From Imperialism to Postcolonialism: Key Concepts

An introduction to the histories of imperialism and the writings of those who grappled with its oppressions and legacies in the twentieth century.

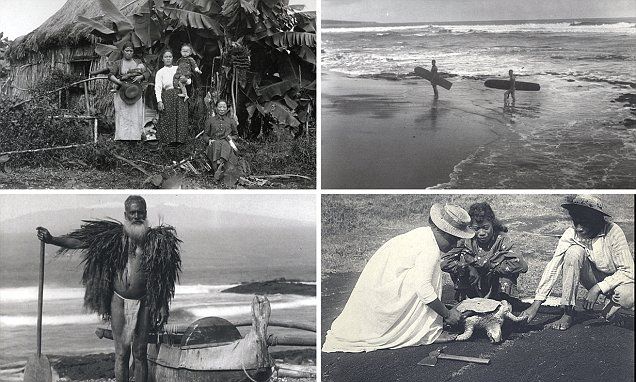

Imperialism, the domination of one country over another country’s political, economic, and cultural systems, remains one of the most significant global phenomena of the last six centuries. Amongst historical topics, Western imperialism is unique because it spans two different broadly conceived temporal frames: “Old Imperialism,” dated between 1450 and 1650, and “New Imperialism,” dated between 1870 and 1919, although both periods were known for Western exploitation of Indigenous cultures and the extraction of natural resources to benefit imperial economies. Apart from India, which came under British influence through the rapacious actions of the East India Company , European conquest between 1650 and the 1870s remained (mostly) dormant. However, following the 1884–85 Berlin Conference, European powers began the “ Scramble for Africa ,” dividing the continent into new colonial territories. Thus, the age of New Imperialism is demarcated by establishment of vast colonies throughout Africa, as well as parts of Asia, by European nations.

These European colonizing efforts often came at the expense of other older, non-European imperial powers, such as the so-called gunpowder empires—the Ottoman, Safavid, and Mughal empires that flourished across South Asia and the Middle East. In the case of the Ottomans , their rise coincided with that of the Old Imperialism(s) of the West and lasted until after World War I. These were not the only imperial powers, however; Japan signaled its interest in creating a pan-Asian empire with the establishment of a colony in Korea in 1910 and expanded its colonial holdings rapidly during the interwar years. The United States, too, engaged in various forms of imperialism, from the conquest of the tribes of the First Nation Peoples, through filibustering in Central America during the mid-1800s, to accepting the imperialist call of Rudyard Kipling’s poem “The White Man’s Burden,” which the poet wrote for President Theodore Roosevelt on the occasion of Philippine-American War. While claiming to reject naked imperialism, Roosevelt still embraced expansionism, promoting the creation of a strong US Navy and advocating for expansion into Alaska, Hawaiʻi, and the Philippines to exert American influence .

The Great War is often considered the end of the new age of imperialism, marked by the rise of decolonization movements throughout the various colonial holdings. The writings of these emergent Indigenous elites, and the often-violent repression they would face from the colonial elite, would not only profoundly shape the independence struggles on the ground but would contribute to new forms of political and philosophical thought. Scholarship from this period forces us to reckon not only with colonial legacies and the Eurocentric categories created by imperialism but also with the continuing exploitation of the former colonies via neo-colonial controls imposed on post-independence countries.

The non-exhaustive reading list below aims to provide readers with both histories of imperialism and introduces readers to the writings of those who grappled with colonialism in real time to show how their thinking created tools we still use to understand our world.

Eduardo Galeano, “ Introduction: 120 Million Children in the Eye of the Hurricane ,” Open Veins of Latin America: Five Centuries of the Pillage of a Continent (NYU Press, 1997): 1 –8.

Taken from the twenty-fifth anniversary edition of this classic text, Eduardo Galeano’s introduction argues that pillaging of Latin America continued for centuries past the Old Imperialism of the Spanish Crown. This work is highly readable and informative, with equal parts of impassioned activism and historical scholarship.

Nancy Rose Hunt, “ ‘Le Bebe En Brousse’: European Women, African Birth Spacing and Colonial Intervention in Breast Feeding in the Belgian Congo ,” The International Journal of African Historical Studies 21, no. 3 (1988): 401–32.

Colonialism affected every aspect of life for colonized peoples. This intrusion into the intimate lives of indigenous peoples is most evident in Nancy Rose Hunt’s examination of Belgian efforts to modify birthing processes in the Belgian Congo. To increase birth rates in the colony, Belgian officials initiated a mass network of health programs focused on both infant and maternal health. Hunt provides clear examples of the underlying scientific racism that underpinned these efforts and acknowledges the effects they had on European women’s conception of motherhood.

Chima J. Korieh, “ The Invisible Farmer? Women, Gender, and Colonial Agricultural Policy in the Igbo Region of Nigeria, c. 1913–1954 ,” African Economic History No. 29 (2001): 117– 62

In this consideration of Colonial Nigeria, Chima Korieh explains how British Colonial officials imposed British conceptions of gender norms on traditional Igbo society; in particular, a rigid notion of farming as a male occupation, an idea that clashed with the fluidity of agricultural production roles of the Igbo. This paper also shows how colonial officials encouraged palm oil production, an export product, at the expense of sustainable farming practices—leading to changes in the economy that further stressed gender relations.

Colin Walter Newbury & Alexander Sydney Kanya-Forstner, “ French Policy and the Origins of the Scramble for West Africa ,” The Journal of African History 10, no. 2 (1969): 253–76.

Newbury and Kanya-Foster explain why the French decided to engage in imperialism in Africa at the end of the nineteenth century. First, they point to mid-century French engagement with Africa—limited political commitment on the African coast between Senegal and Congo, with a plan for the creation of plantations within the Senegalese interior. This plan was emboldened by their military success in Algeria, which laid the foundation of a new conception of Empire that, despite complications (Britain’s expansion of their empire and revolt in Algeria, for instance) that forced the French to abandon their initial plans, would take hold later in the century.

Mark D. Van Ells, “ Assuming the White Man’s Burden: The Seizure of the Philippines, 1898–1902 ,” Philippine Studies 43, no. 4 (1995): 607–22.

Mark D. Van Ells’s work acts as an “exploratory and interpretive” rendering of American racial attitudes toward their colonial endeavors in the Philippines. Of particular use to those wishing to understand imperialism is Van Ells’s explication of American attempts to fit Filipinos into an already-constructed racist thought system regarding formerly enslaved individuals, Latinos, and First Nation Peoples. He also shows how these racial attitudes fueled the debate between American imperialists and anti-imperialists.

Aditya Mukherjee, “ Empire: How Colonial India Made Modern Britain,” Economic and Political Weekly 45, no. 50 (2010): 73–82.

Aditya Mukherjee first provides an overview of early Indian intellectuals and Karl Marx’s thoughts on the subject to answer the question of how colonialism impacted the colonizer and the colonized. From there, he uses economic data to show the structural advantages that led to Great Britain’s ride through the “age of capitalism” through its relative decline after World War II.

Frederick Cooper, “ French Africa, 1947–48: Reform, Violence, and Uncertainty in a Colonial Situation ,” Critical Inquiry 40, no. 4 (2014): 466–78.

It can be tempting to write the history of decolonization as a given. However, in the immediate aftermath of World War II, the colonial powers would not easily give up their territories. Nor is it safe to assume that every colonized person, especially those who had invested in the colonial bureaucratic systems, necessarily wanted complete independence from the colonial metropole. In this article, Frederick Cooper shows how conflicting interests navigated revolution and citizenship questions during this moment.

Hồ Chí Minh & Kareem James Abu-Zeid, “ Unpublished Letter by Hồ Chí Minh to a French Pastor ,” Journal of Vietnamese Studies 7, no. 2 (2012): 1–7.

Written by Nguyễn Ái Quốc (the future Hồ Chí Minh) while living in Paris, this letter to a pastor planning a pioneering mission to Vietnam not only shows the young revolutionary’s commitment to the struggle against colonialism, but also his willingness to work with colonial elites to solve the system’s inherent contradictions.

Aimé Césaire, “ Discurso sobre el Colonialismo ,” Guaraguao 9, no. 20, La negritud en America Latina (Summer 2005): 157–93; Available in English as “From Discourse on Colonialism (1955),” in I Am Because We Are: Readings in Africana Philosophy , ed. by Fred Lee Hord, Mzee Lasana Okpara, and Jonathan Scott Lee, 2nd ed. (University of Massachusetts Press, 2016), 196–205.

This excerpt from Aimé Césaire’s essay directly challenges European claims of moral superiority and the concept of imperialism’s civilizing mission. He uses examples from the Spanish conquest of Latin America and ties them together with the horrors of Nazism within Europe. Césaire claims that through pursuing imperialism, Europeans had embraced the very savagery of which they accused their colonial subjects.

Frantz Fanon, “ The Wretched of the Earth ,” in Princeton Readings in Political Thought: Essential Texts since Plato , ed. Mitchell Cohen, 2nd ed. (Princeton University Press, 2018), 614–20.

Having served as a psychiatrist in a French hospital in Algeria, Frantz Fanon experienced firsthand the violence of the Algerian War. As a result, he would ultimately resign and join the Algerian National Liberation Front. In this excerpt from his longer work, Fanon writes on the need for personal liberation as a precursor to the political awaking of oppressed peoples and advocates for worldwide revolution.

Quỳnh N. Phạm & María José Méndez, “ Decolonial Designs: José Martí, Hồ Chí Minh, and Global Entanglements ,” Alternatives: Global, Local, Political 40, no. 2 (2015): 156–73.

Phạm and Méndez examine the writing of José Martí and Hồ Chí Minh to show that both spoke of anticolonialism in their local contexts (Cuba and Vietnam, respectively). However, their language also reflected an awareness of a more significant global anticolonial movement. This is important as it shows that the connections were intellectual and practical.

Edward Said, “ Orientalism ,” The Georgia Review 31, no. 1 (Spring 1977): 162–206; and “ Orientalism Reconsidered ,” Cultural Critique no. 1 (Autumn 1985): 89–107.

As a Palestinian-born academic trained in British-run schools in Egypt and Jerusalem, Edward Said created a cultural theory that named the discourse nineteenth-century Europeans had about the peoples and places of the Greater Islamic World: Orientalism. The work of academics, colonial officials, and writers of various stripes contributed to a literary corpus that came to represent the “truth” of the Orient, a truth that Said argues reflects the imagination of the “West” more than it does the realities of the “Orient.” Said’s framework applies to many geographic and temporal lenses, often dispelling the false truths that centuries of Western interactions with the global South have encoded in popular culture.

Sara Danius, Stefan Jonsson, and Gayatri Chakravorty Spivak, “ An Interview with Gayatri Chakravorty Spivak ,” boundary 20, No. 2 (Summer 1993), 24–50.

Gayatri Spivak’s 1988 essay, “Can the Subaltern Speak?” shifted the postcolonial discussion to a focus on agency and “the other.” Explicating Western discourse surrounding the practice of sati in India, Spivak asks if the oppressed and the marginalized can make themselves heard from within a colonial system. Can the subordinated, dispossessed indigenous subject be retrieved from the silence spaces of imperial history, or would that be yet another act of epistemological violence? Spivak argues that Western historians (i.e., white men speaking to white men about the colonized), in trying to squeeze out the subaltern voice, reproduce the hegemonic structures of colonialism and imperialism.

Antoinette Burton, “ Thinking beyond the Boundaries: Empire, Feminism and the Domains of History ,” Social History 26, no. 1 (January 2001): 60–71.

In this article, Antoinette Burton considers the controversies around using the social and cultural theory as a site of analysis within the field of imperial history; specifically, concerns of those who saw political and economic history as “outside the realm” of culture. Burton deftly merges the historiographies of anthropology and gender studies to argue for a more nuanced understanding of New Imperial history.

Michelle Moyd, “ Making the Household, Making the State: Colonial Military Communities and Labor in German East Africa ,” International Labor and Working-Class History , no. 80 (2011): 53–76.

Michelle Moyd’s work focuses on an often-overlooked part of the imperial machine, the indigenous soldiers who served the colonial powers. Using German East Africa as her case study, she discusses how these “violent intermediaries” negotiated new household and community structures within the context of colonialism.

Caroline Elkins, “ The Struggle for Mau Mau Rehabilitation in Late Colonial Kenya ,” The International Journal of African Historical Studies 33, no. 1 (2000): 25–57.

Caroline Elkins looks at the both the official rehabilitation policy enacted toward Mau Mau rebels and the realities of what took place “behind the wire.” She argues that in this late colonial period, the colonial government in Nairobi was never truly able to recover from the brutality it used to suppress the Mau Mau movement and maintain colonial control.

Jan C. Jansen and Jürgen Osterhammel, “Decolonization as Moment and Process,” in Decolonization: A Short History , trans. Jeremiah Riemer (Princeton University Press, 2017): 1–34.

In this opening chapter of their book, Decolonization: A Short History , Jansen and Osterhammel lay out an ambitious plan for merging multiple perspectives on the phenomena of decolonization to explain how European colonial rule became de-legitimized. Their discussion of decolonization as both a structural and a normative process is of particular interest.

Cheikh Anta Babou, “ Decolonization or National Liberation: Debating the End of British Colonial Rule in Africa ,” The Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science 632 (2010): 41–54.

Cheikh Anta Babou challenges decolonization narratives that focus on colonial policy-makers or Cold War competition, especially in Africa, where the consensus of colonial elites was that African colonial holdings would remain under dominion for the foreseeable future even if the empire might be rolled back in South Asia or the Middle East. Babou emphasizes the liberation efforts of colonized people in winning their independence while also noting the difficulties faced by newly independent countries due to years of imperialism that had depleted the economic and political viability of the new nation. This view supports Babou’s claim that continued study of imperialism and colonialism is essential.

Mahmood Mamdani, “ Settler Colonialism: Then and Now ,” Critical Inquiry 41, no. 3 (2015): 596–614.

Mahmood Mamdani begins with the premise that “Africa is the continent where settler colonialism has been defeated; America is where settler colonialism triumphed.” Then, he seeks to turn this paradigm on its head by looking at America from an African perspective. What emerges is an evaluation of American history as a settler colonial state—further placing the United States rightfully in the discourse on imperialism.

Antoinette Burton, “S Is for SCORPION,” in Animalia: An Anti-Imperial Bestiary for Our Times , ed. Antoinette Burton and Renisa Mawani (Duke University Press, 2020): 163–70.

In their edited volume, Animalia, Antoinette Burton and Renisa Mawani use the form of a bestiary to critically examine British constructions of imperial knowledge that sought to classify animals in addition to their colonial human subjects. As they rightly point out, animals often “interrupted” imperial projects, thus impacting the physical and psychological realities of those living in the colonies. The selected chapter focuses on the scorpion, a “recurrent figure in the modern British imperial imagination” and the various ways it was used as a “biopolitical symbol,” especially in Afghanistan.

Editor’s Note: The details of Edward Said’s education have been corrected.

Weekly Newsletter

Get your fix of JSTOR Daily’s best stories in your inbox each Thursday.

Privacy Policy Contact Us You may unsubscribe at any time by clicking on the provided link on any marketing message.

Support JSTOR Daily! Join our new membership program on Patreon today.

JSTOR is a digital library for scholars, researchers, and students. JSTOR Daily readers can access the original research behind our articles for free on JSTOR.

Get Our Newsletter

More stories.

- The Post Office and Privacy

- The British Empire’s Bid to Stamp Out “Chinese Slavery”

- Tramping Across the USSR (On One Leg)

- Harvey Houses: Serving the West

Recent Posts

- How Government Helped Birth the Advertising Industry

Support JSTOR Daily

Sign up for our weekly newsletter.

- Search Menu

- Browse content in Arts and Humanities

- Browse content in Archaeology

- Anglo-Saxon and Medieval Archaeology

- Archaeological Methodology and Techniques

- Archaeology by Region

- Archaeology of Religion

- Archaeology of Trade and Exchange

- Biblical Archaeology

- Contemporary and Public Archaeology

- Environmental Archaeology

- Historical Archaeology

- History and Theory of Archaeology

- Industrial Archaeology

- Landscape Archaeology

- Mortuary Archaeology

- Prehistoric Archaeology

- Underwater Archaeology

- Urban Archaeology

- Zooarchaeology

- Browse content in Architecture

- Architectural Structure and Design

- History of Architecture

- Residential and Domestic Buildings

- Theory of Architecture

- Browse content in Art

- Art Subjects and Themes

- History of Art

- Industrial and Commercial Art

- Theory of Art

- Biographical Studies

- Byzantine Studies

- Browse content in Classical Studies

- Classical Literature

- Classical Reception

- Classical History

- Classical Philosophy

- Classical Mythology

- Classical Art and Architecture

- Classical Oratory and Rhetoric

- Greek and Roman Archaeology

- Greek and Roman Epigraphy

- Greek and Roman Law

- Greek and Roman Papyrology

- Late Antiquity

- Religion in the Ancient World

- Digital Humanities

- Browse content in History

- Colonialism and Imperialism

- Diplomatic History

- Environmental History

- Genealogy, Heraldry, Names, and Honours

- Genocide and Ethnic Cleansing

- Historical Geography

- History by Period

- History of Agriculture

- History of Education

- History of Emotions

- History of Gender and Sexuality

- Industrial History

- Intellectual History

- International History

- Labour History

- Legal and Constitutional History

- Local and Family History

- Maritime History

- Military History

- National Liberation and Post-Colonialism

- Oral History

- Political History

- Public History

- Regional and National History

- Revolutions and Rebellions

- Slavery and Abolition of Slavery

- Social and Cultural History

- Theory, Methods, and Historiography

- Urban History

- World History

- Browse content in Language Teaching and Learning

- Language Learning (Specific Skills)

- Language Teaching Theory and Methods

- Browse content in Linguistics

- Applied Linguistics

- Cognitive Linguistics

- Computational Linguistics

- Forensic Linguistics

- Grammar, Syntax and Morphology

- Historical and Diachronic Linguistics

- History of English

- Language Variation

- Language Families

- Language Acquisition

- Language Evolution

- Language Reference

- Lexicography

- Linguistic Theories

- Linguistic Typology

- Linguistic Anthropology

- Phonetics and Phonology

- Psycholinguistics

- Sociolinguistics

- Translation and Interpretation

- Writing Systems

- Browse content in Literature

- Bibliography

- Children's Literature Studies

- Literary Studies (Modernism)

- Literary Studies (Asian)

- Literary Studies (European)

- Literary Studies (Eco-criticism)

- Literary Studies (Romanticism)

- Literary Studies (American)

- Literary Studies - World

- Literary Studies (1500 to 1800)

- Literary Studies (19th Century)

- Literary Studies (20th Century onwards)

- Literary Studies (African American Literature)

- Literary Studies (British and Irish)

- Literary Studies (Early and Medieval)

- Literary Studies (Fiction, Novelists, and Prose Writers)

- Literary Studies (Gender Studies)

- Literary Studies (Graphic Novels)

- Literary Studies (History of the Book)

- Literary Studies (Plays and Playwrights)

- Literary Studies (Poetry and Poets)

- Literary Studies (Postcolonial Literature)

- Literary Studies (Queer Studies)

- Literary Studies (Science Fiction)

- Literary Studies (Travel Literature)

- Literary Studies (War Literature)

- Literary Studies (Women's Writing)

- Literary Theory and Cultural Studies

- Mythology and Folklore

- Shakespeare Studies and Criticism

- Browse content in Media Studies

- Browse content in Music

- Applied Music

- Dance and Music

- Ethics in Music

- Ethnomusicology

- Gender and Sexuality in Music

- Medicine and Music

- Music Cultures

- Music and Culture

- Music and Religion

- Music and Media

- Music Education and Pedagogy

- Music Theory and Analysis

- Musical Scores, Lyrics, and Libretti

- Musical Structures, Styles, and Techniques

- Musicology and Music History

- Performance Practice and Studies

- Race and Ethnicity in Music

- Sound Studies

- Browse content in Performing Arts

- Browse content in Philosophy

- Aesthetics and Philosophy of Art

- Epistemology

- Feminist Philosophy

- History of Western Philosophy

- Metaphysics

- Moral Philosophy

- Non-Western Philosophy

- Philosophy of Action

- Philosophy of Law

- Philosophy of Religion

- Philosophy of Science

- Philosophy of Language

- Philosophy of Mind

- Philosophy of Perception

- Philosophy of Mathematics and Logic

- Practical Ethics

- Social and Political Philosophy

- Browse content in Religion

- Biblical Studies

- Christianity

- East Asian Religions

- History of Religion

- Judaism and Jewish Studies

- Qumran Studies

- Religion and Education

- Religion and Health

- Religion and Politics

- Religion and Science

- Religion and Law

- Religion and Art, Literature, and Music

- Religious Studies

- Browse content in Society and Culture

- Cookery, Food, and Drink

- Cultural Studies

- Customs and Traditions

- Ethical Issues and Debates

- Hobbies, Games, Arts and Crafts

- Lifestyle, Home, and Garden

- Natural world, Country Life, and Pets

- Popular Beliefs and Controversial Knowledge

- Sports and Outdoor Recreation

- Technology and Society

- Travel and Holiday

- Visual Culture

- Browse content in Law

- Arbitration

- Browse content in Company and Commercial Law

- Commercial Law

- Company Law

- Browse content in Comparative Law

- Systems of Law

- Competition Law

- Browse content in Constitutional and Administrative Law

- Government Powers

- Judicial Review

- Local Government Law

- Military and Defence Law

- Parliamentary and Legislative Practice

- Construction Law

- Contract Law

- Browse content in Criminal Law

- Criminal Procedure

- Criminal Evidence Law

- Sentencing and Punishment

- Employment and Labour Law

- Environment and Energy Law

- Browse content in Financial Law

- Banking Law

- Insolvency Law

- History of Law

- Human Rights and Immigration

- Intellectual Property Law

- Browse content in International Law

- Private International Law and Conflict of Laws

- Public International Law

- IT and Communications Law

- Jurisprudence and Philosophy of Law

- Law and Society

- Law and Politics

- Browse content in Legal System and Practice

- Courts and Procedure

- Legal Skills and Practice

- Primary Sources of Law

- Regulation of Legal Profession

- Medical and Healthcare Law

- Browse content in Policing

- Criminal Investigation and Detection

- Police and Security Services

- Police Procedure and Law

- Police Regional Planning

- Browse content in Property Law

- Personal Property Law

- Study and Revision

- Terrorism and National Security Law

- Browse content in Trusts Law

- Wills and Probate or Succession

- Browse content in Medicine and Health

- Browse content in Allied Health Professions

- Arts Therapies

- Clinical Science

- Dietetics and Nutrition

- Occupational Therapy

- Operating Department Practice

- Physiotherapy

- Radiography

- Speech and Language Therapy

- Browse content in Anaesthetics

- General Anaesthesia

- Neuroanaesthesia

- Browse content in Clinical Medicine

- Acute Medicine

- Cardiovascular Medicine

- Clinical Genetics

- Clinical Pharmacology and Therapeutics

- Dermatology

- Endocrinology and Diabetes

- Gastroenterology

- Genito-urinary Medicine

- Geriatric Medicine

- Infectious Diseases

- Medical Oncology

- Medical Toxicology

- Pain Medicine

- Palliative Medicine

- Rehabilitation Medicine

- Respiratory Medicine and Pulmonology

- Rheumatology

- Sleep Medicine

- Sports and Exercise Medicine

- Clinical Neuroscience

- Community Medical Services

- Critical Care

- Emergency Medicine

- Forensic Medicine

- Haematology

- History of Medicine

- Medical Ethics

- Browse content in Medical Dentistry

- Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery

- Paediatric Dentistry

- Restorative Dentistry and Orthodontics

- Surgical Dentistry

- Browse content in Medical Skills

- Clinical Skills

- Communication Skills

- Nursing Skills

- Surgical Skills

- Medical Statistics and Methodology

- Browse content in Neurology

- Clinical Neurophysiology

- Neuropathology

- Nursing Studies

- Browse content in Obstetrics and Gynaecology

- Gynaecology

- Occupational Medicine

- Ophthalmology

- Otolaryngology (ENT)

- Browse content in Paediatrics

- Neonatology

- Browse content in Pathology

- Chemical Pathology

- Clinical Cytogenetics and Molecular Genetics

- Histopathology

- Medical Microbiology and Virology

- Patient Education and Information

- Browse content in Pharmacology

- Psychopharmacology

- Browse content in Popular Health

- Caring for Others

- Complementary and Alternative Medicine

- Self-help and Personal Development

- Browse content in Preclinical Medicine

- Cell Biology

- Molecular Biology and Genetics

- Reproduction, Growth and Development

- Primary Care

- Professional Development in Medicine

- Browse content in Psychiatry

- Addiction Medicine

- Child and Adolescent Psychiatry

- Forensic Psychiatry

- Learning Disabilities

- Old Age Psychiatry

- Psychotherapy

- Browse content in Public Health and Epidemiology

- Epidemiology

- Public Health

- Browse content in Radiology

- Clinical Radiology

- Interventional Radiology

- Nuclear Medicine

- Radiation Oncology

- Reproductive Medicine

- Browse content in Surgery

- Cardiothoracic Surgery

- Gastro-intestinal and Colorectal Surgery

- General Surgery

- Neurosurgery

- Paediatric Surgery

- Peri-operative Care

- Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery

- Surgical Oncology

- Transplant Surgery

- Trauma and Orthopaedic Surgery

- Vascular Surgery

- Browse content in Science and Mathematics

- Browse content in Biological Sciences

- Aquatic Biology

- Biochemistry

- Bioinformatics and Computational Biology

- Developmental Biology

- Ecology and Conservation

- Evolutionary Biology

- Genetics and Genomics

- Microbiology

- Molecular and Cell Biology

- Natural History

- Plant Sciences and Forestry

- Research Methods in Life Sciences

- Structural Biology

- Systems Biology

- Zoology and Animal Sciences

- Browse content in Chemistry

- Analytical Chemistry

- Computational Chemistry

- Crystallography

- Environmental Chemistry

- Industrial Chemistry

- Inorganic Chemistry

- Materials Chemistry

- Medicinal Chemistry

- Mineralogy and Gems

- Organic Chemistry

- Physical Chemistry

- Polymer Chemistry

- Study and Communication Skills in Chemistry

- Theoretical Chemistry

- Browse content in Computer Science

- Artificial Intelligence

- Computer Architecture and Logic Design

- Game Studies

- Human-Computer Interaction

- Mathematical Theory of Computation

- Programming Languages

- Software Engineering

- Systems Analysis and Design

- Virtual Reality

- Browse content in Computing

- Business Applications

- Computer Games

- Computer Security

- Computer Networking and Communications

- Digital Lifestyle

- Graphical and Digital Media Applications

- Operating Systems

- Browse content in Earth Sciences and Geography

- Atmospheric Sciences

- Environmental Geography

- Geology and the Lithosphere

- Maps and Map-making

- Meteorology and Climatology

- Oceanography and Hydrology

- Palaeontology

- Physical Geography and Topography

- Regional Geography

- Soil Science

- Urban Geography

- Browse content in Engineering and Technology

- Agriculture and Farming

- Biological Engineering

- Civil Engineering, Surveying, and Building

- Electronics and Communications Engineering

- Energy Technology

- Engineering (General)

- Environmental Science, Engineering, and Technology

- History of Engineering and Technology

- Mechanical Engineering and Materials

- Technology of Industrial Chemistry

- Transport Technology and Trades

- Browse content in Environmental Science

- Applied Ecology (Environmental Science)

- Conservation of the Environment (Environmental Science)

- Environmental Sustainability

- Environmentalist Thought and Ideology (Environmental Science)

- Management of Land and Natural Resources (Environmental Science)

- Natural Disasters (Environmental Science)

- Nuclear Issues (Environmental Science)

- Pollution and Threats to the Environment (Environmental Science)

- Social Impact of Environmental Issues (Environmental Science)

- History of Science and Technology

- Browse content in Materials Science

- Ceramics and Glasses

- Composite Materials

- Metals, Alloying, and Corrosion

- Nanotechnology

- Browse content in Mathematics

- Applied Mathematics

- Biomathematics and Statistics

- History of Mathematics

- Mathematical Education

- Mathematical Finance

- Mathematical Analysis

- Numerical and Computational Mathematics

- Probability and Statistics

- Pure Mathematics

- Browse content in Neuroscience

- Cognition and Behavioural Neuroscience

- Development of the Nervous System

- Disorders of the Nervous System

- History of Neuroscience

- Invertebrate Neurobiology

- Molecular and Cellular Systems

- Neuroendocrinology and Autonomic Nervous System

- Neuroscientific Techniques

- Sensory and Motor Systems

- Browse content in Physics

- Astronomy and Astrophysics

- Atomic, Molecular, and Optical Physics

- Biological and Medical Physics

- Classical Mechanics

- Computational Physics

- Condensed Matter Physics

- Electromagnetism, Optics, and Acoustics

- History of Physics

- Mathematical and Statistical Physics

- Measurement Science

- Nuclear Physics

- Particles and Fields

- Plasma Physics

- Quantum Physics

- Relativity and Gravitation

- Semiconductor and Mesoscopic Physics

- Browse content in Psychology

- Affective Sciences

- Clinical Psychology

- Cognitive Neuroscience

- Cognitive Psychology

- Criminal and Forensic Psychology

- Developmental Psychology

- Educational Psychology

- Evolutionary Psychology

- Health Psychology

- History and Systems in Psychology

- Music Psychology

- Neuropsychology

- Organizational Psychology

- Psychological Assessment and Testing

- Psychology of Human-Technology Interaction

- Psychology Professional Development and Training

- Research Methods in Psychology

- Social Psychology

- Browse content in Social Sciences

- Browse content in Anthropology

- Anthropology of Religion

- Human Evolution

- Medical Anthropology

- Physical Anthropology

- Regional Anthropology

- Social and Cultural Anthropology

- Theory and Practice of Anthropology

- Browse content in Business and Management

- Business History

- Business Strategy

- Business Ethics

- Business and Government

- Business and Technology

- Business and the Environment

- Comparative Management

- Corporate Governance

- Corporate Social Responsibility

- Entrepreneurship

- Health Management

- Human Resource Management

- Industrial and Employment Relations

- Industry Studies

- Information and Communication Technologies

- International Business

- Knowledge Management

- Management and Management Techniques

- Operations Management

- Organizational Theory and Behaviour

- Pensions and Pension Management

- Public and Nonprofit Management

- Strategic Management

- Supply Chain Management

- Browse content in Criminology and Criminal Justice

- Criminal Justice

- Criminology

- Forms of Crime

- International and Comparative Criminology

- Youth Violence and Juvenile Justice

- Development Studies

- Browse content in Economics

- Agricultural, Environmental, and Natural Resource Economics

- Asian Economics

- Behavioural Finance

- Behavioural Economics and Neuroeconomics

- Econometrics and Mathematical Economics

- Economic Methodology

- Economic Systems

- Economic History

- Economic Development and Growth

- Financial Markets

- Financial Institutions and Services

- General Economics and Teaching

- Health, Education, and Welfare

- History of Economic Thought

- International Economics

- Labour and Demographic Economics

- Law and Economics

- Macroeconomics and Monetary Economics

- Microeconomics

- Public Economics

- Urban, Rural, and Regional Economics

- Welfare Economics

- Browse content in Education

- Adult Education and Continuous Learning

- Care and Counselling of Students

- Early Childhood and Elementary Education

- Educational Equipment and Technology

- Educational Strategies and Policy

- Higher and Further Education

- Organization and Management of Education

- Philosophy and Theory of Education

- Schools Studies

- Secondary Education

- Teaching of a Specific Subject

- Teaching of Specific Groups and Special Educational Needs

- Teaching Skills and Techniques

- Browse content in Environment

- Applied Ecology (Social Science)

- Climate Change

- Conservation of the Environment (Social Science)

- Environmentalist Thought and Ideology (Social Science)

- Natural Disasters (Environment)

- Social Impact of Environmental Issues (Social Science)

- Browse content in Human Geography

- Cultural Geography

- Economic Geography

- Political Geography

- Browse content in Interdisciplinary Studies

- Communication Studies

- Museums, Libraries, and Information Sciences

- Browse content in Politics

- African Politics

- Asian Politics

- Chinese Politics

- Comparative Politics

- Conflict Politics

- Elections and Electoral Studies

- Environmental Politics

- European Union

- Foreign Policy

- Gender and Politics

- Human Rights and Politics

- Indian Politics

- International Relations

- International Organization (Politics)

- International Political Economy

- Irish Politics

- Latin American Politics

- Middle Eastern Politics

- Political Theory

- Political Methodology

- Political Communication

- Political Philosophy

- Political Sociology

- Political Behaviour

- Political Economy

- Political Institutions

- Politics and Law

- Public Administration

- Public Policy

- Quantitative Political Methodology

- Regional Political Studies

- Russian Politics

- Security Studies

- State and Local Government

- UK Politics

- US Politics

- Browse content in Regional and Area Studies

- African Studies

- Asian Studies

- East Asian Studies

- Japanese Studies

- Latin American Studies

- Middle Eastern Studies

- Native American Studies

- Scottish Studies

- Browse content in Research and Information

- Research Methods

- Browse content in Social Work

- Addictions and Substance Misuse

- Adoption and Fostering

- Care of the Elderly

- Child and Adolescent Social Work

- Couple and Family Social Work

- Developmental and Physical Disabilities Social Work

- Direct Practice and Clinical Social Work

- Emergency Services

- Human Behaviour and the Social Environment

- International and Global Issues in Social Work

- Mental and Behavioural Health

- Social Justice and Human Rights

- Social Policy and Advocacy

- Social Work and Crime and Justice

- Social Work Macro Practice

- Social Work Practice Settings

- Social Work Research and Evidence-based Practice

- Welfare and Benefit Systems

- Browse content in Sociology

- Childhood Studies

- Community Development

- Comparative and Historical Sociology

- Economic Sociology

- Gender and Sexuality

- Gerontology and Ageing

- Health, Illness, and Medicine

- Marriage and the Family

- Migration Studies

- Occupations, Professions, and Work

- Organizations

- Population and Demography

- Race and Ethnicity

- Social Theory

- Social Movements and Social Change

- Social Research and Statistics

- Social Stratification, Inequality, and Mobility

- Sociology of Religion

- Sociology of Education

- Sport and Leisure

- Urban and Rural Studies

- Browse content in Warfare and Defence

- Defence Strategy, Planning, and Research

- Land Forces and Warfare

- Military Administration

- Military Life and Institutions

- Naval Forces and Warfare

- Other Warfare and Defence Issues

- Peace Studies and Conflict Resolution

- Weapons and Equipment

- < Previous chapter

- Next chapter >

5 (page 91) p. 91 Colonialism in Africa

- Published: March 2007

- Cite Icon Cite

- Permissions Icon Permissions

The period of colonial rule in Africa came late and did not last very long. Africa was conquered by European imperial powers in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. By the 1960s, it was mostly over. ‘Colonialism in Africa’ considers how this period shaped African history. For some Africans, colonial rule was threatening; for others, an opportunity. Reconstructing the complicated patterns of this time is a massive challenge for historians of Africa. Interest in Africa' colonial past has waxed and waned, and resurged recently. Colonialism was not just about the actions of the Europeans, it was also about the actions of the Africans and what they thought.

Signed in as

Institutional accounts.

- GoogleCrawler [DO NOT DELETE]

- Google Scholar Indexing

Personal account

- Sign in with email/username & password

- Get email alerts

- Save searches

- Purchase content

- Activate your purchase/trial code

- Add your ORCID iD

Institutional access

Sign in with a library card.

- Sign in with username/password

- Recommend to your librarian

- Institutional account management

- Get help with access

Access to content on Oxford Academic is often provided through institutional subscriptions and purchases. If you are a member of an institution with an active account, you may be able to access content in one of the following ways:

IP based access

Typically, access is provided across an institutional network to a range of IP addresses. This authentication occurs automatically, and it is not possible to sign out of an IP authenticated account.

Sign in through your institution

Choose this option to get remote access when outside your institution. Shibboleth/Open Athens technology is used to provide single sign-on between your institution’s website and Oxford Academic.

- Click Sign in through your institution.

- Select your institution from the list provided, which will take you to your institution's website to sign in.

- When on the institution site, please use the credentials provided by your institution. Do not use an Oxford Academic personal account.

- Following successful sign in, you will be returned to Oxford Academic.

If your institution is not listed or you cannot sign in to your institution’s website, please contact your librarian or administrator.

Enter your library card number to sign in. If you cannot sign in, please contact your librarian.

Society Members

Society member access to a journal is achieved in one of the following ways:

Sign in through society site

Many societies offer single sign-on between the society website and Oxford Academic. If you see ‘Sign in through society site’ in the sign in pane within a journal:

- Click Sign in through society site.

- When on the society site, please use the credentials provided by that society. Do not use an Oxford Academic personal account.

If you do not have a society account or have forgotten your username or password, please contact your society.

Sign in using a personal account

Some societies use Oxford Academic personal accounts to provide access to their members. See below.

A personal account can be used to get email alerts, save searches, purchase content, and activate subscriptions.

Some societies use Oxford Academic personal accounts to provide access to their members.

Viewing your signed in accounts

Click the account icon in the top right to:

- View your signed in personal account and access account management features.

- View the institutional accounts that are providing access.

Signed in but can't access content

Oxford Academic is home to a wide variety of products. The institutional subscription may not cover the content that you are trying to access. If you believe you should have access to that content, please contact your librarian.

For librarians and administrators, your personal account also provides access to institutional account management. Here you will find options to view and activate subscriptions, manage institutional settings and access options, access usage statistics, and more.

Our books are available by subscription or purchase to libraries and institutions.

- About Oxford Academic

- Publish journals with us

- University press partners

- What we publish

- New features

- Open access

- Rights and permissions

- Accessibility

- Advertising

- Media enquiries

- Oxford University Press

- Oxford Languages

- University of Oxford

Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the University's objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide

- Copyright © 2024 Oxford University Press

- Cookie settings

- Cookie policy

- Privacy policy

- Legal notice

This Feature Is Available To Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account

This PDF is available to Subscribers Only

For full access to this pdf, sign in to an existing account, or purchase an annual subscription.

European Imperialism in West Africa

- Living reference work entry

- First Online: 26 June 2020

- Cite this living reference work entry

- Mark Omorovie Ikeke 3

133 Accesses

The imperialist venture in West Africa was vast and spanned many years and epochs, and hence, cannot be covered in any chapter comprehensively. It will give a brief definition of imperialism, highlight some aspects of imperialism in West Africa, look at some reasons for imperialism in West Africa, examine the effects of imperialism in West Africa, present some of the responses to imperialism, and thereafter conclude. The study is done from a critical anti-imperialist point of view.

Introduction

It is important to note from the outset that an essay on European imperialism in West Africa cannot be comprehensive as the imperialist venture in West Africa was vast and spanned many years and epochs. No doubt the topic is the subject of entire textbooks and university courses. Because of this, this essay is by its nature skeletal and selective. It will give a brief definition of imperialism, highlight some aspects of imperialism in West Africa, look at some reasons for imperialism...

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this chapter

Institutional subscriptions

Aghalino, S. O. (2006). Dynamics of constitutional development in Nigeria, 1914–1999. Indian Journal of Politics, 40 (2–3), 49–62.

Google Scholar

Akinyeye, Y. (2012). West Africa in British and French geo-politics, 1886–1945. In L. E. Otoide (Ed.), History unlimited: Essays in honour of professor Abednego Ekoko (pp. 145–161). Benin City: Mindex Publishing Co. Ltd..

Asiwaju, A. I. (1977). Migration as an expression of revolt: The example of French West Africa up to 1945. Tarikh, 5 (3), 36–37.

Babatunde, O. O. (2014). Constitutional development: Clifford constitution of 1922. https://profseunoyediji.wordpress.com/2014/10/11/constitutional-development-clifford-constitution-of-1922/ . Accessed 27 May 2015.

Chaturvedi, A. K. (2006). Academic’s dictionary of political science . New Delhi: Academic (India) Publishers.

Chikendu, P. N. (2004). Imperialism & nationalism . Enugu: Academic Publishing Company.

Chilsen, S. (2009). Light in the dark continent: British imperialism in West Africa. www.Minds.wisconsin.edu/bitstream/handle/1793/35478/Chilsen.doc?sequence . Accessed 9 Dec 2013.

Dutt, A. K. (2010). Imperialism and war. In N. J. Young (Ed.), The Oxford international encyclopedia of peace (pp. 393–397). New York: Oxford University Press.

Fanon, F. (1968). The wretched of the earth . New York: Grove Weidenfeld.

Hobson, J. A. (1902). Imperialism: A study . New York: James Pott and Co.

Igwe, O. (2005). Politics and globe dictionary . Aba: Eagle Publishers.

Lenin, V. I. (1917). Imperialism, the highest stage of capitalism . Petrograd: Znaniye Publishers.

Nkrumah, K. (1965). Neo-colonialism: The last stage of imperialism . London: Thomas Nelson & Sons.

Okoduwa, A. I., & Ibhasebhor, S. E. (2005). European imperialism and African reactions . Benin City: Borwin Publishers.

Rodney, W. (1972). How Europe underdeveloped Africa . London: Bogle-Ouverture Publications.

Download references

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Delta State University, Abraka, Nigeria

Mark Omorovie Ikeke

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Mark Omorovie Ikeke .

Editor information

Editors and affiliations.

Graduate Center for Worker Education, Brooklyn College, New York, NY, USA

Immanuel Ness

Independent Scholar, Belfast, UK

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

Copyright information

© 2020 The Author(s), under exclusive licence to Springer Nature Switzerland AG

About this entry

Cite this entry.

Ikeke, M.O. (2020). European Imperialism in West Africa. In: Ness, I., Cope, Z. (eds) The Palgrave Encyclopedia of Imperialism and Anti-Imperialism. Palgrave Macmillan, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-91206-6_206-1

Download citation

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-91206-6_206-1

Received : 29 May 2020

Accepted : 29 May 2020

Published : 26 June 2020

Publisher Name : Palgrave Macmillan, Cham

Print ISBN : 978-3-319-91206-6

Online ISBN : 978-3-319-91206-6

eBook Packages : Springer Reference History Reference Module Humanities and Social Sciences Reference Module Humanities

- Publish with us

Policies and ethics

- Find a journal

- Track your research

- Monthly Review Essays

- Climate & Capitalism

- Money on the Left

Imperialism and Anti-Imperialism in Africa

When international media were broadcasting live video footage of Tunisians gathering in hundreds of thousands in front of the central office in Tunis of the long-terrifying ministry of home security, chanting in one voice “the people want to bring down the regime,” something had already changed: ordinary people realized they could make huge changes. 2 Weeks later, the Egyptian uprising removed the Mubarak regime that had been entrenched in power for over thirty years. Fearmongering, police violence, exploitation, and rigged electoral systems could not stop the wave of protests. The neoliberal forms of imperial rule that had destroyed the hopes of the liberation movements were under attack. In order to counter the possibilities for a massive breakthrough at the popular level, the Western forces mounted an invasion of Libya using the mantra of humanitarianism to disrupt, militarily, political and economic life in Africa. Later in collusion with the counter-revolutionary forces in the Egyptian military, Western imperialism sought to roll back the gains of people in the streets of Tunis and Cairo. NATO, as the force for the defense of the financial oligarchs, sought to squash all forms of anti-imperialism in Africa, but the NATO intervention and its catastrophic aftermath only strengthened the resurgence of anti-imperialist ideas among the peoples of Africa. 3

What developed on the streets of Cairo could not readily emerge into an agreed program for social change because for decades neoliberal ideas about making societies safe for markets and foreign direct investment had polluted the official intellectual spaces. Imperialism in Africa had matured from the cruder colonial forms and worked through the Bretton Woods institutions while unleashing divisive ideas on cultural and religious levels. At the base, fundamentalist religious formations were the vanguard of penetration—spewing ideas about the subordination of women and disrespect for peoples of different faiths.

For the educated, authorities on colonialism such as Geoffrey Kay and Anne Phillips have led to a rejection of the scholarship of Walter Rodney’s book, How Europe Underdeveloped Africa . 4 Rodney had argued that capitalism and imperialism blocked the economic transformation of Africa. Figures like Kay and Phillips joined with colonial apologists such as Lewis Gann and Peter Duignan, who claimed that colonialism was beneficial for Africans, and that capitalism created underdevelopment in Africa because it was not exploitative enough. 5 Even those who disagreed with the outright colonial apologists adopted the balance-sheet approach to European penetration in Africa. They argued that while there may have been excesses and unfortunate incidents, on balance, colonialism brought education, health, and sanitation to Africa. 6 The barbarism of today’s imperialism is often neglected in the left scholarship of figures like Michael Hardt and Antonio Negri in Empire . 7

Yet, Africa remains the space of the worst forms of exploitation of the capitalist system and has inspired continuity in anti-imperialism from colonial times to the present. Today, in the twenty-first century, the older forms of class mobilization of the national liberation era have exhausted their potential and there are new social forces that have arisen that are fighting for reparative justice, peace, life, health, and the repair of the natural environment. These movements, and their anti-imperialist ideas, had kept the flames of African freedom burning. The uprisings of 2011 served to counter the pessimistic notions of Africa that had become an accepted part of Western imperial culture, and with the phrase “failed states,” repeated ad nauseam. The application of Marxist anti-imperialist thought in the work of Amilcar Cabral and Rodney now re-emerges as guide to a new wave of African anti-imperialism.

Piracy on Dry Land

We will simply state that imperialism can be defined as a worldwide expression of the search for profits and the ever-increasing accumulation of surplus value by monopoly-financial capital centered in two parts of the world; first in Europe, and then in North America. And if we wish to place the fact of imperialism within the general trajectory of the evolution of the transcendental factor, which has changed the face of the world, namely capital and the process of its accumulation, we can say that imperialism is piracy transplanted from the seas to dry land. It is piracy reorganized, consolidated, and adapted to the aim of exploiting the natural and human resources of our peoples.

When Cabral, the African freedom fighter, wrote that imperialism was “piracy on dry land,” he was continuing a debate that had started in the early twentieth century about monopoly capital and the export of capital. 8 Lenin had written in the midst of the First World War and had been very clear on the relationship between imperialism and war. However, what was disputed in his analysis was the question of whether there had been the export of capital to Africa similar to the massive export of capital to places such as Argentina, Eastern Europe, or the United States. An important book to propagate the idea of a non-economic, humanitarian impulse behind Britain’s imperial policies is entitled Africa and the Victorians by Ronald Robinson and John Gallagher. The book supposedly challenged Lenin’s theory about the export of capital by drawing attention to the fact that there had been no major export of capital to Africa by the time of the great war between the imperial powers. Robinson and Gallagher were not Marxists, but some Marxists like Bill Warren of the United Kingdom argued, on what were purportedly Leninist grounds, that capitalist imperialism, even in the form of direct colonial rule, performed a historically highly progressive role in non-European societies, economically, culturally, and politically: through capital exports it laid the foundation for a development of the productive forces and of a vibrant, indigenously rooted capitalism. 9

Rodney answered these criticisms of Lenin’s analysis with respect to imperialism as early as 1970, in his little-known essay “The Imperial Partition of Africa.” Lenin, Rodney pointed out, had never argued that the export of capital applied in his time to Africa, which still occupied a marginal role—since the imperialist partition and penetration of Africa was so recent. As Rodney said of the supposed inapplicability of the export of capital to late-nineteenth- and early-twentieth-century capitalism in Africa, “This is a contradiction of Lenin only for those who have not read Lenin.” 10 It had its basis in a confusion of the partition of Africa with the full development of imperialism in the continent, rather than simply its necessary condition. In his historically based analysis, Rodney did not present imperialism as a uniform process but as a general historical process or tendency that took different forms in distinct regions based on varying circumstances, combining a myriad of economic, political, and cultural factors.

Nonetheless, such questions do serve to highlight that Africa was not historically an object of the export of capital, nor integrated directly into the system even in terms of economic dependency, until well into the twentieth century. Rather it was relegated to the position of a natural resource and labor reserve, subject from the beginning to a particularly extreme form of extractivism. This was later developed more fully in the late twentieth century in the context of the emergence of independent African states, without, however, altering the essential relation. Moreover, this was invariably tied to cultural imperialism that was imposed in the form of a hegemonic racism, rooted in the history of the trans-Atlantic slave trade. Political, economic, and cultural forces imposed by the penetration of imperialism into Africa therefore all contributed to the historical process that Rodney described as How Europe Underdeveloped Africa .

The interpretation of capitalist imperialism as a force for cultural and economic progress in Africa is an element in the neoliberal darkness that descended in the last decades, erasing the history of European imperialism in Africa and eluding the reality of imperialism today. In contrast, Cabral’s conception of “imperialism as piracy on dry land” drove home the point that the looting and plunder, both during and after the notorious scramble for Africa, must constitute the beginning of all meaningful analysis in this area. The origins of this system of pillage, and that of industrial capitalism itself, can be found in the European establishment of outposts for the trans-Atlantic slave trade. Karl Marx had grasped the importance of Africa to global capitalist accumulation when he wrote in Capital that the “discovery of gold and silver in America, the extirpation, enslavement and entombment in mines of the aboriginal population, the beginning of the conquest and looting of the East Indies, the turning of Africa into a warren for the commercial hunting of black-skins, signaled the rosy dawn of the era of capitalist production.” 11

By the end of the nineteenth century, European capitalism had accumulated enough military and economic power to impose Western economic domination over most of Asia and the Pacific islands. The notorious scramble for Africa was formalized in the Berlin Conference of 1884–1885 that divided Africa among the European powers. Rodney pointed out that the imperial partition of Africa was merely the preface to its exploitation, which was soon interrupted by war. Indeed, the increasing tensions between the major powers, often over African territory, eventually led to the world war: this had been recognized before Lenin by W.E.B. Du Bois who had written on “The African Roots of War” in 1915. 12 While Du Bois and Lenin grasped the importance of the partitioning of Africa, during the twentieth century the relevance of Lenin’s thesis to Africa was much disputed, with a focus on the export of capital question. In a little known essay, Rodney explained:

Lenin is generally said to have professed an “economic” theory of imperialism. This gave rise to the criticism that his theory was one sided, because Europeans carved up Africa for several reasons, including economic, political, social-humanitarian, and psychological. Of course, Marxism does not concern itself solely with some so-called “economic” aspect of society. It is a world view which perceives the presence of multiple variants within the complexity of human society, and seeks to unravel their relationship with reference to the material conditions of existence. Lenin did not have to spell out this elementary Marxist position in everything he wrote. His essay on imperialism dealt with the question of the expansion of the capitalist economy. The non-economic dimensions were known to exist, and were regarded as secondary. 13

Rodney then quotes Lenin to zero in on the point of the non-economic dimensions of imperialism: “The non-economic superstructure which grows up on the basis of finance capital, its politics and its ideology stimulates the striving for colonial conquest.” 14 The importance of Rodney’s intervention was his highlighting of the deep ways that imperialism affected all the regions of Africa. Rodney excavated the pseudoscientific, religious, and cultural basis of racism, inseparable from the smug self-justified looting of resources in land and minerals. He added that in the period of imperialism, South Africa was the laboratory where the virus of white racism was cultivated. Up to today the two most important non-economic dimensions that connect colonial and post-colonial imperialism are those of military force and racism . Military engagement is still very much present, with the French interventionist forces deployed in places such as Chad, the Central Africa Republic, Mali, and Côte d’Ivoire. The racism of the European Union’s complicity, indifference, and hypocritical response to the ongoing Mediterranean mass drownings needs no comment.

Racism, Sexism, and Imperialism

In his refutation of the bourgeois scholars who had written on the humanitarian motives for colonialism, Rodney was drawing attention to the fact that the rise of Western European racism had an economic base in society. That is, the time around the trans-Atlantic slave trade inspired a new conception of the hierarchy of human beings. The breakthroughs in science and technology in Western Europe during the nineteenth century contributed to ideas about scientific racism and modern eugenics. By the start of the twentieth century, the eugenics movement had refined concepts of white supremacy that polluted all aspects of social and economic life in Western Europe and North America. Lenin had written in Imperialism that, “the receipts of high monopoly capital … makes it economically possible for them to corrupt certain sections of the working class, and for a time a fairly considerable minority and win them to the side of the bourgeoisie of a given industry or nation against all others.” 15 Lenin had drawn attention to how imperialism served to split the working-class movement in Europe by creating opportunism and jingoism among the workers. The two linked aspects go together: imperialism creates the surplus that can be distributed to upper sections of the working classes, and racism directed against the primary victims of imperialism, above all Africans, gives a psychological/cultural benefit to the entire European working class. In order to capture the hearts of the German working classes—and win them away from ideas about revolution and international solidarity—the Nazis stressed cultural principles about family, race, and how the Volk were the foundation for German values. It was in Africa, against the rebellious Herero peoples of Namibia, that the Imperial German military carried out the dress rehearsal for the genocidal policies that were to explode after the capitalist depression of 1929.

Nor were the British much better. The African massacres they perpetrated were many, and the racist system they instituted gave rise eventually to apartheid. 16 John Mackenzie’s book Propaganda and Empire: The Manipulation of British Public Opinion, 1880–1960 detailed the instruments of ideological manipulation that bound the British working classes to imperial adventures, and motivated workers in Britain to fight against other workers in Europe in the meaningless bloodbaths of the First World War.

Both imperialism and colonialism were supported and even impelled by impressive ideological formations that include notions that certain people, often with no more in common than as inhabitants of a certain territory, require and welcome domination as well as forms of knowledge affiliated with domination. We now know that imperialism projected masculinist thinking about power, violence, and male supremacy. Since the end of the last century feminist scholars have enriched our understanding of the masculinist and militarist components of imperial domination. 17 Edward Said’s The Culture of Imperialism helps us to understand the intricate relations between imperialism, race, patriarchy, and some of the most extreme cultural forms of exploitation. 18 Britain was the forerunner of cultural imperialism making Rudyard Kipling (famous for his notion of “the white man’s burden”) its poet laureate.

Both Germany and Britain stood at the apex of the hierarchy of Western imperialism and clashed in wars to dominate the planet. 19 U.S. scholars drew from the intellectual cultures of Germany and Britain in their search for anchors for their own liberalism. Kipling’s “White Man’s Burden,” subtitled “The United States and the Philippine Islands,” was written specifically to urge on the U.S. war on the Philippines. 20

For the oppressed peoples of the world, those now called peoples of color, imperialism was refined by deepening a linear conception of human transformations that placed Europe and capitalism as emerging out of an evolutionary process. White supremacy codified ideas about social Darwinism (“survival of the fittest”), rugged individualism, sexism, the inviolability of the market, private property, and the credo that “Everyone can make it.” The linear view of progress and modernity was also internalized by some Marxists in North America, who believed that revolutions in Africa and other colonized spaces required the leadership of the advanced (mostly white) workers in capitalist countries. Linkages between class and anti-imperialist struggles were slow to develop in such circumstances. Capitalist competition, jingoism, and chauvinism not only precipitated one war, but the ideas of racism and genocidal violence exploded across the world in the Second World War (which was an imperialist war, the expansive nature of which was prefigured by such events as the 1935 Italian invasion of Ethiopia).

The emergence of the United States as the dominant imperial power after the Second World War further exposed the racist basis of capitalism and imperialism, because within the United States resided a large population that suffered from the superexploitation similar to that suffered by Africans in Africa. Even today the growing anti-racist movement in the United States lacks the breadth of the movement against the Vietnam War. In fact the enemy in both cases is exactly the same. The relevant point for an understanding of imperialism today is the reality that war situations emanate directly from acts of resistance to U.S. imperialist domination. Africa in the modern imperium has become a deeply racialized continent, integral to the maintenance of the essential culture of imperialism.

Said, a Palestinian scholar, wrote about the culture of imperial rule and the impact of imperialism on people’s consciousness. He joined Cabral in distinguishing imperialism from colonialism while at the same time linking capitalism and imperialism. Said had defined imperialism as “thinking about, settling on, controlling land that you do not possess, that is distant, that is lived on and owned by others.” 21 He did not expend time on the financial and corporate forms of imperial domination as this work had been done for decades by Marxist and non-Marxist scholars such as Lenin, Rosa Luxemburg, Nikolai Bukharin, Rudolf Hilferding, and John A. Hobson. At the start of the twentieth century these writers had recognized the end of the old forms of competitive industrial capitalism and the emergence of financial and monopolistic capitalism. The concentration and centralization of capital throughout the twentieth century transformed capitalism and by the end of the twentieth century there were scholars writing about super imperialism and the New Imperialism. 22

The specific contribution of Said was the way that he brought out the deeply racist culture of capital which later exploded in the twenty-first century, in what I term the global armaments culture. This armaments culture connects the barons of Wall Street and financialization of the world economy to the arms manufacturers, the media and image managers, information and communication managers, military entrepreneurs, defense contractors, congressional representatives, policy entrepreneurs, university funding, and humanitarian experts. In this way modern imperialism represents itself in racialized forms that are represented to the citizens of imperialist states as agencies for doing good or “aiding Africa.”

U.S. Imperialism, the Military Management of the International System, and Africa

During the period of the Cold War, the United States managed the capitalist international system through anti-Communist ideology (such as “totalitarianism versus democracy”) and, in Said’s sense, culture. With the collapse of the USSR in 1991, the prior ideological management of U.S. dominance became even less coherent, but military resistance was no longer a major obstacle. In the post-Cold War era, the United States was now clearly willing to use military force to achieve political and economic goals. George H.W. Bush had launched a New World Order in the context of the Persian Gulf War, aimed at achieving geopolitical objectives (i.e., control of the pivotal oil region of the world). A little over a decade later, his son George W. Bush invaded Iraq, in what is known in the United States as the Iraq War, to further these same objectives and to impress upon the subordinate imperial states such as Germany and Japan that the United States was more than ever the dominant force among global capitalists. The Persian Gulf War was made possible precisely by the absence of the Soviet Union from the scene—and was prosecuted almost simultaneously with the Soviet demise. For Samir Amin this new imperial domination was set on creating conditions for global apartheid. 23

The emerging international financial system now extended U.S. global dominance in disguised and indirect ways, as well as cruder direct forms. U.S. treasury officials and agents who control the International Monetary Fund (IMF) and World Bank dictated “restructuring” interventions into the internal affairs of supposedly sovereign nations. The resulting unstable system was so rigged that the U.S. dollar benefited from crises that emanated from the skullduggery of U.S. and British bankers. 24 In these moments of crisis, the dollar benefited as a safe haven for international capitalists.

The barons of Wall Street now exercised direct control over the investment portfolios of the countries with large reserves of natural resources. The example of the wide-ranging activities of Goldman Sachs and its dalliance with the Libyan Investment Authority was one of the most recent examples of speculation and scamming, using complex new packages of debt obligations and interest-rate derivatives to appropriate the wealth of what had been the richest of the African states. Predatory capitalism has been most explicit throughout Africa with looting, plunder, massive violence, and the destruction of the natural environment. 25

For Africa, the pre-history of these last disastrous decades was the age of national liberation struggles, evanescent victories, and painful defeats. From the point of view of the anti-imperialist forces, the struggles in Indochina, southern Africa, and Latin America have shaped the politics of the international system since 1945. 26 Vijay Prashad agrees with Amin in placing the volatile relationship between the North and the South from the period of the Bandung conference of 1955 up to the global financial crisis of 2008. In this period, the role of imperial military and economic force underwent substantial change. What has remained constant has been the centrality of African resources for the European states. Belgium, Britain, and France had planned to maintain colonial territories in Africa and link African resources to the British Sterling and the French Franc. The Cold War had dictated that in spite of the post-colonial/neo-colonial basis of U.S. political logic, the United States assisted the remaining European colonialists to suppress freedom fighters in Africa. The United States had opted to leave European military forces to police the African economies. It was in this period that the United States established unified military command structures such as the European Command, the Pacific Command, the Southern Command, the Northern Command, and Central Command. Each command covers an area of responsibility.

When this global command structure was being refined, Africa was an afterthought. Hence, Africa fell under the European Command with its headquarters in Germany. Africa had not been included in the geographic combatant commands because it was expected that France, Britain, Belgium, Germany, Spain, Portugal, and other colonial powers would retain military forces to guarantee Western interests and keep “peace” in Africa. However, the collapse of the Portuguese colonial forces in Mozambique, Angola, Guinea, and Sao Tome, and the collapse of the white racist military forces in Southern Rhodesia (now Zimbabwe), gradually led to a rethinking of this strategy. During this period the United States had labeled all African freedom fighters as terrorists; there was not one African independence struggle that the United States supported. After Congolese leader Patrice Lumumba was assassinated, for thirty-five years the West supported the brutal dictatorship of Mobutu Sese Seko in the Democratic Republic of the Congo. Every credible liberation leader—whether Cabral, Eduardo Mondlane, Samora Machel, Thomas Sankara, Felix Moumie, or Chris Hani—was killed. In fact, in the days when the United States was allied with Osama Bin Laden and Jonas Savimbi, Nelson Mandela had been branded a terrorist. This branding of freedom fighters as terrorists, and the propping up of apartheid and destabilization in Africa, is better understood against the background of the global politics of the Cold War.

The special relationship between the dollar and sterling that had emerged out of the “Atlantic alliance” was eventually to see British financial institutions and the former British colonial territories fall under the domain of U.S. capitalism, as most African states now kept their reserves in the U.S. dollar instead of the pound sterling. In South Africa, Britain’s most valuable sphere of economic dominance in Africa, developmental elements under apartheid were removed along with the regime itself, and replaced by a neoliberal model that forced Britain to share control with U.S.-based corporations and creditors. The case of subjugating French capital was less straightforward. Under de Gaulle, France had let go of Algeria and Guinea but clung on to the remaining African colonial areas with such tenacity that well into the twenty-first century the CFA (Central African Franc) still subjects fourteen former colonies to the monetary control of the French treasury, while a dominating influence is maintained over military, cultural, and economic affairs. France has acted like a gendarme of today’s imperialism, intervening more than thirty times in Africa and most recently leading the charge in the NATO destruction of Libya.

Lessons from the NATO Intervention in Africa