Developmental Domains and Learning of Children Essay

- To find inspiration for your paper and overcome writer’s block

- As a source of information (ensure proper referencing)

- As a template for you assignment

Introduction

Aesthetic domain, affective domain, physical domain, social domain.

The development of children during the early school years requires attention to not only their mental abilities but also some other aspects that affect the overall process of growth and socialization. As the key tools for assessing and analyzing the child’s aptitudes and abilities, the four key domains are taken into account – aesthetic, affective, physical, and social developmental domains. Each of these factors determines special properties that children acquire at the stage of growing up and in the process of gaining new experience. This work is aimed at describing the possibilities provided by the knowledge of the four domains’ features in the context of teaching primary school students and their training in the core content areas.

This domain characterizes children’s ability to convey feelings and sensations through various means of artistic expression – painting, music, literature, and other forms of art. If a child can express certain emotions with the help of aids, it indicates the normal development of his or her cognitive functions and perception of the environment (Tomlinson, 2014). I could use this domain in the process of teaching children as one of the elements for assessing pupils’ creative perception of the material they study and their ability to reflect internal motives and experiences in other forms.

The affective domain is an essential component of children’s cognitive development since the analysis of those emotions and values that develop during the early school years may make it possible to identify any disorders timely and take appropriate corrective measures. According to Christian et al. (2015), the correct interpretation of students’ feelings allows teachers to plan the learning process based on the emotional perception of pupils. This domain is useful for me because when planning my teaching plan, I should understand children’s reactions and take into account their attitude to specific disciplines.

Although the physical domain is not directly related to learning basic sciences, this component is an essential aspect of development. As Tomlinson (2014) argues, “American children are increasingly at risk because of the growing and historic prevalence of childhood obesity” (p. 11). Weak physical activities and insufficient attention to growth parameters indicate an incorrect approach to controlling the child’s behavioral habits, which may affect his or her academic performance. Therefore, I would prefer not to ignore this domain when planning the educational process to avoid further student health problems.

Socialization is one of the four key domains is a significant aspect of child development. Adaptation to the educational environment allows students to establish contact with both peers and teachers, thereby ensuring normal interaction. According to Christian et al. (2015), if this aspect is ignored, it can create significant obstacles to the development of other important functions. In my teaching plan, I would pay considerable attention to how my pupils interact with one another, what behavioral patterns they use, and how they learn to solve difficulties.

Teaching primary school students should be accompanied by analyzing four key development domains to help children develop all crucial skills. Each of the aspects considered has unique properties that allow pupils to gain valuable experience and adapt to an unfamiliar environment. When planning the curriculum, I would prefer to adhere to the provisions of these domains to have a clear idea of my students’ developmental characteristics.

Christian, H., Zubrick, S. R., Foster, S., Giles-Corti, B., Bull, F., Wood, L.,… Boruff, B. (2015). The influence of the neighborhood physical environment on early child health and development: A review and call for research. Health & Place , 33 , 25-36. Web.

Tomlinson, H. B. (2014). An overview of development in the primary grades. In C. Copple, S. Bredekamp, D. G. Koralek, & K. Charner (Eds.), Developmentally appropriate practice (3rd ed.) (pp. 9-38). Washington, DC: National Association for the Education of Young Children.

- Socio- Affective Characteristics and Personalogical Development of the Gifted Child

- Student Developmental Domains. Language Development

- Bloom's Taxonomy and Technology-Rich Projects

- Museum Education: Modern Methods of Teaching Children

- The Professional Learning Community

- Young Children's Perspectives on Learning through Play

- Students' Work Habits in the Library: Field Notes

- Mobile Devices in High School Social Studies

- Chicago (A-D)

- Chicago (N-B)

IvyPanda. (2021, June 9). Developmental Domains and Learning of Children. https://ivypanda.com/essays/developmental-domains-and-learning-of-children/

"Developmental Domains and Learning of Children." IvyPanda , 9 June 2021, ivypanda.com/essays/developmental-domains-and-learning-of-children/.

IvyPanda . (2021) 'Developmental Domains and Learning of Children'. 9 June.

IvyPanda . 2021. "Developmental Domains and Learning of Children." June 9, 2021. https://ivypanda.com/essays/developmental-domains-and-learning-of-children/.

1. IvyPanda . "Developmental Domains and Learning of Children." June 9, 2021. https://ivypanda.com/essays/developmental-domains-and-learning-of-children/.

Bibliography

IvyPanda . "Developmental Domains and Learning of Children." June 9, 2021. https://ivypanda.com/essays/developmental-domains-and-learning-of-children/.

- Search Please fill out this field.

- Newsletters

- Sweepstakes

- Raising Kids

Major Domains in Child Development

There are four major developmental domains: physical, cognitive, language, and social-emotional. As children grow, they develop skills in all areas.

What Are Developmental Domains?

Physical developmental domain.

- Cognitive Developmental Domain

- Social and Emotional Developmental Domain

- Language Developmental Domain

Developmental Domain Delays

When to talk to a health care provider.

A child's development is a multi-faceted process comprised of growth, regression, and change in different domains. These domains include physical , cognitive, socio-emotional, and language development.

Acquiring and mastering skills in certain domains may appear more prominent during specific stages of life. Yet kids virtually always experience some degree of change in all domains as they grow.

Learn more about developmental domains, what to expect in the major areas of development, and when to contact a health care provider.

Phil Boorman / Getty Images

When discussing human development, the word "domain" refers to specific aspects of growth and change. The major domains of development are physical ( fine motor and gross motor skills ), cognitive, language, and social-emotional.

Children often experience a significant and obvious change in one domain at a time. For example, if a baby is focusing on learning to walk , which is in the physical domain, you may not notice as much language development or new words until they have mastered walking.

It might seem like a particular domain is the only one experiencing developmental change during different periods of a child's life. But change typically occurs in the other domains as well—just more gradually and less prominently.

The physical domain covers the development of physical changes, which includes the following:

- Growing in size and strength

Gross motor skills

Fine motor skills.

- Development of the senses

When young, children are learning how to perform different activities with their fingers in coordination with their eyes such as grasping , releasing, reaching, pinching, and turning their wrists. Because these small muscle movements take time to develop, they may not come easily at first.

What Are Fine Motor Skills?

These fine motor skills help kids perform tasks for daily living, like buttoning buttons, picking up finger foods , using a fork, pouring milk, going to the restroom, and washing their hands.

From an early age, give kids opportunities to use their hands and fingers. Give your baby rattles, plush balls, and other toys to grasp.

Later, toys that allow them to pick things up and fit them into slots are good for developing beginning skills. As they get older, teach them how to button buttons, use scissors, hold a pencil, and do other tasks with their fingers and hands.

In addition to these fine motor skills, kids also learn to use their larger muscles, like those in their arms, legs, back, and stomach. Walking, running, throwing, lifting, pulling, pushing, and kicking are all important skills that are related to body awareness, balance, and strength. These skills allow your child to control and move their body in different ways.

Parents can help their child's physical development by providing opportunities for age-appropriate activities . For instance, babies need regular tummy time to build their neck and upper body strength.

Preschoolers and school-aged children need plenty of opportunities to run around and play. Even tweens and teens need regular opportunities for physical activity.

Overall Health Impacts Physical Development

Physical development can also be influenced by nutrition and illness. So, make sure your kids have a healthy diet, regular exercise, and annual wellness check-ups to promote proper child development.

Cognitive Developmental Domain

The cognitive domain includes intellectual development and creativity. As they develop cognitively, kids gain the ability to do the following:

- Process thoughts

- Pay attention

- Develop memories

- Understand their surroundings

- Express creativity

- Make, implement, and accomplish plans

The child psychologist Jean Piaget outlined four stages of cognitive development, known as the Paigentian Theory. These stages are outlined below.

Sensorimotor stage (birth to age 2)

The sensorimotor stage involves learning about the environment through movements and sensations. Infants and toddlers use basic actions like sucking, grasping, looking, and listening to learn about the world around them.

Preoperational stage (ages 2 to 7)

During the preoperational stage, children learn to think symbolically as well as use words or pictures to represent things. Kids in this stage enjoy pretend play, but still struggle with logic and understanding another person's perspective.

Concrete operational stage (ages 7 to 11)

Once they enter the concrete operational stage, kids start to think more logically, but may still struggle with hypothetical situations and abstract thinking. Because they are beginning to see things from another person's perspective, now is a good time to start teaching empathy.

Formal operational stage (age 12 and up)

During the formal operational stage, a child develops an increase in logical thinking. They also develop an ability to use deductive reasoning and understand abstract ideas. As they become more adept at problem-solving, they also are able to think more scientifically about the world around them.

Even older kids and teens need play . You can help your child develop and hone their cognitive skills by giving them opportunities to play with blocks, puzzles, and board games.

You also should create an environment where your child feels comfortable asking questions about the world around them and has plenty of opportunities for free play.

Develop your child's desire to learn by helping them explore topics they are passionate about. Encourage thinking and reasoning skills by asking them open-ended questions and teaching them to expand on their thought processes. As they get older, teach them how to be critical consumers of media and where to find answers to things they don't know.

Social and Emotional Developmental Domain

The social-emotional domain includes a child's growing understanding and control of their emotions. They also begin to identify what others are feeling, develop the ability to cooperate, show empathy, and use moral reasoning.

Friendships

This domain includes developing attachments to others and learning how to interact with them. For instance, young children learn how to share , take turns, and accept differences in others. They also develop many different types of relationships, from parents and siblings to peers, teachers, coaches, and others in the community.

Key Skills of the Social-Emotional Stage

Children develop self-knowledge during the social-emotional stage. They learn how they identify with different groups and their innate temperament will emerge in their relationships.

Tweens, especially, demonstrate significant developments in the social-emotional domain as their peers become more central to their lives and they learn how to carry out long-term friendships . Typically, parents will notice major increases in social skills during this time.

To help your child develop socially and emotionally, look for opportunities for them to interact with kids their age and form relationships with both children and adults. You can arrange playdates, explore playgroups, and look into extracurricular activities. Also, encourage them to talk to their grandparents, teachers, and coaches.

Sense of self

To encourage a sense of self, ask your child about their interests and passions and encourage them to identify their strengths and weaknesses. Teach them about recognizing and managing feelings. As they get older, talk to them about healthy friendships and how to handle peer pressure.

You also should not shy away from challenging talks like those covering sex and consent . All of these different social and emotional facets play into your child's overall development.

Language Developmental Domain

Language development is dependent on the other developmental domains. The ability to communicate with others grows from infancy, but children develop these abilities at different rates. Aspects of language include:

- Phonology : Creating the sounds of speech

- Pragmatics : Communicating verbally and non-verbally in social situations

- Semantics : Understanding the rules of what words mean

- Syntax : Using grammar and putting sentences together

Read to kids

One of the most important things you can do with your child throughout their early life is to read to them —and not just at bedtime.

Make reading and enjoying books a central part of your day. Reading out loud to your kids from birth and beyond has a major impact on their emerging language and literacy skills.

Look for opportunities to read other things, too, like directions to a board game, letters from family members, holiday cards, online articles, and school newsletters. Hearing new words spoken expands a child's vocabulary and helps them identify unfamiliar words when used in context.

Talk to kids

In addition to reading, make sure you talk to your kids even before they can say their first word . Tell them about the things you are doing or what you're buying in the store. Point out different things and engage them in the world around them. Singing to your child is another excellent way to build your child's language skills.

As they get older, try holding regular conversations, answering questions, and asking for your child's ideas or opinions. All of these activities are an important part of their language development.

As children grow and learn, they will pass certain developmental milestones. While every child is different and progresses at a different rate, these milestones provide general guidelines that help parents and caregivers gauge whether or not a child is on track .

You can support your child's growth and development in each of these four areas by understanding these domains and supporting the work your child is doing. Watch the changes taking place in your child and supplement their learning with activities that support their efforts .

The exact time that a child reaches a particular milestone will vary significantly. However, missing one or two milestones can be a cause for concern.

Talk to a health care provider if you're ever worried your child is not meeting milestones in a particular area. If a delay is identified, they can evaluate your child and recommend different services.

Every state in the US offers an early intervention program to support children with developmental delays under the age of 3. Once they are over age 3, the community's local school district must provide programming.

So, don't delay determining whether your child needs assistance. There are resources out there to support them should they need it.

Principles of child development and learning and implications that inform practice . National Association for the Education of Young Children . n.d.

Toddlers (1-2 years old) . Centers for Disease Control and Prevention . 2021.

Transforming the workforce for children birth through age 8: a unifying foundation . Board on Children, Youth, and Families; Institute of Medicine; National Research Council. 2015.

Piagetian theory . American Psychological Association . 2018.

Social development in preschoolers . American Academy of Pediatrics . 2021.

Talking with your teen: Tips for parents . American Academy of Pediatrics . 2021.

Language in brief . American Speech-Language-Hearing Association . n.d.

Helping your child learn to read . American Academy of Pediatrics . 2015.

Is your toddler communicating with you? . American Academy of Pediatrics . 2021.

Related Articles

Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

1 Chapter 1: Introduction to Child Development

Chapter objectives.

After this chapter, you should be able to:

- Describe the principles that underlie development.

- Differentiate periods of human development.

- Evaluate issues in development.

- Distinguish the different methods of research.

- Explain what a theory is.

- Compare and contrast different theories of child development.

Introduction

Welcome to Child Growth and Development. This text is a presentation of how and why children grow, develop, and learn.

We will look at how we change physically over time from conception through adolescence. We examine cognitive change, or how our ability to think and remember changes over the first 20 years or so of life. And we will look at how our emotions, psychological state, and social relationships change throughout childhood and adolescence. 1

Principles of Development

There are several underlying principles of development to keep in mind:

- Development is lifelong and change is apparent across the lifespan (although this text ends with adolescence). And early experiences affect later development.

- Development is multidirectional. We show gains in some areas of development, while showing loss in other areas.

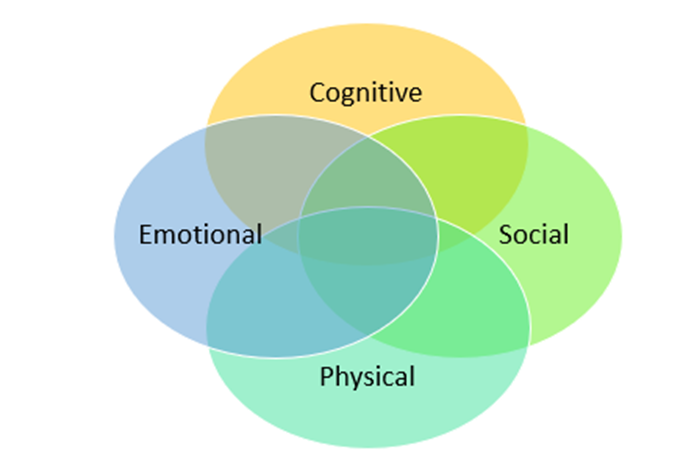

- Development is multidimensional. We change across three general domains/dimensions; physical, cognitive, and social and emotional.

- The physical domain includes changes in height and weight, changes in gross and fine motor skills, sensory capabilities, the nervous system, as well as the propensity for disease and illness.

- The cognitive domain encompasses the changes in intelligence, wisdom, perception, problem-solving, memory, and language.

- The social and emotional domain (also referred to as psychosocial) focuses on changes in emotion, self-perception, and interpersonal relationships with families, peers, and friends.

All three domains influence each other. It is also important to note that a change in one domain may cascade and prompt changes in the other domains.

- Development is characterized by plasticity, which is our ability to change and that many of our characteristics are malleable. Early experiences are important, but children are remarkably resilient (able to overcome adversity).

- Development is multicontextual. 2 We are influenced by both nature (genetics) and nurture (the environment) – when and where we live and our actions, beliefs, and values are a response to circumstances surrounding us. The key here is to understand that behaviors, motivations, emotions, and choices are all part of a bigger picture. 3

Now let’s look at a framework for examining development.

Periods of Development

Think about what periods of development that you think a course on Child Development would address. How many stages are on your list? Perhaps you have three: infancy, childhood, and teenagers. Developmentalists (those that study development) break this part of the life span into these five stages as follows:

- Prenatal Development (conception through birth)

- Infancy and Toddlerhood (birth through two years)

- Early Childhood (3 to 5 years)

- Middle Childhood (6 to 11 years)

- Adolescence (12 years to adulthood)

This list reflects unique aspects of the various stages of childhood and adolescence that will be explored in this book. So while both an 8 month old and an 8 year old are considered children, they have very different motor abilities, social relationships, and cognitive skills. Their nutritional needs are different and their primary psychological concerns are also distinctive.

Prenatal Development

Conception occurs and development begins. All of the major structures of the body are forming and the health of the mother is of primary concern. Understanding nutrition, teratogens (or environmental factors that can lead to birth defects), and labor and delivery are primary concerns.

Figure 1.1 – A tiny embryo depicting some development of arms and legs, as well as facial features that are starting to show. 4

Infancy and Toddlerhood

The two years of life are ones of dramatic growth and change. A newborn, with a keen sense of hearing but very poor vision is transformed into a walking, talking toddler within a relatively short period of time. Caregivers are also transformed from someone who manages feeding and sleep schedules to a constantly moving guide and safety inspector for a mobile, energetic child.

Figure 1.2 – A swaddled newborn. 5

Early Childhood

Early childhood is also referred to as the preschool years and consists of the years which follow toddlerhood and precede formal schooling. As a three to five-year-old, the child is busy learning language, is gaining a sense of self and greater independence, and is beginning to learn the workings of the physical world. This knowledge does not come quickly, however, and preschoolers may initially have interesting conceptions of size, time, space and distance such as fearing that they may go down the drain if they sit at the front of the bathtub or by demonstrating how long something will take by holding out their two index fingers several inches apart. A toddler’s fierce determination to do something may give way to a four-year-old’s sense of guilt for action that brings the disapproval of others.

Figure 1.3 – Two young children playing in the Singapore Botanic Gardens 6

Middle Childhood

The ages of six through eleven comprise middle childhood and much of what children experience at this age is connected to their involvement in the early grades of school. Now the world becomes one of learning and testing new academic skills and by assessing one’s abilities and accomplishments by making comparisons between self and others. Schools compare students and make these comparisons public through team sports, test scores, and other forms of recognition. Growth rates slow down and children are able to refine their motor skills at this point in life. And children begin to learn about social relationships beyond the family through interaction with friends and fellow students.

Figure 1.4 – Two children running down the street in Carenage, Trinidad and Tobago 7

Adolescence

Adolescence is a period of dramatic physical change marked by an overall physical growth spurt and sexual maturation, known as puberty. It is also a time of cognitive change as the adolescent begins to think of new possibilities and to consider abstract concepts such as love, fear, and freedom. Ironically, adolescents have a sense of invincibility that puts them at greater risk of dying from accidents or contracting sexually transmitted infections that can have lifelong consequences. 8

Figure 1.5 – Two smiling teenage women. 9

There are some aspects of development that have been hotly debated. Let’s explore these.

Issues in Development

Nature and nurture.

Why are people the way they are? Are features such as height, weight, personality, being diabetic, etc. the result of heredity or environmental factors-or both? For decades, scholars have carried on the “nature/nurture” debate. For any particular feature, those on the side of Nature would argue that heredity plays the most important role in bringing about that feature. Those on the side of Nurture would argue that one’s environment is most significant in shaping the way we are. This debate continues in all aspects of human development, and most scholars agree that there is a constant interplay between the two forces. It is difficult to isolate the root of any single behavior as a result solely of nature or nurture.

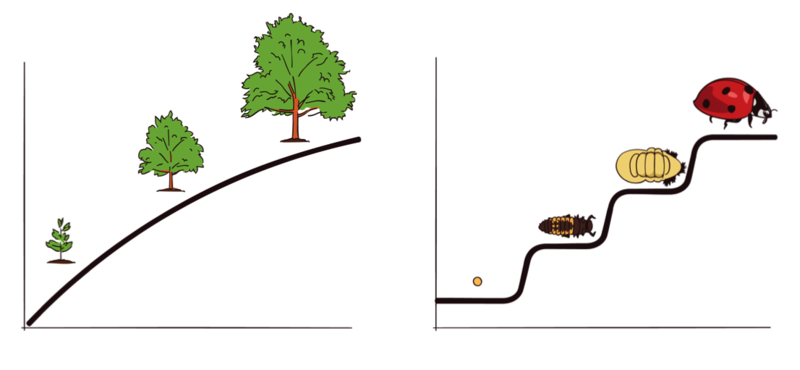

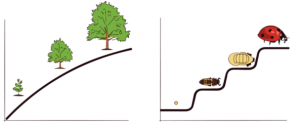

Continuity versus Discontinuity

Is human development best characterized as a slow, gradual process, or is it best viewed as one of more abrupt change? The answer to that question often depends on which developmental theorist you ask and what topic is being studied. The theories of Freud, Erikson, Piaget, and Kohlberg are called stage theories. Stage theories or discontinuous development assume that developmental change often occurs in distinct stages that are qualitatively different from each other, and in a set, universal sequence. At each stage of development, children and adults have different qualities and characteristics. Thus, stage theorists assume development is more discontinuous. Others, such as the behaviorists, Vygotsky, and information processing theorists, assume development is a more slow and gradual process known as continuous development. For instance, they would see the adult as not possessing new skills, but more advanced skills that were already present in some form in the child. Brain development and environmental experiences contribute to the acquisition of more developed skills.

Figure 1.6 – The graph to the left shows three stages in the continuous growth of a tree. The graph to the right shows four distinct stages of development in the life cycle of a ladybug. 10

Active versus Passive

How much do you play a role in your own developmental path? Are you at the whim of your genetic inheritance or the environment that surrounds you? Some theorists see humans as playing a much more active role in their own development. Piaget, for instance believed that children actively explore their world and construct new ways of thinking to explain the things they experience. In contrast, many behaviorists view humans as being more passive in the developmental process. 11

How do we know so much about how we grow, develop, and learn? Let’s look at how that data is gathered through research

Research Methods

An important part of learning any science is having a basic knowledge of the techniques used in gathering information. The hallmark of scientific investigation is that of following a set of procedures designed to keep questioning or skepticism alive while describing, explaining, or testing any phenomenon. Some people are hesitant to trust academicians or researchers because they always seem to change their story. That, however, is exactly what science is all about; it involves continuously renewing our understanding of the subjects in question and an ongoing investigation of how and why events occur. Science is a vehicle for going on a never-ending journey. In the area of development, we have seen changes in recommendations for nutrition, in explanations of psychological states as people age, and in parenting advice. So think of learning about human development as a lifelong endeavor.

Take a moment to write down two things that you know about childhood. Now, how do you know? Chances are you know these things based on your own history (experiential reality) or based on what others have told you or cultural ideas (agreement reality) (Seccombe and Warner, 2004). There are several problems with personal inquiry. Read the following sentence aloud:

Paris in the

Are you sure that is what it said? Read it again:

If you read it differently the second time (adding the second “the”) you just experienced one of the problems with personal inquiry; that is, the tendency to see what we believe. Our assumptions very often guide our perceptions, consequently, when we believe something, we tend to see it even if it is not there. This problem may just be a result of cognitive ‘blinders’ or it may be part of a more conscious attempt to support our own views. Confirmation bias is the tendency to look for evidence that we are right and in so doing, we ignore contradictory evidence. Popper suggests that the distinction between that which is scientific and that which is unscientific is that science is falsifiable; scientific inquiry involves attempts to reject or refute a theory or set of assumptions (Thornton, 2005). Theory that cannot be falsified is not scientific. And much of what we do in personal inquiry involves drawing conclusions based on what we have personally experienced or validating our own experience by discussing what we think is true with others who share the same views.

Science offers a more systematic way to make comparisons guard against bias.

Scientific Methods

One method of scientific investigation involves the following steps:

- Determining a research question

- Reviewing previous studies addressing the topic in question (known as a literature review)

- Determining a method of gathering information

- Conducting the study

- Interpreting results

- Drawing conclusions; stating limitations of the study and suggestions for future research

- Making your findings available to others (both to share information and to have your work scrutinized by others)

Your findings can then be used by others as they explore the area of interest and through this process a literature or knowledge base is established. This model of scientific investigation presents research as a linear process guided by a specific research question. And it typically involves quantifying or using statistics to understand and report what has been studied. Many academic journals publish reports on studies conducted in this manner.

Another model of research referred to as qualitative research may involve steps such as these:

- Begin with a broad area of interest

- Gain entrance into a group to be researched

- Gather field notes about the setting, the people, the structure, the activities or other areas of interest

- Ask open ended, broad “grand tour” types of questions when interviewing subjects

- Modify research questions as study continues

- Note patterns or consistencies

- Explore new areas deemed important by the people being observed

- Report findings

In this type of research, theoretical ideas are “grounded” in the experiences of the participants. The researcher is the student and the people in the setting are the teachers as they inform the researcher of their world (Glazer & Strauss, 1967). Researchers are to be aware of their own biases and assumptions, acknowledge them and bracket them in efforts to keep them from limiting accuracy in reporting. Sometimes qualitative studies are used initially to explore a topic and more quantitative studies are used to test or explain what was first described.

Let’s look more closely at some techniques, or research methods, used to describe, explain, or evaluate. Each of these designs has strengths and weaknesses and is sometimes used in combination with other designs within a single study.

Observational Studies

Observational studies involve watching and recording the actions of participants. This may take place in the natural setting, such as observing children at play at a park, or behind a one-way glass while children are at play in a laboratory playroom. The researcher may follow a checklist and record the frequency and duration of events (perhaps how many conflicts occur among 2-year-olds) or may observe and record as much as possible about an event (such as observing children in a classroom and capturing the details about the room design and what the children and teachers are doing and saying). In general, observational studies have the strength of allowing the researcher to see how people behave rather than relying on self-report. What people do and what they say they do are often very different. A major weakness of observational studies is that they do not allow the researcher to explain causal relationships. Yet, observational studies are useful and widely used when studying children. Children tend to change their behavior when they know they are being watched (known as the Hawthorne effect) and may not survey well.

Experiments

Experiments are designed to test hypotheses (or specific statements about the relationship between variables) in a controlled setting in efforts to explain how certain factors or events produce outcomes. A variable is anything that changes in value. Concepts are operationalized or transformed into variables in research, which means that the researcher must specify exactly what is going to be measured in the study.

Three conditions must be met in order to establish cause and effect. Experimental designs are useful in meeting these conditions.

The independent and dependent variables must be related. In other words, when one is altered, the other changes in response. (The independent variable is something altered or introduced by the researcher. The dependent variable is the outcome or the factor affected by the introduction of the independent variable. For example, if we are looking at the impact of exercise on stress levels, the independent variable would be exercise; the dependent variable would be stress.)

The cause must come before the effect. Experiments involve measuring subjects on the dependent variable before exposing them to the independent variable (establishing a baseline). So we would measure the subjects’ level of stress before introducing exercise and then again after the exercise to see if there has been a change in stress levels. (Observational and survey research does not always allow us to look at the timing of these events, which makes understanding causality problematic with these designs.)

The cause must be isolated. The researcher must ensure that no outside, perhaps unknown variables are actually causing the effect we see. The experimental design helps make this possible. In an experiment, we would make sure that our subjects’ diets were held constant throughout the exercise program. Otherwise, diet might really be creating the change in stress level rather than exercise.

A basic experimental design involves beginning with a sample (or subset of a population) and randomly assigning subjects to one of two groups: the experimental group or the control group. The experimental group is the group that is going to be exposed to an independent variable or condition the researcher is introducing as a potential cause of an event. The control group is going to be used for comparison and is going to have the same experience as the experimental group but will not be exposed to the independent variable. After exposing the experimental group to the independent variable, the two groups are measured again to see if a change has occurred. If so, we are in a better position to suggest that the independent variable caused the change in the dependent variable.

The major advantage of the experimental design is that of helping to establish cause and effect relationships. A disadvantage of this design is the difficulty of translating much of what happens in a laboratory setting into real life.

Case Studies

Case studies involve exploring a single case or situation in great detail. Information may be gathered with the use of observation, interviews, testing, or other methods to uncover as much as possible about a person or situation. Case studies are helpful when investigating unusual situations such as brain trauma or children reared in isolation. And they are often used by clinicians who conduct case studies as part of their normal practice when gathering information about a client or patient coming in for treatment. Case studies can be used to explore areas about which little is known and can provide rich detail about situations or conditions. However, the findings from case studies cannot be generalized or applied to larger populations; this is because cases are not randomly selected and no control group is used for comparison.

Figure 1.7 – Illustrated poster from a classroom describing a case study. 12

Surveys are familiar to most people because they are so widely used. Surveys enhance accessibility to subjects because they can be conducted in person, over the phone, through the mail, or online. A survey involves asking a standard set of questions to a group of subjects. In a highly structured survey, subjects are forced to choose from a response set such as “strongly disagree, disagree, undecided, agree, strongly agree”; or “0, 1-5, 6-10, etc.” This is known as Likert Scale . Surveys are commonly used by sociologists, marketing researchers, political scientists, therapists, and others to gather information on many independent and dependent variables in a relatively short period of time. Surveys typically yield surface information on a wide variety of factors, but may not allow for in-depth understanding of human behavior.

Of course, surveys can be designed in a number of ways. They may include forced choice questions and semi-structured questions in which the researcher allows the respondent to describe or give details about certain events. One of the most difficult aspects of designing a good survey is wording questions in an unbiased way and asking the right questions so that respondents can give a clear response rather than choosing “undecided” each time. Knowing that 30% of respondents are undecided is of little use! So a lot of time and effort should be placed on the construction of survey items. One of the benefits of having forced choice items is that each response is coded so that the results can be quickly entered and analyzed using statistical software. Analysis takes much longer when respondents give lengthy responses that must be analyzed in a different way. Surveys are useful in examining stated values, attitudes, opinions, and reporting on practices. However, they are based on self-report or what people say they do rather than on observation and this can limit accuracy.

Developmental Designs

Developmental designs are techniques used in developmental research (and other areas as well). These techniques try to examine how age, cohort, gender, and social class impact development.

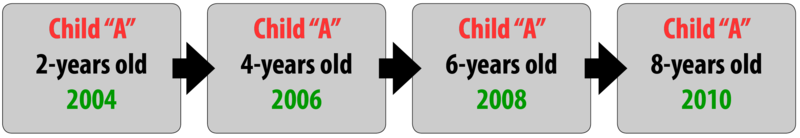

Longitudinal Research

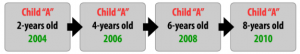

Longitudinal research involves beginning with a group of people who may be of the same age and background, and measuring them repeatedly over a long period of time. One of the benefits of this type of research is that people can be followed through time and be compared with them when they were younger.

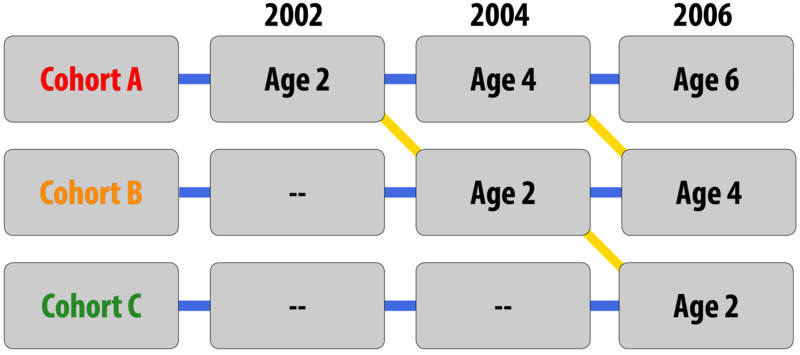

Figure 1.8 – A longitudinal research design. 13

A problem with this type of research is that it is very expensive and subjects may drop out over time. The Perry Preschool Project which began in 1962 is an example of a longitudinal study that continues to provide data on children’s development.

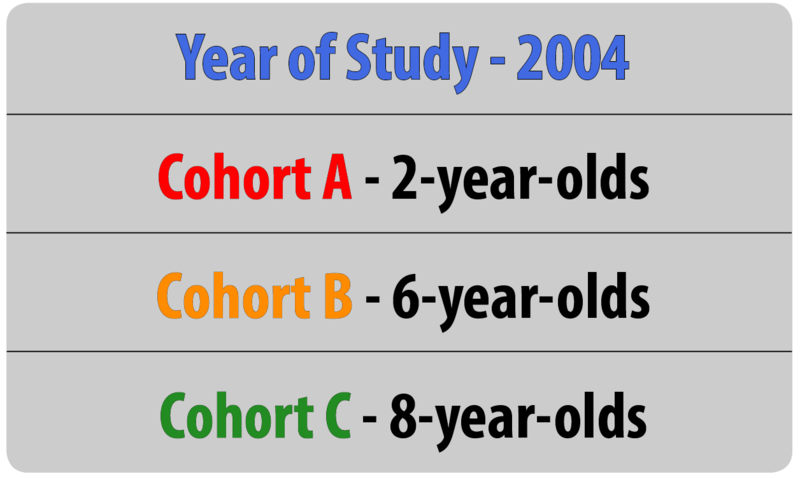

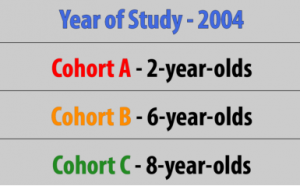

Cross-sectional Research

Cross-sectional research involves beginning with a sample that represents a cross-section of the population. Respondents who vary in age, gender, ethnicity, and social class might be asked to complete a survey about television program preferences or attitudes toward the use of the Internet. The attitudes of males and females could then be compared, as could attitudes based on age. In cross-sectional research, respondents are measured only once.

Figure 1.9 – A cross-sectional research design. 14

This method is much less expensive than longitudinal research but does not allow the researcher to distinguish between the impact of age and the cohort effect. Different attitudes about the use of technology, for example, might not be altered by a person’s biological age as much as their life experiences as members of a cohort.

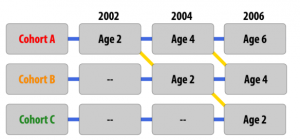

Sequential Research

Sequential research involves combining aspects of the previous two techniques; beginning with a cross-sectional sample and measuring them through time.

Figure 1.10 – A sequential research design. 15

This is the perfect model for looking at age, gender, social class, and ethnicity. But the drawbacks of high costs and attrition are here as well. 16

Table 1 .1 – Advantages and Disadvantages of Different Research Designs 17

Consent and Ethics in Research

Research should, as much as possible, be based on participants’ freely volunteered informed consent. For minors, this also requires consent from their legal guardians. This implies a responsibility to explain fully and meaningfully to both the child and their guardians what the research is about and how it will be disseminated. Participants and their legal guardians should be aware of the research purpose and procedures, their right to refuse to participate; the extent to which confidentiality will be maintained; the potential uses to which the data might be put; the foreseeable risks and expected benefits; and that participants have the right to discontinue at any time.

But consent alone does not absolve the responsibility of researchers to anticipate and guard against potential harmful consequences for participants. 18 It is critical that researchers protect all rights of the participants including confidentiality.

Child development is a fascinating field of study – but care must be taken to ensure that researchers use appropriate methods to examine infant and child behavior, use the correct experimental design to answer their questions, and be aware of the special challenges that are part-and-parcel of developmental research. Hopefully, this information helped you develop an understanding of these various issues and to be ready to think more critically about research questions that interest you. There are so many interesting questions that remain to be examined by future generations of developmental scientists – maybe you will make one of the next big discoveries! 19

Another really important framework to use when trying to understand children’s development are theories of development. Let’s explore what theories are and introduce you to some major theories in child development.

Developmental Theories

What is a theory.

Students sometimes feel intimidated by theory; even the phrase, “Now we are going to look at some theories…” is met with blank stares and other indications that the audience is now lost. But theories are valuable tools for understanding human behavior; in fact they are proposed explanations for the “how” and “whys” of development. Have you ever wondered, “Why is my 3 year old so inquisitive?” or “Why are some fifth graders rejected by their classmates?” Theories can help explain these and other occurrences. Developmental theories offer explanations about how we develop, why we change over time and the kinds of influences that impact development.

A theory guides and helps us interpret research findings as well. It provides the researcher with a blueprint or model to be used to help piece together various studies. Think of theories as guidelines much like directions that come with an appliance or other object that requires assembly. The instructions can help one piece together smaller parts more easily than if trial and error are used.

Theories can be developed using induction in which a number of single cases are observed and after patterns or similarities are noted, the theorist develops ideas based on these examples. Established theories are then tested through research; however, not all theories are equally suited to scientific investigation. Some theories are difficult to test but are still useful in stimulating debate or providing concepts that have practical application. Keep in mind that theories are not facts; they are guidelines for investigation and practice, and they gain credibility through research that fails to disprove them. 20

Let’s take a look at some key theories in Child Development.

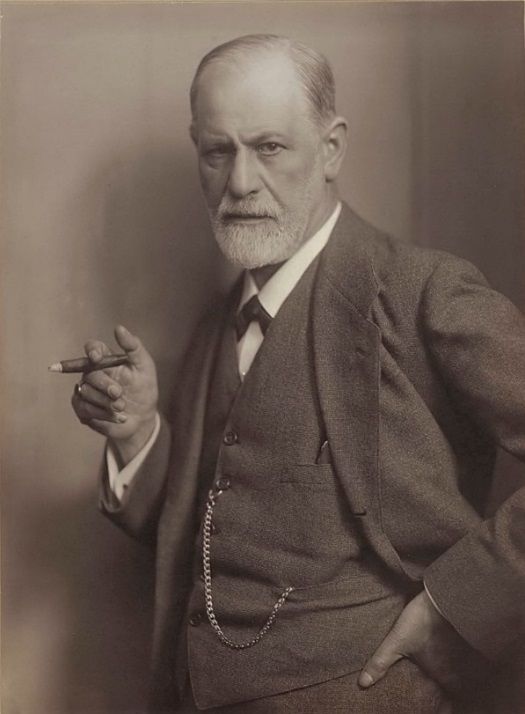

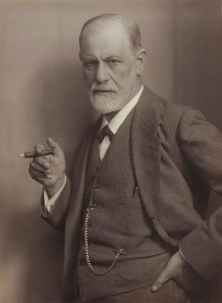

Sigmund Freud’s Psychosexual Theory

We begin with the often controversial figure, Sigmund Freud (1856-1939). Freud has been a very influential figure in the area of development; his view of development and psychopathology dominated the field of psychiatry until the growth of behaviorism in the 1950s. His assumptions that personality forms during the first few years of life and that the ways in which parents or other caregivers interact with children have a long-lasting impact on children’s emotional states have guided parents, educators, clinicians, and policy-makers for many years. We have only recently begun to recognize that early childhood experiences do not always result in certain personality traits or emotional states. There is a growing body of literature addressing resilience in children who come from harsh backgrounds and yet develop without damaging emotional scars (O’Grady and Metz, 1987). Freud has stimulated an enormous amount of research and generated many ideas. Agreeing with Freud’s theory in its entirety is hardly necessary for appreciating the contribution he has made to the field of development.

Figure 1.11 – Sigmund Freud. 21

Freud’s theory of self suggests that there are three parts of the self.

The id is the part of the self that is inborn. It responds to biological urges without pause and is guided by the principle of pleasure: if it feels good, it is the thing to do. A newborn is all id. The newborn cries when hungry, defecates when the urge strikes.

The ego develops through interaction with others and is guided by logic or the reality principle. It has the ability to delay gratification. It knows that urges have to be managed. It mediates between the id and superego using logic and reality to calm the other parts of the self.

The superego represents society’s demands for its members. It is guided by a sense of guilt. Values, morals, and the conscience are all part of the superego.

The personality is thought to develop in response to the child’s ability to learn to manage biological urges. Parenting is important here. If the parent is either overly punitive or lax, the child may not progress to the next stage. Here is a brief introduction to Freud’s stages.

Table 1. 2 – Sigmund Freud’s Psychosexual Theory

Strengths and Weaknesses of Freud’s Theory

Freud’s theory has been heavily criticized for several reasons. One is that it is very difficult to test scientifically. How can parenting in infancy be traced to personality in adulthood? Are there other variables that might better explain development? The theory is also considered to be sexist in suggesting that women who do not accept an inferior position in society are somehow psychologically flawed. Freud focuses on the darker side of human nature and suggests that much of what determines our actions is unknown to us. So why do we study Freud? As mentioned above, despite the criticisms, Freud’s assumptions about the importance of early childhood experiences in shaping our psychological selves have found their way into child development, education, and parenting practices. Freud’s theory has heuristic value in providing a framework from which to elaborate and modify subsequent theories of development. Many later theories, particularly behaviorism and humanism, were challenges to Freud’s views. 22

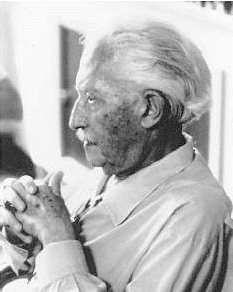

Erik Erikson’s Psychosocial Theory

Now, let’s turn to a less controversial theorist, Erik Erikson. Erikson (1902-1994) suggested that our relationships and society’s expectations motivate much of our behavior in his theory of psychosocial development. Erikson was a student of Freud’s but emphasized the importance of the ego, or conscious thought, in determining our actions. In other words, he believed that we are not driven by unconscious urges. We know what motivates us and we consciously think about how to achieve our goals. He is considered the father of developmental psychology because his model gives us a guideline for the entire life span and suggests certain primary psychological and social concerns throughout life.

Figure 1.12 – Erik Erikson. 23

Erikson expanded on his Freud’s by emphasizing the importance of culture in parenting practices and motivations and adding three stages of adult development (Erikson, 1950; 1968). He believed that we are aware of what motivates us throughout life and the ego has greater importance in guiding our actions than does the id. We make conscious choices in life and these choices focus on meeting certain social and cultural needs rather than purely biological ones. Humans are motivated, for instance, by the need to feel that the world is a trustworthy place, that we are capable individuals, that we can make a contribution to society, and that we have lived a meaningful life. These are all psychosocial problems.

Erikson divided the lifespan into eight stages. In each stage, we have a major psychosocial task to accomplish or crisis to overcome. Erikson believed that our personality continues to take shape throughout our lifespan as we face these challenges in living. Here is a brief overview of the eight stages:

Table 1. 3 – Erik Erikson’s Psychosocial Theory

These eight stages form a foundation for discussions on emotional and social development during the life span. Keep in mind, however, that these stages or crises can occur more than once. For instance, a person may struggle with a lack of trust beyond infancy under certain circumstances. Erikson’s theory has been criticized for focusing so heavily on stages and assuming that the completion of one stage is prerequisite for the next crisis of development. His theory also focuses on the social expectations that are found in certain cultures, but not in all. For instance, the idea that adolescence is a time of searching for identity might translate well in the middle-class culture of the United States, but not as well in cultures where the transition into adulthood coincides with puberty through rites of passage and where adult roles offer fewer choices. 24

Behaviorism

While Freud and Erikson looked at what was going on in the mind, behaviorism rejected any reference to mind and viewed overt and observable behavior as the proper subject matter of psychology. Through the scientific study of behavior, it was hoped that laws of learning could be derived that would promote the prediction and control of behavior. 25

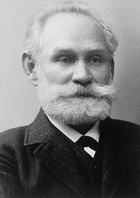

Ivan Pavlov

Ivan Pavlov (1880-1937) was a Russian physiologist interested in studying digestion. As he recorded the amount of salivation his laboratory dogs produced as they ate, he noticed that they actually began to salivate before the food arrived as the researcher walked down the hall and toward the cage. “This,” he thought, “is not natural!” One would expect a dog to automatically salivate when food hit their palate, but BEFORE the food comes? Of course, what had happened was . . . you tell me. That’s right! The dogs knew that the food was coming because they had learned to associate the footsteps with the food. The key word here is “learned”. A learned response is called a “conditioned” response.

Figure 1.13 – Ivan Pavlov. 26

Pavlov began to experiment with this concept of classical conditioning . He began to ring a bell, for instance, prior to introducing the food. Sure enough, after making this connection several times, the dogs could be made to salivate to the sound of a bell. Once the bell had become an event to which the dogs had learned to salivate, it was called a conditioned stimulus . The act of salivating to a bell was a response that had also been learned, now termed in Pavlov’s jargon, a conditioned response. Notice that the response, salivation, is the same whether it is conditioned or unconditioned (unlearned or natural). What changed is the stimulus to which the dog salivates. One is natural (unconditioned) and one is learned (conditioned).

Let’s think about how classical conditioning is used on us. One of the most widespread applications of classical conditioning principles was brought to us by the psychologist, John B. Watson.

John B. Watson

John B. Watson (1878-1958) believed that most of our fears and other emotional responses are classically conditioned. He had gained a good deal of popularity in the 1920s with his expert advice on parenting offered to the public.

Figure 1.14 – John B. Watson. 27

He tried to demonstrate the power of classical conditioning with his famous experiment with an 18 month old boy named “Little Albert”. Watson sat Albert down and introduced a variety of seemingly scary objects to him: a burning piece of newspaper, a white rat, etc. But Albert remained curious and reached for all of these things. Watson knew that one of our only inborn fears is the fear of loud noises so he proceeded to make a loud noise each time he introduced one of Albert’s favorites, a white rat. After hearing the loud noise several times paired with the rat, Albert soon came to fear the rat and began to cry when it was introduced. Watson filmed this experiment for posterity and used it to demonstrate that he could help parents achieve any outcomes they desired, if they would only follow his advice. Watson wrote columns in newspapers and in magazines and gained a lot of popularity among parents eager to apply science to household order.

Operant conditioning, on the other hand, looks at the way the consequences of a behavior increase or decrease the likelihood of a behavior occurring again. So let’s look at this a bit more.

B.F. Skinner and Operant Conditioning

B. F. Skinner (1904-1990), who brought us the principles of operant conditioning, suggested that reinforcement is a more effective means of encouraging a behavior than is criticism or punishment. By focusing on strengthening desirable behavior, we have a greater impact than if we emphasize what is undesirable. Reinforcement is anything that an organism desires and is motivated to obtain.

Figure 1.15 – B. F. Skinner. 28

A reinforcer is something that encourages or promotes a behavior. Some things are natural rewards. They are considered intrinsic or primary because their value is easily understood. Think of what kinds of things babies or animals such as puppies find rewarding.

Extrinsic or secondary reinforcers are things that have a value not immediately understood. Their value is indirect. They can be traded in for what is ultimately desired.

The use of positive reinforcement involves adding something to a situation in order to encourage a behavior. For example, if I give a child a cookie for cleaning a room, the addition of the cookie makes cleaning more likely in the future. Think of ways in which you positively reinforce others.

Negative reinforcement occurs when taking something unpleasant away from a situation encourages behavior. For example, I have an alarm clock that makes a very unpleasant, loud sound when it goes off in the morning. As a result, I get up and turn it off. By removing the noise, I am reinforced for getting up. How do you negatively reinforce others?

Punishment is an effort to stop a behavior. It means to follow an action with something unpleasant or painful. Punishment is often less effective than reinforcement for several reasons. It doesn’t indicate the desired behavior, it may result in suppressing rather than stopping a behavior, (in other words, the person may not do what is being punished when you’re around, but may do it often when you leave), and a focus on punishment can result in not noticing when the person does well.

Not all behaviors are learned through association or reinforcement. Many of the things we do are learned by watching others. This is addressed in social learning theory.

Social Learning Theory

Albert Bandura (1925-) is a leading contributor to social learning theory. He calls our attention to the ways in which many of our actions are not learned through conditioning; rather, they are learned by watching others (1977). Young children frequently learn behaviors through imitation

Figure 1.16 – Albert Bandura. 29

Sometimes, particularly when we do not know what else to do, we learn by modeling or copying the behavior of others. A kindergartner on his or her first day of school might eagerly look at how others are acting and try to act the same way to fit in more quickly. Adolescents struggling with their identity rely heavily on their peers to act as role-models. Sometimes we do things because we’ve seen it pay off for someone else. They were operantly conditioned, but we engage in the behavior because we hope it will pay off for us as well. This is referred to as vicarious reinforcement (Bandura, Ross and Ross, 1963).

Bandura (1986) suggests that there is interplay between the environment and the individual. We are not just the product of our surroundings, rather we influence our surroundings. Parents not only influence their child’s environment, perhaps intentionally through the use of reinforcement, etc., but children influence parents as well. Parents may respond differently with their first child than with their fourth. Perhaps they try to be the perfect parents with their firstborn, but by the time their last child comes along they have very different expectations both of themselves and their child. Our environment creates us and we create our environment. 30

Theories also explore cognitive development and how mental processes change over time.

Jean Piaget’s Theory of Cognitive Development

Jean Piaget (1896-1980) is one of the most influential cognitive theorists. Piaget was inspired to explore children’s ability to think and reason by watching his own children’s development. He was one of the first to recognize and map out the ways in which children’s thought differs from that of adults. His interest in this area began when he was asked to test the IQ of children and began to notice that there was a pattern in their wrong answers. He believed that children’s intellectual skills change over time through maturation. Children of differing ages interpret the world differently.

Figure 1.17 – Jean Piaget. 32

Piaget believed our desire to understand the world comes from a need for cognitive equilibrium . This is an agreement or balance between what we sense in the outside world and what we know in our minds. If we experience something that we cannot understand, we try to restore the balance by either changing our thoughts or by altering the experience to fit into what we do understand. Perhaps you meet someone who is very different from anyone you know. How do you make sense of this person? You might use them to establish a new category of people in your mind or you might think about how they are similar to someone else.

A schema or schemes are categories of knowledge. They are like mental boxes of concepts. A child has to learn many concepts. They may have a scheme for “under” and “soft” or “running” and “sour”. All of these are schema. Our efforts to understand the world around us lead us to develop new schema and to modify old ones.

One way to make sense of new experiences is to focus on how they are similar to what we already know. This is assimilation . So the person we meet who is very different may be understood as being “sort of like my brother” or “his voice sounds a lot like yours.” Or a new food may be assimilated when we determine that it tastes like chicken!

Another way to make sense of the world is to change our mind. We can make a cognitive accommodation to this new experience by adding new schema. This food is unlike anything I’ve tasted before. I now have a new category of foods that are bitter-sweet in flavor, for instance. This is accommodation . Do you accommodate or assimilate more frequently? Children accommodate more frequently as they build new schema. Adults tend to look for similarity in their experience and assimilate. They may be less inclined to think “outside the box.”

Piaget suggested different ways of understanding that are associated with maturation. He divided this into four stages:

Table 1.4 – Jean Piaget’s Theory of Cognitive Development

Criticisms of Piaget’s Theory

Piaget has been criticized for overemphasizing the role that physical maturation plays in cognitive development and in underestimating the role that culture and interaction (or experience) plays in cognitive development. Looking across cultures reveals considerable variation in what children are able to do at various ages. Piaget may have underestimated what children are capable of given the right circumstances. 33

Lev Vygotsky’s Sociocultural Theory

Lev Vygotsky (1896-1934) was a Russian psychologist who wrote in the early 1900s but whose work was discovered in the United States in the 1960s but became more widely known in the 1980s. Vygotsky differed with Piaget in that he believed that a person not only has a set of abilities, but also a set of potential abilities that can be realized if given the proper guidance from others. His sociocultural theory emphasizes the importance of culture and interaction in the development of cognitive abilities. He believed that through guided participation known as scaffolding, with a teacher or capable peer, a child can learn cognitive skills within a certain range known as the zone of proximal development . 34 His belief was that development occurred first through children’s immediate social interactions, and then moved to the individual level as they began to internalize their learning. 35

Figure 1.18- Lev Vygotsky. 36

Have you ever taught a child to perform a task? Maybe it was brushing their teeth or preparing food. Chances are you spoke to them and described what you were doing while you demonstrated the skill and let them work along with you all through the process. You gave them assistance when they seemed to need it, but once they knew what to do-you stood back and let them go. This is scaffolding and can be seen demonstrated throughout the world. This approach to teaching has also been adopted by educators. Rather than assessing students on what they are doing, they should be understood in terms of what they are capable of doing with the proper guidance. You can see how Vygotsky would be very popular with modern day educators. 37

Comparing Piaget and Vygotsky

Vygotsky concentrated more on the child’s immediate social and cultural environment and his or her interactions with adults and peers. While Piaget saw the child as actively discovering the world through individual interactions with it, Vygotsky saw the child as more of an apprentice, learning through a social environment of others who had more experience and were sensitive to the child’s needs and abilities. 38

Like Vygotsky’s, Bronfenbrenner looked at the social influences on learning and development.

Urie Bronfenbrenner’s Ecological Systems Model

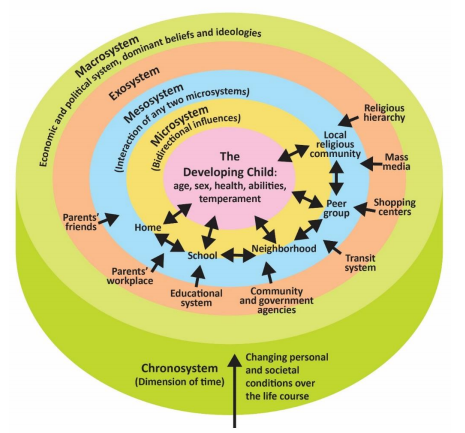

Urie Bronfenbrenner (1917-2005) offers us one of the most comprehensive theories of human development. Bronfenbrenner studied Freud, Erikson, Piaget, and learning theorists and believed that all of those theories could be enhanced by adding the dimension of context. What is being taught and how society interprets situations depends on who is involved in the life of a child and on when and where a child lives.

Figure 1.19 – Urie Bronfenbrenner. 39

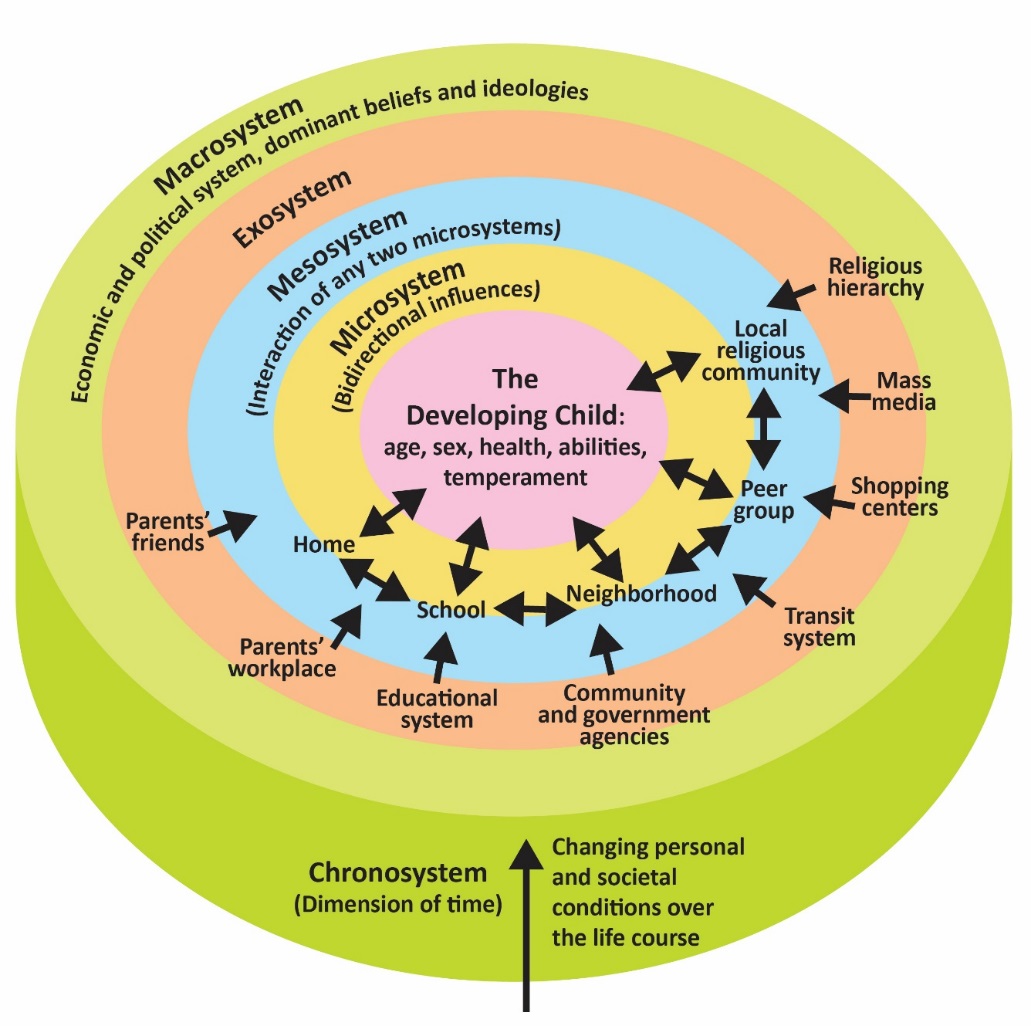

Bronfenbrenner’s ecological systems model explains the direct and indirect influences on an individual’s development.

Table 1.5 – Urie Bronfenbrenner’s Ecological Systems Model

For example, in order to understand a student in math, we can’t simply look at that individual and what challenges they face directly with the subject. We have to look at the interactions that occur between teacher and child. Perhaps the teacher needs to make modifications as well. The teacher may be responding to regulations made by the school, such as new expectations for students in math or constraints on time that interfere with the teacher’s ability to instruct. These new demands may be a response to national efforts to promote math and science deemed important by political leaders in response to relations with other countries at a particular time in history.

Figure 1.20 – Bronfenbrenner’s ecological systems theory. 40

Bronfenbrenner’s ecological systems model challenges us to go beyond the individual if we want to understand human development and promote improvements. 41

In this chapter we looked at:

underlying principles of development

the five periods of development

three issues in development

Various methods of research

important theories that help us understand development

Next, we are going to be examining where we all started with conception, heredity, and prenatal development.

Child Growth and Development Copyright © by Jean Zaar is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Share This Book

- school Campus Bookshelves

- menu_book Bookshelves

- perm_media Learning Objects

- login Login

- how_to_reg Request Instructor Account

- hub Instructor Commons

Margin Size

- Download Page (PDF)

- Download Full Book (PDF)

- Periodic Table

- Physics Constants

- Scientific Calculator

- Reference & Cite

- Tools expand_more

- Readability

selected template will load here

This action is not available.

5.3: Developmental Domains

- Last updated

- Save as PDF

- Page ID 188651

- Angela Blums & Sally Nyblad Holloway

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

While development is complex, four domains have been identified: physical, cognitive, social, and emotional. This section will introduce each of these developmental domains and explain some important features of each domain. keep in mind that developmental domains are interrelated, so consider as you read the next sections how one aspect of development could affect another.

Physical Development

Physical development includes all things related to the body. Sometimes this domain is called biological development because it also encompasses processes that occur inside the body at the biological level.

Brain Development

Brain development is an important part of physical development and was thoroughly covered in Chapter 4. As a reminder, infant brains begin to develop while still in utero. Because of this, it is important to support fetal brain development through proper nutrition and care of the mother. Once born, infant brains develop rapidly. Brain connections, called synapses, develop rapidly during the first few months to the first 3 years of life, making this period critical for healthy brain development. During infancy, babies require responsive interactions with trusted caregivers that include verbal, expressive, face-to-face engagement. Additionally, and above all, they require a safe and secure home environment for healthy brain development.

Motor Skills

Children’s bodies are designed to wiggle and move. Motor skills refer to a child’s ability to move and coordinate motion using their bodies. Motor skills are generally organized into two categories: gross motor skills and fine motor skills. Gross motor skills are related to the large muscle groups in the body: walking, running, climbing, balancing, and jumping are examples of gross motor skills. Fine motor skills are related to small muscle groups in the body. Grasping a spoon, holding a pencil, stringing beads, and stacking blocks are examples of fine motor skills.

In order for gross motor skills to develop successfully, infants and children must be given opportunities to move their bodies freely, safely and without restriction, starting from birth. This is why most pediatric physical therapists recommend against the use of so-called “baby containers” – chairs, bouncy seats, swings, and jumpers that place an infant in an upright position before their body is ready to do so on its own. These devices can hinder development. Instead, babies should play on a blanket or mat and have a few minutes of “tummy time” each day starting at birth. This helps to strengthen neck and shoulder muscles that will later be used in crawling. As children begin to crawl and walk, soft climbers can help to develop gross motor skills.

Once solid on their feet, children need opportunities to practice running, jumping, balancing, and climbing. This is why daily outdoor play is vital. Playgrounds can be great places for children to experiment with gross motor skills. Outdoor play in natural areas is also important. Consider the difference between climbing stairs or monkey bars on a playground vs climbing the branches of a strong, low, tree. Both offer opportunities for using arms and legs, but tree climbing allows children to use muscle groups in new positions and learn to balance in an irregular position. If no safe climbing trees are available, learning to walk or run on uneven ground in a field or meadow can also be beneficial. It is important for children to move their bodies in many different ways.

Playing outdoors on playgrounds and in nature provides children opportunities to take risks. When children climb, they not only build muscle and coordination, but also learn to overcome fears. This can lead to greater self-confidence that carries over into other areas as well. This is one way in which outdoor activity supports not only physical but also emotional development.

Fine motor skills begin to develop in infancy when the child first learns to grasp a toy such as a rattle or a cloth. Later, they learn to throw a ball, hold a crayon, and use scissors. Children can be given opportunities to use their hands in a variety of ways using age-appropriate materials. Young children love to practice fine motor skills using real-life items, such as bucking the clasp of a highchair strap or zipping a zipper. This has the added benefit of fostering independence which supports emotional development. Children can coordinate their finger movements while learning a zipper and they can also feel proud when they can zip their own jacket to go outside. Opportunities for fine motor development are everywhere and can be as simple as picking up a leaf and ripping it into tiny pieces. Teachers can foster fine motor skills by making sure to create challenging activities based on each child’s developmental level.

Cognitive Development

Cognitive development includes all things related to thinking and learning. In the early childhood stage, the focus is on problem solving, memory, and language acquisition.

Executive Function

One key area of cognitive development is called executive function . Executive function is the collection of processes that encompasses attention, working memory, and inhibition, and it develops between the ages of about 3 and 6 years. Attention is the ability of a child to focus on something, like carefully concentrating on a picture in a book. Working memory refers to the ability of a child to maintain several pieces of information in the mind for a short period of time. This could be recalling some items present in the picture in the book, like a tree, a bird, and a house. Inhibition is the ability to block out distractions, such as other background designs on the book or even the sounds of other children playing in the classroom. Development of executive function is key to building social relationships, acquiring, and maintaining learning, and eventual academic success. For example, if a child is going to learn how to add using blocks, she might have to first pay attention to the blocks in front of her, remember that she had three blocks on one side and one block on the other side, and inhibit the distraction of other toys on the table. All of these components come together with executive function. It is important to remember that because executive function is developing between the ages of about 3 and 5 years, young children do not have the ability to pay attention to things for long periods of time. Nor do they have the ability to remember multiple pieces of information or block out distractions. This is important when planning activities for young children. Setting the expectation that young children should sit at a table and focus on one activity will result in frustration of both children and teachers, as children will communicate their lack of executive function with a lot of wiggles and movement! This is healthy, and teachers should keep this in mind when planning activities that require concentration.

Children with Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD) need extra support to develop executive function, as concentration and inhibition are particularly difficult. Children who are in chaotic environments or those who have experienced toxic stress and trauma may struggle with the development of healthy executive function. Strategies that have been successful in promoting executive function are games and activities that practice concentration and task-switching. Such games need to be fun, not tied to punishment or reward. Deep breathing and mediation have also been shown to aid in the development of executive function for children who are struggling.

Problem Solving

When children encounter a challenge, they learn to practice problem solving. Problem solving involves assessing the problem, devising a plan, carrying out the plan, and reflecting on the outcome. Children may do this without actively knowing that they are carrying out these four steps. For instance, if a child is building a block tower on a soft carpet, it might be unstable and fall down. The child might think of a solution: get a tray or a large book to set on the carpet to create a flat surface. The child then gets the tray, builds the block tower, and then checks to see if it is wobbly or stable. Problem solved! Children solve many such problems each day during play. It is helpful for teachers to facilitate problem solving by asking open-ended questions , or questions that do not have a yes or no answer. This type of question helps the child see the main features and problems in the situation, encourages thinking about solutions, and suggests solutions, all without giving the answer. An exchange might look like the following:

Teacher: “It looks like your block tower is falling down a lot. I wonder why?”

Child “Because the carpet is bumpy and soft”

Teacher: “How can you make a more stable base for your tower?”

Child: “I could put a tray underneath it!”

Teacher: “Want to try that and see what happens?”

This exchange of open-ended questions helps the child learn to problem solve on their own. The use of the phrase “see what happens” encourages the child to engage in the fourth step of problem solving, assessing the outcome. After all, a problem-solving strategy may not succeed, and the child might have to try something else. This is all part of the process of learning.

Theory of Mind