The Electoral College – Top 3 Pros and Cons

Pro/Con Arguments | Discussion Questions | Take Action | Sources | More Debates

The debate over the continued use of the Electoral College resurfaced during the 2016 presidential election , when Donald Trump lost the general election to Hillary Clinton by over 2.8 million votes and won the Electoral College by 74 votes. The official general election results indicate that Trump received 304 Electoral College votes and 46.09% of the popular vote (62,984,825 votes), and Hillary Clinton received 227 Electoral College votes and 48.18% of the popular vote (65,853,516 votes). [ 1 ]

Prior to the 2016 election, there were four times in US history when a candidate won the presidency despite losing the popular vote: 1824 ( John Quincy Adams over Andrew Jackson ), 1876 ( Rutherford B. Hayes over Samuel Tilden ), 1888 ( Benjamin Harrison over Grover Cleveland ), and 2000 ( George W. Bush over Al Gore ). [ 2 ]

The Electoral College was established in 1788 by Article II of the US Constitution , which also established the executive branch of the US government, and was revised by the Twelfth Amendment (ratified June 15, 1804), the Fourteenth Amendment (ratified July 1868), and the Twenty-Third Amendment (ratified Mar. 29, 1961). Because the procedure for electing the president is part of the Constitution, a Constitutional Amendment (which requires two-thirds approval in both houses of Congress plus approval by 38 states) would be required to abolish the Electoral College. [ 3 ] [ 4 ] [ 5 ] [ 6 ]

The Founding Fathers created the Electoral College as a compromise between electing the president via a vote in Congress only or via a popular vote only. The Electoral College comprises 538 electors; each state is allowed one elector for each Representative and Senator (DC is allowed 3 electors as established by the Twenty-Third Amendment). [ 3 ] [ 4 ] [ 5 ] [ 6 ]

In each state, a group of electors is chosen by each political party. On election day, voters choosing a presidential candidate are actually casting a vote for an elector. Most states use the “winner-take-all” method, in which all electoral votes are awarded to the winner of the popular vote in that state. In Nebraska and Maine, the candidate that wins the state’s overall popular vote receives two electors, and one elector from each congressional district is apportioned to the popular vote winner in that district. For a candidate to win the presidency, he or she must win at least 270 Electoral College votes. [ 3 ] [ 4 ] [ 5 ] [ 6 ]

At least 700 amendments have been proposed to modify or abolish the Electoral College. [ 25 ]

On Monday Dec. 19, 2016, the electors in each state met to vote for President and Vice President of the United States. Of the 538 Electoral College votes available, Donald J. Trump received 304 votes, Hillary Clinton received 227 votes, and seven votes went to others: three for Colin Powell, one for Faith Spotted Eagle, one for John Kasich, one for Ron Paul, and one for Bernie Sanders). On Dec. 22, 2016, the results were certified in all 50 states. On Jan. 6, 2017, a joint session of the US Congress met to certify the election results and Vice President Joe Biden, presiding as President of the Senate, read the certified vote tally. [ 21 ] [ 22 ]

A Sep. 2020 Gallup poll found 61% of Americans were in favor of abolishing the Electoral College, up 12 points from 2016. [ 24 ]

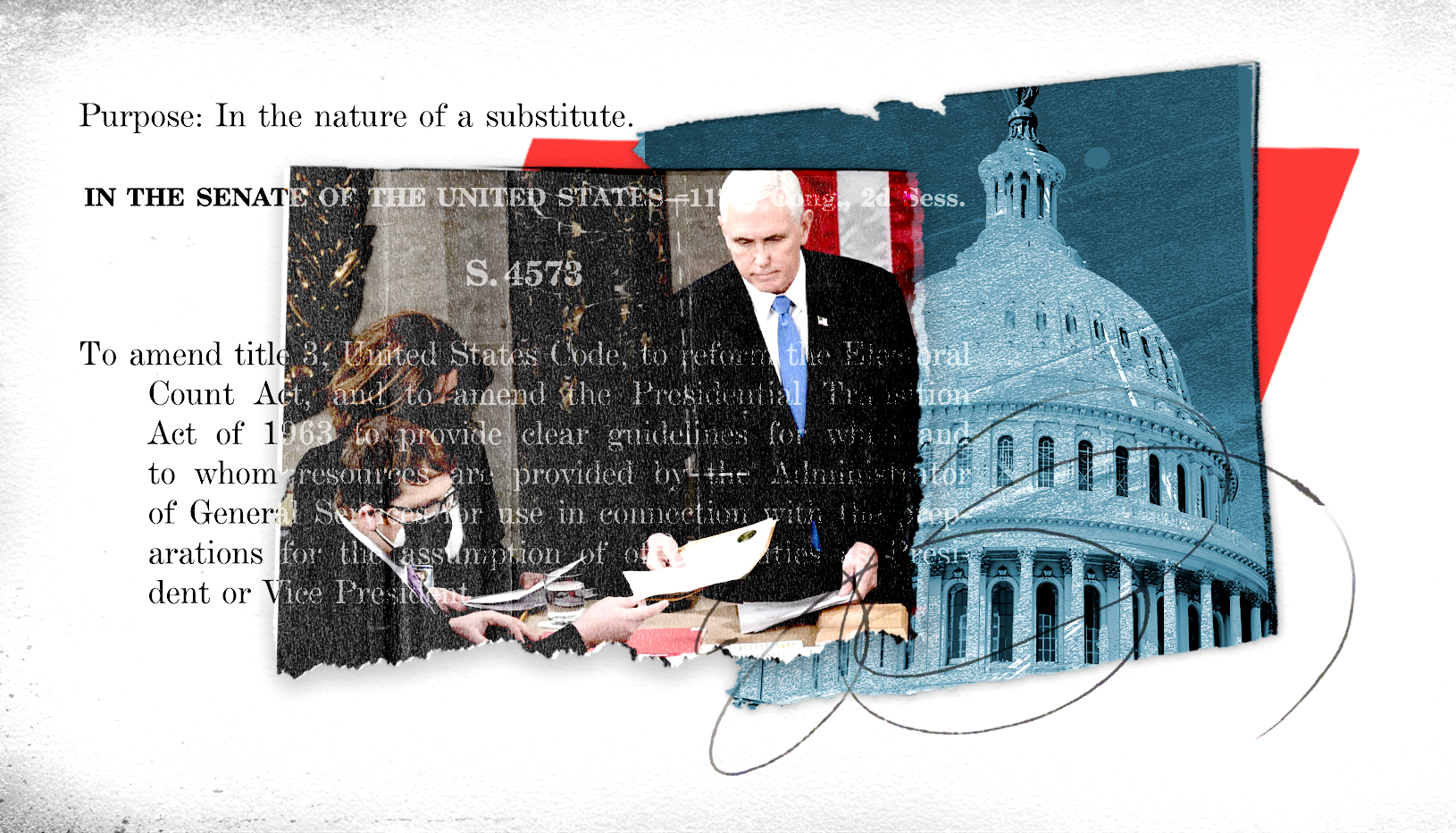

For the 2020 election, electors voted on Dec. 14, and delivered the results on Dec. 23. On Jan. 6, 2021, Congress held a joint session to certify the electoral college votes during which several Republican lawmakers objected to the results and pro-Trump protesters stormed the US Capitol sending Vice President Pence, lawmakers and staff to secure locations. The votes were certified in the early hours of Jan. 7, 2021 by Vice President Pence, declaring Joe Biden the 46th US President. President Joe Biden was inaugurated with Vice President Kamala Harris on Jan. 20, 2021. [ 23 ] [ 26 ]

Should the United States Use the Electoral College in Presidential Elections?

Pro 1 The Electoral College ensures that that all parts of the country are involved in selecting the President of the United States. If the election depended solely on the popular vote, then candidates could limit campaigning to heavily-populated areas or specific regions. To win the election, presidential candidates need electoral votes from multiple regions and therefore they build campaign platforms with a national focus, meaning that the winner will actually be serving the needs of the entire country. Without the electoral college, groups such as Iowa farmers and Ohio factory workers would be ignored in favor of pandering to metropolitan areas with higher population densities, leaving rural areas and small towns marginalized. [ 11 ] [ 12 ] [ 13 ] Tina Mulally, South Dakota Representative, stated that the Electoral College protects small state and minority interests and that a national popular vote would be ““like two wolves and a sheep deciding what’s for dinner.” Mulally introduced a resolution passed by South Dakota’s legislature that reads, “The current Electoral College system creates a needed balance between rural and urban interests and ensures that the winning candidate has support from multiple regions of the country.” [ 32 ] Read More

Pro 2 The Electoral College was created to protect the voices of the minority from being overwhelmed by the will of the majority. The Founding Fathers wanted to balance the will of the populace against the risk of “tyranny of the majority,” in which the voices of the masses can drown out minority interests. [ 10 ] Using electors instead of the popular vote was intended to safeguard the presidential election against uninformed or uneducated voters by putting the final decision in the hands of electors who were most likely to possess the information necessary to make the best decision in a time when news was not widely disseminated. [ 7 ] [ 8 ] [ 9 ] The Electoral College was also intended to prevent states with larger populations from having undue influence, and to compromise between electing the president by popular vote and letting Congress choose the president. [ 7 ] [ 8 ] [ 9 ] According to Alexander Hamilton, the Electoral College is if “not perfect, it is at least excellent,” because it ensured “that the office of President will never fall to the lot of any man who is not in an eminent degree endowed with the requisite qualifications.” [ 7 ] Democratic Nevada Governor Steve Sisolak vetoed a measure in 2019 that would add the state to the National Popular Vote Interstate Compact, which would have obligated the state’s electors to vote for the popular vote winner. Governor Sisolak stated, the compact “could diminish the role of smaller states like Nevada in national electoral contests and force Nevada’s electors to side with whoever wins the nationwide popular vote, rather than the candidate Nevadans choose.” [ 31 ] Hans von Spakovsky, Senior Legal Fellow at the Heritage Foundation and a former commissioner for the FEC, explained, “The Framers’ fears of a ‘tyranny of the majority’ is still very relevant today. One can see its importance in the fact that despite Hillary Clinton’s national popular vote total, she won only about a sixth of the counties nationwide, with her support limited mostly to urban areas on both coasts.” [ 34 ] Read More

Pro 3 The Electoral College can preclude calls for recounts or demands for run-off elections, giving certainty to presidential elections. If the election were based on popular vote, it would be possible for a candidate to receive the highest number of popular votes without actually obtaining a majority. [ 11 ] This happened with President Nixon in 1968 and President Clinton in 1992, when both men won the most electoral votes while receiving just 43% of the popular vote. The existence of the Electoral College precluded calls for recounts or demands for run-off elections. [ 11 ] Richard A. Posner, judge on the U.S. Court of Appeals for the 7th Circuit and a senior lecturer at the University of Chicago Law School, further explained, “There is pressure for runoff elections when no candidate wins a majority of the votes cast; that pressure, which would greatly complicate the presidential election process, is reduced by the Electoral College, which invariably produces a clear winner.” [ 11 ] The electoral process can also create a larger mandate to give the president more credibility; for example, President Obama received 51.3% of the popular vote in 2012 but 61.7% of the electoral votes. [ 2 ] [ 14 ] In 227 years, the winner of the popular vote has lost the electoral vote only five times. This proves the system is working. [ 2 ] [ 14 ] Read More

Con 1 The Electoral College gives too much power to swing states and allows the presidential election to be decided by a handful of states. The two main political parties can count on winning the electoral votes in certain states, such as California for the Democratic Party and Indiana for the Republican Party, without worrying about the actual popular vote totals. Because of the Electoral College, presidential candidates only need to pay attention to a limited number of states that can swing one way or the other. [ 18 ] A Nov. 6, 2016 episode of PBS NewsHour revealed that “Donald Trump and Hillary Clinton have made more than 90% of their campaign stops in just 11 so-called battleground states. Of those visits, nearly two-thirds took place in the four battlegrounds with the most electoral votes — Florida, Pennsylvania, Ohio, and North Carolina.” [ 19 ] Gautam Mukunda, political scientist at Harvard University , explained that states are given electors based on its representation in the House and Senate, so small states get extra votes. Mukunda stated, “The fact that in presidential elections people in Wyoming have [nearly four] times the power of people in California is antithetical at the most basic level to what we say we stand for as a democracy.” [ 33 ] Read More

Con 2 The Electoral College is rooted in slavery and racism. The “minority” interests the Founding Fathers intended the Electoral College to protect were those of slaveowners and states with legal slavery. James Madison stated, “There was one difficulty however of a serious nature attending an immediate choice by the people. The right of suffrage was much more diffusive in the Northern than the Southern States; and the latter could have no influence in the election on the score of the Negroes. The substitution of electors obviated this difficulty and seemed on the whole to be liable to fewest objections.” [ 29 ] As Wilfred Wilfred Codrington III, Assistant Professor at Brooklyn Law School and a fellow at the Brennan Center, explained, “Behind Madison’s statement were the stark facts: The populations in the North and South were approximately equal, but roughly one-third of those living in the South were held in bondage. Because of its considerable, nonvoting slave population, that region would have less clout under a popular-vote system. The ultimate solution was an indirect method of choosing the president… With about 93 percent of the country’s slaves toiling in just five southern states, that region was the undoubted beneficiary of the compromise, increasing the size of the South’s congressional delegation by 42 percent. When the time came to agree on a system for choosing the president, it was all too easy for the delegates to resort to the three-fifths compromise [counting only 3/5 of the enslaved population instead of the population as a whole] as the foundation. The peculiar system that emerged was the Electoral College.” [ 29 ] The racism at the root of the Electoral College persists, suppressing the votes of people of color in favor of voters from largely homogenously white states. [ 29 ] [ 30 ] Read More

Con 3 Democracy should function on the will of the people, allowing one vote per adult. There are over an estimated 332 million people in the United States, with population estimates predicting almost 342 million by 2024, the next presidential election. But just 538 people decide who will be president; that’s about 0.000156% of the population deciding the president. In 2016, Hillary Clinton won the popular vote by more than one million votes, yet still lost the election on electoral votes. [ 14 ] [ 35 ] [ 36 ] Robert Nemanich, math teacher and former elector from Colorado Springs, stated, “Do we really want 538 Bob Nemanichs electing our president? …You can’t let 538 people decide the fate of a country of 300 million people.” [ 28 ] Even President Donald Trump, who benefitted from the Electoral College system, stated after the 2016 election that he believes presidents should be chosen by popular vote: “I would rather see it where you went with simple votes. You know, you get 100 million votes and somebody else gets 90 million votes and you win.” Just as in 2000 when George W. Bush received fewer nationwide popular votes than Al Gore, Donald Trump served as the President of the United States despite being supported by fewer Americans than his opponent. [ 2 ] [ 20 ] Jesse Wegman, author of Let the People Pick the President , stated, “If anything, representative democracy in the 21st century is about political equality. It’s about one person, one vote — everybody’s vote counting equally. You’re not going to convince a majority of Americans that that’s not how you should do it.” [ 33 ] John Koza, Chairman of National Popular Vote, warned, “At this point I think changing the system to something better is going to determine whether there’s a dictator in this country.” [ 27 ] Read More

Discussion Questions

1. Should the Electoral College be abolished? Why or why not?

2. Should the Electoral College be modified? How and why? Or why not?

3. What other voting reforms would you make? Rank choice voting? Voter ID laws? Make a list and offer support for each reform. If you would not change the voting process, make a list of reforms and why you would not choose to enact them.

Take Action

1. Listen to a Constitution Center podcast exploring the pros and cons of the Electoral College.

2. Explore the Electoral College via the US National Archives .

3. Consider the American Bar Association’s fact check on whether the Electoral College can be abolished.

4. Consider how you felt about the issue before reading this article. After reading the pros and cons on this topic, has your thinking changed? If so, how? List two to three ways. If your thoughts have not changed, list two to three ways your better understanding of the “other side of the issue” now helps you better argue your position.

5. Push for the position and policies you support by writing US national senators and representatives .

| 1. | Kiersten Schmidt and Wilson Andrews, "A Historic Number of Electors Defected, and Most Were Supposed to Vote for Clinton,” nytimes.com, Dec. 19, 2016 | |

| 2. | Rachael Revesz, "Five Presidential Nominees Who Won Popular Vote but Lost the Election," independent.co.uk, Nov. 16, 2016 | |

| 3. | National Archives and Records Administration, "The 2016 Presidential Election," archives.gov (accessed Nov. 16, 2016) | |

| 4. | National Archives and Records Administration, "About the Electors," archives.gov (accessed Nov. 16, 2016) | |

| 5. | National Archives and Records Administration, "Presidential Election Laws," archives.gov (accessed Nov. 16, 2016) | |

| 6. | National Archives and Records Administration, "What Is the Electoral College?," archives.gov (accessed Nov. 16, 2016) | |

| 7. | Alexander Hamilton, "The Federalist Papers: No. 68 (The Mode of Electing the President)," congress.gov, Mar. 14, 1788 | |

| 8. | Marc Schulman, "Why the Electoral College," historycentral.com (accessed Nov. 18, 2016) | |

| 9. | Melissa Kelly, "Why Did the Founding Fathers Create Electors?," 712educators.about.com, Jan. 28, 2016 | |

| 10. | Hans A. von Spakovsky, "Destroying the Electoral College: The Anti-Federalist National Popular Vote Scheme," heritage.org, Oct. 27, 2011 | |

| 11. | Richard A. Posner, "In Defense of the Electoral College," slate.com, Nov. 12, 2012 | |

| 12. | Jarrett Stepman, "Why America Uses Electoral College, Not Popular Vote for Presidential Election," cnsnews.com, Nov. 7, 2016 | |

| 13. | Gary Gregg, "Electoral College Keeps Elections Fair," politico.com, Dec. 5, 2012 | |

| 14. | John Nichols, "Obama's 3 Million Vote, Electoral College Landslide, Majority of States Mandate," thenation.com, Nov. 9, 2012 | |

| 15. | Joe Miller, "The Reason for the Electoral College," factcheck.org, Feb. 11, 2008 | |

| 16. | William C. Kimberling, "The Manner of Choosing Electors," uselectionatlas.org (accessed Nov. 18, 2016) | |

| 17. | Sanford V. Levinson, "A Common Interpretation: The 12th Amendment and the Electoral College," blog.constitutioncenter.org, Nov. 17, 2016 | |

| 18. | Andrew Prokop, "Why the Electoral College Is the Absolute Worst, Explained," vox.com, Nov. 10, 2016 | |

| 19. | Sam Weber and Laura Fong, "This System Calls for Popular Vote to Determine Winner," pbs.org, Nov. 6, 2016 | |

| 20. | Leslie Stahl, "President-elect Trump Speaks to a Divided Country on 60 Minutes," cbsnews.com, Nov. 13, 2016 | |

| 21. | Lisa Lerer, "Clinton Wins Popular Vote by Nearly 2.9 Million,” elections.ap.org, Dec. 22, 2016 | |

| 22. | Doina Chiacu and Susan Cornwell, "US Congress Certifies Trump’s Electoral College Victory,” reuters.com, Jan. 6, 2017 | |

| 23. | Congressional Research Service, "The Electoral College: A 2020 Presidential Election Timeline," crsreports.congress.gov, Sep. 3, 2020 | |

| 24. | Jonathen Easley, "Gallup: 61 Percent Support Abolishing the Electoral College," thehill.com, Sep. 24, 2020 | |

| 25. | Fair Vote, "Past Attempts at Reform," fairvote.org (accessed Oct. 1, 2020) | |

| 26. | John Wagner, et al., "Pence Declares Biden Winner of the Presidential Election after Congress Finally Counts Electoral Votes," , Jan. 7, 2021 | |

| 27. | Jeremy Stahl, "This Team Thinks They Can Fix the Electoral College by 2024," slate.com, Dec. 14, 2020 | |

| 28. | Nicholas Casey, "Meet the Electoral College’s Biggest Critics: Some of the Electors Themselves," nytimes.com, Dec. 12, 2020 | |

| 29. | Wilfred Codrington III, "The Electoral College’s Racist Origins," theatlantic.com, Nov. 17, 2019 | |

| 30. | Peniel E. Joseph, "Shut the Door on Trump by Ending the Electoral College," cnn.com, Dec. 15, 2020 | |

| 31. | Steve Sisolak, "Governor Sisolak Statement on Assembly Bill 186," gov.nv.gov, May 30, 2019 | |

| 32. | Andrew Selsky, "Critics of Electoral College Push for Popular Vote Compact," apnews.com, Dec. 12, 2020 | |

| 33. | Mara Liasson, "A Growing Number of Critics Raise Alarms about the Electoral College," , June 10, 2021 | |

| 34. | Faith Karimi, "Why the Electoral College Has Long Been Controversial," cnn.com, Oct. 10, 2020 | |

| 35. | US Census Bureau, "U.S. and World Population Clock," census.gov (accessed Dec. 8, 2021) | |

| 36. | US Census Bureau, 2017 National Population Projections Tables: Main Series," census.gov, 2017 |

More Election Debate Topics

Should People Who Have Completed Felony Sentences Be Allowed to Vote? – The pros and cons of the felon voting debate include arguments about the social contract, voting while in prison, and paying debts.

Should the Voting Age Be Lowered to 16? – Proponents say teens are knowledgeable enough to vote. Opponents say kids aren’t mature enough to vote.

Should Election Day Be Made a National Holiday? – Proponents say an election day holiday will increase voter turnout. Opponents say would disadvantage low-income and blue collar workers.

ProCon/Encyclopaedia Britannica, Inc. 325 N. LaSalle Street, Suite 200 Chicago, Illinois 60654 USA

Natalie Leppard Managing Editor [email protected]

© 2023 Encyclopaedia Britannica, Inc. All rights reserved

- Social Media

- Death Penalty

- School Uniforms

- Video Games

- Animal Testing

- Gun Control

- Banned Books

- Teachers’ Corner

Cite This Page

ProCon.org is the institutional or organization author for all ProCon.org pages. Proper citation depends on your preferred or required style manual. Below are the proper citations for this page according to four style manuals (in alphabetical order): the Modern Language Association Style Manual (MLA), the Chicago Manual of Style (Chicago), the Publication Manual of the American Psychological Association (APA), and Kate Turabian's A Manual for Writers of Term Papers, Theses, and Dissertations (Turabian). Here are the proper bibliographic citations for this page according to four style manuals (in alphabetical order):

[Editor's Note: The APA citation style requires double spacing within entries.]

[Editor’s Note: The MLA citation style requires double spacing within entries.]

Electoral College Pros and Cons

- U.S. Political System

- History & Major Milestones

- U.S. Constitution & Bill of Rights

- U.S. Legal System

- Defense & Security

- Campaigns & Elections

- Business & Finance

- U.S. Foreign Policy

- U.S. Liberal Politics

- U.S. Conservative Politics

- Women's Issues

- Civil Liberties

- The Middle East

- Race Relations

- Immigration

- Crime & Punishment

- Canadian Government

- Understanding Types of Government

- B.S., Texas A&M University

The Electoral College system , long a source of controversy, came under especially heavy criticism after the 2016 presidential election when Republican Donald Trump lost the nationwide popular vote to Democrat Hillary Clinton by over 2.8 million votes but won the Electoral College—and thus the presidency—by 74 electoral votes .

- Gives the smaller states an equal voice.

- Prevents disputed outcomes ensuring a peaceful transition of power

- Reduces the costs of national presidential campaigns.

- Can disregard the will of the majority.

- Gives too few states too much electoral power.

- Reduces voter participation by creating a “my vote doesn’t matter” feeling.

By its very nature, the Electoral College system is confusing . When you vote for a presidential candidate, you are actually voting for a group of electors from your state who have all “pledged” to vote for your candidate. Each state is allowed one elector for each of its Representatives and Senators in Congress. There are currently 538 electors, and to be elected, a candidate must get the votes of at least 270 electors.

The Obsolescence Debate

The Electoral College system was established by Article II of the U.S. Constitution in 1788. The Founding Fathers chose it as a compromise between allowing Congress to choose the president and having the president elected directly by the popular vote of the people. The Founders believed that most common citizens of the day were poorly educated and uninformed on political issues. Consequently, they decided that using the “proxy” votes of the well-informed electors would lessen the risk of “tyranny of the majority,” in which the voices of the minority are drowned out by those of the masses. Additionally, the Founders reasoned that the system would prevent states with larger populations from having an unequal influence on the election.

Critics, however, argue that Founder’s reasoning is no longer relevant as today’s voters are better-educated and have virtually unlimited access to information and to the candidates’ stances on the issues. In addition, while the Founders considered the electors as being “free from any sinister bias” in 1788, electors today are selected by the political parties and are usually “pledged” to vote for the party’s candidate regardless of their own beliefs.

Today, opinions on the future of the Electoral College range from protecting it as the basis of American democracy to abolishing it completely as an ineffective and obsolete system that may not accurately reflect the will of the people. What are some of the main advantages and disadvantages of the Electoral College?

Advantages of the Electoral College

- Promotes fair regional representation: The Electoral College gives the small states an equal voice. If the president was elected by the popular vote alone, candidates would mold their platforms to cater to the more populous states. Candidates would have no desire to consider, for example, the needs of farmers in Iowa or commercial fishermen in Maine.

- Provides a clean-cut outcome: Thanks to the Electoral College, presidential elections usually come to a clear and undisputed end. There is no need for wildly expensive nationwide vote recounts. If a state has significant voting irregularities, that state alone can do a recount. In addition, the fact that a candidate must gain the support of voters in several different geographic regions promotes the national cohesion needed to ensure a peaceful transfer of power.

- Makes campaigns less costly: Candidates rarely spend much time—or money—campaigning in states that traditionally vote for their party’s candidates. For example, Democrats rarely campaign in liberal-leaning California, just as Republicans tend to skip the more conservative Texas. Abolishing the Electoral College could make America’s many campaign financing problems even worse.

Disadvantages of the Electoral College

- Can override the popular vote: In five presidential elections so far—1824, 1876, 1888, 2000, and 2016—a candidate lost the nationwide popular vote but was elected president by winning the Electoral College vote. This potential to override the “will of the majority” is often cited as the main reason to abolish the Electoral College.

- Gives the swing states too much power: The needs and issues of voters in the 14 swing states —those that have historically voted for both Republican and Democratic presidential candidates—get a higher level of consideration than voters in other states. The candidates rarely visit the predictable non-swing states, like Texas or California. Voters in the non-swing states will see fewer campaign ads and be polled for their opinions less often voters in the swing states. As a result, the swing states, which may not necessarily represent the entire nation, hold too much electoral power.

- Makes people feel their vote doesn’t matter: Under the Electoral College system, while it counts, not every vote “matters.” For example, a Democrat’s vote in liberal-leaning California has far less effect on the election’s final outcome that it would in one of the less predictable swing states like Pennsylvania, Florida, and Ohio. The resulting lack of interest in non-swing states contributes to America’s traditionally low voter turnout rate .

The Bottom Line

Abolishing the Electoral College would require a constitutional amendment , a lengthy and often unsuccessful process. However, there are proposals to “reform” the Electoral College without abolishing it. One such movement, the National Popular Vote plan would ensure that the winner of the popular vote would also win at least enough Electoral College votes to be elected president. Another movement is attempting to convince states to split their electoral vote based on the percentage of the state’s popular vote for each candidate. Eliminating the winner-take-all requirement of the Electoral College at the state level would lessen the tendency for the swing states to dominate the electoral process.

The Popular Vote Plan Alternative

As an alternative to the long and unlikely method amending the Constitution, critics of the Electoral College are now perusing the National Popular Vote plan designed to ensure that the candidate who wins the overall popular vote in inaugurated president.

Based on Article II, Section 1 of the Constitution granting the states the exclusive power to control how their electoral votes are awarded, the National Popular Vote plan requires the legislature of each participating state to enact a bill agreeing that the state will award all of its electoral votes to the candidate who receives the most popular votes in all 50 states and the District of Columbia, regardless of the outcome of the popular vote in that specific state.

The National Popular Vote would go into effect when states controlling 270—a simple majority—of the total 538 electoral votes. As of July 2020, a National Popular Vote bill has been signed into law in 16 states controlling a total of 196 electoral votes, including 4 small states, 8 medium-sized states, 3 big states (California, Illinois, and New York), and the District of Columbia. Thus, the National Popular Vote plan will take effect when enacted by states controlling an additional 74 electoral votes.

Sources and Further Reference

- “From Bullets to Ballots: The Election of 1800 and the First Peaceful Transfer of Political Power.” TeachingAmericanHistory.org , https://teachingamericanhistory.org/resources/zvesper/chapter1/.

- Hamilton, Alexander. “The Federalist Papers: No. 68 (The Mode of Electing the President).” congress.gov , Mar. 14, 1788, https://www.congress.gov/resources/display/content/The+Federalist+Papers#TheFederalistPapers-68.

- Meko, Tim. “How Trump won the presidency with razor-thin margins in swing states.” Washington Post (Nov. 11, 2016), https://www.washingtonpost.com/graphics/politics/2016-election/swing-state-margins/.

- Has an Independent Ever Won the Presidency?

- The National Popular Vote Plan

- Reasons to Keep the Electoral College

- How the US Electoral College System Works

- What Happens if There Is a Tie in the Electoral College?

- Presidents Elected Without Winning the Popular Vote

- How Electoral Votes Are Awarded

- Who Invented the Electoral College?

- 12th Amendment: Fixing the Electoral College

- How many Electors does each State have?

- 2000 Presidential Election of George W. Bush vs. Al Gore

- How Many Electoral Votes Does a Candidate Need to Win?

- Swing States in the Presidential Election

- Learn How Many Total Electoral Votes There Are

- What Happens If the Presidential Election Is a Tie

- Purposes and Effects of the Electoral College

- Games & Quizzes

- History & Society

- Science & Tech

- Biographies

- Animals & Nature

- Geography & Travel

- Arts & Culture

- On This Day

- One Good Fact

- New Articles

- Lifestyles & Social Issues

- Philosophy & Religion

- Politics, Law & Government

- World History

- Health & Medicine

- Browse Biographies

- Birds, Reptiles & Other Vertebrates

- Bugs, Mollusks & Other Invertebrates

- Environment

- Fossils & Geologic Time

- Entertainment & Pop Culture

- Sports & Recreation

- Visual Arts

- Demystified

- Image Galleries

- Infographics

- Top Questions

- Britannica Kids

- Saving Earth

- Space Next 50

- Student Center

Pro and Con: Electoral College

To access extended pro and con arguments, sources, and discussion questions about whether should use the Electoral College in presidential elections, go to ProCon.org .

The debate over the continued use of the Electoral College resurfaced during the 2016 presidential election , when Donald Trump lost the general election to Hillary Clinton by over 2.8 million votes and won the Electoral College by 74 votes. The official general election results indicate that Trump received 304 Electoral College votes and 46.09% of the popular vote (62,984,825 votes), and Hillary Clinton received 227 Electoral College votes and 48.18% of the popular vote (65,853,516 votes).

Prior to the 2016 election, there were four times in US history when a candidate won the presidency despite losing the popular vote : 1824 (John Quincy Adams over Andrew Jackson), 1876 (Rutherford B. Hayes over Samuel Tilden), 1888 (Benjamin Harrison over Grover Cleveland), and 2000 (George W. Bush over Al Gore).

The Electoral College was established in 1788 by Article II of the US Constitution, which also established the executive branch of the US government, and was revised by the Twelfth Amendment (ratified June 15, 1804), the Fourteenth Amendment (ratified July 1868), and the Twenty-Third Amendment (ratified Mar. 29, 1961). Because the procedure for electing the president is part of the Constitution, a Constitutional Amendment (which requires two-thirds approval in both houses of Congress plus approval by 38 states) would be required to abolish the Electoral College.

The Founding Fathers created the Electoral College as a compromise between electing the president via a vote in Congress only or via a popular vote only. The Electoral College comprises 538 electors; each state is allowed one elector for each Representative and Senator (DC is allowed 3 electors as established by the Twenty-Third Amendment).

In each state, a group of electors is chosen by each political party. On election day, voters choosing a presidential candidate are actually casting a vote for an elector. Most states use the “winner-take-all” method, in which all electoral votes are awarded to the winner of the popular vote in that state. In Nebraska and Maine, the candidate that wins the state’s overall popular vote receives two electors, and one elector from each congressional district is apportioned to the popular vote winner in that district. For a candidate to win the presidency, he or she must win at least 270 Electoral College votes.

At least 700 amendments have been proposed to modify or abolish the Electoral College.

On Monday Dec. 19, 2016, the electors in each state met to vote for President and Vice President of the United States. Of the 538 Electoral College votes available, Donald J. Trump received 304 votes, Hillary Clinton received 227 votes, and seven votes went to others: three for Colin Powell, one for Faith Spotted Eagle, one for John Kasich, one for Ron Paul, and one for Bernie Sanders). On Dec. 22, 2016, the results were certified in all 50 states. On Jan. 6, 2017, a joint session of the US Congress met to certify the election results and Vice President Joe Biden, presiding as President of the Senate, read the certified vote tally.

A Sep. 2020 Gallup poll found 61% of Americans were in favor of abolishing the Electoral College, up 12 points from 2016.

For the 2020 election, electors voted on Dec. 14, and delivered the results on Dec. 23. [23] On Jan. 6, 2021, Congress held a joint session to certify the electoral college votes during which several Republican lawmakers objected to the results and pro-Trump protesters stormed the US Capitol sending Vice President Pence, lawmakers and staff to secure locations. The votes were certified in the early hours of Jan. 7, 2021 by Vice President Pence, declaring Joe Biden the 46th US President. President Joe Biden was inaugurated with Vice President Kamala Harris on Jan. 20, 2021.

- The Founding Fathers enshrined the Electoral College in the US Constitution because they thought it was the best method to choose the president.

- The Electoral College ensures that all parts of the country are involved in selecting the President of the United States.

- The Electoral College guarantees certainty to the outcome of the presidential election.

- The reasons the Founding Fathers created the Electoral College are no longer relevant.

- The Electoral College gives too much power to "swing states" and allows the presidential election to be decided by a handful of states.

- The Electoral College ignores the will of the people.

This article was published on Jan. 21, 2021, at Britannica’s ProCon.org , a nonpartisan issue-information source.

The Good, the Bad, and the Ugly about The Electoral College

A history professor shares his insights on the governmental institution that has increasingly become the deciding factor in American presidential races.

The 2020 presidential election is fast approaching, which means it’s the perfect time for a refresher on the governmental institution that has increasingly become the deciding factor in American presidential races: the Electoral College. We asked Chris DeRosa, Ph.D., chair of the Department of History and Anthropology, to share his insights on the institution.

THE PURPOSE

The original plan called for each elector to cast two votes for president. Whoever received a majority of votes from electors became president; the runner-up became vice president.

States can do what they want with their electoral votes, says DeRosa. Most give them to the candidate who wins a state majority. An elector who defies that assignment is called a faithless elector, and the state has the choice whether to tolerate them. “You don’t get them very often because they’re chosen as party loyalists, and we’ve never had faithless electors swing an election,” says DeRosa.

One of the advantages is the end result is clear: “Somebody wins; somebody gets a majority of the electoral votes,” says DeRosa. If presidents were elected purely by popular vote, a candidate could win the presidency with less than 50% of the vote. “If you had more than two parties contending for the presidency, you might have somebody winning with 30% of the votes, and that’s a ticket to an extremist candidate.”

The first problem with the Electoral College is that it gives more weight to voters in small states than those in more populous ones, says DeRosa. Every state gets a minimum of three electoral votes. However, each state’s total allotment is based on its representation in the Senate (always two people) and the House (varies by population). “So take Washington, D.C., as an example,” says DeRosa. “More people live in D.C. than in Wyoming, the least populous state in the union; but they both get three electoral votes.” (Plus, unlike Wyoming, D.C. gets no voting representation in Congress.)

The biggest problem with the Electoral College is that it encourages vote suppression, says DeRosa. Southern states always had an advantage in the population count, because they got electoral votes appointed on the basis of their slave populations and their white populations. That gave the states extra representation for people they weren’t really representing at all.

After the Civil War, former slaves were counted as “whole” persons, not three-fifths of one, for purposes of electoral vote allotment. But Black voter suppression still took place through Jim Crow laws. This further “inflated the electoral count of people who were not representing all the people in their state,” says DeRosa. “So the Electoral College became a pillar of white supremacy.”

Love it or hate it, the Electoral College is here to stay because changing it would require “constitutional surgery,” says DeRosa. “You would need three-fourths of the states to ratify any change, and too many states that are intent on suppressing votes benefit from the Electoral College.” The downside? “If you never have to appeal to the electorate because you’re successfully suppressing some large part of it, then you have a broken system.”

Excerpt from an original publication: Kimberling, William C. (1992). Essays in Elections The Electoral College . Washington: National Clearinghouse on Election Administration, Federal Election Commission.

The Pro's and Con's of the Electoral College System

Arguments against the electoral college.

- the possibility of electing a minority president

- the risk of so-called "faithless" Electors,

- the possible role of the Electoral College in depressing voter turnout, and

- its failure to accurately reflect the national popular will.

Opponents of the Electoral College are disturbed by the possibility of electing a minority president (one without the absolute majority of popular votes). Nor is this concern entirely unfounded since there are three ways in which that could happen.

One way in which a minority president could be elected is if the country were so deeply divided politically that three or more presidential candidates split the electoral votes among them such that no one obtained the necessary majority. This occurred, as noted above, in 1824 and was unsuccessfully attempted in 1948 and again in 1968. Should that happen today, there are two possible resolutions: either one candidate could throw his electoral votes to the support of another (before the meeting of the Electors) or else, absent an absolute majority in the Electoral College, the U.S. House of Representatives would select the president in accordance with the 12 th Amendment. Either way, though, the person taking office would not have obtained the absolute majority of the popular vote. Yet it is unclear how a direct election of the president could resolve such a deep national conflict without introducing a presidential run-off election -- a procedure which would add substantially to the time, cost, and effort already devoted to selecting a president and which might well deepen the political divisions while trying to resolve them.

A second way in which a minority president could take office is if, as in 1888, one candidate's popular support were heavily concentrated in a few States while the other candidate maintained a slim popular lead in enough States to win the needed majority of the Electoral College. While the country has occasionally come close to this sort of outcome, the question here is whether the distribution of a candidate's popular support should be taken into account alongside the relative size of it. This issue was mentioned above and is discussed at greater length below.

A third way of electing a minority president is if a third party or candidate, however small, drew enough votes from the top two that no one received over 50% of the national popular total. Far from being unusual, this sort of thing has, in fact, happened 15 times including (in this century) Wilson in both 1912 and 1916, Truman in 1948, Kennedy in 1960, and Nixon in 1968. The only remarkable thing about those outcomes is that few people noticed and even fewer cared. Nor would a direct election have changed those outcomes without a run-off requiring over 50% of the popular vote (an idea which not even proponents of a direct election seem to advocate).

Opponents of the Electoral College system also point to the risk of so-called "faithless" Electors . A "faithless Elector" is one who is pledged to vote for his party's candidate for president but nevertheless votes of another candidate. There have been 7 such Electors in this century and as recently as 1988 when a Democrat Elector in the State of West Virginia cast his votes for Lloyd Bensen for president and Michael Dukakis for vice president instead of the other way around. Faithless Electors have never changed the outcome of an election, though, simply because most often their purpose is to make a statement rather than make a difference. That is to say, when the electoral vote outcome is so obviously going to be for one candidate or the other, an occasional Elector casts a vote for some personal favorite knowing full well that it will not make a difference in the result. Still, if the prospect of a faithless Elector is so fearsome as to warrant a Constitutional amendment, then it is possible to solve the problem without abolishing the Electoral College merely by eliminating the individual Electors in favor of a purely mathematical process (since the individual Electors are no longer essential to its operation).

Opponents of the Electoral College are further concerned about its possible role in depressing voter turnout. Their argument is that, since each State is entitled to the same number of electoral votes regardless of its voter turnout, there is no incentive in the States to encourage voter participation. Indeed, there may even be an incentive to discourage participation (and they often cite the South here) so as to enable a minority of citizens to decide the electoral vote for the whole State. While this argument has a certain surface plausibility, it fails to account for the fact that presidential elections do not occur in a vacuum. States also conduct other elections (for U.S. Senators, U.S. Representatives, State Governors, State legislators, and a host of local officials) in which these same incentives and disincentives are likely to operate, if at all, with an even greater force. It is hard to imagine what counter-incentive would be created by eliminating the Electoral College.

Finally, some opponents of the Electoral College point out, quite correctly, its failure to accurately reflect the national popular will in at least two respects.

First, the distribution of Electoral votes in the College tends to over-represent people in rural States. This is because the number of Electors for each State is determined by the number of members it has in the House (which more or less reflects the State's population size) plus the number of members it has in the Senate (which is always two regardless of the State's population). The result is that in 1988, for example, the combined voting age population (3,119,000) of the seven least populous jurisdiction of Alaska, Delaware, the District of Columbia, North Dakota, South Dakota, Vermont, and Wyoming carried the same voting strength in the Electoral College (21 Electoral votes) as the 9,614,000 persons of voting age in the State of Florida. Each Floridian's potential vote, then, carried about one third the weight of a potential vote in the other States listed.

A second way in which the Electoral College fails to accurately reflect the national popular will stems primarily from the winner-take-all mechanism whereby the presidential candidate who wins the most popular votes in the State wins all the Electoral votes of that State. One effect of this mechanism is to make it extremely difficult for third party or independent candidates ever to make much of a showing in the Electoral College. If, for example, a third party or independent candidate were to win the support of even as many as 25% of the voters nationwide, he might still end up with no Electoral College votes at all unless he won a plurality of votes in at least one State. And even if he managed to win a few States, his support elsewhere would not be reflected. By thus failing to accurately reflect the national popular will, the argument goes, the Electoral College reinforces a two party system, discourages third party or independent candidates, and thereby tends to restrict choices available to the electorate.

In response to these arguments, proponents of the Electoral College point out that is was never intended to reflect the national popular will. As for the first issue, that the Electoral College over-represents rural populations, proponents respond that the United State Senate - with two seats per State regardless of its population - over-represents rural populations far more dramatically. But since there have been no serious proposals to abolish the United States Senate on these grounds, why should such an argument be used to abolish the lesser case of the Electoral College? Because the presidency represents the whole country? But so, as an institution, does the United States Senate.

As for the second issue of the Electoral College's role in reinforcing a two party system, proponents, as we shall see, find this to be a positive virtue.

Arguments for the Electoral College

- contributes to the cohesiveness of the country by requiring a distribution of popular support to be elected president

- enhances the status of minority interests,

- contributes to the political stability of the nation by encouraging a two-party system, and

- maintains a federal system of government and representation.

Recognizing the strong regional interests and loyalties which have played so great a role in American history, proponents argue that the Electoral College system contributes to the cohesiveness of the country be requiring a distribution of popular support to be elected president, without such a mechanism, they point out, president would be selected either through the domination of one populous region over the others or through the domination of large metropolitan areas over the rural ones. Indeed, it is principally because of the Electoral College that presidential nominees are inclined to select vice presidential running mates from a region other than their own. For as things stand now, no one region contains the absolute majority (270) of electoral votes required to elect a president. Thus, there is an incentive for presidential candidates to pull together coalitions of States and regions rather than to exacerbate regional differences. Such a unifying mechanism seems especially prudent in view of the severe regional problems that have typically plagued geographically large nations such as China, India, the Soviet Union, and even, in its time, the Roman Empire. This unifying mechanism does not, however, come without a small price. And the price is that in very close popular elections, it is possible that the candidate who wins a slight majority of popular votes may not be the one elected president - depending (as in 1888) on whether his popularity is concentrated in a few States or whether it is more evenly distributed across the States. Yet this is less of a problem than it seems since, as a practical matter, the popular difference between the two candidates would likely be so small that either candidate could govern effectively. Proponents thus believe that the practical value of requiring a distribution of popular support outweighs whatever sentimental value may attach to obtaining a bare majority of popular support. Indeed, they point out that the Electoral College system is designed to work in a rational series of defaults: if, in the first instance, a candidate receives a substantial majority of the popular vote, then that candidate is virtually certain to win enough electoral votes to be elected president; in the event that the popular vote is extremely close, then the election defaults to that candidate with the best distribution of popular votes (as evidenced by obtaining the absolute majority of electoral votes); in the event the country is so divided that no one obtains an absolute majority of electoral votes, then the choice of president defaults to the States in the U.S. House of Representatives. One way or another, then, the winning candidate must demonstrate both a sufficient popular support to govern as well as a sufficient distribution of that support to govern. Proponents also point out that, far from diminishing minority interests by depressing voter participation, the Electoral College actually enhances the status of minority groups . This is so because the voters of even small minorities in a State may make the difference between winning all of that State's electoral votes or none of that State's electoral votes. And since ethnic minority groups in the United States happen to concentrate in those State with the most electoral votes, they assume an importance to presidential candidates well out of proportion to their number. The same principle applies to other special interest groups such as labor unions, farmers, environmentalists, and so forth. It is because of this "leverage effect" that the presidency, as an institution, tends to be more sensitive to ethnic minority and other special interest groups than does the Congress as an institution. Changing to a direct election of the president would therefore actually damage minority interests since their votes would be overwhelmed by a national popular majority.

Proponents further argue that the Electoral College contributes to the political stability of the nation by encouraging a two party system. There can be no doubt that the Electoral College has encouraged and helps to maintain a two party system in the United States. This is true simply because it is extremely difficult for a new or minor party to win enough popular votes in enough States to have a chance of winning the presidency. Even if they won enough electoral votes to force the decision into the U.S. House of Representatives, they would still have to have a majority of over half the State delegations in order to elect their candidate - and in that case, they would hardly be considered a minor party. In addition to protecting the presidency from impassioned but transitory third party movements, the practical effect of the Electoral College (along with the single-member district system of representation in the Congress) is to virtually force third party movements into one of the two major political parties. Conversely, the major parties have every incentive to absorb minor party movements in their continual attempt to win popular majorities in the States. In this process of assimilation, third party movements are obliged to compromise their more radical views if they hope to attain any of their more generally acceptable objectives. Thus we end up with two large, pragmatic political parties which tend to the center of public opinion rather than dozens of smaller political parties catering to divergent and sometimes extremist views. In other words, such a system forces political coalitions to occur within the political parties rather than within the government. A direct popular election of the president would likely have the opposite effect. For in a direct popular election, there would be every incentive for a multitude of minor parties to form in an attempt to prevent whatever popular majority might be necessary to elect a president. The surviving candidates would thus be drawn to the regionalist or extremist views represented by these parties in hopes of winning the run-off election. The result of a direct popular election for president, then, would likely be frayed and unstable political system characterized by a multitude of political parties and by more radical changes in policies from one administration to the next. The Electoral College system, in contrast, encourages political parties to coalesce divergent interests into two sets of coherent alternatives. Such an organization of social conflict and political debate contributes to the political stability of the nation. Finally, its proponents argue quite correctly that the Electoral College maintains a federal system of government and representation. Their reasoning is that in a formal federal structure, important political powers are reserved to the component States. In the United States, for example, the House of Representatives was designed to represent the States according to the size of their population. The States are even responsible for drawing the district lines for their House seats. The Senate was designed to represent each State equally regardless of its population. And the Electoral College was designed to represent each State's choice for the presidency (with the number of each State's electoral votes being the number of its Senators plus the number of its Representatives). To abolish the Electoral College in favor of a nationwide popular election for president would strike at the very heart of the federal structure laid out in our Constitution and would lead to the nationalization of our central government - to the detriment of the States. Indeed, if we become obsessed with government by popular majority as the only consideration, should we not then abolish the Senate which represents States regardless of population? Should we not correct the minor distortions in the House (caused by districting and by guaranteeing each State at least one Representative) by changing it to a system of proportional representation? This would accomplish "government by popular majority" and guarantee the representation of minority parties, but it would also demolish our federal system of government. If there are reasons to maintain State representation in the Senate and House as they exist today, then surely these same reasons apply to the choice of president. Why, then, apply a sentimental attachment to popular majorities only to the Electoral College? The fact is, they argue, that the original design of our federal system of government was thoroughly and wisely debated by the Founding Fathers. State viewpoints, they decided, are more important than political minority viewpoints. And the collective opinion of the individual State populations is more important than the opinion of the national population taken as a whole. Nor should we tamper with the careful balance of power between the national and State governments which the Founding Fathers intended and which is reflected in the Electoral college. To do so would fundamentally alter the nature of our government and might well bring about consequences that even the reformers would come to regret.

by William C. Kimberling, Deputy Director FEC National Clearinghouse on Election Administration

The views expressed here are solely those of the author and are not necessarily shared by the Federal Election Commission or any division thereof or the Jackson County Board of Election Commissioners.

A Selected Bibliography On the Electoral College Highly Recommended

Berns, Walter (ed.) After the People Vote : Steps in Choosing the President . Washington: American Enterprise Institute for Public Policy Research, 1983. Bickel, Alexander M. Reform and Continuity . New York: Harper & Row, 1971.

Congressional Quarterly's Guide to U.S. Elections (2 nd ed). Washington, D.C.: Congressional Quarterly, 1985.

Schlesinger, Arthur M. Jr. (Ed.) History of Presidential Elections 1789-1968. New York: Chelsea House Publishers, 1971.

Other Sources

American Enterprise Institute for Public Policy Research. Proposals for Revision of the Electoral College System . Washington: 1969.

Best, Judith. The Case Against the Direct Election of the President . Ithica: Cornell University Press, 1975. Longley, Lawrence D. The Politics of Electoral College Reform . New Haven: Yale University Press, 1972. Pierce, Neal R. and Longley, Lawrence D. The People's President: The Electoral College in American History and the Direct-Vote Alternative . New Haven: Yale University Press, 1981. Sayre, Wallace Stanley, Voting for President . Washington: Brookings Institution, c1970. Zeidenstein, Harvey G. Direct Election of the President . Lexington, Mass: Lexington Books, 1973.

Electoral College’s Advantages and Disadvantages Essay

- To find inspiration for your paper and overcome writer’s block

- As a source of information (ensure proper referencing)

- As a template for you assignment

Introduction

Disadvantages of the electoral college, advantages of the electoral college, works cited.

Made up of 538 electors, the Electoral College votes decide the president and vice president of the United States of America. The Electoral College membership is made up of 435 representatives, 100 senators, and 3 electors. In the United States, the electorate does not directly elect the president and the vice-president. On the contrary, the responsibility to do so is vested on the electors in the electorate college. The 538 members are appointed through a popular vote on a state-by-state basis (Kleeb par. 7). The number of electors represented in the electoral college is equal to the number of congress in each state (Kleeb par. 2).

Electors are loyal to a particular candidate for both the president and vice president’s office. In the United States, all the states elect their representatives in the Electoral College on a winner-take-all basis except for Maine Nebraska states (Kleeb par. 8). Every elector is required by law to cast one vote for the president and another for the preferred vice-president. For an individual to be considered a winner in the office of the president and vice-president, they must receive an absolute majority, which currently stands at 270 votes (Kleeb par. 8).

Critics argue that the Electoral College’s dependence on a popular vote is a bone of contention. This process does not allow the national wide popular candidate to be the automatic winner of the elections. It leaves a situation whereby the national wide popular candidate might not be the winner of the election. Most people feel that the winner-take-all elections are the most appropriate. The Electoral College process is biased as the swing states receive the most attention (Kozlowski 34).

Swing states are states that have a long history of a tendency to vote either Republican or Democratic candidates. Candidates pay less attention to such states if electorates have a history of consistently voting for the rival party. Also, the Electoral College process discourages voter turnout in a very significant way. The candidate with the highest popular vote in every state receives all the electoral votes in the states with clear favorites (Kozlowski 34). This discourages the electorates who feel that their vote might not make an impact in such states especially if the voter wanted to vote contrary to the state’s favorite. This system discourages the candidates from campaigning for voter turnout (Kozlowski 34). The system also gives the small states more power to influence the outcome of an election a factor that has always favored the Republican Party.

The Electoral College system makes it pointless and abortive to support a candidate who is not competitive in your state. This leads to the candidates concentrating on fewer states hence ignoring the majority of the country’s voters (Kozlowski 35). The Electoral College process can lead to a situation whereby the winner of an election is not necessarily the winner of the popular vote. The winner of the electoral votes takes precedence and may become the president even after losing on the popular vote but this situation has very serious implications on presidential powers. This weakens the presidential powers hence making governance very difficult since there are mandates that are given to the president only through the popular vote.

The above misgivings notwithstanding, the Electoral College system has positive attributes that make it acceptable. One of the very significant positive sides of the system includes the fact that it prevents victory based on urban areas (Lawler par. 10). This process does not give monopolistic powers to the highly populated areas as other systems like the winner-take-all. For a candidate to win, he or she must pay attention to even the smallest states since concentrating on heavily populated states does not guarantee a win. The system also provides the space for flexibility about voting laws in different states. States can formulate their laws and affect changes on their systems freely without affecting the national elections.

The Electoral College process also is famed for maintaining separation of powers (Lawler par. 5). Having a directly elected president through the popular vote can lead to tyranny. The devolution and separation of powers in the different branches of government were a calculated move in the constitution to provide checks and balances (Lawler par. 7). Having a directly elected president asserts that a president assumes a national popular mandate that can easily compromise and undermine other branches of the government (Lawler par. 8). The system also limits the entrance of a third party hence favoring a two-party system. Although some people see this as a demerit, it has brought the country some political stability. It also reduces the probability of the minority and interest groups swaying voters (Lawler par. 13).

This essay has discussed the negative and positive sides of the Electoral College system in the United States of America. The paper has shown how the system works identifying the possible negative ramifications that the system can influence. However, the paper notes that the system has some positive sides as well and has gone further to discuss some of the advantages of the electoral system.

Kleeb, Jane. Fail: Sen. McCoy’s Partisan Electoral College Bill . 2011. Web.

Kozlowski, Darrell. Federalism , United States, US: inforbase publishing, 2010. Print.

Lawler, Augustine. The Electoral College: top 10strenthgs and weaknesses . 2008.Web.

- Voter Turnout: An Analysis of Three Election Years

- Voter Turnout Problem in America

- Irish General Elections: Low Voter Turnout Reasons

- Running Mates in Presidential Elections

- 2012 Presidential Elections: Republicans vs. Democrats

- Vote Smart Organization's Mission and Activity

- Anti-Trump Protests for Third Night on CNN

- Struggle for Democracy: President Interview

- Chicago (A-D)

- Chicago (N-B)

IvyPanda. (2020, October 1). Electoral College's Advantages and Disadvantages. https://ivypanda.com/essays/electoral-colleges-advantages-and-disadvantages/

"Electoral College's Advantages and Disadvantages." IvyPanda , 1 Oct. 2020, ivypanda.com/essays/electoral-colleges-advantages-and-disadvantages/.

IvyPanda . (2020) 'Electoral College's Advantages and Disadvantages'. 1 October.

IvyPanda . 2020. "Electoral College's Advantages and Disadvantages." October 1, 2020. https://ivypanda.com/essays/electoral-colleges-advantages-and-disadvantages/.

1. IvyPanda . "Electoral College's Advantages and Disadvantages." October 1, 2020. https://ivypanda.com/essays/electoral-colleges-advantages-and-disadvantages/.

Bibliography

IvyPanda . "Electoral College's Advantages and Disadvantages." October 1, 2020. https://ivypanda.com/essays/electoral-colleges-advantages-and-disadvantages/.

You are using an outdated browser. Please upgrade your browser to improve your experience.

Suggested Results

Antes de cambiar....

Esta página no está disponible en español

¿Le gustaría continuar en la página de inicio de Brennan Center en español?

al Brennan Center en inglés

al Brennan Center en español

Informed citizens are our democracy’s best defense.

We respect your privacy .

- Research & Reports

The Electoral College Explained

A national popular vote would help ensure that every vote counts equally, making American democracy more representative.

- Electoral College Reform

In the United States, the presidency is decided not by the national popular vote but by the Electoral College — an outdated and convoluted system that sometimes yields results contrary to the choice of the majority of American voters. On five occasions, including in two of the last six elections, candidates have won the Electoral College, and thus the presidency, despite losing the nationwide popular vote.

The Electoral College has racist origins — when established, it applied the three-fifths clause, which gave a long-term electoral advantage to slave states in the South — and continues to dilute the political power of voters of color. It incentivizes presidential campaigns to focus on a relatively small number of “swing states.” Together, these dynamics have spurred debate about the system’s democratic legitimacy.

To make the United States a more representative democracy, reformers are pushing for the presidency to be decided instead by the national popular vote, which would help ensure that every voter counts equally.

What is the Electoral College and how does it work?

The Electoral College is a group of intermediaries designated by the Constitution to select the president and vice president of the United States. Each of the 50 states is allocated presidential electors equal to the number of its representatives and senators . The ratification of the 23rd Amendment in 1961 allowed citizens in the District of Columbia to participate in presidential elections as well; they have consistently had three electors.

In total, the Electoral College comprises 538 members . A presidential candidate must win a majority of the electoral votes cast to win — at least 270 if all 538 electors vote.

The Constitution grants state legislatures the power to decide how to appoint their electors. Initially, a number of state legislatures directly selected their electors , but during the 19th century they transitioned to the popular vote, which is now used by all 50 states . In other words, each awards its electoral votes to the presidential candidate chosen by the state’s voters.

Forty-eight states and the District of Columbia use a winner-take-all system, awarding all of their electoral votes to the popular vote winner in the state. Maine and Nebraska award one electoral vote to the popular vote winner in each of their congressional districts and their remaining two electoral votes to the statewide winner. Under this system, those two states sometimes split their electoral votes among candidates.

In the months leading up to the general election, the political parties in each state typically nominate their own slates of would-be electors. The state’s popular vote determines which party’s slates will be made electors. Members of the Electoral College meet and vote in their respective states on the Monday after the second Wednesday in December after Election Day. Then, on January 6, a joint session of Congress meets at the Capitol to count the electoral votes and declare the outcome of the election, paving the way for the presidential inauguration on January 20.

How was the Electoral College established?

The Constitutional Convention in 1787 settled on the Electoral College as a compromise between delegates who thought Congress should select the president and others who favored a direct nationwide popular vote. Instead, state legislatures were entrusted with appointing electors.

Article II of the Constitution, which established the executive branch of the federal government, outlined the framers’ plan for the electing the president and vice president. Under this plan, each elector cast two votes for president; the candidate who received the most votes became the president, with the second-place finisher becoming vice president — which led to administrations in which political opponents served in those roles. The process was overhauled in 1804 with the ratification of the 12th Amendment , which required electors to cast votes separately for president and vice president.

How did slavery shape the Electoral College?

At the time of the Constitutional Convention, the northern states and southern states had roughly equal populations . However, nonvoting enslaved people made up about one-third of the southern states’ population. As a result, delegates from the South objected to a direct popular vote in presidential elections, which would have given their states less electoral representation.

The debate contributed to the convention’s eventual decision to establish the Electoral College, which applied the three-fifths compromise that had already been devised for apportioning seats in the House of Representatives. Three out of five enslaved people were counted as part of a state’s total population, though they were nonetheless prohibited from voting.

Wilfred U. Codrington III, an assistant professor of law at Brooklyn Law School and a Brennan Center fellow, writes that the South’s electoral advantage contributed to an “almost uninterrupted trend” of presidential election wins by southern slaveholders and their northern sympathizers throughout the first half of the 19th century. After the Civil War, in 1876, a contested Electoral College outcome was settled by a compromise in which the House awarded Rutherford B. Hayes the presidency with the understanding that he would withdraw military forces from the Southern states. This led to the end of Reconstruction and paved the way for racial segregation under Jim Crow laws.

Today, Codrington argues, the Electoral College continues to dilute the political power of Black voters: “Because the concentration of black people is highest in the South, their preferred presidential candidate is virtually assured to lose their home states’ electoral votes. Despite black voting patterns to the contrary, five of the six states whose populations are 25 percent or more black have been reliably red in recent presidential elections. … Under the Electoral College, black votes are submerged.”

What are faithless electors?

Ever since the 19th century reforms, states have expected their electors to honor the will of the voters. In other words, electors are now pledged to vote for the winner of the popular vote in their state. However, the Constitution does not require them to do so, which allows for scenarios in which “faithless electors” have voted against the popular vote winner in their states. As of 2016, there have been 90 faithless electoral votes cast out of 23,507 in total across all presidential elections. The 2016 election saw a record-breaking seven faithless electors , including three who voted for former Secretary of State Colin Powell, who was not a presidential candidate at the time.

Currently, 33 states and the District of Columbia require their presidential electors to vote for the candidate to whom they are pledged. Only 5 states, however, impose a penalty on faithless electors, and only 14 states provide for faithless electors to be removed or for their votes to be canceled. In July 2020, the Supreme Court unanimously upheld existing state laws that punish or remove faithless electors.

What happens if no candidate wins a majority of Electoral College votes?

If no ticket wins a majority of Electoral College votes, the presidential election is sent to the House of Representatives for a runoff. Unlike typical House practice, however, each state only gets one vote, decided by the party that controls the state’s House delegation. Meanwhile, the vice-presidential race is decided in the Senate, where each member has one vote. This scenario has not transpired since 1836 , when the Senate was tasked with selecting the vice president after no candidate received a majority of electoral votes.

Are Electoral College votes distributed equally between states?

Each state is allocated a number of electoral votes based on the total size of its congressional delegation. This benefits smaller states, which have at least three electoral votes — including two electoral votes tied to their two Senate seats, which are guaranteed even if they have a small population and thus a small House delegation. Based on population trends, those disparities will likely increase as the most populous states are expected to account for an even greater share of the U.S. population in the decades ahead.

What did the 2020 election reveal about the Electoral College?

In the aftermath of the 2020 presidential race, Donald Trump and his allies fueled an effort to overturn the results of the election, spreading repeated lies about widespread voter fraud. This included attempts by a number of state legislatures to nullify some of their states’ votes, which often targeted jurisdictions with large numbers of Black voters. Additionally, during the certification process for the election, some members of Congress also objected to the Electoral College results, attempting to throw out electors from certain states. While these efforts ultimately failed, they revealed yet another vulnerability of the election system that stems from the Electoral College.

The Electoral Count Reform Act , enacted in 2023, addresses these problems. Among other things, it clarifies which state officials have the power to appoint electors, and it bars any changes to that process after Election Day, preventing state legislatures from setting aside results they do not like. The new law also raises the threshold for consideration of objections to electoral votes. It is now one-fifth of each chamber instead of one senator and one representative. Click here for more on the changes made by the Electoral Count Reform Act.

What are ways to reform the Electoral College to make presidential elections more democratic?

Abolishing the Electoral College outright would require a constitutional amendment. As a workaround, scholars and activist groups have rallied behind the National Popular Vote Interstate Compact (NPV), an effort that started after the 2000 election. Under it, participating states would commit to awarding their electoral votes to the winner of the national popular vote.

In other words, the NPV would formally retain the Electoral College but render it moot, ensuring that the winner of the national popular vote also wins the presidency. If enacted, the NPV would incentivize presidential candidates to expand their campaign efforts nationwide, rather than focus only on a small number of swing states.

For the NPV to take effect, it must first be adopted by states that control at least 270 electoral votes. In 2007, Maryland became the first state to enact the compact. As of 2019, a total of 19 states and Washington, DC, which collectively account for 196 electoral votes, have joined.

The public has consistently supported a nationwide popular vote. A 2020 poll by Pew Research Center, for example, found that 58 percent of adults prefer a system in which the presidential candidate who receives the most votes nationwide wins the presidency.

Related Resources

How Electoral Votes Are Counted for the Presidential Election

The Electoral Count Reform Act addresses vulnerabilities exposed by the efforts to overturn the 2020 presidential election.

NATO’s Article 5 Collective Defense Obligations, Explained

Here’s how a conflict in Europe would implicate U.S. defense obligations.

The Supreme Court ‘Shadow Docket’

The conservative justices are increasingly using a secretive process to issue consequential decisions.

Preclearance Under the Voting Rights Act

For decades, the law blocked racially discriminatory election rules and voting districts — and it could do so again, if Congress acts.

Informed citizens are democracy’s best defense

Teaching & Learning

The electoral college: here to stay.

Renowned expert looks at the history of a constitutional provision—and the prospect for changing it

Constitutional Law expert Sanford Levinson focused on the political implications of the Electoral College at Harvard Law School on October 21. He emphasized that the U.S. Electoral College system is unique among the election processes of major countries, which tend towards popular vote models, and he connected it to what he terms “the Constitution of settlement,” the structural provisions of the Constitution that are never litigated and therefore never discussed.