Logos Definition

What is logos? Here’s a quick and simple definition:

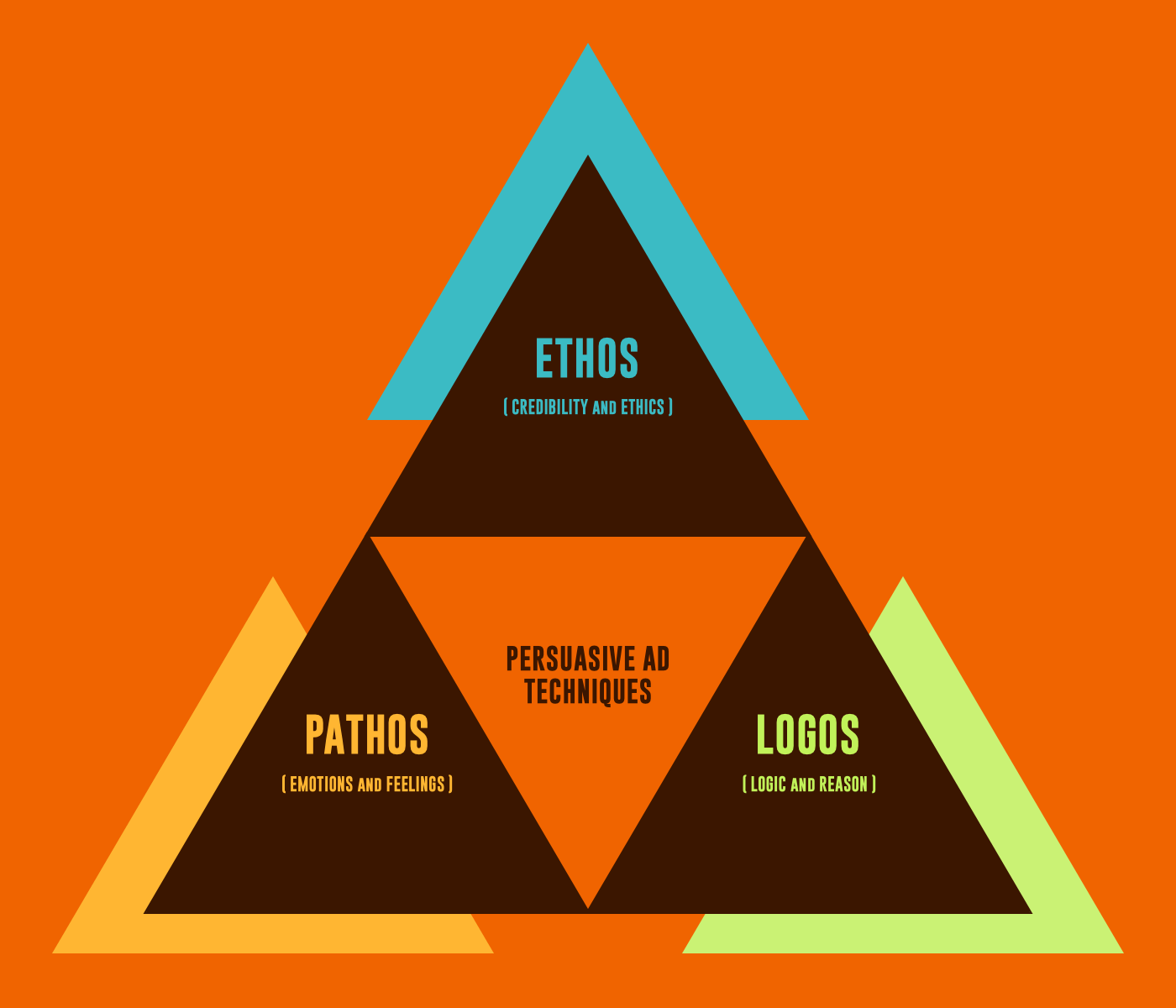

Logos , along with ethos and pathos , is one of the three "modes of persuasion" in rhetoric (the art of effective speaking or writing). Logos is an argument that appeals to an audience's sense of logic or reason. For example, when a speaker cites scientific data, methodically walks through the line of reasoning behind their argument, or precisely recounts historical events relevant to their argument, he or she is using logos.

Some additional key details about logos:

- Aristotle defined logos as the "proof, or apparent proof, provided by the words of the speech itself." In other words, logos rests in the actual written content of an argument.

- The three "modes of persuasion"— pathos , logos , and ethos —were originally defined by Aristotle.

- In contrast to logos's appeal to reason, ethos is an appeal to the audience based on the speaker's authority, while pathos is an appeal to the audience 's emotions.

- Data, facts, statistics, test results, and surveys can all strengthen the logos of a presentation.

How to Pronounce Logos

Here's how to pronounce logos: loh -gos

Logos and Different Types of Proof

While it's easy to spot a speaker using logos when he or she presents statistics or research results, numerical data is only one form that logos can take. Logos is any statement, sentence, or argument that attempts to persuade using facts, and these facts need not be the result of long research. "The facts" of an argument can also be drawn from the speaker's own life or from the world at large, and presenting these examples to support one's view is also a form of logos. Take this example from Sojourner Truth's "Ain't I a Woman?" speech in support of women's rights:

That man over there says that women need to be helped into carriages, and lifted over ditches, and to have the best place everywhere. Nobody ever helps me into carriages, or over mud-puddles, or gives me any best place! And ain't I a woman? Look at me! Look at my arm! I have ploughed and planted, and gathered into barns, and no man could head me! And ain't I a woman?

Truth points to her own strength, as well as to the fact that she can perform physically tiring tasks just as well as a man, as proof of equality between the sexes: she's still appealing to the audience's reason, but instead of presenting abstract truths about reality or numerical evidence, she's presenting the facts of her own experience as evidence. In this case, the logic of the argument is anecdotal (meaning it's derived from a handful of personal experiences) rather than purely theoretical, but it goes to show that logos doesn't have to be dry and clinical just because it's concerned with proving something logically.

Logos: Proof vs. Apparent Proof

Not all speakers who use logos can be blindly trusted. As Aristotle specifies in his definition of the term, logos can be "proof, or apparent proof." A speaker may present facts, figures, and research data simply to show that he or she has "done their homework," in an effort to attain the degree of credibility that is often automatically attributed to scientific studies and evidence-driven arguments. Or a speaker might present facts in a way that is wholly or partially misrepresentative, using those facts (and, by extension, logos ) to make a claim that feels credible while actually arguing something that is untrue. Yet another factor that can cause a speech or text to have the appearance of providing proof is the use of overlong words and technical language—but just because someone sounds smart doesn't mean their argument stands to reason.

Even if the facts have been manipulated, any argument that relies on or even just claims to rely on "facts" to appeal to a listener's reason is still an example of logos. Put another way: logos is not about using facts correctly or accurately , it's about using facts in any way to influence an audience.

Logos Examples

Examples of logos in literature.

While Aristotle defined the term logos with public speaking in mind, there are many examples of logos in literature. Generally, logos appears in literature when characters argue or attempt to convince one another that something is true. The degree to which characters use logos -driven arguments can also provide important insight into their personalities and motives.

Logos in Shakespeare's Othello

In Othello , Iago plots to bring about the downfall of his captain, Othello. Iago engineers a series of events that makes it look like Othello’s wife, Desdemona, is cheating on him. Suspicion of his wife’s infidelity tortures Othello, who only recently eloped with Desdemona against her father’s wishes. In this passage from Act 3, Scene 3, Iago manipulates Othello by means of logos . Iago "warns" Othello not to succumb to paranoia even as he fans the flames of that paranoia:

Oh, beware, my lord, of jealousy! It is the green-eyed monster which doth mock The meat it feeds on….. Who, certain of his fate, loves not his wronger, But, oh, what damnèd minutes tells he o’er Who dotes, yet doubts— suspects, yet soundly loves… She did deceive her father, marrying you… She loved them most…. I humbly do beseech you of your pardon For too much loving you….

Iago here lectures Othello on the abstract dangers of jealousy, but then goes on to use reason and deduction to suggest that, because Desdemona deceived her beloved father by marrying Othello, she'd probably be willing to deceive Othello, too.

Logos in Don DeLillo's White Noise

In this passage from Part 2 of Don Delillo’s novel White Noise, Jack Gladney and his son Heinrich gaze through binoculars at an Airborne Toxic Event—or cloud of poison gas—that has just hit their town. Jack , in denial, tries to reassure his son that the cloud won’t blow in their direction and that there’s no cause for alarm. Heinrich disagrees:

"What do you think?" he said. "It's still hanging there. Looks rooted to the spot." "So you're saying you don't think it'll come this way." "I can tell by your voice that you know something I don't know." "Do you think it'll come this way or not?" "You want me to say it won't come this way in a million years. Then you'll attack with your little fistful of data. Come on, tell me what they said on the radio while I was out there." "It doesn't cause nausea, vomiting, shortness of breath, like they said before." "What does it cause?" "Heart palpitations and a sense of deja vu." "Deja vu?" "It affects the false part of the human memory or whatever. That's not all. They're not calling it the black billowing cloud anymore." "What are they calling it?" He looked at me carefully. "The airborne toxic event." ... "These things are not important. The important thing is location. It's there, we're here." "A large air mass is moving down from Canada," he said evenly. "I already knew that." "That doesn't mean it's not important." "Maybe it is, maybe it isn't. Depends."

Jack tries to reassure himself and his family that the situation isn’t serious. Heinrich tries to counter his father’s irrational, fear-driven response to the catastrophe with his "fistful of data": information he's learned in school from a science video on toxic waste, as well as reports about the disaster that he heard on the radio. He presents the facts so that his father can’t ignore them, thereby strengthening the logos of his argument that the situation is serious and the cloud will come their way. In this particular example, the lack of logos in Jack's argument reveals a lot about his character—even though Jack is a tenured college professor, strong emotions and fear for his own mortality often drive his behavior and speech.

Logos in Harper Lee's To Kill a Mockingbird

In this example from To Kill a Mockingbird , lawyer Atticus Finch uses logos to argue on behalf of a black defendant, Tom Robinson, who stands accused of raping a white woman.

"The state has not produced one iota of medical evidence to the effect that the crime Tom Robinson is charged with ever took place. It has relied instead upon the testimony of two witnesses whose evidence has not only been called into serious question on cross-examination, but has been flatly contradicted by the defendant. The defendant is not guilty, but somebody in this courtroom is."

The logos in this case lies in Atticus' emphasis on the facts of the case, or rather, the fact that there are no facts in the case against Tom. He temporarily ignores questions of racial justice and emotional trauma so that the jury can look clearly at the body of evidence available to them. In short, he appeals to the jury's reason .

Logos in Robert M. Pirsig's Zen and the Art of Motorcycle Maintenance

In Zen and the Art of Motorcycle Maintenance , the narrator takes a cross-country motorcycle trip with his son Chris, and their two friends John and Sylvia. When Chris tells the group in Chapter 3 that his friend Tom White Bear believes in ghosts, the narrator tries to explain that scientific principles only exist in our heads, and therefore are actually modern man's equivalent of ghosts:

"Modern man has his ghosts and spirits too, you know." "What?" "Oh, the laws of physics and of logic...the number system...the principle of algebraic substitution. These are ghosts. We just believe in them so thoroughly they seem real." "They seem real to me," John says. "I don't get it," says Chris. So I go on. "For example, it seems completely natural to presume that gravitation and the law of gravitation existed before Isaac Newton. It would sound nutty to think that until the seventeenth century there was no gravity." "Of course" "So when did this law start? Has it always existed?...What I'm driving at is the notion that before the beginning of the earth, before the sun and the stars were formed, before the primal generation of anything, the law of gravity existed." "Sure." "Sitting there, having no mass of its own, no energy of its own, not in anyone's mind because there wasn't anyone, not in space because there was no space either, not anywhere—this law of gravity still existed?" Now John seems not so sure. "If the law of gravity existed," I say, "I honestly don't know what a thing has to do to be non existent. It seems to me that law of gravity has passed every test of nonexistence there is...And yet it is still 'common sense' to believe that it existed." "I guess I'd have to think about it." "Well, I predict that if you think about it long enough you will find yourself going round and round and round and round until you finally reach only one possible, rational, intelligent conclusion. The law of gravity and gravity itself did not exist before Isaac Newton. No other conclusion makes sense. And what that means... is that that law of gravity exists nowhere except in people's heads! It's a ghost!"

The narrator uses logos in his discourse on scientific concepts by presenting his audience with an example—gravity—and asking them to consider their own experience of gravity as empirical evidence in support of his argument. He urges his friends to come to a "rational, intelligent conclusion" about the concept of gravity, instead of relying on conventional wisdom and unexamined assumptions.

Logos in Political Speeches

Politicians frequently use logos, often by citing statistics or examples, to persuade their listeners of the success or failure of policies, politicians, and ideologies.

Logos in Barack Obama's 2015 State of the Union Address

In this example, Obama cites historical precedent and economic data from past years to strengthen his argument that recent progress has been substantial and that the nation's economy is in good health:

But tonight, we turn the page. Tonight, after a breakthrough year for America, our economy is growing and creating jobs at the fastest pace since 1999. Our unemployment rate is now lower than it was before the financial crisis. More of our kids are graduating than ever before. More of our people are insured than ever before. And we are as free from the grip of foreign oil as we’ve been in almost 30 years.

Logos in Ronald Reagan's 1987 "Tear Down this Wall" Speech

In this speech, Reagan intends for his comparison between the poverty of East Berlin—controlled by the Communists—and the prosperity of Democratic West Berlin to serve as hard evidence supporting the economic superiority of Western capitalism. The way he uses specific details about the physical landscape of West Berlin as proof of Western capitalist economic superiority is a form of logos:

Where four decades ago there was rubble, today in West Berlin there is the greatest industrial output of any city in Germany--busy office blocks, fine homes and apartments, proud avenues, and the spreading lawns of parkland. Where a city's culture seemed to have been destroyed, today there are two great universities, orchestras and an opera, countless theaters, and museums. Where there was want, today there's abundance--food, clothing, automobiles--the wonderful goods of the Ku'damm. From devastation, from utter ruin, you Berliners have, in freedom, rebuilt a city that once again ranks as one of the greatest on earth...In the 1950s, Khrushchev [leader of the communist Soviet Union] predicted: "We will bury you." But in the West today, we see a free world that has achieved a level of prosperity and well-being unprecedented in all human history. In the Communist world, we see failure, technological backwardness, declining standards of health, even want of the most basic kind—too little food. Even today, the Soviet Union still cannot feed itself. After these four decades, then, there stands before the entire world one great and inescapable conclusion: Freedom leads to prosperity. Freedom replaces the ancient hatreds among the nations with comity and peace. Freedom is the victor.

Why Do Writers Use Logos?

It's important to note that the three modes of persuasion often mutually reinforce one another. They don't have to be used in isolation from one other, and the same sentence may even include examples of all three. While logos is different from both ethos (an appeal to the audience based on the speaker's authority) and pathos (an appeal to the audience's emotions), the use of logos can serve as a strong complement to the use of ethos and/or pathos —and vice versa.

For instance, if a politician lists the number of casualties in a war, or rattles off statistics relating to a national issue, these facts may well appeal to the audience's emotions as well as their intellect, thereby strengthening pathos as well as logos as elements in the speech. Consider this passage from Michelle Obama's 2015 speech at The Partnership for a Healthier America Summit, in which she updates listeners on the success of her Let's Move! project for improving children's nutrition:

I mean, just think about what our work together means for a child born today. Maybe that child will be one of the 1.6 million kids attending healthier daycare centers where fruits and vegetables have replaced cookies and juice. And when that child starts school, maybe she’ll be one of the over 30 million kids eating the healthier school lunches that we fought for. Maybe she’ll be one of the 2 million kids with a Let’s Move! salad bar in her school, or one of the nearly 9 million kids in Let’s Move! Active Schools who are getting 60 minutes of physical activity a day, or one of the 5 million kids soon attending healthier after-school programs.

While Obama includes statistics to persuade her audience that Let's Move! has been a success ( logos) , she's also using those facts and figures to stir up enthusiasm for her cause ( pathos).

Other Helpful Logos Resources

- The Wikipedia Page on Logos: A detailed explanation and history of the term.

- The Dictionary Definition of Logos: A definition encompassing the different meanings of the word logos.

- Logos on Youtube: A video from TED-Ed about the three modes of persuasion.

- PDFs for all 136 Lit Terms we cover

- Downloads of 1932 LitCharts Lit Guides

- Teacher Editions for every Lit Guide

- Explanations and citation info for 40,744 quotes across 1932 books

- Downloadable (PDF) line-by-line translations of every Shakespeare play

- Bildungsroman

- Internal Rhyme

- Connotation

- Antanaclasis

- Juxtaposition

- Dramatic Irony

- Pathetic Fallacy

- Figurative Language

What is Logos? Definition, Examples of Logos in Literature

Home » The Writer’s Dictionary » What is Logos? Definition, Examples of Logos in Literature

Logos definition: Logos is a rhetorical device that includes any content in an argument that is meant to appeal to logic.

What is Logos?

What does logos mean in literature? Logos is a rhetorical device that includes any content in an argument that is meant to appeal to logic.

Logos is one of the three Aristotelian appeals. A writer utilizes the three appeals in order to convince his audience of his argument. The other two appeals are ethos (ethics) and pathos (emotion).

Appeals to logos are those that involve or influence the logical reasons an audience should believe an argument.

Examples of logos in an argument for tax reform might include:

- The United States has the highest corporate income tax in the world.

- Our own small businesses cannot compete with such a relatively high tax burden.

- Therefore, the government should lower corporate income tax rates.

The first statement is a fact; the second and third statements create a syllogism. Both are appeals to logos.

Modern Examples of Logos

Whether it’s Mom explaining why you need to do your homework before bedtime, a newspaper columnist commenting on the day’s events, or an engineer explaining a need for new equipment, logical appeals are evident in everyday speech and argument.

However, be mindful that simply stating facts is not an appeal to logos. Writers use appeals to logos when they have an argument they are trying to prove . Yet, just about anything could be an argument.

Look at the above examples—each speaker is trying to convince someone of something. This is where logos might come into play.

The Function of Logos

It is very difficult to believe or support an argument if it does not make logical sense. This is why a writer should include appeals to logos in his argument. The purpose of writing is to convince someone of something. Logos is a tool that helps writers do this.

Not all arguments will have the same “amount” of logical appeals. Some arguments might call for more emotional appeals. It is the writer’s responsibility to evaluate his audience to determine the best appeals for his argument.

Examples of Logos in Literature

Let me start with the economy, and a basic fact: The United States of America, right now, has the strongest, most durable economy in the world. We’re in the middle of the longest streak of private sector job creation in history. More than 14 million new jobs, the strongest two years of job growth since the ‘90s, an unemployment rate cut in half. Our auto industry just had its best year ever. That’s just part of a manufacturing surge that’s created nearly 900,000 new jobs in the past six years. And we’ve done all this while cutting our deficits by almost three-quarters.

With these words, Obama is utilizing facts, numbers, and statistics to logically prove to his audience that American’s economy is on the rise. Here, Obama is appealing to logos to convince his audience that, as President, he has positively made change to affect America’s growth and development.

This is an example of logos.

Summary: Logos Definition Literature

Define logos in literature: the definition of logos in literature is a rhetorical device that appeals to logic and reason.

In summary, logos is:

- an appeal to logic

- one of the three Aristotelian appeals

- usually evident as facts, numbers, or statistics

- used to convince an audience of an argument

Logos Definition

Derived from a Greek word, Logos means “logic.” Logos is a literary device that can be described as a statement, sentence , or argument used to convince or persuade the targeted audience by employing reason or logic. In everyday life, arguments depend upon pathos and ethos besides logos. Let’s take a look at logos examples in literature and debates.

Classification of Logos

Before you learn what logos is, you must first understand its two categories as given below:

- Inductive reasoning – Inductive reasoning involves a piece of specific representative evidence or the case which is drawn towards a conclusion or generalization. However, inductive reasoning requires reliable and convincing evidence that is presented to support the point.

- Deductive Reasoning – Deductive reasoning involves generalization at the initial stage and then moves on towards the specific case. The starting generalization must be based on reliable evidence to support it at the end.

In some cases, both of these methods are used to convince the audience.

Examples of Logos in Literature

Example #1: political ideals (by bertrand russell).

“The wage system has made people believe that what a man needs is work. This, of course, is absurd. What he needs is the goods produced by work, and the less work involved in making a given amount of goods, the better … But owing to our economic system …where a better system would produce only an increase of wages or a diminution in the hours of work without any corresponding diminution of wages.”

In this paragraph, Russell is presenting arguments for the unjust distribution of wealth and its consequences. He answers through logic and states that a reason for this injustice is due to evils in institutions. He deduces that capitalism and the wage system should be abolished to improve the economic system.

Example #2: The Art of Rhetoric (By Aristotle)

“All men are mortal. Socrates is a man. Therefore, Socrates is mortal.”

Aristotle is using syllogistic arguments here, where some of the arguments or assertions remain unstated. Since Socrates is a man; therefore, he is mortal; all men are mortal so. Eventually, they will die. This is the logic presented here.

Example #3: Of Studies (By Francis Bacon)

“Reading maketh a full man; conference a ready man; and writing an exact man.”

This example is exact, precise, and compact with arguments, as well as a deduction or conclusion. At first, Bacon points out what reading, conference (discussion), and writing are, simultaneously giving the logic and reasoning to read, write, or conference.

Example #4: Of Studies (By Francis Bacon)

“Crafty men condemn studies, simple men admire them, and wise men use them; for they teach not their own use; but that is wisdom without them, and above them, won by observation.”

This is also a perfect example of logos. Here, Bacon discusses the matter of theories versus skills. There comes a clash between reading and not reading. He argues that a reader is better than those who cling to what they already know. He uses the logic that reading is necessary because it improves skills.

Example #5: Othello (By William Shakespeare)

“Oh, beware, my lord, of jealousy! It is the green-eyed monster which doth mock The meat it feeds on … Who, certain of his fate, loves not his wronger, But, oh, what damnèd minutes tells he o’er Who dotes, yet doubts — suspects, yet soundly loves … She did deceive her father, marrying you … She loved them most … I humbly do beseech you of your pardon For too much loving you …”

In this excerpt, Iago convinces Othello with logic and reasoning and makes him doubtful that there is a secret relationship between Desdemona and Cassio.

Logos Meaning and Function

Logos is used when citing facts, in addition to statistical, literal, and historical analogies . It is something through which inner thoughts are presented logically, to persuade the audience. In society, rationality and logic are greatly valued, and this type of convincing approach is generally honored more than appeals made by a speaker or character to the audience. On the other hand, scientific reasoning and formal logic are perhaps not suitable for general audiences, as they are more appropriate for scientific professionals only.

Related posts:

- Symbolism in Branding and Logos

Post navigation

I. Definition

Logos is a way of arguing calmly and carefully, using reason alone and not relying on the emotions. Logos (LOH-gohs) is a Greek word meaning “reason” or “rationality.” It comes from the philosopher Aristotle , who emphasized the difference between logos and pathos , or emotion. We might say that logos comes from the mind, while pathos comes from the heart.

II. Examples of Logos

Math is a subject entirely made up of logos. Emotions and personal opinions are not important – all that matters is figuring out the logical truth. This is particularly easy to see in geometry, where students are often given the task of writing logical “proofs.” When written well, these proofs are excellent examples of logs.

“In 2010, as [Obama’s] recovery program kicked in, the job losses stopped and things began to turn around. The recovery act saved or created millions of jobs and cut taxes for 95 percent of the American people. And, in the last 29 months, our economy has produced about 4 1/2 million private sector jobs.” (Bill Clinton, 2012)

Political debate should be a good place to look for logos, but unfortunately our modern politicians often fail at it. There are a few good examples, though: love him or hate him, Bill Clinton is remarkably good at using logos in his speeches, especially in his 2012 DNC speech . Notice how the former president avoids excessive emotion and uses evidence to back up his praise of President Obama’s economic policy. This doesn’t necessarily imply that Clinton is correct on the policy issues – that’s up to you to decide – but he is certainly using logos to make his point.

III. The Importance of Logos

Logos is all about the mind. It’s all about rationally persuading people that your view is correct. Because we value intelligence and reason, we want these things to be the basis for people’s views and opinions; that’s why logos is so important.

However, it’s also important not to use logos in isolation. If you’ve ever tried to read a professional work of analytic philosophy , you know how dry it can be! That’s because analytic philosophy is an attempt to speak through pure logic. Some emotional element is important if you want your work to be interesting and fun to read. Still, it’s best to make sure that the argument itself is based on logos, even if you occasionally use emotional flourishes your writing.

IV. How to Write Logos

It’s important to learn how to use logos in your writing, but it’s a lifelong process! No one is perfect at it, even professional scholars and philosophers. But everything starts with one crucial step:

- Give reasons! Whenever you make a logical statement, you have to back it up with evidence.

- Avoid getting emotional . When you write a paper, you’re probably tempted to write about subjects you feel passionate about. But this isn’t always the best idea! If you’re too passionate about the subject, you won’t be able to look past your own emotional perspectives, and that will make your paper less logical.

- Think about counter-arguments. If you can master this skill, you’ll be an expert at writing persuasive essays. Think carefully about what someone else might say against your argument. What is the strongest possible case you can make against yourself? If you can come up with good counter-arguments and respond to them logically , your argument will be irresistible.

V. When to Use Logos

Logos is the main tool for any formal essay. Academic writing is based on logical, unemotional analysis, and in order to write a good paper you need to spend the majority of your time thinking about logos. As we saw in section 3, there’s also a place for emotional writing in formal essays; but it shouldn’t be the main focus! Logos is the driving force of a formal argument.

In creative writing, you generally don’t need to use logos much. Creative writing is much more based on your intuitions and instincts, and you don’t need to analyze your ideas logically in most cases. However, you may want to have a character use logos. In stories, you’ll often see characters use logical reasoning in their dialogue – it’s a way of showing that the character is rational, intelligent, and analytical.

You can also use bad logos to generate humor! As we’ll see in section 8, it can sometimes be pretty funny when a character thinks he’s being logical, but is actually failing miserably.

VI. Examples of Logos in Philosophy and Literature

In the modern world, we sometimes assume that logos (reason) is the opposite of faith (religion). However, for medieval Christians like Thomas Aquinas, faith and reason were twin sisters, both necessary in the quest to come closer to God. In his Summa Theologica, Aquinas used several logical arguments to prove the existence of God (though his version of God was extremely different from what most modern Christians believe in).

“Mastering his emotion, he half calmly rose, and as he quitted the cabin, paused for an instant and said: “Thou hast outraged, not insulted me, sir; but for that I ask thee not to beware of Starbuck; thou wouldst but laugh; but let Ahab beware of Ahab; beware of thyself, old man.’”

Starbuck in Herman Melville’s Moby Dick is depicted as extremely honorable, noble, and reasonable – the Perfect Man according to the customs of Melville’s time. In contrast to Starbuck is the half-crazed Captain Ahab. In this scene, Starbuck is calmly delivering an argument to Ahab, trying to convince him that he is becoming to inwardly focused and obsessed with his hunt for the whale. Starbuck’s calm logic is especially impressive in this scene when you realize that Ahab is pointing a loaded gun at Starbuck’s face!

Philosophy, like math, is heavily dependent on logos, though it’s used for a very different purpose. Philosophers use logos to figure out answers to questions like: “what is consciousness?” and “what is good/evil?” Philosophy is also a good example of why pure logos is so hard to read! Many philosophers strive to remove the emotional element ( pathos ) from their work, which can make the writing extremely dry and dull on the surface.

VII. Examples of Logos in Media and Popular Culture

In Star Trek , the Vulcans are supposed to be without emotion and entirely rational. This is usually demonstrated by Spock and his logical arguments. However, this never entirely works out – after all, the show’s writers were human and human beings are naturally emotional! So it’s impossible to write a character who is purely logical, and that’s why the Vulcans on Star Trek sometimes failed in their logos, here’s an excerpt of a logical debate between Spock and Khan.

“So…if she weighs the same as a duck…she’s made of wood! And therefore….a witch!!” (Sir Bedevere, Monty Python and the Holy Grail )

In Monty Python’s classic comedy The Holy Grail , Sir Bedevere is an amateur philosopher who wants to rule his peasants through logos. At one point, he leads the peasants through a long, tangled argument that ultimately “proves” that ducks are made of wood, and that if a woman weighs the same as a duck then she must be a witch. Every step in the argument is completely absurd, but Bedevere and his peasants are entirely convinced by it.

“Fact: Time Warner Cable…saves you what could be hundreds of dollars. Fact: you can spend those hundreds of dollars on like a mountain of dog food. Fact: puppies love dog food. Therefore, DirecTV hates puppies . Who hates puppies?”

The same technique (using bad logos for comedy) can be seen in advertisements. An ad from Time Warner Cable , for example, uses a series of bad arguments to “prove” that satellite TV companies hate puppies. Of course, the logos is obviously not working here. The ad actually works by making you laugh, which in turn makes you remember the product.

c. Thanatos

b. Rationality

c. Beautiful sentence construction

d. All of the above

a. Counter-arguments

a. Formal essays

c. Creative writing

Table of Contents

Ai, ethics & human agency, collaboration, information literacy, writing process, logos – logos definition.

- CC BY-NC-ND 4.0 by Emily Lane

What is Logos?

Logos refers to an appeal to logic as opposed to an appeal to pathos or ethos .

Here, logos does not refer to formal logic such as that practiced in mathematics, philosophy, or computer science. Rather, logos refers to the consistency and clarity of an argument as well as the logic of evidence and reasons. It plays a role as one of the main three modes of persuasion:

Utilizing these appeals to reason within our writing and daily life allows us to create more convincing arguments targeted to our audience .

Related Concepts: Evidence ; Inductive Order, Inductive Reasoning, Inductive Writing ; Deductive Order, Deductive Reasoning, Deductive Writing ; Reasoning – Guide to Reasoning with Evidence

In formal logic, in abstraction, the following is the case: if A is true and B is true and A is an instance of B, then the repercussions of B will always be true. The problem, however, is that this kind of logic doesn’t work for real-life situations. This is where the argument comes into play.

Formal logic would say that speeding, for example, is a violation of traffic laws. A repercussion of violating a traffic law is a ticket; therefore, every person who speeds gets a ticket. However, in real life, not in abstract theory, things aren’t that cut and dried. Most people would not agree that all speeders, in every circumstance, should receive a ticket. In an argument about a real-life situation, the audience needs particulars to make their decisions. Sometimes there’s an exception. Why was that person speeding? Well, if an eighteen-year-old is speeding to show off for his friends, then yes, most people would agree that he deserves a ticket. However, if a man is driving his pregnant wife to the hospital, then maybe he does not deserve the ticket. One could, and probably would, make the argument that he should not get a ticket.

How to Appeal to Logos?

Let’s examine how the appeal to logos would work in an argument for the speeding father-to-be.

Because arguments are based on values and beliefs as well as facts and evidence, it is logical that the argument must coincide with accepted values and beliefs.

What are enthymemes?

The enthymeme is the foundation of every argument.

Enthymemes have three parts:

- the unstated assumption that is provided by the audience.

All three of these textual elements must make sense to your audience in order for your argument to be considered logical. The claim of an argument for the father-to-be could be something like, “This man should not get a speeding ticket.” That’s it. The claim is pretty simple. It is your educated opinion on the matter. The reason would be something like “because his wife is in labor in the backseat.” So the two stated parts of your enthymeme would be, “This man should not get a speeding ticket because his wife is in labor in the backseat.” Now, this seems obviously logical to us; however, what is our underlying value, our unstated assumption about this argument? Most of us would probably agree that a hospital is a better place to give birth than a backseat. That is the third part of the enthymeme. Your audience must agree that your assumption is true in order for your argument to be considered logical. If your readers don’t have the same assumption, they are not going to see your logic. You must find an enthymeme that works for your audience. The pregnant wife’s enthymeme is fairly easy to see. In more volatile claims and reasons, the unstated assumptions can be trickier to identify and work out with your audience.

How do enthymemes Relate to Logos?

Reasons like “because his wife is in labor” are motivations for the driver’s actions, not evidence. Most audiences need facts. Evidence is the facts. Both reasons and evidence are used in appeals to logos ; however, reasons cannot be your only support. Evidence as to why the man should speed might include studies about the problems with births in difficult or dangerous circumstances, interviews with women who have given birth in automobiles, and infant mortality rates for births that do not occur in hospitals. As you can see, there are many different kinds of evidence you could provide for this argument.

Consistency means not changing the unstated or stated rules governing your argument. Consistency is essential to logic. Let us continue with the speeding example. If, for instance, you are arguing that the infant mortality rate is too high for babies born outside the hospital and that the father is required to speed for the safety of his unborn child, then you may not want to include evidence of the high infant mortality rate in car crashes. Although this information may be part of the infant mortality rate, it goes against the underlying assumption that speeding is acceptable because of the high risk of harming the baby if it is born in the backseat.

Why is Logos important?

So why should you care about logos? In your own writing, logos is important because it appeals to your readers’ intellect. It makes your readers feel smart. Logos is the part of the argument where you treat your audience like purely rational, “only the facts, ma’am” kind of people. Also, gaps, leaps, and inconsistencies in logic, no matter how well developed the other appeals may be, can tear apart an argument in short order. This is the same reason you cannot ignore logos in others’ arguments either. All the appeals are linked together; for instance, if you use as evidence an article that has leaps in logic, or relies only on authority and pathos , this article could damage your own ethos as an author . It is important to remember that all three appeals must be well developed and work together to make a good argument .

Logos Examples

As you now know, logos can be defined as a writer’s or speaker’s attempt to appeal to the logic or reason of their audience. Let’s look at some examples of logos that you might commonly find when reading texts of various media:

When a writer employs data or statistics within a text, you can probably assume that he or she is attempting to appeal to the logic and reason of the reader. For example, an argument in favor of keeping abortion legal may cite the May 2011 Pew Research poll that found 54 percent of Americans in favor of legal abortion. This figure makes a logical argument: abortion should be legal because the majority of Americans support it, and in a democracy, the majority makes the decisions.

Causal Statements

When you see an “if-then” statement, with credible supporting evidence, the writer is likely appealing to your reason. Consider an argument about lowering the drinking age from 21 to 18: a writer might suggest that, if the legal drinking age were 18, then people between 18 and 21 would be less likely to drive under the influence. If the writer offers evidence that the reason that some between the ages of 18 and 21 drive drunk is that they fear calling a friend or parent because they have illegally ingested alcohol, then this causal statement would be an appeal to a reader’s sense of reason.

Relevant Examples or Other Evidence

You might begin to think about logos as evidence that doesn’t involve an appeal to your emotions. Even expert testimony, which would certainly be an example of ethos, also could be an example of logos, depending on its content. For example, in a discussion about recent cuts in education funding, a statement from the Hillsborough County, Florida, the superintendent would be an appeal to authority. But if that statement contained a discussion of the number of teachers and classes that would have to be cut if the state were to reduce the district’s funding, the statement from the superintendent could also be an appeal to logic.

Fallacies of Logos

Appeal to Nature

Suggesting a certain behavior or action is normal/right because it is “natural.” This is a fallacious argument for two reasons: first, there are multiple, and often competing, ways to define “nature” and “natural.” Because there is no one way to define these terms, a writer cannot assume his or her reader thinks of “nature” in the same way he or she does. Second, we cannot assume that “unnatural” is the same as wrong or evil. We (humans) have made lots of amendments to how we live (e.g., wearing clothes, living indoors, farming) with great benefit.

Argument from Ignorance

Assuming something is true because it has not been proven false. In a court of law, a defendant is, by law, “innocent until proven guilty.” However, judges and jurors must hear testimonies from both sides and receive all facts in order to draw conclusions about the defendant’s guilt or innocence. It would be an argument from ignorance for a judge or juror to reach a verdict without hearing all of the necessary information.

Intentionally misrepresenting your opponent’s position by over-exaggerating or offering a caricature of his or her argument. It would be fallacious to claim to dispute an opponent’s argument by creating a superficially similar position and refuting that position (the “straw man”) instead of the actual argument. For example, “Feminists want to turn men into slaves.” This statement fails to accurately represent feminist motivations—which can be very diverse. Most feminists agree in their goal to ensure women’s equality with men. Conceptions of equality can vary among feminists, but characterizing them as men-haters detracts from their true motivations.

False Dilemma

Assuming that there are only two options when there are, in fact, more. For example, “We either cut Social Security, or we have a huge deficit.” There are many ways to resolve deficit problems, but this statement suggests there is only one.

Hasty Generalization

Drawing a broad conclusion based on a small minority. For instance, if you witnessed a car accident between two women drivers, it would be a hasty generalization to conclude that all women are bad drivers.

Cum Hoc, Ergo Propter Hoc (With This, Therefore Because of This)

Confusing correlation with causation—that is, thinking that because two things happened simultaneously, then one must have caused the other. For example, “There has been an increase in both immigration and unemployment; therefore, immigrants are taking away American jobs.” This statement is fallacious because there is no evidence to suggest that immigration and unemployment are related to each other—other than that their rates increased simultaneously.

The Slippery Slope

The slippery slope argument is often a way to scare readers or listeners into taking (or not taking) a particular action (see “ Fallacious Pathos “). The slippery slope argument can also function as a false invocation of logic or reason in that it involves a causal statement that lacks evidence. For example, I might argue that if the drinking age were lowered from 21 to 18, vast numbers of college students would start drinking, which in turn would lead to alcohol poisoning, binge drinking, and even death. This conclusion requires evidence to connect the legality of drinking with overindulgence. In other words, it does not follow that college students would drink irresponsibly if given the opportunity to drink legally.

Brevity – Say More with Less

Clarity (in Speech and Writing)

Coherence – How to Achieve Coherence in Writing

Flow – How to Create Flow in Writing

Inclusivity – Inclusive Language

The Elements of Style – The DNA of Powerful Writing

Suggested Edits

- Please select the purpose of your message. * - Corrections, Typos, or Edits Technical Support/Problems using the site Advertising with Writing Commons Copyright Issues I am contacting you about something else

- Your full name

- Your email address *

- Page URL needing edits *

- Phone This field is for validation purposes and should be left unchanged.

Featured Articles

Academic Writing – How to Write for the Academic Community

Professional Writing – How to Write for the Professional World

Credibility & Authority – How to Be Credible & Authoritative in Speech & Writing

What is Logos in Literature?

Before you can think about teaching argumentation and persuasion , you must understand the basics of logos, including what it is, why it’s used, and how to spot it in writing or argument. This article teaches you everything you need to know about the logical component of persuasion and argumentation.

Logos Definition

Derived from the Greek word for “word” or “reason,” logos is one of the three primary rhetorical appeals, alongside ethos and pathos. Just like you would assume based on how the word sounds, logos is the elements of an argument that appeal to an audience’s sense of logic and reasoning. Writers use several forms of logical evidence to convince the audience through a rational and well-supported argument, including:

- Test results

- Expert testimony

- Textual evidence

- Historical or literal analogies

- Cause and effect relationships

The term “logos” traces its roots to ancient Greek philosophy, particularly in the works of Aristotle. In his work “Rhetoric,” Aristotle broke down the key elements of persuasive communication, including supporting with logic (logos), appealing to emotions (pathos), and establishing trust and credibility (ethos). According to his work, these three elements work together to create a compelling and convincing argument. While logos can be found in literature, it is often used in academic writing, persuasive speeches, law, political campaigns, marketing, and advertisements.

Logos Pronunciation

Logos is a two-syllable word dating back to ancient Greek philosophy and is pronounced as low-gowz .

What are the Different Types of Logos?

All forms of logos serve the same purpose: to convince an audience using logical evidence and reasoning. However, this can be achieved through logic or perceived logic . Let’s break down the difference:

In rhetoric, logic involves using clear reasoning and concrete evidence to build a compelling argument. It adheres strictly to the principles of deductive and inductive reasoning, using facts, statistics, and logical connections to persuade the audience. Examples of this form of logic include:

- Presenting statistical data to support an argument.

- Defending a thesis with textual evidence and clear explanation.

- Citing well-established facts or scientific evidence.

- Utilizing deductive reasoning to draw a logical conclusion.

Perceived Logic

On the other hand, perceived logic focuses on creating an impression of logic when there isn’t much hard evidence. Instead, this form of logical reasoning relies on using relatable stories, comparisons, and a smooth flow of ideas to give the impression that the argument makes sense. Writers may create a sense of perceived logic using techniques such as:

- Using relatable anecdotes to make a point, even if they are not supported by statistics.

- Employing analogies to convey a sense of similarity or connection.

- Crafting a narrative that feels logically consistent, even if it lacks empirical evidence.

- Appealing to common beliefs to assert that an argument is valid.

Both approaches to logos can be effective in different contexts, catering to the diverse ways in which audiences engage with and understand logical arguments.

What it’s NOT: Logical Fallacies

When using logos, writers never want to unintentionally poking holes in their own argument. (Makes sense, right?) However, it happens all the time. Logical fallacies are errors in reasoning or flawed arguments that can weaken the validity and soundness of an argument. Understanding these fallacies is crucial for critical thinking and effective communication. Here are some common examples:

Ad Hominem: Attacking the character of the person making the argument rather than addressing the substance of the argument itself. Example: bashing someone’s environmental proposals because they are a vegan.

Straw Man: Misrepresenting an opponent’s argument to make it easier to attack instead of addressing the actual position. Example: Claiming that someone proposing a reduction in educational spending wants the population to be dumb.

False Cause , also called Causal Fallacy or Post Hoc: Incorrectly assuming that because one event follows another, the first caused the second. Example: “Since I started eating ice cream, I haven’t been sick. Therefore, ice cream must be keeping me healthy.”

False Dilemma: Presenting only two extreme options when there are actually more nuanced possibilities. Example: “Either you support this policy, or you don’t care about the future of our country.”

Appeal to Authority: Relying on the endorsement of an unqualified or irrelevant celebrity or authority figure rather than substantive evidence. Example: “Tom Brady uses that brand of toothpaste, so it must be the best out there.”

Red Herring: Attempting to shing the focus in a discussion or debate to divert attention away from the original topic or argument. Example: Shifting the focus to personal responsibility during a discussion on systemic issues contributing to healthcare costs.

Other logical fallacies include:

- Hasty Generalization

- Appeal to Ignorance

- Circular Reasoning

- Sunk Cost Fallacy

- Bandwagon Fallacy

- Slippery slope

- Equivocation

Why Do Writers Use Logos?

Writers employ logos as a persuasive strategy to build a rational and well-supported case, making their arguments more convincing and harder to argue against. By presenting concrete evidence and well-developed logic, authors build credibility to their argument. This not only enhances the persuasiveness of the writing but also provides a solid foundation for their claims.

Additionally, logos helps simplify complex ideas. Well-structured logical reasoning helps authors bridge the gap between their argument and the audience’s understanding or experiences, adding a compelling and convincing edge to their argument. Presenting logical connections and evidence makes the material more accessible and engaging for the audience.

How to Spot Logos in Writing

Sometimes logos is very straightforward, while other times, especially in more complex arguments or works of literature, it can be more challenging to pinpoint. However, in either case, the steps below make it easier to identify logos in writing or any form of persuasion:

1. Consider the claim, purpose, and evidence

Logos relies heavily on evidence, whether in the form of statistics, research findings, or real-life examples. Writers employing logos will support their claims with concrete data to strengthen their arguments. As yourself:

- What is the claim or argument the author is trying to make?

- Do they use concrete evidence, such as facts or statistics, to support their claim?

- Does the author reference credible sources or authorities to strengthen their points?

2. Pay attention to suture

The overall structure of the writing says a lot about logos. A well-organized piece will present ideas in a logical sequence, with each point building upon the previous one to form a coherent argument. Ask yourself:

- Is the argument presented in a clear and structured way, establishing a logical flow?

- Do the ideas progress logically, building upon each other to support the overall argument?

3. Look for clarity and precision

A clear argument is a strong argument. Writers using logos will carefully define terms, avoid ambiguity, and ensure that their arguments are presented in a straightforward manner. Ask yourself:

- Do I understand the point the author is trying to make?

- Are there any flaws in the reasoning or logical fallacies poking holes in the argument?

- Are key terms and concepts clearly defined to avoid ambiguity or confusion?

Tips for Teaching Logos

- Start with the definition: Rather than assuming your students know what logos is, begin by providing a clear and concise definition of logos to ensure a foundational understanding.

- Use real-world examples: Add relevance and context to logos by using real-world examples, such as current events and contemporary issues, demonstrating its application in a real-world context.

- Hold debates and discussions: Create an active learning experience by encouraging students to participate in class debates and discussions where students can practice and refine their logical reasoning skills. (Get things started with these engaging argumentative prompts .)

- Guide students through close readings: Analyze written texts together, identifying how authors use logos to build their arguments and discussing the effectiveness of different approaches.

- Look at advertisements: Bring logos to life by reviewing and analyzing advertisements for logical appeals. Look at advertisements such as print ads, social media ads, and commercials for a multimedia experience.

- Don’t skip logical fallacies : Discuss common logical fallacies to help students recognize and avoid them in their own writing and critical analysis of texts—and to save you stress and frustration when grading.

Examples of Logos

1. in literature: to kill a mockingbird by harper lee.

In “To Kill a Mockingbird,” logos shines through as Atticus Finch uses logical arguments and evidence to defend Tom Robinson during trial. For example, Atticus questions the lack of medical evidence to support Mayella Ewell’s claims and even proves Tom Robinson could not have caused the injuries to Mayella’s face due to his injured left arm.

Throughout the trial, Atticus emphasizes the absence of concrete proof, proving the case is rooted in hearsay versus factual reasoning. Unfortunately, despite Atticus’ strong logical reasoning, Tom Robinson is not set free, underscoring the racial injustices of the American South in the 1930s.

2. In a Famous Speech: “I Have a Dream” by Martin Luther King Jr.

Martin Luther King Jr.’s “I Have a Dream” speech is a powerful example of logos as he crafts a logical and persuasive argument for civil rights. Dr. King makes several historical references, particularly to crucial American documents, including the Emancipation Proclamation, the Constitution, and the Declaration of Independence, to make his case. This tactic allows him to highlight the gap between the nation’s founding principles and promises and the reality for many citizens.

King focuses on grounding his speech in logic before moving toward more emotional appeal to resonate with his audience, using the lessons of the past to support his vision for the future. Through a mix of logos and pathos, he presents a powerful, logical argument, calling on the need for racial equality and justice.

3. In an Essay: “Civil Disobedience” by Henry David Thoreau

Thoreau’s essay, iconically written while in jail for not paying a poll tax as an act of peaceful protest, is a classic example of logos. To support his personal beliefs, he presents a logical argument supporting individual resistance against unjust laws and immoral government actions. Through the use of clear and specific examples, he advocates for the moral duty to resist policies that violate one’s personal principles.

Despite being rooted in his personal beliefs, Thoreau crafts a structurally sound argument, allowing the reader to follow along as he logically builds his case. His examples include both local references to drive his points home while drawing comparisons to broader-scale issues, such as the Mexican War, to help paint a clearer picture of reason and support for his argument.

Additional Resources for Teaching Logos

Check out my lesson plan on evaluating arguments to guide students through examining, analyzing, and evaluating arguments in nonfiction passages.

Read this post for more tips on teaching argument and persuasion .

Start here if you’re looking for more on how to teach argumentative message writing .

Looking to incorporate videos? Check these resources out:

- Dive into Ethos, Logs, and Pathos with the help of this TEDed video .

- Your students will have fun spotting the logos in these commercials .

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

15 Logos Examples

Logos is a rhetorical device that uses logic, reasoning, and factual evidence to support an argument or persuade an audience.

Logos refers to one of the three main technical means of persuasion in rhetoric. According to Aristotle, it is the means that has to do with the arguments themselves.

Aristotle claims that there are three technical means of persuasion:

“Now the proofs furnished by the speech are of three kinds. The first depends upon the moral character of the speaker, the second upon putting the hearer into a certain frame of mind, the third upon the speech itself, in so far as it proves or seems to prove” (Aristotle, Rhetoric, ca. 367-322 B.C.E./1926, Book 1, Chapter 2, Section 3).

Each of these corresponds to the three means of persuasion:

- Ethos (Appeal to credibility) : Persuasion through establishing the character of the speaker.

- Pathos (Appeal to emotion) : Persuasion through putting the hearer into a certain frame of mind.

- Logos (Appeal to logic): Persuasion through proof or seeming proof.

For Aristotle, speech consists of three things: the speaker, the hearer, and the speech. These correspond to ethos, pathos, and logos , respectively. The latter is the subject of this article.

Definition of Logos

At its core, logos refers to the use of logic (or perceived logic) to persuade.

However, logos may be the most confusing of the three means of persuasion because the word has been used by different philosophers to mean different but related things.

- Heraclitus of Ephesus used the word logos to refer to something like the message that the world gives us (Graham, 2021).

- The sophists used the term to refer to discourse in general.

- Pyrrhonist skeptics used the term to refer to dogmatic accounts of debatable matters.

- The Stoics meant by it the generative principle of the universe.

I could list further examples, but for this article, Aristotle’s definition will suffice.

Logos, in rhetoric, refers to persuasion through logical argumentation or its simulation (Keith & Lundberg, 2017).

As Aristotle writes,

“… persuasion is produced by the speech itself, when we establish the true or apparently true from the means of persuasion applicable to each individual subject.” (Aristotle, Rhetoric, ca. 367-322 B.C.E./1926, Book 1, Chapter 2, Section 6).

Syllogisms, enthymemes, examples, and other arguments use logos to influence people’s thinking . Due to the structure of this persuasion tool, it is the only one that can directly argue for the speaker’s point of view. What Aristotle stresses over and over again is that deceptive or fallacious arguments can have a persuasive effect if the fallacy is concealed well enough.

Persuasion through logos requires only that the hearers think that something has been proven, whether it actually has been is a different matter.

Logos Examples

- Scientific Research: Any form of scientific research is fundamentally grounded in logos, as it relies on empirical data, statistical analysis, and logical reasoning to draw conclusions. For example, if you were to present the scientific evidence to a consumer about why your product is the best, it may convince them to switch brand loyalty over to you.

- Legal Arguments: In court, attorneys use logos extensively when presenting evidence, citing precedents, or constructing logical arguments to persuade the judge or jury. Generally, it is expected that the jury be presented the best objective evidence in order for them to make an objective decision. However, at times, they will rely on pathos, and the judge’s job is often to curtail this if needed.

- Newspaper Editorials: Newspaper editorials often use logos to make a persuasive point, presenting facts, statistics, and logical analysis to support the writer’s viewpoint. Without facts and data, the readers my close the newspaper and dismiss the writer as simply engaging in hearsay.

- Referencing in Essays: In essays, we are often required to cite our sources. This is, in part, relying on ethos (appeal to credibility), but at the same time, it’s also allowing the reader to go ahead and check the primary data to ensure it’s correct.

- Financial Reports: Financial analysts use logos when they analyze data, financial statements, and market trends to provide investment advice. They know an investor wants to make the most evidence-based decision as possible with the data, so they need to present this evidence as clearly as possible.

- Medical Diagnosis: Doctors use logos when they diagnose patients by interpreting symptoms, medical histories, and test results to arrive at a logical conclusion. Without evidence, customers may distrust the doctor and refuse to follow the doctor’s advice.

- Speeches and Presentations: Speakers and debaters often use logos in their speeches or presentations to make their points more persuasive, providing evidence, statistics, and logical analysis to back up their arguments, with the intent of convincing the audience and winning the debate over the competitors (although, pathos is highly convincing in speeches as well).

- Instruction Manuals: Logos is used in instruction manuals for constructing furniture where a logical sequence of steps is provided to guide users in assembling a product or operating a piece of software. An instruction manual won’t say “if you feel like it,…” because this won’t get the job done – constructing the item!

- Funding Proposals: In making a funding pitch, proposals are often supported by logos in the form of cost-benefit analyses, case studies, and logical reasoning to convince others that their money will be in good hands.

- Problem-Solving: In a group’s blue skies brainstorming session or a problem-solving meeting, logos is used when the participants identify the problem, analyze the factors contributing to the problem, and propose logical solutions based on evidence and reasoning.

- Technological Innovations: When developing a new product or technology, engineers and designers use logos to analyze the needs of the market, create a logical design to meet those needs, and justify their decisions with reasoning and evidence. In fact, engineers need strong analytical skills and have to rely extensively on logos (rather than pathos or ethos) in their daily job roles.

Logos as Perceived Logic

Aristotle writes that even fallacious arguments are examples of logos, because they seem to prove something. In other words, logos isn’t just being logical , rather it’s attempting to appear logical .

Here are some examples:

- Straw Man Fallacy : This happens when an individual distorts, exaggerates, or misrepresents someone’s argument in order to make it easier to attack. For example, “My opponent believes in healthcare reform, he must want to give free healthcare to everyone.” Here, they are attempting to construct some logic that isn’t really there – they’re actually creating false facts to put forward a point of view!

- Slippery Slope Fallacy : This is an argument that suggests taking a minor action will lead to major and often ludicrous consequences. For example, “If we allow students to redo tests, they’ll want to redo homework, quizzes, and even final exams!” Here, the argument sounds like it could be logical, but draws a long bow and makes claims that something will happen, even though it may not (and probably won’t) actually come to pass.

- False Dichotomy Fallacy : This fallacy occurs when an argument presents only two options or sides when there may be more. For example, “You’re either with us, or against us.” Once the false dichotomy is constructed, logos can be used to convince people one perspective is better than the other, as if only the two exist.

- Hasty Generalization Fallacy : This happens when someone makes a broad conclusion based on a small or unrepresentative sample size. For example, “I met a rude person from City X, therefore everyone from City X must be rude.” Here, they are attempting to use logic – and their argument is ostensibly logical – but in reality, it (like the slippery slope) draws a long bow and is unlikely to actually be true.

Logos Strengths

- Appeal to rationality: For many people, the apparent rationality of a speech is its most important and persuasive part. Especially in academic settings where the orator cannot make themselves stand out through appeals to ethos and pathos, logos is often the most important part of the rhetorical triangle.

- Trustworthiness : While pathos and ethos are often viewed with suspicion, there is no such negative stigma attached to logos. Appeals to emotion or personal authority may seem dishonest and manipulative, but arguments, unless fallacious, rarely seem so.

- Counter arguments: Logos is the only mode of persuasion that can directly address objections because the evaluation of opposing views is itself a rational activity.

Logos Weaknesses

- Subjective matters: In certain settings, logos can be far less persuasive than pathos and ethos. This is particularly evident in settings where there are no objective criteria for deciding if the speaker is right or wrong.

See Also: The 5 Types of Rhetorical Situations

Aristotle. (1926). Rhetoric. In Aristotle in 23 Volumes, Vol. 22, translated by J. H. Freese. Harvard University Press. (Original work published ca. 367-322 B.C.E.)

Hansen, H. (2020). Fallacies. In E. N. Zalta (Ed.), The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (Summer 2020). Metaphysics Research Lab, Stanford University. https://plato.stanford.edu/archives/sum2020/entries/fallacies/

Rapp, C. (2022). Aristotle’s Rhetoric. In E. N. Zalta (Ed.), The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (Spring 2022). Metaphysics Research Lab, Stanford University. https://plato.stanford.edu/archives/spr2022/entries/aristotle-rhetoric/

Tio Gabunia (B.Arch, M.Arch)

Tio Gabunia is an academic writer and architect based in Tbilisi. He has studied architecture, design, and urban planning at the Georgian Technical University and the University of Lisbon. He has worked in these fields in Georgia, Portugal, and France. Most of Tio’s writings concern philosophy. Other writings include architecture, sociology, urban planning, and economics.

- Tio Gabunia (B.Arch, M.Arch) #molongui-disabled-link 6 Types of Societies (With 21 Examples)

- Tio Gabunia (B.Arch, M.Arch) #molongui-disabled-link 25 Public Health Policy Examples

- Tio Gabunia (B.Arch, M.Arch) #molongui-disabled-link 15 Cultural Differences Examples

- Tio Gabunia (B.Arch, M.Arch) #molongui-disabled-link Social Interaction Types & Examples (Sociology)

Chris Drew (PhD)

This article was peer-reviewed and edited by Chris Drew (PhD). The review process on Helpful Professor involves having a PhD level expert fact check, edit, and contribute to articles. Reviewers ensure all content reflects expert academic consensus and is backed up with reference to academic studies. Dr. Drew has published over 20 academic articles in scholarly journals. He is the former editor of the Journal of Learning Development in Higher Education and holds a PhD in Education from ACU.

- Chris Drew (PhD) #molongui-disabled-link 15 Social Learning Theory Examples

- Chris Drew (PhD) #molongui-disabled-link 10 Latent Learning Examples

- Chris Drew (PhD) #molongui-disabled-link 13 Sociocultural Theory Examples

- Chris Drew (PhD) #molongui-disabled-link 21 Experiential Learning Examples

Leave a Comment Cancel Reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Logos (Rhetoric)

Glossary of Grammatical and Rhetorical Terms

- An Introduction to Punctuation

- Ph.D., Rhetoric and English, University of Georgia

- M.A., Modern English and American Literature, University of Leicester

- B.A., English, State University of New York

In classical rhetoric , logos is the means of persuasion by demonstration of logical proof, real or apparent. Plural: logoi . Also called rhetorical argument , logical proof , and rational appeal .

Logos is one of the three kinds of artistic proof in Aristotle's rhetorical theory.

" Logos has many meanings," notes George A. Kennedy. "[I]t is anything that is 'said,' but that can be a word, a sentence, part of a speech or of a written work, or a whole speech. It connotes the content rather than the style (which would be lexis ) and often implies logical reasoning. Thus it can also mean ' argument ' and 'reason' . . .. Unlike ' rhetoric ,' with its sometimes negative connotations , logos [in the classical era] was consistently regarded as a positive factor in human life" ( A New History of Classical Rhetoric , 1994).

From the Greek, "speech, word, reason"

Examples and Observations

- "Aristotle's third element of proof [after ethos and pathos ] was logos or logical proof. . . . Like Plato, his teacher, Aristotle would have preferred that speakers use correct reasoning, but Aristotle's approach to life was more pragmatic than Plato's, and he wisely observed that skilled speakers could persuade by appealing to proofs that seemed true."

- Logos and the Sophists "Virtually every person considered a Sophist by posterity was concerned with instruction in logos . According to most accounts, the teaching of the skills of public argument was the key to the Sophists' financial success, and a good part of their condemnation by Plato..."

- Logos in Plato's Phaedrus "Retrieving a more sympathetic Plato includes retrieving two essential Platonic notions. One is the very broad notion of logos that is at work in Plato and the sophists, according to which 'logos' means speech, statement, reason, language, explanation, argument, and even the intelligibility of the world itself. Another is the notion, found in Plato's Phaedrus , that logos has its own special power, psychagogia , leading the soul, and that rhetoric is an attempt to be an art or discipline of this power."

- Logos in Aristotle's Rhetoric - "Aristotle's great innovation in the Rhetoric is the discovery that argument is the center of the art of persuasion. If there are three sources of proof, logos , ethos, and pathos, then logos is found in two radically different guises in the Rhetoric . In I.4-14, logos is found in enthymemes , the body of proof; form and function are inseparable; In II.18-26 reasoning has force of its own. I.4-14 is hard for modern readers because it treats persuasion as logical, rather than emotional or ethical, but it is not in any easily recognizable sense formal."

- Logos vs. Mythos "The logos of sixth- and fifth-century [BC] thinkers is best understood as a rationalistic rival to traditional mythos --the religious worldview preserved in epic poetry. . . . The poetry of the time performed the functions now assigned to a variety of educational practices: religious instruction, moral training, history texts, and reference manuals (Havelock 1983, 80). . . . Because the vast majority of the population did not read regularly, poetry was preserved communication that served as Greek culture's preserved memory."

- Signs : What signs show that this might be true?

- Induction : What examples can I use? What conclusion can I draw from the examples? Can my readers make the "inductive leap" from the examples to an acceptance of the conclusion?

- Cause : What is the main cause of the controversy? What are the effects?

- Deduction : What conclusions will I draw? What general principles, warrants, and examples are they based on?

- Analogies : What comparisons can I make? Can I show that what happened in the past might happen again or that what happened in one case might happen in another?

- Definition : What do I need to define?

- Statistics : What statistics can I use? How should I present them

Pronunciation

- Halford Ryan, Classical Communication for the Contemporary Communicator . Mayfield, 1992

- Edward Schiappa, Protagoras, and Logos: A Study in Greek Philosophy and Rhetoric , 2nd ed. University of South Carolina Press, 2003

- James Crosswhite, Deep Rhetoric: Philosophy, Reason, Violence, Justice, Wisdom . The University of Chicago Press, 2013

- Eugene Garver, Aristotle's Rhetoric: An Art of Character . The University of Chicago Press, 1994

- Edward Schiappa, The Beginnings of Rhetorical Theory in Classical Greece . Yale University Press, 1999

- N. Wood, Perspectives on Argument . Pearson, 2004

- Artistic Proofs: Definitions and Examples

- Proof in Rhetoric

- Definition and Examples of Ethos in Classical Rhetoric

- Techne (Rhetoric)

- What Is Rhetoric?

- Pathos in Rhetoric

- Use Social Media to Teach Ethos, Pathos and Logos

- Definition and Examples of Dialectic in Rhetoric

- Definition and Examples of the New Rhetorics

- Situated Ethos in Rhetoric

- Persuasion and Rhetorical Definition

- What Is Phronesis?

- Definition and Examples of Pistis in Classical Rhetoric

- The Meaning of Rhetor

- Invented Ethos (Rhetoric)

- Ethos, Logos, Pathos for Persuasion

What Are Logos, Pathos & Ethos?

A straight-forward explainer (with examples)

By: Derek Jansen (MBA) | Reviewer: Eunice Rautenbach (DTech) | June 2023

If you spend any amount of time exploring the wonderful world of philosophy, you’re bound to run into the dynamic trio of rhetorical appeals: logos , ethos and pathos . But, what exactly do they mean and how can you use them in your writing or speaking? In this post, we’ll unpack the rhetorical love triangle in simple terms, using loads of practical examples along the way.

Overview: The Rhetorical Triangle

- What are logos , pathos and ethos ?

- Logos unpacked (+ examples)

- Pathos unpacked (+ examples)

- Ethos unpacked (+ examples)

- The rhetorical triangle

What are logos, ethos and pathos?

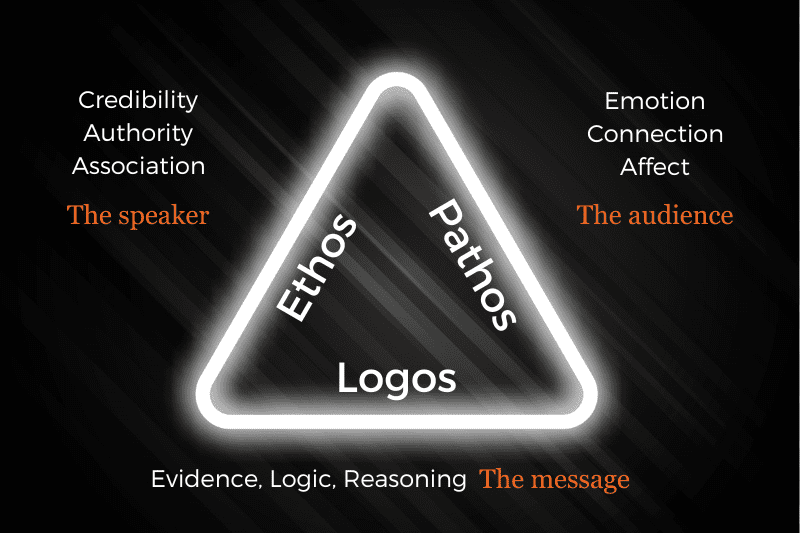

Simply put, logos, ethos and pathos are three powerful tools that you can use to persuade an audience of your argument . At the most basic level, logos appeals to logic and reason, while pathos appeals to emotions and ethos emphasises credibility or authority.

Naturally, a combination of all three rhetorical appeals packs the biggest punch, but it’s important to consider a few different factors to determine the best mix for any given context. Let’s look at each rhetorical appeal in a little more detail to understand how best to use them to your advantage.

Logos appeals to the logical, reason-driven side of our minds. Using logos in an argument typically means presenting a strong body of evidence and facts to support your position. This evidence should then be accompanied by sound logic and well-articulated reasoning .

Let’s look at some examples of logos in action:

- A friend trying to persuade you to eat healthier might present scientific studies that show the benefits of a balanced diet and explain how certain nutrients contribute to overall health and longevity.

- A scientist giving a presentation on climate change might use data from reputable studies, along with well-presented graphs and statistical analyses to demonstrate the rising global temperatures and their impact on the environment.

- An advertisement for a new smartphone might highlight its technological features, such as a faster processor, longer battery life, and a high-resolution camera. This could also be accompanied by technical specifications and comparisons with competitors’ models.

In short, logos is all about using evidence , logic and reason to build a strong argument that will win over an audience on the basis of its objective merit . This contrasts quite sharply against pathos, which we’ll look at next.

Contrasted to logos, pathos appeals to the softer side of us mushy humans. Specifically, it focuses on evoking feelings and emotions in the audience. When utilising pathos in an argument, the aim is to cultivate some feeling of connection in the audience toward either yourself or the point that you’re trying to make.

In practical terms, pathos often uses storytelling , vivid language and personal anecdotes to tap into the audience’s emotions. Unlike logos, the focus here is not on facts and figures, but rather on psychological affect . Simply put, pathos utilises our shared humanness to foster agreement.

Let’s look at some examples of pathos in action:

- An advertisement for a charity might incorporate images of starving children and highlight their desperate living conditions to evoke sympathy, compassion and, ultimately, donations.

- A politician on the campaign trail might appeal to feelings of hope, unity, and patriotism to rally supporters and motivate them to vote for his or her party.

- A fundraising event may include a heartfelt personal story shared by a cancer survivor, with the aim of evoking empathy and encouraging donations to support cancer research.

As you can see, pathos is all about appealing to the human side of us – playing on our emotions to create buy-in and agreement.

Last but not least, we’ve got ethos. Ethos is all about emphasising the credibility and authority of the person making the argument, or leveraging off of someone else’s credibility to support your own argument.