Thank you for visiting nature.com. You are using a browser version with limited support for CSS. To obtain the best experience, we recommend you use a more up to date browser (or turn off compatibility mode in Internet Explorer). In the meantime, to ensure continued support, we are displaying the site without styles and JavaScript.

- View all journals

- My Account Login

- Explore content

- About the journal

- Publish with us

- Sign up for alerts

- Open access

- Published: 06 December 2017

Healthy food choices are happy food choices: Evidence from a real life sample using smartphone based assessments

- Deborah R. Wahl 1 na1 ,

- Karoline Villinger 1 na1 ,

- Laura M. König ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0003-3655-8842 1 ,

- Katrin Ziesemer 1 ,

- Harald T. Schupp 1 &

- Britta Renner 1

Scientific Reports volume 7 , Article number: 17069 ( 2017 ) Cite this article

133k Accesses

54 Citations

262 Altmetric

Metrics details

- Health sciences

- Human behaviour

Research suggests that “healthy” food choices such as eating fruits and vegetables have not only physical but also mental health benefits and might be a long-term investment in future well-being. This view contrasts with the belief that high-caloric foods taste better, make us happy, and alleviate a negative mood. To provide a more comprehensive assessment of food choice and well-being, we investigated in-the-moment eating happiness by assessing complete, real life dietary behaviour across eight days using smartphone-based ecological momentary assessment. Three main findings emerged: First, of 14 different main food categories, vegetables consumption contributed the largest share to eating happiness measured across eight days. Second, sweets on average provided comparable induced eating happiness to “healthy” food choices such as fruits or vegetables. Third, dinner elicited comparable eating happiness to snacking. These findings are discussed within the “food as health” and “food as well-being” perspectives on eating behaviour.

Similar content being viewed by others

Effects of single plant-based vs. animal-based meals on satiety and mood in real-world smartphone-embedded studies

Eating Style and the Frequency, Size and Timing of Eating Occasions: A cross-sectional analysis using 7-day weighed dietary records

Interindividual variability in appetitive sensations and relationships between appetitive sensations and energy intake

Introduction.

When it comes to eating, researchers, the media, and policy makers mainly focus on negative aspects of eating behaviour, like restricting certain foods, counting calories, and dieting. Likewise, health intervention efforts, including primary prevention campaigns, typically encourage consumers to trade off the expected enjoyment of hedonic and comfort foods against health benefits 1 . However, research has shown that diets and restrained eating are often counterproductive and may even enhance the risk of long-term weight gain and eating disorders 2 , 3 . A promising new perspective entails a shift from food as pure nourishment towards a more positive and well-being centred perspective of human eating behaviour 1 , 4 , 5 . In this context, Block et al . 4 have advocated a paradigm shift from “food as health” to “food as well-being” (p. 848).

Supporting this perspective of “food as well-being”, recent research suggests that “healthy” food choices, such as eating more fruits and vegetables, have not only physical but also mental health benefits 6 , 7 and might be a long-term investment in future well-being 8 . For example, in a nationally representative panel survey of over 12,000 adults from Australia, Mujcic and Oswald 8 showed that fruit and vegetable consumption predicted increases in happiness, life satisfaction, and well-being over two years. Similarly, using lagged analyses, White and colleagues 9 showed that fruit and vegetable consumption predicted improvements in positive affect on the subsequent day but not vice versa. Also, cross-sectional evidence reported by Blanchflower et al . 10 shows that eating fruits and vegetables is positively associated with well-being after adjusting for demographic variables including age, sex, or race 11 . Of note, previous research includes a wide range of time lags between actual eating occasion and well-being assessment, ranging from 24 hours 9 , 12 to 14 days 6 , to 24 months 8 . Thus, the findings support the notion that fruit and vegetable consumption has beneficial effects on different indicators of well-being, such as happiness or general life satisfaction, across a broad range of time spans.

The contention that healthy food choices such as a higher fruit and vegetable consumption is associated with greater happiness and well-being clearly contrasts with the common belief that in particular high-fat, high-sugar, or high-caloric foods taste better and make us happy while we are eating them. When it comes to eating, people usually have a spontaneous “unhealthy = tasty” association 13 and assume that chocolate is a better mood booster than an apple. According to this in-the-moment well-being perspective, consumers have to trade off the expected enjoyment of eating against the health costs of eating unhealthy foods 1 , 4 .

A wealth of research shows that the experience of negative emotions and stress leads to increased consumption in a substantial number of individuals (“emotional eating”) of unhealthy food (“comfort food”) 14 , 15 , 16 , 17 . However, this research stream focuses on emotional eating to “smooth” unpleasant experiences in response to stress or negative mood states, and the mood-boosting effect of eating is typically not assessed 18 . One of the few studies testing the effectiveness of comfort food in improving mood showed that the consumption of “unhealthy” comfort food had a mood boosting effect after a negative mood induction but not to a greater extent than non-comfort or neutral food 19 . Hence, even though people may believe that snacking on “unhealthy” foods like ice cream or chocolate provides greater pleasure and psychological benefits, the consumption of “unhealthy” foods might not actually be more psychologically beneficial than other foods.

However, both streams of research have either focused on a single food category (fruit and vegetable consumption), a single type of meal (snacking), or a single eating occasion (after negative/neutral mood induction). Accordingly, it is unknown whether the boosting effect of eating is specific to certain types of food choices and categories or whether eating has a more general boosting effect that is observable after the consumption of both “healthy” and “unhealthy” foods and across eating occasions. Accordingly, in the present study, we investigated the psychological benefits of eating that varied by food categories and meal types by assessing complete dietary behaviour across eight days in real life.

Furthermore, previous research on the impact of eating on well-being tended to rely on retrospective assessments such as food frequency questionnaires 8 , 10 and written food diaries 9 . Such retrospective self-report methods rely on the challenging task of accurately estimating average intake or remembering individual eating episodes and may lead to under-reporting food intake, particularly unhealthy food choices such as snacks 7 , 20 . To avoid memory and bias problems in the present study we used ecological momentary assessment (EMA) 21 to obtain ecologically valid and comprehensive real life data on eating behaviour and happiness as experienced in-the-moment.

In the present study, we examined the eating happiness and satisfaction experienced in-the-moment, in real time and in real life, using a smartphone based EMA approach. Specifically, healthy participants were asked to record each eating occasion, including main meals and snacks, for eight consecutive days and rate how tasty their meal/snack was, how much they enjoyed it, and how pleased they were with their meal/snack immediately after each eating episode. This intense recording of every eating episode allows assessing eating behaviour on the level of different meal types and food categories to compare experienced eating happiness across meals and categories. Following the two different research streams, we expected on a food category level that not only “unhealthy” foods like sweets would be associated with high experienced eating happiness but also “healthy” food choices such as fruits and vegetables. On a meal type level, we hypothesised that the happiness of meals differs as a function of meal type. According to previous contention, snacking in particular should be accompanied by greater happiness.

Eating episodes

Overall, during the study period, a total of 1,044 completed eating episodes were reported (see also Table 1 ). On average, participants rated their eating happiness with M = 77.59 which suggests that overall eating occasions were generally positive. However, experienced eating happiness also varied considerably between eating occasions as indicated by a range from 7.00 to 100.00 and a standard deviation of SD = 16.41.

Food categories and experienced eating happiness

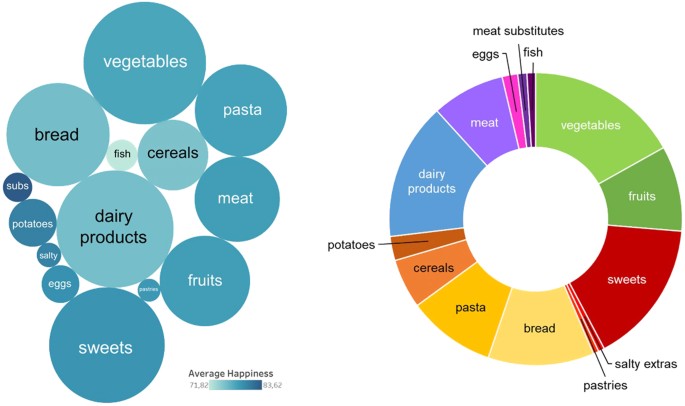

All eating episodes were categorised according to their food category based on the German Nutrient Database (German: Bundeslebensmittelschlüssel), which covers the average nutritional values of approximately 10,000 foods available on the German market and is a validated standard instrument for the assessment of nutritional surveys in Germany. As shown in Table 1 , eating happiness differed significantly across all 14 food categories, F (13, 2131) = 1.78, p = 0.04. On average, experienced eating happiness varied from 71.82 ( SD = 18.65) for fish to 83.62 ( SD = 11.61) for meat substitutes. Post hoc analysis, however, did not yield significant differences in experienced eating happiness between food categories, p ≥ 0.22. Hence, on average, “unhealthy” food choices such as sweets ( M = 78.93, SD = 15.27) did not differ in experienced happiness from “healthy” food choices such as fruits ( M = 78.29, SD = 16.13) or vegetables ( M = 77.57, SD = 17.17). In addition, an intraclass correlation (ICC) of ρ = 0.22 for happiness indicated that less than a quarter of the observed variation in experienced eating happiness was due to differences between food categories, while 78% of the variation was due to differences within food categories.

However, as Figure 1 (left side) depicts, consumption frequency differed greatly across food categories. Frequently consumed food categories encompassed vegetables which were consumed at 38% of all eating occasions ( n = 400), followed by dairy products with 35% ( n = 366), and sweets with 34% ( n = 356). Conversely, rarely consumed food categories included meat substitutes, which were consumed in 2.2% of all eating occasions ( n = 23), salty extras (1.5%, n = 16), and pastries (1.3%, n = 14).

Left side: Average experienced eating happiness (colour intensity: darker colours indicate greater happiness) and consumption frequency (size of the cycle) for the 14 food categories. Right side: Absolute share of the 14 food categories in total experienced eating happiness.

Amount of experienced eating happiness by food category

To account for the frequency of consumption, we calculated and scaled the absolute experienced eating happiness according to the total sum score. As shown in Figure 1 (right side), vegetables contributed the biggest share to the total happiness followed by sweets, dairy products, and bread. Clustering food categories shows that fruits and vegetables accounted for nearly one quarter of total eating happiness score and thus, contributed to a large part of eating related happiness. Grain products such as bread, pasta, and cereals, which are main sources of carbohydrates including starch and fibre, were the second main source for eating happiness. However, “unhealthy” snacks including sweets, salty extras, and pastries represented the third biggest source of eating related happiness.

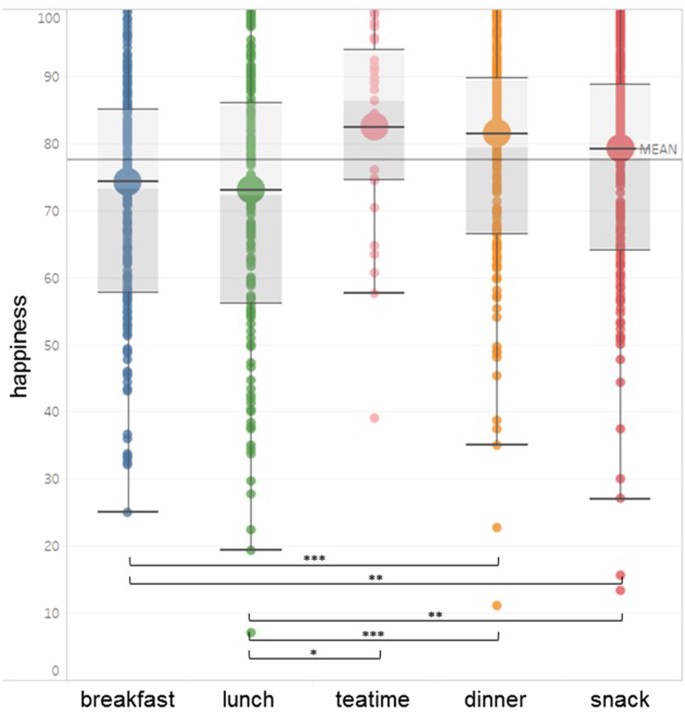

Experienced eating happiness by meal type

To further elucidate the contribution of snacks to eating happiness, analysis on the meal type level was conducted. Experienced in-the-moment eating happiness significantly varied by meal type consumed, F (4, 1039) = 11.75, p < 0.001. Frequencies of meal type consumption ranged from snacks being the most frequently logged meal type ( n = 332; see also Table 1 ) to afternoon tea being the least logged meal type ( n = 27). Figure 2 illustrates the wide dispersion within as well as between different meal types. Afternoon tea ( M = 82.41, SD = 15.26), dinner ( M = 81.47, SD = 14.73), and snacks ( M = 79.45, SD = 14.94) showed eating happiness values above the grand mean, whereas breakfast ( M = 74.28, SD = 16.35) and lunch ( M = 73.09, SD = 18.99) were below the eating happiness mean. Comparisons between meal types showed that eating happiness for snacks was significantly higher than for lunch t (533) = −4.44, p = 0.001, d = −0.38 and breakfast, t (567) = −3.78, p = 0.001, d = −0.33. However, this was also true for dinner, which induced greater eating happiness than lunch t (446) = −5.48, p < 0.001, d = −0.50 and breakfast, t (480) = −4.90, p < 0.001, d = −0.46. Finally, eating happiness for afternoon tea was greater than for lunch t (228) = −2.83, p = 0.047, d = −0.50. All other comparisons did not reach significance, t ≤ 2.49, p ≥ 0.093.

Experienced eating happiness per meal type. Small dots represent single eating events, big circles indicate average eating happiness, and the horizontal line indicates the grand mean. Boxes indicate the middle 50% (interquartile range) and median (darker/lighter shade). The whiskers above and below represent 1.5 of the interquartile range.

Control Analyses

In order to test for a potential confounding effect between experienced eating happiness, food categories, and meal type, additional control analyses within meal types were conducted. Comparing experienced eating happiness for dinner and lunch suggested that dinner did not trigger a happiness spill-over effect specific to vegetables since the foods consumed at dinner were generally associated with greater happiness than those consumed at other eating occasions (Supplementary Table S1 ). Moreover, the relative frequency of vegetables consumed at dinner (73%, n = 180 out of 245) and at lunch were comparable (69%, n = 140 out of 203), indicating that the observed happiness-vegetables link does not seem to be mainly a meal type confounding effect.

Since the present study focuses on “food effects” (Level 1) rather than “person effects” (Level 2), we analysed the data at the food item level. However, participants who were generally overall happier with their eating could have inflated the observed happiness scores for certain food categories. In order to account for person-level effects, happiness scores were person-mean centred and thereby adjusted for mean level differences in happiness. The person-mean centred happiness scores ( M cwc ) represent the difference between the individual’s average happiness score (across all single in-the-moment happiness scores per food category) and the single happiness scores of the individual within the respective food category. The centred scores indicate whether the single in-the-moment happiness score was above (indicated by positive values) or below (indicated by negative values) the individual person-mean. As Table 1 depicts, the control analyses with centred values yielded highly similar results. Vegetables were again associated on average with more happiness than other food categories (although people might differ in their general eating happiness). An additional conducted ANOVA with person-centred happiness values as dependent variables and food categories as independent variables provided also a highly similar pattern of results. Replicating the previously reported analysis, eating happiness differed significantly across all 14 food categories, F (13, 2129) = 1.94, p = 0.023, and post hoc analysis did not yield significant differences in experienced eating happiness between food categories, p ≥ 0.14. Moreover, fruits and vegetables were associated with high happiness values, and “unhealthy” food choices such as sweets did not differ in experienced happiness from “healthy” food choices such as fruits or vegetables. The only difference between the previous and control analysis was that vegetables ( M cwc = 1.16, SD = 15.14) gained slightly in importance for eating-related happiness, whereas fruits ( M cwc = −0.65, SD = 13.21), salty extras ( M cwc = −0.07, SD = 8.01), and pastries ( M cwc = −2.39, SD = 18.26) became slightly less important.

This study is the first, to our knowledge, that investigated in-the-moment experienced eating happiness in real time and real life using EMA based self-report and imagery covering the complete diversity of food intake. The present results add to and extend previous findings by suggesting that fruit and vegetable consumption has immediate beneficial psychological effects. Overall, of 14 different main food categories, vegetables consumption contributed the largest share to eating happiness measured across eight days. Thus, in addition to the investment in future well-being indicated by previous research 8 , “healthy” food choices seem to be an investment in the in-the moment well-being.

Importantly, although many cultures convey the belief that eating certain foods has a greater hedonic and mood boosting effect, the present results suggest that this might not reflect actual in-the-moment experiences accurately. Even though people often have a spontaneous “unhealthy = tasty” intuition 13 , thus indicating that a stronger happiness boosting effect of “unhealthy” food is to be expected, the induced eating happiness of sweets did not differ on average from “healthy” food choices such as fruits or vegetables. This was also true for other stereotypically “unhealthy” foods such as pastries and salty extras, which did not show the expected greater boosting effect on happiness. Moreover, analyses on the meal type level support this notion, since snacks, despite their overall positive effect, were not the most psychologically beneficial meal type, i.e., dinner had a comparable “happiness” signature to snacking. Taken together, “healthy choices” seem to be also “happy choices” and at least comparable to or even higher in their hedonic value as compared to stereotypical “unhealthy” food choices.

In general, eating happiness was high, which concurs with previous research from field studies with generally healthy participants. De Castro, Bellisle, and Dalix 22 examined weekly food diaries from 54 French subjects and found that most of the meals were rated as appealing. Also, the observed differences in average eating happiness for the 14 different food categories, albeit statistically significant, were comparable small. One could argue that this simply indicates that participants avoided selecting bad food 22 . Alternatively, this might suggest that the type of food or food categories are less decisive for experienced eating happiness than often assumed. This relates to recent findings in the field of comfort and emotional eating. Many people believe that specific types of food have greater comforting value. Also in research, the foods eaten as response to negative emotional strain, are typically characterised as being high-caloric because such foods are assumed to provide immediate psycho-physical benefits 18 . However, comparing different food types did not provide evidence for the notion that they differed in their provided comfort; rather, eating in general led to significant improvements in mood 19 . This is mirrored in the present findings. Comparing the eating happiness of “healthy” food choices such as fruits and vegetables to that of “unhealthy” food choices such as sweets shows remarkably similar patterns as, on average, they were associated with high eating happiness and their range of experiences ranged from very negative to very positive.

This raises the question of why the idea that we can eat indulgent food to compensate for life’s mishaps is so prevailing. In an innovative experimental study, Adriaanse, Prinsen, de Witt Huberts, de Ridder, and Evers 23 led participants believe that they overate. Those who characterised themselves as emotional eaters falsely attributed their over-consumption to negative emotions, demonstrating a “confabulation”-effect. This indicates that people might have restricted self-knowledge and that recalled eating episodes suffer from systematic recall biases 24 . Moreover, Boelsma, Brink, Stafleu, and Hendriks 25 examined postprandial subjective wellness and objective parameters (e.g., ghrelin, insulin, glucose) after standardised breakfast intakes and did not find direct correlations. This suggests that the impact of different food categories on wellness might not be directly related to biological effects but rather due to conditioning as food is often paired with other positive experienced situations (e.g., social interactions) or to placebo effects 18 . Moreover, experimental and field studies indicate that not only negative, but also positive, emotions trigger eating 15 , 26 . One may speculate that selective attention might contribute to the “myth” of comfort food 19 in that people attend to the consumption effect of “comfort” food in negative situation but neglect the effect in positive ones.

The present data also show that eating behaviour in the real world is a complex behaviour with many different aspects. People make more than 200 food decisions a day 27 which poses a great challenge for the measurement of eating behaviour. Studies often assess specific food categories such as fruit and vegetable consumption using Food Frequency Questionnaires, which has clear advantages in terms of cost-effectiveness. However, focusing on selective aspects of eating and food choices might provide only a selective part of the picture 15 , 17 , 22 . It is important to note that focusing solely on the “unhealthy” food choices such as sweets would have led to the conclusion that they have a high “indulgent” value. To be able to draw conclusions about which foods make people happy, the relation of different food categories needs to be considered. The more comprehensive view, considering the whole dietary behaviour across eating occasions, reveals that “healthy” food choices actually contributed the biggest share to the total experienced eating happiness. Thus, for a more comprehensive understanding of how eating behaviours are regulated, more complete and sensitive measures of the behaviour are necessary. Developments in mobile technologies hold great promise for feasible dietary assessment based on image-assisted methods 28 .

As fruits and vegetables evoked high in-the-moment happiness experiences, one could speculate that these cumulate and have spill-over effects on subsequent general well-being, including life satisfaction across time. Combing in-the-moment measures with longitudinal perspectives might be a promising avenue for future studies for understanding the pathways from eating certain food types to subjective well-being. In the literature different pathways are discussed, including physiological and biochemical aspects of specific food elements or nutrients 7 .

The present EMA based data also revealed that eating happiness varied greatly within the 14 food categories and meal types. As within food category variance represented more than two third of the total observed variance, happiness varied according to nutritional characteristics and meal type; however, a myriad of factors present in the natural environment can affect each and every meal. Thus, widening the “nourishment” perspective by including how much, when, where, how long, and with whom people eat might tell us more about experienced eating happiness. Again, mobile, in-the-moment assessment opens the possibility of assessing the behavioural signature of eating in real life. Moreover, individual factors such as eating motives, habitual eating styles, convenience, and social norms are likely to contribute to eating happiness variance 5 , 29 .

A key strength of this study is that it was the first to examine experienced eating happiness in non-clinical participants using EMA technology and imagery to assess food intake. Despite this strength, there are some limitations to this study that affect the interpretation of the results. In the present study, eating happiness was examined on a food based level. This neglects differences on the individual level and might be examined in future multilevel studies. Furthermore, as a main aim of this study was to assess real life eating behaviour, the “natural” observation level is the meal, the psychological/ecological unit of eating 30 , rather than food categories or nutrients. Therefore, we cannot exclude that specific food categories may have had a comparably higher impact on the experienced happiness of the whole meal. Sample size and therefore Type I and Type II error rates are of concern. Although the total number of observations was higher than in previous studies (see for example, Boushey et al . 28 for a review), the number of participants was small but comparable to previous studies in this field 20 , 31 , 32 , 33 . Small sample sizes can increase error rates because the number of persons is more decisive than the number of nested observations 34 . Specially, nested data can seriously increase Type I error rates, which is rather unlikely to be the case in the present study. Concerning Type II error rates, Aarts et al . 35 illustrated for lower ICCs that adding extra observations per participant also increases power, particularly in the lower observation range. Considering the ICC and the number of observations per participant, one could argue that the power in the present study is likely to be sufficient to render the observed null-differences meaningful. Finally, the predominately white and well-educated sample does limit the degree to which the results can be generalised to the wider community; these results warrant replication with a more representative sample.

Despite these limitations, we think that our study has implications for both theory and practice. The cumulative evidence of psychological benefits from healthy food choices might offer new perspectives for health promotion and public-policy programs 8 . Making people aware of the “healthy = happy” association supported by empirical evidence provides a distinct and novel perspective to the prevailing “unhealthy = tasty” folk intuition and could foster eating choices that increase both in-the-moment happiness and future well-being. Furthermore, the present research lends support to the advocated paradigm shift from “food as health” to “food as well-being” which entails a supporting and encouraging rather constraining and limiting view on eating behaviour.

The study conformed with the Declaration of Helsinki. All study protocols were approved by University of Konstanz’s Institutional Review Board and were conducted in accordance with guidelines and regulations. Upon arrival, all participants signed a written informed consent.

Participants

Thirty-eight participants (28 females: average age = 24.47, SD = 5.88, range = 18–48 years) from the University of Konstanz assessed their eating behaviour in close to real time and in their natural environment using an event-based ambulatory assessment method (EMA). No participant dropped out or had to be excluded. Thirty-three participants were students, with 52.6% studying psychology. As compensation, participants could choose between taking part in a lottery (4 × 25€) or receiving course credits (2 hours).

Participants were recruited through leaflets distributed at the university and postings on Facebook groups. Prior to participation, all participants gave written informed consent. Participants were invited to the laboratory for individual introductory sessions. During this first session, participants installed the application movisensXS (version 0.8.4203) on their own smartphones and downloaded the study survey (movisensXS Library v4065). In addition, they completed a short baseline questionnaire, including demographic variables like age, gender, education, and eating principles. Participants were instructed to log every eating occasion immediately before eating by using the smartphone to indicate the type of meal, take pictures of the food, and describe its main components using a free input field. Fluid intake was not assessed. Participants were asked to record their food intake on eight consecutive days. After finishing the study, participants were invited back to the laboratory for individual final interviews.

Immediately before eating participants were asked to indicate the type of meal with the following five options: breakfast, lunch, afternoon tea, dinner, snack. In Germany, “afternoon tea” is called “Kaffee & Kuchen” which directly translates as “coffee & cake”. It is similar to the idea of a traditional “afternoon tea” meal in UK. Specifically, in Germany, people have “Kaffee & Kuchen” in the afternoon (between 4–5 pm) and typically coffee (or tea) is served with some cake or cookies. Dinner in Germany is a main meal with mainly savoury food.

After each meal, participants were asked to rate their meal on three dimensions. They rated (1) how much they enjoyed the meal, (2) how pleased they were with their meal, and (3) how tasty their meal was. Ratings were given on a scale of one to 100. For reliability analysis, Cronbach’s Alpha was calculated to assess the internal consistency of the three items. Overall Cronbach’s alpha was calculated with α = 0.87. In addition, the average of the 38 Cronbach’s alpha scores calculated at the person level also yielded a satisfactory value with α = 0.83 ( SD = 0.24). Thirty-two of 38 participants showed a Cronbach’s alpha value above 0.70 (range = 0.42–0.97). An overall score of experienced happiness of eating was computed using the average of the three questions concerning the meals’ enjoyment, pleasure, and tastiness.

Analytical procedure

The food pictures and descriptions of their main components provided by the participants were subsequently coded by independent and trained raters. Following a standardised manual, additional components displayed in the picture were added to the description by the raters. All consumed foods were categorised into 14 different food categories (see Table 1 ) derived from the food classification system designed by the German Nutrition Society (DGE) and based on the existing food categories of the German Nutrient Database (Max Rubner Institut). Liquid intake and preparation method were not assessed. Therefore, fats and additional recipe ingredients were not included in further analyses, because they do not represent main elements of food intake. Further, salty extras were added to the categorisation.

No participant dropped out or had to be excluded due to high missing rates. Missing values were below 5% for all variables. The compliance rate at the meal level cannot be directly assessed since the numbers of meals and snacks can vary between as well as within persons (between days). As a rough compliance estimate, the numbers of meals that are expected from a “normative” perspective during the eight observation days can be used as a comparison standard (8 x breakfast, 8 × lunch, 8 × dinner = 24 meals). On average, the participants reported M = 6.3 breakfasts ( SD = 2.3), M = 5.3 lunches ( SD = 1.8), and M = 6.5 dinners ( SD = 2.0). In comparison to the “normative” expected 24 meals, these numbers indicate a good compliance (approx. 75%) with a tendency to miss six meals during the study period (approx. 25%). However, the “normative” expected 24 meals for the study period might be too high since participants might also have skipped meals (e.g. breakfast). Also, the present compliance rates are comparable to other studies. For example, Elliston et al . 36 recorded 3.3 meal/snack reports per day in an Australian adult sample and Casperson et al . 37 recorded 2.2 meal reports per day in a sample of adolescents. In the present study, on average, M = 3.4 ( SD = 1.35) meals or snacks were reported per day. These data indicate overall a satisfactory compliance rate and did not indicate selective reporting of certain food items.

To graphically visualise data, Tableau (version 10.1) was used and for further statistical analyses, IBM SPSS Statistics (version 24 for Windows).

Data availability

The dataset generated and analysed during the current study is available from the corresponding authors on reasonable request.

Cornil, Y. & Chandon, P. Pleasure as an ally of healthy eating? Contrasting visceral and epicurean eating pleasure and their association with portion size preferences and wellbeing. Appetite 104 , 52–59 (2016).

Article PubMed Google Scholar

Mann, T. et al . Medicare’s search for effective obesity treatments: Diets are not the answer. American Psychologist 62 , 220–233 (2007).

van Strien, T., Herman, C. P. & Verheijden, M. W. Dietary restraint and body mass change. A 3-year follow up study in a representative Dutch sample. Appetite 76 , 44–49 (2014).

Block, L. G. et al . From nutrients to nurturance: A conceptual introduction to food well-being. Journal of Public Policy & Marketing 30 , 5–13 (2011).

Article Google Scholar

Renner, B., Sproesser, G., Strohbach, S. & Schupp, H. T. Why we eat what we eat. The eating motivation survey (TEMS). Appetite 59 , 117–128 (2012).

Conner, T. S., Brookie, K. L., Carr, A. C., Mainvil, L. A. & Vissers, M. C. Let them eat fruit! The effect of fruit and vegetable consumption on psychological well-being in young adults: A randomized controlled trial. PloS one 12 , e0171206 (2017).

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Rooney, C., McKinley, M. C. & Woodside, J. V. The potential role of fruit and vegetables in aspects of psychological well-being: a review of the literature and future directions. Proceedings of the Nutrition Society 72 , 420–432 (2013).

Mujcic, R. & Oswald, A. J. Evolution of well-being and happiness after increases in consumption of fruit and vegetables. American Journal of Public Health 106 , 1504–1510 (2016).

White, B. A., Horwath, C. C. & Conner, T. S. Many apples a day keep the blues away – Daily experiences of negative and positive affect and food consumption in young adults. British Journal of Health Psychology 18 , 782–798 (2013).

Blanchflower, D. G., Oswald, A. J. & Stewart-Brown, S. Is psychological well-being linked to the consumption of fruit and vegetables? Social Indicators Research 114 , 785–801 (2013).

Grant, N., Wardle, J. & Steptoe, A. The relationship between life satisfaction and health behavior: A Cross-cultural analysis of young adults. International Journal of Behavioral Medicine 16 , 259–268 (2009).

Conner, T. S., Brookie, K. L., Richardson, A. C. & Polak, M. A. On carrots and curiosity: Eating fruit and vegetables is associated with greater flourishing in daily life. British Journal of Health Psychology 20 , 413–427 (2015).

Raghunathan, R., Naylor, R. W. & Hoyer, W. D. The unhealthy = tasty intuition and its effects on taste inferences, enjoyment, and choice of food products. Journal of Marketing 70 , 170–184 (2006).

Evers, C., Stok, F. M. & de Ridder, D. T. Feeding your feelings: Emotion regulation strategies and emotional eating. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin 36 , 792–804 (2010).

Sproesser, G., Schupp, H. T. & Renner, B. The bright side of stress-induced eating: eating more when stressed but less when pleased. Psychological Science 25 , 58–65 (2013).

Wansink, B., Cheney, M. M. & Chan, N. Exploring comfort food preferences across age and gender. Physiology & Behavior 79 , 739–747 (2003).

Article CAS Google Scholar

Taut, D., Renner, B. & Baban, A. Reappraise the situation but express your emotions: impact of emotion regulation strategies on ad libitum food intake. Frontiers in Psychology 3 , 359 (2012).

Tomiyama, J. A., Finch, L. E. & Cummings, J. R. Did that brownie do its job? Stress, eating, and the biobehavioral effects of comfort food. Emerging Trends in the Social and Behavioral Sciences: An Interdisciplinary, Searchable, and Linkable Resource (2015).

Wagner, H. S., Ahlstrom, B., Redden, J. P., Vickers, Z. & Mann, T. The myth of comfort food. Health Psychology 33 , 1552–1557 (2014).

Schüz, B., Bower, J. & Ferguson, S. G. Stimulus control and affect in dietary behaviours. An intensive longitudinal study. Appetite 87 , 310–317 (2015).

Shiffman, S. Conceptualizing analyses of ecological momentary assessment data. Nicotine & Tobacco Research 16 , S76–S87 (2014).

de Castro, J. M., Bellisle, F. & Dalix, A.-M. Palatability and intake relationships in free-living humans: measurement and characterization in the French. Physiology & Behavior 68 , 271–277 (2000).

Adriaanse, M. A., Prinsen, S., de Witt Huberts, J. C., de Ridder, D. T. & Evers, C. ‘I ate too much so I must have been sad’: Emotions as a confabulated reason for overeating. Appetite 103 , 318–323 (2016).

Robinson, E. Relationships between expected, online and remembered enjoyment for food products. Appetite 74 , 55–60 (2014).

Boelsma, E., Brink, E. J., Stafleu, A. & Hendriks, H. F. Measures of postprandial wellness after single intake of two protein–carbohydrate meals. Appetite 54 , 456–464 (2010).

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar

Boh, B. et al . Indulgent thinking? Ecological momentary assessment of overweight and healthy-weight participants’ cognitions and emotions. Behaviour Research and Therapy 87 , 196–206 (2016).

Wansink, B. & Sobal, J. Mindless eating: The 200 daily food decisions we overlook. Environment and Behavior 39 , 106–123 (2007).

Boushey, C., Spoden, M., Zhu, F., Delp, E. & Kerr, D. New mobile methods for dietary assessment: review of image-assisted and image-based dietary assessment methods. Proceedings of the Nutrition Society , 1–12 (2016).

Stok, F. M. et al . The DONE framework: Creation, evaluation, and updating of an interdisciplinary, dynamic framework 2.0 of determinants of nutrition and eating. PLoS ONE 12 , e0171077 (2017).

Pliner, P. & Rozin, P. In Dimensions of the meal: The science, culture, business, and art of eating (ed H Meiselman) 19–46 (Aspen Publishers, 2000).

Inauen, J., Shrout, P. E., Bolger, N., Stadler, G. & Scholz, U. Mind the gap? Anintensive longitudinal study of between-person and within-person intention-behaviorrelations. Annals of Behavioral Medicine 50 , 516–522 (2016).

Zepeda, L. & Deal, D. Think before you eat: photographic food diaries asintervention tools to change dietary decision making and attitudes. InternationalJournal of Consumer Studies 32 , 692–698 (2008).

Stein, K. F. & Corte, C. M. Ecologic momentary assessment of eating‐disordered behaviors. International Journal of Eating Disorders 34 , 349–360 (2003).

Bolger, N., Stadler, G. & Laurenceau, J. P. Power analysis for intensive longitudinal studies in Handbook of research methods for studying daily life (ed . Mehl, M. R. & Conner, T. S.) 285–301 (New York: The Guilford Press, 2012).

Aarts, E., Verhage, M., Veenvliet, J. V., Dolan, C. V. & Van Der Sluis, S. A solutionto dependency: using multilevel analysis to accommodate nested data. Natureneuroscience 17 , 491–496 (2014).

Elliston, K. G., Ferguson, S. G., Schüz, N. & Schüz, B. Situational cues andmomentary food environment predict everyday eating behavior in adults withoverweight and obesity. Health Psychology 36 , 337–345 (2017).

Casperson, S. L. et al . A mobile phone food record app to digitally capture dietary intake for adolescents in afree-living environment: usability study. JMIR mHealth and uHealth 3 , e30 (2015).

Download references

Acknowledgements

This research was supported by the Federal Ministry of Education and Research within the project SmartAct (Grant 01EL1420A, granted to B.R. & H.S.). The funding source had no involvement in the study’s design; the collection, analysis, and interpretation of data; the writing of the report; or the decision to submit this article for publication. We thank Gudrun Sproesser, Helge Giese, and Angela Whale for their valuable support.

Author information

Deborah R. Wahl and Karoline Villinger contributed equally to this work.

Authors and Affiliations

Department of Psychology, University of Konstanz, Konstanz, Germany

Deborah R. Wahl, Karoline Villinger, Laura M. König, Katrin Ziesemer, Harald T. Schupp & Britta Renner

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Contributions

B.R. & H.S. developed the study concept. All authors participated in the generation of the study design. D.W., K.V., L.K. & K.Z. conducted the study, including participant recruitment and data collection, under the supervision of B.R. & H.S.; D.W. & K.V. conducted data analyses. D.W. & K.V. prepared the first manuscript draft, and B.R. & H.S. provided critical revisions. All authors approved the final version of the manuscript for submission.

Corresponding authors

Correspondence to Deborah R. Wahl or Britta Renner .

Ethics declarations

Competing interests.

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Supplementary table s1, rights and permissions.

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ .

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article.

Wahl, D.R., Villinger, K., König, L.M. et al. Healthy food choices are happy food choices: Evidence from a real life sample using smartphone based assessments. Sci Rep 7 , 17069 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-017-17262-9

Download citation

Received : 05 June 2017

Accepted : 23 November 2017

Published : 06 December 2017

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-017-17262-9

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

This article is cited by

Financial satisfaction, food security, and shared meals are foundations of happiness among older persons in thailand.

- Sirinya Phulkerd

- Rossarin Soottipong Gray

- Sasinee Thapsuwan

BMC Geriatrics (2023)

Enrichment and Conflict Between Work and Health Behaviors: New Scales for Assessing How Work Relates to Physical Exercise and Healthy Eating

- Sabine Sonnentag

- Maria U. Kottwitz

- Jette Völker

Occupational Health Science (2023)

The value of Bayesian predictive projection for variable selection: an example of selecting lifestyle predictors of young adult well-being

- A. Bartonicek

- S. R. Wickham

- T. S. Conner

BMC Public Health (2021)

Smartphone-Based Ecological Momentary Assessment of Well-Being: A Systematic Review and Recommendations for Future Studies

- Lianne P. de Vries

- Bart M. L. Baselmans

- Meike Bartels

Journal of Happiness Studies (2021)

Exploration of nutritional, antioxidative, antibacterial and anticancer status of Russula alatoreticula: towards valorization of a traditionally preferred unique myco-food

- Somanjana Khatua

- Surashree Sen Gupta

- Krishnendu Acharya

Journal of Food Science and Technology (2021)

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines . If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.

Quick links

- Explore articles by subject

- Guide to authors

- Editorial policies

Sign up for the Nature Briefing newsletter — what matters in science, free to your inbox daily.

Healthy Living Guide 2020/2021

A digest on healthy eating and healthy living.

As we transition from 2020 into 2021, the COVID-19 pandemic continues to affect nearly every aspect of our lives. For many, this health crisis has created a range of unique and individual impacts—including food access issues, income disruptions, and emotional distress.

Although we do not have concrete evidence regarding specific dietary factors that can reduce risk of COVID-19, we do know that maintaining a healthy lifestyle is critical to keeping our immune system strong. Beyond immunity, research has shown that individuals following five key habits—eating a healthy diet, exercising regularly, keeping a healthy body weight, not drinking too much alcohol, and not smoking— live more than a decade longer than those who don’t. Plus, maintaining these practices may not only help us live longer, but also better. Adults following these five key habits at middle-age were found to live more years free of chronic diseases including type 2 diabetes, cardiovascular disease, and cancer.

While sticking to healthy habits is often easier said than done, we created this guide with the goal of providing some tips and strategies that may help. During these particularly uncertain times, we invite you to do what you can to maintain a healthy lifestyle, and hopefully (if you’re able to try out a new recipe or exercise, or pick up a fulfilling hobby) find some enjoyment along the way.

Download a copy of the Healthy Living Guide (PDF) featuring printable tip sheets and summaries, or access the full online articles through the links below.

In this issue:

- Understanding the body’s immune system

- Does an immune-boosting diet exist?

- The role of the microbiome

- A closer look at vitamin and herbal supplements

- 8 tips to support a healthy immune system

- A blueprint for building healthy meals

- Food feature: lentils

- Strategies for eating well on a budget

- Practicing mindful eating

- What is precision nutrition?

- Ketogenic diet

- Intermittent fasting

- Gluten-free

- 10 tips to keep moving

- Exercise safety

- Spotlight on walking for exercise

- How does chronic stress affect eating patterns?

- Ways to help control stress

- How much sleep do we need?

- Why do we dream?

- Sleep deficiency and health

- Tips for getting a good night’s rest

- CBSE Class 10th

- CBSE Class 12th

- UP Board 10th

- UP Board 12th

- Bihar Board 10th

- Bihar Board 12th

- Top Schools in India

- Top Schools in Delhi

- Top Schools in Mumbai

- Top Schools in Chennai

- Top Schools in Hyderabad

- Top Schools in Kolkata

- Top Schools in Pune

- Top Schools in Bangalore

Products & Resources

- JEE Main Knockout April

- Free Sample Papers

- Free Ebooks

- NCERT Notes

- NCERT Syllabus

- NCERT Books

- RD Sharma Solutions

- Navodaya Vidyalaya Admission 2024-25

- NCERT Solutions

- NCERT Solutions for Class 12

- NCERT Solutions for Class 11

- NCERT solutions for Class 10

- NCERT solutions for Class 9

- NCERT solutions for Class 8

- NCERT Solutions for Class 7

- JEE Main 2024

- MHT CET 2024

- JEE Advanced 2024

- BITSAT 2024

- View All Engineering Exams

- Colleges Accepting B.Tech Applications

- Top Engineering Colleges in India

- Engineering Colleges in India

- Engineering Colleges in Tamil Nadu

- Engineering Colleges Accepting JEE Main

- Top IITs in India

- Top NITs in India

- Top IIITs in India

- JEE Main College Predictor

- JEE Main Rank Predictor

- MHT CET College Predictor

- AP EAMCET College Predictor

- GATE College Predictor

- KCET College Predictor

- JEE Advanced College Predictor

- View All College Predictors

- JEE Main Question Paper

- JEE Main Cutoff

- JEE Main Advanced Admit Card

- JEE Advanced Admit Card 2024

- Download E-Books and Sample Papers

- Compare Colleges

- B.Tech College Applications

- KCET Result

- MAH MBA CET Exam

- View All Management Exams

Colleges & Courses

- MBA College Admissions

- MBA Colleges in India

- Top IIMs Colleges in India

- Top Online MBA Colleges in India

- MBA Colleges Accepting XAT Score

- BBA Colleges in India

- XAT College Predictor 2024

- SNAP College Predictor

- NMAT College Predictor

- MAT College Predictor 2024

- CMAT College Predictor 2024

- CAT Percentile Predictor 2023

- CAT 2023 College Predictor

- CMAT 2024 Admit Card

- TS ICET 2024 Hall Ticket

- CMAT Result 2024

- MAH MBA CET Cutoff 2024

- Download Helpful Ebooks

- List of Popular Branches

- QnA - Get answers to your doubts

- IIM Fees Structure

- AIIMS Nursing

- Top Medical Colleges in India

- Top Medical Colleges in India accepting NEET Score

- Medical Colleges accepting NEET

- List of Medical Colleges in India

- List of AIIMS Colleges In India

- Medical Colleges in Maharashtra

- Medical Colleges in India Accepting NEET PG

- NEET College Predictor

- NEET PG College Predictor

- NEET MDS College Predictor

- NEET Rank Predictor

- DNB PDCET College Predictor

- NEET Admit Card 2024

- NEET PG Application Form 2024

- NEET Cut off

- NEET Online Preparation

- Download Helpful E-books

- Colleges Accepting Admissions

- Top Law Colleges in India

- Law College Accepting CLAT Score

- List of Law Colleges in India

- Top Law Colleges in Delhi

- Top NLUs Colleges in India

- Top Law Colleges in Chandigarh

- Top Law Collages in Lucknow

Predictors & E-Books

- CLAT College Predictor

- MHCET Law ( 5 Year L.L.B) College Predictor

- AILET College Predictor

- Sample Papers

- Compare Law Collages

- Careers360 Youtube Channel

- CLAT Syllabus 2025

- CLAT Previous Year Question Paper

- NID DAT Exam

- Pearl Academy Exam

Predictors & Articles

- NIFT College Predictor

- UCEED College Predictor

- NID DAT College Predictor

- NID DAT Syllabus 2025

- NID DAT 2025

- Design Colleges in India

- Top NIFT Colleges in India

- Fashion Design Colleges in India

- Top Interior Design Colleges in India

- Top Graphic Designing Colleges in India

- Fashion Design Colleges in Delhi

- Fashion Design Colleges in Mumbai

- Top Interior Design Colleges in Bangalore

- NIFT Result 2024

- NIFT Fees Structure

- NIFT Syllabus 2025

- Free Design E-books

- List of Branches

- Careers360 Youtube channel

- IPU CET BJMC

- JMI Mass Communication Entrance Exam

- IIMC Entrance Exam

- Media & Journalism colleges in Delhi

- Media & Journalism colleges in Bangalore

- Media & Journalism colleges in Mumbai

- List of Media & Journalism Colleges in India

- CA Intermediate

- CA Foundation

- CS Executive

- CS Professional

- Difference between CA and CS

- Difference between CA and CMA

- CA Full form

- CMA Full form

- CS Full form

- CA Salary In India

Top Courses & Careers

- Bachelor of Commerce (B.Com)

- Master of Commerce (M.Com)

- Company Secretary

- Cost Accountant

- Charted Accountant

- Credit Manager

- Financial Advisor

- Top Commerce Colleges in India

- Top Government Commerce Colleges in India

- Top Private Commerce Colleges in India

- Top M.Com Colleges in Mumbai

- Top B.Com Colleges in India

- IT Colleges in Tamil Nadu

- IT Colleges in Uttar Pradesh

- MCA Colleges in India

- BCA Colleges in India

Quick Links

- Information Technology Courses

- Programming Courses

- Web Development Courses

- Data Analytics Courses

- Big Data Analytics Courses

- RUHS Pharmacy Admission Test

- Top Pharmacy Colleges in India

- Pharmacy Colleges in Pune

- Pharmacy Colleges in Mumbai

- Colleges Accepting GPAT Score

- Pharmacy Colleges in Lucknow

- List of Pharmacy Colleges in Nagpur

- GPAT Result

- GPAT 2024 Admit Card

- GPAT Question Papers

- NCHMCT JEE 2024

- Mah BHMCT CET

- Top Hotel Management Colleges in Delhi

- Top Hotel Management Colleges in Hyderabad

- Top Hotel Management Colleges in Mumbai

- Top Hotel Management Colleges in Tamil Nadu

- Top Hotel Management Colleges in Maharashtra

- B.Sc Hotel Management

- Hotel Management

- Diploma in Hotel Management and Catering Technology

Diploma Colleges

- Top Diploma Colleges in Maharashtra

- UPSC IAS 2024

- SSC CGL 2024

- IBPS RRB 2024

- Previous Year Sample Papers

- Free Competition E-books

- Sarkari Result

- QnA- Get your doubts answered

- UPSC Previous Year Sample Papers

- CTET Previous Year Sample Papers

- SBI Clerk Previous Year Sample Papers

- NDA Previous Year Sample Papers

Upcoming Events

- NDA Application Form 2024

- UPSC IAS Application Form 2024

- CDS Application Form 2024

- CTET Admit card 2024

- HP TET Result 2023

- SSC GD Constable Admit Card 2024

- UPTET Notification 2024

- SBI Clerk Result 2024

Other Exams

- SSC CHSL 2024

- UP PCS 2024

- UGC NET 2024

- RRB NTPC 2024

- IBPS PO 2024

- IBPS Clerk 2024

- IBPS SO 2024

- Top University in USA

- Top University in Canada

- Top University in Ireland

- Top Universities in UK

- Top Universities in Australia

- Best MBA Colleges in Abroad

- Business Management Studies Colleges

Top Countries

- Study in USA

- Study in UK

- Study in Canada

- Study in Australia

- Study in Ireland

- Study in Germany

- Study in China

- Study in Europe

Student Visas

- Student Visa Canada

- Student Visa UK

- Student Visa USA

- Student Visa Australia

- Student Visa Germany

- Student Visa New Zealand

- Student Visa Ireland

- CUET PG 2024

- IGNOU B.Ed Admission 2024

- DU Admission 2024

- UP B.Ed JEE 2024

- LPU NEST 2024

- IIT JAM 2024

- IGNOU Online Admission 2024

- Universities in India

- Top Universities in India 2024

- Top Colleges in India

- Top Universities in Uttar Pradesh 2024

- Top Universities in Bihar

- Top Universities in Madhya Pradesh 2024

- Top Universities in Tamil Nadu 2024

- Central Universities in India

- CUET Exam City Intimation Slip 2024

- IGNOU Date Sheet

- CUET Mock Test 2024

- CUET Admit card 2024

- CUET PG Syllabus 2024

- CUET Participating Universities 2024

- CUET Previous Year Question Paper

- CUET Syllabus 2024 for Science Students

- E-Books and Sample Papers

- CUET Exam Pattern 2024

- CUET Exam Date 2024

- CUET Cut Off 2024

- CUET Exam Analysis 2024

- IGNOU Exam Form 2024

- CUET 2024 Exam Live

- CUET Answer Key 2024

Engineering Preparation

- Knockout JEE Main 2024

- Test Series JEE Main 2024

- JEE Main 2024 Rank Booster

Medical Preparation

- Knockout NEET 2024

- Test Series NEET 2024

- Rank Booster NEET 2024

Online Courses

- JEE Main One Month Course

- NEET One Month Course

- IBSAT Free Mock Tests

- IIT JEE Foundation Course

- Knockout BITSAT 2024

- Career Guidance Tool

Top Streams

- IT & Software Certification Courses

- Engineering and Architecture Certification Courses

- Programming And Development Certification Courses

- Business and Management Certification Courses

- Marketing Certification Courses

- Health and Fitness Certification Courses

- Design Certification Courses

Specializations

- Digital Marketing Certification Courses

- Cyber Security Certification Courses

- Artificial Intelligence Certification Courses

- Business Analytics Certification Courses

- Data Science Certification Courses

- Cloud Computing Certification Courses

- Machine Learning Certification Courses

- View All Certification Courses

- UG Degree Courses

- PG Degree Courses

- Short Term Courses

- Free Courses

- Online Degrees and Diplomas

- Compare Courses

Top Providers

- Coursera Courses

- Udemy Courses

- Edx Courses

- Swayam Courses

- upGrad Courses

- Simplilearn Courses

- Great Learning Courses

Healthy Food Essay

The food that we put into our bodies has a direct impact on our overall health and well-being. Eating a diet that is rich in nutritious, whole foods can help us maintain a healthy weight, prevent chronic diseases, and feel our best. It is important to make conscious, healthy food choices to support our physical and mental well-being. By incorporating a variety of fruits, vegetables, whole grains, and lean proteins into our diets, we can ensure that our bodies are getting the nutrients they need to thrive. Here are a few sample essays on healthy food.

100 Words Essay On Healthy Food

Healthy food is essential to maintaining a healthy and balanced lifestyle. First and foremost, healthy food is food that is nutritious and good for the body. This means that it provides the body with the vitamins, minerals, and other nutrients it needs to function properly. Healthy food can come in many forms, including fruits, vegetables, whole grains, lean proteins, and healthy fats. Healthy food is important for maintaining a healthy body and mind. It provides the nutrients and energy the body needs to function properly and can help to prevent a wide range of health problems. So, if you want to feel your best, be sure to make healthy food a priority in your life.

200 Words Essay On Healthy Food

Healthy food is not just about what you eat – it’s also about how you eat it. For example, eating fresh, whole foods that are prepared at home with love and care is generally considered to be healthier than eating processed, pre-packaged foods that are high in salt, sugar, and unhealthy fats. Additionally, eating in moderation and avoiding excessive portion sizes is key to maintaining a healthy diet.

There are many reasons to eat healthy food, but the most obvious one is that it can help to prevent a wide range of health problems. Eating a diet rich in fruits, vegetables, and other healthy foods can help to lower your risk of heart disease, stroke, obesity, and other chronic conditions. Additionally, healthy food can help to boost your immune system, giving your body the tools it needs to fight off illness and infection. But the benefits of healthy food go beyond just physical health. Eating well can also have a profound impact on your mental and emotional well-being. A healthy diet can help to reduce stress and anxiety, improve mood, and increase energy levels. It can also help to improve cognitive function and memory, making it easier to focus and concentrate.

500 Words Essay On Healthy Food

Healthy food is an essential aspect of a healthy lifestyle. It is not only crucial for maintaining physical health, but it can also have a significant impact on our mental and emotional well-being. Eating a balanced diet that includes a variety of fruits, vegetables, whole grains, and lean proteins can help us feel energised, focused, and happy. But for many people, eating healthy can be a challenge. In a world where fast food and processed snacks are readily available and often more convenient than cooking a meal from scratch, it can be tempting to choose unhealthy options. And with busy schedules and hectic lives, it can be difficult to find the time and energy to plan and prepare healthy meals.

However, the benefits of eating healthy far outweigh the challenges. Not only can it help us maintain a healthy weight and reduce our risk of chronic diseases like heart disease, diabetes, and cancer, but it can also improve our mood, energy levels, and overall quality of life.

My Experience

As I sat down at my desk with a bag of chips and a soda for lunch again, I realised that I had been making unhealthy food choices all week. I had been so busy with work and other obligations that I hadn't taken the time to plan and prepare healthy meals. I decided then and there to make a change. I started by making a grocery list of nutritious, whole foods and meal planning for the week ahead. I also made a commitment to myself to cook at home more often instead of relying on takeout or fast food. It wasn't easy at first, but over time, I started to notice a difference in my energy levels and overall mood. I felt better physically and mentally, and I was able to maintain a healthy weight. Making healthy food choices became a priority for me, and I am now reaping the numerous benefits of a nutritious diet.

One of the key components of a healthy diet is variety. Eating a diverse range of fruits, vegetables, whole grains, and lean proteins can provide our bodies with the nutrients, vitamins, and minerals we need to function at our best. It's important to try to incorporate a rainbow of colours into our diets, as each colour group represents different nutrients and health benefits. For example, orange and yellow fruits and vegetables are rich in vitamin C and beta-carotene, which can support healthy skin and eyesight. Green leafy vegetables like spinach and kale are packed with antioxidants and can help support a healthy immune system. And blue and purple fruits and vegetables, like blueberries and eggplants, are high in flavonoids and can help support brain health and cognitive function.

In addition to eating a variety of fruits and vegetables, it's also important to include whole grains in our diets. Whole grains, like quinoa, brown rice, and oatmeal, are a great source of fibre, which can help keep us feeling full and satisfied. They can also help regulate our blood sugar levels, which can keep our energy levels steady and prevent unhealthy cravings.

Applications for Admissions are open.

Aakash iACST Scholarship Test 2024

Get up to 90% scholarship on NEET, JEE & Foundation courses

ALLEN Digital Scholarship Admission Test (ADSAT)

Register FREE for ALLEN Digital Scholarship Admission Test (ADSAT)

JEE Main Important Physics formulas

As per latest 2024 syllabus. Physics formulas, equations, & laws of class 11 & 12th chapters

PW JEE Coaching

Enrol in PW Vidyapeeth center for JEE coaching

PW NEET Coaching

Enrol in PW Vidyapeeth center for NEET coaching

JEE Main Important Chemistry formulas

As per latest 2024 syllabus. Chemistry formulas, equations, & laws of class 11 & 12th chapters

Download Careers360 App's

Regular exam updates, QnA, Predictors, College Applications & E-books now on your Mobile

Certifications

We Appeared in

Talk to our experts

1800-120-456-456

- Healthy Food Essay

Essay on Healthy Food

Food is essential for our body for a number of reasons. It gives us the energy needed for working, playing and doing day-to-day activities. It helps us to grow, makes our bones and muscles stronger, repairs damaged body cells and boosts our immunity against external harmful elements like pathogens. Besides, food also gives us a kind of satisfaction that is integral to our mental wellbeing, but there are some foods that are not healthy. Only those food items that contain nutrients in a balanced proportion are generally considered as healthy. People of all ages must be aware of the benefits of eating healthy food because it ensures a reasonably disease-free, fit life for many years.

Switching to a healthy diet doesn't have to be a one-size-fits-all approach. You don't have to be perfect, you don't have to eliminate all of your favourite foods and you don't have to make any drastic changes all at once—doing so frequently leads to straying or abandoning your new eating plan.

Making a few tiny modifications at a time is a recommended approach. Maintaining modest goals will help you achieve more in the long run without feeling deprived or overwhelmed by a very drastic diet change. Consider a healthy diet as a series of tiny, accessible actions such as including a salad in your diet once a day. You can slowly add additional healthy options as your minor modifications become habitual.

Cultivating a positive relationship with food is also crucial. Rather than focusing on what you should avoid, consider what you may include on your plate that will benefit your health such as nuts for heart-healthy, predominant fat that reduces low-density lipoprotein levels called monounsaturated fatty acids(raspberries) for fibre and especially the substances that inhibit oxidation which we call antioxidants.

Why is Healthy Food Important?

Living a healthy lifestyle has immense payback. Over time, making smart eating choices lowers your risk of cardiovascular disease, certain malignancies, type 2 diabetes, obesity, and even anxiety and depression. Daily, you will have more energy, feel better and possibly even be in a better mood.

It all boils down to how long and how good your life is. According to several surveys, A healthy diet consists of whole grains, vegetables, fruits, nuts, and fish. A higher diet of red or processed meats on the other hand doubled the chance of dying young.

Types of Healthy Food:

Following are the various types of healthy foods and their respective nutritional value:

Cereals,potatoes,bread and other root vegetables- These are the main sources of carbohydrates. The calories obtained from them enable us to do work.

Pulses, milk and milk products, eggs, bird meat, animal meat in limited quantities - these are great sources of protein. They build muscles and repair the damaged cells of our body, i.e., they are important for our immunity.

Ghee, butter, nuts and dry fruits, edible oil used in restrained quantities- These are rich sources of good fat. They provide more energy to our body than carbohydrates but should be consumed in a smaller amount.

Fresh fruits, vegetables and leafy vegetables, fish, egg, milk-these are good sources of vitamins, minerals and antioxidants are essential for normal functioning of the body. Though they are needed in small amounts, nowadays, nutrition experts prescribe their higher consumption as they help to fight lifestyle diseases like diabetes, obesity and even cancer.

Different types of healthy food when included in our daily diet in the right proportions along with water and roughage comprise a balanced diet. However, a balanced diet is not the same for all individuals considering many factors. It depends on a person’s age, gender, condition of the body-healthy or suffering from any disease and the type of work or physical activity a human does.

Benefits of Eating Healthy

Healthy food intake nourishes both our physical and mental health and helps us stay active for many years. One who break downs this broad benefit into micro-benefits will see that eating healthy:

Helps us in weight management

Makes us agile and increases our productivity

Decreases the risk of heart diseases, stroke, diabetes mellitus, poor bone density, and some cancers, etc.

Helps in uplifting mood

Improves memory

Improves digestion and appetite

Improves sleep cycle

Healthy food habits are inculcated in children by their parents early on. These habits along with the right education and physical exercise lead to an overall development of an individual which ultimately becomes the greatest resource of a country.

What is Unhealthy Food or Junk Food?

To fully understand the prominence of healthy food in our diet, we must also be aware of unhealthy food, that is, the food that we must avoid eating. These are mainly junk food items which are low in nutritional value and contain an excessive amount of salt, sugar and fats which is not healthy for a human body.

Junk food is one of the unhealthy intakes in the present day scenario. It makes us more unfit than ever before. It is high time that one realised this and adopted a healthy food habit for a sustainable lifestyle.

Steps to improve Eating Habits:

Make a detailed plan; break down the timings; kind of food to be included in each meal and keep the plan weekly and avoid making the process dull and repetitive.

Cook your food, minimise eating from outside. It helps keep the ingredients, quality and measurements in check as well as saves money.

Stock your kitchen with healthy snacks for your cravings rather than processed food so that your options are reduced to consuming unhealthy food.

Take the process slowly. You do not have to have a strict plan; ease yourself into a healthy mindset. Your mind and body will adjust gradually. Consistency is important.

Track your eating habits to understand the intake of food, items, portions etc. This motivates you to see the progress over time and make changes according to your needs.

Myths About Healthy Food:

Carrots affect eyesight: According to historic times, during World War II, there was a popular belief that eating a lot of veggies would assist maintain the pilot's eyes in good repair. In actuality, the fighter pilot's eyesight was aided by advanced technology. However, the myth has persisted since then and many parents still use this narrative to get their children to eat more veggies. Carrots are high in vitamin A and make a terrific supplement to any healthy diet, but they don't usually help you see better.

Fat-Free Food : Health foods continue to dominate grocery store shelves but it's always a good idea to look beyond the label before buying. This is especially true when it comes to "fat-free," "low-fat," and "non-fat" foods. It's generally true that anything with less fat is preferable for some dairy and meat items.

Lower fat alternatives in packaged and processed foods contain other dangerous additives as fat substitutes. Manufacturers compensate for the loss of fat in packaged cookies, for example, by adding other undesirable elements like sugar.

Protein shakes: Pre-made smoothie beverages and protein powder mixes which typically claim to contain less sugar than milkshakes, slushies and diet sodas are likely to be the popular choice among customers because of the above mentioned reason. They both have the same amount of sugar and artificial sweeteners.

However, this is not true of all pre-made protein shakes and smoothies. Many of them, particularly the plant-based mixtures, are still nutritious additions to a balanced diet. Check the nutrition label to be sure there are no added sugars or artificially sweetened mixtures.

Organic food is better: Foods that are grown organically are better for you. Nutritionists labelling a product as organic doesn't mean it's superior to non-organic foods. It's a popular misperception that organic produce is nutritionally superior to non-organic produce. Organic produce has the same caloric and nutritional value as non-organic produce since it is grown and prepared according to federal rules.

FAQs on Healthy Food Essay

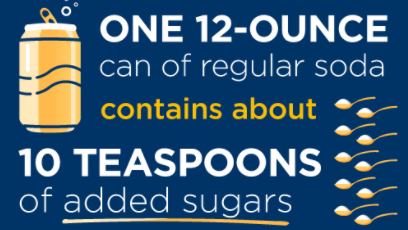

1) Is sugar unhealthy?

Sugar is considered to be harmful for a healthy diet. Since it tastes so good in many foods, humans tend to increase it’s intake. It is also hidden in foods you wouldn't expect. It makes body organs fat, depresses well-being and also leads to heart diseases. However, to maintain a healthy diet, it is necessary to distinguish between natural and added sugars. Sugars are carbs that provide an essential source of energy and nourishment, nevertheless, sugar is often added to many popular dishes, which is when sugar becomes unhealthy. Natural sugars found in fruits and vegetables are regarded as healthy when consumed in moderation. Still added sugars give little nutritional benefit and contribute considerably to weight gain, compromising your healthy diet. As a result, it's critical to double-check the label.

2) What is Omega 3?

Omega-3 is the superfood of the fat group, which is particularly useful for various conditions, since the term "superfood" was coined. Omega-3 fatty acid is a medicine used in treating nutritional deficiencies. It is one of the essential nutrients with good antioxidant properties. Depression, memory loss, heart problems, joint and skin disorders and general improvement of physical and mental health and wellness are among them. Omega-3 which is abundant in fish-based diets is considered a necessary fatty acid for good health.

Healthy Food Essay for Students and Children

500+ words essay on healthy food.

Healthy food refers to food that contains the right amount of nutrients to keep our body fit. We need healthy food to keep ourselves fit.

Furthermore, healthy food is also very delicious as opposed to popular thinking. Nowadays, kids need to eat healthy food more than ever. We must encourage good eating habits so that our future generations will be healthy and fit.

Most importantly, the harmful effects of junk food and the positive impact of healthy food must be stressed upon. People should teach kids from an early age about the same.

Benefits of Healthy Food

Healthy food does not have merely one but numerous benefits. It helps us in various spheres of life. Healthy food does not only impact our physical health but mental health too.

When we intake healthy fruits and vegetables that are full of nutrients, we reduce the chances of diseases. For instance, green vegetables help us to maintain strength and vigor. In addition, certain healthy food items keep away long-term illnesses like diabetes and blood pressure.

Similarly, obesity is the biggest problems our country is facing now. People are falling prey to obesity faster than expected. However, this can still be controlled. Obese people usually indulge in a lot of junk food. The junk food contains sugar, salt fats and more which contribute to obesity. Healthy food can help you get rid of all this as it does not contain harmful things.

In addition, healthy food also helps you save money. It is much cheaper in comparison to junk food. Plus all that goes into the preparation of healthy food is also of low cost. Thus, you will be saving a great amount when you only consume healthy food.

Get the huge list of more than 500 Essay Topics and Ideas

Junk food vs Healthy Food

If we look at the scenario today, we see how the fast-food market is increasing at a rapid rate. With the onset of food delivery apps and more, people now like having junk food more. In addition, junk food is also tastier and easier to prepare.

However, just to satisfy our taste buds we are risking our health. You may feel more satisfied after having junk food but that is just the feeling of fullness and nothing else. Consumption of junk food leads to poor concentration. Moreover, you may also get digestive problems as junk food does not have fiber which helps indigestion.

Similarly, irregularity of blood sugar levels happens because of junk food. It is so because it contains fewer carbohydrates and protein . Also, junk food increases levels of cholesterol and triglyceride.

On the other hand, healthy food contains a plethora of nutrients. It not only keeps your body healthy but also your mind and soul. It increases our brain’s functionality. Plus, it enhances our immunity system . Intake of whole foods with minimum or no processing is the finest for one’s health.

In short, we must recognize that though junk food may seem more tempting and appealing, it comes with a great cost. A cost which is very hard to pay. Therefore, we all must have healthy foods and strive for a longer and healthier life.

FAQs on Healthy Food

Q.1 How does healthy food benefit us?

A.1 Healthy Benefit has a lot of benefits. It keeps us healthy and fit. Moreover, it keeps away diseases like diabetes, blood pressure, cholesterol and many more. Healthy food also helps in fighting obesity and heart diseases.

Q.2 Why is junk food harmful?

A.2 Junk food is very harmful to our bodies. It contains high amounts of sugar, salt, fats, oils and more which makes us unhealthy. It also causes a lot of problems like obesity and high blood pressure. Therefore, we must not have junk food more and encourage healthy eating habits.

Customize your course in 30 seconds

Which class are you in.

- Travelling Essay

- Picnic Essay

- Our Country Essay

- My Parents Essay

- Essay on Favourite Personality

- Essay on Memorable Day of My Life

- Essay on Knowledge is Power

- Essay on Gurpurab

- Essay on My Favourite Season

- Essay on Types of Sports

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Download the App

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.