PERSPECTIVE article

The psychological and social impact of covid-19: new perspectives of well-being.

A commentary has been posted on this article:

Commentary: The psychological and social impact of COVID-19: New perspectives of well-being

- Read general commentary

- 1 Department of Human Sciences, Society and Health, University of Cassino and Southern Lazio of Cassino, Cassino, Italy

- 2 Independent Researcher, Milan, Italy

- 3 Department of Political and Social Studies, Sociology, University of Salerno, Fisciano, Italy

The recent Covid-19 pandemic has had significant psychological and social effects on the population. Research has highlighted the impact on psychological well-being of the most exposed groups, including children, college students, and health workers, who are more likely to develop post-traumatic stress disorder, anxiety, depression, and other symptoms of distress. The social distance and the security measures have affected the relationship among people and their perception of empathy toward others. From this perspective, telepsychology and technological devices assume important roles to decrease the negative effects of the pandemic. These tools present benefits that could improve psychological treatment of patients online, such as the possibility to meet from home or from the workplace, saving money and time and maintaining the relationship between therapists and patients. The aim of this paper is to show empirical data from recent studies on the effect of the pandemic and reflect on possible interventions based on technological tools.

Introduction

The Covid-19 pandemic led to a prolonged exposure to stress. As a consequence, researchers showed an increased interest in measuring social and community uneasiness in order to psychologically support the population. This increased attention might help in managing the current situation and other possible epidemics and pandemics. The security measures adopted in managing the pandemic had different consequences on individuals, according to the social role invested. Some segments of the population seem to be more exposed to the risk of anxious, depressive, and post-traumatic symptoms because they are more sensitive to stress.

The following article has two focuses of interest: (1) the evaluation of the psychological and social effects of the pandemic on the population, mostly children, college students, and health professionals; and (2) the identification of new perspectives of intervention based on digital devices and in line with the social security measures and mental health promotion. Telepsychology, for instance, is a valid tool, effective in taking charge of the psychological suffering caused by the pandemic and in preventing the chronicity of the disease. The prolonged stress could involve anxiety, depression, and the inability to manage traumatic and negative emotions. Furthermore, the constant fear of contagion affects daily life and leads to social isolation, modifying human relations.

COVID-19 and At-Risk Populations: Psychological and Social Impact of the Quarantine

Studies of pandemics faced over time, such as SARS, Ebola, H1N1, Equine Flu, and the current COVID-19, show that the psychological effects of contagion and quarantine is not limited on the fear of contracting the virus ( Barbisch et al., 2015 ). There are some elements related to the pandemic that affect more the population, such as separation from loved ones, loss of freedom, uncertainty about the advancement of the disease, and the feeling of helplessness ( Li and Wang, 2020 ; Cao et al., 2020 ). These aspects might lead to dramatic consequences ( Weir, 2020 ), such as the rise of suicides ( Kawohl and Nordt, 2020 ). Suicidal behaviors are often related to the feeling of anger associated with the stressful condition widely spread among people who lived/live in the most affected areas ( Miles, 2014 ; Suicide Awareness Voices of Education, 2020 ; Mamun and Griffiths, 2020 ). In light of these consequences, a carefully evaluation of the potential benefits of the quarantine is needed, taking into account the high psychological costs ( Day et al., 2006 ; Mazza et al., 2020 ).

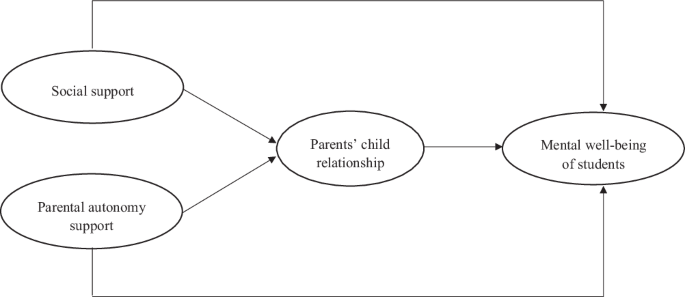

As reported in a recent survey administered during the Covid-19 pandemic, children and young adults are particularly at risk of developing anxious symptoms ( Orgilés et al., 2020 ). The research involved a sample of 1,143 parents of Italian and Spanish children (range 3–18). In general, parents observed emotional and behavioral changes in their children during the quarantine: symptoms related to difficulty concentrating (76.6%), boredom (52%), irritability (39%), restlessness (38.8%), nervousness (38%), sense of loneliness (31.3%), uneasiness (30.4%), and worries (30.1%). From the comparison between the two groups—Spanish and Italian parents—it emerged that the Italian parents reported more symptoms in their children than the Spanish parents. Further data collected on a sample of college students at the time of the spread of the epidemic in China showed how anxiety levels in young adults are mediated by certain protective factors, such as living in urban areas, the economic stability of the family, and cohabitation with parents ( Cao et al., 2020 ). On the contrary, having infected relatives or acquaintances leads to a worsening in anxiety symptoms. Furthermore, the economic problems and the slowdown in academic activities are related with anxious symptoms ( Alvarez et al., 2020 ). In addition, an online survey conducted on the general population in China found that college students are more likely to experiencing stress, anxiety, and depression than others during the pandemic ( Li et al., 2020 ). These results suggest monitoring and promoting mental health of youths in order to reduce the negative impact of the quarantine ( CSTS, 2020 ; Fessell and Goleman, 2020 ; Li et al., 2020 ).

Health-care workers (HCWs) are another segment of population particularly affected by stress ( Garcia-Castrillo et al., 2020 ; Lai et al., 2020 ). HCWs are at risk to develop symptoms common in catastrophic situations, such as post-traumatic stress disorder, burnout syndrome, physical and emotional exhaustion, depersonalization, and dissociation ( Grassi and Magnani, 2000 ; Mache et al., 2012 ; Øyane et al., 2013 ). However, an epidemic presents different peculiarities compared to a catastrophic event, for instance, the stigmatizing attitudes in particular toward health professionals, who are in daily contact with the risk of infection ( Brooks et al., 2020 ). During SARS, up to 50% of health-care professionals suffered from acute psychological stress, exhaustion, and post-traumatic stress, caused by the fear of contagion of their family members and the prolonged social isolation ( Tam et al., 2004 ; Maunder et al., 2006 ).

As a consequence of the pandemic, the health professionals who were overworked suffered high level of psychophysical stress ( Mohindra et al., 2020 ). Health professionals also lived/live in daily life a traumatic condition called secondary traumatic stress disorder ( Zaffina et al., 2014 ), which describes the feeling of discomfort experienced in the helping relationship when treatments are not available for all patients and the professional must select who can access them and who cannot ( Roden-Foreman et al., 2017 ; Rana et al., 2020 ). Data from a survey on 1,257 HCWs who assisted patients in Covid-19 wards and in second- and third-line wards showed high percentages of depression (50%), anxiety (44.6%), insomnia (34%), and distress (71.5%) ( Lai et al., 2020 ). Also, the constant fear of contagion leads to obsessive thoughts ( Brooks et al., 2020 ), increasing the progressive closure of the person and reducing social relationships. In line with these results, Rossi et al. (2020) evaluated mental health outcomes among HCWs in Italy during the pandemic, confirming a high score of mental health issues, particularly among young women and front-line workers. Furthermore, Spoorthy et al. (2020) conducted a review on the gendered impact of Covid-19 and found that 68.7–85.5% of medical staff is composed of women, and the mean age ranged between 26 and 40 years. Also, women are more likely to be affect by anxiety, depression, and distress ( Lai et al., 2020 ; Zanardo et al., 2020 ). Liang et al. (2020) also found a relation between age and depressive symptoms associated with the pandemic. Indeed, the medical staff at younger ages (<30 years) reports higher self-rated depression scores and more concern about infecting their families than those of older age. Staff > 50 years of age reported increased stress due to patient’s death, the prolonged work hours, and the lack of personal protective equipment. Cai et al. (2020) also found that nurses felt more nervous compared to doctors.

As emerged by the recent literature, the promotion of psychological interventions on the specific population who is more likely to develop pathologies and suffering is needed. The Lancet Global Mental Health Commission’s observation ( Patel, 2018 ) reported that the use of digital technologies can provide mental health interventions in order to reduce anxiety and stress levels and increase self-efficacy ( Kang et al., 2020 ; Xiao et al., 2020 ).

Telepsychology: Training and Promotion of Psychological Well-Being

In order to reduce anxiety and depression symptoms widespread among the population, the World Health Organization (2019) and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (2020) proposed specific guidelines on the correct use of health protection with the aim to minimize the distress associated with health-care professions.

At the same time, as a consequence of the emerging issues, psychotherapists provided psychological support online, addressing the technological challenge ( Greenberg et al., 2020 ); Liu et al., 2020 ). In line with the technological progress, professional organizations promoted specific guidelines and policies related to customer protection, privacy, screening, evaluation, and development of self-help products ( Duan and Zhu, 2020 ; Zhou et al., 2020 ). Technological development in mental health foreshadows future trends that include “smart” mobile devices, cloud computing, virtual worlds, virtual reality, and electronic games in addition to the traditional psychotherapy tools. In this perspective, it is important to help future generations of psychologists and patients to collaborate in the potential growth areas, through education and training on the benefits and effectiveness of telepsychology ( Maheu et al., 2012 ).

Indeed, more awareness of the potentials of the online services is needed, exploring the main differences between the devices (chat, video-audio consultation, etc.) in order to use them in relation to the specific purposes identified by the professional. For example, the Italian Service of Online Psychology conducted a study based on a service of helpdesk on Facebook. This service guided people in asking for psychological help, working on their personal motivation. At the same time, another helpdesk on Skype provided some psychological sessions via webcam ( Gabri et al., 2015 ). In this line, telecounseling is a diffuse online method used by counselors and psychologists during the recent pandemic ( De Luca and Calabrò, 2020 ).

One of the future goals of public and private psychological organizations should be the promotion of specific training for psychologists and psychotherapists, with the following aims: (1) developing the basic skills in managing the effects of a pandemic and of emergency situations; and (2) sensitizing patients to online therapeutic relationship, providing the main rules and benefits of the process ( Stoll et al., 2020 ; Joint Task Force for the Development of Telepsychology Guidelines for Psychologists, 2013 ). On this line, a significant example is the Virginia Commonwealth University (VCU) which proposed PhDs in telepsychology, with the aim of training future psychologists in managing the psychological effects of the pandemic through an online psychology service ( Baylor et al., 2019 ). The service provided by the VCU had been effective in reducing anxiety, depression ( Sadock et al., 2017 ), and hospital recoveries ( Lanoye et al., 2017 ). As shown, telepsychology assumes a key role in the improvement of health care. Online psychological services avoid geographical barriers and are suitable to become a useful integrated tool in addition to traditional psychotherapy ( APS, 2020 ; Perrin et al., 2020 ).

Advantages of Psychological Support and Online Psychotherapy

Online psychological services provide several advantages, especially in the current situation of pandemic. First of all, online services help people in a short period of time, reducing the risk of contagion and the strong feeling of anxiety in both psychotherapists and patients, who feel uncomfortable in doing traditional psychotherapy due to the pandemic ( Békés and Aafjes-van Doorn, 2020 ). Furthermore, Pietrabissa et al. (2015) identified some of the main advantages of telepsychology, such as the decrease in waiting for the consultation, because it takes place from home or from the workplace, saving time and expense, less travel and rental costs for the office, for those who provide the service and for those who use it. As reported by the authors, online psychological services facilitate access to people who struggle to find support close to their social environment, avoiding difficulties related to mobility. Also, online services help people who have less confidence in psychotherapy. Indeed, mostly online psychotherapy takes place in one’s comfort zone, facilitating the expression of problems and feelings.

According to the situations, online services could provide a different medium. For instance, the chat is a useful tool to establish a first assessment of a person who feels uncomfortable in using video. Indeed, the online psychotherapy is perceived as more “acceptable.” Suler (2004) defined the term online disinhibition effect demonstrating how the web, unlike the real life, leads to the failure of the hierarchical relationship based on dominant-dominated among individuals; this aspect, according to the author, allows a greater sense of freedom in expressing oneself and less concern related to judgment ( ibid .). Other researchers ( Mantovani, 1995 ; Tosoni, 2004 ) have integrated to the construct of online disinhibition effect the concept of social space, emphasizing the role of the “situation,” of the “social norms” ( Brivio et al., 2010 , p. 811), of the tools (“artifacts”), and of the cyberplace, which allow different levels of interaction. Each person has a different experience of the network and several levels of disinhibition. For instance, a mild disinhibition could be a person who chooses to ask for help talking with a psychologist about their problems; while a high disinhibition could be represented by flaming, an expression of online bullying or cyberstalking.

Online psychological services should be integrated with the various territorial services in order to provide the patients local references in relation to the specific health and economic needs. Finally, the possibility for the therapist and for the patient to record the sessions via chat and in audio/video mode—with the informed consent of the participants ( Wells et al., 2015 )—provides another useful tool to compare the sessions and to underline the positive outcomes and the effectiveness of the therapeutic process. According to this perspective, online psychological support and psychotherapy become a resource for psychotherapists and patients in a co-build relationship ( Algeri et al., 2019 ).

Psychological and Social Suffering and the Empathic Process

In analyzing the psychological impact of the quarantine, the importance for individuals to feel integral part of the society emerged, an aspect often undervalued in psychological well-being. Experts of public health believe that social distancing is the better solution to prevent the spread of the virus. However, although it is not possible to predict the duration of the pandemic, we know very well the serious impact of these measures on the society, on relationships and interactions, in particular on the empathic process. In the early 90s, empathy was described as a form of identification in the psychological and physiological states of others. This definition led to a debate between the disciplines of philosophy of psychology and philosophy of the mind ( Franks, 2010 ). Willard Van Orman Quine (1908–2000) renewed attention to the debate on empathy with a thesis on the development of language and mind in the analytical philosophy. According to Quine, the attribution of the so-called intentional states, through which the psychology commonly explains human behavior, is based on empathy ( Treccani, 2020 ) and leads people to attribute beliefs, desires, and perceptions ( Quine, 1990 , 1992 , Pursuit of Truth: Revised Edition, 1992). Analyzing this aspect within the recent situation of the pandemic, an increment of antithetical positions and attitudes could be noticed. On the one hand, people identify themselves with those who suffer (neighbors, friends, relatives who are living stressful events), promoting activities such as the so-called “suspended expenses.” For instance, solidarity and humanitarian activities, food, and medicine delivery for people who are unable to go to the supermarket. On the other hand, there is a part of the population who experiences a feeling of “forced empathy.” This aspect could be also emphasized by the use of technological devices that might lead to a depersonalization of relationships, forcing the sense of closeness, at least virtually. The hyperconnection of feelings becomes a way to reduce the self-isolation and its consequences, representing the contrary of the idea of Durkheim (1858–1917), who considered society as a specific entity, built on social facts ( Durkheim, 1922 ). The sensation “to be forced to feel” could lead people to distance themselves from others after the emergency situation, incrementing social phobias.

Also, human communication is changing. The formal question “how are you?” at the beginning of a conversation is no longer just a formality, as before the pandemic. For example, the relationship between employee and the manager is different, leading to more responsibilities in listening and understanding feelings expressed during the video call, generating a forced reciprocity. Hence, the aforementioned “forced empathy” may be common in this period because the social distance and the emergency situation make people want to be heard and appreciated, and the simple question “how are you?” becomes an anchor to express fears and emotions ( Pasetti, 2020 ).

The Covid-19 pandemic has affected the way people live interpersonal relationships. The lockdown was characterized of a different organization of daily life, with an incrementation of time at home and a reduction of distance through digital devices. This period was also seen as an evolution in the concept of empathy, producing new perspectives in the study of the phenomenon according to a sociological and neurological points of view. Indeed, empathy—defined as the ability to understand and share the feelings of another—involves several elements, such as: (a) social context and historical period of the individual, (b) neurological mechanisms, and (c) psychological and behavioral responses to feelings of others. The neuro-sociological perspective analyzes the mechanisms involved in the empathic process, focusing on human communication and interpersonal relationships ( Singer and Lamm, 2009 ; Decety and Ickes, 2009 ). Specifically, in this historical period characterized by an increment in the man–machine relationship, neurosociology could become one of the principal sciences for the study of human relations and technology. “We live increasingly in a human–machine world. Anyone who doesn’t understand this, and who is not struggling to adapt to the new environment—whether they like that environment or not—is already being left behind. Adapting to the new, fast-changing, technologically enhanced context is one of the major challenges of our times. And that certainly goes for education” ( Prensky, 2012 , p. 64).

According to the abovementioned considerations, our suggestion consists in:

Primary prevention. Studying the impact of the pandemic toward an at-risk population to reduce symptoms related to stress and providing specific online psychological counseling based on the target (students, medical staff, parents, and teachers).

Secondary prevention. Overcoming the limitations of the human interaction based on digital devices: (1) developing new spaces of inter- and intrasocial communication and new tools of support and psychological treatment, reproducing the multisensory experienced during the face-to-face interaction (Virtual Reality, holograms, serious game etc.); (2) training the next generation of psychotherapists in managing online devices and in implementing their adaptive and personal skills; and (3) sensitizing the general population on telepsychology and its advantages.

Research according to the neurosociological perspective . Studying human interaction mediated by new technologies and the role of empathy, associating neuroscience, sociology, and psychology.

Author Contributions

VS, DA, and VA conceptualized the contribution. VS wrote the paper, reviewed the manuscript, and provided the critical revision processes as PI. All authors approved the submission of the manuscript.

This work did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Algeri, D., Gabri, S., and Mazzucchelli, L. (2019). Consulenza psicologica online. Esperienze pratiche, linee guida e ambiti di intervento. Firenze: Giunti Editore.

Google Scholar

Alvarez, F., Argente, D., and Lippi, F. (2020). A simple planning problem for Covid-19 lockdown. Covid Econ. 14, 1–33. doi: 10.3386/w26981

CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

APS (2020). Psychologists welcome health fund telehealth support of Australians’ mental health during COVID-19 outbreak. Australia: Tratto da Australian Psuchology Society.

Barbisch, D., Koenig, K., and Shih, F. (2015). Is there a case for quarantine? Perspectives from SARS to Ebola . Dis. Med. Pub. Health Prepar. 9, 547–553. doi: 10.1017/dmp.2015.38

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Baylor, C., Burns, M., McDonough, K., Mach, H., and Yorkstona, K. (2019). Teaching Medical Students Skills for Effective Communication With Patients Who Have Communication Disorders. Am. J. Spe. Lang. Pathol. 28, 155–164. doi: 10.1044/2018_ajslp-18-0130

Békés, V., and Aafjes-van Doorn, K. (2020). Psychotherapists’ attitudes toward online therapy during the COVID-19 pandemic. J. Psychother. Integr. 30, 238–247. doi: 10.1037/int0000214

Brivio, E., Ibarra, F., Galimberti, C., and Cilento. (2010). “An Integrated Approach to Interactions in Cyberplaces: The Presentation of Self in Blogs,” in Handbook of Research on Discourse Behavior and Digital Communication: Language Structures and Social Interaction , eds E. Brivio, F. Ibarra, and C. Galimberti (Pennsylvania: Information Science Reference/IGI Global), 810–829. doi: 10.4018/978-1-61520-773-2.ch052

Brooks, S., Webster, R. S., Woodland, L., Wessely, S., Greenberg, N., et al. (2020). The psychological impact of quarantine and how to reduce it: rapid review of the evidence. Lancet 395:10227. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30460-8

Cai, H., Tu, B., Ma, J., Chen, L., Fu, L., Jiang, Y., et al. (2020). Psychological impact and coping strategies of frontline medical staff in Hunan between January and March 2020 during the outbreak of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID19) in Hubei. China. Med. Sci. Monit. 2020:26. doi: 10.12659/MSM.924171

Cao, W., Fang, Z., Hou, G., Han, M., Xu, X., Dong, J., et al. (2020). The psychological impact of the COVID-19 epidemic on college students in China. Psych. Res. 287:112934. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2020.112934

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (2020). Preparedness Tools for Healthcare Professionals and Facilities Responding to Coronavirus (COVID-19) . Available online at: https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/hcp/preparedness-checklists.html

CSTS (2020). Immediate Psychological Responses and Associated Factors during the Initial Stage of the 2019 Coronavirus Disease (COVID-19) Epidemic among the General Population in China. Int. J. Environ. Res. Pub Health 17:1729. doi: 10.3390/ijerph17051729

Day, T., Park, A., Madras, N., Gumel, A., and Wu, J. (2006). When Is Quarantine a Useful Control Strategy for Emerging Infectious Diseases? Am. J. Epidemiol. 163, 479–485. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwj056

De Luca, R., and Calabrò, R. S. (2020). How the COVID-19 Pandemic is Changing Mental Health Disease Management: The Growing Need of Telecounseling in Italy. Innov. Clin. Neurosci. 17, 16–17.

Decety, J., and Ickes, W. (eds) (2009). The Social Neuroscience of Empathy. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Duan, L., and Zhu, G. (2020). Psychological interventions for people affected by the COVID-19 epidemic. Lancet. Psych. 7, 300–302. doi: 10.1016/s2215-0366(20)30073-0

Durkheim, E. (1922). Education et Sociologie. Milano: Ledizioni.

Fessell, D., and Goleman, D. (2020). How Healthcare Personnel Can Take Care of Themselves. US: HBR.

Franks, D. (2010). Neurosociology the nexus between neuroscience and social psychology. Londra. Springer.

Gabri, S., Mazzucchelli, S., and Algeri, D. (2015). The request for psychological help in the digital age: offering counseling through chat and video counseling. E J. Psychother. 2015, 2–10.

Garcia-Castrillo, L., Petrino, R., and Leach, R. (2020). European Society For Emergency Medicine position paper on emergency medical systems’ response to COVID-19. Eur. J. Emerg. Med. 27, 174–1777. doi: 10.1097/mej.0000000000000701

Grassi, L., and Magnani, K. (2000). Psychiatric Morbidity and Burnout in the Medical Profession: An Italian Study of General Practitioners and Hospital Physicians. Psychother. Psychosom. 69, 329–334. doi: 10.1159/000012416

Greenberg, N., Docherty, M., Gnanapragasam, S., and Wessely, S. (2020). Managing mental health challenges faced by healthcare workers during covid-19 pandemic. BMJ 368:m1211. doi: 10.1136/bmj.m1211

Joint Task Force for the Development of Telepsychology Guidelines for Psychologists (2013). Guidelines for the practice of telepsychology. Am. Psychol. 68, 791–800. doi: 10.1037/a0035001

Kang, L., Ma, S., and Chen, M. (2020). Impact on mental health and perceptions of psychological care among medical and nursing staff in Wuhan during the 2019 novel coronavirus disease outbreak: A cross-sectional study. Brain Behav. Immun. 87, 11–17. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2020.03.028

Kawohl, W., and Nordt, C. (2020). COVID-19, unemployment, and suicide. Lancet Psych. 7, 389–390. doi: 10.1016/s2215-0366(20)30141-3

Lai, J., Ma, S., Wang, Y., Cai, Z., Hu, J., Wei, N., et al. (2020). Factors Associated With Mental Health Outcomes Among Health Care Workers Exposed to Coronavirus Disease 2019. JAMA Network Open 3:e203976. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.3976

Lanoye, A., Stewart, K., Rybarczyk, B., Auerbach, S., Sadock, E., Aggarwal, A., et al. (2017). The impact of integrated psychological services in a safety net primary care clinic on medical utilization. J. Clin. Psychol. 73, 681–692. doi: 10.1002/jclp.22367

Li, L. Z., and Wang, S. (2020). Prevalence and predictors of general psychiatric disorders and loneliness during COVID-19 in the United Kingdom. Psych. Res. 291, 0165–1781. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2020.113267

Li, S., Wang, Y., Yang, Y., Lei, X., and Yang, Y. (2020). Analysis of influencing factors of anxiety and emotional disorders in children and adolescents during home isolation during the epidemic of novel coronavirus pneumonia. Chin. J. Child Heal 2020, 1–9.

Liang, Y., Chen, M., Zheng, X., and Liu, J. (2020). Screening for Chinese medical staff mental health by SDS and SAS during the outbreak of COVID-19. J. Psychosom. Res. 133, 1101–1102. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2020.110102

Liu, S., Yang, L., Zhang, C., Xiang, Y. T., Liu, Z., Hu, S., et al. (2020). Online mental health services in China during the COVID-19 outbreak. Lancet. Psych. 7, E17–E18. doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(20)30077-8

Mache, S., Vitzthum, K., and Klapp, B. (2012). Stress, health and satisfaction of Australian and German doctors-a comparative study. World Hosp Health 48, 21–27.

Maheu, M. P., McMenamin, J., and Posen, L. (2012). Future of telepsychology, telehealth, and various technologies in psychological research and practice. Profess. Psychol. Res. Prac. 43, 613–621. doi: 10.1037/a0029458

Mamun, M. A., and Griffiths, M. D. (2020). First COVID-19 suicide case in Bangladesh due to fear of COVID-19 and xenophobia: Possible suicide prevention strategies. Asian J. Psych. 51:102073. doi: 10.1016/j.ajp.2020.102073

Mantovani, G. (1995). Comunicazione e Identità: dalle situazioni quotidiane agli ambienti virtuali. Bologna: il Mulino.

Maunder, R. G., Lancee, W. J., Balderson, K. E., Bennett, J. P., and Borgundvaag, B. (2006). Long-term psychological and occupational effects of providing hospital healthcare during SARS outbreak. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 12, 1924–1932. doi: 10.3201/eid1212.060584

Mazza, C., Ricci, E., Biondi, S., Colasanti, M., Ferracuti, S., Napoli, C., et al. (2020). Nationwide Survey of Psychological Distress among Italian People during the COVID-19 Pandemic: Immediate Psychological Responses and Associated Factors. Int. J. Environ. Res. Publ. Health 17:3165. doi: 10.3390/ijerph17093165

Miles, S. (2014). Kaci Hickox: Public Health and the Politics of Fear. Tratto da Bioethics . Available online at: http://www.bioethics.net/2014/11/kaci-hickox-public-health-and-the-politics-of-fear/ (accessed June 2, 2020).

Mohindra, R. R. R., Suri, V., Bhalla, A., and Singh, S. M. (2020). Issues relevant to mental health promotion in frontline health care providers managing quarantined/isolated COVID19 patients. Asian J. Psych. 51:102084. doi: 10.1016/j.ajp.2020.102084

Orgilés, M., Morales, A., Delvecchio, E., Mazzeschi, C., and Espada, J. (2020). Immediate psychological effects of the COVID-19 quarantine in youth from Italy and Spain. PsyArXiv 2020, 1–13. doi: 10.1017/s0033291720001841

Øyane, N. P. S., Elisabeth, M., Torbjörn, A., and Bjørn, B. (2013). Associations between night work and anxiety, depression, insomnia, sleepiness and fatigue in a sample of Norwegian nurses. PLoS One 2013:e70228. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0070228

Pasetti, J. (2020). Smart-working, costretti all’empatia da convenevoli forzati. Tratto da Sole24Ore . Available online at: https://alleyoop.ilsole24ore.com/2020/03/20/covid-19-empatia/?refresh_ce=1 (accessed June 3, 2020).

Patel, V. (2018). The Lancet Commission on global mental health and sustainable development. Lancet 392, 1553–1598. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(18)31612-X

Perrin, P., Rybarczyk, B., Pierce, B., Jones, H., Shaffer, C., and Islam, L. (2020). Rapid telepsychology deployment during the COVID-19 pandemic: A special issue commentary and lessons from primary care psychology training. Clin. Psychol. 76, 1173–1185. doi: 10.1002/jclp.22969

Pietrabissa, G., Manzoni, A., Algeri, D., Mazzucchelli, L., Carella, A., Pagnini, F., et al. (2015). Facebook Use as Access Facilitator for Consulting Psychology. Austr. Psychol. 50, 299–303. doi: 10.1111/ap.12139

Prensky, M. (2012). What ISN’T Technology Good At? Empathy for One Thing!. Educat. Technol. 52:64.

Quine, W. (1990). Pursuit of Truth. New York: Harvard University Press.

Quine, W. (1992). Pursuit of Truth: Revised Edition. New York: Harvard University Press.

Rana, W., Mukhtar, S., and Mukhtar, S. (2020). Mental health of medical workers in Pakistan during the pandemic COVID-19 outbreak. Asian J. Psych. 51:102080. doi: 10.1016/j.ajp.2020.102080

Roden-Foreman, K., Solis, J., Jones, A., Bennett, M., Roden-Foreman, J., Rainey, E., et al. (2017). Prospective Evaluation of Posttraumatic Stress Disorder and Depression in Orthopaedic Injury Patients With and Without Concomitant Traumatic Brain Injury. J. Orthop. Trauma 31, e275–e280. doi: 10.1097/BOT.0000000000000884

Rossi, R., Socci, V., and Pacitti, F. (2020). Mental Health Outcomes Among Frontline and Second-Line Health Care Workers During the Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) Pandemic in Italy. JAMA Netw Open. 3:e2010185. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.10185

Sadock, E., Perrin, P., Grinnell, R., Rybarczyk, B., and Auerbach, S. (2017). Initial and follow-up evaluations of integrated psychological services for anxiety and depression in a safety net primary care clinic. Am. Psycol. Assoc. 73, 1462–1481. doi: 10.1002/jclp.22459

Singer, T., and Lamm, C. (2009). The Social Neuroscience of Empathy. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 2009, 81–96. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2009.04418.x

Spoorthy, M. S., Pratapa, S. K., and Mahant, S. (2020). Mental health problems faced by healthcare workers due to the COVID-19 pandemic–A review. Asian J. Psych. 51:1876. doi: 10.1016/j.ajp.2020.102119

Stoll, J., Müller, J., and Trachsel, M. (2020). Ethical Issues in Online Psychotherapy: A Narrative Review. Front. Psych. 10:993. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2019.00993

Suicide Awareness Voices of Education (2020). Preventing Suicide During and After the COVID-19 Pandemic . Available online at: https://save.org/blog/preventing-suicide-covid-19-pandemic (accessed June 5, 2020).

Suler, J. (2004). The Online Disinhibition Effect. Cyb. Psychol. Behav. 7, 321–326. doi: 10.1089/1094931041291295

Tam, C., Pang, E., Lam, L., and Chiu, H. (2004). Severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) in Hong Kong in 2003: stress and psychological impact among frontline healthcare workers. Psychol. Med. 34, 1197–1204. doi: 10.1017/s0033291704002247

Tosoni, S. (2004). Identità virtuali: comunicazione mediata da computer e processi di costruzione dell’identità personale. Milano: FrancoAngeli.

Treccani (2020). Einfuhlung. Tratto da Treccani . Available online at: http://www.treccani.it/enciclopedia/einfuhlung/ (accessed June 10, 2020).

Weir, K. (2020). Grief and COVID-19: Mourning our bygonelives. Washington: American Psychological Association.

Wells, S. W., Moreno, L., Butler, E., and Glassman, L. (2015). “The informed consent process for therapeutic communication in clinical videoconferencing,” in Clinical videoconferencing in telehealth: Program development and practice , eds P. W. Tuerk and P. Shore (Berlin: Springer Inernational Publishing), 133–166. doi: 10.1007/978-3-319-08765-8_7

World Health Organization (2019). Emergency Global Supply Chain System (COVID-19) Catalogue . Available online at: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/emergency-global-supply-chain-system-(covid-19)-catalogue (accessed June 10, 2020).

Xiao, H., Zhang, Y., Kong, D., Li, S., and Yang, N. (2020). The effects of social support on sleep quality of medical staff treating patients with coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) in January and February 2020 in China. Med. Sci. Monit. 26:e923549. doi: 10.12659/MSM.923549

Zaffina, S., Camisa, V., Monducci, E., Vinci, M., Vicari, S., and Bergamaschi, A. (2014). Disturbo post traumatico da stress in operatori sanitari coinvolti in un incidente rilevante avvenuto in ambito ospedaliero. La Med. Del Lav. 105:2014.

Zanardo, V., Manghina, V., Giliberti, L., Vettore, M., Severino, L., and Straface, G. (2020). Psychological impact of COVID-19 quarantine measures in northeastern Italy on mothers in the immediate postpartum period. Gynechol. Obst. 150, 184–188. doi: 10.1002/ijgo.13249

Zhou, X., Snoswell, C. L., and Harding, L. E. (2020). The Role of Telehealth in Reducing the Mental Health Burden from COVID-19. Telemed. E Health. 26, 377–379. doi: 10.1089/tmj.2020.0068

Keywords : COVID-19, empathy, psychological disease, psychotherapy, social distancing, telepsychology

Citation: Saladino V, Algeri D and Auriemma V (2020) The Psychological and Social Impact of Covid-19: New Perspectives of Well-Being. Front. Psychol. 11:577684. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2020.577684

Received: 29 June 2020; Accepted: 03 September 2020; Published: 02 October 2020.

Reviewed by:

Copyright © 2020 Saladino, Algeri and Auriemma. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY) . The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Valeria Saladino, [email protected] ; [email protected]

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

The psychological impact of COVID-19 on the mental health in the general population

Affiliations.

- 1 Department of Neuroscience, Rehabilitation, Ophthalmology, Genetics, Maternal and Child Health, Section of Psychiatry, University of Genoa, Genoa, Italy.

- 2 IRCCS Ospedale Policlinico San Martino, Genoa, Italy.

- 3 James J. Peters Veterans' Administration Medical Center, Bronx, NY, USA.

- 4 Department of Psychiatry, Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, New York, NY, USA.

- PMID: 32569360

- PMCID: PMC7337855

- DOI: 10.1093/qjmed/hcaa201

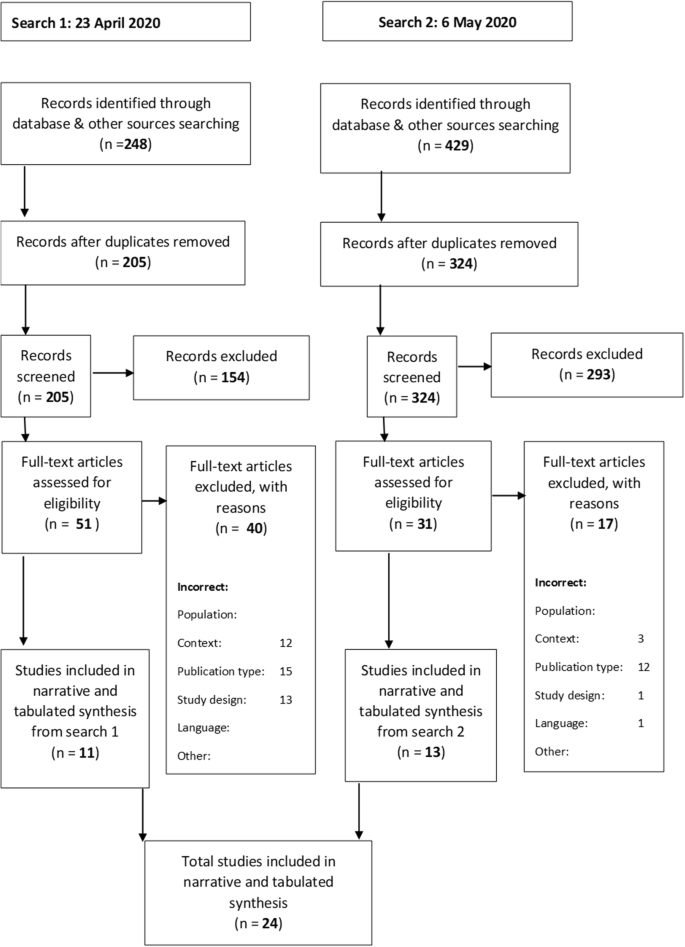

As a result of the emergence of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) outbreak caused by acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) infection in the Chinese city of Wuhan, a situation of socio-economic crisis and profound psychological distress rapidly occurred worldwide. Various psychological problems and important consequences in terms of mental health including stress, anxiety, depression, frustration, uncertainty during COVID-19 outbreak emerged progressively. This work aimed to comprehensively review the current literature about the impact of COVID-19 infection on the mental health in the general population. The psychological impact of quarantine related to COVID-19 infection has been additionally documented together with the most relevant psychological reactions in the general population related to COVID-19 outbreak. The role of risk and protective factors against the potential to develop psychiatric disorders in vulnerable individuals has been addressed as well. The main implications of the present findings have been discussed.

Keywords: COVID-19 infection; mental health; preventive strategies; psychological distress.

© The Author(s) 2020. Published by Oxford University Press on behalf of the Association of Physicians. All rights reserved. For Permissions, please email: [email protected].

- Open access

- Published: 05 December 2022

“…It just broke me…”: exploring the psychological impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on academics

- Lynette Thompson ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-4472-0048 1 &

- Cindy Christian 1

BMC Psychology volume 10 , Article number: 289 ( 2022 ) Cite this article

4 Citations

2 Altmetric

Metrics details

The declaration of COVID-19 as a global pandemic by the World Health Organisation (WHO) in 2020 catapulted institutions of higher education into an emergency transition from face-to-face to online teaching. Given the nature of the COVID-19 pandemic and the continuing after-effects thereof, the study explored the psychological impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on academics.

A qualitative phenomenological research design was used to explore the psychological impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on academics. Data were collected by means of semi-structured interviews from a sample of 11 full-time academics permanently employed at six public and private higher education institutions in South Africa in 2020 and 2021. The data were analysed by means of thematic analysis.

The study found that the COVID-19 pandemic and lockdown restrictions had a largely negative psychological impact on academics in higher education. The most dominant negative emotions reported by participants included stress, anxiety, fear and guilt either due to the threat of the virus itself, potential for loss of life, lockdown restrictions, a new working environment, and/or their perceived inability to assist their students. Participants also reported feelings of emotional isolation and an increase in levels of emotional fatigue.

In conclusion, institutions of higher education need to be aware of the negative psychological impact of COVID-19 on academics, and ensure they create and foster environments that promote mental well-being. Institutions may offer psychological services and/or emotional well-being initiatives to their academic staff. They must create spaces and cultures where academics feel comfortable to request and seek well-being opportunities. In addition to mental and emotional well-being initiatives, institutions must provide academics with tangible teaching and learning support as this would go a long way in reducing much of the stress experienced by academics during the pandemic.

Peer Review reports

In March 2020, the World Health Organisation (WHO) declared COVID-19 a global pandemic [ 1 ]. In response to this declaration, the South African government announced a state of emergency and implemented lockdown measures for most citizens. Institutions of higher education were catapulted into an emergency transition from face-to-face contact teaching to online distance teaching. This change was implemented globally [ 2 ]. The lockdown, which meant working from home, and switching to online teaching, left many academics reeling as they tried to navigate their new working environment [ 3 ]. Given the nature of the COVID-19 pandemic and the continuing after-effects thereof, it is important to explore and understand the psychological impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on academics in higher education.

Research shows that university academics experienced the pandemic in phases, one of which was uncertainty and instability where they had to adjust to the demands of their new working environment [ 4 ]. Many academics experienced a fear of online teaching, increased workloads, and increased demands from students and university management. The study lists how academics experienced these stressors and the associated fatigue as the next phase in their experience of the pandemic [ 4 ]. Worry, fear, and fatigue were also experienced in response to other factors that accompanied living in a time of a pandemic. This finding is corroborated by a UK study that reported high levels of worry and fear in the early stages of the pandemic [ 5 ]. One of the main fears that academics had to contend with during the pandemic was the unexpected propulsion of academics and students into a new level of engagement with technology [ 2 , 6 ]. This transition occurred haphazardly but out of necessity. One author postulated that most academic staff at universities offering contact classes typically lacked the necessary experience in the pedagogy of online learning [ 6 ]. Many academics also reported anxiety over inadequate technological access and resources for themselves and their students [ 2 ]. This challenge was particularly pertinent to the South African context where most of the country’s population live in poverty.

The new work/life environment also brought about many new challenges. During the COVD-19 pandemic, the ability to differentiate between work and home life was demanding for academics. Meeting work deadlines, home-schooling their own children as well as running the household were challenging for many [ 3 ]. This compounded anxieties already experienced by the pandemic [ 7 ]. In addition to navigating their new work/life environment, studies show that academics were living with constant worry and fear over their health and that of their loved ones [ 8 ].

The United Nations has warned that the psychological effects of the pandemic, and lockdown restrictions, are underestimated and people should take care of their mental health and well-being [ 4 ]. The situation is even more dire in South Africa where many people have historic trauma and live in poverty, and the added burden of the pandemic exacerbated the risk of mental illness. It is also reported that mental health has been neglected during the pandemic as there has been an understandable focus on the physical well-being of populations [ 4 ]. The stress associated with the lack of technological and pedagogical readiness to teach completely in an online space, in conjunction with other stressors linked to the pandemic, led many academics to feel drained and emotionally depleted [ 7 ]. However, research shows that psychological impact is influenced by coping mechanisms employed by individuals [ 9 ], and that these coping mechanisms could account for decreased levels of worry and fear in the later stages of the pandemic [ 10 ].

Given the nature of the COVID-19 pandemic and the continuing after-effects thereof, the researchers explored the psychological impact on academics in higher education.

A cross-sectional, exploratory research study was conducted as it allowed the researchers to gather and explore data from multiple participants at a single point in time, based on appropriate inclusion criteria [ 11 ]. This allowed the researchers to explore the experiences of academic staff in public and private higher education institutions in South Africa.

This research was conducted through the lens of an interpretivist paradigm. The interpretivist paradigm argues that reality is fluid and not fixed; realities are therefore subjective where people are studied in their natural settings. According to one author [ 11 ], qualitative research can be used to better understand participants’ views and make meaning of their experiences, contexts and world. Thus, a qualitative phenomenological research design was used to explore the psychological impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on academics. A phenomenological research design was appropriate for this study as it allowed the researchers to access participants’ lived experiences of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Participants

The sample for the study was purposively selected based on specified inclusion criteria. The sample comprised 11 full-time academics employed at six different higher education institutions in the Western Cape (South Africa). During the recruitment process, each participant was asked to report their institution of employment. This information was securely stored. Selection criteria was as follows: being permanently employed at a South African higher education institution in 2020 and 2021. Three of the 11 participants were male and eight were female. The sample was drawn from the following academic disciplines: Psychology; IT; Commerce; Optometry and Law. Table 1 below outlines the participants’ demographics, depicting their discipline and job category:

Instruments

The interviews conducted in this study were guided by a semi-structured interview guide comprising seven questions. The broad domains that were explored during the interviews included: the impact of lockdown restrictions; operational changes to the teaching and learning environment; psychological impact and coping mechanisms. Examples of some of the semi-structured interview questions that participants were asked were as follows: “ What was your initial reaction to hearing about the lockdown restrictions associated with the COVID-19 pandemic?”, “Were there any changes to the teaching and learning environment and assessment strategy at your institution and what was the impact of these changes?” and “What does work-life balance mean to you?” and “How were you impacted by the pandemic emotionally and/or psychologically?”.

Participants were recruited using LinkedIn, a professional, business-oriented social networking platform used by professionals across various industries. This invitation was posted on both researchers’ personal LinkedIn profiles. An invitation to participate in the study was shared with prospective participants who met the inclusion criteria. In the invitation, participants were asked to complete an online consent form which was securely stored in a password-protected Drive that is only accessible by the co-researchers. Each researcher was assigned a set number of participants to initiate contact to set an appointment to conduct an online interview at a time convenient for the participants. Research interviews were split amongst the two researchers (one conducted six and the other conducted five interviews). The duration of the online interviews ranged between 12 and 45 min. All interviews were transcribed by a professional transcription company and the data were securely stored in the online Google Drive.

Data analysis

Data were analysed using thematic analysis (TA) [ 12 ]. When using TA, researchers try to identify, analyse and report on prominent themes or patterns within the data [ 12 ]. Thus, in this study, both the researchers identified and analysed the codes and themes related to the psychological impact of academics at higher education institutions.

This process was conducted manually using a Microsoft Excel spreadsheet to sort and colour-code the data. Undertaking this process manually allowed the researchers to engage in in-depth discussions about the data and ratify the process of assigning and naming of themes. Themes were assigned based on previous literature to ensure alignment in the data. Where new information emerged in the data, the researchers engaged in in-depth discussion to assign the most relevant theme.

Ethical considerations

Ethics approval to conduct the study was obtained from the Independent Institute of Education (IIE) which is the affiliated organisation of the researchers of this study. Participation in the study was voluntary and written informed consent was obtained from all participants. Participants were asked to complete an online confidentiality agreement which was stored in a password-protected location. All participants were informed about the purpose of the study and their right to withdraw at any point, without any consequences. Participants’ anonymity was upheld throughout the research process and all personal identifiers were removed. Participants were referred for counselling support if needed.

Legitimation and trustworthiness

In qualitative research, reality is a social construct. Therefore, the goal is rather to achieve a measure of trustworthiness as a form of legitimation of one’s research. To achieve a measure of trustworthiness in this study, the researchers applied Lincoln and Guba’s (1985) criteria [ 13 ]. Credibility was achieved in this study through the process of triangulation. Comparative analyses were conducted by both researchers who repeatedly identified patterns in the data. Patterns or themes that emerged from the data such as the impact of the lockdown restrictions or the psychological impact of the COVID-19 pandemic. Legitimacy and trustworthiness were also achieved through the transferability of the findings (patterns) in this study. The researchers conclude that the findings of this study may be transferred to other settings with similar contexts, such as academics in other universities during the time of the COVID-19 pandemic.

The researchers employed a process of reflexivity throughout the entire data collection and analysis process and aimed to ensure that their personal experiences did not impact or bias the findings of the study [ 14 ].

The study explored the psychological impact of COVID 19 on academics working in higher education institutions in South Africa. The following section entails the themes that emerged from the data analysis which include:

Impact of lockdown restrictions

A few participants shared that they experienced several emotions in relation to the announcement of the lockdown restrictions, which was largely related to the initial 21-day lockdown period. Participants responded as follows:

P4: “…daunting…horror…shock…anxiety”

P6: “Initially a lot of fear and anxiety around the unknown”

Many participants reported increased stress and anxiety. They reported that the stress and anxiety resulted mainly around the fear of the unknown in terms of the pandemic and the lockdown restrictions and worry about their health and that of their loved ones. The misinformation in the media further amplified the fear and anxiety.

P9: “so the anxiety now is coming from all those different sources around where you are, as you speak to your students and you wonder so what’s going to happen to me, given that…not just to say is this pandemic going to end or the loved ones that are passing away, but also economically you know, what’s going to happen. So those are some of the things that fed into the anxiety in my own personal experience."

Many of the participants shared their struggle of trying to implement boundaries in the workspace. The participants expressed their difficulty with switching off from work while working from home. One participant shared the following excerpt:

P3: “I found it really difficult to switch off because now your home is your office…boundaries are very difficult to maintain working from home, so fatigue was the order of the day”.

The participant shared that a consequence of blurring the lines was constant fatigue. This sentiment was shared by many other participants.

Participants also reported quite a lot of guilt as they felt that they were not spending enough quality time with family where they could give their undivided attention. They reported being unable to be emotionally available to their families as a result of the constant exhaustion and fatigue due to work and home responsibilities.

Some participants went as far as to self-diagnose and claimed to be suffering from depression. They did, however, acknowledge that they are self-diagnosed. While others reported that they were emotionally depleted due to the unending pandemic, underpinned by a false sense of hope that things would be better in 2021. They seemed to have held onto the new calendar year as the turning point for the end to the pandemic. When they realised this was not to be the case, the emotional depletion set in, and hope started to diminish. One participant even reported that their empathy for the students diminished due to mental exhaustion. This participant reported that due to their personal state of mental fatigue, their interest and care for the well-being of their students had reduced. Another participant reported that they had a pre-existing mental illness that was exacerbated by the pandemic:

P6: “I do suffer with anxiety and my anxiety was just pushed to the limit during the lockdown”.

Some participants reported that the pandemic and lockdown restrictions did not have any negative impact on their emotional and/or psychological well-being. They reported, however, that they experienced some financial impact albeit it was not always a direct impact - it was more related to extended family members. This, they claimed, did have an emotional impact on them though. Some reported that because they did not lose a loved one or “death was not close to home”, they were not conscious of any emotional and/or psychological impact on their well-being.

Thus, some participants reported that there was no emotional and/or psychological impact on their well-being. They considered themselves to be rather resilient during these adverse times:

P4: “I’m resilient, I can cope, I can…I’m able to deal with new challenges and I’ve grown because of it, ja and the adaptation, that agility for me was like a big boost to my self-confidence”.

For many participants, this is a positive side effect of the trials and tribulations of what they faced during the pandemic.

Changes to the teaching and learning environment

Most of the participants reported that a major change to the teaching and learning environment at their institution was centred around the move from predominantly face-to-face (i.e. contact) teaching and learning solely online. A few participants mentioned experiencing a sense of emotional isolation due to a lack of support from their institution. They felt unsupported by the institution in terms of the way changes were managed, unrealistic expectations (spoken and unspoken) and a lack of regard for personal wellbeing. This resulted in the participants feeling alone, experiencing panic and a heightened feeling of anxiety related to how best to navigate the implications that the lockdown restrictions had on the teaching and learning environment. The participants reported their experiences of 2020 as follows:

P1: “2020 was a rough year” and P7: “It was a very traumatic year”

This upheaval and disruption impacted lecturers and students in various ways. Both lecturers and students had to navigate technology and learning management systems in ways they did not need to in the days before the pandemic. The adaptation to online teaching left some lecturers feeling ill-prepared and anxious at the daunting task ahead:

P5: “…the switch to online was nerve-wracking”

Participants also reported feeling troubled and burdened when they could not assist their students with technological barriers, especially those that were due to socio-economic reasons, such as lack of connectivity, lack of efficient fibre, lack of devices.

Participants reported an increase in workload that was due to the adaptation to a new unfamiliar teaching and learning mode of delivery, supporting students as well as supporting fellow lecturers. One participant relayed the experience as follows:

P8: “it just broke me…the admin behind it was insane”

The participant explained that the marking load associated with the changes in the assessment strategy was exponential, resulting in increased stress levels. Participants also reported that the ever-changing, reactive nature of institutional decisions was rather stress-inducing and meant that the initial weeks and months of the lockdown were profoundly taxing - emotionally and physically.

P7: “Things changed very fast…. everything was so fluid” and “I even forgot what it feels to relax and what it feels to be at peace, what it feels to be happy…where there’s calmness…”.

One participant reported experiencing feelings of guilt related to all the changes that took place in terms of the lockdown restrictions. This guilt was also linked to the implications thereof for the way the participants had to disperse working hours throughout the day. Additionally, this sense of guilt was related to the different roles that the participant needed to fulfil (i.e., related to work and family). One participant explained that the severity of the stress associated with the day-to-day challenges was further exacerbated by the lockdown restrictions and the constant threat of contracting the coronavirus. This resulted in a negative impact on the participant’s physical and mental health.

The psychological impact of the pandemic on academics

Participants felt that there was no real demarcation between 2020 and 2021. Participants’ perceived lack of ‘closure’ of 2020 felt like 2021 was merely an extension of 2020. This had real implications for academics’ emotional fatigue and exhaustion levels. Many reported that they were emotionally depleted from the negative impact of the pandemic and ensuing lockdown restrictions.

P6: “I feel like this year sort of rolled on from 2020, again there was no real break, there was no switching off…”. P8: “The students are tired, and I am tired…because none of us could recover from 2020”.

This emotional fatigue was compounded by the fact that participants felt that in 2021 their institution did not adequately address the challenges and issues that were encountered in 2020; they felt there was a missed opportunity in 2021 to reflect on lessons learned from 2020 and ensure a less traumatic experience for lecturers and students alike. They felt as if there was a sense of institutional denial in what had occurred in 2020. One participant shared the following excerpt:

P1: “our socio-economic culture that we have in South Africa, and obviously we have quite a big divide between students who financially are able to afford internet and laptops and all of that, and students who aren’t.“

This participant expressed concern for students who did not have the financial resources to adapt to the online learning environment. Further to this, the participant also shared a feeling of helplessness related to not knowing whether students were accessing the content and their understanding of the content.

Coping mechanisms employed by academics

One participant shared that not dealing with the reality of the situation was a means of coping. The following excerpt was shared:

P8: “I adapted to that by not dealing with it”

The participants experienced a sense of avoidance in relation to all the changes which were implemented at their institution. Other participants reported using different coping mechanisms since the start of the pandemic. One participant shared that employing self-reflection practices such as daily positive affirmations was very helpful. The participant explained that it was important to reinforce boundaries with themselves and others, especially given that the physical demarcation of work and home became enmeshed. The participant shared that this meant choosing not to answer work emails after a particular time in order to safeguard quality time with family. The following quote demonstrates this:

P6: "I try to reinforce boundaries with myself”

One participant used faith/spirituality (i.e. prayer) as a coping mechanism while navigating many difficult challenges related to the pandemic. A few participants mentioned that accepting the situation and the realities associated with the pandemic and lockdown restrictions helped them to process what was happening and cope.

Some participants relied on the following coping mechanisms: increased alcohol consumption, listening to music, watching Netflix and reading. For some of these participants, these were new coping mechanisms employed at the start of the pandemic and for others, the coping mechanisms were already used but were used more intently. Many of the participants reported that they implemented physical activity (i.e. yoga and exercise at home) as a coping mechanism. A participant reported that consciously getting sufficient sleep in the evening as a means of coping with the daily responsibilities and changes that occurred at a rapid pace. One participant shared that they tracked the number of COVID-19 infections and deaths on a daily basis as a means of coping. The participant explained that this helped with identifying the ‘enemy’ and understanding the reality of an unfolding situation. Another participant shared that their coping mechanism was undertaking personal studies to escape the reality of the pandemic. The participant explained that studying was very helpful as a means of maintaining a semblance of normalcy. There were also a few participants who did not consciously make use of any coping mechanisms during the lockdown period. There was one participant who shared that they were just focused on surviving till the end of the year (when the pandemic would presumably come to an end). The following quote demonstrates this:

P5: “we just had to make it to the end of the year”

A few participants shared that they found comfort by caring for others and helping their colleagues to navigate all the changes that occurred in their respective institutions. This was a way of coping as participants found that this instilled a sense of hope for them. Others explained that helping others inadvertently helped them find a sense of meaning and purpose. These eudaimonic acts provided these participants with a sense of validation. One participant shared the following experience:

P2: “I think I’m also getting used to it, although it’s not healthy for my side because I can support a lot of students as much as I can but what about me, what am I doing for myself”.

During the interview, the participant identified that helping students and availing themselves to students constantly throughout the period of transition was a means of coping, however, they realised that this was a sacrifice of personal wellbeing in the process.

A few participants shared that connecting with loved ones (i.e. virtually or face to face when allowed) was an important means of coping during the lockdown period. Another participant shared that engaging with therapy throughout the lockdown period was very helpful with managing anxiety associated with the pandemic. In order to cope, a participant shared that planning was helpful during the pandemic because the demarcation between work and home life was compromised by the lockdown restrictions. The following excerpt is evidence of this:

P6: “…it sort of gives me that sense of security knowing that this is what I can control and this is what I’m planning to do for the next”.

The participant went on to explain that planning the things that needed to be done on a daily basis helped them feel a sense of control and a sense of achievement once a task was complete.

On a positive note, however, for some participants, there was a definite acceptance of reality and the new order of things in the pandemic. They reported that they had learned to adapt to the new way of teaching, and they felt more adept in their ability to deliver quality online teaching.

P9: “here’s a marked difference in terms of the systems, routine pattern of doing things, things have sorted of liked settled in…”.

This gave them a sense of achievement as their confidence in being able to get students to engage in the online space grew. This was a real struggle for many participants in 2020 as they linked student disengagement to their identity as an effective lecturer.

This study aimed to explore and better understand the psychological impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on academics. Most participants reported that the COVID-19 pandemic and the associated lockdown restrictions had a significant psychological impact on them. The dominant emotional responses reported by participants included stress and anxiety, fear (of the unknown), worry (related to contracting the coronavirus and the wellbeing of family members), guilt (associated with blurring the lines between work and home life). Most participants shared this sentiment given the physical changes related to where they worked and having to adapt to online learning instantaneously. As seen in this study, the consequences of blurring the lines left some participants feeling guilty for not being emotionally available to those who needed them. This finding is corroborated by previous studies that also found that the participants struggled to demarcate work and home life and in trying to find this balance, many of them ended up feeling stressed [ 3 , 4 ].

The sudden change to online learning at higher education institutions occurred across the world [ 2 ]. The results of this study showed that most of the participants experienced the change as stressful. Having to adapt their teaching and learning strategy, while learning to use technology in a meaningful way significantly contributed to the psychological strain. Additionally, participants shared a deep sense of concern for the wellbeing of their students given the pre-existing challenges (i.e. lack of access to technological devices and internet services). These challenges were further exacerbated by the advent of the pandemic. Academics in this study reported a sense of helplessness associated with being unable to reach students. A study by one author [ 7 ] also revealed how academics’ levels of stress increased when the changes to online learning were implemented.

The results of the study highlighted the psychological impact of the COVID-19 pandemic by demonstrating that academics experienced emotional isolation because of the lockdown restrictions and having to adapt to the new working environment. Further to this, the lack of institutional support in terms of managing the changes (i.e. such as having to navigate technology and learning management system), significantly contributed to the isolation and heightened feelings of panic and anxiety. This is confirmed by a study conducted by [ 7 ]. Many academics reported feeling ill-prepared and anxious about the adaptation. Additionally, the increased workload was highlighted as significantly contributing to their levels of stress. Another author [ 4 ] confirmed this and added that academics reported that their stress was compounded by the fact that they had to teach themselves the new technologies.

The fears of the academics were not restricted to the new working environment; it transcended into their personal lives as well. The findings of this study are supported by another study that found academics to be quite fearful of their health as well as that of their loved ones [ 8 ]. This worry added to their fears and anxieties around navigating their new work/life environment.

Some participants in this study seemed to experience a sense of avoidance in relation to their new work/life environment. This is in line with other findings conducted that also reported on participants who tended to use avoidance as a means of coping with the stressors of the pandemic and resulting lockdown restrictions [ 4 , 8 ]. It must be noted here that their study reported on gender differences as they found this experience to be particular for females, however, this study does not report on gender differences in this regard.

A significant finding of this study was the increase in emotional fatigue reported by most academics. The lack of demarcation between 2020 and 2021 resulted in academics feeling hopeless and helpless in trying to navigate work and life and fulfill all their academic responsibilities. Institutional denial significantly added to this burden and many academics reported experiencing psychological strain because of this. Academics felt that the lack of willingness from institutions to reflect on the impact of the changes which were implemented at the onset of the pandemic directly impacted their ability to pause, take stock, recreate, and innovate. Even though a few academics reported that they tried to be proactive by putting systems in place to support students, they ended up emotionally fatigued. Similar results were reported in a study where their participants experienced emotional fatigue because of the increased workload brought about by additional demands from colleagues and students [ 4 ].

The COVID-19 pandemic and ensuing lockdown restrictions in 2020 and 2021 had a negative psychological impact on many academics in public and private institutions of higher education in South Africa. Institutions must use the lessons learned from 2020 to 2021 to respond to the needs of academics in years to come.

Limitations and future research

The study naturally had some limitations. The first limitation was the limited participation of male academics. Taking into consideration the interplay between gender, gender roles, mental health, coping mechanisms, and the role of gender in academia, it is recommended that future studies on this topic include equal representation of males and females to gain more insight into the experiences and coping mechanisms employed by male academics.

Another limitation is the small sample size of participants and higher education institutions in the study. A small sample size such as the one in this study potentially impacts the transferability of the findings to other academics at other institutions. It may be that academics in other institutions did not share the same experiences as their contexts may have been different from the ones in this study.

Since this was a cross-sectional research study, future research could be conducted longitudinally. It would be interesting to explore the experiences of academics potentially after six to twelve months after this study to ascertain if they are still experiencing any negative psychological impact of COVID-19, but more importantly, if participants are still employing the coping mechanism they utilised during the pandemic.

Implications for practice

Given that academics experience constant pressures to adapt to an ever-changing higher education landscape, engage with students, impart knowledge and skills, produce high-quality research and participate in scholarship activities regularly, it is important that institutions ensure that academics are equipped to deal with rapid change in future—assistance that will help ease the transition from one status quo to another—particularly in times of national and/or international turmoil and upheaval.

Institutions must strive to respond to the psychological and emotional needs of academic staff. Institutions must create working environments and foster cultures where the mental well-being of academics is encouraged and even protected. Institutional management and human resource departments at academic institutions can create support groups for academics where they can share common challenges, share examples of new teaching and learning methodologies, as well as organise wellness activities and events to support academics to overcome or reduce some of the negative psychological impact created by the COVID-19 pandemic.

Institutions must use the lessons learned from 2020 to 2021 to respond to the needs of academics in years to come. They must ensure that academics are equipped to deal with rapid change in the future—assistance that will help ease the transition from one status quo to another—particularly in times of national and/or international turmoil and upheaval.

Institutions must strive to respond to the psychological and emotional needs of academic staff (lecturers and researchers). Institutions must create working environments and foster cultures where the mental well-being of academics is encouraged and even protected. Institutional management and human resource departments at academic institutions can create support groups for academics where they can share common challenges, share examples of new teaching and learning methodologies, as well as organise wellness activities and events to support academics to overcome or reduce some of the negative psychological impact created by the COVID-19 pandemic.

Availability of data and materials

The data analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

World Health Organisation

The Independent Institute of Education

Cucinotta D, Vanelli M. WHO declares COVID-19 a pandemic. Acta Biomed. 2020;91(1):157–60.

Google Scholar

Pokhrel S, Chhetri R. A literature review on Impact of COVID-19 pandemic on teaching and learning. High Educ Future. 2021;8(1):133–41.

Article Google Scholar

Mahesh VJ, Kumar S. Work from home experiences during COVID-19 pandemic among IT employees. J Contemp Issues Bus Gov. 2020;26(2):640–5.

van Niekerk RL, van Gent MM. Mental health and well-being of university staff during the coronavirus disease 2019 levels 4 and 5 lockdown in an eastern cape university, South Africa. South Afr J Psychiatry. 2021;27:1–7.

Kleinberg B, van der Vegt I, Mozes M. Measuring emotions in the COVID-19 real world worry dataset. 2020 [cited 2022 Nov 17]. Available from: https://osf.io/awy7r/ .

Hedding DW, Greve M, Breetzke GD, Nel W, van Vuuren BJ. COVID-19 and the academe in South Africa: not business as usual. S Afr J Sci. 2020;116(8):1–3.

Rapanta C, Botturi L, Goodyear P, Guàrdia L, Koole M. Online university teaching during and after the Covid-19 crisis: refocusing teacher presence and learning activity. 2020. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1007/s42438-020-00155-y .

Al Miskry ASA, Hamid AAM, Darweesh AHM. The impact of COVID-19 pandemic on university faculty, staff, and students and coping strategies used during the lockdown in the United Arab Emirates. Front Psychol. 2021;12:682757.

Sebri V, Cincidda C, Savioni L, Ongaro G, Pravettoni G. Worry during the initial height of the COVID-19 crisis in an italian sample. J Gen Psychol. 2021;148(3):327–59.

Ongaro G, Cincidda C, Sebri V, Savioni L, Triberti S, Ferrucci R, et al. A 6-month follow-up study on worry and its impact on well-being during the first wave of covid-19 pandemic in an Italian sample. Front Psychol. 2021;12:703214.

Aspers P, Corte U. What is qualitative in qualitative research. Qual Sociol. 2019;42(2):139–60.

Braun V, Clarke V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Psychiatric Q. 2014;0887(1):37–41.

Stahl NA, King JR. Expanding approaches for research: understanding and using trustworthiness in qualitative research. J Dev Educ. 2020;44(1):26–8.

Palaganas EC, Sanchez MC, Molintas MVP, Caricativo RD. Reflexivity inqualitative research a journey of learning. Qual Rep. 2017;22(2):426–38.

Download references

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

The authors received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

School of Humanities and Social Sciences, Faculty of Humanities and Social Sciences, The Independent Institute of Education, Cape Town, South Africa

Lynette Thompson & Cindy Christian

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Contributions

LT and CC worked equally on all sections of the journal. Both authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Lynette Thompson .

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate.