- Medical Education

- Research Tools

Research Article Critique Checklist

from Ridsdale; Practitioner, 238:108-13. 1994.

- Is the study relevant & important to our practice?

- Is the work useful & original? Does it add to the fund of useful knowledge?

- Was the study setting similar enough to our working environment that, assuming the results are valid, they may be extrapolated to our practice?

- Was the architecture or design of the study appropriate to answer the questions posed in the introduction?

- Is the connection between the hypothesis & the instruments used clearly justified?

- Is the relationship between outcomes & measures plausible?

- Are the instruments used appropriate to the study & have they been validated previously?

- Are the population & the population sample defined & recognisably similar to that seen in practice?

- Are the recruitment definitions & inclusion/exclusion criteria clearly stated?

- Is the sample size sufficient to answer the questions posed, & has there been an attempt to estimate the required numbers in advance?

- Is the response rate adequate? Are drop-outs well described, & is there any reason to think that they differ materially from responders?

- Are the tables & figures clear?

- Have stastistical tests been applied appropriately?

- Are p values or confidence intervals used?

- Where statistically significant differences are found, are they sufficient to be clinically important?

- Does the discussion show an awareness of the methodological limitations of the study design? Are problems or difficulties acknowledged?

- Are the conclusions drawn justified by the results presented?

- Is a comparison drawn with other published work?

- Do the authors speculate too far beyond the evidence presented?

Search ShoulderDoc.co.uk

Diagnose your shoulder.

This is an interactive guide to help you find relevant patient information for your shoulder problem.

ShoulderDoc.co.uk satisfies the INTUTE criteria for quality and has been awarded 'editor's choice'.

The material on this website is designed to support, not replace, the relationship that exists between ourselves and our patients. Full Disclaimer

SPH Writing Support Services

- Appointment System

- ESL Conversation Group

- Mini-Courses

- Thesis/Dissertation Writing Group

- Career Writing

- Citing Sources

- Critiquing Research Articles

- Project Planning for the Beginner This link opens in a new window

- Grant Writing

- Publishing in the Sciences

- Systematic Review Overview

- Systematic Review Resources This link opens in a new window

- Writing Across Borders / Writing Across the Curriculum

- Conducting an article critique for a quantitative research study: Perspectives for doctoral students and other novice readers (Vance et al.)

- Critique Process (Boswell & Cannon)

- The experience of critiquing published research: Learning from the student and researcher perspective (Knowles & Gray)

- A guide to critiquing a research paper. Methodological appraisal of a paper on nurses in abortion care (Lipp & Fothergill)

- Step-by-step guide to critiquing research. Part 1: Quantitative research (Coughlan et al.)

- Step-by-step guide to critiquing research. Part 2: Qualitative research (Coughlan et al.)

Guidelines:

- Critiquing Research Articles (Flinders University)

- Framework for How to Read and Critique a Research Study (American Nurses Association)

- How to Critique a Journal Article (UIS)

- How to Critique a Research Paper (University of Michigan)

- How to Write an Article Critique

- Research Article Critique Form

- Writing a Critique or Review of a Research Article (University of Calgary)

Presentations:

- The Critique Process: Reviewing and Critiquing Research

- Writing a Critique

- << Previous: Citing Sources

- Next: Project Planning for the Beginner >>

- Last Updated: Apr 30, 2024 12:52 PM

- URL: https://libguides.sph.uth.tmc.edu/writing_support_services

CASP Checklists

How to use our CASP Checklists

Referencing and Creative Commons

- Online Training Courses

- CASP Workshops

- What is Critical Appraisal

- Study Designs

- Useful Links

- Bibliography

- View all Tools and Resources

- Testimonials

Critical Appraisal Checklists

We offer a number of free downloadable checklists to help you more easily and accurately perform critical appraisal across a number of different study types.

The CASP checklists are easy to understand but in case you need any further guidance on how they are structured, take a look at our guide on how to use our CASP checklists .

CASP Checklist: Systematic Reviews with Meta-Analysis of Observational Studies

CASP Checklist: Systematic Reviews with Meta-Analysis of Randomised Controlled Trials (RCTs)

CASP Randomised Controlled Trial Checklist

- Print & Fill

CASP Systematic Review Checklist

CASP Qualitative Studies Checklist

CASP Cohort Study Checklist

CASP Diagnostic Study Checklist

CASP Case Control Study Checklist

CASP Economic Evaluation Checklist

CASP Clinical Prediction Rule Checklist

Checklist Archive

- CASP Randomised Controlled Trial Checklist 2018 fillable form

- CASP Randomised Controlled Trial Checklist 2018

CASP Checklist

Need more information?

- Online Learning

- Privacy Policy

Critical Appraisal Skills Programme

Critical Appraisal Skills Programme (CASP) will use the information you provide on this form to be in touch with you and to provide updates and marketing. Please let us know all the ways you would like to hear from us:

We use Mailchimp as our marketing platform. By clicking below to subscribe, you acknowledge that your information will be transferred to Mailchimp for processing. Learn more about Mailchimp's privacy practices here.

Copyright 2024 CASP UK - OAP Ltd. All rights reserved Website by Beyond Your Brand

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- v.309(6955); 1994 Sep 10

Checklists for review articles.

Preparing a review entails many judgments. The focus of the review must be decided. Studies that are relevant to the focus of the review must be identified, selected for inclusion and critically appraised. Information must be collected and synthesised from the relevant studies, and conclusions must be drawn. Checklists can help prevent important errors in this process. Reviewers, editors, content experts, and users of reviews all have a role to play in improving the quality of published reviews and promoting the appropriate use of reviews by decisionmakers. It is essential that both providers and users appraise the validity of review articles.

Full text is available as a scanned copy of the original print version. Get a printable copy (PDF file) of the complete article (890K), or click on a page image below to browse page by page. Links to PubMed are also available for Selected References .

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Antman EM, Lau J, Kupelnick B, Mosteller F, Chalmers TC. A comparison of results of meta-analyses of randomized control trials and recommendations of clinical experts. Treatments for myocardial infarction. JAMA. 1992 Jul 8; 268 (2):240–248. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- L'Abbé KA, Detsky AS, O'Rourke K. Meta-analysis in clinical research. Ann Intern Med. 1987 Aug; 107 (2):224–233. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Oxman AD, Guyatt GH. Guidelines for reading literature reviews. CMAJ. 1988 Apr 15; 138 (8):697–703. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Detsky AS, Naylor CD, O'Rourke K, McGeer AJ, L'Abbé KA. Incorporating variations in the quality of individual randomized trials into meta-analysis. J Clin Epidemiol. 1992 Mar; 45 (3):255–265. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Gøtzsche PC. Methodology and overt and hidden bias in reports of 196 double-blind trials of nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs in rheumatoid arthritis. Control Clin Trials. 1989 Mar; 10 (1):31–56. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Emerson JD, Burdick E, Hoaglin DC, Mosteller F, Chalmers TC. An empirical study of the possible relation of treatment differences to quality scores in controlled randomized clinical trials. Control Clin Trials. 1990 Oct; 11 (5):339–352. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Laird NM, Mosteller F. Some statistical methods for combining experimental results. Int J Technol Assess Health Care. 1990; 6 (1):5–30. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Eddy DM. Clinical decision making: from theory to practice. Anatomy of a decision. JAMA. 1990 Jan 19; 263 (3):441–443. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Grady D, Rubin SM, Petitti DB, Fox CS, Black D, Ettinger B, Ernster VL, Cummings SR. Hormone therapy to prevent disease and prolong life in postmenopausal women. Ann Intern Med. 1992 Dec 15; 117 (12):1016–1037. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Yusuf S, Wittes J, Probstfield J, Tyroler HA. Analysis and interpretation of treatment effects in subgroups of patients in randomized clinical trials. JAMA. 1991 Jul 3; 266 (1):93–98. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Oxman AD, Guyatt GH. A consumer's guide to subgroup analyses. Ann Intern Med. 1992 Jan 1; 116 (1):78–84. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Sackett DL. Second thoughts. Proposals for the health sciences--I. Compulsory retirement for experts. J Chronic Dis. 1983; 36 (7):545–547. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Evidence-based medicine. A new approach to teaching the practice of medicine. JAMA. 1992 Nov 4; 268 (17):2420–2425. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Guyatt GH, Rennie D. Users' guides to the medical literature. JAMA. 1993 Nov 3; 270 (17):2096–2097. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Oxman AD, Sackett DL, Guyatt GH. Users' guides to the medical literature. I. How to get started. The Evidence-Based Medicine Working Group. JAMA. 1993 Nov 3; 270 (17):2093–2095. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

Criteria for Good Qualitative Research: A Comprehensive Review

- Regular Article

- Open access

- Published: 18 September 2021

- Volume 31 , pages 679–689, ( 2022 )

Cite this article

You have full access to this open access article

- Drishti Yadav ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-2974-0323 1

85k Accesses

28 Citations

72 Altmetric

Explore all metrics

This review aims to synthesize a published set of evaluative criteria for good qualitative research. The aim is to shed light on existing standards for assessing the rigor of qualitative research encompassing a range of epistemological and ontological standpoints. Using a systematic search strategy, published journal articles that deliberate criteria for rigorous research were identified. Then, references of relevant articles were surveyed to find noteworthy, distinct, and well-defined pointers to good qualitative research. This review presents an investigative assessment of the pivotal features in qualitative research that can permit the readers to pass judgment on its quality and to condemn it as good research when objectively and adequately utilized. Overall, this review underlines the crux of qualitative research and accentuates the necessity to evaluate such research by the very tenets of its being. It also offers some prospects and recommendations to improve the quality of qualitative research. Based on the findings of this review, it is concluded that quality criteria are the aftereffect of socio-institutional procedures and existing paradigmatic conducts. Owing to the paradigmatic diversity of qualitative research, a single and specific set of quality criteria is neither feasible nor anticipated. Since qualitative research is not a cohesive discipline, researchers need to educate and familiarize themselves with applicable norms and decisive factors to evaluate qualitative research from within its theoretical and methodological framework of origin.

Similar content being viewed by others

Reporting reliability, convergent and discriminant validity with structural equation modeling: A review and best-practice recommendations

Sampling Techniques for Quantitative Research

How to design bibliometric research: an overview and a framework proposal

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

“… It is important to regularly dialogue about what makes for good qualitative research” (Tracy, 2010 , p. 837)

To decide what represents good qualitative research is highly debatable. There are numerous methods that are contained within qualitative research and that are established on diverse philosophical perspectives. Bryman et al., ( 2008 , p. 262) suggest that “It is widely assumed that whereas quality criteria for quantitative research are well‐known and widely agreed, this is not the case for qualitative research.” Hence, the question “how to evaluate the quality of qualitative research” has been continuously debated. There are many areas of science and technology wherein these debates on the assessment of qualitative research have taken place. Examples include various areas of psychology: general psychology (Madill et al., 2000 ); counseling psychology (Morrow, 2005 ); and clinical psychology (Barker & Pistrang, 2005 ), and other disciplines of social sciences: social policy (Bryman et al., 2008 ); health research (Sparkes, 2001 ); business and management research (Johnson et al., 2006 ); information systems (Klein & Myers, 1999 ); and environmental studies (Reid & Gough, 2000 ). In the literature, these debates are enthused by the impression that the blanket application of criteria for good qualitative research developed around the positivist paradigm is improper. Such debates are based on the wide range of philosophical backgrounds within which qualitative research is conducted (e.g., Sandberg, 2000 ; Schwandt, 1996 ). The existence of methodological diversity led to the formulation of different sets of criteria applicable to qualitative research.

Among qualitative researchers, the dilemma of governing the measures to assess the quality of research is not a new phenomenon, especially when the virtuous triad of objectivity, reliability, and validity (Spencer et al., 2004 ) are not adequate. Occasionally, the criteria of quantitative research are used to evaluate qualitative research (Cohen & Crabtree, 2008 ; Lather, 2004 ). Indeed, Howe ( 2004 ) claims that the prevailing paradigm in educational research is scientifically based experimental research. Hypotheses and conjectures about the preeminence of quantitative research can weaken the worth and usefulness of qualitative research by neglecting the prominence of harmonizing match for purpose on research paradigm, the epistemological stance of the researcher, and the choice of methodology. Researchers have been reprimanded concerning this in “paradigmatic controversies, contradictions, and emerging confluences” (Lincoln & Guba, 2000 ).

In general, qualitative research tends to come from a very different paradigmatic stance and intrinsically demands distinctive and out-of-the-ordinary criteria for evaluating good research and varieties of research contributions that can be made. This review attempts to present a series of evaluative criteria for qualitative researchers, arguing that their choice of criteria needs to be compatible with the unique nature of the research in question (its methodology, aims, and assumptions). This review aims to assist researchers in identifying some of the indispensable features or markers of high-quality qualitative research. In a nutshell, the purpose of this systematic literature review is to analyze the existing knowledge on high-quality qualitative research and to verify the existence of research studies dealing with the critical assessment of qualitative research based on the concept of diverse paradigmatic stances. Contrary to the existing reviews, this review also suggests some critical directions to follow to improve the quality of qualitative research in different epistemological and ontological perspectives. This review is also intended to provide guidelines for the acceleration of future developments and dialogues among qualitative researchers in the context of assessing the qualitative research.

The rest of this review article is structured in the following fashion: Sect. Methods describes the method followed for performing this review. Section Criteria for Evaluating Qualitative Studies provides a comprehensive description of the criteria for evaluating qualitative studies. This section is followed by a summary of the strategies to improve the quality of qualitative research in Sect. Improving Quality: Strategies . Section How to Assess the Quality of the Research Findings? provides details on how to assess the quality of the research findings. After that, some of the quality checklists (as tools to evaluate quality) are discussed in Sect. Quality Checklists: Tools for Assessing the Quality . At last, the review ends with the concluding remarks presented in Sect. Conclusions, Future Directions and Outlook . Some prospects in qualitative research for enhancing its quality and usefulness in the social and techno-scientific research community are also presented in Sect. Conclusions, Future Directions and Outlook .

For this review, a comprehensive literature search was performed from many databases using generic search terms such as Qualitative Research , Criteria , etc . The following databases were chosen for the literature search based on the high number of results: IEEE Explore, ScienceDirect, PubMed, Google Scholar, and Web of Science. The following keywords (and their combinations using Boolean connectives OR/AND) were adopted for the literature search: qualitative research, criteria, quality, assessment, and validity. The synonyms for these keywords were collected and arranged in a logical structure (see Table 1 ). All publications in journals and conference proceedings later than 1950 till 2021 were considered for the search. Other articles extracted from the references of the papers identified in the electronic search were also included. A large number of publications on qualitative research were retrieved during the initial screening. Hence, to include the searches with the main focus on criteria for good qualitative research, an inclusion criterion was utilized in the search string.

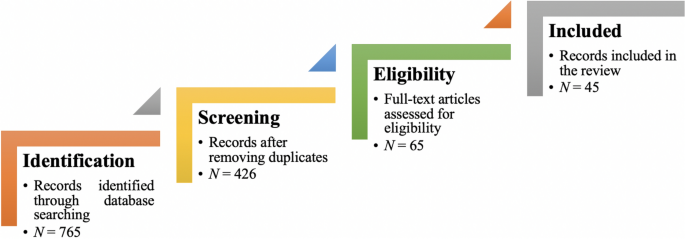

From the selected databases, the search retrieved a total of 765 publications. Then, the duplicate records were removed. After that, based on the title and abstract, the remaining 426 publications were screened for their relevance by using the following inclusion and exclusion criteria (see Table 2 ). Publications focusing on evaluation criteria for good qualitative research were included, whereas those works which delivered theoretical concepts on qualitative research were excluded. Based on the screening and eligibility, 45 research articles were identified that offered explicit criteria for evaluating the quality of qualitative research and were found to be relevant to this review.

Figure 1 illustrates the complete review process in the form of PRISMA flow diagram. PRISMA, i.e., “preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses” is employed in systematic reviews to refine the quality of reporting.

PRISMA flow diagram illustrating the search and inclusion process. N represents the number of records

Criteria for Evaluating Qualitative Studies

Fundamental criteria: general research quality.

Various researchers have put forward criteria for evaluating qualitative research, which have been summarized in Table 3 . Also, the criteria outlined in Table 4 effectively deliver the various approaches to evaluate and assess the quality of qualitative work. The entries in Table 4 are based on Tracy’s “Eight big‐tent criteria for excellent qualitative research” (Tracy, 2010 ). Tracy argues that high-quality qualitative work should formulate criteria focusing on the worthiness, relevance, timeliness, significance, morality, and practicality of the research topic, and the ethical stance of the research itself. Researchers have also suggested a series of questions as guiding principles to assess the quality of a qualitative study (Mays & Pope, 2020 ). Nassaji ( 2020 ) argues that good qualitative research should be robust, well informed, and thoroughly documented.

Qualitative Research: Interpretive Paradigms

All qualitative researchers follow highly abstract principles which bring together beliefs about ontology, epistemology, and methodology. These beliefs govern how the researcher perceives and acts. The net, which encompasses the researcher’s epistemological, ontological, and methodological premises, is referred to as a paradigm, or an interpretive structure, a “Basic set of beliefs that guides action” (Guba, 1990 ). Four major interpretive paradigms structure the qualitative research: positivist and postpositivist, constructivist interpretive, critical (Marxist, emancipatory), and feminist poststructural. The complexity of these four abstract paradigms increases at the level of concrete, specific interpretive communities. Table 5 presents these paradigms and their assumptions, including their criteria for evaluating research, and the typical form that an interpretive or theoretical statement assumes in each paradigm. Moreover, for evaluating qualitative research, quantitative conceptualizations of reliability and validity are proven to be incompatible (Horsburgh, 2003 ). In addition, a series of questions have been put forward in the literature to assist a reviewer (who is proficient in qualitative methods) for meticulous assessment and endorsement of qualitative research (Morse, 2003 ). Hammersley ( 2007 ) also suggests that guiding principles for qualitative research are advantageous, but methodological pluralism should not be simply acknowledged for all qualitative approaches. Seale ( 1999 ) also points out the significance of methodological cognizance in research studies.

Table 5 reflects that criteria for assessing the quality of qualitative research are the aftermath of socio-institutional practices and existing paradigmatic standpoints. Owing to the paradigmatic diversity of qualitative research, a single set of quality criteria is neither possible nor desirable. Hence, the researchers must be reflexive about the criteria they use in the various roles they play within their research community.

Improving Quality: Strategies

Another critical question is “How can the qualitative researchers ensure that the abovementioned quality criteria can be met?” Lincoln and Guba ( 1986 ) delineated several strategies to intensify each criteria of trustworthiness. Other researchers (Merriam & Tisdell, 2016 ; Shenton, 2004 ) also presented such strategies. A brief description of these strategies is shown in Table 6 .

It is worth mentioning that generalizability is also an integral part of qualitative research (Hays & McKibben, 2021 ). In general, the guiding principle pertaining to generalizability speaks about inducing and comprehending knowledge to synthesize interpretive components of an underlying context. Table 7 summarizes the main metasynthesis steps required to ascertain generalizability in qualitative research.

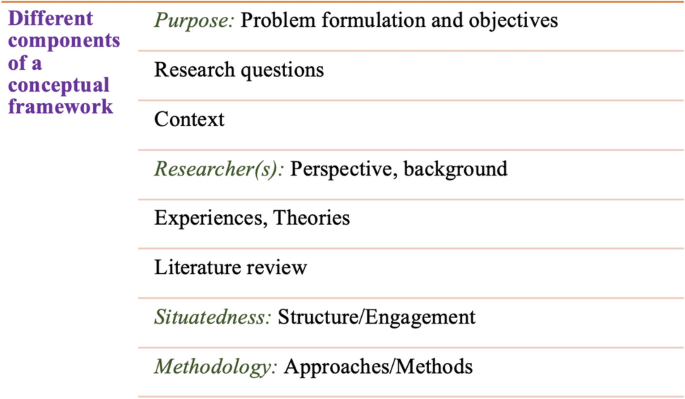

Figure 2 reflects the crucial components of a conceptual framework and their contribution to decisions regarding research design, implementation, and applications of results to future thinking, study, and practice (Johnson et al., 2020 ). The synergy and interrelationship of these components signifies their role to different stances of a qualitative research study.

Essential elements of a conceptual framework

In a nutshell, to assess the rationale of a study, its conceptual framework and research question(s), quality criteria must take account of the following: lucid context for the problem statement in the introduction; well-articulated research problems and questions; precise conceptual framework; distinct research purpose; and clear presentation and investigation of the paradigms. These criteria would expedite the quality of qualitative research.

How to Assess the Quality of the Research Findings?

The inclusion of quotes or similar research data enhances the confirmability in the write-up of the findings. The use of expressions (for instance, “80% of all respondents agreed that” or “only one of the interviewees mentioned that”) may also quantify qualitative findings (Stenfors et al., 2020 ). On the other hand, the persuasive reason for “why this may not help in intensifying the research” has also been provided (Monrouxe & Rees, 2020 ). Further, the Discussion and Conclusion sections of an article also prove robust markers of high-quality qualitative research, as elucidated in Table 8 .

Quality Checklists: Tools for Assessing the Quality

Numerous checklists are available to speed up the assessment of the quality of qualitative research. However, if used uncritically and recklessly concerning the research context, these checklists may be counterproductive. I recommend that such lists and guiding principles may assist in pinpointing the markers of high-quality qualitative research. However, considering enormous variations in the authors’ theoretical and philosophical contexts, I would emphasize that high dependability on such checklists may say little about whether the findings can be applied in your setting. A combination of such checklists might be appropriate for novice researchers. Some of these checklists are listed below:

The most commonly used framework is Consolidated Criteria for Reporting Qualitative Research (COREQ) (Tong et al., 2007 ). This framework is recommended by some journals to be followed by the authors during article submission.

Standards for Reporting Qualitative Research (SRQR) is another checklist that has been created particularly for medical education (O’Brien et al., 2014 ).

Also, Tracy ( 2010 ) and Critical Appraisal Skills Programme (CASP, 2021 ) offer criteria for qualitative research relevant across methods and approaches.

Further, researchers have also outlined different criteria as hallmarks of high-quality qualitative research. For instance, the “Road Trip Checklist” (Epp & Otnes, 2021 ) provides a quick reference to specific questions to address different elements of high-quality qualitative research.

Conclusions, Future Directions, and Outlook

This work presents a broad review of the criteria for good qualitative research. In addition, this article presents an exploratory analysis of the essential elements in qualitative research that can enable the readers of qualitative work to judge it as good research when objectively and adequately utilized. In this review, some of the essential markers that indicate high-quality qualitative research have been highlighted. I scope them narrowly to achieve rigor in qualitative research and note that they do not completely cover the broader considerations necessary for high-quality research. This review points out that a universal and versatile one-size-fits-all guideline for evaluating the quality of qualitative research does not exist. In other words, this review also emphasizes the non-existence of a set of common guidelines among qualitative researchers. In unison, this review reinforces that each qualitative approach should be treated uniquely on account of its own distinctive features for different epistemological and disciplinary positions. Owing to the sensitivity of the worth of qualitative research towards the specific context and the type of paradigmatic stance, researchers should themselves analyze what approaches can be and must be tailored to ensemble the distinct characteristics of the phenomenon under investigation. Although this article does not assert to put forward a magic bullet and to provide a one-stop solution for dealing with dilemmas about how, why, or whether to evaluate the “goodness” of qualitative research, it offers a platform to assist the researchers in improving their qualitative studies. This work provides an assembly of concerns to reflect on, a series of questions to ask, and multiple sets of criteria to look at, when attempting to determine the quality of qualitative research. Overall, this review underlines the crux of qualitative research and accentuates the need to evaluate such research by the very tenets of its being. Bringing together the vital arguments and delineating the requirements that good qualitative research should satisfy, this review strives to equip the researchers as well as reviewers to make well-versed judgment about the worth and significance of the qualitative research under scrutiny. In a nutshell, a comprehensive portrayal of the research process (from the context of research to the research objectives, research questions and design, speculative foundations, and from approaches of collecting data to analyzing the results, to deriving inferences) frequently proliferates the quality of a qualitative research.

Prospects : A Road Ahead for Qualitative Research

Irrefutably, qualitative research is a vivacious and evolving discipline wherein different epistemological and disciplinary positions have their own characteristics and importance. In addition, not surprisingly, owing to the sprouting and varied features of qualitative research, no consensus has been pulled off till date. Researchers have reflected various concerns and proposed several recommendations for editors and reviewers on conducting reviews of critical qualitative research (Levitt et al., 2021 ; McGinley et al., 2021 ). Following are some prospects and a few recommendations put forward towards the maturation of qualitative research and its quality evaluation:

In general, most of the manuscript and grant reviewers are not qualitative experts. Hence, it is more likely that they would prefer to adopt a broad set of criteria. However, researchers and reviewers need to keep in mind that it is inappropriate to utilize the same approaches and conducts among all qualitative research. Therefore, future work needs to focus on educating researchers and reviewers about the criteria to evaluate qualitative research from within the suitable theoretical and methodological context.

There is an urgent need to refurbish and augment critical assessment of some well-known and widely accepted tools (including checklists such as COREQ, SRQR) to interrogate their applicability on different aspects (along with their epistemological ramifications).

Efforts should be made towards creating more space for creativity, experimentation, and a dialogue between the diverse traditions of qualitative research. This would potentially help to avoid the enforcement of one's own set of quality criteria on the work carried out by others.

Moreover, journal reviewers need to be aware of various methodological practices and philosophical debates.

It is pivotal to highlight the expressions and considerations of qualitative researchers and bring them into a more open and transparent dialogue about assessing qualitative research in techno-scientific, academic, sociocultural, and political rooms.

Frequent debates on the use of evaluative criteria are required to solve some potentially resolved issues (including the applicability of a single set of criteria in multi-disciplinary aspects). Such debates would not only benefit the group of qualitative researchers themselves, but primarily assist in augmenting the well-being and vivacity of the entire discipline.

To conclude, I speculate that the criteria, and my perspective, may transfer to other methods, approaches, and contexts. I hope that they spark dialog and debate – about criteria for excellent qualitative research and the underpinnings of the discipline more broadly – and, therefore, help improve the quality of a qualitative study. Further, I anticipate that this review will assist the researchers to contemplate on the quality of their own research, to substantiate research design and help the reviewers to review qualitative research for journals. On a final note, I pinpoint the need to formulate a framework (encompassing the prerequisites of a qualitative study) by the cohesive efforts of qualitative researchers of different disciplines with different theoretic-paradigmatic origins. I believe that tailoring such a framework (of guiding principles) paves the way for qualitative researchers to consolidate the status of qualitative research in the wide-ranging open science debate. Dialogue on this issue across different approaches is crucial for the impending prospects of socio-techno-educational research.

Amin, M. E. K., Nørgaard, L. S., Cavaco, A. M., Witry, M. J., Hillman, L., Cernasev, A., & Desselle, S. P. (2020). Establishing trustworthiness and authenticity in qualitative pharmacy research. Research in Social and Administrative Pharmacy, 16 (10), 1472–1482.

Article Google Scholar

Barker, C., & Pistrang, N. (2005). Quality criteria under methodological pluralism: Implications for conducting and evaluating research. American Journal of Community Psychology, 35 (3–4), 201–212.

Bryman, A., Becker, S., & Sempik, J. (2008). Quality criteria for quantitative, qualitative and mixed methods research: A view from social policy. International Journal of Social Research Methodology, 11 (4), 261–276.

Caelli, K., Ray, L., & Mill, J. (2003). ‘Clear as mud’: Toward greater clarity in generic qualitative research. International Journal of Qualitative Methods, 2 (2), 1–13.

CASP (2021). CASP checklists. Retrieved May 2021 from https://casp-uk.net/casp-tools-checklists/

Cohen, D. J., & Crabtree, B. F. (2008). Evaluative criteria for qualitative research in health care: Controversies and recommendations. The Annals of Family Medicine, 6 (4), 331–339.

Denzin, N. K., & Lincoln, Y. S. (2005). Introduction: The discipline and practice of qualitative research. In N. K. Denzin & Y. S. Lincoln (Eds.), The sage handbook of qualitative research (pp. 1–32). Sage Publications Ltd.

Google Scholar

Elliott, R., Fischer, C. T., & Rennie, D. L. (1999). Evolving guidelines for publication of qualitative research studies in psychology and related fields. British Journal of Clinical Psychology, 38 (3), 215–229.

Epp, A. M., & Otnes, C. C. (2021). High-quality qualitative research: Getting into gear. Journal of Service Research . https://doi.org/10.1177/1094670520961445

Guba, E. G. (1990). The paradigm dialog. In Alternative paradigms conference, mar, 1989, Indiana u, school of education, San Francisco, ca, us . Sage Publications, Inc.

Hammersley, M. (2007). The issue of quality in qualitative research. International Journal of Research and Method in Education, 30 (3), 287–305.

Haven, T. L., Errington, T. M., Gleditsch, K. S., van Grootel, L., Jacobs, A. M., Kern, F. G., & Mokkink, L. B. (2020). Preregistering qualitative research: A Delphi study. International Journal of Qualitative Methods, 19 , 1609406920976417.

Hays, D. G., & McKibben, W. B. (2021). Promoting rigorous research: Generalizability and qualitative research. Journal of Counseling and Development, 99 (2), 178–188.

Horsburgh, D. (2003). Evaluation of qualitative research. Journal of Clinical Nursing, 12 (2), 307–312.

Howe, K. R. (2004). A critique of experimentalism. Qualitative Inquiry, 10 (1), 42–46.

Johnson, J. L., Adkins, D., & Chauvin, S. (2020). A review of the quality indicators of rigor in qualitative research. American Journal of Pharmaceutical Education, 84 (1), 7120.

Johnson, P., Buehring, A., Cassell, C., & Symon, G. (2006). Evaluating qualitative management research: Towards a contingent criteriology. International Journal of Management Reviews, 8 (3), 131–156.

Klein, H. K., & Myers, M. D. (1999). A set of principles for conducting and evaluating interpretive field studies in information systems. MIS Quarterly, 23 (1), 67–93.

Lather, P. (2004). This is your father’s paradigm: Government intrusion and the case of qualitative research in education. Qualitative Inquiry, 10 (1), 15–34.

Levitt, H. M., Morrill, Z., Collins, K. M., & Rizo, J. L. (2021). The methodological integrity of critical qualitative research: Principles to support design and research review. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 68 (3), 357.

Lincoln, Y. S., & Guba, E. G. (1986). But is it rigorous? Trustworthiness and authenticity in naturalistic evaluation. New Directions for Program Evaluation, 1986 (30), 73–84.

Lincoln, Y. S., & Guba, E. G. (2000). Paradigmatic controversies, contradictions and emerging confluences. In N. K. Denzin & Y. S. Lincoln (Eds.), Handbook of qualitative research (2nd ed., pp. 163–188). Sage Publications.

Madill, A., Jordan, A., & Shirley, C. (2000). Objectivity and reliability in qualitative analysis: Realist, contextualist and radical constructionist epistemologies. British Journal of Psychology, 91 (1), 1–20.

Mays, N., & Pope, C. (2020). Quality in qualitative research. Qualitative Research in Health Care . https://doi.org/10.1002/9781119410867.ch15

McGinley, S., Wei, W., Zhang, L., & Zheng, Y. (2021). The state of qualitative research in hospitality: A 5-year review 2014 to 2019. Cornell Hospitality Quarterly, 62 (1), 8–20.

Merriam, S., & Tisdell, E. (2016). Qualitative research: A guide to design and implementation. San Francisco, US.

Meyer, M., & Dykes, J. (2019). Criteria for rigor in visualization design study. IEEE Transactions on Visualization and Computer Graphics, 26 (1), 87–97.

Monrouxe, L. V., & Rees, C. E. (2020). When I say… quantification in qualitative research. Medical Education, 54 (3), 186–187.

Morrow, S. L. (2005). Quality and trustworthiness in qualitative research in counseling psychology. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 52 (2), 250.

Morse, J. M. (2003). A review committee’s guide for evaluating qualitative proposals. Qualitative Health Research, 13 (6), 833–851.

Nassaji, H. (2020). Good qualitative research. Language Teaching Research, 24 (4), 427–431.

O’Brien, B. C., Harris, I. B., Beckman, T. J., Reed, D. A., & Cook, D. A. (2014). Standards for reporting qualitative research: A synthesis of recommendations. Academic Medicine, 89 (9), 1245–1251.

O’Connor, C., & Joffe, H. (2020). Intercoder reliability in qualitative research: Debates and practical guidelines. International Journal of Qualitative Methods, 19 , 1609406919899220.

Reid, A., & Gough, S. (2000). Guidelines for reporting and evaluating qualitative research: What are the alternatives? Environmental Education Research, 6 (1), 59–91.

Rocco, T. S. (2010). Criteria for evaluating qualitative studies. Human Resource Development International . https://doi.org/10.1080/13678868.2010.501959

Sandberg, J. (2000). Understanding human competence at work: An interpretative approach. Academy of Management Journal, 43 (1), 9–25.

Schwandt, T. A. (1996). Farewell to criteriology. Qualitative Inquiry, 2 (1), 58–72.

Seale, C. (1999). Quality in qualitative research. Qualitative Inquiry, 5 (4), 465–478.

Shenton, A. K. (2004). Strategies for ensuring trustworthiness in qualitative research projects. Education for Information, 22 (2), 63–75.

Sparkes, A. C. (2001). Myth 94: Qualitative health researchers will agree about validity. Qualitative Health Research, 11 (4), 538–552.

Spencer, L., Ritchie, J., Lewis, J., & Dillon, L. (2004). Quality in qualitative evaluation: A framework for assessing research evidence.

Stenfors, T., Kajamaa, A., & Bennett, D. (2020). How to assess the quality of qualitative research. The Clinical Teacher, 17 (6), 596–599.

Taylor, E. W., Beck, J., & Ainsworth, E. (2001). Publishing qualitative adult education research: A peer review perspective. Studies in the Education of Adults, 33 (2), 163–179.

Tong, A., Sainsbury, P., & Craig, J. (2007). Consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ): A 32-item checklist for interviews and focus groups. International Journal for Quality in Health Care, 19 (6), 349–357.

Tracy, S. J. (2010). Qualitative quality: Eight “big-tent” criteria for excellent qualitative research. Qualitative Inquiry, 16 (10), 837–851.

Download references

Open access funding provided by TU Wien (TUW).

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Faculty of Informatics, Technische Universität Wien, 1040, Vienna, Austria

Drishti Yadav

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Drishti Yadav .

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest.

The author declares no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher's note.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ .

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Yadav, D. Criteria for Good Qualitative Research: A Comprehensive Review. Asia-Pacific Edu Res 31 , 679–689 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40299-021-00619-0

Download citation

Accepted : 28 August 2021

Published : 18 September 2021

Issue Date : December 2022

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/s40299-021-00619-0

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Qualitative research

- Evaluative criteria

- Find a journal

- Publish with us

- Track your research

GEO 7300: Advanced Geographic Research Design: Critiquing Research

- General Information

- Search Strategies & Keywords

- Finding books

- Finding Articles

- Suggested Geography Databases

- Dissertations

- Citation Analysis

- Critiquing Research

Reviewing Research Articles

When you are reviewing research articles, you will want to evaluate all of the sections of the article. The nursing and health professions fields have created very helpful checklists that, while not entirely relevant to the field of Geography, can be applied to reviewing articles in many disciplines.

In addition, you may want to look at guidelines for peer reviewers of scholarly journal articles. Below are guidelines from Wiley, Emerald, and Elsevier.

When reviewing articles, you may be interested in who has cited the article - where the research has led. You can do this through Citation Analysis databases like Scopus. Please see the Citation Analysis tab for more information.

Critiquing Research Articles

Articles/Websites on Critiquing Research:

- “Critiquing Qualitative Research.” AORN Journal 90 (January): 543–54. doi:10.1016/j.aorn.2008.12.023.

- How to Critique a Research Paper (University of Michigan)

- The Critique Process: Reviewing and Critiquing Research. 2016 Fischler College of Education Summer Institute presentation. Nova Southeastern University.

- How to Write a Good Scientific Paper: a Reviewer ’ s Checklist A Checklist for Editors, Reviewers, and Authors

- Jamie Baxter, and John Eyles. “Evaluating Qualitative Research in Social Geography: Establishing ‘Rigour’ in Interview Analysis.” Transactions of the Institute of British Geographers 22, no. 4 (1997): 505.

- Conducting an article critique for a quantitative research study: perspectives for doctoral students and other novice readers

- Research Proposal Guidelines Created by a Psychology professor, this still can be applied to Geography

Peer-Reviewer Guidelines from Journal Publishers:

- Elsevier - How to review manuscripts — your ultimate checklist

- Emerald - Reviewer Scorecard Questions

- Elsevier - How to Review

- Emerald - Peer Review Guidelines

- Wiley - Step by step guide to reviewing a manuscript

Standards for Reporting Research:

- “Journal Article Reporting Standards for Quantitative Research in Psychology: The APA Publications and Communications Board Task Force Report.” American Psychologist 73 (1): 3–25

- Standards for Reporting Qualitative Research

- COREQ Checklist.- 2007, ‘Consolidated Criteria for Reporting Qualitative Studies Checklist’, International Journal for Quality in Health Care, vol. 19, no. 6, pp. 349–357 http://cdn.elsevier.com/promis_misc/ISSM_COREQ_Checklist.pdf more... less... "The COREQ checklist was developed to promote explicit and comprehensive reporting of qualitative studies (interviews and focus groups). The checklist consists of items specific to reporting qualitative studies and precludes generic criteria that are applicable to all types of research reports."

Example Scholarly Journal Publisher Review Questions

- Emerald Referee Guidelines

Suggested Books

Originally created for the nursing field, the Critical Appraisal Skills Programme checklists can be very useful in evaluating research articles.

- CASP Systematic Review Checklist

- CASP Qualitiative Checklist

- Dept. of General Practice University of Glasgow. CRITICAL APPRAISAL CHECKLIST FOR AN ARTICLE ON QUALITATIVE RESEARCH.

When evaluating resources, you should consider Currency/Timeliness, Relevancy, Accuracy, Authority, and Purpose ( CRAAP test ).

- << Previous: Citation Analysis

- Last Updated: Feb 21, 2024 12:28 PM

- URL: https://guides.library.txstate.edu/geo7300

- Open access

- Published: 21 May 2024

The prevalence and possible risk factors of gaming disorder among adolescents in China

- Lina Zhang 1 ,

- Jiaqi Han 2 ,

- Mengqi Liu 3 , 4 ,

- Cheng Yang 5 &

- Yanhui Liao 6

BMC Psychiatry volume 24 , Article number: 381 ( 2024 ) Cite this article

176 Accesses

Metrics details

Nowadays, moderate gaming behaviors can be a pleasant and relaxing experiences among adolescents. However, excessive gaming behavior may lead to gaming disorder (GD) that disruption of normal daily life. Understanding the possible risk factors of this emerging problem would help to suggest effective at preventing and intervening. This study aimed to investigate the prevalence of GD and analyze its possible risk factors that adolescents with GD.

Data were collected between October 2020 and January 2021. In total, a sample of 7901 students (4080 (52%) boys, 3742 (48%) girls; aged 12–18 years) completed questionnaires regarding the Gaming-Related Behaviors Survey, Gaming Disorder Symptom Questionnaire-21 (GDSQ-21); Behavioral Inhibition System and Behavioral Activation System Scale (BIS/BAS Scale); Emotion Regulation Questionnaire (ERQ); Short-form Egna Minnenav Barndoms Uppfostran for Chinese (s-EMBU-C); and Adolescent Self-Rating Life Events Checklist (ASLEC).

The prevalence of GD was 2.27% in this adolescent sample. The GD gamers were a little bit older (i.e., a higher proportion of senior grades), more boys, with more gaming hours per week in the last 12 months, with more reward responsiveness, maternal rejecting and occurrence of negative life events (e.g., interpersonal relationships, being punished and bereavement factors).

These possible risk factors may influence the onset of GD. Future research in clinical, public health, education and other fields should focus on these aspects for provide target prevention and early intervention strategies.

Peer Review reports

Introduction

Video games (typically online games) have become an immensely popular form of entertainment for adolescents. Although moderate gaming has been found to be associated with relaxation and stress reduction [ 1 , 2 , 3 ], excessive use of games may take an uncontrolled addictive form in some individuals [ 4 , 5 , 6 , 7 , 8 ]. Psychiatrists and other health professionals have suggested that excessive use of gaming may cause negative outcomes for interpersonal relationships, physical well-being, mental health, education, and employment [ 9 ]. In 2013, the Fifth Edition of Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5) introduced Internet gaming disorder (henceforth referred to as IGD) and suggested it as a possible condition for further study [ 10 ]. In June 2018, the 11th Revision of the International Classification of Diseases (ICD-11) included Gaming Disorder (henceforth referred to as GD) as a disease entity. GD is characterized by impaired control over gaming, increasing prioritization of gaming over other life interests and daily activities, and continuation or escalation of gaming despite negative consequences [ 11 ]. For adolescents, the prevalence of IGD has been reported to be 9.9% (CI = 1.0-21.5%) in Asia, 9.4% (95% CI = 8.3-10.5%) in North America, 4.4% (95% CI = 1.9-7.4%) in Australia and 3.9% (95% CI = 2.8-5.3%) in Europe [ 12 ]. In addition, the present research shows that individuals’ gaming behaviours cause not only functional impairments in main areas but also other related mental health issues. Thus, preventing GD seems to be of essential importance, as shown by calls for preventive interventions for groups at high risk of GD (e.g., adolescents) at the social, family and school levels [ 13 ]. To prevent GD from developing, we need to investigate the China prevalence of GD and analyze the possible risk factors that problematic gaming behaviour among adolescents [ 14 ].

Studies on demographic differences have reported higher prevalence rates of IGD among males than among females [ 15 , 16 , 17 ]. Furthermore, IGD may be observed up to five times more often among males than among females in children and adolescents [ 18 ]. As adolescence is a period of transition, some of these minors might lack accurate knowledge of their own behaviour and sufficient self-control, and some might be particularly susceptible to factors associated with persistent on-/off-line gaming [ 19 , 20 , 21 ].

Symptoms of IGD and the underlying neurobiological mechanisms. Kuss et al. [ 22 ]. reported that compared with healthy controls, gaming addicted individuals have poorer response inhibition and emotion regulation, impaired prefrontal cortex function and cognitive control, poorer working memory and decision-making, and deficits in the neural reward system. Several studies of individuals with IGD have shown increased sensitivity to reward and decreased ability to control impulsivity in the face of reward stimuli [ 23 , 24 ]. Additionally, IGD has also been linked to psychological detriments and negative consequences, such as negative and depressed moods [ 25 ], trait anxiety, social phobia, substance abuse and aggressive behaviours [ 26 , 27 ], decreased conscientiousness [ 28 ], higher impulsivity [ 29 ] and lower self-esteem [ 30 ].

The socioenvironment is one of the crucial factors that plays a role in IGD [ 31 ]. Many studies have shown that adolescents with IGD are associated with parental and familial risk factors, including but not limited to insufficient parental care, oppressive and hostile parents, poor parent-child relations, and poor family cohesion and family violence [ 32 , 33 ]. In addition, being bullied at school is more strongly associated with IGD [ 15 ].

The most consistent finding was that game design and video game type were related to IGD symptoms. Modern games provide communication platforms, instant feedback and rewards and are more likely to create an immersive experience for gamers, increasing gamer loyalty and engagement. A study of patients with GD who played ‘online’ games found that the two most common types of game played were massive multiplayer online role-playing games (MMORPGs) [ 7 ] and first-person shooters (FPSs) games [ 34 ].

Despite these contributions, there are still few studies focusing on the prevalence and possible risk factors of GD in adolescents based on the ICD-11 diagnostic guidelines. As GD is recognized as a behavioral addictions, it is necessary to identify risk factors that increase the likelihood of developing the disorder. To sum up, the current study, based on the ICD-11 GD diagnostic guidelines, aimed to investigate the prevalence and undergo a comprehensive synthesis to analyse risk factors such as sociodemographic predictors, psychological factors, parenting styles and negative life events, and game-related factors (e.g. gaming hours per week ) and GD among adolescents.

Participants and procedures

Using convenience sampling, 7901 middle school students were enrolled from twelve middle schools in Urumqi, Kashi and Bole City of Xinjiang Uygur Autonomous Region, China from 2020 to 2021. In each area, two junior high schools and two senior high schools were selected, and in each school, four classes were selected from each grade (grades 1–3 of junior high schools and grades 1–3 of senior high schools). The classes were randomly selected in each school. The inclusion criteria were as follows: being 12–18 years old, voluntary participating in the study; the subjects themselves and at least one of their parents/monitors completed the informed consent. The exclusion criteria for patients were: having mental illness or serious physical illness, having severe cognitive impairment, or any inability to fill out questionnaires.

Ultimately, a valid sample of 7790 students aged between 12 and 18 years (mean = 14.99; SD = 1.65; boy = 52.0%) participated in the current study, for an effective rate of 98.6%.

Sociodemographics and gaming-related behaviours

Sociodemographic data included participants’ age, gender, family structure (having siblings or being an only child), who the student lived with, and socioeconomic status (i.e., the highest level of education of family members, occupational and income strata of the family). Participants subjectively scored the occupational and income strata of the family members living with them from 1 (lowest) to 10 (highest). The detailed information on the occupational and income strata is presented in Supplementary Tables 1 and 2 . Gaming-related behaviours included the types of games most often played and the game hours per week spent playing on primarily online, stand-alone and/or video games.

Assessment of gaming disorder symptoms

The Gaming Disorder Symptom Questionnaire-21 (GDSQ-21) was used to assess GD [ 35 ], which consists of 21 items with three subscales, impaired control, increasing priority, and continued use despite the occurrence of negative consequences. This instrument is used to assess the severity of GD symptoms by examining both online and/or offline gaming activities occurring over a 12-month period. Participants indicated how much they agreed with the statements on a 5-point Likert scale: 0 (“hardly ever”), 1 (“less than once a month”), 2 (“once a month”), 3 (“once a week”), and 4 (“almost every day”). Its three-dimensional structure corresponds to the new ICD-11 diagnostic concept of GD. It has good validity and internal consistency, with a Cronbach’s alpha coefficient of 0.964, and plays an important role in the investigation of GD. The scoring is the same as that of the original version of the GDSQ-21: with the cutoff of ≥ 14 for impaired control dimension, ≥ 11 for increasing priority, ≥ 4 for continued, and ≥ 62 for the whole scale, met each dimension and total score can effectively screen for GD.

Psychological status

To measure participants’ sensitivity to punishment and rewards, the Chinese version of the Behavioral Inhibition System and Behavioral Activation System (BIS/BAS) scale was used [ 36 ], it has 20 items to which participants respond on a 4-point Likert scale from 1(“totally agree”) to 4(“totally disagree”). The BIS/BAS consists of 20-item self-rating questionnaire with good psychometric properties. The questionnaire comprises 13 BAS items and 7 BIS items. The 3 subscales of the BAS assess responsiveness to reward, drive towards appetitive goals, and fun seeking. In the present study, the Cronbach’s alpha coefficient of the scale was 0.891.

Emotion regulation

To assess an individual’s typical level of emotion dysregulation, the Chinese version of the Emotion Regulation Questionnaire (ERQ) scale was used [ 37 ]. The ERQ is a 10-item self-rating questionnaire of how frequently people use two emotion regulation strategies: cognitive reappraisal (6 items), an antecedent-focused strategy, and expressive suppression (4 items), a response-focused strategy. The items are rated on a 7-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (“strongly disagree”) to 7 (“strongly agree”). In this study, the Cronbach’s alpha coefficient of the scale was 0.967, which reflects good reliability.

Family functioning

Parenting styles and behaviours were assessed by the Chinese version of the Short-form Egna Minnenav Barndoms Uppfostran for Chinese (s-EMBU-C) [ 38 ], which has 42 items, divided into paternal and maternal versions. Each version of the scale contains three subscales, namely, refusal, emotional warmth, and overprotection. All items are rated on a 4-point Likert scale, with each subscale being scored as follows: 1 (“never”), 2 (“occasionally”), 3 (“often”), and 4 (“always”). In the current study, the Cronbach’s alpha coefficient of the scale was 0.884.

Negative life events

Negative life events were measured by the Adolescent Self-Rating Life Events Checklist (ASLEC) [ 39 ], which evaluates the impact of negative life events experienced within the past 12 months. The ASLEC consists of 26 items, including 6 subscales: interpersonal relationships, study pressure, being punished, bereavement, health adjustment and others. Each item is scored on a 5-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (“not at all”) to 5 (“extremely severe”). In our study, the Cronbach’s alpha coefficient of internal consistency was 0.938.

Statistical analyses

First, based on the ICD-11 diagnostic guidelines, the GDSQ-21 cut-off point was used to calculate the prevalence of GD. Besides estimating prevalence, Univariate analyses were conducted: independent samples t tests and chi-square tests were used to further compare the sociodemographic variables, psychological factors, parenting styles and negative life events, and game-related factors (e.g., hours spent on game design and types of video games) of the two groups.

Second, binary logistic regressions analyses were carried out with the GDSQ-21 score as the dependent variable and sociodemographic variables, psychological factors, parenting styles and negative life events as independent variables. These variables are summarized in Supplementary Table 3 .

Before conducting the regression analysis, to make the regression model more reasonable, it is necessary to first conduct univariate analysis to determine which variables are related to GD. To avoid omitting variables that may have an effect, variables with a statistically significant difference p < 0.2 should be considered for inclusion in the regression equation as potential predictors.

In addition, in terms of gaming behaviour characteristics, there were differences between GD and Non-GD. Theoretically, these characteristics could be the result of GD, the cause of GD, or the accompanying manifestations of the disorder. Thus, this study does not consider these gaming behaviour characteristics causal variables for the occurrence of GD, but there are differences between GD and Non-GD in these variables. Therefore, univariate analysis of gaming behaviour characteristics was also conducted.

All the statistical analyses were carried out with SPSS software (version 25.0).

Prevalence of GD and sociodemographic characteristics among participants

We identified that the 12-month prevalence was 2.27% ( n = 177) adolescents with GD and 97.73% ( n = 7613) adolescents with Non-GD. All participants were divided into GD (boys/girls = 145/32, mean age: 15.62 ± 1.69) and Non-GD (boys/girls = 3597/4016, mean age: 14.98 ± 1.64). The detailed sociodemographic characteristics of the GD and the Non-GD are presented in Table 1 . Compared to Non-GD, in the GD there were more boys ( χ² = 83.31, p < 0.001), they were a little bit older (i.e., a higher proportion of senior grades), and more likely to be only children ( χ² = 2.01, p < 0.01), who the student lives with ( χ² = 16.50, p < 0.05). Those in the GD were in lower occupational strata by their family ( t = 1.51, p < 0.05) and income strata by their family ( t = 1.72, p < 0.2).

Gaming-related behaviours

Gaming-related behaviours for the whole sample, the GD and the Non-GD are presented in Table 2 . Compared to the Non-GD, the GD spent significantly more hours on online or playing on-/offline games. Moreover, GD prefer to choose specific game genres.

Univariate analysis of psychological factors

For reward processing, emotional characteristics, regulatory strategies, parenting styles and behaviours, and impact of negative life events (i.e., BIS/BAS, ERQ, s-EMBU-C, ASLEC questionnaires), t tests were used to determine the differences between the GD and the Non-GD, as shown in Table 3 . The results showed that the GD and the Non-GD were significantly different in terms of BIS- behavioral inhibition ( t = -1.933, p < 0.02); BAS- reward responsiveness ( t = -4.659, p < 0.001) and drive ( t = -3.451, p < 0.001); ERQ-expressive suppression ( t = 0.480, p < 0.02); s-EMBU-C-paternal refusal ( t = -6.745, p < 0.001), emotional warmth ( t = 2.996, p < 0.01), overprotection ( t = -5.213, p < 0.001), maternal refusal ( t = -7.657, p < 0.001), emotional warmth ( t = 2.936, p < 0.01), and overprotection ( t = -5.419, p < 0.001); and ASLEC-interpersonal relationships ( t = -7.756, p < 0.001), study pressure ( t = -6.280, p < 0.001), being punished ( t = -7.022, p < 0.001), bereavement ( t = -3.458, p < 0.01), and health adjustment ( t = -5.967, p < 0.001). No significant differences were detected between the GD and the Non-GD in terms of BAS-fun seeking or ERQ-cognitive reappraisal.

Logistic regression analysis

The results of the binary logistic regression analysis are shown in Table 4 . Variables that were significantly different in the univariate analysis were included in the regression model as independent variables. These variables consisted of age; gender; being an only child; who the student lived with; family occupational strata, family income strata; BIS- behavioral inhibition; BAS-reward responsiveness and drive; ERQ-expressive suppression; s-EMBU-C-paternal and maternal of refusal, emotional warmth, and overprotection; and ASLEC-interpersonal relationships, study pressure, being punished, bereavement, and health adjustment.

Regarding sociodemographic characteristics, age (odds ratio: 1.261) and gender (odds ratio: 0.211) were significantly associated with GD. The BAS-reward score (odds ratio:1.099) was a significant psychological predictor of GD. s-EMBU-C-maternal refusal (odds ratio: 1.061) was a significant family-environment predictor of GD. ASLEC-interpersonal relationships (odds ratio: 1.070), being punished (odds ratio: 1.073) and bereavement (odds ratio: 0.860) were significant socioenvironmental predictors of GD. Specifically, boys were 0.211 times more likely to have GD than girls. With a one-year increase in age, participants were 1.261 times more likely to be classified as having a GD (participants were between the ages of 12 and 18). With a one-unit score higher for the s-EMBU-C-maternal refusal, ASLEC- interpersonal relationships, being punished and bereavement factors, the probability of GD increased by 1.061, 1.070, 1.073 and 0.86 times, respectively.

This study aimed to investigate the prevalence of GD and analyze its possible risk factors of IGD among adolescents attending school in China based on the diagnostic guidelines the ICD-11 proposes. Three major findings emerged from this investigation: (1) Compared to the Non-GD, GD were a little bit older and more boys. (2) The hours spent on games playing are positively associated with GD. Moreover, GD preferred to choose specific game genres. (3) Some factors (psychological, parenting styles and negative life events) are associated with GD.

Prevalence of GD

Our results reported the 12-month prevalence among adolescents of China. A recent study showed 2.2% of the 28 representative sample studies prevalence estimates, which is nearly comparable to our findings [ 40 ]. The increasing popularity of the Internet in China in recent years may contribute to the growing size of underage Internet users. The number of juvenile internet users reached 193 million in 2022 [ 41 ]. The proportion of underage Internet users who play computer games has also increased. Excessive gaming behavior and poor usage habits can be very engaging, time consuming and easily addictive to some gaming users. As young people are mentally and physically immature, their physical and mental health is highly susceptible to environmental and behavioral influences and they are more likely to develop mental health problems directly related to their gaming behavior.

Sociodemographic characteristics of participants with GD

In terms of age, a greater proportion of patients in the GD were in the upper grades than those in the Non-GD. Previous studies have also suggested that age has an inverted U-shaped relationship with online GD [ 42 , 43 ] and is correlated with the amount of hours spent playing games [ 44 , 45 ]. Adolescents in higher grades were more likely to be gaming addicted [ 46 ].

Gender as a risk factor for GD. In this study, there were more boys with GD than girls. This finding is consistent with previous research showing that GD was more likely to occur in the male users [ 47 , 48 , 49 , 50 ]. This may be because male are more likely to choose competitive [ 51 ] and adversarial activities [ 52 ] for entertainment, and a significant proportion of all types of games have these characteristics. Compared to male gamers, female gamers engage in gaming for entertainment and socializing rather than to experience combat or to alleviate negative emotions [ 53 , 54 , 55 , 56 ], and they also spend less hours online and looking at the screen while playing [ 57 ]. In addition, behavioral addictions such as polysubstance dependence and gambling are generally more prevalent in males than females [ 58 , 59 ]. This suggested that gender, addiction susceptibility and other factors may contribute to the greater susceptibility of males to addiction, which may similarly contribute to the higher prevalence of males than females with GD. In addition, brain imaging studies have shown that the males and females respond differently to gaming cues [ 60 ], with more activation in areas such as the striatum and orbitofrontal cortex in males, which may be the brain mechanism for the aforementioned gender differences [ 61 ].

The greater proportion of only children among those with GD (results of univariate analysis) is consistent with previous research findings that adolescents’ peer interactions are both necessary for their social needs and have recreational properties that allow them to enrich their leisure time [ 62 ]. The peer interactions of only children may be more limited to classmates and friends, and they may be more likely to find ways to interact with peers through the virtual world of online games when social needs are relatively inadequately met.

In terms of the level of education, occupational strata and income strata of the family members living with participants. Previous studies have suggested that the educational level of the family may be associated with the onset of GD [ 63 ], but this study failed to find a difference in this variable between GD and Non-GD. One of the reasons this study failed to find an association between parental education level and GD in adolescents may be that the popularity of smartphones and the mobile Internet in China in recent years has made people’s information sources extremely rich and significantly decreased the threshold of information access [ 64 ], allowing parents with different levels of education to learn about the dangers of GD and preventive measures, thus responding to adolescent gaming. This has led to a homogenization of the response to adolescent gaming problems, making the effect of education level of the family members less significant. On the other hand, this study revealed that family members with GD had lower occupational and income strata than Non-GD. Given that occupational and income are closely related and that higher occupational and income strata are more likely to help families provide good material and spiritual life for their adolescents, this study hypothesizes that gaming is a relatively accessible and inexpensive entertainment for adolescents with relatively low material and mental life, making them more likely to use gaming and more likely to develop GD.

Game hours and game genre preference of GD

This study found that people with GD spent more hours and money on gaming-related behaviours than Non-GD, which is consistent with previous findings [ 65 ]. In addition, previous research has shown that males spend twice as more game hours as females playing video games each week and on weekends [ 66 ], an easily understandable characteristic that is more likely to promote GD as game immersion and game hours per week increase. Importantly, gamers with GD are also more likely to engage in in-game payment behaviour. In recent years, the gaming industry has proliferated the variety of their revenue streams (such as increasing membership fees and selling virtual props and cosmetic skins) [ 67 ]. In addition, online gaming is more addictive than offline gaming, possibly because of its inherent social reinforcement [ 68 ].

In terms of game genre preference, this study revealed that people with GD prefer specific game genres, considering that they may be designed to capture the attention of gamers and promote their addiction to endless gaming experiences, such as multiplayer online battle arenas (MOBAs) games, which provide a social environment built entirely on gaming screens. The short duration of these games, their ability to provide rapid positive feedback and their suitability for use on mobile phones may be important reasons games in this genre were widely played by those with GD. Future research should focus on the regulation of gaming products and genres to effectively prevent and control GD in the future.

Psychological factors, parenting styles and negative life events associated with GD

Among the factors influencing GD, this study focused on psychological factors in terms of reward processing and emotional characteristics. Univariate analysis results showed that compared to Non-GD, GD have lower behavioral inhibition, having greater reward reactivity and drive, using more expressive inhibition in emotion regulation. The logistic regression revealed that the BIS inhibition dimension and ERQ did not predict GD among adolescents, whereas the reward response on the BAS activation dimension was predictive of GD. This suggesting that adolescents primarily seek pleasure and rewards when playing games and that many online games themselves allow players to earn points, level up, and obtain rewards that tend to induce positive pleasure and reward effects.

The parenting styles of paternal and maternal have an important influence on the development of GD among adolescents. Univariate analysis revealed that GD have more experiencing rejection parenting styles, having lower emotional warmth, and experiencing greater overprotection. According to the logistic regression model, maternal rejection was the only significant family correlate. The more the mother rejected and denied the child, used inappropriate parenting styles and punished the child too harshly, the more likely the child was to develop GD. In general, family parenting is a combination of both parents’ parenting attitudes and behaviours, but children general have the most contact with their mothers and develop more attachment to them, so the mother’s feedback and evaluation of the child is particularly important, especially during the adolescent years when self-perception is still unclear. If the mother has a clear tendency to reject the child and has disrespectful thoughts towards the child, this may have a greater negative impact on the child, which may increase more game hours the adolescent spends gaming.

Negative life events also play an important role in the development of gaming problems in adolescents. Univariate analyses revealed that GD have more experiencing more negative life events. The interpersonal relationships, being punished and bereavement factors were significant negative life events in the regression model. When adolescents felt stress or negative emotions in their interpersonal relationships and being punished, some of them adolescents began to use gaming as a way of relieving dissatisfaction and escaping from real-life problems. When experiencing life events such as the loss of family, friends and job, individuals may become consumed with grief and temporarily turn away from games. Later, when the individual is unable to avoid the event or solve the problem in the usual way, the individual may use game to escape from the sadness.

Mannikko et al [ 69 ]. suggested that excessive gameplay can harm adolescents on their psychological, social, and physical health. The results of our study showed that GD have higher reward responsiveness, more maternal rejecting and more occurrence of negative life events (e.g., interpersonal relationships, being punished and bereavement factors). In addition, many other possible risk factors for GD also needs to be further explored. The possible risk factors that have been identified carry clinical importance as they provide a more holistic approach towards adolescent in the prevention of GD.

Limitations of study

As with all research, this study has some limitations and strengths. First, we used a convenience sampling method to conduct this research in twelve schools in the Xinjiang Uygur Autonomous Region, China, so the results should be validated in other regions of China in the future. Second, all of the assessments were self-reported and might have suffered from social desirability bias. Third, this study was that the GD was evaluated only the GDSQ-21, and no evaluation was performed according to psychiatric clinical diagnostic interviews. Therefore, the accuracy, specificity, and sensitivity could not be determined. Future research in the field should compare clinically diagnosed samples using actual GDSQ-21 test scores. Fourth, this study was cross sectional study, which prevents drawing conclusions about the causal relationships between variables. Therefore, further research is needed to explore these longitudinal relationships.

In conclusion, the results of our study showed the prevalence of GD, and possible risk factors, which the reward responsiveness, maternal rejecting and occurrence of negative life events associated with GD. This study showed a positive association between gaming hours and GD, and GD preferred to choose a specific game genre. Furthermore, we found that gender and age were significant predictors of gaming harm with a little bit older males (i.e., a higher proportion of senior grades) being more susceptible. This study may provide some suggestion for real life. In prevention and intervention, prevention efforts should aim at identifying possible risk factors.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the present study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Abbreviations

Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders

Internet gaming disorder

International Classification of Diseases 11th Revision

- Gaming disorder

Gaming Disorder Symptom Questionnaire-21

Behavioral Inhibition System and Behavioral Activation System Scale

Emotion Regulation Questionnaire

Short-form Egna Minnenav Barndoms Uppfostran for Chinese

Adolescent Self-Rating Life Events Checklist

Männikkö N, Ruotsalainen H, Miettunen J, Pontes HM, Kääriäinen M. Problematic gaming behaviour and health-related outcomes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Health Psychol. 2020;25(1):67–81.

Article PubMed Google Scholar

Stevens MW, Dorstyn D, Delfabbro PH, King DL. Global prevalence of gaming disorder: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 2021;55(6):553–68.

Snodgrass JG, Lacy MG, Francois Dengah HJ 2nd, Fagan J, Most DE. Magical flight and monstrous stress: technologies of absorption and mental wellness in Azeroth. Cult Med Psychiatry. 2011;35(1):26–62.

King DL, Potenza MN. Not playing around: gaming disorder in the International classification of diseases (ICD-11). J Adolesc Health. 2019;64(1):5–7.

Young KS. Internet addiction: a new clinical phenomenon and its consequences. Am Behav Sci. 2004;48(4):402–15.

Article Google Scholar

Higuchi S, Nakayama H, Mihara S, Maezono M, Kitayuguchi T, Hashimoto T. Inclusion of gaming disorder criteria in ICD-11: a clinical perspective in favor. J Behav Addict. 2017;6(3):293–5.

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar