- How it works

How to Write the Thesis Or Dissertation Introduction – Guide

Published by Carmen Troy at August 31st, 2021 , Revised On January 24, 2024

Introducing your Dissertation Topic

What would you tell someone if they asked you to introduce yourself? You’d probably start with your name, what you do for a living…etc., etc., etc. Think of your dissertation. How would you go about it if you had to introduce it to the world for the first time?

Keep this forefront in your mind for the remainder of this guide: you are introducing your research to the world that doesn’t even know it exists. Every word, phrase and line you write in your introduction will stand for the strength of your dissertation’s character.

This is not very different from how, in real life, if someone fails to introduce themselves properly (such as leaving out what they do for a living, where they live, etc.) to a stranger, it leaves a lasting impression on the stranger.

Don’t leave your dissertation a stranger among other strangers. Let’s review the little, basic concepts we already have at the back of our minds, perhaps, to piece them together in one body: an introduction.

What Goes Inside an Introduction

The exact ingredients of a dissertation or thesis introduction chapter vary depending on your chosen research topic, your university’s guidelines, and your academic subject – but they are generally mixed in one sequence or another to introduce an academic argument.

The critical elements of an excellent dissertation introduction include a definition of the selected research topic , a reference to previous studies on the subject, a statement of the value of the subject for academic and scientific communities, a clear aim/purpose of the study, a list of your objectives, a reference to viewpoints of other researchers and a justification for the research.

Topic Discussion versus Topic Introduction

Discussing and introducing a topic are two highly different aspects of dissertation introduction writing. You might find it easy to discuss a topic, but introducing it is much trickier.

The introduction is the first thing a reader reads; thus, it must be to the point, informative, engaging, and enjoyable. Even if one of these elements is missing, the reader will not be motivated to continue reading the paper and will move on to something different.

So, it’s critical to fully understand how to write the introduction of a dissertation before starting the actual write-up.

When writing a dissertation introduction, one has to explain the title, discuss the topic and present a background so that readers understand what your research is about and what results you expect to achieve at the end of the research work.

As a standard practice, you might work on your dissertation introduction chapter several times. Once when you’re working on your proposal and the second time when writing your actual dissertation.

“ Want to keep up with the progress of the work done by your writer? ResearchProspect can deliver your dissertation order in three parts; outline, first half, and final dissertation delivery. Here is the link to our online order form .

Many academics argue that the Introduction chapter should be the last section of the dissertation paper you should complete, but by no means is it the last part you would think of because this is where your research starts from.

Write the draft introduction as early as possible. You should write it at the same time as the proposal submission, although you must revise and edit it many times before it takes the final shape.

Considering its importance, many students remain unsure of how to write the introduction of a dissertation. Here are some of the essential elements of how to write the introduction of a dissertation that’ll provide much-needed dissertation introduction writing help.

Below are some guidelines for you to learn to write a flawless first-class dissertation paper.

Steps of Writing a Dissertation Introduction

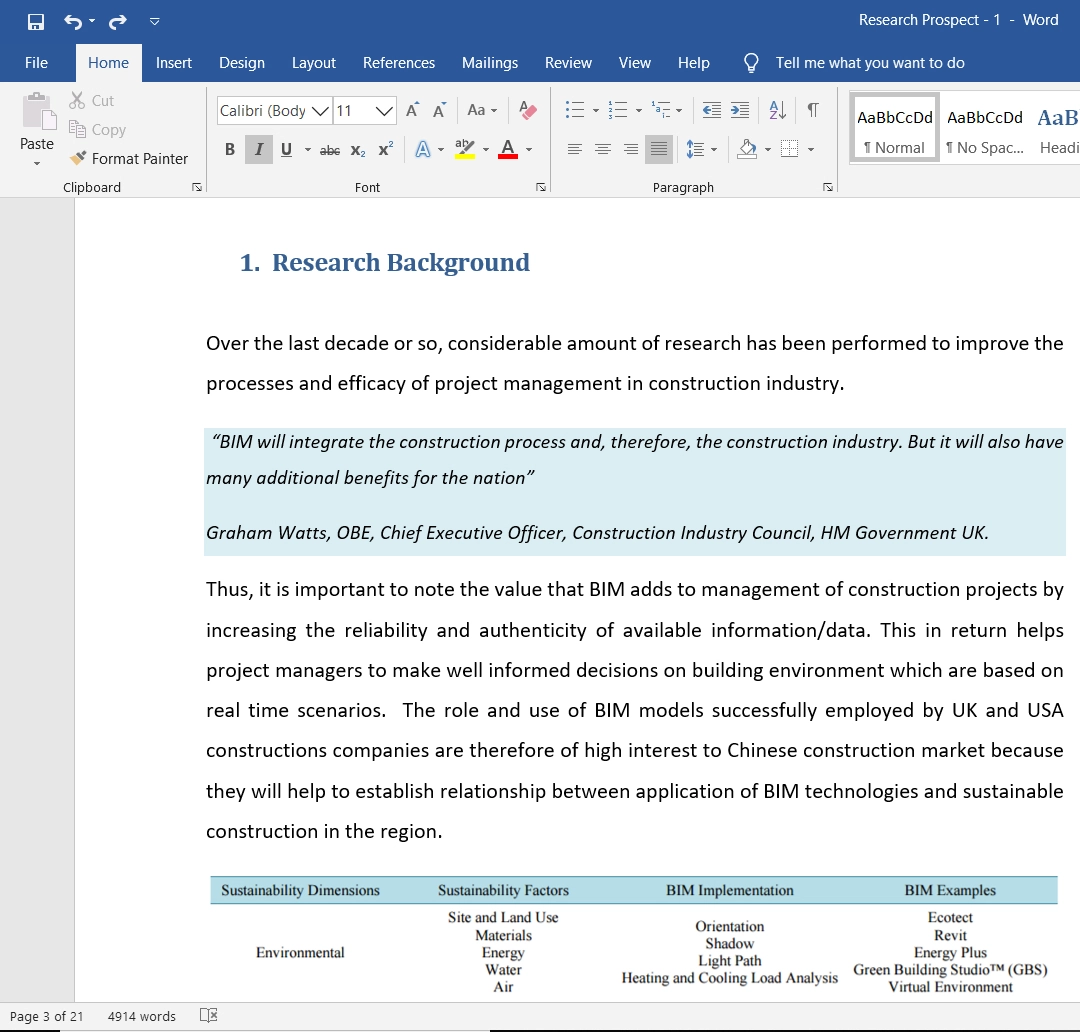

1. research background – writing a dissertation introduction.

This is the very first section of your introduction. Building a background of your chosen topic will help you understand more about the topic and help readers know why the general research area is problematic, interesting, central, important, etc.

Your research background should include significant concepts related to your dissertation topic. This will give your supervisor and markers an idea that you’ve investigated the research problem thoroughly and know the various aspects of your topic.

The introduction to a dissertation shouldn’t talk only about other research work in the same area, as this will be discussed in the literature review section. Moreover, this section should not include the research design and data collection method(s) .

All about research strategy should be covered in the methodology chapter . Research background only helps to build up your research in general.

For instance, if your research is based on job satisfaction measures of a specific country, the content of the introduction chapter will generally be about job satisfaction and its impact.

Hire an Expert Writer

Orders completed by our expert writers are

- Formally drafted in academic style

- Plagiarism free

- Never resold

- Include unlimited free revisions

- Completed to match exact client requirements

2. Significance of the Research

As a researcher, you must demonstrate how your research will provide value to the scientific and academic communities. If your dissertation is based on a specific company or industry, you need to explain why that industry and company were chosen.

If you’re comparing, explain why you’re doing so and what this research will yield. Regardless of your chosen research topic, explain thoroughly in this section why this research is being conducted and what benefits it will serve.

The idea here is to convince your supervisor and readers that the concept should be researched to find a solution to a problem.

3. Research Problem

Once you’ve described the main research problem and the importance of your research, the next step would be to present your problem statement , i.e., why this research is being conducted and its purpose.

This is one of the essential aspects of writing a dissertation’s introduction. Doing so will help your readers understand what you intend to do in this research and what they should expect from this study.

Presenting the research problem competently is crucial in persuading your readers to read other parts of the dissertation paper . This research problem is the crux of your dissertation, i.e., it gives a direction as to why this research is being carried out, and what issues the study will consider.

For example, if your dissertation is based on measuring the job satisfaction of a specific organisation, your research problem should talk about the problem the company is facing and how your research will help the company to solve that.

If your dissertation is not based on any specific organisation, you can explain the common issues that companies face when they do not consider job satisfaction as a pillar of business growth and elaborate on how your research will help them realise its importance.

Citing too many references in the introduction chapter isn’t recommended because here, you must explain why you chose to study a specific area and what your research will accomplish. Any citations only set the context, and you should leave the bulk of the literature for a later section.

4. Research Question(s)

The central part of your introduction is the research question , which should be based on your research problem and the dissertation title. Combining these two aspects will help you formulate an exciting yet manageable research question.

Your research question is what your research aims to answer and around which your dissertation will revolve. The research question should be specific and concise.

It should be a one- or two-line question you’ve set out to answer through your dissertation. For the job satisfaction example, a sample research question could be, how does job satisfaction positively impact employee performance?

Look up dissertation introduction examples online or ask your friends to get an idea of how an ideal research question is formed. Or you can review our dissertation introduction example here and research question examples here .

Once you’ve formed your research question, pick out vital elements from it, based on which you will then prepare your theoretical framework and literature review. You will come back to your research question again when concluding your dissertation .

Sometimes, you might have to formulate a hypothesis in place of a research question. The hypothesis is a simple statement you prove with your results , discussion and analysis .

A sample hypothesis could be job satisfaction is positively linked to employee job performance . The results of your dissertation could be in favour of this dissertation or against it.

Tip: Read up about what alternative, null, one-tailed and two-tailed hypotheses are so you can better formulate the hypothesis for your dissertation. Following are the definitions for each term, as retrieved from Trochim et al.’s Research Methods: The Essential Knowledge Base (2016):

- Alternative hypothesis (H 1 ): “A specific statement of prediction that usually states what you expect will happen in your study.”

- Null hypothesis (H 0 ): “The hypothesis that describes the possible outcomes other than the alternative hypothesis. Usually, the null hypothesis predicts there will be no effect of a program or treatment you are studying.”

- One-tailed hypothesis: “A hypothesis that specifies a direction; for example, when your hypothesis predicts that your program will increase the outcome.”

- Two-tailed hypothesis: “A hypothesis that does not specify a direction. For example, if you hypothesise that your program or intervention will affect an outcome, but you are unwilling to specify whether that effect will be positive or negative, you are using a two-tailed hypothesis.”

Get Help with Any Part of Your Dissertation!

UK’s best academic support services. How would you know until you try?

Interesting read: 10 ways to write a practical introduction fast .

Get Help With Any Part of Your Dissertation!

Uk’s best academic support services. how would you know until you try, 5. research aims and objectives.

Next, the research aims and objectives. Aims and objectives are broad statements of desired results of your dissertation . They reflect the expectations of the topic and research and address the long-term project outcomes.

These statements should use the concepts accurately, must be focused, should be able to convey your research intentions and serve as steps that communicate how your research question will be answered.

You should formulate your aims and objectives based on your topic, research question, or hypothesis. These are simple statements and are an extension of your research question.

Through the aims and objectives, you communicate to your readers what aspects of research you’ve considered and how you intend to answer your research question.

Usually, these statements initiate with words like ‘to explore’, ‘to study’, ‘to assess’, ‘to critically assess’, ‘to understand’, ‘to evaluate’ etc.

You could ask your supervisor to provide some thesis introduction examples to help you understand better how aims and objectives are formulated. More examples are here .

Your aims and objectives should be interrelated and connect to your research question and problem. If they do not, they’ll be considered vague and too broad in scope.

Always ensure your research aims and objectives are concise, brief, and relevant.

Once you conclude your dissertation , you will have to revert back to address whether your research aims and objectives have been met.

You will have to reflect on how your dissertation’s findings , analysis, and discussion related to your aims and objectives and how your research has helped in achieving them.

6. Research Limitations

This section is sometimes a part of the dissertation methodology section ; however, it is usually included in the introduction of a dissertation.

Every research has some limitations. Thus, it is normal for you to experience certain limitations when conducting your study.

You could experience research design limitations, data limitations or even financial limitations. Regardless of which type of limitation you may experience, your dissertation would be impacted. Thus, it would be best if you mentioned them without any hesitation.

When including this section in the introduction, make sure that you clearly state the type of constraint you experienced. This will help your supervisor understand what problems you went through while working on your dissertation.

However, one aspect that you should take care of is that your results, in no way, should be influenced by these restrictions. The results should not be compromised, or your dissertation will not be deemed authentic and reliable.

After you’ve mentioned your research limitations, discuss how you overcame them to produce a perfect dissertation .

Also, mention that your limitations do not adversely impact your results and that you’ve produced research with accurate results the academic community can rely on.

Also read: How to Write Dissertation Methodology .

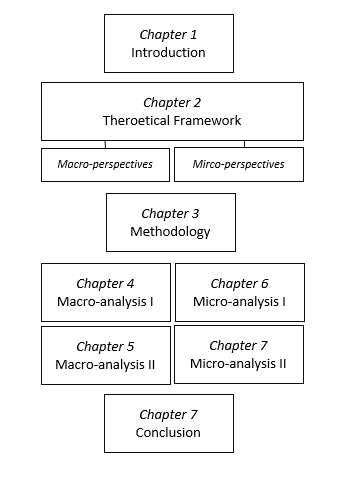

7. Outline of the Dissertation

Even though this isn’t a mandatory sub-section of the introduction chapter, good introductory chapters in dissertations outline what’s to follow in the preceding chapters.

It is also usual to set out an outline of the rest of the dissertation . Depending on your university and academic subject, you might also be asked to include it in your research proposal .

Because your tutor might want to glance over it to see how you plan your dissertation and what sections you’d include; based on what sections you include and how you intend to research and cover them, they’d provide feedback for you to improve.

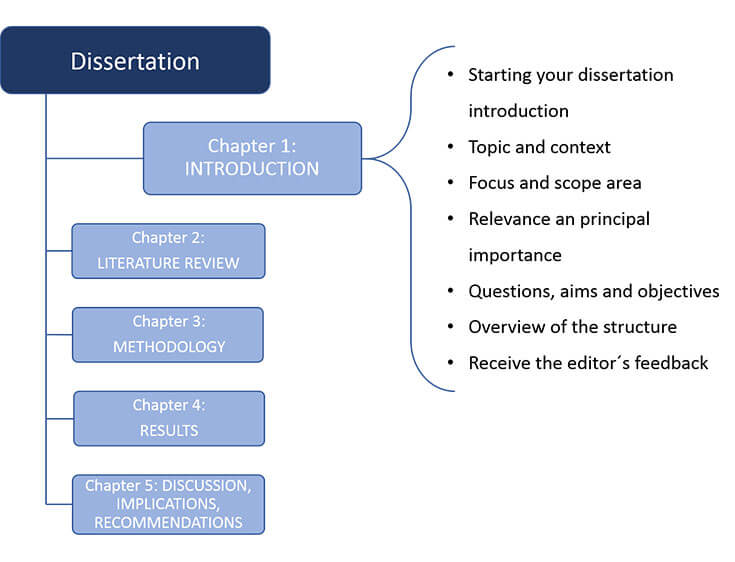

Usually, this section discusses what sections you plan to include and what concepts and aspects each section entails. A standard dissertation consists of five sections : chapters, introduction, literature review , methodology , results and discussion , and conclusion .

Some dissertation assignments do not use the same chapter for results and discussion. Instead, they split it into two different chapters, making six chapters. Check with your supervisor regarding which format you should follow.

When discussing the outline of your dissertation , remember that you’d have to mention what each section involves. Discuss all the significant aspects of each section to give a brief overview of what your dissertation contains, and this is precisely what our dissertation outline service provides.

Writing a dissertation introduction might seem complicated, but it is not if you understand what is expected of you. To understand the required elements and make sure that you focus on all of them.

Include all the aspects to ensure your supervisor and other readers can easily understand how you intend to undertake your research.

“If you find yourself stuck at any stage of your dissertation introduction, get introduction writing help from our writers! At ResearchProspect, we offer a dissertation writing service , and our qualified team of writers will also assist you in conducting in-depth research for your dissertation.

Dissertation Introduction Samples & Examples

Check out some basic samples of dissertation introduction chapters to get started.

FAQs about Dissertation Introduction

What is the purpose of an introduction chapter.

It’s used to introduce key constructs, ideas, models and/or theories etc. relating to the topic; things that you will be basing the remainder of your dissertation on.

How do you start an introduction in a dissertation?

There is more than one way of starting a dissertation’s introductory chapter. You can begin by stating a problem in your area of interest, review relevant literature, identify the gap, and introduce your topic. Or, you can go the opposite way, too. It’s all entirely up to your discretion. However, be consistent in the format you choose to write in.

How long can an introduction get?

It can range from 1000 to 2000 words for a master’s dissertation , but for a higher-level dissertation, it mostly ranges from 8,000 to 10,000 words ’ introduction chapter. In the end, though, it depends on the guidelines provided to you by your department.

Steps to Writing a Dissertation Introduction

You may also like.

Dissertation discussion is where you explore the relevance and significance of results. Here are guidelines to help you write the perfect discussion chapter.

A literature review is a survey of theses, articles, books and other academic sources. Here are guidelines on how to write dissertation literature review.

Make sure to develop a conceptual framework before conducting research. Here is all you need to know about what is a conceptual framework is in a dissertation?

USEFUL LINKS

LEARNING RESOURCES

COMPANY DETAILS

- How It Works

- LEARNING SKILLS

- Writing a Dissertation or Thesis

- Introduction

Search SkillsYouNeed:

Learning Skills:

- A - Z List of Learning Skills

- What is Learning?

- Learning Approaches

- Learning Styles

- 8 Types of Learning Styles

- Understanding Your Preferences to Aid Learning

- Lifelong Learning

- Decisions to Make Before Applying to University

- Top Tips for Surviving Student Life

- Living Online: Education and Learning

- 8 Ways to Embrace Technology-Based Learning Approaches

- Critical Thinking Skills

- Critical Thinking and Fake News

- Understanding and Addressing Conspiracy Theories

- Critical Analysis

- Study Skills

- Exam Skills

- How to Write a Research Proposal

- Ethical Issues in Research

- Dissertation: The Introduction

- Researching and Writing a Literature Review

- Writing your Methodology

- Dissertation: Results and Discussion

- Dissertation: Conclusions and Extras

Writing Your Dissertation or Thesis eBook

Part of the Skills You Need Guide for Students .

- Research Methods

- Teaching, Coaching, Mentoring and Counselling

- Employability Skills for Graduates

Subscribe to our FREE newsletter and start improving your life in just 5 minutes a day.

You'll get our 5 free 'One Minute Life Skills' and our weekly newsletter.

We'll never share your email address and you can unsubscribe at any time.

Writing a Dissertation: The Introduction

The introduction to your dissertation or thesis may well be the last part that you complete, excepting perhaps the abstract. However, it should not be the last part that you think about.

You should write a draft of your introduction very early on, perhaps as early as when you submit your research proposal , to set out a broad outline of your ideas, why you want to study this area, and what you hope to explore and/or establish.

You can, and should, update your introduction several times as your ideas develop. Keeping the introduction in mind will help you to ensure that your research stays on track.

The introduction provides the rationale for your dissertation, thesis or other research project: what you are trying to answer and why it is important to do this research.

Your introduction should contain a clear statement of the research question and the aims of the research (closely related to the question).

It should also introduce and briefly review the literature on your topic to show what is already known and explain the theoretical framework. If there are theoretical debates in the literature, then the introduction is a good place for the researcher to give his or her own perspective in conjunction with the literature review section of the dissertation.

The introduction should also indicate how your piece of research will contribute to the theoretical understanding of the topic.

Drawing on your Research Proposal

The introduction to your dissertation or thesis will probably draw heavily on your research proposal.

If you haven't already written a research proposal see our page Writing a Research Proposal for some ideas.

The introduction needs to set the scene for the later work and give a broad idea of the arguments and/or research that preceded yours. It should give some idea of why you chose to study this area, giving a flavour of the literature, and what you hoped to find out.

Don’t include too many citations in your introduction: this is your summary of why you want to study this area, and what questions you hope to address. Any citations are only to set the context, and you should leave the bulk of the literature for a later section.

Unlike your research proposal, however, you have now completed the work. This means that your introduction can be much clearer about what exactly you chose to investigate and the precise scope of your work.

Remember , whenever you actually write it, that, for the reader, the introduction is the start of the journey through your work. Although you can give a flavour of the outcomes of your research, you should not include any detailed results or conclusions.

Some good ideas for making your introduction strong include:

- An interesting opening sentence that will hold the attention of your reader.

- Don’t try to say everything in the introduction, but do outline the broad thrust of your work and argument.

- Make sure that you don’t promise anything that can’t be delivered later.

- Keep the language straightforward. Although you should do this throughout, it is especially important for the introduction.

Your introduction is the reader’s ‘door’ into your thesis or dissertation. It therefore needs to make sense to the non-expert. Ask a friend to read it for you, and see if they can understand it easily.

At the end of the introduction, it is also usual to set out an outline of the rest of the dissertation.

This can be as simple as ‘ Chapter 2 discusses my chosen methodology, Chapter 3 sets out my results, and Chapter 4 discusses the results and draws conclusions ’.

However, if your thesis is ordered by themes, then a more complex outline may be necessary.

Drafting and Redrafting

As with any other piece of writing, redrafting and editing will improve your text.

This is especially important for the introduction because it needs to hold your reader’s attention and lead them into your research.

The best way to ensure that you can do this is to give yourself enough time to write a really good introduction, including several redrafts.

Do not view the introduction as a last minute job.

Continue to: Writing a Literature Review Writing the Methodology

See also: Dissertation: Results and Discussion Dissertation: Conclusions and Extra Sections Academic Referencing | Research Methods

How to write a fantastic thesis introduction (+15 examples)

The thesis introduction, usually chapter 1, is one of the most important chapters of a thesis. It sets the scene. It previews key arguments and findings. And it helps the reader to understand the structure of the thesis. In short, a lot is riding on this first chapter. With the following tips, you can write a powerful thesis introduction.

Disclosure: This post may contain affiliate links, which means I may earn a small commission if you make a purchase using the links below at no additional cost to you . I only recommend products or services that I truly believe can benefit my audience. As always, my opinions are my own.

Elements of a fantastic thesis introduction

Open with a (personal) story, begin with a problem, define a clear research gap, describe the scientific relevance of the thesis, describe the societal relevance of the thesis, write down the thesis’ core claim in 1-2 sentences, support your argument with sufficient evidence, consider possible objections, address the empirical research context, give a taste of the thesis’ empirical analysis, hint at the practical implications of the research, provide a reading guide, briefly summarise all chapters to come, design a figure illustrating the thesis structure.

An introductory chapter plays an integral part in every thesis. The first chapter has to include quite a lot of information to contextualise the research. At the same time, a good thesis introduction is not too long, but clear and to the point.

A powerful thesis introduction does the following:

- It captures the reader’s attention.

- It presents a clear research gap and emphasises the thesis’ relevance.

- It provides a compelling argument.

- It previews the research findings.

- It explains the structure of the thesis.

In addition, a powerful thesis introduction is well-written, logically structured, and free of grammar and spelling errors. Reputable thesis editors can elevate the quality of your introduction to the next level. If you are in search of a trustworthy thesis or dissertation editor who upholds high-quality standards and offers efficient turnaround times, I recommend the professional thesis and dissertation editing service provided by Editage .

This list can feel quite overwhelming. However, with some easy tips and tricks, you can accomplish all these goals in your thesis introduction. (And if you struggle with finding the right wording, have a look at academic key phrases for introductions .)

Ways to capture the reader’s attention

A powerful thesis introduction should spark the reader’s interest on the first pages. A reader should be enticed to continue reading! There are three common ways to capture the reader’s attention.

An established way to capture the reader’s attention in a thesis introduction is by starting with a story. Regardless of how abstract and ‘scientific’ the actual thesis content is, it can be useful to ease the reader into the topic with a short story.

This story can be, for instance, based on one of your study participants. It can also be a very personal account of one of your own experiences, which drew you to study the thesis topic in the first place.

Start by providing data or statistics

Data and statistics are another established way to immediately draw in your reader. Especially surprising or shocking numbers can highlight the importance of a thesis topic in the first few sentences!

So if your thesis topic lends itself to being kick-started with data or statistics, you are in for a quick and easy way to write a memorable thesis introduction.

The third established way to capture the reader’s attention is by starting with the problem that underlies your thesis. It is advisable to keep the problem simple. A few sentences at the start of the chapter should suffice.

Usually, at a later stage in the introductory chapter, it is common to go more in-depth, describing the research problem (and its scientific and societal relevance) in more detail.

You may also like: Minimalist writing for a better thesis

Emphasising the thesis’ relevance

A good thesis is a relevant thesis. No one wants to read about a concept that has already been explored hundreds of times, or that no one cares about.

Of course, a thesis heavily relies on the work of other scholars. However, each thesis is – and should be – unique. If you want to write a fantastic thesis introduction, your job is to point out this uniqueness!

In academic research, a research gap signifies a research area or research question that has not been explored yet, that has been insufficiently explored, or whose insights and findings are outdated.

Every thesis needs a crystal-clear research gap. Spell it out instead of letting your reader figure out why your thesis is relevant.

* This example has been taken from an actual academic paper on toxic behaviour in online games: Liu, J. and Agur, C. (2022). “After All, They Don’t Know Me” Exploring the Psychological Mechanisms of Toxic Behavior in Online Games. Games and Culture 1–24, DOI: 10.1177/15554120221115397

The scientific relevance of a thesis highlights the importance of your work in terms of advancing theoretical insights on a topic. You can think of this part as your contribution to the (international) academic literature.

Scientific relevance comes in different forms. For instance, you can critically assess a prominent theory explaining a specific phenomenon. Maybe something is missing? Or you can develop a novel framework that combines different frameworks used by other scholars. Or you can draw attention to the context-specific nature of a phenomenon that is discussed in the international literature.

The societal relevance of a thesis highlights the importance of your research in more practical terms. You can think of this part as your contribution beyond theoretical insights and academic publications.

Why are your insights useful? Who can benefit from your insights? How can your insights improve existing practices?

Formulating a compelling argument

Arguments are sets of reasons supporting an idea, which – in academia – often integrate theoretical and empirical insights. Think of an argument as an umbrella statement, or core claim. It should be no longer than one or two sentences.

Including an argument in the introduction of your thesis may seem counterintuitive. After all, the reader will be introduced to your core claim before reading all the chapters of your thesis that led you to this claim in the first place.

But rest assured: A clear argument at the start of your thesis introduction is a sign of a good thesis. It works like a movie teaser to generate interest. And it helps the reader to follow your subsequent line of argumentation.

The core claim of your thesis should be accompanied by sufficient evidence. This does not mean that you have to write 10 pages about your results at this point.

However, you do need to show the reader that your claim is credible and legitimate because of the work you have done.

A good argument already anticipates possible objections. Not everyone will agree with your core claim. Therefore, it is smart to think ahead. What criticism can you expect?

Think about reasons or opposing positions that people can come up with to disagree with your claim. Then, try to address them head-on.

Providing a captivating preview of findings

Similar to presenting a compelling argument, a fantastic thesis introduction also previews some of the findings. When reading an introduction, the reader wants to learn a bit more about the research context. Furthermore, a reader should get a taste of the type of analysis that will be conducted. And lastly, a hint at the practical implications of the findings encourages the reader to read until the end.

If you focus on a specific empirical context, make sure to provide some information about it. The empirical context could be, for instance, a country, an island, a school or city. Make sure the reader understands why you chose this context for your research, and why it fits to your research objective.

If you did all your research in a lab, this section is obviously irrelevant. However, in that case you should explain the setup of your experiment, etcetera.

The empirical part of your thesis centers around the collection and analysis of information. What information, and what evidence, did you generate? And what are some of the key findings?

For instance, you can provide a short summary of the different research methods that you used to collect data. Followed by a short overview of how you analysed this data, and some of the key findings. The reader needs to understand why your empirical analysis is worth reading.

You already highlighted the practical relevance of your thesis in the introductory chapter. However, you should also provide a preview of some of the practical implications that you will develop in your thesis based on your findings.

Presenting a crystal clear thesis structure

A fantastic thesis introduction helps the reader to understand the structure and logic of your whole thesis. This is probably the easiest part to write in a thesis introduction. However, this part can be best written at the very end, once everything else is ready.

A reading guide is an essential part in a thesis introduction! Usually, the reading guide can be found toward the end of the introductory chapter.

The reading guide basically tells the reader what to expect in the chapters to come.

In a longer thesis, such as a PhD thesis, it can be smart to provide a summary of each chapter to come. Think of a paragraph for each chapter, almost in the form of an abstract.

For shorter theses, which also have a shorter introduction, this step is not necessary.

Especially for longer theses, it tends to be a good idea to design a simple figure that illustrates the structure of your thesis. It helps the reader to better grasp the logic of your thesis.

Master Academia

Get new content delivered directly to your inbox.

Subscribe and receive Master Academia's quarterly newsletter.

The most useful academic social networking sites for PhD students

10 reasons not to do a master's degree, related articles.

Dealing with conflicting feedback from different supervisors

How to deal with procrastination productively during thesis writing

The importance of sleep for efficient thesis writing

Theoretical vs. conceptual frameworks: Simple definitions and an overview of key differences

- Most popular requests

- See full list of services at order form

- Essay Writing Service

- British Essay Writers

- Write My Essay

- Law Essay Help

- Dissertation Service

- Write My Dissertation

- Buy Dissertation

- Thesis Service

- Literature Review Service

- Assignment Service

- Buy Assignments

- Do My Assignment

- Do My Homework

- Nursing Assignment Help

- Coursework Service

- Do My Coursework

- Research Paper Service

- Lab Report Service

- Personal Statement Service

- How it works

- Prices & discounts

- Client reviews

This site uses cookies to make sure you get the best experience. By continuing you are agreeing with our cookie policy .

- Vital Tips on How to Write a Dissertation Introduction

Most students start to wonder how to write a dissertation introduction after choosing their project topics. Now, they are sitting in front of their laptop, staring at the blank Word page and pondering where to begin. A dissertation is a lengthy, challenging work that determines how well you understand your subject, what original ideas you can contribute to it, and whether you deserve your degree. To succeed, students must face months of extensive research and brainstorming. Ironically, writing your first words is often the hardest part.

If you’ve been worrying about starting your dissertation, you’ve found the right guide. StateOfWriting team comprises talented experts who have written numerous powerful dissertations. They collaborated to create an academic guide featuring facts, insights, tips, and examples that will help you understand how to write introduction for dissertation. As Maya Angelou wisely said, " Do the best you can until you know better . Then when you know better , do better ." This guide is designed to help you learn more so that you can truly prepare your dissertation better. Examine it and say goodbye to your questions!

Key Suggestions on Writing a Solid Intro for Your Dissertation

What is an introduction? It’s the first section of a work with two major goals. First, it informs readers of what topic you intend to explore: they must feel interested and enlightened, forming a clear idea of what kind of research they’re about to delve into. Its second function is to provide a topic roadmap, showcasing what you’ll be doing to investigate it. Now let’s cover the key components each dissertation introduction should contain.

Dissertation Introduction Structure

Structure is one of the biggest problems with academic writing because most people loathe it. As a student, you’d probably prefer to present your thoughts naturally, giving idea after idea until you think you’ve said everything there was to say. Unfortunately, the education sphere is strict in this regard, especially in Great Britain. All dissertations must have a clearly defined structure; all students must stick to it. Cheer up, though! We will explain everything:

- Hook. What to include in introduction of dissertation first? An interesting sentence. Yes, it’s that simple. This sentence is called a hook because it has a similar purpose to a fish hook: it must reel readers in and catch their attention. When someone reads the first sentence of your introduction, they must feel immediately intrigued. You can achieve this effect by presenting a shocking fact, interesting statistics, or a line that uniquely resonates with people. Give it some thought.

- Context. The next element in our guide on how to write dissertation introduction is background. Give your audience some context on what you’re investigating. Start gradually, leading from general to more specific points. You need to show the context of your key theme, explaining why and how it emerged, its effect, and what can be done about it.

- Scope area. To learn how to write an introduction for a dissertation, you’ll have to see different examples. Once you do, you’ll realise that most of them mention other scholars’ research. That’s what you should include as well. Disclose whether your topic is popular, with many articles and books covering it, or if it’s rare and lacks a substantial body of research. Establish which area or population it affects.

- Overall relevance. Before writing an introduction for a dissertation, students should get dissertation proposal help and get this proposal approved by their professor. If you acquired it already, then you have nothing to worry about. If you were allowed to explore your topic, it must be relevant; now, all you have to do is confirm its relevance again, this time more profoundly. Reveal why researching it is a good idea. Indicate how many implications your study might have and what changes it may lead to. This highlights that a particular topic is not fully explored yet, hence why you chose it for your research.

- Research questions. Another part of the introduction dissertation structure is the leading research questions. At this point, you have formulated your topic and its background. Now you should demonstrate what exactly you’re trying to prove. Present the crucial questions you’ll be seeking to answer.

- Structure overview. This point is closely connected to the previous one. One of the keys to learning how to write a good introduction for a dissertation is being specific. You’ve described your main questions; now explain what each section of your introduction will do to answer them. Consider it a summary that goes through your entire project.

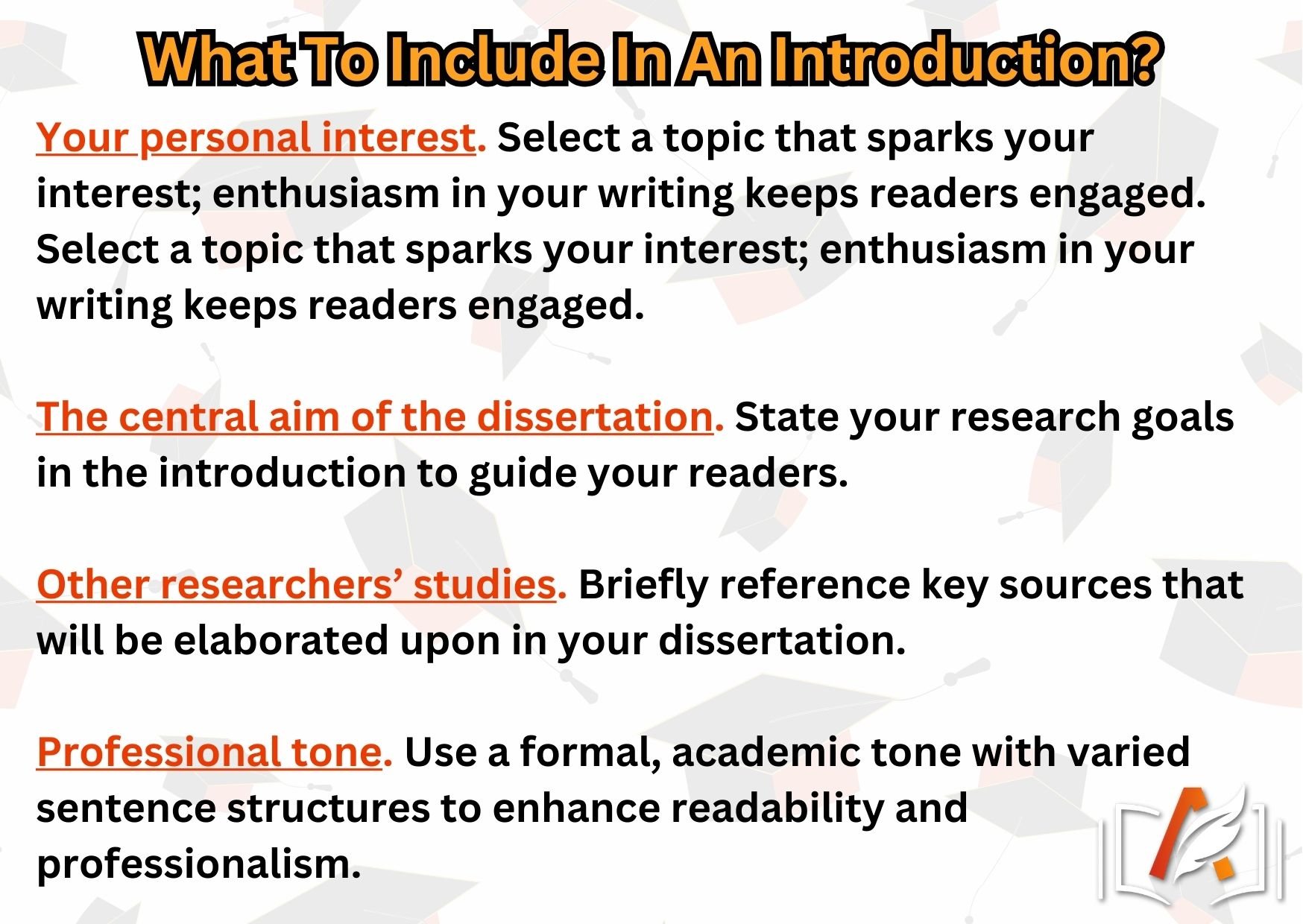

What Should a Dissertation Introduction Include

You’ve understood which elements the introduction consists of. That’s great, but you should know how a professional dissertation writer would approach this task. Every person has a unique vision, so they may spend more time describing some points while nearly omitting the others. Whatever you do, be sure to cover these aspects.

- Your personal interest. Before writing introduction for dissertation, all students decide on their topics. Hopefully, you can choose something you really like. Even if you have mixed thoughts about it, attempt to find something engaging that will allow you to feel at least some passion towards it. You must pour this passion into words, making your tone lively and compelling. If your readers sense your boredom in the disjoined ideas and dry language, they might lose interest in reading further.

- The central aim of the dissertation. What to write in dissertation introduction for certain? Its objectives. Dedicate significant attention to them because you should make it very clear what goals your research is pursuing. Check online examples if you’d like to see how professionals do it. We’ll come back to this little tip later.

- Other researchers’ studies. When writing dissertation introduction, include a couple of references to the major credible sources you’ll be relying on in your research. Don’t perform a literature review here, but present several facts supported by the articles or books you’ve located. This acquaints your audience with the sources they’ll encounter later in the body of your dissertation.

- Professional tone. What should a dissertation introduction include that we haven’t already mentioned? Your overall writing tone. As you probably understand, a dissertation is a serious project that requires a meticulous academic approach. Use more complex words and phrases than you normally do. Utilize synonyms and start your sentences in different ways to avoid repetitions — for example, switch between infinitives, gerunds, and nouns at the start of your lines.

Avoid This When Writing Introductions

You know how to start a dissertation introduction, but you should also learn what you should avoid when writing it. There are many rules. We chose the most relevant ones you should review.

- Direct quotes. Don’t use direct citations in your introduction unless absolutely necessary. This section showcases your ideas. You must present your own thoughts, not rely on someone else’s opinion.

- Topic discussion. Some students ramble in their introduction. Avoid doing the same. Tease your audience with some facts about your topic without giving much away. Introduce, don’t discuss. There’ll be space for it later.

- Informal language. When writing a dissertation introduction, avoid contractions, phrasal verbs, and first-person pronouns. Their usage will damage the validity of your project.

- Conclusion. Never present your study's conclusion in the first section. Even if you have all the numbers and facts, leave them for later sections. Like your readers, you’re supposed to be clueless at this point.

5 Suggestions from Top Dissertation Experts

Our British experts shared advice rooted in their experience with dissertation writing. Hopefully, you’ll find their tips beneficial.

- See online examples. Before writing your dissertation, see how other people did it.

- Write an introduction to dissertation last. Your plans and goals might change after you start performing research, so instead of re-writing your introduction later, create it last.

- Be aware of the size of this section. Typical introductions cannot exceed 10% of the total word count.

- Seek assistance if you feel insecure. If you start thinking, “I’d rather pay someone to write my dissertation instead of doing it myself”, perhaps you should do just that. Don’t rush, though. Order an introduction or any other chapter first, then see how it’ll make you feel. Perhaps, after getting support and seeing an introduction dissertation example, you’ll feel confident again and resume writing your project.

- Edit it at least twice. Re-read your dissertation a day and then preferably a week after writing it. This will give you different perspectives, letting you catch the mistakes your tired eyes might have missed.

Lack of inspiration? Want to Enjoy Free Time?

GRAB YOUR 20% DISCOUNT

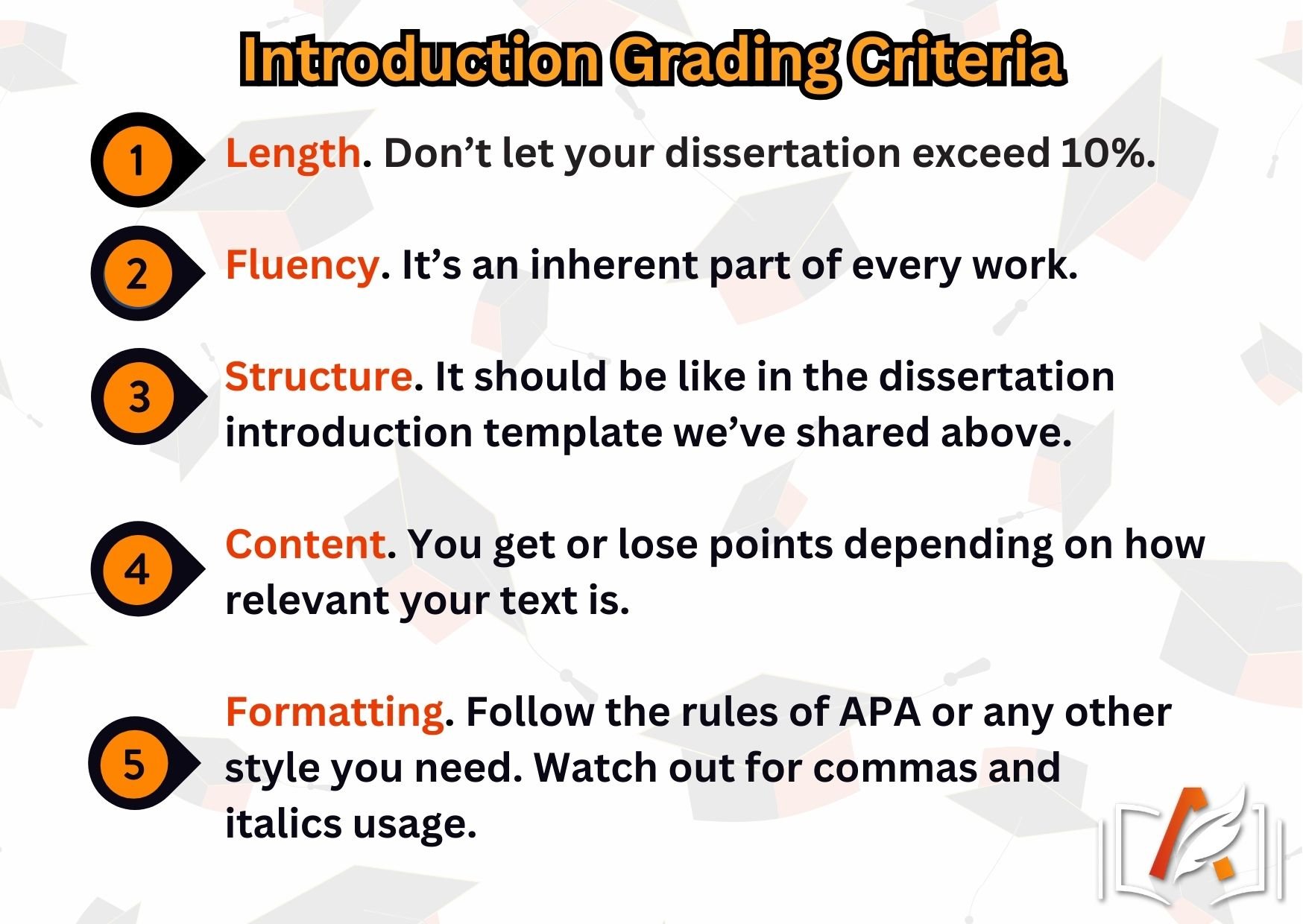

Criteria Judging If You Learned How to Write a Good Dissertation Introduction

If you’ve ever seen the college grading rubric, you probably know how many categories it entails. In Great Britain, professors assess students’ dissertations part by part. The introduction has a separate column, which can either earn you points or make you lose them. Check it out and keep it close when you start your writing process.

- Length. Don’t let your dissertation exceed 10%.

- Fluency. It’s an inherent part of every work.

- Structure. It should be like in the dissertation introduction template we’ve shared above.

- Content. You get or lose points depending on how relevant your text is.

- Formatting. Follow the rules of APA or any other style you need. Watch out for commas and italics usage.

A Well-Written Dissertation Introduction Example

Seeing something once is more impactful than learning theory. We prepared a brief sample of a dissertation introduction on the topic “ How Psychopathy Differs Between Children of Different Genders ”. Then, we analysed it to underline its strengths.

Introduction Example Psychopathy remains an understudied disorder with the power to alter people’s lives indefinitely. There is differing information on how early it emerges in a child, with some sources stating it happens within the first two years (Liren & Tyrell, 2022) and others insisting that it surfaces after age 5 (Makenshin, 2023). Regardless of the specific onset age, it is clear that psychopathy begins to unfold in young children, but few studies covered how it is displayed in males and females. It is important to understand if the genders have different manifestations because it will allow recognising psychopathy sooner as well as developing more appropriate therapy plans. This study aims to answer the following questions: “How does psychopathy differ in young males and females? Do psychopathic males show more aggressiveness?” The work will consist of five sections: a literature review, which analyses the available sources on the topic; methodology, which describes the process and means of investigation; findings, which present the results; discussion, which discusses these results; and conclusion. It will offer recommendations for future researchers.

Analysis of Good Dissertation Introduction

As you see from this example, the first sentence is a hook. It affects readers by addressing the lack of sufficient research on the topic and underlining its devastating effect. The following sentences establish the context and the scope, referencing two important sources. The last sentence of the first paragraph reveals the relevance of the topic and the implications of researching it. The second paragraph presents research questions and a quick dissertation overview. Note the use of complex words and formal language. If you have read this far, it means that you have decided to fully understand this issue. This article and bonus examples of dissertation chapters are for you.

FAQ on How to Start Dissertation Introduction

- How long should a dissertation introduction be?

Count what constitutes 10% of your total text and ensure that your introduction doesn’t exceed this number. For example, if your project has 5000 words, its starting section should be around 500 words.

- How many pages does an intro for a dissertation have?

Don’t consider the number of pages unless you’re ordering your introduction from a writing service (in which case 1 page equals 300 words). Focus on the word count. Remember the 10% rule: this is the maximum permissible length of your introduction.

- Other articles

- Unique Discursive Essay Topics To Try In 2024

- How to Start an Assignment Introduction Like an Expert

- How to Write a Personal Statement for College

- Top Tourist Attractions in England for Students

Writers are verified and tested to comply with quality standards.

Work is completed in time and delivered before deadline.

Wide range of subjects and topics of any difficulty covered.

Read testimonials to learn why customers trust us.

See how it works from order placement to delivery.

Client id #: 000229

You managed to please my supervisor on the first try! Whoa, I've been working with him for over a year and never turned in a paper without having to rewrite it at least once, lol I wonder if he thinks something's wrong with me now.

Client id #: 000154

Your attention to details cannot but makes me happy. Your professional writer followed every single instruction I gave and met the deadline. The text itself is full of sophisticated lexis and well-structured. I was on cloud nine when I looked through it. And my professor is satisfied as well. Million thanks!

Client id #: 000234

I contacted their call-center to specify the possible custom deadline dates prior to making an order decision and it felt like they hadn't even considered a possibility of going beyond the standard urgency. I didn't even want an additional discount for the extended time, just want to make sure I'll have enough time for editing if necessary. Made an order for standard 14 days, we'll see.

Client id #: 000098

I have no idea how you managed to do this research paper so quickly and professionally. But the result is magnificent. Well-structured, brilliantly written and with all the elements I asked for. I am already filling out my next order from you.

- Jump to menu

- Student Home

- Accept your offer

- How to enrol

- Student ID card

- Set up your IT

- Orientation Week

- Fees & payment

- Academic calendar

- Special consideration

- Transcripts

- The Nucleus: Student Hub

- Referencing

- Essay writing

- Learning abroad & exchange

- Professional development & UNSW Advantage

- Employability

- Financial assistance

- International students

- Equitable learning

- Postgraduate research

- Health Service

- Events & activities

- Emergencies

- Volunteering

- Clubs and societies

- Accommodation

- Health services

- Sport and gym

- Arc student organisation

- Security on campus

- Maps of campus

- Careers portal

- Change password

How to Write a Thesis Introduction

What types of information should you include in your introduction .

In the introduction of your thesis, you’ll be trying to do three main things, which are called Moves :

- Move 1 establish your territory (say what the topic is about)

- Move 2 establish a niche (show why there needs to be further research on your topic)

- Move 3 introduce the current research (make hypotheses; state the research questions)

Each Move has a number of stages. Depending on what you need to say in your introduction, you might use one or more stages. Table 1 provides you with a list of the most commonly occurring stages of introductions in Honours theses (colour-coded to show the Moves ). You will also find examples of Introductions, divided into stages with sample sentence extracts. Once you’ve looked at Examples 1 and 2, try the exercise that follows.

Most thesis introductions include SOME (but not all) of the stages listed below. There are variations between different Schools and between different theses, depending on the purpose of the thesis.

Stages in a thesis introduction

- state the general topic and give some background

- provide a review of the literature related to the topic

- define the terms and scope of the topic

- outline the current situation

- evaluate the current situation (advantages/ disadvantages) and identify the gap

- identify the importance of the proposed research

- state the research problem/ questions

- state the research aims and/or research objectives

- state the hypotheses

- outline the order of information in the thesis

- outline the methodology

Example 1: Evaluation of Boron Solid Source Diffusion for High-Efficiency Silicon Solar Cells (School of Photovoltaic and Renewable Energy Engineering)

Example 2: Methods for Measuring Hepatitis C Viral Complexity (School of Biotechnology and Biological Sciences)

Note: this introduction includes the literature review.

Now that you have read example 1 and 2, what are the differences?

Example 3: The IMO Severe-Weather Criterion Applied to High-Speed Monohulls (School of Mechanical and Manufacturing Engineering)

Example 4: The Steiner Tree Problem (School of Computer Science and Engineering)

Introduction exercise

Example 5.1 (extract 1): The effects of Fluoride on the reproduction of three native Australian plant Species (School of Geography)

Example 5.2 (extract 2): The effects of Fluoride on the reproduction of three native Australian plant Species (School of Geography)

Example 5.3

Example 5.4 (extract 4): The effects of Fluoride on the reproduction of three native Australian plant Species (School of Geography)

Example 5.5 (extract 5): The effects of Fluoride on the reproduction of three native Australian plant Species (School of Geography)

Example 5.6 (extract 6): The effects of Fluoride on the reproduction of three native Australian plant Species (School of Geography)

Well, firstly, there are many choices that you can make. You will notice that there are variations not only between the different Schools in your faculty, but also between individual theses, depending on the type of information that is being communicated. However, there are a few elements that a good Introduction should include, at the very minimum:

- Either Statement of general topic Or Background information about the topic;

- Either Identification of disadvantages of current situation Or Identification of the gap in current research;

- Identification of importance of proposed research

- Either Statement of aims Or Statement of objectives

- An Outline of the order of information in the thesis

Engineering & science

- Report writing

- Technical writing

- Writing lab reports

- Introductions

- Literature review

- Writing up results

- Discussions

- Conclusions

- Writing tools

- Case study report in (engineering)

- ^ More support

News and notices

Guide to Using Microsoft Copilot with Commercial Data Protection for UNSW Students Published: 20 May 2024

Ethical and Responsible Use of Artificial Intelligence at UNSW Published: 17 May 2024

Scholarly Resources 4 Students | scite.ai 21 May 2024

Discover your Library: Main Library 21 May 2024

Reference management. Clean and simple.

How to write a good thesis introduction

1. Identify your readership

2. hook the reader and grab their attention, 3. provide relevant background, 4. give the reader a sense of what the paper is about, 5. preview key points and lead into your thesis statement, frequently asked questions about writing a good thesis introduction, related articles.

Many people struggle to write a thesis introduction. Much of your research prep should be done and you should be ready to start your introduction. But often, it’s not clear what needs to be included in a thesis introduction. If you feel stuck at this point not knowing how to start, this guide can help.

Tip: If you’re really struggling to write your thesis intro, consider putting in a placeholder until you write more of the body of your thesis. Then, come back to your intro once you have a stronger sense of the overall content of your thesis.

A good introduction draws readers in while providing the setup for the entire project. There is no single way to write an introduction that will always work for every topic , but the points below can act as a guide. These points can help you write a good thesis introduction.

Before even starting with your first sentence, consider who your readers are. Most likely, your readers will be the professors who are advising you on your thesis.

You should also consider readers of your thesis who are not specialists in your field. Writing with them in your mind will help you to be as clear as possible; this will make your thesis more understandable and enjoyable overall.

Tip: Always strive to be clear, correct, concrete, and concise in your writing.

The first sentence of the thesis is crucial. Looking back at your own research, think about how other writers may have hooked you.

It is common to start with a question or quotation, but these types of hooks are often overused. The best way to start your introduction is with a sentence that is broad and interesting and that seamlessly transitions into your argument.

Once again, consider your audience and how much background information they need to understand your approach. You can start by making a list of what is interesting about your topic:

- Are there any current events or controversies associated with your topic that might be interesting for your introduction?

- What kinds of background information might be useful for a reader to understand right away?

- Are there historical anecdotes or other situations that uniquely illustrate an important aspect of your argument?

A good introduction also needs to contain enough background information to allow the reader to understand the thesis statement and arguments. The amount of background information required will depend on the topic .

There should be enough background information so you don't have to spend too much time with it in the body of the thesis, but not so much that it becomes uninteresting.

Tip: Strike a balance between background information that is too broad or too specific.

Let the reader know what the purpose of the study is. Make sure to include the following points:

- Briefly describe the motivation behind your research.

- Describe the topic and scope of your research.

- Explain the practical relevance of your research.

- Explain the scholarly consensus related to your topic: briefly explain the most important articles and how they are related to your research.

At the end of your introduction, you should lead into your thesis statement by briefly bringing up a few of your main supporting details and by previewing what will be covered in the main part of the thesis. You’ll want to highlight the overall structure of your thesis so that readers will have a sense of what they will encounter as they read.

A good introduction draws readers in while providing the setup for the entire project. There is no single way to write an introduction that will always work for every topic, but these tips will help you write a great introduction:

- Identify your readership.

- Grab the reader's attention.

- Provide relevant background.

- Preview key points and lead into the thesis statement.

A good introduction needs to contain enough background information, and let the reader know what the purpose of the study is. Make sure to include the following points:

- Briefly describe the motivation for your research.

The length of the introduction will depend on the length of the whole thesis. Usually, an introduction makes up roughly 10 per cent of the total word count.

The best way to start your introduction is with a sentence that is broad and interesting and that seamlessly transitions into your argument. Consider the audience, then think of something that would grab their attention.

In Open Access: Theses and Dissertations you can find thousands of recent works. Take a look at any of the theses or dissertations for real-life examples of introductions that were already approved.

Have a language expert improve your writing

Run a free plagiarism check in 10 minutes, automatically generate references for free.

- Knowledge Base

- Dissertation

How to Write a Dissertation | A Guide to Structure & Content

A dissertation or thesis is a long piece of academic writing based on original research, submitted as part of an undergraduate or postgraduate degree.

The structure of a dissertation depends on your field, but it is usually divided into at least four or five chapters (including an introduction and conclusion chapter).

The most common dissertation structure in the sciences and social sciences includes:

- An introduction to your topic

- A literature review that surveys relevant sources

- An explanation of your methodology

- An overview of the results of your research

- A discussion of the results and their implications

- A conclusion that shows what your research has contributed

Dissertations in the humanities are often structured more like a long essay , building an argument by analysing primary and secondary sources . Instead of the standard structure outlined here, you might organise your chapters around different themes or case studies.

Other important elements of the dissertation include the title page , abstract , and reference list . If in doubt about how your dissertation should be structured, always check your department’s guidelines and consult with your supervisor.

Instantly correct all language mistakes in your text

Be assured that you'll submit flawless writing. Upload your document to correct all your mistakes.

Table of contents

Acknowledgements, table of contents, list of figures and tables, list of abbreviations, introduction, literature review / theoretical framework, methodology, reference list.

The very first page of your document contains your dissertation’s title, your name, department, institution, degree program, and submission date. Sometimes it also includes your student number, your supervisor’s name, and the university’s logo. Many programs have strict requirements for formatting the dissertation title page .

The title page is often used as cover when printing and binding your dissertation .

Prevent plagiarism, run a free check.

The acknowledgements section is usually optional, and gives space for you to thank everyone who helped you in writing your dissertation. This might include your supervisors, participants in your research, and friends or family who supported you.

The abstract is a short summary of your dissertation, usually about 150-300 words long. You should write it at the very end, when you’ve completed the rest of the dissertation. In the abstract, make sure to:

- State the main topic and aims of your research

- Describe the methods you used

- Summarise the main results

- State your conclusions

Although the abstract is very short, it’s the first part (and sometimes the only part) of your dissertation that people will read, so it’s important that you get it right. If you’re struggling to write a strong abstract, read our guide on how to write an abstract .

In the table of contents, list all of your chapters and subheadings and their page numbers. The dissertation contents page gives the reader an overview of your structure and helps easily navigate the document.

All parts of your dissertation should be included in the table of contents, including the appendices. You can generate a table of contents automatically in Word.

If you have used a lot of tables and figures in your dissertation, you should itemise them in a numbered list . You can automatically generate this list using the Insert Caption feature in Word.

If you have used a lot of abbreviations in your dissertation, you can include them in an alphabetised list of abbreviations so that the reader can easily look up their meanings.

If you have used a lot of highly specialised terms that will not be familiar to your reader, it might be a good idea to include a glossary . List the terms alphabetically and explain each term with a brief description or definition.

In the introduction, you set up your dissertation’s topic, purpose, and relevance, and tell the reader what to expect in the rest of the dissertation. The introduction should:

- Establish your research topic , giving necessary background information to contextualise your work

- Narrow down the focus and define the scope of the research

- Discuss the state of existing research on the topic, showing your work’s relevance to a broader problem or debate

- Clearly state your objectives and research questions , and indicate how you will answer them

- Give an overview of your dissertation’s structure

Everything in the introduction should be clear, engaging, and relevant to your research. By the end, the reader should understand the what , why and how of your research. Not sure how? Read our guide on how to write a dissertation introduction .

Before you start on your research, you should have conducted a literature review to gain a thorough understanding of the academic work that already exists on your topic. This means:

- Collecting sources (e.g. books and journal articles) and selecting the most relevant ones

- Critically evaluating and analysing each source

- Drawing connections between them (e.g. themes, patterns, conflicts, gaps) to make an overall point

In the dissertation literature review chapter or section, you shouldn’t just summarise existing studies, but develop a coherent structure and argument that leads to a clear basis or justification for your own research. For example, it might aim to show how your research:

- Addresses a gap in the literature

- Takes a new theoretical or methodological approach to the topic

- Proposes a solution to an unresolved problem

- Advances a theoretical debate

- Builds on and strengthens existing knowledge with new data

The literature review often becomes the basis for a theoretical framework , in which you define and analyse the key theories, concepts and models that frame your research. In this section you can answer descriptive research questions about the relationship between concepts or variables.

The methodology chapter or section describes how you conducted your research, allowing your reader to assess its validity. You should generally include:

- The overall approach and type of research (e.g. qualitative, quantitative, experimental, ethnographic)

- Your methods of collecting data (e.g. interviews, surveys, archives)

- Details of where, when, and with whom the research took place

- Your methods of analysing data (e.g. statistical analysis, discourse analysis)

- Tools and materials you used (e.g. computer programs, lab equipment)

- A discussion of any obstacles you faced in conducting the research and how you overcame them

- An evaluation or justification of your methods

Your aim in the methodology is to accurately report what you did, as well as convincing the reader that this was the best approach to answering your research questions or objectives.

Next, you report the results of your research . You can structure this section around sub-questions, hypotheses, or topics. Only report results that are relevant to your objectives and research questions. In some disciplines, the results section is strictly separated from the discussion, while in others the two are combined.

For example, for qualitative methods like in-depth interviews, the presentation of the data will often be woven together with discussion and analysis, while in quantitative and experimental research, the results should be presented separately before you discuss their meaning. If you’re unsure, consult with your supervisor and look at sample dissertations to find out the best structure for your research.

In the results section it can often be helpful to include tables, graphs and charts. Think carefully about how best to present your data, and don’t include tables or figures that just repeat what you have written – they should provide extra information or usefully visualise the results in a way that adds value to your text.

Full versions of your data (such as interview transcripts) can be included as an appendix .

The discussion is where you explore the meaning and implications of your results in relation to your research questions. Here you should interpret the results in detail, discussing whether they met your expectations and how well they fit with the framework that you built in earlier chapters. If any of the results were unexpected, offer explanations for why this might be. It’s a good idea to consider alternative interpretations of your data and discuss any limitations that might have influenced the results.

The discussion should reference other scholarly work to show how your results fit with existing knowledge. You can also make recommendations for future research or practical action.

The dissertation conclusion should concisely answer the main research question, leaving the reader with a clear understanding of your central argument. Wrap up your dissertation with a final reflection on what you did and how you did it. The conclusion often also includes recommendations for research or practice.

In this section, it’s important to show how your findings contribute to knowledge in the field and why your research matters. What have you added to what was already known?

You must include full details of all sources that you have cited in a reference list (sometimes also called a works cited list or bibliography). It’s important to follow a consistent reference style . Each style has strict and specific requirements for how to format your sources in the reference list.

The most common styles used in UK universities are Harvard referencing and Vancouver referencing . Your department will often specify which referencing style you should use – for example, psychology students tend to use APA style , humanities students often use MHRA , and law students always use OSCOLA . M ake sure to check the requirements, and ask your supervisor if you’re unsure.

To save time creating the reference list and make sure your citations are correctly and consistently formatted, you can use our free APA Citation Generator .

Your dissertation itself should contain only essential information that directly contributes to answering your research question. Documents you have used that do not fit into the main body of your dissertation (such as interview transcripts, survey questions or tables with full figures) can be added as appendices .

Is this article helpful?

Other students also liked.

- What Is a Dissertation? | 5 Essential Questions to Get Started

- What is a Literature Review? | Guide, Template, & Examples

- How to Write a Dissertation Proposal | A Step-by-Step Guide

More interesting articles

- Checklist: Writing a dissertation

- Dissertation & Thesis Outline | Example & Free Templates

- Dissertation binding and printing

- Dissertation Table of Contents in Word | Instructions & Examples

- Dissertation title page

- Example Theoretical Framework of a Dissertation or Thesis

- Figure & Table Lists | Word Instructions, Template & Examples

- How to Choose a Dissertation Topic | 8 Steps to Follow

- How to Write a Discussion Section | Tips & Examples

- How to Write a Results Section | Tips & Examples

- How to Write a Thesis or Dissertation Conclusion

- How to Write a Thesis or Dissertation Introduction

- How to Write an Abstract | Steps & Examples

- How to Write Recommendations in Research | Examples & Tips

- List of Abbreviations | Example, Template & Best Practices

- Operationalisation | A Guide with Examples, Pros & Cons

- Prize-Winning Thesis and Dissertation Examples

- Relevance of Your Dissertation Topic | Criteria & Tips

- Research Paper Appendix | Example & Templates

- Thesis & Dissertation Acknowledgements | Tips & Examples

- Thesis & Dissertation Database Examples

- What is a Dissertation Preface? | Definition & Examples

- What is a Glossary? | Definition, Templates, & Examples

- What Is a Research Methodology? | Steps & Tips

- What is a Theoretical Framework? | A Step-by-Step Guide

- What Is a Thesis? | Ultimate Guide & Examples

Dissertation Structure & Layout 101: How to structure your dissertation, thesis or research project.

By: Derek Jansen (MBA) Reviewed By: David Phair (PhD) | July 2019

So, you’ve got a decent understanding of what a dissertation is , you’ve chosen your topic and hopefully you’ve received approval for your research proposal . Awesome! Now its time to start the actual dissertation or thesis writing journey.

To craft a high-quality document, the very first thing you need to understand is dissertation structure . In this post, we’ll walk you through the generic dissertation structure and layout, step by step. We’ll start with the big picture, and then zoom into each chapter to briefly discuss the core contents. If you’re just starting out on your research journey, you should start with this post, which covers the big-picture process of how to write a dissertation or thesis .

*The Caveat *

In this post, we’ll be discussing a traditional dissertation/thesis structure and layout, which is generally used for social science research across universities, whether in the US, UK, Europe or Australia. However, some universities may have small variations on this structure (extra chapters, merged chapters, slightly different ordering, etc).

So, always check with your university if they have a prescribed structure or layout that they expect you to work with. If not, it’s safe to assume the structure we’ll discuss here is suitable. And even if they do have a prescribed structure, you’ll still get value from this post as we’ll explain the core contents of each section.

Overview: S tructuring a dissertation or thesis

- Acknowledgements page

- Abstract (or executive summary)

- Table of contents , list of figures and tables

- Chapter 1: Introduction

- Chapter 2: Literature review

- Chapter 3: Methodology

- Chapter 4: Results

- Chapter 5: Discussion

- Chapter 6: Conclusion

- Reference list

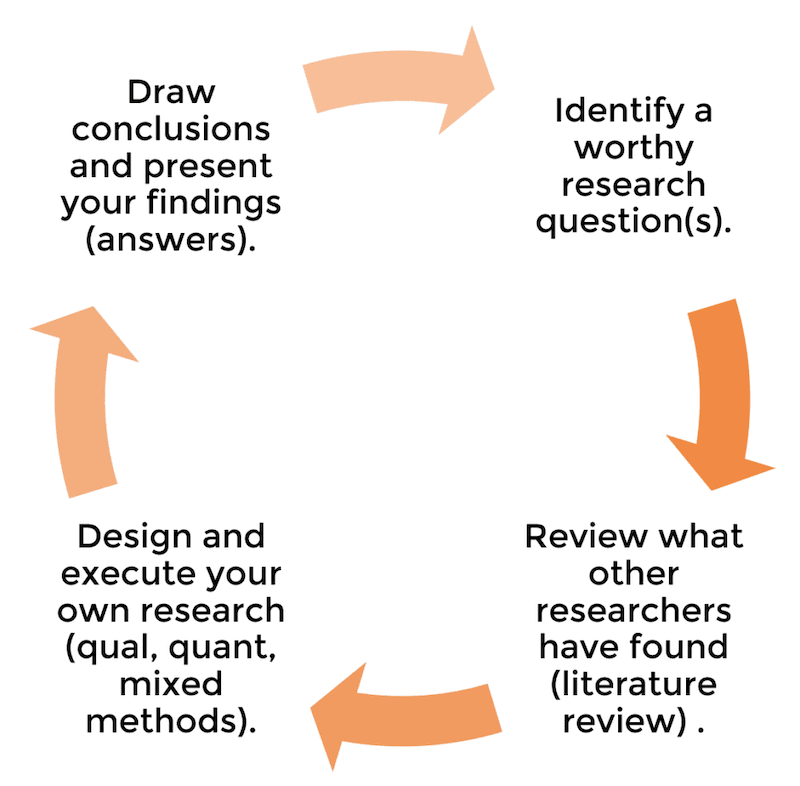

As I mentioned, some universities will have slight variations on this structure. For example, they want an additional “personal reflection chapter”, or they might prefer the results and discussion chapter to be merged into one. Regardless, the overarching flow will always be the same, as this flow reflects the research process , which we discussed here – i.e.:

- The introduction chapter presents the core research question and aims .

- The literature review chapter assesses what the current research says about this question.

- The methodology, results and discussion chapters go about undertaking new research about this question.

- The conclusion chapter (attempts to) answer the core research question .

In other words, the dissertation structure and layout reflect the research process of asking a well-defined question(s), investigating, and then answering the question – see below.

To restate that – the structure and layout of a dissertation reflect the flow of the overall research process . This is essential to understand, as each chapter will make a lot more sense if you “get” this concept. If you’re not familiar with the research process, read this post before going further.

Right. Now that we’ve covered the big picture, let’s dive a little deeper into the details of each section and chapter. Oh and by the way, you can also grab our free dissertation/thesis template here to help speed things up.

The title page of your dissertation is the very first impression the marker will get of your work, so it pays to invest some time thinking about your title. But what makes for a good title? A strong title needs to be 3 things:

- Succinct (not overly lengthy or verbose)

- Specific (not vague or ambiguous)

- Representative of the research you’re undertaking (clearly linked to your research questions)

Typically, a good title includes mention of the following:

- The broader area of the research (i.e. the overarching topic)

- The specific focus of your research (i.e. your specific context)

- Indication of research design (e.g. quantitative , qualitative , or mixed methods ).

For example:

A quantitative investigation [research design] into the antecedents of organisational trust [broader area] in the UK retail forex trading market [specific context/area of focus].

Again, some universities may have specific requirements regarding the format and structure of the title, so it’s worth double-checking expectations with your institution (if there’s no mention in the brief or study material).

Acknowledgements

This page provides you with an opportunity to say thank you to those who helped you along your research journey. Generally, it’s optional (and won’t count towards your marks), but it is academic best practice to include this.

So, who do you say thanks to? Well, there’s no prescribed requirements, but it’s common to mention the following people:

- Your dissertation supervisor or committee.

- Any professors, lecturers or academics that helped you understand the topic or methodologies.

- Any tutors, mentors or advisors.

- Your family and friends, especially spouse (for adult learners studying part-time).

There’s no need for lengthy rambling. Just state who you’re thankful to and for what (e.g. thank you to my supervisor, John Doe, for his endless patience and attentiveness) – be sincere. In terms of length, you should keep this to a page or less.

Abstract or executive summary

The dissertation abstract (or executive summary for some degrees) serves to provide the first-time reader (and marker or moderator) with a big-picture view of your research project. It should give them an understanding of the key insights and findings from the research, without them needing to read the rest of the report – in other words, it should be able to stand alone .

For it to stand alone, your abstract should cover the following key points (at a minimum):

- Your research questions and aims – what key question(s) did your research aim to answer?

- Your methodology – how did you go about investigating the topic and finding answers to your research question(s)?