Common Sense Media

Movie & TV reviews for parents

- For Parents

- For Educators

- Our Work and Impact

Or browse by category:

- Get the app

- Movie Reviews

- Best Movie Lists

- Best Movies on Netflix, Disney+, and More

Common Sense Selections for Movies

50 Modern Movies All Kids Should Watch Before They're 12

- Best TV Lists

- Best TV Shows on Netflix, Disney+, and More

- Common Sense Selections for TV

- Video Reviews of TV Shows

Best Kids' Shows on Disney+

Best Kids' TV Shows on Netflix

- Book Reviews

- Best Book Lists

- Common Sense Selections for Books

8 Tips for Getting Kids Hooked on Books

50 Books All Kids Should Read Before They're 12

- Game Reviews

- Best Game Lists

Common Sense Selections for Games

- Video Reviews of Games

Nintendo Switch Games for Family Fun

- Podcast Reviews

- Best Podcast Lists

Common Sense Selections for Podcasts

Parents' Guide to Podcasts

- App Reviews

- Best App Lists

Social Networking for Teens

Gun-Free Action Game Apps

Reviews for AI Apps and Tools

- YouTube Channel Reviews

- YouTube Kids Channels by Topic

Parents' Ultimate Guide to YouTube Kids

YouTube Kids Channels for Gamers

- Preschoolers (2-4)

- Little Kids (5-7)

- Big Kids (8-9)

- Pre-Teens (10-12)

- Teens (13+)

- Screen Time

- Social Media

- Online Safety

- Identity and Community

Explaining the News to Our Kids

- Family Tech Planners

- Digital Skills

- All Articles

- Latino Culture

- Black Voices

- Asian Stories

- Native Narratives

- LGBTQ+ Pride

- Best of Diverse Representation List

Celebrating Black History Month

Movies and TV Shows with Arab Leads

Celebrate Hip-Hop's 50th Anniversary

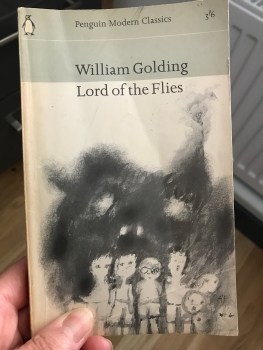

Lord of the flies, common sense media reviewers.

Gripping story of marooned schoolboys and mob mentality.

A Lot or a Little?

What you will—and won't—find in this book.

The book's basic premise is that some people, depr

The novel raises questions about personal choice a

Ralph is the main character who's elected leader i

The British schoolboys depicted in the novel are W

One boy is bullied. Two characters are murdered: O

A taunt includes calling a character's asthma "ass

Parents need to know that Lord of the Flies has been described as dark, brutal, pessimistic, and tragic. Written from the point of view of British author William Golding, the novel tells the story of a group of White British school boys who survive after their plane crash lands on a remote island in the…

Educational Value

The book's basic premise is that some people, deprived of the rules and restrictions of society, will revert to barbaric behavior. This central conflict between nature versus nurture when it comes to morality is found on every page. Readers will also learn something about survival on an unpopulated island.

Positive Messages

The novel raises questions about personal choice and individual humanity in appalling situations. People are capable of selflessness, even when their own lives are at stake. There are times when it's critical to put the needs of the group ahead of individual needs or wants.

Positive Role Models

Ralph is the main character who's elected leader in the name of staying "civilized." He thinks strategically and shows compassion and perseverance, but his motives are questionable, and he does not succeed in his leadership of the group. Piggy, who is brainy and logical, represents the rational side of human beings; unfortunately, he's also deeply unpopular. Only Simon, who looks after the younger boys, seems naturally kind and good, as if born that way. Jack seeks power ruthlessly, but is charismatic, so he's able to command leadership, even when it results in more chaos. Other characters represent baser, more violent human impulses or the innocence of children. The characters, and how they relate to one another, underscore the value of ethics in collaborative situations.

Diverse Representations

The British schoolboys depicted in the novel are White. Their descent into "savagery," a term used repeatedly throughout the book, relies on racist stereotypes of Indigenous peoples from Africa, Asia, and the Americas being more violent and less civilized. The character Jack explicitly differentiates between "savages" and the English, suggesting that only the English know how to "have rules and obey them" and "are best at everything." A boy described as fat is nicknamed Piggy. He also has asthma. For those reasons, he's viewed as weak by the others. Women are not present and are only mentioned when the boys miss their mothers. The comparison to tying their hair back like "a girl" is used in a derogatory manner by the boys.

Did we miss something on diversity? Suggest an update.

Violence & Scariness

One boy is bullied. Two characters are murdered: One is beat to death and another falls to his death after being hit by a boulder pushed by one of the other boys. The acts are described in detail. Frequent mention of blood. Brief torture sequence. Boys hunt a pig and poke a sharp stick up its rear end while it's still alive. The setting and atmosphere are fraught with the potential for violence.

Did you know you can flag iffy content? Adjust limits for Violence & Scariness in your kid's entertainment guide.

A taunt includes calling a character's asthma "ass-mar."

Did you know you can flag iffy content? Adjust limits for Language in your kid's entertainment guide.

Parents Need to Know

Parents need to know that Lord of the Flies has been described as dark, brutal, pessimistic, and tragic. Written from the point of view of British author William Golding, the novel tells the story of a group of White British school boys who survive after their plane crash lands on a remote island in the Pacific Ocean. The boys bully and eventually kill two members of their group, one in a brutal, frenzied beating, in the other murder, a character causes a boy to fall off a cliff. Both scenes are described in bloody detail. The book often compares being "civilized" with Britishness, while the boys' violent behavior is depicted as more primitive and draws on negative stereotypes of Indigenous peoples -- a false idea that was historically used to justify the colonization and oppression of people in places such as Africa, Asia, and the Americas. The story deals with a fundamental issue of humanity: Are people naturally prone to evil? This and other issues in the novel are well-suited for parent-child discussion.

Where to Read

Community reviews.

- Parents say (12)

- Kids say (111)

Based on 12 parent reviews

Great book for deep discussion

The classic of savagery, what's the story.

In LORD OF THE FLIES, a group of British schoolboys is marooned on a tropical island and left to fend for themselves, unsupervised by any adults. At first, the boys enjoy their freedom, playing and exploring the island. But soon the group splits into two factions: those who try to preserve the discipline and order they've learned from society, and those who choose to give in to every instinct and impulse, no matter how chaotic or cruel.

Is It Any Good?

This novel has been a perennial favorite since its first publication in 1954, and when he was awarded the Nobel Prize for Literature, William Golding was lauded for his deep concern for humanity. Today, Lord of the Flies remains a staple of school reading lists, although some of its dated views about the nature of savagery are worth reexamining and discussing. Golding's prose is unadorned and straightforward, and the result is page-turning entertainment -- as well as a highly thought-provoking work of literature.

Talk to Your Kids About ...

Families can talk about how Lord of the Flies is considered a classic and is often required reading in school. Why do you think that is? Are there aspects of the novel that seem dated now? How does the depiction of the boys' bad behavior rely on stereotypes?

The boys on the island hope to survive their ordeal. How do they persevere through their difficult circumstances? What helps them survive?

Do you think people are born "good" or "evil" -- is our behavior always the result of choice? How is it that good people are capable of bad behavior, and vice versa? How do you think you might behave under the circumstances of the novel?

Is it always best to sacrifice your own wants and needs for the common good of a community? What are some examples of when characters show compassion ? What effect does compassion have on the characters and the events of this story?

What do you think some of the prominent elements of the story -- the conch, Piggy's glasses, the sow's head, the island's "beast" -- might symbolize?

Book Details

- Author : William Golding

- Genre : Literary Fiction

- Topics : Adventures , Friendship

- Character Strengths : Compassion , Perseverance

- Book type : Fiction

- Publisher : Perigree

- Publication date : January 1, 1954

- Number of pages : 304

- Last updated : August 16, 2023

Did we miss something on diversity?

Research shows a connection between kids' healthy self-esteem and positive portrayals in media. That's why we've added a new "Diverse Representations" section to our reviews that will be rolling out on an ongoing basis. You can help us help kids by suggesting a diversity update.

Suggest an Update

Our editors recommend.

Animal Farm

The Catcher in the Rye

To Kill a Mockingbird

Yellowjackets

Classic books for kids, summer reading list, related topics.

- Perseverance

Want suggestions based on your streaming services? Get personalized recommendations

Common Sense Media's unbiased ratings are created by expert reviewers and aren't influenced by the product's creators or by any of our funders, affiliates, or partners.

Advertisement

Supported by

Man as an Island

- Share full article

By William Boyd

- July 16, 2010

In the late 1960s, some 15 years after the publication of “Lord of the Flies,” William Golding confessed to a friend that he resented the novel because it meant that he owed his reputation to what he thought of as a minor book, a book that had made him a classic in his lifetime, which was “a joke,” and that the money he had gained from it was “Monopoly money” because he hadn’t really earned it. Golding was drinking heavily at the time (he had a lifelong struggle with alcoholism) and one may have to take his bitterness advisedly, but these remarks reveal an interesting artistic conundrum. What is it like to owe virtually your entire reputation as a writer to a single book? One thinks of J. D. Salinger, Ralph Ellison, Joseph Heller — to cite only the 20th-century American exemplars — but such one-book writers are legion in all literatures. John Carey seems to allude to the category in this biography’s subtitle (even though Carey eventually disputes the implication). However, if anyone thinks of William Golding today, it is almost certain that his name will be conjoined with his extraordinary first novel.

A blessing and then a curse of some sort — though by the time the book finally appeared in 1954, Golding wouldn’t have cared about any downside. He was a 42-year-old provincial schoolteacher, desperate merely to have a novel published (it was the fourth book he had written, incidentally); renown and wealth were not even remotely considered. In fact, even “Lord of the Flies” was rejected by many publishers before an alert junior editor at Faber & Faber, Charles Monteith, saw its potential and encouraged Golding to make changes. By 1980, sales in the United States alone had reached seven million.

Golding, to other writers, is a model of the late starter (along with Anthony Burgess and Muriel Spark). You don’t need to be young to make your name, so his career asserts, and once Golding had achieved that first success it never really left him. “Lord of the Flies” was swiftly followed by “The Inheritors” (1955) and “Pincher Martin” (1956), both published to great, if not universal, acclaim. A new and highly distinctive voice seemed to have arrived in contemporary British literature. The critical reception was not always so favorable for subsequent novels ( “Free Fall,” in 1959, suffered a near-unanimous pasting), but it is fair to say that Golding’s life as a writer was forever financially secure thanks to the rock-solid, never-ending sales of “Lord of the Flies.”

Golding was born in Cornwall in 1911. He was only eight years younger than Evelyn Waugh and is effectively part of that generation of English novelists (including Graham Greene, Anthony Powell and Aldous Huxley) who had reached their maturity by the time of World War II. But we never think of Golding in their company because his success as a writer was entirely postwar — he seems in some way more modern and contemporary.

Golding joined the navy a year after war broke out (he was already married with a child). At D-Day in 1944 and the Battle of Walcheren some months later, he was in command of a rocket-firing landing craft, a vessel designed to deliver a terrifying “shock and awe”-style blanket barrage of thousands of small deadly rockets. Golding, operating the firing mechanism on the bridge of his ship, clearly saw the indiscriminate, devastating effect of the wall of fire and destruction that was unleashed as his myriad rockets erupted on beachheads and coastal villages.

He survived the war unharmed and with some reluctance went back to the tedium of schoolmastering in Wiltshire. Carey makes the valid point that his war in the navy was profoundly destabilizing for him in various ways (both personally and artistically), and many of the key themes in his work can be traced to these formative and disturbing experiences.

Carey summarizes the abiding obsession in the novels as the collision of “the spiritual and the miraculous” with “science and rationality,” and it is this persistent hypersensitivity to the numinous and immaterial aspects of the world and the human condition that sets Golding apart from the broad river of social realism that so defines the 20th-century English novel. He was a kind of maverick in the way D. H. Lawrence was, or Lawrence Durrell, or John Fowles — to name but three — and I think this strangeness explains how throughout his life, after his initial success, the critical responses to his work were so violently divided. You either loved William Golding, it seemed, or you hated him.

Golding himself was abnormally thin-skinned when it came to criticism of his work. He simply could not read even the mildest reservation and on occasion left the country when his books were published. What is fascinating about “William Golding” is the portrait that emerges of a man of almost absurdly dramatic contrasts. He fought with commendable bravery at D-Day, yet in life was the most timid arachnophobe. He was married for more than 50 years, yet was probably a repressed homosexual. He was an accomplished classical musician and excellent chess player and an embarrassing, infantile drunk. He loathed and detested the stilted conventions of the British class system (particular scorn was directed at the Bloomsbury group), and yet when already a Nobel laureate and a member of the elite group to whom the queen grants the title Companion of Literature, he still frenetically lobbied his important friends to secure him a knighthood — successfully — and was a proud member of two of London’s stuffiest gentlemen’s clubs. Time and again the impression is of a man in a form of omnipresent torment of one kind or another: sometimes it would be mild and possibly amusing; at other moments, debilitating and damagingly neurotic.

John Carey has had unrestricted access to the Golding archive, and it is unlikely that this biography will ever be bettered or superseded. Moreover, Carey, an emeritus professor of English literature at Oxford and one of the most respected literary critics in Britain, writes with great wit and lucidity as well as authority and compassionate insight. Perhaps because he has had the opportunity of reading the mass of Golding’s unpublished intimate journals, he brings unusual understanding to the complex and deeply troubled man who lies behind the intriguing but undeniably idiosyncratic novels.

And the fiction is highly unusual and uneven, right up to the end of Golding’s energetic working life — his last novel, “Fire Down Below,” was published in 1989, only four years before his death at the age of 81 — emblematic of the warring forces in his imagination, of a writer (in Carey’s words) “interested in ideas rather than people, and in seeing mankind in a cosmic perspective rather than an everyday social setting.” Anthony Burgess described his talent as “deep and narrow,” and Golding’s own demons often drove him to analyze the extent and limits of his achievement. After the publication of “The Inheritors,” as the acclaim flowed in, Golding remarked that he saw himself “spiraling up towards being a . . . universally admired, but unread,” novelist. This was horribly prescient. With the exception of “Lord of the Flies,” Golding’s strange, haunting, difficult novels have few readers these days, and his posthumous reputation is neglected and in decline. At the very least, Carey’s superb biography should take us back to the work again and allow us to make up our own minds, anew.

WILLIAM GOLDING

The man who wrote “lord of the flies”: a life.

By John Carey

Illustrated. 573 pp. Free Press. $32.50

William Boyd’s most recent novel, “Ordinary Thunderstorms,” was published earlier this year.

Explore More in Books

Want to know about the best books to read and the latest news start here..

As book bans have surged in Florida, the novelist Lauren Groff has opened a bookstore called The Lynx, a hub for author readings, book club gatherings and workshops , where banned titles are prominently displayed.

Eighteen books were recognized as winners or finalists for the Pulitzer Prize, in the categories of history, memoir, poetry, general nonfiction, fiction and biography, which had two winners. Here’s a full list of the winners .

Montreal is a city as appealing for its beauty as for its shadows. Here, t he novelist Mona Awad recommends books that are “both dreamy and uncompromising.”

The complicated, generous life of Paul Auster, who died on April 30 , yielded a body of work of staggering scope and variety .

Each week, top authors and critics join the Book Review’s podcast to talk about the latest news in the literary world. Listen here .

- Search for: Search OK

Review: Lord of the Flies by William Golding

Lord of the Flies William Golding Penguin Books Published December 16, 2003 (Originally Published 1954)

Amazon | bookshop | goodreads, about lord of the flies.

At the dawn of the next world war, a plane crashes on an uncharted island, stranding a group of schoolboys. At first, with no adult supervision, their freedom is something to celebrate; this far from civilization the boys can do anything they want. Anything. They attempt to forge their own society, failing, however, in the face of terror, sin and evil. And as order collapses, as strange howls echo in the night, as terror begins its reign, the hope of adventure seems as far from reality as the hope of being rescued.

Labeled a parable, an allegory, a myth, a morality tale, a parody, a political treatise, even a vision of the apocalypse, LORD OF THE FLIES is perhaps our most memorable novel about “the end of innocence, the darkness of man’s heart.”

LORD OF THE FLIES is one of those iconic books that gets referenced all the time in our culture, but I’d never read it before. My daughter had to read it for school last year, and she had some anxiety about the content. I decided to read it first so she’d be ready for anything that might be difficult for her.

I read the book last fall as things were heating up before the presidential election here in the US. At that time, I actually wrote an initial review. But because I kept pushing back the date for posting the review, I have updated the review and added some more stuff that I’ve thought about on reflection.

Before I started reading LORD OF THE FLIES, I felt really weird reading all these big name authors talking about how pivotal this book has been for their writing. I think it’s Suzanne Collins who says that she reads LORD OF THE FLIES every year. That seemed really weird to me for a book with such a dark reputation. Every year? I mean, no offense meant. When a book resonates with you like that, I get wanting to read it every year. For a long time I had a book that I read every year, too. I guess I just found myself surprised about people feeling that way about a book that’s often referenced to describe uncontrolled violence or mayhem.

Anyway. So I went into the book with both some dread (expecting violence, which can be hard for me to read), and some, I don’t know, fascination, I guess?

The thing that still stands out to me most about the book is how easily some boys began to think of others as not human, as animals to be hunted. There’s a moment, after one boy has been killed where two boys talk around what happened. One boy comes right out and says that it was murder. The other boy recoils and tries to defend what happened as something else. He tries to explain it away as something not evil and wrong. It doesn’t work, and for a moment they’re both confronted with the horrible truth.

Watching the vigilantism and the violent language increasingly used by elected officials and repeated online while reading LORD OF THE FLIES was really creepy, y’all. Like, it seriously marked me. I would read a scene and feel like, this is awfully close to the way people are talking to each other or about each other right now. Or I’d get to a scene and think, well, surely our leaders won’t sink this low. And then. Stuff happened.

I couldn’t stop– and still can’t stop– thinking about the way the story explores the power of fear. The collapse of reason that happens when people are afraid and respond with that fear and anger. The steady shift toward things that once seemed unimaginable. I knew what was coming because I’d heard enough about the book that I basically knew what to expect. And yet, the violence of it and the dehumanization of it still shocked and shook me.

Reading this book, I can see not only from the story why it endures, but also from the writing. Like, I felt genuinely pulled into the tale. Even when I wasn’t reading, I thought about it. I wanted to know what would happen. Even though I already pretty much knew what was coming, I couldn’t look away from what was happening. It gripped me and paralyzed me with horror. (Much the way I felt weeks later watching the coverage of the January 6 insurrection.)

Honestly, I won’t say I enjoyed it– not like, celebrated reading it. But it really moved me. I think I would read it again. I think I NEED to read it again.

Content Notes

Recommended for Ages 16 up.

Representation All the boys are British private school students.

Profanity/Crude Language Content Mild profanity used infrequently.

Romance/Sexual Content None.

Spiritual Content The boys fear a mysterious evil they call the Beast. They leave food sacrifices for it, hoping that this will keep the Beast away from them.

Violent Content At least one racist comment equating Indians with savages. Multiple violent descriptions of hunting and killing pigs. Boys beat another boy to death. A boy falls to his death after being hit with a rock.

Drug Content None.

Note: This post contains affiliate links, which do not cost you anything to use, but which help support the costs of running this blog.

Share this:

- Click to share on Twitter (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Reddit (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Pinterest (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Facebook (Opens in new window)

About Kasey

2 responses to review: lord of the flies by william golding.

My interest is piqued to give the book another chance. I read it a while back, while I was I in middle school, and at that time I had little idea about what was happening (I lost my way about halfway through), and I hadn’t heard much about the story like you had before diving into the text, so I suspect that the full impact (philosophical, political, psychological, social) wasn’t felt.

Yay! Yeah, I have definitely had that experience with books that I read in school before and then again later. I hope that if you read it again, you are able to connect with it a lot more. 🙂 Thanks, Abigail!

Never Miss a Story

Get reviews and book recommendations in your email inbox!

your email here

Donate Your New or Used Books

Follow For More Stories

Search stories reviewed, stories coming soon.

My Book for Authors

Subscribe by Email

Get reviews and book recommendations in your inbox.

Email Address

Follow The Story Sanctuary

Get every new post delivered to your Inbox

Join other followers:

Discover more from The Story Sanctuary

Subscribe now to keep reading and get access to the full archive.

Type your email…

Continue reading

- International edition

- Australia edition

- Europe edition

The 100 best novels: No 74 – Lord of the Flies by William Golding (1954)

L ike all the recent novels in this list (69-73), Lord of the Flies owes much of its dark power and impetus to the second world war, in which Golding served as a young naval officer. His experiences at Walcheren in 1944 nurtured an appetite for quasi-medieval extremes, mixing fiction and philosophy, which is not always a recipe for success in novels. However, Lord of the Flies remains both universal and yet profoundly English, with nods to Defoe, Stevenson and Jack London ( 2 , 24 and 35 in this series).

By the 1950s, now teaching at a boys’ grammar school, Golding was struggling to make his way as a novelist, having had a volume of poems published in 1934. His wife, Ann, who played a crucial role in his creative life, suggested RM Ballantyne’s Coral Island as a source of inspiration. The upshot: a post-apocalyptic, dystopian survivor-fantasy about a bunch of pre-teen and teenage boys on a remote tropical island. But this is a far cry from the world of Robinson Crusoe or Long John Silver.

Lord of the Flies (whose title derives from one transcription of “Beelzebub”) is the work of an English teacher with a taste for big themes, and engages the reader at three levels. First, it’s a brilliantly observed study of adolescents untethered from rules and conventions. The main players – Ralph, Jack and Piggy – represent archetypes of English schoolboy, but Golding gets under their skin and makes them real. He knows how they tick, and draws on his own experience to explore the terrifying breakdown of their community.

Second and third, Lord of the Flies presents a view of humanity unimaginable before the horrors of Nazi Europe, and then plunges into speculations about mankind in the state of nature. Bleak and specific, but universal, fusing rage and grief, Lord of the Flies is both a novel of the 1950s, and for all time. A strange kind of Eden becomes a desolate portrait of life in a post-nuclear world. Perhaps it’s no surprise that it should become a cult classic of the 60s, to be read as avidly as Catcher in the Rye , To Kill a Mocking Bird and On the Road .

A Note on the Text

Before completing this novel, William Golding had been “Scruff”, the shy, oddball English teacher at Bishop Wordsworth’s school in Salisbury. Lord of the Flies , written during 1952-53, suffered successive rejections before its triumphant publication in 1954. At first titled Strangers from Within , the novel not only endured almost universal disdain, it was also the desperate last throw of an awkward schoolmaster who had struggled for years to find an audience.

His daughter, Judy, born at the end of the war, was too young to remember her father writing Lord of the Flies but she told me in an interview some years ago: “I do remember the parcels [of manuscript] going off and coming back. We lived on a very tight budget, so the postage must have been a significant expense.”

The legend of this iconic postwar novel has become hoary with many tellings. When it first arrived at Faber & Faber (its eventual publisher), it was a dog-eared manuscript that had obviously done the rounds. Its first in-house reader, a certain Miss Perkins, famously dismissed it as an “absurd and uninteresting fantasy about the explosion of an atom bomb on the Colonies. A group of children who land in jungle country near New Guinea. Rubbish & dull. Pointless.” However, a newly recruited young Faber editor, Charles Monteith, disagreed. He saw that the first chapter (about the aftermath of the bomb) could be dropped, fought for the book, and then, having persuaded Golding to cut and rewrite, steered it through to publication. Monteith, whom I came to know well, and admire, was doing what Maxwell Perkins did for Thomas Wolfe or Gordon Lish for Raymond Carver. It’s a skill that is rarely found in publishing today.

Eventually, the novel would sell more than 10m copies, but fame and success did not come overnight. The first printing of about 3,000 copies sold slowly. Gradually, the book’s qualities won serious attention. A turning-point occurred when EM Forster chose Lord of the Flies as his “outstanding novel of the year.” Other reviews described it as “not only a first-rate adventure but a parable of our times”. Judy Golding told me it was only “five years later, after the film came out [directed by Peter Brook], that I noticed parents of my friends suddenly becoming interested in Daddy”.

Thereafter, the novel became cult reading. When I worked at Faber in the 1980s, we used to reprint it, 100,000 copies at a time, year after year. I believe this still goes on. That’s one definition of classic, a book which even when we read it for the first time gives us the sense of re-reading something we have read before. In the words of Italo Calvino, “A classic is a book which has never exhausted all it has to say to its readers.”

Lord of the Flies has had a wide influence on many English and American writers, including Alex Garland, whose The Beach pays homage to Golding’s original. Nigel Williams also adapted Lord of the Flies for the stage in a strikingly powerful version that has helped sustain the novel’s afterlife.

Three more From William Golding

The Inheritors (1955); The Spire (1964); Rites of Passage (1980)

Kate Mosse will be talking to Robert McCrum about the selection process for his 100 best novels series at Kings Place, London on 18 February, 7-8.30pm (£10). See membership.theguardian.com/events for details . Lord of the Flies is available in paperback from Faber, £7.99. Click here to buy it for £6.39

- William Golding

- The 100 best novels

Comments (…)

Most viewed.

Notice: All forms on this website are temporarily down for maintenance. You will not be able to complete a form to request information or a resource. We apologize for any inconvenience and will reactivate the forms as soon as possible.

Book Review

Lord of the flies.

- William Golding

- Coming-of-Age

Readability Age Range

- Riverhead Books, a division of Penguin Group

Year Published

This coming-of-age book by William Golding is published by Riverhead Books, a division of Penguin Group and is written for ages 13 and up. The age range reflects readability and not necessarily content appropriateness.

Plot Summary

When a plane wreck strands a group of British boys on a tropical island without adults, the children initially revel in their freedom and try to develop a society by holding assemblies, appointing hunters, and tending a signal fire to alert passing ships. It isn’t long before their “savage natures” take over; they argue, paint their faces and hunt bloodthirstily, eventually even killing some of their own. They fear and stalk “the Beast,” whom they believe to be a dangerous creature on the island. In fact, there is no such animal — their anxiety about the Beast symbolizes their fear of the emerging monster within each of them. In the end, they are rescued and returned to the “civilized” world — a world in the throes of a war.

Christian Beliefs

Literary critics consider Simon a “Christ figure.” He demonstrates compassion for his fellow man and looks for goodness in a rapidly-declining civilization. His conversation with The Lord of the Flies (which is a rotting pig’s head the boys have left as an offering to the Beast) is likened to the temptation Christ experienced during his fasting in the wilderness (Matthew 4:1-11). The loss of innocence the boys experience is sometimes compared to the fall of man (Genesis 3:1-21).

Other Belief Systems

Lord of the Flies contrasts democracy and anarchy.

Authority Roles

The boys initially elect Ralph as their chief; he chooses Jack and Simon to assist him. Ralph’s primary concern is to keep a signal fire going in case a ship passes; he tries to maintain order and structure within the group. As Jack’s lust for hunting and blood increases, he convinces most of the boys to join a new tribe under his leadership. He is dominating and brutal, rousing the boys to kill pigs and, eventually, other humans for sport.

Profanity & Violence

Ralph makes fun of Piggy’s asthma ( a—-mar ). Characters use God’s name in vain, and d–n you once or twice. Violence intensifies as the characters become less civilized: First they kill pigs with spears, enjoying the pigs’ squealing and blood. They often dance and chant, “Kill the pig. Cut her throat. Spill her blood. Bash her in.” They even spear the head of one pig, leaving it as an offering for the Beast. By the end, boys are killing other boys by mobbing and hunting them, simply because they “get caught up” in the frenzy of their savage rituals.

Sexual Content

Discussion topics.

Get free discussion questions for this book and others, at ThrivingFamily.com/discuss-books .

Additional Comments

Golding was awarded the 1983 Nobel Prize in literature.

You can request a review of a title you can’t find at [email protected] .

Book reviews cover the content, themes and worldviews of fiction books, not their literary merit, and equip parents to decide whether a book is appropriate for their children. The inclusion of a book’s review does not constitute an endorsement by Focus on the Family.

Latest Book Reviews

Elf Dog and Owl Head

A Court of Frost and Starlight (A Court of Thorns and Roses Series)

Fog & Fireflies

The Minor Miracle: The Amazing Adventures of Noah Minor

The Eyes and the Impossible

Weekly reviews straight to your inbox.

The Literary Edit

Review: Lord of the Flies – William Golding

When I was about fourteen, one of my best friends Sian and I gate crashed a year-ten drama trip to a near by theatre to watch Lord of the Flies. I remember little of the play itself other than the deeply unsettling feeling I was left with when the curtains closed. Thus upon discovering that William Golding’s Lord of the Flies was featured on the BBC’s Big Read, I was somewhat reluctant to read it. However, having been recommended it by my cousin Hal, and upon finding a battered copy in a book shop near my work, I decided to give it a go.

Published in 1954, Lord of the Flies is a dystopian novel by nobel-prize winning English author William Golding, about a group of boys stuck on an uninhabited island who try to govern themselves with disastrous results. When it was first published, Golding’s debut novel suffered from poor sales but when re-released in the 1960s it went on to be a best-seller, and soon became required reading in many schools and colleges.

The main protagonists are Ralph, Piggy, Roger, Jack and Simon all of whom are vividly portrayed throughout the novel. Ralph is chief of the group; Piggy, poor-sighted and overweight is his side-kick, Roger is one of the first to develop animalistic tendencies, Jack epitomises the worst aspects of human nature while Simon is a representation of peace and tranquility.

The novel follows the boys as they try to survive on the island by implementing a set of rules and regulations to follow. However, as the rules disintegrate, Jack forms his own tribe of terror, and events in the book progress from simple bullying to stylised animal rape and eventually murder. Golding effectively uses these episodes to explore the darkness of man’s heart, and the novel can show us what we are capable of in a similar situation.

A chilling yet compelling read with stunning imagery and great use of symbolism, Lord of the Flies is both a great piece of literature and a dire warning about humanity.

About Lord of the Flies

At the dawn of the next world war, a plane crashes on an uncharted island, stranding a group of schoolboys. At first, with no adult supervision, their freedom is something to celebrate; this far from civilization the boys can do anything they want. Anything. They attempt to forge their own society, failing, however, in the face of terror, sin and evil. And as order collapses, as strange howls echo in the night, as terror begins its reign, the hope of adventure seems as far from reality as the hope of being rescued. Labeled a parable, an allegory, a myth, a morality tale, a parody, a political treatise, even a vision of the apocalypse, Lord of the Flies is perhaps our most memorable tale about “the end of innocence, the darkness of man’s heart.”

About William Golding

Sir William Gerald Golding was a British novelist, poet, and playwright best known for his 1954 novel Lord of the Flies.

Golding spent two years in Oxford focusing on sciences; however, he changed his educational emphasis to English literature, especially Anglo-Saxon. During World War II, he was part of the Royal Navy which he left five years later. His bellic experience strongly influenced his future novels. Later, he became a teacher and focused on writing.

Some of his influences are classical Greek literature, such as Euripides, and The Battle of Maldon , an Anglo-Saxon oeuvre whose author is unknown. The attention given to Lord of the Flies , Golding’s first novel, by college students in the 1950s and 1960s drove literary critics’ attention to it.

He was awarded the Booker Prize for literature in 1980 for his novel Rites of Passage, the first book of the trilogy To the Ends of the Earth. He was awarded the Nobel Prize for Literature in 1983 and was knighted in 1988.

Love this post? Click here to subscribe.

2 comments on “Review: Lord of the Flies – William Golding”

the story shows us the Brutal Truth of life. Normally people blame the society, that because of the society they became evil. But the story tells us that There is evil inside us, sooner or later, we all have to face it.

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

This site uses Akismet to reduce spam. Learn how your comment data is processed .

- Bibliotherapy Sessions

- In the press

- Disclaimer + privacy policy

- Work with me

- The BBC Big Read

- The 1001 Books to Read Before You Die

- Desert Island Books

- Books by Destination

- Beautiful Bookstores

- Literary Travel

- Stylish Stays

- The Journal

- The Bondi Literary Salon

Julia's books

Sharing my passion for books with views, news and reviews

Book review – “Lord of the Flies” by William Golding

When I announced that this book was May’s choice for my Facebook reading challenge (theme, a 20 th century classic), there were mixed feelings – it seems a few of our participants had studied it at school for their ‘O’ level English Literature (predecessor to the GCSE for anyone young enough not to know!). Some were delighted…others less so! I did not study this at school, but I read it at University (I did an English degree). My childhood home was not one filled with books, though I spent a great deal of time at my local library, so when I went to University I had a lot of catching up to do on many of the classics. Golding’s book is one of those and is widely considered to be one of the all-time great novels.

Lord of the Flies was Golding’s first novel, published in 1954. I doubt many people could name any of his other works (I couldn’t!), although he won the Booker Prize in 1980 for his novel Rites of Passage , and the Nobel Prize for Literature in 1983. He died in 1993 at the age of 81. Lord of the Flies has been adapted three times for the big screen, and several times for stage and radio.

The basic plot is that a group of boys (thought to number about thirty, but it’s not entirely clear) are marooned on a Pacific island following a wartime evacuation attempt that ends in a plane crash. There are no adult survivors and the boys, ranging in age from perhaps nine to thirteen years, must learn quickly to survive. Three main characters emerge: Ralph and Jack are the two alpha-males of the group, but have very different instincts about the priorities, and Piggy, an overweight, severely near-sighted boy, probably of lower class than Ralph and Jack, who proves to be the most thoughtful, sensible and self-aware but who lacks the leadership skills to wield any power.

Initially, the boys attempt to organise, with Ralph at the helm. His primary concern is that they should get rescued and stay alive and safe until then. He meets resistance in the form of Jack, who is less keen on the rules and disciplines that Ralph wants to impose. His priorities are “fun” and hunting animals so that they can eat meat. As the days and weeks pass morale drops, particularly among the younger boys, many of whom are clearly terrified. They fear the darkness and the heavy forest on the island and what may be lurking within it – they imagine a terrible beast. Order begins to break down and powerful instincts surface. There is a terrible power struggle between Jack and Ralph which intensifies as the novel progresses. Factions form around the two leaders and the behaviours become increasingly reckless. Simon, one of the other older boys, and a sensitive soul, is killed in a case of mistaken identity, the now savage and adrenalin-fuelled group around Jack believing in his night-time approach to the camp, that he is in fact the much-feared “beast” they imagine stalks them.

Simon’s death at the hands of those who were once his schoolmates, unleashes further savagery, like the genie is out of the bottle. There is also, however, a kind of denial; it seems only Piggy recognises and is able to articulate the danger they are in – from themselves! It seems inevitable that Piggy should also die, brutally; Roger crashes a boulder onto him during a fight between Ralph and Jack in which Piggy is trying to intervene. Jack’s group would have killed Ralph too had it not been for the timely arrival of a rescue ship.

Although it was written in the early 1950s, this is very much a post-war book for me in which the author is reflecting on the base levels human beings can reach. If you simply scratch the surface of society you will find some instincts most of us would rather not admit to. A modern reading of the novel might also see the hazards of excessive masculinity and how lust for power can easily corrupt. You can also look at how easy it is for followers to forget their own moral codes and normal standards of behaviour when seduced by charismatic or persuasive leadership. The younger boys are unable to face the reality of their situation, stranded on a remote island, with an unknown chance of rescue, and the picture of excitement that Jack offers, playing at hunting, escapism from their problems, leads them to follow him down a dangerous path.

Whilst re-reading this book, I couldn’t help thinking about the current political turmoil we are in, both in the UK and globally. Some social norms seem to me to be breaking down. And when it came to the Jack/Ralph power struggle the Conservative party leadership contest came to mind! The only thing I couldn’t decide – who in our current crop of politicians is Piggy?!

A must-read for anyone wanting to gain a serious understanding of English literature.

Did you read Lord of the Flies as a teenager – can you remember what you thought of it?

If you have enjoyed this post, I would love for you to follow my blog. Let’s also connect on social media.

Share this:

Author: Julia's books

Reader. Writer. Mother. Partner. Friend. Friendly. View all posts by Julia's books

6 thoughts on “Book review – “Lord of the Flies” by William Golding”

Wonderful review. I have my stack of Golding’s books (13, in total!) waiting for me. Your review reminded me that I must get to them soon.

Thank you. Yes, I’m ashamed not to have read any of Golding’s other work….

Like Liked by 1 person

- Pingback: Facebook reading challenge – join us in June – Julia's books

This is one, as you say, everyone groaned over being assigned to read in school. But I’ve never known anyone who did read it that wasn’t completely captivated by it. It would be interesting to read again now, to see what I’d get from it now as an adult.

I agree. You also get a different perspective from being at a different stage in life.

- Pingback: Audiobook review – “The New Wilderness” by Diane Cook – Julia's books

Leave a comment Cancel reply

- Already have a WordPress.com account? Log in now.

- Subscribe Subscribed

- Copy shortlink

- Report this content

- View post in Reader

- Manage subscriptions

- Collapse this bar

- ADMIN AREA MY BOOKSHELF MY DASHBOARD MY PROFILE SIGN OUT SIGN IN

Awards & Accolades

Our Verdict

IndieBound Bestseller

LORD OF THE FLIES

by William Golding ‧ RELEASE DATE: Jan. 1, 1954

Pub Date: Jan. 1, 1954

ISBN: 0399501487

Page Count: 212

Publisher: Coward-McCann

Review Posted Online: Nov. 2, 2011

Kirkus Reviews Issue: June 15, 1955

TEENS & YOUNG ADULT LITERARY FICTION | TEENS & YOUNG ADULT GENERAL TEEN

Share your opinion of this book

More by William Golding

BOOK REVIEW

by William Golding

More About This Book

PERSPECTIVES

ZERO O'CLOCK

by C.J. Farley ‧ RELEASE DATE: Sept. 7, 2021

Commendable ambition that may help readers look forward.

Already reeling from loss, a Black high school senior brings her OCD, anxiety, and depression into March 2020.

In the early stages of the Covid-19 pandemic, Gethsemane Montego is a musical-theater–loving, BTS-fangirling, 16-year-old senior at New Rochelle High School. She and her two best friends—Jewish Korean valedictorian Tovah and Cuban American star quarterback Diego—attend the same high school where Geth’s security guard father died tragically three years ago during a shooting. Geth resents how quickly her mother has moved on—with a White man, at that—but, as best they can, her friends help her manage the increases in her anxiety and compulsions as well as her stifling grief. Awaiting admission results from Columbia is an added stressor, but as the coronavirus case numbers quickly shoot up, Geth faces multiple burdens and traumas. Police violence, racial inequity, hyperpartisanship, immigration, economic anxieties, and a complicated coming-out story all pile on top of the pandemic’s hefty body count. Geth is a likable, smart Gen Z protagonist in this modern epistolary work that combines diary entries, text messages, news reports, emails, and English lit essays to immersive effect. Wringing so much content, so much hurt, into a YA novel is a tall order that yields very mixed results. Still, whether through cutting humor or disparate political perspectives, Farley offers readers undeniable value in this retelling of recent, unforgettable history.

Pub Date: Sept. 7, 2021

ISBN: 978-1-61775-975-8

Page Count: 288

Publisher: Black Sheep Press

Review Posted Online: June 23, 2021

Kirkus Reviews Issue: July 15, 2021

TEENS & YOUNG ADULT FICTION | TEENS & YOUNG ADULT LITERARY FICTION | TEENS & YOUNG ADULT SOCIAL THEMES | LITERARY FICTION

More by C.J. Farley

by C.J. Farley

by C.J. Farley ; illustrated by Yongjin Im

by Elana K. Arnold ‧ RELEASE DATE: Feb. 25, 2020

A timely and unabashedly feminist twist on a classic fairy tale.

Sixteen-year-old Bisou Martel’s life takes a profound turn after encountering an aggressive wolf.

Following an embarrassing incident between Bisou and her boyfriend, James, after the homecoming dance, a humiliated Bisou runs into the Pacific Northwest woods. There, she kills a giant wolf who viciously attacks her, upending the quiet life she’s lived with her Mémé, a poet, since her mother’s violent death. The next day it’s revealed that her classmate Tucker— who drunkenly came on to her at the dance—was found dead in the woods with wounds identical to the ones Bisou inflicted on the wolf. When she rescues Keisha, an outspoken journalist for the school paper, from a similar wolf attack, Bisou gains an ally, and her Mémé reveals her bloody and brave legacy, which is inextricably tied to the moon and her menstrual cycle. Bisou needs her new powers in the coming days, as more wolves lie in wait. Arnold ( Damsel , 2018, etc.) uses an intriguing blend of magic realism, lyrical prose, and imagery that evokes intimate physical and emotional aspects of young womanhood. Bisou’s loving relationship with gentle, kind James contrasts with the frank exploration of male entitlement and the disturbing incel phenomenon. Bisou and Mémé seem to be white, Keisha is cued as black, James has light-brown skin and black eyes, and there is diversity in the supporting cast.

Pub Date: Feb. 25, 2020

ISBN: 978-0-06-274235-3

Page Count: 368

Publisher: Balzer + Bray/HarperCollins

Review Posted Online: Nov. 18, 2019

Kirkus Reviews Issue: Dec. 15, 2019

TEENS & YOUNG ADULT SCIENCE FICTION & FANTASY | TEENS & YOUNG ADULT LITERARY FICTION | TEENS & YOUNG ADULT SOCIAL THEMES

More by Elana K. Arnold

by Elana K. Arnold ; illustrated by Dung Ho

by Elana K. Arnold ; illustrated by Magdalena Mora

by Elana K. Arnold

- Discover Books Fiction Thriller & Suspense Mystery & Detective Romance Science Fiction & Fantasy Nonfiction Biography & Memoir Teens & Young Adult Children's

- News & Features Bestsellers Book Lists Profiles Perspectives Awards Seen & Heard Book to Screen Kirkus TV videos In the News

- Kirkus Prize Winners & Finalists About the Kirkus Prize Kirkus Prize Judges

- Magazine Current Issue All Issues Manage My Subscription Subscribe

- Writers’ Center Hire a Professional Book Editor Get Your Book Reviewed Advertise Your Book Launch a Pro Connect Author Page Learn About The Book Industry

- More Kirkus Diversity Collections Kirkus Pro Connect My Account/Login

- About Kirkus History Our Team Contest FAQ Press Center Info For Publishers

- Privacy Policy

- Terms & Conditions

- Reprints, Permission & Excerpting Policy

© Copyright 2024 Kirkus Media LLC. All Rights Reserved.

Popular in this Genre

Hey there, book lover.

We’re glad you found a book that interests you!

Please select an existing bookshelf

Create a new bookshelf.

We can’t wait for you to join Kirkus!

Please sign up to continue.

It’s free and takes less than 10 seconds!

Already have an account? Log in.

Trouble signing in? Retrieve credentials.

Almost there!

- Industry Professional

Welcome Back!

Sign in using your Kirkus account

Contact us: 1-800-316-9361 or email [email protected].

Don’t fret. We’ll find you.

Magazine Subscribers ( How to Find Your Reader Number )

If You’ve Purchased Author Services

Don’t have an account yet? Sign Up.

Book Review: The Lord of the Flies by William Golding

By: Author Laura

Posted on Published: 27th April 2022 - Last updated: 12th April 2024

Categories Book Reviews , Books

Wondering whether Lord of the Flies by William Golding is worth your time? This Lord of the Flies book review explains why you should read this short classic!

Lord of the Flies Summary

William Golding’s Lord of the Flies is a dystopian classic. When a group of schoolboys are stranded on a desert island, what could go wrong?

A plane crashes on a desert island. The only survivors are a group of schoolboys. By day, they discover fantastic wildlife and dazzling beaches, learning to survive; at night, they are haunted by nightmares of a primitive beast.

Orphaned by society, it isn’t long before their innocent childhood games devolve into a savage, murderous hunt …

Lord of the Flies Book Review

Lord of the Flies is a book that had been on my TBR (to-be-read pile) forever. I first read this in my mid-twenties and wish I had studied this at school, which is where most readers encounter this.

It’s all about a group of schoolboys who become stranded on a desert island. But don’t let the young ensemble lead you into thinking this is a children’s book. Lord of the Flies is a lot darker than I imagined and I was horrified at some of the events and scenes that took place.

At first, the young boys attempt to mimic an orderly adult society on the island. They group together to keep a fire lit so that any passing ships will see the smoke from the island.

But without any adults to supervise them, the boys begin to become violent, cruel and brutal in their bid to survive.

The small society they have attempted to build on this remote island eventually descends into chaos, prompting the reader to question the capacity for supposedly civilised humans to be savage.

And trust me when I say the ending really is just that – savage.

Although Lord of the Flies is a relatively simple tale, Golding’s writing is rich and the symbolism is clever. This story aims to show how savage humans can be when left to their own devices and there’s no order or morals.

Although Golding uses the island setting to demonstrate this point, this book leaves you feeling uncomfortable as you start to realise that man in a “civilised” society may not be any better.

Golding reminds us that we all have the capacity for darkness and cruelty. This story stays with readers long after they have turned the last page because it is so haunting. And it’s haunting because it’s clear that this could so easily happen in the society we live in today.

It also poses the interesting political question of democracy vs authoritarianism. Should we be forced to follow someone who is deemed to be a “rational” or “moral” leader, or be allowed to follow whoever presents a view that most aligns with our desires, whatever they may be.

Lord of the Flies is a classic for a reason. It’s well worth a read and really quite readable as classics go. If you’re looking for an short classic book to get yourself into reading classics then Lord of the Flies is a great book to start with.

Reading this book is also important so that you understand some Lord of the Flies references that get bandied about in conversation on occasion. Who are Ralph and Piggy? And what is a conch?

If you haven’t read this classic book yet then add this to your book wishlist ASAP. It’s chilling, but well-written and a good read.

Lord of the Flies Quotes

“Maybe there is a beast… maybe it’s only us.”

“The thing is – fear can’t hurt you any more than a dream.”

“We did everything adults would do. What went wrong?”

“The greatest ideas are the simplest.”

“What are we? Humans? Or animals? Or savages?”

“We’ve got to have rules and obey them. After all, we’re not savages. We’re English, and the English are best at everything.”

Buy Lord of the Flies now: Amazon | Waterstones | Blackwells

If you liked this post, check out these: Books Like The Hunger Games Books Like The Handmaid’s Tale Young Adult Dystopian Books for Teens 15 Gothic Books to Read

Editor of What’s Hot?

FAVBOOKSHELF

Tuesday 30th of August 2022

absolutely adored the review! got convinced to pick it up by the end of the review and the quotes were definitely a cherry on top.

matthew atkinson

Tuesday 3rd of May 2022

What a great review...exactly what i was thinking but was unable to put that into writing! I didn't study this book at school either, i was i had, quite a strange and brutal read and setting.

Themes and Analysis

Lord of the flies, by william golding.

Lord of the Flies by William Golding is a powerful novel. It's filled with interesting themes, thoughtful symbols, and a particular style of writing that has made it a classic of British literature.

Article written by Lee-James Bovey

P.G.C.E degree.

Several key themes are prevalent throughout the book. It is sometimes referred to as a “book of ideas” and these ideas are explored as the plot unfolds.

Lord of the Flies Themes

The impact of humankind on nature.

This is evident from the first chapter when the plane crashing leaves what Golding describes as a “scar” across the island. This idea is explored further in the early chapters the boys light a fire that escapes their control and yet further diminishes what might be considered an unspoiled island. Some interpret the island almost as a Garden of Eden with the children giving in to temptation by slaughtering the animals there. The final chapter furthers the destruction of nature by mankind as the whole island appears to have been ruined thanks to the effects of the boy’s presence on the island.

Civilization versus savagery

This can be seen throughout as the boys struggle with being removed from organized society. To begin with, they cope well. They construct a form of government represented by the conch that theoretically draws them together and gives them all a voice. As they break away from society this adherence to the rules they have constructed is evident. Golding’s ideas of what savagery is might be outdated and rooted in colonial stereotypes but they are evident for all to see as the boys use masks to dehumanize themselves and their increasing obsession with hunting leads to an increasingly animalistic nature.

Nature of humanity

Perhaps the biggest underlying theme is the idea of the true nature of mankind. Golding explores the idea that mankind is innately evil and that it is only the contrast between society and civilization that prevents that nature from being prevalent. Of course, this overlooks that civilization is a human construct and if all men’s biggest motivation were their inner evil, then that construct would never have existed. Golding’s views largely spring from his role in the navy where he was witness to the atrocities of war but are also informed by his work as a teacher.

Analysis of Key Moments in Lord of the Flies

There are many key moments in ‘ Lord of the Flies ‘ that highlight the boy’s descent into savagery.

- Blowing the conch – this introduces us to the conch which acts as a symbol of society and civilization throughout the novel. It is both the device that brings the children together and in theory the object which allows them all to have a say and therefore run a democratic society.

- The fire gets out of control – This shows the effects that the boys are already having on the island. It also demonstrates how lost the boys are without adults there to guide them as they lose one of the boys and nobody even knows his name.

- Jack fails to kill the pig/Roger throws stones – both of these events show how the boys are currently constrained by the expectations of society. We see as time passes these restraints are lifted and that firstly, Jack can kill a pig and finally, and perhaps more dramatically, Roger is not only okay with hitting somebody with a stone but taking their life with one.

- The hunters put on masks – By covering up their faces, they seem to become free from the constraints of society. It is if it liberates them from humanity and allows them to act on more primal, animalistic urges.

- Sam and Eric find “the beast” – When Sam and Eric feel they have discovered the beast it sets a ripple of panic throughout. This fear sways the boys towards Jack’s leadership as he continues to manipulate the situation to his advantage. If not for this then Simon might never be murdered.

- Creating of the Lord of the Flies – Successfully killing the pig is itself an iconic moment but then leaving a pigs head on a pole is both a gruesome image (one worthy of the book’s title) and also plays a pivotal role in Simon’s story arc.

- Simon’s death – Simon is the one character who never seems to succumb to primal urges and therefore his death if looked at symbolically could be seen as the death of hope for boys.

- Piggy’s death – Piggy’s character represents order and reason. With his death, any chance of resolving the issues between Jack and Ralph vanishes. The conch being smashed at the same time is also symbolic and represents the complete destruction of society.

- The rescue – This is not the happy ending that one might expect with all the boys crying due to their loss of innocence. There is an irony as well as the boys will not be rescued and taken to a Utopia but rather to a civilization plagued by a war that mirrors the war zone they have just left.

Style, Literary Devices, and Tone in Lord of the Flies

Throughout this novel, Golding’s style is straightforward and easy to read. There are no lengthy passages nor does he choose particularly poetic words to describe the events. His writing is powerful without these stylistic devices. The same can be said for his use of literary devices. When used, they are direct. For example, the use of symbolism (see below) and metaphor is very thoughtful but not hard to interpret.

William Golding also employs an aloof or distant tone throughout the book. This reflects the way that the boys treat one another.

Symbols in Lord of the Flies

The conch shell.

The conch shell is one of the major symbols of this novel. It’s used from the beginning of the novel to call the boys together for meetings on the beach. It’s a symbol of civilization and government. But, as the boys lose touch with their civilized sides, the conch shell is discarded.

The Signal Fire

The signal fire is a very important symbol in the novel. It’s first lit on the mountain and then later on the beach with the intent of attracting the attention of passion ships. The fire is maintained diligently at first but as the book progresses and the boys slip farther from civilization, their concentration on the fire wanes. They eventually lose their desire to be rescued. Therefore, as one is making their way through the book, gauging the boys’ concentration on the fire is a great way to understand how “civilized” they are.

The beast is an imaginary creature who frightens the boys. It stands in for their savage instincts and is eventually revealed to be a personification of their dark impulses. It’s only through the boy’s behaviour that the beast exists at all.

What are three themes in Lord of the Flies ?

Three themes in ‘ Lord of the Flies ‘ are civilization vs. savagery, the impact of humankind on nature, and the nature of humanity.

What is the main message of the Lord of the Flies ?

The main message is that if left without rules, society devolves and loses its grasp on what is the morally right thing to do. this is even the case with kids.

How does Ralph lose his innocence in Lord of the Flies ?

He loses his innocence when he witnesses the deaths of Simon and Piggy. These losses in addition to the broader darkness of the island change him.

Join Our Community for Free!

Exclusive to Members

Create Your Personal Profile

Engage in Forums

Join or Create Groups

Save your favorites, beta access.

About Lee-James Bovey

Lee-James, a.k.a. LJ, has been a Book Analysis team member since it was first created. During the day, he's an English Teacher. During the night, he provides in-depth analysis and summary of books.

About the Book

Discover literature and connect with others just like yourself!

Start the Conversation. Join the Chat.

There was a problem reporting this post.

Block Member?

Please confirm you want to block this member.

You will no longer be able to:

- See blocked member's posts

- Mention this member in posts

- Invite this member to groups

Please allow a few minutes for this process to complete.

Lord of the Flies: A Critical History

- Study Guides

- Authors & Texts

- Top Picks Lists

- Best Sellers

- Plays & Drama

- Shakespeare

- Short Stories

- Children's Books

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/aburgess3-5c13d94246e0fb0001329055.jpg)

- Ph.D., English Language and Literature, Northern Illinois University

- M.A., English, California State University–Long Beach

- B.A., English, Northern Illinois University

“The boy with the fair hair lowered himself down the last few feet of rock and began to pick his way toward the lagoon. Though he had taken off his school sweater and trailed it now from one hand, his grey shirt stuck to him and his hair was plastered to his forehead. All round him the long scar smashed into the jungle was a bath of head. He was clambering heavily among the creepers and broken trunks when a bird, a vision of red and yellow, flashed upwards with a witch-like cry; and this cry was echoed by another. ‘Hi!’ it said. ‘Wait a minute’” (1).

William Golding published his most famous novel, Lord of the Flies , in 1954. This book was the first serious challenge to the popularity of J.D. Salinger’s Catcher in the Rye (1951) . Golding explores the lives of a group of schoolboys who are stranded after their airplane crashes on a deserted island. How have people perceived this literary work since its release sixty years ago?

The History of Lord of the Flies

Ten years after the release of Lord of the Flies, James Baker published an article discussing why the book is more true to human nature than any other story about stranded men, such as Robinson Crusoe (1719) or Swiss Family Robinson (1812) . He believes that Golding wrote his book as a parody of Ballantyne’s The Coral Island (1858) . Whereas Ballantyne expressed his belief in the goodness of man, the idea that man would overcome adversity in a civilized way, Golding believed that men were inherently savage. Baker believes that “life on the island has only imitated the larger tragedy in which the adults of the outside world attempted to govern themselves reasonably but ended in the same game of hunt and kill” (294). Ballantyne believes, then, that Golding’s intent was to shine a light on “the defects of society” through his Lord of the Flies (296).

While most critics were discussing Golding as a Christian moralist, Baker rejects the idea and focuses on the sanitization of Christianity and rationalism in Lord of the Flies. Baker concedes that the book does flow in “parallel with the prophecies of the Biblical Apocalypse” but he also suggests that “the making of history and the making of myth are [ . . . ] the same process” (304). In “Why Its No Go,” Baker concludes that the effects of World War II have given Golding the ability to write in a way he never had. Baker notes, “[Golding] observed first hand the expenditure of human ingenuity in the old ritual of war” (305). This suggests that the underlying theme in Lord of the Flies is war and that, in the decade or so following the release of the book, critics turned to religion to understand the story, just as people consistently turn to religion to recover from such devastation as war creates.

By 1970, Baker writes, “[most literate people [ . . . ] are familiar with the story” (446). Thus, only fourteen years after its release, Lord of the Flies became one of the most popular books on the market. The novel had become a “modern classic” (446). However, Baker states that, in 1970, Lord of the Flies was on the decline. Whereas, in 1962, Golding was considered “Lord of the Campus” by Time magazine, eight years later no one seemed to be paying it much notice. Why is this? How did such an explosive book suddenly drop off after less than two decades? Baker argues that it is in human nature to tire of familiar things and to go on new discoveries; however, the decline of Lord of the Flies , he writes, is also due to something more (447). In simple terms, the decline in popularity of Lord of the Flies can be attributed to the desire for academia to “keep up, to be avant-garde” (448). This boredom, however, was not the main factor in the decline of Golding’s novel.

In 1970 America, the public was “distracted by the noise and color of [ . . . ] protests, marches, strikes, and riots, by the ready articulation and immediate politicization of nearly all [ . . . ] problems and anxieties” (447). 1970 was the year of the infamous Kent State shootings and all talk was on the Vietnam War, the destruction of the world. Baker believes that, with such destruction and terror ripping apart at people’s everyday lives, one hardly saw fit to entertain themselves with a book that parallels that same destruction. Lord of the Flies would force the public “to recognize the likelihood of apocalyptic war as well as the wanton abuse and destruction of environmental resources [ . . . ]” (447).

Baker writes, “[t]he main reason for the decline of Lord of the Flies is that it no longer suits the temper of the times” (448). Baker believes that the academic and political worlds finally pushed out Golding by 1970 because of their unjust belief in themselves. The intellectuals felt that the world had surpassed the point in which any person would behave the way that the boys of the island did; therefore, the story held little relevance or significance at this time (448).

These beliefs, that the youth of the time could master the challenges of those boys on the island, are expressed by the reactions of school boards and libraries from 1960 through 1970. “ Lord of the Flies was put under lock and key” (448). Politicians on both sides of the spectrum, liberal and conservative, viewed the book as “subversive and obscene” and believed that Golding was out-of-date (449). The idea of the time was that evil spurred from disorganized societies rather than being present in every human mind (449). Golding is criticized once again as being too heavily influenced by Christian ideals. The only possible explanation for the story is that Golding “undermines the confidence of the young in the American Way of Life” (449).

All of this criticism was based on the idea of the time that all human “evils” could be corrected by proper social structure and social adjustments. Golding believed, as is demonstrated in Lord of the Flies , that “[s]ocial and economic adjustments [ . . . ] treat only the symptoms instead of the disease” (449). This clash of ideals is the main cause of the fall-off in popularity of Golding’s most famous novel. As Baker puts it, “we perceive in [the book] only a vehement negativism which we now wish to reject because it seems a crippling burden to carry through the daily task of living with crisis mounting upon crisis” (453).

Between 1972 and the early-2000s, there was relatively little critical work done on Lord of the Flies . Perhaps this is due to the fact that readers simply moved on. The novel has been around for 60 years, now, so why read it? Or, this lack of study could be due to another factor that Baker raises: the fact that there is so much destruction present in everyday life, no one wanted to deal with it in their fantasy time. The mentality in 1972 was still that Golding wrote his book from a Christian point of view. Perhaps, the people of the Vietnam War generation were sick of the religious undertones of an out-of-date book.

It is possible, also, that the academic world felt belittled by Lord of the Flies . The only truly intelligent character in Golding’s novel is Piggy. The intellectuals may have felt threatened by the abuse that Piggy has to endure throughout the book and by his eventual demise. A.C. Capey writes, “the falling Piggy, representative of intelligence and the rule of law, is an unsatisfactory symbol of fallen man ” (146).

In the late 1980s, Golding’s work is examined from a different angle. Ian McEwan analyzes Lord of the Flies from the perspective of a man who endured boarding school. He writes that “as far as [McEwan] was concerned, Golding’s island was a thinly disguised boarding school” (Swisher 103). His account of the parallels between the boys on the island and the boys of his boarding school is disturbing yet entirely believable. He writes: “I was uneasy when I came to the last chapters and read of the death of Piggy and the boys hunting Ralph down in a mindless pack. Only that year we had turned on two of our number in a vaguely similar way. A collective and unconscious decision was made, the victims were singled out and as their lives became more miserable by the day, so the exhilarating, righteous urge to punish grew in the rest of us.”

Whereas in the book, Piggy is killed and Ralph and the boys are eventually rescued, in McEwan’s biographical account, the two ostracized boys are taken out of school by their parents. McEwan mentions that he can never let go of the memory of his first reading of Lord of the Flies . He even fashioned a character after one of Golding’s in his own first story (106). Perhaps it is this mentality, the release of religion from the pages and the acceptance that all men were once boys, that re-birthed Lord of the Flies in the late 1980s.

In 1993, Lord of the Flies again comes under religious scrutiny . Lawrence Friedman writes, “Golding’s murderous boys, the products of centuries of Christianity and Western civilization, explode the hope of Christ’s sacrifice by repeating the pattern of crucifixion” (Swisher 71). Simon is viewed as a Christ-like character who represents truth and enlightenment but who is brought down by his ignorant peers, sacrificed as the very evil he is trying to protect them from. It is apparent that Friedman believes the human conscience is at stake again, as Baker argued in 1970.

Friedman locates “the fall of reason” not in Piggy’s death but in his loss of sight (Swisher 72). It is clear that Friedman believes this time period, the early 1990s, to be one where religion and reason are once again lacking: “the failure of adult morality, and the final absence of God create the spiritual vacuum of Golding’s novel . . . God’s absence leads only to despair and human freedom is but license” (Swisher 74).

Finally, in 1997, E. M. Forster writes a forward for the re-release of Lord of the Flies . The characters, as he describes them, are representational to individuals in everyday life. Ralph, the inexperienced believer, and hopeful leader. Piggy, the loyal right-hand man; the man with the brains but not the confidence. And Jack, the outgoing brute. The charismatic, powerful one with little idea of how to take care of anyone but who thinks he should have the job anyway (Swisher 98). Society’s ideals have changed from generation-to-generation, each one responding to Lord of the Flies depending on the cultural, religious, and political realities of the respective periods.

Perhaps part of Golding’s intention was for the reader to learn, from his book, how to begin to understand people, human nature, to respect others and to think with one’s own mind rather than being sucked into a mob-mentality. It is Forster’s contention that the book “may help a few grown-ups to be less complacent, and more compassionate, to support Ralph, respect Piggy, control Jack, and lighten a little the darkness of man’s heart” (Swisher 102). He also believes that “it is respect for Piggy that seems needed most. I do not find it in our leaders” (Swisher 102).

Lord of the Flies is a book that, despite some critical lulls, has stood the test of time. Written after World War II , Lord of the Flies has fought its way through social upheavals, through wars and political changes. The book and its author have been scrutinized by religious standards as well as by social and political standards. Each generation has had its interpretations of what Golding was trying to say in his novel.

While some will read Simon as a fallen Christ who sacrificed himself to bring us truth, others might find the book asking us to appreciate one another, to recognize the positive and negative characteristics in each person and to judge carefully how best to incorporate our strengths into a sustainable society. Of course, didactic aside, Lord of the Flies is simply a good story worth reading, or re-reading, for its entertainment value alone.

- 'Lord of the Flies' Overview

- 'Lord of the Flies' Summary

- Memorable Quotes From 'Lord of the Flies'

- 'Lord of the Flies' Themes, Symbols, and Literary Devices

- Lord of the Flies Book Profile

- 'Lord of the Flies' Quotes Explained

- 'Lord of the Flies' Characters: Descriptions and Significance

- Why Is 'Lord of the Flies' Challenged and Banned?

- 'Lord of the Flies' Questions for Study and Discussion

- 9 Must-Read Books If You Like 'Lord of the Flies'

- Biography of William Golding, British Novelist

- 10 Classic Novels for Teens

- 'Lord of the Flies' Vocabulary

- The Most Commonly Read Books in High School

- The 10 Most-Banned Classic Novels

- Must-Read Books If You Like 'The Catcher in the Rye'

- Politics & Social Sciences

- Politics & Government