Thank you for visiting nature.com. You are using a browser version with limited support for CSS. To obtain the best experience, we recommend you use a more up to date browser (or turn off compatibility mode in Internet Explorer). In the meantime, to ensure continued support, we are displaying the site without styles and JavaScript.

- View all journals

- Explore content

- About the journal

- Publish with us

- Sign up for alerts

- Open access

- Published: 04 June 2024

Research on the influencing factors of adult learners' intent to use online education platforms based on expectation confirmation theory

- Guoqiang Pan ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0003-1355-2077 1 ,

- Yu Mao ORCID: orcid.org/0009-0002-6508-5458 2 ,

- Ziyuan Song ORCID: orcid.org/0009-0004-7904-8871 3 &

- Hui Nie ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-4529-5397 4

Scientific Reports volume 14 , Article number: 12762 ( 2024 ) Cite this article

357 Accesses

1 Altmetric

Metrics details

- Human behaviour

This study addresses the understanding gap concerning the factors that influence the continuous learning intention of adult learners on online education platforms. The uniqueness and significance of this study stem from its dual focus on both platform features, such as service quality, and course features, including perceived interactivity and added value, aspects often overlooked in previous research. Rooted in Expectation Confirmation Theory, the study constructs a comprehensive model to shed light on the complex interplay of these factors. Empirical evidence collected from a survey of 1592 adult learners robustly validates the effectiveness of this model. The findings of the study reveal that platform service quality, perceived interactivity, and perceived added value significantly amplify adult learners' expectation confirmation and perceived usefulness. These elements subsequently enhance learner satisfaction, fostering their ongoing intention to use online education platforms. These insights offer practical guidance for online education providers, emphasizing the necessity to enhance platform service quality and course features to meet adult learners' expectations and perceived usefulness. The study provides valuable perspectives for devising strategies to boost user satisfaction and stimulate continuous usage intention among adult learners in the intensely competitive online education market. This study enriches the literature by uncovering the relationships among platform features, course features, expectation confirmation, perceived usefulness, and continuous usage intention. By proposing a comprehensive model, this study provides a novel theoretical basis for understanding how platform and course features impact adult learners' ongoing intention to use online education platforms, thereby aiding the evolution and refinement of relevant theories.

Similar content being viewed by others

Hybrid working from home improves retention without damaging performance

Misunderstanding the harms of online misinformation

An overview of clinical decision support systems: benefits, risks, and strategies for success

Introduction.

In the beginning, adult higher education primarily relied on face-to-face instruction, utilizing weekends and evenings for classes. However, frequent issues arising from the pandemic, pronounced contradictions in adult learning, and uneven distribution of time and energy led to subpar teaching quality and low efficiency 1 , 2 . Consequently, the introduction of online education platforms for blended learning became necessary.

Adult learners exhibit a range of learning goals and motivations 3 while concurrently grappling with the constraints of time and space 4 , 5 . These variables significantly impact their inclination towards utilizing online education platforms. Unlike traditional students, adult learners often have a wider spectrum of learning objectives 6 , encompassing facets such as career progression, personal interests, and lifelong learning 7 , 8 , 9 . They also demonstrate stronger learning motivation and autonomy, underscoring the importance of personalized learning experiences and resources 10 . The learning outcomes for adult learners on online education platforms are influenced by factors such as course design, the richness of learning resources, and the selection of learning paths 11 , 12 .

For online education platforms, the associated costs of retaining existing users generally surpass those of acquiring new ones 13 . Since online education platforms function as a type of information system, researchers typically probe user behavior within these systems using technology acceptance models and expectancy confirmation models. When investigating users' continued usage intentions, most scholars extend these models based on the expectancy confirmation model. However, the front-end influencing factors for the key variables of expectancy confirmation and perceived usefulness have not been extensively studied. Currently, the factors influencing perceived usefulness are mainly examined from viewpoints such as perceived ease of use, content-driven factors, social influence, subjective norms, and autonomy 14 , 15 , 16 , 17 , 18 . Meanwhile, the factors affecting expectancy confirmation are explored from perspectives such as perceived playfulness, information quality, and service quality 19 , 20 , 21 . Nonetheless, there is a dearth of comprehensive investigation into the influencing factors of perceived usefulness and expectancy confirmation from the broad perspective of online education platform constituents, namely considering technological platform features and online course features. This gap in systematic analysis impedes the ability of online education platforms to adopt effective service improvement measures aligned with their unique characteristics.

In light of the distinct attributes of adult learners participating in online education, this research conducts a systematic review and a thorough consolidation of the determinants impacting perceived usefulness and expectation confirmation 8 . This is done from the standpoint of both technological platform characteristics and the attributes of online courses 9 . By adopting such a comprehensive approach, we can more effectively aid online education platforms in identifying and implementing service improvement measures that resonate with their unique traits.

This study concentrates on online education platforms and adult learners, examining the potential influence of platform features (such as platform service quality) and course attributes (like perceived interactivity and the perceived added value of the course) on adult learners' perceived usefulness and expectation confirmation when engaging with online education platforms. Furthermore, this study delves into the effects of these factors on adult learners' satisfaction and their continued intention to use these platforms.

In the context of online education platforms, the diverse learning objectives and motivations of adult learners 2 , coupled with the constraints they encounter in terms of time and space 5 , play a crucial role. These elements shape their willingness to engage with online education platforms. In contrast to traditional students, adult learners may have a broader range of learning goals, encompassing career advancement, personal interests, and lifelong learning 12 . They exhibit a heightened sense of learning motivation and autonomy, placing a premium on personalized learning experiences and resources 9 . Furthermore, online education platforms can impact the learning outcomes of adult learners through factors such as course design, the abundance of learning resources, and the selection of learning paths 8 , 22 . Consequently, our research will concentrate on how these factors affect the learning outcomes of adult learners on online education platforms, aiding us in better comprehending and catering to their learning requirements.

Theoretical foundation and research hypotheses

Expectation confirmation theory.

In 1980, Oliver introduced the Expectancy Disconfirmation Theory (EDT). This theory posits that users, prior to purchasing a product or service, hold certain expectations. After the actual use of the product or service, users perceive the performance differential between their expectations and the realized experience, termed as expectancy disconfirmation 23 .

The Expectancy Confirmation Theory (ECT) has evolved from the Expectancy Disconfirmation Theory (EDT) and serves as a crucial foundation for studying user continuance. Patterson et al. were among the pioneers to apply the Expectancy Confirmation Theory in the field of information systems 24 . Bhattacherjee proposed the Expectation Confirmation Model (ECM-ISC), which incorporates four main variables: expectation confirmation, perceived usefulness, satisfaction, and continuance intention 25 . Following the introduction of the Expectation Confirmation Model, studies by Larsen on mobile commerce 26 , Tang and others on blogs 27 , Doong on knowledge sharing 28 , and Kim on mobile data services 29 have all affirmed the effectiveness of the Expectation Confirmation Model.

Research hypotheses

In the online education environment for adult learners, platform features refer to the key factors influencing satisfaction and exert a significant impact on adult learners' continued usage intentions. Among these features, platform service quality is crucial and measures the effectiveness and promptness of services provided by service providers. Bhattacherjee defines expectancy confirmation as the degree to which information system users confirm their expectations before and after using the system, where lower expectations and higher actual experiences enhance expectancy confirmation 25 . Researchers such as Dahan et al. have validated through data the positive impact of service quality on expectancy confirmation and satisfaction 30 . Delone et al. through the Information Success Model they constructed, identified service quality as a critical factor influencing satisfaction and usefulness 31 . Moreover, existing research has confirmed the significant influence of service quality on perceived usefulness and expectancy confirmation 27 , 32 , 33 .

Adult learners in online education place a greater emphasis on personalized learning experiences and resources, making the service quality of the platform crucial to their actual learning experiences 13 , 34 . Based on this, we hypothesize that the higher the platform's service quality, the better the actual learning experience for adult learners. Based on this, the following research hypotheses are proposed:

H1: Platform service quality positively influences the expectancy confirmation of adult learners.

H2: Platform service quality positively influences the perceived usefulness of adult learners.

In online education platforms, in addition to platform features, course characteristics are considered the most crucial factors for adult learners' attention 35 . This study measures course features through perceived interactivity and perceived added value. The more satisfied adult learners are with course features, the stronger their intention to continue using the platform. In traditional educational settings, interactions with teachers and peers positively influence students, and similar positive effects are expected in online education. Emphasizing platform interactivity facilitates communication among adult learners, timely issue resolution, and enhances their expectations 36 . If the platform lacks strong interactivity, it may negatively impact the learning experience 37 . Therefore, platforms need to enhance interactivity to cultivate positive online learning habits among adult learners 38 . The stronger the perceived course features, the higher the adult learners' overall satisfaction with the course experience. Yang's study on MOOC users found that interactivity significantly influences expectancy confirmation 20 . Perceived added value refers to additional or value-added services provided beyond basic services 39 , 40 . As an additional benefit, it further enhances users' perceived value of the course, leading to a more positive evaluation of expectancy confirmation. Online education platforms should focus on improving course features, enhancing interactivity, and providing perceived added value to better meet the needs of adult learners 41 . Based on the characteristics of adult learners in online education, this study proposes the following hypotheses:

H3: Course characteristics significantly influence the expectancy confirmation of adult learners.

H3-1: Perceived interactivity has a significant positive impact on the expectancy confirmation of adult learners.

H3-2: Perceived added value has a significant positive impact on the expectancy confirmation of adult learners.

Based on data from the SPOC platform, Guo et al. found that classroom interaction significantly and positively influences perceived usefulness and perceived ease of use in SPOC learning 42 . A research of Wu et al. indicated that interactivity has an impact on perceived usefulness and expectancy confirmation 43 . The study of Qian et al. revealed that perceived interactivity has a positive effect on perceived usefulness 15 . Additionally, Yang found a positive influence of interactivity on perceived usefulness in research involving MOOC users 20 . In the field of mobile communication services, Liu and Chen examined the impact of added value on perceived usefulness and discovered that value-added services have a positive effect on the perceived usefulness and satisfaction of communication customers 44 . This finding aligns with the personalized learning experience needs of adult learners. Based on these observations, the following research hypotheses are proposed:

H4: Course features have a significant impact on the perceived usefulness of adult learners.

H4-1: Perceived interactivity has a significantly positive influence on the perceived usefulness of adult learners.

H4-2: Perceived added value has a significantly positive impact on the perceived usefulness of adult learners.

Bhattacherjee validated the impact of expectancy confirmation on perceived usefulness in the Expectation Confirmation Model 25 . Perceived usefulness refers to the improvement in learning efficiency and the degree of learning outcomes when users utilize online education platforms. Perceived usefulness not only influences adult learners' initial acceptance 45 but also has a significant impact on adult learners' satisfaction and the intention to continue using the platform 25 . Yang, in his study on MOOC users, confirmed the positive effect of expectancy confirmation on perceived usefulness 20 . Qian's research on online learning users also affirmed the positive influence of expectancy confirmation on perceived usefulness 15 . Studies by Hayashi and Lin further supported the impact of expectancy confirmation on perceived usefulness 46 , 47 . Based on this, the following research hypothesis is proposed:

H5: Expectation confirmation positively influences the perceived usefulness of adult learners.

When adult learners' expectations are met or exceeded by the online education platform, signifying a higher level of expectancy confirmation, it leads to increased satisfaction with the platform. This hypothesis is supported by research done on individual users in Social Networking Sites (SNS) as well as studies conducted by Liu and colleagues on short video users 48 . Further, the findings of Chiu et al. and Wang et al. reinforce the influence of expectancy confirmation on satisfaction 49 , 50 . Moreover, this relationship has been substantiated in various digital contexts, such as e-commerce 51 , and e-learning 52 , suggesting that expectancy confirmation is a significant predictor of user satisfaction across different digital platforms. To further expand on this, it's worth noting that expectancy confirmation can also influence other aspects of user experience. For instance, when users' expectations are confirmed, they may perceive the platform as more useful, which can further enhance their satisfaction 53 . Additionally, expectancy confirmation can also impact users' trust in the platform 9 . When users' expectations are met, they may develop a higher level of trust in the platform, which can also contribute to increased satisfaction. Based on this, the following research hypothesis is proposed:

H6: Expectancy confirmation positively influences user satisfaction with the online education platform.

Wang et al. affirmed the positive influence of perceived usefulness on satisfaction in their study of users of Virtual Reality (VR) library services 54 . In a similar vein, Yin et al.'s research on WeChat users in university libraries corroborated the positive effect of perceived usefulness on satisfaction 55 . The connection between perceived usefulness and satisfaction was further explored and substantiated in studies by Bhattacherjee and Lin et al. 25 , 47 . These findings collectively underscore the importance of perceived usefulness in driving user satisfaction across a variety of digital platforms. Building on these insights, we can argue that perceived usefulness is not just an antecedent of satisfaction, but may also play a role in shaping other user attitudes and behaviors 56 . For example, perceived usefulness could influence users' continued intention to use a platform 52 , their trust in the platform 57 , and their willingness to recommend the platform to others 58 . Based on these findings, the following research hypothesis is proposed:

H7: Perceived usefulness positively influences the satisfaction of adult learners.

This study focuses on the intention to continue use, which refers to adult learners' willingness to continue using online education platforms. Satisfaction is the experiential feeling and overall evaluation that adult learners have after using online education platforms. Cao et al., focusing on WeChat Moments experience, found that satisfaction significantly influences users' intention to continue using 59 . The research of Zhang and Yao on mobile government apps also confirmed the impact of satisfaction on the intention to continue use 60 . Scholars such as Bhattacherjee et al., have all verified the positive influence of satisfaction on the intention to continue use 20 , 25 , 46 . Based on this, the following research hypothesis is proposed:

H8: Satisfaction positively influences the intention to continue use of adult learners.

The extent of users' intention to continue using online education platforms reflects their loyalty to the selected platform. The study of Gao and Hu on users of knowledge community services found that service quality has a positive impact on continued usage 61 . Lin, through research on consumer behaviors using the ABC attitude theory, discovered that service quality positively influences shopping attitudes 62 . Zhou et al., in their study of users in the shopping domain, identified service quality as a significant influencing factor on intention to continue usage 63 .

The influence of platform service quality on the intention to continue use among adult learners may be subject to the mediating effects of other variables. Wang's study on the continued use intention of mobile libraries found that service quality affects users' perceived usefulness 64 . Guo and Ming concluded that service quality positively influences users' expectation confirmation and perceived usefulness 65 . Hsu and Lin discovered in their study of mobile client user behavior that service quality initially affects user satisfaction 66 . Yang also identified service quality as a significant factor influencing user satisfaction in mobile reading 67 . Alali and Salim, in their study on a health forum, found a significant impact of service quality on user satisfaction 68 . In the field of information systems, scholars have confirmed the positive impact of expectation confirmation on user satisfaction 46 , 47 , 69 , 70 . This implies that when users have high expectation confirmation, indicating their expectations and usage experience are satisfied, it can enhance their perceived usefulness and increase satisfaction with the platform. Liu's research on video website users validated the effect of perceived usefulness on satisfaction 71 . Yang's study on e-book users also confirmed the positive impact of perceived usefulness on satisfaction 72 . Concurrently, within the realm of consumer behavior, a multitude of empirical investigations have corroborated the affirmative promotional influence of satisfaction on users' proclivity to sustain usage 15 , 20 , 25 , 67 . This suggests that expectation confirmation has an impact on adult learners' satisfaction, and learner satisfaction may further influence their intention to continue use. Combining the positive influence relationship of platform service quality on adult learners' expectation confirmation and perceived usefulness proposed in H1 and H2, this study posits that platform service quality has a positive impact on the intention to continue use among adult learners. Moreover, this positive influence occurs through multiple mediating effects of perceived usefulness, expectation confirmation, and satisfaction among adult learners. Based on this, the following research hypothesis is proposed:

H9: Platform service quality has a positive impact on the intention to continue use of adult learners.

H9-1: In the process of the impact of platform service quality on the intention to continue use of adult learners, expectation confirmation and satisfaction play a chain-mediating role.

H9-2: In the process of the impact of platform service quality on the intention to continue use of adult learners, perceived usefulness and satisfaction play a chain-mediating role.

In terms of the impact of course features on adult learners' intention to use, researchers have made some important findings. The study of Joo et al. discovered that high-quality interactions can stimulate positive evaluations of educational platforms by users, thereby increasing their intention to continue using 73 . This indicates that high-quality interactions, such as timely answering of questions and sharing ideas, can enhance adult learners' loyalty to the platform. Chow et al. investigated the impact of interactions on users' intention to continue using from the dimensions of teacher interaction and peer interaction 74 . The research of Hoffman and Novak found that the higher the user's interactivity, the better their overall experience 75 . In addition, Zhang and Wu pointed out that perceived interactivity can lead to positive emotional changes in users 76 . Perceived added value is the unexpected gain that adult learners feel, which can effectively increase their favorability towards the platform and satisfaction with the usage process 42 , thereby reinforcing their intention to continue using.

Van Noort et al. found that the higher users' perceived interactivity on a website, the higher their satisfaction and willingness to use the website 77 . Qian validated the positive impact of perceived interactivity on satisfaction and continued intention to use 15 . Gefen et al. argued that user interaction with a website can influence their trust attitudes 78 . Kim's study on travel websites revealed that interactivity can enhance users' trust in the website 79 . Park et al. focused on the impact of perceived interactivity on satisfaction and examined the mediating role of perceived usefulness/perceived value 80 . Song and Zinkhan found that website response speed is a crucial factor influencing user satisfaction 81 . Meanwhile, in the field of information systems, numerous scholars have confirmed the influence of expectation confirmation and perceived usefulness on satisfaction, as well as the impact of satisfaction on intention to continue using 15 , 20 , 25 , 67 . Combining with the proposed positive relationships in H3 and H4 regarding course features (perceived interactivity and perceived added value) and adult learners' expectation confirmation and perceived usefulness, this paper suggests that online education course features have a positive impact on adult learners' intention to continue using. Moreover, this positive influence occurs through multiple mediating pathways involving adult learners' perceived usefulness, expectation confirmation, and satisfaction. Based on this, the following research hypotheses are proposed:

H10: Course features significantly impact adult learners' intention to continue using.

H10-1: We posit that perceived interactivity has a positive influence on the continued use intention of adult learners. In the process of how perceived interactivity influences the intention to continue use, we propose that both expectation confirmation and satisfaction, as well as perceived usefulness and satisfaction, play a chain-mediating role. This suggests that when the perceived interactivity of the course meets or exceeds the expectations of adult learners, it confirms their expectations, enhances their satisfaction, and simultaneously elevates the perceived usefulness of the course, ultimately influencing their intention to continue using the platform.

H10-2: We suggest that perceived added value has a positive influence on the continued use intention of adult learners. In the process of how perceived added value influences the intention to continue use, we propose that both expectation confirmation and satisfaction, as well as perceived usefulness and satisfaction, play a chain-mediating role. This implies that when the perceived added value of the course meets or exceeds the expectations of adult learners, it confirms their expectations, enhances their satisfaction, and simultaneously increases the perceived usefulness of the course, ultimately influencing their intention to continue using the platform.

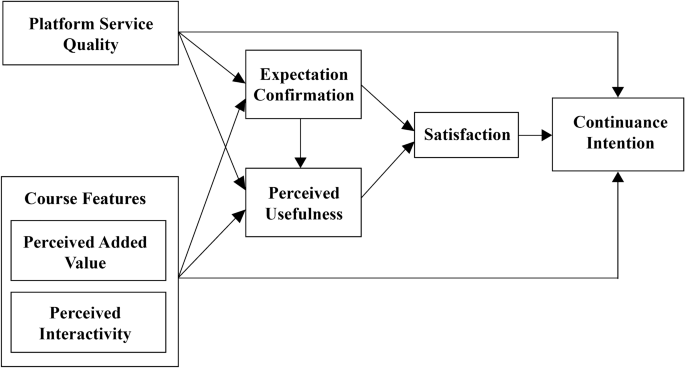

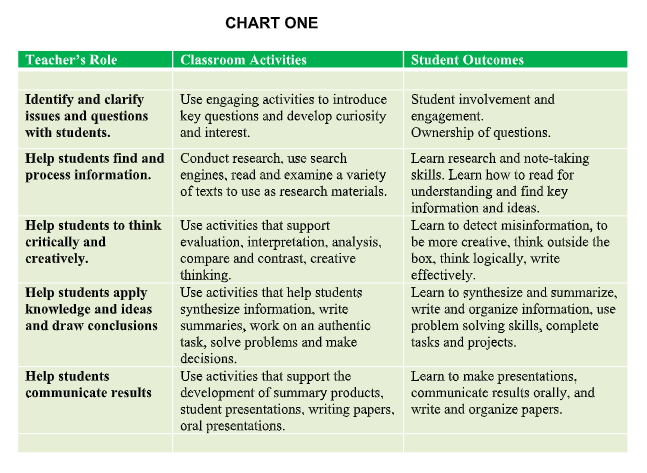

In summary, the research model of factors influencing the intention to continue using online education platforms in this study is illustrated in Fig. 1 .

Research model framework.

Measurement tools

The design of the questionnaire drew inspiration from mature scales used globally to measure the intention to use information systems. Additionally, references were taken from relevant studies on online education platforms both domestically and internationally, with subsequent modifications made to the questionnaire. The questionnaire comprises two parts: the first part gathers adult learners demographic information, while the second part measures the factors influencing the continuous usage behaviour of online education platform adult learners (refer to Table 1 ). The Likert five-point scale method was employed in the questionnaire, where 1 represents strongly disagree , 2 represents disagree , 3 represents neutral , 4 represents agree , a nd 5 represents strongly agree .

Participants

This study selected adult education students from a university in Shanghai as research subjects. By employing a stratified sampling method, we selected participants based on 10% of the total adult student population. This sampling process was carried out stratifying by profession and grade. The total number of participants amounted to 1592, the detailed information of which can be found in Table 2 . Prior to participants answering the questionnaire, there was an introductory statement informing them of the purpose of the survey, emphasizing the confidentiality, anonymity, and voluntary nature of their participation in the research.

Data processing methodology

We used SPSS 23.0 software to first test for common method bias in the data and analyse the correlations between variables. AMOS 24.0 software was employed to test the discriminant validity among variables. Additionally, SPSS 23.0 software and the PROCESS 2.16 macro program with the Bootstrap test method (setting the sample extraction size to 5000 times and the confidence interval to 95%) were used to test for the chained mediation effects.

Informed consent statement

We confirm that informed consent has been obtained from all subjects. Each survey will provide an Informed Consent Form, which will be indicated in the instruction section of the questionnaire.

Common method bias

To avoid the potential issue of substantial common method bias influencing the spurious prediction of independent variables on dependent variables, this study employed two methods (procedural control and statistical control) for control and examination 91 .

Firstly, before distributing the survey questionnaire, this study implemented effective randomization of the various scales used and made a commitment to participants to protect the privacy of their data. Secondly, the study employed the Harman's single-factor test for statistical control. Through exploratory factor analysis conducted on the obtained data without factor rotation, the first factor's variance explained 39.26% (below the critical threshold of 40% variance explained) 92 . Therefore, these methods and results suggest that there is no severe common method bias in the collected data for this study.

Reliability and validity analysis

Through the application of SPSS 23.0, an examination of the reliability and validity of the questionnaire was conducted. The Cronbach's alpha value for the questionnaire was found to be 0.896. Furthermore, the Cronbach's alpha values for each variable were all above 0.689 (refer to Table 3 ), indicating a good level of internal consistency for the variables. Hence, the reliability of the questionnaire is deemed acceptable. The Kaiser–Meyer–Olkin (KMO) value for the questionnaire was 0.914, with individual variable KMO values exceeding 0.5. The overall interpretability is high, justifying the application of principal component analysis. The cumulative variance explanation rate was determined to be 67.779%. Moreover, all factor loading values were above 0.5, signifying good validity of the sample. These results affirm the reliability and validity of the questionnaire, ensuring the robustness of the data analysis and interpretation 93 , 94 , 95 , 96 , 97 .

Fit test analysis

The purpose of model fit testing is to measure the degree of fit between the hypothetical model and the observed data. As shown in Table 4 , overall, the research model exhibits good fit.

Mediation effect testing

Firstly, a preliminary examination of the mediation effect was conducted using the linear hierarchical regression method. The variables showed a correlation, with coefficients between 0.4 and 0.76, and all Composite Reliability (CR) above 0.675, and all Average Variance Extracted (AVE) above 0.5 indicating no severe collinearity among the variables. The correlation results are presented in Table 5 94 , 95 , 96 , 97 .

Furthermore, the Bootstrap method, as implemented in the Process macro program with 5000 resamples and a confidence interval set at 95%, was employed to conduct a more in-depth examination of the chain mediation 46 .

From Fig. 2 and Table 6 , it can be observed that platform service quality significantly influences adult learners' perceived usefulness ( β = 0.378, p < 0.0001) and expectation confirmation ( β = 0.432, p < 0.0001), supporting hypotheses H1 and H2 . Adult learners' perceived interactivity ( β = 0.282, p < 0.0001) and perceived additional value ( β = 0.353, p < 0.0001) significantly positively impact their expectation confirmation, supporting hypothesis H3 . Adult learners' perceived interactivity ( β = 0.333, p < 0.0001) and perceived additional value ( β = 0.374, p < 0.0001) significantly positively influence their perceived usefulness, supporting hypothesis H4 . Adult learners' expectation confirmation positively influences their perceived usefulness ( β = 0.755, p < 0.0001), supporting hypothesis H5 . Adult learners' expectation confirmation positively influences their satisfaction ( β = 0.374, p < 0.0001), supporting hypothesis H6 . Adult learners' perceived usefulness positively influences their satisfaction ( β = 0.493, p < 0.0001), supporting hypothesis H7 . Adult learners' satisfaction positively influences their intention to continue using the platform ( β = 0.587, p < 0.0001), supporting hypothesis H8 . Platform service quality significantly influences adult learners' intention to continue using ( β = 0.374, p < 0.0001), supporting hypothesis H9 . Adult learners' perceived interactivity ( β = 0.243, p < 0.0001) and perceived additional value ( β = 0.305, p < 0.0001) positively influence their intention to continue using, supporting hypothesis H10 . All ten research hypotheses derived from the Expectation Confirmation Model are supported. To separately test the mediating effects of perceived usefulness, expectation confirmation, and satisfaction in the relationships between course characteristics, platform features, and continued usage intention, this study employed the bias-corrected nonparametric percentile Bootstrap method, and the results are presented in Table 7 .

Results of the regression analysis on the continued usage intention of adult learners.

Results indicate that the mediating effects of course characteristics, platform features, and continued usage intention are significant. In the mediation path PSQ → EC → SA → CI , the effect value is 0.0874, with a 95% Bootstrap confidence interval ranging from 0.0515 to 0.1436, excluding 0. This implies that expectation confirmation and satisfaction play a significant mediating role in the relationship between platform service quality and continued usage intention, supporting H9-1 . In the mediation path PSQ → PU → SA → CI , the effect value is 0.0742, with a 95% Bootstrap confidence interval ranging from 0.0395 to 0.1104, excluding 0. This suggests that perceived usefulness and satisfaction significantly mediate the relationship between platform service quality and continued usage intention, supporting H9-2 . In the mediation path PI → EC → SA → CI , the effect value is 0.0983, with a 95% Bootstrap confidence interval ranging from 0.0604 to 0.1548, excluding 0. This indicates that expectation confirmation and satisfaction play a significant mediating role in the relationship between perceived interaction and continued usage intention, supporting H10-1–1 . In the mediation path PI → PU → SA → CI , the effect value is 0.0774, with a 95% Bootstrap confidence interval ranging from 0.0453 to 0.1238, excluding 0. This shows that perceived usefulness and satisfaction significantly mediate the relationship between perceived interaction and continued usage intention, supporting H10-1 . In the mediation path PAV → EC → SA → CI , the effect value is 0.0963, with a 95% Bootstrap confidence interval ranging from 0.0612 to 0.1485, excluding 0. This indicates that expectation confirmation and satisfaction play a significant mediating role in the relationship between perceived added value and continued usage intention, supporting H10-2 . In the mediation path PAV → PU → SA → CI , the effect value is 0.0724, with a 95% Bootstrap confidence interval ranging from 0.0433 to 0.1154, excluding 0. This suggests that perceived usefulness and satisfaction significantly mediate the relationship between perceived added value and continued usage intention, supporting H10 .

This study delves into the factors influencing the continued usage intention of adult learners on online education platforms, focusing on both platform features and course characteristics 56 . Beginning with platform features, we examined the impact of platform service quality on user experience. The research revealed that service quality has a direct relationship with users' expectation confirmation and perceived usefulness of the platform 1 , 98 . This aligns with previous research findings, emphasizing adult learners' expectations for high-quality services, including effectiveness and promptness, when using online education platforms. It also corroborates the Information Success Model constructed by Delone et al. 31 , where service quality is identified as a crucial factor significantly affecting satisfaction and usefulness 41 . The study results indicate that enhancing platform service quality will directly strengthen adult learners' expectation confirmation and perceived usefulness, fostering a more positive online learning habit among adult learners.

Furthermore, concerning course characteristics, we gauged the appeal of courses through perceived interactivity and perceived added value 99 . The research results demonstrate a significant positive relationship between adult learners' positive perceptions of course characteristics and their expectation confirmation, perceived usefulness, satisfaction, and ultimately, their intention to continue using the platform 99 . This validates the importance of interactivity and added value in previous research, particularly in the context of online education 34 . Adult learners anticipate courses to have robust interactivity, fostering positive interactions among students and addressing issues promptly, thereby enhancing adult learners' learning expectations 44 . Simultaneously, adult learners positively evaluate the added value provided by the courses, further reinforcing their perception of the course's value and subsequently increasing expectation confirmation and satisfaction.

Adult learners' intention for continuous usage is a complex process influenced by multiple factors related to platform and course characteristics 57 , 100 , 101 . Improvements in platform service quality and course features have a positive impact on adult learners' expectation confirmation, perceived usefulness, and satisfaction, ultimately encouraging adult learners to actively choose to continue using the online education platform 58 . Furthermore, through the analysis of mediating effects, we have identified that expectation confirmation and satisfaction play a chain-mediated role between platform service quality and adult learners' intention for continuous usage 44 . This suggests that enhancing platform service quality will strengthen users' intention for continuous usage by elevating expectation confirmation and satisfaction 57 . Therefore, educational platforms, in enhancing adult learners experience, should not only focus on improving platform service quality but also prioritize optimizing course characteristics to comprehensively enhance adult learners' online learning experience and loyalty.

This study reveals that learners' expectation confirmation and online learning engagement significantly influence learning satisfaction and perceived outcomes across different educational contexts. In formal education, enhancing teaching quality and learner engagement can boost learning outcomes 102 . In corporate training, practical, work-related content and high-quality teaching can heighten satisfaction and perceived outcomes 103 . In informal learning, catering to individual needs and providing a flexible learning environment can significantly enhance satisfaction and learning outcomes 58 . These insights offer valuable strategies for boosting learning satisfaction and perceived outcomes in diverse learning environments.

In the discussion section, we can further explore how emerging technologies, particularly Artificial Intelligence (AI), could potentially influence the relationships outlined in our hypotheses 104 , 105 . The advent of AI offers new possibilities for online education, especially in enhancing the quality of teaching services 105 , 106 . For instance, AI can be used to develop intelligent tutoring systems that provide personalized learning experiences based on learners' styles and needs, potentially enhancing their expectation confirmation and, consequently, their learning satisfaction and perceived learning outcomes 107 . However, the application of AI in online education also presents challenges, such as ensuring the fairness and transparency of AI systems and protecting learners' privacy.

Implications

Implications for theory.

In terms of theoretical implications, this study offers fresh insights into the learning experiences of adult learners on online education platforms. The findings reveal that the confirmation of adult learners' expectations positively impacts both their perceived usefulness and satisfaction. This underscores the pivotal role of user expectation confirmation in the online learning experience, highlighting the correlation between expectations and experiences 100 . Simultaneously, the research results provide profound insights into the psychological gap in the adult learners' experience of online education platforms, offering a theoretical basis for understanding the relationship between adult learners' expectations and actual experiences.

However, to further enhance the value of the research, it is suggested to integrate new context-specific structures and novel theories to improve the parsimony and novelty of the research. For instance, exploring other potential factors in the online education environment, such as community atmosphere and interaction quality, and how they influence adult learners' expectation confirmation and satisfaction could be beneficial 99 . Additionally, adopting novel theoretical perspectives, such as self-determination theory, can provide a new viewpoint for understanding the motivations and behaviors of adult learners in online learning 101 .

Implications for practice

This research offer practical guidance for online education providers, emphasizing the need to enhance platform service quality and course features to meet adult learners' expectations and perceived usefulness. The study provides valuable insights for formulating strategies to improve user satisfaction and foster continuous usage intention among adult learners in the competitive online education market.

A truthful promotional strategy

The research results suggest that online education platforms should adhere to a truthful approach in their promotion and avoid exaggerated claims. This provides practical guidance for operations, helping the platform establish an authentic and trustworthy image in advertising and marketing 52 . This approach reduces the potential psychological gaps that users might experience after use, thereby enhancing overall user satisfaction. This strategy is universally applicable, not only in a formal education environment but also in corporate training and informal learning settings.

Emphasizing the utility in promotion

Online education platforms should highlight their strengths, features, and content quality to help users profoundly understand the platform's utility 44 . This provides direction for the platform in advertising and promotion, aiding users in gaining a more comprehensive understanding of the platform's value, thereby increasing perceived utility and overall satisfaction 12 . This approach is applicable across various educational settings, benefiting formal education, corporate training, and informal learning alike.

Enhancing service quality

The study reveals a significant positive impact of platform service quality on user expectation confirmation and perceived utility 57 . Therefore, platforms should invest in professional training for customer service to improve service quality, aiming to enhance adult learners' expectations and subsequently elevate perceived utility 52 . This practical recommendation provides online education platforms with actionable insights to improve adult learners' experience and contributes to establishing a solid foundation for user satisfaction 5 . Improving service quality is crucial in all educational environments, whether it's formal education, corporate training, or informal learning.

Optimizing course experience

By emphasizing perceived added value and interactivity, platforms can enhance adult learners' satisfaction with course quality 53 . To achieve this, platforms can offer additional services during adult learners' engagement and establish communication channels, enabling adult learners to better experience the utility of the online education platform 103 . This provides a practical and feasible approach for platforms to optimize the course experience and increase user willingness to continue using the platform 58 . This approach has application value in different educational settings and can help improve the course experience in formal education, corporate training, and informal learning.

Limitations and prospects

This study has made notable discoveries about adult learners' sustained intention to utilize online education platforms, but it has limitations. Firstly, the research mainly hinged on adult education students from a single university, potentially limiting the results' broad applicability due to sample specificity. Future research could enhance the findings' external validity by expanding the sample size and incorporating more diverse user groups. Secondly, despite a comprehensive research model, additional latent variables influencing adult learners' continued intention to use online platforms might have been overlooked. Future studies could explore other potential factors for a more comprehensive understanding of the decision-making process when adult learners opt to persist with online education platforms.

Additionally, this study predominantly employs quantitative research methods, leveraging survey data collection. Future research could contemplate integrating more qualitative research methods, like in-depth interviews or observations, to attain a more comprehensive grasp of adult learners' behavioral motivations and experiences 108 . Future research should also advocate for the use of mixed methods or longitudinal studies to empirically substantiate the proposed hypotheses across various types of online education platforms and diverse adult learner populations.

Subsequent research could incorporate negative outcomes, as current research mainly focuses on positive ones. Considering the potential negative impact of high expectations or poor service quality on user satisfaction and continuance intention can provide a more comprehensive understanding of the online learning experience. The rapid development of online education technology necessitates future research to include factors associated with technological advancement (for example, personalized learning driven by artificial intelligence) and their impact on the learning experience.

The upcoming research has the potential to introduce negative outcomes, given that current studies primarily concentrate on positive results. Taking into account the potential negative influence of high expectations or subpar service quality on user satisfaction and sustained intention can offer a more comprehensive comprehension of the online learning experience. Future research should consider the speedy evolution of online education technology, integrating factors related to technological progress (for instance, AI-driven personalized education) and their repercussions on the learning experience can be highly valuable.

Looking ahead, researchers can dedicate efforts to further deepen the investigation into adult learners' continuous intention to use online education platforms, overcoming current study limitations, and continually enhancing the understanding of the mechanisms behind adult learners behaviors.

Conclusions

Based on the Expectation Confirmation Theory and considering the characteristics of online education platforms, this study constructs a research model by focusing on two crucial variables—expectation confirmation and perceived usefulness—and their influencing factors: platform service quality and course service quality. The results indicate the following key findings: (1) Satisfaction is a critical factor influencing adult learners' continued usage of the platform. (2) Adult learners' perceived usefulness affects satisfaction, and the degree of expectation confirmation significantly influences both perceived usefulness and satisfaction. (3) Platform service quality impacts expectation confirmation and plays an essential role in perceived usefulness. (4) Perceived added value and perceived interactivity of course service quality significantly influence expectation confirmation and also play a crucial role in perceived usefulness. (5) Perceived usefulness, expectation confirmation, and satisfaction serve as significant mediators in the relationship between platform features and the intention to continue usage. (6) Perceived usefulness, expectation confirmation, and satisfaction act as significant mediators in the relationship between course features and the intention to continue usage. In summary, these findings shed light on the factors influencing users' continued usage of online education platforms, providing valuable insights for platform operators to enhance user experience and satisfaction.

Data availability

The datasets generated and analysed during the current study are available in the Zenodo repository, https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.10584056 .

Li, L. & Zhang, P. Research on the impact of online education platforms on adult learners’ learning outcomes. Res. Electrif. Educ. 38 , 4–10. https://doi.org/10.15885/j.cej.2022.06.004 (2022).

Article Google Scholar

Arabacioğlu, T. E-learning system usage continuance intention of adult learners: A data mining approach. Int. J. N. Trends Educ. Implic. (IJONTE). 14 , 187–201 (2023).

Google Scholar

Moore, J. L., Dickson-Deane, C. & Galyen, K. e-Learning, online learning, and distance learning environments: Are they the same?. Internet High. Educ. 14 , 129–135. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.iheduc.2010.10.001 (2011).

Sarker, S. & Wells, J. D. Understanding self-regulated learning in a fifth-grade mathematics classroom through a cultural-historical activity theory lens. Educ. Stud. Math. 54 , 211–236. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1027311524535 (2003).

Cheng, X. et al. Investigating students’ satisfaction with online collaborative learning during the COVID-19 period: An expectation-confirmation model. Group Decis. Negot. 32 , 749–778. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10726-023-09829-x (2023).

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Xie, Y. & Suh, K. Understanding adult learners’ satisfaction and continuance intention in hybrid learning environments: An integrative review. Educ. Technol. Soc. 22 , 177–192. https://doi.org/10.2307/jeductechsoci.22.4.177 (2019).

Broadbent, J. & Poon, W. L. Self-regulated learning strategies & academic achievement in online higher education learning environments: A systematic review. Internet High. Educ. 27 , 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.iheduc.2015.06.003 (2015).

Hossain, M. N. et al. Investigating the factors driving adult learners’ continuous intention to use M-learning application: A fuzzy-set analysis. J. Res. Innov. Teach. Learn. 14 , 245–270 (2020).

Mailloux, M. L. Adult online learners with multiple roles: A qualitative study of emotional experiences. (2023).

Artino, A. R. J. & Stephens, J. M. Academic motivation and self-regulation: A comparative analysis of undergraduate and graduate students learning online. Internet High. Educ. 12 , 146–151. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.iheduc.2009.03.001 (2009).

Chen, K. C. & Jang, S. J. Motivation in online learning: Testing a model of self-determination theory. Comput. Hum. Behav. 26 , 741–752. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2010.01.014 (2010).

Lee, J., Song, H. & Kim, Y. Quality factors that influence the continuance intention to use MOOCs an expectation-confirmation perspective. Eur. J. Psychol. Open. 82 , 109–119. https://doi.org/10.1024/2673-8627/a000047 (2023).

Chen, L. & Wu, H. The mediating role of service quality in the relationship between platform features and adult learners’ continuance intention in online education. Educ. Technol. Res. Dev. 20 , 78–91. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11423-022-10058-z (2023).

Lu, J., Yao, J. E. & Yu, C. S. Personal innovativeness, social influences, and adoption of wireless internet services via mobile technology. J. Strateg. Inf. Syst. 14 , 245–268. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsis.2005.07.003 (2005).

Qian, Y. Research on the influencing factors of continuous use behavior of online learners—From the perspective of social network environment and learning situation positioning. Mod. Inf. 35 , 50–56 (2015).

Wu, B. & Zhang, C. Empirical study on continuance intentions towards e-learning 2.0 systems. Behav. Inf. Technol. 33 , 1027–1038. https://doi.org/10.1080/0144929X.2013.872200 (2014).

Yoon, C. & Rolland, E. Understanding continuance use in social networking services. J. Comput.-Mediat. Commun. 20 , 1–8. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcc4.12099 (2015).

Kwapong, O. A. T. F. Online learning experiences of adult applicants to a university in Ghana during the Covid-19 outbreak. E-Learn. Digit. M. 20 , 598–617. https://doi.org/10.1177/20427530221125858 (2023).

Cheng, Y. M. Why do users intend to continue using the digital library? An integrated perspective. Aslib. J. Inf. Manag. 66 , 1–25. https://doi.org/10.1108/AJIM-03-2014-0033 (2014).

Yang, G. F. Influence factors of MOOC user’s continuous behavior. Open Educ. Res. 22 , 100–111. https://doi.org/10.13966/j.cnki.kfjyyj.2016.01.012 (2016).

Yin, M. & Li, Q. Research on the continuance usage intention of mobile APP based on the theory of integrating ECT and IS success: Taking the health APP as an example. J. Dalian Univ. Technol. Soc. Sci. Edn. 38 , 81–87 (2017).

Tang, W., Zhang, X. & Tian, Y. Investigating lifelong learners’ continuing learning intention moderated by affective support in online learning. Sustain. Basel. 15 , 1901. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15031901 (2023).

Oliver, R. L. A cognitive model of the antecedents and consequences of satisfaction decisions. J. Market. Res. 17 , 460–469. https://doi.org/10.2307/3150499 (1980).

Patterson, P. G., Johnson, L. W. & Spreng, R. A. Modeling the determinants of customer satisfaction for business-to-business professional services. J. Acad. Market. Sci. 24 , 4–17. https://doi.org/10.1177/009207039602400101 (1996).

Bhattacherjee, A. Understanding information systems continuance: An expectation-confirmation model. Mis. Quart. 25 , 351–370. https://doi.org/10.2307/3250921 (2001).

Larsen, T. J., Sørebø, A. M. & Sørebø, Ø. The role of task-technology fit as users’ motivation to continue information system use. Comput. Hum. Behav. 25 , 778–784. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2009.02.004 (2009).

Tan, C. H., Yi, Y. & Li, L. Research on the influencing factors of the continuous use intention of users of academic WeChat public accounts. Mod. Inf. 41 , 50–136 (2021).

Doong, H. S. & Lai, H. Exploring usage continuance of e-negotiation systems: Expectation and disconfirmation approach. Group Decis. Negot. 17 , 111–126. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10726-007-9077-8 (2008).

Kim, B. An empirical investigation of mobile data service continuance: Incorporating the theory of planned behavior into the expectation-confirmation model. Expert Syst. Appl. 37 , 7033–7039. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eswa.2010.03.028 (2010).

Dağhan, G. & Akkoyunlu, B. Modeling the continuance usage intention of online learning environments. Comput. Hum. Behav. 60 , 198–211. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2016.02.095 (2016).

DeLone, W. H. & McLean, E. R. The DeLone and McLean model of information systems success: A ten-year update. J. Manag. Inf. Syst. 19 , 9–30. https://doi.org/10.1080/07421222.2003.11045748 (2003).

Guo, W. Q. Research on the influencing factors for the continuous use intention of online education paid users. Master’s thesis Type, Jilin University (2017).

Guo, X. D. Research on the influencing factors of online education paid users' continuance usage intention. Master’s thesis Type, Lanzhou University of Finance and Economics (2018).

Liu, C. & Wang, D. Understanding the influence of service quality on adult learners’ satisfaction and continuance intention in online education. Int. J. Educ. Technol. 15 , 112–125. https://doi.org/10.1504/IJET.2022.129783 (2022).

Li, S. & Wang, Y. Effects of course features on sustained usage intention: A study of adult learners. J. Distance Educ. 35 , 112–125. https://doi.org/10.5325/jode.35.1.112 (2023).

Liu, G. Q. Analysis of the characteristics of American primary and secondary school education websites and their implications for China. Prim. Second. Sch. Electron. Educ. 2010 , 43–45 (2010).

Mou, S. Interactive research in the network teaching environment. Silicon Valley . 58 (2011).

Ma, L., Xing, Y., Wu, X. Research on influencing factors of intention to use course websites. China Educ. Technol . 72–78 (2013).

De Chernatony, L., Harris, F. & Riley, F. D. Added value: Its nature, roles and sustainability. Eur. J. Market. 30 , 39–56. https://doi.org/10.1108/03090569610105723 (1996).

Xie, S., Hou, M. Empirical research on purchase intentions for air passenger add-on services based on customer perception. Price Mon . (2016). https://doi.org/10.14076/j.issn.1006-2025.2016.08.14 .

Huang, L. & Li, W. Enhancing online learning experience through perceived added value. Int. J. E-Learn. 28 , 78–91. https://doi.org/10.1891/2696-7895.28.2.7 (2022).

Guo, X. Y., Guo, Z. & Li, M. The mechanism of classroom interaction in SPOC on student participation. Exp. Technol. Manag. 36 , 244–273. https://doi.org/10.16791/j.cnki.sjg.2019.06.058 (2019).

Wu, A. Research on the continuous use intention of online education platform users: Based on the verification of expectation confirmation theory model. J. Harbin Inst. 39 , 117–122 (2018).

Liu, Y. & Chen, H. The impact of value-added services on perceived usefulness in mobile communication: A study of adult consumers. J. Mob. Serv. 30 , 46–58. https://doi.org/10.4067/S2236-74392023000200046 (2023).

Davis, F. D. Perceived usefulness, perceived ease of use, and user acceptance of information technology. MIS Q. 13 , 319–340. https://doi.org/10.2307/249008 (1989).

Hayashi, A. et al. The role of social presence and moderating role of computer self efficacy in predicting the continuance usage of e-learning systems. J. Inf. Syst. Educ. 31 , 5–10 (2020).

Lin, C. S., Wu, S. & Tsai, R. J. Integrating perceived playfulness into expectation-confirmation model for web portal continuance. Inf. Manag.-Amster. 42 , 683–693. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.im.2004.04.003 (2005).

Liu, R. & Chai, J. Study on the influencing factors of continuous usage behavior of personal users in SNS social network. Soft Sci. 27 , 132–175 (2013).

ADS Google Scholar

Chiu, C. M., Hsu, M. H. & Lai, H. Re-examining the influence of trust on online repeat purchase intention: The moderating role of habit and its antecedents. Decis. Support Syst. 53 , 835–845. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dss.2012.05.014 (2012).

Wang, L., Zhao, W. & Sun, X. Modeling of causes of Sina Weibo continuance intention with mediation of gender effects. Front. Psychol. 7 , 1–11. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2016.01716 (2016).

Dastane, O. & Haba, H. F. What drives mobile MOOC’s continuous intention? A theory of perceived value perspective. Int. J. Inf. Learn. Technol. 40 , 148–163. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJILT-04-2022-0087 (2023).

Luo, Y. & Wang, F. A qualitative study of the factors influencing the quality of online learning in higher education. Internet High. Educ. 54 , 100834. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.iheduc.2023.100834 (2023).

Wang, F. & Li, M. Research on adult learners’ motivation to learn on online education platforms. Chin. Adult Educ. 33 , 11–16. https://doi.org/10.19387/j.cnki.cn44-1144/g4.2023.02.011 (2023).

Wang, D., Tao, B. X. & Zheng, G. M. Research on the influencing factors of the continuous usage behavior of VR library service users based on expectation confirmation theory. Mod. Inf. 40 , 111–120 (2020).

Yin, M. Z., Yu, W. P., Zhou, T. M. An empirical study on the influence factors of university library WeChat users' continuous use willingness. Libr. Theory Pract . 98–101 (2017).

Wang, X. & Liu, Y. Research on the quality evaluation of online education platforms for adult learners. J. Contin. Educ. 21 , 12–18. https://doi.org/10.15933/j.cnki.cn44-1277/g4.2021.01.012 (2021).

Zhao, L. & Sun, Y. Research on adult learners’ learning behaviors on online education platforms. Res. Mod. Distance Educ. 25 , 1–8. https://doi.org/10.16060/j.cnki.rmde.2023.01.001 (2023).

Jawaid, M. & Haleem, A. A review of online learning platforms: Features, benefits, and challenges. Int. J. Emerg. Technol. 17 , 19–45. https://doi.org/10.3991/ijet.v17i02.28197 (2022).

Cao, Y. Y., Li, J. J. & Qin, X. H. Post-adoption behavior of SNS users: An integrative model of emotional attachment and ECM-IS. Mod. Inf. 36 , 81–88 (2016).

Zhang, H. & Yao, R. H. Research on the influencing factors of the continuous use intention of mobile government APP users from the perspective of ECM-IS. J. Chongqing Univ. Posts Telecommun. (Soc. Sci. Edn). 32 , 92–101. https://doi.org/10.3969/j.issn.1673-5188.2020.01.14 (2020).

Gao, L. & Hu, C. Analysis of the influencing factors on user’s continuous usage behavior in online knowledge community service. Mod. Inf. 34 , 14–17 (2014).

Lin, L. Research on the Influencing Factors of Consumers' Mobile Shopping Behavior in App . (Beijing Institute of Technology, 2015).

Zhou, P., Fu, S. Y. & Zhao, Y. C. Empirical research on the influencing factors of shopping app users’ continuous use. J. Nanjing Norm. Univ. (Nat. Sci. Edn). 43 , 140–148. https://doi.org/10.3969/j.issn.1001-4616.2020.02.15 (2020).

Wang, F. Research on the influencing factors of the continuous use intention of mobile library users. J. Libr. Work Study. 2017 , 50–56. https://doi.org/10.16384/j.cnki.lwas.2017.07.009 (2017).

Guo, C. & Ming, J. Integrated model and empirical research on the continuous use intention of mobile library users. Mod. Inf. 40 , 79–89 (2020).

Hsu, C. L. & Lin, J. C. What drives purchase intention for paid mobile apps?—An expectation confirmation model with perceived value. Electron. Commer. R A. 14 , 46–57. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.elerap.2014.11.002 (2015).

Yang, G. F. Research on the influencing factors of mobile reading user satisfaction and continuous use intention: Taking content aggregation APP as an example. Mod. Inf. 35 , 57–63 (2015).

CAS Google Scholar

Alali, H. & Salim, J. Virtual communities of practice success model to support knowledge sharing behaviour in healthcare sector. Proc. Technol. 9 , 176–183. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.protcy.2013.12.019 (2013).

Hung, M. C., Hwang, H. G. & Hsieh, T. C. An exploratory study on the continuance of mobile commerce: An extension-confirmation model of information system use. Int. J. Mob. Commun. 5 , 409–422 (2007).

Thong, J. Y. L., Hong, S. J. & Tam, K. Y. The effects of post-adoption beliefs on the expectation-confirmation model for technology continuance. Int. J. Hum.-Comput. Stud. 64 , 799–810. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijhcs.2006.05.001 (2006).

Liu, H., Pei, L. & Sun, J. An empirical analysis of the continuous usage of video website users based on expectation confirmation model. Inf. Knowl. 2014 , 94–103. https://doi.org/10.13366/j.dik.2014.03.094 (2014).

Yang, T. User continuous use behavior of electronic books: Extension of the expected confirmation model. J. Libr. Sci. Res. 2016 , 76–83. https://doi.org/10.15941/j.cnki.issn1001-0424.2016.22.014 (2016).

Joo, S. & Choi, N. Understanding users’ continuance intention to use online library resources based on an extended expectation-confirmation model. Electron. Libr. 34 , 554–571. https://doi.org/10.1108/EL-02-2015-0025 (2016).

Chow, W. S. & Shi, S. Investigating students’ satisfaction and continuance intention toward e-learning: An extension of the expectation-confirmation model. Proc. Soc. Behav. Sci. 141 , 1145–1149. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sbspro.2014.05.197 (2014).

Hoffman, D. L. & Novak, T. P. Marketing in hypermedia computer-mediated environments: Conceptual foundations. J. Market. 60 , 50–68 (1996).

Zhang, C. B. & Wu, B. Review of website perceived interactivity research. China Circ. Econ. 30 , 117–127. https://doi.org/10.14089/j.cnki.cn11-3664/f.2016.06.017 (2016).

Van Noort, G., Voorveld, H. A. & Van Reijmersdal, E. A. Interactivity in brand websites: Cognitive, affective, and behavioral responses explained by consumers’ online flow experience. J. Interact. Mark. 26 , 223–234. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.intmar.2011.11.002 (2012).

Gefen, D., Karahanna, E. & Straub, D. W. Trust and TAM in online shopping: An integrated model. MIS Q. 27 , 51–90. https://doi.org/10.2307/30036519 (2003).

Kim, J., Spielmann, N. & McMillan, S. J. Experience effects on interactivity: Functions, processes, and perception in online shopping. J. Bus. Res. 65 , 1543–1550. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2011.10.013 (2012).

Park, M. & Park, J. K. Exploring the influences of perceived interactivity on consumers’ e-shopping effectiveness. J. Custom. Behav. 8 , 361–379. https://doi.org/10.1362/147539209X480990 (2009).

Song, J. H. & Zinkhan, G. M. Determinants of perceived website interactivity. J. Market. 72 , 99–113. https://doi.org/10.1509/jmkg.72.2.99 (2008).

Lee, M. C. Explaining and predicting users’ continuance intention toward e-learning: An extension of the expectation-confirmation model. Comput. Educ. 54 (2), 506–516 (2010).

Venkatesh, R. Computation of elastic moduli and dispersion in (s-d) interactive atomic liquids. The example of liquid Pt and Pd metals. Phys. Status Solidi (b). 176 (1), 91–99 (1993).

Article ADS CAS Google Scholar

Wang, Y. S. & Liao, Y. W. Assessing e-government systems success: A validation of the Delone and McLean model of information systems success. Gov. Inf. Q. 25 (4), 717–733 (2008).

Roca, J. C., Chiu, C. M. & Martínez, F. J. Understanding e-learning continuance intention: An extension of the technology acceptance model. Int. J. Hum.-Comput. Stud. 64 (8), 683–696 (2006).

Kettanurak, V. N., Ramamurthy, K. & Haseman, W. D. User attitude as a mediator of learning performance improvement in an interactive multimedia environment: An empirical investigation of the degree of interactivity and learning styles. Int. J. Hum. Comput. Stud. 54 (4), 541–583 (2001).

Yang, G. F. Research on influencing factors of continuance usage intention of MOOC users. Open Educ. Res. 22 (1), 100–111 (2016).

Zhao, L. & Lu, Y. Enhancing perceived interactivity through network externalities: An empirical study on micro-blogging service satisfaction and continuance intention. Decis. Support Syst. 53 (4), 825–834 (2012).

Grönroos, C. Keynote paper from marketing mix to relationship marketing—Towards a paradigm shift in marketing. Manag. Decis. 35 (4), 322–399 (1997).

Rodríguez-Ardura, I. & Meseguer-Artola, A. What leads people to keep on e-learning? An empirical analysis of learners’ experiences and their effects on continuance intention. Interact. Learn. Environ. 24 (6), 1030–1053 (2016).

Podsakoff, P. M. et al. Common method biases in behavioral research: A critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. J. Appl. Psychol. 88 , 879–950. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.88.5.879 (2003).

Article PubMed Google Scholar

Jordan, P. J. & Troth, A. C. Common method bias in applied settings: The dilemma of researching in organizations. Aust. J. Manag. 45 , 3–14. https://doi.org/10.1177/0312896219871976 (2020).

Brunner, M. & Suess, H. How precisely can cognitive abilities be measured? The distinction between composite and construct reliabilities in intelligence assessment exemplified with the Berlin Intelligence Structure Test. Diagnostica. 53 , 184–193. https://doi.org/10.1026/0012-1924.53.4.184 (2007).

Peterson, R. A. & Kim, Y. On the relationship between coefficient alpha and composite reliability. J. Appl. Psychol. 98 , 194–198. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0030767 (2013).

Aguirre-Urreta, M. I., Ronkko, M. & McIntosh, C. N. A cautionary note on the finite sample behavior of maximal reliability. Psychol. Methods. 24 , 236–252. https://doi.org/10.1037/met0000176 (2019).

Koran, J. Indicators per factor in confirmatory factor analysis: More is not always better. Struct. Equ. Model. Multidiscip. J. 27 , 765–772. https://doi.org/10.1080/10705511.2019.1706527 (2020).

Article MathSciNet Google Scholar

Fu, Y., Wen, Z. & Wang, Y. A comparison of reliability estimation based on confirmatory factor analysis and exploratory structural equation models. Educ. Psychol. Meas. 82 , 205–224. https://doi.org/10.1177/00131644211008953 (2022).

Dhami, S. K. & Al-Emran, M. A meta-analysis of the factors affecting the quality of online learning. Int. J. Educ. Technol. H. 19 , 1–22. https://doi.org/10.1186/s41239-022-00403-3 (2022).

Kim, S. Y. & Frick, T. W. Factors influencing adult learners’ satisfaction with online learning: A meta-analysis. Internet High. Educ. 53 , 100801. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.iheduc.2022.100801 (2022).

Oluwatayo, A. E. & Adepoju, T. O. The challenges and opportunities of online learning for adult learners: A systematic review. Int. J. Educ. Technol. H. 20 , 1–27. https://doi.org/10.1186/s41239-022-00422-0 (2023).

Alzahrani, A. I. & Aljohani, N. R. A systematic review of online learning platforms: Features, affordances, and limitations. J. Comput. Assist. Learn. 37 , 559–588. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcal.12527 (2021).

Sun, C. Teaching reform in classrooms based on college students' course experience and modern educational technology in China. (2021).

Zhang, H. & Zhao, G. Research on adult learners’ satisfaction with online education platforms. J. Distance Educ. 35 , 10–16. https://doi.org/10.16009/j.cnki.cn44-1162/g4.2023.03.010 (2023).

Lee, K. M. et al. Autonomic machine learning platform. Int. J. Inf. Manag. 49 , 491–501. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijinfomgt.2019.07.003 (2019).

Lanubile, F., Martinez-Fernandez, S. & Quaranta, L. Training future machine learning engineers: A project-based course on MLOps. IEEE Softw. 41 , 60–67. https://doi.org/10.1109/MS.2023.3310768 (2024).

Alhothali, A. et al. Predicting student outcomes in online courses using machine learning techniques: A review. Sustainability Basel https://doi.org/10.3390/su14106199 (2022).

Chen, Y. Association analysis of online learning behaviour in interactive education based on an intelligent concept machine. Int. J. Contin. Eng. Educ. 30 , 161–175 (2020).

Alzahrani, A. I. & Aljohani, N. R. Factors affecting the quality of online learning: A systematic review of the literature. Educ. Technol. Soc. 24 , 28–48. https://doi.org/10.14751/et&s.2021.423 (2021).

Download references

Acknowledgements

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Human Participants Ethics Committee Shanghai Normal University (No. 202345). We confirm that we have obtained informed consent from all participants.

This research received no external funding.

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

College of Continuing Education, Shanghai Normal University, Shanghai, China

Guoqiang Pan

School of Humanities, Shanghai Normal University, Shanghai, China

School of Education, Shanghai Normal University, Shanghai, China

Ziyuan Song

School of Foreign Language Studies, Shanghai University of Engineering Science, Shanghai, China

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Contributions

Conceptualization, G.P. and H.N.; methodology, G.P. and H.N.; validation, Z.S; investigation, G.P. and Y.M.; data curation, Y.M. and Z.Y.; writing—original draft preparation, G.P. and H.N.; writing—review and editing, G.P.; supervision, H.N.; project administration, G.P. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Correspondence to Guoqiang Pan or Hui Nie .

Ethics declarations

Competing interests.

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ .

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article.

Pan, G., Mao, Y., Song, Z. et al. Research on the influencing factors of adult learners' intent to use online education platforms based on expectation confirmation theory. Sci Rep 14 , 12762 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-63747-9

Download citation

Received : 12 January 2024

Accepted : 31 May 2024

Published : 04 June 2024

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-63747-9

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Adult learners

- Online education platform

- Expectation confirmation model

- Expectation confirmation

- Continuance intention

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines . If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.

Quick links

- Explore articles by subject

- Guide to authors

- Editorial policies

Sign up for the Nature Briefing newsletter — what matters in science, free to your inbox daily.

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- Elsevier - PMC COVID-19 Collection

A systematic review of research on online teaching and learning from 2009 to 2018

Associated data.

Systematic reviews were conducted in the nineties and early 2000's on online learning research. However, there is no review examining the broader aspect of research themes in online learning in the last decade. This systematic review addresses this gap by examining 619 research articles on online learning published in twelve journals in the last decade. These studies were examined for publication trends and patterns, research themes, research methods, and research settings and compared with the research themes from the previous decades. While there has been a slight decrease in the number of studies on online learning in 2015 and 2016, it has then continued to increase in 2017 and 2018. The majority of the studies were quantitative in nature and were examined in higher education. Online learning research was categorized into twelve themes and a framework across learner, course and instructor, and organizational levels was developed. Online learner characteristics and online engagement were examined in a high number of studies and were consistent with three of the prior systematic reviews. However, there is still a need for more research on organization level topics such as leadership, policy, and management and access, culture, equity, inclusion, and ethics and also on online instructor characteristics.

- • Twelve online learning research themes were identified in 2009–2018.

- • A framework with learner, course and instructor, and organizational levels was used.

- • Online learner characteristics and engagement were the mostly examined themes.

- • The majority of the studies used quantitative research methods and in higher education.

- • There is a need for more research on organization level topics.

1. Introduction

Online learning has been on the increase in the last two decades. In the United States, though higher education enrollment has declined, online learning enrollment in public institutions has continued to increase ( Allen & Seaman, 2017 ), and so has the research on online learning. There have been review studies conducted on specific areas on online learning such as innovations in online learning strategies ( Davis et al., 2018 ), empirical MOOC literature ( Liyanagunawardena et al., 2013 ; Veletsianos & Shepherdson, 2016 ; Zhu et al., 2018 ), quality in online education ( Esfijani, 2018 ), accessibility in online higher education ( Lee, 2017 ), synchronous online learning ( Martin et al., 2017 ), K-12 preparation for online teaching ( Moore-Adams et al., 2016 ), polychronicity in online learning ( Capdeferro et al., 2014 ), meaningful learning research in elearning and online learning environments ( Tsai, Shen, & Chiang, 2013 ), problem-based learning in elearning and online learning environments ( Tsai & Chiang, 2013 ), asynchronous online discussions ( Thomas, 2013 ), self-regulated learning in online learning environments ( Tsai, Shen, & Fan, 2013 ), game-based learning in online learning environments ( Tsai & Fan, 2013 ), and online course dropout ( Lee & Choi, 2011 ). While there have been review studies conducted on specific online learning topics, very few studies have been conducted on the broader aspect of online learning examining research themes.

2. Systematic Reviews of Distance Education and Online Learning Research