Search The Canadian Encyclopedia

Enter your search term

Why sign up?

Signing up enhances your TCE experience with the ability to save items to your personal reading list, and access the interactive map.

- MLA 8TH EDITION

- Cook, Tim. "Documenting the First World War". The Canadian Encyclopedia , 05 May 2020, Historica Canada . www.thecanadianencyclopedia.ca/en/article/documenting-canadas-great-war. Accessed 16 May 2024.

- The Canadian Encyclopedia , 05 May 2020, Historica Canada . www.thecanadianencyclopedia.ca/en/article/documenting-canadas-great-war. Accessed 16 May 2024." href="#" class="js-copy-clipboard b b-md b-invert b-modal-copy">Copy

- APA 6TH EDITION

- Cook, T. (2020). Documenting the First World War. In The Canadian Encyclopedia . Retrieved from https://www.thecanadianencyclopedia.ca/en/article/documenting-canadas-great-war

- The Canadian Encyclopedia . Retrieved from https://www.thecanadianencyclopedia.ca/en/article/documenting-canadas-great-war" href="#" class="js-copy-clipboard b b-md b-invert b-modal-copy">Copy

- CHICAGO 17TH EDITION

- Cook, Tim. "Documenting the First World War." The Canadian Encyclopedia . Historica Canada. Article published August 01, 2014; Last Edited May 05, 2020.

- The Canadian Encyclopedia . Historica Canada. Article published August 01, 2014; Last Edited May 05, 2020." href="#" class="js-copy-clipboard b b-md b-invert b-modal-copy">Copy

- TURABIAN 8TH EDITION

- The Canadian Encyclopedia , s.v. "Documenting the First World War," by Tim Cook, Accessed May 16, 2024, https://www.thecanadianencyclopedia.ca/en/article/documenting-canadas-great-war

- The Canadian Encyclopedia , s.v. "Documenting the First World War," by Tim Cook, Accessed May 16, 2024, https://www.thecanadianencyclopedia.ca/en/article/documenting-canadas-great-war" href="#" class="js-copy-clipboard b b-md b-invert b-modal-copy">Copy

Thank you for your submission

Our team will be reviewing your submission and get back to you with any further questions.

Thanks for contributing to The Canadian Encyclopedia.

Documenting the First World War

Article by Tim Cook

Updated by Andrew McIntosh

Published Online August 1, 2014

Last Edited May 5, 2020

The First World War forever changed Canada. Some 630,000 Canadians enlisted from a nation of not yet eight million. More than 66,000 were killed. As the casualties mounted on the Western Front, an expatriate Canadian, Sir Max Aitken (Lord Beaverbrook), organized a program to document Canada’s war effort through art , photography and film . This collection of war art , made both in an official capacity and by soldiers themselves, was another method of forging a legacy of Canada’s war effort.

As a Dominion within the British Empire, Canada was automatically at war when Britain declared war on Germany on 4 August 1914. Yet Canada decided its level of commitment. Thousands of young men initially flocked to enlist. A First Contingent of more than 30,000 was sent overseas in October. Some 400,000 more would follow in the coming years.

The Canadian government of Prime Minister Sir Robert Borden scrambled to raise these new units. It gave little thought to documenting the epoch-changing event for future generations. At first, most Canadians felt the war would be over by Christmas . But the terrible fighting on the Western Front soon put that notion to rest. The armies on the front — Belgian, French, British, and German — were savaged by high explosives and small arms fire. As casualties mounted, progress on the front stagnated as armies dug into the ground to escape the slaughter.

For Canadians enlisting for King and Country, most were deeply proud of their service. Newly raised battalions and artillery batteries had their photographs taken in Canada or in England, often in large panoramic views of several hundred men. A few private entrepreneurs even used bulky motion picture cameras to capture the soldiers that marched and fired their Canadian-made Ross rifles at the main training camp at Valcartier, Quebec .

Sir Max Aitken and the Canadian War Records Office (CWRO)

The role of capturing the service and sacrifice of the new Canadian fighting forces fell to Sir Max Aitken (Lord Beaverbrook). Aitken was born in 1879 and raised in New Brunswick . From an early age, he had showed a command of business. By his early 30s, Aitken had made millions in Canada through a series of innovative and shady business deals involving the amalgamation of companies and the sale of their stock . He left Canada in 1910 under the cloud of a potential investigation into acts of corruption that involved watering down stock and pocketing enormous profits.

In Britain, Aitken won a seat in Parliament and began to buy up newspapers . He soon became an influential press baron who used his power and newspapers to support his conservative allies — including his friend Winston Churchill, who was serving as First Lord of the Admiralty (political overseer of the Royal Navy) — and destroy his enemies. At the start of the war, the influential Aitken was anxious to serve in the British Cabinet . However, no suitable position could be found for him, so he turned to his conservative friends in Canada, Sir Robert Borden and Minister of Militia and Defence Sam Hughes . They appointed Aitken to the newly created role of official Eye Witness, with the rank of lieutenant colonel.

No one was certain what an official Eye Witness was, but Aitken carved out the position in the Canadian military hierarchy. He would soon reveal himself to be a first class schemer, especially in pulling political and military strings to have his friends appointed to positions in the Canadian Expeditionary Force . But he also wished to raise the profile of his countrymen. He wrote to Borden about his goal, “to enshrine in a contemporary history those exploits which will make the First Division immortal.”

Photographs

British and Canadian soldiers at the front went largely unrecorded by photographers during the first two years of the war. The British high command had forbidden front line soldiers from bringing cameras into the trenches. While some Canadians clandestinely snapped pictures using hand-held Kodaks, there remain huge gaps in the photographic record of the early battles at Second Ypres (April 1915), Festubert (May 1915) and St. Eloi (April 1916). When the War Office and the British high command heard that Aitken sought to document the Canadian war effort, they attempted to block him; they feared potential leaks of secret and sensitive information. But the influential Aitken would not be deterred. He used his connections to overturn the British rules.

By April 1916, Aitken had established an official photographer , Captain Henry E. Knobel. He took powerful images of the Canadians on the Western Front. Knobel’s poor health forced his retirement the next year. He was replaced by Captain Ivor Castle and Lieutenant William Rider-Rider. From the summer of 1916 to the war’s conclusion, Canadian photographers shot more than 6,500 images of the destruction and heroism faced by Canadian soldiers.

In September 1916, the Canadians published — to much acclaim — the first photograph of a tank. However, it was not easy to get good photographs at the front. Cameras were fragile and the glass plate negatives were easily cracked. As one photographer noted, “You sit or crouch in the first-line trench while the enemy do a little strafing, and if you are lucky you get your pictures.”

Some Canadian photographers snapped pictures behind the lines and passed them off as authentic portrayals of infantry in front-line trenches, ready to go “over the top.” Castle was known to employ darkroom tricks that suppressed images or added airburst explosions. Sometimes multiple images were pieced together. Despite these manipulations, there are powerful views of mud-splattered men treading wearily to rear billets from a front-line tour; or of tired Canadian soldiers curled up in fetal positions.

In July 1917, more than 80,000 visitors paid to see the Canadian Official War Photographs exhibition in London. It further publicized the Canadian war effort. One of the most popular images was an enormous photographic canvas, measuring 22 x 11 feet (6.7 x 3.4 m), of Canadian soldiers storming Vimy Ridge in April 1917. The battle and the photographs would eventually become part of a celebrated Canadian war effort.

Art (The Canadian War Memorials Fund)

Sir Max Aitken also established an official art program through the Canadian War Memorials Fund. Artists were commissioned as honorary officers in the Canadian Expeditionary Force (CEF). Expenses were paid and paintings were to be exhibited. In return, after the war, the finished works and sketches were to be given as gifts to the Canadian government .

Canadians A.Y. Jackson , William Beatty , C.W. Simpson, Arthur Lismer , Frank Johnston and Frederick Varley were among those enlisted to paint the war. This rare opportunity had a profound influence on the artists’ subsequent careers and on the development of Canadian art. Jackson, Lismer, Johnston and Varley, for instance, would become members of the Group of Seven . Other artists, including Henrietta Mabel May, Dorothy Stevens , Frances Loring and Florence Wyle , were hired to paint and sculpt home front activities: from munitions workers to women toiling in the fields. ( See Representing the Home Front: The Women of the Canadian War Memorials Fund .)

In Europe, artists were encouraged to travel the front and witness the war firsthand, but all paintings were finished in studios behind the lines. Many of the works illustrate the machines of war and the shattered landscapes. But few artists were able to capture the horror of the struggle or the death of soldiers. The artists seemed to lack the “grammar” to depict such difficult scenes.

Frederick Varley ’s For What? is a notable exception. It is one of the darkest and most poignant renditions of the war. One grim figure leans heavily on his shovel in a blasted landscape. In the foreground is a wagon, piled high with corpses waiting to be buried. Varley wrote home to his wife: “your own countrymen unidentified, thrown into a cart… boys digging a grave in a land of yellow slimy mud and green pools of water under a weeping sky.”

Arthur Doughty went overseas in 1917 to work with Aitken ’s CWRO and British authorities. They ensured that official paper military records were being kept for future generations, and that Canada would receive war trophies from the battlefield. The Canadian Corps captured thousands of enemy artillery pieces and guns during its battles. These tangible representations of victory became important relics for the home front . After the war, 900 German field guns, 4,000 machine guns, 10,000 rifles and a handful of airplanes were sent back to Canada. They were displayed proudly in city halls, churches , libraries and, later, in Legion halls across the country.

The War Record Comes Home

“This strange attractive gnome with an odour of genius about him,” as Lady Diana Manners described Lord Beaverbrook , turned his enormous wealth, drive and commitment towards building a historical legacy of Canada’s war effort. During the war, the official photographers snapped more than 6,500 images; combat cameramen shot thousands of feet of film; and war artists created more than 1,000 paintings, prints and sculptures. The soldiers, too, gathered souvenirs and manufactured trench art, which formed personal archives across the Dominion . Canadians also left behind graffiti and carvings in trench walls and dugouts; some are preserved to this day in the tunnels beneath Vimy Ridge .

After the war, Lord Beaverbrook pressured the federal government to build a war museum for the art collection. He even spent his own money to hire an architect . The museum never went beyond the planning stage, as various governments in the 1920s struggled with the war’s crushing debt . As a result, most of the photographs, films and works of art languished unseen for decades. The official war trophies, however, were displayed proudly in cities, towns and villages across the country until the early years of the Second World War . At that point, many of the steel guns, mortars and machine guns were melted down and used again as weapons of war against the Nazis.

The creation of the Canadian War Museum in 1942, with new buildings added in 1967 and 2005, finally allowed much of the material to be displayed for all Canadians. These artifacts of war allow us to understand, interpret and engage with the long memory of Canada’s Great War.

See also: Representing the Home Front: The Women of the Canadian War Memorials Fund ; Documenting the Second World War ; Monuments of the First and Second World Wars ; Memorials and Honours .

Selected Works of Documenting the First World War

Collection: first world war.

- Second World War

- Lord Beaverbrook

- Group of Seven

- photography

- Sir Robert Borden

- war artists

- Film and Television

- armed forces

- chlorine gas

- Canadian Expeditionary Force

Further Reading

- Maria Tippett. Art at the Service of War: Canada, Art, and the Great War (1984).

- Laura Brandon, Art or Memorial?: The Forgotten History of Canada's War Art. (2006).

- Peter Robertson, Relentless Verity: Canadian Military Photographers Since 1885 (1973).

- Dean F. Oliver and Laura Brandon, Canvas of War: Painting the Canadian Experience, 1914 to 1945 (2000).

- Tim Cook, Clio’s Warriors: Canadian Historians and the Writing of the World Wars (2006).

External Links

First World War in Colour The images featured within this project highlight important battles in Canada’s history, but also life on the home front, wartime industries, the contributions of women, and advances in medical and communications technologies.

Recommended

First world war education guide, first world war timeline.

A window into the Canadian experience during the world wars

Education during the first world war.

Canada’s participation in the First World War has often been described as a coming-of-age – a trial by fire that transformed an immature colonial polity into an independent adult nation. Yet despite the ubiquity of these references to youthfulness and national maturation in Canadian narratives of the war, most histories of the conflict have ignored its effects on actual young people. Drawing on the primary sources found on this website and the small but growing body of scholarship on Canadian children, education, and war, this essay will ask how children and adolescents from across the country learned about the conflict between 1914 and 1918.

On the one hand, the war years were a time of unity and patriotism which many understood as proof of Canada’s importance to the British Empire and the world. But in a population characterized more by diversity than uniformity, these feelings of hope and national unity were often paralleled by contestation, prejudice and fear. The meanings and experiences of wartime therefore differed considerably for the children of enlisted men, German immigrants, interned Ukrainians, conscientious objectors, and the many French Canadians who opposed conscription. Aboriginal youngsters, meanwhile, had to contend with assimilatory education policies and the often divisive effects of the war in their own communities. While this paper will reflect the existing scholarship’s focus on English-Canadian children and education, it will also remain attentive to the ways in which young people’s experiences of wartime were determined by issues of gender, class, ethnicity, and community.

The fact that Canada, as part of the British Empire, was automatically at war following Britain’s declaration of war in August 1914 confounds many twenty-first century students. It would have made perfect sense, however, to early twentieth-century Canadian youths, most of whose educational experiences were profoundly shaped by their nation’s imperial ties. Before the war, most schoolchildren across the country were taught lessons that focused on patriotism, obedience, and loyalty to the British Empire. Formal education, which was compulsory in every province but Quebec, taught young Canadians to read, write, and calculate, but was also an attempt to teach a growing nation’s diverse young population about the ideals and practices of Anglo-Protestant citizenship. For many Canadian teachers and politicians, formal education was the perfect way to assimilate students whose origins weren’t British (a group that included included both Aboriginal youngsters and the children of immigrants from Asia, the United States, and central and eastern Europe). 1 As one English-Canadian Manitoba school inspector wrote, “these incongruous elements have to be assimilated, have to be welded into one harmonious whole if Canada is to attain the position that we, who belong here by right of birth and blood, claim for her. The chief instrument in this process of assimilation is the public school.” 2

While the demands of work and family meant that not all Canadian youngsters attended school all of the time, by 1914 over 80% of Canadian five to fourteen-year-olds (that’s 1.4 million young people) were attending public day schools. Even before the war, much of what they learned in History, Geography, and English classes focused on the British Empire and its military triumphs. Students read literary and historical accounts of brave warriors and epic battles, and they also learned about such Canadian chapters in the imperial story as Loyalism and Dominion participation in the recent South African War. Like the adventure novels and magazines that were popular with many children, Canadian textbooks often portrayed warfare (particularly when it supported the British Empire) as a glamorous and exciting pursuit. But not everyone approved: before the war, as Susan Fisher has shown, some Canadian pacifists – especially the Quakers – were critical of what they saw as the “militarist tendencies in Canadian education.” 3

In wartime, Canadian schools continued to emphasize imperial nationalism, military glory, loyalty, and obedience. Yet these values came to assume a new importance as teachers explained the conflict as a holy war – a fight for democracy, morality, the rights of small nations, and the very future of Britain’s empire. Service and sacrifice, demanded of soldiers and civilians alike, moved to the centre of the Canadian educational experience. The sacrifices made by teachers and former students who had enlisted – some of whom were killed in action – were frequently held up as examples of patriotism and selflessness that young people had a duty to emulate.

Patriotism – defined as enthusiastic support for the Allied war effort – occupied a central place in Canadian schools throughout the conflict, though Francophone schools in Quebec generally did not incorporate the war into lesson plans or activities. 4 The patriotic imperative applied to adults as well as children, and in several places, teachers were even required to swear oaths of loyalty to Britain. Teachers who refused to conform could face harsh punishments: at Toronto’s Annette Street Public School, for example, one teacher was fired in 1915 after several parents complained that he had expressed pro-German sentiments in class discussions of the war. 5

As the conflict continued, provincial Departments of Education and individual teachers developed new war-related teaching materials for students from elementary through to high school. In mathematics classes across the country, for instance, youngsters were regularly asked to calculate interest rates of Victory Bonds and to solve problems featuring Allied soldiers and German prisoners of war. In wartime, the clear division between right and wrong answers that characterized the teaching of arithmetic was also applied to humanities subjects, in an effort to convince young Canadians of the righteousness of the Allied cause. The Manitoba Department of Education’s 1917 Grade XI English Composition Exam, for example, included a compulsory question on “Canada and the War.” The sample answer supplied by the Department was as follows: “The Great War is being fought in the cause of liberty. On the one side the War may be called a war for conquest or plunder and on the other a war for freedom or liberty. It is not the safety of one state or nation that is at stake, it is the freedom of the world.” 6 The Imperial Order Daughters of the Empire, a women’s patriotic organization founded in the wake of the Boer War, also sponsored war-related essay contests (and expected similarly clear-cut answers) on topics including “Why the Empire is at War,” “Soldiers at the Front,” and “Canada in the Present War.” 7

In classrooms across the country, girls and boys also memorized details about European geography and military technology. Students at Havergal College, a private girls’ school in Toronto, made scrapbooks about the war as a way to stay on top of current events. Several of these scrapbooks survive in the school’s archives, and are a valuable record of what a few upper-middle-class Anglo-Canadian girls knew and thought about Canada’s Great War. In the pages of their scrapbooks, Havergal students drew and pasted images of airplanes, zeppelins, tanks, and trenches, and described various technical and tactical systems in detail. They also described significant battles and the causes of the war, in language that echoed the words used in school texts and Allied propaganda. One student, for example, explained that England entered the war because she “would not see other countries bullied, as Belgium was.” 8

Havergal students also documented the war’s effects on the city of Toronto, by photographing soldiers on parade and pasting these images into their scrapbooks. The war enthusiasm and excitement caused by sightings of men in uniform was also evident in the school’s 1916 yearbook. Describing a typical reaction to a group of soldiers marching past the school, one Havergal girl wrote: “The door bursts widely open, precipitating a score of loyal and enthusiastic patriots into the room, bearing all before them in their headlong haste to secure the best places at the window … ‘They’re going down Carlton,’ cries one; ‘No they aren’t, they’re coming down from Wellesley,’ cries another, while a third shouts, ‘They’re coming up Jarvis, here they come! Here they come!” 9

Students in public and private schools also learned about the conflict from The Children’s Story of the War , an ambitious set of books that has been called “the most important and most ambitious” of the numerous war-related textbooks that were produced during the conflict. Written by the well-known textbook writer and (from 1917) British MP Sir Edward Parrott, The Children’s Story of the War was published in fifty-six installments between 1915 and 1918. 10 A detailed and enormous series running to nearly 3000 pages, the complete Children’s Story was read in classrooms and homes across Canada, and was officially recommended by the Ontario Department of Education. Each volume featured detailed descriptions of battles and an unambiguous moral message. According to Anne Millar and Jeff Keshen, “it presented the war as an adventure, as a clash between good and evil, and as a succession of Allied triumphs typified by numerous acts of individual heroism.” The Children’s Story described countless acts of heroism by individual Allied soldiers, but it also sought to inspire students with tales of child heroes like twelve-year-old Louise Haumont, a girl who risked death to warn the commander of a French fort of an impending German attack. 11

Stories of young heroes and brave soldiers clearly appealed to young Canadians, but some adults struggled to find a balance between protecting children and promoting war. In 1916, for instance, a Hamilton teacher named Helena Booker raised this question in a letter to The School , a magazine for teachers published by the Faculty of Education at the University of Toronto. What should teachers, Booker wondered, “say about the present war to our primary classes? We feel a great reluctance to bring so unhappy a subject before such young minds. But what do they hear at home? Many times only words of hatred, ignorant tirades, useless bragging, equally vain of purpose and harmful in their imprint on young minds. So if we speak of war let it be with the sole purpose of teaching patriotism, a love of our own country, not a hatred of our enemies – a positive, not a negative, thing.”

The minority of citizens who opposed the war also expressed concern about the effects of war pedagogy on young Canadians. Pacifist and suffragist Gertrude Richardson used her writing in the socialist periodical Canadian Forward , for example, to warn readers about the dangers of a militarized curriculum. She urged Canadian mothers to monitor what their children were learning at school in order to keep “the bayonet and the rifle … [from] the hands of children to whom we try to teach the ideals of humanity and brotherhood.” Richardson was not alone in her concern, and after the war several pacifist groups including the Quaker Society of Friends and the Women’s International League for Peace and Freedom campaigned for the revision of all textbooks that depicted or glorified the war. 12

Textbooks weren’t the only things to be ‘militarized’ in Canadian schools during the war; young people also learned about the conflict through the activities they took part in, both inside and outside the classroom. Singing songs and acting in plays were no longer confined to Christmas concerts and special events; they too assumed new importance in wartime and were often explained as ways to both inspire and demonstrate young people’s patriotism and support for the Allies. This shift is especially evident in the twenty playlets (patriotic entertainments to be performed by children) written by Toronto educator Edith Groves between 1916 and 1918. Recommended to teachers in The School magazine, the Book Selection Guide , and the Ontario Library Review , Groves’s plays treated wartime themes with a combination of music, dialogue, and marching or drill. Like school textbooks, they celebrated heroism and sacrifice; they also featured anti-German content, as in one episode where the character of a young girl had to tell the audience not to buy dolls made in Germany because they were “Alien Enemies.” Patriotic plays and recitals were performed at at schools and community halls across the country, and proved to be an effective way to raise money for war charities.

Edith Groves’ wartime playlets were also likely performed on Empire Day, an annual celebration, established at the turn of the twentieth century, of the British Empire and Canada’s place in it. In school gymnasia and at larger events like the Toronto School Board’s annual Empire Day concert at Massey Hall, young people from across the country sang songs like “Rule Britannia,” acted out imperial battle scenes and the poems of Kipling, and waved thousands of small Union Jacks. During the first several decades of the twentieth century, Canadian students also celebrated Empire Day by marching in and watching military parades. In Ontario, for example, the Toronto Board of Education based its Empire Day festivities (which also featured a concert at Massey Hall where children from across the city sang patriotic songs) a parade of thousands of high school cadets from the University Avenue armouries to the provincial parliament buildings in Queen’s Park – an event that grew in size and symbolism from 1914 on. In an eerily prescient statement about Toronto’s 1907 Empire Day parade, Premier James Whitney told a reporter for The Globe that “in the children before him he saw the future soldiers of the Crown, who would defend all that the British Empire stood for throughout the world.” 13

Uniforms and marching were part of many schoolboys’ lives throughout the year, and had been since the late nineteenth century, when they were introduced as a way to strengthen their bodies and prepare for armed conflict. (While the outbreak of war surprised many Canadians in 1914, fears of a war with Germany had been building for some time, as shown for instance by the numerous early twentieth-century boys’ stories that dealt with German spies and invasion plots). Marching and military drill were taught in schools across Canada by the early twentieth century, and were often explained as effective ways to teach obedience, discipline, and respect for law and order. This emphasis on drill and martial training increased in 1909-10 with the foundation of the Strathcona Trust, a fund established by Canada’s then High Commissioner to Britain to promote physical training and create military cadet corps in schools across the country. 14

In addition to promoting obedience and strengthening bodies, cadet training in schools was also an effort to teach masculine behavior and ideals while assimilating boys from non-British backgrounds. As Ontario Minister of Education George Ross explained in 1909, cadet training was an ideal activity for male high school students; “no other form of drill,” he insisted, “so effectively develops a manliness of form and bearing, as well as physical force and independence.” Cadet training for boys and physical education for students of both sexes was also promoted as a way to improve the health of Canadians in general and the Anglo-Celtic “race” in particular. As Minister of Militia and Defence Sir Frederick Borden insisted in his annual report for 1908, “the instruction in proper breathing and bearing, as well as the healthful exercise imparted to boys and girls alike, cannot fail to … be of inestimable value to the welfare of our race in its effect upon future generations.” 15 The next year James Hughes, chief inspector of Toronto’s public schools, also explained military training as a good way to teach non-British immigrant youths about discipline and imperial loyalty. “Where we have so many foreign lads,” he opined, “I am sure the quickest and best way we can make them respect the British flag is to march them through the streets in uniform behind that flag.” 16 The meanings of “race” and military training, meanwhile, were different for Aboriginal youngsters: whereas Native adults were initially barred from enlisting in the Canadian Expeditionary Force, military-style training played an important part in many schools for Indigenous children both before and during the Great War. At the Mohawk Institute residential school in Brantford, Ontario, for example, teachers and school inspectors praised cadet training, drill, and rifle shooting as effective ways to assimilate Native youths to “Canadian” cultural norms while teaching them to follow tight schedules and obey orders. 17

By 1914, there were more than three times as many cadets as there were Boy Scouts in Canada. 18 The size and scope of the movement increased still more during the war years, and it began to focus on more explicitly military pursuits like rifle training. Cadets received praise from parents and teachers, were lauded in school newspapers and yearbooks, and their activities were proudly described in the annual reports of school boards and provincial Departments of Education.

Canadian children also learned about the war through consumer goods and popular culture. Like schoolbooks and patriotic drills, wartime consumer goods praised the Canadian contribution to the war, celebrated imperial unity, and demonized Austria-Hungary and particularly Germany. Many youngsters enjoyed collecting special wartime cigarette cards, colourful novelties that included images and detailed information about technology, weapons, battles, and Allied and enemy leaders. Manufacturers of other goods, such as the Cowan’s Royal Milk Chocolate Company, also produced collectible cards featuring games, trivia, and images of men in uniform.

Retailers across the country similarly recognized and sought to profit from young people’s enthusiasm for the conflict, and the wartime catalogues and shop windows of the T. Eaton Company featured a number of war-related goods aimed at children. These included tin soldiers, toy weapons, and child-sized military uniforms. The many surviving family photographs and postcards featuring children dressed in small army uniforms are a testament to the popularity of these consumer goods. But while most Canadians seem to have approved of war games and child-sized soldier suits, some others disapproved. One farm wife, writing to the Saturday Press and Prairie Farmer in 1916, expressed this opposition especially clearly: in a letter decrying the popularity of child-sized army uniforms, she stated that “it seems inconceivable that women should go on making soldiers of their children, instead of teaching them to hate war.” 19

While young people’s impressions of the war were shaped by school, consumer goods, and play, they also learned about the conflict on their own – by reading and listening to discussions among family members. Young people were avid and sometimes fearful consumers of propaganda tracts and published news reports about events in Western Europe, Russia, Africa, the Middle East, the Dardanelles, and the Balkans. Not surprisingly, atrocity propaganda (as disseminated in sermons, political speeches, newspaper articles, and dinner table conversations) seems to have made a particularly strong impression. In 1915, twelve-year-old Mary Chalmers, for example, asked members of the Young Canada Club (a children’s correspondence scheme run by The Grain Growers’ Guide ) if they too “fe[lt] sorry for the children with their hands cut off?” 20

Other books, aimed more specifically at children, sought to explain atrocity stories and other aspects of the war in ways that reassured children while downplaying violence and death. Stories about animals, with titles like The Tale of a Belgian Hare and Me’ow Jones: Belgian Refugee Cat , sought to explain the German invasion in ways that would both comfort children and inspire them to donate to Belgian war charities. Other books that sought to reassure North American readers include Lucy Fitch Perkins’ The Belgian Twins (1917) and The French Twins (1918), books that follow two sets of twins from their lives in the Belgian and French war zones to safety and love in the United States. Stories about young people foiling German spies were also abundant, though only one was published in Canada: Harold C. Lowrey’s Young Canada Boys with the S.O.S. on the Frontier (1918), a novel depicting a group of Boy Scouts who foil a German plot to blow up the Welland Canal. Books like this, which children would likely have read outside of school, shaped their understanding of the war; they also shaped the kinds of stories they wrote in the classroom. Twelve-year-old Fred Hunt of Victoria, for example, wrote a short story entitled “A Spy Hunt,” an account of a group of boys who catch a German spy ring in Canada. Hunt’s tale won first prize in a local contest, and was published in Victoria , the Victoria School District’s magazine for children. 21

Young people on the Canadian home front learned about the Great War in all aspects of their lives: at home, at school, and through propaganda and popular culture. Their understandings of the conflict, as shown in school yearbooks and their own letters and stories, were greatly influenced by the hopes, fears, and expectations of the adults in their lives. These hopes and fears continued to shape children’s formal and informal educational experiences after the war, as well, though in slightly different ways.

In the immediate aftermath of the conflict, much remained the same, as school cadet companies continued to march and parade, and teachers and textbooks continued to praise the British Empire and extol the virtues of martial sacrifice. Across the country, schools used a variety of means to commemorate the war and to honour former students who had made the ultimate sacrifice. Victoria High School in British Columbia, for example, planted an avenue of memorial trees and installed a war memorial in its main hallway. 22 At Jarvis Collegiate in Toronto, four students posed in their cadet uniforms for murals entitled “Patriotism” and “Sacrifice.” Student newspapers and documents in the school’s archives provide compelling evidence of what this mural meant to students: one student called Jarvis Collegiate’s memorial efforts a source of pride to “both staff and students,” and another stated that the unveiling service was “the most interesting and impressive ceremony in the history of our school.” Education and commemoration were also central to the IODE’s postwar work, which included the distribution of sets of War Memorial Pictures to schools (prints of paintings with titles like “The Surrender of the German Fleet”) and the establishment of the IODE War Memorial Scholarship Program, a scheme initially devised to assist the children of Canadian soldiers who had been killed or disabled in the Great War. 23 Young people whose relatives had been killed or injured during the war also learned about its aftereffects in private and more traumatic ways, which would shape many of their lives for decades to come.

Kristine Alexander, Canada Research Chair in Child and Youth Studies, University of Lethbridge

Suggested Reading Alexander, Kristine. “An Honour and a Burden: Canadian Girls and the Great War,” in A Sisterhood of Suffering and Service: Women and Girls of Canada and Newfoundland during the First World War , ed. Sarah Glassford and Amy J. Shaw. Vancouver: UBC Press, 2012. 173-94. Fisher, Susan R. Boys and Girls in No Man’s Land: English-Canadian Children and the First World War . Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2011. Helyar, Frances. “‘Gladly given for the cause’: New Brunswick Teacher and Student Support for the War Effort, 1914-1918.” Journal of New Brunswick Studies 3 (2012): 75-92. Lewis, Norah. “‘Isn’t this a terrible war?’ The Attitudes of Children in Two World Wars.” HSE/RHE 7/2 (1995): 193-215. Millar, Anne and Jeff Keshen. “Rallying Young Canada to the Cause: Anglophone Schoolchildren in Montreal and Toronto during the Two World Wars.” History of Intellectual Culture 9/1 (2010-11). Morton, Desmond. “The Cadet Movement in the Moment of Canadian Militarism.” Journal of Canadian Studies 13 (summer 1978): 56-68. Moss, Mark. Manliness and Militarism: Educating Young Boys in Ontario for War . Don Mills, ON: Oxford University Press, 2001. Sheehan, Nancy M. “Philosophy, Pedagogy, and Practice: The IODE and the Schools in Canada, 1900-1945.” HSE/RHE 2/2 (1990): 307-15. Stamp, Robert. “Empire Day in the Schools of Ontario: The Training of Young Imperialists.” Journal of Canadian Studies 8/3 (1973): 32-42. Thompson, John Herd. The Harvests of War: The Prairie West, 1914-1918 . Toronto: McClelland & Stewart, 1978. Wilton, Shauna. “Manitoba Women Nurturing the Nation: The Manitoba IODE and Maternal Nationalism, 1913-1920.” Journal of Canadian Studies 35/2 (summer 2000): 149-65.

- 1 See for example Paul Axelrod, The Promise of Schooling: Education in Canada, 1800-1914 (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1997); J.R. Miller, Shingwauk’s Vision: A History of Native Residential Schools (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1997); Raymond Huel, “The Public School as a Guardian of Anglo-Saxon Traditions: The Saskatchewan Experience, 1913-1918,” in Ethnic Canadians: Culture and Education , ed. M.L. Kovacs (Regina: Canadian Plains Research Centre, 1978), 295-304.

- 2 Marilyn Barber, “Canadianization through the Schools of the Prairie Provinces before World War I: The Attitudes and Aims of the English-Speaking Majority,” in Ethnic Canadians: Culture and Education , ed. M.L. Kovacs (Regina: Canadian Plains Research Centre, 1978), 282.

- 3 Susan R. Fisher, Boys and Girls in No Man’s Land: English-Canadian Children and the First World War (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2011), 51, 54.

- 4 Anne Millar and Jeff Keshen, “Rallying Young Canada to the Cause: Anglophone Schoolchildren in Montreal and Toronto during the Two World Wars,” History of Intellectual Culture 9/1 (2010-11), 2.

- 5 Robert M. Stamp, The Schools of Ontario, 1876-1976 (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1982), 60.

- 6 John Herd Thompson, The Harvests of War: The Prairie West, 1914-1918 (Toronto: McClelland & Stewart, 1978), 39-41.

- 7 Nancy M. Sheehan, “Women and Imperialism: The IODE, Propaganda and Patriotism in Canadian Schools, 1900-1940,” Aspects of Education 40 (1989), 21.

- 8 “Girls on the Homefront: A Girls’ School 1895-1945,” accessed 25 March 2013. http://www.museevirtuel-virtualmuseum.ca/sgc-cms/histoires_de_chez_nous…

- 10 Millar and Keshen, “Rallying Young Canada to the Cause,” 7. The text is available online at http://archive.org/details/childrensstoryof02parruoft. ; Accessed 20 March 2013.

- 11 Millar and Keshen, 7-8.

- 12 Fisher, Boys and Girls in No Man’s Land , 58, 62, 53.

- 13 Quoted in Stamp, “Empire Day,” 39.

- 14 Mark Moss, Manliness and Militarism: Educating Young Boys in Ontario for War (Don Mills, ON: Oxford University Press, 2001), 96-102; Desmond Morton, “The Cadet Movement in the Moment of Canadian Militarism,” Journal of Canadian Studies 13 (summer 1978): 56-68; Fisher, Boys and Girls in No Man’s Land , 89-92.

- 15 Morton, “The Cadet Movement,” 59, 62.

- 16 Stamp, “Empire Day,” 39; see also Fisher, Boys and Girls in No Man’s Land , 83.

- 17 Alison Norman, “Race, Gender, and Colonialism: Public Life among the Six Nations of the Grand River, 1899-1939” (PhD dissertation, University of Toronto, 2010), 174-7.

- 18 Morton, “The Cadet Movement in the Moment of Canadian Militarism,” 56.

- 19 Fisher, Boys and Girls in No Man’s Land , 108-10.

- 20 The Grain Growers’ Guide , 20 January 1915, 26.

- 21 Fisher, Boys and Girls in No Man’s Land , 164-75.

- 22 The memorial trees were cut down in the late twentieth century, but a campaign is currently underway to re-plant them. “The Great War Project, Victoria High School Alumni Association,” accessed 15 March 2013. http://vichigh.com/history/the-great-war-project.php

- 23 Millar and Keshen, “Rallying Young Canada to the Cause,” 8; Sheehan, “Women and Patriotism,” 22.

Other Essays

Language selection

- Français fr

The role of Canada’s military in the First World War

Canada played many roles in the First World War, as we built a national identity on the world stage. Here are the roles we played in major phases of the war.

Services and information

The conflict begins.

How the First World War began and how Canada joined in.

Canada enters the war

How Canada recruited, trained and mobilized its soldiers at the start of the war.

The war in the air

The role Canada’s aviators played in the First World War.

The war at sea

The role Canadian seamen played in the First World War.

Ten facts about Canada in the First World War

Ten dates and statistics about Canada’s role in the First World War.

The Newfoundland Regiment at Gallipoli

How the Newfoundland Regiment entered the war on the eastern front.

The Royal Canadian Air Force’s role in the First World War

The birth of the RCAF and the role Canadian aviators played in the First World War.

The formation of the Canadian Corps

How Canada created its own military identity during the First World War.

Canadians in other campaigns

Overview of Canadian units in the war effort outside of the Western Front.

End of the First World War

Canadian events on each of the last 100 days of the First World War in 1918.

The aftermath

The impact the war had on building Canada’s reputation on the world’s stage.

What we are doing

Laws and regulations.

- The Wartime Elections Act

- The Military Service Act

- War Measures Act, 1914

All related laws and regulations

Publications

- Canada and the Battle of Vimy Ridge, 9-12 April 1917

- Canadian Airmen and the First World War

- Official History of the Canadian Army in the First World War

- Hell’s Corner – An Illustrated History of Canada’s Great War (1914-1918)

All related publications

Halifax Citadel national historic site of Canada

Plan a trip to the Halifax Citadel, a strategic hilltop location chosen to protect the city in times of war.

Over the top

Set out on an interactive adventure that allows you to experience life in the trenches during the First World War.

Visitor Education Centre at the Canadian National Vimy Memorial

Find updates about the construction of the new Visitor Education Centre at the Canadian National Vimy Memorial.

Page details

Educational Resources on the First World War

From lesson plans to articles to podcasts — a list of resources to remember the First World War.

Written by Canada’s History

Over a century ago, what started as a small conflict in southeast Europe became a global war fought on a scale never before seen. More died in the First World War than in any other war Canada has fought. The war years brought unimaginable pain and horror for our troops and hard times for those back home.

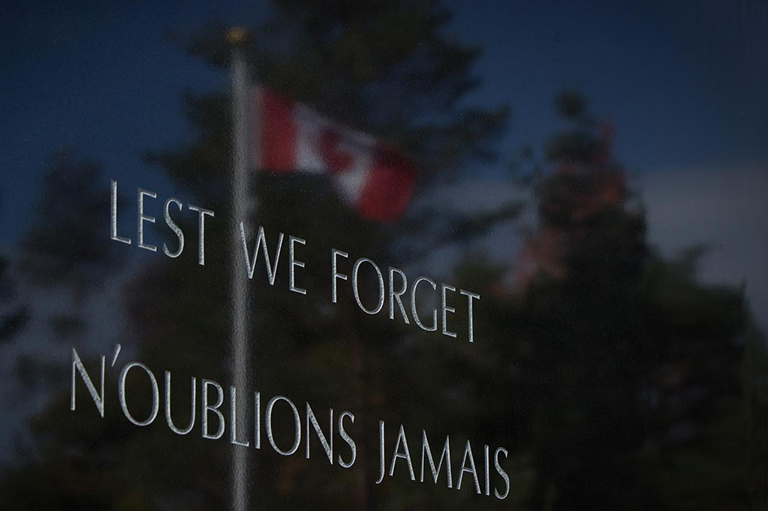

On Remembrance Day we mark the anniversary of the end of the First World War and honour the lives of those who have fallen.

Use these resources to explore the First World War and its legacy with your students.

Lesson Plans

The Canadian Patriotic Fund, 1914–1919

In this lesson students explore the role of the Canadian Patriotic Fund during the First World War.

The Battlefield Landscape of the First World War

In this lesson students explore several seminal Canadian First World War battles with an emphasis on the experiences of soldiers in the trenches.

How should we remember those who fought for Canada?

In this lesson students explore the Lest We Forget Project. They build a class archive of soldier files, engage in research, and create a memorial for their soldier.

Putting it into Perspective: First Nations Soldiers in the First World War

In this lesson students explore the experiences and contributions of Indigenous soldiers to Canada’s role in the First World War.

Slippery Slopes: Preventing War

This exercise attempts to recreate the historical process that helped lead the world into the Great War.

Patriotic Arts: Influencing Canadians at War

This lesson you will discuss with your students: How war has shaped Canada and its citizens; the influences of patriotism, propaganda and music on choices Canadians made during war.

Veteran Appreciation: Participating in Democracy

The purpose of the unit is to encourage students to appreciate our democratic institutions and to recognize the commitment made by our veterans to establish and maintain them.

Classroom Activities

The Battle of Beaumont Hamel Quiz

Use this twelve-question quiz to get your students reading and thinking about the Battle of Beaumont Hamel.

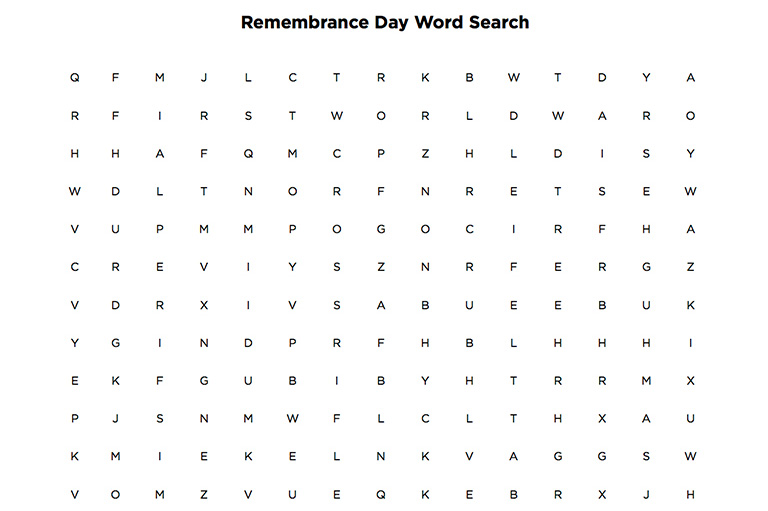

Remembrance Day Word Search

Use this Remembrance Day word search to familiarize your students with key terms from the First World War.

Discover your local cenotaph!

With this activity students are encouraged to explore their community landscape and community history through the local cenotaph.

Classroom Resources

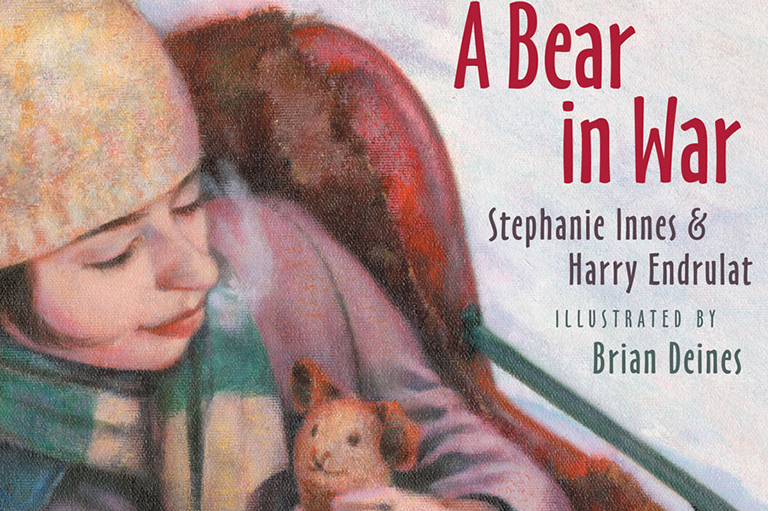

A Bear in War

This book is a great entry point to teaching your young students about the First World War.

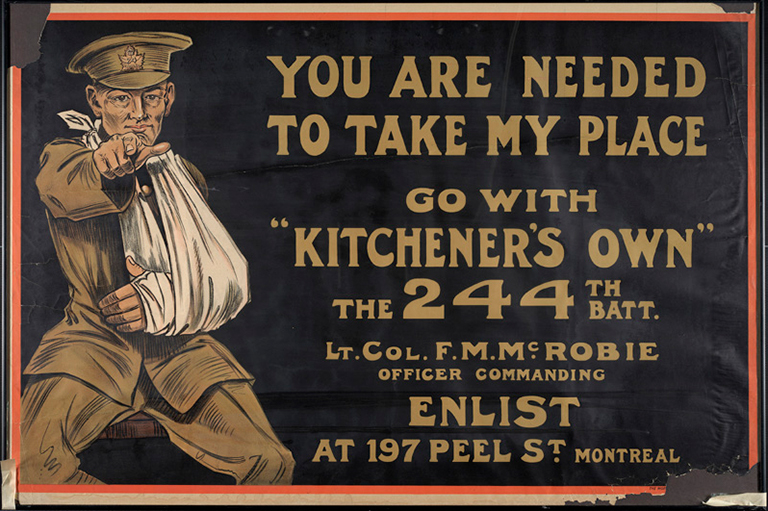

McGill War Poster Collection

This great collection of Canadian war posters will illuminate your history lesson.

Supply Line by the Canadian War Museum

Bringing the museum into your classroom has never been easier.

Veterans' Week Learning Resources

Veterans Affairs offers free, bilingual resources, in hard copy and electronic formats, so students 5 to 18 years old can learn about those who served and why we honour them.

The Battle of Hill 70 Education Program

Bring the story of this historic First World War battle into your classroom.

Kayak in the Classroom

Remembrance Educational Package

The Breakthrough

How, after years of stalemate, did the Allies manage to win the war?

Children of Conflict

Young Canadians worked, worried, and waited during the First World War.

Indigenous Soldiers

Thousands of Indigenous people served both overseas and on the home front.

The Raid on Blécourt

Courageous Canadian action results in mass capture of Germans during the 100 Days Campaign.

Belgian Town Honours Canadian Soldier

A rose christening marks 100 years since the end of the First World War.

Grey War, No More

Colourization project breathes new life into First World War images.

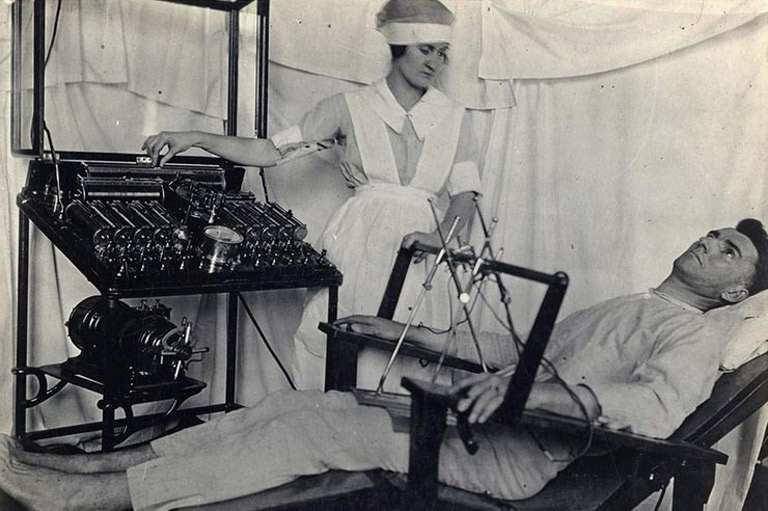

Shell Shock Through the Wars

No one knew how to treat soldiers suffering from shell shock in the First World War, so doctors tried everything including shaming, blaming, and electric shocks.

War of Words

Learn how propaganda was used to sway public opinion during the First World War.

The Hidden History of the Poppy

How a First World War poem about poppies blossomed into an annual Remembrance Day campaign raising $14 million each year to assist veterans.

Voices of Vimy

Listen to the stories of soldiers who fought at the Battle of Vimy Ridge and the loved ones back home who cherished them.

The Great War Video Series

Key Canadian battles during the First World War led to the march to victory in 1918.

Themes associated with this article

- Military & War

- Peace & Conflict

- War and the Canadian Experience

- Canadian Identity

- Canada and the Global Community

Advertisement

Sign up for any of our newsletters and be eligible to win one of many book prizes available.

Related to Classroom Resources

Taking a Stand

Bring labour history into your classroom with these lesson plans and activities.

Remembering the Children

Canadians are still grappling with the truths about residential schools, spurring long-overdue conversations inside and outside the classroom. Remembering the Children offers a way to begin those conversations.

Classroom Treaty

Design a classroom Treaty with your students and use it throughout the year as the typical “class rules.”

War of 1812 Digital Collection

From Canadiana.org, the War of 1812 Digital Collection, brings you primary sources from the War of 1812.

- TOP CATEGORIES

- AS and A Level

- University Degree

- International Baccalaureate

- Uncategorised

- 5 Star Essays

- Study Tools

- Study Guides

- Meet the Team

- History Projects

The Political, Economic and Social Impacts of the First World War on Canada

In 1918, at the end of World War One, sixty thousand Canadians respectfully lost their lives in order for the safekeeping of millions of women, children and men all around the world. Many people at that time questioned the loss of all these lives and whether or not it had been a beneficial outcome for Canada. At that time Canadians were more worried about the nation being divided by conscription, unemployment and thousands of deaths in families. However in the present time, where we have a very different perspective on World War One, we consider the impacts on Canada very positive, taking into account social, economic and political standpoints. World War One was able the way women were thought of at that time, it caused technology and the economy to grow and Canada became and independent nation from Britain and a continued partner with the United States. Canada’s contribution to World War One have been widely credited or and the country has received much praise for it. It is nearly impossible to believe that before the war Canada was only a colony of Britain however soon after emerged it as a respected nation. World War One is the cause of Canada succeeding and the impact it caused on Canada forever changed the way people view this outstanding nation.

A women’s role in the 1900’s was unfortunately at the kitchen sink, where she would cook, clean, take care of the children and ensure the wellbeing of her home. Her husband would return from work, receiving his wages, which would in turn go to his household and he would spend a comfortable evening with his family. However this was dramatically changed when Canada had declared war on Germany and women had to replace the men’s position as well as successfully keeping theirs. It was a huge load on women and they complied with it very well. They stepped into a man’s shoes, so to say, as work in industries, business and farms still needed to be done. They worked a saleswomen, accountants, marketers, publishers, insurance agents and in stores, newspapers, sawmills, paper mills, munitions factories etc 1 . This changed the way women were viewed, as now the world could see they were capable of working just as diligently as men. Many of these jobs were to provide for the war effort, such as fabricating munitions and working as nurses for the war, both of which were very dangerous. Not only were women working very hard in urban cities, they were also working just as hard in rural parts of Canada. 2 Many men had left their farms for war, which reduced much of the labour work. Food still needed to be produced and not only for families on the farm, but also for the war effort, which relied on food from farms to provide for soldiers at the front. Women took at these roles as farmers and were greatly appreciated from all over Canada.

In 1917, Robert Borden, the Prime-Minster during World War One, passed the Wartime Elections Act. 3 This act gave the right to vote for all females who had husbands, brothers or sons enlisted in the war. Even though this was a front for Borden to receive votes in his favour, it was a huge stepping stone in the equality of women. By the end of the war nearly all the women over 21 were given the right to vote as long as they met the racial and property ownership requirement. However, this was not enough for equality, thus Robert Borden’s conservative government passed the 1920 Dominions Elections Act, which gave women the right to be elected for parliament. 4 The first ever to be elected for a seat in the Canadian Parliament was Agnes Campbell Macphail, who fought for the rights of women.

This is a preview of the whole essay

The roles of women were also changed because it was the beginning of a new era of feminist movements. Great women such as Nellie McClung, who was an active female suffragist, had a lot of impact on the modern world today and this great movement was created by the impact of World War One on Canada. These feminist promoted equality between men and women, they believed that women should have the rights to job as much as men have; they should be admitted into government jobs and they should be able to vote. Many of these acts were completed through events that they did, such as Nellie McClung who produced a mock play about the equality of genders. Governments had to agree that the war would have never been won without the constant support of women all around Canada.

Many people believed that the 1900s was the turn of the century, however this is not true in the case for Canada, World War One was its turn of the century. In the years of the war in-between 1914 to 1919, Canada experienced more development in its economy, technology and world trading, then the country had experienced in all of its lifetime. In the beginning years of the war, the economy of Canada was very weak, one-third of the labour force had enlisted, moreover wheat production fell because of drought 5 and debt was soaring every month of the war. However these poor economic times started to change when industries and factories were funded to provide for war. Factories quickly make war supplies such as ammunitions, shells, airplanes and ships as well as factories expanded that made textile, pulp, and paper, steel and food, unemployment virtually disappeared in these years. 6 In addition, Canada’s agricultural industry output increased and Canada exported huge quantities to United Kingdom as well as Untied States. In 1915 Canada established the Imperial Munitions Board (IMB), which produced war supplies for the allied armies producing items such as shells, ships, explosives and training planes and by 1916 IMB was Canada’s largest employer, employing over 250, 000 people, this truly was a step up from factories and industries before war. 7

War brings out the best and the worst out of people and this leads them to do expand their horizons, one of them being the introduction and advancement of technology. The most widely used technology during the war was the use of airplanes as fighter planes which was used by both the Allies and the Central Powers. In Canada alone, they were over 100 plants and training fields that manufactured and trained air force pilots. In addition, submarines were a very deadly weapon that was used by Germany during the war. The Allies had to counteract this weapon, and thus they had developed a device with sensitive microphones, which could detect engines noise and react quickly to an attack. 8 Another advancement in technology that contributed a great amount to the war was the development of the radio. This device was essential for communication between the soldiers and it advance till the point where soldiers could send transmissions of voice rather than code. 9 Electricity also made a huge impact on war by using electrical lights in submarines, having electrically powered turning guns and turrets and creating search lights for night-time navigation to illuminate enemy ships. 10 Other technology developments are the armoured tanks, machine guns, antiaircraft, many different types of rifles and garros. Many of these inventions were fabricated in Canada and were sent out to the Allies. Many of these weapons such as airplanes and radios were very beneficial even after the war. Radios, for example, were used by many Canadians to provide for entertainment as well as a source for information and airplanes later on became a mean of transportation or used in reconnaissance missions. Without many of these advancements, the war would have never progressed and neither would have Canada’s economy or scientific intelligence.

Devastation struck Europe after the end of World War One. Many European countries relied on outside help to retrieve from their war-torn status, one of these countries being Canada. During the war Canada manufactured a significant amount of supplies and continued to do so after the war ended, thus increasing its export rates. In 1919, field crops productions increased by 163 %, fisheries increased by 74%, forest products increased by 70% and minerals increased by 19%. 11 Overall Canada’s exports increased by and outstanding 223% 12 and they were moreover seen as a nation of great economic growth. Canada was one of the few countries in which the economy was very stable after the war, this caused Canada to take a greater stand with the rest of the world and become recognized by many countries all around.

On August 14 th 1914, Britain had officially declared war on Germany, Canada being no more than a colony of Britain automatically declared war also. However, on September 3 rd 1939, a mere 25 years later, Britain had once again declared war on Germany, and Canada’s declaration was not followed until a week later on September 7 th , where Canada declared war, as an independent nation. There were many events which lead to the major development in World War Two, however the most directly connected to World War One, are the following: serving as an independent nation during war, joining the League of Nations apart from Britain and signing the treaty of Versailles separate from Britain. Mackenzie King, prime minster, at that time followed this trend and was able to receive full autonomy by 1931. During wartime, Britain had a great degree of dependence on Canada for food, supplies and men. Canada responded to these requests as effectively as they could which was more than Britain could ask for. Industries such as the Imperial Munitions Board produced solely for the war, one of their more numerous ones being shells. One third of the shells that were used in the British Army were being manufactured in Canada. 13 In addition, Canada sent large amount of wheat for food for the soldiers and send around 600,000 men, a huge contribution for a country of just a population less than 7 million. During these tough times Canada acted no less than an independent nation and Robert Borden was determined to get credited for it.

The Treaty of Versailles in 1919 brought the official end to World War One. The terms of the treaty affected Canada in a slight way, by only receiving a small portion of the reparations Germany had to pay. 14 However, the treaty was able to improve Canada’s national status. Robert Borden insisted that Canada should have the same representations as Belgium and other small countries and also insisted that the treaty should be signed on behalf of Canada. Though they signed underneath the British Empire alongside with the other Dominions, Canada was already seen as a nation that would fight for their independence. This in turn became true, when the League of Nations were set up, to prevent another war from occurring. Robert Borden strongly felt that Canada should be a part of the League of Nations’ General Assembly as well as eligibility for membership in the governing council of the new international body. 17 As a result, Canada received a separate representation and it was its first official contact with foreign governments. These affairs, as well as events such as The Chanac Affair and The Balfour Report were able to steer Canada towards the path of independence and prosperity. The war was able to enhance Canada’s independency, had it never happened it would have taken a much longer time for Canada to transform from a colony to a nation.

Only soldiers know the real authenticity of the Great War, only they can realize the positives and negatives of it, the wrongs and rights, the truths and lies. The rest of the world has no idea the horrors soldiers have gone through and we have no right to judge so critically war, when we have only seen the 2 nd perspective of it. To say that one has studied war, so one knows war, is not equivalent to actually fighting at the front. All we can provide is that the war was not a complete waste, and that the lives of so many benefited the world. Countries such as Canada, should be thanking these soldiers for changing the way that women’s roles were viewed, they should be thanking them for helping their economy and technology grow and they should most of all be thanking them for aiding Canada’s independent status. In the end, no matter who you are, we are all just pawns, waiting patiently, for the actual war to start.

1 Jane Marcellus, Moderns or Moms? : Body Typing and Employed Women Between Word War Years (Routledge: Taylor and Francis Group, 2005), p. 201.

2 Ibid., p. 203.

3 John English, “Wartime Election Act”, The Canadian Encyclopaedia .(Historica-Dominion,)<http://www.thecanadianencyclopedia.com/index.cfm?PgNm=TCE&Params=A1ARTA0008455>

4 Dawn Monroe, “Historical Timeline”, Famous Canadian Women. 11 Sept. 2009. < >

5 Desmond Morton, “World War 1”, The Canadian Encyclopaedia. (Historica- Dominion) < >

6 R.D Francis and Richard Jones, Journeys: A History of Canada (Toronto: Cengage Learning, 2009), p. 399.

7 Ibid., p. 400.

8 “World War 1 Technology”, IEEE Global History Network . 5 Feb. 2009. <http://www.ieeeghn.org/wiki/index.php/World_War_I_Technology.

11 J. Bradely Cruxton and W. Douglas Wilson, Spotlight on Canada (Don Mills: Oxford Press Canada, 2000), p. 171.

12 Ibid., p, 17.

14 W. Stewart WALLACE, The Encyclopaedia of Canada , (Toronto, University Associates of Canada 1948), p. 236.

15 Ibid, p. 237

16 Ibid, p. 237

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Cruxton, J. Bradely and Wilson, W. Douglas. Spotlight on Canada . Don Mills: Oxford Press k Canada., 2000.

Francis, R.D. and Jones, Richard. Journeys: A History of Canada. Toronto: Cengage Learning., k 2009.

Keegan, John. The First World War. Toronto: Key Porter Books Limited.,1998.

Marcellus, Jane. Moderns or Moms? : Body Typing and Employed Women Between Word War j j Years . Routledge: Taylor and Francis Group, 2005.

WALLACE, W. Stewart, The Encyclopaedia of Canada . Toronto, University Associates of k jj jjjjjjjj Canada 1948.

English, John. “Wartime Election Act”, The Canadian Encyclopaedia .Historica- kjjjjjj Dominion.<http://www.thecanadianencyclopedia.com/index.cfm?PgNm=TCE&Params=A kkkk1ARTA0008455>

Monroe, Dawn. “Historical Timeline”, Famous Canadian Women. 11 Sept. 2009. kkkk < >

Morton, Desmond. “World War 1”, The Canadian Encyclopaedia. Historica- Dominion. kkkk < >

“World War 1 Technology”, IEEE Global History Network . 5 Feb. 2009. kkkkk <http://www.ieeeghn.org/wiki/index.php/World_War_I_Technology.

January 14 th 2011

Mr. Palazzo

Document Details

- Word Count 2456

- Page Count 10

- Subject History

Related Essays

Did Canada play a significant role in World War 2

With reference to major battles, the home front, and the aftermath of the w...

Britain and the First World War

Assess the relative importance of the long term and short term causes of th...

Canada and the First World War

- Introduction

- Objects and Photos

- Teacher Resources

- Voluntary Recruitment

Conscription, 1917

The federal government decided in 1917 to conscript young men for overseas military service. Voluntary recruitment was failing to maintain troop numbers, and Prime Minister Sir Robert Borden believed in the military value, and potential post-war influence, of a strong Canadian contribution to the war.

A Momentous Debate

The 1917 conscription debate was one of the fiercest and most divisive in Canadian political history. French-Canadians, as well as many farmers, unionized workers, non-British immigrants, and other Canadians, generally opposed the measure. English-speaking Canadians, led by Prime Minister Borden and senior members of his Cabinet, as well as British immigrants, the families of soldiers, and older Canadians, generally supported it.

The conscription debate echoed public divisions on many other contemporary issues, including language education, agriculture, religion, and the political rights of women and immigrants. It also grew into a test of one’s support for, or opposition to, the war as a whole. Charges of disloyalty, cowardice, and immorality from avid pro-conscription advocates were matched by cries of imperialism, stupidity, and bloodlust by the anti-conscription camp.

The campaign’s viciousness sometimes obscured the debate’s complexity. Many anti-conscription advocates fully supported the war, for example, while not all pro-conscription voices argued their case by using linguistic or racial smears to diminish their opponents.

Conscription Prevails

The conscription debate raged through most of 1917 and into 1918. The required legislation, the Military Service Act, worked its way through Parliament during the summer to be passed in late August. It made all male citizens between the ages of 20 and 45 subject to military service, if called, for the duration of the war.

Conscription was the main issue in the federal election that followed in December, a bitter contest between Conservative / Unionist Sir Robert Borden and Liberal Sir Wilfrid Laurier. Borden, running on a ‘Unionist’ pro-conscription ticket that attracted many English-speaking Liberals, won decisively, but lost heavily in Francophone areas of Quebec.

Wartime Elections Act Changes Who Can Vote

The government had helped pave the way for electoral victory with legislation in the fall that enfranchised likely allies and disenfranchised likely opponents.

The Wartime Elections Act gave the vote to the wives, mothers, and sisters of soldiers, the first women permitted to vote in Canadian federal elections. These groups tended to favour conscription because it supported their men in the field.

The Act then denied the vote to many recent immigrants from enemy countries (“enemy aliens”), unless they had a family member in military service. At the same time, the Military Voters Act extended the vote to all military personnel and nurses, including women, regardless of their period of residence in Canada.

Borden’s margin of victory in December was greater than the votes delivered by either of these controversial measures, but each had been highly successful. More than 90 percent of military votes, for example, were Unionist.

Conscription’s Results

A broadly popular but divisive measure, conscription polarized provinces, ethnic and linguistic groups, communities, and families, and had lasting political effects on the country as a whole. For many Canadians, it was an important and necessary contribution to a faltering war effort; for others, it was an oppressive act passed dishonestly by a government more British than Canadian.

Farmers sought agricultural exemptions from compulsory service until the end of the war. Borden’s government, anxious for farmers’ votes, agreed to limited exemptions, largely for farmers’ labouring sons, but broke the promise after the election. The bitterness among farmers, many of them in the West, led to the development of new federal and provincial parties.

French-speaking Canadians continued their protests as well, and young men by the tens of thousands joined others from across Canada in refusing to register for the selection process. Of those that did register, 93 percent applied for an exemption. An effort to arrest suspected draft dodgers was highly unpopular across the province and, at its worst, resulted in several days of rioting and street battles in Quebec City at Easter, 1918. The violence left four civilians dead and dozens injured, and shocked supporters on both sides.

Conscription had an impact on Canada’s war effort. By the Armistice, 48,000 conscripts had been sent overseas, half of which served at the front, providing crucial soldiers for the Hundred Days campaign. These reinforcements allowed the Canadian Corps to continue fighting in a series of battles, delivering victory after victory, from August to the end of the war on 11 November 1918. More than 50,000 more conscripts remained in Canada. These soldiers would have been required had the war continued into 1919, as many expected it would.

Keep exploring with these topics:

- Sir Robert Borden

- Henri Bourassa

- Sir Wilfrid Laurier

Canadian Military Heritage Project

Created & maintained by OliveTreeGenealogy.com. Resources for all things Canadian military. Find Canadian ancestors in in free searchable military databases for each war and rebellion Canada has been involved in. Build your family tree, and rediscover history. Find your military roots and learn your military history.

World War 1-Women

Ww1: women in the war.

This page is dedicated to that group of people whose contribution and importance is so often overlooked in the story of the Great War.

The years of the Great War saw a remarkable spread, in Canada as well as in other parts of the world, of female suffrage or women’s rights. The demands of the war for huge quantities of fighting men and material provided women with an opportunity to prove themselves like none before. Women found themselves filling many positions that had previously been reserved for men, as well as continuing to maintain more traditional (but no less important) roles such as nursing.

Over 1000 women were employed by the Royal Air Force in Canada on a wide range of duties, such as motor transport work; and many went over seas as ambulance drivers or on other war work. The number of women employed in Munition Factories exceeded 30,000. Between 5,000 and 6,000 were employed in the civil service and untold thousands more in banks, offices, factories and farms. 1

The Great War was the first modern industrial war and it could not have been fought as such without the direct participation of women. Over 2000 women enlisted as nursing sisters in the Canadian Expeditionary Force betwen 1914-1918. 2 The folowing is a partial list of nurses with the Canadian Expeditionary Force taken from two photographs dated 1914. 3

Photo Album

This Photo Archive consists of a small autograph album (6.5″ by 5.25″) kept by Constance (Connie) Philips as a memento of her time serving as a nurse during World War One. There are 184 photos, postcards, and letters, the majority from 1915, when she served as a nurse in France and Britain. The album and all photographs, postcards, and other ephemera contained in the album belong to Karin Armstrong and may not be copied or republished without her written permission. The images are published on Olive Tree Genealogy with her permission. Each image has been designated an “R” for Recto or a “V” for Verso plus a number. Recto is the right-hand side page of a bound book while Verso is the left-hand side page.

CEF Database for Service Files

The full military service records for these Nursing Sisters can be obtained online at the Canadian Expeditionary Force (CEF) database using the References given below each name.

MACLEOD , Margaret Christine

- Box: 7089 – 17

JAMIESON , Mabelle Clara

- Box: 4784 – 43

MILLS , Margaret M

There are three M.M. Mills on the CEF database. I suspect the records are for one individual. The box numbers are 6218-1, 6218-2 and 6218-3

- Box: 6218 – 3

NESBITT , Violet Claire

- Box: 7276 – 3

MCCULLOUGH , Georgianna Beach

- Box: 6677 – 1

WINTER , Dorothy Elizabeth

- Box: 10500 – 15

LAMBKIN , Kathleen

- Box: 5341 – 58

MACALISTER , Charlotte

- Box: 6565 – 9

SMITH , Lydia Vernon

- Box: 9085 – 43

There are two M. M. Muirs found in the CEF database.

- Box: 6462 – 7

- Box: 6462 – 8

BINNING , Daisy Medd

This is probably the E.M. Binning indicated in the photograph but her attestation papers would have to be obtained to be certain.

- Box: 738 – 31

FOLLETTE , Minnie A

- Box: 3172 – 18

DENMARK , Ida

- Box: 2439 – 47

PELLETIER , Juliette

- Box: 7708 – 82

GALT , Cecily

- Box: 3388 – 13

PUGH , Murney May

- Box: 8016 – 51

GOODEVE , Myra Moffatt

- Box: 3626 – 6

GRATTON , Rose Anna Myrtle

- Box: 3742 – 63

GRAHAM , Harriet

- Box: 3702 – 35

HINCHEY , Annie Reaby

- Box: 376 – 37

MABE , Lily Maude

- Box: 5824 – 26

ATTRILL , Alfreda Jean

- Box: 294 – 2

BURPEE , Eleanor Bell

can be found also as

WICKHAM , Eleanor Bell

- Box: 1310 – 30

PONTING , Elizabeth Anne

- Box: 7896 – 3

PENSE , Emma Pense

- Box: 7724 – 29

Bios of Other Nursing Sisters

Ann Doctor Allan Ann was born in Perth Scotland in 1882. She was a graduate nurse at the Military Hosptial in Halifax Nova Scotia when she joined the CEF in September 1914.

Sarah Ann Archard Sarah was born in 1883 in Halifax Nova Scotia to Alfred Archer. She signed up as a Nursing Sister in October 1915.

Mary Ann Buchanan Mary Ann was born in 1888 in Hensall, Ontario, the daughter of Alexander Buchanan. She signed up as a Nursing Sister in Toronto Ontario in November 1915.

Sarah Ann Cannon Sarah Ann was born in 1879 in Toronto Ontario to Thomas E. Cannon. She had spent one year with the French Flag Nursing Corps before signing up with the CEF in July 1917.

Bertha Mary Cromwell Mary Bertha was born 24 Nov. 1890 in Quebec. She joined the CEF on 28 Sept. 1914 in Quebec. Her attestation papers give her next of kin as Leonard A. Cromwell, at the Royal Bank in Quebec. Mary Bertha was a nurse at the Quebec Military Hospital when she joined the CEF, having been found fit for duty.

Mabel Clint Mabel’s next of kin at her enlistment was her mother, Caroline Clinch. Mabel gave her place of birth as Quebec and her address as 131 Metcalfe St., Montreal. She was in the Army Medical Corps at the time of enlistment on 23 Sept. 1913. Mabel filled out an Officer’s Attestation form as well as a regular one 5 days later on 28 Sept. She was with the Royal Canadian Dragoons before enlistment

Footnotes: 1 Canada In the Great War . W. S. Wallace. J. L. Nichols Co. Limited, Toronto. 1919 2 ibid 3 The War Pictorial: The Leading Pictorial Souvenir of the Great War; Depicting Especially the Part Played by Canada and Canadians….. Volume One. Edited by Leslie G. Barnard. Dodd-Simpson Press Limited. Montreal. 1914

Choose from Timeline , Battles , Weapons , Biographies , Letters , Newfoundland , Aces , Victoria Cross Winners , Soldier Tributes , Army , Navy , Air Force , Diaries & Photo Albums , ID Tags & Tributes , Statistics , Home Front , Women in the War , Ancestors , Uniforms , Equipment , Grenades & Mortars , Guns , Identify WW1 Photos , Guest Authors/Articles , CEF Nominal Rolls

Conscription in Canada During World War I

Introduction, introducing of conscription in world war 1, results of conscription in canada, reason for support, reasons for opposition, impact of the division in support for conscription.

Many countries embrace conscription to unite the nation and rally the citizen together for a common course. In Canada, Conscription during World War I was a total failure as it left the nation more divided than it was before.

Conscription is a term used to describe involuntary labor required by the authority to serve in the armed forces of a country. Various countries have different names for conscription.

Many countries introduced conscription during the World War I to boost their overseas forces. Casualty rates in many camps were so high, and the number of volunteers had gone down. These prompted many governments to put up legislation requiring able men and, in some instances, women to enlist in the armed forces to boost the ground forces. All countries that were involved in World War I introduced conscription except Australia and South Africa.