- Skip to main content

- Skip to primary sidebar

- Skip to footer

- QuestionPro

- Solutions Industries Gaming Automotive Sports and events Education Government Travel & Hospitality Financial Services Healthcare Cannabis Technology Use Case NPS+ Communities Audience Contactless surveys Mobile LivePolls Member Experience GDPR Positive People Science 360 Feedback Surveys

- Resources Blog eBooks Survey Templates Case Studies Training Help center

Home Market Research Research Tools and Apps

Action Research: What it is, Stages & Examples

The best way to get things accomplished is to do it yourself. This statement is utilized in corporations, community projects, and national governments. These organizations are relying on action research to cope with their continuously changing and unstable environments as they function in a more interdependent world.

In practical educational contexts, this involves using systematic inquiry and reflective practice to address real-world challenges, improve teaching and learning, enhance student engagement, and drive positive changes within the educational system.

This post outlines the definition of action research, its stages, and some examples.

Content Index

What is action research?

Stages of action research, the steps to conducting action research, examples of action research, advantages and disadvantages of action research.

Action research is a strategy that tries to find realistic solutions to organizations’ difficulties and issues. It is similar to applied research.

Action research refers basically learning by doing. First, a problem is identified, then some actions are taken to address it, then how well the efforts worked are measured, and if the results are not satisfactory, the steps are applied again.

It can be put into three different groups:

- Positivist: This type of research is also called “classical action research.” It considers research a social experiment. This research is used to test theories in the actual world.

- Interpretive: This kind of research is called “contemporary action research.” It thinks that business reality is socially made, and when doing this research, it focuses on the details of local and organizational factors.

- Critical: This action research cycle takes a critical reflection approach to corporate systems and tries to enhance them.

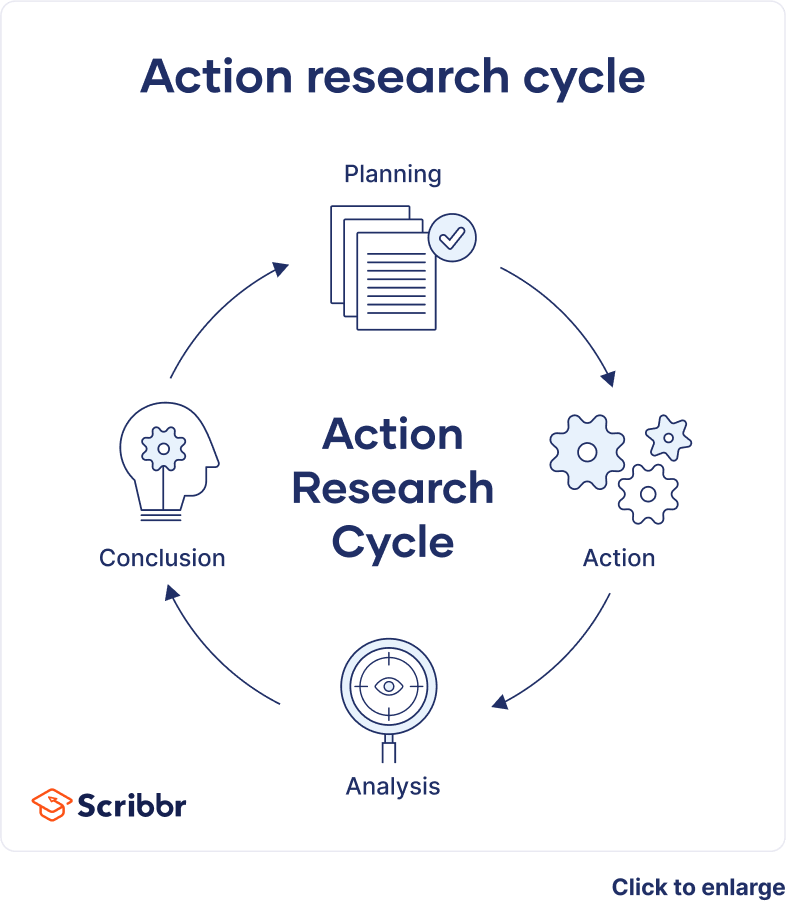

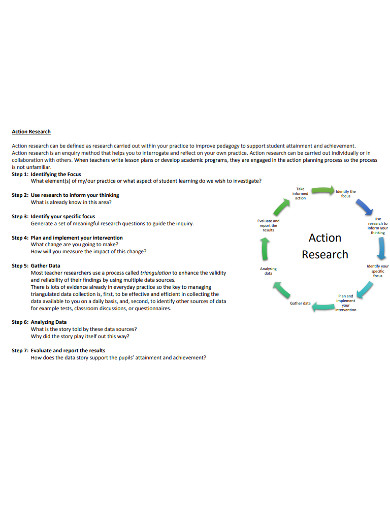

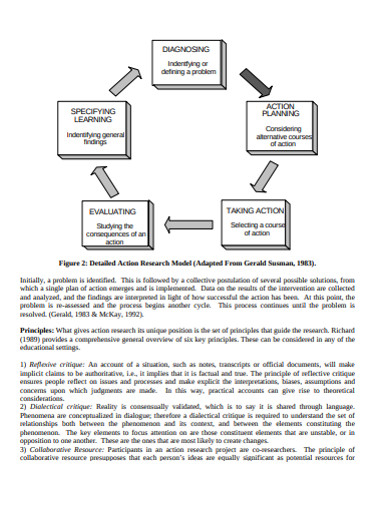

All research is about learning new things. Collaborative action research contributes knowledge based on investigations in particular and frequently useful circumstances. It starts with identifying a problem. After that, the research process is followed by the below stages:

Stage 1: Plan

For an action research project to go well, the researcher needs to plan it well. After coming up with an educational research topic or question after a research study, the first step is to develop an action plan to guide the research process. The research design aims to address the study’s question. The research strategy outlines what to undertake, when, and how.

Stage 2: Act

The next step is implementing the plan and gathering data. At this point, the researcher must select how to collect and organize research data . The researcher also needs to examine all tools and equipment before collecting data to ensure they are relevant, valid, and comprehensive.

Stage 3: Observe

Data observation is vital to any investigation. The action researcher needs to review the project’s goals and expectations before data observation. This is the final step before drawing conclusions and taking action.

Different kinds of graphs, charts, and networks can be used to represent the data. It assists in making judgments or progressing to the next stage of observing.

Stage 4: Reflect

This step involves applying a prospective solution and observing the results. It’s essential to see if the possible solution found through research can really solve the problem being studied.

The researcher must explore alternative ideas when the action research project’s solutions fail to solve the problem.

Action research is a systematic approach researchers, educators, and practitioners use to identify and address problems or challenges within a specific context. It involves a cyclical process of planning, implementing, reflecting, and adjusting actions based on the data collected. Here are the general steps involved in conducting an action research process:

Identify the action research question or problem

Clearly define the issue or problem you want to address through your research. It should be specific, actionable, and relevant to your working context.

Review existing knowledge

Conduct a literature review to understand what research has already been done on the topic. This will help you gain insights, identify gaps, and inform your research design.

Plan the research

Develop a research plan outlining your study’s objectives, methods, data collection tools, and timeline. Determine the scope of your research and the participants or stakeholders involved.

Collect data

Implement your research plan by collecting relevant data. This can involve various methods such as surveys, interviews, observations, document analysis, or focus groups. Ensure that your data collection methods align with your research objectives and allow you to gather the necessary information.

Analyze the data

Once you have collected the data, analyze it using appropriate qualitative or quantitative techniques. Look for patterns, themes, or trends in the data that can help you understand the problem better.

Reflect on the findings

Reflect on the analyzed data and interpret the results in the context of your research question. Consider the implications and possible solutions that emerge from the data analysis. This reflection phase is crucial for generating insights and understanding the underlying factors contributing to the problem.

Develop an action plan

Based on your analysis and reflection, develop an action plan that outlines the steps you will take to address the identified problem. The plan should be specific, measurable, achievable, relevant, and time-bound (SMART goals). Consider involving relevant stakeholders in planning to ensure their buy-in and support.

Implement the action plan

Put your action plan into practice by implementing the identified strategies or interventions. This may involve making changes to existing practices, introducing new approaches, or testing alternative solutions. Document the implementation process and any modifications made along the way.

Evaluate and monitor progress

Continuously monitor and evaluate the impact of your actions. Collect additional data, assess the effectiveness of the interventions, and measure progress towards your goals. This evaluation will help you determine if your actions have the desired effects and inform any necessary adjustments.

Reflect and iterate

Reflect on the outcomes of your actions and the evaluation results. Consider what worked well, what did not, and why. Use this information to refine your approach, make necessary adjustments, and plan for the next cycle of action research if needed.

Remember that participatory action research is an iterative process, and multiple cycles may be required to achieve significant improvements or solutions to the identified problem. Each cycle builds on the insights gained from the previous one, fostering continuous learning and improvement.

Explore Insightfully Contextual Inquiry in Qualitative Research

Here are two real-life examples of action research.

Action research initiatives are frequently situation-specific. Still, other researchers can adapt the techniques. The example is from a researcher’s (Franklin, 1994) report about a project encouraging nature tourism in the Caribbean.

In 1991, this was launched to study how nature tourism may be implemented on the four Windward Islands in the Caribbean: St. Lucia, Grenada, Dominica, and St. Vincent.

For environmental protection, a government-led action study determined that the consultation process needs to involve numerous stakeholders, including commercial enterprises.

First, two researchers undertook the study and held search conferences on each island. The search conferences resulted in suggestions and action plans for local community nature tourism sub-projects.

Several islands formed advisory groups and launched national awareness and community projects. Regional project meetings were held to discuss experiences, self-evaluations, and strategies. Creating a documentary about a local initiative helped build community. And the study was a success, leading to a number of changes in the area.

Lau and Hayward (1997) employed action research to analyze Internet-based collaborative work groups.

Over two years, the researchers facilitated three action research problem -solving cycles with 15 teachers, project personnel, and 25 health practitioners from diverse areas. The goal was to see how Internet-based communications might affect their virtual workgroup.

First, expectations were defined, technology was provided, and a bespoke workgroup system was developed. Participants suggested shorter, more dispersed training sessions with project-specific instructions.

The second phase saw the system’s complete deployment. The final cycle witnessed system stability and virtual group formation. The key lesson was that the learning curve was poorly misjudged, with frustrations only marginally met by phone-based technical help. According to the researchers, the absence of high-quality online material about community healthcare was harmful.

Role clarity, connection building, knowledge sharing, resource assistance, and experiential learning are vital for virtual group growth. More study is required on how group support systems might assist groups in engaging with their external environment and boost group members’ learning.

Action research has both good and bad points.

- It is very flexible, so researchers can change their analyses to fit their needs and make individual changes.

- It offers a quick and easy way to solve problems that have been going on for a long time instead of complicated, long-term solutions based on complex facts.

- If It is done right, it can be very powerful because it can lead to social change and give people the tools to make that change in ways that are important to their communities.

Disadvantages

- These studies have a hard time being generalized and are hard to repeat because they are so flexible. Because the researcher has the power to draw conclusions, they are often not thought to be theoretically sound.

- Setting up an action study in an ethical way can be hard. People may feel like they have to take part or take part in a certain way.

- It is prone to research errors like selection bias , social desirability bias, and other cognitive biases.

LEARN ABOUT: Self-Selection Bias

This post discusses how action research generates knowledge, its steps, and real-life examples. It is very applicable to the field of research and has a high level of relevance. We can only state that the purpose of this research is to comprehend an issue and find a solution to it.

At QuestionPro, we give researchers tools for collecting data, like our survey software, and a library of insights for any long-term study. Go to the Insight Hub if you want to see a demo or learn more about it.

LEARN MORE FREE TRIAL

Frequently Asked Questions(FAQ’s)

Action research is a systematic approach to inquiry that involves identifying a problem or challenge in a practical context, implementing interventions or changes, collecting and analyzing data, and using the findings to inform decision-making and drive positive change.

Action research can be conducted by various individuals or groups, including teachers, administrators, researchers, and educational practitioners. It is often carried out by those directly involved in the educational setting where the research takes place.

The steps of action research typically include identifying a problem, reviewing relevant literature, designing interventions or changes, collecting and analyzing data, reflecting on findings, and implementing improvements based on the results.

MORE LIKE THIS

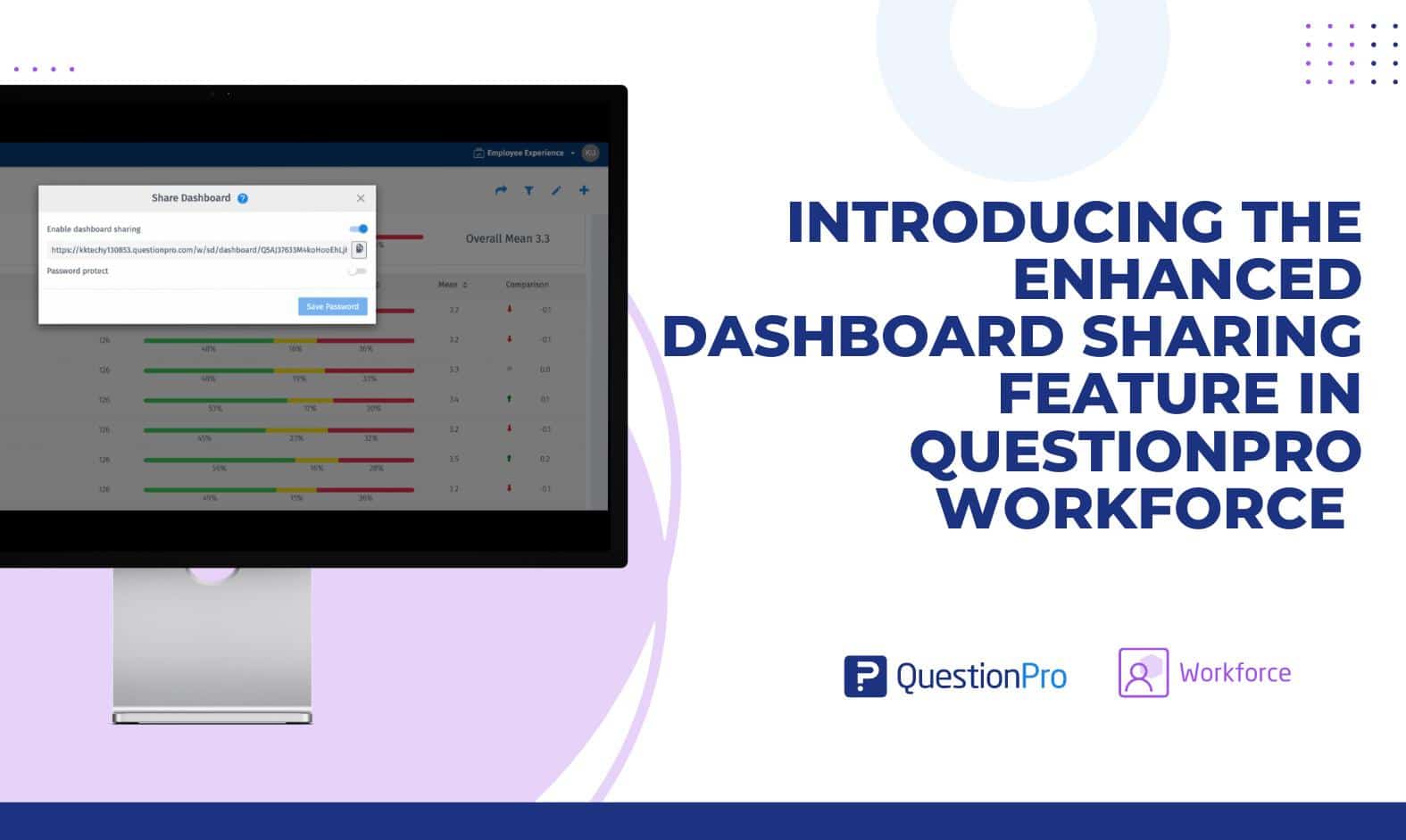

When You Have Something Important to Say, You want to Shout it From the Rooftops

Jun 28, 2024

The Item I Failed to Leave Behind — Tuesday CX Thoughts

Jun 25, 2024

Feedback Loop: What It Is, Types & How It Works?

Jun 21, 2024

QuestionPro Thrive: A Space to Visualize & Share the Future of Technology

Jun 18, 2024

Other categories

- Academic Research

- Artificial Intelligence

- Assessments

- Brand Awareness

- Case Studies

- Communities

- Consumer Insights

- Customer effort score

- Customer Engagement

- Customer Experience

- Customer Loyalty

- Customer Research

- Customer Satisfaction

- Employee Benefits

- Employee Engagement

- Employee Retention

- Friday Five

- General Data Protection Regulation

- Insights Hub

- Life@QuestionPro

- Market Research

- Mobile diaries

- Mobile Surveys

- New Features

- Online Communities

- Question Types

- Questionnaire

- QuestionPro Products

- Release Notes

- Research Tools and Apps

- Revenue at Risk

- Survey Templates

- Training Tips

- Tuesday CX Thoughts (TCXT)

- Uncategorized

- Video Learning Series

- What’s Coming Up

- Workforce Intelligence

21 Action Research Examples (In Education)

Dave Cornell (PhD)

Dr. Cornell has worked in education for more than 20 years. His work has involved designing teacher certification for Trinity College in London and in-service training for state governments in the United States. He has trained kindergarten teachers in 8 countries and helped businessmen and women open baby centers and kindergartens in 3 countries.

Learn about our Editorial Process

Chris Drew (PhD)

This article was peer-reviewed and edited by Chris Drew (PhD). The review process on Helpful Professor involves having a PhD level expert fact check, edit, and contribute to articles. Reviewers ensure all content reflects expert academic consensus and is backed up with reference to academic studies. Dr. Drew has published over 20 academic articles in scholarly journals. He is the former editor of the Journal of Learning Development in Higher Education and holds a PhD in Education from ACU.

Action research is an example of qualitative research . It refers to a wide range of evaluative or investigative methods designed to analyze professional practices and take action for improvement.

Commonly used in education, those practices could be related to instructional methods, classroom practices, or school organizational matters.

The creation of action research is attributed to Kurt Lewin , a German-American psychologist also considered to be the father of social psychology.

Gillis and Jackson (2002) offer a very concise definition of action research: “systematic collection and analysis of data for the purpose of taking action and making change” (p.264).

The methods of action research in education include:

- conducting in-class observations

- taking field notes

- surveying or interviewing teachers, administrators, or parents

- using audio and video recordings.

The goal is to identify problematic issues, test possible solutions, or simply carry-out continuous improvement.

There are several steps in action research : identify a problem, design a plan to resolve, implement the plan, evaluate effectiveness, reflect on results, make necessary adjustment and repeat the process.

Action Research Examples

- Digital literacy assessment and training: The school’s IT department conducts a survey on students’ digital literacy skills. Based on the results, a tailored training program is designed for different age groups.

- Library resources utilization study: The school librarian tracks the frequency and type of books checked out by students. The data is then used to curate a more relevant collection and organize reading programs.

- Extracurricular activities and student well-being: A team of teachers and counselors assess the impact of extracurricular activities on student mental health through surveys and interviews. Adjustments are made based on findings.

- Parent-teacher communication channels: The school evaluates the effectiveness of current communication tools (e.g., newsletters, apps) between teachers and parents. Feedback is used to implement a more streamlined system.

- Homework load evaluation: Teachers across grade levels assess the amount and effectiveness of homework given. Adjustments are made to ensure a balance between academic rigor and student well-being.

- Classroom environment and learning: A group of teachers collaborates to study the impact of classroom layouts and decorations on student engagement and comprehension. Changes are made based on the findings.

- Student feedback on curriculum content: High school students are surveyed about the relevance and applicability of their current curriculum. The feedback is then used to make necessary curriculum adjustments.

- Teacher mentoring and support: New teachers are paired with experienced mentors. Both parties provide feedback on the effectiveness of the mentoring program, leading to continuous improvements.

- Assessment of school transportation: The school board evaluates the efficiency and safety of school buses through surveys with students and parents. Necessary changes are implemented based on the results.

- Cultural sensitivity training: After conducting a survey on students’ cultural backgrounds and experiences, the school organizes workshops for teachers to promote a more inclusive classroom environment.

- Environmental initiatives and student involvement: The school’s eco-club assesses the school’s carbon footprint and waste management. They then collaborate with the administration to implement greener practices and raise environmental awareness.

- Working with parents through research: A school’s admin staff conduct focus group sessions with parents to identify top concerns.Those concerns will then be addressed and another session conducted at the end of the school year.

- Peer teaching observations and improvements: Kindergarten teachers observe other teachers handling class transition techniques to share best practices.

- PTA surveys and resultant action: The PTA of a district conducts a survey of members regarding their satisfaction with remote learning classes.The results will be presented to the school board for further action.

- Recording and reflecting: A school administrator takes video recordings of playground behavior and then plays them for the teachers. The teachers work together to formulate a list of 10 playground safety guidelines.

- Pre/post testing of interventions: A school board conducts a district wide evaluation of a STEM program by conducting a pre/post-test of students’ skills in computer programming.

- Focus groups of practitioners : The professional development needs of teachers are determined from structured focus group sessions with teachers and admin.

- School lunch research and intervention: A nutrition expert is hired to evaluate and improve the quality of school lunches.

- School nurse systematic checklist and improvements: The school nurse implements a bathroom cleaning checklist to monitor cleanliness after the results of a recent teacher survey revealed several issues.

- Wearable technologies for pedagogical improvements; Students wear accelerometers attached to their hips to gain a baseline measure of physical activity.The results will identify if any issues exist.

- School counselor reflective practice : The school counselor conducts a student survey on antisocial behavior and then plans a series of workshops for both teachers and parents.

Detailed Examples

1. cooperation and leadership.

A science teacher has noticed that her 9 th grade students do not cooperate with each other when doing group projects. There is a lot of arguing and battles over whose ideas will be followed.

So, she decides to implement a simple action research project on the matter. First, she conducts a structured observation of the students’ behavior during meetings. She also has the students respond to a short questionnaire regarding their notions of leadership.

She then designs a two-week course on group dynamics and leadership styles. The course involves learning about leadership concepts and practices . In another element of the short course, students randomly select a leadership style and then engage in a role-play with other students.

At the end of the two weeks, she has the students work on a group project and conducts the same structured observation as before. She also gives the students a slightly different questionnaire on leadership as it relates to the group.

She plans to analyze the results and present the findings at a teachers’ meeting at the end of the term.

2. Professional Development Needs

Two high-school teachers have been selected to participate in a 1-year project in a third-world country. The project goal is to improve the classroom effectiveness of local teachers.

The two teachers arrive in the country and begin to plan their action research. First, they decide to conduct a survey of teachers in the nearby communities of the school they are assigned to.

The survey will assess their professional development needs by directly asking the teachers and administrators. After collecting the surveys, they analyze the results by grouping the teachers based on subject matter.

They discover that history and social science teachers would like professional development on integrating smartboards into classroom instruction. Math teachers would like to attend workshops on project-based learning, while chemistry teachers feel that they need equipment more than training.

The two teachers then get started on finding the necessary training experts for the workshops and applying for equipment grants for the science teachers.

3. Playground Accidents

The school nurse has noticed a lot of students coming in after having mild accidents on the playground. She’s not sure if this is just her perception or if there really is an unusual increase this year. So, she starts pulling data from the records over the last two years. She chooses the months carefully and only selects data from the first three months of each school year.

She creates a chart to make the data more easily understood. Sure enough, there seems to have been a dramatic increase in accidents this year compared to the same period of time from the previous two years.

She shows the data to the principal and teachers at the next meeting. They all agree that a field observation of the playground is needed.

Those observations reveal that the kids are not having accidents on the playground equipment as originally suspected. It turns out that the kids are tripping on the new sod that was installed over the summer.

They examine the sod and observe small gaps between the slabs. Each gap is approximately 1.5 inches wide and nearly two inches deep. The kids are tripping on this gap as they run.

They then discuss possible solutions.

4. Differentiated Learning

Trying to use the same content, methods, and processes for all students is a recipe for failure. This is why modifying each lesson to be flexible is highly recommended. Differentiated learning allows the teacher to adjust their teaching strategy based on all the different personalities and learning styles they see in their classroom.

Of course, differentiated learning should undergo the same rigorous assessment that all teaching techniques go through. So, a third-grade social science teacher asks his students to take a simple quiz on the industrial revolution. Then, he applies differentiated learning to the lesson.

By creating several different learning stations in his classroom, he gives his students a chance to learn about the industrial revolution in a way that captures their interests. The different stations contain: short videos, fact cards, PowerPoints, mini-chapters, and role-plays.

At the end of the lesson, students get to choose how they demonstrate their knowledge. They can take a test, construct a PPT, give an oral presentation, or conduct a simulated TV interview with different characters.

During this last phase of the lesson, the teacher is able to assess if they demonstrate the necessary knowledge and have achieved the defined learning outcomes. This analysis will allow him to make further adjustments to future lessons.

5. Healthy Habits Program

While looking at obesity rates of students, the school board of a large city is shocked by the dramatic increase in the weight of their students over the last five years. After consulting with three companies that specialize in student physical health, they offer the companies an opportunity to prove their value.

So, the board randomly assigns each company to a group of schools. Starting in the next academic year, each company will implement their healthy habits program in 5 middle schools.

Preliminary data is collected at each school at the beginning of the school year. Each and every student is weighed, their resting heart rate, blood pressure and cholesterol are also measured.

After analyzing the data, it is found that the schools assigned to each of the three companies are relatively similar on all of these measures.

At the end of the year, data for students at each school will be collected again. A simple comparison of pre- and post-program measurements will be conducted. The company with the best outcomes will be selected to implement their program city-wide.

Action research is a great way to collect data on a specific issue, implement a change, and then evaluate the effects of that change. It is perhaps the most practical of all types of primary research .

Most likely, the results will be mixed. Some aspects of the change were effective, while other elements were not. That’s okay. This just means that additional modifications to the change plan need to be made, which is usually quite easy to do.

There are many methods that can be utilized, such as surveys, field observations , and program evaluations.

The beauty of action research is based in its utility and flexibility. Just about anyone in a school setting is capable of conducting action research and the information can be incredibly useful.

Aronson, E., & Patnoe, S. (1997). The jigsaw classroom: Building cooperation in the classroom (2nd ed.). New York: Addison Wesley Longman.

Gillis, A., & Jackson, W. (2002). Research Methods for Nurses: Methods and Interpretation . Philadelphia: F.A. Davis Company.

Lewin, K. (1946). Action research and minority problems. Journal of SocialIssues, 2 (4), 34-46.

Macdonald, C. (2012). Understanding participatory action research: A qualitative research methodology option. Canadian Journal of Action Research, 13 , 34-50. https://doi.org/10.33524/cjar.v13i2.37 Mertler, C. A. (2008). Action Research: Teachers as Researchers in the Classroom . London: Sage.

- Dave Cornell (PhD) https://helpfulprofessor.com/author/dave-cornell-phd/ 23 Achieved Status Examples

- Dave Cornell (PhD) https://helpfulprofessor.com/author/dave-cornell-phd/ 25 Defense Mechanisms Examples

- Dave Cornell (PhD) https://helpfulprofessor.com/author/dave-cornell-phd/ 15 Theory of Planned Behavior Examples

- Dave Cornell (PhD) https://helpfulprofessor.com/author/dave-cornell-phd/ 18 Adaptive Behavior Examples

- Chris Drew (PhD) https://helpfulprofessor.com/author/chris-drew-phd-2/ 23 Achieved Status Examples

- Chris Drew (PhD) https://helpfulprofessor.com/author/chris-drew-phd-2/ 15 Ableism Examples

- Chris Drew (PhD) https://helpfulprofessor.com/author/chris-drew-phd-2/ 25 Defense Mechanisms Examples

- Chris Drew (PhD) https://helpfulprofessor.com/author/chris-drew-phd-2/ 15 Theory of Planned Behavior Examples

2 thoughts on “21 Action Research Examples (In Education)”

Where can I capture this article in a better user-friendly format, since I would like to provide it to my students in a Qualitative Methods course at the University of Prince Edward Island? It is a good article, however, it is visually disjointed in its current format. Thanks, Dr. Frank T. Lavandier

Hi Dr. Lavandier,

I’ve emailed you a word doc copy that you can use and edit with your class.

Best, Chris.

Leave a Comment Cancel Reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Action Research: Steps, Benefits, and Tips

Introduction

History of action research, what is the definition of action research, types of action research, conducting action research.

Action research stands as a unique approach in the realm of qualitative inquiry in social science research. Rooted in real-world problems, it seeks not just to understand but also to act, bringing about positive change in specific contexts. Often distinguished by its collaborative nature, the action research process goes beyond traditional research paradigms by emphasizing the involvement of those being studied in resolving social conflicts and effecting positive change.

The value of action research lies not just in its outcomes, but also in the process itself, where stakeholders become active participants rather than mere subjects. In this article, we'll examine action research in depth, shedding light on its history, principles, and types of action research.

Tracing its roots back to the mid-20th century, Kurt Lewin developed classical action research as a response to traditional research methods in the social sciences that often sidelined the very communities they studied. Proponents of action research championed the idea that research should not just be an observational exercise but an actionable one that involves devising practical solutions. Advocates believed in the idea of research leading to immediate social action, emphasizing the importance of involving the community in the process.

Applications for action research

Over the years, action research has evolved and diversified. From its early applications in social psychology and organizational development, it has branched out into various fields such as education, healthcare, and community development, informing questions around improving schools, minority problems, and more. This growth wasn't just in application, but also in its methodologies.

How is action research different?

Like all research methodologies, effective action research generates knowledge. However, action research stands apart in its commitment to instigate tangible change. Traditional research often places emphasis on passive observation , employing data collection methods primarily to contribute to broader theoretical frameworks . In contrast, action research is inherently proactive, intertwining the acts of observing and acting.

The primary goal isn't just to understand a problem but to solve or alleviate it. Action researchers partner closely with communities, ensuring that the research process directly benefits those involved. This collaboration often leads to immediate interventions, tweaks, or solutions applied in real-time, marking a departure from other forms of research that might wait until the end of a study to make recommendations.

This proactive, change-driven nature makes action research particularly impactful in settings where immediate change is not just beneficial but essential.

Action research is best understood as a systematic approach to cooperative inquiry. Unlike traditional research methodologies that might primarily focus on generating knowledge, action research emphasizes producing actionable solutions for pressing real-world challenges.

This form of research undertakes a cyclic and reflective journey, typically cycling through stages of planning , acting, observing, and reflecting. A defining characteristic of action research is the collaborative spirit it embodies, often dissolving the rigid distinction between the researcher and the researched, leading to mutual learning and shared outcomes.

Advantages of action research

One of the foremost benefits of action research is the immediacy of its application. Since the research is embedded within real-world issues, any findings or solutions derived can often be integrated straightaway, catalyzing prompt improvements within the concerned community or organization. This immediacy is coupled with the empowering nature of the methodology. Participants aren't mere subjects; they actively shape the research process, giving them a tangible sense of ownership over both the research journey and its eventual outcomes.

Moreover, the inherent adaptability of action research allows researchers to tweak their approaches responsively based on live feedback. This ensures the research remains rooted in the evolving context, capturing the nuances of the situation and making any necessary adjustments. Lastly, this form of research tends to offer a comprehensive understanding of the issue at hand, harmonizing socially constructed theoretical knowledge with hands-on insights, leading to a richer, more textured understanding.

Disadvantages of action research

Like any methodology, action research isn't devoid of challenges. Its iterative nature, while beneficial, can extend timelines. Researchers might find themselves engaged in multiple cycles of observation, reflection, and action before arriving at a satisfactory conclusion. The intimate involvement of the researcher with the research participants, although crucial for collaboration, opens doors to potential conflicts. Through collaborative problem solving, disagreements can lead to richer and more nuanced solutions, but it can take considerable time and effort.

Another limitation stems from its focus on a specific context: results derived from a particular action research project might not always resonate or be applicable in a different context or with a different group. Lastly, the depth of collaboration this methodology demands means all stakeholders need to be deeply invested, and such a level of commitment might not always be feasible.

Examples of action research

To illustrate, let's consider a few scenarios. Imagine a classroom where a teacher observes dwindling student participation. Instead of sticking to conventional methods, the teacher experiments with introducing group-based activities. As the outcomes unfold, the teacher continually refines the approach based on student feedback, eventually leading to a teaching strategy that rejuvenates student engagement.

In a healthcare context, hospital staff who recognize growing patient anxiety related to certain procedures might innovate by introducing a new patient-informing protocol. As they study the effects of this change, they could, through iterations, sculpt a procedure that diminishes patient anxiety.

Similarly, in the realm of community development, a community grappling with the absence of child-friendly public spaces might collaborate with local authorities to conceptualize a park. As they monitor its utilization and societal impact, continual feedback could refine the park's infrastructure and design.

Contemporary action research, while grounded in the core principles of collaboration, reflection, and change, has seen various adaptations tailored to the specific needs of different contexts and fields. These adaptations have led to the emergence of distinct types of action research, each with its unique emphasis and approach.

Collaborative action research

Collaborative action research emphasizes the joint efforts of professionals, often from the same field, working together to address common concerns or challenges. In this approach, there's a strong emphasis on shared responsibility, mutual respect, and co-learning. For example, a group of classroom teachers might collaboratively investigate methods to improve student literacy, pooling their expertise and resources to devise, implement, and refine strategies for improving teaching.

Participatory action research

Participatory action research (PAR) goes a step further in dissolving the barriers between the researcher and the researched. It actively involves community members or stakeholders not just as participants, but as equal partners in the entire research process. PAR is deeply democratic and seeks to empower participants, fostering a sense of agency and ownership. For instance, a participatory research project might involve local residents in studying and addressing community health concerns, ensuring that the research process and outcomes are both informed by and beneficial to the community itself.

Educational action research

Educational action research is tailored specifically to practical educational contexts. Here, educators take on the dual role of teacher and researcher, seeking to improve teaching practices, curricula, classroom dynamics, or educational evaluation. This type of research is cyclical, with educators implementing changes, observing outcomes, and reflecting on results to continually enhance the educational experience. An example might be a teacher studying the impact of technology integration in her classroom, adjusting strategies based on student feedback and learning outcomes.

Community-based action research

Another noteworthy type is community-based action research, which focuses primarily on community development and well-being. Rooted in the principles of social justice, this approach emphasizes the collective power of community members to identify, study, and address their challenges. It's particularly powerful in grassroots movements and local development projects where community insights and collaboration drive meaningful, sustainable change.

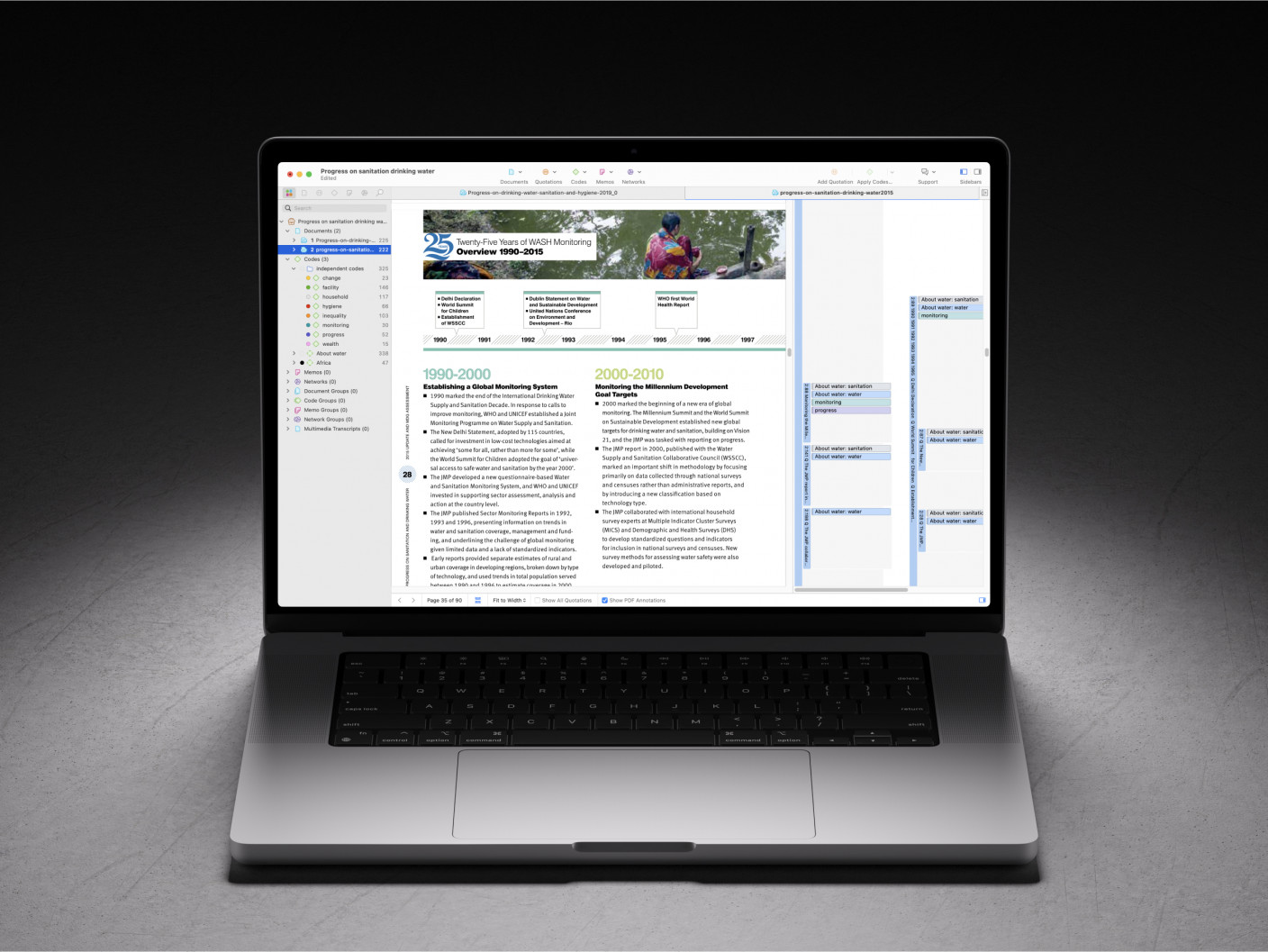

Key insights and critical reflection through research with ATLAS.ti

Organize all your data analysis and insights with our powerful interface. Download a free trial today.

Engaging in action research is both an enlightening and transformative journey, rooted in practicality yet deeply connected to theory. For those embarking on this path, understanding the essentials of an action research study and the significance of a research cycle is paramount.

Understanding the action research cycle

At the heart of action research is its cycle, a structured yet adaptable framework guiding the research. This cycle embodies the iterative nature of action research, emphasizing that learning and change evolve through repetition and reflection.

The typical stages include:

- Identifying a problem : This is the starting point where the action researcher pinpoints a pressing issue or challenge that demands attention.

- Planning : Here, the researcher devises an action research strategy aimed at addressing the identified problem. In action research, network resources, participant consultation, and the literature review are core components in planning.

- Action : The planned strategies are then implemented in this stage. This 'action' phase is where theoretical knowledge meets practical application.

- Observation : Post-implementation, the researcher observes the outcomes and effects of the action. This stage ensures that the research remains grounded in the real-world context.

- Critical reflection : This part of the cycle involves analyzing the observed results to draw conclusions about their effectiveness and identify areas for improvement.

- Revision : Based on the insights from reflection, the initial plan is revised, marking the beginning of another cycle.

Rigorous research and iteration

It's essential to understand that while action research is deeply practical, it doesn't sacrifice rigor . The cyclical process ensures that the research remains thorough and robust. Each iteration of the cycle in an action research project refines the approach, drawing it closer to an effective solution.

The role of the action researcher

The action researcher stands at the nexus of theory and practice. Not just an observer, the researcher actively engages with the study's participants, collaboratively navigating through the research cycle by conducting interviews, participant observations, and member checking . This close involvement ensures that the study remains relevant, timely, and responsive.

Drawing conclusions and informing theory

As the research progresses through multiple iterations of data collection and data analysis , drawing conclusions becomes an integral aspect. These conclusions, while immediately beneficial in addressing the practical issue at hand, also serve a broader purpose. They inform theory, enriching the academic discourse and providing valuable insights for future research.

Identifying actionable insights

Keep in mind that action research should facilitate implications for professional practice as well as space for systematic inquiry. As you draw conclusions about the knowledge generated from action research, consider how this knowledge can create new forms of solutions to the pressing concern you set out to address.

Collecting data and analyzing data starts with ATLAS.ti

Download a free trial of our intuitive software to make the most of your research.

Research Methods and Design

- Action Research

- Case Study Design

- Literature Review

- Quantitative Research Methods

- Qualitative Research Methods

- Mixed Methods Study

- Indigenous Research and Ethics This link opens in a new window

- Identifying Empirical Research Articles This link opens in a new window

- Research Ethics and Quality

- Data Literacy

- Get Help with Writing Assignments

Action research

A type of applied research designed to find the most effective way to bring about a desired social change or to solve a practical problem, usually in collaboration with those being researched.

SAGE Research Methods Videos

How do you define action research.

Professor David Coghlan explains action research as an approach that crosses many academic disciplines yet has a shared focus on taking action to address a problem. He describes the difference between this approach and empirical scientific approaches, particularly highlighting the challenge of getting action research to be taken seriously by academic journals

Dr. Nataliya Ivankova defines action research as using systematic research principles to address an issue in everyday life. She delineates the six steps of action research, and illustrates the concept using an anti-diabetes project in an urban area.

This is just one segment in a whole series about action research. You can find the rest of the series in our SAGE database, Research Methods:

Videos covering research methods and statistics

Further Reading

- << Previous: Home

- Next: Case Study Design >>

- Last Updated: May 7, 2024 9:51 AM

CityU Home - CityU Catalog

the encyclopaedia of pedagogy and informal education

What is action research and how do we do it?

In this article, we explore the development of some different traditions of action research and provide an introductory guide to the literature., contents : what is action research · origins · the decline and rediscovery of action research · undertaking action research · conclusion · further reading · how to cite this article . see, also: research for practice ., what is action research.

In the literature, discussion of action research tends to fall into two distinctive camps. The British tradition – especially that linked to education – tends to view action research as research-oriented toward the enhancement of direct practice. For example, Carr and Kemmis provide a classic definition:

Action research is simply a form of self-reflective enquiry undertaken by participants in social situations in order to improve the rationality and justice of their own practices, their understanding of these practices, and the situations in which the practices are carried out (Carr and Kemmis 1986: 162).

Many people are drawn to this understanding of action research because it is firmly located in the realm of the practitioner – it is tied to self-reflection. As a way of working it is very close to the notion of reflective practice coined by Donald Schön (1983).

The second tradition, perhaps more widely approached within the social welfare field – and most certainly the broader understanding in the USA is of action research as ‘the systematic collection of information that is designed to bring about social change’ (Bogdan and Biklen 1992: 223). Bogdan and Biklen continue by saying that its practitioners marshal evidence or data to expose unjust practices or environmental dangers and recommend actions for change. In many respects, for them, it is linked into traditions of citizen’s action and community organizing. The practitioner is actively involved in the cause for which the research is conducted. For others, it is such commitment is a necessary part of being a practitioner or member of a community of practice. Thus, various projects designed to enhance practice within youth work, for example, such as the detached work reported on by Goetschius and Tash (1967) could be talked of as action research.

Kurt Lewin is generally credited as the person who coined the term ‘action research’:

The research needed for social practice can best be characterized as research for social management or social engineering. It is a type of action-research, a comparative research on the conditions and effects of various forms of social action, and research leading to social action. Research that produces nothing but books will not suffice (Lewin 1946, reproduced in Lewin 1948: 202-3)

His approach involves a spiral of steps, ‘each of which is composed of a circle of planning, action and fact-finding about the result of the action’ ( ibid. : 206). The basic cycle involves the following:

This is how Lewin describes the initial cycle:

The first step then is to examine the idea carefully in the light of the means available. Frequently more fact-finding about the situation is required. If this first period of planning is successful, two items emerge: namely, “an overall plan” of how to reach the objective and secondly, a decision in regard to the first step of action. Usually this planning has also somewhat modified the original idea. ( ibid. : 205)

The next step is ‘composed of a circle of planning, executing, and reconnaissance or fact-finding for the purpose of evaluating the results of the second step, and preparing the rational basis for planning the third step, and for perhaps modifying again the overall plan’ ( ibid. : 206). What we can see here is an approach to research that is oriented to problem-solving in social and organizational settings, and that has a form that parallels Dewey’s conception of learning from experience.

The approach, as presented, does take a fairly sequential form – and it is open to a literal interpretation. Following it can lead to practice that is ‘correct’ rather than ‘good’ – as we will see. It can also be argued that the model itself places insufficient emphasis on analysis at key points. Elliott (1991: 70), for example, believed that the basic model allows those who use it to assume that the ‘general idea’ can be fixed in advance, ‘that “reconnaissance” is merely fact-finding, and that “implementation” is a fairly straightforward process’. As might be expected there was some questioning as to whether this was ‘real’ research. There were questions around action research’s partisan nature – the fact that it served particular causes.

The decline and rediscovery of action research

Action research did suffer a decline in favour during the 1960s because of its association with radical political activism (Stringer 2007: 9). There were, and are, questions concerning its rigour, and the training of those undertaking it. However, as Bogdan and Biklen (1992: 223) point out, research is a frame of mind – ‘a perspective that people take toward objects and activities’. Once we have satisfied ourselves that the collection of information is systematic and that any interpretations made have a proper regard for satisfying truth claims, then much of the critique aimed at action research disappears. In some of Lewin’s earlier work on action research (e.g. Lewin and Grabbe 1945), there was a tension between providing a rational basis for change through research, and the recognition that individuals are constrained in their ability to change by their cultural and social perceptions, and the systems of which they are a part. Having ‘correct knowledge’ does not of itself lead to change, attention also needs to be paid to the ‘matrix of cultural and psychic forces’ through which the subject is constituted (Winter 1987: 48).

Subsequently, action research has gained a significant foothold both within the realm of community-based, and participatory action research; and as a form of practice-oriented to the improvement of educative encounters (e.g. Carr and Kemmis 1986).

Exhibit 1: Stringer on community-based action research

A fundamental premise of community-based action research is that it commences with an interest in the problems of a group, a community, or an organization. Its purpose is to assist people in extending their understanding of their situation and thus resolving problems that confront them….

Community-based action research is always enacted through an explicit set of social values. In modern, democratic social contexts, it is seen as a process of inquiry that has the following characteristics:

• It is democratic , enabling the participation of all people.

• It is equitable , acknowledging people’s equality of worth.

• It is liberating , providing freedom from oppressive, debilitating conditions.

• It is life enhancing , enabling the expression of people’s full human potential.

(Stringer 1999: 9-10)

Undertaking action research

As Thomas (2017: 154) put it, the central aim is change, ‘and the emphasis is on problem-solving in whatever way is appropriate’. It can be seen as a conversation rather more than a technique (McNiff et. al. ). It is about people ‘thinking for themselves and making their own choices, asking themselves what they should do and accepting the consequences of their own actions’ (Thomas 2009: 113).

The action research process works through three basic phases:

Look -building a picture and gathering information. When evaluating we define and describe the problem to be investigated and the context in which it is set. We also describe what all the participants (educators, group members, managers etc.) have been doing.

Think – interpreting and explaining. When evaluating we analyse and interpret the situation. We reflect on what participants have been doing. We look at areas of success and any deficiencies, issues or problems.

Act – resolving issues and problems. In evaluation we judge the worth, effectiveness, appropriateness, and outcomes of those activities. We act to formulate solutions to any problems. (Stringer 1999: 18; 43-44;160)

The use of action research to deepen and develop classroom practice has grown into a strong tradition of practice (one of the first examples being the work of Stephen Corey in 1949). For some, there is an insistence that action research must be collaborative and entail groupwork.

Action research is a form of collective self-reflective enquiry undertaken by participants in social situations in order to improve the rationality and justice of their own social or educational practices, as well as their understanding of those practices and the situations in which the practices are carried out… The approach is only action research when it is collaborative, though it is important to realise that action research of the group is achieved through the critically examined action of individual group members. (Kemmis and McTaggart 1988: 5-6)

Just why it must be collective is open to some question and debate (Webb 1996), but there is an important point here concerning the commitments and orientations of those involved in action research.

One of the legacies Kurt Lewin left us is the ‘action research spiral’ – and with it there is the danger that action research becomes little more than a procedure. It is a mistake, according to McTaggart (1996: 248) to think that following the action research spiral constitutes ‘doing action research’. He continues, ‘Action research is not a ‘method’ or a ‘procedure’ for research but a series of commitments to observe and problematize through practice a series of principles for conducting social enquiry’. It is his argument that Lewin has been misunderstood or, rather, misused. When set in historical context, while Lewin does talk about action research as a method, he is stressing a contrast between this form of interpretative practice and more traditional empirical-analytic research. The notion of a spiral may be a useful teaching device – but it is all too easy to slip into using it as the template for practice (McTaggart 1996: 249).

Further reading

This select, annotated bibliography has been designed to give a flavour of the possibilities of action research and includes some useful guides to practice. As ever, if you have suggestions about areas or specific texts for inclusion, I’d like to hear from you.

Explorations of action research

Atweh, B., Kemmis, S. and Weeks, P. (eds.) (1998) Action Research in Practice: Partnership for Social Justice in Education, London: Routledge. Presents a collection of stories from action research projects in schools and a university. The book begins with theme chapters discussing action research, social justice and partnerships in research. The case study chapters cover topics such as: school environment – how to make a school a healthier place to be; parents – how to involve them more in decision-making; students as action researchers; gender – how to promote gender equity in schools; writing up action research projects.

Carr, W. and Kemmis, S. (1986) Becoming Critical. Education, knowledge and action research , Lewes: Falmer. Influential book that provides a good account of ‘action research’ in education. Chapters on teachers, researchers and curriculum; the natural scientific view of educational theory and practice; the interpretative view of educational theory and practice; theory and practice – redefining the problem; a critical approach to theory and practice; towards a critical educational science; action research as critical education science; educational research, educational reform and the role of the profession.

Carson, T. R. and Sumara, D. J. (ed.) (1997) Action Research as a Living Practice , New York: Peter Lang. 140 pages. Book draws on a wide range of sources to develop an understanding of action research. Explores action research as a lived practice, ‘that asks the researcher to not only investigate the subject at hand but, as well, to provide some account of the way in which the investigation both shapes and is shaped by the investigator.

Dadds, M. (1995) Passionate Enquiry and School Development. A story about action research , London: Falmer. 192 + ix pages. Examines three action research studies undertaken by a teacher and how they related to work in school – how she did the research, the problems she experienced, her feelings, the impact on her feelings and ideas, and some of the outcomes. In his introduction, John Elliot comments that the book is ‘the most readable, thoughtful, and detailed study of the potential of action-research in professional education that I have read’.

Ghaye, T. and Wakefield, P. (eds.) CARN Critical Conversations. Book one: the role of the self in action , Bournemouth: Hyde Publications. 146 + xiii pages. Collection of five pieces from the Classroom Action Research Network. Chapters on: dialectical forms; graduate medical education – research’s outer limits; democratic education; managing action research; writing up.

McNiff, J. (1993) Teaching as Learning: An Action Research Approach , London: Routledge. Argues that educational knowledge is created by individual teachers as they attempt to express their own values in their professional lives. Sets out familiar action research model: identifying a problem, devising, implementing and evaluating a solution and modifying practice. Includes advice on how working in this way can aid the professional development of action researcher and practitioner.

Quigley, B. A. and Kuhne, G. W. (eds.) (1997) Creating Practical Knowledge Through Action Research, San Fransisco: Jossey Bass. Guide to action research that outlines the action research process, provides a project planner, and presents examples to show how action research can yield improvements in six different settings, including a hospital, a university and a literacy education program.

Plummer, G. and Edwards, G. (eds.) CARN Critical Conversations. Book two: dimensions of action research – people, practice and power , Bournemouth: Hyde Publications. 142 + xvii pages. Collection of five pieces from the Classroom Action Research Network. Chapters on: exchanging letters and collaborative research; diary writing; personal and professional learning – on teaching and self-knowledge; anti-racist approaches; psychodynamic group theory in action research.

Whyte, W. F. (ed.) (1991) Participatory Action Research , Newbury Park: Sage. 247 pages. Chapters explore the development of participatory action research and its relation with action science and examine its usages in various agricultural and industrial settings

Zuber-Skerritt, O. (ed.) (1996) New Directions in Action Research , London; Falmer Press. 266 + xii pages. A useful collection that explores principles and procedures for critical action research; problems and suggested solutions; and postmodernism and critical action research.

Action research guides

Coghlan, D. and Brannick, D. (2000) Doing Action Research in your own Organization, London: Sage. 128 pages. Popular introduction. Part one covers the basics of action research including the action research cycle, the role of the ‘insider’ action researcher and the complexities of undertaking action research within your own organisation. Part two looks at the implementation of the action research project (including managing internal politics and the ethics and politics of action research). New edition due late 2004.

Elliot, J. (1991) Action Research for Educational Change , Buckingham: Open University Press. 163 + x pages Collection of various articles written by Elliot in which he develops his own particular interpretation of action research as a form of teacher professional development. In some ways close to a form of ‘reflective practice’. Chapter 6, ‘A practical guide to action research’ – builds a staged model on Lewin’s work and on developments by writers such as Kemmis.

Johnson, A. P. (2007) A short guide to action research 3e. Allyn and Bacon. Popular step by step guide for master’s work.

Macintyre, C. (2002) The Art of the Action Research in the Classroom , London: David Fulton. 138 pages. Includes sections on action research, the role of literature, formulating a research question, gathering data, analysing data and writing a dissertation. Useful and readable guide for students.

McNiff, J., Whitehead, J., Lomax, P. (2003) You and Your Action Research Project , London: Routledge. Practical guidance on doing an action research project.Takes the practitioner-researcher through the various stages of a project. Each section of the book is supported by case studies

Stringer, E. T. (2007) Action Research: A handbook for practitioners 3e , Newbury Park, ca.: Sage. 304 pages. Sets community-based action research in context and develops a model. Chapters on information gathering, interpretation, resolving issues; legitimacy etc. See, also Stringer’s (2003) Action Research in Education , Prentice-Hall.

Winter, R. (1989) Learning From Experience. Principles and practice in action research , Lewes: Falmer Press. 200 + 10 pages. Introduces the idea of action research; the basic process; theoretical issues; and provides six principles for the conduct of action research. Includes examples of action research. Further chapters on from principles to practice; the learner’s experience; and research topics and personal interests.

Action research in informal education

Usher, R., Bryant, I. and Johnston, R. (1997) Adult Education and the Postmodern Challenge. Learning beyond the limits , London: Routledge. 248 + xvi pages. Has some interesting chapters that relate to action research: on reflective practice; changing paradigms and traditions of research; new approaches to research; writing and learning about research.

Other references

Bogdan, R. and Biklen, S. K. (1992) Qualitative Research For Education , Boston: Allyn and Bacon.

Goetschius, G. and Tash, J. (1967) Working with the Unattached , London: Routledge and Kegan Paul.

McTaggart, R. (1996) ‘Issues for participatory action researchers’ in O. Zuber-Skerritt (ed.) New Directions in Action Research , London: Falmer Press.

McNiff, J., Lomax, P. and Whitehead, J. (2003) You and Your Action Research Project 2e. London: Routledge.

Thomas, G. (2017). How to do your Research Project. A guide for students in education and applied social sciences . 3e. London: Sage.

Acknowledgements : spiral by Michèle C. | flickr ccbyncnd2 licence

How to cite this article : Smith, M. K. (1996; 2001, 2007, 2017) What is action research and how do we do it?’, The encyclopedia of pedagogy and informal education. [ https://infed.org/mobi/action-research/ . Retrieved: insert date] .

© Mark K. Smith 1996; 2001, 2007, 2017

- Action Research: What it is, Stages & Examples

Introduction

Action research is an evidence-based approach that has been used for years in the field of education and social sciences. It is used to learn about both good practices and problems with existing practices, as well as being able to develop new strategies by investigating and analyzing data.

In this post, we will explore action research, its purpose, and its stages. Read on!

What Action Research Is

Action research is a methodology of inquiry in which the researcher takes a proactive role in generating knowledge. Action research focuses on learning and can be applied to any field of interest; it is also self-directed, meaning that it is not based on a model or definition but more on an action evaluation framework (Marten, 2000).

An action research project is a cooperative effort between two or more people who are interested in trying new ways of doing things. The common factor between all of these activities is the intention to search for practical solutions for some problem that affects each individual.

Typically, the problem stems from an aspect of society that is amenable to change, although no particular area or business is excluded from this concept. Action research consists of five key components: decision-making, data collection , and analysis, multiple works of literature view, results interpretation , and action development (Marten, 2003).

The goal of action research is to build a better product, service, or process by using the power of people working together. Although the goal is to learn things through this approach, it can be used by anyone from students who want to solve their own problems with technology, to employers teaching their employees new skills.

The Purposes of Conducting Action Research

- The purpose of action research is that it can help academics and learners to find solutions to their problems. To do this, they will know whether their solutions are effective through the scientific method which means that it is more reliable than common sense. It will also make them think harder about what they’re doing.

- Action research can help improve the quality of life by making people aware of what they can do in everyday life.

- Action research is also used for commercial enterprises as it is an effective way to collect information that can help develop new products or services.

The Development of Action Research

Action research is an approach to problem-solving that involves the researcher and others in a process of planning, performing, and evaluating research . It incorporates the evaluation of products or services so that they can be optimized and further developed if necessary. There are four main stages involved in action research: identifying and gathering information, developing a research plan, implementing the plan, and collecting data . Once collected and analyzed, recommendations can be made for improvement within an organization or system.

What is Involved in Action Research

Action research is a research activity that is deliberately designed to achieve some specific practical results in relation to human action problems. Action research activities are characterized by their exploration of possible solutions, with a view toward actualizing these solutions.

Action research involves systematic engagement with the world to comprehend, understand and modify. It helps in learning about the system and the way it works so that you can use this information to help solve problems in your workplace or community.

The stages involved in action research are hypothesis formation, design, implementation, and assessment. A hypothesis is the statement that you are testing.

The Models and Definitions of Action Research

- Practical Action Research : Practical Action Research involves a practitioner working with the researcher to identify a research problem, propose an intervention, and design methods. It is important that the practitioner as well as the researcher clarify differently with each audience, which issues or problems they want to address and with what approach.

- Emancipatory Action Research : It involves working with people in order to solve a problem or meet a goal. Practitioners work together as a group and collectively identify problems and possible solutions. Solutions are as much political and consciousness-raising as practical.

- Technical Action Research: This involves the main researcher in the study identifying the action research problem and proposing an intervention. However, the practitioner will be involved in the implementation of any solutions or interventions.

The Key Characteristics of Action Research

Here are some of the key characteristics of action research.

- Action Research has a form of metacognition that involves the collection of data, through observation and analysis to identify phenomena, exchange ideas while forming hypotheses, and then using feedback to test those hypotheses.

- It is a participative approach to learning based on experimental design.

- Action research focuses on immediate action aiming at change in the organization, community, or individuals.

- The focus of action research is on personal/community development/characteristics so that one’s life can be enriching.

- Action Research leads to interventions that lead to change.

- It is also highly situation based and context-specific.

The Philosophical Worldview of The Action Researcher

Kurt Lewin’s 1946 Rigor of Science Study on Social Issues , is often described as a major landmark in the development of action research as a methodology. Action Research is nothing other than a modern 20th-century manifestation of the pre-modern tradition of practical philosophy.

The book goes on to examine how action research is nothing other than a modern 20th-century manifestation of the pre-modern tradition of practical philosophy. It then draws on Gadamer’s powerful vindication of the contemporary relevance of practical philosophy in order to show how.

This it does, by embracing the idea of ‘methodology’, action research functions to sustain a distorted understanding of what practice is. In fact, it is worth noting that action research has always been connected with practical philosophy hence its importance in research works.

Examples of Action Research Projects.

Here are some examples of how action research is used in projects.

- Observing Individuals or Groups: Action research draws upon the prior knowledge of researchers, specialists, and communities gathered through individual experiences or through cooperative learning partnerships between experts and community members.

- Using Audio and Video Tape Recording: Action research allows the use of audio and video tape recordings which are more accurate and easier to capture every information from the practitioner or user.

- Using structured or semi-structured interviews . Action research can be carried out by conducting interviews in any form.

- Using or Taking Photography: Another example of action research is taking photographs to back up or serve as pictorial evidence for your research project.

- Distributing Surveys or Questionnaires: Another way to carry out action research is by distributing surveys and questionnaires to better understand your users and their behavior toward your focus topic or product.

The development of action research is a process that takes place over several stages, each of which builds on the preceding ones. In order to ensure that your action research project has a chance at success, you will need to plan ahead and take whatever steps possible to ensure that the project is completed on time and within budget.

Connect to Formplus, Get Started Now - It's Free!

- action research

- questionnaires

- science study

- survey questionnaire

You may also like:

The Guide to Deciding on the Best Time to Send a Survey

Introduction Have you been wondering when to send out surveys? We’re here to help, so let’s start by giving you a little background...

Market Research: Types, Methods & Survey Examples

A complete guide on market research; definitions, survey examples, templates, importance and tips.

What Are The Types of Research Hypothesis? + [Examples]

It is vital to fully understand a hypothesis to address the types of research hypotheses. A hypothesis explains an established or known...

Convenience Sampling: Definition, Applications, Examples

In this article, we’d look at why you should adopt convenience sampling in your research and how to reduce the effects of convenience...

Formplus - For Seamless Data Collection

Collect data the right way with a versatile data collection tool. try formplus and transform your work productivity today..

Have a language expert improve your writing

Run a free plagiarism check in 10 minutes, automatically generate references for free.

- Knowledge Base

- Methodology

- What Is Action Research? | Definition & Examples

What Is Action Research? | Definition & Examples

Published on 27 January 2023 by Tegan George . Revised on 21 April 2023.

Table of contents

Types of action research, action research models, examples of action research, action research vs. traditional research, advantages and disadvantages of action research, frequently asked questions about action research.

There are 2 common types of action research: participatory action research and practical action research.

- Participatory action research emphasises that participants should be members of the community being studied, empowering those directly affected by outcomes of said research. In this method, participants are effectively co-researchers, with their lived experiences considered formative to the research process.

- Practical action research focuses more on how research is conducted and is designed to address and solve specific issues.

Both types of action research are more focused on increasing the capacity and ability of future practitioners than contributing to a theoretical body of knowledge.

Prevent plagiarism, run a free check.

Action research is often reflected in 3 action research models: operational (sometimes called technical), collaboration, and critical reflection.

- Operational (or technical) action research is usually visualised like a spiral following a series of steps, such as “planning → acting → observing → reflecting.”

- Collaboration action research is more community-based, focused on building a network of similar individuals (e.g., college professors in a given geographic area) and compiling learnings from iterated feedback cycles.

- Critical reflection action research serves to contextualise systemic processes that are already ongoing (e.g., working retroactively to analyse existing school systems by questioning why certain practices were put into place and developed the way they did).

Action research is often used in fields like education because of its iterative and flexible style.

After the information was collected, the students were asked where they thought ramps or other accessibility measures would be best utilised, and the suggestions were sent to school administrators. Example: Practical action research Science teachers at your city’s high school have been witnessing a year-over-year decline in standardised test scores in chemistry. In seeking the source of this issue, they studied how concepts are taught in depth, focusing on the methods, tools, and approaches used by each teacher.

Action research differs sharply from other types of research in that it seeks to produce actionable processes over the course of the research rather than contributing to existing knowledge or drawing conclusions from datasets. In this way, action research is formative , not summative , and is conducted in an ongoing, iterative way.

| Action research | Traditional research | |

|---|---|---|

| and findings | ||

| and seeking between variables | ||

As such, action research is different in purpose, context, and significance and is a good fit for those seeking to implement systemic change.

Action research comes with advantages and disadvantages.

- Action research is highly adaptable , allowing researchers to mould their analysis to their individual needs and implement practical individual-level changes.

- Action research provides an immediate and actionable path forward for solving entrenched issues, rather than suggesting complicated, longer-term solutions rooted in complex data.

- Done correctly, action research can be very empowering , informing social change and allowing participants to effect that change in ways meaningful to their communities.

Disadvantages

- Due to their flexibility, action research studies are plagued by very limited generalisability and are very difficult to replicate . They are often not considered theoretically rigorous due to the power the researcher holds in drawing conclusions.

- Action research can be complicated to structure in an ethical manner . Participants may feel pressured to participate or to participate in a certain way.

- Action research is at high risk for research biases such as selection bias , social desirability bias , or other types of cognitive biases .

Action research is conducted in order to solve a particular issue immediately, while case studies are often conducted over a longer period of time and focus more on observing and analyzing a particular ongoing phenomenon.

Action research is focused on solving a problem or informing individual and community-based knowledge in a way that impacts teaching, learning, and other related processes. It is less focused on contributing theoretical input, instead producing actionable input.

Action research is particularly popular with educators as a form of systematic inquiry because it prioritizes reflection and bridges the gap between theory and practice. Educators are able to simultaneously investigate an issue as they solve it, and the method is very iterative and flexible.

A cycle of inquiry is another name for action research . It is usually visualized in a spiral shape following a series of steps, such as “planning → acting → observing → reflecting.”

Sources for this article

We strongly encourage students to use sources in their work. You can cite our article (APA Style) or take a deep dive into the articles below.

George, T. (2023, April 21). What Is Action Research? | Definition & Examples. Scribbr. Retrieved 24 June 2024, from https://www.scribbr.co.uk/research-methods/action-research-cycle/

Cohen, L., Manion, L., & Morrison, K. (2017). Research methods in education (8th edition). Routledge.

Naughton, G. M. (2001). Action research (1st edition). Routledge.

Is this article helpful?

Tegan George

Other students also liked, primary research | definition, types, & examples, a quick guide to experimental design | 5 steps & examples, what is an observational study | guide & examples.

Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

4 Preparing for Action Research in the Classroom: Practical Issues

ESSENTIAL QUESTIONS

- What sort of considerations are necessary to take action in your educational context?

- How do you facilitate an action plan without disrupting your teaching?

- How do you respond when the unplanned happens during data collection?

An action research project is a practical endeavor that will ultimately be shaped by your educational context and practice. Now that you have developed a literature review, you are ready to revise your initial plans and begin to plan your project. This chapter will provide some advice about your considerations when undertaking an action research project in your classroom.

Maintain Focus