- +1 0234 56 7890

- [email protected]

Effective Decision-Making: A Case Study

Effective decision-making:, leading an organization through timely and impactful action.

Senior leaders at a top New England insurance provider need to develop the skills and behaviors for better, faster decision-making. This virtually delivered program spans four half-day sessions and includes individual assignments, facilitator-led presentations, and simulation decision-making. Over the past two months, this program touched over 100 leaders, providing them with actionable models and frameworks to use back on the job.

For one of New England’s most iconic insurers, senior leaders are challenged to make timely, effective decisions. These leaders face decisions on three levels: ones they translate to their teams, ones they make themselves, and ones they influence. But in a quickly changing, highly regulated market, risk aversion can lead to slow and ineffective decisions. How can senior leaders practice in a safe environment the quick, yet informed, decision-making necessary for the job while simultaneously learning new models and techniques — and without the learning experience burdening their precious time?

The Effective Decision-Making program was artfully designed to immerse senior leaders in 16 hours of hands-on experience, including reflection and feedback activities, applicable exercises, supporting content, and participation in a business simulation to practice the core content of the program. Participants work together in small groups to complete these activities within a limited time frame, replicating the work environment in which these leaders must succeed. Continuous reflection and group discussion around results create real-time learning for leaders. Application exercises then facilitate the simulation experience and their work back on the job. The program employs a variety of learning methodologies, including:

- Individual assignments that incorporate content and frameworks designed to develop effective decision-making skills.

- Guided reflection activities to encourage self-awareness and commitments for action.

- Large group conversations — live discussions focused on peer input around key learning points.

- Small group activities, including virtual role plays designed to build critical interpersonal and leadership skills.

- A dynamic business simulation in which participants are charged with translating, making, and influencing difficult decisions.

- Facilitator-led discussions and presentations.

Learning Objectives

Participants develop and improve skills to:

- Cultivate a leadership mindset that empowers, inspires, and challenges others.

- Translate decisions for stronger team alignment and performance.

- Make better decisions under pressure.

- Influence individuals across the organization.

- Better understand how one’s leadership actions impact business results

Design Highlights

Program agenda.

As a result of the COVID-19 pandemic and the need for social distancing, this program was delivered virtually. However, this didn't preclude the need to give leaders an opportunity to connect with, and learn from, one another. In response to those needs, Insight Experience developed a fully remote, yet highly interactive, offering delivered over four half-day sessions.

Interactive Virtual Learning Format

Effective Decision-Making was designed to promote both individual and group activities and reflection. Participants access the program via a video-conferencing platform that allows them to work together both in large and small groups. Learning content and group discussions are done as one large group, enabling consistency in learning and opportunities to hear from all participants. The business simulation decision-making and reflection activities are conducted in small groups, allowing teams to develop deeper connections and conversations.

Simulation Overview

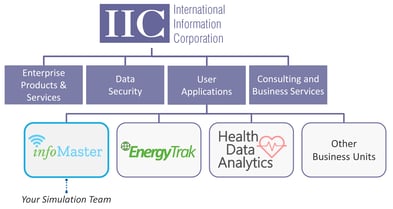

Participants assume the role of a General Manager for InfoMaster, a message management provider. Their leadership challenge as the GM is to translate the broader IIC organizational goals into strategy for their business, support that strategy though the development of organizational capabilities and product offerings, manage multiple divisions and stakeholders, and consider their contribution and responsibility to the broader organization of which they are a part.

Success in the simulation is based on how well teams:

- Understand and translate organizational strategy into goals and plans for their business unit.

- Align organizational initiatives and product development with broader strategies.

- Develop employee capabilities required to execute strategic goals.

- Hold stakeholders accountable to commitments and results.

- Communicate with stakeholders and involve others in plans and decision-making.

- Develop their network and their influence within IIC to help support initiatives for the organization

History and Results

Effective Decision-Making was developed in 2020 as an experience for senior-level leaders. After a successful pilot, the program was then rolled out to two more cohorts in 2021 and 2022. The senior-level leaders who participated in the program then requested we offer the same program to their direct reports. After some small adjustments to make the program more appropriate for director-level leaders, the program was launched in 2022 for approximately 100 directors.

Here is what some participants have said about this program:

- “ One of the better programs we've done here at [our organization]. Pace was very quick but content was excellent and approach made it fun .”

- “ Loved the content and the flow. Very nicely organized and managed. Thank you! ”

- “ Really enjoyed the collaborative nature of the simulation.”

- “ It was wonderful and I felt it is a great opportunity. Learnt and reinforced leadership training and what it would take to be successful.”

- “One of the best I've experienced — especially appreciated how the reality of [our organization] was incorporated and it was with similarly situated peers.”

- “This program was great! It gave good insight into how to enhance my skills as leader by adopting the leadership mindset.”

- “Loved the fast pace, having a sim group that had various backgrounds in the company and seeing the results of our decisions at the corporate level.”

- “Great program — I love the concepts highlighted during these sessions.”

Looking for results like these?

Leave comment, recent posts.

Taking Top Salespeople to Top Sales Leadership: A Case Study

Practice Makes Permanent: Microlearning on the Go (a Case Study)

Transforming Leadership to Support Significant Change: A Case Study

Leadership Foundations for Individual Contributors: A Case Study

Connecting Category Management Decisions and Business Outcomes: A Case Study

Accelerate the Implementation of Manager Expectations: A Case Study

Developing Effective Global Leaders: A Case Study

Delivering Exceptional Internal Customer Service: A Case Study

Bringing Leadership Principles to Life: A Case Study

Navigating the Organization: A Case Study

- Browse All Articles

- Newsletter Sign-Up

DecisionMaking →

No results found in working knowledge.

- Were any results found in one of the other content buckets on the left?

- Try removing some search filters.

- Use different search filters.

- SUGGESTED TOPICS

- The Magazine

- Newsletters

- Managing Yourself

- Managing Teams

- Work-life Balance

- The Big Idea

- Data & Visuals

- Reading Lists

- Case Selections

- HBR Learning

- Topic Feeds

- Account Settings

- Email Preferences

What the Case Study Method Really Teaches

- Nitin Nohria

Seven meta-skills that stick even if the cases fade from memory.

It’s been 100 years since Harvard Business School began using the case study method. Beyond teaching specific subject matter, the case study method excels in instilling meta-skills in students. This article explains the importance of seven such skills: preparation, discernment, bias recognition, judgement, collaboration, curiosity, and self-confidence.

During my decade as dean of Harvard Business School, I spent hundreds of hours talking with our alumni. To enliven these conversations, I relied on a favorite question: “What was the most important thing you learned from your time in our MBA program?”

- Nitin Nohria is the George F. Baker Professor of Business Administration, Distinguished University Service Professor, and former dean of Harvard Business School.

Partner Center

Decision-making approaches in process innovations: an explorative case study

Journal of Manufacturing Technology Management

ISSN : 1741-038X

Article publication date: 10 December 2020

Issue publication date: 17 December 2021

The purpose of this paper is to explore the selection of decision-making approaches at manufacturing companies when implementing process innovations.

Design/methodology/approach

This study reviews the current understanding of decision structuredness for determining a decision-making approach and conducts a case study based on an interactive research approach at a global manufacturer.

The findings show the correspondence of intuitive, normative and combined intuitive and normative decision-making approaches in relation to varying degrees of equivocality and analyzability. Accordingly, the conditions for determining a decision-making choice when implementing process innovations are revealed.

Research limitations/implications

This study contributes to increased understanding of the combined use of intuitive and normative decision making in production system design.

Practical implications

Empirical data are drawn from two projects in the heavy-vehicle industry. The study describes decisions, from start to finish, and the corresponding decision-making approaches when implementing process innovations. These findings are of value to staff responsible for the design of production systems.

Originality/value

Unlike prior conceptual studies, this study considers normative, intuitive and combined intuitive and normative decision making. In addition, this study extends the current understanding of decision structuredness and discloses the correspondence of decision-making approaches to varying degrees of equivocality and analyzability.

- Uncertainty

- Decision making

- Process innovation

- Case studies

- Production systems

- Manufacturing industry

Flores-Garcia, E. , Bruch, J. , Wiktorsson, M. and Jackson, M. (2021), "Decision-making approaches in process innovations: an explorative case study", Journal of Manufacturing Technology Management , Vol. 32 No. 9, pp. 1-25. https://doi.org/10.1108/JMTM-03-2019-0087

Emerald Publishing Limited

Copyright © 2019, Erik Flores-Garcia, Jessica Bruch, Magnus Wiktorsson and Mats Jackson

Published by Emerald Publishing Limited. This article is published under the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY 4.0) licence. Anyone may reproduce, distribute, translate and create derivative works of this article (for both commercial & non-commercial purposes), subject to full attribution to the original publication and authors. The full terms of this licence may be seen at http://creativecommons.org/licences/by/4.0/legalcode

1. Introduction

Process innovations, which involve new or significantly improved production processes or technologies, are essential for increasing manufacturing competitiveness ( Rönnberg, 2019 ; Yu et al. , 2017 ). The benefits of successfully implementing process innovations include reducing time to market, developing strong competitive barriers and increasing market share ( Krzeminska and Eckert, 2015 ; Marzi et al. , 2017 ). However, implementing process innovations does not always lead to desirable results ( Rönnberg et al. , 2016 ; Frishammar et al. , 2011 ). Instead, literature shows that staff frequently encounter difficulties when identifying decision-making approaches during the implementation of process innovations ( Eriksson et al. , 2016 ; Terjesen and Patel, 2017 ). These difficulties originate when staff responsible for implementing process innovations face unfamiliar circumstances ( Gaubinger et al. , 2014 ; Stevens, 2014 ; Jalonen, 2011 ). In particular, staff must deal with a lack of consensus and understanding (equivocality), and absence of rules or processes facilitating the analysis of information (analyzability) ( Piening and Salge, 2015 ; Milewski et al. , 2015 ; Kurkkio et al. , 2011 ; Frishammar et al. , 2011 ).

Operations management research offers diverse decision-making approaches useful for implementing process innovations ( Gino and Pisano, 2008 ; Hämäläinen et al. , 2013 ; Mardani et al. , 2015 ). This paper focuses on normative, intuitive and mixed-method decision-making approaches. Normative decision making involves quantitative analyses based on a systematic assessment of data ( Cochran et al. , 2017 ; Battaïa et al. , 2018 ; Dudas et al. , 2014 ). Intuitive decision making uses affectively charged judgments that arise through rapid, non-conscious, holistic associations ( Elbanna et al. , 2013 ; Dane and Pratt, 2007 ). The mixed-method approach considers both quantitative data and intuition ( Saaty, 2008 ; Thakur and Mangla, 2019 ; Kubler et al. , 2016 ; Hämäläinen et al. , 2013 ). It is vital to know when each decision-making approach is most suitable ( Zack, 2001 ; Eling et al. , 2014 ). Unless decision-making approaches are aligned with their conditions of use, the results could be disappointing ( Luoma, 2016 ).

Different decision-making approaches are used to solve problems when implementing process innovations ( Bellgran and Säfsten, 2010 ; Gershwin, 2018 ). However, it remains unclear when to select a particular decision-making approach ( Calabretta et al. , 2017 ; Dane et al. , 2012 ; Luoma, 2016 ; Matzler et al. , 2014 ). Recently, it is suggested that the degree of equivocality and analyzability of a decision, the structuredness of a decision, may constitute the main criteria for determining a decision-making approach ( Julmi, 2019 ). While this work provides novel insight, two salient issues require further research. First, there is a need for empirical understanding, as current findings remain purely conceptual. For example, manufacturing companies seldom experience a black-and-white divide between equivocality and analyzability when implementing process innovations ( Parida et al. , 2017 ; Eriksson et al. , 2016 ; Zack, 2007 ). Accordingly, it is necessary to remain open to unanticipated findings and the possibility that current explanations about selecting a decision-making approach require adjustments. Second, current findings give precedence to intuitive decision making over normative or mixed approaches. Identifying when and how to use normative and mixed decision making in addition to intuition is essential for implementing process innovations in the context of increasing computational capabilities and the interconnectedness of systems ( Mikalef and Krogstie, 2018 ; Liao et al. , 2017 ; Schneider, 2018 ; Rönnberg et al. , 2018 ). Thus, the purpose of this study is to explore the selection of decision-making approaches at manufacturing companies when implementing process innovations. This study focuses on production system design, including conception and planning, because this stage contributes significantly to the performance of process innovations ( Andersen et al. , 2017 ; Rösiö and Bruch, 2018 ).

2. Frame of reference

2.1 understanding equivocality and analyzability in process innovations.

Equivocality is a central organizational challenge that negatively impacts the implementation of process innovations in manufacturing companies ( Rönnberg et al. , 2016 ; Eriksson et al. , 2016 ; Parida et al. , 2017 ). The current understanding of equivocality is grounded on organization theory ( Galbraith, 1973 ). Equivocality refers to the existence of multiple and conflicting interpretations, and is associated with problems such as a lack of consensus, understanding and confusion ( Daft and Macintosh, 1981 ; Zack, 2007 ; Zack, 2001 ; Koufteros et al. , 2005 ). Equivocality originates when individuals face new or unfamiliar situations in which additional information will not help resolve misunderstandings ( Frishammar et al. , 2011 ). Individuals may experience equivocality of varying degrees ranging from high equivocality, ambiguous unclear events with no immediate suggestions about how to move forward, to low equivocality, clearly defined situations requiring additional information ( Daft and Lengel, 1986 ). The literature suggests that to reduce equivocality, staff must engage in information processing activities that exchange subjective interpretations, form consensus and enact shared understanding ( Rönnberg et al. , 2016 ; Eriksson et al. , 2016 ; Daft and Lengel, 1986 ).

Staff responsible for implementing process innovations frequently encounter problems relating to lack of agreement or consensus, namely, equivocality ( Reichstein and Salter, 2006 ; Jalonen, 2011 ; Stevens, 2014 ). The way individuals respond to such problems is referred to as analyzability ( Daft and Lengel, 1986 ). Analyzability describes the extent to which problems or activities require objective procedures as opposed to personal judgment or experience to resolve a task ( Haußmann et al. , 2012 ; Zelt et al. , 2018 ). Similar to equivocality, analyzability is subject to varying degrees. For example, tasks lacking objectives rules and procedures are regarded as having low analyzability. Conversely, tasks including clear and objective procedures leading to a solution are considered as having high analyzability. The degree of analyzability of a task is associated with its degree of equivocality ( Daft and Lengel, 1986 ; Julmi, 2019 ; Byström, 2002 ). When a task is clear and analyzable, equivocality is low, and staff can rely on the acquisition of explicit information to answer questions. When a task is unclear and of low analyzability, equivocality is high, and staff must process information to generate consensus.

2.2 Decision-making approaches

Operations management literature offers distinct approaches to decision making relevant to implementing process innovations. A first approach involves normative decision making. Normative decision making involves a logical step-by-step analysis involving a quantitative assessment ( Mintzberg et al. , 1976 ) and requires information that is clear, objective and well defined ( Dean and Sharfman, 1996 ). Normative decision making is described as a slow and conscious process where information is logically decomposed and sequentially recombined to generate an output ( Jonassen, 2012 ; Swamidass, 1991 ; Papadakis et al. , 1998 ). The benefits of normative decision-making approaches include economizing cognitive effort, solving cognitively intractable problems, producing insight and integrating knowledge ( Liberatore and Luo, 2010 ). Criticism of the use of normative decision making extend from studies suggesting that individuals are intendedly rational, but only limitedly so ( Luoma, 2016 ; Simon, 1997 ). For example, decision makers may systematically deviate from recommendations produced by decision models ( Käki et al. , 2019 ). Normative decision making, despite its alleged drawbacks, continues to be used by organizations and has frequently led to good outcomes ( Metters et al. , 2008 ; Klein et al. , 2019 ).

A second approach includes intuitive decision making ( Bendoly et al. , 2006 ; Loch and Wu, 2007 ; Gino and Pisano, 2008 ; Elbanna et al. , 2013 ; White, 2016 ). Intuitive decision making involves affectively charged judgments that arise through rapid, non-conscious, holistic association of information ( Dane and Pratt, 2007 ). Intuitive decision making is associated with having a strong hunch or feeling of knowing what is going to occur, and can be advantageous when professionals are confronted with time pressure and possess experience in a field ( Gore and Sadler-Smith, 2011 ; Dane and Pratt, 2007 ; Bennett, 1998 ; Elbanna et al. , 2013 ; Hodgkinson et al. , 2009 ; Khatri and Ng, 2000 ). Intuitive decision making is not without drawbacks. Literature suggests that managers using intuition may ignore relevant facts, have a hard time explaining the reasons for making a choice, or produce gross misjudgments ( Dane et al. , 2012 ; Elbanna et al. , 2013 ; Dane and Pratt, 2007 ).

A third alternative includes the use of mixed decision-making approaches ( Tamura, 2005 ; Hämäläinen et al. , 2013 ). The main strength of this approach lies in reducing personal bias and allowing the comparison of dissimilar alternatives while integrating quantitative analysis ( Saaty, 2008 ). Mixed decision-making approaches provide solutions to problems involving conflicting objectives or criteria affected by uncertainty ( Kahraman et al. , 2015 ). Literature presents a variety of alternatives in relation to mixed decision-making approaches ( Mardani et al. , 2015 ), yet these have the common objective of helping deal with the evaluation, selection and prioritization of problems by imposing a disciplined methodology ( Kubler et al. , 2016 ).

2.3 Structuredness of decisions and decision making

In the past, decisions have been classified along a continuum according to their structure ( Shapiro and Spence, 1997 ). This argument maintains that a decision may range from well- to ill-structured depending on whether rules and processes can be unequivocally applied. Grounded on organization theory, recent studies propose that the structuredness of decisions may provide an indication for understanding the correspondence between the choice of a decision-making approach and its conditions of use ( Julmi, 2019 ).

Well-structured decisions include intellective tasks with a definite objective criterion of success within the definitions, rules, operations and relationships of a particular conceptual system ( Dane and Pratt, 2007 ). A well-structured decision involves rules or procedures and unequivocal interpretations that have developed over time ( March and Simon, 1993 ; Luoma, 2016 ). Therefore, it is argued that well-structured decisions relate to low equivocality and high analyzability, and that normative decision making is appropriate because of the structured rules and computable information involved.

Ill-structured decisions involve judgmental tasks where there are no objective criteria, or demonstrable solutions ( Dane and Pratt, 2007 ). Ill-structured decisions originate from novel situations that do not include widely accepted rules that may help determine the degree to which a decision is correct or biased ( Cyert and March, 1992 ; Luoma, 2016 ; Jacobides, 2007 ). Consequently, it is identified that ill-structured decisions correspond to high equivocality and low analyzability. It is suggested that staff facing ill-structured decisions adopt intuitive decision-making because intuition does not rely on rules to cope with a problem; rather, it relies on integrating information holistically into coherent patterns ( Dane and Pratt, 2007 ). Figure 1 illustrates the correspondence of decision-making approaches to the conditions of use based on the structuredness of decisions.

Conceptually, the structuredness of decisions provides a starting point to understand the correspondence of a decision-making approach to its conditions of use. However, there is a need to submit these conceptual arguments to empirical scrutiny and explore whether the degree of equivocality and analyzability provides guidance in selecting a decision-making approach when implementing process innovations. The empirical study to explore these issues is described in the following section.

3. Methodology

Prior studies have focused on explaining how to choose a decision-making approach; however, there is a need for further empirical insight. This casts doubt on the appropriateness of analysis-based research, which is better suited to evaluating well-developed hypotheses ( Johnson et al. , 2007 ; Mccutcheon and Meredith, 1993 ; Handfield and Melnyk, 1998 ). Accordingly, this study adopts a qualitative-based case study to elaborate on the current theory ( Ketokivi and Choi, 2014 ). Theory elaboration is well suited to explore an empirical context with more latitude, and conduct an in-depth investigation based on identified theoretical concepts ( Whetten, 1989 ). The choice of case study research is justified by prior studies which describe its advantages for observing and describing a complicated research phenomenon such that it conveys information in a way that quantitative data cannot ( Eisenhardt and Graebner, 2007 ; Handfield and Melnyk, 1998 ; Meredith, 1998 ; Mccutcheon and Meredith, 1993 ). In designing and conducting the case study, extant guidelines for qualitative case studies in Operations Management were followed ( Barratt et al. , 2011 ).

The focus of this study is the design of production systems. Decision making at this stage is important for achieving the desired level of competitiveness and the overall goals of implementing process innovations ( Bruch and Bellgran, 2012 ). Process innovations are frequently implemented in the form of projects ( Bellgran and Säfsten, 2010 ). Accordingly, the unit of analysis is the production system design project, and its embedded unit of analysis decisions within these projects. Given the research agenda, the decisions occurring in a production system design project are an appropriate unit of analysis. These decisions should adapt to the structure of the environment ( Gigerenzer and Gaissmaier, 2011 ), and are affected by the information processing capacities of an organization ( Matzler et al. , 2014 ).

This study uses empirical data from two production system design projects at one global manufacturing company, which we refer to as Projects A and B. While case study research at a single organization offers limited generalizability ( Ahlskog et al. , 2017 ), it allows an in-depth exploration of how decision making occurs at manufacturing companies beyond well-structured decisions ( Kihlander and Ritzén, 2012 ). The manufacturing company was selected based on theoretical sampling, with the aim of exploiting opportunities to explore a significant phenomenon under rare or extreme circumstances relevant to the study of single cases ( Yin, 2013 ; Eisenhardt and Graebner, 2007 ). In selecting a manufacturing company, the study focused on four factors associated with the competent implementation of process innovations including: large-sized firms of high capital intensity, established processes for developing production systems, continual design of new products and an emphasis on increasing flexibility of production systems ( Cabagnols and Le Bas, 2002 ; Pisano, 1997 ; Martinez-Ros, 1999 ).

Two aspects influenced the choice of projects. First, the focus was on projects implementing radical process innovations, namely, those projects involving new equipment and management practices and changes in the production processes ( Reichstein and Salter, 2006 ). These types of projects reportedly experience varying degrees of equivocality and analyzability ( Parida et al. , 2017 ; Kurkkio et al. , 2011 ; Frishammar et al. , 2011 ). In addition, radical process innovations depend on normative and intuitive decision-making approaches for their implementation ( Calabretta et al. , 2017 ), which are conditions essential to the focus of this study. Second, this study gave precedence to projects that included experienced staff responsible for implementing process innovations. Prior studies highlight that experience influences the capacity of staff to act under conditions of limited information and equivocality, and facilitates making rapid decisions in the absence of data ( Daft and Macintosh, 1981 ; Liu and Hart, 2011 ; Gershwin, 2018 ; Dane and Pratt, 2007 ). Accordingly, two projects in the heavy-vehicle industry focused on the transition from traditional production systems to multi-product production systems were considered.

One of the authors of this study is a researcher at the manufacturing company. Accordingly, this study adopts an interactive research approach ( Ellström, 2008 ), which is considered a variant of collaborative research. Interactive research is distinguished by the continuous joint learning and close collaboration between industry participants and researchers ( Svensson et al. , 2007 ; Ellström, 2008 ). Despite this close interaction, the primary focus of this study is to provide a theoretical contribution and relevant industrial results.

3.1 Description of Projects A and B

The manufacturing company is a leading producer of heavy-vehicle products with more than 14,000 employees and 13 manufacturing sites in Europe, Asia and North and Latin America. The heavy-vehicle industry is characterized by a high degree of product customization and specialized product families targeting specific markets. Manufacturers of this segment consider a wide offering of products to be a key competitive advantage. Production systems are distinguished by assembly lines that specialize in a single product family, and share little else other than the same manufacturing facility.

The manufacturing company initiated two projects, A and B, which originated from a common corporate goal of reducing time to market, manufacturing footprint, and lead time to customers, and increasing production flexibility. These projects focused on the transformation of traditional production systems to multi-product production systems. Projects A and B were considered process innovations because of their novel approach compared to traditional production in the heavy-vehicle industry, which included: standardizing product interfaces, utilizing new production processes and technologies for product assembly, redesigning facility layouts and developing internal logistic solutions. Projects A and B were considered successful because these upgraded outdated production processes and technologies increased production flexibility, reduced production unit labor cost per output, increased productivity and reduced the assembly area of the production systems. Table I describes Projects A and B, and Table II outlines the profiles of staff participating in these projects.

3.2 Data collection

Data collection took place between January 2014 and January 2016. This period comprised all activities and planning for Projects A and B. Different techniques for data collection were used including field notes, interviews and company documents to help obtain objective and reliable results ( Karlsson, 2010 ). The first author drafted field notes during 12 full-day workshops for Project A and 10 full-day workshops for B. Staff responsible for Projects A and B attended these workshops including project managers, production managers, production engineers, logistics developers, consultants and research and development personnel. These separately held workshops involved three themes. The first theme consisted of generating a common vision of the process innovations, identifying critical issues and proposing solutions to these issues. The second theme included designing, developing and deploying discrete event simulation models. The third theme focused on discussing the results of on-site tests for Projects A and B. In addition, the first author participated regularly as a passive observer in project meetings and drafted field notes, including 60 and 40 1-hour weekly meetings for Projects A and B, respectively.

The authors collected additional data based on five semi-structured interviews for Projects A and B. The interviews began with an explanation of the project, its background and goals. Staff described their professional experience and responsibilities in the project and identified the essential activities and decisions of each project. Next, they narrated the process of achieving agreement for each decision. Finally, they detailed how decisions were made including decision-making approaches, rules, processes, information and outcome. To gain a comprehensive understanding of decision making, the interviews involved staff members from different seniority levels, including project managers, production engineering managers, production engineers, logistics developers and consultants. The authors recorded and transcribed all interviews and sent all transcribed interviews to the interviewees for verification. Finally, data collection included company documents in the form of presentations, minutes and reports drafted during the projects. Table III lists the details of data collection.

3.3 Data analysis

Data analysis included an iterative comparison of the collected data and existing literature, as suggested by Yin (2013) . Following the recommendations of Miles et al. (2013) , data analysis occurred in four steps. First, collected data were concurrently selected, abbreviated and stored in a database during data collection. At this stage, salient decisions were identified for Projects A and B, and the focus was on decisions involving the commitment of resources (e.g. additional meetings, production experts or managerial discussions) leading to actions (selecting a layout, proposing a definition or selecting a group of products) as suggested in the literature ( Frishammar, 2003 ). Afterwards, staff participating in Projects A and B verified these decisions.

The second step involved systematically coding the collected data for Projects A and B. The authors jointly decided on three codes for analyzing data: equivocality, analyzability and decision-making approaches. The literature was heavily relied on to identify the equivocality and analyzability associated with a decision ( Daft and Lengel, 1986 ). High equivocality referred to multiple and conflicting interpretations and ambiguous information. Equivocal situations included partial agreement among the staff and ambiguous information. Low equivocality involved unequivocal interpretations and a lack of information. High analyzability concerned clear rules and processes, and low analyzability a lack of objective rules or rule based procedures. Staff of Projects A and B were left to operate freely when selecting decision-making approaches based on preferences or established processes operating at the manufacturing company. Importantly, no definitions of decision-making approaches were provided to the staff. Instead, the decision-making approach of each decision was identified a posteriori based on the characteristics of intuitive or normative decision making found in literature and shown in Table IV .

Third, the authors reassembled data according to the codes described above and analyzed data in two steps, as suggested by Eisenhardt (1989) . First, the author analyzed the projects separately to become acquainted with and identify patterns. Thereafter, the authors analyzed patterns across Projects A and B.

Fourth, the authors compared all the findings in a joint session with the aim of achieving a comprehensive interpretation of the study. The authors deliberated over differences of interpretation until an agreement was reached. Where there was no agreement, the authors contacted interviewees for further clarification. Finally, the authors drew conclusions and conceptualized the findings of the study. The findings were compared and related to existing theory concerning similarities, contradictions and explanations of differences ( Eisenhardt, 1989 ).

4. Empirical findings

4.1 equivocality.

What is a good assembly sequence for all these different products? You had to propose what to do, and then do it, and then show the results. It is not that you would have asked someone: Are we doing the right thing? Should we do it this way? No one really had an answer for that. (Project manager of Project A)

Each of us (project B) has worked with powertrains for a long time, but this was different. Originally we believed that it was necessary to include the vehicle transmission and an additional component in our scope. This choice was not simple because of the intrinsic differences and functionalities of each product family. In addition, we lacked experience on anything remotely similar, did not have enough information, and held different opinions on the matter. (Production engineer of Project B)

We based all the work on the assumption that there is one common assembly sequence. We regarded that as a backbone in the project. I strongly believe that if you have a common assembly sequence, it has an enormous impact on production. (Project manager of Project A)

First, we decided to do an extensive data collection. That drove the project into the wall. On a second attempt, we decided not to dig so deep into the details and focused on a holistic perspective. We went through our products looking for similarities. Based on discussions with our product and production experts, we identified 17 key components; based on these, we developed a common assembly sequence. (Production engineer of Project B)

After developing a shared understanding of a multi-product assembly, our activities focused on issues that could improve our concept. We collected and analyzed information, and compared alternatives. It was essential to know what choices brought our process innovation closer to objectives set up by management. (Logistics developer of Case A)

4.2 Analyzability

Staff experienced analyzability as a tension between two opposites. On the one hand, staff was subject to familiar circumstances, known problems or decisions encountered in the past. In these situations, they adopted standardized rules and procedures common in production system design projects at the manufacturing company: for example, processes for designing a production system, line balancing strategies or the classification of logistics parts.

On the other hand, staff faced new and unfamiliar decisions originating from the specification of the characteristics of a multi-product production system. For example, the manufacturing company possessed no procedures specifying the grouping of different product families for production in a multi-product production system. Similarly, the manufacturing company did not possess rules for identifying a best choice among alternative product groups. Staff considered both decision-making processes essential for multi-product production systems.

Once we developed a common perspective about a single assembly line, we mapped assembly times, figured out the number of stations, moved as much work as possible to sub-assembly lines, worked with logistics, material handling, kitting in line. With a common objective, it was easier for us to pinpoint what the production system would look like. (Production engineer of Project A)

4.3 Decision-making approaches

Staff of Projects A and B utilized three distinct decision-making approaches including intuitive, normative and a combination of intuitive and normative. Intuitive decision making was frequent at the start of Projects A and B, and relied on gut feeling, best knowledge and a holistic consideration of information. Intuitive decision making did not focus on detailed information. Instead, the staff integrated the results from different reports and argued for a solution based on experience or hunches. The staff utilized intuitive decision making in two distinct instances. First, staff relied on intuitive decision making during open and informal debates to achieve consensus. In these circumstances, they either generated a solution to a decision (e.g. agreeing on the importance of a common assembly sequence) or determined new rules or procedures (e.g. steps for grouping and ranking product groups). Second, they utilized intuitive decision making jointly with normative decision making, e.g. in identifying problems and proposing solutions to the production process. An additional example of the latter includes simulation models. Simulation models originally included rough assumptions and simplifications based on the intuition of experts and their general understanding of the production systems, which were increasingly completed with new information.

The results of the simulation analysis were very important to the outcome of the process innovation. This helped us understand how to eliminate variation in our production process. The simulation also helped us understand how the solutions we tested in the factory floor turned out over weeks or months across different areas. We could not have achieved this detail of understanding any other way. (Consultant of Project A)

Finally, staff jointly applied a combination of intuitive and normative decision-making approaches during Projects A and B. Joint intuitive and normative decision-making approaches were subject to the agreement of the staff, collection of data and clear rules or procedures which could be either new or established ones. Intuitive decision making could precede, follow or be used concurrently with normative decision making (e.g. when determining the advantages or trade-offs of a multi-product production system). In this example, staff utilized normative decision making (e.g. simulations) to compare the production systems of sites in North and Latin America to the multi-product production systems developed in Projects A and B. The results of this comparison were presented in workshops and face-to-face meetings. In these meetings, staff participating in Projects A and B and experts from sites in North and Latin America scrutinized the simulation results and compared them to demand forecasts, production reports and experience. This required several iterations, and the primary concern was that of earning trustworthiness from experts. Afterwards, the results of a decision were escalated to a managerial level. When determining the benefits and trade-offs of a multi-product production system, managers considered information from diverse sources – and not exclusively the results of a simulation analysis. Frequently, managers requested “what if” or sensitivity types of analysis from normative decision-making approaches. Accomplishing this required a new iteration of the steps described above. Finally, managers made decisions based on intuition, considering various sources of information holistically. Tables V and VI describe the salient decisions and equivocality, analyzability and decision making of each decision for Projects A and B.

An important observation is that decisions were subject to different degrees of equivocality and analyzability when implementing process innovations. The findings show that distinct decision-making approaches occur at different degrees of equivocality and analyzability. Understanding the correspondence of equivocality and analyzability to a decision-making choice is difficult to comprehend. Therefore, Figure 2 presents the correspondence and frequency of decision-making approaches to the degree of equivocality and analyzability in Projects A and B.

The correspondence between the degree of equivocality and analyzability of a decision and decision-making approaches is identified based on a synthesis of the choices of decision-making approaches in Projects A and B and extant literature. First, findings show that decision-making approaches were most frequently utilized in conditions of low equivocality and high analyzability. In this approach, the staff interpreted a problem unequivocally, possessed clear rules and procedures; however, they lacked information. The staff utilized three different decision-making approaches in conditions of low equivocality and high analyzability, including intuitive, normative and a combination of intuitive and normative decision making.

Our data show that staff found low equivocality and high analyzability as the only conditions suitable for normative decision making in this study. Normative decision making relied on explicit information, a sequential analysis and well-defined decisions. Staff from Projects A and B utilized normative decision making for detailed technical aspects such as evaluating layouts.

In addition, the staff made use of combined intuitive and normative decision making in conditions of low equivocality and high analyzability. Here, they utilized combined intuitive and normative decision making when facing new situations, having previously agreed on procedures for analysis (e.g. identifying vehicle modules). They utilized combined intuitive and normative decision making for high stake decisions involving an aggregation of prior activities and requiring managerial involvement (e.g. comparing a multi-product production system to existing multi-product production systems).

Finally, the staff utilized intuitive decision making in low equivocality and high analyzability when encountering situations perceived as similar to prior situations. In these instances, they relied on experience, quick decisions and a holistic association of information to produce a result (e.g. agreeing on the need for improving staff competence).

Second, Projects A and B faced conditions of low equivocality and low analyzability. Staff agreed on the nature of a problem; however, they lacked clear rules, procedures and relevant information. They judged that these conditions did not meet the criteria for the exclusive use of normative decision making. Instead, they utilized intuitive or a combination of intuitive and normative decision-making approaches. The staff applied intuitive decision making to decisions where the end goal was that of establishing rules or procedures. In these instances, they were not undecided about the goal of a decision, rather how to arrive at a solution (e.g. establishing the rules and procedures for modular assembly and performance indicators). When combining intuitive and normative decision making, they utilized intuition for agreeing on rules and procedures, associated decisions to those faced in the past, and devised steps that were understandable to others based on experience. Next, quantitative analyses were utilized to provide detailed insight, acquire information and logically decompose a problem (e.g. specifying an assembly sequence).

Third, staff of Projects A and B made decisions in a context of equivocality and high analyzability. This coincided with having clear rules and processes; however, with only a partial agreement about the information necessary to complete a task or the outcome of a decision. In these instances, the staff resorted to intuitive decision making for agreeing on the type of information necessary to complete a task. Next, they utilized normative decision making in the form of quantitative based analysis such as spread sheet calculations or simulations. Finally, they returned to intuitive decision making to arrive at a solution while considering holistic information from a variety of sources. Examples of this include proposing logistics solutions for multi-product production systems, and determining advantages and trade-offs of multi-product production systems. The findings of this study would suggest that the conditions of equivocality and high analyzability do not provide sufficient support for the use of an entirely normative decision-making approach. Empirical results suggest that applying purely intuitive decision-making approaches is undesirable. Actually, the staff recognized that decisions could not rest exclusively on hunches, experience or rapid decisions by acknowledging the need for additional information, and disputing the appropriateness of information to complete a task.

Fourth, staff of Projects A and B made decisions against a backdrop of equivocality and low analyzability. These decisions involved the lack of rules or processes and partial agreement about information necessary to complete a task. Decisions of equivocality and low analyzability were not like small differences of opinion resolved over the course of a meeting or workshop. Instead, these decisions required detailed investigation, resource commitment and weeks of deliberation. Staff in Projects A and B proceeded differently when encountering equivocality and low analyzability.

In Project A, the staff identified the logistics needs for a multi-product production system. They agreed on the need for adapting logistics capabilities; however, the information available did not correspond to the needs of a multi-product production system. They estimated logistics needs based on hunches, discussions and experience. They considered the outcome of this decision provisional and subject to increased knowledge about logistics in a multi-product production system. In Project B, the staff proposed a layout for a multi-product production system. To do so, they utilized intuitive decision making to set an initial direction. This was considered insufficient to finalize a decision, and additional information was acquired, and alternatives were judged based on normative decision making.

Findings suggest that these types of decisions are not readily solvable, and evidence a need for generating agreement about the purpose of the decision, information, rules and processes enabling a solution. Data suggest that intuitive decision making is important in enacting a shared understanding; nevertheless, committing to a decision may require the quantitative insight provided by normative decision making. Consequently, decisions experiencing equivocality and low analyzability were subject to a combined intuitive and normative decision-making approach. Examples include identifying logistics needs for multi-product production systems or proposing layouts for multi-product production systems.

Fifth, findings show that no decisions coincided with high equivocality and high analyzability, namely, multiple and conflicting interpretation, ambiguous information, and clear rules and processes. We argue that high equivocality and high analyzability present a contradiction and suggest that the incidence of decision making in these conditions may signal an error. This error may well indicate the inadequate interpretation of existing rules or processes by staff responsible for implementing process innovations.

Sixth, staff made exclusive use of intuitive decision making in decisions involving high equivocality and low analyzability. These type of decisions were characterized by the absence of objectives rules or processes, multiple and conflicting interpretations, and ambiguous information. These decisions were common in the beginning of Projects A and B, and when the staff faced decisions perceived as different from those encountered in the past. They relied on hunches, approximations or conjectures about the result of a decision to guide consensus. Additional information did not help resolve decisions in high equivocality and low analyzability: for instance, when agreeing on the definition of a powertrain across different product families. Figure 3 outlines the choice of decision-making approaches when implementing process innovations according the degree of equivocality and analyzability of decisions.

5. Discussion and implications

The purpose of this study is to explore the selection of decision-making approaches at manufacturing companies when implementing process innovations. In particular, this study focused on how the conditions of equivocality and analyzability provide guidance to the choice of a decision-making approach. Extant literature is compared to empirical findings from two projects implementing process innovations in the form of a multi-product production system in the heavy-vehicle industry. The findings of this study are particularly relevant in light of the interest from manufacturing managers and academics to better understand when and where a decision-making approach is most suitable during the implementation of process innovations.

5.1 Theoretical implications

Recent studies recommended decision-making approaches in extreme cases of problem structuredness, high equivocality and low analyzability or low equivocality and high analyzability ( Julmi, 2019 ). However, staff face varying degrees of equivocality and analyzability when implementing process innovations ( Parida et al. , 2017 ; Frishammar et al. , 2011 ). This study reveals additional combinations of equivocality and analyzability than those previously described in literature. This finding is important because it extends current understanding of decision structuredness, which thus far had been limited to presenting extreme cases, namely, well- and ill-structured decisions. In addition, this study provides empirical evidence that staff must respond to decisions at varying degrees of equivocality and analyzability when implementing process innovations. In particular, this study identified three degrees of equivocality and two of analyzability when implementing process innovations. This study highlights the need for increased understanding of equivocality and analyzability, which may help manufacturing companies avoid failed choice or erroneous approaches to decision making when implementing process innovations. This finding is important as it may help clarify the selection of decision-making approaches leading to an improved outcome ( Calabretta et al. , 2017 ; Luoma, 2016 ), a situation that is crucial for implementing process innovations ( Frishammar et al. , 2011 ; Milewski et al. , 2015 ).

Current understanding of decision structuredness argues that there are no superior decision-making approaches ( Julmi, 2019 ). Instead, a decision-making approach may be better suited to certain conditions and, under these conditions, lead to an effective outcome ( Gigerenzer and Gaissmaier, 2011 ). Our findings show that, consistent with the literature, well-structured and ill-structured decisions corresponded to normative and intuitive decision making. However, findings show differences with prior studies focused on decision structuredness and decision making. For example, staff applied intuitive decision making at varying degrees of equivocality and analyzability, combined normative and intuitive decision making not described in literature, and utilized more than one decision-making approach in three out of six combinations of equivocality and analyzability. The results of this study suggest that decision structuredness may not prescribe a decision-making approach, but may clarify the conditions in which decisions take place. This finding is important because it suggests that current understanding of decision-making choice based on extreme cases of problem structuredness, namely well- or ill-structured decisions, is insufficient to guide a choice of decision-making approach. Addressing this dearth of understanding, this study outlines the choice of decision-making approaches when implementing process innovations according the degree of equivocality and analyzability of decisions. This findings is essential as it suggests that identifying the fit of a decision-making approach to the structuredness of a problem is as important as the technical acumen, resources and experience necessary for using a particular type of decision making ( Jonassen, 2012 ; Dean and Sharfman, 1996 ).

By classifying decisions in relation to their degree of equivocality, this study shows that decisions occur more frequently in situations involving low equivocality, followed by those of high equivocality, and finally by those involving partial agreement and ambiguous information or equivocal. A higher frequency of decisions in situations of low equivocality is expected when implementing process innovations. However, an intriguing finding of this study involves the frequency in which staff made decisions in situations including multiple and conflicting interpretations and ambiguous information (e.g. high equivocality). These decisions appeared when staff identified a problem (e.g. product, production process, tools and technology, layouts, logistics), were based on intuitive decision making and defined subsequent decisions of Projects A and B. This finding is disquieting as prior studies show that manufacturing companies frequently rely on ad hoc practices when making early decisions in production system design projects ( Rösiö and Bruch, 2018 ). Similarly, the literature highlights a limited understanding of equivocality at manufacturing companies when implementing process innovations ( Parida et al. , 2017 ). Therefore, our findings give credibility to the claim that comprehension of equivocality, its reduction and the effective use of intuition may harness a competitive edge for manufacturing companies implementing process innovations ( Rönnberg et al. , 2016 ; Frishammar et al. , 2012 ).

The literature advocates the use of structured processes for implementing process innovations ( Kurkkio et al. , 2011 ). Accordingly, the need for clear rules and procedures facilitating high analyzability is essential. The results of this study show no telling difference in the frequency of decisions involving high analyzability or low analyzability in Projects A and B. Importantly, data do not indicate that staff forwent rules and processes when these were lacking. Instead, staff developed rules and processes when facing decisions not previously experienced or described in established procedures. This result is significant and suggests that the ability of staff to develop rules and processes, or procedures when facing non-recurring situations ( Luoma, 2016 ), is as likely to be necessary as that of structured processes for implementing process innovations. The development of rules and processes during the implementation of process innovations is rarely discussed in literature, and therefore constitutes a venue for future research.

Mixed decision-making approaches constitute a well-established field that may help staff arrive at decisions under uncertainty ( Kubler et al. , 2016 ). This study showed that decisions were frequently reached as a result of combined intuitive and normative decision making. However, the process for arriving at these decisions was unlike the methods used in the literature. The findings of this study suggest both the need of mixed decision-making approaches when implementing process innovations, and increased efforts to bridge the gap between academic findings and manufacturing practice.

5.2 Practical implications

The findings of this study have direct practical implications that may benefit staff and managers responsible for implementing process innovations. First, this study underscores the importance of a structured process, experienced design teams and familiarity with normative, intuitive or mixed decision making that enable the implementation of process innovations ( Rösiö and Bruch, 2018 ). However, the analysis also shows that although these concepts are necessary, they are not sufficient to successfully implement process innovations. Instead, managers must be aware of the importance of determining a decision-making approach that corresponds to the conditions of a decision. Addressing this point, this study emphasized the importance of equivocality and analyzability when determining a decision-making approach during the implementation of process innovations. Accordingly, this study underscores the importance of information processing activities, which are under prioritized or neglected because of a lack of resources or competence ( Rönnberg et al. , 2016 ; Koufteros et al. , 2005 ).

5.3 Limitations and future research

Some key limitations circumscribe this study. Like all case studies, our contributions are limited by the idiosyncrasies of the context of study ( Eisenhardt, 1989 ). This study draws data from a global manufacturing company. Undoubtedly, smaller sized manufacturing companies may have different access to staff, resources and experienced personnel when implementing process innovations. Prior studies suggest that these elements affect decision-making approaches. Therefore, validating our results against cases from varying company sizes is important. Another limitation constitutes our focus on the production of heavy vehicles and their components. A suggestion for future research includes the investigation of cases in additional context: for example, the process industry or batch production.

Process innovations concern new production processes or technologies. This study, like many other process innovation studies ( Krzeminska and Eckert, 2015 ; Marzi et al. , 2017 ), focused on new material, equipment or reengineering of operational processes. In doing so, concern stemmed from the conditions that may determine the choice of a decision-making approach. Process innovation literature reflects increasing interest in the way artificial intelligence, automation and digital technologies connected to the Internet of Things affect decision making ( Rönnberg et al. , 2018 ). While the interplay of intuitive, normative and mixed decision-making approaches is a concern of this study, technological changes enabling decision making is not. Future research could focus on conceptualizing the domain of novel digital technologies and decision making when implementing process innovations.

Choice of intuitive or normative decision making based on decision structuredness

Correspondence of decision-making approaches to degree of equivocality and analyzability in Projects A and B

Choice of decision-making approaches when implementing process innovations according to the degree of equivocality and analyzability of decisions

Description of production system design Projects A and B focused on implementing a multi-product production system as a process innovation

Profiles of staff participating in Projects A and B

Details of data collection for Projects A and B

Characteristics of intuitive and normative decision-making approaches

Description of salient decisions, equivocality, analyzability and decision making in Project A

Notes: Equivocality (HE, high equivocality; E, equivocality; LE, low equivocality), Analyzability (HA, high analyzability; LA, low analyzability)

Ahlskog , M. , Bruch , J. and Jackson , M. ( 2017 ), “ Knowledge integration in manufacturing technology development ”, Journal of Manufacturing Technology Management , Vol. 28 No. 8 , pp. 1035 - 1054 .

Andersen , A.-L. , Brunoe , T.D. , Nielsen , K. and Rösiö , C. ( 2017 ), “ Towards a generic design method for reconfigurable manufacturing systems: analysis and synthesis of current design methods and evaluation of supportive tools ”, Journal of Manufacturing Systems , Vol. 42 No. 1 , pp. 179 - 195 .

Barratt , M. , Choi , T.Y. and Li , M. ( 2011 ), “ Qualitative case studies in operations management: trends, research outcomes, and future research implications ”, Journal of Operations Management , Vol. 29 No. 4 , pp. 329 - 342 .

Battaïa , O. , Dolgui , A. , Heragu , S.S. , Meerkov , S.M. and Tiwari , M.K. ( 2018 ), “ Design for manufacturing and assembly/disassembly: joint design of products and production systems ”, International Journal of Production Research , Vol. 56 No. 24 , pp. 7181 - 7189 .

Bellgran , M. and Säfsten , K. ( 2010 ), Production Development: Design and Operation of Production Systems , Springer Science & Business Media , New York, NY .

Bendoly , E. , Donohue , K. and Schultz , K.L. ( 2006 ), “ Behavior in operations management: assessing recent findings and revisiting old assumptions ”, Journal of Operations Management , Vol. 24 No. 6 , pp. 737 - 752 .

Bennett , R.H. ( 1998 ), “ The importance of tacit knowledge in strategic deliberations and decisions ”, Management Decision , Vol. 36 No. 9 , pp. 589 - 597 .

Bruch , J. and Bellgran , M. ( 2012 ), “ Creating a competitive edge when designing production systems – facilitating the sharing of design information ”, International Journal of Services Sciences , Vol. 4 Nos 3-4 , pp. 257 - 276 .

Byström , K. ( 2002 ), “ Information and information sources in tasks of varying complexity ”, Journal of the American Society for Information Science and Technology , Vol. 53 No. 7 , pp. 581 - 591 .

Cabagnols , A. and Le Bas , C. ( 2002 ), “ Differences in the determinants of product and process innovations: the french case ”, in Kleinknecht , A. and Mohnen , P. (Eds), Innovation and Firm Performance: Econometric Explorations of Survey Data , Palgrave Macmillan UK , London , pp. 112 - 149 .

Calabretta , G. , Gemser , G. and Wijnberg , N.M. ( 2017 ), “ The interplay between intuition and rationality in strategic decision making: a paradox perspective ”, Organization Studies , Vol. 38 Nos 3-4 , pp. 365 - 401 .

Cochran , D.S. , Foley , J.T. and Bi , Z. ( 2017 ), “ Use of the manufacturing system design decomposition for comparative analysis and effective design of production systems ”, International Journal of Production Research , Vol. 55 No. 3 , pp. 870 - 890 .

Cyert , R.M. and March , J.G. ( 1992 ), A Behavioral Theory of The Firm , Blackwell , Cambridge, MA .

Daft , R.L. and Lengel , R.H. ( 1986 ), “ Organizational information requirements, media richness and structural design ”, Management Science , Vol. 32 No. 5 , pp. 554 - 571 .

Daft , R.L. and Macintosh , N.B. ( 1981 ), “ A tentative exploration into the amount and equivocality of information processing in organizational work units ”, Administrative Science Quarterly , Vol. 26 No. 2 , pp. 207 - 224 .

Dane , E. and Pratt , M.G. ( 2007 ), “ Exploring intuition and its role in managerial decision making ”, Academy of Management Review , Vol. 32 No. 1 , pp. 33 - 54 .

Dane , E. , Rockmann , K.W. and Pratt , M.G. ( 2012 ), “ When should i trust my gut? Linking domain expertise to intuitive decision-making effectiveness ”, Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes , Vol. 119 No. 2 , pp. 187 - 194 .

Dean , J.W. and Sharfman , M.P. ( 1996 ), “ Does decision process matter? A study of strategic decision-making effectiveness ”, Academy of Management Journal , Vol. 39 No. 2 , pp. 368 - 392 .

Dudas , C. , Ng , A.H.C. , Pehrsson , L. and Boström , H. ( 2014 ), “ Integration of data mining and multi-objective optimisation for decision support in production systems development ”, International Journal of Computer Integrated Manufacturing , Vol. 27 No. 9 , pp. 824 - 839 .

Eisenhardt , K.M. ( 1989 ), “ Building theories from case study research ”, Academy of Management Review , Vol. 14 No. 4 , pp. 532 - 550 .

Eisenhardt , K.M. and Graebner , M.E. ( 2007 ), “ Theory building from cases: opportunities and challenges ”, Academy of Management Journal , Vol. 50 No. 1 , pp. 25 - 32 .

Elbanna , S. , Child , J. and Dayan , M. ( 2013 ), “ A model of antecedents and consequences of intuition in strategic decision-making: evidence from egypt ”, Long Range Planning , Vol. 46 No. 1 , pp. 149 - 176 .

Eling , K. , Griffin , A. and Langerak , F. ( 2014 ), “ Using intuition in fuzzy front-end decision-making: a conceptual framework ”, Journal of Product Innovation Management , Vol. 31 No. 5 , pp. 956 - 972 .

Ellström , P.-E. ( 2008 ), “ Knowledge creation through interactive research: a learning approach ”, Proceedings of the ECER Conference , Jönköping .

Eriksson , P.E. , Patel , P.C. , Sjödin , D.R. , Frishammar , J. and Parida , V. ( 2016 ), “ Managing interorganizational innovation projects: Mitigating the negative effects of equivocality through knowledge search strategies ”, Long Range Planning , Vol. 49 No. 6 , pp. 691 - 705 .

Frishammar , J. ( 2003 ), “ Information use in strategic decision making ”, Management Decision , Vol. 41 No. 4 , pp. 318 - 326 .

Frishammar , J. , Florén , H. and Wincent , J. ( 2011 ), “ Beyond managing uncertainty: insights from studying equivocality in the fuzzy front end of product and process innovation projects ”, IEEE Transactions on Engineering Management , Vol. 58 No. 3 , pp. 551 - 563 .

Frishammar , J. , Kurkkio , M. , Abrahamsson , L. and Lichtenthaler , U. ( 2012 ), “ Antecedents and consequences of firm’s process innovation capability: a literature review and a conceptual framework ”, IEEE Transactions on Engineering Management , Vol. 59 No. 4 , pp. 519 - 529 .

Galbraith , J.R. ( 1973 ), Designing Complex Organizations , Addison-Wesley Longman Publishing , Reading, MA .

Gaubinger , K. , Michael , R. , Swan , S. and Werani , T. ( 2014 ), Innovation and Product Management a Holistic and Practical Approach to Uncertainty Reduction , Springer , Berlin and Heidelberg .

Gershwin , S.B. ( 2018 ), “ The future of manufacturing systems engineering ”, International Journal of Production Research , Vol. 56 Nos 1–2 , pp. 224 - 237 .

Gigerenzer , G. and Gaissmaier , W. ( 2011 ), “ Heuristic decision making ”, Annual Review of Psychology , Vol. 62 No. 1 , pp. 451 - 482 .

Gino , F. and Pisano , G. ( 2008 ), “ Toward a theory of behavioral operations ”, Manufacturing & Service Operations Management , Vol. 10 No. 4 , pp. 676 - 691 .

Gore , J. and Sadler-Smith , E. ( 2011 ), “ Unpacking intuition: a process and outcome framework ”, Review of General Psychology , Vol. 15 No. 4 , pp. 304 - 316 .

Hämäläinen , R.P. , Luoma , J. and Saarinen , E. ( 2013 ), “ On the importance of behavioral operational research: the case of understanding and communicating about dynamic systems ”, European Journal of Operational Research , Vol. 228 No. 3 , pp. 623 - 634 .

Handfield , R.B. and Melnyk , S.A. ( 1998 ), “ The scientific theory-building process: a primer using the case of tqm ”, Journal of Operations Management , Vol. 16 No. 4 , pp. 321 - 339 .

Haußmann , C. , Dwivedi , Y.K. , Venkitachalam , K. and Williams , M.D. ( 2012 ), “ A summary and review of galbraith’s organizational information processing theory ”, in Dwivedi , Y.K. , Wade , M.R. and Schneberger , S.L. (Eds), Information Systems Theory: Explaining and Predicting Our Digital Society , Vol. 2 , Springer New York , New York, NY , pp. 71 - 93 .

Hodgkinson , G.P. , Sadler-Smith , E. , Burke , L.A. , Claxton , G. and Sparrow , P.R. ( 2009 ), “ Intuition in organizations: implications for strategic management ”, Long Range Planning , Vol. 42 No. 3 , pp. 277 - 297 .

Jacobides , M.G. ( 2007 ), “ The inherent limits of organizational structure and the unfulfilled role of hierarchy: lessons from a near-war ”, Organization Science , Vol. 18 No. 3 , pp. 455 - 477 .

Jalonen , H. ( 2011 ), “ The uncertainty of innovation: a systematic review of the literature ”, Journal of Management Research , Vol. 4 No. 1 , pp. 1 - 47 .

Johnson , P. , Buehring , A. , Cassell , C. and Symon , G. ( 2007 ), “ Defining qualitative management research: an empirical investigation ”, Qualitative Research in Organizations and Management: An International Journal , Vol. 2 No. 1 , pp. 23 - 42 .

Jonassen , D.H. ( 2012 ), “ Designing for decision making ”, Educational Technology Research and Development , Vol. 60 No. 2 , pp. 341 - 359 .

Julmi , C. ( 2019 ), “ When rational decision-making becomes irrational: a critical assessment and re-conceptualization of intuition effectiveness ”, Business Research , Vol. 12 No. 1 , pp. 291 - 314 .

Kahraman , C. , Onar , S.C. and Oztaysi , B. ( 2015 ), “ Fuzzy multicriteria decision-making: a literature review ”, International Journal of Computational Intelligence Systems , Vol. 8 No. 4 , pp. 637 - 666 .

Käki , A. , Kemppainen , K. and Liesiö , J. ( 2019 ), “ What to do when decision-makers deviate from model recommendations? Empirical evidence from hydropower industry ”, European Journal of Operational Research , Vol. 278 No. 3 , pp. 869 - 882 .

Karlsson , C. ( 2010 ), Researching Operations Management , Routledge , New York, NY .

Ketokivi , M. and Choi , T. ( 2014 ), “ Renaissance of case research as a scientific method ”, Journal of Operations Management , Vol. 32 No. 5 , pp. 232 - 240 .

Khatri , N. and Ng , H.A. ( 2000 ), “ The role of intuition in strategic decision making ”, Human Relations , Vol. 53 No. 1 , pp. 57 - 86 .

Kihlander , I. and Ritzén , S. ( 2012 ), “ Compatibility before completeness – identifying intrinsic conflicts in concept decision making for technical systems ”, Technovation , Vol. 32 No. 2 , pp. 79 - 89 .

Klein , R. , Koch , S. , Steinhardt , C. and Strauss , A.K. ( 2019 ), “ A review of revenue management: recent generalizations and advances in industry applications ”, European Journal of Operational Research , available at: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejor.2019.06.034

Koufteros , X. , Vonderembse , M. and Jayaram , J. ( 2005 ), “ Internal and external integration for product development: the contingency effects of uncertainty, equivocality, and platform strategy ”, Decision Sciences , Vol. 36 No. 1 , pp. 97 - 133 .

Krzeminska , A. and Eckert , C. ( 2015 ), “ Complementarity of internal and external r&d: Is there a difference between product versus process innovations? ”, R and D Management , Vol. 46 No. S3 , pp. 931 - 944 .

Kubler , S. , Robert , J. , Derigent , W. , Voisin , A. and Le Traon , Y. ( 2016 ), “ A state-of the-art survey & testbed of fuzzy AHP (FAHP) applications ”, Expert Systems with Applications , Vol. 65 , pp. 398 - 422 .

Kurkkio , M. , Frishammar , J. and Lichtenthaler , U. ( 2011 ), “ Where process development begins: a multiple case study of front end activities in process firms ”, Technovation , Vol. 31 No. 9 , pp. 490 - 504 .

Liao , Y. , Deschamps , F. , Loures , E.D.F.R. and Ramos , L.F.P. ( 2017 ), “ Past, present and future of industry 4.0 – a systematic literature review and research agenda proposal ”, International Journal of Production Research , Vol. 55 No. 12 , pp. 3609 - 3629 .

Liberatore , M.J. and Luo , W. ( 2010 ), “ The analytics movement: implications for operations research ”, INFORMS Journal on Applied Analytics , Vol. 40 No. 4 , pp. 313 - 324 .

Liu , R. and Hart , S. ( 2011 ), “ Does experience matter? – A study of knowledge processes and uncertainty reduction in solution innovation ”, Industrial Marketing Management , Vol. 40 No. 5 , pp. 691 - 698 .

Loch , C.H. and Wu , Y. ( 2007 ), “ Behavioral operations management ”, Foundations and Trends® in Technology, Information and Operations Management , Vol. 1 No. 3 , pp. 121 - 232 .

Luoma , J. ( 2016 ), “ Model-based organizational decision making: a behavioral lens ”, European Journal of Operational Research , Vol. 249 No. 3 , pp. 816 - 826 .

Mccutcheon , D.M. and Meredith , J.R. ( 1993 ), “ Conducting case study research in operations management ”, Journal of Operations Management , Vol. 11 No. 3 , pp. 239 - 256 .

March , J.G. and Simon , H.A. ( 1993 ), Organizations , Blackwell Business , Oxford .

Mardani , A. , Jusoh , A. and Zavadskas , E.K. ( 2015 ), “ Fuzzy multiple criteria decision-making techniques and applications – two decades review from 1994 to 2014 ”, Expert Systems with Applications , Vol. 42 No. 8 , pp. 4126 - 4148 .

Martinez-Ros , E. ( 1999 ), “ Explaining the decisions to carry out product and process innovations: the spanish case ”, The Journal of High Technology Management Research , Vol. 10 No. 2 , pp. 223 - 242 .

Marzi , G. , Dabić , M. , Daim , T. and Garces , E. ( 2017 ), “ Product and process innovation in manufacturing firms: a 30-year bibliometric analysis ”, Scientometrics , Vol. 113 No. 2 , pp. 673 - 704 .

Matzler , K. , Uzelac , B. and Bauer , F. ( 2014 ), “ Intuition’s value for organizational innovativeness and why managers still refrain from using it ”, Management Decision , Vol. 52 No. 3 , pp. 526 - 539 .

Meredith , J. ( 1998 ), “ Building operations management theory through case and field research ”, Journal of Operations Management , Vol. 16 No. 4 , pp. 441 - 454 .

Metters , R. , Queenan , C. , Ferguson , M. , Harrison , L. , Higbie , J. , Ward , S. , Barfield , B. , Farley , T. , Kuyumcu , H.A. and Duggasani , A. ( 2008 ), “ The ‘killer application’ of revenue management: Harrah’s cherokee casino & hotel ”, INFORMS Journal on Applied Analytics , Vol. 38 No. 3 , pp. 161 - 175 .

Mikalef , P. and Krogstie , J. ( 2018 ), Big Data Analytics As An Enabler of Process Innovation Capabilities: A Configurational Approach , Springer International Publishing , Cham , pp. 426 - 441 .

Miles , M.B. , Huberman , A.M. and Saldaña , J. ( 2013 ), Qualitative Data Analysis: A Methods Sourcebook , Sage Publications , Thousand Oaks, CA .

Milewski , S.K. , Fernandes , K.J. and Mount , M.P. ( 2015 ), “ Exploring technological process innovation from a lifecycle perspective ”, International Journal of Operations & Production Management , Vol. 35 No. 9 , pp. 1312 - 1331 .

Mintzberg , H. , Raisinghani , D. and Théorêt , A. ( 1976 ), “ The structure of ‘unstructured’ decision processes ”, Administrative Science Quarterly , Vol. 21 No. 2 , pp. 246 - 275 .

Papadakis , V.M. , Lioukas , S. and Chambers , D. ( 1998 ), “ Strategic decision-making processes: the role of management and context ”, Strategic Management Journal , Vol. 19 No. 2 , pp. 115 - 147 .

Parida , V. , Patel , P.C. , Frishammar , J. and Wincent , J. ( 2017 ), “ Managing the front-end phase of process innovation under conditions of high uncertainty ”, Quality & Quantity , Vol. 51 No. 5 , pp. 1983 - 2000 .

Piening , E.P. and Salge , T.O. ( 2015 ), “ Understanding the antecedents, contingencies, and performance implications of process innovation: a dynamic capabilities perspective ”, Journal of Product Innovation Management , Vol. 32 No. 1 , pp. 80 - 97 .

Pisano , G.P. ( 1997 ), The Development Factory: Unlocking the Potential of Process Innovation , Harvard Business Press , Boston, MA .

Reichstein , T. and Salter , A. ( 2006 ), “ Investigating the sources of process innovation among uk manufacturing firms ”, Industrial and Corporate Change , Vol. 15 No. 4 , pp. 653 - 682 .

Rönnberg , D.S. ( 2019 ), “ Knowledge processing and ecosystem co-creation for process innovation: Managing joint knowledge processing in process innovation projects ”, International Entrepreneurship and Management Journal , Vol. 15 No. 1 , pp. 135 - 162 .

Rönnberg , D.S. , Frishammar , J. and Eriksson , P.E. ( 2016 ), “ Managing uncertainty and equivocality in joint process development projects ”, Journal of Engineering and Technology Management , Vol. 39 No. 1 , pp. 13 - 25 .

Rönnberg , D.S. , Parida , V. , Leksell , M. and Petrovic , A. ( 2018 ), “ Smart factory implementation and process innovation ”, Research-Technology Management , Vol. 61 No. 5 , pp. 22 - 31 .