Change Password

Your password must have 6 characters or more:.

- a lower case character,

- an upper case character,

- a special character

Password Changed Successfully

Your password has been changed

Create your account

Forget yout password.

Enter your email address below and we will send you the reset instructions

If the address matches an existing account you will receive an email with instructions to reset your password

Forgot your Username?

Enter your email address below and we will send you your username

If the address matches an existing account you will receive an email with instructions to retrieve your username

- June 01, 2024 | VOL. 181, NO. 6 CURRENT ISSUE pp.461-564

- May 01, 2024 | VOL. 181, NO. 5 pp.347-460

- April 01, 2024 | VOL. 181, NO. 4 pp.255-346

- March 01, 2024 | VOL. 181, NO. 3 pp.171-254

- February 01, 2024 | VOL. 181, NO. 2 pp.83-170

- January 01, 2024 | VOL. 181, NO. 1 pp.1-82

The American Psychiatric Association (APA) has updated its Privacy Policy and Terms of Use , including with new information specifically addressed to individuals in the European Economic Area. As described in the Privacy Policy and Terms of Use, this website utilizes cookies, including for the purpose of offering an optimal online experience and services tailored to your preferences.

Please read the entire Privacy Policy and Terms of Use. By closing this message, browsing this website, continuing the navigation, or otherwise continuing to use the APA's websites, you confirm that you understand and accept the terms of the Privacy Policy and Terms of Use, including the utilization of cookies.

The Devastating Clinical Consequences of Child Abuse and Neglect: Increased Disease Vulnerability and Poor Treatment Response in Mood Disorders

- Elizabeth T.C. Lippard , Ph.D. ,

- Charles B. Nemeroff , M.D., Ph.D.

Search for more papers by this author

A large body of evidence has demonstrated that exposure to childhood maltreatment at any stage of development can have long-lasting consequences. It is associated with a marked increase in risk for psychiatric and medical disorders. This review summarizes the literature investigating the effects of childhood maltreatment on disease vulnerability for mood disorders, specifically summarizing cross-sectional and more recent longitudinal studies demonstrating that childhood maltreatment is more prevalent and is associated with increased risk for first mood episode, episode recurrence, greater comorbidities, and increased risk for suicidal ideation and attempts in individuals with mood disorders. It summarizes the persistent alterations associated with childhood maltreatment, including alterations in the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis and inflammatory cytokines, which may contribute to disease vulnerability and a more pernicious disease course. The authors discuss several candidate genes and environmental factors (for example, substance use) that may alter disease vulnerability and illness course and neurobiological associations that may mediate these relationships following childhood maltreatment. Studies provide insight into modifiable mechanisms and provide direction to improve both treatment and prevention strategies.

“It is not the bruises on the body that hurt. It is the wounds of the heart and the scars on the mind.” —Aisha Mirza

“We can deny our experience but our body remembers.” —Jeanne McElvaney, Spirit Unbroken: Abby’s Story

It is now well established that childhood maltreatment, or exposure to abuse and neglect in children under the age of 18, has devastating consequences. Over the past two decades, research has begun not only to define the consequences in the context of health and disease but also to elucidate mechanisms underlying the link between childhood maltreatment and medical, including psychiatric, outcomes. Research has begun to shed light on how childhood maltreatment mediates disease risk and course. Childhood maltreatment increases risk for developing psychiatric disorders (e.g., mood and anxiety disorders, posttraumatic stress disorder [PTSD], antisocial and borderline personality disorders, and substance use disorders). It is associated with an earlier age at onset and a more severe clinical course (i.e., greater symptom severity) and poorer treatment response to pharmacotherapy or psychotherapy. Early-life adversity is also associated with increased vulnerability to several major medical disorders, including coronary artery disease and myocardial infarction, cerebrovascular disease and stroke, type 2 diabetes, asthma, and certain forms of cancer. The net effect is a significant reduction in life expectancy in victims of child abuse and neglect. The focus of this review is to expand on previous reviews by synthesizing the literature and integrating much recent data, with a focus on investigating childhood maltreatment interactions with risk for mood disorders, disease onset, and early disease heterogeneity, as well as emerging data suggesting modifiable mechanisms that could be targeted for early intervention and prevention strategies. A major emphasis of this review is to provide a clinically relevant update to practicing mental health practitioners.

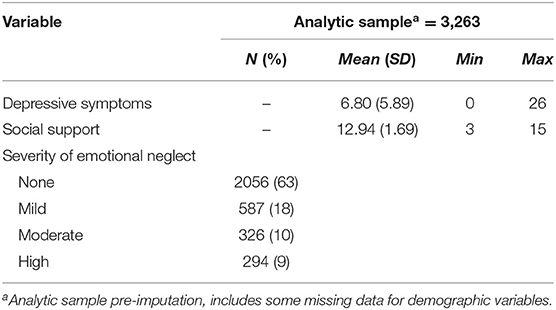

Prevalence and Consequences of Childhood Maltreatment

It is estimated that one in four children will experience child abuse or neglect at some point in their lifetime, and one in seven children have experienced abuse over the past year. In 2016, 676,000 children were reported to child protective services in the United States and identified as victims of child abuse or neglect ( 1 ). However, it is widely accepted that statistics on such reports represent a significant underestimate of the prevalence of childhood maltreatment, because the majority of abuse and neglect goes unreported. This is especially true for certain types of childhood maltreatment (notably emotional abuse and neglect), which may never come to clinical attention but have devastating consequences on health independently of physical abuse and neglect or sexual abuse. Although rates of children being reported to child protective services have remained relatively consistent over recent decades ( Figure 1 ), our understanding of the devastating medical and clinical consequences of childhood maltreatment has grown, and childhood maltreatment is now well established as a major risk factor for adult psychopathology. In this review, we seek to summarize the burgeoning literature on childhood maltreatment, specifically focusing on the link between childhood maltreatment and mood disorders (depression and bipolar disorder). The data converge to point toward future directions for education, prevention, and treatment to decrease the consequences of childhood maltreatment, especially in regard to mood disorders.

FIGURE 1. National estimates of childhood maltreatment in the United States a

a Panel A graphs the prevalence of maltreatment (calculated national estimate/rounded number of victims by year, and panel B graphs rates of victimization per 1,000 children, between 1999 and 2016, as reported by the Children’s Bureau, which produces an annual Child Maltreatment report including data provided by the United States to the National Child Abuse and Neglect Data Systems. Estimated rates of maltreatment have remained high over the past two decades. The asterisk calls attention to the fact that before 2007, the national estimates were based on counting a child each time he or she was the subject of a child protective services investigation. In 2007, unique counts started to be reported. The unique estimates are based on counting a child only once regardless of the number of times he or she is found to be a victim during a reporting year. (Information obtained from https://www.acf.hhs.gov/cb/research-data-technology/statistics-research/child-maltreatment .)

Childhood Maltreatment Increases Risk for Illness Severity and Poor Treatment Response in Mood Disorders

The link between childhood maltreatment and risk for mood disorders and differences in disease course following illness onset has been well documented ( 2 – 8 ). Multiple studies have demonstrated greater rates of childhood maltreatment in patients with major depression and bipolar disorder ( 9 – 11 ). Indeed, a recent meta-analysis revealed that 46% of individuals with depression report childhood maltreatment ( 12 ). Patients with bipolar disorder also report high levels of childhood maltreatment ( 13 , 14 ), with estimates as high as 57% ( 15 ). Childhood maltreatment is associated with an increased risk and earlier onset of unipolar depression, with syndromal depression occurring on average 4 years earlier in individuals with a history of childhood maltreatment compared with those without such a history ( 12 ). Childhood maltreatment is also associated with a more pernicious disease course, including a greater number of lifetime depressive episodes and greater depression severity, with the majority of studies showing more recurrence and greater persistence of depressive episodes ( 16 – 18 ). For example, Wiersma et al. ( 19 ), in an analysis of 1,230 adults with major depressive disorder drawn from the Netherlands Study of Depression and Anxiety, found that childhood maltreatment (measured with the Childhood Trauma Interview) was associated with chronicity of depression, defined as being depressed for ≥24 months over the past 4 years, independent of comorbid anxiety disorders, severity of depressive symptoms, or age at onset. Increased risk for suicide attempts and comorbidities, including increased rates of anxiety disorders, PTSD, and substance use disorders, are reported in individuals with depression who experience childhood maltreatment. Individuals with major depressive disorder and atypical features report significantly more traumatic life events (including physical abuse, sexual abuse, and other forms of trauma) both before and after their first depressive episode, independently of sex, age at onset, or duration of depression ( 20 ). Additionally, childhood maltreatment has consistently been shown to be associated with poor treatment outcome (after psychotherapy, pharmacotherapy, and combined treatment) in depression, as assessed by lack of remission or response or longer time to remission ( 12 , 18 , 21 , 22 ).

Although the studies cited above describe a link between childhood maltreatment and a more pernicious depression course, most studies have been cross-sectional, and the possibility of recall bias and mood effects (owing to the retrospective investigation of childhood maltreatment in individuals who are currently depressed) cannot be ruled out. However, studies over the past few years comparing retrospective and prospective measurement of childhood maltreatment suggest consistency between retrospective reports and prospective designs ( 23 , 24 ), although a recent meta-analysis ( 25 ) suggested poor agreement between these measures, with better agreement observed when retrospective measures were based on interviews and in studies with smaller samples. Longitudinal and prospective studies are emerging that have further confirmed and extended our understanding of the devastating consequences of childhood maltreatment on illness course ( 5 , 7 ). Ellis et al. ( 26 ) recently reported that childhood maltreatment increased risk for more severe trajectories of depressive symptoms during a 7-year longitudinal study in 243 adolescents in the Orygen Adolescent Development Study. Gilman et al. ( 27 ) reported that childhood maltreatment increased the risk for recurrent depressive episodes and suicidal ideation by 20%−30% during a 3-year follow-up of 2,497 participants diagnosed with major depressive disorder in the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions (NESARC). Additionally, Widom et al. ( 7 ), in a study that followed a cohort of 676 children with documented childhood maltreatment and compared risk for major depression in adulthood between them and a cohort of 520 children matched on age, race, sex, and family social class who were not exposed to childhood maltreatment, found a clear association between childhood maltreatment and both increased risk for depression and earlier onset of the disorder.

Although more research has been reported investigating the link between childhood maltreatment and disease onset and course in unipolar depression, more recent evidence supports the link between childhood maltreatment and disease onset and course in bipolar disorder ( 28 ). Childhood maltreatment is associated with increased disease vulnerability and earlier age at onset of bipolar disorder ( 29 ). Jansen et al. ( 30 ) sought to determine whether childhood maltreatment mediated the effect of family history on diagnosis of a mood disorder. The findings indicated that one-third of the effect of family history on risk for mood disorders was mediated by childhood maltreatment. As with depression, studies on bipolar disorder with a prospective or longitudinal approach are few, but they are informative. Using data from the NESARC (N=33,375), Gilman et al. ( 31 ) found that childhood physical and sexual abuse were associated with increased risk for first-onset and recurrent mania independently of recent life stress. An association between childhood maltreatment and prodromal symptoms has also been reported in bipolar disorder ( 32 ), suggesting that childhood maltreatment may contribute to disease vulnerability before onset of the first manic episode. Childhood maltreatment in the context of bipolar disorder is also associated with a more pernicious disease course, including greater frequency and severity of mood episodes (both depressive and manic), greater severity of psychosis symptoms, and greater risk for comorbidities (i.e., anxiety disorders, PTSD, substance use disorders), rapid cycling, inpatient hospitalizations, and suicide attempts ( 28 , 33 – 41 ). Studies are beginning to emerge investigating treatment response in bipolar disorder following childhood maltreatment. Such studies remain few, but they suggest that childhood maltreatment is associated with a poor response to benzodiazepines ( 42 ) and anticonvulsants ( 41 ) in bipolar disorder. The concatenation of findings in depression and bipolar disorder are concordant in that childhood maltreatment increases risk for, and early onset of, first mood episode and episode recurrence. Childhood maltreatment affects disease trajectories, including in its association with more insidious mood episodes, poor treatment response, a greater risk for comorbidities, and a greater risk for suicide ideation, attempts, and completion. The link between childhood maltreatment and increased prevalence of suicide-related behaviors is of particular importance given the high rate of suicide ideation, attempts, and completion in depression and bipolar disorder. Despite many prevention strategies (e.g., education and outreach and clinical studies to identify risk factors for impending suicide attempts in individuals with mood disorders), suicide rates have not decreased but in fact have increased in the United States. The link between childhood maltreatment and suicide-related behavior has been reviewed by several groups ( 21 , 33 , 43 – 47 ). Dube et al. ( 48 ) reported that adverse childhood experiences, including childhood maltreatment, increased the risk for suicide attempts twofold to fivefold in 17,337 adults in the now classic Adverse Childhood Experiences Study. Gomez et al. ( 49 ) reported that physical or sexual abuse increased the odds of suicide ideation, planning, and attempts among the 9,272 adolescents in the U.S. National Comorbidity Survey Adolescent Supplement. Miller et al. ( 50 ) examined the relationship between childhood maltreatment and prospective suicidal ideation in a cohort of 682 youths followed over a 3-year period. Emotional maltreatment predicted suicidal ideation, independently of previous suicidal ideation and depressive symptom severity. Childhood maltreatment is also associated with earlier age at first suicide attempt ( 51 ). Additionally, an association between childhood maltreatment and suicide risk in 449 individuals age 60 or older was recently reported from the Multidimensional Study of the Elderly, in the Family Health Strategy in Porto Alegre, Brazil ( 52 ). The effect was independent of depressive symptom severity. These findings suggest that childhood maltreatment increases risk for suicide-related behavior across the lifespan. More work is warranted in investigating the biological mechanisms that may mediate the association between childhood maltreatment and suicide-related behaviors.

Timing of Childhood Maltreatment: Are There Periods of Heightened Sensitivity?

Although childhood maltreatment at any age can result in long-lasting consequences ( 53 ), there is evidence that the timing, duration, and severity of maltreatment mediate the risk for later psychopathology ( 54 ). Childhood maltreatment that occurs earlier in life and continues for a longer duration is associated with the worst outcomes ( 55 ). This is supported by preclinical models (rodent and nonhuman primate) that investigated maternal separation ( 56 , 57 ), a paradigm more similar to neglect in humans. One study in rodents found that maternal separation during the early postnatal period (days 2–15) but not the later postnatal period (days 7–20) is associated with anxious and depressive-like behaviors in adulthood ( 57 ). Although this postnatal period coincides with in utero development in humans, there is evidence that in utero insults in the form of stress can have consequences similar to early-life trauma ( 58 , 59 ), supporting the translational validity of these models. Clinical studies also support the importance of timing of childhood maltreatment in moderating risk for psychopathology. Cowell et al. ( 60 ) investigated the timing and duration of childhood maltreatment in 223 maltreated children between the ages of 3 and 9 and found that children who were maltreated during infancy and those who experienced chronic maltreatment had poorer inhibitory control and working memory. Dunn et al. ( 61 ) investigated the relationship between timing of childhood maltreatment and depression and suicidal ideation in early adulthood among 15,701 participants in the National Longitudinal Study of Adolescent Health, and found that exposure to early maltreatment, especially during the preschool years (between ages 3 and 5), was most strongly associated with depression. Additionally, sexual abuse occurring during early childhood, compared with adolescence, was reported to be more strongly associated with suicidal ideation ( 61 ). While these studies suggest that childhood maltreatment that occurs earlier in development may further increase risk for developing mood disorders and associated behaviors in adulthood, it is important to emphasize that evidence suggests that exposure to maltreatment during later childhood and adolescence also independently increases risk for mood disorders. Emotional abuse and neglect, especially if it occurs between ages 8 and 9, increases depressive symptoms ( 62 ). Emotional abuse during adolescence also increases risk for depression ( 63 ).

More work is emerging investigating the negative consequences of bullying. A study of 1,420 participants (ages 9–16) revealed that victims of bullying showed an increased prevalence of generalized anxiety disorder, depression, and suicide-related behavior ( 64 ). A recent study of more than 5,000 children that comprised a longitudinal data set (the Avon Longitudinal Study of Parents and Children in England and the Great Smoky Mountains Study in the United States) ( 65 ) found an increased risk for mental health problems, including anxiety, depression, and self-harm, in individuals who experienced bullying, but not other maltreatment. Additionally, an association between childhood bullying by peers and risk for suicide-related behaviors (ideation, planning, attempting, and onset of plan among ideators), independent of childhood maltreatment by adults, was reported in a sample of U.S. Army soldiers ( 66 ).

Some studies suggest that differential periods of sensitivity to different subtypes of maltreatment are distinctly associated with an increased risk for mood disorders. Recently, a stronger relationship was reported between adult depression and early childhood sexual abuse (occurring at age 5 or earlier) and later childhood physical abuse (occurring at age 13 or later), compared with maltreatment that occurred during other developmental periods ( 67 ). Harpur et al. ( 68 ) reported that early childhood maltreatment (between birth and age 4) predicted more anxiety symptoms, and maltreatment that occurred in late childhood or early adolescence (between ages 10 and 12) predicted more depressive symptoms in adolescence. Taken together, these studies suggest that maltreatment at any age and across different contexts (physical and emotional, familial- and peer-induced) often result in long-lasting and severe consequences and that there may be specific sensitive periods in development when exposure to distinct types of maltreatment may differentially increase risk for affective disorders in adulthood. To date, the majority of research investigating the impact of childhood maltreatment timing on illness risk and course in mood disorders has focused on depression. One study ( 69 ) reported that early sexual or physical abuse (before age 11) in 225 early psychosis patients (6.7% with a bipolar disorder diagnosis) coincided with lower scores on the Global Assessment of Functioning Scale and the Social and Occupational Functioning Assessment Scale during a 3-year follow-up period, whereas late sexual or physical abuse (between ages 12 and 15) did not. More work investigating timing of maltreatment and associated clinical outcomes is warranted.

Experiencing Single Subtypes of Abuse and Neglect Versus Experiencing Multiple Types

Several groups have sought to determine the impact of single types of childhood maltreatment on mood disorders. Although all types of childhood maltreatment (physical, emotional, and sexual) increase disease vulnerability and risk for more severe illness course in mood disorders, including increased risk for suicide ( 52 ), there may be some distinctions between individual subtypes and associated outcomes ( 70 ). An association between sexual abuse and lifetime risk for anxiety disorders, depression, and suicide attempts independent of other types of maltreatment has been reported ( 2 , 71 , 72 ). In bipolar disorder, physical abuse and sexual abuse independently increase risk for illness vulnerability and more severe course ( 13 ). One study of 446 youths (ages 7 to 17) found that physical abuse was independently associated with a longer duration of illness in bipolar disorder, a greater prevalence of comorbid PTSD and psychosis, and a greater prevalence of family history of a mood disorder when compared with sexual abuse, which was only associated with a greater prevalence of PTSD ( 13 ). Recent life stress in adulthood was found to increase risk for first-onset mania in individuals with a history of childhood physical maltreatment, but not individuals with a history of sexual maltreatment ( 31 ). However, it should be noted that early-life sexual abuse in the study was a strong risk factor for mania even in the absence of recent life stress.

Neglect is the least studied form of early-life adversity, and emerging data suggest differential consequences following neglect as compared with abuse ( 73 ). Similarly, long-lasting consequences following emotional maltreatment, independently of other forms of maltreatment, have also been reported ( 47 , 74 , 75 ). In a 2015 meta-analysis, emotional abuse showed the strongest association with depression, followed by neglect and sexual abuse ( 76 ), a finding supported by another recent meta-analysis ( 77 ). Spertus et al. ( 78 ) reported that emotional abuse and neglect predicted depressive symptoms even after controlling for physical and sexual abuse, further suggesting emotional abuse and neglect to be independently related to illness severity in depression. Parental “verbal aggression” was found to increase risk for depression and anxiety in adolescents, with risk suggested to be greater following verbal aggression compared with physical abuse ( 79 ). Khan et al. ( 63 ) recently reported that nonverbal emotional abuse in males and peer emotional abuse in females are important predictors of lifetime history of major depression and are more predictive than number of types of maltreatment experienced. Another recent meta-analysis ( 12 ) reported that in individuals with depression, emotional neglect was the most common reported form of childhood maltreatment, and emotional abuse was most closely related to symptom severity. High prevalence of emotional maltreatment is also reported in bipolar disorder (approximately 40%), with emotional maltreatment associated with disease vulnerability and more severe illness course, including rapid cycling, comorbid anxiety or stress disorders, suicide attempts or ideation, and cannabis use ( 80 ).

Although studies on subtypes of maltreatment are only now burgeoning, they are concordant in implicating emotional maltreatment, in addition to physical and sexual maltreatment, in increasing risk for, and differences in disease course of, mood disorders. Emotional maltreatment and neglect are clearly the least studied of all forms of childhood adversity. This is in part because they are often overlooked and least likely to come to clinical attention, as compared with physical and sexual abuse, which can, of course, result in physical injury. Because emotional maltreatment and neglect are likely the most prevalent forms of childhood maltreatment in psychiatric populations ( 81 ), and given findings suggesting that independent of other forms of maltreatment, emotional maltreatment has long-lasting consequences that increase risk for mood disorders and illness outcome ( 74 , 75 ), more research on the role of emotional maltreatment and neglect are urgently needed.

Although the findings described above suggest the hypothesis that different subtypes of early-life adversity may independently increase risk for mood disorders and that some subtypes may be more closely related to specific differences in illness course and severity, it is clear that subtypes of abuse and neglect, as a rule, do not occur in isolation but instead occur together in the same individuals. For example, individuals experiencing physical or sexual abuse likely also experience emotional maltreatment. Some studies have investigated the impact of multiple types of childhood maltreatment. A recent meta-analysis reported that 19% of individuals with major depression report more than one form of childhood maltreatment and, while all childhood maltreatment subtypes have been shown to increase the risk of depression, experiencing multiple forms of childhood maltreatment further elevates this risk ( 12 ). The Adverse Childhood Experiences study provided evidence of an additive effect of eight early-life stress events (including abuse but also other early-life stressors, such as divorce, domestic violence, household substance abuse, and parental loss) on adult psychopathology. Specifically, individuals with four or more early-life stress events had significantly increased risk for depression, anxiety, suicide attempts, substance use disorders, and other detrimental outcomes ( 82 , 83 ). An additive or cumulative effect of early-life stress on increased risk for mood, anxiety, and substance use disorders has also been reported by others ( 5 , 6 ). Multiple adverse childhood experiences (maltreatment plus other forms of stressful events) also result in higher rates of comorbidities ( 7 , 82 ). Likewise, a dose-response relationship between number of types of childhood maltreatment and illness severity in bipolar disorder has been suggested, including increased risk for comorbid anxiety disorders and substance use disorders ( 84 ).

Underlying Mechanisms by Which Childhood Maltreatment Increases Risk for Mood Disorders and Contributes to Disease Course

As depicted in Figure 2 , several putative biological mechanisms by which childhood maltreatment may increase the risk for mood disorders and disease progression have been described ( 21 , 85 ). These include, but are not limited to, inflammation and other immune system perturbations, alterations in the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis, and genetic and epigenetic processes as well as structural and functional brain imaging changes. These studies provide insight into modifiable targets and provide direction to improve both treatment and prevention strategies.

FIGURE 2. Child maltreatment, its consequences, and windows for intervention across development a

a The gray arrow represents the development of disease vulnerability, disease onset, and variations in disease course and treatment. Exposure to childhood maltreatment at any point during development (red bar) can result in long-lasting consequences, including increasing disease vulnerability and illness severity in mood disorders. There may be optimal windows (black arrows) across development when interventions could decrease disease burden by decreasing disease vulnerability and improving illness course; these include before and after birth (parenting classes and parenting support groups), at the time of maltreatment, when prodromal symptoms begin to emerge, immediately following disease onset, and during disease course (e.g., improving treatment response). Modifiable targets are beginning to emerge (green arrows and text) and point to behavioral and environmental factors, as well as genetic and other molecular factors, that could be focused on for interventions.

Biological Abnormalities Associated With Childhood Maltreatment

Several persistent biological alterations associated with childhood maltreatment may mediate the increased risk for development of mood and other disorders. Childhood maltreatment is associated with systemic inflammation ( 86 , 87 ) as assessed by measurements of C-reactive protein (CRP) and inflammatory cytokines including tumor necrosis factor-alpha and interleukin-6. Childhood maltreatment was found to be associated with increased plasma CRP levels and increased body mass index in 483 participants identified as being on the psychosis spectrum ( 88 ). Patients with depression and bipolar disorder have also been reported to exhibit increased levels of inflammatory markers ( 89 – 92 ). It is unclear whether childhood maltreatment–associated inflammation is responsible for the observations in patients with mood disorders. Anti-inflammatory drugs are a promising novel therapeutic strategy in the subgroup of depressed patients with elevated inflammation ( 93 ), although the findings thus far are preliminary, and further study on inflammation as a modifiable target is warranted.

Another mechanism through which childhood maltreatment may increase risk for mood disorders is through alterations of the HPA axis and corticotropin-releasing factor (CRF) circuits that regulate endocrine, behavioral, immune, and autonomic responses to stress. Research documenting how childhood maltreatment contributes to altered HPA axis and CRF circuit activity in preclinical and clinical studies has been reviewed in detail elsewhere ( 21 ). Childhood adversity likely increases sensitivity to the effects of recent life stress on the course of both unipolar and bipolar disorder. Soldiers exposed to childhood maltreatment have a greater risk for depression or anxiety following recent life stressors ( 94 ). Likewise, individuals exposed to childhood maltreatment have a greater risk of mania following recent life stressors compared with individuals without childhood maltreatment ( 31 , 34 ). Individuals with depression or bipolar disorder and early-life stress report lower levels of stress prior to recurrence of a mood episode compared with individuals with depression or bipolar disorder without early-life stress ( 34 , 95 ); this suggests that less stress is required to induce a mood episode in individuals who were exposed to childhood maltreatment. These findings support theoretical sensitization frameworks on the role of stress in unipolar depression and bipolar disorder ( 96 – 99 ). Alterations in the HPA axis and CRF circuits following childhood maltreatment are mechanisms that likely contribute to increased risk for mood episodes following stressful life events and may be modifiable targets. Indeed, Abercrombie et al. ( 100 ) recently reported that therapeutics targeting cortisol signaling may show promise in the treatment of depression in adults with a history of emotional abuse.

In addition to the biological mechanisms noted above, genetic predisposition undoubtedly also plays a role in the pathogenesis of mood disorders following early-life stress. As previously reviewed ( 21 ), studies support the interaction of genetic predisposition and childhood maltreatment in increasing risk for mood disorders and affecting disease course. Indeed, this is now considered a prototype of how gene-by-environment interactions influence disease vulnerability. Polymorphisms in genes comprising components of the HPA axis and CRF circuits increase the risk for adult mood disorders in adults exposed to childhood maltreatment. For example, polymorphisms in the FK506 binding protein 5 (FKBP5) gene interact with childhood maltreatment to increase risk for major depression, suicide attempts, and PTSD ( 101 – 105 ). Caspi et al. ( 106 ) found that adults exposed to childhood maltreatment who carried the short arm allele of the serotonin transporter promoter polymorphism (heterozygotes and homozygotes) exhibited an increased risk for a depressed episode, greater depressive symptoms, and greater risk for suicidal ideation and attempts compared with homozygotes with two long arm alleles. A large number of studies now support the interaction between early-life stress, the serotonin transporter promoter, and other serotonergic gene polymorphisms and disease vulnerability and illness course in depression and bipolar disorder ( 107 – 111 ), although conflicting findings have also been reported ( 112 ). Childhood maltreatment has also been reported to interact with corticotropin-releasing hormone receptor 1 gene (CRHR1) polymorphisms to predict syndromal depression and increase risk for suicide attempts in adults ( 113 – 115 ). Early-life stress interactions with other genetic polymorphisms to influence risk for mood disorders and illness course include, but are not limited to, brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) Val66Met polymorphism ( 116 , 117 ), toll-like receptors ( 118 ), the oxytocin receptor ( 119 ), inflammation pathway genes ( 120 ), and methylenetetrahydrofolate reductase ( 121 ), although negative findings have also been reported ( 122 ). Studies employing polygenic risk score (PRS) analyses, an approach assessing the combined impact of multiple genotyped single-nucleotide polymorphisms, have reported that PRS is differentially related to risk for depression in individuals with a history of childhood maltreatment compared with those without maltreatment ( 123 , 124 ), although negative findings have also been reported ( 125 ).

Studies investigating the role of epigenetics (e.g., the modification of gene expression through DNA methylation and acetylation) in mediating detrimental outcomes following early-life stress have recently appeared ( 126 ). For example, a recent study reported that hypermethylation of the first exon of a monoamine oxidase A (MAOA) gene region of interest mediated the association between sexual abuse and depression ( 127 ). Childhood maltreatment is also associated with epigenetic modifications of the glucocorticoid receptor ( 128 ), the FKBP5 gene ( 101 ), and the serotonin 3A receptor ( 129 ), with these modifications associated with suicide completion, altered stress hormone systems, and illness severity, respectively. Childhood maltreatment–associated epigenetic changes in individuals who died by suicide have been identified in human postmortem studies ( 130 ). These studies, and others not cited here, support gene–by–childhood maltreatment interactions, including epigenetic modifications, in risk for mood disorders and in illness course.

Epigenetics may also be one mechanism that contributes to the intergenerational transmission of trauma ( 131 – 133 ), although it is important to note that nongenomic mechanisms are also implicated in the intergenerational transmission of behavior ( 134 ). There is a robust literature in rodent models supporting the intergenerational transmission of maternal behavior—maternal traits being passed to offspring—including abuse-related phenotypes ( 132 , 135 ). Intergenerational transmission of behavior is also implicated in humans. Yehuda et al. ( 136 , 137 ) investigated risk for psychopathology in offspring of Holocaust survivors. These pivotal studies identified increased risk for PTSD, mood disorders, and substance use disorders in offspring. These offspring also reported having higher levels of emotional abuse and neglect, which correlated with severity of PTSD in the parent ( 136 , 137 ), implicating early-life stress in transmission of psychopathology. While there is evidence that children with developmental disabilities are at a higher risk for neglect ( 138 – 140 ), there is a paucity of studies investigating whether offspring of individuals with mental illness are more liable to abuse. However, as discussed above, higher rates of maltreatment are reported in individuals with mood disorders, but whether and what familial factors may drive these elevated rates, or whether these interactions contribute to the intergenerational transmission of psychopathology, are not known. In light of the emerging data on intergenerational transmission of trauma, this is an important, complex area in need of further study. There have not been many genetic studies in this area. In a study investigating early-life maltreatment in a rodent model, early-life abuse (defined as stepping on, dropping, or dragging offspring, and active avoidance) was associated with altered BDNF expression and methylation in the prefrontal cortex in adult offspring, with adult offspring also showing poorer maternal care patterns when rearing their own offspring ( 135 ). Altered expression and methylation of BDNF is reported in individuals with mood disorders ( 141 , 142 ). These studies highlight the importance of understanding the intergenerational transmission of trauma and psychopathology to identify modifiable targets to improve outcomes, for example, the family unit and interpersonal relationships. It is noteworthy that while the majority of research has focused on intergenerational transmission of maternal traits, research is also emerging that supports the important role of paternal care on intergenerational transmission of behavior ( 131 ). More study on intergenerational transmission of trauma is needed.

Pathways to Mood Disorder Outcomes

More work on mechanisms and pathways by which childhood maltreatment increases risk for and ultimately results in adult mood disorders is essential for early intervention. Childhood maltreatment is associated with a marked increase in medical morbidities and an array of physical symptoms, and in general it predicts poor health and a shorter lifespan ( 143 , 144 ). Higher rates of comorbid substance use disorders in individuals with mood disorders who report experiencing childhood maltreatment is of particular interest. Childhood maltreatment has consistently been associated with a number of high-risk health behaviors, including smoking and alcohol and drug use—behaviors thought to contribute to the association between childhood maltreatment and poor health ( 145 – 148 ). These behaviors on their own increase risk for, and alter disease course in, mood disorders ( 149 – 153 ). More study on the relationship between early-life adversity, substance use disorders, and mood disorders is therefore warranted. For example, childhood maltreatment is associated with increased risky alcohol use, alcohol-related problems, and alcohol use disorders ( 154 , 155 ), and alcohol use disorders are an established risk factor for both depression and bipolar disorder ( 149 – 151 ) in addition to increasing risk for a more severe clinical course, such as further increasing risk for suicide ( 152 , 153 ). A recent study reported that depression mediates the relationship between childhood maltreatment and alcohol abuse ( 156 ). Another study recently reported that sexual abuse increased risk of alcohol use and depression in adolescence, which then influenced risk for adult depression, anxiety, and substance abuse ( 157 ). In a longitudinal study investigating changes in patterns of substance use over time in 937 adolescents, childhood maltreatment was associated with an increased progression toward heavy polysubstance use ( 158 ). More research is needed looking at the interactions between childhood maltreatment and other drugs of abuse. This is especially true in light of the current opioid epidemic, as increased rates of childhood maltreatment are also reported in individuals with opioid use disorders ( 159 – 161 ), and greater reported childhood maltreatment is associated with faster transmission from use to dependence ( 162 ) and with higher rates of suicide attempts in this population ( 163 ).

Interestingly, certain genes described above that exhibit gene–by–childhood maltreatment interactions on risk for mood disorders, including FKBP5 and the serotonin transporter promoter polymorphisms, also exhibit gene-by-childhood maltreatment interactions on risk for alcohol use disorders ( 164 – 168 ). Alterations in the stress hormone system are also associated with an increased risk for alcohol use disorders in individuals with a history of childhood maltreatment ( 169 ), and past-year negative life events have been reported to increase drinking and drug use, an effect that is dependent on genetic variation in the serotonin transporter gene ( 170 ). Childhood maltreatment has been found to be associated with an earlier age at initiation of alcohol and marijuana use, with this association mediated by externalizing behaviors ( 171 ). Impulsivity may mediate the relationship between childhood maltreatment and increased risk for developing alcohol or cannabis abuse ( 172 ). Etain et al. ( 173 ) conducted a path analysis in 485 euthymic patients with bipolar disorder and uncovered a significant association between impulsivity and emotional abuse, and impulsivity was associated with an increased risk for substance use disorders. These studies suggest that in some individuals with a history of childhood maltreatment, although not all, interventions that focus on alcohol or drug use problems, and specifically externalizing behaviors that may mediate the link between childhood maltreatment and alcohol or drug use problems (e.g., impulsivity), could decrease disease burden by decreasing risk for developing mood disorders or by improving illness course (e.g., decreasing symptom severity and risk for suicide).

Substance use disorders are also associated with increases in inflammatory markers ( 174 , 175 ). Inflammation is suggested to contribute to comorbid alcohol use disorders and mood disorders ( 176 ), and it contributes to a variety of medical morbidities ( 177 ), and these in turn are associated with an increased risk for mood disorders ( 177 ). Speculatively, inflammation may be one mechanism by which childhood maltreatment increases risk for medical morbidity and through that pathway increases risk for mood disorders. While there is a paucity of studies on the pathways described above, the associations between childhood maltreatment, risky health behaviors, inflammation, and medical morbidities warrant more study, as identifying pathways (mediators and moderators) to illness outcomes could foster the development of more effective interventions and treatment strategies.

It should be noted that not all individuals who experience childhood maltreatment develop mood disorders. This may be related in part to genetics. However, other resiliency factors are likely of importance. In a recent meta-analysis, Braithwaite et al. ( 178 ) identified interpersonal relationships, cognitive vulnerabilities, and behavioral difficulties as modifiable predictors of depression following childhood maltreatment. Specifically, social support and secure attachments were reported to exert a buffering effect on risk for depression, brooding was suggested to be a cognitive marker of risk, and externalizing behavior was suggested to be a behavioral marker of risk. Other researchers have also reported that social support may be protective and that interventions directed toward enhancing social support may decrease disease vulnerability and improve illness course ( 179 ). Metacognitive beliefs, or beliefs about one’s own cognition, are suggested to mediate the relationship between childhood maltreatment and mood-related and positive symptoms in individuals with psychotic or bipolar disorders ( 180 ). Specifically, beliefs about thoughts being uncontrollable or dangerous mediated the relationship between emotional abuse and depression or anxiety and positive symptom subscale score on the Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale. Affective lability was found to mediate the relationship between childhood maltreatment and several clinical features in bipolar disorder, including suicide attempts, anxiety, and mixed episodes ( 181 ), and social cognition was suggested to moderate the relationship between physical abuse and clinical outcome in an inpatient psychiatric rehabilitation program ( 182 ).

Childhood Maltreatment and Associated Alterations in Neural Structure and Function

Research on neurobiological consequences that may mediate the relationship between childhood maltreatment and risk for, and affect disease course in, mood disorders is clearly integral to addressing the question of whether the consequences of early-life stress are reversible. Although a comprehensive review of neuroimaging findings is beyond the scope of this review, over the past 5 years, review articles summarizing the neurobiological associations with childhood maltreatment have emphasized the long-lasting neurobiological structural and functional changes in the brain following maltreatment ( 21 , 83 , 183 , 184 ). In brief, while null and conflicting findings have been reported, data are converging to suggest that childhood maltreatment is associated with lower gray matter volumes and thickness in the ventral and dorsal prefrontal cortex, including the orbitofrontal and anterior cingulate cortices, hippocampus, insula, and striatum, with more recent studies also suggesting an association with decreased white matter structural integrity within and between these regions ( 185 – 194 ). Smaller hippocampal and prefrontal cortical volumes following childhood maltreatment are consistently reported in unipolar depression and other psychiatric disorders ( 189 , 195 – 199 ), with gene-by-environment interactions suggested ( 200 – 202 ). These studies suggest mechanisms that may cross diagnostic boundaries in conferring risk for psychopathology and genetic variation that may link neurobiology, childhood maltreatment, and vulnerability for detrimental outcomes.

Studies investigating differences in function within, and functional connectivity between, these regions following childhood maltreatment are emerging, with more recent results suggesting that these changes may relate to risk for psychopathology. It was recently reported that decreased prefrontal responses during a verbal working memory task mediated the relationship between childhood maltreatment and trait impulsivity in young adult women ( 203 ). In a study investigating functional responses to emotional faces in 182 adults with a range of anxiety symptoms ( 204 ), the authors found that increased amygdala and decreased dorsolateral prefrontal activity to fearful and angry faces—as well as increased insula activity to fearful and increased ventral but decreased dorsal and anterior cingulate activity to angry faces—mediated the relationship between childhood maltreatment and anxiety symptoms. Differences in functional connectivity, measured with multivariate network-based approaches, within the dorsal attention network and between task-positive networks and sensory systems have been reported in unipolar depression following childhood maltreatment ( 205 ). Altered reward-related functional connectivity between the striatum and the medial prefrontal cortex has also been reported in individuals with greater recent life stress and higher levels of childhood maltreatment, with increased connectivity associated with greater depressive symptom severity ( 206 ). Childhood maltreatment–associated changes in functional connectivity between the amygdala and the dorsolateral and rostral prefrontal cortex have been suggested to contribute to altered stress response and mood in adults ( 207 ). Additionally, childhood maltreatment has been reported to moderate the association between inhibitory control, measured with a Stroop color-word task, and activation in the anterior cingulate cortex while listening to personalized stress cues, an individual’s recounting of his or her own stressful events ( 208 ). As discussed above, it has been hypothesized that childhood maltreatment may increase risk for mood disorders through alterations of the HPA axis and CRF circuits in the brain. Therefore, research aimed at identifying neurobiological changes in function of CRF circuits in the brain that may mediate the relationship between childhood maltreatment and risk for mood disorders and affect disease course, including interactions with recent life stress, is a promising area of investigation.

Recent studies investigating altered function could suggest neurobiological mechanisms of risk but may also suggest possible mechanisms underlying resilience ( 183 ). Functional studies, such as those discussed above, that link functional changes in the brain following childhood maltreatment to mood-related symptoms can provide some clues to help identify mechanisms underlying risk. However, in the absence of longitudinal study of outcomes, these results must still be interpreted with caution. While the majority of studies have been cross-sectional, longitudinal studies are beginning to emerge. Opel et al. ( 209 ) recently reported that reduced insula surface area mediated the association between childhood maltreatment and relapse of depression among 110 patients with unipolar depression followed prospectively. A longitudinal study incorporating structural MRI in 51 adolescents (37% of whom had a history of childhood maltreatment) found that reduced cortical thickness in prefrontal and temporal cortices was associated with psychiatric symptoms at follow-up ( 210 ). Swartz et al. ( 211 ) followed 157 adolescents over a 2-year period and reported results suggesting that early-life stress is associated with amygdala hyperactivity during threat processing, with this finding preceding syndromal mood or anxiety. Longitudinal study of outcomes following childhood maltreatment and underlying neurobiology (predictors and trajectories) is critically needed to identify modifiable targets that confer risk and disentangle mechanisms of risk and resilience.

Only recently have studies investigating childhood maltreatment in bipolar disorder and neurobiological associations begun to emerge. Similar to unipolar depression and other psychiatric disorders, decreased ventral and dorsolateral prefrontal, insula, and hippocampal gray matter volume are reported in individuals with bipolar disorder with a history of childhood maltreatment compared with individuals with bipolar disorder without childhood maltreatment ( 202 , 212 , 213 ). Decreased white matter structural integrity across the whole brain, including lower structural integrity in the corpus callosum and uncinate fasciculus, have been reported in individuals with bipolar disorder who reported having experienced child abuse compared with those who did not and a healthy comparison group ( 214 , 215 ). Interestingly, one study ( 214 ) found that the effects of childhood maltreatment on white matter structural integrity were specific to individuals with bipolar disorder; decreased structural integrity was not observed in healthy comparison individuals with a history of childhood maltreatment compared with healthy individuals without maltreatment. In light of this finding, along with recently published data from other groups ( 216 – 218 ), it is possible that some consequences following childhood maltreatment may be more robust or distinct in some individuals—or that perhaps individuals with a genetic predisposition for mood disorders may be more vulnerable to the detrimental effects of childhood maltreatment.

Altered amygdala and hippocampal volumes are suggested to be differentially modulated following childhood maltreatment in patients with bipolar disorder compared with a healthy comparison group ( 216 ), although interactions with history of treatment (e.g., duration of lithium exposure) cannot be ruled out, as this was not investigated. Souza-Queiroz et al. ( 217 ) found that childhood maltreatment was associated with decreased amygdala volume, decreased ventromedial prefrontal connectivity with the amygdala and hippocampus, and decreased structural integrity in the uncinate fasciculus—the main white matter fiber tract connecting these regions. The bipolar group primarily drove these effects, with only smaller amygdala volume associated with childhood maltreatment in the healthy comparison group. While these findings could be driven by higher rates of maltreatment reported in the bipolar disorder group, or other clinical factors such as medication exposure and history of depressed or manic episodes, they could also suggest interactions between genetic vulnerability to bipolar disorder (or other environmental factors) and neurobiological consequences following childhood maltreatment.

More research is needed to identify genes that may influence neurobiological vulnerability following childhood maltreatment. An example of a potential gene that may mediate this relationship is the serotonin transporter promoter. Genetic variation in the serotonin transporter promoter is associated with differences in structural integrity of white matter in bipolar disorder ( 219 ). Because a large number of studies support the interaction between early-life stress, the serotonin transporter promoter, and disease vulnerability and illness course in depression and bipolar disorder ( 106 – 111 ), this example highlights the potential of genes to contribute to long-lasting structural consequences in the brain following childhood maltreatment in mood disorders. Genetic imaging studies are emerging and suggest gene-by-environment interactions on structural and functional alterations following childhood maltreatment. For example, one study found that hippocampal volume differences following childhood maltreatment are mediated by genetic variation in bipolar disorder ( 202 ). Additionally, polymorphisms in stress system genes, including FKBP5 and NR3C1, are suggested to moderate the effects of childhood maltreatment on amygdala reactivity ( 220 – 222 ) and hippocampal volumes ( 223 ). Studies investigating interactions between familial risk for mood disorders and childhood maltreatment and associated structural and functional changes in the brain would be useful to test whether familial factors (genetic and environmental vulnerability) may interact with childhood maltreatment to alter brain structure and function while avoiding confounders such as medication exposure.

Limitations and Future Directions

A sizable percentage of patients with mood disorders have a history of childhood maltreatment. While the devastating consequences of childhood maltreatment cannot be disavowed, several limitations in research should be noted. Research groups often assess childhood maltreatment differently, and this can result in a measurement bias. Demographic characteristics and differences in assessments (age and sex ratio of participants; clinical versus nonclinical populations being studied; observer-rated versus self-rated depression measures) are all suggested to contribute to differences in prevalence of childhood maltreatment and relation with illness severity ( 12 ). For example, studies using the Childhood Trauma Questionnaire report higher rates of emotional abuse compared with studies using other measures to investigate childhood maltreatment ( 12 ). Further study is warranted investigating the neurobiological mechanisms, underlying genetics, familial factors, and modifiable targets that may drive development of mood disorders following childhood maltreatment. A promising area is network-based approaches to understand this link ( 224 ). Additionally, consequences following different types of maltreatment require further investigation, as different forms of childhood maltreatment may be associated with distinct neural consequences, and a better understanding of these relations is critical for the development of more effective interventions and prevention strategies. For example, Heim et al. ( 225 ) reported that victims of sexual abuse exhibit more alterations in the somatosensory area, whereas victims of emotional abuse exhibit differences in areas mediating emotional processing and self-awareness, including the anterior cingulate and parahippocampal gyrus. More work is needed to investigate whether there are sensitive periods in development when maltreatment has more robust consequences on neurobiology. Humphreys et al. ( 226 ) recently reported that hippocampal volume differences were associated with stress severity during early childhood (≤5 years of age), but there was no association between hippocampal volumes and stress occurring during later childhood. Studies investigating interactions between childhood maltreatment and genetic variation or familial risk for mood disorders could identify mechanisms underlying risk and resiliency in the absence of some study-related confounders (e.g., medication).

Longitudinal studies are critically needed to distinguish what behaviors and mechanisms (genetic and neurobiological) may contribute to risk and whether alterations in behaviors or neurobiology are secondary to mood disorder onset. It is important to emphasize that sex differences likely contribute to outcomes following childhood maltreatment ( 227 ). These include females, compared with males, having a higher risk for internalizing disorders (depression and anxiety) ( 228 , 229 ), greater deficits in neural systems underlying emotional regulation ( 187 , 230 ), and being more susceptible to stress-induced changes in the HPA axis ( 231 ) following maltreatment. Males, compared with females, may be more vulnerable to developing externalizing disorders (conduct disorders and substance use disorders) ( 232 ). However, few studies have investigated sex differences following childhood maltreatment. More research on sex differences is critically needed, including on the underlying neurobiology. As previously reviewed ( 21 ), early-life adversity is associated with increased vulnerability to several major medical disorders, including coronary artery disease and myocardial infarction, cerebrovascular disease and stroke, type 2 diabetes, asthma, and certain forms of cancer. More work is needed on medical morbidities that may increase risk for early mortality following early-life adversity. Additionally, more research is needed on disparities that contribute to, and minority communities that show, elevated rates of early-life adversity. As discussed above, rates of early-life adversity are higher among individuals with developmental disabilities ( 138 – 140 ). Rates of trauma are also higher in youths in the lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and questioning (LGBTQ) community ( 233 ). Few studies have been published in this area. Youths in the LGBTQ community show higher rates of mood disorders, anxiety, suicide, and alcohol and drug use ( 234 ). In a recent study, Rhoades et al. ( 235 ) investigated the relationship between parental rejection, homelessness, and mental health outcomes in LGBTQ youths. Parental rejection was associated with higher rates of homelessness, with experience of homelessness associated with greater feelings of hopelessness, PTSD and depressive symptoms, and greater prevalence of past suicide attempts and more individuals saying they are likely to attempt suicide in the future. More work is critically needed in vulnerable populations, including work focused on interventions that may improve mental health outcomes, for example, interventions that focus on the family unit and interpersonal relationships to foster support and educational interventions, which may decrease peer victimization and cyberbullying ( 236 , 237 ).

In summary, studies converge on and consistently support the finding that childhood maltreatment increases disease vulnerability for mood disorders, as well as a more pernicious disease course. A reduction in the prevalence of childhood maltreatment would have a substantial impact on decreasing disease burden ( 238 ). Studies suggesting modifiable targets are only just beginning to emerge and point to behavioral and environmental factors that could be focused on for early interventions.

Dr. Nemeroff has served as a consultant for Bracket (Clintara), Fortress Biotech, EMA Wellness, Gerson Lehrman Group, Intra-Cellular Therapies, Janssen Research and Development, Magstim, Navitor Pharmaceuticals, Sunovion Pharmaceuticals, Taisho Pharmaceutical, Takeda, TC MSO, and Xhale; he holds stock in AbbVie, Antares, BI Gen Holdings, Celgene, Corcept Therapeutics Pharmaceuticals Company, EMA Wellness, OPKO Health, Seattle Genetics, TC MSO, Trends in Pharma Development, and Xhale; he is a member of the scientific advisory boards of the Anxiety Disorder Association of America (ADAA), the American Foundation for Suicide Prevention (AFSP), Bracket (Clintara), the Brain and Behavior Research Foundation, the Laureate Institute for Brain Research, Skyland Trail, and Xhale and on the boards of directors of ADAA, AFSP, Gratitude America, and Xhale Smart; he has had income sources or equity of $10,000 or more from American Psychiatric Publishing, Bracket (Clintara), CME Outfitters, EMA Wellness, Intra-Cellular Therapies, Magstim, Takeda, TC-MSO, and Xhale; he holds patents on a method and devices for transdermal delivery of lithium (US 6,375,990B1), a method of assessing antidepressant drug therapy via transport inhibition of monoamine neurotransmitter by ex vivo assay (US 7,148,027B2), and compounds, compositions, methods of synthesis, and methods of treatment (CRF receptor binding ligand) (US 8,551,996 B2). Dr. Lippard reports no financial relationships with commercial interests.

Dr. Lippard’s research is supported by NIH grant K01AA027573. Dr. Nemeroff’s research is supported by NIH grants MH117293 and AA-024933.

1 US Department of Health and Human Services, Administration for Children and Families, Administration on Children, Youth and Families, Children’s Bureau: Child Maltreatment 2016. Washington, DC, US Department of Health and Human Services, 2018 ( https://www.acf.hhs.gov/cb/research-data-technology/statistics-research/child-maltreatment) Google Scholar

2 Maniglio R : Child sexual abuse in the etiology of depression: a systematic review of reviews . Depress Anxiety 2010 ; 27 : 631 – 642 Crossref , Medline , Google Scholar

3 Maniglio R : Prevalence of child sexual abuse among adults and youths with bipolar disorder: a systematic review . Clin Psychol Rev 2013 ; 33 : 561 – 573 Crossref , Medline , Google Scholar

4 Lindert J , von Ehrenstein OS , Grashow R , et al. : Sexual and physical abuse in childhood is associated with depression and anxiety over the life course: systematic review and meta-analysis . Int J Public Health 2014 ; 59 : 359 – 372 Crossref , Medline , Google Scholar

5 Scott KM , Smith DR , Ellis PM : Prospectively ascertained child maltreatment and its association with DSM-IV mental disorders in young adults . Arch Gen Psychiatry 2010 ; 67 : 712 – 719 Crossref , Medline , Google Scholar

6 Green JG , McLaughlin KA , Berglund PA , et al. : Childhood adversities and adult psychiatric disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication I: associations with first onset of DSM-IV disorders . Arch Gen Psychiatry 2010 ; 67 : 113 – 123 Crossref , Medline , Google Scholar

7 Widom CS , DuMont K , Czaja SJ : A prospective investigation of major depressive disorder and comorbidity in abused and neglected children grown up . Arch Gen Psychiatry 2007 ; 64 : 49 – 56 Crossref , Medline , Google Scholar

8 Benjet C , Borges G , Medina-Mora ME : Chronic childhood adversity and onset of psychopathology during three life stages: childhood, adolescence, and adulthood . J Psychiatr Res 2010 ; 44 : 732 – 740 Crossref , Medline , Google Scholar

9 Chapman DP , Whitfield CL , Felitti VJ , et al. : Adverse childhood experiences and the risk of depressive disorders in adulthood . J Affect Disord 2004 ; 82 : 217 – 225 Crossref , Medline , Google Scholar

10 Zavaschi ML , Graeff ME , Menegassi MT , et al. : Adult mood disorders and childhood psychological trauma . Br J Psychiatry 2006 ; 28 : 184 – 190 Crossref , Google Scholar

11 Kessler RC : The effects of stressful life events on depression . Annu Rev Psychol 1997 ; 48 : 191 – 214 Crossref , Medline , Google Scholar

12 Nelson J , Klumparendt A , Doebler P , et al. : Childhood maltreatment and characteristics of adult depression: meta-analysis . Br J Psychiatry 2017 ; 210 : 96 – 104 Crossref , Medline , Google Scholar

13 Romero S , Birmaher B , Axelson D , et al. : Prevalence and correlates of physical and sexual abuse in children and adolescents with bipolar disorder . J Affect Disord 2009 ; 112 : 144 – 150 Crossref , Medline , Google Scholar

14 Hyun M , Friedman SD , Dunner DL : Relationship of childhood physical and sexual abuse to adult bipolar disorder . Bipolar Disord 2000 ; 2 : 131 – 135 Crossref , Medline , Google Scholar

15 Post RM , Altshuler L , Leverich G , et al. : More stressors prior to and during the course of bipolar illness in patients from the United States compared with the Netherlands and Germany . Psychiatry Res 2013 ; 210 : 880 – 886 Crossref , Medline , Google Scholar

16 Bernet CZ , Stein MB : Relationship of childhood maltreatment to the onset and course of major depression in adulthood . Depress Anxiety 1999 ; 9 : 169 – 174 Crossref , Medline , Google Scholar

17 Comijs HC , van Exel E , van der Mast RC , et al. : Childhood abuse in late-life depression . J Affect Disord 2013 ; 147 : 241 – 246 Crossref , Medline , Google Scholar

18 Nanni V , Uher R , Danese A : Childhood maltreatment predicts unfavorable course of illness and treatment outcome in depression: a meta-analysis . Am J Psychiatry 2012 ; 169 : 141 – 151 Link , Google Scholar

19 Wiersma JE , Hovens JG , van Oppen P , et al. : The importance of childhood trauma and childhood life events for chronicity of depression in adults . J Clin Psychiatry 2009 ; 70 : 983 – 989 Crossref , Medline , Google Scholar

20 Withers AC , Tarasoff JM , Stewart JW : Is depression with atypical features associated with trauma history? J Clin Psychiatry 2013 ; 74 : 500 – 506 Crossref , Medline , Google Scholar

21 Nemeroff CB : Paradise lost: the neurobiological and clinical consequences of child abuse and neglect . Neuron 2016 ; 89 : 892 – 909 Crossref , Medline , Google Scholar

22 Quilty LC , Marshe V , Lobo DS , et al. : Childhood abuse history in depression predicts better response to antidepressants with higher serotonin transporter affinity: a pilot investigation . Neuropsychobiology 2016 ; 74 : 78 – 83 Crossref , Medline , Google Scholar

23 Scott KM , McLaughlin KA , Smith DA , et al. : Childhood maltreatment and DSM-IV adult mental disorders: comparison of prospective and retrospective findings . Br J Psychiatry 2012 ; 200 : 469 – 475 Crossref , Medline , Google Scholar

24 Fergusson DM , Horwood LJ , Boden JM : Structural equation modeling of repeated retrospective reports of childhood maltreatment . Int J Methods Psychiatr Res 2011 ; 20 : 93 – 104 Crossref , Medline , Google Scholar

25 Baldwin JR , Reuben A , Newbury JB , et al. : Agreement between prospective and retrospective measures of childhood maltreatment: a systematic review and meta-analysis . JAMA Psychiatry ( Epub ahead of print, March 20, 2019 ) Google Scholar

26 Ellis RER , Seal ML , Simmons JG , et al. : Longitudinal trajectories of depression symptoms in adolescence: psychosocial risk factors and outcomes . Child Psychiatry Hum Dev 2017 ; 48 : 554 – 571 Crossref , Medline , Google Scholar

27 Gilman SE , Trinh NH , Smoller JW , et al. : Psychosocial stressors and the prognosis of major depression: a test of axis IV . Psychol Med 2013 ; 43 : 303 – 316 Crossref , Medline , Google Scholar

28 Daruy-Filho L , Brietzke E , Lafer B , et al. : Childhood maltreatment and clinical outcomes of bipolar disorder . Acta Psychiatr Scand 2011 ; 124 : 427 – 434 Crossref , Medline , Google Scholar

29 Anand A , Koller DL , Lawson WB , et al. : Genetic and childhood trauma interaction effect on age of onset in bipolar disorder: an exploratory analysis . J Affect Disord 2015 ; 179 : 1 – 5 Crossref , Medline , Google Scholar

30 Jansen K , Cardoso TA , Fries GR , et al. : Childhood trauma, family history, and their association with mood disorders in early adulthood . Acta Psychiatr Scand 2016 ; 134 : 281 – 286 Crossref , Medline , Google Scholar

31 Gilman SE , Ni MY , Dunn EC , et al. : Contributions of the social environment to first-onset and recurrent mania . Mol Psychiatry 2015 ; 20 : 329 – 336 Crossref , Medline , Google Scholar

32 Noto MN , Noto C , Caribé AC , et al. : Clinical characteristics and influence of childhood trauma on the prodrome of bipolar disorder . Br J Psychiatry 2015 ; 37 : 280 – 288 Crossref , Google Scholar

33 Agnew-Blais J , Danese A : Childhood maltreatment and unfavourable clinical outcomes in bipolar disorder: a systematic review and meta-analysis . Lancet Psychiatry 2016 ; 3 : 342 – 349 Crossref , Medline , Google Scholar

34 Dienes KA , Hammen C , Henry RM , et al. : The stress sensitization hypothesis: understanding the course of bipolar disorder . J Affect Disord 2006 ; 95 : 43 – 49 Crossref , Medline , Google Scholar

35 Leverich GS , McElroy SL , Suppes T , et al. : Early physical and sexual abuse associated with an adverse course of bipolar illness . Biol Psychiatry 2002 ; 51 : 288 – 297 Crossref , Medline , Google Scholar

36 Erten E , Funda Uney A , Saatçioğlu Ö , et al. : Effects of childhood trauma and clinical features on determining quality of life in patients with bipolar I disorder . J Affect Disord 2014 ; 162 : 107 – 113 Crossref , Medline , Google Scholar

37 Carballo JJ , Harkavy-Friedman J , Burke AK , et al. : Family history of suicidal behavior and early traumatic experiences: additive effect on suicidality and course of bipolar illness? J Affect Disord 2008 ; 109 : 57 – 63 Crossref , Medline , Google Scholar

38 Park YM : Relationship between childhood maltreatment, suicidality, and bipolarity: a retrospective study . Psychiatry Investig 2017 ; 14 : 136 – 140 Crossref , Medline , Google Scholar

39 Pavlova B , Perroud N , Cordera P , et al. : Anxiety disorders and childhood maltreatment as predictors of outcome in bipolar disorder . J Affect Disord 2018 ; 225 : 337 – 341 Crossref , Medline , Google Scholar

40 Pavlova B , Perroud N , Cordera P , et al. : Childhood maltreatment and comorbid anxiety in people with bipolar disorder . J Affect Disord 2016 ; 192 : 22 – 27 Crossref , Medline , Google Scholar

41 Cakir S , Tasdelen Durak R , Ozyildirim I , et al. : Childhood trauma and treatment outcome in bipolar disorder . J Trauma Dissociation 2016 ; 17 : 397 – 409 Crossref , Medline , Google Scholar

42 Post RM , Leverich GS , Kupka R , et al. : Clinical correlates of sustained response to individual drugs used in naturalistic treatment of patients with bipolar disorder . Compr Psychiatry 2016 ; 66 : 146 – 156 Crossref , Medline , Google Scholar

43 Short AT , Nemeroff CB : Early life trauma and suicide , in Suicide: Phenomenology and Neurobiology . Edited by Cannon KE , Hudzik TJ . Basel, Springer , 2014 , pp 187– 205 Crossref , Google Scholar

44 Castellví P , Miranda-Mendizábal A , Parés-Badell O , et al. : Exposure to violence, a risk for suicide in youths and young adults: a meta-analysis of longitudinal studies . Acta Psychiatr Scand 2017 ; 135 : 195 – 211 Crossref , Medline , Google Scholar

45 Liu J , Fang Y , Gong J , et al. : Associations between suicidal behavior and childhood abuse and neglect: a meta-analysis . J Affect Disord 2017 ; 220 : 147 – 155 Crossref , Medline , Google Scholar

46 Miller AB , Esposito-Smythers C , Weismoore JT , et al. : The relation between child maltreatment and adolescent suicidal behavior: a systematic review and critical examination of the literature . Clin Child Fam Psychol Rev 2013 ; 16 : 146 – 172 Crossref , Medline , Google Scholar

47 Norman RE , Byambaa M , De R , et al. : The long-term health consequences of child physical abuse, emotional abuse, and neglect: a systematic review and meta-analysis . PLoS Med 2012 ; 9 : e1001349 Crossref , Medline , Google Scholar

48 Dube SR , Anda RF , Felitti VJ , et al. : Childhood abuse, household dysfunction, and the risk of attempted suicide throughout the life span: findings from the Adverse Childhood Experiences Study . JAMA 2001 ; 286 : 3089 – 3096 Crossref , Medline , Google Scholar

49 Gomez SH , Tse J , Wang Y , et al. : Are there sensitive periods when child maltreatment substantially elevates suicide risk? Results from a nationally representative sample of adolescents . Depress Anxiety 2017 ; 34 : 734 – 741 Crossref , Medline , Google Scholar

50 Miller AB , Jenness JL , Oppenheimer CW , et al. : Childhood emotional maltreatment as a robust predictor of suicidal ideation: a 3-year multi-wave, prospective investigation . J Abnorm Child Psychol 2017 ; 45 : 105 – 116 Crossref , Medline , Google Scholar

51 Peyre H , Hoertel N , Stordeur C , et al. : Contributing factors and mental health outcomes of first suicide attempt during childhood and adolescence: results from a nationally representative study . J Clin Psychiatry 2017 ; 78 : e622 – e630 Crossref , Medline , Google Scholar

52 Behr Gomes Jardim G , Novelo M , Spanemberg L , et al. : Influence of childhood abuse and neglect subtypes on late-life suicide risk beyond depression . Child Abuse Negl 2018 ; 80 : 249 – 256 Crossref , Medline , Google Scholar

53 Dunn EC , Nishimi K , Powers A , et al. : Is developmental timing of trauma exposure associated with depressive and post-traumatic stress disorder symptoms in adulthood? J Psychiatr Res 2017 ; 84 : 119 – 127 Crossref , Medline , Google Scholar

54 Teicher MH , Samson JA : Annual research review: enduring neurobiological effects of childhood abuse and neglect . J Child Psychol Psychiatry 2016 ; 57 : 241 – 266 Crossref , Medline , Google Scholar

55 Dunn EC , Nishimi K , Gomez SH , et al. : Developmental timing of trauma exposure and emotion dysregulation in adulthood: are there sensitive periods when trauma is most harmful? J Affect Disord 2018 ; 227 : 869 – 877 Crossref , Medline , Google Scholar

56 Sanchez MM : The impact of early adverse care on HPA axis development: nonhuman primate models . Horm Behav 2006 ; 50 : 623 – 631 Crossref , Medline , Google Scholar

57 Roque S , Mesquita AR , Palha JA , et al. : The behavioral and immunological impact of maternal separation: a matter of timing . Front Behav Neurosci 2014 ; 8 : 192 Crossref , Medline , Google Scholar

58 Goldstein JM , Holsen L , Huang G , et al. : Prenatal stress-immune programming of sex differences in comorbidity of depression and obesity/metabolic syndrome . Dialogues Clin Neurosci 2016 ; 18 : 425 – 436 Crossref , Medline , Google Scholar

59 Heim CM , Entringer S , Buss C : Translating basic research knowledge on the biological embedding of early-life stress into novel approaches for the developmental programming of lifelong health . Psychoneuroendocrinology 2019 ; 105 : 123 – 137 Crossref , Medline , Google Scholar

60 Cowell RA , Cicchetti D , Rogosch FA , et al. : Childhood maltreatment and its effect on neurocognitive functioning: timing and chronicity matter . Dev Psychopathol 2015 ; 27 : 521 – 533 Crossref , Medline , Google Scholar

61 Dunn EC , McLaughlin KA , Slopen N , et al. : Developmental timing of child maltreatment and symptoms of depression and suicidal ideation in young adulthood: results from the National Longitudinal Study of Adolescent Health . Depress Anxiety 2013 ; 30 : 955 – 964 Medline , Google Scholar

62 Schalinski I , Teicher MH , Nischk D , et al. : Type and timing of adverse childhood experiences differentially affect severity of PTSD, dissociative, and depressive symptoms in adult inpatients . BMC Psychiatry 2016 ; 16 : 295 Crossref , Medline , Google Scholar

63 Khan A , McCormack HC , Bolger EA , et al. : Childhood maltreatment, depression, and suicidal ideation: critical importance of parental and peer emotional abuse during developmental sensitive periods in males and females . Front Psychiatry 2015 ; 6 : 42 Crossref , Medline , Google Scholar

64 Copeland WE , Wolke D , Angold A , et al. : Adult psychiatric outcomes of bullying and being bullied by peers in childhood and adolescence . JAMA Psychiatry 2013 ; 70 : 419 – 426 Crossref , Medline , Google Scholar

65 Lereya ST , Copeland WE , Costello EJ , et al. : Adult mental health consequences of peer bullying and maltreatment in childhood: two cohorts in two countries . Lancet Psychiatry 2015 ; 2 : 524 – 531 Crossref , Medline , Google Scholar

66 Campbell-Sills L , Kessler RC , Ursano RJ , et al. : Associations of childhood bullying victimization with lifetime suicidal behaviors among new US Army soldiers . Depress Anxiety 2017 ; 34 : 701 – 710 Crossref , Medline , Google Scholar

67 Jaye Capretto J : Developmental timing of childhood physical and sexual maltreatment predicts adult depression and post-traumatic stress symptoms . J Interpers Violence ( Epub ahead of print, April 1, 2017 ) Google Scholar