It’s Always Been About Discrimination for LGBT People

As a gay person, I grew up knowing I was different. Hearing other kids call anyone who deviated from traditional gender expectations a “fag.” Getting called a “lesbo” at age 11. I hadn’t come out to anyone and didn’t even really understand what it meant, but I knew it was an insult.

At an early age, we learn that it’s at best different to be LGBT. And many of us are taught that this difference is bad — shameful, deviant, disgusting. We might try to hide it. We might wish it away. We learn that even if our family accepts us, there are some relatives who might not; we get asked to hide who we are so as not to make them uncomfortable.

This teaches shame.

We hear about LGBT people who have been physically attacked or even killed for being who they are.

This teaches fear.

While I know I grew up with privilege, and others have stories far worse than mine, I also believe that countless other LGBT people could tell stories like this — not the same, but all rooted in a legacy that made us feel ashamed of who we are. And yet I, like many of us, also learned pride and hope and found a community that loves me and makes me feel welcome.

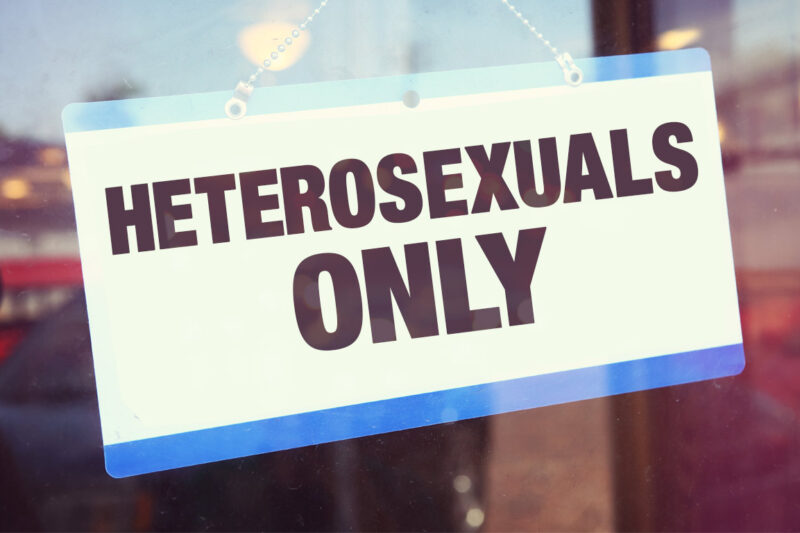

Those experiences are part of why I care so much about the Masterpiece Cakeshop case. A decision in support of the bakery would open the door to sweeping discrimination. What’s at stake isn’t just whether we have the freedom to go about our daily lives and purchase the same things that others are able to buy. That’s part of it, but it’s not the whole picture.

We never leave those initial experiences of shame and discrimination behind completely. Our sexual orientation may or may not be readily visible to others. How we dress or how we act might identify us as gay but it might not, and it won’t in all circumstances.

Even with a girlfriend — even holding hands — people don’t always see a couple. I have to decide whether to come out or hide again and again — at the doctor’s office, at my child’s school, when talking about weekend plans with colleagues — because people usually assume heterosexuality. Gay people think about when to hold hands or kiss goodbye in public. Sometimes, it will be a matter of safety. The fact that straight couples don’t have to think about these questions is a reminder of difference. And every time I do come out, some part of me still wonders whether, in this moment, I’ll find that my community has grown larger or if I’ll face rejection — or worse.

The Colorado law that’s being challenged by the bakery in the Masterpiece Cakeshop case says that businesses that open their doors to the public can’t discriminate based on race, religion, sex, disability, gender identity, or sexual orientation. Laws like Colorado’s aim to make sure that when we walk through the doors of a store or hotel, we all have the same freedom to buy a cake, eat a meal, or rent a room. They say to LGBT people, “you matter, and you shouldn’t be mistreated because you are gay, lesbian, bisexual or transgender.”

This case isn’t about the cake. It’s about a legacy of discrimination and devaluation and a rejection of our shared humanity.

Through laws like Colorado’s, we start to trust those assurances and feel more confident living our lives. But when a business owner says, “No, we won’t serve you because you’re gay,” all that humiliation resurfaces.

That’s why it’s inappropriate to tell us — as the bakery and the federal government do in this case — to just go to a different bakery. This isn’t just about the services. It’s about the harm that being turned away causes. It’s about how shame and fear prevent us from fully feeling safe and participating in public life. It’s about the pain of our children seeing us, and them, rejected, or the pain of our parents watching, unable to protect us. And it doesn’t matter if it’s just one store. Because once we are refused, every time we approach the door of a store, we wonder how we will be treated and are more likely to hide who we are. That comes at a steep cost.

The bakery is arguing to the Supreme Court justices that the Constitution protects their right to refuse to serve gay people, to tell people like me, like Dave and Charlie, and countless others that they object to our relationships and therefore refuse to serve us. But this case isn’t about the cake. It’s about a legacy of discrimination and devaluation and a rejection of our shared humanity.

And yet it’s also a case about hope, promise, and love. The hope that the court will recognize that all of us are worthy of respect and fair treatment. The promise that LGBT young people won’t live in fear and embarrassment as I did. And a mother’s unwavering love for her son and his fiancé , showing us why discrimination has no place in our Constitution.

Learn More About the Issues on This Page

- LGBTQ Rights

- Public Places

- LGBTQ Nondiscrimination Protections

Related Content

ACLU Files Title IX Complaint Against Harrison County School District for Dress Code Discrimination

Fourth Circuit Upholds Dismissal of Gay Teacher from North Carolina Catholic School

National Women’s Law Center Intervenes In Defense of Transgender College Athletes

Kalarchik v. Montana

How do we solve LGBTQ discrimination? One word: visibility

Each of us can play a part in creating an inclusive world and end LGBTQ discrimination Image: Reuters/Tyrone Siu

.chakra .wef-1c7l3mo{-webkit-transition:all 0.15s ease-out;transition:all 0.15s ease-out;cursor:pointer;-webkit-text-decoration:none;text-decoration:none;outline:none;color:inherit;}.chakra .wef-1c7l3mo:hover,.chakra .wef-1c7l3mo[data-hover]{-webkit-text-decoration:underline;text-decoration:underline;}.chakra .wef-1c7l3mo:focus,.chakra .wef-1c7l3mo[data-focus]{box-shadow:0 0 0 3px rgba(168,203,251,0.5);} Simon Freakley

.chakra .wef-9dduvl{margin-top:16px;margin-bottom:16px;line-height:1.388;font-size:1.25rem;}@media screen and (min-width:56.5rem){.chakra .wef-9dduvl{font-size:1.125rem;}} Explore and monitor how .chakra .wef-15eoq1r{margin-top:16px;margin-bottom:16px;line-height:1.388;font-size:1.25rem;color:#F7DB5E;}@media screen and (min-width:56.5rem){.chakra .wef-15eoq1r{font-size:1.125rem;}} Gender Inequality is affecting economies, industries and global issues

.chakra .wef-1nk5u5d{margin-top:16px;margin-bottom:16px;line-height:1.388;color:#2846F8;font-size:1.25rem;}@media screen and (min-width:56.5rem){.chakra .wef-1nk5u5d{font-size:1.125rem;}} Get involved with our crowdsourced digital platform to deliver impact at scale

Stay up to date:, gender inequality.

- Harvey Milk was the first openly gay elected official in the US.

- When in office he sponsored a bill against LGBTQ discrimination and was also the spokesperson for SanFrancisco's LGBTQ+ community.

As many workplaces, and even entire industries, continue to work on building inclusive and diverse environments, I am reminded of Harvey Milk, one of the first openly gay elected officials in the United States. With the 40th anniversary of his assassination recently behind us, there still is much we can learn from him.

The voice against LGBTQ discrimination

Milk was elected to the San Francisco Board of Supervisors in 1977, following a tenure as a political spokesperson for the city’s LGBTQ+ (then known as LGB) community and founder of a business association of predominantly LGBTQ+ merchants.

Once in office, Milk supported LGBTQ+ rights, notably sponsoring an anti-discrimination bill and opposing a ballot initiative that would have mandated the firing of gay teachers in California public schools. He championed inclusive policies for other marginalized groups as well, including women (particularly working mothers) and minorities.

Milk was visionary. He recognized the importance of being seen, and the crucial role visibility could play in changing widespread discriminatory attitudes.

There remains much work to do. In 73 countries homosexuality is still considered a crime, in some places punishable by death. In the US, there still is no federal law barring employment discrimination against LGBTQ - on the basis of sexual orientation or gender identity, and varying state laws make it possible for such discrimination to persist. In addition, according to a leaked memo obtained by the New York Times in October, the US Department of Health and Human Services is considering narrowing the definition of gender – a move that could end the federal recognition of more than a million transgender people.

What we can learn from Milk, though, and what the recent transgender-rights #WontBeErased movement further highlights, is that visibility helps combat LGBTQ discrimination.

A positive shift to deter LGBTQ discrimination

In the US, the 2018 midterm elections served as a continuation of Milk’s legacy. More openly LGBTQ+ people were elected to public office this year than in any previous election – notably Colorado’s Jared Polis, the first openly gay elected governor in the US; Sharice Davids, the first lesbian Native American to be elected to the House of Representatives; and Kyrsten Sinema, the first openly bisexual US senator.

In other parts of the world, attitudes also are changing regarding LGBTQ discrimination. This year, the World Health Organization reclassified “gender incongruence” so transgender people would no longer be deemed mentally ill. In September, India’s Supreme Court unanimously decriminalized gay sex and ruled that gay Indians be given all the protections of the country’s constitution. In 27 countries, same-sex marriage is now legal.

This progress is heartening. Further, it underscores the visibility Milk spoke about, a foundational component to achieving fair treatment for all.

Have you read?

The real cost of lgbt discrimination, the cost of homophobia: ruined lives, stilted economies, as cuba drops same-sex marriage, five lgbt+ advances and setbacks in 2018.

Of course, we do not have to wait for new legislation or an election cycle to have an impact. Each of us can play a part in creating an inclusive world, and we can start in a place where many of us spend so many hours each day: the workplace. If we can foster an environment at work where everyone feels safe – physically and emotionally – to bring their whole selves to the office and be visible, we can each play a small part in affecting change on a much grander scale.

Milk said, “Gay people, we will not win our rights by staying quietly in our closets.” At the heart of his statement is the importance of visibility, the first step toward solving the bigger ills of homophobia and LGBTQ discrimination. It serves us all to remember his words and his bravery, as we build a better world for each other.

Don't miss any update on this topic

Create a free account and access your personalized content collection with our latest publications and analyses.

License and Republishing

World Economic Forum articles may be republished in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International Public License, and in accordance with our Terms of Use.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author alone and not the World Economic Forum.

Related topics:

The agenda .chakra .wef-n7bacu{margin-top:16px;margin-bottom:16px;line-height:1.388;font-weight:400;} weekly.

A weekly update of the most important issues driving the global agenda

.chakra .wef-1dtnjt5{display:-webkit-box;display:-webkit-flex;display:-ms-flexbox;display:flex;-webkit-align-items:center;-webkit-box-align:center;-ms-flex-align:center;align-items:center;-webkit-flex-wrap:wrap;-ms-flex-wrap:wrap;flex-wrap:wrap;} More on Equity, Diversity and Inclusion .chakra .wef-17xejub{-webkit-flex:1;-ms-flex:1;flex:1;justify-self:stretch;-webkit-align-self:stretch;-ms-flex-item-align:stretch;align-self:stretch;} .chakra .wef-nr1rr4{display:-webkit-inline-box;display:-webkit-inline-flex;display:-ms-inline-flexbox;display:inline-flex;white-space:normal;vertical-align:middle;text-transform:uppercase;font-size:0.75rem;border-radius:0.25rem;font-weight:700;-webkit-align-items:center;-webkit-box-align:center;-ms-flex-align:center;align-items:center;line-height:1.2;-webkit-letter-spacing:1.25px;-moz-letter-spacing:1.25px;-ms-letter-spacing:1.25px;letter-spacing:1.25px;background:none;padding:0px;color:#B3B3B3;-webkit-box-decoration-break:clone;box-decoration-break:clone;-webkit-box-decoration-break:clone;}@media screen and (min-width:37.5rem){.chakra .wef-nr1rr4{font-size:0.875rem;}}@media screen and (min-width:56.5rem){.chakra .wef-nr1rr4{font-size:1rem;}} See all

Pay transparency and pay gap reporting may be rising but how effective are they?

Tom Heys and Emanuela Nespoli

May 29, 2024

How focused giving can unlock billions and catapult women’s wealth

Mark Muckerheide

May 21, 2024

Progress for women in the workplace stagnating in four key areas, global study reveals

The care economy is one of humanity's most valuable assets. Here's how we secure its future

This is how AI can empower women and achieve gender equality, according to the founder of Girls Who Code and Moms First

Kate Whiting

May 14, 2024

Here's how rising air pollution threatens millions in the US

Cornell Chronicle

- Architecture & Design

- Arts & Humanities

- Business, Economics & Entrepreneurship

- Computing & Information Sciences

- Energy, Environment & Sustainability

- Food & Agriculture

- Global Reach

- Health, Nutrition & Medicine

- Law, Government & Public Policy

- Life Sciences & Veterinary Medicine

- Physical Sciences & Engineering

- Social & Behavioral Sciences

- Coronavirus

- News & Events

- Public Engagement

- New York City

- Photos of the Week

- Big Red Sports

- Freedom of Expression

- Student Life

- University Statements

- Around Cornell

- All Stories

- In the News

- Expert Quotes

- Cornellians

Discrimination impacts health of LGBT people, analysis finds

In a review of thousands of peer-reviewed studies, the What We Know Project , an initiative of Cornell’s Center for the Study of Inequality , has found a strong link between anti-LGBT discrimination and harms to the health and well-being of LGBT people.

The results of the analysis , the largest-known literature review on the topic, indicates that 286 out of 300 studies, or 95%, found a link between anti-LGBT discrimination and LGBT health harms.

“The research we reviewed makes it crystal clear that discrimination has far-ranging effects on LGBT health,” said Nathaniel Frank, director of the What We Know Project, an online research portal that aggregates existing peer-reviewed LGBT research. “And those consequences are compounded for especially vulnerable populations such as people of color, youth and adolescents, and transgender Americans.”

The research team screened more than 11,000 titles and read more than 1,300 peer-reviewed studies in order to identify those that addressed the question, “What does the scholarly research say about the effects of discrimination on the health of LGBT people?” Among the key findings identified by the report:

- Anti-LGBT discrimination increases the risks of poor mental and physical health for LGBT people, including depression, anxiety, suicidality, PTSD, substance use and cardiovascular disease.

- Discrimination is linked to health harms even for those who are not directly exposed to it, because the presence of discrimination, stigma and prejudice creates a hostile social climate that taxes individuals’ coping resources and contributes to minority stress.

- Minority stress – including internalized stigma, low self-esteem, expectations of rejection and fear of discrimination – helps explain the health disparities seen in LGBT populations.

- Discrimination on the basis of intersecting identities such as gender, race or socioeconomic status can exacerbate the harms of discrimination based on sexual orientation or gender identity.

- Protective factors against the harms of discrimination include community and family support; access to affirming health care and social services; and the establishment of positive social climates, inclusive practices and anti-discrimination policies.

The report is relevant to debates currently unfolding nationally about whether to ban discrimination or, alternatively, allow a “license to discriminate” through religious exemptions from discrimination law, Frank said. The data also offer guidance on what policies and practices can help mitigate the consequences of anti-LGBT discrimination, prejudice and stigma, he said.

“Sometimes research really humanizes a policy debate, and this is one of those times,” said Kellan Baker of the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health, co-lead of the study. “Whatever you think of what the law should say about anti-LGBT discrimination, this research makes indisputable that it inflicts great harm on the LGBT population, and gives policymakers and individuals tools to reduce those harms.”

Focusing on public policy debates around inequality, the What We Know Project connects scholarship, public policy and new media technology.

“The goal is to bring together in one place scholarly evidence that informs LGBT debates, so that policymakers, journalists, researchers and the public can make truly informed decisions about what policies best serve the public interest,” Frank said. “We don’t call ‘balls and strikes’ in our analysis, but simply describe what conclusions the studies reach so visitors may evaluate the research themselves.”

The full research analysis and methodology can be viewed on the project website.

Media Contact

Gillian smith.

Get Cornell news delivered right to your inbox.

You might also like

Gallery Heading

- Skip to main content

- Keyboard shortcuts for audio player

House Passes The Equality Act: Here's What It Would Do

Danielle Kurtzleben

Protesters gather outside the Supreme Court in Washington where the Court on Oct. 8, 2019, as the court heard arguments in the first case of LGBT rights since the retirement of Supreme Court Justice Anthony Kennedy. Susan Walsh/AP hide caption

Protesters gather outside the Supreme Court in Washington where the Court on Oct. 8, 2019, as the court heard arguments in the first case of LGBT rights since the retirement of Supreme Court Justice Anthony Kennedy.

Updated Feb. 25, 4:39 p.m. ET

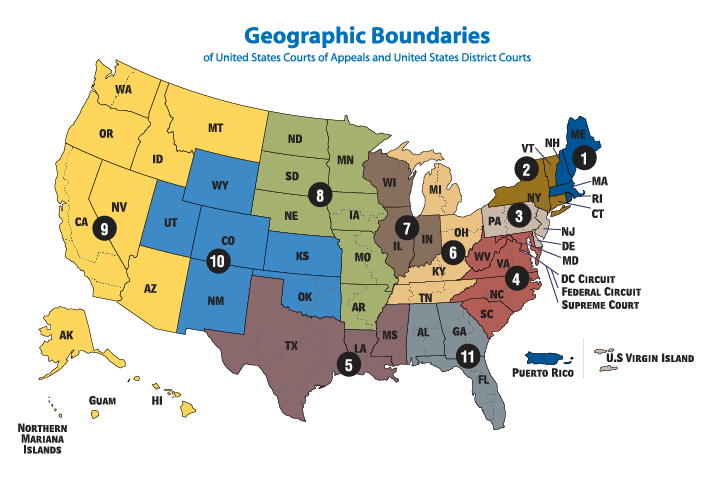

The House of Representatives voted on Thursday to pass the Equality Act, a bill that would ban discrimination against people based on sexual orientation and gender identity. It would also substantially expand the areas to which those discrimination protections apply.

It's a bill that President Biden said on the campaign trail would be one of his top legislative priorities for the first 100 days of his presidency. The House vote was largely along party lines, passing with the support of all Democrats and just three Republicans. The bill now goes to the Senate, where its fate is unclear.

When House Democrats introduced the bill last week, Biden reiterated his support in a statement: "I urge Congress to swiftly pass this historic legislation," he wrote. "Every person should be treated with dignity and respect, and this bill represents a critical step toward ensuring that America lives up to our foundational values of equality and freedom for all."

But it's also controversial — while the Equality Act has broad support among Democrats, many Republicans oppose it, fearing that it would infringe upon religious objections.

Here's a quick rundown of what the bill would do, and what chance it has of becoming law.

What would the Equality Act do?

The Equality Act would amend the 1964 Civil Rights Act to explicitly prevent discrimination based on sexual orientation and gender identity.

The bill has been introduced multiple times before and previously passed the House in 2019. However, the law's impact would be different in practical terms now than it was then.

That's because the Supreme Court ruled in June of last year , in Bostock v. Clayton County , that the protections guaranteed by the 1964 Civil Rights Act on the basis of sex also extend to discrimination against lesbian, gay, and transgender Americans. The logic was that a man who, for example, loses his job because he has a same-sex partner is facing discrimination on the basis of sex — that, were he a woman, he wouldn't have faced that discrimination.

Supreme Court Delivers Major Victory To LGBTQ Employees

This act would explicitly enshrine those nondiscrimination protections into law for sexual orientation and gender identity, rather than those protections being looped in under the umbrella of "sex." However, the Equality Act would also substantially expand those protections.

The Civil Rights Act covered discrimination in certain areas, like employment and housing. The Equality Act would expand that to cover federally funded programs, as well as "public accommodations" — a broad category including retail stores and stadiums, for example.

("Public accommodations" is also a category that the bill broadens, to include online retailers and transportation providers, for example. Because of that, many types of discrimination the Civil Rights Act currently prohibits — like racial or religious discrimination — would now also be explicitly covered at those types of establishments.)

One upshot of all of this, then, is that the Equality Act would affect businesses like flower shops and bakeries that have been at the center of discrimination court cases in recent years — for example, a baker who doesn't want to provide a cake for a same-sex wedding .

In Narrow Opinion, Supreme Court Rules For Baker In Gay-Rights Case

Importantly, the bill also explicitly says that it trumps the Religious Freedom Restoration Act (commonly known by its acronym RFRA). The law, passed in 1993, set a higher bar for the government to defend laws if people argued those laws infringed upon religious freedom.

Under the Equality Act, an entity couldn't use RFRA to challenge the act's provisions, nor could it use RFRA as a defense to a claim made under the act.

What proponents say

Supporters say that the Equality Act simply extends basic, broadly accepted tenets of the Civil Rights Act to classes of people that the bill doesn't explicitly protect.

"Just as [a business] would not be able to turn away somebody for any other prohibited reason in the law, they would not be able to do that for LGBTQ people either. And we think that's a really important principle to maintain," said Ian Thompson, senior legislative representative at the ACLU.

The bill also would be national, covering states that do not have LGBTQ anti-discrimination laws. According to the Human Rights Campaign, an LGBTQ advocacy organization, 27 states do not have those laws.

Supporters additionally say the bill would cement protections that could otherwise be left up to interpretation.

Biden Signs Most Far-Reaching Federal Protections For LGBTQ People Yet

"President Biden issued an executive order directing agencies to appropriately interpret the Bostock ruling to apply not just to employment discrimination, but to other areas of law where sex discrimination is prohibited, including education, housing, and health care," the Human Rights Campaign wrote in support of the bill . "However, a future administration may refuse to interpret the law this way, leaving these protections vulnerable."

And with regard to RFRA, proponents argue that the bill would keep entities from using that law as a "license to discriminate," wording echoed by Human Rights Watch and many other Equality Act supporters.

What opponents say

The question of religious freedom is the main issue animating people against the Equality Act.

Douglas Laycock, a law professor at the University of Virginia, has criticized the Equality Act since its 2019 introduction. He told NPR in an email that the law is "less necessary" now, after the Bostock decision.

Furthermore, while he supports adding sexual orientation and gender identity to federal anti-discrimination statutes, Laycock believes that this bill goes too far in limiting people's ability to defend themselves against discrimination claims.

"It protects the rights of one side, but attempts to destroy the rights of the other side," he said. "We ought to protect the liberty of both sides to live their own lives by their own identities and their own values."

How The Fight For Religious Freedom Has Fallen Victim To The Culture Wars

Another key fear among opponents of the Equality Act is that it would threaten businesses or organizations that have religious objections to serving LGBTQ people, forcing them to choose between operating or following their beliefs.

Could it pass?

The Democratic-led House passed the Equality Act in 2019 with unanimous support from Democrats (as well as support from eight Republicans), and it passed in similar fashion in the current Democratic House.

The Senate is more uncertain. Democrats in the Senate broadly support the bill. Sens. Kyrsten Sinema of Arizona and Joe Manchin of West Virginia, among the most moderate Democratic senators, signed a letter in support of it last year .

But the bill would need 60 votes to avoid a filibuster in the Senate. Maine Republican Sen. Susan Collins cosponsored the bill in 2019, but not all of her fellow, more moderate Republicans are on board. Utah Sen. Mitt Romney, for example, told the Washington Blade that he won't support the act, citing religious liberty.

"Sen. Romney believes that strong religious liberty protections are essential to any legislation on this issue, and since those provisions are absent from this particular bill, he is not able to support it," his spokesperson told the Blade.

It's uncertain how other moderate Republicans might vote. Alaska Sen. Lisa Murkowski, who supported the narrower Employment Nondiscrimination Act (ENDA) in 2013, has yet to respond to NPR's questions about her support of the Equality Act.

And while Ohio Sen. Rob Portman, who likewise supported ENDA, didn't give a definitive answer on his support, his response made it clear that he could object to it on religious grounds.

"Rob opposes discrimination of any kind, and he also believes that it's important that Congress does not undermine protections for religious freedom," his office said in a statement. "He will review any legislation when and if it comes up for a vote in the Senate."

Chapter 7: Prejudice and Discrimination against LGBTQ people

Sean g. massey, sarah r. young, & ann merriwether.

Although progress in terms of LGBTQ rights has been made, and attitudes towards LGBTQ+ people have changed in the past few decades, the implications of anti-LGBTQ prejudice and discrimination remain serious. It is critical that efforts to change these attitudes continue, and that LGBTQ-affirmative social scientists, educators, and practitioners continue to develop a robust knowledge base to guide these efforts. In addition, there is a related literature that highlights the strength and resilience found in the LGBTQ community, even in the face of this adversity.

LGBTQ historians and anthropologists like Chauncey (1995), D’Emilio (1983), Stryker (2008), and Kennedy and Davis (1993) have helped make visible the courage and perseverance of LGBTQ individuals and communities who faced legal risks, social stigma, overt discrimination, and violence across the 20th century. These are the voices and struggles of a resilient community: the Mattachine Society and Daughters of Bilitis who organized and built networks of LGBTQ people in the shadow of McCarthyism and anti-homosexual witch hunts; the transwomen and transmen, drag queens, queer youth of color, street hustlers, butch dykes, and gay men who took a stand at the Stonewall Inn, throwing pennies, nickels, high heeled shoes, and bricksin protest against police harassment; the LGBTQ people who, amid unimaginable death and sadness brought about by the AIDS epidemic, built organizations, took care of each other, acted up, and fought back against government disdain and neglect; the people with AIDS who, many in midst of the ravages of the disease, still found meaning in helping others. These stories of resilience aren’t meant to minimize the dangers or potential for harm. In the words of Harvey Milk, they are simply stories of hope:

“Hope for a better world, hope for a better tomorrow, hope for a better place to come to if the pressures at home are too great. Hope that all will be alright…. and you and you and you, you have to give people hope.” (Milk, 1973).

- Authored by : Sean G. Massey, Sarah R. Young, & Ann Merriwether. License : CC BY: Attribution

Privacy Policy

LGBT People’s Experiences of Workplace Discrimination and Harassment

- Full Report

Using survey data collected in May 2021, this report examines the lifetime, five-year, and past-year experiences of discrimination among LGBT employees. It is one of the first studies to look at LGBT employment discrimination during the COVID-19 pandemic and in the year following Bostock v. Clayton County.

- Brad Sears Founding Executive Director

- Christy Mallory Legal Director

- Andrew R. Flores Affiliated Scholar

- Kerith J. Conron Research Director

Executive Summary

Over 8 million workers in the U.S. identify as LGBT. 1 Employment discrimination and harassment against LGBT people has been documented in a variety of sources and found to negatively impact employees’ health and wellbeing and to reduce job commitment and satisfaction.

This report examines experiences of employment discrimination and harassment against LGBT adults using a survey of 935 LGBT adults conducted in May of 2021. Lifetime, five-year, and past-year discrimination were assessed among adults employed as of March 2020—just before many workplaces were forced to shut down because of COVID-19.

Accordingly, this survey is one of the first to gather in formation about experiences of sexual orientation and gender identity employment discrimination during the COVID-19 pandemic and in the year following the U.S. Supreme Court’s decision in Bostock v. Clayton County , 2 which held that employment discrimination against LGBT people is prohibited by the Title VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964. 3

Our analysis indicates that employment discrimination against LGBT people continues to be persistent and widespread. Over 40% of LGBT workers (45.5%) reported experiencing unfair treatment at work, including being fired, not hired, or harassed because of their sexual orientation or gender identity at some point in their lives. This discrimination and harassment is ongoing: nearly one-third (31.1%) of LGBT respondents reported that they experienced discrimination or harassment within the past five years.

Overall, 8.9% of employed LGBT people reported that they were fired or not hired because of their sexual orientation or gender identity in the past year, including 11.3% of LGBT employees of color and 6.5% of white LGBT employees. The percentage was five times as high for those who were out as LGBT to at least some people at work as compared to those who were not out (10.9% compared to 2.2%).

Over half (57.0%) of LGBT employees who experienced discrimination or harassment at work reported that their employer or co-workers did or said something to indicate that the unfair treatment that they experienced was motivated by religious beliefs. Nearly two-thirds (63.5%) of LGBT employees of color said that religion was a motivating factor in their experiences of workplace discrimination compared to 49.4% of white LGBT employees.

Many employees also reported engaging in behaviors to avoid discrimination and harassment, including hiding their LGBT identity and changing their physical appearance, and many left their jobs or considered leaving their jobs because of unfair treatment.

While the key findings of the report are summarized below, the full report includes several quotes from respondents providing more detail about their experiences of discrimination and harassment in the workplace.

Key Findings

- One-third (33.2%) of LGBT employees of color and one-quarter (26.3%) of white LGBT employees reported experiencing employment discrimination (being fired or not hired) because of their sexual orientation or gender identity.

- LGBT employees of color were significantly more likely to report not being hired because of their sexual orientation or gender identity than white LGBT employees: 29.0% of LGBT employees of color reported not being hired based on their LGBT status compared to 18.3% of white LGBT employees.

Transgender 4 employees were also significantly more likely to experience discrimination based on their LGBT status than cisgender LGB employees: Nearly half (48.8%) of transgender employees reported experiencing discrimination (being fired or not hired) based on their LGBT status compared to 27.8% of cisgender LGB employees. More specifically, over twice as many transgender employees reported not being hired (43.9%) because of their LGBT status compared to LGB employees (21.5%).

- Beyond being fired or not being hired, respondents also reported other types of unfair treatment based on their sexual orientation and gender identity, including not being promoted, not receiving raises, being treated differently than those with different-sex partners, having their schedules changed or reduced, and being excluded from company events.

- One in five (20.8%) LGBT employees reported experiencing physical harassment because of their sexual orientation or gender identity. Reports of physical harassment included being “punched,” “hit,” and ‘beaten up” in the workplace.

- LGBT employees of color were significantly more likely to report experiencing verbal harassment (35.6% compared to 25.9%) at work because of their sexual orientation or gender identity than white LGBT employees. In addition, transgender employees were significantly more likely to report experiencing verbal harassment over the course of their careers than cisgender LGB employees (43.8% compared to 29.3%). In many cases, the verbal harassment came from employees’ supervisors and co-workers, as well as customers.

- One in four (25.9%) LGBT employees reported experiencing sexual harassment in the workplace because of their sexual orientation and gender identity at some point in their careers. Although transgender employees were not more likely than cisgender employees to report sexual harassment over the course of their careers, they were twice as likely to report recent experiences of sexual harassment: 22.4% reported sexual harassment in the past five years compared to 11.9% of cisgender LGB employees.

- Workplace culture: Two-thirds (67.5%) of LGBT employees reported that they have heard negative comments, slurs, or jokes about LGBTQ people at work. Many LGBT people reported being called or hearing words like “f****t,” “queer,” “sissy,” “tranny,” and “dyke” in the workplace.

- LGBT people continue to experience workplace discrimination even after the U.S. Supreme Court extended non-discrimination protections to LGBT people nationwide in Bostock v. Clayton County . Nine percent (8.9%) of LGBT employees reported that they were fired or not hired because of their sexual orientation or gender identity in the past year.

- One in ten (11.3%) LGBT employees of color reported experiencing some form of employment discrimination (including being fired or not hired) based on their sexual orientation or gender identity within the past year.

- Of those employees who experienced discrimination or harassment at some point in their lives, 63.5% of LGBT employees of color said that religion was a motivating factor compared to 49.4% of white LGBT employees.

- Those who are out to at least some people in the workplace were three times more likely to report experiences of discrimination or harassment because of their sexual orientation or gender identity than those who are not out to anyone in the workplace (53.3% compared to 17.9%).

- While approximately 7% of those who are not out to anyone in the workplace reported experiencing verbal (7.4%) or physical (7.4%) harassment because of their sexual orientation or gender identity, of those who are out to at least some people in the workplace, about one in three reported experiencing verbal harassment (37.8%) and one in four (25.0%) reported experiencing physical harassment.

- In terms of discrimination in the past year—post- Bostock —those who are out to at least some people in the workplace were five times more likely to report experiencing discrimination (including being fired or not hired) because of their sexual orientation or gender identity than those who are not out to anyone (10.9% compared to 2.2%).

- Transgender employees were significantly more likely to engage in covering behaviors than cisgender LGB employees. For example, 36.4% of transgender employees said that they changed their physical appearance and 27.5% said they changed their bathroom use at work compared to 23.3% and 14.9% of cisgender LGB employees.

- Retention: One-third (34.2%) of LGBT employees said that they have left a job because of how they were treated by their employer based on their sexual orientation or gender identity.

Download the full report

Related Publications

Lgbt discrimination, subnational public policy, and law in the united states, title vii cases: amicus briefs, legal protections for lgbt people after bostock v. clayton county.

Kerith J. Conron & Shoshana K. Goldberg, Williams Inst., LGBT People in the US Not Protected by State NonDiscrimination Statutes 1 (2020) , https://williamsinstitute.law.ucla.edu/publications/lgbt-nondiscrimination-statutes.

140 S. Ct. 1731 (2020).

42 U.S.C. § 2000e-2(a).

Participants who selected gender identity response options, including male, female, transgender, and nonbinary, that differed from their sex assigned at birth, were classified as transgender.

- Entertainment

- Environment

- Information Science and Technology

- Social Issues

Home Essay Samples Sociology

Essay Samples on LGBTQ

Lgbtq rights: navigating equality and inclusivity.

LGBTQ rights have emerged as a significant social and legal issue, challenging societies worldwide to confront questions of equality, discrimination, and inclusivity. This essay delves into the multifaceted landscape of LGBTQ rights, examining the historical context, legal advancements, challenges, and the ongoing journey towards achieving...

- Human Rights

LGBTQ Rights: An Argumentative Landscape

The rights of the LGBTQ community have emerged as a crucial and contentious issue in today's society. This essay undertakes an in-depth analysis of the argumentative discourse surrounding LGBTQ rights, scrutinizing the diverse perspectives, presenting evidence, and providing critical commentary on this complex matter. By...

Persuading for Equality: Embracing LGBTQ Rights

LGBTQ rights have become a pivotal social issue, demanding our collective attention and action. This persuasive essay aims to advocate for the full acceptance and legal protection of LGBTQ individuals, emphasizing the importance of equality, the negative consequences of discrimination, and the societal benefits of...

The Complexity of LGBTQ Identities: A Personal Opinion

LGBTQ identities constitute a rich tapestry of human diversity that has gained significant visibility and recognition in recent times. This opinion essay aims to provide a personal perspective on the multifaceted nature of LGBTQ identities, acknowledging their significance, challenges, and the evolving societal attitudes that...

LGBTQ Discrimination: Overcoming Prejudice and Fostering Inclusion

LGBTQ discrimination has been a persistent issue, characterized by inequality, prejudice, and systemic biases. This essay delves into the multifaceted nature of LGBTQ discrimination, exploring its origins, manifestations, impact on individuals and society, as well as the efforts to combat it and foster a more...

- Discrimination

Stressed out with your paper?

Consider using writing assistance:

- 100% unique papers

- 3 hrs deadline option

The Argumentative Discourse Surrounding LGBTQ

The discourse surrounding LGBTQ (Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transgender, and Queer) rights has been a prominent and contentious topic in contemporary society. This essay aims to delve into the argumentative nature of discussions about LGBTQ issues, examining the diverse perspectives and providing an analysis of the...

The Argument for LGBTQ Community Empowerment

The LGBTQ community has been at the forefront of a societal revolution, advocating for rights, recognition, and acceptance. This argumentative essay delves into the essential reasons behind supporting and empowering the LGBTQ community, exploring the quest for equality, the promotion of diversity, and the imperative...

Accepting the LGBTQ+ Community: Inclusivity and Equality

In today's global society, acceptance and understanding of diverse identities, particularly those of the LGBTQ+ community, are vital to fostering environments where every individual feels valued and safe. Historically, LGBTQ+ individuals have faced prejudice, discrimination, and significant challenges, but a shift towards inclusivity and equality...

Best topics on LGBTQ

1. LGBTQ Rights: Navigating Equality and Inclusivity

2. LGBTQ Rights: An Argumentative Landscape

3. Persuading for Equality: Embracing LGBTQ Rights

4. The Complexity of LGBTQ Identities: A Personal Opinion

5. LGBTQ Discrimination: Overcoming Prejudice and Fostering Inclusion

6. The Argumentative Discourse Surrounding LGBTQ

7. The Argument for LGBTQ Community Empowerment

8. Accepting the LGBTQ+ Community: Inclusivity and Equality

- Cultural Identity

- National Honor Society

- Social Media

- Communication in Relationships

- American Values

- Ethnocentrism

Need writing help?

You can always rely on us no matter what type of paper you need

*No hidden charges

100% Unique Essays

Absolutely Confidential

Money Back Guarantee

By clicking “Send Essay”, you agree to our Terms of service and Privacy statement. We will occasionally send you account related emails

You can also get a UNIQUE essay on this or any other topic

Thank you! We’ll contact you as soon as possible.

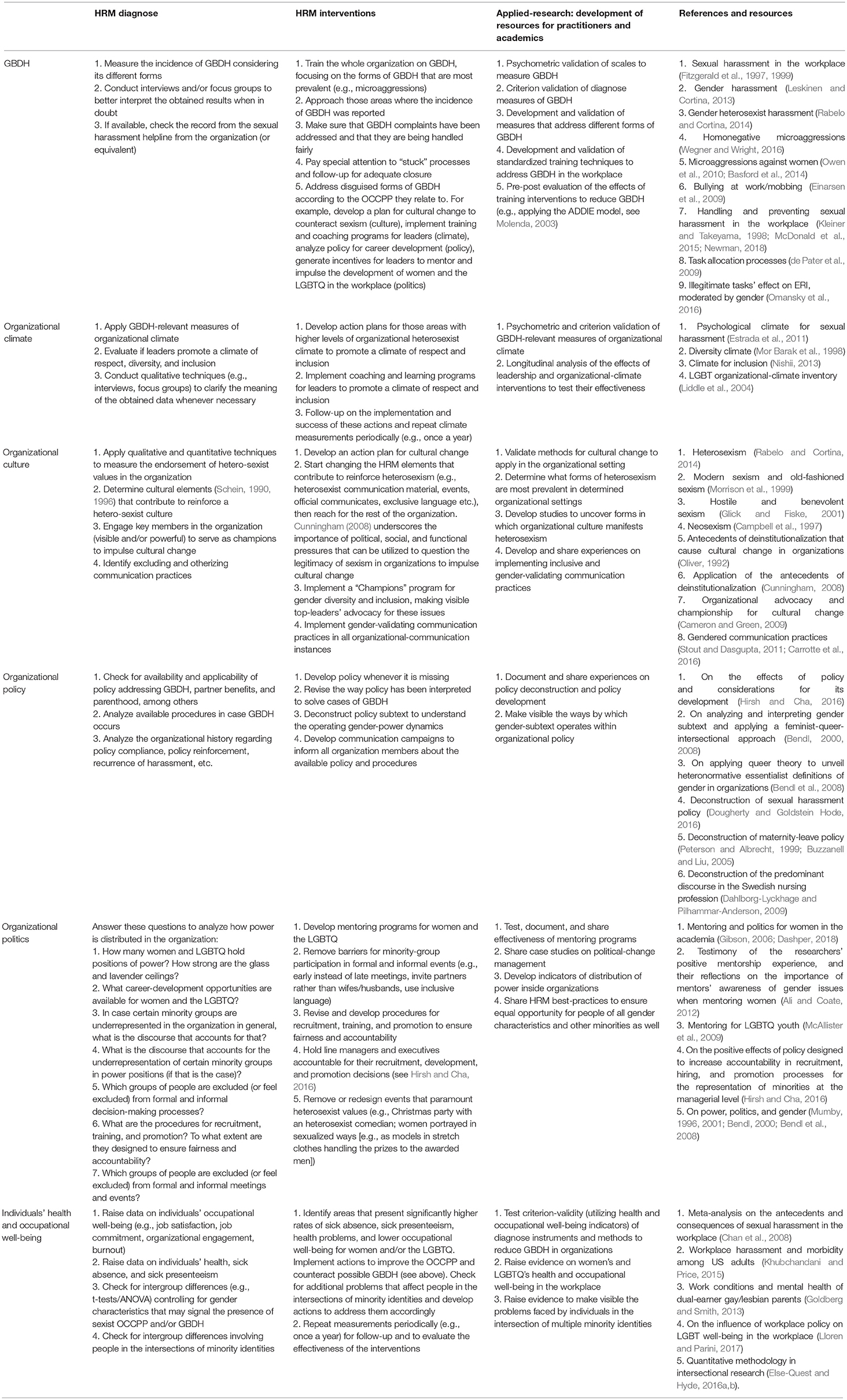

CONCEPTUAL ANALYSIS article

Better together: a model for women and lgbtq equality in the workplace.

- Faculty of Psychology, Work and Organizational Psychology, Philipps University of Marburg, Marburg, Germany

Much has been achieved in terms of human rights for women and people of the lesbian, gay, bisexual, transsexual, and queer (LGBTQ) community. However, human resources management (HRM) initiatives for gender equality in the workplace focus almost exclusively on white, heterosexual, cisgender women, leaving the problems of other gender, and social minorities out of the analysis. This article develops an integrative model of gender equality in the workplace for HRM academics and practitioners. First, it analyzes relevant antecedents and consequences of gender-based discrimination and harassment (GBDH) in the workplace. Second, it incorporates the feminist, queer, and intersectional perspectives in the analysis. Third, it integrates literature findings about women and the LGBTQ at work, making the case for an inclusive HRM. The authors underscore the importance of industry-university collaboration and offer a starters' toolkit that includes suggestions for diagnosis, intervention, and applied research on GBDH. Finally, avenues for future research are identified to explore gendered practices that hinder the career development of women and the LGBTQ in the workplace.

Introduction

Gender has diversified itself. More than four decades have passed since Bem (1974) published her groundbreaking article on psychological androgyny. With her work, she challenged the binary conception of gender in the western academia, calling for the disposal of gender as a stable trait consistent of discrete categories ( Mehta and Keener, 2017 ). Nowadays, people from the LGBTQ community find safe spaces to express their gender in most developed countries (see ILGA-Europe, 2017 ). Also, women-rights movements have impulsed changes for the emancipation and integration of women at every social level, enabling them to achieve things barely imaginable before (see Hooks, 2000 ).

However, there is still a lot to do to improve the situation of women and people from the LGBTQ community ( International Labour Office, 2016 ; ILGA-Europe, 2017 ). Some actions to increase gender inclusion in organizations actually conceal inequality against women, and many problems faced by the LGBTQ originate within frameworks that anti-discrimination policy reinforce (see Benschop and Doorewaard, 1998 , 2012 ; Verloo, 2006 ). For example, the gender equality, gender management, and gender mainstreaming approaches overlook most problems faced by people from the LGBTQ community and from women of color, framing their target stakeholders as white, cisgender, and heterosexual (see Tomic, 2011 ; Hanappi-Egger, 2013 ; Klein, 2016 ). These problems seem to originate in the neoliberalization of former radical movements when adopted by the mainstream (see Cho et al., 2013 ). This translates into actions addressing sexism and heterosexism that overlook other forms of discrimination (e.g., racism, ableism), resisting an intersectional approach that would question white, able-bodied, and other forms of privilege (see Crenshaw, 1991 ; Cho et al., 2013 ; Liasidou, 2013 ; van Amsterdam, 2013 ).

The purpose of this paper is to support the claim that gender equality shall be done within a queer, feminist, and intersectional framework. This argument is developed by integrating available evidence on the antecedents and consequences of GBDH against women and people from the LGBTQ community in the workplace. The authors believe that GBDH against these groups has its origin in the different manifestations of sexism in organizations. A model with the antecedents and consequences of GBDH in the workplace is proposed. It considers an inclusive definition of gender and integrates the queer-feminist approach to HRM ( Gedro and Mizzi, 2014 ) with the intersectional perspective ( Crenshaw, 1991 ; McCall, 2005 ; Verloo, 2006 ). In this way, it provides a framework for HRM scholars and practitioners working to counteract sexism, heterosexism, and other forms of discrimination in organizations.

GBDH in the Workplace

GBDH is the umbrella term we propose to refer to the different manifestations of sexism and heterosexism in the workplace. The roots of GBDH are beyond the forms that discriminatory acts and behaviors take, being rather “about the power relations that are brought into play in the act of harassing” ( Connell, 2006 , p. 838). This requires acknowledging that gender harassment is a technology of sexism, that “perpetuates, enforces, and polices a set of gender roles that seek to feminize women and masculinize men” ( Franke, 1997 , p. 696). Harassment against the LGBTQ is rooted in a heterosexist ideology that establishes heterosexuality as the superior, valid, and natural form of expressing sexuality (see Wright and Wegner, 2012 ; Rabelo and Cortina, 2014 ). Furthermore, women and the LGBTQ are oppressed by the institutionalized sexism that underscores the supremacy of hegemonic masculinity (male, white, heterosexual, strong, objective, rational) over femininity (female, non-white, non-heterosexual, weak, emotional, irrational; Wright, 2013 ; Denissen and Saguy, 2014 ; Dougherty and Goldstein Hode, 2016 ). In addition, GBDH overlaps with other frameworks (e.g., racism, ableism, anti-fat discrimination) that concurrently work to maintain white, able-bodied, and thin privilege, impeding changes in the broader social structure (see Yoder, 1991 ; Yoder and Aniakudo, 1997 ; Buchanan and Ormerod, 2002 ; Acker, 2006 ; Liasidou, 2013 ; van Amsterdam, 2013 ). The next paragraphs offer a definition of some of the most studied forms of GBDH in the workplace.

Sexual Harassment

Sexual harassment was first defined in its different dimensions as gender harassment, unwanted sexual attention, and sexual coercion ( Gelfand et al., 1995 ). Later, Leskinen and Cortina (2013) focused on the gender-harassment subcomponent of sexual harassment and developed a broadened taxonomy of the term. This was motivated by the fact that legal practices gave little importance to gender-harassment forms of sexual harassment, despite of the negative impact they have on the targets' well-being ( Leskinen et al., 2011 ). Gender harassment consists of rejection or “put down” forms of sexual harassment such as sexist remarks, sexually crude/offensive behavior, infantilization, work/family policing, and gender policing ( Leskinen and Cortina, 2013 ). The concepts of sexual harassment and gender harassment were initially developed to refer to the experiences of women in the workplace, but there is also evidence of sexual and gender harassment against LGBTQ individuals ( Lombardi et al., 2002 ; Silverschanz et al., 2008 ; Denissen and Saguy, 2014 ). In addition, studies have shown how gender harassment and heterosexist harassment are complementary and frequently simultaneous phenomena accounting for mistreatment against members of the LGBTQ community ( Rabelo and Cortina, 2014 ).

Gender Microaggressions

Gender microaggressions account for GBDH against women and people from the LGBTQ community that presents itself in ways that are subtle and troublesome to notice ( Basford et al., 2014 ; Galupo and Resnick, 2016 ). Following the taxonomy on racial microaggressions developed by Sue et al. (2007) , the construct was adapted to account for gender-based forms of discrimination ( Basford et al., 2014 ). Gender microaggressions consist of microassaults, microinsults, and microinvalidations, and although they may appear to be innocent, they exert considerably negative effects in the targets' well-being ( Sue et al., 2007 ; Basford et al., 2014 ; Galupo and Resnick, 2016 ). As an example of microassault imagine an individual commenting their colleague that their way of dressing looks unprofessional (because it is not “masculine enough,” “too” feminine, or not according to traditional gender-binary standards). A microinsult is for example when the supervisor asks the subordinate about who helped them with their work (which was “too good” to be developed by the subordinate alone). An example of microinvalidation would be if in a corporate meeting the CEO dismisses information related to women or the LGBTQ in the company regarding it as unimportant, reinforcing the message that women and LGBTQ issues are inexistent or irrelevant (for more examples see Basford et al., 2014 ; Galupo and Resnick, 2016 ). Because gender is not explicitly addressed in microaggressions, it can be especially difficult for the victims to address the offense as such and act upon them (see Galupo and Resnick, 2016 ). Hence, they are not only emotionally distressing, but also tend to be highly ubiquitous, belonging to the daily expressions of a determined context ( Nadal et al., 2011 , 2014 ; Gartner and Sterzing, 2016 ).

Disguised Forms of GBDH

It is also the case that some forms of workplace mistreatment constitute disguised forms of GBDH. Rospenda et al. (2008) found in their US study that women presented higher rates of generalized workplace abuse (i.e., workplace bullying or mobbing). In the UK, a representative study detected that a high proportion of lesbian, gay, and bisexual respondents have faced workplace bullying ( Hoel et al., 2017 ). Specifically, the results indicated that while the bullying rate for heterosexuals over a six-months period was of 6.4%, this number was tripled for bisexuals (19.2%), and more than doubled for lesbians (16.9%) and gay (13.7%) individuals ( Hoel et al., 2017 ). Moreover, 90% of the transgender sample in a US study reported experiencing “harassment, mistreatment or discrimination on the job” ( Grant et al., 2011 , p. 3). These findings suggest that many of the individuals facing workplace harassment that appears to be gender neutral are actually targets of GBDH. Hence, they experience “ disguised gender-based harassment and discrimination” ( Rospenda et al., 2009 , p. 837) that should not be addressed as a gender-neutral issue.

Intersectional, Queer, and Feminist Approaches in Organizations

In this section, a short introduction to the feminist, queer, and intersectional approaches is given, as they are applied to the analyses throughout this article.

Feminist Approaches

In the beginning there was feminism.

In the words of bell hooks, “[f]eminism is a movement to end sexism, sexist exploitation, and oppression” ( Hooks, 2000 , viii). However, feminism can be a movement, a methodology, or a theoretical approach, and it is probably better to talk about feminisms than considering it a unitary concept. In this paper, different feminist approaches (see Bendl, 2000 ) are applied to the analysis. Gender as a variable takes gender as a politically neutral, uncontested variable; the feminist standpoint focuses on women as a group; and the feminist poststructuralist approach searches to deconstruct hegemonic discourses that perpetuate inequality (for the complete definitions see Bendl, 2000 ).

Gender Subtext

The gender subtext refers to an approach to the managerial discourse that brings attention to how official speeches of inclusion work to conceal inequalities ( Benschop and Doorewaard, 1998 ). Its methodology -subtext analysis- brings discourse analysis and feminist deconstruction together to scrutiny the managerial discourse and practices in organizations ( Benschop and Doorewaard, 1998 ; Bendl, 2000 ; Bendl, 2008 ; Benschop and Doorewaard, 2012 ).

Integration and Applications of Feminist Approaches and the Gender Subtext

The gender subtext serves to understand the role that organizational factors play in the occurrence of GBDH. Gender as a variable serves to underscore how the hegemonic definition of gender excludes and otherizes the LGBTQ from HRM approaches to gender equality. The feminist standpoint is applied in this paper as a framework in which two groups—women and the LGBTQ—are recognized in their heterogeneity, and still brought together to search for synergies to counteract sexism as a common source of institutionalized oppression (see Oliver, 1992 ; Franke, 1997 ). Finally, the feminist-poststructuralist approach enables conceiving gender as deconstructed and reconstructed, and to apply the subtext analysis to the organizational discourse (see Benschop and Doorewaard, 1998 ; Monro, 2005 ).

Queer Approach

Queer theory and politics.

The origins of the queer movement can be traced to the late eighties, when lesbians, gays, bisexuals, and the transgender took distance from the LGBT community as a sign of disconformity with the depoliticization of its agenda ( Woltersdorff, 2003 ). However, the “Queer” label was later incorporated in the broader movement ( Woltersdorff, 2003 ). In terms of queer theory, the most recognized scholar is Judith Butler, whose work Gender Trouble (1990) was revolutionary because it made visible the oppressive character of the categories used to signify gender, and insisted in its performative nature (see Butler, 1990 ; Woltersdorff, 2003 ).

Queer Standpoint, the LGBTQ, and HRM

In the presented model, queer theory brings attention to the exclusion of the LGBTQ community from the organizational and HRM speech. This exclusion is observed in the policies and politics supported by the HRM literature and practitioners, as well as in the way the LGBTQ are otherized by their discursive practices (e.g., validating only a binary vision of gender, Carrotte et al., 2016 ). Although the categories that the queer theory criticizes are applied in this model, its constructed nature is acknowledged (see Monro, 2005 ). In this way, McCall's (2005) argument in favor of the strategic use of categories for the intersectional analysis of oppression is supported. This analysis is conducted adopting a queer-feminist perspective ( Marinucci, 2016 ) and the intersectional approach.

Integration of Intersectionality With the Queer and Feminist Approaches

Origin and approaches.

The concept of intersectionality was initially introduced to frame the problem of double exclusion and discrimination that black women face in the United States ( Crenshaw, 1989 , 1991 ). Crenshaw (1991) analyzed how making visible the specific violence faced by black women conflicted with the political agendas of the feminist and anti-racist movements. This situation left those women devoid of a framework to direct political attention and resources toward ending with the violence they were (and still are) subjected to ( Crenshaw, 1991 ). Intersectionality theory has evolved since then, and different approaches exist within it ( McCall, 2005 ). These approaches range from fully deconstructivist (total rejection of categories), to intracategorical (focused on the differences within groups), to intercategorical (exploring the experiences of groups in the intersections), and are compatible with queer-feminist approaches (see Parker, 2002 ; McCall, 2005 ; Chapman and Gedro, 2009 ; Hill, 2009 ).

The intracategorical approach acknowledges the heterogeneity that exist within repressed groups (see Bendl, 2000 ; McCall, 2005 ). Within this framework (also called intracategorical complexity, see McCall, 2005 ), the intersectional analysis emerges, calling for attention to historically marginalized groups, [as in Crenshaw (1989 , 1991 )]. The deconstructivist view helps to de-essentialize categories as gender, race, and ableness, making visible the power dynamics they contribute to maintain (see Acker, 2006 ). The intercategorical approach takes constructed social categories and analyzes the power dynamics occurring between groups ( McCall, 2005 ).

Integration: Queer-Feminist Intersectional Synergy

Applying these complementary approaches helps to analyze how women and people from the LGBTQ community are defined (e.g., deconstructivist approach), essentialized (e.g., deconstructivist and intracategorical approaches), and oppressed by social actors (e.g., intercategorical approach) and institutionalized sexism (e.g., Oliver, 1992 ; Franke, 1997 ). It also allows the analysis of the oppression reinforced by members of the dominant group (intercategorical approach), as well as by minority members that enjoy other forms of privilege (e.g., white privilege), and endorse hegemonic values (deconstructivist and intracategorical approaches). In addition, the analyses within the inter- and intra-categorical framework allow approaching the problems faced by individuals in the intersections between sexism, heterosexism, cissexism, and monosexism (e.g., transgender women, lesbians, bisexuals), as well as considering the way classism, racism, ableism, and ethnocentrism shape their experiences (e.g., disabled women, transgender men of color).

Support for an Integrative HRM Model of GBDH in the Workplace

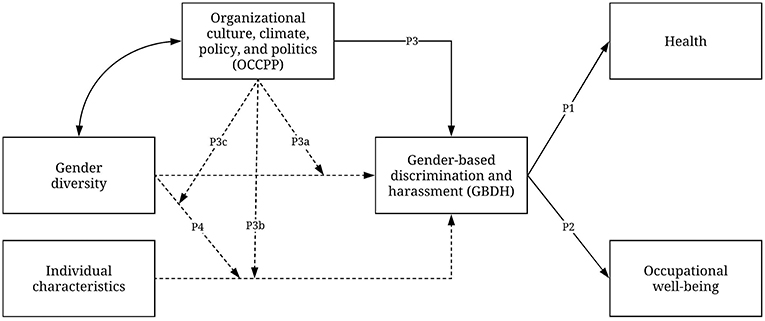

This section describes an integrative model of GBDH in the workplace ( Figure 1 ). First, the effects of GBDH on the health and occupational well-being of targeted individuals are illustrated (P1 and P2). Afterwards, the model deals with the direct and moderation effects of organizational climate, culture, policy, and politics (OCCPP) on GBDH in the workplace. OCCPP acts as a “switch” that enables or disables the other paths to GBDH. OCCPP's effects on GBDH are described as: a direct effect on GBDH (P3), the moderation of the relationship between gender diversity and GBDH (P3a), the moderation of the relationship between individual characteristics and GBDH (P3b), and the moderation (P3c) of the moderation effect of gender diversity on the relationship between individual's characteristics and GBDH (P4). In other words, when OCCPP produce environments that are adverse for gender minorities, gender diversity and gender characteristics become relevant to explain GBDH. When OCCPP generate respectful and integrative environments, gender diversity, and gender characteristics are no longer relevant predictors of harassment.

Figure 1 . Integrative model of GBDH in the workplace. Continuous paths represent direct relationships. Dashed paths represent fully moderated relationships. The double-ended arrow signals the relationship between gender diversity and OCCPP, which follows a circular causation logic.

Consequences of GBDH in the Workplace

Gbdh and individuals' health.

Evidence suggests that exposure to sexist discrimination and harassment in the workplace negatively affects women's well-being ( Yoder and McDonald, 2016 ; Manuel et al., 2017 ), and that different forms of sexual harassment can constitute trauma and lead to posttraumatic stress disorder ( Avina and O'Donohue, 2002 ). In their meta-analysis ( N = 89.382), Chan et al. (2008) found a negative relationship between workplace sexual harassment, psychological health, and physical health conditions. Regarding the LGBTQ at work, Flanders (2015) found a positive relationship between negative identity events, microaggressions, and feelings of stress and anxiety among a sample of bisexual individuals in the US. This is consistent with Galupo and Resnick's (2016) results about the negative effects of microaggressions for the well-being of lesbian, bisexual, and gay workers. In another study, Seelman et al. (2017) found that microaggressions and other forms of gender discrimination relate to lowered self-esteem and increased stress and anxiety in LGBTQ individuals, with the most negative effects reported by the transgender. In a study among gay, lesbian, and bisexual emerging adults in the US, exposure to the phrase “that's so gay” related to feelings of isolation and physical health symptoms as headaches, poor appetite, and eating problems ( Woodford et al., 2012 ). In the literature on gender discrimination, Khan et al. (2017) found that harassment relates to depression risk factors among the LGBTQ. Finally, according to Chan et al. (2008) meta-analysis, targets of workplace sexual harassment suffer its detrimental job-related, psychological, and physical consequences regardless of their gender.

Proposition P1: GBDH negatively affects women and LGBTQ individuals' health in the workplace .

GBDH and Occupational Well-Being

Occupational well-being refers to the relationship between job characteristics and individuals' well-being ( Warr, 1990 ). It is defined “as a positive evaluation of various aspects of one's job, including affective, motivational, behavioral, cognitive, and psychosomatic dimensions” ( Horn et al., 2004 , p. 366). It has a positive relationship with general well-being ( Warr, 1990 ) and work-related outcomes like task performance ( Devonish, 2013 ; Taris and Schaufeli, 2015 ).

There is robust evidence on the negative effects of GBDH on indicators of occupational well-being, such as overall job satisfaction, engagement, commitment, performance, job withdrawal, and job-related stress ( Stedham and Mitchell, 1998 ; Lapierre et al., 2005 ; Chan et al., 2008 ; Cogin and Fish, 2009 ; Sojo et al., 2016 ). Its negative effects have been reported among women ( Fitzgerald et al., 1997 ), gay and heterosexual men ( Stockdale et al., 1999 ), lesbians ( Denissen and Saguy, 2014 ), and transgender individuals ( Lombardi et al., 2002 ), to name some.

Proposition P2: GBDH negatively affects the occupational well-being of women and people from the LGBTQ community in the workplace .

Antecedents of GBDH in the Workplace

Direct effect of occpp on gbdh.

In the next lines, the direct effects of OCCPP on GBDH against women and people from the LGBTQ community are explored, supporting the next proposition of this model.

Proposition P3: OCCPP affect the incidence of GBDH against women and the LGBTQ .

Organizational Culture and GBDH

Organizational culture refers to the shared norms, values, and assumptions that are relatively stable and greatly affect the functioning of organizations ( Schein, 1996 ). The most plausible link between organizational culture and GBDH seems to be the endorsement of sexist beliefs and attitudes. This is supported by evidence that sexism endorsement encourages GBDH attitudes and behavior (see Pryor et al., 1993 ; Fitzgerald et al., 1997 ; Stockdale et al., 1999 ; Stoll et al., 2016 ). The literature on sexism has mainly adopted a binary conception of gender (see Carrotte et al., 2016 ). However, the last decade more research has focused on heterosexism and anti-LGBTQ attitudes, uncovering their negative effects in the lives of LGBTQ individuals.

Sexism Against Women

Scholars focusing on sexism against women have categorized it in different ways. Old-fashioned sexism refers to the explicit endorsement of traditional beliefs about women's inferiority ( Morrison et al., 1999 ). Modern and neo sexism define the denial of gender inequality in society and resentment against measures that support women as a group ( Campbell et al., 1997 ; Morrison et al., 1999 ). Gender-blind sexism refers to the denial of the existence of sexism against women ( Stoll et al., 2016 ). Benevolent sexism defines the endorsement of an idealized vision of women that is used to reinforce their submission ( Glick et al., 2000 ). Finally, ambivalent sexism is the term for the endorsement of both hostile and “benevolent” sexist attitudes ( Glick and Fiske, 1997 , 2001 , 2011 ).

Sexism Against the LGBTQ

Sexism directed against the LGBTQ takes different forms, that can be also held by members of the LGBTQ community, as the evidence about biphobia and transphobia points out (see Vernallis, 1999 ; Weiss, 2011 ). Heterosexism is the endorsement of beliefs stating that heterosexuality is the normal and desirable manifestation of sexuality, while framing other sexual orientations as deviant, inferior, or flawed (see Habarth, 2013 ; Rabelo and Cortina, 2014 ). Monosexism and biphobia refer to negative beliefs toward people that are not monosexual , namely, whose sexual orientation is not defined by the attraction to people from only one gender (see Vernallis, 1999 ). Cissexism (also transphobia ) refers to “an ideology that denigrates and subordinates trans* people because their sex and gender identities exist outside the gender binary. Transgender people are thus positioned as less authentic and inferior to cisgender people” ( Yavorsky, 2016 , p. 950). Hence, transgender individuals experience concurrently sexism, heterosexism, and cissexism/transphobia in their workplaces (see Yavorsky, 2016 ).

Organizational Climate and GBDH

Organizational climate reflects the “social perceptions of the appropriateness of particular behaviors and attitudes [in an organization]” ( Sliter et al., 2014 ). There is evidence linking organizational climate with workplace harassment ( Bowling and Beehr, 2006 ), sexual harassment ( Fitzgerald et al., 1997 , p. 578), and gender microaggressions ( Galupo and Resnick, 2016 ).

Diversity climate is “the extent to which employees perceive their organization to be supportive of underrepresented groups, both in terms of policy implementation and social integration” ( Sliter et al., 2014 ). Hence, a gender-diversity climate reflects the employees' perceptions of their workplace as welcoming and positively appreciating gender differences ( Jansen et al., 2015 ). It has been associated with an increased perception of inclusion by members of an organization, buffering the negative effects of gender dissimilarity (i.e., gender diversity) between individuals in a group ( Jansen et al., 2015 ). Sliter et al. (2014) found a negative relationship between diversity climate perceptions and conflict at work. Also, it has been suggested that it plays a crucial role for workers' active support of diversity initiatives, which is determinant for their successful implementation ( Avery, 2011 ). A similar construct, climate for inclusion has also shown to be a positive factor in gender-diverse groups, protecting against the negative effects of group conflict over unit-level satisfaction ( Nishii, 2013 ).

Heterosexist climate refers to an organizational climate in which heterosexist attitudes and behaviors are accepted and reinforced, propitiating GBDH against the LGBTQ (see Rabelo and Cortina, 2014 ; Galupo and Resnick, 2016 ). For example, Burn et al. (2005) conducted a study using hypothethical scenarios to test the effects of indirect heterosexism on lesbians, gays, and bisexuals. The participants of their study reported that hearing heterosexist comments would be experienced as an offense, affecting their decision to share information about their sexual orientation ( Burn et al., 2005 ). In addition, it has been found that LGBTQ-friendly climates (hence, low in heterosexism), can have a positive impact on the individual and organizational level ( Eliason et al., 2011 ). Examples of positive outcomes are reduced discrimination, better health, increased job satisfaction, job commitment ( Badgett et al., 2013 ), perceived organizational support ( Pichler et al., 2017 ), and feelings of validation for lesbians that become mothers ( Hennekam and Ladge, 2017 ).

Workplace Policy and GBDH

Workplace policy plays an important role in the incidence of GBDH. Finally, evidence shows that policy affects the extent to which the work environment presents itself as LGBTQ-friendly, influencing the experience of LGBTQ individuals at work ( Riger, 1991 ; Eliason et al., 2011 ; Döring, 2013 ; Dougherty and Goldstein Hode, 2016 ; Galupo and Resnick, 2016 ; Gruber, 2016 ). Eliason et al. (2011) found that inclusive language, domestic partner benefits, child-care solutions, and hiring policies are relevant for the constitution of a gender-inclusive work environment for the LGBTQ. Calafell (2014) wrote about how the absence of policy addressing discrimination against people with simultaneous minority identities (e.g., queer Latina) contributes to cover harassment against them. Galupo and Resnick (2016) found that weak policy contributes to the incidence of microaggressions against people from the LGBTQ community. Some of the situations they found include refusal of policy reinforcement, leak of confidential information, and refusal to acknowledge the gender identity of a worker ( Galupo and Resnick, 2016 ). Moreover, existent policy may serve to reinforce inequalities if its discourse is based on power binaries (e.g., rational/masculine vs. emotional/feminine) that discredit, oppress, and marginalize minority groups ( Riger, 1991 ; Dougherty and Goldstein Hode, 2016 ). For example, Peterson and Albrecht (1999) analyzed maternity-policy and found how discourse is shaped to protect organizational interest at the cost of the precarization of women's conditions in organizations. Finally, it is very important to address the mishandling of processes and backlash after GBDH complaints are filed, since they keep targets of harassment from seeking help within their organizations (see Vijayasiri, 2008 ).

Organizational Politics and GBDH

Organizations are political entities ( Mayes and Allen, 1977 ). In the workplace, power, conceived as access to information and resources, is negotiated through political networks embedded in communication practices ( Mayes and Allen, 1977 ; Mumby, 2001 ; Dougherty and Goldstein Hode, 2016 ). These communication practices operate within power dynamics in which the majority group sets the terms of the discussion and frames what is thematized ( Mumby, 1987 , 2001 ). Since gender affects the nature of these power relations, the effects of politics in gender issues and of gender issues in politics must be considered.

Full Moderation of OCCPP of the Relationship Between Gender Diversity and GBDH

Gender diversity refers to heterogeneity regarding gender characteristics of individuals in an organization. Broadly, an organization in which most workers are cisgender, male, and heterosexual would be low in gender diversity, and one in which individuals are evenly distributed in terms of their gender identity, sexual orientation, and gender expression, would be high on gender diversity. In this section, the moderation effect of OCCPP on the relationship between gender diversity and GBDH is discussed to support the next proposition of the model.

Proposition P3a: The relationship between gender diversity and GBDH is fully moderated by OCCPP. When OCCPP propitiate a hostile environment for gender minorities, low gender diversity will lead to high GBDH. When OCCPP propitiate a context of respect and integration of gender minorities, low gender diversity will not lead to higher GBDH .

Male-Dominated Workplace

In male-dominated organizations, a hypermasculine culture is predominant, male workers represent a numerical majority, and most positions of power are occupied by men (e.g., Carrington et al., 2010 ). These organizations present an increased frequency and intensity of GBDH against women, men who do not do gender in a hypermasculine form, and individuals from the LGBTQ community ( Stockdale et al., 1999 ; Street et al., 2007 ; Chan, 2013 ; Wright, 2013 ). Women in a male-dominated workplace may be confronted with misogyny at work ( Denissen and Saguy, 2014 ), becoming targets of more intense and frequent GBDH as they depart from the policed gender-rule that demands them to behave feminine, submissive, and heterosexual ( Berdahl, 2007 ). Women refusing sexual objectification in these contexts may become targets of serious forms of mistreatment, with the case that certain women “—including lesbians and those who present as butch, large, or black—may be less able to access emphasized femininity as a resource and thus [become] more subject to open hostility” ( Denissen and Saguy, 2014 , p. 383). In other words, the more they depart from the sexist and heteronormative standard, the worse is the mistreatment they will face. At the same time, the strategies some women apply to avoid hostility have a high cost for their identity and validation at work, as pointed by Denissen and Saguy (2014 , p. 383),

the presence of lesbians threatens heteronormativity and men's sexual subordination of women […] [b]y sexually objectifying tradeswomen, tradesmen, in effect, attempt to neutralize this threat. While tradeswomen, in turn, are sometimes able to deploy femininity to manage men's conduct and gain some measure of acceptance as women, it often comes at the cost of their perceived professional competence and sexual autonomy and—in the case of lesbians—sexual identity.

However, GBDH is not only directed to women in hypermasculine contexts, as suggested by Denissen and Saguy (2014) , who observed that “tradesmen unapologetically use homophobic slurs to repudiate both homosexuality and femininity (in men)” ( Denissen and Saguy, 2014 , p. 388). Hence, men working in a male-dominated context are also expected to perform hegemonic masculinity, being punished when they do not comply. This leaves men who do not present dominant traits, that are feminine, or that are not heterosexual, at risk of becoming targets of GBDH ( Franke, 1997 ; Stockdale et al., 1999 ; Carrington et al., (2010) .

Female-Dominated Workplace

Female-dominated workplaces are those where women represent a numeric majority. It has been suggested that in these contexts (e.g., nursing) women with care responsibilities can find more tools to balance work-family schedules ( Caroly, 2011 ), and face less harassment ( Konrad et al., 2010 ). However, evidence about heterosexism and harassment against people from the LGBTQ community uncovers heteronormativity in female-dominated workplaces (e.g., among nurses, see Eliason et al., 2011 ). For example, an experiment about discrimination of gays and lesbians in recruitment processes showed that while gay males were discriminated in male-dominated occupations, lesbians were discriminated in female-dominated ones ( Ahmed et al., 2013 ).

Representation of the LGBTQ in the Workplace

At the moment this paper is being written, the authors have not found research that specifically targets LGBTQ-dominated organizations. There is evidence suggesting that having more lesbian, gay, and non-binary coworkers contributes to the development of LGBTQ-friendly workplaces ( Eliason et al., 2011 ). In addition, evidence supports the positive effects of having LGBTQ leaders that advocate for the respect and integration of LGBTQ individuals in organizations ( Moore, 2017 ).

Gender Diversity, Tokenism, Glass Escalator, and GBDH