How to Write a Research Paper: Parts of the Paper

- Choosing Your Topic

- Citation & Style Guides This link opens in a new window

- Critical Thinking

- Evaluating Information

- Parts of the Paper

- Writing Tips from UNC-Chapel Hill

- Librarian Contact

Parts of the Research Paper Papers should have a beginning, a middle, and an end. Your introductory paragraph should grab the reader's attention, state your main idea, and indicate how you will support it. The body of the paper should expand on what you have stated in the introduction. Finally, the conclusion restates the paper's thesis and should explain what you have learned, giving a wrap up of your main ideas.

1. The Title The title should be specific and indicate the theme of the research and what ideas it addresses. Use keywords that help explain your paper's topic to the reader. Try to avoid abbreviations and jargon. Think about keywords that people would use to search for your paper and include them in your title.

2. The Abstract The abstract is used by readers to get a quick overview of your paper. Typically, they are about 200 words in length (120 words minimum to 250 words maximum). The abstract should introduce the topic and thesis, and should provide a general statement about what you have found in your research. The abstract allows you to mention each major aspect of your topic and helps readers decide whether they want to read the rest of the paper. Because it is a summary of the entire research paper, it is often written last.

3. The Introduction The introduction should be designed to attract the reader's attention and explain the focus of the research. You will introduce your overview of the topic, your main points of information, and why this subject is important. You can introduce the current understanding and background information about the topic. Toward the end of the introduction, you add your thesis statement, and explain how you will provide information to support your research questions. This provides the purpose and focus for the rest of the paper.

4. Thesis Statement Most papers will have a thesis statement or main idea and supporting facts/ideas/arguments. State your main idea (something of interest or something to be proven or argued for or against) as your thesis statement, and then provide your supporting facts and arguments. A thesis statement is a declarative sentence that asserts the position a paper will be taking. It also points toward the paper's development. This statement should be both specific and arguable. Generally, the thesis statement will be placed at the end of the first paragraph of your paper. The remainder of your paper will support this thesis.

Students often learn to write a thesis as a first step in the writing process, but often, after research, a writer's viewpoint may change. Therefore a thesis statement may be one of the final steps in writing.

Examples of Thesis Statements from Purdue OWL

5. The Literature Review The purpose of the literature review is to describe past important research and how it specifically relates to the research thesis. It should be a synthesis of the previous literature and the new idea being researched. The review should examine the major theories related to the topic to date and their contributors. It should include all relevant findings from credible sources, such as academic books and peer-reviewed journal articles. You will want to:

- Explain how the literature helps the researcher understand the topic.

- Try to show connections and any disparities between the literature.

- Identify new ways to interpret prior research.

- Reveal any gaps that exist in the literature.

More about writing a literature review. . .

6. The Discussion The purpose of the discussion is to interpret and describe what you have learned from your research. Make the reader understand why your topic is important. The discussion should always demonstrate what you have learned from your readings (and viewings) and how that learning has made the topic evolve, especially from the short description of main points in the introduction.Explain any new understanding or insights you have had after reading your articles and/or books. Paragraphs should use transitioning sentences to develop how one paragraph idea leads to the next. The discussion will always connect to the introduction, your thesis statement, and the literature you reviewed, but it does not simply repeat or rearrange the introduction. You want to:

- Demonstrate critical thinking, not just reporting back facts that you gathered.

- If possible, tell how the topic has evolved over the past and give it's implications for the future.

- Fully explain your main ideas with supporting information.

- Explain why your thesis is correct giving arguments to counter points.

7. The Conclusion A concluding paragraph is a brief summary of your main ideas and restates the paper's main thesis, giving the reader the sense that the stated goal of the paper has been accomplished. What have you learned by doing this research that you didn't know before? What conclusions have you drawn? You may also want to suggest further areas of study, improvement of research possibilities, etc. to demonstrate your critical thinking regarding your research.

- << Previous: Evaluating Information

- Next: Research >>

- Last Updated: Feb 13, 2024 8:35 AM

- URL: https://libguides.ucc.edu/research_paper

- Foundations

- Write Paper

Search form

- Experiments

- Anthropology

- Self-Esteem

- Social Anxiety

- Research Paper >

Parts of a Research Paper

One of the most important aspects of science is ensuring that you get all the parts of the written research paper in the right order.

This article is a part of the guide:

- Outline Examples

- Example of a Paper

- Write a Hypothesis

- Introduction

Browse Full Outline

- 1 Write a Research Paper

- 2 Writing a Paper

- 3.1 Write an Outline

- 3.2 Outline Examples

- 4.1 Thesis Statement

- 4.2 Write a Hypothesis

- 5.2 Abstract

- 5.3 Introduction

- 5.4 Methods

- 5.5 Results

- 5.6 Discussion

- 5.7 Conclusion

- 5.8 Bibliography

- 6.1 Table of Contents

- 6.2 Acknowledgements

- 6.3 Appendix

- 7.1 In Text Citations

- 7.2 Footnotes

- 7.3.1 Floating Blocks

- 7.4 Example of a Paper

- 7.5 Example of a Paper 2

- 7.6.1 Citations

- 7.7.1 Writing Style

- 7.7.2 Citations

- 8.1.1 Sham Peer Review

- 8.1.2 Advantages

- 8.1.3 Disadvantages

- 8.2 Publication Bias

- 8.3.1 Journal Rejection

- 9.1 Article Writing

- 9.2 Ideas for Topics

You may have finished the best research project on earth but, if you do not write an interesting and well laid out paper, then nobody is going to take your findings seriously.

The main thing to remember with any research paper is that it is based on an hourglass structure. It begins with general information and undertaking a literature review , and becomes more specific as you nail down a research problem and hypothesis .

Finally, it again becomes more general as you try to apply your findings to the world at general.

Whilst there are a few differences between the various disciplines, with some fields placing more emphasis on certain parts than others, there is a basic underlying structure.

These steps are the building blocks of constructing a good research paper. This section outline how to lay out the parts of a research paper, including the various experimental methods and designs.

The principles for literature review and essays of all types follow the same basic principles.

Reference List

For many students, writing the introduction is the first part of the process, setting down the direction of the paper and laying out exactly what the research paper is trying to achieve.

For others, the introduction is the last thing written, acting as a quick summary of the paper. As long as you have planned a good structure for the parts of a research paper, both approaches are acceptable and it is a matter of preference.

A good introduction generally consists of three distinct parts:

- You should first give a general presentation of the research problem.

- You should then lay out exactly what you are trying to achieve with this particular research project.

- You should then state your own position.

Ideally, you should try to give each section its own paragraph, but this will vary given the overall length of the paper.

1) General Presentation

Look at the benefits to be gained by the research or why the problem has not been solved yet. Perhaps nobody has thought about it, or maybe previous research threw up some interesting leads that the previous researchers did not follow up.

Another researcher may have uncovered some interesting trends, but did not manage to reach the significance level , due to experimental error or small sample sizes .

2) Purpose of the Paper

The research problem does not have to be a statement, but must at least imply what you are trying to find.

Many writers prefer to place the thesis statement or hypothesis here, which is perfectly acceptable, but most include it in the last sentences of the introduction, to give the reader a fuller picture.

3) A Statement of Intent From the Writer

The idea is that somebody will be able to gain an overall view of the paper without needing to read the whole thing. Literature reviews are time-consuming enough, so give the reader a concise idea of your intention before they commit to wading through pages of background.

In this section, you look to give a context to the research, including any relevant information learned during your literature review. You are also trying to explain why you chose this area of research, attempting to highlight why it is necessary. The second part should state the purpose of the experiment and should include the research problem. The third part should give the reader a quick summary of the form that the parts of the research paper is going to take and should include a condensed version of the discussion.

This should be the easiest part of the paper to write, as it is a run-down of the exact design and methodology used to perform the research. Obviously, the exact methodology varies depending upon the exact field and type of experiment .

There is a big methodological difference between the apparatus based research of the physical sciences and the methods and observation methods of social sciences. However, the key is to ensure that another researcher would be able to replicate the experiment to match yours as closely as possible, but still keeping the section concise.

You can assume that anybody reading your paper is familiar with the basic methods, so try not to explain every last detail. For example, an organic chemist or biochemist will be familiar with chromatography, so you only need to highlight the type of equipment used rather than explaining the whole process in detail.

In the case of a survey , if you have too many questions to cover in the method, you can always include a copy of the questionnaire in the appendix . In this case, make sure that you refer to it.

This is probably the most variable part of any research paper, and depends on the results and aims of the experiment.

For quantitative research , it is a presentation of the numerical results and data, whereas for qualitative research it should be a broader discussion of trends, without going into too much detail.

For research generating a lot of results , then it is better to include tables or graphs of the analyzed data and leave the raw data in the appendix, so that a researcher can follow up and check your calculations.

A commentary is essential to linking the results together, rather than just displaying isolated and unconnected charts and figures.

It can be quite difficult to find a good balance between the results and the discussion section, because some findings, especially in a quantitative or descriptive experiment , will fall into a grey area. Try to avoid repeating yourself too often.

It is best to try to find a middle path, where you give a general overview of the data and then expand on it in the discussion - you should try to keep your own opinions and interpretations out of the results section, saving that for the discussion later on.

This is where you elaborate on your findings, and explain what you found, adding your own personal interpretations.

Ideally, you should link the discussion back to the introduction, addressing each point individually.

It’s important to make sure that every piece of information in your discussion is directly related to the thesis statement , or you risk cluttering your findings. In keeping with the hourglass principle, you can expand on the topic later in the conclusion .

The conclusion is where you build on your discussion and try to relate your findings to other research and to the world at large.

In a short research paper, it may be a paragraph or two, or even a few lines.

In a dissertation, it may well be the most important part of the entire paper - not only does it describe the results and discussion in detail, it emphasizes the importance of the results in the field, and ties it in with the previous research.

Some research papers require a recommendations section, postulating the further directions of the research, as well as highlighting how any flaws affected the results. In this case, you should suggest any improvements that could be made to the research design .

No paper is complete without a reference list , documenting all the sources that you used for your research. This should be laid out according to APA , MLA or other specified format, allowing any interested researcher to follow up on the research.

One habit that is becoming more common, especially with online papers, is to include a reference to your own paper on the final page. Lay this out in MLA, APA and Chicago format, allowing anybody referencing your paper to copy and paste it.

- Psychology 101

- Flags and Countries

- Capitals and Countries

Martyn Shuttleworth (Jun 5, 2009). Parts of a Research Paper. Retrieved Jun 22, 2024 from Explorable.com: https://explorable.com/parts-of-a-research-paper

You Are Allowed To Copy The Text

The text in this article is licensed under the Creative Commons-License Attribution 4.0 International (CC BY 4.0) .

This means you're free to copy, share and adapt any parts (or all) of the text in the article, as long as you give appropriate credit and provide a link/reference to this page.

That is it. You don't need our permission to copy the article; just include a link/reference back to this page. You can use it freely (with some kind of link), and we're also okay with people reprinting in publications like books, blogs, newsletters, course-material, papers, wikipedia and presentations (with clear attribution).

Want to stay up to date? Follow us!

Check out the official book.

Learn how to construct, style and format an Academic paper and take your skills to the next level.

(also available as ebook )

Save this course for later

Don't have time for it all now? No problem, save it as a course and come back to it later.

Footer bottom

- Privacy Policy

- Subscribe to our RSS Feed

- Like us on Facebook

- Follow us on Twitter

- Privacy Policy

Home » Research Paper – Structure, Examples and Writing Guide

Research Paper – Structure, Examples and Writing Guide

Table of Contents

Research Paper

Definition:

Research Paper is a written document that presents the author’s original research, analysis, and interpretation of a specific topic or issue.

It is typically based on Empirical Evidence, and may involve qualitative or quantitative research methods, or a combination of both. The purpose of a research paper is to contribute new knowledge or insights to a particular field of study, and to demonstrate the author’s understanding of the existing literature and theories related to the topic.

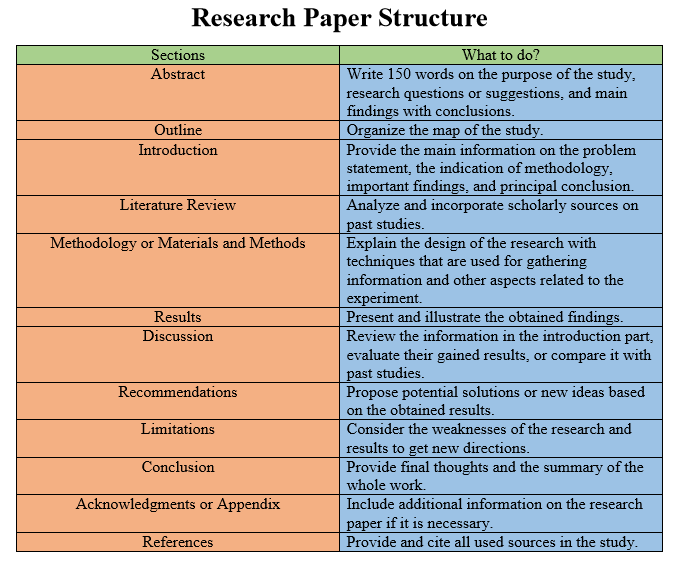

Structure of Research Paper

The structure of a research paper typically follows a standard format, consisting of several sections that convey specific information about the research study. The following is a detailed explanation of the structure of a research paper:

The title page contains the title of the paper, the name(s) of the author(s), and the affiliation(s) of the author(s). It also includes the date of submission and possibly, the name of the journal or conference where the paper is to be published.

The abstract is a brief summary of the research paper, typically ranging from 100 to 250 words. It should include the research question, the methods used, the key findings, and the implications of the results. The abstract should be written in a concise and clear manner to allow readers to quickly grasp the essence of the research.

Introduction

The introduction section of a research paper provides background information about the research problem, the research question, and the research objectives. It also outlines the significance of the research, the research gap that it aims to fill, and the approach taken to address the research question. Finally, the introduction section ends with a clear statement of the research hypothesis or research question.

Literature Review

The literature review section of a research paper provides an overview of the existing literature on the topic of study. It includes a critical analysis and synthesis of the literature, highlighting the key concepts, themes, and debates. The literature review should also demonstrate the research gap and how the current study seeks to address it.

The methods section of a research paper describes the research design, the sample selection, the data collection and analysis procedures, and the statistical methods used to analyze the data. This section should provide sufficient detail for other researchers to replicate the study.

The results section presents the findings of the research, using tables, graphs, and figures to illustrate the data. The findings should be presented in a clear and concise manner, with reference to the research question and hypothesis.

The discussion section of a research paper interprets the findings and discusses their implications for the research question, the literature review, and the field of study. It should also address the limitations of the study and suggest future research directions.

The conclusion section summarizes the main findings of the study, restates the research question and hypothesis, and provides a final reflection on the significance of the research.

The references section provides a list of all the sources cited in the paper, following a specific citation style such as APA, MLA or Chicago.

How to Write Research Paper

You can write Research Paper by the following guide:

- Choose a Topic: The first step is to select a topic that interests you and is relevant to your field of study. Brainstorm ideas and narrow down to a research question that is specific and researchable.

- Conduct a Literature Review: The literature review helps you identify the gap in the existing research and provides a basis for your research question. It also helps you to develop a theoretical framework and research hypothesis.

- Develop a Thesis Statement : The thesis statement is the main argument of your research paper. It should be clear, concise and specific to your research question.

- Plan your Research: Develop a research plan that outlines the methods, data sources, and data analysis procedures. This will help you to collect and analyze data effectively.

- Collect and Analyze Data: Collect data using various methods such as surveys, interviews, observations, or experiments. Analyze data using statistical tools or other qualitative methods.

- Organize your Paper : Organize your paper into sections such as Introduction, Literature Review, Methods, Results, Discussion, and Conclusion. Ensure that each section is coherent and follows a logical flow.

- Write your Paper : Start by writing the introduction, followed by the literature review, methods, results, discussion, and conclusion. Ensure that your writing is clear, concise, and follows the required formatting and citation styles.

- Edit and Proofread your Paper: Review your paper for grammar and spelling errors, and ensure that it is well-structured and easy to read. Ask someone else to review your paper to get feedback and suggestions for improvement.

- Cite your Sources: Ensure that you properly cite all sources used in your research paper. This is essential for giving credit to the original authors and avoiding plagiarism.

Research Paper Example

Note : The below example research paper is for illustrative purposes only and is not an actual research paper. Actual research papers may have different structures, contents, and formats depending on the field of study, research question, data collection and analysis methods, and other factors. Students should always consult with their professors or supervisors for specific guidelines and expectations for their research papers.

Research Paper Example sample for Students:

Title: The Impact of Social Media on Mental Health among Young Adults

Abstract: This study aims to investigate the impact of social media use on the mental health of young adults. A literature review was conducted to examine the existing research on the topic. A survey was then administered to 200 university students to collect data on their social media use, mental health status, and perceived impact of social media on their mental health. The results showed that social media use is positively associated with depression, anxiety, and stress. The study also found that social comparison, cyberbullying, and FOMO (Fear of Missing Out) are significant predictors of mental health problems among young adults.

Introduction: Social media has become an integral part of modern life, particularly among young adults. While social media has many benefits, including increased communication and social connectivity, it has also been associated with negative outcomes, such as addiction, cyberbullying, and mental health problems. This study aims to investigate the impact of social media use on the mental health of young adults.

Literature Review: The literature review highlights the existing research on the impact of social media use on mental health. The review shows that social media use is associated with depression, anxiety, stress, and other mental health problems. The review also identifies the factors that contribute to the negative impact of social media, including social comparison, cyberbullying, and FOMO.

Methods : A survey was administered to 200 university students to collect data on their social media use, mental health status, and perceived impact of social media on their mental health. The survey included questions on social media use, mental health status (measured using the DASS-21), and perceived impact of social media on their mental health. Data were analyzed using descriptive statistics and regression analysis.

Results : The results showed that social media use is positively associated with depression, anxiety, and stress. The study also found that social comparison, cyberbullying, and FOMO are significant predictors of mental health problems among young adults.

Discussion : The study’s findings suggest that social media use has a negative impact on the mental health of young adults. The study highlights the need for interventions that address the factors contributing to the negative impact of social media, such as social comparison, cyberbullying, and FOMO.

Conclusion : In conclusion, social media use has a significant impact on the mental health of young adults. The study’s findings underscore the need for interventions that promote healthy social media use and address the negative outcomes associated with social media use. Future research can explore the effectiveness of interventions aimed at reducing the negative impact of social media on mental health. Additionally, longitudinal studies can investigate the long-term effects of social media use on mental health.

Limitations : The study has some limitations, including the use of self-report measures and a cross-sectional design. The use of self-report measures may result in biased responses, and a cross-sectional design limits the ability to establish causality.

Implications: The study’s findings have implications for mental health professionals, educators, and policymakers. Mental health professionals can use the findings to develop interventions that address the negative impact of social media use on mental health. Educators can incorporate social media literacy into their curriculum to promote healthy social media use among young adults. Policymakers can use the findings to develop policies that protect young adults from the negative outcomes associated with social media use.

References :

- Twenge, J. M., & Campbell, W. K. (2019). Associations between screen time and lower psychological well-being among children and adolescents: Evidence from a population-based study. Preventive medicine reports, 15, 100918.

- Primack, B. A., Shensa, A., Escobar-Viera, C. G., Barrett, E. L., Sidani, J. E., Colditz, J. B., … & James, A. E. (2017). Use of multiple social media platforms and symptoms of depression and anxiety: A nationally-representative study among US young adults. Computers in Human Behavior, 69, 1-9.

- Van der Meer, T. G., & Verhoeven, J. W. (2017). Social media and its impact on academic performance of students. Journal of Information Technology Education: Research, 16, 383-398.

Appendix : The survey used in this study is provided below.

Social Media and Mental Health Survey

- How often do you use social media per day?

- Less than 30 minutes

- 30 minutes to 1 hour

- 1 to 2 hours

- 2 to 4 hours

- More than 4 hours

- Which social media platforms do you use?

- Others (Please specify)

- How often do you experience the following on social media?

- Social comparison (comparing yourself to others)

- Cyberbullying

- Fear of Missing Out (FOMO)

- Have you ever experienced any of the following mental health problems in the past month?

- Do you think social media use has a positive or negative impact on your mental health?

- Very positive

- Somewhat positive

- Somewhat negative

- Very negative

- In your opinion, which factors contribute to the negative impact of social media on mental health?

- Social comparison

- In your opinion, what interventions could be effective in reducing the negative impact of social media on mental health?

- Education on healthy social media use

- Counseling for mental health problems caused by social media

- Social media detox programs

- Regulation of social media use

Thank you for your participation!

Applications of Research Paper

Research papers have several applications in various fields, including:

- Advancing knowledge: Research papers contribute to the advancement of knowledge by generating new insights, theories, and findings that can inform future research and practice. They help to answer important questions, clarify existing knowledge, and identify areas that require further investigation.

- Informing policy: Research papers can inform policy decisions by providing evidence-based recommendations for policymakers. They can help to identify gaps in current policies, evaluate the effectiveness of interventions, and inform the development of new policies and regulations.

- Improving practice: Research papers can improve practice by providing evidence-based guidance for professionals in various fields, including medicine, education, business, and psychology. They can inform the development of best practices, guidelines, and standards of care that can improve outcomes for individuals and organizations.

- Educating students : Research papers are often used as teaching tools in universities and colleges to educate students about research methods, data analysis, and academic writing. They help students to develop critical thinking skills, research skills, and communication skills that are essential for success in many careers.

- Fostering collaboration: Research papers can foster collaboration among researchers, practitioners, and policymakers by providing a platform for sharing knowledge and ideas. They can facilitate interdisciplinary collaborations and partnerships that can lead to innovative solutions to complex problems.

When to Write Research Paper

Research papers are typically written when a person has completed a research project or when they have conducted a study and have obtained data or findings that they want to share with the academic or professional community. Research papers are usually written in academic settings, such as universities, but they can also be written in professional settings, such as research organizations, government agencies, or private companies.

Here are some common situations where a person might need to write a research paper:

- For academic purposes: Students in universities and colleges are often required to write research papers as part of their coursework, particularly in the social sciences, natural sciences, and humanities. Writing research papers helps students to develop research skills, critical thinking skills, and academic writing skills.

- For publication: Researchers often write research papers to publish their findings in academic journals or to present their work at academic conferences. Publishing research papers is an important way to disseminate research findings to the academic community and to establish oneself as an expert in a particular field.

- To inform policy or practice : Researchers may write research papers to inform policy decisions or to improve practice in various fields. Research findings can be used to inform the development of policies, guidelines, and best practices that can improve outcomes for individuals and organizations.

- To share new insights or ideas: Researchers may write research papers to share new insights or ideas with the academic or professional community. They may present new theories, propose new research methods, or challenge existing paradigms in their field.

Purpose of Research Paper

The purpose of a research paper is to present the results of a study or investigation in a clear, concise, and structured manner. Research papers are written to communicate new knowledge, ideas, or findings to a specific audience, such as researchers, scholars, practitioners, or policymakers. The primary purposes of a research paper are:

- To contribute to the body of knowledge : Research papers aim to add new knowledge or insights to a particular field or discipline. They do this by reporting the results of empirical studies, reviewing and synthesizing existing literature, proposing new theories, or providing new perspectives on a topic.

- To inform or persuade: Research papers are written to inform or persuade the reader about a particular issue, topic, or phenomenon. They present evidence and arguments to support their claims and seek to persuade the reader of the validity of their findings or recommendations.

- To advance the field: Research papers seek to advance the field or discipline by identifying gaps in knowledge, proposing new research questions or approaches, or challenging existing assumptions or paradigms. They aim to contribute to ongoing debates and discussions within a field and to stimulate further research and inquiry.

- To demonstrate research skills: Research papers demonstrate the author’s research skills, including their ability to design and conduct a study, collect and analyze data, and interpret and communicate findings. They also demonstrate the author’s ability to critically evaluate existing literature, synthesize information from multiple sources, and write in a clear and structured manner.

Characteristics of Research Paper

Research papers have several characteristics that distinguish them from other forms of academic or professional writing. Here are some common characteristics of research papers:

- Evidence-based: Research papers are based on empirical evidence, which is collected through rigorous research methods such as experiments, surveys, observations, or interviews. They rely on objective data and facts to support their claims and conclusions.

- Structured and organized: Research papers have a clear and logical structure, with sections such as introduction, literature review, methods, results, discussion, and conclusion. They are organized in a way that helps the reader to follow the argument and understand the findings.

- Formal and objective: Research papers are written in a formal and objective tone, with an emphasis on clarity, precision, and accuracy. They avoid subjective language or personal opinions and instead rely on objective data and analysis to support their arguments.

- Citations and references: Research papers include citations and references to acknowledge the sources of information and ideas used in the paper. They use a specific citation style, such as APA, MLA, or Chicago, to ensure consistency and accuracy.

- Peer-reviewed: Research papers are often peer-reviewed, which means they are evaluated by other experts in the field before they are published. Peer-review ensures that the research is of high quality, meets ethical standards, and contributes to the advancement of knowledge in the field.

- Objective and unbiased: Research papers strive to be objective and unbiased in their presentation of the findings. They avoid personal biases or preconceptions and instead rely on the data and analysis to draw conclusions.

Advantages of Research Paper

Research papers have many advantages, both for the individual researcher and for the broader academic and professional community. Here are some advantages of research papers:

- Contribution to knowledge: Research papers contribute to the body of knowledge in a particular field or discipline. They add new information, insights, and perspectives to existing literature and help advance the understanding of a particular phenomenon or issue.

- Opportunity for intellectual growth: Research papers provide an opportunity for intellectual growth for the researcher. They require critical thinking, problem-solving, and creativity, which can help develop the researcher’s skills and knowledge.

- Career advancement: Research papers can help advance the researcher’s career by demonstrating their expertise and contributions to the field. They can also lead to new research opportunities, collaborations, and funding.

- Academic recognition: Research papers can lead to academic recognition in the form of awards, grants, or invitations to speak at conferences or events. They can also contribute to the researcher’s reputation and standing in the field.

- Impact on policy and practice: Research papers can have a significant impact on policy and practice. They can inform policy decisions, guide practice, and lead to changes in laws, regulations, or procedures.

- Advancement of society: Research papers can contribute to the advancement of society by addressing important issues, identifying solutions to problems, and promoting social justice and equality.

Limitations of Research Paper

Research papers also have some limitations that should be considered when interpreting their findings or implications. Here are some common limitations of research papers:

- Limited generalizability: Research findings may not be generalizable to other populations, settings, or contexts. Studies often use specific samples or conditions that may not reflect the broader population or real-world situations.

- Potential for bias : Research papers may be biased due to factors such as sample selection, measurement errors, or researcher biases. It is important to evaluate the quality of the research design and methods used to ensure that the findings are valid and reliable.

- Ethical concerns: Research papers may raise ethical concerns, such as the use of vulnerable populations or invasive procedures. Researchers must adhere to ethical guidelines and obtain informed consent from participants to ensure that the research is conducted in a responsible and respectful manner.

- Limitations of methodology: Research papers may be limited by the methodology used to collect and analyze data. For example, certain research methods may not capture the complexity or nuance of a particular phenomenon, or may not be appropriate for certain research questions.

- Publication bias: Research papers may be subject to publication bias, where positive or significant findings are more likely to be published than negative or non-significant findings. This can skew the overall findings of a particular area of research.

- Time and resource constraints: Research papers may be limited by time and resource constraints, which can affect the quality and scope of the research. Researchers may not have access to certain data or resources, or may be unable to conduct long-term studies due to practical limitations.

About the author

Muhammad Hassan

Researcher, Academic Writer, Web developer

You may also like

Dissertation – Format, Example and Template

Research Paper Abstract – Writing Guide and...

Data Verification – Process, Types and Examples

Institutional Review Board – Application Sample...

Survey Instruments – List and Their Uses

Limitations in Research – Types, Examples and...

- Search This Site All UCSD Sites Faculty/Staff Search Term

- Contact & Directions

- Climate Statement

- Cognitive Behavioral Neuroscience

- Cognitive Psychology

- Developmental Psychology

- Social Psychology

- Adjunct Faculty

- Non-Senate Instructors

- Researchers

- Psychology Grads

- Affiliated Grads

- New and Prospective Students

- Honors Program

- Experiential Learning

- Programs & Events

- Psi Chi / Psychology Club

- Prospective PhD Students

- Current PhD Students

- Area Brown Bags

- Colloquium Series

- Anderson Distinguished Lecture Series

- Speaker Videos

- Undergraduate Program

- Academic and Writing Resources

Writing Research Papers

- Research Paper Structure

Whether you are writing a B.S. Degree Research Paper or completing a research report for a Psychology course, it is highly likely that you will need to organize your research paper in accordance with American Psychological Association (APA) guidelines. Here we discuss the structure of research papers according to APA style.

Major Sections of a Research Paper in APA Style

A complete research paper in APA style that is reporting on experimental research will typically contain a Title page, Abstract, Introduction, Methods, Results, Discussion, and References sections. 1 Many will also contain Figures and Tables and some will have an Appendix or Appendices. These sections are detailed as follows (for a more in-depth guide, please refer to " How to Write a Research Paper in APA Style ”, a comprehensive guide developed by Prof. Emma Geller). 2

What is this paper called and who wrote it? – the first page of the paper; this includes the name of the paper, a “running head”, authors, and institutional affiliation of the authors. The institutional affiliation is usually listed in an Author Note that is placed towards the bottom of the title page. In some cases, the Author Note also contains an acknowledgment of any funding support and of any individuals that assisted with the research project.

One-paragraph summary of the entire study – typically no more than 250 words in length (and in many cases it is well shorter than that), the Abstract provides an overview of the study.

Introduction

What is the topic and why is it worth studying? – the first major section of text in the paper, the Introduction commonly describes the topic under investigation, summarizes or discusses relevant prior research (for related details, please see the Writing Literature Reviews section of this website), identifies unresolved issues that the current research will address, and provides an overview of the research that is to be described in greater detail in the sections to follow.

What did you do? – a section which details how the research was performed. It typically features a description of the participants/subjects that were involved, the study design, the materials that were used, and the study procedure. If there were multiple experiments, then each experiment may require a separate Methods section. A rule of thumb is that the Methods section should be sufficiently detailed for another researcher to duplicate your research.

What did you find? – a section which describes the data that was collected and the results of any statistical tests that were performed. It may also be prefaced by a description of the analysis procedure that was used. If there were multiple experiments, then each experiment may require a separate Results section.

What is the significance of your results? – the final major section of text in the paper. The Discussion commonly features a summary of the results that were obtained in the study, describes how those results address the topic under investigation and/or the issues that the research was designed to address, and may expand upon the implications of those findings. Limitations and directions for future research are also commonly addressed.

List of articles and any books cited – an alphabetized list of the sources that are cited in the paper (by last name of the first author of each source). Each reference should follow specific APA guidelines regarding author names, dates, article titles, journal titles, journal volume numbers, page numbers, book publishers, publisher locations, websites, and so on (for more information, please see the Citing References in APA Style page of this website).

Tables and Figures

Graphs and data (optional in some cases) – depending on the type of research being performed, there may be Tables and/or Figures (however, in some cases, there may be neither). In APA style, each Table and each Figure is placed on a separate page and all Tables and Figures are included after the References. Tables are included first, followed by Figures. However, for some journals and undergraduate research papers (such as the B.S. Research Paper or Honors Thesis), Tables and Figures may be embedded in the text (depending on the instructor’s or editor’s policies; for more details, see "Deviations from APA Style" below).

Supplementary information (optional) – in some cases, additional information that is not critical to understanding the research paper, such as a list of experiment stimuli, details of a secondary analysis, or programming code, is provided. This is often placed in an Appendix.

Variations of Research Papers in APA Style

Although the major sections described above are common to most research papers written in APA style, there are variations on that pattern. These variations include:

- Literature reviews – when a paper is reviewing prior published research and not presenting new empirical research itself (such as in a review article, and particularly a qualitative review), then the authors may forgo any Methods and Results sections. Instead, there is a different structure such as an Introduction section followed by sections for each of the different aspects of the body of research being reviewed, and then perhaps a Discussion section.

- Multi-experiment papers – when there are multiple experiments, it is common to follow the Introduction with an Experiment 1 section, itself containing Methods, Results, and Discussion subsections. Then there is an Experiment 2 section with a similar structure, an Experiment 3 section with a similar structure, and so on until all experiments are covered. Towards the end of the paper there is a General Discussion section followed by References. Additionally, in multi-experiment papers, it is common for the Results and Discussion subsections for individual experiments to be combined into single “Results and Discussion” sections.

Departures from APA Style

In some cases, official APA style might not be followed (however, be sure to check with your editor, instructor, or other sources before deviating from standards of the Publication Manual of the American Psychological Association). Such deviations may include:

- Placement of Tables and Figures – in some cases, to make reading through the paper easier, Tables and/or Figures are embedded in the text (for example, having a bar graph placed in the relevant Results section). The embedding of Tables and/or Figures in the text is one of the most common deviations from APA style (and is commonly allowed in B.S. Degree Research Papers and Honors Theses; however you should check with your instructor, supervisor, or editor first).

- Incomplete research – sometimes a B.S. Degree Research Paper in this department is written about research that is currently being planned or is in progress. In those circumstances, sometimes only an Introduction and Methods section, followed by References, is included (that is, in cases where the research itself has not formally begun). In other cases, preliminary results are presented and noted as such in the Results section (such as in cases where the study is underway but not complete), and the Discussion section includes caveats about the in-progress nature of the research. Again, you should check with your instructor, supervisor, or editor first.

- Class assignments – in some classes in this department, an assignment must be written in APA style but is not exactly a traditional research paper (for instance, a student asked to write about an article that they read, and to write that report in APA style). In that case, the structure of the paper might approximate the typical sections of a research paper in APA style, but not entirely. You should check with your instructor for further guidelines.

Workshops and Downloadable Resources

- For in-person discussion of the process of writing research papers, please consider attending this department’s “Writing Research Papers” workshop (for dates and times, please check the undergraduate workshops calendar).

Downloadable Resources

- How to Write APA Style Research Papers (a comprehensive guide) [ PDF ]

- Tips for Writing APA Style Research Papers (a brief summary) [ PDF ]

- Example APA Style Research Paper (for B.S. Degree – empirical research) [ PDF ]

- Example APA Style Research Paper (for B.S. Degree – literature review) [ PDF ]

Further Resources

How-To Videos

- Writing Research Paper Videos

APA Journal Article Reporting Guidelines

- Appelbaum, M., Cooper, H., Kline, R. B., Mayo-Wilson, E., Nezu, A. M., & Rao, S. M. (2018). Journal article reporting standards for quantitative research in psychology: The APA Publications and Communications Board task force report . American Psychologist , 73 (1), 3.

- Levitt, H. M., Bamberg, M., Creswell, J. W., Frost, D. M., Josselson, R., & Suárez-Orozco, C. (2018). Journal article reporting standards for qualitative primary, qualitative meta-analytic, and mixed methods research in psychology: The APA Publications and Communications Board task force report . American Psychologist , 73 (1), 26.

External Resources

- Formatting APA Style Papers in Microsoft Word

- How to Write an APA Style Research Paper from Hamilton University

- WikiHow Guide to Writing APA Research Papers

- Sample APA Formatted Paper with Comments

- Sample APA Formatted Paper

- Tips for Writing a Paper in APA Style

1 VandenBos, G. R. (Ed). (2010). Publication manual of the American Psychological Association (6th ed.) (pp. 41-60). Washington, DC: American Psychological Association.

2 geller, e. (2018). how to write an apa-style research report . [instructional materials]. , prepared by s. c. pan for ucsd psychology.

Back to top

- Formatting Research Papers

- Using Databases and Finding References

- What Types of References Are Appropriate?

- Evaluating References and Taking Notes

- Citing References

- Writing a Literature Review

- Writing Process and Revising

- Improving Scientific Writing

- Academic Integrity and Avoiding Plagiarism

- Writing Research Papers Videos

Scientific and Scholarly Writing

- Literature Searches

- Tracking and Citing References

Parts of a Scientific & Scholarly Paper

Introduction.

- Writing Effectively

- Where to Publish?

- Capstone Resources

Different sections are needed in different types of scientific papers (lab reports, literature reviews, systematic reviews, methods papers, research papers, etc.). Projects that overlap with the social sciences or humanities may have different requirements. Generally, however, you'll need to include:

INTRODUCTION (Background)

METHODS SECTION (Materials and Methods)

What is a title?

Titles have two functions: to identify the main topic or the message of the paper and to attract readers.

The title will be read by many people. Only a few will read the entire paper, therefore all words in the title should be chosen with care. Too short a title is not helpful to the potential reader. Too long a title can sometimes be even less meaningful. Remember a title is not an abstract. Neither is a title a sentence.

What makes a good title?

A good title is accurate, complete, and specific. Imagine searching for your paper in PubMed. What words would you use?

- Use the fewest possible words that describe the contents of the paper.

- Avoid waste words like "Studies on", or "Investigations on".

- Use specific terms rather than general.

- Use the same key terms in the title as the paper.

- Watch your word order and syntax.

- Avoid abbreviations, jargon, and special characters.

The abstract is a miniature version of your paper. It should present the main story and a few essential details of the paper for readers who only look at the abstract and should serve as a clear preview for readers who read your whole paper. They are usually short (250 words or less).

The goal is to communicate:

- What was done?

- Why was it done?

- How was it done?

- What was found?

A good abstract is specific and selective. Try summarizing each of the sections of your paper in a sentence two. Do the abstract last, so you know exactly what you want to write.

- Use 1 or more well developed paragraphs.

- Use introduction/body/conclusion structure.

- Present purpose, results, conclusions and recommendations in that order.

- Make it understandable to a wide audience.

| The introduction tells the reader why you are writing your paper (ie, identifies a gap in the literature) and supplies sufficient background information that the reader can understand and evaluate your project without referring to previous publications on the topic. The goal is to communicate:

| A good introduction is not the same as an abstract. Where the abstract summarizes your paper, the introduction justifies your project and lets readers know what to expect.

• Keep it brief. You conducted an extensive literature review, so that you can give readers just the relevant information. |

| Generally a methods section tells the reader how you conducted your project. It is also called "Materials and Methods". The goal is to make your project reproducible.

| A good methods section gives enough detail that another scientist could reproduce or replicate your results. • Use very specific language, similar to a recipe in a cookbook.

|

| The results objectively present the data or information that you gathered through your project. The narrative that you write here will point readers to your figures and tables that present your relevant data. Keep in mind that you may be able to include more of your data in an online journal supplement or research data repository.

| A good results section is not the same as the discussion. Present the facts in the results, saving the interpretation for the discussion section. The results section should be written in past tense.

|

| section? | |

| The discussion section is the answer to the question(s) you posed in the introduction section. It is where you interpret your results. You have a lot of flexibility in this section. In addition to your main findings or conclusions, consider:

| A good discussion section should read very differently than the results section. The discussion is where you interpret the project as a whole.

|

- << Previous: Tracking and Citing References

- Next: Writing Effectively >>

- Last Updated: Jun 18, 2024 2:35 PM

- URL: https://libraryguides.umassmed.edu/scientific-writing

Apr 26, 2024

Everything You Need to Know about the Parts of a Research Paper

Not sure where to start with your research paper or how all the parts fit together? Don't worry! From crafting a compelling title page to compiling your references, we'll demystify each section of a research paper.

Learn how to write an attention-grabbing abstract, construct a powerful introduction, and confidently present your results and discussion. With this guide, you'll gain the tools to assemble a polished and impactful piece of work.

What Are Research Papers?

A research paper is a piece of academic writing that presents an original argument or analysis based on independent, in-depth investigation into a specific topic.

Key Characteristics:

Evidence-Driven: Research papers rely on data, analysis, and interpretation of credible sources.

Focused Argument: They develop a clear thesis that is defended with logical reasoning and evidence.

Structured: Research papers follow specific organizational formats and citation styles.

Contribution to Knowledge: They aim to add something new to the existing body of knowledge within a field.

Types of Research Papers

Research papers come in various forms across academic disciplines:

Argumentative Papers : Present a compelling claim and utilize evidence to persuade readers.

Analytical Papers : Break down complex subjects, ideas, or texts, examining their components and implications.

Empirical Studies: Involve collecting and analyzing original data (through experiments, surveys, etc.) to answer specific research questions.

Literature Reviews: Synthesize existing research on a topic, highlighting key findings, debates, and areas for future exploration.

And More! Depending on the field, you may encounter case studies, reports, theoretical proposals, etc.

Defining Research Papers

Here's how research papers stand apart from other forms of writing:

Originality vs. Summary: While essays might recap existing knowledge, research papers offer new insights, arguments, or data.

Depth of Inquiry: Research papers delve deeper, going beyond basic definitions or summaries into a systematic investigation.

Scholarly Audience: Research papers are often written with a specialized academic audience in mind, employing discipline-specific language and conventions.

Important Note: The specific requirements of research papers can vary depending on the subject area, level of study (undergraduate vs. graduate), and the instructor's instructions.

Importance of Research Paper Structure

Think of structure as the backbone of your research paper. Here's why it matters for academic success:

Clarity for the Reader: A logical structure guides the reader through your research journey. They understand your thought process, easily follow your arguments, and grasp the significance of your findings.

Author's Roadmap: Structure serves as your blueprint. It helps you maintain focus, ensures you address all essential elements, and prevents you from veering off-topic.

Enhanced Persuasion: A well-structured paper builds a convincing case. Your ideas flow logically, evidence supports your claims, and your conclusion feels grounded and impactful.

Demonstration of Competence: A clear structure signals to your instructor or peers that you have a thorough understanding of research practices and scholarly writing conventions.

Is a Structured Approach Critical for the Success of Research Papers?

Yes! It's difficult to overstate the importance of structure. Here's why:

Lost in Chaos: Rambling or disorganized papers leave the reader confused and frustrated. Even the most insightful findings risk being overlooked if presented poorly.

Missed Components: Without structure, you might forget to include critical aspects, like a clear methodology section or a thorough literature review, weakening your research.

Hindered Peer Review: Reviewers rely on a standard structure to quickly assess the research's merits. A deviation can make their job harder and might negatively affect how your work is evaluated.

Benefits of a Clear Structure

Enhanced Understanding: Readers can easily follow your chain of reasoning, grasp the connection between your evidence and claims, and critically evaluate your findings.

Efficient Peer Review: A standard structure makes peer review more efficient and focused. Reviewers can easily identify strong points, areas for improvement, and contributions to the field.

Streamlined Writing: Having a structure offers clarity and direction, preventing you from getting stuck mid-flow or overlooking important elements.

Variations of Research Papers

Here's a breakdown of some common types of research papers:

Analytical Papers

Focus: Dissect a complex subject, text, or phenomenon to understand its parts, implications, or underlying meanings.

Structure: Emphasizes a clear thesis statement, systematic analysis, and in-depth exploration of different perspectives.

Example: Examining the symbolism in a literary work or analyzing the economic impact of a policy change.

Argumentative Papers

Focus: Present and defend a specific claim using evidence and logical reasoning.

Structure: Emphasizes a well-defined thesis, persuasive examples, and the anticipation and refutation of counterarguments.

Example: Arguing for the superiority of a particular scientific theory or advocating for a specific social policy.

Experimental Studies (Empirical Research)

Focus: Collect and analyze original data through a designed experiment or methodology.

Structure: Follows scientific practices, including hypothesis, methods, results, discussion, and acknowledgment of limitations.

Example: Measuring the effects of a new drug or conducting psychological experiments on behavior patterns.

Survey-Based Research

Focus: Gather information from a sample population through surveys, questionnaires, or interviews.

Structure: Emphasizes sampling methods, data collection tools, statistical analysis, and cautious interpretation of results.

Example: Investigating public opinion on a political issue or studying consumer preferences for a product.

Do All Research Papers Fit Into Standard Categories?

No. Research is fluid and dynamic. Here's why categorization can get tricky:

Hybrids Exist: Many papers mix elements. An analytical paper might also incorporate arguments to strengthen its interpretation, or an experimental paper might include a review of existing literature to contextualize its findings.

Disciplinary Differences: Fields have specific conventions. A research paper in history differs vastly in style and structure from one in biology.

Innovation: Researchers sometimes develop new structures or methodologies best suited to their unique research questions.

Comparing Research Paper Types

Each type prioritizes different aspects of the research process:

An abstract is like a snapshot of your entire paper, providing a brief but informative overview of your research. It's often the first (and sometimes the only) section readers will engage with.

Key Functions: An effective abstract should:

Briefly state the research problem or topic

Outline your methods (briefly)

Summarize the main findings or results

Highlight the significance or implications of your work

Writing a Compelling Abstract

Here are some guidelines to make your abstract shine:

Concise and Clear: Aim for around 150-250 words. Use direct language and avoid unnecessary jargon.

Structured Approach: Even in its brevity, follow a logical flow (problem, methods, results, significance).

Keywords: Include keywords that accurately describe your research, aiding in discoverability within databases.

Self-Contained: The abstract should make sense on its own, without needing the reader to have read the full paper.

Engaging: While focused, pique the reader's interest and make them want to explore your research further.

Write it Last: Often, it's easiest to write your abstract once the rest of your paper is complete, as you can then distill the most essential elements.

Get Feedback: Ask a peer or instructor to read your abstract to ensure it's clear and accurately represents your research.

Introduction

Think of your introduction as the welcome mat for your research. Here's what it should accomplish:

Establish Context: Provide background information relevant to your specific research question. Orient the reader to the broader field or current debates surrounding the topic.

Define the Problem: Clearly outline the gap in knowledge, issue, or question your research aims to address.

State the Hypothesis: Concisely declare your research hypothesis or thesis statement – the central claim you aim to prove.

Significance: Briefly explain why your research matters. What potential contributions or implications does it hold?

Is the Introduction More Important Than Other Sections?

No. While the introduction plays a big role in initially capturing your reader's attention and setting the stage, it is just one piece of the puzzle. Here's why all sections matter:

Methodology Matters: A sound methodology section is essential for establishing the credibility of your findings. Readers need to trust your process.

Results are Key: The results section presents your hard-earned data. Without it, your research doesn't have a foundation to support your claims.

Discussion is Vital: Here's where you interpret your results, connect them back to your hypothesis, and explore the broader implications of your work.

Conclusion is the Culmination: Your conclusion reinforces your key findings, acknowledges limitations, and leaves the reader with a lasting understanding of your research contribution.

Engaging Your Audience Early

Here are some strategies to capture attention from the start:

Open with a Question: Pose a thought-provoking question directly related to your research.

Surprising Statistic: Share a relevant and eye-opening statistic that highlights the significance of your topic.

Brief anecdote: An illustrative anecdote or a vivid example can provide a compelling hook.

Challenge Assumptions: Question a common belief or assumption within your field to signal that your research offers fresh insights.

Tip: Your opening should be relevant and directly connected to your research topic. Avoid gimmicks that don't authentically lead into your core argument.

Literature Review

A literature review goes beyond simply listing past studies on a topic. It synthesizes existing knowledge, laying the foundation for your own research contribution.

Goals of a Strong Literature Review:

Demonstrate your understanding of the field and its key scholarly conversations.

Identify gaps in current knowledge that your research can address.

Position your research in relation to existing work, showing how it builds upon or challenges previous findings.

Provide theoretical context or support for your chosen methodological approach.

Synthesizing Relevant Studies

Don't just summarize – analyze! Here's how to engage with the literature critically:

Identify Trends: Look for patterns or themes across multiple studies. Are there consistent results or ongoing debates?

Note Inconsistencies: Highlight any contradictions or conflicting findings within the existing research.

Assess Methodology: Consider the strengths and limitations of different research methods used in prior studies. Can you improve upon them in your research?

Connections to Your Work: Show how each source directly relates to your research question. Explain how it supports, challenges, or informs your own study.

Tips for Effective Synthesis:

Organization is Key: Structure your literature review thematically or chronologically to present findings in a logical way.

Your Voice Matters: Avoid stringing together quotes. Analyze the literature and offer your own interpretation of the collective insights.

Cite Accurately: Follow the citation style required by your discipline to give credit and avoid plagiarism.

Methodology

Your methodology section details the step-by-step process of how you conducted your research. It allows others to understand and potentially replicate your study.

Components: A methodology section typically includes:

Research Design: The overall approach (experimental, survey-based, qualitative, etc.)

Data Collection: Description of the tools, procedures, and sources used (experiments, surveys, interviews, archival documents).

Sample Selection: Details on participants (if applicable) and how they were chosen.

Data Analysis: Methods used (statistical tests, qualitative analysis techniques).

Ethical considerations: Explain how you safeguarded participants or addressed any ethical concerns related to your research.

Designing a Robust Methodology

Here's how to make your methodology section shine:

Alignment with Research Question: Your methods should be directly chosen to answer your research question in the most effective and appropriate way.

Rigor: Demonstrate a meticulous approach, considering potential sources of bias or error and outlining steps taken to mitigate them.

Transparency: Provide enough detail for replication. Another researcher should be able to follow your method.

Justification: Explain why you chose specific methods. Connect them to established practices within your field or defend their suitability for your unique research.

Does Methodology Determine the Quality of Research Outcomes?

Absolutely! Here's why a robust methodology is important:

Reliability: A sound methodology ensures your results are consistent. If your study was repeated using your methods, similar results should be attainable.

Validity: Validity ensures you're measuring what you intend to. A strong methodology helps you draw accurate conclusions from your data that address your research question.

Credibility: Your paper will be evaluated based on the thoroughness of your procedures. A clear and rigorous methodology enhances trust in your findings.

Your results section is where you present the data collected from your research. This includes raw data, statistical analyses, summaries of observations, etc.

Key Considerations:

Clarity: Organize results logically. Use tables, graphs, or figures to enhance visual clarity when appropriate.

Objectivity: Present data without bias. Even if findings don't support your initial hypothesis, report them accurately.

Don't Interpret (Yet): Avoid discussing implications here. Focus on a clear presentation of your findings.

Interpreting Data Effectively

Your discussion or analysis section is where you make sense of your results. Here's how to ensure your interpretation is persuasive:

Connect Back to the Hypothesis: State whether your results support, refute, or partially support your hypothesis.

Use Evidence: Reference specific data points, statistics, or observations to back up your claims.

Explanatory Power: Don't merely describe what happened. Explain why you believe your data led to these results.

Context is Key: Relate your findings to the existing literature. Do they align with previous research, or do they raise new questions?

Be Transparent: Acknowledge any limitations of your data or unexpected findings, providing potential explanations.

Tips for Effective Data Discussion:

Visuals as Support: Continue using graphs or figures to illustrate trends or comparisons that reinforce your analysis.

Highlight What Matters: Don't over-discuss insignificant data points. Focus on the results that are most relevant to your research question and contribute to your overall argument.

Tell a Story: Data shouldn't feel disjointed. Weave it into a narrative that addresses your research problem and positions your findings within the broader field.

Your discussion section elevates your findings, moving from simply reporting what you discovered to exploring its significance and potential impact.

Interpret the results in relation to your research question and hypothesis.

Consider alternative explanations for unexpected findings and discuss limitations of the research.

Place your findings in the context of the broader field, connecting them to theories and the existing body of research.

Suggest implications for future research or practical applications.

Linking Results to Theory

Here's how to make your discussion section shine:

Return to the Literature Review: Did your results support a specific theory from your literature review? Challenge it? Offer a nuanced modification?

Contradictions Offer Insights: If your results contradict existing theories, don't dismiss them. Explain possible reasons for the discrepancies and how that pushes your field's understanding further.

Conceptual Contribution: How does your research add to the theoretical frameworks within your area of study?

Building Blocks: Frame your research as one piece of a larger puzzle. Explain how your work contributes to the ongoing scholarly conversation.

Tips for a Strong Discussion:

Avoid Overstating Significance: Maintain a scholarly tone and acknowledge the scope of your research. Don't claim your results revolutionize the field if it's not genuinely warranted.

Consider Future Directions: Responsible research isn't just about the past. Discuss what new questions arise based on your findings and offer avenues for potential future study.

Clarity Remains Key: Even when discussing complex ideas, use accessible language. Make your discussion meaningful to a wider audience within the field.

Conclusions

Your conclusion brings your research full circle. It's your chance to re-emphasize the most important takeaways of your work.

A Strong Conclusion Should:

Concisely restate the key research question or problem you sought to address.

Summarize your major findings and the most compelling evidence.

Briefly discuss the broader implications or contributions of your research.

Acknowledge limitations in the study (briefly).

Propose potential avenues for future research.

Can Conclusions Introduce New Research Questions?

Absolutely! Here's why this is valuable:

Sparking Curiosity: Ending with new questions emphasizes the ongoing nature of research and encourages further exploration beyond your own study.

Identifying Limitations: By highlighting where your work fell short, you guide future researchers toward filling those gaps.

Signaling Progress: Research is a continuous process of evolving knowledge. Your conclusion can be a springboard for others to expand upon your findings.

Crafting a Persuasive Conclusion

Here's how to make your conclusion impactful:

Reiterate, Don't Repeat: Remind the reader of your most significant findings, but avoid restating your thesis verbatim.

Confidence: Project a sense of conviction about the value of your work, without overstating its significance.

Clarity: Even in your conclusion, use direct language free of jargon. Leave the reader with a clear and lasting impression.

The Ripple Effect: Briefly highlight the broader relevance of your research. Why should readers beyond your niche field care?

Important: Your conclusion shouldn't introduce entirely new information or analyses. Rather, it should leave the reader pondering the implications of what you've already presented.

Giving Credit Where It's Due: Your references section lists the full details of every source you cited within your paper. This allows readers to locate those sources and acknowledges the intellectual work of others that you built upon.

Supporting Your Arguments: Credible references add weight to your claims, showing that your analysis is informed by established knowledge or reliable data.

Upholding Academic Standards: Accurate citations signal your commitment to scholarly practices and protect you from accusations of plagiarism.

Maintaining Citation Integrity

Here are the main practices to uphold:

Choose the Right Style: Follow the citation style mandated by your discipline (APA, MLA, Chicago, etc.). They have strict rules on formatting and which elements to include.

Consistency is Key: Use your chosen citation style uniformly throughout your paper. Mixed styles look sloppy and unprofessional.

Accuracy Matters: Double-check the details of each citation (authors, title, publication year, page numbers, etc.). Errors undermine your credibility.

Citation Tools: Use reliable resources like:

Online citation generators

Reference management software (Zotero, EndNote, etc..)

University library guides for your required style

Important Notes:

In-Text vs. References: In-text citations (within your writing) point the reader to the full citation in your references list. Both are needed.

Citation ≠ Bibliography: A bibliography may include sources you consulted but didn't directly cite, while the references list is specifically for cited works.

Writing Effective Research Papers: A Guide

Research papers aren't merely about having brilliant ideas – they're about effectively communicating those ideas. Strong writing allows you to showcase the value and rigor of your work.

Is Effective Writing Alone Sufficient for a Successful Research Paper?

No. Strong writing is vital but not a substitute for the core components of research. Consider this:

Even brilliant findings get lost in poor writing: Disorganized papers, unclear sentences, or misuse of discipline-specific terms hinder the reader from grasping your insights.

Writing is intertwined with research: The process of writing helps you clarify your own thinking, refine your arguments, and identify potential weaknesses in your logic.

Tips for Academic Writing

Here's how to elevate your research paper writing:

Define Your Terms: especially if using specialized jargon or complex concepts.

Favor Active Voice: Use strong verbs and keep the subject of your sentences clear. (Example: "The study demonstrates..." rather than "It is demonstrated...")

Avoid Ambiguity: Choose precise language to leave no room for misinterpretation.

Transitions Are Your Friend: Guide the reader smoothly between ideas and sections using signpost words and phrases.

Logical Structure: Your paper's organization (introduction, methods, etc.) should have an intuitive flow.

One Idea per Paragraph: Avoid overly dense paragraphs. Break down complex points for readability.

Strong Argumentation

Thesis as Roadmap: Your central thesis should be apparent throughout the paper. Each section should clearly connect back to it.

Strong Evidence: Use reliable data and examples to support your claims.

Anticipate Counterarguments: Show you've considered alternative viewpoints by respectfully addressing and refuting them.

Additional Tips

Read widely in your field: Analyze how successful papers are structured and how arguments are developed.

Revise relentlessly: Give yourself time to step away from your draft and return with fresh eyes.

Seek Feedback: Ask peers, instructors, or a writing center tutor to review your work for clarity and logic.

Conclusion: Integrating the Components of Research Papers for Academic Excellence

The journey of writing a research paper is truly transformative. By mastering each component, from a rigorously crafted hypothesis to a meticulously compiled reference list, you develop the essential skills of critical thinking, communication, and scholarly inquiry. It's important to remember that these components are not isolated; they form a powerful, synergistic whole.

Let the process of writing research papers empower you. Embrace the challenge of synthesizing information, developing strong arguments, and communicating your findings with clarity and precision. Celebrate your dedication to the pursuit of knowledge and the contributions you make to your academic community and your own intellectual growth.

Try Jenni for free today

Create your first piece of content with Jenni today and never look back

- Resources Home 🏠

- Try SciSpace Copilot

- Search research papers

- Add Copilot Extension

- Try AI Detector

- Try Paraphraser

- Try Citation Generator

- April Papers

- June Papers

- July Papers

Research Paper Structure: A Comprehensive Guide