- Search Menu

- Sign in through your institution

- Browse content in Disability assessment

- Assessment for capacity to work

- Assessment of functional capability

- Browse content in Fitness for work

- Civil service, central government, and education establishments

- Construction industry

- Emergency Medical Services

- Fire and rescue service

- Healthcare workers

- Hyperbaric medicine

- Military - Other

- Military - Fitness for Work

- Military - Mental Health

- Oil and gas industry

- Police service

- Rail and Roads

- Remote medicine

- Telecommunications industry

- The disabled worker

- The older worker

- The young worker

- Travel medicine

- Women at work

- Browse content in Framework for practice

- Health and Safety at Work etc. Act 1974 and associated regulations

- Health information and reporting

- Ill health retirement

- Questionnaire Reviews

- Browse content in Occupational Medicine

- Blood borne viruses and other immune disorders

- Dermatological disorders

- Endocrine disorders

- Gastrointestinal and liver disorders

- Gynaecology

- Haematological disorders

- Mental health

- Neurological disorders

- Occupational cancers

- Opthalmology

- Renal and urological disorders

- Respiratory Disorders

- Rheumatological disorders

- Browse content in Rehabilitation

- Chronic disease

- Mental health rehabilitation

- Motivation for work

- Physical health rehabilitation

- Browse content in Workplace hazard and risk

- Biological/occupational infections

- Dusts and particles

- Occupational stress

- Post-traumatic stress

- Advance articles

- Editor's Choice

- Themed and Special Issues

- Author Guidelines

- Submission Site

- Open Access

- Books for Review

- Become a Reviewer

- About Occupational Medicine

- About the Society of Occupational Medicine

- Editorial Board

- Advertising and Corporate Services

- Journals Career Network

- Self-Archiving Policy

- Dispatch Dates

- Permissions

- Journals on Oxford Academic

- Books on Oxford Academic

Article Contents

Introduction, acknowledgements, competing interests, data availability.

- < Previous

Healthcare worker burnout during a persistent crisis: a case–control study

- Article contents

- Figures & tables

- Supplementary Data

S Appelbom, A Nordström, A Finnes, R K Wicksell, A Bujacz, Healthcare worker burnout during a persistent crisis: a case–control study, Occupational Medicine , Volume 74, Issue 4, May 2024, Pages 297–303, https://doi.org/10.1093/occmed/kqae032

- Permissions Icon Permissions

During the immediate outbreak of the COVID-19 pandemic, burnout symptoms increased among healthcare workers. Knowledge is needed on how early symptoms developed during the persistent crisis that followed the first pandemic wave.

To investigate if high levels of burnout symptoms during the first pandemic wave led to high burnout and depressive symptoms up to a year later, and if participation in psychological support was related to lower levels of symptoms.

A longitudinal case–control study followed 581 healthcare workers from two Swedish hospitals. Survey data were collected with a baseline in May 2020 and three follow-up assessments until September 2021. The case group was participants reporting high burnout symptoms at baseline. Logistic regression analyses were performed separately at three follow-ups with case–control group assignment as the main predictor and burnout and depression symptoms as outcomes, controlling for frontline work, changes in work tasks and psychological support participation.

One out of five healthcare workers reported high burnout symptoms at baseline. The case group was more likely to have high burnout and depressive symptoms at all follow-ups. Participation in psychological support was unrelated to decreased burnout and depressive symptoms at any of the follow-ups.

During a persistent crisis, healthcare organizations should be mindful of psychological reactions among staff and who they place in frontline work early in the crisis. To better prepare for future healthcare crises, preventive measures on burnout are needed, both at workplaces and as part of the curricula in medical and nursing education.

Increased prevalence of burnout symptoms has been reported among healthcare workers during the COVID-19 pandemic.

For a sub-group of healthcare workers with higher symptoms, burnout rates were elevated also later in the crisis.

It is not known whether burnout and depressive symptoms later in the pandemic were predicted mainly by the early burnout symptoms or the recurring periods of frontline work for this group of healthcare workers.

High burnout symptoms in response to the work environment during the first pandemic wave were the main predictor of both high burnout and depressive symptoms during later periods of the crisis, regardless of the intensity of frontline work or participation in psychological support.

When forming policies on how to respond to future crises in healthcare, healthcare workers’ psychological reactions to the work environment during the initial stages of the crisis should be a key focus.

If the crisis persists over a longer period, healthcare organizations may benefit from being extra mindful of the work environment of staff members who showed signs of burnout right before, or early in the crisis.

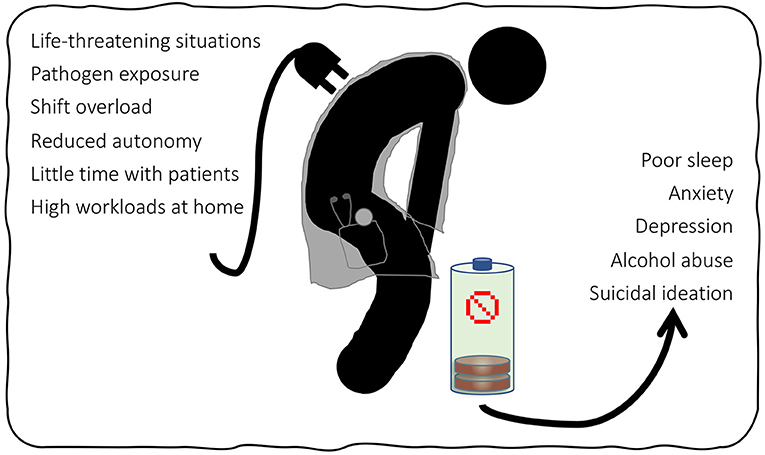

During the immediate outbreak of the COVID-19 pandemic, healthcare workers faced high emotional and physical demands at the same time as resources to cope with them were limited [ 1 , 2 ]. The prevalence of burnout symptoms also increased among healthcare workers during this period with pooled prevalence between 34% and 52% [ 3 , 4 ]. In the ICD-11, the World Health Organization defines burnout as ‘a syndrome conceptualized as resulting from chronic workplace stress that has not been successfully managed’ [ 5 ]. More specifically, burnout refers to the combination of high job demands and insufficient job resources that implicates the workers’ ability to cope with those demands [ 6 , 7 ]. When faced with this imbalance, the worker experiences symptoms of emotional exhaustion and depersonalization from work [ 8 ]. Although burnout is an occupational phenomenon [ 5 ], conflicting demands in personal life can also lead to burnout symptoms [ 9 ].

Even before the COVID-19 pandemic, healthcare workers had increased risks of burnout. In 2020, pre-pandemic burnout prevalence of 12% among early-career nurses in Sweden [ 10 ], and 10% among nurses in Europe and Central Asia [ 11 ] was reported.

Although burnout is not a clinical condition, a long-term imbalance between demands and resources is related to higher risk of sickness absence [ 12 ]. Still, experiencing high burnout symptoms during a shorter period of a demanding work environment does not necessarily mean that the worker will face symptoms long term [ 13 ]. Several studies on burnout trajectories among healthcare workers during the COVID-19 pandemic reported elevated burnout symptoms during the first outbreak of the COVID-19 pandemic, which would later decrease [ 14–17 ].

However, for a sub-group of healthcare workers with strong stress reactions during the first pandemic wave, the high symptom levels were persistent also during later periods of the COVID-19 pandemic [ 14 , 18–20 ]. A possible reason for this may be that their strong reaction to the immediate crisis during the pandemic outbreak led to an elevated risk of later psychological strain in terms of both depressive and burnout-related symptoms [ 10 , 13 , 21 , 22 ]. This group of healthcare workers may, therefore, have been more vulnerable to changes in the work environment during the recurring periods of increased patient intake later in the pandemic [ 15 ].

To the best of our knowledge, only one study has explicitly studied the relationship between early onset of burnout symptoms and the risk of later strain among healthcare workers during the COVID-19 pandemic. The results showed that burnout symptoms during the first pandemic wave predicted about 37% of burnout symptoms among US frontline healthcare workers during the second wave. However, it was not clear how job demands related to the treatment of COVID-19 patients impacted the burnout rates [ 20 ]. More knowledge is needed on the persistence of burnout and depressive symptoms during different stages of a long-term crisis in relation to early onset of burnout rates and changes in the work environment, both between and during consecutive pandemic waves [ 23 ].

Occupational health services can support workplaces in the implementation of organizational changes that prevent burnout by fostering a healthy work environment [ 24 ]. However, during a crisis, demands are high, and the resources limited, so health-promoting interventions should rather focus on secondary interventions that help healthcare workers cope with the crisis [ 24 ]. During the COVID-19 pandemic, many healthcare organizations implemented psychological support with the aim to limit psychological stress reactions, such as burnout and depressive symptoms, caused by the demanding work environment [ 25–27 ].

The aim of the present study was to (i) describe the prevalence of burnout and depressive symptoms among healthcare workers up to a year after the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic, (ii) examine if high levels of burnout symptoms early in the pandemic led to high burnout and depressive symptoms up to a year later, and (iii) additionally examine if those who participated in psychological support initiatives displayed lower levels of burnout or depressive symptoms across the first year of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Healthcare workers from two hospitals in the Stockholm Region, Sweden, were invited to participate in a longitudinal survey during the COVID-19 pandemic. Data were collected at four timepoints with baseline in May and June 2020, and follow-ups in September 2020, February 2021 and June 2021. Compared to the timeline of the COVID-19 pandemic in Sweden, the surveys coincided with the first pandemic wave (baseline), between the first and second waves (follow-up 1), the overlap between the second and third waves (follow-up2), and after the third wave (follow-up 3) [ 28 ]. The study was reviewed and approved by the Swedish Ethical Review authority (reference numbers 2020-01795, 2020-03495, 2020-04959, 2020-06602, 2022-01546-02). The participants involved provided written informed consent before answering the baseline survey.

A case–control design was applied to investigate the association between high burnout symptoms during the early stages of the COVID-19 pandemic and high symptoms throughout the first year of the pandemic. Out of 2262 invited, 681 healthcare workers were enrolled in the study (see Figure 1 , available as Supplementary data at Occupational Medicine Online). Participants ( n = 581) who answered the burnout questionnaire at baseline were included in the analytic sample and assigned to the case and control groups based on high or low burnout symptoms at baseline.

Case and control groups were created based on the level of work-related burnout symptoms measured using the seven-item version of the Oldenburg Burnout Inventory (OLBI). Items were rated on a 4-point scale, ranging from 1 = ‘Not accurate at all’ to 4 = ‘Totally accurate’. A cut-off mean score of 3 or higher was considered a high level of burnout symptoms. The version used in the present study was validated in a Swedish healthcare context, and the cut-off values were established for nurses as the norm group [ 7 ]. To limit missing data, mean values were calculated for all participants who answered at least six out of seven items. Scale means were 2.39, 2.20, 2.35 and 2.41 for baseline and each follow-up, respectively. The scale reliability was high at all timepoints (see Table 4 , available as Supplementary data at Occupational Medicine Online).

At follow-ups, burnout symptoms were measured with the Shirom-Melamed Burnout Questionnaire (SMBQ). SMBQ is a validated screening tool for detecting clinical symptom levels of burnout within a general population in Sweden [ 29 ]. For this study, a six-item version was used, measuring emotional and physical exhaustion, as well as cognitive weariness [ 30 ]. Items were rated on a 7-point scale, ranging from 1 = ‘Almost never’ to 7 = ‘Almost always’. Cut-off values were chosen based on pre-pandemic data from the general population in Sweden, where the 75% percentile corresponded to an average of 4 for women and 3.5 for men on a 7-point scale [ 30 ]. A mean value of 4 was chosen as a cut-off for high burnout symptoms in the present study. A mean value was calculated for all participants who answered at least five out of six items. Scale means were 2.68, 2.97 and 3.02 for each follow-up, respectively. The scale reliability was high for all time points (see Table 4 , available as Supplementary data at Occupational Medicine Online).

Depressive symptoms were measured using the two-item screening version of the Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-2). PHQ-2 measures symptoms of anhedonia and low mood within a 2-week period [ 31 ]. Items were rated on a 4-point scale ranging from 0 = ‘Not at all’ to 3 = ‘Nearly every day’. A cut-off value of 1.5 or higher on the mean scale was considered an indicator of high levels of depressive symptoms [ 31 , 32 ]. Due to high correlations between the two items, a mean value was calculated for all participants who answered at least one out of the two items. Scale means were 0.60, 0.58, 0.76 and 0.69 from baseline and each follow-up, respectively (see Table 5 , available as Supplementary data at Occupational Medicine Online).

Frontline work was recoded based on whether participants were frequently exposed to COVID-19 due to their work at frontline with COVID-19 patients. Participants indicating that they had treated COVID-19 patients within the last 2 weeks on several occasions or daily were coded as 1 = Frontline workers. Participants who had not treated COVID-19 patients or had treated them on one occasion were coded as 0 = non-frontline workers.

Participants stated whether their work tasks had changed due to the COVID-19 pandemic with a single item coded as 1 = Yes, and 0 = No. In the baseline survey, changed tasks since the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic were noted while follow-ups measured changes since the previous survey.

Participants rated their level of participation in seven different psychological support types, using a single item: ‘Have you been offered any of the following types of support during the current pandemic?’, with 1 = ‘No’, 2 = ‘Yes, I have been offered but not used or participated in them’, 3 = ‘Yes, I have occasionally used or participated in them’, and 4 = ‘Yes, I have used them or participated in them on several occasions’ as response options. The response options were dichotomized, with options 1 and 2 coded as having not participated, and options 3 and 4 coded as having participated. The support types were categorized into two variables: passive and active psychological support, presented in Table 1 . Participation in each category (active/passive) was noted if participants had indicated participation in at least one support type belonging to that category.

Description of types of psychological support measured in the surveys

| Support variable . | Type of support . |

|---|---|

| Passive support | Access to a quiet space, for example, a staff room to rest or recover |

| Access to information on stress management or mental health | |

| Education or other training regarding the COVID-19 disease or personal protective equipment | |

| Education or other training in potentially traumatic situations at work | |

| Active support | Scheduled appointments to meet with colleagues to check in on or discuss how they feel |

| Collegial support interventions, for example, peer support or mentorships | |

| Scheduled group sessions lead by psychologists, counsellors, priests, HR or others | |

| Individual conversations led by psychologists, counsellors, priests, HR or others |

| Support variable . | Type of support . |

|---|---|

| Passive support | Access to a quiet space, for example, a staff room to rest or recover |

| Access to information on stress management or mental health | |

| Education or other training regarding the COVID-19 disease or personal protective equipment | |

| Education or other training in potentially traumatic situations at work | |

| Active support | Scheduled appointments to meet with colleagues to check in on or discuss how they feel |

| Collegial support interventions, for example, peer support or mentorships | |

| Scheduled group sessions lead by psychologists, counsellors, priests, HR or others | |

| Individual conversations led by psychologists, counsellors, priests, HR or others |

Prevalence of burnout at baseline and at each of the three follow-ups was estimated for the entire sample. The association between high burnout levels at baseline and symptoms at each follow-up was analysed using logistic regression, with case and control group membership as the main predictor and cut-off scores for high levels of burnout and depressive symptoms as outcome measures (Model 1). Second, the model was extended by controlling for frontline work and change of work tasks (Model 2), and psychological support participation (Model 3). Analyses were conducted for each outcome separately. All statistical analyses were conducted using Jamovi version 2.2 [ 33 ].

Baseline sample characteristics and differences between the case ( n = 119) and control ( n = 462) groups are presented in Table 2 . Of the 581 participants enrolled at baseline, 436 (75%) completed the first follow-up, 385 (66%) the second and 329 (57%) the third. See Supplementary Materials for more details on dropouts. The overall number of responses on burnout (SMBQ) at follow-ups 1, 2 and 3 were 414, 352 and 300, respectively. For depressive symptoms, the number of responses were 405, 339 and 294 for follow-up 1, 2 and 3, respectively. Proportions of participants engaged in frontline work, with changed work tasks, and psychological support participation at follow-ups are outlined in Table 6 (available as Supplementary data at Occupational Medicine Online).

Characteristics of the analytic sample

| Characteristics . | Analytic sample . | Case group . | Control group . | (193) . | χ . | ( ) . | -value . | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| . | (SD) . | (%) . | (SD) . | (%) . | (SD) . | (%) . | . | . | . | . |

| Age | 45 (11.3) | 41 (10.4) | 46 (11.3) | 3.98 | <0.001 | |||||

| Women | 455 (79) | 88 (76) | 367 (80) | 0.781 | 1 (577) | >0.05 | ||||

| Occupation | 30.3 | 3 (577) | <0.001 | |||||||

| Nurse | 218 (38) | 68 (58) | 150 (33) | |||||||

| Assistant nurse | 126 (22) | 24 (20) | 102 (22) | |||||||

| Physician | 102 (18) | 16 (14) | 86 (19) | |||||||

| Non-medical | 131 (23) | 10 (9) | 121 (26) | |||||||

| Previous treatment mental illness | 14.7 | 2 (576) | <0.001 | |||||||

| No treatment | 449 (78) | 77 (65) | 372 (81) | |||||||

| More than 3 months prior | 104 (18) | 32 (27) | 72 (16) | |||||||

| Within 3 months | 23 (4) | 9 (8) | 14 (3) | |||||||

| Frontline work | 313 (62) | 98 (85) | 215 (55) | 33.5 | 1 (509) | <0.001 | ||||

| Changed tasks | 309 (54) | 77 (65) | 232 (51) | 7.26 | 1 (575) | <0.01 | ||||

| Passive support | 442 (78) | 94 (81) | 348 (78) | 0.612 | 1 (564) | >0.05 | ||||

| Active support | 316 (56) | 84 (74) | 232 (52) | 17.7 | 1 (562) | <0.001 | ||||

| Characteristics . | Analytic sample . | Case group . | Control group . | (193) . | χ . | ( ) . | -value . | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| . | (SD) . | (%) . | (SD) . | (%) . | (SD) . | (%) . | . | . | . | . |

| Age | 45 (11.3) | 41 (10.4) | 46 (11.3) | 3.98 | <0.001 | |||||

| Women | 455 (79) | 88 (76) | 367 (80) | 0.781 | 1 (577) | >0.05 | ||||

| Occupation | 30.3 | 3 (577) | <0.001 | |||||||

| Nurse | 218 (38) | 68 (58) | 150 (33) | |||||||

| Assistant nurse | 126 (22) | 24 (20) | 102 (22) | |||||||

| Physician | 102 (18) | 16 (14) | 86 (19) | |||||||

| Non-medical | 131 (23) | 10 (9) | 121 (26) | |||||||

| Previous treatment mental illness | 14.7 | 2 (576) | <0.001 | |||||||

| No treatment | 449 (78) | 77 (65) | 372 (81) | |||||||

| More than 3 months prior | 104 (18) | 32 (27) | 72 (16) | |||||||

| Within 3 months | 23 (4) | 9 (8) | 14 (3) | |||||||

| Frontline work | 313 (62) | 98 (85) | 215 (55) | 33.5 | 1 (509) | <0.001 | ||||

| Changed tasks | 309 (54) | 77 (65) | 232 (51) | 7.26 | 1 (575) | <0.01 | ||||

| Passive support | 442 (78) | 94 (81) | 348 (78) | 0.612 | 1 (564) | >0.05 | ||||

| Active support | 316 (56) | 84 (74) | 232 (52) | 17.7 | 1 (562) | <0.001 | ||||

Notes : Comparison groups were men, non-frontline workers, unchanged work tasks, and not having participated in passive/active support.

At baseline, 119 (21%) participants reported high burnout symptoms (i.e. the case group). The burnout prevalence during each follow-up was then estimated using SMBQ scores, presented in Figure 1 .

Prevalence of burnout (SMBQ) and depressive symptoms (PHQ) at follow-ups.

Figure 2 displays the logistic regression results for each outcome separately. At follow-up 1, cases were more likely to have high burnout symptoms compared to the controls (odds ratio [OR] = 3.061, 95% confidence interval [CI]: 1.798–5.211, P < 0.001, Model 1). The effect remained both at follow-up 2 (OR = 5.018, 95% CI: 2.868–8.780, P < 0.001, Model 1) and follow-up 3 (OR = 4.874, 95% CI: 2.699–8.802, P < 0.001, Model 1).

Odds ratios and 95% CI for each predictor in Model 3 and for each follow-up, respectively (T2 to T4).

Across all follow-ups, the association was unchanged also after controlling for frontline work and change of work tasks in Model 2 (follow-up 1 OR = 3.120, 95% CI: 1.774–5.489, P < 0.001; follow-up 2 OR = 4.594, 95% CI: 2.593–8.140, P < 0.001; follow-up 3 OR = 4.434, 95% CI: 2.383–8.250, P < 0.001), as well as psychological support participation in Model 3 (follow-up 1 OR = 2.979, 95% CI: 1.687–5.260, P < 0.001; follow-up 2 OR = 4.496, 95% CI: 2.451–8.249; follow-up 3 OR = 4.622, 95% CI: 2.443–8.746, P < 0.001).

At the third follow-up, participants categorized as frontline workers were also more likely to report high burnout symptoms. This was the case in both Model 2 (OR = 3.357, 95% CI: 1.741–6.473, P < 0.001), and after adding the psychological support in Model 3 (OR = 3.511, 95% CI: 1.765–6.983, P < 0.001). No other predictor had a statistically significant association with burnout symptoms (see Figure 2 ). A more detailed presentation of all model results is presented in Tables 7–9 (available as Supplementary data at Occupational Medicine Online).

Cases were also more likely to have high depressive symptoms later in the pandemic. The effect was similar at follow-up 1 (Model 1 OR = 3.175, 95% CI: 1.795–5.615, P < 0.001), follow-up 2 (Model 1 OR = 3.415, 95% CI: 1.917–6.083, P < 0.01), and follow-up 3 (Model 1 OR = 2.808, 95% CI: 1.502–5.250, P < 0.01).

This effect remained unchanged also after controlling for frontline work and change of work tasks in Model 2 (follow-up 1 OR = 3.051, 95% CI: 1.669–5.578, P < 0.001; follow-up 2 OR = 3.086, 95% CI: 1.710–5.570, P < 0.001; follow-up 3 OR = 2.657, 95% CI: 1.388–5.088, P < 0.01), and after adding psychological support in Model 3 (follow-up 1 OR = 2.927, 95% CI: 1.591–5.384, P < 0.001; follow-up 2 OR = 2.794, 95% CI: 1.478–5.280, P < 0.01; follow-up 3 OR = 2.872, 95% CI: 1.481–5.569, P < 0.01). No other predictor had a statistically significant association with depressive symptoms (see Figure 2 ). See Tables 10 – 12 for details of all model results (available as Supplementary data at Occupational Medicine Online).

The results of this study showed that one out of five healthcare workers experienced high burnout symptoms during the first wave of the COVID-19 pandemic. Affected healthcare workers were also more likely to experience both high burnout and depressive symptoms during follow-ups, compared to those with low burnout symptoms at baseline. Participation in psychological support was unrelated to the level of reported symptoms at follow-ups.

One strength of this study is the longitudinal design which allowed us to measure burnout symptoms over the course of a persistent crisis. We were also able to capture changes in the work environment over the course of the COVID-19 pandemic. By using burnout instruments validated within a Swedish healthcare context, we were able to compare the burnout prevalence with pre-pandemic levels and generalize our findings to Swedish healthcare workers.

The main limitation of our study is that we lack pre-pandemic data for our sample. It was more common among cases to have a previous history of mental illness and we do not know to what extent previous health problems overshadow the COVID-19-related effects on burnout. Another limitation was the use of self-reported data, which introduces the risk of biases (e.g. social desirability or inaccurate recollections). The low inclusion rate (26%) also introduces the risk of selection bias. Regarding our statistical analysis, the use of a single model might have led to a more straightforward conclusion, but our analytical approach enables a closer perspective on the specific issue of the persistence of high symptoms at different stages of a prolonged crisis.

At baseline, the prevalence of high burnout symptoms was 21%. Which is a considerable increase compared to the reported pre-pandemic prevalence of 10% among nurses in Sweden [ 10 ], and 12% among nurses in Europe and Central Asia [ 11 ]. This indicates that, like other countries [ 34 ], the COVID-19 pandemic negatively impacted the psychological well-being among healthcare workers in Sweden.

Experiencing high burnout symptoms during the first wave was the main predictor of high symptoms of both burnout and depression later in the pandemic. Building on the already existing literature on the long-term consequences of burnout [ 10 , 22 , 35 ], this finding implies that the early onset of symptoms is the main risk factor for continuing symptoms also during a persistent crisis.

When comparing the case to control group at baseline, we found important differences. Known risk factors related to burnout such as being a nurse, work in the frontline and have changed work tasks were more common in the case group [ 16 , 17 , 36–38 ]. It was also more common in the case group to have sought help for mental health issues. This group was therefore likely more vulnerable to the increased demands in the early pandemic [ 21 ].

Interestingly, at the last time point, over a year after the pandemic outbreak, frontline work increased the risk of burnout. This suggests that, over the course of a persistent crisis, there may be an added burden from being re-exposed to high job demands that increase the risk of both burnout and depressive symptoms [ 15 ].

Across all follow-ups, psychological support participation was not related to the likelihood of experiencing high symptoms. However, it was more common among the case group to use the active psychological support at baseline. Because of the strong relationship between case group membership and symptoms, the association between psychological support and stress symptoms may have been difficult to capture within the context of this study. Also, due to lack of pre-pandemic data, the effect of the interventions was not possible to assess.

An effect of psychological support on stress reactions during healthcare crises has been difficult to establish in many studies [ 23 , 27 ]. Future research should use more objective measurements such as participation logs and, if possible, pre-crisis data for comparison. Rather than measuring the changes in symptoms, it might be beneficial to investigate changes in resources that help healthcare workers cope better [ 39 ]. Such a resource could be perceived social support, a resource known to mitigate burnout symptoms when the demands are high [ 40 ].

During a persistent crisis, healthcare workers’ responses to the strained work environment in the immediate outbreak is a major risk factor for developing high burnout and depressive symptoms later in the crisis. A strained work environment may be difficult to avoid, but, if possible, healthcare organizations should be mindful of who they place in the frontline. Especially among those healthcare workers with a strong initial burnout reaction. Future research should address how and when changes in the work environment translate into burnout and depressive symptoms over time during a persistent crisis. Occupational health researchers should focus on identifying individual-centred interventions [ 24 ] that in a feasible way support healthcare workers experiencing strong stress reactions during an ongoing crisis.

The research was funded by a grant from AFA Insurance (AFA Försäkring) reference number 200136.

We thank all participants for answering multiple surveys during the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic. We would also like to thank managers and collaborators at the study sites who helped make the data collection possible.

The authors have no Competing Interests to declare.

Raw data will not be shared due to the constraints in the information included in the written consent.

Cai H , Tu B , Ma J et al. . Psychological impact and coping strategies of frontline medical staff in Hunan Between January and March 2020 during the outbreak of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) in Hubei, China . Med Sci Monit 2020 ; 26 : e924171 .

Google Scholar

Newman KL , Jeve Y , Majumder P. Experiences, and emotional strain of NHS frontline workers during the peak of the COVID19 pandemic . Int J Soc Psychiatr 2021 ; 68 : 783 – 790 .

Salazar de Pablo G , Vaquerizo-Serrano J , Catalan A et al. . Impact of coronavirus syndromes on physical and mental health of health care workers: systematic review and meta-analysis . J Affect Disord 2020 ; 275 : 48 – 57 .

Ghahramani S , Lankarani KB , Yousefi M , Heydari K , Shahabi S , Azmand S. A systematic review and meta-analysis of burnout among healthcare workers during COVID-19 . Front Psychiatry 2021 ; 12 : 758849 .

WHO. World Health Organization . [cited 2022 Nov 13]. Burn-out an ‘occupational phenomenon’: International Classification of Diseases . Available from: https://www.who.int/news/item/28-05-2019-burn-out-an-occupational-phenomenon-international-classification-of-diseases

Aronsson G , Theorell T , Grape T et al. . A systematic review including meta-analysis of work environment and burnout symptoms . BMC Public Health. 2017 ; 17 : 264 .

Gustavsson P , Hallsten L , Rudman A. Early career burnout among nurses: modelling a hypothesized process using an item response approach . Int J Nurs Stud 2010 ; 47 : 864 – 875 .

Demerouti E , Bakker AB , Nachreiner F , Schaufeli WB. The job demands-resources model of burnout . J Appl Psychol 2001 ; 86 : 499 – 512 .

Amoafo E , Hanbali N , Patel A , Singh P. What are the significant factors associated with burnout in doctors ? Occup Med (Lond) 2015 ; 65 : 117 – 121 .

Rudman A , Arborelius L , Dahlgren A , Finnes A , Gustavsson P. Consequences of early career nurse burnout: a prospective long-term follow-up on cognitive functions, depressive symptoms, and insomnia . EClinicalMedicine 2020 ; 27 : 100565 .

Woo T , Ho R , Tang A , Tam W. Global prevalence of burnout symptoms among nurses: a systematic review and meta-analysis . J Psychiatr Res 2020 ; 123 : 9 – 20 .

Glise K , Wiegner L , Jonsdottir IH. Long-term follow-up of residual symptoms in patients treated for stress-related exhaustion . BMC Psychol 2020 ; 8 : 26 .

Williams R , Kemp V. Principles for designing and delivering psychosocial and mental healthcare . BMJ Mil Health. 2020 ; 166 : 105 – 110 .

Dionisi T , Sestito L , Tarli C et al. .; Gemelli Against COVID-19 Group . Risk of burnout and stress in physicians working in a COVID team: a longitudinal survey . Int J Clin Pract 2021 ; 75 : e14755 .

Goss CW , Duncan JG , Lou SS , Holzer KJ , Evanoff BA , Kannampallil T. Effects of persistent exposure to COVID-19 on mental health outcomes among trainees: a longitudinal survey study . J Gen Intern Med 2022 ; 37 : 1204 – 1210 .

Ju TR , Mikrut EE , Spinelli A et al. . Factors associated with burnout among resident physicians responding to the COVID-19 pandemic: a 2-month longitudinal observation study . Int J Environ Res Public Health 2022 ; 19 : 9714 .

Maunder RG , Heeney ND , Hunter JJ et al. . Trends in burnout and psychological distress in hospital staff over 12 months of the COVID-19 pandemic: a prospective longitudinal survey . J Occup Med Toxicol 2022 ; 17 : 11 .

Melnikow J , Padovani A , Miller M. Frontline physician burnout during the COVID-19 pandemic: national survey findings . BMC Health Serv Res 2022 ; 22 : 365 .

Sasaki N , Asaoka H , Kuroda R , Tsuno K , Imamura K , Kawakami N. Sustained poor mental health among healthcare workers in COVID‐19 pandemic: a longitudinal analysis of the four‐wave panel survey over 8 months in Japan . J Occup Health 2021 ; 63 : e12227 .

Kachadourian L , Murrough J , Kaplan C et al. . A prospective study of transdiagnostic psychiatric symptoms associated with burnout and functional difficulties in COVID-19 frontline healthcare workers . J Psychiatr Res 2022 ; 152 : 219 – 224 .

Oosterholt BG , Maes JHR , Van der Linden D , Verbraak MJPM , Kompier MAJ. Getting better, but not well: a 1.5 year follow-up of cognitive performance and cortisol levels in clinical and non-clinical burnout . Biol Psychol 2016 ; 117 : 89 – 99 .

Bianchi R , Schonfeld IS , Laurent E. Burnout—depression overlap: a review . Clin Psychol Rev 2015 ; 36 : 28 – 41 .

Pappa S , Sakkas N , Sakka E. A year in review: sleep dysfunction and psychological distress in healthcare workers during the COVID-19 pandemic . Sleep Med 2022 ; 91 : 237 – 245 .

Kinman G , Dovey A , Teoh K. Burnout in Healthcare: Risk Factors and Solutions [Internet] . London, UK : The Society of Occupational Medicine , 2023 [cited 2024 Feb 4]. Available from: https://www.som.org.uk/sites/som.org.uk/files/Burnout_in_healthcare_risk_factors_and_solutions_July2023_0.pdf

Google Preview

Albott CS , Wozniak JR , McGlinch BP , Wall MH , Gold BS , Vinogradov S. Battle Buddies: rapid deployment of a psychological resilience intervention for healthcare workers during the Covid-19 pandemic . Anesthesia Analgesia 2020 ; 131 : 43 – 54 .

Galanis P , Vraka I , Fragkou D , Bilali A , Kaitelidou D. Nurses’ burnout and associated risk factors during the COVID-19 pandemic: a systematic review and meta-analysis . J Adv Nurs 2021 ; 77 : 3286 – 3302 .

Pollock A , Campbell P , Cheyne J et al. . Interventions to support the resilience and mental health of frontline health and social care professionals during and after a disease outbreak, epidemic or pandemic: a mixed methods systematic review . Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2020 ; 11 : CD013779 .

Bartelink V , Lager A (redaktörer). Folkhälsorapport 2023 . Stockholm : Centrum för Epidemiologi och Samhällsmedicin , 2023 .

Lundgren-Nilsson A , Jonsdottir IH , Pallant J , Ahlborg G. Internal construct validity of the Shirom-Melamed Burnout Questionnaire (SMBQ) . BMC Public Health 2012 ; 12 : 1 .

Almén N , Jansson B. The reliability and factorial validity of different versions of the Shirom-Melamed Burnout Measure/Questionnaire and normative data for a general Swedish sample . Int J Stress Manag. 2021 ; 28 : 314 – 325 .

Gilbody S , Richards D , Brealey S , Hewitt C. Screening for depression in medical settings with the Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ): a diagnostic meta-analysis . J Gen Intern Med 2007 ; 22 : 1596 – 1602 .

Kroenke K , Spitzer RL , Williams JBW. The Patient Health Questionnaire-2: validity of a Two-Item Depression Screener . Med Care 2003 ; 41 : 1284 – 1292 .

The jamovi project . Jamovi [Internet] . 2021 . Available from: https://www.jamovi.org/

van den Broek A , van Hoorn L , Tooten Y , de Vroege L. The moderating effect of the COVID-19 pandemic on the mental wellbeing of health care workers on sustainable employability: a scoping review . Front Psychiatry 2023 ; 13 : 1067228 .

Fagerlind Ståhl AC , Ståhl C , Smith P. Longitudinal association between psychological demands and burnout for employees experiencing a high versus a low degree of job resources . BMC Public Health 2018 ; 18 : 915 .

Guastello AD , Brunson JC , Sambuco N et al. . Predictors of professional burnout and fulfilment in a longitudinal analysis on nurses and healthcare workers in the COVID-19 pandemic . J Clin Nurs 2023 ; 33 : 1 – 16 .

Kok N , van Gurp J , Teerenstra S et al. . Coronavirus disease 2019 immediately increases burnout symptoms in ICU professionals: a longitudinal cohort study . Crit Care Med 2021 ; 49 : 419 – 427 .

Nishimura Y , Miyoshi T , Sato A et al. . Burnout of healthcare workers amid the COVID-19 pandemic: a follow-up study . Int J Environ Res Public Health 2021 ; 18 : 11581 .

de Jonge J , Dormann C. Stressors, resources, and strain at work: a longitudinal test of the triple-match principle . J Appl Psychol 2006 ; 91 : 1359 – 1374 .

Velando‐Soriano A , Ortega‐Campos E , Gómez‐Urquiza JL , Ramírez‐Baena L , De La Fuente EI , Cañadas‐De La Fuente GA. Impact of social support in preventing burnout syndrome in nurses: a systematic review . Jpn J Nurs Sci. 2020 ; 17 : e12269 .

Supplementary data

| Month: | Total Views: |

|---|---|

| May 2024 | 357 |

| June 2024 | 217 |

Email alerts

Citing articles via.

- Contact SOM

- Recommend to your Library

Affiliations

- Online ISSN 1471-8405

- Print ISSN 0962-7480

- Copyright © 2024 Society of Occupational Medicine

- About Oxford Academic

- Publish journals with us

- University press partners

- What we publish

- New features

- Open access

- Institutional account management

- Rights and permissions

- Get help with access

- Accessibility

- Advertising

- Media enquiries

- Oxford University Press

- Oxford Languages

- University of Oxford

Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the University's objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide

- Copyright © 2024 Oxford University Press

- Cookie settings

- Cookie policy

- Privacy policy

- Legal notice

This Feature Is Available To Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account

This PDF is available to Subscribers Only

For full access to this pdf, sign in to an existing account, or purchase an annual subscription.

Featured Topics

Featured series.

A series of random questions answered by Harvard experts.

Explore the Gazette

Read the latest.

Stroke risk higher for the chronically lonely

Testing fitness of aging brain

DNR orders for Down syndrome patients far exceeded pandemic norm

Doctors not the only ones feeling burned out

BWH Communications

COVID survey finds more than half of healthcare workers stressed, overworked, and ready to leave

Although much focus has been placed on physician and nurse burnout, a new study finds the COVID-19 pandemic increased stress across the entire healthcare workforce.

Led by Brigham and Women’s Hospital investigators, the survey included over 15,000 physicians and 11,000 nurses as well as more than 5,000 other clinical staff such as pharmacists, nursing assistants, therapists, medical assistants, or social workers and over 11,000 non-clinical staff including housekeeping, administrative staff, lab technicians, or food service staff. The results are published in the Journal of General Internal Medicine.

“Teams are crucial for good healthcare delivery and our study emphasizes a need to improve the well-being of the many role types that comprise our healthcare teams,” said corresponding author Lisa S. Rotenstein, a primary care physician at the Brigham and assistant professor at Harvard Medical School.

Rotenstein’s team analyzed burnout, intent to leave the profession, and feelings of work overload reported in the American Medical Association’s Coping with COVID Survey from April to December 2020. Through the survey, 43,026 responses were collected from 206 healthcare organizations.

“There’s an opportunity here to both identify and address workload across all role types.” Lisa S. Rotenstein

“Individuals in other clinical roles or non-clinical roles such as technicians, food service workers or nursing assistants may be more likely to be from underrepresented minority groups or hold multiple jobs,” Rotenstein said. “They may be less likely to be in a position to speak up about their own working conditions.”

Approximately 50 percent of all respondents reported burnout, with the highest levels among nurses (56 percent) and other clinical staff (54.1 percent) reporting burnout. Intent to leave the job was reported by 28.7 percent of healthcare workers, with 41 percent of nurses, 32.6 percent of non-clinical staff and 31.1 percent of clinical staff reporting the sentiment. The intent to leave was higher for both physicians and nurses in an in-patient setting compared to out-patient settings.

The prevalence of perceived work overload ranged from 37.1 percent among physicians to 47.4 percent in other clinical staff. And this work overload was significantly associated with both burnout and intent to leave the job.

“That is something potentially actionable. There isn’t a standard way to quantify work overload in the healthcare setting,” said Rotenstein. “There’s an opportunity here to both identify and address workload across all role types.”

Rotenstein advocates for more innovative approaches that do not simply shift responsibilities from some members of the healthcare workforce to others, but to automate or reimagine some of these responsibilities.

Survey completion was voluntary, so the population is not necessarily representative of the healthcare workforce. Additionally, the data were collected at the height of the pandemic, and levels of burnout could have changed. Still, the survey responses underscore the importance of looking at the experience of all healthcare workers.

“We are acutely seeing the effects of burnout across the workforce,” Rotenstein said. “There are staffing shortages in healthcare facilities across the country and it’s not just physicians. It is nurses, medical assistants, and more. We need to take care of all types of healthcare workers.”

Disclosures: Co-author Mark Linzer was supported through his employer Hennepin Healthcare, and by the AMA. His other scholarly work is supported by NIH and AHRQ. Rotenstein has received research support from the American Medical Association, FeelBetter Inc., and AHRQ. Linzer is also supported through his employer for work on burnout reduction projects for IHI, ABIM, ACP, Optum Office for Provider Advancement, Essentia Health Systems, Gillette Children’s Hospital, and the California AHEC System, and consults for Harvard University on a grant assessing relationships between work conditions and diagnostic accuracy (consultation funds donated to Hennepin Healthcare Foundation).

Share this article

You might like.

Study of adults over 50 examines how feelings boost threat over time

Most voters back cognitive exams for older politicians. What do they measure?

Co-author sees need for additional research and earlier, deeper conversations around care

When should Harvard speak out?

Institutional Voice Working Group provides a roadmap in new report

Had a bad experience meditating? You're not alone.

Altered states of consciousness through yoga, mindfulness more common than thought and mostly beneficial, study finds — though clinicians ill-equipped to help those who struggle

College sees strong yield for students accepted to Class of 2028

Financial aid was a critical factor, dean says

- - Google Chrome

Intended for healthcare professionals

- My email alerts

- BMA member login

- Username * Password * Forgot your log in details? Need to activate BMA Member Log In Log in via OpenAthens Log in via your institution

Search form

- Advanced search

- Search responses

- Search blogs

- News & Views

- Burnout in healthcare:...

Burnout in healthcare: the case for organisational change

- Related content

- Peer review

- A Montgomery , professor in work and organizational psychology 1 ,

- E Panagopoulou , associate professor 2 ,

- A Esmail , professor of general practice 3 ,

- T Richards , senior editor, BMJ patient partnership initiative 4 ,

- C Maslach , professor 5

- 1 University of Macedonia, Thessaloniki, Greece

- 2 Hygiene Laboratory, Aristotle Medical School, Aristotle University of Thessaloniki, Thessaloniki, Greece

- 3 Division of Population Health, Health Services Research and Primary Care, University of Manchester, Manchester, UK

- 4 BMJ, London, UK

- 5 University of California, Berkeley, CA, USA

- Correspondence to: A Montgomery monty5429{at}hotmail.com

Burnout is an occupational phenomenon and we need to look beyond the individual to find effective solutions, argue A Montgomery and colleagues

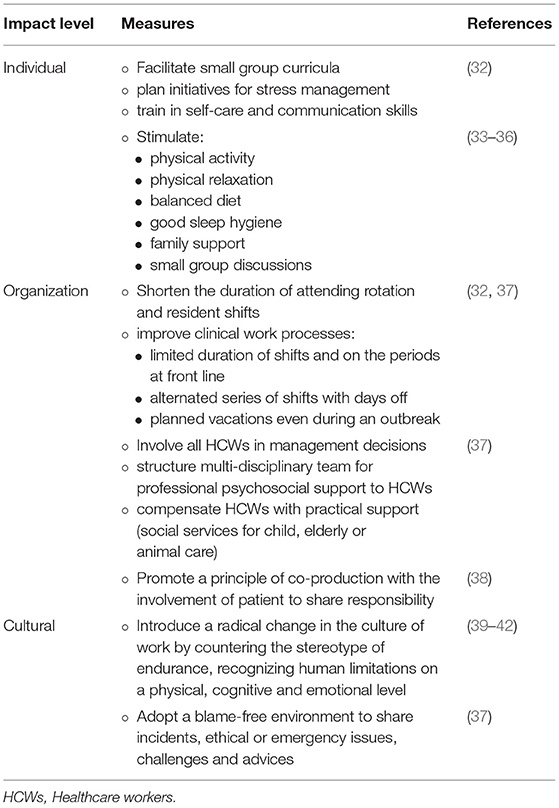

Burnout has become a big concern within healthcare. It is a response to prolonged exposure to occupational stressors, and it has serious consequences for healthcare professionals and the organisations in which they work. 1 Burnout is associated with sleep deprivation, 2 medical errors, 3 4 5 poor quality of care, 6 7 and low ratings of patient satisfaction. 8 Yet often initiatives to tackle burnout are focused on individuals rather than taking a systems approach to the problem.

Evidence on the association of burnout with objective indicators of performance (as opposed to self report) is scarce in all occupations, including healthcare. 9 But the few examples of studies using objective indicators of patient safety at a system level confirm the association between burnout and suboptimal care. For example, in a recent study, intensive care units in which staff had high emotional exhaustion had higher patient standardised mortality ratios, even after objective unit characteristics such as workload had been controlled for. 10

The link between burnout and performance in healthcare is probably underestimated: job performance can still be maintained even when burnt out staff lack mental or physical energy 11 as they adopt “performance protection” strategies to maintain high priority clinical tasks and neglect low priority secondary tasks (such as reassuring patients). 12 Thus, evidence that the system is broken is masked until critical points are reached. Measuring and assessing burnout within a system could act as a signal to stimulate intervention before it erodes quality of care and results in harm to patients.

Burnout does not just affect patient safety. Failing to deal with burnout results in higher staff turnover, lost revenue associated with decreased productivity, financial risk, …

Log in using your username and password

BMA Member Log In

If you have a subscription to The BMJ, log in:

- Need to activate

- Log in via institution

- Log in via OpenAthens

Log in through your institution

Subscribe from £184 *.

Subscribe and get access to all BMJ articles, and much more.

* For online subscription

Access this article for 1 day for: £33 / $40 / €36 ( excludes VAT )

You can download a PDF version for your personal record.

Buy this article

Preventing Nurse Burnout With Workplace Interventions Essay

- To find inspiration for your paper and overcome writer’s block

- As a source of information (ensure proper referencing)

- As a template for you assignment

Introduction

Project proposal topic, capstone proposal, literature review.

This capstone project’s goal is to explore the issue of nurse burnout in the healthcare industry. Burnout is a widespread problem that affects not only the health and well-being of nurses but also the quality of patient care (Fitzpatrick et al., 2019). According to Bogue and Bogue (2020), burnout emerges as an epidemic in healthcare. This research will look at the origins and consequences of nurse burnout and identify strategies for preventing and managing burnout in the workplace. The research is conducted through a review of relevant literature and a survey of healthcare facilities and nurses.

The project proposal focuses on the exploration of nurse burnout in the healthcare industry. The aim is to understand the causes, consequences, and strategies for preventing and managing nurse burnout in the workplace. According to Buckley et al. (2020), peer-reviewed literature ensures the quality of the data reviewed. Therefore, the research will include a literature review and a survey of healthcare facilities and nurses. This project aims to contribute to developing practical solutions for reducing nurse burnout and improving the quality of patient care.

Project Question (PICOT): What is the impact of workplace interventions on reducing nurse burnout in the healthcare industry? Title of the Project: Preventing Nurse Burnout: An Examination of Workplace Interventions. Proposal: Nurse burnout is a serious issue that affects not only the health and well-being of nurses but also the quality of patient care (Fitzpatrick et al., 2019). This capstone project examines workplace interventions’ impact on reducing nurse burnout in the healthcare industry. It sheds light on the effectiveness of workplace interventions in reducing nurse burnout.

One of the interventions that will be explored is the implementation of workplace wellness programs. These programs can include activities such as exercise classes, stress management workshops, and counseling services. Another intervention that will be studied is flexible scheduling, allowing nurses more control over their work-life balance (Mlambo et al., 2021). Generally, the role of nurse managers in promoting a healthy work environment and addressing nurse burnout will also be examined. This project aims to explore the effectiveness of workplace wellness programs.

The findings provide valuable insight into the effectiveness of workplace interventions in reducing nurse burnout. It informs the development of strategies to promote a healthier work environment for nurses. The work environment is the conditions in which nurses work (Buckley et al., 2020). Ultimately, this project aims to improve the quality of patient care by reducing nurse burnout. It also promotes a sustainable work environment for nurses and other healthcare practitioners.

The issue of nurse burnout is a pressing concern in the healthcare industry, affecting the standard of patient care and the nurses’ health and well-being. The signs of burnout entail emotional exhaustion, depersonalization, and decreased personal accomplishment (Bogue & Bogue, 2020). It can lead to reduced job satisfaction and increased healthcare costs. This capstone project aims to address nurse burnout by exploring the impact of workplace interventions on reducing burnout levels. The project addresses nurse burnout by examining the effect of workplace interventions.

A literature study and a survey of hospitals and nurses will be used to conduct the research. It will focus on identifying effective strategies for preventing and managing nurse burnout in the workplace. This project was selected because nurse burnout is a critical issue in the healthcare industry and significantly impacts nurses’ and patients’ care quality (Johnson et al., 2017). Nurses have witnessed the toll that burnout can take on their colleagues. Finding ways to address this issue is crucial for nurses’ well-being and the healthcare industry’s sustainability.

Nurse burnout has multiple causes, including extended hours and high stress. It results in burnout symptoms like exhaustion and feeling overwhelmed. It can also result in excessive workload and increased pressure on nurses to perform their duties efficiently. The study will explore ways to enhance the work environment for nurses and reduce burnout through practical solutions. It aims to contribute to a healthier and more sustainable workplace for nursing professionals.

The literature review plays a crucial role in this capstone project. It provides a comprehensive understanding of the current research on nurse burnout and workplace interventions to reduce burnout levels (Bogue & Bogue, 2020). It will examine peer-reviewed articles and other academic sources to identify the key themes and findings related to the problem of nurse burnout and effective strategies for reducing it (Buckley et al., 2020). This information will inform the design of the survey component and the development of recommendations for improving the work environment for nurses. It serves as a foundation for the project, ensuring that the methodology is well-informed and based on the latest scientific evidence.

Methods of Searching

A literature review was conducted using both electronic and manual resources. Relevant databases such as PubMed, CINAHL, and ProQuest were searched using keywords related to nursing burnout and workplace interventions (Norful et al., 2018). The manual search involved reviewing reference lists of relevant articles and books. The investigation was limited to English language sources published in the last five years. The sources were then evaluated for relevance, quality, and credibility before being included in the literature review. This comprehensive and systematic approach ensured that the information gathered was up-to-date and relevant to the current state of the research.

Review of the Literature

The literature review examined the growing issue of nurse burnout and the potential solutions to address this problem. The study used electronic and manual resources, including PubMed, CINAHL, and ProQuest databases, to compile the most recent information. It was restricted to sources published within the last five years. The restriction ensured that the information gathered was up-to-date and relevant to the current state of the research. Filtering occurred in the database used to produce peer-reviewed articles.

The literature found that nurse burnout is a growing concern in nursing. High levels of burnout impact the quality of care and contribute to high turnover rates. Contributing factors to nurse burnout include heavy workloads, lack of support from colleagues and supervisors, and poor working conditions (Dall’Ora et al., 2020). The nurse will ultimately reduce their work performance, and some will desire to quit. Eventually, the healthcare system faces challenges whenever there are scarce nurses.

The literature review identified several workplace interventions that have shown promise in reducing burnout. These include programs to improve work-life balance and provide nurses with support and resources. Another intervention is to improve the working conditions of the nurses. One study found that a workplace wellness program, which provided education and resources for stress management and self-care, significantly reduced nurse burnout (Johnson et al., 2017). It highlights the significance of nurse burnout and the need for effective interventions to address this issue.

Further research shows more interventions that could reduce nurse burnout. According to another study, offering opportunities for professional development and growth, such as continuing education and leadership training, reduced burnout and improved job satisfaction among nurses (Fitzpatrick et al., 2019). Regular skill renewal and upgrading are necessary for healthcare workers. The literature review also highlighted the importance of addressing burnout at the organizational level. It includes creating a supportive work environment, promoting work-life balance, and providing resources and support for nurses.

Nurse burnout is a significant problem in the healthcare industry. It affects both the well-being of nurses and the quality of patient care. Workplace interventions, such as wellness programs and professional development opportunities, have shown promise in reducing burnout and improving nurses’ job satisfaction (Johnson et al., 2017). However, the most practical methods for reducing nurse burnout and enhancing the working conditions for nurses require more investigation. This capstone project aims to contribute to the ongoing effort to reduce nurse burnout and improve the work environment for nurses.

The literature has shown that nurse burnout is a growing concern in nursing. Burnout harms the quality of care nurses provide. Heavy workloads, a lack of support from peers and managers, and unfavorable working circumstances are all factors that contribute to nursing burnout (Dall’Ora et al., 2020). The literature review identified several workplace interventions that have shown promise in reducing burnout. These include programs to improve work-life balance, provide nurses with support and resources, and improve working conditions.

Additionally, addressing nurse burnout at the organizational level through supportive work environments and involving nurses in decision-making can help reduce burnout. It is found that continued professional development in nursing is an effective strategy for reducing nurse burnout and enhancing the nursing workforce (Mlambo et al., 2021). A nurse practitioner is an example of a registered nurse holding a doctoral degree. The findings intend to lessen nurse burnout and enhance the working conditions for nurses. These findings provide valuable insight into the most successful strategies for promoting a healthy and sustainable work environment for nurses.

The project targets nurse burnout with three objectives. Objective 1: Evaluate the workplace wellness program’s impact on nurse burnout (Ernawati et al., 2022). Objective 2: Boost nurse engagement by involving them in decision-making (Fitzpatrick et al., 2019). Objective 3: Improve nurse work-life balance with flexible arrangements and resources for stress management. These objectives ensure that the project is focused and aligned to reduce nurse burnout.

Two strategies will be employed to achieve the first objective: to identify the extent of nurse burnout in healthcare facilities. Firstly, a survey will be administered to a sample of nurses to assess their level of burnout (Ernawati et al., 2022). The survey will include questions about the frequency and intensity of symptoms associated with burnout. These may entail emotional exhaustion, depersonalization, and a reduced sense of personal accomplishment. Secondly, a focus group will be organized to allow nurses to share their experiences and perspectives on nurse burnout.

The second objective is to understand the contributing factors to nurse burnout. Two strategies will be used in order to achieve this. Firstly, the survey and focus group results will be analyzed to identify patterns or trends. Secondly, a review of the relevant literature will be conducted to identify gaps in the current understanding of nurse burnout (Buckley et al., 2020). All this will ensure that all relevant factors are considered when developing strategies to reduce nurse burnout.

The third objective is to develop and implement an intervention to reduce nurse burnout. A customized program will be designed that addresses the contributing factors identified in the analysis of the survey and focus group results. It may include training sessions on stress management for nurses and healthcare administrators (Ernawati et al., 2022). Secondly, workplace practices will be implemented to support work-life balance for nurses. It includes flexible schedules and opportunities for professional development for nurses.

Evaluation of the project will be crucial to determine its success in achieving the objectives and improving patient outcomes/safety. Several methods will be used to evaluate the capstone project. These include data analysis, surveys, random interviews, and focus groups. The data collected from these methods will be used to determine the effectiveness of the strategies implemented in addressing the objectives (Dall’Ora et al., 2020). One of the required evaluation methods will be data analysis.

The patient data is analyzed to determine any improved outcomes and safety. It includes patient satisfaction levels, patient outcomes, and the number of adverse events. The collection of data is before and after the implementation of the strategies. A comparison of the two data sets will be used to determine if there has been any improvement. In addition to data analysis, surveys and focus groups will gather feedback from patients and healthcare providers.

The evaluations will provide insight into the perceived effectiveness of the strategies and any potential areas for improvement. This feedback will refine the plan and make any necessary changes to improve patient safety (Fitzpatrick et al., 2019). The project evaluation will be ongoing and will provide valuable information on its effectiveness. The assessment results will be used to make necessary changes to the project and ensure that it continues improving patient outcomes and safety. Upon thorough evaluation, the project is ready to be actualized.

The budget for this project will include various items necessary for its successful implementation. These items include resources for conducting workshops and training sessions for the nursing staff, materials for disseminating information and awareness, and software and tools required for data collection and analysis. The funding for these budget items will come from various sources, such as grants, sponsorships, and in-kind contributions from the healthcare organization where the project will be implemented. The total budget required for the successful completion of the project will be determined after carefully considering all the necessary expenses. It will be subject to change as per the needs of the project.

Nurse burnout is a pressing issue affecting the quality of patient care and nursing professionals’ overall health and well-being. The capstone project aims to combat nurse burnout, which affects patient care and health (Ernawati et al., 2022). Evidence supports the need for stress-reducing interventions to enhance work-life balance. The project targets the issue of nurse burnout and its negative impact on patients and healthcare workers. The study aims to offer a solution to improve outcomes for both patients and healthcare professionals.

The objectives and strategies outlined in this proposal are well-defined and achievable. The evaluation plan will help determine the effectiveness of the interventions. The initiative has the potential to significantly influence many people’s lives and the healthcare system as a whole, with sufficient financing and support. It is a valuable contribution to the field of nursing and healthcare. The project will help advance the understanding of mitigating nurse burnout and promoting better patient care outcomes.

The project aims to address the issue of nurse burnout through research and interventions. It, therefore, offers solutions to promote healthy work environments for nurses. New nurses face challenges and often lack resilience, but this project can guide the healthcare industry in supporting these professionals (Buckley et al., 2020). The insights gained will benefit nurses and patients, creating a brighter future in the healthcare field. This project serves as a blueprint for governments and institutions to follow in preventing nurse burnout.

Bogue, T. L., & Bogue, R. L. (2020). Extinguish Burnout in Critical Care Nursing . Critical Care Nursing Clinics of North America , 32 (3), 451–463. Web.

Buckley, L., Berta, W., Cleverley, K., Medeiros, C., & Widger, K. (2020). What is known about paediatric nurse burnout: a scoping review . Human Resources for Health , 18 (1). Web.

Dall’Ora, C., Ball, J., Reinius, M., & Griffiths, P. (2020). Burnout in nursing: a theoretical review . Human Resources for Health , 18 (1). Web.

Ernawati, E., Mawardi, F., Roswiyani, R., Melissa, M., Wiwaha, G., Tiatri, S., & Hilmanto, D. (2022). Workplace wellness programs for working mothers: A systematic review . Journal of Occupational Health , 64 (1). Web.

Fitzpatrick, B., Bloore, K., & Blake, N. (2019). Joy in Work and Reducing Nurse Burnout: From Triple Aim to Quadruple Aim . AACN Advanced Critical Care , 30 (2), 185–188. Web.

Johnson, J., Hall, L. H., Berzins, K., Baker, J., Melling, K., & Thompson, C. (2017). Mental healthcare staff well-being and burnout: A narrative review of trends, causes, implications, and recommendations for future interventions . International Journal of Mental Health Nursing , 27 (1), 20–32. Web.

Mlambo, M., Silén, C., & McGrath, C. (2021). Lifelong learning and nurses’ continuing professional development, a metasynthesis of the literature . BMC Nursing , 20 (1). Web.

Norful, A. A., De Jacq, K., Carlino, R., & Poghosyan, L. (2018). Nurse Practitioner–Physician Comanagement: A Theoretical Model to Alleviate Primary Care Strain . The Annals of Family Medicine , 16 (3), 250–256. Web.

- The Capstone Project: The Analysis of Uipath

- Capstone Change Project Resources in Acute Care

- The Effects of Child Abuse: Capstone Project Time Line

- The H.R. 198 Bill's Impact on Nursing Practice

- Nurse-to-Patient Ratios' Effect on Nurse Retention

- Nurses' Role in National Patient Safety Goals

- Narrative and Bearing Witness in Nursing

- Cultural and Social Considerations in Health Assessment

- Chicago (A-D)

- Chicago (N-B)

IvyPanda. (2024, January 30). Preventing Nurse Burnout With Workplace Interventions. https://ivypanda.com/essays/preventing-nurse-burnout-with-workplace-interventions/

"Preventing Nurse Burnout With Workplace Interventions." IvyPanda , 30 Jan. 2024, ivypanda.com/essays/preventing-nurse-burnout-with-workplace-interventions/.

IvyPanda . (2024) 'Preventing Nurse Burnout With Workplace Interventions'. 30 January.

IvyPanda . 2024. "Preventing Nurse Burnout With Workplace Interventions." January 30, 2024. https://ivypanda.com/essays/preventing-nurse-burnout-with-workplace-interventions/.

1. IvyPanda . "Preventing Nurse Burnout With Workplace Interventions." January 30, 2024. https://ivypanda.com/essays/preventing-nurse-burnout-with-workplace-interventions/.

Bibliography

IvyPanda . "Preventing Nurse Burnout With Workplace Interventions." January 30, 2024. https://ivypanda.com/essays/preventing-nurse-burnout-with-workplace-interventions/.

Understanding and prioritizing nurses’ mental health and well-being

Healthcare organizations continue to feel the effects of the COVID-19 pandemic, including prolonged workforce shortages, rising labor costs, and increased staff burnout. 1 The World Health Organization defines burnout as “a syndrome conceptualized as resulting from chronic workplace stress that has not been successfully managed,” with symptoms including “feelings of energy depletion or exhaustion; increased mental distance from one’s job, or feelings of negativism or cynicism related to one’s job; and reduced professional efficacy.” For more, see “Burn-out an ‘occupational phenomenon’: International Classification of Diseases,” World Health Organization, May 28, 2019; and “Doctors not the only ones feeling burned out,” Harvard Gazette , March 31, 2023. Although nurses routinely experience job-related stress and symptoms of burnout, the COVID-19 pandemic exacerbated the challenges of this high-intensity role.

About the research collaboration between the American Nurses Foundation and McKinsey

The American Nurses Foundation is a national research, educational, and philanthropic affiliate of the American Nurses Association committed to advancing the nursing profession by serving as a thought leader, catalyst for action, convener, and funding conduit. The American Nurses Foundation and McKinsey are partnering to assess and report on trends related to the nursing profession. A foundational part of this effort is jointly publishing novel insights related to supporting nurses throughout their careers.

In April and May 2023, the American Nurses Foundation and McKinsey surveyed 7,419 nurses in the United States to better understand their experiences, needs, preferences, and career intentions. All survey questions were based on the experiences of the individual professional. All questions were also optional for survey respondents; therefore, the number of responses may vary by question. Additionally, publicly shared examples, tools, and healthcare systems referenced in this article are representative of actions that stakeholders are taking to address workforce challenges.

As part of an ongoing, collaborative research effort, the American Nurses Foundation (the Foundation) and McKinsey surveyed more than 7,000 nurses in April and May 2023 to better understand mental health and well-being in the nursing workforce (see sidebar “About the research collaboration between the American Nurses Foundation and McKinsey”). The survey results revealed that symptoms of burnout and mental-health challenges among nurses remain high; the potential long-term workforce and health implications of these persistent pressures are not yet fully understood.

In this report, we share the highlights of our most recent survey and trends over the past few years. As healthcare organizations and other stakeholders continue to evolve their approaches to these important issues, this research provides additional insight into the challenges nurses face today and highlights opportunities to ensure adequate support to sustain the profession and ensure access to care for patients.

Current state of the nursing workforce

Although many organizations have taken steps to address the challenges facing the nursing workforce, findings from the joint American Nurses Foundation and McKinsey survey from May 2023 indicate that continued action is required. Nursing turnover is beginning to decline from its 2021 high but remains above prepandemic levels. 2 2023 NSI national health care retention & RN staffing report , NSI Nursing Solutions, 2023. Intent to leave also remains high: about 20 percent of surveyed nurses indicated they had changed positions in the past six months, and about 39 percent indicated they were likely to leave their current position in the next six months. 3 Based on data from Pulse on the Nation’s Nurses Survey Series: Mental Health and Wellness Survey 4. Intent to leave was roughly 41 percent among nurses who provide direct care to patients, compared with 30 percent for nurses not in direct-patient-care roles. 4 Based on data from Pulse on the Nation’s Nurses Survey Series: Mental Health and Wellness Survey 4.

Surveyed nurses who indicated they were likely to leave cited not feeling valued by their organizations, insufficient staffing, and inadequate compensation as the top three factors influencing their decisions. 5 Based on data from Pulse on the Nation’s Nurses Survey Series: Mental Health and Wellness Survey 4. Insufficient staffing was especially important to respondents with less than ten years of experience 6 Based on data from Pulse on the Nation’s Nurses Survey Series: Mental Health and Wellness Survey 4. —a population that will be critical to retain to ensure future workforce stability.

Key survey insights on mental health and well-being

Our joint research highlighted the magnitude of the health and well-being challenges, both physical and mental, facing the nursing workforce. More than 57 percent of surveyed nurses indicated they had been diagnosed with COVID-19, and 11 percent of those indicated they had been diagnosed with post-COVID-19 conditions (PCC or “long COVID”). Additional research may be needed to fully understand the impact of PCC on nurses, but in the meantime, employers could consider augmenting their PCC services for clinicians.

Research conducted by both the Foundation and McKinsey over the past three years has identified sustained feelings of burnout among surveyed nurses—a trend that continued this year. 7 For more, see the following articles: “Mental health and wellness survey 1,” American Nurses Foundation, August 2020; “Mental health and wellness survey 2,” American Nurses Foundation, December 2020; “Mental health and wellness survey 3,” American Nurses Foundation, September 2021; Gretchen Berlin, Meredith Lapointe, Mhoire Murphy, and Molly Viscardi, “ Nursing in 2021: Retaining the healthcare workforce when we need it most ,” McKinsey, May 11, 2021; Gretchen Berlin, Meredith Lapointe, Mhoire Murphy, and Joanna Wexler, “ Assessing the lingering impact of COVID-19 on the nursing workforce ,” McKinsey, May 11, 2022; “ Nursing in 2023: How hospitals are confronting shortages ,” McKinsey, May 5, 2023. Reported contributors to burnout include insufficient staffing, high patient loads, poor and difficult leadership, and too much time spent on administrative tasks. In our joint survey, 56 percent of nurses reported experiencing symptoms of burnout, such as emotional exhaustion (Exhibit 1). Well more than half (64 percent) indicated they feel “a great deal of stress” because of their jobs. Additionally, although there have been slight improvements year over year in respondents’ reports of stress, anxiety, and feeling overwhelmed, reports of positive emotions such as feeling empowered, grateful, and confident have declined. 8 “Pulse on the Nation’s Nurses Survey Series results,” American Nurses Foundation, accessed October 20, 2023.

Our results indicate that mental health and well-being vary by nurse experience levels (Exhibit 2). Less-tenured nurse respondents were more likely to report less satisfaction with their role, had a higher likelihood of leaving their role, and were more likely to be experiencing burnout.

Despite these sustained and high levels of burnout, approximately two-thirds of surveyed nurses indicated they were not currently receiving mental-health support (a figure that remained relatively consistent in Foundation surveys over the past two years), and 56 percent of surveyed nurses believe there is stigma attached to mental-health challenges. 9 Based on data from Pulse on the Nation’s Nurses Survey Series: Mental Health and Wellness Survey 4; “Pulse on the Nation’s Nurses,” accessed October 20, 2023.

Reasons cited by nurse respondents for not seeking professional mental-health support have remained consistent over the past two years, 10 “Mental health and wellness survey 3,” September 2021. with 29 percent indicating a lack of time, 23 percent indicating they feel they should be able to handle their own mental health, and 10 percent citing cost or a lack of financial resources (Exhibit 3). For nurses with ten or fewer years of experience, lack of time ranked as the top reason for not seeking professional mental help.

Despite slight improvements to the most severe symptoms over the past six to 12 months, reported levels of sustained burnout and well-being challenges have remained consistently high since we began assessing this population in 2021. Moreover, research indicates that burnout has several adverse, long-term health effects; for example, it is a predictor of a wide range of illnesses. 11 Denise Albieri Jodas Salvagioni et al., “Physical, psychological and occupational consequences of job burnout: A systematic review of prospective studies,” PLoS One , October 2017, Volume 12, Number 10; D. Smith Bailey, “Burnout harms workers’ physical health through many pathways,” Monitor on Psychology , June 2006, Volume 37, Number 7. These health conditions incur not only personal costs but also societal and organizational costs because they influence productivity, employee retention, presence at work, and career longevity. 12 Prioritise people: Unlock the value of a thriving workforce , Business in the Community and the McKinsey Health Institute, April 2023.

Actions stakeholders can take to address mental health and well-being

To address these sustained levels of burnout, stakeholders will need to take steps to support nurses’ mental health and well-being. They will also need to address the underlying structural issues—for example, workload and administrative burden—that affect the nursing profession and that have been consistently acknowledged as root causes of burnout. Simultaneously reducing workload demands and increasing resources available to meet those demands will be critical.

A variety of interventions could address the drivers and effects of adverse nursing mental health and well-being, bolstering support for individuals, organizations, and the healthcare system at large. Various stakeholders are deploying a number of initiatives.

Applying process and operating-model interventions

Addressing the underlying drivers of burnout could help to prevent it in the first place. Research from the McKinsey Health Institute shows that the day-to-day work environment has a substantial impact on the mental health and well-being of employees. 13 “ Addressing employee burnout: Are you solving the right problem? ,” McKinsey Health Institute, May 27, 2022. Process and operating-model shifts—in the context of ongoing broader shifts in care models—could enable organizations and care teams to evolve working practices to better support job satisfaction and sustainability.