The Ultimate Guide on How to Organize a Bold Argumentative Essay

by Suzanne Davis | Jun 20, 2021 | Writing Essays and Papers , Writing Organization | 6 comments

Can you argue with me (in writing)?

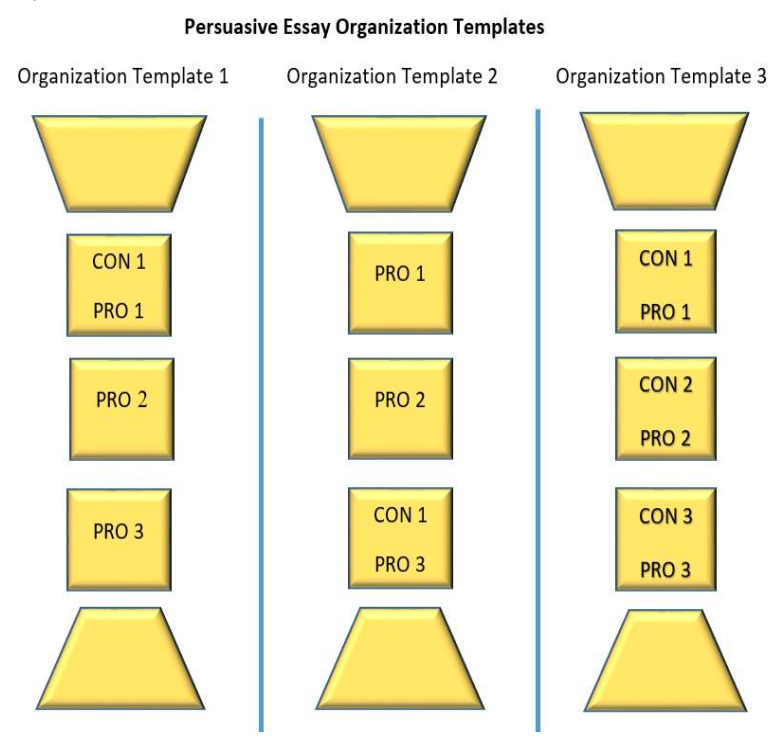

That’s what I want my students to do. I want them to write a compelling argumentative essay that debates and challenges a point of view on a topic. And the secret to accomplishing that is knowing how to organize an argumentative essay. If you understand the parts and pieces that make up an outstanding argumentative essay, then you can write thorough, detailed, and persuasive content.

So, what’s an argumentative essay? It’s an essay where you take a stand on an issue and explain why your position is correct. It’s important to create an argumentative essay that explains and proves your thesis.

The key to doing this is by following a strong argumentative essay plan. There are other ways to organize your argumentative essay. But in this post, we’ll look at an easy plan that covers all the major parts you need in your essay.

And check out the video below to see how to use a checklist to help you organize an argumentative essay.

How to Organize an Argumentative Essay

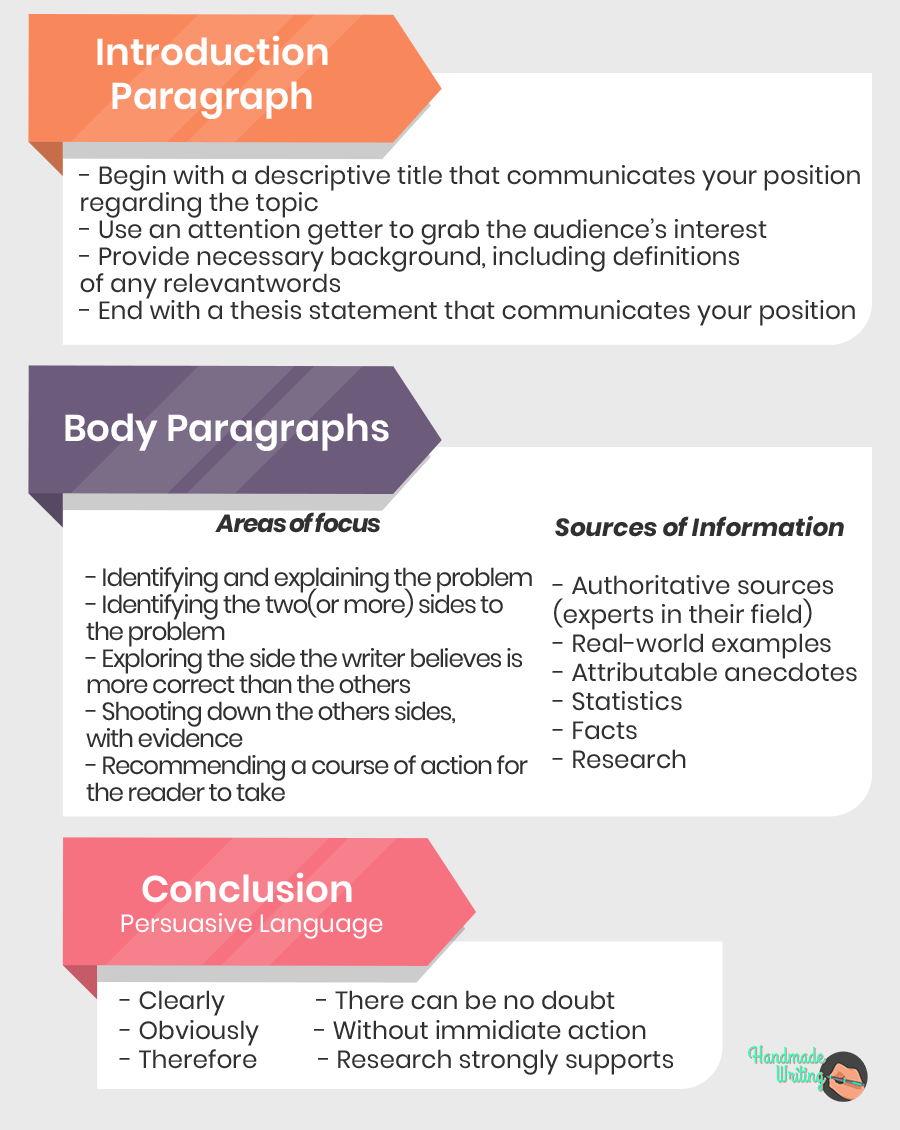

The key pieces of this argumentative essay plan are:

- Introduction

- Body paragraphs that support the thesis

- Rebuttal paragraph/s

The Introduction to an Argumentative Essay

Your introduction is how you show the reader your point of view about the issue. It also sets up the organization of the rest of your essay. A solid introduction is a powerful way to start your essay. The elements of an argumentative essay introduction are:

Hook: This is a sentence that captures grabs your readers’ attention. A hook makes them curious about the topic of your essay.

4 hooks work great with argumentative essays:

- Ask an interesting question

- State a fact/statistic

- Make a strong statement

- Include a relevant and important quotation

Each of these hooks should relate to the specific topic in your paper.

For more information about essay hooks see- https://www.academicwritingsuccess.com/7-sensational-types-of-essay-hooks/

Ask yourself why does this topic matter? Who does it concer n? Write about that in these sentences leading up to your thesis statement.

Thesis Statement: The last sentence is your argumentative essay thesis statement. A thesis statement is your opinion about the main topic of your essay or paper.

An argumentative thesis statement begins with a debatable topic/issue. The thesis statement is your point of view about that issue and how you will prove it. This is the claim of your argumentative essay.

An example argumentative essay thesis statement is: Assault rifles should be banned in the United States because these weapons can kill many people in a matter of seconds.

Next, you write the body of your essay so that it supports this claim and overpowers arguments against it.

The Body of an Argumentative Essay

The body of an argumentative essay has 2 parts: Paragraphs that support your claim and 1 or 2 rebuttal paragraphs.

Supporting paragraphs and rebuttal paragraphs reflect the pros and cons of your claim about the issue.

Body Paragraphs that Support Your Claim

Topic Sentence: This sentence is a supporting idea related to your thesis statement. The main topic of the paragraph is the supporting idea.

Supporting Details : This is the substance of your paragraph. Supporting details are evidence that proves the supporting idea.

Relationship to the thesis statement: This is a concluding sentence that shows how the supporting idea ties back to your thesis statement. It will also connect or lead into the next paragraph that supports your claim.

Write a body paragraph for each of the ideas that support your claim.

Rebuttal Paragraph in an Argumentative Essay

A rebuttal paragraph is important because it shows you considered two sides of an issue. You thought about the other side of an issue, researched it, and found a way to argue against it.

This is a crucial part of your argumentative essay because it’s where you overrule other peoples’ objections.

The 3 parts of the rebuttal paragraph are:

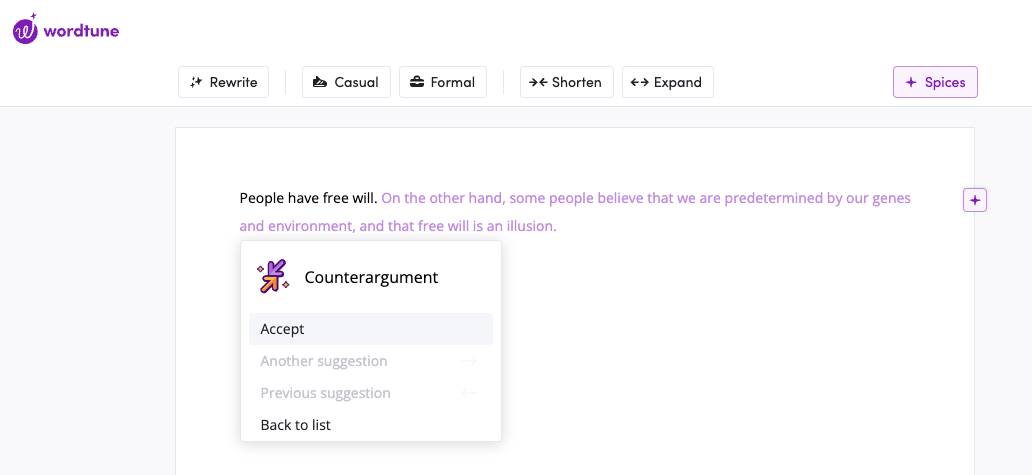

- Counterargument

- Refuting the counterargument

- Concluding Sentence

Counterargument: A counterargument is an objection to your claim. You develop this by thinking of all the things the people opposed to your perspective.

The thesis statement from above is: Pinterest is the best social media platform for small online businesses to advertise their products and services because many people use Pinterest to make buying decisions.

Your counterargument is a reason/s people would argue against that claim:

Ex. Facebook is the largest social media platform, and more people visit Facebook every day. Most people only visit Pinterest a few times a week.

Refuting the counterargument: Here, you explain and prove why these counterarguments are wrong.

Ex. Yet, people who use Pinterest are 10% more likely to buy something they saw on Pinterest than on any other social media platform. https://blog.hootsuite.com/top-social-media-sites-matter-to-marketers/

Concluding sentence : This last part of the rebuttal paragraph sums up the problem with the counterargument.

The Conclusion to an Argumentative Essay

Your conclusion should show readers what you proved and why your thesis matters. These are the things you include in a conclusion to an argumentative essay:

Summary Sentences : Here, you recap the main points of your claim.

Restate the thesis statement : Use different words to restate your claim.

Significance: Here, you explain why the thesis you proved in your argumentative essay matters. Consider how it affects other people, the field you study, or the world. Ask yourself, “What should the reader take away from my paper?”

A solid plan for your argumentative essay will help you see the weaknesses and strengths in your argument before you start writing your essay. You can follow this same organization when you write a longer argumentative paper. The difference is that you add more supporting and rebuttal paragraphs to a longer paper.

Learn how to organize an argumentative essay, and you’ll find it easier to write and revise an argumentative paper too.

Download your free copy of “The Ultimate Argumentative Essay Checklist” to help you write and revise your next argumentative essay.

Wow, this is the most detailed and easy to follow explanation of how to write an argumentative essay. Thank you for how precise and clear you are.

You are very welcome. It’s much easier to write an argumentative essay with a clear plan for how to do things.

Suzanne, I love learning English once more. Most facts are long forgotten due to non-usage of those. But knowing and putting one’s knowledge into practice are completely two different things which is where your guidance becomes so crucial.

Nilanjana, I am glad you like learning English again. There is a difference between knowing a language and using it regularly. Please feel free to share any ideas of things you would like to learn. I love to write about English and writing.

This is an excellent article that give clear directions on how to approach argumentative essays. Students should always value a checklist and use it often. Writing is so much easier with a plan of attack!

Tutorpreneur Hero Award

http://becomeanonlinetutor.com/tutorpreneur-hero/

SSL Certificate Seal

Session expired

Please log in again. The login page will open in a new tab. After logging in you can close it and return to this page.

Privacy Overview

Purdue Online Writing Lab Purdue OWL® College of Liberal Arts

Organizing Your Argument

Welcome to the Purdue OWL

This page is brought to you by the OWL at Purdue University. When printing this page, you must include the entire legal notice.

Copyright ©1995-2018 by The Writing Lab & The OWL at Purdue and Purdue University. All rights reserved. This material may not be published, reproduced, broadcast, rewritten, or redistributed without permission. Use of this site constitutes acceptance of our terms and conditions of fair use.

How can I effectively present my argument?

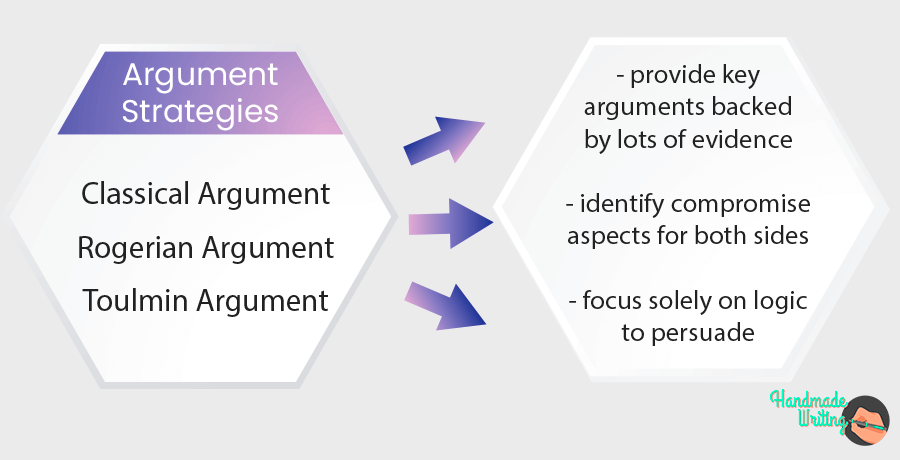

In order for your argument to be persuasive, it must use an organizational structure that the audience perceives as both logical and easy to parse. Three argumentative methods —the Toulmin Method , Classical Method , and Rogerian Method — give guidance for how to organize the points in an argument.

Note that these are only three of the most popular models for organizing an argument. Alternatives exist. Be sure to consult your instructor and/or defer to your assignment’s directions if you’re unsure which to use (if any).

Toulmin Method

The Toulmin Method is a formula that allows writers to build a sturdy logical foundation for their arguments. First proposed by author Stephen Toulmin in The Uses of Argument (1958), the Toulmin Method emphasizes building a thorough support structure for each of an argument's key claims.

The basic format for the Toulmin Method is as follows:

Claim: In this section, you explain your overall thesis on the subject. In other words, you make your main argument.

Data (Grounds): You should use evidence to support the claim. In other words, provide the reader with facts that prove your argument is strong.

Warrant (Bridge): In this section, you explain why or how your data supports the claim. As a result, the underlying assumption that you build your argument on is grounded in reason.

Backing (Foundation): Here, you provide any additional logic or reasoning that may be necessary to support the warrant.

Counterclaim: You should anticipate a counterclaim that negates the main points in your argument. Don't avoid arguments that oppose your own. Instead, become familiar with the opposing perspective. If you respond to counterclaims, you appear unbiased (and, therefore, you earn the respect of your readers). You may even want to include several counterclaims to show that you have thoroughly researched the topic.

Rebuttal: In this section, you incorporate your own evidence that disagrees with the counterclaim. It is essential to include a thorough warrant or bridge to strengthen your essay’s argument. If you present data to your audience without explaining how it supports your thesis, your readers may not make a connection between the two, or they may draw different conclusions.

Example of the Toulmin Method:

Claim: Hybrid cars are an effective strategy to fight pollution.

Data1: Driving a private car is a typical citizen's most air-polluting activity.

Warrant 1: Due to the fact that cars are the largest source of private (as opposed to industrial) air pollution, switching to hybrid cars should have an impact on fighting pollution.

Data 2: Each vehicle produced is going to stay on the road for roughly 12 to 15 years.

Warrant 2: Cars generally have a long lifespan, meaning that the decision to switch to a hybrid car will make a long-term impact on pollution levels.

Data 3: Hybrid cars combine a gasoline engine with a battery-powered electric motor.

Warrant 3: The combination of these technologies produces less pollution.

Counterclaim: Instead of focusing on cars, which still encourages an inefficient culture of driving even as it cuts down on pollution, the nation should focus on building and encouraging the use of mass transit systems.

Rebuttal: While mass transit is an idea that should be encouraged, it is not feasible in many rural and suburban areas, or for people who must commute to work. Thus, hybrid cars are a better solution for much of the nation's population.

Rogerian Method

The Rogerian Method (named for, but not developed by, influential American psychotherapist Carl R. Rogers) is a popular method for controversial issues. This strategy seeks to find a common ground between parties by making the audience understand perspectives that stretch beyond (or even run counter to) the writer’s position. Moreso than other methods, it places an emphasis on reiterating an opponent's argument to his or her satisfaction. The persuasive power of the Rogerian Method lies in its ability to define the terms of the argument in such a way that:

- your position seems like a reasonable compromise.

- you seem compassionate and empathetic.

The basic format of the Rogerian Method is as follows:

Introduction: Introduce the issue to the audience, striving to remain as objective as possible.

Opposing View : Explain the other side’s position in an unbiased way. When you discuss the counterargument without judgement, the opposing side can see how you do not directly dismiss perspectives which conflict with your stance.

Statement of Validity (Understanding): This section discusses how you acknowledge how the other side’s points can be valid under certain circumstances. You identify how and why their perspective makes sense in a specific context, but still present your own argument.

Statement of Your Position: By this point, you have demonstrated that you understand the other side’s viewpoint. In this section, you explain your own stance.

Statement of Contexts : Explore scenarios in which your position has merit. When you explain how your argument is most appropriate for certain contexts, the reader can recognize that you acknowledge the multiple ways to view the complex issue.

Statement of Benefits: You should conclude by explaining to the opposing side why they would benefit from accepting your position. By explaining the advantages of your argument, you close on a positive note without completely dismissing the other side’s perspective.

Example of the Rogerian Method:

Introduction: The issue of whether children should wear school uniforms is subject to some debate.

Opposing View: Some parents think that requiring children to wear uniforms is best.

Statement of Validity (Understanding): Those parents who support uniforms argue that, when all students wear the same uniform, the students can develop a unified sense of school pride and inclusiveness.

Statement of Your Position : Students should not be required to wear school uniforms. Mandatory uniforms would forbid choices that allow students to be creative and express themselves through clothing.

Statement of Contexts: However, even if uniforms might hypothetically promote inclusivity, in most real-life contexts, administrators can use uniform policies to enforce conformity. Students should have the option to explore their identity through clothing without the fear of being ostracized.

Statement of Benefits: Though both sides seek to promote students' best interests, students should not be required to wear school uniforms. By giving students freedom over their choice, students can explore their self-identity by choosing how to present themselves to their peers.

Classical Method

The Classical Method of structuring an argument is another common way to organize your points. Originally devised by the Greek philosopher Aristotle (and then later developed by Roman thinkers like Cicero and Quintilian), classical arguments tend to focus on issues of definition and the careful application of evidence. Thus, the underlying assumption of classical argumentation is that, when all parties understand the issue perfectly, the correct course of action will be clear.

The basic format of the Classical Method is as follows:

Introduction (Exordium): Introduce the issue and explain its significance. You should also establish your credibility and the topic’s legitimacy.

Statement of Background (Narratio): Present vital contextual or historical information to the audience to further their understanding of the issue. By doing so, you provide the reader with a working knowledge about the topic independent of your own stance.

Proposition (Propositio): After you provide the reader with contextual knowledge, you are ready to state your claims which relate to the information you have provided previously. This section outlines your major points for the reader.

Proof (Confirmatio): You should explain your reasons and evidence to the reader. Be sure to thoroughly justify your reasons. In this section, if necessary, you can provide supplementary evidence and subpoints.

Refutation (Refuatio): In this section, you address anticipated counterarguments that disagree with your thesis. Though you acknowledge the other side’s perspective, it is important to prove why your stance is more logical.

Conclusion (Peroratio): You should summarize your main points. The conclusion also caters to the reader’s emotions and values. The use of pathos here makes the reader more inclined to consider your argument.

Example of the Classical Method:

Introduction (Exordium): Millions of workers are paid a set hourly wage nationwide. The federal minimum wage is standardized to protect workers from being paid too little. Research points to many viewpoints on how much to pay these workers. Some families cannot afford to support their households on the current wages provided for performing a minimum wage job .

Statement of Background (Narratio): Currently, millions of American workers struggle to make ends meet on a minimum wage. This puts a strain on workers’ personal and professional lives. Some work multiple jobs to provide for their families.

Proposition (Propositio): The current federal minimum wage should be increased to better accommodate millions of overworked Americans. By raising the minimum wage, workers can spend more time cultivating their livelihoods.

Proof (Confirmatio): According to the United States Department of Labor, 80.4 million Americans work for an hourly wage, but nearly 1.3 million receive wages less than the federal minimum. The pay raise will alleviate the stress of these workers. Their lives would benefit from this raise because it affects multiple areas of their lives.

Refutation (Refuatio): There is some evidence that raising the federal wage might increase the cost of living. However, other evidence contradicts this or suggests that the increase would not be great. Additionally, worries about a cost of living increase must be balanced with the benefits of providing necessary funds to millions of hardworking Americans.

Conclusion (Peroratio): If the federal minimum wage was raised, many workers could alleviate some of their financial burdens. As a result, their emotional wellbeing would improve overall. Though some argue that the cost of living could increase, the benefits outweigh the potential drawbacks.

- Appointments, Policies, and FAQ

- Graduate Writing Consultants

- Undergraduate Writing Consultants

- ESL Students

- Handouts & How-To’s

- Useful Links

- Resources for Instructors

- University Writing Program

- Writers Across Campus

- Writing Consultants

- Resources for Students

Tips for Organizing an Argumentative Essay

Addressing “flow”: tips for organizing an argumentative essay.

“Flow”, in regard to a characteristic of an essay, is a fairly murky and general concept that could cover a wide range of issues. However, most often, if you’re worried about “flow”, your concerns actually have their roots in focus and organization. Paragraphs may not clearly relate back to the thesis or each other, or important points may be buried by less-important information. These tips, though by no means exhaustive, are meant to help you create a cohesive, “flowing” argumentative essay. While this handout was written with argumentative essays (particularly within the humanities) in mind, many of the general ideas behind them apply to a wide range of disciplines.

1) Pre-Write/Outline

- There are not many aspects of the writing process that are as universally dreaded as the outline. Sometimes it can feel like pointless extra work, but it actually is your best safeguard against losing focus in a paper, preserves organization throughout, and just generally makes it easier to sit down and write an essay.

- It doesn’t matter what form your outline takes as long as it’s something that details what points you want to make and in what order. Figuring out your main points before you start drafting keeps you on topic, and considering order will make transitions easier and more meaningful.

2) Make sure you begin each paragraph with a topic sentence.

- Example : Carroll uses Alice’s conversation with the Cheshire Cat about madness both to explain the world of Wonderland and critique a Victorian emphasis on facts and reason.

- Example : In Alice in Wonderland , Alice has a conversation with the Cheshire Cat about madness.

3) Make sure every topic sentence (and therefore, every paragraph) relates directly back to your thesis statement.

- e., If your thesis claims that Alice in Wonderland critiques Victorian education for children by doing x and also y, every topic sentence of each of your body paragraphs should have to relate to Victorian education and x and/or y.

- e., you might want to talk about the White Hare as a symbol for Victorian obsession with time. However, if your paper as a whole is otherwise about passages/paragraphs that critique Victorian education, then it is out of place, and will only confuse your paper’s focus.

4) Use effective transitions between paragraphs

- Paragraph A: talks about Alice’s encounter with the caterpillar

- Transition to Paragraph B: Similarly , Alice encounters another strange creature in the form of the Cheshire Cat, with whom, like the caterpillar, she holds a conversation with larger implications for the world of the novel.

- Paragraph A: details how the madness of Wonderland critiques the fact-based Victorian England

- Transition to Paragraph B: Despite the nature of madness and this criticism of facts and order, there is a kind of logic to Wonderland, and it is deliberately inversive.

- NB: These are only two examples of how to involve transitions in your paper; there are many other ways to do so. But no matter what transition you use, it should in some way establish a relationship between a previous point in your essay and the one you’re about to talk about.

5) Re-read your paper!

- Many issues that might hamper flow are small/general enough that you can catch them just by proofreading–i.e., sentence fragments, clunky/lengthy sentences, etc.

- Reading your paper out loud is especially helpful for catching awkward phrases/sentences

- Active and Passive Voice

- Tips on Writing Effective Dialogue

- Setting Up an Effective Argument for a CC Paper

- be_ixf; php_sdk; php_sdk_1.4.26

- https://www.valpo.edu/writingcenter/resources-for-students/handouts/organizing-argumentative-essay/

- Link to facebook

- Link to linkedin

- Link to twitter

- Link to youtube

- Writing Tips

How to Write an Argumentative Essay

4-minute read

- 30th April 2022

An argumentative essay is a structured, compelling piece of writing where an author clearly defines their stance on a specific topic. This is a very popular style of writing assigned to students at schools, colleges, and universities. Learn the steps to researching, structuring, and writing an effective argumentative essay below.

Requirements of an Argumentative Essay

To effectively achieve its purpose, an argumentative essay must contain:

● A concise thesis statement that introduces readers to the central argument of the essay

● A clear, logical, argument that engages readers

● Ample research and evidence that supports your argument

Approaches to Use in Your Argumentative Essay

1. classical.

● Clearly present the central argument.

● Outline your opinion.

● Provide enough evidence to support your theory.

2. Toulmin

● State your claim.

● Supply the evidence for your stance.

● Explain how these findings support the argument.

● Include and discuss any limitations of your belief.

3. Rogerian

● Explain the opposing stance of your argument.

● Discuss the problems with adopting this viewpoint.

● Offer your position on the matter.

● Provide reasons for why yours is the more beneficial stance.

● Include a potential compromise for the topic at hand.

Tips for Writing a Well-Written Argumentative Essay

● Introduce your topic in a bold, direct, and engaging manner to captivate your readers and encourage them to keep reading.

● Provide sufficient evidence to justify your argument and convince readers to adopt this point of view.

● Consider, include, and fairly present all sides of the topic.

● Structure your argument in a clear, logical manner that helps your readers to understand your thought process.

Find this useful?

Subscribe to our newsletter and get writing tips from our editors straight to your inbox.

● Discuss any counterarguments that might be posed.

● Use persuasive writing that’s appropriate for your target audience and motivates them to agree with you.

Steps to Write an Argumentative Essay

Follow these basic steps to write a powerful and meaningful argumentative essay :

Step 1: Choose a topic that you’re passionate about

If you’ve already been given a topic to write about, pick a stance that resonates deeply with you. This will shine through in your writing, make the research process easier, and positively influence the outcome of your argument.

Step 2: Conduct ample research to prove the validity of your argument

To write an emotive argumentative essay , finding enough research to support your theory is a must. You’ll need solid evidence to convince readers to agree with your take on the matter. You’ll also need to logically organize the research so that it naturally convinces readers of your viewpoint and leaves no room for questioning.

Step 3: Follow a simple, easy-to-follow structure and compile your essay

A good structure to ensure a well-written and effective argumentative essay includes:

Introduction

● Introduce your topic.

● Offer background information on the claim.

● Discuss the evidence you’ll present to support your argument.

● State your thesis statement, a one-to-two sentence summary of your claim.

● This is the section where you’ll develop and expand on your argument.

● It should be split into three or four coherent paragraphs, with each one presenting its own idea.

● Start each paragraph with a topic sentence that indicates why readers should adopt your belief or stance.

● Include your research, statistics, citations, and other supporting evidence.

● Discuss opposing viewpoints and why they’re invalid.

● This part typically consists of one paragraph.

● Summarize your research and the findings that were presented.

● Emphasize your initial thesis statement.

● Persuade readers to agree with your stance.

We certainly hope that you feel inspired to use these tips when writing your next argumentative essay . And, if you’re currently elbow-deep in writing one, consider submitting a free sample to us once it’s completed. Our expert team of editors can help ensure that it’s concise, error-free, and effective!

Share this article:

Post A New Comment

Got content that needs a quick turnaround? Let us polish your work. Explore our editorial business services.

9-minute read

How to Use Infographics to Boost Your Presentation

Is your content getting noticed? Capturing and maintaining an audience’s attention is a challenge when...

8-minute read

Why Interactive PDFs Are Better for Engagement

Are you looking to enhance engagement and captivate your audience through your professional documents? Interactive...

7-minute read

Seven Key Strategies for Voice Search Optimization

Voice search optimization is rapidly shaping the digital landscape, requiring content professionals to adapt their...

Five Creative Ways to Showcase Your Digital Portfolio

Are you a creative freelancer looking to make a lasting impression on potential clients or...

How to Ace Slack Messaging for Contractors and Freelancers

Effective professional communication is an important skill for contractors and freelancers navigating remote work environments....

3-minute read

How to Insert a Text Box in a Google Doc

Google Docs is a powerful collaborative tool, and mastering its features can significantly enhance your...

Make sure your writing is the best it can be with our expert English proofreading and editing.

Choose Your Test

Sat / act prep online guides and tips, 3 key tips for how to write an argumentative essay.

General Education

If there’s one writing skill you need to have in your toolkit for standardized tests, AP exams, and college-level writing, it’s the ability to make a persuasive argument. Effectively arguing for a position on a topic or issue isn’t just for the debate team— it’s for anyone who wants to ace the essay portion of an exam or make As in college courses.

To give you everything you need to know about how to write an argumentative essay , we’re going to answer the following questions for you:

- What is an argumentative essay?

- How should an argumentative essay be structured?

- How do I write a strong argument?

- What’s an example of a strong argumentative essay?

- What are the top takeaways for writing argumentative papers?

By the end of this article, you’ll be prepped and ready to write a great argumentative essay yourself!

Now, let’s break this down.

What Is an Argumentative Essay?

An argumentative essay is a type of writing that presents the writer’s position or stance on a specific topic and uses evidence to support that position. The goal of an argumentative essay is to convince your reader that your position is logical, ethical, and, ultimately, right . In argumentative essays, writers accomplish this by writing:

- A clear, persuasive thesis statement in the introduction paragraph

- Body paragraphs that use evidence and explanations to support the thesis statement

- A paragraph addressing opposing positions on the topic—when appropriate

- A conclusion that gives the audience something meaningful to think about.

Introduction, body paragraphs, and a conclusion: these are the main sections of an argumentative essay. Those probably sound familiar. Where does arguing come into all of this, though? It’s not like you’re having a shouting match with your little brother across the dinner table. You’re just writing words down on a page!

...or are you? Even though writing papers can feel like a lonely process, one of the most important things you can do to be successful in argumentative writing is to think about your argument as participating in a larger conversation . For one thing, you’re going to be responding to the ideas of others as you write your argument. And when you’re done writing, someone—a teacher, a professor, or exam scorer—is going to be reading and evaluating your argument.

If you want to make a strong argument on any topic, you have to get informed about what’s already been said on that topic . That includes researching the different views and positions, figuring out what evidence has been produced, and learning the history of the topic. That means—you guessed it!—argumentative essays almost always require you to incorporate outside sources into your writing.

What Makes Argumentative Essays Unique?

Argumentative essays are different from other types of essays for one main reason: in an argumentative essay, you decide what the argument will be . Some types of essays, like summaries or syntheses, don’t want you to show your stance on the topic—they want you to remain unbiased and neutral.

In argumentative essays, you’re presenting your point of view as the writer and, sometimes, choosing the topic you’ll be arguing about. You just want to make sure that that point of view comes across as informed, well-reasoned, and persuasive.

Another thing about argumentative essays: they’re often longer than other types of essays. Why, you ask? Because it takes time to develop an effective argument. If your argument is going to be persuasive to readers, you have to address multiple points that support your argument, acknowledge counterpoints, and provide enough evidence and explanations to convince your reader that your points are valid.

Our 3 Best Tips for Picking a Great Argumentative Topic

The first step to writing an argumentative essay deciding what to write about! Choosing a topic for your argumentative essay might seem daunting, though. It can feel like you could make an argument about anything under the sun. For example, you could write an argumentative essay about how cats are way cooler than dogs, right?

It’s not quite that simple . Here are some strategies for choosing a topic that serves as a solid foundation for a strong argument.

Choose a Topic That Can Be Supported With Evidence

First, you want to make sure the topic you choose allows you to make a claim that can be supported by evidence that’s considered credible and appropriate for the subject matter ...and, unfortunately, your personal opinions or that Buzzfeed quiz you took last week don’t quite make the cut.

Some topics—like whether cats or dogs are cooler—can generate heated arguments, but at the end of the day, any argument you make on that topic is just going to be a matter of opinion. You have to pick a topic that allows you to take a position that can be supported by actual, researched evidence.

(Quick note: you could write an argumentative paper over the general idea that dogs are better than cats—or visa versa!—if you’re a) more specific and b) choose an idea that has some scientific research behind it. For example, a strong argumentative topic could be proving that dogs make better assistance animals than cats do.)

You also don’t want to make an argument about a topic that’s already a proven fact, like that drinking water is good for you. While some people might dislike the taste of water, there is an overwhelming body of evidence that proves—beyond the shadow of a doubt—that drinking water is a key part of good health.

To avoid choosing a topic that’s either unprovable or already proven, try brainstorming some issues that have recently been discussed in the news, that you’ve seen people debating on social media, or that affect your local community. If you explore those outlets for potential topics, you’ll likely stumble upon something that piques your audience’s interest as well.

Choose a Topic That You Find Interesting

Topics that have local, national, or global relevance often also resonate with us on a personal level. Consider choosing a topic that holds a connection between something you know or care about and something that is relevant to the rest of society. These don’t have to be super serious issues, but they should be topics that are timely and significant.

For example, if you are a huge football fan, a great argumentative topic for you might be arguing whether football leagues need to do more to prevent concussions . Is this as “important” an issue as climate change? No, but it’s still a timely topic that affects many people. And not only is this a great argumentative topic: you also get to write about one of your passions! Ultimately, if you’re working with a topic you enjoy, you’ll have more to say—and probably write a better essay .

Choose a Topic That Doesn’t Get You Too Heated

Another word of caution on choosing a topic for an argumentative paper: while it can be effective to choose a topic that matters to you personally, you also want to make sure you’re choosing a topic that you can keep your cool over. You’ve got to be able to stay unemotional, interpret the evidence persuasively, and, when appropriate, discuss opposing points of view without getting too salty.

In some situations, choosing a topic for your argumentative paper won’t be an issue at all: the test or exam will choose it for you . In that case, you’ve got to do the best you can with what you’re given.

In the next sections, we’re going to break down how to write any argumentative essay —regardless of whether you get to choose your own topic or have one assigned to you! Our expert tips and tricks will make sure that you’re knocking your paper out of the park.

The Thesis: The Argumentative Essay’s Backbone

You’ve chosen a topic or, more likely, read the exam question telling you to defend, challenge, or qualify a claim on an assigned topic. What do you do now?

You establish your position on the topic by writing a killer thesis statement ! The thesis statement, sometimes just called “the thesis,” is the backbone of your argument, the north star that keeps you oriented as you develop your main points, the—well, you get the idea.

In more concrete terms, a thesis statement conveys your point of view on your topic, usually in one sentence toward the end of your introduction paragraph . It’s very important that you state your point of view in your thesis statement in an argumentative way—in other words, it should state a point of view that is debatable.

And since your thesis statement is going to present your argument on the topic, it’s the thing that you’ll spend the rest of your argumentative paper defending. That’s where persuasion comes in. Your thesis statement tells your reader what your argument is, then the rest of your essay shows and explains why your argument is logical.

Why does an argumentative essay need a thesis, though? Well, the thesis statement—the sentence with your main claim—is actually the entire point of an argumentative essay. If you don’t clearly state an arguable claim at the beginning of your paper, then it’s not an argumentative essay. No thesis statement = no argumentative essay. Got it?

Other types of essays that you’re familiar with might simply use a thesis statement to forecast what the rest of the essay is going to discuss or to communicate what the topic is. That’s not the case here. If your thesis statement doesn’t make a claim or establish your position, you’ll need to go back to the drawing board.

Example Thesis Statements

Here are a couple of examples of thesis statements that aren’t argumentative and thesis statements that are argumentative

The sky is blue.

The thesis statement above conveys a fact, not a claim, so it’s not argumentative.

To keep the sky blue, governments must pass clean air legislation and regulate emissions.

The second example states a position on a topic. What’s the topic in that second sentence? The best way to keep the sky blue. And what position is being conveyed? That the best way to keep the sky blue is by passing clean air legislation and regulating emissions.

Some people would probably respond to that thesis statement with gusto: “No! Governments should not pass clean air legislation and regulate emissions! That infringes on my right to pollute the earth!” And there you have it: a thesis statement that presents a clear, debatable position on a topic.

Here’s one more set of thesis statement examples, just to throw in a little variety:

Spirituality and otherworldliness characterize A$AP Rocky’s portrayals of urban life and the American Dream in his rap songs and music videos.

The statement above is another example that isn’t argumentative, but you could write a really interesting analytical essay with that thesis statement. Long live A$AP! Now here’s another one that is argumentative:

To give students an understanding of the role of the American Dream in contemporary life, teachers should incorporate pop culture, like the music of A$AP Rocky, into their lessons and curriculum.

The argument in this one? Teachers should incorporate more relevant pop culture texts into their curriculum.

This thesis statement also gives a specific reason for making the argument above: To give students an understanding of the role of the American Dream in contemporary life. If you can let your reader know why you’re making your argument in your thesis statement, it will help them understand your argument better.

An actual image of you killing your argumentative essay prompts after reading this article!

Breaking Down the Sections of An Argumentative Essay

Now that you know how to pick a topic for an argumentative essay and how to make a strong claim on your topic in a thesis statement, you’re ready to think about writing the other sections of an argumentative essay. These are the parts that will flesh out your argument and support the claim you made in your thesis statement.

Like other types of essays, argumentative essays typically have three main sections: the introduction, the body, and the conclusion. Within those sections, there are some key elements that a reader—and especially an exam scorer or professor—is always going to expect you to include.

Let’s look at a quick outline of those three sections with their essential pieces here:

- Introduction paragraph with a thesis statement (which we just talked about)

- Support Point #1 with evidence

- Explain/interpret the evidence with your own, original commentary (AKA, the fun part!)

- Support Point #2 with evidence

- Explain/interpret the evidence with your own, original commentary

- Support Point #3 with evidence

- New paragraph addressing opposing viewpoints (more on this later!)

- Concluding paragraph

Now, there are some key concepts in those sections that you’ve got to understand if you’re going to master how to write an argumentative essay. To make the most of the body section, you have to know how to support your claim (your thesis statement), what evidence and explanations are and when you should use them, and how and when to address opposing viewpoints. To finish strong, you’ve got to have a strategy for writing a stellar conclusion.

This probably feels like a big deal! The body and conclusion make up most of the essay, right? Let’s get down to it, then.

How to Write a Strong Argument

Once you have your topic and thesis, you’re ready for the hard part: actually writing your argument. If you make strategic choices—like the ones we’re about to talk about—writing a strong argumentative essay won’t feel so difficult.

There are three main areas where you want to focus your energy as you develop a strategy for how to write an argumentative essay: supporting your claim—your thesis statement—in your essay, addressing other viewpoints on your topic, and writing a solid conclusion. If you put thought and effort into these three things, you’re much more likely to write an argumentative essay that’s engaging, persuasive, and memorable...aka A+ material.

Focus Area 1: Supporting Your Claim With Evidence and Explanations

So you’ve chosen your topic, decided what your position will be, and written a thesis statement. But like we see in comment threads across the Internet, if you make a claim and don’t back it up with evidence, what do people say? “Where’s your proof?” “Show me the facts!” “Do you have any evidence to support that claim?”

Of course you’ve done your research like we talked about. Supporting your claim in your thesis statement is where that research comes in handy.

You can’t just use your research to state the facts, though. Remember your reader? They’re going to expect you to do some of the dirty work of interpreting the evidence for them. That’s why it’s important to know the difference between evidence and explanations, and how and when to use both in your argumentative essay.

What Evidence Is and When You Should Use It

Evidence can be material from any authoritative and credible outside source that supports your position on your topic. In some cases, evidence can come in the form of photos, video footage, or audio recordings. In other cases, you might be pulling reasons, facts, or statistics from news media articles, public policy, or scholarly books or journals.

There are some clues you can look for that indicate whether or not a source is credible , such as whether:

- The website where you found the source ends in .edu, .gov, or .org

- The source was published by a university press

- The source was published in a peer-reviewed journal

- The authors did extensive research to support the claims they make in the source

This is just a short list of some of the clues that a source is likely a credible one, but just because a source was published by a prestigious press or the authors all have PhDs doesn’t necessarily mean it is the best piece of evidence for you to use to support your argument.

In addition to evaluating the source’s credibility, you’ve got to consider what types of evidence might come across as most persuasive in the context of the argument you’re making and who your readers are. In other words, stepping back and getting a bird’s eye view of the entire context of your argumentative paper is key to choosing evidence that will strengthen your argument.

On some exams, like the AP exams , you may be given pretty strict parameters for what evidence to use and how to use it. You might be given six short readings that all address the same topic, have 15 minutes to read them, then be required to pull material from a minimum of three of the short readings to support your claim in an argumentative essay.

When the sources are handed to you like that, be sure to take notes that will help you pick out evidence as you read. Highlight, underline, put checkmarks in the margins of your exam . . . do whatever you need to do to begin identifying the material that you find most helpful or relevant. Those highlights and check marks might just turn into your quotes, paraphrases, or summaries of evidence in your completed exam essay.

What Explanations Are and When You Should Use Them

Now you know that taking a strategic mindset toward evidence and explanations is critical to grasping how to write an argumentative essay. Unfortunately, evidence doesn’t speak for itself. While it may be obvious to you, the researcher and writer, how the pieces of evidence you’ve included are relevant to your audience, it might not be as obvious to your reader.

That’s where explanations—or analysis, or interpretations—come in. You never want to just stick some quotes from an article into your paragraph and call it a day. You do want to interpret the evidence you’ve included to show your reader how that evidence supports your claim.

Now, that doesn’t mean you’re going to be saying, “This piece of evidence supports my argument because...”. Instead, you want to comment on the evidence in a way that helps your reader see how it supports the position you stated in your thesis. We’ll talk more about how to do this when we show you an example of a strong body paragraph from an argumentative essay here in a bit.

Understanding how to incorporate evidence and explanations to your advantage is really important. Here’s why: when you’re writing an argumentative essay, particularly on standardized tests or the AP exam, the exam scorers can’t penalize you for the position you take. Instead, their evaluation is going to focus on the way you incorporated evidence and explained it in your essay.

Focus Area 2: How—and When—to Address Other Viewpoints

Why would we be making arguments at all if there weren’t multiple views out there on a given topic? As you do research and consider the background surrounding your topic, you’ll probably come across arguments that stand in direct opposition to your position.

Oftentimes, teachers will ask you to “address the opposition” in your argumentative essay. What does that mean, though, to “ address the opposition ?”

Opposing viewpoints function kind of like an elephant in the room. Your audience knows they’re there. In fact, your audience might even buy into an opposing viewpoint and be waiting for you to show them why your viewpoint is better. If you don’t, it means that you’ll have a hard time convincing your audience to buy your argument.

Addressing the opposition is a balancing act: you don’t want to undermine your own argument, but you don’t want to dismiss the validity of opposing viewpoints out-of-hand or ignore them altogether, which can also undermine your argument.

This isn’t the only acceptable approach, but it’s common practice to wait to address the opposition until close to the end of an argumentative essay. But why?

Well, waiting to present an opposing viewpoint until after you’ve thoroughly supported your own argument is strategic. You aren’t going to go into great detail discussing the opposing viewpoint: you’re going to explain what that viewpoint is fairly, but you’re also going to point out what’s wrong with it.

It can also be effective to read the opposition through the lens of your own argument and the evidence you’ve used to support it. If the evidence you’ve already included supports your argument, it probably doesn’t support the opposing viewpoint. Without being too obvious, it might be worth pointing this out when you address the opposition.

Focus Area #3: Writing the Conclusion

It’s common to conclude an argumentative essay by reiterating the thesis statement in some way, either by reminding the reader what the overarching argument was in the first place or by reviewing the main points and evidence that you covered.

You don’t just want to restate your thesis statement and review your main points and call it a day, though. So much has happened since you stated your thesis in the introduction! And why waste a whole paragraph—the very last thing your audience is going to read—on just repeating yourself?

Here’s an approach to the conclusion that can give your audience a fresh perspective on your argument: reinterpret your thesis statement for them in light of all the evidence and explanations you’ve provided. Think about how your readers might read your thesis statement in a new light now that they’ve heard your whole argument out.

That’s what you want to leave your audience with as you conclude your argumentative paper: a brief explanation of why all that arguing mattered in the first place. If you can give your audience something to continue pondering after they’ve read your argument, that’s even better.

One thing you want to avoid in your conclusion, though: presenting new supporting points or new evidence. That can just be confusing for your reader. Stick to telling your reader why the argument you’ve already made matters, and your argument will stick with your reader.

A Strong Argumentative Essay: Examples

For some aspiring argumentative essay writers, showing is better than telling. To show rather than tell you what makes a strong argumentative essay, we’ve provided three examples of possible body paragraphs for an argumentative essay below.

Think of these example paragraphs as taking on the form of the “Argumentative Point #1 → Evidence —> Explanation —> Repeat” process we talked through earlier. It’s always nice to be able to compare examples, so we’ve included three paragraphs from an argumentative paper ranging from poor (or needs a lot of improvement, if you’re feeling generous), to better, to best.

All of the example paragraphs are for an essay with this thesis statement:

Thesis Statement: In order to most effectively protect user data and combat the spread of disinformation, the U.S. government should implement more stringent regulations of Facebook and other social media outlets.

As you read the examples, think about what makes them different, and what makes the “best” paragraph more effective than the “better” and “poor” paragraphs. Here we go:

A Poor Argument

Example Body Paragraph: Data mining has affected a lot of people in recent years. Facebook has 2.23 billion users from around the world, and though it would take a huge amount of time and effort to make sure a company as big as Facebook was complying with privacy regulations in countries across the globe, adopting a common framework for privacy regulation in more countries would be the first step. In fact, Mark Zuckerberg himself supports adopting a global framework for privacy and data protection, which would protect more users than before.

What’s Wrong With This Example?

First, let’s look at the thesis statement. Ask yourself: does this make a claim that some people might agree with, but others might disagree with?

The answer is yes. Some people probably think that Facebook should be regulated, while others might believe that’s too much government intervention. Also, there are definitely good, reliable sources out there that will help this writer prove their argument. So this paper is off to a strong start!

Unfortunately, this writer doesn’t do a great job proving their thesis in their body paragraph. First, the topic sentence—aka the first sentence of the paragraph—doesn’t make a point that directly supports the position stated in the thesis. We’re trying to argue that government regulation will help protect user data and combat the spread of misinformation, remember? The topic sentence should make a point that gets right at that, instead of throwing out a random fact about data mining.

Second, because the topic sentence isn’t focused on making a clear point, the rest of the paragraph doesn’t have much relevant information, and it fails to provide credible evidence that supports the claim made in the thesis statement. For example, it would be a great idea to include exactly what Mark Zuckerberg said ! So while there’s definitely some relevant information in this paragraph, it needs to be presented with more evidence.

A Better Argument

This paragraph is a bit better than the first one, but it still needs some work. The topic sentence is a bit too long, and it doesn’t make a point that clearly supports the position laid out in the thesis statement. The reader already knows that mining user data is a big issue, so the topic sentence would be a great place to make a point about why more stringent government regulations would most effectively protect user data.

There’s also a problem with how the evidence is incorporated in this example. While there is some relevant, persuasive evidence included in this paragraph, there’s no explanation of why or how it is relevant . Remember, you can’t assume that your evidence speaks for itself: you have to interpret its relevance for your reader. That means including at least a sentence that tells your reader why the evidence you’ve chosen proves your argument.

A Best—But Not Perfect!—Argument

Example Body Paragraph: Though Facebook claims to be implementing company policies that will protect user data and stop the spread of misinformation , its attempts have been unsuccessful compared to those made by the federal government. When PricewaterhouseCoopers conducted a Federal Trade Commission-mandated assessment of Facebook’s partnerships with Microsoft and the makers of the Blackberry handset in 2013, the team found limited evidence that Facebook had monitored or even checked that its partners had complied with Facebook’s existing data use policies. In fact, Facebook’s own auditors confirmed the PricewaterhouseCoopers findings, despite the fact that Facebook claimed that the company was making greater attempts to safeguard users’ personal information. In contrast, bills written by Congress have been more successful in changing Facebook’s practices than Facebook’s own company policies have. According to The Washington Post, The Honest Ads Act of 2017 “created public demand for transparency and changed how social media companies disclose online political advertising.” These policy efforts, though thus far unsuccessful in passing legislation, have nevertheless pushed social media companies to change some of their practices by sparking public outrage and negative media attention.

Why This Example Is The Best

This paragraph isn’t perfect, but it is the most effective at doing some of the things that you want to do when you write an argumentative essay.

First, the topic sentences get to the point . . . and it’s a point that supports and explains the claim made in the thesis statement! It gives a clear reason why our claim in favor of more stringent government regulations is a good claim : because Facebook has failed to self-regulate its practices.

This paragraph also provides strong evidence and specific examples that support the point made in the topic sentence. The evidence presented shows specific instances in which Facebook has failed to self-regulate, and other examples where the federal government has successfully influenced regulation of Facebook’s practices for the better.

Perhaps most importantly, though, this writer explains why the evidence is important. The bold sentence in the example is where the writer links the evidence back to their opinion. In this case, they explain that the pressure from Federal Trade Commission and Congress—and the threat of regulation—have helped change Facebook for the better.

Why point out that this isn’t a perfect paragraph, though? Because you won’t be writing perfect paragraphs when you’re taking timed exams either. But get this: you don’t have to write perfect paragraphs to make a good score on AP exams or even on an essay you write for class. Like in this example paragraph, you just have to effectively develop your position by appropriately and convincingly relying on evidence from good sources.

Top 3 Takeaways For Writing Argumentative Essays

This is all great information, right? If (when) you have to write an argumentative essay, you’ll be ready. But when in doubt, remember these three things about how to write an argumentative essay, and you’ll emerge victorious:

Takeaway #1: Read Closely and Carefully

This tip applies to every aspect of writing an argumentative essay. From making sure you’re addressing your prompt, to really digging into your sources, to proofreading your final paper...you’ll need to actively and pay attention! This is especially true if you’re writing on the clock, like during an AP exam.

Takeaway #2: Make Your Argument the Focus of the Essay

Define your position clearly in your thesis statement and stick to that position! The thesis is the backbone of your paper, and every paragraph should help prove your thesis in one way or another. But sometimes you get to the end of your essay and realize that you’ve gotten off topic, or that your thesis doesn’t quite fit. Don’t worry—if that happens, you can always rewrite your thesis to fit your paper!

Takeaway #3: Use Sources to Develop Your Argument—and Explain Them

Nothing is as powerful as good, strong evidence. First, make sure you’re finding credible sources that support your argument. Then you can paraphrase, briefly summarize, or quote from your sources as you incorporate them into your paragraphs. But remember the most important part: you have to explain why you’ve chosen that evidence and why it proves your thesis.

What's Next?

Once you’re comfortable with how to write an argumentative essay, it’s time to learn some more advanced tips and tricks for putting together a killer argument.

Keep in mind that argumentative essays are just one type of essay you might encounter. That’s why we’ve put together more specific guides on how to tackle IB essays , SAT essays , and ACT essays .

But what about admissions essays? We’ve got you covered. Not only do we have comprehensive guides to the Coalition App and Common App essays, we also have tons of individual college application guides, too . You can search through all of our college-specific posts by clicking here.

Ashley Sufflé Robinson has a Ph.D. in 19th Century English Literature. As a content writer for PrepScholar, Ashley is passionate about giving college-bound students the in-depth information they need to get into the school of their dreams.

Ask a Question Below

Have any questions about this article or other topics? Ask below and we'll reply!

Improve With Our Famous Guides

- For All Students

The 5 Strategies You Must Be Using to Improve 160+ SAT Points

How to Get a Perfect 1600, by a Perfect Scorer

Series: How to Get 800 on Each SAT Section:

Score 800 on SAT Math

Score 800 on SAT Reading

Score 800 on SAT Writing

Series: How to Get to 600 on Each SAT Section:

Score 600 on SAT Math

Score 600 on SAT Reading

Score 600 on SAT Writing

Free Complete Official SAT Practice Tests

What SAT Target Score Should You Be Aiming For?

15 Strategies to Improve Your SAT Essay

The 5 Strategies You Must Be Using to Improve 4+ ACT Points

How to Get a Perfect 36 ACT, by a Perfect Scorer

Series: How to Get 36 on Each ACT Section:

36 on ACT English

36 on ACT Math

36 on ACT Reading

36 on ACT Science

Series: How to Get to 24 on Each ACT Section:

24 on ACT English

24 on ACT Math

24 on ACT Reading

24 on ACT Science

What ACT target score should you be aiming for?

ACT Vocabulary You Must Know

ACT Writing: 15 Tips to Raise Your Essay Score

How to Get Into Harvard and the Ivy League

How to Get a Perfect 4.0 GPA

How to Write an Amazing College Essay

What Exactly Are Colleges Looking For?

Is the ACT easier than the SAT? A Comprehensive Guide

Should you retake your SAT or ACT?

When should you take the SAT or ACT?

Stay Informed

Get the latest articles and test prep tips!

Looking for Graduate School Test Prep?

Check out our top-rated graduate blogs here:

GRE Online Prep Blog

GMAT Online Prep Blog

TOEFL Online Prep Blog

Holly R. "I am absolutely overjoyed and cannot thank you enough for helping me!”

8 Effective Strategies to Write Argumentative Essays

In a bustling university town, there lived a student named Alex. Popular for creativity and wit, one challenge seemed insurmountable for Alex– the dreaded argumentative essay!

One gloomy afternoon, as the rain tapped against the window pane, Alex sat at his cluttered desk, staring at a blank document on the computer screen. The assignment loomed large: a 350-600-word argumentative essay on a topic of their choice . With a sigh, he decided to seek help of mentor, Professor Mitchell, who was known for his passion for writing.

Entering Professor Mitchell’s office was like stepping into a treasure of knowledge. Bookshelves lined every wall, faint aroma of old manuscripts in the air and sticky notes over the wall. Alex took a deep breath and knocked on his door.

“Ah, Alex,” Professor Mitchell greeted with a warm smile. “What brings you here today?”

Alex confessed his struggles with the argumentative essay. After hearing his concerns, Professor Mitchell said, “Ah, the argumentative essay! Don’t worry, Let’s take a look at it together.” As he guided Alex to the corner shelf, Alex asked,

Table of Contents

“What is an Argumentative Essay?”

The professor replied, “An argumentative essay is a type of academic writing that presents a clear argument or a firm position on a contentious issue. Unlike other forms of essays, such as descriptive or narrative essays, these essays require you to take a stance, present evidence, and convince your audience of the validity of your viewpoint with supporting evidence. A well-crafted argumentative essay relies on concrete facts and supporting evidence rather than merely expressing the author’s personal opinions . Furthermore, these essays demand comprehensive research on the chosen topic and typically follows a structured format consisting of three primary sections: an introductory paragraph, three body paragraphs, and a concluding paragraph.”

He continued, “Argumentative essays are written in a wide range of subject areas, reflecting their applicability across disciplines. They are written in different subject areas like literature and philosophy, history, science and technology, political science, psychology, economics and so on.

Alex asked,

“When is an Argumentative Essay Written?”

The professor answered, “Argumentative essays are often assigned in academic settings, but they can also be written for various other purposes, such as editorials, opinion pieces, or blog posts. Some situations to write argumentative essays include:

1. Academic assignments

In school or college, teachers may assign argumentative essays as part of coursework. It help students to develop critical thinking and persuasive writing skills .

2. Debates and discussions

Argumentative essays can serve as the basis for debates or discussions in academic or competitive settings. Moreover, they provide a structured way to present and defend your viewpoint.

3. Opinion pieces

Newspapers, magazines, and online publications often feature opinion pieces that present an argument on a current issue or topic to influence public opinion.

4. Policy proposals

In government and policy-related fields, argumentative essays are used to propose and defend specific policy changes or solutions to societal problems.

5. Persuasive speeches

Before delivering a persuasive speech, it’s common to prepare an argumentative essay as a foundation for your presentation.

Regardless of the context, an argumentative essay should present a clear thesis statement , provide evidence and reasoning to support your position, address counterarguments, and conclude with a compelling summary of your main points. The goal is to persuade readers or listeners to accept your viewpoint or at least consider it seriously.”

Handing over a book, the professor continued, “Take a look on the elements or structure of an argumentative essay.”

Elements of an Argumentative Essay

An argumentative essay comprises five essential components:

Claim in argumentative writing is the central argument or viewpoint that the writer aims to establish and defend throughout the essay. A claim must assert your position on an issue and must be arguable. It can guide the entire argument.

2. Evidence

Evidence must consist of factual information, data, examples, or expert opinions that support the claim. Also, it lends credibility by strengthening the writer’s position.

3. Counterarguments

Presenting a counterclaim demonstrates fairness and awareness of alternative perspectives.

4. Rebuttal

After presenting the counterclaim, the writer refutes it by offering counterarguments or providing evidence that weakens the opposing viewpoint. It shows that the writer has considered multiple perspectives and is prepared to defend their position.

The format of an argumentative essay typically follows the structure to ensure clarity and effectiveness in presenting an argument.

How to Write An Argumentative Essay

Here’s a step-by-step guide on how to write an argumentative essay:

1. Introduction

- Begin with a compelling sentence or question to grab the reader’s attention.

- Provide context for the issue, including relevant facts, statistics, or historical background.

- Provide a concise thesis statement to present your position on the topic.

2. Body Paragraphs (usually three or more)

- Start each paragraph with a clear and focused topic sentence that relates to your thesis statement.

- Furthermore, provide evidence and explain the facts, statistics, examples, expert opinions, and quotations from credible sources that supports your thesis.

- Use transition sentences to smoothly move from one point to the next.

3. Counterargument and Rebuttal

- Acknowledge opposing viewpoints or potential objections to your argument.

- Also, address these counterarguments with evidence and explain why they do not weaken your position.

4. Conclusion

- Restate your thesis statement and summarize the key points you’ve made in the body of the essay.

- Leave the reader with a final thought, call to action, or broader implication related to the topic.

5. Citations and References

- Properly cite all the sources you use in your essay using a consistent citation style.

- Also, include a bibliography or works cited at the end of your essay.

6. Formatting and Style

- Follow any specific formatting guidelines provided by your instructor or institution.

- Use a professional and academic tone in your writing and edit your essay to avoid content, spelling and grammar mistakes .

Remember that the specific requirements for formatting an argumentative essay may vary depending on your instructor’s guidelines or the citation style you’re using (e.g., APA, MLA, Chicago). Always check the assignment instructions or style guide for any additional requirements or variations in formatting.

Did you understand what Prof. Mitchell explained Alex? Check it now!

Fill the Details to Check Your Score

Prof. Mitchell continued, “An argumentative essay can adopt various approaches when dealing with opposing perspectives. It may offer a balanced presentation of both sides, providing equal weight to each, or it may advocate more strongly for one side while still acknowledging the existence of opposing views.” As Alex listened carefully to the Professor’s thoughts, his eyes fell on a page with examples of argumentative essay.

Example of an Argumentative Essay

Alex picked the book and read the example. It helped him to understand the concept. Furthermore, he could now connect better to the elements and steps of the essay which Prof. Mitchell had mentioned earlier. Aren’t you keen to know how an argumentative essay should be like? Here is an example of a well-crafted argumentative essay , which was read by Alex. After Alex finished reading the example, the professor turned the page and continued, “Check this page to know the importance of writing an argumentative essay in developing skills of an individual.”

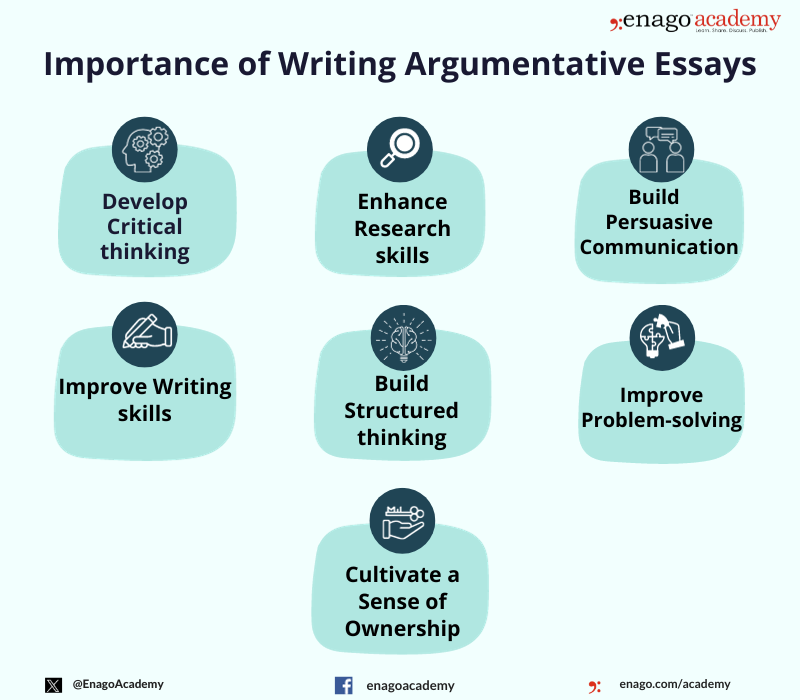

Importance of an Argumentative Essay

After understanding the benefits, Alex was convinced by the ability of the argumentative essays in advocating one’s beliefs and favor the author’s position. Alex asked,

“How are argumentative essays different from the other types?”

Prof. Mitchell answered, “Argumentative essays differ from other types of essays primarily in their purpose, structure, and approach in presenting information. Unlike expository essays, argumentative essays persuade the reader to adopt a particular point of view or take a specific action on a controversial issue. Furthermore, they differ from descriptive essays by not focusing vividly on describing a topic. Also, they are less engaging through storytelling as compared to the narrative essays.

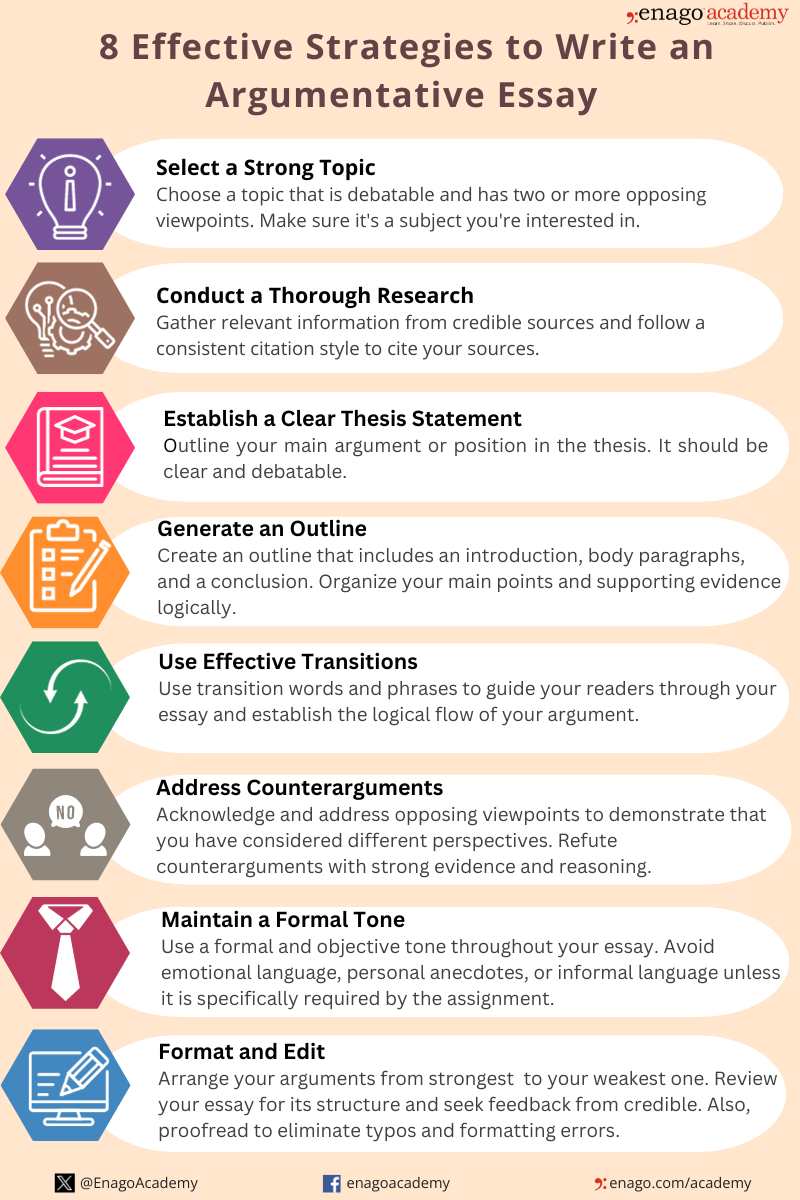

Alex said, “Given the direct and persuasive nature of argumentative essays, can you suggest some strategies to write an effective argumentative essay?

Turning the pages of the book, Prof. Mitchell replied, “Sure! You can check this infographic to get some tips for writing an argumentative essay.”

Effective Strategies to Write an Argumentative Essay

As days turned into weeks, Alex diligently worked on his essay. He researched, gathered evidence, and refined his thesis. It was a long and challenging journey, filled with countless drafts and revisions.

Finally, the day arrived when Alex submitted their essay. As he clicked the “Submit” button, a sense of accomplishment washed over him. He realized that the argumentative essay, while challenging, had improved his critical thinking and transformed him into a more confident writer. Furthermore, Alex received feedback from his professor, a mix of praise and constructive criticism. It was a humbling experience, a reminder that every journey has its obstacles and opportunities for growth.

Frequently Asked Questions

An argumentative essay can be written as follows- 1. Choose a Topic 2. Research and Collect Evidences 3. Develop a Clear Thesis Statement 4. Outline Your Essay- Introduction, Body Paragraphs and Conclusion 5. Revise and Edit 6. Format and Cite Sources 7. Final Review

One must choose a clear, concise and specific statement as a claim. It must be debatable and establish your position. Avoid using ambiguous or unclear while making a claim. To strengthen your claim, address potential counterarguments or opposing viewpoints. Additionally, use persuasive language and rhetoric to make your claim more compelling

Starting an argument essay effectively is crucial to engage your readers and establish the context for your argument. Here’s how you can start an argument essay are: 1. Begin With an Engaging Hook 2. Provide Background Information 3. Present Your Thesis Statement 4. Briefly Outline Your Main 5. Establish Your Credibility

The key features of an argumentative essay are: 1. Clear and Specific Thesis Statement 2. Credible Evidence 3. Counterarguments 4. Structured Body Paragraph 5. Logical Flow 6. Use of Persuasive Techniques 7. Formal Language

An argumentative essay typically consists of the following main parts or sections: 1. Introduction 2. Body Paragraphs 3. Counterargument and Rebuttal 4. Conclusion 5. References (if applicable)

The main purpose of an argumentative essay is to persuade the reader to accept or agree with a particular viewpoint or position on a controversial or debatable topic. In other words, the primary goal of an argumentative essay is to convince the audience that the author's argument or thesis statement is valid, logical, and well-supported by evidence and reasoning.

Great article! The topic is simplified well! Keep up the good work

Rate this article Cancel Reply

Your email address will not be published.

Enago Academy's Most Popular Articles

![how to organize a argumentative essay What is Academic Integrity and How to Uphold it [FREE CHECKLIST]](https://www.enago.com/academy/wp-content/uploads/2024/05/FeatureImages-59-210x136.png)

Ensuring Academic Integrity and Transparency in Academic Research: A comprehensive checklist for researchers

Academic integrity is the foundation upon which the credibility and value of scientific findings are…

- AI in Academia

AI vs. AI: How to detect image manipulation and avoid academic misconduct

The scientific community is facing a new frontier of controversy as artificial intelligence (AI) is…

- Industry News

- Publishing News

Unified AI Guidelines Crucial as Academic Writing Embraces Generative Tools

As generative artificial intelligence (AI) tools like ChatGPT are advancing at an accelerating pace, their…

- Diversity and Inclusion

Need for Diversifying Academic Curricula: Embracing missing voices and marginalized perspectives

In classrooms worldwide, a single narrative often dominates, leaving many students feeling lost. These stories,…

- Reporting Research

How to Effectively Cite a PDF (APA, MLA, AMA, and Chicago Style)

The pressure to “publish or perish” is a well-known reality for academics, striking fear into…

How to Optimize Your Research Process: A step-by-step guide

How to Improve Lab Report Writing: Best practices to follow with and without…

Digital Citations: A comprehensive guide to citing of websites in APA, MLA, and CMOS…

Sign-up to read more

Subscribe for free to get unrestricted access to all our resources on research writing and academic publishing including:

- 2000+ blog articles

- 50+ Webinars

- 10+ Expert podcasts

- 50+ Infographics

- 10+ Checklists

- Research Guides

We hate spam too. We promise to protect your privacy and never spam you.

I am looking for Editing/ Proofreading services for my manuscript Tentative date of next journal submission:

As a researcher, what do you consider most when choosing an image manipulation detector?

How to Write an Argumentative Essay: Step By Step Guide

10 May, 2020

9 minutes read

Author: Tomas White

Being able to present your argument and carry your point in a debate or a discussion is a vital skill. No wonder educational establishments make writing compositions of such type a priority for all students. If you are not really good at delivering a persuasive message to the audience, this guide is for you. It will teach you how to write an argumentative essay successfully step by step. So, read on and pick up the essential knowledge.

What is an Argumentative Essay?

An argumentative essay is a paper that gets the reader to recognize the author’s side of the argument as valid. The purpose of this specific essay is to pose a question and answer it with compelling evidence. At its core, this essay type works to champion a specific viewpoint. The key, however, is that the topic of the argumentative essay has multiple sides, which can be explained, weighed, and judged by relevant sources.

Check out our ultimate argumentative essay topics list!

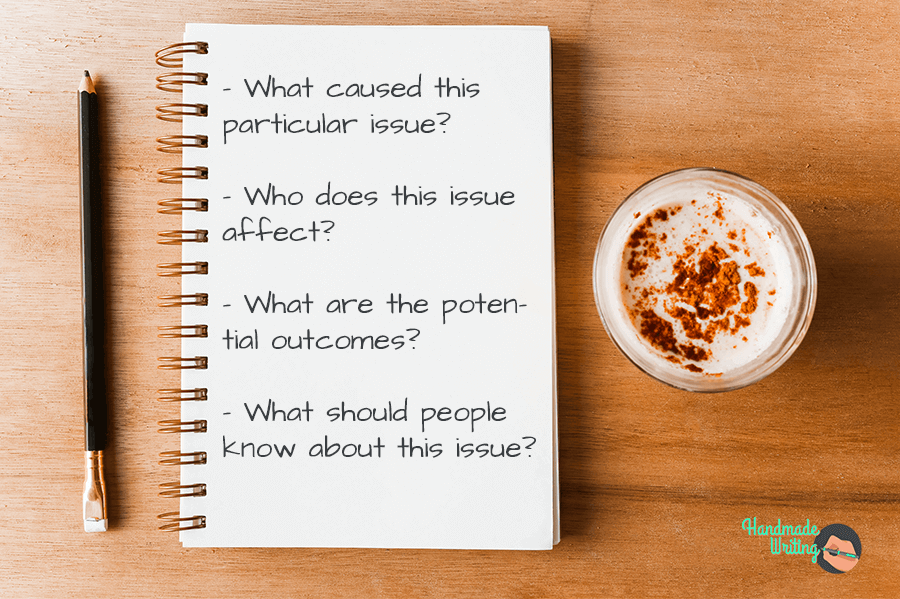

This essay often explores common questions associated with any type of argument including:

Argumentative VS Persuasive Essay

It’s important not to confuse argumentative essay with a persuasive essay – while they both seem to follow the same goal, their methods are slightly different. While the persuasive essay is here to convince the reader (to pick your side), the argumentative essay is here to present information that supports the claim.

In simple words, it explains why the author picked this side of the argument, and persuasive essay does its best to persuade the reader to agree with your point of view.

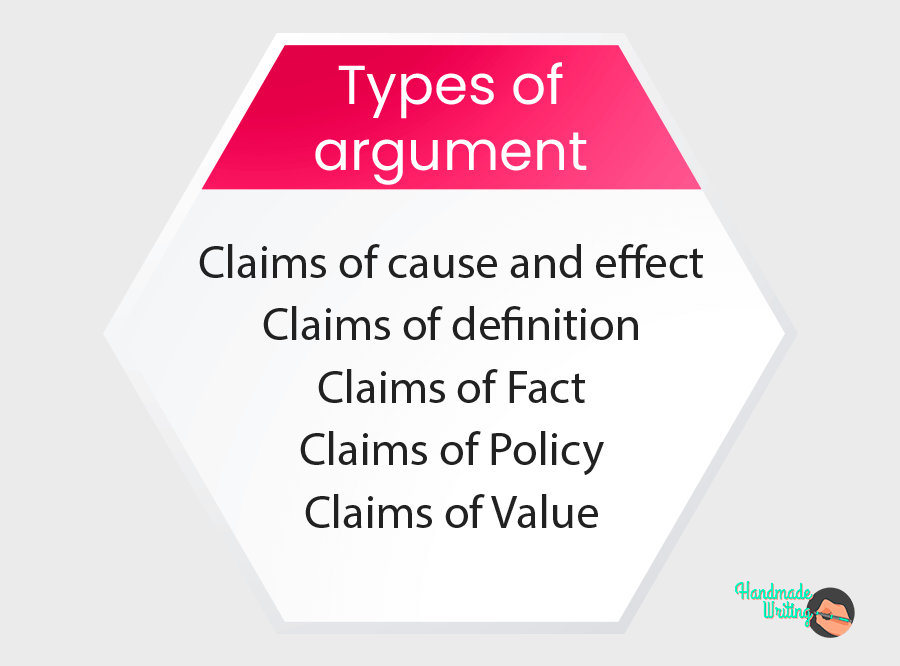

Now that we got this straight, let’s get right to our topic – how to write an argumentative essay. As you can easily recognize, it all starts with a proper argument. First, let’s define the types of argument available and strategies that you can follow.

Types of Argument