Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

4.2 Types of Nonverbal Communication

Learning objectives.

- Define kinesics.

- Define haptics.

- Define vocalics.

- Define proxemics.

- Define chronemics.

- Provide examples of types of nonverbal communication that fall under these categories.

- Discuss the ways in which personal presentation and environment provide nonverbal cues.

Just as verbal language is broken up into various categories, there are also different types of nonverbal communication. As we learn about each type of nonverbal signal, keep in mind that nonverbals often work in concert with each other, combining to repeat, modify, or contradict the verbal message being sent.

The word kinesics comes from the root word kinesis , which means “movement,” and refers to the study of hand, arm, body, and face movements. Specifically, this section will outline the use of gestures, head movements and posture, eye contact, and facial expressions as nonverbal communication.

There are three main types of gestures: adaptors, emblems, and illustrators (Andersen, 1999). Adaptors are touching behaviors and movements that indicate internal states typically related to arousal or anxiety. Adaptors can be targeted toward the self, objects, or others. In regular social situations, adaptors result from uneasiness, anxiety, or a general sense that we are not in control of our surroundings. Many of us subconsciously click pens, shake our legs, or engage in other adaptors during classes, meetings, or while waiting as a way to do something with our excess energy. Public speaking students who watch video recordings of their speeches notice nonverbal adaptors that they didn’t know they used. In public speaking situations, people most commonly use self- or object-focused adaptors. Common self-touching behaviors like scratching, twirling hair, or fidgeting with fingers or hands are considered self-adaptors. Some self-adaptors manifest internally, as coughs or throat-clearing sounds. My personal weakness is object adaptors. Specifically, I subconsciously gravitate toward metallic objects like paper clips or staples holding my notes together and catch myself bending them or fidgeting with them while I’m speaking. Other people play with dry-erase markers, their note cards, the change in their pockets, or the lectern while speaking. Use of object adaptors can also signal boredom as people play with the straw in their drink or peel the label off a bottle of beer. Smartphones have become common object adaptors, as people can fiddle with their phones to help ease anxiety. Finally, as noted, other adaptors are more common in social situations than in public speaking situations given the speaker’s distance from audience members. Other adaptors involve adjusting or grooming others, similar to how primates like chimpanzees pick things off each other. It would definitely be strange for a speaker to approach an audience member and pick lint off his or her sweater, fix a crooked tie, tuck a tag in, or pat down a flyaway hair in the middle of a speech.

Emblems are gestures that have a specific agreed-on meaning. These are still different from the signs used by hearing-impaired people or others who communicate using American Sign Language (ASL). Even though they have a generally agreed-on meaning, they are not part of a formal sign system like ASL that is explicitly taught to a group of people. A hitchhiker’s raised thumb, the “OK” sign with thumb and index finger connected in a circle with the other three fingers sticking up, and the raised middle finger are all examples of emblems that have an agreed-on meaning or meanings with a culture. Emblems can be still or in motion; for example, circling the index finger around at the side of your head says “He or she is crazy,” or rolling your hands over and over in front of you says “Move on.”

Emblems are gestures that have a specific meaning. In the United States, a thumbs-up can mean “I need a ride” or “OK!”

Kreg Steppe – Thumbs Up – CC BY-SA 2.0.

Just as we can trace the history of a word, or its etymology, we can also trace some nonverbal signals, especially emblems, to their origins. Holding up the index and middle fingers in a “V” shape with the palm facing in is an insult gesture in Britain that basically means “up yours.” This gesture dates back centuries to the period in which the primary weapon of war was the bow and arrow. When archers were captured, their enemies would often cut off these two fingers, which was seen as the ultimate insult and worse than being executed since the archer could no longer shoot his bow and arrow. So holding up the two fingers was a provoking gesture used by archers to show their enemies that they still had their shooting fingers (Pease & Pease, 2004).

Illustrators are the most common type of gesture and are used to illustrate the verbal message they accompany. For example, you might use hand gestures to indicate the size or shape of an object. Unlike emblems, illustrators do not typically have meaning on their own and are used more subconsciously than emblems. These largely involuntary and seemingly natural gestures flow from us as we speak but vary in terms of intensity and frequency based on context. Although we are never explicitly taught how to use illustrative gestures, we do it automatically. Think about how you still gesture when having an animated conversation on the phone even though the other person can’t see you.

Head Movements and Posture

I group head movements and posture together because they are often both used to acknowledge others and communicate interest or attentiveness. In terms of head movements, a head nod is a universal sign of acknowledgement in cultures where the formal bow is no longer used as a greeting. In these cases, the head nod essentially serves as an abbreviated bow. An innate and universal head movement is the headshake back and forth to signal “no.” This nonverbal signal begins at birth, even before a baby has the ability to know that it has a corresponding meaning. Babies shake their head from side to side to reject their mother’s breast and later shake their head to reject attempts to spoon-feed (Pease & Pease, 2004). This biologically based movement then sticks with us to be a recognizable signal for “no.” We also move our head to indicate interest. For example, a head up typically indicates an engaged or neutral attitude, a head tilt indicates interest and is an innate submission gesture that exposes the neck and subconsciously makes people feel more trusting of us, and a head down signals a negative or aggressive attitude (Pease & Pease, 2004).

There are four general human postures: standing, sitting, squatting, and lying down (Hargie, 2011). Within each of these postures there are many variations, and when combined with particular gestures or other nonverbal cues they can express many different meanings. Most of our communication occurs while we are standing or sitting. One interesting standing posture involves putting our hands on our hips and is a nonverbal cue that we use subconsciously to make us look bigger and show assertiveness. When the elbows are pointed out, this prevents others from getting past us as easily and is a sign of attempted dominance or a gesture that says we’re ready for action. In terms of sitting, leaning back shows informality and indifference, straddling a chair is a sign of dominance (but also some insecurity because the person is protecting the vulnerable front part of his or her body), and leaning forward shows interest and attentiveness (Pease & Pease, 2004).

Eye Contact

We also communicate through eye behaviors, primarily eye contact. While eye behaviors are often studied under the category of kinesics, they have their own branch of nonverbal studies called oculesics , which comes from the Latin word oculus , meaning “eye.” The face and eyes are the main point of focus during communication, and along with our ears our eyes take in most of the communicative information around us. The saying “The eyes are the window to the soul” is actually accurate in terms of where people typically think others are “located,” which is right behind the eyes (Andersen, 1999). Certain eye behaviors have become tied to personality traits or emotional states, as illustrated in phrases like “hungry eyes,” “evil eyes,” and “bedroom eyes.” To better understand oculesics, we will discuss the characteristics and functions of eye contact and pupil dilation.

Eye contact serves several communicative functions ranging from regulating interaction to monitoring interaction, to conveying information, to establishing interpersonal connections. In terms of regulating communication, we use eye contact to signal to others that we are ready to speak or we use it to cue others to speak. I’m sure we’ve all been in that awkward situation where a teacher asks a question, no one else offers a response, and he or she looks directly at us as if to say, “What do you think?” In that case, the teacher’s eye contact is used to cue us to respond. During an interaction, eye contact also changes as we shift from speaker to listener. US Americans typically shift eye contact while speaking—looking away from the listener and then looking back at his or her face every few seconds. Toward the end of our speaking turn, we make more direct eye contact with our listener to indicate that we are finishing up. While listening, we tend to make more sustained eye contact, not glancing away as regularly as we do while speaking (Martin & Nakayama, 2010).

Aside from regulating conversations, eye contact is also used to monitor interaction by taking in feedback and other nonverbal cues and to send information. Our eyes bring in the visual information we need to interpret people’s movements, gestures, and eye contact. A speaker can use his or her eye contact to determine if an audience is engaged, confused, or bored and then adapt his or her message accordingly. Our eyes also send information to others. People know not to interrupt when we are in deep thought because we naturally look away from others when we are processing information. Making eye contact with others also communicates that we are paying attention and are interested in what another person is saying. As we will learn in Chapter 5 “Listening” , eye contact is a key part of active listening.

Eye contact can also be used to intimidate others. We have social norms about how much eye contact we make with people, and those norms vary depending on the setting and the person. Staring at another person in some contexts could communicate intimidation, while in other contexts it could communicate flirtation. As we learned, eye contact is a key immediacy behavior, and it signals to others that we are available for communication. Once communication begins, if it does, eye contact helps establish rapport or connection. We can also use our eye contact to signal that we do not want to make a connection with others. For example, in a public setting like an airport or a gym where people often make small talk, we can avoid making eye contact with others to indicate that we do not want to engage in small talk with strangers. Another person could use eye contact to try to coax you into speaking, though. For example, when one person continues to stare at another person who is not reciprocating eye contact, the person avoiding eye contact might eventually give in, become curious, or become irritated and say, “Can I help you with something?” As you can see, eye contact sends and receives important communicative messages that help us interpret others’ behaviors, convey information about our thoughts and feelings, and facilitate or impede rapport or connection. This list reviews the specific functions of eye contact:

- Regulate interaction and provide turn-taking signals

- Monitor communication by receiving nonverbal communication from others

- Signal cognitive activity (we look away when processing information)

- Express engagement (we show people we are listening with our eyes)

- Convey intimidation

- Express flirtation

- Establish rapport or connection

Pupil dilation is a subtle component of oculesics that doesn’t get as much scholarly attention in communication as eye contact does. Pupil dilation refers to the expansion and contraction of the black part of the center of our eyes and is considered a biometric form of measurement; it is involuntary and therefore seen as a valid and reliable form of data collection as opposed to self-reports on surveys or interviews that can be biased or misleading. Our pupils dilate when there is a lack of lighting and contract when light is plentiful (Guerrero & Floyd, 2006). Pain, sexual attraction, general arousal, anxiety/stress, and information processing (thinking) also affect pupil dilation. Researchers measure pupil dilation for a number of reasons. For example, advertisers use pupil dilation as an indicator of consumer preferences, assuming that more dilation indicates arousal and attraction to a product. We don’t consciously read others’ pupil dilation in our everyday interactions, but experimental research has shown that we subconsciously perceive pupil dilation, which affects our impressions and communication. In general, dilated pupils increase a person’s attractiveness. Even though we may not be aware of this subtle nonverbal signal, we have social norms and practices that may be subconsciously based on pupil dilation. Take for example the notion of mood lighting and the common practice of creating a “romantic” ambiance with candlelight or the light from a fireplace. Softer and more indirect light leads to pupil dilation, and although we intentionally manipulate lighting to create a romantic ambiance, not to dilate our pupils, the dilated pupils are still subconsciously perceived, which increases perceptions of attraction (Andersen, 1999).

Facial Expressions

Our faces are the most expressive part of our bodies. Think of how photos are often intended to capture a particular expression “in a flash” to preserve for later viewing. Even though a photo is a snapshot in time, we can still interpret much meaning from a human face caught in a moment of expression, and basic facial expressions are recognizable by humans all over the world. Much research has supported the universality of a core group of facial expressions: happiness, sadness, fear, anger, and disgust. The first four are especially identifiable across cultures (Andersen, 1999). However, the triggers for these expressions and the cultural and social norms that influence their displays are still culturally diverse. If you’ve spent much time with babies you know that they’re capable of expressing all these emotions. Getting to see the pure and innate expressions of joy and surprise on a baby’s face is what makes playing peek-a-boo so entertaining for adults. As we get older, we learn and begin to follow display rules for facial expressions and other signals of emotion and also learn to better control our emotional expression based on the norms of our culture.

Smiles are powerful communicative signals and, as you’ll recall, are a key immediacy behavior. Although facial expressions are typically viewed as innate and several are universally recognizable, they are not always connected to an emotional or internal biological stimulus; they can actually serve a more social purpose. For example, most of the smiles we produce are primarily made for others and are not just an involuntary reflection of an internal emotional state (Andersen, 1999). These social smiles, however, are slightly but perceptibly different from more genuine smiles. People generally perceive smiles as more genuine when the other person smiles “with their eyes.” This particular type of smile is difficult if not impossible to fake because the muscles around the eye that are activated when we spontaneously or genuinely smile are not under our voluntary control. It is the involuntary and spontaneous contraction of these muscles that moves the skin around our cheeks, eyes, and nose to create a smile that’s distinct from a fake or polite smile (Evans, 2001). People are able to distinguish the difference between these smiles, which is why photographers often engage in cheesy joking with adults or use props with children to induce a genuine smile before they snap a picture.

Our faces are the most expressive part of our body and can communicate an array of different emotions.

Elif Ayiter – Facial Expression Test – CC BY-NC-ND 2.0.

We will learn more about competent encoding and decoding of facial expressions in Section 4.3 “Nonverbal Communication Competence” and Section 4.4 “Nonverbal Communication in Context” , but since you are likely giving speeches in this class, let’s learn about the role of the face in public speaking. Facial expressions help set the emotional tone for a speech. In order to set a positive tone before you start speaking, briefly look at the audience and smile to communicate friendliness, openness, and confidence. Beyond your opening and welcoming facial expressions, facial expressions communicate a range of emotions and can be used to infer personality traits and make judgments about a speaker’s credibility and competence. Facial expressions can communicate that a speaker is tired, excited, angry, confused, frustrated, sad, confident, smug, shy, or bored. Even if you aren’t bored, for example, a slack face with little animation may lead an audience to think that you are bored with your own speech, which isn’t likely to motivate them to be interested. So make sure your facial expressions are communicating an emotion, mood, or personality trait that you think your audience will view favorably, and that will help you achieve your speech goals. Also make sure your facial expressions match the content of your speech. When delivering something light-hearted or humorous, a smile, bright eyes, and slightly raised eyebrows will nonverbally enhance your verbal message. When delivering something serious or somber, a furrowed brow, a tighter mouth, and even a slight head nod can enhance that message. If your facial expressions and speech content are not consistent, your audience could become confused by the mixed messages, which could lead them to question your honesty and credibility.

Think of how touch has the power to comfort someone in moment of sorrow when words alone cannot. This positive power of touch is countered by the potential for touch to be threatening because of its connection to sex and violence. To learn about the power of touch, we turn to haptics , which refers to the study of communication by touch. We probably get more explicit advice and instruction on how to use touch than any other form of nonverbal communication. A lack of nonverbal communication competence related to touch could have negative interpersonal consequences; for example, if we don’t follow the advice we’ve been given about the importance of a firm handshake, a person might make negative judgments about our confidence or credibility. A lack of competence could have more dire negative consequences, including legal punishment, if we touch someone inappropriately (intentionally or unintentionally). Touch is necessary for human social development, and it can be welcoming, threatening, or persuasive. Research projects have found that students evaluated a library and its staff more favorably if the librarian briefly touched the patron while returning his or her library card, that female restaurant servers received larger tips when they touched patrons, and that people were more likely to sign a petition when the petitioner touched them during their interaction (Andersen, 1999).

There are several types of touch, including functional-professional, social-polite, friendship-warmth, love-intimacy, and sexual-arousal touch (Heslin & Apler, 1983). At the functional-professional level, touch is related to a goal or part of a routine professional interaction, which makes it less threatening and more expected. For example, we let barbers, hairstylists, doctors, nurses, tattoo artists, and security screeners touch us in ways that would otherwise be seen as intimate or inappropriate if not in a professional context. At the social-polite level, socially sanctioned touching behaviors help initiate interactions and show that others are included and respected. A handshake, a pat on the arm, and a pat on the shoulder are examples of social-polite touching. A handshake is actually an abbreviated hand-holding gesture, but we know that prolonged hand-holding would be considered too intimate and therefore inappropriate at the functional-professional or social-polite level. At the functional-professional and social-polite levels, touch still has interpersonal implications. The touch, although professional and not intimate, between hair stylist and client, or between nurse and patient, has the potential to be therapeutic and comforting. In addition, a social-polite touch exchange plays into initial impression formation, which can have important implications for how an interaction and a relationship unfold.

Of course, touch is also important at more intimate levels. At the friendship-warmth level, touch is more important and more ambiguous than at the social-polite level. At this level, touch interactions are important because they serve a relational maintenance purpose and communicate closeness, liking, care, and concern. The types of touching at this level also vary greatly from more formal and ritualized to more intimate, which means friends must sometimes negotiate their own comfort level with various types of touch and may encounter some ambiguity if their preferences don’t match up with their relational partner’s. In a friendship, for example, too much touch can signal sexual or romantic interest, and too little touch can signal distance or unfriendliness. At the love-intimacy level, touch is more personal and is typically only exchanged between significant others, such as best friends, close family members, and romantic partners. Touching faces, holding hands, and full frontal embraces are examples of touch at this level. Although this level of touch is not sexual, it does enhance feelings of closeness and intimacy and can lead to sexual-arousal touch, which is the most intimate form of touch, as it is intended to physically stimulate another person.

Touch is also used in many other contexts—for example, during play (e.g., arm wrestling), during physical conflict (e.g., slapping), and during conversations (e.g., to get someone’s attention) (Jones, 1999). We also inadvertently send messages through accidental touch (e.g., bumping into someone). One of my interpersonal communication professors admitted that she enjoyed going to restaurants to observe “first-date behavior” and boasted that she could predict whether or not there was going to be a second date based on the couple’s nonverbal communication. What sort of touching behaviors would indicate a good or bad first date?

On a first date, it is less likely that you will see couples sitting “school-bus style” (sharing the same side of a table or booth) or touching for an extended time.

Wikimedia Commons – public domain.

During a first date or less formal initial interactions, quick fleeting touches give an indication of interest. For example, a pat on the back is an abbreviated hug (Andersen, 1999). In general, the presence or absence of touching cues us into people’s emotions. So as the daters sit across from each other, one person may lightly tap the other’s arm after he or she said something funny. If the daters are sitting side by side, one person may cross his or her legs and lean toward the other person so that each person’s knees or feet occasionally touch. Touching behavior as a way to express feelings is often reciprocal. A light touch from one dater will be followed by a light touch from the other to indicate that the first touch was OK. While verbal communication could also be used to indicate romantic interest, many people feel too vulnerable at this early stage in a relationship to put something out there in words. If your date advances a touch and you are not interested, it is also unlikely that you will come right out and say, “Sorry, but I’m not really interested.” Instead, due to common politeness rituals, you would be more likely to respond with other forms of nonverbal communication like scooting back, crossing your arms, or simply not acknowledging the touch.

I find hugging behavior particularly interesting, perhaps because of my experiences growing up in a very hug-friendly environment in the Southern United States and then living elsewhere where there are different norms. A hug can be obligatory, meaning that you do it because you feel like you have to, not because you want to. Even though you may think that this type of hug doesn’t communicate emotions, it definitely does. A limp, weak, or retreating hug may communicate anger, ambivalence, or annoyance. Think of other types of hugs and how you hug different people. Some types of hugs are the crisscross hug, the neck-waist hug, and the engulfing hug (Floyd, 2006). The crisscross hug is a rather typical hug where each person’s arm is below or above the other person’s arm. This hug is common among friends, romantic partners, and family members, and perhaps even coworkers. The neck-waist hug usually occurs in more intimate relationships as it involves one person’s arms around the other’s neck and the other person’s arms around the other’s waist. I think of this type of hug as the “slow-dance hug.” The engulfing hug is similar to a bear hug in that one person completely wraps the arms around the other as that person basically stands there. This hugging behavior usually occurs when someone is very excited and hugs the other person without warning.

Some other types of hugs are the “shake-first-then-tap hug” and the “back-slap hug.” I observe that these hugs are most often between men. The shake-first-then-tap hug involves a modified hand-shake where the hands are joined more with the thumb and fingers than the palm and the elbows are bent so that the shake occurs between the two huggers’ chests. The hug comes after the shake has been initiated with one arm going around the other person for usually just one tap, then a step back and release of the handshake. In this hugging behavior, the handshake that is maintained between the chests minimizes physical closeness and the intimacy that may be interpreted from the crisscross or engulfing hug where the majority of the huggers’ torsos are touching. This move away from physical closeness likely stems from a US norm that restricts men’s physical expression of affection due to homophobia or the worry of being perceived as gay. The slap hug is also a less physically intimate hug and involves a hug with one or both people slapping the other person’s back repeatedly, often while talking to each other. I’ve seen this type of hug go on for many seconds and with varying degrees of force involved in the slap. When the slap is more of a tap, it is actually an indication that one person wants to let go. The video footage of then-president Bill Clinton hugging Monica Lewinsky that emerged as allegations that they had an affair were being investigated shows her holding on, while he was tapping from the beginning of the hug.

“Getting Critical”

Airport Pat-Downs: The Law, Privacy, and Touch

Everyone who has flown over the past ten years has experienced the steady increase in security screenings. Since the terrorist attacks on September 11, 2001, airports around the world have had increased security. While passengers have long been subject to pat-downs if they set off the metal detector or arouse suspicion, recently foiled terrorist plots have made passenger screening more personal. The “shoe bomber” led to mandatory shoe removal and screening, and the more recent use of nonmetallic explosives hidden in clothing or in body cavities led to the use of body scanners that can see through clothing to check for concealed objects (Thomas, 2011). Protests against and anxiety about the body scanners, more colloquially known as “naked x-ray machines,” led to the new “enhanced pat-down” techniques for passengers who refuse to go through the scanners or passengers who are randomly selected or arouse suspicion in other ways. The strong reactions are expected given what we’ve learned about the power of touch as a form of nonverbal communication. The new pat-downs routinely involve touching the areas around a passenger’s breasts and/or genitals with a sliding hand motion. The Transportation Security Administration (TSA) notes that the areas being examined haven’t changed, but the degree of the touch has, as screeners now press and rub more firmly but used to use a lighter touch (Kravitz, 2010). Interestingly, police have long been able to use more invasive pat-downs, but only with probable cause. In the case of random selection at the airport, no probable cause provision has to be met, giving TSA agents more leeway with touch than police officers. Experts in aviation security differ in their assessment of the value of the pat-downs and other security procedures. Several experts have called for a revision of the random selection process in favor of more targeted screenings. What civil rights organizations critique as racial profiling, consumer rights activists and some security experts say allows more efficient use of resources and less inconvenience for the majority of passengers (Thomas, 2011). Although the TSA has made some changes to security screening procedures and have announced more to come, some passengers have started a backlash of their own. There have been multiple cases of passengers stripping down to their underwear or getting completely naked to protest the pat-downs, while several other passengers have been charged with assault for “groping” TSA agents in retaliation. Footage of pat-downs of toddlers and grandmothers in wheelchairs and self-uploaded videos of people recounting their pat-down experiences have gone viral on YouTube.

- What limits, if any, do you think there should be on the use of touch in airport screening procedures?

- In June of 2012 a passenger was charged with battery after “groping” a TSA supervisor to, as she claims, demonstrate the treatment that she had received while being screened. You can read more about the story and see the video here: http://www.nydailynews.com/news/national/carol-jean-price-accused-groping-tsa-agent-florida-woman-demonstrating-treatment-received- article-1.1098521 . Do you think that her actions we justified? Why or why not?

- Do you think that more targeted screening, as opposed to random screenings in which each person has an equal chance of being selected for enhanced pat-downs, is a good idea? Why? Do you think such targeted screening could be seen as a case of unethical racial profiling? Why or why not?

We learned earlier that paralanguage refers to the vocalized but nonverbal parts of a message. Vocalics is the study of paralanguage, which includes the vocal qualities that go along with verbal messages, such as pitch, volume, rate, vocal quality, and verbal fillers (Andersen, 1999).

Pitch helps convey meaning, regulate conversational flow, and communicate the intensity of a message. Even babies recognize a sentence with a higher pitched ending as a question. We also learn that greetings have a rising emphasis and farewells have falling emphasis. Of course, no one ever tells us these things explicitly; we learn them through observation and practice. We do not pick up on some more subtle and/or complex patterns of paralanguage involving pitch until we are older. Children, for example, have a difficult time perceiving sarcasm, which is usually conveyed through paralinguistic characteristics like pitch and tone rather than the actual words being spoken. Adults with lower than average intelligence and children have difficulty reading sarcasm in another person’s voice and instead may interpret literally what they say (Andersen, 1999).

Paralanguage provides important context for the verbal content of speech. For example, volume helps communicate intensity. A louder voice is usually thought of as more intense, although a soft voice combined with a certain tone and facial expression can be just as intense. We typically adjust our volume based on our setting, the distance between people, and the relationship. In our age of computer-mediated communication, TYPING IN ALL CAPS is usually seen as offensive, as it is equated with yelling. A voice at a low volume or a whisper can be very appropriate when sending a covert message or flirting with a romantic partner, but it wouldn’t enhance a person’s credibility if used during a professional presentation.

Speaking rate refers to how fast or slow a person speaks and can lead others to form impressions about our emotional state, credibility, and intelligence. As with volume, variations in speaking rate can interfere with the ability of others to receive and understand verbal messages. A slow speaker could bore others and lead their attention to wander. A fast speaker may be difficult to follow, and the fast delivery can actually distract from the message. Speaking a little faster than the normal 120–150 words a minute, however, can be beneficial, as people tend to find speakers whose rate is above average more credible and intelligent (Buller & Burgoon, 1986). When speaking at a faster-than-normal rate, it is important that a speaker also clearly articulate and pronounce his or her words. Boomhauer, a character on the show King of the Hill , is an example of a speaker whose fast rate of speech combines with a lack of articulation and pronunciation to create a stream of words that only he can understand. A higher rate of speech combined with a pleasant tone of voice can also be beneficial for compliance gaining and can aid in persuasion.

Our tone of voice can be controlled somewhat with pitch, volume, and emphasis, but each voice has a distinct quality known as a vocal signature. Voices vary in terms of resonance, pitch, and tone, and some voices are more pleasing than others. People typically find pleasing voices that employ vocal variety and are not monotone, are lower pitched (particularly for males), and do not exhibit particular regional accents. Many people perceive nasal voices negatively and assign negative personality characteristics to them (Andersen, 1999). Think about people who have very distinct voices. Whether they are a public figure like President Bill Clinton, a celebrity like Snooki from the Jersey Shore , or a fictional character like Peter Griffin from Family Guy , some people’s voices stick with us and make a favorable or unfavorable impression.

Verbal fillers are sounds that fill gaps in our speech as we think about what to say next. They are considered a part of nonverbal communication because they are not like typical words that stand in for a specific meaning or meanings. Verbal fillers such as “um,” “uh,” “like,” and “ah” are common in regular conversation and are not typically disruptive. As we learned earlier, the use of verbal fillers can help a person “keep the floor” during a conversation if they need to pause for a moment to think before continuing on with verbal communication. Verbal fillers in more formal settings, like a public speech, can hurt a speaker’s credibility.

The following is a review of the various communicative functions of vocalics:

- Repetition. Vocalic cues reinforce other verbal and nonverbal cues (e.g., saying “I’m not sure” with an uncertain tone).

- Complementing. Vocalic cues elaborate on or modify verbal and nonverbal meaning (e.g., the pitch and volume used to say “I love sweet potatoes” would add context to the meaning of the sentence, such as the degree to which the person loves sweet potatoes or the use of sarcasm).

- Accenting. Vocalic cues allow us to emphasize particular parts of a message, which helps determine meaning (e.g., “ She is my friend,” or “She is my friend,” or “She is my friend ”).

- Substituting. Vocalic cues can take the place of other verbal or nonverbal cues (e.g., saying “uh huh” instead of “I am listening and understand what you’re saying”).

- Regulating. Vocalic cues help regulate the flow of conversations (e.g., falling pitch and slowing rate of speaking usually indicate the end of a speaking turn).

- Contradicting. Vocalic cues may contradict other verbal or nonverbal signals (e.g., a person could say “I’m fine” in a quick, short tone that indicates otherwise).

Proxemics refers to the study of how space and distance influence communication. We only need look at the ways in which space shows up in common metaphors to see that space, communication, and relationships are closely related. For example, when we are content with and attracted to someone, we say we are “close” to him or her. When we lose connection with someone, we may say he or she is “distant.” In general, space influences how people communicate and behave. Smaller spaces with a higher density of people often lead to breaches of our personal space bubbles. If this is a setting in which this type of density is expected beforehand, like at a crowded concert or on a train during rush hour, then we make various communicative adjustments to manage the space issue. Unexpected breaches of personal space can lead to negative reactions, especially if we feel someone has violated our space voluntarily, meaning that a crowding situation didn’t force them into our space. Additionally, research has shown that crowding can lead to criminal or delinquent behavior, known as a “mob mentality” (Andersen, 1999). To better understand how proxemics functions in nonverbal communication, we will more closely examine the proxemic distances associated with personal space and the concept of territoriality.

Proxemic Distances

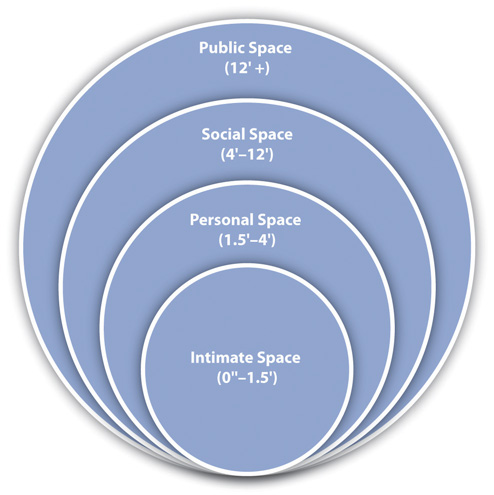

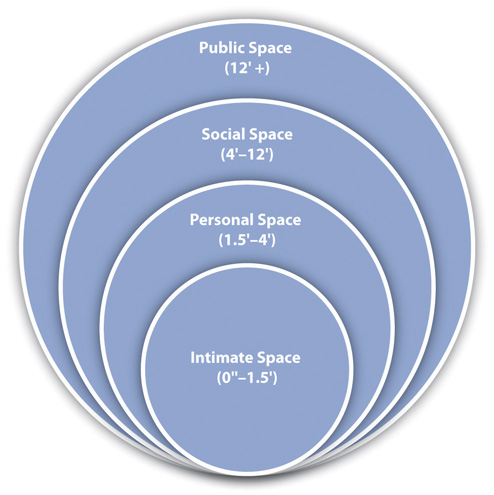

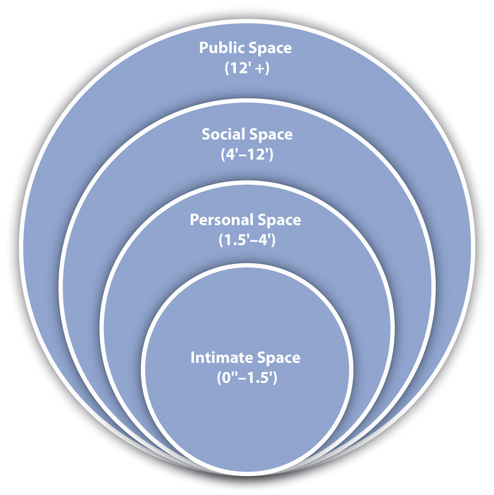

We all have varying definitions of what our “personal space” is, and these definitions are contextual and depend on the situation and the relationship. Although our bubbles are invisible, people are socialized into the norms of personal space within their cultural group. Scholars have identified four zones for US Americans, which are public, social, personal, and intimate distance (Hall, 1968). The zones are more elliptical than circular, taking up more space in our front, where our line of sight is, than at our side or back where we can’t monitor what people are doing. You can see how these zones relate to each other and to the individual in Figure 4.1 “Proxemic Zones of Personal Space” . Even within a particular zone, interactions may differ depending on whether someone is in the outer or inner part of the zone.

Figure 4.1 Proxemic Zones of Personal Space

Public Space (12 Feet or More)

Public and social zones refer to the space four or more feet away from our body, and the communication that typically occurs in these zones is formal and not intimate. Public space starts about twelve feet from a person and extends out from there. This is the least personal of the four zones and would typically be used when a person is engaging in a formal speech and is removed from the audience to allow the audience to see or when a high-profile or powerful person like a celebrity or executive maintains such a distance as a sign of power or for safety and security reasons. In terms of regular interaction, we are often not obligated or expected to acknowledge or interact with people who enter our public zone. It would be difficult to have a deep conversation with someone at this level because you have to speak louder and don’t have the physical closeness that is often needed to promote emotional closeness and/or establish rapport.

Social Space (4–12 Feet)

Communication that occurs in the social zone, which is four to twelve feet away from our body, is typically in the context of a professional or casual interaction, but not intimate or public. This distance is preferred in many professional settings because it reduces the suspicion of any impropriety. The expression “keep someone at an arm’s length” means that someone is kept out of the personal space and kept in the social/professional space. If two people held up their arms and stood so just the tips of their fingers were touching, they would be around four feet away from each other, which is perceived as a safe distance because the possibility for intentional or unintentional touching doesn’t exist. It is also possible to have people in the outer portion of our social zone but not feel obligated to interact with them, but when people come much closer than six feet to us then we often feel obligated to at least acknowledge their presence. In many typically sized classrooms, much of your audience for a speech will actually be in your social zone rather than your public zone, which is actually beneficial because it helps you establish a better connection with them. Students in large lecture classes should consider sitting within the social zone of the professor, since students who sit within this zone are more likely to be remembered by the professor, be acknowledged in class, and retain more information because they are close enough to take in important nonverbal and visual cues. Students who talk to me after class typically stand about four to five feet away when they speak to me, which keeps them in the outer part of the social zone, typical for professional interactions. When students have more personal information to discuss, they will come closer, which brings them into the inner part of the social zone.

Personal Space (1.5–4 Feet)

Personal and intimate zones refer to the space that starts at our physical body and extends four feet. These zones are reserved for friends, close acquaintances, and significant others. Much of our communication occurs in the personal zone, which is what we typically think of as our “personal space bubble” and extends from 1.5 feet to 4 feet away from our body. Even though we are getting closer to the physical body of another person, we may use verbal communication at this point to signal that our presence in this zone is friendly and not intimate. Even people who know each other could be uncomfortable spending too much time in this zone unnecessarily. This zone is broken up into two subzones, which helps us negotiate close interactions with people we may not be close to interpersonally (McKay, Davis, & Fanning, 1995). The outer-personal zone extends from 2.5 feet to 4 feet and is useful for conversations that need to be private but that occur between people who are not interpersonally close. This zone allows for relatively intimate communication but doesn’t convey the intimacy that a closer distance would, which can be beneficial in professional settings. The inner-personal zone extends from 1.5 feet to 2.5 feet and is a space reserved for communication with people we are interpersonally close to or trying to get to know. In this subzone, we can easily touch the other person as we talk to them, briefly placing a hand on his or her arm or engaging in other light social touching that facilitates conversation, self-disclosure, and feelings of closeness.

Intimate Space

As we breach the invisible line that is 1.5 feet from our body, we enter the intimate zone, which is reserved for only the closest friends, family, and romantic/intimate partners. It is impossible to completely ignore people when they are in this space, even if we are trying to pretend that we’re ignoring them. A breach of this space can be comforting in some contexts and annoying or frightening in others. We need regular human contact that isn’t just verbal but also physical. We have already discussed the importance of touch in nonverbal communication, and in order for that much-needed touch to occur, people have to enter our intimate space. Being close to someone and feeling their physical presence can be very comforting when words fail. There are also social norms regarding the amount of this type of closeness that can be displayed in public, as some people get uncomfortable even seeing others interacting in the intimate zone. While some people are comfortable engaging in or watching others engage in PDAs (public displays of affection) others are not.

So what happens when our space is violated? Although these zones are well established in research for personal space preferences of US Americans, individuals vary in terms of their reactions to people entering certain zones, and determining what constitutes a “violation” of space is subjective and contextual. For example, another person’s presence in our social or public zones doesn’t typically arouse suspicion or negative physical or communicative reactions, but it could in some situations or with certain people. However, many situations lead to our personal and intimate space being breached by others against our will, and these breaches are more likely to be upsetting, even when they are expected. We’ve all had to get into a crowded elevator or wait in a long line. In such situations, we may rely on some verbal communication to reduce immediacy and indicate that we are not interested in closeness and are aware that a breach has occurred. People make comments about the crowd, saying, “We’re really packed in here like sardines,” or use humor to indicate that they are pleasant and well adjusted and uncomfortable with the breach like any “normal” person would be. Interestingly, as we will learn in our discussion of territoriality, we do not often use verbal communication to defend our personal space during regular interactions. Instead, we rely on more nonverbal communication like moving, crossing our arms, or avoiding eye contact to deal with breaches of space.

Territoriality

Territoriality is an innate drive to take up and defend spaces. This drive is shared by many creatures and entities, ranging from packs of animals to individual humans to nations. Whether it’s a gang territory, a neighborhood claimed by a particular salesperson, your preferred place to sit in a restaurant, your usual desk in the classroom, or the seat you’ve marked to save while getting concessions at a sporting event, we claim certain spaces as our own. There are three main divisions for territory: primary, secondary, and public (Hargie, 2011). Sometimes our claim to a space is official. These spaces are known as our primary territories because they are marked or understood to be exclusively ours and under our control. A person’s house, yard, room, desk, side of the bed, or shelf in the medicine cabinet could be considered primary territories.

Secondary territories don’t belong to us and aren’t exclusively under our control, but they are associated with us, which may lead us to assume that the space will be open and available to us when we need it without us taking any further steps to reserve it. This happens in classrooms regularly. Students often sit in the same desk or at least same general area as they did on the first day of class. There may be some small adjustments during the first couple of weeks, but by a month into the semester, I don’t notice students moving much voluntarily. When someone else takes a student’s regular desk, she or he is typically annoyed. I do classroom observations for the graduate teaching assistants I supervise, which means I come into the classroom toward the middle of the semester and take a seat in the back to evaluate the class session. Although I don’t intend to take someone’s seat, on more than one occasion, I’ve been met by the confused or even glaring eyes of a student whose routine is suddenly interrupted when they see me sitting in “their seat.”

Public territories are open to all people. People are allowed to mark public territory and use it for a limited period of time, but space is often up for grabs, which makes public space difficult to manage for some people and can lead to conflict. To avoid this type of situation, people use a variety of objects that are typically recognized by others as nonverbal cues that mark a place as temporarily reserved—for example, jackets, bags, papers, or a drink. There is some ambiguity in the use of markers, though. A half-empty cup of coffee may be seen as trash and thrown away, which would be an annoying surprise to a person who left it to mark his or her table while visiting the restroom. One scholar’s informal observations revealed that a full drink sitting on a table could reserve a space in a university cafeteria for more than an hour, but a cup only half full usually only worked as a marker of territory for less than ten minutes. People have to decide how much value they want their marker to have. Obviously, leaving a laptop on a table indicates that the table is occupied, but it could also lead to the laptop getting stolen. A pencil, on the other hand, could just be moved out of the way and the space usurped.

Chronemics refers to the study of how time affects communication. Time can be classified into several different categories, including biological, personal, physical, and cultural time (Andersen, 1999). Biological time refers to the rhythms of living things. Humans follow a circadian rhythm, meaning that we are on a daily cycle that influences when we eat, sleep, and wake. When our natural rhythms are disturbed, by all-nighters, jet lag, or other scheduling abnormalities, our physical and mental health and our communication competence and personal relationships can suffer. Keep biological time in mind as you communicate with others. Remember that early morning conversations and speeches may require more preparation to get yourself awake enough to communicate well and a more patient or energetic delivery to accommodate others who may still be getting warmed up for their day.

Personal time refers to the ways in which individuals experience time. The way we experience time varies based on our mood, our interest level, and other factors. Think about how quickly time passes when you are interested in and therefore engaged in something. I have taught fifty-minute classes that seemed to drag on forever and three-hour classes that zipped by. Individuals also vary based on whether or not they are future or past oriented. People with past-time orientations may want to reminisce about the past, reunite with old friends, and put considerable time into preserving memories and keepsakes in scrapbooks and photo albums. People with future-time orientations may spend the same amount of time making career and personal plans, writing out to-do lists, or researching future vacations, potential retirement spots, or what book they’re going to read next.

Physical time refers to the fixed cycles of days, years, and seasons. Physical time, especially seasons, can affect our mood and psychological states. Some people experience seasonal affective disorder that leads them to experience emotional distress and anxiety during the changes of seasons, primarily from warm and bright to dark and cold (summer to fall and winter).

Cultural time refers to how a large group of people view time. Polychronic people do not view time as a linear progression that needs to be divided into small units and scheduled in advance. Polychronic people keep more flexible schedules and may engage in several activities at once. Monochronic people tend to schedule their time more rigidly and do one thing at a time. A polychronic or monochronic orientation to time influences our social realities and how we interact with others.

Additionally, the way we use time depends in some ways on our status. For example, doctors can make their patients wait for extended periods of time, and executives and celebrities may run consistently behind schedule, making others wait for them. Promptness and the amount of time that is socially acceptable for lateness and waiting varies among individuals and contexts. Chronemics also covers the amount of time we spend talking. We’ve already learned that conversational turns and turn-taking patterns are influenced by social norms and help our conversations progress. We all know how annoying it can be when a person dominates a conversation or when we can’t get a person to contribute anything.

Personal Presentation and Environment

Personal presentation involves two components: our physical characteristics and the artifacts with which we adorn and surround ourselves. Physical characteristics include body shape, height, weight, attractiveness, and other physical features of our bodies. We do not have as much control over how these nonverbal cues are encoded as we do with many other aspects of nonverbal communication. As Chapter 2 “Communication and Perception” noted, these characteristics play a large role in initial impression formation even though we know we “shouldn’t judge a book by its cover.” Although ideals of attractiveness vary among cultures and individuals, research consistently indicates that people who are deemed attractive based on physical characteristics have distinct advantages in many aspects of life. This fact, along with media images that project often unrealistic ideals of beauty, have contributed to booming health and beauty, dieting, gym, and plastic surgery industries. While there have been some controversial reality shows that seek to transform people’s physical characteristics, like Extreme Makeover , The Swan , and The Biggest Loser , the relative ease with which we can change the artifacts that send nonverbal cues about us has led to many more style and space makeover shows.

Have you ever tried to consciously change your “look?” I can distinctly remember two times in my life when I made pretty big changes in how I presented myself in terms of clothing and accessories. In high school, at the height of the “thrift store” craze, I started wearing clothes from the local thrift store daily. Of course, most of them were older clothes, so I was basically going for a “retro” look, which I thought really suited me at the time. Then in my junior year of college, as graduation finally seemed on the horizon and I felt myself entering a new stage of adulthood, I started wearing business-casual clothes to school every day, embracing the “dress for the job you want” philosophy. In both cases, these changes definitely impacted how others perceived me. Television programs like What Not to Wear seek to show the power of wardrobe and personal style changes in how people communicate with others.

Aside from clothes, jewelry, visible body art, hairstyles, and other political, social, and cultural symbols send messages to others about who we are. In the United States, body piercings and tattoos have been shifting from subcultural to mainstream over the past few decades. The physical location, size, and number of tattoos and piercings play a large role in whether or not they are deemed appropriate for professional contexts, and many people with tattoos and/or piercings make conscious choices about when and where they display their body art. Hair also sends messages whether it is on our heads or our bodies. Men with short hair are generally judged to be more conservative than men with long hair, but men with shaved heads may be seen as aggressive. Whether a person has a part in their hair, a mohawk, faux-hawk, ponytail, curls, or bright pink hair also sends nonverbal signals to others.

Jewelry can also send messages with varying degrees of direct meaning. A ring on the “ring finger” of a person’s left hand typically indicates that they are married or in an otherwise committed relationship. A thumb ring or a right-hand ring on the “ring finger” doesn’t send such a direct message. People also adorn their clothes, body, or belongings with religious or cultural symbols, like a cross to indicate a person’s Christian faith or a rainbow flag to indicate that a person is gay, lesbian, bisexual, transgender, queer, or an ally to one or more of those groups. People now wear various types of rubber bracelets, which have become a popular form of social cause marketing, to indicate that they identify with the “Livestrong” movement or support breast cancer awareness and research.

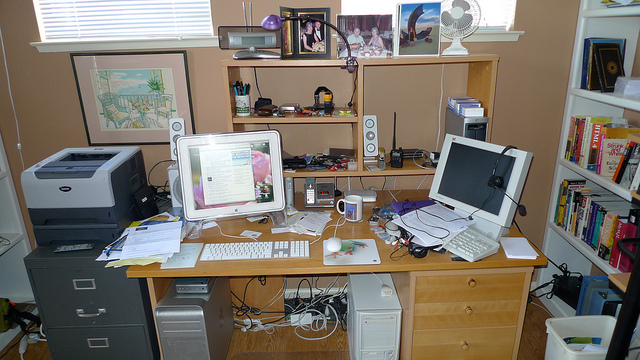

The objects that surround us send nonverbal cues that may influence how people perceive us. What impression does a messy, crowded office make?

Phil Stripling – My desk – CC BY-NC 2.0.

Last, the environment in which we interact affects our verbal and nonverbal communication. This is included because we can often manipulate the nonverbal environment similar to how we would manipulate our gestures or tone of voice to suit our communicative needs. The books that we display on our coffee table, the magazines a doctor keeps in his or her waiting room, the placement of fresh flowers in a foyer, or a piece of mint chocolate on a hotel bed pillow all send particular messages and can easily be changed. The placement of objects and furniture in a physical space can help create a formal, distant, friendly, or intimate climate. In terms of formality, we can use nonverbal communication to convey dominance and status, which helps define and negotiate power and roles within relationships. Fancy cars and expensive watches can serve as symbols that distinguish a CEO from an entry-level employee. A room with soft lighting, a small fountain that creates ambient sounds of water flowing, and a comfy chair can help facilitate interactions between a therapist and a patient. In summary, whether we know it or not, our physical characteristics and the artifacts that surround us communicate much.

“Getting Plugged In”

Avatars are computer-generated images that represent users in online environments or are created to interact with users in online and offline situations. Avatars can be created in the likeness of humans, animals, aliens, or other nonhuman creatures (Allmendinger, 2010). Avatars vary in terms of functionality and technical sophistication and can include stationary pictures like buddy icons, cartoonish but humanlike animations like a Mii character on the Wii, or very humanlike animations designed to teach or assist people in virtual environments. More recently, 3-D holographic avatars have been put to work helping travelers at airports in Paris and New York (Strunksy, 2012; Tecca, 2012). Research has shown, though, that humanlike avatars influence people even when they are not sophisticated in terms of functionality and adaptability (Baylor, 2011). Avatars are especially motivating and influential when they are similar to the observer or user but more closely represent the person’s ideal self. Appearance has been noted as one of the most important attributes of an avatar designed to influence or motivate. Attractiveness, coolness (in terms of clothing and hairstyle), and age were shown to be factors that increase or decrease the influence an avatar has over users (Baylor, 2011).

People also create their own avatars as self-representations in a variety of online environments ranging from online role-playing games like World of Warcraft and Second Life to some online learning management systems used by colleges and universities. Research shows that the line between reality and virtual reality can become blurry when it comes to avatar design and identification. This can become even more pronounced when we consider that some users, especially of online role-playing games, spend about twenty hours a week as their avatar.

Avatars do more than represent people in online worlds; they also affect their behaviors offline. For example, one study found that people who watched an avatar that looked like them exercising and losing weight in an online environment exercised more and ate healthier in the real world (Fox & Bailenson, 2009). Seeing an older version of them online led participants to form a more concrete social and psychological connection with their future selves, which led them to invest more money in a retirement account. People’s actions online also mirror the expectations for certain physical characteristics, even when the user doesn’t exhibit those characteristics and didn’t get to choose them for his or her avatar. For example, experimental research showed that people using more attractive avatars were more extroverted and friendly than those with less attractive avatars, which is also a nonverbal communication pattern that exists among real people. In summary, people have the ability to self-select physical characteristics and personal presentation for their avatars in a way that they can’t in their real life. People come to see their avatars as part of themselves, which opens the possibility for avatars to affect users’ online and offline communication (Kim, Lee, & Kang, 2012).

- Describe an avatar that you have created for yourself. What led you to construct the avatar the way you did, and how do you think your choices reflect your typical nonverbal self-presentation? If you haven’t ever constructed an avatar, what would you make your avatar look like and why?

- In 2009, a man in Japan became the first human to marry an avatar (that we know of). Although he claims that his avatar is better than any human girlfriend, he has been criticized as being out of touch with reality. You can read more about this human-avatar union through the following link: http://articles.cnn.com/2009-12-16/world/japan.virtual.wedding_1_virtual-world-sal-marry?_s=PM:WORLD . Do you think the boundaries between human reality and avatar fantasy will continue to fade as we become a more technologically fused world? How do you feel about interacting more with avatars in customer service situations like the airport avatar mentioned above? What do you think about having avatars as mentors, role models, or teachers?

Key Takeaways

Kinesics refers to body movements and posture and includes the following components:

- Gestures are arm and hand movements and include adaptors like clicking a pen or scratching your face, emblems like a thumbs-up to say “OK,” and illustrators like bouncing your hand along with the rhythm of your speaking.

- Head movements and posture include the orientation of movements of our head and the orientation and positioning of our body and the various meanings they send. Head movements such as nodding can indicate agreement, disagreement, and interest, among other things. Posture can indicate assertiveness, defensiveness, interest, readiness, or intimidation, among other things.

- Eye contact is studied under the category of oculesics and specifically refers to eye contact with another person’s face, head, and eyes and the patterns of looking away and back at the other person during interaction. Eye contact provides turn-taking signals, signals when we are engaged in cognitive activity, and helps establish rapport and connection, among other things.

- Facial expressions refer to the use of the forehead, brow, and facial muscles around the nose and mouth to convey meaning. Facial expressions can convey happiness, sadness, fear, anger, and other emotions.

- Haptics refers to touch behaviors that convey meaning during interactions. Touch operates at many levels, including functional-professional, social-polite, friendship-warmth, and love-intimacy.

- Vocalics refers to the vocalized but not verbal aspects of nonverbal communication, including our speaking rate, pitch, volume, tone of voice, and vocal quality. These qualities, also known as paralanguage, reinforce the meaning of verbal communication, allow us to emphasize particular parts of a message, or can contradict verbal messages.

- Proxemics refers to the use of space and distance within communication. US Americans, in general, have four zones that constitute our personal space: the public zone (12 or more feet from our body), social zone (4–12 feet from our body), the personal zone (1.5–4 feet from our body), and the intimate zone (from body contact to 1.5 feet away). Proxemics also studies territoriality, or how people take up and defend personal space.

- Chronemics refers the study of how time affects communication and includes how different time cycles affect our communication, including the differences between people who are past or future oriented and cultural perspectives on time as fixed and measured (monochronic) or fluid and adaptable (polychronic).

- Personal presentation and environment refers to how the objects we adorn ourselves and our surroundings with, referred to as artifacts , provide nonverbal cues that others make meaning from and how our physical environment—for example, the layout of a room and seating positions and arrangements—influences communication.

- Provide some examples of how eye contact plays a role in your communication throughout the day.

- One of the key functions of vocalics is to add emphasis to our verbal messages to influence the meaning. Provide a meaning for each of the following statements based on which word is emphasized: “ She is my friend.” “She is my friend.” “She is my friend .”

- Getting integrated: Many people do not think of time as an important part of our nonverbal communication. Provide an example of how chronemics sends nonverbal messages in academic settings, professional settings, and personal settings.

Allmendinger, K., “Social Presence in Synchronous Virtual Learning Situations: The Role of Nonverbal Signals Displayed by Avatars,” Educational Psychology Review 22, no. 1 (2010): 42.

Andersen, P. A., Nonverbal Communication: Forms and Functions (Mountain View, CA: Mayfield, 1999), 36.

Baylor, A. L., “The Design of Motivational Agents and Avatars,” Educational Technology Research and Development 59, no. 2 (2011): 291–300.

Buller, D. B. and Judee K. Burgoon, “The Effects of Vocalics and Nonverbal Sensitivity on Compliance,” Human Communication Research 13, no. 1 (1986): 126–44.

Evans, D., Emotion: The Science of Sentiment (New York: Oxford University Press, 2001), 107.

Floyd, K., Communicating Affection: Interpersonal Behavior and Social Context (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2006), 33–34.

Fox, J. and Jeremy M. Bailenson, “Virtual Self-Modeling: The Effects of Vicarious Reinforcement and Identification on Exercise Behaviors,” Media Psychology 12, no. 1 (2009): 1–25.

Guerrero, L. K. and Kory Floyd, Nonverbal Communication in Close Relationships (Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum, 2006): 176.

Hall, E. T., “Proxemics,” Current Anthropology 9, no. 2 (1968): 83–95.

Hargie, O., Skilled Interpersonal Interaction: Research, Theory, and Practice , 5th ed. (London: Routledge, 2011), 63.

Heslin, R. and Tari Apler, “Touch: A Bonding Gesture,” in Nonverbal Interaction , eds. John M. Weimann and Randall Harrison (Longon: Sage, 1983), 47–76.

Jones, S. E., “Communicating with Touch,” in The Nonverbal Communication Reader: Classic and Contemporary Readings, 2nd ed., eds. Laura K. Guerrero, Joseph A. Devito, and Michael L. Hecht (Prospect Heights, IL: Waveland Press, 1999).

Kim, C., Sang-Gun Lee, and Minchoel Kang, “I Became an Attractive Person in the Virtual World: Users’ Identification with Virtual Communities and Avatars,” Computers in Human Behavior , 28, no. 5 (2012): 1663–69

Kravitz, D., “Airport ‘Pat-Downs’ Cause Growing Passenger Backlash,” The Washington Post , November 13, 2010, accessed June 23, 2012, http://www.washingtonpost.com/wp-dyn/content/article/2010/11/12/AR2010111206580.html?sid=ST2010113005385 .

Martin, J. N. and Thomas K. Nakayama, Intercultural Communication in Contexts , 5th ed. (Boston, MA: McGraw-Hill, 2010), 276.

McKay, M., Martha Davis, and Patrick Fanning, Messages: Communication Skills Book , 2nd ed. (Oakland, CA: New Harbinger Publications, 1995), 59.

Pease, A. and Barbara Pease, The Definitive Book of Body Language (New York, NY: Bantam, 2004), 121.

Strunksy, S., “New Airport Service Rep Is Stiff and Phony, but She’s Friendly,” NJ.COM , May 22, 2012, accessed June 28, 2012, http://www.nj.com/news/index.ssf/2012/05/new_airport_service_rep_is_sti.html .

Tecca, “New York City Airports Install New, Expensive Holograms to Help You Find Your Way,” Y! Tech: A Yahoo! News Blog , May 22, 2012, accessed June 28, 2012, http://news.yahoo.com/blogs/technology-blog/york-city-airports-install-expensive-holograms-help-way-024937526.html .

Thomas, A. R., Soft Landing: Airline Industry Strategy, Service, and Safety (New York, NY: Apress, 2011), 117–23.

Communication in the Real World Copyright © 2016 by University of Minnesota is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

- Bipolar Disorder

- Therapy Center

- When To See a Therapist

- Types of Therapy

- Best Online Therapy

- Best Couples Therapy

- Best Family Therapy

- Managing Stress

- Sleep and Dreaming

- Understanding Emotions

- Self-Improvement

- Healthy Relationships

- Student Resources

- Personality Types

- Guided Meditations

- Verywell Mind Insights

- 2024 Verywell Mind 25

- Mental Health in the Classroom

- Editorial Process

- Meet Our Review Board

- Crisis Support

Types of Nonverbal Communication

Often you don't need words at all

Kendra Cherry, MS, is a psychosocial rehabilitation specialist, psychology educator, and author of the "Everything Psychology Book."

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/IMG_9791-89504ab694d54b66bbd72cb84ffb860e.jpg)

Tim Robberts / Getty Images

Why Nonverbal Communication Is Important

- How to Improve

Nonverbal communication means conveying information without using words. This might involve using certain facial expressions or hand gestures to make a specific point, or it could involve the use (or non-use) of eye contact, physical proximity, and other nonverbal cues to get a message across.

A substantial portion of our communication is nonverbal. In fact, some researchers suggest that the percentage of nonverbal communication is four times that of verbal communication, with 80% of what we communicate involving our actions and gestures versus only 20% being conveyed with the use of words.

Every day, we respond to thousands of nonverbal cues and behaviors, including postures, facial expressions, eye gaze, gestures, and tone of voice. From our handshakes to our hairstyles, our nonverbal communication reveals who we are and impacts how we relate to other people.

9 Types of Nonverbal Communication

Scientific research on nonverbal communication and behavior began with the 1872 publication of Charles Darwin's The Expression of the Emotions in Man and Animals . Since that time, a wealth of research has been devoted to the types, effects, and expressions of unspoken communication and behavior .

Nonverbal Communication Types

While these signals can be so subtle that we are not consciously aware of them, research has identified nine types of nonverbal communication. These nonverbal communication types are:

- Facial expressions

- Paralinguistics (such as loudness or tone of voice)

- Body language

- Proxemics or personal space

- Eye gaze, haptics (touch)

- Artifacts (objects and images)

Facial Expressions

Facial expressions are responsible for a huge proportion of nonverbal communication. Consider how much information can be conveyed with a smile or a frown. The look on a person's face is often the first thing we see, even before we hear what they have to say.

While nonverbal communication and behavior can vary dramatically between cultures, the facial expressions for happiness, sadness, anger, and fear are similar throughout the world.

Deliberate movements and signals are an important way to communicate meaning without words. Common gestures include waving, pointing, and giving a "thumbs up" sign. Other gestures are arbitrary and related to culture.

For example, in the U.S., putting the index and middle finger in the shape of a "V" with your palm facing out is often considered to be a sign of peace or victory. Yet, in Britain, Australia, and other parts of the world, this gesture can be considered an insult.

Nonverbal communication via gestures is so powerful and influential that some judges place limits on which ones are allowed in the courtroom, where they can sway juror opinions. An attorney might glance at their watch to suggest that the opposing lawyer's argument is tedious, for instance. Or they may roll their eyes during a witness's testimony in an attempt to undermine that person's credibility.

Paralinguistics

Paralinguistics refers to vocal communication that is separate from actual language. This form of nonverbal communication includes factors such as tone of voice, loudness, inflection, and pitch.

For example, consider the powerful effect that tone of voice can have on the meaning of a sentence. When said in a strong tone of voice, listeners might interpret a statement as approval and enthusiasm. The same words said in a hesitant tone can convey disapproval and a lack of interest.

Body Language and Posture

Posture and movement can also provide a great deal of information. Research on body language has grown significantly since the 1970s, with popular media focusing on the over-interpretation of defensive postures such as arm-crossing and leg-crossing, especially after the publication of Julius Fast's book Body Language .

While these nonverbal communications can indicate feelings and attitudes , body language is often subtle and less definitive than previously believed.

People often refer to their need for "personal space." This is known as proxemics and is another important type of nonverbal communication.

The amount of distance we need and the amount of space we perceive as belonging to us are influenced by several factors. Among them are social norms , cultural expectations, situational factors, personality characteristics, and level of familiarity.

The amount of personal space needed when having a casual conversation with another person can vary between 18 inches and four feet. The personal distance needed when speaking to a crowd of people is usually around 10 to 12 feet.

The eyes play a role in nonverbal communication, with such things as looking, staring, and blinking being important cues. For example, when you encounter people or things that you like, your rate of blinking increases and your pupils dilate.

People's eyes can indicate a range of emotions , including hostility, interest, and attraction. People also often utilize eye gaze cues to gauge a person's honesty. Normal, steady eye contact is often taken as a sign that a person is telling the truth and is trustworthy. Shifty eyes and an inability to maintain eye contact, on the other hand, is frequently seen as an indicator that someone is lying or being deceptive.

However, some research suggests that eye gaze does not accurately predict lying behavior.

Communicating through touch is another important nonverbal communication behavior. Touch can be used to communicate affection, familiarity, sympathy, and other emotions .

In her book Interpersonal Communication: Everyday Encounters , author Julia Wood writes that touch is also often used to communicate both status and power. High-status individuals tend to invade other people's personal space with greater frequency and intensity than lower-status individuals.

Sex differences also play a role in how people utilize touch to communicate meaning. Women tend to use touch to convey care, concern, and nurturance. Men, on the other hand, are more likely to use touch to assert power or control over others.

There has been a substantial amount of research on the importance of touch in infancy and early childhood. Harry Harlow's classic monkey study , for example, demonstrated how being deprived of touch impedes development. In the experiments, baby monkeys raised by wire mothers experienced permanent deficits in behavior and social interaction.

Our choice of clothing, hairstyle, and other appearance factors are also considered a means of nonverbal communication. Research on color psychology has demonstrated that different colors can evoke different moods. Appearance can also alter physiological reactions, judgments, and interpretations.

Just think of all the subtle judgments you quickly make about someone based on their appearance. These first impressions are important, which is why experts suggest that job seekers dress appropriately for interviews with potential employers.

Researchers have found that appearance can even play a role in how much people earn. Attractive people tend to earn more and receive other fringe benefits, including higher-quality jobs.

Culture is an important influence on how appearances are judged. While thinness tends to be valued in Western cultures, some African cultures relate full-figured bodies to better health, wealth, and social status.

Objects and images are also tools that can be used to communicate nonverbally. On an online forum, for example, you might select an avatar to represent your identity and to communicate information about who you are and the things you like.

People often spend a great deal of time developing a particular image and surrounding themselves with objects designed to convey information about the things that are important to them. Uniforms, for example, can be used to transmit a tremendous amount of information about a person.

A soldier will don fatigues, a police officer will wear a specific uniform, and a doctor will wear a white lab coat. At a mere glance, these outfits tell others what that person does for a living. That makes them a powerful form of nonverbal communication.

Nonverbal Communication Examples

Think of all the ways you communicate nonverbally in your own life. You can find examples of nonverbal communication at home, at work, and in other situations.

Nonverbal Communication at Home

Consider all the ways that tone of voice might change the meaning of a sentence when talking with a family member. One example is when you ask your partner how they are doing and they respond with, "I'm fine." How they say these words reveals a tremendous amount about how they are truly feeling.

A bright, happy tone of voice would suggest that they are doing quite well. A cold tone of voice might suggest that they are not fine but don't wish to discuss it. A somber, downcast tone might indicate that they are the opposite of fine but may want to talk about why.

Other examples of nonverbal communication at home include:

- Going to your partner swiftly when they call for you (as opposed to taking your time or not responding at all)