- Patient Care & Health Information

- Diseases & Conditions

- Alcohol use disorder

Alcohol use disorder is a pattern of alcohol use that involves problems controlling your drinking, being preoccupied with alcohol or continuing to use alcohol even when it causes problems. This disorder also involves having to drink more to get the same effect or having withdrawal symptoms when you rapidly decrease or stop drinking. Alcohol use disorder includes a level of drinking that's sometimes called alcoholism.

Unhealthy alcohol use includes any alcohol use that puts your health or safety at risk or causes other alcohol-related problems. It also includes binge drinking — a pattern of drinking where a male has five or more drinks within two hours or a female has at least four drinks within two hours. Binge drinking causes significant health and safety risks.

If your pattern of drinking results in repeated significant distress and problems functioning in your daily life, you likely have alcohol use disorder. It can range from mild to severe. However, even a mild disorder can escalate and lead to serious problems, so early treatment is important.

Products & Services

- A Book: Mayo Clinic Family Health Book, 5th Edition

- Newsletter: Mayo Clinic Health Letter — Digital Edition

Alcohol use disorder can be mild, moderate or severe, based on the number of symptoms you experience. Signs and symptoms may include:

- Being unable to limit the amount of alcohol you drink

- Wanting to cut down on how much you drink or making unsuccessful attempts to do so

- Spending a lot of time drinking, getting alcohol or recovering from alcohol use

- Feeling a strong craving or urge to drink alcohol

- Failing to fulfill major obligations at work, school or home due to repeated alcohol use

- Continuing to drink alcohol even though you know it's causing physical, social, work or relationship problems

- Giving up or reducing social and work activities and hobbies to use alcohol

- Using alcohol in situations where it's not safe, such as when driving or swimming

- Developing a tolerance to alcohol so you need more to feel its effect or you have a reduced effect from the same amount

- Experiencing withdrawal symptoms — such as nausea, sweating and shaking — when you don't drink, or drinking to avoid these symptoms

Alcohol use disorder can include periods of being drunk (alcohol intoxication) and symptoms of withdrawal.

- Alcohol intoxication results as the amount of alcohol in your bloodstream increases. The higher the blood alcohol concentration is, the more likely you are to have bad effects. Alcohol intoxication causes behavior problems and mental changes. These may include inappropriate behavior, unstable moods, poor judgment, slurred speech, problems with attention or memory, and poor coordination. You can also have periods called "blackouts," where you don't remember events. Very high blood alcohol levels can lead to coma, permanent brain damage or even death.

- Alcohol withdrawal can occur when alcohol use has been heavy and prolonged and is then stopped or greatly reduced. It can occur within several hours to 4 to 5 days later. Signs and symptoms include sweating, rapid heartbeat, hand tremors, problems sleeping, nausea and vomiting, hallucinations, restlessness and agitation, anxiety, and occasionally seizures. Symptoms can be severe enough to impair your ability to function at work or in social situations.

What is considered 1 drink?

The National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism defines one standard drink as any one of these:

- 12 ounces (355 milliliters) of regular beer (about 5% alcohol)

- 8 to 9 ounces (237 to 266 milliliters) of malt liquor (about 7% alcohol)

- 5 ounces (148 milliliters) of wine (about 12% alcohol)

- 1.5 ounces (44 milliliters) of hard liquor or distilled spirits (about 40% alcohol)

When to see a doctor

If you feel that you sometimes drink too much alcohol, or your drinking is causing problems, or if your family is concerned about your drinking, talk with your health care provider. Other ways to get help include talking with a mental health professional or seeking help from a support group such as Alcoholics Anonymous or a similar type of self-help group.

Because denial is common, you may feel like you don't have a problem with drinking. You might not recognize how much you drink or how many problems in your life are related to alcohol use. Listen to relatives, friends or co-workers when they ask you to examine your drinking habits or to seek help. Consider talking with someone who has had a problem with drinking but has stopped.

If your loved one needs help

Many people with alcohol use disorder hesitate to get treatment because they don't recognize that they have a problem. An intervention from loved ones can help some people recognize and accept that they need professional help. If you're concerned about someone who drinks too much, ask a professional experienced in alcohol treatment for advice on how to approach that person.

There is a problem with information submitted for this request. Review/update the information highlighted below and resubmit the form.

From Mayo Clinic to your inbox

Sign up for free and stay up to date on research advancements, health tips, current health topics, and expertise on managing health. Click here for an email preview.

Error Email field is required

Error Include a valid email address

To provide you with the most relevant and helpful information, and understand which information is beneficial, we may combine your email and website usage information with other information we have about you. If you are a Mayo Clinic patient, this could include protected health information. If we combine this information with your protected health information, we will treat all of that information as protected health information and will only use or disclose that information as set forth in our notice of privacy practices. You may opt-out of email communications at any time by clicking on the unsubscribe link in the e-mail.

Thank you for subscribing!

You'll soon start receiving the latest Mayo Clinic health information you requested in your inbox.

Sorry something went wrong with your subscription

Please, try again in a couple of minutes

Genetic, psychological, social and environmental factors can impact how drinking alcohol affects your body and behavior. Theories suggest that for certain people drinking has a different and stronger impact that can lead to alcohol use disorder.

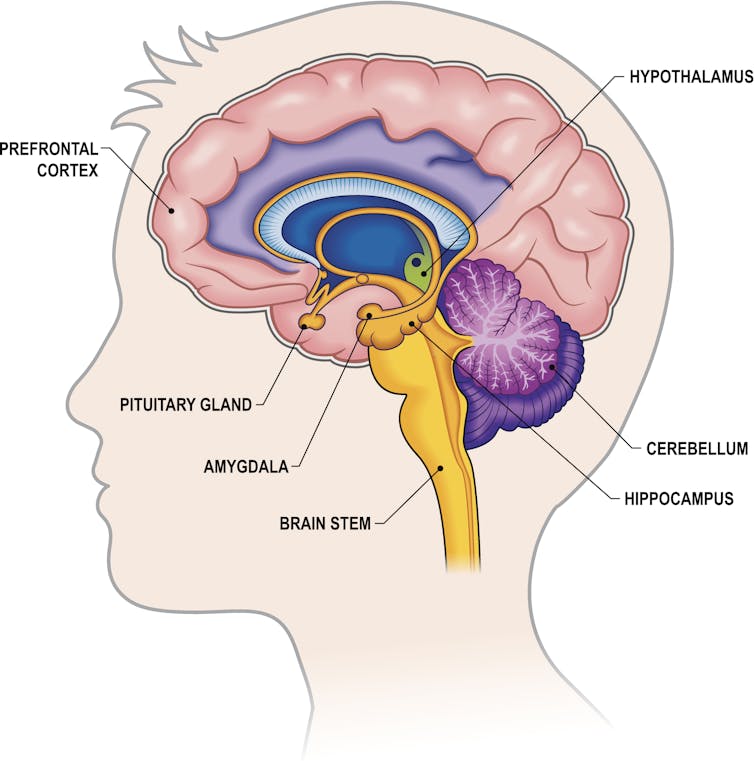

Over time, drinking too much alcohol may change the normal function of the areas of your brain associated with the experience of pleasure, judgment and the ability to exercise control over your behavior. This may result in craving alcohol to try to restore good feelings or reduce negative ones.

Risk factors

Alcohol use may begin in the teens, but alcohol use disorder occurs more frequently in the 20s and 30s, though it can start at any age.

Risk factors for alcohol use disorder include:

- Steady drinking over time. Drinking too much on a regular basis for an extended period or binge drinking on a regular basis can lead to alcohol-related problems or alcohol use disorder.

- Starting at an early age. People who begin drinking — especially binge drinking — at an early age are at a higher risk of alcohol use disorder.

- Family history. The risk of alcohol use disorder is higher for people who have a parent or other close relative who has problems with alcohol. This may be influenced by genetic factors.

- Depression and other mental health problems. It's common for people with a mental health disorder such as anxiety, depression, schizophrenia or bipolar disorder to have problems with alcohol or other substances.

- History of trauma. People with a history of emotional trauma or other trauma are at increased risk of alcohol use disorder.

- Having bariatric surgery. Some research studies indicate that having bariatric surgery may increase the risk of developing alcohol use disorder or of relapsing after recovering from alcohol use disorder.

- Social and cultural factors. Having friends or a close partner who drinks regularly could increase your risk of alcohol use disorder. The glamorous way that drinking is sometimes portrayed in the media also may send the message that it's OK to drink too much. For young people, the influence of parents, peers and other role models can impact risk.

Complications

Alcohol depresses your central nervous system. In some people, the initial reaction may feel like an increase in energy. But as you continue to drink, you become drowsy and have less control over your actions.

Too much alcohol affects your speech, muscle coordination and vital centers of your brain. A heavy drinking binge may even cause a life-threatening coma or death. This is of particular concern when you're taking certain medications that also depress the brain's function.

Impact on your safety

Excessive drinking can reduce your judgment skills and lower inhibitions, leading to poor choices and dangerous situations or behaviors, including:

- Motor vehicle accidents and other types of accidental injury, such as drowning

- Relationship problems

- Poor performance at work or school

- Increased likelihood of committing violent crimes or being the victim of a crime

- Legal problems or problems with employment or finances

- Problems with other substance use

- Engaging in risky, unprotected sex, or experiencing sexual abuse or date rape

- Increased risk of attempted or completed suicide

Impact on your health

Drinking too much alcohol on a single occasion or over time can cause health problems, including:

- Liver disease. Heavy drinking can cause increased fat in the liver (hepatic steatosis) and inflammation of the liver (alcoholic hepatitis). Over time, heavy drinking can cause irreversible destruction and scarring of liver tissue (cirrhosis).

- Digestive problems. Heavy drinking can result in inflammation of the stomach lining (gastritis), as well as stomach and esophageal ulcers. It can also interfere with your body's ability to get enough B vitamins and other nutrients. Heavy drinking can damage your pancreas or lead to inflammation of the pancreas (pancreatitis).

- Heart problems. Excessive drinking can lead to high blood pressure and increases your risk of an enlarged heart, heart failure or stroke. Even a single binge can cause serious irregular heartbeats (arrhythmia) called atrial fibrillation.

- Diabetes complications. Alcohol interferes with the release of glucose from your liver and can increase the risk of low blood sugar (hypoglycemia). This is dangerous if you have diabetes and are already taking insulin or some other diabetes medications to lower your blood sugar level.

- Issues with sexual function and periods. Heavy drinking can cause men to have difficulty maintaining an erection (erectile dysfunction). In women, heavy drinking can interrupt menstrual periods.

- Eye problems. Over time, heavy drinking can cause involuntary rapid eye movement (nystagmus) as well as weakness and paralysis of your eye muscles due to a deficiency of vitamin B-1 (thiamin). A thiamin deficiency can result in other brain changes, such as irreversible dementia, if not promptly treated.

- Birth defects. Alcohol use during pregnancy may cause miscarriage. It may also cause fetal alcohol spectrum disorders (FASDs). FASDs can cause a child to be born with physical and developmental problems that last a lifetime.

- Bone damage. Alcohol may interfere with making new bone. Bone loss can lead to thinning bones (osteoporosis) and an increased risk of fractures. Alcohol can also damage bone marrow, which makes blood cells. This can cause a low platelet count, which may result in bruising and bleeding.

- Neurological complications. Excessive drinking can affect your nervous system, causing numbness and pain in your hands and feet, disordered thinking, dementia, and short-term memory loss.

- Weakened immune system. Excessive alcohol use can make it harder for your body to resist disease, increasing your risk of various illnesses, especially pneumonia.

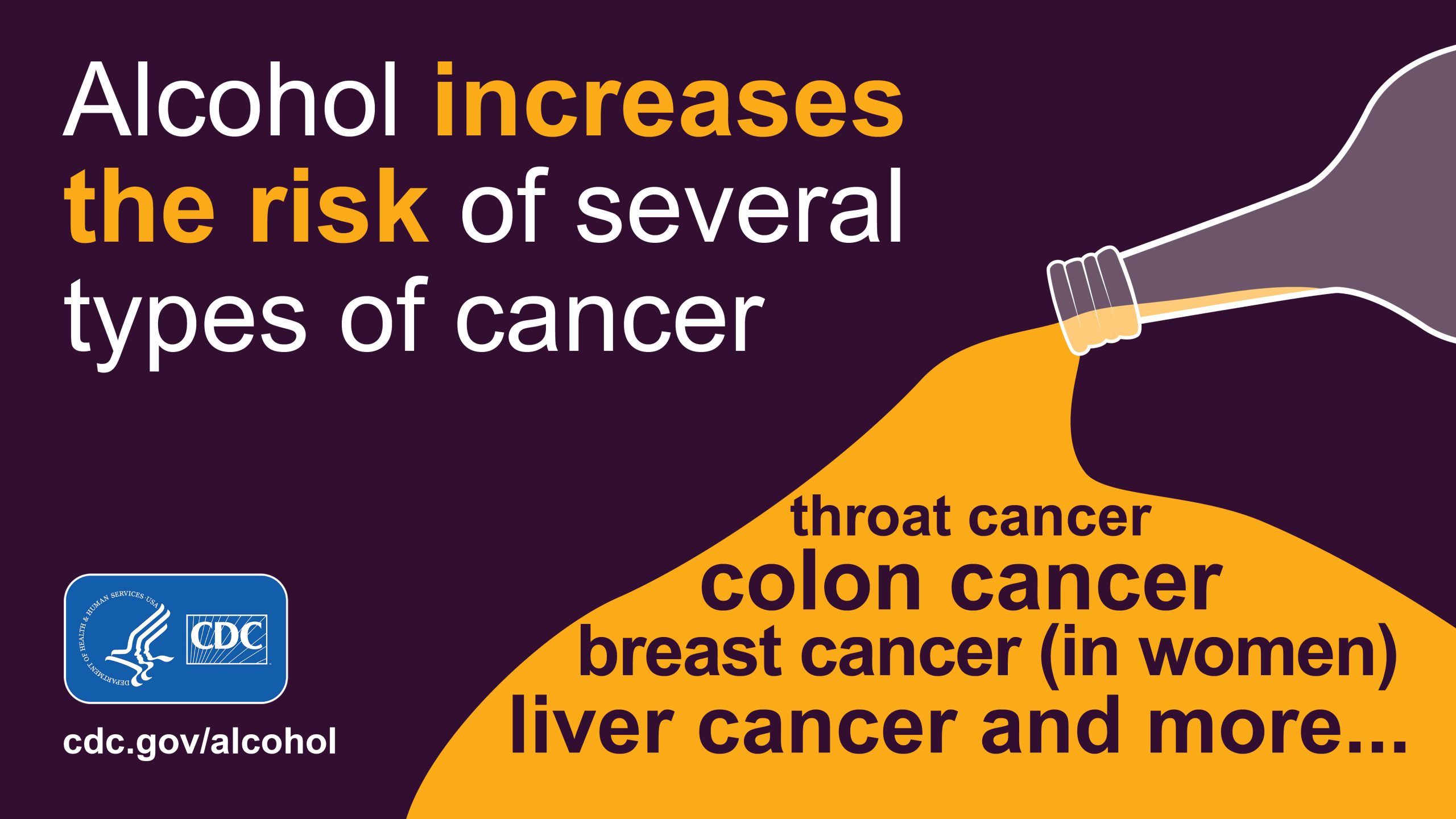

- Increased risk of cancer. Long-term, excessive alcohol use has been linked to a higher risk of many cancers, including mouth, throat, liver, esophagus, colon and breast cancers. Even moderate drinking can increase the risk of breast cancer.

- Medication and alcohol interactions. Some medications interact with alcohol, increasing its toxic effects. Drinking while taking these medications can either increase or decrease their effectiveness, or make them dangerous.

Early intervention can prevent alcohol-related problems in teens. If you have a teenager, be alert to signs and symptoms that may indicate a problem with alcohol:

- Loss of interest in activities and hobbies and in personal appearance

- Red eyes, slurred speech, problems with coordination and memory lapses

- Difficulties or changes in relationships with friends, such as joining a new crowd

- Declining grades and problems in school

- Frequent mood changes and defensive behavior

You can help prevent teenage alcohol use:

- Set a good example with your own alcohol use.

- Talk openly with your child, spend quality time together and become actively involved in your child's life.

- Let your child know what behavior you expect — and what the consequences will be for not following the rules.

Alcohol use disorder care at Mayo Clinic

- Nguyen HT. Allscripts EPSi. Mayo Clinic. May 5, 2022.

- What is A.A.? Alcoholics Anonymous. https://www.aa.org/what-is-aa. Accessed April 1, 2022.

- Mission statement. Women for Sobriety. https://womenforsobriety.org/about/#. Accessed April 1, 2022.

- Al-Anon meetings. Al-Anon Family Groups. https://al-anon.org/al-anon-meetings/. Accessed April 1, 2022.

- Substance-related and addictive disorders. In: Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders DSM-5. 5th ed. American Psychiatric Association; 2013. https://dsm.psychiatryonline.org. Accessed April 26, 2018.

- Rethinking drinking: Alcohol and your health. National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism. https://www.rethinkingdrinking.niaaa.nih.gov/. Accessed April 1, 2022.

- Treatment for alcohol problems: Finding and getting help. National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism. https://www.niaaa.nih.gov/publications/brochures-and-fact-sheets/treatment-alcohol-problems-finding-and-getting-help. Accessed April 1, 2022.

- Alcohol's effect on the body. National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism. https://www.niaaa.nih.gov/alcohols-effects-health/alcohols-effects-body. Accessed April 1, 2022.

- Understanding the dangers of alcohol overdose. National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism. https://www.niaaa.nih.gov/publications/brochures-and-fact-sheets/understanding-dangers-of-alcohol-overdose. Accessed April 1, 2022.

- Frequently asked questions: About alcohol. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. https://www.cdc.gov/alcohol/faqs.htm. Accessed April 1, 2022.

- Harmful interactions: Mixing alcohol with medicines. National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism. https://www.niaaa.nih.gov/publications/brochures-and-fact-sheets/harmful-interactions-mixing-alcohol-with-medicines. Accessed April 1, 2022.

- Parenting to prevent childhood alcohol use. National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism. https://www.niaaa.nih.gov/publications/brochures-and-fact-sheets/parenting-prevent-childhood-alcohol-use. Accessed April 1, 2022.

- Tetrault JM, et al. Risky drinking and alcohol use disorder: Epidemiology, pathogenesis, clinical manifestations, course, assessment, and diagnosis. https://www.uptodate.com/contents/search. Accessed April 1, 2022.

- Holt SR. Alcohol use disorder: Pharmacologic management. https://www.uptodate.com/contents/search. Accessed April 1, 2022.

- Saxon AJ. Alcohol use disorder: Psychosocial treatment. https://www.uptodate.com/contents/search. Accessed April 1, 2022.

- Charness ME. Overview of the chronic neurologic complications of alcohol. https://www.uptodate.com/contents/search. Accessed April 1, 2022.

- Chen P, et al. Acupuncture for alcohol use disorder. International Journal of Physiology, Pathophysiology and Pharmacotherapy. 2018;10:60.

- Ng S-M, et al. Nurse-led body-mind-spirit based relapse prevention intervention for people with diagnosis of alcohol use disorder at a mental health care setting, India: A pilot study. Journal of Addictions Nursing. 2020; doi:10.1097/JAN.0000000000000368.

- Lardier DT, et al. Exercise as a useful intervention to reduce alcohol consumption and improve physical fitness in individuals with alcohol use disorder: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Frontiers in Psychology. 2021; doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2021.675285.

- Sliedrecht W, et al. Alcohol use disorder relapse factors: A systematic review. Psychiatry Research. 2019; doi:10.1016/j.psychres.2019.05.038.

- Thiamin deficiency. Merck Manual Professional Version. https://www.merckmanuals.com/professional/nutritional-disorders/vitamin-deficiency,-dependency,-and-toxicity/thiamin-deficiency. Accessed April 2, 2022.

- Alcohol & diabetes. American Diabetes Association. https://www.diabetes.org/healthy-living/medication-treatments/alcohol-diabetes. Accessed April 2, 2022.

- Marcus GM, et al. Acute consumption of alcohol and discrete atrial fibrillation events. Annals of Internal Medicine. 2021; doi:10.7326/M21-0228.

- Means RT. Hematologic complications of alcohol use. https://www.uptodate.com/contents/search. Accessed April 1, 2022.

- What people recovering from alcoholism need to know about osteoporosis. NIH Osteoporosis and Related Bone Diseases National Resource Center. https://www.bones.nih.gov/health-info/bone/osteoporosis/conditions-behaviors/alcoholism. Accessed April 2, 2022.

- How to tell if your child is drinking alcohol. Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. https://www.samhsa.gov/talk-they-hear-you/parent-resources/how-tell-if-your-child-drinking-alcohol. Accessed April 2, 2022.

- Smith KE, et al. Problematic alcohol use and associated characteristics following bariatric surgery. Obesity Surgery. 2018; doi:10.1007/s11695-017-3008-8.

- Fairbanks J, et al. Evidence-based pharmacotherapies for alcohol use disorder: Clinical pearls. Mayo Clinic Proceedings. 2020; doi:10.1016/j.mayocp.2020.01.030.

- U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. Screening and behavioral counseling interventions to reduce unhealthy alcohol use in adolescents and adults: U.S. Preventive Services Task Force Recommendation Statement. JAMA. 2018; doi:10.1001/jama.2018.16789.

- Hall-Flavin DK (expert opinion). Mayo Clinic. April 25, 2022.

- Celebrate Recovery. https://www.celebraterecovery.com/. Accessed April 26, 2022.

- SMART Recovery. https://www.smartrecovery.org/. Accessed April 26, 2022.

- Symptoms & causes

- Diagnosis & treatment

- Doctors & departments

- Care at Mayo Clinic

Mayo Clinic does not endorse companies or products. Advertising revenue supports our not-for-profit mission.

- Opportunities

Mayo Clinic Press

Check out these best-sellers and special offers on books and newsletters from Mayo Clinic Press .

- Mayo Clinic on Incontinence - Mayo Clinic Press Mayo Clinic on Incontinence

- The Essential Diabetes Book - Mayo Clinic Press The Essential Diabetes Book

- Mayo Clinic on Hearing and Balance - Mayo Clinic Press Mayo Clinic on Hearing and Balance

- FREE Mayo Clinic Diet Assessment - Mayo Clinic Press FREE Mayo Clinic Diet Assessment

- Mayo Clinic Health Letter - FREE book - Mayo Clinic Press Mayo Clinic Health Letter - FREE book

Your gift holds great power – donate today!

Make your tax-deductible gift and be a part of the cutting-edge research and care that's changing medicine.

Thank you for visiting nature.com. You are using a browser version with limited support for CSS. To obtain the best experience, we recommend you use a more up to date browser (or turn off compatibility mode in Internet Explorer). In the meantime, to ensure continued support, we are displaying the site without styles and JavaScript.

- View all journals

- Explore content

- About the journal

- Publish with us

- Sign up for alerts

- Published: 22 December 2022

Hazardous drinking and alcohol use disorders

- James MacKillop ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-8695-1071 1 , 2 ,

- Roberta Agabio ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0001-7395-6845 3 , 4 ,

- Sarah W. Feldstein Ewing 5 , 6 ,

- Markus Heilig 7 ,

- John F. Kelly 8 ,

- Lorenzo Leggio 9 , 10 ,

- Anne Lingford-Hughes 11 , 12 ,

- Abraham A. Palmer 13 ,

- Charles D. Parry 14 , 15 ,

- Lara Ray 16 &

- Jürgen Rehm ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0001-5665-0385 17 , 18 , 19 , 20 , 21 , 22

Nature Reviews Disease Primers volume 8 , Article number: 80 ( 2022 ) Cite this article

3918 Accesses

30 Citations

89 Altmetric

Metrics details

- Human behaviour

- Translational research

Alcohol is one of the most widely consumed psychoactive drugs globally. Hazardous drinking, defined by quantity and frequency of consumption, is associated with acute and chronic morbidity. Alcohol use disorders (AUDs) are psychiatric syndromes characterized by impaired control over drinking and other symptoms. Contemporary aetiological perspectives on AUDs apply a biopsychosocial framework that emphasizes the interplay of genetics, neurobiology, psychology, and an individual’s social and societal context. There is strong evidence that AUDs are genetically influenced, but with a complex polygenic architecture. Likewise, there is robust evidence for environmental influences, such as adverse childhood exposures and maladaptive developmental trajectories. Well-established biological and psychological determinants of AUDs include neuroadaptive changes following persistent use, differences in brain structure and function, and motivational determinants including overvaluation of alcohol reinforcement, acute effects of environmental triggers and stress, elevations in multiple facets of impulsivity, and lack of alternative reinforcers. Social factors include bidirectional roles of social networks and sociocultural influences, such as public health control strategies and social determinants of health. An array of evidence-based approaches for reducing alcohol harms are available, including screening, pharmacotherapies, psychological interventions and policy strategies, but are substantially underused. Priorities for the field include translating advances in basic biobehavioural research into novel clinical applications and, in turn, promoting widespread implementation of evidence-based clinical approaches in practice and health-care systems.

This is a preview of subscription content, access via your institution

Access options

Access Nature and 54 other Nature Portfolio journals

Get Nature+, our best-value online-access subscription

24,99 € / 30 days

cancel any time

Subscribe to this journal

Receive 1 digital issues and online access to articles

92,52 € per year

only 92,52 € per issue

Buy this article

- Purchase on Springer Link

- Instant access to full article PDF

Prices may be subject to local taxes which are calculated during checkout

Similar content being viewed by others

Determinants of behaviour and their efficacy as targets of behavioural change interventions

Adults who microdose psychedelics report health related motivations and lower levels of anxiety and depression compared to non-microdosers

Psilocybin microdosers demonstrate greater observed improvements in mood and mental health at one month relative to non-microdosing controls

Dudley, R. Evolutionary origins of human alcoholism in primate frugivory. Q. Rev. Biol. 75 , 3–15 (2000).

Article CAS Google Scholar

Dudley, R. & Maro, A. Human evolution and dietary ethanol. Nutrients 13 , 2419 (2021).

World Health Organization. Global status report on alcohol and health 2018 (WHO, 2018).

Humphreys, K. & Kalinowski, A. Governmental standard drink definitions and low-risk alcohol consumption guidelines in 37 countries. Addiction 111 , 1293–1298 (2016).

Article Google Scholar

American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders: DSM-5 (American Psychiatric Association, 2013).

World Health Organization. International statistical classification of diseases and related health problems. World Health Organization https://icd.who.int/ (2018).

Babor, T. F., Higgins-Biddle, J. C., Saunders, J. B. & Monteiro, M. G. AUDIT. The Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test: Guidelines for Use in Primary Care (WHO, 2001).

Volkow, N. D. Stigma and the toll of addiction. N. Engl. J. Med. 382 , 1289–1290 (2020).

Kilian, C. et al. Stigmatization of people with alcohol use disorders: an updated systematic review of population studies. Alcohol. Clin. Exp. Res. 45 , 899–911 (2021).

Volkow, N. D., Gordon, J. A. & Koob, G. F. Choosing appropriate language to reduce the stigma around mental illness and substance use disorders. Neuropsychopharmacology 46 , 2230–2232 (2021).

Saitz, R., Miller, S. C., Fiellin, D. A. & Rosenthal, R. N. Recommended use of terminology in addiction medicine. J. Addict. Med. 15 , 3–7 (2021).

White, A. et al. Converging patterns of alcohol use and related outcomes among females and males in the United States, 2002 to 2012. Alcohol. Clin. Exp. Res. 39 , 1712–1726 (2015).

Grant, B. F. et al. Epidemiology of DSM-5 alcohol use disorder: results from the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions III. JAMA Psychiatry 72 , 757–766 (2015).

Kittirattanapaiboon, P. et al. Prevalence of mental disorders and mental health problems: Thai national mental health survey 2013. J. Ment. Health Thail. 25 , 1–19 (2017).

Google Scholar

Rehm, J., Room, R., van den Brink, W. & Jacobi, F. Alcohol use disorders in EU countries and Norway: an overview of the epidemiology. Eur. Neuropsychopharmacol. 15 , 377–388 (2005).

Rehm, J. et al. Prevalence of alcohol use disorders in primary health-care facilities in Russia in 2019. Addiction 117 , 1640–1646 (2022).

World Health Organization. ICD-11 for mortality and morbidity statistics. WHO https://icd.who.int/browse11/l-m/en (2018).

Puddephatt, J. A., Irizar, P., Jones, A., Gage, S. H. & Goodwin, L. Associations of common mental disorder with alcohol use in the adult general population: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Addiction 117 , 1543–1572 (2022).

National Institute on Drug Abuse. Why is there comorbidity between substance use disorders and mental illnesses? National Institute on Drug Abuse https://www.drugabuse.gov/publications/research-reports/common-comorbidities-substance-use-disorders/why-there-comorbidity-between-substance-use-disorders-mental-illnesses (2020).

Chassin, L., Sher, K. J., Hussong, A. & Curran, P. The developmental psychopathology of alcohol use and alcohol disorders: research achievements and future directions. Dev. Psychopathol. 25 , 1567–1584 (2013).

Kendler, K. S., Prescott, C. A., Myers, J. & Neale, M. C. The structure of genetic and environmental risk factors for common psychiatric and substance use disorders in men and women. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry 60 , 929–937 (2003).

Hicks, B. M., Krueger, R. F., Iacono, W. G., McGue, M. & Patrick, C. J. Family transmission and heritability of externalizing disorders: a twin-family study. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry 61 , 922–928 (2004).

Dick, D. M. & Agrawal, A. The genetics of alcohol and other drug dependence. Alcohol. Res. Health 31 , 111–118 (2008).

Barr, P. B. & Dick, D. M. The genetics of externalizing problems. Curr. Top. Behav. Neurosci. 47 , 93–112 (2020).

Rehm, J., Rovira, P., Llamosas-Falcon, L. & Shield, K. D. Dose-response relationships between levels of alcohol use and risks of mortality or disease, for all people, by age, sex and specific risk factors. Nutrients 13 , 2652 (2021).

Eckardt, M. J. et al. Effects of moderate alcohol consumption on the central nervous system. Alcohol. Clin. Exp. Res. 22 , 998–1040 (1998).

Morojele, N. K., Shenoi, S. V., Shuper, P. A., Braithwaite, R. S. & Rehm, J. Alcohol use and the risk of communicable diseases. Nutrients 13 , 3317 (2021).

Rehm, J. et al. The relationship between different dimensions of alcohol use and the burden of disease – an update. Addiction 112 , 968–1001 (2017).

Rehm, J. et al. The role of alcohol use in the aetiology and progression of liver disease: a narrative review and a quantification. Drug Alcohol. Rev. 40 , 1377–1386 (2021).

Wild, C. P., Weiderpass, E. & Stewart, B. W. (eds) World Cancer Report: Cancer Research for Cancer Prevention (International Agency for Research on Cancer, 2020).

White, I. R., Altmann, D. R. & Nanchahal, K. Alcohol consumption and mortality: modelling risks for men and women at different ages. BMJ 325 , 191 (2002).

Shield, K. et al. National, regional, and global burdens of disease from 2000 to 2016 attributable to alcohol use: a comparative risk assessment study. Lancet Public. Health 5 , e51–e61 (2020).

Zahr, N. M., Kaufman, K. L. & Harper, C. G. Clinical and pathological features of alcohol-related brain damage. Nat. Rev. Neurol. 7 , 284 (2011).

Sullivan, E. V., Harris, R. A. & Pfefferbaum, A. Alcohol’s effects on brain and behavior. Alcohol. Res. Health 33 , 127–143 (2010).

Sullivan, E. V. & Pfefferbaum, A. Alcohol use disorder: neuroimaging evidence for accelerated aging of brain morphology and hypothesized contribution to age-related dementia. Alcohol https://doi.org/10.1016/J.ALCOHOL.2022.06.002 (2022).

Schwarzinger, M. et al. Contribution of alcohol use disorders to the burden of dementia in France 2008-13: a nationwide retrospective cohort study. Lancet Public Health 3 , e124–e132 (2018).

Lange, S. et al. Global prevalence of fetal alcohol spectrum disorder among children and youth: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Pediatr. 171 , 948–956 (2017).

Traccis, F. et al. Alcohol-medication interactions: a systematic review and meta-analysis of placebo-controlled trials. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 132 , 519–541 (2021).

Laslett, A.-M., Room, R., Waleewong, O., Stanesby, O. & Callinan, S. (eds) Harm to Others from Drinking: Patterns in Nine Societies (WHO, 2019).

Nutt, D. J., King, L. A. & Phillips, L. D. Drug harms in the UK: a multicriteria decision analysis. Lancet 376 , 1558–1565 (2010).

Manthey, J. et al. What are the economic costs to society attributable to alcohol use? A systematic review and modelling study. Pharmacoeconomics 39 , 809–822 (2021).

Cloninger, C. R., Bohman, M. & Sigvardsson, S. Inheritance of alcohol abuse. Cross-fostering analysis of adopted men. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry 38 , 861–868 (1981).

Cloninger, C. R. Etiologic factors in substance abuse: an adoption study perspective. NIDA Res. Monogr. 89 , 52–72 (1988).

CAS Google Scholar

Heath, A. C. Genetic influences on alcoholism risk: a review of adoption and twin studies. Alcohol. Health Res. World 19 , 166 (1995).

Verhulst, B., Neale, M. C. & Kendler, K. S. The heritability of alcohol use disorders: a meta-analysis of twin and adoption studies. Psychol. Med. 45 , 1061–1072 (2015).

True, W. R. et al. Common genetic vulnerability for nicotine and alcohol dependence in men. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry 56 , 655–661 (1999).

Bierut, L. J. Genetic vulnerability and susceptibility to substance dependence. Neuron 69 , 618 (2011).

Morozova, T. V., Goldman, D., Mackay, T. F. C. & Anholt, R. R. H. The genetic basis of alcoholism: multiple phenotypes, many genes, complex networks. Genome Biol. 13 , 239 (2012).

Zhou, H. et al. Genome-wide meta-analysis of problematic alcohol use in 435,563 individuals yields insights into biology and relationships with other traits. Nat. Neurosci. 23 , 809–818 (2020).

Edenberg, H. J., Gelernter, J. & Agrawal, A. Genetics of alcoholism. Curr. Psychiatry Rep. 21 , 26 (2019).

Luczak, S. E., Glatt, S. J. & Wall, T. L. Meta-analyses of ALDH2 and ADH1B with alcohol dependence in Asians. Psychol. Bull. 132 , 607–621 (2006).

Luo, H. R. et al. Origin and dispersal of atypical aldehyde dehydrogenase ALDH2487Lys. Gene 435 , 96–103 (2009).

Higuchi, S. et al. Aldehyde dehydrogenase genotypes in Japanese alcoholics. Lancet 343 , 741–742 (1994).

Brooks, P. J., Enoch, M. A., Goldman, D., Li, T. K. & Yokoyama, A. The alcohol flushing response: an unrecognized risk factor for esophageal cancer from alcohol consumption. PLoS Med. 6 , 0258–0263 (2009).

Edenberg, H. J. & McClintick, J. N. Alcohol dehydrogenases, aldehyde dehydrogenases, and alcohol use disorders: a critical review. Alcohol. Clin. Exp. Res. 42 , 2281–2297 (2018).

Ray, L. A. & Hutchison, K. E. Effects of naltrexone on alcohol sensitivity and genetic moderators of medication response: a double-blind placebo-controlled study. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry 64 , 1069–1077 (2007).

Ray, L. A. & Hutchison, K. E. A polymorphism of the µ,-opioid receptor gene (OPRM1) and sensitivity to the effects of alcohol in humans. Alcohol. Clin. Exp. Res. 28 , 1789–1795 (2004).

Schuckit, M. A. A critical review of methods and results in the search for genetic contributors to alcohol sensitivity. Alcohol. Clin. Exp. Res. 42 , 822–835 (2018).

Ramchandani, V. A. et al. A genetic determinant of the striatal dopamine response to alcohol in men. Mol. Psychiatry 16 , 809–817 (2011).

King, A. C., de Wit, H., McNamara, P. J. & Cao, D. Rewarding, stimulant, and sedative alcohol responses and relationship to future binge drinking. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry 68 , 389–399 (2011).

King, A. C., Hasin, D., O’Connor, S. J., McNamara, P. J. & Cao, D. A prospective 5-year re-examination of alcohol response in heavy drinkers progressing in alcohol use disorder. Biol. Psychiatry 79 , 489–498 (2016).

King, A. et al. Subjective responses to alcohol in the development and maintenance of alcohol use disorder. Am. J. Psychiatry 178 , 560–571 (2021).

Sanchez-Roige, S., Palmer, A. A. & Clarke, T. K. Recent efforts to dissect the genetic basis of alcohol use and abuse. Biol. Psychiatry 87 , 609–618 (2020).

Liu, M. et al. Association studies of up to 1.2 million individuals yield new insights into the genetic etiology of tobacco and alcohol use. Nat. Genet. 51 , 237–244 (2019).

Walters, R. K. et al. Transancestral GWAS of alcohol dependence reveals common genetic underpinnings with psychiatric disorders. Nat. Neurosci. 21 , 1656–1669 (2018).

Kranzler, H. R. et al. Genome-wide association study of alcohol consumption and use disorder in 274,424 individuals from multiple populations. Nat. Commun. 10 , 1499 (2019).

Sanchez-Roige, S. et al. Genome-wide association study of alcohol use disorder identification test (AUDIT) scores in 20 328 research participants of European ancestry. Addiction Biol. 24 , 121–131 (2019).

Sanchez-Roige, S. et al. Genome-wide association study meta-analysis of the alcohol use disorders identification test (AUDIT) in two population-based cohorts. Am. J. Psychiatry 176 , 107–118 (2019).

Mallard, T. T. et al. Item-level genome-wide association study of the alcohol use disorders identification test in three population-based cohorts. Am. J. Psychiatry 179 , 58–70 (2022).

Kuo, S. I. C. et al. Mapping pathways by which genetic risk influences adolescent externalizing behavior: the interplay between externalizing polygenic risk scores, parental knowledge, and peer substance use. Behav. Genet. 51 , 543 (2021).

Dodge, N. C., Jacobson, J. L. & Jacobson, S. W. Effects of fetal substance exposure on offspring substance use. Pediatr. Clin. North. Am. 66 , 1149–1161 (2019).

Hughes, K. et al. The effect of multiple adverse childhood experiences on health: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Public Health 2 , e356–e366 (2017).

Pilowsky, D. J., Keyes, K. M. & Hasin, D. S. Adverse childhood events and lifetime alcohol dependence. Am. J. Public Health 99 , 258–263 (2009).

Capusan, A. J. et al. Re-examining the link between childhood maltreatment and substance use disorder: a prospective, genetically informative study. Mol. Psychiatry 26 , 3201–3209 (2021).

Lee, R. S., Oswald, L. M. & Wand, G. S. Early life stress as a predictor of co-occurring alcohol use disorder and post-traumatic stress disorder. Alcohol Res. 39 , 147–159 (2018).

Price, A., Cook, P. A., Norgate, S. & Mukherjee, R. Prenatal alcohol exposure and traumatic childhood experiences: a systematic review. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 80 , 89–98 (2017).

Hemingway, S. J. A. et al. Twin study confirms virtually identical prenatal alcohol exposures can lead to markedly different fetal alcohol spectrum disorder outcomes–fetal genetics influences fetal vulnerability. Adv. Pediatr. Res. 5 , 23 (2018).

Rossow, I., Keating, P., Felix, L. & Mccambridge, J. Does parental drinking influence children’s drinking? A systematic review of prospective cohort studies. Addiction 111 , 204–217 (2016).

Sharmin, S. et al. Parental supply of alcohol in childhood and risky drinking in adolescence: systematic review and meta-analysis. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public. Health 14 , 287 (2017).

Ryan, S. M., Jorm, A. F. & Lubman, D. I. Parenting factors associated with reduced adolescent alcohol use: a systematic review of longitudinal studies. Aust. NZ J. Psychiatry 44 , 774–783 (2010).

Resnick, M. D. et al. Protecting adolescents from harm. Findings from the National Longitudinal Study on Adolescent Health. JAMA 278 , 823–832 (1997).

Johnson, V. & Pandina, R. J. Effects of the family environment on adolescent substance use, delinquency, and coping styles. Am. J. Drug Alcohol Abus. 17 , 71–88 (1991).

Bailey, J. A., Hill, K. G., Oesterle, S. & Hawkins, J. D. Parenting practices and problem behavior across three generations: monitoring, harsh discipline, and drug use in the intergenerational transmission of externalizing behavior. Dev. Psychol. 45 , 1214–1226 (2009).

Iacono, W. G., Malone, S. M. & McGue, M. Behavioral disinhibition and the development of early-onset addiction: common and specific influences. Annu. Rev. Clin. Psychol. 4 , 325–348 (2008).

Hussong, A. M., Jones, D. J., Stein, G. L., Baucom, D. H. & Boeding, S. An internalizing pathway to alcohol use and disorder. Psychol. Addict. Behav. 25 , 390–404 (2011).

Khoury, J. E., Jamieson, B. & Milligan, K. Risk for childhood internalizing and externalizing behavior problems in the context of prenatal alcohol exposure: a meta-analysis and comprehensive examination of moderators. Alcohol. Clin. Exp. Res. 42 , 1358–1377 (2018).

Johnston, L. D., O’Malley, P. M. & Miech, R. A. Monitoring the Future national survey results on drug use, 1975–2013: overview, key findings on adolescent drug use (ERIC, 2014).

Lee, M. R. & Sher, K. J. ‘Maturing out’ of binge and problem drinking. Alcohol. Res. 39 , 31–42 (2018).

Maimaris, W. & McCambridge, J. Age of first drinking and adult alcohol problems: systematic review of prospective cohort studies. J. Epidemiol. Community Health 68 , 268–274 (2014).

Prescott, C. A. & Kendler, K. S. Age at first drink and risk for alcoholism: a noncausal association. Alcohol. Clin. Exp. Res. 23 , 101–107 (1999).

Bachman, J. G. et al. The Decline of Substance Use in Young Adulthood: Changes in Social Activities, Role, and Beliefs (Erlbaum, 2002).

Gotham, H. J., Sher, K. J. & Wood, P. K. Alcohol involvement and developmental task completion during young adulthood. J. Stud. Alcohol 64 , 32–42 (2003).

Wood, M. D., Sher, K. J. & McGowan, A. K. Collegiate alcohol involvement and role attainment in early adulthood: findings from a prospective high-risk study. J. Stud. Alcohol 61 , 278–289 (2000).

Lee, M. R., Chassin, L. & MacKinnon, D. P. Role transitions and young adult maturing out of heavy drinking: evidence for larger effects of marriage among more severe premarriage problem drinkers. Alcohol. Clin. Exp. Res. https://doi.org/10.1111/acer.12715 (2015).

Lee, M. R., Chassin, L. & Villalta, I. K. Maturing out of alcohol involvement: transitions in latent drinking statuses from late adolescence to adulthood. Dev. Psychopathol. 25 , 1137–1153 (2013).

Dawson, D. A., Grant, B. F., Stinson, F. S. & Chou, P. S. Maturing out of alcohol dependence: the impact of transitional life events. J. Stud. Alcohol 67 , 195–203 (2006).

Spanagel, R. Alcoholism: a systems approach from molecular physiology to addictive behavior. Physiol. Rev. 89 , 649–705 (2009).

Holmes, A., Spanagel, R. & Krystal, J. H. Glutamatergic targets for new alcohol medications. Psychopharmacology 229 , 539–554 (2013).

Heilig, M., Egli, M., Crabbe, J. C. & Becker, H. C. Acute withdrawal, protracted abstinence and negative affect in alcoholism: are they linked? Addiction Biol. 15 , 169–184 (2010).

Heilig, M. et al. Reprogramming of mPFC transcriptome and function in alcohol dependence. Genes Brain Behav. 16 , 86–100 (2017).

Xiao, P. R. et al. Regional gray matter deficits in alcohol dependence: a meta-analysis of voxel-based morphometry studies. Drug Alcohol Depend. 153 , 22–28 (2015).

Wise, R. A. & Bozarth, M. A. A psychomotor stimulant theory of addiction. Psychol. Rev. 94 , 469–492 (1987).

Spanagel, R., Herz, A. & Shippenberg, T. S. Opposing tonically active endogenous opioid systems modulate the mesolimbic dopaminergic pathway. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 89 , 2046–2050 (1992).

Tanda, G. & di Chiara, G. A dopamine-mu1 opioid link in the rat ventral tegmentum shared by palatable food (Fonzies) and non-psychostimulant drugs of abuse. Eur. J. Neurosci. 10 , 1179–1187 (1998).

Koob, G. F. Drugs of abuse: anatomy, pharmacology and function of reward pathways. Trends Pharmacol. Sci. 13 , 177–184 (1992).

Martin, C. S., Earleywine, M., Musty, R. E., Perrine, M. W. & Swift, R. M. Development and validation of the Biphasic Alcohol Effects Scale. Alcohol. Clin. Exp. Res. 17 , 140–146 (1993).

Pohorecky, L. A. Biphasic action of ethanol. Biobehav. Rev. 1 , 231–240 (1977).

Koob, G. F. & le Moal, M. Plasticity of reward neurocircuitry and the ‘dark side’ of drug addiction. Nat. Neurosci. 8 , 1442–1444 (2005).

Gilpin, N. W., Herman, M. A. & Roberto, M. The central amygdala as an integrative hub for anxiety and alcohol use disorders. Biol. Psychiatry 77 , 859–869 (2015).

Koob, G. & Kreek, M. J. Stress, dysregulation of drug reward pathways, and the transition to drug dependence. Am. J. Psychiatry 164 , 1149–1159 (2007).

Koob, G. F. Alcoholism, corticotropin-releasing factor, and molecular genetic allostasis. Biol. Psychiatry 63 , 137–138 (2008).

Augier, E. et al. A molecular mechanism for choosing alcohol over an alternative reward. Science 360 , 1321–1326 (2018).

Domi, E. et al. A neural substrate of compulsive alcohol use. Sci. Adv. 7 , eabg9045 (2021).

Seif, T. et al. Cortical activation of accumbens hyperpolarization-active NMDARs mediates aversion-resistant alcohol intake. Nat. Neurosci. 16 , 1094–1100 (2013).

Siciliano, C. A. et al. A cortical-brainstem circuit predicts and governs compulsive alcohol drinking. Science 366 , 1008–1012 (2019).

Heilig, M., Goldman, D., Berrettini, W. & O’Brien, C. P. Pharmacogenetic approaches to the treatment of alcohol addiction. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 12 , 670–684 (2011).

Goldstein, R. Z. & Volkow, N. D. Dysfunction of the prefrontal cortex in addiction: neuroimaging findings and clinical implications. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 12 , 652–669 (2011).

Sullivan, E. V. & Pfefferbaum, A. Brain-behavior relations and effects of aging and common comorbidities in alcohol use disorder: a review. Neuropsychology 33 , 760–780 (2019).

Fritz, M., Klawonn, A. M. & Zahr, N. M. Neuroimaging in alcohol use disorder: from mouse to man. J. Neurosci. Res. 100 , 1140–1158 (2019).

Lees, B. et al. Promising vulnerability markers of substance use and misuse: a review of human neurobehavioral studies. Neuropharmacology 187 , 10850 (2021).

Schumann, G. et al. The IMAGEN study: reinforcement-related behaviour in normal brain function and psychopathology. Mol. Psychiatry 15 , 1128–1139 (2010).

Volkow, N. D. et al. The conception of the ABCD study: from substance use to a broad NIH collaboration. Dev. Cogn. Neurosci. 32 , 4–7 (2018).

Brown, S. A. et al. The National Consortium on Alcohol and Neurodevelopment in Adolescence (NCANDA): a multisite study of adolescent development and substance use. J. Stud. Alcohol Drugs 76 , 895–908 (2015).

Schacht, J. P., Anton, R. F. & Myrick, H. Functional neuroimaging studies of alcohol cue reactivity: a quantitative meta-analysis and systematic review. Addict. Biol. 18 , 121–133 (2013).

Courtney, K. E., Schacht, J. P., Hutchison, K., Roche, D. J. & Ray, L. A. Neural substrates of cue reactivity: association with treatment outcomes and relapse. Addict. Biol. 21 , 3–22 (2016).

Bach, P. et al. Incubation of neural alcohol cue reactivity after withdrawal and its blockade by naltrexone. Addict. Biol. 25 , e12717 (2020).

Karl, D. et al. Nalmefene attenuates neural alcohol cue-reactivity in the ventral striatum and subjective alcohol craving in patients with alcohol use disorder. Psychopharmacology 238 , 2179–2189 (2021).

Wrase, J. et al. Dysfunction of reward processing correlates with alcohol craving in detoxified alcoholics. Neuroimage 35 , 787–794 (2007).

Murphy, A. et al. Acute D3 antagonist GSK598809 selectively enhances neural response during monetary reward anticipation in drug and alcohol dependence. Neuropsychopharmacology 42 , 1049–1057 (2017).

Zhang, R. & Volkow, N. D. Brain default-mode network dysfunction in addiction. Neuroimage 200 , 313–331 (2019).

Orban, C. et al. Chronic alcohol exposure differentially modulates structural and functional properties of amygdala: a cross-sectional study. Addiction Biol. 26 , e12980 (2021).

Urban, N. B. L. et al. Sex differences in striatal dopamine release in young adults after oral alcohol challenge: a positron emission tomography imaging study with [11C]raclopride. Biol. Psychiatry 68 , 689–696 (2010).

Hansson, A. C. et al. Dopamine and opioid systems adaptation in alcoholism revisited: convergent evidence from positron emission tomography and postmortem studies. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 106 , 141–164 (2019).

Erritzoe, D. et al. In vivo imaging of cerebral dopamine D3 receptors in alcoholism. Neuropsychopharmacology 39 , 1703–1712 (2014).

Heinz, A. et al. Correlation of stable elevations in striatal mu-opioid receptor availability in detoxified alcoholic patients with alcohol craving: a positron emission tomography study using carbon 11-labeled carfentanil. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry 62 , 57–64 (2005).

Hermann, D. et al. Low mu-opioid receptor status in alcohol dependence identified by combined positron emission tomography and post-mortem brain analysis. Neuropsychopharmacology 42 , 606–614 (2017).

Turton, S. et al. Blunted endogenous opioid release following an oral dexamphetamine challenge in abstinent alcohol-dependent individuals. Mol. Psychiatry 25 , 1749–1758 (2020).

Verplaetse, T. L., Cosgrove, K. P., Tanabe, J. & McKee, S. A. Sex/gender differences in brain function and structure in alcohol use: a narrative review of neuroimaging findings over the last 10 years. J. Neurosci. Res. 99 , 309–323 (2021).

Grace, S. et al. Sex differences in the neuroanatomy of alcohol dependence: hippocampus and amygdala subregions in a sample of 966 people from the ENIGMA Addiction Working Group. Transl Psychiatry 11 , 156 (2021).

Qi, S. et al. Reward processing in novelty seekers: a transdiagnostic psychiatric imaging biomarker. Biol. Psychiatry 90 , 529–539 (2021).

Bigelow, G. E. in Inter nationa l Handb ook of Alcohol Dependence and Problems (eds Heather, N., Peters, T. J. & Stockwell, T.) 299–315 (Wiley, 2001).

Higgins, S. T., Heil, S. H. & Lussier, J. P. Clinical implications of reinforcement as a determinant of substance use disorders. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 55 , 431–461 (2004).

Bickel, W. K., Johnson, M. W., Koffarnus, M. N., MacKillop, J. & Murphy, J. G. The behavioral economics of substance use disorders: reinforcement pathologies and their repair. Annu. Rev. Clin. Psychol. 10 , 641–677 (2014).

Mello, N. K. & Mendelson, J. H. Operant analysis of drinking patterns of chronic alcoholics. Nature 206 , 43–46 (1965).

Mendelson, J. H. & Mello, N. K. Experimental analysis of drinking behavior of chronic alcoholics. Ann. NY Acad. Sci. 133 , 828–845 (1966).

Petry, N. M. Delay discounting of money and alcohol in actively using alcoholics, currently abstinent alcoholics, and controls. Psychopharmacology 154 , 243–250 (2001).

MacKillop, J. et al. Alcohol demand, delayed reward discounting, and craving in relation to drinking and alcohol use disorders. J. Abnorm. Psychol. 119 , 106–114 (2010).

Mackillop, J. The behavioral economics and neuroeconomics of alcohol use disorders. Alcohol. Clin. Exp. Res. 40 , 672–685 (2016).

MacKillop, J. et al. Delayed reward discounting and addictive behavior: a meta-analysis. Psychopharmacology 216 , 305–321 (2011).

Amlung, M., Vedelago, L., Acker, J., Balodis, I. & MacKillop, J. Steep delay discounting and addictive behavior: a meta-analysis of continuous associations. Addiction 112 , 51–62 (2017).

Martínez-Loredo, V., González-Roz, A., Secades-Villa, R., Fernández-Hermida, J. R. & MacKillop, J. Concurrent validity of the Alcohol Purchase Task for measuring the reinforcing efficacy of alcohol: an updated systematic review and meta-analysis. Addiction 116 , 2635–2650 (2021).

Acuff, S. F., Dennhardt, A. A., Correia, C. J. & Murphy, J. G. Measurement of substance-free reinforcement in addiction: a systematic review. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 70 , 79–90 (2019).

Carter, B. L. & Tiffany, S. T. Meta-analysis of cue-reactivity in addiction research. Addiction 94 , 327–340 (1999).

MacKillop, J. et al. Behavioral economic analysis of cue-elicited craving for alcohol. Addiction 105 , 1599–1607 (2010).

Acuff, S. F., Amlung, M., Dennhardt, A. A., MacKillop, J. & Murphy, J. G. Experimental manipulations of behavioral economic demand for addictive commodities: a meta-analysis. Addiction 115 , 817–831 (2020); erratum 117, 2367 (2022).

Bouton, M. E., Maren, S. & McNally, G. P. Behavioral and neurobiological mechanisms of pavlovian and instrumental extinction learning. Physiol. Rev. 101 , 611–681 (2021).

Bouton, M. E. Context, attention, and the switch between habit and goal-direction in behavior. Learn. Behav. 49 , 349–362 (2021).

Hogarth, L. Addiction is driven by excessive goal-directed drug choice under negative affect: translational critique of habit and compulsion theory. Neuropsychopharmacology 45 , 720–735 (2020).

Brown, S. A., Christiansen, B. A. & Goldman, M. S. The Alcohol Expectancy Questionnaire: an instrument for the assessment of adolescent and adult alcohol expectancies. J. Stud. Alcohol 48 , 483–491 (1987).

Darkes, J., Greenbaum, P. E. & Goldman, M. S. Alcohol expectancy mediation of biopsychosocial risk: complex patterns of mediation. Exp. Clin. Psychopharmacol. 12 , 27–38 (2004).

Smith, G. T., Goldman, M. S., Greenbaum, P. E. & Christiansen, B. A. Expectancy for social facilitation from drinking: the divergent paths of high-expectancy and low-expectancy adolescents. J. Abnorm. Psychol. 104 , 32–40 (1995).

Christiansen, B. A., Smith, G. T., Roehling, P. V. & Goldman, M. S. Using alcohol expectancies to predict adolescent drinking behavior after one year. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 57 , 93–99 (1989).

Cooper, M. L., Frone, M. R., Russell, M. & Mudar, P. Drinking to regulate positive and negative emotions: a motivational model of alcohol use. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 69 , 990–1005 (1995).

Simons, J., Correia, C. J. & Carey, K. B. A comparison of motives for marijuana and alcohol use among experienced users. Addict. Behav. 25 , 153–160 (2000).

Kuntsche, E., Knibbe, R., Gmel, G. & Engels, R. Why do young people drink? A review of drinking motives. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 25 , 841–861 (2005).

Rooke, S. E., Hine, D. W. & Thorsteinsson, E. B. Implicit cognition and substance use: a meta-analysis. Addict. Behav. 33 , 1314–1328 (2008).

Cox, W. M., Hogan, L. M., Kristian, M. R. & Race, J. H. Alcohol attentional bias as a predictor of alcohol abusers’ treatment outcome. Drug Alcohol Depend. 68 , 237–243 (2002).

Rettie, H. C., Hogan, L. M. & Cox, W. M. Negative attentional bias for positive recovery-related words as a predictor of treatment success among individuals with an alcohol use disorder. Addict. Behav. 84 , 86–91 (2018).

Jarmolowicz, D. P. et al. in The Wiley-Blackwell Handbook of Addiction Psychopharmacology (eds MacKillop, J. & de Wit, H.) 27–61 (Wiley, 2013).

Ray, L. A., MacKillop, J., Leventhal, A. & Hutchison, K. E. Catching the alcohol buzz: an examination of the latent factor structure of subjective intoxication. Alcohol. Clin. Exp. Res. 33 , 2154–2161 (2009).

Quinn, P. D. & Fromme, K. Subjective response to alcohol challenge: a quantitative review. Alcohol. Clin. Exp. Res. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1530-0277.2011.01521.x (2011).

Schuckit, M. A. A longitudinal study of children of alcoholics. Recent Dev. Alcohol. 9 , 5–19 (1991).

Schuckit, M. A. Biological, psychological and environmental predictors of the alcoholism risk: a longitudinal study. J. Stud. Alcohol 59 , 485–494 (1998).

Hendershot, C. S., Wardell, J. D., McPhee, M. D. & Ramchandani, V. A. A prospective study of genetic factors, human laboratory phenotypes, and heavy drinking in late adolescence. Addict. Biol. https://doi.org/10.1111/adb.12397 (2016).

Sher, K. J. & Trull, T. J. Personality and disinhibitory psychopathology: alcoholism and antisocial personality disorder. J. Abnorm. Psychol. 103 , 92–102 (1994).

Malouff, J. M., Thorsteinsson, E. B., Rooke, S. E. & Schutte, N. S. Alcohol involvement and the five-factor model of personality: a meta-analysis. J. Drug Educ. 37 , 277–294 (2007).

Malouff, J. M., Thorsteinsson, E. B. & Schutte, N. S. The five-factor model of personality and smoking: a meta-analysis. J. Drug Educ. 36 , 47–58 (2006).

Kotov, R., Gamez, W., Schmidt, F. & Watson, D. Linking ‘big’ personality traits to anxiety, depressive, and substance use disorders: a meta-analysis. Psychol. Bull. 136 , 768–821 (2010).

Maclaren, V. V., Fugelsang, J. A., Harrigan, K. A. & Dixon, M. J. The personality of pathological gamblers: a meta-analysis. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 31 , 1057–1067 (2011).

Dick, D. M. et al. Understanding the construct of impulsivity and its relationship to alcohol use disorders. Addiction Biol. 15 , 217–226 (2010).

Patton, J. H., Stanford, M. S. & Barratt, E. S. Factor structure of the Barratt impulsiveness scale. J. Clin. Psychol. 51 , 768–774 (1995).

Whiteside, S. P. & Lynam, D. R. The five factor model and impulsivity: using a structural model of personality to understand impulsivity. Pers. Individ. Dif. 30 , 669–689 (2001).

Cyders, M. A., Littlefield, A. K., Coffey, S. & Karyadi, K. A. Examination of a short English version of the UPPS-P impulsive behavior scale. Addictive Behav. 39 , 1372–1376 (2014).

Coskunpinar, A., Dir, A. L. & Cyders, M. A. Multidimensionality in impulsivity and alcohol use: a meta-analysis using the UPPS model of impulsivity. Alcohol. Clin. Exp. Res. 37 , 1441–1450 (2013).

MacKillop, J. et al. The latent structure of impulsivity: impulsive choice, impulsive action, and impulsive personality traits. Psychopharmacology 233 , 3361–3370 (2016).

Fernie, G. et al. Multiple behavioural impulsivity tasks predict prospective alcohol involvement in adolescents. Addiction 108 , 1916–1923 (2013).

Sanchez-Roige, S. et al. Genome-wide association study of delay discounting in 23,217 adult research participants of European ancestry. Nat. Neurosci. 21 , 16–18 (2018).

MacKillop, J. et al. The brief alcohol social density assessment (BASDA): convergent, criterion-related and incremental validity. J. Stud. Alcohol Drugs 74 , 810–815 (2013).

Borgatti, S. P., Mehra, A., Brass, D. J. & Labianca, G. Network analysis in the social sciences. Science 323 , 892–895 (2009).

Rosenquist, J. N. Lessons from social network analyses for behavioral medicine. Curr. Opin. Psychiatry 24 , 139–143 (2011).

Burt, R. S., Kilduff, M. & Tasselli, S. Social network analysis: foundations and frontiers on advantage. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 64 , 527–547 (2013).

Rosenquist, J. N., Murabito, J., Fowler, J. H. & Christakis, N. A. The spread of alcohol consumption behavior in a large social network. Ann. Intern. Med. 152 , 426–433 (2010).

Bullers, S., Cooper, M. L. & Russell, M. Social network drinking and adult alcohol involvement: a longitudinal exploration of the direction of influence. Addict. Behav. 26 , 181–199 (2001).

Lau-Barraco, C., Braitman, A. L., Leonard, K. E. & Padilla, M. Drinking buddies and their prospective influence on alcohol outcomes: alcohol expectancies as a mediator. Psychol. Addict. Behav. 26 , 747–758 (2012).

Fortune, E. E. et al. Social density of gambling and its association with gambling problems: an initial investigation. J. Gambl. Stud. 29 , 329–342 (2013).

Fujimoto, K. & Valente, T. W. Social network influences on adolescent substance use: disentangling structural equivalence from cohesion. Soc. Sci. Med. 74 , 1952–1960 (2012).

Ennett, S. T. et al. The peer context of adolescent substance use: findings from social network analysis. J. Res. Adolesc. 16 , 159–186 (2006).

Meisel, M. K. et al. Egocentric social network analysis of pathological gambling. Addiction 108 , 584–591 (2013).

Stout, R. L., Kelly, J. F., Magill, M. & Pagano, M. E. Association between social influences and drinking outcomes across three years. J. Stud. Alcohol Drugs 73 , 489–497 (2012).

Longabaugh, R., Wirtz, P. W., Zywiak, W. H. & O’Malley, S. S. Network support as a prognostic indicator of drinking outcomes: the COMBINE study. J. Stud. Alcohol Drugs 71 , 837–846 (2010).

Kelly, J. F., Stout, R. L., Magill, M. & Tonigan, J. S. The role of Alcoholics Anonymous in mobilizing adaptive social network changes: a prospective lagged mediational analysis. Drug Alcohol Depend. 114 , 119–126 (2011).

Litt, M. D., Kadden, R. M., Kabela-Cormier, E. & Petry, N. Changing network support for drinking: initial findings from the Network Support Project. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 75 , 542–555 (2007).

Litt, M. D., Kadden, R. M., Kabela-Cormier, E. & Petry, N. M. Changing network support for drinking: network Support Project 2-year follow-up. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 77 , 229–242 (2009).

Agrawal, A. et al. Assortative mating for cigarette smoking and for alcohol consumption in female Australian twins and their spouses. Behav. Genet. 36 , 553–566 (2006).

Grant, J. D. et al. Spousal concordance for alcohol dependence: evidence for assortative mating or spousal interaction effects? Alcohol. Clin. Exp. Res. 31 , 717–728 (2007).

Leonard, K. E. & Eiden, R. D. Marital and family processes in the context of alcohol use and alcohol disorders. Annu. Rev. Clin. Psychol. 3 , 285–310 (2007).

AlMarri, T. S. K. & Oei, T. P. S. Alcohol and substance use in the Arabian Gulf region: a review. Int. J. Psychol. 44 , 222–233 (2009).

Russell, A. M., Yu, B., Thompson, C. G., Sussman, S. Y. & Barry, A. E. Assessing the relationship between youth religiosity and their alcohol use: a meta-analysis from 2008 to 2018. Addict. Behav. 106 , 106361 (2020).

Lin, H. C., Hu, Y. H., Barry, A. E. & Russell, A. Assessing the associations between religiosity and alcohol use stages in a representative U.S. sample. Subst. Use Misuse 55 , 1618–1624 (2020).

Roberts, S. C. M. Macro-level gender equality and alcohol consumption: a multi-level analysis across U.S. states. Soc. Sci. Med. 75 , 60–68 (2012).

Wagenaar, A. C., Salois, M. J. & Komro, K. A. Effects of beverage alcohol price and tax levels on drinking: a meta-analysis of 1003 estimates from 112 studies. Addiction 104 , 179–190 (2009).

Xuan, Z., Blanchette, J., Nelson, T. F., Heeren, T. & Oussayef, N. The alcohol policy environment and policy subgroups as predictors of binge drinking measures among US adults. Am. J. Public Health 105 , 816–822 (2015).

Subbaraman, M. S. et al. Relationships between US state alcohol policies and alcohol outcomes: differences by gender and race/ethnicity. Addiction 115 , 1285–1294 (2020).

Lamb, S., Greenlick, M. R. & McCarty, D (eds) Bridging the Gap between Practice and Research: Forging Partnerships with Community-Based Drug and Alcohol Treatment (National Academy Press, 1998).

Oliva, E. M., Maisel, N. C., Gordon, A. J. & Harris, A. H. S. Barriers to use of pharmacotherapy for addiction disorders and how to overcome them. Curr. Psychiatry Rep. 13 , 374–381 (2011).

Carroll, K. M. Lost in translation? Moving contingency management and cognitive behavioral therapy into clinical practice. Ann. NY Acad. Sci. 1327 , 94–111 (2014).

Room, R. Stigma, social inequality and alcohol and drug use. Drug Alcohol Rev. 24 , 143–155 (2005).

Xu, Y. et al. The socioeconomic gradient of alcohol use: an analysis of nationally representative survey data from 55 low-income and middle-income countries. Lancet Glob . Health 10 , e1268–e1280 (2022).

Roche, A. et al. Addressing inequities in alcohol consumption and related harms. Health Promot. Int. 30 (Suppl. 2), ii20–ii35 (2015).

American Psychiatric Association. Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-5: Research Version (American Psychiatric Association Publishing, 2015).

Schneider, L. H. et al. The diagnostic assessment research tool in action: a preliminary evaluation of a semistructured diagnostic interview for DSM-5 disorders. Psychol. Assess. 34 , 21–29 (2022).

Hallgren, K. A. et al. Practical assessment of alcohol use disorder in routine primary care: performance of an alcohol symptom checklist. J. Gen. Intern. Med. 37 , 1885–1893 (2022).

Hallgren, K. A. et al. Practical assessment of DSM-5 alcohol use disorder criteria in routine care: high test-retest reliability of an alcohol symptom checklist. Alcohol. Clin. Exp. Res. 46 , 458–467 (2022).

Levitt, E. E. et al. Optimizing screening for depression, anxiety disorders, and post-traumatic stress disorder in inpatient addiction treatment: a preliminary investigation. Addict. Behav. 112 , 106649 (2021).

Spanakis, P. et al. Problem drinking recognition among UK military personnel: prevalence and associations. Soc. Psychiatry Psychiatr. Epidemiol. https://doi.org/10.1007/S00127-022-02306-X (2022).

Roberts, E. et al. The prevalence of wholly attributable alcohol conditions in the United Kingdom hospital system: a systematic review, meta-analysis and meta-regression. Addiction 114 , 1726–1737 (2019).

Curry, S. J. et al. Screening and behavioral counseling interventions to reduce unhealthy alcohol use in adolescents and adults: US Preventive Services Task Force recommendation statement. JAMA 320 , 1899–1909 (2018).

McNeely, J. et al. Comparison of methods for alcohol and drug screening in primary care clinics. JAMA Netw. Open 4 , E2110721 (2021).

Singh, J. A. & Cleveland, J. D. Trends in hospitalizations for alcohol use disorder in the US from 1998 to 2016. JAMA Netw. Open 3 , e2016580 (2020).

Sword, W. et al. Screening and intervention practices for alcohol use by pregnant women and women of childbearing age: results of a Canadian survey. J. Obstet. Gynaecol. Can. 42 , 1121–1128 (2020).

Brothers, T. D. & Bach, P. Challenges in prediction, diagnosis, and treatment of alcohol withdrawal in medically ill hospitalized patients: a teachable moment. JAMA Intern. Med. 180 , 900–901 (2020).

Göransson, M., Magnusson, Å. & Heilig, M. Identifying hazardous alcohol consumption during pregnancy: implementing a research-based model in real life. Acta Obstet. Gynecol. Scand. 85 , 657–662 (2006).

Anderson, P., O’Donnell, A. & Kaner, E. Managing alcohol use disorder in primary health care. Curr. Psychiatry Rep. 19 , 79 (2017).

Bobb, J. F. et al. Evaluation of a pilot implementation to integrate alcohol-related care within primary care. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 14 , 1030 (2017).

Chan, P. S.-f et al. Using Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research to investigate facilitators and barriers of implementing alcohol screening and brief intervention among primary care health professionals: a systematic review. Implement. Sci. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13012-021-01170-8 (2021).

Vaca, F. E. & Winn, D. The basics of alcohol screening, brief intervention and referral to treatment in the emergency department. West. J. Emerg. Med. 8 , 88 (2007).

Solberg, L. I., Maciosek, M. V. & Edwards, N. M. Primary care intervention to reduce alcohol misuse ranking its health impact and cost effectiveness. Am. J. Prev. Med. 34 , 143–152.e3 (2008).

Miller, W. R. & Rollnick, S. Motivational Interviewing: Helping People Change (Guilford Press, 2013).

Glass, J. E. et al. Specialty substance use disorder services following brief alcohol intervention: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Addiction 110 , 1404–1415 (2015).

Frost, M. C., Glass, J. E., Bradley, K. A. & Williams, E. C. Documented brief intervention associated with reduced linkage to specialty addictions treatment in a national sample of VA patients with unhealthy alcohol use with and without alcohol use disorders. Addiction 115 , 668–678 (2020).

Leggio, L. & Lee, M. R. Treatment of alcohol use disorder in patients with alcoholic liver disease. Am. J. Med. 130 , 124–134 (2017).

Litten, R. Z., Bradley, A. M. & Moss, H. B. Alcohol biomarkers in applied settings: recent advances and future research opportunities. Alcohol Clin. Exp. Res. 34 , 955–967 (2010).

Fairbairn, C. E. & Bosch, N. A new generation of transdermal alcohol biosensing technology: practical applications, machine-learning analytics and questions for future research. Addiction 116 , 2912–2920 (2021).

Walsham, N. E. & Sherwood, R. A. Ethyl glucuronide and ethyl sulfate. Adv. Clin. Chem. 67 , 47–71 (2014).

Philibert, R. et al. Genome-wide and digital polymerase chain reaction epigenetic assessments of alcohol consumption. Am. J. Med. Genet. B Neuropsychiatr. Genet. 177 , 479–488 (2018).

Miller, S., Mills, J. A., Long, J. & Philibert, R. A comparison of the predictive power of DNA methylation with carbohydrate deficient transferrin for heavy alcohol consumption. Epigenetics 16 , 969 (2021).

World Health Organization. The SAFER technical package. WHO https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/the-safer-technical-package (2019).

Stockwell, T., Giesbrecht, N., Vallance, K. & Wettlaufer, A. Government options to reduce the impact of alcohol on human health: obstacles to effective policy implementation. Nutrients 13 , 2846 (2021).

Sandmo, A. in The New Palgrave Dictionary of Economics (eds Durlauf, S. & Blume, L. E.) 1–4 (Palgrave Macmillan, 2008).

Chaloupka, F. J., Powell, L. M. & Warner, K. E. The use of excise taxes to reduce tobacco, alcohol, and sugary beverage consumption. Annu. Rev. Public Health 40 , 187–201 (2019).

Cabinet Secretary for Health and Social Care. Alcohol and drugs: minimum unit pricing. Scottish Government https://www.gov.scot/policies/alcohol-and-drugs/minimum-unit-pricing/ (2018).

Boniface, S., Scannell, J. W. & Marlow, S. Evidence for the effectiveness of minimum pricing of alcohol: a systematic review and assessment using the Bradford Hill criteria for causality. BMJ Open 7 , e013497 (2017).

Jones-Webb, R. et al. The effectiveness of alcohol impact areas in reducing crime in Washington neighborhoods. Alcohol. Clin. Exp. Res. 45 , 234–241 (2021).

Nepal, S. et al. Effects of extensions and restrictions in alcohol trading hours on the incidence of assault and unintentional injury: systematic review. J. Stud. Alcohol Drugs 81 , 5–23 (2020).

Wagenaar, A. C. & Toomey, T. L. Effects of minimum drinking age laws: review and analyses of the literature from 1960 to 2000. J. Stud. Alcohol Suppl. 63 , 206–225 (2002).

Green, R., Jason, H. & Ganz, D. Underage drinking: does the minimum age drinking law offer enough protection? Int. J. Adolesc. Med. Health 27 , 117–128 (2015).

Inchley, J. et al. Spotlight on Adolescent Health and Well-being. Findings from the 2017/2018 Health Behaviour in School-aged Children (HBSC) Survey in Europe and Canada . International report. Vol. 1. Key findings. (WHO, 2020).

Johnston, L. D. et al. Monitoring the Future national survey results on drug use 2015 (ERIC, 2015).

The Lancet. Russia’s alcohol policy: a continuing success story. Lancet 394 , 1205 (2019).

Lynam, D. R. et al. Project DARE: no effects at 10-year follow-up. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 67 , 590–593 (1999).

Burton, R. et al. A rapid evidence review of the effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of alcohol control policies: an English perspective. Lancet 389 , 1558–1580 (2017).

Agabio, R. et al. Alcohol consumption is a modifiable risk factor for breast cancer: are women aware of this relationship? Alcohol Alcohol . https://doi.org/10.1093/ALCALC/AGAB042 (2021).

Sigfúsdóttir, I. D., Thorlindsson, T., Kristjánsson, A. L., Roe, K. M. & Allegrante, J. P. Substance use prevention for adolescents: the Icelandic Model. Health Promot. Int. 24 , 16–25 (2009).

D’Amico, E. J. & Feldstein Ewing, S. W. in The Ox f ord H andbook of Adolescent Substance Abuse (eds Zucker, R. A. & Brown, S. A.) 627–654 (Oxford Univ. Press, 2016).

Fachini, A., Aliane, P. P., Martinez, E. Z. & Furtado, E. F. Efficacy of brief alcohol screening intervention for college students (BASICS): a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Subst. Abus. Treat. Prev. Policy 7 , 40 (2012).

Edalati, H. & Conrod, P. J. A review of personality-targeted interventions for prevention of substance misuse and related harm in community samples of adolescents. Front. Psychiatry 9 , 770 (2019).

National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism. NIAAA Recovery Research Definitions. NIAAA https://www.niaaa.nih.gov/research/niaaa-recovery-from-alcohol-use-disorder/definitions (2022).

Witkiewitz, K. et al. Clinical validation of reduced alcohol consumption after treatment for alcohol dependence using the World Health Organization risk drinking levels. Alcohol. Clin. Exp. Res. 41 , 179–186 (2017).

Hartwell, E. E., Feinn, R., Witkiewitz, K., Pond, T. & Kranzler, H. R. World Health Organization risk drinking levels as a treatment outcome measure in topiramate trials. Alcohol. Clin. Exp. Res. https://doi.org/10.1111/acer.14652 (2021).

Preusse, M., Neuner, F. & Ertl, V. Effectiveness of psychosocial interventions targeting hazardous and harmful alcohol use and alcohol-related symptoms in low- and middle-income countries: a systematic review. Front. Psychiatry 11 , 768 (2020).

Day, E. & Daly, C. Clinical management of the alcohol withdrawal syndrome. Addiction 117 , 804–814 (2022).

Reus, V. I. et al. The American Psychiatric Association practice guideline for the pharmacological treatment of patients with alcohol use disorder. Am. J. Psychiatry 175 , 86–90 (2018).

Agabio, R. & Leggio, L. Thiamine administration to all patients with alcohol use disorder: why not? Am. J. Drug Alcohol. Abus. 47 , 651–654 (2021).

Skinner, M. D., Lahmek, P., Pham, H. & Aubin, H. J. Disulfiram efficacy in the treatment of alcohol dependence: a meta-analysis. PLoS ONE 9 , e87366 (2014).

Jørgensen, C. H., Pedersen, B. & Tønnesen, H. The efficacy of disulfiram for the treatment of alcohol use disorder. Alcohol. Clin. Exp. Res. 35 , 1749–1758 (2011).

Jonas, D. E. et al. Pharmacotherapy for adults with alcohol use disorders in outpatient settings: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA 311 , 1889–1900 (2014).

Kranzler, H. R. & Soyka, M. Diagnosis and pharmacotherapy of alcohol use disorder: a review. JAMA 320 , 815–824 (2018).

Canidate, S. S., Carnaby, G. D., Cook, C. L. & Cook, R. L. A systematic review of naltrexone for attenuating alcohol consumption in women with alcohol use disorders. Alcohol. Clin. Exp. Res. 41 , 466–472 (2017).

Ray, L. A. et al. Combined pharmacotherapy and cognitive behavioral therapy for adults with alcohol or substance use disorders: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Netw . Open 3 , e208279 (2020).

Garbutt, J. C. et al. Clinical and biological moderators of response to naltrexone in alcohol dependence: a systematic review of the evidence. Addiction 109 , 1274–1284 (2014).

Rubio, G. et al. Clinical predictors of response to naltrexone in alcoholic patients: who benefits most from treatment with naltrexone? Alcohol Alcohol. 40 , 227–233 (2005).

Fucito, L. M. et al. Cigarette smoking predicts differential benefit from naltrexone for alcohol dependence. Biol. Psychiatry 72 , 832–838 (2012).

Agabio, R., Pani, P. P., Preti, A., Gessa, G. L. & Franconi, F. Efficacy of medications approved for the treatment of alcohol dependence and alcohol withdrawal syndrome in female patients: a descriptive review. Eur. Addict. Res. 22 , 1–16 (2016).

Pierce, M., Sutterland, A., Beraha, E. M., Morley, K. & van den Brink, W. Efficacy, tolerability, and safety of low-dose and high-dose baclofen in the treatment of alcohol dependence: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur. Neuropsychopharmacol. 28 , 795–806 (2018).

Rose, A. K. & Jones, A. Baclofen: its effectiveness in reducing harmful drinking, craving, and negative mood. A meta-analysis. Addiction 113 , 1396–1406 (2018).

Garbutt, J. C. et al. Efficacy and tolerability of baclofen in a U.S. community population with alcohol use disorder: a dose-response, randomized, controlled trial. Neuropsychopharmacology 46 , 2250–2256 (2021).

Agabio, R., Baldwin, D. S., Amaro, H., Leggio, L. & Sinclair, J. M. A. The influence of anxiety symptoms on clinical outcomes during baclofen treatment of alcohol use disorder: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 125 , 296–313 (2021).

Agabio, R. et al. Baclofen for the treatment of alcohol use disorder: the Cagliari Statement. Lancet Psychiatry 5 , 957–960 (2018).

Ray, L. A. et al. State-of-the-art behavioral and pharmacological treatments for alcohol use disorder. Am. J. Drug Alcohol. Abus. 45 , 124–140 (2019).

Leggio, L., Falk, D. E., Ryan, M. L., Fertig, J. & Litten, R. Z. Medication development for alcohol use disorder: a focus on clinical studies. Handb. Exp. 258 , 443–462 (2020).

Witkiewitz, K., Litten, R. Z. & Leggio, L. Advances in the science and treatment of alcohol use disorder. Sci. Adv. 5 , eaax4043 (2019).

Johnson, B. A. et al. Oral topiramate for treatment of alcohol dependence: a randomised controlled trial. Lancet 361 , 1677–1685 (2003).

Hägg, S., Jönsson, A. K. & Ahlner, J. Current evidence on abuse and misuse of gabapentinoids. Drug Saf. 43 , 1235–1254 (2020).

Simpson, T. L. et al. Double-blind randomized clinical trial of prazosin for alcohol use disorder. Am. J. Psychiatry 175 , 1216–1224 (2018).

Grodin, E. N. et al. Ibudilast, a neuroimmune modulator, reduces heavy drinking and alcohol cue-elicited neural activation: a randomized trial. Transl Psychiatry 11 , 355 (2021).

MacKillop, J. et al. D-cycloserine to enhance extinction of cue-elicited craving for alcohol: a translational approach. Transl Psychiatry 5 , e544 (2015).

Miller, W. R., Zweben, A., DiClemente, C. C. & Rychtarik, R. G. Motivational Enhancement Therapy Manual: A Clinical Research Guide for Therapists Treating Individuals With Alcohol Abuse and Dependence . Project MATCH Monograph Series, Vol. 2 (National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism, 1999).

Hettema, J., Steele, J. & Miller, W. R. Motivational Interviewing. Annu. Rev. Clin. Psychol. 1 , 91–111 (2005).

Frost, H. et al. Effectiveness of Motivational Interviewing on adult behaviour change in health and social care settings: a systematic review of reviews. PLoS ONE 13 , e0204890 (2018).

Steele, D. W. et al. Brief behavioral interventions for substance use in adolescents: a meta-analysis. Pediatrics 146 , e20200351 (2020).

Hendershot, C. S., Witkiewitz, K., George, W. H. & Marlatt, G. A. Relapse prevention for addictive behaviors. Subst. Abus. Treat. Prev. Policy 6 , 17 (2011).

Monti, P. M. & O’Leary, T. A. Coping and social skills training for alcohol and cocaine dependence. Psychiatr. Clin. North Am. 22 , 447–470 (1999).

Magill, M. et al. A meta-analysis of cognitive-behavioral therapy for alcohol or other drug use disorders: treatment efficacy by contrast condition. J. Consult. 87 , 1093–1105 (2019).

Kiluk, B. D. et al. Technology-delivered cognitive-behavioral interventions for alcohol use: a meta-analysis. Alcohol. Clin. Exp. 43 , 2285–2295 (2019).

Bowen, S. et al. Relative efficacy of mindfulness-based relapse prevention, standard relapse prevention, and treatment as usual for substance use disorders. JAMA Psychiatry 71 , 547–556 (2014).

Schwebel, F. J., Korecki, J. R. & Witkiewitz, K. Addictive behavior change and mindfulness-based interventions: current research and future directions. Curr. Addict. 7 , 117–124 (2020).

McCrady, B. S., Epstein, E. E., Cook, S., Jensen, N. & Hildebrandt, T. A randomized trial of individual and couple behavioral alcohol treatment for women. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 77 , 243–256 (2009).

Powers, M. B., Vedel, E. & Emmelkamp, P. M. G. Behavioral couples therapy (BCT) for alcohol and drug use disorders: a meta-analysis. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 28 , 952–962 (2008).

McCrady, B. S. et al. Alcohol-focused behavioral couple therapy. Fam. Process. 55 , 443–459 (2016).

Petry, N. M. A comprehensive guide to the application of contingency management procedures in clinical settings. Drug Alcohol Depend. 58 , 9–25 (2000).

Benishek, L. A. et al. Prize-based contingency management for the treatment of substance abusers: a meta-analysis. Addiction 109 , 1426–1436 (2014).