10 Positive and Negative Effects of Social Media on Society

Nowadays, social media is so popular among the young, children, and adults. Each of us uses social media to be updated, to entertain ourselves, to communicate with others, to explore new things, and to connect with the world. Facebook, Instagram, WhatsApp, YouTube, etc. are examples of social media. Social media is a part of our lives today, and consciously or unconsciously, it is becoming our habit to continuously go through it and check the notifications.

What is social media?

Social media is a platform where we can communicate with a large number of people, make connections, and interact with them. It operates on the internet.A user usually creates an account on such a platform and allows interaction with the millions of other users available on it according to their preferences and choices. Apart from the interaction, it also allows users to share information, chat with other people, share their opinions, create content, and embrace their differences.

In today’s world, social media is an important part of young people’s lives, determining and shaping their perspectives.The youth typically adopt and pursue social media trends; for example, in dressing styles, the youth adopt dresses and styles that are promoted as trends by social media.

Social media not only allows people to share their opinions, but it also shapes the opinions of its users.Social media have an impact on their users as well as society as a whole, both positive and negative.

Here we will now discuss the negative and positive impacts of social media on society.

Positive impact of social media on society.

- Builds connectivity and connection: Social media facilitates better communication as well as the development of stronger connections and connectivity around the world. One can talk to a person who lives thousands of miles away from him or her. One can also make connections in his or her respective field or area to promote his or her venture, business, or idea. LinkedIn is an example of social media where you can build connections from across the world and increase your connectivity. Hence, social media is not only connecting people within a society but also connecting people from different societies and cultures, allowing them to exchange their values and beliefs.

- People are empowered by social media because it educates them, makes them aware of them, and gives them a platform to raise their voices, showcase their talents, and promote their businesses. For instance, people on Instagram not only communicate with each other but are also establishing their small businesses and creating content on various things such as dressing style, make-up, fashion hacks, and educational content. Likewise, on YouTube, people do the same thing except chat and earn money through their talent, opinions, and content. Therefore, social media helps generate employment in society and educate its members.

- People are helped both economically and emotionally by social media : Economically, by providing customers to businesses and providing jobs to the unemployed. Emotionally, by demonstrating empathy and love to the people.The person who feels alone should communicate with people online and talk to them. Sometimes, when you post something on your social media account—a sad or happy post—people react accordingly. If you post something sad, people try to cheer you up or console you, and vice versa. Social media in society provides an equal opportunity to be social and interact, especially for those who find it difficult to communicate with others in person.

- Knowledge: on social media, people post massive amounts of content on a wide range of issues and topics. YouTube is a platform where you can find information in English, Hindi, or any other language you are comfortable with. From the fundamentals to the advanced, from simple to complex topics, one can learn for free on social media. There are many teachers, motivators, and religious gurus who provide knowledge in various fields and aspects.

- Provides new skills: Through social media, you can acquire and learn new skills. You can, for example, learn to knit on YouTube or do it yourself (DIY) on Instagram, Facebook, and YouTube. You can acquire as many skills as you want: cooking, knitting, floral design, rangoli making, python, ethical hacking, etc. Moreover, learning new skills helps one find work and empowers oneself.

- Source to news: social media is a source of news nowadays; people watch news more on YouTube, Instagram, and Facebook as compared to news channels and newspapers. People believe that news on social media is more trustworthy and presented in a more interesting format than traditional news channels.

- Sharing of ideas: social media allows the sharing of ideas beyond boundaries, nations, and states. Social media facilitates the exchange of ideas about one’s culture, religion, state, nationality, and environment.

- Raising funds: social media helps many people raise funds for noble causes. Through the help of social media, people start campaigns for donations for a particular case, and everyone can participate in these donations. For Example, Fundraising for blind orphan children

- Creates communities: Social media creates communities of people from various backgrounds who share common interests. People with the same interests connect more with each other. Examples include the science community, the arts community, and the poets’ community. The nature of a community depends on the interests of its members.

- Multiple sources of learning: social media is a hub of knowledge where you can learn anything and everything. The education is provided at no cost. There is not only educational or academic learning, but also other types of learning; you can learn how to improve your personality, improve your communication skills, be more confident, and develop your public speaking skills.

Negative impacts of social media on society

- Contributes to the digital divide: The “digital divide” refers to the gap between those who can access the internet and those who cannot because of illiteracy, poverty, and a lack of resources. Social media is contributing to this by setting trends and engaging more youth, and youth who cannot access or understand the trends, as well as adults, are falling behind.

- Increasing cybercrimes and cyberfrauds : An increase in the use of social media is leading to an increase in cybercrimes and frauds. Cyberbullying, harassment, and stalking are on the rise nowadays, and mostly teenage women are becoming victims of them. Cyber fraud is also on the rise because most people lack digital literacy and are unaware of things like when fraudsters create an account to impersonate someone you know and demand money from you for various reasons.The nature of the frauds varied and could cause confusion and restlessness in your minds.

- Negative information, news, and rumours spread quickly: As the elders say, negativity spreads faster than positivity; similarly, false news or negative news, rumours, and information spread quickly and cause chaos and instability in the social order.Because of the rapid transfer of information, false news or information spreads in no time, which furthers the happenings in society. For example, if you come across WhatsApp messages that claim prejudice or hatred against a particular community, they will spread with more intensity and rage. This false claim creates a false image among people regarding the thing, and the false information is spread. Sometimes, it leads to violent situations in society.

- Social media affects the mental health of individuals: The stalking, cybercrimes, frauds, and hate comments adversely affect people; problems of depression, anxiety, severe tension, and fear are emerging. Sometimes, the conditions get worse, leading to suicide as well. As Durkheim mentioned, suicide is a social fact; either more or less social involvement leads to suicide in an individual, and social media manifests and roots both. For instance, if a user posts her critical view on a sensitive topic, chances are high that she will feel instant backlash from those who are against her views. Another example is that victims of cyberfraud fear using social media. Because of social media, people get traumatised and spend years of their lives living in that trauma and fear.

- People are becoming more addicted to their phones as a result of being disconnected from social reality. People frequently ignore and neglect those around them; they are unaware of what is going on in society because they are constantly immersed in their virtual world, engaging with entertainment and people in their virtual world. People who lack social and communication skills use social media to escape and ignore people in the real world. For instance, we all know a person who has no friends in the real world but has a following of hundreds of thousands on their social media account.

- Effects on health: Social media has an impact not only on mental health, but also on physical health. The constant use of screens such as phones, laptops, and tablets directly impacts the eyes by weakening the eyesight. It also negatively impacts our creativity; it basically lessens our level of creativity. The constant use of social media also makes us lazy and less active, as we are constantly using our devices. People also suffer from insomnia, irritation, and the fear of missing out. As Parsons stated, when an individual is sick, it becomes a non-functional member of society, and sickness is socially sanctioned deviance. In our opinion, social media is also making functional members of society non-functional.

- Unverified information: While social media is undeniably a knowledge hub, not all knowledge and information on it is correct or verified. Due to the large amount of data present on social media, most of it is unverified, and the chances of receiving false information are high. For example, on Facebook and Instagram, you’ll frequently see a post with the words “more you cry, the stronger you become,” and above or below it, “psychological facts”. People consume this false information as fact. There are enormous posts like this. But, in reality, this is far from factual knowledge or information.

- Undermine people: social media do not support people; they often lack support, empathy, and rational behavior. The moment people post something sad or controversial, they start getting backlash, hate comments, and threats, because of which people suffer from anxiety, stress, and depression. People who are unable to follow trends feel isolated. People who are not on social media also feel alienated. People on social media also spread hatred and prejudices against others instead of supporting and appreciating them. People compare themselves to others on social media, which lowers their self-esteem and confidence.

- Make conscious decisions about yourself: People post pictures according to socially constructed beauty standards, in which they seem slim, have radiant skin, and have clear lips (by using filters). Other people who are overweight or slimmer, have acne or pimples on their skin, lack makeup skills, and become self-conscious about their bodies. Teens start to diet, go to the gym, and try to maintain the trending body. Adults also suffer from this. People become self-conscious, which leads to feelings of inadequacy about their bodies and appearance.

- Increased use of poor language: on social media, people use language that has poor grammar, speech, and spelling. LOL, WYD, etc. words are used while chatting with people on social media. The quality of language is deteriorating, and people are losing their culture.

Conclusion-

From the above discussion, we can conclude that despite the various uses of social media, there are many misuses and negative impacts of it on society as a whole as well as on individuals.

Also read: Why do people share everything online?

Yachika Yadav is a sociology post graduate student at Banasthali Vidyapith. She loves to capture moments in nature, apart from drawing and writing poetries. Field of research attracts her the most and in future she want to be a part of that. She is a good listener, learner. And tries to always help others.

Feb 15, 2023

6 Example Essays on Social Media | Advantages, Effects, and Outlines

Got an essay assignment about the effects of social media we got you covered check out our examples and outlines below.

Social media has become one of our society's most prominent ways of communication and information sharing in a very short time. It has changed how we communicate and has given us a platform to express our views and opinions and connect with others. It keeps us informed about the world around us. Social media platforms such as Facebook, Twitter, Instagram, and LinkedIn have brought individuals from all over the world together, breaking down geographical borders and fostering a genuinely global community.

However, social media comes with its difficulties. With the rise of misinformation, cyberbullying, and privacy problems, it's critical to utilize these platforms properly and be aware of the risks. Students in the academic world are frequently assigned essays about the impact of social media on numerous elements of our lives, such as relationships, politics, and culture. These essays necessitate a thorough comprehension of the subject matter, critical thinking, and the ability to synthesize and convey information clearly and succinctly.

But where do you begin? It can be challenging to know where to start with so much information available. Jenni.ai comes in handy here. Jenni.ai is an AI application built exclusively for students to help them write essays more quickly and easily. Jenni.ai provides students with inspiration and assistance on how to approach their essays with its enormous database of sample essays on a variety of themes, including social media. Jenni.ai is the solution you've been looking for if you're experiencing writer's block or need assistance getting started.

So, whether you're a student looking to better your essay writing skills or want to remain up to date on the latest social media advancements, Jenni.ai is here to help. Jenni.ai is the ideal tool for helping you write your finest essay ever, thanks to its simple design, an extensive database of example essays, and cutting-edge AI technology. So, why delay? Sign up for a free trial of Jenni.ai today and begin exploring the worlds of social networking and essay writing!

Want to learn how to write an argumentative essay? Check out these inspiring examples!

We will provide various examples of social media essays so you may get a feel for the genre.

6 Examples of Social Media Essays

Here are 6 examples of Social Media Essays:

The Impact of Social Media on Relationships and Communication

Introduction:.

The way we share information and build relationships has evolved as a direct result of the prevalence of social media in our daily lives. The influence of social media on interpersonal connections and conversation is a hot topic. Although social media has many positive effects, such as bringing people together regardless of physical proximity and making communication quicker and more accessible, it also has a dark side that can affect interpersonal connections and dialogue.

Positive Effects:

Connecting People Across Distances

One of social media's most significant benefits is its ability to connect individuals across long distances. People can use social media platforms to interact and stay in touch with friends and family far away. People can now maintain intimate relationships with those they care about, even when physically separated.

Improved Communication Speed and Efficiency

Additionally, the proliferation of social media sites has accelerated and simplified communication. Thanks to instant messaging, users can have short, timely conversations rather than lengthy ones via email. Furthermore, social media facilitates group communication, such as with classmates or employees, by providing a unified forum for such activities.

Negative Effects:

Decreased Face-to-Face Communication

The decline in in-person interaction is one of social media's most pernicious consequences on interpersonal connections and dialogue. People's reliance on digital communication over in-person contact has increased along with the popularity of social media. Face-to-face interaction has suffered as a result, which has adverse effects on interpersonal relationships and the development of social skills.

Decreased Emotional Intimacy

Another adverse effect of social media on relationships and communication is decreased emotional intimacy. Digital communication lacks the nonverbal cues and facial expressions critical in building emotional connections with others. This can make it more difficult for people to develop close and meaningful relationships, leading to increased loneliness and isolation.

Increased Conflict and Miscommunication

Finally, social media can also lead to increased conflict and miscommunication. The anonymity and distance provided by digital communication can lead to misunderstandings and hurtful comments that might not have been made face-to-face. Additionally, social media can provide a platform for cyberbullying , which can have severe consequences for the victim's mental health and well-being.

Conclusion:

In conclusion, the impact of social media on relationships and communication is a complex issue with both positive and negative effects. While social media platforms offer many benefits, such as connecting people across distances and enabling faster and more accessible communication, they also have a dark side that can negatively affect relationships and communication. It is up to individuals to use social media responsibly and to prioritize in-person communication in their relationships and interactions with others.

The Role of Social Media in the Spread of Misinformation and Fake News

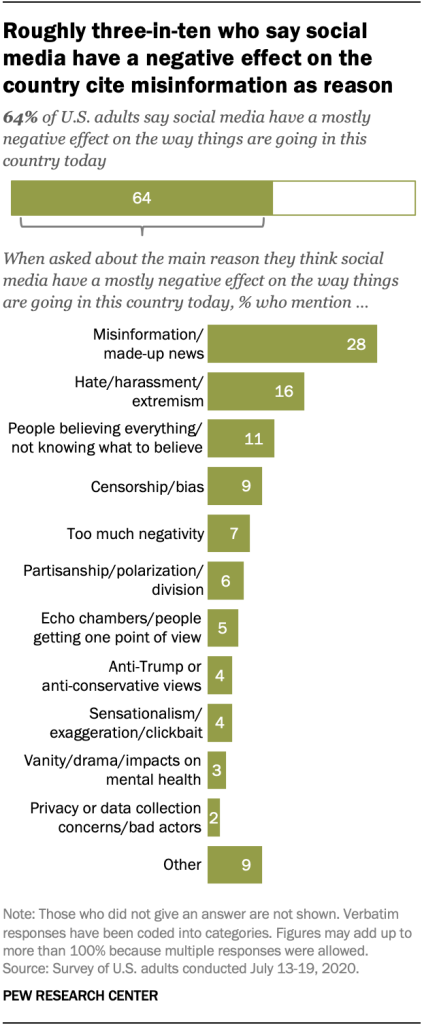

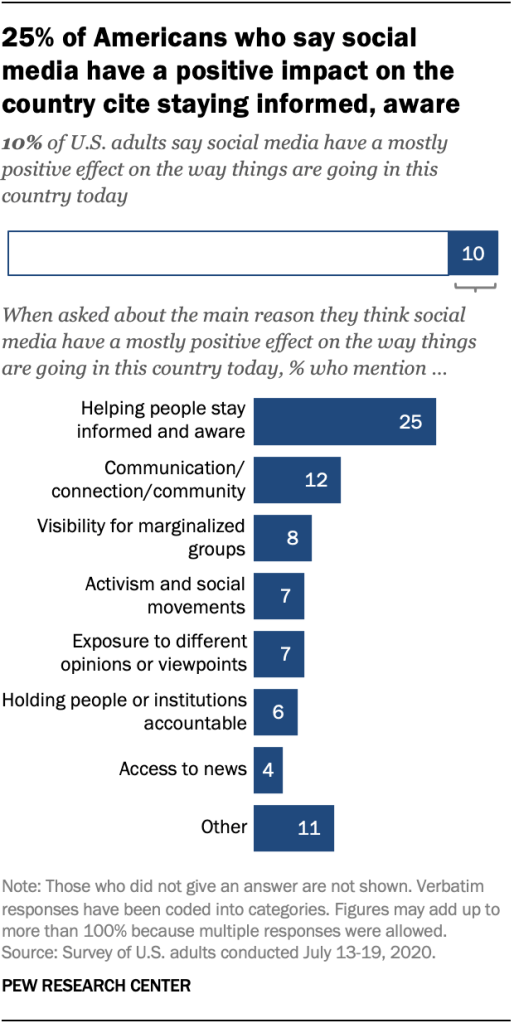

Social media has revolutionized the way information is shared and disseminated. However, the ease and speed at which data can be spread on social media also make it a powerful tool for spreading misinformation and fake news. Misinformation and fake news can seriously affect public opinion, influence political decisions, and even cause harm to individuals and communities.

The Pervasiveness of Misinformation and Fake News on Social Media

Misinformation and fake news are prevalent on social media platforms, where they can spread quickly and reach a large audience. This is partly due to the way social media algorithms work, which prioritizes content likely to generate engagement, such as sensational or controversial stories. As a result, false information can spread rapidly and be widely shared before it is fact-checked or debunked.

The Influence of Social Media on Public Opinion

Social media can significantly impact public opinion, as people are likelier to believe the information they see shared by their friends and followers. This can lead to a self-reinforcing cycle, where misinformation and fake news are spread and reinforced, even in the face of evidence to the contrary.

The Challenge of Correcting Misinformation and Fake News

Correcting misinformation and fake news on social media can be a challenging task. This is partly due to the speed at which false information can spread and the difficulty of reaching the same audience exposed to the wrong information in the first place. Additionally, some individuals may be resistant to accepting correction, primarily if the incorrect information supports their beliefs or biases.

In conclusion, the function of social media in disseminating misinformation and fake news is complex and urgent. While social media has revolutionized the sharing of information, it has also made it simpler for false information to propagate and be widely believed. Individuals must be accountable for the information they share and consume, and social media firms must take measures to prevent the spread of disinformation and fake news on their platforms.

The Effects of Social Media on Mental Health and Well-Being

Social media has become an integral part of modern life, with billions of people around the world using platforms like Facebook, Instagram, and Twitter to stay connected with others and access information. However, while social media has many benefits, it can also negatively affect mental health and well-being.

Comparison and Low Self-Esteem

One of the key ways that social media can affect mental health is by promoting feelings of comparison and low self-esteem. People often present a curated version of their lives on social media, highlighting their successes and hiding their struggles. This can lead others to compare themselves unfavorably, leading to feelings of inadequacy and low self-esteem.

Cyberbullying and Online Harassment

Another way that social media can negatively impact mental health is through cyberbullying and online harassment. Social media provides a platform for anonymous individuals to harass and abuse others, leading to feelings of anxiety, fear, and depression.

Social Isolation

Despite its name, social media can also contribute to feelings of isolation. At the same time, people may have many online friends but need more meaningful in-person connections and support. This can lead to feelings of loneliness and depression.

Addiction and Overuse

Finally, social media can be addictive, leading to overuse and negatively impacting mental health and well-being. People may spend hours each day scrolling through their feeds, neglecting other important areas of their lives, such as work, family, and self-care.

In sum, social media has positive and negative consequences on one's psychological and emotional well-being. Realizing this, and taking measures like reducing one's social media use, reaching out to loved ones for help, and prioritizing one's well-being, are crucial. In addition, it's vital that social media giants take ownership of their platforms and actively encourage excellent mental health and well-being.

The Use of Social Media in Political Activism and Social Movements

Social media has recently become increasingly crucial in political action and social movements. Platforms such as Twitter, Facebook, and Instagram have given people new ways to express themselves, organize protests, and raise awareness about social and political issues.

Raising Awareness and Mobilizing Action

One of the most important uses of social media in political activity and social movements has been to raise awareness about important issues and mobilize action. Hashtags such as #MeToo and #BlackLivesMatter, for example, have brought attention to sexual harassment and racial injustice, respectively. Similarly, social media has been used to organize protests and other political actions, allowing people to band together and express themselves on a bigger scale.

Connecting with like-minded individuals

A second method in that social media has been utilized in political activity and social movements is to unite like-minded individuals. Through social media, individuals can join online groups, share knowledge and resources, and work with others to accomplish shared objectives. This has been especially significant for geographically scattered individuals or those without access to traditional means of political organizing.

Challenges and Limitations

As a vehicle for political action and social movements, social media has faced many obstacles and restrictions despite its many advantages. For instance, the propagation of misinformation and fake news on social media can impede attempts to disseminate accurate and reliable information. In addition, social media corporations have been condemned for censorship and insufficient protection of user rights.

In conclusion, social media has emerged as a potent instrument for political activism and social movements, giving voice to previously unheard communities and galvanizing support for change. Social media presents many opportunities for communication and collaboration. Still, users and institutions must be conscious of the risks and limitations of these tools to promote their responsible and productive usage.

The Potential Privacy Concerns Raised by Social Media Use and Data Collection Practices

With billions of users each day on sites like Facebook, Twitter, and Instagram, social media has ingrained itself into every aspect of our lives. While these platforms offer a straightforward method to communicate with others and exchange information, they also raise significant concerns over data collecting and privacy. This article will examine the possible privacy issues posed by social media use and data-gathering techniques.

Data Collection and Sharing

The gathering and sharing of personal data are significant privacy issues brought up by social media use. Social networking sites gather user data, including details about their relationships, hobbies, and routines. This information is made available to third-party businesses for various uses, such as marketing and advertising. This can lead to serious concerns about who has access to and uses our personal information.

Lack of Control Over Personal Information

The absence of user control over personal information is a significant privacy issue brought up by social media usage. Social media makes it challenging to limit who has access to and how data is utilized once it has been posted. Sensitive information may end up being extensively disseminated and may be used maliciously as a result.

Personalized Marketing

Social media companies utilize the information they gather about users to target them with adverts relevant to their interests and usage patterns. Although this could be useful, it might also cause consumers to worry about their privacy since they might feel that their personal information is being used without their permission. Furthermore, there are issues with the integrity of the data being used to target users and the possibility of prejudice based on individual traits.

Government Surveillance

Using social media might spark worries about government surveillance. There are significant concerns regarding privacy and free expression when governments in some nations utilize social media platforms to follow and monitor residents.

In conclusion, social media use raises significant concerns regarding data collecting and privacy. While these platforms make it easy to interact with people and exchange information, they also gather a lot of personal information, which raises questions about who may access it and how it will be used. Users should be aware of these privacy issues and take precautions to safeguard their personal information, such as exercising caution when choosing what details to disclose on social media and keeping their information sharing with other firms to a minimum.

The Ethical and Privacy Concerns Surrounding Social Media Use And Data Collection

Our use of social media to communicate with loved ones, acquire information, and even conduct business has become a crucial part of our everyday lives. The extensive use of social media does, however, raise some ethical and privacy issues that must be resolved. The influence of social media use and data collecting on user rights, the accountability of social media businesses, and the need for improved regulation are all topics that will be covered in this article.

Effect on Individual Privacy:

Social networking sites gather tons of personal data from their users, including delicate information like search history, location data, and even health data. Each user's detailed profile may be created with this data and sold to advertising or used for other reasons. Concerns regarding the privacy of personal information might arise because social media businesses can use this data to target users with customized adverts.

Additionally, individuals might need to know how much their personal information is being gathered and exploited. Data breaches or the unauthorized sharing of personal information with other parties may result in instances where sensitive information is exposed. Users should be aware of the privacy rules of social media firms and take precautions to secure their data.

Responsibility of Social Media Companies:

Social media firms should ensure that they responsibly and ethically gather and use user information. This entails establishing strong security measures to safeguard sensitive information and ensuring users are informed of what information is being collected and how it is used.

Many social media businesses, nevertheless, have come under fire for not upholding these obligations. For instance, the Cambridge Analytica incident highlighted how Facebook users' personal information was exploited for political objectives without their knowledge. This demonstrates the necessity of social media corporations being held responsible for their deeds and ensuring that they are safeguarding the security and privacy of their users.

Better Regulation Is Needed

There is a need for tighter regulation in this field, given the effect, social media has on individual privacy as well as the obligations of social media firms. The creation of laws and regulations that ensure social media companies are gathering and using user information ethically and responsibly, as well as making sure users are aware of their rights and have the ability to control the information that is being collected about them, are all part of this.

Additionally, legislation should ensure that social media businesses are held responsible for their behavior, for example, by levying fines for data breaches or the unauthorized use of personal data. This will provide social media businesses with a significant incentive to prioritize their users' privacy and security and ensure they are upholding their obligations.

In conclusion, social media has fundamentally changed how we engage and communicate with one another, but this increased convenience also raises several ethical and privacy issues. Essential concerns that need to be addressed include the effect of social media on individual privacy, the accountability of social media businesses, and the requirement for greater regulation to safeguard user rights. We can make everyone's online experience safer and more secure by looking more closely at these issues.

In conclusion, social media is a complex and multifaceted topic that has recently captured the world's attention. With its ever-growing influence on our lives, it's no surprise that it has become a popular subject for students to explore in their writing. Whether you are writing an argumentative essay on the impact of social media on privacy, a persuasive essay on the role of social media in politics, or a descriptive essay on the changes social media has brought to the way we communicate, there are countless angles to approach this subject.

However, writing a comprehensive and well-researched essay on social media can be daunting. It requires a thorough understanding of the topic and the ability to articulate your ideas clearly and concisely. This is where Jenni.ai comes in. Our AI-powered tool is designed to help students like you save time and energy and focus on what truly matters - your education. With Jenni.ai , you'll have access to a wealth of examples and receive personalized writing suggestions and feedback.

Whether you're a student who's just starting your writing journey or looking to perfect your craft, Jenni.ai has everything you need to succeed. Our tool provides you with the necessary resources to write with confidence and clarity, no matter your experience level. You'll be able to experiment with different styles, explore new ideas , and refine your writing skills.

So why waste your time and energy struggling to write an essay on your own when you can have Jenni.ai by your side? Sign up for our free trial today and experience the difference for yourself! With Jenni.ai, you'll have the resources you need to write confidently, clearly, and creatively. Get started today and see just how easy and efficient writing can be!

Try Jenni for free today

Create your first piece of content with Jenni today and never look back

The Pros and Cons of Social Media for Youth

A new review article looks at how social media affects well-being in youth...

Posted October 16, 2021 | Reviewed by Lybi Ma

- Social media has both positive and negative effects on well-being in youth.

- Social media impacts four distinct areas for youth: connections, identity, learning, and emotions.

More than 90 percent of teenagers in the U.S. have a smartphone. Access to this type of technology and social networking changes the playing field for young people who are simultaneously developing a sense of identity and new social relationships.

We have certainly heard about the downside of teens and smartphones: cyberbullying, anxiety , and a misrepresented sense of body image . Research demonstrates there are some benefits too, including the ability to keep in touch with friends and loved ones – especially when the COVID-19 pandemic limited in-person social interactions.

A new systematic review published in the journal Adolescent Research Review combines the evidence from qualitative studies that investigate adolescent social media use.

The authors found, in short, that the links between adolescent well-being and social media are complicated and depend on a broad range of factors.

“Adults have always been concerned about how the latest technology will harm children,” said Amanda Purington, director of evaluation and research for ACT for Youth in the BCTR and a doctoral candidate in Cornell’s Social Media Lab. “This goes back to radio programs, comic books, novels – you name it, adults were worried about it. The same is now true for social media. And yes, there are concerns – there are many potential risks and harms. But there are potential benefits, too.”

Reviewing 19 studies of young people ages 11 to 20, the authors identified four major themes related to social media and well-being that ultimately affected aspects of young people’s mental health and sense of self.

The first theme, connections, describes how social media either supports or hinders young people’s relationships with their peers, friends, and family. The studies in the review provided plenty of examples of ways that social media helped youth build connections with others. Participants reported that social media helped to create intimacy with friends and could improve popularity. Youth who said they were shy reported having an easier time making friends through social media. Studies also found social media was useful in keeping in touch with family and friends who live far away and allowing groups to communicate in masse. In seven papers, participants identified social media as a source of support and reassurance.

In 13 of the papers, youth reported that social media also harmed their connections with others. They provided examples of bullying and threats and an atmosphere of criticism and negativity during social media interactions. Youth cited the anonymity of social media as part of the problem, as well as miscommunication that can occur online.

Study participants also reported a feeling of disconnection associated with relationships on social media. Some youth felt rejected or left out when their social media posts did not receive the feedback they expected. Others reported feeling frustrated, lonely , or paranoid about being left out.

The second theme, identity, describes how adolescents are supported or frustrated on social media in trying to develop their identities.

Youth in many of the studies described how social media helped them to “come out of their shells” and express their true identities. They reported liking the ability to write and edit their thoughts and use images to express themselves. They reported that feedback they received on social media helped to bolster their self-confidence and they reported enjoying the ability to look back on memories to keep track of how their identity changed over time.

In eight studies, youth described ways that social media led to inauthentic representations of themselves. They felt suspicious that others would use photo editing to disguise their identities and complained about how easy it was to deliver communications slyly, rather than with the honesty required in face-to-face communication. They also felt self-conscious about posting selfies, and reported that the feedback they received would affect their feelings of self-worth .

The third theme, learning, describes how social media use supports or hinders education . In many studies, participants reported how social media helped to broaden their perspectives and expose them to new ideas and topics. Many youths specifically cited exposure to political and social movements, such as Black Lives Matter.

On the flip side, youth in five studies reported that social media interfered with their education. They said that phone notifications and the pressure to constantly check in on social media distracted them from their studies. Participants reported that they found it difficult to spend quiet time alone without checking their phones. Others said the 24-7 nature of social media kept them up too late at night, making it difficult to get up for school the next day.

The fourth theme, emotions, describes the ways that social media impacts young people’s emotional experiences in both positive and negative ways. In 11 papers, participants reported that social media had a positive effect on their emotions. Some reported it improved their mood, helped them to feel excited, and often prompted laughter . (Think funny animal videos.) Others reported that social media helped to alleviate negative moods, including annoyance, anger , and boredom . They described logging onto social media as a form of stress management .

But in nearly all of the papers included in the review, participants said social media was a source of worry and pressure. Participants expressed concern about judgment from their peers. They often felt embarrassed about how they looked in images. Many participants expressed worry that they were addicted to social media. Others fretted about leaving a digital footprint that would affect them later in life. Many participants reported experiencing pressure to constantly respond and stay connected on social media. And a smaller number of participants reported feeling disturbed by encountering troubling content, such as self-harm and seeing former partners in new relationships.

“As this review article highlights, social media provides spaces for adolescents to work on some of the central developmental tasks of their age, such as forming deeper connections with peers and exploring identity,” Purington said. “I believe the key is to help youth maximize these benefits while minimizing risks, and we can do this by educating youth about how to use social media in ways that are positive, safe, and prosocial.”

The take-home message: The body of evidence on social media and well-being paints a complicated picture of how this new technology is affecting youth. While there are certainly benefits when young people use social media, there is also a broad range of pressures and negative consequences.

The Bronfenbrenner Center for Translational Research at Cornell University is focused on using research findings to improve health and well-being of people at all stages of life.

- Find a Therapist

- Find a Treatment Center

- Find a Psychiatrist

- Find a Support Group

- Find Online Therapy

- United States

- Brooklyn, NY

- Chicago, IL

- Houston, TX

- Los Angeles, CA

- New York, NY

- Portland, OR

- San Diego, CA

- San Francisco, CA

- Seattle, WA

- Washington, DC

- Asperger's

- Bipolar Disorder

- Chronic Pain

- Eating Disorders

- Passive Aggression

- Personality

- Goal Setting

- Positive Psychology

- Stopping Smoking

- Low Sexual Desire

- Relationships

- Child Development

- Self Tests NEW

- Therapy Center

- Diagnosis Dictionary

- Types of Therapy

At any moment, someone’s aggravating behavior or our own bad luck can set us off on an emotional spiral that threatens to derail our entire day. Here’s how we can face our triggers with less reactivity so that we can get on with our lives.

- Emotional Intelligence

- Gaslighting

- Affective Forecasting

- Neuroscience

The Ups and Downs of Social Media

- Posted May 16, 2018

- By Leah Shafer

Watch teenagers using social media, and you witness an emotional rollercoaster: they are intermittently ecstatic, furious, envious, heartbroken, charmed, anxious, obsessive, and bored.

Research has begun to zero in on nearly every part of this spectrum, with findings that run from alarming (screen time is linked to depression and suicide ) to reassuring (many teens find social media empowering ). B ut for those looking for a clear-cut "good or bad" verdict on social media, the reality is that it's a little of each — but generally a much more positive experience than many parents might think.

A new study finds that teenagers report feeling all kinds of positive and negative emotions when describing the same social media experiences — posting selfies, Snapchatting, browsing videos — but the majority rate their overall experiences as positive.

Understanding these nuances can help families better grasp their teens’ up-and-down experiences in the digital world, the study suggests, offering new insight on how best to support them.

A Study on Adolescent Social Media Use

In the study, adolescent social media expert Emily Weinstein analyzed surveyed responses from 568 high school students at a suburban public high school in the United States. The students, who were evenly split between female and male, were heavier users of social media than the average American teen: 98 percent said that they were online “almost constantly” or “several times a day,” compared to 80 percent of teens nationally. Eighty-seven percent of these students used Instagram, 87 percent used Snapchat, and 76 percent used Facebook.

Teens felt empowered and excited when they shared important aspects of their identities with others. But they also worried about being judged by peers and expressed anxiety over not getting enough likes.

The surveys asked students to check off any of 11 listed emotions that they typically felt while using social media, as well as the emotions they believed their peers felt while using those apps.

Weinstein also analyzed data from 26 in-depth interviews with those surveyed (16 females and 10 males). These students walked the researchers through their experiences on Instagram and Snapchat, describing the content they saw and how they reacted to it.

A Spectrum of Positive and Negative Feelings — with Positive Prevailing

The study found that teens had four main ways of using social media — and although they acknowledged negative emotions from each, most described their experiences as generally positive.

Teenagers use social media:

- for self-expression (sharing posts that portray who you are and what you care about);

- for relational interactions (messaging and connecting with family, friends, and romantic interests);

- for exploration (searching areas of interest); and

- for browsing (general scrolling through feeds and apps).

None of these modes of social media use resulted in purely negative emotions, as reported by teens. Each led to both positive and negative emotions.

- In self-expression mode, teens felt empowered and excited when they shared important aspects of their identities with others, and they enjoyed looking back at their personal Instagram feeds to reflect on how they’d developed over time. But they also worried about being judged by peers and expressed anxiety over not getting enough likes.

- For relational interactions, teens felt happy to stay connected with peers, and many actually strengthened offline relationships with friends and significant others through social media. They enjoyed keeping in touch with faraway family members, too. But they also felt overwhelmed by the number of messages they had to respond to, and many felt left out when they saw friends posting together without them.

- When exploring, teens enjoyed learning more about their interests, such as cooking or sports, or exploring new passions, such as activism or gun control. But they also reported viewing distressing and graphic images and stories.

- When browsing, teens often felt amused and inspired by the different photos and videos they came across. But they also saw things that made them envious, insecure, or sad: a peer with thousands of followers, a deluge of images of attractive people, or even posts expressing appreciation for a parent or sibling, if they personally didn’t have that type of familial relationship.

Despite this variety of emotions, most teens described their experiences in mainly positive terms , found Weinstein, who is a postdoctoral fellow at the Harvard Graduate School of Education . Seventy-two percent of the teens reported feeling happy on social media, 68.5 percent amused, 59.3 percent closer to friends, and 57.8 percent interested in the experience. Only 6.7 percent reported feeling upset, 7.9 percent irritated, 10.2 percent anxious, 16.9 percent jealous, and 15.3 percent left out. And 70 percent of the teens described their general experiences on social media using only the positive descriptors.

Just cutting teens off from social media entirely may not be the best solution, since that will likely cut them off from positive experiences as well.

For Families, Helping Teens Ride the Rollercoaster

- As parents grapple with their own anxiety over teens’ smartphone use, they should keep in mind that many teens are having routinely positive experiences on social media. Yes, teens are aware of negative emotions — fear, distress, jealousy, but from their perspective, feelings of connection, amusement, and inspiration also abound.

- Families also need to remember that many of these negative feelings are developmentally normal . “Self-disclosure, validation, and concerns about acceptance and belonging are core components of adolescent development and friendship that predate and are present in youths’ digital interactions,” writes Weinstein. And teens’ online experiences often mirror their offline strengths and struggles , so insecurity or anxiety may not stem solely from social media use.

- Parents should take teens’ negative experiences seriously , especially if their mood or behavior has changed, or if these negative feelings are affecting daily activities. But cutting them off from social media entirely may not be the best solution, since that will likely cut them off from positive experiences as well.

- At all points, families should talk to their teens about their experiences on social media. Figure out together what exactly they enjoy, and what challenges they are facing. Oftentimes, parents and teens can come up with tailored solutions to unique challenges — unfollowing a certain account that contributes to a negative body image, or refraining from posting on a certain app that leads to anxiety, for example — that still allow teens to hold onto what they enjoy.

The Rise of Smartphones

Listen to a conversation with pyschologist Jean Twenge about smart smartphone use — how smartphones have transformed teens' lives, and how teens who limit their phone use to two hours a day have the highest levels of wellbeing,

Usable Knowledge

Connecting education research to practice — with timely insights for educators, families, and communities

Related Articles

Askwith Education Forum Highlights Teen Well-Being in a Tech-Filled World

U.S. Surgeon General Vivek Murthy detailed the struggle many adolescents have with social media and what can be done to help

Teens in a Digital World

Strengthening Teen Digital Well-Being

Tips for talking with teens about social media and thinking traps

Social media use can be positive for mental health and well-being

January 6, 2020— Mesfin Awoke Bekalu , research scientist in the Lee Kum Sheung Center for Health and Happiness at Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health, discusses a new study he co-authored on associations between social media use and mental health and well-being.

What is healthy vs. potentially problematic social media use?

Our study has brought preliminary evidence to answer this question. Using a nationally representative sample, we assessed the association of two dimensions of social media use—how much it’s routinely used and how emotionally connected users are to the platforms—with three health-related outcomes: social well-being, positive mental health, and self-rated health.

We found that routine social media use—for example, using social media as part of everyday routine and responding to content that others share—is positively associated with all three health outcomes. Emotional connection to social media—for example, checking apps excessively out of fear of missing out, being disappointed about or feeling disconnected from friends when not logged into social media—is negatively associated with all three outcomes.

In more general terms, these findings suggest that as long as we are mindful users, routine use may not in itself be a problem. Indeed, it could be beneficial.

For those with unhealthy social media use, behavioral interventions may help. For example, programs that develop “effortful control” skills—the ability to self-regulate behavior—have been widely shown to be useful in dealing with problematic Internet and social media use.

We’re used to hearing that social media use is harmful to mental health and well-being, particularly for young people. Did it surprise you to find that it can have positive effects?

The findings go against what some might expect, which is intriguing. We know that having a strong social network is associated with positive mental health and well-being. Routine social media use may compensate for diminishing face-to-face social interactions in people’s busy lives. Social media may provide individuals with a platform that overcomes barriers of distance and time, allowing them to connect and reconnect with others and thereby expand and strengthen their in-person networks and interactions. Indeed, there is some empirical evidence supporting this.

On the other hand, a growing body of research has demonstrated that social media use is negatively associated with mental health and well-being, particularly among young people—for example, it may contribute to increased risk of depression and anxiety symptoms.

Our findings suggest that the ways that people are using social media may have more of an impact on their mental health and well-being than just the frequency and duration of their use.

What disparities did you find in the ways that social media use benefits and harms certain populations? What concerns does this raise?

My co-authors Rachel McCloud , Vish Viswanath , and I found that the benefits and harms associated with social media use varied across demographic, socioeconomic, and racial population sub-groups. Specifically, while the benefits were generally associated with younger age, better education, and being white, the harms were associated with older age, less education, and being a racial minority. Indeed, these findings are consistent with the body of work on communication inequalities and health disparities that our lab, the Viswanath lab , has documented over the past 15 or so years. We know that education, income, race, and ethnicity influence people’s access to, and ability to act on, health information from media, including the Internet. The concern is that social media may perpetuate those differences.

— Amy Roeder

- Open access

- Published: 06 July 2023

Pros & cons: impacts of social media on mental health

- Ágnes Zsila 1 , 2 &

- Marc Eric S. Reyes ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-5280-1315 3

BMC Psychology volume 11 , Article number: 201 ( 2023 ) Cite this article

452k Accesses

16 Citations

107 Altmetric

Metrics details

The use of social media significantly impacts mental health. It can enhance connection, increase self-esteem, and improve a sense of belonging. But it can also lead to tremendous stress, pressure to compare oneself to others, and increased sadness and isolation. Mindful use is essential to social media consumption.

Social media has become integral to our daily routines: we interact with family members and friends, accept invitations to public events, and join online communities to meet people who share similar preferences using these platforms. Social media has opened a new avenue for social experiences since the early 2000s, extending the possibilities for communication. According to recent research [ 1 ], people spend 2.3 h daily on social media. YouTube, TikTok, Instagram, and Snapchat have become increasingly popular among youth in 2022, and one-third think they spend too much time on these platforms [ 2 ]. The considerable time people spend on social media worldwide has directed researchers’ attention toward the potential benefits and risks. Research shows excessive use is mainly associated with lower psychological well-being [ 3 ]. However, findings also suggest that the quality rather than the quantity of social media use can determine whether the experience will enhance or deteriorate the user’s mental health [ 4 ]. In this collection, we will explore the impact of social media use on mental health by providing comprehensive research perspectives on positive and negative effects.

Social media can provide opportunities to enhance the mental health of users by facilitating social connections and peer support [ 5 ]. Indeed, online communities can provide a space for discussions regarding health conditions, adverse life events, or everyday challenges, which may decrease the sense of stigmatization and increase belongingness and perceived emotional support. Mutual friendships, rewarding social interactions, and humor on social media also reduced stress during the COVID-19 pandemic [ 4 ].

On the other hand, several studies have pointed out the potentially detrimental effects of social media use on mental health. Concerns have been raised that social media may lead to body image dissatisfaction [ 6 ], increase the risk of addiction and cyberbullying involvement [ 5 ], contribute to phubbing behaviors [ 7 ], and negatively affects mood [ 8 ]. Excessive use has increased loneliness, fear of missing out, and decreased subjective well-being and life satisfaction [ 8 ]. Users at risk of social media addiction often report depressive symptoms and lower self-esteem [ 9 ].

Overall, findings regarding the impact of social media on mental health pointed out some essential resources for psychological well-being through rewarding online social interactions. However, there is a need to raise awareness about the possible risks associated with excessive use, which can negatively affect mental health and everyday functioning [ 9 ]. There is neither a negative nor positive consensus regarding the effects of social media on people. However, by teaching people social media literacy, we can maximize their chances of having balanced, safe, and meaningful experiences on these platforms [ 10 ].

We encourage researchers to submit their research articles and contribute to a more differentiated overview of the impact of social media on mental health. BMC Psychology welcomes submissions to its new collection, which promises to present the latest findings in the emerging field of social media research. We seek research papers using qualitative and quantitative methods, focusing on social media users’ positive and negative aspects. We believe this collection will provide a more comprehensive picture of social media’s positive and negative effects on users’ mental health.

Data Availability

Not applicable.

Statista. (2022). Time spent on social media [Chart]. Accessed June 14, 2023, from https://www.statista.com/chart/18983/time-spent-on-social-media/ .

Pew Research Center. (2023). Teens and social media: Key findings from Pew Research Center surveys. Retrieved June 14, 2023, from https://www.pewresearch.org/short-reads/2023/04/24/teens-and-social-media-key-findings-from-pew-research-center-surveys/ .

Boer, M., Van Den Eijnden, R. J., Boniel-Nissim, M., Wong, S. L., Inchley, J. C.,Badura, P.,… Stevens, G. W. (2020). Adolescents’ intense and problematic social media use and their well-being in 29 countries. Journal of Adolescent Health , 66(6), S89-S99. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jadohealth.2020.02.011.

Marciano L, Ostroumova M, Schulz PJ, Camerini AL. Digital media use and adolescents’ mental health during the COVID-19 pandemic: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Front Public Health. 2022;9:2208. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2021.641831 .

Article Google Scholar

Naslund JA, Bondre A, Torous J, Aschbrenner KA. Social media and mental health: benefits, risks, and opportunities for research and practice. J Technol Behav Sci. 2020;5:245–57. https://doi.org/10.1007/s41347-020-00094-8 .

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Harriger JA, Thompson JK, Tiggemann M. TikTok, TikTok, the time is now: future directions in social media and body image. Body Image. 2023;44:222–6. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bodyim.2021.12.005 .

Article PubMed Google Scholar

Chi LC, Tang TC, Tang E. The phubbing phenomenon: a cross-sectional study on the relationships among social media addiction, fear of missing out, personality traits, and phubbing behavior. Curr Psychol. 2022;41(2):1112–23. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-022-0135-4 .

Valkenburg PM. Social media use and well-being: what we know and what we need to know. Curr Opin Psychol. 2022;45:101294. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.copsyc.2020.101294 .

Bányai F, Zsila Á, Király O, Maraz A, Elekes Z, Griffiths MD, Urbán R, Farkas J, Rigó P Jr, Demetrovics Z. Problematic social media use: results from a large-scale nationally representative adolescent sample. PLoS ONE. 2017;12(1):e0169839. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0169839 .

American Psychological Association. (2023). APA panel issues recommendations for adolescent social media use. Retrieved from https://apa-panel-issues-recommendations-for-adolescent-social-media-use-774560.html .

Download references

Acknowledgements

Ágnes Zsila was supported by the ÚNKP-22-4 New National Excellence Program of the Ministry for Culture and Innovation from the source of the National Research, Development and Innovation Fund.

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Institute of Psychology, Pázmány Péter Catholic University, Budapest, Hungary

Ágnes Zsila

Institute of Psychology, ELTE Eötvös Loránd University, Budapest, Hungary

Department of Psychology, College of Science, University of Santo Tomas, Manila, 1008, Philippines

Marc Eric S. Reyes

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Contributions

AZ conceived and drafted the Editorial. MESR wrote the abstract and revised the Editorial. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Marc Eric S. Reyes .

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate, consent for publication, competing interests.

The authors have no competing interests to declare relevant to the content of this article.

Additional information

Publisher’s note.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ . The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver ( http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/ ) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article.

Zsila, Á., Reyes, M.E.S. Pros & cons: impacts of social media on mental health. BMC Psychol 11 , 201 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1186/s40359-023-01243-x

Download citation

Received : 15 June 2023

Accepted : 03 July 2023

Published : 06 July 2023

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1186/s40359-023-01243-x

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Social media

- Mental health

BMC Psychology

ISSN: 2050-7283

- General enquiries: [email protected]

Home — Essay Samples — Sociology — Social Media — Social Media Impact On Society

Social Media Impact on Society

- Categories: Social Media

About this sample

Words: 614 |

Published: Mar 13, 2024

Words: 614 | Page: 1 | 4 min read

Cite this Essay

Let us write you an essay from scratch

- 450+ experts on 30 subjects ready to help

- Custom essay delivered in as few as 3 hours

Get high-quality help

Verified writer

- Expert in: Sociology

+ 120 experts online

By clicking “Check Writers’ Offers”, you agree to our terms of service and privacy policy . We’ll occasionally send you promo and account related email

No need to pay just yet!

Related Essays

6 pages / 2525 words

3 pages / 1329 words

1 pages / 563 words

2 pages / 689 words

Remember! This is just a sample.

You can get your custom paper by one of our expert writers.

121 writers online

Still can’t find what you need?

Browse our vast selection of original essay samples, each expertly formatted and styled

Related Essays on Social Media

Abel, J. P., Buff, C. L., & Burr, S. A. (2016). Social Media and the Fear of Missing Out: Scale Development and Assessment. Journal of Business & Economics Research (JBER), 14(1), 33-44. [...]

“God and Gloria THANK YOU SO MUCH for giving me life! I promise I’ll continue to make the both of you proud of me!”, a simple message Lebron James conducts to his twitter feed that carries a deeper meaning. Lebron is [...]

Primack, B. A. (n.d.). Social Media Use and Perceived Social Isolation Among Young Adults in the U.S. Emotion, 17(6), 1026–1032. DOI: 10.1037/emo0000525Hobson, K. (n.d.). The Social Media Paradox: Are We Really More Connected? [...]

The advancements of technology have brought upon many positive and negative effects on society. The most recent technology provides easier access to our everyday needs such as the way we purchase products and the way we [...]

In the era of science and technology, it would be quite unusual to find anyone who does not have a social media account. Based on a research carried out by the Pew Research Center in 2013, forty-two percent of the internet users [...]

In the previous times, 10 years ago from now people use social media only to connect with the friends and families and to chat with them. But todays young generation they use social media in a very effective manner. They can be [...]

Related Topics

By clicking “Send”, you agree to our Terms of service and Privacy statement . We will occasionally send you account related emails.

Where do you want us to send this sample?

By clicking “Continue”, you agree to our terms of service and privacy policy.

Be careful. This essay is not unique

This essay was donated by a student and is likely to have been used and submitted before

Download this Sample

Free samples may contain mistakes and not unique parts

Sorry, we could not paraphrase this essay. Our professional writers can rewrite it and get you a unique paper.

Please check your inbox.

We can write you a custom essay that will follow your exact instructions and meet the deadlines. Let's fix your grades together!

Get Your Personalized Essay in 3 Hours or Less!

We use cookies to personalyze your web-site experience. By continuing we’ll assume you board with our cookie policy .

- Instructions Followed To The Letter

- Deadlines Met At Every Stage

- Unique And Plagiarism Free

- Search Menu

- Sign in through your institution

- Browse content in Arts and Humanities

- Browse content in Archaeology

- Anglo-Saxon and Medieval Archaeology

- Archaeological Methodology and Techniques

- Archaeology by Region

- Archaeology of Religion

- Archaeology of Trade and Exchange

- Biblical Archaeology

- Contemporary and Public Archaeology

- Environmental Archaeology

- Historical Archaeology

- History and Theory of Archaeology

- Industrial Archaeology

- Landscape Archaeology

- Mortuary Archaeology

- Prehistoric Archaeology

- Underwater Archaeology

- Zooarchaeology

- Browse content in Architecture

- Architectural Structure and Design

- History of Architecture

- Residential and Domestic Buildings

- Theory of Architecture

- Browse content in Art

- Art Subjects and Themes

- History of Art

- Industrial and Commercial Art

- Theory of Art

- Biographical Studies

- Byzantine Studies

- Browse content in Classical Studies

- Classical History

- Classical Philosophy

- Classical Mythology

- Classical Literature

- Classical Reception

- Classical Art and Architecture

- Classical Oratory and Rhetoric

- Greek and Roman Papyrology

- Greek and Roman Epigraphy

- Greek and Roman Law

- Greek and Roman Archaeology

- Late Antiquity

- Religion in the Ancient World

- Digital Humanities

- Browse content in History

- Colonialism and Imperialism

- Diplomatic History

- Environmental History

- Genealogy, Heraldry, Names, and Honours

- Genocide and Ethnic Cleansing

- Historical Geography

- History by Period

- History of Emotions

- History of Agriculture

- History of Education

- History of Gender and Sexuality

- Industrial History

- Intellectual History

- International History

- Labour History

- Legal and Constitutional History

- Local and Family History

- Maritime History

- Military History

- National Liberation and Post-Colonialism

- Oral History

- Political History

- Public History

- Regional and National History

- Revolutions and Rebellions

- Slavery and Abolition of Slavery

- Social and Cultural History

- Theory, Methods, and Historiography

- Urban History

- World History

- Browse content in Language Teaching and Learning

- Language Learning (Specific Skills)

- Language Teaching Theory and Methods

- Browse content in Linguistics

- Applied Linguistics

- Cognitive Linguistics

- Computational Linguistics

- Forensic Linguistics

- Grammar, Syntax and Morphology

- Historical and Diachronic Linguistics

- History of English

- Language Evolution

- Language Reference

- Language Acquisition

- Language Variation

- Language Families

- Lexicography

- Linguistic Anthropology

- Linguistic Theories

- Linguistic Typology

- Phonetics and Phonology

- Psycholinguistics

- Sociolinguistics

- Translation and Interpretation

- Writing Systems

- Browse content in Literature

- Bibliography

- Children's Literature Studies

- Literary Studies (Romanticism)

- Literary Studies (American)

- Literary Studies (Asian)

- Literary Studies (European)

- Literary Studies (Eco-criticism)

- Literary Studies (Modernism)

- Literary Studies - World

- Literary Studies (1500 to 1800)

- Literary Studies (19th Century)

- Literary Studies (20th Century onwards)

- Literary Studies (African American Literature)

- Literary Studies (British and Irish)

- Literary Studies (Early and Medieval)

- Literary Studies (Fiction, Novelists, and Prose Writers)

- Literary Studies (Gender Studies)

- Literary Studies (Graphic Novels)

- Literary Studies (History of the Book)

- Literary Studies (Plays and Playwrights)

- Literary Studies (Poetry and Poets)

- Literary Studies (Postcolonial Literature)

- Literary Studies (Queer Studies)

- Literary Studies (Science Fiction)

- Literary Studies (Travel Literature)

- Literary Studies (War Literature)

- Literary Studies (Women's Writing)

- Literary Theory and Cultural Studies

- Mythology and Folklore

- Shakespeare Studies and Criticism

- Browse content in Media Studies

- Browse content in Music

- Applied Music

- Dance and Music

- Ethics in Music

- Ethnomusicology

- Gender and Sexuality in Music

- Medicine and Music

- Music Cultures

- Music and Media

- Music and Religion

- Music and Culture

- Music Education and Pedagogy

- Music Theory and Analysis

- Musical Scores, Lyrics, and Libretti

- Musical Structures, Styles, and Techniques

- Musicology and Music History

- Performance Practice and Studies

- Race and Ethnicity in Music

- Sound Studies

- Browse content in Performing Arts

- Browse content in Philosophy

- Aesthetics and Philosophy of Art

- Epistemology

- Feminist Philosophy

- History of Western Philosophy

- Metaphysics

- Moral Philosophy

- Non-Western Philosophy

- Philosophy of Language

- Philosophy of Mind

- Philosophy of Perception

- Philosophy of Science

- Philosophy of Action

- Philosophy of Law

- Philosophy of Religion

- Philosophy of Mathematics and Logic

- Practical Ethics

- Social and Political Philosophy

- Browse content in Religion

- Biblical Studies

- Christianity

- East Asian Religions

- History of Religion

- Judaism and Jewish Studies

- Qumran Studies

- Religion and Education

- Religion and Health

- Religion and Politics

- Religion and Science

- Religion and Law

- Religion and Art, Literature, and Music

- Religious Studies

- Browse content in Society and Culture

- Cookery, Food, and Drink

- Cultural Studies

- Customs and Traditions

- Ethical Issues and Debates

- Hobbies, Games, Arts and Crafts

- Natural world, Country Life, and Pets

- Popular Beliefs and Controversial Knowledge

- Sports and Outdoor Recreation

- Technology and Society

- Travel and Holiday

- Visual Culture

- Browse content in Law

- Arbitration

- Browse content in Company and Commercial Law

- Commercial Law

- Company Law

- Browse content in Comparative Law

- Systems of Law

- Competition Law

- Browse content in Constitutional and Administrative Law

- Government Powers

- Judicial Review

- Local Government Law

- Military and Defence Law

- Parliamentary and Legislative Practice

- Construction Law

- Contract Law

- Browse content in Criminal Law

- Criminal Procedure

- Criminal Evidence Law

- Sentencing and Punishment

- Employment and Labour Law

- Environment and Energy Law

- Browse content in Financial Law

- Banking Law

- Insolvency Law

- History of Law

- Human Rights and Immigration

- Intellectual Property Law

- Browse content in International Law

- Private International Law and Conflict of Laws

- Public International Law

- IT and Communications Law

- Jurisprudence and Philosophy of Law

- Law and Politics

- Law and Society

- Browse content in Legal System and Practice

- Courts and Procedure

- Legal Skills and Practice

- Primary Sources of Law

- Regulation of Legal Profession

- Medical and Healthcare Law

- Browse content in Policing

- Criminal Investigation and Detection

- Police and Security Services

- Police Procedure and Law

- Police Regional Planning

- Browse content in Property Law

- Personal Property Law

- Study and Revision

- Terrorism and National Security Law

- Browse content in Trusts Law

- Wills and Probate or Succession

- Browse content in Medicine and Health

- Browse content in Allied Health Professions

- Arts Therapies

- Clinical Science

- Dietetics and Nutrition

- Occupational Therapy

- Operating Department Practice

- Physiotherapy

- Radiography

- Speech and Language Therapy

- Browse content in Anaesthetics

- General Anaesthesia

- Neuroanaesthesia

- Clinical Neuroscience

- Browse content in Clinical Medicine

- Acute Medicine

- Cardiovascular Medicine

- Clinical Genetics

- Clinical Pharmacology and Therapeutics

- Dermatology

- Endocrinology and Diabetes

- Gastroenterology

- Genito-urinary Medicine

- Geriatric Medicine

- Infectious Diseases

- Medical Toxicology

- Medical Oncology

- Pain Medicine

- Palliative Medicine

- Rehabilitation Medicine

- Respiratory Medicine and Pulmonology

- Rheumatology

- Sleep Medicine

- Sports and Exercise Medicine

- Community Medical Services

- Critical Care

- Emergency Medicine

- Forensic Medicine

- Haematology

- History of Medicine

- Browse content in Medical Skills

- Clinical Skills

- Communication Skills

- Nursing Skills

- Surgical Skills

- Browse content in Medical Dentistry

- Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery

- Paediatric Dentistry

- Restorative Dentistry and Orthodontics

- Surgical Dentistry

- Medical Ethics

- Medical Statistics and Methodology

- Browse content in Neurology

- Clinical Neurophysiology

- Neuropathology

- Nursing Studies

- Browse content in Obstetrics and Gynaecology

- Gynaecology

- Occupational Medicine

- Ophthalmology

- Otolaryngology (ENT)

- Browse content in Paediatrics

- Neonatology

- Browse content in Pathology

- Chemical Pathology

- Clinical Cytogenetics and Molecular Genetics

- Histopathology

- Medical Microbiology and Virology

- Patient Education and Information

- Browse content in Pharmacology

- Psychopharmacology

- Browse content in Popular Health

- Caring for Others

- Complementary and Alternative Medicine

- Self-help and Personal Development

- Browse content in Preclinical Medicine

- Cell Biology

- Molecular Biology and Genetics

- Reproduction, Growth and Development

- Primary Care

- Professional Development in Medicine

- Browse content in Psychiatry

- Addiction Medicine

- Child and Adolescent Psychiatry

- Forensic Psychiatry

- Learning Disabilities

- Old Age Psychiatry

- Psychotherapy

- Browse content in Public Health and Epidemiology

- Epidemiology

- Public Health

- Browse content in Radiology

- Clinical Radiology

- Interventional Radiology

- Nuclear Medicine

- Radiation Oncology

- Reproductive Medicine

- Browse content in Surgery

- Cardiothoracic Surgery

- Gastro-intestinal and Colorectal Surgery

- General Surgery

- Neurosurgery

- Paediatric Surgery

- Peri-operative Care

- Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery

- Surgical Oncology

- Transplant Surgery

- Trauma and Orthopaedic Surgery

- Vascular Surgery

- Browse content in Science and Mathematics

- Browse content in Biological Sciences

- Aquatic Biology

- Biochemistry

- Bioinformatics and Computational Biology

- Developmental Biology

- Ecology and Conservation

- Evolutionary Biology

- Genetics and Genomics

- Microbiology

- Molecular and Cell Biology

- Natural History

- Plant Sciences and Forestry

- Research Methods in Life Sciences

- Structural Biology

- Systems Biology

- Zoology and Animal Sciences

- Browse content in Chemistry

- Analytical Chemistry

- Computational Chemistry

- Crystallography

- Environmental Chemistry

- Industrial Chemistry

- Inorganic Chemistry

- Materials Chemistry

- Medicinal Chemistry

- Mineralogy and Gems

- Organic Chemistry

- Physical Chemistry

- Polymer Chemistry

- Study and Communication Skills in Chemistry

- Theoretical Chemistry

- Browse content in Computer Science

- Artificial Intelligence