The Impact of Technology on Mental Health

In the contemporary world, symptoms of depression, stress, anxiety, and other mental disorders have become more prevalent among university students. Researchers have proven that time spent on social media, videos, and Instant messaging is directly associated with psychological distress. This bibliography examines different literature discussing how technology affects mental wellness.

The scope of this research is to uncover the consequences of technology use on mental health. The research question above will help examine the relationship between technology use and how this action results in mental illnesses such as anxiety and depression. Information used in this study includes both primary and secondary sources focusing on their observational and experimental data analysis.

The article explores how web-based social networking is a significant limitation to mental health. Deepa and Priya (2020) introduce a concept of time whereby they explain that the hours spent on social networking platforms promote depression and anxiety (Deepa & Priya, 2020). Some of the digital technology students use are Instagram, Facebook, Twitter, YouTube, and other web-based sites platforms, which have become a threat to mental health (Deepa & Priya, 2020). The authors explain that researchers discovered that excessive social media use was linked to mental illnesses during schooling. However, it may be alleviated by dialectical thinking, positivity, meditation, and active coping.

The authors used descriptive research using simple sampling questionnaires and ANOVA to study different groups of students and the social media platforms they use. This system provided mixed results based on these groups and examinations (Deepa & Priya, 2020). The research findings revealed a relationship between being active on social media and depression. The authors contradict a study done by Gordon et al. (2007) that mentions that the time spent on the internet has nothing to do with depression (Deepa & Priya, 2020). Instead, it is what students engage in when they are active online. This study is credible because it is not outdated and involved many participants, which helped strengthen the hypothesis created. This source will be integral in answering the types of technology students use and their consequences on mental wellness. Additionally, the journal’s credibility is guaranteed, considering that the article is an international publication. This title indicates that the journal has been peer-reviewed by many other scholars to ensure the information provided is accurate.

The article examines how internet use affects well-being by analyzing the rate of internet use among college students. Gordon et al. (2007) mention that technology use is triggered by self-expression, consumptive motives, and sharing information. In this study, Gordon et al. (2007) posit that frequency of internet use does not affect mental illness. Instead, they mention that what students do on those platforms is the factor that contributes to mental illness.

First, they mention that the internet has provided ways for students to get new acquaintances, find intimate partners, and conduct research for their college assignments, among other things. This factor indicates that these students’ daily life has become increasingly reliant on the internet (Gordon et al., 2007). Therefore, increased internet use has formed a new environment, full of peer pressure. This explanation is an indication of what they do on the internet. The reason is that they see, admire, and adopt new habits which increase stress and depressive symptoms. Additionally, overdependence on technology has affected family cohesion and social connectedness.

The article provides similar ideologies as Junco et al. (2011) that technology causes social isolation by keeping students from the realities in their environment. It explains that students live a fictional life by actively engaging in technology to hide their true selves (Gordon et al., 2007). The research is valid considering it applies rationales from different authors to justify their deduction that technology use has become an avenue for peer pressure among students. This article is essential since it explains the negative impact of technology on mental health, which is explored in this research. It is also a scholarly article considering that these authors have doctors of philosophy in education, indicating vast knowledge and command to undertake this research.

These researchers use unique survey data to investigate the adverse effects of instant messaging on academic achievement. They explain that instant messaging is not destructive since it can provide company when needed. However, excessive use of instant messaging reduces concentration by diverting the mind’s attention away from the facts of the surroundings. Students lose focus when multitasking activities like chatting while studying (Junco & Cotten, 2011). It also impacts the essential, incidental, and representational processing systems, the foundation for learning and memory. When they fail their tests, they become withdrawn with significant effects, such as anxiety and depression.

Additionally, the authors mention that students using IM become socially disengaged since IM becomes their point of contact with others. Considering all these effects, it is evident that IM can cause anxiety, depression, and social isolation if not regulated. Unlike Gordon et al. (2007), who mention only the detrimental effects of using technology, these authors mention that IM, an example of technology, helps students manage stress (Junco & Cotten, 2011). They explain that through a survey of a target group whereby students reported that IM and other online platforms such as video games had provided contact with the outside world, which relieves stress.

This article’s viability is uncertain because most arguments presented are derived from other researchers’ work (Junco & Cotten, 2011). However, the article is helpful for my research because it provides the negative and positive effects of using technology. The position of this research is that IM can help deal with stress. The viability of this research is verified considering the research has been reviewed by Mendeley Company which generates citations for scholarly articles.

Karim et al. (2020) explore how social media impacts mental health. They begin by conducting a qualitative analysis of 16 different studies provided by various researchers on the topic (Karim et al., 2020). First, they listed different types of social media platforms, including Twitter, Linkedin, Facebook, Instagram, and Snapchat, to be the most widely used social media platforms among the youth. They also mention that social media has become an influential technology in the contemporary world (Karim et al., 2020). Although social media has incredible benefits, it is linked to various mental health issues such as depression and anxiety. Some works agreed that social media use is detrimental to mental well-being, and the timing does not matter (Karim et al., 2020). In contrast, other studies suggested that no evidence justifies the maximum time one should be active on social media. None of the research provided the limit of time recommended for anyone to be active on social media.

The credibility of the piece is jeopardized because the researchers did not conduct their study to identify the correlation between mental health and technology (Karim et al., 2020). However, it provides substantial ideas drawn from other credible sources, which are essential in providing information addressing this topic. For example, their position is that long hours of social media use contribute to depression and anxiety (Karim et al., 2020). This focus is integral in my research since it addresses the impact of technology on mental health by explaining the possible avenues for mental health crises.

Lattie et al. (2019) investigate how the rise in mental disorders such as anxiety and depression correlates with computing technologies. According to these authors, personal computing technologies such as smartphones have become the source of mental health crises since they provide access to social media (Lattie et al., 2019). This platform has promoted harmful ideas that make people experience peer comparison. For instance, “fear of missing out (FOMO) is a pressure promoted by media which dictates how people interact, behave and talk within these platforms” (Lattie et al., 2019, para. 8). FOMO is when people feel the need to fit in with a specific trend by emulating verbatim how their internet friends behave, dress or talk. For instance, if all the girls on social media put on branded clothes for attention, every girl on the platform would also want to be like them. This pressure will result in stress to keep up with the standards set, promoting mental health disorders. These authors conclude that the pressure to feel accepted has increased the number of students negatively affected by technology.

However, the authors also mention that this digital platform has played a significant role in promoting mental health wellness. In addition, some of the interventions available such as the Headspace and Pacifica applications, are technology-enabled and provide coping skills when students face a crisis (Lattie et al., 2019). Lattie et al. (2019) provide similar sentiments as Junco et al. (2011), who also stated that technology is not entirely to blame for mental crises considering that activities such as assimilation of culture affect well-being. Additionally, this article is relevant since it has applied different up-to-date scholarly reasoning to create a hypothesis (Lattie et al., 2019). Finally, the article’s position is that social media promotes mental health by providing coping skills while also deteriorating it by contributing to disorders such as depression. However, this information is contrary to what Junco et al. (2011) mention that technology has the power to relieve stress by providing a coping mechanism.

The article provides informative discussions on the risks that digital presence has promoted. Skillbred-Fjeld et al. (2020) mention that many people have experienced harassment online based on their appearance, ethnicity, age, race, and religion. This exposure to bullying has resulted in psychological distress such as depression and suicidal thoughts. The authors indicate that most students spend more hours on digital media than how they spend with families and friends while also being more exposed to harassment. This disconnect is also a challenge to maintaining mental health, considering it breaks the bond between families and friends.

These authors stress that cyberbullying is a prevalent occurrence in online engagement and has detrimental effects on individuals. This article does not share similar rationales with other articles in this search since it focuses on proving how cyberbullying results in mental illness. The article answers the proposed research question, and its position is that cyberbullying affects most students using digital communication systems (Skilbred-Fjeld et al., 2020). The article is credible for this research since the author engaged in intensive searches, which enhanced the viability of the information provided.

In her article “Cyberspace and Identity,” Turkle (1999) posits that the development of cyberspace interactions has extended the range of identities. The author establishes her case with four essential points. Her first observation is that digital presence is based on fiction and not reality. Second, she claims that digital profile results from a digital exhibition that does not last. The third point made by Turkle (1999) is that online identity affects real self-considering the fact that it affects thoughts and behaviors). Finally, she claims that online identity exemplifies a cultural conception of diversity.

This author introduces the aspect of role-playing promoted by digital presence. She mentions that people are given a chance to portray themselves in a different light from reality on digital platforms considering the anonymity established when altering self-image through textual construction (Turkle, 1999). The research by Gordon et al. (2007) reinforced this claim when they mentioned that digital engagement does not cause mental illness. Instead, what students do on those platforms is the primary factor contributing to mental illness (Turkle, 1999). This factor is relatable in the current digital world since people share their adventurous moments, making others who cannot enjoy such things feel unworthy, posing a significant threat to mental wellness. The article’s position is that images portrayed on digital platforms are illusions, and they have promoted peer pressure, anxiety, and depression in people who believe them to be true (Turkle, 1999). The same sentiments are shared by Skilbred-Fjeld et al. (2020) since they mention that social media has become a site to dehumanize others who are less privileged. This occurrence promotes fear, self-hate, and depression, indicating a match in reasoning among these authors.

Deepa, M., & Priya, K. (2020). Impact of social media on mental health of students. International Journal of Scientific & Technology Research , 9 (03). Web.

Gordon, C., Juang, L., & Syed, M. (2007). Internet use and well-being among college students: Beyond frequency of use. Journal of College Student Development , 48( 6), 674-688. Web.

Junco, R., & Cotten, S. R. (2011). Perceived academic effects of instant messaging use.

Computer & Education , 56 (2), 370-378. Web.

Karim, F., Oyewande, A. A., Abdalla, L. F., Ehsanullah, R. C., & Khan, S. (2020). Social media use and its connection to mental health: A systematic review. Cureus , 12 (6). Web.

Lattie, E. G., Lipson, S. K., & Eisenberg, D. (2019). Technology and college student mental health: Challenges and opportunities. Frontiers in psychiatry , (10) , 246. Web.

Skilbred-Fjeld, S., Reme, S. E., & Mossige, S. (2020). Cyberbullying involvement and mental health problems among late adolescents. Cyberpsychology: Journal of Psychosocial Research on Cyberspace , 14 (1). Web.

Turkle, S. (1999). Looking toward cyberspace: Beyond grounded sociology. Cyberspace and identity. Contemporary Sociology , 28 (6), Web.

Cite this paper

- Chicago (N-B)

- Chicago (A-D)

StudyCorgi. (2022, December 10). The Impact of Technology on Mental Health. https://studycorgi.com/the-impact-of-technology-on-mental-health/

"The Impact of Technology on Mental Health." StudyCorgi , 10 Dec. 2022, studycorgi.com/the-impact-of-technology-on-mental-health/.

StudyCorgi . (2022) 'The Impact of Technology on Mental Health'. 10 December.

1. StudyCorgi . "The Impact of Technology on Mental Health." December 10, 2022. https://studycorgi.com/the-impact-of-technology-on-mental-health/.

Bibliography

StudyCorgi . "The Impact of Technology on Mental Health." December 10, 2022. https://studycorgi.com/the-impact-of-technology-on-mental-health/.

StudyCorgi . 2022. "The Impact of Technology on Mental Health." December 10, 2022. https://studycorgi.com/the-impact-of-technology-on-mental-health/.

This paper, “The Impact of Technology on Mental Health”, was written and voluntary submitted to our free essay database by a straight-A student. Please ensure you properly reference the paper if you're using it to write your assignment.

Before publication, the StudyCorgi editorial team proofread and checked the paper to make sure it meets the highest standards in terms of grammar, punctuation, style, fact accuracy, copyright issues, and inclusive language. Last updated: December 10, 2022 .

If you are the author of this paper and no longer wish to have it published on StudyCorgi, request the removal . Please use the “ Donate your paper ” form to submit an essay.

Subscribe or renew today

Every print subscription comes with full digital access

Science News

Social media harms teens’ mental health, mounting evidence shows. what now.

Understanding what is going on in teens’ minds is necessary for targeted policy suggestions

Most teens use social media, often for hours on end. Some social scientists are confident that such use is harming their mental health. Now they want to pinpoint what explains the link.

Carol Yepes/Getty Images

Share this:

By Sujata Gupta

February 20, 2024 at 7:30 am

In January, Mark Zuckerberg, CEO of Facebook’s parent company Meta, appeared at a congressional hearing to answer questions about how social media potentially harms children. Zuckerberg opened by saying: “The existing body of scientific work has not shown a causal link between using social media and young people having worse mental health.”

But many social scientists would disagree with that statement. In recent years, studies have started to show a causal link between teen social media use and reduced well-being or mood disorders, chiefly depression and anxiety.

Ironically, one of the most cited studies into this link focused on Facebook.

Researchers delved into whether the platform’s introduction across college campuses in the mid 2000s increased symptoms associated with depression and anxiety. The answer was a clear yes , says MIT economist Alexey Makarin, a coauthor of the study, which appeared in the November 2022 American Economic Review . “There is still a lot to be explored,” Makarin says, but “[to say] there is no causal evidence that social media causes mental health issues, to that I definitely object.”

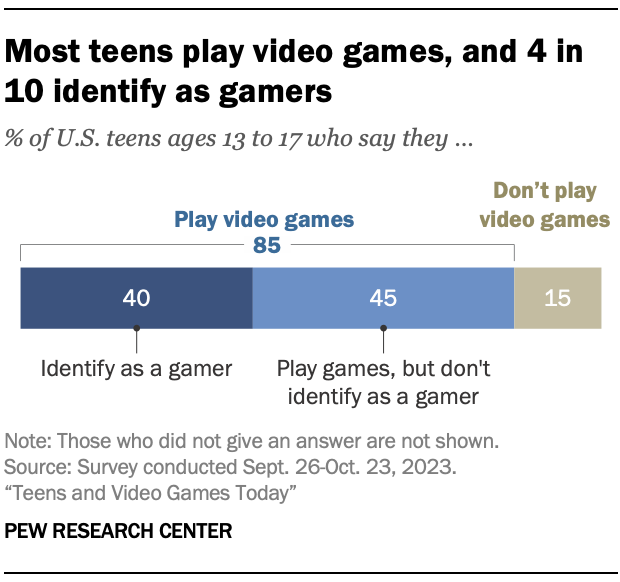

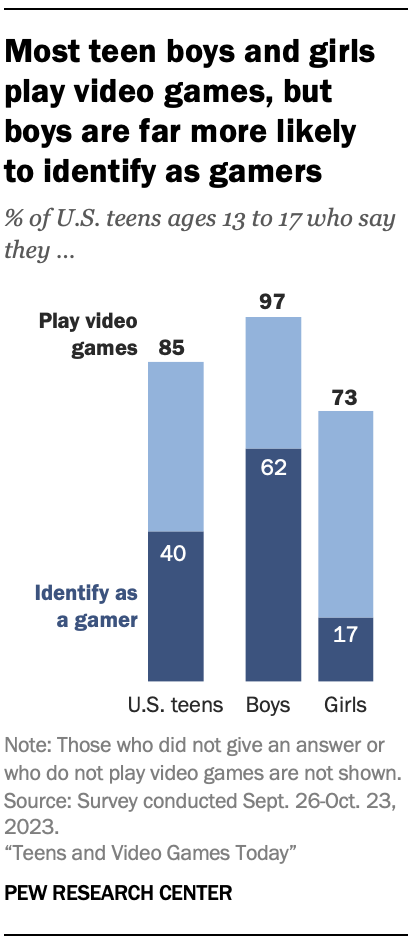

The concern, and the studies, come from statistics showing that social media use in teens ages 13 to 17 is now almost ubiquitous. Two-thirds of teens report using TikTok, and some 60 percent of teens report using Instagram or Snapchat, a 2022 survey found. (Only 30 percent said they used Facebook.) Another survey showed that girls, on average, allot roughly 3.4 hours per day to TikTok, Instagram and Facebook, compared with roughly 2.1 hours among boys. At the same time, more teens are showing signs of depression than ever, especially girls ( SN: 6/30/23 ).

As more studies show a strong link between these phenomena, some researchers are starting to shift their attention to possible mechanisms. Why does social media use seem to trigger mental health problems? Why are those effects unevenly distributed among different groups, such as girls or young adults? And can the positives of social media be teased out from the negatives to provide more targeted guidance to teens, their caregivers and policymakers?

“You can’t design good public policy if you don’t know why things are happening,” says Scott Cunningham, an economist at Baylor University in Waco, Texas.

Increasing rigor

Concerns over the effects of social media use in children have been circulating for years, resulting in a massive body of scientific literature. But those mostly correlational studies could not show if teen social media use was harming mental health or if teens with mental health problems were using more social media.

Moreover, the findings from such studies were often inconclusive, or the effects on mental health so small as to be inconsequential. In one study that received considerable media attention, psychologists Amy Orben and Andrew Przybylski combined data from three surveys to see if they could find a link between technology use, including social media, and reduced well-being. The duo gauged the well-being of over 355,000 teenagers by focusing on questions around depression, suicidal thinking and self-esteem.

Digital technology use was associated with a slight decrease in adolescent well-being , Orben, now of the University of Cambridge, and Przybylski, of the University of Oxford, reported in 2019 in Nature Human Behaviour . But the duo downplayed that finding, noting that researchers have observed similar drops in adolescent well-being associated with drinking milk, going to the movies or eating potatoes.

Holes have begun to appear in that narrative thanks to newer, more rigorous studies.

In one longitudinal study, researchers — including Orben and Przybylski — used survey data on social media use and well-being from over 17,400 teens and young adults to look at how individuals’ responses to a question gauging life satisfaction changed between 2011 and 2018. And they dug into how the responses varied by gender, age and time spent on social media.

Social media use was associated with a drop in well-being among teens during certain developmental periods, chiefly puberty and young adulthood, the team reported in 2022 in Nature Communications . That translated to lower well-being scores around ages 11 to 13 for girls and ages 14 to 15 for boys. Both groups also reported a drop in well-being around age 19. Moreover, among the older teens, the team found evidence for the Goldilocks Hypothesis: the idea that both too much and too little time spent on social media can harm mental health.

“There’s hardly any effect if you look over everybody. But if you look at specific age groups, at particularly what [Orben] calls ‘windows of sensitivity’ … you see these clear effects,” says L.J. Shrum, a consumer psychologist at HEC Paris who was not involved with this research. His review of studies related to teen social media use and mental health is forthcoming in the Journal of the Association for Consumer Research.

Cause and effect

That longitudinal study hints at causation, researchers say. But one of the clearest ways to pin down cause and effect is through natural or quasi-experiments. For these in-the-wild experiments, researchers must identify situations where the rollout of a societal “treatment” is staggered across space and time. They can then compare outcomes among members of the group who received the treatment to those still in the queue — the control group.

That was the approach Makarin and his team used in their study of Facebook. The researchers homed in on the staggered rollout of Facebook across 775 college campuses from 2004 to 2006. They combined that rollout data with student responses to the National College Health Assessment, a widely used survey of college students’ mental and physical health.

The team then sought to understand if those survey questions captured diagnosable mental health problems. Specifically, they had roughly 500 undergraduate students respond to questions both in the National College Health Assessment and in validated screening tools for depression and anxiety. They found that mental health scores on the assessment predicted scores on the screenings. That suggested that a drop in well-being on the college survey was a good proxy for a corresponding increase in diagnosable mental health disorders.

Compared with campuses that had not yet gained access to Facebook, college campuses with Facebook experienced a 2 percentage point increase in the number of students who met the diagnostic criteria for anxiety or depression, the team found.

When it comes to showing a causal link between social media use in teens and worse mental health, “that study really is the crown jewel right now,” says Cunningham, who was not involved in that research.

A need for nuance

The social media landscape today is vastly different than the landscape of 20 years ago. Facebook is now optimized for maximum addiction, Shrum says, and other newer platforms, such as Snapchat, Instagram and TikTok, have since copied and built on those features. Paired with the ubiquity of social media in general, the negative effects on mental health may well be larger now.

Moreover, social media research tends to focus on young adults — an easier cohort to study than minors. That needs to change, Cunningham says. “Most of us are worried about our high school kids and younger.”

And so, researchers must pivot accordingly. Crucially, simple comparisons of social media users and nonusers no longer make sense. As Orben and Przybylski’s 2022 work suggested, a teen not on social media might well feel worse than one who briefly logs on.

Researchers must also dig into why, and under what circumstances, social media use can harm mental health, Cunningham says. Explanations for this link abound. For instance, social media is thought to crowd out other activities or increase people’s likelihood of comparing themselves unfavorably with others. But big data studies, with their reliance on existing surveys and statistical analyses, cannot address those deeper questions. “These kinds of papers, there’s nothing you can really ask … to find these plausible mechanisms,” Cunningham says.

One ongoing effort to understand social media use from this more nuanced vantage point is the SMART Schools project out of the University of Birmingham in England. Pedagogical expert Victoria Goodyear and her team are comparing mental and physical health outcomes among children who attend schools that have restricted cell phone use to those attending schools without such a policy. The researchers described the protocol of that study of 30 schools and over 1,000 students in the July BMJ Open.

Goodyear and colleagues are also combining that natural experiment with qualitative research. They met with 36 five-person focus groups each consisting of all students, all parents or all educators at six of those schools. The team hopes to learn how students use their phones during the day, how usage practices make students feel, and what the various parties think of restrictions on cell phone use during the school day.

Talking to teens and those in their orbit is the best way to get at the mechanisms by which social media influences well-being — for better or worse, Goodyear says. Moving beyond big data to this more personal approach, however, takes considerable time and effort. “Social media has increased in pace and momentum very, very quickly,” she says. “And research takes a long time to catch up with that process.”

Until that catch-up occurs, though, researchers cannot dole out much advice. “What guidance could we provide to young people, parents and schools to help maintain the positives of social media use?” Goodyear asks. “There’s not concrete evidence yet.”

More Stories from Science News on Science & Society

Should we use AI to resurrect digital ‘ghosts’ of the dead?

A hidden danger lurks beneath Yellowstone

Online spaces may intensify teens’ uncertainty in social interactions

Want to see butterflies in your backyard? Try doing less yardwork

Ximena Velez-Liendo is saving Andean bears with honey

‘Flavorama’ guides readers through the complex landscape of flavor

Rain Bosworth studies how deaf children experience the world

Separating science fact from fiction in Netflix’s ‘3 Body Problem’

Subscribers, enter your e-mail address for full access to the Science News archives and digital editions.

Not a subscriber? Become one now .

- Bipolar Disorder

- Therapy Center

- When To See a Therapist

- Types of Therapy

- Best Online Therapy

- Best Couples Therapy

- Best Family Therapy

- Managing Stress

- Sleep and Dreaming

- Understanding Emotions

- Self-Improvement

- Healthy Relationships

- Student Resources

- Personality Types

- Guided Meditations

- Verywell Mind Insights

- 2024 Verywell Mind 25

- Mental Health in the Classroom

- Editorial Process

- Meet Our Review Board

- Crisis Support

For Better or Worse, Technology Is Taking Over the Health World

Sarah Fielding is a freelance writer covering a range of topics with a focus on mental health and women's issues.

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/SarahFieldingHeadshot1-afe3609d152d4e409fc179f68c17e652-0ddbe13118414f25ae9e00030fea1fae.jpg)

Steven Gans, MD is board-certified in psychiatry and is an active supervisor, teacher, and mentor at Massachusetts General Hospital.

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/steven-gans-1000-51582b7f23b6462f8713961deb74959f.jpg)

Nick Blackmer is a librarian, fact-checker, and researcher with more than 20 years’ experience in consumer-oriented health and wellness content. He keeps a DSM-5 on hand just in case.

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/NickBlackmer-1a9957221fee406e85bcdefd1b05a136.jpg)

For many people over the past year and a half, the world has existed primarily through a screen. With social distancing measures in place to protect individuals from becoming infected with the coronavirus, technology has stepped in to fill the void of physical connections. It’s also become a space for navigating existing and new mental health conditions through virtual therapy sessions, meditation apps, mental health influencers, and beyond.

“Over the years, mental health and technology have started touching each other more and more, and the pandemic accelerated that in an unprecedented way,” says Naomi Torres-Mackie, PhD , the head of research at The Mental Health Coalition , a clinical psychologist at Lenox Hill Hospital, and an adjunct professor at Columbia University. “This is especially the case because the pandemic has highlighted the importance of mental health for everyone as we struggle to make sense of an overwhelming new world and can find mental health information and services online.”

This shift is especially critical, with a tremendous spike occurring in mental health conditions. In the period between January and June 2019, 11% of US adults reported experiencing symptoms of an anxiety or depressive disorder. In January 2021, 10 months into the pandemic, in one survey that number increased to 41.1%. Research also points to a potential connection for some between having COVID-19 and developing a mental health condition—whether or not you previously had one.

The pandemic’s bridge between mental health and technology has helped to “meet the needs of many suffering from depression, anxiety, life transition, grief, family conflict, and addiction,” says Miyume McKinley, MSW, LCSW , a psychotherapist and founder of Epiphany Counseling, Consulting & Treatment Services.

Naomi Torres-Mackie, PhD

The risk of greater access is that the floodgates are open for anyone to say anything about mental health, and there’s no vetting process or way to truly check credibility.

This increased reliance on technology to facilitate mental health care and support appears to be a permanent one. Torres-Mackie has witnessed mental health clinicians drop their apprehension around virtual services throughout the pandemic and believes they will continue for good.

“Almost all therapists seem to be at least offering virtual sessions, and a good portion have transitioned their practices to be entirely virtual, giving up their traditional in-person offices,” adds Carrie Torn, MSW, LCSW , a licensed clinical social worker and psychotherapist in private practice in Charlotte, North Carolina.

The general public is also more receptive to technology’s expanded role in mental health care. “The pandemic has created a lasting relationship between technology, and it has helped increase access to mental health services across the world,” says McKinley. “There are lots of people seeking help who would not have done so prior to the pandemic, either due to the discomfort or because they simply didn’t know it was possible to obtain such services via technology.”

Accessibility Is a Tremendous Benefit of Technology

Every expert interviewed agreed: Accessibility is an undeniable and indispensable benefit of mental health’s increasing presence online. Torn points out, “We can access information, including mental health information and treatment like never before, and it’s low cost.”

A 2018 study found that, at the time, 74% of Americans didn’t view mental health as accessible to everyone. Participants cited long wait times, a lack of affordable options, low awareness, and social stigma as barriers to mental health care. The evolution of mental health and technology has alleviated some of these issues—whether it be through influencers creating open discussions around mental health and normalizing it or low-cost therapy apps . In addition, wait times may reduce when people are no longer tied to seeing a therapist in their immediate area.

While some people may still be apprehensive about trying digital therapy, research has shown that it is an effective strategy for managing your mental health. A 2020 review of 17 studies published in EClinicalMedicine found that online cognitive-behavioral therapy sessions were at least as effective at reducing the severity of depression symptoms than in-person sessions. There wasn’t a significant difference in participant satisfaction between the two options.

There Are Limitations to Mental Health and Technology’s Increasing Closeness

One of the most prevalent limitations of technology-fueled mental health care and awareness is the possibility of misleading or inaccurate information.

If you’re attending digital sessions with a therapist, it’s easy to check their qualifications and reviews. However, for most other online mental health resources, it can be more challenging but remains just as critical to verify their expertise and benefits. “The risk of greater access is that the floodgates are open for anyone to say anything about mental health, and there’s no vetting process or way to truly check credibility,” says Torres-Mackle.

To that point, James Giordano, PhD, MPhil , professor of neurology and ethics at Georgetown University Medical Center and author of the book “Neurotechnology: Premises, Potential, and Problems,” cautions that, while there are guiding institutions, the market still contains “unregulated products, resources, and services, many of which are available via the internet. Thus, it’s very important to engage due diligence when considering the use of any mental health technology .”

Verywell / Alison Czinkota

McKinley raises another valuable point: A person’s home is not always a space they can securely explore their mental health. “For many individuals, home is not a safe place due to abuse, addiction, toxic family, or unhealthy living environments,” she says. “Despite technology offering a means of support, if the home is not a safe place, many people won’t seek the help or mental health treatment that they need. For some, the therapy office is the only safe place they have.” Due to the pandemic and a general limit on private places outside of the home to dive into your personal feelings, someone in this situation may struggle to find opportunities for help.

Miyume McKinley, MSW, LCSW

There are lots of people seeking help that would not have done so prior to the pandemic, either due to the discomfort or because they simply didn’t know it was possible to obtain such services via technology.

Torn explains that therapists who work for tech platforms can also suffer due to burnout and low pay. She claims that some of these platforms prioritize seeing new clients instead of providing time for existing clients to grow their relationship. “I’ve heard about clients having to jump from one therapist to the next, or therapists who can’t even leave stops open for their existing clients, and instead their schedule gets filled with new clients,” she says. “Therapists are burning out in general right now, and especially on these platforms, which leads to a lower quality of care for clients.”

Screen Time Can Also Have a Negative Impact

As mental health care continues to spread into online platforms, clinicians and individuals must contend with society’s growing addiction to tech and extended screen time’s negative aspects.

Social media, in particular, has been shown to impact an individual’s mental health negatively. A 2019 study looked at how social media affected feelings of social isolation in 1,178 students aged 18 to 30. While having a positive experience on social media didn’t improve it, each 10% increase in negative experiences elevated social isolation feelings by 13%.

Verywell / Alison Czinkota

While certain aspects like Zoom therapy and mental health influencers require looking at a screen, you can use other digital options such as meditation apps without constantly staring at your device.

What to Be Mindful of as You Explore Mental Health Within Technology

Nothing is all bad or all good and that stands true for mental health’s increased presence within technology. What’s critical is being aware that “technology is a tool, and just like any tool, its impact depends on how it's used,” says Torres-Mackie.

For example, technology can produce positive results if you use the digital space to access treatment that you may have struggled to otherwise, support your mental well-being, or gather helpful—and credible—information about mental health. In contrast, she explains that diving into social media or other avenues only to compare yourself with others and avoid your responsibilities can have negative repercussions on your mental health and relationships.

Giordano expresses the importance of staying vigilant about your relationship with and reliance on tech and your power to control it.

With that in mind, pay attention to how much time you spend online. “We are spending less time outside, and more time glued to our screens. People are constantly comparing their lives to someone else's on social media, making it harder to be present in the moment and actually live our lives,” says Torn.

Between the increase in necessary services moving online and trying to connect with people through a screen, it’s critical to take time away from your devices. According to a 2018 study, changing your social media habits, in particular, can improve your overall well-being . Participants limited Instagram, Facebook, and Snapchat use to 10 minutes a day per platform for three weeks. At the end of the study, they showed significant reductions in depression and loneliness compared to the control group. However, even the increased awareness of their social media use appeared to help the control group lower feelings of anxiety and fear of missing out.

“Remember, it’s okay to turn your phone off. It’s okay to turn notifications off for news, apps, and emails,” says McKinley. Take opportunities to step outside, spend time with loved ones, and explore screen-free self-care activities. She adds, “Most of the things in life that make life worthwhile cannot be found on our devices, apps, or through technology—it’s found within ourselves and each other.”

Kaiser Family Foundation. The implications of COVID-19 for mental health and substance use .

Taquet M, Luciano S, Geddes JR, Harrison PJ. Bidirectional associations between COVID-19 and psychiatric disorder: retrospective cohort studies of 62 354 COVID-19 cases in the USA . Lancet Psychiatry . 2021;8(2):130-140. doi:10.1016/S2215-0366(20)30462-4

Luo C, Sanger N, Singhal N, et al. A comparison of electronically-delivered and face to face cognitive behavioural therapies in depressive disorders: a systematic review and meta-analysis . EClinicalMedicine . 2020;24:100442. doi:10.1016/j.eclinm.2020.100442

Primack BA, Karim SA, Shensa A, Bowman N, Knight J, Sidani JE. Positive and negative experiences on social media and perceived social isolation . Am J Health Promot . 2019;33(6):859-868. doi:10.1177/0890117118824196

Hunt MG, Marx R, Lipson C, Young J. No more FOMO: Limiting social media decreases loneliness and depression . J Soc Clin Psychol . 2018;37(10):751-768. doi:10.1521/jscp.2018.37.10.751

How Does Technology Affect Mental Health?

View all blog posts under Articles | View all blog posts under Counseling Resources

Upon completion of a Master of Arts in Counseling degree , individuals can choose to work as mental health counselors — individuals who help clients living with varying mental health and/or interpersonal issues. For example, a mental health counselor may meet with a bereaved woman in the morning who recently has lost her husband, and then a young man in his 20s in the afternoon who is living with an anxiety disorder. The role is challenging and rewarding, and necessitates understanding and expertise for a whole spectrum of mental health concerns.

Given the ubiquity of technology in daily life — particularly the internet and internet-based platforms such as social media sites and smartphone apps — mental health counselors working today likely will encounter clients who are experiencing issues that may be directly or indirectly linked to the use of digital media. According to Dr. Igor Pantic, writing in the literature review “Online Social Networking and Mental Health,” published by the U.S. National Library of Medicine, there is little doubt that the internet and social media platforms such as Facebook have had a notable impact on the way that individuals communicate.

Pantic further explained that a number of recent studies have observed a link between social media use and certain mental health problems, including anxiety and depression. Pantic is quick to assert, however, that the studies are by no means conclusive and that endeavors to understand the relationship between mental health and technology remain in their infancy.

Still, it is useful for mental health counselors to have an understanding of the research and insights into technology’s impact on mental health, which extends to the positive impacts, as well. After all, drawbacks aside, technology continues to improve many aspects of daily life for the better, and the arena of mental health is no exception: there are a number of observable areas in which the development of technology has helped clients take charge of their mental health care in a positive way.

Technology: A force for good?

Despite progress in terms of mental health awareness, journalist Conor Farrington, writing for the Guardian, explained how mental health care still receives a notable lack of funding from international governments. For example, Farrington reported that the per capita expenses on mental health care in industrialized nations such as the U.S. and U.K. amounts to just over $33, which equates to a little under £33. The amount is considerably less in developing countries. Consequently, Farrington argued that technology holds promise as a vehicle for improving access to mental health care, particularly in nations where such services are elementary at best.

Technology is improving mental health care in a number of ways, Lena H. Sun explained, writing for the Los Angeles Times, and it is primarily through platforms such as apps based on smartphones and computers that can help provide services and information to clients in a more cost-effective way. For example, Sun explained how there are now, in addition to smartphone apps that promote mental wellness, certain platforms available that allow patients to complete courses of cognitive behavioral therapy online. In her article, Sun profiled a British-based service known as the Big White Wall, which has been endorsed by the U.K.’s government-funded National Health Service. Big White Wall is an online platform that enables users living with mental health problems such as anxiety and depression to manage their symptoms from home via tools such as educational resources, online conversations and virtual classes on issues of mental health. The efficacy of Big White Wall is conspicuous — Sun reported on a 2009 study that found that a vast majority of the service’s users —some 95 percent —noted an improvement in their symptoms.

How can counselors harness technology?

Mental health counselors can play an important role in facilitating access to services such as Big White Wall and also can help promote smartphone apps and other online services that can be used to help improve general mental health. Technology can be used alongside in-person counseling, as opposed to being employed as a substitution. Counselors even may find that digital platforms allow the development of deeper working relationships with clients, particularly younger clients who are used to utilizing technology on a daily basis. Bethany Bay, writing in an article for Counseling Today, interviewed Sarah Spiegelhoff, a counselor from Syracuse, N.Y., who elaborated on this important point :

“I find technology resources to be great tools to supplement traditional counseling services, as well as a way for counselors to reach larger populations than we typically serve on an individual basis […] I find that college students are quicker to check Facebook and Twitter statuses than their email, so using social media has been one way for us to promote and distribute information on healthy living and outreach events […] I also share information related to new apps that promote wellness both through our social media accounts and directly in counseling sessions. For example, during alcohol awareness programming, we encouraged students to download free blood alcohol calculator apps. We also offer free mindfulness meditation MP3s through iTunes. I find the MP3s to be a great resource because I am able to present them to clients in session, talk about their experiences listening to and practicing the meditations and then develop a treatment plan that includes their use of the meditations outside of the counseling sessions.”

Counselors also can use platforms to connect with clients who may be situated in underserved or rural areas and are unable to travel for in-person meetings. As Farrington explained, some studies, including one from Oxford University, have found that text messaging and phone calls can be effective ways for counselors to connect with clients. Furthermore, telehealth platforms, which include instant messaging or video calling, already are proving useful in primary care settings for helping counselors reach clients. For example, Rob Reinhardt, writing for Counseling Today, interviewed Tasha Holland-Kornegay, a counseling professional who primarily provides counseling services to clients living with HIV via a messaging platform, which incorporates the option for video and audio calls.

Reinhardt, writing in a different piece published by Tame Your Practice, explained how the use of telemedicine platforms in mental health counseling has been shown to be beneficial in a number of ways. Perhaps most importantly, Reinhardt cited a study from researchers based at the University of Zurich, as detailed by Science Daily, which found that counseling conducted online actually can be more effective than face-to-face sessions. Researchers examined two groups of clients — one group received in-person therapy and the other received therapy via a telemedicine platform. Researchers found that the clients who received counseling sessions online actually experienced better outcomes — 53 percent reported that their depression had abated, compared to 50 percent reporting the same in the group that received in-person counseling. Other benefits include the fact that it is cheaper and allows a wider net of clients to be seen and treated, particularly those who are unable to access mental health services in person, whether due to geography, lack of funds or issues such as social anxiety disorder.

A point of clarification needs to be made, however. Whereas counselors may indeed use online technologies to aid the counseling process or to provide counseling services, they always must abide by the ethical guidelines on the use of technologies. These guidelines can be found in the Ethics Code of American Counseling Association and through the National Board for Certified Counselors’ website. Furthermore, counselors are required by law to be licensed in the locations where their clients reside.

Can technology have an adverse impact on mental health?

Although the use of technology can have a positive impact in terms of helping clients manage and get treated for certain mental health conditions, some research has indicated that the use of technology in general — and especially the internet — actually can be connected with the development of mental health conditions, such as anxiety and depression in some individuals. As Pantic noted, while more research is needed in this area, it is useful to take a closer look at what has been published on this topic so far:

Internet addiction

As detailed by Dr. Romeo Vitelli, writing in an article published by Psychology Today, research has indicated that addiction to the internet , particularly among younger demographics such as adolescents, is becoming a notable issue. Vitelli explained that internet addiction disorder shares many similar features when compared with other forms of addiction, such as withdrawal symptoms when online access is precluded. While the internet can be an agent for good in terms of education and the strengthening of interpersonal relationships, internet addiction can be problematic because it can negatively impact academic success and one’s ability to communicate effectively in person. Vitalli noted that research also has observed a link between certain mental illnesses and internet addiction, including depression, low self-esteem and loneliness.

The link between social media use and mental illness

In his literature review, Pantic explained how several studies have shown a link between depression and the use of social media sites, such as Facebook, Twitter and Instagram. Pantic is quick to caution that much more research is needed before the conclusions reached in the aforementioned studies are widely accepted as fact within the counseling community. Still, the findings are worth examining. Pantic reported on one study from 2013, which found that younger adults who frequently used the social networking site Facebook tended to report feeling less happy, with the use of the social platform possibly to blame. Pantic also reported on a study that he personally was involved with that found among high school students, rates of depression tended to be higher among those who regularly utilized social media sites.

Pantic proffered some possible reasons for the findings, explaining that social media sites, for some individuals, can trigger feelings of low self-esteem. For example, a social media site user may see other people on the site and assume those individuals are more successful, beautiful, intelligent and so on. Pantic explained that a study examining students at a Utah university found those who routinely used social media sites tended to feel as though their peers were more successful and happier than they were. Pantic noted that although these feelings are not necessarily linked to depression, there can be a relationship between them, particularly if the individuals in question already experience or are likely to experience mental health problems.

Dr. Saju Mathew was interviewed for an article by Piedmont Health, wherein he elaborated on this important point : “When we get on social media, we are looking for affirmation and consciously or not, we are comparing our life to the lives of others. As a result, we may not enjoy what’s in the moment.”

In conclusion

The impact of technology has extended into the realm of health care, and it is clear that technology also is making positive changes in terms of mental health care. Research has indicated, however, that the very tools that can help alleviate mental health issues, such as smartphone apps, may be linked with the experience of mental health problems in different contexts. As Pantic stressed, more research is needed before definitive conclusions are drawn. Still, for mental health counselors entering the field, a comprehensive understanding of the nuanced relationship between technology and mental health is necessary for effective practice. Counselors are compelled to expand their technological competencies but always in compliance with their respective ethical guidelines and the rule of law.

Consider Bradley University

If you are interested in pursuing a career as a mental health counselor, consider applying to Bradley University’s online Master of Arts in Counseling — Clinical Mental Health Counseling program. Designed with a busy schedule in mind, completion of the degree program will put you on a direct path to becoming licensed to practice.

Recommended Readings

Substance abuse counseling: What you can learn in a MAC program

What are the Clinical Mental Health specialty courses?

Bradley University Online Counseling Programs

- #5 Among Regional Universities (Midwest) – U.S. News & World Report: Best Colleges (2021)

- #5 Best Value Schools, Regional Universities (Midwest) – U.S. News & World Report (2019)

- Bradley Ranked Among Nation’s Best Universities – The Princeton Review: The Best 384 Colleges (2019). Only 15% of all four-year colleges receive this distinction each year, and Bradley has regularly been included on the list.

- Bradley University has been named a Military Friendly School – a designation honoring the top 20% of colleges, universities and trade schools nationwide that are doing the most to embrace U.S. military service members, veterans and spouses to ensure their success as students.

- Open access

- Published: 06 July 2023

Pros & cons: impacts of social media on mental health

- Ágnes Zsila 1 , 2 &

- Marc Eric S. Reyes ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-5280-1315 3

BMC Psychology volume 11 , Article number: 201 ( 2023 ) Cite this article

435k Accesses

15 Citations

107 Altmetric

Metrics details

The use of social media significantly impacts mental health. It can enhance connection, increase self-esteem, and improve a sense of belonging. But it can also lead to tremendous stress, pressure to compare oneself to others, and increased sadness and isolation. Mindful use is essential to social media consumption.

Social media has become integral to our daily routines: we interact with family members and friends, accept invitations to public events, and join online communities to meet people who share similar preferences using these platforms. Social media has opened a new avenue for social experiences since the early 2000s, extending the possibilities for communication. According to recent research [ 1 ], people spend 2.3 h daily on social media. YouTube, TikTok, Instagram, and Snapchat have become increasingly popular among youth in 2022, and one-third think they spend too much time on these platforms [ 2 ]. The considerable time people spend on social media worldwide has directed researchers’ attention toward the potential benefits and risks. Research shows excessive use is mainly associated with lower psychological well-being [ 3 ]. However, findings also suggest that the quality rather than the quantity of social media use can determine whether the experience will enhance or deteriorate the user’s mental health [ 4 ]. In this collection, we will explore the impact of social media use on mental health by providing comprehensive research perspectives on positive and negative effects.

Social media can provide opportunities to enhance the mental health of users by facilitating social connections and peer support [ 5 ]. Indeed, online communities can provide a space for discussions regarding health conditions, adverse life events, or everyday challenges, which may decrease the sense of stigmatization and increase belongingness and perceived emotional support. Mutual friendships, rewarding social interactions, and humor on social media also reduced stress during the COVID-19 pandemic [ 4 ].

On the other hand, several studies have pointed out the potentially detrimental effects of social media use on mental health. Concerns have been raised that social media may lead to body image dissatisfaction [ 6 ], increase the risk of addiction and cyberbullying involvement [ 5 ], contribute to phubbing behaviors [ 7 ], and negatively affects mood [ 8 ]. Excessive use has increased loneliness, fear of missing out, and decreased subjective well-being and life satisfaction [ 8 ]. Users at risk of social media addiction often report depressive symptoms and lower self-esteem [ 9 ].

Overall, findings regarding the impact of social media on mental health pointed out some essential resources for psychological well-being through rewarding online social interactions. However, there is a need to raise awareness about the possible risks associated with excessive use, which can negatively affect mental health and everyday functioning [ 9 ]. There is neither a negative nor positive consensus regarding the effects of social media on people. However, by teaching people social media literacy, we can maximize their chances of having balanced, safe, and meaningful experiences on these platforms [ 10 ].

We encourage researchers to submit their research articles and contribute to a more differentiated overview of the impact of social media on mental health. BMC Psychology welcomes submissions to its new collection, which promises to present the latest findings in the emerging field of social media research. We seek research papers using qualitative and quantitative methods, focusing on social media users’ positive and negative aspects. We believe this collection will provide a more comprehensive picture of social media’s positive and negative effects on users’ mental health.

Data Availability

Not applicable.

Statista. (2022). Time spent on social media [Chart]. Accessed June 14, 2023, from https://www.statista.com/chart/18983/time-spent-on-social-media/ .

Pew Research Center. (2023). Teens and social media: Key findings from Pew Research Center surveys. Retrieved June 14, 2023, from https://www.pewresearch.org/short-reads/2023/04/24/teens-and-social-media-key-findings-from-pew-research-center-surveys/ .

Boer, M., Van Den Eijnden, R. J., Boniel-Nissim, M., Wong, S. L., Inchley, J. C.,Badura, P.,… Stevens, G. W. (2020). Adolescents’ intense and problematic social media use and their well-being in 29 countries. Journal of Adolescent Health , 66(6), S89-S99. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jadohealth.2020.02.011.

Marciano L, Ostroumova M, Schulz PJ, Camerini AL. Digital media use and adolescents’ mental health during the COVID-19 pandemic: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Front Public Health. 2022;9:2208. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2021.641831 .

Article Google Scholar

Naslund JA, Bondre A, Torous J, Aschbrenner KA. Social media and mental health: benefits, risks, and opportunities for research and practice. J Technol Behav Sci. 2020;5:245–57. https://doi.org/10.1007/s41347-020-00094-8 .

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Harriger JA, Thompson JK, Tiggemann M. TikTok, TikTok, the time is now: future directions in social media and body image. Body Image. 2023;44:222–6. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bodyim.2021.12.005 .

Article PubMed Google Scholar

Chi LC, Tang TC, Tang E. The phubbing phenomenon: a cross-sectional study on the relationships among social media addiction, fear of missing out, personality traits, and phubbing behavior. Curr Psychol. 2022;41(2):1112–23. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-022-0135-4 .

Valkenburg PM. Social media use and well-being: what we know and what we need to know. Curr Opin Psychol. 2022;45:101294. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.copsyc.2020.101294 .

Bányai F, Zsila Á, Király O, Maraz A, Elekes Z, Griffiths MD, Urbán R, Farkas J, Rigó P Jr, Demetrovics Z. Problematic social media use: results from a large-scale nationally representative adolescent sample. PLoS ONE. 2017;12(1):e0169839. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0169839 .

American Psychological Association. (2023). APA panel issues recommendations for adolescent social media use. Retrieved from https://apa-panel-issues-recommendations-for-adolescent-social-media-use-774560.html .

Download references

Acknowledgements

Ágnes Zsila was supported by the ÚNKP-22-4 New National Excellence Program of the Ministry for Culture and Innovation from the source of the National Research, Development and Innovation Fund.

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Institute of Psychology, Pázmány Péter Catholic University, Budapest, Hungary

Ágnes Zsila

Institute of Psychology, ELTE Eötvös Loránd University, Budapest, Hungary

Department of Psychology, College of Science, University of Santo Tomas, Manila, 1008, Philippines

Marc Eric S. Reyes

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Contributions

AZ conceived and drafted the Editorial. MESR wrote the abstract and revised the Editorial. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Marc Eric S. Reyes .

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate, consent for publication, competing interests.

The authors have no competing interests to declare relevant to the content of this article.

Additional information

Publisher’s note.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ . The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver ( http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/ ) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article.

Zsila, Á., Reyes, M.E.S. Pros & cons: impacts of social media on mental health. BMC Psychol 11 , 201 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1186/s40359-023-01243-x

Download citation

Received : 15 June 2023

Accepted : 03 July 2023

Published : 06 July 2023

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1186/s40359-023-01243-x

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Social media

- Mental health

BMC Psychology

ISSN: 2050-7283

- General enquiries: [email protected]

Advertisement

Social Media and Mental Health: Benefits, Risks, and Opportunities for Research and Practice

- Published: 20 April 2020

- Volume 5 , pages 245–257, ( 2020 )

Cite this article

- John A. Naslund 1 ,

- Ameya Bondre 2 ,

- John Torous 3 &

- Kelly A. Aschbrenner 4

371k Accesses

184 Citations

148 Altmetric

12 Mentions

Explore all metrics

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Social media has become a prominent fixture in the lives of many individuals facing the challenges of mental illness. Social media refers broadly to web and mobile platforms that allow individuals to connect with others within a virtual network (such as Facebook, Twitter, Instagram, Snapchat, or LinkedIn), where they can share, co-create, or exchange various forms of digital content, including information, messages, photos, or videos (Ahmed et al. 2019 ). Studies have reported that individuals living with a range of mental disorders, including depression, psychotic disorders, or other severe mental illnesses, use social media platforms at comparable rates as the general population, with use ranging from about 70% among middle-age and older individuals to upwards of 97% among younger individuals (Aschbrenner et al. 2018b ; Birnbaum et al. 2017b ; Brunette et al. 2019 ; Naslund et al. 2016 ). Other exploratory studies have found that many of these individuals with mental illness appear to turn to social media to share their personal experiences, seek information about their mental health and treatment options, and give and receive support from others facing similar mental health challenges (Bucci et al. 2019 ; Naslund et al. 2016b ).

Across the USA and globally, very few people living with mental illness have access to adequate mental health services (Patel et al. 2018 ). The wide reach and near ubiquitous use of social media platforms may afford novel opportunities to address these shortfalls in existing mental health care, by enhancing the quality, availability, and reach of services. Recent studies have explored patterns of social media use, impact of social media use on mental health and wellbeing, and the potential to leverage the popularity and interactive features of social media to enhance the delivery of interventions. However, there remains uncertainty regarding the risks and potential harms of social media for mental health (Orben and Przybylski 2019 ) and how best to weigh these concerns against potential benefits.

In this commentary, we summarized current research on the use of social media among individuals with mental illness, with consideration of the impact of social media on mental wellbeing, as well as early efforts using social media for delivery of evidence-based programs for addressing mental health problems. We searched for recent peer reviewed publications in Medline and Google Scholar using the search terms “mental health” or “mental illness” and “social media,” and searched the reference lists of recent reviews and other relevant studies. We reviewed the risks, potential harms, and necessary safety precautions with using social media for mental health. Overall, our goal was to consider the role of social media as a potentially viable intervention platform for offering support to persons with mental disorders, promoting engagement and retention in care, and enhancing existing mental health services, while balancing the need for safety. Given this broad objective, we did not perform a systematic search of the literature and we did not apply specific inclusion criteria based on study design or type of mental disorder.

Social Media Use and Mental Health

In 2020, there are an estimated 3.8 billion social media users worldwide, representing half the global population (We Are Social 2020 ). Recent studies have shown that individuals with mental disorders are increasingly gaining access to and using mobile devices, such as smartphones (Firth et al. 2015 ; Glick et al. 2016 ; Torous et al. 2014a , b ). Similarly, there is mounting evidence showing high rates of social media use among individuals with mental disorders, including studies looking at engagement with these popular platforms across diverse settings and disorder types. Initial studies from 2015 found that nearly half of a sample of psychiatric patients were social media users, with greater use among younger individuals (Trefflich et al. 2015 ), while 47% of inpatients and outpatients with schizophrenia reported using social media, of which 79% reported at least once-a-week usage of social media websites (Miller et al. 2015 ). Rates of social media use among psychiatric populations have increased in recent years, as reflected in a study with data from 2017 showing comparable rates of social media use (approximately 70%) among individuals with serious mental illness in treatment as compared with low-income groups from the general population (Brunette et al. 2019 ).

Similarly, among individuals with serious mental illness receiving community-based mental health services, a recent study found equivalent rates of social media use as the general population, even exceeding 70% of participants (Naslund et al. 2016 ). Comparable findings were demonstrated among middle-age and older individuals with mental illness accessing services at peer support agencies, where 72% of respondents reported using social media (Aschbrenner et al. 2018b ). Similar results, with 68% of those with first episode psychosis using social media daily were reported in another study (Abdel-Baki et al. 2017 ).

Individuals who self-identified as having a schizophrenia spectrum disorder responded to a survey shared through the National Alliance of Mental Illness (NAMI) and reported that visiting social media sites was one of their most common activities when using digital devices, taking up roughly 2 h each day (Gay et al. 2016 ). For adolescents and young adults ages 12 to 21 with psychotic disorders and mood disorders, over 97% reported using social media, with average use exceeding 2.5 h per day (Birnbaum et al. 2017b ). Similarly, in a sample of adolescents ages 13–18 recruited from community mental health centers, 98% reported using social media, with YouTube as the most popular platform, followed by Instagram and Snapchat (Aschbrenner et al. 2019 ).

Research has also explored the motivations for using social media as well as the perceived benefits of interacting on these platforms among individuals with mental illness. In the sections that follow (see Table 1 for a summary), we consider three potentially unique features of interacting and connecting with others on social media that may offer benefits for individuals living with mental illness. These include: (1) Facilitate social interaction; (2) Access to a peer support network; and (3) Promote engagement and retention in services.

Facilitate Social Interaction

Social media platforms offer near continuous opportunities to connect and interact with others, regardless of time of day or geographic location. This on demand ease of communication may be especially important for facilitating social interaction among individuals with mental disorders experiencing difficulties interacting in face-to-face settings. For example, impaired social functioning is a common deficit in schizophrenia spectrum disorders, and social media may facilitate communication and interacting with others for these individuals (Torous and Keshavan 2016 ). This was suggested in one study where participants with schizophrenia indicated that social media helped them to interact and socialize more easily (Miller et al. 2015 ). Like other online communication, the ability to connect with others anonymously may be an important feature of social media, especially for individuals living with highly stigmatizing health conditions (Berger et al. 2005 ), such as serious mental disorders (Highton-Williamson et al. 2015 ).

Studies have found that individuals with serious mental disorders (Spinzy et al. 2012 ) as well as young adults with mental illness (Gowen et al. 2012 ) appear to form online relationships and connect with others on social media as often as social media users from the general population. This is an important observation because individuals living with serious mental disorders typically have few social contacts in the offline world and also experience high rates of loneliness (Badcock et al. 2015 ; Giacco et al. 2016 ). Among individuals receiving publicly funded mental health services who use social media, nearly half (47%) reported using these platforms at least weekly to feel less alone (Brusilovskiy et al. 2016 ). In another study of young adults with serious mental illness, most indicated that they used social media to help feel less isolated (Gowen et al. 2012 ). Interestingly, more frequent use of social media among a sample of individuals with serious mental illness was associated with greater community participation, measured as participation in shopping, work, religious activities, or visiting friends and family, as well as greater civic engagement, reflected as voting in local elections (Brusilovskiy et al. 2016 ).

Emerging research also shows that young people with moderate to severe depressive symptoms appear to prefer communicating on social media rather than in-person (Rideout and Fox 2018 ), while other studies have found that some individuals may prefer to seek help for mental health concerns online rather than through in-person encounters (Batterham and Calear 2017 ). In a qualitative study, participants with schizophrenia described greater anonymity, the ability to discover that other people have experienced similar health challenges and reducing fears through greater access to information as important motivations for using the Internet to seek mental health information (Schrank et al. 2010 ). Because social media does not require the immediate responses necessary in face-to-face communication, it may overcome deficits with social interaction due to psychotic symptoms that typically adversely affect face-to-face conversations (Docherty et al. 1996 ). Online social interactions may not require the use of non-verbal cues, particularly in the initial stages of interaction (Kiesler et al. 1984 ), with interactions being more fluid and within the control of users, thereby overcoming possible social anxieties linked to in-person interaction (Indian and Grieve 2014 ). Furthermore, many individuals with serious mental disorders can experience symptoms including passive social withdrawal, blunted affect, and attentional impairment, as well as active social avoidance due to hallucinations or other concerns (Hansen et al. 2009 ), thus potentially reinforcing the relative advantage, as perceived by users, of using social media over in person conversations.

Access to a Peer Support Network

There is growing recognition about the role that social media channels could play in enabling peer support (Bucci et al. 2019 ; Naslund et al. 2016b ), referred to as a system of mutual giving and receiving where individuals who have endured the difficulties of mental illness can offer hope, friendship, and support to others facing similar challenges (Davidson et al. 2006 ; Mead et al. 2001 ). Initial studies exploring use of online self-help forums among individuals with serious mental illnesses have found that individuals with schizophrenia appeared to use these forums for self-disclosure and sharing personal experiences, in addition to providing or requesting information, describing symptoms, or discussing medication (Haker et al. 2005 ), while users with bipolar disorder reported using these forums to ask for help from others about their illness (Vayreda and Antaki 2009 ). More recently, in a review of online social networking in people with psychosis, Highton-Williamson et al. ( 2015 ) highlight that an important purpose of such online connections was to establish new friendships, pursue romantic relationships, maintain existing relationships or reconnect with people, and seek online peer support from others with lived experience (Highton-Williamson et al. 2015 ).

Online peer support among individuals with mental illness has been further elaborated in various studies. In a content analysis of comments posted to YouTube by individuals who self-identified as having a serious mental illness, there appeared to be opportunities to feel less alone, provide hope, find support and learn through mutual reciprocity, and share coping strategies for day-to-day challenges of living with a mental illness (Naslund et al. 2014 ). In another study, Chang ( 2009 ) delineated various communication patterns in an online psychosis peer-support group (Chang 2009 ). Specifically, different forms of support emerged, including “informational support” about medication use or contacting mental health providers, “esteem support” involving positive comments for encouragement, “network support” for sharing similar experiences, and “emotional support” to express understanding of a peer’s situation and offer hope or confidence (Chang 2009 ). Bauer et al. ( 2013 ) reported that the main interest in online self-help forums for patients with bipolar disorder was to share emotions with others, allow exchange of information, and benefit by being part of an online social group (Bauer et al. 2013 ).

For individuals who openly discuss mental health problems on Twitter, a study by Berry et al. ( 2017 ) found that this served as an important opportunity to seek support and to hear about the experiences of others (Berry et al. 2017 ). In a survey of social media users with mental illness, respondents reported that sharing personal experiences about living with mental illness and opportunities to learn about strategies for coping with mental illness from others were important reasons for using social media (Naslund et al. 2017 ). A computational study of mental health awareness campaigns on Twitter provides further support with inspirational posts and tips being the most shared (Saha et al. 2019 ). Taken together, these studies offer insights about the potential for social media to facilitate access to an informal peer support network, though more research is necessary to examine how these online interactions may impact intentions to seek care, illness self-management, and clinically meaningful outcomes in offline contexts.

Promote Engagement and Retention in Services

Many individuals living with mental disorders have expressed interest in using social media platforms for seeking mental health information (Lal et al. 2018 ), connecting with mental health providers (Birnbaum et al. 2017b ), and accessing evidence-based mental health services delivered over social media specifically for coping with mental health symptoms or for promoting overall health and wellbeing (Naslund et al. 2017 ). With the widespread use of social media among individuals living with mental illness combined with the potential to facilitate social interaction and connect with supportive peers, as summarized above, it may be possible to leverage the popular features of social media to enhance existing mental health programs and services. A recent review by Biagianti et al. ( 2018 ) found that peer-to-peer support appeared to offer feasible and acceptable ways to augment digital mental health interventions for individuals with psychotic disorders by specifically improving engagement, compliance, and adherence to the interventions and may also improve perceived social support (Biagianti et al. 2018 ).