Change Password

Your password must have 6 characters or more:.

- a lower case character,

- an upper case character,

- a special character

Password Changed Successfully

Your password has been changed

Create your account

Forget yout password.

Enter your email address below and we will send you the reset instructions

If the address matches an existing account you will receive an email with instructions to reset your password

Forgot your Username?

Enter your email address below and we will send you your username

If the address matches an existing account you will receive an email with instructions to retrieve your username

- June 01, 2024 | VOL. 181, NO. 6 CURRENT ISSUE pp.461-564

- May 01, 2024 | VOL. 181, NO. 5 pp.347-460

- April 01, 2024 | VOL. 181, NO. 4 pp.255-346

- March 01, 2024 | VOL. 181, NO. 3 pp.171-254

- February 01, 2024 | VOL. 181, NO. 2 pp.83-170

- January 01, 2024 | VOL. 181, NO. 1 pp.1-82

The American Psychiatric Association (APA) has updated its Privacy Policy and Terms of Use , including with new information specifically addressed to individuals in the European Economic Area. As described in the Privacy Policy and Terms of Use, this website utilizes cookies, including for the purpose of offering an optimal online experience and services tailored to your preferences.

Please read the entire Privacy Policy and Terms of Use. By closing this message, browsing this website, continuing the navigation, or otherwise continuing to use the APA's websites, you confirm that you understand and accept the terms of the Privacy Policy and Terms of Use, including the utilization of cookies.

Substance Use Disorders and Addiction: Mechanisms, Trends, and Treatment Implications

- Ned H. Kalin , M.D.

Search for more papers by this author

The numbers for substance use disorders are large, and we need to pay attention to them. Data from the 2018 National Survey on Drug Use and Health ( 1 ) suggest that, over the preceding year, 20.3 million people age 12 or older had substance use disorders, and 14.8 million of these cases were attributed to alcohol. When considering other substances, the report estimated that 4.4 million individuals had a marijuana use disorder and that 2 million people suffered from an opiate use disorder. It is well known that stress is associated with an increase in the use of alcohol and other substances, and this is particularly relevant today in relation to the chronic uncertainty and distress associated with the COVID-19 pandemic along with the traumatic effects of racism and social injustice. In part related to stress, substance use disorders are highly comorbid with other psychiatric illnesses: 9.2 million adults were estimated to have a 1-year prevalence of both a mental illness and at least one substance use disorder. Although they may not necessarily meet criteria for a substance use disorder, it is well known that psychiatric patients have increased usage of alcohol, cigarettes, and other illicit substances. As an example, the survey estimated that over the preceding month, 37.2% of individuals with serious mental illnesses were cigarette smokers, compared with 16.3% of individuals without mental illnesses. Substance use frequently accompanies suicide and suicide attempts, and substance use disorders are associated with a long-term increased risk of suicide.

Addiction is the key process that underlies substance use disorders, and research using animal models and humans has revealed important insights into the neural circuits and molecules that mediate addiction. More specifically, research has shed light onto mechanisms underlying the critical components of addiction and relapse: reinforcement and reward, tolerance, withdrawal, negative affect, craving, and stress sensitization. In addition, clinical research has been instrumental in developing an evidence base for the use of pharmacological agents in the treatment of substance use disorders, which, in combination with psychosocial approaches, can provide effective treatments. However, despite the existence of therapeutic tools, relapse is common, and substance use disorders remain grossly undertreated. For example, whether at an inpatient hospital treatment facility or at a drug or alcohol rehabilitation program, it was estimated that only 11% of individuals needing treatment for substance use received appropriate care in 2018. Additionally, it is worth emphasizing that current practice frequently does not effectively integrate dual diagnosis treatment approaches, which is important because psychiatric and substance use disorders are highly comorbid. The barriers to receiving treatment are numerous and directly interact with existing health care inequities. It is imperative that as a field we overcome the obstacles to treatment, including the lack of resources at the individual level, a dearth of trained providers and appropriate treatment facilities, racial biases, and the marked stigmatization that is focused on individuals with addictions.

This issue of the Journal is focused on understanding factors contributing to substance use disorders and their comorbidity with psychiatric disorders, the effects of prenatal alcohol use on preadolescents, and brain mechanisms that are associated with addiction and relapse. An important theme that emerges from this issue is the necessity for understanding maladaptive substance use and its treatment in relation to health care inequities. This highlights the imperative to focus resources and treatment efforts on underprivileged and marginalized populations. The centerpiece of this issue is an overview on addiction written by Dr. George Koob, the director of the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (NIAAA), and coauthors Drs. Patricia Powell (NIAAA deputy director) and Aaron White ( 2 ). This outstanding article will serve as a foundational knowledge base for those interested in understanding the complex factors that mediate drug addiction. Of particular interest to the practice of psychiatry is the emphasis on the negative affect state “hyperkatifeia” as a major driver of addictive behavior and relapse. This places the dysphoria and psychological distress that are associated with prolonged withdrawal at the heart of treatment and underscores the importance of treating not only maladaptive drug-related behaviors but also the prolonged dysphoria and negative affect associated with addiction. It also speaks to why it is crucial to concurrently treat psychiatric comorbidities that commonly accompany substance use disorders.

Insights Into Mechanisms Related to Cocaine Addiction Using a Novel Imaging Method for Dopamine Neurons

Cassidy et al. ( 3 ) introduce a relatively new imaging technique that allows for an estimation of dopamine integrity and function in the substantia nigra, the site of origin of dopamine neurons that project to the striatum. Capitalizing on the high levels of neuromelanin that are found in substantia nigra dopamine neurons and the interaction between neuromelanin and intracellular iron, this MRI technique, termed neuromelanin-sensitive MRI (NM-MRI), shows promise in studying the involvement of substantia nigra dopamine neurons in neurodegenerative diseases and psychiatric illnesses. The authors used this technique to assess dopamine function in active cocaine users with the aim of exploring the hypothesis that cocaine use disorder is associated with blunted presynaptic striatal dopamine function that would be reflected in decreased “integrity” of the substantia nigra dopamine system. Surprisingly, NM-MRI revealed evidence for increased dopamine in the substantia nigra of individuals using cocaine. The authors suggest that this finding, in conjunction with prior work suggesting a blunted dopamine response, points to the possibility that cocaine use is associated with an altered intracellular distribution of dopamine. Specifically, the idea is that dopamine is shifted from being concentrated in releasable, functional vesicles at the synapse to a nonreleasable cytosolic pool. In addition to providing an intriguing alternative hypothesis underlying the cocaine-related alterations observed in substantia nigra dopamine function, this article highlights an innovative imaging method that can be used in further investigations involving the role of substantia nigra dopamine systems in neuropsychiatric disorders. Dr. Charles Bradberry, chief of the Preclinical Pharmacology Section at the National Institute on Drug Abuse, contributes an editorial that further explains the use of NM-MRI and discusses the theoretical implications of these unexpected findings in relation to cocaine use ( 4 ).

Treatment Implications of Understanding Brain Function During Early Abstinence in Patients With Alcohol Use Disorder

Developing a better understanding of the neural processes that are associated with substance use disorders is critical for conceptualizing improved treatment approaches. Blaine et al. ( 5 ) present neuroimaging data collected during early abstinence in patients with alcohol use disorder and link these data to relapses occurring during treatment. Of note, the findings from this study dovetail with the neural circuit schema Koob et al. provide in this issue’s overview on addiction ( 2 ). The first study in the Blaine et al. article uses 44 patients and 43 control subjects to demonstrate that patients with alcohol use disorder have a blunted neural response to the presentation of stress- and alcohol-related cues. This blunting was observed mainly in the ventromedial prefrontal cortex, a key prefrontal regulatory region, as well as in subcortical regions associated with reward processing, specifically the ventral striatum. Importantly, this finding was replicated in a second study in which 69 patients were studied in relation to their length of abstinence prior to treatment and treatment outcomes. The results demonstrated that individuals with the shortest abstinence times had greater alterations in neural responses to stress and alcohol cues. The authors also found that an individual’s length of abstinence prior to treatment, independent of the number of days of abstinence, was a predictor of relapse and that the magnitude of an individual’s neural alterations predicted the amount of heavy drinking occurring early in treatment. Although relapse is an all too common outcome in patients with substance use disorders, this study highlights an approach that has the potential to refine and develop new treatments that are based on addiction- and abstinence-related brain changes. In her thoughtful editorial, Dr. Edith Sullivan from Stanford University comments on the details of the study, the value of studying patients during early abstinence, and the implications of these findings for new treatment development ( 6 ).

Relatively Low Amounts of Alcohol Intake During Pregnancy Are Associated With Subtle Neurodevelopmental Effects in Preadolescent Offspring

Excessive substance use not only affects the user and their immediate family but also has transgenerational effects that can be mediated in utero. Lees et al. ( 7 ) present data suggesting that even the consumption of relatively low amounts of alcohol by expectant mothers can affect brain development, cognition, and emotion in their offspring. The researchers used data from the Adolescent Brain Cognitive Development Study, a large national community-based study, which allowed them to assess brain structure and function as well as behavioral, cognitive, and psychological outcomes in 9,719 preadolescents. The mothers of 2,518 of the subjects in this study reported some alcohol use during pregnancy, albeit at relatively low levels (0 to 80 drinks throughout pregnancy). Interestingly, and opposite of that expected in relation to data from individuals with fetal alcohol spectrum disorders, increases in brain volume and surface area were found in offspring of mothers who consumed the relatively low amounts of alcohol. Notably, any prenatal alcohol exposure was associated with small but significant increases in psychological problems that included increases in separation anxiety disorder and oppositional defiant disorder. Additionally, a dose-response effect was found for internalizing psychopathology, somatic complaints, and attentional deficits. While subtle, these findings point to neurodevelopmental alterations that may be mediated by even small amounts of prenatal alcohol consumption. Drs. Clare McCormack and Catherine Monk from Columbia University contribute an editorial that provides an in-depth assessment of these findings in relation to other studies, including those assessing severe deficits in individuals with fetal alcohol syndrome ( 8 ). McCormack and Monk emphasize that the behavioral and psychological effects reported in the Lees et al. article would not be clinically meaningful. However, it is feasible that the influences of these low amounts of alcohol could interact with other predisposing factors that might lead to more substantial negative outcomes.

Increased Comorbidity Between Substance Use and Psychiatric Disorders in Sexual Identity Minorities

There is no question that victims of societal marginalization experience disproportionate adversity and stress. Evans-Polce et al. ( 9 ) focus on this concern in relation to individuals who identify as sexual minorities by comparing their incidence of comorbid substance use and psychiatric disorders with that of individuals who identify as heterosexual. By using 2012−2013 data from 36,309 participants in the National Epidemiologic Study on Alcohol and Related Conditions–III, the authors examine the incidence of comorbid alcohol and tobacco use disorders with anxiety, mood disorders, and posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD). The findings demonstrate increased incidences of substance use and psychiatric disorders in individuals who identified as bisexual or as gay or lesbian compared with those who identified as heterosexual. For example, a fourfold increase in the prevalence of PTSD was found in bisexual individuals compared with heterosexual individuals. In addition, the authors found an increased prevalence of substance use and psychiatric comorbidities in individuals who identified as bisexual and as gay or lesbian compared with individuals who identified as heterosexual. This was most prominent in women who identified as bisexual. For example, of the bisexual women who had an alcohol use disorder, 60.5% also had a psychiatric comorbidity, compared with 44.6% of heterosexual women. Additionally, the amount of reported sexual orientation discrimination and number of lifetime stressful events were associated with a greater likelihood of having comorbid substance use and psychiatric disorders. These findings are important but not surprising, as sexual minority individuals have a history of increased early-life trauma and throughout their lives may experience the painful and unwarranted consequences of bias and denigration. Nonetheless, these findings underscore the strong negative societal impacts experienced by minority groups and should sensitize providers to the additional needs of these individuals.

Trends in Nicotine Use and Dependence From 2001–2002 to 2012–2013

Although considerable efforts over earlier years have curbed the use of tobacco and nicotine, the use of these substances continues to be a significant public health problem. As noted above, individuals with psychiatric disorders are particularly vulnerable. Grant et al. ( 10 ) use data from the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions collected from a very large cohort to characterize trends in nicotine use and dependence over time. Results from their analysis support the so-called hardening hypothesis, which posits that although intervention-related reductions in nicotine use may have occurred over time, the impact of these interventions is less potent in individuals with more severe addictive behavior (i.e., nicotine dependence). When adjusted for sociodemographic factors, the results demonstrated a small but significant increase in nicotine use from 2001–2002 to 2012–2013. However, a much greater increase in nicotine dependence (46.1% to 52%) was observed over this time frame in individuals who had used nicotine during the preceding 12 months. The increases in nicotine use and dependence were associated with factors related to socioeconomic status, such as lower income and lower educational attainment. The authors interpret these findings as evidence for the hardening hypothesis, suggesting that despite the impression that nicotine use has plateaued, there is a growing number of highly dependent nicotine users who would benefit from nicotine dependence intervention programs. Dr. Kathleen Brady, from the Medical University of South Carolina, provides an editorial ( 11 ) that reviews the consequences of tobacco use and the history of the public measures that were initially taken to combat its use. Importantly, her editorial emphasizes the need to address health care inequity issues that affect individuals of lower socioeconomic status by devoting resources to develop and deploy effective smoking cessation interventions for at-risk and underresourced populations.

Conclusions

Maladaptive substance use and substance use disorders are highly prevalent and are among the most significant public health problems. Substance use is commonly comorbid with psychiatric disorders, and treatment efforts need to concurrently address both. The papers in this issue highlight new findings that are directly relevant to understanding, treating, and developing policies to better serve those afflicted with addictions. While treatments exist, the need for more effective treatments is clear, especially those focused on decreasing relapse rates. The negative affective state, hyperkatifeia, that accompanies longer-term abstinence is an important treatment target that should be emphasized in current practice as well as in new treatment development. In addition to developing a better understanding of the neurobiology of addictions and abstinence, it is necessary to ensure that there is equitable access to currently available treatments and treatment programs. Additional resources must be allocated to this cause. This depends on the recognition that health care inequities and societal barriers are major contributors to the continued high prevalence of substance use disorders, the individual suffering they inflict, and the huge toll that they incur at a societal level.

Disclosures of Editors’ financial relationships appear in the April 2020 issue of the Journal .

1 US Department of Health and Human Services: Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, Center for Behavioral Health Statistics and Quality: National Survey on Drug Use and Health 2018. Rockville, Md, SAMHSA, 2019 ( https://www.samhsa.gov/data/nsduh/reports-detailed-tables-2018-NSDUH ) Google Scholar

2 Koob GF, Powell P, White A : Addiction as a coping response: hyperkatifeia, deaths of despair, and COVID-19 . Am J Psychiatry 2020 ; 177:1031–1037 Link , Google Scholar

3 Cassidy CM, Carpenter KM, Konova AB, et al. : Evidence for dopamine abnormalities in the substantia nigra in cocaine addiction revealed by neuromelanin-sensitive MRI . Am J Psychiatry 2020 ; 177:1038–1047 Link , Google Scholar

4 Bradberry CW : Neuromelanin MRI: dark substance shines a light on dopamine dysfunction and cocaine use (editorial). Am J Psychiatry 2020 ; 177:1019–1021 Abstract , Google Scholar

5 Blaine SK, Wemm S, Fogelman N, et al. : Association of prefrontal-striatal functional pathology with alcohol abstinence days at treatment initiation and heavy drinking after treatment initiation . Am J Psychiatry 2020 ; 177:1048–1059 Link , Google Scholar

6 Sullivan EV : Why timing matters in alcohol use disorder recovery (editorial). Am J Psychiatry 2020 ; 177:1022–1024 Abstract , Google Scholar

7 Lees B, Mewton L, Jacobus J, et al. : Association of prenatal alcohol exposure with psychological, behavioral, and neurodevelopmental outcomes in children from the Adolescent Brain Cognitive Development Study . Am J Psychiatry 2020 ; 177:1060–1072 Link , Google Scholar

8 McCormack C, Monk C : Considering prenatal alcohol exposure in a developmental origins of health and disease framework (editorial). Am J Psychiatry 2020 ; 177:1025–1028 Abstract , Google Scholar

9 Evans-Polce RJ, Kcomt L, Veliz PT, et al. : Alcohol, tobacco, and comorbid psychiatric disorders and associations with sexual identity and stress-related correlates . Am J Psychiatry 2020 ; 177:1073–1081 Abstract , Google Scholar

10 Grant BF, Shmulewitz D, Compton WM : Nicotine use and DSM-IV nicotine dependence in the United States, 2001–2002 and 2012–2013 . Am J Psychiatry 2020 ; 177:1082–1090 Link , Google Scholar

11 Brady KT : Social determinants of health and smoking cessation: a challenge (editorial). Am J Psychiatry 2020 ; 177:1029–1030 Abstract , Google Scholar

- Cited by None

- Substance-Related and Addictive Disorders

- Addiction Psychiatry

- Transgender (LGBT) Issues

- Open access

- Published: 13 November 2021

Risk and protective factors of drug abuse among adolescents: a systematic review

- Azmawati Mohammed Nawi 1 ,

- Rozmi Ismail 2 ,

- Fauziah Ibrahim 2 ,

- Mohd Rohaizat Hassan 1 ,

- Mohd Rizal Abdul Manaf 1 ,

- Noh Amit 3 ,

- Norhayati Ibrahim 3 &

- Nurul Shafini Shafurdin 2

BMC Public Health volume 21 , Article number: 2088 ( 2021 ) Cite this article

139k Accesses

101 Citations

20 Altmetric

Metrics details

Drug abuse is detrimental, and excessive drug usage is a worldwide problem. Drug usage typically begins during adolescence. Factors for drug abuse include a variety of protective and risk factors. Hence, this systematic review aimed to determine the risk and protective factors of drug abuse among adolescents worldwide.

Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) was adopted for the review which utilized three main journal databases, namely PubMed, EBSCOhost, and Web of Science. Tobacco addiction and alcohol abuse were excluded in this review. Retrieved citations were screened, and the data were extracted based on strict inclusion and exclusion criteria. Inclusion criteria include the article being full text, published from the year 2016 until 2020 and provided via open access resource or subscribed to by the institution. Quality assessment was done using Mixed Methods Appraisal Tools (MMAT) version 2018 to assess the methodological quality of the included studies. Given the heterogeneity of the included studies, a descriptive synthesis of the included studies was undertaken.

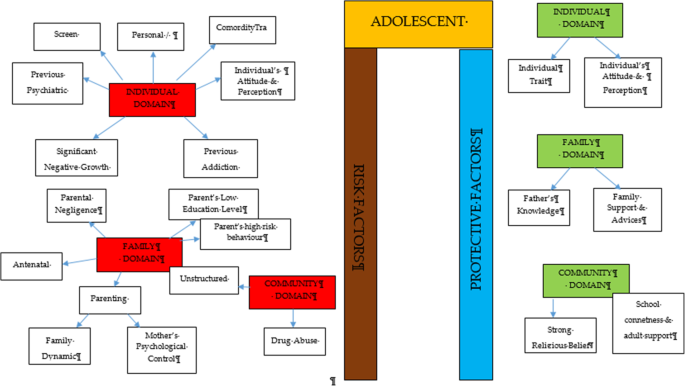

Out of 425 articles identified, 22 quantitative articles and one qualitative article were included in the final review. Both the risk and protective factors obtained were categorized into three main domains: individual, family, and community factors. The individual risk factors identified were traits of high impulsivity; rebelliousness; emotional regulation impairment, low religious, pain catastrophic, homework completeness, total screen time and alexithymia; the experience of maltreatment or a negative upbringing; having psychiatric disorders such as conduct problems and major depressive disorder; previous e-cigarette exposure; behavioral addiction; low-perceived risk; high-perceived drug accessibility; and high-attitude to use synthetic drugs. The familial risk factors were prenatal maternal smoking; poor maternal psychological control; low parental education; negligence; poor supervision; uncontrolled pocket money; and the presence of substance-using family members. One community risk factor reported was having peers who abuse drugs. The protective factors determined were individual traits of optimism; a high level of mindfulness; having social phobia; having strong beliefs against substance abuse; the desire to maintain one’s health; high paternal awareness of drug abuse; school connectedness; structured activity and having strong religious beliefs.

The outcomes of this review suggest a complex interaction between a multitude of factors influencing adolescent drug abuse. Therefore, successful adolescent drug abuse prevention programs will require extensive work at all levels of domains.

Peer Review reports

Introduction

Drug abuse is a global problem; 5.6% of the global population aged 15–64 years used drugs at least once during 2016 [ 1 ]. The usage of drugs among younger people has been shown to be higher than that among older people for most drugs. Drug abuse is also on the rise in many ASEAN (Association of Southeast Asian Nations) countries, especially among young males between 15 and 30 years of age. The increased burden due to drug abuse among adolescents and young adults was shown by the Global Burden of Disease (GBD) study in 2013 [ 2 ]. About 14% of the total health burden in young men is caused by alcohol and drug abuse. Younger people are also more likely to die from substance use disorders [ 3 ], and cannabis is the drug of choice among such users [ 4 ].

Adolescents are the group of people most prone to addiction [ 5 ]. The critical age of initiation of drug use begins during the adolescent period, and the maximum usage of drugs occurs among young people aged 18–25 years old [ 1 ]. During this period, adolescents have a strong inclination toward experimentation, curiosity, susceptibility to peer pressure, rebellion against authority, and poor self-worth, which makes such individuals vulnerable to drug abuse [ 2 ]. During adolescence, the basic development process generally involves changing relations between the individual and the multiple levels of the context within which the young person is accustomed. Variation in the substance and timing of these relations promotes diversity in adolescence and represents sources of risk or protective factors across this life period [ 6 ]. All these factors are crucial to helping young people develop their full potential and attain the best health in the transition to adulthood. Abusing drugs impairs the successful transition to adulthood by impairing the development of critical thinking and the learning of crucial cognitive skills [ 7 ]. Adolescents who abuse drugs are also reported to have higher rates of physical and mental illness and reduced overall health and well-being [ 8 ].

The absence of protective factors and the presence of risk factors predispose adolescents to drug abuse. Some of the risk factors are the presence of early mental and behavioral health problems, peer pressure, poorly equipped schools, poverty, poor parental supervision and relationships, a poor family structure, a lack of opportunities, isolation, gender, and accessibility to drugs [ 9 ]. The protective factors include high self-esteem, religiosity, grit, peer factors, self-control, parental monitoring, academic competence, anti-drug use policies, and strong neighborhood attachment [ 10 , 11 , 12 , 13 , 14 , 15 ].

The majority of previous systematic reviews done worldwide on drug usage focused on the mental, psychological, or social consequences of substance abuse [ 16 , 17 , 18 ], while some focused only on risk and protective factors for the non-medical use of prescription drugs among youths [ 19 ]. A few studies focused only on the risk factors of single drug usage among adolescents [ 20 ]. Therefore, the development of the current systematic review is based on the main research question: What is the current risk and protective factors among adolescent on the involvement with drug abuse? To the best of our knowledge, there is limited evidence from systematic reviews that explores the risk and protective factors among the adolescent population involved in drug abuse. Especially among developing countries, such as those in South East Asia, such research on the risk and protective factors for drug abuse is scarce. Furthermore, this review will shed light on the recent trends of risk and protective factors and provide insight into the main focus factors for prevention and control activities program. Additionally, this review will provide information on how these risk and protective factors change throughout various developmental stages. Therefore, the objective of this systematic review was to determine the risk and protective factors of drug abuse among adolescents worldwide. This paper thus fills in the gaps of previous studies and adds to the existing body of knowledge. In addition, this review may benefit certain parties in developing countries like Malaysia, where the national response to drugs is developing in terms of harm reduction, prison sentences, drug treatments, law enforcement responses, and civil society participation.

This systematic review was conducted using three databases, PubMed, EBSCOhost, and Web of Science, considering the easy access and wide coverage of reliable journals, focusing on the risk and protective factors of drug abuse among adolescents from 2016 until December 2020. The search was limited to the last 5 years to focus only on the most recent findings related to risk and protective factors. The search strategy employed was performed in accordance with the Preferred Reporting Items for a Systematic Review and Meta-analysis (PRISMA) checklist.

A preliminary search was conducted to identify appropriate keywords and determine whether this review was feasible. Subsequently, the related keywords were searched using online thesauruses, online dictionaries, and online encyclopedias. These keywords were verified and validated by an academic professor at the National University of Malaysia. The keywords used as shown in Table 1 .

Selection criteria

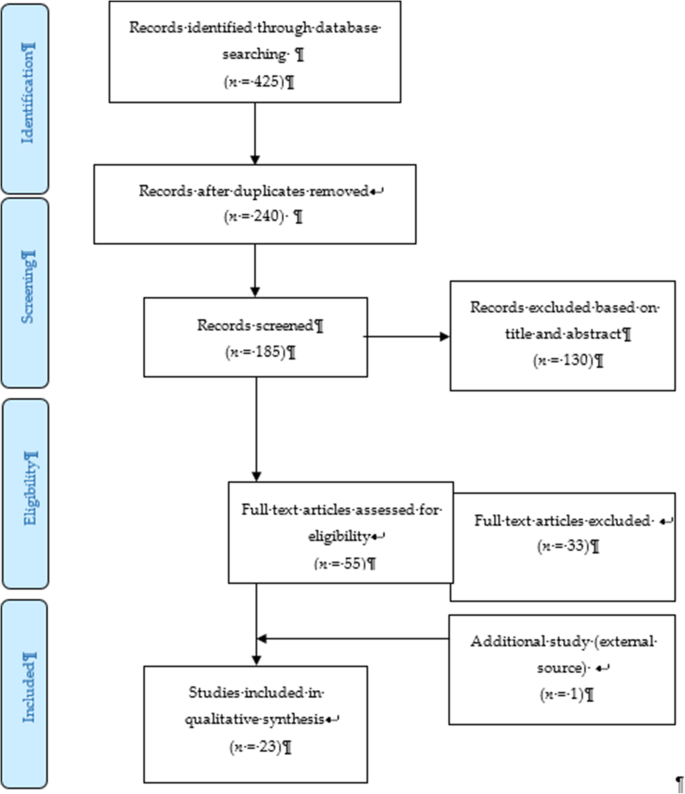

The systematic review process for searching the articles was carried out via the steps shown in Fig. 1 . Firstly, screening was done to remove duplicate articles from the selected search engines. A total of 240 articles were removed in this stage. Titles and abstracts were screened based on the relevancy of the titles to the inclusion and exclusion criteria and the objectives. The inclusion criteria were full text original articles, open access articles or articles subscribed to by the institution, observation and intervention study design and English language articles. The exclusion criteria in this search were (a) case study articles, (b) systematic and narrative review paper articles, (c) non-adolescent-based analyses, (d) non-English articles, and (e) articles focusing on smoking (nicotine) and alcohol-related issues only. A total of 130 articles were excluded after title and abstract screening, leaving 55 articles to be assessed for eligibility. The full text of each article was obtained, and each full article was checked thoroughly to determine if it would fulfil the inclusion criteria and objectives of this study. Each of the authors compared their list of potentially relevant articles and discussed their selections until a final agreement was obtained. A total of 22 articles were accepted to be included in this review. Most of the excluded articles were excluded because the population was not of the target age range—i.e., featuring subjects with an age > 18 years, a cohort born in 1965–1975, or undergraduate college students; the subject matter was not related to the study objective—i.e., assessing the effects on premature mortality, violent behavior, psychiatric illness, individual traits, and personality; type of article such as narrative review and neuropsychiatry review; and because of our inability to obtain the full article—e.g., forthcoming work in 2021. One qualitative article was added to explain the domain related to risk and the protective factors among the adolescents.

PRISMA flow diagram showing the selection of studies on risk and protective factors for drug abuse among adolescents.2.2. Operational Definition

Drug-related substances in this context refer to narcotics, opioids, psychoactive substances, amphetamines, cannabis, ecstasy, heroin, cocaine, hallucinogens, depressants, and stimulants. Drugs of abuse can be either off-label drugs or drugs that are medically prescribed. The two most commonly abused substances not included in this review are nicotine (tobacco) and alcohol. Accordingly, e-cigarettes and nicotine vape were also not included. Further, “adolescence” in this study refers to members of the population aged between 10 to 18 years [ 21 ].

Data extraction tool

All researchers independently extracted information for each article into an Excel spreadsheet. The data were then customized based on their (a) number; (b) year; (c) author and country; (d) titles; (e) study design; (f) type of substance abuse; (g) results—risks and protective factors; and (h) conclusions. A second reviewer crossed-checked the articles assigned to them and provided comments in the table.

Quality assessment tool

By using the Mixed Method Assessment Tool (MMAT version 2018), all articles were critically appraised for their quality by two independent reviewers. This tool has been shown to be useful in systematic reviews encompassing different study designs [ 22 ]. Articles were only selected if both reviewers agreed upon the articles’ quality. Any disagreement between the assigned reviewers was managed by employing a third independent reviewer. All included studies received a rating of “yes” for the questions in the respective domains of the MMAT checklists. Therefore, none of the articles were removed from this review due to poor quality. The Cohen’s kappa (agreement) between the two reviewers was 0.77, indicating moderate agreement [ 23 ].

The initial search found 425 studies for review, but after removing duplicates and applying the criteria listed above, we narrowed the pool to 22 articles, all of which are quantitative in their study design. The studies include three prospective cohort studies [ 24 , 25 , 26 ], one community trial [ 27 ], one case-control study [ 28 ], and nine cross-sectional studies [ 29 , 30 , 31 , 32 , 33 , 34 , 35 , 36 , 37 , 38 , 39 , 40 , 41 , 42 , 43 , 44 , 45 ]. After careful discussion, all reviewer panels agreed to add one qualitative study [ 46 ] to help provide reasoning for the quantitative results. The selected qualitative paper was chosen because it discussed almost all domains on the risk and protective factors found in this review.

A summary of all 23 articles is listed in Table 2 . A majority of the studies (13 articles) were from the United States of America (USA) [ 25 , 26 , 27 , 29 , 30 , 31 , 34 , 36 , 37 , 38 , 39 , 40 , 41 , 42 , 43 , 44 , 45 ], three studies were from the Asia region [ 32 , 33 , 38 ], four studies were from Europe [ 24 , 28 , 40 , 44 ], and one study was from Latin America [ 35 ], Africa [ 43 ] and Mediterranean [ 45 ]. The number of sample participants varied widely between the studies, ranging from 70 samples (minimum) to 700,178 samples (maximum), while the qualitative paper utilized a total of 100 interviewees. There were a wide range of drugs assessed in the quantitative articles, with marijuana being mentioned in 11 studies, cannabis in five studies, and opioid (six studies). There was also large heterogeneity in terms of the study design, type of drug abused, measurements of outcomes, and analysis techniques used. Therefore, the data were presented descriptively.

After thorough discussion and evaluation, all the findings (both risk and protective factors) from the review were categorized into three main domains: individual factors, family factors, and community factors. The conceptual framework is summarized in Fig. 2 .

Conceptual framework of risk and protective factors related to adolescent drug abuse

DOMAIN: individual factor

Risk factors.

Almost all the articles highlighted significant findings of individual risk factors for adolescent drug abuse. Therefore, our findings for this domain were further broken down into five more sub-domains consisting of personal/individual traits, significant negative growth exposure, personal psychiatric diagnosis, previous substance history, comorbidity and an individual’s attitude and perception.

Personal/individual traits

Chuang et al. [ 29 ] found that adolescents with high impulsivity traits had a significant positive association with drug addiction. This study also showed that the impulsivity trait alone was an independent risk factor that increased the odds between two to four times for using any drug compared to the non-impulsive group. Another longitudinal study by Guttmannova et al. showed that rebellious traits are positively associated with marijuana drug abuse [ 27 ]. The authors argued that measures of rebelliousness are a good proxy for a youth’s propensity to engage in risky behavior. Nevertheless, Wilson et al. [ 37 ], in a study involving 112 youths undergoing detoxification treatment for opioid abuse, found that a majority of the affected respondents had difficulty in regulating their emotions. The authors found that those with emotional regulation impairment traits became opioid dependent at an earlier age. Apart from that, a case-control study among outpatient youths found that adolescents involved in cannabis abuse had significant alexithymia traits compared to the control population [ 28 ]. Those adolescents scored high in the dimension of Difficulty in Identifying Emotion (DIF), which is one of the key definitions of diagnosing alexithymia. Overall, the adjusted Odds Ratio for DIF in cannabis abuse was 1.11 (95% CI, 1.03–1.20).

Significant negative growth exposure

A history of maltreatment in the past was also shown to have a positive association with adolescent drug abuse. A study found that a history of physical abuse in the past is associated with adolescent drug abuse through a Path Analysis, despite evidence being limited to the female gender [ 25 ]. However, evidence from another study focusing at foster care concluded that any type of maltreatment might result in a prevalence as high as 85.7% for the lifetime use of cannabis and as high as 31.7% for the prevalence of cannabis use within the last 3-months [ 30 ]. The study also found significant latent variables that accounted for drug abuse outcomes, which were chronic physical maltreatment (factor loading of 0.858) and chronic psychological maltreatment (factor loading of 0.825), with an r 2 of 73.6 and 68.1%, respectively. Another study shed light on those living in child welfare service (CWS) [ 35 ]. It was observed through longitudinal measurements that proportions of marijuana usage increased from 9 to 18% after 36 months in CWS. Hence, there is evidence of the possibility of a negative upbringing at such shelters.

Personal psychiatric diagnosis

The robust studies conducted in the USA have deduced that adolescents diagnosed with a conduct problem (CP) have a positive association with marijuana abuse (OR = 1.75 [1.56, 1.96], p < 0.0001). Furthermore, those with a diagnosis of Major Depressive Disorder (MDD) showed a significant positive association with marijuana abuse.

Previous substance and addiction history

Another study found that exposure to e-cigarettes within the past 30 days is related to an increase in the prevalence of marijuana use and prescription drug use by at least four times in the 8th and 10th grades and by at least three times in the 12th grade [ 34 ]. An association between other behavioral addictions and the development of drug abuse was also studied [ 29 ]. Using a 12-item index to assess potential addictive behaviors [ 39 ], significant associations between drug abuse and the groups with two behavioral addictions (OR = 3.19, 95% CI 1.25,9.77) and three behavioral addictions (OR = 3.46, 95% CI 1.25,9.58) were reported.

Comorbidity

The paper by Dash et al. (2020) highlight adolescent with a disease who needs routine medical pain treatment have higher risk of opioid misuse [ 38 ]. The adolescents who have disorder symptoms may have a risk for opioid misuse despite for the pain intensity.

Individual’s attitudes and perceptions

In a study conducted in three Latin America countries (Argentina, Chile, and Uruguay), it was shown that adolescents with low or no perceived risk of taking marijuana had a higher risk of abuse (OR = 8.22 times, 95% CI 7.56, 10.30) [ 35 ]. This finding is in line with another study that investigated 2002 adolescents and concluded that perceiving the drug as harmless was an independent risk factor that could prospectively predict future marijuana abuse [ 27 ]. Moreover, some youth interviewed perceived that they gained benefits from substance use [ 38 ]. The focus group discussion summarized that the youth felt positive personal motivation and could escape from a negative state by taking drugs. Apart from that, adolescents who had high-perceived availability of drugs in their neighborhoods were more likely to increase their usage of marijuana over time (OR = 11.00, 95% CI 9.11, 13.27) [ 35 ]. A cheap price of the substance and the availability of drug dealers around schools were factors for youth accessibility [ 38 ]. Perceived drug accessibility has also been linked with the authorities’ enforcement programs. The youth perception of a lax community enforcement of laws regarding drug use at all-time points predicted an increase in marijuana use in the subsequent assessment period [ 27 ]. Besides perception, a study examining the attitudes towards synthetic drugs based on 8076 probabilistic samples of Macau students found that the odds of the lifetime use of marijuana was almost three times higher among those with a strong attitude towards the use of synthetic drugs [ 32 ]. In addition, total screen time among the adolescent increase the likelihood of frequent cannabis use. Those who reported daily cannabis use have a mean of 12.56 h of total screen time, compared to a mean of 6.93 h among those who reported no cannabis use. Adolescent with more time on internet use, messaging, playing video games and watching TV/movies were significantly associated with more frequent cannabis use [ 44 ].

Protective factors

Individual traits.

Some individual traits have been determined to protect adolescents from developing drug abuse habits. A study by Marin et al. found that youth with an optimistic trait were less likely to become drug dependent [ 33 ]. In this study involving 1104 Iranian students, it was concluded that a higher optimism score (measured using the Children Attributional Style Questionnaire, CASQ) was a protective factor against illicit drug use (OR = 0.90, 95% CI: 0.85–0.95). Another study found that high levels of mindfulness, measured using the 25-item Child Acceptance and Mindfulness Measure, CAMM, lead to a slower progression toward injectable drug abuse among youth with opioid addiction (1.67 years, p = .041) [ 37 ]. In addition, the social phobia trait was found to have a negative association with marijuana use (OR = 0.87, 95% CI 0.77–0.97), as suggested [ 31 ].

According to El Kazdouh et al., individuals with a strong belief against substance use and those with a strong desire to maintain their health were more likely to be protected from involvement in drug abuse [ 46 ].

DOMAIN: family factors

The biological factors underlying drug abuse in adolescents have been reported in several studies. Epigenetic studies are considered important, as they can provide a good outline of the potential pre-natal factors that can be targeted at an earlier stage. Expecting mothers who smoke tobacco and alcohol have an indirect link with adolescent substance abuse in later life [ 24 , 39 ]. Moreover, the dynamic relationship between parents and their children may have some profound effects on the child’s growth. Luk et al. examined the mediator effects between parenting style and substance abuse and found the maternal psychological control dimension to be a significant variable [ 26 ]. The mother’s psychological control was two times higher in influencing her children to be involved in substance abuse compared to the other dimension. Conversely, an indirect risk factor towards youth drug abuse was elaborated in a study in which low parental educational level predicted a greater risk of future drug abuse by reducing the youth’s perception of harm [ 27 , 43 ]. Negligence from a parental perspective could also contribute to this problem. According to El Kazdouh et al. [ 46 ], a lack of parental supervision, uncontrolled pocket money spending among children, and the presence of substance-using family members were the most common negligence factors.

While the maternal factors above were shown to be risk factors, the opposite effect was seen when the paternal figure equipped himself with sufficient knowledge. A study found that fathers with good information and awareness were more likely to protect their adolescent children from drug abuse [ 26 ]. El Kazdouh et al. noted that support and advice could be some of the protective factors in this area [ 46 ].

DOMAIN: community factors

- Risk factor

A study in 2017 showed a positive association between adolescent drug abuse and peers who abuse drugs [ 32 , 39 ]. It was estimated that the odds of becoming a lifetime marijuana user was significantly increased by a factor of 2.5 ( p < 0.001) among peer groups who were taking synthetic drugs. This factor served as peer pressure for youth, who subconsciously had desire to be like the others [ 38 ]. The impact of availability and engagement in structured and unstructured activities also play a role in marijuana use. The findings from Spillane (2000) found that the availability of unstructured activities was associated with increased likelihood of marijuana use [ 42 ].

- Protective factor

Strong religious beliefs integrated into society serve as a crucial protective factor that can prevent adolescents from engaging in drug abuse [ 38 , 45 ]. In addition, the school connectedness and adult support also play a major contribution in the drug use [ 40 ].

The goal of this review was to identify and classify the risks and protective factors that lead adolescents to drug abuse across the three important domains of the individual, family, and community. No findings conflicted with each other, as each of them had their own arguments and justifications. The findings from our review showed that individual factors were the most commonly highlighted. These factors include individual traits, significant negative growth exposure, personal psychiatric diagnosis, previous substance and addiction history, and an individual’s attitude and perception as risk factors.

Within the individual factor domain, nine articles were found to contribute to the subdomain of personal/ individual traits [ 27 , 28 , 29 , 37 , 38 , 39 , 40 , 43 , 44 ]. Despite the heterogeneity of the study designs and the substances under investigation, all of the papers found statistically significant results for the possible risk factors of adolescent drug abuse. The traits of high impulsivity, rebelliousness, difficulty in regulating emotions, and alexithymia can be considered negative characteristic traits. These adolescents suffer from the inability to self-regulate their emotions, so they tend to externalize their behaviors as a way to avoid or suppress the negative feelings that they are experiencing [ 41 , 47 , 48 ]. On the other hand, engaging in such behaviors could plausibly provide a greater sense of positive emotions and make them feel good [ 49 ]. Apart from that, evidence from a neurophysiological point of view also suggests that the compulsive drive toward drug use is complemented by deficits in impulse control and decision making (impulsive trait) [ 50 ]. A person’s ability in self-control will seriously impaired with continuous drug use and will lead to the hallmark of addiction [ 51 ].

On the other hand, there are articles that reported some individual traits to be protective for adolescents from engaging in drug abuse. Youth with the optimistic trait, a high level of mindfulness, and social phobia were less likely to become drug dependent [ 31 , 33 , 37 ]. All of these articles used different psychometric instruments to classify each individual trait and were mutually exclusive. Therefore, each trait measured the chance of engaging in drug abuse on its own and did not reflect the chance at the end of the spectrum. These findings show that individual traits can be either protective or risk factors for the drugs used among adolescents. Therefore, any adolescent with negative personality traits should be monitored closely by providing health education, motivation, counselling, and emotional support since it can be concluded that negative personality traits are correlated with high risk behaviours such as drug abuse [ 52 ].

Our study also found that a history of maltreatment has a positive association with adolescent drug abuse. Those adolescents with episodes of maltreatment were considered to have negative growth exposure, as their childhoods were negatively affected by traumatic events. Some significant associations were found between maltreatment and adolescent drug abuse, although the former factor was limited to the female gender [ 25 , 30 , 36 ]. One possible reason for the contrasting results between genders is the different sample populations, which only covered child welfare centers [ 36 ] and foster care [ 30 ]. Regardless of the place, maltreatment can happen anywhere depending on the presence of the perpetrators. To date, evidence that concretely links maltreatment and substance abuse remains limited. However, a plausible explanation for this link could be the indirect effects of posttraumatic stress (i.e., a history of maltreatment) leading to substance use [ 53 , 54 ]. These findings highlight the importance of continuous monitoring and follow-ups with adolescents who have a history of maltreatment and who have ever attended a welfare center.

Addiction sometimes leads to another addiction, as described by the findings of several studies [ 29 , 34 ]. An initial study focused on the effects of e-cigarettes in the development of other substance abuse disorders, particularly those related to marijuana, alcohol, and commonly prescribed medications [ 34 ]. The authors found that the use of e-cigarettes can lead to more severe substance addiction [ 55 ], possibly through normalization of the behavior. On the other hand, Chuang et al.’s extensive study in 2017 analyzed the combined effects of either multiple addictions alone or a combination of multiple addictions together with the impulsivity trait [ 29 ]. The outcomes reported were intriguing and provide the opportunity for targeted intervention. The synergistic effects of impulsiveness and three other substance addictions (marijuana, tobacco, and alcohol) substantially increased the likelihood for drug abuse from 3.46 (95%CI 1.25, 9.58) to 10.13 (95% CI 3.95, 25.95). Therefore, proper rehabilitation is an important strategy to ensure that one addiction will not lead to another addiction.

The likelihood for drug abuse increases as the population perceives little or no harmful risks associated with the drugs. On the opposite side of the coin, a greater perceived risk remains a protective factor for marijuana abuse [ 56 ]. However, another study noted that a stronger determinant for adolescent drug abuse was the perceived availability of the drug [ 35 , 57 ]. Looking at the bigger picture, both perceptions corroborate each other and may inform drug use. Another study, on the other hand, reported that there was a decreasing trend of perceived drug risk in conjunction with the increasing usage of drugs [ 58 ]. As more people do drugs, youth may inevitably perceive those drugs as an acceptable norm without any harmful consequences [ 59 ].

In addition, the total spent for screen time also contribute to drug abuse among adolescent [ 43 ]. This scenario has been proven by many researchers on the effect of screen time on the mental health [ 60 ] that leads to the substance use among the adolescent due to the ubiquity of pro-substance use content on the internet. Adolescent with comorbidity who needs medical pain management by opioids also tend to misuse in future. A qualitative exploration on the perspectives among general practitioners concerning the risk of opioid misuse in people with pain, showed pain management by opioids is a default treatment and misuse is not a main problem for the them [ 61 ]. A careful decision on the use of opioids as a pain management should be consider among the adolescents and their understanding is needed.

Within the family factor domain, family structures were found to have both positive and negative associations with drug abuse among adolescents. As described in one study, paternal knowledge was consistently found to be a protective factor against substance abuse [ 26 ]. With sufficient knowledge, the father can serve as the guardian of his family to monitor and protect his children from negative influences [ 62 ]. The work by Luk et al. also reported a positive association of maternal psychological association towards drug abuse (IRR 2.41, p < 0.05) [ 26 ]. The authors also observed the same effect of paternal psychological control, although it was statistically insignificant. This construct relates to parenting style, and the authors argued that parenting style might have a profound effect on the outcomes under study. While an earlier literature review [ 63 ] also reported such a relationship, a recent study showed a lesser impact [ 64 ] with regards to neglectful parenting styles leading to poorer substance abuse outcomes. Nevertheless, it was highlighted in another study that the adolescents’ perception of a neglectful parenting style increased their odds (OR 2.14, p = 0.012) of developing alcohol abuse, not the parenting style itself [ 65 ]. Altogether, families play vital roles in adolescents’ risk for engaging in substance abuse [ 66 ]. Therefore, any intervention to impede the initiation of substance use or curb existing substance use among adolescents needs to include parents—especially improving parent–child communication and ensuring that parents monitor their children’s activities.

Finally, the community also contributes to drug abuse among adolescents. As shown by Li et al. [ 32 ] and El Kazdouh et al. [ 46 ], peers exert a certain influence on other teenagers by making them subconsciously want to fit into the group. Peer selection and peer socialization processes might explain why peer pressure serves as a risk factor for drug-abuse among adolescents [ 67 ]. Another study reported that strong religious beliefs integrated into society play a crucial role in preventing adolescents from engaging in drug abuse [ 46 ]. Most religions devalue any actions that can cause harmful health effects, such as substance abuse [ 68 ]. Hence, spiritual beliefs may help protect adolescents. This theme has been well established in many studies [ 60 , 69 , 70 , 71 , 72 ] and, therefore, could be implemented by religious societies as part of interventions to curb the issue of adolescent drug abuse. The connection with school and structured activity did reduce the risk as a study in USA found exposure to media anti-drug messages had an indirect negative effect on substances abuse through school-related activity and social activity [ 73 ]. The school activity should highlight on the importance of developmental perspective when designing and offering school-based prevention programs [75].

Limitations

We adopted a review approach that synthesized existing evidence on the risk and protective factors of adolescents engaging in drug abuse. Although this systematic review builds on the conclusion of a rigorous review of studies in different settings, there are some potential limitations to this work. We may have missed some other important factors, as we only included English articles, and article extraction was only done from the three search engines mentioned. Nonetheless, this review focused on worldwide drug abuse studies, rather than the broader context of substance abuse including alcohol and cigarettes, thereby making this paper more focused.

Conclusions

This review has addressed some recent knowledge related to the individual, familial, and community risk and preventive factors for adolescent drug use. We suggest that more attention should be given to individual factors since most findings were discussed in relation to such factors. With the increasing trend of drug abuse, it will be critical to focus research specifically on this area. Localized studies, especially those related to demographic factors, may be more effective in generating results that are specific to particular areas and thus may be more useful in generating and assessing local control and prevention efforts. Interventions using different theory-based psychotherapies and a recognition of the unique developmental milestones specific to adolescents are among examples that can be used. Relevant holistic approaches should be strengthened not only by relevant government agencies but also by the private sector and non-governmental organizations by promoting protective factors while reducing risk factors in programs involving adolescents from primary school up to adulthood to prevent and control drug abuse. Finally, legal legislation and enforcement against drug abuse should be engaged with regularly as part of our commitment to combat this public health burden.

Data availability and materials

All data generated or analysed during this study are included in this published article.

Nation, U. World Drug Report 2018 (United Nations publication, Sales No. E.18X.XI.9. United Nation publication). 2018. Retrieved from https://www.unodc.org/wdr2018

Google Scholar

Degenhardt L, Stockings E, Patton G, Hall WD, Lynskey M. The increasing global health priority of substance use in young people. Lancet Psychiatry. 2016;3(3):251–64. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2215-0366(15)00508-8 Elsevier Ltd.

Article PubMed Google Scholar

Ritchie H, Roser M. Drug Use - Our World in Data: Global Change Data Lab; 2019. https://ourworldindata.org/drug-use [10 June 2020]

Holm S, Sandberg S, Kolind T, Hesse M. The importance of cannabis culture in young adult cannabis use. J Subst Abus. 2014;19(3):251–6.

Luikinga SJ, Kim JH, Perry CJ. Developmental perspectives on methamphetamine abuse: exploring adolescent vulnerabilities on brain and behavior. Progress Neuro Psychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 2018;87(Pt A):78–84. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pnpbp.2017.11.010 Elsevier Inc.

Article CAS Google Scholar

Ismail R, Ghazalli MN, Ibrahim N. Not all developmental assets can predict negative mental health outcomes of disadvantaged youth: a case of suburban Kuala Lumpur. Mediterr J Soc Sci. 2015;6(1):452–9. https://doi.org/10.5901/mjss.2015.v6n5s1p452 .

Article Google Scholar

Crews F, He J, Hodge C. Adolescent cortical development: a critical period of vulnerability for addiction. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 2007;86(2):189–99. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pbb.2006.12.001 .

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar

Schulte MT, Hser YI. Substance use and associated health conditions throughout the lifespan. Public Health Rev. 2013;35(2). https://doi.org/10.1007/bf03391702 Technosdar Ltd.

Somani, S.; Meghani S. Substance Abuse among Youth: A Harsh Reality 2016. doi: https://doi.org/10.4172/2165-7548.1000330 , 6, 4.

Book Google Scholar

Drabble L, Trocki KF, Klinger JL. Religiosity as a protective factor for hazardous drinking and drug use among sexual minority and heterosexual women: findings from the National Alcohol Survey. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2016;161:127–34. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2016.01.022 .

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Goliath V, Pretorius B. Peer risk and protective factors in adolescence: Implications for drug use prevention. Soc Work. 2016;52(1):113–29. https://doi.org/10.15270/52-1-482 .

Guerrero LR, Dudovitz R, Chung PJ, Dosanjh KK, Wong MD. Grit: a potential protective factor against substance use and other risk behaviors among Latino adolescents. Acad Pediatr. 2016;16(3):275–81. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.acap.2015.12.016 .

National Institutes on Drug Abuse. What are risk factors and protective factors? National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA); 2003. Retrieved from https://www.drugabuse.gov/publications/preventing-drug-use-among-children-adolescents/chapter-1-risk-factors-protective-factors/what-are-risk-factors

Nguyen NN, Newhill CE. The role of religiosity as a protective factor against marijuana use among African American, White, Asian, and Hispanic adolescents. J Subst Abus. 2016;21(5):547–52. https://doi.org/10.3109/14659891.2015.1093558 .

Schinke S, Schwinn T, Hopkins J, Wahlstrom L. Drug abuse risk and protective factors among Hispanic adolescents. Prev Med Rep. 2016;3:185–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pmedr.2016.01.012 .

Macleod J, Oakes R, Copello A, Crome PI, Egger PM, Hickman M, et al. Psychological and social sequelae of cannabis and other illicit drug use by young people: a systematic review of longitudinal, general population studies. Lancet. 2004;363(9421):1579–88. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(04)16200-4 .

Moore TH, Zammit S, Lingford-Hughes A, Barnes TR, Jones PB, Burke M, et al. Cannabis use and risk of psychotic or affective mental health outcomes: a systematic review. Lancet. 2007;370(9584):319–28. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(07)61162-3 .

Semple DM, McIntosh AM, Lawrie SM. Cannabis as a risk factor for psychosis: systematic review. J Psychopharmacol. 2005;19(2):187–94. https://doi.org/10.1177/0269881105049040 .

Nargiso JE, Ballard EL, Skeer MR. A systematic review of risk and protective factors associated with nonmedical use of prescription drugs among youth in the united states: A social ecological perspective. J Stud Alcohol Drugs. 2015;76(1):5–20. https://doi.org/10.15288/jsad.2015.76.5 .

Guxensa M, Nebot M, Ariza C, Ochoa D. Factors associated with the onset of cannabis use: a systematic review of cohort studies. Gac Sanit. 2007;21(3):252–60. https://doi.org/10.1157/13106811 .

Susan MS, Peter SA, Dakshitha W, George CP. The age of adolescence. Lancet Child Adolesc Health. 2018;2(Issue 3):223–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2352-4642(18)30022-1 .

Hong QN, Fàbregues S, Bartlett G, Boardman F, Cargo M, Dagenais P, et al. The mixed methods appraisal tool (MMAT) version 2018 for information professionals and researchers. Educ Inf. 2018;34(4):285–91. https://doi.org/10.3233/EFI-180221 .

McHugh ML. Interrater reliability: The kappa statistic. Biochem Med. 2012;22(3):276–82. https://doi.org/10.11613/bm.2012.031 .

Cecil CAM, Walton E, Smith RG, Viding E, McCrory EJ, Relton CL, et al. DNA methylation and substance-use risk: a prospective, genome-wide study spanning gestation to adolescence. Transl Psychiatry. 2016;6(12):e976. https://doi.org/10.1038/tp.2016.247 Nature Publishing Group.

Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Kobulsky JM. Gender differences in pathways from physical and sexual abuse to early substance use. Child Youth Serv Rev. 2017;83:25–32. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.childyouth.2017.10.027 .

Luk JW, King KM, McCarty CA, McCauley E, Stoep A. Prospective effects of parenting on substance use and problems across Asian/Pacific islander and European American youth: Tests of moderated mediation. J Stud Alcohol Drugs. 2017;78(4):521–30. https://doi.org/10.15288/jsad.2017.78.521 .

Guttmannova K, Skinner ML, Oesterle S, White HR, Catalano RF, Hawkins JD. The interplay between marijuana-specific risk factors and marijuana use over the course of adolescence. Prev Sci. 2019;20(2):235–45. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11121-018-0882-9 .

Dorard G, Bungener C, Phan O, Edel Y, Corcos M, Berthoz S. Is alexithymia related to cannabis use disorder? Results from a case-control study in outpatient adolescent cannabis abusers. J Psychosom Res. 2017;95:74–80. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpsychores.2017.02.012 .

Chuang CWI, Sussman S, Stone MD, Pang RD, Chou CP, Leventhal AM, et al. Impulsivity and history of behavioral addictions are associated with drug use in adolescents. Addict Behav. 2017;74:41–7. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.addbeh.2017.05.021 .

Gabrielli J, Jackson Y, Brown S. Associations between maltreatment history and severity of substance use behavior in youth in Foster Care. Child Maltreat. 2016;21(4):298–307. https://doi.org/10.1177/1077559516669443 .

Khoddam R, Jackson NJ, Leventhal AM. Internalizing symptoms and conduct problems: redundant, incremental, or interactive risk factors for adolescent substance use during the first year of high school? Drug Alcohol Depend. 2016;169:48–55. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2016.10.007 .

Li SD, Zhang X, Tang W, Xia Y. Predictors and implications of synthetic drug use among adolescents in the gambling Capital of China. SAGE Open. 2017;7(4):215824401773303. https://doi.org/10.1177/2158244017733031 .

Marin S, Heshmatian E, Nadrian H, Fakhari A, Mohammadpoorasl A. Associations between optimism, tobacco smoking and substance abuse among Iranian high school students. Health Promot Perspect. 2019;9(4):279–84. https://doi.org/10.15171/hpp.2019.38 .

Miech RA, O’Malley PM, Johnston LD, Patrick ME. E-cigarettes and the drug use patterns of adolescents. Nicotine Tob Res. 2015;18(5):654–9. https://doi.org/10.1093/ntr/ntv217 .

Schleimer JP, Rivera-Aguirre AE, Castillo-Carniglia A, Laqueur HS, Rudolph KE, Suárez H, et al. Investigating how perceived risk and availability of marijuana relate to marijuana use among adolescents in Argentina, Chile, and Uruguay over time. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2019;201:115–26. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2019.03.029 .

Traube DE, Yarnell LM, Schrager SM. Differences in polysubstance use among youth in the child welfare system: toward a better understanding of the highest-risk teens. Child Abuse Negl. 2016;52:146–57. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chiabu.2015.11.020 .

Wilson JD, Vo H, Matson P, Adger H, Barnett G, Fishman M. Trait mindfulness and progression to injection use in youth with opioid addiction. Subst Use Misuse. 2017;52(11):1486–93. https://doi.org/10.1080/10826084.2017.1289225 .

Dash GF, Feldstein Ewing SW, Murphy C, Hudson KA, Wilson AC. Contextual risk among adolescents receiving opioid prescriptions for acute pain in pediatric ambulatory care settings. Addict Behav. 2020;104:106314. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.addbeh.2020.106314 Epub 2020 Jan 11. PMID: 31962289; PMCID: PMC7024039.

Osborne V, Serdarevic M, Striley CW, Nixon SJ, Winterstein AG, Cottler LB. Age of first use of prescription opioids and prescription opioid non-medical use among older adolescents. Substance Use Misuse. 2020;55(14):2420–7. https://doi.org/10.1080/10826084.2020.1823420 .

Zuckermann AME, Qian W, Battista K, Jiang Y, de Groh M, Leatherdale ST. Factors influencing the non-medical use of prescription opioids among youth: results from the COMPASS study. J Subst Abus. 2020;25(5):507–14. https://doi.org/10.1080/14659891.2020.1736669 .

De Pedro KT, Esqueda MC, Gilreath TD. School protective factors and substance use among lesbian, gay, and bisexual adolescents in California public schools. LGBT Health. 2017;4(3):210–6. https://doi.org/10.1089/lgbt.2016.0132 .

Spillane NS, Schick MR, Kirk-Provencher KT, Hill DC, Wyatt J, Jackson KM. Structured and unstructured activities and alcohol and marijuana use in middle school: the role of availability and engagement. Substance Use Misuse. 2020;55(11):1765–73. https://doi.org/10.1080/10826084.2020.1762652 .

Ogunsola OO, Fatusi AO. Risk and protective factors for adolescent substance use: a comparative study of secondary school students in rural and urban areas of Osun state, Nigeria. Int J Adolesc Med Health. 2016;29(3). https://doi.org/10.1515/ijamh-2015-0096 .

Doggett A, Qian W, Godin K, De Groh M, Leatherdale ST. Examining the association between exposure to various screen time sedentary behaviours and cannabis use among youth in the COMPASS study. SSM Population Health. 2019;9:100487. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ssmph.2019.100487 .

Afifi RA, El Asmar K, Bteddini D, Assi M, Yassin N, Bitar S, et al. Bullying victimization and use of substances in high school: does religiosity moderate the association? J Relig Health. 2020;59(1):334–50. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10943-019-00789-8 .

El Kazdouh H, El-Ammari A, Bouftini S, El Fakir S, El Achhab Y. Adolescents, parents and teachers’ perceptions of risk and protective factors of substance use in Moroccan adolescents: a qualitative study. Substance Abuse Treat Prevent Policy. 2018;13(1):–31. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13011-018-0169-y .

Sussman S, Lisha N, Griffiths M. Prevalence of the addictions: a problem of the majority or the minority? Eval Health Prof. 2011;34(1):3–56. https://doi.org/10.1177/0163278710380124 .

Aldao A, Nolen-Hoeksema S, Schweizer S. Emotion-regulation strategies across psychopathology: a meta-analytic review. Clin Psychol Rev. 2010;30(2):217–37. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2009.11.004 .

Ricketts T, Macaskill A. Gambling as emotion management: developing a grounded theory of problem gambling. Addict Res Theory. 2003;11(6):383–400. https://doi.org/10.1080/1606635031000062074 .

Williams AD, Grisham JR. Impulsivity, emotion regulation, and mindful attentional focus in compulsive buying. Cogn Ther Res. 2012;36(5):451–7. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10608-011-9384-9 .

National Institutes on Drug Abuse. Drugs, brains, and behavior the science of addiction national institute on drug abuse (nida). 2014. Retrieved from https://www.drugabuse.gov/sites/default/files/soa_2014.pdf

Hokm Abadi ME, Bakhti M, Nazemi M, Sedighi S, Mirzadeh Toroghi E. The relationship between personality traits and drug type among substance abuse. J Res Health. 2018;8(6):531–40.

Longman-Mills S, Haye W, Hamilton H, Brands B, Wright MGM, Cumsille F, et al. Psychological maltreatment and its relationship with substance abuse among university students in Kingston, Jamaica, vol. 24. Florianopolis: Texto Contexto Enferm; 2015. p. 63–8.

Rosenkranz SE, Muller RT, Henderson JL. The role of complex PTSD in mediating childhood maltreatment and substance abuse severity among youth seeking substance abuse treatment. Psychol Trauma Theory Res Pract Policy. 2014;6(1):25–33. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0031920 .

Krishnan-Sarin S, Morean M, Kong G, et al. E-Cigarettes and “dripping” among high-school youth. Pediatrics. 2017;139(3). https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2016-3224 .

Adinoff B. Neurobiologic processes in drug reward and addiction. Harvard review of psychiatry. NIH Public Access. 2004;12(6):305–20. https://doi.org/10.1080/10673220490910844 .

Kandel D, Kandel E. The gateway hypothesis of substance abuse: developmental, biological and societal perspectives. Acta Paediatrica. 2014;104(2):130–7.

Dempsey RC, McAlaney J, Helmer SM, Pischke CR, Akvardar Y, Bewick BM, et al. Normative perceptions of Cannabis use among European University students: associations of perceived peer use and peer attitudes with personal use and attitudes. J Stud Alcohol Drugs. 2016;77(5):740–8.

Cioffredi L, Kamon J, Turner W. Effects of depression, anxiety and screen use on adolescent substance use. Prevent Med Rep. 2021;22:101362. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pmedr.2021.101362 .

Luckett T, NewtonJohn T, Phillips J, et al. Risk of opioid misuse in people with cancer and pain and related clinical considerations:a qualitative study of the perspectives of Australian general practitioners. BMJ Open. 2020;10(2):e034363. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2019-034363 .

Lipari RN. Trends in Adolescent Substance Use and Perception of Risk from Substance Use. The CBHSQ Report. Substance Abuse Mental Health Serv Admin. 2013; Retrieved from http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/27656743 .

Muchiri BW, dos Santos MML. Family management risk and protective factors for adolescent substance use in South Africa. Substance Abuse. 2018;13(1):24. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13011-018-0163-4 .

Becoña E, Martínez Ú, Calafat A, Juan M, Fernández-Hermida JR, Secades-Villa R. Parental styles and drug use: a review. In: Drugs: Education, Prevention and Policy: Taylor & Francis; 2012. https://doi.org/10.3109/09687637.2011.631060 .

Berge J, Sundel K, Ojehagen A, Hakansson A. Role of parenting styles in adolescent substance use: results from a Swedish longitudinal cohort study. BMJ Open. 2016;6(1):e008979. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2015-008979 .

Opara I, Lardier DT, Reid RJ, Garcia-Reid P. “It all starts with the parents”: a qualitative study on protective factors for drug-use prevention among black and Hispanic girls. Affilia J Women Soc Work. 2019;34(2):199–218. https://doi.org/10.1177/0886109918822543 .

Martínez-Loredo V, Fernández-Artamendi S, Weidberg S, Pericot I, López-Núñez C, Fernández-Hermida J, et al. Parenting styles and alcohol use among adolescents: a longitudinal study. Eur J Invest Health Psychol Educ. 2016;6(1):27–36. https://doi.org/10.1989/ejihpe.v6i1.146 .

Baharudin MN, Mohamad M, Karim F. Drug-abuse inmates maqasid shariah quality of lifw: a conceotual paper. Hum Soc Sci Rev. 2020;8(3):1285–94. https://doi.org/10.18510/hssr.2020.83131 .

Henneberger AK, Mushonga DR, Preston AM. Peer influence and adolescent substance use: a systematic review of dynamic social network research. Adolesc Res Rev. 2020;6(1):57–73. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40894-019-00130-0 Springer.

Gomes FC, de Andrade AG, Izbicki R, Almeida AM, de Oliveira LG. Religion as a protective factor against drug use among Brazilian university students: a national survey. Rev Bras Psiquiatr. 2013;35(1):29–37. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rbp.2012.05.010 .

Kulis S, Hodge DR, Ayers SL, Brown EF, Marsiglia FF. Spirituality and religion: intertwined protective factors for substance use among urban American Indian youth. Am J Drug Alcohol Abuse. 2012;38(5):444–9. https://doi.org/10.3109/00952990.2012.670338 .

Miller L, Davies M, Greenwald S. Religiosity and substance use and abuse among adolescents in the national comorbidity survey. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2000;39(9):1190–7. https://doi.org/10.1097/00004583-200009000-00020 .

Moon SS, Rao U. Social activity, school-related activity, and anti-substance use media messages on adolescent tobacco and alcohol use. J Hum Behav Soc Environ. 2011;21(5):475–89. https://doi.org/10.1080/10911359.2011.566456 .

Simone A. Onrust, Roy Otten, Jeroen Lammers, Filip smit, school-based programmes to reduce and prevent substance use in different age groups: what works for whom? Systematic review and meta-regression analysis. Clin Psychol Rev. 2016;44:45–59. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2015.11.002 .

Download references

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge The Ministry of Higher Education Malaysia and The Universiti Kebangsaan Malaysia, (UKM) for funding this study under the Long-Term Research Grant Scheme-(LGRS/1/2019/UKM-UKM/2/1). We also thank the team for their commitment and tireless efforts in ensuring that manuscript was well executed.

Financial support for this study was obtained from the Ministry of Higher Education, Malaysia through the Long-Term Research Grant Scheme-(LGRS/1/2019/UKM-UKM/2/1). The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Department of Community Health, Universiti Kebangsaan Malaysia, Cheras, 56000, Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia

Azmawati Mohammed Nawi, Mohd Rohaizat Hassan & Mohd Rizal Abdul Manaf

Centre for Research in Psychology and Human Well-Being (PSiTra), Faculty of Social Sciences and Humanities, Universiti Kebangsaan Malaysia, 43600, Bangi, Selangor, Malaysia

Rozmi Ismail, Fauziah Ibrahim & Nurul Shafini Shafurdin

Clinical Psychology and Behavioural Health Program, Faculty of Health Sciences, Universiti Kebangsaan Malaysia, Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia

Noh Amit & Norhayati Ibrahim

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Contributions

Manuscript concept, and drafting AMN and RI; model development, FI, NI and NA.; Editing manuscript MRH, MRAN, NSS,; Critical revision of manuscript for important intellectual content, all authors. The authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Rozmi Ismail .

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate.

This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Secretariat of Research Ethics, Universiti Kebangsaan Malaysia, Faculty of Medicine, Cheras, Kuala Lumpur (Reference no. UKMPPI/111/8/JEP-2020.174(2). Dated 27 Mac 2020.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors AMN, RI, FI, MRM, MRAM, NA, NI NSS declare that they have no conflict of interest relevant to this work.

Additional information

Publisher’s note.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ . The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver ( http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/ ) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article.

Nawi, A.M., Ismail, R., Ibrahim, F. et al. Risk and protective factors of drug abuse among adolescents: a systematic review. BMC Public Health 21 , 2088 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-021-11906-2

Download citation

Received : 10 June 2021

Accepted : 22 September 2021

Published : 13 November 2021

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-021-11906-2

Share this article