Propaganda in the Philippines: Past and present

THERE was a time — two generations ago — when Filipinos deeply loved their country and knew how to fight for their motherland’s freedom because it was the right thing to do.

The year was 1944. It had been two years since 100,000 Filipino and American troops in Bataan and Corregidor surrendered to an invading Japanese army. Filipinos have been waiting for General Douglas MacArthur to fulfill his famous “I shall return” pledge and liberate the Philippines, then a US colony. Over 200,000 guerrillas have been working behind enemy lines, continuing the resistance.

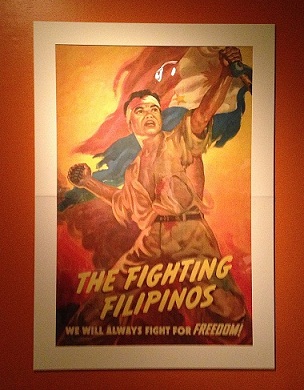

To keep the Filipinos’ spirits up, the Philippine commonwealth government, in exile in the United States, commissioned a poster. The task fell on a Filipino immigrant, Manuel Rey Isip, who left the Philippines in 1925 and settled in New York City. A talented artist, Isip drew illustrations for newspapers and movie posters for Columbia Pictures and 20th Century Fox.

The result was a propaganda poster, measuring 27 by 41 inches, that would make Isip famous. It depicts a wounded Filipino soldier about to hurl a grenade. With his left hand he holds aloft a Philippine flag — tattered but defiant — with the red field up, signifying that the country is in a state of war.

Fifteen thousand copies of “The Fighting Filipinos” poster were smuggled into the Philippines. It was quickly welcomed, especially by guerrilla groups, for it embodied the Filipino spirit of freedom.

Lopez Museum curators Ethel Villafranca and Ricky Francisco initially planned an exhibit to commemorate the 70th anniversary of the Battle of Manila and the end of World War II. Then they realized that the museum’s collection had so much more to share. “We discovered that our nation’s history can be categorized according to different types of propaganda,” says Francisco.

These days, think of the word “propaganda” and you’ll most likely associate it with lies, deceit and politicians. But a long time ago, the word didn’t have a pejorative definition — and, in fact, it was very much a part of Philippine history.

In 1872, Filipino emigres in Europe formed a literary and cultural organization, El Movimiento de Propaganda (The Propaganda Movement), to lobby Spain for reforms in its sole Asian colony. Among its famous members were Jose Rizal, Marcelo del Pilar and several others.

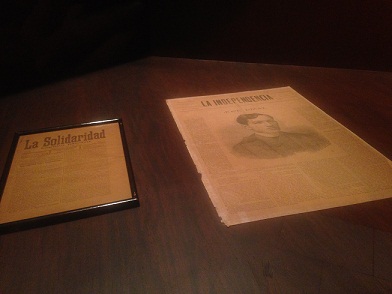

In 1889, they launched a biweekly Spanish-language magazine, La Solidaridad (Solidarity), which became the organ of the lobby group. Before the bolo and the gun, the pen was the instrument of democracy.

A rare copy of La Solidaridad is currently on display at the Lopez Museum, which is part of an exhibit, simply named “Propaganda.”. The exhibt runs until May 30.

Beside the magazine in a display case is a Spanish-language newspaper, La Independencia (Independence), a brainchild of Philippine Army chief General Antonio Luna, a member of the Propaganda Movement and one of La Solidaridad’s contributors before the Philippine Revolution.

Launched shortly after the Philippine declaration of independence in 1898, La Independencia was envisioned by Luna to help mold the new nation via hearts and minds. The paper was the most prominent among the nascent Philippine press.

Among its staff was soldier and writer Jose Palma, who wrote the original Spanish lyrics of the Philippine national anthem, published in La Independencia on September 3, 1899. Another staffer would gain immortality, academician Epifanio de los Santos, better known to Filipinos today by the initials EDSA, the main Manila highway that bears his name.

Inspiring as it may seem, what Villafranca and Francisco want from visitors, however, is for them to leave with another kind of inspiration. Whatever the forms of propaganda throughout Philippine history, as the two have discovered, the common message is that it is often about freedom from ills afflicting Filipino society.

“Research for this exhibit was a little bit hard emotionally because it was a reminder that we are just going around in circles,” says Villafranca. “It’s history repeating itself. It feels that we don’t learn from our history.”

Villafranca makes an example of a collection of editorial cartoons, published in the 1960s by the now-defunct Manila Chronicle newspaper. An arch critic of the dictator Ferdinand Marcos, the Chronicle was shuttered by the government in 1972 after Marcos declared martial law.

Depicted in the cartoons are some of the headaches that are very familiar to Filipinos today, such as corruption and politicians making empty promises. “Take a look at the editorial cartoons. If you remove the dates, you’d think that they were drawn only yesterday,” says Villafranca.

That the struggle for the nation’s destiny began in the hearts and minds of Filipinos with the Propaganda Movement was no wonder. As much of the population in his day was uneducated, Rizal once concluded that the Filipino intelligentsia like himself, the ilustrados , should run the country some day.

And the battle for hearts and minds continues to this day.

With the 2016 presidential elections nearing, Francisco and Villafranca urge voters to be discerning for the sake of the nation amid the barrage of propaganda that characterize Filipino politics.

“We could see that a lot of problems facing the nation 100 years ago are still the country’s problems now. We’re hoping that it’s not a hopeless situation,” says Francisco. “Of course, there have been a lot of changes. We have more freedoms today — and hopefully people will use those freedoms to create change.”

Read other interesting stories:

Click thumbnails to read related articles.

Celebrating world-class Filipinos — circa 1884

Would you believe ballot-buying during beauty pageants in the American colonial era?

- Share on Facebook

- Share on Twitter

- Share on Reddit

- Save to your Google bookmark

- Save to Pocket

- Utility Menu

GA4 tracking code

- For Educators

- For Professionals

- For Students

dbe16fc7006472b870d854a97130f146

Propaganda movement, the.

The Propaganda Movement (1872-1892) was the first Filipino nationalist movement, led by a Filipino elite and inspired by the protonationalist activism of figures such as José Burgos and by his execution at the hands of colonial authorities. Propagandists were largely young men, often mestizos and creoles whose families could afford to send them to study in Spanish universities in Madrid and Barcelona. There, they encountered the tumult of 19 th century political movements inspired by Enlightenment thought, individual rights, constitutionalism, and anti-clericalism.

It was an assimilationist movement in that the propagandists—many of whom were of half Spanish parentage and saw themselves as inheritors of Spanish civilization—believed that the Philippines should be fully incorporated into Spain as a Spanish province and not merely as a colony, with Filipinos granted the same citizenship rights accorded to Spanish citizens. Second, it sought the expulsion of the Spanish friars from the Philippines and the empowerment of a native Filipino clergy. Lastly, as a cultural movement, it showcased the writing and artistic production of the young Filipino elite as a means of demonstrating their intellectual sophistication, on par with their Spanish peers.

The Propaganda Movement targeted the Spanish government and public, but as an elite movement failed to engage with the wider Filipino population. The Spanish government was little interested in the conditions of the Philippines, particularly with the immense political foment in the Spanish political environment, and the movement ultimately received scant support and made little headway in Spain. The propagandists themselves were considered to be rebels at home in the Philippines, and many were exiled. Despite its overall failure, the movement generated a political consciousness that fed into the nationalist revolution of 1896 and the struggle for independence that followed.

John N. Schumacher, The Propaganda Movement, 1880-1895: The Creation of a Filipino Consciousness, The Making of the Revolution (Quezon City: Ateneo de Manila University Press, 2000),

Glossary of Terms

Filter by religion.

- African-Derived Religions (1)

- Baha'i Faith (4)

- Buddhism (5)

- Christianity (99)

- Hinduism (1)

- Indigenous Religions (1)

- Judaism (17)

Filter By Country

- Brazil (12)

- France (11)

- Lebanon (2)

- Myanmar (26)

- Nigeria (33)

- Pakistan (3)

- Palestine (1)

- Philippines (24)

- Somalia (19)

- Turkey (29)

Filter by Region

- Central America (1)

- Central Europe (1)

- East Africa (2)

- Eastern Europe (1)

- Latin America (2)

- Middle East (9)

- North Africa (2)

- South America (3)

Jos� Rizal and the Propaganda Movement

Academia.edu no longer supports Internet Explorer.

To browse Academia.edu and the wider internet faster and more securely, please take a few seconds to upgrade your browser .

Enter the email address you signed up with and we'll email you a reset link.

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

A Legacy of the Propaganda: The Tripartite View of Philippine History

Salazar, Zeus A. "A Legacy of the Propaganda: The Tripartite View of Philippine History." Nasa The Ethnic Dimension: Papers on Philippine Culture, History and Psychology, pat., Zeus A. Salazar, 107-126. Cologne: Counselling Center for Filipinos, Caritas Association for the City of Cologne, 1983.

Related Papers

Mário Varela Gomes

Caetano de Mello Beirão, Mário Varela Gomes, 1985, Grafitos da Idade do Ferro do Centro e Sul de Portugal. In: Actas del III Coloquio sobre Lenguas y Culturas Paleohispanicas, pp. 465-499, Ediciones Universidad de Salamanca, Salamanca.

hjhjgfg freghrf

硕士研究生毕业证书 英文『海外假学位证书学位认证』《QMU学位证书真的一样》微信95270640【利兹三一大学全套毕业证文凭证书,入学offer录取通知书】购买学士成绩单利兹三一大学学位证书(微信95270640)制作QMU学士毕业证成绩单精仿/高仿利兹三一大学硕士学位文凭证书微信95270640《利兹三一大学入学offer录取通知书全套文凭》《QMU学士学历认证毕业证》利兹三一大学文凭证书学位证书学历认证报告怎么弄【毕业证书成绩单】{毕业证书} 【微信95270640】《毕业证明信-推荐信做学费单》成绩单,录取通知书,Offer,在读证明,雅思托福成绩单,真实大使馆教育部认证,回国人员证明,留信网认证。网上存档永久可查! ◆办理degree,Transcripts(一对一服务包括毕业院长签字,专业课程,学位类型,专业或教育领域,以及毕业日期.不要忽视这些细节.这两份文件同样重要!毕业证成绩单文凭留信网学历认证!)

Conference proceedings : ... Annual International Conference of the IEEE Engineering in Medicine and Biology Society. IEEE Engineering in Medicine and Biology Society. Annual Conference

Masood Mehmood Khan

The debilitating pathology of stress fracture accounts for 10% of all athletic injuries[2], with prevalence as high as 20% in modern military basic training cohorts [3]. Increasing concerns surrounding adverse effects of radiology [5], combined with the 12.5% contribution of diagnostic imaging to Australian Medicare benefits paid in 2009-10 [6], have prompted the search for alternative/adjunct electronic decision support systems[7]. Within conducive physioanatomic milieu, thermal infrared imaging (TIRI) may feasibly be used to remotely detect and topographically map diagnostically useful signs of suprathreshold thermodynamic pathophysiology. This paper details a three month clinical pilot study into TIRI-based detection of osseous stress pathology in the lower legs of Australian Army basic trainees. A dataset of over 500 TIRI's was amassed. The apparent 'normal' thermal profile of the anterior aspect of the asymptomatic lower leg is topographically defined and validated ...

Nur Ramadhania Oktaviani

Internal Medicine

Sho Matsushita

帕森斯设计学院文凭证书 Parsons毕业证成绩单

有工商管理专业文凭UTulsa毕业证成绩单,Q微77200097,#办塔尔萨大学学位证,#办本科Tulsa文凭,#办UTulsa毕业证书,#有UTulsa硕士学历,办塔尔萨大学文凭证书University of Tulsa Bachelor/Master Diploma Degree Transcript

Open Journal of Inorganic Non-metallic Materials

Arturo Ayon

Water Research

The Scientific World Journal

Masyhuri Masyhuri

Some experts believe that organic agriculture is more adaptable compared to conventional agriculture. Accordingly, the purpose of this study is to assess organic and conventional farmers’ perception and adaptation to climate change and analyse the factors that influence such decisions. The survey was conducted in Java, involving 112 organic farmers and 112 conventional farmers. The chi-square test was used to differentiate climate change perceptions and adaptation strategies applied by farmers. The factors that influenced the selection of the adaptation strategies were analysed using logistic regression. The results of analysis found that organic farmers have more precise perceptions of climate change than that of conventional farmers. Organic farmers more commonly implement mixed cropping, crop rotation, increasing organic manure, using shade, and changing irrigation techniques as their adaptation strategies, while conventional farmers more commonly prefer to adjust planting and ha...

Vedat Bulut

Loading Preview

Sorry, preview is currently unavailable. You can download the paper by clicking the button above.

RELATED PAPERS

Proceedings of the 2008 ACM SIGMOD international conference on Management of data - SIGMOD '08

Gems & Gemology

John Koivula

Interface - Comunicação, Saúde, Educação

Selma Lancman

Hadi Thamer

Odgojne Znanosti

Vesnica Mlinarević

Mahfuz Alam

hjhds jyuttgf

Choice Reviews Online

Leigh Fought

International Journal of Spine Surgery

Annals of the Rheumatic Diseases

Noemí Garrido

Biochemical Journal

Rona Ramsay

RELATED TOPICS

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

- Find new research papers in:

- Health Sciences

- Earth Sciences

- Cognitive Science

- Mathematics

- Computer Science

- Academia ©2024

The Philippines Today

The Philippines Today, Yesterday, and Tomorrow

The Propaganda Movement in the Philippines

The Propaganda Movement was a time before the Philippine Revolution when educated Filipinos, known as illustrados, were calling for reforms in colonial governance.

Important members included Jose Rizal, Graciano Lopez Jaena , Mariano Ponce , and Marcelo H. del Pilar . The propagandists advocated for the secularization of the clergy, representation of the Philippines in the Cortes Generales of Spain, the granting of Spanish citizenship to Filipinos, recognition of the Philippines as a province of Spain, the guarantee of basic freedoms, and equal opportunities for Filipinos in government service, among others.

However, the calls were not heeded by the Spanish colonial government, giving rise to a revolution that would spark in 1896.

You may want to read:

- Arrest and Trial of Jose Rizal

Share this:

- Click to share on Twitter (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Pinterest (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Facebook (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on WhatsApp (Opens in new window)

The Philippine Revolution constructs ‘Asia’ and Civilization from the periphery

By Nicole CuUnjieng Aboitiz, Clare Hall, University of Cambridge

Filipinos, on the whole, are famously pro-American. In 2014, the Philippines topped the Global Attitudes Survey with regard to global public approval of the United States, coming in with a ninety two percent favorability rating. [1] In 2013, a higher percentage of surveyed Filipinos held America favorably and had confidence in the US President, including the former president George W. Bush, than Americans themselves held and had. [2] The entrenched, orthodox Philippine narrative of the Second World War presents the Japanese occupation of the islands as a Dark Age shattering the golden period of American colonial peace, prosperity, and tutelage toward independence. Reynaldo C. Ileto wrote that Pres. Sergio Osmeña “spoke of Douglas MacArthur’s return as a repetition of his father Arthur’s arrival in 1898 to free the Philippines from Spain,” and that Pres. Elpidio Quirino asked Filipinos “[w]hat was the ‘Death March’. . . if not the common pasyon or Christ-like suffering and death, of Filipinos and Americans?” [3] Yet not all Filipinos viewed Douglas MacArthur’s fulfilled promise in 1945 as the redemptive return of their liberating savior. Though they were a minority, it is nevertheless worth exploring those narratives—and asking how they came to be a minority.

What were the intellectual roots and political lives of that contrarian position? What intellectual histories have the streamlined national historiography shed? What alternative visions of political possibility emerge if one does not begin asking such questions in the second half of the twentieth century, when global American geopolitical and economic dominance naturalized a special relationship with the erstwhile colonizer as the most expedient, realpolitik for the postcolonial Philippine state?

The turn of the twentieth century is an important moment globally—with all the changes in technology, sovereignty, human exchange, and ideology that it wrought. It is also a deep turning point for a more concentrated area: Southeast Asia—with imperial subjugation and incorporation hardening empires and firing local resistance across the entire region. The Philippines is both singular and microcosmic in this, featuring a very early instance of the regional transition of power that would take place over the twentieth century—from the Old World, European imperial powers to the emerging, New World, American global power and the rise of Japan—as well as the brief creation of the first modern, secular, native republic in Asia: the First Philippine Republic. But, in 1872, at the start of the period I studied, two decades prior to the First Philippine Republic and three decades prior to American colonization, Las Filipinas is, still, one of the final vestiges of the fading Spanish Empire.

The diverse islands of Filipinas are riven with ethno-linguistic variety, and the contours of what would become the Philippine nation-state were in no way presumed. What geographies of political affinity and what intellectual histories of place would attend the Philippine Revolution and the construction of the Philippine nation? Despite the fact that this is the single most studied history in all of the Philippine literature, answers to such questions are sorely missing from the historiography or have been stymied by Eurocentric assumptions. Indeed, the transformative late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries are too often apprehended in Asian historiography through a bilateral framework privileging relations with the West. Beyond merely the Philippines, meanwhile, I wondered: how do anti-colonial and proto-nationalist constructions of ‘place’ relate theoretically and genealogically to empire and imperial claims to space?

Colonized by Spain and the United States, the Philippines has long been considered closer to Latin America than to Asia, but do the islands’ important transnational and comparative histories run only along imperial lines—only with/against their former colonizers and those colonizers’ former colonies/possessions? What could such postcoloniality in our analysis be obscuring? The traditional assumption of the literature is that the Filipino self-image is historically non-Asian—seeing itself as belonging, instead, to the Western hemisphere. Many early postwar/Cold War Southeast Asian studies, such as D.G.E. Hall’s seminal work A History of Southeast Asia (1955), excluded the Philippines from the Southeast Asian ambit of scholarly consideration. This begs the question: what is Southeast Asia? For that matter, what is Asia? Existing at the “periphery” and serving as the litmus test for both, the Philippines is a singularly rich site to explore such questions.

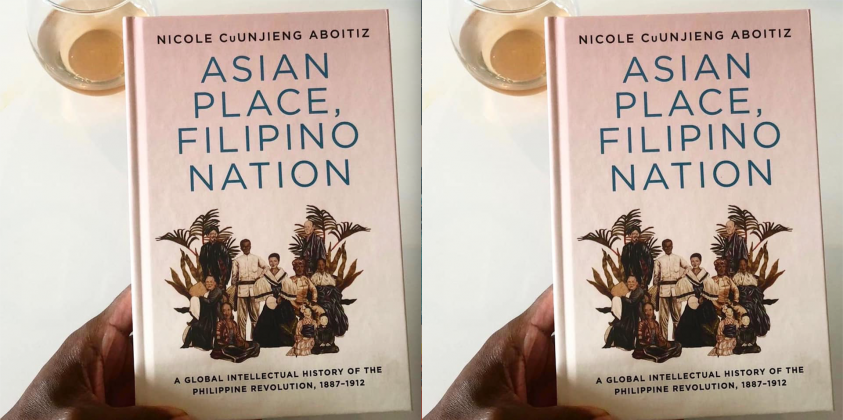

In tracing the intellectual genealogy of the Philippine nation, I excavated what turned out to be far more complex theoretical and historical bases to the construction not only of the Filipino, but also of Asia, race, and a concept of place that could challenge imperial claims of rightful sovereignty. My book Asian Place, Filipino Nation: A Global Intellectual History of the Philippine Revolution, 1887-1912 (Columbia University Press, June 2020) investigates precisely what ground the Philippine nation built itself upon intellectually, excavating its neglected cosmopolitan and transnational Asian moorings in particular, in order to reconnect Philippine history to that of Southeast and East Asia. It also recovers the “periphery” of the discourse of Pan-Asianism, which was built on material aid and the fantasy and affect of transnational anti-colonial Asian solidarity. The book seeks to make that periphery legible to the center and to expand our discursive, East Asia-centric understanding of Pan-Asianism more generally.

For the ilustrado (educated elite) Filipinos, who constructed the Philippine nation through their Propaganda Movement, and the succeeding revolutionaries, who sought to enact it through the Philippine Revolution and First Philippine Republic, one of the central theoretical problems that their nationalism needed to work through was that of civilization. This was because their intellectual armature and politics of the proto-nation had to grapple with then-current Social Darwinist interpretations of history and geopolitics, which had conventionally placed Filipinas as uncompetitive and unfit for self-rule. Their Social Darwinist interpretations of universal history and the place of Asia, however, subverted the racial denigration usually associated with Western Social Darwinism, revealing the anticolonial and emancipatory possibilities embedded in the discourse. How would the Filipinos appropriate, construct, and reimagine Asia towards these ends? Though the book ranges widely in its study of the various intellectual histories attending the Philippine Revolution, today, I wish to draw attention exclusively to the Filipinos’ construction of Asia through a historical argument on Civilization. It is no small matter, for despite the traditional assumption that Filipinos have historically seen themselves as non-Asian, this argument about universal Civilization and identification with Asia formed a ballast of their claims for anti-colonial nationalist sovereignty.

The Propagandists inscribed the new Filipino nation they were seeking to construct within a more ancient Asian landscape, imbued with a civilizational importance that would be recognizable even to Europeans. They apparently thought this association with an older, richer documented civilizational realm necessary, due to the visible lack of ancient kingdoms and ruins around which Filipinos could assemble their nationalism. It was also a way to counter the argument of Spanish and European thinkers who described the archipelago as overrun by an anarchy of tribes and races. In the Propagandists’ mouthpiece, La Solidaridad , Asia largely appears as constructed through the history of Civilization, and is noted for its heights of achievement—albeit in a defensive tone.

An important feature in their construction of Asia through the history of Civilization was the premise that there is something like universal Civilization, and that it merely passed from one incarnation to another, from East to West and back again. This ephemeral, unitary concept of Civilization formed the mechanism by which the civilizational construction of Asia reconciled itself with the history of the rise and fall of great powers and the current state of material inequality between East and West. The national hero José Rizal discussed the civilizational tenet in his article on May 15, 1889:

…Religion, civilization, science, laws, and customs came therefore from Egypt, but in travelling along the pleasant shores of the Elaides, they were shorn of their mystic robes and they put on the simple and charming clothes of the sons of Greece…All their learning, science, philosophy, fine arts, and literature passed on to Rome, losing something of their grace and beauty, but gaining in return grandeur and majesty which reflected the genius of a proud nation. The same thing that happened to Rome is happening today to civilized nations in relation to Gallicization. Hellenism was introduced everywhere, its poetry and its music were transmitted from mouth to mouth; its customs and its mores were copied and practised. Science and civilization had been until then the patrimony of the Orient, but following the natural course of the stars, it directed its step to the Occident, and when it got to the heart of the world, it tarried as if to draw all nation and races together. [4]

From here he spoke explicitly of the uses of travel and of learning from others, while he implicitly worked to reinscribe the East into the history of high civilization. Indeed, this is precisely the theoretical premise and intellectual moves that would characterize the Japanese-sponsored World War Two wartime Philippine President Jose P. Laurel’s historical and political thinking, and that grounded his Pan-Asianism.

The Philippine revolutionary and First Philipine Republic’s Minister of Foreign Affairs Apolinario Mabini’s writings echoed the thinking on race, Asia, and universal civilization that Rizal the Propagandists articulated in La Solidaridad . “Please pardon me,” Mabini wrote his friend on November 3, 1899, “if I cannot agree with you that the cradle of mankind was in the neighborhood of the equator.” [5] After citing his reason based on the history of the passing ice ages and development of animal life, he clarified: “I think we find in the town near the equator not the cradle but the future of the human race.” [6] Mabini reasoned that God allowed for the existence of avarice because it gave him a tool through which to “extend civilization” and to eventually “humiliate the proud and exult the humble.” [7] This statement explains the existence of unequal progress across civilizations at different points in time, but unifies them as existing within a single universal narrative. He argued that it was the law of nature that the “route of civilization” leave wide tracks in the “vast field of history” passing from “Babylon and Phoenicia, now Syria, in Asia, Egypt and Carthage in Africa, Greece and Rome, in Europe; the United States, in America” onto the “Philippines, in Oceania.” [8] Universal civilization is carried continuously and housed by many, he believed, indifferent to whether it lands East or West, above or below the equator, geographically. This was not only civilizational, but in Mabini’s argumentation, racial. “It is true,” he wrote, “that the colored race, compared to the white race, is inferior up to the present in culture and civilization.” [9] But Mabini did not believe this state to be permanent, innate, or fixed. Slipping from race to culture, Mabini argued:

History teaches us that culture takes root, not to perpetuate itself in a certain locality, but to flower and bear fruit, in order that the wind may spread its seeds to all distant regions. Besides, in the same manner that the earth turns sterile with continuous civilization, to the point where the artificial fertilizer is no longer capable of giving life and substance to new plants by such a superior process, a society with a rich life and corrupted customs, which brings always abuse to refined culture and towards which man is always inclined, weakens and degenerates until it lacks the necessary vigor to continue advancing up the road of civilization. [10]

It is at this point, he asserted, that the youthful vigor of a new nation takes up the mantle of civilization. “Present and future wars will serve for the aggrandizement of the races that now groan under the weight of ignominy and slavery,” he warned. [11]

Of the Philippines, he declared: “When this young nation, full of strength and abundant in love, inherits the experience of another which is already old and worn out, the sciences will advance greatly and will humanize, so to say, the sentiments to the extent required by the aspired universal equilibrium.” [12] In this manner, Mabini theorized a role for inequality of progress across cultures—it allowed for the inevitable process of creeping decadence and decay not to stifle universal civilization. At the point of decay, a youthful, adapted, different nation would take up the mantle of universal civilization and breathe into it new life. In this way, Mabini’s thinking on universal civilization advanced that of the Propagandists.

The Propagandists’ theorization of universal civilization had turned to history in order to diminish the importance of the Philippines’ perceived cultural and racial inferiority (which they now theorized as a temporary, historicized state) as well as to tie the Philippines to a history of past and universal greatness. Mabini then took their theorization of universal civilization, which was oriented toward the past, and built into it a causal process that predicted the Philippines’ future greatness. This intellectual move mirrors the one that took place more broadly in the transition from the Propaganda Movement to the Philippine Revolution. The Propaganda Movement had established a foundation for a Filipino nation built upon “reclaimed” Asian history and a “reawakened” racial Malay consciousness, thereby drawing from the past to buttress the grounds, the place , upon which a Filipino nation could stand. The Philippine Revolution took this intellectual armature, which was oriented toward the past, and prescribed a future for it, theorizing and mobilizing the action that would achieve it.

Book available at: https://cup.columbia.edu/book/asian-place-filipino-nation/9780231192156

[1] https://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2014/07/15/which-countries-dont-like-america-and-which-do/

[2] https://www.rappler.com/nation/56085-philippines-usa-pew-research

[3] Reynaldo C. Ileto, “World War II: Transient and enduring legacies for the Philippines” in Legacies of World War II in South and East Asia , ed. David Koh Wee Hock (Singapore: Institute of Southeast Asian Studies, 2007), 84.

[4] Laon Laan, “Los Viajes,” La Solidaridad I, 7 (May 15, 1889).

[5] Apolinario Mabini, “Letter to Remontado: November 3, 1899,” in The Letters of Apolinario Mabini (Manila: National Heroes Commission, 1965), 231.

[7] Ibid., 232.

These include essential cookies that are necessary for the operation of the site, as well as others that are used only for anonymous statistical purposes, for comfort settings or to display personalized content. You can decide for yourself which categories you want to allow. Please note that based on your settings, not all functions of the website may be available.

- External Media

To load this element, it is required to consent to the following cookie category: {category}.

By providing an email address. I agree to the Terms of Use and acknowledge that I have read the Privacy Policy .

Propaganda: Good or bad?

Filipinos love to play with words. We effortlessly form puns or terms with double or conflicting meanings for a laugh, often unmindful of the power of words to communicate, conceal, or confuse.

Take propaganda. Textbook history taught me that propaganda was good. Wasn’t the 19th century Propaganda Movement in Spain peopled by the likes of Jose Rizal, Graciano López Jaena, Marcelo H. del Pilar, Mariano Ponce, Antonio Luna, and other patriots who contributed to La Solidaridad? When and why did propaganda earn a bad rap, especially from our Red-tagging military? In the late 1990s, Jing Monis opened an upscale Makati salon called Propaganda, but with emphasis on the last two syllables, “ganda,” or beauty.

With everyone railing against a coming tsunami of historical distortion, I have been reflecting on the way words have changed or lost their meanings over time. Growing up during martial law, I recall dissonances between what I learned in school and what I heard and saw outside the classroom. Araling Panlipunan was not designed to teach history or critical thinking, it was designed to teach civics with an emphasis on love of country. We were not taught to contest facts but to simply memorize them without question. Facts were not to be interrogated for context and meaning. The formation of the nation was preordained, rosy, with all our heroes perfect, some even superhuman. Reading primary sources in college taught me that history and life is more complicated than textbooks made it out to be.

Words and meanings changed during martial law. School taught me that KKK was short for Kataastaasan, Kagalanggalangang Katipunan ng mga Anak ng Bayan, the revolutionary movement headed by Andres Bonifacio. In the real world, KKK meant a marketing coordination center created by Ferdinand Marcos in 1981 as the Kilusang Kabuhayan at Kaunlaran. Worse, I grew up knowing that “pag-ibig” was the Filipino word for “love,” but as an adult looking at the deductions in my payslip, I see contributions to Pag-IBIG, not love but a home development mutual fund with the contrived name: “PAGtutulungan sa kinabukasan: Ikaw, Bangko, Industriya at Gobyerno.”

Jesuit historian John Schumacher’s Ph.D. thesis “The Propaganda Movement, 1880-1895: The Creators of a Filipino Consciousness, the Makers of Revolution” did not need church review for a “nihil obstat,” certifying that it contained nothing opposed to faith and morals that led to “imprimatur,” the license to print. Instead, the manuscript went through the Armed Forces Office of Civil Relations in 1973 and was almost disapproved because the reviewer presumed from the title that the contents were subversive. An explanation in the introduction said:

“The period of the formation of a nationalist ideology is commonly known in Philippine historiography as the ‘Propaganda Movement’ and its protagonists as the ‘Propagandists.’ In spite of the somewhat unsavory connotations the term has elsewhere acquired in English, the Spanish equivalent does not have such a derogatory sense. The organization La Propaganda or the Comite de Propaganda [formed in 1880 that sent Marcelo H. del Pilar to Spain] from which the period has taken its name in English is too well consecrated by usage to be misunderstood in the Philippines.”

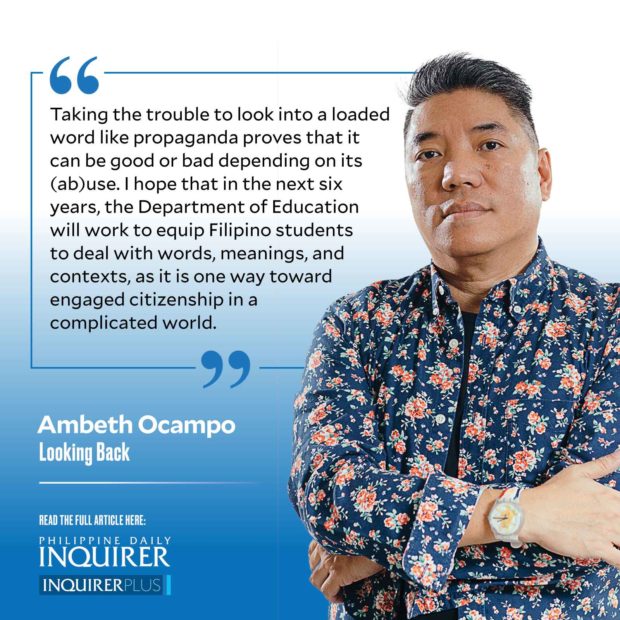

Well, in 1622, Pope Gregory XV created a group of cardinals to promote the faith in heathen lands that later developed into the Congregatio de Propaganda Fide, known under more nuanced translation today as the Congregation for the Evangelization of Peoples. With a 25-million euro budget, Propaganda Fide, administered by Luis Antonio Cardinal Tagle, oversees priests training for missions, support for mission churches and property, and even the vetting of episcopal nominations in mission lands. Here, propaganda is positive, from the Latin “propagare” meaning to set forward, extend, spread, or increase. Taken in an agricultural context, propagation means the cultivation of plants and animals for reproduction. Taking the trouble to look into a loaded word like propaganda proves that it can be good or bad depending on its (ab)use. I hope that in the next six years, the Department of Education will work to equip Filipino students to deal with words, meanings, and contexts, as it is one way toward engaged citizenship in a complicated world.

—————-

Comments are welcome at [email protected]

Subscribe to our daily newsletter

Fearless views on the news

Disclaimer: Comments do not represent the views of INQUIRER.net. We reserve the right to exclude comments which are inconsistent with our editorial standards. FULL DISCLAIMER

© copyright 1997-2024 inquirer.net | all rights reserved.

We use cookies to ensure you get the best experience on our website. By continuing, you are agreeing to our use of cookies. To find out more, please click this link.

Araling Panlipunan

Module 1: rise of nationalism.

- Teaching Resources

Author: Francis Ross M. Padrelanan

Nationalism is a sense of national consciousness exalting one nation above all others and placing primary emphasis on promotion of its culture and interests as opposed to those other nations or supranational groups (Merriam-Webster Dictionary). It is a strong belief of loyalty and devotion to one’s nation that you will do everything just to make sure your country is free from any foreign dictatorship. The father of the Philippine Revolution, Andres Bonifacio, said that Nationalism is the highest and purest kind of love that we can give to our country. It is the love that a certain person or group of people can give to his country.

The Rise of Philippine Nationalism covers the events that led Filipinos to fight for their rights and equal opportunities. These are the events that led to the turning point that Filipinos are now aware of the concept of freedom, independence, and equality. Although the true manifestation of Philippine Nationalism happened many years after these events, it made the Filipinos realize and feel that we should gain our independence no matter what it takes. The desire for reform of Filipinos is what brought them to revolt against colonial Spain.

This self-learning module will help you understand the meaning of Nationalism in the context of Filipinos during the colonial period. These are the events that led to the rise of Filipino Nationalism and how these affects in intensifying the feeling of Nationalism to Filipino people. This will also guide the learners to explain how the propagandists and the events caused them to strengthen and heighten their love for our country.

| Most Essential Learning Competencies

- Analyze the factors that led to the rise of Filipino nationalism;

- Examine how liberalism affected the emergence of nationalist sentiment; and

- Analyze the aspirations of the Propaganda Movement and the Katipunan in the formation of Philippine Nationalism.

| Content Standards

By the end of this module, learners are expected to demonstrate an understanding of:

- The factors that led to the rise of Filipino Nationalism;

- People that contributed to the rise of Filipino Nationalism; and

- Getting acquainted with the events that led to Filipino Nationalism.

| Performance Standards

By the end of this module, learners are expected to:

- Demonstrate their knowledge of the relevance of the contribution of the Philippines in responding to global issues, challenges, and problems.

| Self-Evaluation Form (Part I)

Answer the following questions.

- What are the events that led to the Emergence of Filipino Nationalism?

- How the Filipino Propagandist influenced others to seek reform from the colonizers and the organizations they had?

________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

Lesson 1: Factors that led to the Rise of Filipino Nationalism

| Lesson Objectives

- At the end of the lesson, the student is able to:

- Identify and discuss the events that led to Filipino Nationalism;

- Assess the effects of the factors that led to the rise of Filipino Nationalism or Nationalist Consciousness; and

- Understand the Propaganda Movement.

| Lesson Overview

The emergence of Filipino Nationalism could be traced through various historical events in the country and Europe, as well as its contributing factors. It occurred when Filipinos had been conscious of the oppression they experienced through the socio-economic policies implemented by Spain that only affected them. This shared consciousness paved the way for the idea of a community that has its own aspirations. Thus, Filipinos, led by Filipino propagandists, demanded reforms. When these demands were not met, Filipinos realized the necessity of independence from the colonizers.

| Key Concepts

- Events that led to the Rise of Filipino Nationalism

- The Effects of the Factors that led to the Rise of Filipino Nationalism

- The Filipino Propagandist

- The Movements for Reform

- The Events that led to the Rise of Filipino Nationalism

- Propaganda Movement

The Propagandists were the Filipinos who had a chance to study in Europe where they experienced liberal leadership and brought such ideas to the Philippines. They created the Propaganda Movement which aims to create reforms in the Philippines that is why they are also called reformists. The most influential Propagandists were Jose P. Rizal, Graciano Lopez-Jaena and Marcelo H. Del Pilar. They work through writings that will influence the Filipino people to fight for their independence.

Jose P. Rizal

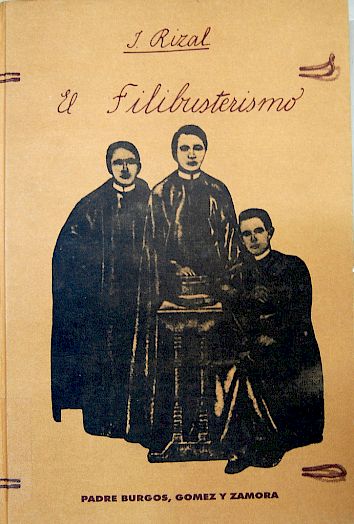

He is considered the greatest reformist in the Philippines. He considered the Philippines as a nation and believed that the Filipinos should be united and enlightened in order to implement reform in the country. His two famous novels, Noli Me Tangere which he dedicated to Fatherland and the El Filibusterismo which he dedicated to GomBurZa tackles the cancer of the society, the racism, the maltreatment, and the injustice Filipinos have experienced to the Spaniards. These two novels and essays contributed to intensifying the patriotic feeling of Filipinos during that time. One of his works was Sa aking mga Kabata, a poem that teaches the love of one’s language. He started his formal education in Ateneo Municipal until he continued in Europe there he joined other propagandists and joined La Solidaridad that writes expositions and discontentment of Filipinos in Philippine society. He used pen names such as Dimas Alang and Laong Laan to hide his identity, until the time that he went back to the Philippines where he founded La Liga Filipina. On July 6,1892 Rizal was secretly arrested because he was considered dangerous by the Spanish authorities and deported to Dapitan. The Liga continues through the support of its members until the time that they get tired of paying their dues. His four years staying in Dapitan was dedicated to helping the less fortunate and teaching young boys until he asked permission from the governor-general to be a volunteer doctor in Cuba. The request was permitted but before the ship docked in Barcelona, he was arrested for the charge of treason and returned to the Philippines. He was sentenced to die by firing squad on December 30, 1896.

Graciano Lopez-Jaena

He was born in Jaro, Iloilo on December 17, 1856. The first editor in chief of the La Solidaridad which he founded in 1889, a newspaper published to expose the true condition of the Philippines. It is also a credit to him for the initiative to create a reform movement. He wrote the Fray Botod or Fat Friars, a novel about friars which he described as a big bellied man, abusive, immoral and selfish. He enrolled in University of Valencia and took up medicine and transferred to Madrid. He is one of the greatest Filipino orators, one of his greatest triumphs in this field happened in Madrid in 1882 during the International Congress of Commercial Geography. He suffered from tuberculosis and died on January 20, 1895 in Barcelona, Spain.

He founded The La Solidaridad on January 1,1889, but its first publication was on February 15, 1889. It was a newspaper that was published to expose the sentiments of the Philippines against the Spanish colonial government. The Propagandists used pen names to hide their identities, Rizal hid under the names Dimas Alang and Laong Laan, Mariano Ponce used Tikbalang, Naning and Kalipulako, Antonio Luna was Taga-Ilog, Plaridel was the pen name of Marcelo H. del Pilar and Jose Ma. Panganiban wrote under the name Jomapa. This became successful in its goal to expose the evils in Philippine society but ended its existence because of the lack of funds and disunity among its members.

Marcelo H. Del Pilar

He was born in Bulakan, Bulacan on August 30, 1850, of Julian H. Del Pilar a Filipino poet whom he inherited his love for arts and Elasa Gatmaitan. The political analyst became the second editor in chief of La Solidaridad, his pen name was Plaridel. The founder of Diariong Tagalog, a nationalistic newspaper that publishes the sentiments of Filipinos. It became influential since it can easily be understood by the natives. One of his works was Caiingat kayo, a manuscript that defended Rizal from the friars. He also wrote Dasalan at Tocsohan which criticizes the prayer of Our Lady and Hail Mary. He died on July 4, 1896b because of Tuberculosis.

Filipino propagandists founded organizations to collaborate and help each other achieve their goals which was to open the eyes of the Spaniards in the true situation of the Philippines. At first they worked individually until they realized that it is more advantageous if they gather together and combine all their resources and efforts to have a bigger voice and influence.

The Circulo-Hispano Filipino Association

The reformists movement consisting of Spanish and Filipino in Madrid founded in 1882 that aimed for social reform from the Spanish government in the Philippines. Prominent members were Miguel Morayta, professor of History in Madrid and Felipe de la Corte an author. Morayta became the president. For the propaganda to become successful the movement was divided into three sections. The political section was under Marcelo H. Del Pilar, the literary was headed by Mariano Ponce and the sports was under the leadership of Tomas Arejola. The joint campaign of the organization resulted in passing laws and petitions in the Spanish Cortez that are good for the interests of Filipinos and made a representation through Emilio Junoy on February 21, 1895. The existence of the movement ended when it was discouraged by the Minister to fight for its aim.

The La Liga Filipina

A civic society founded by Dr. Jose P. Rizal on the night of July 3, 1892 at the house of Doroteo Ongjunco in Tondo Manila. The group aimed to directly involve the people to seek reform, also to unify the archipelago for mutual protection of law, defense against violence and injustice, and reforms needed for the society. After days of its foundation Rizal was exiled to Dapitan and because of the conflicts of its members it split up into two groups. At first it was active until the members got tired of paying their dues.

- List of Activities

Synchronous Activities

Asynchronous activities.

Activity 1: Reflection

Description: The student will write a 300-500 essay that discusses how liberalism affected the rise of Philippine nationalism. The essay should also include the student’s reflection on whether and how these kinds of ideas affect our way of thinking today.

Self-Paced Learning (Optional Activities)

Activity 1: Desk Research

Instructions.

- Answer, what event in Philippine history do you think was the greatest catalyst or factor in the rise of Filipino Nationalism? Why?

- Aside from what we had discussed, research about the life of other Filipino Propagandists.

Note to teacher: This can support students’ development of research skills. Preferably done asynchronously to give students enough time to conduct desk research.

Self-Evaluation Form (Part 2)

- Do you agree with what Andres Bonifacio has said that nationalism is the highest and purest kind of love?

________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

| Rubric for Written Outputs

| Rubric for Creative Outputs

- Introduction

- Rubrics for Grading

The Mindsmith

"To mend and mold and shape minds, let's first break the barriers of learning…"

Propaganda period

Welcome to our Propaganda period topic! Propaganda period is a turning point in our Philippine literary journey. This period marked the beginning of the awakening of our sense of nationalism. The seeds of liberty, equality, and fraternity are well starting to germinate from the many failures experienced by the early waves of armed insurrections which were largely self-contained, isolated and doomed from the start. The adage, “the pen is mightier than the sword” will be pitted to good use here, too. So, what are you waiting for, join me as we take a closer look at the Propaganda period, some of the major members of the propaganda movement, and their salient contributions to the Philippine literary tradition.

Intended learning outcomes

At the end of this topic, you should be able to:

- Recognize notable selections during the Propaganda period;

- Identify significant writers during the Propaganda period; and

- Discuss the theme/message of the literary texts written during the Propaganda period.

Historical background

- The emergence of the “principalia” paved the way to the rise of the intellectual indios called “Ilustrados”.

- The sons of these middle class indios were able to study abroad and gain knowledge on other countries, ideas and concepts of freedom, equality and democracy.

- They, in turn, looked back at the deplorable condition of the Philippines and sought for much needed reforms and improvements.

The awakening of nationalism

The proven and tested formula of Spanish subjugation and colonization was institutionalized in the doctrine of “ divide et sempera” (divide and rule) seemed to be invincible. The Spanish colonial authorities succeeded in quelling and suppressing the budding ethnic and regionalistic rebellions and insurrections by pitting one ethnic group against the other ethnic group. For instance, when the Ilokanos rebelled when their beloved “basi” (sugarcane wine) was taxed heavily; the colonial masters send in the Kapampangans to fight them. This pattern has to be repeated time and again until sporadic rebellions were silenced and the indios were “pacified” with the whip, the sword and the cross.

However, as nothing remains forever on this earth, the long slumber of Filipino nationalism is destined to be awaken. There were several events led to the awakening of the Filipinos’ spirit of nationalism, namely:

- Opening of the Philippines to World Trade.

- The coming of liberal leader Gov. Gen. Carlos Ma. dela Torre.

- The Secularization Issue.

- The Cavite Mutiny.

- The Execution of Gom-Bur-Za

If we are to add a sixth one, that would be the emergence of the Propaganda Movement.

What is the Propaganda period?

Propaganda period was a period of Philippine history and literature when the “Ilustrados” (intellectual indios) started calling for reforms, equality and improvement which lasted approximately from 1868 to 1898 although most of their activities happened between 1880-1895.

The propaganda movement was spearheaded mostly by the intellectual middle-class like Rizal, del Pilar, Lopez-Jaena, Ponce and among others. There were also other writers and persons who, through peaceful means, advocated for reforms such as:

- To get equal treatment for the Filipinos and the Spaniards under the law.

- To make the Philippines a province of Spain.

- To restore Filipino representation in the Spanish Cortes.

- To “Filipinize” the parishes.

- To give the Filipinos freedom of speech, of the press, assembly and for redress of grievances.

The Propaganda stalwarts

Jose rizal (the national hero).

- His full name is Jose Protacio Rizal Mercado Alonzo y Realonda.

- He was born June 19, 1861 at Calamba, Laguna.

- He studied at Ateneo, UST, Universidad Central de Madrid, Univ. of Berlin, Univ. of Leipzig, and Univ. of Heidelberg.

- Executed by musketry on Dec. 30, 1896 with charges of sedition and rebellion.

- Pen names include Dimasalang, Laong-Laan and P. Jacinto.

- Noli Me Tangere – the novel that exposed the evils in society.

- El Filibusterismo – the sequel of Noli which exposed the evils in the government and in the church.

- Mi Ultimo Adios – a poem written by Rizal in his prison cell in Fort Bonifacio.

- Sobre La Indolencia de los Filipinos (On the Indolence of the Filipinos) – an essay defending the Filipinos on the accusation of laziness of the Filipinos and the evaluation of the reasons behind it.

- Filipinas Dentro de Cien Años (The Philippines within a Century) – an essay predicting the future colonizer of the Philippines is America.

- La Juventud Filipina (To the Filipino Youth) – a prize-winning poem dedicated to the Filipino Youth.

- El Consejo de los Dioses (The Council of the Gods) – an allegorical play manifesting his admiration for Cervantes.

- Junto al Pasig (Beside the Pasig River) – an idyll he wrote when he was 14 years old.

- Sa aking mga Kababata (To my fellow children) – a poem he wrote when he was 8 years old.

- Me Piden Versos (They asked me for Verses) – written as requested by his compatriots during a reunion of Filipino expatriates.

- A Las Flores de Heidelberg (To the Flowers of Heidelberg) – written while he was studying at the Univ. of Heidelberg. It shows Rizal’s depth of emotion in outpouring his love of his native land.

- Notas a la Obra Sucesos de las Islas Filipinas for El Dr. Antonio de Morga (Notes on Philippine Events by Dr. Antonio de Morga) 1889.

- P. Jacinto: Memorias de Un Estudiante de Manila (P. Jacinto: Memoirs of a Manila Student) 1882.

- Diario de Viaje de Norte America (Diary of a Voyage to North America)

Marcelo H. Del Pilar (The Consummate Journalist/Propagandist)

- He used pen names such as Plaridel, Pupdoh, Piping Dilat, and Dolores Manapat.

- He attended Colegio de San Jose and UST and took up Law.

- He established Diariong Tagalog where he exposed the evils of Spanish Government.

- He succeeded Lopez-Jaena as editor of La Solidaridad , the official newspaper of Propaganda Movement.

- To escape Spanish wrath, he self-exiled in Barcelona, Spain, where he died of tuberculosis.

- Pag-ibig sa Tinubuang Lupa (Love of Country) – he translated Rizal’s Amor Patria.

- Kaiingat Kayo (Be Careful) – a humorous and sarcastic dig in response to Fr. Jose Rodriguez’s attack on the Noli of Rizal.

- Dasalan at Tocsohan (Prayers and Jokes) – similar to catechism but sarcastically done against the parish priests.

- Ang Cadaquilaan ng Dios (God’s Goodness) – it contains a philosophy of the power and intelligence of God.

- Sagot ng Espanya sa Hibik ng Pilipinas (Answer of Spain on the Plea of the Filipinos) – a poem pleading for change from Spain but that Spain is already weak and old to grant any aid to the Philippines.

- Dupluhan, dalit, mga Bugtong (A poetical contest in narrative sequence, psalms, riddles) – a compilation of poems on the oppression by the priests in the Philippines

- La Soberania en Filipinas (Sovereignty in the Philippines) – shows the injustices of the friars to the Filipinos.

- Por Telefono (By Telephone).

- Pasiong Dapat Ipag-aalab ng Puso ng Taong Babasa (Passion that should Arouse the Hearts of the Readers).

Graciano Lopez-Jaena (The Greatest Orator)

- He wrote 100 speeches in Spanish, and published by Remigio Garcia.

- He escaped to Valencia, Spain to avoid arrest due to his “Fray Botod.”

- Moved to Barcelona, Spain and established La Solidaridad , as its 1st Editor-in-Chief.

- The La Soli became the official paper of the Associacion Hispano de Filipinas, and the official newspaper of Propaganda Movement.

- Ang Fray Botod – he exposed some of the friars were greedy, ambitious and immoral.

- La Hija del Fraile (The Child of the Friar) and

- Everything is Hambug (Everything is a mere Show) – here he explains the tragedy of marrying a Spaniard.

- Sa mga Pilipino – a speech aimed to improve the condition of the Filipinos to become free and progressive.

- Talumpating Paggunita kay Columbus – speech he delivered in Madrid on the anniversary of the discovery of America.

- En honor del Presidente Morayta de la Associacion Hispano Filipino – he praises Gen. Morayta for his equal treatment of the Filipinos.

- En honor de los Artistas Luna y Resurrecion-Hidalgo – a sincere expression of praise for the paintings of Hidalgo on the condition of the Filipinos under Spain.

- El Bandolerismo en Filipinas (Banditry in the Philippines) – he refuted the existence of banditry in the Phils. and how laws and reforms were needed.

- Honor en Filipinas (Honor in the Philippines) – the triumphant exposition of Luna, Resurrecion, and Pardo de Tavera.

- Pag-alis sa Buwis sa Pilipinas (Abolition of Taxes in the Philippines).

- Institucion ng Pilipinas (Sufferings of the Philippines).

Antonio Luna (The pharmacist, writer and general)

- A pharmacist who was banished by the Spaniards to Spain

- He became contributor of La Soli

- His pen name was Tagailog

- He wrote about Filipino customs and how Spain mismanaged the Philippines.

- He became a general of the revolution against Spain.

- He was murdered by Aguinaldo’s men at the age of 33.

- Noche Buena (Christmas Eve) – pictures true Filipino life.

- Se devierten (How they Diverted Themselves) – a dig at a dance of the Spaniards where the people are very crowded.

- La Tertulia Filipina (A Filipino Conference or Feast) – depicts a Filipino custom which he believed was much better than the Spanish.

- Por Madrid (For Madrid) – a denouncement of Spaniards who claim that the Philippines is a colony of Spain but who think of Filipinos as foreigners when it comes to collecting taxes for stamps.

- La Casa de Huespedes (The Landlady’s House) – depicts a landlady who looks for boarders not for money but in order to get a husband for her child.

Mariano Ponce (The secretary)

- He became an editor-in-chief, biographer and researcher of Propaganda movement.

- He used Tikbalang, Naning and Kalipulako as pen names

- He wrote about the values of education and how the Filipinos were oppresed by the foreigners as well as problems of his countrymen.

- Ang Alamat ng Bulacan (Legend of Bulacan) – contains legends and folklores of his native town.

- Pagpugot kay Longinos (The Beheading of Longinus) – a play shown at the plaza of Malolos, Bulacan.

- Sobre Filipinos (About the Filipinos).

- Ang mga Pilipino sa Indo-Tsina (The Filipinos in Indo-China).

Pedro Paterno

- He is a scholar, dramatist, researcher and novelist.

- He is also a mason of the Confraternity of Masons.

- He was the first Filipino writer who escaped censorship of the press.

- Ninay – the first social novel in Spanish written by a Filipino.

- A Mi Madre (To my Mother) – shows the importance of mothers especially in the homes.

- Sampaguita y Poesias Varias (Sampaguitas and Varied Poems) – a collection of his poems.

Jose Maria Panganiban

- He used JOMAPA as his pen name.

- He was known for his photographic mind.

- He was a member of various movements in the country.

- Ang Lupang Tinubuan (My Native Land)

- Ang Aking Buhay (My Life)

- Su Plano de Estudio (Your Study Plan)

- El Pensamiento (The Thinking)

- Soriano-Baldonado, Rizza. (2013). Readings from World Literatures: Understanding People’s Culture, Traditions and Beliefs: A Task-Based Approach. Quezon City: Great Books Publishing.

- Vinuya, Remedios V. (2012). Philippine Literature: A Statement of Ourselves. Metro Manila: Grandbooks Publishing, Inc.

- Kahayon, Alicia & Zulueta, Erlinda. (2009) Philippine Literature Through the Years. Manila: National Book Store.

Show Comments Hide Comments

Leave a Reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

This site uses Akismet to reduce spam. Learn how your comment data is processed .

Seamless Theme Starry Food , made by Altervista

Create a website and earn with Altervista - Disclaimer - Report Abuse - Web Push Notification - Privacy Policy - Customize advertising tracking

Advertisement

Supported by

In Singapore, China Warns U.S. While Zelensky Seeks Support

The annual Shangri-La Dialogue became a stage for competing demands on U.S. global power, including the war in Ukraine and tensions over Taiwan.

- Share full article

By Chris Buckley and Damien Cave

Reporting from Singapore

The competing strains on U.S. global power came into sharp focus at a security conference on Sunday, where China accused the United States of stoking tensions around Taiwan and the South China Sea, and President Volodymyr Zelensky of Ukraine sought greater support for his embattled country.

These scenes played out at the Shangri-La Dialogue, an annual security forum in Singapore that has long been a barometer of the ups and downs of U.S.-China relations.

This year, the United States defense secretary, Lloyd J. Austin III, and China’s defense minister, Adm. Dong Jun, held talks , something the top defense officials from the two countries have not always done at this gathering. But Admiral Dong made clear that China remained antagonistic to U.S. influence and alliance-building across Asia, especially American support for Taiwan, the island democracy that Beijing claims as its territory.

“These malign intentions are drawing Taiwan to the dangers of war,” Admiral Dong told the meeting after making an oblique but unmistakable reference to U.S. military and political support for Taiwan. “Anyone who dares split Taiwan from China will be smashed to pieces and court their own destruction.”

Admiral Dong’s warnings, and other combative comments from Chinese military officers at the meeting, reflected how far apart Beijing and Washington remain over basic issues, even as they discuss ways to keep military friction at sea and in the air from spiraling into crisis.

Last month, China held two days of menacing military exercises around Taiwan, accusing its new president, Lai Ching-te , of trying to advance independence for the island. Mr. Lai has said he wants to preserve Taiwan’s ambiguous status quo — self-governed, yet short of full formal independence — but Chinese officials describe him as a menace to Beijing’s claims to the island.

“I think that in essence it was a step toward Taiwan independence,” Lt. Gen. He Lei, a former vice president of China’s Academy of Military Sciences, said of Mr. Lai’s inaugural speech last month. “As long as he goes further and further down the road of Taiwan independence, going deeper and deeper, the dangers in the Taiwan Strait will only increase.”

Wen Lii, a spokesman for the Taiwanese president, said the Chinese officials’ comments in Singapore “willfully distorted” Taiwan’s position, and that the recent People’s Liberation Army exercises sent “a dangerous and irresponsible message.”

Mr. Austin warned in a speech on Saturday against “actions in this region that erode the status quo and threaten peace and stability,” an indirect reference to Chinese pressure on Taiwan. Mr. Austin also said “we all share an interest in ensuring that the South China Sea remains open and free.”

But Admiral Dong accused an unnamed Southeast Asian country — clearly the Philippines — of stirring up trouble over disputed islands and shoals in the sea, and again suggested that the United States was the real culprit.

“A certain country, incited by external forces, has abandoned bilateral agreements, broken its promises, and taken premeditated action to stir up incidents,” he said in his speech to diplomats, military officials and experts, many from Asian countries. “China has exercised sufficient restraint in responding to these provocations, but this restraint has its limits.”

The Philippines has been at odds with China over their rival claims in the South China Sea, in an area that Manila calls the West Philippine Sea. In 2016, an international tribunal under the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea rejected China’s expansive claims in the South China Sea, which included shoals near the Philippines. Beijing ignored that ruling.

At the meeting in Singapore, the Philippines’ president, Ferdinand Marcos Jr., warned on Friday that his government could call on support from the United States under a mutual defense treaty in the event that a Chinese vessel caused the death of a Philippine sailor.

A U.S. official who heard Admiral Dong’s speech took issue with his portrayal of China as the innocent victim in regional disputes. The official, speaking on condition of anonymity to discuss geopolitical tensions, said the admiral’s assertion was at odds with the Chinese military’s “coercive activity” in the region.

Even in Singapore, Mr. Austin and other Western officials were also reminded that Ukraine’s more than two-year war against Russian invasion continues to demand their leaders’ attention and their taxpayers’ resources.

Mr. Zelensky, a last-minute addition to the gathering, met on Sunday with Mr. Austin, who provided an update on U.S. security assistance, according to a Pentagon readout of the meeting. Then Mr. Zelensky addressed the conference.

Faced with Russian military advances in his country , Mr. Zelensky has been urging the United States and Europe to step up support for his forces and overcome fears about letting Ukraine fire American missiles and other weapons at military targets inside Russia.

There is no clear evidence yet that Ukraine has struck inside Russia with weapons provided by its allies in NATO, after the Biden administration acceded last week to a request from the government in Kyiv to be able to hit targets across the border. That shift in U.S. policy had followed declarations from nearly a dozen European governments and Canada that their weapons could be used in this way.

Nonetheless, regional authorities in Russia said on Sunday that a barrage of near-daily artillery attacks from Ukraine had continued.

Before delivering a speech promoting a peace summit on Ukraine in Switzerland next month that Mr. Zelensky said officials from 106 countries had agreed to join, he was greeted with loud applause. He appealed to leaders across the Indo-Pacific to support the gathering with their attendance or ideas, adding that only diplomacy with persistence would end the conflict.

“The world has to be resilient; it has to be strong; it has to put pressure on Russia,” he told the gathering. “There is no other way to stop Putin.”

In a news conference afterward, Mr. Zelensky told reporters that Russia had persuaded China to try to help limit Asian participation. He gave no details; the Chinese foreign ministry did not immediately respond to the allegation. He also said that Chinese economic and technology flows to Russia were helping it wage war. The Chinese government has repeatedly denied sending weapons to Russia.

On Sunday, Russian forces continued pounding frontline areas of Ukraine, which is fighting to stave off an offensive by Moscow that has gathered pace in recent weeks.

Matthew Mpoke Bigg contributed reporting from London.

Chris Buckley , the chief China correspondent for The Times, reports on China and Taiwan from Taipei, focused on politics, social change and security and military issues. More about Chris Buckley

Damien Cave is an international correspondent for The Times, covering the Indo-Pacific region. He is based in Sydney, Australia. More about Damien Cave

Our Coverage of the War in Ukraine

News and Analysis

The decision by the Biden administration to allow Ukraine to strike inside Russia with American-made weapons fulfills a long-held wish by officials in Kyiv that they claimed was essential to level the playing field.

In recent days, Ukraine has conducted a series of drone attacks inside Russia that target radar stations used as early nuclear warning systems by Moscow.

Top Ukrainian military officials have warned that Russia is building up troops near northeastern Ukraine , raising fears that a new offensive push could be imminent.

Zelensky Interview: In an interview with the New York Times, President Volodymyr Zelensky of Ukraine challenged the West over its reluctance to take bolder action.

Russia’s RT Network : RT, which the U.S. State Department describes as a key player in the Kremlin’s propaganda apparatus, has been blocked in Europe since Russia invaded Ukraine. Its content is still spreading .

Striking a Chord: A play based on a classic 19th-century novel, “The Witch of Konotop,” is a smash hit among Ukrainians who see cultural and historical echoes in the story of what they face after two years of war.

How We Verify Our Reporting

Our team of visual journalists analyzes satellite images, photographs , videos and radio transmissions to independently confirm troop movements and other details.

We monitor and authenticate reports on social media, corroborating these with eyewitness accounts and interviews. Read more about our reporting efforts .

IMAGES

VIDEO

COMMENTS

Propaganda Movement, reform and national consciousness movement that arose among young Filipino expatriates in the late 19th century. Although its adherents expressed loyalty to the Spanish colonial government, Spanish authorities harshly repressed the movement and executed its most prominent member, José Rizal. Public education did not arrive in the Philippines until the 1860s, and even then ...

college and the editor of the journal Philippine Studies- De la Costa made every effort to participate in the heated debates in the 1950s over the shape and course of Philippine history. This essay examines his initial intervention in 1952 as a Catholic voice in the midst of a largely secular-nationalist "New Propaganda Movement."

and the Philippine Propaganda Movement Singapore: National University of Singapore, 2008; Seattle: University of Washington Press, 2008. x, 304 pages. Raquel Reyes s Love , Passion and Patriotism commences with an account of the sexual dalliance of the Filipino ilustrado Jose Panganiban with a married

1973. The purpose of this essay is to explore the hypothesis that the propaganda of the Marcos government during the first year of martial law attempted to win political legitimacy through a rhetorical celebration of various Philippine myths such as traditional values, enemies to the people, 5 The idea of myth in rhetoric has been treated by many.

During the Propaganda and the Revolution, however, this tripartite view of our national history had a positive effect on the burgeoning national psyche. Its power as an idée-force came from its being a highly emotive reaction against the Spanish bipartite view of Philippine history which had supplanted an earlier Filipino historical consciousness.

The task fell on a Filipino immigrant, Manuel Rey Isip, who left the Philippines in 1925 and settled in New York City. A talented artist, Isip drew illustrations for newspapers and movie posters for Columbia Pictures and 20th Century Fox. The result was a propaganda poster, measuring 27 by 41 inches, that would make Isip famous.

History of the Philippines. The Propaganda Movement encompassed the activities of a group of Filipinos who called for political reforms in their land in the late 19th century, and produced books, leaflets, and newspaper articles to educate others about their goals and issues they were trying to solve. They were active approximately from 1880 to ...

The Death of Gomburza & The Propaganda Movement . In February 17, 1872, Fathers Mariano Gomez, Jose Burgos and Jocinto Zamora (Gomburza), all Filipino priest, was executed by the Spanish colonizers on charges of subversion. The charges against Fathers Gomez, Burgos and Zamora was their alleged complicity in the uprising of workers at the Cavite Naval Yard.

Propaganda Movement. The Filipinos suffered so much under the Spanish rule. There were many revolts to fight against the Spaniards but to no avail. When Fathers Mariano Gomez, Jose Burgos and Jacinto Zamora on February 17, 1872 awakened the intense feelings of anger and resentment among the Filipinos. The execution of Gomburza helped to inspire ...

The Propaganda Movement (1872-1892) was the first Filipino nationalist movement, led by a Filipino elite and inspired by the protonationalist activism of figures such as José Burgos and by his execution at the hands of colonial authorities. Propagandists were largely young men, often mestizos and creoles whose families could afford to send them to study in Spanish universities in Madrid and ...

The Propaganda Movement languished after Rizal's arrest and the collapse of the Liga Filipina. La Solidaridad went out of business in November 1895, and in 1896 both del Pilar and Lopez Jaena died in Barcelona, worn down by poverty and disappointment. An attempt was made to reestablish the Liga Filipina, but the national movement had become ...

Semantic Scholar extracted view of "The Propaganda Movement, 1880-1895: The Creation of a Filipino Consciousness, the Making of the Revolution" by J. Schumacher ... Search 218,749,550 papers from all fields of science. Search. Sign In Create Free ... ABSTRACT The Philippines celebrates nationalist Jose Rizal as the 'First Filipino' who laid ...

Salazar, Zeus A. "A Legacy of the Propaganda: The Tripartite View of Philippine History." Nasa The Ethnic Dimension: Papers on Philippine Culture, History and Psychology, pat., Zeus A. Salazar, 107-126. Cologne: Counselling Center for Filipinos, Caritas Association for the City of Cologne, 1983.

The Propaganda Movement was a time before the Philippine Revolution when educated Filipinos, known as illustrados, were calling for reforms in colonial governance. Important members included Jose Rizal, Graciano Lopez Jaena, Mariano Ponce, and Marcelo H. del Pilar. The propagandists advocated for the secularization of the clergy, representation ...

Reform-minded Filipinos took refuge in Europe, where they carried on a literary campaign known as the Propaganda Movement.Dr. José Rizal quickly emerged as the leading Propagandist. His novel Noli me tángere (1886; The Social Cancer, 1912) exposed the corruption of Manila Spanish society and stimulated the movement for independence.. By 1892 it became obvious that Spain was unwilling to ...

The novel pictured a society on the brink of a revolution. To buttress his defense of the native's pride and dignity as people, Rizal wrote three significant essays while abroad: The Philippines a Century hence, the Indolence of the Filipinos and the Letter to the Women of Malolos. These writings were his brilliant responses to the vicious ...

The Propaganda Movement had established a foundation for a Filipino nation built upon "reclaimed" Asian history and a "reawakened" racial Malay consciousness, thereby drawing from the past to buttress the grounds, the place, upon which a Filipino nation could stand. The Philippine Revolution took this intellectual armature, which was ...

Revolution and Independence Movement. The Propaganda Movement was a political and cultural organization founded by Filipino intellectuals in the late 19th century. They aimed to educate the Filipinos and expose the injustices and abuses of Spanish colonial rule through the publication of articles, essays, and books.

"The period of the formation of a nationalist ideology is commonly known in Philippine historiography as the 'Propaganda Movement' and its protagonists as the 'Propagandists.' In spite of the somewhat unsavory connotations the term has elsewhere acquired in English, the Spanish equivalent does not have such a derogatory sense.

They created the Propaganda Movement which aims to create reforms in the Philippines that is why they are also called reformists. ... The student will write a 300-500 essay that discusses how liberalism affected the rise of Philippine nationalism. The essay should also include the student's reflection on whether and how these kinds of ideas ...

Propaganda period was a period of Philippine history and literature when the "Ilustrados" (intellectual indios) started calling for reforms, equality and improvement which lasted approximately from 1868 to 1898 although most of their activities happened between 1880-1895. The propaganda movement was spearheaded mostly by the intellectual ...

In order to help achieve its goals, the Propaganda Movement put up its own newspaper, called La Solidaridad. The Soli, as the reformists fondly called their official organ, came out once every two weeks. The first issue saw print was published on November 15, 1895. The Solidaridad's first editor was Graciano Lopez Jaena. Marcelo H. del Pilar ...

While Zelensky Seeks Support. The annual Shangri-La Dialogue became a stage for competing demands on U.S. global power, including the war in Ukraine and tensions over Taiwan. China's minister of ...