Sentenced to death, but innocent: These are stories of justice gone wrong.

Since 1973, more than 8,700 people in the U.S. have been sent to death row. At least 182 weren’t guilty—their lives upended by a system that nearly killed them.

A version of this story appears in the March 2021 issue of National Geographic magazine.

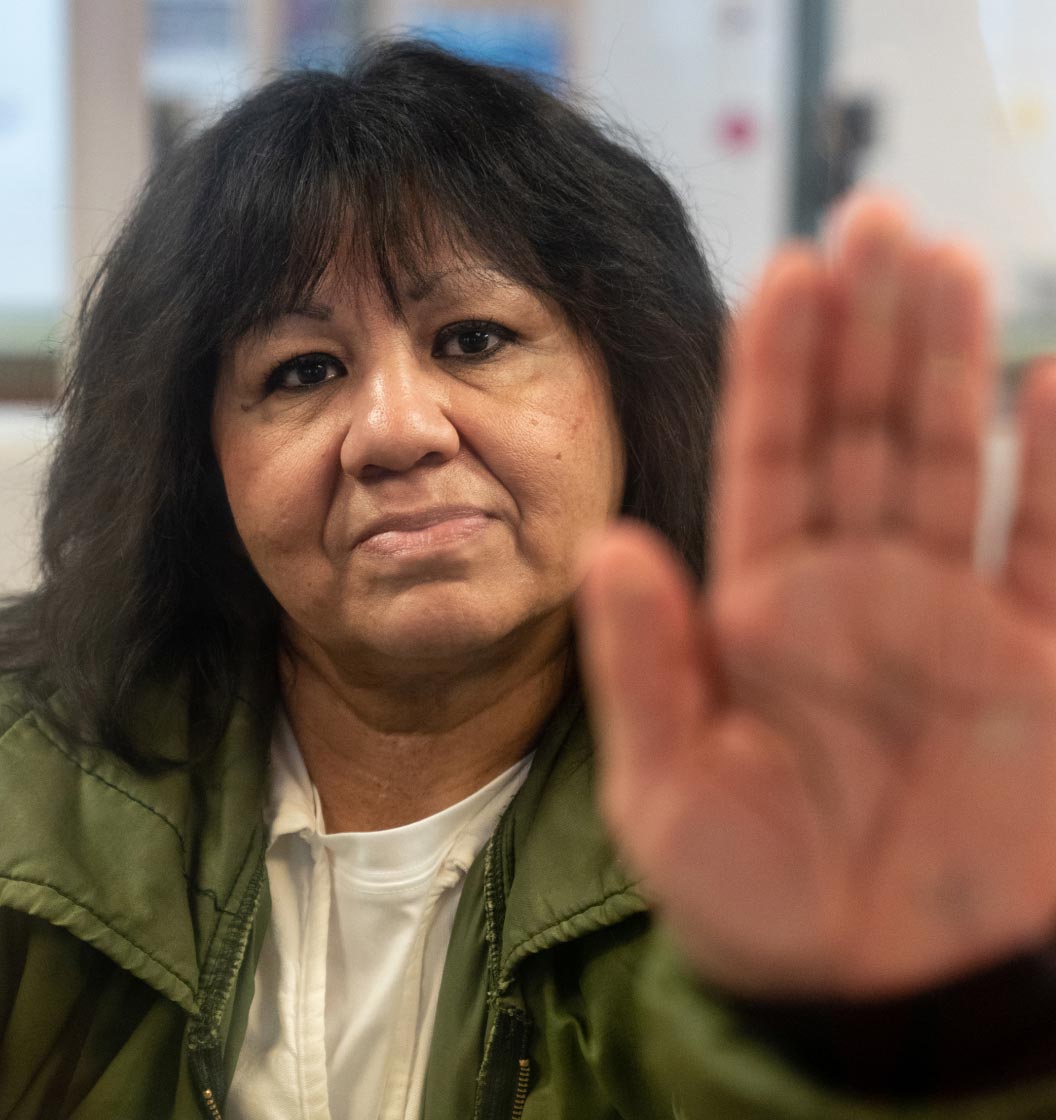

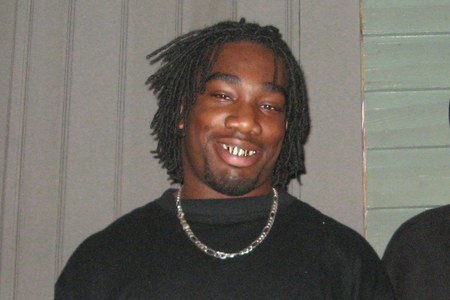

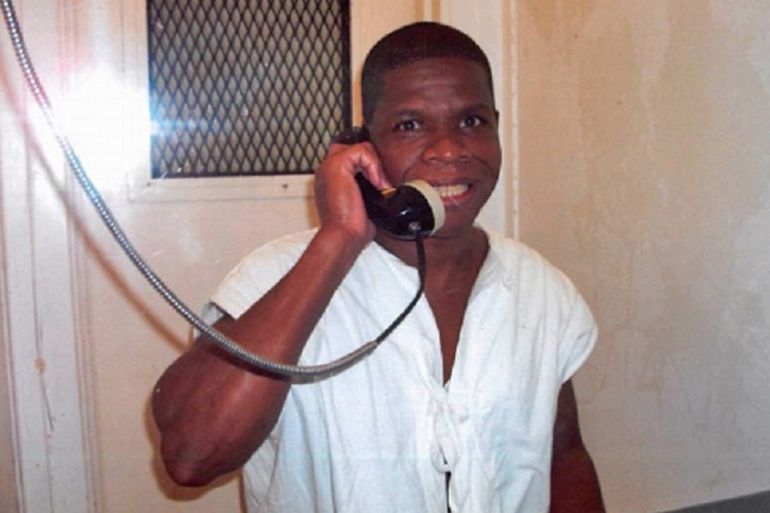

A 63-year-old man named Kwame Ajamu lives walking distance from my house in a suburb of Cleveland, Ohio. Ajamu was sentenced to death in 1975 for the murder of Harold Franks, a money order salesman on Cleveland’s east side. Ajamu was 17 when he was convicted.

Ajamu, then named Ronnie Bridgeman, was found guilty primarily because of the testimony of a 13-year-old boy, who said he saw Bridgeman and another young male violently attack the salesman on a city street corner. Not a shred of evidence, forensic or physical, connected Bridgeman to the slaying. He had no prior criminal record. Another witness testified that Bridgeman was not on the street corner when Franks was killed. Yet mere months after his arrest, the high school junior was condemned to die.

It would be publicly revealed 39 years later that the boy who testified against him had immediately tried to recant his statement. But Cleveland homicide detectives told the boy they would arrest and charge his parents with perjury if he changed his story, according to his later court testimony. Ajamu was released on parole in 2003 after 27 years in prison, but the state of Ohio would not declare him innocent of the murder for nearly another 12 years, when the boy’s false statement and police misconduct were revealed in a related court hearing.

I interviewed Ajamu and others who represent vastly different backgrounds but share a similar, soul-crushing burden: They were sentenced to death after being convicted of crimes they didn’t commit.

(*Figures in all captions are rounded to the nearest year and don’t include time in jail pre-sentencing.)

The daily paths they travel as former death-row inmates are every bit as daunting, terrifying, and confusing as the burden of innocence that once taunted them. The post-traumatic stress faced by a wrongly convicted person who has awaited execution by the government doesn’t dissipate simply because the state frees the inmate, apologizes, or even provides financial compensation—which often is not the case.

The lesson is as charged as superbolt lightning: An innocent man or woman sentenced to die is the perfect witness against what many see as the inherent immorality and barbarity of continuing capital punishment.

It’s a particularly poignant lesson in a nation that executes people at a rate outpaced by few others—and where factors such as a defendant’s or victim’s race, low income, or inability to counter overly zealous police and prosecutors can put the accused at increased risk of a wrongful conviction that could lead to execution. Race is a particularly strong determinant: As of April 2020, Black people made up more than 41 percent of those on death row but only 13.4 percent of the U.S. population.

During the past three decades, groups such as the Innocence Project have shed light on how dangerously fallible the U.S. justice system can be, particularly in capital cases. DNA testing and scrutiny of actions by police, prosecutors, and public defenders have helped exonerate 182 people from death row since 1972, and as of December 2020 had led to more than 2,700 exonerations overall since 1989.

Each of the former death-row inmates I interviewed belongs to an organization called Witness to Innocence . Based in Philadelphia since 2005, WTI is a nonprofit led by exonerated death-row inmates. Its primary goal is to see the death penalty abolished in the U.S. by shifting public opinion on the morality of capital punishment.

During the past 15 years, WTI’s outreach targeting the U.S. Congress, state legislatures, policy advisers, and academics has been credited with helping to abolish the death penalty in several states, though it remains legal in 28 states, the federal government, and the U.S. military. In 2020, 17 people were executed in the U.S., 10 by the federal government. It was the first time more prisoners were executed by the federal government than by all of the states combined.

“I was abducted by the state of Ohio when I was 17 years old,” Ajamu began our conversation when we met on my backyard patio.

“I was a child when I was sent to prison to be killed,” Ajamu, now chairman of WTI’s board, told me. “I did not understand what was happening to me or how it could happen. At first I begged God for mercy, but soon it dawned on me that there would be no mercy coming.”

The day Ajamu arrived at the Southern Ohio Correctional Facility, a maximum-security prison in rural Ohio, he was escorted to a cellblock filled with condemned men. At the end of death row was a room that held Ohio’s electric chair. Before the guards put him in his cell, they made a point of walking him past that room.

“One of the guards really wanted me to see that chair,” Ajamu recalled. “I’ll never forget his words: ‘That’s gonna be your hot date.’ ”

From the time Ajamu was sentenced to die until 2005—when the U.S. Supreme Court ruled that executing juveniles violated the Constitution’s ban on cruel and unusual punishment—the nation executed 22 people who were convicted of a crime committed when they were under age 18, according to the Death Penalty Information Center (DPIC) .

The high court’s ruling countered a history of executing juveniles that began long before the United States was conceived. The first known case of a juvenile executed in the British colonies was in 1642 in the Plymouth Colony, where Thomas Granger, 17, was hanged. His alleged offense was sodomy with livestock.

In the earliest days of the nation, even younger children were subject to the harshest of all judicial penalties. Hannah Ocuish, 12, a Native American girl, was hanged in New London, Connecticut, in 1786 for murder. Two enslaved boys—a 12-year-old convicted of murder and a 13-year-old convicted of arson—were hanged in Virginia in 1787 and 1796, respectively.

For most of the next 200 years, age was ignored as a factor in sentencing. Juveniles and adults alike were tried, convicted, and executed based on their crimes, not their maturity. Available criminal records don’t cite the age of the executed regularly until around 1900. By 1987, when the U.S. Supreme Court first agreed to consider the constitutionality of the death penalty for minors, some 287 juvenile executions had been documented. When the Supreme Court ruled in 1978 that Ohio’s death penalty law violated the Eighth Amendment’s ban on cruel and unusual punishment, as well as the 14th Amendment’s requirement of equal protection under the law, Ajamu’s death sentence was reduced to life in prison. Still, he lingered behind bars for another quarter of a century, when he was released on parole. He wouldn’t be exonerated until 2014, after a crusading reporter for a Cleveland magazine and the Ohio Innocence Project helped unravel the lie that had sent Ajamu to death row.

“There is a wide array of blunders that can cause erroneous convictions in capital cases,” said Michael Radelet, a death penalty scholar and sociologist at the University of Colorado Boulder. “Police officers might secure a coerced or otherwise false confession. Prosecutors occasionally suppress exculpatory evidence. Sometimes there is a well-intentioned but mistaken eyewitness identification. Most common is perjury by prosecution witnesses.”

Few opponents of capital punishment summarize the case against state-sponsored executions more bluntly than Sister Helen Prejean, co-founder of WTI and author of Dead Man Walking, the best-selling book that inspired the 1995 film of the same title, starring Susan Sarandon and Sean Penn.

The plainspoken nun described how her animus toward the death penalty became personal by recalling her fear of a fairly routine dental experience she underwent years ago.

“I had to have a root canal on a Monday morning,” she told me. “The whole week before that root canal, I dreamt about it. As the appointment got closer, the more nervous I became.”

She continued, “Now imagine anticipating your scheduled appointment to be put to death. The six people that I’ve accompanied onto death row all had the same nightmare. The guards were dragging them from their cells. They cry for help and struggle. Then they wake up and realize that they are still in their cells. They realize it’s just a dream. But they know that one day the guards are really going to come for them, and it won’t be a dream. That’s the torture. It’s a torture that as of yet our Supreme Court refuses to recognize as a violation of the Constitution’s prohibition against cruel and unusual punishments.”

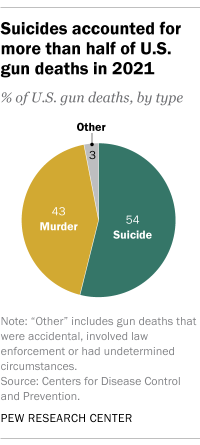

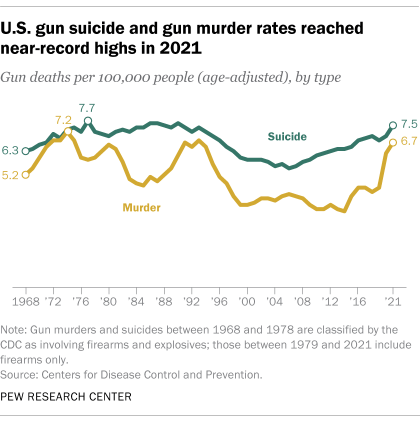

More than 70 percent of the world’s nations have rejected the death penalty in either law or practice , according to the DPIC. Of the places where Amnesty International has recorded recent executions, the U.S.—which has the highest incarceration rates in the world—was one of just 13 countries that held executions every one of the past five years. Americans’ support for capital punishment has dropped significantly since 1996, when 78 percent supported the death penalty for people convicted of murder. By 2018, support had fallen to 54 percent, according to the Pew Research Center.

“If I were to be murdered,” wrote Prejean, “I would not want my murderer executed. I would not want my death avenged— especially by government —which can’t be trusted to control its own bureaucrats or collect taxes equitably or fill a pothole, much less decide which of its citizens to kill.”

Before Ray Krone was sentenced to die, his life bore no resemblance to Ajamu’s. From tiny Dover, Pennsylvania, Krone was the eldest of three children and a typical small-town American boy. Raised a Lutheran, he sang in a church choir, joined the Boy Scouts, and as a teenager was known as a fairly smart kid, a bit of a prankster. He pre-enlisted in the Air Force during high school; after graduating, he served for six years.

Having received an honorable discharge, he stayed in Arizona and went to work for the U.S. Postal Service, a job he planned to keep until retirement.

That career dream—and his life—were abruptly shattered in December 1991, when Kim Ancona, a 36-year-old bar manager, was found stabbed to death in the men’s bathroom of a Phoenix lounge that Krone frequented.

Police immediately zeroed in on Krone as a suspect after learning that he’d given Ancona, whom he knew casually, a ride to a Christmas party a few days earlier. The day after her body was discovered, Krone was ordered to provide blood, saliva, and hair samples. A dental cast of his teeth also was created. The next day he was arrested and charged with aggravated murder.

Investigators said the distinctive misalignment of Krone’s teeth matched bite marks on the victim’s body. Media reports would soon derisively refer to Krone as the “snaggletooth” killer. As was the case with Ajamu, there was no forensic evidence linking Krone to the crime. DNA was a fairly new science, and none of the saliva or blood collected at the crime scene was tested for DNA. Simpler blood, saliva, and hair tests were inconclusive. Exculpatory evidence was available but ignored, such as shoe prints found around the victim’s body that didn’t match the size of Krone’s feet or any shoes he owned.

Based on little more than the testimony of a dental analyst who said the bite marks on the victim’s body matched Krone’s misaligned front teeth, a jury found Krone guilty. He was sentenced to death.

“It’s a devastating feeling when you recognize that everything you’ve ever believed in and stood for has been taken away from you, and without just cause,” Krone told me. “I was so naive. I didn’t believe this could actually happen to me. I had served my country in uniform. I worked for the post office. I wasn’t perfect, but I had never been in trouble. I’d never even gotten a parking ticket, but here I was on death row. That’s when I realized that if it could happen to me, it could happen to anyone.”

The Maricopa County Attorney’s Office spent upwards of $50,000 on the prosecution, centered on its bite-mark theory, while the consulting dental expert for Krone’s publicly funded defense was paid $1,500. This discrepancy in resources available to prosecutors and defendants in capital cases has long been replicated across the nation, leading to predictable outcomes for defendants staked to under-resourced and often ineffective legal counsel.

Krone got a new trial in 1995, when an appeals court ruled that prosecutors had wrongly withheld a videotape of the bite evidence until the day before the trial. Again, he was found guilty. Prosecutors relied on the same dental analysts who’d helped convict Krone the first time. But this time the sentencing judge ruled that a life sentence was appropriate, not death.

Krone’s mother and stepfather refused to give up on their belief in their son’s innocence. They mortgaged their house, and the family hired their own lawyer to look into the physical evidence collected during the original investigation. Over objections by the prosecution, a judge granted a request by the family’s lawyer to have an independent lab examine DNA samples, including saliva and blood from the crime scene.

In April 2002 the DNA test results showed that Krone was innocent. A man named Kenneth Phillips, who lived less than a mile from the bar where Ancona was killed, had left his DNA on clothes Ancona had been wearing. Phillips was easy to find: He already was in prison for sexually assaulting and choking a seven-year-old girl.

When Krone was released from prison four days after the DNA test results were announced, he became known as the hundredth man in the United States since 1973 who’d been sentenced to death but later proved innocent and freed.

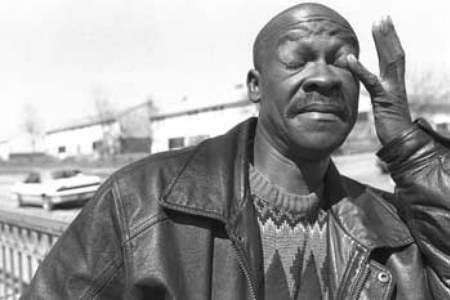

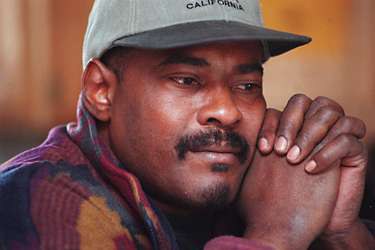

Gary Drinkard was no choirboy. He’d had prior brushes with the law when Dalton Pace, a junk dealer, was robbed and killed in Decatur, Alabama, in August 1993.

Police arrested Drinkard, then 37, two weeks later when Beverly Robinson, Drinkard’s half sister, and Rex Segars, her partner, struck a deal with police that implicated Drinkard in the slaying. Facing unrelated robbery charges that also potentially implicated Drinkard, the couple agreed, in exchange for the charges being dropped against them, to cooperate with police and testify that Drinkard told them he’d killed Pace.

When I spoke with Drinkard, he reminded me of a weather-beaten man straight out of a Merle Haggard song. He wore coveralls and chain-smoked Newports. He spoke slowly and guardedly in a deep southern drawl. He grew exasperated only when I asked him to describe his time on death row.

“I thought they were going to kill me,” Drinkard said. That certainly seemed to be the plan. Using testimony from their star witnesses (the half sister and her partner), prosecutors hammered home the alleged confession while improperly influencing the jury with references to Drinkard’s alleged involvement in those earlier thefts. Drinkard’s public defenders, who had no experience in capital cases and very little in criminal law, mostly stood mute. They made no real attempt to introduce evidence that could have proved their client’s innocence. Drinkard was found guilty in 1995 and sentenced to death. He would spend close to six years on death row.

In 2000 the Supreme Court of Alabama ordered a new trial because of the prosecution’s introduction of Drinkard’s criminal history.

“Evidence of a defendant’s prior bad acts … is generally inadmissible. Such evidence is presumptively prejudicial because it could cause the jury to infer that, because the defendant has committed crimes in the past, it is more likely that he committed the particular crime with which he is charged,” the court wrote in granting a new trial.

Drinkard’s case had drawn the attention of the Southern Center for Human Rights, an organization that fights capital punishment. It provided him with legal counsel. At Drinkard’s 2001 retrial, his lawyers introduced evidence that indicated Drinkard was suffering from a debilitating back injury and was heavily medicated at the time of the slaying. Drinkard’s lawyers argued that he had been at home and on workers’ compensation when Pace was killed, so he couldn’t have committed the crime. A county jury found Drinkard not guilty within one hour, and he was released.

“I was not opposed to capital punishment until the state tried to kill me,” Drinkard said.

There have been more than 2,700 exonerations overall in the U.S. since 1989, the first year that DNA became a factor, according to the National Registry of Exonerations.

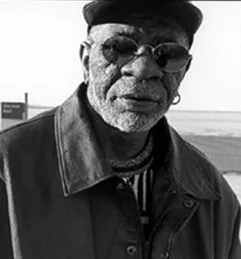

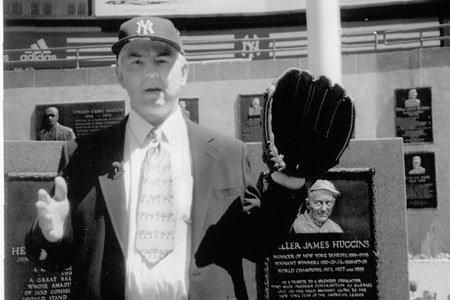

In 1993 Kirk Bloodsworth was the first person in the nation to be exonerated from death row based on DNA evidence. Bloodsworth was arrested in 1984 and charged with raping and murdering Dawn Hamilton, a nine-year-old girl, near Baltimore, Maryland. Police were alerted to Bloodsworth, who had just moved to the area, when an anonymous tipster reported him after seeing a televised police sketch of the suspect.

Bloodsworth bore little resemblance to the suspect in the police sketch. No physical evidence linked him to the crime. He had no prior criminal record. Yet Bloodsworth was convicted and sentenced to death based primarily on the testimony of five witnesses, including an eight-year-old and a 10-year-old, who said they could place him near the murder scene. Witness misidentification is a factor in many wrongful convictions, according to the DPIC.

“Give him the gas and kill his ass,” Bloodsworth recalled people in the courtroom chanting after he was sentenced. All the while, he wondered how he could be sentenced to die for a ghastly crime he hadn’t committed.

He was granted a second trial nearly two years later, after it was shown on appeal that prosecutors had withheld potentially exculpatory evidence from his defense, namely that police had identified another suspect but failed to pursue that lead. Again, Bloodsworth was found guilty. A different sentencing judge handed Bloodsworth two life sentences, rather than death.

You May Also Like

Why are U.S. presidents allowed to pardon anyone—even for treason?

Innocent on death row: Hear their stories

The missing heiress at the center of New York’s oldest cold case

“I had days when I was giving up hope. I thought I was going to spend the rest of my life in prison. And then I saw a copy of Joseph Wambaugh’s book,” Bloodsworth said.

That 1989 book, The Blooding, describes the then emerging science of DNA testing and how law enforcement had first used it to both clear suspects and solve a rape and murder case.

Bloodsworth wondered whether that science could somehow clear his name.

When he asked whether DNA evidence could be tested to prove that he was not at the crime scene, he was told the evidence had been destroyed inadvertently. That wasn’t true. The evidence, including the girl’s underwear, later was found in the courthouse. Prosecutors, sure of their case, agreed to release the items.

Once the items were tested, usable DNA was detected—none of it Bloodsworth’s. He was freed, and six months later, in December 1993, Maryland’s governor granted him a full pardon. It would be almost another decade before the actual killer was charged. The DNA belonged to a man named Kimberly Shay Ruffner, who had been released from jail two weeks before the girl’s murder. For a time Ruffner, who was given a 45-year sentence for an attempted rape and attempted murder soon after Bloodsworth’s arrest, and Bloodsworth were housed in the same prison. Ruffner pleaded guilty to Hamilton’s murder and was sentenced to life in prison.

Today Bloodsworth is the executive director of WTI and a tireless campaigner against capital punishment. The Innocence Protection Act, signed into law by President George W. Bush in 2004, established the Kirk Bloodsworth Post-Conviction DNA Testing Grant Program to help defray the cost of DNA testing after conviction.

“I was poor and had only been in the Baltimore area for 30 days when I was arrested,” said Bloodsworth, now 60. “When I tell people my story and how easy it is to be convicted of something of which you’re innocent, it often causes them to rethink the way the criminal justice system works. It doesn’t require much of a stretch to believe that innocent people have been executed.”

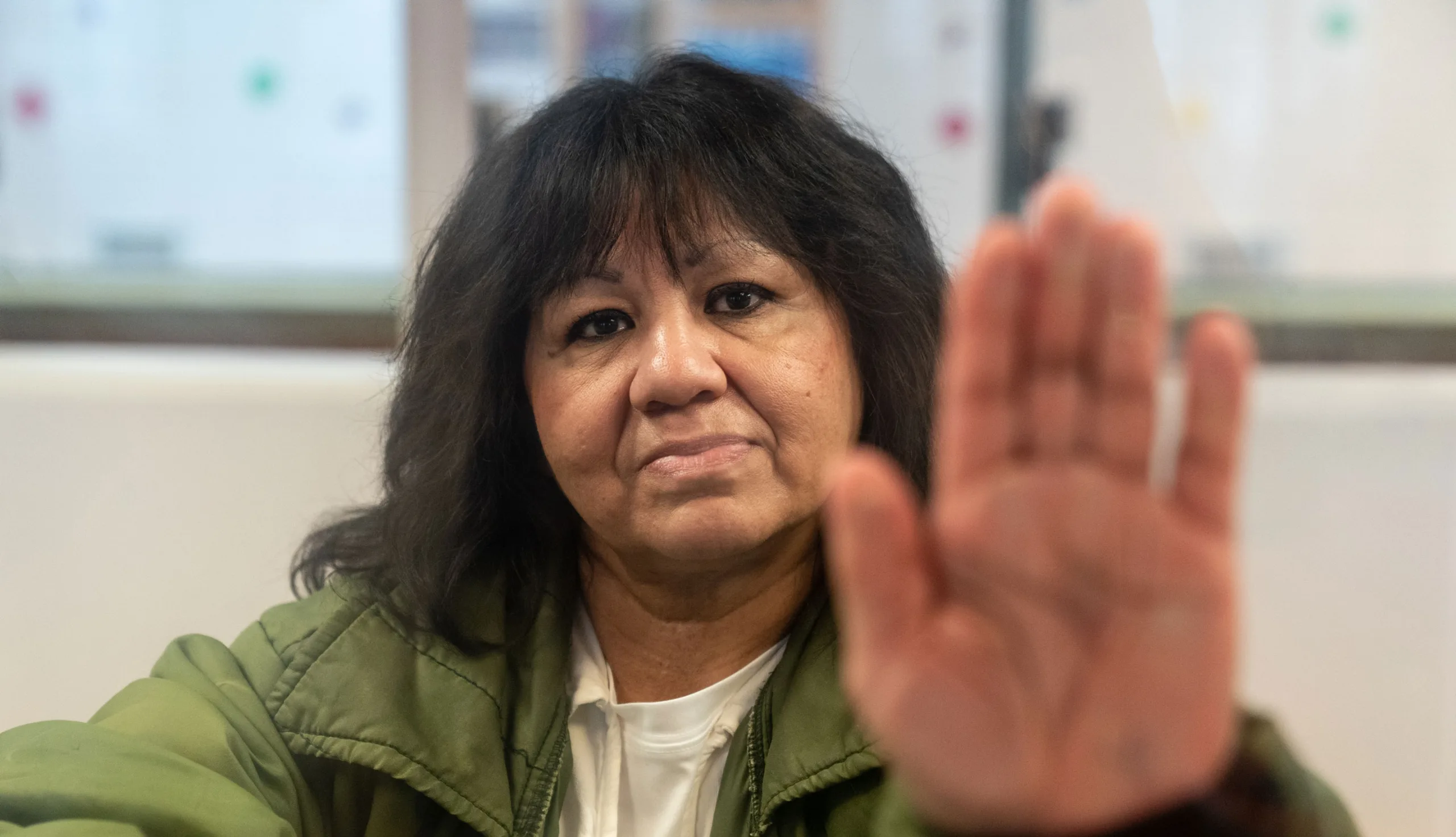

Sabrina Butler discovered that Walter, her nine-month-old son, had stopped breathing shortly before midnight on April 11, 1989. An 18-year-old single mother, Butler responded with urgent CPR. When the child could not be revived after several minutes, she raced him to a hospital in Columbus, Mississippi, where he was pronounced dead on arrival. Less than 24 hours later she was charged with murder.

Walter had serious internal injuries when he died. Butler told police investigators she believed that the injuries were caused by her efforts to revive him. Police doubted her story, and after several hours of interrogation, without a lawyer present, she signed a statement that said she’d struck her baby in the stomach after he wouldn’t stop crying. Eleven months later Butler was convicted of murder and sentenced to die.

Butler’s defense team called no witnesses. A medical expert might have testified that Walter’s injuries were consistent with the clumsy CPR of a desperate mother. A neighbor—who was called as a witness during a subsequent trial—could have provided helpful testimony of Butler’s attempts to save her son’s life. Instead Butler’s court-appointed lawyers, including one who specialized in divorce law, neither called witnesses nor put Butler on the witness stand to support her case.

“Here I was, this young Black child in a room full of white adults,” Butler, now Sabrina Smith, recalled. “I did not understand the proceedings. All that I had been told by my attorneys was to sit quietly and look at the jury. When I realized my defense wasn’t going to call any witnesses to help prove my innocence, I knew my life was over.”

Butler’s conviction and sentence were set aside in August 1992, after Mississippi’s supreme court ruled that the prosecutor had improperly commented on her failure to testify at trial. A new trial was ordered.

The second trial, with better lawyers, working pro bono, resulted in exoneration. A neighbor testified about Butler’s frantic attempts to revive her child. A medical expert testified that the child’s injuries could have resulted from the CPR efforts. Evidence also was introduced indicating that Walter had a preexisting kidney condition that likely contributed to his sudden death. Butler was released after spending five years in prison, the first half of that on death row.

Less than two years after her exoneration, Butler, the first of just two American women ever to be exonerated from death row, received a summons for jury duty.

“I was so appalled,” she told me. “I went downtown and spoke to the court administrator. I explained to him that the state of Mississippi had tried to kill me. I told him I was quite certain that I would not make a good juror.” She was dismissed.

A question that frequently confounds exonerees and the general public alike is whether a consistent formula exists for compensating the falsely convicted, especially those sentenced to die. The short answer is no. A small number of exonerees have been compensated for millions of dollars depending on the laws of the state that convicted them, but many receive little or nothing.

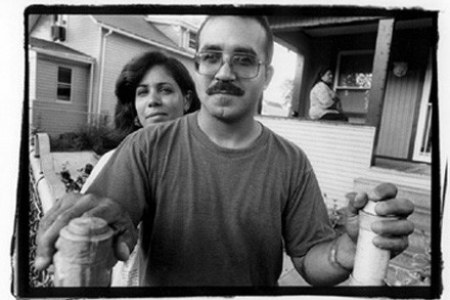

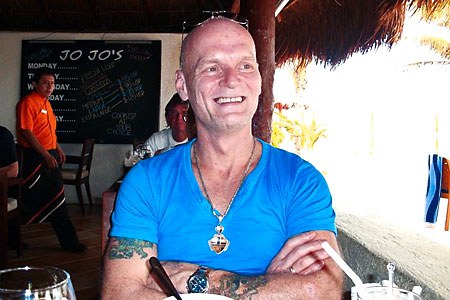

Few death-row exonerees more closely follow the issue of compensation than Ron Keine, who lives in southeastern Michigan. Keine has made it part of his life’s mission to improve the plight of the wrongly convicted, who often reenter society with meager survival skills. He wasn’t always so benevolent.

Growing up in Detroit, Keine ran with a rough crowd. He’d been shot and stabbed before he turned 16. At age 21, he and his closest friend, who both belonged to a notorious motorcycle club, decided to drive a van across the U.S.

The extended open-road party was going as planned until he and four others were arrested in 1974 in Oklahoma and extradited to New Mexico, where they were charged with the murder and mutilation of a 26-year-old college student in Albuquerque. A motel housekeeper reported that the group raped her and that she then saw the group kill the student at the same motel.

The problem with the story should have been readily apparent. The bikers weren’t in Albuquerque when William Velten, Jr., the student, was killed. They were partying in Los Angeles and had a dated traffic citation to prove it. The housekeeper later recanted her story.

In September 1975 a drifter, Kerry Rodney Lee, confessed to killing Velten, possibly because he felt guilty knowing that four men were on death row for his crime. The gun used in Velten’s slaying matched a gun stolen from the father of Lee’s girlfriend. Based on this evidence, Keine and his biker friends were granted new trials and the prosecutor decided not to indict them. Lee was convicted in May 1978 of murdering Velten.

“When I was on death row, I knew I was innocent, but I still came within nine days of my first scheduled execution date,” said Keine, now 73. “I didn’t have a voice. So when I got out, I decided I was going to spend my life being a thorn” in the side of the criminal justice system. “I decided that I was going to go from dead man walking to dead man talking.”

Keine, who founded several successful small businesses after his exoneration, has testified before state legislators seeking to overturn capital punishment laws. Having received only a $2,200 settlement from the county that put him on death row, he has been vocal in calling for a system of compensation for others wrongly sentenced to death.

“When people get off death row, they feel like a piece of shit,” he said. “They don’t have any self-worth—no self-esteem, and they usually don’t have two nickels in their pocket. We try to build them up. We try and help them find the resources they need to survive.”

Related Topics

- CAPITAL PUNISHMENT

- LAW AND LEGISLATION

Why human bodies are medicine's most essential taboo

A German werewolf's 'confessions' horrified 1500s Europe

Who gets to claim the ‘world’s richest shipwreck’?

Who are the real queens of 'Six'?

Exclusive: This is how you solve one of history's greatest cold cases

- Perpetual Planet

- Environment

History & Culture

- History & Culture

- History Magazine

- Mind, Body, Wonder

- Adventures Everywhere

- Paid Content

- Terms of Use

- Privacy Policy

- Your US State Privacy Rights

- Children's Online Privacy Policy

- Interest-Based Ads

- About Nielsen Measurement

- Do Not Sell or Share My Personal Information

- Nat Geo Home

- Attend a Live Event

- Book a Trip

- Inspire Your Kids

- Shop Nat Geo

- Visit the D.C. Museum

- Learn About Our Impact

- Support Our Mission

- Advertise With Us

- Customer Service

- Renew Subscription

- Manage Your Subscription

- Work at Nat Geo

- Sign Up for Our Newsletters

- Contribute to Protect the Planet

Copyright © 1996-2015 National Geographic Society Copyright © 2015-2024 National Geographic Partners, LLC. All rights reserved

- Share full article

Advertisement

Supported by

A Vast Racial Gap in Death Penalty Cases, New Study Finds

Defendants convicted of killing white people, the study found, were far more likely to be executed than the killers of Black people.

By Adam Liptak

WASHINGTON — Black lives do not matter nearly as much as white ones when it comes to the death penalty, a new study has found. Building on data at the heart of a landmark 1987 Supreme Court decision, the study concluded that defendants convicted of killing white victims were executed at a rate 17 times greater than those convicted of killing Black victims.

There is little chance that the new findings would alter the current Supreme Court’s support for the death penalty. Its conservative majority has expressed impatience with efforts to block executions, and last month it issued a pair of 5-to-4 rulings in the middle of the night that allowed federal executions to resume after a 17-year hiatus .

But the court came within one vote of addressing racial bias in the administration of the death penalty in the 1987 decision, McCleskey v. Kemp . By a 5-to-4 vote, the court ruled that even solid statistical evidence of race discrimination in the capital justice system did not offend the Constitution.

The decision has not aged well.

In 1991, after he retired, Justice Lewis F. Powell Jr. , the author of the majority opinion, was asked whether there was any vote he would like to change.

“Yes,” he told his biographer. “McCleskey v. Kemp.”

One of the dissenters in the case, Justice John Paul Stevens, was still stewing over it after his own retirement in 2010.

“That the murder of Black victims is treated as less culpable than the murder of white victims provides a haunting reminder of once-prevalent Southern lynchings,” he wrote that year in The New York Review of Books.

We are having trouble retrieving the article content.

Please enable JavaScript in your browser settings.

Thank you for your patience while we verify access. If you are in Reader mode please exit and log into your Times account, or subscribe for all of The Times.

Thank you for your patience while we verify access.

Already a subscriber? Log in .

Want all of The Times? Subscribe .

- Find a Lawyer

- Ask a Lawyer

- Research the Law

- Law Schools

- Laws & Regs

- Newsletters

- Justia Connect

- Pro Membership

- Basic Membership

- Justia Lawyer Directory

- Platinum Placements

- Gold Placements

- Justia Elevate

- Justia Amplify

- PPC Management

- Google Business Profile

- Social Media

- Justia Onward Blog

Death Penalty & Criminal Sentencing Supreme Court Cases

The Eighth Amendment to the U.S. Constitution prohibits the imposition of cruel and unusual punishment. The Supreme Court most often considers Eighth Amendment principles in the context of the death penalty, which remains in effect in many states and at the federal level. However, “three strikes” laws and certain other sentencing provisions may trigger Eighth Amendment scrutiny as well.

The Supreme Court has emphasized that a sentence does not need to be strictly proportionate to the crime to meet constitutional requirements. Meanwhile, it has limited capital punishment to a narrow range of crimes and forbidden its imposition on certain types of defendants.

Below is a selection of Supreme Court cases involving the death penalty and criminal sentencing, arranged from newest to oldest.

Author: Brett Kavanaugh

A sentencer need not make a separate factual finding of permanent incorrigibility before sentencing a murderer under 18 to life without parole.

Author: Neil Gorsuch

To establish that a state's chosen method cruelly “superadds” pain to the death sentence, a prisoner must show a feasible and readily implemented alternative method that would significantly reduce a substantial risk of severe pain and that the state has refused to adopt without a legitimate penological reason.

Author: Elena Kagan

The Eighth Amendment may permit executing a prisoner even if he cannot remember committing his crime. On the other hand, the Eighth Amendment may prohibit executing a prisoner even though he suffers from dementia or another disorder, rather than psychotic delusions.

Author: Samuel A. Alito, Jr.

To succeed in an Eighth Amendment method of execution claim, a prisoner must establish that the method creates a demonstrated risk of severe pain and that the risk is substantial when compared to the known and available alternatives.

The Eighth Amendment forbids a sentencing scheme that mandates life in prison without possibility of parole for juvenile homicide offenders.

Author: Anthony Kennedy

The Eighth Amendment does not permit a juvenile offender to be sentenced to life in prison without parole for a non-homicide crime.

The Eighth Amendment is defined by the evolving standards of decency that mark the progress of a maturing society. This principle requires that resort to capital punishment be restrained, limited in its instances of application, and reserved for the worst of crimes, those that, in the case of crimes against individuals, take the victim's life.

Author: Ruth Bader Ginsburg

Without an appeal or cross-appeal by the prosecution, a federal appellate court cannot order an increase in the sentence of a defendant on its own initiative.

Author: John Roberts

To constitute cruel and unusual punishment, an execution method must present a substantial or objectively intolerable risk of serious harm.

Author: Clarence Thomas

A state death penalty statute may direct imposition of the death penalty when the state has proved beyond a reasonable doubt that mitigators do not outweigh aggravators, including when the two are in equipoise.

Author: Stephen Breyer

A state may limit the innocence-related evidence that a capital defendant can introduce at a sentencing proceeding to the evidence introduced at the original trial.

The Eighth and Fourteenth Amendments forbid imposition of the death penalty on offenders who were under the age of 18 when their crimes were committed.

Author: Sandra Day O’Connor

Nothing in the Eighth Amendment prohibits a state from choosing to incapacitate criminals who have already been convicted of at least one serious or violent crime.

Author: John Paul Stevens

Executions of mentally retarded criminals are cruel and unusual punishments prohibited by the Eighth Amendment.

The Constitution requires that any fact that increases the penalty for a crime beyond the prescribed statutory maximum, other than the fact of a prior conviction, must be submitted to a jury and proved beyond a reasonable doubt.

Author: Antonin Scalia

The Eighth Amendment does not require strict proportionality between crime and sentence but instead forbids only extreme sentences that are grossly disproportionate to the crime.

Author: Byron White

The Constitution does not require that every finding of fact underlying a sentencing decision be made by a jury rather than a judge.

Author: Lewis Powell

A complex statistical study indicating a risk that racial considerations enter into capital sentencing determinations does not necessarily prove that a particular defendant's capital sentence was unconstitutional.

The Eighth Amendment does not prohibit the death penalty as disproportionate in the case of a defendant whose participation in a felony that results in murder is major and whose mental state is one of reckless indifference.

Author: Thurgood Marshall

The Eighth Amendment prohibits a state from inflicting the death penalty on a prisoner who is insane.

The Eighth Amendment does not require that a state appellate court, before it affirms a death sentence, compare the sentence in the case before it with the penalties imposed in similar cases if requested to do so by the defendant.

Criteria to consider in an Eighth Amendment proportionality analysis include the gravity of the offense and the harshness of the penalty, the sentences imposed on other criminals in the same jurisdiction, and the sentences imposed for the commission of the same crime in other jurisdictions.

The death sentence may not constitutionally be imposed after a jury verdict of guilt of a capital offense when the jury was not permitted to consider a verdict of guilt of a lesser included offense.

Author: Warren Burger

The Eighth Amendment generally requires that the sentencer not be precluded from considering mitigating factors related to any aspect of a defendant's character or record and any of the circumstances of the offense that the defendant proffers as a basis for a sentence less than death.

The sentence of death for the crime of rape violates the Eighth Amendment.

Author: John Paul Stevens , Lewis Powell , Potter Stewart

The punishment of death for the crime of murder does not, under all circumstances, violate the Eighth and Fourteenth Amendments. (This decision ended the temporary moratorium on the death penalty imposed by Furman .)

Author: Per Curiam

The imposition of the death penalty in these cases constituted cruel and unusual punishment in violation of the Eighth Amendment. (Concerns over the arbitrary and potentially discriminatory manner in which death sentences had been imposed led to a temporary nationwide moratorium on the death penalty as legislatures reviewed laws governing its administration.)

Author: Hugo Black

In considering the sentence to be imposed after a conviction, the sentencing judge is not restricted to information received in open court. This is true even when a death sentence is imposed.

Author: Joseph McKenna

The Eighth Amendment is progressive and may acquire wider meaning as public opinion becomes enlightened by humane justice.

- Criminal Trials & Prosecutions

- Miranda Rights

- Search & Seizure

- Constitutional Law

- Criminal Law

- Bankruptcy Lawyers

- Business Lawyers

- Criminal Lawyers

- Employment Lawyers

- Estate Planning Lawyers

- Family Lawyers

- Personal Injury Lawyers

- Estate Planning

- Personal Injury

- Business Formation

- Business Operations

- Intellectual Property

- International Trade

- Real Estate

- Financial Aid

- Course Outlines

- Law Journals

- US Constitution

- Regulations

- Supreme Court

- Circuit Courts

- District Courts

- Dockets & Filings

- State Constitutions

- State Codes

- State Case Law

- Legal Blogs

- Business Forms

- Product Recalls

- Justia Connect Membership

- Justia Premium Placements

- Justia Elevate (SEO, Websites)

- Justia Amplify (PPC, GBP)

- Testimonials

Invest in news coverage you can trust.

Donate to PBS NewsHour by June 30 !

What do you think? Leave a respectful comment.

Laura Santhanam Laura Santhanam

- Copy URL https://www.pbs.org/newshour/nation/death-penalty-bring-closure-victims-family

Does the death penalty bring closure to a victim’s family?

The last time anyone saw julie heath alive was oct. 3, 1993, when the 18-year-old set out to visit her boyfriend in hot springs, arkansas..

A week later, a hunter discovered Heath’s body, less than eight miles from where her broken-down car was found. She wore a black shirt, socks and underwear, but they were inside-out. Her black jeans were partially unzipped. Her throat was slashed.

Police later arrested Eric Randall Nance for Heath’s murder. Investigators said he picked her up near her vehicle, before DNA evidence proved he raped and killed her. In 1994, he was handed the death penalty. At the time, 80 percent of Americans nationwide favored the death penalty , according to a Gallup poll. But the only reason Belinda Crites needs to support the death penalty is “what Eric Nance did to my cousin.”

“She wasn’t just my cousin, she was my best friend,” Crites told the NewsHour. “He tore my whole family apart.”

Nance’s execution in 2005 marked the last time Arkansas put a prisoner to death. This week, Arkansas executed Ledell Lee, the first of eight men the state had originally planned to put to death in the 11 days after Easter Sunday. No state has executed so many people so quickly since 1976 when the Supreme Court reinstated capital punishment, said Robert Dunham with the Death Penalty Information Center.

The conflict in Arkansas is the latest to politicize the death penalty — but for families of the victims and the prisoners, it also resurfaces the complicated issues of closure and the long-reaching effect of these executions on their communities.

Arkansas justified its unusually swift schedule by saying the state’s supply of lethal injection drugs were about to expire, and pharmaceutical companies have refused to replenish stocks. A series of judicial rulings blocked the scheduled executions of the first four men: Jason McGehee, Bruce Ward, Don Davis and Stacey Johnson. The three men who remain are, at the moment, still scheduled to die before the month is out.

The idea of closure is powerful. It’s something Arkansas invoked in an April 15 motion that tried to fight a temporary restraining order that McKesson Medical Surgical, Inc., has used to block the use of its drug vecuronium bromide in state executions. (The drug is typically used as general anesthesia to relax muscles before surgery).

“The friends and family of those killed or injured by Jason McGehee, Stacey Johnson, Marcel Williams, Kenneth Williams, Bruce Ward, Ledell Lee, Jack Jones, Don Davis, and Terrick Nooner have waited decades to receive some closure for their pain,” it read.

But even when executions take place, a surviving family’s pain doesn’t disappear with the perpetrator’s pulse.

It’s been more than two decades since Heath’s death. But Belinda Crites, a 41-year-old caregiver who still lives in her hometown of Malvern, Arkansas, finds laughter in her sweet memories of her cousin. A high school cheerleader, Heath wanted to be a police officer one day. She worked two jobs — at Taco Bell and a blue jean factory — and before she died, she earned enough money to buy a beat-up 1957 black Mustang. With each paycheck, Julie bought a new part, and she and her father, William Heath, restored the car together.

Whenever Crites visited her cousin’s house, they’d pile into bed together and watch episodes of their favorite television sitcom, “Family Matters.” For Christmas, Crites, Heath and both of their mothers dressed in matching outfits — nice jeans, ties or whatever was the latest fad — and baked cookies. The two mothers were inseparable, working and raising their families together. Crites and her cousin “always said we’d be just like them,” Crites said.

But after Heath’s murder, Crites said her family fell apart. Her mother, aunt and grandmother were all diagnosed with depression and needed medication. When Nancy Heath — her aunt and Julie’s mother — hugged Crites, she ran her fingers through Crites’ hair, long like her dead cousin’s; she held her tight, Crites said, as if she were “just trying to get a piece of Julie back.”

The family watched as Nancy Heath wasted away. They cried and hugged each other on March 31, 1994, when a jury sentenced Nance to death. But after the family left the courtroom and got into their cars to drive home, Heath became incoherent. Her husband rushed her to the hospital, where doctors observed her overnight, Crites said.

Nancy Heath’s psychologist later begged her to at least eat bananas and watermelon, but she refused food. If she left Crites’ house to go to the store, her family knew to follow her — often, she drove instead in the direction of the cemetery where Julie was buried. Crites’ mother once found Nancy Heath there overdosed on pills. Crites said her aunt attempted suicide at least four times before she killed herself on Christmas morning in 1994, 15 months after her daughter’s murder.

“Some people wanted to judge [Nancy for her] suicide,” Crites said. “But my aunt — she couldn’t cope. She couldn’t go on. She wanted to go on so bad. She tried so hard.”

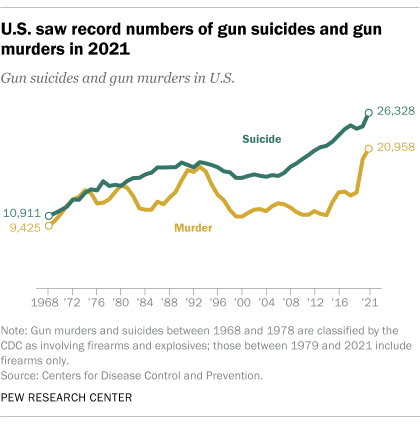

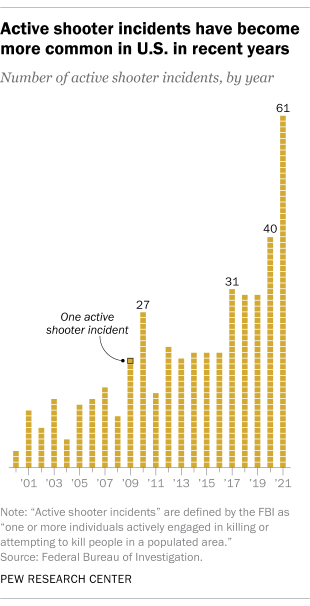

In 2015, the FBI reported nearly 15,700 homicides nationwide. And a 2007 study suggested that for every homicide victim, six to 10 family members are “indirectly victimized.” That figure excludes the many friends, colleagues, neighbors or other people who also suffer when a person they know is murdered. When they grieve, survivors must not only figure out how life goes on without their loved one in it, but also process the violence behind that person’s death.

Death penalty advocates and politicians, including Arkansas Attorney General Leslie Rutledge, argue that when the state executes a person who has committed a terrible crime, the act brings closure to victim’s family. But it’s not that simple.

If you ask murder victims’ families, “closure is the F-word,” said Marilyn Armour, who directs the Institute for Restorative Justice and Restorative Dialogue at the University of Texas at Austin. She’s researched homicide survivors for two decades. “They’ll tell you over and over and over again that there’s no such thing as closure.”

In 2012, Armour and University of Minnesota researcher Mark Umbreit interviewed 20 families of crime victims in Texas — a state which regularly uses the death penalty — and 20 more families in Minnesota, which instead offers life without parole. They were curious about how families in both states coped with the sentences.

The 2012 study concluded families in Minnesota were able to move on sooner; because their loved ones’ killers were sentenced to life without parole, rather than the death penalty, they weren’t retraumatized in the multiple appeals that often precede an execution. Armour cautions their sample was small. But over the last two decades, murder victims’ families have received better treatment and far more rights, Armour said. Rather than listen to the families homicide victims leave behind, society often uses these people and their pain to score political points in the death penalty debate, Armour said.

“Murder victims families are cast aside,” Armour said. “Nobody is giving survivors voice value.”

What Armour sees unfolding in Arkansas is political, she told the NewsHour. She doesn’t think it should be.

Arkansas State Representative Rebecca Petty, on the other hand, has made her mission to bring the issue to politics. In 1999, Petty’s 12-year-old daughter, Andria Brewer, was kidnapped from her younger sister’s birthday party by her uncle, Karl Roberts. He raped and strangled her, covering her body with leaves on an old logging road near Mena, Arkansas.

Andria Nichole Brewer, 12, was attending her youngest sister’s fourth birthday party when Brewer’s uncle, Karl Roberts, abducted her. He then raped and killed her, hiding her body near an old logging road near Mena, Arkansas, about 10 miles from her home. Photo courtesy of Rebecca Petty

Before that happened, Petty said her family had never experienced crime, so she never gave the death penalty much thought. “When it happens to your own child you gave birth to, you taught to walk and talk and [lived with] 12 years, that’s the point — it makes up your mind for you.”

In June 2000, Roberts waived his right to appeal the case in court . He confessed and was convicted for murdering his niece; he was sentenced to die on Jan. 6, 2004. Petty said she and her family prayed and decided to go watch Roberts’ execution. But shortly before he was supposed to be lethally injected, Roberts said he changed his mind and wanted to appeal after all. Petty left the prison that bitterly cold night in disbelief. Roberts still sits on death row, but his execution remains unscheduled.

Since then, Petty entered politics and has advocated for victims’ rights. She secured funding to expand the witness area attached to the execution chamber on Arkansas’ death row. When she considered what would result from Arkansas’ original plan to execute eight men in 11 days, Petty said it won’t offer closure, but “will close chapters for these families.”

“In your life, you have chapters,” Petty said. “This is going to be a chapter for these families they can close. It’s not going to be an easy chapter. For some of them it could be one of the last chapters of their life.”

But Judith Elane, a lifelong death penalty abolitionist and former attorney who lives in Little Rock, Arkansas, doesn’t see it that way. The 72-year-old said because the death penalty is not applied to all homicides, it leaves surviving family members with the impression that the justice system values some victims more than others.

Her principles were put to the test after her brother, Gene Schlatter was shot and killed in November 1968 in a Denver bar with four witnesses. He was 36. Elane drove from western Canada, where she lived at the time, to his funeral, where she mourned with his three children and widow. Four decades later, in 2009, detectives traced evidence to a woman they believed was guilty of the crime. But witnesses disappeared, changed their story or suffered dementia and couldn’t testify in court. Despite other evidence, the woman walked away, and no one was prosecuted for the murder.

To manage her grief, Elane joined support groups and now leads Murder Victims Families for Reconciliation in Arkansas. She scoffed at politicians who offer closure through capital punishment. “The governor likes to say he does this because victims’ families deserve closure,” she said. “Every time I hear that, I think, ‘you’re not doing it for me. It didn’t help me.’”

Six out of 10 Arkansans favor use of the death penalty, according to a recent poll of 550 Arkansas voters from Talk Business & Politics and Hendrix College, bolstering Gov. Asa Hutchinson’s call for expedited execution . But nationwide, support for the death penalty is at its lowest point in four decades, with half of U.S. adults saying states should not execute their worst criminals, according to Pew Research Center.

When states use capital punishment, the decision has consequences not only for the murder victims’ families, jurors and the person sentenced to die, but also for the prison personnel responsible for carrying out death sentences and the families of people who sit on death row.

Unlike politicians, correctional officers who work on death row are also “going to go home and live with the psychological consequences for the rest of their lives and so will their families,” said Patrick Crane, who worked on Arkansas’ death row from 2007 to 2008. Turnover is high, he said. And the state’s series of executions has taken advantage of prison staff who live in rural farm communities with few jobs, where households “still have an old way of thinking and doing and being.”

“Metaphysically, I think it’s going to be a cloud over the state, especially over the area in which it happens,” Crane said. “Clouds last a long time down there.”

In Arkansas’ expedited schedule to execute people on death row, the voices of victims families and the victims themselves are lost in sensationalism, Elane said. If politicians and policymakers care about homicide victims and their families, she said those voices need to be heard. The money saved by issuing life without parole sentences — which tends to have fewer appeals — could improve law enforcement and investigations, she said.

For now, she campaigns on behalf of murder victims families, bringing attention to their needs immediately following the death of a loved one.

“Regardless of how we feel about the death penalty, we all experienced the same suffering and the same dilemmas,” Elane said.

For 12 years, Nance sat on “The Row” in the Varner Supermax penitentiary near Pine Bluff, Arkansas, while his attorneys tried to appeal his execution. For years, they argued he had the mental capacity of a third grader, and that the state would be cruel to kill him because he did not fully understand rape and murder were wrong. His case made it all the way to the U.S. Supreme Court. There, the justices decided not to spare Nance’s life.

Members of the Nance family who testified on his behalf did not return NewsHour’s request for comment.

For his final meal before his Nov. 28, 2005, execution, Nance asked for two bacon cheeseburgers, French fries, two pints of chocolate chip cookie dough ice cream and two cans of Coca-Cola. More than a decade later, Crites still resents that Nance had a chance to choose that meal.

“My cousin died with tater tots and a Coke on her stomach,” she said.

READ MORE: Painter immortalizes last meals of 600 prisoners put to death

Crites and her family drove a van to the prison and were escorted to the warden’s office, where they watched the execution chamber on a tiny closed-circuit television set. On the screen, Crites saw Nance strapped flat on his back to a gurney with a white sheet pulled up to his neck. He said nothing.

Prison staff injected Nance with a lethal cocktail. He closed his eyes, remained silent, and then died, Crites said.

But the memory of what he did to her cousin — and how life then changed — still haunts Crites. She knows Nance’s execution didn’t change how things had turned out.

“When he was gone, it gave us a relief,” she said. “Did it make things better? I don’t know. We think of him everyday.”

Crites, the mother of three sons and one daughter, said she only recently allowed her 16-year-old daughter to spend the night at a friend’s house and never permitted her daughter to sit on the porch of their home without someone sitting with her.

“You have to teach your family how evil people are,” she said.

Laura Santhanam is the Health Reporter and Coordinating Producer for Polling for the PBS NewsHour, where she has also worked as the Data Producer. Follow @LauraSanthanam

Support Provided By: Learn more

Support PBS NewsHour:

Educate your inbox

Subscribe to Here’s the Deal, our politics newsletter for analysis you won’t find anywhere else.

Thank you. Please check your inbox to confirm.

The Case Against the Death Penalty

The American Civil Liberties Union believes the death penalty inherently violates the constitutional ban against cruel and unusual punishment and the guarantees of due process of law and of equal protection under the law. Furthermore, we believe that the state should not give itself the right to kill human beings – especially when it kills with premeditation and ceremony, in the name of the law or in the name of its people, and when it does so in an arbitrary and discriminatory fashion.

Capital punishment is an intolerable denial of civil liberties and is inconsistent with the fundamental values of our democratic system. The death penalty is uncivilized in theory and unfair and inequitable in practice. Through litigation, legislation, and advocacy against this barbaric and brutal institution, we strive to prevent executions and seek the abolition of capital punishment.

The ACLU’s opposition to capital punishment incorporates the following fundamental concerns:

The death penalty system in the US is applied in an unfair and unjust manner against people, largely dependent on how much money they have, the skill of their attorneys, race of the victim and where the crime took place . People of color are far more likely to be executed than white people, especially if thevictim is white

The death penalty is a waste of taxpayer funds and has no public safety benefit. The vast majority of law enforcement professionals surveyed agree that capital punishment does not deter violent crime; a survey of police chiefs nationwide found they rank the death penalty lowest among ways to reduce violent crime. They ranked increasing the number of police officers, reducing drug abuse, and creating a better economy with more jobs higher than the death penalty as the best ways to reduce violence. The FBI has found the states with the death penalty have the highest murder rates.

Innocent people are too often sentenced to death. Since 1973, over 156 people have been released from death rows in 26 states because of innocence. Nationally, at least one person is exonerated for every 10 that are executed.

INTRODUCTION TO THE “MODERN ERA” OF THE DEATH PENALTY IN THE UNITED STATES

In 1972, the Supreme Court declared that under then-existing laws “the imposition and carrying out of the death penalty… constitutes cruel and unusual punishment in violation of the Eighth and Fourteenth Amendments.” ( Furman v. Georgia , 408 U.S. 238). The Court, concentrating its objections on the manner in which death penalty laws had been applied, found the result so “harsh, freakish, and arbitrary” as to be constitutionally unacceptable. Making the nationwide impact of its decision unmistakable, the Court summarily reversed death sentences in the many cases then before it, which involved a wide range of state statutes, crimes and factual situations.

But within four years after the Furman decision, several hundred persons had been sentenced to death under new state capital punishment statutes written to provide guidance to juries in sentencing. These statutes require a two-stage trial procedure, in which the jury first determines guilt or innocence and then chooses imprisonment or death in the light of aggravating or mitigating circumstances.

In 1976, the Supreme Court moved away from abolition, holding that “the punishment of death does not invariably violate the Constitution.” The Court ruled that the new death penalty statutes contained “objective standards to guide, regularize, and make rationally reviewable the process for imposing the sentence of death.” ( Gregg v. Georgia , 428 U.S. 153). Subsequently 38 state legislatures and the Federal government enacted death penalty statutes patterned after those the Court upheld in Gregg. Congress also enacted and expanded federal death penalty statutes for peacetime espionage by military personnel and for a vast range of categories of murder.

Executions resumed in 1977. In 2002, the Supreme Court held executions of mentally retarded criminals are “cruel and unusual punishments” prohibited by the Eighth Amendment to the Constitution. Since then, states have developed a range of processes to ensure that mentally retarded individuals are not executed. Many have elected to hold proceedings prior to the merits trial, many with juries, to determine whether an accused is mentally retarded. In 2005, the Supreme Court held that the Eighth and Fourteenth Amendments to the Constitution forbid imposition of the death penalty on offenders who were under the age of 18 when their crimes were committed, resulting in commutation of death sentences to life for dozens of individuals across the country. As of August 2012, over 3,200 men and women are under a death sentence and more than 1,300 men, women and children (at the time of the crime) have been executed since 1976 .

ACLU OBJECTIONS TO THE DEATH PENALTY

Despite the Supreme Court’s 1976 ruling in Gregg v. Georgia , et al, the ACLU continues to oppose capital punishment on moral, practical, and constitutional grounds:

Capital punishment is cruel and unusual . It is cruel because it is a relic of the earliest days of penology, when slavery, branding, and other corporal punishments were commonplace. Like those barbaric practices, executions have no place in a civilized society. It is unusual because only the United States of all the western industrialized nations engages in this punishment. It is also unusual because only a random sampling of convicted murderers in the United States receive a sentence of death.

Capital punishment denies due process of law. Its imposition is often arbitrary, and always irrevocable – forever depriving an individual of the opportunity to benefit from new evidence or new laws that might warrant the reversal of a conviction, or the setting aside of a death sentence.

The death penalty violates the constitutional guarantee of equal protection . It is applied randomly – and discriminatorily. It is imposed disproportionately upon those whose victims are white, offenders who are people of color, and on those who are poor and uneducated and concentrated in certain geographic regions of the country.

The death penalty is not a viable form of crime control. When police chiefs were asked to rank the factors that, in their judgment, reduce the rate of violent crime, they mentioned curbing drug use and putting more officers on the street, longer sentences and gun control. They ranked the death penalty as least effective . Politicians who preach the desirability of executions as a method of crime control deceive the public and mask their own failure to identify and confront the true causes of crime.

Capital punishment wastes limited resources . It squanders the time and energy of courts, prosecuting attorneys, defense counsel, juries, and courtroom and law enforcement personnel. It unduly burdens the criminal justice system, and it is thus counterproductive as an instrument for society’s control of violent crime. Limited funds that could be used to prevent and solve crime (and provide education and jobs) are spent on capital punishment.

Opposing the death penalty does not indicate a lack of sympathy for murder victims . On the contrary, murder demonstrates a lack of respect for human life. Because life is precious and death irrevocable, murder is abhorrent, and a policy of state-authorized killings is immoral. It epitomizes the tragic inefficacy and brutality of violence, rather than reason, as the solution to difficult social problems. Many murder victims do not support state-sponsored violence to avenge the death of their loved one. Sadly, these victims have often been marginalized by politicians and prosecutors, who would rather publicize the opinions of pro-death penalty family members.

Changes in death sentencing have proved to be largely cosmetic. The defects in death-penalty laws, conceded by the Supreme Court in the early 1970s, have not been appreciably altered by the shift from unrestrained discretion to “guided discretion.” Such so-called “reforms” in death sentencing merely mask the impermissible randomness of a process that results in an execution.

A society that respects life does not deliberately kill human beings . An execution is a violent public spectacle of official homicide, and one that endorses killing to solve social problems – the worst possible example to set for the citizenry, and especially children. Governments worldwide have often attempted to justify their lethal fury by extolling the purported benefits that such killing would bring to the rest of society. The benefits of capital punishment are illusory, but the bloodshed and the resulting destruction of community decency are real.

CAPITAL PUNISHMENT IS NOT A DETERRENT TO CAPITAL CRIMES

Deterrence is a function not only of a punishment’s severity, but also of its certainty and frequency. The argument most often cited in support of capital punishment is that the threat of execution influences criminal behavior more effectively than imprisonment does. As plausible as this claim may sound, in actuality the death penalty fails as a deterrent for several reasons.

A punishment can be an effective deterrent only if it is consistently and promptly employed. Capital punishment cannot be administered to meet these conditions .

The proportion of first-degree murderers who are sentenced to death is small, and of this group, an even smaller proportion of people are executed. Although death sentences in the mid-1990s increased to about 300 per year , this is still only about one percent of all homicides known to the police . Of all those convicted on a charge of criminal homicide, only 3 percent – about 1 in 33 – are eventually sentenced to death. Between 2001-2009, the average number of death sentences per year dropped to 137 , reducing the percentage even more. This tiny fraction of convicted murderers do not represent the “worst of the worst”.

Mandatory death sentencing is unconstitutional. The possibility of increasing the number of convicted murderers sentenced to death and executed by enacting mandatory death penalty laws was ruled unconstitutional in 1976 ( Woodson v. North Carolina , 428 U.S. 280).

A considerable time between the imposition of the death sentence and the actual execution is unavoidable, given the procedural safeguards required by the courts in capital cases. Starting with selecting the trial jury, murder trials take far longer when the ultimate penalty is involved. Furthermore, post-conviction appeals in death-penalty cases are far more frequent than in other cases. These factors increase the time and cost of administering criminal justice.

We can reduce delay and costs only by abandoning the procedural safeguards and constitutional rights of suspects, defendants, and convicts – with the attendant high risk of convicting the wrong person and executing the innocent. This is not a realistic prospect: our legal system will never reverse itself to deny defendants the right to counsel, or the right to an appeal.

Persons who commit murder and other crimes of personal violence often do not premeditate their crimes.

Most capital crimes are committed in the heat of the moment. Most capital crimes are committed during moments of great emotional stress or under the influence of drugs or alcohol, when logical thinking has been suspended. Many capital crimes are committed by the badly emotionally-damaged or mentally ill. In such cases, violence is inflicted by persons unable to appreciate the consequences to themselves as well as to others.

Even when crime is planned, the criminal ordinarily concentrates on escaping detection, arrest, and conviction. The threat of even the severest punishment will not discourage those who expect to escape detection and arrest. It is impossible to imagine how the threat of any punishment could prevent a crime that is not premeditated. Furthermore, the death penalty is a futile threat for political terrorists, like Timothy McVeigh, because they usually act in the name of an ideology that honors its martyrs.

Capital punishment doesn’t solve our society’s crime problem. Threatening capital punishment leaves the underlying causes of crime unaddressed, and ignores the many political and diplomatic sanctions (such as treaties against asylum for international terrorists) that could appreciably lower the incidence of terrorism.

Capital punishment has been a useless weapon in the so-called “war on drugs.” The attempt to reduce murders in the drug trade by threat of severe punishment ignores the fact that anyone trafficking in illegal drugs is already risking his life in violent competition with other dealers. It is irrational to think that the death penalty – a remote threat at best – will avert murders committed in drug turf wars or by street-level dealers.

If, however, severe punishment can deter crime, then permanent imprisonment is severe enough to deter any rational person from committing a violent crime.

The vast preponderance of the evidence shows that the death penalty is no more effective than imprisonment in deterring murder and that it may even be an incitement to criminal violence. Death-penalty states as a group do not have lower rates of criminal homicide than non-death-penalty states. Use of the death penalty in a given state may actually increase the subsequent rate of criminal homicide. Why? Perhaps because “a return to the exercise of the death penalty weakens socially based inhibitions against the use of lethal force to settle disputes…. “

In adjacent states – one with the death penalty and the other without it – the state that practices the death penalty does not always show a consistently lower rate of criminal homicide. For example, between l990 and l994, the homicide rates in Wisconsin and Iowa (non-death-penalty states) were half the rates of their neighbor, Illinois – which restored the death penalty in l973, and by 1994 had sentenced 223 persons to death and carried out two executions . Between 2000-2010, the murder rate in states with capital punishment was 25-46% higher than states without the death penalty.

On-duty police officers do not suffer a higher rate of criminal assault and homicide in abolitionist states than they do in death-penalty states. Between 1976 and 1989, for example, lethal assaults against police were not significantly more or less frequent in abolitionist states than in death-penalty states. Capital punishment did not appear to provide officers added protection during that time frame. In fact, the three leading states in law enforcement homicide in 1996 were also very active death penalty states : California (highest death row population), Texas (most executions since 1976), and Florida (third highest in executions and death row population). The South, which accounts for more than 80% of the country’s executions, also has the highest murder rate of any region in the country. If anything, the death penalty incited violence rather than curbed it.

Prisoners and prison personnel do not suffer a higher rate of criminal assault and homicide from life-term prisoners in abolition states than they do in death-penalty states. Between 1992 and 1995, 176 inmates were murdered by other prisoners. The vast majority of those inmates (84%) were killed in death penalty jurisdictions. During the same period, about 2% of all inmate assaults on prison staff were committed in abolition jurisdictions . Evidently, the threat of the death penalty “does not even exert an incremental deterrent effect over the threat of a lesser punishment in the abolitionist states.” Furthermore, multiple studies have shown that prisoners sentenced to life without parole have equivalent rates of prison violence as compared to other inmates.

Actual experience thus establishes beyond a reasonable doubt that the death penalty does not deter murder. No comparable body of evidence contradicts that conclusion.

Furthermore, there are documented cases in which the death penalty actually incited the capital crimes it was supposed to deter. These include instances of the so-called suicide-by-execution syndrome – persons who wanted to die but feared taking their own lives, and committed murder so that the state would kill them. For example, in 1996, Daniel Colwell , who suffered from mental illness, claimed that he killed a randomly-selected couple in a Georgia parking lot so that the state would kill him – he was sentenced to death and ultimately took his own life while on death row.

Although inflicting the death penalty guarantees that the condemned person will commit no further crimes, it does not have a demonstrable deterrent effect on other individuals. Further, it is a high price to pay when studies show that few convicted murderers commit further crimes of violence. Researchers examined the prison and post-release records of 533 prisoners on death row in 1972 whose sentences were reduced to incarceration for life by the Supreme Court’s ruling in Furman. This research showed that seven had committed another murder. But the same study showed that in four other cases, an innocent man had been sentenced to death. (Marquart and Sorensen, in Loyola of Los Angeles Law Review 1989)

Recidivism among murderers does occasionally happen, but it occurs less frequently than most people believe; the media rarely distinguish between a convicted offender who murders while on parole, and a paroled murderer who murders again. Government data show that about one in 12 death row prisoners had a prior homicide conviction . But as there is no way to predict reliably which convicted murderers will try to kill again, the only way to prevent all such recidivism is to execute every convicted murderer – a policy no one seriously advocates. Equally effective but far less inhumane is a policy of life imprisonment without the possibility of parole.

CAPITAL PUNISHMENT IS UNFAIR

Constitutional due process and elementary justice both require that the judicial functions of trial and sentencing be conducted with fundamental fairness, especially where the irreversible sanction of the death penalty is involved. In murder cases (since 1930, 88 percent of all executions have been for this crime), there has been substantial evidence to show that courts have sentenced some persons to prison while putting others to death in a manner that has been arbitrary, racially biased, and unfair.

Racial Bias in Death Sentencing

Racial discrimination was one of the grounds on which the Supreme Court ruled the death penalty unconstitutional in Furman . Half a century ago, in his classic American Dilemma (1944), Gunnar Myrdal reported that “the South makes the widest application of the death penalty, and Negro criminals come in for much more than their share of the executions.” A study of the death penalty in Texas shows that the current capital punishment system is an outgrowth of the racist “legacy of slavery.” Between 1930 and the end of 1996, 4,220 prisoners were executed in the United States; more than half (53%) were black .

Our nation’s death rows have always held a disproportionately large population of African Americans, relative to their percentage of the total population. Comparing black and white offenders over the past century, the former were often executed for what were considered less-than-capital offenses for whites, such as rape and burglary. (Between 1930 and 1976, 455 men were executed for rape, of whom 405 – 90 percent – were black.) A higher percentage of the blacks who were executed were juveniles; and the rate of execution without having one’s conviction reviewed by any higher court was higher for blacks. (Bowers, Legal Homicide 1984; Streib, Death Penalty for Juveniles 1987)

In recent years, it has been argued that such flagrant racial discrimination is a thing of the past. However, since the revival of the death penalty in the mid-1970s, about half of those on death row at any given time have been black . More striking is the racial comparison of victims . Although approximately 49% of all homicide victims are white, 77% of capital homicide cases since 1976 have involved a white victim.

Between 1976 and 2005 , 86% of white victims were killed by whites (14% by other races) while 94% of black victims were killed by blacks (6% by other races). Blacks and whites are murder victims in almost equal numbers of crimes – which is a very high percentage given that the general US population is 13% black. African-Americans are six times as likely as white Americans to die at the hands of a murderer, and roughly seven times as likely to murder someone. Young black men are fifteen times as likely to be murdered as young white men.

So given this information, when those under death sentence are examined more closely, it turns out that race is a decisive factor after all.

Further, studies like that commissioned by the Governor of Maryland found that “black offenders who kill white victims are at greater risk of a death sentence than others, primarily because they are substantially more likely to be charged by the state’s attorney with a capital offense.”

The classic statistical study of racial discrimination in capital cases in Georgia presented in the McCleskey case showed that “the average odds of receiving a death sentence among all indicted cases were 4.3 times higher in cases with white victims.” (David C. Baldus et al., Equal Justice and the Death Penalty 1990) In 1987 these data were placed before the Supreme Court in McCleskey v. Kemp and while the Court did not dispute the statistical evidence, it held that evidence of an overall pattern of racial bias was not sufficient. Mr. McCleskey would have to prove racial bias in his own case – a virtually impossible task. The Court also held that the evidence failed to show that there was “a constitutionally significant risk of racial bias….” (481 U.S. 279) Although the Supreme Court declared that the remedy sought by the plaintiff was “best presented to the legislative bodies,” subsequent efforts to persuade Congress to remedy the problem by enacting the Racial Justice Act were not successful. (Don Edwards & John Conyers, Jr., The Racial Justice Act – A Simple Matter of Justice, in University of Dayton Law Review 1995)

In 1990, the U.S. General Accounting Office reported to the Congress the results of its review of empirical studies on racism and the death penalty. The GAO concluded : “Our synthesis of the 28 studies shows a pattern of evidence indicating racial disparities in the charging, sentencing, and imposition of the death penalty after the Furman decision” and that “race of victim influence was found at all stages of the criminal justice system process…”

Texas was prepared to execute Duane Buck on September 15, 2011. Mr. Buck was condemned to death by a jury that had been told by an expert psychologist that he was more likely to be dangerous because he was African American. The Supreme Court stayed the case, but Mr. Buck has not yet received the new sentencing hearing justice requires.

These results cannot be explained away by relevant non-racial factors, such as prior criminal record or type of crime, as these were factored for in the Baldus and GAO studies referred to above. They lead to a very unsavory conclusion: In the trial courts of this nation, even at the present time, the killing of a white person is treated much more severely than the killing of a black person . Of the 313 persons executed between January 1977 and the end of 1995, 36 had been convicted of killing a black person while 249 (80%) had killed a white person. Of the 178 white defendants executed, only three had been convicted of murdering people of color . Our criminal justice system essentially reserves the death penalty for murderers (regardless of their race) who kill white victims.

Another recent Louisiana study found that defendants with white victims were 97% more likely to receive death sentences than defendants with black victims. [1]

Both gender and socio-economic class also determine who receives a death sentence and who is executed. Women account for only two percent of all people sentenced to death , even though females commit about 11 percent of all criminal homicides. Many of the women under death sentence were guilty of killing men who had victimized them with years of violent abuse . Since 1900, only 51 women have been executed in the United States (15 of them black).

Discrimination against the poor (and in our society, racial minorities are disproportionately poor) is also well established. It is a prominent factor in the availability of counsel.