Have a language expert improve your writing

Run a free plagiarism check in 10 minutes, generate accurate citations for free.

- Knowledge Base

Methodology

- Systematic Review | Definition, Example, & Guide

Systematic Review | Definition, Example & Guide

Published on June 15, 2022 by Shaun Turney . Revised on November 20, 2023.

A systematic review is a type of review that uses repeatable methods to find, select, and synthesize all available evidence. It answers a clearly formulated research question and explicitly states the methods used to arrive at the answer.

They answered the question “What is the effectiveness of probiotics in reducing eczema symptoms and improving quality of life in patients with eczema?”

In this context, a probiotic is a health product that contains live microorganisms and is taken by mouth. Eczema is a common skin condition that causes red, itchy skin.

Table of contents

What is a systematic review, systematic review vs. meta-analysis, systematic review vs. literature review, systematic review vs. scoping review, when to conduct a systematic review, pros and cons of systematic reviews, step-by-step example of a systematic review, other interesting articles, frequently asked questions about systematic reviews.

A review is an overview of the research that’s already been completed on a topic.

What makes a systematic review different from other types of reviews is that the research methods are designed to reduce bias . The methods are repeatable, and the approach is formal and systematic:

- Formulate a research question

- Develop a protocol

- Search for all relevant studies

- Apply the selection criteria

- Extract the data

- Synthesize the data

- Write and publish a report

Although multiple sets of guidelines exist, the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews is among the most widely used. It provides detailed guidelines on how to complete each step of the systematic review process.

Systematic reviews are most commonly used in medical and public health research, but they can also be found in other disciplines.

Systematic reviews typically answer their research question by synthesizing all available evidence and evaluating the quality of the evidence. Synthesizing means bringing together different information to tell a single, cohesive story. The synthesis can be narrative ( qualitative ), quantitative , or both.

Prevent plagiarism. Run a free check.

Systematic reviews often quantitatively synthesize the evidence using a meta-analysis . A meta-analysis is a statistical analysis, not a type of review.

A meta-analysis is a technique to synthesize results from multiple studies. It’s a statistical analysis that combines the results of two or more studies, usually to estimate an effect size .

A literature review is a type of review that uses a less systematic and formal approach than a systematic review. Typically, an expert in a topic will qualitatively summarize and evaluate previous work, without using a formal, explicit method.

Although literature reviews are often less time-consuming and can be insightful or helpful, they have a higher risk of bias and are less transparent than systematic reviews.

Similar to a systematic review, a scoping review is a type of review that tries to minimize bias by using transparent and repeatable methods.

However, a scoping review isn’t a type of systematic review. The most important difference is the goal: rather than answering a specific question, a scoping review explores a topic. The researcher tries to identify the main concepts, theories, and evidence, as well as gaps in the current research.

Sometimes scoping reviews are an exploratory preparation step for a systematic review, and sometimes they are a standalone project.

A systematic review is a good choice of review if you want to answer a question about the effectiveness of an intervention , such as a medical treatment.

To conduct a systematic review, you’ll need the following:

- A precise question , usually about the effectiveness of an intervention. The question needs to be about a topic that’s previously been studied by multiple researchers. If there’s no previous research, there’s nothing to review.

- If you’re doing a systematic review on your own (e.g., for a research paper or thesis ), you should take appropriate measures to ensure the validity and reliability of your research.

- Access to databases and journal archives. Often, your educational institution provides you with access.

- Time. A professional systematic review is a time-consuming process: it will take the lead author about six months of full-time work. If you’re a student, you should narrow the scope of your systematic review and stick to a tight schedule.

- Bibliographic, word-processing, spreadsheet, and statistical software . For example, you could use EndNote, Microsoft Word, Excel, and SPSS.

A systematic review has many pros .

- They minimize research bias by considering all available evidence and evaluating each study for bias.

- Their methods are transparent , so they can be scrutinized by others.

- They’re thorough : they summarize all available evidence.

- They can be replicated and updated by others.

Systematic reviews also have a few cons .

- They’re time-consuming .

- They’re narrow in scope : they only answer the precise research question.

The 7 steps for conducting a systematic review are explained with an example.

Step 1: Formulate a research question

Formulating the research question is probably the most important step of a systematic review. A clear research question will:

- Allow you to more effectively communicate your research to other researchers and practitioners

- Guide your decisions as you plan and conduct your systematic review

A good research question for a systematic review has four components, which you can remember with the acronym PICO :

- Population(s) or problem(s)

- Intervention(s)

- Comparison(s)

You can rearrange these four components to write your research question:

- What is the effectiveness of I versus C for O in P ?

Sometimes, you may want to include a fifth component, the type of study design . In this case, the acronym is PICOT .

- Type of study design(s)

- The population of patients with eczema

- The intervention of probiotics

- In comparison to no treatment, placebo , or non-probiotic treatment

- The outcome of changes in participant-, parent-, and doctor-rated symptoms of eczema and quality of life

- Randomized control trials, a type of study design

Their research question was:

- What is the effectiveness of probiotics versus no treatment, a placebo, or a non-probiotic treatment for reducing eczema symptoms and improving quality of life in patients with eczema?

Step 2: Develop a protocol

A protocol is a document that contains your research plan for the systematic review. This is an important step because having a plan allows you to work more efficiently and reduces bias.

Your protocol should include the following components:

- Background information : Provide the context of the research question, including why it’s important.

- Research objective (s) : Rephrase your research question as an objective.

- Selection criteria: State how you’ll decide which studies to include or exclude from your review.

- Search strategy: Discuss your plan for finding studies.

- Analysis: Explain what information you’ll collect from the studies and how you’ll synthesize the data.

If you’re a professional seeking to publish your review, it’s a good idea to bring together an advisory committee . This is a group of about six people who have experience in the topic you’re researching. They can help you make decisions about your protocol.

It’s highly recommended to register your protocol. Registering your protocol means submitting it to a database such as PROSPERO or ClinicalTrials.gov .

Step 3: Search for all relevant studies

Searching for relevant studies is the most time-consuming step of a systematic review.

To reduce bias, it’s important to search for relevant studies very thoroughly. Your strategy will depend on your field and your research question, but sources generally fall into these four categories:

- Databases: Search multiple databases of peer-reviewed literature, such as PubMed or Scopus . Think carefully about how to phrase your search terms and include multiple synonyms of each word. Use Boolean operators if relevant.

- Handsearching: In addition to searching the primary sources using databases, you’ll also need to search manually. One strategy is to scan relevant journals or conference proceedings. Another strategy is to scan the reference lists of relevant studies.

- Gray literature: Gray literature includes documents produced by governments, universities, and other institutions that aren’t published by traditional publishers. Graduate student theses are an important type of gray literature, which you can search using the Networked Digital Library of Theses and Dissertations (NDLTD) . In medicine, clinical trial registries are another important type of gray literature.

- Experts: Contact experts in the field to ask if they have unpublished studies that should be included in your review.

At this stage of your review, you won’t read the articles yet. Simply save any potentially relevant citations using bibliographic software, such as Scribbr’s APA or MLA Generator .

- Databases: EMBASE, PsycINFO, AMED, LILACS, and ISI Web of Science

- Handsearch: Conference proceedings and reference lists of articles

- Gray literature: The Cochrane Library, the metaRegister of Controlled Trials, and the Ongoing Skin Trials Register

- Experts: Authors of unpublished registered trials, pharmaceutical companies, and manufacturers of probiotics

Step 4: Apply the selection criteria

Applying the selection criteria is a three-person job. Two of you will independently read the studies and decide which to include in your review based on the selection criteria you established in your protocol . The third person’s job is to break any ties.

To increase inter-rater reliability , ensure that everyone thoroughly understands the selection criteria before you begin.

If you’re writing a systematic review as a student for an assignment, you might not have a team. In this case, you’ll have to apply the selection criteria on your own; you can mention this as a limitation in your paper’s discussion.

You should apply the selection criteria in two phases:

- Based on the titles and abstracts : Decide whether each article potentially meets the selection criteria based on the information provided in the abstracts.

- Based on the full texts: Download the articles that weren’t excluded during the first phase. If an article isn’t available online or through your library, you may need to contact the authors to ask for a copy. Read the articles and decide which articles meet the selection criteria.

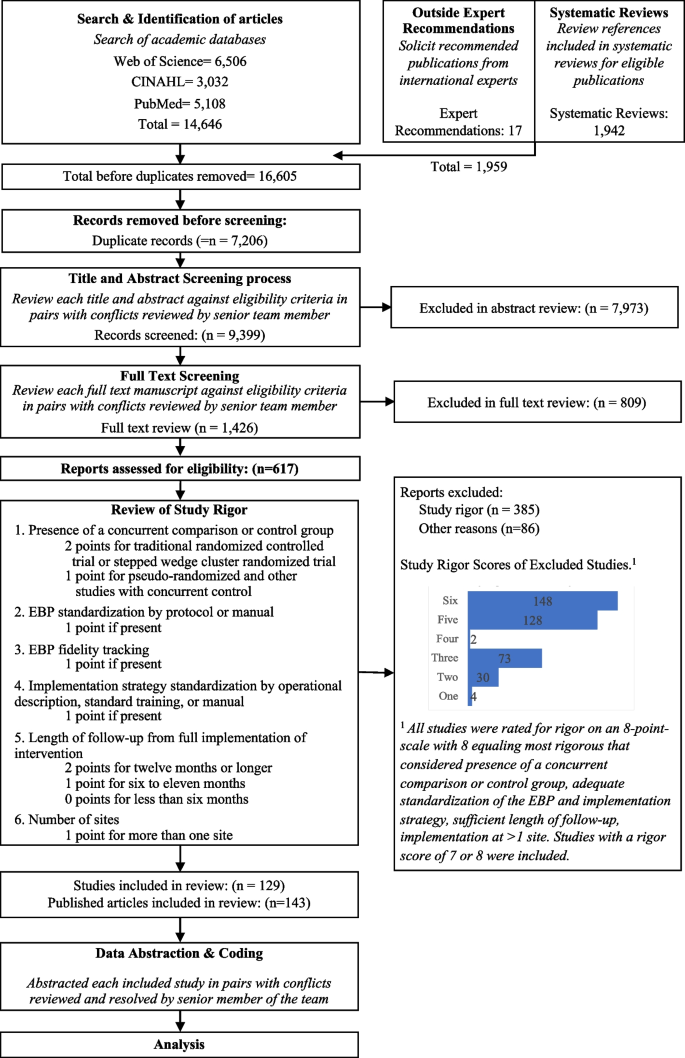

It’s very important to keep a meticulous record of why you included or excluded each article. When the selection process is complete, you can summarize what you did using a PRISMA flow diagram .

Next, Boyle and colleagues found the full texts for each of the remaining studies. Boyle and Tang read through the articles to decide if any more studies needed to be excluded based on the selection criteria.

When Boyle and Tang disagreed about whether a study should be excluded, they discussed it with Varigos until the three researchers came to an agreement.

Step 5: Extract the data

Extracting the data means collecting information from the selected studies in a systematic way. There are two types of information you need to collect from each study:

- Information about the study’s methods and results . The exact information will depend on your research question, but it might include the year, study design , sample size, context, research findings , and conclusions. If any data are missing, you’ll need to contact the study’s authors.

- Your judgment of the quality of the evidence, including risk of bias .

You should collect this information using forms. You can find sample forms in The Registry of Methods and Tools for Evidence-Informed Decision Making and the Grading of Recommendations, Assessment, Development and Evaluations Working Group .

Extracting the data is also a three-person job. Two people should do this step independently, and the third person will resolve any disagreements.

They also collected data about possible sources of bias, such as how the study participants were randomized into the control and treatment groups.

Step 6: Synthesize the data

Synthesizing the data means bringing together the information you collected into a single, cohesive story. There are two main approaches to synthesizing the data:

- Narrative ( qualitative ): Summarize the information in words. You’ll need to discuss the studies and assess their overall quality.

- Quantitative : Use statistical methods to summarize and compare data from different studies. The most common quantitative approach is a meta-analysis , which allows you to combine results from multiple studies into a summary result.

Generally, you should use both approaches together whenever possible. If you don’t have enough data, or the data from different studies aren’t comparable, then you can take just a narrative approach. However, you should justify why a quantitative approach wasn’t possible.

Boyle and colleagues also divided the studies into subgroups, such as studies about babies, children, and adults, and analyzed the effect sizes within each group.

Step 7: Write and publish a report

The purpose of writing a systematic review article is to share the answer to your research question and explain how you arrived at this answer.

Your article should include the following sections:

- Abstract : A summary of the review

- Introduction : Including the rationale and objectives

- Methods : Including the selection criteria, search method, data extraction method, and synthesis method

- Results : Including results of the search and selection process, study characteristics, risk of bias in the studies, and synthesis results

- Discussion : Including interpretation of the results and limitations of the review

- Conclusion : The answer to your research question and implications for practice, policy, or research

To verify that your report includes everything it needs, you can use the PRISMA checklist .

Once your report is written, you can publish it in a systematic review database, such as the Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews , and/or in a peer-reviewed journal.

In their report, Boyle and colleagues concluded that probiotics cannot be recommended for reducing eczema symptoms or improving quality of life in patients with eczema. Note Generative AI tools like ChatGPT can be useful at various stages of the writing and research process and can help you to write your systematic review. However, we strongly advise against trying to pass AI-generated text off as your own work.

If you want to know more about statistics , methodology , or research bias , make sure to check out some of our other articles with explanations and examples.

- Student’s t -distribution

- Normal distribution

- Null and Alternative Hypotheses

- Chi square tests

- Confidence interval

- Quartiles & Quantiles

- Cluster sampling

- Stratified sampling

- Data cleansing

- Reproducibility vs Replicability

- Peer review

- Prospective cohort study

Research bias

- Implicit bias

- Cognitive bias

- Placebo effect

- Hawthorne effect

- Hindsight bias

- Affect heuristic

- Social desirability bias

A literature review is a survey of scholarly sources (such as books, journal articles, and theses) related to a specific topic or research question .

It is often written as part of a thesis, dissertation , or research paper , in order to situate your work in relation to existing knowledge.

A literature review is a survey of credible sources on a topic, often used in dissertations , theses, and research papers . Literature reviews give an overview of knowledge on a subject, helping you identify relevant theories and methods, as well as gaps in existing research. Literature reviews are set up similarly to other academic texts , with an introduction , a main body, and a conclusion .

An annotated bibliography is a list of source references that has a short description (called an annotation ) for each of the sources. It is often assigned as part of the research process for a paper .

A systematic review is secondary research because it uses existing research. You don’t collect new data yourself.

Cite this Scribbr article

If you want to cite this source, you can copy and paste the citation or click the “Cite this Scribbr article” button to automatically add the citation to our free Citation Generator.

Turney, S. (2023, November 20). Systematic Review | Definition, Example & Guide. Scribbr. Retrieved July 2, 2024, from https://www.scribbr.com/methodology/systematic-review/

Is this article helpful?

Shaun Turney

Other students also liked, how to write a literature review | guide, examples, & templates, how to write a research proposal | examples & templates, what is critical thinking | definition & examples, "i thought ai proofreading was useless but..".

I've been using Scribbr for years now and I know it's a service that won't disappoint. It does a good job spotting mistakes”

Have a language expert improve your writing

Run a free plagiarism check in 10 minutes, automatically generate references for free.

- Knowledge Base

- Methodology

- Systematic Review | Definition, Examples & Guide

Systematic Review | Definition, Examples & Guide

Published on 15 June 2022 by Shaun Turney . Revised on 17 October 2022.

A systematic review is a type of review that uses repeatable methods to find, select, and synthesise all available evidence. It answers a clearly formulated research question and explicitly states the methods used to arrive at the answer.

They answered the question ‘What is the effectiveness of probiotics in reducing eczema symptoms and improving quality of life in patients with eczema?’

In this context, a probiotic is a health product that contains live microorganisms and is taken by mouth. Eczema is a common skin condition that causes red, itchy skin.

Table of contents

What is a systematic review, systematic review vs meta-analysis, systematic review vs literature review, systematic review vs scoping review, when to conduct a systematic review, pros and cons of systematic reviews, step-by-step example of a systematic review, frequently asked questions about systematic reviews.

A review is an overview of the research that’s already been completed on a topic.

What makes a systematic review different from other types of reviews is that the research methods are designed to reduce research bias . The methods are repeatable , and the approach is formal and systematic:

- Formulate a research question

- Develop a protocol

- Search for all relevant studies

- Apply the selection criteria

- Extract the data

- Synthesise the data

- Write and publish a report

Although multiple sets of guidelines exist, the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews is among the most widely used. It provides detailed guidelines on how to complete each step of the systematic review process.

Systematic reviews are most commonly used in medical and public health research, but they can also be found in other disciplines.

Systematic reviews typically answer their research question by synthesising all available evidence and evaluating the quality of the evidence. Synthesising means bringing together different information to tell a single, cohesive story. The synthesis can be narrative ( qualitative ), quantitative , or both.

Prevent plagiarism, run a free check.

Systematic reviews often quantitatively synthesise the evidence using a meta-analysis . A meta-analysis is a statistical analysis, not a type of review.

A meta-analysis is a technique to synthesise results from multiple studies. It’s a statistical analysis that combines the results of two or more studies, usually to estimate an effect size .

A literature review is a type of review that uses a less systematic and formal approach than a systematic review. Typically, an expert in a topic will qualitatively summarise and evaluate previous work, without using a formal, explicit method.

Although literature reviews are often less time-consuming and can be insightful or helpful, they have a higher risk of bias and are less transparent than systematic reviews.

Similar to a systematic review, a scoping review is a type of review that tries to minimise bias by using transparent and repeatable methods.

However, a scoping review isn’t a type of systematic review. The most important difference is the goal: rather than answering a specific question, a scoping review explores a topic. The researcher tries to identify the main concepts, theories, and evidence, as well as gaps in the current research.

Sometimes scoping reviews are an exploratory preparation step for a systematic review, and sometimes they are a standalone project.

A systematic review is a good choice of review if you want to answer a question about the effectiveness of an intervention , such as a medical treatment.

To conduct a systematic review, you’ll need the following:

- A precise question , usually about the effectiveness of an intervention. The question needs to be about a topic that’s previously been studied by multiple researchers. If there’s no previous research, there’s nothing to review.

- If you’re doing a systematic review on your own (e.g., for a research paper or thesis), you should take appropriate measures to ensure the validity and reliability of your research.

- Access to databases and journal archives. Often, your educational institution provides you with access.

- Time. A professional systematic review is a time-consuming process: it will take the lead author about six months of full-time work. If you’re a student, you should narrow the scope of your systematic review and stick to a tight schedule.

- Bibliographic, word-processing, spreadsheet, and statistical software . For example, you could use EndNote, Microsoft Word, Excel, and SPSS.

A systematic review has many pros .

- They minimise research b ias by considering all available evidence and evaluating each study for bias.

- Their methods are transparent , so they can be scrutinised by others.

- They’re thorough : they summarise all available evidence.

- They can be replicated and updated by others.

Systematic reviews also have a few cons .

- They’re time-consuming .

- They’re narrow in scope : they only answer the precise research question.

The 7 steps for conducting a systematic review are explained with an example.

Step 1: Formulate a research question

Formulating the research question is probably the most important step of a systematic review. A clear research question will:

- Allow you to more effectively communicate your research to other researchers and practitioners

- Guide your decisions as you plan and conduct your systematic review

A good research question for a systematic review has four components, which you can remember with the acronym PICO :

- Population(s) or problem(s)

- Intervention(s)

- Comparison(s)

You can rearrange these four components to write your research question:

- What is the effectiveness of I versus C for O in P ?

Sometimes, you may want to include a fourth component, the type of study design . In this case, the acronym is PICOT .

- Type of study design(s)

- The population of patients with eczema

- The intervention of probiotics

- In comparison to no treatment, placebo , or non-probiotic treatment

- The outcome of changes in participant-, parent-, and doctor-rated symptoms of eczema and quality of life

- Randomised control trials, a type of study design

Their research question was:

- What is the effectiveness of probiotics versus no treatment, a placebo, or a non-probiotic treatment for reducing eczema symptoms and improving quality of life in patients with eczema?

Step 2: Develop a protocol

A protocol is a document that contains your research plan for the systematic review. This is an important step because having a plan allows you to work more efficiently and reduces bias.

Your protocol should include the following components:

- Background information : Provide the context of the research question, including why it’s important.

- Research objective(s) : Rephrase your research question as an objective.

- Selection criteria: State how you’ll decide which studies to include or exclude from your review.

- Search strategy: Discuss your plan for finding studies.

- Analysis: Explain what information you’ll collect from the studies and how you’ll synthesise the data.

If you’re a professional seeking to publish your review, it’s a good idea to bring together an advisory committee . This is a group of about six people who have experience in the topic you’re researching. They can help you make decisions about your protocol.

It’s highly recommended to register your protocol. Registering your protocol means submitting it to a database such as PROSPERO or ClinicalTrials.gov .

Step 3: Search for all relevant studies

Searching for relevant studies is the most time-consuming step of a systematic review.

To reduce bias, it’s important to search for relevant studies very thoroughly. Your strategy will depend on your field and your research question, but sources generally fall into these four categories:

- Databases: Search multiple databases of peer-reviewed literature, such as PubMed or Scopus . Think carefully about how to phrase your search terms and include multiple synonyms of each word. Use Boolean operators if relevant.

- Handsearching: In addition to searching the primary sources using databases, you’ll also need to search manually. One strategy is to scan relevant journals or conference proceedings. Another strategy is to scan the reference lists of relevant studies.

- Grey literature: Grey literature includes documents produced by governments, universities, and other institutions that aren’t published by traditional publishers. Graduate student theses are an important type of grey literature, which you can search using the Networked Digital Library of Theses and Dissertations (NDLTD) . In medicine, clinical trial registries are another important type of grey literature.

- Experts: Contact experts in the field to ask if they have unpublished studies that should be included in your review.

At this stage of your review, you won’t read the articles yet. Simply save any potentially relevant citations using bibliographic software, such as Scribbr’s APA or MLA Generator .

- Databases: EMBASE, PsycINFO, AMED, LILACS, and ISI Web of Science

- Handsearch: Conference proceedings and reference lists of articles

- Grey literature: The Cochrane Library, the metaRegister of Controlled Trials, and the Ongoing Skin Trials Register

- Experts: Authors of unpublished registered trials, pharmaceutical companies, and manufacturers of probiotics

Step 4: Apply the selection criteria

Applying the selection criteria is a three-person job. Two of you will independently read the studies and decide which to include in your review based on the selection criteria you established in your protocol . The third person’s job is to break any ties.

To increase inter-rater reliability , ensure that everyone thoroughly understands the selection criteria before you begin.

If you’re writing a systematic review as a student for an assignment, you might not have a team. In this case, you’ll have to apply the selection criteria on your own; you can mention this as a limitation in your paper’s discussion.

You should apply the selection criteria in two phases:

- Based on the titles and abstracts : Decide whether each article potentially meets the selection criteria based on the information provided in the abstracts.

- Based on the full texts: Download the articles that weren’t excluded during the first phase. If an article isn’t available online or through your library, you may need to contact the authors to ask for a copy. Read the articles and decide which articles meet the selection criteria.

It’s very important to keep a meticulous record of why you included or excluded each article. When the selection process is complete, you can summarise what you did using a PRISMA flow diagram .

Next, Boyle and colleagues found the full texts for each of the remaining studies. Boyle and Tang read through the articles to decide if any more studies needed to be excluded based on the selection criteria.

When Boyle and Tang disagreed about whether a study should be excluded, they discussed it with Varigos until the three researchers came to an agreement.

Step 5: Extract the data

Extracting the data means collecting information from the selected studies in a systematic way. There are two types of information you need to collect from each study:

- Information about the study’s methods and results . The exact information will depend on your research question, but it might include the year, study design , sample size, context, research findings , and conclusions. If any data are missing, you’ll need to contact the study’s authors.

- Your judgement of the quality of the evidence, including risk of bias .

You should collect this information using forms. You can find sample forms in The Registry of Methods and Tools for Evidence-Informed Decision Making and the Grading of Recommendations, Assessment, Development and Evaluations Working Group .

Extracting the data is also a three-person job. Two people should do this step independently, and the third person will resolve any disagreements.

They also collected data about possible sources of bias, such as how the study participants were randomised into the control and treatment groups.

Step 6: Synthesise the data

Synthesising the data means bringing together the information you collected into a single, cohesive story. There are two main approaches to synthesising the data:

- Narrative ( qualitative ): Summarise the information in words. You’ll need to discuss the studies and assess their overall quality.

- Quantitative : Use statistical methods to summarise and compare data from different studies. The most common quantitative approach is a meta-analysis , which allows you to combine results from multiple studies into a summary result.

Generally, you should use both approaches together whenever possible. If you don’t have enough data, or the data from different studies aren’t comparable, then you can take just a narrative approach. However, you should justify why a quantitative approach wasn’t possible.

Boyle and colleagues also divided the studies into subgroups, such as studies about babies, children, and adults, and analysed the effect sizes within each group.

Step 7: Write and publish a report

The purpose of writing a systematic review article is to share the answer to your research question and explain how you arrived at this answer.

Your article should include the following sections:

- Abstract : A summary of the review

- Introduction : Including the rationale and objectives

- Methods : Including the selection criteria, search method, data extraction method, and synthesis method

- Results : Including results of the search and selection process, study characteristics, risk of bias in the studies, and synthesis results

- Discussion : Including interpretation of the results and limitations of the review

- Conclusion : The answer to your research question and implications for practice, policy, or research

To verify that your report includes everything it needs, you can use the PRISMA checklist .

Once your report is written, you can publish it in a systematic review database, such as the Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews , and/or in a peer-reviewed journal.

A systematic review is secondary research because it uses existing research. You don’t collect new data yourself.

A literature review is a survey of scholarly sources (such as books, journal articles, and theses) related to a specific topic or research question .

It is often written as part of a dissertation , thesis, research paper , or proposal .

There are several reasons to conduct a literature review at the beginning of a research project:

- To familiarise yourself with the current state of knowledge on your topic

- To ensure that you’re not just repeating what others have already done

- To identify gaps in knowledge and unresolved problems that your research can address

- To develop your theoretical framework and methodology

- To provide an overview of the key findings and debates on the topic

Writing the literature review shows your reader how your work relates to existing research and what new insights it will contribute.

Cite this Scribbr article

If you want to cite this source, you can copy and paste the citation or click the ‘Cite this Scribbr article’ button to automatically add the citation to our free Reference Generator.

Turney, S. (2022, October 17). Systematic Review | Definition, Examples & Guide. Scribbr. Retrieved 2 July 2024, from https://www.scribbr.co.uk/research-methods/systematic-reviews/

Is this article helpful?

Shaun Turney

Other students also liked, what is a literature review | guide, template, & examples, exploratory research | definition, guide, & examples, what is peer review | types & examples.

Systematic Reviews and Meta Analysis

- Getting Started

- Guides and Standards

- Review Protocols

- Databases and Sources

- Randomized Controlled Trials

- Controlled Clinical Trials

- Observational Designs

- Tests of Diagnostic Accuracy

- Software and Tools

- Where do I get all those articles?

- Collaborations

- EPI 233/528

- Countway Mediated Search

- Risk of Bias (RoB)

Systematic review Q & A

What is a systematic review.

A systematic review is guided filtering and synthesis of all available evidence addressing a specific, focused research question, generally about a specific intervention or exposure. The use of standardized, systematic methods and pre-selected eligibility criteria reduce the risk of bias in identifying, selecting and analyzing relevant studies. A well-designed systematic review includes clear objectives, pre-selected criteria for identifying eligible studies, an explicit methodology, a thorough and reproducible search of the literature, an assessment of the validity or risk of bias of each included study, and a systematic synthesis, analysis and presentation of the findings of the included studies. A systematic review may include a meta-analysis.

For details about carrying out systematic reviews, see the Guides and Standards section of this guide.

Is my research topic appropriate for systematic review methods?

A systematic review is best deployed to test a specific hypothesis about a healthcare or public health intervention or exposure. By focusing on a single intervention or a few specific interventions for a particular condition, the investigator can ensure a manageable results set. Moreover, examining a single or small set of related interventions, exposures, or outcomes, will simplify the assessment of studies and the synthesis of the findings.

Systematic reviews are poor tools for hypothesis generation: for instance, to determine what interventions have been used to increase the awareness and acceptability of a vaccine or to investigate the ways that predictive analytics have been used in health care management. In the first case, we don't know what interventions to search for and so have to screen all the articles about awareness and acceptability. In the second, there is no agreed on set of methods that make up predictive analytics, and health care management is far too broad. The search will necessarily be incomplete, vague and very large all at the same time. In most cases, reviews without clearly and exactly specified populations, interventions, exposures, and outcomes will produce results sets that quickly outstrip the resources of a small team and offer no consistent way to assess and synthesize findings from the studies that are identified.

If not a systematic review, then what?

You might consider performing a scoping review . This framework allows iterative searching over a reduced number of data sources and no requirement to assess individual studies for risk of bias. The framework includes built-in mechanisms to adjust the analysis as the work progresses and more is learned about the topic. A scoping review won't help you limit the number of records you'll need to screen (broad questions lead to large results sets) but may give you means of dealing with a large set of results.

This tool can help you decide what kind of review is right for your question.

Can my student complete a systematic review during her summer project?

Probably not. Systematic reviews are a lot of work. Including creating the protocol, building and running a quality search, collecting all the papers, evaluating the studies that meet the inclusion criteria and extracting and analyzing the summary data, a well done review can require dozens to hundreds of hours of work that can span several months. Moreover, a systematic review requires subject expertise, statistical support and a librarian to help design and run the search. Be aware that librarians sometimes have queues for their search time. It may take several weeks to complete and run a search. Moreover, all guidelines for carrying out systematic reviews recommend that at least two subject experts screen the studies identified in the search. The first round of screening can consume 1 hour per screener for every 100-200 records. A systematic review is a labor-intensive team effort.

How can I know if my topic has been been reviewed already?

Before starting out on a systematic review, check to see if someone has done it already. In PubMed you can use the systematic review subset to limit to a broad group of papers that is enriched for systematic reviews. You can invoke the subset by selecting if from the Article Types filters to the left of your PubMed results, or you can append AND systematic[sb] to your search. For example:

"neoadjuvant chemotherapy" AND systematic[sb]

The systematic review subset is very noisy, however. To quickly focus on systematic reviews (knowing that you may be missing some), simply search for the word systematic in the title:

"neoadjuvant chemotherapy" AND systematic[ti]

Any PRISMA-compliant systematic review will be captured by this method since including the words "systematic review" in the title is a requirement of the PRISMA checklist. Cochrane systematic reviews do not include 'systematic' in the title, however. It's worth checking the Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews independently.

You can also search for protocols that will indicate that another group has set out on a similar project. Many investigators will register their protocols in PROSPERO , a registry of review protocols. Other published protocols as well as Cochrane Review protocols appear in the Cochrane Methodology Register, a part of the Cochrane Library .

- Next: Guides and Standards >>

- Last Updated: Feb 26, 2024 3:17 PM

- URL: https://guides.library.harvard.edu/meta-analysis

| | |

Introduction to Systematic Reviews

In this guide.

- Introduction

- Lane Research Services

- Types of Reviews

- Systematic Review Process

- Protocols & Guidelines

- Data Extraction and Screening

- Resources & Tools

- Systematic Review Online Course

What is a Systematic Review?

Knowledge synthesis is a term used to describe the method of synthesizing results from individual studies and interpreting these results within the larger body of knowledge on the topic. It requires highly structured, transparent and reproducible methods using quantitative and/or qualitative evidence. Systematic reviews, meta-analyses, scoping reviews, rapid reviews, narrative syntheses, practice guidelines, among others, are all forms of knowledge syntheses. For more information on types of reviews, visit the "Types of Reviews" tab on the left.

A systematic review varies from an ordinary literature review in that it uses a comprehensive, methodical, transparent and reproducible search strategy to ensure conclusions are as unbiased and closer to the truth as possible. The Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions defines a systematic review as:

"A systematic review attempts to identify, appraise and synthesize all the empirical evidence that meets pre-specified eligibility criteria to answer a given research question. Researchers conducting systematic reviews use explicit methods aimed at minimizing bias, in order to produce more reliable findings that can be used to inform decision making [...] This involves: the a priori specification of a research question; clarity on the scope of the review and which studies are eligible for inclusion; making every effort to find all relevant research and to ensure that issues of bias in included studies are accounted for; and analysing the included studies in order to draw conclusions based on all the identified research in an impartial and objective way." ( Chapter 1: Starting a review )

What are systematic reviews? from Cochrane on Youtube .

- Next: Lane Research Services >>

- Last Updated: Jun 21, 2024 2:50 PM

- URL: https://laneguides.stanford.edu/systematicreviews

Systematic Review

- Library Help

- What is a Systematic Review (SR)?

- Steps of a Systematic Review

- Framing a Research Question

- Developing a Search Strategy

- Searching the Literature

- Managing the Process

- Meta-analysis

- Publishing your Systematic Review

Introduction to Systematic Review

- Introduction

- Types of literature reviews

- Other Libguides

- Systematic review as part of a dissertation

- Tutorials & Guidelines & Examples from non-Medical Disciplines

|

A "high-level overview of primary research on a focused question" utilizing high-quality research evidence through: Source: Kysh, Lynn (2013): Difference between a systematic review and a literature review. [figshare]. Available at:

|

Depending on your learning style, please explore the resources in various formats on the tabs above.

For additional tutorials, visit the SR Workshop Videos from UNC at Chapel Hill outlining each stage of the systematic review process.

Know the difference! Systematic review vs. literature review

| It is common to confuse systematic and literature reviews as both are used to provide a summary of the existent literature or research on a specific topic. Even with this common ground, both types vary significantly. Please review the following chart (and its corresponding poster linked below) for a detailed explanation of each as well as the differences between each type of review. Source: Kysh, L. (2013). What’s in a name? The difference between a systematic review and a literature review and why it matters. [Poster] Retrieved from . Check the website from UNC at Chapel Hill, |

Types of literature reviews along with associated methodologies

JBI Manual for Evidence Synthesis . Find definitions and methodological guidance.

- Systematic Reviews - Chapters 1-7

- Mixed Methods Systematic Reviews - Chapter 8

- Diagnostic Test Accuracy Systematic Reviews - Chapter 9

- Umbrella Reviews - Chapter 10

- Scoping Reviews - Chapter 11

- Systematic Reviews of Measurement Properties - Chapter 12

Systematic reviews vs scoping reviews -

Grant, M. J., & Booth, A. (2009). A typology of reviews: an analysis of 14 review types and associated methodologies. Health Information and Libraries Journal , 26 (2), 91–108. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1471-1842.2009.00848.x

Gough, D., Thomas, J., & Oliver, S. (2012). Clarifying differences between review designs and methods. Systematic Reviews, 1 (28). htt p s://doi.org/ 10.1186/2046-4053-1-28

Munn, Z., Peters, M., Stern, C., Tufanaru, C., McArthur, A., & Aromataris, E. (2018). Systematic review or scoping review ? Guidance for authors when choosing between a systematic or scoping review approach. BMC medical research methodology, 18 (1), 143. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12874-018-0611-x. Also, check out the Libguide from Weill Cornell Medicine for the differences between a systematic review and a scoping review and when to embark on either one of them.

Sutton, A., Clowes, M., Preston, L., & Booth, A. (2019). Meeting the review family: Exploring review types and associated information retrieval requirements . Health Information & Libraries Journal , 36 (3), 202–222. https://doi.org/10.1111/hir.12276

Temple University. Review Types . - This guide provides useful descriptions of some of the types of reviews listed in the above article.

UMD Health Sciences and Human Services Library. Review Types . - Guide describing Literature Reviews, Scoping Reviews, and Rapid Reviews.

Whittemore, R., Chao, A., Jang, M., Minges, K. E., & Park, C. (2014). Methods for knowledge synthesis: An overview. Heart & Lung: The Journal of Acute and Critical Care, 43 (5), 453–461. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.hrtlng.2014.05.014

Differences between a systematic review and other types of reviews

Armstrong, R., Hall, B. J., Doyle, J., & Waters, E. (2011). ‘ Scoping the scope ’ of a cochrane review. Journal of Public Health , 33 (1), 147–150. https://doi.org/10.1093/pubmed/fdr015

Kowalczyk, N., & Truluck, C. (2013). Literature reviews and systematic reviews: What is the difference? Radiologic Technology , 85 (2), 219–222.

White, H., Albers, B., Gaarder, M., Kornør, H., Littell, J., Marshall, Z., Matthew, C., Pigott, T., Snilstveit, B., Waddington, H., & Welch, V. (2020). Guidance for producing a Campbell evidence and gap map . Campbell Systematic Reviews, 16 (4), e1125. https://doi.org/10.1002/cl2.1125. Check also this comparison between evidence and gaps maps and systematic reviews.

Rapid Reviews Tutorials

Rapid Review Guidebook by the National Collaborating Centre of Methods and Tools (NCCMT)

Hamel, C., Michaud, A., Thuku, M., Skidmore, B., Stevens, A., Nussbaumer-Streit, B., & Garritty, C. (2021). Defining Rapid Reviews: a systematic scoping review and thematic analysis of definitions and defining characteristics of rapid reviews. Journal of clinical epidemiology , 129 , 74–85. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclinepi.2020.09.041

|

Image: by WeeblyTutorials |

under the tab on the left side menu. |

- Müller, C., Lautenschläger, S., Meyer, G., & Stephan, A. (2017). Interventions to support people with dementia and their caregivers during the transition from home care to nursing home care: A systematic review . International Journal of Nursing Studies, 71 , 139–152. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2017.03.013

- Bhui, K. S., Aslam, R. W., Palinski, A., McCabe, R., Johnson, M. R. D., Weich, S., … Szczepura, A. (2015). Interventions to improve therapeutic communications between Black and minority ethnic patients and professionals in psychiatric services: Systematic review . The British Journal of Psychiatry, 207 (2), 95–103. https://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.bp.114.158899

- Rosen, L. J., Noach, M. B., Winickoff, J. P., & Hovell, M. F. (2012). Parental smoking cessation to protect young children: A systematic review and meta-analysis . Pediatrics, 129 (1), 141–152. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2010-3209

Scoping Review

- Hyshka, E., Karekezi, K., Tan, B., Slater, L. G., Jahrig, J., & Wild, T. C. (2017). The role of consumer perspectives in estimating population need for substance use services: A scoping review . BMC Health Services Research, 171-14. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-017-2153-z

- Olson, K., Hewit, J., Slater, L.G., Chambers, T., Hicks, D., Farmer, A., & ... Kolb, B. (2016). Assessing cognitive function in adults during or following chemotherapy: A scoping review . Supportive Care In Cancer, 24 (7), 3223-3234. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-016-3215-1

- Pham, M. T., Rajić, A., Greig, J. D., Sargeant, J. M., Papadopoulos, A., & McEwen, S. A. (2014). A scoping review of scoping reviews: Advancing the approach and enhancing the consistency . Research Synthesis Methods, 5 (4), 371–385. https://doi.org/10.1002/jrsm.1123

- Scoping Review Tutorial from UNC at Chapel Hill

Qualitative Systematic Review/Meta-Synthesis

- Lee, H., Tamminen, K. A., Clark, A. M., Slater, L., Spence, J. C., & Holt, N. L. (2015). A meta-study of qualitative research examining determinants of children's independent active free play . International Journal Of Behavioral Nutrition & Physical Activity, 12 (5), 121-12. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12966-015-0165-9

Videos on systematic reviews

| This video lecture explains in detail the steps necessary to conduct a systematic review (44 min.) | Here's a brief introduction to how to evaluate systematic reviews (16 min.) |

Systematic Reviews: What are they? Are they right for my research? - 47 min. video recording with a closed caption option.

More training videos on systematic reviews:

| from Yale University (approximately 5-10 minutes each) | with Margaret Foster (approximately 55 min each) |

Books on Systematic Reviews

Books on Meta-analysis

- University of Toronto Libraries - very detailed with good tips on the sensitivity and specificity of searches.

- Monash University - includes an interactive case study tutorial.

- Dalhousie University Libraries - a comprehensive How-To Guide on conducting a systematic review.

Guidelines for a systematic review as part of the dissertation

- Guidelines for Systematic Reviews in the Context of Doctoral Education Background by University of Victoria (PDF)

- Can I conduct a Systematic Review as my Master’s dissertation or PhD thesis? Yes, It Depends! by Farhad (blog)

- What is a Systematic Review Dissertation Like? by the University of Edinburgh (50 min video)

Further readings on experiences of PhD students and doctoral programs with systematic reviews

Puljak, L., & Sapunar, D. (2017). Acceptance of a systematic review as a thesis: Survey of biomedical doctoral programs in Europe . Systematic Reviews , 6 (1), 253. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13643-017-0653-x

Perry, A., & Hammond, N. (2002). Systematic reviews: The experiences of a PhD Student . Psychology Learning & Teaching , 2 (1), 32–35. https://doi.org/10.2304/plat.2002.2.1.32

Daigneault, P.-M., Jacob, S., & Ouimet, M. (2014). Using systematic review methods within a Ph.D. dissertation in political science: Challenges and lessons learned from practice . International Journal of Social Research Methodology , 17 (3), 267–283. https://doi.org/10.1080/13645579.2012.730704

UMD Doctor of Philosophy Degree Policies

Before you embark on a systematic review research project, check the UMD PhD Policies to make sure you are on the right path. Systematic reviews require a team of at least two reviewers and an information specialist or a librarian. Discuss with your advisor the authorship roles of the involved team members. Keep in mind that the UMD Doctor of Philosophy Degree Policies (scroll down to the section, Inclusion of one's own previously published materials in a dissertation ) outline such cases, specifically the following:

" It is recognized that a graduate student may co-author work with faculty members and colleagues that should be included in a dissertation . In such an event, a letter should be sent to the Dean of the Graduate School certifying that the student's examining committee has determined that the student made a substantial contribution to that work. This letter should also note that the inclusion of the work has the approval of the dissertation advisor and the program chair or Graduate Director. The letter should be included with the dissertation at the time of submission. The format of such inclusions must conform to the standard dissertation format. A foreword to the dissertation, as approved by the Dissertation Committee, must state that the student made substantial contributions to the relevant aspects of the jointly authored work included in the dissertation."

| by CommLab India |

|

- Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions - See Part 2: General methods for Cochrane reviews

- Systematic Searches - Yale library video tutorial series

- Using PubMed's Clinical Queries to Find Systematic Reviews - From the U.S. National Library of Medicine

- Systematic reviews and meta-analyses: A step-by-step guide - From the University of Edinsburgh, Centre for Cognitive Ageing and Cognitive Epidemiology

| by Vinova |

|

Bioinformatics

- Mariano, D. C., Leite, C., Santos, L. H., Rocha, R. E., & de Melo-Minardi, R. C. (2017). A guide to performing systematic literature reviews in bioinformatics . arXiv preprint arXiv:1707.05813.

Environmental Sciences

Collaboration for Environmental Evidence. 2018. Guidelines and Standards for Evidence synthesis in Environmental Management. Version 5.0 (AS Pullin, GK Frampton, B Livoreil & G Petrokofsky, Eds) www.environmentalevidence.org/information-for-authors .

Pullin, A. S., & Stewart, G. B. (2006). Guidelines for systematic review in conservation and environmental management. Conservation Biology, 20 (6), 1647–1656. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1523-1739.2006.00485.x

Engineering Education

- Borrego, M., Foster, M. J., & Froyd, J. E. (2014). Systematic literature reviews in engineering education and other developing interdisciplinary fields. Journal of Engineering Education, 103 (1), 45–76. https://doi.org/10.1002/jee.20038

Public Health

- Hannes, K., & Claes, L. (2007). Learn to read and write systematic reviews: The Belgian Campbell Group . Research on Social Work Practice, 17 (6), 748–753. https://doi.org/10.1177/1049731507303106

- McLeroy, K. R., Northridge, M. E., Balcazar, H., Greenberg, M. R., & Landers, S. J. (2012). Reporting guidelines and the American Journal of Public Health’s adoption of preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses . American Journal of Public Health, 102 (5), 780–784. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2011.300630

- Pollock, A., & Berge, E. (2018). How to do a systematic review. International Journal of Stroke, 13 (2), 138–156. https://doi.org/10.1177/1747493017743796

- Institute of Medicine. (2011). Finding what works in health care: Standards for systematic reviews . https://doi.org/10.17226/13059

- Wanden-Berghe, C., & Sanz-Valero, J. (2012). Systematic reviews in nutrition: Standardized methodology . The British Journal of Nutrition, 107 Suppl 2, S3-7. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0007114512001432

Social Sciences

- Bronson, D., & Davis, T. (2012). Finding and evaluating evidence: Systematic reviews and evidence-based practice (Pocket guides to social work research methods). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Petticrew, M., & Roberts, H. (2006). Systematic reviews in the social sciences: A practical guide . Malden, MA: Blackwell Pub.

- Cornell University Library Guide - Systematic literature reviews in engineering: Example: Software Engineering

- Biolchini, J., Mian, P. G., Natali, A. C. C., & Travassos, G. H. (2005). Systematic review in software engineering . System Engineering and Computer Science Department COPPE/UFRJ, Technical Report ES, 679 (05), 45.

- Biolchini, J. C., Mian, P. G., Natali, A. C. C., Conte, T. U., & Travassos, G. H. (2007). Scientific research ontology to support systematic review in software engineering . Advanced Engineering Informatics, 21 (2), 133–151.

- Kitchenham, B. (2007). Guidelines for performing systematic literature reviews in software engineering . [Technical Report]. Keele, UK, Keele University, 33(2004), 1-26.

- Weidt, F., & Silva, R. (2016). Systematic literature review in computer science: A practical guide . Relatórios Técnicos do DCC/UFJF , 1 .

| by Day Translations |

Resources for your writing |

- Academic Phrasebank - Get some inspiration and find some terms and phrases for writing your research paper

- Oxford English Dictionary - Use to locate word variants and proper spelling

- << Previous: Library Help

- Next: Steps of a Systematic Review >>

- Last Updated: May 8, 2024 1:44 PM

- URL: https://lib.guides.umd.edu/SR

Systematic Reviews

- What is a Systematic Review?

A systematic review is an evidence synthesis that uses explicit, reproducible methods to perform a comprehensive literature search and critical appraisal of individual studies and that uses appropriate statistical techniques to combine these valid studies.

Key Characteristics of a Systematic Review:

Generally, systematic reviews must have:

- a clearly stated set of objectives with pre-defined eligibility criteria for studies

- an explicit, reproducible methodology

- a systematic search that attempts to identify all studies that would meet the eligibility criteria

- an assessment of the validity of the findings of the included studies, for example through the assessment of the risk of bias

- a systematic presentation, and synthesis, of the characteristics and findings of the included studies.

A meta-analysis is a systematic review that uses quantitative methods to synthesize and summarize the pooled data from included studies.

Additional Information

- How-to Books

- Beyond Health Sciences

- Cochrane Handbook For Systematic Reviews of Interventions Provides guidance to authors for the preparation of Cochrane Intervention reviews. Chapter 6 covers searching for reviews.

- Systematic Reviews: CRD’s Guidance for Undertaking Reviews in Health Care From The University of York Centre for Reviews and Dissemination: Provides practical guidance for undertaking evidence synthesis based on a thorough understanding of systematic review methodology. It presents the core principles of systematic reviewing, and in complementary chapters, highlights issues that are specific to reviews of clinical tests, public health interventions, adverse effects, and economic evaluations.

- Cornell, Sytematic Reviews and Evidence Synthesis Beyond the Health Sciences Video series geared for librarians but very informative about searching outside medicine.

- << Previous: Getting Started

- Next: Levels of Evidence >>

- Getting Started

- Levels of Evidence

- Locating Systematic Reviews

- Searching Systematically

- Developing Answerable Questions

- Identifying Synonyms & Related Terms

- Using Truncation and Wildcards

- Identifying Search Limits/Exclusion Criteria

- Keyword vs. Subject Searching

- Where to Search

- Search Filters

- Sensitivity vs. Precision

- Core Databases

- Other Databases

- Clinical Trial Registries

- Conference Presentations

- Databases Indexing Grey Literature

- Web Searching

- Handsearching

- Citation Indexes

- Documenting the Search Process

- Managing your Review

Research Support

- Last Updated: Jun 6, 2024 9:14 AM

- URL: https://guides.library.ucdavis.edu/systematic-reviews

1.2.2 What is a systematic review?

A systematic review attempts to collate all empirical evidence that fits pre-specified eligibility criteria in order to answer a specific research question. It uses explicit, systematic methods that are selected with a view to minimizing bias, thus providing more reliable findings from which conclusions can be drawn and decisions made (Antman 1992, Oxman 1993) . The key characteristics of a systematic review are:

a clearly stated set of objectives with pre-defined eligibility criteria for studies;

an explicit, reproducible methodology;

a systematic search that attempts to identify all studies that would meet the eligibility criteria;

an assessment of the validity of the findings of the included studies, for example through the assessment of risk of bias; and

a systematic presentation, and synthesis, of the characteristics and findings of the included studies.

Many systematic reviews contain meta-analyses. Meta-analysis is the use of statistical methods to summarize the results of independent studies (Glass 1976). By combining information from all relevant studies, meta-analyses can provide more precise estimates of the effects of health care than those derived from the individual studies included within a review (see Chapter 9, Section 9.1.3 ). They also facilitate investigations of the consistency of evidence across studies, and the exploration of differences across studies.

- A-Z Publications

Annual Review of Psychology

Volume 70, 2019, review article, how to do a systematic review: a best practice guide for conducting and reporting narrative reviews, meta-analyses, and meta-syntheses.

- Andy P. Siddaway 1 , Alex M. Wood 2 , and Larry V. Hedges 3

- View Affiliations Hide Affiliations Affiliations: 1 Behavioural Science Centre, Stirling Management School, University of Stirling, Stirling FK9 4LA, United Kingdom; email: [email protected] 2 Department of Psychological and Behavioural Science, London School of Economics and Political Science, London WC2A 2AE, United Kingdom 3 Department of Statistics, Northwestern University, Evanston, Illinois 60208, USA; email: [email protected]

- Vol. 70:747-770 (Volume publication date January 2019) https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-psych-010418-102803

- First published as a Review in Advance on August 08, 2018

- Copyright © 2019 by Annual Reviews. All rights reserved

Systematic reviews are characterized by a methodical and replicable methodology and presentation. They involve a comprehensive search to locate all relevant published and unpublished work on a subject; a systematic integration of search results; and a critique of the extent, nature, and quality of evidence in relation to a particular research question. The best reviews synthesize studies to draw broad theoretical conclusions about what a literature means, linking theory to evidence and evidence to theory. This guide describes how to plan, conduct, organize, and present a systematic review of quantitative (meta-analysis) or qualitative (narrative review, meta-synthesis) information. We outline core standards and principles and describe commonly encountered problems. Although this guide targets psychological scientists, its high level of abstraction makes it potentially relevant to any subject area or discipline. We argue that systematic reviews are a key methodology for clarifying whether and how research findings replicate and for explaining possible inconsistencies, and we call for researchers to conduct systematic reviews to help elucidate whether there is a replication crisis.

Article metrics loading...

Full text loading...

Literature Cited

- APA Publ. Commun. Board Work. Group J. Artic. Rep. Stand. 2008 . Reporting standards for research in psychology: Why do we need them? What might they be?. Am. Psychol . 63 : 848– 49 [Google Scholar]

- Baumeister RF 2013 . Writing a literature review. The Portable Mentor: Expert Guide to a Successful Career in Psychology MJ Prinstein, MD Patterson 119– 32 New York: Springer, 2nd ed.. [Google Scholar]

- Baumeister RF , Leary MR 1995 . The need to belong: desire for interpersonal attachments as a fundamental human motivation. Psychol. Bull. 117 : 497– 529 [Google Scholar]

- Baumeister RF , Leary MR 1997 . Writing narrative literature reviews. Rev. Gen. Psychol. 3 : 311– 20 Presents a thorough and thoughtful guide to conducting narrative reviews. [Google Scholar]

- Bem DJ 1995 . Writing a review article for Psychological Bulletin. Psychol . Bull 118 : 172– 77 [Google Scholar]

- Borenstein M , Hedges LV , Higgins JPT , Rothstein HR 2009 . Introduction to Meta-Analysis New York: Wiley Presents a comprehensive introduction to meta-analysis. [Google Scholar]

- Borenstein M , Higgins JPT , Hedges LV , Rothstein HR 2017 . Basics of meta-analysis: I 2 is not an absolute measure of heterogeneity. Res. Synth. Methods 8 : 5– 18 [Google Scholar]

- Braver SL , Thoemmes FJ , Rosenthal R 2014 . Continuously cumulating meta-analysis and replicability. Perspect. Psychol. Sci. 9 : 333– 42 [Google Scholar]

- Bushman BJ 1994 . Vote-counting procedures. The Handbook of Research Synthesis H Cooper, LV Hedges 193– 214 New York: Russell Sage Found. [Google Scholar]

- Cesario J 2014 . Priming, replication, and the hardest science. Perspect. Psychol. Sci. 9 : 40– 48 [Google Scholar]

- Chalmers I 2007 . The lethal consequences of failing to make use of all relevant evidence about the effects of medical treatments: the importance of systematic reviews. Treating Individuals: From Randomised Trials to Personalised Medicine PM Rothwell 37– 58 London: Lancet [Google Scholar]

- Cochrane Collab. 2003 . Glossary Rep., Cochrane Collab. London: http://community.cochrane.org/glossary Presents a comprehensive glossary of terms relevant to systematic reviews. [Google Scholar]

- Cohn LD , Becker BJ 2003 . How meta-analysis increases statistical power. Psychol. Methods 8 : 243– 53 [Google Scholar]

- Cooper HM 2003 . Editorial. Psychol. Bull. 129 : 3– 9 [Google Scholar]

- Cooper HM 2016 . Research Synthesis and Meta-Analysis: A Step-by-Step Approach Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage, 5th ed.. Presents a comprehensive introduction to research synthesis and meta-analysis. [Google Scholar]

- Cooper HM , Hedges LV , Valentine JC 2009 . The Handbook of Research Synthesis and Meta-Analysis New York: Russell Sage Found, 2nd ed.. [Google Scholar]

- Cumming G 2014 . The new statistics: why and how. Psychol. Sci. 25 : 7– 29 Discusses the limitations of null hypothesis significance testing and viable alternative approaches. [Google Scholar]

- Earp BD , Trafimow D 2015 . Replication, falsification, and the crisis of confidence in social psychology. Front. Psychol. 6 : 621 [Google Scholar]

- Etz A , Vandekerckhove J 2016 . A Bayesian perspective on the reproducibility project: psychology. PLOS ONE 11 : e0149794 [Google Scholar]

- Ferguson CJ , Brannick MT 2012 . Publication bias in psychological science: prevalence, methods for identifying and controlling, and implications for the use of meta-analyses. Psychol. Methods 17 : 120– 28 [Google Scholar]

- Fleiss JL , Berlin JA 2009 . Effect sizes for dichotomous data. The Handbook of Research Synthesis and Meta-Analysis H Cooper, LV Hedges, JC Valentine 237– 53 New York: Russell Sage Found, 2nd ed.. [Google Scholar]

- Garside R 2014 . Should we appraise the quality of qualitative research reports for systematic reviews, and if so, how. Innovation 27 : 67– 79 [Google Scholar]

- Hedges LV , Olkin I 1980 . Vote count methods in research synthesis. Psychol. Bull. 88 : 359– 69 [Google Scholar]

- Hedges LV , Pigott TD 2001 . The power of statistical tests in meta-analysis. Psychol. Methods 6 : 203– 17 [Google Scholar]

- Higgins JPT , Green S 2011 . Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions, Version 5.1.0 London: Cochrane Collab. Presents comprehensive and regularly updated guidelines on systematic reviews. [Google Scholar]

- John LK , Loewenstein G , Prelec D 2012 . Measuring the prevalence of questionable research practices with incentives for truth telling. Psychol. Sci. 23 : 524– 32 [Google Scholar]

- Juni P , Witschi A , Bloch R , Egger M 1999 . The hazards of scoring the quality of clinical trials for meta-analysis. JAMA 282 : 1054– 60 [Google Scholar]

- Klein O , Doyen S , Leys C , Magalhães de Saldanha da Gama PA , Miller S et al. 2012 . Low hopes, high expectations: expectancy effects and the replicability of behavioral experiments. Perspect. Psychol. Sci. 7 : 6 572– 84 [Google Scholar]

- Lau J , Antman EM , Jimenez-Silva J , Kupelnick B , Mosteller F , Chalmers TC 1992 . Cumulative meta-analysis of therapeutic trials for myocardial infarction. N. Engl. J. Med. 327 : 248– 54 [Google Scholar]

- Light RJ , Smith PV 1971 . Accumulating evidence: procedures for resolving contradictions among different research studies. Harvard Educ. Rev. 41 : 429– 71 [Google Scholar]

- Lipsey MW , Wilson D 2001 . Practical Meta-Analysis London: Sage Comprehensive and clear explanation of meta-analysis. [Google Scholar]

- Matt GE , Cook TD 1994 . Threats to the validity of research synthesis. The Handbook of Research Synthesis H Cooper, LV Hedges 503– 20 New York: Russell Sage Found. [Google Scholar]

- Maxwell SE , Lau MY , Howard GS 2015 . Is psychology suffering from a replication crisis? What does “failure to replicate” really mean?. Am. Psychol. 70 : 487– 98 [Google Scholar]

- Moher D , Hopewell S , Schulz KF , Montori V , Gøtzsche PC et al. 2010 . CONSORT explanation and elaboration: updated guidelines for reporting parallel group randomised trials. BMJ 340 : c869 [Google Scholar]

- Moher D , Liberati A , Tetzlaff J , Altman DG PRISMA Group. 2009 . Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. BMJ 339 : 332– 36 Comprehensive reporting guidelines for systematic reviews. [Google Scholar]

- Morrison A , Polisena J , Husereau D , Moulton K , Clark M et al. 2012 . The effect of English-language restriction on systematic review-based meta-analyses: a systematic review of empirical studies. Int. J. Technol. Assess. Health Care 28 : 138– 44 [Google Scholar]

- Nelson LD , Simmons J , Simonsohn U 2018 . Psychology's renaissance. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 69 : 511– 34 [Google Scholar]

- Noblit GW , Hare RD 1988 . Meta-Ethnography: Synthesizing Qualitative Studies Newbury Park, CA: Sage [Google Scholar]

- Olivo SA , Macedo LG , Gadotti IC , Fuentes J , Stanton T , Magee DJ 2008 . Scales to assess the quality of randomized controlled trials: a systematic review. Phys. Ther. 88 : 156– 75 [Google Scholar]

- Open Sci. Collab. 2015 . Estimating the reproducibility of psychological science. Science 349 : 943 [Google Scholar]

- Paterson BL , Thorne SE , Canam C , Jillings C 2001 . Meta-Study of Qualitative Health Research: A Practical Guide to Meta-Analysis and Meta-Synthesis Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage [Google Scholar]

- Patil P , Peng RD , Leek JT 2016 . What should researchers expect when they replicate studies? A statistical view of replicability in psychological science. Perspect. Psychol. Sci. 11 : 539– 44 [Google Scholar]

- Rosenthal R 1979 . The “file drawer problem” and tolerance for null results. Psychol. Bull. 86 : 638– 41 [Google Scholar]

- Rosnow RL , Rosenthal R 1989 . Statistical procedures and the justification of knowledge in psychological science. Am. Psychol. 44 : 1276– 84 [Google Scholar]

- Sanderson S , Tatt ID , Higgins JP 2007 . Tools for assessing quality and susceptibility to bias in observational studies in epidemiology: a systematic review and annotated bibliography. Int. J. Epidemiol. 36 : 666– 76 [Google Scholar]

- Schreiber R , Crooks D , Stern PN 1997 . Qualitative meta-analysis. Completing a Qualitative Project: Details and Dialogue JM Morse 311– 26 Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage [Google Scholar]

- Shrout PE , Rodgers JL 2018 . Psychology, science, and knowledge construction: broadening perspectives from the replication crisis. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 69 : 487– 510 [Google Scholar]

- Stroebe W , Strack F 2014 . The alleged crisis and the illusion of exact replication. Perspect. Psychol. Sci. 9 : 59– 71 [Google Scholar]

- Stroup DF , Berlin JA , Morton SC , Olkin I , Williamson GD et al. 2000 . Meta-analysis of observational studies in epidemiology (MOOSE): a proposal for reporting. JAMA 283 : 2008– 12 [Google Scholar]

- Thorne S , Jensen L , Kearney MH , Noblit G , Sandelowski M 2004 . Qualitative meta-synthesis: reflections on methodological orientation and ideological agenda. Qual. Health Res. 14 : 1342– 65 [Google Scholar]

- Tong A , Flemming K , McInnes E , Oliver S , Craig J 2012 . Enhancing transparency in reporting the synthesis of qualitative research: ENTREQ. BMC Med. Res. Methodol. 12 : 181– 88 [Google Scholar]

- Trickey D , Siddaway AP , Meiser-Stedman R , Serpell L , Field AP 2012 . A meta-analysis of risk factors for post-traumatic stress disorder in children and adolescents. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 32 : 122– 38 [Google Scholar]

- Valentine JC , Biglan A , Boruch RF , Castro FG , Collins LM et al. 2011 . Replication in prevention science. Prev. Sci. 12 : 103– 17 [Google Scholar]

- Article Type: Review Article

Most Read This Month

Most cited most cited rss feed, job burnout, executive functions, social cognitive theory: an agentic perspective, on happiness and human potentials: a review of research on hedonic and eudaimonic well-being, sources of method bias in social science research and recommendations on how to control it, mediation analysis, missing data analysis: making it work in the real world, grounded cognition, personality structure: emergence of the five-factor model, motivational beliefs, values, and goals.

- Duke NetID Login

- 919.660.1100

- Duke Health Badge: 24-hour access

- Accounts & Access

- Databases, Journals & Books

- Request & Reserve

- Training & Consulting

- Request Articles & Books

- Renew Online

- Reserve Spaces

- Reserve a Locker

- Study & Meeting Rooms

- Course Reserves

- Pay Fines/Fees

- Recommend a Purchase

- Access From Off Campus

- Building Access

- Computers & Equipment

- Wifi Access

- My Accounts

- Mobile Apps

- Known Access Issues

- Report an Access Issue

- All Databases

- Article Databases

- Basic Sciences

- Clinical Sciences

- Dissertations & Theses

- Drugs, Chemicals & Toxicology

- Grants & Funding

- Interprofessional Education

- Non-Medical Databases

- Search for E-Journals

- Search for Print & E-Journals

- Search for E-Books

- Search for Print & E-Books

- E-Book Collections

- Biostatistics

- Global Health

- MBS Program

- Medical Students

- MMCi Program

- Occupational Therapy

- Path Asst Program

- Physical Therapy

- Researchers

- Community Partners

Conducting Research

- Archival & Historical Research

- Black History at Duke Health

- Data Analytics & Viz Software

- Data: Find and Share

- Evidence-Based Practice

- NIH Public Access Policy Compliance

- Publication Metrics

- Qualitative Research

- Searching Animal Alternatives

Systematic Reviews

- Test Instruments

Using Databases

- JCR Impact Factors

- Web of Science

Finding & Accessing

- COVID-19: Core Clinical Resources

- Health Literacy

- Health Statistics & Data

- Library Orientation

Writing & Citing

- Creating Links

- Getting Published

- Reference Mgmt

- Scientific Writing

Meet a Librarian

- Request a Consultation

- Find Your Liaisons

- Register for a Class

- Request a Class

- Self-Paced Learning

Search Services

- Literature Search

- Systematic Review

- Animal Alternatives (IACUC)

- Research Impact

Citation Mgmt

- Other Software

Scholarly Communications

- About Scholarly Communications

- Publish Your Work

- Measure Your Research Impact

- Engage in Open Science

- Libraries and Publishers

- Directions & Maps

- Floor Plans

Library Updates

- Annual Snapshot

- Conference Presentations

- Contact Information

- Gifts & Donations

What is a Systematic Review?

- Types of Reviews

- Manuals and Reporting Guidelines

- Our Service

- 1. Assemble Your Team

- 2. Develop a Research Question

- 3. Write and Register a Protocol

- 4. Search the Evidence

- 5. Screen Results

- 6. Assess for Quality and Bias

- 7. Extract the Data

- 8. Write the Review

- Additional Resources

- Finding Full-Text Articles

A systematic review attempts to collate all empirical evidence that fits pre-specified eligibility criteria in order to answer a specific research question. The key characteristics of a systematic review are:

- a clearly defined question with inclusion and exclusion criteria;

- a rigorous and systematic search of the literature;

- two phases of screening (blinded, at least two independent screeners);

- data extraction and management;

- analysis and interpretation of results;

- risk of bias assessment of included studies;

- and report for publication.

Medical Center Library & Archives Presentations

The following presentation is a recording of the Getting Started with Systematic Reviews workshop (4/2022), offered by the Duke Medical Center Library & Archives. A NetID/pw is required to access the tutorial via Warpwire.

- << Previous: Overview

- Next: Types of Reviews >>

- Last Updated: Jun 18, 2024 9:41 AM

- URL: https://guides.mclibrary.duke.edu/sysreview

- Duke Health