- Account details

AQA A-level Psychology Psychopathology

This section provides revision resources for AQA A-level psychology and the Psychopathology chapter. The revision notes cover the AQA exam board and the new specification. As part of your A-level psychology course, you need to know the following topics below within this chapter:

- A-Level Revision

- AQA Psychology

- Psychopathology

We've covered everything you need to know for this Psychopathology chapter to smash your exams.

- The latest AQA AS/A-level Psychology specification (2024 onwards) has been followed exactly so if it's not in this resource pack, you don't need to know it.

- Practice questions at the end of each topic to consolidate your learning (including 2023 exam questions! Perfect for mock exam preparation!)

- Completely free for schools , just get in touch using the contact form at the bottom.

- Teachers can print and distribute this resource freely in classrooms to aid students and teaching.

- Instant download, no waiting.

Definitions of Abnormality

Psychopathology is the scientific study of psychological disorders of the mind but how do you determine if someone is unwell?

With physical illnesses, doctors can identify actual physical symptoms however this becomes difficult when you have someone suffering from a psychological problem.

To determine if someone is unwell, doctors look to see if their behaviour falls into the realms of ‘abnormal’.

The term abnormality refers to when someone behaves in a way that would not be defined as normal and there are 4 definitions we will explore that help determine this.

The definitions for abnormality are:

- Statistical infrequency

- Deviation from social norms

- Failure to function adequately

- Deviation from ideal mental health

No single definition is adequate on its own as you will learn however each captures elements of what we might expect to be abnormal behaviour in some form.

Statistical Infrequency

Statistical infrequency defines abnormality in terms of behaviours seen as statistically rare or which deviate from the mean average or norm.

Statistics that measure certain characteristics and behaviours are gathered with the aim of showing how they are distributed among the general population.

A normal distribution curve can be generated from such data which demonstrates which behaviours people share in common. Most people will be on or near the mean average however individuals which fall outside this “normal distribution” and two standard deviation points away are defined as abnormal.

The majority of normal behaviours cluster in the middle of the distribution graph with abnormal characteristics around the edges or tails making them statistically rare and therefore a deviation from statistical norms.

The difference between normal behaviour and abnormal then becomes one of quantity rather than quality.

Evaluating Statistical Infrequency

- Defining abnormality using statistical criteria can be appropriate in many situations; for example in the definition of mental retardation or intellectual ability. In such cases normal mental ability can be effectively measured with anyone whose IQ falling more than two standard deviation points than most the general population being judged as having some mental disorder. When used in conjunction with other definitions such as the failure to function adequately, statistical infrequency provides an appropriate measure for abnormality.

- A weakness, however, is in other occasions defining peoples characteristics on statistical rarity solely is unsuitable. For example, people with exceptionally high IQ’s could, in theory, be diagnosed as having a mental disorder as their intelligence may be two deviations above the rest of the population and technically “abnormal”. This is why statistical infrequency is best used in conjunction with other tools to define abnormality.

- Statistical infrequency provides an objective measure for abnormality. Once a way of collecting data on behaviour/characteristics and a cut-off point is agreed, this provides an objective way of deciding who is abnormal. However, a weakness here is that the cut-off point is subjectively determined as we need to decide where to separate normal behaviour from abnormal and again this blurs the line in some cases. For example, one trait for diagnosing depression may be sleep difficulty but sleep patterns may vary considerably and someone who functions perfectly adequately may be classed as depressed. Elderly people generally sleep less due to changing sleep cycles and they could technically fall under this label incorrectly.

- A major weakness is that statistical infrequency has an imposed etic of whatever culture is measuring the behaviour, usually western cultures and therefore suffers from cultural bias. It does not consider cultural factors in determining abnormal behaviour and what is a normal behaviour in one culture may be seen as abnormal in another due to its infrequency. Also, behaviours which were statistically rare many years ago may not be rare now (and vice versa). Therefore this tool could run the risk of being era-dependent by adopting a statistical norm based on behaviours that may later become outdated.

Deviation from Social Norms

Deviation from social norms defines abnormality in terms of social norms and expected behaviours within society and certain situations.

Within society there are standards of acceptable behaviour which are set by the social group and everyone within this social group is expected to follow these behaviours. Such behaviours form an important glue for society as they usually address fundamental needs.

Social norms can be explicit written rules or even laws and an example of this is the respect for human life and property which belongs to others. These are norms enforced by a legal system within the UK however other social norms are unwritten but still generally accepted as normal behaviour.

For example, queuing at a bus stop without pushing in is one such norm that has no written law for it but is defined by society as acceptable behaviour. When someone “deviates” from these socially accepted behaviours, by this definition they may be classed as abnormal.

Social norms may also be context-dependent; in some places, it may be acceptable to eat without forks or knives and use our hands (barbecues) however in others (a restaurant) this may be seen as abnormal.

Evaluating Deviation From Social Norms

- One major issue with basing abnormal behaviour on a set of social norms is that they are subject to change over time. Behaviour that is socially acceptable now may suddenly be seen as socially deviant later and vice versa. Today homosexuality is seen as socially acceptable however based on this definition it was seen as socially deviant and classed as a mental disorder in the past. Therefore this definition is very era-dependent.

- Another issue is this form of diagnosis is open to abuse. In Russia, during the late 1950s, anyone who disagreed with the government ran the risk of being diagnosed as insane and placed in a mental institution. Therefore defining people based on a deviation from socially acceptable behaviour allows people to be persecuted for being non-conformist. Major changes in society happen through such socially deviant behaviour in some cases; for example, the suffragette’s movement was initially seen as socially deviant initially but paved the way for women to vote.

- Another weakness is social norms usually separated by blurred lines as what is acceptable in one context may not be acceptable in another. For example, a person wearing little clothing at a beach may be seen as normal however someone doing the same again walking along the streets in town may be seen as abnormal. Therefore there is no clear distinction on where this divide between normal and abnormal is as such behaviour may simply be eccentric but not due to any mental disorders. Therefore social deviance on its own cannot offer a holistic definition of abnormal behaviour.

- A strength of using deviations from social norms to define abnormality is it can if used correctly, help people as it gives society the right to intervene to improve the lives of people suffering from mental disorders who may not be able to help themselves. This definition also helps protect members of society itself as a deviation from norms usually comes at the expense of others as social norms are usually designed to keep society functioning adequately.

- Deviation from social norms is subject to cultural bias. For example, western social norms reflect the majority of the white western population and ethnic groups which behave differently could be seen as “abnormal” simply because their customs or behaviours are based on eastern or European values. For example, black people are were found to be most commonly diagnosed as schizophrenic (Cochrane (1977) compared to white people or Asians. When this is compared to countries like Jamaica who have a majority black population but low diagnosis rate for schizophrenia, it becomes clear that cultural values may influence diagnosis.

Failure to Function Adequately

Defining abnormality on the basis of failure to function adequately takes to account a persons ability to cope with the daily demands of life.

Most adults need to wake up and work to earn an income as well as maintain themselves, cleaning themselves, their home, paying bills and meet their responsibilities and relationships with others.

When someone’s behaviour suggests they are unable to meet these demands then they may be diagnosed as abnormal. This inability to cope may cause the individual or others around them distress and this is factored into this definition as some people with mental disorders may themselves not be distressed but cause it to those around them.

Rosenhan et al (1989) suggested certain features which would help in the diagnosis of abnormality based on them failing to function adequately.

These include:

- Observer discomfort: The persons behaviour may cause discomfort or distress for the observer.

- Irrationality: The individual may display irrational behaviours which have rationale explanations.

- Maladaptive behaviours: The person may display behaviours which hinder them or stop them from achieving life goals, socially or occupationally.

- Unpredictability: The individual may display unpredictable behaviours which are unexpected or show a loss of control.

- Personal distress: The individual may display personal suffering and distress.

Evaluating Failure to Function

- One weakness with this definition is it needs someone to judge whether the behaviour someone displays is abnormal or not and this may be subjective. A patient experiencing personal distress through being unable to meet their bills or get to work may be judged as abnormal by one judge while another individual may see this as one of the many pitfalls of adult life. This definition creates ideal expectations which many people may struggle to adhere to and risk being classed as abnormal.

- A strength of this definition, however, is it does recognise the subjective experience of the individual themselves who may be struggling to function adequately and wish to seek intervention. This definition takes a patient-centred view by allowing mental disorders to be regarded from the perception of sufferers.

- Such a definition suffers from cultural bias as it will inevitably be related to how one culture believes an individual should live their lives. Basing abnormality on the basis of failing to function is likely to lead to different diagnoses when applied to people from different cultures or even socio-economic classes. For example, people from lower-class non-white backgrounds are often diagnosed with more mental disorders and their lifestyles and values being different may be one explanation for this.

- Some behaviour deemed by others as dysfunctional may actually have a functional purpose. For example, individuals with an eating disorder may find it brings affection and attention from others which they crave and find rewarding.

- In other cases, the abnormality may not always be followed by observable dysfunctional traits. For example, psychopaths and people with dangerous personality disorders can cause great harm to others yet still appear normal. An example of this is Harold Shipman, an English doctor who murdered over 200 of his patients. He was clearly abnormal but displayed no signs of dysfunctional behaviour or inability to function. Therefore this explanation does not offer a holistic explanation that explains abnormality.

Deviation From Ideal Mental Health

Deviation from ideal mental health assesses abnormality by assessing mental health in the same way physical health would be assessed. This definition looks for signs that suggest there is an absence of wellbeing and deviation away from normal functioning would be classed as abnormal. Jahoda (1958) provides a set of characteristics which are defined as normal and deviation from these traits would define a person as abnormal.

These characteristics are:

- Positive attitudes towards oneself: Having high self-esteem and a strong sense of personal identity.

- Self-actualisation: Experiences personal growth and development towards their potential.

- Autonomy: Being independent, self-reliant and able to make personal decisions.

- Accurate perception of reality: Perceiving the world in a non-distorted way with an objective and realistic view.

- Resisting stress: Having effective coping strategies and cope with everyday anxiety-provoking situations.

- Environmental mastery: Being competent in all aspects of life and able to meet the demands of all situations while having the flexibility to adapt to changes in life circumstances.

The focus is on behaviours which define a person as being normal rather than defining abnormal behaviour and the more characteristics a person fails to meet the more likely they are to be classed as abnormal.

Evaluating Deviation from Ideal Mental Health

- The criteria for being classed as normal are over-demanding and unrealistic which is a major criticism of this definition. By Jahoda’s standard, most people would be classed as abnormal as they fail to meet these requirements which means this diagnosis is more a set of ideals on how you would like to be rather than how you actually are.

- The criteria Jahoda puts forth are subjective and difficult to measure due to being vague. Measuring physical health is more objective through the use of equipment however mental health through these criteria is difficult to measure. For example, measuring self-esteem, personal growth or environmental mastery would all be difficult and require a subjective opinion on where the cut-off point would be. Also, generalisation to everyone’s own situation is again difficult and requires the person doing the diagnosis to once again put forth their own subjective opinion on how well the patient is able to meet the criteria.

- This definition would be culturally biased as these set of ideals put forth by Jahoda are based on western ideals of what ideal health looks like within one particular culture. If this used to judge the behaviour of people from different cultures then this may provide an incorrect diagnosis of abnormality as they have different beliefs on what “ideal mental health” would look like. For example, collectivist cultures focus on communal goals rather than personal autonomy and such criteria would be ill-suited for diagnosing abnormality in such cultures. This is likely true for people from different socio-economic backgrounds too as people of poorer backgrounds may be found to struggle more with achieving these ideal criteria than someone who has vast resources and support.

Possible exam questions for the definition of abnormality include:

- Outline and evaluate statistical infrequency can be used to define abnormality

- Outline and evaluate how deviation from social norms can be used to define abnormality

- Outline and evaluate how failure to function adequately can be used to define abnormality

- Outline and evaluate how deviation from ideal mental health can be used to define abnormality (3 marks)

- Describe and evaluate two or more definitions of abnormality (12 marks AS, 16 marks A-level)

The Behavioural, Emotional and Cognitive Characteristics of Mental Disorders

This section focuses on the characteristics of 3 mental disorders such as phobias, depression and OCD with the focus being on their emotional, behavioural and cognitive characteristics.

So breaking this down, each disorder has a total of 3 questions each which means there are at least 9 possible questions you need to know.

Let’s break each section down:

The Emotional Characteristics of Phobias

Irrational, persistent and excessive fear with high levels of anxiety in the anticipation or presence of the feared object or situation.

May produce panic attacks once presented with the object or situation.

The Behavioural Characteristics of Phobias

Avoidance/anxiety-based response is demonstrated when confronted by feared objects or situations.

A person may be seen to make efforts to avoid this from occurring e.g. a person who fears social situations is seen to actively avoid groups of people. There may also be a disruption of functioning affecting the ability to work or social functioning.

The individual may also freeze or even faint due to the situation or object.

The Cognitive Characteristics of Phobias

This relates to the thinking/thought processes of the person which are irrational in nature and resistance to rational perspectives offered.

The individual may also recognise their fear is unreasonable or excessive which helps distinguish them from having a mental disorder such as schizophrenia.

The Emotional Characteristics of Depression

Major depressive disorder requires at least 5 symptoms including sadness or loss of interest and pleasure in normal activities.

The person may also report feeling empty, worthless and experience low self-esteem and a lack of control in their lives. Anger may also be prevalent towards others or oneself. The focus is on these negative emotions being apparent.

The Behavioural Characteristics of Depression

Behavioural characteristics of depression include loss of energy resulting in fatigue, lethargy and highly inactive.

The individual may also demonstrate social impairment and lack of social interaction with friends and family. Weight loss or increase as well as poor personal hygiene (less washing, wearing clean clothes). Constant insomnia or oversleeping may also be apparent.

The Cognitive Characteristics of Depression

Cognitive characteristics of depression include symptoms such as negative irrational thinking patterns or beliefs about themselves or the world outlook. Expectations of things going badly which become self-fulfilling due to lack of effort/ motivation which further reinforces depressive thinking patterns. Lack of concentration, focus and indecisiveness. Suicidal thoughts and poor memory may be evident.

The emotional characteristics of OCD

Extreme anxiety and distress. Being aware of OCD tendencies may create embarrassment or shame. Disgust may be apparent in people with obsessions with hygiene or germs.

The behavioural characteristics of OCD

Obsessive behaviours are repetitive and observable e.g. hand washing or repeatedly checking the same things. Sufferers may engage in behaviours they feel they need to do due to fear of something dreadful happening which in turn creates further anxiety. Everyday functioning may be hindered due to anxiety. Social impairment and difficulty conducting social interpersonal relationships may be evident.

The cognitive characteristics of OCD

Reoccurring intrusive thoughts encouraging acts they think will reduce anxiety e.g. cleaning door handles, washing hands. May experience doubtful thoughts such as the fear of overlooking something. Sufferers may realise their thoughts are irrational or inappropriate to share with others and struggle to control them consciously causing further anxiety.

Possible exam questions for mental disorders include:

- Outline the emotional characteristics of phobias/depression/OCD

- Outline the behavioural characteristics of phobias/depression/OCD

- Outline the cognitive characteristics of phobias/depression/OCD

The Behavioural Approach to Explaining Phobias

The behavioural approach to explaining phobia focuses on the two-process model which includes classical and operant conditioning.

The Two-Process Model (Mowrer 1947)

Mowrer (1947) proposed the two-process model which attempts to explain phobias through the behaviourist explanation of either classical or operant conditioning.

Behaviourists propose phobias are learned through experience and association and through classical conditioning phobias are acquired by a stimulus becoming associated with a negative outcome.

An example of this would be Watson (1920) and the little Albert study.

A child was in introduced to a loud noise (unconditioned stimulus) which produced the fear response (unconditioned response). A white rat (neutral stimulus) was introduced and paired with this loud noise which over time became paired with the fear response towards this white rat (conditioned response). The rat then becomes a conditioned stimulus as it produces the conditioned response of fear.

This same concept is applied to other phobias which develop for particular objects, animals or situations. Traumatic events that occur produce negative feelings which then become conditioned responses to such objects, animals or situations which are conditioned stimuli. Phobias are then maintained by operant conditioning which explains why people continue to remain fearful or avoid the object or situation in question. This proposes that behaviour is likely to be repeated if the outcome is rewarding in some way, this is known as positive reinforcement.

If the behaviour results in the avoidance of something unpleasant, this is known as negative reinforcement. In the case of phobia’s and through negative reinforcement; the avoidance of the object/situation in question reduces anxiety or fear which the individual finds rewarding. This then reinforces the avoidance behaviour further.

Another behavioural explanation is social learning theory and this explains phobias as having been acquired through modelling behaviours observed from others. An individual may see a phobic response and emulate the reaction as it appears rewarding in some form i.e. attention.

Two-Process Model Evaluation

- The two-process model is generally supported through phobia sufferers being able to recall a traumatic or specific event which triggers it. However, a weakness is not everyone is able to link their phobia to a specific event they can recall. This is not to say it never occurred however as Ost (1987) suggests it may have merely been forgotten over time.

- A case study by Bagby (1922) lends support for classical conditioning explaining her phobia of running water which caused her extreme distress. The sound of running water had become associated with the fear and distress she experienced demonstrating how the two-process model has validity in some explanations of phobias.

- However, with single case studies, we may not necessarily be able to generalise the findings to the wider population as the circumstances for that phobia developing may lack external validity to other peoples conditions. In addition to this such case studies are time-consuming and almost impossible to replicate to test the reliability of findings to confirm they occurred as patients may describe.

- Rachman 1984) offered an alternative view through the Safety signals hypothesis which undermines the two-process model. This proposed that avoidance behaviour towards the object/animal in question is not motivated by negative reinforcement and the reduction in anxiety as the two-process model proposes but by the positive feelings the person associates with safety. Support for this comes from agoraphobics who travel to work on certain routes as these are the ones they see as trusted and representative of safety signals.

- Another major weakness for the two-process model is through the fact that not everyone who suffers a traumatic event then goes on to develop a phobia. This suggests the two-process model is overly simplistic and not a holistic explanation as other factors must be at work.

- The diathesis-stress model may offer a better explanation which combines both psychological factors such as the two-process model and combines this with a genetic vulnerability. This suggests that some people may inherit a genetic vulnerability for developing mental disorders such as phobias provided the right environmental stressors trigger this. This would explain why phobias develop in some people but not necessarily others. However again this would be incredibly difficult to validate for certain.

Possible exam questions for the behavioural approach to explaining phobias:

- Outline the two-process model as an explanation of phobias

- Explain how classical conditioning can be used to explain the development of phobias

- Give one criticism of the two-process model

- Outline and evaluate the behavioural approach to explaining phobias (12 marks AS, 16 marks A-level)

The Behavioural Approach To Treating Phobias

The behavioural approach in the treatment of phobias focuses on systematic desensitisation , and a technique known as flooding .

Systematic Desensitisation

Systematic desensitisation is based on the assumption that if phobias are a learned response as classical and operant conditioning suggests, then they can be unlearnt.

Phobics may avoid the stimulus that causes them to fear hence they never learn the irrationality of this fear. Through a process of classical conditioning, systematic desensitisation teaches patients to replace their fearful feelings through a process of hierarchal stages which gradually introduces the person to their feared situation one step at a time.

The hierarchy is constructed prior to treatment starting from the least feared to most feared situation working towards contact and exposure. Throughout these stages, patients are taught relaxation techniques that help manage their anxiety and distress levels to help them cope but also to associate these feelings of calmness towards the phobia. Earlier stages may involve pictures of the phobic situation (a picture of a snake for example if this is their fear) which may then lead to the goal of holding one. As patients master each step they move on to the next. For other scenario’s covert desensitisation is used which involves imagining contact instead.

Relaxation techniques taught may help the patient focus on their breathing and taking slower, deeper breaths as anxiety often results in faster, shallow breathing and this helps manage this. Mindfulness techniques such as “here and now” skills may also be used which involves focusing on a particular object or visualising a relaxing scene. Progressive muscle relaxation involves straining and relaxing muscle groups gently and this can help relax the body from tension too.

Counter-conditioning involves classical condition and may also be used as part of systematic desensitisation by creating a new association which runs alongside the current phobic situation. For example, the patient may be taught to associate relaxation instead of fear to their phobic situation and as fear and relaxation are incompatible with one another, anxiety is reduced.

Systematic Desensitisation Evaluation

A weakness for systematic desensitisation is that it is not appropriate for all patients and only those who have the capacity to learn relaxation strategies and for those who have imaginations vivid enough to imagine the feared situations in question. There is also no guarantee that learning to imagine and cope with phobic situations will actually translate into it working in the real world either.

Another weakness is systematic desensitisation is time-consuming and costly for people to use which may make it inappropriate. Patients need to attend numerous appointments and to build trust with their practitioner who is a stranger which can in itself be difficult. Also, the strategy is dependent on the skill-set of the practitioner themselves which can affect how long this treatment takes or if it works at all.

A strength, however, is that there is strong evidence that suggests systematic desensitisation is effective with numerous research studies finding it a success. McGrath et al (1990) reported 75% of patients responded positively with S and exposure to the feared stimulus (Vivo techniques) was believed to be one of the main reasons. Vitro techniques which involve patients imagining the feared stimulus were less effective in comparison (Choy et al 2007). There are ethical issues which arise with SD as it deliberately exposes patients to their fears which can cause psychological harm as there is no guarantee they will cope with it well. They may go on to have nightmares or their fear may even get worse to a point their life becomes dysfunctional. With this in mind, it may not always be appropriate for all patients and a cost-benefit analysis may be needed to weigh the benefits and costs with both short-term and long-term in mind.

A strength of systematic desensitisation over CBT is it requires relatively little insight from the patient. Where CBT requires a person to have a good level of insight and self-awareness into their thinking to challenge their irrational thoughts, systematic desensitisation relies on simple conditioning which is easily learnt by patients.

Systematic Desensitisation: Flooding

Flooding is an alternative approach to systematic desensitisation and either exposes the patient directly to their phobia or they are asked to imagine an extreme form of it.

The client is also taught and encouraged to use relaxation techniques prior to the exposure to the phobic situation which continues until the patient is able to fully relax.

In fear-based situations, the patient will release adrenaline however this will eventually cease with relaxation being associated with their feared stimulus as they are unable to use their normal avoidance methods. The procedure can be conducted using virtual reality too.

Evaluating Systematic Desensitisation: Flooding

Flooding raises serious ethical issues as it deliberately exposes patients to their fears which can cause severe psychological harm as there is no guarantee they can eventually cope with the situation. They may go on to have nightmares or even make their phobia worse to a point that their life becomes dysfunctional. With this in mind, it may not always be appropriate for all patients and a cost-benefit analysis may be needed to weigh the benefits and costs with both short-term and long-term in mind.

As not everyone may be able to cope with this form of treatment, its effectiveness may be down to individual differences. Not everyone enjoys good physical health and subjecting such individuals to highly stressful situations through flooding may risk health problems i.e. heart attacks.

A benefit to flooding, however, is the treatment is relatively quick to administer and effective with Choy et al (2007) reporting it to be more effective than SD.

Possible exam questions for the behavioural approach to treating phobias:

- Outline and evaluate how systematic desensitisation can be used to treat phobias

- Outline and evaluate how flooding is used to treat phobias

- Outline and evaluate the behavioural approach to treating phobias (12 marks AS, 16 marks A-level).

The Cognitive Approach to Explaining Depression

The specification states you need to know Ellis’s ABC model (1962) and Beck’s Negative Triad (1967). These two are specifically named in the A-level psychology specification which means you need to know them intricately.

Fortunately, as they are both cognitive models, much of the general evaluation for one model can be used for the other.

Ellis’ ABC Model

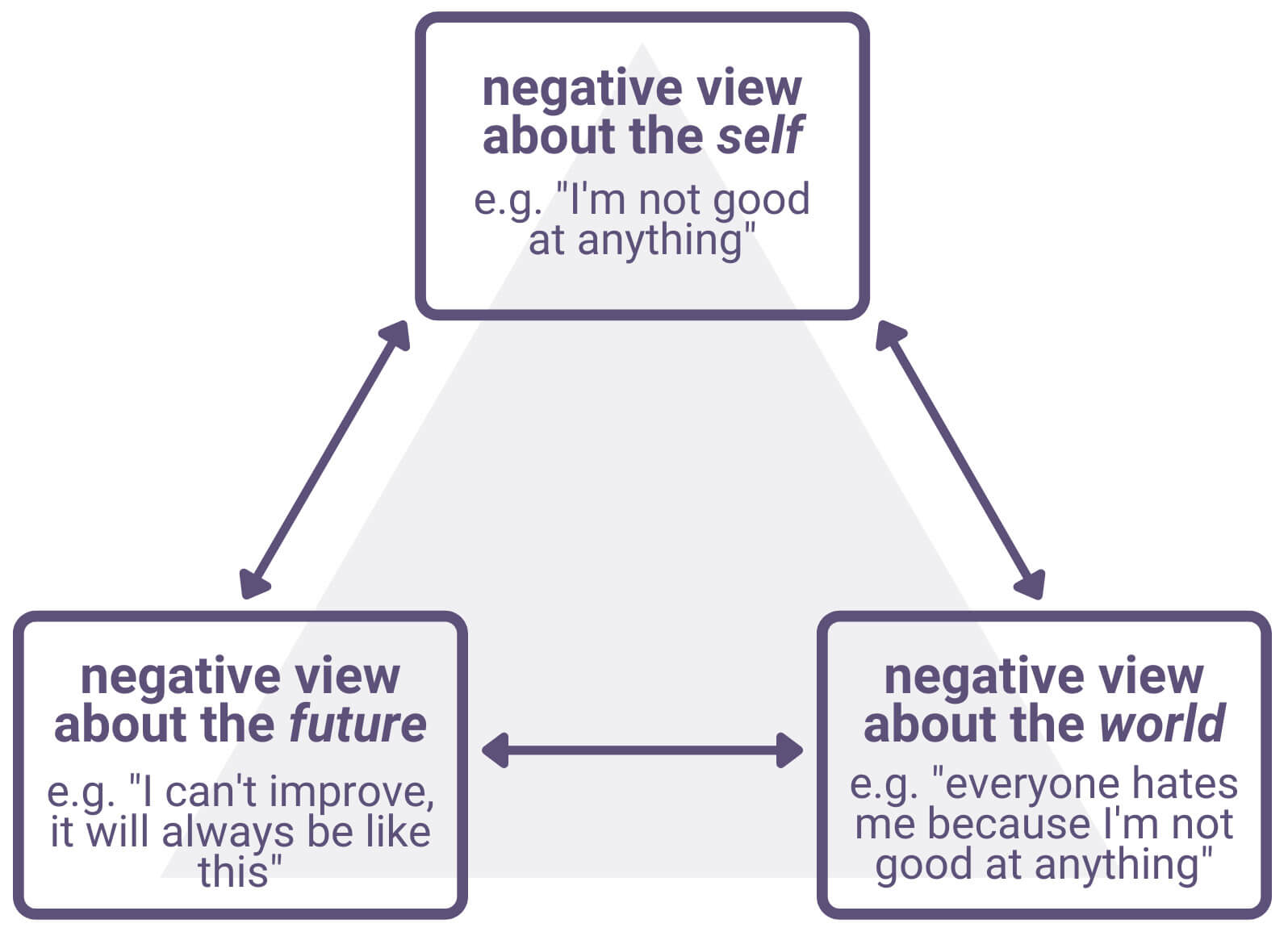

Ellis’ proposed the ABC model which attempted to explain how disorders such as depression occurred due to irrational thoughts and beliefs. Ellis believed that it was the interpretation of events by patients that was to blame for their distress and to explain this he referred to his ABC model.

A – Stands for activating event which may be a trigger or something happening in the environment. This may be someone giving you a poor evaluation of your work for example.

B – Stands for beliefs and this is the belief the person holds about the event or situation that has just occurred. This may be rational or irrational. For example, the person may think of themselves as a failure if it were irrational. A rational belief may be to try and work harder to change this evaluation.

C – Stands for the consequence and this is the consequence of what the persons belief is. In the context of depression, this is the emotion they experience although it can also affect behaviour.

If a person thinks and starts to believe they are a failure they are likely to have an emotional response such as feeling worthless. Rational beliefs tend to lead to healthy rational emotions while irrational beliefs cause unhealthy emotions which may lead to depression.

Mustabatory thinking is believed to play a role in irrational beliefs as they form expectations for individuals and failure to meet these expectations results in negative thoughts which lead to disorders such as depression.

Examples of mustabatory thinking is “I must be approved” or “I must be liked, I must achieve this to be happy”. These are a set of irrational belief systems which inevitably lead to disappointment with extreme feelings leading to depression.

Ellis’ ABC Model Evaluation

One strength for this Ellis’ ABC model is it provides us with real-world applications.

As thinking is identified as the cause for depression then therapies such as CBT can be used to tackle this. There is also strong research support for a cognitive basis for depression. Stronger negative thinking has also been found to be more associated with stronger forms of depression with more severe cases displaying a greater tendency for maladaptive attitudes and beliefs (Evans et al). This suggests Ellis’ ABC model explanation has validity as the cause appears to be primarily negative thinking which may be irrational in nature. This is further supported when considering CBT based treatments are highly effective for treating depression which highlights this explanation has validity.

A concern and weakness for the ABC model is it blames the patient rather than situational factors for their disorder.

This explanation suggests it is the client who is responsible for their irrational thoughts and for making themselves depressed rather than the situations they have faced and these may be overlooked. This theory assumes a person can simply “think themselves better” which isn’t so straight forward and over-simplified.

A weakness for cognitive explanations however is that much of the research is based on correlational data. It is not clear if negative cognitions cause depression or whether they are a symptom of the disorder itself. Therefore we cannot infer cause and effect for certain between these two variables.

A diathesis-stress explanation may be better suited to explaining why some people have irrational negative thinking towards situations which leads to depression and while others do not. It may be that some people have a genetic vulnerability for the disorder and the right environmental situations trigger negative thinking biases which lead to depression. There is support for biological explanations as depression has been linked to low levels of serotonin in depressed patients which suggests this cognitive explanation may be over-simplified, masking the true biological cause.

Possible exam questions for the cognitive approach to explaining depression:

- Outline Ellis’ ABC model as an explanation for depression

- Outline Beck’s negative triad as an explanation for depression

- Give one criticism of Ellis’ ABC model as an explanation for depression

- Outline and evaluate the cognitive approach to explaining depression (12 marks AS, 16 marks A-level)

The Cognitive Approach to Treating Depression

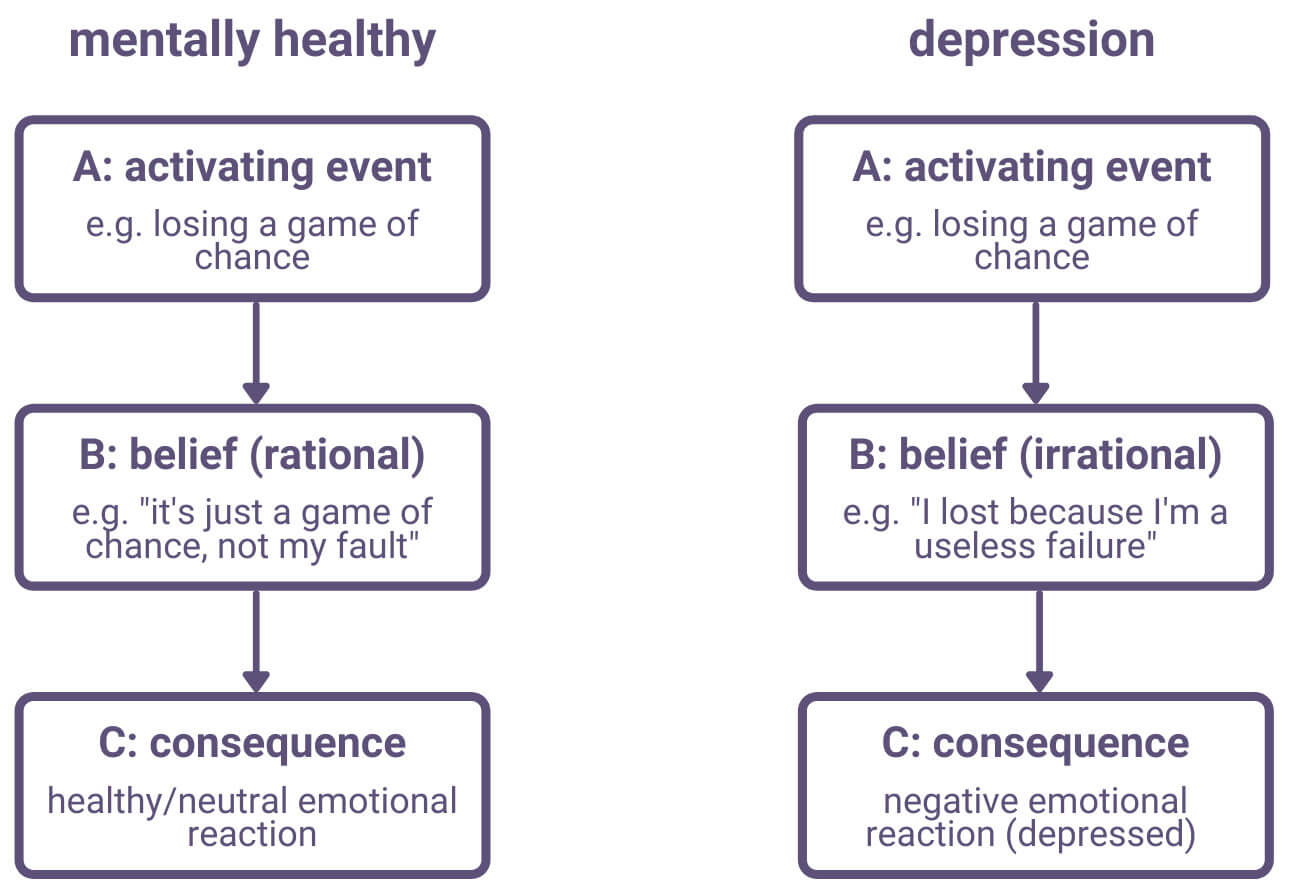

Cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT) is the main psychological treatment used to treat people suffering from depression and was first introduced by Ellis’ as REBT (rational emotive behavioural therapy).

CBT assumes that maladaptive thoughts and beliefs cause and maintain depression in individuals.

CBT focuses on helping patients identify and change these maladaptive thought processes with the belief that changing thinking will then change behaviour and emotions, as this is seen to be generated by thinking.

The idea is that individuals have beliefs, expectations and cognitive assessments of themselves, the environment and the problems they face that are irrational and by replacing these with more positive and productive thinking and behaviour, emotions will also become more positive breaking the depressive cycle.

The behavioural element is through encouraging the patient to engage in rewarding experiences and activities in the hope that their thoughts begin to become more positive also. The treatment is usually short and between 16 to 20 sessions and two of the main techniques often used are “challenging irrational thoughts” and “Behavioural activation”.

With challenging their irrational thoughts, patients learn to see the link between how their thinking affects their emotions and to record any emotionally arousing events (or activating events) that may occur. They then think about the negative thoughts associated with this event and encouraged to challenge them with more positive thoughts. They do this by questioning themselves on whether what they think is logical and makes sense, whether it is empirical and has evidence and whether the thought is pragmatic and helpful.

Through this type of thinking patients are taught to become more objective and replace dysfunctional thoughts with constructive ways of thinking which should improve their emotional state too.

Behavioural activation is based on the idea that being active will lead to more positive rewards that will help alleviate depressive symptoms. Many depressed people become withdrawn and do not engage in previously pleasurable activities and with the help of the therapist, the patient identifies enjoyable activities and encourages the patient to challenge any negative thoughts they may have in regards to them to help them become active again.

Cognitive Behavioural Therapy Evaluation

A major issue of whether CBT is appropriate for some patients is the time and cost factor. Unlike drug therapies, CBT requires multiple sessions with a trained therapist which can be incredibly costly and sometimes this is unaffordable time and cost-wise making it inappropriate. Drug therapies are cheaper and the patient only has to remember to take the drugs without sharing their intimate feelings of insecurity to a stranger (the therapist) and for this reason, CBT may be inappropriate for patients who are severely withdrawn and already struggling to engage with others. Such patients may feel overwhelmed and disappointed which may strengthen their depressive symptoms rather than reduce them making it ineffective and inappropriate in some cases.

Another issue into the effectiveness of CBT is down to the skill level of the therapist themselves. CBT is only effective provided the therapist is well skilled and able to form a collaborative relationship with the patient. Not all therapists will always be as enthusiastic or as capable as one another and this may make CBT ineffective for some patients. Kuyken et al concluded in their findings that as much as 15% of the variance in outcome could be attributed to the therapists level of competency supporting this.

A strength of CBT which makes it more appropriate and effective is that the therapy has no side effects, unlike drug therapies. Drugs can have severe side-effects affecting the heart and has even been linked to suicides and murder. Some drug therapies require patients to avoid certain foods such as cheeses and wines which can have adverse and fatal reactions. For patients suffering from health conditions or those who are unable to make such lifestyle changes, CBT may be more appropriate for them.

Another strength of CBT is it seen to treat the root cause of depression which is psychological in nature, unlike drug therapies which may simply mask and treat the symptoms. Therefore CBT is a more curative and holistic approach as the benefits should be longer-lasting, unlike drug therapies which are generally only effective as long as the patient continues to take the medication. Follow up studies have also found CBT to have lower relapse rates than other treatments making it more effective (Evans et al). In addition to this, there are no concerns with possible addiction or dependency with CBT, unlike antidepressants which would make it more appropriate with patients who have had drug dependency issues in the past.

A study by Rush et al showed CBT is just as effective as antidepressants in treating depression while by Keller et al found it is most effective when used in conjunction with antidepressants. Whitfield and Williams found that CBT had the strongest research base for effectiveness but the difficulty in providing weekly face to face sessions made it inappropriate considering current health budgets. This does, however, provide us with real-world applications as self-help versions such as the SPIRIT course could be used which teaches core cognitive behavioural skills through self-help materials instead.

Possible exam questions for the cognitive approach to treating depression:

- Explain how cognitive-behavioural therapy (CBT) is used in the treatment of depression.

- Explain how challenging irrational thoughts can work as a treatment of depression.

- Outline one criticism of cognitive-behavioural therapy as a treatment for depression.

- Outline and evaluate the cognitive approach to treating depression (12 marks, 16 marks for A-level)

The Biological Approach to Explaining OCD

The biological approach to explaining OCD focuses on genetics and neural explanations.

You may get a question that specifies one of the two or even asks a broad question that wants you to describe and evaluate biological explanations that uses both.

Therefore, you need to ensure you know both of them well.

Genetic explanations for OCD

Genetic explanations suggest OCD is transmitted through specific genes and there is a biological basis for the disorder.

To investigate this, family and twin studies have been conducted to compare the probability of OCD between them and the general population. Specific genes have also been investigated to understand their influence as well as gene-mapping studies to compare sufferers with non-sufferers.

Grootheest et al (2005) conducted a meta-analysis of over 70 years worth of twin studies into OCD. Twin studies involve comparing identical twins with non-identical twins. As identical twins have the exact same genetics, if their probability of having OCD is significantly higher than non-identical twins this would imply a genetic influence for the disorder supporting genetic explanations. If non-identical twins have a higher rate then this would imply environmental factors play a strong role (psychological) which would undermine genetic explanations.

This meta-analysis concluded that OCD did appear to have a strong genetic basis with genetic influence ranging from 45-65% within children. In adults, it was estimated that genetic influences ranged from 27-47%. First degree relatives have also been found to have an 11.7% chance of OCD compared to only 2.7% of the general population when compared to non-sufferers Nestadt et al (2000).

Other genetic explanations have suggested the COMT gene, which regulates and causes higher dopamine production, may contribute to OCD as it has been more commonly found in sufferers of OCD than non-sufferers (Tukel et al 2003). Other genetic explanations have focused on the SERT gene which affects the transportation of serotonin and causing lower levels of this. In one case study, a mutation of this gene was found in two unrelated families where six of the seven members had OCD (Ozaki et al 2003).

Evaluating genetic explanations of OCD

There is strong research evidence that supports genetic explanations. Twin and family studies have been found to show higher concordance rates for OCD compared to the general population. This suggests there is some element of genetics involved however how much is uncertain.

The fact that not all twins share OCD tendencies despite having the exact same genetics suggest that it cannot be genes alone which cause OCD and this biological explanation is reductionist and oversimplified. This clearly shows there are environmental stressors that must play a part in triggering OCD which needs to be factored in too and genetic explanations are unable to account for this.

A diathesis-stress model may be better suited to explaining OCD as it factors in both genetics and psychological factors such as environmental stressors. This suggests some people may have a genetic vulnerability to develop OCD providing the right environmental triggers cause its onset. This would be a more appropriate explanation as it effectively explains why identical twins may not both share the disorder. It can also successfully account for the high concordance rates between family members too and provide a more holistic explanation for the development of OCD.

Research evidence suggests it is not one specific gene responsible for OCD and many scattered genes throughout the human genome contribute in small ways towards an individual’s overall risk of developing OCD. Research by Leckman et al (1986) found OCD was one form of expression for the same genes that determine Tourettes syndrome. The obsessional behaviours seen between the two disorders are similar to what is found in autistic children as well as those suffering anorexia nervosa. This suggests OCD is not one specific gene nor a single isolated disorder but one on a spectrum linked to other disorders. The fact that OCD appears in childhood more commonly due to genetic factors than adulthood implies there may be different types of OCD with different causes too.

Another weakness is family members may often display different forms of OCD behaviour; while some adults become obsessive about constantly washing dishes, children may become obsessed with arranging dolls for example. If the disorder was indeed inherited it would be assumed that the behaviour would be similar between family members but this is not always the case. This is where psychological explanations may be better suited as the child may learn the obsessive behaviour from their parents modelling it. They may then demonstrate the same tendencies due to learning rather than genetics. This may actually explain the high concordance rates among family members as the behaviour may be learned from one another rather than genetic.

Neural explanations for OCD

Neural explanations for OCD have focused primarily on Serotonin and Dopamine levels affecting OCD behaviour.

High levels of dopamine causing OCD is one explanation and a study by Szechtman et al 1998 found that when animals were given drugs that increased dopamine levels, their behaviours resembled that of obsessive behaviours found in people with OCD.

In contrast, low levels of serotonin in patients has been linked to OCD.

This link is drawn on the fact that Pigott et al (1990) found anti-depressant drugs which increase serotonin activity have been found to reduce obsessive tendencies and symptoms in patients. Other types of antidepressants which do not increase serotonin activity have been found to be ineffective which suggests low levels of serotonin is linked to the disorder. PET scans on the brain have also found low levels of serotonin in sufferers providing more physical evidence for this neurotransmitter being involved.

Other neural explanations suggest that several areas within the frontal lobe of sufferers are abnormal and this may cause the disorder.

PET scans have shown OCD sufferers having high levels of activity in the orbital frontal cortex (OFC) which is associated with higher-level thought processes and converting sensory information into thoughts. The caudate nucleus located in the basal ganglia is responsible for suppressing signals from the OFC and when this is damaged or abnormal, it fails to suppress minor “worry” signals alerting the thalamus which in turn signals the OFC which acts as a “worry circuit”.

Comer (1998) linked serotonin and dopamine to these areas of the frontal lobe, believing they caused them to malfunction. This appears to have validity as the main neurotransmitter in the basal ganglia is Dopamine.

Evaluating neural explanations for OCD

Research support for neural explanations comes from a study by Pichichero (2009). Case studies from the US National Institute Of Health showed children with throat infections often displayed sudden indications of OCD symptoms as well as Tourette’s shortly after infection. This supports neural explanations as infections can affect the neural mechanisms which may underpin OCD itself and the two disorders are thought to occur through similar gene activations.

If there are abnormalities in neural mechanisms these would be caused by genetic factors which influence these abnormalities developing. Therefore neural explanations are reductionist and over-simplified as they alone can not explain the disorder as genetics are likely the root cause.

The research into serotonin and dopamine being linked to OCD is based on correlational research and we cannot for certain establish cause and effect due to this. It may well be that high dopamine levels or low serotonin levels are the effects of having OCD rather than the cause itself. The fact that not all sufferers of OCD respond to serotonin enhancing drugs adds weight to this possibility and other causes need to be considered.

Although research seems to suggest a link with neural mechanisms, we still can not completely explain how they may cause OCD. It’s possible unknown variables may lay in between that are actually causing the disorder which are unaccounted for.

Possible exam questions for the biological approach to explaining OCD:

- Outline genetic explanations for obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD)

- Outline neural explanations for obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD)

- Outline a criticism for genetic explanations for obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD)

- Outline and evaluate the biological approach to explaining OCD (12 marks AS, 16 marks A-level)

Biological Therapies for OCD

For biological therapies for obsessive-compulsive disorder, the AQA A-level psychology specification states you need to only know about drug therapies .

Which drugs are used to treat OCD?

Antidepressants are the most commonly used treatment for both OCD and depression.

Drug Therapy

Antidepressants are the most commonly used biological therapy for treating OCD as well as depression.

Low serotonin levels are believed to play a role in influencing OCD with the orbital frontal cortex (also known as the worry circuit) malfunctioning. By using antidepressants, this is believed to bring levels back to normal but also help reduce anxiety which is associated with OCD too.

The preferred drugs are SSRI’s (selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors) with adults commonly prescribed Fluoxetine (Prozac).

Children aged 6 years are prescribed Sertraline while those aged 8 or over, are prescribed Fluvoxamine.

The treatment lasts between 12 to 16 weeks and SSRI’s work by inhibiting reuptake of serotonin which is released into the synapses from neurons by blocking receptor cells. This increases serotonin levels and stimulation at the synapses alleviating OCD tendencies.

Tricyclics are also used exclusively for OCD and block the transportation mechanism which reabsorbs serotonin and noradrenaline into the pre-synaptic cell after firing. As serotonin builds up in the synapse, this prolongs their activity and eases transmission of the next impulse.

Anti-psychotic drugs have also been used which aid in lowering dopamine levels as high levels have also been associated with the disorder. These are normally given if SSRI’s do not prove effective due to their side effects.

Drugs such as Benzodiazepines lower anxiety levels by slowing down activity in the central nervous system by enhancing GABA activity (gamma-aminobutyric acid). GABA has a dampening effect on many neurons within the brain and work by locking on to GABA receptors. This opens a flow of chloride ions into the neuron which reduce the effects of other neurotransmitters and reduce activity in the central nervous system, relaxing the individual.

Drug Therapy Evaluation

- Research evidence shows drug therapies are effective compared to placeboes in the treatment of OCD. Pigott et al (1999) reviewed studies testing the effectiveness of drug therapies and concluded that SSRI’s have been consistently proven as effective in reducing OCD symptoms.

- Tricyclic drugs have also been found to be more effective than SSRI’s however they carry more serious side effects which may make them inappropriate as the initial drug to use. SSRI’s may be more appropriate as a first option and if they are not effective, then Tricyclic trials may be considered appropriate.

- Drug therapies do not cure OCD which may make them inappropriate as they may simply mask the symptoms of a biological disorder rather than cure it. Also, CBT has been shown to be effective in treating OCD for some patients and this treatment carries no risk of side-effects, unlike drug therapies. Therefore CBT may be more appropriate to try first rather than drug therapies.

- Drug therapies such as SSRI’s carry side effects such as heightened levels of suicidal thinking, loss of sexual appetite, irritability, sleep disturbance, headaches and loss of appetite. Dependent on the patient themselves they may not always be appropriate, especially if sufferers of OCD have a history of depression or children who may struggle to cope.

- Antidepressant drugs are cheap to manufacture, easy to administer and user-friendly when compared to psychological treatments such as CBT which can be time-consuming.

- They are fast-acting and effective allowing individuals to manage their symptoms and lead normal lives. For these reasons of convenience alone they may be more appropriate for many patients who are unable to spare the time to try other more time-consuming options.

Possible exam questions for the biological therapies for OCD:

- Outline how drug therapies are used to treat obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD)

- Outline and evaluate biological therapies for obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD)

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.

Get Free Resources For Your School!

Welcome Back.

Don’t have an account? Create Now

Username or Email Address

Remember Me

Create a free account.

Already have an account? Login Here

PMT Education is looking for a Content Intern over the summer

AQA A-level Psychology Revision

A-level paper 1, a-level paper 2, a-level paper 3.

- Revision Courses

- Past Papers

- Solution Banks

- University Admissions

- Numerical Reasoning

- Legal Notices

Overview – Psychopathology

Psychopathology is the study of mental disorders and conditions that are considered psychologically abnormal . Defining ‘abnormal’ is a topic in itself, with the syllabus mentioning 4 definitions of abnormality: deviation from social norms , failure to function adequately , statistical infrequency , and deviation from ideal mental health .

The A level psychology syllabus lists 3 specific mental disorders. Each of these mental disorders is approached from a different psychological viewpoint – both in terms of explanation and treatment:

- Phobias (explained from a behaviourist perspective)

- Depression (explained from a cognitive perspective)

- OCD (explained from a biological perspective)

Note that these are not the only valid psychological approaches to these disorders. For example, phobias can be treated biologically (e.g. with drugs) and OCD can be treated cognitively (e.g. cognitive behavioural therapy). These alternative approaches can be used to evaluate the approach listed in the syllabus.

Definitions of abnormality

The syllabus mentions 4 candidate definitions of psychological abnormality :

Deviation from social norms

Failure to function adequately, statistical infrequency, deviation from ideal mental health.

Each of these definitions has various strengths and weaknesses, which are covered in the AO3 evaluation points below.

Social norms are the expected rules of behaviour in society. They differ between cultures and between the same culture at different periods in time. Some typical examples of social norms include:

- Wearing clothes in public

- Saying “thank you” when someone does something for you

- Respecting people’s personal space

We can define abnormality as behaviour that deviates from these social norms . For example, going up and touching random strangers or walking around naked is abnormal.

The degree to which a behaviour is abnormal depends on how extreme the deviation is and how important the norm is. For example, not saying “thank you” might be somewhat abnormal – but it’s not dangerous, just rude. However, going up to and touching random strangers is a more extreme deviation of a more important rule and so may justify intervention from other people to stop this behaviour.

Strengths of the deviation from social norms definition:

- The social dimension of this definition can help both the abnormal individual and wider society. For example, intervention by society may protect citizens from the potentially dangerous behaviours of abnormal individuals. Further, intervention may also help the abnormal individual (who may not be able to help themself) by teaching them to interact successfully in society and avoid potentially dangerous consequences of abnormal behaviour.

- Social norms are flexible to account for the individual and situation. For example, throwing tantrums and hitting people is socially normal for a toddler , but would be a sign of mental disorder in adulthood . Similarly, walking around naked in your house might be normal, but walking around naked in the street would be a sign of mental disorder.

Weaknesses of the deviation from social norms definition:

- Social norms are not objective facts that definitively say which behaviours are most healthy, but instead are subjective (and somewhat arbitrary) rules created by other people.

- Social norms change over time and so what is considered a mental disorder today might not be in the future. For example, homosexuality was diagnosed as a mental disorder by the American Psychiatric Association until 1973.

- Social norms vary between cultures. For example, it is normal for someone to blow their nose in public, whereas in India such behaviour would go against social norms.

- A person who deviates from social norms may simply be eccentric rather than psychologically abnormal. For example, it goes against social norms to dress in 18th century clothes today, but it’s not exactly a mental disorder – the person might just like to dress that way.

Another definition of abnormality is failure to function adequately . This means a person is unable to navigate everyday life or behave in the necessary ways to live a ‘normal’ life. For example, failure to function adequately would prevent a person from having successful interpersonal interactions or get and keep a job.

Rosenhan and Seligman (1989) identify various features of dysfunction, including:

- Personal distress (e.g. anxiety , depression , excessive fear)

- Maladaptive behaviour (i.e. behaviour that prevents the person achieving goals)

- Irrationality

- Unpredictability

- Discomfort to others

Strengths of the failure to function definition:

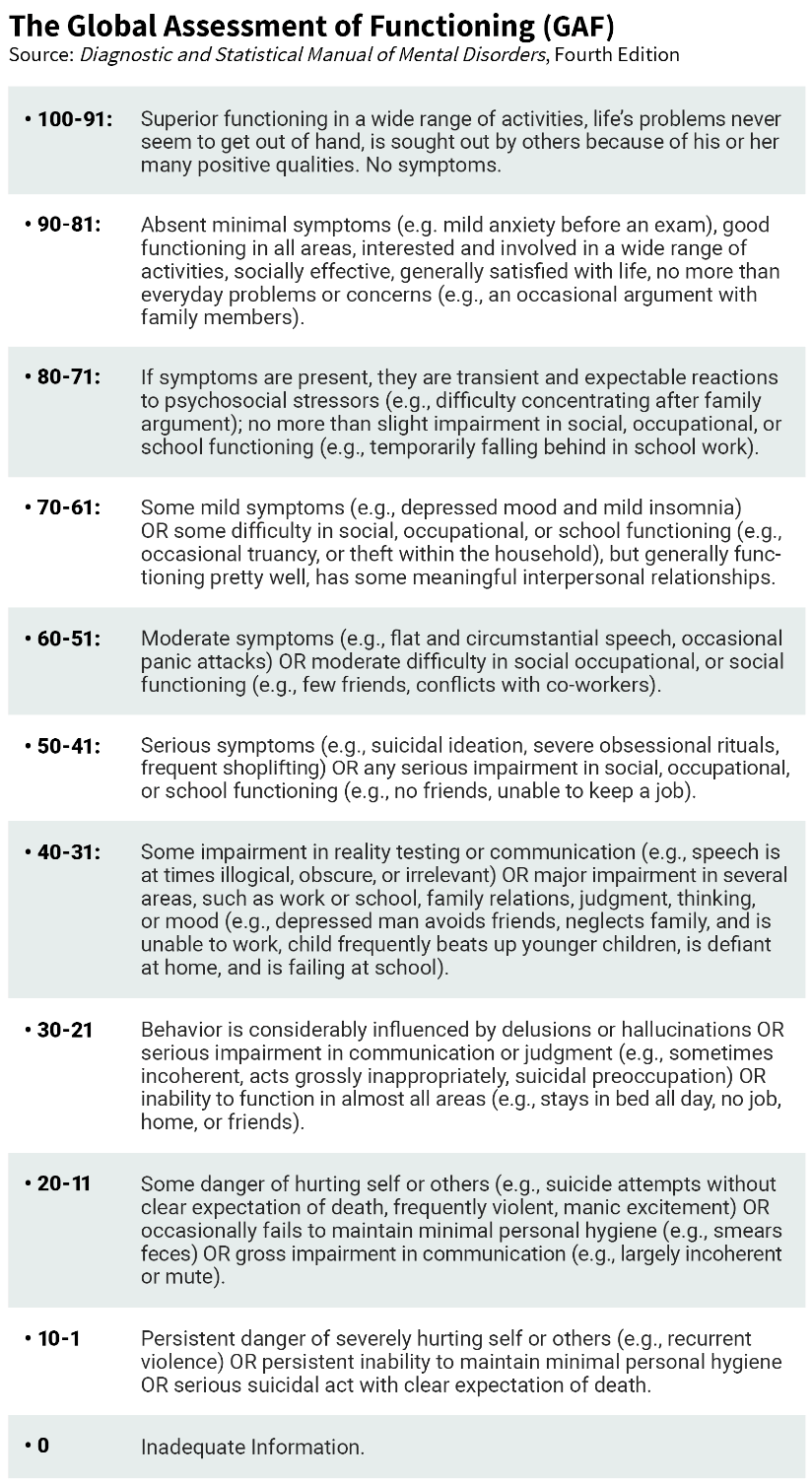

- The GAF provides a practical and measurable way of quantifying abnormality.

- The majority of people who seek clinical help for psychological disorders do so because they believe the disorder is affecting their ability to function normally. So, this definition is well-supported by the individuals themselves who suffer from mental disorders.

Weaknesses of the failure to function definition:

- Not everyone with a mental disorder is unable to function in society. For example, there have been many instances of serial killers who managed to maintain a normal – or even highly successful – life despite being psychopaths. The fictional character of Patrick Bateman in American Psycho illustrates this.

- Not everyone who is unable to function is suffering from a mental disorder. In some contexts, psychologically healthy people may (temporarily) be unable to function adequately. For example, a person who has just lost a close friend or relative may be unable to go to work or have fun with friends due to the grief they are feeling.

- What counts as failure to function adequately may differ between cultures.

The statistical infrequency definition of abnormality is a mathematical one. It defines abnormality as statistically rare characteristics and behaviours. The further a characteristic or behaviour is from the mathematical average, the more rare or statistically infrequent it is.

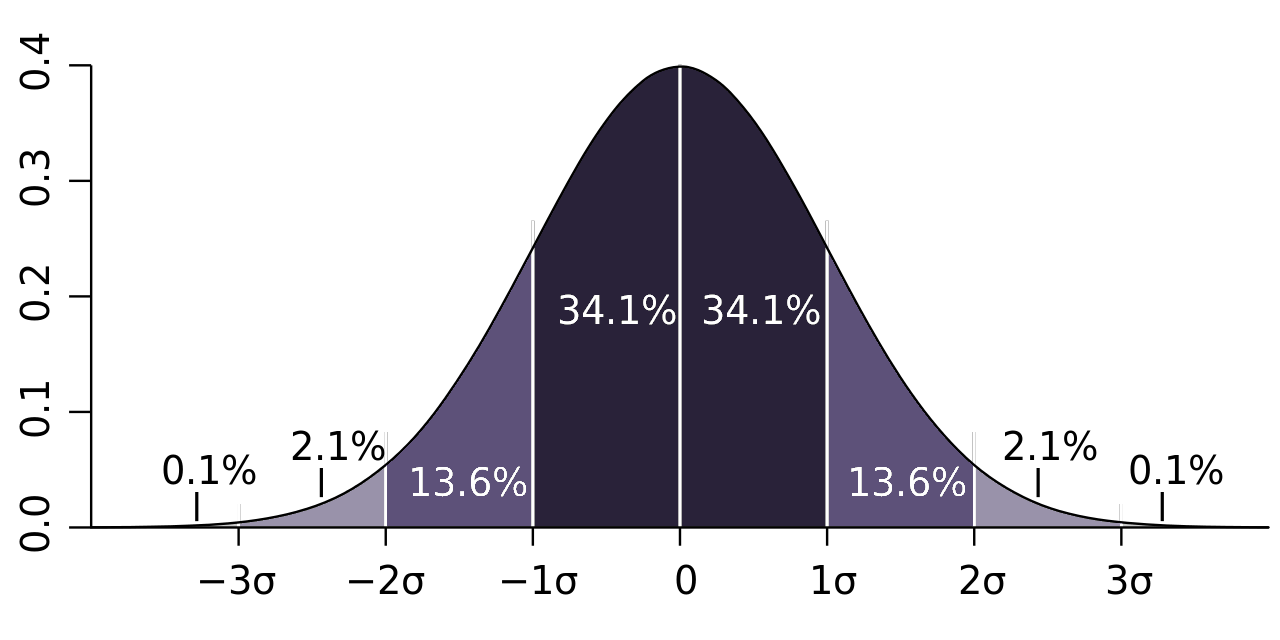

Statistical frequency can be plotted on a histogram like the one below:

The average here is indicated by 0 on the X-axis. The other figures indicate standard deviations (σ) from this average. The more a figure deviates from the average, the rarer it is.

For example, 68.2% of people – the majority – will be within 1 standard deviation of this average (34.1% above and 34.1% below). It is statistically more rare to be above or below 1 standard deviation from the average, and much rarer still to be more than 2 standard deviations from the average.

Many psychological traits and behaviours can be quantified and plotted on a graph like the one above. For example, intelligence can be quantified by IQ tests. The average IQ is 100, and most people will have an IQ within 1 standard deviation of this (i.e. between 85 and 115). An IQ above 130 or below 70 is statistically infrequent – it occurs in only around 2% of people – and so, according to this definition, would be considered psychologically abnormal.

Strengths of the statistical infrequency definition:

- Statistical infrequency provides a clear and objective way of determining whether something is abnormal or not. It is not just the subjective opinion of one person, but something that can be measured and quantified.

- Statistical infrequency does not imply any value judgements, i.e. whether something is good or bad. For example, homosexuality has historically been defined as a mental disorder – but not because it is bad or wrong, but because it is statistically rare compared to heterosexuality.

- Statistical infrequency is a good measure for many psychological disorders. For example, intellectual disability has historically been defined as having an IQ lower than 70 (2 standard deviations below the mean).

Weaknesses of the statistical infrequency definition:

- Infrequency does not always mean abnormality or mental disorder. For example, having an IQ above 140 is statistically infrequent, but it’s not a mental disorder and is actually quite desirable.

- And vice versa: Abnormality does not necessarily mean infrequency . For example, ‘abnormal’ mental conditions such as anxiety and depression are statistically quite common.

- Some psychological disorders are difficult to measure objectively and thus difficult to quantify as statistically infrequent. For example, how do you quantify how depressed or anxious someone is in order to determine whether they are statistically infrequent?

Another definition of abnormality is deviation from ideal mental health .

But in order to understand what it means to deviate from ideal mental health, we first need to define what ideal mental health is. Jahoda (1958) identified 6 features of ideal mental health:

| Being happy with who you are and having self-respect and self-esteem. | |

| Achieving personal growth and progress, realising one’s potential. | |

| Being independent, self-reliant, and able to make decisions for yourself. | |

| Being able to effectively deal with the challenges of life without excessive stress. | |

| Being realistic and objective about oneself and the external world. | |

| The ability to successfully navigate work, social, and other situations |

Someone with ideal mental health would tick all 6 of these boxes. However, if a person fails to tick most of these boxes, or deviates significantly from one of them (e.g. they constantly hallucinate pink elephants and thus do not have an accurate perception of reality), they would be classified as abnormal according to the deviation from ideal mental health definition.

Strengths of the deviation from ideal mental health definition:

- The holistic description of ideal mental health focuses on the entire person rather than atomised elements, which may provide a more effective and long-lasting means of treating mental disorders. For example, a person with depression might have low self-esteem and not be achieving self-actualisation. Addressing the overall deviation from mental health might be a more effective treatment avenue than focusing on specific symptoms in isolation.

- The deviation from ideal mental health definition provides a positive goal to strive towards: Rather than focusing on what is ‘abnormal’ or ‘undesirable’, this definition focuses on what is optimal and desirable and aims towards that.

Weaknesses of the deviation from ideal mental health definition:

- Too idealistic. Very few people meet all of Jahoda’s 6 criteria all the time. For example, many people have times when they lack self-esteem, and very few people are self-actualising all the time. So, according to this defintion, most people are psychologically unhealthy or ‘abnormal’.

- Jahoda’s criteria are somewhat subjective and hard to measure. For example, it is hard to quantify how much a person is self-actualising, or the extent to which they are able to master their environment. There are methods for measuring such characteristics (e.g. patient self-reports) but these may be unreliable, as each individual is likely to have different standards.

- What is understood by ideal mental health may differ between cultures. For example, Jahoda mentions autonomy as an important characteristic of ideal mental health, but more collectivist cultures may view individual autonomy as undesirable.

- Arachno phobia: fear of spiders

- Aero phobia: fear of flying in aeroplanes

- Agora phobia: fear of leaving one’s house

- Social phobias, such as fear of crowds or public speaking

Characteristics of phobias

Emotional characteristics: It is natural to feel some fear in response to potential danger. But people with phobias experience extreme fear that is uncontrollable and disproportionate to the situation.

Behavioural characteristics: Screaming, crying, freezing, or running away from the feared stimuli. A phobic person will typically try to avoid the feared stimuli – for example, a person with aerophobia might stay away from airports.

Cognitive characteristics: Most people with phobias recognise that their fear is irrational and disproportionate. However, this recognition does little to reduce the fear the phobic person feels.

Behaviourist approach to phobias

There are many competing and complementary approaches to psychology, including behaviourism , the cognitive approach , and the biological approach . The syllabus focuses on the behaviourist approach to phobias, but other approaches can serve as a means to evaluate this approach.

Behaviourist explanations of phobias

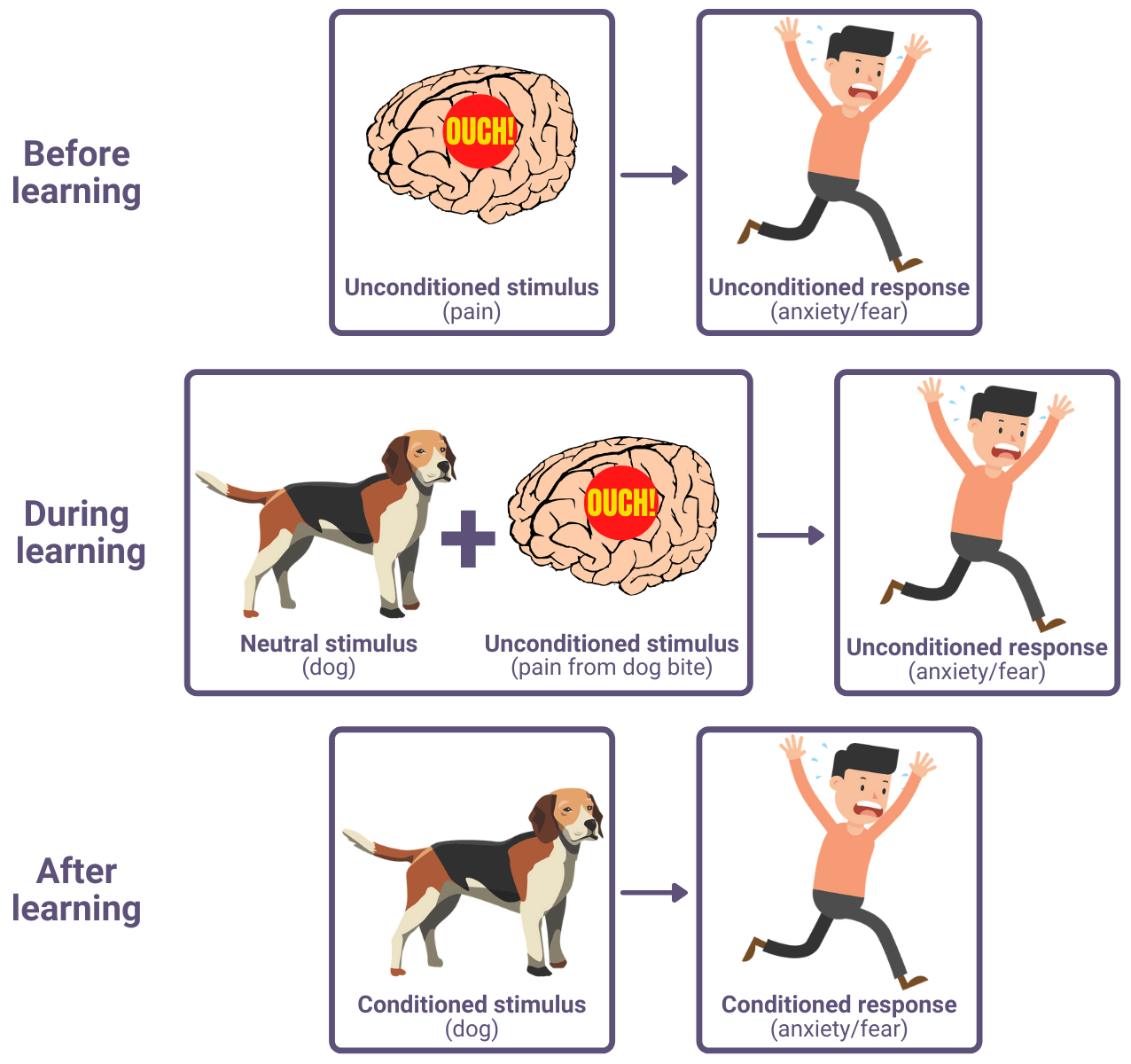

The behavioural approach (behaviourism) analyses phobias based on external observations of environmental stimuli and behavioural responses (rather than e.g. the underlying thought processes). The two-process model explains how phobias are developed and maintained through behavioural conditioning .

The two-process model

The two-process model explains phobias as:

- Acquired through classical conditioning , and

- Maintained through operant conditioning .

Classical conditioning (acquisition of phobia)

An example of how a person could be conditioned to develop a phobia of dogs is as follows:

Humans naturally fear pain, and so a fear response to pain is unconditioned. But when this natural (unconditioned) response is associated with a neutral stimulus (e.g. a dog) through experience (e.g. a dog biting them), then a person can become conditioned to associate the response (fear) with the stimulus (dogs). This is an example of classical conditioning , which is based on the work of Ivan Pavlov .

An example of this humans can be found in Watson & Rayner (1920) . In their experiment, an 11 month old baby – ‘Little Albert’ – was given a white rat to play with. Albert did not demonstrate a fear response towards the rat initially, but the researchers then made a loud noise which frightened Albert. This process was repeated several times, after which Albert demonstrated fear behaviour (e.g. crawling away, whimpering) when presented with the rat (and similar stimuli such as a rabbit and a fur coat) even without the loud noise.

Operant conditioning (maintenance of phobia)

Classical conditioning is outside a person’s conscious control – the conditioned response develops automatically. In contrast, operant conditioning occurs in response to behaviour, which is under a person’s control. If a person behaves in a way that produces a pleasurable outcome, then that behaviour is positively reinforced , making the person more likely to behave that way again. Similarly, if a person behaves in a way that reduces an unpleasant feeling, then that behaviour is negatively reinforced , also making them more likely to behave that way again.

Within the two-process model, this sort of operant conditioning explains how phobias are maintained. Returning to the phobia of dogs example: A person with a conditioned phobia of dogs will feel anxiety in the presence of dogs. And so, avoiding dogs (e.g. by running away from them or avoiding parks) will lessen this anxiety , which negatively reinforces these dog-avoiding behaviours. This pattern of behaviour and reward via operant conditioning reinforces and thus maintains the phobia.

Strengths of behaviourist explanations of phobias:

- Supporting evidence: In addition to Watson and Rayner (1920) above, there are several case studies that support the behaviourist explanation of phobias. For example, King et al (1998) describe several case studies of children who acquired phobias after a traumatic experience.

Weaknesses of behaviourist explanations of phobias:

- Alternative explanations: Rather than focusing on behaviours , the cognitive approach explains phobias in terms of thought processes . For example, there is evidence that phobic people may have an attentional bias (i.e. disproportionate focus of thought) towards the scariest features of the stimuli (e.g. a dog’s teeth or a spider’s venom).

- Not everyone who has an unpleasant experience at the same time as a neutral stimulus goes on to develop a phobia. For example, a person who gets bitten by a dog will not always develop a phobia of dogs. This weakens the behaviourist claim that phobias are acquired through classical conditioning .

Behaviourist treatment of phobias

Systematic desensitisation.

One behavioural treatment for phobias is systematic desensitisation . This involves gradually increasing exposure to the feared stimuli until it no longer induces anxiety . For example, someone with a fear of spiders (arachnophobia) may initially be asked to imagine spiders and guided through relaxation strategies until they can stay calm. Then, the process may be repeated with pictures of spiders, then real-life spiders in cages , and then repeated again with the subject actually holding a spider.

Systematic desensitisation is another example of classical conditioning : the subject is conditioned to associate the object with relaxation instead of anxiety .

An example of successful treatment of phobia using systematic desensitisation is described in Jones (1924) . A 2 year old boy – Peter – had a phobia of white rats and similar stimuli. Jones was able to remove Peter’s phobia over several sessions with him by progressively increasing his exposure to a white rabbit.

Another behavioural approach to treating phobias is flooding . Whereas systematic desensitisation increases exposure step-by-step, flooding involves exposing the subject to the most extreme scenarios straight away. For example, returning to arachnophobia, the subject would be placed in direct contact with spiders until their anxiety response subsides.

The idea behind flooding is that extreme anxiety cannot be maintained indefinitely. Eventually, the fear subsides and, in theory, the phobia.

An example of successful treatment of phobia using flooding is described in Wolpe (1969) . A girl with a phobia of cars was driven around in a car for four hours until she calmed down and her phobia disappeared.

Strengths of behaviourist treatment approaches of phobias:

- Supporting evidence: See studies above.

Weaknesses of behaviourist treatment approaches of phobias:

- Behavioural treatment works better with some phobias than others. For example, simple phobias such as of dogs or spiders are more amenable to behavioural treatments than social phobias. This suggests that not all phobias can be explained or treated in behaviourist terms.

- Behaviourist treatment of phobias – particularly flooding – may raise ethical concerns. For example, forcing a girl with a phobia of cars into one for four hours may be seen as cruel.

Depression is a mood disorder characterised by feelings of low mood, loss of motivation, and inability to feel pleasure.

Characteristics of depression

Emotional characteristics: People with depression experience persistent feelings of sadness and hopelessness. This low mood may come and go in cycles lasting months or years. Depression is also typically accompanied by feelings of worthlessness and a lack of enthusiasm.

Behavioural characteristics: Low energy, reduced activity, and reduced social interaction. Depressed people may also have irregular sleep patterns (either sleeping too much or too little (insomnia)) and gain or lose weight from over- or under-eating.

Cognitive characteristics: Depressed people may have exaggerated or delusional negative thoughts about themselves and what people think of them. They may have difficulty concentrating and remembering things. A depressed person may also regularly think about death and suicide.

Cognitive approach to depression

There are many competing and complementary approaches to psychology, including behaviourism , the cognitive approach , and the biological approach . The syllabus focuses on the cognitive approach to depression, but other approaches can serve as a means to evaluate this approach.

Cognitive explanations of depression

Example question: Discuss cognitive explanations of depression. [16 marks]

Beck’s negative triad

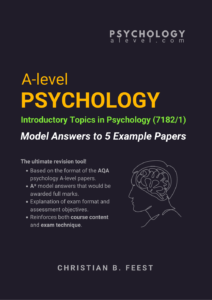

Beck (1979) argues that depression is characterised by a negative triad of beliefs about the self, the world, and the future:

He argues that this negative triad results from and is maintained by two cognitive processes:

- Negative schema

- Cognitive biases

Schema are patterns of thought – shortcuts/generalisations/frameworks – that are learned from experience to help make sense of the world and categorise information. Beck argued that experiences in childhood, such as criticism or failure to meet expectations, can cause depression-prone individuals to develop negative schema (i.e. a negative lens through which the individual views themself and the world). For example, experiences of failure in childhood may lead an individual to develop an ineptness schema whereby they constantly expect to fail.

These negative schema are caused by and amplify cognitive biases . Biases are systematic deviations from an accurate perception of reality in favour of some less accurate interpretation. For example, a person who loses a game of chance may falsely interpret this as proof that he is simply an unlucky person.

Together, these negative schema and cognitive biases maintain a negative triad of depressive beliefs about the self, the world, and the future.

Ellis’ ABC model

Ellis (1962) argued that depression results from irrational interpretation of negative events, rather than the negative events themselves. He explains this process using the ABC model of a ctivating event, b elief, and c onsequence.

According to Ellis, we all have assumptions and beliefs (think schema ) about ourselves and the world. With depressed people, though, these beliefs are often irrational and this leads them to interpret events (activating events) in an unrealistic way that causes a negative emotional reaction (consequence).