Professional Learning and Development in Classroom Management for Novice Teachers: A Systematic Review

- Published: 27 August 2021

- Volume 44 , pages 291–307, ( 2021 )

Cite this article

- Shanna E. Hirsch ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0003-3044-9338 1 ,

- Kristina Randall ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0001-7868-6549 2 ,

- Catherine Bradshaw 3 &

- John Wills Lloyd ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-2597-6216 4

1359 Accesses

6 Citations

Explore all metrics

There is a growing awareness that novice teachers in particular are in need of support and additional professional learning and development (PLD), especially in the area of classroom management. Yet there is limited information regarding effective approaches for building novice teachers’ skills related to classroom management. To address this gap, we conducted a systematic review of experimental studies related to novice teacher PLD in classroom management. We identified eight original experimental peer-reviewed studies published. We explored the research base, applying the Council for Exceptional Children Quality Indicators and coding studies to identify elements of practice-based professional development. Together, the available studies suggested that providing PLD increases classroom management practices while increasing student engagement. We discuss the implications of this review and conclude with implications for practice and future research related to novice teacher PLD.

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this article

Price includes VAT (Russian Federation)

Instant access to the full article PDF.

Rent this article via DeepDyve

Institutional subscriptions

Similar content being viewed by others

An Expert Teacher’s Use of Teaching with Variation to Support a Junior Mathematics Teacher’s Professional Learning

Unpacking Teacher Quality: Key Issues for Early Career Teachers

A Collaborative Classroom-Based Teacher Professional Learning Model

Ball, D. L., & Cohen, D. K. (1999). Developing practice, developing practitioners: Toward a practice-based theory of professional education. In L. Darling-Hammond & G. Sykes (Eds.), Teaching as the learning profession: Handbook of policy and practice (pp. 3-32). Jossey.

Bateman, B. D. (2007). Elements of teaching: A best practices handbook for beginning teachers. Attainment.

Begeny, J. C., & Martens, B. K. (2006). Assessing pre-service teachers’ training in empirically-validated behavioral instruction practices. School Psychology Quarterly, 21 , 262–285.

Article Google Scholar

Billingsley, B., & Bettini, E. (2019). Special Education Teacher Attrition and Retention: A Review of the Literature. Review of Educational Research, 89 (5), 697–744. https://doi.org/10.3102/0034654319862495 .

*Briere, D. E., Simonsen, B., Sugai, G., & Myers, D. (2015). Increasing new teachers’ specific praise rates using a within-school consultation intervention. Journal of Positive Behavior Interventions, 17, 50-60. https://doi.org/10.1177/1098300713497098

Browers, A., & Tomic, W. (2000). A longitudinal study of teacher burnout and perceived self-efficacy in classroom management. Teaching and Teacher Education, 16 , 239–253. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0742-051X(99)00057-8

Boardman, A. G., Arguelles, M. E., Vaughn, S., Hughes, M. T., & Klingner, J. (2005). Special education teacher’s views of research-based practices. The Journal of Special Education, 39 , 168–180.

Borko, H., Koellner, K., Jacobs, J., & Seago, N. (2011). Using video representations of teaching in practice-based professional development programs. Mathematics Education, 43 , 175–187.

Google Scholar

Bowsher, A., Sparks, D., & Hoyer, K. M. (2018). Preparation and support for teachers in public schools: Reflections on the first years of teaching (NCES 2018-143). Stats in Brief, U.S. Department of Education.

Burns, M. K., & Ysseldyke, J. E. (2009). Reported prevalence of evidence-based instructional practices in special education. The Journal of Special Education, 43 , 3–11.

Conroy, M. A., & Sutherland, K. S. (2012). Effective teachers for students with emotional/behavioral disorders: Active ingredients leading to positive teacher and student outcomes. Beyond Behavior, 22 (1), 7–13.

Cook, B. G., Buysse, V., Klingner, J., Landrum, T. J., McWilliam, R. A., Tankersley, M., & Test, D. W. (2015). CEC’s standards for classifying the evidence base of practices in special education. Remedial and Special Education, 36 , 220–234. https://doi.org/10.1177/0741932514557271 .

Council for Exceptional Children. (2014). Council for Exceptional Children standards for evidence-based practices in special education .

Council for Exceptional Children: Standards for Evidence-Based Practices in Special Education. (2014). TEACHING Exceptional Children, 46 (6), 206–212. https://doi.org/10.1177/0040059914531389

Darling-Hammond, L., Hyler, M. E., & Gardner, M. (2017). Effective teacher professional development . Learning Policy Institute.

Darling-Hammond, L., Wei, R., Andree, A., Richardson, N., & Orphanos, S. (2009). Professional learning in the learning profession: A status report on teacher development in the United States and abroad. National Staff Development Council. http://www.nsdc.org/news/NSDCstudy2009.PLDf

*Dicke, T., Elling, J., Schmeck, A., & Leutner, D. (2015). Reducing reality shock: The effects of classroom management skills training on beginning teachers. Teaching and Teacher Education, 48 , 1-12. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2015.01.013

Drummond, T. (1994). The Student Risk Screening Scale (SRSS). Josephine County Mental Health Program.

Emmer, E. T., & Evertson, C. M. (2008). Classroom management for middle and high school teachers (with MyEducationLab) (8th ed.). Allyn & Bacon.

Espinoza, D., Saunders, R., Kini, T., & Darling-Hammond, L. (2018). Taking the long view: State efforts to solve teacher shortages by strengthening the profession. Learning Policy Institute. https://learningpolicyinstitute.org/product/long-view

*Evertson, C. M., & Smithey, M. W. (2000). Mentoring effects on protégés’ classroom practice: An experimental field study. Journal of Educational Research, 93, 294-304.

Festas, I., Oliveira, A. L., Rebelo, J. A., Damiao, M. H., Harris, K. R., & Graham, S. (2014). Professional development in self-regulated strategy development: Effects on the writing performance of eighth grade Portuguese students. Contemporary Educational Psychology, 40 , 17–27. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cedpsych.2014.05.004 .

Fischer, S. H., Rose, A. J., McBain, R. K., Faherty, L. J., Sousa, J., & Martineau, M. (2019). Evaluation of technology-enabled collaborative learning and capacity building models: Material for a report to Congress . RAND Corporation.

Fixsen, D. L., & Paine, S. (2009). Implementation: Promising practices to sustained results (Sustainability Series No. 5) . RMC Research Corporation.

Fixsen, D. L., Naoom, S. F., Blase, K. A., Friedman, R. M., & Wallace, F. (2005). Implementation research: A synthesis of the literature (FMHI Publication No. 231). Louis de la Parte Florida Mental Health Institute, University of South Florida, The National Implementation Research Network. https://nirn.fpg.unc.edu/sites/nirn.fpg.unc.edu/files/resources/NIRNMonographFull-01-2005.pdf

Flores, M. A., & Day, C. (2006). Contexts which shape and reshape new teachers’ identities: a multi-perspective study. Teaching and Teacher Education, 22 , 219–232.

Freeman, J., Simonsen, B., Briere, D., & MacSuga-Gage, A. M. (2014). Pre-service teacher training in classroom management: A review of state accreditation policy and teacher preparation programs. Teacher Education and Special Education, 37 (2), 106–120. https://doi.org/10.1177/0888406413507002 .

*Gage, N. A., Grasley-Boy, N., & MacSuga-Gage, A. S. (2018). Professional development for teacher behavior specific praise: A single-case design replication. Psychology in the Schools, 55 , 264-277. https://doi.org/10.1002/pits.22106

*Gage, N. A., MacSuga-Gage, A. S., & Crews, E. (2017). Increasing teachers’ use of behavior specific praise using a multi-tiered system for professional development. Journal of Positive Behavior Interventions, 19 , 239-251. https://doi.org/10.1177/1098300717693568

Gersten, R., Fuchs, L. S., Compton, D., Coyne, M., Greenwood, C., Innocenti, M. S. (2005). Quality indicators for group experimental and quasi-experimental research in special education. Exceptional Children, 71 , 149–164.

Gersten, R., Vaughn, S., Deshler, D., & Schiller, E. (1997). What we know about using research findings: Implications for improving special education practice. Journal of Learning Disabilities, 30 , 466–476.

Goodson, B., Caswell, L., Dynarski, M., Price, C., Litwok, D., Crowe, E., Meyer, R., & Rice, A. (2019). Teacher preparation experiences and early teaching effectiveness: Executive summary (NCEE 2019-4010). In National Center for Education Evaluation and Regional Assistance . U.S. Department of Education.

Guarino, C. M., Santibanez, L., & Daley, G. A. (2006). Teacher recruitment and retention: A review of the recent empirical literature. Review of Educational Research, 76 , 173–208. https://doi.org/10.3102/00346543076002173 .

Harris, K. R., Lane, K. L., Graham, S., Driscoll, S. A., Sandmel, K., Brindle, M., & Schatschneider, C. (2012). Practice-based professional development for self-regulated strategies development in writing: A randomized controlled study. Journal of Teacher Education, 63 , 103–119.

Herro, D., Hirsch, S. E., & Quigley, C. (2019). Faculty-in-Residence program: Enacting practice-based professional development in a STEAM-focused middle school. Professional Development in Education . https://doi.org/10.1080/19415257.2019.1702579 .

*Hirsch, S. E., Lloyd, J. W., & Kennedy, M. J. (2019). Professional development in practice: Improving novice teachers’ use of universal classroom management practices. Elementary School Journal, 120 , 61-87. https://doi.org/10.1086/704492

Hirsch, S. E., Randall, T., Common, E., & Lane, K. L. (2020). Results of practice-based professional development for supporting special educators in learning how to design functional assessment-based interventions. Teacher Education and Special Education, 43 (4), 281–295. https://doi.org/10.1177/0888406419876926 .

Horner, R. H., Carr, E. G., Halle, J., McGee, G., Odom, S., & Wolery, M. (2005). The use of single-subject research to identify evidence-based practice in special education. Exceptional Children, 71 , 165–179. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022487111429005 .

Ingersoll, R. M. (2012). Beginning teacher induction: What the data tell us. Phi Delta Kappa, 93 , 47–51.

Ingersoll, R., Merrill, L., & Stuckey, D. (2014). Seven trends: The transformation of the teaching force, uPLDated April 2014. CPRE Report (#RR-80). Consortium for Policy Research in Education, University of Pennsylvania.

Ingersoll, R., Merrill, E., Stuckey, D., & Collins, G. (2018). Seven trends: The transformation of the teaching force, uPLDated October 2018. Research Report (# R.R. 2018–2). Consortium for Policy Research in Education, University of Pennsylvania.

Ingersoll, R., & Smith, T. M. (2003, May). The wrong solution to the teacher shortage. Educational Leadership, 60 (8), 30–33.

Joyce, B., & Showers, B. (2002). Student achievement through staff development. In B. Joyce & B. Showers (Eds.), Designing training and peer coaching: Our needs for learning, Association for Supervision and Curriculum Development.

King, S., Davidson, K., Chitiyo, A., & Apple, D. (2020). Evaluating article search and selection procedures in special education literature reviews. Remedial and Special Education, 41 (1), 3–17. https://doi.org/10.1177/0741932518813142 .

Landrum, T. J., Cook, B. G., Tankersley, M., & Fitzgerald, S. (2007). Teacher perceptions of the usability of intervention information from personal versus data-based sources. Education and Treatment of Children, 30 (4), 27–42.

Lane, K. L., Common, E. A., Royer, D. J., & Muller, K. (2014). Group comparison and single-case research design quality indicator matrix using Council for Exceptional Children 2014 standards. Unpublished tool. Retrieved from http://www.ci3t.org/practice

Lane, K. L., Oakes, W. P., Powers, L., Diebold, T., Germer, K., Common, E. A., & Brunsting, N. (2015). Improving teachers’ knowledge of functional assessment-based interventions: Outcomes of a professional development series. Education and Treatment of Children, 38 , 93–120.

Lewis, T. J., & Sugai, G. (1999). Effective behavior support: A systems approach to proactive schoolwide management. Focus on Exceptional Children, 31 (6), 1–24.

Lewis, R., Roache, J., & Romi, S. (2011). Coping styles as mediators of teachers’ classroom management techniques. Research in Education, 85 , 53–68.

Leko, M. M., & Brownell, M. T. (2009). Crafting quality professional development for special educators: What school leaders should know. TEACHING Exceptional Children, 42 (1), 64–70.

Loucks-Horsley, S., Hewson, P. W., Love, N., & Stiles, K. E. (1999). Designing professional development for teachers of science and mathematics. Corwin Press.

Mager, R. F. (1997). Preparing instructional objectives: A critical tool in the development of effective instruction (3rd ed.). CEP Press.

Maggin, D. M., Talbott, E., Van Acker, E. Y., & Kumm, S. (2017). Quality indicators for systematic reviews in behavioral disorders. Behavioral Disorders, 42 , 52–64. https://doi.org/10.1177/0198742916688653 .

Martens, B. K., Witt, J. C., Elliott, S. N., & Darveaux, D. X. (1985). Teacher judgments concerning the acceptability of school-based interventions. Professional Psychology Research and Practice., 16 , 191.

Marzano, R. J. (2003). What works in schools: Translating research into action . ASCD.

McCarthy, C. J., Lineback, S., & Reiser, J. (2015). Teacher stress, emotion, and classroom management. In E. T. Emmer & E. J. Sabornie (Eds.), Handbook of Classroom Management (2nd ed., pp. 301-321). Routledge.

MetLife Inc. (2013). The MetLife survey of the American teacher: Challenges for school leadership. https://www.metlife.com/content/dam/microsites/about/corporate-profile/MetLife-Teacher-Survey-2012.PLDf

Moher, D., Shamseer, L., Clarke, M., Ghersi, D., Liberati, A., Petticrew, M., & Stewart, L. A. (2015). Preferred reporting items for systematic review and meta-analysis protocols (PRISMA-P) 2015 statement. Systematic Reviews, 4 , Article 1.

National Center for Education Statistics. (2015). Schools and Staffing Survey. Institute of Education Sciences. Retrieved from https://nces.ed.gov/surveys/sass/

Office of Special Education Programs. (2015). Supporting and responding to student behavior: Evidence-based classroom strategies for teachers. Office of Special Education Programs. Retrieved from http://www.pbis.org/resources/supporting-and-responding-to-behavior-evidence-based-classroom-strategies-for-teachers

Oliver, R. M., & Reschly, D. J. (2007). Effective classroom management: Teacher preparation and professional development. National Comprehensive Center for Teacher Quality. http://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED543769.PLDf .

Pogodzinski, B., Youngs, P., & Frank, K. A. (2013). Collegial climate and novice teachers’ intent to remain teaching. American Journal of Education, 120 , 27–54.

*Rathel, J. M., Drasgow, E., Brown, W. H., & Marshall, K. J. (2014). Increasing induction-level teachers’ positive-to-negative communication ratio and use of behavior-specific praise through e-mailed performance feedback and its effect on students’ task engagement. Journal of Positive Behavior Interventions , 16 , 219–233. https://doi.org/10.1177/1098300713492856

Reinke, W. M., Herman, K. C., & Sprick, R. (2011). Motivational interviewing for effective classroom management: The classroom check-up. Guilford Press.

Reinke, W. M., Stormont, M., Herman, K. C., Wachsmuth, S., & Newcomer, L. (2015). The Brief Classroom Interaction Observation –Revised: An observation system to inform and increase teacher use of universal classroom management practices. Journal of Positive Behavior Intervention, 17 , 159–169. https://doi.org/10.1177/1098300715570640 .

Root-Elledge, S., Hardesty, C., Hidecker, M. J. C., Bowser, G., Leki, E., Wagner, S., & Moody, E. (2018). The ECHO model for enhancing assistive technology implementation in schools. Assistive Technology Outcomes and Benefits, 12 , 37–55.

Royer, D. J., Lane, K. L., & Common, E. A. (2017). Group comparison and single-case research design quality indicator matrix using Council for Exceptional Children 2014 standards: Standards overview and walk-through guide . Unpublished tool. Retrieved from https://www.ci3t.org/practice

Simonsen, B., Fairbanks, S., Briesch, A., Myers, D., & Sugai, G. (2008). Evidence-based practices in classroom management: Considerations for research to practice. Education and Treatment of Children, 31 , 351 – 380 .

Smith, T. M., & Ingersoll, R. M. (2004). What are the effects of induction and mentoring on beginning teacher turnover? American Educational Research Journal, 41 , 681–714.

Stallion, B. K., & Zimpher, N. L. (1991). Classroom management intervention: The effects of training and mentoring on the inductee teacher’s behavior. Action in Teacher Education, 13 , 42–50.

Stevenson, N. A., VanLone, J., & Barber, B. R. (2020). A commentary on the misalignment of teacher education and the need for classroom behavior management skills. Education and Treatment of Children . https://doi.org/10.1007/s43494-020-00031-1 .

Stokes, T. F., & Baer, D. M. (1977). An implict technology of generalization. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, 10 , 349–367.

Stough, L. A., & Montague, M. L. (2015). How teachers learn to be classroom managers. In E. T. Emmer & E. J. Sabornie (Eds.), Handbook of Classroom Management (2nd ed., pp. 446-458). Routledge.

Sutcher, L., Darling-Hammond, L., & Carver-Thomas, D. (2016). A coming crisis in teaching? Teacher supply, demand, and shortages in the U.S. Learning Policy Institute.

Sutton, R., Mudrey-Camino, R., & Knight, C. C. (2009). Teachers’ emotion regulation and classroom management. Theory into Practice, 38 , 130–137.

*Tolan, P., Elreda L. M., Bradshaw, C. P., Downer, J. T., & Ialongo, N. (2020). Randomized trial testing the integration of the Good Behavior Game and MyTeachingPartner TM :The moderating role of distress among new teachers on student outcomes. Journal of School Psychology, 78 , 75-95. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsp.2019.12.002

Tschannen-Moran, M., & Hoy, A. W. (2007). The differential antecedents of self-efficacy beliefs of novice and experienced teachers. Teaching and Teacher Education, 23 , 944–956.

Wei, R. C., Darling-Hammond, L., & Adamson, F. (2009). Professional development in the United States: Trends and challenges . National Staff Development Council.

Yoon, K. S., Duncan, T., Lee, S. W. Y., Scarloss, B., & Shapley, K. (2007). Reviewing the evidence on how teacher professional development affects student achievement (Issues & Answers Report, REL 200 No. 033). U.S. Department of Education, Institute of Education Sciences. Retrieved from http://ies.ed.gov/ncee/edlabs

Download references

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Education and Human Development, Clemson University, 228 Holtzendorff Hall, Clemson, SC, 29634, USA

Shanna E. Hirsch

Department of Human Performance and Health, University of South Carolina Upstate, Spartanburg, SC, USA

Kristina Randall

Department of Human Services, University of Virginia, Charlottesville, VA, USA

Catherine Bradshaw

Curriculum, Instruction, and Special Education, University of Virginia, Charlottesville, VA, USA

John Wills Lloyd

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Shanna E. Hirsch .

Ethics declarations

Conflicts of interest/competing interests.

The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Code availability

Not applicable

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Hirsch, S.E., Randall, K., Bradshaw, C. et al. Professional Learning and Development in Classroom Management for Novice Teachers: A Systematic Review. Educ. Treat. Child. 44 , 291–307 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s43494-021-00042-6

Download citation

Accepted : 30 May 2021

Published : 27 August 2021

Issue Date : December 2021

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/s43494-021-00042-6

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- behavior management

- classroom management

- new teacher

- novice teacher

- professional development

- quality indicators

- Find a journal

- Publish with us

- Track your research

- Reference Manager

- Simple TEXT file

People also looked at

Original research article, teachers’ perceptions of their role and classroom management practices in a technology rich primary school classroom.

- 1 Department of Education and Sports Science, Faculty of Arts and Education, University of Stavanger, Stavanger, Norway

- 2 Department of Education, Faculty of Psychology, University of Bergen, Bergen, Norway

This case study investigates primary school teachers’ perceptions of their role and practices regarding classroom management in technology-rich classrooms. The data was collected through individual and focus group interviews, observation and a survey at a school where implementation of digital technologies has been a high priority over several years. The study identifies complexity and contemporary elements in teachers’ perceived role and practices, as the rapid evolution of ICT requires teachers to constantly keep up-to-date, gain new competencies and evaluate their practices to be able to facilitate learning in physical classrooms that have expanded to the digital space. In this process, the role of leadership, collegial collaboration, good teacher-pupil relationships and teachers’ ability to adapt and take up a role of a learner have been found pivotal.

Introduction

Digitalization has advanced in leaps in Norwegian schools, and pupils’ and teachers’ personal digital devices have become standard pieces of equipment in the majority of classrooms, including primary education ( Fjørtoft et al., 2019 ). This consequently sets new demands to effective classroom management ( Bolick and Bartels, 2015 ; Ministry of Education and Research, 2017 ). Traditionally, the purpose of classroom management has been establishing a safe, supportive and orderly environment to optimize opportunities for learning and social, emotional and moral growth ( Evertson and Weinstein, 2006 ; Wubbels, 2011 ). While the definition of classroom management itself is still valid, the rapid development in digitalization at all levels of schooling forces us to reconsider the means to reach its goals. Research shows that in general, teachers have expressed insufficient pedagogical digital competence and fear of losing control when digital technologies have been introduced and implemented ( Krumsvik et al., 2013 , 2016 ; Bolick and Bartels, 2015 ; Moltudal et al., 2019 ). However, a synthesis of Cho et al. (2020) finds some positive features and implications in both abovementioned areas, in using digital technologies to aid in classroom management, as well as in understanding the role of digital technologies in the overall flow of classroom practices ( Cho et al., 2020 ). Schools have for example implemented applications that focus on pupil behavior and employed virtual platforms for a variety of classroom management tasks ( Pas et al., 2016 ; Sanchez et al., 2017 ; Cho et al., 2020 ). Overall, there is still little research documenting how introducing digital resources actually influences classroom management in primary school level ( Bolick and Bartels, 2015 ; Cho et al., 2020 ).

The aim of this article is to position the study toward the current state of knowledge, as well as to contribute toward increasing this knowledge base on how teachers perceive their role regarding classroom management in learning environments that are characterized by frequent access and use of digital technologies, and how they practice this role in their everyday classroom management. The context for the case study is particularly related to Norwegian primary schools, and the data was collected in a school that could be defined as a leading-edge school ( Schofield, 1995 ) due to its notable investments in pioneering in ICT implementation. The article examines the following research question:

How does the use of digital technologies influence teachers’ perceptions of their role and practices in terms of classroom management in a technology-rich primary school classroom?

Norwegian Context

In Norway, primary school is divided between lower primary school (ages 6-9, grades 1-4) and upper primary school (ages 10-12, grades 5-7). Norwegian teachers enjoy a significant amount of autonomy compared to their colleagues in many other countries and as a rule, have a fair amount of influence regarding their pedagogical work. The national curriculum (known as LK20) allows a wide spectrum of methods and teaching strategies, while highlighting the importance of educating digitally competent citizens ( Ministry of Education and Research, 2019 ). Teachers and pupils in Norwegian schools have a good access to educational technology, such as one-on-one digital devices, projectors and digital whiteboards ( Fjørtoft et al., 2019 ), and competence in classroom management in technology-rich learning environments has been named as one of the central aspects in the national digitalization strategy for Norwegian schools ( Ministry of Education and Research, 2017 ).

For instance, Blikstad-Balas (2012) , Krumsvik et al. (2013) , Krumsvik (2014) , Fjørtoft et al. (2019) have cast light on the impact of digital technologies to teachers’ role and classroom management practices in secondary education. Some of the main findings are that teachers and school leaders both fear and experience that use of technology causes distractions, and that a large body of pupils do not use technology as instructed. Teachers have expressed doubts regarding their pupils’ maturity to demonstrate an adequate amount of self-regulation and responsibility when the temptations of digital devices are constantly within the reach, but it has been argued that many of such issues could be resolved by better competence in classroom management ( Krumsvik et al., 2013 ). Although several Norwegian studies have examined the relationship between digitalization and classroom disruptions, a recent systematic review shows that this topic has received little attention internationally ( Meinokat and Wagner, 2021 ). Studies also show that while the access to and the use of digital technologies has increased significantly during the past years, there is still great variation in digital practices within and between Norwegian schools ( Krumsvik et al., 2016 ; Fjørtoft et al., 2019 ). National studies and international comparison indicate that in spite of teachers’ positive attitudes and good access to digital technologies, the use of ICT in Norwegian schools has been generally rather mediocre ( Ottestad et al., 2013 ; Throndsen and Hatlevik, 2015 ; Blikstad-Balas and Klette, 2020 ).

Teacher’s Role and Classroom Management

For a long time, classroom management has been considered as one of the teacher’s basic tasks, and in several studies classroom management has been found to be a key predictor of student success ( Hattie, 2009 ; Marquez et al., 2016 ). While traditional classrooms tend to be rather teacher-centered, a technology-rich learning environment requires a paradigm shift toward a more constructivist approach where technology is no longer treated as a mere tool but viewed more holistically in regards to its potential and influence in classroom dynamics and culture ( Säljö, 2010 ; Bolick and Bartels, 2015 ). What separates classroom management in elementary grades from classroom management in secondary level is that everything blends with everything: academic, social, emotional and behavioral aspects merge in such manner that individual achievements are often a result of all of the above, rather than a consequence from formal instruction ( Carter and Doyle, 2006 ). Research has also found that quality classroom management has a stronger footing in primary education, and as pupils get older, teachers have a tendency to assume less need for classroom management or focus on subject-related curriculums and educational goals, at the expense of classroom management ( Beijaard et al., 2000 ; Bru, 2013 ; Kalin et al., 2017 ).

Carter and Doyle (2006) divide classroom management in elementary level in two main strands: firstly, classroom management has emphasis on procedures (methods, techniques, skills and cognitions) that contribute toward an orderly learning environment by capturing pupils’ attention, engagement and focus, in order to allow and execute curricular activities. Secondly, there are the consequences of how classrooms are being managed. This strand consists of the moral and emotional aspect of classroom management, and the outcomes of interacting with children in a school setting. Powell et al. (2001) call this the social curriculum of a classroom. This aspect has been considered to be particularly important in successful classroom management ( Korpershoek et al., 2016 ). Researchers argue that authoritative teachers focusing on positive behavior support are more successful in the prevention of unwanted behavior than those employing reactive strategies and attributing problems to external factors ( Alter and Haydon, 2017 ; Hepburn and Beamish, 2019 ). It is noteworthy that positive behavior support does not rule out negative consequences, as long as they are a logical fit for the rule, and it can be argued that teaching rules with clear positive and negative consequences can be an effective strategy when managing a primary school classroom ( Alter and Haydon, 2017 ).

Teachers and researchers worldwide generally agree that the march of digital technologies has a major influence on teachers’ role in a classroom, and the rapid changes in digital technologies force teachers to adopt a dynamic role where they keep themselves up-to-date regarding new educational technologies ( Albion et al., 2015 ; Martin et al., 2016 ). As the emphasis in the more contemporary way of viewing classroom management is more constructivist and less teacher-centered, it has a direct influence on teachers’ role in the classroom: teachers are urged to become facilitators of learning rather than just transmit knowledge, as well as initiate, guide and influence the way their pupils think about learning ( Beijaard et al., 2000 ). In fact, in order to succeed with digital technologies, teachers themselves should be open to become learners themselves, take some risks, adopt a somewhat playful and curious attitude toward using educational technologies and continuously reflect on the learning and new practices in their professional community ( Desimone, 2009 ). This type of cognitive playfulness, as defined by Webster and Martocchio (1992) , Goodwin et al. (2015) , is a set of personality traits, affective styles and motivational orientations, which often occur spontaneously in an inventive and imaginary way and has been found to have a positive influence in perceived importance of ICT and sense of competence.

Teacher’s Professional Digital Competence and Classroom Management

There have been many attempts to create a framework that explains, defines or facilitates teacher’s pedagogical digital competence, such as TPACK ( Mishra and Koehler, 2006 ), SAMR ( Puentedura, 2015 ), and DigCompEdu ( Punie and Redecker, 2017 ); however, these models offer little concrete recommendations and guidelines for defining and developing teacher’s professional digital competence (PDC) and can therefore be seen as quite generic ( Hjukse et al., 2020 ). Professional Digital Competence Framework for Teachers framework, developed by Kelentrić et al. (2017) for The Norwegian Centre for ICT in Education, was launched by the Norwegian Directory of Education and Training and was chosen to frame this study due to its relevance to the context and design that has targeted primary and secondary education in particular. This PDC framework is divided into seven different categories: Subjects and basic skills, School in society, Ethics, Pedagogy and subject didactics, Leadership of learning processes, Interaction and communication , and Change and development . Particularly the category leadership of learning processes offers relevant outlines to classroom management in a technology rich classroom.

“A professional, digitally competent teacher possesses the competence to guide learning work in a digital environment. This entails understanding and managing how this environment is constantly changing, and challenging the role of the teacher. The teacher makes use of the opportunities inherent in digital resources in order to develop a constructive and inclusive learning environment—” ( Kelentrić et al., 2017 , p.8).

When discussing teachers’ pedagogical digital competence, it is noteworthy to point out that the term is more than a compilation of technical skills and knowledge. Krumsvik (2011) has defined teacher’s digital competence as their proficiency in using ICT in school with good pedagogical judgment and with their awareness of its implications for learning strategies and the digital Bildung of their pupils. Based on this definition, Krumsvik and colleagues found a significant correlation between teachers’ classroom management and their digital competence ( Krumsvik et al., 2013 ). Recent trends in research indicate that in a broader context, teachers should view digital technologies not only as tools but artifacts, which act as cultural extensions and reflect how knowledge and social aspects of our lives are organized and presented in our society ( Säljö, 2010 ; Lund et al., 2014 ). In other words, a teacher with pedagogical digital competence sees technology as a more comprehensive concept than just a collection of applications, software and devices, and understands how a digital culture in 21st century schools and society influences their role and everyday practices beyond the tool-value of technologies. It is not unusual that variety in teachers’ PDC – and their willingness to use technology to facilitate learning – has led to a variety of different classroom practices, which in a broader context could even widen the gap between practices ( Moltudal et al., 2019 ). Therefore, to support a cohesive development of pedagogical competence and practices, school leaders should, through support and supervision, shift the teachers’ focus from their individual motives and preferences to a mutual goal, and create a supportive, motivating community ( Phelps and Graham, 2014 ).

Case Study Design

This article examines teachers’ perceptions of their role and practices regarding classroom management in technology-rich classrooms The data draws from a more comprehensive case study, with the aim of generating a holistic picture of how the teachers generally perceive their role in a technology-rich primary school environment, and how using technology has influenced their perceived classroom management practices. The study follows the principles of an intrinsic case study design, as defined by Stake (1995) , with its focus on empirical, descriptive and interpretive knowledge of that one particular case. The complexity of the phenomenon advised a qualitatively driven mixed methods study, where the data was collected cumulatively by employing individual interviews, observation, focus group interviews and a survey. Triangulation of qualitative data was used to increase validity and reliability when analyzing and interpreting the results. This article has a focus on teachers’ own perceptions; therefore the main sources of data for this paper are the interviews and the survey, while observation findings have a more supplementary role in providing examples and adding in-depth information to interview results.

Context and Participants

Due to the nature of this case study, it served the purpose to apply the principles of purposeful sampling ( Bryman, 2016 ; Creswell and Guetterman, 2021 ). The data was collected in a Norwegian primary school where PDC training of the staff and ICT implementation have a high priority. The school has made significant investments in utilizing digital technologies in a best possible way; thus, a social constructivist approach highlighting the interaction between individual experiences, ideas and environment was considered a relevant epistemological standpoint. Seven teachers on two different grade levels were first interviewed individually and then observed. Focus group interviews rounded the qualitative data collection, and the same seven teachers were then interviewed in their respective grade level teams. The survey was sent to all teachers teaching in the school after a thorough analysis of interview and observation data, and all 19 teachers working at the time submitted their answers, as well as one informant with a combined role as a teacher and administrator. The participants had been working in primary and lower secondary education for varying lengths of time: their seniority ranged from 3 to 27 years, with the median value of 14.

Instruments

Seven one-on-one interviews were chosen to start the data collection process, to map out how the teachers themselves perceived their role and changes in their classroom management practices. An abductive approach in their interviews enabled a semi-structured interview design where the interviewer was able to collect data about some of the preselected topics, while also enabling elaboration and ranging out when the interviewees brought up other perspectives. One of the well-known disadvantages of individual interviews ( Creswell and Guetterman, 2021 ) is that the informants can present somewhat deceptive data by answering based on their assumptions about what the interviewer wants to hear. To address this disadvantage, the interviewees were observed for a duration of four weeks (56 observed lessons, 3515 min in total) after the individual interviews had been conducted. Observation data has also been used to exemplify and to get a more in-depth understanding of the information the participants provided in the interviews. The observation part was based on Merriam and Tisdell’s (2015) checklist of elements important for observation (1) the physical settings, (2) the participants, (3) activities and interactions, (4) conversation, (5) subtle factors, and (6) the researchers’ own behavior.

Two focus group interviews were carried out after the observation period, mainly for two purposes. Firstly, they were executed to gain more in-depth information and understanding of the individual interview and observation data. The same participants who were interviewed individually, and thereafter observed in action, were also interviewed in groups. A semi-structured interview guide was developed in line with the conceptual framework and tentative analysis of the one-on-one interviews and observation data. Focus group approach was considered relevant, as talking to the teachers as a group allowed them to challenge and elaborate on each other’s answers, as well as help the researcher understand how they collectively made sense of their role and classroom management practices in a technology-rich classroom ( Bryman, 2016 ). Focus group interviews also helped avoid misinterpretations and validate previously collected data. The second purpose for focus group interviews was to gain some information regarding the school’s resources and philosophy regarding technology, teaching and learning in general. This third focus group interview was carried out with the school’s development team (three members of the school leadership and a teacher member). Also in this interview, it was of interest to find out how individuals discuss the matter as a group, building out an understanding from the interaction between the members of the group ( Bryman, 2016 ).

The survey was based on an analysis of the interview and observation data and took place approximately 9 months after the focus interviews. The purpose of the survey was to verify interpretations of the qualitative data and to obtain a more representative sample of the qualitative data ( Maxwell, 2010 ; Hesse-Biber et al., 2015 ). In addition, the intention with the survey was to identify and check for diversity vs. uniformity in the data material, in order to avoid the claim of cherrypicked data for only supporting certain interpretations ( Maxwell, 2009 ). The survey consisted of 56 questions. Five of these questions were administered to gain more knowledge about the participant demographics, and nine of the questions were open-ended, allowing the informants to comment freely or complement their other answers. The main part of the questionnaire consisted of 42 questions where the informants reflected on their personal beliefs, experiences and practices in regards to education and technology. They used two different scales to provide their answers: one to express their personal beliefs, and another one to reflect on their own practices and experiences.

A simultaneous analysis and collection of data was used during the project, during which the methodological approaches built on and informed the subsequent steps ( Merriam, 1998 ). This cumulative process was carried out to increase the ecological validity ( Gehrke, 2014 ) and minimize researcher bias and reactivity ( Maxwell, 2009 ). Such approach to the analysis is considered both relevant and necessary in a case study with constructive epistemological commitments and holistic perspectives as some of the central characteristics ( Stake, 1995 ; Merriam, 1998 ).

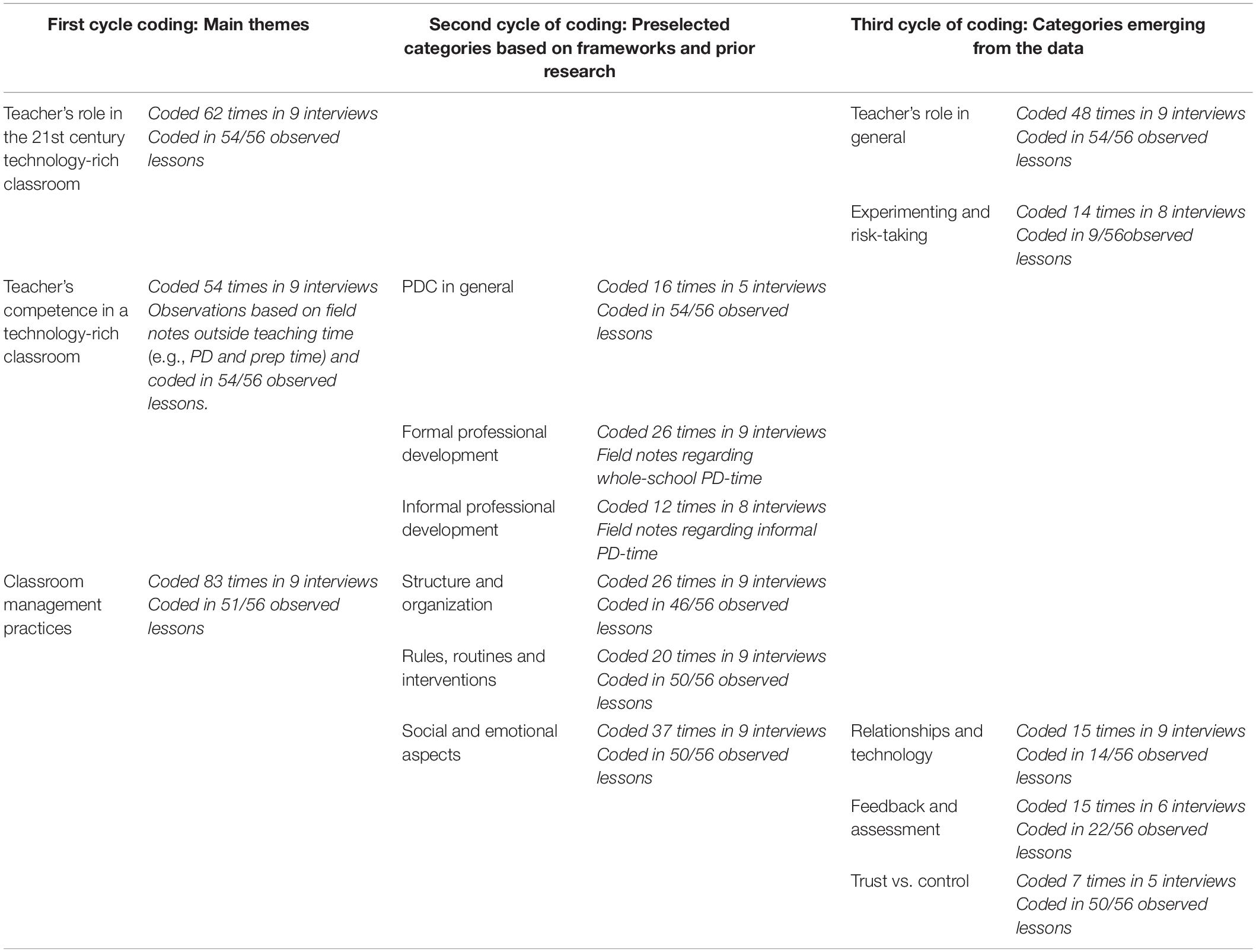

The analysis of individual interviews followed the main principles of thematic analysis ( Bryman, 2016 ), and NVivo was used to organize and code the interview data. Once all interviews were transcribed, the data was first organized in main themes that draw from the research questions of the case study. This was done to separate results relevant for this particular article from all case study data and coded using the main themes as codes. During the second cycle, the data was coded into preselected categories that derive from the most relevant frameworks and literature, which were also employed when developing interview and observation guides. These frameworks and literature define and discuss teacher’s role in a 21st century classroom (e.g., Hattie, 2009 ), teacher’s competence in a technology-rich classroom (e.g., Kelentrić et al., 2017 ) and different aspects of classroom management (e.g., Bolick and Bartels, 2015 ). The third cycle of interview data analysis prompted new codes, which emerged from the data itself. Ryan and Bernard’s (2003) checklist was employed to identify and develop possible new categories, as well as for analyzing the data. During this phase, for instance repetition, similarities, differences, transitions and what is missing from the data were analyzed. The same procedure was used to code and analyze the focus group interviews; however, no new categories emerged from focus group interview data. During the interviews, the topics had a tendency to overlap and emerge several times during one interview. For instance, during the 9 interviews, teacher’s competence was discussed – or at least mentioned – 54 times, so 54 excerpts of the data were tagged with the code ‘teacher’s competence’. All codes and their frequency in data are presented in Table 1 .

Table 1. Overview of coding of the interviews and observations.

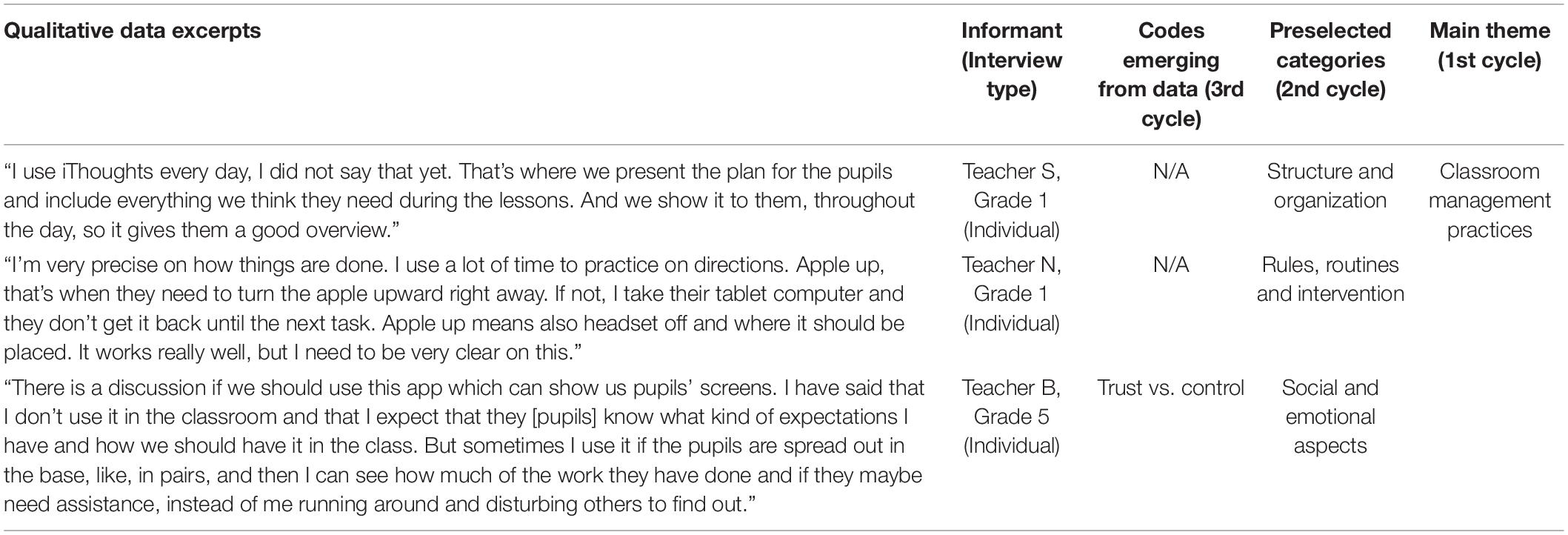

Table 2. Example of qualitative interview data coding: classroom management practices.

Observation data was coded analogically twice: first, using cycle 1 categories and later, cross-referencing with cycle 2 and 3 categories from the interviews. While many of the categories were present during all lessons, the focus was on how technology influenced either teacher’s role or their chosen classroom management practices. For instance, all lessons were organized in one way or the other, and teacher-pupil relationships are an integral part of every single lesson, but when coding and categorizing the contents of the observed lessons, only lessons where technology clearly influenced teachers’ role or classroom management practices were coded.

As the interview and observation data were used to develop the survey , there were questions directly and indirectly linked to all categories. Due to the small sample size, Microsoft Excel offered sufficient tools for analysis of quantitative data. All multiple-choice survey data was converted into numeric values, after which an analysis was run to detect patterns, repetition and other features. Sorting, filtering, conditional formatting and visualization of data were used to not only detect patterns in general, but also to compare results between teachers with and without higher education PDC training.

Results are presented in Tables 3 , 4 in the Section “Results” and divided into categories matching the coding cycles and categories.

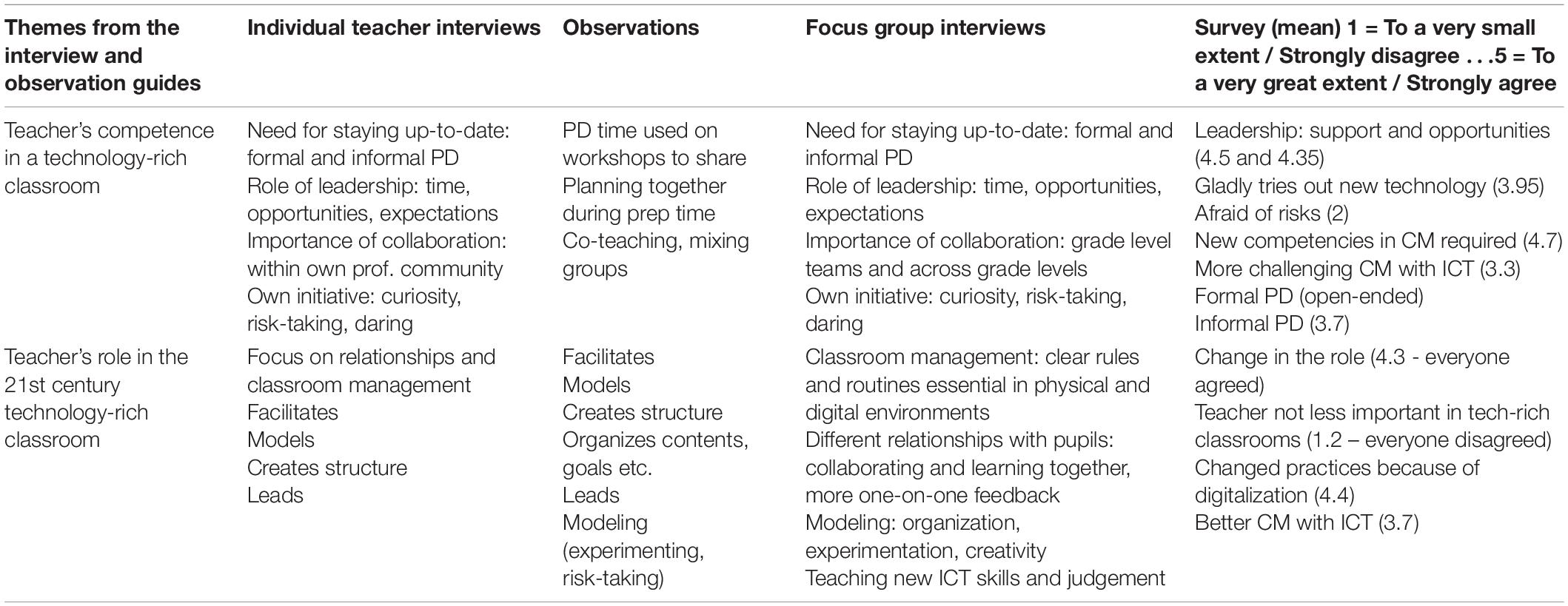

Table 3. Teachers’ perceptions of their role and competence in regard to classroom management in a technology-rich primary school classroom – summary of data.

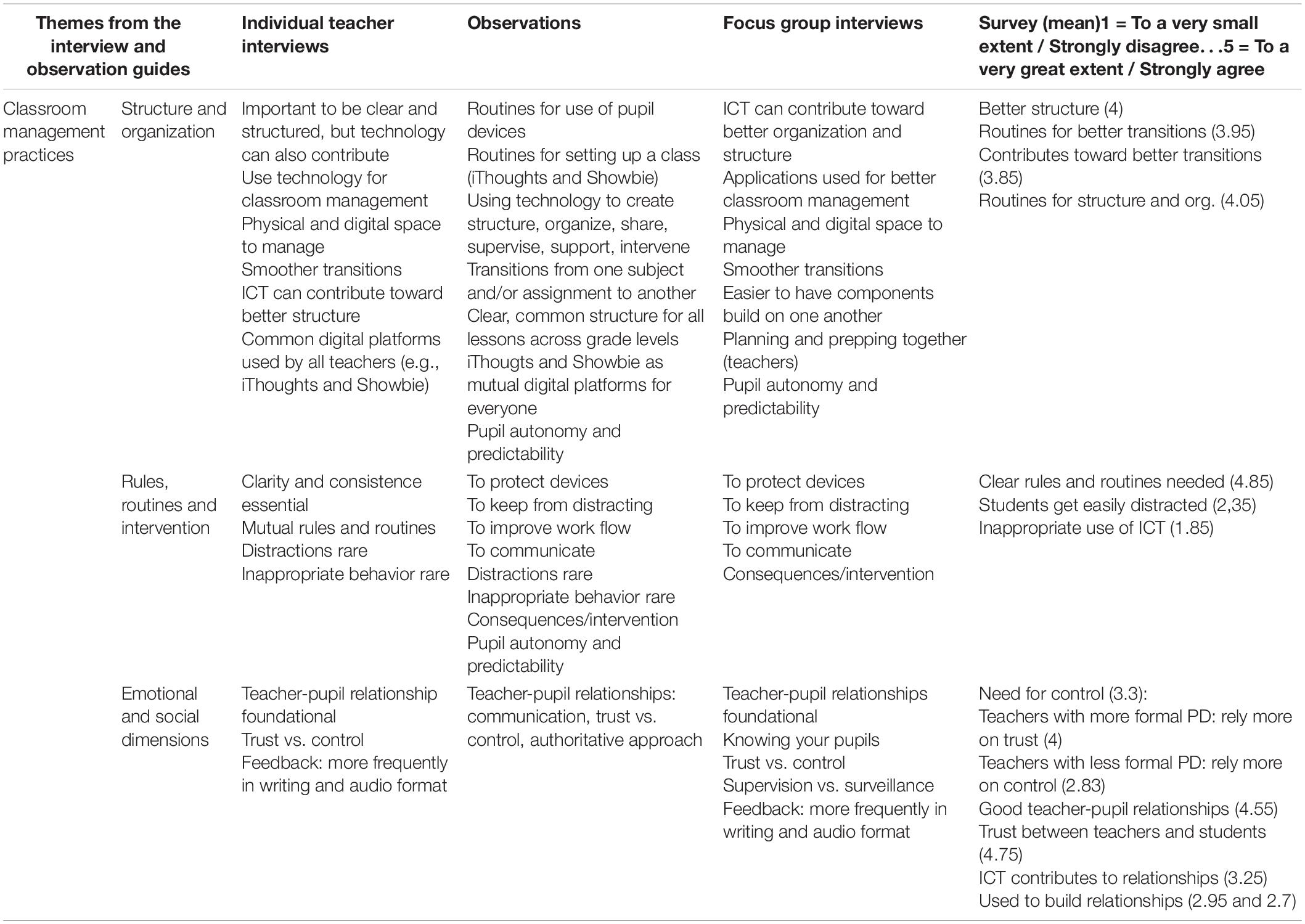

Table 4. Teachers’ perceptions of classroom management in a technology-rich primary school classroom – summary of data.

The main findings regarding classroom management from each stage of data collection were organized in tables, as pictured below ( Tables 3 , 4 ). As visible in the tables, the same themes were often discussed in both, individual interviews and focus group interviews, and the participants in both types of interviews were the same teachers. In most cases, a topic was first brought up by the interviewer or the interviewee in one or more one-on-one interviews, and later, the topic was revisited in a focus group interview, in order to elaborate, gain more perspectives and find out about the informants’ collective views on it. The actual results from both types of interviews were very similar, with the focus group perspectives commonly offering more detail and exemplification, and that is why all interviews in the Section “Results” are simply referred to as “interviews,” without making a distinction between individual and focus group results.

The results of the coding and analysis introduce several interesting aspects of classroom management, such as changes in the traditional role and competence of a teacher. In what follows, these aspects will be further investigated in terms of the categories presented in Tables 1 – 4 . All interviewees considered teacher’s role in a classroom somewhat different today than what it used to be, prior to the march of educational technologies. Teacher interviews indicated that one of the most notable changes regarding teacher’s role as a classroom manager is having to constantly keep up-to-date with the rapid developments of digital technologies and understanding how technology can be used – or abused – in a classroom.

“You have to be ready for change yourself.—. That’s how it is with technology, too, all the time. You can’t just stop. You have to keep developing yourself to secure learning.” (Teacher T, Grade 5).

Some interviewees pointed out that in their busy work days, it could be difficult to find time for keeping up with the rapid developments of educational technologies, finding out about new possibilities and taking full advantage of the existing technologies. They noted that the leadership in the school has a major role in securing enough time for teachers to get the time and training that they need to perform their job in a satisfactory manner. The interviewees found that professional development opportunities offered by the school and particularly sharing in their own professional community had been important sources of new competencies, but that one also has to take initiative oneself and want to learn more.

“But we have PD time when we sit together and get a glimpse of and learn so that everyone can feel that they can use it [ICT]. And they [leadership] want that we use it, so that all the pupils can use it. So, there is a little bit of pressure, but that just fun. — And it’s important to have a little bit of a push, so that everyone learns it.” (Teacher S, Grade 1).

In the survey, teachers reported that they gain new competencies through formal professional development, such as attending higher education courses and programs, courses offered by the municipality or a commercial provider, and workshops within their own professional community. Informal professional development channels, such as social media and particularly impromptu collegial collaboration, also held a significant role. In the survey, 18 out of 20 informants reported that their employer offered them opportunities for professional development in regard to educational technologies to a great or very great extent, and 19 out of 20 informants felt that their leaders supported the development of their professional digital competence in other ways to a large or very large extent. 13 out of 20 informants had completed or were in the process of completing a formal PDC training program in higher education (30 ECTS points) and 13 out of 20 teachers reported that they use informal methods, for example social media and other web resources, for professional development to a great, or very great extent.

All interviewees found that while they are just as needed in the technology-rich classrooms than before, the way they view themselves as the classroom authority has changed. In the interviews the teachers described how the more traditional leader role, where a teacher should know and be able to do everything, has become obsolete in the 21st century.

“It’s always difficult to know what’s happening, but we are a little bit more exploratory together with our pupils. Like, we were always the know-it-alls, but we don’t have to be that anymore. We are a team with them [pupils], and I think it’s a good thing. More exciting: we can’t do this; we need to find out!” (Teacher I, Grade 1).

During the observed lessons, teachers exercised this type of approach for example by allocating time for experimenting and exploring with their pupils, for example when learning about the basic principles of coding and using robotics to measure and define angles. The teachers had created a structure for these lessons and guided their pupils, but had chosen an approach similar to guided inquiry, where they helped their student to learn through exploration, investigation and active dialogue. While there were several examples where the teachers had adopted more of a facilitator role in their pupils’ learning process, more traditional use of technologies, such as to search information, create digital products that reproduce old knowledge or using an application targeting specific skills, were also used regularly.

All 20 survey informants agreed teachers are as much needed in the classrooms than before, but that it is necessary to gain new competencies in regard to classroom management, such as knowledge about digital technologies, solid basic skills with technology, student-active approaches to pedagogy, and ability to let go of some of the control in the classroom.

Structure and Organization

All interviewees reported that they use technology in their classrooms to organize contents and create structure for their lessons, and they found that digital technology had made contributions to classroom management in this area, such as better transitions between subjects and assignments, and easy platforms for lesson plans and contents.

“It can actually create better structure in teaching because the different parts we work on build on one another.” (Teacher D, Grade 1).

“You have lots of tools available right there on your iPad, so when you transition from one exercise to another you use digital tools, so you don’t have to get up and fetch things.” (Teacher T, Grade 5).

When observing how teachers used digital tools to organize instruction and create structure for their lessons, much of what they did and used was based on mutual agreements of tools used within the professional community. They used the same applications, for example iThoughts and Showbie, to organize and distribute information, resources and assignments, and pupils could find assignments and resources, as well as organize and submit their own work through these platforms. This, according to the teacher interviews, was a result of leadership, collaboration and ongoing professional development, to help teachers feel confident and competent when managing the pedagogical work, and to create predictability and frequent opportunities for self-direction for their pupils. Interviewees found that the ease of access to pupils’ work and giving feedback had enabled the teachers to give more feedback to their pupils, which in return had contributed toward better teacher-student relationships. They also felt that they were given the freedom to try out and experiment with new potential technologies or how to use old technologies in a new way.

“They (leadership) are not going to make you accountable if you have used… you have taught and tried… wanted to try something. They won’t make you accountable. They rather say that cool that you tried that, and now you can rather learn from it, how to do it.” (Teacher T, Grade 5).

Survey results reveal that only one of the 20 teachers did not believe that technology could contribute toward better structure, and similarly only one informant reported little or no routines in the structure and organization in a technology-rich classroom. 13 out of 20 informants found that digital technologies make transitions easier, and 14 out of 20 teachers had routines in their classroom where technology contributed toward smoother transitions.

Risk-Taking and Relationships

When discussing different themes during the interviews and reading comments on the survey, a recurring aspect of teacher’s role was teacher’s willingness to take risks and its importance in personal professional development and when using technology to model learning to the pupils. One of the seven interviewees admitted that they sometimes feel somewhat anxious about trying new things, while the other interviewees reported no fear toward technologies, as long as they can test out the new technologies beforehand. Some of the interviewees pointed out that while they had received a significant amount of professional development within educational technologies and felt rather confident about working in technology-rich learning environments, they also found that with technology, unexpected setbacks inevitably happen; however, it did not frighten them or make them shun technology. They found it important to “take the plunge” and dare to model also a trial-and-error approach to their pupils, and be a teacher who takes risks and learns together with their pupils. Such approach was observed for example when using the new podcast studio for the first time and composing music with micro:bit.

Survey results indicate that the teachers in this school are generally not avoiding risk taking, nor are they afraid of making mistakes in front of their pupils: 14 out of 20 teachers reported little or no fear toward taking risks or failing in front of their pupils when using digital technologies, while 5 out of 20 teachers had concerns about this to some or great extent.

While it was emphasized in many of the interviews and comments in the survey that it is important to plan meticulously and be well-prepared when incorporating digital technologies in everyday classroom work, the informants also found that witnessing a teacher fail with their plan could provide learning opportunities for the students.

“I think that the kids learn also from it, that things don’t always work out as they should. That’s how it is.” (Teacher S, Grade 1).

In the individual interviews, teachers mentioned good relationships in the classroom as the main reason for not being afraid to try something new and take a risk. The importance of having good teacher-pupil relationships in the classroom was also highlighted in the survey, as 17 of the 20 informants agreed that good teacher-pupil relationships are particularly important in technology-rich classrooms. Also trust between teachers and pupils was seen as an important factor, as 18 of the 20 informants agreed that trust between teachers and pupils is particularly important in a technology-rich environment. When pupils and teachers knew each other and were comfortable in each other’s presence, teachers were more willing to take risks.

“When I have good relationships with them… that’s important to have first because I understand if someone finds it uncomfortable, pupils that I haven’t had much, but now I can luckily say that you know what, this is the first time I try this, first time that you try this, so we’ll see together how it works out.” (Teacher B, grade 5).

While good relationships and trust were highlighted as a prerequisite for effective work with digital technologies also in the survey, routines where technology actually contributes toward building relationships were found in a great or very great extent in only seven classrooms, and to some extent in ten classrooms. Three teachers reported little use of technology in regard to promoting relationships.

Rules and Routines

Having clear rules and routines has been a classroom management corner stone as long as classroom management has existed, and according to the participants in this case study, this isn’t any different in a technology-rich classroom. When asked about such rules in the interviews, teachers listed mostly rules and routines that were created to protect the devices and diminish distractions; however, some teachers focused on rules that were more relevant for ethical aspects of using digital technologies.

“Perhaps we need to be extra clear with technology. — It can be damaged if it falls on the floor. With a pencil it’s not that dangerous if it’s lying on the floor.” (Teacher N, Grade 1).

“The importance of privacy and everything that goes with netiquette, yes, we have rules at school about how that works.” (Teacher O, Grade 5).

Much like with structure and organization, also with rules and routines the interviewees found it to be important that there are some mutual agreements across the whole school, to create consistence for pupils and assist them with delf-direction and self-regulation. For example, when a teacher called “Apple up” in any of the observed classrooms, all the pupils knew what to do and placed their devices on the desks screen down. With rules also came consequences for not following the rules, and in the few observed violations the consequence was always the same: after a few reminders from the teacher, the pupil had to shift from digital devices to paper and pen.

All the data in this study indicates that the pupils across grade levels had generally a good understanding of how to treat their devices and when and how to use them. Teacher interviews indicated very little distractions and inappropriate use of technology, and the interviewees mentioned single cases where a student had misused their device during class, but none of the interviewees found it to be a recurring problem; however, the interviewees did acknowledge that without clear structures, instructions and routines, technology could become a distraction or lead to accidents with devices. Only few minor incidents were detected during the observed lessons, as well: in a typical scenario, a pupil spend a short time on a website with no relevance to the task, but was quickly returned to the task either by a peer, teacher or themselves. In the survey, 18 out of 20 informants agreed with the statement “it is particularly important to have clear rules and routines in a technology-rich classroom.” 17 out of 20 teachers reported very or quite little inappropriate use of technology during their lessons, and three teachers reported it to some extent. 17 out of 20 teachers found it to be a good idea to include pupils in the decision-making when the rules and routines where formed.

While the teachers had rather similar thoughts about changes regarding teacher’s role, rules, risk-taking and structure and organization, an aspect which they did not entirely agree on was how much they needed to be in control over what was happening on pupils’ personal devices. Some interviewees found that younger pupils, who were new to technology and school, had perhaps more need for teacher’s monitoring. Some teachers, however, found that it was the older pupils who might have to be monitored more closely, but that teachers can have a great influence on how well pupils follow up by planning ahead well.

“Yes, yes, one has to create such structure that they actually stay focused. I think this specifically concerns older pupils, as they would like to surf on the Internet and get distracted with other things.” (Teacher S, Grade 1).

Observations revealed that it was rather common in this school that groups got mixed and teachers and pupils took advantage of expanded physical learning space outside their classrooms, for instance hallways, library and smaller work rooms. The interviewees found that digital technologies are useful when the physical learning space expands but that it sets challenges to classroom management, as the teacher is no longer physically in the same space with the student. Using applications that allow teachers to view and partially control pupils’ devices, such as Apple Classroom and ZuluDesk, was observed mostly in grade 5, where the students were also more often trusted to spread out in the physical space. Using such applications was something that teachers had somewhat controversial views and practices on. Those using them found it important to always inform their students when they were using the apps and explain why. They wanted to emphasize that they used it for supervision, not for surveillance: the purpose was not to “get” pupils that had gotten distracted but to communicate and support the pupils through the application when the teacher could not be physically present. Teachers also used it to get an overview for themselves, and in some rare cases for intervention. The complexity of using such applications was reflected in the interview dialogue:

“I believe that the pupils should get the… they should feel trusted to do what they are supposed to do. But sometimes, you see, like generally in the working environment, it gets a little out of hand. It makes it a little more effective, also for myself. I use it more with some groups than the others, because there is a greater need for motivating. So, the danger with these things is that you almost monitor the pupils constantly, that they… like, that they are under surveillance. But the positive is that you can help those who don’t always stick with what they are supposed to. — I use it a lot to, in a way, to get a glimpse myself, where everyone’s at. I can’t do that if they’re using books. — With Classroom app it is easy to see where everyone’s at, is it time to move on with the class or do we need to wait a little.” (Teacher T, Grade 5).

Also survey results reveal variation, and that teachers with more formal PDC training (minimum of 30 ECTS points in PDC in higher education, either in process or completed) seemed to find it less necessary to have constant control over pupil screens (average value 3) than those who had less formal training (average value 3.86). There were no obvious differences between grade levels; however, during the observations, control-related aspects seemed to play a larger role in lower grades than in upper primary school. There teachers reinforced particularly rules revolving around safety of the device: how to hold it, where to store it and how to carry it. In upper primary grades, pupils were more often taking advantage of an extended physical learning space, and more use of applications that allow access to pupils’ devices was more common.

Discussion and Concluding Remarks

The purpose of this study was to find out how the use of digital technologies influences the way teachers perceive their role and classroom management practices in a technology-rich primary school. To sum up the informants’ perceptions of their role in technology-rich environment, they agreed in many aspects regarding the teacher’s role. They found that a teacher has become more of a facilitator, who creates structure and opportunities for learning and models learning processes, for example through experimenting and collaborating with their pupils. An authoritative teacher role in a classroom environment characterized by good relationships and clear routines and rules was considered foundational, and such appreciation was in line in many of the informants’ classroom management practices. The informants also agreed that due to the rapid developments of digital technologies, keeping up-to-date and gaining new competences, such as mastering basic technological skills and understanding the possibilities and pitfalls of digital technologies, has become increasingly important. They found that the leadership has a crucial role in not only offering professional development opportunities, but also expecting the teachers to take advantage of them. School leaders that facilitate for a school culture where experimenting with technologies was encouraged, and which builds on collegial collaboration, was found important for supporting teachers in their never-ending quest for those new competencies and skills. These components had helped the informants to “take the plunge” and elevate their PDC in regards to classroom management.

The contemporary aspects of teacher’s role as a classroom manager in a technology-rich environment are reflected in many of the classroom management practices of the informants. It is important to emphasize that the data for this case study was collected in a school that can rather be viewed as a frontrunner than mainstream, as they had made significant investments in digital technologies, teacher training and generally building a school culture where digital technologies are a natural part of everyday practices. This can in part explain the generally positive and progressive perceptions the informants had toward classroom management in technology-rich learning environment, as well as explain some of the interesting deviation from previous research. One of such elements is the informants’ willingness to adopt practices that demonstrate experimenting and playfulness. The teachers in this study reported very little fear for risk-taking and failing when using digital technologies, in contrast to many previous studies ( Blikstad-Balas, 2012 ; Krumsvik et al., 2013 ). The reasons can be many, but one could assume that the investment in teachers’ PDC has made the teachers more confident when implementing new technologies, and thus, they are also more willing to be more exploratory in their own practices. An indication that supports the abovementioned assumption is that in this case study, teachers with more formal PDC training were generally less concerned about control and more often found that digital technologies contribute toward better classroom management than their colleagues with less formal professional development. Such results imply that although collegial collaboration is often seen as one of the most significant ways of gaining more competence ( Borko, 2004 ; Voogt et al., 2011 ; Fjørtoft et al., 2019 ), the role of more systematic, knowledge-based professional development should not be undervalued ( Hughes, 2005 ). A good socio-emotional learning environment has also been found meaningful in technology-rich settings ( Nordenbo et al., 2008 ), and the teachers in this study found good teacher-pupil relationships foundational for establishing an environment where also a teacher can experiment with new approaches, reflecting a somewhat playful attitude, which is in line with the concept of cognitive playfulness and its affordances ( Webster and Martocchio, 1992 ; Goodwin et al., 2015 ). As mentioned earlier in this article, teacher’s ability to build good relationships and an encouraging learning environment can be viewed as one of the key classroom management competences ( Powell et al., 2001 ; Evertson and Weinstein, 2006 ; Korpershoek et al., 2016 ) and teachers have a tendency to invest in quality classroom management more in primary level than in later years ( Beijaard et al., 2000 ; Bru, 2013 ; Kalin et al., 2017 ). As much of the previous research has been executed in secondary and higher education settings, an intriguing question is how much of the fear and negative experiences teachers have experienced when using digital technologies derive from the lack of time or effort in developing good relationships and a safe social classroom environment.

Results from national mappins of digitalization of Norwegian schools also report about a trend where disruptions and inappropriate use of digital technologies are steadily decreasing in Norwegian schools ( Hatlevik et al., 2013 ; Egeberg et al., 2016 ; Fjørtoft et al., 2019 ). While the informants in this study acknowledged that there had been single events where pupils had misused their devices, and that technology could potentially cause distractions, none of them found this to be a recurring issue. The informants in this study could name multiple factors that can contribute toward better engagement and less issues with non-instructional use of technology: teachers’ own competence in classroom management, meticulous planning, good relationships with their students and a school culture with mutual and clear rules and routines for technology use worked effectively in preventing such behavior ( Erstad, 2012 ; Wang et al., 2014 ; Baker et al., 2016 ; Alter and Haydon, 2017 ; Tondeur et al., 2017 ; Moltudal et al., 2019 ). Bjørgen (2021) suggests that we should in a much larger extent invite pupils’ framings and priorities into school-related digital practices, to learn and understand how they engage in digital practices outside school. Building such a connection could assist in creating an engaging and supportive learning environment, which is essential for quality classroom management.

During the past decade, as teachers’ awareness and competence regarding digital technologies has increased ( Fjørtoft et al., 2019 ), rules and routines framing how and when to use technology at school have also evolved substantially. While teachers and pupils reported less mutual rules for technology use in class a decade ago ( Krumsvik and Jones, 2015 ), the teachers in this study found that practicing classroom management with clear and consistent rules and routines is foundational in technology-rich learning environments. It could be argued that while there was some variation between grade levels in this study, the mutual ground rules for technology use across the whole school can help pupils internalize the rules and routines and makes it more predictable and consistent for them, which in turn makes it easier for the pupils to follow them and easier for the teachers to reinforce them. A positive socio-emotional learning environment does not rule out negative consequences, should rules be violated ( Alter and Haydon, 2017 ), and logical consequences that the pupils are aware of, such as having their device confiscated, can be effective in preventing disruptions ( Baker et al., 2016 ; Bjørgen, 2021 ).

A somewhat contradictory finding in this case study is that while the teachers in the interviews and survey highlighted the importance of trust, good relationships and risk-taking, more than half of the teachers still found that a teacher should have control over pupils’ screens at all times. A similar perspective was visible in some of the other findings, as well; for instance, some teachers wanted the devices to be placed and held in a certain way in a classroom, to have a visual on the screens, and teachers used applications that allowed them access to pupils’ screens from a distance. This invites us to ponder why so many teachers still feel a need to have control over pupils’ screens at all times , when they self-report very little non-instructional and otherwise disruptive use of digital technologies. Active monitoring can be efficient to prevent disruptions ( Storch and Juarez-Paz, 2019 ), but one can nevertheless speculate if the pupils still feel trusted – a perspective also discussed in the focus group interviews. It is natural that the teachers want to know what their pupils are doing, and not just to find out if they’re on-task but also to see how far along they’ve come, but this alone does not explain why so many teachers find it important to know about their pupils’ screen activity at all times .

The informants found also that digital technologies have many affordances in creating structure for their lessons. Also in this context, teachers had uniform approaches, in order to create consistency and to support their own professional development, and the findings in all data accentuate the high appreciation of collegial collaboration. In this school, much of the practices, awareness and competence in regards to PDC and digital technologies in general derive from mutual agreements and collaboration. Such approach addresses the risk of widening the gap between teachers’ PDC and classroom practices, and helps create a supportive and motivating community – for teachers and pupils ( Phelps and Graham, 2014 ; Moltudal et al., 2019 ). Meanwhile, the teachers felt that they were allowed and even encouraged to experiment with alternative approaches, and such culture can be highly valuable to make sure that common practices can be questioned, re-evaluated and even criticized.

The results presented in this article confirm what previous research already has suggested: technology-rich learning environments require contemporary competencies and pedagogical approaches to classroom management. A somewhat playful attitude, meticulous planning, frequent opportunities for professional development, collegial collaboration and good teacher-pupil relationships all seem to make considerable contributions toward more effective classroom management in technology-rich classroom environment, while ethical and philosophical questions regarding the overall understanding of the use of ICT in classroom management seem to require further attention. Naturally, as an intrinsic case study ( Stake, 1995 ), these findings have their limitations regarding generalizability, but at the same time, they do provide us with important descriptions and examples regarding teacher’s role and classroom management practices in a technology-rich primary school. In this study, we have delved into teachers’ perceptions in order to cast light on how they perceive their role and classroom management practices in technology-rich environments, but the field certainly has more space for pupils’ voices, as well ( Meinokat and Wagner, 2021 ). In the light of lack of uniform definitions and practices, as well as scarcity of relevant studies from primary education ( Bolick and Bartels, 2015 ; Cho et al., 2020 ; Meinokat and Wagner, 2021 ) we find these results promising regarding implications toward succeeding in classroom management in technology-rich learning environments but acknowledge the need for gaining more knowledge and further research focusing particularly on classroom management in primary education.

Limitations

In this case study certain limitations can be identified. One limitation is related to that the majority of the empirical data applied in this article is based on self-reported data (interviews, focus groups and survey) and might reflect the teachers’ intentions more than the actual situation in their daily practices. Another limitation might be that the selected school has a clear digital agenda, the majority of the sample consists of teachers participating in professional development within PDC and the study has been carried out among young pupils (grades 1 to 7) with less pronounced digital lifestyle and with less digital distractions in classrooms than among older pupils ( Fjørtoft et al., 2019 ). In terms of coding, all coding was executed by a single person. While this eliminates discussion regarding intercoder reliability, it can raise questions about the reliability of the results and a researcher looking to confirm certain expectations or hypothesis. Potential bias related to one coder has been addressed in the design, which relies on triangulation of rich qualitative data, as well as mixed methods design. Executing an excessive cumulative data collection process and analysis during a long period of time allowed the researcher to confirm their interpretations along the way, as well as detect contrary evidence and reach saturation during the coding and analysis ( Creswell and Guetterman, 2021 ).

Data Availability Statement

The anonymized datasets generated for this study are available on request to the corresponding author.

Ethics Statement

The studies involving human participants were reviewed and approved by the NSD - Norwegian Centre for Research Data. The patients/participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Author Contributions

MJ is the primary author of the manuscript. RJK, HEB, and NH have made significant contributions to article revisions. All authors have approved the submitted version.

This research and the publication fees related to it were funded by the University of Stavanger as a part of Johler’s doctorate training program.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s Note