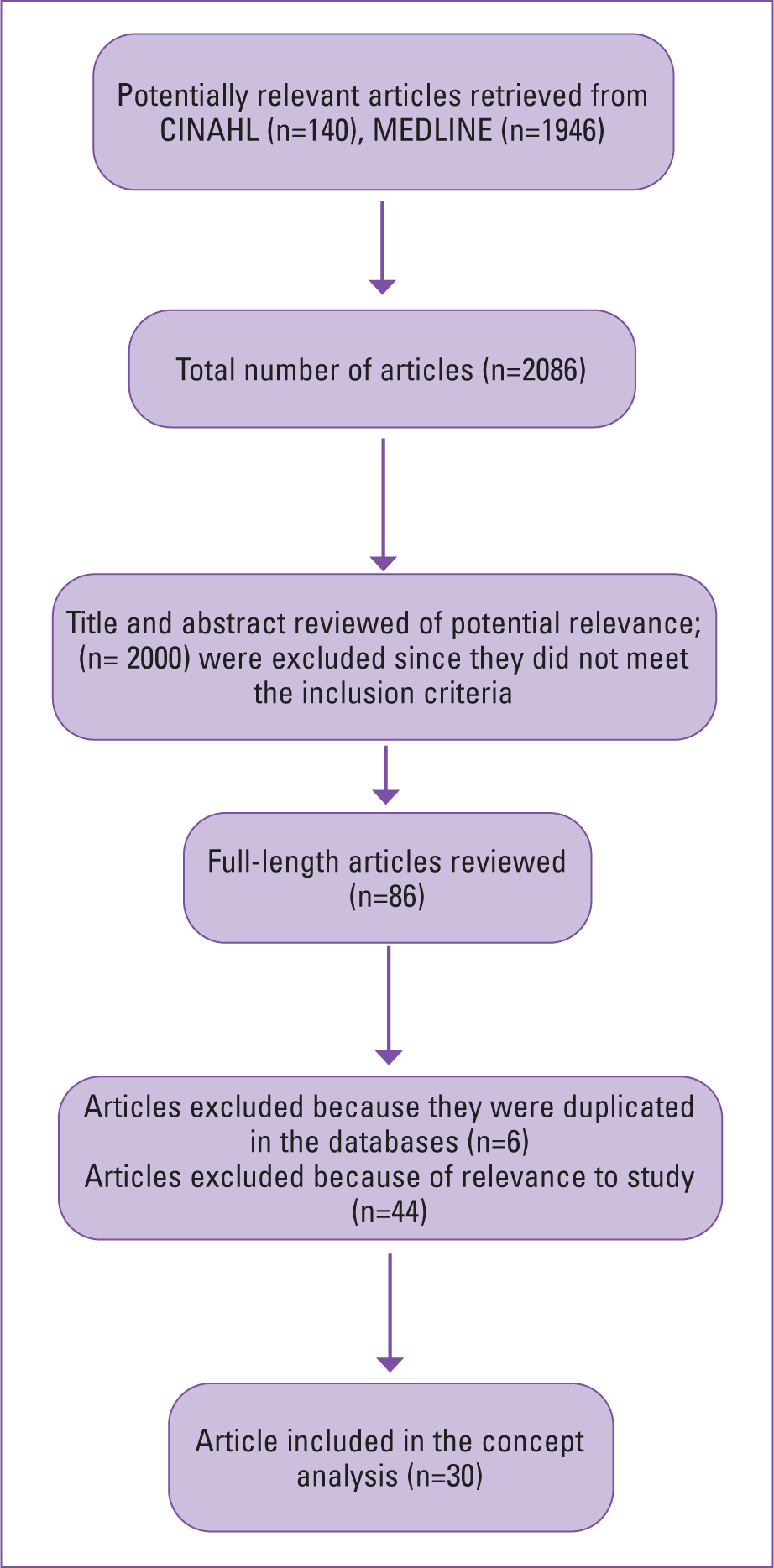

Communication, as a key element in providing high-quality health care services, leads to patient satisfaction and health. The present Cross sectional, descriptive analytic study was conducted on 70 nurses and 50 patients in two hospitals affiliated to Alborz University of Medical Sciences, in 2012. Two separate questionnaires were used for nurses and patients, and the reliability and validity of the questionnaires were assessed. In both groups of nurses and patients, nurse-related factors (mean scores of 2.45 and 2.15, respectively) and common factors between nurses and patients (mean scores of 1.85 and 1.96, respectively) were considered the most and least significant factors, respectively. Also, a significant difference was observed between the mean scores of nurses and patients regarding patient-related (p=0.001), nurse-related (p=0.012), and environmental factors (p=0.019). Despite the attention of nurses and patients to communication, there are some barriers, which can be removed through raising the awareness of nurses and patients along with creating a desirable environment. We recommend that nurses be effectively trained in communication skills and be encouraged by constant monitoring of the obtained skills.

1. Introduction

Communication is a multi-dimensional, multi-factorial phenomenon and a dynamic, complex process, closely related to the environment in which an individual’s experiences are shared. Since the time of Florence Nightingale in 19 th century until today, specialists and nurses have paid a great deal of attention to communication and interaction in nursing ( Fleischer, Berg, Zimmermann, Wüste, & Behrens, 2009 ). Effective communication is an important aspect of patient care, which improves nurse-patient relationship and has a profound effect on the patient’s perceptions of health care quality and treatment outcomes ( Li, Ang, & Hegney, 2012 ). Effective communication is the key element in providing high-quality nursing care, and leads to patient satisfaction and health ( Cossette, Cara, Ricard, & Pepin, 2005 ). Effective communication skills of health professionals are vital to effective health care provision, and can have positive outcomes including decreased anxiety, guilt, pain, and disease symptoms. Moreover, they can increase patient satisfaction, acceptance, compliance, and cooperation with the medical team, and improve physiological and functional status of the patient; it also has a great impact on the training provided for the patient ( Aghabarari, Mohammadi, & Varvani, 2009 ).

However, most studies have reported poor nurse-patient relationships ( McCabe, 2004 ; Jangland, Gunningberg, & Carlsson, 2009 ; Gilmartin, & Wright 2008 ). Therefore, overall, nurse-patient communication has not led to personal satisfaction ( Jangland, Gunningberg, & Carlsson, 2009 ). This is due to the fact that health care quality is strongly affected by nurse-patient relationship, and lack of communication skills (or not using them) has a negative impact on services provided for the patients. The results of previous studies have shown that nurses have been trained to establish an effective communication; however, they do not use these skills to interact with their patients in clinical environments ( Heaven, Clegg, & Maguire, 2006 ). Similarly, the results of other studies show that nurses and nursing professionals in general, have not made a lot of effort for establishing positive interactions with the patients. Many reported problems are related to the decreased sense of altruism among hospital staff including nurses ( Bridges et al., 2013 ).

Communication pitfalls are 5-10% in general population and more than 15% in hospital admissions ( Bartlett, Blais, Tamblyn, Clermont, & MacGibbon, 2008 ). Hospitalized patients in all ages often experience complex communication needs including mobility, sensory, and cognitive needs as well as language barriers during their stay ( Downey & Happ, 2013 ). Hospitalization is potentially stressful and involves unpleasant experiences for patients and their families. All aspects of care and nursing are of high importance in communication with patients, as the patients consider interaction with the nurses as a key to their treatment. Also, through communication, nurses become familiar with the needs of their patients, and therefore, they can deliver high-quality health care services ( Cossette et al., 2005 ; Sheldon, Barrett, & Ellington, 2006 ; Thorsteinsson, 2002 ). Patients with communication disability were three times more likely to experience medical or clinical complications compared to other patients ( Bartlett et al., 2008 ).

Iran is a multicultural country with recognized cultural pluralism. In Iranian religious context, nurses are not allowed to gaze or touch patients of the opposite-sex, except in emergency cases. In addition, although Iranian formal language is Farsi, there are many dialects such as Lurish, Kurdish, and Baluchi, which might act as communication barriers between nurses and patients ( Anoosheh, Zarkhah, Faghihzadeh, & Vaismoradi, 2009 ). In Iran, some communication facilitators and barriers have been reported including low educational preparation, governmental policies, and inappropriate environment as barriers, and religious and cultural norms, role modeling, and previous exposure of patients as facilitators ( Rejeh, Heravi-Karimooi, & Vaismoradi, 2011 ).

The first step in eradicating the problems related to nurse-patient communication is two-sided (nurse and patient) awareness of communication barriers. It is of no doubt that building an effective relationship is dependent on the understanding of both sides of the interaction ( Park & Song, 2005 ). In this study, we aimed to determine the barriers to nurse-patient relationship from the perspective of nurses and patients. Through this evaluation, we can improve the quality of nursing services and increase the satisfaction of patients and their families. We also assessed the barriers to using communication skills by the nurses in nurse-patient interactions.

2.1 Study Design

Cross sectional, descriptive analytic study.

2.2 Participants

This study was conducted on nurses and patients of two public hospitals affiliated to Alborz University of Medical Sciences, Karaj, Iran. Simple random sampling method was applied.

2.3 Questionnaires

Data were collected via two separate questionnaires for nurses and patients. The reliability and validity of the questionnaires were assessed. Content validity was approved by eight professors of Tehran University of Medical Sciences and Tarbiat Modares University, and reliability was assessed using the split-half method. Pearson’s correlation coefficient between the two halves was calculated, and reliability of patient (correlation coefficient of 0.76) and nurse (correlation coefficient of 0.82) questionnaires were approved.

The questionnaires consisted of two sections. The first part included demographic questions and the second part was concerned with the present barriers to nurses’ use of communication skills. The nurse questionnaire contained 44 items and patient questionnaire consisted of 29 items; each item included 5 options: none, little, average, high, and not included. The participants chose one of the options with regard to the importance of each barrier; “not included” was selected if the subjects had not dealt with such a barrier before.

The barriers were divided to four categories: common barriers between patient and nurse, nurse-related barriers, patient-related barriers, and environmental barriers. To determine the importance of each barrier, the qualitative data were converted to quantitative data and the options were scored as follows: none: 1 score, low: 2 scores, average: 3 scores, and high: 4 scores. The difference in the number of items between patient and nurse questionnaires was related to the number of nurse-related factors. Some items were designed with regard to nurses’ working conditions, and there was a possibility that patients were unaware of these conditions; therefore, these cases were removed from the patient questionnaire, and the remainders were included in both questionnaires.

2.4 Data Collection

After obtaining the required approval, nurses and patients in the two hospitals were asked to participate in the study. In order to collect the data, the researchers visited the wards on a daily basis during different shifts. After explaining the study objectives to the nurses and taking informed consents, the questionnaires were given to the participants; after completion, the questionnaires were collected by the researchers.

The nurse sample included nurses of medical, surgical, intensive care unit, and emergency wards. They were working in morning, evening, night, evening and night, and circulating shifts. The sample size was calculated according to the number of nurses in the ward.

The inclusion criteria for the nurse group were as follows: 1) bachelor’s degree (minimum education level), 2) minimum of 6-month working experience, and 3) willingness to participate in the study.

The participants in the patient group were selected based on the inclusion criteria of the patient sample: 1) willingness to participate in the study, 2) ability to establish communication, 3) literacy, and 4) older than 15 years of age. The exclusion criteria for the patients were poor speech ability, hearing difficulty, language impairment following a stroke, and intubation.

The subjects were selected from hospitalized patients. After explaining the objectives of the study, an informed consent was obtained and the patient was given a questionnaire, which was collected after 1 hour. The patient sample was randomly selected from medical, surgical, and emergency wards.

2.5 Statistical Analysis

For data analysis, descriptive and inferential statistics (Binomial, Mann-Whitney, and Friedman tests) were used and SPSS version 14 was utilized. P-value less than or equal to 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

3.1 Demographic Characteristics

According to the results, the mean age of the nurses was 30.95 yrs, and the mean working experience was 7.02 yrs. The mean age of the patients was 29.30 yrs and the mean of hospitalization days was 2.3 days. Tables Tables1 1 and and2 2 show the demographic characteristics of the subjects.

Demographic characteristics of nurses

Demographic characteristics of patients

3.2 The Most and Least Important Barriers

The findings suggest that among four categories of communication barriers in nurse and patient groups, nurse-related factors (mean scores of 2.45 and 2.15, respectively) and common factors between nurses and patients (mean scores of 1.85 and 1.96, respectively) were the most and least important factors, respectively.

3.3 Compare the Nurses and Patients’ Viewpoint

Regarding patient-related factors (P=0.001), nurse-related factors (P=0.012) and environmental factors (P=0.019), there was a significant difference between the mean scores of nurses and patients ( Table 3 ).

Comparison of four groups of barriers in two groups of nurses and patients

The most frequent communication barriers from the nurses’ viewpoint were as follows: differences in colloquial languages of nurses and patients, nurses’ being overworked, family interference, and presence of emergency patients in the ward. According to the patients, gender differences between nurse and patient, nurse’s reluctance for communication, hectic environment of the ward, and patient’s anxiety, pain, and physical discomfort were the most important barriers to communication ( Table 4 ).

The most important barriers from the viewpoint of nurses and, based on the type of barrier

According to the data obtained from Man Whitney Test, comparison of patients’ and nurses’ mean scores of barriers (to using communication skills by nurses) indicated that of 29 items common between nurse and patient questionnaires, the mean scores of 13 items were significantly different ( Table 5 ).

Comparison of the mean scores of barriers to communication skills by nurses in interacting with patients from the viewpoint of nurses and patients

4. Discussion

The results of this study showed that in both groups of nurses and patients, the most and the least important barriers were nurse-related factors and common factors between nurses and patients, respectively. These results were consistent with the findings of Aghabarari et al., who performed a study to determine the barriers to applying communication skills by nurses, from the viewpoint of nurses and patients ( Aghabarari et al., 2009 ). Also, in the study of Aghamolaei et al., nurse- and patient-related barriers were more important than environmental barriers ( Aghamolaei & Hasani, 2011 ). In terms of common factors between nurses and patients, colloquial language, and cultural and gender differences were of high importance; however, priorities were not quite similar between nurses and patients. Through establishing an appropriate verbal communication, the nurse could thoroughly understand the patient’s problems; hence, in many studies, the nurse’s unfamiliarity with the patient’s colloquial language has been mentioned as a communication barrier ( Anoosheh et al., 2009 ; Baraz, Shariati, Alijani, & Moein, 2010 ; del Pino, Soriano, & Higginbottom, 2013 ; Li et al., 2012 ). If there is a difference in spoken language, effective communication cannot be established; even non-verbal communication in different cultures may have different interpretations. Patients are also less acceptant of nurses with different languages and cultures (culture has an impact on individuals’ attitudes and behaviors). Based on previous studies, communicative needs and ways of expressing emotions vary in different cultures and religions. Sufficient knowledge of nurses regarding patients’ culture, language, customs, and beliefs can help them communicate with the patients without having any pre-judgments or prejudice. Indeed, culture can act as both a facilitator and a barrier to communication ( Okougha & Tilki, 2010 ).

Alborz province is also called “little Iran”, meaning that all ethnicities and cultures are present in this region; therefore, the variety of cultures should not be neglected. Considering the population concentration of specific ethnic groups in particular regions of this province, it is recommended that the patient’s language and ethnicity be considered for the allocation of medical staff.

In this study, another factor affecting communication, particularly from the viewpoint of patients, was gender differences; the results were consistent with those of previous studies ( Anoosheh et al., 2009 ; Baraz et al., 2010 ). The impact of gender differences on communication is mostly emphasized by the patients; in fact, nurses are less affected by patients’ gender while performing their professional duties. According to cultural and religious beliefs in Iran, touching and gazing are inconsistent with the principles of the society ( Anoosheh et al., 2009 ). Similar to many Asian cultures, speaking about sexual problems is also considered impolite ( Im et al., 2008 ). Given the aforementioned principles, the number of male nursing students should increase considering the shortage of male nurses in hospital wards.

As to the patients’ viewpoint, another influential factor was age differences. Similarly, Sung and Park considered generation gap as a communication barrier ( Park & Song, 2005 ). In another study, differences in age and social class were included as communication barriers ( Anoosheh et al., 2009 ). However, according to a study by Baraz, age differences had no negative impact on nurse-patient relationship ( Baraz et al., 2010 ). Generally, communicating with different age groups has its own challenges and complexities. Nurses can have good interactions with patients through developing awareness of each age group’s attitudes to health, disease, and body function ( Bridges et al., 2013 ).

Evaluation of the viewpoints of nurses and patients showed that among nurse-related barriers, being overworked, shortage of nurses, and lack of time were the most important barriers for the nurse group. Also, the nurses’ unwillingness to communicate, and lack of understanding of patients’ needs were the most important barriers from the patients’ perspective. Shortage of nurses increases the work load, and therefore, there is not enough time to establish a good therapeutic relationship ( Park & Song, 2005 ); also, nurses’ low income has been mentioned as a barrier to nurse-patient interaction ( Aghamolaei & Hasani, 2011 ; Baraz et al., 2010 ; Mendes, Trevizan, Nogueira, & Sawada, 1999 ). Stress, being overworked, and lack of welfare facilities could decrease nurses’ satisfaction and quality of health care provision ( Nayeri, Nazari, Salsali, & Ahmadi, 2005 ). Based on the results of the study by Park and Song, being overworked is a nurse-related communication barrier, which affects the quality and quantity of the relationship between nurses and patients ( Park & Song, 2005 ).

In the present study, comparison of the viewpoints of nurses and patients regarding patient-related barriers showed that interference by family, patients’ unawareness of the status and duties of the nurses, patients’ physical pain, discomfort, and anxiety, lack of attention, and the presence of patients’ companions were the most important factors; these results were considerably consistent with previous studies ( Aghabarari et al., 2009 ).

Definitely, the patient’s disease and dependence after hospitalization result in anxiety, tension, and fear in the patient; moreover, the patient’s family also experiences a difficult time and has different needs and demands. Negligence of the patient and the family of the status and duties of nurses leads to misconceptions about the nurses’ role in the improvement or deterioration of the patient’s health and may even result in the patient’s death. If nurses are not successful in establishing an effective communication with the patients, they can apply communication facilitators; if they still do not succeed, they can explain the problems to the patients so that they can obtain positive treatment results without having a good communication ( Ammentorp, Sabroe, Kofoed, & Mainz, 2007 ).

Nurse is considered the direct care provider and the smallest delay in care provision will be considered as medical negligence. However, it is quite obvious that a medical team consisting of physicians, nurses, clinical departments, and even medical center crew are all responsible for the patient’s health care. Thus, given the direct relationship between nurses and patients, the image created by nurses affects their being accepted as professional staff, and their role will be highlighted in establishing an effective communication ( Aghabarari et al., 2009 ).

In terms of environmental barriers, the presence of critically ill patients in the ward, the hectic environment of the hospital, and unsuitable environmental conditions are considered the main barriers in both groups. The findings of previous studies confirm the aforementioned results. The shortage of nurses and the presence of critically ill patients in the ward cause a lot of stress for the patient and lead to decreased ability and motivation to communicate with other patients; on the other hand, medical environment conditions have great effects on the quantity and quality of communication ( Bartlett et al., 2008 ). Factors disturbing the communication process can be improper temperature, excessive noise, poor ventilation, and lack of respect for the privacy of the two sides of the relationship ( Mendes et al., 1999 ). Thus, providing a safe and comfortable environment leads to psychological and physical comfort of the nurse and patient, and facilitates using communication skills and establishing an effective communication.

One of the limitations of this study was the low number of male nurses. Another limitation was lack of evaluation of cultural forces operating between patients and nurses, regardless of the country of origin or background in the hospitals (active, passive, or power relationships). It is recommended that future studies pay more attention to communication facilitators and divide the participants to male and female groups. It is also suggested that religious and cultural beliefs as well as language barriers be more thoroughly evaluated in patients and nurses.

5. Conclusion

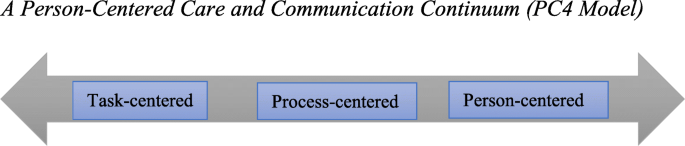

The purpose of any system is to provide services with optimal quality and quantity, and health care systems are no exception. One of the best ways to gain the patients’ satisfaction, as major clients of health care systems, is through establishing effective and appropriate communication. Thus, according to the results of this study and previous studies, the following measures will be considerably helpful in establishing an effective nurse-patient communication: allocation of medical staff with regard to the language and culture of the region, motivating nurses to provide high-quality health care services, upgrading medical clinics and facilities, holding periodic workshops of communication skills, holding nursing quality assurance committees, and most importantly, changing attitudes of nursing managers and administrators from offering task-based services toward following a holistic approach.

Acknowledgments

This study is financially supported by Research Affairs, Alborz University of Medical Sciences, Karaj, Iran. The authors wish to express their sincere gratitude to the study participants without whom this study could not have been conducted.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interests regarding the publication of this paper.

- Aghabarari M, Mohammadi I, Varvani-Farahani A. Barriers to Application of Communication Skills by Nurses in Nurse-Patient Interaction. Nurses and Patients’ Perspective. Iranian Journal of Nursing. 2009; 22 (16):19–31. [ Google Scholar ]

- Aghamolaei T, Hasani L. Communication barriers among nurses and elderly patients. Bimonthly Journal of Hormozgan University of Medical Sciences. 2011; 14 (4):312–318. [ Google Scholar ]

- Ammentorp J, Sabroe S, Kofoed P.-E, Mainz J. The effect of training in communication skills on medical doctors’ and nurses’ self-efficacy: A randomized controlled trial. Patient Education and Counseling. 2007; 66 (3):270–277. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.pec.2006.12.012 . [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Anoosheh M, Zarkhah S, Faghihzadeh S, Vaismoradi M. Nurse-patient communication barriers in Iranian nursing. International Nursing Review. 2009; 56 (2):243–249. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1466-7657.2008.00697.x . [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Baraz P. S, Shariati A. A, Alijani R. H, Moein M. S. Assessing barriers of nurse-patient’s effective communication in educational hospitals of Ahwaz. Iranian Journal of Nursing Research. 2010; 5 (16):45–52. [ Google Scholar ]

- Bartlett G, Blais R, Tamblyn R, Clermont R. J, MacGibbon B. Impact of patient communication problems on the risk of preventable adverse events in acute care settings. Canadian Medical Association Journal. 2008; 178 (12):1555–1562. http://dx.doi.org/10.1503/cmaj.070690 . [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Bridges J, Nicholson C, Maben J, Pope C, Flatley M, Wilkinson C, Tziggili M. Capacity for care: Meta-ethnography of acute care nurses’ experiences of the nurse-patient relationship. Journal of Advanced Nursing. 2013; 69 (4):760–772. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/jan.12050 . [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Cossette S, Cara C, Ricard N, Pepin J. Assessing nurse-patient interactions from a caring perspective: Report of the development and preliminary psychometric testing of the Caring Nurse-Patient Interactions Scale. International Journal of Nursing Studies. 2005; 42 (6):673–686. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2004.10.004 . [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Del Pino F. J. P, Soriano E, Higginbottom G. M. Sociocultural and linguistic boundaries influencing intercultural communication between nurses and Moroccan patients in southern Spain: A focused ethnography. BMC Nursing. 2013; 12 (1):14. http://dx.doi.org/10.1186/1472-6955-12-14 . [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Downey D, Happ M. B. The Need for Nurse Training to Promote Improved Patient-Provider Communication for Patients with Complex Communication Needs. Perspectives on Augmentative and Alternative Communication. 2013; 22 (2):112–119. http://dx.doi.org/10.1044/aac22.2.112 . [ Google Scholar ]

- Fleischer S, Berg A, Zimmermann M, Wüste K, Behrens J. Nurse-patient interaction and communication: A systematic literature review. Journal of Public Health. 2009; 17 (5):339–353. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s10389-008-0238-1 . [ Google Scholar ]

- Gilmartin J, Wright K. Day surgery: Patients’ felt abandoned during the preoperative wait. Journal of Clinical Nursing. 2008; 17 (18):2418–2425. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2702.2008.02374.x . [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Heaven C, Clegg J, Maguire P. Transfer of communication skills training from workshop to workplace: The impact of clinical supervision. Patient Education and Counseling. 2006; 60 (3):313–325. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.pec.2005.08.008 . [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Im E.-O, Chee W, Guevara E, Lim H.-J, Liu Y, Shin H. Gender and ethnic differences in cancer patients’ needs for help: An Internet survey. International Journal of Nursing Studies. 2008; 45 (8):1192–1204. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2007.09.006 . [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Jangland E, Gunningberg L, Carlsson M. Patients’ and relatives’ complaints about encounters and communication in health care: Evidence for quality improvement. Patient Education and Counseling. 2009; 75 (2):199–204. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.pec.2008.10.007 . [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Li H, Ang E, Hegney D. Nurses’ perceptions of the barriers in effective communicaton with impatient cancer adults in Singapore. Journal of Clinical Nursing. 2012; 21 (17-18):2647–2658. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2702.2011.03977.x . [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- McCabe C. Nurse-patient communication: An exploration of patients’ experiences. Journal of Clinical Nursing. 2004; 13 (1):41–49. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2702.2004.00817.x . [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Mendes I. A. C, Trevizan M, Nogueira M, Sawada N. Humanizing nurse-patient communication: A challenge and a commitment. Medicine and Law. 1999; 18 (1):639–644. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Nayeri N. D, Nazari A. A, Salsali M, Ahmadi F. Iranian staff nurses’ views of their productivity and human resource factors improving and impeding it: A qualitative study. Human Resources for Health. 2005; 3 (1):9. http://dx.doi.org/10.1186/1478-4491-3-9 . [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Okougha M, Tilki M. Experience of overseas nurses: The potential for misunderstanding. British Journal of Nursing. 2010; 19 (2):102–106. http://dx.doi.org/10.12968/bjon.2010.19.2.46293 . [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Park E.-k, Song M. Communication barriers perceived by older patients and nurses. International Journal of Nursing Studies. 2005; 42 (2):159–166. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2004.06.006 . [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Rejeh N, Heravi-Karimooi M, Vaismoradi M. Iranian nursing students’ perspectives regarding caring for elderly patients. Nursing & Health Sciences. 2011; 13 (2):118–125. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1442-2018.2011.00588.x . [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Sheldon L. K, Barrett R, Ellington L. Difficult communication in nursing. Journal of Nursing Scholarship. 2006; 38 (2):141–147. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1547-5069.2006.00091.x . [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Thorsteinsson L. S. The quality of nursing care as perceived by individuals with chronic illnesses: The magical touch of nursing. Journal of Clinical Nursing. 2002; 11 (1):32–40. http://dx.doi.org/10.1046/j.1365-2702.2002.00575.x . [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Work Environment

10 Ways to Overcome Communication Barriers in Nursing

Effective communication plays a vital role in nursing, fostering understanding, collaboration, and ultimately improving patient outcomes. However, various barriers can hinder communication within healthcare settings.

In this article, we will explore ten practical ways to overcome these communication barriers and enhance the delivery of care.

Importance of Effective Communication in Nursing

Effective communication lies at the heart of nursing practice. It forms the foundation for building relationships with patients, their families, and the interprofessional healthcare team.

When communication breaks down, patient safety, satisfaction, and overall quality of care are compromised. By understanding and addressing communication barriers, you, as a nurse, can ensure effective and meaningful interactions, leading to improved patient outcomes.

Common Communication Barriers in Nursing

Language and cultural differences.

Language barriers pose significant challenges in nursing, especially in multicultural healthcare settings. Nurses must communicate with patients who have limited English proficiency or speak a different native language. Additionally, cultural differences can influence communication styles and expectations. These barriers can lead to misunderstandings, inadequate information exchange, and reduced patient satisfaction.

Technological Challenges

With the increasing use of technology in healthcare, nurses face communication barriers related to unfamiliarity with electronic health records (EHRs) and other digital systems. Technical difficulties, such as system crashes or slow response times, can impede timely communication and information sharing among healthcare providers.

Hierarchy and Power Dynamics

In healthcare settings, hierarchical structures and power dynamics can hinder effective communication. Nurses may feel hesitant to express their opinions or concerns to physicians or higher-ranking professionals, resulting in vital information being overlooked. Open communication channels and a culture of collaboration are necessary to overcome these barriers.

Emotional and Psychological Factors

Nursing can be emotionally demanding, and stress, fatigue, and burnout can affect communication skills. These factors may lead to misinterpretation of messages, increased conflicts, and decreased empathy. Addressing the emotional well-being of nurses is essential to maintain effective communication in healthcare environments.

1. Active Listening

Active listening is a fundamental skill for effective communication in nursing. By actively engaging with patients, you can demonstrate empathy, gain valuable insights, and establish trust. Here are some techniques to enhance active listening:

- Maintain eye contact : Show your attentiveness and interest in what the patient is saying.

- Provide verbal and non-verbal cues : Nodding or smiling encourages patients to express themselves more openly.

- Practice reflective listening : Summarize and rephrase what the patient has said to ensure mutual understanding.

- Avoid interruptions : Allow patients to fully express their concerns and thoughts without interruption.

2. Clear and Concise Communication

Clear and concise communication is essential to ensure information is accurately conveyed and understood. When communicating with patients, consider the following strategies:

- Use simple language : Avoid complex medical jargon and explain information in a way that patients can easily comprehend.

- Avoid assumptions : Ensure that patients understand by asking open-ended questions and confirming their understanding.

- Confirm understanding through paraphrasing : Summarize the information shared by the patient to validate comprehension.

- Encourage questions and feedback : Create a safe environment for patients to ask questions and provide feedback, ensuring effective communication.

3. Open and Transparent Communication Channels

Creating open and transparent communication channels within healthcare settings is crucial for overcoming barriers. Here’s how you can achieve this:

- Foster a culture of open communication where all team members feel comfortable sharing their thoughts and concerns.

- Encourage feedback from colleagues and actively listen to their perspectives.

- Utilize regular team huddles or meetings to discuss communication challenges and find solutions collaboratively.

- Implement mechanisms such as suggestion boxes or anonymous feedback systems to provide an avenue for open communication.

- Share relevant information and updates with the healthcare team in a timely manner to ensure everyone is well-informed.

4. Empathy and Understanding

Empathy is the ability to understand and share the feelings of another person. In nursing, empathy promotes trust and patient-centered care. Enhance empathy and understanding by:

- Practice active empathy : Put yourself in the patient’s shoes and consider their emotions and experiences.

- Strive for cultural competence : Be mindful of cultural differences and tailor your communication to respect diverse backgrounds.

- Maintain a non-judgmental attitude : Create a supportive environment where patients feel comfortable expressing themselves without fear of judgment.

5. Non-Verbal Communication

Non-verbal cues, such as body language, facial expressions, and gestures, significantly influence communication in nursing. Utilize effective non-verbal communication to enhance your interactions with patients:

- Be aware of your body language and posture : Maintain an open and welcoming stance to convey approachability.

- Use facial expressions : Show empathy, concern, and reassurance through appropriate facial expressions.

- Utilize gestures and touch : Use gentle gestures and appropriate touch to convey comfort and support, when appropriate.

6. Use of Technology

In the modern healthcare landscape, technology plays a significant role in communication. While it offers numerous advantages, it can also present challenges. Embrace technology and leverage its potential for effective communication:

- Utilize electronic health records : Ensure accurate and timely documentation, promoting continuity of care.

- Explore telemedicine and video conferencing : Facilitate remote consultations and improve access to healthcare services.

- Leverage mobile communication devices : Use secure messaging platforms to communicate efficiently with colleagues and share important patient information.

7. Team Collaboration

Collaboration among healthcare professionals is crucial for providing holistic patient care. Effective team communication ensures that everyone involved is well-informed, contributing to seamless coordination. Foster effective collaboration through:

- Interprofessional communication: Maintain open lines of communication with colleagues from different disciplines.

- Participate in regular team meetings : Discuss patient care plans, exchange information, and address any communication challenges.

- Establish clear role expectations : Define each team member’s responsibilities and ensure everyone understands their role in patient care.

8. Patient Education

Patient education empowers individuals to actively participate in their care. As a nurse, you play a vital role in educating patients and breaking down complex medical information. Enhance patient education through:

- Use visual aids : Utilize diagrams, charts, and models to simplify complex concepts and enhance understanding.

- Provide written materials and handouts : Give patients written instructions and resources they can refer to after their interaction with you.

- Ensure patient comprehension : Use teach-back techniques to confirm that patients understand the information you have shared.

9. Language and Cultural Considerations

Language and cultural barriers can significantly impact communication in healthcare. Address these barriers by:

- Utilizing professional interpreters : When language barriers exist, engage the services of interpreters to facilitate effective communication.

- Understanding cultural norms and beliefs : Be culturally sensitive and adapt your communication style to accommodate diverse cultural backgrounds.

- Providing translated materials : Offer translated written materials and resources to assist patients who may have language limitations.

10. Feedback and Continuous Improvement

Feedback is essential for growth and development in nursing communication. Seek feedback from patients and colleagues to identify areas for improvement. Foster a culture of continuous improvement by:

- Seeking feedback from patients : Encourage patients to share their experiences and suggestions for better communication.

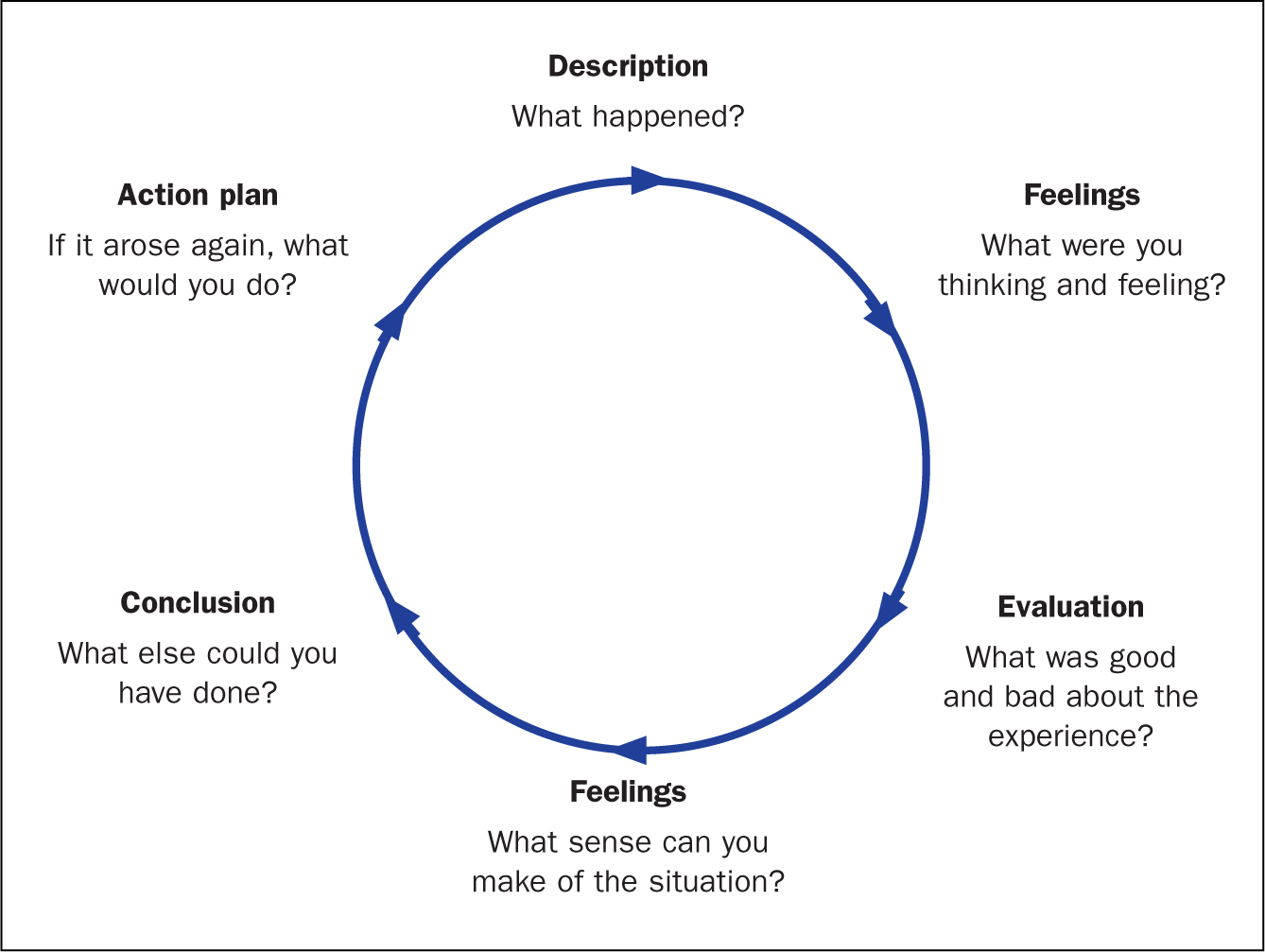

- Reflecting on your communication practices : Take time to evaluate your communication techniques and identify areas where you can improve.

- Participating in training and workshops : Attend professional development opportunities to enhance your communication skills and stay up-to-date with best practices.

Benefits of Overcoming Communication Barriers

By overcoming communication barriers, nursing professionals can experience numerous benefits:

- Improved Patient Outcomes: Effective communication leads to better patient understanding of their condition and treatment plans, reducing the risk of medical errors and improving overall healthcare outcomes.

- Enhanced Collaboration and Teamwork: Clear communication fosters collaboration among healthcare professionals, facilitating coordinated care and shared decision-making, ultimately benefiting patient outcomes.

- Increased Patient Satisfaction: When patients feel heard and understood, their satisfaction with the healthcare experience increases, leading to greater patient engagement and adherence to treatment plans.

- Reduced Errors and Misunderstandings: Overcoming communication barriers minimizes the likelihood of misinterpretations, misunderstandings, and errors that can compromise patient safety.

Training and Education for Effective Communication

To equip nurses with effective communication skills, various training and educational opportunities can be provided:

- Communication Skills Workshops: Organizing workshops that focus on active listening, conflict resolution, and effective communication techniques can enhance nurses’ interpersonal skills.

- Cultural Competency Training: Offering training programs that promote cultural awareness, sensitivity, and understanding helps nurses navigate diverse patient populations and communicate effectively across cultures.

- Technology Integration Training: Providing comprehensive training on using digital systems, EHRs, and other communication tools ensures nurses can leverage technology for efficient and secure communication.

In conclusion, effective communication in nursing is vital for providing safe, quality care. By implementing these ten strategies we mentioned above, you can overcome communication barriers, establish meaningful connections, and optimize patient outcomes. Remember, communication is a skill that can always be honed, and fostering open, empathetic, and clear interactions is key to delivering exceptional nursing care.

Q: How can you overcome communication barriers with patients who have limited English proficiency?

A: To overcome language barriers, you can utilize professional interpreters, use visual aids and gestures, and provide translated written materials. It’s important to create a supportive environment and allow extra time for communication with patients who have limited English proficiency.

Q: What are some effective strategies for communicating with patients from diverse cultural backgrounds?

A: When communicating with patients from diverse cultural backgrounds, it is important to be culturally sensitive, respect cultural norms and beliefs, and use culturally appropriate communication styles. Take the time to learn about different cultures, ask open-ended questions, and actively listen to foster effective communication.

Q: How can you promote effective communication during challenging situations, such as delivering difficult news to patients or their families?

A: When delivering difficult news, you can promote effective communication by demonstrating empathy, providing a calm and supportive environment, and using clear and compassionate language. Allow patients and their families to express their emotions, actively listen to their concerns, and offer appropriate support and resources.

Q: What can you do to improve communication within interdisciplinary healthcare teams?

A: To improve communication within interdisciplinary teams, actively participate in regular team meetings, clarify roles and responsibilities, and maintain open and respectful communication channels. Share information, seek input from team members, and foster a collaborative environment to enhance teamwork and patient outcomes.

Q: How can you ensure effective communication during patient handoffs or transitions of care?

A: To ensure effective communication during patient handoffs, use standardized protocols, document important information accurately, and engage in face-to-face or electronic communication with the receiving healthcare team. Provide a comprehensive and concise summary of the patient’s condition, treatment plan, and any ongoing concerns.

Q: How can you incorporate feedback from patients into your communication practices?

A: Actively seek feedback from patients by encouraging them to share their experiences, concerns, and suggestions. Provide patient satisfaction surveys or feedback forms to facilitate the collection of valuable input. By listening to patient feedback and implementing necessary improvements, you can continuously enhance your communication skills.

Sophia Miller

Similar posts.

6 Ways to Overcome Interdisciplinary Challenges in…

10 Ways to Build Positive Workplace Culture…

20 Most Common Ethical Dilemmas in Nursing…

10 Ways to Overcome Leadership Challenges in…

Are Male Nurses Attractive?

Can Nurses Wear Rings?

- Career Advancement 29

- Career Transection 20

- Job Satisfaction 16

- Managing Difficult Situations 6

- Work-Life Balance 14

- NCLEX Guide 50

- New Grad Nurse 21

- Nursing Practice Challenges 35

- Work Environment 23

- Emotional Challenges 3

POPULAR POSTS

What Does Baylor Shift Mean?

Can Male Nurses Have Long Hair?

Can You Take a Picture of Your Nurse?

Do School Nurses Wear Scrubs?

Can Nurses Carry Guns?

How Often Do Travel Nurses Get Audited?

- school Campus Bookshelves

- menu_book Bookshelves

- perm_media Learning Objects

- login Login

- how_to_reg Request Instructor Account

- hub Instructor Commons

Margin Size

- Download Page (PDF)

- Download Full Book (PDF)

- Periodic Table

- Physics Constants

- Scientific Calculator

- Reference & Cite

- Tools expand_more

- Readability

selected template will load here

This action is not available.

3.7: Barriers to Effective Communication

- Last updated

- Save as PDF

- Page ID 49264

- Maureen Nokuthula Sibiya

- Gümüşhane University via IntechOpen

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

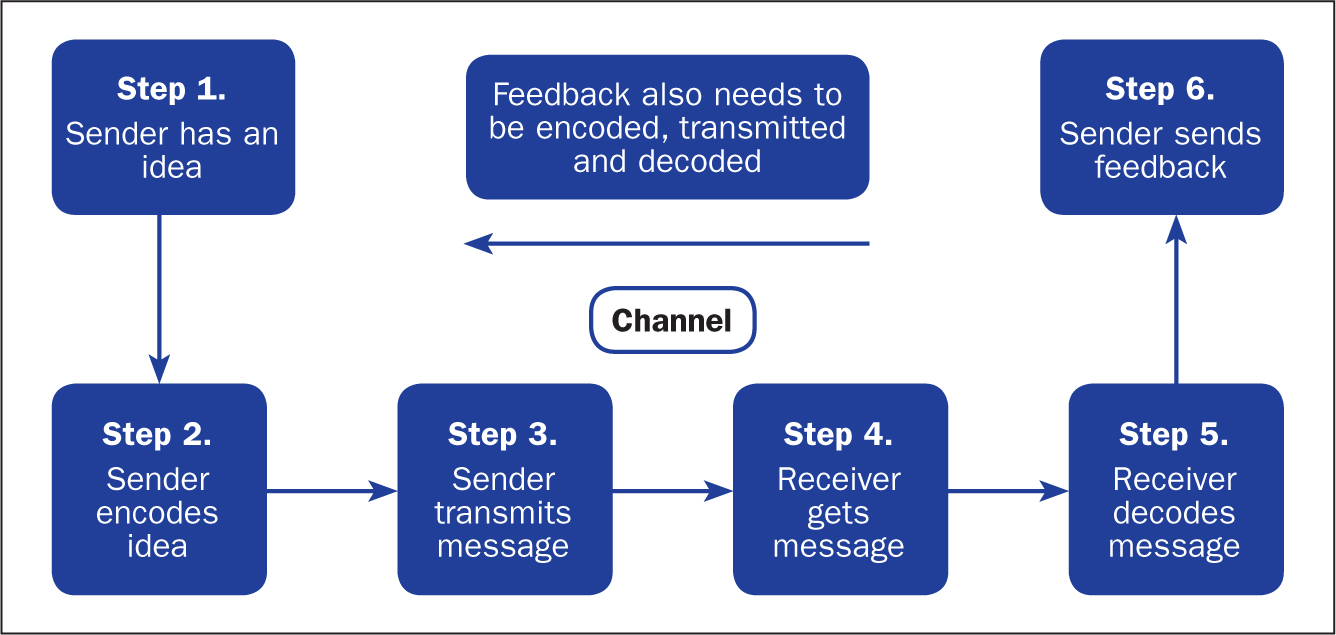

Effective communication skills and strategies are important for nurses. Clear communication means that information is conveyed effectively between the nurse, patients, family members and colleagues. However, it is recognized that such skills are not always evident and nurses do not always communicate well with patients, family members and colleagues. The message sent may not be the message received. The meaning of a message depends on its literal meaning, the non-verbal indicators accompanying it and the context in which it is delivered. It is therefore, easy to misinterpret the message, or to interpret it correctly, but to decide not to pursue its hidden meaning this leads to obstruction to communication. Continuous barriers to effective communication brings about a gradual breakdown in relationships. The barriers to effective communication outlined below will help nurses to understand the challenges [ 8 ].

Language Barrier

Language differences between the patient and the nurse are another preventive factor in effective communication. When the nurse and the patient do not share a common language, interaction between them is strained and very limited [ 9 , 10 , 11 ]. Consequently, a patient may fail to understand the instructions from a nurse regarding the frequency of taking medication at home.

Cultural Differences

Culture is another hindrance. The patient’s culture may block effective nurse–patient interactions because perceptions on health and death are different between patients [ 12 , 13 , 14 ]. The nurse needs to be sensitive when dealing with a patient from a different culture [ 9 , 15 , 16 ]. What is acceptable for one patient may not be acceptable for another. Given the complexity of culture, no one can possibly know the health beliefs and practices of every culture. The nurse needs check with the patient whether he/she prefers to be addressed by first name or surname. The use of eye contact, touching and personal space is different in various cultures and rules about eye contact are usually complex, varying according to race, social status and gender. Physical contact between sexes is strictly forbidden in some cultures and can include handshakes, hugging or placing a hand on the arm or shoulder. A ‘yes’ does not always mean ‘yes’. A smile does not indicate happiness, recognition or agreement. Whenever people communicate, there is a tendency to make value judgements regarding those perceived as being different. Past experiences can change the meaning of the message. Culture, background and bias can be good if they allow one to use past experiences to understand something new; it is when they change meaning of the message that they interfere with the communication process [ 12 ]. It is important for nurses to think about their own experiences when considering cultural differences in communication and how these can challenge health professionals and service users.

Conflict is a common effect of two or more parties not sharing common ground. Conflict can be healthy in that it offers alternative views and values. However, it becomes a barrier to communication when the emotional ‘noise’ detracts from the task or purpose. Nurses aim for collaborative relationships with patients, families and colleagues.

Setting in Which Care is Provided

The factors in care setting may lead to reduction in quality of nurse–patient communication. Increased workload and time constraints restrict nurses from discussing their patients concerns effectively [ 16 ]. Nurses work in busy environments where they are expected to complete a specific amount of work in a day and work with a variety of other professionals, patients and their families. The roles are hard, challenging and tiring. There is a culture to get the work done. Some nurses may consider colleagues who spend time talking with patients to be avowing the ‘real’ work and lazy. Nurses who might have been confident in spending time with patients in an area where this was valued, when faced with a task-orientated culture have the dilemma of fitting into the group or being outside the group and spending time engaging with patients. Lack of collaboration between the nurses and the doctors in information sharing also hinder effective communication. This leads to inconsistencies in the information given to patients making comprehension difficult for the patient and their families.

Internal Noise, Mental/Emotional Distress

Internal noise has an impact on the communication process. Fear and anxiety can affect the person’s ability to listen to what the nurse is saying. People with feelings of fear and anger can find it difficult to hear. Illness and distress can alter a person’s thought processes. Reducing the cause of anxiety, distress, and anger would be the first step to improving communication.

If a healthcare professional feels that the person is talking too fast, not fluently, or does not articulate clearly etc., he/she may dismiss the person. Our preconceived attitudes affect our ability to listen. People tend to listen uncritically to people of high status and dismiss those of low status.

Difficulty With Speech and Hearing

People can experience difficulty in speech and hearing following conditions like stroke or brain injury. Stroke or trauma may affect brain areas that normally enable the individual to comprehend and produce speech, or the physiology that produces sound. These will present barriers to effective communication.

Medication can have a significant effect on communication for example it may cause dry mouth or excess salivation, nausea and indigestion, all of which influence the person’s ability and motivation to engage in conversation. If patients are embarrassed or concerned that they will not be able to speak properly or control their mouth, they could be reluctant to speak.

Equipment or environmental noise impedes clear communication. The sender and the receiver must both be able to concentrate on the messages they send to each other without any distraction.

- Login / Register

‘Let’s hear it for the midwives and everything they do’

STEVE FORD, EDITOR

- You are here: Assessment skills

Communication skills 2: overcoming the barriers to effective communication

18 December, 2017 By NT Contributor

This article, the second in a six-part series on communication skills, a discusses the barriers to effective communication and how to overcome them

Competing demands, lack of privacy, and background noise are all potential barriers to effective communication between nurses and patients. Patients’ ability to communicate effectively may also be affected by their condition, medication, pain and/or anxiety. Nurses’ and patients’ cultural values and beliefs can also lead to misinterpretation or reinterpretation of key messages. This article, the second in a six-part series on communication skills , suggests practical ways of overcoming the most common barriers to communication in healthcare.

Citation: Ali M (2017) Communication skills 2: overcoming barriers to effective communication Nursing Times ; 114: 1, 40-42.

Author: Moi Ali is a communications consultant, a board member of the Scottish Ambulance Service and of the Professional Standards Authority for Health and Care, and a former vice-president of the Nursing and Midwifery Council.

- This article has been double-blind peer reviewed

- Scroll down to read the article or download a print-friendly PDF here

- Click here to see other articles in this series

- Read Moi Ali’s comment

Introduction

It is natural for patients to feel apprehensive about their health and wellbeing, yet a survey in 2016 found that only 38% of adult inpatients who had worries or fears could ‘definitely’ find someone in hospital to talk to about them (Care Quality Commission, 2017). There are numerous barriers to effective communication including:

- Time constraints;

- Environmental issues such as noise and privacy;

- Pain and fatigue;

- Embarrassment and anxiety;

- Use of jargon;

- Values and beliefs;

- Information overload.

Time constraints

Time – or lack of it – creates a significant barrier to communication for nurses (Norouzinia et al, 2016). Hurried communication is never as effective as a leisurely interaction, yet in pressured workplaces, nurses faced with competing demands may neglect the quality of communication. It is important to remember that communication does not need to be time-consuming – a smile, hello, or some ‘small talk’ about the weather may suffice. Even when there is no pressing news to tell individual patients, taking the time to get to know them can prepare the ground for difficult conversations that may need to take place in the future.

In a pressured ward or clinic, conversations between patients and nurses may be delayed or interrupted because of the needs of other patients – for example, they may need to respond to an emergency or pain relief. This can be frustrating for patients who may feel neglected. If interruptions occur it is important to explain to patients that you have to leave and why. Arranging to return within a specified time frame may be enough to reassure them that you are aware that their concerns are important (Box 1).

Box 1. Making time for communication

Nurse Amy Green was allocated a bay of four patients and two side wards for her shift. Halfway through the morning one of her patients in a side ward became very ill and Amy realised that she needed to spend a lot of time with him. She quickly visited her other patients to explain what was happening, and reassured them that she had not forgotten about them. She checked that they were comfortable and not in pain, asked them to ring the call bell if they needed her, and explained that she would return as soon as she could. The patients understood the situation and were reassured that their immediate needs had been assessed and they were not being neglected.

Environmental factors

You may be so familiar with your surroundings that you no longer notice the environmental factors that can create communication difficulties. Background noise in a busy clinic can affect patients’ ability to hear, and some may try to disguise this by nodding and ‘appearing’ to hear. If you think your patient has hearing problems, reduce background noise, find a quiet corner or step into a quiet side room or office. Check whether your patient uses physical aids, such as hearing aids or spectacles and that these are in working order.

Noise and other distractions can impede communication with patients with dementia and other cognitive impairments, who find concentration challenging. If you have to communicate an important message to a patient with poor concentration, it is useful to plan ahead and identify the best place and time to talk. It can be helpful to choose a time when you are less busy, without competing activities such as medicine rounds or meal times to interrupt your discussion.

Patients may be reticent to provide sensitive personal information if they are asked about their clinical history within earshot of other people, such as at a busy reception desk or in a cubicle with just a curtain for privacy. It is important to avoid asking sensitive questions where others may hear patients’ replies. Consider alternative ways of gathering pertinent information, such as asking the patient to complete a written form – but remember that some patients struggle with reading and writing or may need the form to be provided in a different language or have someone translate for them.

Pain and fatigue

We often need to gain important information from patients when they are acutely ill and distressed, and symptoms such as pain can reduce concentration. If you urgently need to gather information, it is important to acknowledge pain and discomfort: “I know that it is painful, but it’s important that we discuss.”

Patients may also be tired from a sleepless night, drowsy after an anaesthetic or experiencing the side-effects of medicines. Communicating with someone who is not fully alert is difficult, so it is important to prioritise the information you need, assess whether it is necessary to speak to the patient and ask yourself:

- Is this the best time for this conversation?

- Can my message wait?

- Can I give part of the message now and the rest later?

When patients cannot give their full attention, consider whether your message could be broken down into smaller pieces so there is less to digest in one go: “I will explain your medication now. I’ll return after lunch to tell you about how physiotherapy may help.” Ask if they would like any of the information repeated.

If you have to impart an important piece of information, acknowledge how the patient is feeling: “I know that you’re tired, but …”. Showing empathy can build rapport and make patients more receptive. It may also be useful to stress the need to pay attention: “It’s important that you listen because …”. Consider repeating the message: “It can be difficult to take everything in when you’re tired, so I just wanted to check that you’re clear about …”. If the communication is important, ask the patient to repeat it back to you to check it has been understood.

Embarrassment and anxiety

Would you feel comfortable undressing in front of a complete stranger, or talking about sex, difficult family circumstances, addictions or bowel problems? Patients’ and health professionals’ embarrassment can result in awkward encounters that may hamper effective communication. However, anticipating potential embarrassment, minimising it, and using straightforward, open communication can ease difficult conversations. For example, in a clinic, a patient may need to remove some clothes for an examination. It is important to be direct and specific. Do not say: “Please undress”, as patients may not know what to remove; give specific instructions: “Please remove your trousers and pants, but keep your shirt on”. Clear directions can ease stress and embarrassment when delivered with matter-of-fact confidence.

Patients may worry about embarrassing you or themselves by using inappropriate terms for anatomical parts or bodily functions. You can ease this embarrassment by introducing words such as “bowel movements” or “penis” into your questions, if you think they are unsure what terminology to use. Ambiguous terms such as “stool”, which have a variety of everyday meanings, should be avoided as they may cause confusion.

Many patients worry about undergoing intimate procedures such as bowel and bladder investigations. Explain in plain English what an examination involves, so that patients know what to expect. Explaining any side-effects of procedures – such as flatulence or vomiting – not only warns patients what to expect but reassures them that staff will not be offended if these occur.

Box 2 provides some useful tips on dealing with embarrassment.

Box 2. Managing embarrassment

- Look out for signs of embarrassment – not just obvious ones like blushing, but also laughter, joking, fidgeting and other behaviours aimed at masking it

- Think about your facial expressions when communicating with patients, and use positive, open body language such as appropriate eye contact or nodding

- Avoid disapproving or judgmental statements by phrasing questions carefully: “You don’t drink more than 10 glasses of wine a week, do you?” suggests that the ‘right’ or desired answer is ‘no’. A neutral, open question will elicit a more honest response: “How many glasses of wine do you drink in a typical week?”

Some patients are reluctant to ask questions, seek clarification or request that information be repeated for fear of wasting nurses’ time. It is important to let them know that their health or welfare is an integral part of your job. They also need to know that there is no such thing as a silly question. Encourage questions by using prompts and open questions such as: “You’re bound to have questions – are there any that I can answer for you now?”; “What else can I tell you about the operation?”. It is also possible to anticipate and address likely anxieties such as “Will it be painful?”; “Will I get better?”; or “Will I die?”.

Jargon can be an important communication aid between professionals in the same field, but it is important to avoid using technical jargon and clinical acronyms with patients. Even though they may not understand, they may not ask you for a plain English translation. It is easy to slip into jargon without realising it, so make a conscious effort to avoid it.

A report on health literacy from the Royal College of General Practitioners (2014) cited the example of a patient who took the description of a “positive cancer diagnosis” to be good news, when the reverse was the case. If you have to use jargon, explain what it means. Wherever possible, keep medical terms as simple as possible – for example, kidney, rather than renal and heart, not cardiac. The Plain English website contains examples of healthcare jargon.

Box 3 gives advice on how to avoid jargon when speaking with patients.

Box 3. Avoiding jargon

- Avoid ambiguity: words with one meaning for a nurse may have another in common parlance – for example, ‘acute’ or ‘stool’

- Use appropriate vocabulary for the audience and age-appropriate terms, avoiding childish or over-familiar expressions with older people

- Avoid complex sentence structures, slang or speaking quickly with patients who are not fluent in English

- Use easy-to-relate-to analogies when explaining things: “Your bowel is a bit like a garden hose”

- Avoid statistics such as “There’s an 80% chance that …” as even simple percentages can be confusing. “Eight in every 10 people” humanises the statistic

Values, beliefs and assumptions

Everyone makes assumptions based on their social or cultural beliefs, values, traditions, biases and prejudices. A patient might genuinely believe that female staff must be junior, or that a man cannot be a midwife. Be alert to patients’ assumptions that could lead to misinterpretation, reinterpretation, or even them ignoring what you are telling them. Think about how you can address such situations; for example explain your role at the outset: “Hello, I am [your name], the nurse practitioner who will be examining you today.”

It is important to be aware of your own assumptions, prejudices and values and reflect on whether they could affect your communication with patients. A nurse might assume that a patient in a same-sex relationship will not have children, that an Asian patient will not speak good English, or that someone with a learning disability or an older person will not be in an active sexual relationship. Incorrect assumptions may cause offence. Enquiries such as asking someone’s “Christian name” may be culturally insensitive for non-Christians.

Information overload

We all struggle to absorb lots of facts in one go and when we are bombarded with statistics, information and options, it is easy to blank them out. This is particularly so for patients who are upset, distressed, anxious, tired, in shock or in pain. If you need to provide a lot of information, assess how the patient is feeling and stick to the pertinent issues. You can flag up critical information by saying: “You need to pay particular attention to this because …”.

Box 4 provides tips on avoiding information overload.

Box 4. Avoiding information overload

- Consider suggesting that your patient involves a relative or friend in complex conversations – two pairs of ears are better than one. However, be aware that some patients may not wish others to know about their health

- Suggest patients take notes if they wish

- With patients’ consent, consider making a recording (or asking whether the patient wishes to record part of the consultation on their mobile phone) so they can replay it later or share it with a partner who could not accompany them

- Give written information to supplement or reinforce the spoken word

- Arrange another meeting if necessary to go over details again or to provide further information

It is vital that all nurses are aware of potential barriers to communication, reflect on their own skills and how their workplace environment affects their ability to communicate effectively with patients. You can use this article and the activity in Box 5 to reflect on these barriers and how to improve and refine your communication with patients.

Box 5. Reflective activity

Think about recent encounters with patients:

- What communication barriers did you encounter?

- Why did they occur?

- How can you amend your communication style to take account of these factors so that your message is not missed, diluted or distorted?

- Do you need support to make these changes?

- Who can you ask for help?

- Nurses need to be aware of the potential barriers to communication and adopt strategies to address them

- Environmental factors such as background noise can affect patients’ ability to hear and understand what is being said to them

- Acute illness, distress and pain can reduce patients’ concentration and their ability to absorb new information

- Anticipating potential embarrassment and taking steps to minimise it can facilitate difficult conversations

- It is important to plan ahead and identify the best place and time to have important conversations

Also in this series

- Communication skills 1: benefits of effective communication for patients

- Communication skills 3: non-verbal communication

- Communication 4: the influence of appearance and environment

- Communication 5: effective listening and observation skills

- Communication skills 6: difficult and challenging conversations

Related files

171220 communication skills 2 overcoming barriers to effective communication.

- Add to Bookmarks

Related articles

Have your say.

Sign in or Register a new account to join the discussion.

This website is intended for healthcare professionals

- { $refs.search.focus(); })" aria-controls="searchpanel" :aria-expanded="open" class="hidden lg:inline-flex justify-end text-gray-800 hover:text-primary py-2 px-4 lg:px-0 items-center text-base font-medium"> Search

Search menu

Abdolrahimi M, Ghiyasvandian S, Zakerimoghadam M, Ebadi A. Therapeutic communication in nursing student: a Walker and Avant concept analysis. Electron Physician.. 2017; 9:(8)4968-4977 https://doi.org/10.19082/4968

Communication skills 1: benefits of effective communication for patients. 2017. https://tinyurl.com/y3nzu222 (accessed 10 August 2020)

Communication skills 3: non-verbal communication. 2018. https://tinyurl.com/y5ay4uhd (accessed 10 August 2020)

Bandura A. Self-efficacy: toward a unifying theory of behavior change. Psychol Rev.. 1977; 84:191-215 https://doi.org/10.1016/0146-6402(78)90002-4

Barratt J. Developing clinical reasoning and effective communication skills in advanced practice. Nurs Stand.. 2019; 34:(2)37-44 https://doi.org/10.7748/ns.2018.e11109

Bergdahl E, Berterö CM. Concept analysis and the building blocks of theory: misconceptions regarding theory development. J Adv Nurs.. 2016; 72:(10)2558-2566 https://doi.org/10.1111/jan.13002

Bloomfield J, Pegram A. Care, compassion and communication. Nurs Stand.. 2015; 29:(25)45-50 https://doi.org/10.7748/ns.29.25.45.e7653

Bramhall E. Effective communication skills in nursing practice. Nurs Stand.. 2014; 29:(14)53-59 https://doi.org/10.7748/ns.29.14.53.e9355

Brown R. An analysis of loneliness as a concept of importance for dying persons. In: McKenna H, Cutcliffe J (eds). Philadelphia (PA): Elsevier Churchill Livingstone; 2005

Burley D. Better communication in the emergency department. Emerg Nurse.. 2011; 19:(2)32-36 https://doi.org/10.7748/en2011.05.19.2.32.c8509

Cambridge University Press. Effective. 2018. https://tinyurl.com/y7dqcypc (accessed 10 August 2020)

Campbell JD, Lavallee LF. Who am I? The role of self-concept confusion in understanding the behavior of people with low self-esteem. In: Baumeister RF (ed). New York (NY): Plenum Press; 1993

Carment DW, Miles CG, Cervin VB. Persuasiveness and persuasibility as related to intelligence and extraversion. Br J Soc Clin Psychol.. 1965; 4:(1)1-7 https://doi.org/10.1111/j.2044-8260.1965.tb00433.x

Casey A, Wallis A. Effective communication: principle of nursing practice E. Nurs Stand.. 2011; 25:(32)35-37 https://doi.org/10.7748/ns2011.04.25.32.35.c8450

Daly L. Effective communication with older adults. Nurs Stand.. 2017; 31:(41)55-62 https://doi.org/10.7748/ns.2017.e10832

Department of Health and Social Care. Essence of care 2010: benchmarks for the fundamental aspects of care. 2010. https://tinyurl.com/y3z8grqe (accessed 10 August 2020)

Dithole KS, Thupayagale-Tshweneagae G, Akpor AO, Moleki MM. Communication skills intervention: promoting effective communication between nurses and mechanically ventilated patients. BMC Nurs.. 2017; 16:(74)1-6 https://doi.org/10.1186/s12912-017-0268-5

Draper P. A critique of concept analysis. J Adv Nurs.. 2014; 70:(6)1207-1208 https://doi.org/10.1111/jan.12280

Duldt BW, Giffin K, Patton BR. Interpersonal communication in nursing: a humanistic approach.Philadelphia (PA): FA Davis; 1983

Fakhr-Movahedi A, Salsali M, Negharandeh R, Rahnavard Z. Exploring contextual factors of the nurse-patient relationship: a qualitative study. Koomesh.. 2011; 13:(1)23-34

Fleischer S, Berg A, Zimmermann M, Wuste K, Behrens J. Nurse-patient interaction and communication: a systematic literature review. J Public Health.. 2009; 17:339-353 https://doi.org/10.1007/s10389-008-0238-1

Foley A, Davis A. A guide to concept analysis. Clin Nurse Spec.. 2017; 31:(2)70-73 https://doi.org/10.1097/NUR.0000000000000277

Gadamer HG. Philosophical hermeneutics. Translated by DE Linge.Berkeley (CA): University of California Press; 1976

Gallagher L. Continuing education in nursing: a concept analysis. Nurse Educ Today.. 2007; 27:(5)466-473 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nedt.2006.08.007

Ghafouri R, Rafii F, Oskouie F, Parvizy S, Mohammadi N. Nursing professional regulation: Rodgers' evolutionary concept analysis. Int J Med Res Health Sci. 2016; 5:(9S)436-442

Griffiths J. Person-centred communication for emotional support in district nursing: SAGE and THYME model. Br J Community Nurs.. 2017; 22:(12)593-597 https://doi.org/10.12968/bjcn.2017.22.12.593

Hazzard A, Harris W, Howell D. Taking care: practice and philosophy of communication in a critical care follow-up clinic. Intensive Crit Care Nurs.. 2013; 29:(3)158-165 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.iccn.2013.01.003

Jevon P. Clinical examination skills.Chichester: Wiley-Blackwell Publications; 2009

Jones A. The foundation of good nursing practice: effective communication. J Renal Nurs.. 2012; 4:(1)37-41 https://doi.org/10.12968/jorn.2012.4.1.37

Kelton D, Davis C. The art of effective communication. Nurs Made Incred Easy.. 2013; 11:(1)55-56 https://doi.org/10.1097/01.NME.0000423378.98763.96

Kourkouta L, Papathanasiou IV. Communication in nursing practice. Mater Sociomed.. 2014; 26:(1)65-67 https://doi.org/10.5455/msm.2014.26.65-67

McCabe C. Nurse patient communication: an exploration of patients' experiences. J Clin Nurs.. 2004; 13:41-49 https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2702.2004.00817.x

McCabe C, Timmins F. Communication skills for nursing practice, 2nd edn. Basingstoke: Palgrave; 2013

McCarthy DM, Buckley BA, Engel KG, Forth VE, Adams JG, Cameron KA. Understanding patient-provider conversations: what are we talking about?. Acad Emerg Med.. 2013; 20:(5)441-448 https://doi.org/10.1111/acem.12138

McCroskey JC, Richmond VP. Willingness to communicate: differing cultural perspectives. South Commun J.. 1990; 56:(1)72-77 https://doi.org/10.1080/10417949009372817

McCuster M. Apathy: who cares? A concept analysis. Ment Health Nurs.. 2015; 36:693-697 https://doi.org/10.3109/01612840.2015.1022844

McKenna HP. Nursing theories and models.London: Routledge; 1997

McKinnon J. The case for concordance: value and application in nursing practice. Br J Nurs.. 2013; 22:(13)16-21 https://doi.org/10.12968/bjon.2013.22.13.766

Miller L. Effective communication with older people. Nurs Stand.. 2002; 17:(9)45-50 https://doi.org/10.7748/ns2002.11.17.9.45.c3298

Newell S, Jordan Z. The patient experience of patient-centered communication with nurses in the hospital settings: a qualitative systematic review protocol. JBI Database System Rev Implement Rep.. 2015; 13:(1)76-87 https://doi.org/10.11124/jbisrir-2015-1072

Norouzinia R, Aghabarari M, Shiri M, Karimi M, Samami E. Communication barriers perceived by nurses and patients. Glob J Health Sci.. 2016; 8:(6)65-74 https://doi.org/10.5539/gjhs.v8n6p65

Nuopponen A. Methods of concept analysis: a comparative study. LSP.. 2010; 1:(1)4-12

Nursing and Midwifery Council. The code: professional standards of practice and behaviour for nurses, midwives and nursing associates. 2018. https://tinyurl.com/zy7syuo (accessed 10 August 2020)

O'Hagan S, Manias E, Elder C What counts as effective communication in nursing? Evidence from nurse educators' and clinicians' feedback on nurse interactions with simulated patients. J Adv Nurs.. 2013; 70:(6)1344-1355 https://doi.org/10.1111/jan.12296

Orem DE. Nursing: concepts of practice, 4th edn. St. Louis (MO): Mosby-Year Book; 1991

Oxford University Press. Communication. 2018. https://tinyurl.com/y7k22yxb (accessed 10 August 2020)

Communication barriers. 2016. https://tinyurl.com/y3sn342h (accessed 10 August 2020)

Reader TW, Gillespie A, Roberts J. Patient complaints in healthcare systems: a systematic review and coding taxonomy. BMJ Qual Saf.. 2014; 23:(8)678-689 https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjqs-2013-002437

Rodgers BL. Concepts, analysis and the development of nursing knowledge: the evolutionary cycle. J Adv Nurs.. 1989; 14:(4)330-335 https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2648.1989.tb03420.x

Rodgers BL, Knafi KA. Concept development in nursing: foundations, techniques and applications, 2nd edn. Philadelphia (PA): WB Saunders; 2000

Royal College of Nursing. Communication-end of life care. 2015. https://tinyurl.com/go28vsm (accessed 10 August 2020)

Schirmer JM, Mauksch L, Lang F Assessing communication competence: a review of current tools. Fam Med.. 2005; 37:(3)184-192

Skär L, Söderberg S. Patients' complaints regarding healthcare encounters and communication. Nurs Open.. 2018; 5:(2)224-232 https://doi.org/10.1002/nop2.132

Snowden A, Martin C, Mathers B, Donnell A. Concordance: a concept analysis. J Adv Nurs.. 2014; 70:(1)46-59 https://doi.org/10.1111/jan.12147

Tay LH, Ang E, Hegney D. Nurses' perceptions of the barriers in effective communication with inpatient cancer adults in Singapore. J Clin Nurs. 2011; 21:(17-18)2647-2658 https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2702.2011.03977.x

Thompson CJ. Nursing theory and philosophy terms: a guide.South Fork (CO): CJT Consulting and Education; 2017

Tofthagen R, Fagerstrøm LM. Rodgers' evolutionary concept analysis – a valid method for developing knowledge in nursing science. Scand J Caring Sci. 2010; 24:21-31 https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1471-6712.2010.00845.x

Nursing, admission assessment and examination. 2018. https://tinyurl.com/y4ykv2uo (accessed 10 August 2020)

Walker LO, Avant KC. Strategies for theory construction in nursing, 5th edn. Norwalk (CT): Appleton and Lange; 2011

Webb L. Exploring the characteristics of effective communicators in healthcare. Nurs Stand.. 2018; 33:(9)47-51 https://doi.org/10.7748/ns.2018.e11157

Wikström B, Svidén G. Exploring communication skills training in undergraduate nurse education by means of a curriculum. Nurs Rep.. 2011; 1:(1) https://doi.org/10.4081/nursrep.2011.e7

Effective communication between nurses and patients: an evolutionary concept analysis

Dorothy Afriyie