- History Classics

- Your Profile

- Find History on Facebook (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on Twitter (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on YouTube (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on Instagram (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on TikTok (Opens in a new window)

- This Day In History

- History Podcasts

- History Vault

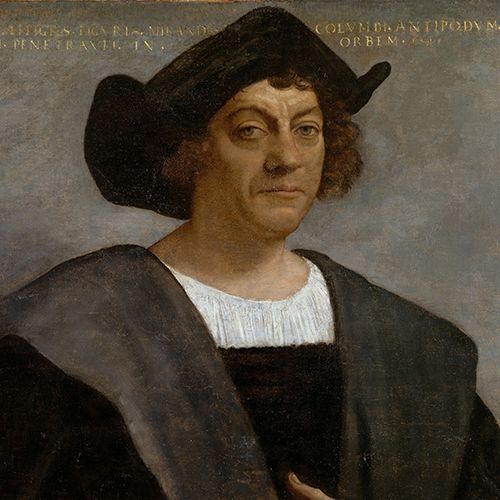

Christopher Columbus

By: History.com Editors

Updated: August 11, 2023 | Original: November 9, 2009

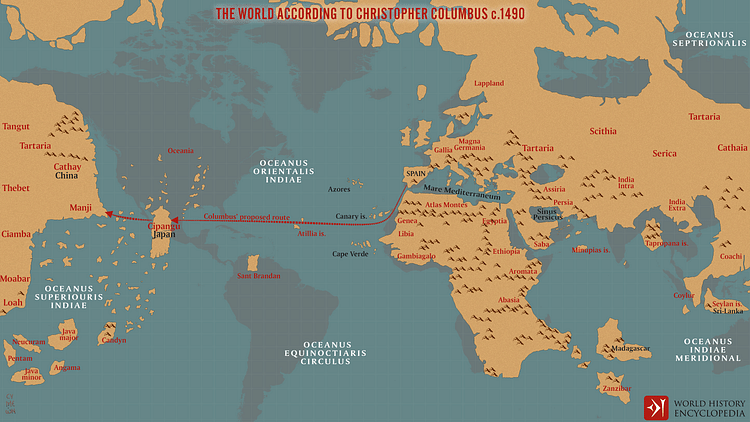

The explorer Christopher Columbus made four trips across the Atlantic Ocean from Spain: in 1492, 1493, 1498 and 1502. He was determined to find a direct water route west from Europe to Asia, but he never did. Instead, he stumbled upon the Americas. Though he did not “discover” the so-called New World—millions of people already lived there—his journeys marked the beginning of centuries of exploration and colonization of North and South America.

Christopher Columbus and the Age of Discovery

During the 15th and 16th centuries, leaders of several European nations sponsored expeditions abroad in the hope that explorers would find great wealth and vast undiscovered lands. The Portuguese were the earliest participants in this “ Age of Discovery ,” also known as “ Age of Exploration .”

Starting in about 1420, small Portuguese ships known as caravels zipped along the African coast, carrying spices, gold and other goods as well as enslaved people from Asia and Africa to Europe.

Did you know? Christopher Columbus was not the first person to propose that a person could reach Asia by sailing west from Europe. In fact, scholars argue that the idea is almost as old as the idea that the Earth is round. (That is, it dates back to early Rome.)

Other European nations, particularly Spain, were eager to share in the seemingly limitless riches of the “Far East.” By the end of the 15th century, Spain’s “ Reconquista ”—the expulsion of Jews and Muslims out of the kingdom after centuries of war—was complete, and the nation turned its attention to exploration and conquest in other areas of the world.

Early Life and Nationality

Christopher Columbus, the son of a wool merchant, is believed to have been born in Genoa, Italy, in 1451. When he was still a teenager, he got a job on a merchant ship. He remained at sea until 1476, when pirates attacked his ship as it sailed north along the Portuguese coast.

The boat sank, but the young Columbus floated to shore on a scrap of wood and made his way to Lisbon, where he eventually studied mathematics, astronomy, cartography and navigation. He also began to hatch the plan that would change the world forever.

Christopher Columbus' First Voyage

At the end of the 15th century, it was nearly impossible to reach Asia from Europe by land. The route was long and arduous, and encounters with hostile armies were difficult to avoid. Portuguese explorers solved this problem by taking to the sea: They sailed south along the West African coast and around the Cape of Good Hope.

But Columbus had a different idea: Why not sail west across the Atlantic instead of around the massive African continent? The young navigator’s logic was sound, but his math was faulty. He argued (incorrectly) that the circumference of the Earth was much smaller than his contemporaries believed it was; accordingly, he believed that the journey by boat from Europe to Asia should be not only possible, but comparatively easy via an as-yet undiscovered Northwest Passage .

He presented his plan to officials in Portugal and England, but it was not until 1492 that he found a sympathetic audience: the Spanish monarchs Ferdinand of Aragon and Isabella of Castile .

Columbus wanted fame and fortune. Ferdinand and Isabella wanted the same, along with the opportunity to export Catholicism to lands across the globe. (Columbus, a devout Catholic, was equally enthusiastic about this possibility.)

Columbus’ contract with the Spanish rulers promised that he could keep 10 percent of whatever riches he found, along with a noble title and the governorship of any lands he should encounter.

Where Did Columbus' Ships, Niña, Pinta and Santa Maria, Land?

On August 3, 1492, Columbus and his crew set sail from Spain in three ships: the Niña , the Pinta and the Santa Maria . On October 12, the ships made landfall—not in the East Indies, as Columbus assumed, but on one of the Bahamian islands, likely San Salvador.

For months, Columbus sailed from island to island in what we now know as the Caribbean, looking for the “pearls, precious stones, gold, silver, spices, and other objects and merchandise whatsoever” that he had promised to his Spanish patrons, but he did not find much. In January 1493, leaving several dozen men behind in a makeshift settlement on Hispaniola (present-day Haiti and the Dominican Republic), he left for Spain.

He kept a detailed diary during his first voyage. Christopher Columbus’s journal was written between August 3, 1492, and November 6, 1492 and mentions everything from the wildlife he encountered, like dolphins and birds, to the weather to the moods of his crew. More troublingly, it also recorded his initial impressions of the local people and his argument for why they should be enslaved.

“They… brought us parrots and balls of cotton and spears and many other things, which they exchanged for the glass beads and hawks’ bells," he wrote. "They willingly traded everything they owned… They were well-built, with good bodies and handsome features… They do not bear arms, and do not know them, for I showed them a sword, they took it by the edge and cut themselves out of ignorance. They have no iron… They would make fine servants… With fifty men we could subjugate them all and make them do whatever we want.”

Columbus gifted the journal to Isabella upon his return.

Christopher Columbus's Later Voyages

About six months later, in September 1493, Columbus returned to the Americas. He found the Hispaniola settlement destroyed and left his brothers Bartolomeo and Diego Columbus behind to rebuild, along with part of his ships’ crew and hundreds of enslaved indigenous people.

Then he headed west to continue his mostly fruitless search for gold and other goods. His group now included a large number of indigenous people the Europeans had enslaved. In lieu of the material riches he had promised the Spanish monarchs, he sent some 500 enslaved people to Queen Isabella. The queen was horrified—she believed that any people Columbus “discovered” were Spanish subjects who could not be enslaved—and she promptly and sternly returned the explorer’s gift.

In May 1498, Columbus sailed west across the Atlantic for the third time. He visited Trinidad and the South American mainland before returning to the ill-fated Hispaniola settlement, where the colonists had staged a bloody revolt against the Columbus brothers’ mismanagement and brutality. Conditions were so bad that Spanish authorities had to send a new governor to take over.

Meanwhile, the native Taino population, forced to search for gold and to work on plantations, was decimated (within 60 years after Columbus landed, only a few hundred of what may have been 250,000 Taino were left on their island). Christopher Columbus was arrested and returned to Spain in chains.

In 1502, cleared of the most serious charges but stripped of his noble titles, the aging Columbus persuaded the Spanish crown to pay for one last trip across the Atlantic. This time, Columbus made it all the way to Panama—just miles from the Pacific Ocean—where he had to abandon two of his four ships after damage from storms and hostile natives. Empty-handed, the explorer returned to Spain, where he died in 1506.

Legacy of Christopher Columbus

Christopher Columbus did not “discover” the Americas, nor was he even the first European to visit the “New World.” (Viking explorer Leif Erikson had sailed to Greenland and Newfoundland in the 11th century.)

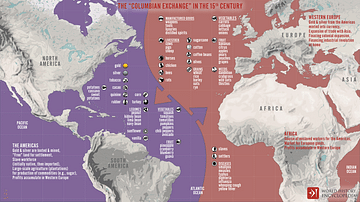

However, his journey kicked off centuries of exploration and exploitation on the American continents. The Columbian Exchange transferred people, animals, food and disease across cultures. Old World wheat became an American food staple. African coffee and Asian sugar cane became cash crops for Latin America, while American foods like corn, tomatoes and potatoes were introduced into European diets.

Today, Columbus has a controversial legacy —he is remembered as a daring and path-breaking explorer who transformed the New World, yet his actions also unleashed changes that would eventually devastate the native populations he and his fellow explorers encountered.

HISTORY Vault: Columbus the Lost Voyage

Ten years after his 1492 voyage, Columbus, awaiting the gallows on criminal charges in a Caribbean prison, plotted a treacherous final voyage to restore his reputation.

Sign up for Inside History

Get HISTORY’s most fascinating stories delivered to your inbox three times a week.

By submitting your information, you agree to receive emails from HISTORY and A+E Networks. You can opt out at any time. You must be 16 years or older and a resident of the United States.

More details : Privacy Notice | Terms of Use | Contact Us

Christopher Columbus

Italian explorer Christopher Columbus discovered the “New World” of the Americas on an expedition sponsored by King Ferdinand of Spain in 1492.

c. 1451-1506

Quick Facts

Where was columbus born, first voyages, columbus’ 1492 route and ships, where did columbus land in 1492, later voyages across the atlantic, how did columbus die, santa maria discovery claim, columbian exchange: a complex legacy, columbus day: an evolving holiday, who was christopher columbus.

Christopher Columbus was an Italian explorer and navigator. In 1492, he sailed across the Atlantic Ocean from Spain in the Santa Maria , with the Pinta and the Niña ships alongside, hoping to find a new route to Asia. Instead, he and his crew landed on an island in present-day Bahamas—claiming it for Spain and mistakenly “discovering” the Americas. Between 1493 and 1504, he made three more voyages to the Caribbean and South America, believing until his death that he had found a shorter route to Asia. Columbus has been credited—and blamed—for opening up the Americas to European colonization.

FULL NAME: Cristoforo Colombo BORN: c. 1451 DIED: May 20, 1506 BIRTHPLACE: Genoa, Italy SPOUSE: Filipa Perestrelo (c. 1479-1484) CHILDREN: Diego and Fernando

Christopher Columbus, whose real name was Cristoforo Colombo, was born in 1451 in the Republic of Genoa, part of what is now Italy. He is believed to have been the son of Dominico Colombo and Susanna Fontanarossa and had four siblings: brothers Bartholomew, Giovanni, and Giacomo, and a sister named Bianchinetta. He was an apprentice in his father’s wool weaving business and studied sailing and mapmaking.

In his 20s, Columbus moved to Lisbon, Portugal, and later resettled in Spain, which remained his home base for the duration of his life.

Columbus first went to sea as a teenager, participating in several trading voyages in the Mediterranean and Aegean seas. One such voyage, to the island of Khios, in modern-day Greece, brought him the closest he would ever come to Asia.

His first voyage into the Atlantic Ocean in 1476 nearly cost him his life, as the commercial fleet he was sailing with was attacked by French privateers off the coast of Portugal. His ship was burned, and Columbus had to swim to the Portuguese shore.

He made his way to Lisbon, where he eventually settled and married Filipa Perestrelo. The couple had one son, Diego, around 1480. His wife died when Diego was a young boy, and Columbus moved to Spain. He had a second son, Fernando, who was born out of wedlock in 1488 with Beatriz Enriquez de Arana.

After participating in several other expeditions to Africa, Columbus learned about the Atlantic currents that flow east and west from the Canary Islands.

The Asian islands near China and India were fabled for their spices and gold, making them an attractive destination for Europeans—but Muslim domination of the trade routes through the Middle East made travel eastward difficult.

Columbus devised a route to sail west across the Atlantic to reach Asia, believing it would be quicker and safer. He estimated the earth to be a sphere and the distance between the Canary Islands and Japan to be about 2,300 miles.

Many of Columbus’ contemporary nautical experts disagreed. They adhered to the (now known to be accurate) second-century BCE estimate of the Earth’s circumference at 25,000 miles, which made the actual distance between the Canary Islands and Japan about 12,200 statute miles. Despite their disagreement with Columbus on matters of distance, they concurred that a westward voyage from Europe would be an uninterrupted water route.

Columbus proposed a three-ship voyage of discovery across the Atlantic first to the Portuguese king, then to Genoa, and finally to Venice. He was rejected each time. In 1486, he went to the Spanish monarchy of Queen Isabella of Castile and Ferdinand II of Aragon. Their focus was on a war with the Muslims, and their nautical experts were skeptical, so they initially rejected Columbus.

The idea, however, must have intrigued the monarchs, because they kept Columbus on a retainer. Columbus continued to lobby the royal court, and soon, the Spanish army captured the last Muslim stronghold in Granada in January 1492. Shortly thereafter, the monarchs agreed to finance his expedition.

In late August 1492, Columbus left Spain from the port of Palos de la Frontera. He was sailing with three ships: Columbus in the larger Santa Maria (a type of ship known as a carrack), with the Pinta and the Niña (both Portuguese-style caravels) alongside.

On October 12, 1492, after 36 days of sailing westward across the Atlantic, Columbus and several crewmen set foot on an island in present-day Bahamas, claiming it for Spain.

There, his crew encountered a timid but friendly group of natives who were open to trade with the sailors. They exchanged glass beads, cotton balls, parrots, and spears. The Europeans also noticed bits of gold the natives wore for adornment.

Columbus and his men continued their journey, visiting the islands of Cuba (which he thought was mainland China) and Hispaniola (now Haiti and the Dominican Republic, which Columbus thought might be Japan) and meeting with the leaders of the native population.

During this time, the Santa Maria was wrecked on a reef off the coast of Hispaniola. With the help of some islanders, Columbus’ men salvaged what they could and built the settlement Villa de la Navidad (“Christmas Town”) with lumber from the ship.

Thirty-nine men stayed behind to occupy the settlement. Convinced his exploration had reached Asia, he set sail for home with the two remaining ships. Returning to Spain in 1493, Columbus gave a glowing but somewhat exaggerated report and was warmly received by the royal court.

In 1493, Columbus took to the seas on his second expedition and explored more islands in the Caribbean Ocean. Upon arrival at Hispaniola, Columbus and his crew discovered the Navidad settlement had been destroyed with all the sailors massacred.

Spurning the wishes of the local queen, Columbus established a forced labor policy upon the native population to rebuild the settlement and explore for gold, believing it would be profitable. His efforts produced small amounts of gold and great hatred among the native population.

Before returning to Spain, Columbus left his brothers Bartholomew and Giacomo to govern the settlement on Hispaniola and sailed briefly around the larger Caribbean islands, further convincing himself he had discovered the outer islands of China.

It wasn’t until his third voyage that Columbus actually reached the South American mainland, exploring the Orinoco River in present-day Venezuela. By this time, conditions at the Hispaniola settlement had deteriorated to the point of near-mutiny, with settlers claiming they had been misled by Columbus’ claims of riches and complaining about the poor management of his brothers.

The Spanish Crown sent a royal official who arrested Columbus and stripped him of his authority. He returned to Spain in chains to face the royal court. The charges were later dropped, but Columbus lost his titles as governor of the Indies and, for a time, much of the riches made during his voyages.

After convincing King Ferdinand that one more voyage would bring the abundant riches promised, Columbus went on his fourth and final voyage across the Atlantic Ocean in 1502. This time he traveled along the eastern coast of Central America in an unsuccessful search for a route to the Indian Ocean.

A storm wrecked one of his ships, stranding the captain and his sailors on the island of Cuba. During this time, local islanders, tired of the Spaniards’ poor treatment and obsession with gold, refused to give them food.

In a spark of inspiration, Columbus consulted an almanac and devised a plan to “punish” the islanders by taking away the moon. On February 29, 1504, a lunar eclipse alarmed the natives enough to re-establish trade with the Spaniards. A rescue party finally arrived, sent by the royal governor of Hispaniola in July, and Columbus and his men were taken back to Spain in November 1504.

In the two remaining years of his life, Columbus struggled to recover his reputation. Although he did regain some of his riches in May 1505, his titles were never returned.

Columbus probably died of severe arthritis following an infection on May 20, 1506, in Valladolid, Spain. At the time of his death, he still believed he had discovered a shorter route to Asia.

There are questions about the location of his burial site. According to the BBC , Columbus’ remains moved at least three or four times over the course of 400 years—including from Valladolid to Seville, Spain, in 1509; then to Santo Domingo, in what is now the Dominican Republic, in 1537; then to Havana, Cuba, in 1795; and back to Seville in 1898. As a result, Seville and Santo Domingo have both laid claim to being Columbus’ true burial site. It is also possible his bones were mixed up with another person’s amid all of their travels.

In May 2014, Columbus made headlines as news broke that a team of archaeologists might have found the Santa Maria off the north coast of Haiti. Barry Clifford, the leader of this expedition, told the Independent newspaper that “all geographical, underwater topography and archaeological evidence strongly suggests this wreck is Columbus’ famous flagship the Santa Maria.”

After a thorough investigation by the U.N. agency UNESCO, it was determined the wreck dates from a later period and was located too far from shore to be the famed ship.

Columbus has been credited for opening up the Americas to European colonization—as well as blamed for the destruction of the native peoples of the islands he explored. Ultimately, he failed to find that what he set out for: a new route to Asia and the riches it promised.

In what is known as the Columbian Exchange, Columbus’ expeditions set in motion the widespread transfer of people, plants, animals, diseases, and cultures that greatly affected nearly every society on the planet.

The horse from Europe allowed Native American tribes in the Great Plains of North America to shift from a nomadic to a hunting lifestyle. Wheat from the Old World fast became a main food source for people in the Americas. Coffee from Africa and sugar cane from Asia became major cash crops for Latin American countries. And foods from the Americas, such as potatoes, tomatoes and corn, became staples for Europeans and helped increase their populations.

The Columbian Exchange also brought new diseases to both hemispheres, though the effects were greatest in the Americas. Smallpox from the Old World killed millions, decimating the Native American populations to mere fractions of their original numbers. This more than any other factor allowed for European domination of the Americas.

The overwhelming benefits of the Columbian Exchange went to the Europeans initially and eventually to the rest of the world. The Americas were forever altered, and the once vibrant cultures of the Indigenous civilizations were changed and lost, denying the world any complete understanding of their existence.

As more Italians began to immigrate to the United States and settle in major cities during the 19 th century, they were subject to religious and ethnic discrimination. This included a mass lynching of 11 Sicilian immigrants in 1891 in New Orleans.

Just one year after this horrific event, President Benjamin Harrison called for the first national observance of Columbus Day on October 12, 1892, to mark the 400 th anniversary of his arrival in the Americas. Italian-Americans saw this honorary act for Columbus as a way of gaining acceptance.

Colorado became the first state to officially observe Columbus Day in 1906 and, within five years, 14 other states followed. Thanks to a joint resolution of Congress, the day officially became a federal holiday in 1934 during the administration of Franklin D. Roosevelt . In 1970, Congress declared the holiday would fall on the second Monday in October each year.

But as Columbus’ legacy—specifically, his exploration’s impacts on Indigenous civilizations—began to draw more criticism, more people chose not to take part. As of 2023, approximately 29 states no longer celebrate Columbus Day , and around 195 cities have renamed it or replaced with the alternative Indigenous Peoples Day. The latter isn’t an official holiday, but the federal government recognized its observance in 2022 and 2023. President Joe Biden called it “a day in honor of our diverse history and the Indigenous peoples who contribute to shaping this nation.”

One of the most notable cities to move away from celebrating Columbus Day in recent years is the state capital of Columbus, Ohio, which is named after the explorer. In 2018, Mayor Andrew Ginther announced the city would remain open on Columbus Day and instead celebrate a holiday on Veterans Day. In July 2020, the city also removed a 20-plus-foot metal statue of Columbus from the front of City Hall.

- I went to sea from the most tender age and have continued in a sea life to this day. Whoever gives himself up to this art wants to know the secrets of Nature here below. It is more than forty years that I have been thus engaged. Wherever any one has sailed, there I have sailed.

- Speaking of myself, little profit had I won from twenty years of service, during which I have served with so great labors and perils, for today I have no roof over my head in Castile; if I wish to sleep or eat, I have no place to which to go, save an inn or tavern, and most often, I lack the wherewithal to pay the score.

- They say that there is in that land an infinite amount of gold; and that the people wear corals on their heads and very large bracelets of coral on their feet and arms; and that with coral they adorn and inlay chairs and chests and tables.

- This island and all the others are very fertile to a limitless degree, and this island is extremely so. In it there are many harbors on the coast of the sea, beyond comparison with others that I know in Christendom, and many rivers, good and large, which is marvelous.

- Our Almighty God has shown me the highest favor, which, since David, he has not shown to anybody.

- Already the road is opened to gold and pearls, and it may surely be hoped that precious stones, spices, and a thousand other things, will also be found.

- I have now seen so much irregularity, that I have come to another conclusion respecting the earth, namely, that it is not round as they describe, but of the form of a pear.

- In all the countries visited by your Highnesses’ ships, I have caused a high cross to be fixed upon every headland and have proclaimed, to every nation that I have discovered, the lofty estate of your Highnesses and of your court in Spain.

- I ought to be judged as a captain sent from Spain to the Indies, to conquer a nation numerous and warlike, with customs and religions altogether different to ours.

Fact Check: We strive for accuracy and fairness. If you see something that doesn’t look right, contact us !

The Biography.com staff is a team of people-obsessed and news-hungry editors with decades of collective experience. We have worked as daily newspaper reporters, major national magazine editors, and as editors-in-chief of regional media publications. Among our ranks are book authors and award-winning journalists. Our staff also works with freelance writers, researchers, and other contributors to produce the smart, compelling profiles and articles you see on our site. To meet the team, visit our About Us page: https://www.biography.com/about/a43602329/about-us

Tyler Piccotti first joined the Biography.com staff as an Associate News Editor in February 2023, and before that worked almost eight years as a newspaper reporter and copy editor. He is a graduate of Syracuse University. When he's not writing and researching his next story, you can find him at the nearest amusement park, catching the latest movie, or cheering on his favorite sports teams.

Watch Next .css-avapvh:after{background-color:#525252;color:#fff;margin-left:1.8rem;margin-top:1.25rem;width:1.5rem;height:0.063rem;content:'';display:-webkit-box;display:-webkit-flex;display:-ms-flexbox;display:flex;}

Possible Evidence of Amelia Earhart’s Plane

Charles Lindbergh

Was Christopher Columbus a Hero or Villain?

History & Culture

27 Essential Memoirs That Will Leave You Inspired

Who Designed the American Flag?

Hunter Biden

Karl Lagerfeld

Plane Flown by ‘Ace of Aces’ Pilot Finally Found

Barron Trump

Alexander McQueen

Christopher Columbus

Christopher Columbus (l. 1451-1506 CE, also known as Cristoffa Corombo in Ligurian and Cristoforo Colombo in Italian) was a Genoese explorer (identified as Italian) who became famous in his own time as the man who discovered the New World and, since the 19th century CE, is credited with the discovery of North America, specifically the region comprising the United States.

Actually, owing to the early 16th-century CE popularity of the published letters of the Florentine explorer Amerigo Vespucci (l. 1454-1512 CE), detailing his three voyages to the “New World” between 1497-1504 CE, the discovery of the Americas has been credited to him on world maps beginning in 1506 CE which is why the continents bear the feminine version of his name.

Columbus made four voyages to the area of the Caribbean, exploring Cuba, Central America, South America, Puerto Rico, the Virgin Islands, the Dominican Republic, Haiti, the islands of the Bahamas, and others between 1492-1504 CE:

- First Voyage: 1492-1493 CE

- Second Voyage: 1493-1496 CE

- Third Voyage: 1498-1500 CE

- Fourth Voyage: 1502-1504 CE

Columbus never set out to discover a New World, but to find a western sea route to the Far East to facilitate trade after the land route of the Silk Road , between Europe and the East, had been closed by the Ottoman Empire in 1453 CE, initiating the so-called Age of Exploration (also known as the Age of Discovery) which launched many European sea expeditions. Columbus' first voyage brought him to one of the islands of the Bahamas on 12 October 1492 CE, which he claimed in the name of the monarchs Ferdinand II of Aragon and his wife Isabella of Castile of Spain. His next three voyages were made to consolidate Spain's control of the region and establish colonies.

Columbus is acknowledged as the first to establish contact between Europe and the Americas known as the Columbian Exchange whereby people, plants, technology, and other aspects of culture passed between the Old and the New World, transforming both and establishing the foundation for the modern age.

Although modern-day detractors of Columbus cite the Norse community in Newfoundland as the first “discovery of America”, the Vikings under Leif Erikson , who landed in North America centuries before Columbus, had no effect on the indigenous population and their return to Greenland afterwards inspired no further expeditions.

Columbus' journeys, by contrast, opened the way for later European expeditions, but he himself never claimed to have discovered America. The story of his “discovery of America” was established and first celebrated in A History of the Life and Voyages of Christopher Columbus by the American author Washington Irving (l. 1783-1859 CE) published in 1828 CE and this narrative (largely fictional) would eventually contribute to the establishment of Columbus Day as a United States' holiday in 1906 CE, observed up through the present.

In the 1970s CE, however, a revaluation of Columbus and the effects of his voyages on the culture and people of the Americas has increasingly called for discarding this tradition in favor of honoring the indigenous people adversely affected by the four expeditions he made to the New World and the poor treatment of the original population at the hands of the European immigrants afterwards. This debate continues in the present.

Early Life & the Silk Road Closure

Columbus was born in Genoa in 1451 CE which was then in the region of Liguria and only much later (in 1861 CE) would become part of Italy . He had three brothers – Bartolomeo, Giovanni, and Giacomo (regularly referred to as Diego), and a sister, Bianchinetta. His father, Domenico, was a weaver and tavern-keeper whose love of sea travel would significantly influence young Columbus and his mother, Susanna, a housewife.

Little is known of Columbus' early life (though he claims to have been sailing by age ten) but, by the time he was 20 years old, he was already experienced at seamanship (having traveled to Iceland and the Aegean Sea) and, by 1476 CE, he was entrusted with his own command of a trading vessel. He was married to the Portuguese noblewoman Filipa Moniz Perestrelo and had a son, Diego, by 1480 CE and, by 1485 CE, was piloting ships to areas along the coast of West Africa in the service of Portugal's trade interests.

The Silk Road was comprised of numerous routes, parts of which fell under the control of one group or nationality or another at various times in its history. The European explorer Marco Polo (l. 1254-1324 CE) traveled the Silk Road and dictated details of it in his book after he returned which provided later travelers with a kind of guide and also helped them establish distances between Europe and the East.

The Silk Road was predominantly controlled by the Mongol Empire until its fall in 1368 CE after which the Byzantine Empire (330-1453 CE) kept goods flowing in both directions. The Byzantines fell to the Ottoman Turks in 1453 CE, however, who then closed the overland routes and cut European merchants off from Eastern goods. In an effort to re-establish trade with the East, European merchants took to the sea, launching the so-called Age of Discovery.

The Age of Discovery & Funding

This is not to say that Europeans had no knowledge of sea travel at this time nor that European merchants suddenly scrambled to build ships or hastily draw inaccurate maps. The magnetic compass was known in Europe by 1180 CE and, using ancient texts such as Strabo's Geography and Pliny the Elder 's Natural History as well as long-established maps, European pilots were able to navigate the waters and continue trade with the East via the Black Sea.

The problem they faced, however, was Muslim Arab traders who controlled a number of significant sea routes to the East. Portuguese mariners began looking into other possible sea routes to the East, and one contributor to this effort was the Florentine astrologer and mathematician Paolo dal Pozzo Toscanelli (l. 1397-1482 CE) who had transcribed a map of the world of the ancient geographer Strabo (l. 63 BCE - 23 CE) and presented a copy to King Alfonso V of Portugal (r. 1438-1481 CE), suggesting sailing west in order to reach the Cathay (China) in the East.

Sign up for our free weekly email newsletter!

Alfonso V rejected Toscanelli's proposal and so the latter sent the copy of the map to Columbus, who by now had a reputation as an expert navigator and seaman, in 1474 CE. Columbus was still sailing in the interests of Portugal at this time, and he and his brothers were also engaged in working out a sea route to Cathay. Columbus had taught himself Latin, Spanish, and Portuguese and so was able to access a wide range of documents and maps in developing his vision of a voyage across the Atlantic Ocean to establish a new trade route with Cathay.

The Columbus brothers put together a plan and, c. 1484 CE, Columbus approached King John II of Portugal (r. 1481-1495 CE) to request funding. Columbus, basing his calculations on Toscanelli's map, Marco Polo's work, and other documents, estimated the distance from the Canary Islands to Cathay at around 2,300 miles (3,700 km), but King John II rejected the plan on the grounds that Columbus' estimate of the distance was too low (which proved to be true, as the distance was actually 12,200 statute miles or 19,600 km). Columbus then brought his proposal to the governments of Genoa and Venice but was rejected by both.

He then turned to Ferdinand II and Isabella I of Spain who also rejected him but were intrigued enough by his plan that they kept him on retainer, paying him a significant sum to keep him from proposing the expedition to any other government. Ferdinand and Isabella were in the midst of their own problems trying to drive the Muslim Arabs, known as the Moors, from their territory in the effort which has since come to be known as the Reconquista (711-1492 CE). The last stronghold of the Moors at Granada fell in 1492 CE, and, afterwards, Columbus was granted the three ships and funding he had requested.

The Voyages

Columbus left port on 3 August 1492 CE in his famous ships the Nina , Pinta , and Santa Maria . His main objective was reaching Cathay, but it was also made clear that he was to claim any lands not already under a sovereign nation for Spain and to the honor of the Catholic Church. To this end, he was given two official documents:

- A contract between him and the crown promising the monarchy 90% of the profits of the venture in return for funding and stipulating that Columbus was awarded the position of viceroy or governor of any lands he took for the crown.

- A letter of introduction from Ferdinand and Isabella requesting any monarch Columbus came in contact with to provide him safe passage and provision as his mission was in the service of the Christian faith.

First Voyage - 1492-1493 CE : He arrived at an island in the Caribbean on 12 October 1492 CE and was greeted by a large gathering of indigenous people on the beach. He summoned the captains of the Nina and Pinta and rowed to shore along with the secretary of the fleet and the royal inspector. He knew he had not landed at Cathay but believed he had discovered an island near to his objective which, as far as he could tell, was not claimed by any sovereign nation and so he claimed it for Spain, and this was duly noted by his witnesses.

He was given to understand by the natives that their island was called Guanahani, but he named it San Salvador (still its present name in the Bahamas). The natives (the Arawaks) probably also gave him the name they called themselves, but he referred to them as indios and so established the use of the term Indian for the people of the region and, later, for those of North, Central, and South America. No mention is made of the reactions of the people who had come to greet them, and, shortly afterwards, the five Europeans and the native islanders exchanged gifts of friendship.

Second Voyage - 1493-1496 CE : Columbus arrived back in the New World as governor of the lands he had claimed with a fleet of 17 ships full of colonists to establish communities for Spain as well as a number of dogs to be used in subduing the natives. The Mastiff had been successfully used by the Spanish against the Moors in the Reconquista and so were included as an important asset in Columbus' second voyage.

The dogs terrorized the native people, hunted down those who were accused of dereliction of duty, and broke any attempts at resistance to the European conquest . When he arrived in Jamaica in 1494 CE, he was opposed by defenders on the beach until he released the savage mastiffs which terrorized the indigenous warriors and scattered them.

The Second Voyage established the encomienda system in which Spanish settlers claimed a large tract of land on which the natives provided labor in return for food, shelter, and protection from those they labored for. By 1495 CE, the indigenous population had decreased, according to the later works of Las Casas, by 50,000 and, although that number is considered an exaggeration by many modern scholars, it is most likely too low.

The natives of the region were reduced from autonomous individuals with an established culture to slaves who could be tortured or killed for any reason at any time and suffered significant losses through European diseases they had no immunity from. Losses also stemmed from a significant portion of the populace shipped off to Europe as slaves.

Third Voyage - 1498-1500 CE : Although the Europeans had now firmly established themselves in the New World, Columbus had yet to find a way through the islands he had so far visited and reach Cathay. He was certain that the lands he had colonized for Spain were outliers of the continent of Asia and so, after his return to Spain in 1496 CE, his Third Voyage was funded to establish this; instead, he located the regions of modern-day Central and South America.

By this time, Columbus' colonists were actively engaged in capturing and selling the natives as slaves and further abusing them daily. Columbus objected to this treatment of the natives and punished the colonists severely which resulted in a charge of tyranny and corruption (as he was interfering with business practices) brought against him in 1499 CE. He and his brother Diego were arrested and sent back to Spain to answer charges. They were acquitted by Ferdinand and Isabella, equipped with new ships, and sent back to the New World.

On his own, Columbus explored the islands off Honduras, mapped Costa Rica and other sites, and was sailing on when a storm drove his ship toward Jamaica where it was wrecked. The natives despised him and refused any aid, and the regional governors of the area felt the same and would not send a rescue ship. Columbus finally frightened the natives into assisting him by claiming he would take the great light from the sky if they did not and then accurately predicted the lunar eclipse of 29 February 1504 CE, claiming to have restored the light once help was promised. He and his men were eventually rescued, largely through their own efforts, and Columbus returned to Spain where, in ill health, he died in Valladolid in May of 1506 CE.

Modern-day evaluations of historical figures and events are frequently guilty of the fallacy of presentism – judging the past by the standards and ideologies of the present – and the life and voyages of Christopher Columbus stand as one of the best, if not the best, examples of this. Prior to the publication in 1828 CE of A History of the Life and Voyages of Christopher Columbus by Washington Irving, Columbus was almost unknown in the United States. His book on Columbus, more historical or romantic fiction than history, was interpreted as a scholarly work on the life and adventures of an intrepid European explorer who had “discovered America” and went on to inform United States' history up to the present day.

Columbus never claimed to have “discovered America” and neither is there anything in his journals or the writings of near-contemporaries to suggest that scholars of his day believed the earth was flat while he proved it was round (it was well known in 1492 CE that the earth was round), nor that he “got lost” while searching for a route to India , landed in some strange place he thought was his destination, and so named the native people Indians. Most, if not all, of the myths commonly cited as history concerning Columbus were the creations of Irving who was only trying to tell a good story.

Irving's Columbus was a brave and noble adventurer who risked his life and that of his crew to extend European knowledge of the world and establish a vital link between the Old World and New. The book was so popular that it informed the decision of U.S. President Benjamin Harrison (served 1889-1893 CE) to proclaim a national day of observance in Columbus' honor in 1892 CE, on the 400th anniversary of Columbus' arrival. The state of Colorado would later be the first to observe this holiday in 1906 CE and other states followed suit afterwards.

The present movement to rename and rededicate Columbus Day in honor of indigenous people is understandable and admirable, but the opposing side, arguing to continue the tradition of honoring him, also has merit, especially when one considers what it meant to Italian-Americans, frequently persecuted in the United States in the late 19th and early 20th centuries CE, to have an "American Hero" defined as "Italian" by Irving and recognized as such by the American majority. It was largely the efforts of Italian-American community groups, in fact, which helped establish the holiday to begin with.

Healing past wounds must begin with a dialogue which recognizes the underlying causes and long-term effects of Columbus' atrocities while also acknowledging his accomplishments. However one judges Columbus in the present day, he was a product of his time who behaved toward non-Europeans precisely as one would expect a 15th-century CE European Christian to do and, unfortunately, far better than the colonizers and conquerors who came to the New World after him.

Subscribe to topic Related Content Books Cite This Work License

Bibliography

- Columbus, C. & Cohen, J. The Four Voyages of Christopher Columbus. Penguin, 2004.

- Crosby Jr., A. W. The Columbian Exchange: Biological and Cultural Consequences of 1492. Praeger, 2003.

- de Las Casas, B. & Griffin, N. & Pagden, A. A Short Account of the Destruction of the Indies. Penguin Classics, 2000.

- Five Myths about Christopher Columbus by Kris Lane for the Washington Post Accessed 8 Oct 2020.

- Hansen, V. The Silk Road. Oxford University Press, 2010.

- Introduction to Christopher Columbus, Journal of the First Voyage by B. W. Ife Accessed 8 Oct 2020.

- Irving, W. History of the Life and Voyages of Christopher Columbus. Wentworth Press, 2010.

- Morison, S. E. Admiral of the Ocean Sea - A Life of Christopher Columbus. Morison Press, 2007.

- Osborne, R. Civilization: A New History of the Western World. Pegasus Books, 2008.

- Parker, C. H. Global Interactions in the Early Modern Age, 1400 -1800. Cambridge University Press, 2010.

About the Author

Translations

We want people all over the world to learn about history. Help us and translate this definition into another language!

Related Content

European Colonization of the Americas

Silk in Antiquity

Columbian Exchange

How an Adventure-loving American Saved the Thai Silk Industry

Free for the world, supported by you.

World History Encyclopedia is a non-profit organization. For only $5 per month you can become a member and support our mission to engage people with cultural heritage and to improve history education worldwide.

Recommended Books

| , published by Wentworth Press (2019) |

| , published by Pegasus Books (2008) |

| , published by Penguin (2004) |

| , published by Read Books (2007) |

| , published by Praeger (2003) |

External Links

Cite this work.

Mark, J. J. (2020, October 12). Christopher Columbus . World History Encyclopedia . Retrieved from https://www.worldhistory.org/Christopher_Columbus/

Chicago Style

Mark, Joshua J.. " Christopher Columbus ." World History Encyclopedia . Last modified October 12, 2020. https://www.worldhistory.org/Christopher_Columbus/.

Mark, Joshua J.. " Christopher Columbus ." World History Encyclopedia . World History Encyclopedia, 12 Oct 2020. Web. 27 Jun 2024.

License & Copyright

Submitted by Joshua J. Mark , published on 12 October 2020. The copyright holder has published this content under the following license: Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike . This license lets others remix, tweak, and build upon this content non-commercially, as long as they credit the author and license their new creations under the identical terms. When republishing on the web a hyperlink back to the original content source URL must be included. Please note that content linked from this page may have different licensing terms.

Library of Congress

Exhibitions.

- Ask a Librarian

- Digital Collections

- Library Catalogs

- Exhibitions Home

- Current Exhibitions

- All Exhibitions

- Loan Procedures for Institutions

- Special Presentations

1492: An Ongoing Voyage Christopher Columbus: Man and Myth

After five centuries, Columbus remains a mysterious and controversial figure who has been variously described as one of the greatest mariners in history, a visionary genius, a mystic, a national hero, a failed administrator, a naive entrepreneur, and a ruthless and greedy imperialist.

Columbus' enterprise to find a westward route to Asia grew out of the practical experience of a long and varied maritime career, as well as out of his considerable reading in geographical and theological literature. He settled for a time in Portugal, where he tried unsuccessfully to enlist support for his project, before moving to Spain. After many difficulties, through a combination of good luck and persuasiveness, he gained the support of the Catholic monarchs, Isabel and Fernando.

The widely published report of his voyage of 1492 made Columbus famous throughout Europe and secured for him the title of Admiral of the Ocean Sea and further royal patronage. Columbus, who never abandoned the belief that he had reached Asia, led three more expeditions to the Caribbean. But intrigue and his own administrative failings brought disappointment and political obscurity to his final years.

In Search and Defense of Privileges

Queen Isabel and King Fernando had agreed to Columbus' lavish demands if he succeeded on his first voyage: he would be knighted, appointed Admiral of the Ocean Sea, made the viceroy of any new lands, and awarded ten percent of any new wealth. By 1502, however, Columbus had every reason to fear for the security of his position. He had been charged with maladministration in the Indies.

The Library's vellum copy of the Book of Privileges is one of four that Columbus commissioned in 1502 to record his agreements with the Spanish crown. It is unique in preserving an unofficial transcription of a Papal Bull of September 26, 1493 in which Pope Alexander VI extended Spain's rights to the New World.

Much concerned with social status, Columbus was granted a coat of arms in 1493. By 1502, he had added several new elements, such as an emerging continent next to islands and five golden anchors to represent the office of the Admiral of the Ocean Sea.

As a reward for his successful voyage of discovery, the Spanish sovereigns granted Columbus the right to a coat of arms. According to the blazon specified in letters patent dated May 20, 1493, Columbus was to bear in the first and the second quarters the royal charges of Castile and Léon—the castle and the lion—but with different tinctures or colors. In the third quarter would be islands in a wavy sea, and in the fourth, the customary arms of his family.

The earliest graphic representation of Columbus' arms is found in his Book of Privileges and shows the significant modifications Columbus ordered by his own authority. In addition to the royal charges that were authorized in the top quarters, Columbus adopted the royal colors as well, added a continent among the islands in the third quarter, and for the fourth quarter borrowed five anchors in fess from the blazon of the Admiral of Castille. Columbus' bold usurpation of the royal arms, as well as his choice of additional symbols, help to define his personality and his sense of the significance of his service to the Spanish monarchs.

Columbus' Coat of Arms in Christopher Columbus, His Book of Privileges, 1502 . Facsimile. London, 1893. Harisse Collection, Rare Book and Special Collections Division , Library of Congress

The Book of Privileges is a collection of agreements between Columbus and the crowns of Spain prepared in Seville in 1502 before his 4th and final voyage to America. The compilation of documents includes the 1497 confirmation of the rights to titles and profits granted to the Admiral by the 1492 Contract of Santa Fé and augmented in 1493 and 1494, as well as routine instructions and authorizations related to his third voyage. We know that four copies of his Book of Privileges existed in 1502, three written on vellum and one on paper.

All three vellum copies have thirty-six documents in common, including the Papal Bull Inter caetera of May 4, 1493, defining the line of demarcation of future Spanish and Portuguese explorations, and specifically acknowledging Columbus' contributions. The bull is the first document on vellum in the Library's copy and the thirty-sixth document in the Genoa and the Paris codices. The Library copy does not have the elaborate rubricated title page, the vividly colored Columbus coat of arms, or the authenticating notarial signatures contained in the other copies. The Library's copy, however, does have a unique transcription of the Papal Bull Dudum siquidem of September 26, 1493, extending the Spanish donation. The bull is folded and addressed to the Spanish sovereigns.

This intriguing Library copy is the only major compilation of Columbus' privileges that has not received modern documentary editing. Comprehensive textual analysis and careful comparison with other known copies is essential to establishing its definitive place in Columbus scholarship.

Book of Privileges in [Christopher Columbus], [ Códice Diplomatico Columbo-Americano ], Vellum. [Seville, ca. 1502]. Manuscript Division , Library of Congress

Back to top

Connect with the Library

All ways to connect

Subscribe & Comment

- RSS & E-Mail

Download & Play

- iTunesU (external link)

About | Press | Jobs | Donate Inspector General | Legal | Accessibility | External Link Disclaimer | USA.gov

Exploration of America: Christopher Columbus

- Christopher Columbus

- Colonial America This link opens in a new window

- Leif Erikson & the Vikings

- Spanish Explorers

- Native Americans and the Early Explorers

- Westward Expansion

- Lewis and Clark & Sacagawea

- The Gold Rush

- Help This link opens in a new window

Internet Resources

- Christopher Columbus: History.com Christopher Columbus was an Italian explorer who stumbled upon the Americas and whose journeys marked the beginning of centuries of transatlantic colonization.

- Podcast- Christopher Columbus In 1492, Genoese mariner Christopher Columbus – sailing for Spain – became the first European to reach the Americas since the Vikings 500 years earlier. It is one of the most significant events in world history. Columbus would go on to make four voyages to the New World in his lifetime, and our 7-part series on him covers all his exploits. He is, arguably, the most famous explorer in history.

Christopher Columbus Reading List

Research & Reference

- Christopher Columbus: Credo Reference Christopher Columbus, whose voyages to the New World greatly changed the world's history, was born in Genoa, Italy, in 1451, the son of a middle-class merchant. As a young man, he apprenticed as a business agent for a trading company, and his travels took him as far as Ireland. Europe had long been interested in asea passage to the Far East because the longoverland trip was not very economical

Discovering Columbus

This segment of Sunday Morning is about Christopher Columbus. Mo Rocca embarks on a journey to discover more about the explorer we honor each year.

Source: AVON

Christopher Columbus: Explorer of the New World

Christopher Columbus set out to find a new route to Asia, but instead became the first Spaniard to set foot in the New World. Evidence now proves that the Vikings reached North America long before him, yet even in his own time, other explorers usurped his glory. From the dream that led him across the horizon to the fortunes that deserted him and the ongoing controversy over his true place in history, this episode of Biography sheds light on the life of Christopher Columbus—the man, not the legend. Period accounts, rare art and artifacts, and interviews with world-renowned historians are featured. Distributed by A&E Television Networks. (48 minutes) Distributed by A&E Television Networks.

Source: Films on Demand

Books & Films: Check Out at McKee Library

From the author of the Magellan biography, Over the Edge of the World, a mesmerizing new account of the great explorer. Christopher Columbus's 1492 voyage across the Atlantic Ocean in search of a trading route to China, and his unexpected landfall in the Americas, is a watershed event in world history. Yet Columbus made three more voyages within the span of only a decade, each designed to demonstrate that he could sail to China within a matter of weeks and convert those he found there to Christianity. These later voyages were even more adventurous, violent, and ambiguous, but they revealed Columbus's uncanny sense of the sea, his mingled brilliance and delusion, and his superb navigational skills. In all these exploits he almost never lost a sailor. By their conclusion, however, Columbus was broken in body and spirit. If the first voyage illustrates the rewards of exploration, the latter voyages illustrate the tragic costs- political, moral, and economic. In rich detail Laurence Bergreen re-creates each of these adventures as well as the historical background of Columbus's celebrated, controversial career. Written from the participants' vivid perspectives, this breathtakingly dramatic account will be embraced by readers of Bergreen's previous biographies of Marco Polo and Magellan and by fans of Nathaniel Philbrick, Simon Winchester, and Tony Horwitz.

The Catalogue of Shipwrecked Books

"Like a Renaissance wonder cabinet, full of surprises and opening up into a lost world." --Stephen Greenblatt "A captivating adventure...For lovers of history, Wilson-Lee offers a thrill on almost every page...Magnificent." --The New York Times Book Review Named a Best Book of the Year by: * Financial Times * New Statesman * History Today * The Spectator * The impeccably researched and vividly rendered account of the quest by Christopher Columbus's illegitimate son to create the greatest library in the world--"a perfectly pitched poetic drama" (Financial Times) and an amazing tour through sixteenth-century Europe. In this innovative work of history, Edward Wilson-Lee tells the extraordinary story of Hernando Colón, a singular visionary of the printing press-age who also happened to be Christopher Columbus's illegitimate son. At the peak of the Age of Exploration, Hernando traveled with Columbus on his final voyage to the New World, a journey that ended in disaster, bloody mutiny, and shipwreck. After Columbus's death in 1506, the eighteen-year-old Hernando sought to continue--and surpass--his father's campaign to explore the boundaries of the known world by building a library that would collect everything ever printed: a vast holding organized by summaries and catalogues, the first ever search engine for the exploding diversity of written matter as the printing press proliferated across Europe.

Columbus and the World Around Him

This series meets National Curriculum Standards for: Social Studies: Civic Ideals & Practices Individuals, Groups, & Institutions Power, Authority, & Goverance Time, Continuity, & Change

A deeply engaging new history of how European settlements in the post-Colombian Americas shaped the world, from the bestselling author of 1491. Presenting the latest research by biologists, anthropologists, archaeologists, and historians, Mann shows how the post-Columbian network of ecological and economic exchange fostered the rise of Europe, devastated imperial China, convulsed Africa, and for two centuries made Mexico City--where Asia, Europe, and the new frontier of the Americas dynamically interacted--the center of the world. In this history, Mann uncovers the germ of today's fiercest political disputes, from immigration to trade policy to culture wars. In 1493, Mann has again given readers an eye-opening scientific interpretation of our past, unequaled in its authority and fascination.

Manifest Destinies

A sweeping history of the 1840s, Manifest Destinies captures the enormous sense of possibility that inspired America’s growth and shows how the acquisition of western territories forced the nation to come to grips with the deep fault line that would bring war in the near future. Steven E. Woodworth gives us a portrait of America at its most vibrant and expansive. It was a decade in which the nation significantly enlarged its boundaries, taking Texas, New Mexico, California, and the Pacific Northwest; William Henry Harrison ran the first modern populist campaign, focusing on entertaining voters rather than on discussing issues; prospectors headed west to search for gold; Joseph Smith founded a new religion; railroads and telegraph lines connected the country’s disparate populations as never before. When the 1840s dawned, Americans were feeling optimistic about the future: the population was growing, economic conditions were improving, and peace had reigned for nearly thirty years. A hopeful nation looked to the West, where vast areas of unsettled land seemed to promise prosperity to anyone resourceful enough to take advantage. And yet political tensions roiled below the surface; as the country took on new lands, slavery emerged as an irreconcilable source of disagreement between North and South, and secession reared its head for the first time. Rich in detail and full of dramatic events and fascinating characters, Manifest Destinies is an absorbing and highly entertaining account of a crucial decade that forged a young nation’s character and destiny.

Christopher Columbus and the Enterprise of the Indies

Focused on Columbus' voyages and their impact on Europe and the indigenous peoples of the Caribbean, Christopher Columbus and the Enterprise of the Indies presents the voyager as a significant historical actor who improvised responses to a changed world while helping link Africa, Europe, and the Americas in a conflicted economic and cultural symbiosis.

The Worlds of Christopher Columbus

When Columbus was born in the mid-fifteenth century, Europe was isolated in many ways from the rest of the Old World and Europeans did not even know that the world of the Western Hemisphere existed. The voyages of Christopher Columbus opened a period of European exploration and empire building that breached the boundaries of those isolated worlds and changed the course of human history. This book describes the life and times of Christopher Columbus. The story is not just of one man's rise and fall. Seen in its broader context, his life becomes a prism reflecting the broad range of human experience for the past five hundred years.

YouTube Videos

Many people in the United States and Latin America have grown up celebrating the anniversary of Christopher Columbus’s voyage. But was he an intrepid explorer who brought two worlds together or a ruthless exploiter who brought colonialism and slavery? And did he even discover America at all? Alex Gendler puts Columbus on the stand in History vs. Christopher Columbus.

Secrets & Mysteries Of Christopher Columbus

Was Christopher Columbus born in Genoa, Italy? An unlikely collection of experts from European royalty, DNA science, university scholars, even Columbus's own living family so he definitely was not.

Source: Kanopy

The Real Life Of Christopher Columbus | The Secrets And Lies Of Columbus | Timeline

Was Christopher Columbus born in Genoa, Italy? Most definitely not, say an unlikely collection of experts from European royalty, DNA science, university scholars, even Columbus's own living family. This ground breaking documentary follows a trail of proof to show he might have been much more than we know.

Source: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=u0yoVsZfypQ

- << Previous: Home

- Next: Colonial America >>

- Last Updated: May 4, 2023 11:35 AM

- URL: https://southern.libguides.com/explorationofamerica

Christopher Columbus and Early European Exploration

This research guide will focus on primary and secondary sources in the collection of the New York Public Library pertinent to the four voyages made by Columbus. It will also cover other Spanish explorations, Native American reactions, and the methodology for researching the Library's catalogs for material on other relevant explorers and countries.

Christopher Columbus undertook his first voyage across the Atlantic over 500 years ago. Since then, the course of history for both the civilizations he encountered and those he represented has been irrevocably altered. This research guide will focus on primary and secondary sources in the collection of the New York Public Library pertinent to the four voyages made by Columbus. It will also cover other Spanish explorations, Native American reactions, and the methodology for researching the Library's catalogs for material on other relevant explorers and countries.

If you need further assistance, visit our reference desk, or e-mail us at [email protected] .

Using the Library’s Catalogs

General instructions for locating materials are given in the Research Guide, How Do I Find a Book? . Specific methods for locating additional materials on this topic are located at the end of each section.

Primary Documentation

The four voyages of Columbus (1492-93; 1493-96; 1498-1500; 1502-04) opened the way for the exploration, exploitation, and colonization of the Americas by Europe. There are no surviving manuscripts in Columbus' own hand describing these voyages. Instead, historians have relied upon the following documents:

Letters Journals

The term "Columbus letter" usually refers to one of the fifteenth-century printed editions of a letter from his first voyage announcing his "discovery" of America. A traditional view holds that Columbus wrote three letters: one addressed to Luis de Santangel, Keeper of Accounts of Aragon, dated February 15th, 1493; a second addressed to King Ferdinand and Queen Isabella, of which no copy has survived; a third sent to Gabriel Sanchez, Treasurer of Aragon, dated March 15th, 1493. Recent thinking on the subject is that all three letters were derived from a single manuscript sent to Ferdinand and Isabella from which copies were then made and endorsed to several court officials.

The New York Public Library has facsimile copies of all seventeen surviving editions known to have been published before 1501 in Spanish, Latin, Italian, and German. While the Library is in actual possession of unique copies of both the Santangel and Sanchez letters, these, for obvious reasons, are not offered for public viewing or access. A copy of the Santangel Letter is kept at the Information Desk in Room 315. Ask a librarian there for assistance.

The following list of books includes translations and analyses of these letters which are suitable for most research needs.

Columbus, Christopher, The Letter of Columbus on His Discovery of the New World (Los Angeles: USC Fine Arts Press, 1989). HAN 89-21486.

Major, Richard Henry, The Bibliography of the First Letter of Christopher Columbus Describing His Discovery of the New World (London: Ellis & White, 1872). HAM.

A New and Fresh English Translation of the Letter of Columbus Announcing the Discovery of America (by) Samuel Eliot Morison (Madrid: Graficas Yagues, 1959). JAX B-2175.

Columbo, Cristoforo, The Spanish Letter of Columbus to Luis de Sant' Angel, Escribano de Racion of the Kingdom of Aragon, Dated 15 February, 1493 (London: G. Norman and Son, Printers, 1893). *ZH-654.

In the Dictionary Catalog, further items can be found under the relevant subject headings:

- Columbus, Christopher. Letters. Columbus, Christopher. Letter to Sanchez. Columbus, Christopher. Letter to Santagel.

In CATNYP, use a subject or keyword search on:

Columbus Christopher correspondence

The journal that Columbus kept of his first voyage to America and presented to Ferdinand and Isabella upon his return to Spain has not survived in its original form. The journal is known to us today only in the abridgement of Bartolome de las Casas, a partly quoted and partly summarized version of the original. The following are scholarly transcriptions and translations of this document.

Columbus, Christopher, The Diario of Christopher Columbus's First Voyage to America, 1492-1493, abstracted by Fray Bartolome de las Casas, Oliver Dunn and James E. Kelley, Jr., trs. (Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 1989). HAN 89-4493.

Columbus, Christopher, The Journal of Christopher Columbus, Cecil Jane, tr. (L.A. Vigneras, reviser and annotator) (London: The Hakluyt Society, 1960). HAN 1960.

Columbus, Christopher, Journal of the First Voyage of Christopher Columbus, B.W. Ife, ed./tr. (Westminster, England: Aris & Phillips, Ltd., 1990). HAN 91-5853.

Columbus, Christopher, The Log of Christopher Columbus, Robert H. Fuson, tr. (Camden, ME: International Marine Publishing Co., 1987). HAN 88-288.

Columbus, Christopher, Select Documents Illustrating the Four Voyages of Columbus, Including Those Contained in R.H. Major's Select Letters of Christopher Columbus (Reprint: Hakluyt Society, Works, Second Series) (Nendeln, Liechtenstein: Kraus Reprint, 1967). JFL 75-29 / 2nd Series, nos. 65 & 70.

Henige, David, In Search of Columbus: The Sources for the First Voyage (Tucson: University of Arizona Press, 1991). HAN 91-8063.

In the Dictionary Catalog, subject headings for additional items are:

- Columbus, Christopher. Journal

- Columbus Christopher diaries

Secondary/Biographical Sources

There are as many books about Columbus as there are viewpoints about the man and his accomplishments. The following is just a sampling of these divergent perspectives.

Adams, Herbert Baxter, and Henry Wood, Columbus and His Discovery of America (New York: AMS Press, 1971). HAM 72-2082.

Bradford, Ernle Dusgate Selby, Christopher Columbus (New York: Viking Press, 1973). HAM 74-1511; HAM 75-1334.

The Christopher Columbus Encyclopedia, Silvia A. Bedini, ed. (New York: Simon & Schuster, 1992). *R-HAM 91-9569.

Collis, John Stewart, Christopher Columbus (London: Macdonald and Jane's, Ltd., 1976). JFD 77-953; HAM 90-5225.

Columbus, Ferdinand, The Life of the Admiral Christopher Columbus by His Son Ferdinand, Benjamin Keen, tr. (New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press, 1959). HAM.

Columbus and His World: Proceedings of the First San Salvador Conference, Donald T. Gerace, ed. (Fort Lauderdale: Bahamian Field Station, 1987). HAM 90-8696.

Fernandez-Armesto, Felipe, Columbus (Oxford; New York: Oxford University Press, 1991). *R-HAM 91-8489.

Fernandez-Armesto, Felipe, Columbus and the Conquest of the Impossible (London: Weidenfeld and Nicolson, 1974). HAM 76-937.

Floyd, Troy S., The Columbus Dynasty in the Caribbean, 1492-1526 (Albuquerque, NM: University of New Mexico Press, 1973). HNB 74-1175.

In the Wake of Columbus: Islands and Controversy, Louis De Vorsey, Jr. and John Parker, eds. (Detroit: Wayne State University Press, 1985). HAM 85-3309.

Koningsberger, Hans, Columbus: His Enterprise (New York: Monthly Review Press, 1976). HAM 76-1910.

Litvinoff, Barnet, Fourteen Ninety-Two: The Year and the Era (London: Constable, 1991). JFE 91-7068.

McKee, Alexander, A World Too Vast: The Four Voyages of Columbus (London: Souvenir Press, 1990). HAM 90-9819.

Morison, Samuel Eliot, Admiral of the Ocean Sea: A Life of Christopher Columbus (Boston: Little, Brown and Company, 1942). HAM 1942.

Morison, Samuel Eliot, Christopher Columbus, Mariner (Boston: Little, Brown and Company, 1955). HAM.

Morison, Samuel Eliot, The Second Voyage of Christopher Columbus (London: Oxford University Press, 1939). HAM 1939.

Morison, Samuel Eliot, and Mauricio Obregon, The Caribbean as Columbus Saw It (Boston: Little, Brown and Company, 1964). HAI 1964.

Provost, Foster, Columbus: An Annotated Guide to the Study On His Life and Writings, 1750-1988 (Detroit, MI: Published for the John Carter Brown Library by Omnigraphics, Inc., 1991). *RS-HAM 91-5358; available at the South Hall Desk.

Sale, Kirkpatrick, The Conquest of Paradise: Christopher Columbus and the Columbia Legacy (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1990). HAM 90-13326.

Taviani, Paolo Emilio, Christopher Columbus: The Grand Design (London: Orbis, 1985). HAM 87-738.

Taviani, Paolo Emilio, Columbus, The Great Adventure: His Life, His Times, and His Voyages (New York: Orion Books, 1991). JFE 91-8810.

United States. Library of Congress. Division of Bibliography. Christopher Columbus: A Selected List of Books and Articles, Donald H. Mugridge, ed. (Washington, D.C., 1950). HAE p.v. 305.

Wilford, John Noble, The Mysterious History of Columbus: An Exploration of the Man, The Myth, The Legacy (New York: Knopf: Distributed by Random House, 1991). HAM 91-9629.

Look under Columbus, Christopher in the catalogs to find further biographies. Similarly, look under the names of any other specific explorers to find works written about, or by, them.

Post-Columbus: Conquest And Colonization

Subsequent voyages to the Americas by the major European sea powers followed rapidly after Columbus's initial expedition. Following is a brief sampling of the many items in the Library's collection relevant to these travels.

Spain Other European

First Encounters: Spanish Explorations in the Caribbean and the United States, 1492-1570

MDNM¯, Jerald T. Milanich and Susan Milbrath, eds. (Gainesville: University of Florida Press: Florida Museum of Natural History, 1989).

HAI 90-4586.

Gordon, Thomas Francis, The History of America: Containing the History of the Spanish Discoveries Prior to 1520 (Philadelphia: Carey & Lea, 1831). *Z-5583 no. 1.

Hoffman, Paul E., A New Andalucia and a Way to the Orient: The American Southeast During the Sixteenth Century (Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 1990). HAI 90-12962.

Kirkpatrick, Frederick Alexander, The Spanish Conquistadores (London: The Cresset Library, 1988). HAI 89-17074.

Nebenzahl, Kenneth, Atlas of Columbus and the Great Discoveries (Chicago: Rand McNally, 1990). Map Division 91-7246.

New American World: A Documentary History of North America to 1612 in Five Volumes, David B. Quinn, Alison M. Quinn, Susan Hillier, eds. (New York: Arno Press, 1979). HV 79-1250.

The Spanish in America: 1513-1979: A Chronology and Fact Book, Arthur A. Natella, Jr., ed. (Dobbs Ferry, NY: Oceana Publications, 1980). HAI 80-3036.

Spanish Colonial Frontier Research, Henry F. Dobyns, ed. (Albuquerque, NM: Center for Anthropological Studies, 1980). IT 88-1041.

Spanish Exploration in the Southwest, 1542-1706 (Original Narratives of Early American History), Herbert Eugene Bolton, ed. (New York: C. Scribner's Sons, 1930). *Z-5572 no.2.

Spanish Explorers in the Southern United States, 1526-1543 (Original Narratives of Early American History) (Austin, TX: Texas State Historical Society, 1990). HAI 90-11356.

Weddle, Robert S., Spanish Sea: The Gulf of Mexico in North American Discovery, 1500-1685 (College Station, TX: Texas A&M University Press, 1985). HAI 85-2619.

Other European

Discovery, An Exhibition of Books Relating to the Age of Geographical Discovery and Exploration

(Bloomington, Indiana: Lilly Library, 1965).

The Hakluyt Handbook, David Beers Quinn, ed. (London: The Hakluyt Society, 1974). *R-KBC 76-3402 and JFL 75-29 2nd Series, nos. 144-145. Lists all the works published by the Society, established in 1846 and renowned for its scholarly editions of records of voyages, travels, and other geographical material.

Pioneers and Explorers in North America: Summaries of Biographical Articles in History Journals, Pamela R. Byrne and Susan K. Kinnell, eds. (Santa Barbara, CA: ABC-Clio, 1988). JFE 88-1948.

Morison, Samuel Eliot, The European Discovery of America (New York: Oxford University Press, 1971-1974). HAI 71-450.

Morison, Samuel Eliot, The Great Explorers: The European Discovery of America (New York: Oxford University Press, 1978). *R-KH 79-4650.

Quinn, David Beers, England and the Discovery of America, 1481-1620 (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1974). HAI 75-216.

Quinn, David Beers, North America From the Earliest Discovery to First Settlements: The Norse Voyages to 1612 (New York: Harper & Row, 1977). HAI 77-2442.

Tomlinson, Regina Johnson, The Struggle for Brazil: Portugal and "The French Interlopers" (1500-1550) (New York: Las Americas Publishing Co., 1970). HFB 72-795.

The following list encompasses the subject headings used to search for further items:

In the Dictionary Catalog:

- America - Description and Travel, to 1800 America - Discovery America - Discovery, Pre-Columbian America - Discovery, Post-Columbian Voyages and Travels, to 1500 Voyages and Travels, 1500-1600 Voyages and Travels, 1600-1700 Voyages and Travels, History (By Century)

(Note: See also names of individual explorers)

- America - Discovery and Exploration Explorers

(Note: these can be geographically subdivided: -Spain; -France; -England; -Portugal; see also names of individual explorers)

The Clash of Cultures

The civilizations and cultures of Native Americans were irrevocably altered after the events of 1492. The resulting clash of cultures continues to the present day.

Berhofer, Robert F., The White Man's Indian: The History of an Idea From Columbus to the Present (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1978). HBC 78-1802.

Casas, Bartolome de las, Historia de las Indias (Mexico: Fondo de Cultura Economica, 1951). HBC.

Chamberlin. J.E., The Harrowing of Eden: White Attitudes Toward Native Americans (New York: Seabury Press, 1975). HBC 76-216.

Cultures in Contact: The Impact of European Contacts on Native American Cultural Institutions A.D. 1000-1800, William W. Fitzhugh, ed. (Washington: Smithsonian Institution Press, 1985). HBC 86-1574.

Garcilaso de la Vega, el Inca, Comentarios Reales de los Incas (Lima: Libreria Internacional del Peru, 1959). HHH.

Hanke, Lewis, The First Social Experiments in America: A Study in the Development of Spanish Indian Policy in the Sixteenth Century (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1935). HNB.

Hecht, Robert, Continents in Collision: The Impact of Europe on the North American Indian Societies (Lanham, MD: University Press of America, 1980). HBC 81-981 and HBC 81-981 Suppl.

Huddleston, Lee E., Origins of the American Indians: European Concepts, 1492-1729 (Austin, TX: University of Texas Press, 1967). HBC.

Jennings, Francis, The Invasion of America: Indians, Colonialism, and the Cant of Conquest (Chapel Hill, NC: University of North Carolina Press, 1975). IQ 79-525.

Sale, Kirkpatrick, The Conquest of Paradise: Christopher Columbus and the Columbian Legacy (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1990). HAM 90-13326.

Thornton, Russell, American Indian Holocaust and Survival: A Population History Since 1492 (Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 1987). HBC 88-564.

Tyler, S. Lyman, Two Worlds: The Indian Encounter With the European, 1492-1509 (Salt Lake City: University of Utah Press, 1988). HBC 88-2810.

Additional items can be found under these subject headings:

- Indians, American Indians, N.A. Indians, S.A.

- Indians of North America - First Contact With Occidental Civilization

(Note: see also Research Guide, Native North America )

Journals And Periodical Literature

Journals and periodicals are a sometimes overlooked source of scholarly research. The following indexes provide citations to a broad array of journals dealing with the field of history, in general, and Columbus and the Quincentennial, in particular.

America: History and Life, Vol. 0 (1954-1963)- (Santa Barbara, CA: American Bibliographical Center: Clio Press, 1972- ). *R-IAA+ (America History and Life).

C.R.I.S.: The Combined Retrospective Index to Journals in History, 1838-1974, Annadel N. Wile and Deborah Purcell, eds. (Washington: Carrollton Press, 1977-78). *RS-BAA 77-4040.

Hispanic American Periodical Index (HAPI) (Los Angeles: University of California Latin American Center Publications, 1970- ). *R-*D 78-578.

Historical Abstracts (the series splits after Vol. 17; beginning with Vol. 18 use only Part A: Modern History Abstracts 1450-1914) (Santa Barbara, CA: ABC-Clio, 1955- ). *RB-BAA 74-867.

Humanities Index (New York: H.W. Wilson, 1974- ). *R-*D 75-1125 (online from February, 1984- ).

Readers' Guide to Periodical Literature (New York: H.W. Wilson, 1900- ). *R-*D (online from 1983- ).

In addition, there are numerous journals chronicling the events and issues related to the Quincentennial. Recent issues (i.e., past year) are available in Current Periodicals, located in Room 108 of the Library.

America 92: Boletin Informativo de la Comision Nacional del V Centenario del Descubrimiento de America (Madrid: La Comision, 1984- ). Available in Room 108.

Cultural Survival Quarterly (Cambridge, MA: Cultural Survival, Inc., 1982- ). JFM 85-121.

Encounters: A Quincentenary Review (Albuquerque, NM: Latin American Institute of the University of New Mexico, 1989- ). JFM 90-214.

(See also Research Guide, How to Find Periodicals .)

The Ages of Exploration

Christopher columbus, age of discovery.

Quick Facts: